Musculoskeletal crosstalk is a fundamental

physiological process that maintains human health, involving the

dynamic interaction and regulation between bone and muscle through

intricate molecular signaling mechanisms (1). Myokines such as insulin-like growth

factor-1 (IGF-1) and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) are pivotal

in mediating this crosstalk (2).

IGF-1 regulates muscle growth and metabolism by promoting myocyte

proliferation and repair, while FGF-2 plays a critical role in

muscle regeneration and repair (3). Notably, both IGF-1 and FGF-2 not

only regulate muscle growth but also markedly influence bone

metabolism, bone density maintenance and the repair and

regeneration of bone tissue (4).

This inter-system regulatory mechanism highlights the importance of

musculoskeletal crosstalk as a critical area of research (5). Recent developments in intercellular

communication have identified macrophage-derived exosomes as

emerging signaling mediators, gaining increasing attention in the

scientific community (6).

Exosomes are small extracellular vesicles secreted by cells that

carry a range of bioactive molecules, including proteins, RNAs, and

lipids, facilitating intercellular communication and the regulation

of cellular functions and tissue physiology (7).

Macrophages regulate musculoskeletal interactions

through the secretion of exosomes (8). Exosomes derived from M1 and M2

macrophages exhibit distinct effects on musculoskeletal metabolism

(Tables I and II) (9-13). M1 macrophages, which are

pro-inflammatory, release exosomes enriched with pro-inflammatory

cytokines that can stimulate osteoclastic bone resorption,

potentially contributing to osteoporosis and bone damage. By

contrast, M2 macrophages, which possess anti-inflammatory

properties, secrete exosomes containing anti-inflammatory factors

that promote bone formation and repair. Macrophages modulate

muscle-bone signaling through the secretion of specific exosome

subtypes. Exosome-associated factors like IGF-1 and FGF-2 regulate

bone metabolic homeostasis, either promoting or inhibiting bone

remodeling.

The present review aimed to synthesize recent

insights into macrophage-derived exosomes and their role in

regulating musculoskeletal crosstalk, with a focus on their

involvement in IGF-1- and FGF-2-mediated signaling pathways. It

examined how exosomes influence the functions of these key factors

in bone metabolism, elucidated their roles in muscle and bone

homeostasis and suggested future research avenues. Additionally, it

sought to provide a theoretical framework for the development of

therapeutic strategies targeting exosomes, particularly for the

treatment of bone metabolic disorders and musculoskeletal diseases

(14).

Within the musculoskeletal system, muscle-derived

factors such as IGF-1 and FGF-2 are essential in mediating tissue

crosstalk (Table III)

(15-18). These factors coordinate the

development and repair of both bone and muscle by regulating their

bidirectional interactions. IGF-1 is a pivotal growth factor that

promotes muscle cell proliferation and differentiation while also

exerting significant regulatory effects on the skeletal system

(19). Binding to its receptor

activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, fostering muscle growth and

enhancing bone mineralization and density, thereby serving as a

critical link between bone and muscle (20). FGF-2 is a key regulator of

fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived cells, playing an indispensable

role in bone repair and muscle regeneration (21). Upon binding to fibroblast growth

factor receptors (FGFRs), FGF-2 activates downstream pathways,

including MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt, that promote the growth and

differentiation of osteoblasts and myocytes (22). Notably, FGF-2 supports effective

repair of muscle and bone tissues following exercise or trauma.

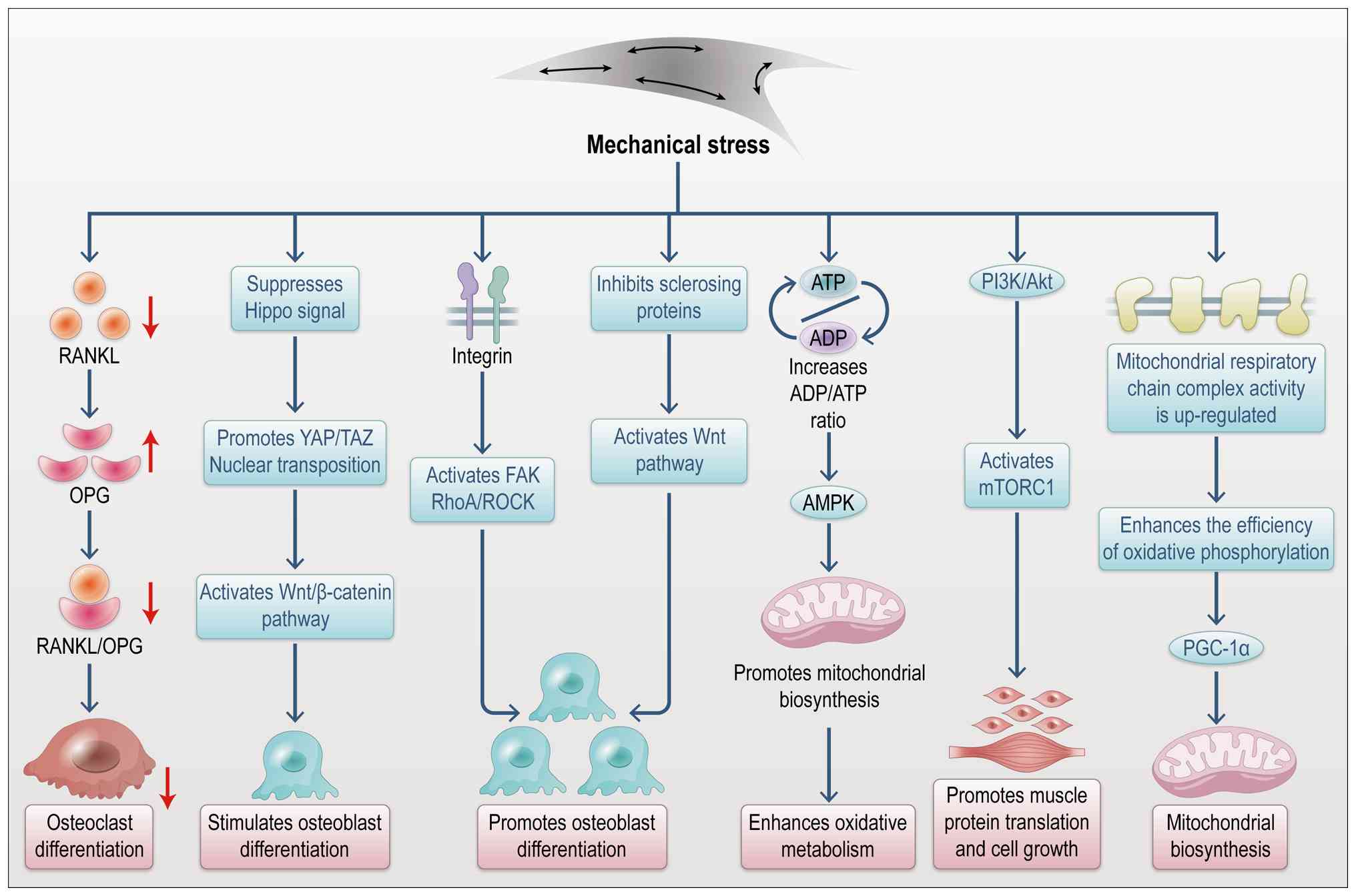

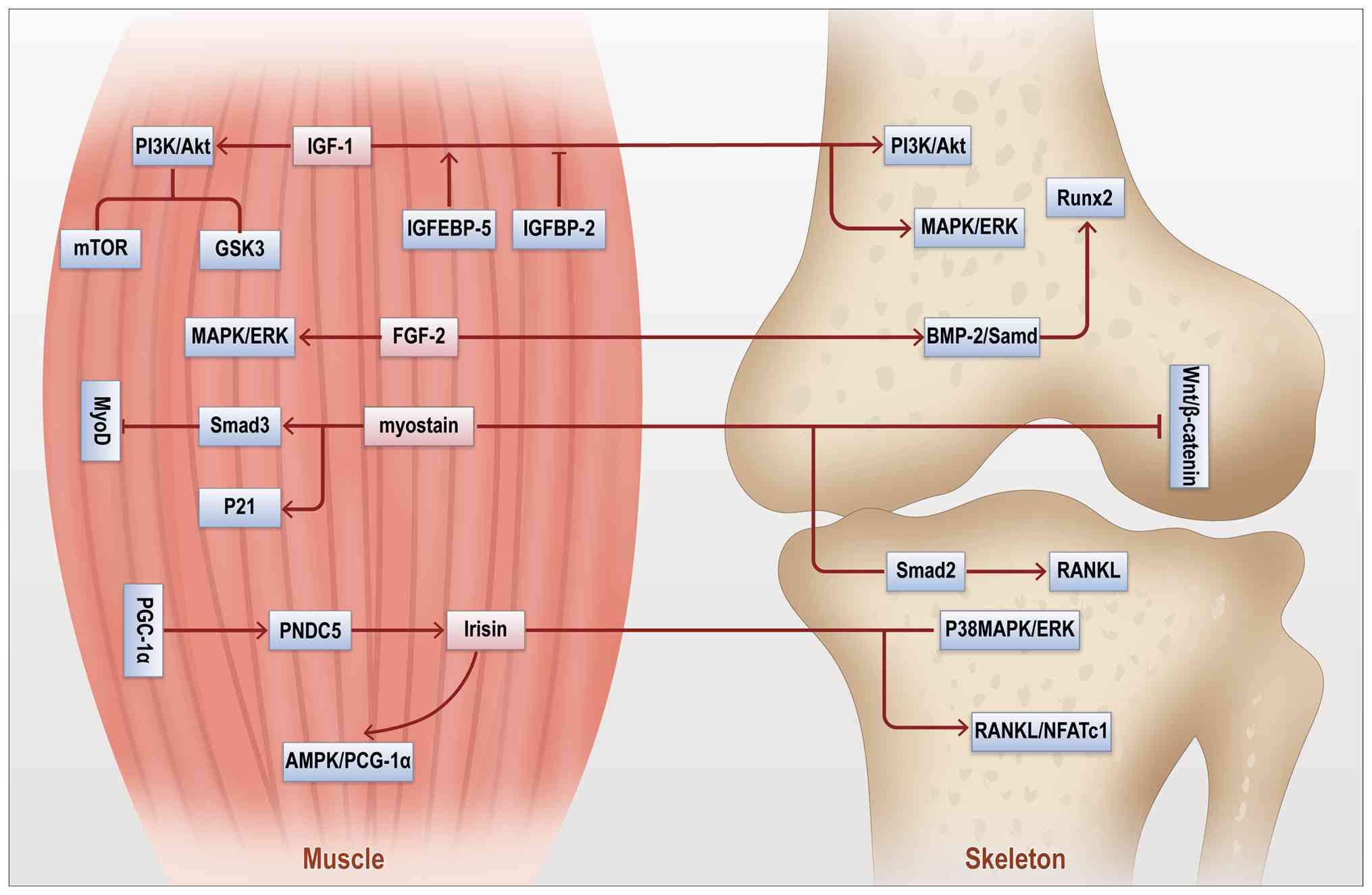

Beyond mechanical signals, endocrine factors also

play a vital role in musculoskeletal crosstalk (31). Muscles and bones mutually

regulate and support each other via various endocrine factors,

including IGF-1, growth hormone, sex hormones and FGF-2 (Fig. 2) (32). During growth, IGF-1 secreted by

muscles promotes muscle development and, via circulation, also

affects the skeletal system, facilitating bone formation (33). Binding to the IGF-1 receptor

(IGF-1R) in bone activates the PI3K-Akt and MAPK pathways,

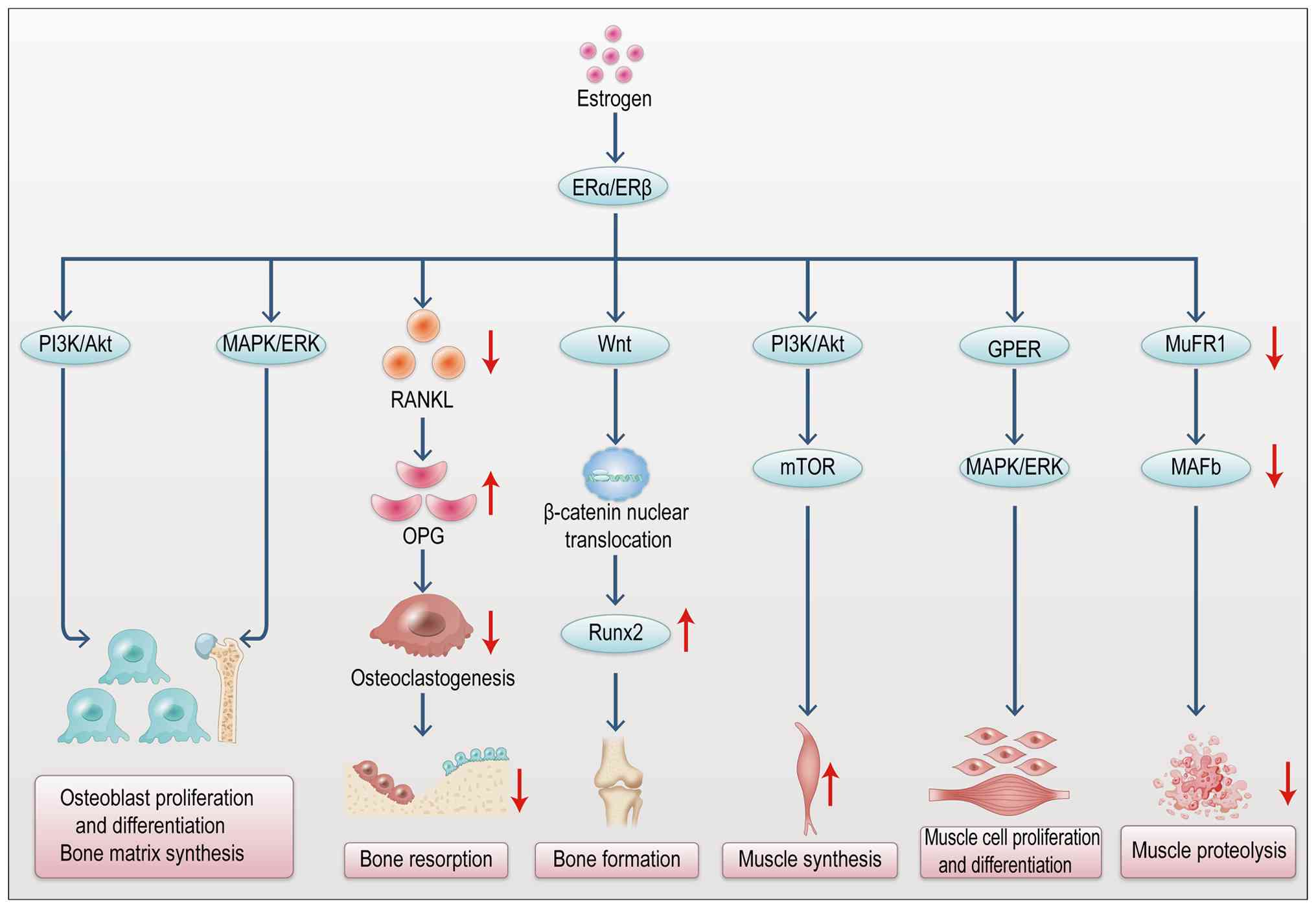

regulating osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (34). Sex hormones, particularly

estrogen, are critical in regulating muscle-bone interactions

(35). Estrogen maintains bone

density and mass by promoting bone formation and inhibiting

resorption, while also enhancing musculoskeletal synergy by

regulating muscle strength and endurance (Fig. 3) (35). FGF-2, as an endocrine factor in

bone, contributes to bone repair and regulates growth and

mineralization by binding to FGFRs (Fig. 2) (36). Particularly during aging or

following fracture, FGF-2 supports bone repair by stimulating

osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (37).

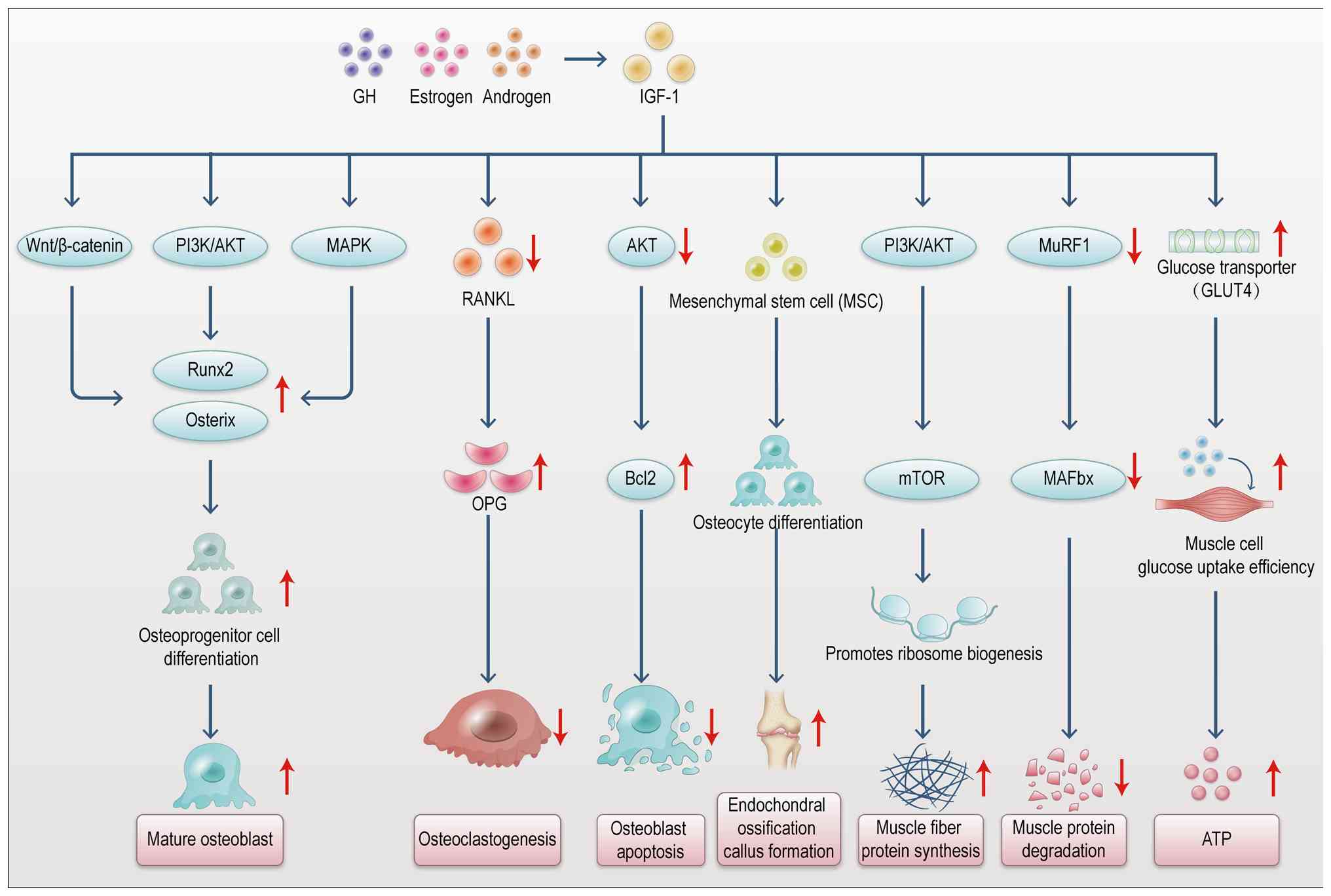

As a pivotal growth factor in muscle-bone

communication, IGF-1 regulates musculoskeletal crosstalk through

multiple signaling pathways (Fig.

4) (38). Upon binding to

its receptor, IGF-1 activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, promoting

muscle fiber proliferation and repair while modulating bone cell

metabolism (39). In the

skeletal system, the PI3K/Akt pathway influences osteoblast and

osteoclast activity via downstream mTOR signaling, thus regulating

bone formation and resorption (40). Activation of PI3K/Akt leads to

Akt kinase phosphorylation, which in turn activates proteins

involved in cell growth and metabolism, promoting proliferation,

survival and differentiation (41). In bone, the PI3K/Akt pathway is

essential for bone formation by stimulating osteoblast

proliferation and differentiation, while enhancing bone matrix

mineralization (42). IGF-1

activation of this pathway improves bone density and accelerates

fracture healing, highlighting its role in bone repair (43).

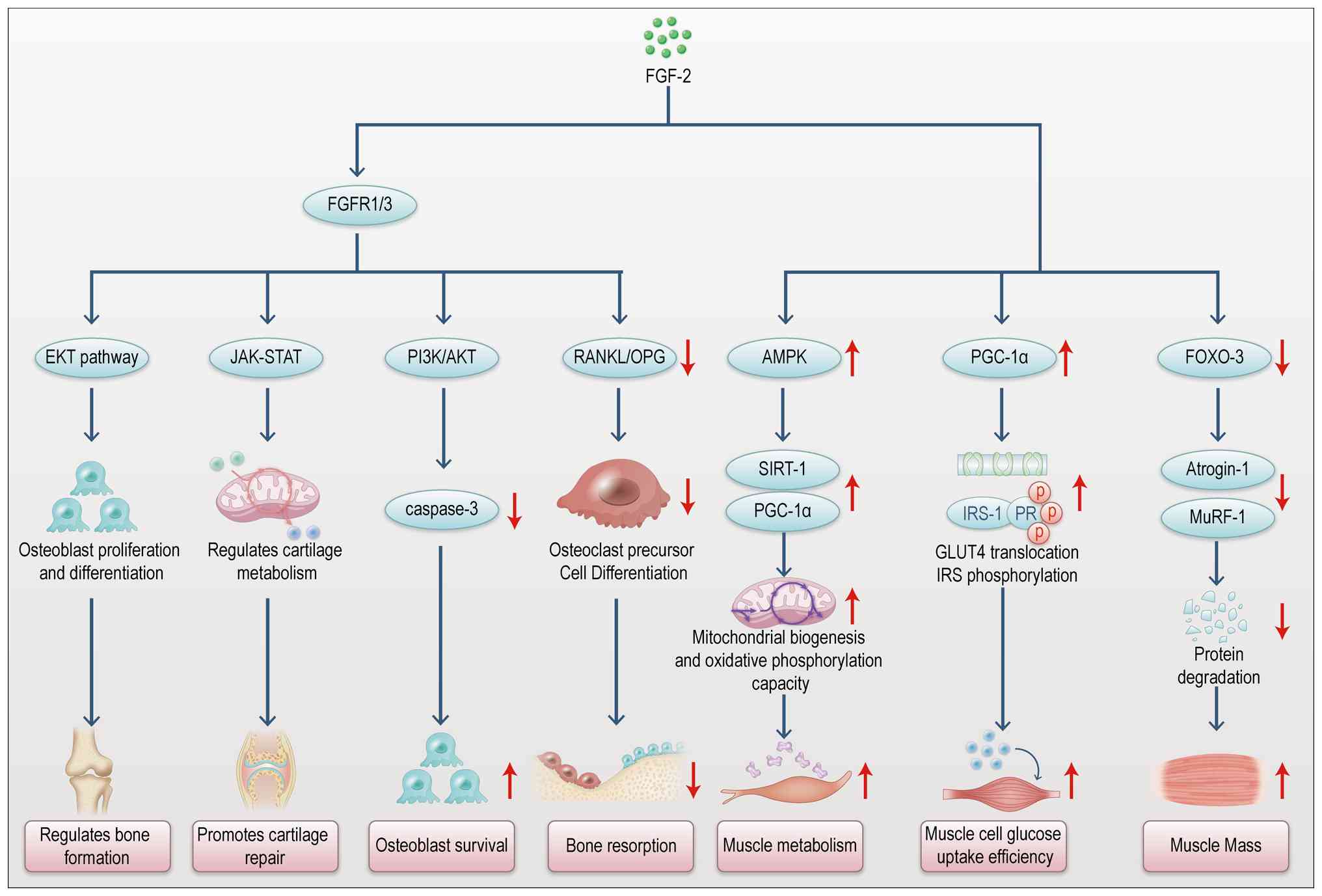

FGF-2 contributes to musculoskeletal crosstalk by

promoting muscle growth and regulating bone formation and repair

through the FGFR (Fig. 5)

(44,45). In bone metabolism, FGF-2

modulates osteoblast and osteoclast functions, influencing bone

formation and resorption via the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway

(46). Research shows that FGF-2

enhances bone repair by stimulating osteoblast proliferation and

migration, accelerating new bone formation during fracture healing

(47). Additionally, FGF-2 helps

maintain bone density by balancing osteoblast and osteoclast

activity, thus reducing bone resorption (48). FGF-2 exerts a bidirectional

regulatory effect in musculoskeletal crosstalk, promoting bone

formation while inhibiting excessive bone resorption. In summary,

both IGF-1 and FGF-2 are crucial in musculoskeletal interactions,

regulating bone and muscle growth and repair through their

respective signaling pathways and coordinating the development and

repair of the musculoskeletal system through their interplay.

Exosomes are small, bilayer lipid-enclosed vesicles

secreted by cells, encompassing exosomes, microvesicles and

apoptotic bodies (7). Among

these, exosomes are the most extensively studied subtype (49). They carry a variety of cargo,

including proteins, metabolites, nucleic acids and lipids, derived

from their parent cells, exerting biological effects similar to

those of the original cells (Table

IV) (50-53). Exosomes can bind to recipient

cells through surface ligands or be internalized via paracrine

signaling and membrane fusion (such as endocytosis) (54), facilitating the transfer of

bioactive molecules and modulating recipient cell functions.

Macrophage-derived exosomes play critical roles in regulating

inflammation and influencing the progression of bone diseases, such

as osteoporosis, fractures and osteoarthritis, markedly affecting

bone metabolism and homeostasis (55-57). Research indicates that both the

composition and quantity of exosomes vary depending on the

macrophage polarization state (58-60). In recent years,

macrophage-derived exosomes have gained growing research interest,

following extensive earlier studies on exosomes from mesenchymal

stem cells (MSCs).

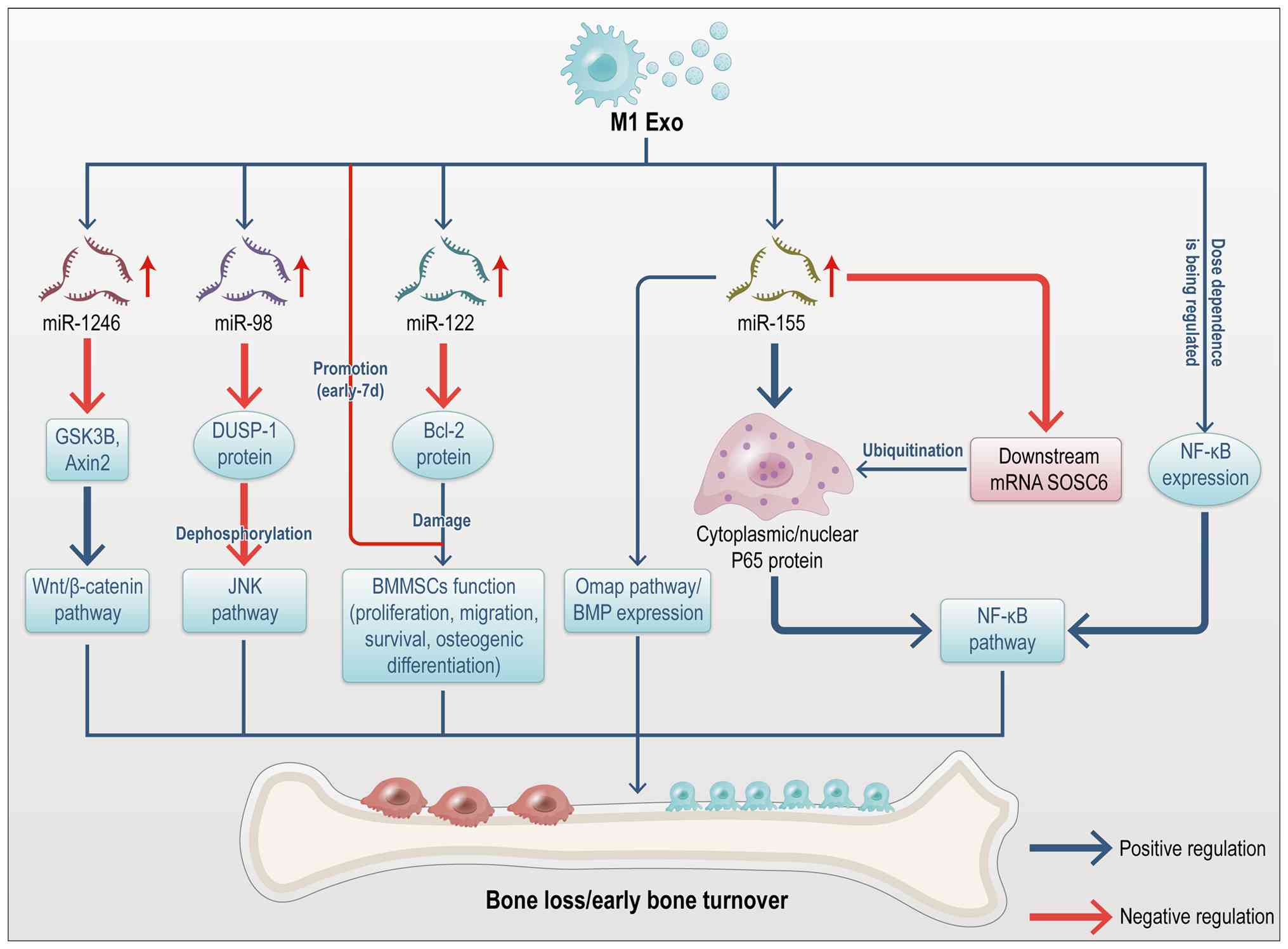

M1-polarized macrophages promote the release of

chemotactic and inflammatory mediators, which facilitate osteoclast

activation and debris clearance at fracture sites (61-63). MicroRNAs (miRNAs), highly

conserved non-coding RNAs, post-transcriptionally regulate gene

expression and play a key role in intercellular communication as

integral components of exosomes (64). The miRNA profiles of M1 and M2

polarized macrophages exhibit significant differences. Kang et

al (59) demonstrated that

M1 exosomes are enriched with miR-155, which inhibits the bone

morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway by downregulating

BMP2, BMP9, and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2). Given

that BMP2 is critical for osteoblast differentiation (65), its downregulation impedes bone

regeneration. Ge et al (60) reported that exosomal miR-155 from

M1 macrophages targets SOCS6, resulting in elevated p65 protein

levels. This activation of the nuclear factor

kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway

exacerbates inflammation. Additionally, miR-222 is highly expressed

in M1 macrophages (66). Studies

have shown that exosomal miR-222 from M1 macrophages induces

apoptosis in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) by

inhibiting Bcl-2 expression (67-69). Yu et al (70) demonstrated that exosomal miR-98

from M1 macrophages targets DUSP1 in MC3T3-E1 cells and a

postmenopausal osteoporosis murine model, inhibiting osteogenic

differentiation. Another study showed that M1 exosomes are enriched

with miR-1246, which activates the Wnt pathway by downregulating

GSK3β and Axin2, thereby promoting cartilage inflammation and

degradation (71). These

findings were primarily validated using bioinformatics analyses,

sequencing and related methodologies. In summary, M1

macrophage-derived exosomes, which are enriched with miRNAs such as

miR-155, miR-222, miR-98 and miR-1246, modulate downstream

signaling pathways to promote inflammation and impair bone repair

both in vitro and in vivo. The specific miRNA cargo

determines the downstream signaling effects by targeting key nodes

within signaling networks. Exosomes serve as specific carriers,

enabling macrophage-derived miRNAs to function as promising

biomarkers for monitoring and regulating bone remodeling. However,

the complete repertoire of miRNAs and other cargo within macrophage

exosomes remains incompletely characterized. Further investigation

is needed to understand how macrophage polarization influences

exosomal miRNA cargo and the precise mechanisms through which these

miRNAs regulate downstream pathways. The effects of macrophage

exosomes on BMMSC differentiation have been extensively studied. He

et al (72) collected

conditioned medium (CM) from M1 macrophages and observed enhanced

BMMSC proliferation, adipogenic differentiation and extracellular

matrix deposition. Upon isolating exosomes from this CM, it was

found that M1 exosomes, but not M2 exosomes, promoted stem cell

proliferation, osteogenesis and adipogenesis. This finding was

corroborated by Xia et al (73). By contrast, Kang et al

(59) reported that co-culture

with M1 macrophages markedly reduced BMP2 and BMP9 expression in

mouse MSCs, suggesting that M1 macrophage-derived exosomes impair

the osteoinductive effects of BMPs and suppress osteogenic gene

expression in MSCs. Through exosomal communication, M1 macrophages

primarily enhance early and mid-stage osteogenesis, exerting

stronger effects on BMMSC proliferation, osteogenesis and

adipogenesis compared with M2 macrophages. These differing effects

on osteogenesis may be attributed to variations in recipient cell

sources. Experimental discrepancies could stem from multiple

factors, including macrophage maturity, co-culture conditions, the

presence of other cytokines in the CM, recipient cell lineage, and

technical differences in exosome isolation from specific

conditioned media (62,73). The balance between osteogenic and

adipogenic differentiation in BMMSCs is essential for maintaining

bone mass. Investigating the mechanisms by which M1

macrophage-derived exosomes regulate this balance in BMMSCs may

offer insights into clinical disease pathogenesis and aid in the

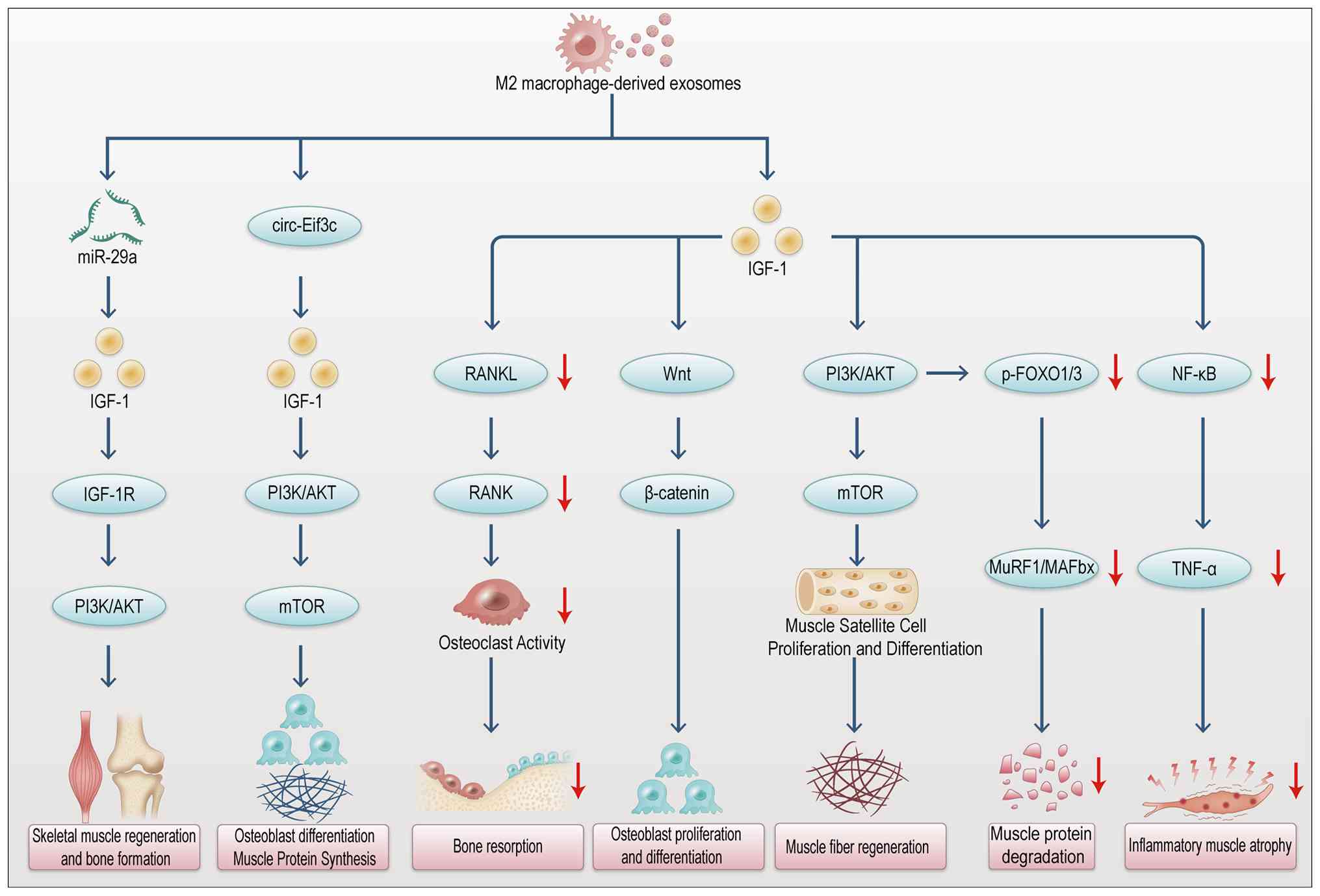

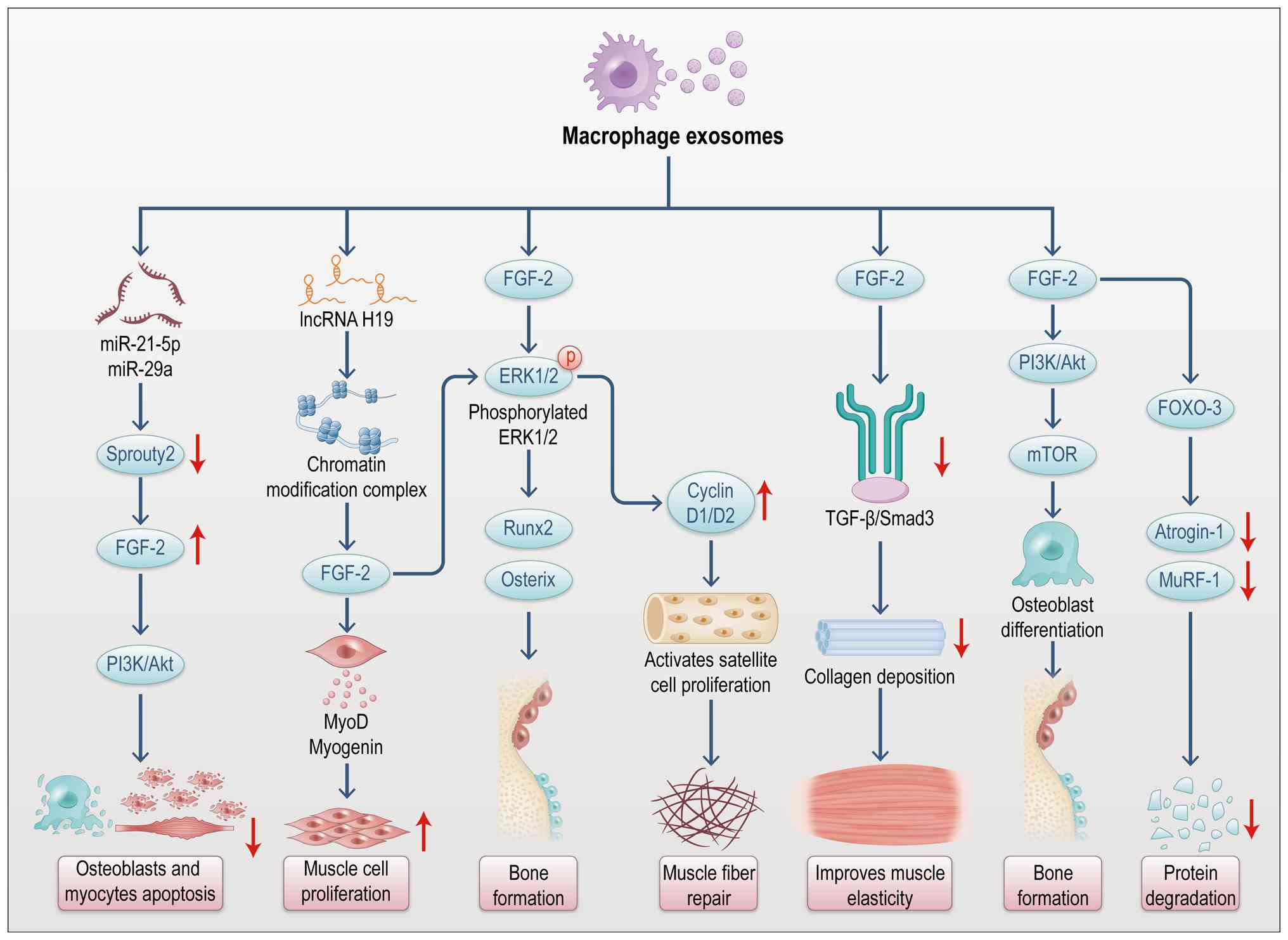

development of targeted therapies. Fig. 6 summarizes the regulation of bone

remodeling signaling pathways by M1 macrophage-derived

exosomes.

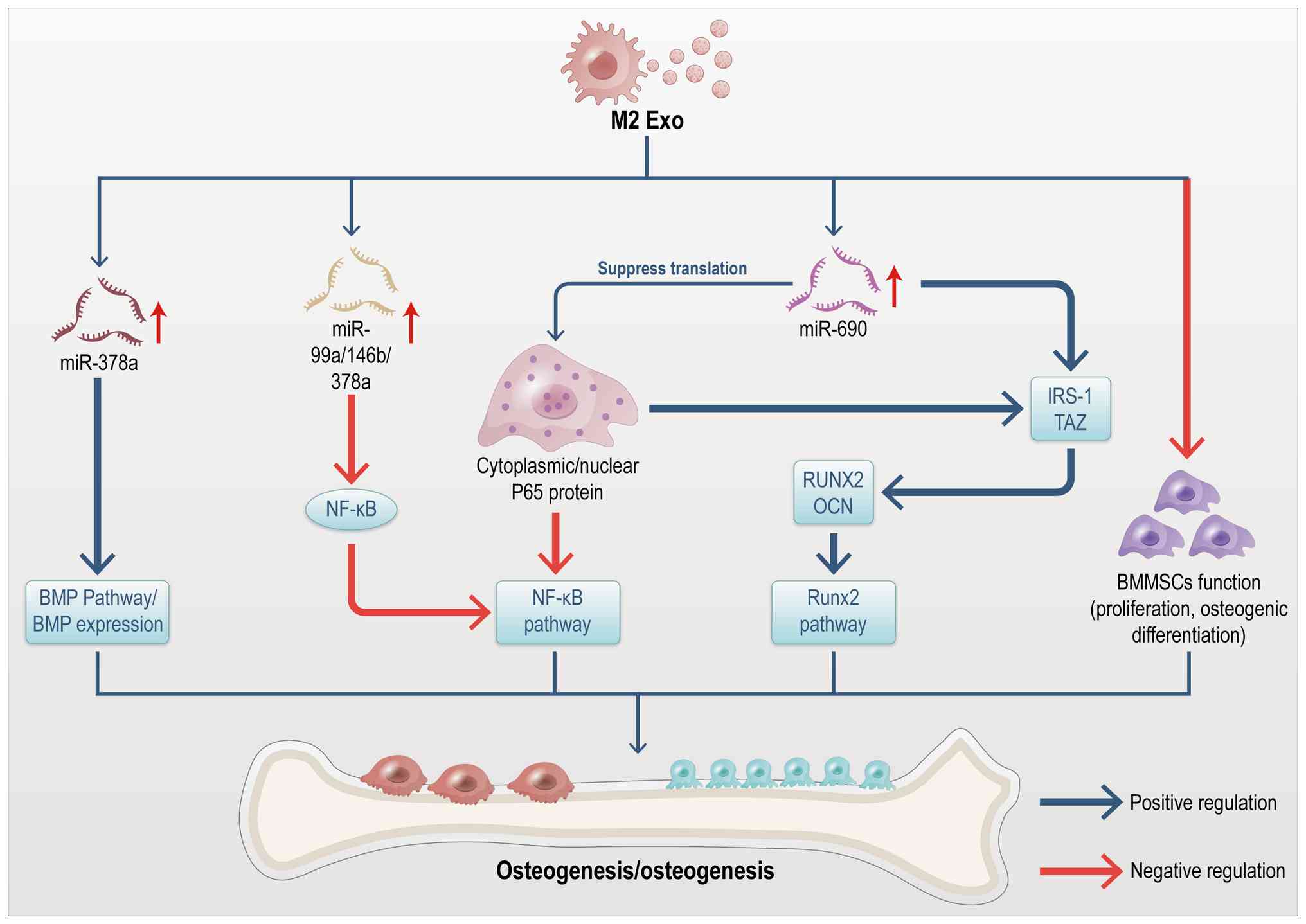

A critical event in bone healing is the transition

from the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage phenotype to the

anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (74). In the later stages of bone

healing, M2 macrophages establish an anti-inflammatory environment

that promotes osteogenesis in BMMSCs. Li et al (56) identified exosomes as key

mediators of the osteogenic process induced by M2 macrophages. BMPs

are key endogenous regulators of osteogenesis, with the loss of

BMP2 or BMP4 function leading to significant impairments in

osteogenesis. BMPs activate Smad proteins and upregulate Runx2

expression, driving MSC differentiation into osteoblasts (75,76). Using an in vivo bone

defect model, Kang et al (59) demonstrated that M2

macrophage-derived exosomes promote bone regeneration. Further

analysis revealed that M2 exosomes are enriched with miR-378a,

which enhances osteoinduction by modulating the BMP signaling

pathway, thus promoting cranial bone regeneration in mice. Studies

also indicate that exosomes from IL-4-stimulated M2 macrophages,

enriched with miRNAs such as miR-99a-5p, miR-146b-5p and

miR-378-3p, suppress inflammation by downregulating the TNF-α and

NF-κB signaling pathways in Apoe−/− mice (77). Moreover, exosomes derived from M2

macrophages promote osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs through

miR-690, IRS-1 and TAZ, while inhibiting adipogenic differentiation

(56). Yu et al (78) reported that miR-690, enriched in

M2 macrophage-derived exosomes, upregulates osteogenic

differentiation in C2C12 myogenic progenitor cells by inhibiting

the translation of the NF-κB p65 protein. M2 macrophage-derived

exosomes are also shown to carry high levels of miR-221-5p, which

promotes tissue repair and regeneration by binding to the 3'

untranslated region (UTR) of E2F2 mRNA and negatively regulating

its expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (79). Collectively, these studies

suggest that M2 macrophage-derived exosomes infiltrate the bone

marrow microenvironment and transfer specific miRNAs (such as

miR-378a, miR-690, miR-99a-5p) to BMMSCs, facilitating osteogenic

differentiation and fracture healing (80,81). These miRNAs likely function as

pro-osteogenic agents by modulating key pathways such as BMP

signaling to enhance osteogenesis. However, the precise roles of M2

exosome-derived miRNAs in bone formation and osteoclastogenesis

remain to be fully elucidated (82). Emerging evidence suggests that

interactions between BMMSCs and extracellular signals from M2

macrophages markedly contribute to bone formation. However, the

exact mechanisms underlying these interactions remain debated,

possibly due to differences in cell sources, co-culture conditions,

and macrophage polarization protocols. Some studies propose that CM

from M0 or M2 macrophages promotes the mineralization of BMMSCs in

the later stages of osteogenesis (83-86). By contrast, other studies report

opposing findings. For instance, Xia et al (73) found that exosomes derived from M2

macrophages inhibit BMMSC proliferation, with no significant effect

on the expression of osteogenic or adipogenic genes in BMMSCs, and

possibly even suppress chondrogenic differentiation. The regulatory

effects of M2 macrophage-derived exosomes on bone remodeling

signaling pathways are summarized in Fig. 7.

Exosomes play a pivotal role in regulating protein

synthesis and muscle regeneration by promoting satellite cell

proliferation and myofiber formation. This regulation occurs

through the delivery of myogenic growth factors such as IGF, FGF-2,

and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (87). Forterre et al (88) employed proteomic analysis to

identify numerous proteins associated with muscle growth and

metabolism in exosomes secreted by skeletal muscle. For example,

exosomes extracted from C2C12-derived myotubes contained key

components, such as integrin subunit β1, CD9, CD81, neural cell

adhesion molecule (NCAM), CD44 and myosin, that are potentially

crucial for myocyte differentiation. Similarly, Mobley et al

(89) demonstrated that exosomes

derived from whey protein enhance muscle protein synthesis in

vitro. Autophagy plays a critical role in maintaining muscle

mass and function; its inhibition exacerbates muscle atrophy

(90). AMPK, a central

intracellular energy sensor, alleviates sarcopenia (SP) symptoms

and mitochondrial dysfunction (91). Chen et al (92) discovered that exosomes from MSCs

ameliorate muscle atrophy by enhancing AMPK/ULK1-mediated

autophagy. Guescini et al (93) observed that exosomal miR-133b and

miR-181a-5p are rapidly released into the bloodstream

post-exercise, promoting muscle regeneration. This mechanism may

partially explain how exercise mitigates SP. Furthermore,

Chaturvedi et al (94)

demonstrated in animal models that exercise-induced exosomes

promote skeletal muscle regeneration through the upregulation of

miR-9b and miR-29.

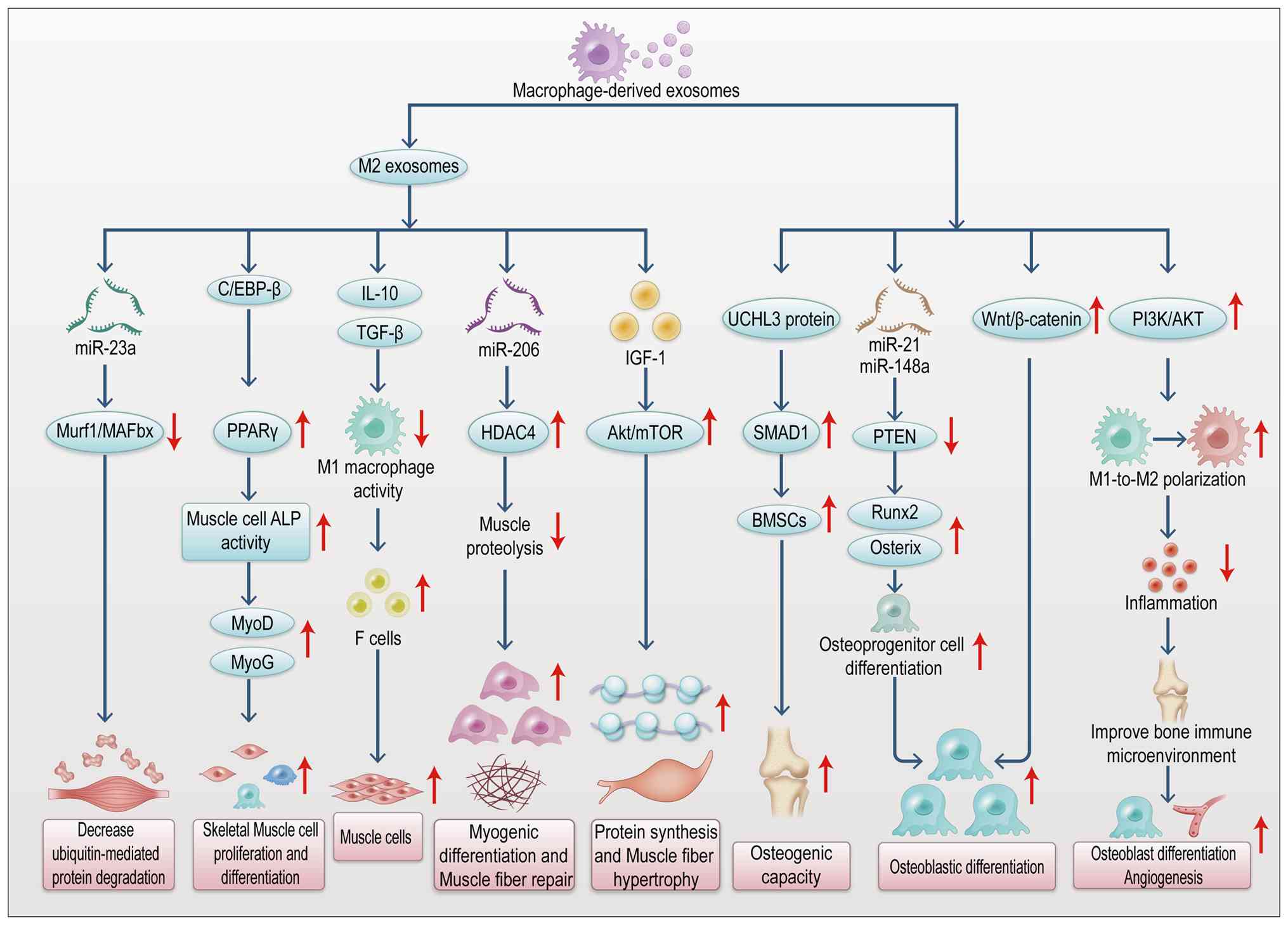

Additionally, extracellular vesicles from M1

macrophages can polarize recipient macrophages toward an M2-like

phenotype, thereby altering skeletal muscle homeostasis under

high-glucose conditions. Collectively, these findings highlight the

roles of both M1- and M2-derived macrophage exosomes in regulating

SP.

Exosomes serve as critical messengers in muscle-bone

crosstalk, enabling skeletal muscles to influence bone activity

through EV-mediated communication. This exosome-mediated

communication between skeletal muscle cells occurs via autocrine,

paracrine, or endocrine pathways (95-98). Exosomes derived from C2C12

myoblasts promote the osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1

preosteoblasts, likely mediated by the upregulation of miR-27a-3p

in recipient cells. This miRNA suppresses specific target genes and

activates β-catenin signaling, thereby enhancing osteogenesis

(99). Additionally, exosomes

from C2C12 myoblasts enhance Wnt/β-catenin signaling in

TOPflash-MLOY4 osteocyte-like cells, promoting cell survival and

providing protection against apoptosis and oxidative stress. This

protective effect is likely due to exosomes-mediated inactivation

of Wnt inhibitors, such as SOST, DKK2, and SFRP2 (100). Li et al (101) showed that myoblast-derived

exosomes carry Prrx2, which activates miR22HG transcription,

promoting osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs via the YAP pathway

and miR-128. Furthermore, CXCR4, present on exosomes produced by

mouse fibroblasts, targets these vesicles to the bone marrow, where

miR-188-containing exosomes fuse with lipids to form hybrid

nanoparticles. These nanoparticles then release miR-188 in a

targeted manner, inhibiting adipogenesis and promoting BMMSC

differentiation into osteoblasts (102). Regarding the influence of bone

cell-derived exosomes on skeletal muscle, long non-coding RNAs

(lncRNAs) are critical. For example, Zheng et al (103) found that osteoblasts induce

myogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts via exosomal lncRNAs,

specifically TUG1 and DANCR. Toita et al (104) demonstrated that collagen

patches releasing phosphatidylserine-containing liposomes promote

M1-to-M2 macrophage polarization, facilitating concurrent bone and

muscle tissue healing. Transcriptome analysis via next-generation

sequencing revealed that M1 macrophage secretory products inhibit

the differentiation of preosteoblasts and myoblasts, while M2

macrophage secretory products promote it. This highlights the

importance of timely M1-to-M2 polarization for effective tissue

regeneration. As shown in Fig.

8, macrophages, particularly the M2 phenotype, release exosomes

carrying the transcription factor C/EBPβ. This factor promotes

skeletal muscle cell proliferation and differentiation via the

PPARγ signaling pathway (105).

Depletion of macrophage exosomes containing C/EBPβ markedly

inhibits ALP activity in muscle cells and reduces the expression of

myogenic markers (such as MyoD and MyoG), delaying muscle injury

repair (105). M2

macrophage-derived exosomes suppress M1 macrophage activity by

delivering anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-10 and TGF-β,

while mitigating the damaging effects of pro-inflammatory factors

like TNF-α and IL-6 on muscle fibers. They also promote the

directed differentiation of stem cells into myocytes (106). Additionally, M2 macrophage

exosomes activate the PI3K/AKT pathway, facilitating the shift from

M1 to M2 polarization. This process leads to reduced inflammatory

cytokine levels, improved bone immune microenvironment and enhanced

osteoblast differentiation and angiogenesis (107). Under mechanical stimulation,

macrophages increase exosome secretion. These exosomes carry the

UCHL3 protein, which enhances the osteogenic potential of BMMSCs

and drives callus formation through the SMAD1 signaling pathway

(108). Exosome-encapsulated

miRNAs, including miR-21 and miR-148a, inhibit osteogenic

inhibitors like PTEN and upregulate RUNX2 and osterix (106). In osteosarcoma models, exosomes

coordinate osteoclast and osteoblast activity by transmitting

Wnt/β-catenin signals, contributing to the maintenance of bone

homeostasis (106). These

findings highlight the critical role of macrophage-derived exosomes

in regulating the proliferation and repair of both bone and muscle

tissues, modulating muscle-bone crosstalk and enhancing tissue

regeneration.

Exosomes function as essential intercellular

signaling vehicles, transporting a variety of biologically active

molecules, including miRNAs, mRNAs, proteins and lipids (109). These components regulate bone

metabolism by modulating signaling pathways in target cells

(110). Notably, miRNAs within

macrophage-derived exosomes are recognized as key regulatory

factors (111). Research

indicates that macrophage-derived exosomal miRNAs influence bone

metabolism indirectly by regulating key signaling molecules such as

IGF-1 and FGF-2 (Figs. 9 and

10) (112). miRNAs modulate gene expression

by binding to target mRNAs, resulting in translational repression

or mRNA degradation (113). In

musculoskeletal crosstalk, exosomal miRNAs from macrophages play

pivotal roles in the regulation of IGF-1, FGF-2 and other signaling

pathways (Figs. 9 and 10) (114). For instance, macrophage-derived

exosomal miR-21 promotes IGF-1 signaling by targeting inhibitory

molecules within the PI3K-Akt pathway, thereby enhancing bone

formation (115). Similarly,

macrophage-derived exosomal miR-29 boosts osteoblast function,

promoting bone matrix synthesis and mineralization through the

regulation of FGF-2 expression (116). By contrast, M1 exosomal miR-155

directly inhibits IGF-1R and downstream PI3K/Akt signaling,

diminishing osteoblast differentiation (117). Additionally, M1 exosomal

miR-143 exacerbates insulin-resistant muscle atrophy by inhibiting

IRS-1 and obstructing the pro-muscle protein synthesis effect of

IGF-1 (118). Thus,

macrophage-derived exosomes regulate musculoskeletal crosstalk via

exosomal miRNAs during IGF-1 and FGF-2 signaling, revealing a novel

molecular mechanism (Figs. 9 and

10).

Exosomes carry a diverse array of cargo molecules

that regulate bone and muscle metabolism through interactions with

receptors on the surface of musculoskeletal cells (119). Signal transduction by IGF-1 and

FGF-2 in bone metabolism is initiated when these factors bind to

their specific cell surface receptors (120). Macrophage-derived exosomes can

modulate bone metabolism by transporting receptors or receptor

ligands that facilitate the binding of signaling factors to their

target cells (121). Exosomal

ligands for IGF-1R and FGFR directly bind to their corresponding

receptors on bone or muscle cells, triggering signal transduction

(122). Upon IGF-1 binding,

IGF-1R activates intracellular signaling cascades, primarily via

the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, to regulate bone and muscle growth

and repair (123,124). Macrophage-derived exosomes can

deliver IGF-1R or its ligands, thereby enhancing IGF-1 signaling to

promote bone formation and muscle repair (Fig. 9) (125). Similarly, FGF-2 binding to FGFR

initiates signaling cascades that regulate the proliferation and

differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells and osteoblasts

(126). FGF-2 targets

sclerostin in bone and myostatin in skeletal muscle to counteract

the harmful effects of glucocorticoids on musculoskeletal

degradation (127). The

exosome-mediated interaction between FGF-2 and FGFR enhances bone

repair and plays a pivotal role in musculoskeletal crosstalk

(Fig. 10) (128). In summary, macrophage-derived

exosomes facilitate signal transduction and regulate bone

metabolism by transporting receptors (such as IGF-1R, FGFR) and

their ligands, strengthening bone formation and repair, and

promoting musculoskeletal crosstalk.

Osteoblast proliferation, differentiation and

mineralization are essential processes in bone metabolism,

regulated by macrophage-derived exosomes through various mechanisms

(129). During osteogenesis,

active molecules such as miRNAs and proteins facilitate osteoblast

proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization (130). Exosomal miRNAs secreted by

macrophages, including miR-21 and miR-29, can activate the PI3K/Akt

and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in osteoblasts, promoting

their proliferation and differentiation (131); M1 macrophage-derived exosomes

aggravate bone loss in postmenopausal osteoporosis via a

miR-98/dual specificity phosphatase 1 (Dusp1)/c-Jun N-terminal

kinase (JNK) axis (132); M2

macrophagy-derived exosomal miRNA-26a-5p induces osteogenic

differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells (133); Exosomal miR-486-5p secreted by

M2 macrophage influences the differentiation potential of bone

marrow mesenchymal stem cells and osteoporosis (134). These miRNAs enhance osteoblast

differentiation and bone matrix deposition by inhibiting negative

regulatory factors and activating key transcription factors, such

as Runx2 and Osterix (135,136). Additionally, exosomal proteins

such as TGF-β and BMPs support mineralization by regulating

osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (137). TGF-β activates the Smad

signaling pathway through receptor binding, enhancing osteoblast

mineralization (138). BMPs, on

the other hand, activate the Smad1/5/8 pathway, which promotes

osteoblast differentiation and stimulates bone matrix synthesis and

mineralization (139), as

summarized in Table V (140-143).

The function of osteoblasts is further regulated by

a series of transcription factors, with Runx2 and Osterix being two

critical regulators of osteogenic differentiation (144). Macrophage-derived exosomes

influence osteoblast function by modulating the expression of these

transcription factors (145,146). Exosomes secreted by macrophages

carry specific miRNAs, such as miR-124-3p and miR-146a, which

regulate Runx2 and Osterix expression (147,148). For example, miR-224-5p targets

the 3' UTR of Runx2, preventing its degradation and thereby

promoting osteoblast differentiation (149); miR-6879-5p carried by M2

macrophage-derived exosomes increases Runx2 expression and promotes

osteogenic differentiation and aerobic glycolysis in human

periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) via modulating

TRIM26-mediated ubiquitination of pyruvate kinase M (PKM) (150); M2 macrophage exosomes carrying

miRNA-26a-5p can induce osteogenic differentiation of bone

marrow-derived stem cells to inhibit lipogenic differentiation by

promoting the expression of RUNX-2 (151). Additionally, miR-664-3p

promotes osteoblast differentiation and mineralization by

regulating Osterix expression (152). As a key transcription factor

downstream of Runx2, Osterix drives bone matrix formation and

mineralization (147). As well

as miRNAs, proteins such as TGF-β and BMP in macrophage-derived

exosomes also promote osteoblast differentiation by modulating

Runx2 and Osterix expression (153,154). TGF-β enhances Runx2 expression

through the activation of the Smad2/3 signaling pathway, promoting

osteoblast differentiation (136). BMPs stimulate Osterix

expression and enhance bone matrix deposition and mineralization

via the Smad1/5/8 signaling pathway (155).

The formation and activation of osteoclasts, the

primary cells responsible for bone resorption, are essential

processes in bone metabolism (156). Macrophage-derived exosomes

contribute to bone resorption and regulate bone metabolism by

modulating osteoclast formation and activation (157). Osteoclast formation is governed

by various factors, including Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor

κ-B Ligand (RANKL) and Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF)

(158,159). Macrophage-derived exosomes

promote osteoclast formation by carrying RANKL and M-CSF (160,161). Specifically, exosomal RANKL

binds to the RANK receptor on osteoclasts, activating the NF-κB and

MAPK signaling pathways to drive osteoclast formation and

activation (162,163). By binding to its receptor

c-Fms, M-CSF activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, accelerating

osteoclast differentiation (164). Additionally, macrophage-derived

exosomes can further promote osteoclast formation by modulating

other cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF-α, which enhance RANKL

expression through the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway,

thereby promoting osteoclast activation (57). Consequently, macrophage-derived

exosomes facilitate bone resorption by carrying RANKL, M-CSF, and

other factors that regulate osteoclast formation and

activation.

IGF-1 and FGF-2 play pivotal roles in both bone and

muscle metabolism. Osteoporosis, often accompanied by SP, is a

condition that involves diminished bone density and function,

alongside muscle degradation. Macrophage-derived extracellular

vesicles have been shown to improve both osteoporosis and SP by

regulating IGF-1 and FGF-2 signaling.

Osteoporosis is characterized by reduced bone

density, deterioration of bone microarchitecture and increased

fracture risk, primarily affecting older adults (172). Recent studies suggest that

osteoporosis is not only associated with abnormal bone metabolism

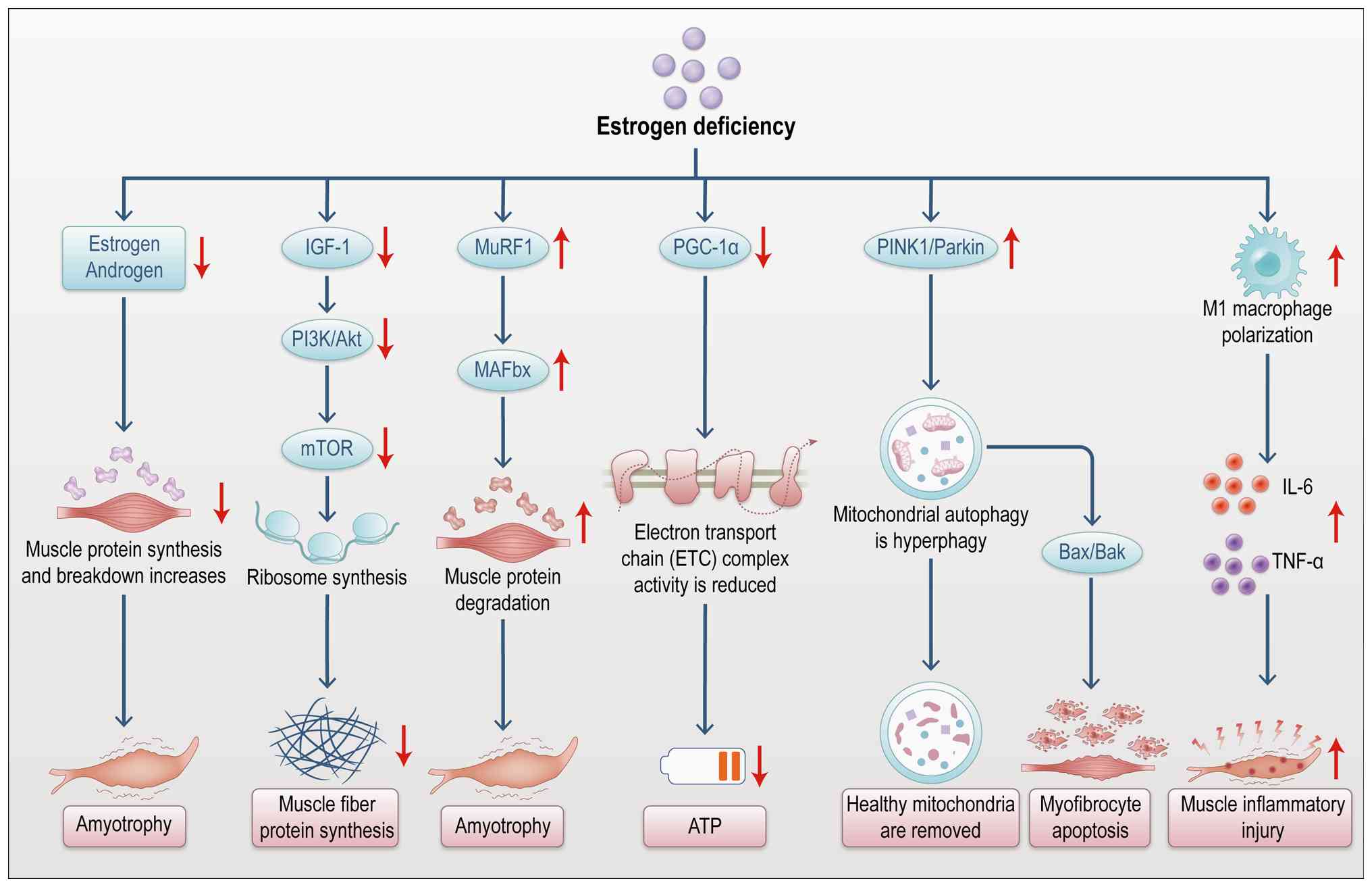

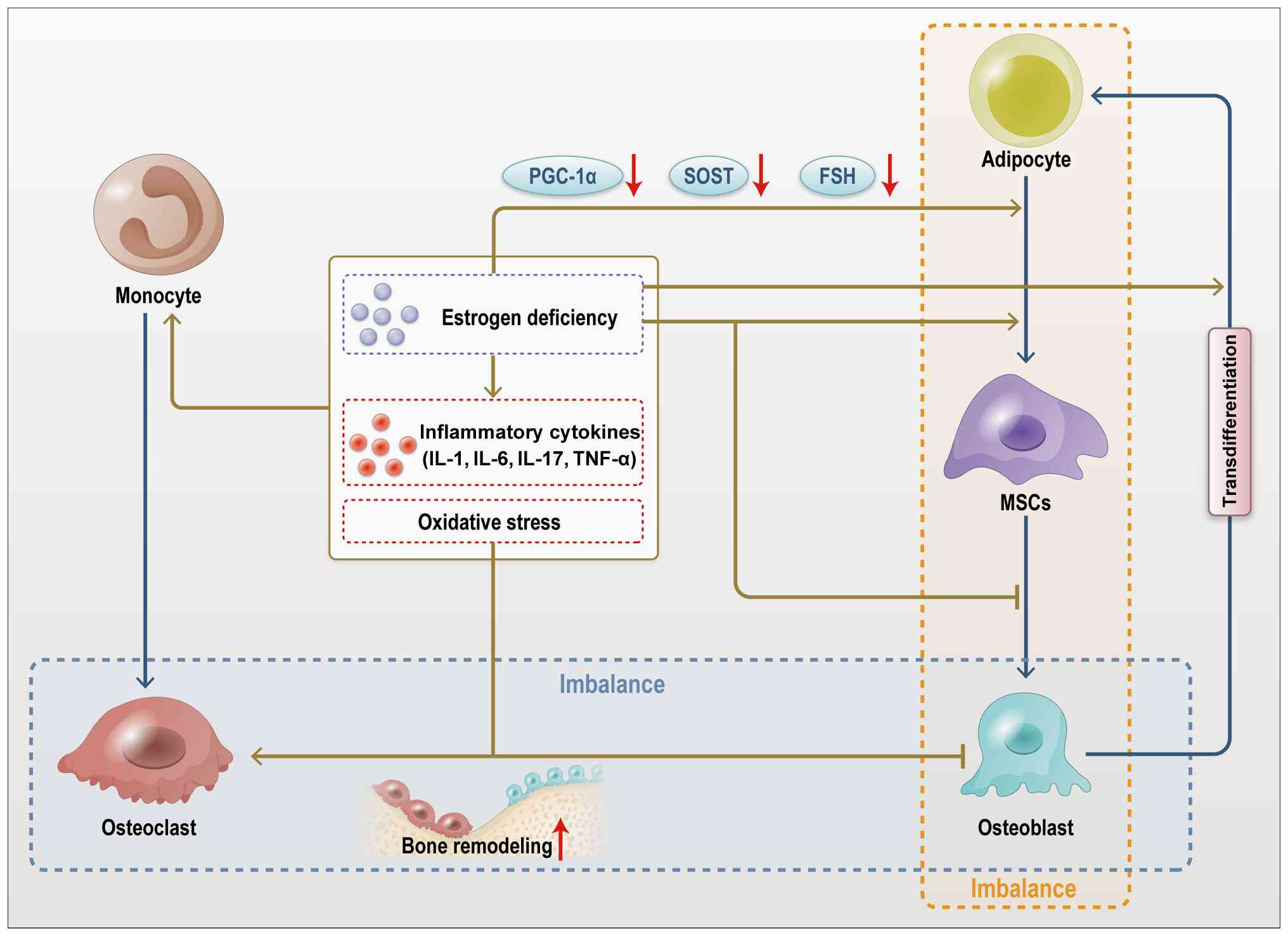

but also with impaired muscle function (Figs. 11 and 12), highlighting the significance of

musculoskeletal crosstalk in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis

(Figs. 11 and 12) (172,173). In osteoporosis, the functions

of macrophage-derived exosomes, IGF-1, and FGF-2 are markedly

altered. Macrophages, as key immune cells (174,175), contribute to bone metabolism

through exosomes that transport a variety of signaling molecules,

including cytokines, miRNAs, and proteins (176). Impaired macrophage function in

patients with osteoporosis alters the signaling molecule profile

within exosomes (177). These

changes may accelerate bone loss by disrupting the balance between

bone resorption and formation through various signaling pathways.

IGF-1 plays a central role in bone metabolism by regulating bone

formation, primarily through the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling

pathways (178,179).

The primary manifestations of osteoporosis, bone

loss and reduced bone strength, are influenced by the interaction

of macrophage-derived exosomes, IGF-1 and FGF-2 (180). These components synergistically

regulate bone formation and resorption, thereby affecting bone mass

(181). Exosomal miRNAs, such

as miR-21 and miR-146a, derived from macrophages, can promote

osteoclast differentiation and activity by modulating the

RANKL/RANK pathway, leading to excessive bone resorption (182). Additionally, exosomal protein

factors such as TGF-β and BMP further inhibit bone formation by

regulating osteoblast function (183). In osteoporosis, IGF-1, a key

osteogenic factor, is often underexpressed, impairing osteogenesis

and leading to reduced bone formation (184). Similarly, FGF-2 signaling is

suppressed in osteoporosis, contributing to further bone density

loss (185). This disruption in

signaling between IGF-1 and FGF-2 exacerbates bone loss. Exosomes

carrying RANKL and TGF-β promote osteoclastogenesis and bone

resorption (186), while the

deficiency of IGF-1 and FGF-2 signaling further impairs bone

formation. Disruption of this delicate musculoskeletal crosstalk

and the associated molecular pathways plays a pivotal role in the

pathogenesis of osteoporosis (187).

SP refers to the age-related progressive loss of

skeletal muscle mass and function (188). It is not only a natural part of

aging but is also closely linked to various diseases and

pathological conditions. The relationship between SP and abnormal

bone metabolism has gained considerable attention in recent years.

Muscle atrophy and bone metabolism interact bidirectionally,

forming a critical regulatory mechanism for maintaining bone health

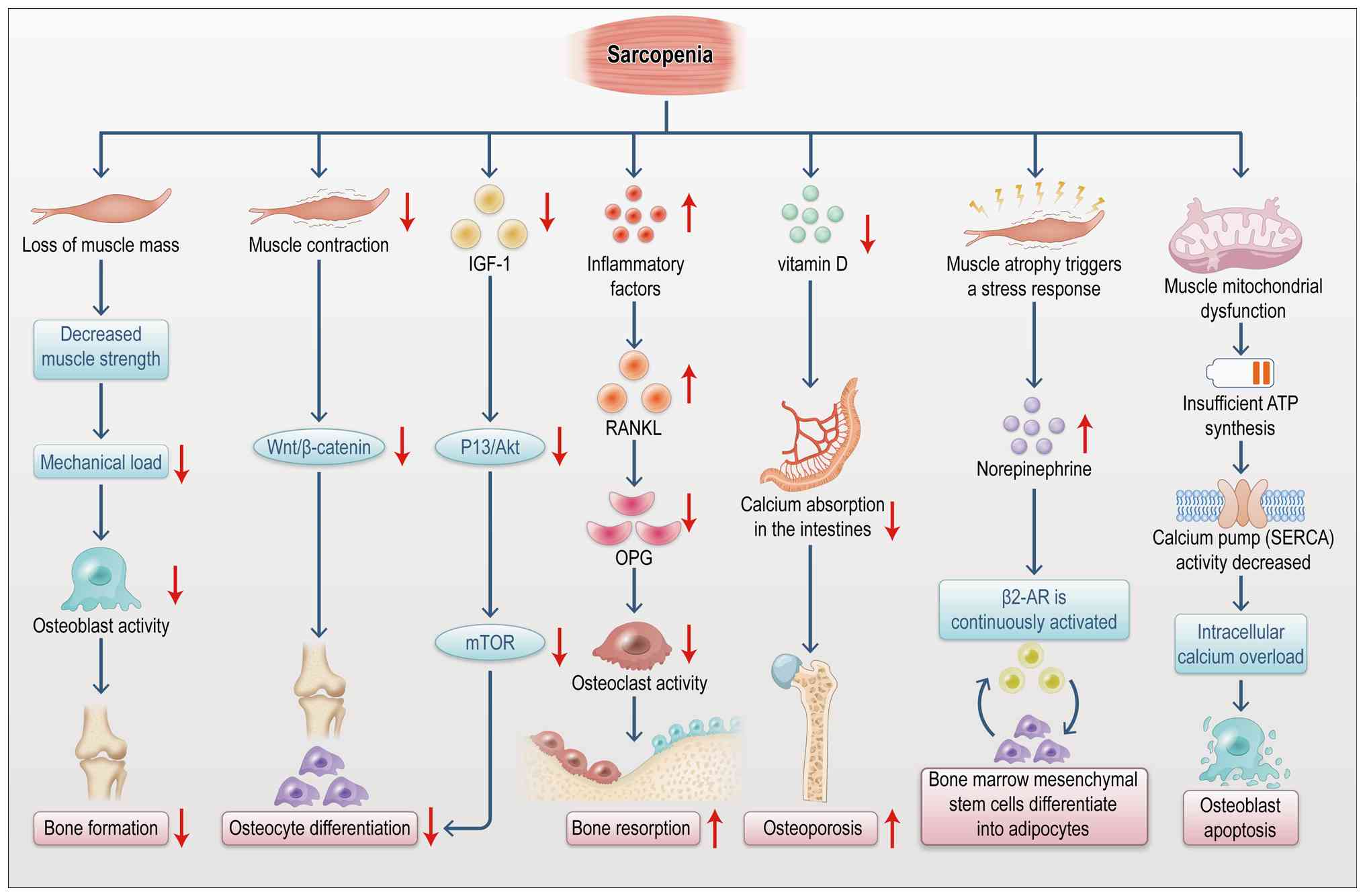

(189). As depicted in Fig. 13, the onset of SP is often

accompanied by decreased bone density and altered bone metabolism.

Muscle atrophy influences bone metabolism through multiple

mechanisms (190). It reduces

muscle strength and load-bearing capacity, thereby diminishing

mechanical stress on bones. This reduction in mechanical

stimulation leads to increased bone resorption and decreased bone

formation (190). Additionally,

SP affects bone metabolism through the secretion of inflammatory

factors, such as IL-6 and TNF-α (191). These inflammatory mediators

activate osteoclast signaling pathways, enhancing bone resorption

and consequently reducing bone density (192). Moreover, endocrine dysfunction

linked to SP plays a significant role in abnormal bone metabolism.

Muscle atrophy leads to reduced secretion of myokines, such as

IGF-1 and FGF-2, impairing bone formation.

Macrophage-derived exosomes, along with IGF-1 and

FGF-2, play pivotal roles in the bone metabolism abnormalities

associated with SP (193,194). Macrophages, as key immune

cells, secrete exosomes carrying a range of cytokines and miRNAs

that are essential for musculoskeletal crosstalk (195). The miRNAs, cytokines and growth

factors transported by macrophage exosomes affect all aspects of

bone metabolism (196). For

example, macrophage-derived exosomes promote osteoclast formation

and activity by delivering miRNAs (such as miR-146a and miR-21),

thus enhancing bone resorption (197). These exosomal miRNAs can

activate specific signaling pathways by binding to receptors on

bone cells, influencing the pathogenesis of conditions such as

osteoporosis and bone loss (197). Moreover, the roles of IGF-1 and

FGF-2 in SP are particularly important (198). IGF-1 is well-established as

essential for muscle tissue, promoting not only muscle growth and

repair but also bone matrix formation by enhancing osteoblast

function (199). However,

circulating IGF-1 levels are often reduced in patients with SP,

contributing to bone metabolism disorders. Similarly, FGF-2 is

another key osteogenic factor involved in SP.

Exosome isolation from macrophages typically

involves techniques such as ultracentrifugation, size exclusion

chromatography, immunoaffinity capture, and kit-based methods.

Identification techniques include transmission electron microscopy

(TEM), nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), western blotting (WB)

and nanoflow cytometry. Each method offers distinct advantages and

limitations. In muscle and bone metabolism experiments, in

vitro methods include osteoblast differentiation assays,

osteoclast inhibition tests, muscle cell differentiation

experiments, and muscle metabolism studies. In vivo

approaches include osteoporosis models, fracture healing models,

and SP models.

Exosomes are nanoscale extracellular vesicles

(30-150 nm in diameter) secreted by cells and are widely

distributed in various body fluids (200). The isolation and purification

of exosomes from macrophages is a critical step in studying

musculoskeletal crosstalk and its impact on bone metabolism

(201). Conventional methods

for exosome isolation primarily include ultracentrifugation and

commercial kit-based approaches (201). Ultracentrifugation is regarded

as the gold-standard technique for exosome separation, relying on

density-based differentiation to isolate exosomes from other

cellular components (202).

This process involves removing cellular debris through low-speed

centrifugation, followed by high-speed ultracentrifugation to

pellet exosomes (202).

Although this method is widely adopted, straightforward and

cost-effective, it is time-consuming and requires significant

technical expertise (202).

Despite these limitations, ultracentrifugation remains the most

commonly used method due to its high yield and efficiency in

exosome collection (203). By

contrast, commercial kit-based methods use reagents for exosome

separation, often employing immunomagnetic beads or affinity

capture technologies (204).

These kits are convenient, easy to use, and improve exosome purity

markedly (204). However, they

tend to be expensive and may exhibit lower extraction efficiency,

especially in samples with high levels of contaminating cellular

material (204). A comparative

summary of these techniques is provided in Tables VI and VII (205-216).

Investigating the impact of macrophage-derived

exosomes, IGF-1, and FGF-2 on musculoskeletal crosstalk requires

the establishment of a co-culture system that incorporates both

muscle cells and osteocytes. Commonly used bone cell models include

the MC3T3-E1 murine pre-osteoblastic cell line and the RAW264.7

murine monocytic cell line (222). These cell lines exhibit high

proliferative and differentiation capacities, making them ideal for

in vitro investigations (222). For muscle cell models, the

C2C12 mouse myoblast cell line and the L6 rat skeletal muscle cell

line are frequently used (223). The C2C12 cell line, in

particular, differentiates into myotubes under appropriate

conditions and is widely employed in muscle biology research

(224). This co-culture model

simulates the in vivo physiological environment and serves

as a robust platform for studying muscle-bone interactions.

Co-culture systems are typically established using either Transwell

inserts or direct contact methods. In the Transwell system, a

porous membrane (typically 0.4 μm) separates the cell types,

enabling paracrine signaling via soluble factors while preventing

direct cell-cell contact (225). This setup allows for precise

control over the transfer of soluble factors between cell

compartments (225). However,

direct contact co-culture more accurately replicates the physical

interactions and signaling processes, including mechanical

stimulation, between muscle and bone cells (226).

Experimental designs investigating the interactions

between macrophage-derived exosomes, IGF-1, and FGF-2 typically

involve four key components: Exosome isolation and processing, gene

interference, protein expression analysis and functional assays. A

critical step in this experimental design is the processing of

exosomes, typically secreted by macrophage cell lines such as

RAW264.7. Exosomes from M1 macrophages are enriched with

pro-inflammatory factors, while exosomes derived from M2

macrophages carry anti-inflammatory and tissue-repair factors

(227). In experiments,

exosomes isolated from macrophage cell lines (such as RAW264.7) are

introduced into muscle and bone cell co-culture systems to assess

their effects on cellular proliferation, differentiation, and

mineralization (228). To

determine the specific influence of IGF-1 and FGF-2, their

functions can be inhibited using specific antagonists or gene

interference techniques, such as siRNA, to confirm their roles in

mediating musculoskeletal crosstalk. Additionally, techniques such

as WB and qPCR can be employed to analyze how M1 and M2 exosomes

regulate IGF-1 and FGF-2 expression, as well as the activity of

their downstream signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt and MAPK

(229). Functional assays, such

as osteogenic evaluation via Alizarin Red staining and osteoclastic

activity assessment using TRAP staining, can be used to verify the

effects of exosomes on bone cell function (230). Collectively, this experimental

approach provides a framework for elucidating the complex

interactions and regulatory mechanisms involving M1- and

M2-macrophage-derived exosomes, IGF-1, and FGF-2 in bone

metabolism.

In animal studies, various intervention strategies

are employed to investigate the effects of macrophage-derived

exosomes (from M1 or M2 phenotypes), IGF-1, FGF-2 and related

factors on bone metabolism. These agents, such as M1- or M2-derived

exosomes, IGF-1 and FGF-2, are typically administered through local

injection or systemic intravenous delivery. Researchers establish

multiple experimental groups, including those treated with

M1-derived exosomes, M2-derived exosomes, IGF-1, FGF-2, and vehicle

controls, to enable direct comparison of the specific effects of

each intervention on bone metabolism. Standard detection endpoints

include bone densitometry such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry,

histological analysis of bone tissue (such as hematoxylin and eosin

[H&E] staining, Alizarin Red staining) and serum biomarkers of

bone metabolism (such as osteocalcin, C-terminal telopeptide of

type I collagen, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase) (246). These parameters offer a

comprehensive evaluation of bone metabolism, allowing for an

in-depth assessment of the effects mediated by M1 and M2

macrophage-derived exosomes. Collectively, these animal experiments

shed light on how M1 and M2 macrophage-derived exosomes modulate

IGF-1 and FGF-2 signaling within the musculoskeletal crosstalk

network, influencing osteocyte proliferation, differentiation and

mineralization. These findings provide a foundation for developing

novel therapeutic strategies.

Estrogen influences bone and muscle metabolism

differently in males and females (Table IX) (261-271). The decline in estrogen levels

is the primary cause of postmenopausal osteoporosis in women

(240), leading to reduced bone

mass, muscle atrophy and an increased risk of falls and fractures

(240). SP often coexists with

osteoporosis, resulting in osteosarcopenia (272). While male androgens

predominantly regulate muscle and bone metabolism, estrogen remains

crucial for maintaining bone strength and muscle metabolic

adaptability (267). Further

studies indicate that in obesity or infection models, male

macrophages tend to be M1 polarized, with their exosomes rich in

pro-inflammatory miRNAs (such as miR-155) that inhibit the insulin

signaling pathway (273). By

contrast, macrophage extracellular vesicles in female models carry

higher levels of anti-inflammatory factors (such as miR-125a-5p),

enhancing tissue repair (274).

The decrease in estrogen levels in postmenopausal women leads to an

M1/M2 imbalance, accelerating bone loss (with osteoporosis rates

twice as high as in men) (274). In males, high testosterone

levels are positively associated with muscle mass (275). However, obese males exhibit

higher expression of miR-155 in macrophage exosomes from adipose

tissue, which increases the risk of insulin resistance (276). M2 macrophage exosomes mediate

the polarization of macrophages into anti-inflammatory phenotypes

in female models, accelerating muscle regeneration (277). These findings suggest that

estrogen exerts distinct effects on bone and muscle metabolism

across sexes, leading to different regulatory mechanisms of

macrophage exosomes in estrogen-induced muscle-bone metabolism

abnormalities, influenced by sex-specific factors.

Although RAB-GTPase-modified exosomes (RAB-EXOs),

engineered via click chemistry, can target bone tissue in complex

in vivo environments, their targeting and enrichment

efficiencies remain suboptimal (278). Drug concentrations at sites of

deep-seated bone infections, such as osteomyelitis, are often

insufficient and systemic administration can result in off-target

effects and potential adverse reactions. Studies show that

intravenously injected exosomes are primarily taken up by the

liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (279-281). Enhancing exosome enrichment at

specific bone lesion sites remains a critical challenge that needs

urgent resolution (282).

Exosomes derived from macrophages of different sources and

polarization states exhibit significant differences in composition

and biological function. Exosomes from M1 and M2 macrophages can

exert opposing biological effects, and this heterogeneity presents

a considerable challenge for developing standardized therapies. One

study demonstrated that exosomes secreted by adipose tissue

macrophages in obese mice promote insulin resistance (283), whereas those from M2

macrophages improve insulin sensitivity (284). Ensuring batch-to-batch

consistency and functional stability of therapeutic exosomes is a

major challenge, as is overcoming technical bottlenecks in their

large-scale production. Exosomes isolated from 20-25 lean mice are

needed to treat one obese mouse, yielding too little for clinical

translation. Although in vitro induction of M2 macrophages

can partially address source limitations, optimization of culture

conditions, purification protocols and storage stability remains

necessary. The use of composite technologies with carrier materials

(such as hydrogels) also faces challenges in large-scale

production. While specific miRNAs, such as miR-690, mediate the

insulin-sensitizing effects of M2 macrophage-derived exosomes

(284) and the PI3K/AKT pathway

regulates macrophage polarization, significant knowledge gaps

remain regarding their application in treating musculoskeletal

tissues. The full molecular network underlying bone metabolic

diseases is not yet fully understood (285). Key questions concerning

exosomal release kinetics, interactions with host cells, and

long-term effects of exosomal cargo require further in-depth

investigation. This lack of knowledge hinders the precise design

and optimization of therapeutic regimens.

Exosomes are nanoscale extracellular vesicles with

diverse bioactivities; however, their long-term safety profile

remains incompletely characterized. Although animal studies have

shown that RAB-EXOs induce no adverse reactions within a 28-day

period in osteomyelitis treatment (286), their immunogenicity, potential

toxicity and the risk of off-target effects in human applications

require systematic evaluation. This is especially important for

patients with metabolic diseases, as exosome-based therapies may

have complex and unpredictable effects on systemic metabolic

networks. Consequently, a comprehensive safety evaluation framework

and robust risk mitigation strategies must be established.

In conclusion, exosomes derived from M1 and M2

macrophages play pivotal roles in muscle-bone crosstalk,

particularly within molecular signaling pathways mediated by

myokines such as IGF-1 and FGF-2. These factors are essential

regulators of muscle growth and bone metabolism, promoting muscle

cell proliferation and differentiation while influencing bone cell

function through various signaling pathways. Their roles extend

beyond direct regulation of local cellular behavior, modulating

bone metabolic homeostasis via macrophage-derived exosomes. Ongoing

research continues to uncover the complex mechanisms through which

M1 and M2 macrophage-derived exosomes affect bone metabolism.

Exosomes facilitate intercellular communication by transporting

bioactive molecules (such as proteins, RNAs and lipids), regulating

bone tissue formation and remodeling. Specifically, exosomes

secreted by M1 and M2 macrophages can modulate bone density and

strength by influencing osteoblast and osteoclast activity,

promoting bone health and aiding in repair. These findings provide

valuable insights into the intricate mechanisms governing bone

metabolism and lay the groundwork for developing new therapeutic

strategies.

To address current challenges, researchers are

exploring several strategies, including engineering targeted

modification technologies to enhance exosomal tissue specificity,

establishing standardized production and quality control protocols,

applying multi-omics approaches to clarify mechanisms of action and

developing smart, responsive carrier systems to improve delivery

efficiency. Innovative solutions, such as M2 macrophage

exosome-hydrogel composites, show promise for bone regeneration

therapy, but further preclinical and clinical studies are essential

to evaluate their safety and efficacy. Interdisciplinary

collaboration will be vital in advancing this field. Further

investigation into the mechanisms of M1 and M2 macrophage-derived

exosomes is expected to lead to more effective interventions for

bone-related diseases, including osteoporosis and fracture

repair.

Not applicable.

Conceptualization was by RMC, MZ, and JBH. Data

curation was by ZXW and YFC. Funding acquisition was secured by

MWL. Investigation was by SJG and YLZ. Project administration was

performed by YLZ. Software management was overseen by ZBY. Figures 1-13 were prepared by MWL and RMC.

Supervision was led by MWL. Validation was performed by RMC and

visualization was by MZ. The original draft of the manuscript was

written by MWL, who contributed to the review and editing. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Union Foundation of

Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department and Kunming

Medical University (grant no. 202201AY070001-091), Yunnan Province

Clinical Center for Skin Immune Diseases (grant no.

YWLCYXZX2023300076) and the Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant no. 81960350).

|

1

|

Kirk B, Lombardi G and Duque G: Bone and

muscle crosstalk in ageing and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

21:375–390. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shirvani H, Shamsoddini A, Bazgir B,

McAinch AJ, Najjari A and Arabzadeh E: Metabolic crosstalk between

skeletal muscle and cartilage tissue: Insights into myokines in

osteoarthritis. Mol Biol Rep. 52:9572025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chuang YH, Chuang WL, Huang SP and Huang

CH: Expression of epidermal growth factor, basic fibroblast growth

factor and insulin growth factor-1 and relation to myocyte

regeneration of obstructed ureters in rats. Scand J Urol Nephrol.

39:7–14. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cecerska-Heryć E, Goszka M, Serwin N,

Roszak M, Grygorcewicz B, Heryć R and Dołęgowska B: Applications of

the regenerative capacity of platelets in modern medicine. Cytokine

Growth Factor Rev. 64:84–94. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Gries KJ, Zysik VS, Jobe TK, Griffin N,

Leeds BP and Lowery JW: Muscle-derived factors influencing bone

metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 123:57–63. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Pieters BCH, Cappariello A, van den Bosch

MHJ, van Lent PLEM, Teti A and van de Loo FAJ: Macrophage-derived

extracellular vesicles as carriers of alarmins and their potential

involvement in bone homeostasis. Front Immunol. 10:19012019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chen Y, Liu H, He Y, Yang B, Lu W and Dai

Z: Roles for exosomes in the pathogenesis, drug delivery and

therapy of psoriasis. Pharmaceutics. 17:512025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yue Y, Cao S, Cao F, Wei Y, Li A, Wang D,

Liu P, Zeng H and Lin J: Unveiling research hotspots: A

bibliometric study on macrophages in musculoskeletal diseases.

Front Immunol. 16:15193212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zheng A, Liu H, Yin G and Xie Q:

Macrophage-derived exosomes in autoimmune diseases: Mechanistic

insights and therapeutic implications. Immunol Res. 73:1712025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fan C, Wang W, Yu Z, Wang J, Xu W, Ji Z,

He W, Hua D, Wang W, Yao L, et al: M1 macrophage-derived exosomes

promote intervertebral disc degeneration by enhancing nucleus

pulposus cell senescence through LCN2/NF-κB signaling axis. J

Nanobiotechnology. 22:3012024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wen Z, Li S, Liu Y, Liu X, Qiu H, Che Y,

Bian L and Zhou M: An engineered M2 macrophage-derived

exosomes-loaded electrospun biomimetic periosteum promotes cell

recruitment, immunoregulation, and angiogenesis in bone

regeneration. Bioact Mater. 50:95–115. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu M, Ng M, Phu T, Bouchareychas L,

Feeley BT, Kim HT, Raffai RL and Liu X: Polarized macrophages

regulate fibro/adipogenic progenitor (FAP) adipogenesis through

exosomes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 14:3212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou M, Li B, Liu C, Hu M, Tang J, Min J,

Cheng J and Hong L: M2 Macrophage-derived exosomal miR-501

contributes to pubococcygeal muscle regeneration. Int

Immunopharmacol. 101(Pt B): 1082232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yuan Z, Jiang D, Yang M, Tao J, Hu X, Yang

X and Zeng Y: Emerging roles of macrophage polarization in

osteoarthritis: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Orthop Surg.

16:532–550. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ascenzi F, Barberi L, Dobrowolny G, Villa

Nova Bacurau A, Nicoletti C, Rizzuto E, Rosenthal N, Scicchitano BM

and Musarò A: Effects of IGF-1 isoforms on muscle growth and

sarcopenia. Aging Cell. 18:e129542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Park SH, Park J, Yoo JY, Kim HS, Lee M and

Kim OK: Humulus japonicus enhances bone growth and

microarchitecture in rats: Potential Involvement of IGF-1

signaling. J Med Food. 28:542–552. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Qiu Y, Yu B, Jiang C, Yin H, Meng J, Wang

H, Chen L, Cai Y, Ren T, Qin Q, et al: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells overexpressing FGF-2 loaded onto a decellularized

extracellular matrix hydrogel for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Biomater Sci. 14:9–30. 2026. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Jaśkiewicz Ł, Romaszko-Wojtowicz A,

Chmielewski G, Kuna J and Krajewska-Włodarczyk M: Effect of

myokines on bone tissue metabolism: a systematic review. Bone.

201:1176542025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Zhao Z, Yan K, Guan Q, Guo Q and Zhao C:

Mechanism and physical activities in bone-skeletal muscle

crosstalk. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14:12879722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yin L, Lu L, Lin X and Wang X: Crucial

role of androgen receptor in resistance and endurance

trainings-induced muscle hypertrophy through

IGF-1/IGF-1R-PI3K/Akt-mTOR pathway. NutrMetab (Lond). 17:262020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Fu S, Yin L, Lin X, Lu J and Wang X:

Effects of cyclic mechanical stretch on the proliferation of L6

myoblasts and its mechanisms: PI3K/Akt and MAPK signal pathways

regulated by IGF-1 receptor. Int J Mol Sci. 19:16492018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shen L, Li Y and Zhao H: Fibroblast growth

factor signaling in macrophage polarization: Impact on health and

diseases. Front Immunol. 15:13904532024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang Z, Cao F, Liang D, Pan M, Lu WW, Lyu

H, Xie Y, Zhang L and Tang P: Mechanical effects in aging of the

musculoskeletal system: Molecular signaling and spatial scale

alterations. J Orthop Translat. 52:464–477. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mao Y, Jin Z, Yang J, Xu D, Zhao L, Kiram

A, Yin Y, Zhou D, Sun Z, Xiao L, et al: Muscle-bone cross-talk

through the FNIP1-TFEB-IGF2 axis is associated with bone metabolism

in human and mouse. Sci Transl Med. 16:eadk98112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yin P, Chen M, Rao M, Lin Y, Zhang M, Xu

R, Hu X, Chen R, Chai W, Huang X, et al: Deciphering immune

landscape remodeling unravels the underlying mechanism for

synchronized muscle and bone aging. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e23040842024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Gómez-Bruton A, Matute-Llorente Á,

González-Agüero A, Casajús JA and Vicente-Rodríguez G: Plyometric

exercise and bone health in children and adolescents: A systematic

review. World J Pediatr. 13:112–121. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Han J, Zhang J, Zhang X, Luo W, Liu L, Zhu

Y, Liu Q and Zhang XA: Emerging role and function of Hippo-YAP/TAZ

signaling pathway in musculoskeletal disorders. Stem Cell Res Ther.

15:3862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Schiaffino S, Reggiani C, Akimoto T and

Blaauw B: molecular mechanisms of skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J

Neuromuscul Dis. 8:169–183. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

29

|

Von den Hoff JW, Carvajal Monroy PL,

Ongkosuwito EM, van Kuppevelt TH and Daamen WF: Muscle fibrosis in

the soft palate: Delivery of cells, growth factors and

anti-fibrotics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 146:60–76. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Savadipour A, Palmer D, Ely EV, Collins

KH, Garcia-Castorena JM, Harissa Z, Kim YS, Oestrich A, Qu F,

Rashidi N and Guilak F: The role of PIEZO ion channels in the

musculoskeletal system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 324:C728–C740.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kirk B, Feehan J, Lombardi G and Duque G:

Muscle, bone, and fat crosstalk: The biological role of myokines,

osteokines, and adipokines. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 18:388–400. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Guo L, Quan M, Pang W, Yin Y and Li F:

Cytokines and exosomal miRNAs in skeletal muscle-adipose crosstalk.

Trends Endocrinol Metab. 34:666–681. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Calejo I, Costa-Almeida R, Reis RL and

Gomes ME: A physiology-inspired multifactorial toolbox in

soft-to-hard musculoskeletal interface tissue engineering. Trends

Biotechnol. 38:83–98. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Adamičková A, Chomaničová N, Gažová A,

Maďarič J, Červenák Z, Valášková S, Adamička M and Kyselovic J:

Effect of atorvastatin on angiogenesis-related genes VEGF-A, HGF

and IGF-1 and the modulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR transcripts in

bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Issues Mol Biol.

45:2326–2337. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Xu L, Zhao Q, Li K, Zhang Y, Wang C, Hind

K, Wang L, Liu Y and Cheng X: The role of sex hormones on bone

mineral density, marrow adiposity, and muscle adiposity in

middle-aged and older men. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13:8174182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang Z, Wang Y, Tang Y, Guo X, Gao Q, Shao

Y, Wang J, Tian R and Shi Y: Sodium benzoate inhibits osteoblast

differentiation and accelerates bone loss by regulating the

FGF2/p38/RUNX2 pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 73:13891–13901. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ogura H, Nakamura T, Ishii T, Saito A,

Onodera S, Yamaguchi A, Nishii Y and Azuma T: Mechanical

stress-induced FGF-2 promotes proliferation and consequently

induces osteoblast differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 684:1491452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Bakker AD and Jaspers RT: IL-6 and IGF-1

signaling within and between muscle and bone: How important is the

mTOR pathway for bone metabolism? Curr Osteoporos Rep. 13:131–139.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yoshida T and Delafontaine P: Mechanisms

of IGF-1-mediated regulation of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and

atrophy. Cells. 9:19702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chai J, Xu L and Liu N: miR-23b-3p

regulates differentiation of osteoclasts by targeting PTEN via the

PI3k/AKT pathway. Arch Med Sci. 18:1542–1557. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu X, Liu L, Chen K, Sun L, Li W and

Zhang S: Huaier shows anti-cancer activities by inhibition of cell

growth, migration and energy metabolism in lung cancer through

PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 25:2228–2237. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Hang K, Wang Y, Bai J, Wang Z, Wu W, Zhu

W, Liu S, Pan Z, Chen J and Chen W: Chaperone-mediated autophagy

protects the bone formation from excessive inflammation through

PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway. FASEB J. 38:e236462024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Peifer C, Oláh T, Venkatesan JK, Goebel L,

Orth P, Schmitt G, Zurakowski D, Menger MD, Laschke MW, Cucchiarini

M and Madry H: locally directed recombinant adeno-associated

virus-mediated igf-1 gene therapy enhances osteochondral repair and

counteracts early osteoarthritis in vivo. Am J Sports Med.

52:1336–1349. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhang C, Wang J, Xie Y, Wang L, Yang L, Yu

J, Miyamoto A and Sun F: Development of FGF-2-loaded electrospun

waterborne polyurethane fibrous membranes for bone regeneration.

Regen Biomater. 8:rbaa0462020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kogure K, Hasuike A, Kurachi R, Igarashi

Y, Idesawa M and Sato S: Effect of a recombinant human basic

fibroblast growth factor 2 (rhFGF-2)-Impregnated atelocollagen

sponge on vertical guided bone regeneration in a rat calvarial

model. Dent J (Basel). 13:1772025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Yu X, Qi Y, Zhao T, Fang J, Liu X, Xu T,

Yang Q and Dai X: NGF increases FGF2 expression and promotes

endothelial cell migration and tube formation through PI3K/Akt and

ERK/MAPK pathways in human chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

27:526–534. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Yin J, Qiu S, Shi B, Xu X, Zhao Y, Gao J,

Zhao S and Min S: Controlled release of FGF-2 and BMP-2 in tissue

engineered periosteum promotes bone repair in rats. Biomed Mater.

13:0250012018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wu H, Yin G, Pu X, Wang J, Liao X and

Huang Z: Inhibitory effects of combined bone morphogenetic protein

2, vascular endothelial growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth

factor on osteoclast differentiation and activity. Tissue Eng Part

A. 27:1387–1398. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lötvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Buzás EI,

Di Vizio D, Gardiner C, Gho YS, Kurochkin IV, Mathivanan S,

Quesenberry P, et al: Minimal experimental requirements for

definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: A

position statement from the International Society for Extracellular

Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 3:269132014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Akbar N, Paget D and Choudhury RP:

Extracellular vesicles in innate immune cell programming.

Biomedicines. 9:7132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Garzetti L, Menon R, Finardi A, Bergami A,

Sica A, Martino G, Comi G, Verderio C, Farina C and Furlan R:

Activated macrophages release microvesicles containing polarized M1

or M2 mRNAs. J Leukoc Biol. 95:817–825. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Guan X, Li C, Wang X, Yang L, Lu Y and Guo

Z: Engineered M2 macrophage-derived exosomes: mechanisms and

therapeutic potential in inflammation regulation and regenerative

medicine. Acta Biomater. 203:38–58. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Mäki-Mantila K, Niskanen EA, Kainulainen

K, Pardas LP, Aaltonen N, Wahbi W, Takabe P, Rönkä A, Rilla K and

Pasonen-Seppänen S: Extracellular vesicles derived from

pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages induce an inflammatory and invasive

phenotype in melanoma cells. Cell Commun Signal. 24:102025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, Schneider J and

Perez-Fernandez R: Mesenchymal stem cell secretome: Toward

cell-free therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Int J

Mol Sci. 18:18522017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Liu S, Chen J, Shi J, Zhou W, Wang L, Fang

W, Zhong Y, Chen X, Chen Y, Sabri A and Liu S: M1-like

macrophage-derived exosomes suppress angiogenesis and exacerbate

cardiac dysfunction in a myocardial infarction microenvironment.

Basic Res Cardiol. 115:222020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Li Z, Wang Y, Li S and Li Y: Exosomes

derived from M2 macrophages facilitate osteogenesis and reduce

adipogenesis of BMSCs. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12:6803282021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang Y, Liang Y and Zhou Y: M2

polarization of RAW264.7-derived exosomes inhibits osteoclast

differentiation and inflammation via PKM2/HIF-1α axis. Immunol

Invest. 54:1195–1209. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Huang R, Wang X, Zhou Y and Xiao Y:

RANKL-induced M1 macrophages are involved in bone formation. Bone

Res. 5:170192017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kang M, Huang CC, Lu Y, Shirazi S,

Gajendrareddy P, Ravindran S and Cooper LF: Bone regeneration is

mediated by macrophage extracellular vesicles. Bone.

141:1156272020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ge X, Tang P, Rong Y, Jiang D, Lu X, Ji C,

Wang J, Huang C, Duan A, Liu Y, et al: Exosomal miR-155 from

M1-polarized macrophages promotes Endo MT and impairs mitochondrial

function via activating NF-κB signaling pathway in vascular

endothelial cells after traumatic spinal cord injury. Redox Biol.

41:1019322021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Hu Y, Wang Y, Chen T, Hao Z, Cai L and Li

J: Exosome: Function and application in inflammatory bone diseases.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:63249122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Pajarinen J, Lin T, Gibon E, Kohno Y,

Maruyama M, Nathan K, Lu L, Yao Z and Goodman SB: Mesenchymal stem

cell-macrophage crosstalk and bone healing. Biomaterials.

196:80–89. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Paschalidi P, Gkouveris I, Soundia A,

Kalfarentzos E, Vardas E, Georgaki M, Kostakis G, Erovic BM,

Tetradis S, Perisanidis C and Nikitakis NG: The role of M1 and M2

macrophage polarization in progression of medication-related

osteonecrosis of the jaw. Clin Oral Investig. 25:2845–2857. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

64

|

Boldin MP and Baltimore D: MicroRNAs, new

effectors and regulators of NF-κB. Immunol Rev. 246:205–220. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Salhotra A, Shah HN, Levi B and Longaker

MT: Mechanisms of bone development and repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 21:696–711. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Wang Z, Zhu H, Shi H, Zhao H, Gao R, Weng

X, Liu R, Li X, Zou Y, Hu K, et al: Exosomes derived from M1

macrophages aggravate neointimal hyperplasia following carotid

artery injuries in mice through miR-222/CDKN1B/CDKN1C pathway. Cell

Death Dis. 10:4222019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Qi Y, Zhu T, Zhang T, Wang X, Li W, Chen

D, Meng H and An S: M1 macrophage-derived exosomes transfer miR-222

to induce bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis. Lab Invest.

101:1318–1326. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Li L, Zheng B, Zhang F, Luo X, Li F, Xu T,

Zhao H, Shi G, Guo Y, Shi J and Sun J: LINC00370 modulates

miR-222-3p-RGS4 axis to protect against osteoporosis progression.

Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 97:1045052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Jiang C, Xia W, Wu T, Pan C, Shan H, Wang

F, Zhou Z and Yu X: Inhibition of microRNA-222 up-regulates TIMP3

to promotes osteogenic differentiation of MSCs from fracture rats

with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cell Mol Med. 24:686–694. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Yu L, Hu M, Cui X, Bao D, Luo Z, Li D, Li

L, Liu N, Wu Y, Luo X and Ma Y: M1 macrophage-derived exosomes

aggravate bone loss in postmenopausal osteoporosis via a

microRNA-98/DUSP1/JNK axis. Cell Biol Int. 45:2452–2463. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Peng S, Yan Y, Li R, Dai H and Xu J:

Extracellular vesicles from M1-polarized macrophages promote

inflammation in the temporomandibular joint via miR-1246 activation

of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1503:48–59. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

He XT, Li X, Yin Y, Wu RX, Xu XY and Chen

FM: The effects of conditioned media generated by polarized

macrophages on the cellular behaviours of bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 22:1302–1315. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

73

|

Xia Y, He XT, Xu XY, Tian BM, An Y and

Chen FM: Exosomes derived from M0, M1 and M2 macrophages exert

distinct influences on the proliferation and differentiation of

mesenchymal stem cells. PeerJ. 8:e89702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Schlundt C, Fischer H, Bucher CH,

Rendenbach C, Duda GN and Schmidt-Bleek K: The multifaceted roles

of macrophages in bone regeneration: A story of polarization,

activation and time. Acta Biomater. 133:46–57. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wei F, Zhou Y, Wang J, Liu C and Xiao Y:

The immunomodulatory role of BMP-2 on macrophages to accelerate

osteogenesis. Tissue Eng Part A. 24:584–594. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Wang J, Xue Y, Wang Y, Liu C, Hu S, Zhao

H, Gu Q, Yang H, Huang L, Zhou X and Shi Q: BMP-2 functional

polypeptides relieve osteolysis via bi-regulating bone formation

and resorption coupled with macrophage polarization. NPJ Regen Med.

8:62023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Bouchareychas L, Duong P, Covarrubias S,

Alsop E, Phu TA, Chung A, Gomes M, Wong D, Meechoovet B, Capili A,

et al: Macrophage exosomes resolve atherosclerosis by regulating

hematopoiesis and inflammation via microRNA cargo. Cell Rep.

32:1078812020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Yu S, Geng Q, Pan Q, Liu Z, Ding S, Xiang

Q, Sun F, Wang C, Huang Y and Hong A: miR-690, a Runx2-targeted

miRNA, regulates osteogenic differentiation of C2C12 myogenic

progenitor cells by targeting NF-kappaB p65. Cell Biosci. 6:102016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Yang Y, Guo Z, Chen W, Wang X, Cao M, Han

X, Zhang K, Teng B, Cao J, Wu W, et al: M2 macrophage-derived

exosomes promote angiogenesis and growth of pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma by targeting E2F2. Mol Ther. 29:1226–1238. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

80

|

Xu T, Luo Y, Wang J, Zhang N, Gu C, Li L,

Qian D, Cai W, Fan J and Yin G: Exosomal miRNA128-3pfrom

mesenchymal stem cells of aged rats regulates osteogenesis and bone

fracture healing by targeting Smad5. J Nanobiotechnology.

18:472020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Zhang D, Wu Y, Li Z, Chen H, Huang S, Jian

C and Yu A: miR-144-5p, an exosomal miRNA from bone marrow-derived

macrophage in type 2 diabetes, impairs bone fracture healing via