Ear and nose diseases are often neglected; however,

for most patients, the symptoms persist and recur. The low cure

rates and high recurrence rates inevitably influence the quality of

learning, living and work of patients, particularly of children and

adolescents, resulting in significant healthcare costs as diseases

progress (1,2). The upper respiratory tract is the

first stop in the fight against viral infections and

otolaryngological disorders have attracted wide attention,

especially after the sudden outbreak of the severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in December 2019

(3). Numerous investigations

have reported the etiology, pathogenesis, progression and prognosis

of ear and nose diseases, in which air pollution and meteorological

factors play key roles (4,5).

Over the past decade, climate change and weather

events have gained widespread attention (6). Recent research has established that

air pollution has an effect on ear and nose diseases, specifically

aggravating these diseases by evoking oxidative stress,

exacerbating inflammatory responses and inducing autoimmunity

(7,8). Air pollution is currently one of

the greatest risk factors for diseases and premature death.

Specifically, air pollution (both household and ambient air

pollution) caused 6.7 million deaths in 2019, of which ambient air

pollution contributed to 4.5 million deaths, an increase from 4.2

million deaths in 2015 and 2.9 million deaths in 2000 (9). Ambient air pollution is primarily

caused by particulate matter (PM) and toxic gases. Based on the

aerodynamic diameter, PM can be further classified into coarse

particles (≤10 μm, PM10), fine particles (≤2.5

μm, PM2.5) and ultrafine particles (≤1 μm,

PM1) (10). Toxic

gases include CO, black carbon (BC), nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides

and ozone (O3). The impact of indoor air pollution on

human health has gained increasing attention (11,12). A study has shown that indoor dust

and bio-super particles are closely linked to the onset of various

diseases, with this effect being independent of environmental air

pollution (13). Additionally,

human activities also significantly influence indoor air quality

(14). Research indicates that

indoor microbial communities may pose potential health risks

(15). Therefore, indoor air

pollution is treated as an independent topic of discussion in the

present review. Household air pollutants include environmental

tobacco smoke (ETS), volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and indoor

allergens.

In addition to air pollution, the role of

meteorological factors has become increasingly important.

Meteorological factors, including temperature, relative humidity

(RH) and wind speed increase not only the activity of pathogens but

also the susceptibility of the population (16,17). Conversely, meteorological factors

and environmental pollution are deeply interrelated. For example,

drier and cooler conditions can boost O3 pollution by

enhancing the rate of photochemical production (18). In addition, bacterial communities

in indoor air are affected by environmental pollution and

meteorological factors. Studies have indicated that airborne

bacterial populations may be altered due to the influence of

household activities, such as burning scented candles, which leads

to significant changes in bacterial diversity (14,15). The interaction between

environmental pollution and meteorological factors promotes the

onset and exacerbation of ear and nose diseases, particularly

allergic rhinitis (AR), otitis media (OM) and sudden sensorineural

hearing loss (SSNHL) (19,20). This emphasizes the importance of

improving indoor ventilation and surface hygiene to reduce health

risks.

To thoroughly analyze the impact of air pollution

and meteorological factors on the onset and progression of ear and

nose diseases, while considering the comorbidity and holistic

characteristics of ear and nose diseases as well as the mechanisms

of known environmental factors, the present study provides, to the

best of our knowledge, the first review of the interactions between

air pollution, meteorological factors and SARS-CoV-2 on ear and

nose diseases. The present review focuses on ear and nose diseases

that are closely associated with inflammatory responses or

autoimmunity, including AR, OM and SSNHL. We propose that

chemosensory dysfunction (olfactory and auditory impairment) may

serve as an early indicator of environmental neurotoxicity,

offering a new perspective for assessing the impact of

environmental pollution on neurological health. Additionally, the

present review explores the effects of environmental factors on

sensory organ function from both the olfactory and auditory

dimensions with the aim of implementing disease prevention and

control through environmental management. The coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, as an environmental factor, has imposed a

significant economic burden on healthcare systems and exacerbated

environmental and climate crises (3,21). The respiratory system is the

primary target of SARS-CoV-2 infection. As direct portals for viral

infection, the ear and nose may be repeatedly attacked, leading to

symptoms such as nasal congestion, runny nose and hearing loss.

Therefore, the present review discusses the impact of COVID-19 as a

unique environmental factor in ear and nose diseases. The detailed

search strategies to identify relevant literature can be found in

Tables SI-SIV.

The ear and nose are closely interconnected

functionally, with the eustachian tube (ET) playing a key role in

this relationship. The ET, located in the petrous bone of the

temporal lobe, extends from the anterior wall of the middle ear to

the nasopharynx and connects the two structures. The main functions

of the ET include ventilation of the middle ear, clearance of

secretions and protection against direct sound transmission and

pathogenic microorganisms (22).

Environmental factors such as air pollution and meteorological

conditions can influence the physiological functions of ET and

contribute to its dysfunction. For example, exposure to air

pollutants can lead to oxidative stress, inflammation and immune

response changes, which may impair the ability of the ET to

maintain middle ear pressure and clear secretions, creating

conditions conducive to infection and inflammation. This

dysfunction eventually leads to otological symptoms (23). Therefore, understanding the

impact of environmental factors on the physiological systems of the

ear and nose is crucial for improving the prevention and management

of related diseases such as OM and other middle ear disorders.

Tables I and II present the results of population

and laboratory studies on the impact of environmental factors on

the ear and nose physiological systems.

AR, an inflammatory disease, is an IgE-mediated type

1 hypersensitivity response to inhaled allergens characterized by

rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, sneezing and nasal itching (24). AR primarily consists of

sensitization and effector phases. In the sensitization phase, the

allergen induces a shift in the T helper (Th)1/Th2 balance towards

a predominant Th2 response, ultimately stimulating B cells to

produce IgE. In the effector phase, IgE mediates the degranulation

of basophils and mast cells, releasing various bioactive substances

that ultimately trigger allergic symptoms (4).

The effect of ambient air pollution on the incidence

of AR in humans has garnered widespread attention. In 2016, a

multicenter epidemiological study of 18 major cities in mainland

China found a significant increase in self-reported adult AR in

2011 compared with 2005 and reported that the prevalence of AR was

positively associated with short-term outdoor air pollution

exposure, especially the concentration of SO2 (25). A recent retrospective registry

study in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (China)

observed that each 10 μg/m3 increment in the

concentration of SO2, NO2, PM2.5,

PM10 and O3 corresponded to a significant

increase in the daily number of hospital outpatients with AR by

7.69, 2.43, 1.84, 1.55 and 0.34%, respectively (26). Two additional studies based on

the European Community Respiratory Health Survey and the

Epidemiological Study on the Genetics and Environment on Asthma

revealed that higher PM2.5 exposure is related to an

increased severity of AR. However, no association was found between

air pollution exposure and the incidence of AR (27,28). Possible reasons for this include

population heterogeneity and the duration of exposure. Therefore,

future studies should gather more comprehensive data and focus on

diverse ethnicities and different exposure durations.

Recently, the role of ambient air pollution on human

growth and development has attracted considerable attention. A

retrospective observational study surveyed 3,177 preschoolers in

five districts of Shanghai (China) and indicated that prenatal and

postnatal exposure to NO2 led to a higher prevalence of

AR in childhood in a single-pollutant model, an association that

remained significant in a multi-pollutant model (29). Similarly, another study that

adopted machine learning approaches based on a 14-year follow-up

birth cohort revealed that both the dose and duration of prenatal

exposure to NO2 were significant predictors of AR

incidence until adolescence (30). These studies suggest that younger

individuals require more attention when considering the impact of

air pollution on AR onset.

In addition to outdoor air pollution, the home

environment is also closely related to the occurrence of AR. Since

children spend most of their time indoors, the impact of indoor

pollution on the incidence of AR in children has become a growing

concern (31). In children,

whose immune systems are not fully developed, early exposure to

mold may increase the risk of immune responses to inhaled allergens

and irritants (32).

Specifically, a study on indoor mold exposure has shown that

children living in environments with high mold concentrations have

a significantly increased risk of developing AR (33). Several epidemiological studies

have also indicated that children raised in environments with

elevated mold levels are at a higher risk of AR, particularly in

those with prolonged mold exposure (34-36). Furthermore, early exposure to

mold may affect the development of the immune system, making

children more susceptible to allergic reactions, which is closely

related to the maturity of their immune systems (37). Additionally, exposure to ETS has

been positively correlated with an increased prevalence of AR in

children (38-40). Harmful substances in ETS,

especially inflammatory factors and oxidative stress reaction

products, can damage the upper respiratory tract barrier in

children, leading to the development of allergic diseases (40). A study has found that inhaling

environmental smoke not only increases the risk of AR in children

but may also exacerbate pre-existing allergic symptoms (41). Specifically, a questionnaire

study conducted in China showed that behaviors such as home

renovation, purchasing new furniture, cooking with natural gas and

burning mosquito coils were associated with an increased incidence

of AR in children, with a particularly significant impact observed

in girls (11). Moreover,

another study across seven cities in northeastern China found that

girls exposed to ETS had a higher likelihood of developing AR

compared with those not exposed (2.33 vs. 1.61%) (42). These findings suggest that the

effect of environmental smoke on AR in children involves a complex

mechanism that requires further investigation to improve the

understanding of its specific pathways.

VOCs, such as chemicals commonly found in paints and

furniture, have also been found to increase the risk of allergies

in children. These VOCs include harmful substances such as benzene,

toluene and xylene, and prolonged exposure may trigger immune

responses in children, leading to the development of AR (43). This is particularly true during

home renovation or when purchasing new furniture, as the

concentration of VOCs significantly increases, thereby raising the

risk of children being exposed to these chemicals (44). The impact of these household

exposure sources on the health of children may be related to the

incomplete development of their immune and respiratory systems.

Children's immune systems are more sensitive compared with adults,

making them more susceptible to exposure to indoor pollutants,

which increases the likelihood of developing allergic diseases.

Particularly in indoor environments, household pollution sources

such as mold, ETS and VOCs have a more notable impact on children's

health, as they spend a substantial amount of time indoors and are

thus exposed to these pollutants more frequently. Therefore,

improving the home environment and controlling air quality are

crucial for the prevention of allergic diseases in children.

PM from urban air pollution consists primarily of a

mixture of carbonaceous cores, organic compounds and metallic

compounds and is considered to affect AR through three major

biological pathways: Allergy, oxidative stress and inflammation

(45,46). PM can enhance allergen

sensitization and induce a local inflammatory response in the nasal

passages (47). Bowatte et

al (48) demonstrated that

early childhood exposure to traffic-related PM enhances allergic

sensitization and the degree of this association increases with

increasing age. Castañeda et al (49) found that PM possesses

adjuvant-like properties and can synergize with allergens to

promote the allergic inflammatory response. A recent experimental

study in an ovalbumin (OVA)-induced combined AR and asthma syndrome

mouse model demonstrated that exposure to PM2.5 may

increase the levels of GATA binding protein 3, retinoic acid

receptor-related orphan receptor γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IL-17 and

decrease the production of Th1-associated cytokines, IL-12 and

IFN-γ, in nasal lavage fluid by activating the nuclear factor κβ

signaling pathway, thereby exacerbating nasal inflammatory response

(7). Notably, a growing body of

research has shown that PM can also induce inflammatory cell

infiltration in the nasal cavity, independent of allergens

(47,50,51). A previous in vitro study

suggested that urban PM (UPM) alone stimulates the generation of

Th2, Th1 and Th17 effector phenotypes as a source of antigens.

Moreover, the study observed a decrease in allergen-specific memory

T cell cytokine responses in dendritic cells (DCs) loaded with both

the UPM and house dust mites compared with DCs loaded with UPM

alone (52). These findings

reveal the complex mechanisms of PM in AR development and imply

that future studies should consider other coexisting factors.

In addition to air pollution, meteorological factors

also affect the number of patients with AR. For instance a

low-latitude multi-city study in China revealed that low

temperatures, low humidity and high wind speeds can lead to

increased outpatient visits for AR. Notably, in a stratified

analysis, the study found that adolescents and younger adults were

more sensitive to low humidity than children and older adults

(26). Similarly, another

retrospective study in an area with a humid subtropical monsoon

climate found an increased incidence of AR during childhood for

children exposed to low RH, wind speed and mean air pressure

(62). However, the results of

investigations on the effects of RH on AR are inconsistent. For

instance, a hospital-based study in Beijing (China) reported more

outpatient visits for AR at higher RH levels (16). A study focusing on classroom

humidity level in ten North Carolina schools showed that both high

RH (>50%) and low RH (<30%) increased the risk of allergic

diseases (63). These

inconsistencies may arise from various factors, such as differences

in study design, regional allergen distribution, environmental

confounders and different biological mechanisms by which high and

low RH may affect AR.

Environmental pollution and meteorological factors

may play a role in the development of AR. High temperature, low

humidity and environmental pollution increase the risk of AR caused

by airborne pollen (64-66). A study by Wu et al

(16) indicated that low

temperatures and high RH enhanced the effects of air pollution on

AR. The study further revealed that each 10 mg/m3

increase in PM2.5 concentration led to an increase in AR

outpatient visits by 2.34% at low temperature and 1.82% at high

RH.

As aforementioned, high-humidity environments

facilitate the growth of allergens such as mold (67). Aspergillus fumigatus can

stimulate human basophils to express B-cell activating factor,

which promotes the proliferation and differentiation of B cells,

further inducing IgE production and intensifying the immune

response to allergens in patients with AR (68). Furthermore, both air humidity and

cloud cover thickness can affect the amount of ultraviolet B (UVB)

exposure received by an individual. Narrow-band UVB therapy, based

on UVB, has become a routine clinical treatment for AR (69). An in vivo study revealed

that rats treated with narrowband UVB exhibit significant

downregulation of H1R gene expression in the nasal mucosa (70). H1R is associated with allergic

diseases, and H1R antagonists have become the first-line treatment

for AR (71,72). Thus, the inhibitory effect of UVB

on AR may primarily result from modulation of H1R expression in the

nasal mucosa. High temperatures can also accelerate the spread and

range of pollen in the air. Pollen is a common allergen widely

studied for its effects on allergic diseases. Previous studies have

found that in the context of AR, pollen can induce DCs to secrete

immune regulatory factors, such as IL-5 and IL-13, thereby

enhancing the differentiation of Th2 cells (73-75). Additionally, IL-5, IL-4 and IL-13

promote B cell activation and IgE secretion, thereby exacerbating

the onset of AR (76).

Results from evidence-based medicine suggest that

low levels of vitamin D may increase susceptibility to AR (77). A meta-analysis revealed that

in vitro vitamin D supplementation alleviated the symptoms

of AR (78). Although direct

evidence is lacking, a study on allergic diseases found a positive

correlation between increased exposure to solar radiation and

decreased incidence of allergic diseases in children. Furthermore,

providing vitamin D supplements to mothers during pregnancy can

modify the association between meteorological exposure patterns and

allergen sensitization of children (79). Although few intervention studies

are available, it is reasonable to conclude from existing research

that a potential link between 'environmental factors-vitamin D-AR'

is possible and that supplementation of vitamin D could serve as a

potential preventive strategy for AR.

OM is a common infection in early childhood and is

particularly prevalent among children under the age of 3 years

(80). OM not only affects

children's hearing but may also be associated with hearing loss in

older adults. A study has shown that hearing loss is linked to

age-related cognitive decline and prolonged hearing problems may

exacerbate the health burden in the elderly (81). A major consequence of recurrent

OM is conductive hearing loss, which affects the development of

speech, language, balance and learning abilities, while imposing a

notable economic burden on healthcare systems (82,83).

Increasing evidence suggests that environmental

pollution plays a notable role in OM onset. A 2024 European

birth-cohort study observed a dose-response relationship between

prenatal and early-postnatal exposure to traffic-related air

pollution (such as NO2) and the risk of ear infections

(including OM) in infants (84).

Another retrospective cohort study conducted in Changsha (China)

revealed a correlation between prenatal exposure to SO2

and the occurrence of OM (85).

Additionally, the effect of PM on OM has attracted increasing

attention. A retrospective study based on data from the Korean

National Health Insurance Service indicated that exposure to

PM2.5/PM10 was associated with the incidence

of acute OM (AOM) in children under the age of 2 years, with every

10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5

concentration corresponding to a 4.5% increase in the relative risk

of AOM (86). Notably, the study

found that PM2.5 and PM10 had the most

significant negative effects on children under 2 years, typically

occurring on the day of exposure. Besides, a combined

cross-sectional and retrospective cohort study in Changsha (China)

indicated that prenatal and postnatal exposure to PM increased the

lifetime risk of OM in childhood and further revealed a cumulative

effect of PM2.5 exposure during the 9 gestational months

and PM10 exposure during the early post-natal period on

OM development (87). Similarly,

a retrospective study using time-series analysis showed that

exposure to PM2.5 within 5 days led to an increase in

the incidence of AOM in children aged 0 to 3 years, this

association was more pronounced during the warm seasons and in

children with a history of upper respiratory infections (47).

Compared with outdoor air pollution, indoor air

pollution may have a greater impact on the incidence of OM,

particularly given that children spend most of their time indoors.

A recent national cross-sectional study on Australian children

found a positive correlation between indoor environmental factors

(such as the use of gas heating, reverse-cycle air conditioning and

pet ownership) and the lifetime risk of OM (88). Another retrospective cohort study

in China indicated that postnatal exposure to indoor renovations

(such as new furniture and redecoration) significantly increased

the lifetime risk of OM in preschool children; this association was

particularly pronounced in girls (85). ETS, which is a major indoor

pollutant, is a critical factor. It is estimated that ~40% of

children are exposed to ETS globally (89). Numerous studies have confirmed

that ETS is a significant risk factor for OM in children (90,91). Despite the growing body of

literature, data is lacking on the control of indoor pollutants.

Therefore, proper monitoring of indoor environmental pollution is

crucial for preventing OM in children.

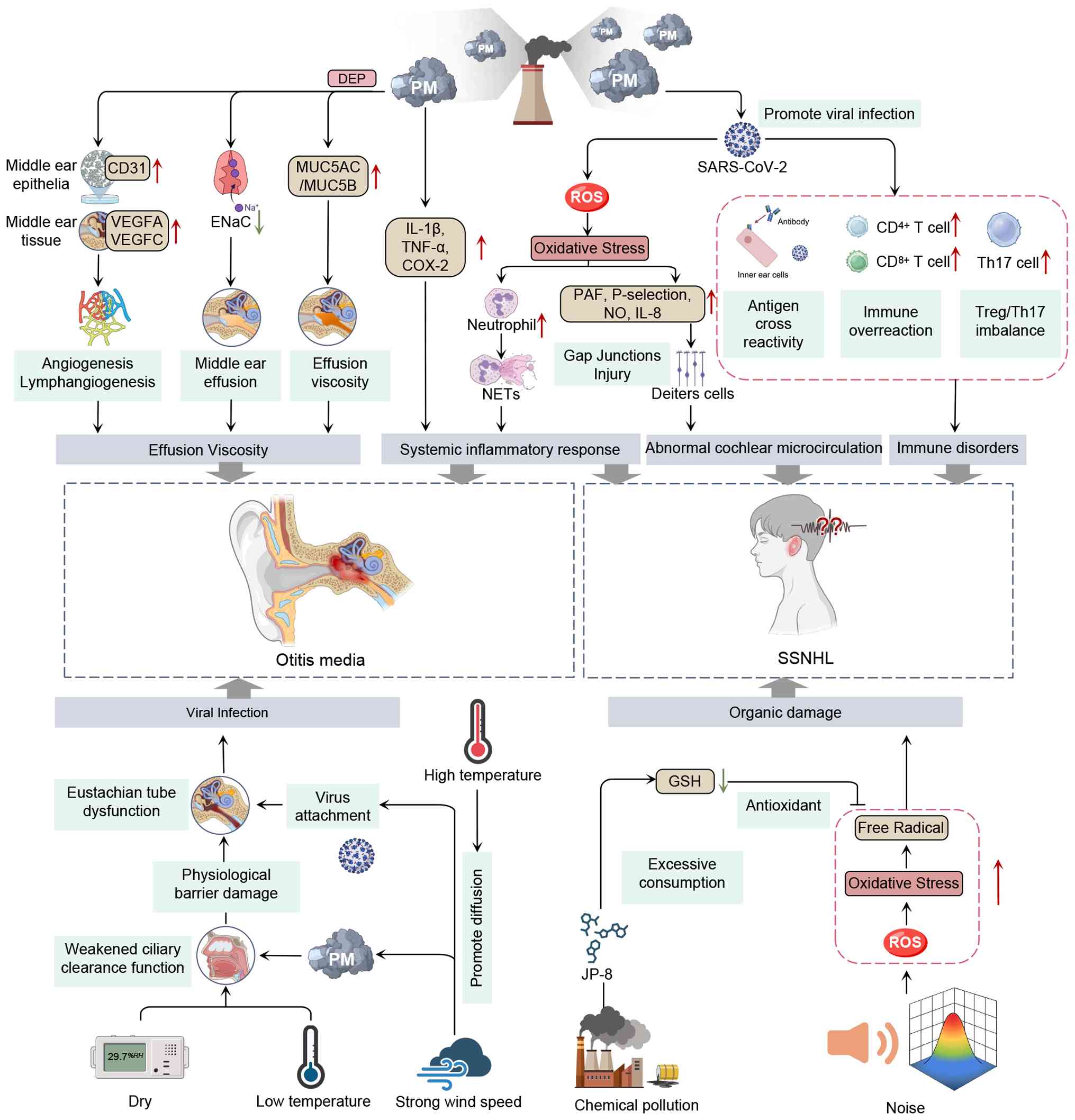

Extensive research has been conducted on the

pathogenic mechanisms by which PM affects OM. Recent mechanistic

research indicates that fine PM influences the onset and

progression of OM through several biological pathways such as

inflammation, oxidative stress, mucin-gene upregulation and

angiogenesis/lymphangiogenesis (92,93). For instance, ultrafine

combustion-derived particles (such as DEPs) constitute a

significant fraction of fine and ultrafine PM capable of traversing

the alveolar-capillary barrier and eliciting systemic inflammatory

responses. In vitro studies have shown that PM exposure

activates inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α and IL-1β) and

upregulates mucin genes such as MUC5AC and MUC5B in human middle

ear epithelial cell lines (HMEECs), resulting in viscous middle-ear

effusions that hinder fluid clearance and contribute to both acute

and chronic OM (94,95). Using in vivo animal models

(rats), it has been demonstrated that PM exposure leads to

goblet-cell hyperplasia in the ET and middle-ear mucosa, thickens

sub-epithelial layers, increases capillary density and

angiogenic/lymphangiogenic factor expression (such as VEGF, VEGFC

and CD31) and disrupts epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) expression,

which is essential for perimucosal fluid absorption and middle-ear

homeostasis, thereby suggesting that early ENaC-targeted

intervention may have therapeutic potential (5). In addition, a previous in

vitro study indicated that potential involvement of ROS could

be induced by PM in the progression of OM, as it was found that ROS

may promote mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory responses,

thereby leading to HMEEC apoptosis (96). However, clinical evidence

supporting the use of MUC5AC and MUC5B as diagnostic or prognostic

biomarkers in OM remains very limited. Although mucin expression

has been evaluated in respiratory and airway diseases (such as

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchitis) and shown to

be associated with disease progression, ear-specific, large-scale

clinical studies validating these biomarkers in patients with OM

are lacking (97). Consequently,

despite their mechanistic importance, these biomarkers have not yet

been adopted in routine clinical practice, mainly due to small

sample sizes, heterogeneity in design and the absence of

standardized assays. Large-scale, standardized clinical studies are

therefore required to assess whether inflammatory,

oxidative-stress, mucin- and angiogenesis/lymphangiogenesis-related

biomarkers (including MUC5AC and MUC5B) can serve as reliable

diagnostic or prognostic indicators in OM management.

In addition to air pollution, meteorological factors

are associated with the onset and progression of OM. A

retrospective observational study conducted in Cuneo (Italy)

revealed a distinct seasonal pattern in the incidence of AOM in

children, with more emergency visits (EVs) in winter and fewer

visits in summer. Moreover, this seasonal pattern was closely

related to upper respiratory tract infections (19). Similarly, a recent retrospective

study in Vienna found that EVs related to AOM were more frequent in

the winter. The study also observed that a 3-day period of cold

weather could increase the risk of AOM-related EVs within 1 day of

the temperature event (98).

Notably, this study and another study found that high atmospheric

pressure (AP), low wind speed and high humidity contributed to an

increased incidence of AOM (19,98). However, Vienna, which has a

temperate continental climate, typically experiences higher AP and

humidity during winter; therefore, further statistical analysis is

needed to establish causal relationships while controlling for

potential confounding effects among meteorological factors. A

retrospective cross-sectional study conducted in Shanghai confirmed

that RH has a significant impact on the incidence of AOM in

preschool children. The study reported that for every 1% increase

in RH, the number of AOM-related visits by preschool children

increased by 10.84% (99). Given

the increasing frequency of weather events due to climate change,

further research in other countries and regions is necessary.

In addition to air pollution, meteorological

factors, including low temperatures and dry air, can increase the

risk of AOM. Viral upper respiratory tract infections have been

proposed as a possible bridge linking meteorological factors and

AOM since AOM is often secondary to acute upper respiratory tract

infections (19,100). Cold and dry weather conditions

have been shown to reduce nasal mucociliary clearance and lead to

fluid loss in the nasal passages and ET, thereby weakening the

upper respiratory defense and heightening susceptibility to viral

infection (98). Moreover,

viruses can trigger nasopharyngeal inflammation and ET dysfunction,

which in turn facilitates further invasion by viruses and bacteria

into the middle ear, enhances epithelial cell bacterial adherence

and colonization and thus promotes the onset and development of AOM

(101). Notably, influenza

incidence also peaks in the cold, dry winter months, which provides

an additional explanation for the high winter incidence of AOM.

Notably, PM has been shown to compromise the barrier function of

nasal mucosal epithelial cells (100), thereby increasing the risk and

severity of upper respiratory tract infections, which inevitably

increases the incidence of AOM (102). Cold and dry air further amplify

this effect, underscoring the combined influence of air pollution

and meteorological factors on OM (103). Beyond temperature and humidity,

other meteorological elements such as AP and wind speed may also

contribute to OM. For example, high AP may exacerbate negative

middle ear pressure under ET dysfunction, facilitating pathogen

ingress, whereas strong winds can enhance the spread of PM and

viruses (104). Children, due

to their higher respiratory rate and anatomical features (notably,

a shorter and flatter ET), are particularly susceptible to

environmental pollutants and meteorological stresses. This

anatomical disadvantage also makes them more prone to developing

OM, especially during upper respiratory tract infections (105).

SSNHL is a subset of sudden hearing loss, which is

sensorineural in nature and typically defined as a drop of at least

30 decibels (dB) across at least three consecutive audiometric

frequencies occurring within a 72-h window (106). Although its incidence remains

relatively low (estimated at 5 to 27 cases per 100,000 individuals

annually), SSNHL remains a worrying otological emergency that can

lead to persistent hearing impairment and tinnitus, imposing

notable psychological distress and financial burden on patients

(107).

Despite considerable research, the complex etiology

of SSNHL remains unclear. Recent epidemiological evidence

implicates air pollution as a risk factor for SSNHL (108). Additionally, a cross-sectional

study in Taiwan observed an increased incidence of SSNHL from 2000

to 2015 and further revealed that SSNHL episodes occur more

frequently in Southern Taiwan, which possesses a higher mean

PM2.5 annual concentration compared with Norther Taiwan

(109). Additionally, a

case-control study in South Korea examining short-term exposure to

various air pollutants, including SO2, NO2,

O3, CO and PM10, found that SSNHL occurrence

is significantly associated with elevated NO2

concentrations (110). By

contrast, a long-term cohort study combining two large datasets

provided strong evidence that chronic exposure to PM2.5,

CO, NO and NO2 increases the risk of SSNHL (111). These contradictory findings may

be explained by the cumulative time-dependent effect of air

pollution on promoting SSNHL. Additionally, recent data indicate

that individuals >30 years are particularly sensitive to

NO2 exposure (112).

A large epidemiological study conducted in Taiwan revealed a

dose-dependent relationship between NO2 and SSNHL

(113). In addition to PM and

gaseous air pollutants, the roles of ETS and heavy-metal exposure

in SSNHL have also been investigated (114-116). Zinc, as an effective

supplement, has been shown to significantly aid in the hearing

recovery of patients with SSNHL when used in combination with other

treatments (117). However,

current research primarily focuses on a limited number of countries

and large-scale studies involving diverse ethnic groups and regions

are needed to further validate these effects.

The exact pathological mechanisms of SSNHL remain

unclear; however, possible mechanisms include viral infections,

immune-mediated cellular stress responses and vascular occlusion

(118,119). PM exposure has been shown to

increase susceptibility to viral infections by allowing viruses to

reach the inner ear via the bloodstream or other routes, ultimately

inducing cochleitis or neuritis (120). Recent experimental evidence

demonstrates that PM2.5 exposure significantly alters

airway and systemic immune responses, such as impaired innate

immunity, disrupted epithelial barriers and skewing of adaptive

immunity, thereby facilitating viral infection and propagation

(121). After viral invasion,

the adaptive immune system is activated, triggering processes

including antigenic cross-reactivity, T cell-mediated cellular

immunity and regulatory T cell (Treg)/Th17 imbalance in the inner

ear; these immune alterations exacerbate inner-ear damage and

contribute to the onset of SSNHL (122,123). Notably, large-scale

epidemiological data from the COVID-19 era show increased rates of

SSNHL and vestibular neuritis following systemic viral infections

(21).

The role of PM in neurological diseases has also

attracted much attention. Several studies have demonstrated that PM

can induce the expression of inflammatory mediators and the

generation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (NOS) in the

central nervous system (CNS), resulting in neuroinflammation, lipid

denaturation, microglial dysfunction and even blood-brain barrier

dysfunction, which may be associated with SSNHL (8,124,125). Notably, under inflammatory

conditions, inducible NOS released by inflammatory cells may

produce higher and prolonged NO concentrations. Elevated NO levels

in the cochlea have been reported to accelerate the uncoupling of

gap junctions in Deiters' cells and delay synaptic transmission,

both of which can lead to hearing impairment or even deafness

(126,127). Endothelial dysfunction-driven

microthrombosis is increasingly being recognized as a key feature

of SSNHL (128). Exposure to

fine PM induces excessive oxidative stress, depletes cellular NO

bioavailability and promotes the upregulation of adhesion molecules

(such as P-selectin), platelet-activating factors, leukotriene B4

and cytokines, including IL-8, thereby driving endothelial injury

and microvascular compromise (129). Notably, blood supply to the

cochlea is provided by the labyrinthine artery and lacks collateral

circulation. Once thrombosis disrupts microcirculation, it leads to

edema, ischemia and hypoxia in the inner ear tissues; this damage

might be one reason for hearing loss. In addition to air pollution,

strong wind speeds and extreme heat cause viral transmission, which

may contribute to the pathophysiology of SSNHL (20) (Fig. 2).

Meteorological factors are considered to be involved

in multiple neurological diseases (130); however, the role of

meteorological conditions as risk factors for SSNHL remains

controversial. A retrospective study in Busan (Republic of Korea)

reported that increased mean wind speed, maximum wind speed and a

wider daily AP range were weakly associated with a higher incidence

of SSNHL. The study also found a weak negative association between

mean temperature and SSNHL admissions (17). However, a 2024 time-series study

from Hefei (China) examining the mean temperature (T-mean), diurnal

temperature range (DTR), AP and RH, found that a lower T-mean,

higher DTR and all levels of AP were significantly associated with

increased SSNHL admissions, whereas wind speed did not emerge as a

strong independent predictor (131). Similarly, another

hospital-based study observed that SSNHL episodes occurred more

frequently on or immediately after days with higher wind speeds

(20). However, several

investigations have failed to confirm a consistent correlation

between meteorological variables and SSNHL (132,133). Furthermore, the seasonal

pattern of SSNHL onset remains controversial; some authors have

observed a higher incidence in autumn (134,135), whereas others found no clear

seasonal imbalances (20,136).

These conflicting epidemiological findings do not support any

definitive conclusions. According to our analysis of the relevant

literature, several factors may have accounted for these results.

First, the duration of several studies was too short to evaluate

the influence of meteorological factors on SSNHL onset (131). Second, some studies had small

samples and some were limited to specific regions, making it easier

to draw conflicting conclusions (17). Finally, given the low prevalence

of SSNHL, common weather conditions do not allow for significant

impacts (20); therefore, it may

be more appropriate to focus on extreme weather conditions.

Although population studies have revealed

associations between various climatic factors and the incidence of

SSNHL, current research has yet to clearly elucidate the specific

molecular mechanisms by which climatic factors alter the incidence

of SSNHL. Notably, existing studies have suggested that climatic

factors significantly regulate the chemical sensory functions of

the ear at the molecular level (137,138). Therefore, analyzing and

exploring the impact of environmental factors on ear sensory

receptors will provide valuable insights for future research on the

relationship between environmental factors and ear disease.

In recent years, the complex interactions between

environmental pollution and climate factors have received

increasing attention (139-141). A 2020 study found significant

seasonal variations in air pollutants in Beijing. Specifically, the

concentrations of PM2.5, PM10,

SO2, NO2 and CO decreased in summer, whereas

O3 concentrations increased. Furthermore, the incidence

of nasal bleeding significantly correlated with these pollutant

indicators (P<0.05) (142).

Further research indicated that although air pollutants negatively

affect ear and nose health in other seasons, the concentrations of

PM10, NO2 and SO2 are positively

correlated with the number of ear and nose outpatient visits in

winter (143). Therefore,

analyzing the interaction between meteorological conditions and

environmental exposure can help uncover potential pathogenic

mechanisms and identify vulnerable populations. Additionally,

further research based on this perspective can provide important

theoretical support for the development of precise preventive

strategies and optimization of public health policies in the

context of climate change.

Climate change, due to rising temperatures, changes

in precipitation patterns and an increase in extreme weather

events, may exacerbate the generation and diffusion of air

pollutants. For example, higher temperatures can promote the

formation of O3 (144) and O3, as an air

pollutant, is associated with an increased incidence of OM in

children following exposure in pregnant women (145). In addition, climate change may

alter the diffusion pathways and concentrations of air pollutants

(146,147). Strong winds can rapidly spread

pollutants and alter their deposition patterns. These changes are

particularly significant in areas where urbanization is

accelerating. High-rise buildings and narrow streets often create

the 'street canyon effect', restricting air circulation and leading

to the accumulation of pollutants at localized points (148,149). High concentrations of PM and

volatile organic gases directly affect the human ear and nose,

increasing the risk of chemical sensory damage (150-152). At the same time, the

accumulated high concentrations of PM may also reduce the UVB

radiation that reaches the skin surface. UVB has been shown to

promote the synthesis of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D3]

in the human body, thereby protecting ear and nose chemical sensory

functions (153,154). Strong winds can extend the

range of viral transmission and exacerbate ear and nose diseases.

However, environmental pollution, particularly air pollution,

industrial emissions and traffic emissions, may affect the rate and

pattern of climate change by altering local climate systems. The

emission of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen

oxides and sulfur oxides is one of the main drivers of global

warming (155). The effects of

temperature on ear and nose diseases have been reported previously

(20,136). Moreover, rising temperatures

can exacerbate fungal growth and promote the spread of allergens

such as pollen, increasing the risk of allergic diseases. An

increased airborne concentration of allergens contributes

significantly to the incidence of nasal diseases (32).

Atmospheric pollution and meteorological

variability are emerging global environmental issues that involve

complex interactions between specific substances, chemicals and

pathogens. Given that olfactory organs are directly exposed to the

external environment, various environmental xenobiotics, including

chemicals, dust and viruses, constitute important risk factors.

Consequently, the olfactory system is a primary biological target

of air-pollution exposure (156). A key question is whether

pollution exacerbates olfactory decline independently or

accelerates age-related degenerative processes. Existing evidence

suggests that pollutants may independently affect olfactory

function by triggering chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and

other mechanisms, and this effect is independent of the aging

process (157). However, a

study has indicated that the effects of pollution may be more

pronounced due to accelerated age-related degeneration,

particularly in older populations (158).

Although there are few direct reports on the

association between meteorological factors and olfactory

dysfunction (159,160), it is not difficult to determine

whether meteorological factors, including temperature, sunlight,

wind speed, heavy rainfall and humidity, play an important role in

olfactory dysfunction. AR can cause swelling of the nasal mucosa,

chronic inflammation of the nasal cavity as well as damage to the

olfactory bulb and the olfactory nerve, which is an important

bridge between meteorological conditions and olfactory dysfunction

(161,162). The previous section elucidated

the close connection between meteorological factors and AR. In

addition, Shin et al (153) found that serum

25[OH]D3 deficiency is significantly associated with

olfactory dysfunction in children and that this association is

independent of olfactory dysfunction caused by AR. The mechanism

can be explained by the following two aspects: First, receptors for

25[OH]D3 are present in nerve cells and its deficiency

can cause olfactory nerve dysfunction, resulting in olfactory

decline (154). Second,

25[OH]D3 reduces inflammation by downregulating the

production of the Th17 cell signature, cytokine IL-17, and

upregulating the number of IL-10+ and Foxp3+

Treg cells (163,164). Serum 25[OH]D3

deficiency may contribute to chronic inflammation in the olfactory

neuroepithelium and, thus, olfactory dysfunction. As a precursor of

25[OH]D3, vitamin D is primarily derived from sunlight

(165) (Fig. 1).

Air pollution is categorized into physical

(including PM and nanoparticles) and chemical (including DEPs,

heavy metals, pesticides and herbicides) pollutants. Andersson

et al (156) found a

statistically significant association between long-term exposure to

PM2.5 and olfactory identification. When the established

model was corrected for age, the association was stronger in older

populations. Therefore, the interaction between PM2.5

and age significantly affects olfactory discrimination. However,

the study did not find an association between short-term

PM2.5 exposure and olfactory function. The cumulative

effects of air pollutants on the olfactory system may result in

olfactory loss during aging even at relatively low levels of

pollution exposure. Numerous studies have shown that long-term

exposure to PM10, SO2, NO2, CO,

cadmium and ammonia can induce and exacerbate inflammatory

responses in the nasal cavity, leading to olfactory dysfunction

(166,167). A study by Bernal-Meléndez et

al (168) showed that

repeated exposure to diesel engine exhaust fumes during gestation

not only affects fetal olfactory tissues and systems but also

influences monoaminergic neurotransmission in the fetal olfactory

bulb, leading to altered olfactory behavior at birth. During

breathing, due to reduced filtration and clearance by the nasal

mucosa, poorer mucosal cilia transport rates prolong PM retention

time, which in turn may increase the risk of carcinogenic effects

(169). Airborne PM and other

pollutants not only contact the olfactory epithelium (OE) and bind

to olfactory neurons but can also pass through various abundantly

expressed transporters and reach the olfactory bulb via the

olfactory nerve. When chemical pollutants attach to ultrafine

particles, the resulting complexes are transported across cell

membranes via endocytosis. At the same time, the binding of

PM2.5 to chemical pollutants may put additional stress

on the physical structure of the OE, allowing the mixture to reach

the CNS through the paracellular pathway as some viruses do, and

this binding may also affect the transformation of chemicals in the

body (170).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies

emphasized the integral role of chemosensory systems in the

airborne airways of viruses entering the human body, a pathway that

may also be exploited by environmental contaminants (171,172). SARS-CoV-2 virulence may be

altered in contaminated areas (169). COVID-19 elicits strong systemic

and localized immune responses, leading to the release of cytokines

and other inflammatory molecules. These molecules can cross the

blood-brain barrier and affect the olfactory system, directly or

indirectly causing and exacerbating inflammation and damage to the

olfactory neurons (173). A

cohort study conducted among young adults in Sweden indicated that

long-term exposure to air pollution in living environments was

associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 following SARS-CoV-2

infection. The association between exposure to PM2.5 and

COVID-19 was significantly stronger than that of PM10,

BC and nitrogen oxides (174).

A recent study has shown that ~80% of patients with long-term

COVID-19 still experience olfactory dysfunction 2 years after

infection, with some patients continuing to experience complete

anosmia, whereas those without apparent anosmia still commonly

report a reduction in olfactory function (175). These symptoms are closely

related to changes in the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)

receptor and oxidative stress, supporting the possibility that air

pollution and SARS-CoV-2 infection synergistically promote

long-term ear and nose sensory dysfunctions (176). ACE2 is widely expressed in the

upper respiratory tract and olfactory epithelial cells and acts as

the primary receptor for SARS-CoV-2. ACE2 facilitates the entry of

the virus and the infection of epithelial cells by interacting with

viral spike proteins (177).

Population studies have found that individual differences in the

response to SARS-CoV-2 are closely related to molecular differences

in ACE2 expression (172,178). Furthermore, air pollutants,

especially fine PM2.5, upregulate ACE2 expression

through oxidative stress pathways, significantly increasing the

susceptibility of the host to SARS-CoV-2 infection, causing

epithelial cell damage and further exacerbating olfactory and

gustatory dysfunction (171,179,180). Air pollution may alter the

distribution of ACE2 receptors in the olfactory system, making it a

more vulnerable target for viral transmission, thereby increasing

the risk of olfactory disorders (181). Oxidative stress plays a crucial

role in the pathological process of SARS-CoV-2 infection, leading

to the production of ROS, which directly damages cells and

activates inflammatory responses (182). Air pollutants, such as

PM2.5, further damage the OE and neurons by inducing

oxidative stress, worsening the recovery of olfactory function.

Therefore, oxidative stress is considered a key mechanism linking

environmental pollution and the sensory dysfunction of the ear and

nose caused by SARS-CoV-2. Susceptible factors (including genetic,

epigenetic and immune factors), the combined effects of past and

current air pollution exposure and SARS-CoV-2 infection may lead to

long-term COVID symptoms. Long-term olfactory training can help

patients recover their sense of smell to pre-infection levels

(173).

As a serious public health problem, hearing loss

has resulted in growing disease burden, especially among the older

population (183,184). Air pollutants and extreme

meteorological factors can cause peripheral and central auditory

dysfunction and appear to be associated with noise exposure and

viral infections (such as SARS-CoV-2), which increase

susceptibility to hearing loss through superimposed or synergistic

mechanisms.

The potential synergistic effects of noise and air

pollution on hearing function have been proposed in multiple

studies, and quantitative tests have been conducted to analyze this

interaction. For example, a prospective cohort study of 1,179

oilfield workers found that both air pollution and noise exposure

significantly increased the risk of occupational hearing loss, both

independently and in combination (185). Studies suggest that noise and

air pollution may jointly affect hearing function through common

biological pathways, such as oxidative stress, inflammation and

endothelial dysfunction (186,187). For instance, PM2.5,

which induces oxidative stress by generating ROS, may cause

endothelial dysfunction, which affects the cochlear blood supply

and increases the risk of hearing loss (188).

The global climate crisis is worsening and the

frequency and severity of extreme meteorological conditions are

increasing. The relationship between meteorological conditions and

auditory health has become a major epidemiological concern;

however, a study has argued that there is no direct relationship

(189). We hypothesize that the

direct mechanism of auditory impairment may not be meteorological

factors, but rather interaction with ototoxic environmental

confounders (including environmental pollutants, viruses and

bacteria) or exacerbation of pre-existing otological diseases.

Specifically, high wind speeds facilitate viral transmission,

inducing a systemic immune response that causes SSNHL and central

auditory dysfunction. Moreover, inflammation of the upper

respiratory tract due to infection can lead to ET dysfunction,

which in turn can cause inflammatory lesions in the otological

region. As the disease progresses, the tympanic membrane mobility

decreases, ultimately leading to conductive hearing loss (190). Under high APs, bacteria and

viruses can diffuse further and exacerbate hearing loss. Future

studies may need to collect more data, incorporate factors such as

upper respiratory infections and explore interactions between

multiple weather factors (Fig.

2).

Hydrocarbon fuels contain long-chain and

short-chain aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons. Epidemiological

evidence and animal studies have demonstrated that exposure to jet

fuel causes lethality in presynaptic sensory cells, which in turn

exacerbates noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) in air force

personnel. This fuel has recently been shown to increase

susceptibility to NIHL. For example, the levels of the distortion

product otoacoustic emission, a measure of non-linear transduction

from outer hair cells, have been shown to be reduced after exposure

to Jet Propellant 8 (JP-8), with a no-damage level of 97 dB (no

hearing loss or cell death) noise (191). In addition, cytocochleograms

plotting the percentage of sensory cell death revealed a

significant loss of outer hair cells. Compound action potentials

recorded from the peripheral auditory nerve showed that loss of

outer hair cells was responsible for permanent hearing loss. A

possible mechanism is that JP-8 depletes glutathione both in

vitro and in vivo and the depletion of this important

antioxidant increases the likelihood of noise-induced oxidative

stress (192). Notably, as

reported in a study by Guthrie et al (193) that investigated the effect of

JP-8 on the development of hearing loss, this fuel might cause

central auditory processing dysfunction (CAPD) in normal-hearing

Long Evans rats without detectable sensory cell damage, suggesting

that CAPD might exist in the absence of hearing loss (194). Therefore, it is recommended

that individuals at risk of hydrocarbon fuel exposure undergo an

audiological assessment, which should include a conventional

audiological assessment in addition to neurophysiological and/or

psychoacoustic assessments of the central auditory function.

Notably, in a study by Fechter et al (195), male rats appeared to be more

susceptible to enhanced NIHL from JP-8 exposure. The enhanced

sensitivity of male rats to JP-8 and noise may reflect true sex

differences in noise susceptibility. However, this might also

reflect toxicodynamic factors related to body lipid storage, rather

than sexual dimorphism, as male and female F344 rats exhibit

significantly different weight gain patterns. Differences in body

fat levels between sexes may lead to greater JP-8 fuel stores in

male rats, thereby prolonging the duration of the elevated JP-8

body burden (196).

COVID-19 is thought to cause CNS and peripheral

nervous system dysfunction. Growing evidence suggests that patients

infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at an increased risk for hearing

impairment, particularly SSNHL (197,198). A study based on data from

visits to tertiary hospitals in China reported an increase in the

incidence of SSNHL and tinnitus during the COVID-19 pandemic

(3). Another hospital-based

study in Eastern India included 452 patients with COVID-19, of whom

28 developed hearing impairment and 24 developed SSNHL (199). Possible mechanisms of hearing

loss due to SARS-CoV-2 infection include induction of cochlear

microcirculatory dysfunction (200,201), inflammation of the nervous

system (including the CNS, peripheral nervous system and auditory

centers in the temporal lobe) (202,203) and activation of systemic immune

responses due to viral infection (204,205). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 causes

organ ischemia, tissue inflammation and a hypercoagulable state by

inducing endothelial cell inflammation, which may lead to cochlear

microcirculatory dysfunction and hearing loss (206). Degen et al (207) observed a cochlear inflammatory

response on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with hearing

impairment complicated by COVID-19 and hypothesized that hearing

loss was due to the spread of meningitis to the cochlea as a result

of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, hearing loss increases

the risk of depression and anxiety in infected patients (208,209). Early screening of patients with

SARS-CoV-2 infection plays a key role in promoting hearing recovery

and psychological well-being (207). As aforementioned, pollutants

and meteorological conditions increase the risk of OM and SSNHL,

thereby causing hearing loss. PM enhances human susceptibility to

the virus by damaging the respiratory mucosa and may carry viral

particles in conjunction with strong wind speeds to facilitate

transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Epidemiological evidence demonstrates

that exposure to environmental pollutants increases the incidence

of, and mortality from, COVID-19 (210,211). In conclusion, we consider that

environmental pollution and meteorological factors may be

associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection through synergistic and/or

superimposed effects that cause hearing loss (Fig. 2).

Although the present review provides an in-depth

exploration of the relationship between environmental factors,

SARS-CoV-2 infection and ear and nose diseases, several limitations

remain in the current research, particularly regarding population

heterogeneity and exposure assessment methods. Individuals of

different ethnicities, ages, sexes and socioeconomic backgrounds

may have different sensitivities to environmental pollution, which

affects the generalizability of the research findings. Moreover, a

number of studies rely on environmental air quality monitoring data

or self-reported exposure, which may not accurately reflect the

actual exposure level of individuals, particularly when pollution

sources are complex or exposure varies over time and space.

Therefore, future studies should adopt more precise exposure

assessment methods, such as personal air quality monitoring and

biomarker analysis, to improve the accuracy of assessments and

account for the effects of long-term exposure. This will help

provide an improved understanding of the relationship between

environmental factors and diseases.

To the best of knowledge, the present review

provides the first systematic comprehensive examination of the

interactions among air pollution, meteorological factors and

SARS-CoV-2 in ear and nose diseases, filling a critical gap in the

literature. We propose that chemosensory dysfunction (olfactory and

auditory impairments) may serve as an early indicator of

environmental neurotoxicity, offering a novel perspective on how

environmental pollution can affect the nervous system. The present

review highlights the complex roles of environmental factors in

diseases such as RH, OM and SSNHL, emphasizing the need for further

research on these interactions. Despite existing research, several

unknowns remain that warrant future studies focusing on: i)

Longitudinal research, to explore the cumulative effects of

long-term exposure to air pollution and meteorological changes; ii)

molecular mechanisms, to elucidate how these factors induce

diseases through immune and inflammatory pathways; and iii)

mitigation strategies, to reduce the impact of these environmental

factors through environmental management, personal protective

measures and policy interventions.

Not applicable.

YCZ and PTZ made significant intellectual and

technical contributions, including conceptualizing the study,

conducting the initial literature review, refining the core content

and designing the manuscript structure. In addition, YCZ and PTZ

created the figures and formatted the references using appropriate

software. LZ, ZHX, WJZ and MF contributed to data curation and

writing the original draft. YXH and YCL contributed to organizing

tables, conducting preliminary literature reviews and investigating

of the innovative positioning of this manuscript. YHL contributed

to conception, supervision and writing/revising the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The study was supported by funding National Natural Science

Foundation (grant no. 82171127).

|

1

|

Wu S, Yu Y, Zheng Z and Cheng Q: High

mobility group box-1: A potential therapeutic target for allergic

rhinitis. Eur J Med Res. 28:4302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liu ZB, Zhu WY, Fei B and Lv LY: Effects

of oral steroids combined with postauricular steroid injection on

patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss with delaying

intervention: A retrospective analysis. Niger J Clin Pract.

26:760–764. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jin L, Fan K, Tan S, Liu S, Wang Y and Yu

S: Analysis of the characteristics of outpatient and emergency

diseases in the department of otolaryngology during the 'COVID-19'

pandemic. Sci Prog. 104:3685042110363192021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhu Y, Yu J, Zhu X, Yuan J, Dai M, Bao Y

and Jiang Y: Experimental observation of the effect of

immunotherapy on CD4+ T cells and Th1/Th2 cytokines in mice with

allergic rhinitis. Sci Rep. 13:52732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Park MK, Chae SW, Kim HB, Cho JG and Song

JJ: Middle ear inflammation of rat induced by urban particles. Int

J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 78:2193–2197. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang S, Zhang C, Cai W, Bai Y, Callaghan

M, Chang N, Chen B, Chen H, Cheng L, Dai H, et al: The 2023 China

report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: Taking

stock for a thriving future. Lancet Public Health. 8:e978–e995.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Piao CH, Fan Y, Nguyen TV, Song CH, Kim HT

and Chai OH: PM2.5 exposure regulates Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokine

production through NF-κB signaling in combined allergic rhinitis

and asthma syndrome. Int Immunopharmacol. 119:1102542023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lamorie-Foote K, Liu Q, Shkirkova K, Ge B,

He S, Morgan TE and Mack WJ, Sioutas C, Finch CE and Mack WJ:

Particulate matter exposure and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion

promote oxidative stress and induce neuronal and oligodendrocyte

apoptosis in male mice. J Neurosci Res. 101:384–402. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

9

|

Fuller R, Landrigan PJ, Balakrishnan K,

Bathan G, Bose-O'Reilly S, Brauer M, Caravanos J, Chiles T, Cohen

A, Corra L, et al: Pollution and health: A progress update. Lancet

Planet Health. 6:e535–e547. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Verhoeven JI, Allach Y, Vaartjes ICH,

Klijn CJM and de Leeuw FE: Ambient air pollution and the risk of

ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Lancet Planet Health.

5:e542–e552. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang J, Zhang Y, Li B, Zhao Z, Huang C,

Zhang X, Deng Q, Lu C, Qian H, Yang X, et al: Asthma and allergic

rhinitis among young parents in China in relation to outdoor air

pollution, climate and home environment. Sci Total Environ.

751:1417342021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yang J, Seo JH, Jeong NN and Sohn JR:

Effects of legal regulation on indoor air quality in facilities for

sensitive populations-A field study in Seoul, Korea. Environ

Manage. 64:344–352. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang J, Kim YK, Kang TS, Jee YK and Kim

YY: Importance of indoor dust biological ultrafine particles in the

pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory lung diseases. Environ Health

Toxicol. 32:e20170212017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yun H, Seo JH, Kim YG and Yang J: Impact

of scented candle use on indoor air quality and airborne

microbiome. Sci Rep. 15:101812025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang J, Kim JS, Jeon HW, Lee J and Seo JH:

Integrated culture-based and metagenomic profiling of airborne and

surface-deposited bacterial communities in residential

environments. Environ Pollut. 382:1267032025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu R, Guo Q, Fan J, Guo C, Wang G, Wu W

and Xu J: Association between air pollution and outpatient visits

for allergic rhinitis: Effect modification by ambient temperature

and relative humidity. Sci Total Environ. 821:1529602022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lee HM, Kim MS, Kim DJ, Uhm TW, Yi SB, Han

JH and Lee IW: Effects of meteorological factor and air pollution

on sudden sensorineural hearing loss using the health claims data

in Busan, Republic of Korea. Am J Otolaryngol. 40:393–399. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lu K, Fuchs H, Hofzumahaus A, Tan Z, Wang

H, Zhang L, Schmitt SH, Rohrer F, Bohn B, Broch S, et al: Fast

photochemistry in wintertime haze: Consequences for pollution

mitigation strategies. Environ Sci Technol. 53:10676–10684. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gestro M, Condemi V, Bardi L, Fantino C

and Solimene U: Meteorological factors, air pollutants, and

emergency department visits for otitis media: a time series study.

Int J Biometeorol. 61:1749–1764. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Seo JH, Jeon EJ, Park YS, Kim J, Chang KH

and Yeo SW: Meteorological conditions related to the onset of

idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Yonsei Med J.

55:1678–1682. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ko HY and Kim MH: A nationwide

population-based study for audio-vestibular disorders following

COVID-19 infection. Audiol Neurootol. 30:245–251. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Janzen-Senn I, Schuon RA, Tavassol F,

Lenarz T and Paasche G: Dimensions and position of the eustachian

tube in humans. PLoS One. 15:e02326552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Juszczak H, Aubin-Pouliot A, Sharon JD and

Loftus PA: Sinonasal risk factors for eustachian tube dysfunction:

Cross-sectional findings from NHANES 2011-2012. Int Forum Allergy

Rhinol. 9:466–472. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liva GA, Karatzanis AD and Prokopakis EP:

Review of rhinitis: Classification, types, pathophysiology. J Clin

Med. 10:31832021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang XD, Zheng M, Lou HF, Wang CS, Zhang

Y, Bo MY, Ge SQ, Zhang N, Zhang L and Bachert C: An increased

prevalence of self-reported allergic rhinitis in major Chinese

cities from 2005 to 2011. Allergy. 71:1170–1180. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Luo X, Hong H, Lu Y, Deng S, Wu N, Zhou Q,

Chen Z, Feng P, Zhou Y, Tao J, et al: Impact of air pollution and

meteorological factors on incidence of allergic rhinitis: A

low-latitude multi-city study in China. Allergy. 78:1656–1659.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Burte E, Leynaert B, Marcon A, Bousquet J,

Benmerad M, Bono R, Carsin AE, de Hoogh K, Forsberg B, Gormand F,

et al: Long-term air pollution exposure is associated with

increased severity of rhinitis in 2 European cohorts. J Allergy

Clin Immunol. 145:834–842.e6. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Burte E, Leynaert B, Bono R, Brunekreef B,

Bousquet J, Carsin AE, De Hoogh K, Forsberg B, Gormand F, Heinrich

J, et al: Association between air pollution and rhinitis incidence

in two European cohorts. Environ Int. 115:257–266. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu W, Huang C, Cai J, Fu Q, Zou Z, Sun C

and Zhang J: Prenatal and postnatal exposures to ambient air

pollutants associated with allergies and airway diseases in

childhood: A retrospective observational study. Environ Int.

142:1058532020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Huang Y, Wen HJ, Guo YL, Wei TY, Wang WC,

Tsai SF, Tseng VS and Wang SJ: Prenatal exposure to air pollutants

and childhood atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis adopting

machine learning approaches: 14-Year follow-up birth cohort study.

Sci Total Environ. 777:1459822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bornehag CG, Sundell J and Sigsgaard T:

Dampness in buildings and health (DBH): Report from an ongoing

epidemiological investigation on the association between indoor

environmental factors and health effects among children in Sweden.

Indoor Air. 14(Suppl 7): S59–S66. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kidon MI, See Y, Goh A, Chay OM and

Balakrishnan A: Aeroallergen sensitization in pediatric allergic

rhinitis in Singapore: Is air-conditioning a factor in the tropics?

Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 15:340–343. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li S, Cao S, Duan X, Zhang Y, Gong J, Xu

X, Guo Q, Meng X and Zhang J: Household mold exposure in

association with childhood asthma and allergic rhinitis in a

northwestern city and a southern city of China. J Thorac Dis.

14:1725–1737. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Thacher JD, Gruzieva O, Pershagen G, Melén

E, Lorentzen JC, Kull I and Bergström A: Mold and dampness exposure

and allergic outcomes from birth to adolescence: Data from the

BAMSE cohort. Allergy. 72:967–974. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Weber A, Fuchs N, Kutzora S, Hendrowarsito

L, Nennstiel-Ratzel U, von Mutius E, Herr C and Heinze S; GME Study

Group: Exploring the associations between parent-reported

biological indoor environment and airway-related symptoms and

allergic diseases in children. Int J Hyg Environ Health.

220:1333–1339. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen HI, Lin YT, Jung CR and Hwang BF:

Interaction between catalase gene promoter polymorphisms and indoor

environmental exposure in childhood allergic rhinitis.

Epidemiology. 28(Suppl 1): S126–S132. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pirker AL and Vogl T: Development of

systemic and mucosal immune responses against gut microbiota in

early life and implications for the onset of allergies. Front

Allergy. 5:14393032024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Shargorodsky J, Garcia-Esquinas E,

Navas-Acien A and Lin SY: Allergic sensitization, rhinitis, and

tobacco smoke exposure in U.S. children and adolescents. Int Forum

Allergy Rhinol. 5:471–476. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yang HJ: Impact of perinatal environmental

tobacco smoke on the development of childhood allergic diseases.

Korean J Pediatr. 59:319–327. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yigit E, Yuksel H, Ulman C and Yilmaz O:

Nasal effects of environmental tobacco smoke exposure in children

with allergic rhinitis. Respir Med. 236:1078862025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Choi MJ, Park J and Kim SY: Association

between secondhand smoke and allergic diseases in Korean

adolescents: Cross-sectional analysis of the 2019 KYRBS. Healthcare

(Basel). 11:8512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Dong GH, Qian ZM, Wang J, Trevathan E, Ma

W, Chen W, Xaverius PK, Buckner-Petty S, Ray A, Liu MM, et al:

Residential characteristics and household risk factors and

respiratory diseases in Chinese women: The seven northeast cities

(SNEC) study. Sci Total Environ. 463-464:389–394. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhou L, Huang C, Lu R, Wang X, Sun C and

Zou Z: Volatile organic compounds in children's bedrooms, Shanghai,

China: Sources and influential factors. Atmos Pollut Res.

14:1017512023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ridolo E, Pederzani A, Barone A, Ottoni M,

Crivellaro M and Nicoletta F: Indoor air pollution and atopic

diseases: A comprehensive framework. Explor Asthma Allergy.

2:170–185. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Bell ML, Dominici F, Ebisu K, Zeger SL and

Samet JM: Spatial and temporal variation in PM(2.5) chemical

composition in the United States for health effects studies.

Environ Health Perspect. 115:989–995. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Rumelhard M, Ramgolam K, Hamel R, Marano F

and Baeza-Squiban A: Expression and role of EGFR ligands induced in

airway cells by PM2.5 and its components. Eur Respir J.

30:1064–1073. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Joubert IA, Geppert M, Johnson L,

Mills-Goodlet R, Michelini S, Korotchenko E, Duschl A, Weiss R,

Horejs-Höck J and Himly M: Mechanisms of particles in

sensitization, effector function and therapy of allergic disease.

Front Immunol. 11:13342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bowatte G, Lodge C, Lowe AJ, Erbas B,

Perret J, Abramson MJ, Matheson M and Dharmage SC: The influence of

childhood traffic-related air pollution exposure on asthma, allergy

and sensitization: A systematic review and a meta-analysis of birth

cohort studies. Allergy. 70:245–256. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Castañeda AR, Bein KJ, Smiley-Jewell S and

Pinkerton KE: Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) enhances

allergic sensitization in BALB/c mice. J Toxicol Environ Health A.

80:197–207. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lubitz S, Schober W, Pusch G, Effner R,

Klopp N, Behrendt H and Buters JT: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

from diesel emissions exert proallergic effects in birch pollen

allergic individuals through enhanced mediator release from

basophils. Environ Toxicol. 25:188–197. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Lorenz G, Ernst S and Probst J:

Significance of ultrasound study in accident surgery. Aktuelle

Traumatol. 15:187–194. 1985.In German. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Matthews NC, Pfeffer PE, Mann EH, Kelly

FJ, Corrigan CJ, Hawrylowicz CM and Lee TH: urban particulate

matter-activated human dendritic cells induce the expansion of

potent inflammatory Th1, Th2, and Th17 effector cells. Am J Respir

Cell Mol Biol. 54:250–262. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

53

|

Xia M, Harb H, Saffari A, Sioutas C and

Chatila TA: A Jagged 1-Notch 4 molecular switch mediates airway

inflammation induced by ultrafine particles. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 142:1243–1256.e17. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|