The development and progression of cancer is a

complex, multi-step process driven by factors such as the aberrant

expression of multiple genes, disruption of key signaling pathways

and remodeling of the tumor microenvironment (TME) (1-7).

A deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying the key drivers

of cancer is crucial for revealing the malignant nature of tumors,

and developing novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies

(8-10).

Zymogen granule protein 16B (ZG16B), also known as

pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor, was discovered and

identified in 2009, and was revealed to be highly expressed in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (11). ZG16B is a secretory lectin-like

protein (12), capable of

regulating intracellular signaling cascades in various cell types,

including tumor cells, endothelial cells and immune cells. ZG16B is

involved in key biological processes, such as tumor cell

proliferation, migration, invasion, angiogenesis and immune

suppression within the TME (13-16). As an oncogenic factor, ZG16B

expression is upregulated in malignant tumors, such as pancreatic

cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer and gastric cancer, and

is closely associated with the tumorigenesis and progression of

these types of cancer (17-19). Currently, drugs targeting ZG16B

are under investigation in preclinical studies and clinical trials,

with promising prospects for future clinical application (20-25).

The present review aims to integrate the existing

research findings, and systematically elucidate the molecular

characteristics, biological functions, signaling pathway regulatory

networks, expression profiles and clinical relevance of ZG16B. In

addition, new advancements in the roles of ZG16B in cancer

diagnosis and prognosis, and its potential in targeted therapy, are

described. The current review not only provides a new perspective

for understanding the complex mechanisms underlying tumor malignant

progression, but also lays the theoretical foundation for the

development of ZG16B-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies,

which holds notable scientific and clinical value in improving

patient prognosis.

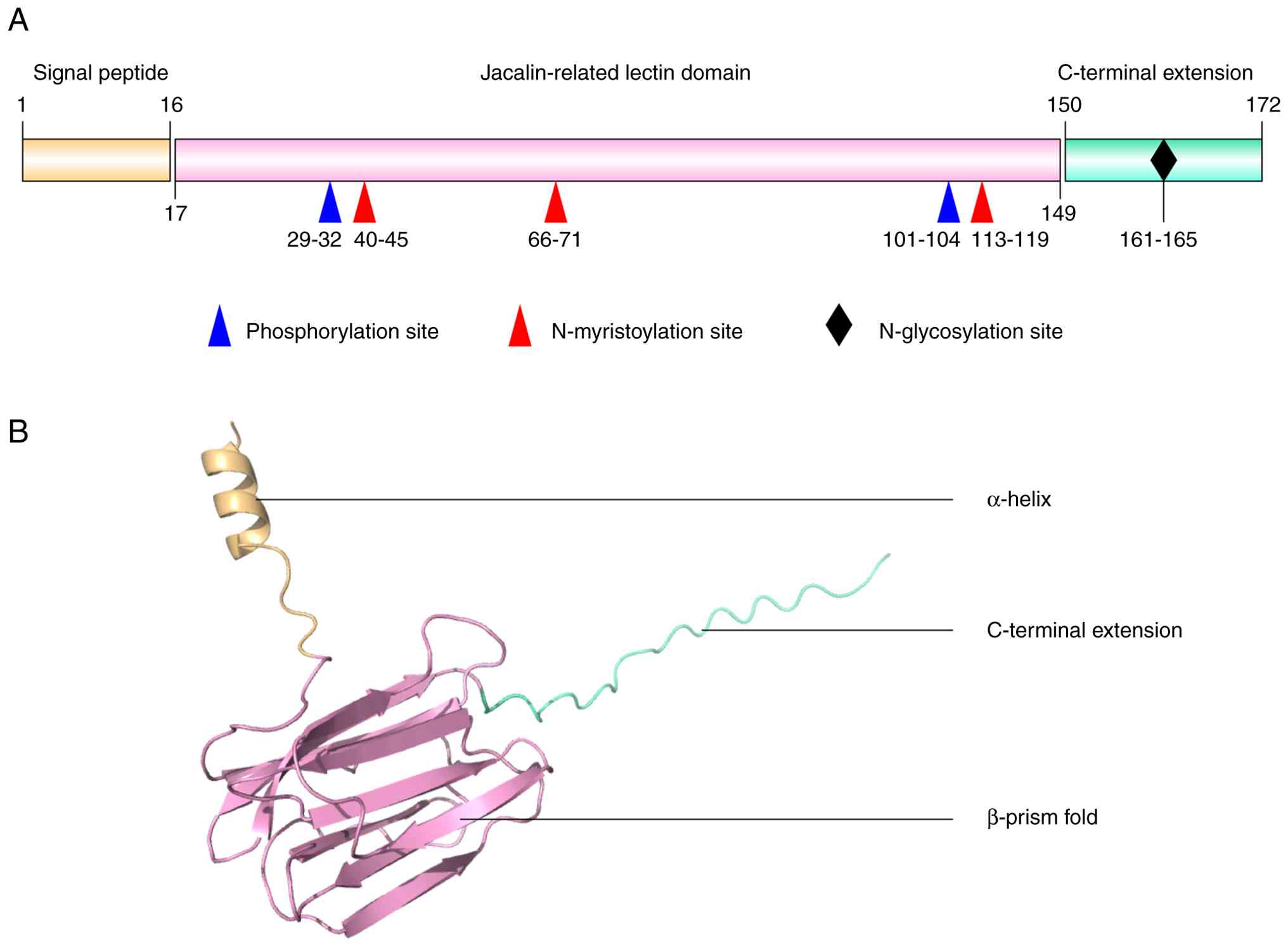

The ZG16B protein is a secretory lectin-like protein

that predominantly exists as a monomer in solution (11). The initially translated ZG16B

precursor consists of 172 amino acids (aa) and contains three major

regions: An N-terminal hydrophobic signal peptide (1-16 aa), a

central jacalin-related lectin domain (17-149 aa), and a C-terminal

extension (150-172 aa) (Fig. 1A)

(12). After cleavage of the

signal peptide, the mature protein comprises 156 aa. The

theoretical molecular mass of ZG16B is ~17 kDa, whereas the

secreted form exhibits an apparent molecular weight of ~25 kDa due

to N-linked glycosylation (11).

The N-terminal signal peptide directs ZG16B into the endoplasmic

reticulum-Golgi secretory pathway, ensuring its proper secretion

and transport (30).

The conserved GXXXD motif at the

carbohydrate-binding site is crucial for the carbohydrate-binding

specificity of proteins, and replacing this motif with the QLLGIK

sequence in ZG16B alters its carbohydrate-binding preference,

abolishing its ability to bind monosaccharides (12,31). Surrounding this site, positively

charged residues Lys87, Arg131, and Lys147 form a potential

glycosaminoglycan-binding region (11). The lectin domain also harbors

several potential post-translational modification (PTM) sites,

which may be essential for protein function and stability (Fig. 1A); these PTM sites include two

phosphorylation sites at aa 29-32 and 101-104, and three

N-myristoylation sites at aa 40-45, 66-71 and 113-119 (11). The C-terminal extension contains

a classical N-linked glycosylation motif (NXS/T; Fig. 1A).

Evolutionarily, the ZG16B protein is highly

conserved among primates. The aa sequence identity between humans

and chimpanzees reaches 98% (with 100% similarity), and that

between humans and rhesus monkeys is 92% (with 95% similarity)

(11). By contrast, the

conservation of the ZG16B protein is reduced in rodents with 31%

identity and 45% similarity between humans and mice, suggesting

that ZG16B is a rapidly evolving, primate-specific gene

likely associated with specialized physiological functions in

primates (11).

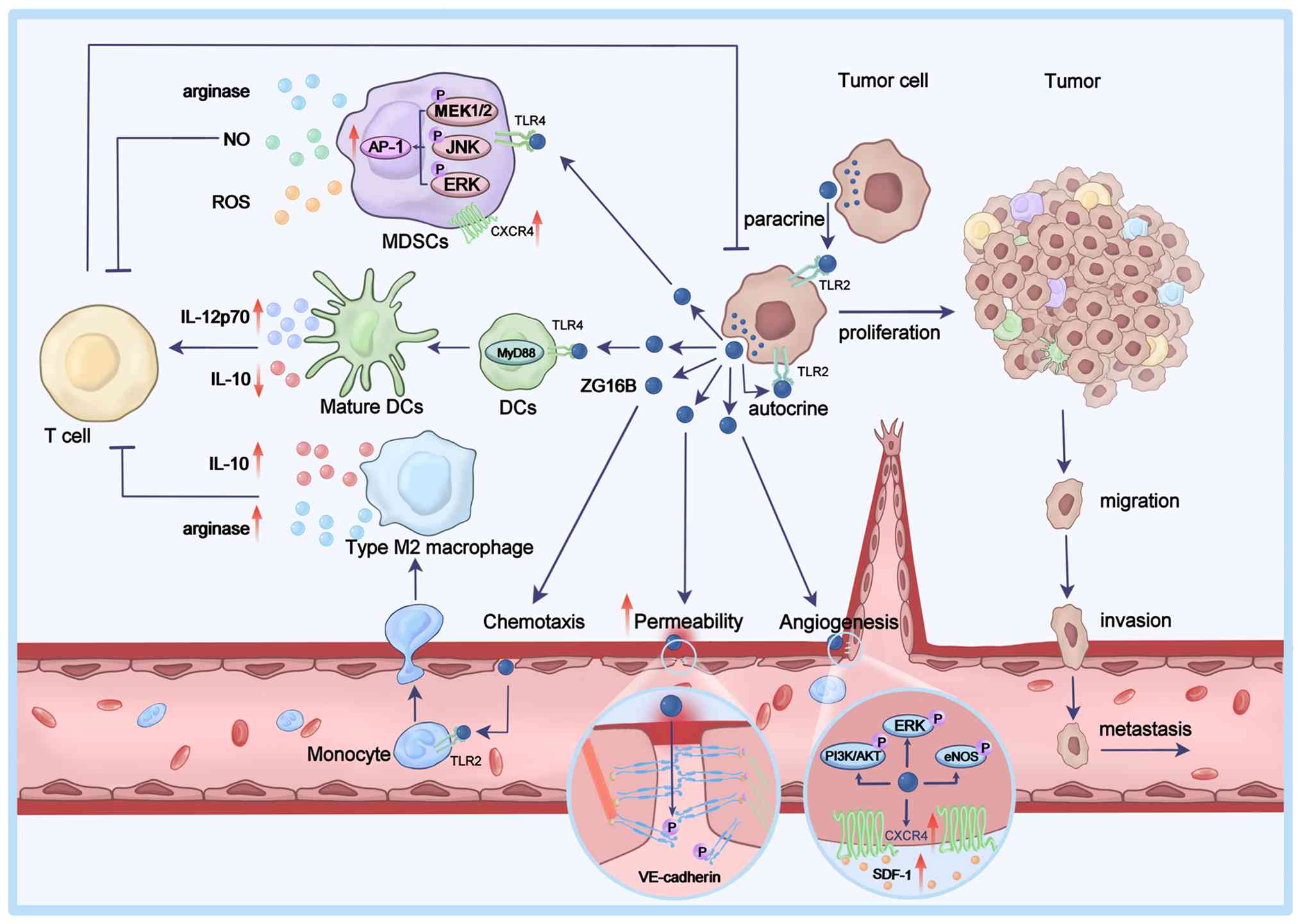

ZG16B can be secreted by tumor cells and can act on

tumor cells through autocrine or paracrine mechanisms to promote

their proliferation, migration and invasion. ZG16B can also affect

vascular endothelial cells in the TME, enhancing angiogenesis and

vascular permeability. Additionally, ZG16B can modulate immune

cells within the TME, regulating T cell-mediated anti-tumor

immunity (Fig. 2).

ZG16B induces rapid proliferation of pancreatic

cancer cells by specifically activating the AKT/GSK-3β signaling

pathway to stabilize β-catenin (47). Furthermore, ZG16B can activate

the ERK, JNK and AKT signaling pathways to upregulate the

expression of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), promoting

the in vitro proliferation, migration and invasion of

pancreatic cancer cells, as well as in vivo metastasis of

pancreatic cancer (15).

Moreover, ZG16B interacts with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) to

activate the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB and TLR4/MEK/ERK signaling pathways,

and enhances the migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells

(14,16). Notably, the high expression of

ZG16B is significantly associated with positive lymph node

metastasis and worse prognosis in patients with pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (17).

ZG16B activates the PI3K/AKT1 pathway to enhance the

proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells. Notably,

ZG16B-induced proliferation, but not migration, of breast cancer

cells depends on ERK1/2 phosphorylation and the presence of the

estrogen receptor (48). In

ovarian cancer, ZG16B promotes cell proliferation by activating the

TLR4-mediated ERK, JNK and p38 signaling pathways, while it

enhances migration, invasion and adhesion through the Src, ERK and

AKT signaling pathways (18,49). Similarly, ZG16B enhances the

proliferation, migration, invasion and adhesion of colorectal

cancer cells by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Notably, silencing ZG16B suppresses these processes by inducing

cell-cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase and

apoptosis (19,50). Furthermore, ZG16B promotes the

proliferation and invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells

while inhibiting apoptosis. High expression of ZG16B is

significantly associated with positive lymph node metastasis and

worse prognosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

(51).

Collectively, ZG16B expression is upregulated in

various types of cancer, and promotes the proliferation, migration

and invasion of different types of cancer cells by regulating

multiple signaling pathways.

Tumor angiogenesis and vascular density are closely

associated with tumor growth, maintenance and metastasis (52-58). ZG16B has been identified as a new

endothelial cell activator, distinct from vascular endothelial

growth factors, and its expression is markedly associated with

tumor microvascular density (59). ZG16B can activate ERK and

PI3K/AKT signaling to induce the expression of endothelial nitric

oxide synthase (eNOS) in a time- and dose-dependent manner,

promoting the proliferation, migration and tubular network

formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

(59). ZG16B also enhances

angiogenesis by upregulating CXCR4 expression in HUVECs to enhance

the angiogenic activity of its ligand, stromal cell-derived

factor-1 (SDF-1) (59,60).

ZG16B can also induce the Src-dependent

phosphorylation of VE-cadherin, resulting in the disruption of

cell-cell junctions between endothelial cells to increase vascular

permeability (59,61). This suggests that ZG16B may serve

as a potential biomarker for angiogenesis-related diseases, and a

novel molecular target for the development of antitumor

angiogenesis therapy (62).

MDSCs are a group of immature myeloid cells,

including immature granulocytes, monocytes and DC precursors

(73,74). In the TME, MDSCs can suppress

T-cell activity, block antitumor immune responses and promote tumor

progression (75-79). ZG16B secreted by tumor cells can

enhance the migration of MDSCs by upregulating CXCR4 expression,

inducing their recruitment to tumor tissues (13). Additionally, ZG16B interacts with

TLR4 on the surface of MDSCs to activate the MEK1/2, ERK, and JNK

signaling and the transcription factor activator protein-1 (AP-1).

This promotes the production of immune suppressive factors such as

arginase, nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in

tumor-infiltrating MDSCs, inducing oxidative damage to T cells and

inhibiting CD8+ T-cell responses, exerting an

immunosuppressive effect (13).

TAMs are a type of specialized macrophages present

in the TME. Depending on the stimulating signals, mature

macrophages can differentiate into M1 and M2 types (80-85). M1 macrophages have antitumor

functions, whereas M2 macrophages exhibit protumor functions and

become the predominant macrophages during tumor progression, which

are associated with a poor prognosis (86-88). ZG16B in the TME, through binding

to TLR2 on monocytes, recruits circulating monocytes into the TME,

where ZG16B can induce the differentiation of monocytes into M2

macrophages (89). The

ZG16B-induced M2 macrophages can secrete immune suppressive factors

such as IL-10 and arginase, inhibiting the proliferation of

CD4+ T cells and the activity of CD8+ T

cells. This weakens T cell-mediated antitumor immune responses,

allowing tumor cells to evade immune surveillance, and promoting

tumor growth and progression (89).

DCs are the professional antigen-presenting cells in

the TME, and their maturation and activation status directly

influence the strength of T-cell immune responses (78,90-93). ZG16B activates TLR4/MyD88

signaling in DCs, promoting their maturation, activation and

migration. ZG16B can also upregulate IL-12p70 expression and

downregulate IL-10 expression in DCs, favoring the activation and

differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into T helper 1

cells, enhancing the levels of cytotoxic T lymphocyte immune

activity, and mediating antitumor immunity (94). Furthermore, when DCs treated with

recombinant ZG16B are pulsed with tumor-associated antigen peptides

HPV16 E7 and OVA257-264, they can activate antigen peptide-specific

CD8+ T cells and induce memory T-cell responses, leading

to effective antitumor responses and long-term tumor suppression,

prolonging the survival of tumor-bearing mice. This result suggests

that ZG16B may enhance the antitumor efficacy of DC vaccines and

serve as a potential novel adjuvant in humans (94).

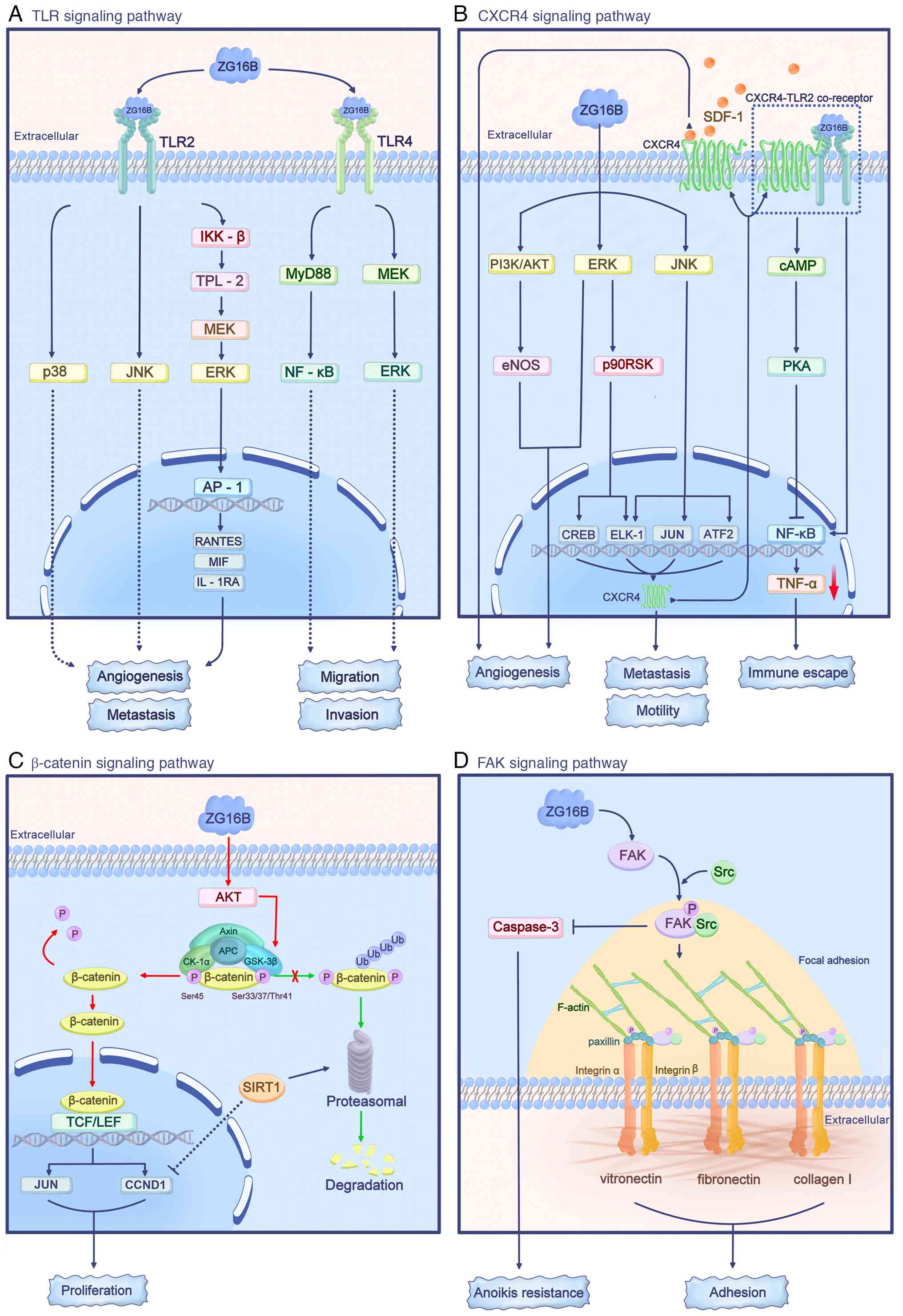

ZG16B in the TME can act on signaling pathways such

as the TLR, CXCR4, β-catenin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK)

pathways, regulating the functions of tumor cells, endothelial

cells and immune cells (Fig. 3).

Additionally, the expression of ZG16B in tumor cells can be induced

by TGF-β.

TLRs are key components of the innate immune system.

As a type of pattern recognition receptor, they can recognize

pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated

molecular patterns, initiating both innate and adaptive immune

responses (95-97). Additionally, TLR signaling

regulates tumor cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and

contributes to the process of immune evasion (98-100).

ZG16B can act as an endogenous ligand for TLR2 and

TLR4 on the cell surface to activate the TLR2-mediated ERK, JNK and

p38 signaling in human acute monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells

(31). Similarly, ZG16B

activates IKK-β and tumor progression locus 2/MEK/ERK signaling in

293T cells through exogenously expressed TLR2 (31). As a result, ZG16B increases AP-1

expression to promote the secretion of cytokines, such as RANTES,

macrophage migration inhibitory factor and IL-1RA, which favor

tumor progression, metastasis and angiogenesis (31). However, ZG16B does not activate

TLR2 or TLR4-mediated NF-κB signaling in THP-1 and 293T cells

(31). By contrast, ZG16B can

induce the migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by

activating the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling, independent of the

TLR4/TRIF pathway (16).

Additionally, through TLR4, ZG16B activates MEK/ERK signaling to

promote the migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells

(14).

The CXCR4 signaling pathway is crucial for

organ-specific metastasis in various types of malignancies. The

increased expression of CXCR4 by ZG16B markedly enhances the

migration and invasion of tumor cells (101-103).

In pancreatic cancer cells, ZG16B can induce rapid

and transient activation of the ERK, JNK and PI3K/AKT signaling

pathways in an autocrine manner. Activated ERK can activate p90

ribosomal s6 kinase, and downstream transcription factors

cAMP-responsive element binding protein and ELK-1; activated JNK

can activate the transcription factors c-Jun (JUN),

activating transcription factor 2 and ELK-1. These

transcription factors synergistically regulate the expression of

CXCR4 to promote the motility and metastasis of pancreatic cancer

cells (15). In addition, ZG16B

enhances the responses of endothelial cells to SDF-1, the CXCR4

ligand, by activating the ERK and PI3K/AKT/eNOS signaling pathways,

and upregulating CXCR4 expression, thus enhancing angiogenesis.

This creates a TME that favors tumor progression and metastasis

(59,60). In THP-1 cells, ZG16B binds to the

CXCR4/TLR2 receptor complex to activate cAMP and cAMP-dependent

protein kinase A (PKA). Subsequently, PKA inhibits the

TLR2-mediated NF-κB activation, reducing TNF-α production and

contributing to the immune evasion of tumor cells (31).

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling is aberrantly activated

in various types of cancer and is crucial for biological processes,

such as tumor cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis

resistance (104-108). In resting non-tumor cells,

β-catenin binds to a destruction complex consisting of APC, Axin,

casein kinase-1α (CK-1α) and GSK-3β. CK-1α and GSK-3β phosphorylate

β-catenin at the Ser45 and Ser33/37/Thr41 sites, respectively,

leading to β-catenin ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation to

maintain β-catenin levels at a low baseline (109).

In pancreatic cancer cells, ZG16B can activate the

AKT/GSK-3β pathway, leading to slight phosphorylation of β-catenin

at Ser33/37/Thr41 and Ser675, while greatly reducing

phosphorylation at Ser45, thus stabilizing and activating β-catenin

(47). In the nucleus, β-catenin

forms a complex with the T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor

family, activating the expression of β-catenin-targeted genes, such

as CCND1 and JUN, to promote the rapid proliferation

of pancreatic cancer cells (47). The deacetylase sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)

can mediate the proteasomal degradation of β-catenin and inhibit

the expression of the target gene CCND1, thereby suppressing

the ZG16B-mediated pancreatic cancer cell proliferation,

independent of SIRT1 nuclear translocation (110).

FAK is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase usually

present at cell focal adhesion sites. FAK is important for tumor

cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and regulating the

interactions between tumor cells and the extracellular matrix. FAK

is a marker of tumor progression and an indicator of poor prognosis

(111-113).

In pancreatic cancer cells, ZG16B activates FAK

signaling, which recruits Src to the focal adhesion sites, forming

a stable FAK/Src complex; this can phosphorylate the scaffold

protein paxillin to promote the formation of F-actin. This process

increases the focal adhesion density and enhances tumor cell

adhesion to extracellular matrix molecules, such as fibronectin,

collagen I and vitronectin (114). Additionally, ZG16B activates

the FAK/Src signaling to inhibit the activity of the

apoptosis-related protein caspase-3, thereby enhancing the

resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to anoikis, and promoting the

progression and metastasis of pancreatic cancer (114,115).

TGF-β is a pleiotropic cytokine, which activates

Smad signaling through its receptors; this is important in

regulating processes such as immune regulation and wound healing

(116,117). The TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway

can promote TME remodeling by inducing the epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT), regulating angiogenesis, immune suppression,

activating fibroblasts, extracellular matrix remodeling and

inflammation modulation, ultimately promoting malignant tumor

progression (118-120).

In pancreatic cancer cells, TGF-β binds to the TGF-β

receptor 2 to activate the phosphorylation of Smad2/3, and

facilitate the formation of a complex of Smad2/3 and Smad4 in the

cytoplasm. Subsequently, this complex translocates into the nucleus

and binds to the Smad-binding element in the ZG16B promoter,

enhancing ZG16B expression (14). TGF-β/Smad-mediated ZG16B

expression promotes the expression of transcription factors

SNAI1 and ZEB1 via the MEK/ERK signaling pathway,

upregulating mesenchymal vimentin and α-SMA expression, while

downregulating epithelial E-cadherin and ZO-1 expression, inducing

the EMT process in pancreatic cancer (14).

Physiologically, ZG16B is expressed at a low level

in most non-tumor tissues, but it is highly expressed in the

placenta (11). Additionally,

ZG16B expression is markedly upregulated in various types of tumor

tissues, including pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, ovarian

cancer and gastric cancer (11).

ZG16B is crucial for the pathogenesis of multiple types of cancer

and disease, and ZG16B has broad activities and clinical

potential.

ZG16B expression is low or undetectable in non-tumor

pancreatic tissues, whereas its expression is notably upregulated

in pancreatic cancer cells at the tumor margins. High ZG16B

expression is associated with cancer progression and cachexia

(15,17,121). Similarly, ZG16B is highly

expressed in colorectal cancer (19,50), ovarian cancer (18,122) and cervical cancer (123,124), and its high expression is an

independent prognostic risk factor, markedly associated with tumor

stage progression, shorter overall survival, disease-free survival

and progression-free survival. Furthermore, ZG16B is highly

expressed in prostate cancer (125,126) and oral squamous cell carcinoma

(51,127), supporting malignant behaviors.

By contrast, high ZG16B expression in breast cancer is associated

with a favorable prognosis (128). This may be explained by the

fact that ZG16B is co-expressed with several tumor-suppressive

genes, such as SPINT1, TFAP2A, FOXA1 and

FAM96B in breast cancer; its high expression predominantly

occurs in hormone receptor-positive breast cancers, which are

intrinsically associated with better outcomes; and its upregulation

is mainly driven by promoter demethylation rather than oncogenic

mutations (128). Functionally,

ZG16B can act as a marker of hormone receptor-related

differentiation or luminal epithelial differentiation, but not a

driver factor, or an indicator of tumor aggressiveness in breast

cancer (128). This clinical

association suggests that the function of ZG16B may vary among

different types of cancer.

Additionally, ZG16B appears to participate in the

physiological processes and pathogenesis of several non-tumor

diseases. Notably, ZG16B is highly expressed in reflex tears

(129) and amniotic fluid

(130), constituting a part of

their specific protein components. In the oral cavity, through its

lectin structure, ZG16B binds to the cell wall lipopolysaccharides

of the commensal bacterium Streptococcus vestibularis and

interacts with salivary mucin 7. This inhibits the growth of these

microorganisms through mucin-assisted clearance mechanisms,

contributing to the maintenance of oral micro-ecological balance

(131). ZG16B also binds to the

lipoteichoic acid of the oral bacterium Enterococcus

faecalis, inhibiting activation of the TLR2/NF-κB pathway in

macrophages, alleviating inflammation and regulating immune

responses to oral infections (132). ZG16B expression is

downregulated in the oral salivary glands and saliva of patients

with chronic graft-vs.-host disease, which may be related to

salivary gland dysfunction (133). Furthermore, ZG16B has potential

value as a biomarker or therapeutic target in diseases such as

atherosclerosis (decreased expression in urine), acute coronary

syndrome (decreased expression in urine) (134), dry eye syndrome (decreased

expression in tear fluid) (135), multiple sclerosis (decreased

expression in tear fluid) (136), Parkinson's disease (elevated

expression in brain tissue) (137) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

(elevated expression in lung tissue) (138).

Overall, ZG16B shows promise as a biomarker for both

diagnosis and prognosis. Its high expression in pancreatic,

colorectal and ovarian cancers supports its potential for use in

early diagnosis. Elevated ZG16B levels are also associated with

worse survival in patients with colorectal or ovarian cancer,

whereas they are linked to a more favorable prognosis in patients

with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. These findings

highlight the value of ZG16B in cancer diagnosis and prognosis,

with potential for tailored therapies.

Notably, while most current research focuses on the

tissue-level expression of ZG16B and its relevance to cancer,

clinical evidence supporting the detection of circulating ZG16B for

early diagnosis or prognostic prediction in patient cohorts remains

lacking (19). As a secreted

protein with carbohydrate-binding sites and

glycosaminoglycan-binding capabilities, ZG16B possesses the

biological potential to be released into blood and other body

fluids, making it a promising candidate for liquid biopsy (139-144). Future prospective cohort

studies are required to validate critical parameters such as

sensitivity, specificity and area under the curve for testing

circulating ZG16B in patients with cancer, and to compare its

performance with existing biomarkers.

Targeting ZG16B has potential for tumor prevention

and therapy in different types of cancer. In a mouse model

susceptible to breast cancer, treatment with both the

chemopreventive agents bexarotene and carvedilol has been reported

to suppress ZG16B expression, reducing the proliferation and

migration of non-malignant breast cells (48). Similarly, treatment with

anti-ZG16B antibody, together with docetaxel displays strong

antitumor effects in an ovarian cancer mouse model (49). Furthermore, inhibiting ZG16B

expression in pancreatic cancer stem cells can reduce the

expression levels of multidrug resistant protein 5 and

ribonucleotide reductase M2, thus increasing the sensitivity of

these cells to gemcitabine and 5-fluorouracil in a pancreatic

cancer mouse model (145,146). Additionally, ZG16B can

upregulate the expression of type I interferon-α receptor in

pancreatic cancer cells to activate downstream TYK2 and STAT1,

which increases their resistance to oncolytic virus H-1 infection,

suggesting the important role of targeting ZG16B in oncolytic

virotherapy (147).

A multicenter, open-label Phase I/IIa clinical

trial is currently testing the efficacy and safety of humanized

anti-ZG16B for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer

(NCT05141149, ClinicalTrials.gov) (23-25). The study population consists of

adults with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who

have relapsed in response to multiple lines of chemotherapy. These

patients receive PBP1510, a novel humanized IgG1 monoclonal

antibody against ZG16B, either as monotherapy or in combination

with gemcitabine. If successful, this therapeutic strategy may

offer new treatment options for patients with pancreatic cancer in

the future.

In summary, targeting ZG16B offers promising

therapeutic strategies across multiple types of cancer. Preclinical

studies have demonstrated that inhibiting ZG16B expression in

cancer models may reduce tumor cell proliferation, migration and

resistance to chemotherapy. Therapeutic approaches include RNA

aptamers, TSRs and monoclonal antibodies, such as PMAb83, which

have potential to inhibit tumor growth, metastasis and

angiogenesis. Additionally, the ongoing clinical trial of PBP1510,

a monoclonal antibody against ZG16B for patients with pancreatic

cancer, holds potential for providing new treatment options for

patients with advanced cancer.

ZG16B is a promising regulator in tumor progression

and immune responses, but several challenges remain. The lack of

high-resolution structural data, unclear role of PTMs and

unidentified receptors hinder a full understanding of its molecular

mechanisms. Its multifunctional roles and varied expression across

diseases further complicate its therapeutic targeting. Overcoming

these challenges will require advanced structural studies,

molecular profiling and disease-specific models to fully explore

its therapeutic potential.

Future research should clarify the

carbohydrate-binding specificity of the ZG16B lectin domain and

determine how PTMs, such as phosphorylation, N-myristoylation and

glycosylation, affect its structural stability and downstream

signaling. Integrating high-resolution structural approaches with

site-directed mutagenesis or PTM-deficient ZG16B mutants will

enable to precisely map its modification-dependent functional

motifs. These studies will reveal how ZG16B orchestrates tumor

progression and immune modulation at the molecular level.

Defining the upstream and downstream regulatory

networks of ZG16B remains essential for understanding its

pleiotropic roles across different types of cancer. Particular

attention should be paid to transcriptional and

post-transcriptional regulation by noncoding RNAs (such as

microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs) as well as modulation by major

oncogenic pathways, such as NF-κB, MAPK and PI3K/AKT. Parallel

efforts to identify and validate ZG16B receptors, including

integrins, TLR family members or as-yet-uncharacterized surface

proteins, will clarify how extracellular ZG16B is converted into

cellular responses. CRISPR-based regulatory screening and

multi-omics profiling may accelerate the discovery of

ZG16B-centered signaling hubs and refine the understanding of its

functional connectivity in the TME.

A deeper understanding of ZG16B-receptor

interactions will lay the foundation for developing ZG16B-targeted

precision therapies. High-resolution structural studies should map

critical binding interfaces to support rational design of

small-molecule inhibitors using computational docking and molecular

dynamics modeling. Concurrently, developing monoclonal antibodies

or biologics that disrupt ZG16B or its receptor engagement may

provide new options for modulating immune suppression or tumor

progression. Rigorous evaluation of these therapeutic strategies in

in vitro and in vivo models, particularly in tumors

with high ZG16B expression, will be crucial for determining

feasibility and guiding translational development.

ZG16B expression dysregulation in cardiovascular,

neurological and autoimmune diseases suggests that its biological

relevance extends far beyond malignancy. Investigating its roles in

chronic inflammation, endothelial activation or immune

dysregulation using disease-specific models, such as

atherosclerosis, neuroinflammation or autoimmune liver disease, may

reveal conserved mechanisms shared with cancer biology. These

studies have the potential not only to define ZG16B as a

cross-disease biomarker but also to provide therapeutic

opportunities in non-oncological conditions where ZG16B-driven

pathways remain largely unexplored.

The present review comprehensively summarizes the

research progress on the oncogenic roles of ZG16B. As a secretory

protein, ZG16B can activate multiple signaling pathways, including

TLR, CXCR4, β-catenin and FAK, to promote tumor cell proliferation,

migration, invasion and angiogenesis. ZG16B is crucial for tumor

development and metastasis by reshaping the TME and regulating

immune cell functions, including MDSCs, TAMs and DCs. ZG16B is

highly expressed in various types of cancer, and also has potential

value for non-invasive tumor diagnosis and prognosis. Furthermore,

treatment strategies targeting ZG16B have potential to serve as new

therapeutic options for multiple types of cancer.

Not applicable.

PW and YK conceived and designed the study. XMC,

YBL, JXZ, ZSY, LYZ and XYZ contributed equally to literature

review, interpretation, synthesis, and writing the first draft of

the manuscript and preparing the figures. PW and YK edited the

manuscript and were responsible for critical revisions. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82460461), the Medical

Subject Leader of Yunnan Province (General Surgery) (grant no.

D-2024029), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Project for Excellent

Young Scholars (grant no. 202401AW070003), the Young and Mid-aged

Academic and Technical Leader Reserve Talent Program of Yunnan

Province (grant no. 202205AC160063), the Beijing Bethune Charitable

Foundation (grant no. STLKY0089), the Top Talent Project of Kunming

Medical University-Yang Ke to Yang Ke, and the Graduate Research

Project of the Yunnan Provincial Department of Education Scientific

Research Fund (grant no. 2025Y0385) to Yu-Bo Liang.

|

1

|

Xiang J, Li Y, Mei S, Ou Z, Wang L, Ke Y

and Li Z: Novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies based on

PANoptosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Med.

22:928–939. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li J, Wang QB, Liang YB, Chen XM, Luo WL,

Li YK, Chen X, Lu QY and Ke Y: Tumor-associated lymphatic vessel

density is a reliable biomarker for prognosis of esophageal cancer

after radical resection: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Front

Immunol. 15:14534822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Li J, Liang YB, Wang QB, Li YK, Chen XM,

Luo WL, Lakang Y, Yang ZS, Wang Y, Li ZW and Ke Y: Tumor-associated

lymphatic vessel density is a postoperative prognostic biomarker of

hepatobiliary cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front

Immunol. 15:15199992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Xia F, Yi Q, Xu Z, Zhou Z, Tang H, Zhang K

and Yan Y: Microbial modulation as a game changer: Boosting

immunotherapy efficacy in breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol.

117:152–167. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xu Z, Zhou H, Li T, Yi Q, Thakur A, Zhang

K, Ma X, Qin JJ and Yan Y: Application of biomimetic nanovaccines

in cancer immunotherapy: A useful strategy to help combat

immunotherapy resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 75:1010982024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang R, Wang C, Lu L, Yuan F and He F:

Baicalin and baicalein in modulating tumor microenvironment for

cancer treatment: A comprehensive review with future perspectives.

Pharmacol Res. 199:1070322024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Du M, Sun L, Guo J and Lv H: Macrophages

and tumor-associated macrophages in the senescent microenvironment:

From immunosuppressive TME to targeted tumor therapy. Pharmacol

Res. 204:1071982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xu M, Li Y, Liu Y, Chang J, Zhou C, Weng

W, Sun H, Tan C, Wang X, Wang X, et al: The development and

implementation of pathological parameters and molecular testing

impact prognosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Natl Cancer Cent.

4:74–85. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang Y, Nong J, Lu B, Gao Y, Hu M, Chen C,

Zhang L, Tan J, Yang X, Lin PP, et al: Disseminated tumor cells in

bone marrow as predictive classifiers for small cell lung cancer

patients. J Natl Cancer Cent. 4:335–345. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li N, Song K, Chen H and Dai M: Advance

and challenge of DNA methylation as cancer biomarkers for risk

stratification, screening and early detection. J Natl Cancer Cent.

5:108–112. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim SA, Lee Y, Jung DE, Park KH, Park JY,

Gang J, Jeon SB, Park EC, Kim YG, Lee B, et al: Pancreatic

adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor (PAUF), a novel up-regulated

secretory protein in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci.

100:828–836. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kanagawa M, Satoh T, Ikeda A, Nakano Y,

Yagi H, Kato K, Kojima-Aikawa K and Yamaguchi Y: Crystal structures

of human secretory proteins ZG16p and ZG16b reveal a

Jacalin-related β-prism fold. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

404:201–205. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Song J, Lee J, Kim J, Jo S, Kim YJ, Baek

JE, Kwon ES, Lee KP, Yang S, Kwon KS, et al: Pancreatic

adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor (PAUF) enhances the accumulation

and functional activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 7:51840–51853. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lee M, Ham H, Lee J, Lee ES, Chung CH,

Kong DH, Park JR and Lee DK: TGF-β-induced PAUF plays a pivotal

role in the migration and invasion of human pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma cell line panc-1. Int J Mol Sci. 25:114202024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lee Y, Kim SJ, Park HD, Park EH, Huang SM,

Jeon SB, Kim JM, Lim DS and Koh SS: PAUF functions in the

metastasis of human pancreatic cancer cells and upregulates CXCR4

expression. Oncogene. 29:56–67. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Youn SE, Jiang F, Won HY, Hong DE, Kang

TH, Park YY and Koh SS: PAUF induces migration of human pancreatic

cancer cells exclusively via the TLR4/MyD88/NF-ĸB signaling

pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 23:114142022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kim JH, Na HY, Jung K, Jang D, Youn Y, Kim

DH, Han HD and Hwang JH: Quantitative immunohistochemistry analysis

of pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor expression in

pancreatic cancer and its prognostic significance. World J

Gastrointest Oncol. 17:1090552025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Choi CH, Kang TH, Song JS, Kim YS, Chung

EJ, Ylaya K, Kim S, Koh SS, Chung JY, Kim JH, et al: Elevated

expression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor (PAUF)

is associated with poor prognosis and chemoresistance in epithelial

ovarian cancer. Sci Rep. 8:121612018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Barderas R, Mendes M, Torres S, Bartolome

RA, Lopez-Lucendo M, Villar-Vazquez R, Pelaez-Garcia A, Fuente E,

Bonilla F and Casal JI: In-depth characterization of the secretome

of colorectal cancer metastatic cells identifies key proteins in

cell adhesion, migration, and invasion. Mol Cell Proteomics.

12:1602–1620. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kim YH, Moon JY, Kim EO, Lee SJ, Kang SH,

Kim SK, Heo K, Lee Y, Kim H, Kim KT, et al: Efficient targeting and

tumor retardation effect of pancreatic adenocarcinoma up-regulated

factor (PAUF)-specific RNA replacement in pancreatic cancer mouse

model. Cancer Lett. 344:223–231. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kim SJ, Chang S, Lee Y, Kim NY, Hwang Y,

Min HJ, Yoo KS, Park EH, Kim S, Chung YH, et al: A

PAUF-neutralizing antibody targets both carcinoma and endothelial

cells to impede pancreatic tumor progression and metastasis.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 454:144–150. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kim YH, Sung HJ, Kim S, Kim EO, Lee JW,

Moon JY, Choi K, Jung JE, Lee Y, Koh SS, et al: An RNA aptamer that

specifically binds pancreatic adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor

inhibits migration and growth of pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer

Lett. 313:76–83. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

King D, Tai D, Feliú J, Kim J,

Mandakhalikar KD, Lim ML, Pradhan S and Park YY: First-in-human

phase 1/2a study of PBP1510 (anti-PAUF mAb) in advanced/metastatic

pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Safety results from early combination

cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 43:e163632025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Feliu J, Ghanem I, King D, Park YY, Kim J,

Pradhan S, Ho J, Loh WQ and Mandakhalikar KD: PBP1510, a novel

monoclonal antibody targeting pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated

factor (PAUF): Phase 1/2a monotherapy and combination with

gemcitabine in patients with advanced/metastatic pancreatic cancer.

J Clin Oncol. 42:e162962024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Mandakhalikar KD, Koh SS, Jeong SY,

Moshinsky D, Feyaerts P, Karuna R, Kim J, Jaison L, Pradhan S, Kim

YJ and Park J: First-in-class monoclonal antibody (mAb) PBP1510

targeting pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor (PAUF) for

pancreatic cancer (PC) treatment: Preclinical perspectives. J Clin

Oncol. 40:e162742022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhang H, Yngvadottir B, Andreou A, Cole Y,

Woodward ER, Whitworth J and Maher ER: Clinical and genetic

features of multiple primary tumours cohorts with a renal cell

carcinoma: Implications for molecular genetic investigations. Int J

Cancer. 157:2532–2543. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Turner JA, Van Gulick RJ, Robinson WA,

Mughal T, Tobin RP, MacBeth ML, Holman B, Classon A, Bagby SM,

Yacob BW, et al: Expanding the landscape of oncogenic drivers and

treatment options in acral and mucosal melanomas by targeted

genomic profiling. Int J Cancer. 155:1792–1807. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mullins JJ, Mullins LJ, Dunbar DR, Brammar

WJ, Gross KW and Morley SD: Identification of a human ortholog of

the mouse Dcpp gene locus, encoding a novel member of the

CSP-1/Dcpp salivary protein family. Physiol Genomics. 28:129–140.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Song H, Song J, Kim YJ, Jeong HH, Min HJ

and Koh SS: DCPP1 is the mouse ortholog of human PAUF that

possesses functional analogy in pancreatic cancer. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 493:1498–1503. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang S, He Z, Wang H and Zhai J: Signal

peptides: From molecular mechanisms to applications in protein and

vaccine engineering. Biomolecules. 15:8972025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Park HD, Lee Y, Oh YK, Jung JG, Park YW,

Myung K, Kim KH, Koh SS and Lim DS: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

upregulated factor promotes metastasis by regulating TLR/CXCR4

activation. Oncogene. 30:201–211. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Cheng M, Guan Y, Xin X, Yi X and Liu Y:

Targeting p38 MAPK signaling pathway: Quercetin as a novel therapy

for TMJ synovitis. Int J Mol Med. 57:212026.

|

|

33

|

Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer

G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer TAP, Rempfer C,

Bordoli L, et al: SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein

structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:W296–W303. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kumazawa-Inoue K, Mimura T,

Hosokawa-Tamiya S, Nakano Y, Dohmae N, Kinoshita-Toyoda A, Toyoda H

and Kojima-Aikawa K: ZG16p, an animal homolog of beta-prism fold

plant lectins, interacts with heparan sulfate proteoglycans in

pancreatic zymogen granules. Glycobiology. 22:258–266. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kleene R, Dartsch H and Kern HF: The

secretory lectin ZG16p mediates sorting of enzyme proteins to the

zymogen granule membrane in pancreatic acinar cells. Eur J Cell

Biol. 78:79–90. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kanagawa M, Liu Y, Hanashima S, Ikeda A,

Chai W, Nakano Y, Kojima-Aikawa K, Feizi T and Yamaguchi Y:

Structural basis for multiple sugar recognition of Jacalin-related

human ZG16p lectin. J Biol Chem. 289:16954–16965. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Tateno H, Yabe R, Sato T, Shibazaki A,

Shikanai T, Gonoi T, Narimatsu H and Hirabayashi J: Human ZG16p

recognizes pathogenic fungi through non-self polyvalent mannose in

the digestive system. Glycobiology. 22:210–220. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hanashima S, Gotze S, Liu Y, Ikeda A,

Kojima-Aikawa K, Taniguchi N, Varon Silva D, Feizi T, Seeberger PH

and Yamaguchi Y: Defining the interaction of human soluble lectin

ZG16p and mycobacterial phosphatidylinositol mannosides.

Chembiochem. 16:1502–1511. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mito A, Nakano Y, Saitoh T, Gouraud SSS,

Yamaguchi Y, Sato T, Sasaki N and Kojima-Aikawa K: Lectin ZG16p

inhibits proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells via its

carbohydrate-binding sites. Glycobiology. 28:21–31. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Mito A, Kumazawa-Inoue K and Kojima-Aikawa

K: ZG16p, an animal homologue of plant beta-prism fold lectins:

Purification methods of natural and recombinant ZG16p and

inhibition assay of cancer cell growth using ZG16p. Methods Mol

Biol. 2132:339–347. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Thevenod F, Braun M, Roussa E and Fuller

CM: Molecular characterisation of pancreatic zymogen granule ion

channel and regulator proteins involved in exocytosis. J Korean Med

Sci. 15(Suppl 1): S51–52. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Braun M and Thevenod F: Photoaffinity

labeling and purification of ZG-16p, a high-affinity

dihydropyridine binding protein of rat pancreatic zymogen granule

membranes that regulates a K(+)-selective conductance. Mol

Pharmacol. 57:308–316. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kalus I, Hodel A, Koch A, Kleene R,

Edwardson JM and Schrader M: Interaction of syncollin with GP-2,

the major membrane protein of pancreatic zymogen granules, and

association with lipid microdomains. Biochem J. 362:433–442. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Cronshagen U, Voland P and Kern HF: cDNA

cloning and characterization of a novel 16 kDa protein located in

zymogen granules of rat pancreas and goblet cells of the gut. Eur J

Cell Biol. 65:366–377. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Schmidt K, Schrader M, Kern HF and Kleene

R: Regulated apical secretion of zymogens in rat pancreas.

Involvement of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored

glycoprotein GP-2, the lectin ZG16p, and

cholesterol-glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains. J Biol Chem.

276:14315–14323. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Schmidt K, Dartsch H, Linder D, Kern HF

and Kleene R: A submembranous matrix of proteoglycans on zymogen

granule membranes is involved in granule formation in rat

pancreatic acinar cells. J Cell Sci. 113(Pt 12): 2233–2242. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cho IR, Koh SS, Min HJ, Kim SJ, Lee Y,

Park EH, Ratakorn S, Jhun BH, Oh S, Johnston RN and Chung YH:

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor (PAUF) enhances the

expression of β-catenin, leading to a rapid proliferation of

pancreatic cells. Exp Mol Med. 43:82–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lengyel M, Molnar A, Nagy T, Jdeed S,

Garai I, Horvath Z and Uray IP: Zymogen granule protein 16B (ZG16B)

is a druggable epigenetic target to modulate the mammary

extracellular matrix. Cancer Sci. 116:81–94. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

49

|

Kim YJ, Jiang F, Park J, Jeong HH, Baek

JE, Hong SM, Jeong SY and Koh SS: PAUF as a target for treatment of

high PAUF-expressing ovarian cancer. Front Pharmacol.

13:8906142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liu PF, Wu YY, Hu Y, Wang L, He SB, Zhu YB

and Zhu XG: Silencing of pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated

factor by RNA interference inhibits the malignant phenotypes of

human colorectal cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 30:213–220. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Sasahira T, Kurihara M, Nishiguchi Y,

Nakashima C, Kirita T and Kuniyasu H: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

up-regulated factor has oncogenic functions in oral squamous cell

carcinoma. Histopathology. 70:539–548. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Wang P and Kong G: Comprehensive analysis

of angiogenesis and ferroptosis genes for predicting the survival

outcome and immunotherapy response of hepatocellular carcinoma. J

Hepatocell Carcinoma. 11:1845–1859. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hong X, Hu D, Zhou WJ, Wang XD, Huang LH,

Huang TA, Guan YW, Qian J and Ding WB: ALBI grade analyses of TACE

combined with anti-angiogenesis therapies plus PD-1 inhibitors

versus anti-angiogenesis therapies plus PD-1 inhibitors in advanced

HCC. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 11:2505–2514. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Li YK, Wu S, Wu YS, Zhang WH, Wang Y, Li

YH, Kang Q, Huang SQ, Zheng K, Jiang GM, et al: Portal venous and

hepatic arterial coefficients predict post-hepatectomy overall and

recurrence-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma:

A retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 11:1389–1402. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang QB, Luo WL, Li YK, Li J, Yang ZS,

Zhao K, Lakang Y, Liang YB, Chen XM, Zuo JX, et al: Tumor

compression of the hepatic or portal vein predicts the presence of

microvascular invasion and satellite nodules in hepatocellular

carcinoma: A retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma.

12:2055–2067. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhu Y, Hu Y, Yang C, Huang S, Wen J, Huang

W and Xiao S: Progress of angiogenesis signal pathway and

antiangiogenic drugs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Curr Mol

Pharmacol. 17:e187614292909332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liu Y, Liu Y, Sun X, Wang Y, Du C and Bai

J: Morphologically transformable peptide nanocarriers coloaded with

doxorubicin and curcumin inhibit the growth and metastasis of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Mater Today Bio. 24:1009032023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Luo WL, Wang QB, Li YK, Liang YB, Li J,

Chen XM, Lakang Y, Yang ZS, Zuo JX, Wang W, et al: Impact of middle

hepatic vein resection during hemihepatectomy on surgical outcomes

and long-term prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma: A

retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 12:2681–2692. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kim SJ, Lee Y, Kim NY, Hwang Y, Hwang B,

Min JK and Koh SS: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor, a

novel endothelial activator, promotes angiogenesis and vascular

permeability. Oncogene. 32:3638–3647. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Bao S, Darvishi M, H Amin A, Al-Haideri

MT, Patra I, Kashikova K, Ahmad I, Alsaikhan F, Al-Qaim ZH,

Al-Gazally ME, et al: CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) blockade in

cancer treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:7945–7968. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wakasugi R, Suzuki K and Kaneko-Kawano T:

Molecular mechanisms regulating vascular endothelial permeability.

Int J Mol Sci. 25:64152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang QB, Li J, Zhang ZJ, Li YK, Liang YB,

Chen XM, Luo WL, Lakang Y, Yang ZS, Liu GY, et al: The

effectiveness and safety of therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma

with tumor thrombus in the hepatic vein, inferior vena cave and/or

right atrium: A systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis.

Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 25:561–570. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Racacho KJ, Shiau YP, Villa R, Mahri S,

Tang M, Lin TY and Li Y: The tumor immune microenvironment:

Implications for cancer immunotherapy, treatment strategies, and

monitoring approaches. Front Immunol. 16:16218122025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Liang X, Guo J, Wang X, Luo B, Fu R, Chen

H, Yang Y, Jin Z, Lin C, Zang A, et al: Overexpression of ornithine

decarboxylase 1 mediates the immune-deserted microenvironment and

poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Natl Cancer

Cent. 5:57–74. 2024.

|

|

65

|

Xu W, Lu J, Zhang H and Ye D: Decoding the

tumor microenvironment: Insights into immunotherapy and beyond. J

Natl Cancer Cent. 5:426–428. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Wang X, Wang C, Liu W, Thakur A, Zhang K,

Xu Z and Li J: The roles of ultrasound-responsive nanomaterials in

enhancing cancer immunotherapy. Pharmacol Res. 221:1079752025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Jiang Q, He J, Zhang H, Chi H, Shi Y and

Xu X: Recent advances in the development of tumor

microenvironment-activatable nanomotors for deep tumor penetration.

Mater Today Bio. 27:1011192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Bao X, Sun M, Meng L, Zhang H, Yi X and

Zhang P: Applications of pyroptosis activators in tumor

immunotherapy. Mater Today Bio. 28:1011912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Wang J, Chen Z, Liu W, Xu Z, Liu H, Li Y

and Yan Y: Harnessing plant-derived natural compounds to target

ferroptosis, pyroptosis, immune modulation and renin-angiotensin

system in renal cell carcinoma. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone

Syst. 26:147032032513863092025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Wang D, Zhang Z, Yang L, Zhao L, Liu Z and

Lou C: PD-1 inhibitors combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors

with or without hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy for the

first-line treatment of HBV-related advanced hepatocellular

carcinoma: A retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma.

11:1157–1170. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Chen H, Li J, Cao D and Tang H:

Construction of a prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma

based on macrophage polarization-related genes. J Hepatocell

Carcinoma. 11:857–878. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Wang Z, Ge Q, Mo R, Lu J, Tian X, Anwaier

A, Ye S, Zhou S, Guo W, Cai C, et al: Spatial and maturity

heterogeneity of tertiary lymphoid structures shapes immune

microenvironment and progression in prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer

Cent. 5:501–514. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Li J, Liang YB, Wang QB, Luo WL, Chen XM,

Lakang Y, Yang ZS, Zuo JX, Li YK, Li ZW, et al: Rechallenge with

immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma: A narrative review. Liver Cancer. Oct 31–2025.Epub ahead

of print. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Kudo M: Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose

positron emission tomography: A potential imaging biomarker for

predicting response to combination immunotherapy in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 14:511–517. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Zhao Q, Wei T, Ma R, Fu Y, Yang R, Su Y,

Yu Y, Li B and Li Y: Progress on immuno-microenvironment and

immune-related therapies in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei.

Cancer Biol Med. 21:586–605. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Zhang W, Wang S, Zhang H, Meng Y, Jiao S,

An L and Zhou Z: Modeling human gastric cancers in immunocompetent

mice. Cancer Biol Med. 21:553–570. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Aoki T, Kudo M, Ueshima K, Morita M,

Chishina H, Takita M, Hagiwara S, Ida H, Minami Y, Tsurusaki M and

Nishida N: Incidence of hyper progressive disease in combination

immunotherapy and anti-programmed cell death protein 1/programmed

death-ligand 1 monotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular

carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 13:56–69. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Aoki T, Nishida N, Kurebayashi Y, Sakai K,

Morita M, Chishina H, Takita M, Hagiwara S, Ida H, Ueshima K, et

al: Two distinct characteristics of immune microenvironment in

human hepatocellular carcinoma with Wnt/β-catenin mutations. Liver

Cancer. 13:285–305. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Lin Y, Ruze R, Zhang R, Tuergan T, Wang M,

Tulahong A, Zhu D, Yuan Z, Jiang T, Aji T and Shao Y:

Immunometabolic targets in CD8(+) T cells within the tumor

microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer.

14:474–496. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Luo M, Zhao F, Cheng H, Su M and Wang Y:

Macrophage polarization: An important role in inflammatory

diseases. Front Immunol. 15:13529462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Yang L, Zhang Y and Yang L: Adenosine

signaling in tumor-associated macrophages and targeting adenosine

signaling for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Med. 21:995–1011.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Nishida N and Kudo M: Genetic/Epigenetic

alteration and tumor immune microenvironment in intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma: Transforming the immune microenvironment with

molecular-targeted agents. Liver Cancer. 13:136–149. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Xu Z, Zhou Z, Yang X, Thakur A, Han N, Li

HT, Li LG, Hu J, Li TF and Yan Y: Determining M2 macrophages

content for the anti-tumor effects of metal-organic

framework-encapsulated pazopanib nanoparticles in breast cancer. J

Nanobiotechnology. 22:4292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zhang J, Wang L, Guo H, Kong S, Li W, He

Q, Ding L and Yang B: The role of Tim-3 blockade in the tumor

immune microenvironment beyond T cells. Pharmacol Res.

209:1074582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lv Q, Zhang Y, Gao W, Wang J, Hu Y, Yang

H, Xie Y, Lv Y, Zhang H, Wu D, et al: CSF1R inhibition reprograms

tumor-associated macrophages to potentiate anti-PD-1 therapy

efficacy against colorectal cancer. Pharmacol Res. 202:1071262024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Wang X, Chen J and Jia G: From dichotomy

to diversity: Deciphering the multifaceted roles of

tumor-associated macrophages in cancer progression and therapy.

Cancer Biol Med. 21:132–138. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Chen J, Li H, Zhuo J, Lin Z, Hu Z, He C,

Wu X, Jin Y, Lin Z, Su R, et al: Impact of immunosuppressants on

tumor pulmonary metastasis: New insight into transplantation for

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Med. 21:1033–1049. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Dong Y, Khan L and Yao Y: Immunological

features of EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer and clinical

practice: A narrative review. J Natl Cancer Cent. 4:289–298.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Kim YJ, Nanda SS, Jiang F, Pyo SY, Han JY,

Koh SS and Kang TH: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor

(PAUF) transforms human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages

with immunosuppressive action. Int J Mol Sci. 25:115452024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhang Y, Ji S, Miao G, Du S, Wang H, Yang

X, Li A, Lu Y, Wang X and Zhao X: The current role of dendritic

cells in the progression and treatment of colorectal cancer. Cancer

Biol Med. 21:769–783. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Kudo M: Challenges in adjuvant

immunotherapy after resection or ablation for hepatocellular

carcinoma at high-risk of recurrence. Liver Cancer. 13:573–578.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Tang X, Zhang J, Sui D, Xu Z, Yang Q, Wang

T, Li X, Liu X, Deng Y and Song Y: Durable protective efficiency

provide by mRNA vaccines require robust immune memory to antigens

and weak immune memory to lipid nanoparticles. Mater Today Bio.

25:1009882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Chen X, Yang Z and Li M: Molecular

regulatory mechanisms and diagnostic potential of dendritic

cell-derived exosomes in liver transplantation: From immune

tolerance induction to translational challenges. Front Immunol.

16:16579562025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Kang TH, Kim YS, Kim S, Yang B, Lee JJ,

Lee HJ, Lee J, Jung ID, Han HD, Lee SH, et al: Pancreatic

adenocarcinoma upregulated factor serves as adjuvant by activating

dendritic cells through stimulation of TLR4. Oncotarget.

6:27751–27762. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Liao Y and Yang H: Metabolic regulation of

innate immunity in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Med.

20:898–902. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Xi W, Wu W, Zhou L, Zhang Q, Yang S, Huang

L, Lu Y, Wang J, Chi X and Kang Y: Multifunctional nanoparticles

confers both multiple inflammatory mediators scavenging and

macrophage polarization for sepsis therapy. Mater Today Bio.

30:1014212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Qu Z, Guo Z, Yang C, Guan X, Cheng M, Wang

P and Xu D: Role of toll-like receptors in pulmonary immunity:

Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol.

16:16826492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Yang Y, Cui H, Li D, Chen L, Liu Y, Zhou

C, Li L, Feng M, Chen X, Cao Y and Gao Y: S100A8 promotes tumor

progression by inducing phenotypic polarization of microglia

through the TLR4/IL-10 signaling pathway in glioma. J Natl Cancer

Cent. 4:369–381. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Wang T, Liu C, Hu X, Yang N and Qiu C:

Senescent macrophages in cancer: Roles in tumor progression and

treatment opportunities. Cancer Biol Med. 22:439–459.

2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Fang Z, Ding X, Huang H, Jiang H, Jiang J

and Zheng X: Revolutionizing tumor immunotherapy: Unleashing the

power of progenitor exhausted T cells. Cancer Biol Med. 21:499–512.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Bauckneht M and Filippi L: Pentixather:

Paving the way for radioligand therapy in oncohematology. Expert

Rev Anticancer Ther. 24:205–209. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Gupta T, Mani S, Chatterjee A, Dasgupta A,

Epari S and Chinnaswamy G: Risk-stratification for treatment

de-intensification in WNT-pathway medulloblastoma: Finding the

optimal balance between survival and quality of survivorship.

Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 24:589–598. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Li SR, Wu ZZ, Yu HJ and Sun ZJ: Targeting

erythroid progenitor cells for cancer immunotherapy. Int J Cancer.

155:1928–1938. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Liang Y, Xie Y, Dang Z, Li M, Yu L, Wang

X, Wang P and Yang Z: Yiqi Liangxue Jiedu prescription inhibited

the canonical wnt pathway to prevent hepatocellular precancerous

lesions. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 11:2293–2308. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Wang J, Gao W, Yu H, Xu Y, Bai C, Cong Q

and Zhu Y: Research progress on the role of epigenetic methylation

modification in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma.

11:1143–1156. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Tyraskis A, Zen Y, Strautnieks S, Cook R,

Foskett P, De Vito C, Deheragoda M, Quaglia A, Heaton N, Davenport

M and Thompson RJ: High frequency of CTNNB1 variants associated

with benign and malignant liver tumors in patients with congenital

porto-systemic shunts. Liver Cancer. 14:408–419. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Higuchi Y, Nguyen C, Chimge NO, Ouyang C,

Teo JL and Kahn M: E7386 is not a specific CBP/β-catenin

antagonist. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 17:e2905232174092024.

|

|

108

|

Xue W, Zhu B, Zhao K, Huang Q, Luo H, Shou

Y, Huang Z and Guo H: Targeting LRP6: A new strategy for cancer

therapy. Pharmacol Res. 204:1072002024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Zhu X, Trehan R and Xie C: Primary liver

cancer organoids and their application to research and therapy. J

Natl Cancer Cent. 4:195–202. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Cho IR, Koh SS, Malilas W, Srisuttee R,

Moon J, Choi YW, Horio Y, Oh S and Chung YH: SIRT1 inhibits

proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells expressing pancreatic

adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor (PAUF), a novel oncogene, by

suppression of β-catenin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 423:270–275.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Du F, Xie Y, Wu S, Ji M, Dong B and Zhu C:

Expression and targeted application of claudins family in

hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases. J Hepatocell Carcinoma.

11:1801–1821. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Xia J, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Wang Y and Liu G:

Regulation of neutrophil extracellular traps in cancer. Int J

Cancer. 154:773–785. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Toshida K, Itoh S, Iseda N, Tanaka S,

Nakazono K, Tomiyama T, Yoshiya S, Toshima T, Harada N, Kohashi K,

et al: The impact of TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis

regulator on prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma: Association

with tumor microenvironment and ferroptosis. Liver Cancer.

14:36–57. 2024.

|

|

114

|

Lee YS, Kim SJ, Min HJ, Jo JY, Park EH and

Koh SS: PAUF promotes adhesiveness of pancreatic cancer cells by

modulating focal adhesion kinase. Exp Mol Med. 43:291–297. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Wang Y, Cheng S, Fleishman JS, Chen J,

Tang H, Chen ZS, Chen W and Ding M: Targeting anoikis resistance as

a strategy for cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat. 75:1010992024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Deng Z, Fan T, Xiao C, Tian H, Zheng Y, Li

C and He J: TGF-β signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9:612024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Elkoshi Z: TGF-β, IL-1β, IL-6 levels and

TGF-β/Smad pathway reactivity regulate the link between allergic

diseases, cancer risk, and metabolic dysregulations. Front Immunol.

15:13717532024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Du YQ, Yuan B, Ye YX, Zhou FL, Liu H,

Huang JJ and Wei YF: Plumbagin regulates snail to inhibit

hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vivo

and in vitro. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 11:565–580. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Qiu X, Dong L, Wang K, Zhong X, Xu H, Xu

S, Guo H, Wei X, Chen W and Xu X: Development and validation of a

novel nomogram integrated with hypoxic and lactate metabolic

characteristics for prognosis prediction in hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 11:241–255. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Wang P, Ke B and Ma G: Drug-tolerant

persister cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Cent. 4:1–5. 2023.

|

|

121

|

Yoo W, Choi H, Son YH, Lee J, Jo S, Jung

D, Kim YJ, Koh SS, Yang YR, Kwon ES, et al: Pancreatic cancer

induces muscle wasting by promoting the release of pancreatic

adenocarcinoma upregulated factor. Exp Mol Med. 53:432–445. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Kim SK, Song SY, Kim S, Cho NH, Yim GW,

Kim SW, Kim YT and Nam EJ: Association of pancreatic adenocarcinoma

up-regulated factor expression in ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma

with poor prognosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7:5103–5110.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Kim J, Chung JY, Kim TJ, Lee JW, Kim BG,

Bae DS, Choi CH and Hewitt SM: Genomic network-based analysis

reveals pancreatic adenocarcinoma up-regulating factor-related

prognostic markers in cervical carcinoma. Front Oncol. 8:4652018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Choi CH, Chung JY, Park HS, Jun M, Lee YY,

Kim BG and Hewitt SM: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor

expression is associated with disease-specific survival in cervical

cancer patients. Hum Pathol. 46:884–893. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Zhang T, Wang Y, Dong Y, Liu L, Han Y,

Wang H, Wei Q, Xia P, Ma W and Li L: Identification of novel

diagnostic biomarkers in prostate adenocarcinoma based on the

stromal-immune score and analysis of the WGCNA and ceRNA network.

Dis Markers. 2022:19091962022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Jin HJ, Jung S, DebRoy AR and Davuluri RV:

Identification and validation of regulatory SNPs that modulate

transcription factor chromatin binding and gene expression in

prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 7:54616–54626. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Chen W, Liao L, Lai H, Yi X and Wang D:

Identification of core biomarkers associated with pathogenesis and

prognostic outcomes of laryngeal squamous-cell cancer using

bioinformatics analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 277:1397–1408.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Lu H, Shi C, Liu X, Liang C, Yang C, Wan

X, Li L and Liu Y: Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic

biomarker in breast cancer. Open Med (Wars). 16:1–13. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Perumal N, Funke S, Wolters D, Pfeiffer N

and Grus FH: Characterization of human reflex tear proteome reveals

high expression of lacrimal proline-rich protein 4 (PRR4).

Proteomics. 15:3370–3381. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Wang Y, Luo H, Che G, Li Y, Gao J, Yang Q,

Zhou B, Gao L, Wang T, Liang Y, et al: Placental protein 14 as a

potential biomarker for diagnosis of preterm premature rupture of

membranes. Mol Med Rep. 18:113–122. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Ghosh S, Ahearn CP, Isabella CR, Marando

VM, Dodge GJ, Bartlett H, McPherson RL, Dugan AE, Jain S, Neznanova

L, et al: Human oral lectin ZG16B acts as a cell wall

polysaccharide probe to decode host-microbe interactions with oral

commensals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 120:e22163041202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Baik JE, Choe HI, Hong SW, Kang SS, Ahn

KB, Cho K, Yun CH and Han SH: Human salivary proteins with affinity

to lipoteichoic acid of Enterococcus faecalis. Mol Immunol.

77:52–59. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Costa-da-Silva AC, Aure MH, Dodge J,

Martin D, Dhamala S, Cho M, Rose JJ, Bassim CW, Ambatipudi K, Hakim

FT, et al: Salivary ZG16B expression loss follows exocrine gland

dysfunction related to oral chronic graft-versus-host disease.

iScience. 25:1035922021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

134

|

Martin-Lorenzo M, Zubiri I, Maroto AS,

Gonzalez-Calero L, Posada-Ayala M, de la Cuesta F, Mourino-Alvarez

L, Lopez-Almodovar LF, Calvo-Bonacho E, Ruilope LM, et al: KLK1 and

ZG16B proteins and arginine-proline metabolism identified as novel

targets to monitor atherosclerosis, acute coronary syndrome and

recovery. Metabolomics. 11:1056–1067. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Perumal N, Funke S, Pfeiffer N and Grus

FH: Proteomics analysis of human tears from aqueous-deficient and

evaporative dry eye patients. Sci Rep. 6:296292016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Salvisberg C, Tajouri N, Hainard A,

Burkhard PR, Lalive PH and Turck N: Exploring the human tear fluid:

Discovery of new biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Proteomics Clin

Appl. 8:185–194. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Sun Y, Ye L, Zheng Y and Yang Z:

Identification of crucial genes associated with Parkinson's disease

using microarray data. Mol Med Rep. 17:3775–3782. 2018.

|

|

138

|

Hu W and Xu Y: Transcriptomics in

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis unveiled: A new perspective from

differentially expressed genes to therapeutic targets. Front

Immunol. 15:13751712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Kunimune Y, Suehiro Y, Saeki I, Yamauchi

Y, Tanabe N, Matsumoto T, Higaki S, Fujii I, Suzuki C, Okayama N,

et al: Combination assay of methylated HOXA1 with tumor markers

shows high sensitivity for detection of early-stage hepatocellular

carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 13:487–497. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Zezulinski D, Hoteit MA, Kaplan DE,

Simeone A, Zhan T, Doria C, Ahmed FY, Roberts LR, Block TM and

Sayeed A: Detection of circulating mRNA variants in hepatocellular

carcinoma patients using targeted RNAseq. Liver Cancer. 14:555–586.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Garcia-Silva S, Marchetti D and Gallardo

M: Editorial: Liquid biopsies in hematological malignancies. Front

Immunol. 15:14403942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Li M, Zhang Y, Yu D, Yu Y and Ma W:

Immunotherapy biomarkers in brain metastases: Insights into tumor

microenvironment dynamics. Front Immunol. 16:16002612025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Zhang S, Zhao H, Wang K, Li L, Pan Q, Lu M

and Zhang X: Tracing the history of clinical practice of liquid

biopsy: A bibliometric analysis. Front Immunol. 16:15747362025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Sato K, Toh S, Murakami T, Nakano T, Hongo

T, Matsuo M, Hashimoto K, Sugasawa M, Yamazaki K, Ueki Y, et al:

Nationwide multi-centric prospective study for the identification

of biomarkers to predict the treatment responses of nivolumab

through comprehensive analyses of pretreatment plasma exosome mRNAs

from head and neck cancer patients (BIONEXT study). Front Immunol.

15:14644192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Cho JH, Kim SA, Park SB, Kim HM and Song

SY: Suppression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor

(PAUF) increases the sensitivity of pancreatic cancer to

gemcitabine and 5FU, and inhibits the formation of pancreatic

cancer stem like cells. Oncotarget. 8:76398–76407. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Gao CC, Xu XL, Li F, Gong BG, Liu S, Cui

YQ, Sun HC, Xu PY, Zheng YM and Jiang H: Silencing pancreatic

adenocarcinoma upregulated factor (PAUF) increases the sensitivity

of pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine. Tumour Biol.

37:7555–7564. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

147

|

Kaowinn S, Cho IR, Moon J, Jun SW, Kim CS,

Kang HY, Kim M, Koh SS and Chung YH: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

upregulated factor (PAUF) confers resistance to pancreatic cancer

cells against oncolytic parvovirus H-1 infection through IFNA

receptor-mediated signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

459:313–318. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|