Mitochondria, which serve as the 'powerhouses' of

cells, play crucial roles in cellular energy metabolism,

intracellular and extracellular signaling, reactive oxygen species

(ROS) production and apoptosis signaling regulation. Within the

digestive system-an organ characterized by high turnover rates and

metabolic activity-cells demand an exceptional energy supply and

precise regulatory control. Consequently, mitochondrial dysfunction

can trigger or exacerbate digestive disorders through multiple

mechanisms (5,6). The sirtuin family comprises seven

members: SIRT1, SIRT6 and SIRT7, which reside in the nucleus;

SIRT2, which is localized to the cytoplasm; and SIRT3-5, which are

found within mitochondria (7,8).

Among these, SIRT3 functions as an NAD+-dependent

deacetylase. Within the mitochondrial matrix, it regulates energy

balance and redox status by modifying enzymes involved in metabolic

pathways, including the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, the urea

cycle, amino acid metabolism, fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and

glucose metabolism (9). In

addition to regulating material metabolism, SIRT3 acetylation also

modulates numerous mitochondrial proteins involved in metabolic

homeostasis, oxidative stress and cell survival. SIRT3 has been

demonstrated to control mitochondrial DNA repair, participate in

maintaining mitochondrial integrity and regulate apoptosis. Of

note, SIRT3 is the only sirtuin reported to influence human

lifespan (10). Studies have

indicated that SIRT3 also regulates multiple processes critical for

mitochondrial structural integrity and function, including

oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), mitochondrial dynamics, the

mitochondrial unfolded protein response and mitochondrial autophagy

(7,9,11). Thus, SIRT3 plays a vital role in

maintaining mitochondrial function and homeostasis. Concurrently,

SIRT3 is highly expressed in the brain, heart, kidneys, brown

adipose tissue and liver-an organ with high oxidative capacity-in

which its core enzyme undergoes lysine acetylation (12). In the absence of SIRT3, many of

these proteins undergo hyperacetylation. Acetylated proteins induce

significant conformational changes in substrate proteins,

potentially altering the function and impairing the catalytic

activity of most mitochondrial enzymes (13). This disruption may trigger a

series of digestive system disorders (14). Therefore, this review describes

the role of SIRT3 in digestive system diseases and its potential

therapeutic targets, providing new strategies for the diagnosis and

treatment of digestive system diseases.

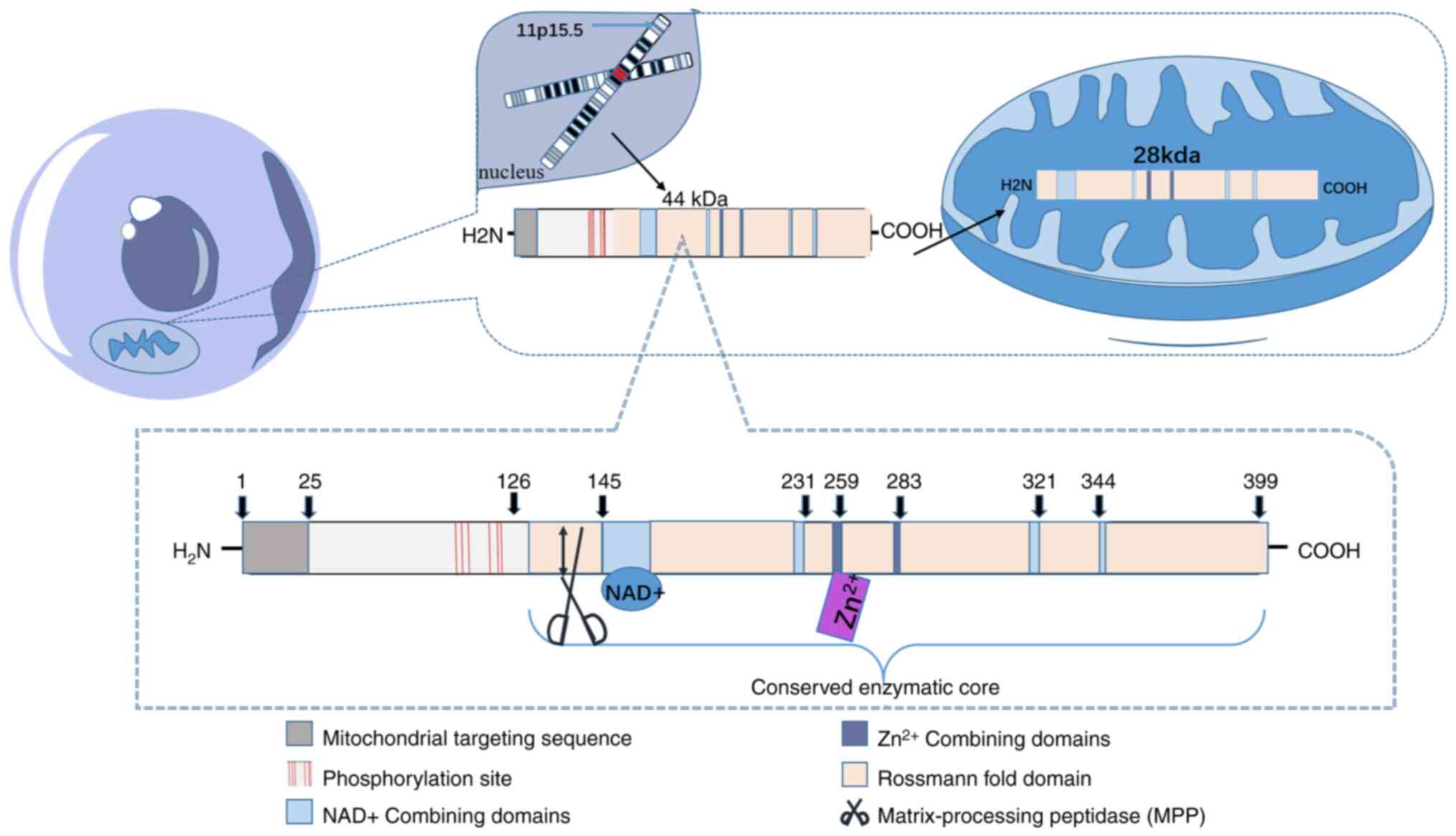

The human SIRT3 protein exists in two forms: A long

isoform and a short isoform. Both forms of SIRT3 exhibit

NAD+-dependent deacetylase activity (15). SIRT3 is transcribed in the

11p15.5 chromosomal region of the cell nucleus. The fully

transcribed, 399-residue full-length SIRT3 (FLSIRT3) constitutes

the long isoform. The mitochondrial targeting sequence located

between N-terminal residues 1-25 is crucial for subsequent

mitochondrial localization and proteolytic processing. Residues

101, 103, 105, 114, 117 and 118 can prevent substrates from

prematurely binding to the SIRT3 active site before mitochondrial

transfer (9,12). Upon localization to mitochondria

via its mitochondrial targeting sequence, FLSIRT3 is cleaved at

residue 142 by mitochondrial proline protease in the mitochondrial

matrix, yielding a short isoform with ~28 kDa of class III histone

deacetylase activity (16). The

conserved catalytic core domain positions SIRT3 as one of the most

critical deacetylases, featuring a large Rossmann fold domain that

binds NAD+ and a small domain composed of a helical

bundle and zinc-binding motif, formed by two loops extending from

the larger domain (8). The

remainder of the enzyme core comprises the binding site for SIRT3

substrates (9) (Fig. 1). Each structural feature of

SIRT3 directly governs its biological function: The cleft between

the Rossmann fold domain and the zinc finger domain forms the

substrate binding pocket. Its size and chemical properties

determine the ability of SIRT3 to recognize and bind specific

acetylated lysine residues; for instance, leucyl-tRNA synthetase 2

specifically binds to SIRT3, and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase

subunit V3 specifically binds to SIRT5 (17). The mitochondrial targeting

sequence ensures its localization to the mitochondrial matrix,

while SIRT3 exclusively deacetylates substrates within

mitochondria, guaranteeing its role in regulating mitochondrial

activity. The zinc ion-binding domain not only maintains the

overall structural stability of the SIRT3 protein but also

determines the specific structures of various Sirtuins (18). The highly conserved Rossmann fold

domain within SIRT3 perfectly complements NAD+,

initiating the deacetylase reaction by hydrolyzing the cofactor

NAD+. This hydrolysis yields two molecules, nicotinamide

and ADP-ribose. The acetylated lysine residue on the substrate

protein transfers its acetyl group to ADP-ribose. At this point,

the C1'-alkylamide intermediate is converted into a bicyclic

intermediate with the assistance of the conserved His 224 residue.

This induces a nucleophilic attack by the 2'-OH group of ribose on

the amine carbon of the o-alkylamide intermediate. The intermediate

is then cleaved by an activated water molecule, ultimately forming

20-acetyl-ADP-ribose to complete deacetylation (8,9).

NAD+, as a cofactor of SIRT3, directly regulates its

activity (19). Consequently,

SIRT3 expression and activity are modulated by the

NAD+:NADH ratio. Elevated ratios-such as those during

starvation, exercise or stress-increase SIRT3 activity and

expression, whereas low ratios or aging decrease SIRT3 levels

(11,12). Thus, the structure of SIRT3 plays

a crucial role in linking cellular metabolic states to

mitochondrial functional adaptation. Alterations in SIRT3 structure

lead to reduced enzyme activity, causing cellular metabolic

reprogramming and increased genomic instability, thereby promoting

tumorigenesis (20). Similarly,

reduced SIRT3 activity diminishes mitochondrial capacity to adapt

to metabolic stress, increasing susceptibility to hepatic

steatosis, insulin resistance and oxidative damage. This

significantly increases the risk and severity of non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (21,22).

SIRT3 performs deacetylation functions because of

its conserved enzyme core. Deacetylation by SIRT3 is the most

common posttranslational modification of mitochondrial proteins,

altering the structure and functional activity of substrate

proteins via histone/lysine acetyltransferases (13). Peterson et al (23) reported that SIRT3 deacetylates

626 sites across 242 proteins, including 32 sites in 12 FAO

proteins, 27 sites in 14 proteins involved in the TCA cycle, 18

sites in 11 proteins involved in the electron transport chain

(ETC), 18 sites in 9 proteins involved in protein quality control,

and 9 sites in 6 proteins involved in ROS detoxification. In SIRT3

knockout (SIRT3-KO) cells, acetylation levels at mitochondrial

protein sites increase twofold (24). These proteins are involved in

various pathways, such as the TCA cycle, amino acid metabolism,

FAO, ETC/OXPHOS and mitochondrial dynamics. Consequently, they

regulate oxidative stress, apoptosis, energy metabolism,

inflammation, DNA damage and aging.

Studies reported 283 SIRT3-specific targets among

136 mitochondrial proteins in a SIRT3-KO mouse liver model,

particularly within fatty acid metabolism pathways. These include

acetyl-CoA synthase 2, long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD),

and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase 2, as well as

the stress-responsive enzymes isocitrate dehydrogenase 2,

superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and manganese superoxide dismutase

(MnSOD) (15,25). When SIRT3 is absent or its

activity is reduced, the ability of the liver to oxidize fatty

acids decreases. Large amounts of free fatty acids (FFAs) are

esterified into triglycerides (TGs) and deposited within

hepatocytes, leading to hepatic steatosis. Simultaneously, SOD2

inactivation leads to massive ROS accumulation, triggering

oxidative stress that causes hepatocyte injury, ballooning

degeneration and cell death. In digestive system cancers, SIRT3

suppresses Bax-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis pathways by

deacetylating and activating Ku70, enabling its binding to the

pro-apoptotic protein Bax (26).

Previous studies revealed that SIRT3 deficiency increases ROS

levels, activating hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α. In mice, this

leads to HIF-1α-dependent tumor growth patterns, indicating that

SIRT3 suppresses the carcinogenic effects of HIF-1α by regulating

ROS, thereby inhibiting tumor growth (27). SIRT3 deacetylation activates

pyruvate dehydrogenase, promoting pyruvate entry into the TCA cycle

and inhibiting the characteristics of aerobic glycolysis in cancer

cells (28).

Increasing evidence has indicated that SIRT3

regulates proteins extensively involved in mitochondrial reactions,

including energy production, signaling and apoptosis. When SIRT3 is

absent, numerous mitochondrial proteins involved in metabolism and

stress undergo hyperacetylation, directly contributing to the onset

and progression of various digestive system diseases (11,28,29).

NAFLD encompasses simple steatosis (SS) and

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and is characterized by

inflammation and ballooning degeneration with or without fibrosis.

NASH-associated cirrhosis features the formation of cirrhotic

nodules due to fibrotic septa, potentially progressing to HCC

(29,30).

Globally, the prevalence of NAFLD and NASH has

increased in tandem with that of obesity and metabolic syndrome,

indicating that these conditions are becoming serious health

threats (31). In NAFLD

pathogenesis, hepatocytes exhibit adipocyte-like functions and

maintain the balance of lipid metabolism by regulating the

production, oxidation, and transport of TGs, FFAs, cholesterol and

bile acids (32). When the

capacity of hepatocytes is exceeded, lipid metabolism disorders

lead to hepatic fat accumulation. Cells exposed to a high-fat

environment experience lipotoxicity, which impairs mitochondrial

function by activating mitochondrial defects, endoplasmic reticulum

(ER) stress and oxidative stress. Concurrently, mitochondria can

reduce cellular β-oxidation levels through multiple pathways,

including cell division, oxidative stress, autophagy and

mitochondrial quality control, thereby promoting hepatic fat

accumulation and injury, accelerating NAFLD progression and

ultimately causing a rapid decline in liver function (33). Furthermore, disruption of

mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated lipid metabolism in patients

with NAFLD leads to excessive TG accumulation (>5%) and hepatic

steatosis in hepatocytes (34).

When obesity remains uncontrolled during the SS stage, innate

immune cells within the liver-including Kupffer cells, dendritic

cells and hepatic stellate cells-become activated, leading to

progressive immune cell infiltration of the liver (35). In the liver, these immune cells

release cytokines that exacerbate the inflammatory process,

propelling hepatocytes from the SS stage into the NASH stage and

ultimately triggering fibrosis (36). Liver biopsy tissues from patients

with NAFLD showed hypermethylation of NADH dehydrogenase-6, which

correlated with disease severity (37). These changes in hypermethylation

were associated with loss of the inner mitochondrial membrane, deep

crista folding and loss of mitochondrial granules, indicating that

mitochondrial structural stability is critical for normal hepatic

physiological activity. Previous studies revealed reduced SIRT3

expression in animals fed a high-fat diet (HFD). When

SIRT3-knockout mice were fed an HFD, hepatic steatosis worsened

(25). These findings suggest

that SIRT3 plays a role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. A further

study revealed that SIRT3 upregulates β-oxidation and ATP

production, suppresses ROS and enhances mitochondrial biogenesis

through the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor (PPAR) gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) (38). Conversely, SIRT3 deficiency leads

to excessive acetylation at the K24 site of the mitochondrial

metabolic enzyme LCAD. When an acetyl group is covalently modified

at this site, the LCAD conformation changes, impairing enzyme

activity and obstructing FAO. This results in abnormal lipid

metabolism, manifested as massive accumulation of lipid droplets in

the liver (25). Furthermore, it

affects transcription coactivators involved in FAO, such as PPARα

and several target genes involved in FAO, leading to reduced

DNA-binding activity and increased acetylation of several hepatic

proteins involved in lipid uptake, ultimately resulting in NAFLD

development (39). Additionally,

SIRT3 promotes β-oxidation by driving LCAD activity and enhancing

ketone body production by promoting the deacetylation of

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase. In SIRT3-deficient mice,

hyperacetylation of mitochondrial FAO-related enzymes and reduced

enzyme activity lead to increased FFA levels and hepatic steatosis

(40). In SIRT3-deficient mice

fed an HFD, hepatic steatosis is exacerbated by the activation of

oxidative stress-induced nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

(Nrf)2, which increases the expression and protein levels of genes

involved in lipid uptake (very low-density lipoprotein receptor and

CD36) in the liver (41).

Concurrently, it reduces the activity of respiratory complexes III

and IV, exacerbating oxidative stress (42). The administration of adenovirus

expressing SIRT3 to mice alleviated obesity, insulin resistance,

hyperlipidemia, hepatic steatosis and inflammation in

SIRT3-deficient mice (43).

Currently, NAFLD treatment relies primarily on lifestyle

modifications such as weight reduction, increased exercise and

dietary control; however, the adherence to and efficacy of these

measures remain suboptimal. Identifying isoenzyme-specific SIRT

activators and their target signaling pathways to enhance hepatic

mitochondrial function may represent a novel therapeutic strategy

for NAFLD. A study revealed that Polygonum cuspidatum

glycoside (PD), a natural resveratrol precursor isolated from

Polygonum cuspidatum, activates SIRT3, which in turn

activates the deacetylase-activated transcription factor forkhead

box (FOX)O3a. FOXO3a induces the interaction between BCL2 and the

B19kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), which promotes

mitochondrial autophagy (44).

This herbal compound, PD, improves NAFLD liver function,

histopathology and mitochondrial function through the

aforementioned SIRT3-FOXO3-BNIP3 signaling axis and PINK1/parikin

(PRKN)-dependent mitochondrial autophagy regulatory mechanism,

PINK1 detects mitochondrial damage and recruits PRKN to the

mitochondrial surface, thereby mediating ubiquitin-tagging and

ultimately initiating the autophagy pathway for the clearance of

damaged mitochondria. demonstrating therapeutic efficacy against

NAFLD (45). PD has demonstrated

broad potential in preclinical studies, but its practical

application in clinical settings still faces several challenges

(46-48). Although the vitamin D analogue

paricalcitol is well-established in clinical treatment for

secondary hyperparathyroidism caused by chronic kidney disease, its

application in addressing liver inflammation remains in the

preclinical stage. The vitamin D analog paricalcitol reduced the

acetylation of the transcription factors FOXO3a and NF-κB in the

rat liver by increasing SIRT1 and SIRT3 expression, thereby

alleviating hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress activation

(49).

Primary liver cancer includes HCC (accounting for

75-85% of cases) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (10-15%),

along with other rare types (50). During the past decade, most

patients were diagnosed at an advanced stage when surgery and local

treatments were no longer feasible (51). Although clinical chemotherapy and

immunotherapy have demonstrated efficacy in treating HCC, its

incidence and prevalence continue to increase (52,53).

Research has indicated that HCC progression and

metastasis are associated with altered mitochondrial metabolism

(50). Mitochondrial

dysfunction, stress responses and protein aberrations in cancer

cells lead to mitochondrial defects. In damaged hepatocytes, ROS

production, metabolic reprogramming and mitochondrial hormone

responses within mitochondria drive tumor growth and metastasis.

Previous studies have indicated that when cells lack SIRT3, the

inability to deacetylate MnSOD leads to increased ROS levels,

readily causing mitochondrial metabolic abnormalities. Under

specific intracellular conditions, this triggers genetic

instability mutations, ultimately resulting in dedifferentiation

and carcinogenesis (54).

Compared with that in normal liver cells, SIRT3 expression is

downregulated in HCC cells, and this downregulation is associated

with tumor size and grade. These findings indicate that SIRT3 plays

a tumor-suppressing role in humans and suggest that it can serve as

a reliable prognostic indicator (55,56). Cancer cells primarily rely on

aerobic glycolysis for energy production, a process that also

creates favorable conditions for their survival in the

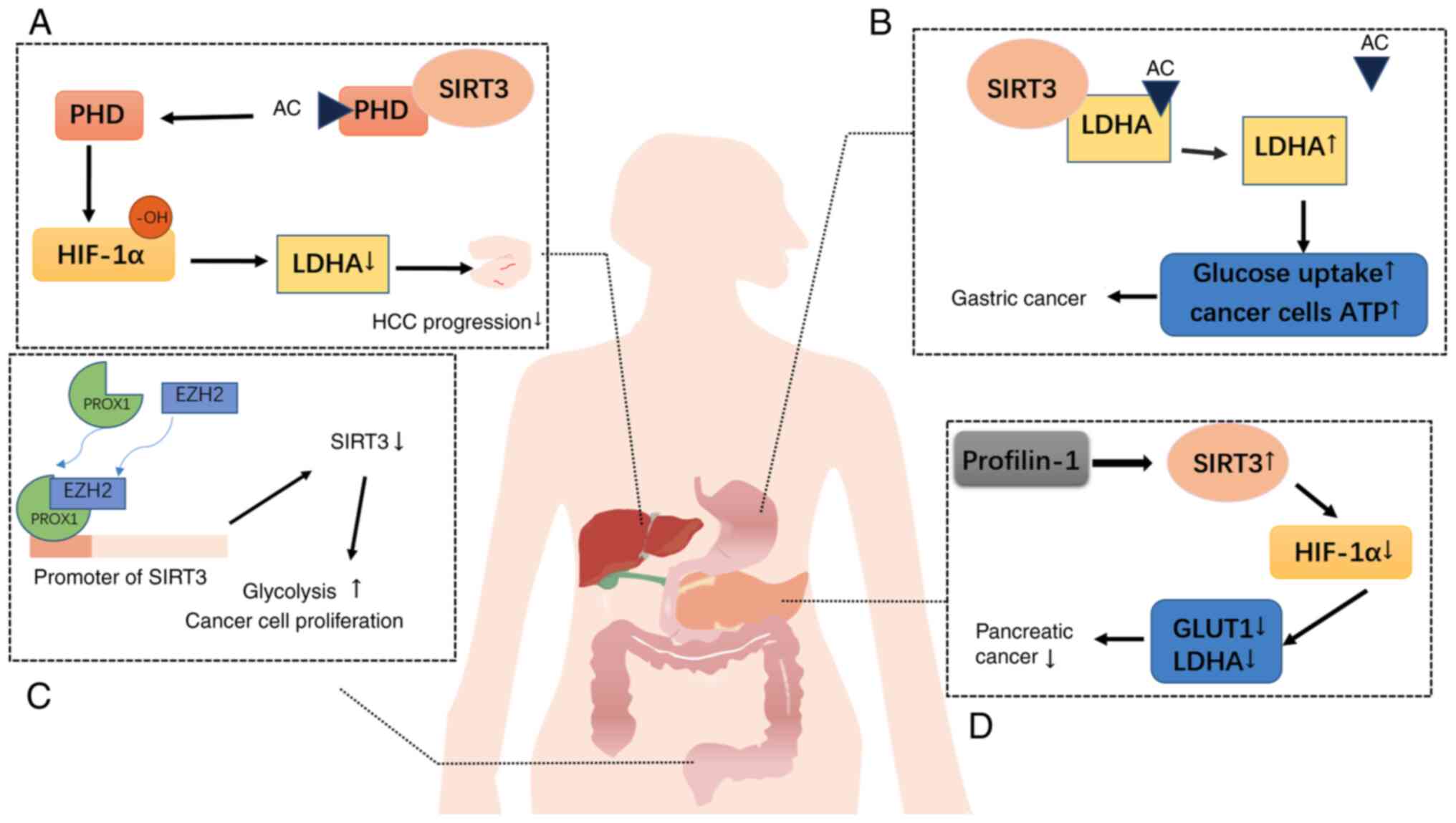

microenvironment-known as the Warburg effect (57). SIRT3 acts as a tumor suppressor

gene by promoting oxidative phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting

glycolysis and regulating metabolism to suppress the Warburg

effect. The most extensively studied mechanism involves the

inhibition of HIF-1α by SIRT3. Since many cancer cells extensively

consume glucose to produce lactate via lactate dehydrogenase A

(LDHA), which is encoded by c-Myc target genes and HIF-1α, HIF1α

has been identified as a key factor that activates glycolytic

pathways in tumors. SIRT3 modulates HIF1α activity by deacetylating

prolyl hydroxylase (PHD). Activated PHDs hydroxylate the substrate

HIF-1α, affecting its stability and preventing aerobic glycolysis

in tumors (58,59). Additionally, pyruvate

dehydrogenase complexes (PDCs) serve as SIRT3 substrates linked to

glycolysis. As an upstream deacetylase of PDCs, SIRT3 deacetylates

and activates these substrates, thereby inhibiting tumor cell

glycolysis and promoting apoptosis (60) (Fig. 2). SIRT3/SIRT4 reduces the high

expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in tumor tissues. Since

COX-2 impedes PINK1/PRKN-mediated mitochondrial autophagy, its

reduction enhances mitochondrial autophagy, contributing to the

early prevention of HCC (61).

As HCC is a chemoresistant cancer and its multidrug resistance

characteristics contribute to high recurrence and metastasis rates

(62). Consequently, drugs that

enhance anticancer activity are urgently needed. Given the critical

role of SIRT3 in tumors, researchers are now focusing on the

function of SIRT3 modulators in HCC. Among these, the small

molecule 7-hydroxy-3-(4'-methoxyphenyl)coumarin, a SIRT3 activator,

binds to SIRT3 to specifically increase MnSOD deacetylation and

activity (63). It also

increases sensitivity to HCC treatments such as sorafenib (55,64). Furthermore, the SIRT3 activator

resveratrol enables SIRT3 to deacetylate mitochondrial

cyclooxygenase-2 (mito-COX-2), thereby inhibiting

mito-COX-2/dintenin-1-driven mitochondrial fission, inducing cancer

apoptosis and increasing the sensitivity of HCC cells to cisplatin

chemotherapy (63). Both of

these activators are currently in preclinical trials. Although

several effective SIRT3 activators have been identified, further

research is still needed to discover and develop specific and

potent SIRT3 activators.

The gut serves as a barrier against harmful external

substances and pathogenic infections, interacting with the gut

microbiome and food antigens. Consequently, the intestinal immune

system responds to both internal and external environments to

maintain homeostasis. Disruption of this equilibrium can lead to

IBD (65). IBD is a chronic,

recurrent disease that encompasses ulcerative colitis (UC) and

Crohn's disease. Its etiology remains unclear, although it is

widely considered an autoimmune disorder in which key pathogenic

factors involve the dysregulation of T-cell subsets (66). Compared with healthy individuals,

patients with IBD exhibit increased levels of helper T cells (Th17)

and the corresponding transcription factor retinoic acid-related

orphan receptor gamma-t (RORγt). Additionally, both SIRT3 gene

transcription and protein expression are downregulated in the

colonic tissue of patients with UC (67). RORγt is a key transcription

factor for Th17 cell development. Its signaling is regulated by

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which

directly activates RORγt by modulating STAT3, thereby inducing Th17

cells (68). Thus, STAT3 plays a

crucial role in regulating the Th17/T-regulatory cell (Treg)

balance and the release of inflammation-related cytokines (69). Increased STAT3 promotes Th17-cell

differentiation, disrupting the Th17/Treg balance and triggering

inflammatory events (70).

Honokiol (HKL), an activator of SIRT3, was used to treat an

inflammatory cell model and a dextran sulfate sodium-induced mouse

colitis model. Compared with untreated mice, HKL-treated mice

exhibited reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, significantly

less structural damage and relatively lower edema levels. As a

SIRT3 activator, HKL inhibits STAT3-induced RORγt activity, reduces

the Th17 ratio and does not affect Th-cell differentiation, thereby

regulating the Th17-cell mechanism to alleviate colitis symptoms

(67). Dysregulation of

intestinal macrophages also plays a crucial role in the

pathogenesis of IBD. Macrophage NAD+ synthesis exerts

immunoregulatory effects by enhancing oxidative phosphorylation

(71). This maintains intestinal

immune homeostasis by clearing infections while preventing chronic

inflammation and inducing tissue repair. During this process,

macrophages polarize into classically activated macrophages (M1)

and alternatively activated macrophages (M2) (72). SIRT3 deacetylates glutamate

dehydrogenase 1 to promote α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) production. α-KG

accumulation not only enhances OXPHOS metabolism but also reduces

histone H3 K27 trimethylation in the nucleus, leading to the

upregulation of genes associated with M2 polarization (73). Given that IBD is a chronic,

recurrent disease imposing a significant health burden, the

discovery of the role of SIRT3 in IBD potentially reveals a

pharmacological target.

The ENS is a vast, complex and autonomous system

distinct from the central nervous system. Neurons within the ENS

regulate critical functions such as digestion, nutrient absorption

and intestinal motility. The ENS, intestinal epithelium, gut

microbiota and immune cells work in concert to ensure the

maintenance of normal intestinal function (74). ENS-related neurodegeneration is

particularly pronounced in individuals with aging and

neurodegenerative diseases. Stress from antibiotic treatment also

affects ENS function by altering the gut microbiota (75). ENS dysfunction can lead to

numerous disorders associated with motility alterations and

inflammation, including primary achalasia (76,77) and irritable bowel syndrome

(78). Owing to high energy

demands, neurotransmitter autooxidation and limited replication

capacity, ENS neurons are highly susceptible to oxidative damage

from free radicals. Oxidative stress has also been demonstrated to

alter electrophysiological properties, damage neuronal membranes

and trigger neuronal death (79). Currently, the known mechanisms of

oxidative stress in enteric neurons can be categorized into those

associated with endogenous nitrosative damage, mitochondrial

dysfunction or inflammation (79). Studies have revealed that SIRT3

protects cortical and dopaminergic neurons from oxidative stress by

regulating mitochondrial homeostasis (80). The SIRT3 activator

hexafluoromagnol activates SIRT3 and its downstream target PGC-1α

to counteract stress-induced ROS production (81). Concurrently, PGC-1α directly

enhances SIRT3 transcription to mitigate oxidative damage, thereby

promoting intestinal neuronal survival and differentiation

(82). Furthermore, SIRT3

significantly increased the density of neural networks and axons in

intestinal neurons while increasing neuronal nitric oxide synthase

and choline acetyltransferase mRNA levels. SIRT3 exerts

neuroprotective effects by inhibiting superoxide release, thereby

suppressing palmitate and lipopolysaccharide-induced neuronal

pyroptosis, which play crucial roles in promoting intestinal

neuronal survival and differentiation (83,84). Beyond regulating host energy

balance, the gut microbiota modulates numerous metabolic processes

by participating in the complex bidirectional communication system

known as gut-brain crosstalk, which is mediated by signaling

molecules such as short-chain fatty acids produced by the

microbiota (85). Short-chain

fatty acids generated by gut bacteria regulate NAD+

metabolism to influence SIRT3 activity (86). In summary, SIRT3 plays a crucial

role in maintaining normal ENS function. Investigating the role of

SIRT3 in the ENS provides direction for disease prevention and

treatment.

CRC is a malignant tumor arising from the mucosal

epithelium and glands of the large intestine. Its incidence is

increasing annually and the 5-year survival rate significantly

decreases once tumor cells infiltrate the submucosal layer.

Prognosis worsens and survival decreases upon metastasis to

extraintestinal organs (87). In

CRC, SIRT3 functions as a tumor suppressor to inhibit cancer

progression. Compared with those in adjacent normal colorectal

epithelium, the expression levels of proco-related homeobox 1

(PROX1) are significantly greater in colorectal tumor cells. As a

homologous transcription factor, PROX1 regulates cellular

differentiation and development during embryonic growth and is

positively correlated with tumor glucose metabolism (88). The mechanism involves the

recruitment of the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) to the SIRT3

promoter region in CRC cells by PROX1, thereby inhibiting SIRT3

transcription. This increases glucose metabolism in cancer cells to

sustain proliferation (89).

When PROX1 is highly expressed, it binds to the SIRT3 promoter

region, inhibiting SIRT3 transcription and translation and

ultimately leading to low SIRT3 expression. Knocking down PROX1

expression increases SIRT3 expression and reverses the malignant

characteristics of CRC (90)

(Fig. 2). SIRT3 regulates the

expression of PGC1α and NRF1. Reduced SIRT3 expression impairs

mitochondrial dynamics and affects the malignancy of CRC cells

(91). Of note, SIRT3 may also

promote cancer cell growth. Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark

of cancer and is closely linked to cancer progression and

metastasis. To enable rapid cell division, cancer cells exhibit

abnormal glycolysis, glutamine catabolism and lipid synthesis

(92). Previous studies revealed

disrupted serine-to-glycine ratios in CRC, where serine/glycine

synthesis influences the tumor status by regulating cellular

antioxidant capacity (93). The

expression of serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2), a key

serine/glycine interconverting enzyme, is significantly elevated in

patients with CRC and is correlated with poor survival outcomes.

Further study revealed acetylation at the K95 site of SHMT2.

Acetylated K95 disrupts the SHMT2 tetrameric conformation to

inhibit its enzymatic activity and promotes SHMT2 degradation via

the K63-ubiquitin-lysosomal pathway. This leads to reduced serine

consumption and decreased NADPH levels, thereby suppressing tumor

growth and cell proliferation (94). In the aforementioned SHMT2-K95-Ac

pathway, SIRT3 acts as a deacetylase for SHMT2, deacetylating K95.

Deacetylation of K95 fails to inhibit SHMT2 activity, leading to

SHMT2 overexpression, which promotes colorectal tumorigenesis.

These tumors are highly invasive and have poor prognosis (95). SIRT3 also deacetylates

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 2, increasing its activity and

promoting cell proliferation and cancer progression (96). These studies indicate that SIRT3

influences cancer cell proliferation by controlling whether

endogenous regulatory factors undergo deacetylation. In recent

years, researchers have been exploring novel therapeutic and

preventive strategies against cancer. It should not be overlooked

that dietary prevention can reduce the risk of CRC. Apigenin, a

natural antioxidant found in fruits and vegetables, reduces the

expression of SHMT2, SIRT3 and their upstream long intergenic

noncoding RNA LINC01234 when CRC cells are treated. This activity

inhibits metabolic reprogramming by regulating the

LINC01234/SIRT3/SHMT2 axis (97). Ergothioneine, a dietary betaine,

exerts anti-CRC effects by activating SIRT3 (98). Clinically, SGLT2 inhibitors such

as canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, tolvogliflozin and empagliflozin

are commonly used as hypoglycemic agents. A recent study revealed

their novel anticancer activity by reducing glucose uptake and

severely impairing cancer-specific cellular metabolism (99). In CRC, canagliflozin can be

repurposed to specifically inhibit CRC cell proliferation and

induce S-phase arrest through mechanisms of regulating metabolism,

mitochondrial function and ER stress via the SGLT2/SIRT3/dipeptidyl

peptidase-4 axis (100). It

should be noted that the aforementioned drugs remain in the

preclinical exploration phase. The findings from preclinical

studies provide crucial theoretical foundations and preliminary

scientific hypotheses for future formal clinical trials. Radiation

therapy is among the primary treatments for cancer patients.

However, prolonged radiotherapy can induce radiation resistance in

cancer cells, often leading to treatment failure and poor prognosis

in patients receiving radiotherapy (101). Research has indicated that

SIRT3 promotes radiation resistance in tumor cells by enhancing DNA

damage repair through excessive activation of mitochondrial

autophagy, which is mediated by PINK1/PRKN (102). In addition to promoting

radiation resistance during radiotherapy, SIRT3 modulates

chemotherapy resistance in CRC cells via the regulation of SOD2 and

PGC-1α during chemotherapy. SIRT3 serves as an independent

prognostic factor for colorectal cancer (99). Undoubtedly, the role of SIRT3 in

colon cancer is a double-edged sword. Whether its ultimate effect

is tumor suppression or promotion depends on a complex

decision-making network. Different colon cancer subtypes, tumor

microenvironments and tumor stages influence whether SIRT3 promotes

or inhibits tumorigenesis in CRC. Therefore, further understanding

of the underlying molecular mechanisms is warranted for the future

clinical development of SIRT3-targeted therapeutic agents.

AP is a localized inflammatory response in

pancreatic tissue caused by the activation of pancreatic enzymes

due to various etiologies. The activation of pancreatic enzymes is

a prerequisite for local inflammation in pancreatitis (100). When pancreatic cells undergo

necrosis and vascular permeability increases, the pancreas

experiences edema, necrosis and hemorrhage. Concurrently, impaired

pancreatic function affects other organs, such as through gut

microbiota dysbiosis, increased intestinal barrier permeability and

bacterial translocation (103).

Unlike conventional treatments that primarily reduce disease

severity by alleviating pancreatic burden, fecal microbiota

transplantation (FMT) achieves similar effects by mitigating tissue

damage and inflammation through the reversal of dysbiosis (104). Research has indicated that FMT

modulates the intestinal microbiota to concentrate nicotinamide

mononucleotide in the pancreas, thereby increasing pancreatic

NAD+ levels and reducing disease severity. This process

requires an NAD+-dependent enzyme for conversion. SIRT3,

an NAD+-dependent deacetylase, mitigates AP-induced

oxidative stress and inflammation by reducing the acetylation of

the mitochondrial protein peroxiredoxin-5 (PRDX5) in acinar cells

and increasing the expression of PRDX5 (105). These findings indicate that

SIRT3 exerts an inhibitory effect on AP and that its expression

levels in patients may serve as a therapeutic biomarker.

Pancreatic cancer, particularly pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (PDAC), is characterized by late symptom onset,

early metastasis and rapid progression, resulting in low patient

survival rates. Therefore, identifying potential biomarkers for

patients with pancreatic cancer is critically important (106). Studies of sirtuin protein

expression profiles in PDAC have revealed that in the absence of

chemotherapy intervention, low SIRT3 expression in the tumor

cytoplasm is associated with high-grade, poorly differentiated

tumors. Low SIRT3 expression is associated with high invasiveness,

high recurrence rates and poor prognosis (107). These findings indicate that

SIRT3 functions as a tumor suppressor in pancreatic cancer. As an

enzyme that regulates macronutrient metabolism, SIRT3 redirects

cellular glycolysis toward oxidative phosphorylation and the TCA

cycle, suppressing the Warburg effect in tumor cells and reducing

proliferation (108). Research

has revealed that Profilin1 (Pfn1) expression is downregulated in

pancreatic cancer. Pfn1 fails to increase HIF1-α stability by

upregulating SIRT3, thereby exerting a growth-inhibitory function

in pancreatic cancer. HIF1α promotes metabolic reprogramming and

plays a crucial role in maintaining glycolysis in pancreatic cancer

(109,110) (Fig. 2). SIRT3 also regulates iron

metabolism in PDAC by modulating the activity of iron regulatory

protein 1 (IRP1), a key regulator of cellular iron levels that

control genes containing iron response elements (IREs) (111). SIRT3 reduces the binding

affinity of IRP1 for IREs, leading to decreased expression of

iron-related genes such as transferrin receptor and thereby

inhibiting pancreatic cancer cell proliferation (112). Furthermore, ZMAT1 belongs to a

5-member family (ZMAT1-5) in humans, in which all encoded proteins

contain zinc finger domains, functions as tumor suppressors by

triggering cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. ZMAT1 expression is

downregulated in PDAC and is associated with tumor differentiation,

tumor stage and patient survival. ZMAT1 promotes SIRT3

transcription by binding to three sites on its promoter,

subsequently upregulating p53 expression and inhibiting cancer cell

proliferation (113). SIRT3

also participates in regulating the ETC in pancreatic cancer,

specifically by modulating mitochondrial complex II (CII) activity.

Dysfunction of SIRT3 leads to decreased CII activity, causing

mitochondrial dysfunction and promoting tumor progression. Recent

research has identified a pharmacological agent, poplar

nanocapsules, that targets the ubiquinone site to restore CII

activity and SIRT3 expression, thereby inducing apoptosis and

reducing pancreatic cancer cell survival (114). Given that pancreatic cancer is

characterized by rapid growth and high resistance to

chemoradiotherapy, developing novel effective treatments targeting

its pathogenesis is critically important (115). Identifying SIRT3-regulated

pathways that drive PDAC initiation and progression is important

for identifying potential therapeutic targets. Reconstructing SIRT3

activity or activating upstream components of SIRT3-associated

oncogenic signaling suppression pathways offers a novel,

multifaceted strategy to promote cancer progression and improve

patient prognosis.

Gastric cancer ranks fourth among cancer types.

Although its global incidence has shown an overall downward trend,

long-term trends in incidence and mortality vary significantly

across countries (116).

Increasing experimental evidence has demonstrated that SIRT3

deficiency leads to increased ROS production and oxidative stress

in the body, potentially causing cellular dedifferentiation or

carcinogenesis. SIRT3 plays a crucial role in protecting cells and

preventing cancer progression during carcinogenesis and tumor

development. For instance, SIRT3 regulates MnSOD activity to reduce

ROS levels in gastric cancer cells, thereby shielding them from

oxidative stress-induced damage (117-119). However, in SIRT3-positive

gastric tumor cells, SIRT3 acts as an oncogenic factor. By

deacetylating LDHA, it enhances enzyme activity. Increased LDHA

activity increases glucose uptake and lactic acid production,

reducing mitochondrial oxygen consumption while increasing the

mitochondrial membrane potential. This increases overall ATP

production and aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells, accelerating

tumor growth. Concurrently, the expression of glycolysis-related

genes is upregulated in SIRT3-overexpressing gastric tumor cells

(119) (Fig. 2). Although the incidence and

mortality rates of gastric cancer have generally declined, it

remains among the leading causes of death worldwide (120). Decreasing gastric cancer

mortality may be achieved by developing drugs through studying the

regulatory mechanisms of SIRT3 in gastric cancer.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a common malignant tumor

of the biliary tract. Early stages show no specific symptoms, but

when significant weight loss, jaundice, abdominal pain and diarrhea

occur, the disease has already progressed and is often missing the

optimal treatment window. Radical cholecystectomy is the preferred

treatment, but owing to its high degree of invasiveness and

susceptibility to peritoneal and intrahepatic metastasis, early

prevention and treatment are particularly crucial (121). SIRT3 plays a role in the

pathogenesis of GBC. Studies have revealed that SIRT3 expression is

significantly lower in GBC cells than in adjacent nontumor tissue,

and patients with low SIRT3 expression exhibit poorer overall

survival than those with high SIRT3 expression (122). As a mitochondrial deacetylase,

SIRT3 enhances ferroptosis by inhibiting AKT to increase acyl-CoA

synthetase long-chain family member 4 expression (123). When SIRT3 expression is

reduced, inhibition of AKT-dependent ferroptosis protects cancer

cells from ferroptosis. Simultaneously, activating AKT in GBC cells

induces the upregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

markers, enhancing tumor cell invasion activity and migration

capacity (124). Reduced SIRT3

expression promotes tumor cell respiration, ATP production and ROS

reduction (122,125). Thus, in GBC pathogenesis, SIRT3

induces Akt-mediated ferroptosis while inhibiting EMT, thereby

suppressing tumor progression.

As early as 2003, studies reported an association

between SIRT3 expression and lifespan (126). It protects vital human tissues

such as the heart, liver, brain and kidneys from disease through

the deacetylation of substrates. SIRT3 also participates in the

overall progression of cancer. Current research on sirtuin targets

has made significant progress. Studies on these targets can be

extended to identify sirtuin-activating compounds (STACs) or

inhibitory compounds (8). Most

STACs belong to the natural product polyphenol family, with

resveratrol being the first compound discovered to increase SIRT1

activity nearly 10-fold (127).

Compounds such as SRT1720, SRT2183 and SRT3025 have been developed

to increase sirtuin enzymatic activity, and these drugs have been

shown to limit kidney damage (128). Currently, most SIRT3 activators

are natural products. These compounds can deacetylate SIRT3 or

regulate its expression levels through various mechanisms. HKL, a

SIRT3 activator, is a natural compound that increases SIRT3

expression and deacetylase activity. In mice with cardiac

hypertrophy, it inhibits cardiac hypertrophy by regulating the AKT

and ERK1/2 pathways (82). HKL

exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in mice with enterotoxin-induced

diarrhea by promoting intestinal barrier function and regulating

intestinal epithelial apoptosis. It can also cross the blood-brain

barrier to directly act on neuronal cells in the central nervous

system (84). The novel

fluorinated synthetic HKL analog hexafluoro-HKL exhibits protective

effects against melanoma and enhances SIRT3 expression (129). Dihydromyricetin, which is

structurally similar to resveratrol, enhances SIRT3 expression

through SIRT3-mediated cell protection and inflammation resistance,

thereby treating osteoarthritis (130). In a mouse model of sulfur

mustard-induced liver injury, this natural product was shown to

exert its hepatoprotective effects via SIRT3 (131). Another natural product,

pyrroloquinoline quinone, improves hepatic metabolic disorders by

increasing SIRT3 expression (132). In the treatment of HCC,

sorafenib is a clinically used drug for treating HCC. Sorafenib has

been shown to reduce SIRT3 expression, thereby decreasing drug

sensitivity, while upregulating SIRT3 can restore HCC sensitivity

to sorafenib therapy (82).

These findings indicate that SIRT3 is a promising therapeutic

target for liver diseases. However, the dual role of SIRT3 in

cancer poses risks to its use as a cancer treatment target

(9). In addition to natural

compounds, SIRT3 activators can be developed through

high-throughput screening and structural optimization. Recent

discoveries have identified 2-APQC, a structurally selected

SIRT3-targeted small-molecule activator. By activating SIRT3, it

modulates the AKT-mTOR and TGFβ-Smad3 signaling pathways, thereby

inhibiting myocardial hypertrophy and alleviating myocardial

fibrosis (133). Unlike

traditional 'inhibitory' or 'blocking' drugs, SIRT3 activators aim

to 'restore and optimize' cellular physiological functions,

offering broad and profound application prospects. However, further

development through preclinical and clinical studies is needed to

address their pleiotropic effects and enhance their specificity.

Furthermore, achieving tissue-specific targeting remains

challenging, as other members of the sirtuin family are widely

expressed in the digestive system and regulate both tumor-promoting

and tumor-suppressing processes. Currently, allosteric activators

are gaining attention in the design of SIRT-targeting activators

(e.g., SIRT1 and -6). Further elucidation of the structure and

biological functions of SIRT3 will facilitate the development of

small-molecule activators targeting SIRT3 (9).

Compared with the development of SIRT3 activators,

the development of inhibitors within the dynamic deacetylation

process is somewhat simpler. By leveraging the peptide-binding

region within the SIRT3 crystal structure, a structure-based

approach can be used to identify novel isoform-specific inhibitors

(134). With respect to

deacetylation substrates, competitive inhibition of SIRT3

deacetylation activity can be achieved by synthesizing structural

analogs of endogenous acetylated substrates. Alternatively,

NAD+ coenzyme competitive inhibitors accelerate the

reverse reaction of deacetylation, thereby inhibiting the

deacetylation process. Tenovin-6 is a bioactive p53 activator that

was later identified as a SIRT3 inhibitor with antitumor activity.

Its mechanism of SIRT3 inhibition remains elusive, but it has been

demonstrated to act as a noncompetitive inhibitor (135). LC-0296 is a synthetic SIRT3

inhibitor whose mechanism of action is currently unknown. On the

basis of its structure, LC-0296 may act as a competitive inhibitor

of NAD+. It exhibits potent antiproliferative and

proapoptotic activity against head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(136). As summarized in

Table I, an increasing number of

natural and synthetic compounds have been identified as SIRT3

activators or inhibitors, providing a critical resource for

developing targeted therapeutic strategies (Table I). Research on SIRT3 activators

is promising, yet their practical clinical application remains

challenging. For instance, precisely delivering drugs to specific

diseased organs while minimizing effects on other tissues is

crucial for enhancing efficacy and reducing side effects. This

precise targeting becomes particularly vital when SIRT3 expression

levels exhibit either pro- or antitumor effects across different

cancers. Careful monitoring of future research is essential,

especially in preclinical and clinical settings, to explore

SIRT3-modulating therapies for digestive system diseases.

As a member of the sirtuin family, SIRT3 influences

mitochondrial energy balance, redox homeostasis and mitochondrial

DNA repair by regulating the acetylation status of mitochondrial

proteins. The functional integrity of mitochondria is vital for

maintaining the health of digestive organs. Dysfunction of SIRT3

leads to mitochondrial disruption and serves as a common pathway

linking multiple pathophysiological processes. This review

summarizes the structure and deacetylase function of SIRT3,

highlighting its vital role in digestive system diseases. In such

diseases, loss of SIRT3 activity leads to metabolic disorders,

oxidative stress-induced accumulation of energy and substances,

cellular damage and mutations, and genomic instability. Ultimately,

this leads to tissue carcinogenesis. Notably, however, SIRT3

expression exhibits duality in certain digestive system tumors,

such as CRC, and influences chemoresistance in CRC cells.

Therefore, when SIRT3 activators are designed, combining SIRT3

modulators with chemotherapeutic agents or metabolic inhibitors

could significantly improve clinically observed chemoresistance.

Although a series of SIRT3-targeting small molecules have

demonstrated efficacy, the vast majority of SIRT3 activators remain

in preclinical stages. SIRT3 remains a largely unexplored

therapeutic target, and future research should focus on optimizing

SIRT3-targeted therapies by enhancing their specificity and

improving their efficacy when combined with conventional

treatments. Despite these existing challenges, this approach offers

novel therapeutic strategies for digestive system diseases.

Not applicable.

JL was responsible for conceptualization of the

review, methodological design, literature search, drafting of the

manuscript, and visualization of charts and graphs. QL performed

the literature review and data organization and participated in

drafting portions of the initial manuscript. SY provided resources

and performed quality assessment. XL provided resources and was

involved in formal analysis. LZ provided resources and was involved

in data curation. YW supervised the study and was responsible for

methodology. GW, JA and HJ acquired funding, performed project

administration, provided resources and supervision and were

involved in writing-review and editing. BT acquired funding and

contributed to writing-review and editing. Data authentication is

not applicable. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81960507, 82073087

and 82160112), the Science and Technology Plan Project of Guizhou

Province (grant no. QIAN KE HE JI CHU-ZK (2024)YI BAN 323) and the

Medical Research Union Fund for High-Quality Health Development of

Guizhou Province (grant no. 2024GZYXKYJJXM0019).

|

1

|

Zhang Y, Zhao L, Gao H, Zhai J and Song Y:

Potential role of irisin in digestive system diseases. Biomed

Pharmacother. 166:1153472023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chakraborty E and Sarkar D: Emerging

therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Cancers (Basel).

14:27982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Menini S, Iacobini C, Vitale M, Pesce C

and Pugliese G: Diabetes and pancreatic cancer-a dangerous liaison

relying on carbonyl stress. Cancers (Basel). 1:3132021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hu JX, Zhao CF, Chen WB, Liu QC, Li QW,

Lin YY and Gao F: Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology,

trend, and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol. 27:4298–321. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Haque PS, Kapur N, Barrett TA and Theiss

AL: Mitochondrial function and gastrointestinal diseases. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21:537–555. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

LeFort KR, Rungratanawanich W and Song BJ:

Contributing roles of mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatocyte

apoptosis in liver diseases through oxidative stress,

post-translational modifications, inflammation, and intestinal

barrier dysfunction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 81:342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhou L, Pinho R, Gu Y and Radak Z: The

role of SIRT3 in exercise and aging. Cells. 11:25962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Feldman JL, Dittenhafer-Reed KE and Denu

JM: Sirtuin catalysis and regulation. J Biol Chem. 287:42419–42427.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang J, Xiang H, Liu J, Chen Y, He RR and

Liu B: Mitochondrial sirtuin 3: New emerging biological function

and therapeutic target. Theranostics. 10:8315–8342. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Grabowska W, Sikora E and Bielak-Zmijewska

A: Sirtuins, a promising target in slowing down the ageing process.

Biogerontology. 18:447–476. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Verdin E, Hirschey MD, Finley LW and

Haigis MC: Sirtuin regulation of mitochondria: Energy production,

apoptosis, and signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 35:669–675. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mishra Y and Kaundal RK: Role of SIRT3 in

mitochondrial biology and its therapeutic implications in

neurodegenerative disorders. Drug Discov Today. 28:1035832023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang Y, Wen P, Luo J, Ding H, Cao H, He

W, Zen K, Zhou Y, Yang J and Jiang L: Sirtuin 3 regulates

mitochondrial protein acetylation and metabolism in tubular

epithelial cells during renal fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 12:8472021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hebert AS, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Yu W,

Bailey DJ, Selen ES, Boersma MD, Carson JJ, Tonelli M, Balloon AJ,

Higbee AJ, et al: Calorie restriction and SIRT3 trigger global

reprogramming of the mitochondrial protein acetylome. Mol Cell.

49:186–199. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Iwahara T, Bonasio R, Narendra V and

Reinberg D: SIRT3 functions in the nucleus in the control of

stress-related gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 32:5022–5034. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Onyango P, Celic I, McCaffery JM, Boeke JD

and Feinberg AP: SIRT3, a human SIR2 homologue, is an NAD-dependent

deacetylase localized to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

99:13653–13658. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yang W, Nagasawa K, Münch C, Xu Y,

Satterstrom K, Jeong S, Hayes SD, Jedrychowski MP, Vyas FS,

Zaganjor E, et al: Mitochondrial sirtuin network reveals dynamic

SIRT3-dependent deacetylation in response to membrane

depolarization. Cell. 167:985–1000.e21. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shen H, Qi X, Hu Y, Wang Y, Zhang J, Liu Z

and Qin Z: Targeting sirtuins for cancer therapy: Epigenetics

modifications and beyond. Theranostics. 14:6726–6767. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Griffiths HBS, Williams C, King SJ and

Allison SJ: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+): Essential

redox metabolite, co-substrate and an anti-cancer and anti-ageing

therapeutic target. Biochem Soc Trans. 48:733–744. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ouyang S, Zhang Q, Lou L, Zhu K, Li Z, Liu

P and Zhang X: The double-edged sword of SIRT3 in cancer and its

therapeutic applications. Front Pharmacol. 13:8715602022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen LJ, Guo J, Zhang SX, Xu Y, Zhao Q,

Zhang W, Xiao J and Chen Y: Sirtuin3 rs28365927 functional variant

confers to the high risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in

Chinese Han population. Lipids Health Dis. 20:922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kane AE and Sinclair DA: Sirtuins and

NAD+ in the development and treatment of metabolic and

cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 123:868–885. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Peterson BS, Campbell JE, Ilkayeva O,

Grimsrud PA, Hirschey MD and Newgard CB: Remodeling of the

acetylproteome by SIRT3 manipulation fails to affect insulin

secretion or β cell metabolism in the absence of overnutrition.

Cell Rep. 24:209–223.e6. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Sol EM, Wagner SA, Weinert BT, Kumar A,

Kim HS, Deng CX and Choudhary C: Proteomic investigations of lysine

acetylation identify diverse substrates of mitochondrial

deacetylase sirt3. PLoS One. 7:e505452012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Jing E, Grueter

CA, Collins AM, Aouizerat B, Stančáková A, Goetzman E, Lam MM,

Schwer B, et al: SIRT3 deficiency and mitochondrial protein

hyperacetylation accelerate the development of the metabolic

syndrome. Mol Cell. 44:177–190. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu J, Li D, Zhang T, Tong Q, Ye RD and

Lin L: SIRT3 protects hepatocytes from oxidative injury by

enhancing ROS scavenging and mitochondrial integrity. Cell Death

Dis. 8:e31582017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bell EL, Emerling BM, Ricoult SJ and

Guarente L: SirT3 suppresses hypoxia inducible factor 1α and tumor

growth by inhibiting mitochondrial ROS production. Oncogene.

30:2986–2996. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fukushi A, Kim HD, Chang YC and Kim CH:

Revisited metabolic control and reprogramming cancers by means of

the warburg effect in tumor cells. Int J Mol Sci. 23:100372022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA,

Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE and

Loomba R: AASLD practice guidance on the clinical assessment and

management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology.

77:1797–1835. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Paternostro R and Trauner M: Current

treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Intern Med.

292:190–204. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Grander C, Grabherr F and Tilg H:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathophysiological concepts and

treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 119:1787–1798. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Di Ciaula A, Passarella S, Shanmugam H,

Noviello M, Bonfrate L, Wang DQ and Portincasa P: Nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Mitochondria as players and targets of

therapies? Int J Mol Sci. 22:53752021.

|

|

33

|

Zheng Y, Wang S, Wu J and Wang Y:

Mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction and non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease: New insights from pathogenic mechanisms to clinically

targeted therapy. J Transl Med. 21:5102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Pirola CJ, Gianotti TF, Burgueño AL,

Rey-Funes M, Loidl CF, Mallardi P, Martino JS, Castaño GO and

Sookoian S: Epigenetic modification of liver mitochondrial DNA is

associated with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease. Gut. 62:1356–1363. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Mazzoccoli G, De Cosmo S and Mazza T: The

biological clock: A pivotal hub in non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease pathogenesis. Front Physiol. 9:1932018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Polyzos SA, Kountouras J and Mantzoros CS:

Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathophysiology

to therapeutics. Metabolism. 92:82–97. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ramanathan R, Ali AH and Ibdah JA:

Mitochondrial dysfunction plays central role in nonalcoholic fatty

liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 23:72802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kong X, Wang R, Xue Y, Liu X, Zhang H,

Chen Y, Fang F and Chang Y: Sirtuin 3, a new target of PGC-1alpha,

plays an important role in the suppression of ROS and mitochondrial

biogenesis. PLoS One. 5:e117072010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Barroso E, Rodríguez-Rodríguez R, Zarei M,

Pizarro-Degado J, Planavila A, Palomer X, Villarroya F and

Vázquez-Carrera M: SIRT3 deficiency exacerbates fatty liver by

attenuating the HIF1α-LIPIN 1 pathway and increasing CD36 through

Nrf2. Cell Commun Signal. 18:1472020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Chen DD, Shi Q, Liu X, Liang DL, Wu YZ,

Fan Q, Xiao K, Chen C and Dong XP: Aberrant SENP1-SUMO-Sirt3

signaling causes the disturbances of mitochondrial deacetylation

and oxidative phosphorylation in prion-infected animal and cell

models. ACS Chem Neurosci. 14:1610–1621. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang Z, Dou X, Li S, Zhang X, Sun X, Zhou

Z and Song Z: Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

activation-induced hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein receptor

overexpression in response to oxidative stress contributes to

alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 59:1381–1392. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Green MF and Hirschey MD: SIRT3 weighs

heavily in the metabolic balance: A new role for SIRT3 in metabolic

syndrome. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 68:105–107. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kendrick AA, Choudhury M, Rahman SM,

McCurdy CE, Friederich M, Van Hove JL, Watson PA, Birdsey N, Bao J,

Gius D, et al: Fatty liver is associated with reduced SIRT3

activity and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation. Biochem J.

433:505–514. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Lai CS, Tsai ML, Badmaev V, Jimenez M, Ho

CT and Pan MH: Xanthigen suppresses preadipocyte differentiation

and adipogenesis through down-regulation of PPARγ and C/EBPs and

modulation of SIRT-1, AMPK, and FoxO pathways. J Agric Food Chem.

60:1094–1101. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

He J, Qian YC, Yin YC, Kang JR and Pan TR:

Polydatin: A potential NAFLD therapeutic drug that regulates

mitochondrial autophagy through SIRT3-FOXO3-BNIP3 and PINK1-PRKN

mechanisms-a network pharmacology and experimental investigation.

Chem Biol Interact. 398:1111102024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Ren B, Kwah MX, Liu C, Ma Z, Shanmugam MK,

Ding L, Xiang X, Ho PC, Wang L, Ong PS and Goh BC: Resveratrol for

cancer therapy: Challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett.

515:63–72. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Karami A, Fakhri S, Kooshki L and Khan H:

Polydatin: Pharmacological mechanisms, therapeutic targets,

biological activities, and health benefits. Molecules. 27:64742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Imtiyaz K, Shafi M, Fakhri KU, Uroog L,

Zeya B, Anwer ST and Rizvi MMA: Polydatin: A natural compound with

multifaceted anticancer properties. J Tradit Complement Med.

15:447–466. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Malladi N, Lahamge D, Somwanshi BS, Tiwari

V, Deshmukh K, Balani JK, Chakraborty S, Alam MJ and Banerjee SK:

Paricalcitol attenuates oxidative stress and inflammatory response

in the liver of NAFLD rats by regulating FOXO3a and NFκB

acetylation. Cell Signal. 121:1112992024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ladd AD, Duarte S, Sahin I and Zarrinpar

A: Mechanisms of drug resistance in HCC. Hepatology. 79:926–940.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Ahmed O and Pillai A: Hepatocellular

carcinoma: A contemporary approach to locoregional therapy. Am J

Gastroenterol. 115:1733–1736. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, Salem R

and Saborowski A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 400:1345–1362.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang B, Qin L, Zhou CJ, Liu YL, Qian HX

and He SB: SIRT3 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and its

impact on proliferation and invasion of hepatoma cells. Asian Pac J

Trop Med. 6:649–652. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang JX, Yi Y, Li YW, Cai XY, He HW, Ni

XC, Zhou J, Cheng YF, Jin JJ, Fan J and Qiu SJ: Down-regulation of

sirtuin 3 is associated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular

carcinoma after resection. BMC Cancer. 14:2972014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

De Matteis S, Scarpi E, Granato AM,

Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, La Barba G, Foschi FG, Bandini E, Ghetti

M, Marisi G, Cravero P, et al: Role of SIRT-3, p-mTOR and HIF-1α in

hepatocellular carcinoma patients affected by metabolic

dysfunctions and in chronic treatment with metformin. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:15032019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Liu H, Li S, Liu X, Chen Y and Deng H:

SIRT3 overexpression inhibits growth of kidney tumor cells and

enhances mitochondrial biogenesis. J Proteome Res. 17:3143–3152.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Le A, Cooper CR, Gouw AM, Dinavahi R,

Maitra A, Deck LM, Royer RE, Vander Jagt DL, Semenza GL and Dang

CV: Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A induces oxidative stress

and inhibits tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:2037–2042. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kwon SM, Lee YK, Min S, Woo HG, Wang HJ

and Yoon G: Mitoribosome defect in hepatocellular carcinoma

promotes an aggressive phenotype with suppressed immune reaction.

iScience. 23:1012472020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Fan J, Shan C, Kang HB, Elf S, Xie J,

Tucker M, Gu TL, Aguiar M, Lonning S, Chen H, et al: Tyr

phosphorylation of PDP1 toggles recruitment between ACAT1 and SIRT3

to regulate the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Mol Cell.

53:534–548. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Che L, Wu JS, Du ZB, He YQ, Yang L, Lin

JX, Lei Z, Chen XX, Guo DB, Li WG, et al: Targeting mitochondrial

COX-2 enhances chemosensitivity via Drp1-dependent remodeling of

mitochondrial dynamics in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers

(Basel). 14:8212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ceballos MP, Quiroga AD and Palma NF: Role

of sirtuins in hepatocellular carcinoma progression and multidrug

resistance: Mechanistical and pharmacological perspectives. Biochem

Pharmacol. 212:1155732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lu J, Zhang H, Chen X, Zou Y, Li J, Wang

L, Wu M, Zang J, Yu Y, Zhuang W, et al: A small molecule activator

of SIRT3 promotes deacetylation and activation of manganese

superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med. 112:287–297. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

De Matteis S, Granato AM, Napolitano R,

Molinari C, Valgiusti M, Santini D, Foschi FG, Ercolani G,

Vespasiani Gentilucci U, Faloppi L, et al: Interplay between

SIRT-3, metabolism and its tumor suppressor role in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 62:1872–1880. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kim YI, Ko I, Yi EJ, Kim J, Hong YR, Lee W

and Chang SY: NAD+ modulation of intestinal macrophages

renders anti-inflammatory functionality and ameliorates gut

inflammation. Biomed Pharmacother. 185:1179382025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Guan Q: A comprehensive review and update

on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res.

2019:72472382019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Chen X, Zhang M, Zhou F, Gu Z, Li Y, Yu T,

Peng C, Zhou L, Li X, Zhu D, et al: SIRT3 activator honokiol

inhibits Th17 cell differentiation and alleviates colitis. Inflamm

Bowel Dis. 29:1929–1940. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Nistala K and Wedderburn LR: Th17 and

regulatory T cells: Rebalancing pro- and anti-inflammatory forces

in autoimmune arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 48:602–606. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Yu R, Zuo F, Ma H and Chen S:

Exopolysaccharide-producing Bifidobacterium adolescentis strains

with similar adhesion property induce differential regulation of

inflammatory immune response in Treg/Th17 axis of DSS-colitis mice.

Nutrients. 11:7822019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zhang M, Zhou L, Xu Y, Yang M, Xu Y,

Komaniecki GP, Kosciuk T, Chen X, Lu X, Zou X, et al: A STAT3

palmitoylation cycle promotes TH17 differentiation and

colitis. Nature. 586:434–439. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Cros C, Margier M, Cannelle H, Charmetant

J, Hulo N, Laganier L, Grozio A and Canault M: Nicotinamide

mononucleotide administration triggers macrophages reprogramming

and alleviates inflammation during sepsis induced by experimental

peritonitis. Front Mol Biosci. 9:8950282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Vergadi E, Ieronymaki E, Lyroni K,

Vaporidi K and Tsatsanis C: Akt signaling pathway in macrophage

activation and M1/M2 polarization. J Immunol. 198:1006–1014. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhou W, Hu G, He J, Wang T, Zuo Y, Cao Y,

Zheng Q, Tu J, Ma J, Cai R, et al: SENP1-Sirt3 signaling promotes

α-ketoglutarate production during M2 macrophage polarization. Cell

Rep. 39:1106602022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Furness JB: The enteric nervous system and

neurogastroenterology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9:286–294.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Warnecke T, Schäfer KH, Claus I, Del

Tredici K and Jost WH: Gastrointestinal involvement in Parkinson's

disease: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. NPJ Parkinsons

Dis. 8:312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Gockel I, Müller M and Schumacher J:

Achalasia-a disease of unknown cause that is often diagnosed too

late. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 109:209–214. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Niesler B, Kuerten S, Demir IE and Schäfer

KH: Disorders of the enteric nervous system-a holistic view. Nat

Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18:393–410. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Wood JD, Liu S, Drossman DA, Ringel Y and

Whitehead WE: Anti-enteric neuronal antibodies and the irritable

bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 18:78–85. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Brown IAM, McClain JL, Watson RE, Patel BA

and Gulbransen BD: Enteric glia mediate neuron death in colitis

through purinergic pathways that require connexin-43 and nitric

oxide. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2:77–91. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Shi H, Deng HX, Gius D, Schumacker PT,

Surmeier DJ and Ma YC: Sirt3 protects dopaminergic neurons from

mitochondrial oxidative stress. Hum Mol Genet. 26:1915–1926. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Zhang X, Ren X, Zhang Q, Li Z, Ma S, Bao

J, Li Z, Bai X, Zheng L, Zhang Z, et al: PGC-1α/ERRα-Sirt3 pathway

regulates daergic neuronal death by directly deacetylating SOD2 and

ATP synthase β. Antioxid Redox Signal. 24:312–328. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

82

|

Pillai VB, Samant S, Sundaresan NR,

Raghuraman H, Kim G, Bonner MY, Arbiser JL, Walker DI, Jones DP,

Gius D and Gupta MP: Honokiol blocks and reverses cardiac

hypertrophy in mice by activating mitochondrial Sirt3. Nat Commun.

6:66562015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Pillai VB, Kanwal A, Fang YH, Sharp WW,

Samant S, Arbiser J and Gupta MP: Honokiol, an activator of

Sirtuin-3 (SIRT3) preserves mitochondria and protects the heart

from doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in mice. Oncotarget.

8:34082–34098. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Balasubramaniam A, Li G, Ramanathan A,

Mwangi SM, Hart CM, Arbiser JL and Srinivasan S: SIRT3 activation

promotes enteric neurons survival and differentiation. Sci Rep.

12:220762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Sudo N: Biogenic amines: Signals between

commensal microbiota and gut physiology. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 10:5042019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Munteanu C, Onose G, Poștaru M, Turnea M,

Rotariu M and Galaction AI: Hydrogen sulfide and gut microbiota:

Their synergistic role in modulating sirtuin activity and potential

therapeutic implications for neurodegenerative diseases.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17:14802024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM

and Wallace MB: Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 394:1467–1480. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Sánchez-Aragó M, Chamorro M and Cuezva JM:

Selection of cancer cells with repressed mitochondria triggers

colon cancer progression. Carcinogenesis. 31:567–576. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Ku M, Koche RP, Rheinbay E, Mendenhall EM,

Endoh M, Mikkelsen TS, Presser A, Nusbaum C, Xie X, Chi AS, et al:

Genomewide analysis of PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy identifies two

classes of bivalent domains. PLoS Genet. 4:e10002422008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Gan L, Li Q, Nie W, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Tan

C, Zhang L, Zhang J, Li Q, Hou P, et al: PROX1-mediated epigenetic

silencing of SIRT3 contributes to proliferation and glucose

metabolism in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 19:50–65. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Torrens-Mas M, Hernández-López R, Pons DG,

Roca P, Oliver J and Sastre-Serra J: Sirtuin 3 silencing impairs

mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism in colon cancer cells. Am J

Physiol Cell Physiol. 317:C398–C404. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Pavlova NN and Thompson CB: The emerging

hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metabol. 23:27–47. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Amelio I, Cutruzzolá F, Antonov A,

Agostini M and Melino G: Serine and glycine metabolism in cancer.

Trends Biochem Sci. 39:191–198. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Lee GY, Haverty PM, Li L, Kljavin NM,

Bourgon R, Lee J, Stern H, Modrusan Z, Seshagiri S, Zhang Z, et al:

Comparative oncogenomics identifies PSMB4 and SHMT2 as potential

cancer driver genes. Cancer Res. 74:3114–3126. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wei Z, Song J, Wang G, Cui X, Zheng J,

Tang Y, Chen X, Li J, Cui L, Liu CY and Yu W: Deacetylation of