Cell death is a fundamental biological process that

governs cell fate, tissue regeneration and host immune responses

(1). Among the various forms of

cell death, ferroptosis has recently emerged as a unique,

iron-dependent modality of programmed cell death that has gained

significant scientific interest (2). Morphologically, biochemically and

genetically, ferroptosis is distinct from other well-established

cell death modalities, including apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy

(3). Rather than being a

stochastic or uncontrolled process, ferroptosis is precisely

orchestrated by complex signaling pathways and metabolic networks;

its core mechanism involves the dysregulation and interplay of

three pivotal modules: Iron, lipid and amino acid metabolism

(4,5).

Cognitive impairment represents a major global

public health challenge, encompassing a clinical spectrum from mild

cognitive impairment to severe dementia. This condition profoundly

affects the quality of life of patients and imposes a significant

socioeconomic burden (6). This

dysfunction serves as a common pathological endpoint for a

multitude of neurological disorders. The present review focuses on

the following key categories of disorders closely associated with

cognitive impairment: Neurodegenerative diseases including

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), which are

pathologically characterized by the progressive loss of neurons in

specific brain regions and the abnormal aggregation of functional

proteins (7), and

diabetes-associated cognitive impairment (DACI), which is caused

mainly by factors such as insulin resistance and neuroinflammation

(8).

Accumulating evidence indicates that ferroptosis

plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of the aforementioned

cognitive disorders. However, despite the rapid expansion of

research into ferroptosis within the field of neuroscience, the

existing body of knowledge remains relatively fragmented and

unsystematized (9). Therefore,

the present review aims to systematically dissect the core

molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis, elucidate its specific

pathogenic roles in cognitive disorders including AD, PD and DACI

as well as provide a comprehensive overview of emerging diagnostic

biomarkers and therapeutic strategies targeting this cell death

pathway. By synthesizing current research advancements, the present

review aims to provide new perspectives on the common pathological

pathways underlying these diseases and to establish a theoretical

foundation to guide the development of effective clinical

interventions.

Although several reviews have discussed the role of

ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases, most have focused on a

single disorder, isolated pathways or specific mechanistic aspects

(7,10,11). By contrast, the novelty of the

present review is its cross-disease perspective. The present review

summarizes ferroptosis-related mechanisms across AD, PD and DACI,

emphasizing both the common molecular features and the unique

triggers in each disease. Moreover, the present review integrates

recent progress in ferroptosis-related biomarkers and evaluates the

translational potential of ferroptosis-targeted therapeutic

strategies. By discussing the practical challenges, clinical

feasibility and workflow integration of these biomarkers, the

present review aims to bridge the gap between basic mechanistic

research and clinical application.

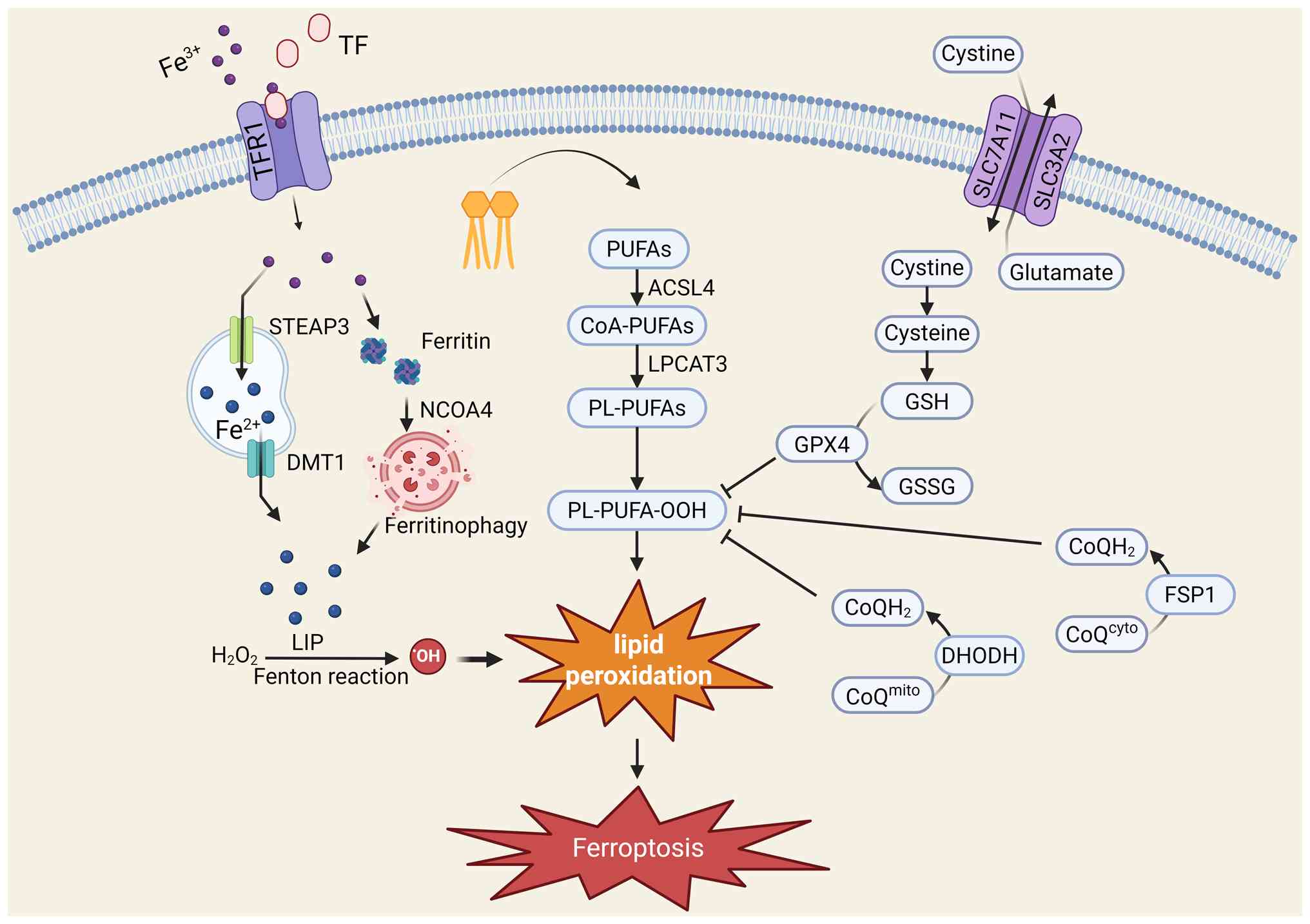

Ferroptosis is a complex biological process

regulated by the interplay of multiple metabolic pathways (Fig. 1); its hallmark feature is the

uncontrolled, iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides on

cellular membranes (12),

ultimately leading to the destruction of membrane integrity and

cell death. Understanding the interplay among lipid metabolism,

iron metabolism and the antioxidant defense system is fundamental

to elucidating the role of ferroptosis in disease.

Lipid peroxidation constitutes the final step of

ferroptosis execution, the occurrence of which depends on specific

lipid substrates and catalytic enzymes. Owing to its high lipid

content, particularly its enrichment in polyunsaturated fatty acids

(PUFAs), the brain is especially vulnerable to ferroptosis

(13).

PUFAs, especially arachidonic acid and adrenic acid,

are the primary substrates for lipid peroxidation during

ferroptosis. The bis-allylic hydrogen atoms within the molecular

chains of these fatty acids are chemically labile and highly

susceptible to abstraction, thereby initiating the chain reaction

of lipid peroxidation (14). The

content and composition of PUFAs within the cell membrane directly

determine a cell's sensitivity to ferroptosis.

PUFAs cannot be directly peroxidized; they must

first be integrated into membrane phospholipids. This process is

accomplished through the synergistic actions of two key enzymes:

ACSL4 and LPCAT3. ACSL4 is responsible for esterifying PUFAs into

their corresponding acyl-CoA derivatives, after which LPCAT3

catalyzes the incorporation of these activated PUFAs into membrane

phospholipids to form phospholipid-containing polyunsaturated fatty

acids (PL-PUFAs) (14).

Consequently, ACSL4 is considered a critical 'gatekeeper' enzyme

for ferroptosis, as its expression level and activity cellular

sensitivity to ferroptosis; its high expression enriches the cell

membrane with oxidizable PUFAs, effectively 'priming' the cell for

ferroptosis (15).

Once incorporated into the membrane, PL-PUFAs are

oxidized to phospholipid hydroperoxides (PL-PUFA-OOH) through

enzymatic or non-enzymatic pathways. The enzymatic pathway is

primarily catalyzed by members of the lipoxygenase family (16). The non-enzymatic pathway is

driven by the Fenton reaction, which is catalyzed by intracellular

labile Fe2+ (17).

The accumulation of these PL-PUFA-OOH molecules disrupts the

integrity and fluidity of the cell membrane, ultimately leading to

membrane rupture, the release of the cellular contents and cell

death (18).

Although iron is an essential trace element for

life, its dyshomeostasis is a key catalyst for ferroptosis. Cells

possess an intricate system to regulate iron uptake, storage,

utilization and efflux; disruptions at any point can lead to

ferroptosis.

Cells store excess iron within ferritin, a spherical

protein shell composed of 24 subunits, to mitigate the toxicity of

free iron in the LIP (21,22). However, upon exposure to specific

signaling cues, cells can degrade ferritin through a selective

autophagic process known as ferritinophagy (23). This process is mediated by a

specific cargo receptor, nuclear receptor coactivator 4, which

recognizes and binds to ferritin, targeting it for lysosomal

degradation (24). This process

releases large amounts of stored iron into the LIP (23). Ferritinophagy is a key mechanism

for rapidly increasing the iron content of the LIP when needed and

is important for increasing cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis

(25).

Cells have evolved a complex, multilayered

antioxidant defense network to counteract the onset of ferroptosis.

This network maintains cellular redox homeostasis by eliminating

lipid peroxides or inhibiting their formation. These defense

mechanisms can be broadly categorized into the canonical

glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)-dependent pathway and

non-canonical, independent pathways.

The canonical axis defending against ferroptosis is

centered on the GPX4/GSH system (26). This pathway begins with the cell

membrane-bound cystine/glutamate antiporter, System Xc−

(27). Composed of the light

chain subunit solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and the

heavy chain subunit SLC3A2, System Xc− imports

extracellular cystine, which is then rapidly reduced to cysteine

intracellularly (28). Cysteine

serves as the rate-limiting substrate for the synthesis of GSH

(29). As the core effector

molecule of this pathway, GPX4 is a unique selenoprotein and the

only member of the GPX family capable of directly catalyzing the

reduction of membrane phospholipid hydroperoxides (30). GPX4 utilizes GSH as a cofactor to

efficiently reduce toxic lipid hydroperoxides into non-toxic

phospholipid alcohols, thereby halting the lipid peroxidation chain

reaction and effectively suppressing ferroptosis (31). Consequently, the inactivation of

GPX4, either through the inhibition of System Xc− or the

depletion of intracellular GSH, represents a classic experimental

method for inducing ferroptosis.

In addition to the canonical GPX4/GSH axis, cells

possess other parallel, GPX4-independent anti-ferroptotic pathways

that provide additional layers of protection. One key non-canonical

system is the ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)/coenzyme Q10

(CoQ10) pathway (32). Localized

to the plasma membrane, FSP1 utilizes NADPH as an electron donor to

reduce CoQ10 to its antioxidant form, ubiquinol. Ubiquinol acts as

a lipophilic radical-trapping antioxidant that can effectively

scavenge lipid peroxyl radicals, thus providing a critical

alternative line of defense when GPX4 function is compromised.

Another important independent anti-ferroptotic axis is the GTP

cyclohydrolase-1/tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) pathway (33). BH4 is not only a crucial enzyme

cofactor but also a potent radical scavenger. Studies have shown

that it exerts powerful anti-ferroptotic effects through two

mechanisms: Protecting CoQ10 from depletion and directly inhibiting

lipid peroxidation (34,35). In parallel to the plasma

membrane-localized FSP1 system, a distinct, mitochondria-specific

antioxidant axis that counteracts ferroptosis centered on the

enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) has been identified

(36). DHODH is a flavoprotein

of the electron transport chain that is anchored to the inner

mitochondrial membrane, where it performs its canonical function in

de novo pyrimidine synthesis (37). Crucially, this enzymatic process

reduces CoQ10 to its active antioxidant form, ubiquinol (36). This dedicated mitochondrial pool

of ubiquinol acts as a potent, radical-trapping antioxidant,

directly neutralizing lipid peroxyl radicals within the inner

mitochondrial membrane and thereby shielding the organelle from

lipid peroxidation and subsequent ferroptotic collapse (38). Given that mitochondria are both a

primary source of endogenous ROS and a central hub for iron

metabolism, their membranes are uniquely vulnerable to ferroptotic

insults. This defense system thus provides a critical layer of

localized protection specifically within this susceptible

organelle, offering new insights for understanding cellular

resilience and identifying potential therapeutic targets in

neurodegenerative disorders where mitochondrial dysfunction is a

core pathological feature.

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)

acts as the 'master regulator' of the cellular response to

oxidative stress. Under oxidative or electrophilic stress, NRF2 is

activated and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to

antioxidant response elements to initiate the transcription of a

number of downstream genes. The proteins encoded by these genes

have diverse functions, including promoting GSH synthesis,

regenerating NADPH and upregulating iron storage proteins

(ferritin), thereby constructing a robust, multilayered defense

against ferroptosis (32).

The classic tumor suppressor p53 plays a complex,

dual role in the regulation of ferroptosis. On the one hand, p53

can promote ferroptosis by inhibiting the expression of SLC7A11

(39). On the other hand, it can

also suppress ferroptosis by regulating other metabolic pathways

(such as activating CDKN1A/p21) (40). The ultimate effect of p53 is

highly dependent on the cell type and the specific stress context

(41).

The regulatory mechanisms of ferroptosis are not

isolated but are intimately linked to the core metabolic activities

of cells. The initiation of ferroptosis is deeply integrated with

amino acid metabolism (glutamate/cystine balance), lipid metabolism

(PUFA availability) and metal homeostasis (iron regulation). For

instance, the activity of System Xc− is directly linked

to the levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate and the synthesis

of the antioxidant GSH (42).

The execution phase depends on the biological properties of the

cell membrane and the activity of lipid-modifying enzymes (ACSL4

and LPCAT3) (20). Moreover,

iron is a critical cofactor for core bioenergetic processes such as

mitochondrial respiration and oxygen transport and the

Fe2+ required for ferroptosis (32). This intrinsic connectivity

implies that ferroptosis is not merely a simple 'death switch' but

rather a composite reflection of the overall metabolic state of the

cell. Any pathological process that can disrupt these

interconnected metabolic hubs, such as mitochondrial dysfunction in

PD or oxidative stress in AD, may inadvertently lower the cellular

threshold for resistance to ferroptosis. This explains why

ferroptosis has emerged as a common pathological pathway in

multiple, seemingly unrelated diseases; it represents a shared

downstream execution point where diverse upstream damage signals

converge.

The fundamental molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis

are specifically activated and regulated in different disease

contexts and are emerging as key factors driving the pathological

progression of cognitive impairment (Table I). This section describes the

specific mechanisms of ferroptosis in AD, PD and DACI.

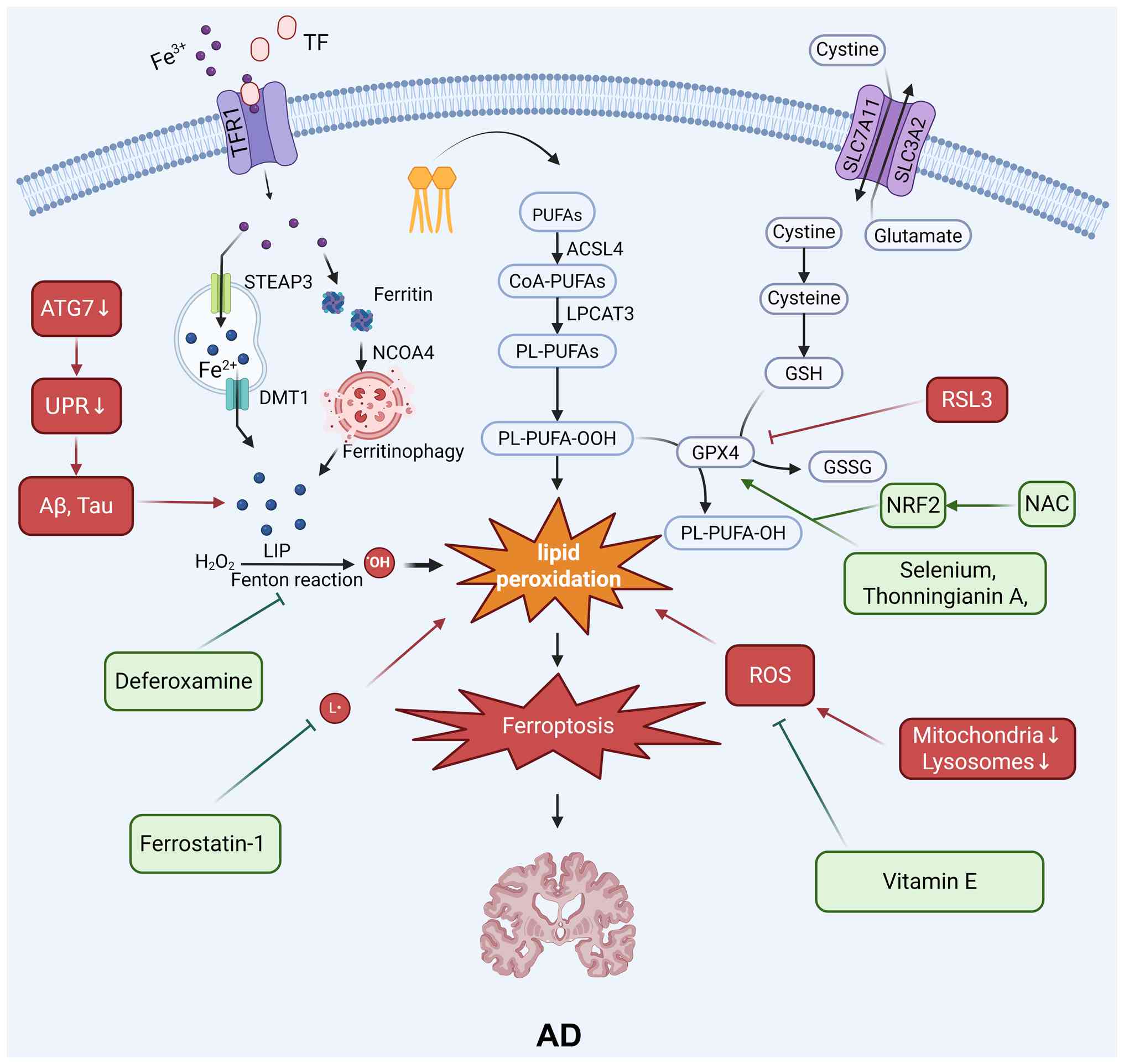

The regulation of ferroptosis can impact AD through

multiple mechanisms, including the regulation of GSH levels, the

Fenton reaction, amyloid-β (Aβ), lipid metabolism, iron metabolism

and the NRF2 signaling pathway (Fig.

2).

An abnormal increase in iron levels in the AD brain

is a well-documented phenomenon, especially in the regions most

severely affected by neurodegeneration (6). Iron dyshomeostasis is not only an

epiphenomenon but is also strongly implicated in the core

pathological processes of AD. On the one hand, excess iron ions can

directly catalyze ROS production, exacerbating oxidative stress,

while also promoting the generation and aggregation of Aβ and

catalyzing the hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein. On the

other hand, Aβ and tau aggregates can disrupt iron homeostasis, for

instance, by interfering with the function of iron-efflux proteins,

thereby further intensifying iron accumulation. This positive

feedback loop, or 'vicious cycle', between iron and Aβ/tau

significantly lowers the threshold for neuronal resistance to

ferroptosis, rendering them exceptionally vulnerable (43).

The AD brain is in a state of chronic, sustained

oxidative stress. Aβ oligomers and fibrils are themselves sources

of ROS and can directly induce lipid peroxidation. Critically, a

study has shown that the levels of GSH, a key antioxidant, are

significantly reduced in the AD brain and that the extent of this

depletion correlates positively with the severity of cognitive

impairment (43). The depletion

of GSH leads directly to the failure of the GPX4 antioxidant

system, resulting in cells being unable to effectively neutralize

lipid peroxides and thereby allowing the onset of ferroptosis.

In recent years, a new paradigm in AD pathology has

emerged: The ferroptosis of microglia, the resident immune cells of

the brain. In the pathological environment of AD, microglia are

activated to clear Aβ plaques, damaged myelin, and cellular debris.

However, this debris (particularly myelin) is rich in iron. During

the phagocytosis and degradation of this iron-rich material, the

microglia themselves can undergo ferroptosis due to iron overload

(44). This process not only

results in the loss of protective immune cells but also the release

of proinflammatory cytokines and damage-associated molecular

patterns during their death, further exacerbating the

neuroinflammatory response (45). This process creates a

self-amplifying cycle of damage that promotes neurodegeneration

(46).

Genetic studies have provided direct evidence for

the involvement of ferroptosis in AD (47,48). Transcriptomic analyses of brain

tissue samples from patients with AD have revealed significant

alterations in the expression of a range of ferroptosis-related

genes (FRGs). For example, the genes encoding transferrin receptor

(TFRC), glucose transporters and the master antioxidant regulator

NRF2 are closely associated with the pathological progression of AD

(49).

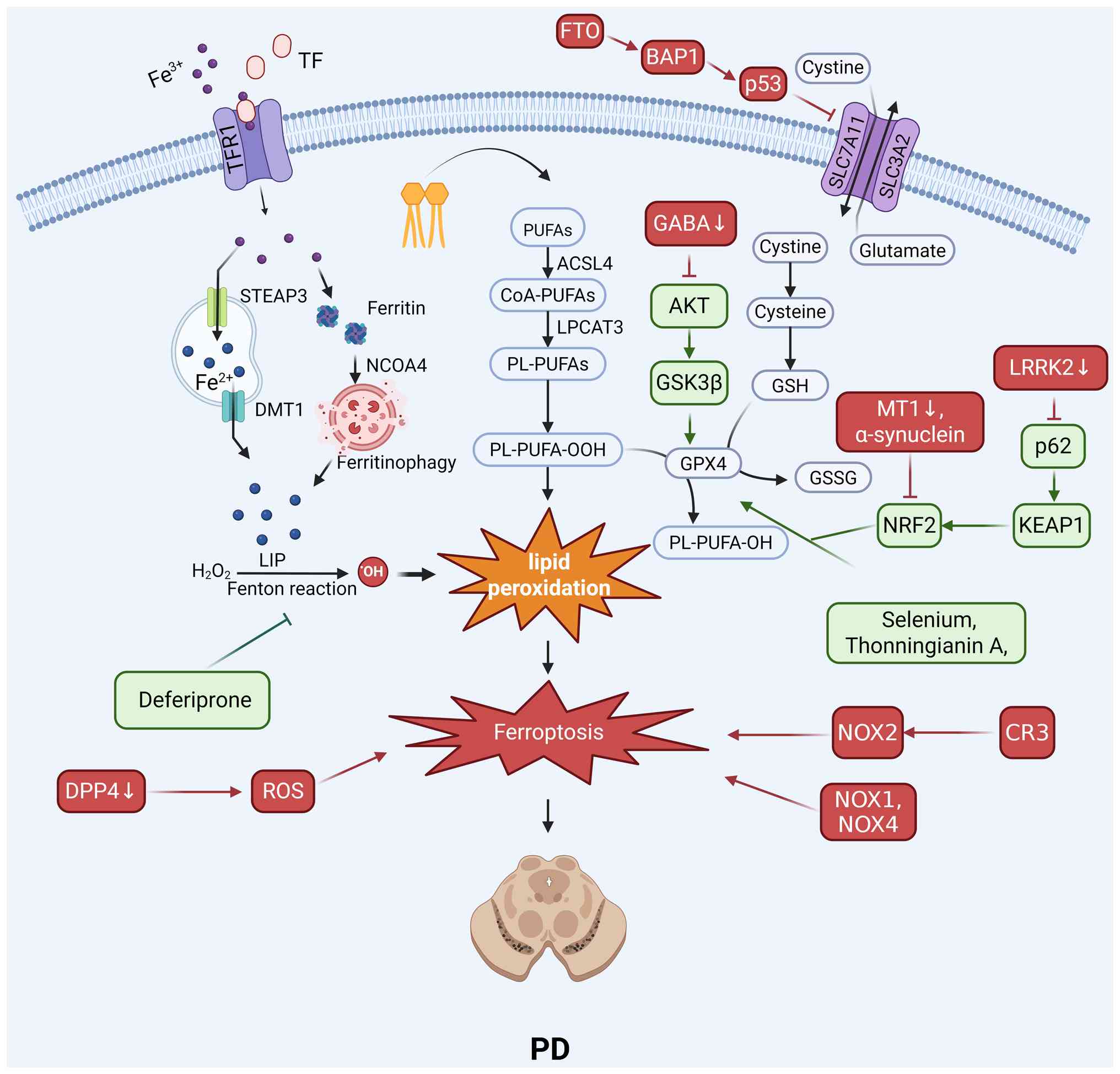

Ferroptosis is regulated by multiple interconnected

pathways, including the GPX4/GSH system, iron and lipid metabolism,

the NRF2 signaling pathway and mitochondrial function, in PD

(Fig. 3).

The integrity of the GPX4/GSH antioxidant axis is

critical for dopaminergic neuron survival. The oxidation product of

dopamine can induce ferroptosis by covalently modifying GPX4 and

mediating its ubiquitination and degradation (50). Conversely, experimental GPX4

overexpression exerts neuroprotective effects as it reduces

neuronal death (50). This

pathway is also targeted by other PD-related factors; the

leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) protein induces ferroptosis by

acting on the System Xc−/GSH/GPX4 pathway (51) and the m6A demethylase fat mass

and obesity-associated protein can promote ferroptosis via the

p53/SLC7A11 axis (39).

Given the central role of iron, therapeutic

strategies have focused on its chelation. The drug deferiprone has

been shown to inhibit ferroptosis by chelating excess iron within

the substantia nigra in vivo (52). This result is compounded by the

fact that α-synuclein aggregation, a hallmark of PD, can also

induce ferroptosis through mechanisms such as membrane disruption

and altered calcium influx (53).

The regulation of lipid metabolism, particularly

through the enzyme ACSL4, is a key control point. The PD-relevant

neurotoxin salsolinol induces ferroptosis by upregulating ACSL4

expression (54). By contrast,

the natural compound acteoside exerts a protective effect by

downregulating ACSL4 (54).

Downstream lipid peroxidation can be directly inhibited by

radical-trapping antioxidants such as ferrostatin-1 (55).

The NRF2 antioxidant response pathway is a major

defensive system whose impairment contributes to PD. Pathological

α-synuclein upregulation induces ferroptosis by reducing NRF2

protein levels and impairing antioxidant defenses (56). The therapeutic activation of this

pathway with compounds such as dimethyl fumarate,

tert-butylhydroquinone and sulforaphane can inhibit ferroptosis by

upregulating the expression of downstream antioxidant genes

(57). Additionally, the

activation of melatonin MT1 receptors can suppress ferroptosis

through the sirtuin 1/NRF2/heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1)/GPX4 signaling

cascade (58).

Mitochondrial dysfunction acts as a core driver of

ferroptosis through a combination of iron homeostasis imbalance and

oxidative stress (59). This

oxidative environment is further exacerbated by neuroinflammatory

processes. Microglial complement receptor 3 can induce ferroptosis

via NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) (60), and other NADPH oxidases,

including NOX1 (61) and NOX4

(62), are also key contributors

to the ferroptotic process.

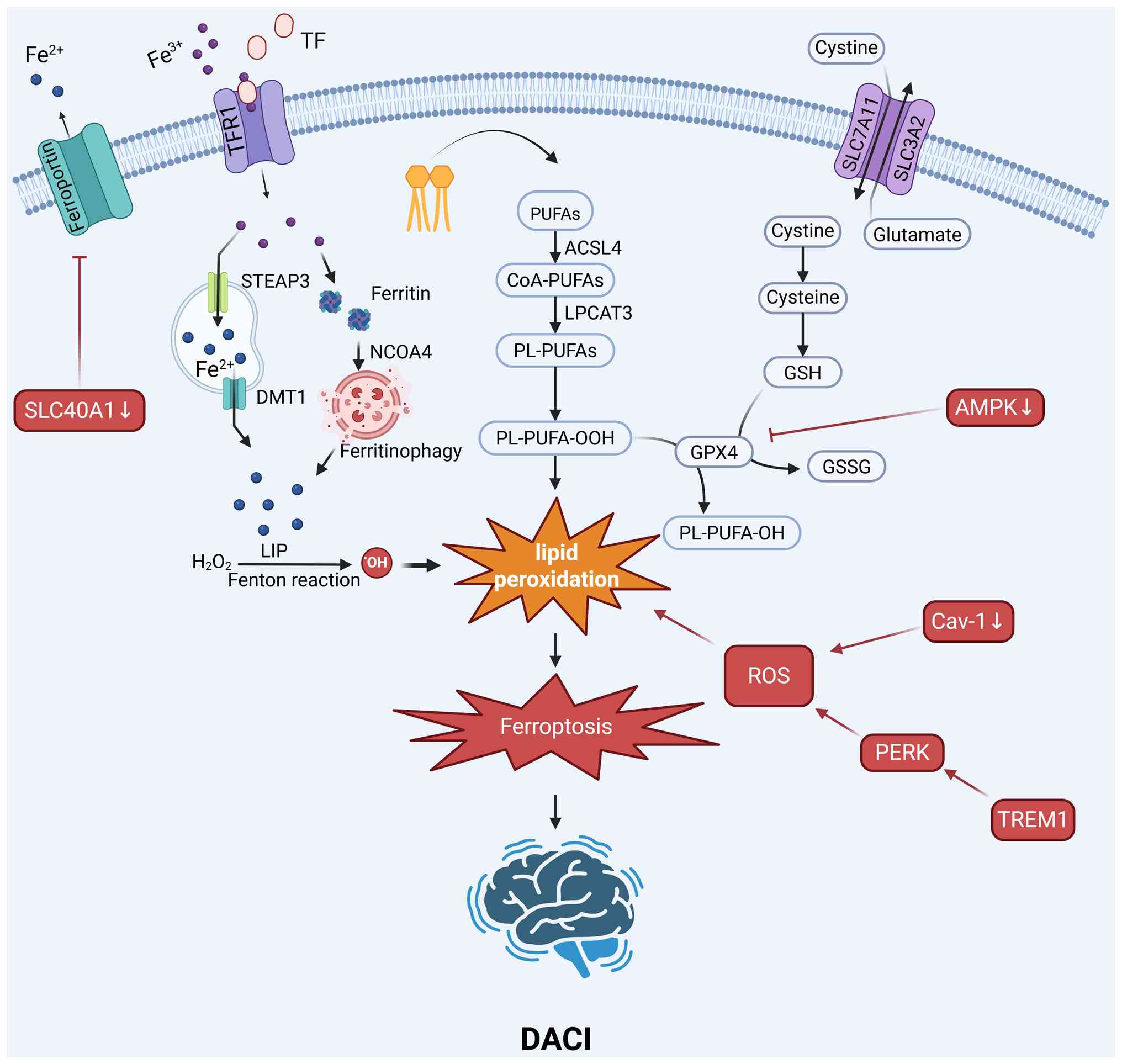

The regulation of ferroptosis can affect DACI

through multiple mechanisms, including the modulation of the

GPX4/GSH system, iron and ROS metabolism, mitochondrial homeostasis

and the NRF2 and PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK)

signaling pathways (Fig. 4).

The metabolic state in DACI significantly affects

the activity of the GPX4 antioxidant axis and the sensitivity of

cells to ferroptosis. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)

pathway, a key sensor of cellular energy, plays a protective role.

AMPK agonists inhibit ferroptosis by activating AMPK, which

subsequently upregulates GPX4 expression and downregulates

lipocalin-2 expression in vivo (63). Additionally, berberine has been

shown to protect against high glucose-induced damage to glomerular

podocytes by activating the NRF2/HO-1/GPX4 pathway, thereby

inhibiting ferroptosis (64).

The diabetic state creates a pro-ferroptotic

environment characterized by iron dyshomeostasis (65). Extensive iron deposition is

observed in the hippocampus of diabetic models and elevated plasma

Fe2+ levels correlate with cognitive decline in patients

(66,67). The increased iron levels can

catalyze the Fenton reaction, leading to lipid peroxidation.

Therapeutic interventions aim to mitigate this iron-induced stress.

Erythropoietin has been shown to inhibit ferroptosis by reducing

iron overload and lipid peroxidation both in vitro and in

vivo (68). Similarly, the

antioxidant liproxstatin-1 can effectively inhibit ferroptosis by

attenuating iron accumulation and oxidative stress in vivo

(63).

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1

(TREM1) is a key driver of microglial-mediated ferroptosis in

individuals with DACI (69).

Under high-glucose conditions, the expression of TREM1 is

upregulated, activating the PERK pathway (69). This process leads to the

inactivation of antioxidant systems and increased lipid

peroxidation and ROS levels, ultimately inducing ferroptosis in

microglia and exacerbating neuroinflammation.

The transcription factor NRF2 is a master regulator

of the antioxidant response and a key target for inhibiting

ferroptosis in individuals with DACI. Several compounds have been

shown to confer protection by modulating this pathway. Quercetin

inhibits ferroptosis by activating the NRF2/HO-1 pathway in models

of diabetic nephropathy, a mechanism that is potentially relevant

to DACI (72). Berberine also

leverages this pathway, activating the NRF2/HO-1/GPX4 axis to

suppress ferroptosis (64).

Furthermore, vitamin D can inhibit ferroptosis by activating the

vitamin D receptor, which in turn upregulates the NRF2/HO-1

signaling cascade, as shown in in vitro and in vivo

models (73).

Although the initial etiologies of AD, PD and DACI

are distinct, they all ultimately converge on the common cell death

pathway of ferroptosis. These diseases share several core

pathological features: Oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and

mitochondrial dysfunction (74).

Oxidative stress directly generates ROS to initiate lipid

peroxidation (32);

neuroinflammation, particularly the activation of microglia, alters

iron metabolism and promotes ROS release (44); and mitochondrial dysfunction is a

major source of both ROS and the LIP (75). The specific upstream triggers of

each disease (such as Aβ, ischemia and hemorrhage) activate these

common downstream pathological processes, which in turn are the

direct upstream activators of the core ferroptosis machinery (iron

overload, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant system depletion).

Therefore, ferroptosis is not merely another form of cell death, it

acts as a 'central executioner', a common endpoint where diverse

neural injury signals converge. This recognition highlights the

potential of ferroptosis as a therapeutic target. Theoretically, an

effective antiferroptotic agent could possess broad value as a

treatment for multiple mechanistically distinct cognitive

disorders.

Given the central role of ferroptosis in the

pathological processes of various cognitive disorders, its

associated molecules and metabolites hold immense potential as

novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. At present, diagnostic

tools for neurodegenerative diseases primarily rely on the

assessment of late-stage clinical symptoms or costly neuroimaging

examinations and lack pathology-based biomarkers that would enable

intervention in the early stages of the disease (76). The development of biomarkers that

can reflect the state of ferroptosis in the brain is crucial for

enabling early diagnosis, assessing disease progression and

monitoring therapeutic responses (Table II).

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood represent two

vital biofluids for accessing pathological information regarding

the central nervous system. Detecting changes in

ferroptosis-related molecules within these biofluids holds promise

for the development of minimally invasive diagnostic methods.

Measuring the levels of iron homeostasis-related

proteins in CSF or serum is a direct strategy. For example,

multiple studies have shown that the levels of ferritin in the CSF

of patients with AD are elevated and this increase is associated

with faster rates of cognitive decline and brain atrophy,

suggesting that CSF ferritin levels could be a valuable prognostic

biomarker (77,78). Urbano et al (79) demonstrated that CSF ferritin

levels are associated with the conversion from mild cognitive

impairment to dementia. Furthermore, CSF iron levels correlate

positively with tau protein levels (80). In the BioFINDER cohort study, CSF

ferritin levels reaching a threshold value of 12.47 ng/ml predicted

cognitive deterioration in patients with mild cognitive impairment

(81). Moreover, Apolipoprotein

E4 carrier status strengthens the diagnostic association between

brain iron content and AD pathology (81). A study also found that patients

with PD with substantia nigra hyperechogenicity exhibit

significantly lower cognitive function than those without

hyperechogenicity; among patients with PD and poorer cognitive

function, CSF iron levels are significantly elevated while

transferrin levels are significantly reduced (82). Additionally, the levels of

transferrin and non-transferrin-bound iron may also reflect the

status of iron load in the brain (77).

Lipid peroxidation is the key step in the execution

of ferroptosis and its metabolites are direct indicators of

ferroptotic activity. Malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal are two

major end-products of lipid peroxidation and their elevated levels

in CSF or blood have been shown to be correlated with the

pathological severity of AD and PD (33,83).

The state of the antioxidant system reflects the

capacity of the cell to resist ferroptosis. GSH is central to the

GPX4 system and its reduced levels in CSF are closely associated

with severe cognitive impairment in patients with AD, suggesting

that GSH could serve as a marker for the failure of the brain's

antioxidant capacity and the risk of ferroptosis (43).

Using high-throughput sequencing technologies,

researchers can identify ferroptosis-related molecular markers at

the genetic and transcriptomic levels.

Through bioinformatics methods, the expression

profile of a set of FRGs can be analyzed in patient tissues or

peripheral blood cells to construct prognostic models. For example,

in AD research, an FRG signature composed of genes such as DNA

damage inducible transcript 4, mucin 1 and CD44 was found to not

only distinguish patients with AD from healthy controls but also to

predict disease severity and immune cell infiltration in the brain

(43). Such multigene signatures

offer greater robustness and predictive power than single-gene

markers.

Certain genes that play key roles in the ferroptosis

pathway may also serve as independent prognostic indicators based

on their expression levels. Measuring the expression levels of

genes such as TFRC or SLC7A11 in brain tissue or blood from

patients with neurodegenerative diseases could provide clues for

assessing ferroptotic activity and disease progression (49).

Neuroimaging techniques, particularly magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI), represent a non-invasive, in vivo

method for assessing iron deposition in the brain and can serve as

an indirect means of evaluating ferroptosis risk. Advanced MRI

sequences, such as T2* relaxometry, are highly sensitive to iron

deposition. Compared with elderly individuals negative for AD

biomarkers, cognitively normal elderly individuals positive for AD

biomarkers show significantly higher R2* levels in the caudate

nucleus, putamen and globus pallidus, suggesting increased iron

content (84). In PD research,

this technique can be used to precisely quantify the iron content

in the substantia nigra region and has been found to be closely

correlated with disease severity and motor deficits (85). This method is useful not only for

diagnosis but also for tracking disease progression and evaluating

the efficacy of iron-targeted therapies.

Although numerous potential biomarkers have been

identified, the vast majority are still in the preclinical or early

clinical research stages (11).

Transforming these research findings into stable, reliable and

easily accessible clinical diagnostic tools remains a significant

challenge.

Given the insidious and progressive nature of

neurodegenerative diseases, the utility of a single biomarker

measurement is questionable. Early in the disease course,

ferroptotic processes may be subtle and localized, potentially

yielding false-negative results. Longitudinal monitoring,

therefore, represents a more clinically meaningful approach.

Tracking the trajectory of changes in a panel of

ferroptosis-related markers within accessible biofluids offers

greater prognostic value than a single snapshot measurement. This

dynamic monitoring is essential for identifying high-risk

individuals, tracking disease progression and evaluating

therapeutic responses.

Biomarker sources profoundly impact clinical

feasibility. While analysis of postmortem brain tissue is the gold

standard for research, it is not relevant for clinical diagnosis. A

study on human postmortem brain tissue has revealed that the

pathological progression of AD is accompanied by decreased

expression of nuclear receptor coactivator 4 and GPX4 in gray

matter (86). Meanwhile,

research using human brain organoid models has demonstrated that

ferroptosis inhibitors (Ferrostatin-1) can block Aβ pathology,

reduce lipid peroxidation and restore iron storage function in AD

organoids (86).

By contrast, CSF provides a more direct window into

central nervous system pathology, yet the invasiveness of lumbar

puncture limits its utility for routine screening or frequent

monitoring. Consequently, developing biomarkers in easily

accessible peripheral biofluids, such as blood, is a key priority.

However, this approach faces several challenges, including the

potential for the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to mask or dilute

CNS-specific signals and the difficulty in distinguishing

brain-derived markers from those originating systemically (87,88). In particular, the development of

peripheral blood biomarkers that can accurately reflect the state

of local ferroptosis within the brain is key and represents a major

hurdle for future research. Future research must therefore focus on

identifying markers capable of specifically crossing the BBB and on

developing ultrasensitive technologies for reliable peripheral

detection.

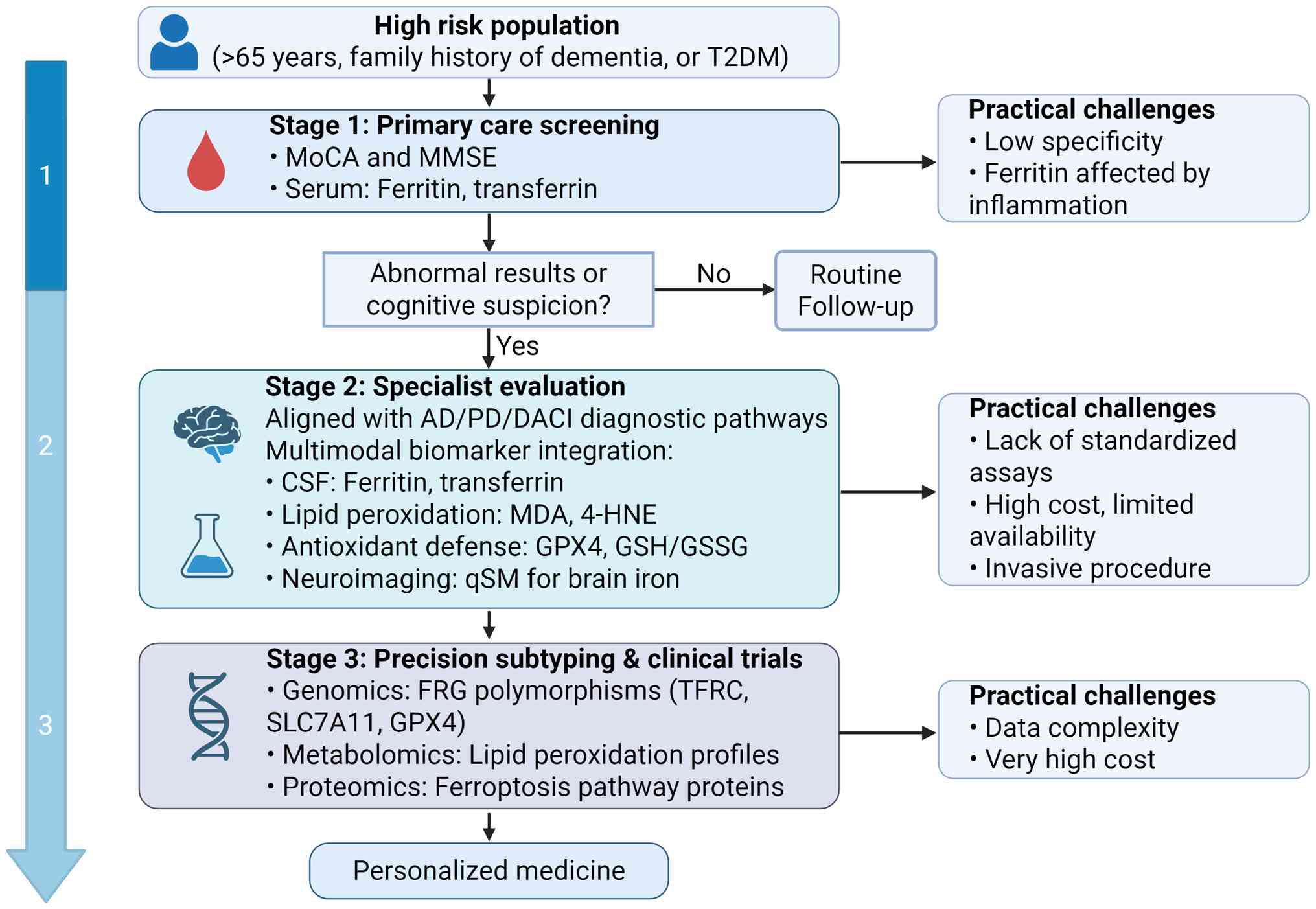

A major challenge in translating ferroptosis

research from the laboratory to clinical practice is how to

integrate ferroptosis biomarkers into current diagnostic pathways

for cognitive impairment. A stepwise clinical workflow may provide

a practical framework for this translation (Fig. 5).

At the first stage, ferroptosis-related tests could

be added to primary care as part of low-cost, population-wide

screening. For individuals at increased risk, such as those >65

years of age, with a family history of dementia or with comorbid

type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (89-91), routine blood tests may be

expanded to include serum ferritin and transferrin levels. These

tests could be combined with simple cognitive assessments, such as

the Montreal Cognitive Assessment or the Mini-Mental State

Examination (92,93). Individuals who show both mild

cognitive changes and abnormal iron metabolism could be flagged as

high-risk and referred for specialist evaluation. This approach is

affordable and easy to implement, but its specificity is low as

ferritin and related markers are affected by inflammation and liver

disease (94).

At the specialist evaluation stage, diagnosis could

be refined in memory clinics or neurology departments using more

specific ferroptosis biomarkers. Key measurements include lipid

peroxidation markers such as malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal,

antioxidant defense markers such as GPX4 activity and the

GSH/oxidized GSH ratio and advanced MRI-based assessments such as

quantitative susceptibility mapping to quantify brain iron

deposition (95,96). These ferroptosis markers should

be interpreted together with established diagnostic tools,

including CSF Aβ42, phosphorylated tau, total tau and Aβ PET

imaging (97). Signs of

increased ferroptosis activity, when combined with these

biomarkers, may improve diagnostic accuracy and help with

differential diagnosis. The main barriers at this stage are the

lack of standardized laboratory assays and the high cost and

limited availability of advanced imaging.

The advanced research stage focuses on precision

subtyping and clinical trial applications. Multi-omics approaches,

such as metabolomics to identify lipid peroxidation profiles and

genomics to characterize polymorphisms in ferroptosis-regulating

genes, may allow more accurate pathological classification.

Although these approaches are currently limited by high cost and

complex data processing, they show strong potential for identifying

patient groups that may benefit from ferroptosis-targeted

treatments.

Advanced age is the most significant non-modifiable

risk factor for major cognitive disorders, including AD, PD and

DACI (98-100). A compelling body of evidence

suggests that the aging process itself fosters a 'pro-ferroptotic'

state in the brain, thereby lowering the threshold for

neurodegeneration (101,102).

This connection is rooted in several age-related physiological

changes that directly impinge on the core regulatory axes of

ferroptosis.

Physiological aging systematically increases

neuronal susceptibility to ferroptosis through the synergistic

action of four interconnected mechanisms. First, normal aging is

associated with the progressive dysregulation of iron homeostasis,

often leading to iron accumulation in vulnerable brain regions such

as the hippocampus and substantia nigra (52). This expands the labile,

catalytically active iron pool, providing ample 'fuel' to initiate

destructive lipid peroxidation via the Fenton reaction. Second, the

efficiency of endogenous antioxidant systems decreases with age, a

core feature of which is the reduction in the levels of the master

intracellular antioxidant, GSH (103,104). As GPX4 is entirely dependent on

GSH to neutralize toxic lipid peroxides, the depletion of GSH

directly weakens the cell's most critical line of defense against

ferroptosis (105). Third,

age-related mitochondrial dysfunction is another key contributor.

Senescent mitochondria not only produce more ROS due to inefficient

electron transport but also exhibit impaired iron-sulfur cluster

biogenesis, leading to improper iron handling and accumulation

within the mitochondria, thus creating a potent internal source of

oxidative stress (106,107). Finally, although the total

brain lipid content may decrease with age, the enzymes responsible

for incorporating PUFAs into membrane phospholipids remain active,

ensuring the continued presence of the necessary substrates for the

final execution step of ferroptosis (75).

In summary, age-dependent changes such as increased

catalytic iron levels, weakened antioxidant defenses, elevated

mitochondrial-derived oxidative stress and sustained membrane

vulnerability to peroxidation, collectively place neurons in the

aging brain in a fragile state. This underlying vulnerability

explains why the pathological triggers of various neurodegenerative

diseases can converge on ferroptosis in the aging brain. Therefore,

ferroptosis emerges as a core mechanism that intimately links age,

the most universal risk factor, to cognitive decline, the shared

pathological outcome.

Given the core pathogenic role of ferroptosis in

various cognitive disorders, targeting this pathway has emerged as

a highly attractive and novel therapeutic strategy. To this end,

researchers have developed or screened a range of drugs and

compounds capable of inhibiting ferroptosis through various

approaches and have validated their neuroprotective effects using

various disease models (Table

III).

Cognitive impairment in AD is closely associated

with disrupted iron homeostasis, excessive oxidative stress and the

accumulation of Aβ and tau proteins, which collectively promote

ferroptosis. Several natural compounds have been found to be

effective at modulating ferroptosis-related pathways to counteract

these processes.

A common strategy involves activating the NRF2

signaling pathway, a master regulator of antioxidant responses. For

example, ganoderic acid A activates the NRF2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis

(108), whereas saponins

derived from Astragalus membranaceus act on the NOX4/NRF2

pathway to restore iron balance (109). Lignans from Schisandra

chinensis activate the NRF2/FPN1 pathway, reducing

phosphorylated tau levels and improving cognitive function

(110). Similarly, avicularin

enhances cognition by modulating NOX4/NRF2 signaling (111) and artemisinin derivatives

increase NRF2 activity by targeting its inhibitor kelch-like

ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) (112).

Some compounds work by directly supporting the

GPX4/GSH antioxidant defense system. Thonningianin A, a newly

identified ferroptosis inhibitor, activates GPX4 through the

AMPK/NRF2 pathway (113). Total

lignans from Schisandra increase the activity of the

NADK/NADPH/GSH system to reduce Aβ deposition (114) and schisandrin B downregulates

glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) expression to promote NRF2/GPX4

signaling (115). Clinical

studies suggest that selenium may help slow cognitive decline

(116,117). Reduced selenium levels in the

brains of patients with AD are associated with disease progression.

In addition, selenium-loaded nanospheres can deliver selenium, an

essential cofactor for GPX4, and markedly improve cognition in AD

models (118).

Other strategies target molecules other than NRF2

and GPX4. Berberine reduces oxidative damage by inhibiting the

JNK/p38 MAPK pathway (119).

Neuritin protects against cognitive impairment by activating

PI3K/Akt (120), whereas

ghrelin mitigates neuroinflammation by acting on the bone

morphogenetic protein 6/SMAD1 pathway (121). In addition, tetrahedral

framework nucleic acids have been developed to directly neutralize

Aβ toxicity and restore synaptic integrity (122).

The degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in PD is

fueled by iron overload, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative

stress, all of which are tightly linked to ferroptosis. Therapeutic

strategies have therefore focused on disrupting these pathological

cycles.

Iron chelation remains a straightforward

intervention. Deferoxamine (DFO) has been shown to preserve

dopaminergic neurons in animal models (123). However, the clinical outcomes

associated with deferiprone, an oral iron chelator, have been

inconsistent. For instance, one trial reported worsening motor

symptoms in patients with early-stage PD, highlighting the

complexity of iron-targeted therapy (52,60,124).

Several natural compounds activate endogenous

antioxidant pathways to increase the resilience of the brain to

oxidative stress. Acteoside inhibits ACSL4 (54) while simultaneously activating

NRF2 (125). Granulathiazole A

reduces α-synuclein accumulation through NRF2/HO-1 activation

(126) and betulinic acid

improves behavioral outcomes by reducing ROS levels (127). Dingzhen pills, a traditional

herbal formulation, inhibit the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator

of interferon genes pathway to protect dopaminergic neurons

(128).

Efforts have also been directed at modulating key

proteins in the ferroptosis cascade. γ-aminobutyric acid from

Lactobacillus reuteri alleviates pathology by activating the

Akt/GSK3β/GPX4 axis (129),

emodin upregulates the mitochondrial protein ubiquitin-cytochrome C

reductase core protein 1 to suppress ferroptosis (130) and corilagin protects neurons by

regulating the Toll-like receptor 4/Src/NOX2 pathway (131). Additionally, the inhibition of

LRRK2 has been linked to reduced ferroptotic damage via the

p62/Keap1/NRF2 axis (132) and

teneligliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, decreases ROS

levels and prevents ferroptosis (133).

Therapeutic interventions for DACI often target the

metabolic dysregulation that creates a pro-ferroptotic environment.

Several repurposed diabetes drugs and natural compounds have been

shown to exert neuroprotective effects by inhibiting ferroptosis.

The GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide improves cognition by

repairing mitochondria and modulating the GPX4/SLC7A11 pathway

(134).

Activation of the NRF2 antioxidant pathway is a

common strategy. The natural product sinomenine improves cognition

by regulating the EGF/NRF2/HO-1 pathway (135). Artemisinin has also been shown

to ameliorate cognitive impairment in T2DM mice by activating NRF2

(136). Other compounds work by

inhibiting inflammatory signaling; dihydromyricetin alleviates

hippocampal ferroptosis by inhibiting the JNK pathway (137).

Other approaches aim to correct the iron and ROS

imbalance directly. Erythropoietin has been shown to improve

cognition by reducing iron overload and lipid peroxidation in

diabetic models (68).

Resveratrol inhibits the ability of microRNA-9-3p to upregulate

SLC7A11 expression, thereby improving cognition in the context of

DACI (138).

Ferroptosis, a distinct form of iron-dependent cell

death driven by lipid peroxidation, has emerged as a key

pathological mechanism underlying multiple cognitive disorders,

including AD, PD and DACI. Preclinical studies have consistently

shown that targeting ferroptosis with drugs such as iron chelators,

lipid peroxidation inhibitors or NRF2 activators can produce

significant neuroprotective effects. However, translating these

promising findings into clinical success remains a formidable

challenge.

One of the major pharmacological barriers is the

BBB, which restricts the entry of most therapeutic agents into the

central nervous system. A number of compounds with robust in

vitro efficacy, such as DFO and certain natural products, fail

to exert therapeutic effects in vivo due to their poor BBB

permeability (139). Thus,

improving drug delivery across the BBB (through molecular

optimization or nanotechnology-based delivery systems) is a

critical priority.

Target specificity and off-target effects represent

other challenges. Iron homeostasis plays dual roles in maintaining

normal brain function and contributes to pathology. Broad-spectrum

iron chelation, as highlighted by the 'Deferiprone Paradox', risks

impairing physiological processes while attempting to block

ferroptosis. Similarly, electrophilic NRF2 activators may

non-specifically react with other thiol-containing proteins,

causing cytotoxicity (140).

Future therapeutics must achieve high specificity and ideally be

selectively activated under pathological conditions.

A number of currently available ferroptosis

modulators also face limitations in drug-like properties, such as

poor water solubility, instability and suboptimal pharmacokinetics,

which hinder their development into clinically viable agents

(141). Improving these

characteristics through medicinal chemistry is essential.

Compounding these pharmacological issues is the

lack of reliable biomarkers for monitoring ferroptosis in the human

brain. In the absence of validated protein, metabolite or genetic

markers in CSF or blood, identifying patients most likely to

benefit from ferroptosis-targeting therapies, assessing the

treatment response or dose adjustment are difficult (9). Most proposed biomarkers are still

in the exploratory stage and require rigorous clinical

validation.

Several innovative strategies should be prioritized

to overcome these obstacles. Nanodelivery systems can facilitate

BBB penetration, improve drug solubility and stability, and enable

targeted delivery to pathological brain regions (142,143). Combination therapies that

integrate ferroptosis inhibitors with other modalities, such as

dopamine replacement therapy for PD, anti-Aβ or anti-tau agents for

AD and anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic neuroinflammation, may

yield synergistic benefits. Personalized medicine approaches that

incorporate individual disease stages, genetic profiles and

biomarker status are critical for optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

Furthermore, mechanistic research is essential to elucidate the

unresolved aspects of ferroptosis, including the final molecular

executors and the crosstalk between ferroptosis and other cell

death pathways, such as apoptosis and autophagy. These insights

will inform the discovery of more precise and effective drug

targets. At present, the field of ferroptosis is at a critical

inflection point, shifting from mechanistic discovery to

translational application. While preclinical data highlight its

therapeutic potential (74),

clinical progress has been slow due to unresolved delivery and

diagnostic issues (144).

Animal models are indispensable for mechanistic exploration but

cannot fully replicate the long-term, multifactorial progression of

human neurodegenerative diseases.

Therefore, the future of ferroptosis-targeted

therapy depends not only on discovering new inhibitors or inducers

but also on solving the core issues of how to deliver the right

drug to the right brain region in the right patient and how to

reliably monitor ferroptosis in clinical settings.

Interdisciplinary collaboration among researchers from the

neuroscience, pharmacology, medicinal chemistry and biomarker

fields is essential. Without such concerted efforts, the enormous

therapeutic promise of ferroptosis modulation may remain confined

to the preclinical realm.

Not applicable.

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation

of China (grant no. 82271967), the Nanjing Medical Science and

Technology Development Fund (grant no. ZKX22038) and the China

Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2024M751466).

Not applicable.

JM and WX provided supervision and assisted with

writing and editing. SG conducted the literature search and drafted

and compiled the manuscript and created the figures. DK, SF, YL, XY

and ZJ provided constructive suggestions for the article and

contributed to its design and structuring. JM and WX modified and

adjusted the figures, ensuring their accuracy and clarity. All

authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Chen X, Comish PB, Tang D and Kang R:

Characteristics and biomarkers of ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:6371622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang H and Xie Y: Advances in ferroptosis

research: A comprehensive review of mechanism exploration, drug

development, and disease treatment. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

18:3342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ma W, Jiang X, Jia R and Li Y: Mechanisms

of ferroptosis and targeted therapeutic approaches in urological

malignancies. Cell Death Discov. 10:4322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yan HF, Zou T, Tuo QZ, Xu S, Li H, Belaidi

AA and Lei P: Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zheng J and Conrad M: Ferroptosis: When

metabolism meets cell death. Physiol Rev. 105:651–706. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Huang X: A concise review on oxidative

stress-mediated ferroptosis and cuproptosis in Alzheimer's disease.

Cells. 12:13692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Naderi S, Khodagholi F, Janahmadi M,

Motamedi F, Torabi A, Batool Z, Heydarabadi MF and Pourbadie HG:

Ferroptosis and cognitive impairment: Unraveling the link and

potential therapeutic targets. Neuropharmacology. 263:1102102025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Pang J, Höhn A,

Dong W, Gao R, Liu Y, Wang D, She Y, et al: Methionine restriction

alleviates Diabetes-associated cognitive impairment via activation

of FGF21. Redox Biol. 77:1033902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ryan SK, Ugalde CL, Rolland AS, Skidmore

J, Devos D and Hammond TR: Therapeutic inhibition of ferroptosis in

neurodegenerative disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 44:674–688. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Khan G, Hussain MS, Khan Y, Fatima R,

Ahmad S, Sultana A and Alam P: Ferroptosis and its contribution to

cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease: Mechanisms and

therapeutic potential. Brain Res. 1864:1497762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ma M, Jing G, Tian Y, Yin R and Zhang M:

Ferroptosis in cognitive impairment associated with diabetes and

Alzheimer's disease: Mechanistic insights and new therapeutic

opportunities. Mol Neurobiol. 62:2435–2449. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jacquemyn J, Ralhan I and Ioannou MS:

Driving factors of neuronal ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol.

34:535–546. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yan N and Zhang JJ: The emerging roles of

ferroptosis in vascular cognitive impairment. Front Neurosci.

13:8112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li Y, Li Z, Ran Q and Wang P: Sterols in

ferroptosis: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies.

Trends Mol Med. 31:36–49. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Li QS and Jia YJ: Ferroptosis: A critical

player and potential therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury

and spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 18:506–512. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Shui S, Zhao Z, Wang H, Conrad M and Liu

G: Non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation initiated by photodynamic

therapy drives a distinct ferroptosis-like cell death pathway.

Redox Biol. 45:1020562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chang S, Zhang M, Liu C, Li M, Lou Y and

Tan H: Redox mechanism of glycerophospholipids and relevant

targeted therapy in ferroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 11:3582025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Fei W, Chen D, Tang H, Li C, Zheng W, Chen

F, Song Q, Zhao Y, Zou Y and Zheng C: Targeted GSH-exhausting and

hydroxyl radical self-producing manganese-silica nanomissiles for

MRI guided ferroptotic cancer therapy. Nanoscale. 12:16738–16754.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lee J and Hyun DH: The interplay between

intracellular iron homeostasis and neuroinflammation in

neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:9182023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang XD, Liu ZY, Wang MS, Guo YX, Wang

XK, Luo K, Huang S and Li RF: Mechanisms and regulations of

ferroptosis. Front Immunol. 14:12694512023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

21

|

Kakhlon O and Cabantchik ZI: The labile

iron pool: Characterization, measurement, and participation in

cellular processes(1). Free Radic Biol Med. 33:1037–1046. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Arosio P, Elia L and Poli M: Ferritin,

cellular iron storage and regulation. IUBMB Life. 69:414–422. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW and

Kimmelman AC: Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo

receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 509:105–109. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mancias JD, Pontano Vaites L, Nissim S,

Biancur DE, Kim AJ, Wang X, Liu Y, Goessling W, Kimmelman AC and

Harper JW: Ferritinophagy via NCOA4 is required for erythropoiesis

and is regulated by iron dependent HERC2-mediated proteolysis.

Elife. 4:e103082015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ajoolabady A, Aslkhodapasandhokmabad H,

Libby P, Tuomilehto J, Lip GYH, Penninger JM, Richardson DR, Tang

D, Zhou H, Wang S, et al: Ferritinophagy and ferroptosis in the

management of metabolic diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab.

32:444–462. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Forcina GC and Dixon SJ: GPX4 at the

crossroads of lipid homeostasis and ferroptosis. Proteomics.

19:e18003112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bridges RJ, Natale NR and Patel SA: System

xc− Cystine/glutamate antiporter: An update on molecular

pharmacology and roles within the CNS. Br J Pharmacol. 165:20–34.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

28

|

Conrad M and Sato H: The oxidative

stress-inducible cystine/glutamate antiporter, system x (c) (-):

Cystine supplier and beyond. Amino Acids. 42:231–246. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Xue Z, Nuerrula Y, Sitiwaerdi Y and Eli M:

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 promotes

radioresistance by regulating glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier

subunit and its unique immunoinvasive pattern. Biomol Biomed.

24:545–559. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ursini F and Maiorino M: Lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic

Biol Med. 152:175–185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME,

Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji

AF, Clish CB and Brown LM: Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell

death by GPX4. Cell. 156:317–331. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Benarroch E: What is the role of

ferroptosis in neurodegeneration? Neurology. 101:312–319. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhou M, Xu K, Ge J, Luo X, Wu M, Wang N

and Zeng J: Targeting ferroptosis in Parkinson's disease:

Mechanisms and emerging therapeutic strategies. Int J Mol Sci.

25:130422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP cyclohydrolase

1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 6:41–53. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Soula M, Weber RA, Zilka O, Alwaseem H, La

K, Yen F, Molina H, Garcia-Bermudez J, Pratt DA, Birsoy K, et al:

Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to canonical

ferroptosis inducers. Nat Chem Biol. 16:1351–1360. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee

H, Koppula P, Wu S, Zhuang L, Fang B, et al: DHODH-mediated

ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer.

Nature. 593:586–590. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Teng D, Swanson KD, Wang R, Zhuang A, Wu

H, Niu Z, Cai L, Avritt FR, Gu L, Asara JM, et al: DHODH modulates

immune evasion of cancer cells via CDP-choline dependent regulation

of phospholipid metabolism and ferroptosis. Nat Commun.

16:38672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cao J, Chen X, Chen L, Lu Y, Wu Y, Deng A,

Pan F, Huang H, Liu Y, Li Y, et al: DHODH-mediated mitochondrial

redox homeostasis: A novel ferroptosis regulator and promising

therapeutic target. Redox Biol. 85:1037882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li Z, Chen X, Xiang W, Tang T and Gan L:

m6A demethylase FTO-mediated upregulation of BAP1 induces neuronal

ferroptosis via the p53/SLC7A11 axis in the MPP+/MPTP-induced

Parkinson's disease model. ACS Chem Neurosci. 16:405–416. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Tarangelo A, Magtanong L, Bieging-Rolett

KT, Li Y, Ye J, Attardi LD and Dixon SJ: p53 suppresses metabolic

stress-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells. Cell Rep. 22:569–575.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Jiang M, Qiao M, Zhao C, Deng J, Li X and

Zhou C: Targeting ferroptosis for cancer therapy: Exploring novel

strategies from its mechanisms and role in cancers. Transl Lung

Cancer Res. 9:1569–1584. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, Lambros M,

Gout PW, Kalivas PW, Massie A, Smolders I, Methner A, Pergande M,

et al: The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(-) in health

and disease: From molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic

opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 18:522–555. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

43

|

Sun Y, Xiao Y, Tang Q, Chen W and Lin L:

Genetic markers associated with ferroptosis in Alzheimer's disease.

Front Aging Neurosci. 16:13646052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Streit WJ, Phan L and Bechmann I:

Ferroptosis and pathogenesis of neuritic plaques in Alzheimer

disease. Pharmacol Rev. 77:1000052025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Proneth B and Conrad M: Ferroptosis and

necroinflammation, a yet poorly explored link. Cell Death Differ.

26:14–24. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

McIntosh A, Mela V, Harty C, Minogue AM,

Costello DA, Kerskens C and Lynch MA: Iron accumulation in

microglia triggers a cascade of events that leads to altered

metabolism and compromised function in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Pathol.

29:606–621. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhao H, Wang J, Li Z, Wang S, Yu G and

Wang L: Identification Ferroptosis-related hub genes and diagnostic

model in Alzheimer's disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 16:12806392023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tian M, Shen J, Qi Z, Feng Y and Fang P:

Bioinformatics analysis and prediction of Alzheimer's disease and

alcohol dependence based on Ferroptosis-related genes. Front Aging

Neurosci. 15:12011422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhang Y, Wang M and Chang W: Iron

dyshomeostasis and ferroptosis in Alzheimer's disease: Molecular

mechanisms of cell death and novel therapeutic drugs and targets

for AD. Front Pharmacol. 13:9836232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Sun J, Lin XM, Lu DH, Wang M, Li K, Li SR,

Li ZQ, Zhu CJ, Zhang ZM, Yan CY, et al: Midbrain dopamine oxidation

links ubiquitination of glutathione peroxidase 4 to ferroptosis of

dopaminergic neurons. J Clin Invest. 133:e1731102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zheng Z, Zhang S, Liu X, Wang X, Xue C, Wu

X, Zhang X, Xu X, Liu Z, Yao L and Lu G: LRRK2 regulates

ferroptosis through the system xc-GSH-GPX4 pathway in the

neuroinflammatory mechanism of Parkinson's disease. J Cell Physiol.

239:e312502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Negida A, Hassan NM, Aboeldahab H, Zain

YE, Negida Y, Cadri S, Cadri N, Cloud LJ, Barrett MJ and Berman B:

Efficacy of the Iron-chelating agent, deferiprone, in patients with

Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. CNS

Neurosci Ther. 30:e146072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Angelova PR, Choi ML, Berezhnov AV,

Horrocks MH, Hughes CD, De S, Rodrigues M, Yapom R, Little D, Dolt

KS, et al: Alpha synuclein aggregation drives ferroptosis: An

Interplay of iron, calcium and lipid peroxidation. Cell Death

Differ. 27:2781–2796. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wang H, Wu S, Li Q, Sun H and Wang Y:

Targeting ferroptosis: Acteoside as a neuroprotective agent in

salsolinol-induced Parkinson's disease models. Front Biosci

(Landmark Ed). 30:266792025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yan J, Bao L, Liang H, Zhao L, Liu M, Kong

L, Fan X, Liang C, Liu T, Han X, et al: A druglike ferrostatin-1

analogue as a ferroptosis inhibitor and photoluminescent indicator.

Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 64:e2025021952025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

A A, W C, N N, L M, M D and Zhang DD:

α-Syn overexpression, NRF2 suppression, and enhanced ferroptosis

create a vicious cycle of neuronal loss in Parkinson's disease.

Free Radic Biol Med. 192:130–140. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Gong K, Zhou S, Xiao L, Xu M, Zhou Y, Lu

K, Yu X, Zhu J, Liu C and Zhu Q: Danggui shaoyao san ameliorates

Alzheimer's disease by regulating lipid metabolism and inhibiting

neuronal ferroptosis through the AMPK/Sp1/ACSL4 signaling pathway.

Front Pharmacol. 16:15883752025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Lv QK, Tao KX, Yao XY, Pang MZ, Cao BE,

Liu CF and Wang F: Melatonin MT1 receptors regulate the

Sirt1/Nrf2/ho-1/Gpx4 pathway to prevent α-synuclein-induced

ferroptosis in Parkinson's disease. J Pineal Res. 76:e129482024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Wang W, Thomas ER, Xiao R, Chen T, Guo Q,

Liu K, Yang Y and Li X: Targeting mitochondria-regulated

ferroptosis: A new frontier in Parkinson's disease therapy.

Neuropharmacology. 274:1104392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wang Q, Liu J, Zhang Y, Li Z, Zhao Z,

Jiang W, Zhao J, Hou L and Wang Q: Microglial CR3 promotes neuron

ferroptosis via NOX2-mediated iron deposition in rotenone-induced

experimental models of Parkinson's disease. Redox Biol.

77:1033692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang H, Mao W, Zhang Y, Feng W, Bai B, Ji

B, Chen J, Cheng B and Yan F: NOX1 triggers ferroptosis and

ferritinophagy, contributes to Parkinson's disease. Free Radic Biol

Med. 222:331–343. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lin Z, Ying C, Si X, Xue N, Liu Y, Zheng

R, Chen Y, Pu J and Zhang B: NOX4 exacerbates Parkinson's disease

pathology by promoting neuronal ferroptosis and neuroinflammation.

Neural Regen Res. 20:2038–2052. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Xie Z, Wang X, Luo X, Yan J, Zhang J, Sun

R, Luo A and Li S: Activated AMPK mitigates Diabetes-related

cognitive dysfunction by inhibiting hippocampal ferroptosis.

Biochem Pharmacol. 207:1153742023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Wei M, Liu X, Tan Z, Tian X, Li M and Wei

J: Ferroptosis: A new strategy for Chinese herbal medicine

treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14:11880032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Sha W, Hu F, Xi Y, Chu Y and Bu S:

Mechanism of ferroptosis and its role in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

J Diabetes Res. 2021:99996122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Liu J, Hu X, Xue Y, Liu C, Liu D, Shang Y,

Shi Y, Cheng L, Zhang J, Chen A and Wang J: Targeting hepcidin

improves cognitive impairment and reduces iron deposition in a

diabetic rat model. Am J Transl Res. 12:4830–4839. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Tang W, Li Y, He S, Jiang T, Wang N, Du M,

Cheng B, Gao W, Li Y and Wang Q: Caveolin-1 alleviates

diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction through modulating

neuronal ferroptosis-mediated mitochondrial homeostasis. Antioxid

Redox Signal. 37:867–886. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Guo T, Yu Y, Yan W, Zhang M, Yi X, Liu N,

Cui X, Wei X, Sun Y, Wang Z, et al: Erythropoietin ameliorates

cognitive dysfunction in mice with type 2 diabetes mellitus via

inhibiting iron overload and ferroptosis. Exp Neurol.

365:1144142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhao Y, Guo H and Li Q, Wang N, Yan C,

Zhang S, Dong Y, Liu C, Gao W, Zhu Y and Li Q: TREM1 induces

microglial ferroptosis through the PERK pathway in

diabetic-associated cognitive impairment. Exp Neurol.

383:1150312025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Ma H, Jiang T, Tang W, Ma Z, Pu K, Xu F,

Chang H, Zhao G, Gao W, Li Y and Wang Q: Transplantation of

platelet-derived mitochondria alleviates cognitive impairment and

mitochondrial dysfunction in db/db mice. Clin Sci (Lond).

134:2161–2175. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Asterholm IW, Mundy DI, Weng J, Anderson

RGW and Scherer PE: Altered mitochondrial function and metabolic

inflexibility associated with loss of caveolin-1. Cell Metab.

15:171–185. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Feng Q, Yang Y, Qiao Y, Zheng Y, Yu X, Liu

F, Wang H, Zheng B, Pan S, Ren K, et al: Quercetin ameliorates

diabetic kidney injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via activating

Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Am J Chin Med. 51:997–1018. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Li J, Cao Y, Xu J, Li J, Lv C, Gao Q,

Zhang C, Jin C, Wang R, Jiao R and Zhu H: Vitamin D improves

cognitive impairment and alleviates ferroptosis via the Nrf2

signaling pathway in aging mice. Int J Mol Sci. 24:153152023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Wei Z, Yu H, Zhao H, Wei M, Xing H, Pei J,

Yang Y and Ren K: Broadening horizons: Ferroptosis as a new target

for traumatic brain injury. Burns Trauma. 12:tkad0512024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Abdukarimov N, Kokabi K and Kunz J:

Ferroptosis and iron homeostasis: Molecular mechanisms and

neurodegenerative disease implications. Antioxidants (Basel).

14:5272025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang B, Fu C, Wei Y, Xu B, Yang R, Li C,

Qiu M, Yin Y and Qin D: Ferroptosis-related biomarkers for

alzheimer's disease: Identification by bioinformatic analysis in

hippocampus. Front Cell Neurosci. 16:10239472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Ficiarà E, Munir Z, Boschi S, Caligiuri ME

and Guiot C: Alteration of iron concentration in Alzheimer's

disease as a possible diagnostic biomarker unveiling ferroptosis.

Int J Mol Sci. 22:44792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Ayton S, Faux NG and Bush AI; Alzheimer's

disease neuroimaging initiative: Ferritin levels in the

cerebrospinal fluid predict Alzheimer's disease outcomes and are

regulated by APOE. Nat Commun. 6:67602015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Urbano T, Michalke B, Chiari A, Malagoli

C, Bedin R, Tondelli M, Vinceti M and Filippini T: Iron species in

cerebrospinal fluid and dementia risk in subjects with mild

cognitive impairment: A cohort study. Neurotoxicology. 110:1–9.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Urbano T, Vinceti M, Carbone C, Wise LA,

Malavolti M, Tondelli M, Bedin R, Vinceti G, Marti A, Chiari A, et

al: Exposure to cadmium and other trace elements among individuals

with mild cognitive impairment. Toxics. 12:9332024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

81

|

Ayton S, Janelidze S, Kalinowski P,

Palmqvist S, Belaidi AA, Stomrud E, Roberts A, Roberts B, Hansson O

and Bush AI: CSF ferritin in the clinicopathological progression of

Alzheimer's disease and associations with APOE and inflammation

biomarkers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 94:211–219. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Yu SY, Cao CJ, Zuo LJ, Chen ZJ, Lian TH,

Wang F, Hu Y, Piao YS, Li LX, Guo P, et al: Clinical features and

dysfunctions of iron metabolism in Parkinson disease patients with

hyper echogenicity in Substantia nigra: A Cross-sectional study.

BMC Neurol. 18:92018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Padurariu M, Ciobica A, Hritcu L, Stoica

B, Bild W and Stefanescu C: Changes of some oxidative stress

markers in the serum of patients with mild cognitive impairment and

Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 469:6–10. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Lin Q, Shahid S, Hone-Blanchet A, Huang S,

Wu J, Bisht A, Loring D, Goldstein F, Levey A, Crosson B, et al:

Magnetic resonance evidence of increased iron content in

subcortical brain regions in asymptomatic Alzheimer's disease. Hum

Brain Mapp. 44:3072–3083. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Dusek P, Hofer T, Alexander J, Roos PM and

Aaseth JO: Cerebral iron deposition in neurodegeneration.

Biomolecules. 12:7142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Majerníková N, Marmolejo-Garza A, Salinas

CS, Luu MDA, Zhang Y, Trombetta-Lima M, Tomin T, Birner-Gruenberger

R, Lehtonen Š, Koistinaho J, et al: The link between amyloid β and

ferroptosis pathway in Alzheimer's disease progression. Cell Death

Dis. 15:7822024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Kang JH, Korecka M, Lee EB, Cousins KAQ,

Tropea TF, Chen-Plotkin AA, Irwin DJ, Wolk D, Brylska M, Wan Y and

Shaw LM: Alzheimer disease biomarkers: Moving from CSF to plasma

for reliable detection of amyloid and tau pathology. Clin Chem.

69:1247–1259. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Hampel H, O'Bryant SE, Molinuevo JL,

Zetterberg H, Masters CL, Lista S, Kiddle SJ, Batrla R and Blennow

K: Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer disease: Mapping the road

to the clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 14:639–652. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames

D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Brayne C, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J,

Cooper C, et al: Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020

report of the lancet commission. Lancet. 396:413–446. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Biessels GJ and Despa F: Cognitive decline

and dementia in diabetes mellitus: Mechanisms and clinical

implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 14:591–604. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Andrews SJ, Tolosa-Tort P, Jonson C,

Fulton-Howard B, Renton AE, Yokoyama JS and Yaffe K; Alzheimer's

Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: The role of genomic-informed risk

assessments in predicting dementia outcomes. Alzheimers Dement.

21:e708262025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V,

Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL and Chertkow H:

The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for

mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 53:695–699. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Folstein MF, Folstein SE and McHugh PR:

'Mini-mental state'. A practical method for grading the cognitive

state of patients for the clinician J Psychiatr Res. 12:189–198.

1975.

|

|

94

|

Cullis JO, Fitzsimons EJ, Griffiths WJ,

Tsochatzis E and Thomas DW; British Society for Haematology:

Investigation and management of a raised serum ferritin. Br J

Haematol. 181:331–340. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Wang Y and Liu T: Quantitative