Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn's

disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis, is a chronic idiopathic

inflammatory disease of gastrointestinal tract with unknown

etiology and recurrent episodes (1). IBD might be the result of a complex

interaction between genetic susceptibility, environmental factors

and intestinal microflora (2).

Autophagy is a conserved cellular process that delivers cytoplasmic

material and organelles to lysosomes for breakdown, which plays a

key role for cellular renovation and homeostasis (3). A number of studies have also shown

that autophagy is involved in regulation of IBD. Impaired autophagy

leads to impaired protection against intestinal infection, abnormal

Paneth cells morphology, inhibition of intestinal stem cells

proliferation and accelerated intestinal epithelial cells (IECs)

apoptosis (4). Autophagy related

gene 7 knockdown in mice decreases intestinal tight junction

proteins levels, exacerbating inflammation of intestinal tract

(5). Moreover, knockdown of

ATG16L1, a gene associated with autophagy, enhances inflammation

and accelerates epithelial cells death in mice (6). In addition, promoting IECs

autophagy alleviates colitis in mice (7).

Metabolism provides energy and biomass for

maintaining cellular function and proliferation. IECs use oxidative

phosphorylation to meet metabolism demand generally. The impaired

mitochondrial function in IBD leads to a shift in IECs energy

metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis (8-10). Increased glycolysis levels are

observed in the colonic epithelium in patients with IBD (11,12). Meanwhile, the metabolomics

analysis of mouse colitis model showed that the level of lactic

acid, a metabolite of glycolysis, was increased (13). Inhibition of IECs glycolysis

could alleviate colitis in mice and recover intestinal barrier

function (14,15).

In the present study, impaired autophagy and

abnormal glycolysis levels were observed in the colonic IECs of

DSS-induced colitis mice and TNF-α treated NCM460 cells.

Subsequently, it demonstrated that autophagy negatively regulated

the glycolysis of intestinal epithelial cells by ubiquitin-mediated

selective degradation of the key glycolytic enzyme

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3).

Furthermore, inhibition of PFKFB3 enzyme activity relieved DSS

induced intestinal inflammation and intestinal epithelial barrier

damage.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1,000

unless otherwise indicated. The antibodies were: Anti-Flag (cat.

no. 20543-1-AP), anti-β-actin (cat. no. 20536-1-AP),

anti-P62/SQSTM1 (cat. no. 18420-1-AP), anti-occludin (cat. no.

27260-1-AP), anti-claudin-1 (cat. no. 13050-1-AP), anti-fizzy and

cell division cycle 20 related 1 (FZR1/Cdh1) (cat. no. 16368-1-AP),

anti-claudin-2 (cat. no. 26912-1-AP) from Proteintech Group, Inc.;

anti-LC3B (cat. no. 2775S), anti-E-cadherin (cat. no. 14472S) from

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; anti-ATG7 (WL02793),

anti-phosphofructokinase, muscle 2 (PKM2; cat. no. WL03290) from

Wanleibio Co., Ltd.; anti-PFKP (cat. no. HA500472) from HUABIO;

anti-hexokinase 2 (HK2; cat. no. CQA9312) from Cohesion

Biosciences; anti-lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA; cat. no. ab52488)

and anti-PFKFB3 (cat. no. ab181861) from Abcam; anti-GAPDH (cat.

no. TA310153) from OriGene Technologies, Inc.; anti-Claudin-5 (cat.

no. AF5216) from Affinity Biosciences; anti-Claudin-8 (cat. no.

GTX77832) from GeneTex, Inc.; anti-K48-linkage specific ubiquitin

(cat. no. bsm-63005R) and anti-K63-linkage specific ubiquitin (cat.

no. bsm-63006R) from BIOSS. Glucose Content Assay Kit (cat. no.

BC2505), Lactic Acid (LA) Content Assay Kit (cat. no. BC2235),

Phosphofructokinase (PFK) Activity Assay Kit (cat. no. BC0535) and

2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF; cat. no.

IB1750) were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.. PFKFB3 inhibitor PFK15 (cat. no. S7289),

autophagy agonists Rapamycin (cat. no. S1039), autophagy inhibitor

Bafilomycin A1 (Baf-A1; cat. no. (S1413) was purchased from Selleck

Chemicals. TNF-α (HY-P70426A) was purchased from MedChemExpress.

2-NBDG (cat. no. 72987) was purchased from MilliporeSigma. Fetal

bovine serum and DMEM were purchased from Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.

Animal models

A total of 50 C57BL/6 mice (male, 6-8 weeks old and

23-26 g) were purchased from the Experiment Animal Center (Third

Military Medical University, Chongqing, China) for use in the in

vivo experiments. The C57BL/6 mice were housed under controlled

environmental conditions with a temperature of 26°C, relative

humidity of 60% and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Acute colitis was

induced by administration of 2.5% dextran sulphate sodium (DSS),

which was dissolved in the animals' drinking water, for 7 days.

Chronic colitis was induced by administration of 2% DSS, which was

dissolved in the drinking water for 21 days. Control mice were

provided with distilled water. PFK15 (25 mg/kg) was administered by

intraperitoneal injection daily, beginning on the first day of DSS

administration. Body weight and stool blood were monitored and

recorded every day during DSS feeding. All mice were anesthetized

via continuous inhalation of 5% isoflurane for 2 min prior to

euthanasia by cervical dislocation. All animal experiments were

conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved

by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Third

Military Medical University (approval no. AMUWEC20224496).

IEC isolation

The whole colon intestine was removed and placed in

tissue culture medium (RPMI 1640, with 10% fetal bovine serum;

Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.). The section was cut into 5-mm pieces,

washed in an isolation buffer containing 190 mg

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 80 mg Dithiothreitol (DTT)

dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 500 ml and incubated

in the same buffer with continuous brisk stirring at 37°C for 30

min. The supernatant was filtered rapidly through 70 and 30

μm filter screen. Following centrifugation at 600 × g for 5

min at 37°C, the cells recovered in the suspension were collected

for RNA or protein extraction. Intestinal epithelial cell isolation

was used for western blotting and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR.

Cell culture and transfection

The normal intestinal epithelium cell line NCM460

was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCCSA).

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1%

Penicillin-streptomycin solution. The dry powder small interfering

(si)RNA was dissolved in sterile, nuclease-free water (cat. no.

R1600; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) to a

concentration of 20 μM. Cell transfection with siRNA was

performed following the manufacturer's instructions for the

riboFECT CP (cat. no. C10502-05; Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.)

Transfection Kit. The procedure is outlined as follows: Seed

5×105 cells into 6-well plates, then prepare a

transfection mixture by combining 100 μl of transfection

buffer, 100 nM siRNA, and 12 μl of transfection reagent.

Incubate the mixture at 25°C for 15 min before adding it to the

cells. After 12 h of co-incubation of the cells with the mixture,

replace the culture medium. Following medium replacement, continue

culturing the cells for an additional 48 h, and then evaluate the

gene silencing effect using qPCR and western blotting. The negative

control siRNA is transfected into the cells using an identical

transfection protocol. The siRNA was constructed by Sangon Biotech

Co., Ltd. The siRNA used were: siPFKFB3 no.1 sense:

(5'-CGUGUCGGUUCCAUUCCAUUU-3'); siPFKFB3 no.2 sense:

(5'-ACCCGCUCAUGAGACGCAAUA-3'); siPFKFB3 no.3 sense:

(5'-GGGACUUGUCGCUGAUCAAGG-3'); siATG7 sense:

(5'-CCCAGCUAUUGGAACACUGUA-3'); negative control siRNA sense:

(5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3').

Short hairpin (sh)RNA and siRNA

For stable ATG7 siRNA, PFKFB3 siRNA, FZR1 siRNA

expression, the retroviral encoding hairpin RNA sequences were

constructed. shRNA sequence against ATG7, PFKFB3, FZR1 were

generated and cloned into the expression vector. Recombinant

lentiviruses expressing GFP-tagged shATG7, shPFKFB3 were

constructed by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. The lentiviral expressing

shFZR1, PFKFB3(NM_004566)-PCDH-PURO-3XFlag, SQSTM1(N

M_003900)-PCDH-PURO-3XFlag and FZR1 (NM_0011361

98)-PCDH-GFP+PURO-3XFlag were constructed by YouBio.

psPAX2 (cat no. VT1444) and pMD2.G (cat no. VT1443) were purchased

from YouBio. Polyethylenimine (PEI) (cat no. 306185) was purchased

from MilliporeSigma. The 293T cell line (cat no. CL-0005) was

obtained from Procell and used in experiments after culture for at

least three generations. The transfection reagents were prepared in

advance as follows: A solution (psPAX2 8.34 μg, pMD2.G 2.52

μg, DMEM 481.1 μl); B solution (lentiviral plasmid

8.04 μg, PEI 59.7 μg, DMEM 440.3 μl). The A

solution was mixed with the B solution at room temperature and

incubated for 15 min. The mixture was added to a 10 cm culture dish

containing 293T cells at 60-70% confluence, and incubated at 37°C

for 12 h. The supernatant was removed and the cells washed twice

with PBS and 10 ml of complete DMEM medium added. Culture was

continued at 37°C for an additional 48 h. The supernatant was

collected and transferred it into a 15 ml centrifuge tube then

centrifuged at 200 × g and 25°C for 5 min. Concurrently, the

supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm pore-size filter

membrane (cat no. SLHVM33RS; MilliporeSigma). The viral stock

solution was concentrated with 100 kDa Millipore ultrafiltration

tubes (cat no. UFC9100; MilliporeSigma) and stored at −80°C.

Concentrated viruses (10 MOI) were used to infect 5×105

cells in a 6 cm dish. Infected cells underwent sorting by 2

μg/ml puromycin for 48 h for stably target expression. The

shRNA used were: shATG7 (5'-CCCAGCTATTGGAACACTGTA-3'); shPFKFB3

no.1 (5'-CGTGTCGGTTCCATTCCATTT-3'); shPFKFB3 no.2

(5'-ACCCGCTCATGAGACGCAATA-3'); shPFKFB3 no.3

(5'-GGGACTTGTCGCTGATCAAGG-3'); shFZR1

(5'-GTGAACTTCCACAGGATTAAC-3')

Metabolite measurements

Glucose content in cell was measured using

colorimetric kits (cat. no. BC2505; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) and lactic acid content in the culture

supernatants was measured using colorimetric kits (cat. no. BC2235;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance of glucose was

measured at 505 nm and lactic acid was measured at 570 nm using a

SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC).

Phosphofructokinase (PFK) activity in cell was measured using

colorimetric kits (cat. no. BC0535; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The absorbance of phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1) was measured at 340

nm using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices,

LLC). All experiments were performed in triplicate as described

previously.

RT-qPCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted from

5×105 cells in a 6 cm dish with RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio,

Inc.) and used the Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) for

reverse transcription. The procedure was performed as follows:

First, RNAiso Plus (1 ml) was added to the cell pellet to ensure

complete cell lysis. Next, 200 μl of chloroform was added,

mixed thoroughly and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C.

Then, transfer the aqueous phase and mix with an equal volume of

isopropanol to precipitate RNA, followed by centrifugation at

15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant

was carefully discarded and the RNA pellet washed twice with

absolute ethyl alcohol to remove impurities. Finally, the pellet

was briefly air-dried to remove residual ethanol and the resulting

white precipitate dissolved in RNase-free water. The purified

material represented the total RNA extracted from the cells. RNA

was converted into cDNA through reverse transcription reaction on

the Applied Biosystems thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The reverse transcription reaction was performed as follows:

Incubation at 37°C for 15 min, followed by enzyme inactivation at

85°C for 5 sec and storage at 4°C for 10 min. qPCR was performed

using the SYBRPrime qPCR kit (cat. no. BG0014; BioGround Corp.)

under the following conditions: Initial pre-denaturation at 94°C

for 20 sec, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 10

sec and annealing and extension at 60°C for 30 sec. Relative

quantitation of all transcripts was calculated using the

comparative Ct method with β-actin as an internal control (16). This assay was performed in

triplicate. The primers used for detection are in Table I.

| Table IPrimers used in quantitative PCR. |

Table I

Primers used in quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|

| PFKP | F:

5'-GGAGTGGAGTGGGCTGCTGGAG-3' |

| R:

5'-CATGTCGGTGCCGCAGAAATCA-3' |

| LDHA | F:

5'-ATGGCAACTCTAAAGGATCAGC-3' |

| R:

5'-CCAACCCCAACAACTGTAATCT-3' |

| HK2 | F:

5'-CATCCAGAGGAGAGGGGACT-3' |

| R:

5'-TCATCGCCTTCCACCATGTC-3' |

| PKM2 | F:

5'-CTGTGGACTTGCCTGCTGTG-3' |

| R:

5'-TGCCTTGCGGATGAATGACG-3' |

| PFKFB3 | F:

5'-CAGTTGTGGCCTCCAATATC-3' |

| R:

5'-GGCTTCATAGCAACTGATCC-3' |

| GAPDH | F:

5'-CCTTCCGTGTCCCCACT-3' |

| R:

5'-GCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC-3' |

| ATG7 | F:

5'-GTTGTTTGCTTCCGTGAC-3' |

| R:

5'-TGCCTCCTTTCTGGTTCT-3' |

| IL-1β | F:

5'-AGTTGACGGACCCCAAA-3' |

| R:

5'-TCTTGTTGATGTGCTGCTG-3' |

| IL-6 | F:

5'-ACAGAAGGAGTGGCTAAGGA-3' |

| R:

5'-AGGCATAACGCACTAGGTTT-3' |

| TNF-α | F:

5'-CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTACTG-3' |

| R:

5'-GGGCTACGGGCTTGTCACTC-3' |

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation

For immunoblotting, 5×106 Cells were

lysed by 300 μl RIPA buffer (cat. no. R0020; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) supplemented with 3

μl protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. P0100-01; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at 4°C.

Then, it was centrifuged at 4°C and 12,000 × g for 10 min. The

protein was denatured by adding 5X SDS loading buffer and boiled at

100°C for 10 min, then separated by sodium dodecyl-sulfate

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). β-actin antibody and

the target protein antibody were diluted separately in primary

antibody dilution buffer (cat no. C1240; Applygen) at 1:1,000,

followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. On the following day, the

goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (cat no. BA1056; Wuhan

Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) was diluted in secondary

antibody diluent buffer (cat no. C1241; Applygen) at 1:5,000 and

incubated at 37°C for 1 h before being washed three times with PBST

buffer, 5 min per wash. The PBST solution was prepared by adding

500 μl of Tween 20 to 500 ml of phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS). Immunodetection was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence

(ECL System; Azure Biosystems, Inc.). For immunoprecipitation

assays, the cells were washed and collected with cold PBS from 10

cm dish. Cells were collected into a 1.5 ml Eppendorf (EP) tube

(cat no. FTUB015; Beyotime Biotechnology) and placed the tube on

ice for pre-cooling. Freshly prepared 0.3% IP lysis buffer (1 ml)

containing protease inhibitor cocktail was added, mixed gently by

inverting or pipetting and incubated at 4°C on a rotating mixer for

60 min at a moderate to slightly increased rotation speed. After

completed lysis, the EP tube was kept on ice and followed by

ultrasonic homogenization using the following settings: 20%

amplitude, 1-sec pulse duration, 1-sec interval, for a total of 30

cycles. Subsequently, the sample was centrifuged at 4°C and 15,000

× g for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully collected without

disturbing the pellet and transferred to a new pre-chilled EP tube.

A total of 300 μl of the supernatant was taken as the Input

sample, 75 μl of 5X Loading Buffer added and mixed

thoroughly and boiled in a water bath at 100°C for 10 min. The

sample was immediately transferred to −80°C for long-term storage.

The remaining supernatant was divided equally into two portions,

which were then incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotator with either

the target primary antibody (2 μg) or the immunoglobin G

(IgG) control antibody (1 μl), respectively. The following

day, 30 μl of Protein A/G magnetic bead suspension was added

to each tube and incubated with rotation at 4°C for 4 h. After

incubation, the tubes were placed on a magnetic stand to immobilize

the beads, then carefully aspirated the supernatant. The beads were

washed by adding 1 ml of 0.1% IP lysis buffer to each tube,

followed by rotating incubation at a slightly increased speed for 5

min. The washing procedure was repeated five times. After the final

wash the was complete removal of residual liquid. Subsequently, 20

μl of 2X loading buffer was added to each tube to thoroughly

resuspend the magnetic beads, the samples boiled at 100°C for 10

min, and immediately transferred to −80°C for storage until further

use for western blot analysis. The IP lysis buffer was prepared by

mixing 10% NP-40, 1 M Tris-HCl, 5 M NaCl, 0.5 M EDTA, and deionized

water (ddH2O) to final concentrations in accordance with

standard immunoprecipitation protocols.

Detection of protein stability by the

cycloheximide (CHX)

NCM460 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml CHX

alone or in combination with 200 nM rapamycin. Cell samples were

collected at indicated time points (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h), and

the expression levels of the target protein were analyzed by

western blotting. The resulting data were fitted to a linear

regression model to calculate the half-life of the target protein

in NCM460 cells.

Analysis of autophagic flux

The viral infection of cells was performed according

to the instructions provided in the adenovirus user manual. When

the cells in 50 mm dish reached a density of ~30%, 1 μl of

mRFP-GFP-LC3 adenovirus (cat no. GENE-497, Shanghai GeneChem Co.,

Ltd.) (1×10¹¹ PFU/ml) was added to each well for transfection. The

dish was then incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Then cells were cultured

for 24 h with or without TNF-α. The images were acquired using an

inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). Yellow

(merge of GFP signal and RFP signal) puncta represented early

autophagosomes, while red (RFP signal) puncta indicated late

autolysosomes. Autophagic flux was evaluated by the change of

yellow puncta/red puncta.

Glucose uptake assay

Cells were treated with bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1),

Rapamycin, TNF-α or transfected with siATG7. The DMEM culture

medium was replaced by glucose-free medium for 2 h. 2-NBDG was

added at a concentration of 100 μM for 30 min. Then, cells

were washed by PBS twice. The images were acquired using an

inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). The

fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG was detected at λex 494 nm, λem

551 nm by using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular

Devices, LLC).

Determination of intracellular pH

The intracellular pH was detected by fluorescence

measurements using the dye BCECF-AM (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). Cells grown in 96-well microtiter plate were

washed with PBS for twice and incubated with 3 μM BCECF-AM

for 30 min at 37°C. The medium of cells was removed and cells were

washed twice with PBS. The images were acquired using an inverted

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). The fluorescence

intensity of BCECF-AM was detected at λex 488 nm, λem 535 nm by

using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices,

LLC).

Immunohistochemistry and

immunofluorescence

Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at 4°C overnight. The

fixed tissues were sequentially immersed in 50, 70, 85, 95 and 100%

ethanol solutions for 90 min each to achieve gradual dehydration to

ensure complete water removal. The tissue was immersed in a 1:1

mixture of ethanol and xylene for 60 min, followed by immersion in

pure xylene for an additional 60 min. Subsequently, the tissue was

transferred to a 1:1 mixture of xylene and paraffin for 60 min,

then placed in pure paraffin solution for 120 min. Finally, the

tissue was incubated in molten paraffin at 62°C for 2 h to ensure

complete infiltration of the colon tissue. The colon tissue was

placed in a mold and molten paraffin was added. After waiting for

the paraffin to solidify, the tissue wax blocks were cut into thin

slices ~3 μm thick using a microtome. The

immunohistochemical sections were incubated with the PFKFB3 primary

antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with the

anti-rabbit secondary antibody at 37°C for 1 h. The

immunofluorescence sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with

the primary antibodies against PFKFB3 and E-cadherin, followed by

incubation at 37°C for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated and

Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated secondary antibodies in the dark. The

cell nuclei were stained with DAPI at a temperature of 37°C for 10

min. Images were acquired by using fluorescence microscopy (Olympus

Corporation). A total of 19 blood samples from patients with

Crohn's disease and 21 blood samples from healthy individuals were

collected. Additionally, five colon tissue samples were obtained

from patients with Crohn's disease. The male-to-female ratio across

all patient samples was ~2:1, with an age range of 22-50 years. All

human tissue were collected using protocols approved by Medical

Ethics Committee of Second Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical

University, PLA and informed consent had been obtained from the

patients (approval no. 2022-188-01).

Statistical analysis

Crohn's disease datasets were downloaded from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo.

High-throughput transcriptome data from blood samples of healthy

individuals and IBD patients, retrieved from the GEO database

(accession numbers GSE119600, GSE112057 and GSE126124), were

analyzed to mRNA expression of the PFKFB3 between the two groups.

The ubiquitin ligase associated with the PFKFB3 protein was

predicted and analyzed using the http://ubibrowser.ncpsb.org.cn. Statistical analyses

of all data were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0;

Dotmatics). Comparisons between two groups were analyzed by a

two-tailed, unpaired Student's t-test. One-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post-hoc test was used for multiple comparisons Data from

at least three independent experiments unless otherwise noted.

Error bars represent SEM and statistical significance is indicated

as *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Impaired autophagy and elevated

glycolysis levels in IBD

First, to elucidate the changes of autophagy in IBD,

acute and chronic colitis models were established in C57BL/6 mice.

DSS concentration of 2.5% (w/vol) in the drinking water for 7 days

induce marked colitis in C57BL/6 mice. In addition, chronic colitis

model was induced in C57BL/6 mice by three cycles of 2% DSS (7 days

of DSS induction, 14 days water) (Fig. 1A). The present study extracted

the colonic epithelial cells of colitis mice and detected the

expression of autophagy marker proteins (P62 and LC3b) by western

blotting. As shown in Fig. 1B,

the expression of P62 and LC3b were markedly increased in colonic

epithelial cells of acute and chronic colitis mice. The mRNA levels

of key glycolysis enzymes were detected to explore the glycolysis

levels. PCR data showed that the expression levels of PFKP, LDHA

and PFKFB3 were markedly increased in DSS group (Fig. 1C). However, the mRNA levels of

HK2 and PKM2 were decreased in DSS group (Fig. 1C).

![Impaired autophagy and upregulated

glycolysis levels in IECs were observed under inflammatory

conditions. (A) Establishment of acute colitis mouse model and

chronic colitis mouse model. (B) The protein levels of P62 and LC3b

in colonic epithelial cells of acute DSS-induced mice (n=3) and

chronic DSS-induced mice (n=3) determined by western blot analysis.

(C) mRNA levels of PFKP, LDHA, HK2, PKM2, PFKFB3 in DSS-induced

mice epithelial cells. (D) Autophagic flux was measured by

transfecting cells with mRFP-GFP-LC3 dual-fluorescence adenovirus

(Ad-LC3), allowing differentiation between autophagosomes

(mRFP+/GFP+ fluorescence, appearing as yellow puncta) and

autolysosomes (mRFP+/GFP-fluorescence, appearing as red puncta).

TNF-α (200 ng/ml) induced epithelial cells for 48 h. Representative

immunofluorescence images were shown. (Original magnification,

×20). Quantification of LC3 puncta number of representative cells.

(E) Relative glucose content and lactate (Lac) production in

control vs. TNF-α induced epithelial cells. (F) 2-NBDG and (G)

BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in TNF-α induced epithelial

cells vs. control. Representative immunofluorescence images were

shown. (Original magnification, ×20). Quantitative fluorescence

intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF (n=3). Data were presented as the

mean ± SD of n=3 per group. Statistical analysis was performed

using unpaired t-tests. ****P<0.0001,

***P<0.001, **P<0.01,

*P<0.05, ns, non-significant vs. control group. IECs,

intestinal epithelial cells; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium salt;

2-NBDG, 2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)

amino]-D-glucose; BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein.](/article_images/ijmm/57/2/ijmm-57-02-05714-g00.jpg) | Figure 1Impaired autophagy and upregulated

glycolysis levels in IECs were observed under inflammatory

conditions. (A) Establishment of acute colitis mouse model and

chronic colitis mouse model. (B) The protein levels of P62 and LC3b

in colonic epithelial cells of acute DSS-induced mice (n=3) and

chronic DSS-induced mice (n=3) determined by western blot analysis.

(C) mRNA levels of PFKP, LDHA, HK2, PKM2, PFKFB3 in DSS-induced

mice epithelial cells. (D) Autophagic flux was measured by

transfecting cells with mRFP-GFP-LC3 dual-fluorescence adenovirus

(Ad-LC3), allowing differentiation between autophagosomes

(mRFP+/GFP+ fluorescence, appearing as yellow puncta) and

autolysosomes (mRFP+/GFP-fluorescence, appearing as red puncta).

TNF-α (200 ng/ml) induced epithelial cells for 48 h. Representative

immunofluorescence images were shown. (Original magnification,

×20). Quantification of LC3 puncta number of representative cells.

(E) Relative glucose content and lactate (Lac) production in

control vs. TNF-α induced epithelial cells. (F) 2-NBDG and (G)

BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in TNF-α induced epithelial

cells vs. control. Representative immunofluorescence images were

shown. (Original magnification, ×20). Quantitative fluorescence

intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF (n=3). Data were presented as the

mean ± SD of n=3 per group. Statistical analysis was performed

using unpaired t-tests. ****P<0.0001,

***P<0.001, **P<0.01,

*P<0.05, ns, non-significant vs. control group. IECs,

intestinal epithelial cells; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium salt;

2-NBDG, 2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)

amino]-D-glucose; BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein. |

Meanwhile, TNF-α (200 ng/ml) was used to induce

inflammation in NCM460, one of the human IECs lines. Autophagic

flux was detected by transfecting mRFP-GFP-LC3 double fluorescence

adenovirus in IECs. Autophagosome with double limiting membrane

structure was marked by both mRFP and GFP, which appeared as yellow

puncta. GFP fluorescent protein was known to quench under acidic

conditions. Therefore, autolysosomes with low pH were marked by

only mRFP which appeared as red puncta. Quantification of LC3

puncta number of representative cells is shown in Fig. 1D. Compared with the control

group, the number of autophagosomes in the TNF-α group increased

while the number of autolysosomes decreased. This suggested that

the process of fusion of autophagosome and lysosome was blocked in

inflammatory IECs and the accumulation of autophagosome occurred in

inflammatory IECs. In vivo and in vitro models of

colitis both suggested impaired autophagy of colon epithelial cells

under inflammation. Subsequently, the glycolysis levels in model of

inflammatory IECs was further investigated. Intracellular glucose

content and lactic acid production were measured in TNF-α induced

IECs. Glucose content decreased markedly and lactic acid production

increased in inflammatory IECs, suggesting an enhanced glycolysis

level (Fig. 1E). A

2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]-D-glucose

(2-NBDG) fluorescence probe was then used to detect the rate of

glucose uptake in IECs (Fig. 1F)

and a pH-sensitive dye 2',7'-Bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxy-fluorescein BCECF

fluorescence probe to detect intracellular acidity (Fig. 1G). It was known that 2-NBDG

fluorescence density increased with the increased of cellular

glucose uptake rate, while BCECF fluorescence density increases

with the decreased of pH in IECs. Quantitative statistics of

fluorescence density showed that the density of 2-NBDG and BCECF

markedly increased in inflammatory IECs, suggesting that

inflammatory stimulation resulted in increasing glucose uptake rate

and cell acidity. These data indicated that the level of glycolysis

was increased under inflammation.

Autophagy negatively regulates glycolysis

in intestinal epithelial cells

Autophagy-related genes (ATGs) are core conserved

genes that coordinate and mediate the formation of the double

membrane structure of autophagosomes in eukaryotic cells and

transfer the contents of cytoplasm to lysosome degradation

(17). ATG7 protein encoded by

autophagy-related genes participates in the lipidation process of

autophagosome formation, driving phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to

bind to LC3-I to generate LC3-II which promotes autophagy. ATG7

impairment classically results in autophagy defects in cells and

tissues (18). The present study

stably expressed retrovirus shRNA against ATG7 in IECs (Fig. 2A). In ATG7 knock-down cells,

glucose content decreased while lactate production increased

(Fig. 2B). In addition,

increased rate of glucose uptake (Fig. 2C) and intracellular acidity

(Fig. 2D) were observed in ATG7

knockdown cells. Furthermore, the enzyme activity of PFK-1, one of

the key rate-limiting enzymes in glycolysis was detected and it was

found that PFK-1 activity was enhanced in ATG7 knockdown cells

(Fig. 2E). This might be related

to the increased rate of glycolysis. Taken together, these data

suggested that impaired autophagy caused by ATG7 knockdown in IECs

lead to increased glycolysis levels.

![Knockdown of ATG7 in IECs resulted in

increased glycolysis levels. (A) mRNA levels of ATG7 in control vs.

sh-ATG7 epithelial cells. (B) Relative glucose content and lactate

(Lac) production in control vs. sh-ATG7 epithelial cells. (C)

2-NBDG and (D) BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in ATG7 knockdown

epithelial cells vs. control. Representative immunofluorescence

images were shown. (Original magnification, ×20). Quantitative

fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF. (E) Enzymatic

activities of PFK-1 in ATG7-knockdown epithelial cells vs. control

(n=3). P-values were calculated using an unpaired t-test. The

values were presented as the means ± SEM, n=3,

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ATG,

autophagy related gene; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; sh,

short hairpin; si, small interfering; 2-NBDG,

2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]-D-glucose;

BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein; PFK-1,

phosphofructokinase-1.](/article_images/ijmm/57/2/ijmm-57-02-05714-g01.jpg) | Figure 2Knockdown of ATG7 in IECs resulted in

increased glycolysis levels. (A) mRNA levels of ATG7 in control vs.

sh-ATG7 epithelial cells. (B) Relative glucose content and lactate

(Lac) production in control vs. sh-ATG7 epithelial cells. (C)

2-NBDG and (D) BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in ATG7 knockdown

epithelial cells vs. control. Representative immunofluorescence

images were shown. (Original magnification, ×20). Quantitative

fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF. (E) Enzymatic

activities of PFK-1 in ATG7-knockdown epithelial cells vs. control

(n=3). P-values were calculated using an unpaired t-test. The

values were presented as the means ± SEM, n=3,

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ATG,

autophagy related gene; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; sh,

short hairpin; si, small interfering; 2-NBDG,

2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]-D-glucose;

BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein; PFK-1,

phosphofructokinase-1. |

Subsequently, to further elucidate the regulation of

autophagy on glycolysis, IECs was treated by autophagy activator

rapamycin, or the autophagy inhibitor Baf A1. Glucose content and

lactate production were measured in rapamycin or Baf A1 treated

IECs (Fig. 3A and B). Data

showed that activation of autophagy inhibited the production of

glycolytic metabolites and reduced glycolysis level. Furthermore,

increased rate of glucose uptake and intracellular acidity were

observed in Baf A1 treated IECs, while decreased rate of glucose

uptake and intracellular acidity were observed in rapamycin treated

IECs (Fig. 3C and D). Moreover,

PFK-1 enzyme activity was detected in IECs treated with rapamycin

or Baf A1 (Fig. 3E). Similar to

ATG7 knockdown cells, activation of autophagy negatively regulated

PFK-1 enzyme activity. The aforementioned data indicated that

activation of autophagy promotes decreased of glycolysis level in

IECs and inhibition of autophagy resulted in elevated

glycolysis.

![Autophagy agonists and inhibitors

regulated glycolysis. (A) Relative glucose content and Lac

production in control vs. Baf A1 treated IECs. (B) Relative glucose

content and Lac production in control vs. rapamycin treated IECs.

(C and D) 2-NBDG and BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in

rapamycin or BafA1 treated IECs vs. control. Representative

immunofluorescence images were shown. (Original magnification,

×20). Quantitative fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF

(n=3). (E) Enzymatic activities of PFK-1 in rapamycin or BafA1

treated IECs vs. control (n=3). P-values were calculated using

One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. The values were

presented as the means ± SEM, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. Lac, lactate; Baf A1, bafilomycin A1;

IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; 2-NBDG,

2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]-D-glucose;

BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein; PFK-1,

phosphofructokinase-1.](/article_images/ijmm/57/2/ijmm-57-02-05714-g02.jpg) | Figure 3Autophagy agonists and inhibitors

regulated glycolysis. (A) Relative glucose content and Lac

production in control vs. Baf A1 treated IECs. (B) Relative glucose

content and Lac production in control vs. rapamycin treated IECs.

(C and D) 2-NBDG and BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in

rapamycin or BafA1 treated IECs vs. control. Representative

immunofluorescence images were shown. (Original magnification,

×20). Quantitative fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF

(n=3). (E) Enzymatic activities of PFK-1 in rapamycin or BafA1

treated IECs vs. control (n=3). P-values were calculated using

One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. The values were

presented as the means ± SEM, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. Lac, lactate; Baf A1, bafilomycin A1;

IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; 2-NBDG,

2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]-D-glucose;

BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein; PFK-1,

phosphofructokinase-1. |

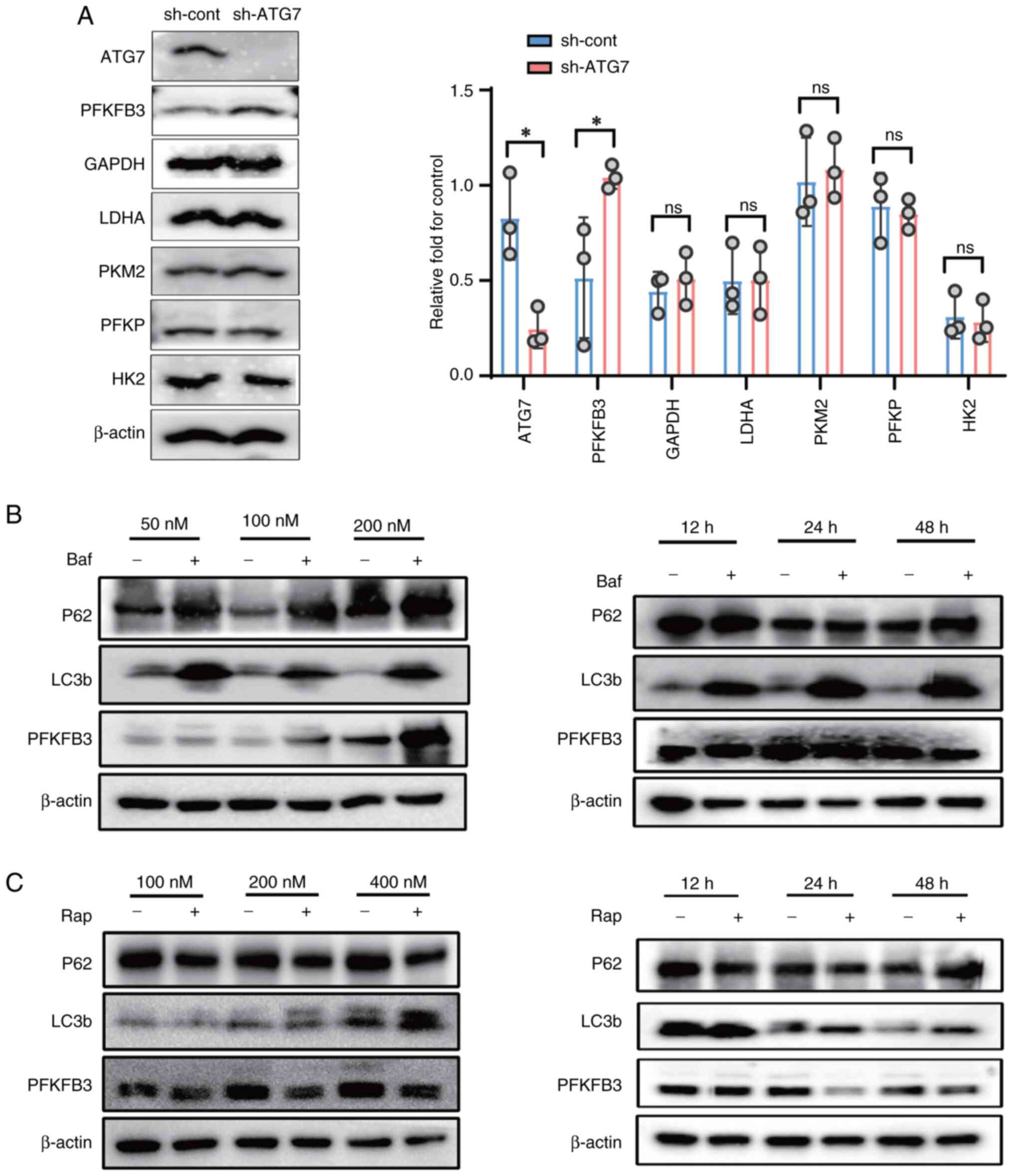

PFKFB3 is required for autophagy to

regulate glycolysis in IECs

The present study next attempted to identify

possible key protein in the process of autophagy regulation of

glycolysis. It examined the protein expression levels of six key

glycolytic enzymes, HK2, PKM2, LDHA, PFKP, GAPDH and PFKFB3 in

control group and autophagy deficient (ATG7 knockdown) cells group.

Notably, only PFKFB3 protein levels increased in ATG7 knockdown

IECs. There was no significant difference in the protein expression

of other key glycolytic enzymes in ATG7 knockdown IECs group and

control group (Fig. 4A). Base on

aforementioned results, it was next examined whether rapamycin or

Baf A1 regulated the protein expression of PFKFB3 in IECs. IECs

were treated with different concentrations (50, 100 and 200 nM) of

Baf A1 or different concentrations (100, 200 and 400 nM) of

rapamycin for 24 h. Meanwhile, IECs were treated with 200 nM Baf A1

or rapamycin for different times (12, 24 and 48 h). Western

blotting showed that Baf A1 inhibited autophagy and increased

expression of PFKFB3 protein. In contrast to the Baf A1, rapamycin

activated autophagy and reduced levels of PFKFB3 protein (Fig. 4B and C).

To further elucidate the importance of PFKFB3,

PFKFB3 knockdown and overexpression intestinal epithelial cells

were constructed (Fig. 5A).

PFKFB3 knockdown cells were treated with Baf A1 for 24 h. After

autophagy was inhibited in PFKFB3 knockdown cells, it was observed

that compared with normal epithelial cells treated with Baf A1, the

glucose content of PFKFB3 knockdown cells were markedly increased

and lactic acid production was decreased (Fig. 5B). Result of 2-NBDG and BCECF,

indicated that PFKFB3 knockdown reduced the rate of intracellular

glycolysis and impaired the ability of autophagy inhibitors to

promote glycolysis (Fig. 5C and

D). Moreover, compared with PFKFB3 knockdown cells without

rapamycin, the relative glucose content and lactic acid production

of PFKFB3 knockdown cells treated with rapamycin were not markedly

changed (Fig. 5E). Furthermore,

the results of 2-NBDG and BCECF also indicated that rapamycin has

no effect on the glycolysis rate following PFKFB3 knockdown

(Fig. 5F and G). All of these

results indicated that PFKFB3 plays a key role in autophagy

regulation of intestinal epithelial cells glycolysis. Subsequently,

the role of the autophagy activator rapamycin was validated in

PFKFB3-overexpressing NCM460 cells. Overexpression of PFKFB3

increased glucose content and decreased lactic acid production in

intestinal epithelial cells following treatment with rapamycin

(Fig. 5H). Flag-tagged PFKFB3

overexpression cells had shown high level of 2-NBDG and BCECF,

while rapamycin treatment reduced it (Fig. 5I and J). It suggested that PFKFB3

increased in intestinal epithelial cells induced high level of

glycolysis, while promoting autophagy can alleviate the level of

PFKFB3-induced glycolysis.

![PFKFB3 played a key role in autophagy

regulating of the glycolysis of IECs. (A) The verification of

PFKFB3 knockdown and overexpression by western blotting. Relative

glucose content and Lac production in PFKFB3 knockdown IECs treated

with (B) Baf A1 (200 nM) or (E) rapamycin (200 nM). (C and F)

2-NBDG and (D and G) BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in

rapamycin or BafA1 treated PFKFB3 knockdown IECs vs. control.

Representative immunofluorescence images are shown. (Original

magnification, ×20) with quantitative fluorescence intensity of

2-NBDG and BCECF (n=3). (H) Relative glucose content and Lac

production in PFKFB3 OE IECs treated with rapamycin (200 nM). (I)

2-NBDG and (J) BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in rapamycin

treated PFKFB3 OE IECs vs. control. Representative

immunofluorescence images are shown (Original magnification, ×20)

and quantitative fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF (n=3).

P-values were calculated using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post-hoc test. The values were presented as the means ± SEM,

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. PFKFB3,

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3; Lac,

lactate; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; Baf A1, bafilomycin A1;

2-NBDG, 2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)

amino]-D-glucose; BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein; OE,

overexpression.](/article_images/ijmm/57/2/ijmm-57-02-05714-g04.jpg) | Figure 5PFKFB3 played a key role in autophagy

regulating of the glycolysis of IECs. (A) The verification of

PFKFB3 knockdown and overexpression by western blotting. Relative

glucose content and Lac production in PFKFB3 knockdown IECs treated

with (B) Baf A1 (200 nM) or (E) rapamycin (200 nM). (C and F)

2-NBDG and (D and G) BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in

rapamycin or BafA1 treated PFKFB3 knockdown IECs vs. control.

Representative immunofluorescence images are shown. (Original

magnification, ×20) with quantitative fluorescence intensity of

2-NBDG and BCECF (n=3). (H) Relative glucose content and Lac

production in PFKFB3 OE IECs treated with rapamycin (200 nM). (I)

2-NBDG and (J) BCECF fluorescent counter-staining in rapamycin

treated PFKFB3 OE IECs vs. control. Representative

immunofluorescence images are shown (Original magnification, ×20)

and quantitative fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG and BCECF (n=3).

P-values were calculated using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post-hoc test. The values were presented as the means ± SEM,

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. PFKFB3,

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3; Lac,

lactate; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; Baf A1, bafilomycin A1;

2-NBDG, 2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)

amino]-D-glucose; BCECF, 2',7'-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein; OE,

overexpression. |

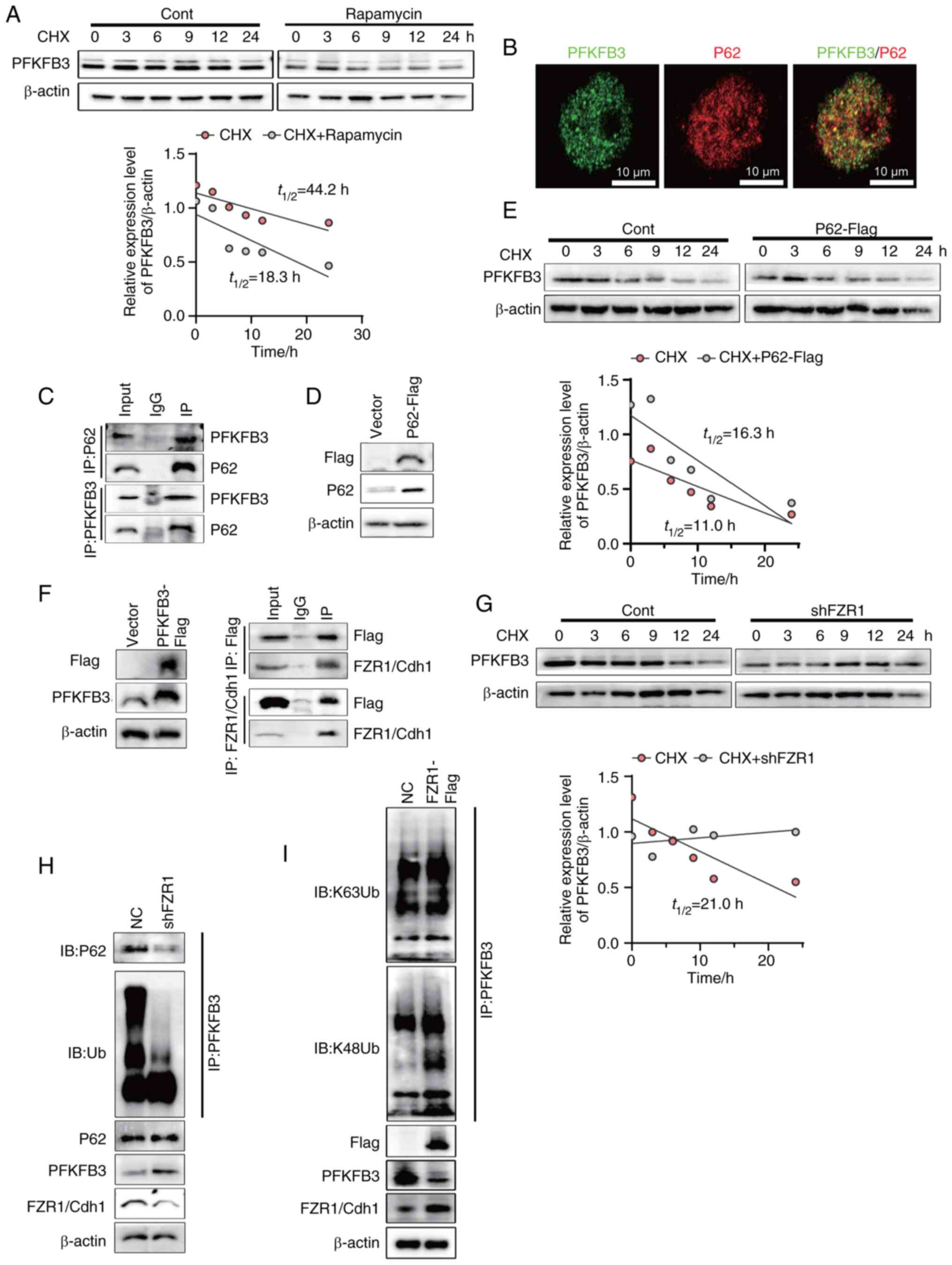

P62 specifically targets FZR1/Cdh1

ubiquitination PFKFB3 and mediates its autophagic degradation in

IEC

The present authors have previously verified that

autophagy can regulate the expression of PFKFB3 protein. Foerster

et al (4) reported that

selective autophagy regulated intestinal environmental homeostasis

by degrading specific proteins. This implied that autophagy might

regulate PFKFB3 protein stability. To test this hypothesis, NCM460

cells with or without rapamycin were treated with cycloheximide

(CHX) to inhibit protein synthesis, followed by monitoring the

levels of remaining PFKFB3 at the indicated time points (Fig. 6A). The results indicated that

PFKFB3 protein stability was disrupted by rapamycin and the PFKFB3

degradation was mediated by autophagy. Selective autophagy is

mediated by autophagy receptors and P62/SQSTM1 is a common

autophagy receptor in mammals (19). It was hypothesized that P62

receptor mediated the degradation of PFKFB3 protein in intestinal

epithelial cells. First, PFKFB3 and P62 were labelled by

immunofluorescence, which showed that PFKFB3 and P62 were

co-localized (Fig. 6B). The

results indicated that PFKFB3 might interacted with P62.

Subsequently, the coimmunoprecipitation assays showed that P62

could interact with PFKFB3, suggesting that P62 played a key role

in PFKFB3 degradation (Fig. 6C).

To further elucidate the effect of P62 on the degradation of

PFKFB3, Flag-tagged P62 overexpression NCM460 was constructed

(Fig. 6D). NCM460 cells with or

without P62 overexpression were treated with CHX at indicated

times. The results showed that P62 overexpression promoted the

degradation of PFKFB3 (Fig. 6E).

P62 were characterized by the ubiquitin binding domains allowing

them to bridge cargo (20). It

was hypothesized that an E3 ubiquitin ligase mediated PFKFB3

ubiquitination which was recognized by P62. Using the UbiBrowser,

E3 ubiquitin ligase prediction website, it was found that FZR1/Cdh1

might be the E3 ubiquitin ligase of PFKFB3 in intestinal epithelial

cells. To verify this hypothesis, Flag-tagged PFKFB3 overexpression

cells were constructed and the interaction of PFKFB3 with FZR1/Cdh1

was analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 6F). Subsequently, to verify the

effect of E3 ubiquitin ligase FZR1/Cdh1 on the degradation of

PFKFB3, FZR1 knockdown NCM460 cells were constructed. With or

without FZR1 knockdown, NCM460 cells were treated with CHX at the

indicated times. FZR1 knockdown NCM460 cells and control group were

treated with CHX. The remaining PFKFB3 proteins were detected and

FZR1 knockdown inhibited the degradation of PFKFB3 (Fig. 6G). Finally, endogenous PFKFB3

ubiquitination levels were analyzed in FZR1 knockdown cells. FZR1

knockdown led to the decreased incorporation of ubiquitin.

Furthermore, FZR1 knockdown disrupted the interaction between P62

and PFKFB3. FZR1 knockdown increased the expression of PFKFB3 while

P62 was not affected (Fig. 6H).

The E3 ubiquitin ligase catalyzed the formation of eight potential

isomeric ubiquitin chains by conjugating ubiquitin to one of the

seven lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine of the

substrate. As specific molecular tags, these ubiquitin chains

directed the substrate toward distinct biological outcomes, a

concept referred to as the ubiquitin code. Of these, K48- and

K63-linked polyubiquitin chains are the two most prevalent types

(21). The E3 ubiquitin ligase

exhibits inherent selectivity in ubiquitin chain linkage formation

(22). To investigate this

specificity, an in vitro analysis of the ubiquitin chains

generated by FZR1 was performed, focusing on K48- and K63-linked

polyubiquitin chains. The results demonstrated that FZR1

predominantly promoted the assembly of K48-linked ubiquitin chains,

with minimal effect on the formation of K63-linked chains (Fig. 6I). These results indicated that

FZR1/Cdh1 mediated the formation of K48-linked ubiquitin chains on

PFKFB3, which were subsequently recognized by p62 and delivered via

autophagosomes to lysosomes in intestinal epithelial cells for

degradation.

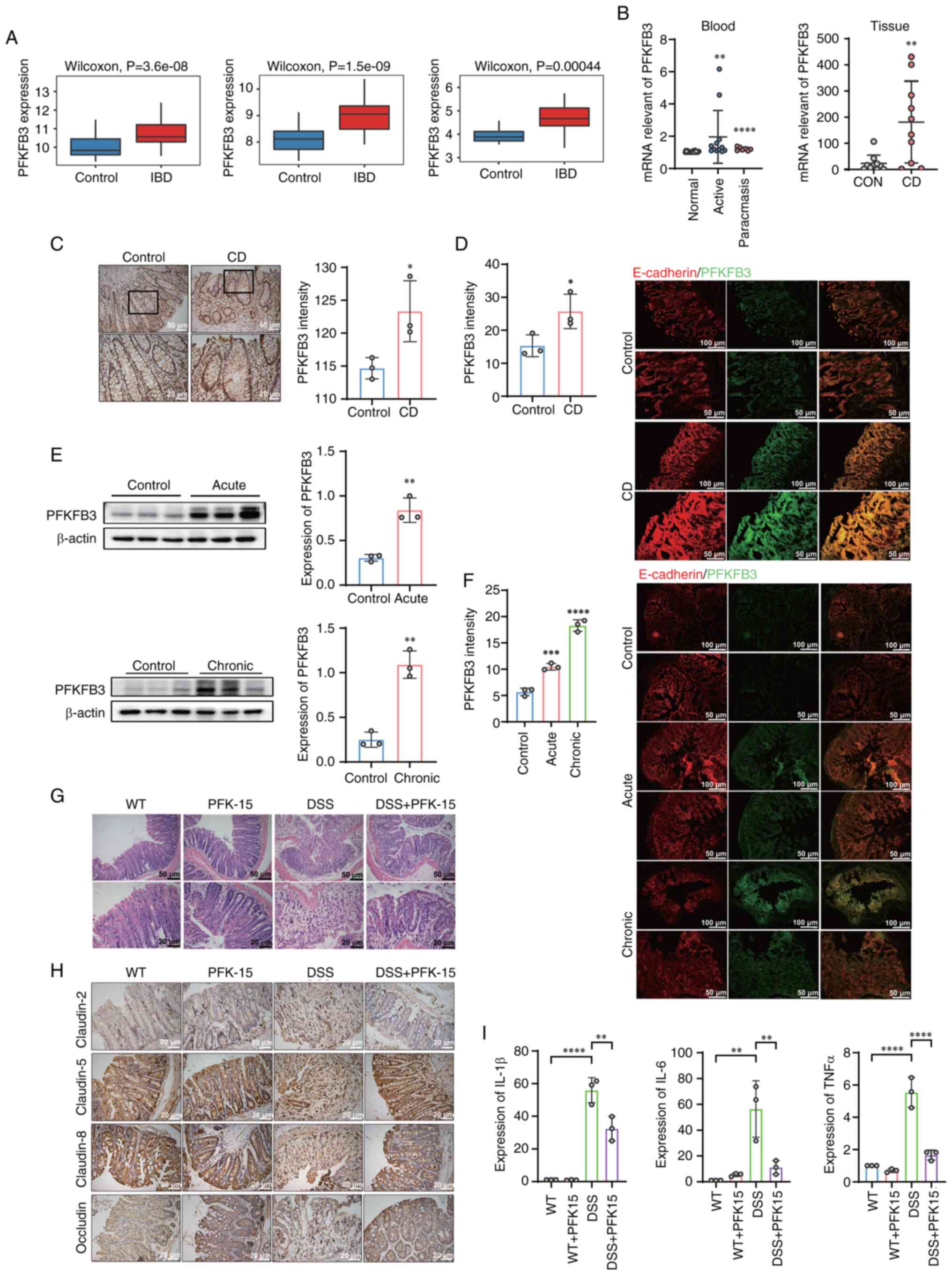

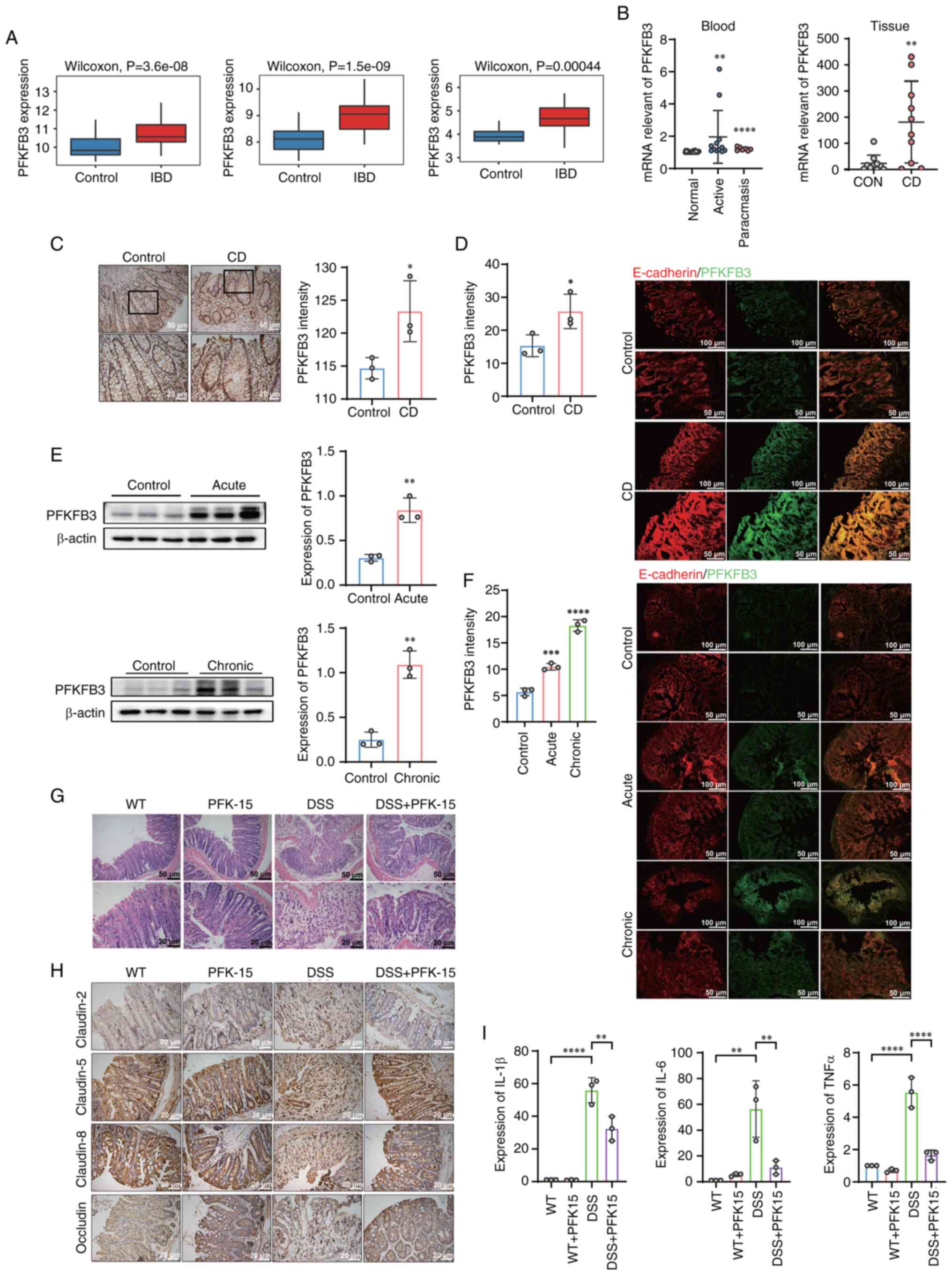

Elevated PFKFB3 protein is observed in

the colonic epithelium of IBD

To clarify the key role of PFKFB3 in IBD, the

expression of PFKFB3 was investigated in IBD. The present study

evaluated PFKFB3 expression using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets

from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Results indicated that PFKFB3

was upregulated in CD group, compared with normal tissues group

(Fig. 7A). PFKFB3 mRNA levels

were further detected in the blood and tissues of patients with CD.

The mRNA expression of PFKFB3 in the blood of patients with CD in

both active and remission stages were markedly higher than of

normal patients. In addition, the elevated mRNA expression of

PFKFB3 was also observed in the tissues of patients with CD

(Fig. 7B). The expression of

PFKFB3 is displayed by immunohistochemical staining of intestinal

epithelium of patients with CD (Fig.

7C). To further validate, PFKFB3 and E-cadherin fluorescence

staining in colon tissue of patients with CD were performed

(Fig. 7D). E-cadherin was one of

the epithelial marker proteins. The expression of PFKFB3 in

intestinal epithelium was elucidated by co-localization of PFKFB3

with E-cadherin. Semiquantitative analysis of immunohistochemical

staining and fluorescence intensity revealed that PFKFB3 highly

expression in patients with CD' colonic epithelium tissue.

| Figure 7PFKFB3 was upregulated in IBD. (A)

Analysis of PFKFB3 mRNA expression in normal and Crohn's disease

tissues within public datasets (GSE119600, GSE126124, GSE112057).

(B) mRNA levels of PFKPFB3 in control (n=10) vs. tissue of patients

with Crohn's disease (n=10), control (n=26) vs. blood of patients

with Crohn's disease (active stage n=12; remission stage n=7). (C)

Immunohistochemical staining of PFKFB3 in tissue of patients with

Crohn's disease and semiquantitative analysis (n=3). (D)

Immunofluorescence images of PFKFB3 in colonic epithelial tissue of

patients with Crohn's disease and quantification of the

fluorescence intensity of PFKFB3 (n=3). (E) Protein levels of

PFKFB3 in control vs. colonic epithelium of DSS-induced mice (acute

n=3, chronic n=3). (F) Immunofluorescence images of PFKFB3 in

colonic epithelium of DSS-induced mice and quantification of the

fluorescence intensity of PFKFB3 (acute n=3, chronic n=3). (G)

Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of the colon.

DSS-induced colitis mice were treated with intraperitoneal

injection of PFK-15 every three days. (H) Immunohistochemical

staining of claudin-5, claudin-8, claudin-2 and occludin in colon

tissue. (I) mRNA levels of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β. The P values for

all figures except B, F, and H were calculated using unpaired

t-tests, while one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple

comparisons test was used for B, F and H. The values were presented

as the means ± SEM, *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. PFKFB3,

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3; IBD,

inflammatory bowel disease; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium salt;

PFK-1, phosphofructokinase-1; CD, Crohn's disease; WT,

Wild-type. |

The expression of PFKFB3 was further observed in

colitis mouse model. First, colonic epithelial cells were extracted

from mouse model of DSS induced colitis and the PFKFB3 protein

level detected in IECs by western blotting. It showed that the

expression of PFKFB3 protein was elevated both in acute and chronic

colitis model (Fig. 7E). PFKFB3

and E-cadherin immunofluorescence staining were performed. The

result of fluorescence co-localization of PFKFB3 and E-cadherin in

colitis mouse model revealed that PFKFB3 expression was elevated in

colitis colonic epithelium (Fig.

7F). The above results suggested that PFKFB3 plays an important

role in inflammatory bowel disease.

PFKFB3 regulates tight junction proteins

and inflammatory factors in the intestinal epithelium

Given that the findings proved that the expression

of PFKFB3 increased in IBD. To verify whether PFKFB3 as a

therapeutic target could alleviate colitis in mice, the present

study established DSS-induced colitis mice and treated them with

PFK15, a PFKFB3 inhibitor. The colonic morphology of four groups

was observed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. Compared with the

normal group, the colon villi of mice in DSS colitis group were

destroyed and a large number of neutrophils were infiltrated.

However, the villus morphology of DSS-induced colitis mice markedly

recovered after treatment with PFK15 (Fig. 7G). Immunohistochemical staining

assays of claudin-5, claudin-8, claudin-2 and occludin were

performed in colons of four groups mice. Among them, claudin-5,

claudin-8 and occludin increased interepithelial resistance and

decreased barrier permeability, while claudin-2 was found to

increase paracellular barrier permeability. The results showed that

the expression of claudin-5, claudin-8 and occludin decreased in

DSS group, while the expression of claudin-2 increased. Following

PFK15 treatment, claudin-5, claudin-8, occludin and claudin-2

recovered (Fig. 7H). mRNA levels

of intestinal epithelial cells in four groups of mice were examined

and it was found that the inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6,

TNF-α and IL-1β, decreased markedly after PFK15 treatment (Fig. 7I).

Discussion

Autophagy is involved in intestinal homeostasis and

repair by mediating the recycling of organelles and protein

aggregates, as well as the destruction of intracellular pathogens

(23). Impaired intestinal

autophagy results in the disruption of intestinal epithelial

barrier, increased intestinal permeability, impaired antimicrobial

peptide secretion, promotion of apoptosis of intestinal epithelial

cells and excessive accumulation of ROS (24). Impaired autophagy is observed in

mouse colitis models, LPS-induced IEC inflammation models and IECs

inpatients with active CD (4,25,26). The present study also found

impaired autophagy both in colonic epithelial cells of DSS induced

colitis mice and TNF-α induced NCM460 cells.

Glycolysis is a metabolic process of glucose in the

cytoplasm to produce energy and metabolites for macromolecular

biosynthesis. Glycolysis involved the conversion of glucose to

pyruvate and the conversion of pyruvate to lactic acid (27). The mRNA levels of key glycolysis

enzymes are elevated in the blood of patients with IBD (12). Moreover, lactic acid production

is increased in mice with IL-10-deficient idiopathic colitis

(28). Khaloian et al

(15) also indicated that

inhibition of glycolysis was able to alleviate intestinal stem

cells damage caused by inflammation. Consistent with these, the

present study also found increased glycolysis level in the

inflammatory NCM460 cells. Furthermore, mRNA levels of key

glycolytic enzymes PFKFB3, LDHA and PFKP were elevated in colon

IECs from DSS-induced colitis.

Increasing evidence suggests a mutually regulatory

relationship between autophagy and glycolysis (29). For example, inhibition of PKM2

enzymatic activity activates autophagy in lung carcinoma cell lines

(30). Sorafenib-induced

autophagy promotes glycolysis by elevated glycolytic enzyme PKM2

activity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (31). The present study found that

autophagy negatively regulated glycolysis by the degradation of

PFKFB3 in IECs. Therefore, the findings suggested a significant

correlation between autophagy in the intestinal epithelium and

metabolic processes.

PFKFB3 protein is one of the isoenzymes of

PFK-2/FBPase-2 and is mainly responsible for the conversion of

fructose-6-phosphat to fructose-2,6-bisphosphate. With the highest

kinase/phosphatase ratio among all PFK/FBPase-2 family members,

PFKFB3 promotes increased cellular glycolysis flux (32). The present study also

demonstrated that lactic acid production increased in an

PFKFB3-dependent manner in vitro.

To further elucidate the mechanism of PFKFB3

autophagic degradation, the present study first identified the

autophagy receptor for PFKFB3. Multiple autophagy receptors, such

as NDP52, OPTN, p62, and TAX1BP1, are capable of specifically

recognizing cargo proteins (20). PFKFB3 is reported as an autophagy

substrate bound to P62 in breast cancer stem cells (33). Consistently, the results of our

preliminary immunoprecipitation experiment also demonstrated P62

interacted with PFKFB3. For P62, it interacted with ubiquitinated

cargo due to its C-terminal UBA domain (19). Based on this, the present study

predicted and screened FZR1/Cdh1 as a PFKFB3 ubiquitination E3

ligase using the UbiBrowser website. PFKFB3 is degraded by

ubiquitination of FZR1/Cdh1 in astrocytes from rat brains (34). Notably, the present study also

found that FZR1/Cdh1 interacted with PFKFB3 in NCM460 cells and the

degradation of PFKFB3 was mediated by FZR1/Cdh1 ubiquitination.

Mechanistic analysis revealed that the K48-linked polyubiquitin

chain served as the specific ubiquitin code mediating

FZR1/Cdh1-induced degradation of PFKFB3 in intestinal epithelial

cells.

Subsequently, the present study investigated the

important effect of PFKFB3 on IBD. Inhibition of PFKFB3 activity

reduced inflammatory damage in DSS-induced colitis. Zhou et

al (35) also reported

increased stromal PFKFB3-mediated glycolysis contributed to

intestinal inflammation in IBD. In addition, inhibited PFKFB3

activity with PFK-15 prevented DSS induced reduction of claudin-5,

claudin-8 and occludin and increase of claudin-2 in colonic

epithelium. Claudin-5, claudin-8 and occludin are known as

'Sealing' tight junction proteins maintaining intestinal barrier

integrity. By contrast, the leaking protein claudin-2 is reported

to increase barrier permeability (36). The above results revealed that

inhibition of PFKFB3 expression could reduce inflammatory damage in

IBD and restored intestinal barrier function. In addition, the

present study underscored the critical interplay between intestinal

metabolism and inflammation, offering novel insights into the

regulation of intestinal epithelial metabolism in IBD and

suggesting potential avenues for therapeutic development.

A previous study demonstrated that urinary lactate

levels accurately reflect PFKFB3-mediated glycolytic abnormalities

and declining renal function in patients with chronic kidney

disease (CKD), suggesting their potential as a biomarker for

monitoring CKD progression (37). These findings raise an important

question: Could fecal lactate levels similarly reflect

PFKFB3-driven glycolytic dysregulation in IECs and serve as a

non-invasive biomarker for identifying IBD? At this stage, it was

recognized that the present study still had certain

limitations.

The present study demonstrated through both in

vivo and in vitro experiments that PFKFB3 intervention

exerted a significant therapeutic effect on intestinal damage

associated with IBD. Currently, the PFKFB3 small molecule inhibitor

has entered Phase I clinical trials and preliminary results have

demonstrated its favorable safety profile and promising anti-cancer

activity in patients with cancer (38). Accumulating evidence indicates

that PFKFB3 is closely linked to intestinal inflammatory responses,

suggesting the potential therapeutic utility of this inhibitor in

the clinical management of IBD. To facilitate the clinical

translation of PFKFB3 inhibitors, future research should prioritize

the development of advanced delivery systems, such as nanocarriers

or targeted encapsulation platforms, to minimize systemic toxicity

and improve tissue-specific targeting. Such an approach could

markedly accelerate the clinical application of PFKFB3-targeted

therapies for IBD treatment.

Based on the findings of the present study, a novel

strategy for combined autophagy and glycolysis-targeted therapy in

the treatment of IBD is proposed. Currently used clinical

therapeutics for IBD, such as corticosteroids and 5-aminosalicylic

acid, may exert part of their therapeutic effects through

inhibition of the glycolytic pathway (39). Meanwhile, a growing number of

studies have focused on developing therapeutic strategies for IBD

by modulating autophagy, with some promising advances achieved

(40-42). However, autophagy-based therapies

primarily aim to maintain the dynamic equilibrium of autophagic

activity in intestinal cells, rather than merely activating or

inhibiting the process. Consequently, precise control of drug

dosage remains a significant challenge (43). Although the dual-targeted

combined therapy strategy that simultaneously modulates autophagy

and glycolysis holds therapeutic potential, it may also give rise

to drug efficacy interference due to pharmacological interactions.

Moreover, the systemic physiological consequences of multi-pathway

interventions require thorough assessment. Therefore, precise

optimization of dosage regimens and temporal administration

schedules will be critical in determining the clinical viability of

this approach. It is noteworthy that recent studies have

demonstrated that specific dietary components can alleviate

intestinal symptoms of IBD by modulating intestinal autophagy

(44). These findings suggest

that combining pharmacological inhibition of abnormal intestinal

glycolysis with dietary interventions targeting autophagy

regulation may enhance the therapeutic efficacy of IBD

treatment.

In conclusion, increase of PFKFB3-mediated

glycolysis in IECs is involved in IBD intestinal inflammatory

damage and epithelial barrier breakdown. Autophagy in IECs could

inhibit glycolysis and maintain intestinal homeostasis by selective

degradation of PFKFB3. The present study indicated that PFKFB3 was

both a key glycolytic enzyme and an autophagy substrate,

establishing crosstalk between autophagy and glycolysis in IECs.

Combined therapy targeting autophagy and glycolysis might become a

new choice for clinical treatment of IBD.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

The project was designed and directed by MY, WX, TY

and HY. The experiments were performed by YP and FY. MY, YP and FY

analyzed the data. MY and YP wrote the manuscript. GD, LW and CX

collected clinical samples. MY, FY and YP confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal procedures were performed under the

guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of

the Third Military Medical University (approval no. AMUWEC20224496)

and was approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics

Committee of the Third Military Medical University (approval no.

AMUWEC20224496). Patient tissue collection followed the guidelines

and principles of the Helsinki Declaration and received approval

from the Ethics Committee of Second Affiliated Hospital of Army

Medical University (approval no. 2022-188-01). Written informed

consent was obtained from all study participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

IBD

|

inflammatory bowel disease

|

|

CD

|

Crohn's disease

|

|

IECs

|

intestinal epithelial cells

|

|

PFKFB3

|

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3

|

|

DSS

|

dextran sulfate sodium salt

|

|

2-NBDG

|

2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]-D-glucose

|

|

PFK-1

|

phosphofructokinase-1

|

|

FZR1/Cdh1

|

Fizzy and cell division cycle 20

related 1

|

|

Baf A1

|

bafilomycin A1

|

|

HK2

|

hexokinase 2

|

|

PKM2

|

phosphofructokinase, muscle 2

|

|

LDHA

|

lactate dehydrogenase A

|

|

PFKP

|

phosphofructokinase, platelet

|

|

CHX

|

cycloheximide

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported in part by grants from Natural

Science Foundation of Chongqing (grant no. CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0027 to

Min Yu), grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (grant no. NSFC 81970468 to Min Yu), grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. NSFC 82270585 to

Weidong Xiao) and grants from the Senior Medical Talents Program of

Chongqing for Young and Middle-aged (Min Yu).

References

|

1

|

Li S, Zhang F and Zhang Q: Pathological

features-based targeted delivery strategies in IBD therapy: A mini

review. Biomed Pharmacother. 151:1130792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF and

Peyrin-Biroulet L: Crohn's disease. Lancet. 389:1741–1755. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Foerster EG, Mukherjee T, Cabral-Fernandes

L, Rocha JDB, Girardin SE and Philpott DJ: How autophagy controls

the intestinal epithelial barrier. Autophagy. 18:86–103. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

5

|

Saha K, Ganapathy AS, Wang A, Morris NM,

Suchanec E, Ding W, Yochum G, Koltun W, Nighot M, Ma T and Nighot

P: Autophagy reduces the degradation and promotes membrane

localization of occludin to enhance the intestinal epithelial tight

junction barrier against paracellular macromolecule flux. J Crohns

Colitis. 17:433–449. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Aden K, Tran F, Ito G, Sheibani-Tezerji R,

Lipinski S, Kuiper JW, Tschurtschenthaler M, Saveljeva S,

Bhattacharyya J, Häsler R, et al: ATG16L1 orchestrates

interleukin-22 signaling in the intestinal epithelium via

cGAS-STING. J Exp Med. 215:2868–2886. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhou C, Li L, Li T, Sun L, Yin J, Guan H,

Wang L, Zhu H, Xu P, Fan X, et al: SCFAs induce autophagy in

intestinal epithelial cells and relieve colitis by stabilizing

HIF-1alpha. J Mol Med (Berl). 98:1189–1202. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pral LP, Fachi JL, Corrêa RO, Colonna M

and Vinolo MAR: Hypoxia and HIF-1 as key regulators of gut

microbiota and host interactions. Trends Immunol. 42:604–621. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rath E, Moschetta A and Haller D:

Mitochondrial function-gatekeeper of intestinal epithelial cell

homeostasis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15:497–516. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ho GT and Theiss AL: Mitochondria and

inflammatory bowel diseases: Toward a stratified therapeutic

intervention. Ann Rev Physiol. 84:435–459. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Adolph TE, Meyer M, Schwärzler J, Mayr L,

Grabherr F and Tilg H: The metabolic nature of inflammatory bowel

diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 19:753–767. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Vermeulen N, Vermeire S, Arijs I, Michiels

G, Ballet V, Derua R, Waelkens E, Van Lommel L, Schuit F, Rutgeerts

P and Bossuyt X: Seroreactivity against glycolytic enzymes in

inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 17:557–564. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Shimshoni E, Ghini V, Solomonov I,

Luchinat C, Sagi I and Turano P: Integrated metabolomics and

proteomics of symptomatic and early pre-symptomatic states of

colitis. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.002196.

|

|

14

|

Hamade H, Stamps JT, Stamps DT, More SK,

Thomas LS, Blackwood AY, Lahcene NL, Castanon SL, Salumbides BC,

Shimodaira Y, et al: BATF3 protects against metabolic syndrome and

maintains intestinal epithelial homeostasis. Front Immunol.

13:8410652022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Khaloian S, Rath E, Hammoudi N, Gleisinger

E, Blutke A, Giesbertz P, Berger E, Metwaly A, Waldschmitt N, Allez

M and Haller D: Mitochondrial impairment drives intestinal stem

cell transition into dysfunctional Paneth cells predicting Crohn's

disease recurrence. Gut. 69:1939–1951. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2 (-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Levine B and Kroemer G: Biological

functions of autophagy genes: A disease perspective. Cell.

176:11–42. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Collier JJ, Oláhová M, McWilliams TG and

Taylor RW: ATG7 safeguards human neural integrity. Autophagy.

17:2651–2653. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lane JD, Korolchuk VI, Murray JT, Lamark

T, Svenning S and Johansen T: Regulation of selective autophagy:

The p62/SQSTM1 paradigm. Essays in Biochemistry. 61:609–624. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Vargas JNS, Hamasaki M, Kawabata T, Youle

RJ and Yoshimori T: The mechanisms and roles of selective autophagy

in mammals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:167–185. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ohtake F, Saeki Y, Ishido S, Kanno J and

Tanaka K: The K48-K63 branched ubiquitin chain regulates NF-κB

signaling. Mol Cell. 64:251–266. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Renz C, Asimaki E, Meister C, Albanèse V,

Petriukov K, Krapoth NC, Wegmann S, Wollscheid HP, Wong RP, Fulzele

A, et al: Ubiquiton-An inducible, linkage-specific

polyubiquitylation tool. Mol Cell. 84:386–400.e311. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Telpaz S and Bel S: Autophagy in

intestinal epithelial cells prevents gut inflammation. Trends Cell

Biol. 33:817–819. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Larabi A, Barnich N and Nguyen HTT: New

insights into the interplay between autophagy, gut microbiota and

inflammatory responses in IBD. Autophagy. 16:38–51. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

25

|

Zhou M, Xu W, Wang J, Yan J, Shi Y, Zhang

C, Ge W, Wu J, Du P and Chen Y: Boosting mTOR-dependent autophagy

via upstream TLR4-MyD88-MAPK signalling and downstream NF-kappaB

pathway quenches intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress

injury. EBioMedicine. 35:345–360. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shi W, Peng K, Yu H, Wang Z, Xia S, Xiao

S, Tian D, Vallance BA and Yu Q: Autotaxin (ATX) inhibits autophagy

leading to exaggerated disruption of intestinal epithelial barrier

in colitis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1869:1666472023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bian X, Jiang H, Meng Y, Li YP, Fang J and

Lu Z: Regulation of gene expression by glycolytic and gluconeogenic

enzymes. Trends Cell Biol. 32:786–799. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Martin FP, Rezzi S, Philippe D, Tornier L,

Messlik A, Hölzlwimmer G, Baur P, Quintanilla-Fend L, Loh G, Blaut

M, et al: Metabolic assessment of gradual development of moderate

experimental colitis in IL-10 deficient mice. J Proteome Res.

8:2376–2387. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yang J, Zhou RM and Ma ZY: Autophagy and

energy metabolism. Autophagy: Biology and diseases: Basic Science.

1206:329–357. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Prakasam G, Singh RK, Iqbal MA, Saini SK,

Tiku AB and Bamezai RNK: Pyruvate kinase M knockdown-induced

signaling via AMP-activated protein kinase promotes mitochondrial

biogenesis, autophagy, and cancer cell survival. J Biol Chem.

292:15561–15576. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yan X, Tian R, Sun J, Zhao Y, Liu B, Su J,

Li M, Sun W and Xu X: Sorafenib-induced autophagy promotes

glycolysis by upregulating the p62/HDAC6/HSP90 axis in

hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Front Pharmacol. 12:7886672022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kotowski K, Rosik J, Machaj F, Supplitt S,

Wiczew D, Jabłońska K, Wiechec E, Ghavami S and Dzięgiel P: Role of

PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 in cancer: Genetic basis, impact on disease

development/progression, and potential as therapeutic targets.

Cancers (Basel). 13:9092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

La Belle Flynn A, Calhoun BC, Sharma A,

Chang JC, Almasan A and Schiemann WP: Autophagy inhibition elicits

emergence from metastatic dormancy by inducing and stabilizing

Pfkfb3 expression. Nat Commun. 10:36682019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Almeida A, Bolaños JP and Moncada S: E3

ubiquitin ligase APC/C-Cdh1 accounts for the Warburg effect by

linking glycolysis to cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:738–741. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhou Z, Plug LG, Patente TA, de

Jonge-Muller ESM, Elmagd AA, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Everts B,

Barnhoorn MC and Hawinkels LJAC: Increased stromal PFKFB3-mediated

glycolysis in inflammatory bowel disease contributes to intestinal

inflammation. Front Immunol. 13:2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Pan YY, Deng Y, Su S, Yin JH, Chen YH,

Wang LC, Sun LH, Xiao WD and Du GS: Structure composition and

intracellular transport of clathrin-mediated intestinal

transmembrane tight junction protein. Inflammation. 46:18–34. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang Y, Li H, Jiang S, Fu D, Lu X, Lu M,

Li Y, Luo D, Wu K, Xu Y, et al: The glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 drives

kidney fibrosis through promoting histone lactylation-mediated

NF-κB family activation. Kidney Int. 106:226–240. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Shi L, Pan H, Liu Z, Xie J and Han W:

Roles of PFKFB3 in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

2:170442017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen N, Xie QM, Song SM, Guo SN, Fang Y,

Fei GH and Wu HM: Dexamethasone protects against asthma via

regulating Hif-1α-glycolysis-lactate axis and protein lactylation.

Int Immunopharmacol. 131:1117912024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Zhang H, Cui Z, Cheng D, Du Y, Guo X, Gao

R, Chen J, Sun W, He R, Ma X, et al: RNF186 regulates EFNB1 (ephrin

B1)-EPHB2-induced autophagy in the colonic epithelial cells for the