The concept of autism spectrum disorder and

recent progress

Core symptoms and current epidemiological

status

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) encompasses a group

of pervasive neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by a broad

spectrum of symptoms, broadly categorized into core and associated

symptoms. Core symptoms include persistent deficits in social

interaction and communication, as well as restricted and repetitive

patterns of behavior and interests that significantly impair daily

functioning. By contrast, associated symptoms encompass attention

deficits, mood disturbances, sensory processing abnormalities,

sleep disorders, language impairment, anxiety, epilepsy, mania and

self-injurious behaviors. Core symptoms typically emerge in early

childhood and persist throughout life (1-3).

In recent years, increasing public awareness of ASD has coincided

with a steady increase in its rate of diagnosis, rendering it a

significant global public health concern. According to 2022 data

from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the

incidence of ASD in the USA reached ~1 in 31 children. Moreover,

the prevalence of ASD among boys is notably higher than that among

girls, with a male-to-female ratio of ~3.44:1 (4). Furthermore, advances in early

screening and diagnostic tools have enabled the identification of a

greater number of individuals with milder ASD phenotypes, thereby

enhancing epidemiological research in this field.

Large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

(5) and family-based genetic

analyses (6) have revealed that

ASD possesses a complex and highly heterogeneous genetic

background. Genetic factors are estimated to account for ~81% of

the risk of developing ASD, whereas environmental factors

contribute to a ~14-22% risk. Of note, >100 ASD-associated risk

genes have been identified, including neurexin 1 (NRXN1),

Src homology 3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 2/3 (SHANK2,

SHANK3) and chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 8

(CHD8). The principal mutation types include de novo

truncating mutations, missense mutations and copy number variations

(CNVs). These risk-associated genes influence gene expression,

neurogenesis, synaptic function and chromatin regulatory networks

(6-8).

By contrast, environmental factors primarily

influence early fetal development through maternal health

conditions and external exposures. A previous large-scale study

involving 22,156 cases of ASD across three Nordic countries

underscored the crucial role of perinatal and prenatal factors.

Maternal gestational hypertension (odds ratio, 1.4), preeclampsia

[relative risk (RR), 1.3], overweight or obesity (RR, 1.3) and an

advanced maternal age (≥35 years; RR, 1.3) were all shown to be

significantly associated with an increased risk of offspring

developing ASD. Moreover, an advanced paternal age (each 10-year

increase corresponding to a 21% rise in the risk of ASD),

interpregnancy intervals that are either too short (<12 months)

or too long (≥72 months) and exposure to specific medications, such

as valproic acid (VPA) during pregnancy, were also closely linked

to elevated risk of developing ASD (5). A previous study demonstrated that

the absolute risk of developing ASD reached 4.4% in the VPA-exposed

group as compared to the unexposed group with 1.5%. Thus, beyond

genetic predisposition, aberrations in the intrauterine environment

and maternal metabolic dysregulation may play a critical role in

disrupting fetal neurodevelopment and represent important triggers

for ASD (9).

Current treatment strategies and key

challenges

Early diagnosis and intervention for ASD are deemed

pivotal for improving the quality of life of affected children.

Such early interventions can enhance language abilities, social

communication skills and behavioral regulation, particularly when

administered during the rapid phase of neurodevelopment (<3

years of age). This timing is critical for optimizing long-term

outcomes, helping to maximize the cognitive, linguistic and social

capacities of children (8,10). The American Academy of Pediatrics

recommends autism screening at 18 and 24 months of age (https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/autism).

Currently, the primary diagnostic tools include the Modified

Checklist for Autism in Toddlers Revised (M-CHAT-R) (11), the Autism Diagnostic Observation

Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) and the Autism Diagnostic

Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (12).

Children who screen positive require comprehensive evaluations,

including behavioral observation and an in-depth analysis of

developmental history (3,8).

However, as the symptoms of ASD are heterogeneous and vary greatly

among individuals, early diagnosis remains challenging,

particularly in cases with atypical or mild presentations.

At present, treatment for ASD primarily focuses on

behavioral interventions and symptom management, as there is no

universally accepted cure (3).

The behavioral intervention remains the first-line approach,

commonly implemented through Early Intensive Behavioral

Intervention (EIBI) and Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral

Interventions (NDBI) (13).

EIBI is grounded in the principles of Applied

Behavior Analysis (ABA) and is typically designed for children

<5 years of age. It involves intensive therapy, usually at least

25 h per week over a minimum period of 1 year, to strengthen

social, language, cognitive and adaptive behaviors. Among NDBI, the

Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) (14) is the most representative

approach. It integrates multiple developmental domains, including

cognition, language, social interaction, motor skills and

imitation, into behavioral interventions. ESDM emphasizes creating

meaningful activities for children, fostering interactive

relationships and emotional engagement, and promoting the

generalization of learning. Motivating activities are incorporated

into daily routines to help children acquire new skills, improve

language, social and cognitive functioning, and reduce disruptive

behaviors (15). These

behavioral strategies currently constitute the cornerstone of ASD

therapy.

Pharmacological interventions are mainly used to

address comorbid symptoms, such as risperidone and aripiprazole,

which effectively reduce irritability and aggressive behaviors

(16). Methylphenidate,

atomoxetine and guanfacine may alleviate hyperactivity and

attention deficits. For sleep disturbances, melatonin is commonly

prescribed (8).

These interventions mainly aim to alleviate symptoms

and minimize the effect on daily life and quality of life, rather

than addressing the underlying causes of ASD. To date, to the best

of our knowledge, no medication has been shown to effectively treat

the core symptoms of ASD, and treatment outcomes vary widely among

individuals. Consequently, there is an urgent need to explore novel

treatment strategies, particularly those targeting the underlying

pathophysiological mechanisms, which have become a central focus of

contemporary ASD research.

Future directions for early diagnosis and

intervention

The future of early ASD diagnosis and intervention

hinges on precision, personalization and enhanced accessibility.

First, personalized intervention plans are crucial for addressing

the heterogeneity of ASD (17).

By integrating assessments of the behavioral, cognitive and

language abilities of a child, along with data-driven analytical

methods, more tailored interventions can be designed to meet

individual needs (18). In

addition, using biomarkers (e.g., miRNAs or exosomal components) to

aid in diagnosis and treatment offers a potential avenue for

refining interventions (19),

such as identifying neuroinflammatory features, which may enable

more targeted immunomodulatory therapies (20).

The integration of emerging technologies presents

new opportunities for the treatment of ASD. For instance,

mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exhibit tremendous promise owing to

their multilineage differentiation potential, immunomodulatory

properties, and capacity to secrete various neuroprotective factors

(21,22). Beyond enhancing the

neuroinflammatory microenvironment and supporting neuroplasticity

in vivo, MSCs also release exosomes that transport essential

proteins, nucleic acids, and miRNAs to repair damaged neurons and

glial cells (23). These

molecules, in turn, modulate gene expression and cell function,

mitigate neuroinflammation and repair synaptic structures (24). Exosomes possess low

immunogenicity, the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, and

the capacity for targeted delivery of specific bioactive molecules

(25,26). A number of studies have focused

on the use of MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) in ASD interventions,

exploring their potential mechanisms and translational applications

for improving social, communication and cognitive functions

(22,27-29).

Moreover, developing novel evaluation metrics is

crucial for assessing the efficacy of interventions. Researchers

can more comprehensively track the progress of a child in detection

and intervention by integrating behavioral data, neuroimaging

findings (30,31) and biomarker changes (32). Long-term follow-up assessments

further elucidate how specific strategies affect social adaptation

and overall quality of life in adulthood (33).

Lastly, enhancing the social awareness of ASD and

strengthening policy support are also required. Public education

campaigns can help reduce societal bias, and training programs for

parents and educators can improve the effectiveness of early

diagnosis and intervention (34). In this regard, additional funding

from government research agencies and related organizations can

expand the reach of innovative research and healthcare services for

individuals with ASD.

Overall, the advancements in ASD diagnosis and

intervention hinge on technological progress, cross-disciplinary

collaboration, and strategic resource allocation. By harmonizing

scientific breakthroughs with robust policy support, current

treatment barriers can be addressed and this may help foster

renewed optimism for children with ASD and their families.

Molecular genetics and neuropathology of

ASD

With deepening insight into ASD, research on its

etiology and pathogenesis has expanded from early, straightforward

genetic associations to a comprehensive framework encompassing

molecular pathology, neural network disruptions and

interdisciplinary approaches. In recent years, emerging

technologies, such as high-throughput single-cell sequencing

(35) and brain organoid models

(36), have rapidly evolved,

enabling a more in-depth analysis of gene-environment interactions

and neurodevelopmental abnormalities in ASD. These advances also

provide novel approaches to potential interventions and therapies.

Against this backdrop, the following sections provide a systematic

review of current research on ASD, focusing on genetic landscapes,

synaptic imbalances, inflammatory regulation, glial cell activation

and immune dysregulation (37).

Genetic characteristics and polygenic

complexity of ASD

Epidemiological studies in recent years have

underscored the dominant role of genetic factors in ASD, which is

recognized as a complex disorder driven largely by heritability.

Multiple twin studies consistently demonstrate much higher

concordance for ASD in monozygotic (MZ) than dizygotic (DZ) twins.

In a population-based study using standardized ADI-R/ADOS

assessments, probandwise concordance ranged from ~58-77% for MZ

twins and ~21-36% for DZ twins across strict-autism and broader ASD

definitions; rare sex-specific DZ subgroups can be lower (38). A previous meta-analysis further

indicates near-perfect MZ correlations (~98%) with DZ correlations

that vary by the assumed prevalence threshold, yielding substantial

heritability (~64-91%) and showing that estimates of the shared

environmental component are sensitive to modelled prevalence

(39). Through GWAS and familial

genetic analyses comparing large-scale datasets of individuals with

ASD and healthy controls, numerous ASD-associated susceptibility

genes and variations have been identified, including CHD8,

NRXN1, SHANK2, SHANK3 and contactin associated

protein 2 (CNTNAP2) (6-8,40). Among these genes, CHD8

encodes a chromatin remodeler that regulates a wide array of

neurodevelopmental genes by binding to their promoters and

enhancers. Previous studies have reported that CHD8

haploinsufficiency results in dysregulated transcriptional

programs, aberrant neurogenesis, and epigenetic abnormalities

(41). NRXN1 encodes the

presynaptic adhesion molecule neurexin-1, which interacts with

postsynaptic ligands such as neuroligins to form trans-synaptic

connections and is essential for synapse formation and homeostasis.

In ASD mouse models carrying NRXN1 mutations, CNVs have been

shown to cause synaptic connectivity defects, impairments in neural

circuit development and synaptic transmission, ultimately leading

to deficits in social interaction and communication (42). The SHANK gene family,

particularly SHANK3, functions as a core scaffolding and

signaling component of the postsynaptic density (PSD) at excitatory

synapses, orchestrating the organization of

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid and

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, cytoskeletal structures, and

intracellular signaling pathways. SHANK deficiency leads to

PSD disassembly, impaired synaptic plasticity, altered dendritic

spine morphology and excitatory/inhibitory imbalance, thereby

contributing to ASD-related behavioral abnormalities. Both animal

models and patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells studies

have provided strong evidence supporting these mechanisms (43,44). The CNTNAP2, a member of

the neurexin superfamily, is involved in axon-myelin interactions,

synaptic function and neuronal positioning. Early candidate gene

studies identified CNTNAP2 as being associated with ASD,

language impairment and epilepsy. The loss or mutation of

CNTNAP2 has been linked to abnormal neuronal migration

during development, defects in axonal and myelin function, and

disrupted excitatory neuronal activity (45).

The analysis of the Simons Simplex Collection (SSC)

has identified six key risk loci (1q21.1, 3q29, 7q11.23, 16p11.2,

15q11.2-13 and 22q11.2). These large CNVs likely harbor multiple

risk genes of moderate effect, primarily involving upstream

regulators of gene expression during neural development, as well as

synapse-related genes that directly impact neuronal structure and

function (6).

Exome sequencing data, when integrated with

functional annotations of different types of genetic variants

(e.g., rare single-nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions and

CNVs) and selection-pressure metrics, e.g., Loss of Function

Observed and Expected Upper Bound Fraction (LOEUF) scores, indicate

that the risk of developing ASD is strongly associated with rare

coding variants and de novo mutations. Among the genes

significantly linked to ASD (false discovery rate ≤0.001), de

novo protein-truncating variants, damaging missense variants

and CNVs account for 57.5, 21.1 and 8.44% of the genetic risk,

respectively. Notably, CNVs carry a markedly high relative risk

since they alter the copy number of large genomic segments,

potentially affecting multiple genes and leading to cumulative

effects (7).

CNVs frequently occur in gene-dense, functionally

important regions critical for neurodevelopment, synaptic

plasticity and chromatin regulation. Abnormalities in these regions

may lead to extensive functional disruption (46). In addition, CNVs can alter gene

dosage (e.g., an increase or decrease in gene copies), and

dosage-sensitive genes can exhibit significant biological effects

when copy numbers deviate from the normal (47,48). A number of CNVs also exhibit

pleiotropy, where a single gene may influence multiple biological

processes or phenotypes, so its dysregulation can affect various

systems concurrently (49).

Moreover, CNVs can disrupt regulatory elements (e.g., enhancers and

promoters) in non-coding regions, thereby altering gene expression

and regulatory networks (48).

The Genes associated with ASD exhibit a higher

expression in mature neurons, aligning with their roles in neuronal

maturation and synaptic connectivity. By contrast, genes linked to

developmental delay are predominantly active in immature neurons

and progenitor cells. This suggests that different gene networks

affect the nervous system at specific developmental stages

(7).

Core neuropathological mechanisms of

ASD

A primary pathological hallmark of ASD is abnormal

synaptic development and plasticity, primarily manifested as

disruptions in synapse formation and pruning. This leads to

excessive or insufficient synaptic connections, compromising the

precise establishment of neuronal networks (50-52). The excitatory and inhibitory

ratio, a core mechanism in synaptic signaling, is critically

disrupted in a number of cases, typically manifesting as excessive

excitatory activity [e.g., elevated glutamate receptor function

(53)] or diminished inhibitory

signaling (e.g., reduced gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor levels),

both of which may lead to neuronal circuit instability, driving

hyperexcitability or network dysregulation (54). Either scenario can result in

hyperactive or imbalanced neuronal networks. Furthermore, mutations

in ASD-associated genes, such as neuroligin 4 (NLGN4)

(55) and SHANK3

(56) can impair presynaptic

neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic receptor responsiveness,

thereby reducing synaptic transmission efficiency. Abnormalities in

synaptic plasticity processes, including long-term potentiation

(LTP) and long-term depression, further exacerbate these

dysfunctions, as reflected by impaired modulation of synaptic

strength in key brain regions, such as the hippocampus, prefrontal

cortex and amygdala (57).

Additionally, synaptic protein misfolding and the

activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress can lead not only to a

loss of synaptic function, but also to heightened neuroinflammation

via the unfolded protein response, thereby aggravating ASD

pathophysiology (58).

Collectively, these disruptions in synaptic development and

plasticity underlie prominent deficits in social interaction,

cognitive function, and behavioral patterns in ASD, providing

essential clues for understanding its molecular mechanisms and for

developing potential therapeutic approaches (59).

Developmental abnormalities in specific brain

regions are a crucial aspect of the neurobiological features of

ASD. Research indicates that both structure and function are

significantly affected in the prefrontal cortex (60), hippocampus (61) and basal ganglia (62). Alterations in causal connectivity

within the prefrontal cortex are closely linked to deficits in

social behaviors and cognitive functions, typified by an

excitatory/inhibitory signaling imbalance and diminished synaptic

plasticity (60). In the central

region of the hippocampus, which is critical for learning and

memory, reduced synaptic density and impaired LTP are commonly

observed in ASD and directly correlate with decreases in spatial

memory (61). Moreover,

abnormalities in basal ganglia circuitry, particularly those

involved in gating motor output, have been implicated in repetitive

and stereotypic behaviors; changes in synaptic transmission within

these pathways may affect behavior by modulating motor control and

reward mechanisms (62).

Such developmental anomalies manifest at the

micro-level of neuronal connections and alter interregional network

communication, thereby contributing to the diverse and complex

behavioral phenotypes of ASD. In-depth research into these brain

regions' developmental perturbations is instrumental in elucidating

the pathological mechanisms of ASD and lays the groundwork for

precision-targeted therapies.

Cytological basis of neuroinflammation in

ASD

Neuroinflammation and aberrant immune regulation

play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of ASD, with the activation

of microglia and astrocytes constituting a core cellular foundation

of this neuroinflammatory process. Microglia and astrocytes exhibit

distinct polarization states in the neuroinflammatory

microenvironment of ASD, with M1/A1 subtypes promoting injury and

M2/A2 subtypes supporting repair. The interplay of these brain

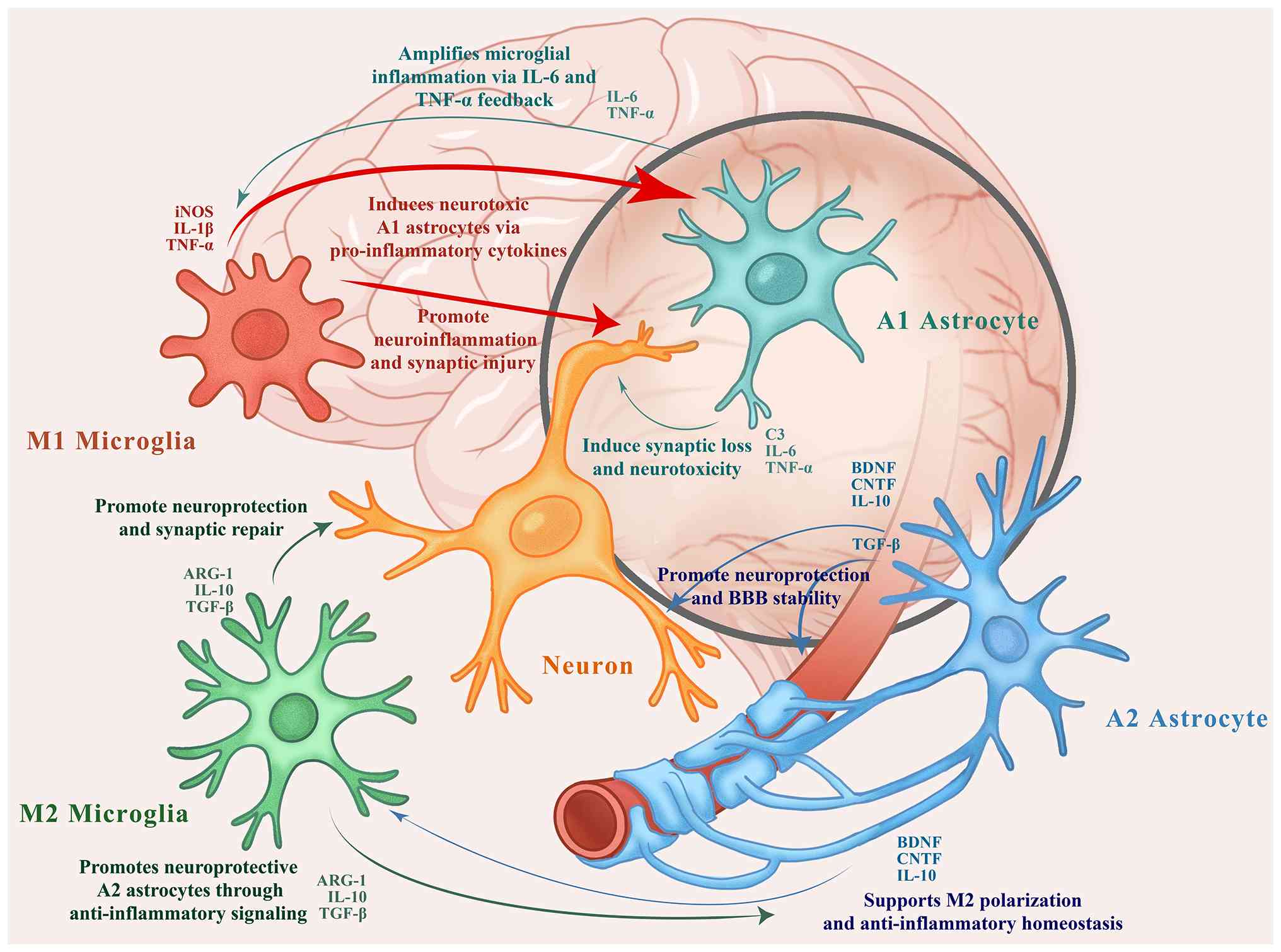

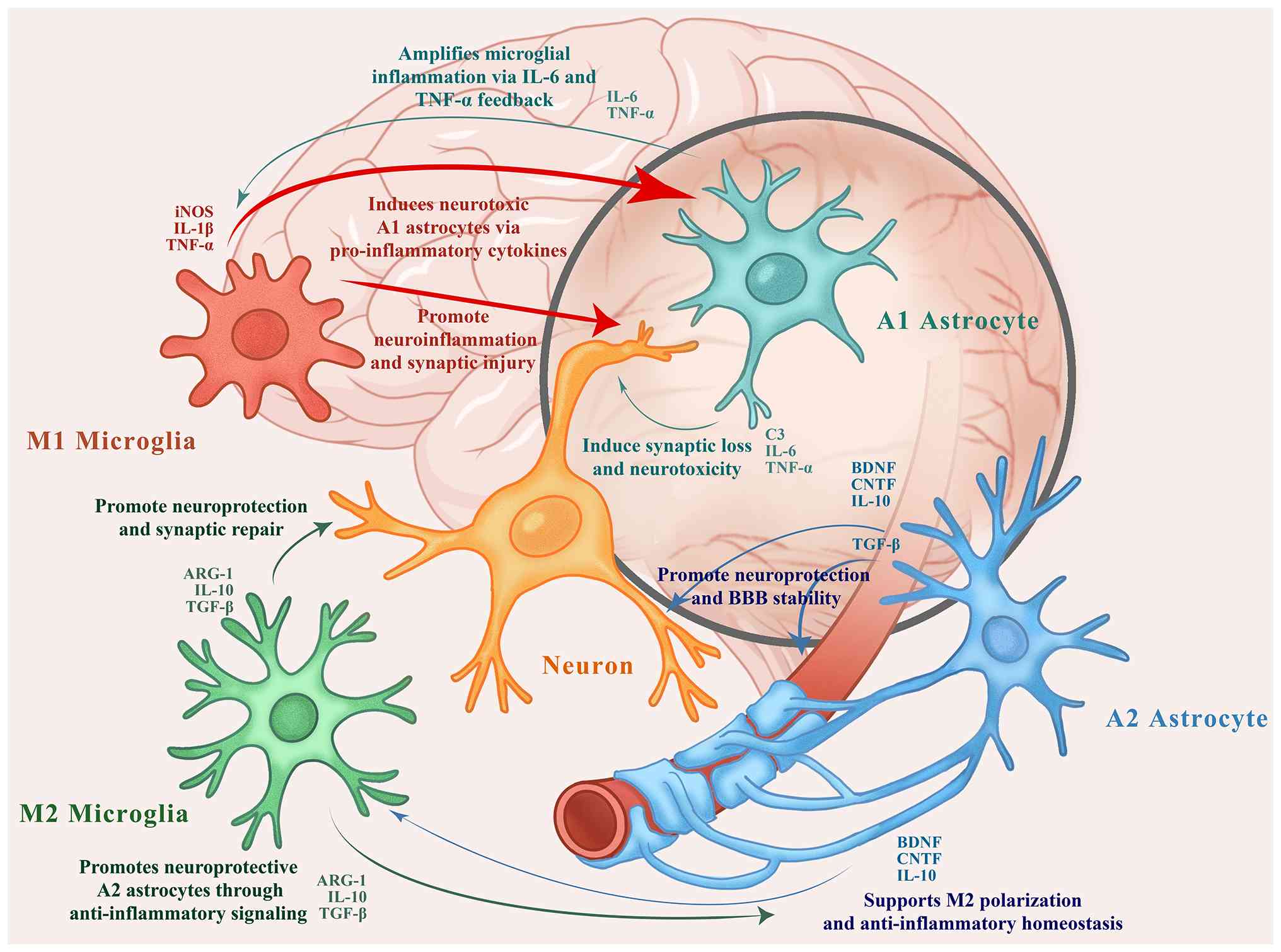

cells is summarized below and illustrated in Fig. 1.

| Figure 1Interactions between microglia,

astrocytes, and neurons in the autism spectrum disorder-affected

brain. M1 microglia and A1 astrocytes release pro-inflammatory

cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) that amplify

neuroinflammation and induce synaptic damage. In contrast, M2

microglia and A2 astrocytes secrete anti-inflammatory and

neurotrophic factors (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β, BDNF and CNTF), promoting

synaptic repair, BBB stability and homeostasis. Arrows indicate

intercellular regulatory pathways. The authors created this figure

referencing multiple sources (40-56,62-68,74-82). TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α;

IL, interleukin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; BMP, bone

morphogenetic protein; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; iNOS,

inducible nitric oxide synthase; BBB, blood brain barrier. |

Microglia: Dual polarization and

synaptic phagocytosis

Microglia are the primary immune cells of the

central nervous system (CNS) and exhibit dual polarization states,

i.e., M1 (classical activation) and M2 (alternative activation). In

response to inflammatory stimuli, M1-type microglia secrete

proinflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α),

interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 (63-65) and reactive oxygen species

(66), driving neuroinflammation

and pathological damage. They can also enhance phagocytic activity,

causing direct harm to neurons and synapses (67). Conversely, M2-type microglia are

induced by anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-4 and IL-13

(68), and promote the release

of neuroprotective mediators, including IL-10 and transforming

growth factor-β (TGF-β) (68-70). This balance between M1 and M2

polarization is crucial for regulating neuronal activity, synaptic

plasticity, and the clearance of apoptotic cells, thus helping

maintain CNS homeostasis under normal conditions.

Microglial synaptic phagocytosis plays a critical

role in shaping neural circuits; however, its dysregulation can

occur in either direction, either through excessive elimination of

synapses or insufficient pruning. This bidirectional imbalance

contributes to abnormal neural connectivity, underscoring the

complex and multifaceted role of microglia in the pathophysiology

of ASD. During normal development, microglia refine neural circuits

by pruning superfluous synapses. However, the hyperactivation of

microglia in ASD may lead to aberrant over-pruning of synapses,

thereby reducing synaptic density and impairing neural circuits,

particularly in brain regions linked to social behavior and

cognition. This phenomenon may underlie the synaptic deficits

observed in specific ASD subtypes (71). By contrast, a dysregulated

microglial function can result in insufficient synaptic pruning,

leading to excessive synaptic connections and abnormal network

synchronization, as well as reduced information-processing

efficiency. This effect may be more pronounced in other ASD

subgroups. This imbalance in synaptic pruning is influenced by

pro-inflammatory cytokines, microglial signaling pathways [e.g.,

TREM2 (72,73) and STING (74)] and region-specific factors.

Consequently, the dual role of microglial phagocytosis highlights

the complexity and heterogeneity of the pathogenesis of ASD,

supporting the rationale for therapeutic strategies that target

microglial modulation.

Astrocytes: Reactive transformation

and neuroinflammatory regulation

Astrocytes are instrumental in maintaining CNS

homeostasis and supporting neuronal function. However, in ASD,

astrocyte activation is likewise closely tied to the progression of

neuroinflammation (75).

Activated astrocytes can release both pro-inflammatory and

anti-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6 (76) and IL-10 (77), exerting a bidirectional influence

on the inflammatory process. Moreover, intermediate filament

proteins in astrocytes, including glial fibrillary acidic protein

(78) and vimentin (79), exhibit an altered expression and

distribution. These proteins regulate the degradation of

extracellular matrix components (80). In the brains of patients with

ASD, astrocytes often display morphological changes characteristic

of reactive astrocytes, i.e., hypertrophic, with thicker and

shorter processes, particularly the neurotoxic A1 subtype. These

alterations are linked to astrocyte dysfunction, disrupted

neurogenesis and neuroinflammation, thereby exacerbating

neurological abnormalities in individuals with ASD (81-83).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines and

neuroinflammatory signaling

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are key factors driving

neuroinflammation in ASD. Their dysregulated expression signifies

aberrant immune activation and may directly or indirectly inflict

neuronal damage. Elevated levels of IL-1β and TNF-α have been

strongly associated with compromised synaptic function and reduced

neuronal viability (84).

Furthermore, cytokines can modify neurotransmitter metabolism and

release, further destabilizing neural networks. For example, IL-6

has been shown to regulate glutamate transporter expression,

thereby exacerbating excitotoxicity (85). These inflammatory mediators also

function through signaling cascades, such as nuclear factor

κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and JAK-STAT to

regulate the intensity and duration of the immune response, thereby

exacerbating neuronal dysfunction and cell death (86).

In summary, the activation of microglia and

astrocytes significantly modulates neuroinflammation and immune

responses in ASD, profoundly influencing pathological progression.

By releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and altering synaptic

function, aberrant glial activation not only promotes neuronal

damage, but also undermines the stability of neuronal networks. A

more precise understanding of the atypical inflammatory and immune

mechanisms in ASD is therefore pivotal for illuminating its

pathophysiology and developing effective therapeutic

strategies.

Mesenchymal stem cells and their derived

exosomes in ASD: Research and applications

Biological characteristics and

immunoregulatory mechanisms of action of MSCs

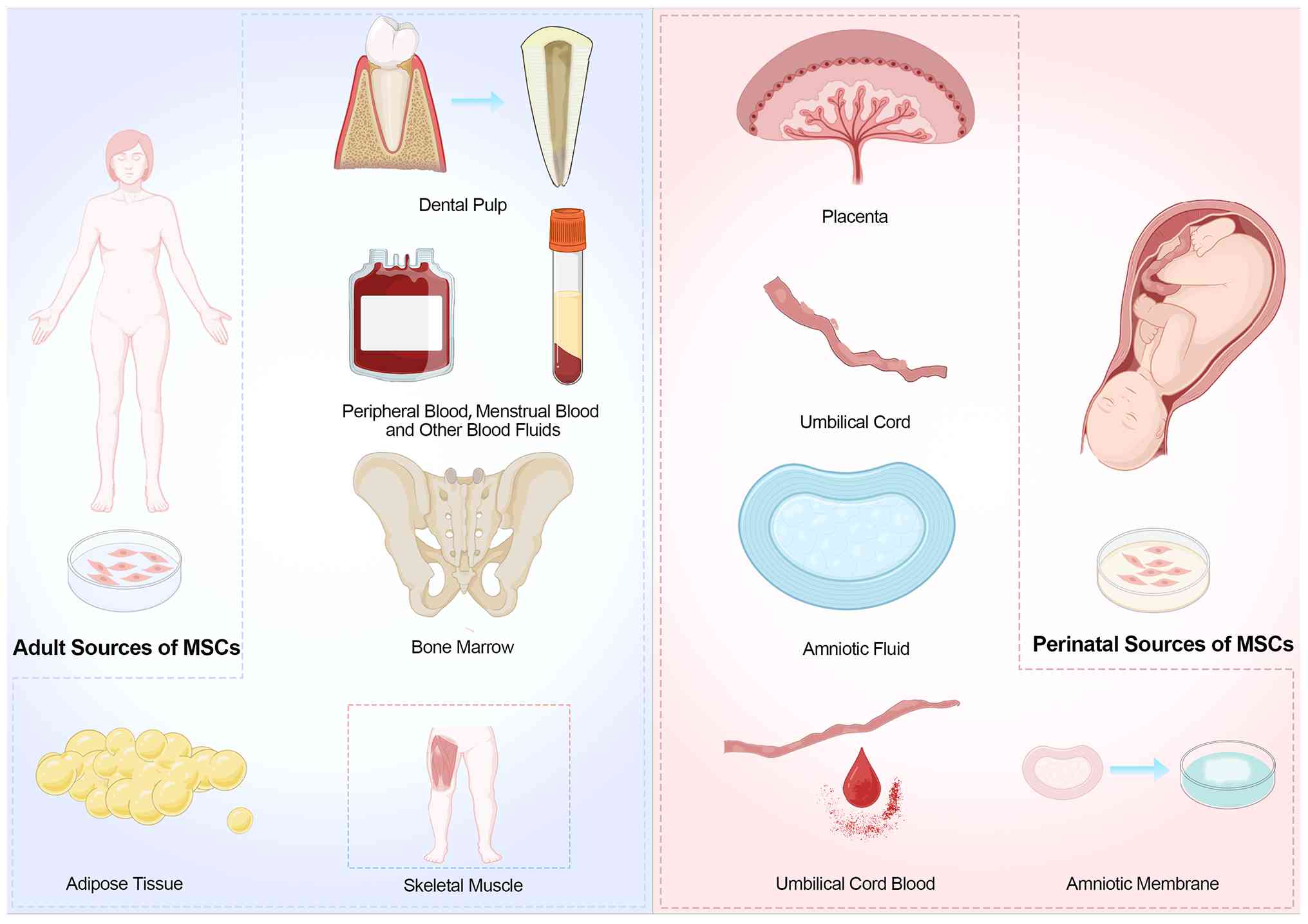

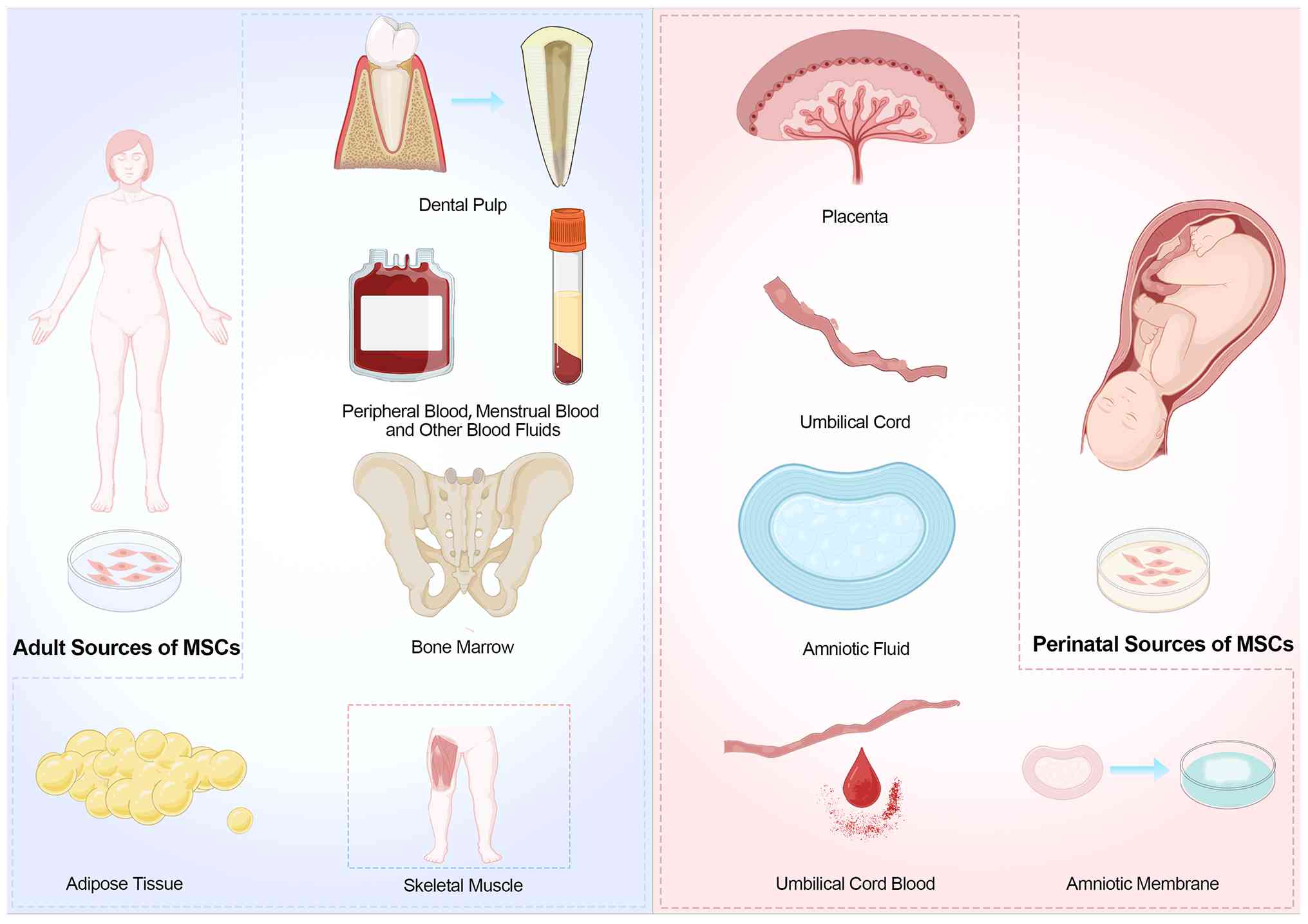

MSCs are adult stem cells characterized by

multipotent differentiation and self-renewal capacities, initially

identified in bone marrow by Friedenstein et al (87). These cells adhere to plastic

culture flasks and exhibit robust biological functions. They are

widely distributed in various tissues, such as bone marrow, adipose

tissue, umbilical cord, placenta, and dental pulp (88). A schematic overview of these MSC

sources is illustrated in Fig.

2. Owing to their diverse sources and distinct functional

properties, have emerged as a significant research focus in

regenerative medicine and cell therapy.

| Figure 2Sources of MSCs. Adult MSCs can be

derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, peripheral blood,

skeletal muscle, and dental pulp. Perinatal MSCs are typically

harvested from the placenta, umbilical cord, cord blood, amniotic

fluid, and amniotic membrane. This figure was created based on data

or concepts adapted from the study by Brown et al (88), but was drawn and designed by the

authors. MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells. |

Firstly, MSCs possess notable multipotent

differentiation potential under specific conditions; they can

differentiate into various cell types, including osteoblasts,

chondrocytes, myocytes, adipocytes, and neuron-like cells. This

property is under precise genetic regulation (89). For instance, RUNX family

transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) plays a pivotal role in

osteogenic differentiation (90); peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor γ (PPAR-γ) controls adipogenic differentiation

(91); SRY-Box transcription

factor 9 (SOX9) is crucial for chondrogenesis (92); and the differentiation of

neuron-like cells relies on the expression of proteins, such as

Nestin and neuronal differentiation 1 (NeuroD1) under the induction

of neurotrophic factors (93).

These genes, which fine-tune the Wnt/β-catenin TGF-β/bone

morphogenetic protein (BMP) and Notch 1 signaling pathways, provide

the molecular underpinnings for the applications of MSCs in

regenerative medicine.

Secondly, MSCs play a prominent role in

immunomodulation. Research suggests that MSCs can secrete multiple

immunoregulatory factors and interact with immune cells, thus

exerting immunosuppressive and immunobalancing effects. For

example, PGE2, TGF-β, IL-10 and HLA-G secreted by MSCs can

effectively inhibit T-cell proliferation and induce the generation

of regulatory T-cells (Tregs), thereby promoting immune tolerance

(94). Furthermore, by causing

the polarization of macrophages toward the M2 phenotype, MSCs can

significantly reduce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines,

such as IL-6 and TNF-α (95),

thereby improving the pathological environment associated with

inflammation. These properties render MSCs promising therapeutic

candidates for various immune-related diseases (96).

Additionally, the low immunogenicity of MSCs aids in

their long-term survival in the host. This advantage arises from

their low expression of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC)

class I molecules and the lack of MHC class II and costimulatory

molecules (e.g., CD80 and CD86) (97). Such features markedly reduce

T-cell activation and diminish strong host immune rejection.

Moreover, MSCs secrete multiple immunosuppressive factors (e.g.,

PGE2, IDO1 and HLA-G) to attenuate immune responses further

(98). These combined mechanisms

enable MSCs to survive and exert therapeutic effects in allogeneic

transplantation settings, with minimal reliance on

immunosuppressants.

Research advances of MSCs in ASD

MSCs promote neuroprotection and functional recovery

in various neurological disorders through multiple pathways. For

instance, MSCs secrete brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF),

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and neurotrophin-3

(NT-3), which can enhance neuronal survival, axonal regeneration,

and synaptic function by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3

kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) and MAPK/ERK signaling

pathways (99,100). Through reducing

neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, MSCs have been shown to

attenuate disease progression in Alzheimer's disease and

Parkinson's disease, while improving neurological and cognitive

functions (101,102). In spinal cord injury models,

MSCs facilitate axonal regeneration and functional recovery

(103).

Notably, relevant studies on ASD also demonstrate

promising results. In a rat model of VPA-induced ASD, MSC

transplantation was shown to markedly improve social interaction,

mitigate repetitive behaviors and alleviate anxiety-like behaviors

(104). These effects may be

attributed to the immunomodulatory and neuroprotective functions of

MSCs which reduce neuroinflammation and enhance synaptic

plasticity, ultimately improving core behavioral symptoms.

Despite the considerable therapeutic potential of

MSCs in ASD, challenges remain regarding clinical translation,

including immunorejection, diminished proliferative capacity over

time, and concerns over transplantation safety. In this regard,

exosomes secreted by MSCs have emerged as a research hotspot in

recent years due to their critical roles in immune regulation and

tissue repair (105). Compared

with conventional cell transplantation, MSC-derived exosomes offer

a 'cell-free therapy' strategy characterized by small size, ease of

storage, low immunogenicity, and suitability for standardized

production and quality control. These features not only provide new

perspectives and directions for the precision treatment of

neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD, but may also enhance the

feasibility of clinical translation (106).

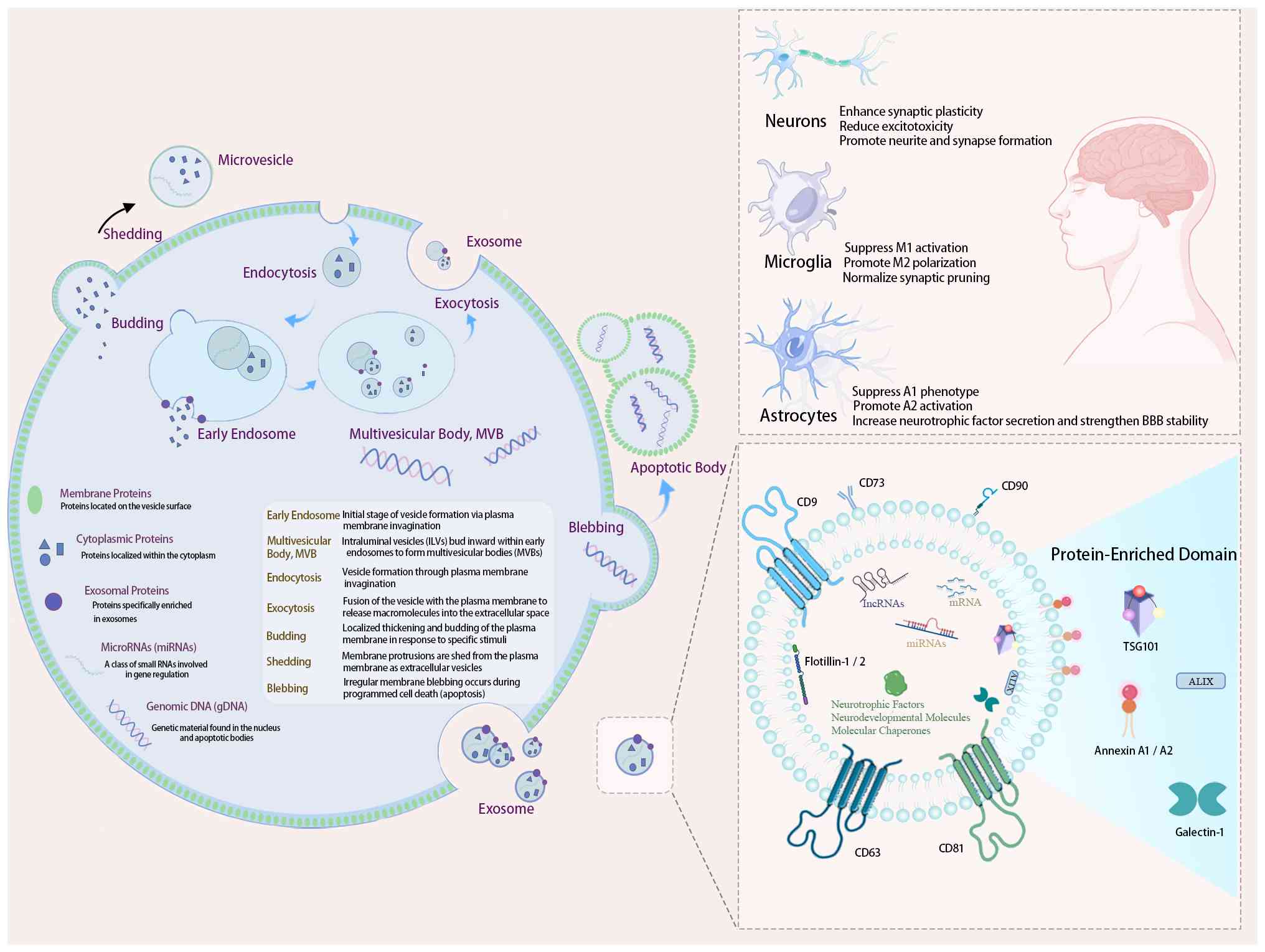

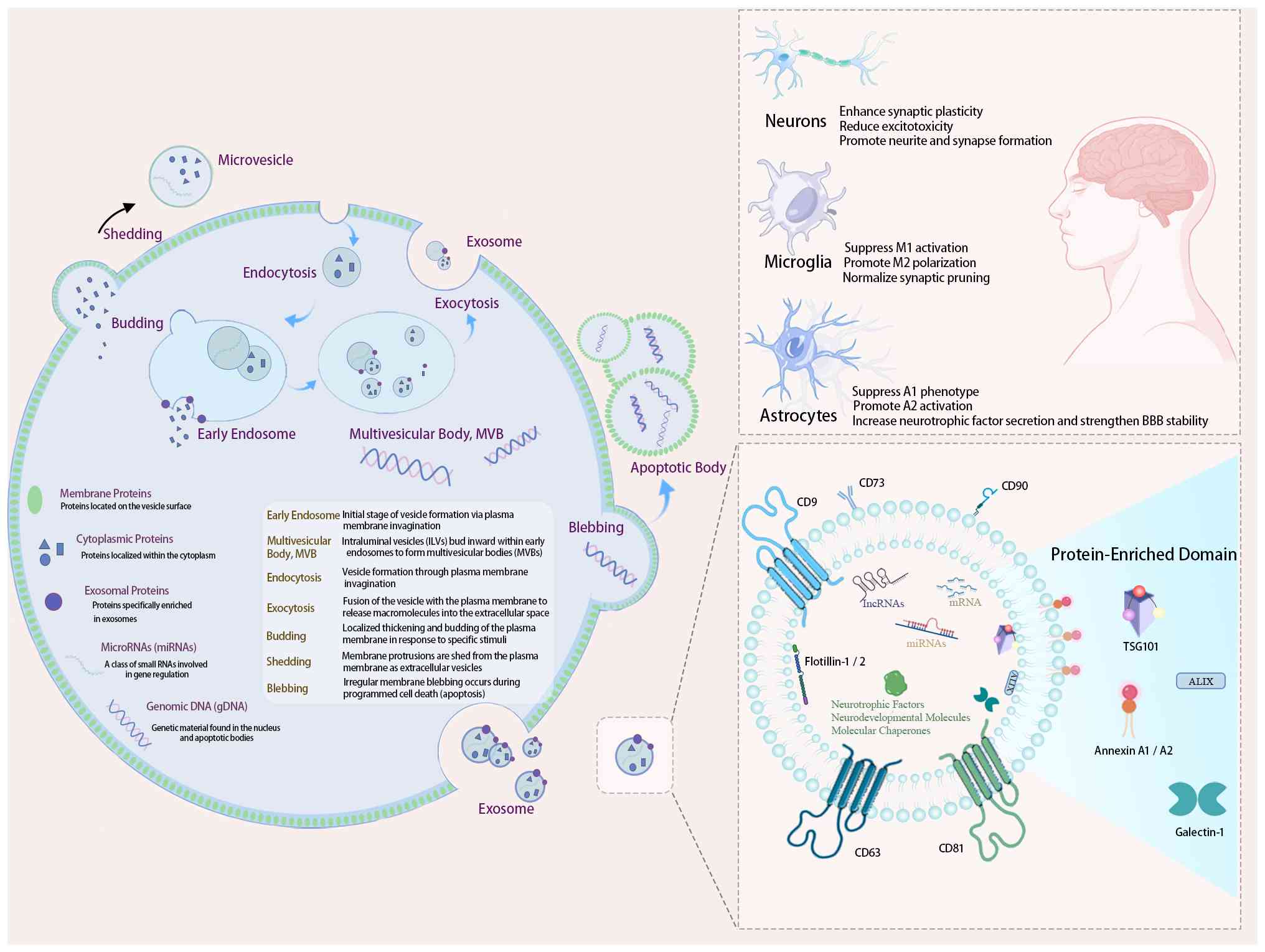

Structure and biological functions of

exosomes

Exosomes are extracellular vesicles measuring

~30-150 nm in diameter, originating from endosomal pathways and

released into bodily fluids through the fusion of multivesicular

bodies with the cell membrane (107,108). A lipid bilayer encases exosomes

enriched with various biologically active components, including

proteins, nucleic acids (mRNAs, miRNAs and lncRNAs, etc.) and

lipids. Their stable structure enables exosomes to serve as unique

mediators of intercellular communication and regulation, thus

providing a theoretical basis for potential therapeutic

applications (109). The

composition and biogenesis pathways of MSC-Exos, as well as their

downstream effects on neuronal and glial cells in ASD models, are

summarized in Fig. 3. Exosomes

exert their therapeutic effects primarily through interacting with

their cargo in recipient cells. Exosomes deliver their contents

directly into target cells, either by fusing with the plasma

membrane or undergoing receptor-mediated endocytosis, and thereby

modulate gene expression and signaling pathways.

| Figure 3Biogenesis, molecular contents and

mechanisms of MSC-derived exosomes in ASD therapy. (Left panel)

MSC-derived exosomes originate from endosomal pathways. They

encapsulate proteins, mRNAs and miRNAs. (Top right panel) These

exosomes interact with neurons, microglia and astrocytes,

modulating synaptic plasticity, microglial polarization, and

astrocyte phenotype to alleviate neuroinflammation associated with

ASD. (Bottom right panel) Exosomal surface and cargo proteins

include CD63, CD81, CD9, CD73, flotillin-1/2, TSG101, Annexin

A1/A2, galectin-1, neurotrophic factors and molecular chaperones.

The authors created a figure referencing multiple sources (119-123,133-139,141-143). ASD, autism spectrum disorder;

MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells. |

Nucleic acid cargo and gene

regulation

The miRNAs in exosomes play vital roles in

regulating gene expression, as they can modulate inflammation,

neuronal survival, and synaptic plasticity by targeting specific

signaling cascades (110,111). Previous studies have

demonstrated that miRNAs encapsulated in exosomes, such as miR-124

packaged within exosomes, have been demonstrated to enhance

neuronal regeneration and reduce neuroinflammation (112-115). Other miRNAs, such as miR-21,

miR-155 and miR-146a, can suppress the NF-κB pathway, thereby

reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-6 and

TNF-α) and increasing the levels of anti-inflammatory IL-10,

ultimately mitigating neuroinflammation. These miRNAs may also

inhibit excessive activation of the mTOR pathway, reducing aberrant

neuronal activity (115-118).

Additionally, miR-873a-5p within exosomes can promote microglial

polarization toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (120). Apart from miRNAs, mRNAs and

lncRNAs, exosomes can also contain these molecules, which can

affect recipient cell functions through translation or

transcriptional regulation, influencing tissue repair and immune

modulation (121-123).

Protein cargo and neural repair

Exosomes also harbor proteins, such as heat shock

proteins (HSPs) (124),

neuronal adhesion molecules [e.g., intercellular adhesion molecule

1 (125)] and cytokines [e.g.,

TGF-β (126)] that can directly

modulate axonal growth, promote synaptic remodeling, and strengthen

neural network connectivity, are considered critical processes in

immune regulation, neuroprotection, and tissue repair. Furthermore,

exosomal membrane lipids (e.g., sphingomyelin and

phosphatidylserine) can enhance synapse formation and stability,

thereby influencing the functional properties of recipient cells

(127). These molecular

mechanisms provide a basis for improving cognitive and behavioral

deficits in ASD.

Neurotrophic factors and signaling

pathways

Exosomes are often enriched with neurotrophic

factors and neurodevelopmental molecules, such as Nestin, NeuroD1,

BDNF and VEGF. These factors act through signaling pathways,

including the Wnt/β-catenin, TGF-β/BMP and PI3K/Akt pathways,

thereby supporting neuronal proliferation, migration and

differentiation (128-130).

Gut microbiota and the gut-brain

axis

ASD has been closely linked to gut microbiome

dysbiosis. Exosomes can modulate gut microbiota diversity by

increasing the abundance of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli and

improving gut barrier function (131). Exosomes containing miR-155,

miR-181a and TGF-β can reduce intestinal inflammation and

permeability. Exosomes containing miR-155, miR-181a and TGF-β can

reduce intestinal inflammation and permeability, ultimately

influencing the gut-brain axis and indirectly affecting the central

nervous system function (132-134).

Exosomes carry a versatile repertoire of bioactive

molecules that can modulate inflammatory responses, promote neural

repair and regulate the gut-brain axis. These properties underscore

the potential of exosome-based, cell-free therapy for ASD and other

neurodevelopmental disorders.

Potential value of exosomes in the

treatment of ASD

In recent years, MSC-Exos have exhibited immense

promise in ASD research and interventions due to their unique

composition and diverse functionalities (29,129). Compared with direct cell

transplantation, exosomes provide greater safety, controllability

and ease of storage. By carrying various miRNAs, proteins and

bioactive molecules, MSC-Exos can exert immunomodulatory,

neuroprotective and synaptic repair effects in the CNS (135,136). Their ability to regulate

neuroinflammation, restore synaptic plasticity, and rebalance the

gut-brain axis underscores the potential of exosome-based

'cell-free therapy' (129),

paving the way for new avenues of research and clinical

applications in ASD.

Studies using animal models of ASD have demonstrated

that the intranasal administration of MSC-Exos markedly improves

social interaction, cognition and repetitive behaviors (22,29,135,136). These effects may be attributed

to miRNAs and anti-inflammatory agents delivered by exosomes, which

modulate immune responses and neuronal network functionality. For

example, exosomal miRNAs [such as miR-21-5p (137), miR-17-92 (138) and miR-146a (139)] and multiple bioactive proteins

[including HSP70 and TGF-β (140)] help regulate neuroinflammation,

synaptic plasticity, and neurogenesis via intercellular signaling.

Additionally, research suggests that neurotrophic factors present

in exosomes can enhance neuronal survival and differentiation,

thereby improving behavioral outcomes. These factors also enhance

synaptic plasticity, promote network-level functional integration,

and reduce CNS inflammation by increasing anti-inflammatory

cytokines (22,29,135,141).

In summary, MSC-Exos, owing to their diverse

bioactive molecules and stable delivery system repertoire, have

shown comprehensive effects on immunoregulation, neural repair and

synaptic regeneration in ASD. They are thus emerging as a promising

therapeutic alternative to conventional cell-based treatments.

Ongoing research will further elucidate the underlying mechanisms

of exosomes in ASD, optimize exosome preparation and administration

strategies, and, through multidisciplinary collaboration, develop

safe, efficacious and scalable exosome-based therapeutics. These

efforts hold the potential to propel the field toward precision

interventions and clinical translation for ASD.

Clinical progress of stem cells and exosomes

in ASD

In recent years, stem cell-based therapy has emerged

as one of the key areas of interest for the treatment of ASD. By

employing stem cells or their exosomes, researchers aim to modulate

immune responses, improve cerebral blood flow, and enhance neuronal

repair in individuals with ASD (21). Early clinical trials have

documented varying degrees of improvement in behavior, language

skills and social abilities among ASD patients receiving MSC

therapy (142) with minimal

adverse events (143).

Additionally, these trials noted decreases in inflammatory markers

and improvements in brain metabolic activity, further supporting

the potential role of MSCs in the treatment of ASD (142).

Current status of clinical research and

key findings

Several completed clinical trials worldwide have

investigated the use of stem cell therapy for the treatment of ASD.

The following paragrpahs summarizes the primary clinical studies

and their principal outcomes:

Use of umbilical cord blood-derived

stem cells

Lv et al (144) conducted a study combining cord

blood mononuclear cells (CBMNCs) with umbilical cord-derived

mesenchymal stem cells, enrolling 37 patients with ASD. Their

results revealed that the combination treatment group had

significantly greater improvements in the Childhood Autism Rating

Scale (CARS) and Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) scores compared

to either the CBMNC-only group or the control group (which received

only rehabilitative interventions). No severe adverse events were

reported, underscoring both the safety and the superior efficacy of

combination therapy (144).

Preliminary attempts with human

embryonic stem cells

Shroff (145)

reported outcomes for 3 patients with ASD treated with human

embryonic stem cells. Improvements were observed in motor skills,

cognition, social interaction and sensory sensitivities, with no

adverse events noted. Although the sample size was small, this

study highlights the potential of stem cell therapies for

alleviating core symptoms of ASD (145).

Potential of autologous umbilical cord

blood therapy

Chez et al (146) conducted a randomized,

double-masked, placebo-controlled crossover study involving 29

children with ASD aged 2 to 6 years, evaluating the safety and

efficacy of autologous umbilical cord blood transfusions. Although

treatment did not significantly improve its primary endpoints, some

participants exhibited trends toward improved socialization and

language skills. No severe adverse events occurred, suggesting that

stem cell therapy may hold promise for enhancing social functioning

(146).

Changes in brain network

connectivity

Simhal et al (147) used diffusion tensor imaging to

assess the effect of umbilical cord blood stem cell therapy on

white matter networks in patients with ASD. Their study revealed

that post-treatment, the robustness of the white matter network was

markedly increased, especially in regions involved in social and

communication functions. These findings may be related to the

ability of stem cells to regulate neuroinflammation and promote

neuroplasticity (147).

Stem cells combined with behavioral

interventions

Thanh et al (148) conducted an open-label clinical

trial in Vietnam, enrolling 30 children with ASD aged 3 to 7 years.

The intervention combined autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell

transplantation with the ESDM, an early behavioral intervention.

The results revealed a reduction in median CARS scores from 50 to

46.5 (P<0.05) and an increase in Vineland Adaptive Behavior

Scale scores from 53.5 to 60.5, indicating substantial improvements

in social interaction, language abilities, and daily living skills,

with no severe adverse events reported (148).

Collectively, the aforementioned clinical studies

suggest that MSC-based and MSC exosome therapies hold promise for

improving social communication, language skills, behavioral

challenges and cognition in individuals with ASD. Notably, combined

treatments, including the incorporation of behavioral interventions

or personalized therapeutic regimens that appear effective, may be

due to their multi-target mechanisms of action. The majority of

studies did not report severe adverse events, reflecting an overall

favorable safety profile. However, a number of existing studies

involve small sample sizes and open-label designs, lacking the

robust evidence from large-scale randomized controlled trials

(RCTs). Additionally, the precise mechanisms underlying the

observed therapeutic effects remain incompletely understood. Future

investigations should further refine treatment protocols, clarify

the role of exosomes in cell therapy, and establish the long-term

safety and efficacy of these interventions. Expanding multicenter,

large-sample RCTs is crucial for evaluating the performance of

different stem cell types and administration strategies. Moreover,

exploring synergistic effects between stem cells and behavioral or

pharmacological interventions will help optimize individualized

treatment plans. Finally, integrating gene-editing technologies and

engineered exosomes could enhance their clinical utility. Such

efforts will provide a more robust theoretical and practical

foundation for applying stem cell and exosome-based therapies in

ASD.

Potential for clinical translation and

existing barriers

Due to pronounced immunomodulatory properties,

tissue repair potential and favorable safety profile, MSCs have

attracted widespread attention in recent years, gradually becoming

an essential focus of stem cell-based therapies. As MSC research

advances, the exosomes they secrete (MSC-Exos) have been identified

as a key functional mediator and are expected to play a potential

role in ASD interventions (149). The majority of clinical studies

on MSCs and MSC-Exos remain in phase I/II trials (150). Early data suggest that patients

with ASD treated with these therapies experience improved social

interaction and language skills, as well as decreased inflammatory

markers, such as TNF-α and IL-6 (151,152). Nonetheless, the clinical

translation of MSCs and their exosomes depends on the efficacy of

preclinical studies, as well as substantial practical and

regulatory challenges. Although preliminary findings are

encouraging, limitations in sample size, follow-up duration, and

study design mean that large-scale, multicenter clinical data are

still required to confirm their long-term efficacy and safety. A

discussion of the advantages and challenges inherent in clinical

translation is presented below:

Core advantages and multifaceted

mechanisms

Multifunctionality: Immunomodulation and

neuroprotection

The immunomodulatory and neuroprotective properties

of MSCs render them attractive for addressing multiple pathological

mechanisms underlying ASD. Research indicates that MSC-Exos can

regulate T- and B-cell activation, induce immune tolerance, and

suppress the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, thus improving

neuroinflammatory conditions (22). Growth factors, miRNAs, and other

bioactive substances in MSC-Exos also promote neuronal survival and

synaptic plasticity (111).

Owing to their differentiation potential, MSCs and their exosomes

may also serve as tools for neural repair, providing potential

therapeutic value for ASD-related neurodevelopmental anomalies.

Low immunogenicity and favorable safety

profile

MSCs exhibit relatively low immunogenicity in

allogeneic transplantation (153). Their exosomes, which lack

complete cell-surface antigen expression (154) and do not carry a nucleus or

full genomic content (155),

further minimize risks of immune rejection and tumorigenesis.

Consequently, MSC-Exos do not require stringent donor-recipient

matching to the same extent as allogeneic MSCs, reducing potential

complications and ethical concerns.

Targeted action and personalized therapy

Exosomes can enter target cells through

receptor-mediated endocytosis or membrane fusion, delivering a

diverse array of active molecules that influence cell

proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and immune responses.

Owing to their nanoscale size and lipid bilayer structure, exosomes

demonstrate relatively high transmembrane delivery efficiency;

research suggests that exosomes can traverse the blood-brain

barrier (156). As the

pathogenesis of ASD involves abnormal neural networks and central

neuroinflammation, MSC-Exos capable of penetrating the CNS may help

restructure the brain microenvironment and enhance therapeutic

outcomes. Moreover, engineering MSCs or modifying exosome cargo

based on individual patient pathology (e.g., through gene editing)

may enable more precise, personalized treatments.

Large-scale production, transport and

storage

Under specific culture conditions, exosomes can be

produced and purified in large quantities. Compared to cell

transplantation, which requires highly viable, well-characterized

cells in sufficient numbers, exosomes are easier to standardize and

mass-produce, rendering clinical deployment more feasible.

Additionally, exosomes can be stored for extended periods under

appropriate conditions while retaining their bioactivity, thereby

circumventing many of the stability challenges encountered with

live MSCs. This facilitates large-scale manufacturing, clinical

stockpiling, and broader geographic distribution.

Real-world challenges and

bottlenecks

Production techniques and quality control

Variations in MSC culture conditions and tissue

sources can produce substantial differences in exosome yield and

quality. Standard protocols for extracting, purifying and

characterizing exosomes have yet to be universally adopted.

Reagents, equipment and technical approaches vary greatly among

laboratories, which can potentially affect the reproducibility of

results. To achieve industrial-scale production and clinical

adoption of MSC-Exos, international or national-level

standardization is needed, encompassing MSC culture conditions,

exosome extraction, purification, and the establishment of quality

metrics. Key parameters include identifying and quantifying cargo

molecules, particle size distribution and surface markers. Without

such standards, ensuring the stability and consistency of MSC-Exos

across different batches remains difficult.

Heterogeneity in sources and cell states

MSCs can be derived from various sources, including

bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and other tissues,

resulting in variability based on tissue origin, donor

characteristics and passage number. For instance, adipose-derived

MSCs generally have more substantial adipogenic potential, whereas

bone marrow-derived MSCs may be more adept at osteogenic

differentiation (157). In the

context of ASD therapy, MSC-Exos from different sources or

differing cell expansion histories may yield divergent

immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects. A systematic

investigation is required to determine an optimal source or a

combination strategy for clinical use.

Complexity of mechanisms

Although a number of studies have documented the

neuroprotective, immunoregulatory and neural network repair

functions of MSC-Exos, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying

these functions remain incompletely understood (22,136,149). It remains to be determined

which miRNAs or proteins in MSC-Exos are essential for regulating

neuronal repair and immune balance in ASD. In addition, the

mechanisms through which exosomes interact with target cells and

influence downstream signaling pathways remain to be elucidated.

Further research using in vitro and in vivo models is

required to clarify these mechanisms, improving the specificity and

reliability of future clinical applications.

Safety and ethical oversight

While MSC-Exos are associated with a lower

immunogenicity and tumorigenic risk than direct cell

transplantation, comprehensive preclinical safety evaluations and

multicenter clinical trials are necessary to assess long-term

risks. The clinical use of stem cells and their derivatives is

strictly regulated in many countries, requiring compliance with

guidelines for pharmaceutical and biological products, as well as

adherence to ethical considerations, including donor sourcing and

traceability during preparation and application (158).

Large-scale manufacturing and

cost-effectiveness

Generating MSC-Exos on a large scale requires

efficient isolation and concentration protocols for MSC culture.

Once translated to clinical practice, cost and patient

accessibility become critical factors. In the event that production

remains prohibitively costly without relevant policy support, the

widespread adoption of MSC-Exos in the treatment of ASD may be

limited.

Delivery efficiency and long-term safety

Achieving the efficient, targeted delivery of

exosomes to the CNS and specific lesion sites to enhance

therapeutic specificity poses a significant challenge. Moreover,

current exosome-related clinical trials typically feature short

follow-up periods (144,146,147).

Exosomes hold potential as a long-term intervention strategy;

however, their extended use may carry unknown risks, including

effects on the immune system and neural function. Rigorous

long-term monitoring and evaluation are therefore necessary.

Individual differences and clinical

applicability

ASD is highly heterogeneous, with variability in

age, subtype and comorbid conditions affecting treatment responses

to MSCs or MSC-Exos. Personalized therapies tailored to individual

disease stages and pathological profiles remain a significant

challenge. Biomarker analysis and molecular subtyping may enhance

individualized treatment strategies. Systematic clinical trials are

necessary to establish optimal dosing and administration protocols

for diverse patient populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, MSCs and MSC-Exos have demonstrated

considerable therapeutic potential in the treatment of ASD. MSCs

and MSC-Exos can alleviate neuroinflammation, enhance synaptic

plasticity, and promote neural network repair through their

immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects. MSC-Exos offers

substantial advantages for ASD treatment, including multifaceted

therapeutic mechanisms, low immunogenicity and potential for

large-scale production. Nevertheless, critical hurdles, such as

manufacturing protocols, quality control, elucidation of the

mechanism, long-term safety, and personalized application, need to

be overcome before MSC-Exos can be widely integrated into ASD

therapies. Addressing these challenges through multidisciplinary

collaboration and further research will pave the way for more

precise, safe, and effective interventions. With their low

immunogenicity, ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, and

efficient delivery of bioactive molecules, exosomes are promising

candidates for treating ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

However, several critical challenges remain, including issues

related to large-scale production, quality control, and elucidation

of underlying mechanisms. Moreover, rigorous clinical trials under

strict regulatory and ethical frameworks are required to establish

the safety and efficacy of MSC-Exos. Therefore, it is urgent to

clarify their mechanisms of action, develop standardized

manufacturing and quality control protocols, and optimize long-term

safety and personalized treatment strategies. With the integration

of high-throughput omics technologies, interdisciplinary

collaboration, and continuous innovation, MSC-Exos are expected to

advance in basic research and clinical application, offering

greater precision and broader therapeutic potential in ASD.

Ultimately, only by overcoming key scientific and technical hurdles

can MSC-Exos become a viable strategy for individualized

interventions.

Future perspectives and application

directions

Advancing the therapeutic efficacy and clinical

translation of MSC-derived exosomes in ASD will require sustained

innovation across multiple dimensions. To improve in vivo

delivery efficiency, various delivery platforms, such as magnetic

nanoparticles (159) and

hydrogels (160), have been

developed to enhance targeting and stability in the central nervous

system. Additionally, chemical modifications (161) and genetic engineering

techniques (162) have been

employed to increase the therapeutic specificity and prolong the

half-life of exosomes. Engineered MSCs that overexpress functional

proteins and miRNAs, such as neurotrophic factors or

anti-inflammatory molecules (163), have shown promise in enhancing

the neuroprotective and immunoregulatory effects of their exosomes,

thereby broadening their application potential in ASD and other

neurological disorders. To meet the demands of personalized

medicine, customized exosome formulations and treatment protocols

tailored to individual patient profiles may improve therapeutic

outcomes and reduce adverse effects. The application of

high-throughput omics technologies, such as genomics, proteomics

and metabolomics continues to unveil the key molecular pathways and

networks through which MSCs and their exosomes modulate neurorepair

and immune responses. In particular, in-depth investigations into

the roles and interactions of miRNAs, proteins, and other bioactive

cargos will provide a robust foundation for evaluating therapeutic

efficacy and guiding the engineering of exosomes. For clinical

translation, it is essential to establish standardized and

efficient protocols for MSC cultivation and exosome purification,

along with internationally recognized quality control standards to

ensure batch-to-batch and inter-institutional consistency.

Large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials will be

crucial for validating the safety and efficacy of MSC-Exos,

necessitating refined trial designs that address patient selection,

dosage regimens, outcome measures, and long-term follow-up. Given

the complexity of ASD pathogenesis and its clinical heterogeneity,

future breakthroughs in MSC-Exos therapy will depend on

interdisciplinary collaboration across neuroscience, molecular

biology, immunology, and materials science, combined with

pharmacological and behavioral interventions. Continuous

technological innovation and integrative strategies will ultimately

pave the way for more effective and safer treatment options for

individuals with ASD.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZS was involved in the conceptualization of the

study. ZS and NA were involved in the collection and curation data

from the literature, and in the writing and preparation of the

original draft of the manuscript. MM was involved in visualization

and literature analysis. ZL supervised the study. ZS, NA and ZL

reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentications is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

Abbreviations:

|

ASD

|

autism spectrum disorder

|

|

CNV

|

copy number variation

|

|

MSC

|

mesenchymal stem cell

|

|

MSC-Exos

|

mesenchymal stem cell-derived

exosomes

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer

of activated B cells

|

|

PSD

|

postsynaptic density

|

|

PI3K

|

phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

|

|

Akt

|

protein kinase B

|

|

RR

|

relative risk

|

|

TGF-β

|

transforming growth factor β

|

|

BMP

|

bone morphogenetic protein

|

|

VPA

|

valproic acid

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from the Enterprise

Joint Fund Project of Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation

(grant no. 2024JJ9097).

References

|

1

|

Hung LY and Margolis KG: Autism spectrum

disorders and the gastrointestinal tract: Insights into mechanisms

and clinical relevance. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21:142–163.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kanner L: Autistic disturbances of

affective contact. Nerv Child. 2:217–250. 1943.

|

|

3

|

Association AP: Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders. 2022.

|

|

4

|

Shaw KA, Williams S, Patrick ME,

Valencia-Prado M, Durkin MS, Howerton EM, Ladd-Acosta CM, Pas ET,

Bakian AV, Bartholomew P, et al: Prevalence and early

identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4

and 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring

network, 16 sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill Summ.

74:1–22. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bai D, Yip BHK, Windham GC, Sourander A,

Francis R, Yoffe R, Glasson E, Mahjani B, Suominen A, Leonard H, et

al: Association of genetic and environmental factors with autism in

a 5-country cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 76:1035–1043. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sanders SJ, He X, Willsey AJ,

Ercan-Sencicek AG, Samocha KE, Cicek AE, Murtha MT, Bal VH, Bishop

SL, Dong S, et al: Insights into autism spectrum disorder genomic

architecture and biology from 71 risk loci. Neuron. 87:1215–1233.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Fu JM, Satterstrom FK, Peng M, Brand H,

Collins RL, Dong S, Wamsley B, Klei L, Wang L, Hao SP, et al: Rare

coding variation provides insight into the genetic architecture and

phenotypic context of autism. Nat Genet. 54:1320–1331. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hirota T and King BH: Autism spectrum

disorder: A review. JAMA. 329:157–168. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Christensen J, Grønborg TK, Sørensen MJ,

Schendel D, Parner ET, Pedersen LH and Vestergaard M: Prenatal

valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and

childhood autism. JAMA. 309:1696–1703. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zwaigenbaum L, Brian J and Ip A: Early

detection for autism spectrum disorder in young children. Paediatr

Child Health. 24:424–443. 2019.In English, French. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Robins DL, Casagrande K, Barton M, Chen

CMA, Dumont-Mathieu T and Fein D: Validation of the modified

checklist for Autism in toddlers, revised with follow-up

(M-CHAT-R/F). Pediatrics. 133:37–45. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

12

|

Volkmar F, Siegel M, Woodbury-Smith M,

King B, McCracken J and State M; American Academy of Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI):

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and

adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 53:237–257. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Song J, Reilly M and Reichow B: Overview

of meta-analyses on naturalistic developmental behavioral

interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism

Dev Disord. 55:1–13. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M,

Winter J, Greenson J, Donaldson A and Varley J: Randomized,

controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The

early start denver model. Pediatrics. 125:e17–e23. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang Z, Loh S, Tian J and Chen QJ: A

meta-analysis of the effect of the early start denver model in

children with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Dev Disabil.

68:587–597. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fieiras C, Chen M, Liquitay CE, Meza N,

Rojas V, Franco J and Madrid E: Risperidone and aripiprazole for

autism spectrum disorder in children: an overview of systematic

reviews. BMJ Evid Based Med. 28:7–14. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Aglinskas A, Hartshorne J and Anzellotti

S: Contrastive machine learning reveals the structure of

neuroanatomical variation within autism. Science. 376:1070–1074.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pizzano M, Shire S, Shih W, Levato L,

Landa R, Lord C, Smith T and Kasari C: Profiles of minimally verbal

autistic children: Illuminating the neglected end of the spectrum.

Autism Res. 17:1218–1229. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Konečná B, Radošinská J, Keményová P and

Repiská G: Detection of disease-associated microRNAs-application

for autism spectrum disorders. Rev Neurosci. 31:757–769. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yao TT, Chen L, Du Y, Jiang ZY and Cheng

Y: MicroRNAs as regulators, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets in

autism spectrum disorder. Mol Neurobiol. 62:5039–5056. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen W, Ren Q, Zhou J and Liu W:

Mesenchymal stem cell-induced neuroprotection in pediatric

neurological diseases: Recent update of underlying mechanisms and

clinical utility. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 196:5843–5858. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liang Y, Duan L, Xu X, Li X, Liu M, Chen

H, Lu J and Xia J: Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for

treatment of autism spectrum disorder. ACS Appl Bio Mater.

3:6384–6393. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hedayat M, Ahmadi M, Shoaran M and Rezaie

J: Therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cells derived

exosomes in neurodegenerative diseases: A focus on non-coding RNAs

cargo, drug delivery potential, perspective. Life Sci.

320:1215662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Su R: Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes as

nanotherapeutic agents for neurodegenerative diseases. Highl Sci

Eng Technol. 2:7–14. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Tian MS and Yi XN: The role of mesenchymal

stem cell exosomes in the onset and progression of Alzheimer's

Disease. Biomed Sci. 10:6–13. 2024.

|

|

26

|

Ge Y, Wu J, Zhang L, Huang N and Luo Y: A

new strategy for the regulation of neuroinflammation: Exosomes

derived from mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 44:242024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Elsherif R, Abdel-Hafez AM, Hussein O,

Sabry D, Abdelzaher L and Bayoumy AA: The potential ameliorative

effect of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes on cerebellar

histopathology and their modifying role on PI3k-mTOR signaling in

rat model of autism spectrum disorder. J Mol Histol. 56:652025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhao S, Zhong Y, Shen F, Cheng X, Qing X

and Liu J: Comprehensive exosomal microRNA profile and construction

of competing endogenous RNA network in autism spectrum disorder: A

pilot study. Biomol Biomed. 24:292–301. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

29

|

Perets N, Oron O, Herman S, Elliott E and

Offen D: Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells improved core

symptoms of genetically modified mouse model of autism Shank3B. Mol

Autism. 11:1–13. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ressa HJ, Newman BT, Jacokes Z, McPartland

JC, Kleinhans NM, Druzgal TJ, Pelphrey KA and Van Horn JD:

Widespread associations between behavioral metrics and brain

microstructure in ASD suggest age mediates subtypes of ASD.

BioRxiv. 28:2024.09.04.611183. 2024.

|

|

31

|

Almuqhim F and Saeed F: ASD-GResTM: Deep

learning framework for ASD classification using Gramian angular

field. Proceedings (IEEE Int Conf Bioinforma Biomed).

2023:2837–2843. 2023.

|

|

32

|

Tang X, Ran X, Liang Z, Zhuang H, Yan X,

Feng C, Qureshi A, Gao Y and Shen L: Screening biomarkers for

autism spectrum disorder using plasma proteomics combined with

machine learning methods. Clin Chim Acta. 565:1200182025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Herbrecht E, Lazari O, Notter M, Kievit E,

Schmeck K and Spiegel R: Short-term and highly intensive early

intervention FIAS: Two-year outcome results and factors of

influence. Front Psychiatry. 11:6872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Manohar H and Kandasamy P: Clinical

outcomes of children with ASD-preliminary findings from a 18 month

follow up study. Asian J Psychiatry. 64:1028162021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Yuan B, Wang M, Wu X, Cheng P, Zhang R,

Zhang R, Yu S, Zhang J, Du Y, Wang X and Qiu Z: Identification of

de novo Mutations in the Chinese autism spectrum disorder cohort

via whole-exome sequencing unveils brain regions implicated in

autism. Neurosci Bull. 39:1469–1480. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Levy RJ and Paşca SP: What have organoids

and assembloids taught us about the pathophysiology of

neuropsychiatric disorders? Biol Psychiatry. 93:632–641. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Al-Beltagi M, Saeed NK, Bediwy AS, Bediwy

EA and Elbeltagi R: Decoding the genetic landscape of autism: A

comprehensive review. World J Clin Pediatr. 13:984682024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A,

Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, Miller J, Fedele A, Collins J,

Smith K, et al: Genetic heritability and shared environmental

factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

68:1095–1102. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tick B, Bolton P, Happé F, Rutter M and

Rijsdijk F: Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: A

meta-analysis of twin studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

57:585–595. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Shaw KA, Bilder DA, McArthur D, Williams

AR, Amoakohene E, Bakian AV, Durkin MS, Fitzgerald RT, Furnier SM,

Hughes MM, et al: Early identification of autism spectrum disorder

among children aged 4 years-autism and developmental disabilities

monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill

Summ. 72:1–15. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Barnard RA, Pomaville MB and O'Roak BJ:

Mutations and modeling of the chromatin remodeler CHD8 define an

emerging autism etiology. Front Neurosci. 9:4772015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Xu B, Ho Y, Fasolino M, Medina J, O'Brien

WT, Lamonica JM, Nugent E, Brodkin ES, Fuccillo MV, Bucan M and

Zhou Z: Allelic contribution of Nrxn1α to autism-relevant

behavioral phenotypes in mice. PLoS Genet. 19:e10106592023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chiola S, Napan KL, Wang Y, Lazarenko RM,

Armstrong CJ, Cui J and Shcheglovitov A: Defective AMPA-mediated

synaptic transmission and morphology in human neurons with

hemizygous SHANK3 deletion engrafted in mouse prefrontal cortex.

Mol Psychiatry. 26:4670–4686. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Guo B, Chen J, Chen Q, Ren K, Feng D, Mao

H, Yao H, Yang J, Liu H, Liu Y, et al: Anterior cingulate cortex

dysfunction underlies social deficits in Shank3 mutant mice. Nat

Neurosci. 22:1223–1234. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Vogt D, Cho KKA, Shelton SM, Paul A, Huang

ZJ, Sohal VS and Rubenstein JLR: Mouse Cntnap2 and human CNTNAP2

ASD alleles cell autonomously regulate PV+ cortical interneurons.

Cereb Cortex. 28:3868–3879. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Kushima I, Nakatochi M, Aleksic B, Okada

T, Kimura H, Kato H, Morikawa M, Inada T, Ishizuka K, Torii Y, et

al: Cross-Disorder analysis of genic and regulatory copy number

variations in bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum