Introduction

Sarcopenia is a progressive and multifactorial

condition characterized by the loss of skeletal muscle mass,

strength, and function and is frequently observed in older adults

(1). This age-associated decline

contributes to frailty, functional deterioration, and increased

healthcare costs (2,3). Despite the clinical burden, no

approved pharmacological treatments are available to effectively

enhance muscle regeneration in patients with sarcopenia (4,5).

Developing novel strategies to improve muscle repair remains a

significant challenge.

Impaired function of skeletal muscle satellite cells

(MuSCs), which are indispensable for post-injury muscle

regeneration, is recognized as a central mechanism underlying

sarcopenia. In response to muscle damage, MuSCs become activated,

proliferate, and differentiate along the myogenic lineage to

support effective repair of damaged fibers (6,7).

Aging leads to a decline in both the number and functional capacity

of MuSCs, resulting in impaired regenerative ability and

exacerbated muscle wasting (8).

Although direct cell transplantation has been proposed as a

potential approach, clinical application is limited by technical

and immunological barriers, such as challenges in determining the

optimal timing, delivery route, and transplantation site (9,10). Therefore, stem cell-mediated

therapy has gained attention as a potential strategy to support

muscle regeneration in aging muscles, particularly to overcome the

practical challenges associated with transplantation-based

therapies (5).

Among various candidates, a disintegrin and

metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1 (ADAMTS-1) has been

identified as a regulator of early myogenesis (11). Its expression increases during

MuSC proliferation and promotes myogenic differentiation, partly by

reducing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which modulates the

Notch signaling pathway (12).

Given the importance of Notch signaling in balancing MuSC

quiescence and activation, targeting this axis via ADAMTS-1 may

offer therapeutic benefits for enhancing muscle regeneration in

aging populations (13).

The present study investigated whether recombinant

ADAMTS-1 (rADAMTS-1), comprising a condensed pro-domain and

metalloproteinase domain, enhances MuSC-mediated regeneration by

modulating myogenic signaling. The effects of rADAMTS-1 on MuSC

proliferation, differentiation, and functional recovery were

evaluated using in vivo and in vitro models. A barium

chloride (BaCl2)-induced acute skeletal muscle injury

model was employed to induce localized myofiber necrosis while

sparing MuSCs, thereby enabling reproducible assessment of muscle

regeneration (14). Although

this model does not mimic the chronic features of sarcopenia, it

provides a robust platform for studying rapid muscle damage and

subsequent MuSC self-renewal and myoblast expansion (15). Findings from this model may

contribute to the development of strategies to address delayed

muscle regeneration in the elderly, where impaired MuSC function

and altered regeneration timing hinder effective recovery (8).

The present study evaluated whether rADAMTS-1

promoted MuSC proliferation and differentiation, highlighting its

role in muscle regeneration and the Notch signaling pathway. This

approach may help overcome limitations associated with MuSC

transplantation and support the advancement of targeted therapies

for sarcopenia.

Materials and methods

Production and purification of

rADAMTS-1

The cloning and mutagenesis of ADAMTS-1 were

performed following protocols previously described by Lee et

al (13). Full-length

ADAMTS-1 cDNA was generated by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using

a human cDNA library and subcloned into a mammalian expression

pEF/V5-polyhistidine (His) vector (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Various randomly deleted ADAMTS-1 mutants were

generated using In-Fusion® cloning tools (Takara Bio,

Inc.). The ADAMTS-1 expression plasmid used in the present study

was prepared in-house and a 1 mg/ml stock was generated for

transfection.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells (CCL-61; ATCC)

were used for the production of rADAMTS-1. rADAMTS-1 overexpressed

CHO cells were cultured in an ExpiCHO expression medium (cat. no.

A2910002; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a

humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were transfected with

4 μg plasmid DNA per 100 mm dish using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, and single

cell-derived clones were selected using 5 μg/ml blasticidin

(cat. no. SBR00022; MilliporeSigma) for ~2 weeks to establish

stable clonal CHO cells. A stable CHO-K1 line transfected with the

pEF/V5-His empty vector was generated in parallel and used as the

negative control.

rADAMTS-1 was purified from cell culture

supernatants of stable clones using a nickel nitrilotriacetic acid

agarose column (cat. no. 31314; Qiagen GmbH). Proteins were bound

for 1 h at 16°C with gentle agitation, followed by washing and

elution. The eluted rADAMTS-1 proteins were dialyzed at 4°C

overnight in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and used for

intraperitoneal (IP) injection in mice or in vitro

experiments. Overexpression of rADAMTS-1 was confirmed by western

blot analysis (Fig. S1).

Animal study

A total of 96 mice were used in the present study

and weighed 20-22 g at the start of the experiment.

Specific-pathogen-free male C57BL/6 mice (7 weeks old) were

obtained from Samtako Bio Korea Co., Ltd. The mice were housed

under standard laboratory conditions (22±2°C with 55±5% humidity

and a 12-h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to tap

water and standard rodent chow (Samyang Foods Co., Ltd.). All

experimental procedures received approval from Chungnam National

University Animal Care and Use Committee (approval no.

202310A-CNU-169).

After 1-week acclimation period, the mice were

divided into four groups based on time points post-injection: 1, 3,

7 and 14 days (dpi). Each time point included four subgroups (n=6

per group): i) the non-injured control (NC), ii) BaCl2

(cat. no. 202738; MilliporeSigma): BaCl2 intramuscular

(IM) injection, iii) low-dose rADAMTS-1 [rADAMTS-1 (L)]:

BaCl2 IM + 5 mg/kg rADAMTS-1 IP injection and iv)

high-dose rADAMTS-1 [rADAMTS-1 (H)]: BaCl2 IM + 10 mg/kg

rADAMTS-1 IP injection. A single injection of 1.2% (w/v)

BaCl2 solution in saline was injected into the tibialis

anterior (TA) of each mouse (except the NC group) under 2%

isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesia was induced over 5-7 min and

maintained throughout the procedure to minimize pain and distress.

Daily IP administration of rADAMTS-1 at low and high concentrations

was continued until autopsy.

In addition, to examine whether rADAMTS-1 alone

affects myogenic marker expression under non-injury conditions, a

separate validation experiment was conducted. Mice received IP

injection of rADAMTS-1 (10 mg/kg) without BaCl2-induced

injury, and TA muscles were analyzed using western blotting.

The dose of 5 and 10 mg/kg rADAMTS-1 were selected

based on pilot experiments, in which a higher dose (20 mg/kg) did

not produce a substantial difference compared with 10 mg/kg

(Fig. S2). Therefore, 5 and 10

mg/kg were chosen as effective and practical doses for subsequent

analyses. IP administration was employed because it ensures

minimizing stress and potential injury to rodent (16). In addition, IP injection allows

rapid and efficient absorption while avoiding degradation or

modification in the gastrointestinal tract (17).

Autopsies were performed at 1, 3, 7, and 14 dpi to

evaluate the temporal progression of muscle recovery after injury.

Mice were euthanized by 5% of isoflurane inhalation prior to

mortality and loss of respiration and reflexes was confirmed before

tissue collection. For pharmacokinetic profiling, blood samples

were collected at 0 (immediately after dosing), 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8,

24, and 48 h after a single IP injection of rADAMTS-1 (10 mg/kg)

and plasma rADAMTS-1 concentrations were quantified using an

immunoassay according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Grip strength

The grip strength test is widely used to assess

skeletal muscle function (18).

A computerized grip-strength meter (cat. no. 47200; Ugo Basile SRL)

was used to measure grip strength in mice. To prevent interference

during the assessment, the mice were gently held at the base of the

tail and allowed to grasp a wooden stick with their forepaws. The

hind paws then grasped the transducer metal bar of the apparatus,

while the conductor pulled the mice backward by the tails until the

grip was released. The device recorded the peak force exerted

during this procedure in grams (g). All measurements were performed

in a blinded manner. Each mouse underwent a minimum of 10 trials,

and the median force value was recorded. Grip strength values were

normalized to body weight to account for weight fluctuations

throughout the experimental period.

Histopathological analysis of skeletal

muscle tissue

TA tissue samples were preserved in 10% (v/v)

neutral-buffered formalin, and fixation was performed at 20-23°C.

After 1 week of fixation, the tissues were dehydrated using an

automated tissue processor (TP1020; Leica Biosystems), which

sequentially transferred the samples through graded ethanol (70,

80, 95, and 100%) and xylene solutions, with each step lasting 1 h.

The processed tissues were then paraffin-embedded, with the

transverse plane positioned downward, and sectioned into

4-μm-thick slices using HistoCore BIOCUT (cat. no.

149BIO000C1; Leica Biosystems). Following a standard rehydration

procedure, the slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (cat.

nos. H08-500R and EY07-500R; TissuePro Technology). The slides were

then mounted using VectaMount® Express mounting medium

(cat. no. H5700; VectorLabs).

MuSC counts in TA

The harvested TA muscles were minced and digested in

0.2% collagenase type II (cat. no. 17101015; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; cat.

no. SH30243.01; Cytiva) for 90 min at 37°C, following a modified

isolation protocol previously reported (19). The digested suspensions were

centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and then passed through

70- and 40-μm cell strainers (cat. no. 93070, 93040; SPL

Life Sciences). Cell counting was performed using a hemocytometer,

and the suspensions were diluted to 1×106 cells/ml in

staining buffer (cat. no. 554657; BD Pharmingen) for analysis. All

the cells were stained with antibodies recognizing MuSC markers,

including cluster of differentiation (CD) 45 (1:100; cat. no.

557235; BD Biosciences), CD 31 (1:100; cat. no. 558738; BD

Biosciences), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1; 1:100;

cat. no. orb623587; Biorbyt, Ltd.), and stem cell antigen 1 (Sca1;

1:100; cat. no. 108122; BioLegend, Inc.). Staining was conducted on

ice for 30 min in the dark. After washing, flow cytometry data were

collected using the BD Accrui C6 Plus flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence

Histological sections underwent antigen retrieval in

citrate buffer (pH 6.0; cat. no. 21545; MilliporeSigma) for 15 min

at 95°C. Subsequently, sections were blocked/permeabilized with PBS

containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin (cat. no.

A3311; MilliporeSigma) for 30 min at 25°C. Slides were stained with

primary antibodies and diluted in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight.

MuSCs were visualized by staining for paired box protein 7 (Pax7;

1:100; cat. no. ab187339; Abcam), and regenerating myofibers were

identified through MyoD staining (1:100; cat. no. GTX636812;

GeneTex, Inc.). After staining, all samples were washed with PBS

containing 0.1% Tween 20 (0.1% PBST) and incubated at 25°C for 1 h

with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488; 1:500; cat.

no. ab150081; Abcam). Nuclei were visualized using DAPI mounting

medium (cat. no. ab104139; Abcam). The samples were viewed using a

fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH), and quantitative

image analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH;

1.49v).

Primary skeletal muscle cells were seeded at a

density of 5×104 cells/well in a 24-well plate

containing 1 ml of complete expansion medium. After the cells

reached >90% confluence, rADAMTS-1 protein was added to the

skeletal muscle differentiation medium at concentrations of 0.001,

0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ng/ml. After 72 h of differentiation, the

cells were fixed, washed, and treated with anti-myosin heavy chain

antibodies (1:100; cat. no. 05-716; MilliporeSigma). Differentiated

myotubes were visualized with goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 555

antibodies (1:500; cat. no. A-21422; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) via fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence images

were obtained using a microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ts2-FL; Nikon

Corporation). Myotube length was measured and calculated as the

average of five samples using NIS-Elements imaging software (Nikon

Corporation; 5.00v).

Immunohistochemistry

Embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMyHC) expression in

TA tissues was evaluated using VECTASTAIN®

Elite® ABC-HRP Kits (cat. no. PK-6101 and PK-6102;

Vector Laboratories, Inc.) following the manufacturer's

instructions. The paraffin sections were deparaffinized,

rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval for 5 min at 121°C

in citric acid buffer (pH 6.0). The slides were subsequently

blocked with 10% goat serum supplied within the kit (Vector

Laboratories, Inc.) for 30 min at 20-23°C and incubated with the

primary antibody (eMyHC; 1:100; cat. no. F1.652; Developmental

Studies Hybridoma Bank) overnight at 4°C. The biotinylated

secondary antibody working solution was prepared according to the

manufacturer's drop-based protocol and applied for 30 min at

20-23°C. The ABC reagent was prepared using the manufacturer's

recommended drop-based protocol and incubated with the

avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex for 30 min at 20-23°C. Protein

expression was analyzed using a 3,3'-diaminobenzidine substrate kit

(cat. no. ab64238; Abcam). The sections were counterstained with

hematoxylin for 30 sec at 20-23°C and images were captured using a

light microscope, with scale bars indicated in the figure legends.

The quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH;

1.49v).

Western blotting

The harvested TA tissues were homogenized at a 1:10

(w/v) ratio in tissue lysis/extraction reagent (cat. no. C3228;

MilliporeSigma) supplemented with protease and phosphatase

inhibitors (cat. nos. 04693116001, 4906837001; Roche Diagnostics).

Homogenization was performed using a BIOPREP-24R (Hangzhou Allsheng

Instruments Co., Ltd.). Protein concentrations were determined

using bicinchoninic acid reagents (cat. nos. 23228 and 1859078;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of total protein (20

μg) were separated by 6, 10 and 15% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto

polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (cat. no. IPVH00010;

MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at 20-23°C in

5% bovine serum albumin (cat. no. A9418; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

in 0.1% PBST, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary

antibodies: myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD) (1:1,000; cat.

no. ab64159; Abcam), myogenin (MyoG) (1:1,000; cat. no. ab124800;

Abcam), ADAMTS-1 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab276133; Abcam), NICD (1:500;

cat. no. ab52301; Abcam), and Hes-1 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab71559;

Abcam). After two washes with 0.1% PBST, the membranes were

incubated at 25°C for 2 h with a 1:5,000 dilution of horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (rabbit: cat. no.

LF-SA8001; mouse: cat. no. LF-SA8002; Abfrontier Co., Ltd.). Next,

the blots were washed twice with 0.1% PBST and developed using an

enhanced chemiluminescence kit (cat. no. BWF0100; Biomax Co.,

Ltd.). Protein bands were visualized using a ChemiDoc device

(io-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and quantified using ImageJ software

(NIH; 1.49v). Total protein loading was assessed by Ponceau S

staining (Fig. S3), which

served as the normalization standard instead of housekeeping

proteins such as β-actin, GAPDH, or α-tubulin, whose expression

varies in skeletal muscle (20,21). Following previous reports

(22,23), the intensity of each target band

was normalized to the total lane density, calculated as the sum of

all visible bands within the same lane, and expressed as relative

intensity.

Primary skeletal muscle cells were treated with

rADAMTS-1 protein at a concentration of 10 ng/ml at the onset of

differentiation using skeletal muscle differentiation tool medium.

After 3 days of differentiation, the cells were harvested for

western blot analysis. Primary skeletal muscle cells were lysed in

CelLytic M buffer (cat. no. C2978; MilliporeSigma) and all

subsequent steps followed the same procedures as described for the

in vivo western blot protocol.

Cell culture and differentiation

Primary skeletal muscle cells (cat. no. PCS-950-010;

ATCC) were cultured in a complete expansion medium (cat. no.

PCS-500-030; ATCC) using a primary skeletal muscle cell growth kit

(cat. no. PCS-950-040; ATCC). For differentiation, the cells were

treated with a skeletal muscle differentiation tool (cat. no.

PCS-950-050; ATCC) upon reaching 90% confluence. Mouse myoblast

C2C12 cells (cat. no. CRL-1772; ATCC) were obtained from ATCC.

C2C12 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. 35-015-CV;

Corning Life Sciences). C2C12 cells were incubated in DMEM

containing 2% horse serum until they reached 90% confluence. Cells

were used within 10 passages from thawing to ensure phenotypic

consistency.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) assay

Primary skeletal muscle cells were seeded in 96-well

plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well and incubated

with 10X BrdU solution from the BrdU assay kit (cat. no. 6813; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) at concentrations of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1,

1, or 10 ng/ml rADAMTS-1 for 24 h. The cells were fixed and treated

with a detection antibody solution at 24°C for 1 h. After removing

the solution and washing the plate three times, the cells were

incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary

antibody for 30 min at 24°C. The cells were then incubated at 24°C

for 30 min with 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine substrate, and

absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

RNA-seq analysis

C2C12 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml rADAMTS-1 and

differentiated for 3 days. Total RNA was isolated using the

Quant-it RiboGreen RNA assay kit (cat. no. R11490; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The total RNA integrity of the samples was assessed using

the TapeStation RNA ScreenTape (cat. no. 5067-5576; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Only high-quality RNA samples (RNA integrity

number >7.0) were used for RNA library preparation. cDNA was

prepared using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (cat. no.

18064014; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and random

primers. The products were purified and enriched using PCR to

construct a final cDNA library. Library concentration was measured

using KAPA Library Quantification kits for Illumina sequencing

platforms, following the qPCR Quantification Protocol Guide (Kapa

Biosystems, Inc.), and their quality was assessed using TapeStation

ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Indexed libraries were

submitted for paired-end (2×100 bp) sequencing on the Illumina

NovaSeq platform (Illumina Inc.), which was conducted by Macrogen

Inc.

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)

PCR

For RT-qPCR validation, total RNA was extracted

using the easy-BLUE Total RNA Extraction Kit (cat. no. 17061;

iNtRON Biotechnology DR), and 1 μg RNA was reverse

transcribed using the HiSense cDNA Synthesis Master Mix (cat. no.

CDS-400, CellSafe Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's

instructions. The qPCR was performed using the QuantStudio 3

Real-Time PCR System (cat. no. A28567; Applied Biosystems; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (cat. no.

4344463; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

thermocycling protocol was: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10

min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 15 sec, and

72°C for 45 sec. A melting curve analysis was performed from 60°C

to 95°C to verify amplification specificity. Gene expression levels

were calculated using the 2ΔΔCq method (24) and all reactions were performed in

triplicates. The following primers were used (5'-3'): Myomixer

(Mymx), forward (F): GACCACTCCCAGAGGAAGGA, reverse (R):

GGACCGACGCCTGGACTAAC; myogenic factor 6 (Myf6), F:

TGCTAAGGAAGGAGGAGCAA, R: CCTGCTGGGTGAAGAATGTT; myosin heavy chain 1

(Myh1), F: CGGAGGAACAATCCAATGTC, R: TGGTCACTTTCCTGCACTTG;

myosin heavy chain 2 (Myh2), F: TCTCAGGCTTCAGGATTTGG, R:

CAGCTTGTTGACCTGGGACT; myosin heavy chain 4 (Myh4), F:

CGTCAAGGGTCTTCGTAAGC, R: ATTGTTCCTCAGCCTCCTCA; and

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), F:

CCAATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCT, R: GTTGAAGTCGCAGGAGACAACC. All primers were

synthesized by Bioneer.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard

deviation. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

For normally distributed data, one-way analysis of variance with

Tukey's post hoc test was used to evaluate differences among

groups. The data were analyzed and the statistical graphs were

constructed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics). Statistical

significance was defined as *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and

***P<0.001. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of rADAMTS-1 on functional and

histological recovery in injured skeletal muscle

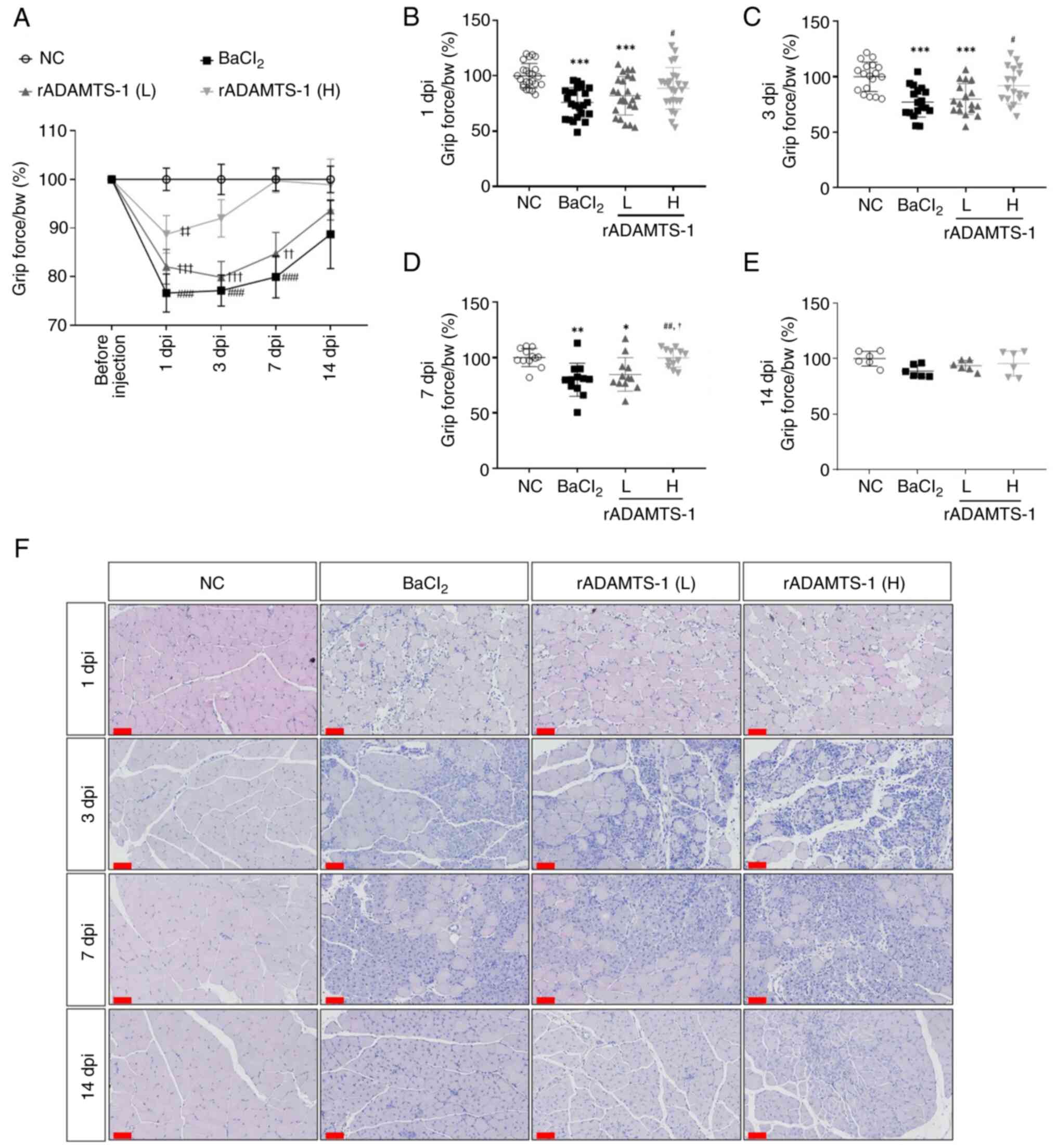

Prior to assessing its regenerative effects,

systemic exposure of rADAMTS-1 following IP administration was

confirmed (Fig. S4). Grip

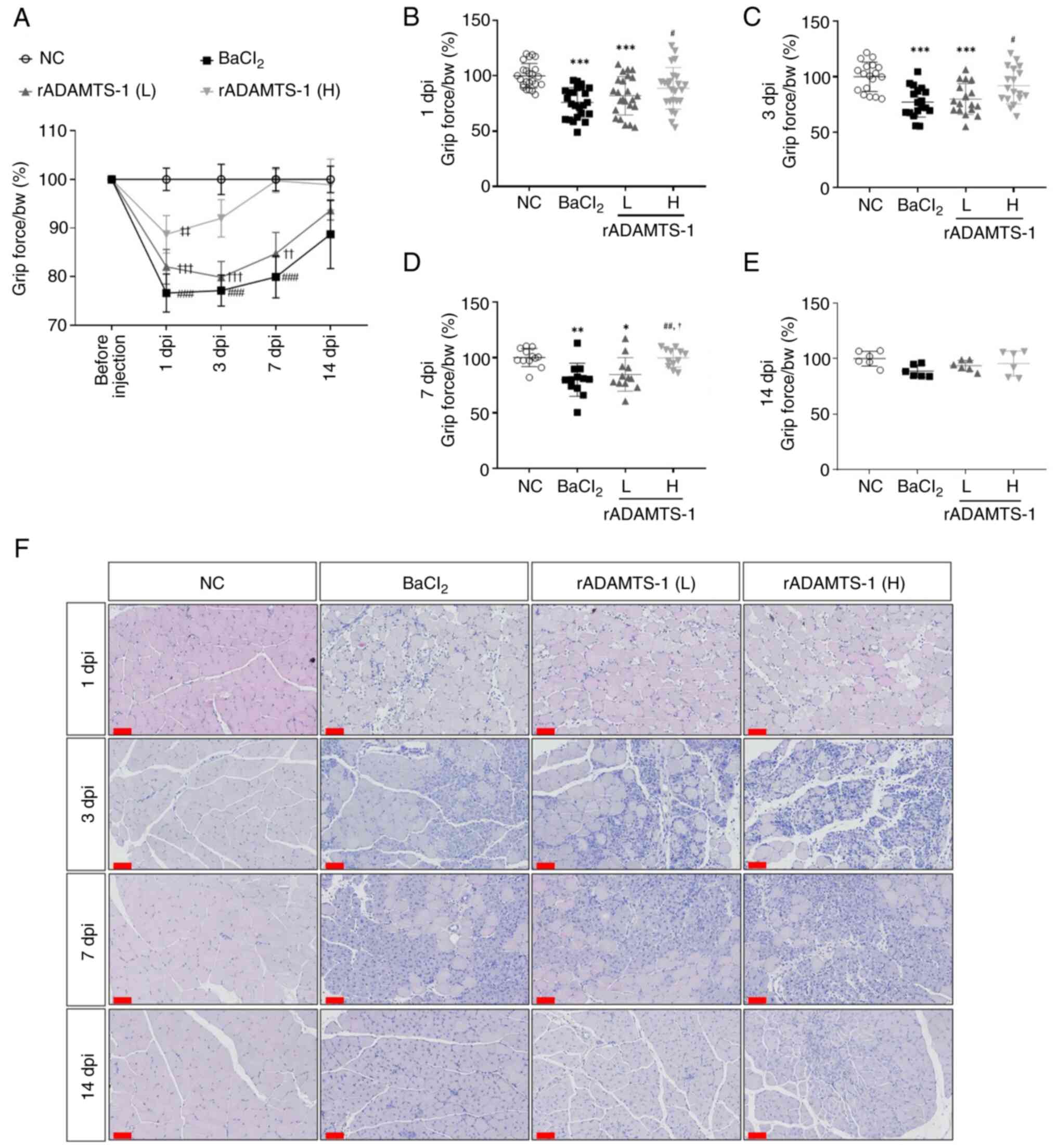

strength analysis revealed rapid recovery of grip force in the

high-dose treatment group (Fig.

1A). At 1 dpi, grip force relative to body weight decreased by

~25% in the BaCl2 group compared with the NC group

(P<0.001; Fig. 1B).

Furthermore, the rADAMTS-1 (H) group exhibited an increase of ~16%

(P<0.05) compared with the BaCl2 group after 1 dpi. A

marked improvement in grip strength was observed in the rADAMTS-1

(H) group after 3 dpi, reaching nearly 90% of the NC group's

performance (ns) and exceeding the BaCl2 group by 19%

(P<0.05) (Fig. 1C). By

contrast, during the first 7 days, the BaCl2 group

exhibited a decrease of ~20% compared with the NC group

(P<0.01). The rADAMTS-1 (H) group exhibited higher grip force

values than both the BaCl2 and rADAMTS-1 (L) groups

(P<0.01 and <0.5, respectively) (Fig. 1D). At 14 days after muscle

damage, the grip force values in the rADAMTS-1 (H) group were

similar to those in the NC group. By contrast, decreases of ~10 and

7% were observed in the BaCl2 and rADAMTS-1 (L) groups,

respectively (ns; Fig. 1E).

| Figure 1Effects of rADAMTS-1 on recovery

following BaCl2-induced TA muscle injury. Groups

included NC, BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 treatment groups (L) and

(H). Daily intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1 (L) or (H) were

initiated immediately after injury and continued until the

designated endpoint. (A) Grip strength measurements, normalized to

body weight, were recorded throughout the experimental period.

Statistical significance was determined using two-way analysis of

variance as follows: ###P<0.001 vs. BaCl2

group at day 0; ††P<0.01 and †††P<0.001

vs. rADAMTS-1 (L) at day 0; ‡‡P<0.01 vs. rADAMTS-1

(H) at day 0. (B-E) Grip strength at 1, 3, 7, and 14 dpi. Each dot

represents an individual mouse, with error bars indicating the

standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined using

one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post hoc test;

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. NC group; #P<0.05 and

##P<0.01 vs. BaCl2 group;

†P<0.05 vs. rADAMTS-1 (L). (F) Representative

histological images of TA muscle sections stained with hematoxylin

and eosin (scale bar, 60 μm) at the corresponding time

points. ADAMTS-1, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with

thrombospondin motifs 1; rADAMTS-1, recombinant ADAMTS-1;

BaCl2, barium chloride; TA, tibialis anterior; NC,

non-injured control; rADAMTS-1 (L), rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg; rADAMTS-1

(H), rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg. |

Histological changes were assessed by group based on

the time elapsed after BaCl2 injection (Fig. 1F). At 1 dpi, the margins of the

TA muscle appeared rounded, with mild infiltration of inflammatory

cells in the injured groups. Inflammatory cell infiltration

increased at 3 dpi, at which point the myofibers maintained rounded

margins and proliferating cells were evident. The presence of

centrally located myonuclei, irregularly shaped fibers, and small

myofibers at 7 dpi indicates proliferation (25). The rADAMTS-1 (H) group exhibited

active proliferation patterns at 7 dpi, with myonuclei mainly

located at the center of most muscle fibers at 14 dpi. The TA

muscles exhibited angular margins, comparable with those in the NC

group, indicating maturation at 14 dpi in both the BaCl2

and rADAMTS-1 groups. The rADAMTS-1 (H) group showed a more

extensive proliferative region than the BaCl2 group at 7

and 14 dpi.

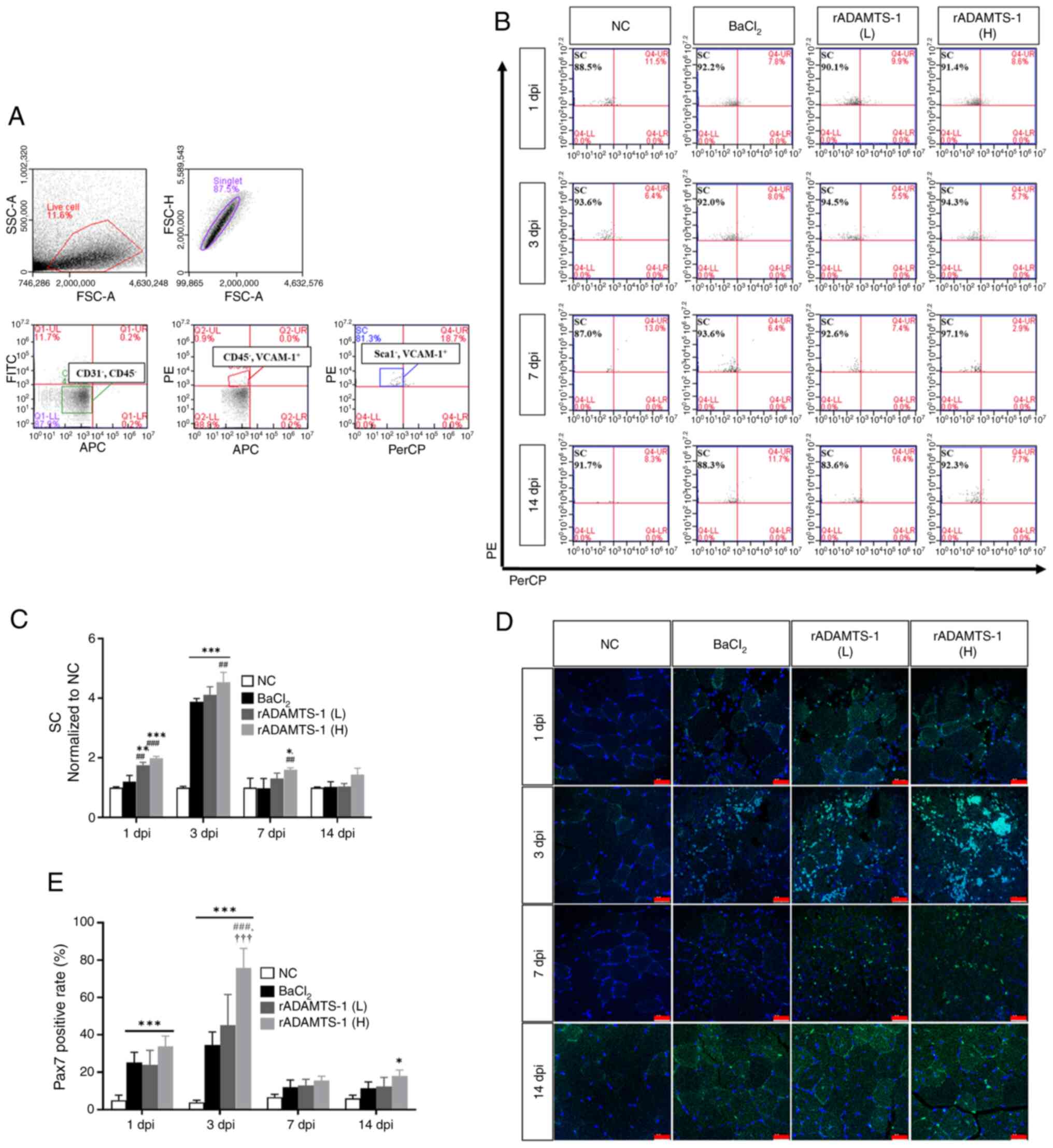

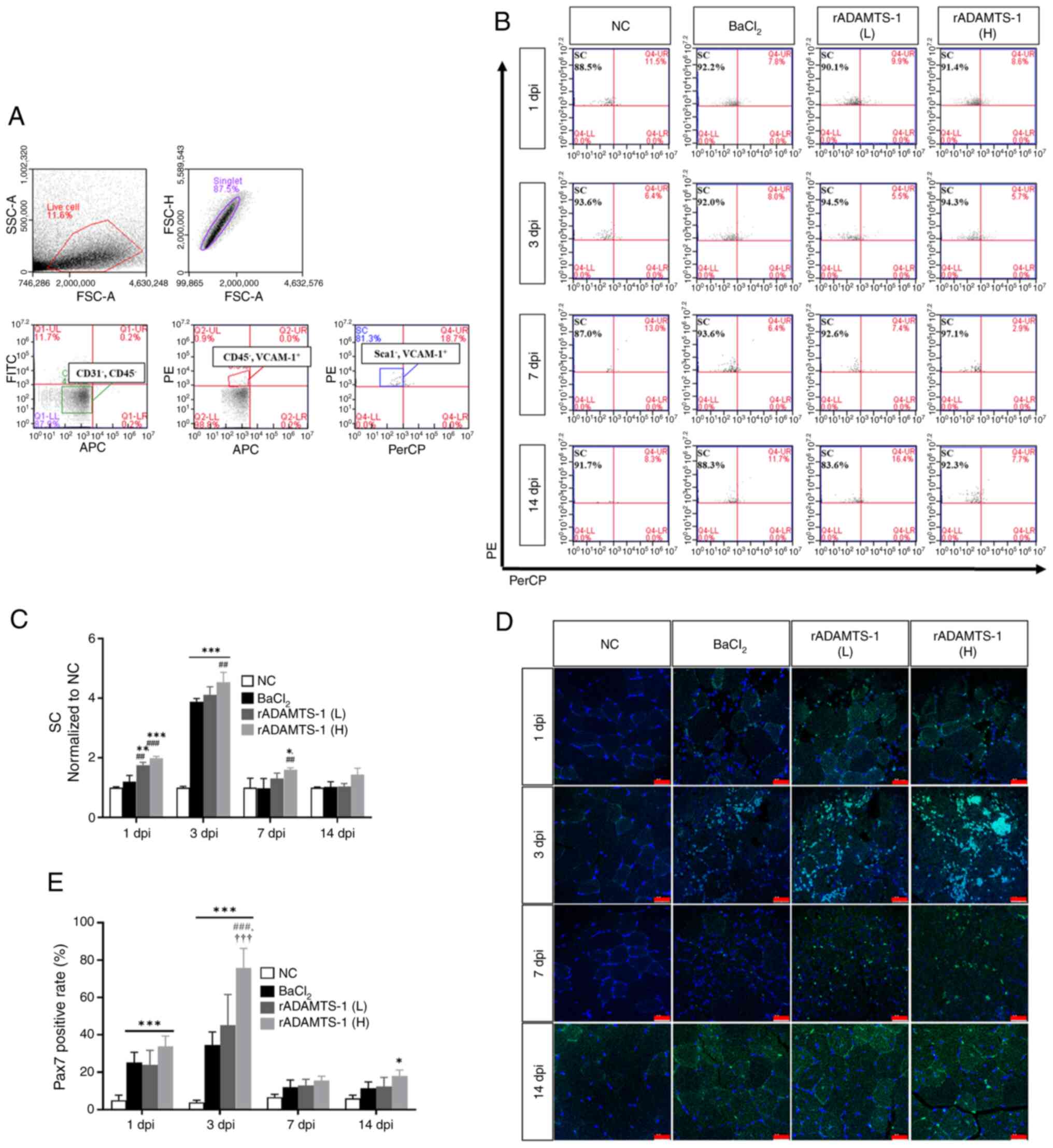

Effects of rADAMTS-1 on MuSCs population

over time after BaCl2 injury

Research on mouse skeletal muscle has demonstrated

that MuSCs can be isolated (26)

and are characterized by negative expression of CD45, CD31, and

Sca1, and positive expression of VCAM-1 (Fig. 2A). Compared with the NC group, a

marked increase in MuSC numbers was observed in all

BaCl2-treated groups following muscle injury (Fig. 2B). The temporal pattern indicated

a significant increase in MuSC numbers at 3 dpi in all the injured

groups, followed by a gradual decline over time (Fig. 2C). At 3 dpi, the number of MuSCs

(normalized to NC) in the rADAMTS-1 (H) group was ~4.5-fold higher

than that in the NC group (P<0.001) and ~1.2-fold higher than

that in the BaCl2 group (P<0.01). At 7 dpi, the

rADAMTS-1 (H) group exhibited an ~1.6-fold increase compared with

the BaCl2 group (P<0.01). A further decrease was

observed in all injured groups at 14 dpi, with the levels remaining

~1.4-fold higher in the high-dose group than in the NC group (ns).

Pax7 expression was analyzed throughout the experimental period to

assess MuSC abundance (Fig. 2D).

Similar to the flow cytometry results, Pax7 expression in the

injury group significantly increased at 3 dpi and then decreased

over time. The rADAMTS-1 (H) group exhibited 1.3-, 2-, 1.3-, and

1.6-fold higher expression at 1 (ns), 3 (P<0.001), 7 (ns), and

14 (ns) dpi, respectively, than the BaCl2 group,

consistently maintaining a slightly higher expression (Fig. 2E).

| Figure 2Effect of rADAMTS-1 on MuSCs

following BaCl2-induced TA muscle injury. Groups

included NC, BaCl2, and two treatment groups receiving

rADAMTS-1 (L) and (H). Daily intraperitoneal injections of

rADAMTS-1 were initiated immediately after injury and continued

until the designated time point for analysis. (A) Flow cytometry

analysis of MuSCs isolated from injured TA muscles, defined by

surface marker expression

(CD45−/CD31−/Sca1−/VCAM1+).

(B) Representative gating strategy for MuSCs across experimental

groups at different time points. (C) Relative number of MuSCs

normalized to the NC group over time. Statistical significance was

determined using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's

post hoc test: *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. NC; ##P<0.01 and

###P<0.001 vs. BaCl2 group. (D)

Representative immunofluorescence images of Pax7+ cells

in injured TA muscle at different time points (scale bar, 25

μm). (E) Quantification of Pax7+ cell percentages

over time. Statistical significance was determined using one-way

analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test:

*P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs. NC;

###P<0.001 vs. BaCl2;

†††P<0.001 vs. rADAMTS-1 (L). ADAMTS-1, a disintegrin

and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1; rADAMTS-1,

recombinant ADAMTS-1; MuSCs, skeletal muscle satellite cells;

BaCl2, barium chloride; TA, tibialis anterior; NC,

non-injured control; rADAMTS-1 (L), rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg; rADAMTS-1

(H), rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg; CD, cluster of differentiation; Sca1,

stem cell antigen 1; VCAM1, vascular cell adhesion molecule; Pax7,

paired box protein. |

Effects of rADAMTS-1 on ADAMTS-1, NICD,

and Hes-1 expression in TA tissue after BaCl2

injection

The temporal expression patterns of ADAMTS-1, NICD,

and Hes-1 were investigated during muscle regeneration following

injury by performing western blot analysis at 1, 3, 7, and 14 dpi

(Fig. 3A). In the

BaCl2-induced muscle injury group, expression levels of

ADAMTS-1, NICD, and Hes-1 were notably upregulated at 1 dpi and

gradually decreased thereafter. Throughout the experiment, the

rADAMTS-1 (H) group consistently showed higher ADAMTS-1 expression

(1.2-1.5-fold) compared with the BaCl2 group, with

statistically significant differences on days 1 (P<0.01), 3

(P<0.001), 7 (P<0.01), and 14 (P<0.5; Fig. 3B). Within-group comparisons of

NICD and Hes-1 levels demonstrated a consistent decrease in the

rADAMTS-1 (H) group at all time points (Fig. 3C and D). A supplementary

validation experiment confirmed that rADAMTS-1 alone (10 mg/kg) did

not change these marker expressions under non-injury conditions

(Fig. S5).

![Effects of rADAMTS-1 on the

expression of ADAMTS-1-associated markers in

BaCl2-injured TA muscle. Groups included NC,

BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 treatment groups (L), and (H). Daily

intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1 were initiated immediately

after injury and continued until the designated time point for

analysis. (A) Temporal expression patterns of ADAMTS-1, NICD, and

Hes-1 in the NC and BaCl2 groups at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days

post-injury (dpi). Comparative expression levels of (B) ADAMTS-1,

(C) NICD, and (D) Hes-1 among treatment groups [NC,

BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 (L), and rADAMTS-1 (H)] at each time

point. Mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1

until the designated dpi. Each data point represents an individual

biological replicate; error bars indicate standard deviation.

Statistical significance in panels (A) was determined using one-way

analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's honestly significant

difference post hoc test, as indicated as follows:

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 1 dpi;

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. 3 dpi. For

panels (B-D), statistical comparisons were made using one-way

analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test:

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. NC; #P<0.05

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs.

BaCl2; †P<0.05, ††P<0.01 and

†††P<0.001 vs. rADAMTS-1 (L). ADAMTS-1, a disintegrin

and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1; rADAMTS-1,

recombinant ADAMTS-1; BaCl2, barium chloride; TA,

tibialis anterior; NC, non-injured control; rADAMTS-1 (L),

rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg; rADAMTS-1 (H), rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg; NICD,

Notch intracellular domain; Hes-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1;

dpi, days post-injury.](/article_images/ijmm/57/2/ijmm-57-02-05718-g02.jpg) | Figure 3Effects of rADAMTS-1 on the

expression of ADAMTS-1-associated markers in

BaCl2-injured TA muscle. Groups included NC,

BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 treatment groups (L), and (H). Daily

intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1 were initiated immediately

after injury and continued until the designated time point for

analysis. (A) Temporal expression patterns of ADAMTS-1, NICD, and

Hes-1 in the NC and BaCl2 groups at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days

post-injury (dpi). Comparative expression levels of (B) ADAMTS-1,

(C) NICD, and (D) Hes-1 among treatment groups [NC,

BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 (L), and rADAMTS-1 (H)] at each time

point. Mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1

until the designated dpi. Each data point represents an individual

biological replicate; error bars indicate standard deviation.

Statistical significance in panels (A) was determined using one-way

analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's honestly significant

difference post hoc test, as indicated as follows:

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 1 dpi;

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. 3 dpi. For

panels (B-D), statistical comparisons were made using one-way

analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test:

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. NC; #P<0.05

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs.

BaCl2; †P<0.05, ††P<0.01 and

†††P<0.001 vs. rADAMTS-1 (L). ADAMTS-1, a disintegrin

and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1; rADAMTS-1,

recombinant ADAMTS-1; BaCl2, barium chloride; TA,

tibialis anterior; NC, non-injured control; rADAMTS-1 (L),

rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg; rADAMTS-1 (H), rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg; NICD,

Notch intracellular domain; Hes-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1;

dpi, days post-injury. |

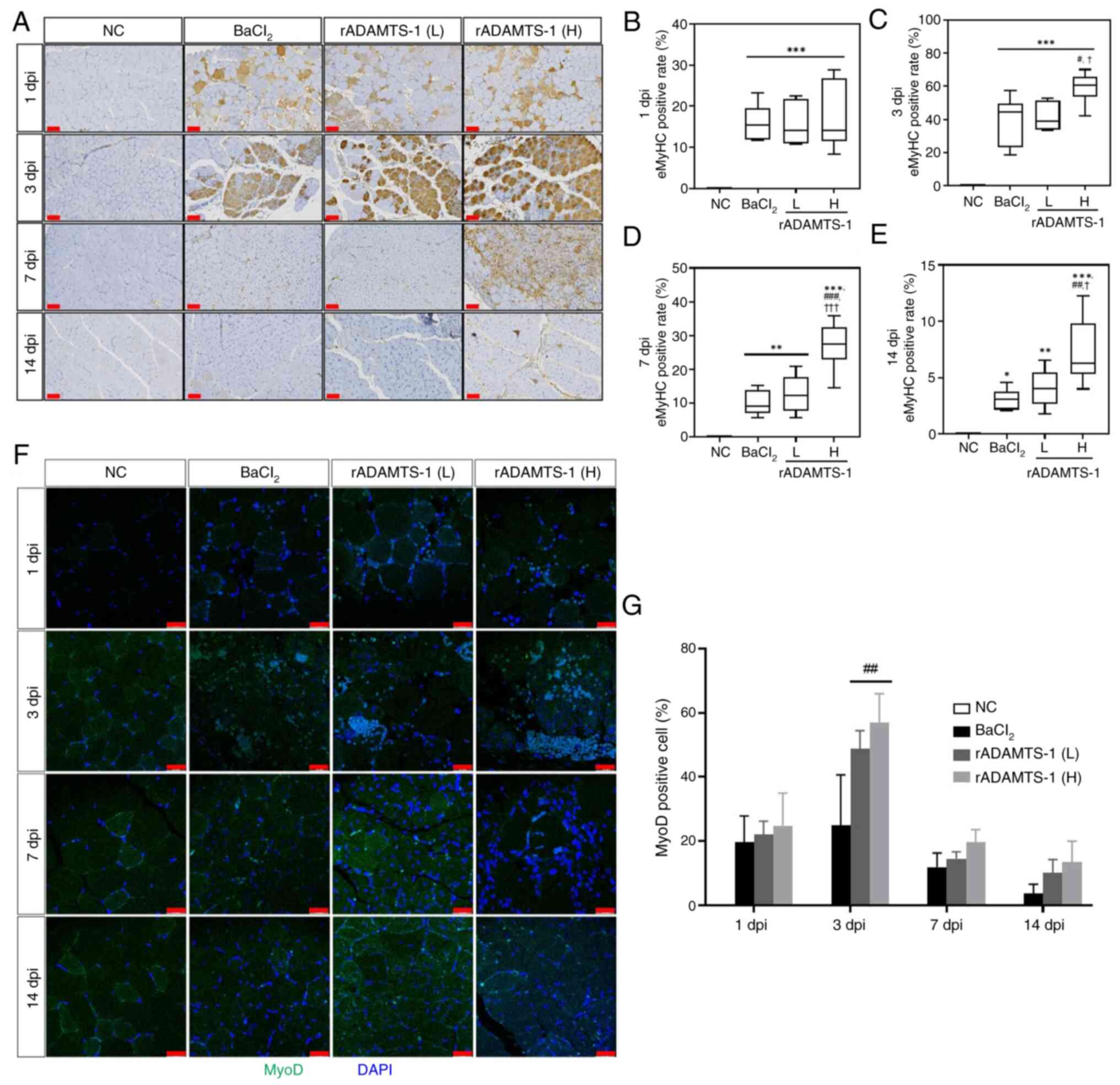

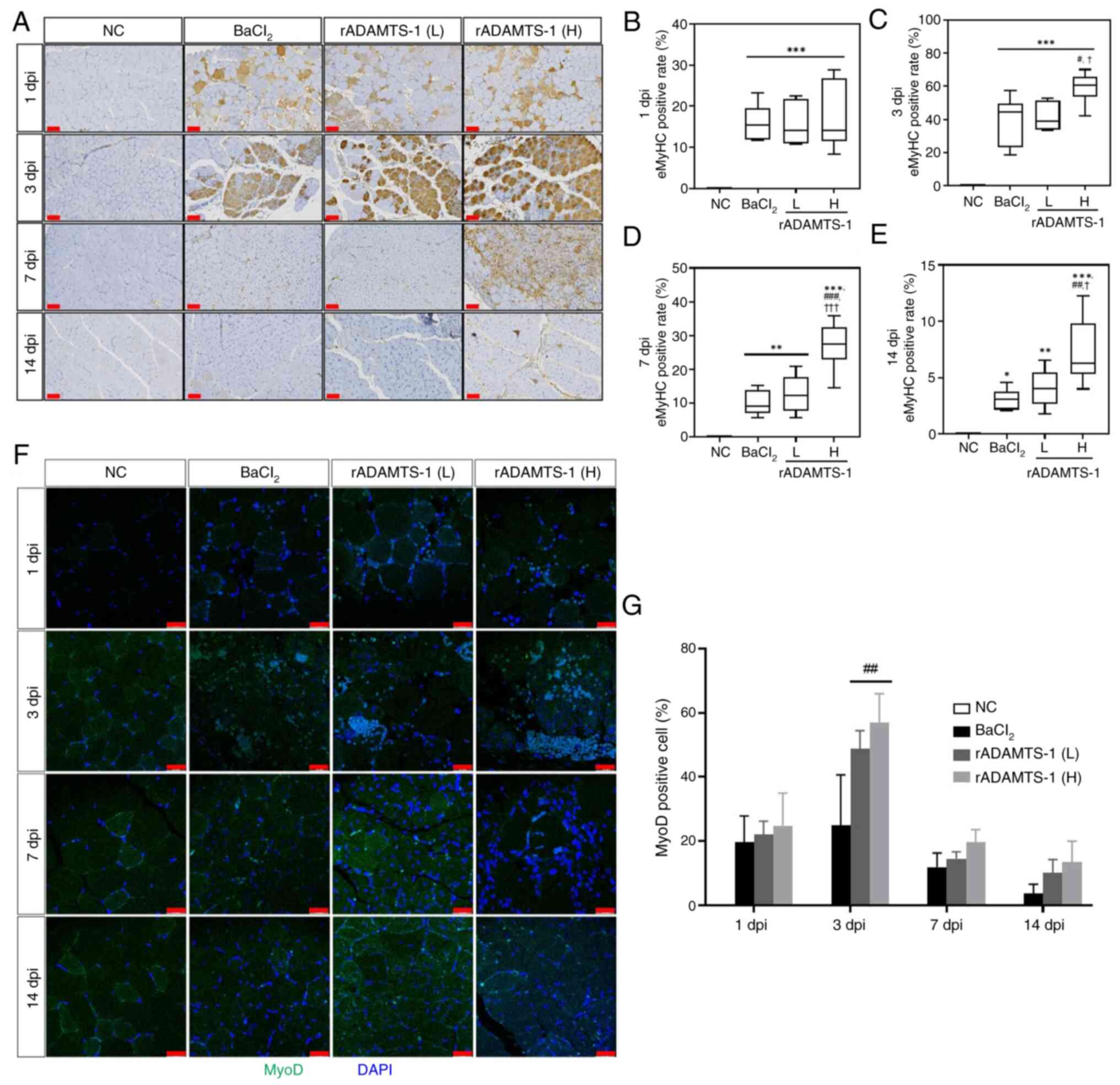

Effects of rADAMTS-1 on the expression of

myogenic markers in TA tissue

eMyHC expression was examined in all the

experimental groups throughout the study period (Fig. 4A). IHC analysis revealed a

significant increase in eMyHC-positive muscle fibers at 3 dpi in

all groups injected with BaCl2, followed by a subsequent

decline over time. Compared with the NC group, all other groups

exhibited ~a 15-fold increase in eMyHC expression at 1 dpi

(P<0.001) (Fig. 4B). Compared

with the BaCl2 group, the rADAMTS-1 (H) group showed

significantly higher numbers of eMyHC-positive muscle fibers, with

increases of ~1.5-, 2.7- and 3.4-fold at 3 (P<0.05), 7

(P<0.001) and 14 (P<0.01) dpi, respectively (Fig. 4C-E).

| Figure 4Effects of rADAMTS-1 on muscle

regeneration markers in BaCl2-injured TA muscle. Groups

included NC, BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 treatment groups (L), and

(H). Daily intraperitoneal injections were given starting

immediately after injury and maintained until the designated

analysis point. (A) Representative immunohistochemical staining of

eMyHC in injured TA muscles treated with rADAMTS-1 at 1, 3, 7, and

14 days dpi (scale bar, 60 μm). (B-E) Quantification was

performed using image analysis software to assess the

eMyHC-positive area at each time point. (F) Representative

immunofluorescence images of MyoD-positive cells in injured TA

muscle (scale bar, 25 μm) treated with rADAMTS-1 at 1, 3, 7,

and 14 dpi. (G) Quantification of MyoD-positive cell percentages

over time across groups. All data are presented as mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical significance was determined using one-way

analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post hoc test:

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. NC group; #P<0.05

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs.

BaCl2 group; †P<0.05 and

†††P<0.001 vs. rADAMTS-1 (L) group. ADAMTS-1, a

disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1;

rADAMTS-1, recombinant ADAMTS-1; BaCl2, barium chloride;

TA, tibialis anterior; NC, non-injured control; rADAMTS-1 (L),

rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg; rADAMTS-1 (H), rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg; eMyHC,

embryonic myosin heavy chain; dpi, days post-injury; MyoD, myoblast

determination protein 1; dpi, days post-injury. |

Immunofluorescence analysis was conducted at each

time point to evaluate MyoD expression in myoblasts in all

experimental groups (Fig. 4F).

MyoD expression significantly peaked at 3 dpi in the injury group

and then gradually declined, which was consistent with the IHC

results. The rADAMTS-1 (H) group consistently demonstrated elevated

MyoD expression compared with the BaCl2 group, with fold

increases of 1.3 (ns), 2.3 (P<0.01), 1.7 (ns), and 3.7 (ns) at

1, 3, 7, and 14 dpi, respectively (Fig. 4G).

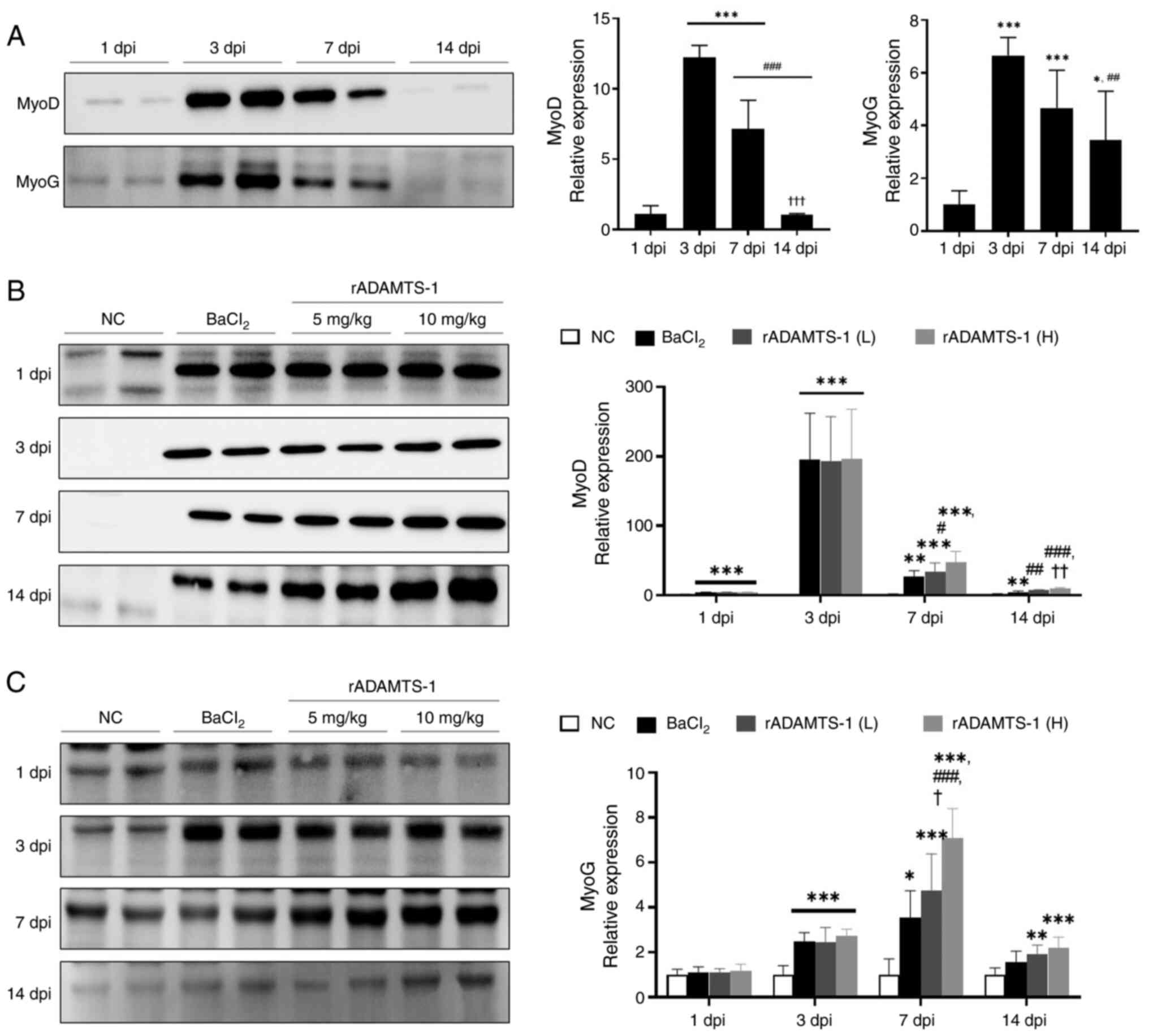

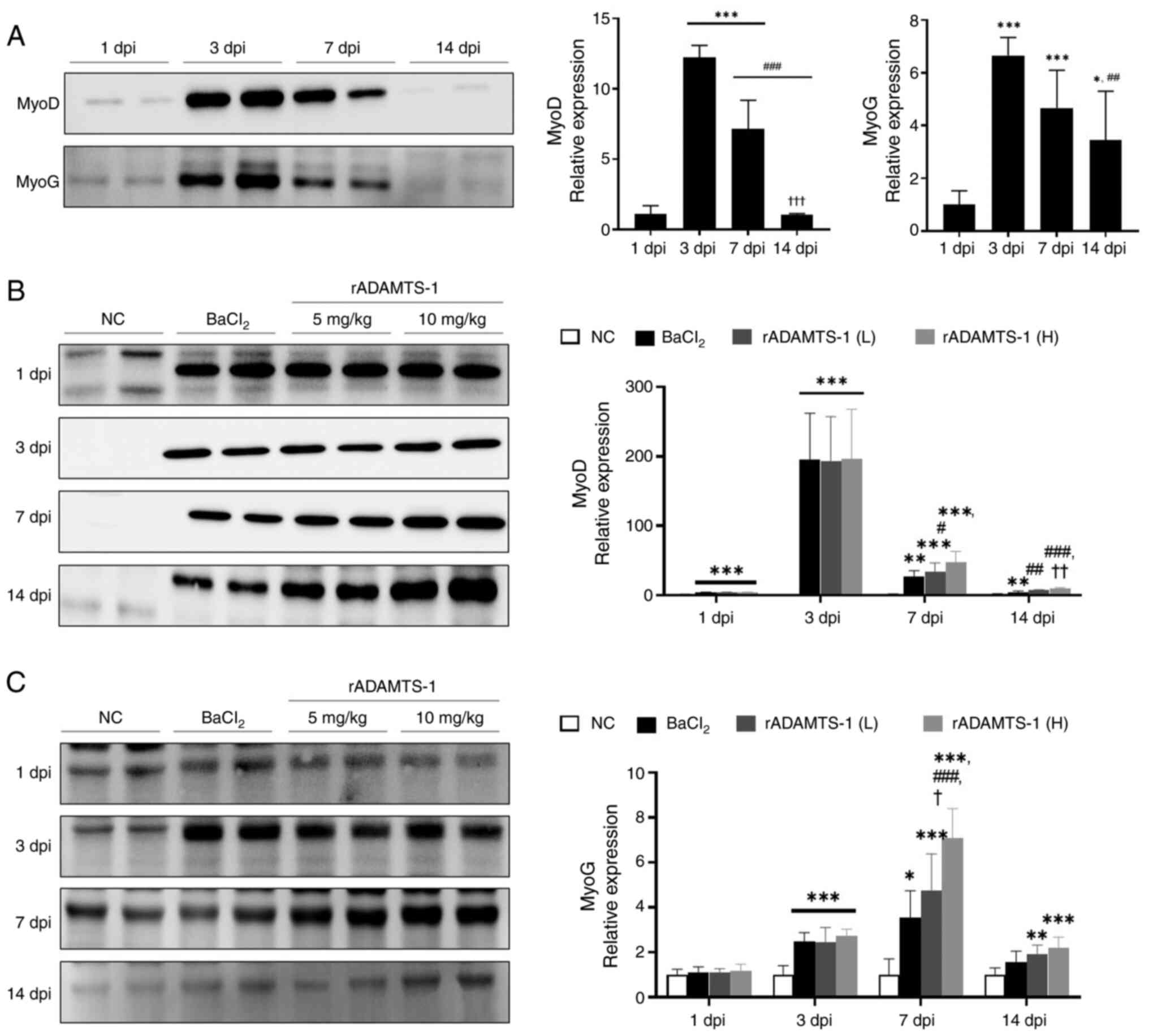

Effects of rADAMTS-1 on myogenic

regulatory transcription factors in TA tissue after

BaCl2-induced injury

MyoD and MyoG expression peaked at 3 dpi and then

gradually decreased (Fig. 5A).

On day 14, MyoD levels had significantly decreased ~12-fold

compared with day 3, and 7-fold compared with day 7 (P<0.001 for

both). MyoG expression also significantly declined (~2-fold)

compared with day 3 (P<0.01), whereas the decrease compared with

day 7 (1.4-fold) was not statistically significant (ns).

Comparative analysis of western blot data over the same timeframe

consistently revealed the highest expression levels of MyoD and

MyoG in the high-dose rADAMTS-1 (H) group (Fig. 5B and C). On days 7 and 14, the

rADAMTS-1 (L) and (H) treatment groups exhibited increased MyoG

expression compared with the BaCl2 group. A

supplementary validation experiment confirmed that rADAMTS-1 alone

(10 mg/kg) did not alter myogenic marker expression under

non-injury conditions (Fig.

S5).

| Figure 5Effects of rADAMTS-1 on early

myogenic markers in BaCl2-injured TA muscle. Groups

included NC, BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 treatment groups (L), and

(H). Daily intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1 were

administered at two doses starting immediately after injury and

continuing until the designated time point of analysis. Temporal

expression of (A) MyoD and MyoG in the injured TA at 1, 3, 7, and

14 dpi. Comparative expression of (B) MyoD and (C) MyoG across

experimental groups at each time point. Each data point represents

an individual replicate; error bars indicate standard deviation.

Statistical significance in (A) was determined using one-way

analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post hoc test and is

indicated as follows: *P<0.05 and

***P<0.001 vs. 1 dpi; ##P<0.01 and

###P<0.001 vs. 3 dpi; †††P<0.001 vs. 7

dpi. Statistical significance in (B) and (C) is indicated as

follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. the NC group; #P<0.05

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. the

BaCl2 group; †P<0.05 and

††P<0.01 vs. the rADAMTS-1 (L) group. ADAMTS-1, a

disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1;

rADAMTS-1, recombinant ADAMTS-1; BaCl2, barium chloride;

TA, tibialis anterior; NC, non-injured control; rADAMTS-1 (L),

rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg; rADAMTS-1 (H), rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg; MyoD,

myoblast determination protein 1; MyoG, myogenin; dpi, days

post-injury. |

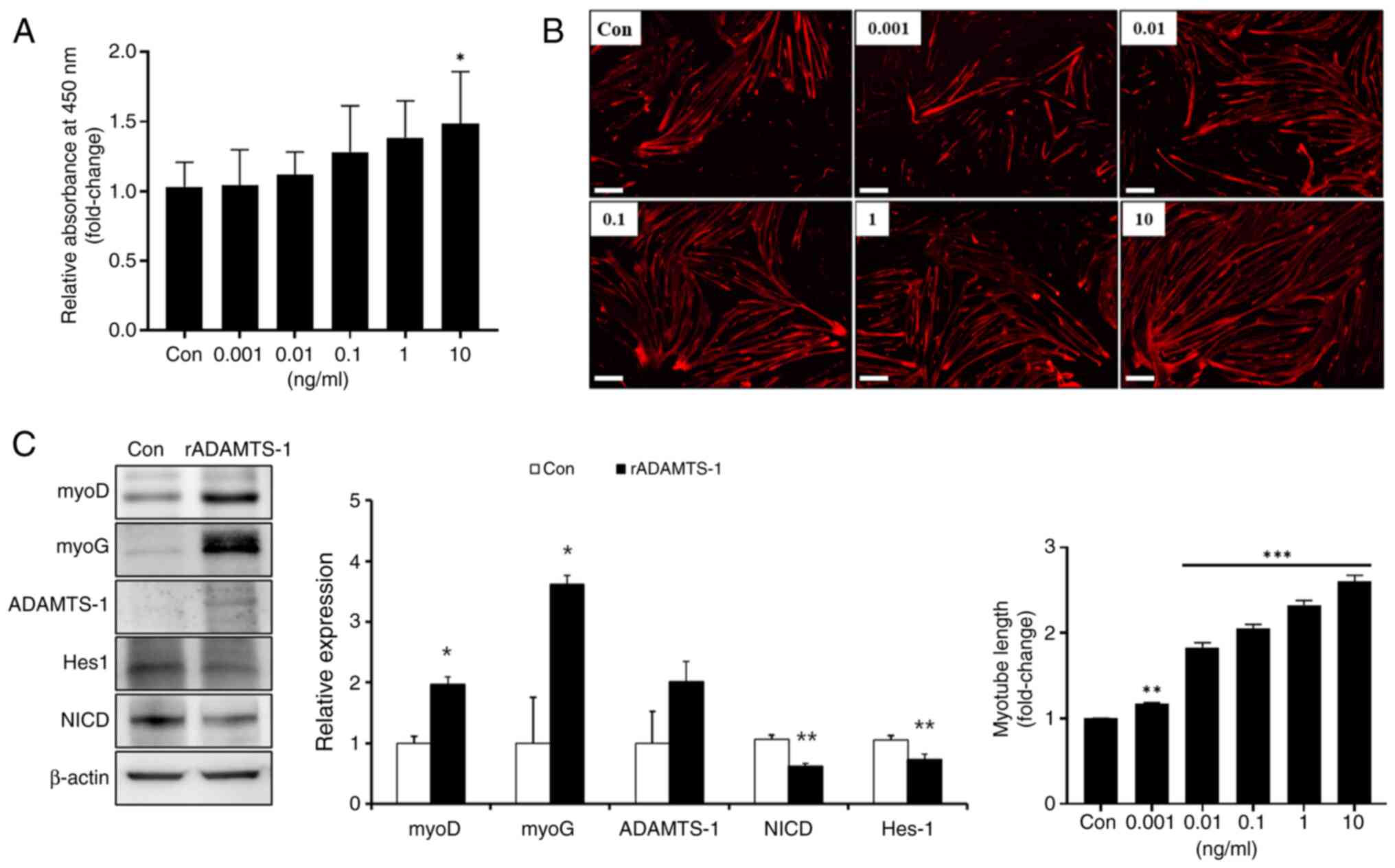

Effect of rADAMTS-1 on the proliferation

and differentiation stage of myogenesis in vitro

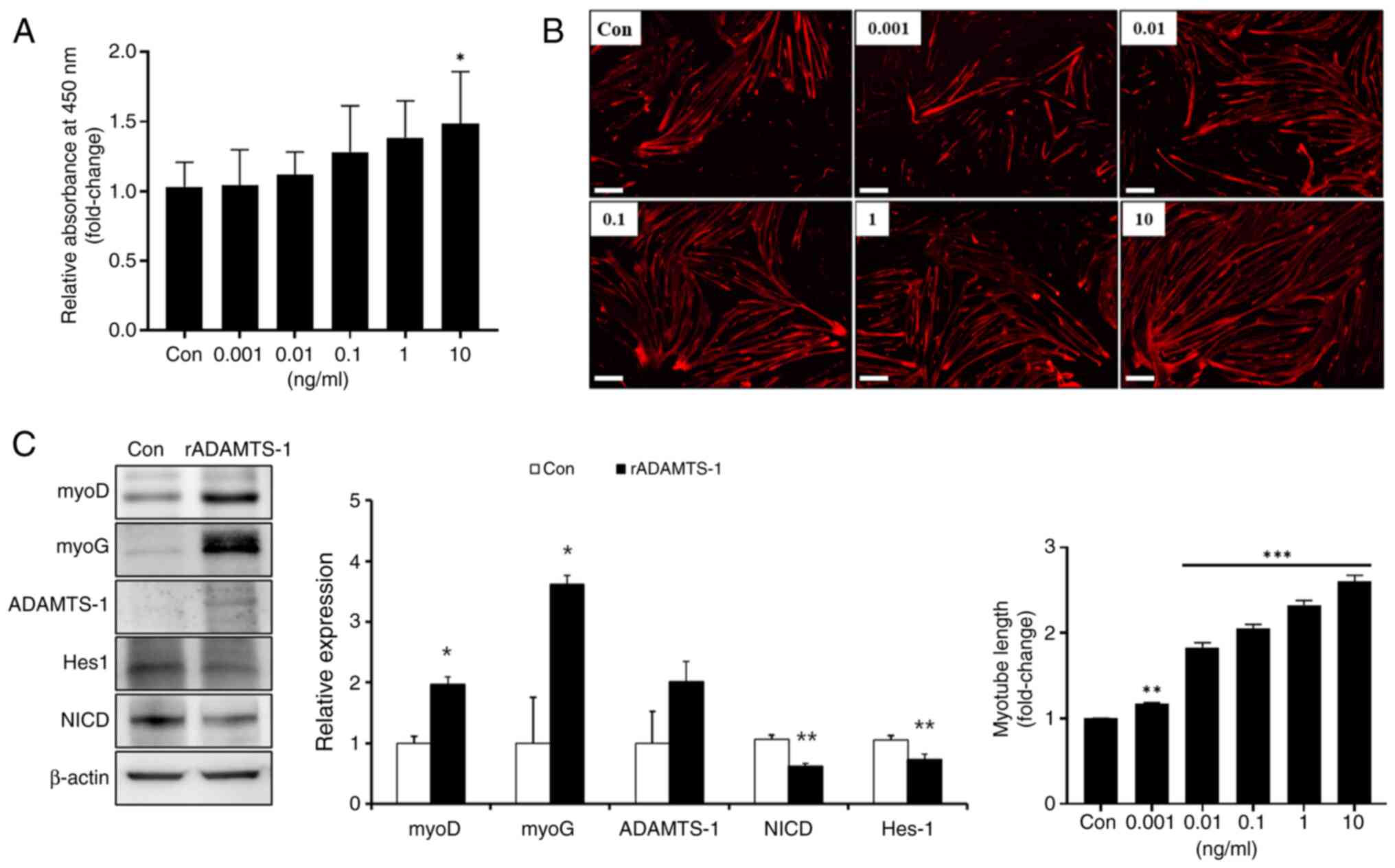

Primary skeletal muscle cells were treated with

rADAMTS-1, followed by a BrdU assay to investigate its role in

skeletal muscle cell activation (Fig. 6A). Activation increased in a

concentration-dependent manner, with treatment at 10 ng/ml

rADAMTS-1 producing a significant 1.4-fold increase compared with

the control (Con) group (P<0.5). The effects of rADAMTS-1 on

primary skeletal muscle cell differentiation were investigated

(Fig. 6B). The myotube length

increased in a dose-dependent manner, and treatment with 10 ng/ml

rADAMTS-1 resulted in an ~2.5-fold increase compared with the Con

group (P<0.001). rADAMTS-1 treatment also significantly

increased the expression of myogenic markers. MyoD and MyoG levels

elevated ~2- and 3.5-fold, respectively, compared with those in the

Con group (P<0.05; Fig. 6C).

In addition, ADAMTS-1 expression level increased ~2-fold in the

rADAMTS-1-treated group, whereas NICD and Hes-1 expression levels

were ~0.6-fold and 0.7-fold lower, respectively, than in the Con

group (P<0.01).

| Figure 6Effects of rADAMTS-1 on proliferation

and differentiation of primary skeletal muscle cells. (A)

Dose-dependent proliferative effects of rADAMTS-1 (0.001-10 ng/ml)

on primary skeletal muscle cells, assessed using the

bromodeoxyuridine assay. (B) Dose-dependent effect of rADAMTS-1

(0.001-10 ng/ml) on the differentiation of primary skeletal muscle

cells. Quantification of myotube length following differentiation

(scale bar, 200 μm). (C) Western blot analysis showing the

expression of myogenic and ADAMTS-1 related markers (MyoD, MyoG,

ADAMTS-1, NICD, Hes-1, and β-actin) following rADAMTS-1 treatment

at a concentration of 10 ng/ml, indicating its promotion of

early-stage myogenic differentiation through inhibition of NICD

signaling. Each data point represents an individual measurement;

error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical significance

was determined using one-way analysis of variance followed by

Tukey's honestly significant difference post hoc test and is

indicated as follows: (A) *P<0.05 vs. Con group; (B)

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. Con group;

(C) *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. Con group.

ADAMTS-1, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin

motifs 1; rADAMTS-1, recombinant ADAMTS-1; MyoD, myoblast

determination protein 1; MyoG, myogenin; NICD, Notch intracellular

domain; HES-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1; Con, control. |

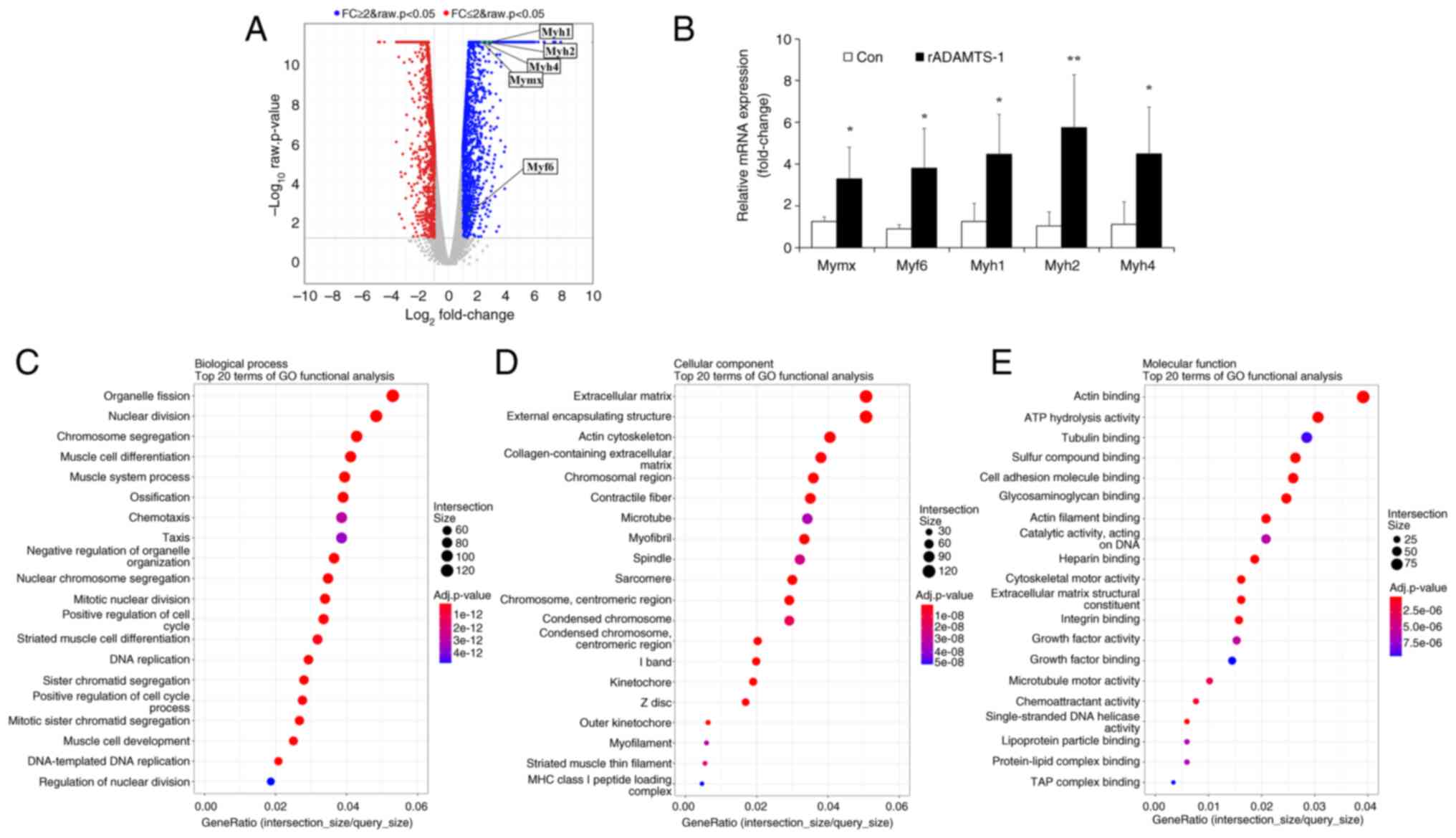

Effects of rADAMTS-1 on

myogenesis-related genes in vitro

RNA-seq analysis was performed to identify

differentially expressed genes in response to rADAMTS-1 treatment

during muscle cell differentiation. A total of 3,185 differentially

expressed genes (P<0.05), including 1,959 upregulated and 1,226

downregulated genes. Genes encoding skeletal muscle-associated

factors, such as Myh1, Myh2, Myh4, Myf6

and Mymx, were significantly upregulated following rADAMTS-1

treatment (Fig. 7A), and qPCR

validation confirmed these increases compared with the Con group

(Fig. 7B).

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that

rADAMTS-1 promoted the expression of genes involved in myogenic

differentiation and contractile apparatus formation. In the

biological process category, 25% of the top 20 enriched terms were

related to muscle development and regeneration, including

'organelle fission,' 'nuclear division,' 'muscle cell

differentiation' and 'muscle system process' (Fig. 7C). This pattern suggested that

rADAMTS-1 facilitates the transcriptional activation of myogenic

programs that drive myotube maturation.

In the cellular component category, enrichment of

'extracellular matrix,' 'external encapsulating structure,' 'actin

cytoskeleton,' 'collagen-containing extracellular matrix,'

'contractile fiber' and 'myofibril' indicated coordinated

remodeling of extracellular and cytoskeletal structures (Fig. 7D). Such enrichment implied that

rADAMTS-1 not only enhanced myogenic gene expression but may also

contribute to structural organization and matrix remodeling during

differentiation.

Molecular function analysis highlighted genes

involved in 'actin filament binding,' 'cytoskeletal motor activity'

and 'growth factor binding' (Fig.

7E). These functional groups suggest enhanced cytoskeletal

dynamics and intracellular signaling, which are critical for

myoblast fusion and alignment during myotube formation.

Consistently, differentiated C2C12 cells showed

increased myotube formation in the rADAMTS-1 treated group

(Fig. S6), supporting the

transcriptomic results of enhanced myogenic differentiation.

Discussion

With the rapidly aging global population, the need

for effective therapies targeting sarcopenia has become

increasingly urgent (27). The

present study evaluated the therapeutic potential of rADAMTS-1 in

promoting muscle regeneration. The results suggested that rADAMTS-1

promoted MuSC activation and differentiation, potentially

counteracting the age-related decline in regenerative capacity. In

addition, rADAMTS-1 sustained the expression of myogenic factors

over time, indicating possible long-term benefits for restoring

compromised regenerative mechanisms in older adults.

To assess these effects in vivo, a

BaCl2-induced muscle injury model was used. Compared

with the BaCl2 group, the rADAMTS-1 (H) group exhibited

significantly improved functional recovery, as indicated by

enhanced grip strength and sustained histological evidence of

muscle regeneration up to 14 dpi. Flow cytometry and

immunofluorescence analyses revealed a significant increase in MuSC

numbers at 3 dpi in all BaCl2-injected groups, although

these numbers decreased over time. Specifically, the rADAMTS-1 (H)

group showed a marked increase in MuSCs at 3 dpi. Despite a gradual

reduction over time, MuSC levels in this group remained

significantly higher than those in the other groups through 14 dpi.

This sustained increase in MuSCs likely facilitates prolonged

proliferative activity prior to differentiation, thereby

contributing to effective regeneration (10,28,29).

In parallel, downstream indicators of regeneration,

including eMyHC and MyoD expression, were assessed. The expression

pattern of eMyHC, an early marker of muscle regeneration (20), closely mirrored the abundance of

MuSCs. MyoD, a transcription factor guiding MuSCs toward the

skeletal muscle lineage (30),

also showed sustained expression. eMyHC and MyoD levels were both

significantly elevated in the rADAMTS-1 (H) group at 3 dpi and

remained higher than those in the other groups through 14 dpi,

despite eMyHC being classified as an early-phase marker (31). These results suggest that

rADAMTS-1-induced MuSC expansion, coupled with suppressed Notch

signaling, contributes to prolonged regenerative activity.

Although the results demonstrated reduced NICD and

Hes-1 levels following rADAMTS-1 treatment, these observations are

associative and did not establish a direct causal link between

rADAMTS-1 and Notch inhibition. Downregulation of Notch signaling

leads to upregulation of MyoD and promotes myogenic differentiation

(32). Activation of NICD or

RBP-J represses MyoD transcription by interacting with its basic

helix-loop-helix domain (33,34). Given this established inhibitory

relationship, the decrease in NICD and Hes-1 expression and the

increase in MyoD and MyoG observed in the present study suggested

that rADAMTS-1 facilitates muscle regeneration by attenuating Notch

signaling activity rather than by directly cleaving Notch

components.

Recent evidence from a study by Lee et al

(13) demonstrated that

rADAMTS-1 directly binds to Notch1 and inhibits ADAM10-mediated S2

cleavage within its extracellular TMIC domain. This proteolytic

regulation prevents the release of the active NICD, thereby

downregulating Hes-1 expression and promoting myogenic

differentiation (11). In

agreement with this mechanism, the present data showed reduced NICD

and Hes-1 levels in rADAMTS-1-treated muscles, supporting that

rADAMTS-1 can negatively regulate Notch signaling through its

metalloproteinase activity.

Myogenic differentiation was further examined by

analyzing MyoG expression. MyoD-positive precursor cells

differentiate and fuse to restore damaged muscle fibers (35), while MyoG triggers the final

stages of myogenic differentiation (36). As myofibers mature, MyoG

expression typically decreases (37). In the BaCl2-treated

group, both MyoD and MyoG peaked at 3 dpi and declined thereafter.

However, the rADAMTS-1 (H) group exhibited sustained expression of

both factors at 7 and 14 dpi, indicating a prolonged activation of

the myogenic program. These results are consistent with those

reported by Du et al (11), who observed that ADAMTS-1

influences the persistent MuSC activation.

To validate these findings in vitro, primary

skeletal muscle cells were treated with rADAMTS-1. These cells were

selected for their close resemblance to MuSCs in terms of myogenic

potential and regenerative capacity (38). rADAMTS-1 treatment suppressed

NICD expression and upregulated MyoD and MyoG, mirroring the in

vivo results. These findings suggested that rADAMTS-1 exerts a

sustained effect on early myogenic differentiation by modulating

key regulatory proteins involved in myoblast commitment. In

particular, the findings from human primary skeletal muscle cells

support the translational relevance of rADAMTS-1, indicating that

its myogenic effects are potentially applicable to human muscle

regeneration. To further explore the transcriptional landscape

associated with rADAMTS-1 treatment, RNA-seq analysis was conducted

using the C2C12 myoblast cell line, a reproducible and widely used

in vitro model for transcriptomic studies (39,40). rADAMTS-1 treatment upregulated

myogenic genes, such as Myh and Mymx. Myh is

associated with muscle contractility and cellular motility

(41), while Mymx plays a

key role in myoblast fusion during muscle regeneration and organ

development (42). In addition,

Myf6, a transcription factor essential for maintaining the

MuSC pool by inhibiting premature differentiation, was upregulated

(43). These RNA-seq findings,

confirmed by qPCR, indicate that rADAMTS-1 activates a

transcriptional program that supports muscle development and

maintenance. GO enrichment analysis further revealed significant

activation of pathways involved in muscle cell differentiation and

extracellular matrix (ECM) organization, suggesting that rADAMTS-1

may contribute to an ECM remodeling during muscle regeneration.

Taken together with its metalloproteinase-mediated regulation of

Notch signaling, these data indicate that rADAMTS-1 enhances muscle

regeneration through dual modulation.

In a supplementary validation study, rADAMTS-1

administration alone (10 mg/kg) did not induce significant changes

in myogenic marker expression compared with the NC group These

findings suggested that rADAMTS-1 does not activate myogenic

processes under normal conditions, but rather facilitates

regeneration during muscle differentiation. It is consistent with

previous reports indicating that ADAMTS-1 primarily modulates the

extracellular microenvironment during regenerative conditions

rather than in intact tissue (11,44). As rADAMTS-1 administration alone

did not cause detectable changes in muscles or systemic conditions,

this group was not included in the main experimental design.

As ADAMTS family proteins can modulate extracellular

matrix turnover, and excessive activity may theoretically lead to

fibrosis, inflammation, or ECM degradation. However, no abnormal

histological findings, inflammatory infiltration, or fibrotic

changes were observed in any of the rADAMTS-1 treated groups during

the 14-day observation period, suggesting that rADAMTS-1 does not

elicit overt toxicity under the conditions tested. Additionally,

time-dependent plasma concentration analysis confirmed systemic

absorption of rADAMTS-1 following IP administration.

The present study has clear methodological

limitations that should be acknowledged. Only male mice were used,

following most previous studies employing the

BaCl2-induced skeletal muscle injury model (45-47). Although this approach minimizes

biological variability and ensures experimental consistency, it

inevitably limits the generalizability of the results, as potential

sex-dependent differences could not be evaluated. Another important

limitation lies in the use of the BaCl2-induced acute

injury model rather than a chronic or age-related paradigm. This

model provides a reproducible and temporally defined framework for

assessing MuSC-driven regeneration but does not fully capture the

chronic and multifactorial pathophysiology of sarcopenia (48). While an aging model would have

offered greater physiological relevance, it could not be

implemented within the scope and timeframe of the present study.

Moreover, naturally aged rodents are known to exhibit variable

manifestations of muscle mass and functional decline depending on

strain, sex, and environmental conditions (49,50), suggesting that chronological

aging alone may not reliably reproduce the human sarcopenia

phenotype. Thus, the BaCl2 model should be regarded as a

mechanistic surrogate rather than a direct model of age-related

muscle degeneration. Although the RNA-seq analysis and validation

were performed using the well-established C2C12 myoblast cell line

(51), this represents another

limitation of the study, as the results were not verified using

in vivo samples. Future study will need on regenerated

muscle tissues to validate the key RNA-seq-identified genes in

vivo. The study also focused exclusively on the early phase of

muscle repair, emphasizing MuSC activation and early regenerative

events. Although this phase represents a critical window for

effective regeneration, long-term outcomes such as sustained muscle

function and structural remodeling were not addressed. These

limitations collectively indicate that additional studies using

senescence-accelerated mice or naturally aged models will be

essential to validate the long-term efficacy and translational

potential of rADAMTS-1 under physiological aging conditions.

In conclusion, rADAMTS-1 enhances muscle

regeneration by activating MuSCs and upregulating myogenic factors,

thereby driving the expression of genes essential for muscle

development. Given the clinical challenges posed by sarcopenia,

rADAMTS-1 represents a promising therapeutic candidate for

mitigating muscle loss in older adults. Its ability to promote

MuSCs proliferation and differentiation, potentially overcoming

some limitations of current MuSCs transplantation strategies.

Overall, The present study highlighted the potential of rADAMTS-1

for sarcopenia treatment, although further research is needed to

confirm its long-term efficacy, safety, and clinical

applicability.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The RNA-sequencing dataset in the present study may

be found in the Zenodo database under accession number DOI:

10.5281/zenodo.17579631 or at the following URL: https://zenodo.org/records/17579631. Other data

generated in the present study are included in the figures of this

article.

Authors' contributions

JHK was responsible for investigation, methodology,

formal analysis and writing the original draft. SHL was responsible

for investigation, methodology, formal analysis and resources. SYK

investigation, methodology and resources. JWKim, JSJ, EHC, SHL and

CYK were responsible for investigation and methodology. BKC was

responsible for conceptualization and resources. JWKo and TWK were

responsible for conceptualization, project administration,

supervision, writing, reviewing and editing. JWKo and TWK confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All the experimental procedures were reviewed and

approved by the Chungnam National University Animal Care and Use

Committee (202310A-CNU-169).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

ADAMTS-1

|

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

with thrombospondin motifs 1

|

|

BaCl2

|

barium chloride

|

|

Con

|

control

|

|

CD

|

cluster of differentiation

|

|

dpi

|

days post-injection

|

|

eMyHC

|

embryonic myosin heavy chain

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

Hes-1

|

hairy and enhancer of split-1

|

|

MuSC

|

skeletal muscle satellite cells

|

|

Myf6

|

myogenic factor 6

|

|

Myh1

|

myosin heavy chain 1

|

|

Myh 2

|

myosin heavy chain 2

|

|

Myh4

|

myosin heavy chain 4

|

|

Mymx

|

myomixer

|

|

MyoD

|

myoblast determination protein 1

|

|

MyoG

|

myogenin

|

|

NC

|

non-injured control

|

|

NICD

|

Notch intracellular domain

|

|

Pax7

|

paired box protein 7

|

|

rADAMTS-1

|

recombinant ADAMTS-1

|

|

rADAMTS-1 (L)

|

rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg

|

|

rADAMTS-1 (H)

|

rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg

|

|

Sca1

|

stem cell antigen 1

|

|

TA

|

tibialis anterior

|

|

VCAM1

|

vascular cell adhesion molecule

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Korea Drug Development

Fund, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of

Trade, Industry, and Energy, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare

(grant no. RS-2022-00165803).

References

|

1

|

Tournadre A, Vial G, Capel F, Soubrier M

and Boirie Y: Sarcopenia. Joint Bone Spine. 86:309–314. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Larsson L, Degens H, Li M, Salviati L, Lee

YI, Thompson W, Kirkland JL and Sandri M: Sarcopenia: Aging-related

loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol Rev. 99:427–511. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Cruz-Jentoft AJ and Sayer AA: Sarcopenia.

Lancet. 393:2636–2646. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Petrocelli JJ, Mahmassani ZS, Fix DK,

Montgomery JA, Reidy PT, McKenzie AI, de Hart NM, Ferrara PJ,

Kelley JJ, Eshima H, et al: Metformin and leucine increase

satellite cells and collagen remodeling during disuse and recovery

in aged muscle. FASEB J. 35:e218622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kim HJ, Jung DW and Williams DR: Age is

just a number: Progress and obstacles in the discovery of new

candidate drugs for sarcopenia. Cells. 12:26082023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Huo F, Liu Q and Liu H: Contribution of

muscle satellite cells to sarcopenia. Front Physiol. 13:8927492022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Schmidt M, Schüler SC, Hüttner SS, von

Eyss B and von Maltzahn J: Adult stem cells at work: Regenerating

skeletal muscle. Cell Mol Life Sci. 76:2559–2570. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Haroon M, Boers HE, Bakker AD, Bloks NGC,

Hoogaars WMH, Giordani L, Musters RJP, Deldicque L, Koppo K, Le

Grand F, et al: Reduced growth rate of aged muscle stem cells is

associated with impaired mechanosensitivity. Aging (Albany NY).

14:28–53. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Qazi TH, Duda GN, Ort MJ, Perka C,

Geissler S and Winkler T: Cell therapy to improve regeneration of

skeletal muscle injuries. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 10:501–516.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Judson RN and Rossi FMV: Towards stem cell

therapies for skeletal muscle repair. NPJ Regen Med. 5:102020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Du H, Shih CH, Wosczyna MN, Mueller AA,

Cho J, Aggarwal A, Rando TA and Feldman BJ: Macrophage-released

ADAMTS1 promotes muscle stem cell activation. Nat Commun.

8:6692017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mourikis P, Sambasivan R, Castel D,

Rocheteau P, Bizzarro V and Tajbakhsh S: A critical requirement for

notch signaling in maintenance of the quiescent skeletal muscle

stem cell state. Stem Cells. 30:243–252. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lee SH, Kim SY, Gwon YG, Lee C, Cho IH,

Kim TW and Choi BK: Recombinant ADAMTS1 promotes muscle cell

differentiation and alleviates muscle atrophy by repressing NOTCH1.

BMB Rep. 57:539–545. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tarum J, Degens H, Turner MD, Stewart C,

Sale C and Santos L: Modelling skeletal muscle ageing and repair in

vitro. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2023:98022352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pawlikowski B, Betta ND, Antwine T and

Olwin BB: Skeletal muscle stem cell self-renewal and

differentiation kinetics revealed by EdU lineage tracing during

regeneration. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/627851.

|

|

16

|

Al Shoyaib A, Archie SR and Karamyan VT:

Intraperitoneal route of drug administration: Should it be used in

experimental animal studies? Pharm Res. 37:122019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ibraheem D, Elaissari A and Fessi H:

Administration strategies for proteins and peptides. Int J Pharm.

477:578–589. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Takeshita H, Yamamoto K, Nozato S, Inagaki

T, Tsuchimochi H, Shirai M, Yamamoto R, Imaizumi Y, Hongyo K,

Yokoyama S, et al: Modified forelimb grip strength test detects

aging-associated physiological decline in skeletal muscle function

in male mice. Sci Rep. 7:423232017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ghaibour K, Rizk J, Ebel C, Ye T, Philipps

M, Schreiber V, Metzger D and Duteil D: An efficient protocol for

CUT&RUN analysis of FACS-isolated mouse satellite cells. J Vis

Exp. 197:e652152023.

|

|

20

|

Gilda JE and Gomes AV: Stain-Free total

protein staining is a superior loading control to β-actin for

Western blots. Anal Biochem. 440:186–188. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fortes MA, Marzuca-Nassr GN, Vitzel KF, da

Justa Pinheiro CH, Newsholme P and Curi R: Housekeeping proteins:

How useful are they in skeletal muscle diabetes studies and muscle

hypertrophy models? Anal Biochem. 504:38–40. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Paul RG, Hennebry AS, Elston MS, Conaglen

JV and McMahon CD: Regulation of murine skeletal muscle growth by

STAT5B is age- and sex-specific. Skelet Muscle. 9:192019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang R, Kumar B, Doud EH, Mosley AL,

Alexander MS, Kunkel LM and Nakshatri H: Skeletal muscle-specific

overexpression of miR-486 limits mammary tumor-induced skeletal

muscle functional limitations. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 28:231–248.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Forcina L, Cosentino M and Musarò A:

Mechanisms regulating muscle regeneration: Insights into the

interrelated and time-dependent phases of tissue healing. Cells.

9:12972020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Choo HJ, Canner JP, Vest KE, Thompson Z

and Pavlath GK: A tale of two niches: Differential functions for

VCAM-1 in satellite cells under basal and injured conditions. Am J

Physiol Cell Physiol. 313:C392–C404. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gustafsson T and Ulfhake B: Aging skeletal

muscles: What are the mechanisms of age-related loss of strength

and muscle mass, and can we impede its development and progression?

Int J Mol Sci. 25:109322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xing HY, Liu N and Zhou MW: Satellite cell

proliferation and myofiber cross-section area increase after

electrical stimulation following sciatic nerve crush injury in

rADAMTS-1. Chin Med J (Engl). 133:1952–1960. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Meng J, Lv Z, Chen X, Sun C, Jin C, Ding K

and Chen C: LBP1C-2 from Lycium barbarum maintains skeletal muscle

satellite cell pool by interaction with FGFR1. iScience.

26:1065732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Agarwal M, Sharma A, Kumar P, Kumar A,

Bharadwaj A, Saini M, Kardon G and Mathew SJ: Myosin heavy

chain-embryonic regulates skeletal muscle differentiation during

mammalian development. Development. 147:dev1845072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang Y, Xiao Y, Zheng Y, Yang L and Wang

D: An anti-ADAMTS1 treatment relieved muscle dysfunction and

fibrosis in dystrophic mice. Life Sci. 281:1197562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Mierzejewski B, Grabowska I, Michalska Z,

Zdunczyk K, Zareba F, Irhashava A, Chrzaszcz M, Patrycy M,

Streminska W, Janczyk-Ilach K, et al: SDF-1 and NOTCH signaling in

myogenic cell differentiation: The role of miRNA10a, 425, and 5100.

Stem Cell Res Ther. 14:2042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Buas MF and Kadesch T: Regulation of

skeletal myogenesis by Notch. Exp Cell Res. 316:3028–3033. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Luo D, de Morree A, Boutet S, Quach N,

Natu V, Rustagi A and Rando TA: Deltex2 represses MyoD expression

and inhibits myogenic differentiation by acting as a negative

regulator of Jmjd1c. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E3071–E3080. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Isesele PO and Mazurak VC: Regulation of

skeletal muscle satellite cell differentiation by Omega-3

polyunsaturated fatty acids: A critical review. Front Physiol.

12:6820912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Adhikari A, Kim W and Davie J: Myogenin is

required for assembly of the transcription machinery on muscle

genes during skeletal muscle differentiation. PLoS One.

16:e02456182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Faralli H and Dilworth FJ: Turning on

myogenin in muscle: A paradigm for understanding mechanisms of

tissue-specific gene expression. Comp Funct Genomics.

2012:8363742012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

38

|

Owens J, Moreira K and Bain G:

Characterization of primary human skeletal muscle cells from

multiple commercial sources. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim.

49:695–705. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ding R, Horie M, Nagasaka S, Ohsumi S,

Shimizu K, Honda H, Nagamori E, Fujita H and Kawamoto T: Effect of

cell-extracellular matrix interaction on myogenic characteristics

and artificial skeletal muscle tissue. J Biosci Bioeng. 130:98–105.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Sanvee GM, Bouitbir J and Krähenbühl S:

C2C12 myoblasts are more sensitive to the toxic effects of

simvastatin than myotubes and show impaired proliferation and

myotube formation. Biochem Pharmacol. 190:1146492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Henderson CA, Gomez CG, Novak SM, Mi-Mi L

and Gregorio CC: Overview of the muscle cytoskeleton. Compr

Physiol. 7:891–944. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lehka L and Rędowicz MJ: Mechanisms

regulating myoblast fusion: A multilevel interplay. Semin Cell Dev

Biol. 104:81–92. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Lazure F, Blackburn DM, Corchado AH,

Sahinyan K, Karam N, Sharanek A, Nguyen D, Lepper C, Najafabadi HS,

Perkins TJ, et al: Myf6/MRF4 is a myogenic niche regulator required

for the maintenance of the muscle stem cell pool. EMBO Rep.

21:e494992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Krampert M, Kuenzle S, Thai SN, Lee N,

Iruela-Arispe ML and Werner S: ADAMTS1 proteinase is up-regulated

in wounded skin and regulates migration of fibroblasts and

endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 280:23844–23852. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Dungan CM, Murach KA, Zdunek CJ, Tang ZJ,

Nolt GL, Brightwell CR, Hettinger Z, Englund DA, Liu Z, Fry CS, et

al: Deletion of SA β-Gal+ cells using senolytics improves muscle

regeneration in old mice. Aging Cell. 21:e135282022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Always SE, Paez HG, Pitzer CR, Ferrandi

PJ, Khan MM, Mohamed JS, Carson JA and Deschenes MR: Mitochondria

transplant therapy improves regeneration and restoration of injured

skeletal muscle. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14:493–507. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Kim JW, Manickam R, Sinha P, Xuan W, Huang

J, Awad K, Brotto M and Tipparaju SM: P7C3 ameliorates barium

chloride-induced skeletal muscle injury activating transcriptomic

and epigenetic modulation of myogenic regulatory factors. J Cell

Physiol. 239:e313462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang YX and Rudnicki MA: Sataellite cells,

the engines of muscle repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 13:127–133.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kerr HL, Krumm K, Anderson B, Christiani

A, Strait L, Li T, Irwin B, Jiang S, Rybachok A, Chen A, et al:

Mouse sarcopenia model reveals sex-and age-specific differences in

phenotypic and molecular characteristics. J Clin Invest.

134:e1728902024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Owen AM and Fry CS: Decoding the decline:

Unveiling drivers of sarcopenia. J Clin Invest. 134:e1833022024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Tao L, Huang W, Li Z, Wang W, Lei X, Chen

J, Song X, Lu F, Fan S and Zhang L: Transcriptome analysis of

differentially expressed genes and molecular pathways involved in

C2C12 cells myogenic differentiation. Mol Biotechnol. 67:3640–3655.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

![Effects of rADAMTS-1 on the

expression of ADAMTS-1-associated markers in

BaCl2-injured TA muscle. Groups included NC,

BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 treatment groups (L), and (H). Daily

intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1 were initiated immediately

after injury and continued until the designated time point for

analysis. (A) Temporal expression patterns of ADAMTS-1, NICD, and

Hes-1 in the NC and BaCl2 groups at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days

post-injury (dpi). Comparative expression levels of (B) ADAMTS-1,

(C) NICD, and (D) Hes-1 among treatment groups [NC,

BaCl2, rADAMTS-1 (L), and rADAMTS-1 (H)] at each time

point. Mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of rADAMTS-1

until the designated dpi. Each data point represents an individual

biological replicate; error bars indicate standard deviation.

Statistical significance in panels (A) was determined using one-way

analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's honestly significant

difference post hoc test, as indicated as follows:

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 1 dpi;

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. 3 dpi. For

panels (B-D), statistical comparisons were made using one-way

analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test:

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. NC; #P<0.05

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs.

BaCl2; †P<0.05, ††P<0.01 and

†††P<0.001 vs. rADAMTS-1 (L). ADAMTS-1, a disintegrin

and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1; rADAMTS-1,

recombinant ADAMTS-1; BaCl2, barium chloride; TA,

tibialis anterior; NC, non-injured control; rADAMTS-1 (L),

rADAMTS-1 at 5 mg/kg; rADAMTS-1 (H), rADAMTS-1 at 10 mg/kg; NICD,

Notch intracellular domain; Hes-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1;

dpi, days post-injury.](/article_images/ijmm/57/2/ijmm-57-02-05718-g02.jpg)