Introduction

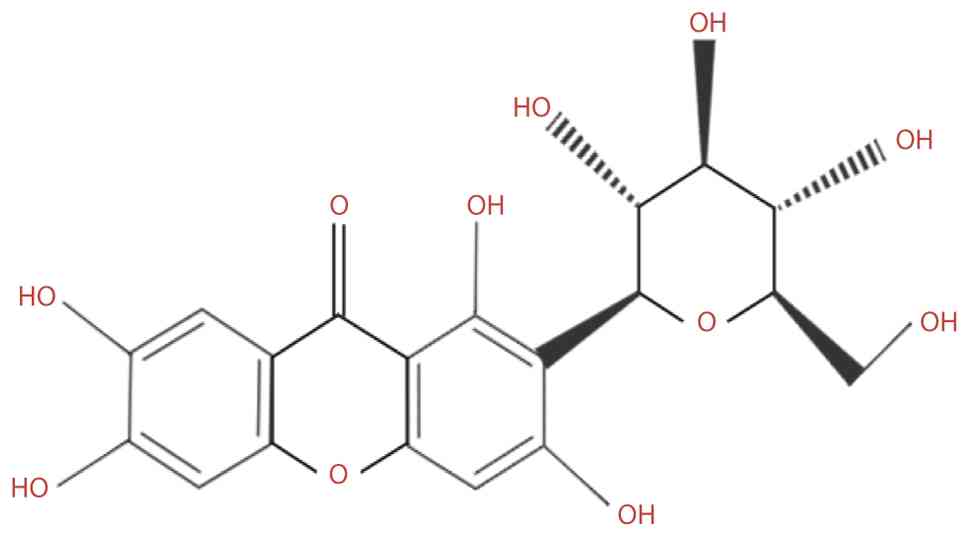

Mangiferin (MGF) is a yellow crystalline flavonoid

with a molecular weight of 422.34 g/mol (Fig. 1). Despite its low water

solubility (0.111 mg/ml) (1) and

poor oral bioavailability (~1.2%) (2,3),

due to its limited lipophilicity and intestinal permeability

(4), MGF has been identified in

96 species, 28 genera and 19 families of angiosperms (5). Its unique structure, featuring a

catechol moiety and a C-glucosidic linkage, contributes to its

interactions with diverse biological targets and underpins its

broad pharmacological activities. Moreover, MGF complies with

Lipinski's rule of five, suggesting favorable drug-like properties

despite its absorption limitations (6). MGF isolated from indica rice leaves

has various pharmacological benefits; notably, it exhibits potent,

broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against diverse fungal and

bacterial pathogens, with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

values of 1.95-62.5 and 1.95-31.25 μg/ml, respectively

(7). In addition, it exerts

wide-ranging pharmacological effects by modulating key metabolic

pathways, including glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle,

and lipid and amino acid metabolism, supporting its potential use

in treating metabolic disorders such as hyperlipidemia and

hyperglycemia (8). Additionally,

MGF has neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects

by reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting proinflammatory signaling,

and suppressing tumor proliferation and metastasis. Advances in

formulation and drug delivery strategies are expected to further

improve its clinical applicability across various diseases

(4,9).

The present review has three objectives. First, the

current evidence on MGF was organized by mechanism, focusing on

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, MAPK and NLR

family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) pathways, and their

relation to metabolic regulation, oxidative stress, apoptosis,

angiogenesis and immune modulation. Second, the preclinical

efficacy of MGF across metabolic, inflammatory and cancer models

was evaluated using reproducible endpoints, such as insulin

sensitivity, fibrotic markers, tumor growth, invasion and MMP-9

activity. Third, key barriers to translation, including low

solubility, poor oral bioavailability and rapid metabolism, were

examined, and delivery and structural optimization strategies that

may improve exposure were assessed. Evidence selection prioritized

primary studies and systematic analyses with prespecified methods.

By integrating data on molecular mechanisms, pharmacology and

drug-delivery strategies, the present review aims to identify

consistent efficacy signals, highlight areas of uncertainty and

propose priorities for future human studies.

Literature search strategy

To ensure the comprehensiveness and reliability of

the present review, a structured literature search was conducted in

the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web of Science

(http://www.webofscience.com/), Scopus

(http://www.scopus.com/) and Google Scholar

(http://scholar.google.com/) databases.

The search included studies published between January 2000 and June

2025. The following key words and their combinations were searched:

'mangiferin', 'pharmacological activity', 'bioavailability',

'metabolism', 'toxicity', 'mechanism of action' and 'therapeutic

potential'. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Original

research or review articles investigating the pharmacological,

biochemical or clinical properties of MGF; ii) studies providing

mechanistic, pharmacokinetic (PK) or toxicological data; and iii)

publications written in English and indexed in peer-reviewed

journals. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Non-peer-reviewed materials, conference abstracts or duplicated

data; ii) studies using complex herbal mixtures without

quantifiable MGF content; and iii) articles lacking sufficient

methodological detail or outcome data. References were screened by

title, abstract and full text, and only those meeting the inclusion

criteria were included in the final review.

Historical discovery, botanical sources and

early pharmacological insights into MGF

The chemical structure of MGF, identified as a

1,3,6,7-tetrahydroxyxanthone C-glucoside, was first elucidated by

Aritomi and Kawasaki in 1969 (10). However, detailed structural

characterization via nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and

X-ray diffraction was not achieved until the early 2000s (11). Between the 1960s and 1980s, MGF

and its isomers were isolated from several botanical sources,

including Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge. A subsequent

study broadened its known distribution: In 1995, MGF was detected

in ferns from New Zealand, and in 2008, markedly high

concentrations (up to 6.12%) were reported in the leaves of wild

coffee plants (7). MGF is most

abundant in members of the Anacardiaceae family, particularly

Mangifera indica L., but it has also been isolated from

other medicinal plants, such as Prunus dulcis, Gentiana

manshurica, Swertia mussotii and Pyrrosia calvata

(12). Advances in phytochemical

techniques, including high-performance liquid chromatography and

mass spectrometry, have notably improved the precision of MGF

identification and quantification across diverse plant

matrices.

An early pharmacological study explored the

physiological and therapeutic effects of MGF (10). A previous study demonstrated that

the substance possesses a spectrum of biological activities beyond

its initial inotropic effect on frog hearts, including

immunomodulatory, reproductive, antitumor and antiviral properties

(13). Metabolic investigations

have indicated that MGF is biotransformed by the human intestinal

microbiota, with deglycosylation to norathyriol a key step

(8). In preclinical PK studies,

oral MGF has been shown to exhibit low systemic exposure, which is

reflected by its limited detection in the plasma and urine of

rodent models (14). These

observations have motivated formulation strategies to improve

exposure. In 2012, nanostructured lipid carriers were applied to

MGF, providing a basis for subsequent nanotechnology-oriented

approaches that aim to increase its solubility, stability and oral

bioavailability (15).

Absorption and metabolism of MGF

Absorption of MGF

Despite its wide pharmacological spectrum, MGF has

low oral bioavailability, largely due to its poor solubility and

limited membrane permeability. The stability of its C-glycosidic

bond prevents enzymatic cleavage and reduces transmembrane

transport, thereby restricting passive absorption across the

intestinal epithelium (16). A

previous in vivo study demonstrated that only 1.15% of

orally administered MGF (30 mg/kg) is bioavailable in mice, whereas

intraperitoneal administration results in markedly increased

systemic levels. Additionally, extensive first-pass hepatic

metabolism further decreases the amount of active MGF entering

systemic circulation (17).

Regional differences in intestinal absorption have

been reported in rats. In situ perfusion experiments have

indicated greater apparent permeability in the duodenum compared

with that in the jejunum, and greater permeability in the jejunum

than in the ileum, which suggests that the upper small intestine is

the principal site of uptake (18). After absorption, MGF is

distributed via the circulation to multiple organs, including the

heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, testes and prostate. In rats

administered oral MGF, peak concentrations in the plasma, lungs and

kidneys have been reported to occur 4-6 h after dosing. Under the

reported analytical conditions, MGF is not detected in brain

tissue, which is consistent with limited penetration across the

blood-brain barrier in this model (19).

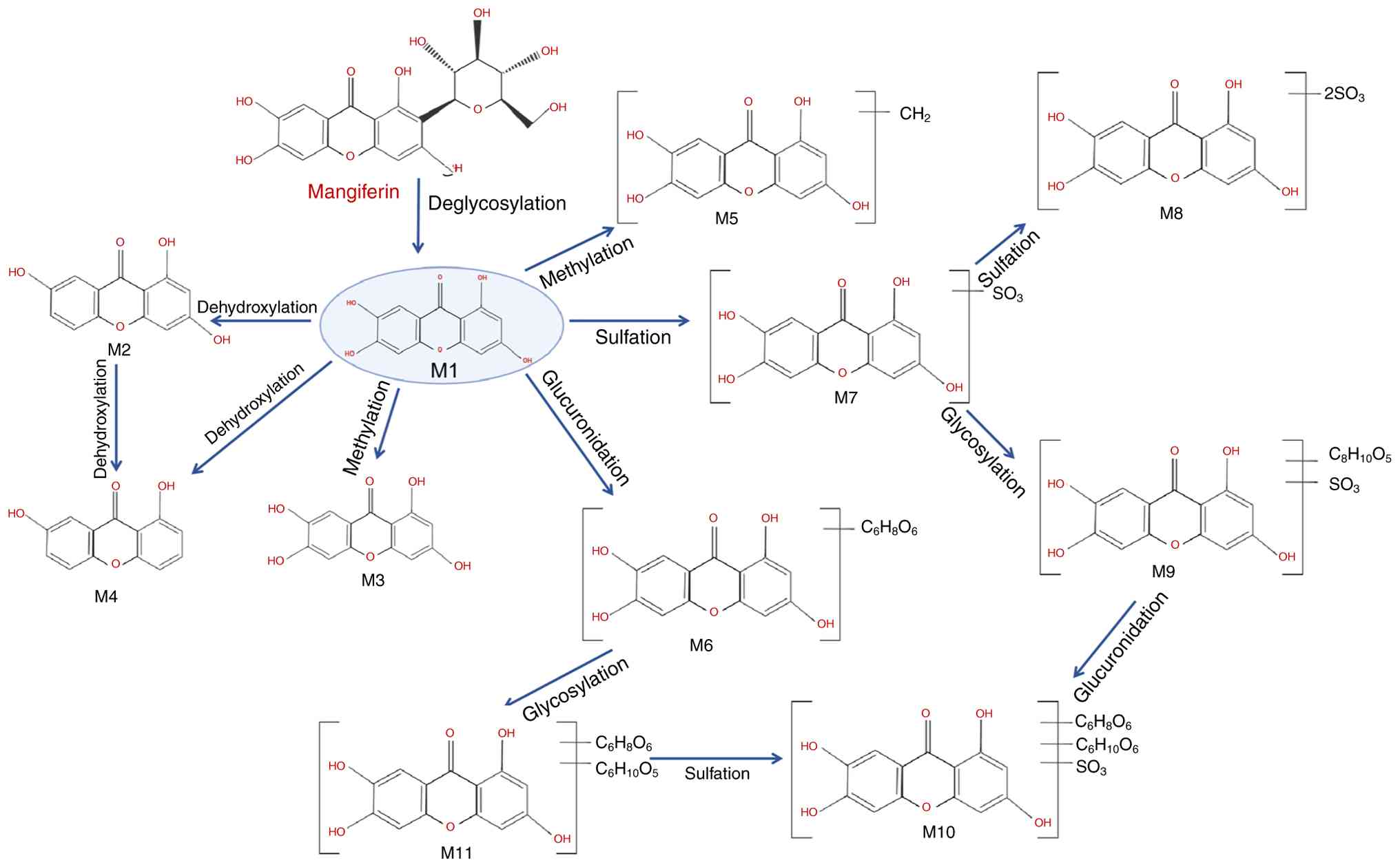

Metabolism of MGF

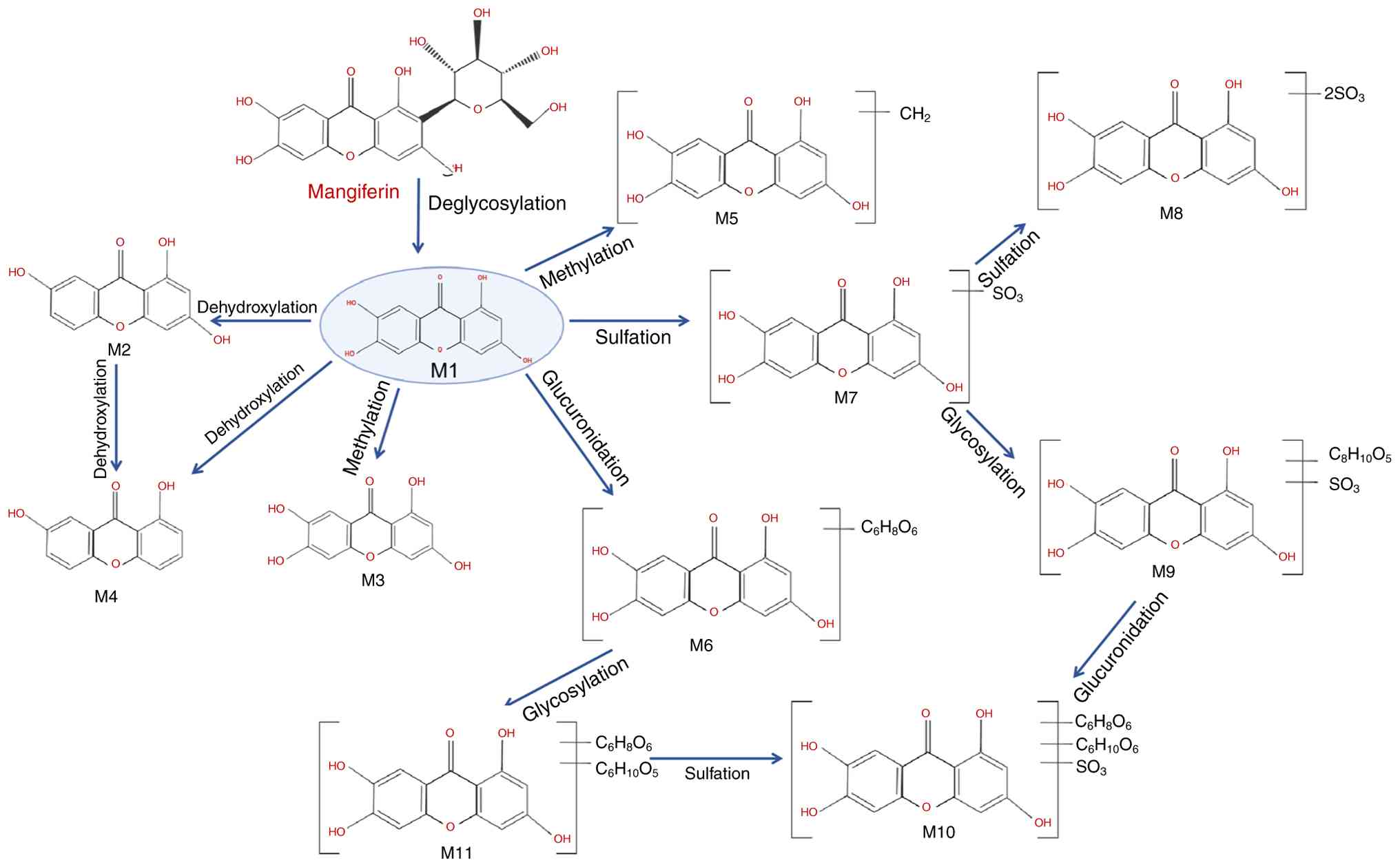

MGF undergoes biotransformation through both

microbial and host enzymatic systems. A frequently observed pathway

is microbial or enzymatic deglycosylation of C-glucoside,

generating the aglycone norathyriol (metabolite M1), which has

greater membrane permeability than the parent compound (20). Subsequent phase I reactions (for

example, dehydroxylation and O-methylation) and phase II

conjugations (including glucuronidation and sulfation) yield

additional metabolites with distinct physicochemical properties

(21). These steps can occur

sequentially or in parallel within the gut lumen and microbiota,

the intestinal epithelium and the liver, and the relative

contribution of each route depends on the species, dose and

formulation (21). A schematic

overview of these metabolic routes and representative metabolites

is provided in Fig. 2. Thus,

while the formation of M1 is well documented (20,21), it should be considered a

predominant rather than obligatory initial event in the overall

metabolic scheme.

| Figure 2Diagram of the relevant

pharmacological properties of mangiferin and its potential

mechanism of action. The metabolic pathways include the following:

M1, deglycosylation to norathyriol; M2, 1,3,7-trihydroxyxanthone;

M3, methylation to 1,3,6-trihydroxy-7-methoxyxanthone; M4,

dehydroxylation to 1,7-dihydroxyxanthone; M5, further methylation

to methoxy dimethyl xanthone; M6, glucuronidation products; M7,

sulfated derivatives; M8, dithio-sulfate norathyriol; M9, sulfate

norathyriol glucoside; M10, norathyriol glucuronide sulfate; and

M11, norathyriol glucuronide. |

Specifically, M1 is dehydroxylated to form

1,3,7-trihydroxyxanthone (M2) and 1,7-dihydroxyxanthone (M4), with

M2 being the predominant urinary metabolite in rodents (22). Methylation of M1 yields compounds

such as 1,3,6-trihydroxy-7-methoxyxanthone (M3) and methoxy

dimethyl xanthone (M5). Conjugation reactions generate glucuronide

(M6), sulfate (M7) and mixed derivatives, including dithio-sulfate

norathyriol (M8), sulfate norathyriol glucoside (M9), norathyriol

glucuronide (M11) and its sulfated form (M10) (11,23).

The gut microbiota serves a critical role in the

deglycosylation and subsequent metabolism of MGF, representing a

key determinant of its systemic availability and pharmacological

effects (24). Although

microbial metabolism enables the formation of bioactive

metabolites, it remains unclear whether MGF itself modulates the

composition and function of the gut microbiota. Further research is

needed to clarify this bidirectional interaction, and to

characterize the full spectrum of bioactive metabolites relevant to

disease prevention and therapy (25).

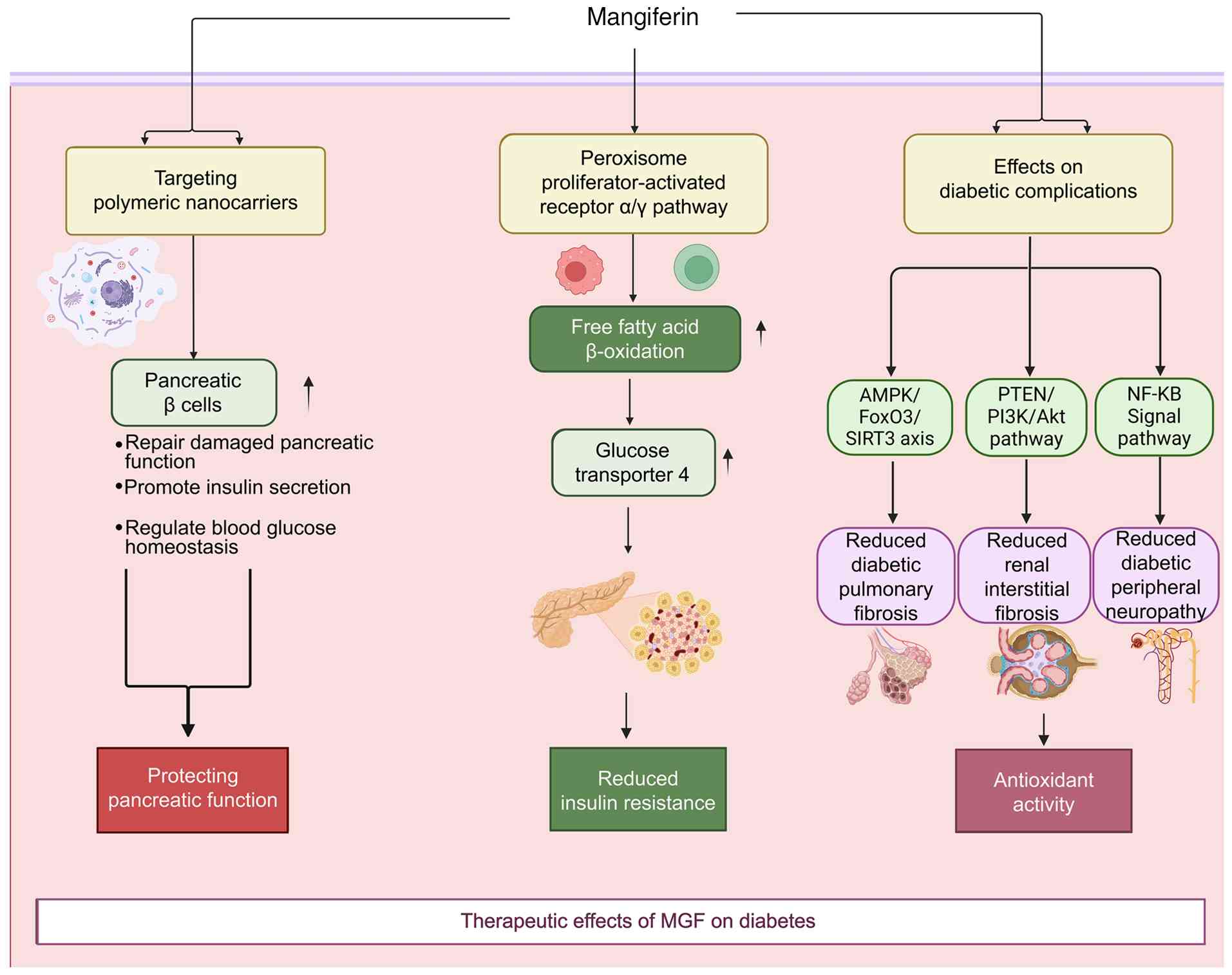

Pharmacological effects of MGF on

diabetes

Diabetes mellitus results from impaired pancreatic

β-cell function and/or peripheral insulin resistance, ultimately

disrupting glucose homeostasis. MGF has notable antidiabetic

potential due to its insulinotropic and insulin-sensitizing effects

(Fig. 3).

β-cell protection and pancreatic

regeneration

MGF supports pancreatic function by preserving and

regenerating β cells. In animal models of type 1 and type 2

diabetes, tail vein administration of MGF-loaded polymeric

nanocarriers (5-10 mg/kg) have been reported to increase β-cell

proliferation, inhibit apoptosis and restored insulin secretion,

thereby improving glycemic control (26). Similarly, repeated oral

administration of MGF (30 or 90 mg/kg for 14 days) in partially

pancreatectomized mice may promote islet regeneration through the

upregulation of key cell-cycle regulators (such as cyclin D1 and

Ki-67) and pancreatic progenitor markers, including Pdx1 and Ngn3

(27).

Insulin sensitization and glucose

metabolism

MGF also alleviates insulin resistance by modulating

metabolic, inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways. Activation

of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α/γ axis

enhances fatty acid β-oxidation and upregulates glucose transporter

4 (GLUT4), thereby improving insulin sensitivity (28). Given that chronic inflammation

and oxidative stress are central to the development of diabetes

(29), MGF mitigates these

processes through the inhibition of HIF-1α and NF-κB signaling, the

suppression of JNK phosphorylation, and the reduction in

endoplasmic reticulum stress, collectively restoring insulin

signaling (30).

In addition, MGF directly regulates glucose

metabolism. It promotes glycolysis and glycogen synthesis while

inhibiting gluconeogenesis by modulating key enzymes such as

glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), glucose-6-phosphatase and

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Furthermore, MGF reverses high

glucose-induced impairment of GLUT4 translocation and glucose

uptake, partly via AMPK activation and Akt phosphorylation, thereby

improving hepatic energy metabolism and overall insulin

responsiveness (31).

Structural derivatives and therapeutic

effects on diabetic complications

Structural modification of MGF has produced more

potent derivatives. For example, compound X-3, a semi-synthetic

derivative prepared from MGF, has been reported to markedly reduce

hyperglycemia and obesity in mice after 8 weeks of oral treatment

(40-120 mg/kg), primarily through AMPK pathway activation (32).

In addition to its ability to control glycemia, MGF

has shown activity against diabetic complications in preclinical

models. In a mouse model of diabetic pulmonary fibrosis, oral

administration of 60 mg/kg MGF every 3 days for 4 weeks has been

shown to reduce the progression of fibrosis. Reported effects

include the inhibition of endothelial-mesenchymal transition and

modulation of the AMPK/FoxO3/sirtuin (SIRT)3 pathway, as evidenced

by changes in pathway proteins and fibrosis markers (33). In streptozotocin-induced diabetic

mice, oral administration of 15-60 mg/kg/day MGF for 4 weeks may

attenuate renal injury, which is consistent with diabetic

nephropathy. This previous study reported downregulation of

phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)/PI3K/Akt signaling, and

reduced expression of fibronectin, collagen I and α-smooth muscle

actin (α-SMA), along with decreases in renal fibrosis, inflammation

and oxidative stress endpoints (34). Taken together, these data support

a potential role for MGF in mitigating pulmonary and renal

complications of diabetes under experimental conditions, while

confirming that the proposed mechanisms, including inhibition of

endothelial-mesenchymal transition and modulation of

AMPK/FoxO3/SIRT3 signaling in diabetic pulmonary fibrosis, and

downregulation of PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling with reduced

fibronectin/collagen I/α-SMA expression in diabetic nephropathy,

are supported by molecular endpoints measured in these models

(33,34).

In models of diabetic peripheral neuropathy, MGF

alleviates neuroinflammation by reducing TNF-α, TGF-β1, IL-1β and

IL-6 levels in the sciatic nerve. Concurrently, it enhances

antioxidant defenses and upregulates nerve growth factor, thereby

promoting nerve regeneration and functional recovery (35).

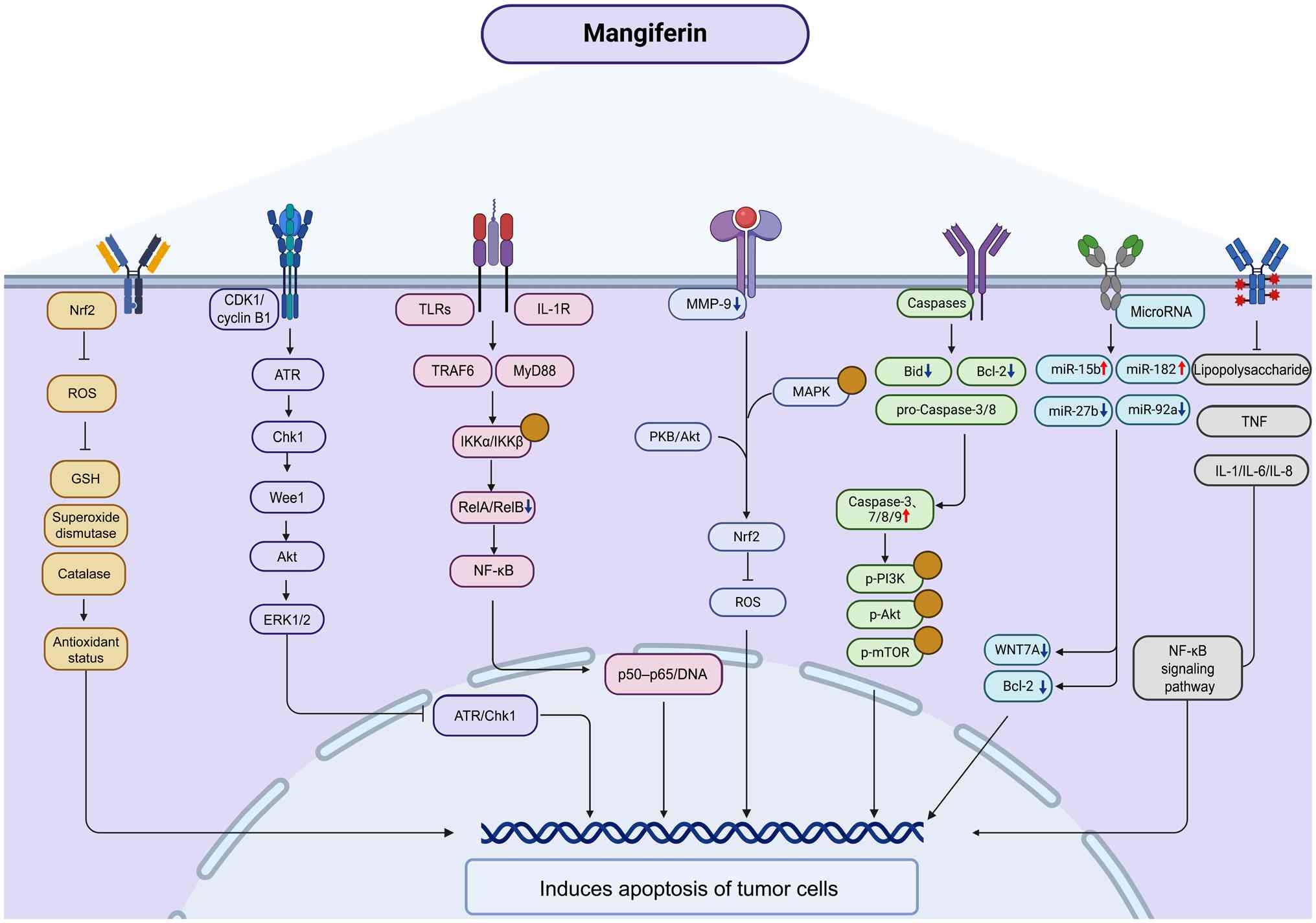

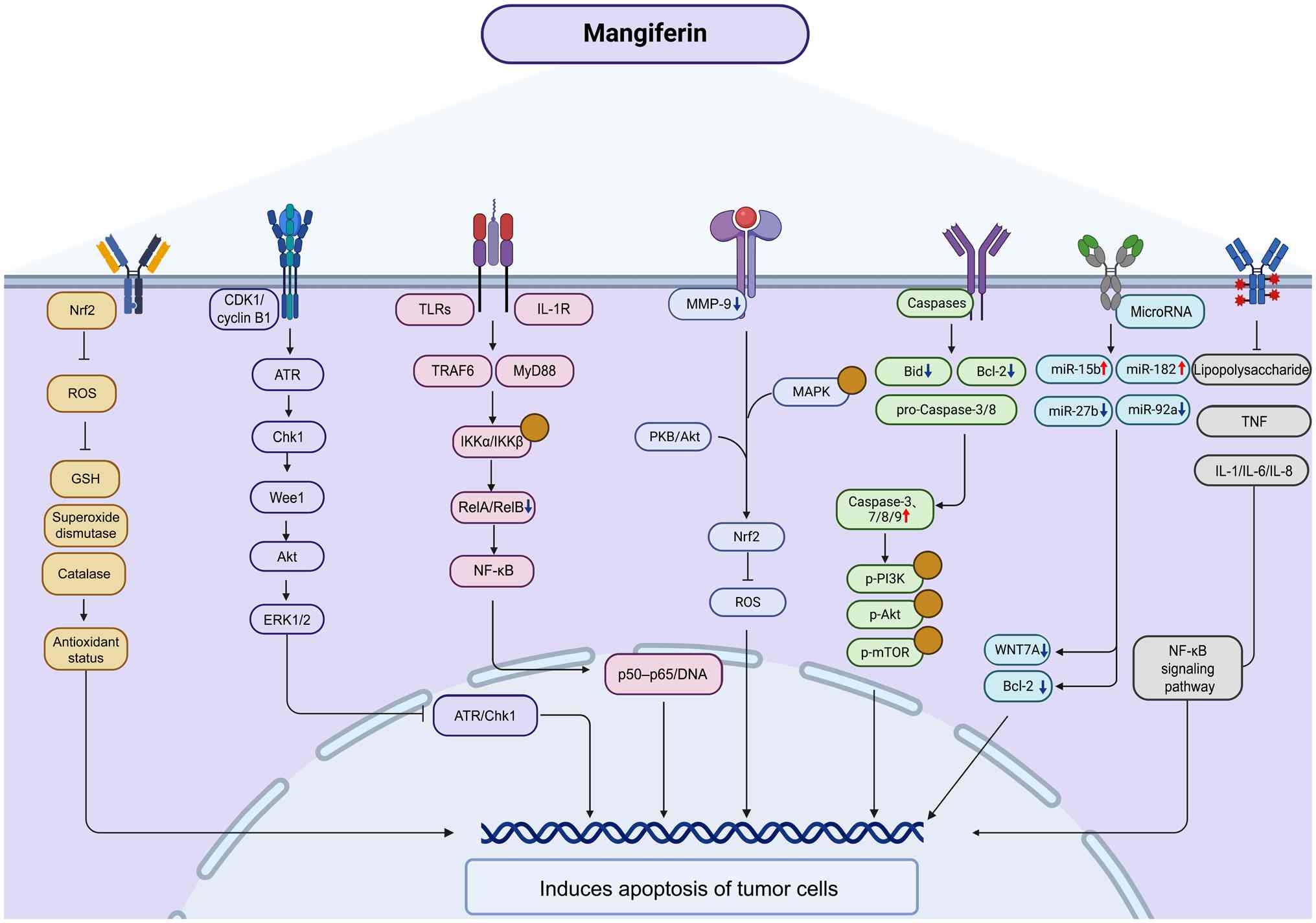

Anticancer mechanisms of MGF

MGF exerts potent anticancer activity through

multiple mechanisms that target key cellular processes underlying

tumor initiation and progression. These include the induction of

cell cycle arrest, the promotion of apoptosis through various

intracellular pathways, the inhibition of tumor invasion and

metastasis, the modulation of immune responses, and the enhancement

of radiosensitivity in cancer such as glioblastoma (GBM) (36,37). Fig. 4 schematically summarizes the

major signaling pathways [such as nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/reactive oxygen species (ROS), ATR/Chk1,

CDK1/cyclin B1, NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, MAPK, caspases and microRNAs

(miRNAs/miRs)] through which MGF induces apoptosis of tumor

cells.

| Figure 4Molecular mechanism of the anticancer

effect of MGF. MGF suppresses tumor growth by promoting apoptosis,

exerting anti-inflammatory effects, regulating mitochondrial

function, modulating autophagy and enhancing immune responses.

Upward and downward arrows indicate activation/upregulation or

inhibition/downregulation by MGF, respectively. Yellow circles

indicate activation of the indicated signaling nodes. GSH,

glutathione; IL-1R, IL-1 receptor; MGF, mangiferin; miR, microRNA;

Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; p-,

phosphorylated proteins; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TLRs,

Toll-like receptors; TRAF6, TNF receptor-associated factor 6. |

According to previous cancer-related experiments,

MGF most consistently modulates four signaling axes that share

common upstream triggers and downstream responses (38,39). For NF-κB, typical engagement is

inferred from reduced IKKα/IKKβ phosphorylation, stabilization of

IκBα, and reduced nuclear p65 DNA binding, with downstream

decreases in pro-survival and invasive effectors, such as BCL2L1,

BIRC5 and MMP-9 (40-43). For Nrf2, evidence includes

diminished Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1-mediated

ubiquitination, increased nuclear Nrf2, and the induction of heme

oxygenase (HO)-1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) and other

phase II enzymes, aligning with decreased ROS and lipid

peroxidation (44,45). MAPK modulation is context

dependent; a number of models show attenuation of ERK1/2, JNK and

p38 phosphorylation, reduced activator protein (AP)-1 activity, and

consequent decreases in proliferation and cytokine output (38,46). For PI3K/Akt, changes in Akt

Thr308/Ser473, and downstream GSK3β and mTOR complex 1 lead to

reduced protein synthesis and survival signaling in tumor cells,

whereas in metabolic tissues, they support GLUT4 translocation and

glycogen synthesis (16,47-54). Notably, crosstalk is evident:

AMPK activation can suppress NF-κB priming and MAPK activity,

whereas redox shifts through Nrf2 dampen inflammasome priming,

which converges on MMP-9 and invasion programs. To aid

interpretation, each subsequent subsection in the present review

reports on the model, exposure, phosphorylation status of key

signaling proteins and a disease-relevant functional endpoint (for

example, apoptosis markers, invasion or tumor growth), and provides

a brief appraisal of sample size and risks of bias.

Cell cycle arrest via CDK1/cyclin B1

In HL-60 cells, some studies have reported increased

CDK1 and cyclin B1 mRNA following MGF exposure, indicating

regulation at the transcriptional level in this model (55). However, across tumor cell

systems, the functional consequence remains G2/M arrest,

with reduced proliferation and increased susceptibility to

apoptosis. This outcome is consistent with reports of decreased

CDK1/cyclin B1 activity, altered phosphorylation of CDK1 with

reduced activating phosphorylation and increased inhibitory

phosphorylation, and engagement of checkpoint signaling, including

ATR-dependent Chk1 activation, in other tumor cell lines exposed to

MGF (56,57). This evidence supports multilevel

regulation of the CDK1/cyclin B1 axis by MGF. Differences at the

mRNA level are plausibly attributable to the assay, timing, dose

and cellular context, whereas the consistent phenotype is

G2/M blockade with growth suppression (55-57).

Apoptosis pathways

Caspase activation

The induction of apoptosis via caspase activation is

a well-established anticancer mechanism. Caspases are a family of

cysteine proteases that execute programmed cell death through a

proteolytic cascade. Initiator caspases (such as caspase-8 and -9)

activate effector caspases (including caspase-3, -6 and -7),

leading to degradation of intracellular components and apoptotic

cell death (58,59). MGF has been shown to promote this

cascade through multiple upstream regulators, including the Bcl-2

protein family and cytochrome c-mediated pathways (60).

MGF induces apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma

cells by modulating the mitochondrial pathway, decreasing

antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and increasing proapoptotic Bax expression

(61). In HeLa cervical cancer

cells, ethanolic mango peel extract enriched with MGF downregulates

Bid, Bcl-2 and pro-caspase-3 and -8, while activating caspases-3,

-7, -8 and -9, and cleaving poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

(PARP)-hallmarks of caspase-mediated apoptosis (62).

In SGC-7901 gastric cancer cells, MGF suppresses

Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 expression, and increases Bax, Bad, and

cleaved caspase-3 and -9 levels. Additionally, it inhibits the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling axis, further promoting apoptosis and

suppressing cell survival (47).

Modulation of miRNAs

miRNAs are short, noncoding RNAs that

post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression and serve dual

roles in cancer as oncogenes or tumor suppressors (63). MGF influences the expression of

several miRNAs associated with tumor suppression and apoptosis.

In glioma cells, MGF upregulates miR-15b, which

induces apoptosis by downregulating the expression of oncogenic

targets such as WNT7A (37,64). Similarly, in prostate cancer PC3

cells, MGF elevates miR-182 levels, leading to decreased Bcl-2

expression and increased apoptotic activity (65). In lung adenocarcinoma models, MGF

reduces the expression of miR-27b and miR-92a, two oncogenic miRNAs

highly expressed in tumor tissues, thereby inhibiting tumor cell

proliferation and promoting apoptosis (66).

Induction of the mitochondrial

pathway

MGF also initiates intrinsic apoptosis via the

mitochondrial pathway (67).

Disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential is a critical early

event in the apoptotic cascade and is often regulated by

intracellular calcium homeostasis and endoplasmic reticulum stress

(68). MGF reduces the

mitochondrial membrane potential in HT29 colon cancer cells,

leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and

apoptosis (69). In lung cancer

mouse models, MGF alters mitochondrial metabolism by increasing

lipid peroxidation and suppressing key TCA cycle and electron

transport enzymes, including isocitrate dehydrogenase, succinate

dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate

dehydrogenase (70). Notably, in

models of fluoride-induced neurotoxicity, MGF restores

mitochondrial integrity by inhibiting proapoptotic proteins (Bax,

caspase-3 and caspase-9) and upregulating Bcl-2. These protective

effects are mediated via JNK inhibition and activation of the

Nrf2/HO-1 pathway (71). Thus,

the ability of MGF to induce mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer

cells and preserve mitochondrial health in normal cells reflects

its selective cytotoxic potential.

Induction of oxidative stress

ROS serve a paradoxical role in cancer, contributing

to tumor initiation while also serving as apoptotic triggers when

in excess (72). MGF modulates

oxidative stress pathways by interacting with both pro-oxidant and

antioxidant systems. MGF activates the Nrf2 pathway, stabilizing

Nrf2 protein levels by inhibiting its ubiquitination, which leads

to increased transcription of antioxidant enzymes, such as NQO1

(73,74). This activity suppresses

intracellular ROS accumulation and induces apoptosis in leukemia

HL-60 cells (75). In

neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells, MGF reduces ROS production and the

activity of key antioxidants, such as glutathione (GSH), superoxide

dismutase (SOD), catalase and GSH peroxidase (GSH-Px), pushing the

redox balance toward apoptosis (9,76). Additionally, MGF enhances phase

II detoxifying enzymes, including GSH S-transferase, quinone

reductase and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, while reducing lipid

peroxidation in lung cancer models (77,78).

In a diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular

carcinoma rat model, treatment with MGF has been shown to improve

hepatic oxidative stress markers, as follows: Malondialdehyde (MDA)

content was reduced, whereas SOD activity and GSH levels were

elevated, and tumor formation was attenuated (79). In colorectal cancer, an

azoxymethane-induced rat model treated with MGF has been shown to

exhibit improved antioxidant enzyme activity, reduced aberrant

crypt foci formation and modulation of apoptotic proteins, such as

Bax, Bcl-2 and caspase-3, have been reported, linking redox control

to tumor suppression in colon tissue (80).

In malignant contexts where antioxidant defenses

become critically depleted, MGF-mediated redox modulation may serve

as an initiating event that dictates cell fate. Sustained ROS

accumulation disrupts mitochondrial integrity, diminishes the

membrane potential and promotes apoptotic signaling, as observed in

tumor and myoblast models (81).

In addition to this proapoptotic cascade, accumulating evidence has

suggested that redox regulation itself constitutes a primary

mechanistic axis rather than a subordinate branch of apoptosis,

reflecting broader control of mitochondrial and metabolic

homeostasis (82,83).

In malignant settings with severely depleted

antioxidant defenses, persistent ROS elevation can damage

mitochondria, impair membrane potential and promote apoptotic

signaling. However, available data suggest that MGF-driven

restoration of redox homeostasis represents a central mechanistic

axis of its antitumor activity, rather than merely a downstream

branch of apoptosis (84,85).

Inhibition of tumor invasion via MMP-9

suppression

MMPs, particularly MMP-2, MMP-9 and MMP-11, are

critical enzymes involved in tumor invasion, metastasis and

angiogenesis (86). Among these

proteins, MMP-9 serves a central role in degrading extracellular

matrix components, facilitating tumor cell dissemination. MGF has

been demonstrated to have a selective inhibitory effect on MMP-9,

making it a promising candidate for antimetastatic therapy

(87).

MGF inhibits tumor invasion in part by selectively

suppressing MMP-9 expression and activity. In human glioma models,

MGF reduces phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced MMP-9 without

materially affecting other MMP family members, which is consistent

with decreased NF-κB and AP-1 binding to the MMP-9 promoter, and

with upstream attenuation of Akt and MAPK signaling (41). A Computational study has provided

support for direct interactions between MGF derivatives and the

MMP-9 catalytic site, which may contribute to enzymatic inhibition

(88).

MGF has also been shown to sensitize glioma cells by

modulating signaling pathways involved in MMP-9 regulation,

including the NF-κB and PKB/Akt pathways. In metastatic melanoma

models, low-dose MGF enhances the antitumor activity of

citrus-derived glycosides, partly by increasing TNF-α expression

and inhibiting metastasis (89).

Immunomodulatory activity

Suppression of NF-κB signaling

In addition to its downstream effects on apoptosis,

NF-κB signaling represents a key immunomodulatory axis. Chronic

inflammation drives tumorigenesis in ~20% of cancers (90), largely through activation of the

NF-κB pathway (91,92). MGF interferes with multiple nodes

of NF-κB signaling, thereby limiting inflammation-driven

carcinogenesis (93). NF-κB

transcription factors, particularly RelA (p65) and RelB, promote

the expression of pro-survival and proinflammatory genes (94). MGF suppresses RelA and RelB

expression, reduces NF-κB transcriptional activity, and induces

apoptosis in malignancies such as multiple myeloma (95).

In the canonical NF-κB pathway, extracellular

stimuli such as pathogen-associated molecular patterns or

proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1 and TNF-α) activate

Toll-like receptors and IL-1 receptor (IL-1R), leading to

recruitment of the MyD88-IL-1R-associated kinase 1/4-TNF

receptor-associated factor 6 complex (96,97). This initiates downstream

signaling via TAK1-TAB1/2 and the IKK complex (IKKα, IKKβ and

NEMO), ultimately phosphorylating IκB and releasing the NF-κB

p50/p65 dimer for nuclear translocation (98).

MGF effectively interferes with this cascade. In

vitro studies have shown that pretreatment with MGF or its

enriched extract Vimang reduces the phosphorylation of IKKα and

IKKβ without altering their total protein levels (99). Furthermore, MGF impairs the

nuclear translocation and DNA-binding activity of p65 in response

to TNF-α stimulation (100),

thereby disrupting NF-κB-driven transcription and weakening the

survival response in tumor cells (101). This NF-κB inhibition is

accompanied by classical apoptotic hallmarks. MGF upregulates

proapoptotic markers, including cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP-1,

p53, phosphorylated-p53 and p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis,

while downregulating antiapoptotic proteins, such as survivin and

Bcl-xL (40). Additionally, MGF

suppresses NF-κB-inducing kinase, further reinforcing the blockade

of both the canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathways, ultimately

limiting cancer cell proliferation, metastasis and survival.

MGF also modulates stress and survival pathways that

converge on NF-κB. In HL-60 leukemia cells, MGF activates Nrf2 and

lowers intracellular ROS, which is consistent with the attenuation

of oxidative stress (75). In

epithelial cancer models, MGF enhances the cytotoxic effects of

chemotherapeutics while suppressing NF-κB activation. In HeLa and

HT29 cells, this suppression coincides with improved responses to

oxaliplatin and reduced drug resistance. In A549 lung cancer cells,

MGF increases the antiproliferative impact of chemotherapy in

association with G2/M arrest and inhibition of the

PKC-NF-κB axis (56). These

apoptotic outcomes are considered secondary to the primary

immunomodulatory role of MGF through NF-κB inhibition.

Modulation of immune cells and

cytokine responses

In addition to its direct cytotoxicity, MGF

modulates host immune responses, enhancing antitumor immunity. It

influences various immune cell populations, including macrophages,

neutrophils, splenocytes and natural killer (NK) cells, which are

critical components of the tumor microenvironment (78). MGF induces cytoskeletal

rearrangement in macrophages, alters their morphology and enhances

their phagocytic capacity (102). It also modulates immune

responses triggered by lipopolysaccharides (LPS), TNF-α and IL-1,

potentially limiting tumor-induced DNA damage in normal tissues and

mitigating tumor-promoting inflammation (103).

In MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, MGF disrupts

Rac1/WAVE2 signaling and inhibits cytokine secretion (for example,

IL-6 and IL-8), thereby reducing invasive capacity and inflammatory

crosstalk (104).

Dose-dependent immunostimulatory effects have also been observed in

murine models; low concentrations (5-40 mg/ml) enhance the

proliferation of splenocytes and thymocytes, whereas higher doses

inhibit tumor cell proliferation. MGF activates splenocytes,

facilitates plant lectin agglutination and stimulates NK-resistant

tumor cell killing by macrophages (105,106).

Radiosensitization in GBM

GBM is a highly aggressive brain tumor with a poor

prognosis and a limited response to conventional radiotherapy.

While radiotherapy remains a cornerstone of GBM treatment, tumor

recurrence due to radioresistance remains a major challenge.

Radiosensitizers are pharmacological agents that increase tumor

sensitivity to radiation while minimizing harm to normal tissues,

representing an attractive adjunct strategy in GBM management.

Recent evidence has suggested that MGF enhances

radiosensitivity in GBM through multiple mechanisms. It

synergistically inhibits the proliferation of U87 and U118 GBM

cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner when combined with

radiation. MGF exerts these effects by downregulating MMP-9

expression and modulating miR-15b, thereby disrupting tumor cell

survival and invasion (35).

Notably, MGF selectively inhibits the nonhomologous end joining

pathway, a major DNA repair mechanism in GBM cells, thereby

impairing DNA repair following radiation and enhancing

radiotherapeutic efficacy. By sensitizing tumor cells to

radiation-induced DNA damage, MGF improves therapeutic outcomes

without necessitating an increase in radiation dose (36). A comprehensive summary of the

targets, dosages, study models, signaling pathways and mechanistic

insights associated with MGF across different cancer-related

contexts is presented in Table I

(4,5,7,8,13-17,55,56,107-114).

| Table ISummary of representative studies on

MGF and the underlying molecular mechanisms. |

Table I

Summary of representative studies on

MGF and the underlying molecular mechanisms.

| Target/pathway | Dose and

duration | Experimental

model/sample size | Type of study | Major signaling

pathways | Principal

findings/cellular products |

Limitations/remarks | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Apoptosis | 12.5-200

μM | CNE2, SGC-7901

gastric carcinoma cells | In

vitro | Caspase;

PI3K-Akt | Bax (up), Bad (up),

Bcl-2 (down); activation of caspase-3/9; | Limited to gastric

cell lines | (4,5) |

| miRNA

modulation | 12.5-100 mg/ml | H2030/H1299/A549

lung cancer cells | In

vitro | miR-92a,

miR-27b | Downregulated

oncogenic miRNAs; suppressed proliferation and induced apoptosis in

LUAD cells | No animal or human

data | (7) |

| miRNA

modulation | 25-100

μM | Human U87 glioma

cells | In

vitro | MMP-9/miR-15b | MMP-9 (down),

miR-15b (down); attenuated invasion | Mechanism indirect;

requires in vivo validation | (8) |

| Mitochondrial

pathway | 1/50/400

μM | HT-29 colon

adenocarcinoma cells (ATCC HTB-38) | In

vitro | PPAR, SIRT, NF-κB,

STAT3, HIF, Wnt | Multitargeting of

mitochondrial oxidoreductases and β-oxidation; inhibited

proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis | In vitro

only; pharmacokinetic data were not available | (13) |

| Mitochondrial

pathway | 10/25/50

μM | SH-SY5Y

neuroblastoma cells | In

vitro | JNK; Nrf2/HO-1 | Normalized

mitochondrial dynamics, reduced oxidative stress | Limited neuronal

model | (14) |

| Lipid

peroxidation | 10

μg/ml | U-937

macrophages | In

vitro | NF-κB | Inhibited

TNF-induced lipid peroxidation; catalase (up); apoptosis

protection | Preclinical

only | (15) |

| Lipid

peroxidation | 50 mg/kg |

Benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung cancer in

Swiss albino mice (n=6/group) | In vivo | NF-κB;

mitochondrial genes | Reduced

mitochondrial lipid peroxidation; altered TCA/ETC enzymes; induced

apoptosis | No chronic safety

data | (16) |

| Oxidative-stress

pathway | 50/100/200 mg/kg

×14 days | Wistar rats

(n=8/group) | In vivo | Nrf2 | Breg levels,

activated Nrf2 antioxidant pathway; proinflammatory mediators

(down) | Rodent model; needs

clinical validation | (17) |

| Cell-cycle

proteins | 0.5/0.75/1

μM | HL-60 leukemia

cells | In

vitro | CDK1/cyclin B1 | Increased cyclin

B1; triggered G2/M arrest | Short-term

exposure; lacks mechanistic protein validation | (55) |

| Cell-cycle

proteins | 10/50/100

mg/kg | A549 lung carcinoma

cells | In

vitro | CDK1/cyclin B1 | Induced

G2/M-phase arrest; apoptosis via NF-κB inhibition | Only cell-line

data; no in vivo validation | (56) |

|

Pharmacokinetics/absorption | 30 mg/kg (single

oral dose) | Wistar rats

(n=6) | In vivo | - | Peak tissue level

in small intestine at 0.5 h (754 ng/ml); nonlinear absorption | No human PK

association | (107) |

|

Anti-invasion/anti-metastasis | 1 mg/ml; 50

μl/well | U87MG/U373MG/CRT-MG

glioma cells | In

vitro | MMP-9; PI3K-Akt;

MAPK | Suppressed MMP-9

via inhibition of NF-κB and AP-1; Akt/MAPK phosphorylation

(down) | No in vivo

validation | (108) |

|

Anti-inflammatory | 4.2 mg | RAW 264.7

macrophages | In

vitro | NF-κB | IL-12 (down), TNF-α

(up), IL-1 (up), IL-6 (down); anti-inflammatory shift | Lacks time-course

data | (109) |

| miRNA

modulation | 10/20/40

μM | PC3 human prostate

cancer cells | In

vitro | Bcl-2/miR-182 | Bcl-2 (down),

miR-182 (up); promoted apoptosis | Single-cell

model | (110) |

| Mitochondrial

pathway | 100 mg/kg × 21

days | ER−

breast-cancer xenograft mice (n=8) | In vivo | NF-κB;

caspase-3 | Tumor volume

reduced by ~89%, comparable to cisplatin (91.5%) | Short duration; no

toxicity endpoints | (111) |

| Inflammatory

models | 20-40

μM/5-20 mg/kg | RAW264.7 cells and

mouse air-pouch model (n=6/group) | In vitro and

in vivo | ROS; NF-κB | Reduced ROS;

blocked NF-κB nuclear translocation; suppressed cytokines | Dose-dependent

effects only short term | (112) |

|

Safety/toxicity | ≤1,000 mg/kg × 28

days | Sprague-Dawley rats

(n=10/group) | In vivo | - | No abnormal

hematology; LD50 >2,000 mg/kg | Limited to 28

days | (113) |

| Clinical cognition

study | 300 mg/day × 7

days | 60 healthy adults,

randomized double-blind | Clinical |

Cognitive/antioxidant | Improved attention

and working memory; no adverse events | Short duration;

healthy subjects only | (114) |

Applications in other diseases

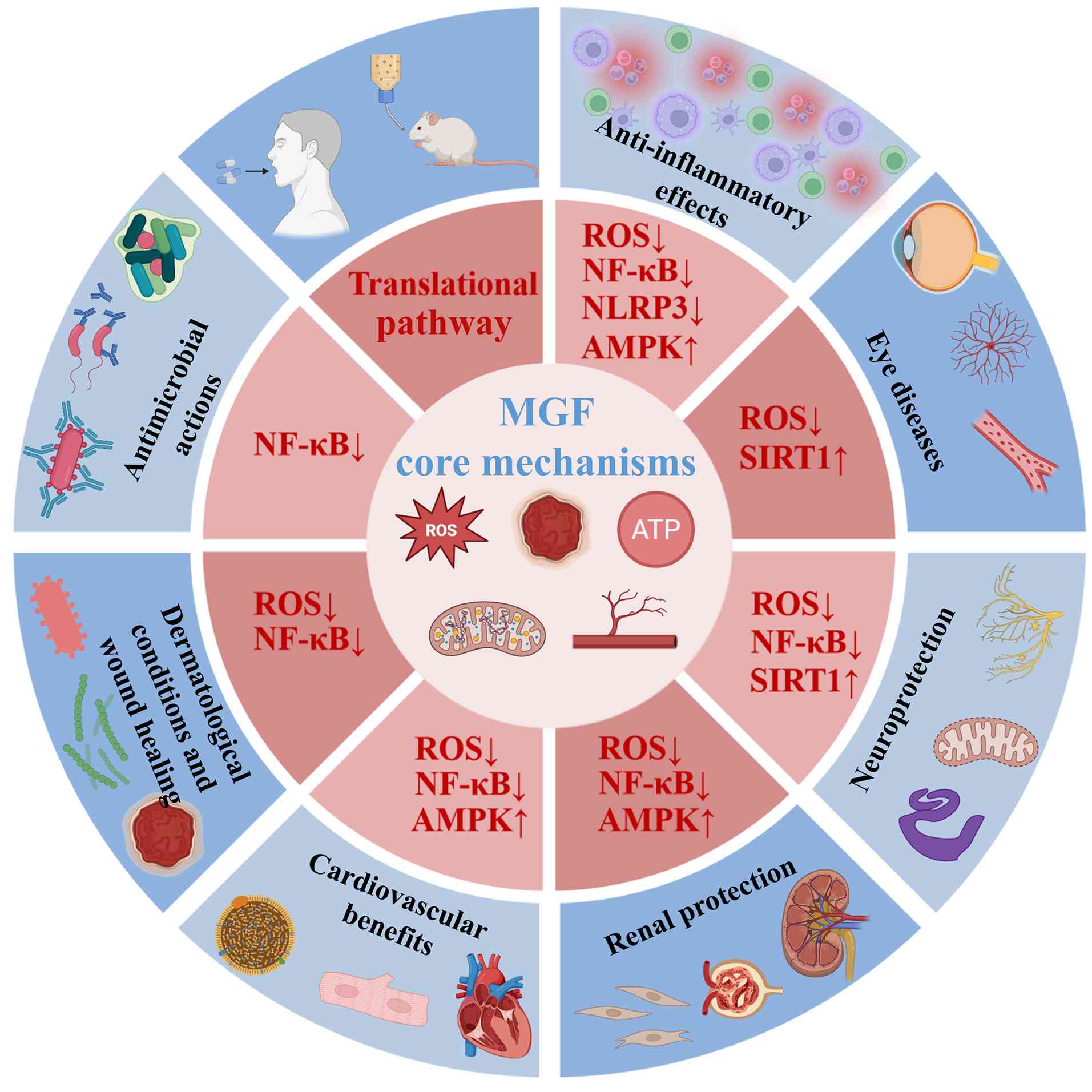

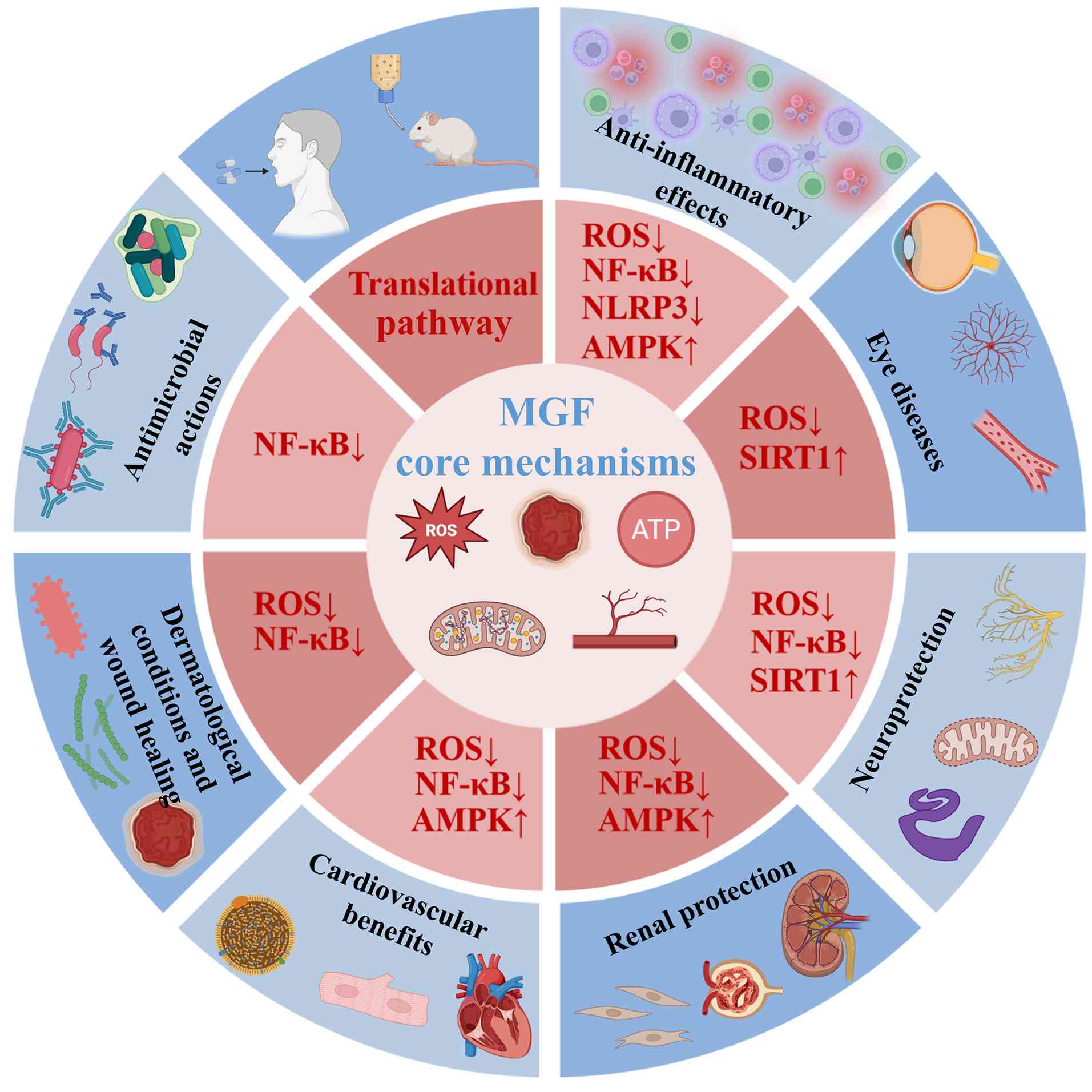

In addition to its well-characterized roles in

diabetes and cancer, MGF exerts protective effects across a broad

spectrum of pathological conditions. These include inflammatory,

neurodegenerative, ocular, renal, cardiovascular, dermatological

and infectious diseases (7,36,106,115-118). Although the mechanistic depth

of investigation in these fields is comparatively limited,

accumulating preclinical and early clinical evidence has

underscored the versatile pharmacodynamic (PD) profile of MGF. Its

therapeutic actions converge on several core molecular pathways,

particularly the suppression of oxidative stress and NF-κB-mediated

inflammation, and the activation of AMPK and SIRT1 signaling

(119-121). Fig. 5 provides an overview of these

shared mechanisms and representative disease contexts, illustrating

the diverse yet interconnected pharmacological potential of MGF

beyond metabolic and oncological disorders.

| Figure 5Representative therapeutic

applications of MGF and its core molecular mechanisms. MGF exhibits

broad pharmacological activity across multiple organ systems, which

is primarily mediated through the attenuation of oxidative stress

and inflammatory signaling. The core mechanisms include a reduction

in ROS levels, suppression of NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome

activation, and activation of the AMPK and SIRT1 pathways. These

convergent regulatory effects underpin the diverse protective

actions of MGF in inflammatory, neurodegenerative, ocular, renal,

cardiovascular, dermatological and infectious diseases. The listed

conditions represent key examples rather than an exhaustive account

of the therapeutic potential of MGF, highlighting its versatility

as a pleiotropic bioactive compound. AMPK, AMP-activated protein

kinase; MGF, mangiferin; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain-containing

3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SIRT, sirtuin. |

Anti-inflammatory effects

Chronic inflammation is a key driver of various

pathological conditions, including degenerative, autoimmune and

metabolic diseases. MGF, characterized by its C-glucosyl and

polyhydroxylated xanthone structure, exhibits potent antioxidant

and anti-inflammatory activities by scavenging free radicals and

modulating key signaling pathways.

In intervertebral disc degeneration, MGF has been

shown to attenuate mitochondrial dysfunction and reduce ROS in

human nucleus pulposus cells. It suppresses TNF-α-induced NF-κB

activation and downregulates the expression of apoptosis-related

markers, including pro-apoptotic caspases and Bcl-2 family

proteins, indicating its therapeutic potential for treating

degenerative disc disorders (122).

In a rat model of rheumatoid arthritis, MGF (15-45

mg/kg, 2-week administration) inhibits the MAPK and NF-κB pathways,

thereby reducing inflammatory cell proliferation, migration and

cytokine secretion. MGF also promotes inflammatory apoptosis and

attenuates the pathogenic activity of fibroblast-like synoviocytes

in arthritic rats (123).

In metabolic inflammation, MGF improves insulin

sensitivity and lipid metabolism. In a rodent model of high-fat

diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), MGF (25-100

mg/kg, 12 weeks) activates AMPK and suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome

signaling, reducing hepatic inflammation and steatosis (124). An additional study has

confirmed the ability of MGF to inhibit the NF-κB and JNK pathways,

with reduced body weight and plasma triglyceride and cholesterol

levels in NAFLD mouse models (125).

In models of acute lung injury, pre-administration

of MGF (100 mg/kg) suppresses LPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome

activation in macrophages via NF-κB inhibition. This results in

reduced inflammatory cytokine production and amelioration of

pulmonary pathology (126).

Eye diseases

Oxidative stress serves a central role in the

pathogenesis of ocular disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and

macular degeneration. MGF has demonstrated therapeutic benefits in

preclinical models of retinal and lens injury through antioxidant

and antiangiogenic mechanisms (127).

In ischemic retinal injury, MGF downregulates HIF-1α

and glial fibrillary acidic protein while upregulating SIRT1,

thereby protecting retinal ganglion cells from oxidative damage in

mouse models (128). In

diabetic retinopathy, MGF inhibits angiogenesis and endothelial

cell migration by targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, suggesting

potential for clinical translation (129).

Notably, the capacity of MGF to cross the

blood-retinal barrier enhances its therapeutic efficacy (130). In streptozotocin-induced

diabetic rats, biochemical analysis has revealed that MGF increases

antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, GSH-Px), reduces lipid

peroxidation (MDA), and decreases advanced glycation end-products

(AGEs) and sorbitol levels in the lens and serum, thereby

contributing to the prevention of diabetic ocular complications

(131).

Neuroprotection

MGF exhibits robust neuroprotective properties

across multiple animal models of neurodegeneration, ischemia and

cognitive impairment. Its mechanisms include the modulation of

oxidative stress, mitochondrial protection and anti-inflammatory

signaling (132).

In

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced mouse models

and α-synuclein overexpression transgenic mouse models of

Parkinson's disease, MGF reduces neuroinflammation and oxidative

stress by inhibiting NF-κB signaling, resulting in improved motor

coordination and neuronal survival in the substantia nigra

(133). It also improves memory

by enhancing cholinergic transmission through acetylcholinesterase

inhibition and NF-κB suppression (134).

In hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced N2a neuroblastoma

cell models of ischemic injury, MGF activates the SIRT1/PPARγ

coactivator-1α axis to preserve mitochondrial function and reduce

neuronal damage (135). A

placebo-controlled human study demonstrated that acute MGF

administration enhances attention, long-term memory and cognitive

performance in healthy adults (136).

MGF also protects against β-amyloid-induced

oxidative damage, restoring redox balance and preserving

mitochondrial integrity in Alzheimer's disease models, such as

amyloid β-treated neuronal cultures and APP/PS1 transgenic mice

(137). In aging mice, MGF

improves memory, reduces hippocampal pathology, and decreases the

β-amyloid burden and lipid peroxidation (138). Furthermore, it enhances

hippocampal neuronal excitability and cognitive processing,

supporting its potential as a neurocognitive enhancer (139).

Renal protection

Renal dysfunction, often driven by oxidative stress

and inflammation, contributes to the pathogenesis of acute and

chronic kidney diseases. MGF has demonstrated renoprotective

effects across a range of kidney injury models by modulating

inflammation, oxidative stress and fibrotic signaling pathways

(140).

In vitro studies have shown that MGF

suppresses IL-6 and IL-8 production by inhibiting the MAPK and

NF-κB pathways, thereby attenuating inflammatory responses in renal

epithelial cells (141). In a

mouse model of ischemia-reperfusion injury, MGF (10, 30 or 100

mg/kg) protects renal tubular cells by reducing inflammation and

apoptosis through activation of the adenosine-CD73 pathway

(141). Similarly, in

D(+)-galactosamine-induced nephrotoxicity, MGF exhibits antioxidant

properties by inhibiting inducible nitric oxide synthase and

downregulating NF-κB signaling, leading to improved renal function

and histology (142).

MGF (20, 50 or 100 mg/kg) also protects against

sepsis-induced acute kidney injury in an LPS-induced sepsis mouse

model by preserving the endothelial glycocalyx component

syndecan-1, reducing ROS and MDA production, enhancing tight

junction integrity, and limiting vascular leakage and inflammation

(142).

Diabetic nephropathy is a common microvascular

complication of type 1 and type 2 diabetes (143). MGF (50 mg/kg) mitigates renal

injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice by modulating

hexokinase II-mitochondrial interactions and inhibiting NADPH

oxidase 4, thereby reducing oxidative stress (144). Moreover, MGF (12.5, 25 or 50

mg/kg) enhances autophagic flux via AMPK-mTOR signaling, delaying

the progression of diabetic nephropathy (145).

MGF also attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis, a

hallmark of diabetic kidney disease. In streptozotocin-induced

diabetic mice, MGF (15, 30 or 60 mg/kg) suppresses inflammation and

oxidative stress by modulating the PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway, leading

to reduced expression of fibrotic markers such as collagen I,

fibronectin and α-SMA (34).

Cardiovascular benefits

MGF has lipid-lowering, antioxidant and

anti-inflammatory properties that contribute to cardiovascular

protection. A randomized, double-blind clinical trial demonstrated

that MGF supplementation can markedly decrease serum triglyceride

and free fatty acid levels in overweight individuals with

hyperlipidemia, highlighting its clinical potential (146).

In high-fat diet-induced hyperlipidemic rats, MGF

(50, 100 or 150 mg/kg, orally administered for 6 weeks) has been

shown to activate hepatic AMPK, resulting in improved lipid

metabolism and reduced circulating free fatty acids (147). Furthermore, in high-fat

diet-induced hyperlipidemic rats, MGF-loaded

N-succinyl-chitosan-grafted alginate nanoparticles enhance

therapeutic efficacy by increasing the hepatic expression of PPARα,

carnitine palmitoyltransferase I and FAT/CD36, while suppressing

lipogenic genes, such as SREBP-1c, ACC, DGAT2 and MTP (148).

In rat models of diabetic cardiomyopathy, MGF (20

mg/kg for 16 weeks) has been shown to notably decrease ROS

production and AGE accumulation, partly through the inhibition of

NF-κB signaling. This preserves myocardial function and delays

cardiomyopathic remodeling (149).

Dermatological benefits and wound

healing

In murine models of contact dermatitis induced by

oxazolone, MGF suppresses TNF-α-stimulated macrophage activation

and inhibits NF-κB pathway activation, resulting in decreased

production of inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress markers

(150). Its C-glucosylxanthone

structure contributes to its efficacy as a skin-targeted

anti-inflammatory compound.

Oxygenated anthraquinone derivatives of MGF,

including isobavachalcone, gartanin and glucosylated xanthone, have

demonstrated antimicrobial activity against acne-causing bacteria

such as Staphylococcus epidermidis. These compounds also

inhibit inflammatory pathways, including PPAR and prostaglandin

cascades, suggesting their therapeutic potential in both acne and

inflammatory dermatoses (151).

In wound healing, MGF-loaded hydrogels or liposomes

(10, 20 and 40 μM) have been reported to accelerate flap

regeneration in rat models of skin injury. This treatment may

inhibit oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, increase the Bcl-2/Bax

ratio and decrease cleaved caspase-3 expression (29). MGF also enhances PPARγ expression

and suppresses NF-κB activity, further promoting anti-inflammatory

and cytoprotective effects in dermal tissues (29).

Antimicrobial actions

MGF possesses broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity

against both fungal and bacterial pathogens, including strains

involved in drug resistance and biofilm formation. Purified MGF has

MIC values ranging from 1.95 to 62.5 μg/ml for fungi and

from 1.95 to 31.25 μg/ml for bacteria, with a time-kill

study confirming its bactericidal and fungicidal efficacy (1). Extracts from mango leaves, which

are rich in MGF, have shown inhibitory activity against

gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus

subtilis, Streptococcus pneumoniae) and gram-negative pathogens

(Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa, Shigella spp.) (114,152,153). Furthermore, MGF derivatives

have demonstrated efficacy against K. pneumoniae by

disrupting biofilms, impairing virulence factor expression and

increasing antibiotic susceptibility (154).

In a murine periodontitis model, oral

administration of MGF (50 mg/kg for 8 weeks) has been reported to

suppress Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced alveolar bone

loss, downregulate TNF-α production and inhibit NF-κB and

JAK1/STAT1/3 phosphorylation in the gingival epithelium (155). In Caenorhabditis elegans

models infected with P. aeruginosa, MGF compounds regulate

quorum sensing pathways and reduce bacterial virulence in both

dauer larvae and adult stages, further supporting their

anti-infective potential (156).

Translational aspects

PK, and absorption, distribution,

metabolism and excretion overview

Orally administered MGF shows low aqueous

solubility and limited intestinal permeability, resulting in poor

systemic exposure at conventional doses (157-160). After uptake in the proximal

small intestine, extensive first-pass metabolism and gut

microbiota-mediated deglycosylation (yielding norathyriol and

downstream conjugates) further reduce parent drug levels (21,160-162). The tissue distribution in

rodents indicates measurable concentrations in the liver, kidney

and lung with delayed plasma peaks, whereas brain penetration

appears limited under standard conditions (107,163). These properties underscore the

need to link PD readouts to exposures achievable with clinically

realistic regimens, and to report unbound concentrations where

possible.

Key barriers to translation

The main obstacles include: i) Low solubility and

permeability [constraining Cmax/area under the curve

(AUC) after oral dosing] ((164-166), ii) metabolic lability and

conjugation that curtails exposure to the parent compound MGF

(21,167,168), iii) variability introduced by

microbiome-dependent deglycosylation (165,169), and iv) inconsistent reporting

of dose-exposure relationships across preclinical studies (170,171). These issues complicate

cross-study comparisons and dose selection for human studies.

Delivery/formulation strategies

Multiple approaches have improved exposure in

preclinical systems, including nanostructured lipid carriers,

polymeric and chitosan-based nanogels, phospholipid complexes

(2,172,173), and targeted nanoparticles

designed to enhance intestinal uptake or lymphatic transport and to

stabilize MGF against rapid metabolism (172,174-176). Early structure-led strategies

(for example, monosodium salts/derivatives) have also reported

increased apparent potency or improved tissue delivery in disease

models (166,177,178). In the future, head-to-head

comparisons using common dose units, matched controls and

standardized PK endpoints (AUC, bioavailability, tissue-plasma

ratios) will be essential for identifying clinically scalable

options (170,179).

Safety/toxicity signals

A nonclinical study has previously reported

favorable tolerability at pharmacologically relevant exposures,

with adverse findings emerging at substantially higher doses

(180). However, several safety

uncertainties remain: i) Limited chronic toxicity datasets for

purified MGF (as opposed to plant extracts) (108); ii) sparse evaluation of

drug-drug interaction risks given pathway cross-talk (for example,

with PI3K/Akt, AMPK or NF-κB modulators) (181-183); and iii) incomplete reporting of

standardized laboratory safety assessments and histopathology in a

number of efficacy-focused studies (184). Extract-based toxicology (such

as that assessing mango leaf preparations) should not be

overextrapolated to the purified compound without compositional

bridging.

Clinical evidence and next steps

Early human data are limited, heterogeneous (often

extract-based) and not yet definitive for purified MGF. Small

studies suggest metabolic or performance signals in select

contexts, but they seldom include rigorous PK/PD integration,

dose-ranging or long-term safety monitoring (139,166,185). The next steps include: i) Phase

I studies with single- and multiple-ascending doses of purified MGF

and exposure-enhancing formulations; ii) assessment of the effects

of food intake on MGF PKs and bioequivalence for leading delivery

platforms, including nanostructured lipid carriers, phospholipid

complexes and chitosan-based nanoparticles; iii) PK/PD modeling

anchored to validated mechanistic biomarkers (such as p65 nuclear

translocation, Nrf2 target induction) and disease-relevant

functional endpoints; and iv) randomized, controlled phase II

trials using clinically translatable doses and standardized safety

surveillance.

Evidence gaps

Preclinical findings regarding MGF are promising;

however, the evidence base shows important gaps that limit

translation. Notably, the results vary across cell lines and animal

strains, and several mechanisms that are frequently cited (for

example, NF-κB or MMP-9 modulation, G2/M arrest and AMPK

activation) appear to be highly context dependent, with

inconsistent replication under different stimuli or dosing

conditions (4,13,117,124,186,187). A number of studies rely on

single models, small or unreported sample sizes, and pretreatment

designs rather than therapeutic intervention after disease onset,

which reduces external validity (117,188). PK constraints remain

under-characterized, including oral exposure at clinically relevant

doses, the relative contribution of metabolites such as

norathyriol, tissue penetration in target organs and the

variability introduced by different formulations (21,159,162). Material standardization is

uneven, with frequent use of extracts or nanoparticles without full

reporting of purity, content uniformity or release profiles, making

cross-study comparisons difficult and weakening conclusions

regarding the active entity (161,181). Mechanistic claims often rely on

surrogate protein readouts, such as changes in pathway marker

proteins (for example, NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation or AMPK

phosphorylation), without orthogonal validation or causal rescue

experiments, and dose-response and time-course data are incomplete

for several indications (13,186,189). Comparative efficacy vs.

standard of care is rarely tested, and combination studies seldom

include PK or PD interaction assessments. Furthermore, safety

reporting is inconsistent, with limited long-term toxicity,

immunomodulatory risk and drug-drug interaction data, and with few

studies that stratify patients by sex or age (184,185,190). Human evidence remains sparse,

with a lack of standardized endpoints, validated translational

biomarkers, and prospective trials that incorporate randomization,

blinding and predefined primary outcomes (184,191). Addressing these gaps will

require well-powered, rigorously controlled studies that integrate

exposure-response relationships, prespecified functional end points

and reproducible materials, together with head-to-head and

combination designs that reflect real clinical use.

Conclusion and future prospects

MGF, a natural C-glucosylxanthone, has broad

pharmacological effects, including antidiabetic, anticancer,

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and neuroprotective activities, with

low toxicity and good biocompatibility, making it a promising

therapeutic candidate.

Notably, the clinical use of MGF is limited by poor

solubility and low oral bioavailability. Advances such as nanogels,

lipid carriers and phospholipid complexes have improved absorption

and stability (23,192,193). Structural modifications and

derivatives such as monosodium MGF also enhance efficacy, partly

via the modulation of oxidative stress pathways (194). Future work should focus on

optimized delivery systems, rational structural designs, and

rigorous clinical trials to confirm safety and dosing (170). Building on the growing

preclinical base, next-step studies should prioritize clinically

scalable formulations, such as polymeric or lipid nanocarriers,

self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (forming fine

oil-in-water microemulsions in the gastrointestinal tract) and

solid lipid nanoparticles (lipid-based colloidal carriers),

cyclodextrin inclusions and phospholipid complexes, supported by

standardized chemistry, manufacturing and controls characterization

and direct PK comparisons with conventional extracts (195,196). This approach is justified by

consistent improvements in solubility, uptake and systemic exposure

demonstrated in nanodelivery research, as well as by early human PK

findings that MGF monosodium salt substantially increases

bioavailability compared with the parent compound (166,195). These PK advantages make dose

finding and scheduling practically feasible in phase I/II trials.

To ensure translational credibility, forthcoming clinical studies

should integrate exposure-response analysis and biomarker

verification, quantifying indicators such as Nrf2 target induction,

NF-κB suppression, and oxidative or DNA damage markers in

accessible tissues or circulating immune cells. Consistent with the

development principles proposed by previous scholars, these

strategies effectively integrate formulation, dosage and PDs into a

coherent translational framework (166,195,197).

Deeper investigations into signaling pathways,

including the NF-κB, Nrf2 and AMPK pathways, will further clarify

the underlying mechanisms of MGF and support its clinical

translation (184,198,199). Mechanistically enriched studies

should define, for each indication discussed in this review (for

example, cancer, inflammatory disorders and liver disease), the

predominant signaling axis, distinguishing between redox-regulated

Nrf2 signaling, inflammatory NF-κB activation and metabolic AMPK

modulation, as summarized in reviews of the molecular mechanisms of

MGF in cancer/inflammation and liver disease, including the NF-κB,

Nrf2 and AMPK pathways (198,199). Such resolution will guide

rational combinations, for example, pairing MGF with radiotherapy

or cytotoxic drugs where redox priming or DNA-repair interference

is desired or combining with immunomodulators where NF-κB/innate

signaling is dominant (200-202). This pathway-specific

combination strategy, which pairs MGF with radiotherapy or

cytotoxic agents for redox priming or DNA-repair interference, or

with immunomodulators that act on the dominant NF-κB/innate

signaling pathway, is inspired by prior 'redox-directed'

therapeutic approaches, and is further supported by MGF studies

showing Nrf2-centred and AMPK-linked anti-inflammatory effects

(75,120). Together, a biomarker-driven,

pathway-specific strategy may result in MGF progressing from a

broadly-acting pleiotropic lead compound to a precisely targeted

therapeutic candidate for defined patient subgroups.

In conclusion, MGF represents a compelling natural

compound with substantial therapeutic potential. With continued

advancements in formulation science, structural modification and

clinical validation, MGF may emerge as a clinically valuable agent

in modern pharmacotherapy. Overcoming its current limitations

through interdisciplinary innovation will be essential to

determining its full potential in the prevention and treatment of

metabolic, inflammatory, infectious, degenerative and neoplastic

diseases.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YD, QH and MT contributed equally to the conception

and design of the review, performed the literature search, screened

the articles, extracted and synthesized the data, and drafted the

initial manuscript. SZ and ZW participated in the literature search

and data extraction, performed extensive analysis and

interpretation of the data, summarized and organized the extracted

findings, and assisted with figure and table preparation. CJ

contributed to the organization and interpretation of the extracted

data, and critically revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. ZL and SS conceived and supervised the study,

resolved discrepancies in study selection and data interpretation,

provided critical revision of the manuscript, and are the

corresponding authors. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

AGE

|

advanced glycation end-products

|

|

AMPK

|

AMP-activated protein kinase

|

|

PPAR

|

peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor

|

|

PTEN

|

phosphatase and tensin homolog

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

SIRT

|

sirtuin

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Yi Wang

(University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu,

China), for her valuable guidance and assistance in preparing this

manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fujian Provincial Natural Science

Foundation (grant no. 2025J08106), the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82505722) and the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82474616).

References

|

1

|

Wang M, Liang Y, Chen K, Wang M, Long X,

Liu H, Sun Y and He B: The management of diabetes mellitus by

mangiferin: Advances and prospects. Nanoscale. 14:2119–2135. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bhattacharyya S, Ahmmed SM, Saha BP and

Mukherjee PK: Soya phospholipid complex of mangiferin enhances its

hepatoprotectivity by improving its bioavailability and

pharmacokinetics. J Sci Food Agric. 94:1380–1388. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mei S, Perumal M, Battino M, Kitts DD,

Xiao J, Ma H and Chen X: Mangiferin: A review of dietary sources,

absorption, metabolism, bioavailability, and safety. Crit Rev Food

Sci Nutr. 63:3046–3064. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Morozkina SN, Nhung Vu TH, Generalova YE,

Snetkov PP and Uspenskaya MV: Mangiferin as new potential

anti-cancer agent and mangiferin-integrated polymer systems-a novel

research direction. Biomolecules. 11:792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang M, Zhang Z, Huo Q, Wang M, Sun Y, Liu

H, Chang J, He B and Liang Y: Targeted polymeric nanoparticles

based on mangiferin for enhanced protection of pancreatic β-cells

and type 1 diabetes mellitus efficacy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces.

14:11092–11103. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Akkewar AS, Mishra KA and Sethi KK:

Mangiferin: A natural bioactive immunomodulating glucosylxanthone

with potential against cancer and rheumatoid arthritis. J Biochem

Mol Toxicol. 38:e237652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yehia RS and Altwaim SA: An insight into

in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and apoptosis

induction potential of mangiferin, a bioactive compound derived

from mangifera indica. Plants (Basel). 12:15392023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xiang G, Guo S, Xing N, Du Q, Qin J, Gao

H, Zhang Y and Wang S: Mangiferin, a potential supplement to

improve metabolic syndrome: Current status and future

opportunities. Am J Chin Med. 52:355–386. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Li HW, Lan TJ, Yun CX, Yang KD, Du ZC, Luo

XF, Hao EW and Deng JG: Mangiferin exerts neuroprotective activity

against lead-induced toxicity and oxidative stress via Nrf2

pathway. Chin Herb Med. 12:36–46. 2020.

|

|

10

|

Aritomi M and Kawasaki T: A new xanthone

C-glucoside, position isomer of mangiferin, from anemarrhena

asphodeloides bunge. Tetrahedron Lett. 12:941–944. 1969. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Talamond P, Conejero GV, Verdeil JL and

Poëssel JL: Isolation of C-glycosyl xanthones from coffea

pseudozanguebariae and their location. Nat Prod Commun.

6:1885–1888. 2011.

|

|

12

|

Vyas A, Syeda K, Ahmad A, Padhye S and

Sarkar FH: Perspectives on medicinal properties of mangiferin. Mini

Rev Med Chem. 12:412–425. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Du S, Liu H, Lei T, Xie X, Wang H, He X,

Tong R and Wang Y: Mangiferin: An effective therapeutic agent

against several disorders (review). Mol Med Rep. 18:4775–4786.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kavitha M, Nataraj J, Essa MM, Memon MA

and Manivasagam T: Mangiferin attenuates MPTP induced dopaminergic

neurodegeneration and improves motor impairment, redox balance and

bcl-2/bax expression in experimental Parkinson's disease mice. Chem

Biol Interact. 206:239–247. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hudecová A, Kusznierewicz B, Hašplová K,

Huk A, Magdolenová Z, Miadoková E, Gálová E and Dušinská M:

Gentiana asclepiadea exerts antioxidant activity and enhances DNA

repair of hydrogen peroxide- and silver nanoparticles-induced DNA

damage. Food Chem Toxicol. 50:3352–3359. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Andreu GP, Delgado R, Velho JA, Curti C

and Vercesi AE: Iron complexing activity of mangiferin, a naturally

occurring glucosylxanthone, inhibits mitochondrial lipid

peroxidation induced by Fe2+-citrate. Eur J Pharmacol. 513:47–55.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gu PC, Wang L, Han MN, Peng J, Shang JC,

Pan YQ and Han WL: Comparative pharmacokinetic study of mangiferin

in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats after oral and

intravenous administration by UPLC-MS/MS. Pharmacology. 103:30–37.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Liu H, Wu B, Pan G, He L, Li Z, Fan M,

Jian L, Chen M, Wang K and Huang C: Metabolism and pharmacokinetics

of mangiferin in conventional rats, pseudo-germ-free rats, and

streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Drug Metab Dispos.

40:2109–2118. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gelabert-Rebato M, Wiebe JC, Martin-Rincon

M, Gericke N, Perez-Valera M, Curtelin D, Galvan-Alvarez V,

Lopez-Rios L, Morales-Alamo D and Calbet JAL: Mangifera indica l.

Leaf extract in combination with luteolin or quercetin enhances

VO2peak and peak power output, and preserves skeletal muscle

function during ischemia-reperfusion in humans. Front Physiol.

9:7402018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

20

|

Ehianeta TS, Laval SP and Yu B: Bio- and

chemical syntheses of mangiferin and congeners. Biofactors.

42:445–458. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tian X, Gao Y, Xu Z, Lian S, Ma Y, Guo X,

Hu P, Li Z and Huang C: Pharmacokinetics of mangiferin and its

metabolite-norathyriol, part 1: Systemic evaluation of hepatic

first-pass effect in vitro and in vivo. Biofactors. 42:533–544.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hasanah U, Miki K, Nitoda T and Kanzaki H:

Aerobic bioconversion of c-glycoside mangiferin into its aglycone

norathyriol by an isolated mouse intestinal bacterium. Biosci

Biotechnol Biochem. 85:989–997. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li X, Jafari SM, Zhou F, Hong H, Jia X,

Mei X, Hou G, Yuan Y, Liu B, Chen S, et al: The intracellular fate

and transport mechanism of shape, size and rigidity varied

nanocarriers for understanding their oral delivery efficiency.

Biomaterials. 294:1219952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Furlanetto V, Kalyani DC, Kostelac A, Puc

J, Haltrich D, Hällberg BM and Divne C: Structural and functional

characterization of a gene cluster responsible for deglycosylation

of C-glucosyl flavonoids and xanthonoids by deinococcus aerius. J

Mol Biol. 436:1685472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pereira QC, Fortunato IM, Oliveira FS,

Alvarez MC, Santos TWD and Ribeiro ML: Polyphenolic compounds:

Orchestrating intestinal microbiota harmony during aging.

Nutrients. 16:10662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kaur P, Gupta RC, Dey A, Malik T and

Pandey DK: Optimization of harvest and extraction factors by full

factorial design for the improved yield of C-glucosyl xanthone

mangiferin from swertia chirata. Sci Rep. 11:163462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Suman RK, Borde MK, Mohanty IR and Singh

HK: Mechanism of action of natural dipeptidyl peptidase-IV

inhibitors (berberine and mangiferin) in experimentally induced

diabetes with metabolic syndrome. Int J Appl Basic Med Res.

13:133–142. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Shimada T, Nagai E, Harasawa Y, Watanabe

M, Negishi K, Akase T, Sai Y, Miyamoto K and Aburada M: Salacia

reticulata inhibits differentiation of 3T3-l1 adipocytes. J

Ethnopharmacol. 136:67–74. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mao X, Liu L, Cheng L, Cheng R, Zhang L,

Deng L, Sun X, Zhang Y, Sarmento B and Cui W: Adhesive

nanoparticles with inflammation regulation for promoting skin flap

regeneration. J Control Release. 297:91–101. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yang CQ, Xu JH, Yan DD, Liu BL, Liu K and

Huang F: Mangiferin ameliorates insulin resistance by inhibiting

inflammation and regulatiing adipokine expression in adipocytes

under hypoxic condition. Chin J Nat Med. 15:664–673.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fan X, Jiao G, Pang T, Wen T, He Z, Han J,

Zhang F and Chen W: Ameliorative effects of mangiferin derivative

TPX on insulin resistance via PI3k/AKT and AMPK signaling pathways

in human HepG2 and HL-7702 hepatocytes. Phytomedicine.

114:1547402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Han J, Yi J, Liang F, Jiang B, Xiao Y, Gao

S, Yang N, Hu H, Xie WF and Chen W: X-3, a mangiferin derivative,

stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase and reduces hyperglycemia

and obesity in db/db mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 405:63–73. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fu TL, Li GR, Li DH, He RY, Liu BH, Xiong

R, Xu CZ, Lu ZL, Song CK, Qiu HL, et al: Mangiferin alleviates

diabetic pulmonary fibrosis in mice via inhibiting

endothelial-mesenchymal transition through AMPK/FoxO3/SIRT3 axis.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 45:1002–1018. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Song Y, Liu W, Tang K, Zang J, Li D and

Gao H: Mangiferin alleviates renal interstitial fibrosis in

streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice through regulating the

PTEN/PI3k/Akt signaling pathway. J Diabetes Res. 2020:94817202020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Shivam and Gupta AK: Neuroprotective

effects of isolated mangiferin from swertia chirayita leaves

regulating oxidative pathway on streptozotocin-induced diabetic

neuropathy in experimental rats. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem.

24:182–195. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Iqbal H, Inam-Ur-Raheem M, Munir S, Rabail

R, Kafeel S, Shahid A, Mousavi Khaneghah A and Aadil RM:

Therapeutic potential of mangiferin in cancer: unveiling regulatory

pathways, mechanisms of action, and bioavailability enhancements-an

updated review. Food Sci Nutr. 12:1413–1429. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Xiao J, Liu L, Zhong Z, Xiao C and Zhang

J: Mangiferin regulates proliferation and apoptosis in glioma cells

by induction of microRNA-15b and inhibition of MMP-9 expression.

Oncol Rep. 33:2815–2820. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gold-Smith F, Fernandez A and Bishop K: