Copper is an essential trace mineral required for

numerous physiological processes, including aerobic respiration,

oxidative stress regulation and biosynthesis (1-4).

Despite its key role in biological activities, intracellular copper

levels are tightly regulated because both copper deficiency, such

as in Menkes disease, anemia, and neurodegeneration, and copper

excess, as seen in Wilson disease, liver injury, neurodegenerative

disorder and several types of cancer, can lead to severe

pathological conditions (5-9).

When intracellular copper accumulates excessively, the organism

initiates specific regulatory programs to decrease the copper

content (10,11). Programmed cell death (PCD) refers

to an orderly, gene-regulated process that maintains cell and

systemic homeostasis and is key for both physiological and

pathological cell turnover (12). The classical forms of PCD include

apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis and autophagy

(13). Apoptosis is

characterized primarily by caspase activation and the release of

cytochrome C from mitochondria under genetic control (14). Necroptosis involves both necrosis

and apoptosis and is typically triggered by the binding of death

receptors (such as tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and the Fas

receptor) to their respective ligands (15). Pyroptosis is mediated by

pore-forming gasdermin proteins, which are activated by caspase-1

and the inflammasome complex, leading to cell membrane rupture

(16). Ferroptosis is an

iron-dependent process driven by lipid peroxidation of unsaturated

fatty acids under the action of ferrous ions or lipoxygenase

(17). Autophagy promotes the

degradation and recycling of intracellular components under stress

conditions to maintain cell homeostasis (18). In recent years, as the mechanisms

of cell death have been elucidated, cuproptosis has emerged as a

newly discovered form of PCD (19). Unlike traditional pathways such

as apoptosis, necroptosis, autophagy or ferroptosis, cuproptosis

depends on the intracellular accumulation of copper, which directly

binds lipoylated proteins in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle,

causing protein aggregation and iron-sulfur cluster degradation.

This results in proteotoxic stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and

cell death (19). In addition to

direct copper accumulation, copper also induces other forms of cell

death. For example, copper-induced apoptosis occurs via the

catalytic generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to

oxidative stress, DNA damage and the activation of apoptotic

pathways (20). Copper can also

directly or indirectly modulate apoptosis-associated proteins, such

as by activating p53 and enhancing its pro-death function (21). Copper-induced ferroptosis may

occur via promotion of iron absorption and utilization, increasing

intracellular iron levels and exacerbating lipid peroxidation,

thereby increasing ferroptotic death (22). Copper also produces hydroxyl

radicals through Fenton-like reactions, triggering lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis (23). In addition, copper may induce the

autophagic degradation of GPX4, facilitating ferroptosis (24). Copper-induced autophagy is

triggered by the activation of AMPK, inhibition of mTOR or direct

interaction with UNC-51-like kinase ½ (25). This process also occurs via

upregulation of autophagy-related genes and activation of the

transcription factor (TF)EB, promoting autophagosome and

autolysosome formation, which may lead to autophagy-dependent cell

death (26). Moreover,

copper-induced ROS generation and endoplasmic reticulum stress

promote NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and gasdermin D activation,

thus triggering pyroptosis (6).

Recent research has revealed an association between copper

metabolism dysregulation and tumor initiation and progression

(6). Copper serves a dual role

in cancer: Imbalanced copper metabolism promotes tumor cell

proliferation and survival by activating the receptor tyrosine

kinase, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways (6,27) and modulating the tumor

microenvironment (TME) through angiogenesis and immune evasion

(28), while cuproptosis

suppresses tumor growth by inducing cell death and activating

immune responses (6). Copper

stimulates apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, ferroptosis and

cuproptosis and enhances antitumor immunity by activating immune

cells (11). As copper

dysregulation is common in cancer cells, targeting copper levels or

metabolic pathways can trigger cuproptosis, thereby inhibiting

tumor growth and progression. Cuproptosis may thus represent a

promising anticancer strategy. Furthermore, the potential effects

of cuproptosis and other forms of cell death, such as ferroptosis

and apoptosis, provide a theoretical basis for combination therapy

(22). In recent years,

therapeutic strategies for gastrointestinal cancer have shifted

from local surgical resection to systemic, multimodal therapy

(29). Although progress has

been made in terms of conventional chemotherapy and targeted

therapies in certain patients, drug resistance and relapse remain

challenges. With the advent of precision medicine and

immunotherapy, gastrointestinal cancer management has evolved from

single-modality chemotherapy to integrated metabolic regulation,

immune remodeling, and microenvironmental intervention. Immune

checkpoint inhibitors (PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 antibodies) and

antiangiogenic agents have demonstrated promising efficacy and

potential for application in patients with gastrointestinal and

hepatocellular tumors (30,31). Concurrently, metabolism-immune

integrated therapy has been proposed to enhance immune responses by

modulating tumor energy metabolism and redox balance (32). The regulation of metal ion

homeostasis has been recognized as a key component of systemic

therapy, with copper serving a pivotal role in the regulation of

mitochondrial respiration and oxidative stress (19). As a copper-dependent PCD pathway,

cuproptosis may serve as a link between metabolism and immunity.

Studies (30,31,33) have highlighted the interplay

between ion metabolism, oxidative stress and immune signaling as a

central axis in systemic therapy for gastrointestinal tumors,

thereby providing a theoretical foundation for incorporating

cuproptosis into therapeutic frameworks. Accordingly, the present

review systematically summarizes the mechanisms of copper

metabolism and cuproptosis to understand metabolic and immune

microenvironmental remodeling in gastrointestinal cancer, offering

conceptual and theoretical support for metabolic targeting and

systemic treatment strategies.

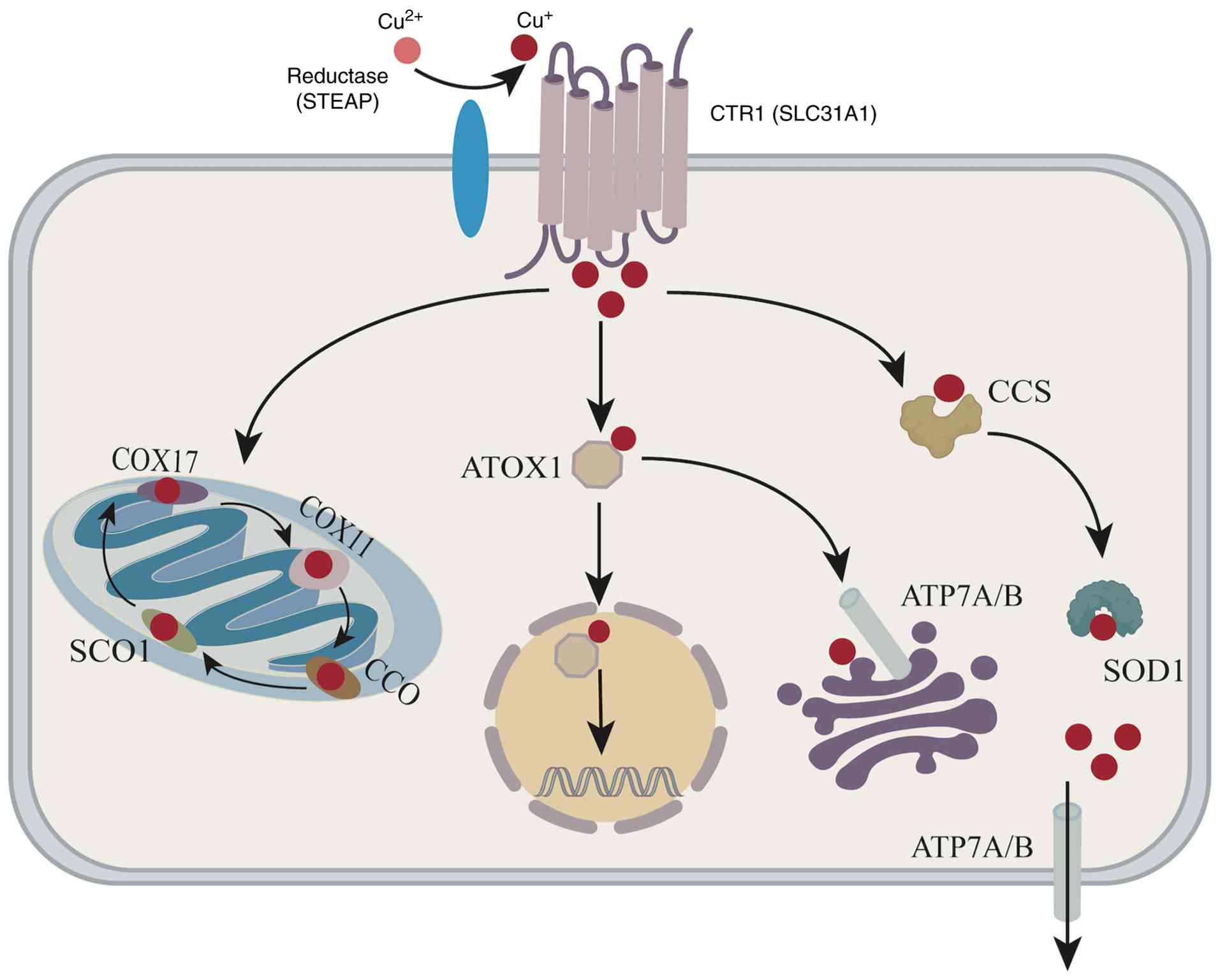

Copper, a widely distributed metallic element in

nature, is an essential trace element for the human body. Most

dietary copper exists in the form of Cu2+ and is

absorbed primarily in the duodenum and small intestine (34). After absorption through the

gastrointestinal tract into the bloodstream, ~90% of copper binds

to ceruloplasmin in the plasma, while the remaining portion is

associated with albumin, transcuprein and histidine. These copper

complexes are transported via the portal vein to the liver and

other organs where copper exerts physiological effects (35). The liver serves as the primary

storage organ for copper (5).

Mitochondria are the notable sites of copper utilization due to the

presence of copper-dependent enzymes such as cytochrome c oxidase,

which is involved in oxidative phosphorylation, and 1-5% of total

cellular superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), which serves a critical

role in mitigating oxidative stress within the mitochondrial

matrix. These enzymes highlight the essential role of copper in

maintaining mitochondrial function and cellular health (36). Excess copper is secreted into the

bile and blood, excreted via the intestine or delivered to

peripheral tissues to catalyze physiological reactions (37). A small portion is excreted in

urine, sweat and menstrual fluid (37). Extracellular copper exists

predominantly in the divalent Cu2+ state and cannot be

directly used by cells (38,39). At the cellular level,

Cu2+ enters through divalent metal transporter 1 or is

reduced to Cu+ by six-transmembrane epithelial antigens

such as Six-Transmembrane Epithelial Antigen of the Prostate 1

(STEAP1) or duodenal cytochrome b, after which Cu+ is

imported into the cytoplasm via the high-affinity copper

transporter 1 (CTR1) (40,41). Once inside the cytosol, excess

copper is sequestered by metallothioneins (34) or delivered to specific organelles

by copper chaperone proteins. For example, the copper chaperone for

SOD (CCS) transfers copper to SOD1, enabling copper insertion,

disulfide bond formation and the localization of SOD1 to the

cytosol or mitochondria (42).

Cytochrome c oxidase 17 (COX17) transfers copper to the

mitochondrial inner membrane subunits COX1 and COX2 (38), which participate in the assembly

of the respiratory chain. In addition, copper is transported

through the secretory pathway via antioxidant-1 copper chaperone

(ATOX1), which delivers copper to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and

copper-transporting ATPases (ATP7A and ATP7B) located in the Golgi

or plasma membrane, maintaining cell copper homeostasis (26). The overall process of copper

metabolism is illustrated in Fig.

1.

In addition to the aforementioned transporters, CTR1

is the primary plasma membrane protein responsible for cellular

copper uptake. CTR1, which has the highest copper-binding affinity

among known transporters, specifically binds extracellular

Cu2+ and transports it into the cytoplasm, where it

serves as a major copper chaperone for enzymes such as SOD

(5,43) (Table I). Following exposure to

extracellular copper, CTR1 recognizes and binds copper, undergoes

conformational changes and transports copper into cells to sustain

normal physiological function (44). Once internalized, copper binds to

chaperones such as ATOX1 and COX17, which deliver copper to target

enzymes, mitochondria or metalloproteins in the endoplasmic

reticulum, ensuring proper copper distribution (45). The upregulation of CTR1 leads to

cellular copper overload (46).

Additionally, solute carrier family 25 member 3 (SLC25A3), a

mitochondrial phosphate carrier, is capable of copper transport,

and its upregulation results in mitochondrial matrix copper

overload (47).

ATPase copper-transporting α (ATP7A) and β (ATP7B)

are P-type copper-transporting ATPases that regulate copper efflux

and intracellular distribution (48). They use the energy derived from

ATP hydrolysis to actively transport copper across membranes

against their concentration gradients, thereby maintaining copper

homeostasis (48,49). ATP7A is expressed ubiquitously,

whereas ATP7B is expressed primarily in the liver (50). In hepatocytes, ATP7B mediates the

excretion of excess copper into bile, while unabsorbed copper is

eliminated through feces (51).

Copper efflux is essential for preventing copper-induced

cytotoxicity. When the intracellular Cu+ concentration

increases above a threshold, ATOX1 mediates Cu+ transfer

to ATP7A/B in the TGN, after which these proteins relocate to the

plasma membrane to export Cu+ (26). ATP7A and ATP7B thus serve central

roles in maintaining systemic copper balance. Dysfunction of these

ATPases leads to severe multisystem disorders such as Menkes

(52) and Wilson's disease

(53). Copper imbalance

contributes to cardiovascular disease (54), retinal disorders (55) and tumorigenesis (43) and also perturbs mitochondrial

respiration, glycolysis, insulin resistance and lipid metabolism

(56-58).

As a heavy metal element, copper is typically

associated with toxicity, however, copper also has essential

physiological functions as a cofactor for numerous proteins and

enzymes (5). For example,

cytochrome c oxidase is a copper-dependent enzyme that is key for

the final step in the electron transport chain, where it

facilitates the transfer of electrons to oxygen during oxidative

phosphorylation (59). SOD1),

another copper-containing enzyme, protects cells from oxidative

damage by converting superoxide radicals to hydrogen peroxide and

oxygen (60). Its versatile

redox activity, which involves cycling between Cu+ and

Cu2+, enables copper to serve as a crucial catalytic

cofactor in biochemical reactions (61), including oxidative stress

regulation (1,2), cellular respiration (56), neurotransmitter synthesis and

metabolism (62) and epigenetic

modification (63). In addition

to redox functions, copper contributes to hematopoiesis, immune

regulation, melanin and connective tissue formation and central

nervous system protection (8,64,65). Copper has also been implicated in

cancer diagnosis and therapy. Advances in metal-based medicine have

focused on achieving targeted toxicity through chemical

coordination and controlled drug delivery (19,66). Conversely, copper-depleting

therapy [tetrathiomolybdate (TTM)] exerts antitumor effects by

chelating copper in the serum, decreasing vascular endothelial

growth factor expression and modulating the immunosuppressive TME.

These mechanisms demonstrate antimetastatic and antiangiogenic

effects in models of breast, colorectal and hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) (67-69). Although other metals, such as

platinum and technetium, have been applied in chemotherapy, imaging

and radiotherapy (70,71), the dual nature of copper, in

which it is both physiologically essential and potentially toxic,

links it with energy metabolism and immune regulation.

Consequently, copper homeostasis has emerged as a frontier topic in

the study of metal-based anticancer therapeutics (72,73).

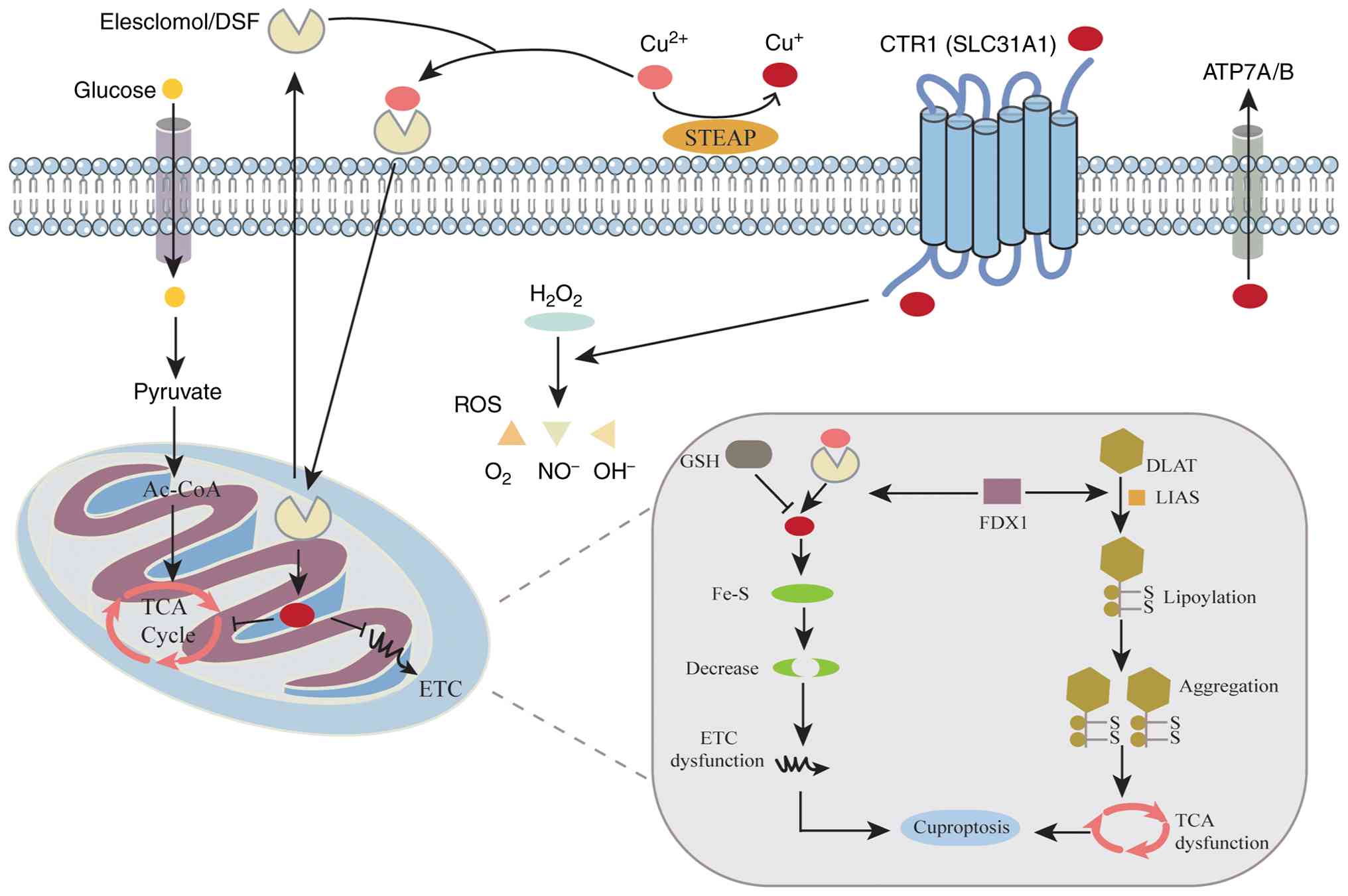

Copper can trigger multiple forms of cell death,

including apoptosis, oxidative stress-induced necrosis, autophagy

and ferroptosis (74). Recent

study have revealed that under the action of copper ionophores such

as elesclomol (ES), copper induces cuproptosis, a distinct form of

PCD, through unique mechanisms involving the disruption of

iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster proteins and the induction of lipid

peroxidation (19). The key

hallmark of cuproptosis is the abnormal aggregation of lipoylated

proteins and depletion of Fe-S cluster proteins, leading to

mitochondrial contraction, chromatin fragmentation and cell

membrane rupture (75).

Mechanistically, ES transports Cu2+ into the cytoplasm,

where it is reduced to Cu+ by ferredoxin 1 (FDX1). The

reduced Cu+ enters mitochondria and binds directly to

key lipoylated enzymes in the TCA cycle, such as dihydrolipoamide

S-acetyltransferase (DLAT) and dihydrolipoamide

S-succinyltransferase (DLST). This interaction induces protein

aggregation and the loss of Fe-S clusters (19). Fe-S clusters are key cofactors

for numerous mitochondrial enzymes and respiratory chain complexes,

such as succinate dehydrogenase subunit A and NADH:ubiquinone

oxidoreductase subunit S1. Their disruption impairs the electron

transport chain and decreases ATP synthesis and mitochondrial

membrane potential (76).

Consequently, mitochondrial energy production decreases,

accompanied by increased inner membrane permeability, elevated

Ca2+ concentration and the accumulation of ROS (77). The aggregation of lipoylated

proteins further induces proteotoxic stress, disrupting

proteostasis and exacerbating mitochondrial injury. Together, these

molecular events define the mitochondrial mechanism of cuproptosis

(Fig. 2).

Increasing evidence has demonstrated that the

dysregulation of copper metabolism is associated with the onset and

progression of various diseases, particularly malignancy (6,7,103). As a key signaling metal, copper

participates in cancer development by promoting cell proliferation,

angiogenesis and metastasis (104). Copper serves dual roles in

cancer biology; it is indispensable for cellular metabolism, but

its dysregulation is associated with oncogenesis. Elevated copper

levels have been detected in tumor tissue or serum in patients with

multiple types of cancer, including breast (105-109), lung (110-112) and gastrointestinal cancer

(113-116), oral (117), thyroid (118) and gallbladder carcinoma

(119) and gynecological

(115,116) and prostate cancer (120). These findings indicate that

copper is not only a key factor in tumor growth and metastasis but

also a necessary micronutrient for tumor cells (73,121). Mechanistically, copper promotes

tumor progression through multiple pathways. First, copper

stimulates angiogenesis by activating angiogenic factors and

enhancing the proliferation and migration of vascular endothelial

cells (122), thereby

supporting tumor initiation, growth and metastasis (73,74,123,124). Newly formed vasculature

provides key nutrients and serves as a conduit for tumor cell

dissemination. Second, copper serves as a cofactor for several

metalloenzymes, including MMP-9, SOD1, vascular adhesion protein-1

and lysyl oxidase (LOX), all of which are key for cancer invasion

and metastasis (125-128). The ATOX1-ATP7A-LOX axis

promotes metastatic dissemination by facilitating the

copper-dependent activation of LOX and LOX-like enzymes, which

remodel the extracellular matrix and increase tumor invasiveness

(73,129). Third, copper activates the

MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, thereby promoting tumor cell

proliferation (130). In

addition to these direct mechanisms, copper also modulates the TME

to promote cancer progression. Copper influences tumor metabolic

reprogramming, enhancing cell survival under hypoxic conditions

(6). Moreover, copper

contributes to immune evasion by regulating immune cell activity or

promoting the expansion of immunosuppressive cell populations,

allowing tumor cells to escape host immune surveillance (131). For example, copper alters

macrophage polarization, shifting tumor-associated macrophages

toward the M2 phenotype, which enhances immune suppression and

facilitates tumor invasion and metastasis (11,132). Collectively, these findings

suggest that copper serves multiple roles in tumorigenesis and

disease progression, including roles in cell proliferation,

angiogenesis, metastasis, metabolic reprogramming and immune

escape, positioning copper as both a potential biomarker and

therapeutic target in cancer biology.

The global incidence of ESCA in 2020 was ~604,000

new cases, and about 544,000 people died from ESCA; ESCA ranks 11th

in terms of global cancer incidence and 7th in terms of

cancer-associated mortality (133). Despite notable advances in

diagnosis and therapy, the 5-year survival rate of patients with

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma remains 20% owing to its late

detection and rapid progression (134). Therefore, identifying novel

diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies is key for

improving prognosis and survival outcomes. Methyltransferase-like 3

(METTL3) expression is markedly elevated in ESCA tissue compared

with that in normal esophageal epithelium, particularly in highly

malignant tumors, and is associated with disease progression

(135). Liu et al

(136) investigated the role of

METTL3 in ESCA and revealed its association with glycolysis,

cuproptosis and the competing endogenous (ce) RNA regulatory

network. These findings demonstrated that METTL3 serves as a

critical mediator of ESCA progression by modulating

glycolysis-associated gene expression. Upregulation of METTL3 in

esophageal carcinoma enhances glycolytic flux, increases glucose

uptake and lactate production and promotes tumor growth (128). Moreover, METTL3 expression is

associated with the expression of genes associated with

cuproptosis. Mechanistically, METTL3 serves dual regulatory roles

in glycolysis and cuproptosis via N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA

modification. Specifically, METTL3 alters and stabilizes

glycolysis-associated mRNAs, thereby altering tumor cell energy

metabolism and proliferation. Concurrently, METTL3 may regulate

genes associated with copper homeostasis, affecting intracellular

copper levels and inducing cell death. Additionally, METTL3 is

involved in the ceRNA network, in which long non-coding (lnc) and

circular RNAs compete for shared microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs),

influencing posttranscriptional regulation. By modulating the

stability or function of ceRNA components, METTL3 indirectly

affects gene expression and tumor progression. These findings

indicate that targeting METTL3 and its associated pathways may

represent a promising therapeutic strategy for ESCA, especially in

highly glycolytic and copper-enriched subtypes. The aforementioned

study provides valuable insights into the epigenetic and metabolic

regulation of ESCA, underscoring the potential of METTL3 as a

therapeutic target that links epigenetic modification, metabolic

reprogramming and copper-induced cell death. Further study have

identified the cuproptosis-associated genes Centromere Protein E

and SHC SH2 Domain-Binding Protein 1 as key biomarkers of Barrett's

esophagus (BE) progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC)

(137). These genes may

influence the immune microenvironment and promote the

transformation from BE to EAC, offering molecular targets for early

diagnosis and treatment. Metabolic abnormalities (lactate

accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction) within tumor cells and

the surrounding microenvironment impair immune responses and

promote immune evasion (33).

Moreover, disruption of metal ion homeostasis, particularly copper

imbalance, alters oxidative stress and mitochondrial metabolism,

further influencing tumor survival and therapeutic resistance

(32,138). Therefore, integrating

cuproptosis pathways into chemoradiotherapy or immunotherapy

regimens may enhance radiosensitivity and remodel the tumor immune

microenvironment, offering a rational framework for combination

treatment strategies in ESCA.

GC is an epithelial malignancy originating in the

stomach. In 2022, there were ~968,000 new cases of GC worldwide,

accounting for 4.9% of all new cancer cases, making it the fifth

most common cancer by incidence globally (139). At the same time, gastric cancer

accounted for approximately 6.8% of cancer-related deaths globally,

with around 660,000 deaths, ranking fifth among the leading causes

of cancer death worldwide (139). Disruptions in PCD serve a

crucial role in GC pathogenesis (140,141). Copper levels are notably

elevated in gastric tumor tissue compared with normal gastric

mucosa, particularly in high-grade malignancy. Moreover, the copper

content is positively associated with the TNM stage of GC (142). In a recent study, Sun et

al (79) investigated the

mechanism of cuproptosis in GC, identifying its association with

METTL16, an atypical m6A RNA METTL involved in m6A modification.

METTL16 serves as a key mediator of cuproptosis by regulating FDX1

mRNA through m6A modification (79). Elevated copper levels in GC

tissue promote the lactylation of METTL16 at lysine residue K229,

which enhances its enzymatic activity and upregulates FDX1

expression, inducing cell death. Mechanistically, SIRT2 serves as a

critical delactylase, removing lactyl groups from METTL16-K229 and

inhibiting METTL16 activity. Treatment with

(Z)-2-cyano-3-[5-(2,5-dichlorophenyl)

furan-2-yl]-N-quinolin-5-ylprop-2-enamide, a selective SIRT2

inhibitor, increases METTL16 lactylation and FDX1 expression,

thereby promoting cuproptosis. These findings suggest that the

combined use of copper ionophores (such as ES) and SIRT2 inhibitors

may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for GC, particularly

in aggressive, high-copper and high-lactate subtypes such as

mucinous adenocarcinoma. Sun et al provided valuable

mechanistic insight into the role of METTL16-mediated RNA

modification and lactylation in copper-induced cell death,

highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting the

METTL16-SIRT2-FDX1 axis in GC treatment. Polypyrimidine

tract-binding protein 3 (PTBP3) is markedly upregulated in

peritoneal metastases of GC and is associated with poor prognosis

(143). Single-cell RNA

sequencing and transcriptome analysis reveal that PTBP3 regulates

its downstream target COX11, impairing its function and decreasing

the mitochondrial copper content, which enables tumor cells to

evade cuproptosis. Researchers have developed an antisense

oligonucleotide (ASO) targeting the short isoform of COX11 pre-mRNA

exon 4 (136), effectively

degrading COX11 mRNA and disrupting copper homeostasis. In a

patient-derived organoid xenograft model combination therapy using

exogenous copper ionophores and ASO drugs leads to excessive

mitochondrial copper accumulation, proteotoxic stress and the

induction of cuproptosis, thereby suppressing peritoneal metastasis

(143). This provides a new

therapeutic strategy targeting PTBP3-mediated COX11 splicing to

restore copper-dependent cell death in metastatic GC. In stomach

adenocarcinoma (STAD), FDX1, lipoic Acid Synthase (LIAS), Metal

Regulatory Transcription Factor 1 (MTF1) and Pyruvate Dehydrogenase

E1 Subunit Alpha 1 have been identified as key genes associated

with cuproptosis (144). FDX1

is highly expressed in STAD tumor tissues, associated with poor

prognosis and increased chemosensitivity to cisplatin and

5-fluorouracil, making FDX1 a potential predictive biomarker for

chemotherapy response (145).

LIAS and MTF1 exhibit notable prognostic value, where higher

expression levels are associated with improved survival.

Collectively, these molecular markers not only contribute to

prognostic evaluation but also provide a foundation for the

development of copper-targeted anticancer drugs. Aberrant copper

homeostasis in GC is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and

ROS accumulation, whereas cuproptosis promotes energy metabolism

collapse and cell death (146,147). Future studies should explore

the potential synergy between copper-modulating drugs (such as ES)

and immunotherapy or antiangiogenic therapy with the aim of

achieving a coordinated antitumor effect through the simultaneous

regulation of metabolic, immune and redox networks.

Based on GLOBOCAN 2020, HCC ranks sixth in incidence

and third in cancer-associated mortality worldwide (148). Although notable therapeutic

progress has been made over the past decade, the prognosis of HCC

remains poor, largely because most patients are diagnosed at

advanced stages, precluding surgical or localized treatment

(149,150). Hence, identifying effective

molecular targets and therapeutic strategies for HCC is key.

Clinical studies have reported significantly elevated serum copper

levels (151,152), increased copper-protein

complexes and enhanced expression of copper-binding proteins in

patients with HCC (153,154),

as well as the downregulation of copper transporters such as

ATP7A/B and SLC31A1/2 (155).

Copper concentrations in HCC tissue are markedly higher than those

in normal liver tissue and elevated serum copper levels are

associated with tumor progression (156). In a recent study, Li et

al (157) investigated the

mechanism of cuproptosis in HCC, focusing on DLAT, a key gene

associated with copper-induced cell death. The aforementioned study

reported that maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK)

serves as a key mediator of cuproptosis by activating the PI3K/mTOR

signaling pathway. Elevated copper levels in HCC promote MELK

expression and activity, which upregulate DLAT expression and

support mitochondrial function, thus facilitating HCC progression.

Mechanistically, treatment with the copper ionophore ES decreases

the expression of translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20

and enhances DLAT oligomerization, thereby suppressing MELK

activity and triggering cuproptosis. These findings indicate that

the combination of copper ionophores and PI3K/mTOR pathway

inhibitors may represent a promising therapeutic approach for

treating HCC. Li et al (157) provided key mechanistic insight

into the MELK-DLAT regulatory axis, highlighting its potential as a

therapeutic target in liver cancer. Exposure of Hep3B hepatoma

cells to Cu2+ suppresses histone acetyltransferase

activity, leading to hypoacetylation of histones H3 and H4, which

promotes cell proliferation (19). Copper also binds pyruvate

dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1), enhancing its interaction with AKT,

thereby activating the PDK1-AKT oncogenic signaling cascade and

promoting HCC progression (158). Conversely, copper chelators or

CTR1 inhibitors downregulate the CTR1-AKT axis, thus inhibiting

tumor growth (158). CTR1 is

aberrantly upregulated in breast cancer and is negatively regulated

by NEDD4-like E3 ubiquitin ligase (NEDD4l), which promotes CTR1

ubiquitination and degradation. NEDD4l exerts tumor-suppressive

effects by inhibiting CTR1-mediated AKT signaling. These findings

reveal an association between the CTR1/Cu pathway and PDK1-AKT

oncogenic signaling, underscoring the therapeutic potential of

targeting the CTR1-Cu axis in cancers driven by AKT

hyperactivation. By contrast with copper accumulation, FDX1

expression is notably lower in HCC tissues than in normal liver

tissue, and its expression is positively associated with patient

survival, with higher FDX1 expression predicting longer overall

survival. Moreover, FDX1 levels are positively associated with

oxaliplatin sensitivity. In a recent study, Quan et al

(159) elucidated the molecular

mechanism of cuproptosis in HCC, focusing on the FDX1-associated

lncRNA/miRNA regulatory axis. Through bioinformatic analyses, the

aforementioned study identified LINC02362 as a ceRNA that modulates

miR-18a-5p, which directly targets FDX1. Upregulation of the

LINC02362/miR-18a-5p/FDX1 pathway signaling suppresses HCC cell

proliferation. Conversely, LINC02362 knockdown decreases

intracellular copper concentrations and induces resistance to

ES-Cu-mediated cell death. Additionally, upregulation of this axis

enhances the sensitivity of HCC to oxaliplatin by promoting

cuproptosis. These findings suggest that LINC02362/miR-18a-5p/FDX1

is a novel regulatory pathway capable of overcoming oxaliplatin

resistance in HCC through cuproptotic mechanisms. Recent

preclinical studies have shown that copper chelators, including

triethylenetetramine and D-penicillamine, significantly decrease

copper levels and inhibit tumor growth in HCC (160). By restoring copper homeostasis,

these agents may also overcome resistance to conventional therapy,

supporting their potential clinical use in HCC treatment. Emerging

research indicates that metabolic reprogramming and copper

imbalance are common features of HCC (161). Excess copper disrupts

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and lipoyl enzyme complex

activity, leading to lipid metabolic disorder and energy collapse

(19). Moreover, the expression

of genes associated with cuproptosis, such as FDX1, LIAS and DLAT,

is downregulated in HCC tissue and the expression of these genes is

significantly associated with immune phenotypes and overall

survival (162). In conclusion,

copper serves as both a metabolic cofactor and a potential

therapeutic target in HCC. Regulation of copper levels or

exploitation of its bioactive properties offers a promising avenue

for novel anticancer strategies. Future studies should elucidate

the mechanisms of copper-targeted therapy, optimize therapeutic

regimens and conduct rigorous clinical trials to validate their

safety and efficacy.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020, pancreatic cancer is a

highly aggressive malignancy, ranking twelfth in incidence but

sixth in overall cancer-associated mortality worldwide (163). Despite advances in treatment,

the 5-year overall survival rate remains ~ 10% (164). Pancreatic cancer remains among

the most common types of treatment-refractory malignancy. Elevated

serum copper levels may contribute to pancreatic cancer development

(165). Novel

nanomaterial-based strategies to exploit cuproptosis for

therapeutic benefit (166). For

example, tussah silk fibroin (TSF)-based nanoparticles (NPs) use

TME-responsive release mechanisms to deliver copper and the

cuproptosis-inducing drug ES directly to pancreatic cancer cells.

Upon targeted delivery, TSF@ ES-Cu NPs induce cuproptosis,

releasing damage-associated molecular patterns that activate

antitumor immunity (166). This

promotes dendritic cell maturation and macrophage M1 polarization,

thereby reshaping the TME and enhancing immune responses.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that TSF@ ES-Cu NPs

suppress pancreatic cancer growth through a dual mechanism of

cuproptosis induction and immune microenvironment remodeling,

offering a promising avenue for clinical translation. In addition,

other research have explored the prognostic and therapeutic roles

of cuproptosis-associated lncRNAs in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (PAAD) (167).

Researchers have developed a cuproptosis-immune-related (CIR) score

to characterize the interaction between cuproptosis and the tumor

immune microenvironment (168).

By integrating single-cell sequencing and transcriptomic data,

researchers have identified immune- and cuproptosis-related genes

associated with PAAD and constructed a CIR score model (168). This score not only predicts

prognosis in patients and the immune landscape but also reflects

the tumor mutational burden (TMB), immune checkpoint sensitivity,

and drug responsiveness. Patients in the high CIR score group

exhibit higher TMB and poorer survival, whereas those in the low

CIR score group exhibit stronger immune activation and greater

potential responsiveness to immunotherapy. Mouse model experiments

have validated the predictive power of the CIR score in guiding

combination therapy involving immunotherapy, targeted therapy and

chemotherapy (168). Such

combined regimens significantly inhibit PAAD progression,

highlighting the translational potential of cuproptosis-based

prognostic markers in personalized immunotherapy. Mechanistically,

these findings indicate that the cuproptosis-metabolic

reprogramming-immune activation axis represents a novel paradigm

for the systemic treatment of pancreatic cancer. The integration of

copper homeostasis regulation into individualized therapeutic

frameworks provides both theoretical and practical foundations for

precision medicine in PAAD.

CRC, one of the most common malignant tumors of the

digestive system, is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer

worldwide, with approximately 1.9 million new cases annually

(169). Cuproptosis-related

genes, such as FDX1, SDHB, DLAT and DLST, are expressed at higher

levels in normal compared with tumor tissues (170). Moreover, higher expression of

these genes in tumor tissue is associated with better prognosis

(170). When ES, a copper

carrier, combines with copper, the proliferation of CRC cells is

significantly inhibited and apoptosis is promoted. This effect is

markedly suppressed by the copper chelator TTM, further confirming

the mechanism of copper-induced cell death. Furthermore,

2-deoxy-D-glucose, a glycolysis inhibitor, can significantly

enhance cuproptosis (170). In

addition, galactose promotes oxidative phosphorylation by

inhibiting the glycolytic pathway in tumor cells, thereby enhancing

copper-induced cell death (170). These results indicate that the

inhibition of glycolysis can increase the sensitivity of tumor

cells to cuproptosis. Studies have also shown that 4-octyl

itaconate (4-OI), a cell-permeable derivative of itaconic acid,

inhibits glycolysis by targeting the key glycolytic enzyme GAPDH,

thereby enhancing cuproptosis. 4-OI suppresses GAPDH activity,

decreases lactate production and subsequently promotes

copper-induced cell death. Furthermore, in vivo experiments

demonstrated that 4-OI has significant antitumor effects and that

its combination with ES markedly decreases tumor volume. Yang et

al (170) provided new

insights into the role of cuproptosis in CRC and revealed that 4-OI

enhances copper-induced cell death by inhibiting glycolysis. These

findings not only provide a novel therapeutic strategy for CRC but

also establish theoretical support for cuproptosis as a potential

anticancer approach. Cuproptosis-associated genes demonstrate

important prognostic value in colon adenocarcinoma because their

expression levels are associated with patient survival, TME

characteristics and drug sensitivity (171). To the best of our knowledge,

the aforementioned study was the first to systematically analyze

the roles of genes associated with cuproptosis in colon

adenocarcinoma and to elucidate their potential mechanisms in tumor

progression and immune microenvironment regulation. Similarly,

genes associated with cuproptosis serve a significant role in the

prognosis and treatment of rectal adenocarcinoma (172). Copper chelators or carriers may

synergize with chemotherapy or immunotherapy, thereby improving the

prognosis of liver-metastatic CRC (173).

Cuproptosis-associated drugs have demonstrated

antitumor potential in clinical trials for gastrointestinal cancer

(174,175). For example, the

disulfiram/copper complex inhibits the proliferation of GC cells by

inducing oxidative stress and DNA damage while increasing the

sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents (174). In addition, TTM, a copper

chelator, exerts antiangiogenic and chemosensitizing effects in

metastatic CRC (175). The

potential clinical applications of these drugs include combining

them with chemotherapy to enhance therapeutic efficacy, targeting

copper metabolism-associated proteins to improve treatment

precision and using biomarkers such as serum copper levels to guide

medication strategies. Nevertheless, further research is needed to

optimize the design of cuproptosis-associated drugs to improve

their efficacy and decrease side effects. However, future in-depth

studies on the molecular mechanisms of these drugs and additional

clinical trials to verify their safety and effectiveness are

needed.

As a newly identified form of regulated cell death,

cuproptosis has become a prominent focus in tumor biology,

particularly in gastrointestinal cancer. The present review

summarizes the mechanistic pathways and therapeutic potential of

cuproptosis, emphasizing key molecular events such as mitochondrial

damage, oxidative stress and protein lipoylation, as well as copper

imbalance and its association with tumor initiation and

development. Current evidence indicates that disruption of copper

metabolism is associated with tumor growth and progression. By

modulating intracellular copper levels, cuproptosis inhibits tumor

cell proliferation through various mechanisms, including the

induction of PCD and the enhancement of antitumor immune responses.

Moreover, cuproptosis-associated drugs, such as disulfiram/copper

complexes and TTM, have demonstrated promising anticancer potential

in preclinical and clinical studies because they induce oxidative

stress, increase chemosensitivity and inhibit angiogenesis.

However, the clinical application of these drugs faces several

challenges, including limited efficacy, toxicity management and a

lack of large-scale validation. Future studies should further

clarify the molecular mechanisms of cuproptosis, develop novel

copper-dependent therapeutic agents with improved selectivity and

safety and conduct clinical trials to assess their translational

value. In conclusion, cuproptosis offers a novel conceptual and

therapeutic direction for gastrointestinal oncology, holding

promise for treatment options that could improve prognosis and

survival outcomes.

Not applicable.

LZ and YC conceived the study. LT, JZ and BT edited

the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82073087) and

Medical Research Union Fund for High-quality Health Development of

Guizhou Province (grant no. 2024GZYXKYJJXM0019).

|

1

|

Lutsenko S, Roy S and Tsvetkov P:

Mammalian copper homeostasis: Physiological roles and molecular

mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 105:441–491. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

2

|

Locatelli M and Farina C: Role of copper

in central nervous system physiology and pathology. Neural Regen

Res. 20:1058–1068. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chen G, Li J, Han H, Du R and Wang X:

Physiological and molecular mechanisms of plant responses to copper

stress. Int J Mol Sci. 23:129502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Verdejo-Torres O, Klein DC, Novoa-Aponte

L, Carrazco-Carrillo J, Bonilla-Pinto D, Rivera A, Bakhshian A,

Fitisemanu FM, Jiménez-González ML, Flinn L, et al: Cysteine rich

intestinal protein 2 is a copper-responsive regulator of skeletal

muscle differentiation and metal homeostasis. PLoS Genet.

20:e10114952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen L, Min J and Wang F: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:3782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Guo Z, Chen D, Yao L, Sun Y, Li D, Le J,

Dian Y, Zeng F, Chen X and Deng G: The molecular mechanism and

therapeutic landscape of copper and cuproptosis in cancer. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 10:1492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yang Y, Wu J, Wang L, Ji G and Dang Y:

Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. MedComm

(2020). 5:e7242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Myint ZW, Oo TH, Thein KZ, Tun AM and

Saeed H: Copper deficiency anemia: Review article. Ann Hematol.

97:1527–1534. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gromadzka G, Tarnacka B, Flaga A and

Adamczyk A: Copper dyshomeostasis in neurodegenerative

diseases-therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci. 21:92592020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sailer J, Nagel J, Akdogan B, Jauch AT,

Engler J, Knolle PA and Zischka H: Deadly excess copper. Redox

Biol. 75:1032562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang S, Huang Q, Ji T, Li Q and Hu C:

Copper homeostasis and copper-induced cell death in tumor immunity:

Implications for therapeutic strategies in cancer immunotherapy.

Biomark Res. 12:1302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang XR and Cull B: Apoptosis and

autophagy: Current understanding in tick-pathogen interactions.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 12:7844302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hong Y, He J, Deng D, Liu Q, Zu X and Shen

Y: Targeting kinases that regulate programmed cell death: A new

therapeutic strategy for breast cancer. J Transl Med. 23:4392025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bertheloot D, Latz E and Franklin BS:

Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell

death. Cell Mol Immunol. 18:1106–1121. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gao W, Wang X, Zhou Y, Wang X and Yu Y:

Autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in tumor

immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rao Z, Zhu Y, Yang P, Chen Z, Xia Y, Qiao

C, Liu W, Deng H, Li J, Ning P and Wang Z: Pyroptosis in

inflammatory diseases and cancer. Theranostics. 12:4310–4329. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon

M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, Rossen J, Joesch-Cohen L, Humeidi R,

Spangler RD, et al: Copper induces cell death by targeting

lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 375:1254–1261. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhao G, Sun H, Zhang T and Liu JX: Copper

induce zebrafish retinal developmental defects via triggering

stresses and apoptosis. Cell Commun Signal. 18:452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ostrakhovitch EA and Cherian MG: Role of

p53 and reactive oxygen species in apoptotic response to copper and

zinc in epithelial breast cancer cells. Apoptosis. 10:111–121.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li Y, Du Y, Zhou Y, Chen Q, Luo Z, Ren Y,

Chen X and Chen G: Iron and copper: Critical executioners of

ferroptosis, cuproptosis and other forms of cell death. Cell Commun

Signal. 21:3272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Vana F, Szabo Z, Masarik M and

Kratochvilova M: The interplay of transition metals in ferroptosis

and pyroptosis. Cell Div. 19:242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xue Q, Yan D, Chen X, Li X, Kang R,

Klionsky DJ, Kroemer G, Chen X, Tang D and Liu J: Copper-dependent

autophagic degradation of GPX4 drives ferroptosis. Autophagy.

19:1982–1996. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fu Y, Zeng S, Wang Z, Huang H, Zhao X and

Li M: Mechanisms of copper-induced autophagy and links with human

diseases. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 18:992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Xue Q, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D, Liu J

and Chen X: Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy.

Autophagy. 19:2175–2195. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang Y, Qiao S, Wang P, Li M, Ma X, Wang H

and Dong J: Copper's new role in cancer: How cuproptosis-related

genes could revolutionize glioma treatment. BMC Cancer. 25:8592025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tang X, Yan Z, Miao Y, Ha W, Li Z, Yang L

and Mi D: Copper in cancer: From limiting nutrient to therapeutic

target. Front Oncol. 13:12091562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shoda K, Kawaguchi Y, Maruyama S and

Ichikawa D: Essential updates 2023/2024: Recent advances of

multimodal approach in patients for gastric cancer. Ann

Gastroenterol Surg. 9:1119–1127. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ricci AD, Rizzo A and Brandi G: DNA damage

response alterations in gastric cancer: knocking down a new wall.

Future Oncol. 17:865–868. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Rizzo A and Ricci AD: Challenges and

future trends of hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:113632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Vitale E, Rizzo A, Santa K and Jirillo E:

Associations between 'Cancer Risk', 'Inflammation' and 'Metabolic

Syndrome': A scoping review. Biology (Basel). 13:3522024.

|

|

33

|

Brandi G, Ricci AD, Rizzo A, Zanfi C,

Tavolari S, Palloni A, De Lorenzo S, Ravaioli M and Cescon M: Is

post-transplant chemotherapy feasible in liver transplantation for

colorectal cancer liver metastases? Cancer Commun (Lond).

40:461–464. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mason KE: A conspectus of research on

copper metabolism and requirements of man. J Nutr. 109:1979–2066.

1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Eisses JF and Kaplan JH: The mechanism of

copper uptake mediated by human CTR1: A mutational analysis. J Biol

Chem. 280:37159–37168. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zischka H and Einer C: Mitochondrial

copper homeostasis and its derailment in Wilson disease. Int J

Biochem Cell Biol. 102:71–75. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jiayi H, Ziyuan T, Tianhua X, Mingyu Z,

Yutong M, Jingyu W, Hongli Z and Li S: Copper homeostasis in

chronic kidney disease and its crosstalk with ferroptosis.

Pharmacol Res. 202:1071392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen J, Jiang Y, Shi H, Peng Y, Fan X and

Li C: The molecular mechanisms of copper metabolism and its roles

in human diseases. Pflugers Arch. 472:1415–1429. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lutsenko S: Dynamic and cell-specific

transport networks for intracellular copper ions. J Cell Sci.

134:jcs2405232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

McKie AT, Barrow D, Latunde-Dada GO, Rolfs

A, Sager G, Mudaly E, Mudaly M, Richardson C, Barlow D, Bomford A,

et al: An iron-regulated ferric reductase associated with the

absorption of dietary iron. Science. 291:1755–1759. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mastrogiannaki M, Matak P, Keith B, Simon

MC, Vaulont S and Peyssonnaux C: HIF-2alpha, but not HIF-1alpha,

promotes iron absorption in mice. J Clin Invest. 119:1159–1166.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kawamata H and Manfredi G: Import,

maturation, and function of SOD1 and its copper chaperone CCS in

the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Antioxid Redox Signal.

13:1375–1384. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wang Z, Jin D, Zhou S, Dong N, Ji Y, An P,

Wang J, Luo Y and Luo J: Regulatory roles of copper metabolism and

cuproptosis in human cancers. Front Oncol. 13:11234202023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ohrvik H and Thiele DJ: How copper

traverses cellular membranes through the mammalian copper

transporter 1, Ctr1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1314:32–41. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yu Q, Xiao Y, Guan M, Zhang X, Yu J, Han M

and Li Z: Copper metabolism in osteoarthritis and its relation to

oxidative stress and ferroptosis in chondrocytes. Front Mol Biosci.

11:14724922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kim H, Wu X and Lee J: SLC31 (CTR) family

of copper transporters in health and disease. Mol Aspects Med.

34:561–570. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cobine PA, Moore SA and Leary SC: Getting

out what you put in: Copper in mitochondria and its impacts on

human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1868:1188672021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Chen Z, Li YY and Liu X: Copper

homeostasis and copper-induced cell death: Novel targeting for

intervention in the pathogenesis of vascular aging. Biomed

Pharmacother. 169:1158392023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Andersson M, Mattle D, Sitsel O, Klymchuk

T, Nielsen AM, Moller LB, White SH, Nissen P and Gourdon P:

Copper-transporting P-type ATPases use a unique ion-release

pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 21:43–48. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

50

|

Telianidis J, Hung YH, Materia S and

Fontaine SL: Role of the P-Type ATPases, ATP7A and ATP7B in brain

copper homeostasis. Front Aging Neurosci. 5:442013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Fanni D, Pilloni L, Orru S, Coni P,

Liguori C, Serra S, Lai ML, Uccheddu A, Contu L, Van Eyken P and

Faa G: Expression of ATP7B in normal human liver. Eur J Histochem.

49:371–378. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kaler SG: ATP7A-related copper transport

diseases-emerging concepts and future trends. Nat Rev Neurol.

7:15–29. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yang GM, Xu L, Wang RM, Tao X, Zheng ZW,

Chang S, Ma D, Zhao C, Dong Y, Wu S, et al: Structures of the human

Wilson disease copper transporter ATP7B. Cell Rep. 42:1124172023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M and Kaplan JH:

Copper transporters and copper chaperones: Roles in cardiovascular

physiology and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 315:C186–C201.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ugarte M, Osborne NN, Brown LA and Bishop

PN: Iron, zinc, and copper in retinal physiology and disease. Surv

Ophthalmol. 58:585–609. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ishida S, Andreux P, Poitry-Yamate C,

Auwerx J and Hanahan D: Bioavailable copper modulates oxidative

phosphorylation and growth of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

110:19507–19512. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wooton-Kee CR, Robertson M, Zhou Y, Dong

B, Sun Z, Kim KH, Liu H, Xu Y, Putluri N, Saha P, et al: Metabolic

dysregulation in the Atp7b(-/-) Wilson's disease mouse model. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:2076–2083. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yang H, Ralle M, Wolfgang MJ, Dhawan N,

Burkhead JL, Rodriguez S, Kaplan JH, Wong GW, Haughey N and

Lutsenko S: Copper-dependent amino oxidase 3 governs selection of

metabolic fuels in adipocytes. PLoS Biol. 16:e20065192018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kim E, Chufan EE, Kamaraj K and Karlin KD:

Synthetic models for heme-copper oxidases. Chem Rev. 104:1077–1133.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Anwar S, Sarwar T, Khan AA and Rahmani AH:

Therapeutic applications and mechanisms of superoxide dismutase

(SOD) in different pathogenesis. Biomolecules. 15:11302025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Grubman A and White AR: Copper as a key

regulator of cell signalling pathways. Expert Rev Mol Med.

16:e112014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Heffern MC, Park HM, Au-Yeung HY, Van de

Bittner GC, Ackerman CM, Stahl A and Chang CJ: In vivo

bioluminescence imaging reveals copper deficiency in a murine model

of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

113:14219–14224. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Herranz N, Dave N, Millanes-Romero A,

Morey L, Diaz VM, Lorenz-Fonfria V, Gutierrez-Gallego R, Jerónimo

C, Di Croce L, García de Herreros A and Peiró S: Lysyl oxidase-like

2 deaminates lysine 4 in histone H3. Mol Cell. 46:369–376. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Percival SS: Copper and immunity. Am J

Clin Nutr. 67(5 Suppl): 1064S–1068S. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

An Y, Li S, Huang X, Chen X, Shan H and

Zhang M: The role of copper homeostasis in brain disease. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:138502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Cheng YF, Zhao YJ, Chen C and Zhang F:

Heavy metals toxicity: Mechanism, health effects, and therapeutic

interventions. MedComm (2020). 6:e702412025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zheng P, Zhou C, Lu L, Liu B and Ding Y:

Elesclomol: A copper ionophore targeting mitochondrial metabolism

for cancer therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:2712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kong R and Sun G: Targeting copper

metabolism: A promising strategy for cancer treatment. Front

Pharmacol. 14:12034472023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Nan L, Yuan W, Guodong C and Yonghui H:

Multitargeting strategy using tetrathiomolybdate and lenvatinib:

Maximizing antiangiogenesis activity in a preclinical liver cancer

model. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 23:786–793. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Cohen R, Raeisi M, Chibaudel B, Yothers G,

Goldberg RM, Bachet JB, Wolmark N, Yoshino T, Schmoll HJ, Haller

DG, et al: Impact of tumor and node stages on the efficacy of

adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer

patients: An ACCENT pooled analysis. ESMO Open. 10:1044812025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Nawar MF and Turler A: New strategies for

a sustainable (99m) Tc supply to meet increasing medical demands:

Promising solutions for current problems. Front Chem.

10:9262582022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Wang W, Mo W, Hang Z, Huang Y, Yi H, Sun Z

and Lei A: Cuproptosis: Harnessing transition metal for cancer

therapy. ACS Nano. 17:19581–19599. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Ge EJ, Bush AI, Casini A, Cobine PA, Cross

JR, DeNicola GM, Dou QP, Franz KJ, Gohil VM, Gupta S, et al:

Connecting copper and cancer: From transition metal signalling to

metalloplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 22:102–113. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

74

|

Li Y: Copper homeostasis: Emerging target

for cancer treatment. IUBMB Life. 72:1900–1908. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Cong Y, Li N, Zhang Z, Shang Y and Zhao H:

Cuproptosis: Molecular mechanisms, cancer prognosis, and

therapeutic applications. J Transl Med. 23:1042025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Shim D and Han J: Coordination chemistry

of mitochondrial copper metalloenzymes: Exploring implications for

copper dyshomeostasis in cell death. BMB Rep. 56:575–583. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Cheng H, Yang B, Ke T, Li S, Yang X,

Aschner M and Chen P: Mechanisms of metal-induced mitochondrial

dysfunction in neurological disorders. Toxics. 9:1422021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Tsvetkov P, Detappe A, Cai K, Keys HR,

Brune Z, Ying W, Thiru P, Reidy M, Kugener G, Rossen J, et al:

Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress.

Nat Chem Biol. 15:681–689. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Sun L, Zhang Y, Yang B, Sun S, Zhang P,

Luo Z, Feng T, Cui Z, Zhu T, Li Y, et al: Lactylation of METTL16

promotes cuproptosis via m(6)A-modification on FDX1 mRNA in gastric

cancer. Nat Commun. 14:65232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Polishchuk EV, Concilli M, Iacobacci S,

Chesi G, Pastore N, Piccolo P, Paladino S, Baldantoni D, van

IJzendoorn SC, Chan J, et al: Wilson disease protein ATP7B utilizes

lysosomal exocytosis to maintain copper homeostasis. Dev Cell.

29:686–700. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Yang L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Jiang P, Liu F

and Feng N: Ferredoxin 1 is a cuproptosis-key gene responsible for

tumor immunity and drug sensitivity: A pan-cancer analysis. Front

Pharmacol. 13:9381342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Sheftel AD, Stehling O, Pierik AJ,

Elsasser HP, Muhlenhoff U, Webert H, Hobler A, Hannemann F,

Bernhardt R and Lill R: Humans possess two mitochondrial

ferredoxins, Fdx1 and Fdx2, with distinct roles in steroidogenesis,

heme, and Fe/S cluster biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:11775–11780. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Huang X, Wang T, Ye J, Feng H and Zhang X,

Ma X, Wang B, Huang Y and Zhang X: FDX1 expression predicts

favourable prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma identified

by bioinformatics and tissue microarray analysis. Front Genet.

13:9947412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Mayr JA, Zimmermann FA, Fauth C, Bergheim

C, Meierhofer D, Radmayr D, Zschocke J, Koch J and Sperl W: Lipoic

acid synthetase deficiency causes neonatal-onset epilepsy,

defective mitochondrial energy metabolism, and glycine elevation.

Am J Hum Genet. 89:792–797. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Cai Y, He Q, Liu W, Liang Q, Peng B, Li J,

Zhang W, Kang F, Hong Q, Yan Y, et al: Comprehensive analysis of

the potential cuproptosis-related biomarker LIAS that regulates

prognosis and immunotherapy of pan-cancers. Front Oncol.

12:9521292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Casteel J, Miernyk JA and Thelen JJ:

Mapping the lipoylation site of Arabidopsis thaliana plastidial

dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase using mass spectrometry and

site-directed mutagenesis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 49:1355–1361.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Rumping L, Tessadori F, Pouwels PJW,

Vringer E, Wijnen JP, Bhogal AA, Savelberg SMC, Duran KJ, Bakkers

MJG, Ramos RJJ, et al: GLS hyperactivity causes glutamate excess,

infantile cataract and profound developmental delay. Hum Mol Genet.

28:96–104. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Rumping L, Buttner B, Maier O, Rehmann H,

Lequin M, Schlump JU, Schmitt B, Schiebergen-Bronkhorst B, Prinsen

HCMT, Losa M, et al: Identification of a loss-of-function mutation

in the context of glutaminase deficiency and neonatal epileptic

encephalopathy. JAMA Neurol. 76:342–350. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

89

|

Agarwal P, Sandey M, DeInnocentes P and

Bird RC: Tumor suppressor gene p16/INK4A/CDKN2A-dependent

regulation into and out of the cell cycle in a spontaneous canine

model of breast cancer. J Cell Biochem. 114:1355–1363. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Serrano M, Hannon GJ and Beach D: A new

regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition

of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature. 366:704–407. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Bian Z, Yu Y, Yang T, Quan C, Sun W and Fu

S: Effect of tumor suppressor gene cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitor 2A wild-type and A148T mutant on the cell cycle of human

ovarian cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 7:1229–1232. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Samimi G, Safaei R, Katano K, Holzer AK,

Rochdi M, Tomioka M, Goodman M and Howell SB: Increased expression

of the copper efflux transporter ATP7A mediates resistance to

cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin in ovarian cancer cells.

Clin Cancer Res. 10:4661–4669. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Tian Z, Jiang S, Zhou J and Zhang W:

Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in mitochondria. Life Sci.

334:1222232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Mangala LS, Zuzel V, Schmandt R, Leshane

ES, Halder JB, Armaiz-Pena GN, Spannuth WA, Tanaka T, Shahzad MM,

Lin YG, et al: Therapeutic targeting of ATP7B in ovarian carcinoma.

Clin Cancer Res. 15:3770–3780. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Yun Y, Wang Y, Yang E and Jing X:

Cuproptosis-related gene - SLC31A1, FDX1 and ATP7B-polymorphisms

are associated with risk of lung cancer. Pharmgenomics Pers Med.

15:733–742. 2022.

|

|

96

|

Wang D, Tian Z, Zhang P, Zhen L, Meng Q,

Sun B, Xu X, Jia T and Li S: The molecular mechanisms of

cuproptosis and its relevance to cardiovascular disease. Biomed

Pharmacother. 163:1148302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Halliwell B, Adhikary A, Dingfelder M and

Dizdaroglu M: Hydroxyl radical is a significant player in oxidative

DNA damage in vivo. Chem Soc Rev. 50:8355–8360. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Chandimali N, Bak SG, Park EH, Lim HJ, Won

YS, Kim EK, Park SI and Lee SJ: Free radicals and their impact on

health and antioxidant defenses: A review. Cell Death Discov.

11:192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Wong-Ekkabut J, Xu Z, Triampo W, Tang IM,

Tieleman DP and Monticelli L: Effect of lipid peroxidation on the

properties of lipid bilayers: A molecular dynamics study. Biophys

J. 93:4225–4236. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Kehm R, Baldensperger T, Raupbach J and

Höhn A: Protein oxidation - Formation mechanisms, detection and

relevance as biomarkers in human diseases. Redox Biol.

42:1019012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Vo TTT, Peng TY, Nguyen TH, Bui TNH, Wang

CS, Lee WJ, Chen YL, Wu YC and Lee IT: The crosstalk between

copper-induced oxidative stress and cuproptosis: A novel potential

anticancer paradigm. Cell Commun Signal. 22:3532024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Chen W, Jiang T, Wang H, Tao S, Lau A,

Fang D and Zhang DD: Does Nrf2 contribute to p53-mediated control

of cell survival and death? Antioxid Redox Signal. 17:1670–1675.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Shan D, Song J, Ren Y, Zhang Y, Ba Y, Luo

P, Cheng Q, Xu H, Weng S, Zuo A, et al: Copper in cancer: Friend or

foe? Metabolism, dysregulation, and therapeutic opportunities.

Cancer Commun (Lond). 45:577–607. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Dow JA: The essential roles of metal ions

in insect homeostasis and physiology. Curr Opin Insect Sci.

23:43–50. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Ding X, Jiang M, Jing H, Sheng W, Wang X,

Han J and Wang L: Analysis of serum levels of 15 trace elements in

breast cancer patients in Shandong, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res

Int. 22:7930–7935. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Kuo HW, Chen SF, Wu CC, Chen DR and Lee

JH: Serum and tissue trace elements in patients with breast cancer

in Taiwan. Biol Trace Elem Res. 89:1–11. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Pavithra V, Sathisha TG, Kasturi K,

Mallika DS, Amos SJ and Ragunatha S: Serum levels of metal ions in

female patients with breast cancer. J Clin Diagn Res. 9:BC25–c27.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Feng JF, Lu L, Zeng P, Yang YH, Luo J,

Yang YW and Wang D: Serum total oxidant/antioxidant status and

trace element levels in breast cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol.

17:575–583. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Zowczak M, Iskra M, Torlinski L and Cofta

S: Analysis of serum copper and zinc concentrations in cancer

patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 82:1–8. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Diez M, Cerdan FJ, Arroyo M and Balibrea

JL: Use of the copper/zinc ratio in the diagnosis of lung cancer.

Cancer. 63:726–730. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Jin Y, Zhang C, Xu H, Xue S, Wang Y, Hou

Y, Kong Y and Xu Y: Combined effects of serum trace metals and

polymorphisms of CYP1A1 or GSTM1 on non-small cell lung cancer: A

hospital based case-control study in China. Cancer Epidemiol.

35:182–187. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Oyama T, Matsuno K, Kawamoto T, Mitsudomi

T, Shirakusa T and Kodama Y: Efficiency of serum copper/zinc ratio

for differential diagnosis of patients with and without lung

cancer. Biol Trace Elem Res. 42:115–127. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Stepien M, Jenab M, Freisling H, Becker

NP, Czuban M, Tjonneland A, Olsen A, Overvad K, Boutron-Ruault MC,

Mancini FR, et al: Pre-diagnostic copper and zinc biomarkers and

colorectal cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation

into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Carcinogenesis. 38:699–707. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Sohrabi M, Gholami A, Azar MH, Yaghoobi M,

Shahi MM, Shirmardi S, Nikkhah M, Kohi Z, Salehpour D, Khoonsari

MR, et al: Trace element and heavy metal levels in colorectal

cancer: Comparison between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues.

Biol Trace Elem Res. 183:1–8. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Margalioth EJ, Schenker JG and Chevion M:

Copper and zinc levels in normal and malignant tissues. Cancer.

52:868–872. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Yaman M, Kaya G and Yekeler H:

Distribution of trace metal concentrations in paired cancerous and

non-cancerous human stomach tissues. World J Gastroenterol.

13:612–618. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Khanna SS and Karjodkar FR: Circulating

immune complexes and trace elements (Copper, Iron and Selenium) as

markers in oral precancer and cancer: A randomised, controlled

clinical trial. Head Face Med. 2:332006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Baltaci AK, Dundar TK, Aksoy F and

Mogulkoc R: Changes in the serum levels of trace elements before

and after the operation in thyroid cancer patients. Biol Trace Elem

Res. 175:57–64. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Basu S, Singh MK, Singh TB, Bhartiya SK,

Singh SP and Shukla VK: Heavy and trace metals in carcinoma of the

gallbladder. World J Surg. 37:2641–2646. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Saleh SAK, Adly HM, Abdelkhaliq AA and

Nassir AM: Serum levels of selenium, zinc, copper, manganese, and

iron in prostate cancer patients. Curr Urol. 14:44–49. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Blockhuys S, Celauro E, Hildesjo C, Feizi

A, Stal O, Fierro-Gonzalez JC and Wittung-Stafshede P: Defining the

human copper proteome and analysis of its expression variation in

cancers. Metallomics. 9:112–123. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Wang W, Lu K, Jiang X, Wei Q, Zhu L, Wang

X, Jin H and Feng L: Ferroptosis inducers enhanced cuproptosis

induced by copper ionophores in primary liver cancer. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 42:1422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Harris ED: A Requirement for Copper in

Angiogenesis. Nutr Rev. 62:60–64. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

De Luca A, Barile A, Arciello M and Rossi

L: Copper homeostasis as target of both consolidated and innovative

strategies of anti-tumor therapy. J Trace Elem Med Biol.

55:204–213. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Barker HE, Cox TR and Erler JT: The

rationale for targeting the LOX family in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

12:540–552. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Groleau J, Dussault S, Haddad P, Turgeon

J, Menard C, Chan JS and Rivard A: Essential role of copper-zinc

superoxide dismutase for ischemia-induced neovascularization via

modulation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 30:2173–2181. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Lowndes SA and Harris AL: Copper chelation

as an antiangiogenic therapy. Oncol Res. 14:529–539. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

128

|

Pannecoeck R, Serruys D, Benmeridja L,

Delanghe JR, van Geel N, Speeckaert R and Speeckaert MM: Vascular

adhesion protein-1: Role in human pathology and application as a

biomarker. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 52:284–300. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Wong CC, Tse AP, Huang YP, Zhu YT, Chiu

DK, Lai RK, Au SL, Kai AK, Lee JM, Wei LL, et al: Lysyl

oxidase-like 2 is critical to tumor microenvironment and metastatic

niche formation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology.

60:1645–1658. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|