The liver orchestrates its vital functions through

intricate cellular crosstalk among diverse cell populations

(1). Hepatic stellate cells

(HSCs), a specialized lineage of mesenchymal cells, are

strategically positioned within the perisinusoidal space (space of

Disse), forming critical anatomical interfaces between liver

sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) and hepatocyte cords (2-4).

As key constituents of the non-parenchymal cell (NPC) compartment

of the liver, comprising approximately one-third of NPCs in

homeostasis (5,6), HSCs functionally interact with

resident macrophages, LSECs, Kupffer cells (KCs), portal

fibroblasts and recruited immune cells to regulate hepatic

pathophysiology (1,7). This cellular interplay positions

HSCs as central orchestrators of tissue responses during both liver

injury and regeneration (8,9).

In a quiescent state, HSCs maintain hepatic

homeostasis through vitamin A (VitA) storage and metabolism,

immunomodulatory signaling, and the paracrine secretion of

cytokines, growth factors and apolipoproteins (6,10,11). Following liver injury,

mesenchymal cell activation drives pathogenic extracellular matrix

(ECM) deposition, with transdifferentiated myofibroblasts serving

as the principal ECM producers (12,13). While multiple cellular sources,

including portal fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived progenitors,

contribute to the myofibroblast pool (14,15), lineage-tracing studies

unequivocally identify HSCs as the dominant progenitors in the

majority of liver fibrogenic contexts (16,17).

Conventional paradigms have portrayed HSCs as a

functionally homogeneous population uniformly transitioning into

profibrotic myofibroblasts (18,19). Acute injury triggers HSC

activation through paracrine signals from neighboring cells,

initiating transient myofibroblastic differentiation to support

ECM-mediated tissue repair (6).

By contrast, chronic injury leads to sustained HSC activation,

resulting in pathological ECM accumulation and architectural

distortion (20). Emerging

evidence indicates that HSCs exhibit dynamic activation states

beyond simple binary (quiescent vs. activated) classification.

While activated HSCs (aHSCs) predominantly drive fibrogenesis,

specific subpopulations demonstrate paradoxical anti-fibrotic or

hepatoprotective functions (21). This functional diversity

underscores the inherent heterogeneity and phenotypic plasticity of

HSCs across disease phases.

The resolution of single-cell RNA sequencing

(scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of mesenchymal

cell diversity (22,23). High-dimensional analyses reveal

spatially and temporally restricted HSC subpopulations in both

healthy and diseased livers, each exhibiting unique transcriptional

programs and functional specializations during fibrogenesis,

immunomodulation and tissue regeneration (24). These discoveries not only

redefine HSC biology, but also unveil novel therapeutic

opportunities for the precision targeting of pathogenic HSC

subsets, while preserving their reparative functions (25,26).

The present review synthesizes current insights into

HSC heterogeneity, delineates context-dependent phenotypic switches

driven by niche-specific cues and metabolic reprogramming, and

discusses emerging strategies that can be used to therapeutically

target HSC subpopulations in liver diseases.

By integrating marker-based analyses, single-cell

sequencing and spatial transcriptomic techniques, the multilayered

heterogeneity of HSCs across transcriptional, functional and

spatial dimensions has been revealed (27). Collectively, these perspectives

converge to portray HSCs as context-dependent regulators whose

identities vary with analytical scale and tissue niche (Table I). Single-cell transcriptomic

profiling and lineage tracing have resolved a long-standing

controversy, establishing quiescent HSCs (qHSCs) as progenitors of

injury-induced myofibroblasts across liver diseases (28,29). Pseudotime analyses have revealed

a dynamic continuum in which transitioning HSCs undergo

transcriptional priming, fate bifurcation and context-dependent

functional specialization during fibrogenesis (17). Crucially, this plasticity is

spatially constrained by hepatic zonation, with periportal HSCs

more responsive to inflammatory signals and pericentral HSCs more

attuned to metabolic stress (17,30). Disease etiology further imprints

epigenetic memory on aHSCs, reinforcing pathological feedback

loops. Such multidimensional adaptability positions HSCs as

biomechanical integrators that decode parenchymal damage patterns

into spatially calibrated fibrotic responses, offering therapeutic

entry points for precision anti-fibrotic strategies (Table II).

Previous studies have broadly categorized qHSCs as a

single transcriptional cluster characterized by VitA storage and

homeostatic functions (19,31-33). These cells are molecularly

defined by the high expression of lecithin retinol acyltransferase

(LRAT), a canonical marker of VitA metabolism, alongside

quiescence-associated genes, such as peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and adipogenic genes,

such as perilipin 2 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP),

that enforce their dormant state (22,34). The maintenance of this inactive

phenotype further involves stellate-specific markers, such as Reln

and Ecm1, which regulate ECM interactions and signaling quiescence

(35,36). Transcriptomically, qHSCs marked

by nerve growth factor receptor (Ngfr), LRAT, and ADAMTS-like

protein 2 (Adamtsl2) serve as the precursor pool for aHSCs,

predominantly functioning as VitA reservoirs and homeostatic

regulators in uninjured livers (17).

Under physiological conditions, the liver lobule is

divided into three functional zones, namely the periportal (zone

1), midlobular (zone 2) and pericentral (zone 3). Each zone is

characterized by distinct oxygen tension, metabolite concentrations

and signaling molecules (37).

Building on this spatial framework, recent scRNA-seq and spatial

transcriptomic analyses have redefined zonally restricted qHSC

subpopulations. qHSCs bifurcate into portal vein-associated HSC

(PaHSC, Ngfrhigh) and central vein-associated HSC

(CaHSC, Adamtsl2high) subpopulations (30,38,39). This zonation aligns with lobular

gradients of oxygen, nutrients and signaling molecules, shaping HSC

functional identities with PaHSCs primed for pro-fibrotic

activation, while CaHSCs are more associated with detoxification

(26).

Notably, a pre-specified qHSC subtype, termed

1-HSCs, has recently been identified in zone 1 of the healthy liver

lobule (40). Although

functionally quiescent under homeostatic conditions, 1-HSCs are

spatially localized and poised for activation upon injury. Unlike

conventional myofibroblast precursors, 1-HSCs primarily orchestrate

sinusoidal capillarization in response to damage, revealing a

reparative trajectory distinct from classical fibrogenesis

(40). The identification of

1-HSCs further reinforces the notion that HSCs constitute a

spatially organized ecosystem, wherein certain subpopulations are

preconfigured for specialized responses despite appearing

phenotypically dormant in steady-state conditions. These

discoveries collectively illustrate that even in homeostasis, HSCs

exist as a functionally partitioned ecosystem, their phenotypic

diversity spatially encoded and primed for context-dependent

responses.

Notably, the functional zonation of HSCs has

identified VitA-enriched and VitA-deficient HSC subsets occupying

distinct lobular niches, with VitA droplet size and distribution

exhibiting zonation-dependent patterns (6,41). While PaHSCs display heightened

VitA storage with desmin expression (42), VitA-poor HSCs near central veins

may act as 'first responders' to injury, transitioning more rapidly

into activated states (43).

Transcriptomic stratification in human livers

further reveals a dichotomy within HSC subpopulations. Glypican

3-expressing HSC1 localize to portal-central vascular regions and

is enriched in elastic fiber-related genes, consistent with

structural maintenance roles. By contrast, dopamine

beta-hydroxylase -high HSC2 distribute diffusely along sinusoids,

displaying antigen presentation pathways suggestive of

immunomodulatory potential (44). Furthermore, developmental

research has identified embryonic HSCs transiently express collagen

type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a1) alongside GFAP and Desmin, but lack α

smooth muscle actin [α-SMA; also known as actin alpha 2 (Acta2)],

mirroring qHSC signatures, while retaining the plasticity required

for later activation (45).

The injury-activated transformation of HSCs reveals

a dynamic spectrum of phenotypic states in which qHSC populations

undergo significant changes that drive their differentiation and

mobilization in response to tissue damage (17). However, despite this

activation-driven depletion, a resilient subset of qHSCs persists

across various disease models. These residual qHSC pools exhibit

unique phenotypic and functional adaptations that enable their

survival and potential contribution to tissue repair and

regeneration (30,46-48). For instance, in carbon

tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis, a distinct

subset of stress-adapted qHSCs emerges, characterized by the

expression of specific markers, such as betaine-homocysteine

S-methyltransferase and fatty acid binding protein (Fabp)1

(49). This subset appears to

represent a metabolically reprogrammed survival state by altering

their metabolic pathways to adapt to the fibrotic environment,

thereby preserving a reservoir capable of contributing to

regeneration (17,49).

The myofibroblastic aHSCs conventionally

characterized by Acta2, Col1a1 and tissue inhibitor of

metalloproteinases 1 (Timp1) signatures (17,50-52), have been further delineated along

the transitional activation gradients, revealing discrete clusters

from quiescent reservoirs to fully differentiated matrix-producing

myofibroblasts (53). For

example, in early-stage non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), qHSCs

undergo partial activation, contributing to low-grade fibrosis

through controlled ECM deposition (30). As the disease progresses, a

subset of HSCs acquires a highly profibrogenic phenotype, driven by

pro-inflammatory signals from macrophages and damaged hepatocytes

(30). Indeed, scRNA-seq

indicates that HSC activation encompasses a spectrum of cell states

rather than a uniform transition, with distinct subsets exhibiting

transcriptional programs related to collagen synthesis, immune

modulation, or matrix remodeling (27,54). Additionally, zonally restricted

HSC activation patterns are observed, with PaHSCs exhibiting

heightened responsiveness to cholestatic injury, whereas CaHSCs

dominate in metabolic stress-induced fibrosis (55).

Notably, previous studies have uncovered a third

'inactive' HSC state (iHSCs) across various disease models in both

human and mouse livers. These cells are transcriptionally distinct

from classical qHSCs, exhibiting a low expression of fibrogenic

genes and the upregulation of quiescence-associated genes, but not

adipogenic genes (30,45). As an intermediate population,

iHSCs are closer to qHSCs than to aHSCs, although they do not fully

revert to qHSCs and remain poised for swift reactivation if

fibrogenic stimuli recur (45).

However, compared with terminally differentiated aHSCs, they retain

partial quiescence features with reversible traits, making them a

promising therapeutic target because restoring iHSCs to a quiescent

state is easier than deactivating fully activated myofibroblasts.

This concept has been functionally validated using in vivo

fate-mapping experiments in fibrotic regression models (45).

While α-SMA remains a canonical activation marker,

its restricted expression to discrete HSC subsets in fibrotic

niches underscores the existence of heterogeneous myofibroblast

differentiation states (35,54). A breakthrough came with the

identification of syndecan-4 as a pan-activation marker universally

expressed in diverse injury contexts, mechanistically linked to HSC

migration through integrin signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling

(56).

Of note, HSC activation dynamics differ based on the

underlying pathogenic stimulus. For example, NASH models induce

lipid-associated activation signatures characterized by Fabp4 and

perilipin 2 (Plin2) expression, while cholestatic injury promotes

Twist1-driven ductular reaction phenotypes (32,57,58). Within similar pathologies,

spatially restricted activation programs emerge in liver disease,

with peri-injury HSCs becoming proliferative [platelet-derived

growth factor (PDGF)Rβhigh], while periportal HSCs

adopting inflammatory [C-C motif chemokine ligand 2

(Ccl2)-expressing] states (21).

This phenotypic mosaicism reflects microenvironmental instructive

signals ranging from transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) gradients

to mechanical stiffness thresholds.

The single-cell transcriptomic analyses of fibrotic

liver models has revealed dynamic HSC activation states, ranging

from quiescent VitA-storing cells to fully differentiated

collagen-producing myofibroblasts. The activation cascade begins

with early-responsive HSCs

(Cdc20high/Birc5high) that proliferate

rapidly upon injury, creating an expansion pool for downstream

differentiation (38,55). These cells give rise to a

matrix-remodeling HSC population [Acta2+/regulator of

G-protein signaling 5 (Rgs5)+], which serves as central

executors of fibrogenesis by secreting provisional ECM components,

while simultaneously regulating neighboring HSC fate through

paracrine signaling (55). A

critical transitional Adamtsl2+/Alcam+

subpopulation emerges at this stage, exhibiting hybrid

quiescent-activated features and functioning as a pivotal decision

point (49). It is capable of

either progressing toward terminal metabolically-committed HSCs or

potentially reverting toward quiescence under appropriate signals

such as PPARγ agonists (34,59).

Spatiotemporal analyses further demonstrate

model-specific activation patterns, with CCl4-induced

injury favoring VitA+ HSCs that retain metabolic

capacity, while bile duct ligation models promote VitA-depleted

progenitor-like populations (45,60,61). Functional specialization occurs

through distinct phases, including inflammatory-phase [C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand 5 (Cxcl5)+/serum amyloid A3

(Saa3)+], migratory-phase [Spp1+/matrix

metalloproteinase (Mmp)+] and ECM-producing (C-type

lectin domain family 3 member B-positive) hybrid cells, with

vascular zonation dictating myofibroblast origins, as evidenced by

transcription factor 21 (Tcf21)+ CaHSCs driving

CCl4-mediated fibrosis vs. portal Tcf21+ populations

dominating cholestatic injury (17,22,29).

Human cirrhosis exhibits an amplified, yet conserved

differentiation trajectory progressing from

RGS5+/FABP4+ transitional HSCs to fibulin

(FBLN)1+/COL1A1+ terminal myofibroblasts,

with spatial transcriptomics identifying periostin-positive aHSCs

as primary fibrogenic effectors alongside rare RGS5+

subsets potentially regulating inflammatory niches (55,62,63). The complexity of HSC

heterogeneity is further compounded by aging through the emergence

of distinct senescent subpopulations that perpetuate fibrotic

microenvironments via senescence-associated secretory phenotype

(SASP) mediated signaling, highlighting the multi-faceted nature of

HSC biology in liver fibrosis pathogenesis across different injury

models and disease stages.

Recent advances in single-cell technologies have

revealed both conserved and disease-specific patterns of HSC

activation across various liver pathologies. A core transitional

pathway (HSC1-HSC4), marked by sequential surface marker changes,

emerges in both non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and

CCl4-induced injury, demonstrating conserved mechanisms

in the progression from quiescence to myofibroblastic states

(35,54). Notably, this shared activation

trajectory coexists with disease-specific adaptations.

Particularly, in NAFLD, a unique endothelial-chimeric protein

tyrosine phosphatase receptor type B (Ptprb)+/lumican

(Lum)+ subset suggests vascular niche-dependent

reprogramming (35), while

alcoholic hepatitis features a multifunctional

Lrat+/Fbln2+ population that simultaneously

drives fibrosis through collagen deposition, modulates immunity and

sustains proliferation through programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)

and autocrine PDGFRβ signaling (61).

The NASH microenvironment further diversifies HSC

functionality, where different subpopulations cooperate to promote

disease progression. While Timp1+ cells initiate matrix

remodeling, interferon regulatory factor (Irf)7+ subsets

recruit inflammatory macrophages, Cd36+ populations

perpetuate steatosis and cyclin-dependent kinase 1

(Cdk1)+ clusters expand the myofibroblast pool (30). This functional specialization is

evolutionarily conserved, as human NASH biopsies similarly exhibit

ACTA2+ subsets mediating reparative ductular reactions,

while retinol binding protein 1-positive populations directly drive

fibrogenesis (64). The

transition to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) reveals an additional

layer of complexity, with the balance between tumor-suppressive

cytokine-producing Cxcl9+ HSCs and pro-carcinogenic

Col1a1+ myofibroblastic subsets determining clinical

outcomes (65,66). Spatial transcriptomics of HCC

further reveal region-specific HSC subsets, with COL1A1-high HSC1

supporting tumor growth through matrix-rich desmoplasia, whereas

ACTA2-high HSC2 adopts a contractile, pro-invasive phenotype

(67). These findings

collectively demonstrate how HSC heterogeneity creates distinct

pathological niches, with disease progression depending on both

conserved activation pathways and context-dependent adaptations

that emerge in specific etiologies.

Across diverse hepatotoxic agents, a core fibrogenic

program emerges through the consistent appearance of

collagen-producing myofibroblast subsets

(Acta2+/Col1a1+), suggesting a fundamental

response pathway to parenchymal damage (29). However, the specific

manifestation of HSC activation varies significantly with toxicant

type, creating distinct pathological microenvironments.

Glyphosate exposure induces a characteristic

four-subpopulation response that includes not only the expected

fibrogenic clusters but also prominently features an inflammatory

IL-6+/Ccl6+ subset, indicating strong

immunomodulatory effects (68).

Similarly, triclosan triggers ECM-producing and proliferative

populations, while uniquely generating migratory

chemokine-expressing clusters (Cxcl2+/Ccl2+),

potentially facilitating immune cell recruitment (69). The paradoxical effects of

triptolide are particularly noteworthy, as it drives simultaneous

pro-inflammatory [NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing

3 (NLRP3) activation] and reparative

(Acta2+/Myh11+) HSC states, reflecting its

complex therapeutic-toxic duality (46,70).

Acute liver failure models reveal another dimension

of HSC plasticity, where fibrotic collagen-producing populations

coexist with specialized Acta2+ repair-promoting subsets

that orchestrate macrophage polarization through STAT6 signaling

(71,72). This reparative population appears

particularly prominent in acetaminophen and thioacetamide models,

suggesting its potential role in acute injury resolution (48). The universal presence of cycling

HSC populations, marked by Mki67/Cdk1 or Ccnb1 across all models,

underscores the fundamental need for cellular expansion in injury

response, while the varying proportions of fibrotic, inflammatory

and reparative subpopulations reflect toxicant-specific

microenvironmental programming (48).

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that while

HSCs maintain core response modules to hepatic injury, their

activation spectrum adjusts in a compound-specific manner, forming

distinct cellular ecosystems that influence disease progression and

recovery potential. The balance between these conserved and

adaptive responses likely determines the ultimate pathological

outcome, providing novel targets for tailored therapeutic

interventions based on injury etiology.

The HSC response during liver regeneration following

partial hepatectomy (PH) exhibits a distinct activation spectrum

compared with pathological fibrosis, with specialized

subpopulations orchestrating regenerative rather than fibrotic

programs. The predominant weakly activated cluster

(Acta2low/Lrat+) represents a novel

adaptation to regenerative demands, maintaining quiescence markers

while likely serving as a rapidly mobilizable reserve pool, a

feature rarely observed in chronic injury settings where HSCs

typically progress rapidly to full activation (73).

A PH-specific proliferative population emerges as a

hallmark of regenerative HSC activation, co-expressing mitotic

regulators (Cdk1/DNA topoisomerase II alpha) alongside regenerative

cytokines (73). This dual

functionality suggests an elegant coupling of self-renewal with

paracrine support for hepatocyte proliferation that is

conspicuously absent in the majority of injury models, where

proliferating HSCs primarily contribute to fibrogenesis rather than

regeneration (30,68,69).

Computational modeling reveals a sophisticated

division of labor among regenerating HSCs, with pro-regenerative

subsets [hepatocyte growth factor

(Hgf)high/Vegfahigh/Col1a1low]

actively suppressing fibrogenic programs to prioritize growth

factor production, reflecting reprogramming that prevents the

scarring typical of pathological responses (47). Notably, the discovery of a

transitional 'mixed' state

(Col1a1high/Hgfhigh) introduces a previously

unrecognized layer of regulation, where these cells appear to

function as biological rheostats that use Yes-associated protein

(YAP)/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ)

mechanosensing to dynamically adjust the fibro-reparative balance

according to microenvironmental demands (47).

The progression from aHSCs to senescent phenotypes

represents a critical adaptation in chronic liver disease, with

cells exiting the cell cycle, yet remaining metabolically active

and shaping disease outcomes context-dependently (74). In fibrotic environments, aHSCs

transition into senescent HSCs (sHSCs) marked by

TP53/CDKN1A-mediated cell cycle arrests yet paradoxically acquire

pro-tumorigenic potential through SASP components, including

inflammatory cytokines and matrix-remodeling proteases (18,75-77). Early metabolic dysfunction adds

further complexity to this transition, generating

Mrc1+/Slc9a9+ sHSCs that evolve into

inflammatory-senescent hybrids

(Cxcl10+/Ccl5+), linking steatosis injury to

progressive microenvironmental dysfunction (78).

The functional duality of sHSCs becomes particularly

evident in HCC, where early TP53high sHSCs suppress

tumor growth via CXCL9-driven immune recruitment, while persistent

NASH-derived sHSCs promote malignancy through TGFβ1/PDGFA-induced

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (79-81). Contrastingly, in liver

regeneration, transient sHSCs [interleukin

(IL)-6+/CXCL2+] enhance hepatocyte

proliferation, illustrating how senescence duration and niche

signals determine beneficial vs. detrimental outcomes (82).

Parallel to senescence, aHSCs may also adopt

inactivated states during injury resolution (34). These cells downregulate

fibrogenic markers and partially regain quiescence-associated genes

but retain epigenetic scars of activation, such as loss of lipid

droplets (45). NASH regression

models have identified a specialized

CXCL1+/GABRA3+ iHSC subset that balances

reduced ECM production with heightened sensitivity to reactivation

(30), while PH induces

metabolically reprogrammed COL1A1low iHSCs that persist

in peri-sinusoidal niches (73).

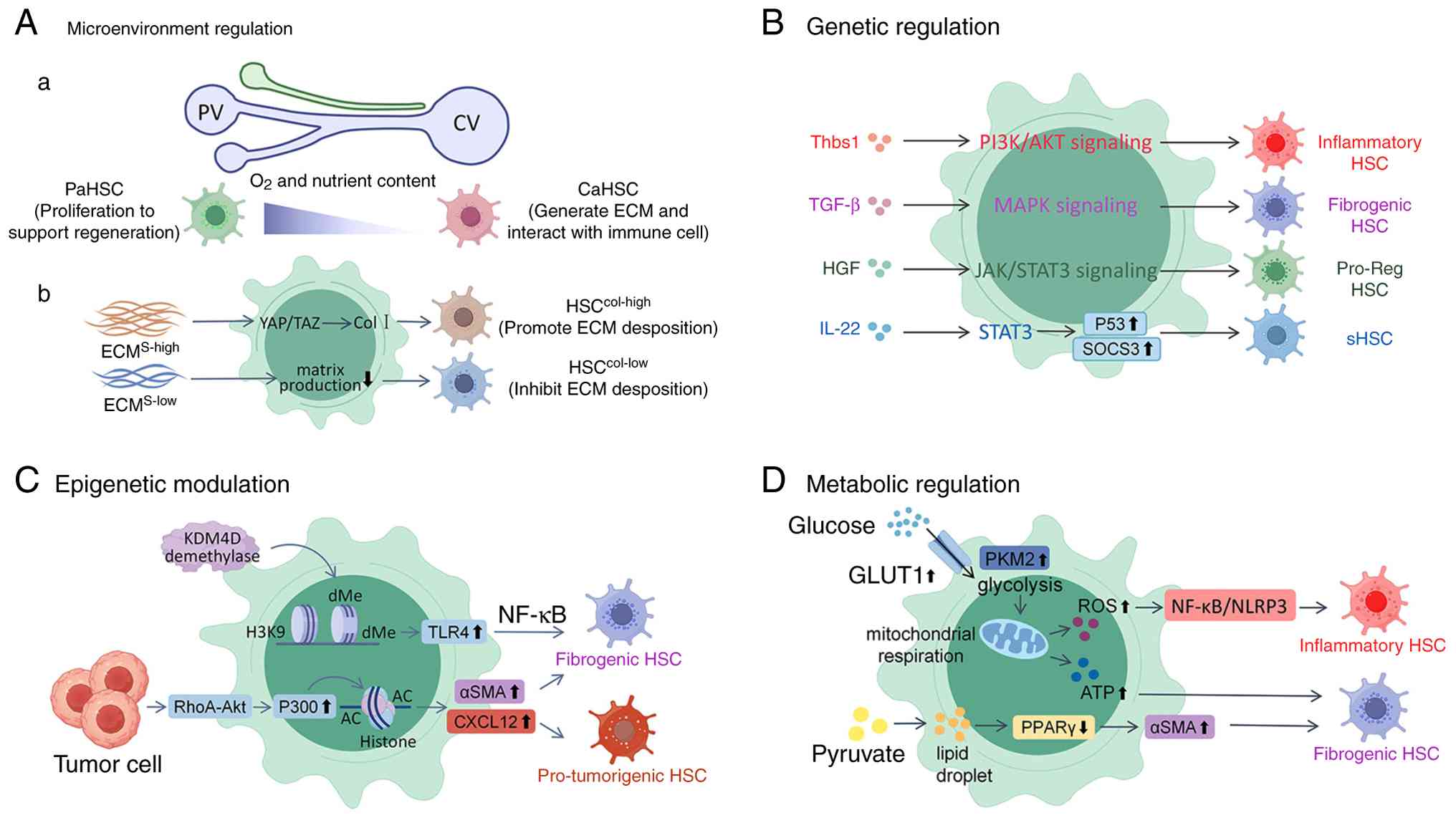

HSC heterogeneity largely arises from

microenvironmental regulation, genetic or epigenetic modulation,

and metabolic reprogramming (Fig.

1). Within the liver lobule, the spatial distribution of HSCs

establishes functional diversity driven by zonation-specific

gradients of oxygen, metabolites and signaling molecules (37,83). CaHSCs, residing in hypoxic and

metabolite-rich zones, acquire pro-fibrogenic traits through

hypoxia-inducible and CYP450-dependent pathways (37,84). By contrast, PaHSCs near the

oxygen- and nutrient-rich portal triad serve as a proliferative

reservoir during regeneration (85). Midlobular HSCs exhibit

intermediate phenotypes balancing ECM remodeling and immune

modulation (85).

Biomechanical heterogeneity further amplifies these

zonal responses. Uneven ECM deposition generates stiffness

gradients that differentially activate mechanotransduction

pathways, YAP/TAZ signaling predominates in stiff pericentral

regions to promote fibrosis, while softer periportal areas favor

HSC migration and proliferation via integrin-dependent cues

(49,86,87).

Spatial specialization is also shaped by paracrine

and juxtacrine interactions with neighboring cells (88). Pericentral LSECs secrete Hedgehog

ligands and pericentral KCs produce TGF-β to polarize HSCs toward a

fibrogenic phenotype, whereas periportal LSECs release nitric oxide

and periportal KCs secrete IL-10 to suppress excessive

proliferation and support reparative functions (20,89-91). Hepatocytes also contribute to

this zonation: Oxidative stress products from pericentral

hepatocytes activate adjacent HSCs, while periportal hepatocytes

provide pro-regenerative signals supporting proliferation (92,93).

HSCs further shape immune-metabolic niches through

crosstalk with infiltrating immune cells. Pericentral subsets

recruit monocytes via CCL2 and CXCL5 to exacerbate inflammation,

whereas periportal HSCs modulate lipid antigen presentation and

perpetuate steatoinflammation in NASH (22,30,55). These interactions integrate local

damage-associated molecular patterns with systemic immune inputs,

forming spatially organized regulatory networks that determine HSC

behavior across disease contexts.

Emerging single-cell and spatial transcriptomic

technologies have validated these mechanisms, revealing

zonation-specific ligand-receptor interactions between HSCs and

neighboring cell types and identifying spatially restricted

activation markers. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that

HSC heterogeneity represents an adaptive response to

microenvironmental demands rather than random variation (37,85). Understanding such spatial

organization provides therapeutic opportunities, selectively

targeting pericentral HSCs to mitigate fibrosis or modulating

periportal subsets to enhance regeneration. The future integration

of spatial omics and functional mapping will further refine

precision interventions for liver diseases.

The activation of HSCs involves a tightly regulated

transcriptional program that governs phenotypic transitions between

quiescent, activated, and inactivated/senescent states. In their

quiescent state, HSCs maintain lipid droplets and express

adipogenic transcription factors (TFs), such as C/EBPα and PPARγ,

which suppress fibrogenic genes such as Col1a1 and α-SMA (34,55,94). Upon liver injury,

lineage-determining TFs, including E26 transformation-specific

transcription factor ½ (ETS1/2), GATA binding protein 4/6 (GATA4/6)

and IRF1/2, which maintain quiescent phenotype in qHSCs, are

repressed during activation, leading to the disruption of

quiescence-associated genes such as PPARγ (34,59,95). During fibrosis resolution, PPARγ

is re-expressed in iHSCs, collaborating with GATA6 to restore

quiescence, highlighting the potential of GATA6 and PPARγ agonists

as a promising target in anti-fibrotic therapy (34,59).

Similarly, in NASH models, ETS1 has been shown to

preserve the quiescent identity of HSCs by suppressing

pro-fibrogenic gene programs and maintaining lipid storage

capacity, while IRF1 marks aHSCs and promotes inflammatory cytokine

production and collagen deposition during the progression of NASH

(30). Furthermore, the genetic

ablation of GATA6 in HSCs disrupts their ability to revert to a

quiescent state post-injury, as GATA6-deficient cells fail to

upregulate lipid-droplet-associated proteins, such as PLIN2 and

downregulate α-SMA expression, directly linking this TF to HSC

deactivation and metabolic reprogramming (30). These findings underscore a

TF-centric regulatory hierarchy governing HSC phenotypic

plasticity.

The hierarchical integration of upstream signaling

pathways dictates the fate of HSCs through metabolic and mechanical

checkpoints. TGF-β and PDGF function as dominant fibrogenic

drivers. TGF-β activates SMAD3 to enforce myofibroblast

transdifferentiation (20,96), while PDGFRβ signaling licenses

proliferative expansion via mechanistic target of rapamycin

(mTOR)-dependent glycolytic reprogramming (97). Conversely, Wnt pathway

modulators, such as Dickkopf-related protein 1 exert

context-dependent control (98).

While transient Wnt inhibition restores lipid storage by activating

PPARγ-dependent lipogenic genes, chronic Wnt activation promotes

senescence evasion via p21 suppression (99,100). Notably, telomerase-positive

HSCs exemplify this regulatory plasticity, coupling TERT-mediated

replicative longevity with retinol-responsive metabolic switching,

as retinol uptake is reported to reactivate RXRα-driven lipid

droplet biogenesis, enabling reversion to quiescence despite

persistent activation cues (101,102).

Emerging evidence reveals that the induction of

senescence in HSC operates through interconnected tumor suppressor

networks, which integrate inflammatory, metabolic, and mechanical

signals to enforce growth arrest and restrict ECM overproduction.

For example, IL-22 signaling initiates a senescence cascade through

the STAT3-mediated upregulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling

3 and TP53, driving HSC into growth arrest (103). This process is reinforced by

the parallel activation of the p16/Rb pathway, which stabilizes the

senescent phenotype by blocking cell cycle progression (75). sHSCs undergo dual transcriptional

reprogramming. They suppress ECM-producing genes while enhancing

immune surveillance molecules, such as major histocompatibility

complex class II and PD-L1 (104,105). Notably, HSCs lacking both TP53

and INK4a/ARF evade senescence entirely, leading to

hyperproliferation and aggravated fibrotic responses, highlighting

the cooperative action of these tumor suppressor pathways in

constraining pathological HSC activation (75). Concurrently, the loss of

YAP-mediated mechanosensing disrupts cytoskeletal tension, inducing

p21-dependent quiescence against aberrant activation (106). These overlapping pathways

collectively indicate a 'senescence barrier' to suppress HSC-driven

matrix deposition.

Of note, the integrity of this barrier determines

pathological outcomes. Compromised TP53 or p16/Rb signaling

dismantles senescence enforcement, releasing HSCs from growth

constraints and permitting their transition into aggressive

profibrotic effectors that functionally mirror tumorigenic stromal

cells. Thus, this senescence-mediated barrier underscores the

evolutionary conservation of tumor suppressor networks in fibrosis

containment, where senescence acts not only as an anti-aging

mechanism, but also as a spatial regulator ensuring fidelity of

tissue repair.

The phenotypic plasticity of HSCs during fibrosis

is also governed by coordinated epigenetic reprogramming involving

DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA

networks, which collectively translate microenvironmental stimuli

into transcriptional outputs (107). Genome-wide methylation

profiling reveals activation-state-specific 5-methylcytosine

patterns, particularly at pericentromeric regions, with

hypermethylation silencing anti-fibrotic loci, such as PPARγ and

hypomethylation enabling pro-fibrotic drivers, such as spondin 2

via Wnt/β-catenin activation (108-110). The pharmacological inhibition

of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) counteracts this shift, restoring

quiescence by suppressing TGF-β receptor signaling (111).

Complementing these DNA-centric modifications,

histone post-translational dynamics have been shown to reinforce

fibrogenic commitment. For example, histone deacetylases (HDACs)

remove H3K27 acetylation at ACTA2 promoters to sustain

myofibroblast identity (112),

while mechanical cues from fibrotic ECM stiffening trigger nuclear

accumulation of p300, amplifying histone acetylation at fibrotic

loci to lock HSCs into self-reinforcing activation (86,87,113). Concurrently, H3K9me3 deposition

at senescence-associated genes and H3K9me2 demethylation at TLR4

enhancers link chromatin states to inflammatory fibrosis (114,115).

Non-coding RNAs further integrate metabolic and

epigenetic regulation. The age-dependent decline of geromiRs

derepresses IL-6/tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), fueling

inflammation and pre-metastatic niches (116), while miR-23a and miR-195

coordinate lipid metabolism with DNA methylation patterns during

phenotype switching (117).

Moreover, the hypermethylation of SAD1/UNC84 domain protein 2

perturbs nuclear lamina dynamics, destabilizing the genome and

driving chronic pathogenic activation (118).

This multilayered epigenetic plasticity positions

HSCs as microenvironmental rheostats, dynamically calibrating

fibrogenic responses. Targeting nodal regulators, such as DNMTs in

early fibrosis or p300 in established scarring, could selectively

disrupt pathological subsets, while preserving reparative

functions.

The phenotypic diversity of HSCs stems from their

marked metabolic plasticity, where dynamic shifts in glucose, lipid

and mitochondrial metabolism govern their activation states.

Following liver injury, HSCs undergo a metabolic reprogramming

characterized by enhanced glucose transporter type 1-mediated

glucose uptake and pyruvate kinase M2-driven glycolytic flux,

fueling mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for myofibroblast

differentiation (119). This

transition is accompanied by reactive oxygen species accumulation

that activates NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathways, driving

pro-inflammatory polarization (120). Notably, although aHSCs were

traditionally considered lipid-depleted, recent evidence indicates

they maintain active lipid metabolism. Mechanistically, the

metabolic reprogramming redirects pyruvate toward lipid synthesis,

leading to lipid droplet reformation, a paradoxical feature that

actually sustains fibrotic activity through PPARγ suppression and

TGF-β activation (121).

Mitochondrial dynamics play a pivotal role in

regulating the fate of HSCs. Studies have indicated that qHSCs

maintain fusion-dominant states that support efficient β-oxidation,

while aHSCs exhibit fission-prone mitochondria that generate

oncometabolites such as succinate and 2-hydroxyglutarate (122-124). These metabolites stabilize

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and promote angiogenic secretomes

(120).

In the tumor microenvironment, a metabolic

cross-talk emerges between cancer cells and HSCs (125). Malignant cells export lactate

through monocarboxylate transporter 4, creating an acidic

microenvironment that reprograms neighboring HSCs (126,127). This acid adaptation triggers

the release of MMP9 from HSCs, thereby fostering a permissive

environment for metastatic spread (128,129).

The complex interplay between ammonia metabolism

and HSC biology reveals an intriguing paradox. Disrupted

ureagenesis in injured livers results in the accumulation of

nitrogenous metabolites, which paradoxically elicit two opposing

outcomes in HSCs (130). While

promoting fibrogenic activation through mitochondrial stress, these

metabolites simultaneously induce growth arrest through

p53/p21-mediated senescence (131-133). This dual effect creates a

biological checkpoint that limits uncontrolled HSC expansion while

permitting controlled ECM deposition during tissue repair.

While notable progress has been made in

understanding HSC metabolism, several fundamental questions persist

about what drives their functional diversity. Currently available

research has largely illuminated the metabolic changes occurring

during initial activation; however, the exact mechanisms through

which distinct HSC subpopulations, particularly those with

immunomodulatory vs. pro-angiogenic properties, establish and

maintain their unique metabolic identities, remain to be fully

elucidated. Moreover, critical gaps remain in the knowledge of how

nutrient-sensing mechanisms interface with epigenetic regulation to

control HSC subset specification. The potential involvement of

NAD+-dependent metabolic sensors in coordinating

mitochondrial function across different HSC activation states also

warrants further investigation (134).

Resolving these unanswered questions could pave the

way for more sophisticated therapeutic strategies. Such approaches

would ideally target disease-promoting metabolic pathways in aHSCs,

while sparing their beneficial roles in liver repair and

regeneration. This precision targeting represents a crucial next

step in developing effective anti-fibrotic treatments that maintain

the innate regenerative capacity of the liver.

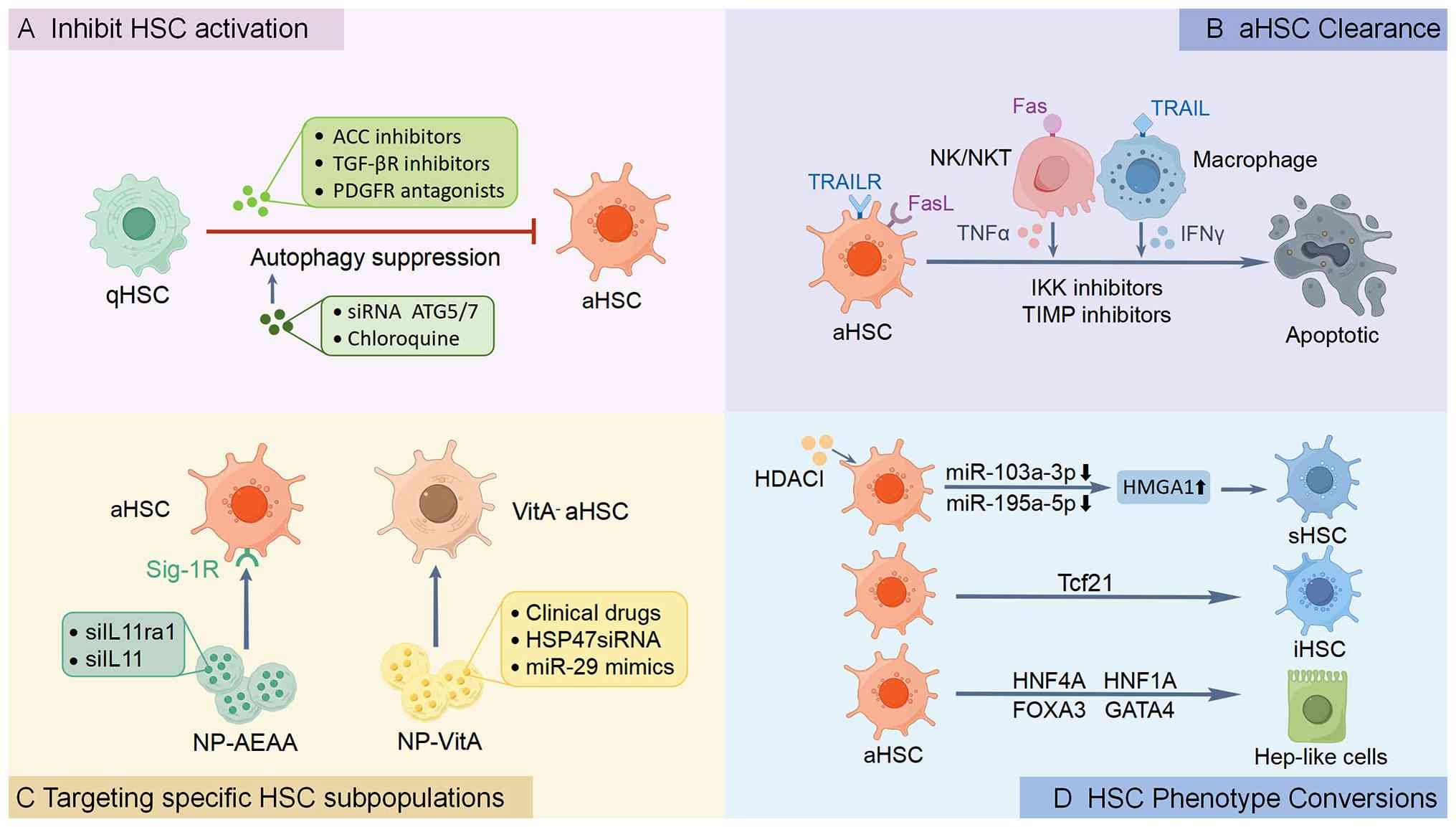

Current approaches to modulate HSC activity focus

on four primary mechanisms: i) The interruption of activation

signaling cascades; ii) the selective induction of aHSC apoptosis;

iii) targeting specific HSC subsets with defined pathogenic roles;

and iv) reprogramming aHSCs toward quiescent or alternative

functional phenotypes (Fig. 2).

Single-cell transcriptomic studies have revolutionized the

understanding of HSC heterogeneity, identifying distinct

pro-fibrotic and pro-regenerative subpopulations that coexist in

injured livers (135). These

findings support the development of precision therapies capable of

selectively targeting pathological subsets while sparing

regenerative populations.

HSC inactivation has emerged as a cornerstone in

the treatment of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, aiming to halt or

reverse the pathological accumulation of ECM in chronic liver

diseases. HSC activation is orchestrated by an intricate signaling

network integrating paracrine cues and metabolic reprogramming

(136), including TGF-β/Smad3

(137,138), Wnt/β-catenin (139) and Akt/mTOR (22,140). Among these pathways, TGF-β

signaling enhances glycolysis and de novo lipogenesis, both of

which are indispensable for the activation of HSCs. This process

can be disrupted by Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitors, such as

firsocostat, which has exhibited potential in reducing steatosis

and fibrosis in preclinical models and in patients with NASH,

although further investigations are warranted (NCT02856555)

(119,141). The inhibition of stearoyl-CoA

desaturase-1 by aramchol has been shown to attenuate HSC activation

and fibrogenesis independently of steatosis reduction, highlighting

the lipogenic contribution to HSC plasticity (142,143). Likewise, thyroid hormone

receptor agonists exert direct anti-fibrotic effects by suppressing

profibrogenic gene expression in HSCs and improving fibrosis

through coordinated metabolic and stellate cell-mediated mechanisms

(144,145). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor

agonists, primarily known for alleviating steatosis and insulin

resistance, further attenuate fibrosis when combined with the

ATP-citrate lyase inhibitor, bempedoic acid, in mice with NASH,

revealing a synergistic link between hormonal and metabolic

signaling in HSC inactivation (146,147).

Beyond metabolic reprogramming, anti-fibrotic

strategies also target canonical signaling pathways that drive HSC

activation. Inhibitors such as galunisertib, a TGF-β receptor I

kinase inhibitor, have been shown to exert anti-fibrotic effects in

preclinical models, although clinical trials have revealed limited

efficacy in advanced-stag cirrhosis, possibly due to the

compensatory mechanisms or off-target effects (NCT01246986)

(Table III) (148,149). Similarly, PDGF signaling,

critical for HSC proliferation, can be blocked by tyrosine kinase

inhibitors, such as imatinib or receptor antagonists; however,

challenges in specificity persist (150,151). In addition, probiotics such as

Mutaflor® inhibit HSC activation and fibrogenic

signaling in NAFLD/NASH models via the Hedgehog and Hippo pathways,

underscoring gut-liver crosstalk as a complementary anti-fibrotic

target (152).

Emerging evidence highlights the critical role of

epigenetic dysregulation in maintaining HSC activation. DNMT

inhibitors (DNMTIs, e.g., 5-azacytidine) and HDAC inhibitors

(HDACIs, e.g., vorinostat) have demonstrated anti-fibrotic effects

by remodeling chromatin architecture and suppressing collagen

expression in aHSCs (153,154). The therapeutic potential of

targeting non-coding RNAs is particularly promising, with microRNA

(miRNA/miR)-29 family members showing efficacy in restoring

epigenetic homeostasis and attenuating fibrogenesis in preclinical

models (155).

Building upon the epigenetic mechanisms discussed

earlier, autophagy emerges as another critical regulator of HSC

behavior during liver fibrosis progression. In chronic liver

injury, dysregulated autophagy plays a dual role in modulating HSC

activation, survival and fibrogenic activity (156). During the early stages of HSC

activation, autophagy serves as a crucial survival mechanism by

providing energy substrates to sustain proliferation and collagen

production under conditions of metabolic stress (156). This pro-fibrotic function is

supported by preclinical evidence showing that pharmacological

inhibitors such as chloroquine or genetic ablation of

autophagy-related genes such as autophagy-related gene 5/7

significantly attenuate collagen deposition and HSC activation in

rodent models (157,158).

However, the association between autophagy and

fibrosis becomes more complex in advanced stages of disease.

Paradoxically, excessive autophagic flux can trigger HSC senescence

through p53/p21 pathway activation, leading to cell cycle arrest

and reduced fibrogenic output (159,160). This dual nature has inspired

innovative therapeutic strategies, including combination approaches

that synergize autophagy inhibitors with pro-apoptotic agents to

enhance HSC clearance.

The clearance of aHSCs is orchestrated through

complex cellular crosstalk within the liver microenvironment, where

multiple cell types collectively determine the fate of HSCs

(161). LSECs play a dual

regulatory role, maintaining HSC quiescence under physiological

conditions through mediators including nitric oxide and hedgehog

inhibitors (162); yet,

transforming into pro-fibrotic stimulators upon injury-induced

capillarization (162,163). This phenotypic switch

highlights the therapeutic potential of vascular normalization

strategies to restore LSEC function and mitigate fibrogenesis

(163). The immune compartment

further modulates HSC clearance through coordinated actions.

Natural killer (NK) cells induce activated HSC apoptosis via

interferon γ secretion and death receptor engagement (20,164,165), while macrophage subsets

differentially regulate fibrosis progression (166). For example, pro-inflammatory M1

macrophages promote HSC death through TNF-α signaling and

potentiate NK cell cytotoxicity (167,168), whereas specialized restorative

macrophages drive fibrosis resolution by secreting MMPs to degrade

the ECM (169).

Pharmacological interventions targeting HSC

clearance have emerged through multiple approaches, including IKK

inhibitors and TIMP antagonists that rebalance NF-κB signaling and

MMPs activity (170,171), as well as drug repurposing

strategies exemplified by the antiviral agent tenofovir disoproxil

fumarate which suppresses HSC survival through PI3K/Akt/mTOR

pathway inhibition (172).

While the selective depletion of aHSCs accelerates fibrosis

resolution (106,173), excessive elimination risks

compromising hepatic function through reduced liver mass and

exacerbated inflammation (26,174). These observations underscore

the need for precision therapeutics capable of discriminating

between pathogenic and reparative HSC subpopulations (175).

The advent of single-cell omics technologies has

unmasked the functional diversity of HSC subpopulations, paving the

way for precision interventions that selectively neutralize

fibrosis-driving subsets, while preserving homeostatic or

regenerative HSCs. Clinically validated targets include

VitA-depleted aHSCs, which can be selectively addressed using

VitA-coupled liposomal nanoparticles (NPs). For instance,

BMS-986263, a lipid NP encapsulating siRNA against heat shock

protein 47 associated with collagen production, utilizes VitA to

target aHSCs in fibrotic livers (176). In a phase II trial

(NCT03420768), BMS-986263 reduced collagen production in patients

with advanced hepatic fibrosis, demonstrating proof-of-concept for

HSC-specific delivery (177).

Preclinically, VitA-coupled NPs loaded with miR-29 mimics restored

miR-29, a key anti-fibrotic miRNA in aHSCs of

CCl4-treated mice, reversing fibrosis without

hepatotoxicity (155,178). Another clinical-stage

candidate, nanoparticle aminoethyl anisamide (NP-AEAA), utilizes

aminoethyl anisamide surface modifications to selectively target

sigma-1 receptors that are upregulated on aHSCs in NASH

progression. In mice with diet-induced NASH, NP-AEAA delivering

siRNA against IL-11 reduced liver inflammation and fibrosis by

~50%, with ongoing optimization for first-in-human trials (179).

Furthermore, receptor-specific NP systems have

demonstrated significant potential for precision anti-fibrotic

therapy. The IGF2 E12-C21 peptide-conjugated NP platform

selectively binds IGF2R that are markedly upregulated during HSC

transdifferentiation. In bile duct ligation models, this targeted

delivery system enhanced fibrosis resolution through the

preferential transport of anti-fibrotic compounds such as

pentoxifylline to aHSC populations (180).

Complementary genetic approaches have further

advanced the ability to precisely manipulate HSC activity.

Preclinical studies utilizing GFAP-thymidine kinase transgenic

models achieved the selective elimination of proliferating HSCs

through ganciclovir administration, yielding a 70% reduction in

fibrosis, while preserving qHSC pools and maintaining hepatic

regenerative capacity (51,181). The parallel development of

inducible genetic systems, such as PDGFRβ-CreERT2, has enabled

temporal control over collagen-producing HSC ablation via tamoxifen

induction, demonstrating the feasibility of promoter-specific

interventions (182).

These approaches collectively represent significant

advances in cell-type-specific therapeutic strategies, offering

improved specificity compared to conventional broad-acting

anti-fibrotics.

Nevertheless, the translation of HSC-targeted

therapies from bench to bedside has encountered substantial

challenges that underscore the complexity of liver fibrosis

pathogenesis. The discouraging clinical performance of simtuzumab,

a monoclonal antibody targeting lysyl oxidase like 2, in phase II

cirrhosis trials revealed critical limitations in therapeutic

specificity and the adaptive capacity of the liver for compensatory

ECM remodeling (183).

Similarly, the TGF-β receptor inhibitor, galunisertib, despite

exhibiting robust efficacy in preclinical models, demonstrated only

modest clinical benefits in patients with advanced-stage fibrosis

(184). These clinical

experiences have catalyzed the development of more sophisticated

therapeutic strategies designed to overcome these limitations.

Emerging solutions currently focus on

dual-targeting approaches that combine VitA conjugates with PDGFRβ

ligands to better address HSC heterogeneity, as well as

microenvironment-responsive carriers that utilize fibrotic

niche-specific enzymes like MMPs for spatially controlled drug

release (185). Notably, recent

breakthroughs in gene-editing platforms, particularly CRISPR-Cas9

targeting aHSC-specific phosphorylation sites of A-kinase anchoring

protein 12, have demonstrated notable efficacy in preclinical

fibrosis models through precise silencing of profibrotic pathways

(186).

The notable plasticity of HSCs presents multiple

therapeutic avenues for combating liver fibrosis, while promoting

regeneration. Research has revealed that ~50% of aHSCs avoid

apoptosis during fibrosis resolution, instead undergoing phenotypic

reversion characterized by downregulation of fibrogenic markers and

acquisition of a quiescent-like state resistant to reactivation

(34,45). This plasticity has been

conclusively demonstrated through transplantation studies where

human aHSCs engrafted in immunodeficient mice regained

lipid-storing capacity and other quiescent cell features (34). PPARγ activation plays a central

role by restoring lipogenic programs that promote HSC inactivation

(34,187). Equally critical is Tcf21, a TF

that simultaneously suppresses profibrotic pathways, while

activating quiescence-associated genes in both cellular and animal

models (188). Complementary to

these reversion pathways, the targeted induction of senescence

through p53 activation has been shown to exert significant

anti-fibrotic effects (189-191).

Emerging evidence demonstrates that targeted

epigenetic modulation can effectively redirect aHSC fate toward

beneficial phenotypes. The small molecule, CM272, a dual inhibitor

of G9a histone methyltransferase and DNMT1, drives aHSC conversion

into adipocyte-like cells by demethylating and reactivating the

PPARγ promoter, resulting in the significant attenuation of

fibrosis in preclinical NASH models (10,192). The therapeutic potential of

this approach is further supported by the ability of CM272 to

simultaneously suppress pro-fibrotic signaling pathways. while

restoring metabolic functions characteristic of qHSCs (193).

HDACIs represent another class of epigenetic

modifiers with significant anti-fibrotic effects. Valproic acid

(VPA), a clinically approved HDACI, mediates aHSC senescence

through miRNA-dependent mechanisms. By downregulating miR-103a-3p

and miR-195-5p, VPA promotes the expression of high mobility group

AT-hook 1, a critical driver of cellular senescence (194). This epigenetic-miRNA cascade

not only induces growth arrest, but also shifts aHSCs toward an

anti-fibrotic secretome phenotype characterized by enhanced MMP

activity and reduced collagen production (22,195).

Notably, the complete lineage reprogramming of

aHSCs has been achieved through TF overexpression. The

combinatorial expression of forkhead box A3 (FOXA3), GATA4,

hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)1A and HNF4A converts aHSCs into

functional hepatocyte-like cells in vitro, which upon

transplantation, can repopulate damaged liver parenchyma and

ameliorate fibrosis (196,197). This direct reprogramming

approach bypasses pluripotent intermediates, while maintaining the

epigenetic memory of hepatic identity, providing potential

advantages for regenerative applications. Mechanistically, FOXA3, a

canonical pioneer factor, initiates this process by binding to

compacted chromatin at hepatocyte-specific enhancers and displacing

linker histone H1, thereby initiating local chromatin opening

(198). GATA4 acts

synergistically with FOXA3, and together they prime the epigenetic

landscape for the core hepatocyte regulators (197). Subsequently, HNF4A binds to

these accessible regulatory elements to activate a comprehensive

suite of genes defining hepatocyte identity, including those

governing metabolism and synthetic function (199). HNF1A reinforces this program by

stabilizing the transcriptional network and activating HNF4A

expression, creating a positive feedback loop that locks in the

hepatocyte fate (197).

Concurrently, the expression of the aHSC genetic program is

effectively silenced, as evidenced by the downregulation of key

markers including α-SMA and COL1A1. The reprogramming process also

suppresses critical aHSC maintenance pathways, such as YAP/TAZ

signaling, which is essential for maintaining the myofibroblastic

phenotype (200,201). This combinatorial action of the

four factors thereby orchestrates a complete phenotypic conversion,

overriding the fibrogenic identity of aHSCs to re-establish

functional hepatocyte properties in vivo.

The advent of single-cell and spatial

transcriptomics has established HSC heterogeneity and plasticity as

foundational to liver fibrogenesis and resolution. Given the

recurrent failure of broad-spectrum anti-fibrotics, future

therapeutic breakthroughs must leverage precision strategies

capable of distinguishing pathogenic from reparative HSC

subpopulations. Achieving this will require combinatorial

approaches, such as cell-specific NP delivery or temporally

controlled epigenetic reprogramming, to therapeutically guide HSC

fate decisions, thereby selectively inhibiting fibrosis while

actively promoting regeneration.

Not applicable.

DY conceived and supervised the study. DY and CG

wrote the manuscript. GC and HJ contributed to the literature

collection and the revision of the manuscript. HZ and YC assisted

with the literature search, figure preparation and revision of the

manuscript. KZ and DY finalized the manuscript and made the

conceptual evaluation of the manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by grants from the Key

Laboratory Open Project Foundation of Jiangsu University (no.

8161280002), Science and Technology Plan (Apply Basic Research) of

Changzhou City (no. CJ20230002), Science and Technology Plan (Apply

Basic Research) of Changzhou City (no. CJ20241041), the Soft

Science Research Program of Zhenjiang City (no. RK2025040), the

Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82100666) and the Young

Scientists Initiative Foundation of Jiangsu University.

|

1

|

Campana L, Esser H, Huch M and Forbes S:

Liver regeneration and inflammation: From fundamental science to

clinical applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:608–624. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wake K: 'Sternzellen' in the liver.

Perisinusoidal cells with special reference to storage of vitamin

A. Am J Anat. 132:429–462. 1971. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cogliati B, Yashaswini CN, Wang S, Sia D

and Friedman SL: Friend or foe? The elusive role of hepatic

stellate cells in liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

20:647–661. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kamm DR and McCommis KS: Hepatic stellate

cells in physiology and pathology. J Physiol. 600:1825–1837. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen L, Ye X, Yang L, Zhao J, You J and

Feng Y: Linking fatty liver diseases to hepatocellular carcinoma by

hepatic stellate cells. J Natl Cancer Cent. 4:25–35.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Friedman SL: Hepatic stellate cells:

Protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol

Rev. 88:125–172. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yang T, Gu Z, Feng J, Shan J, Qian C and

Zhuang N: Non-parenchymal cells: Key targets for modulating chronic

liver disease. Front Immunol. 16:15767392025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Shu W, Yang M, Yang J, Lin S, Wei X and Xu

X: Cellular crosstalk during liver regeneration: unity in

diversity. Cell Commun Signal. 20:1172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Trefts E, Gannon M and Wasserman DH: The

liver. Curr Biol. 27:R1147–R1151. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Carter JK and Friedman SL: Hepatic

stellate cell-immune interactions in NASH. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:8679402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Xia M, Li J, Martinez Aguilar LM, Wang J,

Trillos Almanza MC, Li Y, Buist-Homan M and Moshage H: Arctigenin

attenuates hepatic stellate cell activation via endoplasmic

reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD)-Mediated restoration of

lipid homeostasis. J Agric Food Chem. 73:13918–13933. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kisseleva T: The origin of fibrogenic

myofibroblasts in fibrotic liver. Hepatology. 65:1039–1043. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wiering L, Subramanian P and Hammerich L:

Hepatic stellate cells: Dictating outcome in nonalcoholic fatty

liver disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15:1277–1292. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Acharya P, Chouhan K, Weiskirchen S and

Weiskirchen R: Cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis. Front

Pharmacol. 12:6716402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nishio T, Hu R, Koyama Y, Liang S,

Rosenthal SB, Yamamoto G, Karin D, Baglieri J, Ma HY, Xu J, et al:

Activated hepatic stellate cells and portal fibroblasts contribute

to cholestatic liver fibrosis in MDR2 knockout mice. J Hepatol.

71:573–585. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kim HY, Sakane S, Eguileor A, Carvalho

Gontijo Weber R, Lee W, Liu X, Lam K, Ishizuka K, Rosenthal SB,

Diggle K, et al: The origin and fate of liver myofibroblasts. Cell

Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17:93–106. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yang W, He H, Wang T, Su N, Zhang F, Jiang

K, Zhu J, Zhang C, Niu K, Wang L, et al: Single-Cell transcriptomic

analysis reveals a hepatic stellate cell-activation roadmap and

myofibroblast origin during liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology.

74:2774–2790. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hernandez-Gea V and Friedman SL:

Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 6:425–456. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Krenkel O, Hundertmark J, Ritz TP,

Weiskirchen R and Tacke F: Single Cell RNA sequencing identifies

subsets of hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts in liver

fibrosis. Cells. 8:5032019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tsuchida T and Friedman SL: Mechanisms of

hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

14:397–411. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ramachandran P, Dobie R, Wilson-Kanamori

JR, Dora EF, Henderson BEP, Luu NT, Portman JR, Matchett KP, Brice

M, Marwick JA, et al: Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver

cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature. 575:512–518. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cheng S, Zou Y, Zhang M, Bai S, Tao K, Wu

J, Shi Y, Wu Y, Lu Y, He K, et al: Single-cell RNA sequencing

reveals the heterogeneity and intercellular communication of

hepatic stellate cells and macrophages during liver fibrosis.

MedComm (2020). 4:e3782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Deng G, Liang X, Pan Y, Luo Y, Luo Z, He

S, Huang S, Chen Z, Wang J and Fang S: Single-cell transcriptomic

analysis of different liver fibrosis models: Elucidating molecular

distinctions and commonalities. Biomedicines. 13:17882025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang ZY, Keogh A, Waldt A, Cuttat R, Neri

M, Zhu S, Schuierer S, Ruchti A, Crochemore C, Knehr J, et al:

Single-cell and bulk transcriptomics of the liver reveals potential

targets of NASH with fibrosis. Sci Rep. 11:193962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Peyser R, MacDonnell S, Gao Y, Cheng L,

Kim Y, Kaplan T, Ruan Q, Wei Y, Ni M, Adler C, et al: Defining the

activated fibroblast population in lung fibrosis using single-cell

sequencing. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 61:74–85. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sugimoto A, Saito Y, Wang G, Sun Q, Yin C,

Lee KH, Geng Y, Rajbhandari P, Hernandez C, Steffani M, et al:

Hepatic stellate cells control liver zonation, size and functions

via R-spondin 3. Nature. 640:752–761. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Geng Y and Schwabe RF: Hepatic stellate

cell heterogeneity: Functional aspects and therapeutic

implications. Hepatology. May 8–2025.Epub ahead of print.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, Huebener

P, Mu X, Dapito DH, Pradere JP and Schwabe RF: Fate tracing reveals

hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis

independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun. 4:28232013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang SS, Tang XT, Lin M, Yuan J, Peng YJ,

Yin X, Shang G, Ge G, Ren Z and Zhou BO: Perivenous stellate cells

are the main source of myofibroblasts and cancer-associated

fibroblasts formed after chronic liver injuries. Hepatology.

74:1578–1594. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rosenthal SB, Liu X, Ganguly S, Dhar D,

Pasillas MP, Ricciardelli E, Li RZ, Troutman TD, Kisseleva T, Glass

CK and Brenner DA: Heterogeneity of HSCs in a mouse model of NASH.

Hepatology. 74:667–685. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

MacParland SA, Liu JC, Ma XZ, Innes BT,

Bartczak AM, Gage BK, Manuel J, Khuu N, Echeverri J, Linares I, et

al: Single cell RNA sequencing of human liver reveals distinct

intrahepatic macrophage populations. Nat Commun. 9:43832018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Xiong X, Kuang H, Ansari S, Liu T, Gong J,

Wang S, Zhao XY, Ji Y, Li C, Guo L, et al: Landscape of

intercellular crosstalk in healthy and NASH liver revealed by

single-cell secretome gene analysis. Mol Cell. 75:644–660.e5. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lotto J, Drissler S, Cullum R, Wei W,

Setty M, Bell EM, Boutet SC, Nowotschin S, Kuo YY, Garg V, et al:

Single-cell transcriptomics reveals early emergence of liver

parenchymal and non-parenchymal cell lineages. Cell. 183:702–716

e14. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu X, Xu J, Rosenthal S, Zhang LJ,

McCubbin R, Meshgin N, Shang L, Koyama Y, Ma HY, Sharma S, et al:

Identification of lineage-specific transcription factors that

prevent activation of hepatic stellate cells and promote fibrosis

resolution. Gastroenterology. 158:1728–1744.e14. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Su Q, Kim SY, Adewale F, Zhou Y, Aldler C,

Ni M, Wei Y, Burczynski ME, Atwal GS, Sleeman MW, et al:

Single-cell RNA transcriptome landscape of hepatocytes and

non-parenchymal cells in healthy and NAFLD mouse liver. iScience.

24:1032332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Fan W, Liu T, Chen W, Hammad S, Longerich

T, Hausser I, Fu Y, Li N, He Y, Liu C, et al: ECM1 prevents

activation of transforming growth factor β, hepatic stellate cells,

and fibrogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 157:1352–1367.e13.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ben-Moshe S and Itzkovitz S: Spatial

heterogeneity in the mammalian liver. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 16:395–410. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dobie R, Wilson-Kanamori JR, Henderson

BEP, Smith JR, Matchett KP, Portman JR, Wallenborg K, Picelli S,

Zagorska A, Pendem SV, et al: Single-cell transcriptomics uncovers

zonation of function in the mesenchyme during liver fibrosis. Cell

Rep. 29:1832–1847.e8. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Watson BR, Paul B, Rahman RU,

Amir-Zilberstein L, Segerstolpe Å, Epstein ET, Murphy S,

Geistlinger L, Lee T, Shih A, et al: Spatial transcriptomics of

healthy and fibrotic human liver at single-cell resolution. Nat

Commun. 16:3192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Khan MA, Fischer J, Harrer L, Schwiering

F, Groneberg D and Friebe A: Hepatic stellate cells in zone 1

engage in capillarization rather than myofibroblast formation in

murine liver fibrosis. Sci Rep. 14:188402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ramm GA, Britton RS, O'Neill R, Blaner WS

and Bacon BR: Vitamin A-poor lipocytes: A novel desmin-negative

lipocyte subpopulation, which can be activated to myofibroblasts.

Am J Physiol. 269(4 Pt 1): G532–G541. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ballardini G, Groff P, Badiali de Giorgi

L, Schuppan D and Bianchi FB: Ito cell heterogeneity:

Desmin-negative Ito cells in normal rat liver. Hepatology.

19:440–446. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

D'Ambrosio DN, Walewski JL, Clugston RD,

Berk PD, Rippe RA and Blaner WS: Distinct populations of hepatic

stellate cells in the mouse liver have different capacities for

retinoid and lipid storage. PLoS One. 6:e249932011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Payen VL, Lavergne A, Alevra Sarika N,

Colonval M, Karim L, Deckers M, Najimi M, Coppieters W, Charloteaux

B, Sokal EM and El Taghdouini A: Single-cell RNA sequencing of

human liver reveals hepatic stellate cell heterogeneity. JHEP Rep.

3:1002782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kisseleva T, Cong M, Paik Y, Scholten D,

Jiang C, Benner C, Iwaisako K, Moore-Morris T, Scott B, Tsukamoto

H, et al: Myofibroblasts revert to an inactive phenotype during

regression of liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

109:9448–9453. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Guo Q, Wu J, Wang Q, Huang Y, Chen L, Gong

J, Du M, Cheng G, Lu T, Zhao M, et al: Single-cell transcriptome

analysis uncovers underlying mechanisms of acute liver injury

induced by tripterygium glycosides tablet in mice. J Pharm Anal.

13:908–925. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cook D, Achanta S, Hoek JB, Ogunnaike BA

and Vadigepalli R: Cellular network modeling and single cell gene

expression analysis reveals novel hepatic stellate cell phenotypes

controlling liver regeneration dynamics. BMC Syst Biol. 12:862018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kolodziejczyk AA, Federici S, Zmora N,

Mohapatra G, Dori-Bachash M, Hornstein S, Leshem A, Reuveni D,

Zigmond E, Tobar A, et al: Acute liver failure is regulated by MYC-

and microbiome-dependent programs. Nat Med. 26:1899–1911. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kostallari E, Wei B, Sicard D, Li J,

Cooper SA, Gao J, Dehankar M, Li Y, Cao S, Yin M, et al: Stiffness

is associated with hepatic stellate cell heterogeneity during liver

fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 322:G234–G246.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

50

|

Andrews TS, Atif J, Liu JC, Perciani CT,

Ma XZ, Thoeni C, Slyper M, Eraslan G, Segerstolpe A, Manuel J, et

al: Single-cell, single-nucleus, and spatial RNA sequencing of the

human liver identifies cholangiocyte and mesenchymal heterogeneity.

Hepatol Commun. 6:821–840. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Wang S, Li K, Pickholz E, Dobie R,

Matchett KP, Henderson NC, Carrico C, Driver I, Borch Jensen M,

Chen L, et al: An autocrine signaling circuit in hepatic stellate

cells underlies advanced fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Sci Transl Med. 15:d39492023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

He W, Huang C, Shi X, Wu M, Li H, Liu Q,

Zhang X, Zhao Y and Li X: Single-cell transcriptomics of hepatic

stellate cells uncover crucial pathways and key regulators involved

in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Endocr Connect. 12:e2205022023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

53

|

Cavalli M, Diamanti K, Pan G, Spalinskas

R, Kumar C, Deshmukh AS, Mann M, Sahlén P, Komorowski J and

Wadelius C: A multi-omics approach to liver diseases: Integration

of single nuclei transcriptomics with proteomics and HiCap bulk

data in human liver. OMICS. 24:180–194. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Terkelsen MK, Bendixen SM, Hansen D, Scott

EAH, Moeller AF, Nielsen R, Mandrup S, Schlosser A, Andersen TL,

Sorensen GL, et al: Transcriptional dynamics of hepatic

sinusoid-associated cells after liver injury. Hepatology.

72:2119–2133. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhang W, Conway SJ, Liu Y, Snider P, Chen

H, Gao H, Liu Y, Isidan K, Lopez KJ, Campana G, et al:

Heterogeneity of hepatic stellate cells in fibrogenesis of the

liver: Insights from single-cell transcriptomic analysis in liver

injury. Cells. 10:21292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yin L, Qi Y, Xu Y, Xu L, Han X, Tao X,

Song S and Peng J: Dioscin Inhibits HSC-T6 cell migration via

adjusting SDC-4 Expression: Insights from iTRAQ-Based quantitative

proteomics. Front Pharmacol. 8:6652017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Krenkel O, Puengel T, Govaere O, Abdallah

AT, Mossanen JC, Kohlhepp M, Liepelt A, Lefebvre E, Luedde T,

Hellerbrand C, et al: Therapeutic inhibition of inflammatory

monocyte recruitment reduces steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis.

Hepatology. 67:1270–1283. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Nevi L, Costantini D, Safarikia S, Di

Matteo S, Melandro F, Berloco PB and Cardinale V:

Cholest-4,6-Dien-3-One promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

(EMT) in biliary tree stem/progenitor cell cultures in vitro.

Cells. 8:14432019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Wang Y, Nakajima T, Gonzalez FJ and Tanaka

N: PPARs as metabolic regulators in the liver: Lessons from

liver-specific PPAR-Null mice. Int J Mol Sci. 21:20612020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Katsumata LW, Miyajima A and Itoh T:

Portal fibroblasts marked by the surface antigen Thy1 contribute to

fibrosis in mouse models of cholestatic liver injury. Hepatol

Commun. 1:198–214. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Balog S, Fujiwara R, Pan SQ, El-Baradie

KB, Choi HY, Sinha S, Yang Q, Asahina K, Chen Y, Li M, et al:

Emergence of highly profibrotic and proinflammatory Lrat+Fbln2+ HSC

subpopulation in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 78:212–224. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Li X, Wang Q, Ai L and Cheng K: Unraveling

the activation process and core driver genes of HSCs during

cirrhosis by single-cell transcriptome. Exp Biol Med (Maywood).

248:1414–1424. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chung BK, Ogaard J, Reims HM, Karlsen TH

and Melum E: Spatial transcriptomics identifies enriched gene

expression and cell types in human liver fibrosis. Hepatol Commun.

6:2538–2550. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Fred RG, Steen PJ, Thompson JJ, Lee J,

Timshel PN, Stender S, Opseth Rygg M, Gluud LL, Bjerregaard

Kristiansen V, Bendtsen F, et al: Single-cell transcriptome and

cell type-specific molecular pathways of human non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis. Sci Rep. 12:134842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wang Z, Zhao Z, Xia Y, Cai Z, Wang C, Shen

Y, Liu R, Qin H, Jia J and Yuan G: Potential biomarkers in the

fibrosis progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). J

Endocrinol Invest. 45:1379–1392. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Filliol A, Saito Y, Nair A, Dapito DH, Yu

LX, Ravichandra A, Bhattacharjee S, Affo S, Fujiwara N, Su H, et

al: Opposing roles of hepatic stellate cell subpopulations in

hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature. 610:356–365. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Yu Y, Li Y, Zhou L, Cheng X and Gong Z:

Hepatic stellate cells promote hepatocellular carcinoma development