Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is an inherited retinal

disease (IRD) characterized by progressive degeneration of

photoreceptor cells, with a global prevalence of ~1/4,000, and it

currently has no effective cure (1-4).

X-linked RP (XLRP) is one of the most severe forms of RP. Mutations

in the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR)

gene are the main cause of XLRP and are also associated with

cone-rod dystrophy (CORD) (5-9).

The RPGR gene is located on the short arm of

the human X chromosome (Xp11.4) (3,10). RPGR proteins interact with other

proteins at the connecting cilium (CC) of photoreceptor cells to

form a complex regulatory network, which maintains the functional

stability of the CC by coordinating key processes such as vesicle

transport. Mutations in the RPGR gene lead to loss of RPGR

function. This disruption impairs the normal protein transport

system in photoreceptor cells, which subsequently disturbs

metabolic and synthetic homeostasis [such as, renewal of outer

segment (OS) disc membranes] and alters light signaling cascades.

Together, these changes ultimately lead to photoreceptor damage and

retinal structural degeneration (1,11,12).

Although considerable progress has been made in gene

therapy research on RPGR mutations worldwide and multiple

relevant animal models have been established, the key pathogenic

mechanisms and pathological features underlying RP caused by

RPGR mutations remain incompletely elucidated. Moreover, the

translation of these findings into clinical applications continues

to face key challenges. For patients with RPGR

mutation-associated retinal degeneration, the development of highly

sensitive genetic detection technologies (such as long-read

sequencing) and functional validation systems is important. A

systematic analysis of the population genetic characteristics and

the pathogenic mechanisms of RPGR gene mutations will

provide a theoretical basis for individualized diagnostic

stratification and targeted gene therapy. The present review

assesses the types of RPGR gene mutations, pathogenic

mechanisms and their effects on photoreceptor cell function

reported in recent years. In the present review, the research

progress in cross-species models (such as mouse, dog and zebrafish)

is summarized and the effectiveness of existing gene therapy

strategies [such as adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated gene

replacement and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing] in preclinical models is

evaluated. Meanwhile, preclinical studies of RPGR gene therapy are

also discussed and recent clinical advances are analyzed.

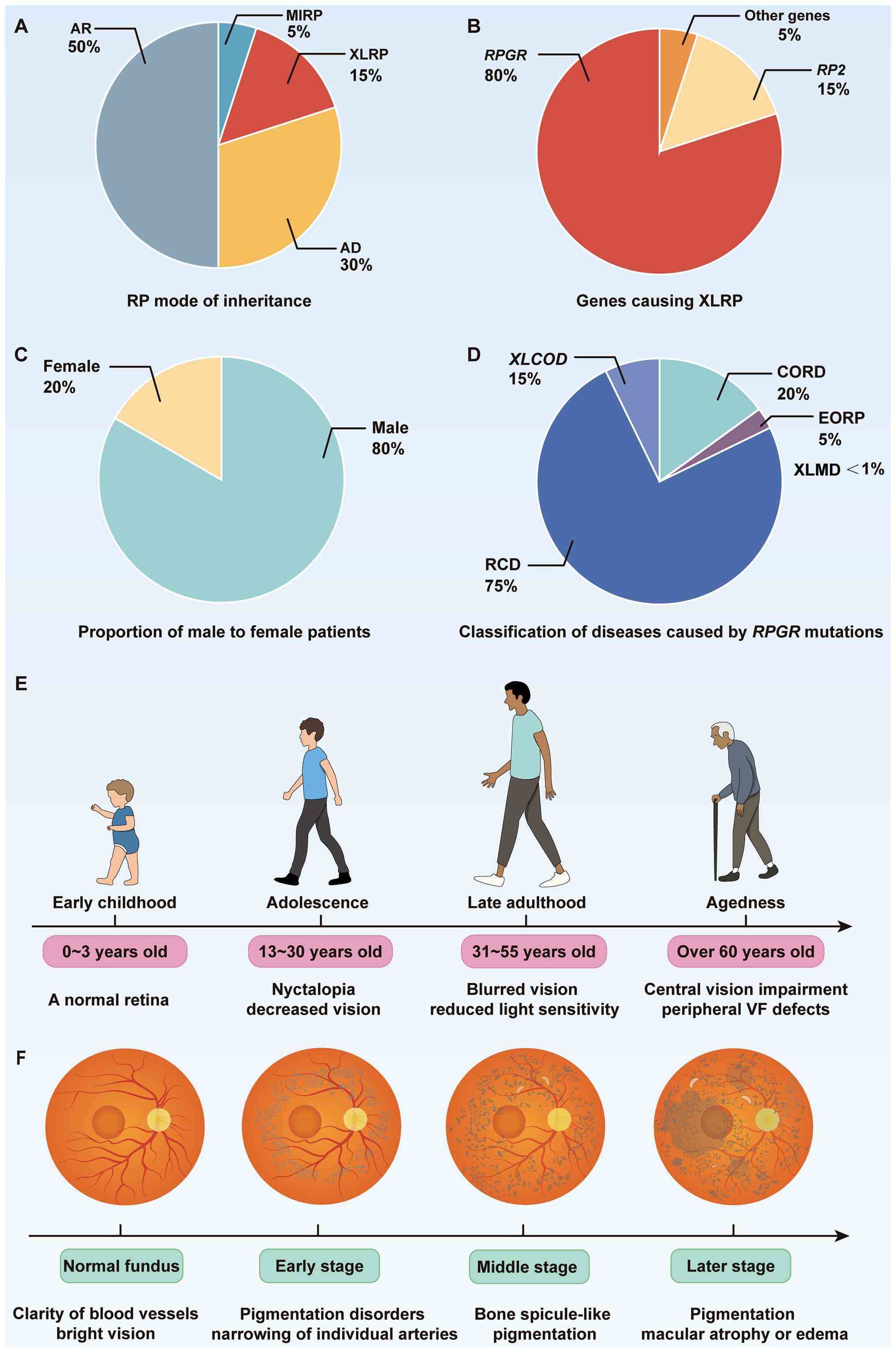

Clinical and genetic features of

RPGR-associated retinopathies

Based on the inheritance pattern, RP can be

categorized into four types: Autosomal recessive (AR) RP, autosomal

dominant (AD) RP, X-linked RP and mitochondrial RP (Fig. 1A) (13). Global statistics show that the

total number of patients with RP is >1 million (3,10,13,14). Clinical statistics show that AR

accounts for ~50% of cases, whereas AD accounts for ~30% (15,16). XLRP has a relatively low

prevalence of ~20%, but its patients are found across all age

groups (17,18). Individuals with RP show

considerable differences in disease severity and progression rates,

and this heterogeneity is determined by both the type of causative

mutation and the molecular mechanisms that the mutation mediates

(3). In addition, >100

causative genes have been identified (2,4,10,12). The majority of patients with RP

show an age-related pattern of progression. The disease initially

presents with night blindness due to rod dysfunction, followed by

rod degeneration that results in peripheral visual field (VF)

defects. As the disease progresses, secondary cone damage leads to

loss of central vision, with progressive loss of metabolic support

from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), ultimately leading to

blindness (1,11,12).

XLRP is a severe form of retinal ciliopathy,

characterized by the progressive degeneration of rod and cone

photoreceptor function in the retina (7). XLRP typically has a rapid onset and

progression. Some patients first experience nighttime vision loss

during adolescence, which progresses to pronounced night blindness

in early adulthood and eventually leads to central vision

impairment (19). As the disease

progresses, patients are observed to have retinal vascular

narrowing and bone spicule-like pigmentation on fundus imaging

(2,20). The risk of blindness markedly

increases in patients >50 years of age (Fig. 1). In patients with XLRP, ~70 to

80% of cases are caused by RPGR mutations, whereas

RP2 mutations account for ~10 to 15%. Notably, XLRP

resulting from RPGR mutations tends to present with a more

severe phenotype (20-22). Although both RPGR and

RP2 mutations can cause XLRP, the patterns of disease

progression are distinct. Patients with RPGR mutations

typically develop night blindness in early childhood and may

experience severe vision loss in their early 20s. In addition,

mutations in this gene have been associated with rod-cone dystrophy

(RCD), CORD, X-linked cone dystrophy (XLCOD), X-linked macular

dystrophy (XLMD) and early-onset RP (1,20,23,24). Mutations in the RPGR gene

account for 73% of X-linked CORD cases. Affected individuals

typically present with reduced visual acuity (VA), color vision

deficits, central VF defects and photophobia. They usually have a

late onset at ~40 years (25).

Clinical studies have found that vision loss

progresses relatively rapidly in these patients, with a decline in

best-corrected VA (BCVA) of ~7% per year and >60% exhibit a BCVA

of 1 logMAR or worse by the age of 50 years (26,27). There is a notable phenotypic

difference between male and female patients with

RPGR-associated XLRP. Male patients typically present with

progressive night blindness and peripheral VF reduction in early

childhood, reaching legal blindness by ~40 years of age (3,28,29). A long-term follow-up of 74 male

patients with RPGR mutations by Talib et al (24) demonstrated that the therapeutic

window for gene therapy in RPGR-associated retinal

dystrophies is relatively wide. Another 10-year study evaluating

139 male patients with RPGR-associated RP found that

binocular VA was highly associated with age, with the difference

being more pronounced in patients with worse vision (30). The study found that VA began to

decline sharply at an average age of 44 years, with the median age

at legal blindness being 45 years, consistent with previous

findings. Women who carry XLRP display a more variable phenotype,

with differing degrees of vision loss, and often exhibit color

vision deficits (31).

Some individuals with a family history of the

disease may exhibit X-linked dominant traits, and this phenotypic

variability may be associated with random or skewed X-chromosome

inactivation (XCI) (18,29,32). Fahim et al (33) found that skewed XCI of the

RPGR allele was positively associated with disease severity

in a study of 77 RPGR mutation-carrying female patients from

41 family lines, and could serve as an important predictor of

disease progression. Notably, the same RPGR gene mutation

may present with different phenotypes and severities in different

patients or even among members of the same family, suggesting that

additional factors may influence disease development. Tuekprakhon

et al (34) reported that

an 8-year-old individual who carried XLRP showed only mild

early-onset progressive CORD, although they carried the same

disease-causing mutation as their affected father. Recent studies

have also found that some female patients who carry RPGR

mutations exhibit increased levels of myopia (31,33,35-40). In a case study, Seliniotaki et

al (31) described a

4-year-old girl with no family history or other notable medical

history, but whole exome sequencing revealed a pathogenic

heterozygous stop codon variant c.212C>G (p.Ser71Ter) in the

RPGR gene, accompanied by XCI. These findings highlight the

complexity of phenotypic variation associated with the RPGR

mutation and the potential role of XCI in modulating disease

severity.

The study of RPGR-associated XLRP faces two

major problems. First, the difficulty of obtaining data from

patients at different stages of the disease course limits a

detailed understanding of pathogenic mechanisms. Second, the high

genetic heterogeneity of RPGR-associated XLRP complicates

the generalization of the results of individual studies to the

entire spectrum of the disease. This poses a challenge for studying

the pathogenic mechanisms of RPGR-associated XLRP.

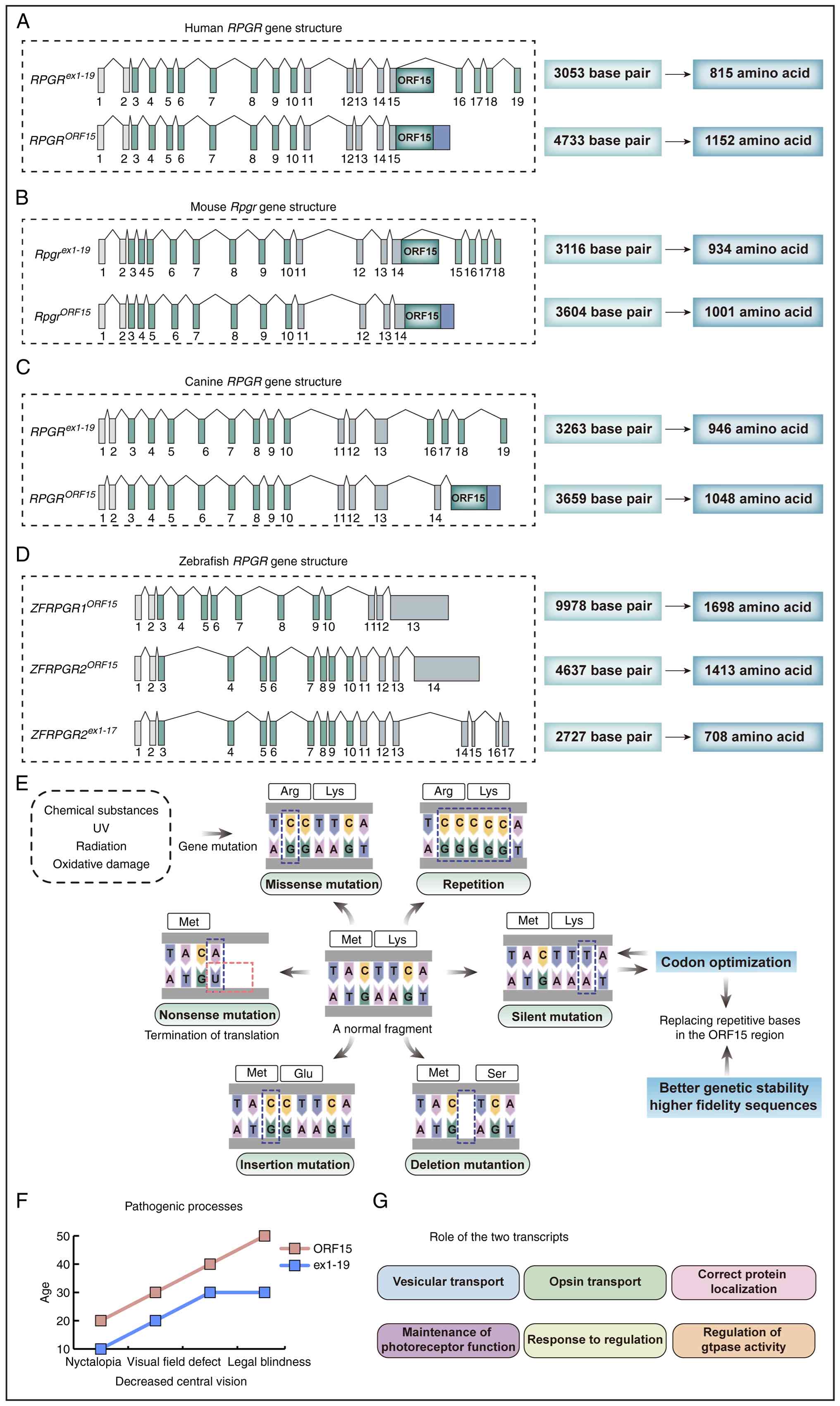

Molecular features of RPGR and disease

associations

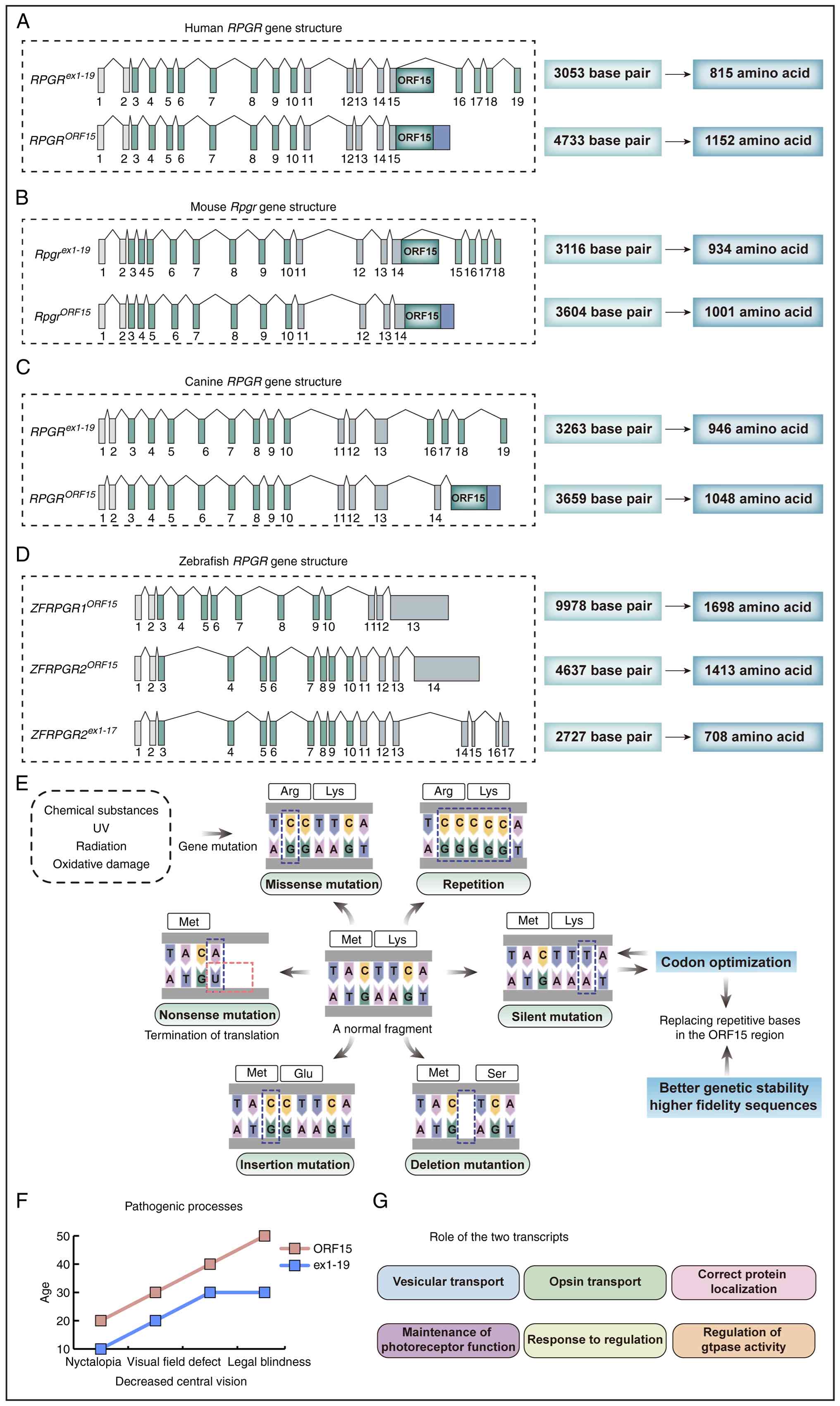

The complete sequence of the human RPGR gene

in the GRCh38 reference genome is 58,347 bp (NC_000023.11) and

includes all introns and exons. The gene produces multiple splice

variants at the transcriptional stage through extensive alternative

splicing, thereby generating functionally distinct isoforms. The

RPGR gene generates >10 alternative transcripts, of which

at least five (for example, RPGRORF15 and

RPGRex1-19) have been shown to encode functional

proteins (41). It has been

reported that RPGRex1-19 is widely expressed in a

variety of tissues, while the expression level of

RPGRORF15 is highest in retinal tissues (10).

The RPGRex1-19 transcript

(NM_000328.3) includes exons 1-19, with a full length of 3,053 bp,

encoding an 815-amino-acid protein with a molecular weight of ~90

kDa (41-42). The transcript is expressed in

several human tissues, including the testis, kidney, lung, RPE and

photoreceptors. In the retina, the primary function of this

transcript is to maintain the structural integrity and functional

stability of photoreceptor cells. The RPGRORF15

transcript (NM_001034853) consists of exons 1-14 and an open

reading frame (ORF15) derived from the variably spliced exon 15 and

intron 15. It is 4,377 bp in length, encodes a protein of 1,152

amino acids and is localized primarily to the CC of photoreceptor

cells (Fig. 2A) (34,36). The ORF15 region is a specialized

exonic region of the RPGR gene with a highly repetitive

sequence rich in purines [adenine (A) and guanine (G)]. It encodes

a region of the protein consisting of low-complexity sequences with

high glutamate (Glu) and glycine (Gly) content. The region is ~1 kb

and contains 567 amino acids. A probe targeting exons 16-19

detected an 8.9 kb band but failed to detect a 5 kb band for exons

3-10, 14 and 15 (24).

Therefore, exon ORF15 may function as a terminal exon or be

co-spliced with exons 16-19. However, ORF15 contains an internal

stop codon and does not include exons 16-19. To the best of our

knowledge, to date, no detailed studies focusing on mutations in

exons 16-19 have been reported.

| Figure 2Information on the structure and

mutation of RPGR genes in different species. Structure of

the RPGR gene in (A) human, (B) mice, (C) canines and (D)

zebrafish, including exon-intron composition, number of base pairs

and amino acid length of the different transcripts. (E) Common

mutations in RCC1-like domains. (F) Pathogenic processes resulting

from mutations in the two transcripts leading to age-dependent

phenotypic changes. The horizontal axis represents age, and the

vertical axis reflects the severity of ocular symptoms. From left

to right, the symptoms progress from night blindness to central

vision loss, VF defects, and eventually legal blindness,

illustrating the trajectory of disease development under different

transcript mutations. (G) Role of the two transcripts in the

organism. RPGR gene, retinitis pigmentosa GTPase

regulator gene; VF, visual field. |

The exon and intron structures and mRNA expression

patterns of RPGR transcripts from different species differ

(Fig. 2B-D). For example, the

murine RpgrORF15 type (NM_001177950) is 3,604 bp

in length and encodes 1,001 amino acids, whereas the murine

Rpgrex1-19 type (NM_001177951) is 3,116 bp in

length and encodes 934 amino acids. To further assess the

evolutionary conservation among species, it is necessary to

determine the chromosomal localization of the RPGR gene.

Rpgr is located at 4.62 cM of the mouse X chromosome genetic

map, while in rats it maps to Xq12. In zebrafish, two transcripts,

rpgra and rpgrb, are located on chromosomes 9 and 11,

respectively. In dogs and rhesus monkeys, the gene is also situated

on the X chromosome, the chromosomal position most similar to that

of human RPGR.

The two major RPGR transcripts share an

identical N-terminal structure, that is, exons 1-14. Mutations

within exons 1-14 are typically associated with earlier disease

onset, faster progression and more severe visual impairment.

Patients carrying mutations in this region generally exhibit worse

visual preservation compared with those harboring ORF15 mutations

(43). Statistical analyses show

that several individuals with exon 1-14 mutations develop night

blindness and VF defects at the age of ~10 and often present with

moderate to severe RP. Missense mutations, small insertions or

deletions, and nonsense mutations are the most common types

observed (Fig. 2E). Mutations

within the ORF15 region account for ~66% of XLRP cases, making it

the most prevalent pathogenic hotspot in human XLRP (7,18,44). However, ORF15 mutations generally

exhibit a milder phenotype, with later onset and slower disease

progression (Fig. 2F). In

addition to the aforementioned mutation types, ORF15 variants may

also introduce aberrant splicing sites, thereby affecting normal

mRNA processing (10,32,44-46). Moreover, mutations in this region

have been implicated in X-linked CORD and XLMD. These phenotypic

differences highlight the complex relationship between gene

structure and function. Understanding this

structure-function-phenotype association not only provides insight

into the molecular pathology of RPGR-related diseases but

also lays the theoretical foundation for the development of

precision therapies targeting specific transcripts or mutation

types. The following section will further explore the mechanisms by

which RPGR mutations lead to photoreceptor dysfunction and

retinal degeneration.

Mechanistic insights into RPGR-associated

retinal degeneration

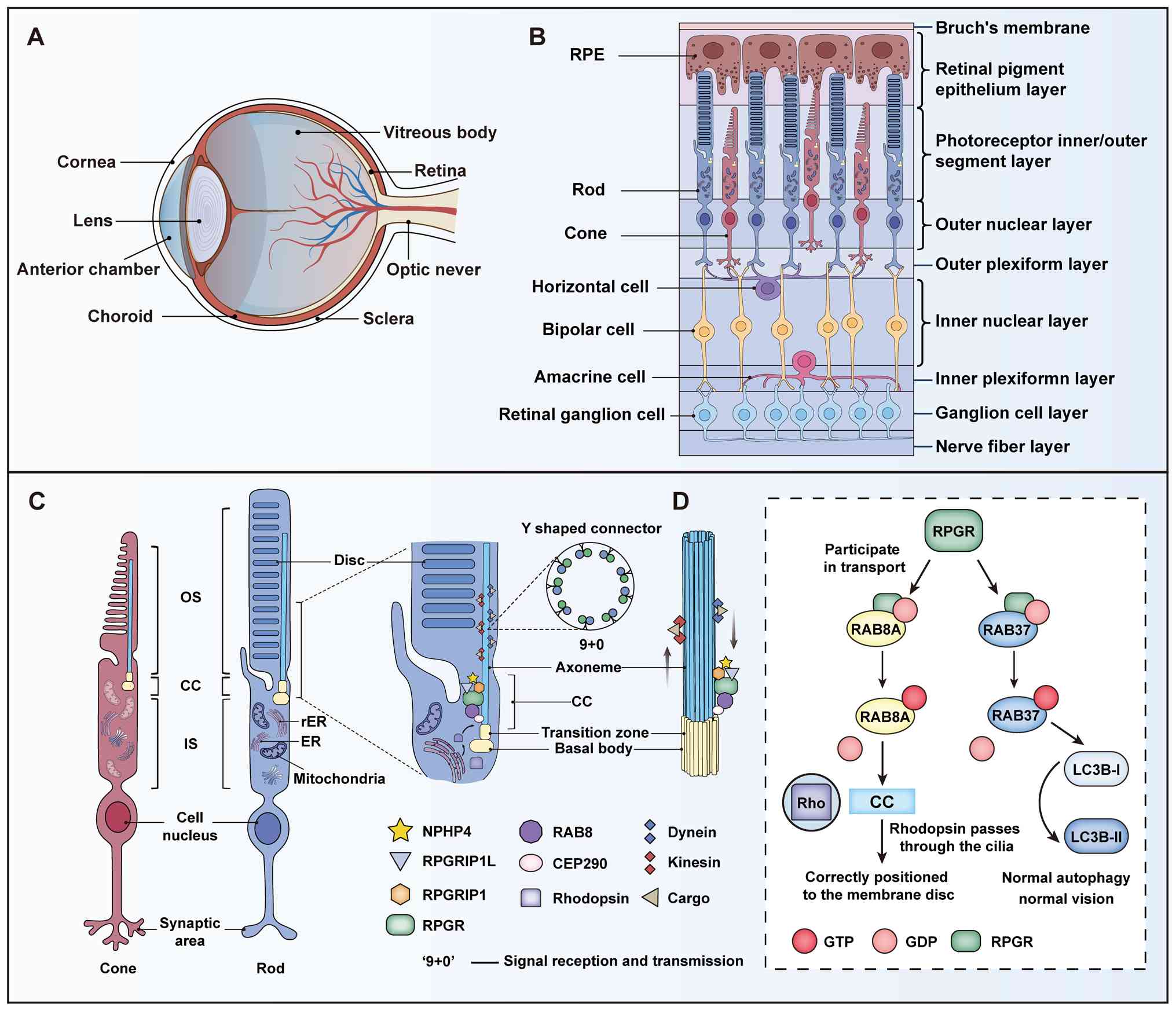

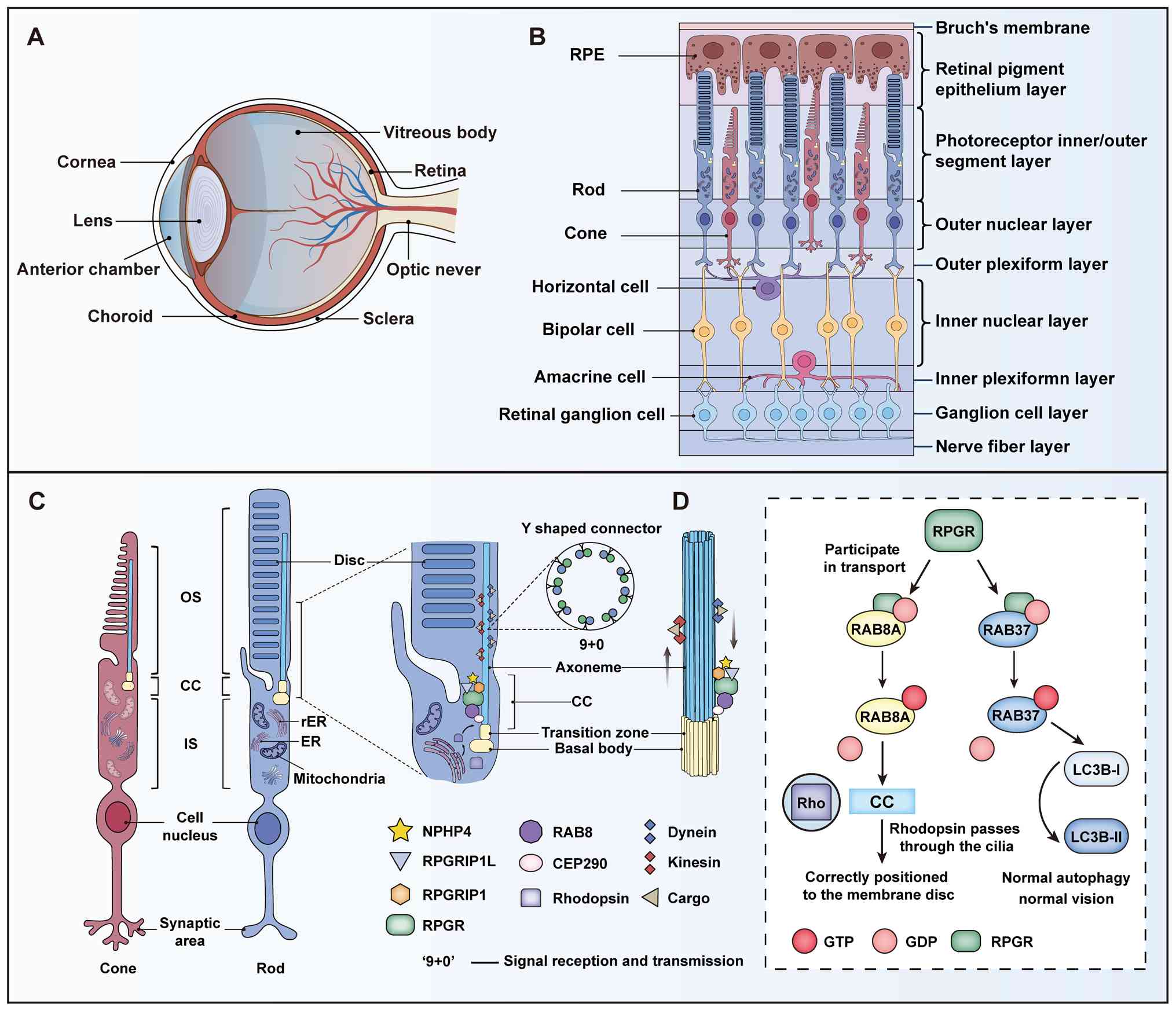

Photoreceptor architecture and the

functional significance of RPGR

The retina is located at the back of the eye as a

curved, multilayered structure comprising photoreceptors, bipolar

cells and ganglion cells (Fig. 3A

and B). From the outside to the inside, the retinal structure

includes the RPE, outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer,

inner nuclear layer (INL), inner plexiform layer, ganglion cell

layer (GCL) and nerve fiber layer, each of which contributes to the

capture and processing of light signals (47-49). Photoreceptors are responsible for

detecting light and converting it into electrical signals (50). Rods, which are primarily

distributed in the peripheral retina, contain rhodopsin and mediate

scotopic vision (51). By

contrast, cones are concentrated in the central region and contain

three distinct opsins that mediate color discrimination and fine VA

under bright light conditions (51,52). Both cell types consist of four

main components: The synaptic terminal, the inner segment (IS), the

OS and the CC linking the IS and OS (Fig. 3C). The OS is a highly specialized

primary cilium characterized by densely stacked membranous discs

that serve as the central site of phototransduction. The IS

contains organelles such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and

Golgi apparatus, which sustain the high metabolic activity required

for photoreceptor function. The CC is structurally homologous to

the transition zone of the primary cilium and is essential for the

efficient trafficking of proteins and lipids. Owing to their

exceptionally high metabolic demands, photoreceptors rely on

efficient transport of proteins synthesized in the IS through the

CC. This transport is essential to sustain their structure and

function (7). As a key component

of this intersegmental transport system, the CC requires specific

proteins to preserve its structural stability and regulate

molecular trafficking. Among these proteins, RPGR acts as a

ciliary-associated protein, carrying out a central role in

sustaining these processes.

| Figure 3Structure of the eye and the role of

RPGR in photoreceptors. (A) Layered structure of the eye and

retina. (B) Retinal layers organized into three functional domains:

The support layer (BrM; RPE), the light-signal-processing layer

(OS, IS and ONL) and the neurointegrative layer (OPL, INL, IPL, GCL

and NFL). (C) Photoreceptor subcellular structures and the '9+0'

signaling axis, representing the microtubule arrangement pattern

unique to non-motile cilia. (D) Mechanisms of internal ciliary

transport involving the RPGR complex. IFT: KIF3A and Dynein mediate

bi-directional cargo transport. RAB8A participates in vesicle

transport and regulates photoreceptor OS disc membrane renewal.

Mechanisms involving RPGR, RAB8A and RAB37 in vision-related

physiological processes. RPGR participates in the transport

processes involving RAB8A and RAB37. These GTPases exert their

functions through cycling between GTP-bound and GDP-bound states.

RAB8A is involved in the correct localization of RHO to CC, thereby

maintaining normal vision. RAB37 facilitates the conversion of

LC3B-I to LC3B-II to support normal autophagy, which in turn helps

maintain vision. Key regulatory proteins: RPGR (green), RPGRIP1

(orange), NPHP4 (earthy yellow), RAB8A (bright yellow), GTP (red),

GDP (light red), RHO (purple), CC (blue), RAB37 (blue), LC3B-I

(light blue), LC3B-II (dark blue). BrM, Bruch's membrane; RPE,

retinal pigment epithelium; OS, outer segment; ONL, outer nuclear

layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL,

inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; NFL, nerve fiber

layer. RPGR, retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator; RHO, Rhodopsin;

RPGRIP1L, RPGRIP1-like protein; RPGRIP1, RPGR-interacting protein

1; RAB8A, RAS-related protein Rab-8A; IFT, intraflagellar

transport; KIF3A, kinesin family member 3A; NPHP4, nephrocystin 4;

CC, connecting cilium; LC3B-I, microtubule-associated protein 1

light chain 3 β-I; LC3B-II, microtubule-associated protein 1 light

chain 3 β-II. |

The N-terminus of the RPGR protein contains six

complete tandem repeats, each comprising 52-54 amino acids

(32). It has structural

homology with Regulator of Chromosome Condensation 1 (RCC1),

forming RCC1-like domains (RLDs) (53). The RLDs possess nucleotide

exchange factor (GEF) activity, promoting the conversion of small

GTPases from the GDP-bound to GTP-bound forms and thereby carrying

out a key role in ciliary function and intracellular transport.

RPGR is predominantly localized in the CC between the IS and OS of

the photoreceptor (Fig. 3C)

(3,8,54,55). In the retina, the RPGR

gene primarily produces two major isoforms,

RPGRex1-19 and RPGRORF15. Both

isoforms contain identical RLDs (exons 1-14) at the N-terminus but

differ markedly in their C-terminal sequences.

RPGRex1-19 contains an isoprenylation domain that

mediates its localization to the CC. By contrast,

RPGRORF15 features a unique C-terminal ORF15 region rich

in glutamic acid and glycine residues. Early studies suggested that

RPGR might not be essential for photoreceptor development and early

function (55-58). However, subsequent studies have

confirmed that RPGR is indispensable for protein trafficking,

ciliary stability and signal maintenance during photoreceptor

maturation. It also serves as a 'longevity factor' key for

preserving their structural and functional integrity (7,48).

Disruption of RPGR-mediated protein

trafficking and proteostasis leads to photoreceptor

degeneration

RPGR carries out a key role in maintaining ciliary

function and stability, as well as in regulating opsin transport,

vesicular trafficking and proper protein localization. It forms

complexes with multiple cilia-associated proteins, including

RPGR-interacting protein 1 (RPGRIP1), RPGRIP1-like protein

(RPGRIP1L), centrosomal protein 290 (CEP290) and IQ motif

containing B1 (IQCB1) (59).

Among these, RPGRIP co-localizes with RPGR in the photoreceptor OS

and CC, contributing to structural maintenance and protein

trafficking (45,56). Distinct RPGR-associated complexes

function at different stages of molecular trafficking, and loss of

RPGR function disrupts its pivotal role within the ciliary

transport network. Under normal conditions, RPGR forms complexes

with RPGRIP1 and IQCB1 to mediate rhodopsin trafficking. When the

interaction between RPGR and either RPGRIP1 or IQCB1 is disrupted

by RPGR mutations, the severity of the associated disease is

further exacerbated (18,59).

In wild-type photoreceptors, RPGR interacts with CEP290 within the

transition zone (60). However,

in RPGR mutant mice, this interaction is altered, leading to

transition zone defects that impair molecular transport.

RPGRORF15 interacts with transition zone proteins such

as CEP290 to facilitate the transport and renewal of photoreceptor

discs in the photoreceptor OS. This interaction helps maintain the

integrity of the transition zone and the Y-link structure (Fig. 3C).

In addition to its interactions with RPGRIP1 and

IQCB1, RPGR further facilitates molecular transport and signaling

in photoreceptors by interacting proteins such as the δ subunit of

rod-specific photoreceptor cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDEδ) and

ADP-ribosylation factor-like 3 (ARL3). It is also involved in

regulating vesicular trafficking and intracellular signaling

pathways. Using a yeast two-hybrid screen, Linari et al

(61) identified that PDEδ binds

to the RLDs of RPGR. The researchers therefore proposed that RPGR

mutations may cause protein mislocalization and trafficking

defects, ultimately leading to retinal degeneration. RPGR also

associates with ARL3, linking the cell membrane to the

photoreceptor cytoskeleton and participating in specific signaling

and vesicular transport processes (62,63). A study published in 2024 reported

that RPGR functions as a GEF, facilitating the conversion of

RAS-related protein Rab-37 (RAB37) from the GDP-bound to GTP-bound

state (Fig. 3D) (64). This activation of RAB37 promotes

vesicular trafficking, particularly within the lysosome-autophagy

pathway, thereby supporting normal autophagic activity and visual

function. The role of RPGR in maintaining photoreceptor function

may therefore involve the regulation of intracellular signaling and

vesicular transport. Moreover, RPGR helps preserve protein

homeostasis and functional stability in mature photoreceptors by

modulating proteasome activity and the expression of key transport

proteins (65).

Studies have shown that RPGR mutations are

prevalent in various ciliopathies characterized by severe

photoreceptor degeneration. In a 2023 study using rpgra

mutant zebrafish, the mutation was found to cause downregulation

and mislocalization of RAS-related protein Rab-8A (RAB8A) within

the cilium, thereby disrupting the trafficking of essential

photoreceptor molecules (66).

Similarly, a 2010 study showed that RPGR knockdown in

hTERT-RPE1 cells resulted in shortened primary cilia and

mislocalization of RAB8A (67).

Proper binding of RPGR to RAB8A ensures the efficient incorporation

of rhodopsin into the OS disk membranes for light-signal capture

(Fig. 3D). Mutations in

RPGR lead to abnormal accumulation of rhodopsin in the IS or

CC, resulting in disorganization of the OS disk structure (66,67). Multiple Rpgr animal models

have confirmed that such trafficking defects are a major cause of

both rod and cone photoreceptor degeneration (68).

At the molecular level, RPGR encodes a protein

essential for the assembly and maintenance of photoreceptor cilia,

serving as a key regulator of CC integrity (55). Its N-terminal domain shares

homology with RCC1 and catalyze the conversion of Ran guanosine

diphosphate (RanGDP) to Ran guanosine triphosphate (RanGTP). Based

on this, researchers have proposed that RPGR may regulate

intraphotoreceptor protein transport through a RanGTP-dependent

mechanism. Under normal conditions, the concentration of RanGTP is

increased in the CC compared with the IS and this gradient is

considered to underlie the directionality of protein trafficking.

Loss of RPGR function may disrupt this gradient, leading to

impaired opsin transport. In 2021, Moreno-Leon et al

(7) reported that imbalanced

expression of the two major RPGR transcripts may cause

XLRP-associated ciliopathy, suggesting that transcriptional

dysregulation may contribute to the pathogenesis. Furthermore, some

studies have proposed a potential association between RPGR

mutations and primary ciliary dyskinesia, suggesting that shared

molecular mechanisms may underlie different ciliopathies (69-72). These findings provide new

insights into the ciliary aspects of XLRP and offer perspectives

for developing future therapeutic targets.

Mechanisms of RPGR gene mutations in

photoreceptor cells

Mutations in exons 1-14 of the RPGR gene

usually lead to abnormalities of the RCC1-like domain. By contrast,

mutations in the ORF15 region are more complex and can affect

multiple aspects, including DNA conformation, protein stability,

trafficking and ciliary function (73). As aforementioned, the ORF15

region represents a mutational hotspot of RPGR (Fig. 4A), with the majority of

pathogenic variants clustered between 949 and 1,047 bp (18,32,74). The majority of these are small

deletions of 1-5 bp, typically resulting in truncated or

frameshifted proteins (41).

Although such truncations may retain a modest role in genomic

stability, evidence from the XLPRA2 canine model shows that ORF15

frameshift mutations nonetheless cause severe retinal degeneration

(32,75). Subsequent studies have shown that

missense mutations disrupt the interaction of RPGR isoforms with

their endogenous partners, including Inositol

polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E (INPP5E), Phosphodiesterase 6 delta

subunit (PDE6D) and RPGRIP1L (65,76-78) The C-terminus of

RPGRex1-19 contains a prenylation site that regulates

its interaction with PDE6D, INPP5E and RPGRIP1L (Fig. 4C) (76,78). Both RPGR isoforms also

interact with CEP290 and INPP5E at the genetic and physical levels,

and this interaction is important for maintaining the function and

survival of the photoreceptor OS (7).

![Interaction network of RPGR proteins

and their functional mechanism in cilium. (A) Structural domain

characterization of RPGR protein isoforms, where blue dots indicate

sites of frameshift mutations. RPGRex1-19

contains exons 1-10, 11-14 and 16-19; its N terminus includes the

RLD, and its C terminus contains several regions of unknown

function. RPGRORF15 consists of exons 1-10, 11-14

and ORF15; it contains an acidic, glutamate-rich domain (EG-rich

domain) and a basic domain. (B) Interacting protein networks of

RPGR. Proteins directly binding to the RLDs: RPGRIP1, RPGRIP1L,

RAB8A and PDE6D. Complex-associated proteins:

Cilium-transport-related proteins (CEP290, IFT88, KIF3A, RAB11 and

γ-Tubulin); signaling-regulation-related [NPHP family proteins

(NPHP1/4/5), TTLL5, ARL2/3]; and structure-maintenance-related

(SMC1/3, SPATA7). (C) Functional pathways of RPGR in ciliary

signaling. RPGR is involved in the regulation of

phosphatidylinositol metabolism. INPP5E is isoprenylated through

its C-terminal CAAX motif and binds PDE6D to form a complex, which

ensures its proper membrane localization. ARL3 promotes the release

of PDE6D in the activated state. ARL3, in its activated state,

promotes the release of INPP5E from PDE6D and the dissociated

INPP5E is translocated to the ciliary membrane via the IFT

mechanism. ARL13B ensures the stable localization of INPP5E to the

ciliary membrane by binding to INPP5E. RPGR, retinitis pigmentosa

GTPase regulator; RLDs, RCC1-like domains; RPGRIP1,

RPGR-interacting protein 1; RPGRIP1L, RPGRIP1-like protein; RAB8A,

RAS-related protein Rab-8A; PDE6D, Phosphodiesterase 6 δ subunit,

CEP290, Centrosomal Protein 290; IFT88, Intraflagellar Transport

88; KIF3A, Kinesin Family Member 3A; RAB11, Ras-Related Protein

Rab-11; NPHP1, Nephrocystin 1; NPHP4, Nephrocystin 4; NPHP 5,

Nephrocystin 5; TTLL5, Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family member

5; ARL2, ADP-Ribosylation Factor-Like Protein 2; ARL3,

ADP-Ribosylation Factor-Like Protein 3; ARL13B, ADP-Ribosylation

Factor-Like Protein 13B; SMC1, Structural maintenance of

chromosomes protein 1; SMC3, Structural maintenance of chromosomes

protein 3; SPATA7, Spermatogenesis-Associated Protein 7; INPP5E,

Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E.](/article_images/ijmm/57/3/ijmm-57-03-05723-g03.jpg) | Figure 4Interaction network of RPGR proteins

and their functional mechanism in cilium. (A) Structural domain

characterization of RPGR protein isoforms, where blue dots indicate

sites of frameshift mutations. RPGRex1-19

contains exons 1-10, 11-14 and 16-19; its N terminus includes the

RLD, and its C terminus contains several regions of unknown

function. RPGRORF15 consists of exons 1-10, 11-14

and ORF15; it contains an acidic, glutamate-rich domain (EG-rich

domain) and a basic domain. (B) Interacting protein networks of

RPGR. Proteins directly binding to the RLDs: RPGRIP1, RPGRIP1L,

RAB8A and PDE6D. Complex-associated proteins:

Cilium-transport-related proteins (CEP290, IFT88, KIF3A, RAB11 and

γ-Tubulin); signaling-regulation-related [NPHP family proteins

(NPHP1/4/5), TTLL5, ARL2/3]; and structure-maintenance-related

(SMC1/3, SPATA7). (C) Functional pathways of RPGR in ciliary

signaling. RPGR is involved in the regulation of

phosphatidylinositol metabolism. INPP5E is isoprenylated through

its C-terminal CAAX motif and binds PDE6D to form a complex, which

ensures its proper membrane localization. ARL3 promotes the release

of PDE6D in the activated state. ARL3, in its activated state,

promotes the release of INPP5E from PDE6D and the dissociated

INPP5E is translocated to the ciliary membrane via the IFT

mechanism. ARL13B ensures the stable localization of INPP5E to the

ciliary membrane by binding to INPP5E. RPGR, retinitis pigmentosa

GTPase regulator; RLDs, RCC1-like domains; RPGRIP1,

RPGR-interacting protein 1; RPGRIP1L, RPGRIP1-like protein; RAB8A,

RAS-related protein Rab-8A; PDE6D, Phosphodiesterase 6 δ subunit,

CEP290, Centrosomal Protein 290; IFT88, Intraflagellar Transport

88; KIF3A, Kinesin Family Member 3A; RAB11, Ras-Related Protein

Rab-11; NPHP1, Nephrocystin 1; NPHP4, Nephrocystin 4; NPHP 5,

Nephrocystin 5; TTLL5, Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family member

5; ARL2, ADP-Ribosylation Factor-Like Protein 2; ARL3,

ADP-Ribosylation Factor-Like Protein 3; ARL13B, ADP-Ribosylation

Factor-Like Protein 13B; SMC1, Structural maintenance of

chromosomes protein 1; SMC3, Structural maintenance of chromosomes

protein 3; SPATA7, Spermatogenesis-Associated Protein 7; INPP5E,

Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E. |

Mutations within exons 1-14 and the proximal ORF15

region are generally associated with RCD, whereas mutations in the

distal ORF15 region are more often linked to CORD or XLCOD. The

genotype-phenotype association of RPGR mutations is largely

attributed to glutamylation. This post-translational modification

carries out a key role in maintaining the structural stability of

the ORF15 domain. Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like 5 (TTLL5) interacts

with the basic domain of ORF15 and serves as a key regulator of its

glutamylation. Loss of this modification leads to

RPGRORF15 dysfunction and may even cause a phenotypic

shift from RCD to CORD. In a cohort of 116 male patients, mutations

located near the C-terminal ORF15 were found to shift the disease

phenotype from rod-dominant to cone-dominant (74). Further investigations revealed

that truncations in the distal ORF15 region disrupt its interaction

with TTLL5, impair RPGR glutamylation and consequently result in

cone photoreceptor degeneration. However, the C-terminal ORF15

domain contains 11 glutamate-rich consensus motifs, and the

artificial addition of negatively charged glutamate residues in

this region may alter protein folding and stability, thereby

affecting protein-protein interactions (22). Therefore, therapeutic strategies

involving artificial modification of the ORF15 region should be

approached with caution.

Globally, the major types of RPGR mutations

identified in patients include codon deletions, duplications,

nonsense mutations and frameshift mutations (79-85). These variants can lead to

abnormal protein synthesis, structural alterations, loss of

function and disruption of protein-protein interaction networks

(Fig. 4B), thereby compromising

ciliary stability and ultimately resulting in retinal degeneration.

Studies have also revealed regional differences in the distribution

of RPGR mutations. Buraczynska et al (46) analyzed 80 unrelated patients with

XLRP and found that the majority of RPGR mutations were located

within the N-terminal RLDs. In another study, Pusch et al

(45) screened 37 European

patients with XLRP and identified mutations in the ORF15 region

that resulted in premature translation termination, thereby

affecting the structure and function of the RPGR protein (7,45). Similarly, in a cohort of 25

familial XLRP cases, both a previously reported mutation (c.3317)

and a novel deletion mutation in the ORF15 region (c.3300_3301del)

were identified. These mutations were located at the 3'end of the

exon, causing premature termination of translation and the loss of

40-50 amino acids from the RPGR C-terminus (86). All affected individuals exhibited

relatively preserved rod photoreceptor function despite these

truncations.

Different types of mutations lead to loss of RPGR

protein function, resulting in varying degrees of clinical

severity. To accurately identify pathogenic variants, the ORF15

region must be analyzed using high-throughput, robust and scalable

sequencing approaches (87).

Future studies should first aim to precisely identify mutation

sites and then develop targeted therapeutic strategies tailored to

each mutation type. RPGR-XLRP exhibits high clinical

phenotypic heterogeneity (53,88). This phenotypic heterogeneity may

arise from population differences or environmental factors

(89). Therefore, studying the

association between different mutations and their corresponding

phenotypes is important for understanding the pathogenic mechanisms

of RPGR. In addition, analyzing modifier genes that can markedly

influence RPGR mutant phenotypes is important for developing

potential therapeutic strategies (53,71).

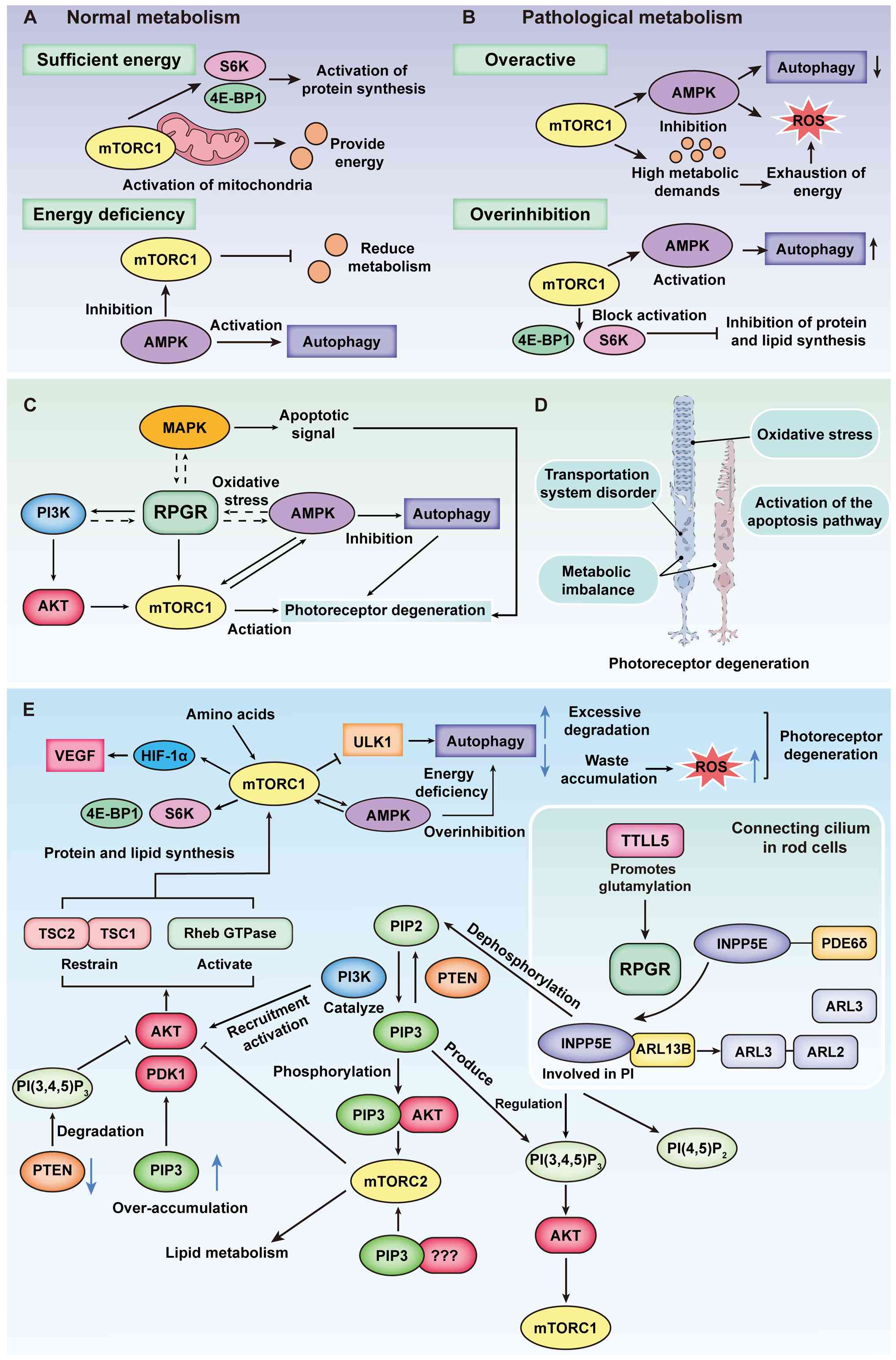

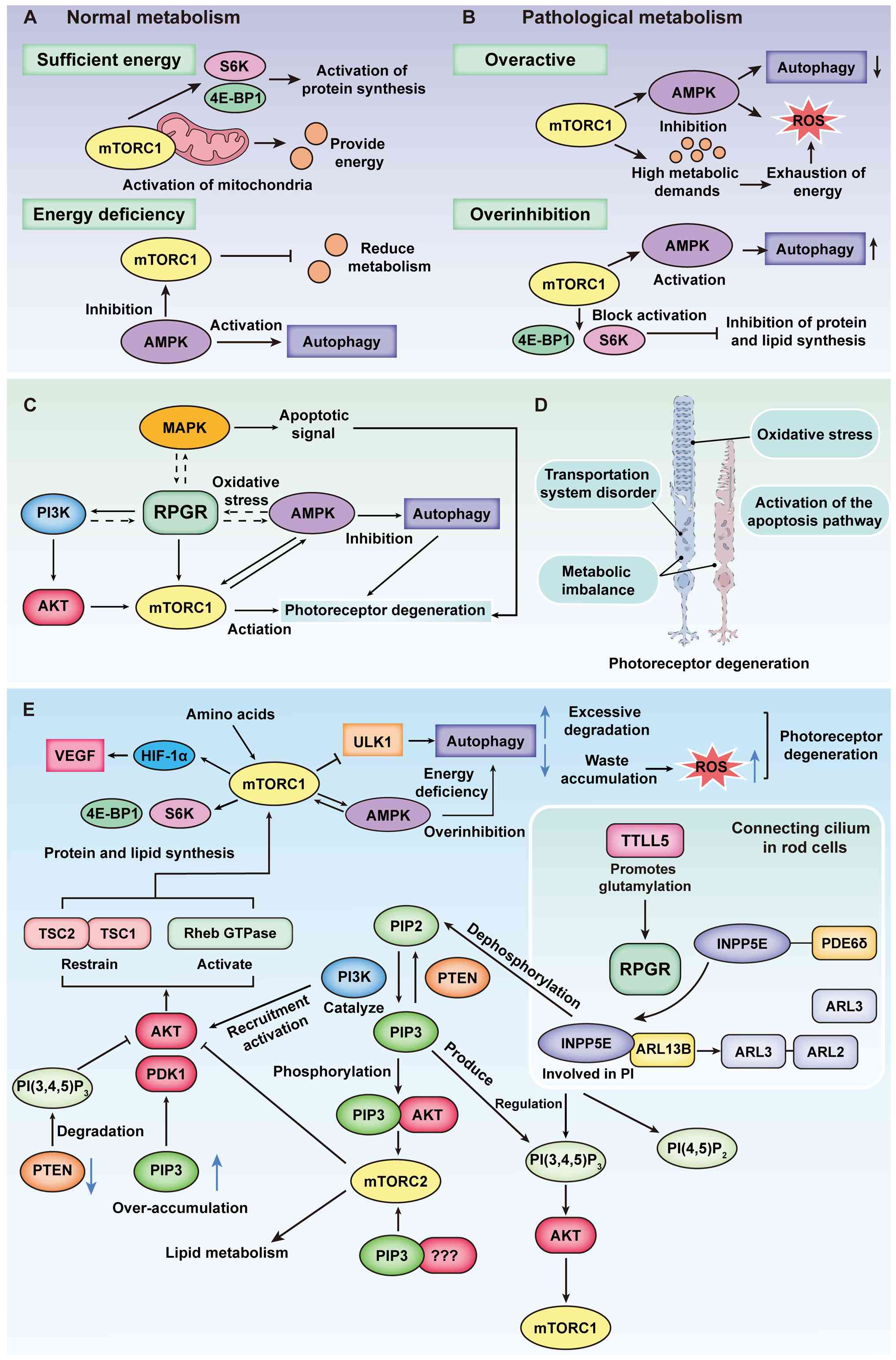

Potential involvement of RPGR in

photoreceptor metabolic signaling via the mTOR/AMPK axis

Similar to other neurodegenerative diseases, RP

exhibits disruptions in core cellular metabolic pathways, with its

pathogenesis involving dysregulation of multi-level molecular

signaling networks. Abnormalities in multiple signaling pathways

have been shown to lead to photoreceptor loss and apoptosis. These

abnormalities include transmembrane signaling disruptions,

metabolic dysregulation, oxidative stress and apoptotic pathway

activation. Given that RPGR mutations also contribute to

photoreceptor degeneration, we hypothesized that RPGR might be

associated with these signaling pathways (Fig. 5D). Metabolic homeostasis carries

out a key regulatory role in photoreceptor degeneration (Fig. 5A-C). RPGR mutation may

disrupt the metabolic homeostasis of photoreceptors through

aberrant activation of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway,

accelerating their degeneration. mTOR serves as a central regulator

of cellular metabolism, primarily controlling lipid synthesis,

autophagy and cell growth through the mTORC1 complex (90-92). At the mechanistic level, we

hypothesized that the RPGR protein affects phosphatidylinositol

metabolism in rods through interactions with PDE6D and INPP5E,

leading to the degradation triggered during transport (Fig. 5E). Its deletion results in

abnormally elevated levels of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate. This elevation in turn

activates the protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway, promotes

phosphorylation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and disrupts

Rheb function, resulting in continuous activation of mTORC1. This

activation not only promotes anabolic metabolism but also inhibits

autophagy and disrupts cellular metabolic homeostasis.

| Figure 5Impact of RPGR-associated

phosphoinositide signaling on cellular energy homeostasis. (A)

Normal metabolic conditions. In retinal cells under normal

metabolic conditions, mTORC1 is activated in the presence of

sufficient energy, promoting mitochondrial activity to sustain

cellular survival. Additionally, mTORC1 activates S6K and 4E-BP1,

thereby enhancing protein synthesis. Conversely, during energy

depletion, AMPK inhibits mTORC1, reducing metabolic activity while

simultaneously activating autophagy to provide an alternative

energy source for the cell. (B) Pathological metabolic conditions.

In pathological retinal cells, excessive activation of mTORC1

occurs when energy is abundant. Under these conditions, mTORC1

suppresses the AMPK pathway, leading to decreased autophagy and an

inability to efficiently clear intracellular waste. AMPK activity

also contributes to increased ROS levels. Meanwhile, the heightened

metabolic demand results in energy exhaustion, further triggering

ROS activation, excessive intracellular waste accumulation and

oxidative stress. By contrast, severe energy deprivation leads to

excessive inhibition of mTORC1, which blocks the activation of S6K

and 4E-BP1, thereby suppressing protein and lipid synthesis and

disrupting normal cellular metabolism. This energy-deficient state

also activates the AMPK pathway, increasing intracellular

autophagy. (C) RPGR may regulate photoreceptor degeneration through

multiple signaling pathways. Solid lines indicate pathways

supported by existing studies, such as PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 and AMPK in

autophagy regulation; dashed lines represent hypothetical

mechanisms suggesting potential involvement of MAPK and metabolic

stress pathways. (D) RPGR dysfunction leads to structural and

functional degeneration of photoreceptors. Key mechanisms include

transport defects, metabolic imbalance, oxidative stress and

activation of apoptotic pathways. (E) Indirect role of RPGR in

phosphoinositide metabolism. mTOR, in complex with mTORC1, serves

as a central regulator influenced by multiple factors, including

AMPK, the TSC1-TSC2 complex and AKT. These pathways collectively

modulate protein and lipid synthesis as well as autophagy. In

phosphoinositide metabolism, AKT is activated via the

PI3K-PIP3 pathway, while PTEN dephosphorylates

PIP3 to maintain homeostasis. PTEN dysfunction leads to

excessive PIP3 accumulation. TTLL5 facilitates the

proper glutamylation of RPGR, enabling INPP5E to function correctly

within the phosphoinositide pathway, thereby indirectly regulating

the mTOR pathway and sustaining normal cellular growth and

metabolism. mTOR, mechanistic Target of Rapamycin; mTORC1, mTOR

Complex 1; S6K, Ribosomal protein S6 kinase; 4E-BP1, Eukaryotic

Translation Initiation Factor 4E-Binding Protein 1; AMPK,

AMP-activated protein kinase signaling pathway; ROS, Reactive

oxygen species; PI3K/AKT, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT signaling

pathway; MAPK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway;

PI3K-PIP3, Phosphoinositide

3-kinase–phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate signaling pathway;

PTEN, Phosphatase and tensin homolog; TTLL5, Tubulin tyrosine

ligase-like family member 5; INPP5E, Inositol

polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E; TSC1, Tuberous sclerosis complex 1;

TSC2, Tuberous sclerosis complex 2. |

mTORC1 is a key kinase that regulates cell

metabolism by balancing demand with supply (93,94). Its activity is modulated by AMPK,

a central energy sensor whose impairment may cause photoreceptor

degeneration by disrupting cellular energy homeostasis (95). RPGR-mutant mice exhibit

early autophagic dysfunction, with vesicular structures

progressively accumulating in photoreceptor IS (64,96). Proteomic analysis further

revealed a notable reduction in mTOR protein expression. Notably,

Pde6b mutant mice display similar metabolic alterations,

including elevated pAKT levels (96). mTORC1 activity is modulated by

multiple upstream signals, including AMPK and various growth factor

receptors. These signals form a highly intricate feedback

regulatory network that highlights its central role in

photoreceptor degeneration. RPGR mutations likely trigger a

cascade of downstream events by disrupting photoreceptor metabolic

homeostasis (Fig. 5C). AMPK is

an energy sensor that regulates metabolic homeostasis. Upon

activation, AMPK phosphorylates TSC2 or Raptor, inhibiting protein

translation and fatty acid synthesis to maintain cellular energy

balance (97). In age-related

macular degeneration (AMD) mouse models, treatment with glucosamine

activates AMPK phosphorylation and suppresses mTORC1

phosphorylation via the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. This leads to

a reduction in lipofuscin-like autofluorescence in the RPE

(98). Meanwhile, in a study of

retinal autophagy homeostasis in wAMD mice, the treatment targeting

the AMPK/mTOR/hypoxia inducible factor-1α/vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) and AMPK/reactive oxygen species (ROS)/heme

oxygenase-1/VEGF pathways reduced retinal damage (99). Although direct evidence of

AMPK-mTOR dysregulation in the retinas of Rpgr-KO mice is

still limited, mitochondrial stress and reduced basal respiration

observed in RpgrEx3d8 retinas indicate altered

energy states. This suggests that RPGR mutations may trigger

activation of the AMPK/mTOR pathway and decreased AMPK activity can

compromise mTORC1 inhibition, thereby promoting increased lipid and

protein synthesis. This dysregulation also impairs autophagic

clearance, exacerbating the accumulation of metabolic waste

products such as lipofuscin (Fig.

5B). Moreover, this metabolic imbalance is conserved across

species in RPGR-deficient models, as lipid droplet

accumulation has been found in the RPE of rpgra-knockout

zebrafish (66). These

pathological features suggest that RPGR mutations may

disrupt retinal metabolic homeostasis by interfering with the

AMPK/mTOR pathway. However, in Rpgr-KO mice, the activity

markers of this pathway (such as p-AMPK, p-S6K and p-4EBP1) and

potential functional interventions have not yet been evaluated,

which is essential for developing therapies targeting metabolic

dysregulation in RP.

In addition to the mTORC1 pathway, other key

signaling pathways including PI3K-AKT and MAPK are also implicated

in photoreceptor degeneration (96,100). The PI3K-AKT pathway carries out

a key role in cell survival and metabolism, and its dysregulation

may contribute to photoreceptor apoptosis by affecting downstream

targets including mTORC1. Meanwhile, the MAPK pathway, particularly

JNK and p38 kinases, is involved in pro-inflammatory responses and

stress-induced apoptosis during retinal degeneration (101-104). Although the PI3K-AKT and MAPK

pathways both carry out key roles in photoreceptor degeneration,

their functional interactions during disease progression in

RPGR-deficient models remain poorly understood. Emerging

evidence indicates that the interplay between these pathways may

generate a vicious cycle of metabolic stress, oxidative damage and

inflammation, thereby exacerbating photoreceptor cell death. Future

studies targeting these signaling cascades may uncover novel

therapeutic approaches for RPGR-associated retinal

degeneration.

Interventional therapy targeting mTOR has emerged

as a potential strategy. Rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, enhances

autophagic activity by upregulating beclin-1 and

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3, effectively

counteracting z-VAD-induced necroptosis and markedly improving

photoreceptor survival (105).

Rapamycin markedly increases photoreceptor survival by activating

autophagy and inhibiting the ROS-apoptosis-inducing factor pathway

in the z-VAD-induced necrotic apoptosis model. However, its

therapeutic potential has not yet been systematically evaluated in

degeneration models caused by RPGR mutations. RPGR

mutations typically result in impaired protein transport and

mitochondrial stress, with hyperactivation of the mTORC1 pathway

further exacerbating degeneration. Theoretically, rapamycin could

alleviate endoplasmic reticulum stress by inhibiting mTORC1 and

restoring autophagic activity, thereby facilitating clearance of

mutant RPGR protein aggregates. It also enhances mitochondrial

autophagy to reduce ROS production, inhibiting secondary necrotic

apoptosis and helping maintain retinal microenvironmental

homeostasis. Given the key role of the mTOR signaling axis in

retinal degeneration, further exploration of the mechanisms

regulating its activity in RPGR-associated retinopathy could

provide a theoretical basis for the development of new intervention

strategies (106).

RPGR, oxidative stress and apoptotic

mechanisms in photoreceptors

Photoreceptor cells exhibit extremely high

metabolic activity and are highly sensitive to oxidative damage.

Early studies in a pig model of RP showed that following rod death,

the resulting increase in local retinal oxygen tension induces

oxidative stress, ultimately leading to secondary cone cell death

(107). Campochiaro and Mir

(108) noted that excess oxygen

can disrupt the mitochondrial electron transport chain and activate

NADPH oxidase. These processes promote the generation of superoxide

and peroxynitrite, thereby causing sustained oxidative damage to

cone cells. In RP, the gradual degeneration of cone cells following

rod cell death is mainly caused by oxidative damage. Based on the

metabolic imbalance observed in RPGR models, we hypothesize

that initial rod cell injury may trigger oxidative stress in cones,

thereby accelerating disease progression. Thus, antioxidant therapy

shows notable potential in slowing disease progression. ERG

assessments by Komeima et al (109) demonstrated that systemic

administration of antioxidants can markedly delay functional loss

in cone cells. In RD10 mice, long-term oral antioxidant treatment

using compounds such as naringenin or quercetin reduced

intracellular ROS levels, preserved retinal morphology and improved

retinal function (110).

However, the protective effects of antioxidants have not yet been

validated in other mutant models, such as Rpgr-KO mice.

Under sustained oxidative stress, photoreceptor

cells may undergo programmed cell death. The core regulatory

mechanisms involve the coordinated activation of both

caspase-dependent and mitochondrial pathways. RPGR mutations

destabilize the OS disc membranes, impairing normal mitochondrial

function. Aberrantly activated caspase-3 and caspase-9 initiate a

canonical proteolytic cascade. There is a synergistic effect

between mitochondrial damage and caspase activation, and

ligand-dependent activation of the death receptor signaling further

amplifies the process through the assembly of the death-inducing

signaling complex (DISC), triggering downstream effector caspase

cascades and ultimately accelerating photoreceptor cell death.

Notably, in 2017, Venkatesh et al (111) demonstrated through a

conditional knockout model that specific deletion of caspase-7 did

not notably affect cone survival in the RP model. This suggests

that the mechanism of secondary cone death may be independent of

the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway and involves signaling

pathways beyond the unfolded protein response. Currently, the

specific effects of RPGR mutations on mitochondrial

homeostasis and apoptotic signaling remain to be further elucidated

in animal models.

Regardless of the initial pathogenic mechanism,

gene defects eventually lead to photoreceptor cell death.

Therefore, investigating the mechanisms underlying photoreceptor

cell death is essential. By analyzing the diverse clinical

phenotypes resulting from specific site mutations, researchers can

further explore the potential mechanisms of interaction and provide

a theoretical basis for the development of future therapeutic

targets. Additionally, biochemical analyses can help assess the

physiological and metabolic status of patients, thereby

facilitating the development of targeted therapies. Currently, the

expression pattern of RPGR protein remains incompletely understood,

but its functionally distinct isoforms, generated by alternative

splicing, are closely associated with specific roles in retinal

photoreceptors. Strategies to compensate for the loss of RPGR and

its isoforms, as well as to modulate physiological and metabolic

processes to mitigate the consequences of RPGR deficiency, may

become key directions for future research and therapy.

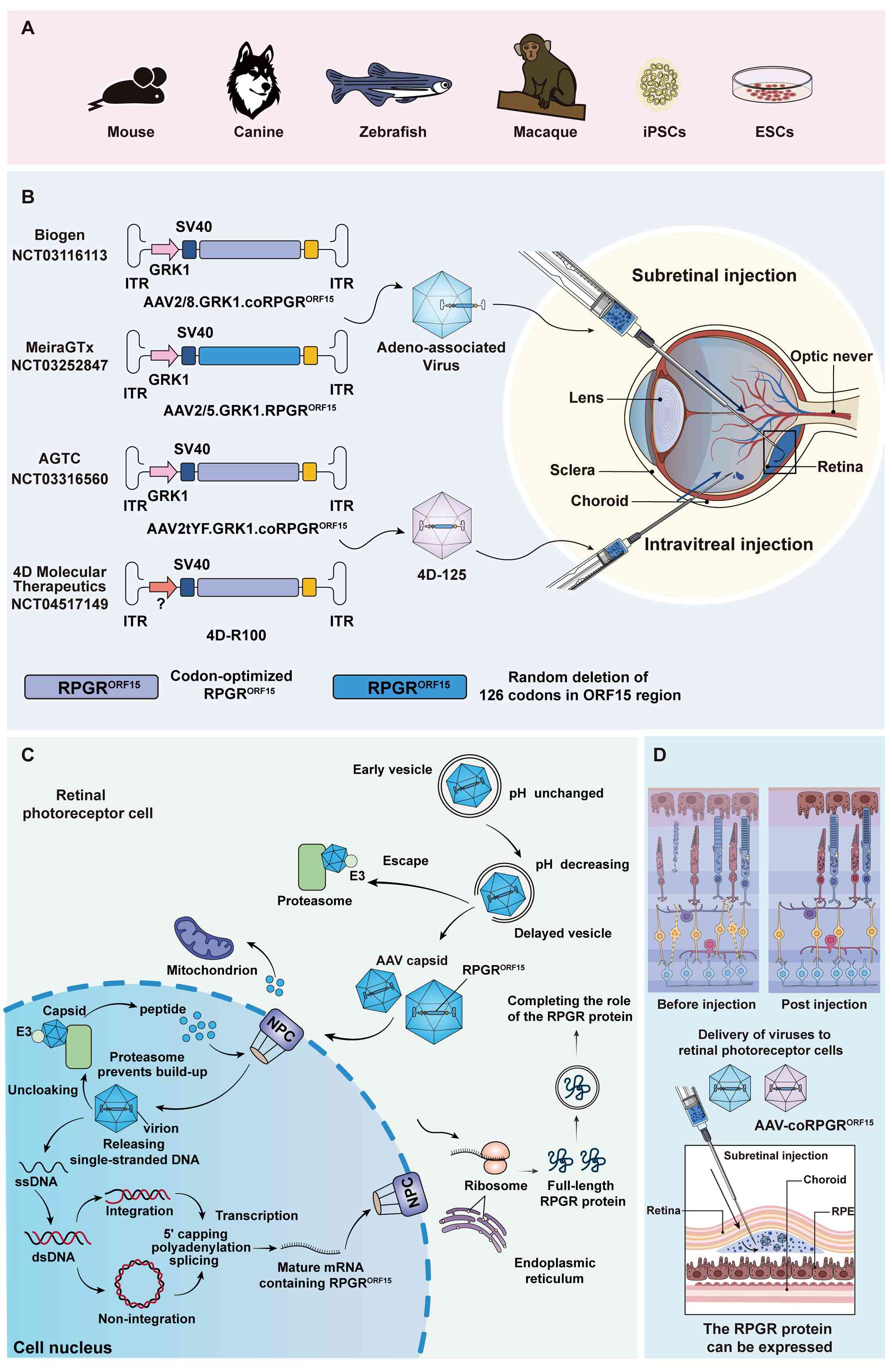

Preclinical research progress in RPGR

mutation

Preclinical animal models for RPGR

mutation studies

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying

RPGR-related retinal degeneration and to develop effective

gene therapy strategies, a variety of animal models have been

established to recapitulate the genetic and phenotypic features of

RPGR-associated XLRP (Fig.

6A). Mice have a short life cycle, strong reproductive capacity

and a high degree of genetic homology with humans, allowing

long-term disease progression to be observed within a relatively

short period. These characteristics make them valuable for

identifying pathogenic factors and associated signaling pathways

(13). In Rpgr mutation

studies, the RD9 mice represent one of the naturally occurring

mutants (17,112-114). In addition, researchers have

constructed mouse models carrying known mutation sites, including

the Rpgr knockout (Rpgr-KO) and conditional knockout

(Rpgr-CKO) models, using gene editing techniques to

facilitate further studies (17).

The RD9 mouse is a naturally occurring mutant model

carrying 32 bp duplication in the ORF15 region, which causes a

frameshift mutation and introduces a premature stop codon (17,115). In this model, the

RpgrORF15 transcript can be detected, but the

corresponding protein is absent, whereas the

Rpgrex1-19 protein remains detectable. At the

early stage, a mottled fundus appearance is observed, along with

mislocalization of M-opsin to the IS, perinuclear region and

synaptic terminals. As the disease progresses to the mid-stage,

rhodopsin expression decreases markedly, whereas no mislocalization

of S-opsin is observed. In the late stage, severe cell loss is

observed in the ONL, with the thickness of the photoreceptor layer

reduced by ~50% of its normal thickness (17). ERG recordings show a continuous

decline in retinal function starting as early as one month of age.

The notably reduced oscillatory potential (OP) amplitudes indicate

that both photoreceptors (OP1) and inner retinal neurons (OP2-OP4)

are affected by degenerative changes. The retinal degeneration in

this model is primarily driven by rod cell death (115). This serves as an important tool

for investigating the pathogenic mechanisms of ORF15 mutations in

XLRP and for evaluating potential therapeutic strategies.

The Rpgr-KO (Rpgr−/−)

mouse was generated on a C57BL/6 genetic background by replacing

exons 4-6 of the Rpgr gene with an antibiotic selection

cassette. This modification truncates both major transcripts

(Rpgrex1-19 and RpgrORF15) and

results in complete loss of RPGR protein expression. Although ERG

responses remain normal at postnatal day 20, some proteins that

should be localized to the OS are aberrantly distributed within the

IS (48). Müller cells exhibit

reactive gliosis, which becomes progressively more pronounced over

time. Even in the absence of overt degenerative changes, these

findings indicate that the retina has already initiated a

damage-response process. At mid-to-late stages, ONL thickness is

markedly reduced and ERG a-wave and b-wave amplitudes are decreased

by ~25 and 31%, respectively (48). Similar findings have been

reported in another study of Rpgr-KO mice, where rhodopsin

was abnormally localized to the CC, accompanied by mistrafficking

of proteins to the IS and ONL (116).

The Rpgr-CKO model was generated by deleting

the proximal promoter and exons 1-3 (3,189 bp). In this model,

nephrocystin-4 fails to localize properly to the CC, leading to

structural abnormalities in the OS. Consistent with previous

observations, mislocalization of rhodopsin and M-opsin is apparent

at early stages and is accompanied by progressive photoreceptor

degeneration. By late stages, >50% of the ONL is lost. Two new

Rpgr-KO mouse lines (L1 and L2) have been generated using

CRISPR-Cas9 technology (64).

Unlike the exons 4-6 deletion model, this version deletes exons

7-13, resulting in the deletion of 502 amino acids.

The zebrafish model is not as homologous to human

genes as the mouse model, but it has a faster growth rate and

developmental cycle, which helps researchers obtain study samples

quickly. Liu et al (66)

showed that zebrafish rpgra possesses a single transcript

homologous to human RPGRORF15. In this model,

visual dysfunction and early degenerative features can manifest as

early as 5 days post-fertilization. With increasing age,

photoreceptor OS progressively shorten, the ONL progressively thins

and OS architecture becomes disorganized, concomitant with declines

in ERG amplitudes. By mid-to-late stages, the cone OS begins to

degenerate, accompanied by substantial downregulation of retinal

phototransduction genes. Concurrently, the OS disc membranes are

disorganized and loosely stacked, with vesicular accumulation

around the cilia. Shu et al (117) identified two RPGR

homologs in zebrafish, ZFRPGR1 and ZFRPGR2, with

ZFRPGR2 regarded as the functional homolog of human

RPGR. Knockdown of ZFRPGR2 results in abnormal eye

development and retinal lamination defects, including failure of

the retina to form the normal three-layer structure (GCL, INL and

ONL) as well as underdevelopment of the photoreceptor OS, leading

to widespread retinal cell apoptosis, a phenotype distinct from

that observed in mammalian Rpgr mutant models.

Two natural mutations in the ORF15 region were

detected in canines that are collectively referred to as

progressive retinal atrophy and are homologous to human RP

(13). The loss of

photoreceptors in the naturally mutated canine model is similar to

previous RD9 models, rpgra models and RPGR ablation

in human photoreceptors (112).

In XLPRA1, a 5-nucleotide deletion in this region results in a

230-amino acid truncation at the C-terminus, but does not affect

normal photoreceptor development (32). Photoreceptors initially develop

normally and function properly, but rod degeneration initiates at

~11 months. In XLPRA2, a comparable degeneration pattern is

observed, albeit with an earlier onset, beginning at 4 weeks of age

(89).

Animal models of RPGR mutations have been

instrumental in understanding XLRP pathophysiology, identifying

early markers of the disease, evaluating the efficacy of genetic

and pharmacological treatments and elucidating the mechanisms by

which RPGR mutations drive the retinal degeneration. A

comparative overview of the strengths and limitations of these

models is presented in Table I

(13,17,55,57,66,117-132). However, these models still have

limitations: The rodent retina is dominated by rods, whereas the

human retina contains a higher proportion of cones, especially

concentrated in the central concave region, which poses challenges

for translating these findings to humans (13,116). Existing mouse models exhibit a

slower progression of retinal degeneration, which is not entirely

consistent with the more severe and rapidly progressive phenotype

of human XLRP. In terms of disease progression, histopathologic

features and molecular mechanisms, these models do not fully

recapitulate the diverse clinical manifestations observed in humans

with RPGR mutations. Due to the complexity of alternative

splicing of the RPGR gene, the expression patterns and

functions of RPGR isoforms can differ substantially between

species, thereby restricting the translational potential of

findings obtained from animal models. Existing animal models have

limited capacity to accurately replicate the systemic

manifestations of RPGR mutations, as demonstrated by

respiratory infections and hearing loss observed in some patients

(41). In translational and

therapeutic studies, judicious selection of animal models according

to research goals, disease phenotypes and experimental parameters

is important. Despite their inherent limitations, these models

offer a vital preclinical platform for testing and refining gene

therapy approaches for RPGR-related retinal

degeneration.

| Table IComparison of different animal models

as treatment models for RPGR mutations. |

Table I

Comparison of different animal models

as treatment models for RPGR mutations.

| Models | Advantages | Disadvantages | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Mouse | i) The genetic

background is clear; ii) nature gene editing technology; iii) low

cost; iv) abundant data from existing studies. | i) Retinal

structure is very different from humans; ii) slow progression of

the RPGR mutant phenotype; iii) differences in immune

response exist. | (13,17,55,57,118,119) |

| Zebrafish | i) Transparent

embryo; ii) fast reproduction and low cost; iii) easy gene editing;

iv) retinal development: Human retina development is highly

similar. | i) Simple retinal

structure; ii) RPGR mutation phenotype may not be as

pronounced as mammals; iii) drug metabolism is different from

mammals. | (57,66,117,120,121) |

| Canine | i) Retinal

structure is close to that of humans; ii) the RPGR mutant

canine model exhibits retinal degeneration similar to that of

humans; iii) suitable for long-term studies. | i) High cost of

breeding and experimentation; ii) difficulty of gene editing; iii)

canine models face more ethical controversies compared with other

anima models. | (13,57,118,119,122,123) |

| Hog | i) The structure of

the retina is highly similar to that of humans; ii) the RPGR

mutant pig model exhibits retinal degeneration similar to that of

humans; iii) close to human size suitable for surgical eye and gene

therapy studies. | i) High breeding

and experimental costs; ii) long breeding cycle; iii) difficult for

gene editing. | (13,124,125) |

| Macaque | i) Retinal

structure almost identical to humans; ii) disease phenotypes are

closest to humans; iii) suitable for preclinical studies, with

results of gene therapy and surgical operations directly

extrapolated to humans. | i) Extremely high

cost; ii) study on apes and monkeys face serious ethical

controversies as experimental animals; iii) long breeding

cycle. | (126-132) |

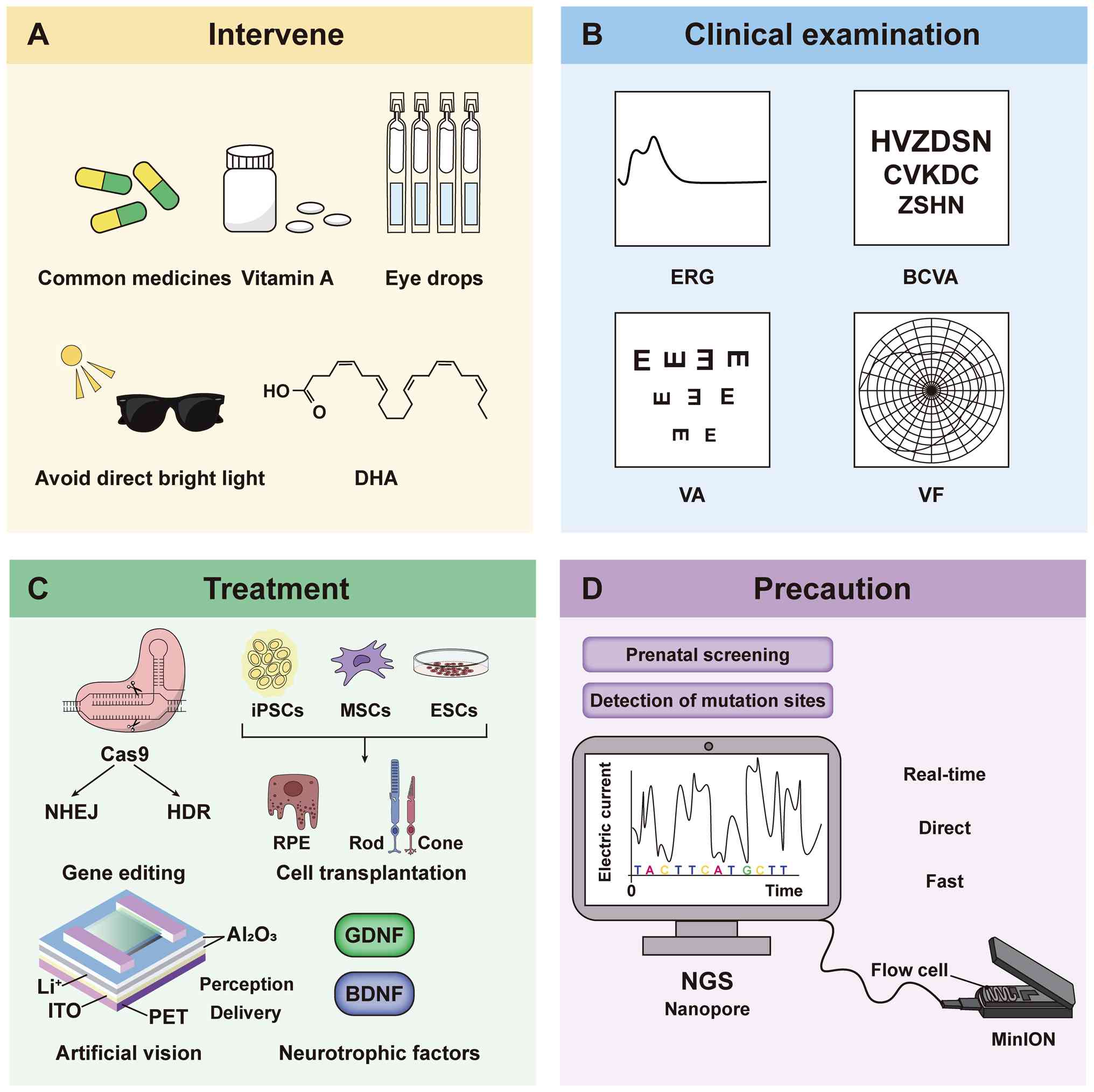

Progression of treatment strategies in

RPGR-related XLRP

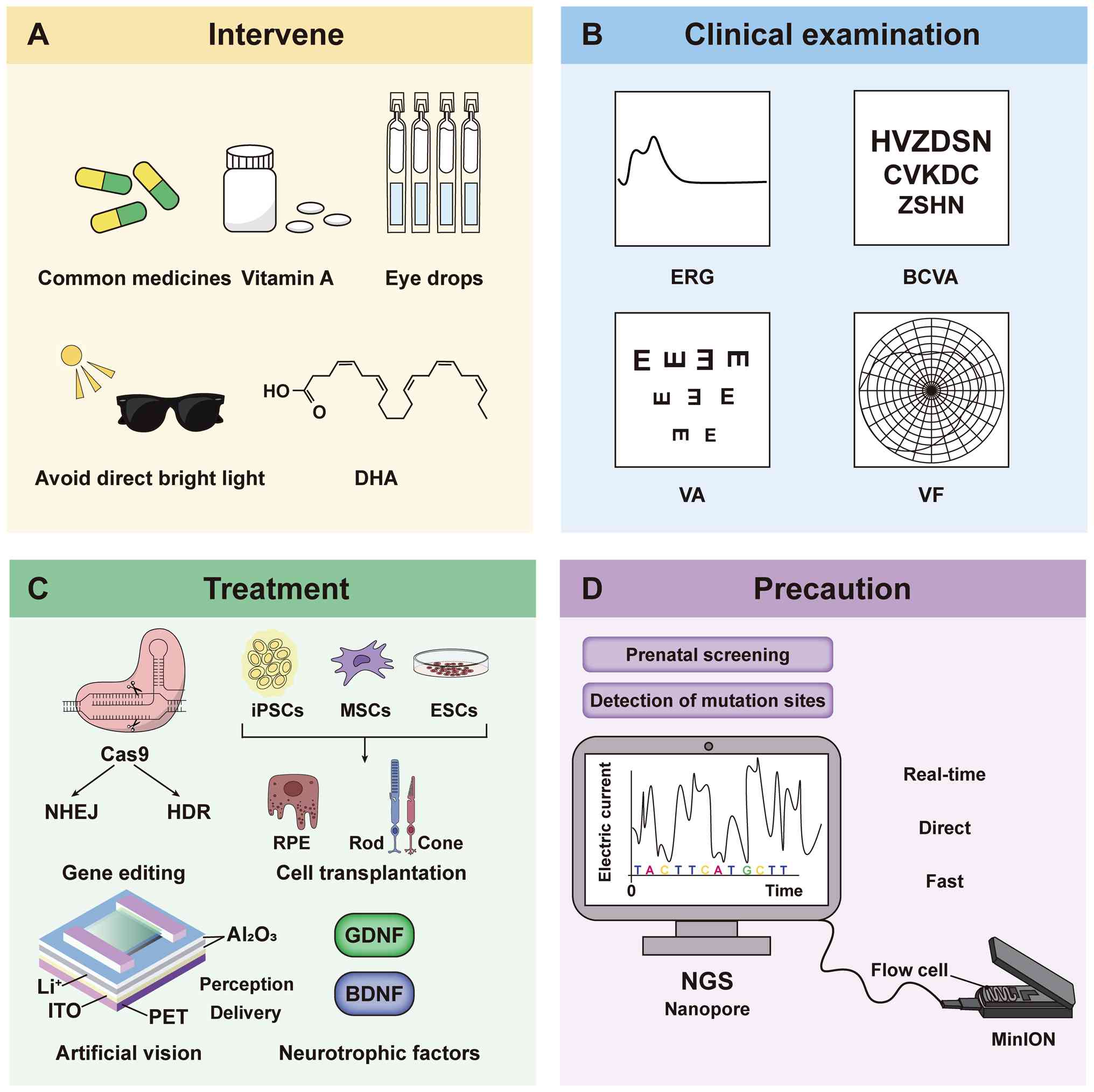

Early therapeutic strategies for

RPGR-related XLRP primarily focus on nutritional

supplementation aimed at slowing photoreceptor degeneration.

Vitamin A is converted into 11-cis-retinal, whereas omega-3

polyunsaturated fatty acids (such as docosahexaenoic acid, DHA)

contribute to the structural stability of the photoreceptor

membrane by integrating into the phospholipid bilayer (133-135). Such supplements are considered

to delay photoreceptor degeneration during the early stages of XLRP

(136,137). These interventions merely slow

visual deterioration and do not repair the retinal structural

damage caused by the RPGR mutation (138). Moreover, long-term DHA

supplementation may lead to side effects such as gastrointestinal

discomfort (139). To address

the limitations of such supplements, researchers have also explored

neuroprotective strategies, including supplementation with

brain-derived neurotrophic factor. These factors have shown

efficacy in conditions such as macular degeneration and glaucoma by

promoting the survival of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and

reducing microglia-mediated inflammation (140,141). Unlike supplement intervention

strategies, neuroprotective strategies target the secondary

neurodegenerative processes of XLRP. However, the majority of

studies of these neuroprotective strategies have been performed in

non-RPGR models (142-146), leaving their applicability to

XLRP unconfirmed. Importantly, supplements and neuroprotective

strategies are not mutually exclusive; rather, they may exert

complementary effects by targeting different pathological stages of

XLRP. Combination approaches may synergistically delay disease

progression through multiple pathways. Future studies using

RPGR mutation models are needed to systematically evaluate

the timing, dosage and interactions of such combined

strategies.

Although these interventions may help preserve

residual vision, they cannot fundamentally correct the underlying

genetic defect. By contrast, gene therapy aims to directly restore

normal RPGR function, thereby halting ongoing photoreceptor

degeneration at its source and potentially altering the natural

course of XLRP. It has emerged as a promising and potentially

transformative approach for treating IRDs, particularly those

associated with RPGR mutations (29,147-150). Because the majority of

inherited retinal disorders are monogenic, and the eye possesses

immune privilege as well as direct accessibility for observation

and intervention, a single gene therapy treatment may achieve

long-term, even lifelong, therapeutic benefits (151-153). Among various gene therapy

approaches, viral vector-mediated gene replacement represents the

primary strategy for treating RPGR-related diseases.

Gene therapy studies in Rpgr mutant

models

Despite inherent limitations, animal models remain

the primary experimental systems for evaluating the safety and

efficacy of gene therapy strategies. The therapeutic outcomes

largely depend on factors such as promoter choice, vector platform,

AAV serotype, capsid modification strategy and host immune

response.

In retinal gene therapy, the use of cell

type-specific promoters is important for achieving stable and

precise transgene expression. Researchers have compared the

transcriptional activities of several promoters in rod and cone

photoreceptors, including rhodopsin kinase (RK), human

interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (hIRBP) and human RK

(hGRK1). The hGRK1 promoter exhibited more sustained expression in

rod photoreceptors, making it an optimal candidate for

RPGR-related gene therapy (10,122). In an XLRP canine model,

delivery of human RPGRORF15 using an AAV2/5

vector driven by either the hIRBP or hGRK1 promoter successfully

preserved photoreceptor nuclei and normal retinal structure. This

treatment restored both rod and cone function and corrected

rhodopsin mislocalization (122).

In terms of vector design, continuous improvements

in recombinant AAV (rAAV) vectors have enabled targeted expression

in specific retinal cells and markedly enhanced transduction

efficiency (154-156). With a packaging capacity of

~4.8 kb, AAV vectors can readily accommodate the RPGR gene

(116,156). Because different diseases

affect retinal photoreceptors in distinct ways, vector design must

be approached with particular caution. Future optimization of AAV

vectors should focus on several key aspects: i) Selecting

appropriate and cell type-specific promoters; ii) designing safer

vectors with minimal off-target effects; iii) simplifying gene

expression regulatory mechanisms while enhancing expression

stability; iv) improving transduction efficiency alongside scalable

production; and v) systematically evaluating the durability and

safety of the therapy. Because the ORF15 region undergoes complex

post-transcriptional processing with multiple alternatively spliced

isoforms and possesses intrinsic sequence instability, maintaining

its integrity during vector production and therapeutic application

remains a key challenge (157).

Fischer et al (22)

carried out codon optimization of the Rpgr sequence and

constructed the AAV8-hRK-coRPGR system, which successfully restored

retinal function in two animal models (Rpgr−/y

and C57BL/6JRD9/Boc), markedly ameliorating retinal

degeneration phenotypes. Giacalone et al (158) used a bioinformatics approach to

introduce synonymous mutations into a highly repetitive region of

ORF15, enhancing sequence stability and expression efficiency while

maintaining amino acid sequence invariance. Hong et al

(159) demonstrated earlier

that a shortened version of RPGRORF15, with a 654

bp deletion in the repetitive region, effectively alleviated

retinal degeneration in Rpgr-KO mice. Pawlyk et al

(75) further compared the

effects of varying degrees of linker region truncation and found

that moderate truncation (removing ~33% of the sequence) preserved

protein function while markedly improving retinal morphology and

function in Rpgr-KO mice.

Currently, preclinical RPGR gene therapy studies

have primarily focused on highly efficient AAV-based delivery

systems (8,160-162). AAV is the most widely used

viral vector in clinical research on IRDs, with different serotypes

exhibiting tropism for specific tissues and cell types. For

example, AAV2 shows high affinity for RPE cells and is commonly

used for targeted delivery to RGCs (163,164). In animal models of retinal

degeneration, AAV2 has successfully restored both retinal structure

and function (165-167). AAV8, which is associated with a

reduced incidence of neutralizing antibodies and improved immune

tolerance, is considered a clinically promising alternative to

AAV2. In therapeutic studies using RPGR-mutant animal

models, AAV2, AAV5 and AAV8 are commonly employed (22,122,123). Different AAV serotypes have

distinct capsid protein structures, which influence their

transduction efficiency, tropism and immunogenicity. Therefore,

gene therapy design requires careful consideration of both serotype

selection and administration route to achieve an optimal balance

among efficacy, safety and immune tolerance (168,169). The AAV capsid is a key factor

in triggering immune responses. Once the capsid proteins are

recognized, T cells can be activated, leading to local

inflammation. Meanwhile, pre-existing neutralizing antibodies may

bind the capsid, thereby blocking vector entry into target cells

(170). Song et al

(123) evaluated the AAV2

vector in which three tyrosine residues of the capsid were

substituted with phenylalanine (AAV2tYF). The rAAV2tYF-GRK1-hRPGRco

demonstrated excellent transduction efficiency in the RPGR

mutant canine model and subsequently became a candidate vector for

clinical evaluation in the AGTC-501 study. Additionally, the

engineered AAV7m8 and modified AAV8 capsids have demonstrated

superior transduction efficiency, achieving notably higher delivery

rates in developing photoreceptor organoids compared with AAV5 and

standard AAV8 (8,171). Pavlou et al (172) developed a novel AAV capsid in

2021 that exhibited markedly enhanced delivery efficiency and lower

invasiveness across mouse, canine and non-human primate models,

confirming its cross-species applicability. These capsid

engineering strategies, which modify surface amino acids, provide a

foundation for more efficient and targeted gene delivery.

Beyond gene replacement therapy, gene-editing

approaches have also demonstrated promising therapeutic potential.

In a 2020 study, a single subretinal delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 via

AAV in Rpgr-KO mice precisely corrected the RPGR

mutation in vivo, protecting photoreceptors for ≥12 months

without detectable off-target effects (173). In the RD9 mouse model,

CRISPR-Cas9 targeted and excised the ORF15 mutation region,

allowing repair via non-homologous end joining and successfully

restoring the normal RPGR reading frame and protein expression

(113). This markedly improved

the retinal pathological phenotype, further confirming the efficacy

of gene editing for in vivo repair of RPGR mutations.

Additionally, prime editing has demonstrated a notable effect in

treating mice with RP (4,174).

Animal studies have also verified the feasibility

of RPGR gene therapy from the perspective of long-term efficacy. Wu

et al (175) conducted a

two-year dose-response study in Rpgr-KO mice, delivering

full-length RPGRORF15 via AAV8 and AAV9 vectors.

The results showed that treated mice maintained retinal structure

and function over the long term, as evidenced by higher ERG

amplitudes, a thicker photoreceptor layer and correct localization

of photoreceptor proteins (10,175). While animal models have been

invaluable in advancing RPGR gene therapy, emerging organoid models

provide promising platforms for therapeutic evaluation and

mechanistic insights, as discussed in the following section.

Application of organoid models in RPGR

gene therapy

Researchers have utilized human induced pluripotent

stem cell (hiPSC) differentiated organoid models to investigate

both the simulation and therapeutic targeting of RPGR

mutations. Organoids are highly organized three-dimensional

structures that serve dual roles in disease modeling and

therapeutic research. These models can differentiate into retinal

tissues containing all major cell types, exhibiting highly refined

structural organization and functional characteristics that closely

resemble those of native retinal tissue (8,116). Previous studies have

investigated the potential of hiPSC-derived organoids as a platform

for biomarker screening in RPGR-mutant patients (171,176,177). The first study employing

CRISPR-Cas9 to correct autologous hiPSC from patients with

RPGR mutations achieved 13% repair efficiency, and the

corrected cells could be used for subsequent transplantation

studies, underscoring the potential of precision medicine for

RPGR-related diseases (178). Similarly, a 2018 study at the

in vitro stage demonstrated that the application of

CRISPR-Cas9 to correct RPGR mutations successfully restored

the structure and electrophysiological properties of photoreceptors

(177). In addition, Sladen

et al (8) used

CRISPR-Cas9 to repair RPGR-mutated hiPSC, differentiated

them into photoreceptor cells and evaluated the effects of the AAV

delivery system, providing preliminary data to support subsequent

clinical trials (8). Another

study conducted single-cell RNA sequencing on organoids derived

from normal and RPGR-mutant hiPSCs, providing key insights

into the molecular mechanisms of RPGR-associated retinal

degeneration and informing the development of precision-targeted

gene therapy strategies (179).

Although hiPSC-derived organoids show great

potential for modeling RPGR-related diseases and testing

gene therapy strategies, they still face several challenges. The

majority of organoids have not yet developed structured

photoreceptor OS, making it difficult to fully replicate the

pathological process of cilia-associated diseases. Additionally

generating organoids is time-consuming and expensive (116,180). Although studies have attempted

to introduce antioxidants, lipid supplements and hyaluronic acid to

promote photoreceptor OS maturation, the results have been limited

(180,181). Overall, organoids cannot yet

fully replicate the in vivo microenvironment, and their

findings should therefore be interpreted cautiously when

considering clinical translation.

Delivery routes for ocular RPGR gene

therapy

In addition to the aforementioned factors

influencing gene therapy, the success of treatment largely depends

on the delivery route of the vector. The route of administration

not only affects the spatial distribution and cellular uptake

efficiency of the therapeutic gene but also directly influences the

magnitude of immune responses and the overall precision of

treatment. Therefore, the choice of injection modality is important

in RPGR gene therapy studies. Currently, the commonly used delivery

routes for ocular gene therapy include intravitreal injection,

subretinal injection and suprachoroidal injection. Table II summarizes the key features

and applicability differences of the three delivery modalities

(128,169,182-197). Intravitreal injection delivers

the AAV vector carrying the RPGR gene directly into the

vitreous cavity but may result in reduced therapeutic efficacy and

a stronger immune response due to uneven vector distribution. By

contrast, subretinal injection administers the vector into the

subretinal space between the RPE and photoreceptors, achieving a

higher concentration and more efficient transduction in target

cells. This approach is particularly suited for targeted and

precise RPGR gene therapy (Fig.

6D). Subretinal injection has also become the primary

administration route in current clinical trials for patients with

RPGR-associated RP (Fig.

6B).

| Table IIComparison of different injection

methods for ocular drug delivery. |

Table II