Introduction

Ferroptosis, first described by Dixon in 2012 as an

iron-dependent regulated form of cell death, has emerged as a

critical determinant of cellular fate across diverse physiological

and pathological contexts (1).

This unique mode of cell death is primarily driven by phospholipid

peroxidation and iron overload, extending from decades of research

that recognized the cytotoxic consequences of iron and lipid

peroxidation (2,3). The elucidation of antioxidant

defense systems in ferroptosis regulation has advanced our

integrated understanding of the interplay between iron metabolism

and oxidative stress in regulated cell death. Emerging evidence

further indicates that ferroptosis significantly contributes to

tumor suppression, immune regulation and the maintenance of

metabolic homeostasis (4).

Concurrently, lactate has undergone a profound

conceptual transformation from a metabolic waste product to a

sophisticated signaling molecule. Once considered merely a

metabolic waste product associated with hypoxic stress and

detrimental effects, subsequent research has revealed that lactate

is actively produced and utilized even under aerobic conditions

(5). The lactate shuttle

hypothesis further revealed its pivotal roles in oxidative

substrate transport and cellular signaling via monocarboxylate

transporters (MCTs), leading to its recognition as a potent

signaling metabolite, particularly through its receptor GPR81

(6-8). subsequent discoveries have revealed

the epigenetic functions of lactate through histone lysine

lactylation (Kla), a post-translational modification analogous to

acetylation and succinylation (9,10). This modification impacts

transcriptional regulation and extends to non-histone proteins,

thereby regulating enzyme activities (11,12). However, a paradox has emerged:

Lactate exhibits opposing effects on ferroptosis, promoting cell

death in certain contexts while conferring protection in others,

particularly when comparing tumor vs. normal cells. To the best of

our knowledge, no relevant articles currently summarize and explain

these contradictory observations.

The present review elucidates the molecular

mechanisms underlying the lactate-ferroptosis axis, examining how

lactate influences ferroptosis through lactylation-independent and

-dependent pathways that modulate iron homeostasis, lipid

metabolism, redox balance and the immune response. Meanwhile, the

'dual role' refers to the context-dependent, bidirectional

regulation of ferroptosis by lactate. In non-tumor tissues, lactate

tends to promote ferroptosis, potentially accelerating disease

progression. Conversely, in tumor microenvironments, lactate tends

to inhibit ferroptosis, facilitating cancer cell survival and

therapeutic resistance. Furthermore, the present review highlights

the key contextual determinants that may dictate the divergent

roles of lactate. Understanding these context-specific mechanisms

promises new therapeutic strategies targeting a broad spectrum of

diseases ranging from cancer to neurodegeneration.

Unless otherwise specified, the term 'lactate'

throughout the present review refers to L-lactate, the predominant

enantiomer produced by mammalian lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). By

contrast, D-lactate, though present in trace amounts from bacterial

metabolism and certain metabolic disorders, has not yet been

systematically investigated in ferroptosis contexts.

Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms

Ferroptosis is mediated by multiple mechanisms

including lipid peroxidation, iron overload and dysfunction of the

antioxidant system (Fig. 1). A

hallmark of ferroptotic initiation and execution is the upregulated

peroxidation of phospholipid-bound polyunsaturated fatty acids

(PUFAs) within cellular membranes, a process facilitated by labile

iron pools (LIPs) and amplified through autocatalytic radical

reactions (13,14). In this context, redox-active

iron, principally existing as ferrous (Fe2+) ions,

serves as a critical cofactor, driving Fenton reactions that

generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS abstract hydrogen

atoms from bis-allylic positions within PUFA chains, producing

lipid radicals that react with molecular oxygen to yield lipid

peroxyl radicals. This initiates a self-perpetuating cascade of

membrane lipid peroxidation, ultimately compromising membrane

integrity and triggering cell death (14).

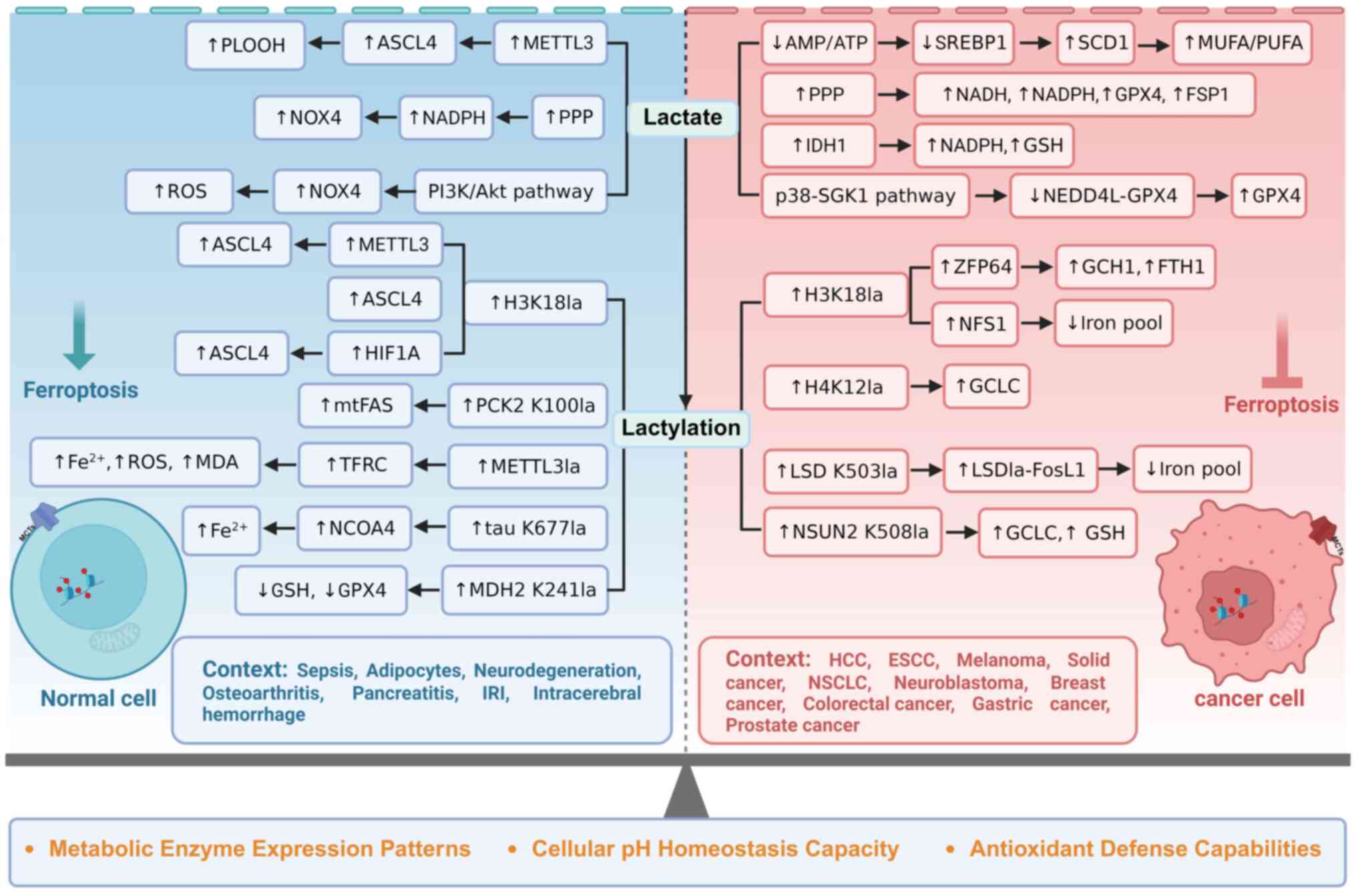

| Figure 1Molecular mechanism of ferroptosis.

(A) The canonical ferroptosis-regulating axis involves cystine

uptake via system Xc−, GSH biosynthesis and

GPX4-mediated reduction of PLOOH into their corresponding alcohols

(PLOH). NADPH provides electrons for recycling GSSG. (B) The

FSP1/CoQ10, DHODH/CoQ10 and GCH1/BH4/BH2 system serves as parallel

pathways to inhibit lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. (C) The

peroxidation of phospholipids in the plasma membrane activates

PIEZO1, leading to the influx of Ca2+ and

Na+. This process, combined with the inactivation of the

Na+/K+ ATPase, results in the efflux of

K+. (D) The initiation and propagation of PLOOH form a

chain reaction with positive feedback. (E) PUFA and MUFA metabolic

pathways promote and inhibit lipid peroxidation, respectively. GSH,

glutathione; PLOOH, phospholipid hydroperoxides; PLOH, phospholipid

alcohol; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor

protein 1; CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; DHODH, dihydroorotate

dehydrogenase; GCH1, GTP cyclohydrolase 1; BH4,

tetrahydrobiopterin; BH2, dihydrobiopterin; PIEZO1, piezo-type

mechanosensitive ion channel component 1; PUFA, polyunsaturated

fatty acid; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; PL, phospholipid;

SFA, saturated fatty acid. Created with BioRender.com. |

This process of lipid peroxidation is regulated by a

complex network of metabolic and enzymatic regulators. Glutathione

peroxidase 4 (GPX4) plays a central role in counteracting

ferroptosis by reducing membrane lipid hydroperoxides to their

corresponding alcohols, utilizing glutathione (GSH) as a reducing

substrate (15). Perturbation of

this axis, either through direct GPX4 inhibition or GSH depletion

via impaired cystine import (for example, via system Xc−

inhibition), markedly sensitizes cells to ferroptotic death

(1,16). In parallel, ferroptosis

suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)/ubiquinol (CoQH2), dihydroorotate

dehydrogenase/CoQH2 and GTP cyclohydrolase 1

(GCH1)/tetrahydrobiopterin have been identified as independent

systems that scavenge free radicals to exert their antioxidative

effects and suppress ferroptosis (17-21).

The execution of the Fenton response is dependent on

iron availability. Cellular iron metabolism is exquisitely

regulated, with transferrin-mediated uptake, ferritin-based storage

and transferrin-transferrin receptor (TFRC)-mediated export

collectively maintaining intracellular iron homeostasis (22). Perturbations that expand the LIP,

whether through increased iron import, mobilization from stores or

diminished export, potentiate ferroptosis by providing increased

substrate levels for lipid peroxidation reactions (1,23). In addition, the membrane

susceptibility to ferroptotic damage is modulated by its lipidomic

composition, with phospholipids enriched in PUFAs, particularly

arachidonic acid (AA) and adrenic acid (AdA), being especially

prone to peroxidation, thereby rendering membrane vulnerability to

ferroptosis (24).

Lactate metabolism and regulation

Recently, a growing body of evidence has

demonstrated that lactate is not merely a metabolic by-product but

also serves as a key energy source and a critical signaling

molecule involved in memory formation, neuroprotection, modulation

of inflammatory responses, wound healing, ischemic injury repair,

as well as tumor growth and metastasis (5,25-27). In this section, a comprehensive

overview of the metabolic pathways of lactate is presented and its

specific mechanistic roles, with particular emphasis on its dual

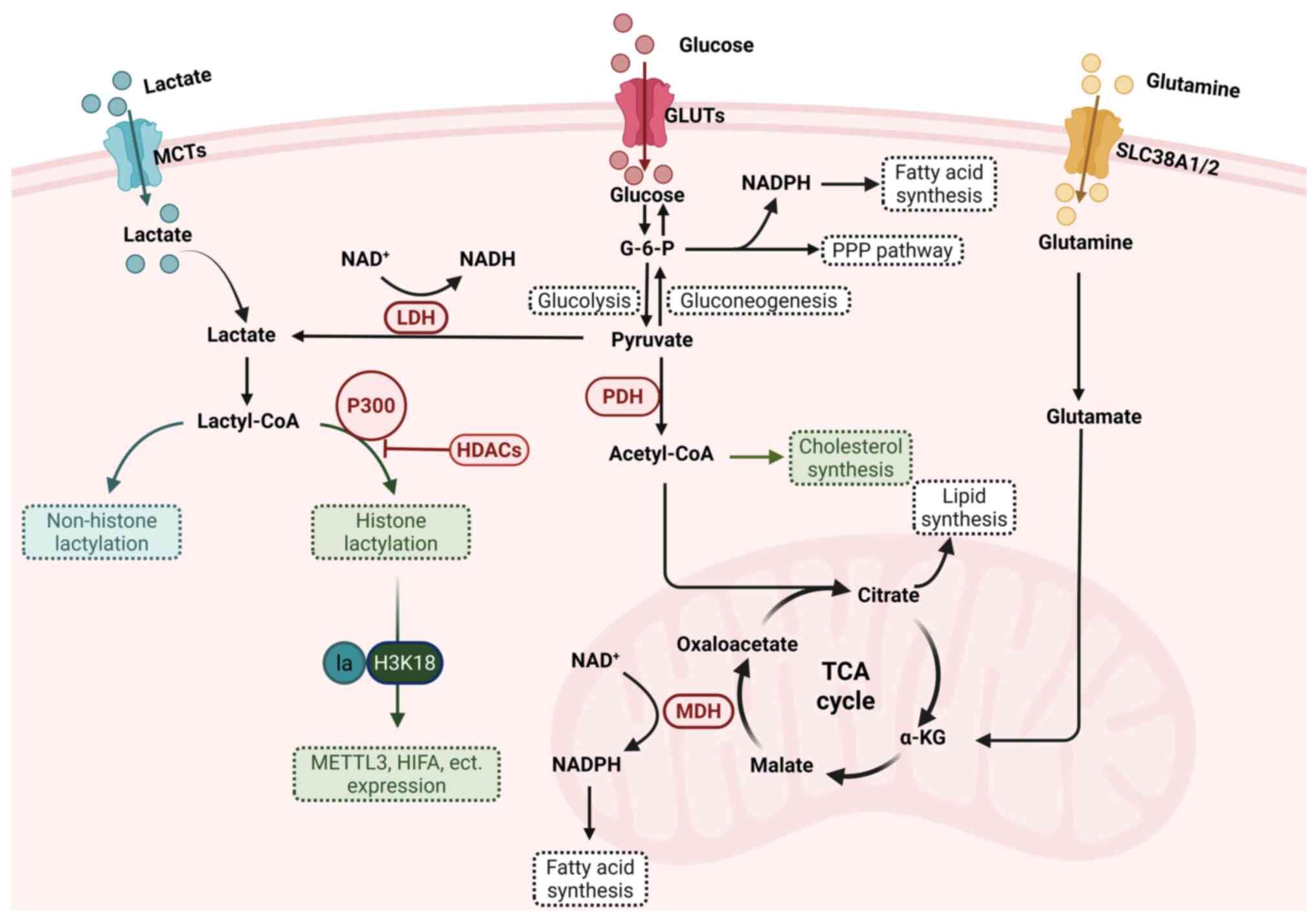

role in regulating ferroptosis, are examined (Fig. 2).

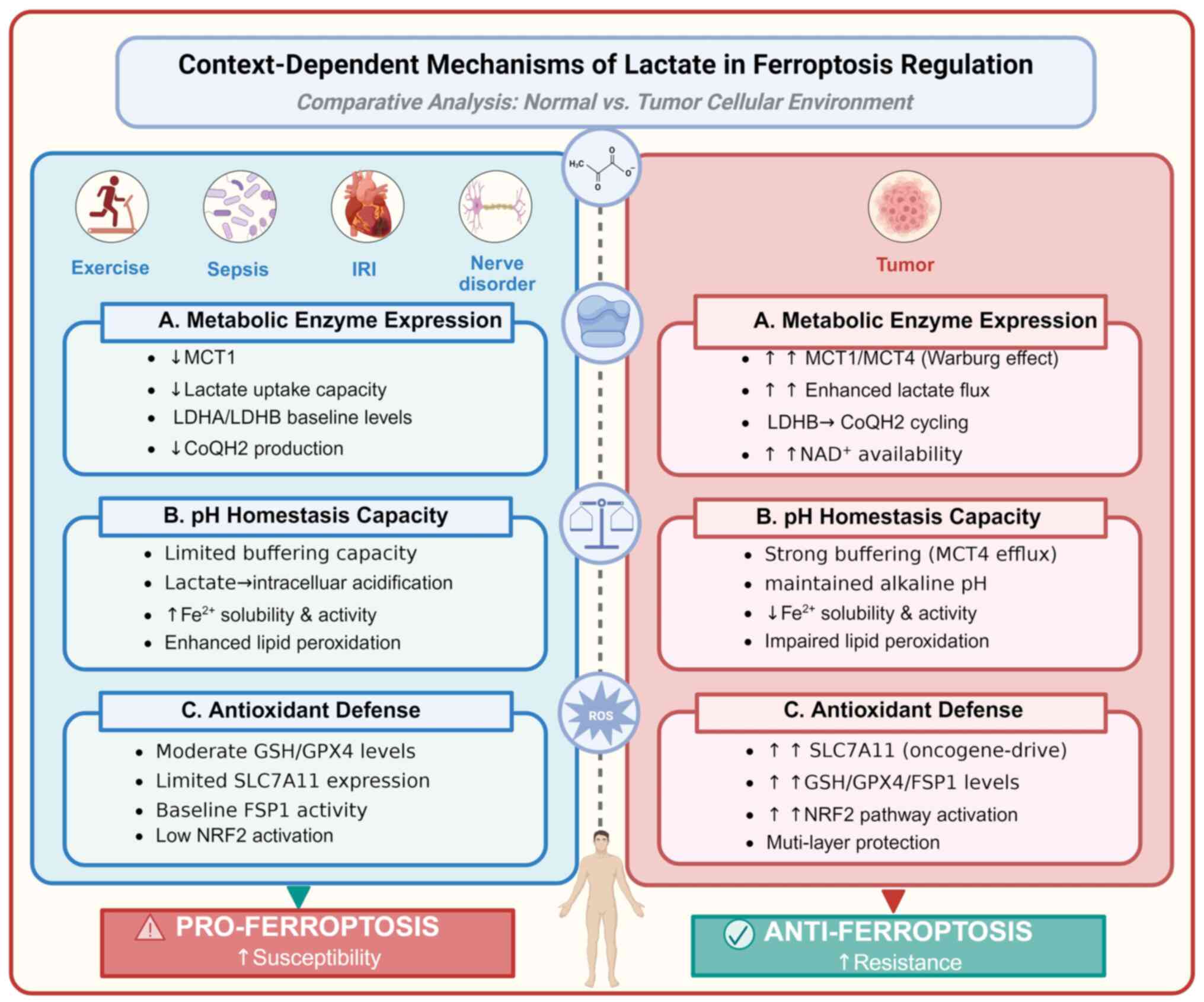

| Figure 2Lactate metabolism, lactylation and

the pathways involved in cells. Lactate is transported into cells

via MCTs and is generated through glycolysis or glutamine

decomposition in the cytoplasm. Once oxidized to pyruvate, pyruvate

can be metabolized through two major pathways: i) Entering

mitochondria for metabolism via the TCA cycle; or i) being

converted to glucose via gluconeogenesis. Intermediate products of

glycolysis and gluconeogenesis contribute to NADPH production

through the PPP. Malate can be converted to oxaloacetate via MDH,

generating NADPH, which supports fatty acid synthesis and GSSG

recycling. Citrate, another key metabolite, serves as a precursor

for lipid synthesis. Additionally, lactate can be converted into

lactyl-CoA, facilitating the lactylation of histone and non-histone

proteins, linking metabolism to epigenetic regulation. MCTs,

monocarboxylate transporters; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle;

PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; GSSG,

oxidized glutathione; GLUTs, glucose transporters; LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase; HDACs, histone deacetylases; PDH, pyruvate

dehydrogenase; METTL3, methyltransferase like 3; HIFA,

hypoxia-inducible factor α; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; SLC38a1/2,

solute carrier family 38 member a 1/2. Created with BioRender.com. |

Lactate biosynthesis and metabolism

When cellular energy demands exceed the capacity of

aerobic metabolism, as occurs during intense exercise or infection,

lactate is generated via glycolysis to serve as an alternative

energy source. Under hypoxic conditions, cytoplasmic glucose is

metabolized into pyruvate through a series of enzymatic reactions.

However, instead of being transported into mitochondria for

oxidative metabolism, pyruvate is converted into lactate by LDHA,

coupled with NADH/NAD+ interconversion (5). This reaction is reversible: Under

sufficient oxygen availability, lactate can be reconverted into

pyruvate by LDHB, which is then subsequently oxidized to acetyl-CoA

by pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and enters the tricarboxylic acid

cycle (TCA) for efficient energy production (5). Furthermore, an electrochemical

gradient driving ATP synthesis is created as electrons shuttle

through NAD+/NADH and FAD/FADH2 to the

electron transport chain (28).

Studies have highlighted that the conversion of

glucose to lactate by cells constitutes a tightly regulated

metabolic state, which may confer advantages during periods of

heightened biosynthetic demand (29,30). By channeling excess pyruvate

toward lactate production, proliferating cells effectively prevent

cytosolic NADH accumulation and prevent excessive ATP generation.

This regulation ensures the continuation of cytosolic glucose

metabolism without feedback inhibition from mitochondrial ATP

overproduction. Furthermore, glucose-6-phosphate derived from

glycolysis can be diverted into branching metabolic pathways, such

as the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), where it is partially

oxidized to generate NADPH (28). This NADPH serves as a critical

reducing equivalent for fatty acid synthesis and other anabolic

processes. Additionally, isotope tracing studies have demonstrated

that lactate functions as a major fuel in the TCA cycle, where

13C-lactate labeled TCA intermediates in every tissue of

the body, even in tumors (31,32). However, the accumulation of

lactate carries significant risks to the human body. Elevated serum

lactate levels can result in lactic acidosis, a condition that

poses a greater physiological threat compared with other metabolic

intermediates (33).

In addition to glycolysis, other biochemical

pathways, such as glutamine metabolism, contribute significantly to

lactate production in vivo particularly in cancer cells

(34). Under the regulation of

the oncogene c-Myc, glutamine is metabolized through the TCA cycle

to generate pyruvate, which is subsequently converted into lactate

by LDH (35). This process

provides an alternative and critical source of lactate in rapidly

proliferating cells, supporting energy production and

biosynthesis.

Hypoxia-induced lactate accumulation

Hypoxia represents a hallmark of pathological

conditions, including tumors, infections, ischemia-reperfusion

injury (IRI) and inflammation (36); it occurs when cells experience

reduced oxygen availability and activate an adaptive response to

cope with it. In response to reduced oxygen availability, cells

activate adaptive signaling cascades mediated by hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α (HIF-1α). Under this condition, HIF-1α becomes stabilized

and subsequently translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to

hypoxia-responsive elements within target genes, thereby promoting

metabolic programming, notably the upregulation of anaerobic

glycolysis (37,38). Under hypoxic conditions, the

reduced oxygen availability diminishes the activity of prolyl

hydroxylase domain enzymes (PHDs), which typically employ oxygen

and α-ketoglutarate as substrates to hydroxylate HIF-1α, thereby

targeting it for degradation. Consequently, the decreased PHD

activity leads to HIF-1α stabilization (39).

Cellular adaptation to hypoxia involves an enhanced

glycolytic flux, primarily mediated by HIF-dependent

transcriptional upregulation of genes encoding glucose transporters

and glycolytic enzymes. This metabolic shift is accompanied by an

active suppression of mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation and

respiratory activity (40-43). These biochemical adaptations

result in a metabolic reprogramming that promotes lactate

production and accumulation, thereby reinforcing the hypoxic

cellular response.

LDHA/B

LDHA and LDHB constitute the subunits of the

catalytically active LDH enzyme, which has long been recognized for

its pivotal role in ATP generation and energy homeostasis under

both anaerobic and aerobic glycolytic conditions (44). LDHA possesses a higher affinity

for pyruvate and preferentially catalyzes its reduction to lactate,

thereby sustaining anaerobic glycolysis. By contrast, LDHB

catalyzes the reverse reaction (oxidizing lactate to pyruvate)

which subsequently fuels mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation

(44). However, accumulating

evidence suggests that all LDH isoforms retain the inherent

capacity to mediate pyruvate-to-lactate conversion accompanied by

NAD+ regeneration, and that LDHA and LDHB can

functionally compensate for each other under metabolic stress

(44,45). By regulating the

NAD+/NADH ratio, mitochondrial function and ROS levels,

LDH isoforms indirectly modulate ferroptosis susceptibility. For

instance, LDHA has been demonstrated to promote tumor cell survival

by mitigating oxidative stress, whereas LDHB deficiency induces

mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage, ultimately leading

to neurodegeneration in the adult mouse brain (46,47). More recently, non-canonical roles

of LDHA and LDHB have been identified, with both isoforms

contributing to ferroptosis resistance in IRI and cancer through

mechanisms associated with GPX4 activity or GSH availability

(48,49).

MCTs and GPR81/HCAR1

MCTs serve as the principal mediators of lactate

transport across cell membranes. By coupling lactate translocation

with proton co-transport, these transporters help maintain

acid-base balance and cellular metabolic stability (7). For instance, inhibition of MCT1

disrupts lactate homeostasis and impairs both glycolytic flux and

GSH biosynthesis in MYC-driven cancer, resulting in reduced glucose

uptake and depletion of ATP, NADPH and GSH (50). Furthermore, extracellular lactate

must enter cells through MCTs before contributing to lactylation

reactions, which have been demonstrated to modulate ferroptosis

through multiple mechanisms (51).

GPR81/HCAR1 is a cell-surface G protein-coupled

receptor that recognizes lactate as its endogenous ligand and

coordinates metabolic signaling across diverse tissues (8). In adipocytes, GPR81 acts

synergistically with insulin to lower intracellular cyclic

adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels, thereby suppressing

postprandial lipolysis (52).

Beyond adipose tissue, GPR81 is abundantly expressed in skeletal

muscle, kidney, brain, heart and various cancer types (8). Elevated extracellular lactate, a

defining feature of the tumor microenvironment, predicts poor

outcomes, and high GPR81 expression correlates with poorer survival

(8,53,54). Analogous to its role in

adipocytes, GPR81 activation in cancer cells decreases

intracellular cAMP and suppresses proteinkinase A (PKA) activity,

thereby modulating lipid remodeling (55,56).

Elevated lactate concentrations within the tumor

microenvironment can activate GPR81 receptors located on the

cytoplasmic membrane of cells, subsequently facilitating

MCT1-mediated lactate uptake (57,58). Through this pathway, lactate

disrupts AMPK signaling, which in turn downregulates sterol

regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and its downstream

target stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1). Consequently, cells

produce more anti-ferroptotic monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs),

thereby suppressing lipid peroxidation. Simultaneously, long-chain

acyl-CoA synthetase 4 (ACSL4) expression decreases, reducing the

availability of oxidizable PUFAs, although the exact mechanism

underlying this remains unclear. Notably, blocking lactate

transport by inhibiting MCT1 or GPR81 promotes ferroptosis

primarily through alterations in lipid metabolism rather than

through conventional ferroptosis regulators, as evidenced by

unchanged GPX4 and FSP1 levels (57). Additionally, other research has

demonstrated that intracellular lactate accumulation following MCT

inhibition may lead to end-product inhibition of LDH, thereby

impairing NAD+ regeneration capacity (59). This sustained disruption of

glycolysis can result in the depletion of ATP, NADPH and GSH

(50). These findings suggest

that therapeutic strategies targeting the function of MCTs could

prove effective against both oxidative and hypoxic tumors.

Dual roles of lactate in ferroptosis

Accumulating evidence indicates that lactate

metabolism modulates ferroptosis through both

lactylation-independent and dependent pathways. Notably, this

regulation exhibits context-dependent effects. The

lactylation-independent mechanisms, including the iron handling,

lipid remodeling, redox regulation and immune responses in

ferroptosis, are summarized in this section. Additionally, evidence

supporting lactylation-dependent mechanisms has been compiled.

Lactate regulates iron homeostasis in

ferroptosis

Lactate-hepcidin axis in

ferroptosis

Clinical and experimental evidence has consistently

demonstrated a robust association between hyperlactatemia and

anemia, indicating a functional interconnection between lactate

metabolism and systemic iron homeostasis (60). For instance, in endurance

athletes, repeated bouts of exercise induces transient elevations

in plasma lactate concentrations, which have been correlated with

the development of iron-restrictive anemia in 10-15% of

individuals, particularly among those engaging in >10 h of

training per week (61).

Hepcidin, a peptide hormone predominantly synthesized by

hepatocytes, regulates iron homeostasis by binding to ferroportin

(FPN), the sole identified cellular iron exporter. This interaction

triggers FPN internalization and degradation, consequently

restricting iron efflux and leading to the elevation of

intracellular iron pools. Concurrently, it limits systemic iron

availability by reducing intestinal iron absorption, ultimately

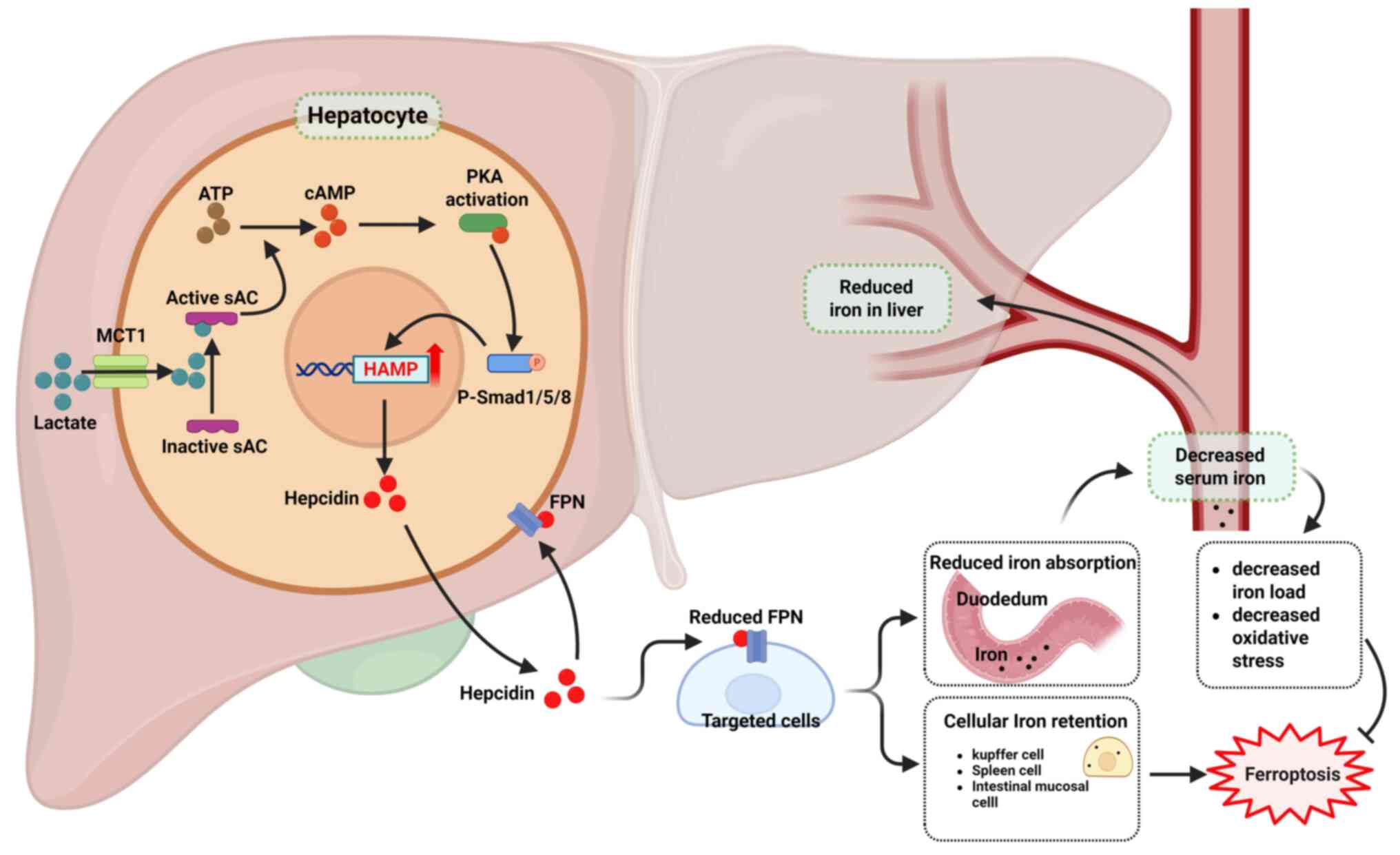

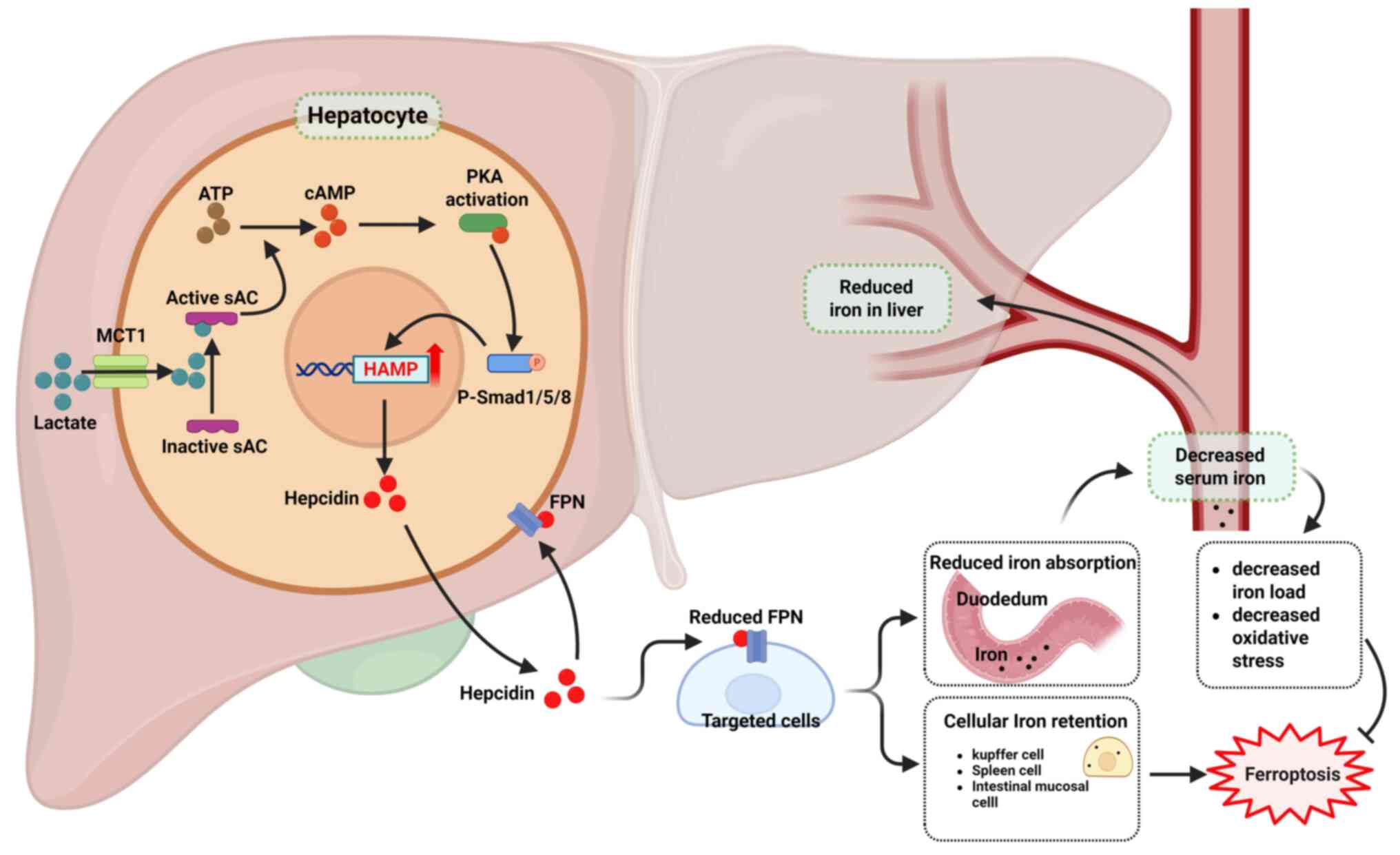

resulting in decreased serum iron concentrations (62) (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3Lactate-hepcidin axis regulates iron

homeostasis. Lactate enters cells via MCT1 and binds sAC,

triggering its conversion of ATP to cAMP. The cAMP activates PKA,

which enhances SMAD signaling. Activated SMAD upregulates HAMP

transcription, increasing hepcidin, the master regulator of iron

homeostasis. Hepcidin then binds FPN, causing its internalization

and degradation, which promotes cellular iron retention and lowers

circulating iron. MCT1, monocarboxylate transporter 1; sAC, soluble

adenylyl cyclase; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PKA,

protein kinase A; HAMP, human hepcidin gene; FPN, ferroportin 1.

Created with BioRender.com. |

Liu et al (63) recently elucidated the molecular

mechanism by which lactate regulates hepcidin expression and,

consequently, systemic iron homeostasis. Their findings revealed

that lactate, transported into cells via MCT1, directly interacts

with soluble adenylyl cyclase, resulting in elevated cAMP levels.

This, in turn, activates the PKA-Smad1/5/8 signaling cascade,

ultimately upregulating hepcidin transcription (63). Further investigation demonstrated

that lactate administration in mice induced hepcidin expression,

leading to reduced FPN levels. This resulted in increased splenic

iron sequestration, diminished duodenal iron absorption and,

consequently, decreased serum and tissue iron content accompanied

by attenuation of oxidative stress (63,64). Although tissue-specific

differences in hepcidin sensitivity, along with variations in

critical thresholds, time kinetics and the compensatory capability

of cellular antioxidant defense systems, may modulate iron

accumulation and ferroptotic outcomes, existing evidence supports a

pro-ferroptotic role of hepcidin in Kupffer cells, neurons and

hepatocytes (65-67).

Although current evidence supports a sophisticated

mechanistic framework linking lactate-mediated hepcidin induction

to ferroptosis, the tissue- and cell-type-specific effects of

elevated lactate levels induced by diverse physiological and

pathophysiological processes on iron homeostasis and ferroptosis

throughout the body warrant further investigation.

Lactate regulates iron via the

TFRC

Iron can be imported into the cell via the TFRC

system. In this process, Fe3+-transferrin complexes are

internalized through TFRC and eventually trafficked to and

liberated within the acidic environment of the lysosome mediated by

nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) (2). TFRC silencing and NCOA4 disruption

reduce ferroptotic sensitivity by restricting iron retrieval from

ferritin and thereby limiting the LIP (68,69). Lactylation of histones or

non-histone proteins involved in iron autophagy-related pathways

can modulate iron handling, thereby regulating ferroptosis

(70-72). Notably, this regulatory effect

appears to be context-dependent; for instance, H3K14 lactylation

has been demonstrated to promote ferroptosis in endothelial cells

exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by transcriptionally

upregulating the TFRC (73).

Conversely, lactylation of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) in

melanoma promotes its interaction with Fos-like antigen 1 (FosL1),

resulting in repression of TFRC-mediated iron uptake and conferring

resistance to ferroptosis (70).

However, at present, there is no direct evidence demonstrating that

histone lactylation regulates the TFRC in tumor cells. Notably,

ferroptotic susceptibility is determined not only by iron overload

but also by the lipid ratio and the capacity of antioxidant defense

systems.

Lactate-lipid remodeling in

ferroptosis

Beyond its established roles in energy metabolism

and immune modulation within the tumor microenvironment, lactate

serves as a crucial metabolic substrate that supports the TCA cycle

in major organs under physiological conditions (31). Tracer studies employing

13C-labeled lactate have demonstrated robust

incorporation of lactate-derived carbon into TCA intermediates

across a wide array of tissues, encompassing both healthy and

malignant cells (31,32).

Mechanistically, lactate contributes to the

intracellular acetyl-CoA pool through its conversion to pyruvate,

followed by subsequent metabolism (74). Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) then

catalyzes the rate-limiting carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to

malonyl-CoA, a critical intermediate in fatty acid biosynthesis

(75). Fatty acid synthase

subsequently utilizes malonyl-CoA to synthesize palmitic acid

(C16:0), which can be elongated to stearic acid (C18:0) through the

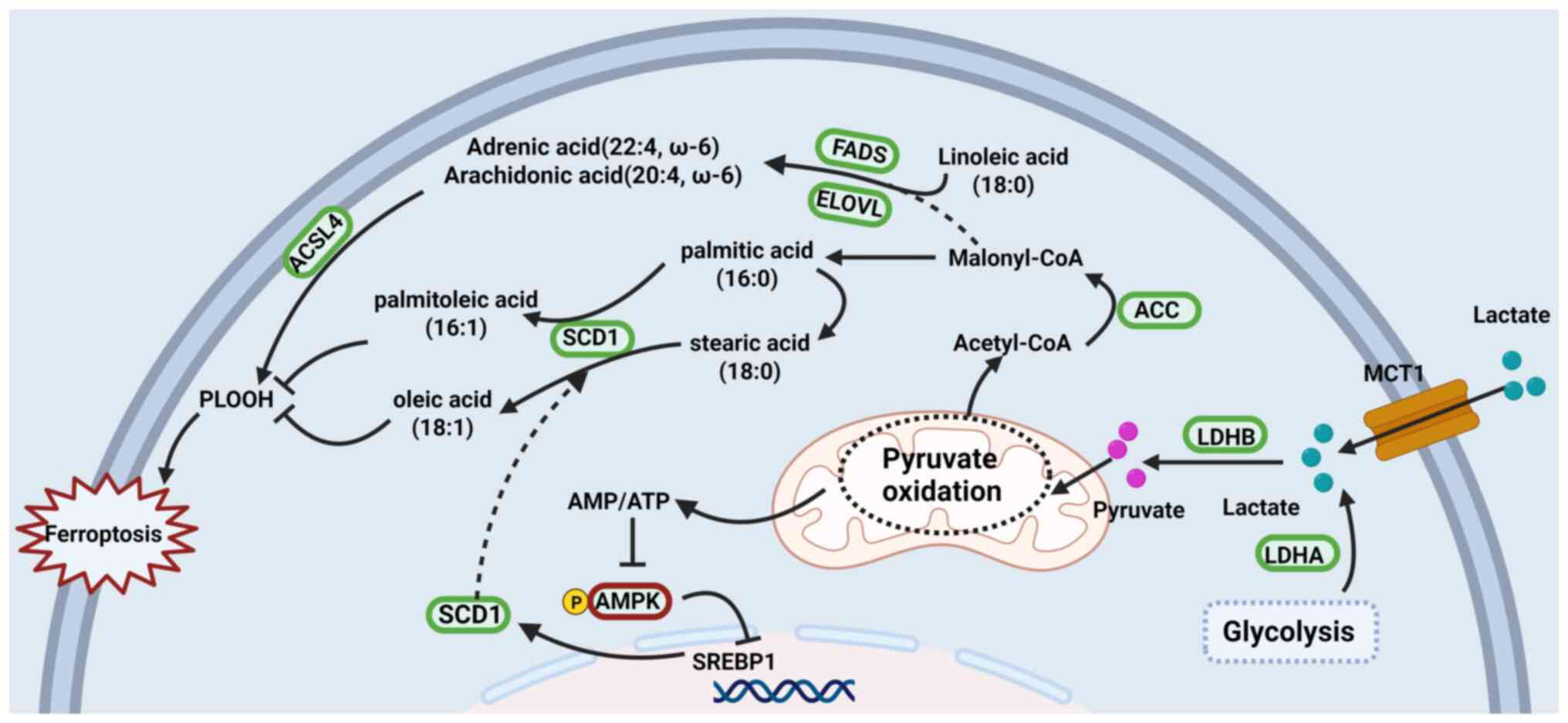

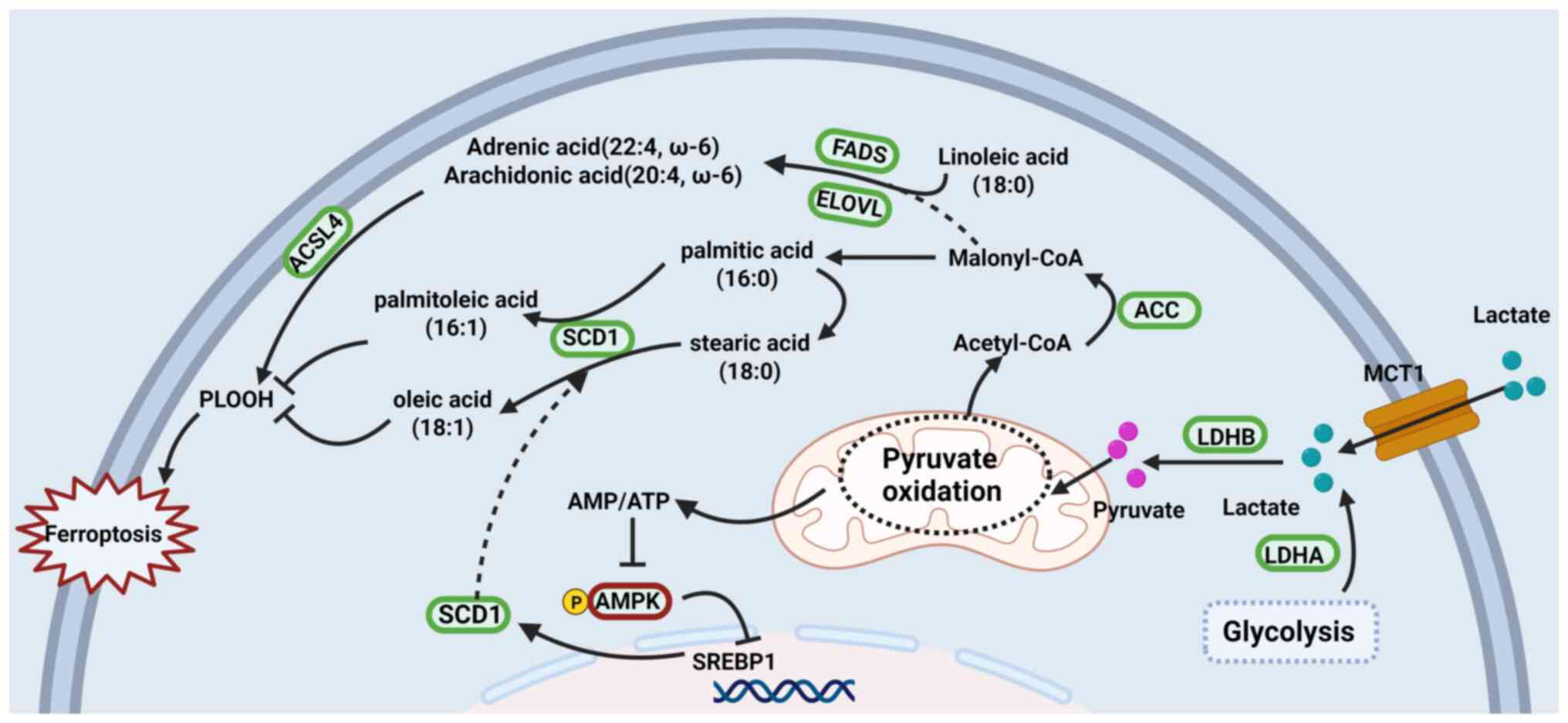

action of elongation-of-very-long-chain-fatty acids 6 (Fig. 4). SCD1 then introduces a double

bond at the Δ9 position, converting these saturated fatty acids to

palmitoleic and oleic acids, respectively. Malonyl-CoA also plays a

vital role in PUFA synthesis, where dietary linoleic acid undergoes

sequential desaturation and elongation reactions catalyzed by fatty

acid desaturase (FADS)2, ELOVL5 and FADS1, leading to the formation

of AA (C20:4, ω-6), which can be further elongated by ELOVL2/4 to

generate AdA (C22:4, ω-6) (76).

These interconnected pathways highlight the pivotal role of

ACC-derived malonyl-CoA in fatty acid metabolism, with ACC

inhibition potentially attenuating lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis (77-79). Additionally, lactate metabolism

enhances cellular NADPH availability through a glucose-sparing

mechanism: When cells use lactate as their primary fuel source,

glucose is redirected towards the PPP, which generates NADPH

essential for fatty acid biosynthesis (28).

| Figure 4Lactate promotes lipid remodeling in

cells. Lactate is taken up via MCT1 and converted by LDH to

pyruvate and acetyl-CoA, which fuels de novo lipogenesis

through ACC, FASN, SCD1, FADS and ELOVL under the control of the

AMPK-SREBP1 axis. The resulting balance between MUFAs and PUFAs,

and their ACSL4-dependent incorporation into membranes, governs

lipid peroxidation and cellular susceptibility to ferroptotic cell

death. MCT1, monocarboxylate transporter 1; LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase; ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; FASN, fatty acid

synthase; SCD1, stearyl-CoA desaturase 1; FADS, fatty acid

desaturases; ELOVL, elongation of very long-chain fatty acid; AMPK,

AMP-activated protein kinase; SREBP1, sterol regulatory

element-binding protein 1; MUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids;

PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids; ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase

long-chain family member 4. Created with BioRender.com. |

A study by Zhao et al (57) demonstrated that lactate-enriched

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells exhibit enhanced resistance to

ferroptotic damage induced by RAS-selective lethal 3 (RSL3) and

Erastin. The authors elucidated a mechanism wherein MCT1-mediated

lactate uptake promotes ATP production, leading to AMPK

deactivation and subsequent upregulation of SREBP1 and SCD1,

enhancing the production of MUFAs that confer protection against

ferroptosis (57). Corroborating

these findings, Yang et al (58) demonstrated that lactate-induced

alterations in SCD1/ACSL4 expression and ferroptosis resistance are

correlated with lactate production levels in esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma (ESCC). The conservation of this lactate/SCD1

regulatory axis across diverse tissue types has been substantiated

by multiple studies (80,81).

ACSL4 is an enzyme that esterifies CoA into specific PUFAs, such as

AA and AdA, contributing to ferroptosis execution by triggering

phospholipid peroxidation. In sepsis, lactate promotes ferroptosis

via GPR81-mediated upregulation of methyltransferase like 3

(METTL3), which may mediate ACSL4 mRNA stability via

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification in pulmonary epithelial cells

(82).

Although regulating the MUFA/PUFA ratio by lactate

through the SCD1/ASCL4 pathway does affect membrane lipid

peroxidation sensitivity, this protective effect against

ferroptosis may be more highly dependent on the state of the

intracellular antioxidant system (83).

Lactate-redox regulation in

ferroptosis

Disruptions in redox balance, whether toward

excessive oxidation or reduction, are generally deleterious to

cellular function. Lactate acts as a redox buffer by modulating the

NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio and serves as a signaling molecule

that regulates the activity of antioxidant enzymes involved in ROS

metabolism.

NADH/NAD+ balance in

lactate-ferroptosis crosstalk

The interconversion of lactate and pyruvate,

catalyzed by LDHA/B, is closely coupled to the NAD+/NADH

redox pair, thereby modulating cellular redox balance in a

context-dependent manner (84,85). Elevated lactate concentrations

have been demonstrated to increase the NADH/NAD+ ratio,

leading to the inhibition of key glycolytic enzymes such as

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and

phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, ultimately suppressing both

glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration (85). When the cellular demand for

NAD+ to sustain oxidation exceeds the rate of ATP

turnover, particularly in cells exhibiting active aerobic

glycolysis, NAD+ regeneration becomes a limiting factor

under conditions of compromised mitochondrial respiration. In such

circumstances, cells preferentially rely on glycolysis, resulting

in an elevated NAD+/NADH ratio. Under these conditions,

activation of PDH facilitates pyruvate oxidation, attenuates

lactate accumulation and restores the NAD+/NADH

equilibrium (86). Conversely,

when lactate is oxidized to pyruvate and enters mitochondrial

oxidative pathways, it can indirectly elevate ROS production

through electron leakage from the respiratory chain (87-89). In adipocytes, lactate exposure

transiently elevates the NADH/NAD+ ratio, which

normalizes after 24 h due to elevated NAD+ levels

associated with increased mitochondrial membrane potential and

enhanced ROS production (90).

Similarly, Jia et al (91) reported that elevated neuronal

lactate uptake augments ROS production and mitochondrial oxidative

metabolism, thereby disrupting the balance between ROS generation

and detoxification, impairing ATP synthesis and ultimately leading

to peripheral axonal degeneration. The mitochondrial enzyme

nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase further modulates redox

status by catalyzing the reversible conversion of NADH and

NADP+ into NAD+ and NADPH, the latter serving

as a crucial factor for GSH reductase-mediated recycling of reduced

GSH (92). Unlike observations

in normal cells, lactate uptake in melanoma cells via MCT1 elevates

NADH, NADPH, GPX4 and FSP1 levels, thereby conferring resistance to

ferroptosis (93). The net

effect of lactate on redox status is governed by the balance

between reducing equivalents of NADH and ROS production, which may

differ between normal and cancer cells due to variations in

oxidative phosphorylation activity and NADH-processing pathways.

This apparent contradiction may reflect a critical evolutionary

adaptation in which cancer cells reprogram lactate metabolism to

attain dual benefits (enhanced metabolic flexibility coupled with

augmented oxidative stress resistance) thereby facilitating

survival under adverse microenvironmental conditions.

NADPH/NADP+ balance in

lactate-ferroptosis

Within glucose metabolism, glucose-6-phosphate

generated either through glycolysis or via gluconeogenesis from

lactate can enter the PPP, where it is partially oxidized to

generate NADPH (94,95). Moreover, lactate metabolism

contributes to NADPH production through TCA cycle-linked pathways,

particularly those catalyzed by malic enzyme 1 (ME1) and isocitrate

dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) (94,96). Similar to NADH, NADPH fulfills

dual roles in cellular redox regulation: It is indispensable for

antioxidant defense by facilitating GSH reduction yet

simultaneously serves as a substrate for NADPH oxidases that

generate ROS production (97).

Under glucose-deprived conditions, the knockout of IDH1 or ME1

significantly reduces the NADPH/NADP+ and GSH/oxidized

GSH ratios, leading to elevated ROS levels and increased cell death

in cancer cells (94).

Conversely, excessive NADPH accumulation can induce reductive

stress, leading to the upregulation of NADPH oxidase 4 through

activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, thereby promoting ROS

generation, as observed in osteoarthritis (96).

Collectively, cellular redox homeostasis is

maintained by a delicate equilibrium between NAD(P)H-dependent

antioxidant defense mechanisms and NAD(P)H-mediated reductive

stress. By engaging in NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ redox cycling,

lactate functions as a dynamic redox buffer that modulates cellular

responses to oxidative and reductive stress.

Antioxidant enzymes in

lactate-ferroptosis

Under physiological conditions, lactate indirectly

regulates cellular antioxidant systems through modulation of the

NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ redox balance. Specifically,

uncontrolled elevated intracellular lactate concentrations disrupt

the NADH/NAD+ ratio, thereby impairing the activity of

key glycolytic enzymes, particularly GAPDH due to NAD+

depletion (50,57). This metabolic perturbation,

coupled with lactate-mediated feedback inhibition of

phosphofructokinase-1, ultimately impairs cellular ATP homeostasis

and compromises GSH biosynthesis, the predominant intracellular

antioxidant (50). GPX4 plays a

pivotal role in counteracting ferroptosis. A recent investigation

has demonstrated that intracellular lactate accumulation under

ischemic conditions can inactivate the AMPK/GPX4 axis to promote

myocardial ferroptosis (98).

Conversely, emerging evidence indicates that lactate can

paradoxically potentiate antioxidant defense mechanisms through

alternative signaling cascades. Metabolically reprogrammed lactate

has been demonstrated to augment GPX4 expression and confer

resistance to ferroptosis via activation of the p38-serum

glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 signaling axis. This pathway

mitigates GPX4 ubiquitination and subsequent degradation in

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (99). Furthermore, an additional study

has elucidated that lactate activates antioxidant defense and

pro-survival pathways, including the unfolded protein response and

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) signaling

cascades, by inducing mild oxidative stress in neuroblastoma cells

(100). Notably, lactate has

also been shown to alleviate oxidative stress-induced cell death

through autophagy activation in retinal pigment epithelial cells

(101).

Lactate-ferroptosis axis in

immunometabolism

The immunomodulatory properties of lactate

significantly influence ferroptosis susceptibility within both

inflammatory conditions and the tumor microenvironment, carrying

notable therapeutic relevance (102,103).

Inflammatory response and sepsis

Sepsis-induced metabolic reprogramming drives

increased lactate accumulation and systemic oxidative stress,

triggering multiple cell death pathways in both immune and

parenchymal cells (82,104). In septic lung injury, elevated

lactate levels exacerbate alveolar epithelial cell ferroptosis

through lactylated histone H3 lysine 18 (H3K18la)-mediated

upregulation of METTL3, which enhances m6A modification of ACSL4,

ultimately contributing to the development of acute respiratory

distress syndrome (82). Lactate

further augments neutrophil functions, including chemotaxis,

phagocytosis, oxidative burst and neutrophil extracellular trap

formation, via energy provision and PI3K/Akt signaling, which may

exacerbate tissue cell ferroptosis (105). Nevertheless, lactate

simultaneously exerts immunomodulatory effects in sepsis; it

suppresses LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production in

macrophages and promotes M2 polarization through MCTs and HIF-1α

activation (106). Moreover,

lactate-induced histone lactylation drives macrophages toward a

reparative phenotype characterized by reduced pro-inflammatory

cytokine expression, thereby potentially constraining excessive

inflammation (107,108). This dual role of lactate in

modulating ferroptosis and inflammation may account for the

inconsistent therapeutic outcomes associated with hypertonic sodium

lactate administration in sepsis, as these effects appear to be

highly dependent on factors such as timing of intervention, dosage

and the specific experimental animal models employed (104,109).

Tumor immunity context

The lactate-ferroptosis axis influences anti-tumor

immunity through multifaceted mechanisms that reshape the tumor

microenvironment. Lactate accumulation within the tumor

microenvironment suppresses effector T cell proliferation and

cytotoxic activity via GPR81-mediated signaling and metabolic

competition, while simultaneously polarizing tumor-associated

macrophages toward an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype that promotes

tumor progression (8). Notably,

ferroptosis induction in cancer cells can trigger immunogenic cell

death (ICD), leading to the release of damage-associated molecular

patterns that activate dendritic cells and stimulate antitumor T

cell responses (110). However,

lactate-mediated ferroptosis resistance through SCD1 upregulation

and enhanced antioxidant capacity diminishes this immunogenic

potential, effectively creating an immune-evasive tumor phenotype

(57,58). Recent evidence demonstrates that

targeting the lactate-ferroptosis axis can reprogram the

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Specifically, the

combination of MCT4 inhibition with ferroptosis inducers not only

depletes lactate accumulation but also enhances CD8+ T

cell infiltration and ferroptosis-driven ICD, thereby

synergistically improving checkpoint blockade efficacy (111). This immunometabolic

reprogramming represents a promising approach to convert 'cold'

tumors into 'hot' tumors that are more responsive to

immunotherapy.

Epigenetic regulation via protein

lactylation

Kla was initially identified as an enzymatically

catalyzed post-translational modification, wherein lactyl groups

derived from lactate are covalently attached to lysine residues

(9). Originally identified on

histones, Kla has been indicated to accumulate at gene promoters in

response to diverse stimuli, including hypoxia, interferon-γ, LPS

exposure and bacterial infections. This modification directly

modulates transcriptional activity and gene expression, thereby

establishing a mechanistic link between cellular metabolism and

transcriptional regulation (107,108). Subsequent investigations have

expanded the functional repertoire of Kla, demonstrating its

presence on non-histone proteins, particularly metabolic enzymes

(11,12). The lactylation of these enzymes

regulates cellular metabolism by modulating enzymatic activity,

notably through feedback mechanisms that regulate glycolytic flux

(108,112). However, the precise enzymatic

machinery responsible for Kla deposition and removal remains

incompletely characterized and the relative contributions of

enzymatic vs. non-enzymatic lactylation pathways warrant further

clarification.

Histone lactylation

Nuclear Kla is predominantly observed at H3K18, with

p300-mediated H3K18la at gene promoters serving as a key

determinant of transcriptional regulation. For instance, H3K18la

enrichment at the METTL3 promoter upregulates METTL3 expression,

subsequently augmenting m6A modification of ACSL4 mRNA (82). This cascade stabilizes ACSL4

transcripts, elevates ACSL4 protein levels and promotes

mitochondrial ROS accumulation, ultimately driving ferroptosis in

alveolar epithelial cells during sepsis (82). Furthermore, H3K18la facilitates

ACSL4 expression through direct promoter engagement and activation

of the HIF-1α signaling pathway (113,114). Under hypoxic conditions,

elevated lactate levels stimulate H3K18la at the HIF-1α promoter,

leading to upregulation of HIF-1α expression (115). This signaling cascade

subsequently elevates ACSL4 expression, driving lipid peroxidation

and ferroptosis through the ACSL4/lysophosphatidylcholine

acyltransferase 3/arachidonate lipoxygenase 15 axis, as

demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo models of

severe acute pancreatitis (114). Paradoxically, Kla modifications

can also confer cytoprotective effects in specific cancer contexts.

In triple-negative breast cancer, cancer-associated fibroblasts

exhibit elevated H3K18la levels, which enhance zinc finger protein

64 expression and subsequently activate the transcription of GCH1

and FTH. This cascade facilitates iron sequestration and protects

cells from doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis (71). Similarly, in colorectal cancer

stem cells, p300-mediated H4K12la upregulates glutamate-cysteine

ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC), thereby expanding the GSH pool and

conferring ferroptosis resistance (116). Furthermore, H3K18la enhances

the transcriptional activity of NFS1 cysteine desulfurase, a

cysteine desulfurase essential for iron-sulfur cluster

biosynthesis, consequently reducing the susceptibility of HCC to

ferroptosis following microwave ablation (117). These findings underscore the

notable tissue-specific and context-dependent nature of histone Kla

function. However, the molecular determinants underlying this

functional dichotomy remain poorly understood, and the systematic

frameworks capable of predicting whether Kla will promote or

suppress ferroptosis within specific cellular contexts are still

lacking.

Non-histone lactylation

Beyond its role in chromatin regulation, Kla also

influences the activity and stability of various non-histone

proteins, including key metabolic and RNA-modifying enzymes that

regulate ferroptosis. Notably, lactate-primed lysine

acetyltransferase 8 directly lactylates mitochondrial

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 at K100, thereby enhancing its

kinase activity and reprogramming mitochondrial fatty-acid

synthesis to promote ferroptotic processes (118). Additionally, Kla of METTL3

stabilizes the protein and promotes m6A modifications on ACSL4 and

TFRC transcripts, thereby accelerating ferroptosis in PC12 cells

(72). In the context of

Alzheimer's disease, reduced lactylation of tau at K677 inhibits

ferroptosis by disrupting ferritinophagy, resulting in dysregulated

iron metabolism and increased resistance to cell death (119). Similarly, decreased lactylation

of malate dehydrogenase 2 at K241, coupled with reduced lactate

production, leads to elevated levels of GSH and GPX4, thereby

alleviating ferroptosis and improving mitochondrial function in

myocardial IRI (120). By

contrast, lactylation of LSD1 in melanoma promotes its interaction

with FosL1, resulting in repression of TFRC-mediated iron uptake

and thereby conferring resistance to ferroptosis (70). Similarly, lactylation of NOP2/Sun

RNA methyltransferase 2 enhances its catalytic activity and

stabilizes GCLC mRNA via m5C modifications, leading to increased

intracellular GSH levels and ferroptosis resistance in gastric

cancer cells (121). These

findings underscore the versatility of Kla as a regulatory

mechanism capable of either promoting or inhibiting ferroptotic

cell death through modulation of enzymatic activity.

The bidirectional influence of Kla on ferroptosis is

of significant therapeutic interest. In cancer, Kla-driven

modulation of ferroptosis has been implicated in developing

resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. For example, evodiamine

has been found to inhibit histone lactylation at the HIF-1α

promoter, suppressing angiogenesis and programmed death-ligand 1

expression while inducing ferroptosis in prostate cancer cells

(122). This highlights the

potential of targeting Kla 'writers', 'erasers' or 'readers' to

selectively induce ferroptosis in cancer cells, thereby enhancing

the efficacy of cancer therapies while minimizing damage to normal

tissues. Conversely, Kla manipulation could also hold promise in

treating degenerative diseases and ischemic injury by reducing

ferroptotic damage (123).

However, the clinical translation of Kla-targeted therapies faces

notable challenges, including the lack of specific inhibitors,

potential off-target effects and the complex tissue-specific

functions of lactylation.

In summary, Kla represents a critical metabolic

regulator integrating cellular metabolic status with ferroptotic

outcomes. Although the context-dependent, bidirectional modulation

of ferroptosis by Kla presents promising therapeutic avenues,

notable barriers remain between current mechanistic insights and

clinical implementation. This underscores the need for more

rigorous investigations into tissue-specific regulatory networks

and the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

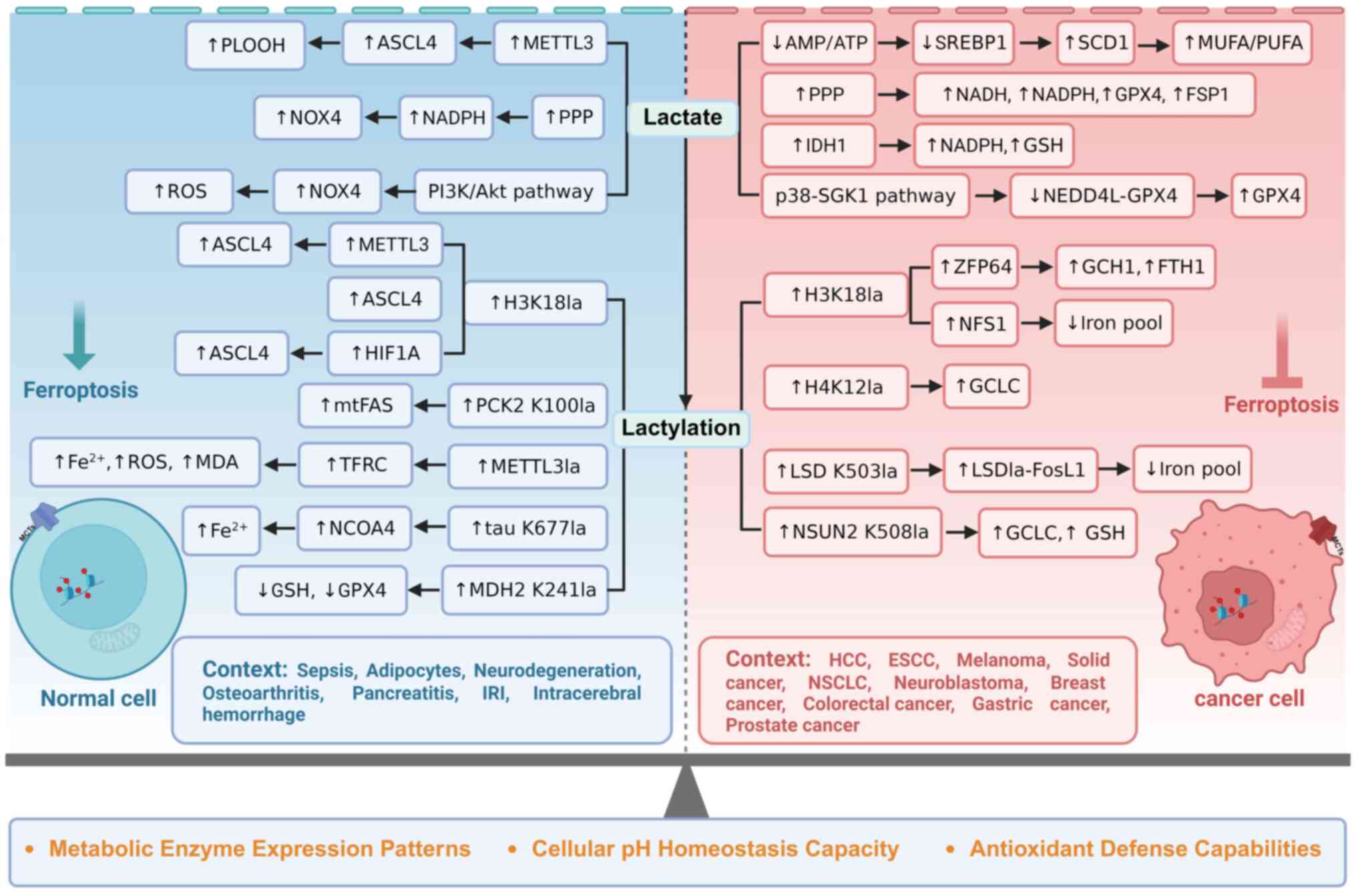

Putative context-dependent mechanisms

The seemingly contradictory roles of lactate in

ferroptosis (its capacity to both promote and inhibit this

regulated form of cell death) highlight the complex interplay among

cellular metabolism, redox homeostasis and iron regulation. In the

previous section, the factors that determine whether lactate

functions in a pro-ferroptotic or anti-ferroptotic manner within

specific cellular contexts were systematically examined (Fig. 5). In pathological conditions such

as sepsis (73,82), neurodegeneration (91,119), osteoarthritis (96), pancreatitis (114), IRI (120), intracerebral hemorrhage

(72) and adipocytes browning

(90), lactate promotes

ferroptosis. Conversely, in various malignancies, including HCC

(57,117), ESCC (58), melanoma (70), NSCLC (99), neuroblastoma (100), breast cancer (71), colorectal cancer (116), gastric cancer (121) and prostate cancer (122), lactate suppresses ferroptosis.

Table I summarizes recent in

vitro studies examining the role of lactate in ferroptosis

regulation. In this section, three potential mechanisms underlying

this context-dependent regulation are discussed: Differences in

metabolic enzyme expression, pH homeostatic capacity and

antioxidant defense systems (Fig.

6).

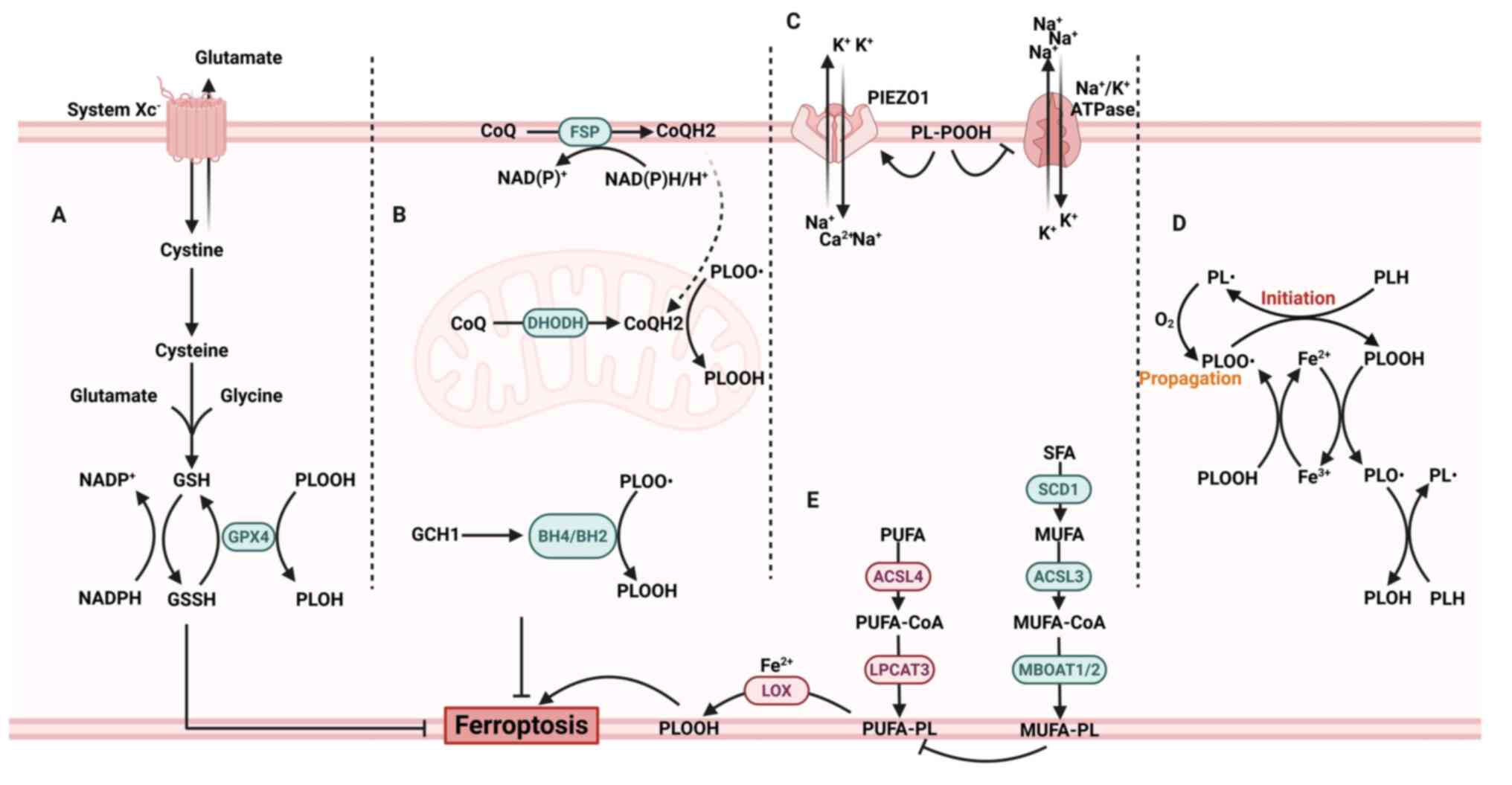

| Figure 5Dual roles of lactate and lactylation

in ferroptosis regulation across cellular contexts. Lactate and

lactylation exhibit contrasting regulatory effects on ferroptosis

in normal vs. tumor cells through both lactylation-dependent and

-independent mechanisms. In lactylation-independent pathways,

lactate modulates cellular metabolism and redox homeostasis via

MCTs and GPR81 receptor signaling, with contrasting outcomes

observed between normal and malignant cell populations. In

lactylation-dependent pathways, lactate similarly demonstrates

contrasting effects in normal vs. tumor cell contexts through

post-translational protein modifications. PLOOH, phospholipid

hydroperoxides; ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member

4; METTL3, methyltransferase like 3; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; PPP,

pentose phosphate pathway; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SREBP1,

sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA

desaturase 1; MUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFAs,

polyunsaturated fatty acids; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; FSP1,

ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; IDH1, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1;

GSH, glutathione; SGK1, serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase

1; NEDD4L, neural precursor cell expressed developmental

downregulated protein; PCK2, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2;

mtFAS, mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis; TFRC,

transferrin-transferrin receptor; MDA, malondialdehyde; NCOA4,

nuclear receptor coactivator 4; MDH2, malate dehydrogenase 2;

ZFP64, zinc finger protein 64; GCH1, GTP cyclohydrolase 1; FTH1,

ferritin heavy chain 1; NFS1, NFS1 cysteine desulfurase; GCLC,

glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; LSD1, lysine-specific

demethylase 1; FosL1, Fos-like antigen 1; NSUN2, NOP2/Sun RNA

methyltransferase family member 2; IRI, ischemia-reperfusion

injury; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ESCC, esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; MCT (1,4),

monocarboxylate transporter (1,4);

GPR81, G protein-coupled receptor 81. Created with BioRender.com. |

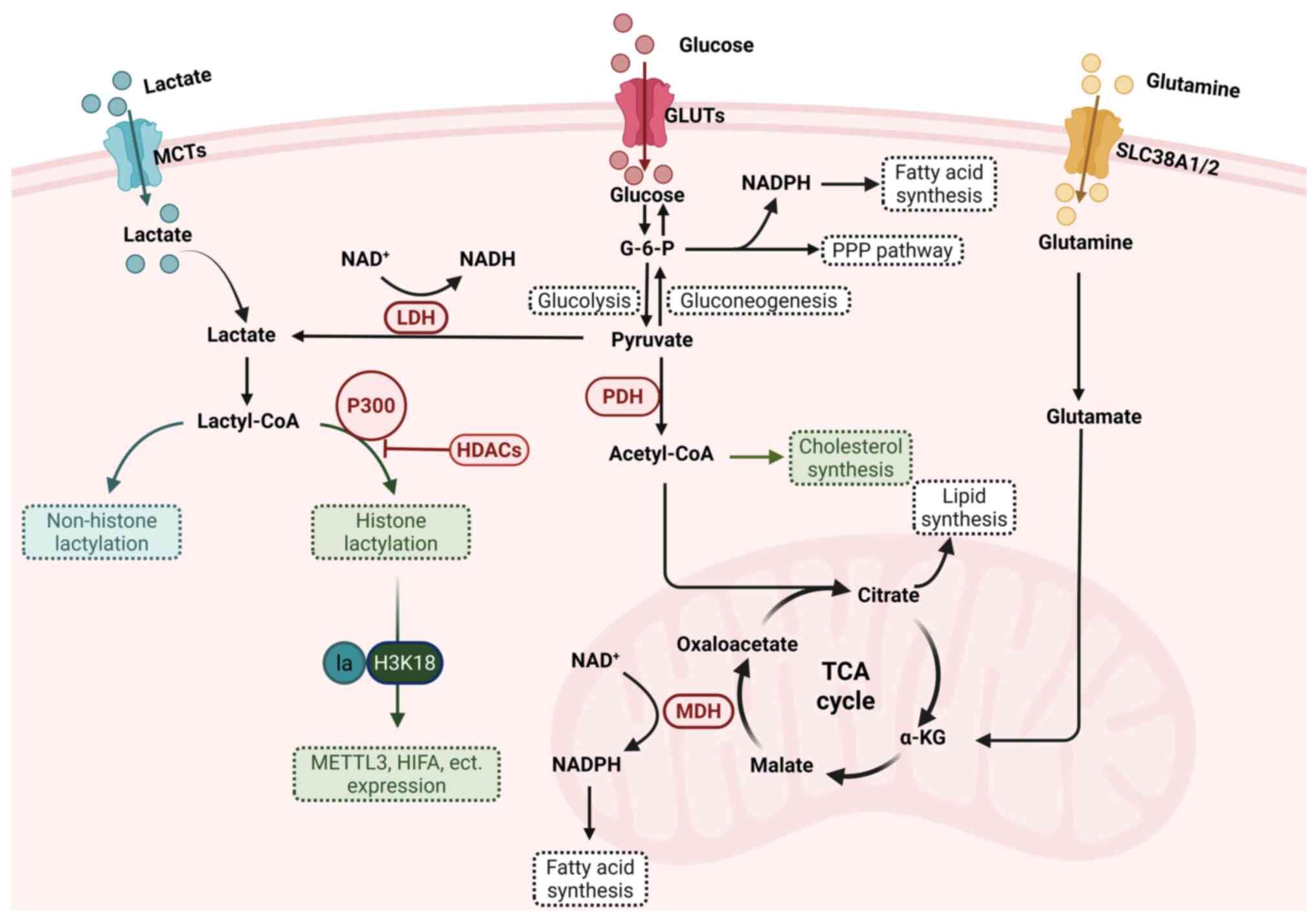

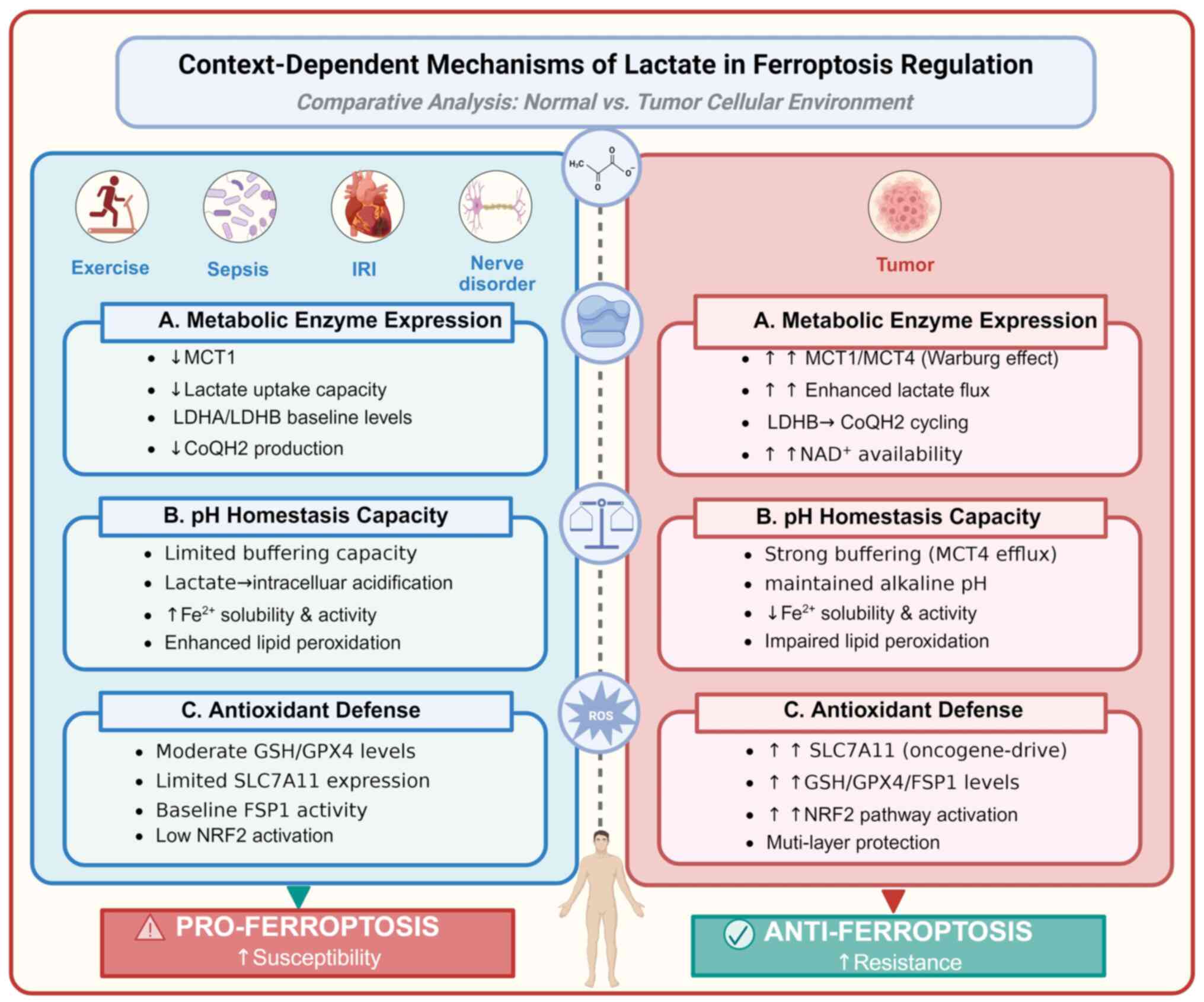

| Figure 6Context-dependent mechanisms of

lactate in ferroptosis regulation. The context-dependent mechanisms

of lactate in ferroptosis regulation include: (A) Differential

metabolic enzyme expression profiles, (B) distinct cellular pH

homeostasis capacities and (C) varying antioxidant defense

capabilities. These mechanisms may underlie the distinct effects of

the context-dependent lactate-ferroptosis axis. IRI,

ischemia-reperfusion injury; MCT (1,4),

monocarboxylate transporter (1,4);

LDHA/B, lactate dehydrogenase A/B; CoQH2, ubiquinol; GSH,

glutathione; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; SLC7A11,

cystine/glutamate antiporter solute carrier family 7 member 11;

FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; NRF2, nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2. Created with BioRender.com. |

| Table IIn vitro evidence of lactate

regulating ferroptosis. |

Table I

In vitro evidence of lactate

regulating ferroptosis.

| Authors, year | Cell type | Lactate

concentration | Phenotype | Mechanism | Disease

context | Reduce/promote

ferroptosis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhao et al,

2020 | Hep3B and

Huh-7 | 20 mM | MUFAs↑ | SCD1↑ | Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Reduce | (57) |

| Yang et al,

2024 | EC109 | 20 μM | MUFAs↑ | SCD1↑ | Esophageal

cancer | Reduce | (58) |

| Jia et al,

2021 | Primary spinal and

DRG neuron | 1 and 10 mM | mtROS↑ | Alters energy

metabolism | Neurodegenerative

disease | Promote | (91) |

| Huang et al,

2023 | Chondrocyte | 10, 20 and 40

mM | ROS↑ | NADPH/NOX4,

GPR81/NOX4 | Osteoarthritis | Promote | (96) |

| Lin et al,

2022 | COMM-SUS | 10 and 30 mM | NADPH↑, NADH↑ | PPP activation | Melanoma | Reduce | (93) |

| Bauzá-Thorbrügge

et al, 2023 | Adipocyte | 25 mM | ROS↑ | NADH↑ | Adipose tissue | Promote | (90) |

| Cheng et al,

2023 | H1229 and A549 | 5, 10, 15 and 25

mM | GPX4↑ | Inhibits GPX4

ubiquitination by inactivating the E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4L | NSCLC | Reduce | (99) |

| Tauffenberger et

al, 2019 | SH-SY5Y | 20 mM | UPR↑, NRF↑ | ROS burst | Neuroblastoma | Reduce | (100) |

| Zou et al,

2023 | ARPE-19 | 20 mM | ROS↓ | Activate autophagy

pathway | A cell line derived

from the retina | Reduce | (101) |

| Wu et al,

2024 | MLE12 | 10 mM | GPX4↓,

GSH/GSSG↓, |

GPR81/H3K18la/METTL3/ACSL4 | Mouse lung

epithelial cells in sepsis | Promote | (82) |

| Zhang et al,

2025 | AR42J | 5, 10, 15 and 25

mM | ACSL4↑, LPCAT3↑,

ALOX15↑ | H3K18la in HIF-1α

promoter | Pancreatitis | Promote | (114) |

| Zhang et al,

2025 | DOX-resistant

TNBC | 25 mM | GCH1↑, FTH1↑ | H3K18la in ZFP64

promoter | TNBC | Reduce | (71) |

| Deng et al,

2025 | LoVo, SW-620 and

HCT-116 | 5, 10 and 15

mM | ROS↓, MDA↓,

GPX4↑ | GCLC↑ | Colorectal

cancer | Reduce | (116) |

| Huang et al,

2025 | MHCC-97H and

Huh7. | 5 and 10 mM | ROS↓, free

iron↓ | H3K18la in NFS1

promoter | Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Reduce | (117) |

| Yuan et al,

2025 | THLE2 | 5, 10 and 20

mM | GPX4↓, COX2↑,

TFRC↑ | Lactylation in PCK2

(K100) induces mtFAS remodeling, potentiation of oxidative

phosphorylation and the tricarboxylic acid cycle | Human liver

epithelial cell line | Promote | (118) |

| She et al,

2024 | H9c2 | 10, 20 and 50

mM | GSH↓, GPX4↓, MDA↑,

iron↑ | Lactylation in MDH2

(K241) | Cardiomyocyte cell

lines from the rat heart | Promote | (120) |

| Niu et al,

2025 | HEK293T and

MKN45 | 10 and 20 mM | GSH↑, Lipid

perioxidation↓ | Lactylation in

NSUN2 (K508) stabilizes GCLC mRNA via promoting m5C

modification | Gastric cancer | Reduce | (121) |

| Yu et al,

2023 | DU145 | 10 mM | ROS↓, iron↓ | H3K18la in HIF-1α

promoter | Prostate

cancer | Reduce | (122) |

Metabolic enzyme expression patterns

Cancer cells characterized by the Warburg effect

demonstrate elevated expression of MCT1 and MCT4, which promote

enhanced lactate uptake and consequent metabolic reprogramming.

Notably, identical lactate concentrations exert diametrically

contrasting effects on ferroptosis susceptibility in malignant lung

cancer cells compared with their normal epithelial counterparts,

highlighting fundamental differences in lactate metabolism between

these cellular contexts (82,99). Although LDHA has been extensively

characterized as a tumor survival factor through its role in

mitigating ROS, targeted depletion via small interfering RNA or

pharmacological inhibition (GSK2837808A or R-GNE-140) fails to

sensitize A549 cells to ferroptosis inducers, including RSL3 or

erastin (49). This observation

necessitates the existence of LDHA-independent anti-ferroptosis

mechanisms. In KRAS-driven NSCLC, LDHB has been identified as a key

regulator of GSH-dependent ferroptosis resistance through STAT1

signaling, although the precise molecular mechanisms underlying

LDHB-mediated STAT1 activation remain incompletely elucidated

(49). A recent investigation

propose that LDHB mediates a complex three-step reaction cycle,

wherein reducing equivalents are transferred from lactate to

reduced CoQH2, with NAD+ serving as a cycling cofactor

(124). The markedly elevated

NAD+ concentrations observed in tumor cells compared

with normal tissues may provide enhanced substrate availability for

LDHB-mediated lactate oxidation cycles (125). Given that CoQH2 serves as an

alternative anti-ferroptosis system operating in parallel with

GPX4, the differential metabolic environments between malignant and

normal cells likely contribute to the divergent effects of lactate

on ferroptosis sensitivity observed across these cellular contexts.

Nevertheless, this proposed mechanism lacks direct biochemical

validation and relies heavily on circumstantial evidence from

functional studies. Despite these limitations, this finding

provides an important avenue for subsequent research.

Cellular pH homeostasis capacity

The differential expression of MCTs between normal

and malignant cells provides a mechanistic framework for

understanding lactate-mediated modulation of ferroptosis

susceptibility. Normal cells predominantly express MCT1, which

confers a relatively limited capacity for lactate transport

(126). By contrast, cancer

cells typically co-express MCT1 and MCT4, facilitating highly

efficient lactate efflux that preserves intracellular pH

homeostasis even within the acidic tumor microenvironment (127). This enhanced acid-extruding

capacity enables tumor cells to sustain intracellular pH at neutral

or slightly alkaline levels, potentially exceeding those observed

in normal cells under comparable conditions (128). The pH dependence of

Fe2+-catalyzed lipid peroxidation constitutes a critical

determinant of ferroptotic sensitivity, proceeding efficiently

under acidic conditions but being markedly impaired at neutral or

basic pH due to reduced Fe2+ solubility. Consequently,

the efficacy of ferroptosis-inducing therapies may be limited in

alkaline cytoplasmic environments (129). However, the proposed

lactate-acidification-ferroptosis axis warrants careful evaluation

in light of emerging contradictory evidence. An early study by

Jackson and Halestrap (130)

documented lactate-induced intracellular acidification in rat

hepatocytes, whereas Bozzo et al (131) observed only modest pH

reductions following 5 mM lactate treatment in mouse neurons. These

findings suggest that normal cells possess notable buffering

capacity against lactate-induced acidification, challenging the

assumption that lactate uniformly acidifies the cytoplasm across

diverse cell types. Moreover, LDHA-mediated lactate accumulation

has been reported to promote ferroptosis resistance in a

pH-dependent manner in tumors, a mechanism that may involve

inhibition of Piezo1 in an acidic environment (132-134). Accordingly, the mechanistic

link between lactate-mediated pH changes and iron-dependent

ferroptosis remains inadequately characterized.

Antioxidant defense capabilities

Tumor cells have developed intricate adaptive

mechanisms to evade ferroptosis, a key tumor-suppressive process.

In response to the heightened oxidative stress associated with

malignant transformation, cancer cells activate a comprehensive

antioxidant defense pathway that, paradoxically, shields them from

ferroptotic cell death (4). At

the core of this protective adaptation lies the upregulation of

cystine/glutamate antiporter solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11), driven by the inactivation of key tumor suppressors

including TP53, BRCA1 associated protein 1 and alternate reading

frame (16,135). This dysregulation fundamentally

alters the cellular redox balance, conferring ferroptosis

resistance while simultaneously promoting tumor proliferation and

survival. The oncogenic KRAS signaling cascade further amplifies

this effect by directly upregulating SLC7A11 expression, thereby

establishing a robust anti-ferroptotic defense that is particularly

pronounced in lung adenocarcinoma progression (136). Beyond cystine import, the

ferroptosis evasion machinery encompasses the upregulation of

critical antioxidant enzymes, notably GSH and GPX4, which are

consistently upregulated across multiple tumor types (137,138). Complementing these classical

antioxidant systems, cancer cells also exploit radical-trapping

antioxidant mechanisms mediated by FSP1 and GCH1, both of which are

frequently upregulated in diverse malignancies and markedly

contribute to ferroptosis resistance (21,139). Furthermore, NRF2 activation, a

hallmark of numerous cancer types, serves as both a driver of tumor

progression and a coordinator of therapy resistance. Through its

transcriptional control of ferroptosis-regulatory components,

including SLC7A11, GPX4 and FSP1, NRF2 creates a unified resistance

program that simultaneously promotes tumor progression and confers

therapeutic resistance (140).

Notably, this mechanism of ferroptosis evasion may

be closely associated with altered lactate metabolism in tumor

cells. While lactate has been reported to promote ferroptosis in

normal cellular contexts by modulating iron homeostasis and lipid

peroxidation, tumor cells appear to exploit lactate signaling

pathways to reinforce their anti-ferroptotic defenses. This

metabolic rewiring suggests that the Warburg effect and ferroptosis

evasion may be mechanistically linked, representing complementary

adaptive strategies that collectively support malignant

transformation and tumor progression.

Crosstalk between the lactate-ferroptosis

axis and other cell death modalities

The lactate-ferroptosis axis does not function

independently but rather integrates with other forms of programmed

cell death, constituting a complex regulatory network that

modulates therapeutic outcomes. Growing evidence suggests that

lactate metabolism exerts regulatory control over multiple cell

death modalities, with the dominant pathway contingent upon the

specific cellular context and magnitude of stress stimuli.

Lactate-mediated coordination of

ferroptosis and apoptosis

In cancer cells, increased lactate concentrations

have been reported to suppress apoptosis through HIF-1α-mediated

upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins, including BCL-2 and

survivin, while concurrently promoting ferroptosis resistance via

SCD1 upregulation (58,141). This coordinated suppression of

apoptotic and ferroptotic pathways confers a metabolic survival

advantage under stress conditions. Conversely, in certain

therapeutic contexts, lactate depletion strategies have been

demonstrated to induce a synergistic activation of both apoptotic

and ferroptotic pathways. For instance, MCT1 inhibition in

glycolytic tumors induces a metabolic catastrophe that triggers

caspase-dependent apoptosis alongside GSH depletion-mediated

ferroptosis, thereby yielding enhanced antitumor efficacy relative

to the activation of either pathway alone (142). A study has demonstrated that

GPX4 inhibition can simultaneously activate the caspase-8-mediated

apoptotic pathway and ferroptosis, suggesting shared upstream

signaling mechanisms (143).

Furthermore, the tumor suppressor p53 serves as a critical node

connecting these pathways as it can promote ferroptosis via SLC7A11

repression while simultaneously regulating apoptotic gene

expression (144).

Autophagy as a double-edged sword in

lactate-ferroptosis

The interplay between lactate, autophagy and

ferroptosis is notably intricate. Lactate has been reported to

induce protective autophagy in retinal pigment epithelial cells,

mitigating oxidative stress and cell death through AMPK activation

(101,145). However, in the context of

ferroptosis, selective autophagy pathways such as ferritinophagy

(autophagic degradation of ferritin) and lipophagy (degradation of

lipid droplets) can paradoxically facilitate ferroptosis by

elevating the LIP and releasing PUFAs for peroxidation (146,147). Studies have demonstrated that

lactate-induced autophagy activation can dictate cellular fate

between survival and ferroptotic death based on the iron-handling

capacity and antioxidant reserve of specific cell types (101,119,148). In Alzheimer's disease,

diminished tau lactylation suppresses ferritinophagy, resulting in

iron accumulation and altered susceptibility to ferroptosis,

highlighting the complex interplay among lactate metabolism,

autophagy and iron homeostasis (119). Additionally, clockophagy

(selective degradation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear

translocator-like protein 1, a core clock gene) has been reported

to enhance ferroptosis sensitivity by disrupting the circadian

regulation of lipid metabolism and antioxidant defenses (149).

Therapeutic approaches in

lactate-ferroptosis

As the role of lactate in disease progression

becomes increasingly evident, strategies aimed at modulating

lactate metabolism are receiving growing attention in conditions

including neurodegenerative disorders, IRI, sepsis and cancer.

These approaches encompass systemic administration of

lactate-enriched solutions to provide metabolic support, as well as

interventions aimed at inhibiting lactate production or transport

as well as promoting its depletion to disrupt metabolic symbiosis

in tumors, highlighting the dual therapeutic potential of lactate

(150,151).

Lactate in therapeutic contexts

Neurodegenerative diseases and

IRI

Increasing evidence implicates ferroptosis in the

pathogenesis of major neurodegenerative disorders, including

Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease,

multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (152). In these chronic conditions,

persistent elevations in lactate are associated with oxidative

stress and disrupted iron homeostasis, collectively promoting

ferroptotic neuronal death (153-155). Similarly, lactate accumulation

during prolonged ischemia or late reperfusion has detrimental

effects. Sun et al (98)

demonstrated that intracellular lactate overload under prolonged

ischemia inactivates the AMPK/NRF2/GPX4 protective axis, thereby

promoting myocardial ferroptosis and exacerbating cardiac injury.

By contrast, lactate exhibits striking neuroprotective properties

in acute ischemic stroke. Intraventricular administration following

reperfusion markedly reduces infarct volume and ameliorates

neurological deficits (156).

This protective action is attributed to the role of lactate as an

alternative energy substrate, whereby its conversion to pyruvate

enables mitochondrial oxidation once oxygen is restored (157). However, lactate accumulated

during the ischemic phase itself, when oxygen tension is absent,

cannot fuel oxidative metabolism. Instead, it drives protein

lactylation in ischemic tissues, a post-translational modification

that exacerbates cellular injury (158).

The neuroprotective effects of exogenous lactate

are highly dependent on both dose and timing. Following

oxygen-glucose deprivation, 4 mM lactate markedly attenuates

hippocampal neuronal death, whereas 20 mM exerts neurotoxic effects

(159). Optimal neuroprotection

is observed at ~10 mM, with concentrations below this threshold

insufficient to alleviate the metabolic crisis associated with

cerebral ischemia (160).

Similarly, perfusion of isolated mouse hearts with 20 mmol/l

L-lactate for only 15 min at reperfusion onset reduced infarct size

from 44.74 to 21.46% (161).

Clinical and preclinical studies suggest that lactate-enriched

solutions confer notable benefits in traumatic brain injury and

myocardial ischemia, including reductions in cognitive deficits,

improvements in cerebral blood flow and attenuation of reperfusion

injuries through mechanisms such as anti-inflammatory effects and

provision of alternative energy substrates (156,162). Moreover, lactate-enriched

solutions exhibit promising effects by producing a positive

inotropic response in both healthy individuals and patients with

acute heart failure, and they may further mitigate reperfusion

injuries following myocardial ischemia (163-165). Collectively, these findings

underscore the context-dependent duality of lactate: It acts as a

metabolic burden in chronic neurodegeneration and hypoxic

conditions; however, it serves as a therapeutic asset during

reperfusion when oxidative capacity is restored.

Sepsis

Elevated serum lactate levels serve as a prognostic

indicator in sepsis, with higher concentrations correlating with

increased mortality (166). A

mechanistic study has further implicated lactate in

ferroptosis-mediated lung injury during sepsis progression

(82). However, Besnier et

al (104) reported that

hypertonic sodium lactate solutions protected against cardiac

dysfunction, microcirculatory impairment and vascular leakage in

septic animals, while simultaneously attenuating inflammation and

promoting ketogenesis. This paradox, wherein lactate exhibits

context-dependent anti-inflammatory effects while promoting

ferroptosis, represents a significant challenge for its clinical

translation.

Targeting lactate therapy in tumor

Lactate production inhibition

Given its role in catalyzing the conversion of

pyruvate to lactate in glycolytic cancer cells and the observation

that LDHA deficiency results in only relatively mild symptoms, such

as exertional myopathy, LDHA represents a pivotal and safe

therapeutic target (150,167). Inhibitors, including gossypol

(AT-101) and its derivative FX-11, have demonstrated efficacy in

preclinical and early clinical studies, while other molecules, such

as galloflavin, oxamate, quinoline derivatives and

N-hydroxyindole-based compounds, demonstrate potential in

suppressing tumor progression (168-173). Despite these promising

findings, challenges, including isoform-specific expression (LDHA

vs. LDHB) and tumor metabolic plasticity, have limited their

broader application (174).

Targeting other metabolic enzymes, including hexokinase 2 and PDH

kinase 1, using agents such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose and

dichloroacetate (DCA), has demonstrated potential in reducing

lactate production and suppressing tumor growth (175,176).

Nanomedicines, owing to their nanoscale size and

multi-functional design, facilitate precise tumor targeting,

controlled drug release and enhanced bioavailability, thereby

offering innovative solutions to modulate tumor lactate metabolism

and amplify antitumor efficacy (150). For example, Zhang et al

(177) developed PMVL, a

lonidamine-loaded nanoplatform that enhances ferroptosis and immune

activation through dual inhibition of glycolysis and the PPP,

effectively reducing lactate production.

Lactate clearance enhancement

Lactate oxidase provides a direct strategy by

catalyzing lactate oxidation to pyruvate and

H2O2, reducing lactate levels, exacerbating

tumor hypoxia and increasing oxidative stress (150). This approach enhances antitumor

immune responses and activates hypoxia-sensitive prodrugs. A recent

study reported that an engineered biohybrid of DH5α Escherichia

coli with hypoxia-inducible lactate oxidase and iron-doped

zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 nanoparticles enables targeted

lactate depletion, immune activation and ferroptosis, significantly

inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis (178). However, systemic administration

of lactate oxidase carries the risk of off-target

H2O2 toxicity, underscoring the need for

tumor-specific delivery systems to improve safety and therapeutic

outcomes.

MCT-mediated transport inhibition

Inhibiting MCT-mediated lactate transport offers

another avenue to disrupt tumor metabolic symbiosis. MCT1

inhibition compels cancer cells to compete for glucose, thereby

inducing apoptosis in hypoxic cancer cells, while MCT4 inhibition

triggers intracellular acidosis under hypoxic conditions (142). Early inhibitors

(hydroxycinnamate and lonidamine) lacked isoform selectivity,

limiting their clinical potential (179,180). However, next-generation

inhibitors, such as AZD3965, AR-C155858, SR13800 and VB124,

demonstrate improved specificity, with AZD3965 progressing to phase

I trials (111,181-183). Additionally, CD147-targeting

therapies, including anti-CD147 antibodies, modulate MCT1/4 surface

expression, although off-target effects remain a concern (184). Certain statin drugs demonstrate

MCT4 inhibitory activity, with lipophilic statins exhibiting

greater potency compared with their hydrophilic counterparts

(185,186). Recently, Chen et al

(187) developed a folic

acid-decorated, manganese dioxide-coated mesoporous silica

nanoparticle to co-deliver fluvastatin sodium (MCT4 inhibitor) and

metformin, effectively targeting tumor lactate metabolism by

promoting lactate production and inhibiting lactate efflux, thereby

exacerbating intracellular acidosis and inducing cancer cell death.

This nanomedicine demonstrated enhanced antitumor efficacy,

suppressed tumor cell migration and suppressed metastasis by

disrupting the MCT4-mediated lactate shuttling in breast cancer

models. Targeting lactate metabolism has therefore emerged as a

promising therapeutic approach in oncology, and the aforementioned

strategies are summarized in Table

II.

| Table IITargeting lactate in tumor

therapeutic strategies. |

Table II

Targeting lactate in tumor

therapeutic strategies.

A, Targeting

lactate production

|

|---|

| Targeted drugs | Mechanism | Research

development | (Refs.) |

|---|

| AT-101 | Inhibits LDH | Phase Ⅱ clinical

trials | (168) |

| FX-11 | Inhibits LDHA | Preclinical

research | (169) |

| Oxamate | Inhibits LDHA | Preclinical

research | (170) |

| Galloflavin | Inhibits LDHA | Preclinical

research | (171) |

| LDHA short

interfering RNA | Suppresses LDHA

expression | Preclinical

research | (204) |

|

N-hydroxyindole-based compounds | Inhibits LDHA

activity | Preclinical

research | (172) |

| Quinoline

derivatives | Inhibits LDHA | Preclinical

research | (173) |

| 2-DG | Inhibits HK2 | Phase I clinical

trials | (175) |

| DCA | Inhibits PDK1 | Preclinical

research | (176) |

|

| B, Targeting

lactate transport |

|

| AZD3965 | Blocks MCT1 | Phase I clinical

trials | (181) |

| AR-C155858 | Blocks MCT1 | Preclinical

research | (182) |

| SR13800 | Blocks MCT1 | Preclinical

research | (183) |

| VB124 | Inhibits MCT4 | Preclinical

research | (111) |

| Fluvastatin

Sodium | Inhibits MCT4 | Preclinical

research | (185) |

| Lonidamine | Inhibits MCT

activity | Preclinical/early

clinical research | (179,180) |

|

| C, Enhancing

lactate depletion |

|

| Lactate

oxidase | Catalyzes lactate

oxidation | Preclinical

research | (205) |

| Biohybrid Materials

(e.g., iron-doped ZIF-8 nanoparticles) | Enables targeted

lactate depletion via lactate oxidase delivery | Animal models | (178) |

Targeting lactate therapy in

neurodegenerative diseases, IRI and sepsis

Therapeutic approaches aimed at modulating lactate

metabolism have demonstrated some potential in regulating

ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases, IRI and sepsis. However,

their effectiveness is critically context-dependent, varying

according to the metabolic characteristics of the specific tissues

and cell types (48,188,189). Approaches that suppress lactate

production, such as using PDK inhibitors (DCA and thiamine), have

been demonstrated to alleviate organ damage and mitigate

ferroptosis in sepsis by reversing the pathological Warburg

effect-like state, thereby improving mitochondrial function and

reducing ROS accumulation (189,190). Conversely, in myocardial IRI,

activation of LDHA has been found to phosphorylate and stabilize

the ferroptosis-suppressing enzyme GPX4 via its kinase activity,

suggesting that direct inhibition of LDHA could be detrimental

(48).

Enhancing lactate clearance has also emerged as a

promising strategy in sepsis, as increased lactate elimination has

been positively correlated with improved clinical outcomes in

patients with sepsis (191).

Beyond merely correcting metabolic acidosis, this approach also

restricts lactate-driven histone lactylation, which influences the

epigenetic regulation of TFRC expression and ferroptosis

susceptibility (73,192). By contrast, controlled

utilization of lactate, such as lactate post-conditioning, has been

demonstrated to exert neuroprotective effects in cerebral IRI

(156).