Introduction

Fibrosis is defined as the overabundant deposition

of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which includes collagen and

fibronectin (FN), leading to the accumulation of substantial

fibrous connective tissue in areas of inflammatory infiltration or

within and around damaged tissues (1). It is a pathological condition that

eventually triggers severe scar hyperplasia; organ dysfunction,

such as heart failure, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF),

end-stage renal disease (ESRD), end-stage liver disease and even

death (2). If epithelial or

endothelial regeneration capacity cannot be synchronized with

recurrent damage during cell infection, exposure to toxic factors,

or autoimmunity, or if other uncertain factors continuously induce

epithelial or endothelial damage, then the corresponding

mesenchymal cells are activated and a considerable amount of ECM is

deposited; this phenomenon is also the mechanism of fibrotic

reaction in most organs (3).

Organ fibrosis is a dynamic pathological process. In contrast to

irreversible scar tissue formation, it is highly plastic and can

reversely change the course of fibrosis by targeting key effector

cells or signaling (4).

Epidemiological data have shown that fibrosis-related health events

pose a great threat to the health of a quarter of the population

worldwide and that the annual incidence of major fibrosis-related

diseases is close to 1 in 20 (5). Nintedanib and pirfenidone are

prescription drugs approved by a number of developed and developing

countries for intervening in fibrosis in specific organs and are

available to patients with IPF. Thus far, however, drugs that

specifically target the fibrosis of the liver, kidney, or heart

have yet to be approved in the medical market. In addition,

although nintedanib has been approved for the medical management of

systemic sclerosis (SSc)-related interstitial lung disease and

progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disorders, marked advances

are needed regarding the development of fibrotic drugs, especially

highly effective drugs that can specifically act on affected

organs, thereby achieving reversible intervention in organ fibrosis

diseases (6).

Multiple mechanisms determine the progression of

fibrotic diseases and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) can exert

multicomponent, multitarget and multipathway therapeutic benefits.

Medicinal resources, including Chinese herbal compounds, materials,

extracts and formulas and their combinations may improve fibrotic

diseases comprehensively with reduced pharmacological toxicity

under the cumulative effects of the aforementioned therapeutic

characteristics (7,8). Chinese herbal medicine has a

protective effect against multiorgan fibrosis. This effect mainly

manifests by improving myocardial perfusion and hemodynamic

function, repairing ultrastructural damage in cardiac tissue,

inhibiting cell apoptosis and cardiac remodeling and alleviating

cardiac dysfunction (8). Active

products derived from single herbs and TCM formulas effectively

intervene in pulmonary fibrosis (PF) by targeting inflammation,

oxidative stress and fibrotic effector molecules (7). Furthermore, a main mechanism

through which Chinese herbal medicines alleviate renal fibrosis is

the regulation of growth factors and fibrotic effector cytokines

and the activation of related signaling pathways. These activities

further improve the renal inflammatory microenvironment and inhibit

reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and renal cell

proliferation (9). Given that

multiple signaling molecules are involved in the development of

liver fibrosis, treatment strategies for liver fibrosis are no

longer limited to a single targeted inflammatory response and the

multitarget therapeutic effects of Chinese herbal medicine may meet

the needs of the multimodal alleviation of liver fibrosis (10). Intervention modes targeting

metabolic mechanisms may become a key strategy to delay fibrosis.

The widespread application of network pharmacology is conducive to

constructing the affiliation between the main active ingredients in

herbal medicines and metabolic targets, implying that the medical

value of Chinese herbal medicine is receiving increasing attention

(5,11). The present review is based on

databases, such as PubMed, Web of Science, Elsevier and

ScienceDirect and SpringerLink. 'Astragaloside IV (AS-IV)',

'fibrosis', 'pharmacokinetics', 'toxicity', 'bioavailability', and

other keywords were used for retrieval, with relevant case reports,

conference abstracts and duplicate studies being excluded. The

present review mainly focuses on AS-IV, the natural saponin

compound purified from Astragalus membranaceus Bunge

(Astragalus), named Huangqi in Chinese and summarizes

and discusses its metabolic regulatory mechanisms and key drug

targets in alleviating fibrotic diseases from 63 basic experimental

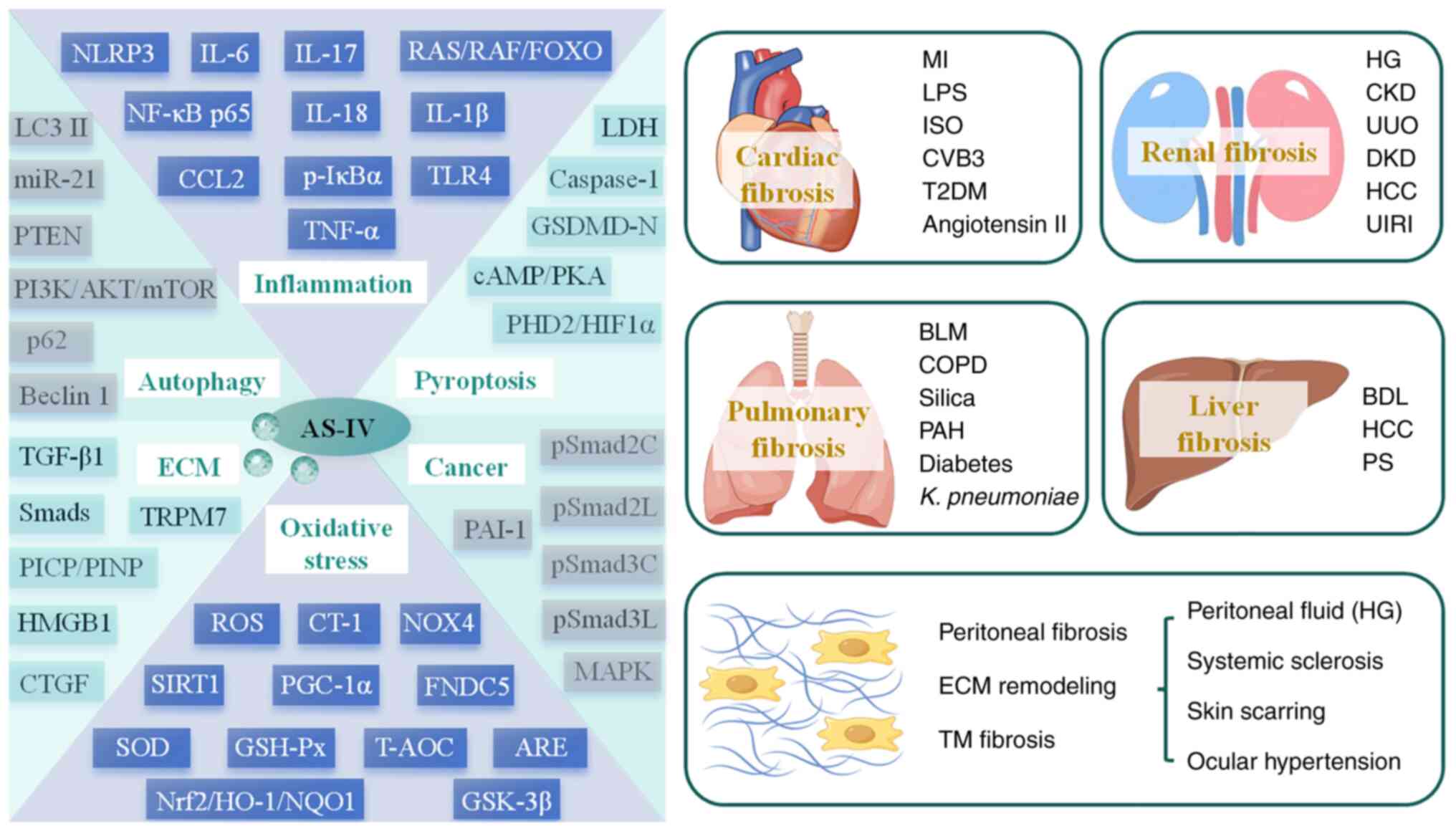

literatures (Fig. 1). It is

hoped that the present review will provide additional theoretical

support for the intervention of tissue fibroses by TCM or a

combination of traditional Chinese and Western medicine and it

calls for optimizing the bioavailability of natural products to

improve the effectiveness of drug-targeted organ therapy.

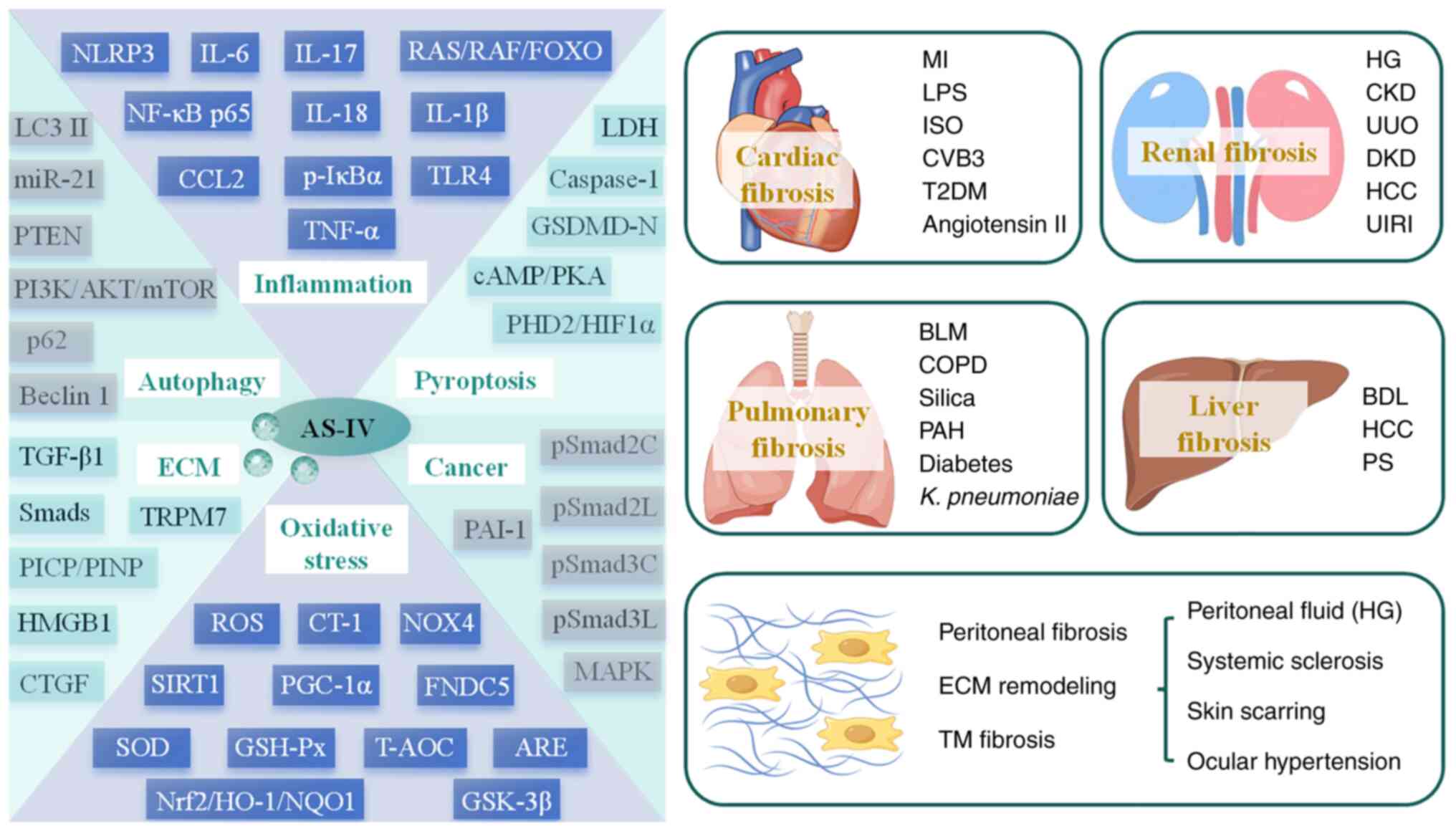

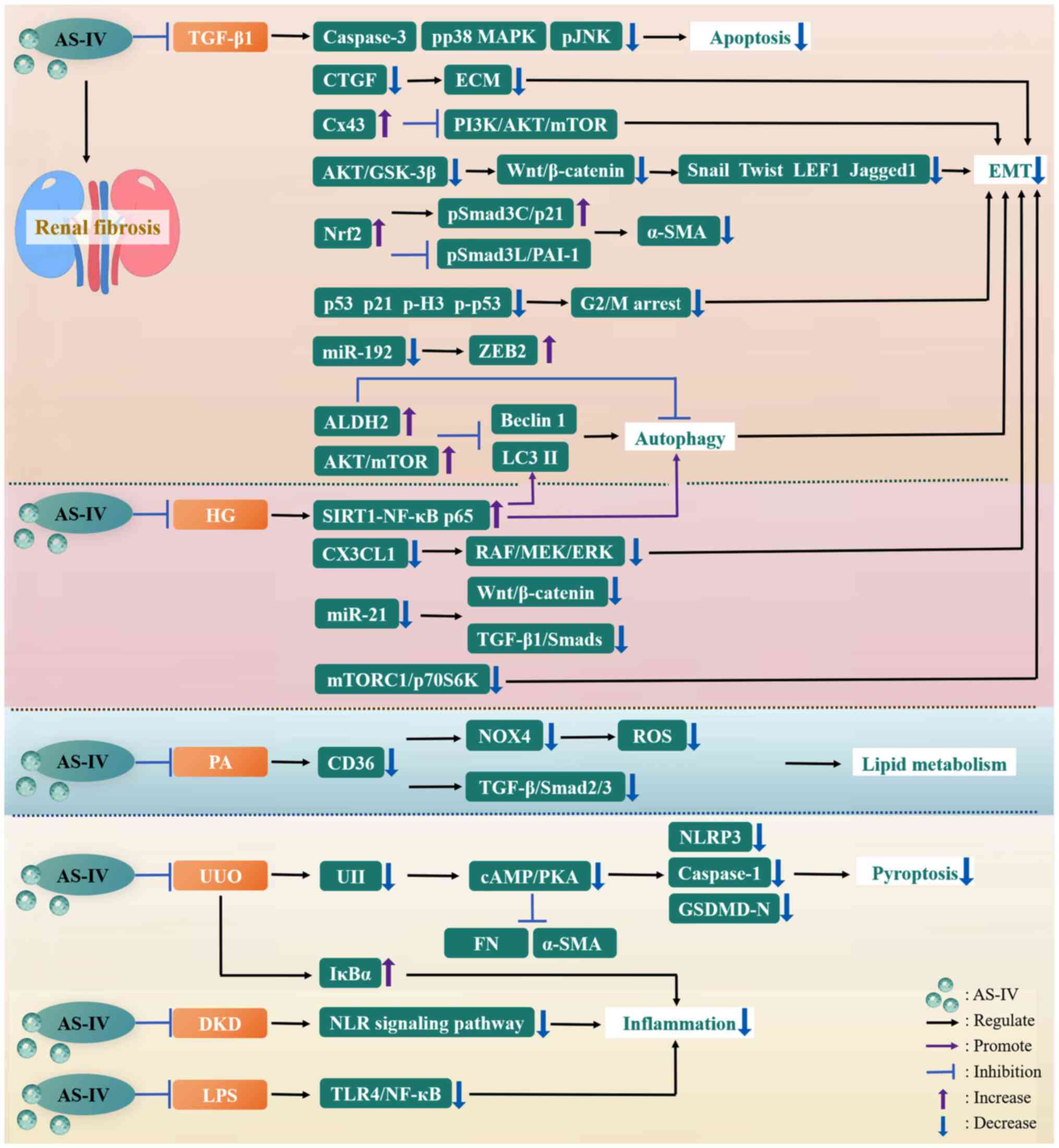

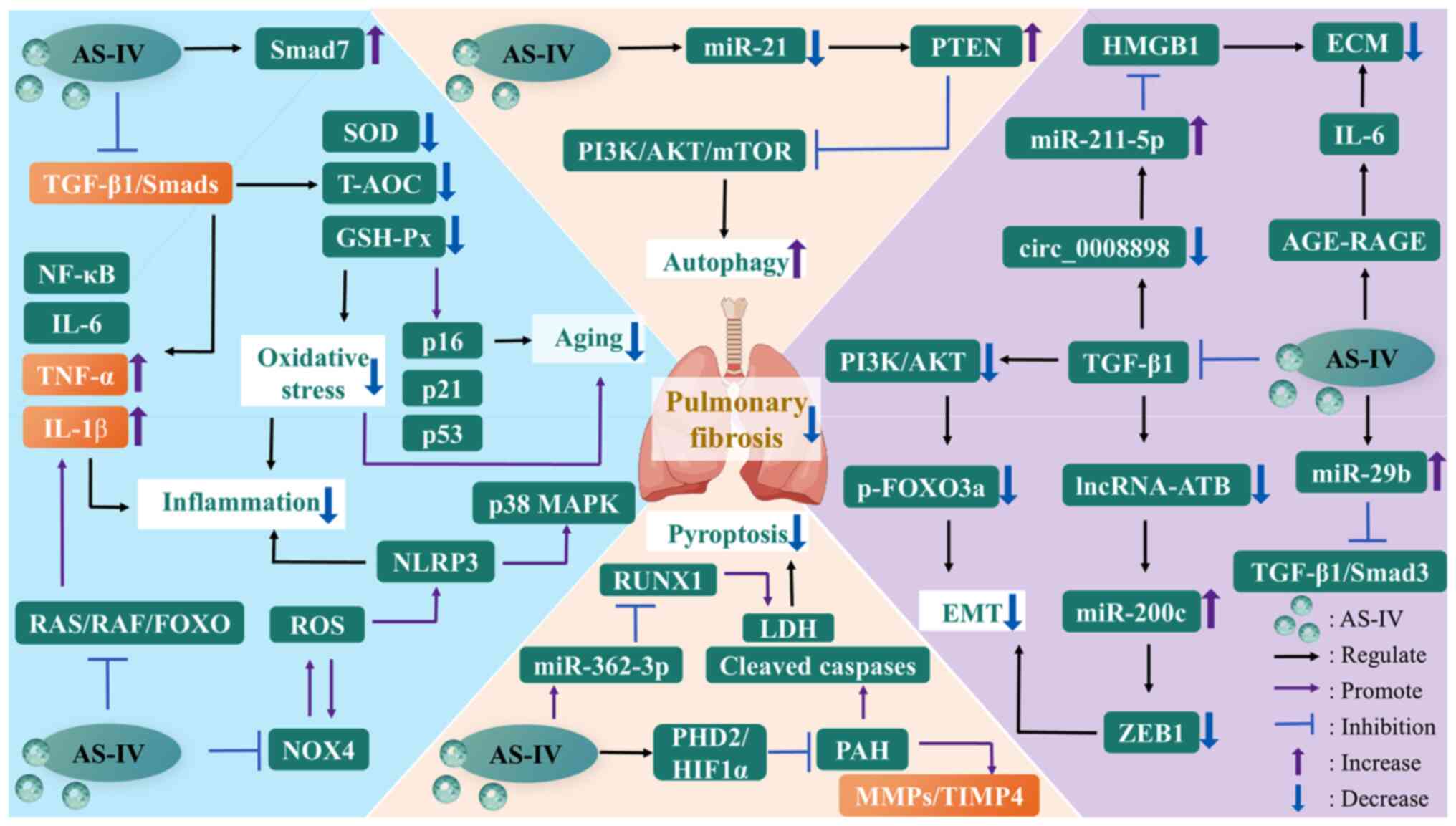

| Figure 1A general overview of AS-IV

regulation of fibrotic diseases. AKT, protein kinase B; ARE,

antioxidant response element; AS-IV, astragaloside IV; BDL, bile

duct ligation; BLM, bleomycin; cAMP, cyclic adenosine

monophosphate; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; CKD, chronic

kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT-1,

cardiotrophin-1; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; CVB3,

coxsackievirus B3; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; ECM, extracellular

matrix; FNDC5, fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5;

FOXO, forkhead box O; GSDMD-N, gasdermin D N-terminal domain;

GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase

kinase-3β; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HG, high glucose; HIF1α,

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; HMGB1, high mobility group box-1;

HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; IL-6, interleukin-6; ISO, isoproterenol;

IκBα, inhibitor of NF-kappa B α; K. pneumoniae,

Klebsiella pneumoniae; LC3 II, light chain 3 II; LDH,

lactate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAPK,

mitogen-activated protein kinase; MI, myocardial infarction;

miR-21, microRNA-21; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-κB,

nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization

domain-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3;

NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; NQO1, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1;

Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PAH, pulmonary

artery hypertension; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1;

PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1

α; PHD2, prolyl-4-hydroxylase 2; PI3K,

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; PICP, procollagen type I

carboxy-terminal propeptide; PINP, procollagen type I N-terminal

propeptide; PKA, protein kinase A; PS, porcine-serum; pSmad3C,

COOH-terminal phosphorylation of Smad3; pSmad3L, phosphorylation of

the linker region of Smad3; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog;

RAF, rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; RAS, rat sarcoma; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SOD, superoxide

dismutase; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; T-AOC, total antioxidant

capacity; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1; TLR4, toll-like

receptor 4; TM, trabecular meshwork; TNF-α, tumor necrosis

factor-α; TRPM7, transient receptor potential cation channel,

subfamily M, member 7; UIRI, unilateral ischemia-reperfusion

injury; UUO, unilateral ureteral obstruction. |

Overview of AS-IV

Biological characteristics of AS-IV

Astragalus, a member of the leguminous

family, is a perennial herb that is mostly produced in temperate

and subtropical regions (12).

It has been used as medicine for >2,000 years (13). More than 200 compounds, such as

flavonoids, polysaccharides, triterpene saponins and certain trace

elements, are found in Astragalus (14,15). Furthermore, in addition to being

a type of TCM with tonic properties, Astragalus contains

various antifibrotic pharmacological ingredients, including

calycosin, AS-IV, polysaccharides and formononetin (16). Astragalus encompasses

>2,000 species and different Astragalus species often

have varying pharmacological components. This situation leads to

variances in pharmacokinetics in mice administered

Astragalus from different sources (16,17). Current pharmacokinetic research

on Astragalus is limited because of seasonal diversity,

growth location and planting years (16).

Astragalosides include various components, such as

astragalosides I, II and IV. Among these natural compounds,

high-purity AS-IV extracted from Astragalus has the

strongest pharmacological activity (18). It can also be used as a

representative marker to quantify the quality of Astragalus

(19). Astragaloside undergoes

mutual transformation during oral and intestinal digestion. This

transformation is mainly reflected in the changes in AS-IV content.

After the acetyl group is hydrolyzed, astragaloside II can undergo

biotransformation, resulting in a corresponding increase in the

amount of AS-IV during oral digestion. AS-IV content is stable

during gastric digestion. During intestinal digestion, the contents

of the three family members of astragaloside increase, indicating

that other cycloartane-type triterpenoid saponins in

Astragalus have been transformed into AS-IV. Moreover, this

phenomenon reveals that transacetylation is involved in the

quantitative change in astragaloside during digestion (20).

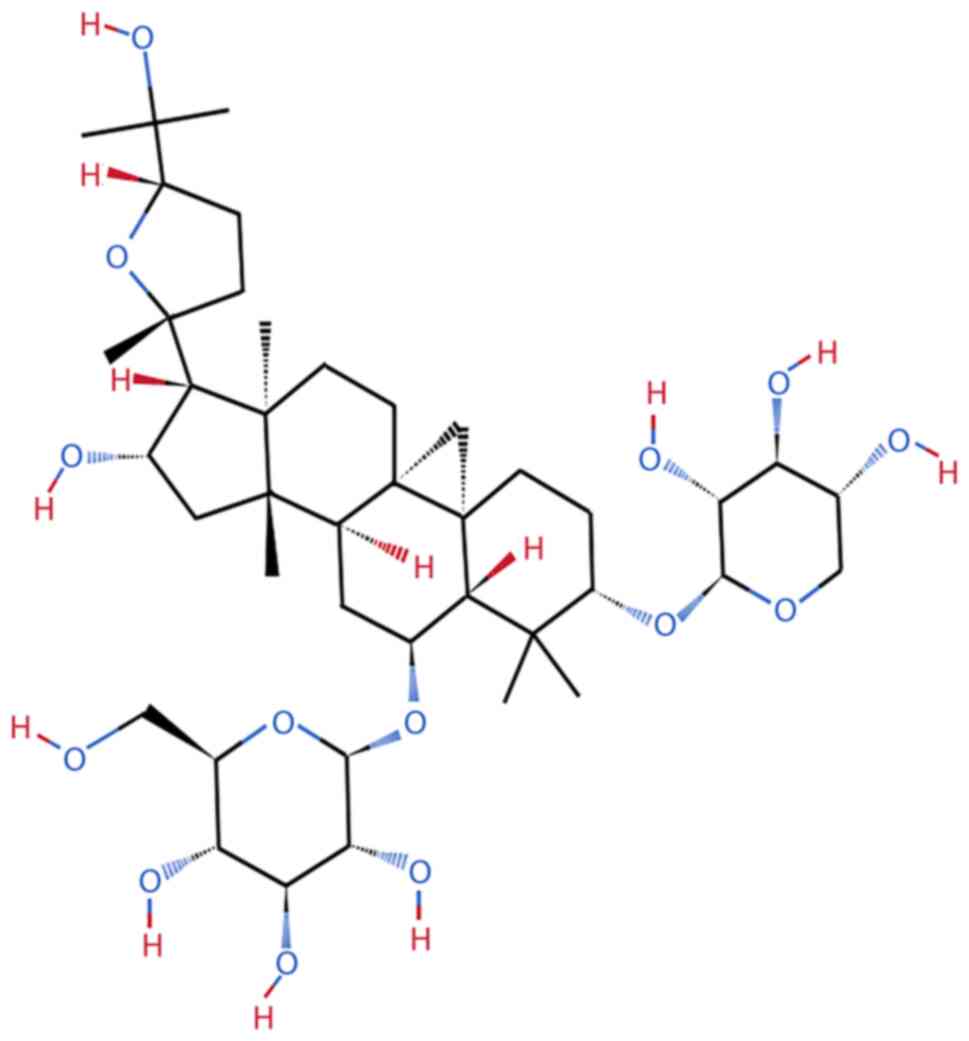

AS-IV is a highly polar lanolin alcohol-shaped

tetracyclic triterpenoid saponin; it has poor hydrophilicity, the

molecular formula of C41H68O14 and

molecular weight of 784.97 Da and is easily soluble in ethanol,

methanol, or acetone (21,22) (Fig. 2). The extraction and separation

of AS-IV through ultrafiltration, high-speed centrifugation and

ultrasonic extraction can reduce the effect of the low water

solubility of AS-IV and yield high contents of AS-IV with a

shortened production cycle and reduced loss. This also indicates

that the innovation of drug extraction and separation technology

facilitates the gradual identification of various saponin

components of Astragalus via gas chromatography-mass

spectrometry and high-performance liquid chromatography. AS-IV,

which has been approved as a medicine and food homologous bioactive

product in China, has become increasingly popular in the clinical

and food markets (23-25). It demonstrates considerable

pharmacological benefits in improving hypertension (26), diabetes (27), infectious diseases (28), viral infections (29), ischemia-reperfusion injury

(30) and anxiety (31), as well as anti-inflammation

(32), antioxidative stress

(33), antiperspirant and

antidiarrheal (34) effects.

Cycloastragenol (CA) is an aglycone and metabolite of AS-IV. The

use of AS-IV and CA in the pharmaceutical market as telomerase

activators indicates that AS-IV could also potentially be a viable

antiaging medication (24).

Toxicity of AS-IV

The median lethal dose of Astragalus after

acute oral administration to rats was found to exceed 250 g/kg body

weight and no toxic reactions occurred after the oral

administration of Astragalus for 90 days at a dose of 15

g/kg body weight (16).

Furthermore, no adverse reactions were observed after the

intraperitoneal injection or intravenous administration of extracts

containing Astragalus saponins and polysaccharides to rats

and beagle dogs for three months. The safe dose ranges for rats and

beagle dogs are 5.7-39.9 and 2.85-19.95 g/kg, respectively, which

are 70 or 35 times that for humans (0.57 g/kg for an average weight

of 70 kg) (35). AS-IV does not

cause obvious symptoms or organ toxicity when used in clinical

treatment and the oral administration of the conventional doses of

AS-IV has no side effects on liver and kidney function (36). Notably, in Sprague-Dawley rats

and New Zealand rabbits, the intravenous administration of 0.5-1.0

mg/kg AS-IV during pregnancy can produce certain toxic effects on

the mother and fetus but does not cause fetal malformations

(37). Further studies have

shown that in rats, the administration of 1.0 mg/kg AS-IV for up to

four weeks during gestation can induce fur formation, eye opening

and neurodevelopmental lag in newborn rats but does not affect the

cognitive function of newborn rats (38). Furthermore, the intravenous

administration of 0.25-1.0 mg/kg AS-IV is detrimental to the

reproductive ability of rats. Administering AS-IV at a dosage of

1.0 mg/kg/day to treat cardiovascular disease (CVD) during

pregnancy may also induce side effects (37,38). Therefore, although AS-IV poses

almost no toxicity risk to the general population, attention should

be paid to the safe dose range of AS-IV during pregnancy and AS-IV

should be taken with caution.

Compared with the oral administration of single

drugs, the intravenous administration of AS-IV preparations often

exhibits more remarkable bioavailability. In a test population,

after the intravenous injection of 200-500 ml of astragaloside

containing AS-IV for one week, only mild symptoms, such as

transient episodes of elevated total bilirubin and rashes, appeared

and subsided spontaneously (39). In addition, various organs or

tissues of the body show good tolerance to astragaloside injection,

with the highest tolerated dose reaching 600 ml. Even if

astragaloside is intravenously infused at a rate of up to 4 ml/min,

no remarkable adverse reactions in humans occurred (39).

Antifibrotic effects of AS-IV

Cardiac fibrosis

The occurrence of cardiac fibrosis is closely

related to various CVDs, including chronic heart failure, atrial

fibrillation, cardiac remodeling after acute myocardial infarction

(MI), valvular heart disease, hypertension and ischemic injury

(40). Between 60-70% of human

heart cells are in the form of fibroblasts, which

over-differentiate into myofibroblasts when the heart is stimulated

by proinflammatory factors or ROS. These myofibroblasts are a major

source of ECM deposited in the cardiac interstitium. They can

further induce cardiac contractile and diastolic dysfunction and

trigger pathological cardiac remodeling (41,42). ECM in the cardiac interstitium is

mainly composed of type I collagen (collagen I). Myocardial

fibrosis (MF) may lead to electrical heterogeneity and destroy

cardiac ejection function. Severe cardiac fibrosis even predisposes

to irreversible cardiovascular lesions, such as excessive

arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (43). Given that cardiovascular events

have gradually become the main cause of global mortality and that

fatal events related to CVDs once accounted for >40% of deaths

in China, active intervention focusing on cardiac fibrosis has

become a key strategy for promoting the development of human health

(44). Anticoagulation,

antiplatelet, thrombolysis and myocardial reperfusion strategies

are widely used to reduce the area of MI and are the main medical

means to relieve MI. However, they are often accompanied with side

effects. For example, they indirectly lead to the aggravation of

the extent of myocardial injury. Therefore, the application of

high-efficiency drugs with low myocardial toxicity can help achieve

ideal prognostic effects. Among these drugs, AS-IV is a derivative

of Chinese herbal medicine that not only lacks organ toxicity when

administered at regular doses but can also achieve considerable

therapeutic benefits in anticardiac fibrosis.

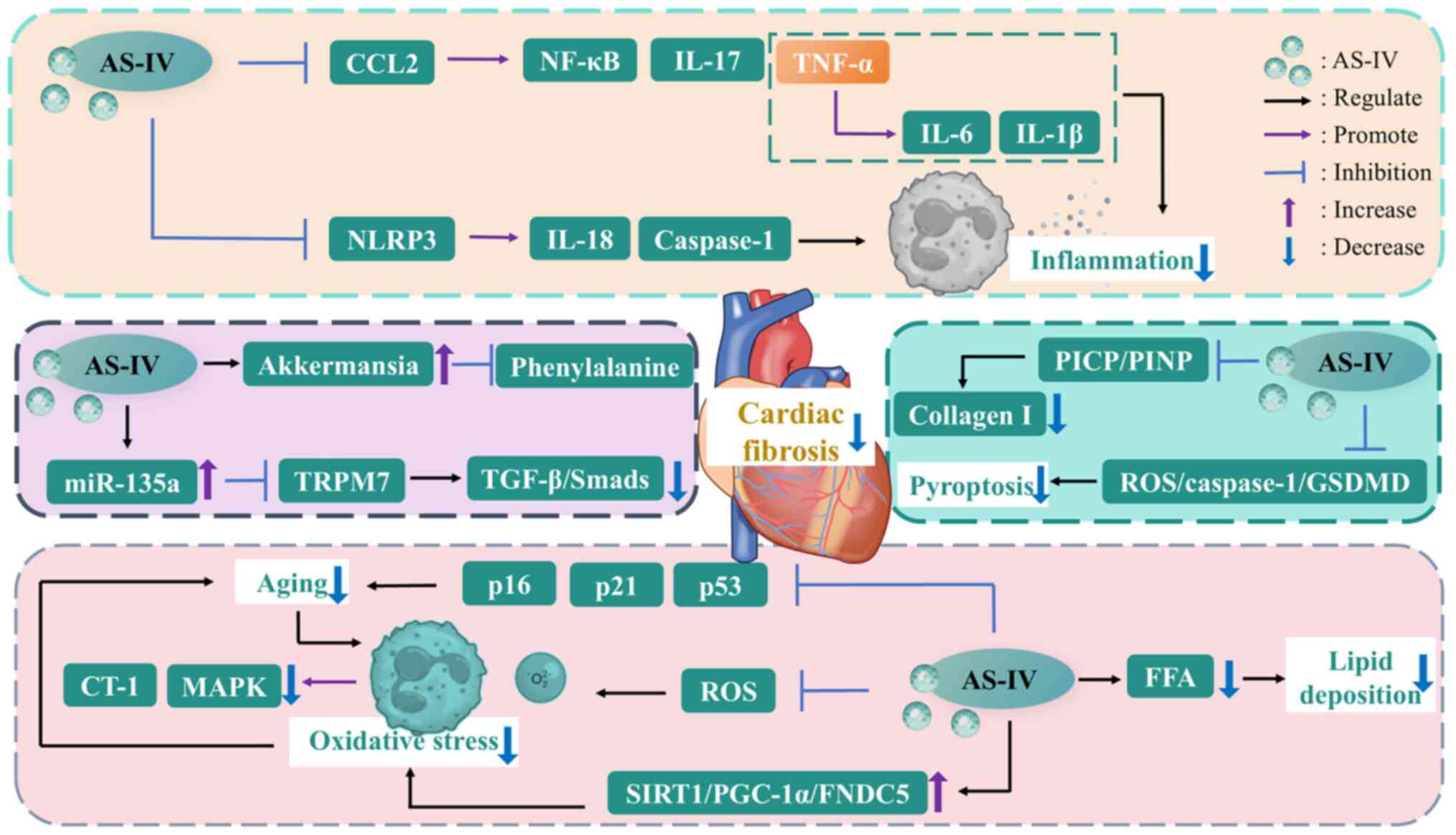

Inflammation

The nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like

receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3)

inflammasome acts as a multiprotein complex that concurrently

facilitates the onset of inflammation and cardiac fibrosis

(45). The activated NLRP3

inflammasome not only maintains myocardial interstitial

inflammatory infiltration, but its induced proinflammatory factors,

such as interleukin (IL)-18 and IL-1β, also activate profibrotic

growth factors and promote the deposition of collagen and

development of a profibrotic population of fibroblasts (46). AS-IV administration markedly

inhibits MF induced by isoproterenol (ISO) treatment. This effect

may be associated with a decrease in the expression of caspase-1

and IL-18 in cardiac tissue caused by AS-IV through the targeted

inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation (41). In addition, ventricular

remodeling phenomena, such as myocardial hypertrophy, fibrosis and

cardiomyocyte apoptosis, are closely related to the development of

end-stage CVDs. The C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) gene can

regulate the expression of inflammatory factors, such as the

proinflammatory factor IL-6, enriched in the nuclear factor-κ B

(NF-κB) signaling pathway. Therefore, CCL2 is defined as a

mechanistic target of AS-IV for antilipopolysaccharide-induced

inflammation in H9C2 cardiomyoblasts. This relationship can be

attributed to the ability of CCL2 inactivation to regulate

negatively the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated NF-κB signaling

pathway and the high expression of its target genes IL-17 and tumor

necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Moreover, CCL2 may be an effector

molecule for MF and the overexpression of fibrosis-related genes

(proliferating cell nuclear antigen, collagen I and collagen III)

induced by LPS is favorably connected with CCL2 activity. AS-IV can

also serve as a potential CCL2 inhibitor to improve LPS-induced

myocardial remodeling. Furthermore, AS-IV blocks NF-κB from

entering the cytosol and hinders the inactivated inhibitor of NF-κB

(IκB) to drive LPS-induced NF-κB p65 overexpression, thereby

effectively inhibiting cardiac hypertrophy and the fibrosis of

LPS-induced H9C2 cells (47).

Oxidative stress

Evidence indicate that cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), as a

key mediator of cardiac remodeling, is involved in cardiac

fibroblast (CF) and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation,

collagen I deposition and ECM synthesis to a certain extent, with

CT-1 being closely related to cardiomyocyte survival and cardiac

hypertrophy (48,49). Notably, driving CT-1

overexpression is related to the release of ROS and treatment with

AS-IV and the ROS inhibitor N-acetylcysteine targets the

production of ROS in CFs, inhibits ISO-induced CF proliferation and

CT-1 overexpression and reduces collagen I deposition in

cardiomyocytes. These effects indicate that inhibiting the driving

effect of ROS on CT-1 expression is a potential mechanism of the

anti-MF effect of AS-IV. However, whether mitochondrial NADPH

oxidase 4, mitochondrial superoxide dismutase and mitochondrial

catalase contribute to the negative regulation of oxidative stress

in myocardial tissue by AS-IV remains inconclusive (50). ISO is a typical inducer of

cardiac fibrosis and its profibrotic mechanism is intimately linked

to the generation of ROS and activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase

(JNK), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and

extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (51,52). Notably, Dai et al

(53) found that AS-IV can

prevent profibrotic MAPK family members from undergoing

phosphorylation and that the ROS inhibitor N-acetylcysteine

mimics AS-IV's suppressive effect on MAPK activation. That is,

their study finally demonstrated that AS-IV may exert an

anticardiac fibrotic benefit by downregulating oxidative

stress-mediated MAPK phosphorylation through the targeted

inhibition of ISO-induced ROS production. Fibronectin type III

domain-containing protein 5 (FNDC5) is highly active in the brain

and heart and crosstalk has been found between the sirtuin 1

(SIRT1)/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1

α (PGC-1α)/FNDC5 signaling cascade and improvement in diabetic MF

(54). Cong et al found

that in mice, AS-IV activates the SIRT1/PGC-1α/FNDC5 signaling

pathway, therefore effectively inhibiting atrial fibrosis, atrial

fibrillation and oxidative stress induced by angiotensin II

(55).

Lipid metabolism

Although the heart is not a typical organ for lipid

storage, a pathological increase in serum lipid levels causes fatty

acids to enter myocardial cells and some fatty acids are forced to

be stored in myocardial cells in the form of triglycerides. When

lipid deposition reaches a certain extent, the production of

lipid-toxic intermediates, such as ceramides, diacylglycerols and

ROS, become an important mechanism mediating myocardial

inflammation and fibrosis in patients with diabetes and obesity

(56). AS-IV not only helps

alleviate cardiac lipid deposition by regulating plasma

triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein and

myocardial free fatty acid (FFA) contents but also inhibits type 2

diabetes mellitus (T2DM)-related myocardial damage induced by

increased serum creatine kinase isoenzyme and lactate dehydrogenase

(LDH) levels and suppresses the driving effect of inflammatory

infiltration on MF. AS-IV mainly exerts these effects by targeting

the downregulation of TNF-α expression and alleviating the

aggravating effect of TNF-α-activated inflammatory cytokines,

including IL-1β and IL-6, on MF. It thereby simultaneously inhibits

the proinflammatory and pro-MF effects of TNF-α because TNF-α not

only originates from the heart but can also be targeted to change

the pathophysiology of the heart (57). Therefore, AS-IV can inhibit

inflammatory infiltration and fibrosis-induced myocardial damage.

This inhibitory effect may be associated with mitigating the toxic

damage of lipid deposition on the myocardium (57).

Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is a form of programmed cell death that

is intimately associated with the initiation of proinflammatory

responses mediated by caspase-1 (58). However, the cleavage of

pro-caspase-1 into active caspase-1 can be inhibited through the

targeted inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, further

blocking the transformation of the cytokine precursors pro-IL-1β

and pro-IL-18 into bioactive IL-1β and IL-18, respectively.

Therefore, this process is beneficial to relieve cardiac

dysfunction caused by cardiomyocyte pyroptosis and inflammatory

infiltration after MI. Zhang et al (59) clarified the upstream and

downstream relationships between oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte

pyroptosis. That is, AS-IV can inhibit MI-induced ROS release,

thereby alleviating NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cardiomyocyte

pyroptosis. This effect is achieved mainly through the suppression

of the levels of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, cleaved IL-1β and

cleaved IL-18 and the pyroptosis-related protein gasdermin D

N-terminal domain (GSDMD-N) induced by MI. Furthermore, α-smooth

muscle actin (α-SMA) and FN overexpression, as well as collagen I

and III deposition, can be suppressed by AS-IV. AS-IV also

decreases the number of apoptotic cardiomyocytes and compensatory

hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes to improve cardiac function. AS-IV

has been found to downregulate the ROS/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling

pathway, thereby attenuating MF and cardiac remodeling induced by

MI. This mechanism has also been demonstrated at the cellular

level. That is, AS-IV may exert an anti-inflammatory effect by

inhibiting macrophage pyroptosis in vitro (59).

Aging

The senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)

continuously drives inflammatory infiltration and ECM synthesis and

progressively aggravates collagen deposition and fibrosis by

inducing the release of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1),

matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and the inflammatory cytokines

TNF-α and IL-1β. Therefore, selectively regulating the release of

SASP components effectively interferes with MF (60,61). Shi et al (62) detected a high correlation between

cellular senescence and p53 signaling pathway-related genes and

proteins through transcriptomics and proteomics analysis and found

that the activity of the aging-related indicators p16, p21 and p53

of this pathway are markedly inhibited by AS-IV treatment in the

ISO-induced MF group. Given that the senescence of CFs and release

of SASP are triggered by oxidative stress and SASP secreted by

senescent cells also promotes the oxidative stress effect again,

these phenomena form a vicious cycle and induce a progressive

exacerbation of the degree of MF. Therefore, the mechanism by which

AS-IV inhibits MF may be attributed to regulatory effects on

oxidative stress and the release of aging markers (62-64).

Collagen deposition

Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) not only serves as a human

pathogen that induces acute and chronic viral myocarditis in

adolescents but is also an important inducer of dilated

cardiomyopathy (DCM) with MF (65). The synthesis and degradation of

collagen I in cardiomyocytes depends on serum procollagen type I

N-terminal propeptide (PINP) and procollagen type I

carboxy-terminal propeptide (PICP) concentrations. AS-IV inhibits

collagen deposition and TGF-β1 expression in the cardiomyocytes of

a DCM model after CVB3 infection. Notably, although collagens I and

III are substantially deposited in patients with DCM, only the

content of collagen I in the myocardial tissue of DCM is markedly

decreased by AS-IV. This effect is consistent with the

downregulation of the PICP:PINP ratio and serum PICP concentration,

both of which represent the excessive synthesis of collagen I in

the myocardium. It also indirectly proves that AS-IV can exert

considerable resistance against fibrosis induced by ISO and CVB3

regardless of whether cardiac fibrosis is induced by the

β-adrenergic receptor or not (65).

Gut microbiota

Various gut microbiota and fecal metabolites

establish metabolic communication with the host or the intestinal

microenvironment, thus forming metabolic crosstalk with cardiac

fibrosis (66). In mammals,

intestinal Akkermansia abundance plays a vital part in

negatively regulating the development of metabolic syndrome and

CVDs, such as atherosclerosis. In addition, intestinal

Akkermansia can intervene in cardiovascular events by

regulating the levels of fecal metabolites. Fecal metabolites, such

as hydroxyprolyl-leucine, valyl-isoleucine and

nepsilon-acetyl-L-lysine, are positively associated with the

abundance of Akkermansia. Akkermansia negatively

regulates phenylacetylglycine content. This phenomenon may be

related to the increased risk of macrovascular disease because of

the upregulation of phenylalanine, which is the hydrolysis product

of phenylacetylglycine, in plasma (67,68). Studies have found that AS-IV can

lessen the severity of ISO-induced cardiac fibrosis by increasing

the abundance of the gut microorganism Akkermansia, reducing

phenylalanine levels and increasing leucine and lysine levels

(68).

TRPM7

Endogenous microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are a perennial

research hotspot in the field of fibrotic disorders because of

their involvement in regulating the Smad3-mediated TGF-β/Smads

pathway. Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M,

member 7 (TRPM7) participates in inducing the proliferation and

differentiation of fibroblasts and promoting ECM synthesis and

collagen deposition. Among miRNAs, miR-135a is an upstream mediator

that regulates the expression of the profibrotic factor TRPM7.

AS-IV may alleviate cardiac fibrosis through the targeted

intervention of miR-135a expression (42). Wei et al (42) revealed that AS-IV can inhibit the

downregulation of miR-135a expression in ISO-treated rats and

promote the negative regulation of TRPM7 by miR-135a and the

inhibition of TRPM7 activity further promotes the inactivation of

the TGF-β/Smads pathway. Furthermore, AS-IV treatment leads to a

reduction in the expression levels of TGF-β1 and phosphorylated

(p-)Smad3 while promoting the activation of Smad7 and intervention

in rat neonatal CFs also shows a similar antifibrotic effect,

indicating that the key mechanism for AS-IV to alleviate cardiac

fibrosis may be the regulation of the miR-135a-TRPM7-TGF-β/Smads

axis. Notably, TRPM7 channels can also regulate Ca2+

input in fibroblasts lacking voltage-gated calcium channels.

Therefore, the mechanism through which AS-IV exerts its anti-MF

effect may also involve the suppression of TRPM7 channel activity

in CFs under hypoxic conditions, as well as downregulation in the

ion-channel currents of fibroblasts (43) (Fig. 3).

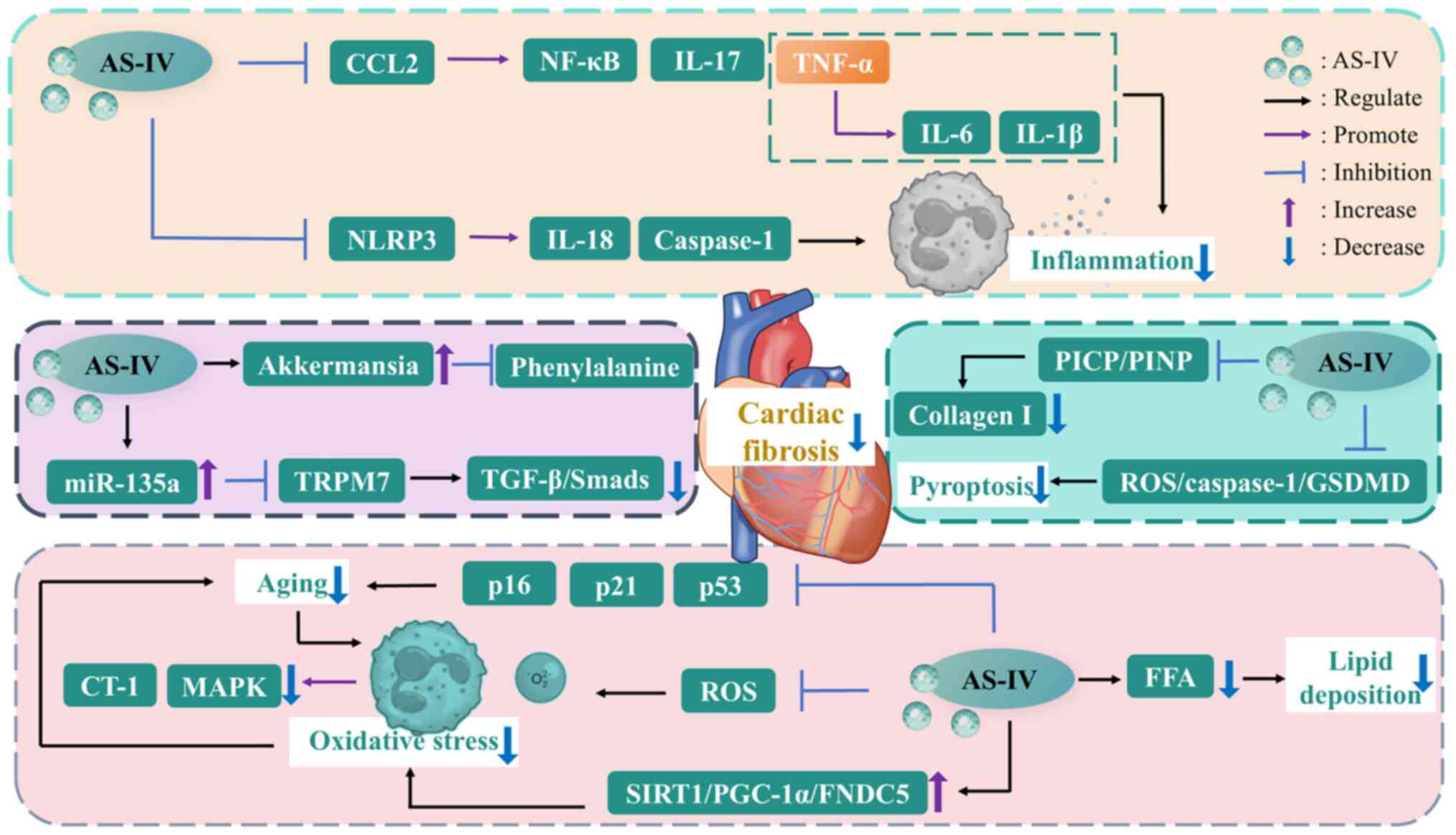

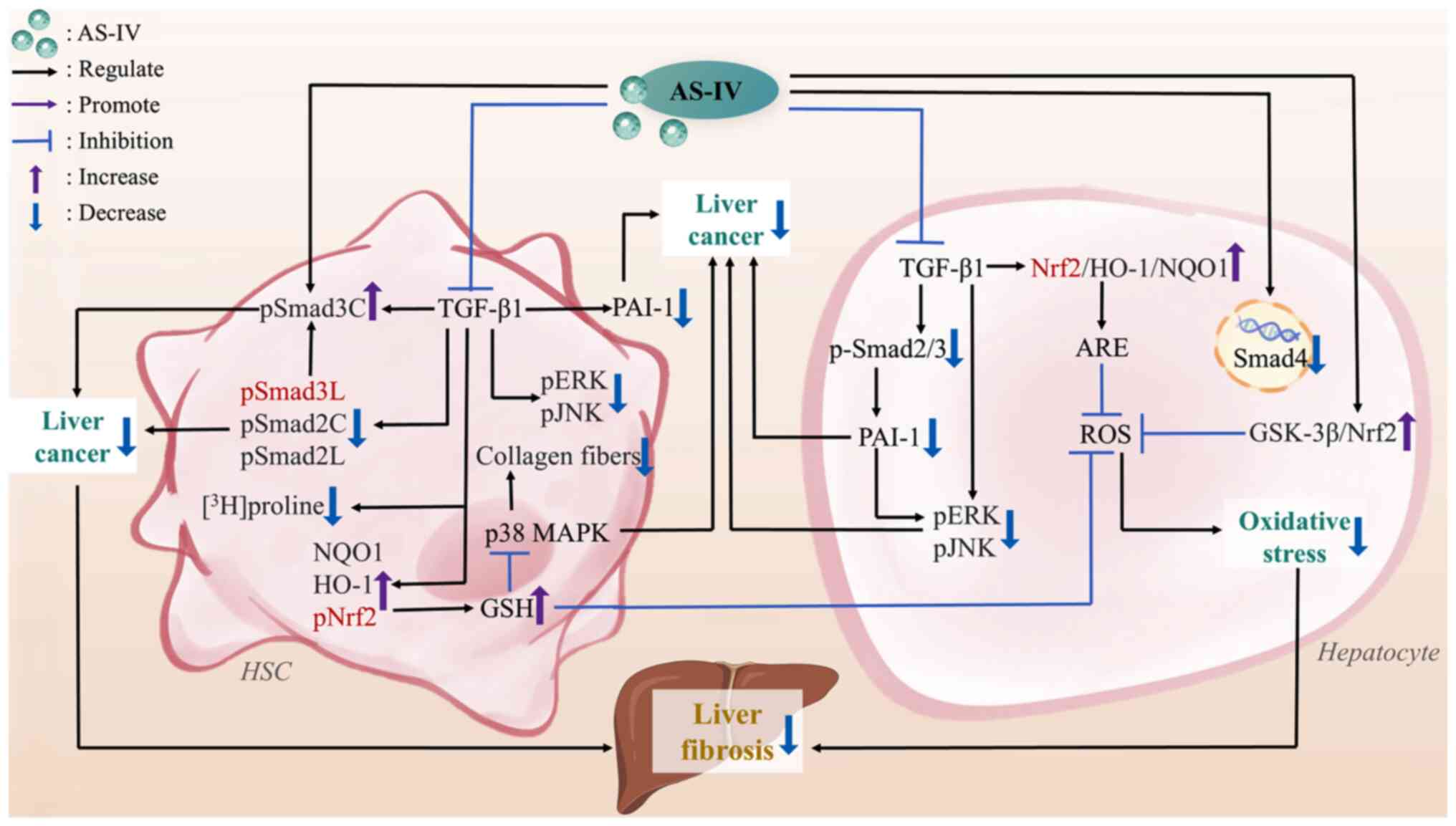

| Figure 3The mechanisms of AS-IV against

cardiac fibrosis. AS-IV, astragaloside IV; CCL2, C-C motif

chemokine ligand 2; collagen I, type I collagen; CT-1,

cardiotrophin-1; FFA, free fatty acid; FNDC5, fibronectin type III

domain-containing protein 5; GSDMD, gasdermin D; IL-17,

interleukin-17; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB,

nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization

domain-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3;

PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1

α; PICP, procollagen type I carboxy-terminal propeptide; PINP,

procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide; ROS, reactive oxygen

species; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β;

TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; TRPM7, transient receptor potential

cation channel, subfamily M, member 7. |

Notably, most of the existing studies on the

anticardiac fibrosis effect of AS-IV are based on in vitro

and in vivo models with remarkable differences in

pathophysiology from human cardiac fibrosis. Clinical research in

this area is limited and the role of AS-IV in ischemic or

nonischemic cardiac fibrosis remains unclear. Furthermore, although

AS-IV is relatively safe, whether its coadministration with other

drugs for CVD treatment leads to drug interactions and whether the

risks of such drug interactions increase the liver and kidney

burden of patients with other comorbidities and trigger potential

toxicity are unknown. Further studies, by incorporating the

detection of indicators, such as ejection fraction and cardiac

systolic or diastolic function, enrich the research value of

AS-IV's anticardiac fibrosis effect. In addition, no research data

on the targeting and accumulation of AS-IV in cardiac tissue exist.

Therefore, evaluating the effective anticardiac fibrosis

therapeutic dose, administration frequency and treatment course of

AS-IV is difficult and the universality and clinical applicability

of research results still need verification.

Pulmonary fibrosis

Diverse heterogeneous interstitial lung diseases can

eventually develop into PF (69). PF can lead to the deposition of

scar tissue in the lung parenchyma, impaired gas exchange function

and even respiratory failure. IPF is also considered a chronic,

fatal interstitial pneumonia with complex causes (70). Smoking, dust inhalation, drug

use, gastroesophageal reflux, genetic factors, viral infection and

autoimmunity are listed as clear PF-related risk factors (71). In the early stage of fibrosis,

the lungs are dominated by chronic inflammation, tissue edema and

congestion. This stage is followed by damage to alveolar epithelial

cells; the massive migration and proliferation of mesenchymal

cells; and the degradation of ECM, including collagen, laminin and

tenascin-C. The continuously deposited ECM promotes scar tissue

hyperplasia, eventually causing a progressive decline in lung

function (72). The typical

pathological features of PF include the persistent inflammatory

responses and structural remodeling of the airways triggered by the

gradual decline in lung function (73). Although glucocorticoids are

mainly used to treat PF, they cannot achieve the expected clinical

efficacy because of their certain side effects on the body

(74). Pirfenidone and

nintedanib, which target the inhibition of inflammasome and

tyrosine kinase activities, respectively, have been approved for

use in the global medical market and are mainly employed to improve

symptoms of dyspnea and lung function decline related to IPF

(75). Although the application

of nanomaterials in the development of new antifibrotic drugs has

begun to receive focus, paying attention to natural Chinese herbal

resources against PF remains necessary (76).

Inflammation and oxidative stress

Exposing the body to silica dust particles for a

long time can induce the diffuse nodular fibrosis of the lungs and

chronic pulmonary inflammation involving alveolar macrophages,

alveolar epithelial cells, fibroblasts, lymphocytes and other

mediators. This condition, which is a typical pathological

manifestation of silicosis, further promotes lung function decline,

dyspnea and even death (77). In

addition, the long-term stimulation of alveolar macrophages by

silica particles drives the release of ROS and oxidative stress can

further exacerbate inflammatory effects in the feed-forward cycle.

AS-IV inhibits silicosis-related inflammation and oxidative stress

by downregulating the expression of inflammatory factors, such as

TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 and upregulating the activities of the

antioxidant enzymes SOD and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px). This

effect may stem from the ability of AS-IV to block the TGF-β1/Smads

signaling pathway, thereby alleviating silicosis-related fibrosis

(77). In summary, AS-IV

negatively regulates fibroblast fibrosis, as primarily indicated by

the remarkable promotion of the dephosphorylation of Smad2 and

Smad3 in fibroblasts and restoration of Smad7 activity, indicating

that AS-IV mediates positive feedback inhibition and the negative

feedback enhancement of the TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathway

(77,78). As aforementioned, NLRP3 is a

multiprotein complex involved in fibrosis-related inflammatory

responses. Hou et al (79) found that AS-IV administration

could promote the inactivation of NLRP3 and the fibrosis-related

effector proteins collagen I, collagen II and α-SMA in

TGF-β-induced PF, thereby alleviating epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT). Furthermore, AS-IV dose-dependently inhibits

pulmonary inflammatory infiltration and fibrosis induced by

bleomycin (BLM) injection. This effect is associated with the

downregulation of total cell, neutrophil, macrophage and lymphocyte

counts in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid targeted by AS-IV (80). AS-IV can also inhibit increased

levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and ROS, as well as promotes the

activity of the endogenous antioxidant indicator SOD and the total

antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), thereby exerting considerable

pharmacological benefits in alleviating BLM-induced PF-related

oxidative stress (80).

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae),

a Gram-negative capsulated bacterium, is known to induce pneumonia

(81). Li et al (82) found that AS-IV administration can

target the downregulation of p-Smad2/Smad2, p-Smad3/Smad3 and

p-IκBα/IκBα levels induced by K. pneumoniae. This finding

suggests that the mechanism by which AS-IV downregulates the NF-κB

inflammatory signaling pathway may be attributed to the negative

regulation of the TGF-β1/Smad pathway. However, although the study

demonstrated AS-IV's mediating function on the Smad and NF-κB

pathways, it did not explore whether the quantity of lung

colony-forming units during K. pneumoniae infection changed

markedly with AS-IV intervention, suggesting that the effect of

AS-IV on bacterial load in lung tissue is unclear (82). AS-IV and ligustrazine extracted

from Astragalus and Ligusticum chuanxiong,

respectively, are natural Chinese herbal components with

antifibrotic activity (83,84). However, in view of their poor

hydrophilicity, the introduction of nanoparticles is beneficial to

improve their penetration into the mucosa. Therefore, AS-IV and LIG

have been coloaded onto inhalable nanoparticles (AS_LIG@PPGC NPs)

to achieve the maximum intervention for PF through noninvasive

pulmonary inhalation therapy (85). NPs are not easily degraded after

being inhaled by the body, can target lung tissue for more than 24

h and are heavily enriched in the right lower lobe and left lung.

In addition, they are diffusely distributed in lung tissue,

demonstrating that the use of polyethylene

glycol-polylactic-co-glycolic acid NPs (PPGC NPs) can improve the

ability of a single agent to target tissue (85). Zheng et al (85) found that the administration of

AS_LIG@ PPGC NPs inhibits the overexpression of the myofibroblast

marker α-SMA and fibrotic effector factor TGF-β1. Moreover, it

reduces the deposition of the ECM component collagen 1A1 and the

release of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β. In

addition, the authors highlighted the therapeutic benefits of AS-IV

in mitigating the levels of pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis

from the perspective of integrated traditional Chinese and Western

medicine. These effects are mainly attributed to the ability of

AS-IV to regulate the release of NOX4-derived ROS negatively and

hinder ROS to drive the proinflammatory and profibrotic effects of

the activated NLRP3 inflammasome (85). Targeting the reduction of ROS

production can also prevent p38 MAPK from being activated and the

excessive release of ROS further aggravates the upregulation of

NOX4 activity. AS-IV's negative regulatory effect on the

NOX4/NLRP3/p38 MAPK axis is complicated by the closed-loop chain

formed among NOX4, ROS, the NLRP3 inflammasome and p38 MAPK.

Applying AS_LIG@PPGC NPs to intervene in PF can further compensate

for the limitations of treatment with a single TCM preparation

(85).

Pyroptosis

The progressive pulmonary artery structural

remodeling exhibited by pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) induces

a surge in right ventricular pressure. Hypoxia is a key inducer of

pulmonary artery remodeling. The ability of mammalian cells to

adapt to hypoxic signal stimulation relies on the promotion of

oxygen transport and body metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

(HIF1α) (86,87). Under normoxic conditions, HIF1α

hydroxylation and degradation depend on the catalytic effect of

prolyl-4-hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) and the downregulation of PHD2

activity is positively associated with pulmonary vascular

remodeling and PAH (88,89). Drugs, such as endothelin receptor

blockers and prostacyclin, are insufficient to decrease the 20-30%

mortality rate of patients with PAH. Xi et al (87) focused on natural herbal medicine

to treat PAH-related fibrosis and found that AS-IV can inhibit the

activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The authors also discovered

that AS-IV can diminish the release of the proinflammatory

cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 in the lung tissue of PAH rats; interfere

with the upregulation of MMPs/tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease 4

and the deposition of FN and collagen I induced by PAH and

negatively regulate the expression of the pyroptosis-related

markers GSDMD-N and cleaved caspase-1 under hypoxic conditions and

the activity of LDH in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells

(PASMCs). Furthermore, AS-IV promotes an increase in PHD2

expression and concurrently suppresses the expression of HIF1α. In

short, NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis and fibrosis in PASMCs can be

markedly inhibited by AS-IV targeting PHD2/HIF1α signaling.

Aging

In network pharmacology analysis, Yuan et al

(90) selected PF-related

signaling pathways through the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes pathway enrichment analysis and used cytohubba to analyze

the protein-protein interaction network associated with AS-IV and

its PF targets. Given that the authors found that the top 10 key

target proteins were markedly enriched in the cellular senescence

pathways, they further used molecular docking to verify that the

cellular senescence marker proteins p53, p21 and p16 are potential

binding targets of AS-IV. By focusing on the mechanism of

PF-related cell aging, they found that AS-IV further reduces

oxidative stress-induced senescence by limiting ROS generation in

the BLM-induced PF mouse model and alveolar epithelial (A549)

cells. The metabolic imbalance in senescent cells induces

pathological changes in protein expression and SASP release.

However, AS-IV not only enhances the expression of the epithelial

protein marker E-cadherin while blocking the synthesis of the

mesenchymal protein marker vimentin but also suppresses the

expression levels of the aging markers p53, p21 and p16. Therefore,

alleviating EMT and cellular senescence is an anti-PF mechanism of

AS-IV (90).

Collagen deposition

High mobility group box-1 (HMGB1), in addition to

inducing inflammatory reactions, is an effector molecule related to

PF. This function is related to its promotion of the

transdifferentiation of fibroblasts and induction of EMT and ECM

protein deposition (91).

However, the extent of ECM protein deposition depends on the

activity of cells that synthesize ECM. Such activity can be

reflected by the expression of the myofibroblast marker α-SMA. ECM

proteins contain a variety of collagen components. Given that

hydroxyproline (HYP) is a primary ingredient of collagen, its

content may be positively associated with the progression of PF

(92). Li et al (92) revealed that AS-IV can target the

downregulation of α-SMA, HMGB1, HYP and collagen III in lung tissue

and further inhibit the synthesis of ECM components, including

laminin and hyaluronic acid. This effect is mediated by promoting

the inactivation of HMGB1, thereby effectively alleviating

BLM-induced PF.

Non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) is

involved in the regulation of the transcription factor networks

linked to EMT and is a key inducer of PF (93). lncRNAs mediate the regulation of

miRNAs, among which miR-200c, a member of the miR-200 family, is

closely related to fibrotic effects, such as EMT, cell invasion and

proliferation (94,95). Through dual-luciferase reporter

gene experiments and bioinformatics, Guan et al (70) found that miR-200c has a

consistent binding site with lncRNA-activated by transforming

growth factor β (lncRNA-ATB) and that the downstream of miR-200c

can regulate the expression of ZEB1. These findings are consistent

with the fact that in patients with silicosis, overexpressed

lncRNA-ATB can interact with miR-200c and target ZEB1 expression

upregulation, thus driving EMT occurrence (70,96). However, in A549 cells used as an

IPF-associated EMT model, AS-IV was found to inhibit lncRNA-ATB by

acting as a competitive endogenous RNA to mediate the sponging of

miR-200c in IPF to target the expression of ZEB1. That is, AS-IV

negatively regulates the level of lncRNA-ATB, promotes the

overexpression of miR-200c and further downregulates the nuclear

level of ZEB1 in TGFβ1-induced EMT model cells, indicating that the

lncRNA-ATB/miR-200c/ZEB1 regulatory axis is a target of AS-IV to

alleviate IPF (70). Circular

RNAs, a member of the endogenous non-coding RNA family, can combine

with miRNA and serve as miRNA sponges to target changes in the

biological functions of downstream genes (97). circ_0008898 overexpression is

positively associated with PF progression. Zhu et al

(98) discovered that

TGF-β1-induced circ_0008898 overexpression in human fetal lung

fibroblast 1 (HFL1) cells could be negatively regulated by AS-IV

(98,99). TGF-β1 can also induce a reduction

in miR-211-5p expression in HFL1 cells. That is, miR-211-5p may

serve as a potential binding target of circ_0008898 given that

miRNAs can target changes in mRNA expression and a rise in

miR-211-5p expression is strongly connected to the inactivation of

HMGB1 in HFL1 cells. HMGB1 has been further confirmed to be a

downstream regulator of miR-211-5p through bioinformatics

prediction and experimental validation (98). Notably, HMGB1 overexpression in

TGF-β1-treated HFL1 cells has a crucial role in driving the

advancement of PF. In summary, AS-IV may rely on the

circ_0008898/miR-211-5p/HMGB1 axis as a key signaling target to

inhibit PF progression in TGF-β1-treated HFL1 cells (98).

The application of Danggui Buxue Decoction (DBT) as

an antifibrotic supplement mainly relies on the pharmacological

activities of AS-IV and ferulic acid (FA) (100). In addition, miRNA can pair with

mRNA and mediate changes in protein expression through the

transcription pathway. miR-29 can inhibit collagen fiber deposition

by targeting various cytokines. For example, the 3'-UTR of the

target gene TGF-β1 is one of its main sites of action. Tong et

al (101) found that on the

basis of the antifibrotic properties of miR-29, AS-IV + FA

(AF) can use miR-29b as a drug target to induce Smad3

dephosphorylation further and alleviate oxidative stress and PF by

triggering nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)

activation and interfering with TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling. This

finding also indirectly shows that the antifibrotic effect of

supplementation with combinations of Chinese herbal medicine

preparations may be improved than that of supplementation with

single drugs. Autophagy deficiency is a key cause of IPF. Its

profibrotic mechanism mainly stems from fibrotic effects, such as

inducing fibroblast transdifferentiation and ECM deposition

(102). According to Li et

al (103), AS-IV could

prevent TGF-β1-treated A549 cells from showing a reduction in light

chain 3B fluorescence signal intensity, indicating that AS-IV may

function as an autophagy agonist. Although some studies have found

that TGF-β1 treatment may motivate fibroblasts to overexpress

miR-21 and overactivated miR-21 further exacerbates the induction

effect of TGF-β1 on PF, AS-IV can inhibit the pathological

upregulation of miR-21 expression. This effect is mainly attributed

to the fact that the antifibrotic effect of AS-IV is reversibly

mediated by miR-21 agonists (103,104). Bioinformatics analysis provides

evidence that phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is one of the

binding targets of miR-21 (103). Given that PTEN, a molecular

inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), can negatively

regulate PI3K/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR) signaling through downstream effects and mTOR is an effector

molecule that drives autophagy blockage, in-depth research has

confirmed that AS-IV can negatively regulate PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling by targeting the upregulation of PTEN activity, thereby

promoting the inhibitory effect of autophagy on IPF (103,105,106).

PM2.5 is a fine particulate matter involved in the

formation of haze. PM2.5 suspended in the air can adsorb

microorganisms and directly enter alveoli, markedly downregulating

the activity of the anti-inflammatory factor miR-362-3p in alveolar

epithelial cells and promoting the overexpression of the downstream

target runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) of miR-362-3p,

in which RUNX1 induces the transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into

myofibroblasts, driving the occurrence of respiratory diseases,

such as PF (107,108). AS-IV targets the overexpression

of miR-362-3p and negatively regulates the activity of its

downstream transcription factor RUNX1 in rat lung tissue and

alveolar epithelial cells to alleviate the inhibitory effect of

PM2.5 on the proliferation of rat alveolar epithelial cells L2 and

its driving effect on LDH release. In addition, AS-IV suppresses

PM2.5-induced alveolar wall thickening and collagen III deposition

in lung tissue. Furthermore, it reverses the apoptosis rate of rat

lung tissue and L2 cells; the secretion of the proinflammatory

factors TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6; and the overactivation of cleaved

caspase-3, p-p65 and α-SMA, thereby inhibiting PM2.5-driven PF

(108). Therefore, AS-IV may be

a natural therapeutic agent for alleviating air pollution-related

PF by regulating the miR-362-3p/RUNX1 signaling cascade.

Forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a)

FOXO3a is extensively expressed in the majority of

bodily tissues and cells. TGF-β1 is an upstream factor that

activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and promotes AKT

phosphorylation, thereby markedly downregulating the activity of

FOXO transcription factors. FOXO3a inactivation is an important

factor for promoting fibroblast collagen deposition and α-SMA

overexpression, which further induces the occurrence of IPF

(109,110). However, AS-IV regulates the

inactivation of the PI3K/AKT pathway by targeting TGF-β1, further

blocking the hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of FOXO3a,

downregulating EMT and the expression of α-SMA and increasing the

levels of the epithelial cell marker E-cadherin, thus resulting in

considerable resistance to BLM-induced IPF (84). Smoking has been confirmed to a

key risk factor for inducing PF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD) is often triggered by excessive smoking and

accompanied with persistent respiratory inflammatory infiltration,

which further increases the risk of PF (111). Given that rat sarcoma (RAS) can

regulate the downstream expression of the fibrotic effector

molecule FOXO3a, RAS activity and EMT development have been

demonstrated to be markedly positively associated (112). Through multiple protein and

small-molecule interaction experiments and amino acid site mutation

approaches, Zhang et al (113) found that RAS is a binding

target of AS-IV. AS-IV can inhibit RAS expression to induce the

dephosphorylation of c-Raf338 and FOXO3a. Therefore, by

targeting the expression of the non-Smad signaling pathway

RAS/rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF)/FOXO signaling cascade

and its downstream inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-1β, AS-IV

markedly inhibits the transdifferentiation of fibroblasts and

alleviates LPS and cigarette smoke treatment-induced COPD-related

EMT progression.

Advanced glycation end-product

(AGE)-receptor for AGE (RAGE)

Patients with T2DM can be complicated with diabetic

PF (114). In view of the

epidemiological data showing that T2DM and its complications have

become the cause of death of ~6.7 million individuals, focusing on

the application of Bu Yang Huan Wu Decoction, which has the effect

of reducing blood sugar and blood lipids, in PF intervention

(115) is essential. Elevated

blood glucose concentration induces the nonenzymatic glycosylation

of proteins, such as collagen and elastin, thereby promoting the

production of AGEs. RAGE, which is found to be widely expressed in

lung tissue, can act as an AGE inhibitor (115). Through network pharmacology

analysis, Guo et al (115) discovered that regulating the

AGE-RAGE signaling cascade and the gene expression of its

downstream effector molecules is the key mechanism through which

bioactive ingredients, such as AS-IV, in Bu Yang Huan Wu Decoction

exert anti-PF effects. Hydrogen bonding is a key parameter

indicating the binding degree of a protein to a ligand. Evidence

from molecular docking and dynamics simulations supports that the

complex system formed by the downstream target gene IL-6 of the

AGE-RAGE signaling pathway and AS-IV has certain stability likely

because IL-6-AS-IV binds to an average of three hydrogen bonds.

This phenomenon indicates that the binding affinity between the two

is strong and also implies that AS-IV can target AGE-RAGE signaling

and negatively regulate the induction of collagen deposition and

ECM synthesis in lung tissue by IL-6, the downstream fibrotic

effector molecule of the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway. That is, AS-IV

can markedly inhibit high glucose (HG)-induced PF (Fig. 4).

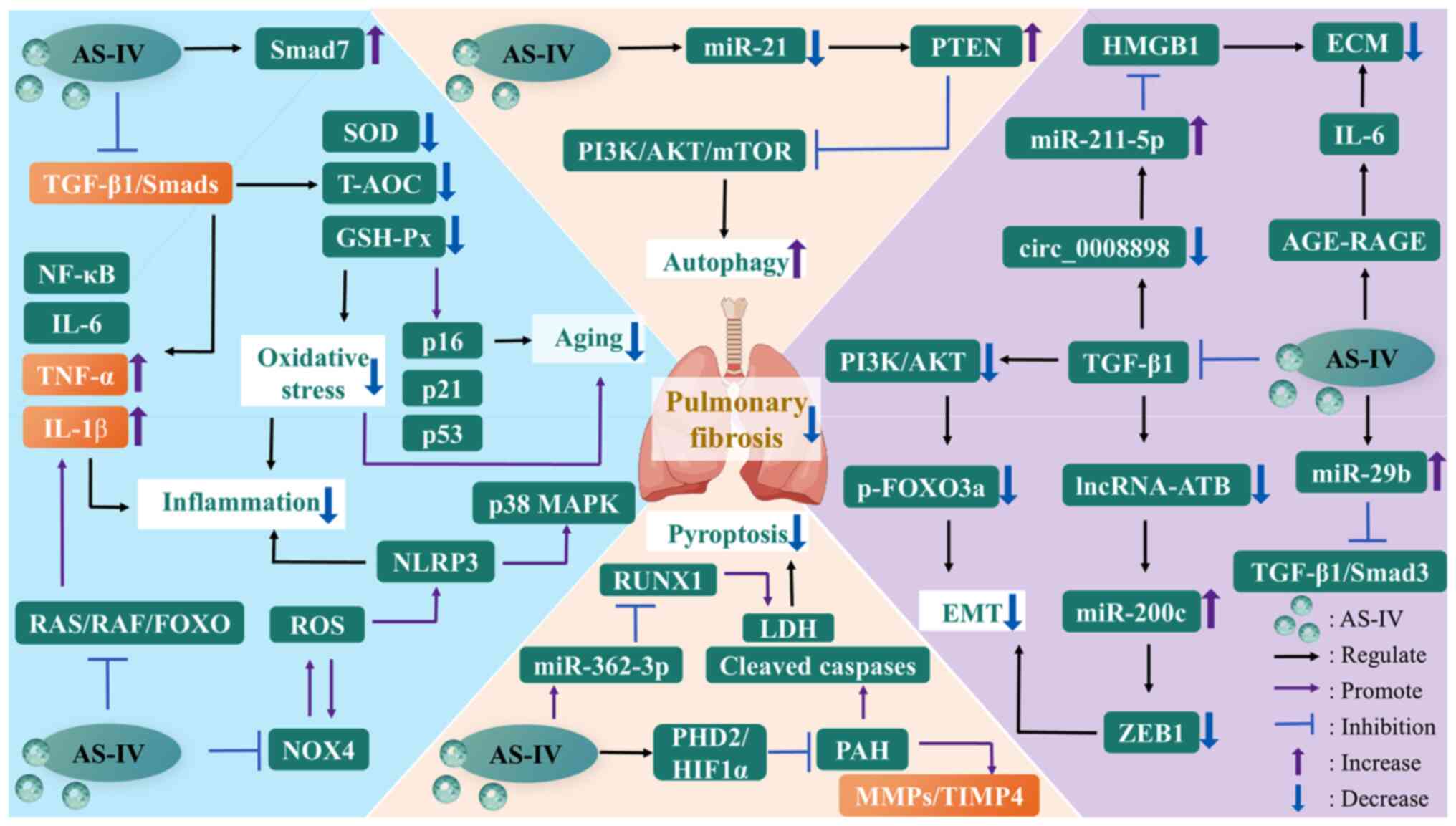

| Figure 4The mechanisms of AS-IV against

pulmonary fibrosis. AGE, advanced glycation end-product; AKT,

protein kinase B; AS-IV, astragaloside IV; ECM, extracellular

matrix; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; FOXO, forkhead box

O; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor

1α; HMGB1, high mobility group box-1; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; LDH,

lactate dehydrogenase; lncRNA-ATB, long non-coding RNA activated by

transforming growth factor β; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein

kinase; miR-21, microRNA-21; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; mTOR,

mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B;

NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor

thermal protein domain associated protein 3; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4;

PAH, pulmonary artery hypertension; PHD2, prolyl-4-hydroxylase 2;

PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin

homolog; RAF, rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; RAGE, receptor for

AGE; RAS, rat sarcoma; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RUNX1,

runt-related transcription factor 1; SOD, superoxide dismutase;

T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity; TGF-β1, transforming growth

factor-β1; TIMP4, tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease 4; TNF-α,

tumor necrosis factor-α; ZEB1, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox

1. |

PF is a heterogeneous disease and the therapeutic

effect of AS-IV may vary across different subtypes of PF. In

addition, animal models usually simulate acute or subacute PF,

whereas PF in humans is a progressive condition. Therefore, the

long-term intervention effect of AS-IV still needs to be verified

in human clinical studies. The triggers of human PF, such as PF

induced by drugs, connective tissue diseases, or inhaled dust, are

difficult to replicate fully through animal experiments. Moreover,

the evidence from tests encompassing pulmonary function indicators,

including vital capacity and diffusion capacity, remains

insufficient. Not only that, the comparative analysis of the

therapeutic effects between AS-IV and anti-PF drugs, such as

pirfenidone and nintedanib and the dose-response relationship

between the dosage and anti-PF effect of AS-IV remain unclear.

Finally, the oral bioavailability of AS-IV is limited. Additional

data are required to confirm whether approaches, such as aerosol

inhalation and dosage form optimization, can increase the

concentration of AS-IV in lung tissues, ensure its accumulation in

damaged lung tissues and enable its effective interaction with lung

cells.

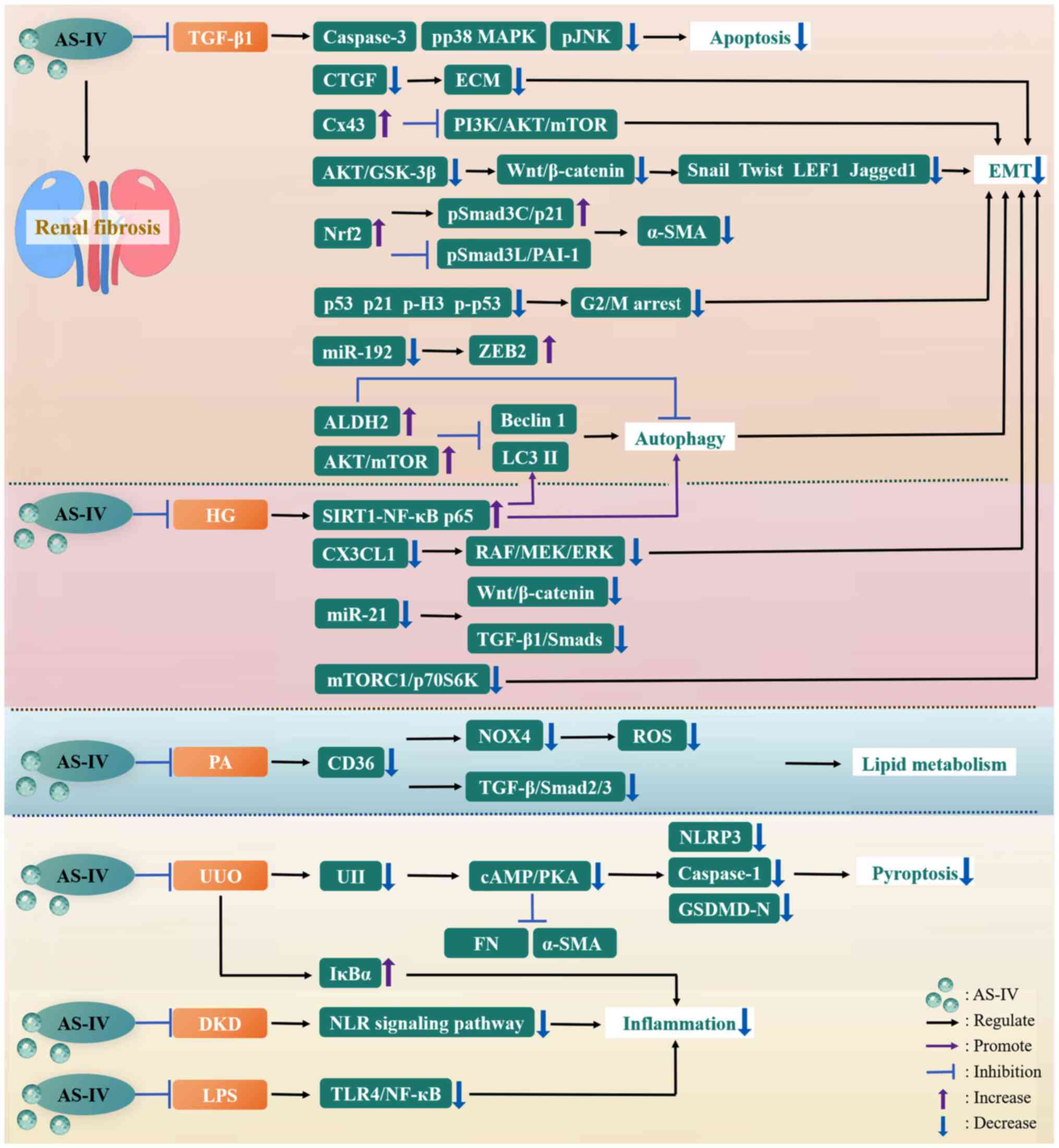

Renal fibrosis

The main characteristics of chronic kidney disease

(CKD) include progressive renal tissue structural lesions and

impaired renal excretory function, which may be due to functional

nephron defects caused by diverse causative variables, including

diabetes, interstitial nephritis, glomerulonephritis, obstructive

nephropathy and polycystic kidney disease (116). CKD affects >10% of the

overall population worldwide and in the United States alone, ~14%

of adults are affected by pathological factors related to CKD

(117,118). Among these factors, renal

fibrosis is often a unified pathological manifestation of

progressive CKD regardless of the progression of CKD. If the

prognosis is inappropriate, then end-stage renal failure is often

the final outcome (119). The

transdifferentiation of intrinsic renal cells, such as mesangial

cells (MCs), epithelial cells, endothelial cells, or fibroblasts,

into myofibroblasts is a key mechanism for inducing renal fibrosis.

Various cytokines that maintain the homeostasis of ECM deposition

and degradation and proinflammatory mediators are also involved in

the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis (120). In addition, the excessive

deposition of fibrous connective tissue has adverse effects on the

physiological function of renal tubules and glomerular filtration

rate; this phenomenon also causes the tubulointerstitial space and

glomerulus to become key sites for frequent fibrosis (121,122). Although dialysis and kidney

transplantation are currently commonly used to intervene in ESRD,

renal replacement therapy may induce some uncertain risk factors,

necessitating intervening in CKD as early as possible to avoid its

progressive deterioration into ESRD (123). Given that whether fibrosis is a

cause or a pathological manifestation of CKD is unclear and

intervening in the progression of CKD by directly targeting the

treatment of renal fibrosis requires further in-depth research,

conservative antifibrotic treatments, such as the use of

well-tolerated Chinese herbal medicines, may achieve the negative

regulation of various kidney diseases in their initial phases

(124).

Diabetic kidney disease-induced renal

fibrosis

Lipid metabolism

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) can cause glomerular

ultrastructural alterations by inducing the deposition of ECM

proteins, such as FN and DKD, lacking effective prognosis may cause

the induction of ESRD. This situation can explain why ~1/3 of

individuals with diabetes develop irreversible end-stage renal

failure (125). Human

glomerular mesangial cells (HMCs) can participate in the occurrence

of DKD-related fibrosis via the uptake of FFAs flowing into the

kidney. The uptake of medium- and long-chain FFAs mainly depends on

the transport activity of cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36)

protein, which is widely expressed in renal glomeruli and involved

in the induction effect of FFAs on HMC fibrosis to a certain

extent. AS-IV can negatively regulate the expression of FN and type

IV collagen α 1 and the TGF-β1/Smad2/3 signaling pathway in the

palmitic acid (PA)-treated HMC fibrosis model. It can also inhibit

the activation of CD36 expression in a high-fat environment induced

by PA. Given that NOX4-derived ROS play a vital role in regulating

the progression of DKD and NOX4 can cross-talk with the

TGF-β1/Smad2/3 pathway and become a fibrotic effector molecule,

NOX4 may be the key target for the inhibition of DKD-related renal

fibrosis (125). Nath et

al (126) also verified the

profibrotic effect of CD36. That is, the uptake of PA by CD36

induces the TGF-β1/Smad2/3 signaling cascade and mediates the

occurrence of EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This situation

indicates that NOX4 and TGF-β1 overexpression may be attributed to

the regulatory effects of upstream CD36 activation. However, AS-IV

markedly reduces the expression of CD36, NOX4 and TGF-β1 in

PA-treated HMCs (125).

Inflammation and oxidative stress

In the diabetic phase, renal cells exhibit high

glucose uptake. However, other cell populations, such as glomerular

MCs, are unable to regulate the decrease in glucose transport

rates. This inability induces an imbalance in intracellular glucose

homeostasis and promotes cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS release

(127). In addition,

ROS-mediated oxidative stress induces the activation of the

TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway, which in turn regulates the fibrosis

of renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs). Du et al

(127) found that the combined

administration of ginsenoside Rg1 (G-Rg1) and AS-IV is more

effective than monotherapy in interfering with TGF-β1/Smads

signaling mainly because G-Rg1 has strong pharmacological activity

in the negative regulation of TGF-β1 expression, whereas Smad7

activity targeted by AS-IV is remarkably upregulated. In the

treatment of DKD, AS-IV acts as an enhancer of the antioxidative

stress effect of G-Rg1. The main manifestation of this effect is

that after coadministration, the levels of catalase, GSH-Px and

T-AOC maximally increase, whereas MDA shows reduced activity

(127). In addition, abnormally

elevated blood glucose concentrations can drive ROS release and

oxidative stress. AGEs are protein derivatives that can mediate

proinflammatory responses and oxidative stress. They all have an

intimate connection with the occurrence of DKD. Zhang et al

(128) found that in DKD rats,

AS-IV administration can reduce the excessive synthesis of AGEs and

the overexpression of inflammatory factors. Moreover, AS-IV

treatment can reduce the excessive synthesis of collagen IV in the

basement membrane and the excessive deposition of FN in the renal

mesangium and interstitium. The authors also verified the

activation effect of the excessive release of ROS on cytokines and

transcription factors. This phenomenon is not only a reason for the

induction of the massive deposition of ECM in the kidney area but

also aggravates renal fibrosis complicated by DKD and the

development of end-stage renal failure (129). Furthermore, transcriptomic

analysis has shown that the inflammation-related NLR signaling

pathway is a pharmacological target of AS-IV and can potentially

participate in the way that AS-IV ameliorates renal fibrosis

complicated by DKD in rats (128).

mTORC1/p70S6K

mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) can regulate the

phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 kinase β-1 (p70S6K)

downstream, thus participating in cell proliferation or growth to

some extent. However, the development of DKD is intimately

associated with pathologically driven mTORC1/p70S6K signaling,

which may further induce DKD complicated by RTEC

transdifferentiation (130).

Chen et al (131) found

that in human proximal tubular epithelial (HK-2) cells treated with

different concentrations of HG, AS-IV can target the upregulation

of the epithelial cell marker E-cadherin and negatively regulate

α-SMA. Moreover, AS-IV downregulates the phosphorylation of mTOR

and its downstream molecule p70S6K. That is, it has an inhibitory

effect on the signal transduction of the mTORC1/p70S6K pathway. In

addition, a negative correlation exists between zinc finger

transcription factors (Snail, Slug, Twist and ZEB1) and E-cadherin

expression. Nevertheless, the mTORC1/p70S6K pathway is also highly

associated with the activities of the transcription factors Snail

and Twist (130). AS-IV can

target the inactivation of HG-induced Snail and Twist proteins and

that the ECM protein components FN and collagen IV are

downregulated when AS-IV intervenes in DKD (131). In summary, AS-IV further

negatively regulates renal tubular EMT induced by HG concentration

by inhibiting the overactivation of the mTORC1/p70S6K signaling

pathway and downregulates the expression of the transcription

factors Snail and Twist in HK-2 cells, simulating DKD in

vitro (131).

miRNA

Proteinuria is mainly used as a clinical diagnostic

criterion of DKD, a microvascular complication of diabetes and is

often accompanied with renal fibrosis. Highly differentiated

podocytes participate in forming the outermost layer of defense for

glomerular filtration. Adverse stress reactions may affect the

differentiation structure of podocytes, further causing

macromolecular plasma proteins to penetrate the damaged filtration

barrier directly and flow into the urinary filtrate, thus

aggravating the occurrence of renal fibrosis (132). MCs are a type of glomerular

cells. Their excessive activation also induces the enhanced

expression of α-SMA and promotes the deposition of large amounts of

ECM proteins, thereby participating in the formation of DKD-related

renal fibrosis (133). The

progression of mammalian kidney disease is known to be markedly

associated with the expression of miR-21, which transcriptionally

suppresses the expression of downstream target genes (134). However, AS-IV

concentration-dependently decreases the levels of miR-21 and the

mesenchymal marker α-SMA in HG-induced podocytes and MCs and the

level of the epithelial marker nephrin in podocytes is positively

associated with the concentration of AS-IV administration (135). In addition, podocyte damage and

MC proliferation are inextricably linked to the involvement of the

Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β1/Smads signaling cascades. However, AS-IV

markedly lowers the upregulated β-catenin, TGF-β1 and p-Smad3

levels in podocytes and MCs with miR-21 overexpression and promotes

the recovery of Smad7 activity. In summary, AS-IV impedes the

advancement of DKD-related renal fibrosis and maintains highly

differentiated podocyte morphology and MC stability by negatively

regulating the levels of highly activated miR-21 and inhibiting the

driving effect of miR-21 on the downstream Wnt/β-catenin and

TGF-β1/Smads signaling cascades. These functions provide new

insights into the AS-IV targeted treatment of glomerular-related

diseases (135).

Autophagy

As a deacetylase, SIRT1 plays a key role in

mediating renal dysfunction, such as podocyte injury (136). In addition, during HG-induced

podocyte apoptosis, activated NF-κB can serve as a signaling

molecule that inhibits autophagy by targeting LC3 II

downregulation. However, according to Wang et al (137), AS-IV further impedes podocyte

EMT by reversing the negative effect of HG treatment on the

activity of the autophagy markers Beclin1 and LC3 II. By contrast,

SIRT1 activator helps enhance this phenomenon, indicating that

AS-IV activates SIRT1 to deacetylate the NF-κB p65 subunit and may

execute pharmacological activity as an autophagy agonist. At the

same time, N-cadherin and α-SMA expression by AS-IV in podocytes

treated with different HG concentrations are reversed under the

mediation of the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine, the

activation of E-cadherin and nephrin levels and the inhibition of

TGF-β. This effect further demonstrates that AS-IV can serve as a

pharmacological autophagy inducer in DKD, thereby protecting

glomerular structure and alleviating the HG environment that drives

podocyte EMT (137). Moreover,

Wang et al (138) found

that AS-IV pretreatment concentration-dependently suppresses α-SMA,

FN and collagen IV expression in MCs induced by HG and the

prohibitive effect of AS-IV on the activation and proliferation of

MCs induced by HG is still related to autophagy activation mediated

by SIRT1-NF-κB signaling transduction.

RAF/MEK/ERK

The pathological upregulation of plasma C-X3-C

motif ligand 1 (CX3CL1) concentrations in adult patients with CKD

is often a key risk variable associated with the occurrence of CVD

and diabetes (139).

Furthermore, EMT is intricately linked to the activation of the

RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/ERK signaling cascade

(140). Hu et al

(141) revealed that AS-IV

administration can negatively regulate the expression of the

mesenchymal marker vimentin and myofibroblast marker α-SMA in db/db

mice and HK-2 cells treated with HG; partially inhibit the

overexpression of CX3CL1 and p-c-Raf/c-Raf, p-MEK/MEK and

p-ERK/ERK; and upregulate the activity of the epithelial cell

marker E-cadherin (141). In

summary, AS-IV further inhibits the induction of EMT by the

RAF/MEK/ERK signaling cascade by targeting the downregulation of

CX3CL1 expression, thereby effectively alleviating the occurrence

of EMT in DKD.

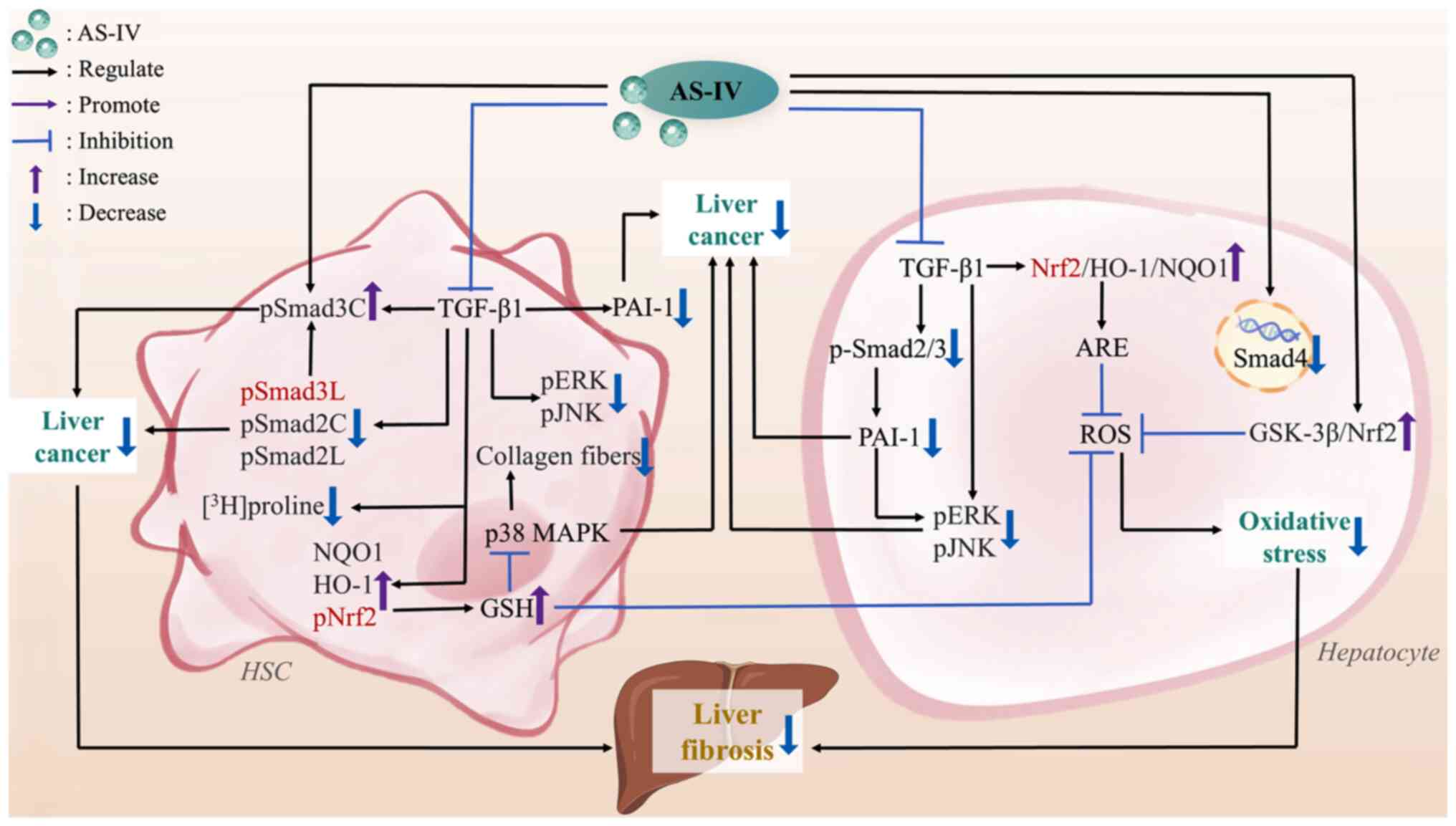

TGF-β1/UUO treatment-induced renal

fibrosis

Inflammation

Renal function repair is facilitated by the

synergistic action of fibroblasts, RTECs, endothelial cells, renal

interstitial lymphocytes and macrophages that are involved in the

inflammatory response and the preservation of ECM homeostasis when

the kidney is under adverse stress (142). During repair, if the synthesis

and degradation of ECM are out of balance and a large amount of

collagen fibers are deposited, then the activation and

proliferation of fibroblasts is induced and intrinsic renal cells

are replaced. These processes constitute the occurrence of renal

fibrosis. According to Zhou et al (143), AS-IV could inhibit the

inflammatory infiltration induced by macrophages and lymphocytes in

unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO)-treated mice and upregulate

IκBα expression. By contrast, in LPS-treated RTECs in vitro,

AS-IV could negatively regulate Toll-like receptor 4/NF-кB

signaling. This finding shows that AS-IV's anti-inflammatory action

on RTECs and inflammatory cells may be one of its potential

pharmacological mechanisms to impede the course of renal fibrosis

and CKD.

Autophagy

EMT is associated with the G2/M cycle

and partial RTEC lesions induce G2/M arrest and

participate in the occurrence of EMT under the mediation of

fibrotic effector cells. Furthermore, the mitochondrial

physiological function is markedly positively associated with the

activity of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2). ALDH2 can target

the inhibition of autophagic activity to mitigate the functional

damage caused by LPS to the heart (144). Li et al (123) found that AS-IV can reverse the

upregulation of the autophagy indicators ATG7, Beclin1 and LC3

II/LC3 I in an adenine-treated CKD rat model and a TGF-β1-induced

in vitro HK-2 fibrosis model and drive p62 accumulation by

inhibiting autophagy. The inhibitory effects of AS-IV on

CKD-induced autophagy could be explained by the activation of the

AKT/mTOR signaling cascade and upregulation of ALDH2 activity. In

addition, following AS-IV administration, the activity of the

mediators involved in G2/M cell cycle arrest, including

p21, p53, p-p53 and p-histone H3, markedly decreased, indicating

that AS-IV can target CKD-related G2/M cell cycle

change. AS-IV induces the expression of the epithelial cell marker

E-cadherin to be upregulated and that of renal mesenchymal cell

markers to be downregulated; these effects further illustrate its

inhibitory effect on EMT (123).

TGF-β/Smad

The TGF-β receptor activates the phosphorylation of

the downstream fibrotic effector proteins Smad2 and Smad3, which

form a complex with Smad4 and are transported into the nucleus.

Smad family members, including Smad7, an inducer that promotes

TGF-β1 receptor degradation and Smad2/3 inactivation, are mostly

involved in the transcription of target genes. However, TGF-β1 has

two sides: In addition to being an inducer driving fibrotic and

anti-inflammatory responses, its inactivation may also mean

exacerbating proinflammatory effects, suggesting that antifibrotic

intervention that directly targets TGF-β may trigger other unknown

risks (145). Wang et al

(146) reported that the

expression of the myofibroblast marker a-SMA and the formation of

fibrous connective tissue in a UUO-treated rat model were

negatively regulated by AS-IV intervention. In addition, AS-IV has

been shown in vitro to promote the inactivation of fibrotic

effector connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in rat renal

fibroblasts (NRK-49F) treated with TGF-β1, thereby inhibiting its

downstream induction of ECM synthesis and further resisting renal

fibrosis. An in vitro experiment has also shown that AS-IV

can activate the dephosphorylation of Smad2 or Smad3. Silencing the

expression of the Smad7 gene in NRK-49F cells via the small

interfering RNA technique further demonstrated that AS-IV

alleviates renal fibrosis associated with obstructive nephropathy

because of its targeted effect on the upregulation of Smad7

activity. In summary, AS-IV's antitubulointerstitial fibrosis

effect and its targeted inactivation of the TGF-β/Smad signaling

pathway are markedly positively associated (146).

PI3K/AKT/mTOR

Renal interstitial fibrosis often occurs when

various CKDs progress to advanced stages (147). Gap junctions promote

intercellular communication by mediating intercellular material

transport and signal transmission. Connexin43 (Cx43) may crosstalk

with the occurrence of fibrotic diseases (148). In addition, the inactivated

PI3K/AKT signaling cascade can mitigate TGF-β1-induced EMT and

highly activated mTOR is markedly positively associated with the

occurrence of EMT (147,149).

Lian et al (147) found

that the inactivated AKT/mTOR pathway may be an integral mediating

factor in the mechanism through which Cx43 negatively regulates EMT

in TGF-β1-treated RTECs. That is, by inhibiting the TGF-β1-induced

downregulation of Cx43 protein levels, AS-IV can interfere with

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, attenuate the expression of the

mesenchymal marker α-SMA and vimentin and further prevent

TGF-β1-induced RTEC EMT. This phenomenon suggests that AS-IV may be

an effective drug for preventing EMT in RTECs and renal

interstitial fibrosis.

PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β and Wnt/β-catenin

TGF-β1 not only targets the Smad transcriptional

activator family but also regulates non-Smad-dependent signaling

pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT signaling cascade, which contributes

to fibroblast transdifferentiation and fibrosis. Network

pharmacology analysis showed that AS-IV and renal fibrosis share

multiple targets and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

pathway enrichment analysis found that the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway has intersectionality with these shared targets, among

which AKT1 and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) are markedly

enriched in the PI3K/AKT signaling cascade (150). Further in vitro cell

experiments revealed that AS-IV treatment inhibits the

TGF-β1-induced upregulation of AKT phosphorylation in rat renal

tubular epithelial (NRK-52E) and NRK-49F cells in a

concentration-dependent manner, thereby promoting its induction of

GSK-3β dephosphorylation (150). In addition, the

dephosphorylation of GSK-3β can induce β-catenin degradation,

thereby negatively regulating the progression of EMT. Consequently,

the mechanism by which AS-IV can prevent TGF-β1 from activating

β-catenin is linked to AS-IV targeting the inactivation of the

AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway, which alleviates EMT and further

inhibits β-catenin to promote Wnt signaling pathway activation

(150). Notably, disheveled

(Dsh or Dvl) proteins often promote the dephosphorylation of

β-catenin, thereby interfering with its degradation mainly because

activated Dsh proteins drive the separation of GSK-3β from the

degradation complex, thereby promoting Wnt/β-catenin signaling and

targeting the elevation of downstream gene expression. According to

Wang et al (151), AS-IV

suppresses the overexpression of Wnt and Frizzled genes in a

UUO-induced renal interstitial fibrosis rat model, with the