Post-translational modifications (PTMs) increase

proteomic functional diversity by covalently adding functional

groups, regulating the proteolytic cleavage of subunits or the

degradation of entire proteins. These include glycosylation,

ubiquitination, small ubiquitin-like modification, acetylation,

phosphorylation and palmitoylation, affecting nearly all aspects of

cell biology and pathology (1-5).

Lactate, once considered a waste product of glucose metabolism, has

been revealed in recent years as not only a key circulating energy

substrate, but also as a signaling molecule. Notably, it profoundly

regulates gene expression and cell fate through a novel PTM, lysine

lactylation (Kla) (6-10). In 2019, Zhang et al

(11) first reported histone Kla

in Nature, inaugurating a new era in lactate biology research. Kla

has rapidly emerged as a research hotspot in life sciences, with

its mechanisms and pathological significance providing

transformative insights in fields such as cancer, immunology and

neurological diseases (11-16). Kla involves the transfer of a

lactyl group to the amino group of lysine residues, a process

regulated by a series of enzymes and metabolites, including

lactate, 'writer' enzymes, 'reader' proteins and 'eraser' enzymes

(17). Lactate accumulation is

the core trigger for Kla, with its level being positively

associated with the degree of Kla modification (18,19). Under the action of 'writers',

L-lactyl-CoA derived from lactate is transferred to proteins,

initiating Kla. Erasers remove L-lactyl-CoA from proteins to

terminate Kla, while 'reader' proteins recognize Kla and transduce

signals to downstream targets (20-23).

The concept of ferroptosis was first proposed in

2012, referring to a unique form of programmed cell death triggered

by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation pathways. It participates in

multiple physiological and pathological processes and is prevalent

in various diseases (24-28).

In recent years, significant progress has been made in

understanding the mechanisms of ferroptosis, including iron

homeostasis imbalance, lipid peroxidation and the disruption of

antioxidant systems (29-33).

Furthermore, numerous factors regulate cellular sensitivity to

ferroptosis under pathological conditions, thereby influencing

disease progression (27).

System xCT is an antiporter, with solute carrier family (SLC)7A11

as a key component, responsible for transporting cysteine and

glutamate. It increases cellular cysteine uptake, which is

converted to glutathione (GSH) under the action of thioredoxin

reductase 1. Glutathione (GSH) peroxidase 4 (GPX4) relies on GSH as

a substrate to enhance its activity, promoting the conversion of

phospholipid hydroperoxides (PL-OOH) to lipid alcohols. Thus,

system xCT prevents ferroptosis by reducing PL-OOH accumulation.

Erastin and RAS-selective lethal 3 (RSL3, a ferroptosis inducer),

as inhibitors of system xCT and GPX4, respectively, promote

ferroptosis (34-36). An imbalance in iron homeostasis

is another classical pathway in ferroptosis, primarily regulated by

a network involving transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1), iron regulatory

protein (IRP)1 and IRP2, affecting cellular iron uptake, storage

and release (30,37,38). Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

generation and phospholipid peroxidation require numerous metabolic

enzymes, with iron acting as their catalyst and essential element.

Iron-dependent Fenton reactions rapidly amplify PL-OOH and generate

various reactive radicals, inducing ferroptosis in cancer cells

(39-41). Unrestricted lipid peroxidation is

a hallmark of ferroptosis. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family

member 4 (ACSL4) is a key enzyme converting polyunsaturated fatty

acids (PUFAs) to phospholipids (PUFA-PEs). PUFA-PEs promote

intracellular lipid peroxide accumulation under the action of

various enzymes. Phospholipids rich in PUFAs in cell membranes and

phospholipid peroxidation are considered the direct executors of

ferroptosis (42,43).

Kla was initially discovered as a process modifying

histone lysine residues, thereby altering binding to target gene

promoters and activating transcription to exert biological effects.

Subsequently, it expanded to non-histone lactylation. In

ferroptosis, lactylation primarily involves Kla on histones H3 and

H4, binding to promoter regions of target genes to alter

transcriptional activity. On the other hand, Kla can directly

modify non-histone lysine residues to mediate ferroptosis,

demonstrating the multifaceted nature of Kla in regulating

ferroptosis. Furthermore, Kla is subject to a complex interplay of

upstream signals. A key determinant involves the participating

lactyltransferases ('writers') and delactylases.

EP300/p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP) are well-established

'writers' of histone lactylation (50-52), while other transferases such as

lysine acetyltransferase (KAT), acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2

(ACAT2) and N-alpha-acetyltransferase 10 (NAA10) are emerging as

modifiers of non-histone substrates (53-55). By contrast, histone deacetylase 1

(HDAC1) and HDAC3 have been identified as possessing delactylase

activity (56,57). Their substrate specificity is

influenced by expression patterns, spatial localization and

interactions with specific factors in different cellular

microenvironments. Additionally, metabolic status serves as a

fundamental upstream signal. Lactate accumulation can directly

drive lactyltransferase-catalyzed lactylation (55,58,59). Local pH in microenvironments,

such as tumors, can also influence enzyme kinetics and substrate

accessibility (60). Finally,

crosstalk with other PTMs creates a regulatory network; for

instance, prior acetylation or phosphorylation at or near lysine

residues may competitively inhibit or cooperatively promote

subsequent lactylation (56).

This intricate network, comprising writers, metabolic signals and

competitive PTMs, ultimately determines whether lactylation at

specific sites on given proteins promotes or suppresses ferroptosis

under particular pathophysiological conditions.

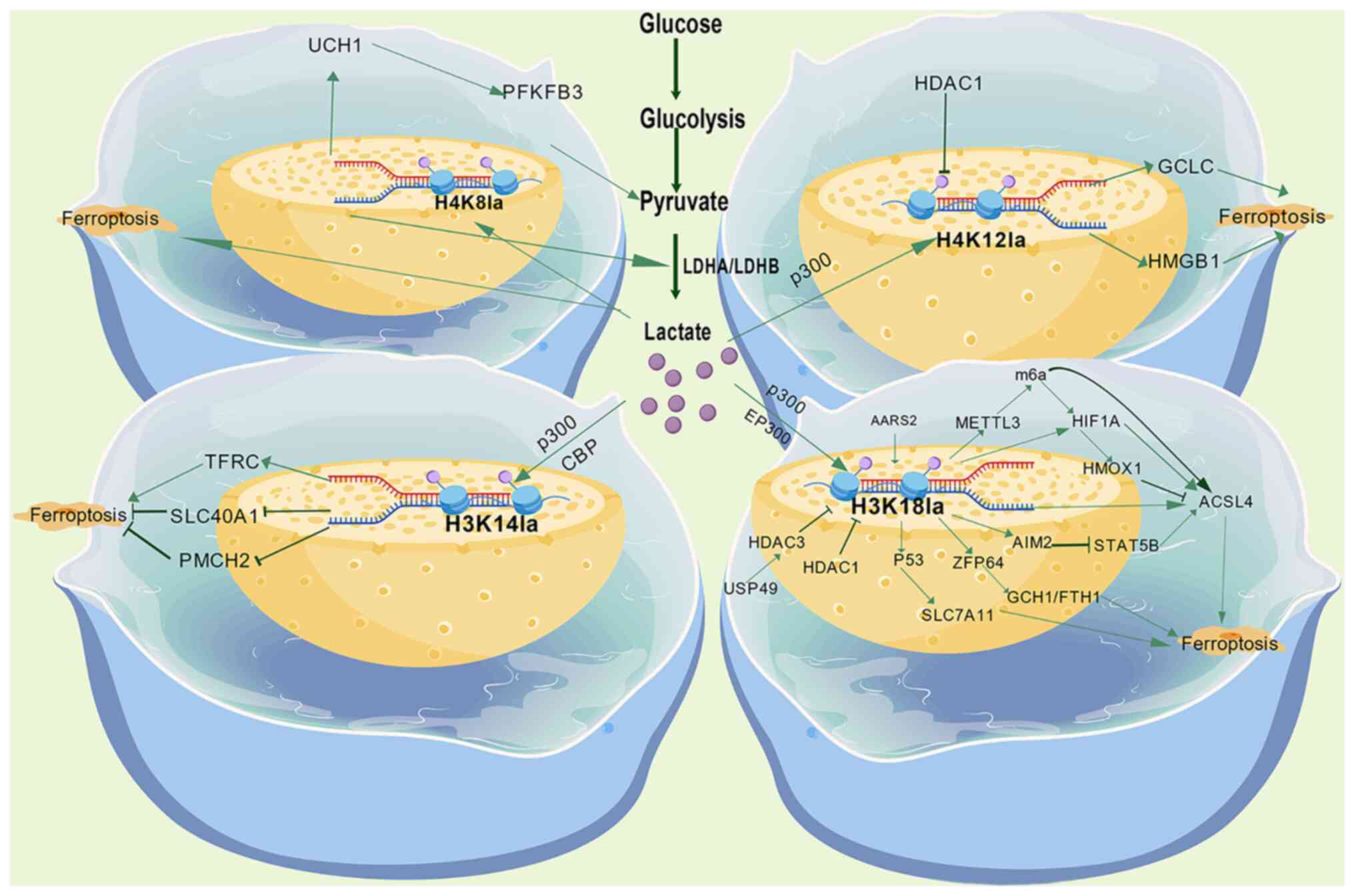

The nucleosome, consisting of a core histone octamer

(two each of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) and wrapped DNA, is the

fundamental unit of chromatin. Typically, PTMs are key mechanisms

dynamically regulating chromatin structure and DNA templating

processes such as gene transcription (61,62). Lactylation modifications at

histone H3 lysine 18 (H3K18la), lysine 14 (H3K14la) and histone H4

lysine 8 (H4K8la), and lysine 12 (H4K12la) alter histone function

by the covalent addition of a lactyl group, mediating epigenetic

reprogramming to regulate ferroptosis. The effect is dependent on

the modification site, target gene and disease microenvironment

(Fig. 1).

H3K18la is the most extensively studied histone

lactylation site in ferroptosis. One of its core regulatory targets

is the key fatty acid metabolism enzyme, ACSL4; elevated ACSL4

protein levels can induce transient mitochondrial activation, ROS

accumulation and lipid peroxidation, ultimately driving

ferroptosis. Notably, H3K18la plays context-dependent dual roles in

regulating ACSL4. However, despite differing regulatory directions

in different diseases, the outcome consistently promotes disease

progression. In inflammatory diseases, lactate accumulation

upregulates ACSL4 via H3K18la, promoting ferroptosis-mediated

disease progression. The mechanisms involved include H3K18la

enrichment in promoter regions, which enhances hypoxia-inducible

factor (HIF)1A transcriptional activity, thereby transcriptionally

activating ACSL4. Additionally, H3K18la can directly bind the ACSL4

gene promoter region to increase transcription (53,54). Simultaneously, in sepsis-mediated

lung injury, H3K18la upregulates methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3)

by enhancing its promoter activity, increasing ACSL4 mRNA stability

via N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA methylation

modification and reader protein YTH domain-containing protein 1

dependency, leading to an elevated protein expression of ACSL4

(63). Conversely, in cancer,

H3K18la suppresses ACSL4 expression, enhancing ferroptosis

resistance and promoting disease progression. In endometriosis,

H3K18la binds the promoter of methyltransferase METTL3, promoting

its expression, which subsequently stabilizes HIF1A mRNA via m6ARNA

methylation and upregulates heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1), ultimately

downregulating ACSL4 (64).

H3K18la binding to the promoter region significantly enhances

absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) transcription, downregulating ACSL4

expression by promoting ubiquitin-mediated degradation of

transcription factor STAT5B. This leads to decreased cellular lipid

peroxidation, reduced GSH depletion and limited ferrous iron

(Fe2+) accumulation, ultimately inhibiting ferroptosis

(65). Furthermore, H3K18la can

influence ferroptosis by regulating other key genes. H3K18la

binding promotes transcription of zinc finger protein (ZFP)64,

which directly binds the promoter regions of ferroptosis-related

genes GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) and ferritin heavy chain 1

(FTH1), promoting their transcription. GCH1 reduces ROS

accumulation by inhibiting lipid peroxidation, while FTH1 reduces

iron-dependent lipid peroxidation triggered by sequestering

intracellular free Fe2; both synergistically inhibit

ferroptosis (60). The reduced

expression of H3K18la specifically decreases ferroptosis driver

genes [activating transcription factor (ATF3), ATF4 and ChaC

glutathione specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1)],

thereby inhibiting ferroptosis (66). H3K18la enrichment at the promoter

region of the key iron-sulfur cluster synthesis enzyme NSF1

cysteine desulfurase (NFS1) enhances its transcription. NFS1

inhibits lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by maintaining iron ion

homeostasis (67).

H3K14la represents lactylation at another H3 site,

K14, and is a clear signal promoting ferroptosis. H3K14la

transcriptionally activates transferrin receptor (TFRC) and

suppresses ferroportin SLC40A1 expression by binding the promoter

regions of ferroptosis-related genes, leading to intracellular iron

overload, lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial damage, ultimately

triggering endothelial cell ferroptosis (52).

H4K8la represents lactylation at histone H4 K8. Its

core mechanism involves tight coupling with glycolysis.

6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), a

key glycolytic rate-limiting enzyme, is stabilized by

deubiquitinase ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1), cleaving

its K48-linked ubiquitin chains, promoting lactate production.

Increased lactate levels further induce H4K8la modification,

forming a positive feedback loop that activates UCHL1 and

glycolytic-related genes [e.g., LDHA, pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM), MYC

and Yes-associated protein 1], amplifying the inhibition of

ferroptosis (68).

H4K12la, catalyzed by lactyltransferase p300 at

histone H4 lysine 12, is enriched at the glutamate-cysteine ligase

catalytic subunit (GCLC) promoter region, enhancing glutathione

synthesis, inhibiting lipid peroxide accumulation and ultimately

blocking the ferroptosis pathway (51).

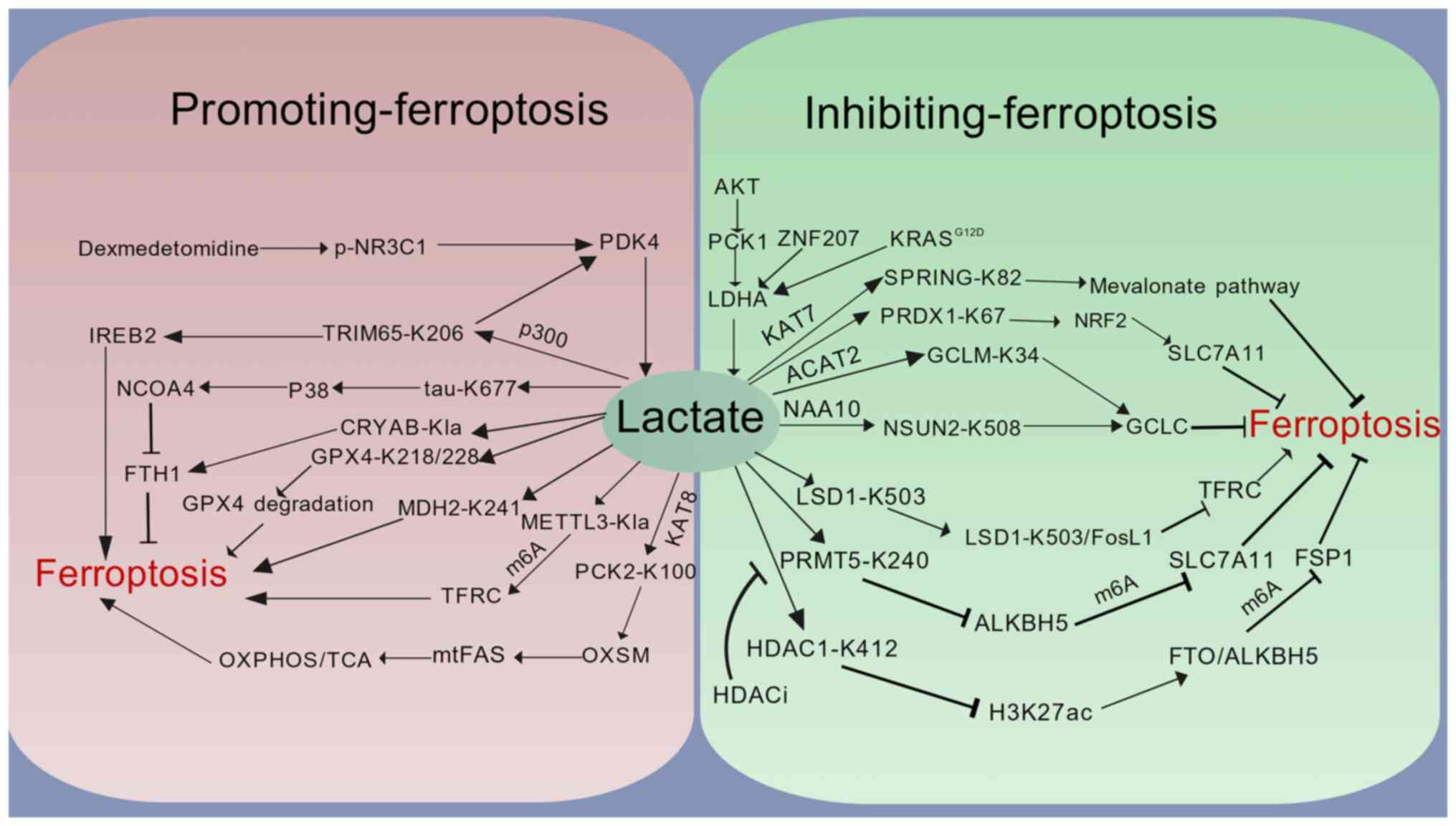

Beyond histones, Kla precisely regulates cell fate

by directly modifying key ferroptosis enzymes. This regulation

operates through three core mechanisms: By directly targeting key

ferroptosis effectors, remodeling cellular metabolic pathways and

reprogramming the epigenetic landscape, collectively constituting a

dynamic hub for ferroptosis regulation in response to metabolic

stress (Fig. 2).

At the level of the direct targeting of key

molecules, lactylation acts directly on core ferroptosis proteins,

altering their stability or functional activity to regulate

cellular antioxidant capacity and iron metabolism, thereby

influencing ferroptosis progression. GPX4 is a key inhibitor of

oxidative stress-induced ferroptosis. Lactate-driven lactylation at

lysines 218 and 228 (K218/K228) of GPX4 significantly reduces its

protein stability, impairing its ability to clear lipid peroxides

and enhancing ferroptosis sensitivity (69,70). FTH1 alters intracellular iron

homeostasis by influencing iron storage and release, and iron

imbalance is a major trigger for ferroptosis (71,72). Tau protein lactylation at K677

upregulates nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) expression by

activating p38 phosphorylation signaling, subsequently lowering

FTH1 levels and inducing ferroptosis (73). Conversely, alpha-crystallin B

chain (CRYAB), via lactylation, directly binds and stabilizes the

FTH1 protein to enhance ferroptosis resistance (74).

Metabolic reprogramming constitutes the second major

mechanism by which lactylation regulates ferroptosis, driving lipid

peroxidation by intervening in mitochondrial energy metabolism and

lipid synthesis pathways. The lactylation of the mitochondrial

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 (PCK2) protein at K100

competitively inhibits E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin-mediated

ubiquitination and degradation of mitochondrial 3-oxoacyl-ACP

synthase (OXSM), the rate-limiting enzyme of mitochondrial fatty

acid synthesis (mtFAS). This promotes mtFAS pathway metabolic

reprogramming, exacerbating ferroptosis (75). The inhibition of lactylation at

K241 of malate dehydrogenase 2 (MDH2) maintains MDH2 catalytic

activity, sustaining the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and

blocking ferroptosis (76).

Lactylation at K82 of sterol regulatory element-binding protein

(SREBP) pathway regulator in Golgi (SPRING) protein activates the

SREBP2-driven mevalonate pathway, ultimately conferring ferroptosis

resistance to cancer cells through enhanced antioxidant capacity

(53).

Epigenetic reprogramming forms the third pillar of

lactylation-mediated ferroptosis regulation. It dynamically affects

the transcription and mRNA stability of ferroptosis-related genes

by modifying epigenetic regulators, such as RNA methylation enzymes

and histone modifiers. In the epitranscriptome, m6A methylation

bidirectionally regulates ferroptosis by increasing mRNA stability.

On the one hand, lactylation of the m6A writer, METTL3, increases

m6A methylation on TFRC mRNA, promoting TFRC mRNA stability,

accelerating cellular iron uptake and inducing ferroptosis

(77). De-lactylation at K412 of

HDAC1 activates the transcription of the m6A erasers, fat mass and

obesity-associated protein (FTO) and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5),

suppressing m6A modification on ferroptosis suppressor protein 1

(FSP1) mRNA and accelerating its degradation, thereby enhancing

ferroptosis sensitivity (56).

Conversely, lactylation at K240 of protein arginine

methyltransferase 5 inhibits the transcription of the m6A eraser

ALKBH5, leading to increased m6A modification and enhanced

stability of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) mRNA,

conferring resistance to ferroptosis (78). m5C methylation is another way to

regulate mRNA stability. Lactylation at K508 of NOP2/Sun RNA

methyltransferase 2 (NSUN2) catalyzes m5C formation, maintaining

GCLC mRNA stability, promoting GCLC-dependent glutathione synthesis

and avoiding ferroptosis in cancer cells within the acidic tumor

microenvironment (55).

Furthermore, in epigenomics, lactylation can regulate gene

transcription through key proteins beyond histones. For instance,

lactylation at K503 of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1)

enhances the formation of a stable complex with transcription

factor FosL1, specifically enriching at the ferroportin receptor

TFRC promoter region to suppress TFRC transcription, reduce iron

uptake and enhance ferroptosis resistance (79).

As an emerging metabolic-epigenetic regulatory

mechanism, Kla plays a core role in reshaping cell fate by

targeting ferroptosis in inflammatory injury, neurodegenerative

diseases, cancer and I/R injury, altering disease outcomes through

actions on key targets. This section integrates the latest research

progress on Kla-mediated ferroptosis in diseases, discusses the

underlying pathological mechanisms and explores translational

therapeutic potential (Table

I).

Lactylation drives pro-ferroptotic pathways

promoting disease progression. Previous studies have suggested that

the inhibition of ferroptosis holds broad prospects for the

prevention and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Lactate, the end

product of glycolysis, accumulates in the extracellular

environment, and the resulting acidosis is a hallmark of

inflammatory diseases. Lactate in the microenvironment promotes

inflammatory disease progression via Kla-mediated ferroptosis,

rendering the inhibition of glycolysis and ferroptosis a promising

therapeutic approach (7,80-82). Sepsis is a major cause of

mortality in infectious diseases, and among organs susceptible to

its harmful effects, the lungs are most frequently affected

(83,84). Research indicates that

lactylation-mediated ferroptosis promotes sepsis-associated lung

injury. In sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome,

H3K14la in pulmonary vascular endothelial cells transcriptionally

activates TFRC and suppresses ferroportin SLC40A1, leading to iron

overload and mitochondrial-damaging ferroptosis, promoting disease

progression. Oxamate, an LDHA inhibitor reducing lactate

production, lowers H3K14la modification levels, subsequently

downregulating TFRC transcription, reducing iron uptake and

alleviating endothelial cell ferroptosis (52). Sepsis-induced lung injury further

reveals the core role of the H3K18la-METTL3-ACSL4 axis, inducing

mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation-dependent ferroptosis; the

METTL3 inhibitor, STM2457, effectively blocks this pathway

(63). Severe acute pancreatitis

(SAP) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are non-infectious

inflammatory diseases. In SAP, aberrant glycolysis causes lactate

accumulation, enhancing HIF1A promoter activity via histone H3K18

lactylation, which transcriptionally activates the

ACSL4/lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3/arachidonate

lipoxygenase pathway, inducing pancreatic acinar cell ferroptosis

and ultimately exacerbating organ damage. As previously

demonstrated, combining a glycolysis inhibitor with a ferroptosis

inducer (Ferrostatin-1) significantly alleviates organ damage

(85). Previous research has

also confirmed that Qing Xia Jie Yi Formula granules alleviate

acute pancreatitis by inhibiting the glycolysis pathway (86). In NASH, irisin (TEC) recruits

HDAC1 via tRF-31R9J to clear H3K18la, suppressing ferroptosis

driver genes such as ATF3/CHAC1, protecting hepatocytes from

ferroptosis and providing a novel intervention target for metabolic

liver disease (66). These

findings establish the 'lactylation-pro-ferroptosis gene

activation' axis as a hub in the inflammatory cascade. The

inhibition of glycolysis and lactylation may thus be a strategy for

the treatment of infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Ferroptosis is a critical factor in degenerative

diseases and its pharmacological inhibition is a therapeutic target

for these conditions (87-89). Lactylation is a novel mechanism

regulating ferroptosis, and modulating this process provides new

hope for treatment. In degenerative diseases, one disease-promoting

mechanism involves lactylation-mediated iron overload to trigger

ferroptosis by regulating key genes in iron homeostasis. Research

on Alzheimer's disease has found that tau protein de-lactylation

(K677R mutation) inhibits p38 phosphorylation, downregulates NCOA4

and reduces ferritinophagy-dependent free iron release, thereby

alleviating neuronal ferroptosis and improving cognitive function

(73). Breakthrough research in

osteoporosis (OP) revealed significantly downregulated CRYAB/FTH1

expression in patients with OP. CRYAB de-lactylation promotes

ferroptosis in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and

inhibits osteogenic differentiation (74). These studies highlight the impact

of lactylation on cell survival and disease progression via iron

homeostasis regulation. Promoting ACSL4 expression via lactylation

is another key mechanism regulating ferroptosis in degenerative

diseases. LDHB promotes H3K18la and ACSL4 expression by increasing

microenvironment lactylation levels, inducing chondrocyte

ferroptosis and further promoting osteoarthritis development;

inhibiting glycolysis alleviates osteoarthritis (90). During inflammation-induced human

intervertebral disc degeneration, the shift from aerobic to

anaerobic metabolism produces lactate that not only promotes

H3K18la and ACSL4 transcription, but also increases ACSL4

lactylation at K412. Concurrently, lactate reduces the expression

of sirtuin 3 (a Kla eraser), suppressing the clearance of ACSL4

lactylation. These factors increase cellular ferroptosis and

promote disease progression (91).

Ferroptosis is recognized as a cause of reperfusion

injury and organ failure, and the development of ferroptosis

modulators provides novel opportunities for the treatment of I/R

injury (92). Lactate

accumulation is a hallmark of ischemia, and lactate-driven

ferroptosis is often a key factor in disease progression. The

inhibition of lactylation-mediated ferroptosis has been shown to

exert positive effects in various studies on diseases. Research

indicates that lactate accumulation upregulates METTL3 expression

via EP300-mediated H3K18la, subsequently accelerating SLC7A11 mRNA

degradation in an m6A modification- and YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA

binding protein F2-dependent manner, ultimately inducing macrophage

ferroptosis and promoting coronary heart disease progression

(50). In myocardial I/R,

enhanced glycolysis and lactate accumulation promote the

lactylation of GPX4 at K218 and K228, destabilizing GPX4 and

enhancing cardiomyocyte sensitivity to ferroptosis, exacerbating

injury (70). Dexmedetomidine

provides a novel cardioprotective strategy by inhibiting lactate

production, blocking MDH2 K241 lactylation, restoring TCA cycle

function and upregulating GPX4 (76). In intestinal ischemia,

mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2 epigenetically upregulates

ACSL4 transcriptional activity by enhancing H3K18la, driving lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis to worsen intestinal injury (93). In mice with intestinal I/R injury

and intestinal epithelial cells subjected to hypoxia-reoxygenation,

the nuclear translocation of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) dimers

promotes the expression of glycolytic key enzymes (GLUT1/enolase

1/LDHA) and lactate accumulation. Lactate drives histone modifier

p300 to specifically catalyze H4K12la, enriching at the promoter

region to significantly enhance high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)

transcription. This disrupts the ferroptosis regulatory balance

(ACSL4↑/GPX4↓), promoting intestinal damage. Targeting PKM2

dimerization (ML265) or HMGB1 (Gly-cyrrhizin) blocks this pathway

and alleviates tissue injury (59). Research on liver I/R has revealed

that lactate activates PCK2 K100 lactylation, stabilizing

mitochondrial fatty acid synthase OXSM, and promoting lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis. KAT8 inhibitors or adeno-associated

virus-short hairpin RNA targeting PCK2 significantly reduce liver

injury (75). Intracerebral

hemorrhage causes lactate accumulation and an acidic

microenvironment within neurons. Lactate, mediated by histone

acetyltransferases p300/CBP, specifically promotes lactylation at

the H3K14 site. H3K14la functions as an epigenetic mark, directly

inhibiting the transcription of the calcium pump plasma membrane

Ca2+ ATPase 2 gene, hindering intracellular calcium

efflux, causing calcium overload and exacerbating neuronal

ferroptosis. The elevated lactate microenvironment induces the

lactylation of METTL3 protein, increasing m6A methylation on TFRC

mRNA, accelerating cellular iron uptake, leading to Fe2+

accumulation, elevated ROS and malondialdehyde levels, and

ultimately inducing ferroptosis (77,94). In diabetic nephropathy, a

high-lactate microenvironment inhibits the E3 ubiquitin ligase

activity of tripartite motif-containing protein 65 (TRIM65) via

p300-mediated lactylation at K206, preventing the degradation of

its two key substrates, glycolytic kinase pyruvate dehydrogenase

kinase 4 and iron regulatory protein iron-responsive

element-binding protein 2. This promotes glycolytic flux and

induces iron overload and lipid peroxidation, activating

ferroptosis. Targeting the TRIM65-K206 lactylation site or reducing

lactate production via sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors

restores the dual inhibition of ferroptosis and glycolysis by

TRIM65 (58). However, lactate

accumulation is not always detrimental to tissue injury. In spinal

cord injury, deubiquitinase UCHL1 stabilizes the key glycolytic

enzyme PFKFB3 by cleaving its K48-linked ubiquitin chains,

enhancing glycolysis and lactate production in astrocytes. The

produced lactate serves as an energy substrate for neurons and

inhibits neuronal ferroptosis. Furthermore, elevated lactate levels

induce H4K8la in astrocytes, promoting UCHL1 and glycolytic gene

(e.g., PKM and LDHB) transcription, forming a positive feedback

loop that amplifies the protective effect (62).

Under both hypoxic and aerobic conditions, tumor

cells prefer glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation as their

primary energy source to meet rapid growth and proliferation

demands, resulting in high glycolytic flux, massive lactate

production and an acidic tumor microenvironment (94-98). Lactate accumulation in the tumor

microenvironment promotes tumor cell invasion, metastasis and drug

resistance by facilitating lactylation (12,79,99-101). Lactylation regulates key

ferroptosis molecules through diverse targets, serving not only as

a survival strategy for tumor cells to adapt to the

microenvironment, but also as a crucial mechanism to evade

therapeutic pressure.

Lactate is considered the initiator of

lactylation-regulated ferroptosis. Therefore, reducing lactate

production by inhibiting key glycolytic enzymes can suppress tumor

growth. Aberrant glycolysis in lung cancer cells causes lactate

accumulation, inducing histone H3K18 lactylation at the AIM2 gene

promoter region, significantly enhancing AIM2 transcription. This

promotes the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the transcription

factor STAT5B, downregulating its downstream target gene ACSL4 and

ultimately inhibiting ferroptosis. The natural compound Shikonin

can target and inhibit PKM2 (a key glycolytic enzyme) and AIM2

expression, reversing histone lactylation-mediated AIM2 activation

(65). Cancer-associated

fibroblasts enhance histone H3K18 lactylation by secreting lactate,

activating ZFP64, which promotes GCH1 and FTH1 transcription. GCH1

reduces ROS accumulation by inhibiting lipid peroxidation, and FTH1

reduces iron-dependent lipid peroxidation triggered by sequestering

free Fe2+; both synergistically inhibit ferroptosis,

enhancing tumor cell drug resistance. The lactate production

inhibitor Oxamate can reverse this resistant phenotype (60). ZNF207 increases lactate levels by

upregulating LDHA expression, inducing lactylation at lysine 67

(K67 lactylation) of antioxidant protein peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1).

Lactylated PRDX1 binds the transcription factor nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) and promotes its nuclear

translocation, activating the NRF2 antioxidant pathway and

upregulating ferroptosis inhibitor genes, such as SLC7A11, GPX4 and

HMOX1, ultimately causing drug resistance in hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) cells. Knockdown of ZNF207, blocking PRDX1

lactylation at K67, or inhibition of NRF2 activity, restore

regorafenib sensitivity and induce ferroptosis (102).

The inhibition of the lactylation of key ferroptosis

proteins is considered an effective anti-cancer strategy, as it can

promote ferroptosis and suppress tumor growth. Lactate maintains

GCLC mRNA stability via the NAA10-mediated lactylation of NSUN2

K508, evading cancer cell ferroptosis in the acidic tumor

microenvironment (55). The

re-activation of glycolysis causes lactate re-accumulation,

inducing lactylation at lysine 503 of LSD1, blocking

TRIM21-mediated LSD1 degradation and altering its genomic

localization. The inhibition of H3K4me2 modification suppresses

TFRC transcription, reducing cellular iron uptake, inhibiting

ferroptosis and promoting the survival of resistant cells.

Inhibition of LSD1 activates ferroptosis and effectively suppresses

tumor growth (79). HDAC

inhibitors reduce the lactylation of HDAC1 at K412, which in turn

activates the transcription of the m6A demethylases, FTO and ALKBH5

via H3K27ac. This reduces m6A modification on ferroptosis

suppressor protein FSP1 mRNA, accelerating its degradation and

ultimately enhancing lipid peroxide accumulation and sensitivity to

ferroptosis. Vorinostat (SAHA) and Trichostatin A (TSA) both

significantly reduce HDAC1 K412 lactylation and inhibit tumor

growth (56). As previously

demonstrated, following incomplete microwave ablation, a sublethal

temperature zone forms in the residual tumor area, triggering

enhanced glycolysis and lactate accumulation in HCC cells,

specifically upregulating H3K18la. This enhances NFS1

transcription, suppressing lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by

maintaining iron ion homeostasis, thereby enhancing the metastatic

capacity of HCC cells. NFS1 deletion combined with oxaliplatin

(OXA) synergistically inhibits HCC metastasis and overcomes

resistance to OXA (67).

Evodiamine inhibits monocarboxylate transporter 4 (MCT4) function

to block lactate signaling, directly reducing H3K18la to restore

Semaphorin 3A transcription and suppress programmed cell death

ligand 1. It also downregulates GPX4, inducing ferroptosis, and

ultimately inhibiting tumor growth (103).

Lactate enhances the resistance of tumor cells to

ferroptosis through lactyltransferase-mediated lactylation.

Therefore, the inhibition of lactyltransferase activity to promote

ferroptosis is a potential strategy for cancer therapy. Driven by

AKT hyperactivation, phosphorylated PCK1 interacts with LDHA,

enhancing glycolytic activity and lactate production, promoting the

KAT7-mediated lactylation of SPRING at K82. This subsequently

activates the SREBP2-driven mevalonate pathway, promoting

resistance to ferroptosis (53).

Lactyltransferase p300 catalyzes H4K12la, which transcriptionally

activates GCLC, enhancing glutathione synthesis, inhibiting lipid

peroxide accumulation and ultimately blocking the ferroptosis

pathway. The inhibition of p300, LDHA or GCLC enhances sensitivity

to chemotherapy (51). KRAS G12D

mutation enhances LDHA phosphorylation via the MEK/ERK pathway,

promoting glycolysis and lactate generation. This induces the

ACAT2-mediated lactylation of glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier

subunit (GCLM) at K34, elevating GCL activity, increasing GSH

synthesis and conferring ferroptosis resistance to KRASG 12D-mutant

cancer cells. Inhibiting ACAT2 or mutating GCLM-K34R restores the

sensitivity of cancer cells to ferroptosis inducers (e.g.,

erastin/RSL3) and significantly suppresses tumor growth (54).

As an emerging epigenetic regulatory mechanism, the

precise detection of lactylation is crucial for elucidating its

functions in physiological and pathological processes. The

detection of lactylation primarily relies on mass spectrometry and

specific antibody-based detection. Mass spectrometry, particularly

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, serves as the core

method, enabling the highly sensitive identification of specific

sites and quantification of modification levels. This method

involves digesting protein samples with proteases to generate a

mixture of peptides. These peptides are then separated by liquid

chromatography and are subjected to precise mass detection and

sequence analysis via mass spectrometry. This allows for the

unbiased identification of specific lactylation sites and their

absolute or relative quantification. However, challenges include

potential misidentification due to the similar chemical properties

of lactylation and acetylation, and the need for higher-resolution

instruments due to low modification abundance (11,100,104-107). Specific antibody-based

detection utilizes antibodies targeting specific modification

sites. Techniques such as western blot analysis for quantification,

immunofluorescence for observing intranuclear distribution and

co-immunoprecipitation for exploring protein interactions enable

the in situ and intuitive observation of the subcellular

localization and tissue distribution characteristics of

lactylation. This approach provides advantages, such as operational

simplicity and high sensitivity; however, it is associated with

risks of non-specific binding and the limited availability of

commercial antibodies (108-112). The comprehensive application of

these methods provides key technical support for elucidating the

role of lactylation in tumorigenesis and development, laying the

foundation for its clinical translation.

The intricate interplay between lactylation and

ferroptosis has positioned the Kla-ferroptosis axis as an

attractive novel therapeutic frontier across a broad spectrum of

human diseases. Although basic research continues to uncover the

enzymatic regulation, site-specific functions and context-dependent

outcomes of this axis, its translational potential demands focused

exploration. Looking ahead, clinical development targeting this

axis may proceed through the following strategies: First, directly

targeting lactylation regulatory mechanisms holds significant

promise. Developing inhibitors of specific lactyltransferases

('writers') or activators of delactylases ('erasers') could enable

precise control over pro-ferroptotic or anti-ferroptotic

lactylation events (17,20). For example, p300/CBP inhibitors

(e.g., SGC-CBP30, A-485) and KAT8 inhibitors (KAT8-IN-1/MC4033) may

disrupt lactylation that drives disease progression (51,75). Conversely, deacetylase inhibitors

(SAHA, TSA and TEC) can modulate lactylation and sensitize cells to

ferroptosis, highlighting the therapeutic feasibility of targeting

'erasers' (56,66). Second, regulating lactate

metabolism provides a broader, yet effective strategy with which to

indirectly modulate the entire Kla-ferroptosis axis (7,101). Inhibiting key glycolytic

enzymes (Oxamate, 2-DG, Shikonin and Simvastatin) or disrupting

lactate transport via monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), e.g.,

using Syrosingopine to inhibit MCT4, can effectively deplete

lactate, the fundamental driver of lactylation (60,65,103). This approach is particularly

attractive in tumors and inflammatory microenvironments

characterized by a high glycolytic flux (12,82).

To date, to the best of our knowledge, no clinical

studies have been designed with 'direct regulation of protein

lactylation' as the primary endpoint. However, some drugs targeting

lactylation-regulating enzymes and lactate metabolism-related

proteins have entered clinical trials. Among them, the most

advanced is CCS1477 (inobrodib). It is a highly effective p300/CBP

bromodomain inhibitor. Its phase I/IIa clinical trials in advanced

solid tumors and hematological malignancies have been initiated

(NCT04068597) (113,114). In patients with metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), CCS1477 monotherapy

was shown to reduce the expression of key oncogenic protein MYC and

proliferation marker Ki-67 in tumor tissues (113). In trials for

relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma,

the drug demonstrated the ability to induce leukemia cell

differentiation and significantly reduce myeloma-related

serum/urine biomarkers. Notably, in the hematological malignancy

cohort, about one-third of heavily pretreated patients responded to

CCS1477 monotherapy. Some of these patients had progression-free

survival exceeding 12 months (114). Another potent p300/CBP

bromodomain inhibitor, FT-7051, has also shown early clinical

progress. Early results from an open-label phase I trial in

patients with mCRPC indicated that its monotherapy achieved the

effective exposure threshold predicted by

pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models. However, safety concerns

exist. Approximately 80% of patients experienced mild to moderate

treatment-related adverse events, including hyperglycemia (115). NEO2734 (EP31670) is a dual

bromodomain inhibitor targeting both p300/CBP and bromodomain and

extra-terminal motif proteins. Due to its broader mechanism, it has

entered a phase I trial. This trial aims to treat patients with

advanced cancer, including those with metastatic nuclear protein in

testis midline carcinoma and refractory mCRPC (NCT05488548); the

results are not yet available. Furthermore, drug development

targeting HDAC has advanced significantly. Currently, five HDAC

inhibitors are approved for clinical use in hematological

malignancies. These include Vorinostat and Romidepsin for cutaneous

T-cell lymphoma, Belinostat for peripheral T-cell lymphoma,

Panobinostat for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma and

Tucidinostat for peripheral T-cell lymphoma (116-119). In solid tumors, HDAC inhibitor

monotherapy shows limited efficacy. However, combination strategies

with other agents hold promise. For example, the selective HDAC

inhibitors Tucidinostat and Entinostat combined with endocrine

therapy (e.g., Exemestane) improved progression-free survival and

the objective response rate in hormone receptor-positive breast

cancer trials (120,121). Combining HDAC inhibitors with

immune checkpoint inhibitors also demonstrated synergistic

anti-tumor activity in various solid tumors, such as melanoma and

colorectal cancer (122,123).

Challenges and failures exist in this field. Some trial results did

not meet primary endpoints. For instance, Mocetinostat monotherapy

was ineffective in urothelial carcinoma. Entinostat combined with

Atezolizumab did not significantly prolong progression-free

survival in advanced triple-negative breast cancer (124). Additionally, HDAC inhibitor

applications are expanding into non-oncological areas. Romidepsin

is being explored for HIV latency reversal (125), and Givinostat and Ricolinostat

show potential in clinical studies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

and diabetic neuropathic pain, respectively (126,127). Overall, further development of

HDAC inhibitors in solid tumors still faces toxicity issues. Future

efforts should focus on optimizing combination strategies and

developing more subtype-selective inhibitors to enhance their

therapeutic value.

Research on lactate metabolism-related proteins

remains limited. Glycolysis is the primary source of lactate.

2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) is a broad-spectrum glycolysis inhibitor.

Intranasal administration of 3.5% 2-DG was safe and well-tolerated

in healthy volunteers. Systemic exposure was almost negligible.

Local nasal concentrations reached effective anti-viral levels

in vitro (NCT05314933) (128). LDHA is a key enzyme for lactate

production in glycolysis. Its inhibitors show extensive

pre-clinical evidence across multiple cancers. They can inhibit

glycolysis, reduce lactate and acidification, suppress invasion and

metastasis, and enhance chemo/radiotherapy sensitivity. However,

most findings are still at the pre-clinical stage (129). For lactate transmembrane

transport inhibition, only one MCT-targeting drug, AZD3965 (an MCT1

inhibitor), has entered clinical trials. It aims to evaluate safety

and preliminary efficacy in patients with advanced cancer

(NCT01791595). Preliminary results indicate manageable safety

(130-132). Specific MCT4 inhibitors are

mostly in pre-clinical development. However, dual inhibition or

combination with LDH/GLUT inhibitors appears more promising. This

approach may sustainably reduce lactate supply, improve the acidic

microenvironment and restore sensitivity to ferroptosis (133).

In summary, clinical interventions directly

regulating lactylation are still emerging. However, drugs targeting

its key nodes have established a considerable clinical and

translational foundation. Based on metabolic resistance mechanisms

and solid tumor treatment experience, it may be recommended to

prioritize combination therapies that integrate

metabolic-epigenetic-ferroptosis signaling. This should be

accompanied by biomarker stratification and optimized

administration strategies, such as intranasal delivery for high

lesion exposure and low systemic exposure. These steps will help

accelerate the clinical translation of the Kla-ferroptosis

axis.

Notably, the cross-regulatory mechanisms between

lactylation and other programmed cell death pathways are

increasingly becoming a focus of research. Beyond ferroptosis, Kla

may modulate processes such as necroptosis, apoptosis and autophagy

by modifying key proteins, forming a complex network governing cell

fate decisions (134). For

instance, preliminary studies suggest that lactate accumulation can

influence the activity of receptor interacting serine/threonine

kinase 3, a core necroptosis protein, via lactylation, thereby

modulating cell death patterns in inflammatory diseases (135). In tumor models, Kla may promote

cell survival and resistance to therapy by inhibiting apoptotic

signaling pathways (e.g., BCL-2 family proteins) or enhancing the

stability of autophagy-related proteins (e.g., light chain 3)

(136,137). Such cross-regulation not only

reveals the central role of metabolic-epigenetic networks in

multiple death pathways, but also provides new insight for

developing combination therapies targeting lactylation. Future

studies are required to systematically elucidate the site-specific

functions of Kla in necroptosis, apoptosis and autophagy, and

clarify the dynamic interactions among these pathways to more

comprehensively evaluate the therapeutic potential of targeting

Kla.

However, the field still faces multiple challenges:

Structural similarities between lactylation-regulating enzymes and

other acyltransferases/deacetylases necessitate highly specific

drugs to avoid off-target effects on PTMs such as acetylation; the

dual role of the Kla-ferroptosis axis in diseases (e.g., promoting

injury in sepsis while exerting protection in spinal cord injury)

calls for cell- and microenvironment-specific targeted delivery

systems; notably, dynamic detection technologies for lactylation

remain underdeveloped, requiring novel in vivo imaging

probes to facilitate patient stratification and treatment

monitoring (108,112,138). Further studies are thus

required to focus on designing highly specific modulators,

constructing intelligent delivery systems and validating dynamic

lactylation biomarkers. This may broaden the understanding of cell

fate regulation mechanisms and may provide novel paradigms for the

treatment of cancer, as well as inflammatory, degenerative and

ischemic diseases.

Not applicable.

All authors contributed to the study conception and

design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were

performed by ZL, YZ and SZ. The first draft of the manuscript was

written by ZL and KW. All authors commented on previous versions of

the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

No funding was received.

|

1

|

Miao C, Huang Y, Zhang C, Wang X, Wang B,

Zhou X, Song Y, Wu P, Chen ZS and Feng Y: Post-translational

modifications in drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 78:1011732025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hirano A, Fu YH and Ptáček LJ: The

intricate dance of post-translational modifications in the rhythm

of life. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 23:1053–1060. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tharuka MDN, Courelli AS and Chen Y:

Immune regulation by the SUMO family. Nat Rev Immunol. 25:608–620.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhong Q, Xiao X, Qiu Y, Xu Z, Chen C,

Chong B, Zhao X, Hai S, Li S, An Z and Dai L: Protein

posttranslational modifications in health and diseases: Functions,

regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. MedComm.

4:e2612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang Y, Hu J, Wu S, Fleishman JS, Li Y, Xu

Y, Zou W, Wang J, Feng Y, Chen J and Wang H: Targeting epigenetic

and posttranslational modifications regulating ferroptosis for the

treatment of diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:4492023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rabinowitz JD and Enerbäck S: Lactate: The

ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat Metab. 2:566–571. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Brooks GA: The science and translation of

lactate shuttle theory. Cell Metab. 27:757–785. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hui S, Ghergurovich JM, Morscher RJ, Jang

C, Teng X, Lu W, Esparza LA, Reya T, Le Zhan, Yanxiang Guo J, et

al: Glucose feeds the TCA cycle via circulating lactate. Nature.

551:115–118. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Brooks GA, Osmond AD, Arevalo JA, Duong

JJ, Curl CC, Moreno-Santillan DD and Leija RG: Lactate as a myokine

and exerkine: drivers and signals of physiology and metabolism. J

Appl Physiol (1985). 134:529–548. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yao S, Chai H, Tao T, Zhang L, Yang X, Li

X, Yi Z, Wang Y, An J, Wen G, et al: Role of lactate and lactate

metabolism in liver diseases (Review). Int J Mol Med. 54:592024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li H, Sun L, Gao P and Hu H: Lactylation

in cancer: Current understanding and challenges. Cancer Cell.

42:1803–1807. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen J, Huang Z, Chen Y, Tian H, Chai P,

Shen Y, Yao Y, Xu S, Ge S and Jia R: Lactate and lactylation in

cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen L, Huang L, Gu Y, Cang W, Sun P and

Xiang Y: Lactate-lactylation hands between metabolic reprogramming

and immunosuppression. Int J Mol Sci. 23:119432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu J, Zhao F and Qu Y: Lactylation: A

novel post-translational modification with clinical implications in

CNS Diseases. Biomolecules. 14:11752024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li R, Yang Y, Wang H, Zhang T, Duan F, Wu

K, Yang S, Xu K, Jiang X and Sun X: Lactate and lactylation in the

brain: Current progress and perspectives. Cell Mol Neurobiol.

43:2541–2555. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Peng X and Du J: Histone and non-histone

lactylation: Molecular mechanisms, biological functions, diseases,

and therapeutic targets. Mol Biomed. 6:382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Certo M, Llibre A, Lee W and Mauro C:

Understanding lactate sensing and signalling. Trends Endocrinol

Metab. 33:722–735. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y,

Zou Y, Wang JX, Wang Z and Yu T: Lactate metabolism in human health

and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:3052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Shang S, Liu J and Hua F: Protein

acylation: Mechanisms, biological functions and therapeutic

targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:3962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fan Z, Liu Z, Zhang N, Wei W, Cheng K, Sun

H and Hao Q: Identification of SIRT3 as an eraser of H4K16la.

iScience. 26:1077572023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Moreno-Yruela C, Zhang D, Wei W, Bæk M,

Liu W, Gao J, Danková D, Nielsen AL, Bolding JE, Yang L, et al:

Class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1-3) are histone lysine

delactylases. Sci Adv. 8:eabi66962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hu X, Huang X, Yang Y, Sun Y, Zhao Y,

Zhang Z, Qiu D, Wu Y, Wu G and Lei L: Dux activates

metabolism-lactylation-MET network during early iPSC reprogramming

with Brg1 as the histone lactylation reader. Nucleic Acids Res.

52:5529–5548. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zheng J and Conrad M: Ferroptosis: When

metabolism meets cell death. Physiol Rev. 105:651–706. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang Z, Wu C, Yin D and Do K: Ferroptosis:

Mechanism and role in diabetes-related cardiovascular diseases.

Cardiovasc Diabetol. 24:602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhao L, Zhou X, Xie F and Zhang L, Yan H,

Huang J, Zhang C, Zhou F, Chen J and Zhang L: Ferroptosis in cancer

and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun (Lond). 42:88–116. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tang D, Chen X, Kang R and Kroemer G:

Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell

Res. 31:107–125. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

29

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rochette L, Dogon G, Rigal E, Zeller M,

Cottin Y and Vergely C: Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: Two

corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:4492022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Alves F, Lane D, Nguyen TPM, Bush AI and

Ayton S: In defence of ferroptosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

10:22025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ and Tang

D: Ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Autophagy. 17:2054–2081.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

33

|

Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis turns 10:

Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic

applications. Cell. 185:2401–2421. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li FJ, Long HZ, Zhou ZW, Luo HY, Xu SG and

Gao LC: System Xc -/GSH/GPX4 axis: An important antioxidant system

for the ferroptosis in drug-resistant solid tumor therapy. Front

Pharmacol. 13:9102922022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Du Y and Guo Z: Recent progress in

ferroptosis: Inducers and inhibitors. Cell Death Discov. 8:5012022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Pal D and Sandur SK: Novel role of

peroxiredoxin 6 in ferroptosis: Bridging selenium transport with

enzymatic functions. Free Radic Biol Med. 238:611–620. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ru Q, Li Y, Chen L, Wu Y, Min J and Wang

F: Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: mechanisms

and therapeutic prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9:2712024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang Y, Zou L, Li X, Guo L, Hu B, Ye H

and Liu Y: SLC40A1 in iron metabolism, ferroptosis, and disease: A

review. WIREs Mech Dis. 16:e16442024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zheng D, Liu J, Piao H, Zhu Z, Wei R and

Liu K: ROS-triggered endothelial cell death mechanisms: Focus on

pyroptosis, parthanatos, and ferroptosis. Front Immunol.

13:10392412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu J, Kang R and Tang D: Signaling

pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J.

289:7038–7050. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wang B, Wang Y, Zhang J, Hu C, Jiang J, Li

Y and Peng Z: ROS-induced lipid peroxidation modulates cell death

outcome: mechanisms behind apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis.

Arch Toxicol. 97:1439–1451. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Liang D, Minikes AM and Jiang X:

Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular

signaling. Mol Cell. 82:2215–2227. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Pope LE and Dixon SJ: Regulation of

ferroptosis by lipid metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 33:1077–1087.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Tilton WM, Seaman C, Carriero D and

Piomelli S: Regulation of glycolysis in the erythrocyte: role of

the lactate/pyruvate and NAD/NADH ratios. J Lab Clin Med.

118:146–152. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ying W: NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in

cellular functions and cell death: Regulation and biological

consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal. 10:179–206. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Pucino V, Certo M, Bulusu V, Cucchi D,

Goldmann K, Pontarini E, Haas R, Smith J, Headland SE, Blighe K, et

al: Lactate buildup at the site of chronic inflammation promotes

disease by inducing CD4+ T cell metabolic rewiring. Cell Metab.

30:1055–1074.e8. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Reddy A, Winther S, Tran N, Xiao H, Jakob

J, Garrity R, Smith A, Ordonez M, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Rothstein

JD, et al: Monocarboxylate transporters facilitate succinate uptake

into brown adipocytes. Nat Metab. 6:567–577. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ding K, Liu C, Li L, Yang M, Jiang N, Luo

S and Sun L: Acyl-CoA synthase ACSL4: An essential target in

ferroptosis and fatty acid metabolism. Chin Med J (Engl).

136:2521–2537. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lan H, Gao Y, Zhao Z, Mei Z and Wang F:

Ferroptosis: Redox imbalance and hematological tumorigenesis. Front

Oncol. 12:8346812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chen J, Liu Z, Yue Z, Tan Q, Yin H, Wang

H, Chen Z, Zhu Y and Zheng J: EP300-mediated H3K18la regulation of

METTL3 promotes macrophage ferroptosis and atherosclerosis through

the m6A modification of SLC7A11. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj.

1869:1308382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Deng J, Li Y, Yin L, Liu S, Li Y, Liao W,

Mu L, Luo X and Qin J: Histone lactylation enhances GCLC expression

and thus promotes chemoresistance of colorectal cancer stem cells

through inhibiting ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 16:1932025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gong F, Zheng X, Xu W, Xie R, Liu W, Pei

L, Zhong M, Shi W, Qu H, Mao E, et al: H3K14la drives endothelial

dysfunction in sepsis-induced ARDS by promoting

SLC40A1/transferrin-mediated ferroptosis. MedComm. 6:e700492025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhu J, Xiong Y, Zhang Y, Liang H, Cheng K,

Lu Y, Cai G, Wu Y, Fan Y, Chen X, et al: Simvastatin overcomes the

pPCK1-pLDHA-SPRINGlac axis-mediated ferroptosis and

chemo-immunotherapy resistance in AKT-hyperactivated intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond). 45:1038–1071. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen Y, Yan Q, Ruan S, Cui J, Li Z, Zhang

Z, Yang J, Fang J, Liu S, Huang S, et al: GCLM lactylation mediated

by ACAT2 promotes ferroptosis resistance in

KRASG12D-mutant cancer. Cell Rep. 44:1157742025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Niu K, Chen Z, Li M, Ma G, Deng Y, Zhang

J, Wei D, Wang J and Zhao Y: NSUN2 lactylation drives cancer cell

resistance to ferroptosis through enhancing GCLC-dependent

glutathione synthesis. Redox Biol. 79:1034792025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yang Z, Su W, Zhang Q, Niu L, Feng B,

Zhang Y, Huang F, He J, Zhou Q, Zhou X, et al: Lactylation of HDAC1

confers resistance to ferroptosis in colorectal cancer. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24088452025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liu J, Li Y, Ma R, Chen Y, Wang J, Zhang

L, Wang B, Zhang Z, Huang L, Zhang H, et al: Cold atmospheric

plasma drives USP49/HDAC3 axis mediated ferroptosis as a novel

therapeutic strategy in endometrial cancer via reinforcing

lactylation dependent p53 expression. J Transl Med. 23:4422025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yang G, Liu X, Li Y, Li L, Xiang J, Liang

Z, Jiang M and Yang S: TRIM65 as a key regulator of ferroptosis and

glycolysis in lactate-driven renal tubular injury and diabetic

kidney disease. Cell Rep. 44:1160912025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Liu Z, Zhou Y, Li M, Xiao Z, Zhao Z and Li

Y: Dimeric PKM2 induces ferroptosis from intestinal

ischemia/reperfusion in mice by histone H4 lysine 12

lactylation-mediated HMGB1 transcription activation through the

lactic acid/p300 axis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1871:1679982025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhang K, Guo L, Li X, Hu Y and Luo N:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote doxorubicin resistance in

triple-negative breast cancer through enhancing ZFP64 histone

lactylation to regulate ferroptosis. J Transl Med. 23:2472025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Lai WKM and Pugh BF: Understanding

nucleosome dynamics and their links to gene expression and DNA

replication. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 18:548–562. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Millán-Zambrano G, Burton A, Bannister AJ

and Schneider R: Histone post-translational modifications-cause and

consequence of genome function. Nat Rev Genet. 23:563–580. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Wu D, Spencer CB, Ortoga L, Zhang H and

Miao C: Histone lactylation-regulated METTL3 promotes ferroptosis

via m6A-modification on ACSL4 in sepsis-associated lung injury.

Redox Biol. 74:1031942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Liang Z, Liu J, Gou Y, Wang H, Li Z, Cao

Y, Zhang H, Bai R and Zhang Z: Elevated histone lactylation

mediates ferroptosis resistance in endometriosis through the

METTL3-Regulated HIF1A/HMOX1 signaling pathway. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e082202025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wu S, Liu M, Wang X and Wang S: The

histone lactylation of AIM2 influences the suppression of

ferroptosis by ACSL4 through STAT5B and promotes the progression of

lung cancer. FASEB J. 39:e703082025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Zhu J, Wu X, Mu M, Zhang Q and Zhao X:

TEC-mediated tRF-31R9J regulates histone lactylation and

acetylation by HDAC1 to suppress hepatocyte ferroptosis and improve

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Epigenetics. 17:92025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Huang J, Xie H, Li J, Huang X, Cai Y, Yang

R, Yang D, Bao W, Zhou Y, Li T and Lu Q: Histone lactylation drives

liver cancer metastasis by facilitating NSF1-mediated ferroptosis

resistance after microwave ablation. Redox Biol. 81:1035532025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Xiong J, Ge X, Pan D, Zhu Y, Zhou Y, Gao

Y, Wang H, Wang X, Gu Y, Ye W, et al: Metabolic reprogramming in

astrocytes prevents neuronal death through a UCHL1/PFKFB3/H4K8la

positive feedback loop. Cell Death Differ. 32:1214–1230. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Liu J, Tang D and Kang R: Targeting GPX4

in ferroptosis and cancer: chemical strategies and challenges.

Trends Pharmacol Sci. 45:666–670. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wang Y, Yue Q, Song X, Du W and Liu R:

Hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced glycolysis mediates myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury through promoting the lactylation of

GPX4. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 18:762–774. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Di Sanzo M, Quaresima B, Biamonte F,

Palmieri C and Faniello MC: FTH1 pseudogenes in cancer and cell

metabolism. Cells. 9:25542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Muhoberac BB and Vidal R: Iron, ferritin,

Hereditary ferritinopathy, and neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci.

13:11952019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

An X, He J, Xie P, Li C, Xia M, Guo D, Bi

B, Wu G, Xu J, Yu W and Ren Z: The effect of tau K677 lactylation

on ferritinophagy and ferroptosis in Alzheimer's disease. Free

Radic Biol Med. 224:685–706. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Tian B, Li X, Li W, Shi Z, He X, Wang S,

Zhu X, Shi N, Li Y, Wan P and Zhu C: CRYAB suppresses ferroptosis

and promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow stem

cells via binding and stabilizing FTH1. Aging (Albany NY).

16:8965–8979. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Yuan J, Yang M, Wu Z, Wu J, Zheng K, Wang

J, Zeng Q, Chen M, Lv T, Shi Y, et al: The Lactate-Primed KAT8-PCK2

axis exacerbates hepatic ferroptosis during ischemia/reperfusion

injury by reprogramming OXSM-Dependent mitochondrial fatty acid

synthesis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24141412025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

She H, Hu Y, Zhao G, Du Y, Wu Y, Chen W,

Li Y, Wang Y, Tan L, Zhou Y, et al: Dexmedetomidine ameliorates

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting MDH2

lactylation via regulating metabolic reprogramming. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 11:e24094992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zhang L, Wang X, Che W, Zhou S and Feng Y:

METTL3 silenced inhibited the ferroptosis development via

regulating the TFRC levels in the Intracerebral hemorrhage

progression. Brain Res. 1811:1483732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Qu S, Feng B, Xing M, Qiu Y, Ma L, Yang Z,

Ji Y, Huang F, Wang Y, Zhou J, et al: PRMT5 K240lac confers

ferroptosis resistance via ALKBH5/SLC7A11 axis in colorectal

cancer. Oncogene. 44:2814–2830. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Li A, Gong Z, Long Y, Li Y, Liu C, Lu X,

Li Q, He X, Lu H, Wu K, et al: Lactylation of LSD1 is an acquired

epigenetic vulnerability of BRAFi/MEKi-resistant melanoma. Dev

Cell. 60:1974–1990.e11. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Deng L, He S, Guo N, Tian W, Zhang W and

Luo L: Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and relevance to

inflammation. Inflamm Res. 72:281–299. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Chen Y, Fang ZM, Yi X, Wei X and Jiang DS:

The interaction between ferroptosis and inflammatory signaling

pathways. Cell Death Dis. 14:2052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Fang Y, Li Z, Yang L, Li W, Wang Y, Kong

Z, Miao J, Chen Y, Bian Y and Zeng L: Emerging roles of lactate in

acute and chronic inflammation. Cell Commun Signal. 22:2762024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Qiao X, Yin J, Zheng Z, Li L and Feng X:

Endothelial cell dynamics in sepsis-induced acute lung injury and

acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and therapeutic

implications. Cell Commun Signal. 22:2412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Li W, Li D, Chen Y, Abudou H, Wang H, Cai

J, Wang Y, Liu Z, Liu Y and Fan H: Classic signaling pathways in

alveolar injury and repair involved in sepsis-induced ALI/ARDS: New

research progress and prospect. Dis Markers.

2022:63623442022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Zhang T, Huang X, Feng S and Shao H:

Lactate-Dependent HIF1A transcriptional activation exacerbates

severe acute pancreatitis through the ACSL4/LPCAT3/ALOX15 pathway

induced ferroptosis. J Cell Biochem. 126:e306872025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Han X, Bao J, Ni J, Li B, Song P, Wan R,

Wang X, Hu G and Chen C: Qing Xia Jie Yi Formula granules

alleviated acute pancreatitis through inhibition of M1 macrophage

polarization by suppressing glycolysis. J Ethnopharmacol.

325:1177502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Wang Y, Wu S, Li Q, Sun H and Wang H:

Pharmacological inhibition of ferroptosis as a therapeutic target

for neurodegenerative diseases and strokes. Adv Sci (Weinh).

10:e23003252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Sheng W, Liao S, Wang D, Liu P and Zeng H:

The role of ferroptosis in osteoarthritis: Progress and prospects.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 733:1506832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wang J, Chen T and Gao F: Mechanism and

application prospect of ferroptosis inhibitors in improving

osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15:14926102024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhang Y, Zhao CY, Zhou Z, Li CC and Wang

Q: The effect of lactate dehydrogenase B and its mediated histone

lactylation on chondrocyte ferroptosis during osteoarthritis. J

Orthop Surg. 20:4932025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Sun K, Shi Y, Yan C, Wang S, Han L, Li F,

Xu X, Wang Y, Sun J, Kang Z and Shi J: Glycolysis-derived lactate

induces ACSL4 Expression and lactylation to activate ferroptosis

during intervertebral disc degeneration. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e24161492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Li X, Ma N, Xu J, Zhang Y, Yang P, Su X,

Xing Y, An N, Yang F, Zhang G, et al: Targeting ferroptosis:

pathological mechanism and treatment of ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:15879222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Dong W, Huang SX, Qin ML and Pan Z:

Mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2 mediates histone lactylation

to promote ferroptosis in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury.

World J Gastrointest Surg. 17:1067772025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Sun T, Zhang JN, Lan T, Shi L, Hu L, Yan

L, Wei C, Hei L, Wu W, Luo Z, et al: H3K14 lactylation exacerbates

neuronal ferroptosis by inhibiting calcium efflux following

intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke. Cell Death Dis. 16:5532025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Apostolova P and Pearce EL: Lactic acid

and lactate: Revisiting the physiological roles in the tumor

microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 43:969–977. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Sun Q, Wu J, Zhu G, Li T, Zhu X, Ni B, Xu

B, Ma X and Li J: Lactate-related metabolic reprogramming and

immune regulation in colorectal cancer. Front Endocrinol.

13:10899182023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Zhang W, Xia M, Li J, Liu G, Sun Y, Chen X

and Zhong J: Warburg effect and lactylation in cancer: Mechanisms

for chemoresistance. Mol Med. 31:1462025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Liao M, Yao D, Wu L, Luo C, Wang Z, Zhang

J and Liu B: Targeting the Warburg effect: A revisited perspective

from molecular mechanisms to traditional and innovative therapeutic

strategies in cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 14:953–1008. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Boedtkjer E and Pedersen SF: The acidic

tumor microenvironment as a driver of cancer. Annu Rev Physiol.

82:103–126. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Wang T, Ye Z, Li Z, Jing DS, Fan GX, Liu

MQ, Zhuo QF, Ji SR, Yu XJ, Xu XW and Qin Y: Lactate-induced protein

lactylation: A bridge between epigenetics and metabolic

reprogramming in cancer. Cell Prolif. 56:e134782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Sun Y, Wang H, Cui Z, Yu T, Song Y, Gao H,

Tang R, Wang X, Li B, Li W and Wang Z: Lactylation in cancer

progression and drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 81:1012482025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Yang T, Zhang S, Nie K, Cheng C, Peng X,

Huo J and Zhang Y: ZNF207-driven PRDX1 lactylation and NRF2

activation in regorafenib resistance and ferroptosis evasion. Drug

Resist Updat. 82:1012742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Yu Y, Huang X, Liang C and Zhang P:

Evodiamine impairs HIF1A histone lactylation to inhibit

Sema3A-mediated angiogenesis and PD-L1 by inducing ferroptosis in

prostate cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 957:1760072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Tong Q, Huang C, Tong Q and Zhang Z:

Histone lactylation: A new frontier in laryngeal cancer research

(Review). Oncol Lett. 30:4212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Bao C, Ma Q, Ying X, Wang F, Hou Y, Wang

D, Zhu L, Huang J and He C: Histone lactylation in macrophage

biology and disease: From plasticity regulation to therapeutic

implications. EBioMedicine. 111:1055022025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

106

|

Bao Q, Wan N, He Z, Cao J, Yuan W, Hao H

and Ye H: Subcellular proteomic mapping of lysine lactylation. J Am

Soc Mass Spectrom. 35:3221–3232. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Zhao W, Zhang J, Chen K, Yuan J, Zhai L

and Tan M: Mass spectrometry-based characterization of histone

post-translational modification. Curr Opin Chem Biol.

88:1026222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Sun Y, Chen Y and Peng T: A bioorthogonal

chemical reporter for the detection and identification of protein

lactylation. Chem Sci. 13:6019–6027. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Zhang X, Liu Y, Rekowski MJ and Wang N:

Lactylation of tau in human Alzheimer's disease brains. Alzheimers

Dement. 21:e144812025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Chu X, Di C, Chang P, Li L, Feng Z, Xiao

S, Yan X, Xu X, Li H, Qi R, et al: Lactylated Histone H3K18 as a

potential biomarker for the diagnosis and predicting the severity

of septic shock. Front Immunol. 12:7866662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Nuñez R, Sidlowski PFW, Steen EA,

Wynia-Smith SL, Sprague DJ, Keyes RF and Smith BC: The TRIM33

bromodomain recognizes histone lysine lactylation. ACS Chem Biol.

19:2418–2428. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Wang Y, Fan J, Meng X, Shu Q, Wu Y, Chu

GC, Ji R, Ye Y, Wu X, Shi J, et al: Development of nucleus-targeted

histone-tail-based photoaffinity probes to profile the epigenetic

interactome in native cells. Nat Commun. 16:4152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Crabb S, Plummer R, Greystoke A, Carter L,

Pacey S, Walter H, Coyle VM, Knurowski T, Clegg K, Ashby F, et al:

560TiP a phase I/IIa study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of

CCS1477, a first in clinic inhibitor of p300/CBP, as monotherapy in

patients with selected molecular alterations. Ann Oncol.

32:S6172021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Nicosia L, Spencer GJ, Brooks N, Ciceri F,

Wiseman DH, Pegg N, West W, Knurowski T, Frese K, Clegg K, et al:

Therapeutic targeting of EP300/CBP by bromodomain inhibition in

hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell. 41:2136–2153.e13. 2023.