Introduction

Pain, recognized as one of humanity's most

fundamental physiological and psychological experiences, has been

designated by the international medical community as the 'fifth

vital sign' following blood pressure, temperature, respiration, and

pulse (1). With global aging

populations and increasing burdens of chronic diseases, the

prevalence of pain has risen steadily and severely compromised

patients' quality of life (2).

This highlights the urgent need for innovative analytical

approaches. To address this, the present study used the integration

of multi-pathway analysis to establish a systematic analytical

framework, aiming to advance precision diagnosis and treatment of

pain.

Definition of pain

In medical science, pain is defined as a complex

feeling that extends beyond mere physiological tissue injury. It

involves intricate interactions among psychological, emotional and

social factors (3). The

International Association for the Study of Pain revised its

definition in 2020, emphasizing that pain is 'an unpleasant sensory

and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue

damage, or described in terms of such damage' (4). This definition transcends

traditional biological perspectives, underscoring the subjectivity

and variability of pain. Individual perceptions of pain are

influenced by multiple factors, including physiological status,

psychological cognition, cultural background, and social

environment (5).

Classification of pain

Modern medicine classifies pain into three

categories (6): i) Nociceptive

pain: Arising from direct or potential tissue injury. Nociceptive

pain is generally unrelated to nerve distribution but is associated

with pathological damage causing the pain, such as degenerative

changes, trauma, muscle spasm, or visceral disorders (7-10). ii) Neuropathic pain: Resulting

from peripheral or central nervous system lesions. It is typically

linked to abnormal sensory perception caused by damage to nerves

responsible for pain signal transduction and transmission (11). Clinically, neuropathic pain often

manifests as spontaneous, persistent severe pain (12). iii) Central sensitization-induced

pain: Caused by central nervous system sensitization in the absence

of overt tissue damage or neurological lesions (13).

Clinical evaluation, management and

medical significance

The clinical evaluation and management of pain must

incorporate both objective and subjective dimensions. Quantitative

tools such as the visual analogue scale (VAS) or numeric rating

scale (NRS) are commonly used to quantify pain assessment, while

multidimensional instruments such as the McGill pain questionnaire

(MPQ) further analyze pain characteristics, emotional experiences

and effects on quality of life (14). For neuropathic pain, definitive

diagnosis requires combined neuroelectrophysiological testing.

Therapeutic strategies emphasize concurrent use of pharmacological

and non-pharmacological interventions (15). For chronic pain,

multidisciplinary collaboration models have become mainstream,

aiming to restore functional capacity through comprehensive

medical, psychological and social support interventions rather than

solely pursuing 'pain-free' outcomes (16). The medical significance of pain

lies not only in its role as a pathological warning signal but also

in its status as a critical global public health issue. The

resulting socioeconomic burdens and diminished quality of life

demand systematic solutions (17).

Research objectives and innovations

The present review aimed to achieve three

interrelated and clinically oriented goals, while addressing the

limitations of traditional reviews and opening up new perspectives

for pain research. However, existing research has mostly focused on

analyzing analgesic mechanisms through a single pathway (18-20). To overcome this limitation, the

present review integrated multi-channel analysis methods and

established a systematic analysis framework. The present review

innovatively combined research methods such as in-depth analysis of

molecular mechanisms, optimization of transformation models and

interdisciplinary technology integration. In summary, the aims and

innovations of these summaries and analyses are to bridge the gap

between basic research and clinical practice, providing theoretical

support for developing personalized pain management strategies and

constructing a precise pain diagnosis and treatment system, to

accelerate the transformation and application of mechanism oriented

therapies and ultimately to promote pain management research into a

new era of high-efficiency, low toxicity and personalized

treatment.

Methods

To comprehensively review the research progress on

models, mechanisms, therapies and prospect of pain, the present

review conducted a search in existing scientific databases using

the terms 'pain model', 'pain mechanism', 'pain therapy', 'pain

prospect'. Relevant literature on pain was obtained from both

online and offline databases, covering the period from 1987-2025,

totaling 334 references. Online databases included Elsevier

(https://www.elsever.com/), PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web of Science

(https://www.webof-science.com/), Google

Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), Wiley

(https://www.wiley.com/), EMBASE (https://www.embase.com/), SpringerLink (https://link.springer.com/), Cochrane Library

(https://clinicaltrials.gov/) and China

national knowledge infrastructure (CNKI) (https://www.cnki.net/). Other related references were

sourced from pharmacopoeias and other articles. To ensure a

comprehensive review, the literature search strategy was designed

to encompass both modern scientific research and historical

scholarly works. For official pharmacopoeias (such as Chinese

Pharmacopoeia) and articles from non-mainstream journals, specific

inclusion criteria were established. These sources were included

based on their recognized historical importance, foundational role

in theory development, or provision of unique data not available in

peer-reviewed journals. Figs.

1-6 were drawn by BioGDP

(https://biogdp.com/) in this paper.

Models of pain

The selection of experimental animals for pain

models demonstrates remarkable diversity (Data S1). Primate species

exhibit high anatomical and physiological similarity to humans,

enabling superior simulation of human disease progression and

serving as ideal candidates for chronic pain modeling. Notably,

their advanced nervous systems, including complex cortical pain

processing pathways and homologous pain-related brain regions (such

as the anterior cingulate cortex and insula), allow for the study

of subjective pain-like experiences (such as pain-related anxiety

or cognitive modulation of pain) that are difficult to replicate in

lower-order species; this unique advantage makes primates

invaluable for validating the translational potential of novel

analgesics targeting central pain mechanisms, especially for

chronic conditions such as post-herpetic neuralgia where human

cognitive and emotional factors strongly influence pain outcomes.

However, their demanding husbandry conditions, limited

availability, high costs and ethical constraints have restricted

their widespread adoption. Successful pain studies have been

conducted using large mammals such as pigs, dogs and cats (21), though their adoption is limited

by substantial practical and ethical challenges, further limiting

their scalability. Rodents are the most widely used models due to

their physiological similarity to humans, low cost, ease of

handling and scalability, enabling reliable mechanistic and

translational studies (22).

Additionally, zebrafish, fruit flies and nematodes (23,24) demonstrate significant promise in

pain genetics and molecular mechanism studies. Their

well-characterized genome sequences, controllable genetic

manipulations, simple body architectures and short life cycles

offer unique advantages for investigating pain-related cellular and

molecular pathways, warranting broader application in this

field.

Since experimental animals cannot express pain

directly as can humans, specific assessment methods are needed to

indirectly judge their pain status. Clinical evaluation of pain in

patients relies on methods such as medical interviews, physical

examinations and standardized questionnaire assessments. However,

experimental animals cannot verbally communicate discomfort during

nociceptive stimulation, so pain assessment for them mainly falls

into two categories: Naturalistic readouts based on spontaneous

behaviors and stimulus-evoked readouts via calibrated

interventions.

Spontaneous behaviors

Spontaneous behaviors refer to unprovoked behavioral

manifestations that reflect animals' inherent responses to pain.

These include foot withdrawal reflexes, excessive grooming,

scratching, vocalization, reduced exploratory activity, increased

immobility and changes in facial expression. In pathological pain

states, animals further exhibit hyperalgesic symptoms

(characterized by enhanced responsiveness to stimuli and reduced

reaction thresholds), where mild provocation can induce spontaneous

defensive behaviors such as foot withdrawal, licking, or abdominal

retraction.

Stimulus-evoked readouts

Unlike naturalistic readouts, stimulus-evoked

readouts require active induction of behavioral alterations using

specialized equipment, instruments, or reagents with calibrated

stimuli. This approach converts pain perception into numerically

representable outcomes, enabling indirect objective assessment of

pain intensity and sensitivity. Common stimulus-evoked assessment

methods for pain sensitivity in animals include mechanical,

thermal, and cold hyperalgesia tests, as well as specialized

detection protocols. i) Mechanical hyperalgesia assessment:

Mechanical pain thresholds are determined using Von Frey filaments

applied to the plantar or abdominal regions, with the threshold

defined as the minimum stimulus intensity eliciting a rapid

withdrawal reflex (25). ii)

Thermal hyperalgesia assessment: Thermal pain thresholds are

assessed by irradiating the animal's paw with a radiant heat source

and recording the latency to withdrawal (26). Cold hyperalgesia assessment: For

cold hyperalgesia evaluation, animals are placed on a 4°C thermal

plate, and withdrawal responses (foot withdrawal, licking, jumping)

are measured by latency or frequency within a specified time frame

(27). iii) Specialized

detection method: The abdominal withdrawal reflex (AWR) experiment

evaluates visceral sensitivity and pain thresholds through gradual

pressure inflation of the rectum. Metrics such as the pressure

required to elicit abdominal muscle contractions and arching of the

spine, or the number of contractions observed under fixed pressure

over time, are recorded to assess changes in visceral

nociception.

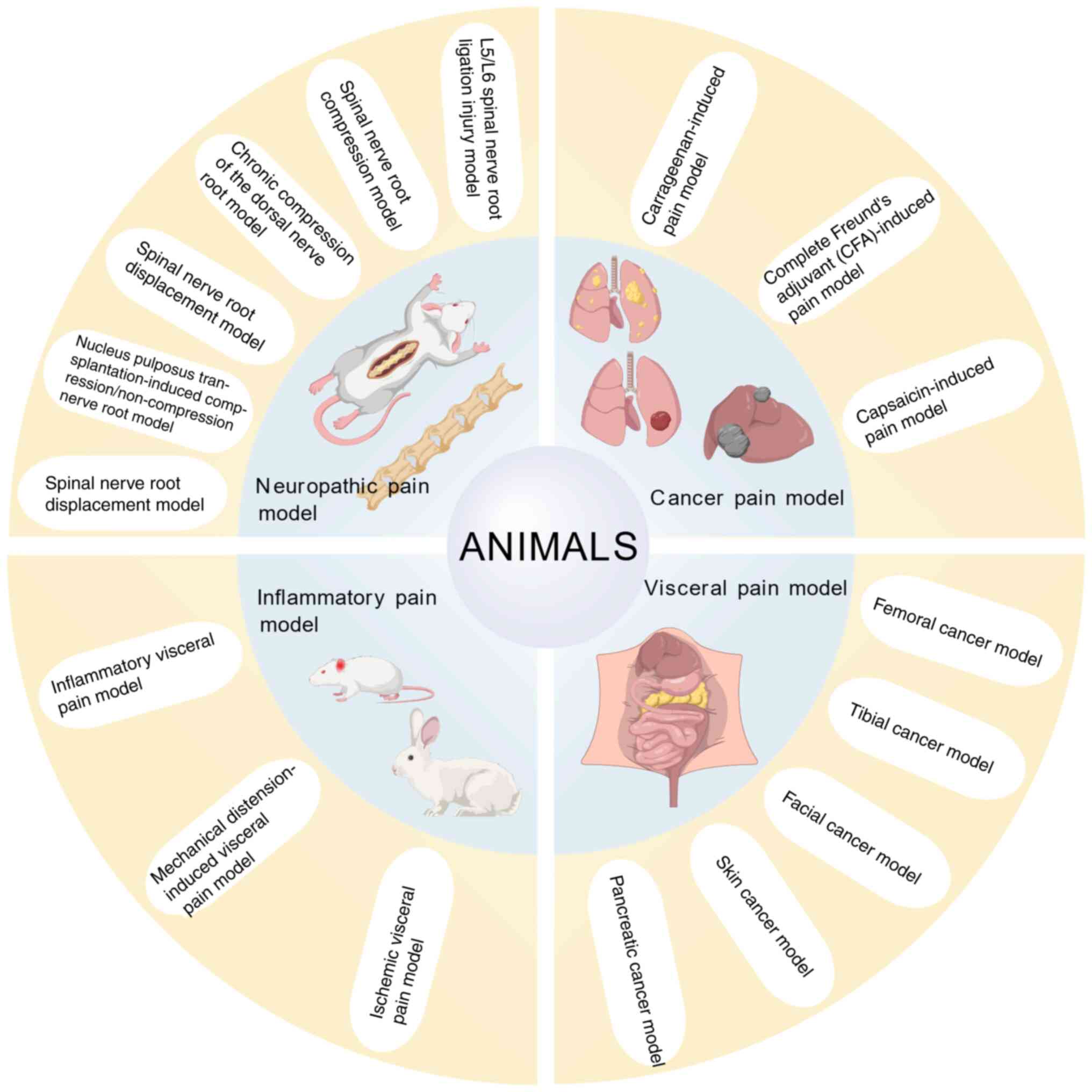

The classification of pain models is mainly based on

three core dimensions: Etiological source, pathological mechanism

characteristics and technology construction. Integrating

longitudinal disease evolution, horizontal mechanistic interactions

and cross-validated assessments, the four pain models (neuropathic

pain, cancer-induced pain, visceral pain and inflammatory pain

animal models) constitute a systematic framework. This approach

maintains the distinctiveness of each model while collectively

illuminating the dynamic pain network, offering a stratified and

multi-faceted perspective for exploring mechanisms and devising

treatments.

The present study systematically reviewed the

preparation methods and experimental cycles of commonly used pain

models across four major categories: neuropathic pain model,

cancer-induced pain model, visceral pain model and inflammatory

pain animal model. The present review summarized the evaluation

criteria along with their advantages and limitations. The novelty

of the present review lies in its emphasis on the hierarchical,

multi-dimensional framework for pain model classification and

analysis. Unlike typical pain model reviews that predominantly

focus on individual model types, the present review highlighted the

established framework, integrating etiological sources,

pathological mechanisms and construction technologies, enabling

effective cross-validation across different pain types. By

constructing such an interconnected analytical framework, the

present review goes beyond the scope of traditional reviews that

merely catalog models and their parameters; it provided a

translational research tool to bridge gaps between different pain

model systems, guiding researchers to design more comprehensive

experiments and promoting the development of targeted analgesic

strategies applicable to multiple pain conditions. To visually

demonstrate the classification framework and representative

examples of these models, schematic diagrams are specifically

illustrated in Fig. 1.

Neuropathic pain model

Neuropathic pain arises from damage or dysfunction

of the peripheral or central somatosensory nervous system, commonly

occurring secondary to trauma, ischemia, metabolic disorders, or

toxin exposure (28). Modern

medical research has identified three primary mechanisms underlying

radicular neuropathic pain: Mechanical compression, neural root

inflammatory response and neurohumoral response. Establishing an

idealized animal model is crucial for studying these mechanisms, as

it serves as an excellent experimental platform for exploring

various clinical treatment strategies, testing novel drugs and

conducting fundamental experimental research. In the process of

researching neuropathic pain models, there are also some research

bottlenecks: i) Ethical concerns (severity of pain induction). ii)

Lack of full human translation (rodent models cannot capture

subjective aspects of pain). The present review systematically

summarized the current modeling methods, technical features and

methodological advantages and limitations of mainstream neuropathic

pain models (Table I), providing

a structured reference framework for researchers to screen models

based on experimental objectives. In Table I, SD rats were mainly selected as

experimental animals and the indicator was mechanical pain

threshold.

| Table ICharacteristics of different types of

neuropathic pain models. |

Table I

Characteristics of different types of

neuropathic pain models.

| Authors, year | Type | Animal | Method | Time | Indicators | Advantages | Disadvantages | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Bennett et

al, 1988; Zhang et al, 2019 | Sciatic nerve

chronic constriction injury pain model | ICR mice | Sciatic nerve

ligation | 14 days | Spontaneous pain,

mechanical pain threshold, thermal pain threshold, cold pain

threshold | Simple operation,

stable pain sensitivity | Variable ligation

tightness causing inconsistent injury severity | (45,46) |

| Kim et al,

1992 | SNL pain model | SD rats | L5/L6 SNL | 16 weeks | Mechanical pain

threshold, thermal pain threshold | Consistent ligation

position and degree | Relatively complex

procedure, severe trauma with high infection risk | (29) |

| Zhu et al,

2018 | SNL pain model | ICR mice | L5 spinal nerve

ligation | 17 days | Mechanical pain

threshold, thermal pain threshold | Consistent ligation

position and degree | Relatively complex

procedure, severe trauma with high infection risk | (47) |

| Meng et al,

2020 | Spinal cord

injury | SD rats | Weight-drop impact

on central spinal cord | 28 days | Mechanical pain

threshold | Cost-effective

implementation, clinically relevant pathogenesis | Difficult impact

localization, potential rebound-induced secondary injury | (48) |

| Shih et al,

2017 | CPSP pain

model | SD rats | Collagenase

injection into thalamic ventral posterolateral nucleus | 4 weeks | Mechanical pain

threshold, thermal pain threshold | High hemorrhage

stability, high success rate, low mortality | Chronic minor

vascular leakage, Minimal hematoma mass effect | (49) |

| Lu et al,

2018 | CPSP pain

model | SD rats | Autologous blood

injection into thalamic ventral posterolateral nucleus | 35 days | Mechanical pain

threshold | Clinically

consistent intracerebral hemorrhage progression | Needle track blood

reflux impairing hematoma formatio | (50) |

| Li et al,

2019 | Infraorbital nerve

chronic constriction injury pain model | SD rats | Infraorbital nerve

ligation | 35 days | Mechanical pain

threshold | Simplified

procedure mimicking clinical trigeminal compression-induced

allodynia | Technically

demanding with significant tissue damage | (51) |

| Cao et al,

2013 | Infraorbital nerve

transection pain model | SD rats | Partial transection

of lateral infraorbital nerve | 35 days | Mechanical pain

threshold | Consistent injury

severity, prolonged pain sensitivity duration | Variable ligation

tightness causing inconsistent injury severity | (52) |

L5/L6 spinal nerve root ligation (SNL)

injury model

The SNL injury model was first established by Kim

and Chung (29). This model

employed Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats as experimental subjects. The

modeling procedure involved: ligation of the L5 and L6 spinal

nerves following exposure via a dorsal surgical approach. The SNL

model induces reliable neuropathic pain phenotypes, including

mechanical hyperalgesia and allodynia, which closely mirror

clinical radicular pain (30,31).

Subsequent studies by Huang et al (32) compared the effects of preserving

compared with resecting paravertebral muscle groups on neuropathic

pain, muscle damage and inflammatory markers. Their findings

confirmed that SNL models retaining paravertebral muscles

effectively reduce postoperative muscle injury and inflammatory

responses, thereby enhancing reproducibility and clinical

relevance. This model's strengths include precise nerve root

segment localization, facilitating nerve root-specific studies, and

controllable surgical trauma, meeting animal ethics requirements.

However, technical challenges of SNL models persist: standardized

ligation procedures directly affect reproducibility, as minor

deviations in parameters such as ligature tension, fixation

position, or surgical technique may induce inter-individual

variability, representing the primary technical bottleneck for this

model. Furthermore, the model inherently induces moderate to severe

neuropathic pain, raising ethical concerns regarding animal

welfare. Its primary translational limitation lies in the

fundamental species differences in pain processing; rodent models

cannot capture the multidimensional subjective experience of human

chronic neuropathic pain. Compared with chronic compression models,

the SNL model offers superior technical reproducibility due to its

straightforward surgical approach but demonstrates lower

pathophysiological fidelity in simulating the gradual progression

of clinical degenerative disorders. While highly suited for

studying acute nerve injury mechanisms and screening analgesic

efficacy, its utility for evaluating long-term therapeutic

interventions may be limited by the static nature of

ligation-induced injury.

Spinal nerve root compression model

The chronic spinal nerve root compression model

(CSNRC) was first established by Wang et al (33). This model used SD rats as

experimental subjects. Experimental validation confirms that

mechanical compression in this model induces axonal demyelination

of the nerve root and activates interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor

necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inflammatory cytokine cascades mediated

by spinal dorsal horn microglia, ultimately triggering classic

neuropathic pain phenotypes such as mechanical allodynia and

spontaneous pain (34). These

pathological characteristics exhibit significant correlation with

clinical radicular pain caused by lumbar spinal stenosis and

intervertebral disc herniation, establishing this model as a

reliable platform for investigating chronic compressive nerve

injury. The CSNRC model demonstrates significant technical

advancements over traditional nerve ligation approaches.

Furthermore, the model enables quantifiable stratification of

neural injury severity through precise adjustments to the

compression device thickness (0.3-0.5 mm). Additionally, its

reversible compression design provides a dynamic investigative

platform for studying decompression therapeutics. Postoperative

material displacement may introduce experimental deviations,

indicating that procedural stability optimization remains a

critical challenge requiring resolution.

Ethical considerations must be noted due to the

persistent pain state induced by chronic compression. More

importantly, while the model replicates structural compression, it

cannot model the complex psychosocial factors that markedly

influence chronic pain perception and disability in human patients.

In contrast to ligation models that create acute axonal injury,

compression models such as CSNRC provide superior

pathophysiological fidelity for degenerative conditions by

mimicking the progressive nature of clinical nerve root

compression. They exhibit clinical relevance for spinal stenosis

research and offer unique advantages for testing decompression

therapies and chronic drug interventions. However, this enhanced

fidelity comes at the cost of technical reproducibility, as the

requirement for microscopic precision in compression device

placement introduces greater procedural variability compared with

ligation techniques. The progressive nature of compression in the

CSNRC model may offer improved predictive validity for long-term

drug efficacy against chronic neuropathic pain compared with acute

injury models. However, its ability to forecast clinical outcomes

remains constrained by the same fundamental limitations of rodent

models: simplified neuroanatomy, lack of comorbid conditions, and

an inability to assess the effect of therapy on pain-related

quality of life and affect.

Chronic compression of dorsal root

ganglia model (CCDRG)

The CCDRG model was optimized by Zhang et al

(35). This model involved

implanting customized stainless steel rods into the L5

intervertebral foramen to induce sustained compression of dorsal

root ganglia. Experimental evidence confirms that the CCDRG model

triggers abnormal neuronal discharges in compressed dorsal root

ganglia, leading to mechanical hyperalgesia and spontaneous pain

behaviors. Its pathological mechanisms involve increased neuronal

excitability, inflammatory factor release and glial cell

activation, demonstrating significant correlation with clinically

observed radicular pain caused by intervertebral foramen stenosis

(36). The advantage of this

model is its minimally invasive foraminal approach, which achieves

ganglia-specific compression without spinal canal opening, thereby

reducing surgical infection risks while preserving neural pathway

integrity. A study has shown that compared with traditional nerve

root exposure models, the CCDRG model increases postoperative

survival rates by ~30% and more accurately simulates the chronic

compressive pathology of intervertebral disc herniation (35). However, anatomical differences in

the intervertebral foramen of different sizes of rats require

custom steel rod sizes, resulting in higher experimental costs and

potential implant displacement-key technical bottlenecks that can

affect the stability of experimental data. From an ethical

standpoint, the chronic nature of the compression involves

prolonged animal suffering. A fundamental limitation for clinical

translation is the model's inability to account for the top-down

neuromodulatory and psychological components that are integral to

the human chronic pain experience.

Spinal nerve root displacement model

The spinal nerve root displacement model was

developed by Finskas et al (37) and employs biomechanical

stimulation of nerve roots through intervertebral disc puncture.

Some studies demonstrate that mechanical traction in this model

induces abnormal neuronal discharges in dorsal root ganglia,

leading to ipsilateral hindpaw mechanical hyperalgesia and motor

dysfunction, with pain characteristics closely mimicking the

pathological progression of nerve root edema secondary to clinical

intervertebral disc herniation (38). Mechanistic investigations reveal

a positive correlation between puncture depth and disc degeneration

rate, with radicular pain arising from dual mechanisms: Enhanced

mechanical stimulation due to reduced intervertebral space height

and peripheral sensitization triggered by elevated pro-inflammatory

cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) in dorsal root ganglia. This combined

structural injury and inflammatory activation makes the model an

ideal platform for studying dynamic nerve root compression

mechanisms. Compared with traditional static compression models,

its advantages lie in simulating the pathophysiological process of

post-herniation nerve root displacement, retaining vascular supply

system integrity, and exhibiting pronounced laterality-specific

pain behavioral indices. However, precise control of the puncture

angle and bony fixation stability of the puncture needle are

critical technical factors ensuring experimental reproducibility.

Ethical oversight is crucial given the invasive disc puncture

procedure. The model's translational relevance is constrained by

the inherent inability of rodent models to replicate the human

subjective pain experience and the complex brain-level changes

associated with chronic pain.

Nucleus pulposus transplantation

model

The autologous nucleus pulposus transplantation

model, co-developed by Shamji et al (39) and Kim et al (40), focuses on exploiting the chemical

irritative effects of autologous disc tissue. This model employs SD

rats as experimental subjects. Experimental validation confirms

that transplanted nucleus pulposus tissue directly activates

transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) 1 channels in dorsal

root ganglia by releasing inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and

prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), inducing classic neuropathic pain

manifestations (41). Cho et

al (42) demonstrated

through model modifications that even without mechanical

compression, chemical stimulation from nucleus pulposus tissue

alone can activate satellite glial cells in dorsal root ganglia,

upregulate the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway and

ultimately induce inflammatory radicular pain. These pathological

features closely resemble non-compressive radicular pain in

clinical disc herniation patients, providing a critical

experimental platform for studying chemically mediated radicular

pain mechanisms. The model reduces immune rejection by using

autologous tissue. It also simulates mechanical compression and

chemical stimulation, and includes stable, quantifiable behavioral

indicators of pain. However, individual differences in the

absorption rate of the nucleus pulposus may affect the duration of

the inflammatory response, so preoperative magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) is needed to assess the severity of disc degeneration

to enhance experimental consistency. The model's limitation for

translational research stems from the rodent nervous system's

simplified processing of nociception compared with humans, failing

to incorporate the supraspinal and psychosocial determinants of

chronic pain.

Spinal nerve root chemical stimulation

model

Zhao et al (43) established the spinal nerve root

chemical stimulation model, which uses formaldehyde to simulate

non-compressive radicular pain by mimicking chemical inflammatory

mediators. Experimental evidence confirmed that

formaldehyde-induced chemical stimulation activated transient

receptor potential ankyrin (TRPA)1 channels in dorsal root ganglia,

triggering neuropeptide release (CGRP, substance P) and resulting

in persistent mechanical hyperalgesia with behavioral

characteristics highly analogous to clinical discogenic radiculitis

(44). This model transcends

traditional mechanical compression frameworks by elucidating

inflammation-mediated radicular pain mechanisms via controlling

chemical stimulation. Compared with autologous nucleus pulposus

transplantation models, its advantages includes eliminating

mechanical compression variables to focus on chemical

pathogenicity, strong dose-response controllability of formaldehyde

concentration and minimal surgical trauma with high procedural

standardization. However, technical challenges persist: Different

chemical stimulants may activate divergent pain signaling pathways,

requiring multi-group controlled experiments to validate specific

inflammatory mediators' nociceptive roles, a critical bottleneck

for broader model application. The core translational limitation

shared by all rodent models is their inability to emulate the

complex, subjective and emotionally charged nature of human chronic

pain, which is profoundly influenced by higher-order brain

functions and psychosocial context. Contemporary neuropathic pain

modeling has evolved from singular mechanical compression to

multidimensional pathological mechanism simulations, with various

models demonstrating marked specificity and complementarity in pain

mechanism research. The L5/L6 ligation model provides an ideal

platform for investigating acute nerve injury mechanisms through

precise nerve root localization, while chronic compression models

(CSNRC, CCDRG) more closely approximate the progressive

pathological processes of clinical degenerative disorders. Recently

developed dynamic compression models (spinal nerve root

displacement) and chemical stimulation models (nucleus pulposus

transplantation/formaldehyde stimulation) have transcended

traditional mechanical injury paradigms, offering novel

perspectives for deciphering inflammation-mechanics interactions in

radicular pain pathogenesis (45-47). Current model systems still face

critical bottlenecks between mechanistic fidelity and clinical

translatability. On one hand, significant neuroanatomical

disparities between rodents and humans, such as nerve root vascular

supply patterns and spatial distribution of dorsal root ganglia,

may compromise pathological translation of mechanical stimuli. On

the other hand, overreliance on reflexive nociceptive behavioral

metrics in model evaluation fails to capture the

affective-cognitive dimensions of chronic pain.

A critical and universal limitation is the inherent

inability of models to replicate the human subjective pain

experience, which is shaped by complex cortical processing,

psychological state and social factors. All models involve

ethically significant pain induction, necessitating rigorous

justification and mitigation of suffering. The selection between

ligation and compression models involves fundamental trade-offs:

While ligation offers technical simplicity and reproducibility for

acute injury studies, compression models provide superior

pathophysiological fidelity for chronic degenerative conditions

(48-50). Similarly, chemical stimulation

models excel in isolating inflammatory mechanisms but lack the

mechanical component central to a number of clinical conditions.

The optimal model choice therefore depends on the specific research

objectives, whether prioritizing mechanistic isolation, clinical

relevance, therapeutic testing applicability, or technical

practicality.

A paramount consideration that underpins all model

selection is their documented track record in predicting clinical

efficacy. The high failure rate of neuropathic pain drugs

transitioning from robust preclinical results to successful human

trials highlights a pervasive translational crisis. This disconnect

is multifactorial, stemming from over-reliance on reflexive pain

measures in animals that do not capture the multidimensional human

pain experience, fundamental species differences in drug metabolism

and pharmacokinetics, and the absence of common comorbidities (such

as anxiety or depression) in animal models that markedly modulate

drug response in patients (51,52). Therefore, while animal models

remain indispensable for mechanistic insight and initial screening,

researchers must interpret preclinical efficacy data with caution.

Future model development must prioritize the integration of outcome

measures that bridge this translational gap, such as non-reflexive

pain behaviors, functional outcomes, and if possible, measures of

affective pain components. Furthermore, employing a battery of

models that capture different aspects of the human condition,

rather than relying on a single model, may provide a more realistic

and predictive preclinical assessment of therapeutic potential.

Future model development should prioritize constructing

large-animal chronic compression models to enhance anatomical

comparability, integrating advanced behavioral assessments such as

functional neuroimaging and conditioning place aversion and

engineering transgenic animals for spatiotemporally controlling

activation of specific pain pathways.

Cancer-related pain model

Cancer-related pain is caused by malignant tumors

themselves, metastatic lesions, or anti-tumor therapies (53), commonly observed in a number of

patients with advanced-stage cancers. Bone cancer pain results from

bone metastasis in various advanced malignancies, which is a

primary pain inducer. Injecting controlled quantities of tumor

cells into different anatomical sites enables the development of

multiple cancer pain models, including facial, cutaneous and

visceral cancer pain. Rodent bone cancer pain models currently

represent the most widely used chronic cancer pain paradigms. Rats,

owing to their larger body mass and skeletal structure, permit

controllable ranges for tumor cell injection volumes, making them

prevalent in bone cancer pain model preparation. Based on tumor

type and modeling site, the following systematically summarized and

compared construction methods, characteristics and methodological

advantages/limitations of prevalent cancer pain models, providing

researchers with a reference framework for model selection aligned

with experimental objectives (Table

II).

| Table IICharacteristics of different types of

cancer pain models. |

Table II

Characteristics of different types of

cancer pain models.

| Authors, year | Type | Animal | Method | Time | Indicators | Advantages | Disadvantages | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Schwei et

al, 1999 | Femoral cancer pain

model | B6C3-Fe-a/a,

C3H/HeJ mice | Injection of

fibrosarcoma cells into distal femoral marrow cavity | 21 days | Spontaneous pain,

mechanical pain threshold | High stability,

mass reproducibility possible | Technically

demanding, requires precise tumor cell concentration control | (72) |

| Wang et al,

2019 | Tibial cancer pain

model | SD rats | Injection of Walker

256 cells into tibial marrow cavity | 21 days | Spontaneous pain,

mechanical pain threshold | High viability and

invasiveness of Walker 256 cells | High in vivo

culture costs, prolonged experimental cycles | (73) |

| Kopruszinski et

al, 2018 | Facial cancer pain

model | Wistar rats | Injection of Walker

256 cell suspension into right vibrissal pad | 6 days | Spontaneous pain,

mechanical pain threshold, thermal pain threshold | High viability and

invasiveness of Walker 256 cells | High in vivo

culture costs, prolonged experimental cycles | (58) |

| Huang et al,

2019 | Cutaneous cancer

pain model l | SD rats | Subcutaneous

injection of Walker 256 cells into hindpaw plantar region | 17 days | Mechanical pain

threshold, thermal pain threshold | High viability and

invasiveness of Walker 256 cells | High in vivo

culture costs, prolonged experimental cycles | (74) |

| Wang et al,

2017 | Pancreatic cancer

pain model | BALB/c-nu mice | Orthotopic

implantation of SW1990 cells into pancreas | 14-28 days | Spontaneous pain,

mechanical pain threshold | High stability,

mass reproducibility possible | Technically

demanding, requires precise tumor cell concentration control | (75) |

Femoral cancer pain model

The femoral cancer model replicates clinical

pathological features of metastatic bone pain through orthotopic

tumor cell inoculation into rodent femoral marrow cavities. A study

indicated that model construction required consideration of three

key factors: Animal strain, tumor cell type and inoculation

technique (54). Critical

femoral cancer model replication technologies involved precise cell

inoculation and systematic validation. Surgical procedures require

anesthesia-assisted exposure of the femoral intercondylar fossa,

followed by slow marrow cavity infusion of cell suspensions using

26G microinjectors, with bone wax sealing post-injection to prevent

cell leakage. Pain behavioral assessments employ dynamic

monitoring: Von Frey filament testing reveals 40-60% reductions in

mechanical withdrawal thresholds post-modeling; tail compression

tests show markedly elevated pressure sensitivity correlating

positively with radiographic bone destruction severity.

Radiographic verification identifies periosteal thickening at 14

days and pathological fractures at 21 days via X-ray, while

micro-CT quantifies bone microstructure parameters to establish

structural-pain correlations (55). Histopathological analyses

confirms tumor cell infiltration and osteoclast activation, with

molecular assays demonstrating upregulated spinal dorsal horn glial

fibrillary acidic protein and IL-1β expression, indicating

neuroinflammatory involvement in pain maintenance.

Tibial cancer pain model

The tibial cancer pain model was served as a

critical tool for investigating cancer-induced bone pain mechanisms

and therapeutic strategies. The most prevalent model involves

intratibial marrow cavity injection of breast carcinoma cells,

effectively mimicking human metastatic the pathological features

and pain behaviors of bone cancer. The core mechanisms of the model

involves tumor cell-induced osteolysis and neuroinflammation

(56,57). The model also facilitates

analgesic intervention evaluation: Electroacupuncture attenuated

pain via autophagy-mediated NLRP3 suppression or NRG1/ErbB2

signaling modulation of glial activation, while opioids

paradoxically promoted tumor angiogenesis through μ opioid

receptor (MOR) upregulation. Despite standardized operability and

clear pathology, strict control of inoculation parameters and

postoperative infection prevention remain essential for model

stability and reproducibility.

Facial cancer pain model

In preclinical facial cancer pain research, the

Walker-256 tumor cell-induced rat model has become predominant

(58). Derived from rat mammary

carcinoma and maintained via intraperitoneal passage, these cells

form facial tumors demonstrating local tissue infiltration, neural

compression and inflammatory mediator release, closely resembling

clinical head/neck cancer pain mechanisms. Key evaluation metrics

included thermal hyperalgesia, mechanical allodynia and spontaneous

face-grooming behaviors (59).

Conditioned place preference testing quantifies pain relief

motivation through analgesic-paired environment preference, while

comorbid anxiety-like behaviors facilitates the study of

pain-emotion interactions (60).

The model has validated analgesics (morphine, bosentan and

pregabalin) and revealed peripheral endothelin receptor-trigeminal

sensitization linkages (61).

Despite its usefulness, interspecies differences limit

translational relevance, prompting recent attempts to engraft human

carcinoma cells in immunocompromised hosts, though applications

remained exploratory. Overall, the Walker-256 facial cancer model,

with standardized protocols, phenotype clarity and clinical pain

mimicry, remain indispensable for mechanistic and therapeutic

investigation.

Cutaneous cancer pain model

Malignant melanoma, a highly aggressive and lethal

form of skin cancer, exhibits extremely high mortality rates as

most patients are diagnosed at advanced stages (62). Although pain is not a primary

clinical symptom, 7% of patients experience pain, with >50% of

metastatic melanoma cases requiring palliative care and morphine

treatment due to neuropathic pain components (63). However, current models

predominantly target limb skin, lacking successful constructions

for other anatomical regions. Furthermore, a toe cancer model

developed ulceration and hemorrhage 14 days post-inoculation

(64), precluding oral herbal

analgesic evaluation while remaining valuable for injectable drug

mechanism studies. The plantar skin cancer model has emerged as a

novel paradigm for cancer pain following bone cancer and

chemotherapy models. Despite its limited variety, it provides

critical platforms for mechanistic and therapeutic exploration. Xie

and Wang (65) established a

validated toe skin tumor model through murine left hindpaw plantar

tumor cell injections, demonstrating pain behavior alterations.

Intrathecal amiloride administration elevated thermal pain

thresholds, alleviated thermal hypersensitivity and suppressed

spinal dorsal horn acid-sensing ion channel 3 protein expression,

offering novel clinical therapeutic insights. Tabata et al

(66) constructed melanoma pain

models via hindlimb subcutaneous melanoma cell inoculation,

revealing that tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA) inhibitory

peptides reduced paw edema and melanoma-induced pain through TrkA

receptor modulation.

Pancreatic cancer pain model

The establishment of pancreatic cancer pain model is

fundamental for investigating pathogenesis and therapeutic

strategies. Current models include chemically induced, transplanted

tumor, genetically engineered, organoid and diabetes-associated

composite paradigms (67).

Ectopic grafts facilitate tumor monitoring but poorly replicate

tumor microenvironments, whereas orthotopic injections improve

emulated clinical pathology despite surgical complexity (68). Patient-derived xenograft model

preserved tumor heterogeneity by engrafting human tumors into

immunocompromised mice, though host stromal cell replacement occurs

during passaging (69).

Genetically engineered models simulate pancreatic carcinogenesis

through clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic

repeats-associated protein 9-mediated mutations, providing

human-like tumor progression for mechanistic/targeted therapy

studies despite high costs and technical demands. Organoid models

reconstructed 3D tumor architectures from patient tissues, enable

orthotopic transplantation to recapitulate malignant transformation

with high fidelity and personalized potential, though

standardization and microenvironmental completeness required

refinement (67-69). Diabetes-associated composite

models combine high-fat diets with streptozotocin-induced type 2

diabetes, followed by luciferase-tagged pancreatic cancer cell

implantation. Integrated with bioluminescence imaging, these models

illuminated metabolic-tumor interactions by dynamically visualizing

hyperglycemia-driven tumor growth (70). Modern cancer pain models have

transcended traditional tumor transplantation methods, establishing

a three-dimensional framework focused on bone-derived pain, soft

tissue invasion pain and neuroinvasive pain (71). In bone metastasis models, lower

limb bone injection systems successfully replicate clinical

intermittent severe pain and mechanical hyperalgesia by simulating

osteolytic processes, while spinal metastasis models complete the

research toolkit for vertebral metastatic pain. Notably, the

neuroinvasive triple-negative breast cancer model, established via

MDA-MB-231 cell injection into nerve bundles, achieved breakthrough

precision in neuropathic cancer pain simulation, with mechanical

allodynia phenotypes persisting one month longer than conventional

models (72,73). However, current bone cancer

evaluation systems overly focus on osteoclast activity indicators,

inadequately reflecting astrocyte-CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling-mediated

pain sensitization within tumor microenvironments. Additionally,

existing pain assessment criteria fail to distinguish neural

mechanisms between resting spontaneous pain and movement-associated

pain (74,75).

Visceral pain model

Appropriate experimental visceral pain models are

prerequisites for mechanistic investigations. Advances in

anatomical and neurobiological research have enabled the

development of multiple visceral pain models, laying foundations

for basic/clinical studies. Effective models must simulate clinical

pathophysiological features while ensuring reproducibility,

operability and cost-effectiveness. Visceral pain exhibited unique

characteristics due to sparse sensory neuron distribution and

complex convergent nociceptive pathways: i) Diffuse localization

with ambiguous pain origins, ii) referred pain at distant somatic

sites, iii) organ-specific pain susceptibility linked to nociceptor

distribution, iv) autonomic/motor reflexes and v) non-correlation

with visceral damage (76).

Visceral pain exhibits characteristics of ambiguous localization,

referred pain and non-fully injury-associated features, owing to

sparse sensory neuron distribution, peripheral cross-innervation of

nociceptive afferent fibers, and complex multichannel nociceptive

pathways (77). The construction

of visceral pain model must meet requirements for clinical

pathophysiological similarity, high reproducibility and operational

feasibility. Current models are categorized into inflammatory,

mechanical distension, ischemic and electrical stimulation types

based on modeling stimuli (78).

The present review systematically summarized and compared the

construction methods, characteristics and advantages/limitations of

major visceral pain models to guide researchers in selecting

appropriate models based on experimental objectives (Table III).

| Table IIICharacteristics of different types of

visceral pain models. |

Table III

Characteristics of different types of

visceral pain models.

| Authors, year | Type | Animal | Method | Time | Indicators | Advantages | Disadvantages | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Wang et al,

2021 | Capsaicin-induced

inflammatory pain model | C57BL/6J mice | Gastric gavage of

capsaicin | 7 days | Spontaneous

pain | Simple operation

without surgery/injection | High individual

variability requiring strict dose control; mild inflammatory marker

changes | (101) |

| Yao et al,

2020 | Stress pain

model | SD rats | Senna leaf extract

gavage + physical stress | 14 days | Colorectal

distension and abdominal withdrawal | Mimics IBS under

stress conditions | Divergence from

multifactorial IBS etiology; stability needs improvement | (102) |

| Felice et

al, 2014 | Neonatal maternal

separation pain model | SD rats | Maternal separation

rearing | 10 days | Colorectal

distension and abdominal withdrawal | Non-invasive, high

operability | Requires neonatal

pups; long modeling cycle; low success rate | (103) |

| Wu et al,

2018 | Colitis pain

model | SD rats | TNBS enema | 4 weeks | Colorectal

distension and abdominal withdrawal | Direct colonic

action with minimal systemic effects | Long modeling

cycle; high mortality if improperly operated | (104) |

| Liu et al,

2020 | Pancreatitis pain

model | SD rats | DBTC tail vein

injection | 7 days | Spontaneous pain,

Mechanical pain threshold | Simple

implementation | Significant

systemic impacts; uncontrolled ethanol intake in drinking

water | (105) |

| Furuta et

al, 2018 | Interstitial

cystitis pain model | F344 rats | Hydrochloric acid

bladder perfusion | 2 weeks | Spontaneous

pain | Direct bladder

action with minimal systemic effects | Urethral

catheterization-induced trauma affecting behavioral

performance | (106) |

| Denget al,

2024 | Acetic acid

writhing pain model | C57/BL6 mice | Intraperitoneal

acetic acid injection | 21 days | Spontaneous

pain | Rapid behavioral

responses, high reproducibility | Uncontrolled

diffusion rate/direction of acetic acid | (107) |

Inflammatory visceral pain model

The inflammatory visceral pain model simulates pain

through chemical or biological stimulation-induced local

inflammation (79,80). An acute pancreatitis model

employed retrograde sodium taurocholate injection into the

pancreatic duct or subcapsular punctures to replicate biliary

pancreatitis pathology but suffered from high surgical trauma and

mortality (81,82). Sigmoid colon pain model induced

localized inflammation using 5% formaldehyde submucosal injection,

eliciting abdominal licking and arching within 45 min, with

self-limiting inflammation facilitating self-controlled drug

studies (83,84). In ulcerative colitis model,

dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) drinking ad libitum or

2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)/ethanol rectal

administration induced bloody stools and mucosal damage, with TNBS

offering superior reproducibility despite interindividual DSS

intake variability (85-87). A neonatal colorectal inflammation

model established chronic visceral hypersensitivity through dilute

acetic acid enemas in pups, mirroring irritable bowel syndrome

pathophysiology by single-injury induction (88). A bladder pain model used

intravesical mustard oil or acrolein to provoke dysuria, though

murine urethral injury risks exist. A cyclophosphamide-induced

acrolein metabolite model improved mimicking of natural bladder

mucosa irritation mechanisms (89-91).

Mechanical distension pain model

Mechanical distension model replicated organ

expansion or obstruction via physical stimuli. The gastroduodenal

distension model triggered teeth grinding and back arching by

inflating intragastric balloon catheters, though invasive surgery

restricted application (92).

Colorectal distension (CRD) involved anal balloon inflation to

induce abdominal contractions and pelvic lifts, with inflammatory

priming enhancing pain sensitivity, albeit with intestinal

perforation risks at excessive pressures (93-94). Neonatal repetitive CRD in pups

induced persistent visceral hypersensitivity in adulthood, serving

as a tool for chronic pain mechanism research (95).

Ischemic visceral pain model

An ischemic visceral pain model simulated myocardial

ischemia via coronary artery occlusion, yet vascular anatomical

variations caused significant behavioral heterogeneity, limiting

its use to qualitative studies (96). An electrical stimulation model

applied controlled parameters to visceral nerves to evoke pain but

lacked physiological relevance (97). A specialized maternal separation

model induced gut hypersensitivity and anxiety-like behaviors in

neonatally separated rodents through hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

(HPA) axis dysregulation and intestinal barrier disruption, making

them ideal for irritable bowel syndrome research (98-100). In summary, inflammatory models

excels in drug screening despite low specificity, mechanical

distension models improve approximate physiological stimuli and

maternal separation models facilitated chronic pain mechanism

exploration. Future advances require multimodal assessment systems

integrating imaging and molecular biomarkers to enhance

translational value.

Inflammatory-driven, ischemia-induced and functional

disorder paradigms have become mainstream modeling frameworks in

visceral pain research. In gut-brain axis dysfunction studies,

programmed colorectal distension techniques have established

gold-standard evaluation systems by quantifying viscerosomatic pain

correlation indices (101).

Innovative mechano-chemical pancreatic stimulation models (35 mmHg

sustained pressure combined with dynamic pH monitoring) precisely

replicate the synergistic effects of mechanical stress and acidic

microenvironments in pancreatitis pain. The research highlighted

the bladder chemo-optogenetic platform and successfully constructed

reversible neuromodulation frameworks for visceral pain pathways

(102,103). Current model systems face dual

bottlenecks in mechanistic resolution: Intestinal mechanical

stimulation models struggle to specifically regulate enteric

glial-TRPA1 ion channel signaling networks, while chronic

pancreatic injury models exhibit 48-72 h temporal discrepancies

between peripheral stellate cell activation and central

sensitization markers (104).

Technological advances such as Sox10-CreERT2-mediated conditional

gene editing of enteric glial subsets, development of bidirectional

gut-brain modulation models and deployment of miniaturized

multimodal biosensor arrays enabling synchronized autonomic rhythm

and visceral pain threshold tracking (sampling frequency ≥100 Hz)

will propel visceral pain research toward precision modulation and

systemic integration (105).

Inflammatory pain model

Inflammatory pain arises from tissue injury or

infection-triggered inflammatory responses, commonly observed in

arthritis, postoperative inflammation, or infectious diseases.

Inflammatory mediators (prostaglandins, bradykinin and cytokines)

activate peripheral nociceptors, inducing pain sensitization and

central nervous system remodeling. Clinical manifestations included

redness, swelling, heat and dysfunction, with characteristic

'protective' features and sensitivity to nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)/glucocorticoids (106). While inflammatory and visceral

pain overlap in mechanisms, they differ fundamentally: Visceral

pain exhibits diffuse localization and referral, whereas

inflammatory pain is typically well-localized and

injury-associated. The inflammatory pain model simulates

acute/chronic inflammatory states via local injections of specific

irritants into skin, plantar surfaces, muscles, or joints (107). These models induce acute

inflammation through neutrophil chemotaxis and sustained pain via

macrophage infiltration, with pain modulation mechanisms closely

linked to opioid peptide analgesia (108). Table IV systematically summarized and

compared the construction methods, characteristics, and

advantages/limitations of major inflammatory pain models to guide

researchers in selecting appropriate models based on experimental

objectives.

| Table IVCharacteristics of different types of

inflammatory pain models. |

Table IV

Characteristics of different types of

inflammatory pain models.

| Authors, year | Type | Animal | Method | Time | Indicators | Advantages | Disadvantages | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Melo-Carrillo et

al, 2013 | Dural

neuroinflammation pain model | Wistar rats | Inflammatory

stimulant injection into dura mater via cranial drilling | 16 days | Spontaneous

pain | Closely mimics

clinical manifestations | Technically complex

with significant animal trauma | (112) |

| Burgos-Vega et

al, 2019 | Dural

neuroinflammation pain model | ICR mice | Inflammatory

stimulant injection into dura mater via cranial sutures | 7 days | Spontaneous

pain | Minimal animal

injury | Requires high

precision, suitable only for mice | (113) |

| Sufka et al,

2016 |

Nitroglycerin-induced pain model | SD rats | Intraperitoneal

injection of nitroglycerin | 2 weeks | Spontaneous

pain | Simple,

cost-effective, anesthesia-free | Systemic effects

limit intracranial vascular specificity | (114) |

| Philpott et

al, 2020 | Intra-articular

injection pain model | Wistar rats | Sodium iodoacetate

injection into knee joint cavity | 14 days | Mechanical pain

threshold | Rapid

implementation with low animal stress | Dose-dependent

effects difficult to control | (115) |

| Shi et al,

2020 | Joint

immobilization pain model | New Zealand

rabbits | 6-week left

hindlimb knee extension fixation | 6 weeks | Mechanical pain

threshold | Non-invasive joint

protection | Fixation device

detachment risks experimental validity | (116) |

| Katri et al,

2019 | Meniscus resection

pain model | Lewis rats | Medial collateral

ligament transection with meniscectomy | 44 days | Mechanical pain

threshold, cold pain threshold | Severe/persistent

osteoarthritis induction | Surgical

variability affects injury severity consistency | (117) |

| He et al,

2024 | CFA-induced

arthritis pain model | SD rats | Complete Freund's

Adjuvant (CFA) injection into right hindpaw plantar region | 42 days | Spontaneous

pain | Gold standard for

rheumatoid arthritis research | Prolonged modeling

period; systemic inflammation affects model stability | (118) |

| Bai et al,

2025 | Collagen-induced

arthritis pain model | SD rats | Bovine type II

collagen emulsified with Incomplete Freund's Adjuvant (IFA) | 28 days | Spontaneous

pain | Mimics human RA

autoimmune mechanisms | Collagen

purity/emulsion quality affects success; multi-dose

immunization | (119) |

| Koo et al,

2002 | Ankle joint

overloading pain model | SD rats | Mechanical ankle

overextension with 180° inversion | 7 days | Spontaneous

pain | No chemical

inducers required | Short pain duration

requiring rapid assessment; operator-dependent | (120) |

| Wu et al,

2023 | Carrageenan-induced

Inflammation pain model | SD rats | 1% carrageenan

injection into left hindpaw plantar region | 7 days | Spontaneous

pain | Rapid inflammatory

response | Transient

hypersensitivity; unsuitable for chronic studies | (121) |

Carrageenan-induced pain model

Local carrageenan injection triggers biphasic

inflammation: Acute neutrophil-dominant phase (24-48 h) transitions

to chronic monocyte/macrophage phase over two weeks. The model

induces thermal/mechanical hypersensitivity at injection sites and

secondary hyperalgesia in remote areas, pathologically resembling

rheumatoid arthritis (109).

Complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA)

model

CFA injection into tails or joint cavities elicits

stronger persistent inflammation than carrageenan. The CFA model

exhibits injection site swelling, 60-70% reduced hindlimb

weight-bearing, and 40% decreased wheel-running activity. Previous

studies confirmed electroacupuncture combined with spinal orphanin

FQ receptor antagonists modulates such pain, validating acupuncture

analgesia in chronic inflammation (110,111).

Capsaicin-induced pain model

Local capsaicin injection activates TRPV1 channels,

provoking neurogenic inflammation. The model features 50% thermal

hyperalgesia and 80% mechanical allodynia around injection site

with secondary mechanical hypersensitivity distally (112). Transient C-fiber

depolarization-induced hypoalgesia at injection cores provides

unique insights into spatiotemporal pain conduction dynamics

(109). The classic CFA chronic

inflammatory model establishes the temporal correlation between

macrophage M1 polarization phenotypes and mechanical hyperalgesia

through dynamic TNF-α/IL-1β expression profiling (28 days)

(113). The IL-23 local

sensitization model pioneered a γδT cell-IL-17A signaling

axis-driven neural sensitization purification system, overcoming

traditional adjuvant model heterogeneity (114). The TLR4/ATP bimodal stimulation

model achieves molecular-level spatiotemporal synchronization of

NLRP3 inflammasome activation and neuropeptide (CGRP, substance P)

release via two-photon intravital imaging. Cross-species neutrophil

metabolic cycle displays impaired biological validity in chronic

inflammatory microenvironment reconstruction (rodents <8 h vs.

humans 5-90 days) (115-117).

A peripheral innervation model exhibits clinical phenotype

disconnects, as synovial C-fiber density (<25%) inadequately

explains rheumatoid pain persistence. The lactate-ASIC3 signaling

axis in pain regulation lacks standardized paradigms from metabolic

reprogramming perspectives. Emerging solutions include dorsal root

ganglion organoid-chip models co-cultured with polarized

macrophages, microelectrode arrays for neuro-immune interaction

kinetics, optogenetic delivery systems (TRPV1-liposome carriers)

for submillimeter IL-6 control in joints and humanized chemokine

models (IL8-CXCR1 transgenics) to establish cross-species pain

translation metrics, collectively advancing inflammatory pain

research toward personalized precision medicine (118,119).

Other pain models

Somatic pain can be simulated using the formalin

model (97). Injection of 1%

formalin into the dorsal surface of the right hindpaw in rodents

induces biphasic pain responses: Phase I (immediate pain lasting

for10 min post-injection) and Phase II (delayed pain commencing

15-20 min post-injection and persisting 1 h). Phase II, which is

commonly used in experimental studies, involves distinct mechanisms

from Phase I. NSAIDs effectively attenuate Phase II pain but fail

to modulate phase I responses. Species-specific behavioral

differences are observed: Rats exhibit paw withdrawal, whereas mice

displayed licking behaviors. Phase II pain is now recognized as

peripherally mediated inflammatory pain associated with central

sensitization, making this model valuable for investigating tissue

injury-induced hyperalgesia mechanisms (120).

Pain behavioral assessments evaluate nociceptive

thresholds by applying acute noxious stimuli to elicit withdrawal

reflexes. These methods simulate physiological acute pain but lack

pathological validity, precluding standalone model development.

They are primarily employed to verify threshold changes in existing

pain models (121).

Mechanical nociceptive response testing

predominantly utilized the Von Frey test (122). Originally developed by

Maximilian Von Frey in the 19th century, this method applies

calibrated filaments to the plantar surface in ascending force

order to determine mechanical withdrawal thresholds. Alternatively,

fixed-force filaments delivered repetitive stimuli to quantify

withdrawal frequency/duration. Chaplan et al (25) subsequently optimized threshold

determination protocols. Current practice favors electronic Von

Frey systems for standardized force application. Colorectal

distension via transanal balloon inflation simulates visceral pain,

with pain thresholds assessed through AWR scoring.

However, behavioral interpretation introduce

subjectivity. Thermal/cold nociception assessments are widely

adopted in rodents. The tail-flick test measures heat avoidance

latency by applying thermal stimuli to the tail (123). The hot plate test eliminates

restraint-induced stress by observing escape behaviors on a heated

surface. The Hargreaves test quantifies hindpaw withdrawal latency

to radiant heat (124). Cold

sensitivity evaluation substituted hot water with ice baths in

tail-flick paradigms. Acetone droplet application induces cold

allodynia in hypersensitive rats but elicits nonspecific responses

(mechanical/chemical irritation) in mice (125). Semiconductor-cooled plates

dominate cold pain studies, minimizing ambient temperature

artifacts while retaining mechanical stimulation limitations

(126). Recent advances in

rodent pain assessment methodologies continue to refine precision

and translational relevance.

Targets of pain

The convergence of structural biology and

computational pharmacology has shifted to pain targets from

single-receptor antagonism to multidimensional regulatory systems.

Traditional targets such as MOR employ allosteric modulation

strategies that stabilize receptor-G protein-biased conformations,

addressing the analgesia-addiction dissociation challenge.

Discoveries at neuroimmune interfaces drive the paradigm shift from

neuron-centric to tripartite neuron-glial-immune network

modulation. This section systematically elaborated conformational

control of classical membrane receptors, ion channel

subtype-specific drug design breakthroughs, mechanistic insights

into neuroimmune interface targets and epigenetic modulation

strategies, establishing a theoretical framework for

multidimensional analgesic development.

Ionotropic channel receptors

Voltage-gated ion channels

Voltage-gated sodium channel

Voltage-gated sodium channels, transmembrane protein

complexes comprising an α-subunit and β-subunits, are classified

into nine subtypes (Nav1.1-1.9) based on α-subunit variations.

These channels mediate action potential generation/conduction and

are critically involved in neuropathic pain pathogenesis.

Specifically, Nav1.3, Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 play pivotal roles

in nociceptive signaling. Nav1.3 is predominantly expressed in

embryonic/neonatal central nervous system (CNS) with minimal adult

expression, but its upregulation following peripheral/central nerve

injury is associated with neuropathic pain. miR-30b downregulation

under neuropathic conditions reduces SCN3A mRNA inhibition,

elevating Nav1.3 expression to enhance neuronal excitability

(127). Nav1.7 is predominantly

expressed in small C-fiber nociceptors of dorsal root ganglia

(DRG), mediating action potential generation in an endogenous

opioid-independent manner. Its unique slow activation/inactivation

kinetics enabled ramp current generation, lowering action potential

thresholds and amplifying subthreshold depolarizations to

critically regulate pain transduction (128,129). Nav1.8, a tetrodotoxin-resistant

sodium channel enriched in trigeminal ganglia and DRG nociceptors,

represents a high-selectivity analgesic target (130). Co-expressed with Nav1.7/1.8 in

small DRG neurons, Nav1.9 participates in familial episodic pain

syndromes and GM-CSF-induces hyperalgesia through Jak2-Stat3

pathway co-activation (131).

Pharmacological blockade of Nav1.7/1.8 channels reduces ectopic

discharges and elevates peripheral firing thresholds to alleviate

pain (132), with

Nav1.7-selective inhibitors emerging as promising next-generation

analgesics through therapeutic index optimization (133).

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel regulates

cytosolic Ca2+ levels to influence cellular excitability

and signaling, with N-type and T-type subtypes implicated in pain

pathophysiology. The N-type blocker ziconotide, approved by the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for intrathecal

administration in severe chronic pain, exhibits potent analgesia

limited by narrow safety margins. T-type channels in

central/peripheral neurons mediated somatic/visceral pain

transduction, making their modulators potential analgesics

(134).

Voltage-gated K+ channel

Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily KQT member

4 (KCNQ) validates analgesic targets, as evidenced by retigabine's

efficacy in chronic inflammatory/neuropathic pain models (135). Genetic studies of inherited

erythromelalgia identified KCNQ2-encoded Kv7.2 channels as

peripheral determinants of pain susceptibility (136), suggesting intrinsic analgesic

mechanisms beyond conventional modulation (137). Flupirtine, a retigabine analog

targeting Kv7.2, has been clinically used since 1984 despite

adverse effects. Cryo-EM structures of apo-state human Kv7.2 and

ligand-bound complexes with retigabine/ztz240 provided molecular

blueprints for improved KCNQ agonist design (138). While numerous pharmaceutical

efforts focused on KCNQ openers, only retigabine and flupirtine

have reached clinical application, underscoring the need for

optimized subtype-selective agents.

Mechanosensitive ion channel-TREK-1

As a key member of the K2P potassium channel family,

TREK-1 is regulated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and

enriched in small sensory neurons (139). TREK-1 knockout mice exhibit

enhanced thermal sensitivity and mechanical allodynia, with

diminished osmotic pain responses particularly in PGE2-sensitized

models (140), establishing

TREK-1 as a promising multitarget analgesic candidate.

Ligand-gated ion channels

Acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC)

ASIC, a proton (H+)-activated cation

channel expressed in both peripheral and central nervous systems,

plays critical roles in pain signal transmission and modulation.

The ASIC family comprises ASIC1-ASIC4 subtypes, with ASIC1

predominating in spinal neurons and brain regions such as the

cerebral cortex and hippocampus (141). Duan et al (142) demonstrated that intrathecal

administration of ASIC1a-specific inhibitors or antisense

oligonucleotides in CFA-induced inflammatory rats markedly reduced

thermal/mechanical hyperalgesia via ASIC1a downregulation.

Stauntonia PTS extract inhibited ASIC currents and downregulated

ASIC3 protein expression, exhibiting analgesic effects in animal

models. Key active compounds YF-33 and YF-49 show dose-dependent

ASIC current suppression and potent analgesia (143). Paeoniflorin alleviates pain by

inhibiting ASIC-mediated H+-activated currents through

adenosine A1 receptor interaction, shortening Phase II pain

duration in formalin tests (144). Dexmedetomidine

concentration-dependently inhibited ASIC electrophysiological

activity via α2-adrenergic receptors (α2-ARs), mitigating

acid-induced nociceptive behaviors through peripheral α2A-Ars

(145). These findings

highlighted diverse pharmacological strategies targeting ASICs for

pain management.

α4B2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

The α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR),

a ligand-gated ion channel widely expressed in the CNS/PNS,

modulates pain signaling through acetylcholine, dopamine,

γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and norepinephrine regulation. Its

agonists/partial agonists exhibit analgesic efficacy in

neuropathic/inflammatory pain models, reversible by nAChR

antagonists (146). However,

novel α4β2 nAChR-targeted analgesics remained preclinical,

necessitating further development.

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor

NMDA receptor, an ionotropic glutamate receptor

abundant in spinal dorsal horn neurons, is a validated mediator of

pathological pain and hyperalgesia across formalin, CFA,

carrageenan and neuropathic models. Studies have revealed NMDA

receptor expression on spinal keratinocytes and involvement in

astrocyte activation during sciatic nerve injury-induced

neuropathic pain. Li et al (147) demonstrated NMDA receptor

participation in spinal microglial activation and neuroactive

substance release during acute peripheral inflammatory pain,

expanding their therapeutic potential.

Purinergic receptor

ATP-gated P2X receptor facilitates K+

efflux and Na+/Ca2+ influx through seven

subtypes (P2X1-7) expressed on neurons, immune cells and cancer

cells. P2X3 mediates acute pain in sensory neurons, P2X4

neuropathic pain in glia and P2X7 inflammatory pain in immune cells

(148). Emerging evidence

positions purinergic signaling via P2X receptors as a dual

therapeutic target for cancer progression and pain. Franceschini

and Adinolfi (148) proposed

combining standard chemotherapeutics with P2X2/3/4/7 antagonists to

simultaneously address tumor growth and cancer-related pain.

Capsaicin receptor

The transient receptor potential (TRP) channel

constitutes a family of cellular channel proteins initially

discovered in Drosophila photoreceptors, where TRP mutations

abolished sustained light-induced responses while permitting

transient voltage currents. TRP channels are expressed across

multiple tissues, with their activation via diverse stimuli

triggering cation influx to modulate cellular states. The TRP

family comprises six subfamilies: Canonical (TRPC), melastatin

(TRPM), vanilloid (TRPV), ankyrin (TRPA), polycystin (TRPP) and

mucolipin (TRPML) (149). Among

them, TRPV1, TRPA1 and TRPM8 play pivotal roles in analgesic

mechanisms. TRPV1 channel, recognized as a critical regulator of

nociception, exhibits sensitivity to thermal and chemical stimuli.

Activation induces inflammatory mediator/neurotransmitter release

from nociceptive nerve terminals to generate pain signals,

positioning TRPV1 antagonists as validated analgesic agents

(150). TRPA1 channel,

activated by reactive oxygen species and cold temperatures,

represents emerging therapeutic targets through their involvement

in mechanical/allodynic pain pathways (151). TRPM8 channel, cold-sensitive

thermoreceptors, paradoxically mediate analgesia when they activate

their agonists in neuropathic pain management (152,153). Preclinical studies confirm

TRPV1's therapeutic relevance across cancer, neuropathic,

postoperative and musculoskeletal pain models. Its selective

expression in primary nociceptors underpinned targeted intervention

strategies. Emerging approaches include potassium current enhancers

to suppress nociceptive signaling and Cav2.2/Cav3.2 calcium channel

blockade, demonstrating complementary analgesic potential (154).

GPCRs

Opioid receptor

Opioid receptors, a class of GPCRs, include

multiple subtypes such as central MOR, δ-opioid receptor (DOR),

κ-opioid receptor (KOR) and peripheral Mrg opioid receptor, all of

which modulated pain signaling (155). Despite severe adverse effects