As a sentinel of the immune system, macrophages are

characterized by the robust phagocytic capacity to play a pivotal

role in pathogen clearance and tissue homeostasis (1). Based on their developmental

origins, macrophages are categorized into hematopoietic

monocyte-derived macrophages and embryonic-derived tissue-resident

macrophages (2).

Hematopoietic-derived macrophages originate from CD34+

hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow, progressing

through granulocyte-monocyte progenitors and monocytic stages,

before entering systemic circulation (3). Under specific microenvironmental

signals, such as inflammatory mediators and chemokines, circulating

monocytes are recruited to tissues and subsequently differentiate

into functionally specialized macrophages. By contrast,

embryonic-derived tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk

sac precursors during organogenesis (4-9),

including microglia in the central nervous system (10), Kupffer cells in the liver

(11) and Langerhans cells in

the skin (12). These

developmentally distinct populations differ fundamentally from

their hematopoietic counterparts in both ontogeny and functional

specialization (2,6,8,13-16).

Macrophages exhibit extraordinary plasticity and

functional heterogeneity, dynamically adapting their polarization

states in response to microenvironmental stimuli (17). The classical paradigm classifies

macrophages into pro-inflammatory M1 and

anti-inflammatory/reparative M2 phenotypes (18-20). M1 macrophages, activated by

interferon (IFN)-γ and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (21,22), amplify inflammatory responses and

resist pathogenic infection through the production of IL-1β, IL-6,

IL-12, TNF-α and chemokines (23-26). While being critical for pathogen

containment, sustained M1 activation leads to chronic inflammation

and tissue destruction. Conversely, M2 macrophages polarized by

IL-4/IL-13 secrete immunosuppressive cytokines (such as IL-10 and

TGF-β) to alleviate inflammation and promote tissue regeneration

through growth factor-mediated extracellular matrix remodeling and

angiogenesis (27). However,

their immunosuppressive function may facilitate tumor progression

by establishing pro-tumorigenic microenvironments. Importantly, the

M1/M2 classification is considered an oversimplification of

macrophage functional spectrum. Under pathophysiological

conditions, macrophages exhibit a continuous spectrum of

polarization from M1 to M2 phenotypes, rather than discrete binary

states (28-31). Tissue macrophages frequently

exhibit hybrid phenotypes with overlapping M1-M2 characteristics,

reflecting their capacity to adapt to dynamic microenvironmental

changes. To further clarify this conceptual framework, it is

essential to distinguish between the processes of macrophage

activation and polarization. Macrophage activation refers to the

early process by which macrophages sense external stimuli through

receptor-mediated signaling pathways, initiating intracellular

cascades that endow them with enhanced responsiveness and effector

potential. Macrophage activation represents a transition from

resting state to functionally poised state. By contrast, macrophage

polarization, dictated by specific cytokine milieu and

environmental cues, denotes a more specialized process in which

activated macrophages differentiate along a continuous spectrum

into distinct functional phenotypes (32,33). Therefore, activation represents

the initiation of macrophage responsiveness, whereas polarization

describes the directional specification that follows.

Through coordinated phagocytosis, antigen

presentation, cytokine secretion and crosstalk with immune and

non-immune cells, macrophages play a central role in regulating

inflammatory responses, host defense and tissue homeostasis.

Dysregulated macrophage function underlies numerous pathologies.

For instance, macrophages take up lipids from the blood to

transform into foam cells, thereby promoting plaque formation and

atherosclerotic progression (34-39). Obesity-associated metabolic

disorders are featured by the macrophage-mediated chronic low-grade

inflammation, which triggers the development of insulin resistance

and type 2 diabetes (40-47).

In certain cases, M2 macrophages may promote tumor cell growth,

metastasis, invasion and drug resistance by secreting

immunosuppressive factors and enhancing tumor angiogenesis through

cytokines (such as VEGF) (48-52). As highly plastic innate immune

cells derived from myeloid precursors, the differentiation of

macrophage is orchestrated by the macrophage colony-stimulating

factor (M-CSF, also known as CSF1) (53-55). This process is fundamentally

governed by the transcription factor purine-rich U-box binding

protein 1, which drives macrophage lineage differentiation through

transcriptional activation of the M-CSF receptor CSF1R (56-58). NF-κB and STAT1 pathways drive

classical M1 polarization (59,60), while alternative M2 polarization

is mediated by JAK1/3-STAT6 signaling and nuclear receptor

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) (61-65). Collectively, these observations

underscore that macrophage differentiation, activation and

polarization are governed by intricate transcriptional networks.

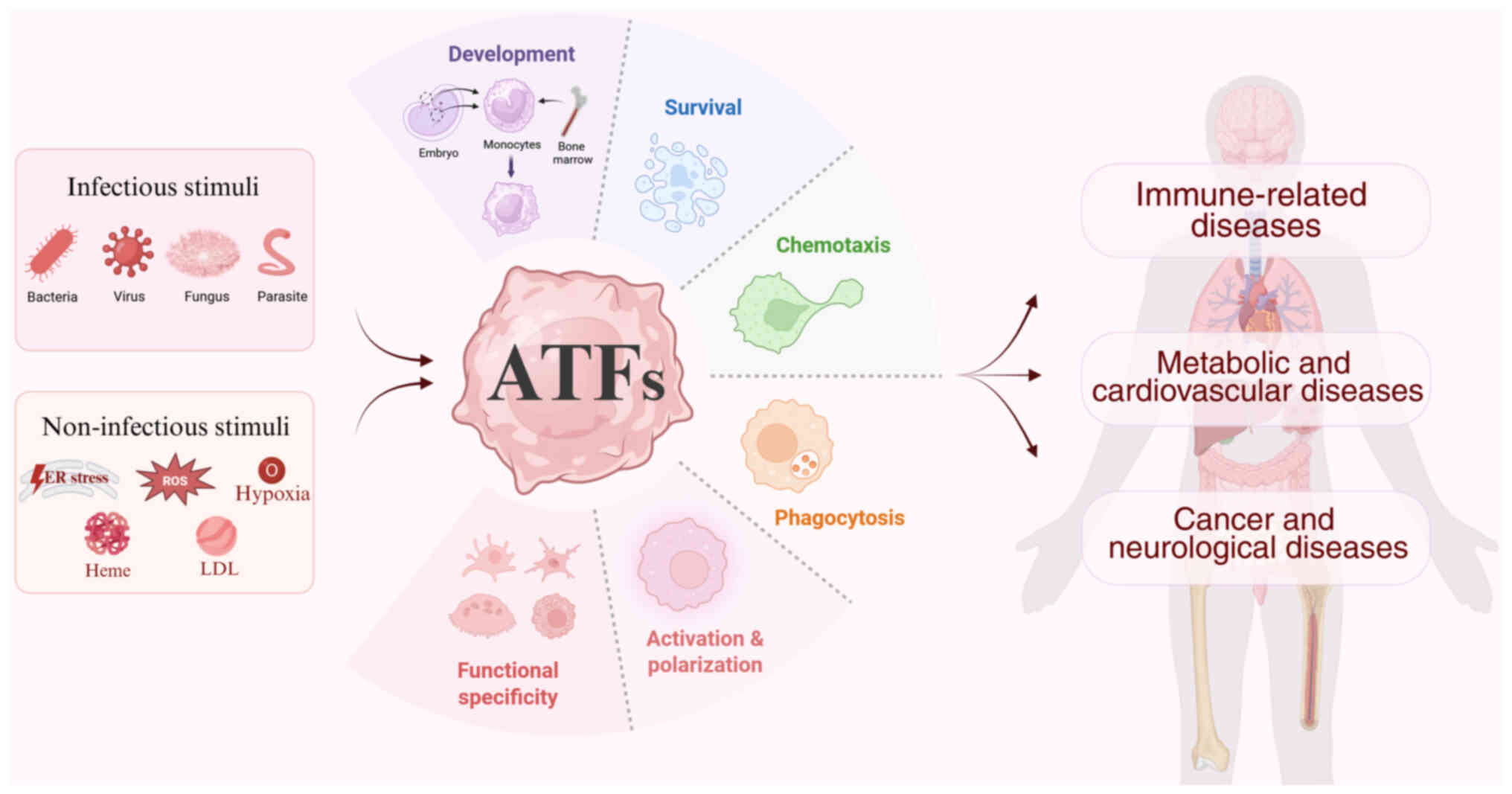

Among these, the activating transcription factors (ATFs) have

emerged as pivotal integrators of immune and metabolic cues,

orchestrating macrophage responses under diverse physiological and

pathological conditions. The current review sought to summarize the

recent findings on how activated ATFs regulate macrophage

development, survival, migration, phagocytosis, activation,

cytokine secretion, polarization and their involvement in immune,

metabolic, cardiovascular, neurological disorders and cancer, with

a particular emphasis on their therapeutic potential (Fig. 1).

The ATF family, comprising seven members (ATF1-7),

was initially characterized in 1987, as a group of transcriptional

factors involved in the regulation of gene expression across

diverse biological contexts (66). All ATF members share a highly

conserved basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain comprising a basic

region responsible for DNA binding and a leucine zipper structure

that mediates dimerization (67,68). ATFs are activated by upstream

signals and exert transcriptional activities by forming either

homodimers or heterodimers with other bZIP transcription factors

such as AP-1 or C/EBP family members. ATF1 commonly forms

heterodimers with cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) or

cAMP response element modulator (CREM) family members to bind to

DNA and regulate target gene transcription (69-72). ATF2 dimerizes with c-Jun to form

a canonical AP-1 complex (73,74), while its structurally related

homolog ATF7 could interact with ATF2 to generate functional

heterodimers (75-77). ATF3 cooperates with bZIP proteins

including c-Jun, JunB, or C/EBP to regulate responsive genes

(78,79). ATF4 integrates stress and

metabolic signals through heterodimerization with members of the

C/EBP family or with nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

(NRF2) to coordinate adaptive transcriptional programs (80-82). Similarly, ATF5 forms functional

heterodimers with C/EBPγ (83).

ATF6, however, undergoes a unique activation process. At steady

state, ATF6 resides in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane as a

monomer, dimer, or oligomer. Upon the challenge of ER stress, ATF6

translocates into the Golgi apparatus, where it is cleaved by

S1P/S2P proteases to release its N-terminal fragment (50 kDa) that

enters the nucleus. The nuclear p50 ATF6 forms homodimers or

heterodimers with its homolog ATF6β (84) and both of them can associate with

nuclear transcription factor Y (NF-Y) to form transcriptional

complexes (85). In addition,

ATF6 has been shown to heterodimerize with XBP1s, thereby

broadening its target gene repertoire (86).

The specific dimerization partners of each ATF

member largely determine its DNA-binding specificity and

transcriptional outcomes. Accordingly, ATF1 and ATF5 predominantly

recognize canonical CRE sequences (70,87), whereas the binding preferences of

ATF2, ATF3 and ATF7 are largely determined by their dimerization

partners (88-91). Once they form homodimers or

heterodimers with the CREB family members, they preferentially bind

to the CRE consensus sequence. By contrast, heterodimerization with

AP-1 family proteins, such as c-Jun, redirects their binding toward

AP-1 sites (74,78,92-94). Moreover, ATF3 and ATF4 can

recognize C/EBP-ATF response elements (CARE), to composite motifs

containing both CCAAT-box and CRE characteristics (95). Under stress conditions, the

C/EBPγ-ATF4 heterodimer constitutes the predominant form to bind to

the CARE motifs (81), whereas

ATF4 can also form a complex with C/EBPβ to regulate

differentiation-related gene expression (80). When ATF4 forms heterodimers with

NRF2, the complex can recognize both antioxidant response elements

(AREs) and ATF/CRE motifs, thereby synergistically activating

antioxidant and detoxifying gene transcription (96). Likewise, ATF6α/ATF6β

heterodimers, as well as ATF6α homodimers, associate with NF-Y to

recognize ER stress response elements, which comprise a 5'-CCAAT-3'

core, a GC-rich spacer and a terminal 5'-CCACG-3' motif (97-101). Within this composite motif, the

CCAAT box serves as the NF-Y binding site, whereas ATF6 recognizes

and binds to the terminal CCACG half-site to initiate transcription

of target genes (85,102). Notably, CRE sequences vary

among genes, often exhibiting one or two base substitutions and

even half-CRE sites (such as TGACG or CGTCA) can be recognized by

ATFs, suggesting that while the core CRE motif is evolutionarily

conserved, a certain degree of sequence flexibility is tolerated

(103).

The activation and function of the ATF family are

governed by multi-layered regulatory mechanisms operating across

epigenetic, transcriptional and post-translational dimensions.

Epigenetic control involves DNA methylation (such as ATF3 silencing

through promoter hypermethylation) (104), dynamic histone modifications

and mRNA m6A modifications. Transcriptionally, factors, such as

SP1/MYC and p53, modulate ATF activity via promoter binding

(104). Post-translationally,

numerous ATFs are activated through phosphorylation (PKA or MAPK)

(105), while others undergo

regulated proteolysis (such as cleavage of ATF6) or

ubiquitin-mediated turnover (106), all of which influence their

stability, localization and activity. Specifically, under stress

conditions, JNK/p38 MAPK phosphorylates ATF2 to enhance its

transcriptional activity (107), while ER stress activates ATF4

and ATF6 via the unfolded protein response (UPR) to restore

proteostasis (106,108). Moreover, ATFs could also be

regulated by signals such as IL-6, LPS or growth factors (109-111), thereby integrating immune and

metabolic cues into coordinated transcriptional responses. Once

activated, ATFs execute their transcriptional regulatory functions

primarily through the recruitment of a wide range of

transcriptional cofactors and chromatin-modifying complexes that

sculpt gene expression programs. Among them, ATF family members

recruit diverse histone-modifying enzymes and chromatin-remodeling

complexes to mediate epigenetic regulation. For example,

phosphorylated ATF1 recruits the histone acetyltransferase CBP/p300

to enhance local H3/H4 acetylation and chromatin accessibility

(112,113). Similarly, following LPS

stimulation, ATF2 recruits histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) to remove

repressive acetylation marks, thereby facilitating target gene

transcription (114). However,

activated ATF3 recruits HDAC1 onto promoters of proinflammatory

genes to erase permissive acetylation marks and repress gene

transcription, implying the complex nature of ATF-related

epigenetic regulation (115,116). Upon the insult of ER stress,

ATF6α recruits the mediator complex together with multiple histone

acetyltransferase assemblies, including SAGA and ATAC, to promoters

such as HSPA5, to increase local histone acetylation level

(117,118). ATF7 persistently recruits the

histone H3K9 methyltransferase G9a in resting macrophages to

deposit the repressive H3K9me2 mark, which silences the

transcription of innate immune genes and maintain the quiescent

state (119). Moreover, ATF6α

recruits arginine methyltransferases such as PRMT1, to methylate

histone arginine residues at target genes, by which it remodels

chromatin architecture and regulates stress-responsive gene

expression (120). Moreover,

some ATF members can directly or indirectly recruit ATP-dependent

chromatin-remodeling complexes, altering nucleosome positioning and

conformation to reorganize the chromatin landscape (112).

ATFs play a crucial role in various biological

processes. For instance, ATF family members regulate antioxidant

gene expression during ER stress and oxidative stress responses,

serving as a critical regulator in stress adaptation (121-123). In glucose and lipid metabolism,

ATF proteins modulate the expression of multiple metabolic genes to

maintain glucose and lipid homeostasis (111,124). Furthermore, ATF members

participate in immune responses by regulating inflammatory cascades

and immune evasion (125-128), the balance between autophagy

and apoptosis (129) and the

process of cell senescence (126). Notably, perturbation of ATF

signaling networks demonstrates strong association with tumor

(130), metabolic disorders

(121), neurodegenerative

diseases (121) and

immune-related diseases (124,131). Such dynamic nature warrants

ATFs as a crucial hub for developing targeted therapeutic

strategies.

ATFs exert multidimensional regulatory effect on

macrophage development and functional homeostasis through

regulating the proliferation, differentiation and metabolic

pathways. During macrophage development, ATF4 serves as a master

regulator to govern monocytes differentiation to gut-resident

macrophages (gMac). In septic models, ATF4 depletion in

Ly6C+ monocyte precursors (P1 cells) disrupts gMac (P4

cell) differentiation coupled with aberrant proliferation and

increased apoptosis of P1 cells, leading to exacerbated intestinal

barrier dysfunction (132).

ATF2 orchestrates monocyte differentiation through modulating the

expression of phosphatase PPM1A by binding to its promoter

(133). In atherosclerosis, the

accumulation of macrophages is markedly reduced in plaques of mice

overexpressing ATF3. ATF3 overexpression suppresses the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway, by which it downregulates the expression of

matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2/MMP-9) and reduces

macrophage-mediated extracellular matrix degradation, coupled with

plaque stabilization (134).

Notably, the anti-proliferative effect of ATF3 persists throughout

the macrophage lifespan by suppressing cell cycle genes

(Mem2 and Cdk2) and inhibiting the Clec4e-Csf1 axis

(135,136).

Regarding macrophage senescence and cell death, ATF4

is identified as the core responder to hypoxic stress and it

rapidly accumulates in macrophage nuclei within 1-h of hypoxic

challenge to activate adaptive gene networks to sustain cell

viability (137). ATF3 exhibits

anti-senescence properties in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

infection models. Macrophages deficient in ATF3 exhibit

elevated ROS levels and accelerated senescence, while ectopic ATF3

overexpression partially reverses these phenotypes (138). Additionally, in LPS-stimulated

microglia, ATF2 exacerbates inflammatory pyroptosis by upregulating

IL-1β, NLRP3 and key pyroptotic effector molecules such as GSDMDC1

and Caspase-1 (139).

ATF family members essentially regulate macrophage

chemotaxis and phagocytosis by modulating chemokine expression and

cytoskeletal remodeling. LPS induces phosphorylation of ATF2 in

alveolar epithelial cells, which subsequently upregulates

macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) to promote macrophage

recruitment (140).

Additionally, LPS enhances macrophage chemotactic capacity

via ATF3, which binds to the CRE/AP-1 motif within the

promoter of Regulated upon Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed and

Secreted (RANTES) (141). Notably, ATF3 also regulates

macrophage migration through other mechanisms. Transwell assays

suggest that ATF3-overexpressing macrophages exhibit markedly

enhanced migration under MCP-1 treatment (142,143). Mechanistically, ATF3 suppresses

gelsolin expression and F-actin de-polymerization to promote

cytoskeleton reorganization (144). On the other hand, ATF3

activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to upregulate

extracellular matrix protein tenascin C, which subsequently

reinforces macrophage migration (142). These findings elucidate the

molecular basis by which ATF family members, ATF3 in particular,

integrate chemokine networks and cytoskeletal dynamics to precisely

orchestrate macrophage migration.

Macrophage activation and cytokine secretion are

orchestrated by ATFs that integrate microbial, metabolic and

stress-derived signals, into coordinated transcriptional programs.

ATF1, ATF5 and ATF6 predominantly act as pro-inflammatory drivers,

while ATF3 and ATF7 serve as negative feedback regulators.

Intriguingly, ATF2 and ATF4 exhibit context-dependent dual

functions, capable of both amplifying and restraining inflammatory

responses depending on the microenvironmental cues. The upstream

stimuli, signaling connections and differential impacts on cytokine

expression are summarized in Fig.

2 and Table I, which

together outline the overall regulatory network and highlight the

synergistic and antagonistic interactions among ATF members. The

dynamic equilibrium among these ATF subsets ultimately determines

the intensity and persistence of macrophage activation and cytokine

production.

ATF family members regulate macrophage

pro-inflammatory activation through multiple pathways. ATF1,

activated via sensing bacterial peptidoglycan (PGN), drives

pro-inflammatory cytokine transcription either in its

phosphorylated form or as a dimer with CREB (153). ATF5 directly amplifies

inflammatory responses by upregulating TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6

expression (154). ATF6, a key

regulatory factor in ER stress (155), is essential for initiating the

UPR triggered by pattern recognition receptors such as

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2

(NOD2) (106). Upon the

challenge of oxLDL, ATF6 dissociates from the ER membrane, moves

into the Golgi apparatus, where it is cleaved into its active form

(p50-ATF6), which subsequently translocates into the nucleus to

regulate target genes, such as GRP78 and XBP-1 (156). Activated ATF6 stimulates the

expression of genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, but

represses the genes associated with cholesterol efflux (Abca1,

Abcg1, Lxrα), to drive cholesterol accumulation (157). ATF6 directly binds to the

Tnf-α promoter to enhance its transcriptional activity,

thereby activating the NF-κB and TNF signaling pathways and driving

macrophages to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα,

IL-1β and IL-6 (156). In liver

Kupffer cells, ATF6 also mediates the pro-inflammatory enhancement

of TLR4 response and cytokine production (158). Markedly, ubiquitination at K152

residue of ATF6 is essential for its antimicrobial function.

Mutations at this site (ATF6-K152A) exhibit defective bacterial

uptake, coupled with reduced ROS generation, diminished LC3II/ATG5

expression and impaired intracellular pathogen clearance (159). Together, these findings

establish ATF1, ATF5 and ATF6 as central mediators that translate

microbial and metabolic stress into potent inflammatory cytokine

programs.

In sharp contrast, ATF3 and ATF7 largely hinder the

activation of macrophages. Under physiological condition, ATF7 acts

as an epigenetic repressor by recruiting histone H3K9

dimethyltransferase G9a to the promoters of activation-related

genes (such as Cxcl2, Ccl3, Stat1,

Myo10, Nfkb2 and Tap1), thereby maintaining

macrophage at the resting state. However, LPS stimulation induces

p38-dependent phosphorylation of ATF7, prompting ATF7 dissociation

from chromatin, which leads to a significant reduction of H3K9me2

levels at target genes and the unleashing of transcriptional

repression. Such epigenetic change persists for weeks, which

sustains low H3K9me2 levels and high transcriptional activity to

confer long-term immune memory (119). Similarly, ATF3 functions as an

essential effector in curbing excessive macrophage activation.

First, ATF3 inhibits the phosphorylation of JNK, ERK and p38 MAPK,

thereby reducing the production of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-12β

induced by LPS, ROS, or Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection

(125,138,160-162). Second, NRF2 binds to the

antioxidant response elements (ARE1) within the Atf3

promoter to initiate Atf3 transcription (161). Activated ATF3 then recruits

HDAC1 to pro-inflammatory gene promoters (143,163), thereby reducing H3/H4 histone

acetylation (138,164) and counteracting Rel/NF-κB

transcriptional activity (115,164,165). This epigenetic pathway is

further reinforced in Clec4e-mediated response, in which ATF3

inhibits the downstream NF-κB/JNK pathway and reduces TNF-α and

CCL2 secretion (136).

Moreover, ATF3 also promotes GDF15 expression to foster the

adaptation of macrophages to metabolic stress (125). Collectively, by counteracting

the effects of ATF1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, ATF3 and ATF7 serve as critical

rheostats in maintaining macrophage homeostasis.

ATF2 and ATF4 display dual regulatory activities

that depend on the nature, strength and duration of environmental

stimuli. As a key regulator in Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling,

ATF2 undergoes p38 MAPK-dependent phosphorylation at Thr71

(107,166), through which it promotes the

expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as inducible nitric

oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), TNF-α, IL-6 and

IL-1β (167-172). This process is further

amplified by the formation of AP-1 complex with c-JUN, which

enhances the production of nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin

E2 (PGE2) (173). Notably, ATF2 is highly

expressed in M1 macrophages within the white adipose tissue from

obese mice, where its phosphorylation is induced by ROS and LPS

(139) and sustains the

pro-inflammatory phenotype by suppressing the expression of

anti-inflammatory ATF3 (174).

Furthermore, ATF2 forms heterodimers with HDAC1 to induce

Socs-3 transcription to negatively regulate TLR4-mediated

inflammation (118),

demonstrating its dual regulatory nature. Under metabolic stress,

such as cholesterol accumulation, ATF4 is activated via the

protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK)-eukaryotic translation

initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α) pathway. During transient stress,

ATF4 promotes macrophage survival, whereas persistent stress

induces the expression of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP),

triggering macrophage apoptosis along with the release of

inflammatory mediators (175,176). In obese microenvironments, ATF4

acts as a metabolic stress sensor, transcriptionally upregulating

protein disulfide isomerase a3 (PDIA3) to drive TNF-α, IL-6 and

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) production, thereby

intensifying adipose tissue inflammation (177). The dual regulatory role of ATF4

is further reflected in its ability to influence antioxidant

defenses. Knockdown of ATF4 reduces NRF2 activity and HO-1

expression, leading to attenuated antioxidant defenses and

increased NO production (82).

Overall, ATF2 and ATF4 act as context-dependent signal integrators

that fine-tune macrophage activation, coordinating inflammatory,

oxidative and metabolic pathways to define the amplitude and

persistence of cytokine responses.

ATFs exert multidimensional roles in macrophage

polarization via metabolic reprogramming and signal transduction.

ATF1 drives macrophage polarization toward the antioxidant 'Mhem'

phenotype through coordinated regulation of iron and lipid

metabolism. This involves the induction of HO-1, which promotes the

degradation of heme into iron and antioxidant metabolites

(biliverdin and bilirubin) to help mitigate oxidative stress.

Furthermore, ATF1 activates liver X receptor-β (LXR-β) to augment

the expression of cholesterol efflux proteins ABCA1 and ApoE, by

which it reduces lipid accumulation and prevents foam cell

formation (178).

Phosphorylated ATF1 further improves macrophage adaptation to

intraplaque hemorrhage, thus maintaining the homeostasis under

dural iron-lipid stress (178).

ATF2 deficiency (THP-ΔATF2) induces abnormal macrophage morphology,

whereas ATF2 overexpression (THP-ATF2) triggers a rounded,

flattened morphology resembling M1 macrophages, along with elevated

expression of MHC class II, IL-1β and interferon-γ-induced protein

10 (133). Mechanistically,

ATF2 drives M1 polarization by enhancing glycolytic flux.

Metabolomic profiling confirmed that those ATF2-overexpressing

macrophages recapitulate the classical M1 metabolic signatures

(139).

ATF3 also plays a pivotal role in macrophage

polarization. Overexpression of ATF3 suppresses the differentiation

of M1 (pro-inflammatory) macrophage, as evidenced by the decreased

expression of M1 markers such as TNF-α and CD11c in adipose

tissues, thereby attenuating local inflammation (179). In atherosclerotic lesions, ATF3

mediated inhibition of M1 polarization reduces inflammatory

responses and lowers the risk of plaque rupture. In tumor

microenvironments, cyclophosphamide (CTX)-induced pro-tumor

macrophage traits are reversed in ATF3-knockout mice, shifting

macrophages toward anti-tumor phenotypes (147). ATF3 also enhances M2

(anti-inflammatory) macrophage program through indirect pathways.

ATF3 suppresses the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway, leading to the

death of renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs). The resulting

apoptotic RTECs release miR-1306-5p-containing exosomes, which in

turn inhibit M1 activation while enhance M2 polarization (180). In placental accreta spectrum

(PAS) lesions, upregulated ATF3 facilitates M2 macrophage

polarization by enhancing the expression of PD-L1, which interacts

with PD-1 to strengthen the immunosuppressive microenvironment

(181). Conversely, during

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL)-induced

osteoclastogenesis, ATF3 overexpression promotes osteoclast

formation and activity. ATF3 directly binds to the promoters of key

transcription factors c-Fos and NFATc1, to drive

macrophage-to-osteoclast differentiation. However, as a

pro-inflammatory ATF member, ATF4 could otherwise promote M2

program (122,182). Upon hypoxic insult, ATF4

upregulates the expression of M-CSF in hemangioma stem cells

(HemSCs), to facilitate M2 macrophage polarization (183). ATF4 also activates RANKL

signaling by promoting NFATc1 expression, synergistically

regulating the differentiation of osteoclasts (184,185). Furthermore, ATF4 drives the

transition of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) into foam cells,

as evidenced by the upregulation of macrophage markers such as

Cd68 and Lgals3 (186).

Under various pathological conditions, macrophages

exhibit disease-specific functional plasticity. Emerging evidence

indicates that members of the ATF family in macrophages display

distinct and highly disease-specific activation patterns rather

than a uniform stress response. Overall, ATF1, ATF2, ATF4, ATF5 and

ATF6 are persistently upregulated in most inflammatory, metabolic

and stress-related diseases, acting primarily as transcriptional

activators that drive pro-inflammatory programs or adaptive stress

responses. By contrast, ATF3 and ATF7 are predominantly induced as

negative feedback regulators to restrain excessive inflammation or

mediate innate immune memory. Importantly, the direction and

magnitude of these expression changes are strongly

context-dependent. For instance, ATF1 is markedly upregulated

during sepsis and atherosclerosis but suppressed in tissue

hemorrhage (150,153,178). In addition, ATF3 is rapidly

induced during the early hyperinflammatory phase of sepsis to

attenuate cytokine storm, whereas its sustained overexpression at

later stage contributes to immunosuppression (142,161,162,187). Furthermore, ATF4 is

downregulated during early acute sepsis, but is elevated under

chronic metabolic stress (132,177,182,186). These observations suggest that

ATF activation is finely orchestrated by disease-specific

microenvironments through the selective engagement of distinct

upstream signaling pathways. A detailed summary of ATF expression

dynamics in various diseases and their pathophysiological

consequences, along with related signaling pathways, is presented

in Table II.

In infectious and immune-related diseases,

macrophages situate at the first line of defense (1,188). During the early inflammatory

phase, they rapidly recognize and phagocytose pathogens, release

pro-inflammatory cytokines and recruit other immune cells to the

infection sites, thereby amplifying host defense (189-191). However, excessive or prolonged

activation can lead to systemic inflammatory syndromes, such as

sepsis and cause secondary tissue injury (191,192). As inflammation resolves,

macrophages adopt a reparative phenotype that clears apoptotic

cells and produces anti-inflammatory mediators to promote tissue

repair (193). Moreover,

macrophages can acquire innate immune memory, known as trained

immunity, which enables them to respond more effectively to

secondary challenges through enhanced cytokine production and

antimicrobial activity (194).

By contrast, excessive suppression of macrophage activation impairs

pathogen clearance and increases vulnerability to secondary

infections, thereby disturbing immune homeostasis (195,196). In chronic inflammatory

conditions, persistent low-grade activation or failure to

transition into a reparative state drive sustained cytokine

production, tissue remodeling and fibrosis, all of which predispose

to disease progression (197).

During bacterial infection, ATF3 exhibits pathogen-specific

regulatory effect. Specifically, ATF3 enhances macrophage clearance

of Staphylococcus aureus by directly binding to the

promoters of antimicrobial peptide genes, such as Reg3β and

S100A8/9, to bolster host defense (198). Conversely, during

Pseudomonas aeruginosa or uropathogenic E. coli

infection, ATF3 attenuates host resistance by downregulating

pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α and IL-6) and upregulating IL-10

(138). Following

Leishmania infection, ATF3 expression reaches the highest

after 1-h of infection, which establishes an anti-inflammatory

environment in favor of parasite survival (163). ATF4 enhances macrophage

antioxidant capacity by promoting HO-1 expression to limit NO

production, thus creating an environment conducive to Leishmania

amazonensis survival (82).

By contrast, ATF7 contributes to innate immune memory by modulating

STAT1/NF-κB-dependent inflammatory networks (such as CXCL9/10),

thus enhancing macrophage-mediated responses against bacteria and

fungi (119). In antiviral

immunity, ATF2 activates the p38 MAPK/ATF2/AP-1 axis to promote the

secretion of interferon-stimulated genes and IFN-β, thereby

enhancing the resistance to vesicular stomatitis virus,

Newcastle disease virus and herpes simplex virus

(105). However, ATF3 may

compromise murine norovirus clearance by suppressing type I

interferon expression or impairing Mx1 activity (125). During Aspergillus

fumigatus infection, ATF4 is upregulated via the

TLR4/LOX-1/MAPK pathway, which modulates corneal macrophage barrier

function and disease severity (199).

In acute inflammatory diseases, ATFs exhibit a

dynamic and balanced role. Hyperactivation of ATF1 induces

excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine release from macrophages,

contributing to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or

septic shock (153). ATF3 plays

a complex part at different septic stages. In LPS-induced septic

models, ATF3 reduces TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β levels in plasma,

potentially mitigating early-stage hyperinflammation (162,187). Additionally, ATF3 promotes

macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype, enhances the

expression of anti-inflammatory factors such as Arg-1 and PPARγ,

but suppresses M1 markers (such as iNOS and TNF-α), thereby

alleviating inflammatory responses and facilitating tissue repair

(142). However, during the

sepsis-associated immunosuppression phase, persistent ATF3

overexpression impairs immune responses and increases

susceptibility to secondary infections (161). During septic progression,

reduced ATF4 expression in P1 cells leads to diminished gMacs,

which promotes bacterial translocation across the epithelial

barrier and worsens systemic inflammation (132). ATF5 contributes to

sepsis-associated liver injury by promoting the accumulation of

inflammatory macrophages (CD45+ CD11b+

Ly6C+) through an NF-κB-dependent pathway, leading to

the release of inflammatory cytokines (154). Excessive activation of ATF1 is

also associated with the progression of SIRS and sepsis by

enhancing macrophage cytokine secretion (153).

In chronic inflammatory diseases, ATF family

members influence macrophage polarization and amplify inflammatory

signaling, contributing to disease pathology. In LPS-induced acute

lung injury, ATF2 exacerbates pulmonary inflammation by

upregulating MIP-2 to further recruit macrophages (140), while ATF6 intensifies

macrophage activation and cytokine release via ER stress

signaling (200). ATF2

activation also amplifies TLR signaling cascades and exacerbating

chronic inflammation (107,170). Moreover, upon LPS stimulation,

ATF2 promotes IL-23 secretion in macrophages, which then induces

pathogenic Th17 cell expansion in autoimmune disorders, such as

multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid

arthritis (201). In

organ-specific inflammatory injuries, ATF3 exhibits bidirectional

regulatory properties. ATF3 attenuates renal ischemia-reperfusion

injury (IRI) by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB pathway (165). However, IRI-induced ATF3

overexpression in RTECs exacerbates ferroptosis and promotes the

release of exosomes carrying miR-1306-5p. These exosomes, upon

uptake by macrophages, drive M2 polarization and accelerate

interstitial fibrosis (180).

In alcohol-induced immunosuppression, ATF3 upregulation leads to

enhanced Kupffer cell tolerance to LPS and reduced TNF-α

production, impairing pathogen clearance and exacerbating alcoholic

liver disease (143). In

dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis, activation of the

ATF4-CHOP pathway drives excessive release of inflammatory

cytokines, intensifying intestinal inflammation and epithelial

damage (176). It was also

noted that ATF6 deficiency impairs macrophage antibacterial

responses, worsening intestinal inflammation (106). During hepatic

ischemia-reperfusion injury, ATF6 aggravates tissue damage by

enhancing NF-κB activation and suppressing the anti-inflammatory

Akt-GSK3β signaling pathway in Kupffer cells (158). However, during early acute

liver injury, ATF6 activation via ER stress promotes IL-1α

production, activating HSCs and driving liver fibrosis (159). ATF6 deficiency in microglia

attenuates inflammation in autoimmune encephalomyelitis by

promoting NF-κB p65 degradation (202).

In metabolic disorders, adipose tissue macrophages

produce pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β

to impair insulin signaling and disrupt adipocyte homeostasis,

thereby contributing to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome

(203-207). ATF4 exacerbates chronic

inflammation in adipose tissue, driving the progression of

metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus (177,182). By contrast, ATF3 mitigates

obesity-associated inflammation by suppressing TLR4-mediated

macrophage activation. Therefore, mice deficient in ATF3

exhibit aggravated obesity-related inflammation and insulin

resistance, underscoring its protective role in maintaining

metabolic homeostasis (162).

Conversely, ATF2 activation intensifies macrophage M1 program

within adipose tissue by perpetuating an 'inflammation-hypoxia-ROS'

vicious cycle, worsening insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome

(173). Additionally, ATF2

aggravates inflammation and metabolic disturbances in white adipose

tissue by suppressing ATF3 expression, further enhancing M1 program

(139).

In atherosclerosis, macrophages take up OxLDL to

form foam cells and orchestrate inflammatory and reparative

responses within vascular lesions, thereby playing a pivotal role

in plaque formation and progression (28,34,36). ATFs influence disease progression

by regulating macrophage lipid metabolism and plaque stability.

ATF3 exerts an atheroprotective effect through multiple mechanisms.

ATF3 suppresses cholesterol 25-hydroxylase to reduce oxidized

cholesterol accumulation and promotes macrophage RCT, thereby

limiting foam cell formation (148,208). Furthermore, ATF3 stabilizes

plaque structure by inhibiting macrophage apoptosis and the release

of inflammatory mediators, lowering the risk of myocardial

infarction and stroke (134).

ATF3 deficiency impairs ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux,

aggravating oxLDL-induced lipid deposition (136). Moreover, ATF1 induces Mhem

macrophage polarization and activates the HO-1/LXR-β pathway to

enhance cholesterol efflux and iron chelation, thereby delaying

plaque progression and rupture (150,178). By contrast, ATF6 activation

positively correlates with the severity of atherosclerotic lesion

and accelerates plaque development by facilitating cholesterol

accumulation (157). ATF4

drives necrotic core expansion and plaque destabilization

via switching an SMC phenotype ('transdifferentiated SMCs'

which express both macrophage and fibroblast markers) and inducing

CHOP-dependent cell apoptosis (186). As a downstream effector of PKCθ

signaling, ATF2 upregulates CD36 to accelerate foam cell formation

and plaque progression. PKCθ-deficient mice exhibit blunted ATF2

activation, along with reduced CD36 levels and markedly smaller

plaque areas (149). Moreover,

ATF1 deficiency impairs the segregation of iron and lipid within

macrophages, resulting in their colocalization, which disrupts iron

metabolic homeostasis, delays hematoma clearance following tissue

hemorrhage and exacerbates oxidative stress-related damage

(150). Collectively, ATFs

spatiotemporally modulate macrophage inflammatory state, thus

influencing the pathological progression of metabolic and

cardiovascular diseases.

Macrophages are major immune infiltrates that

regulate angiogenesis, immune suppression, antigen presentation and

metastatic dissemination in the tumor microenvironment (1,209). In bone lesions, macrophages

further contribute to osteoclast differentiation and tumor-induced

bone destruction (210-212). ATF4 regulates tumor-associated

macrophage polarization and promotes the differentiation of

monocyte-macrophage precursors into osteoclasts to enhance bone

resorption. In parallel, ATF4 exacerbates inflammation through the

NF-κB signaling axis, further accelerating cancer-associated bone

destruction (184). Unlike

ATF4, ATF3 exhibits functional heterogeneity in tumor

immunomodulation. Tumor-derived IL-1β upregulates ATF3 in bone

marrow hematopoietic stem cells, driving myeloid precursor

expansion and increasing peripheral CD11b+ myeloid

cells, including TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages. In a breast

cancer model, ATF3 deficiency inhibits monocyte-macrophage

differentiation, while its overexpression serves as an early

biomarker distinguishing malignant lesions (213). Furthermore, ATF3 activates

immune checkpoint pathways to amplify CD14+

immunosuppressive macrophages in PAS lesions, exacerbating

pathological progression (181).

In neurological diseases, macrophages and microglia

not only phagocytose neuronal debris but also release

neuroregulatory substances and inflammatory mediators, thereby

modulating neuronal survival and degeneration (214,215). ATF2 promotes neuroinflammatory

cascades in multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease (AD) and

Parkinson's disease by promoting pyroptosis in macrophages and

microglia (139). Additionally,

ATF4 is the core transcription factor for AD microglial cells to

integrate stress response, by inducing them to enter the neurotoxic

state and mediating neurodegeneration through lipid secretion

(216). Furthermore, ATF4

synergizes with HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions in infantile

hemangioma (IH) proliferative phases, driving M2 macrophage

infiltration to fuel lesion expansion (183).

Targeting ATFs in macrophages offers a promising

therapeutic strategy, as these key transcription factors

orchestrate diverse macrophage functional states, thereby enabling

precise modulation of disease processes (Table III). Currently, therapeutic

strategies targeting ATFs can be broadly divided into three

categories: Direct intervention, which employs small-molecule

agonists or inhibitors and gene-editing approaches to directly

modulate ATF expression or activity; indirect modulation, which

targets upstream signaling pathways or downstream effector

molecules to influence ATF-dependent regulatory networks; and

emerging innovative techniques, including proteolysis-targeting

chimera (PROTAC)-mediated protein degradation, peptide or

peptidomimetic modulators and molecular glue technologies, which

offer more efficient and specific manipulation of ATF

functions.

Blocking the function of ATFs through small

inhibitors, short interference (si)RNA, or gene-editing

technologies offers a strategic approach to precisely control

disease states driven by macrophages. Targeted inhibition of ATF1

reduces osteoclastogenesis by suppressing the miR-214-5p/ITGA7

axis, suggesting a novel direction for osteoporosis treatment

(217). The traditional herbal

medicine, HangAmDan-B (HAD-B), reduces LPS-induced NO and

PGE2 production in macrophages by blocking ATF2

phosphorylation, consequently limiting tumor-promoting activity of

TAMs in gastric and colorectal cancers (166). Ginsenoside Rc markedly reduces

LPS-induced TNF-α release by suppressing the p38/ATF2 pathway,

presenting a candidate strategy for rheumatoid arthritis and other

inflammatory diseases (168).

Moreover, the traditional compound formula Qingfei Paidu Decoction

and its active component wogonoside, inhibit ATF2 phosphorylation

and enhance its ubiquitin-mediated degradation, curbing

macrophage-mediated inflammation and showing potential as adjunct

therapies for coronavirus pneumonia and colitis (169). Moreover, extracts from

Vaccinium oldhamii stems reduce ATF2 nuclear accumulation,

which blocks MAPK signaling pathway activation and limits

macrophage-driven osteoclast differentiation to mitigate bone

resorption (218). Exosomes

derived from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) or mesenchymal stem

cells attenuate ATF2 expression, resulting in reduced NF-κB

activation, decreased ROS generation and diminished macrophage

infiltration, thereby mitigating vascular dysfunction (219). Similarly, perfluorocarbon (PFC)

could reduce inflammatory cell infiltration and alleviate acute

lung injury by decreasing ATF2 activity in macrophages (140). The dynamic modulation of ATF3

requires consideration of disease progression. During the early

hyperinflammatory phase of sepsis, induction of ATF3 expression in

macrophages may counteract cytokine storms, while its inhibition

during the immunosuppressive phase may help mitigate secondary

infection risk (138). ATF4

suppression also requires meticulous evaluation due to its

dualistic effect. The application of small-molecule inhibitors or

siRNA-mediated knockdown of ATF4 has been shown to attenuate M-CSF

secretion and limit M2 macrophage infiltration (183), which in turn impedes the

progression of infantile hemangioma while simultaneously

counteracts the pro-tumorigenic properties of TAMs (122). Inhibiting ATF4 can also

mitigate Leishmania infection (82), though excessive inhibition might

compromise the antifungal defense. Therefore, therapies targeting

ATF4 must balance the anti-inflammatory outcomes with host immune

protection (199). Naringenin,

a flavanone compound found in grapefruits and other citrus fruits,

could reduce ATF6 nuclear translocation and activity, by which it

decreases the expression of ER stress markers while enhances the

expression of cholesterol efflux genes (ABCA1, ABCG1 and LXRα).

This action promotes macrophage cholesterol efflux, reducing

atherosclerotic plaque formation (157). Furthermore, siRNA-mediated ATF6

knockdown alleviates macrophage-driven inflammation and fibrosis,

highlighting its potential for treating chronic inflammatory

disorders (159).

By contrast, activating or overexpressing ATFs

through gene-editing technologies (such as adenoviral vectors) and

small-molecule agonists offer an approach to enhance

anti-inflammatory, anti-infectious and tissue-repairing functions

of macrophages. Developing small-molecule drugs or gene therapies

to enhance ATF1 activity presents a potential intervention for

atherosclerosis by inducing the protective macrophage subset

(178). ATF2 activation

inhibits viral replication, with its agonists serving as potential

therapeutics for chronic viral infections (167). High-salt diets have also been

proposed as a strategy to enhance antiviral immunity via

ATF2-mediated pathways in macrophages (105). Targeted activation or

overexpression of ATF3 exhibited a promising therapeutic potential

in inflammatory diseases, infections and metabolic disorders.

Gene-editing technologies, such as lentiviral and adenoviral

deliveries (Ad/ATF3) of ATF3, alleviate excessive inflammation

following Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection (160), protect renal tubular cells from

inflammatory damage (165) and

reduce the risk of atherosclerosis development (134). ATF3 overexpression further

diminishes LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine release, thus

improving the outcomes in chronic inflammatory diseases (138,164). In bacterial infections,

enhancing ATF3 activity optimizes immune responses and promotes

macrophage activation, migration and bactericidal activity, coupled

with increased host clearance of Staphylococcus aureus

(144). Across multiple disease

models, berberine and metformin have been demonstrated to enhance

ATF3 expression (162,220) and attenuates LPS-induced

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages (164). In particular, metformin exerts

its anti-inflammatory effects by engaging the AMPK/ATF3 signaling

axis, through which it potently manages inflammation associated

with type 2 diabetes and obesity (187). ATF4 may represent a novel

strategy for treating sepsis-related intestinal injury (142). Enhancing ATF4 expression

through pharmacological or gene therapies help the restoration of

monocyte differentiation into gMacs, thereby strengthening

intestinal barrier function, reducing bacterial translocation and

mitigating sepsis-induced inflammatory damage (132). In type 2 diabetes, upregulating

ATF4 can improve insulin resistance by promoting M2 macrophage

polarization (182). Targeting

ATF7-mediated epigenetic modifications offers a strategy to refine

vaccine adjuvant efficacy, by promoting macrophage activation and

memory formation, ultimately advancing the development of more

durable and effective vaccine-induced protection (119).

However, the clinical translation of strategies

that directly targeting ATFs faces multiple inherent challenges.

The first obstacle lies in the intrinsic 'undruggability' of these

transcription factors. The interaction surfaces of ATFs with DNA or

partner proteins are typically broad and shallow, lacking

well-defined pockets that allow high-affinity binding of small

molecules, thereby rendering the development of conventional

inhibitors or agonists extremely difficult. Second, substantial

structural similarity exists among ATF family members, particularly

within their DNA-binding domains. As a result, small molecules

targeting ATFs may suffer from poor subtype selectivity,

potentially leading to off-target toxicity. Therefore, developing

compounds capable of precisely distinguishing individual ATF

isoforms or specific ATF homo- and heterodimers remains a

formidable challenge, which warrants further intensive

investigations (221).

Given the challenges associated with direct

targeting, indirect modulation of upstream signaling pathways or

downstream effector molecules have emerged as an attractive

alternative strategy. Studies show that PERK inhibitors (such as

integrated stress response inhibitor (ISRIB)) suppress the

PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 pathway, thereby reducing foam cell formation and

alleviating atherosclerotic plaque burden (186). The small molecule Limonin

blocks the PERK-ATF4-CHOP axis to attenuate inflammatory cytokine

release (186). Moreover,

drugs, such as FTY720, modulate ATF4 expression via histone

deacetylase 4 (HDAC4), thus reducing osteoclastic activity in

inflammatory bone diseases (184). For ATF2, multiple upstream

intervention strategies have been explored, including p38 MAPK

inhibitors (SB203580) and JNK inhibitors (SP600125), which reduce

inflammation by suppressing ATF2 phosphorylation (166). Additionally, PAR1 antagonists

(such as SCH79797) or PKCθ inhibitors decrease ATF2 activation to

improve insulin sensitivity (149). Novel compounds, such as

bis(5-methyl)2-furylmethane and Javamide-II, reduce inflammatory

mediator production by suppressing the p38 MAPK/ATF2 pathway.

Particularly, Javamide-II manifests lower systemic toxicity

compared with BFNM due to its selective inhibition of specific

inflammatory cytokines without affecting TNF-α or IL-1β (107,170). For ATF1, anti-CD14 monoclonal

antibodies (MY4) showed potential as an adjunctive therapy for

sepsis by inhibiting PGN-induced ATF1 activation (153). Similarly, AMPK agonists (such

as AICAR) induce ATF3 expression and offer therapeutic benefits for

metabolic disorders (162).

Conversely, the NRF2 inhibitor, trigonelline hydrochloride,

markedly reduces parasitic loads in the liver and spleen by

diminishing ATF3 expression (163). Additionally, NF-κB inhibitors

[such as dehydroxy-methylepoxy-quinomicin (DHMEQ)] alleviate

sepsis-associated liver damage by inhibiting ATF5-mediated

pro-inflammatory macrophage differentiation (154).

Nevertheless, indirect modulation strategies also

present substantial limitations. The fundamental drawback of such

approaches lies in their lack of specificity. Upstream kinases or

signaling pathways targeted by these interventions are often

ubiquitously expressed across multiple cell types, leading to

severe off-target effects and systemic toxicity. Second, the high

redundancy of intracellular signaling networks frequently triggers

compensatory activation of alternative pathways, thereby

diminishing therapeutic efficacy or even resulting in treatment

failure. Moreover, the regulatory effects of pathway-level

interventions tend to attenuate along the signaling cascade and are

highly dependent on the disease microenvironment, rendering the

ultimate modulation of specific ATFs indirect and unpredictable.

Finally, this relatively 'coarse-grained' mode of regulation is

insufficient to precisely govern the bidirectional functions of ATF

members or their heterodimeric interactions, limiting its ability

to achieve fine-tuned control over their specific physiological and

pathological activities.

To overcome the aforementioned obstacles,

researchers have explored intervention strategies such as PROTACs

and molecular glues, aiming to target traditionally 'undruggable'

molecules through novel mechanisms of action. The advent of PROTAC

technology has provided a new avenue for addressing such targets

(222-225). A PROTAC molecule contains two

functional domains, one binds to the target protein and the other

recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase, thereby tagging the target for

selective proteasomal degradation (226,227). Although no highly potent

small-molecule ligands have yet been reported for ATF proteins,

researchers are creatively adapting the PROTAC concept for

transcription factor degradation. One proposed generalizable

strategy involves using DNA fragments recognized by transcription

factors as targeting elements, which are linked to E3 ligase

ligands to induce ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of

transcription factor-DNA complexes (228). For example, the antioxidant

response factor NRF2, a bZIP transcription factor that

heterodimerizes with small Maf proteins to bind to the AREs, can be

targeted by a chimeric molecule termed 'ARE-PROTAC', which

successfully induced simultaneous degradation of the NRF2-MafG

complex and synergistically suppressed Nrf2 signaling (229). This design suggests that

DNA-binding factors, such as ATF/CREB, DNA mimetics or DNA-derived

small molecules, could serve as decoy binding modules to achieve

targeted degradation via the PROTAC mechanism. Unlike

conventional inhibitors that merely block protein activity, this

approach eliminates the target protein itself, offering more

complete and durable inhibition while potentially alleviating

feedback activation caused by persistent protein accumulation.

Nevertheless, applying this technology to ATF targeting remains

challenging. It requires the discovery of small, high-affinity

ligands specific for ATF proteins and the relatively large

molecular weight of PROTACs limits their intracellular delivery,

especially into macrophages. To address this issue, recent studies

have explored macrophage-targeted nanocarrier systems utilizing

surface receptors such as citrate or scavenger receptors, enabling

PROTAC accumulation and selective degradation at the inflammatory

or tumor sites (230,231).

Building on this concept, molecular glues have

emerged as another promising and simplified strategy for targeted

protein degradation. Molecular glues are typically single small

molecules that 'glue' the target protein and an E3 ubiquitin

ligase, thereby promoting their interaction and inducing target

degradation (232). Unlike

PROTACs, molecular glues do not require a linker and can directly

induce contact between transcription factors and E3 ligases,

offering a simpler architecture and easier optimization. The

classic example is lenalidomide, which remodels the

substrate-binding surface of the CRBN E3 ligase, enabling selective

recognition and degradation of the transcription factors IKZF1 and

IKZF3 (233). This mechanism

holds particular interest for targeting ATF family members. First,

molecular glues generally have much smaller molecular weights than

PROTACs, conferring superior membrane permeability and drug-like

properties, thereby facilitating macrophage penetration. Second,

their activity does not depend on identifying traditional

ligand-binding pockets, which is advantageous for transcription

factors lacking well-defined active sites. Nevertheless, challenges

remain, including the difficulty of identifying suitable adaptor

molecules and the dependency on specific E3 ligases, which may

restrict the target spectrum.

In addition, peptide mimetics and interfering

peptides offer new avenues for disrupting transcription factor

activity. Researchers have developed a dominant-negative form of

ATF5 (dn-ATF5) by deleting its N-terminal activation domain while

retaining the bZIP dimerization and DNA-binding regions and further

conjugated it to an HIV-TAT sequence to generate a cell-permeable

synthetic peptide (CP-dn-ATF5) (234,235). This peptide can get into the

nucleus and compete with endogenous ATF5 for partner proteins or

DNA-binding sites, thereby blocking its transcriptional activity.

The advantages of peptide-based therapies lie in their high

specificity and flexible design. With advances in peptide drug

modification techniques, such as cyclization, D-amino acid

substitution and nanocarrier encapsulation, peptide-based ATF

inhibitors are expected to become an important complement to

small-molecule strategies.

Of note, enhancing the spatiotemporal specificity

of ATF-targeting interventions is critical for improving

therapeutic efficacy and safety. Advanced delivery systems are

under development to achieve tissue- or cell-specific targeting,

ensuring that drugs could be selectively delivered into macrophages

in affected tissues (236).

Encouragingly, advances in nanocarrier and bioengineering

technologies now enable the precise delivery of therapeutic agents

to macrophages, allowing for selective modulation of ATF-associated

pathways without affecting other cell types. For instance, in

atherosclerosis models, macrophage-targeted nanoparticles have been

utilized to deliver drugs directly to macrophages within the

plaques (237). These

nanoparticles substantially improved the pharmacokinetic profiles

of the encapsulated drugs, enhancing their accumulation at the

lesion site and promoting the therapeutic efficacy. Similarly, in

viral pneumonia models, lipid nanoparticles conjugated with

macrophage-specific antibodies (such as anti-F4/80) have been used

to deliver siRNA to lung macrophages, effectively silenced upstream

inflammatory molecules such as TAK1 (238). These findings underscore the

feasibility of macrophage-targeted delivery for therapeutic

interventions and highlight the substantial potential of

integrating delivery technologies into ATF-targeted therapies.

Therefore, innovative targeted technologies coupled with advanced

delivery systems, might overcome the barrier of ATFs-targeted

therapies and accelerate their clinical translation.

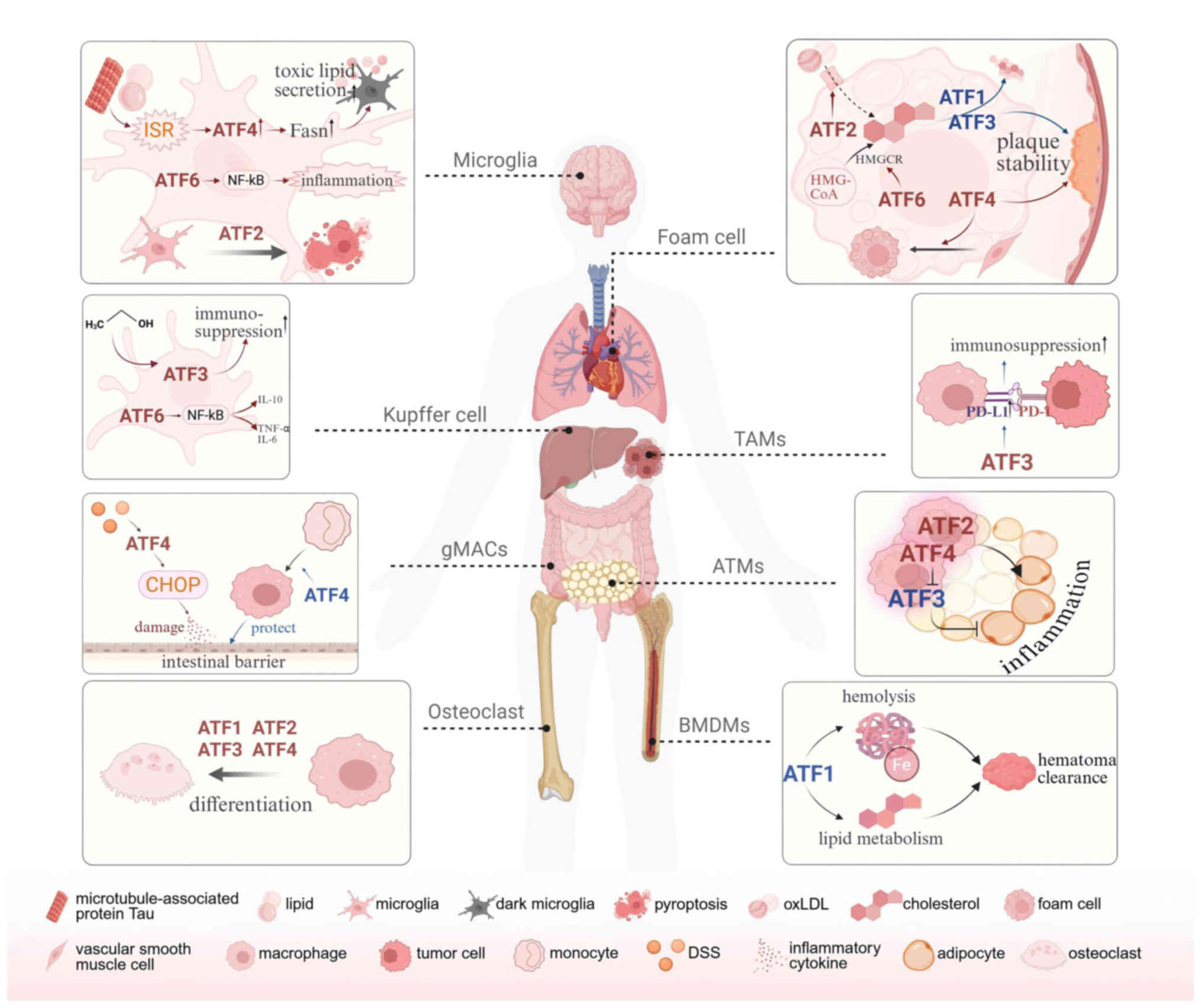

By integrating mechanistic insights and

disease-specific evidence, this review delineated how ATFs

orchestrate macrophage development, survival, migration,

phagocytosis, activation, cytokine secretion and polarization and

how these regulatory axes converge to shape macrophage-driven

pathology in infectious, inflammatory, metabolic, oncologic and

neurodegenerative settings. Through transcriptional control of

macrophage-expressed genes across diverse tissues and organs, ATFs

are not only implicated in the initiation and progression of

multiple disorders but also emerged as nodal regulators integrating

pathophysiological signals with immune and metabolic reprogramming

(Fig. 3). Of note, ATFs exhibit

complex context-dependent versatility in macrophage-mediated immune

responses. Mechanistically, the effector outcomes of ATFs largely

hinge on the variety of stimuli and upstream signaling pathways in

macrophages. For instance, TLR2 activation by Gram-positive

bacteria induces moderate inflammation, during which ATF3 promotes

antimicrobial gene expression, whereas LPS-TLR4 signaling from

Gram-negative bacteria elicits strong NF-κB and IRF3 activation

that rapidly induces ATF3 as a negative feedback regulator to

suppress excessive cytokine production (115,144,161,239-242). In addition, the intensity and

duration of stimulation further shape ATF activity. During early

sepsis, ATF3 alleviates hyperinflammation and promotes tissue

recovery, whereas its sustained overexpression contributes to

late-phase immunosuppression and secondary infections (142,161,162,187). Transient stress activates ATF4

via the PERK-eIF2α pathway, upregulating adaptive and

survival-related genes to enhance macrophage resilience; however,

prolonged stress leads to persistent ATF4-CHOP signaling, promoting

apoptosis and pro-inflammatory mediator release (175,176). Similarly, ATF6 activation under

acute ER stress (such as triggered by pattern-recognition

receptors) induces chaperone and autophagy programs that facilitate

pathogen clearance (106,155,159). By contrast, during chronic

metabolic stress, such as obesity or hyperlipidemia, sustained ATF6

activation increases cholesterol biosynthesis, suppresses

cholesterol efflux, promotes foam cell formation and amplifies

inflammatory responses (156,157). In addition, as bZIP

transcription factors, ATF family members exert highly

context-dependent effects determined by their interacting partners

and chromatin accessibility. Microenvironmental factors, such as

oxidative stress, metabolic stress and ER stress, not only regulate

ATF activation levels but also influence their combination with

c-Jun, CHOP, C/EBP, or HDAC1, thereby switching their

transcriptional output between activation and repression. Upon

inflammatory stimulation, ATF2 forms an AP-1 complex with c-Jun to

transcribe Inos and Cox-2 expression, promoting NO

and PGE2 production (156,168-173), while during inflammatory

resolution stage, ATF2 recruits HDAC1 to transcribe Socs3

and suppresses excessive TLR4 signaling (162). ATF3 similarly shifts its

binding preference. Under mild stimulation, ATF3 partners with

c-Jun or CHOP to activate antimicrobial and metabolic genes, but

under strong LPS-TLR4 signaling, ATF3 recruits HDAC1 to repress

NF-κB target genes (115,138,143,163-165). The functional direction of ATF4

also depends on its binding partners. ATF4-NRF2 heterodimers drive

adaptive metabolism and cell survival (82), while heterodimers formed with

CHOP mediate inflammation and cell apoptosis (175,176). Likewise, ATF6 enhances

cytoprotective UPR genes such as Grp78 and Xbp1

during acute stress, but under chronic lipotoxicity, it

preferentially targets inflammatory and lipid metabolic genes to

amplify macrophage inflammation (156). Moreover, changes in chromatin

accessibility under infection or metabolic stress might reshape

cis-element exposure, determining the preferential binding sites of

ATFs and their downstream transcriptional outcomes. Collectively,

these mechanisms highlight ATFs as crucial 'rheostats' that balance

inflammatory signaling, metabolic adaptation and stress responses

in macrophages. However, this functional duality also underscores

the caution in therapeutic targeting: suppressing ATFs in

pathogenic conditions must not compromise their protective roles

and activating them to resolve inflammation should avoid inducing

immunosuppression. A deeper understanding of the context-dependent

mechanisms of ATF signaling is be essentially required.

It is noteworthy that alternative splicing may

represent another critical but insufficiently investigated layer of

ATF modulation. Except for ATF4, most ATF family members possess

alternatively spliced isoforms, although their roles in macrophages

remain largely unknown. Distinct ATF1 isoforms differ in

DNA-binding affinity and subnuclear localization (243), whereas multiple ATF2 variants,

including the human isoforms ATF2-sm and ATF2 (SV5) as well as the

murine variant Atf2(Δ8,9) (244-246), exhibit reduced transcriptional

activity and may alter gene expression by modifying

nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking or by interfering with canonical

ATF2/AP-1 dimerization. Moreover, a truncated ATF3 isoform (ΔZip)

lacking the leucine-zipper domain antagonizes the transcriptional

repressive function mediated by full-length ATF3 (247), while cytoplasmic ATF7-4 acts as

a molecular 'decoy' to sequester upstream kinases responsible for

ATF7/ATF2 phosphorylation (77).

These findings suggest that alternative splicing may establish

negative-feedback circuits and intermolecular counter-regulatory

balances responsible for the precise modulation of ATF function.

Although their implications in macrophages remain to be defined,

exploring ATF splicing isoforms represents an important direction

for elucidating the dynamic regulatory mechanisms by which ATFs

regulate immune homeostasis and stress responses.

The central involvement of ATFs in

macrophage-driven pathologies positions them as promising

therapeutic targets and biomarkers. On the one hand, ATF expression

dynamics serve as diagnostic or prognostic indicators. Rapid ATF3

upregulation (8-fold within 24 h) in silicosis macrophages is an

early diagnostic biomarker for silicosis detection (248). Additionally, due to its

plaque-stabilizing effects on atherosclerosis, ATF3 expression aids

in the identification of high-risk patients and guides personalized

treatments (134). On the other

hand, single-target interventions may be limited by compensatory

mechanisms, necessitating the need for multi-target synergistic

approaches for the regulation of macrophage functionality. Lastly,

ATF-targeting strategies such as siRNA interference, gene editing,

or more advanced protein degradation technologies such as PROTACs,

all face common challenges related to in vivo delivery

efficiency, tissue and cell specificity, immunogenicity and the

durability of their effects. Although these interventions have

shown remarkable efficacy in preclinical models, extensive studies

are still required to validate their safety, efficacy and

controllability in complex physiological settings and to further

optimize targeted delivery systems to facilitate clinical

translation.

Not applicable.

YCL conceived the study, wrote the manuscript and

prepared the figures. JWZ, QJC and XTL curated data and collected

references. SJR and FS organized the tables. SWL, CLY and CYW

reviewed and revised the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic

Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project

(2024ZD0531400,2023ZD0507302), the National Key R&D Program of

China (2022YFA0806101), the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (81920108009, 82130023, 82570968, 82200923), the Research and

Innovative Team Project for Scientific Breakthroughs at Shanxi

Bethune Hospital (2024AOXIANG03), the Continuous Funding Program

for High-Level Research Achievements at Shanxi Bethune Hospital

(2024GSPYJ10 and 2024GSPYJ13) and the IGP Funding from QBRI, Hamad

Bin Khalifa University.

|

1

|

Chen S, Saeed AFUH, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H,

Xiao GG, Rao L and Duo Y: Macrophages in immunoregulation and

therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:2072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mass E, Ballesteros I, Farlik M,

Halbritter F, Günther P, Crozet L, Jacome-Galarza CE, Händler K,

Klughammer J, Kobayashi Y, et al: Specification of tissue-resident

macrophages during organogenesis. Science. 353:aaf42382016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kuznetsova T, Prange KHM, Glass CK and de

Winther MPJ: Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of

macrophages in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 17:216–228. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

4

|

Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W

and Rossi FM: Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia

maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci.

10:1538–1543. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bian Z, Gong Y, Huang T, Lee CZW, Bian L,

Bai Z, Shi H, Zeng Y, Liu C, He J, et al: Deciphering human

macrophage development at single-cell resolution. Nature.

582:571–576. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C,

Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L, Garner H, Trouillet C, de Bruijn MF,

Geissmann F and Rodewald HR: Tissue-resident macrophages originate

from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature.

518:547–551. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Guan F, Wang R, Yi Z, Luo P, Liu W, Xie Y,

Liu Z, Xia Z, Zhang H and Cheng Q: Tissue macrophages: Origin,

heterogenity, biological functions, diseases and therapeutic

targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:932025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P,

Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, Becker CD, See P, Price J, Lucas D, et al:

Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult

life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes.

Immunity. 38:792–804. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rosmus DD, Koch J, Hausmann A, Chiot A,

Arnhold F, Masuda T, Kierdorf K, Hansen SM, Kuhrt H, Fröba J, et

al: Redefining the ontogeny of hyalocytes as yolk sac-derived

tissue-resident macrophages of the vitreous body. J

Neuroinflammation. 21:1682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Masuda T, Amann L, Monaco G, Sankowski R,

Staszewski O, Krueger M, Del Gaudio F, He L, Paterson N, Nent E, et

al: Specification of CNS macrophage subsets occurs postnatally in

defined niches. Nature. 604:740–748. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kazankov K, Jorgensen SMD, Thomsen KL,

Møller HJ, Vilstrup H, George J, Schuppan D and Grønbæk H: The role

of macrophages in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:145–159. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Appios A, Davies J, Sirvent S, Henderson

S, Trzebanski S, Schroth J, Law ML, Carvalho IB, Pinto MM, Carvalho

C, et al: Convergent evolution of monocyte differentiation in adult

skin instructs Langerhans cell identity. Sci Immunol.

9:eadp03442024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hassnain Waqas SF, Noble A, Hoang AC,

Ampem G, Popp M, Strauß S, Guille M and Röszer T: Adipose tissue

macrophages develop from bone marrow-independent progenitors in

Xenopus laevis and mouse. J Leukoc Biol. 102:845–855. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Perdiguero EG and Geissmann F: The

development and maintenance of resident macrophages. Nat Immunol.

17:2–8. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Sakai M, Troutman TD, Seidman JS, Ouyang

Z, Spann NJ, Abe Y, Ego KM, Bruni CM, Deng Z, Schlachetzki JCM, et

al: Liver-derived signals sequentially reprogram myeloid enhancers

to initiate and maintain kupffer cell identity. Immunity.

51:655–670 e8. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol

D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, et

al: Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and

tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 38:79–91. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Murray PJ and Wynn TA: Protective and

pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol.

11:723–737. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Martinez FO and Gordon S: The M1 and M2

paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment.

F1000Prime Rep. 6:132014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mills CD: Anatomy of a discovery: m1 and

m2 macrophages. Front Immunol. 6:2122015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

20

|

Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ

and Hill AM: M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J

Immunol. 164:6166–6173. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bosco MC: Macrophage polarization:

Reaching across the aisle? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 143:1348–1350.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Locati M, Curtale G and Mantovani A:

Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity.

Annu Rev Pathol. 15:123–147. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ivashkiv LB: Epigenetic regulation of

macrophage polarization and function. Trends Immunol. 34:216–223.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Mosser DM and Edwards JP: Exploring the

full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 8:958–969.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S,

Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, Seifi B, Mohammadi

A, Afshari JT and Sahebkar A: Macrophage plasticity, polarization,

and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 233:6425–6440.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Dong T, Chen X, Xu H, Song Y, Wang H, Gao

Y, Wang J, Du R, Lou H and Dong T: Mitochondrial metabolism

mediated macrophage polarization in chronic lung diseases.

Pharmacol Ther. 239:1082082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gordon S and Martinez FO: Alternative

activation of macrophages: Mechanism and functions. Immunity.

32:593–604. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Colin S, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G and Staels B:

Macrophage phenotypes in atherosclerosis. Immunol Rev. 262:153–166.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|