B-cells develop from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)

in the bone marrow (BM) of adult mammals or in the fetal liver

during embryogenesis (1). The

sequential and coordinated expression of lineage-specifying

transcription factors, including E2A, PU.1, Ikaros and EBF1, drives

HSCs into early lymphoid progenitors (ELPs), which activate

lymphoid-restricted gene programs indicative of B-cell potential

(2). ELPs, characterized by

interleukin (IL)-7 receptor (IL-7R, CD127) negativity, subsequently

differentiate into common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) in the BM.

CLPs serve as immediate precursors not only for B-cells, but also

for T-cells, natural killer cells and dendritic cells (3). B-cell maturation proceeds through

discrete stages, including pro-B, pre-B, immature B and mature

B-cells, under the coordinated control of transcription factors

(including E2A, Pax5, PU.1, Ikaros, EBF1, Sox4, IRF4 and IRF8) and

cytokines such as IL-7 (1).

During these stages, developing B-cells undergo tightly ordered

V(D)J recombination events to assemble a functional,

non-autoreactive heterodimeric B-cell receptor (BCR), thereby

equipping them for antigen recognition and adaptive immune

responses. Once they migrate to secondary lymphoid organs, mature

B-cells can be activated via T-cell-dependent (TD) or

T-cell-independent (TI) pathways and differentiate into

antibody-secreting plasma cells (PCs) and long-lived memory B-cells

(MBCs) (4).

In contrast to genetic mechanisms, epigenetic

mechanisms regulate gene expression without altering the DNA

sequence, thereby modulating cellular metabolism and function

(5). Emerging evidence indicates

that epigenetic regulation plays a crucial role in establishing

B-cell lineage identity and effector functions. The dysregulation

of DNA methylation, histone modifications and the altered

expression of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs

(miRNAs/miRs) can impair B-cell tolerance and contribute to the

pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid

arthritis (RA), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular

lymphoma (FL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) (6-8).

Dissecting the specific epigenetic perturbations that drive these

pathologies may reveal novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Indeed, clinical and preclinical studies of autoimmune disorders

and B-cell malignancies have shown that agents capable of reversing

aberrant epigenetic states, such as histone deacetylase and DNA

methyltransferase inhibitors, hold significant therapeutic

potential (7,9). A comprehensive understanding of

epigenetic dysregulation in disease is crucial for elucidating

pathogenic mechanisms and designing targeted epigenetic therapies.

The present review aimed to provide an overview of current insights

into the epigenetic regulation of B-cell development and the

consequences of its dysregulation in autoimmune diseases and B-cell

lymphomas.

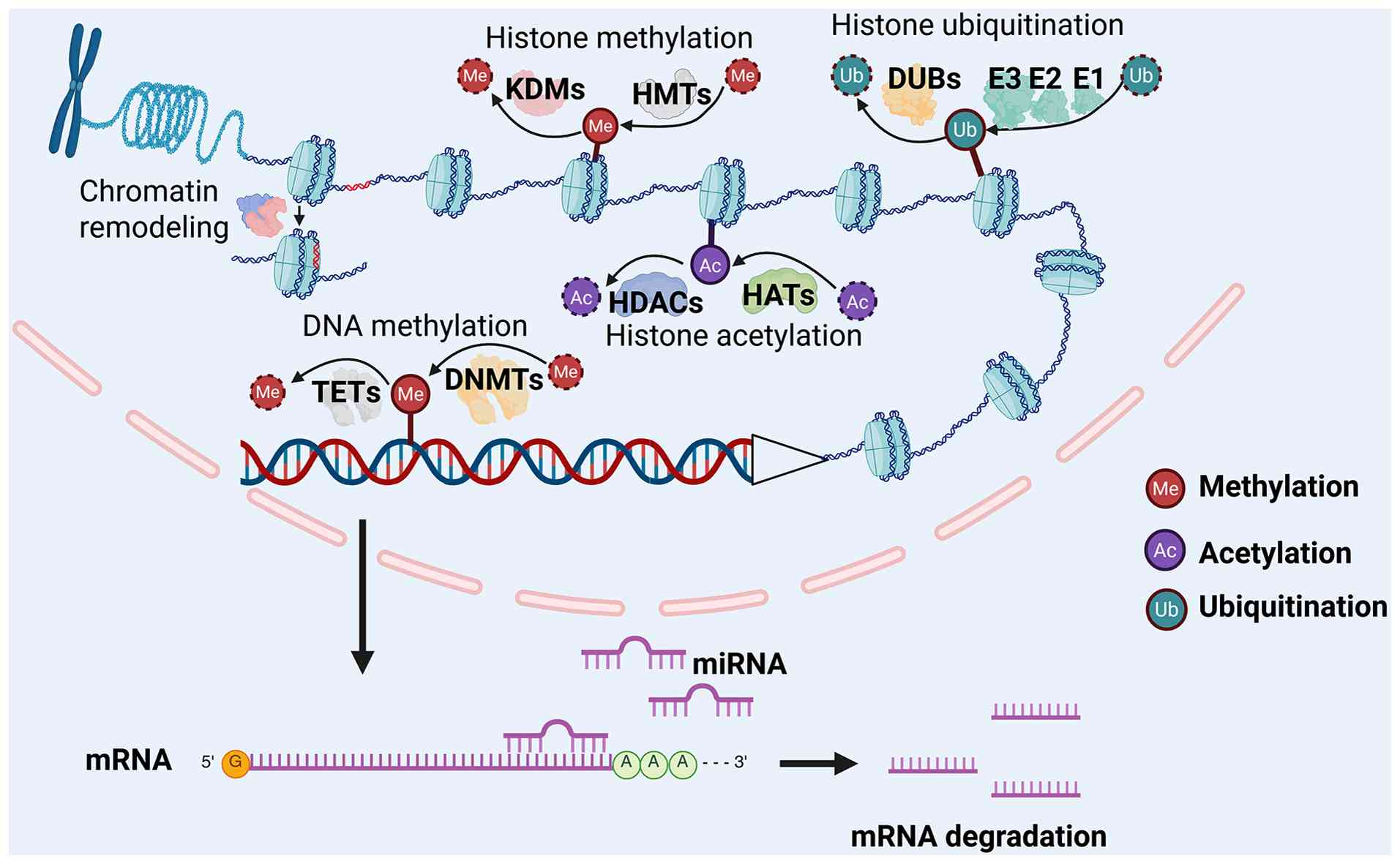

Eukaryotic DNA is organized into chromatin, with the

nucleosome as the fundamental repeating unit, consisting of ~147

base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histones

(10). Nucleosomes are further

compacted and folded to form higher-order chromatin structures.

Dynamic changes in chromatin structure play a crucial role in gene

transcription. Generally, the chromatin in the transcriptional

silencing region is highly packaged, while the chromatin structure

is loosed in the active transcriptional region, which facilitates

the binding of transcription regulators (11,12). Increasing evidence indicates that

epigenetic modifications, including chromatin remodeling, DNA

methylation, histone modifications, lncRNAs and miRNA activity, are

key drivers of chromatin structural dynamics and gene regulation

(13,14). The processes of chromatin

remodeling (with nucleosome sliding as an illustrative example),

DNA methylation, major histone modifications, and miRNA-mediated

regulation are illustrated in Fig.

1.

Chromatin remodeling is an ATP-dependent process

that modulates nucleosome architecture to regulate both

transcription initiation and elongation. Of note, four principal

families of remodelers have been defined based on their

Swi2/Snf2-like ATPase domains: SWI/SNF (such as BAF, PBAF and WINAC

complexes), ISWI (such as ACF and NURF complexes), CHD (such as

NURD complexes) and INO80/SWR1 (such as SRCAP and Tip60/EP400

complexes) (15,16). These complexes target specific

genomic loci through interactions with sequence-specific

transcription factors or histone marks, where they function as

coactivators or corepressors. Mechanistically, chromatin remodelers

promote gene activation or repression by sliding or evicting

nucleosomes, exchanging core histones for histone variants, or

altering nucleosome spacing to fine-tune DNA accessibility for the

transcriptional machinery (15,17). Beyond transcriptional control,

remodelers also coordinate with histone-modifying enzymes and the

RNA polymerase II complex to ensure proper promoter clearance,

pause release and elongation processivity, and they play critical

roles in development, cell differentiation and disease pathogenesis

(18).

As a prototypical epigenetic mark, DNA methylation

persists throughout the lifespan of the cell. During the

methylation process, a methyl group is covalently added to a

specific base in the DNA sequence, catalyzed by DNA

methyltransferases (DNMTs). DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and the catalytically

inactive DNMT3L establish de novo methylation patterns in

mammals, while DNMT1 maintains these patterns during DNA

replication (19). DNA

methylation is reversible; it can be actively removed by ten-eleven

translocation (TET) enzymes or passively lost through

replication-dependent dilution (20). In eukaryotes, methylation occurs

predominantly at cytosine residues in CpG dinucleotides

(5'-CpG-3'), although adenine methylation has also been observed.

DNA methylation exerts a profound impact on gene expression by

interfering with transcription factor binding, influencing

chromatin compaction, and recruiting methyl-CpG binding domain

proteins (21).

Four core histones and their variant isoforms

assemble into the fundamental repeating unit of chromatin, the

nucleosome. These nucleosomal histones undergo a variety of

covalent post-translational modifications, such as methylation,

acetylation, phosphorylation, ADP-ribosylation, ubiquitination, and

SUMOylation, which collectively constitute a complex 'histone code'

(22). A cohort of specialized

enzymes catalyzes the 'writing', 'erasing' and 'reading' of these

marks. For instance, histone acetylation is catalyzed by histone

acetyltransferases (HATs) such as PCAF, GCN5 and the CREBBP/p300

complex, whereas histone deacetylases (HDACs), including HDAC1-3

and the sirtuin family (SIRT1-7), remove acetyl groups to

facilitate chromatin compaction and transcriptional repression

(23,24). Histone methylation is installed

by histone methyltransferases (HMTs), including the KMT2 family,

PRC2 complex, SUV39H1/2, and PRMT1, which deposit mono-, di- and

tri-methyl marks on lysine (K) or arginine (R) residues (25). Conversely, histone demethylases

(KDMs), such as LSD1/KDM1A and members of the jumonji domain

family, 'erase' methyl modifications in a residue- and

methylation-state-specific manner (25). Histone ubiquitination involves a

cascade of reactions that covalently attach ubiquitin to lysine

side chains, mediated by the E1 activating enzyme, E2 conjugating

enzyme, and E3 ligases (such as RNF20/40 and RING1A/B). This

modification is reversed by deubiquitinases, such as USP16, USP22

and BAP1 (26,27). Functionally, these histone

modifications modulate chromatin biophysics, govern the recruitment

or exclusion of transcriptional regulators, and delineate distinct

chromatin domains, such as euchromatin and heterochromatin, thereby

providing a pivotal epigenetic layer of gene expression control

(28).

miRNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs, ~21 to 25

nucleotides in length, that primarily regulate gene expression at

the post-transcriptional level (29). Intergenic miRNAs possess

independent promoters and are transcribed as discrete

transcriptional units, whereas intragenic miRNAs share promoters

with their host genes; additionally, a number of miRNAs are

arranged in polycistronic clusters and co-transcribed as a single

primary transcript (primary microRNAs, pri-miRNAs) (30). Within the nucleus, the

microprocessor complex (Drosha-DGCR8) cleaves pri-miRNAs to release

~70-nucleotide stem-loop precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) (31). Pre-miRNAs are exported from the

nucleus by Exportin-5 in a Ran-GTP-dependent manner. In the

cytoplasm, the RNase III enzyme Dicer and TRBP cleave pre-miRNA to

produce a miRNA duplex (32,33). This duplex is then loaded into an

Argonaute protein in an ATP-dependent manner, leading to passenger

strand ejection and mature single-stranded miRNA formation

(34). In addition to this

canonical pathway, certain miRNAs arise via non-canonical

(Drosha-independent and/or Dicer-independent) pathways (35). Accumulating evidence indicates

that miRNAs orchestrate diverse biological processes, such as cell

differentiation, apoptosis and immune responses, and that aberrant

miRNA expression contributes to various pathologies, highlighting

their potential as therapeutic targets (30,36).

lncRNAs are transcripts typically >200

nucleotides with minimal protein-coding potential (37,38). The majority of lncRNAs are

transcribed by RNA polymerase II and undergo 5' capping, splicing

and 3' polyadenylation. Despite low sequence conservation and

generally weaker expression than protein-coding genes, lncRNAs

exhibit highly tissue-, cell type- and developmental stage-specific

expression. Advances in RNA sequencing, single-cell

transcriptomics, multi-omics and RNA-protein interaction studies

have established that lncRNAs play critical regulatory roles in

embryonic development, immune modulation, and tumorigenesis, rather

than representing mere transcriptional noise (38,39).

lncRNAs regulate gene expression through diverse

mechanisms, including epigenetic, transcriptional,

post-transcriptional and macromolecular complex-mediated processes

(40,41). Some recruit chromatin modifiers,

such as PRC2, to induce H3K27me3 and other repressive histone

marks, thereby modulating chromatin accessibility and gene

silencing (42).

Enhancer-associated lncRNAs regulate nearby gene transcription by

altering enhancer-promoter interactions and local chromatin

architecture (43). Certain

lncRNAs function as competing endogenous RNAs, sequestering miRNAs

and relieving repression of target mRNAs (41,44). lncRNAs can also interact with

mRNAs, miRNAs, or RNA-binding proteins to influence splicing,

stability, localization and translation (41).

Early B-cell development in the BM is orchestrated

by chemokines (such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 and C-X-C

motif chemokine ligand 13) and cytokines (such as IL-7 and stem

cell factor) produced by stromal cells (45-47). The transcription factors, ZBTB7A

and ZBTB17, are indispensable for the transition of CLPs to

pre-pro-B-cells through modulation of Notch signaling, JAK-STAT5

pathway and IL-7R signaling (48,49). Rearrangement of the

immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene segments is the hallmark of

pro-B-cells and requires expression of RAG-1 and RAG-2 (50). In addition, pro-B-cells express

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, which increases

antigen-receptor diversity by adding non-templated nucleotides at

V(D)J junctions. Pro-B-cells also express the surrogate light chain

(VpreB/λ5), which pairs with μ heavy chains to form the

pre-B-cell receptor (pre-BCR). Pre-BCR signaling then drives

progression to the large and subsequently small pre-B-cell stages.

Subsequently, light-chain gene rearrangement occurs under strict

allelic and isotypic exclusion, ensuring each B-cell expresses

either κ or λ light chains exclusively. B-cells enter

IgM-expressing immature B-cells after completing both heavy and

light chains rearrangement.

In peripheral lymphoid tissues, B-cell activator of

the TNF-α family (BAFF) signals provided by the follicle are

important for B-cell survival (51). The mature B-cells differentiate

into MBCs and PCs when activated by antigens in the peripheral

lymphoid tissues. In addition to antigenic signals, TD or TI

co-stimulation signals are also required for the B-cell activation.

TI antigens typically drive differentiation into short-lived PCs,

whereas TD responses initiate germinal center (GC) response

(52). Within GCs,

immunoglobulin genes undergo class-switch recombination (CSR) and

somatic hypermutation (SHM) (53). GC responses are governed by a

transcriptional network in which Bcl6, Pax5, PU.1, Bach2 and IRF8

enforce the GC B-cell program, whereas Blimp-1 (encoded by

Prdm1), IRF4 and XBP1 drive differentiation into MBCs and

PCs (54). Bcl6 is essential for

GC B-cell identity by upregulating Bach2 and repressing

Prdm1, thereby preventing premature Blimp-1-mediated

differentiation (55). Blimp-1

represses Bcl6 and other B-cell fate factors, while inducing

Irf4 and Xbp1. Deletion of Prdm1 in mice

abolishes PC formation (56).

IRF4 further reinforces PC differentiation by activating

Prdm1 and repressing Bcl6 (54).

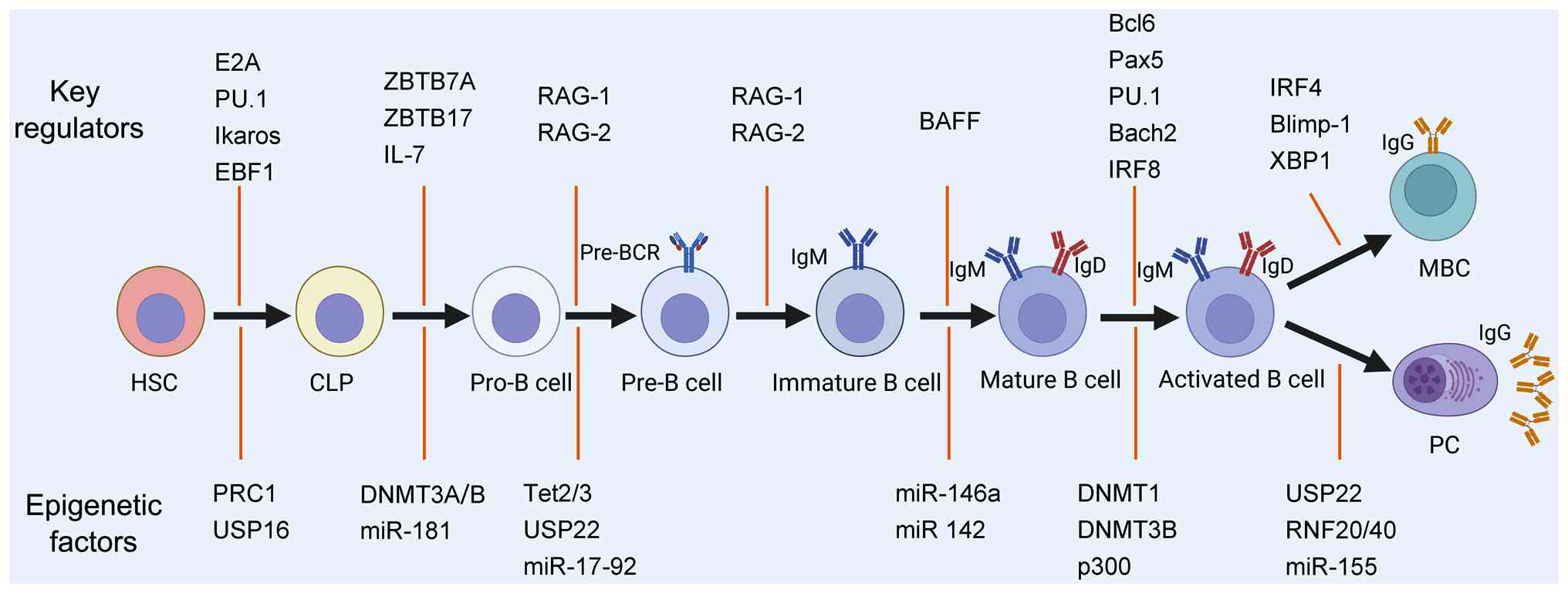

In addition to the intricate networks of

transcription factors, an increasing body of evidence suggests that

epigenetic regulation plays a pivotal role in B-cell development

and differentiation. The involvement of epigenetic regulators in

B-cell lymphopoiesis is illustrated in Fig. 2.

In the immune system, B-cells exhibit a highly

dynamic DNA methylation landscape, particularly during

differentiation. Approximately one-third of CpG sites undergo

methylation changes throughout B-cell development (57). The transition from naïve B-cells

to GC B-cells is characterized by extensive methylome remodeling,

whereas subsequent shifts from GC B-cells to MBCs and PCs involve

comparatively modest alterations (58). Notably, CTCF-binding sites

exhibit dynamic methylation changes during B-cell maturation,

indicating subset-specific epigenetic regulation within the immune

system (59). Furthermore, DNA

methylation also influences SHM by targeting V(D)J gene segments

and promoting an open chromatin state in coordination with histone

modifications (60,61).

B-cells respond to a wide array of immunological

stimuli, such as pathogens, commensal microbes, tumors and other

environmental cues (1,62). During immune responses,

activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) drives SHM and CSR by

deaminating deoxycytidine to deoxyuracil, thereby generating U:G

mismatches that are processed to effect antibody diversification

(63). The precise control of

AID expression is essential to maintain genomic integrity. In naïve

B-cells, Aicda (the gene encoding AID) is transcriptionally

silenced by promoter hypermethylation (64), whereas upon activation, it

undergoes demethylation-dependent induction. Moreover, the

differentiation of MBC is dependent on DNA methylation, where high

levels of DNMTs are observed (58).

Histone post-translational modifications are a core

epigenetic mechanism that regulate gene expression by remodeling

chromatin and recruiting effector proteins (22,69). In general, histone acetylation is

associated with transcriptional activation, whereas specific

methylation marks are frequently associated with gene repression

(70). Histone phosphorylation,

mediated by protein kinases, modulates DNA-histone interactions and

facilitates the assembly of DNA repair and transcriptional

complexes. In addition, the ubiquitination of histones H2A and H2B

contribute to both gene regulation and DNA damage repair (71).

B-cell development occurs in two sequential phases:

An antigen-independent stage in the BM and an antigen-dependent

stage in peripheral lymphoid tissues (1). During the latter, naive B-cells

undergo CSR and SHM upon activation, eventually differentiating

into MBCs and PCs (4). These

differentiation steps coincide with marked changes in histone

modification patterns. In resting naïve B-cells, chromatin at the

immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IgH) locus is enriched in

repressive marks and depleted of activating modifications,

resulting in a compact configuration and low transcriptional

activity (72). Upon activation,

extensive histone remodeling leads to the induction of genes

essential for B-cell effector function. For example, stimulation

with lipopolysaccharide and IL-4 has been shown to result in a

marked increase in histone H3 acetylation at regulatory elements of

the Aicda locus (73).

These elements also become enriched in H3K9ac, H3K14ac, and H3K4me3

and undergo DNA demethylation, thereby enabling robust AID

expression (73). Moreover,

activated B-cells exhibit increased expression of the histone

acetyltransferase p300, resulting in global histone

hyperacetylation. p300-mediated histone lysine acetylation at the

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) promoter enhances Btk

transcription, thereby potentiating BCR signaling and B-cell

activation (74).

Histone ubiquitination also critically influences

B-cell development. The major H2A ubiquitin ligase, polycomb

repressive complex 1 (PRC1), along with the deubiquitinase USP16,

controls H2A ubiquitination. PRC1 is essential for HSC self-renewal

(75), and Usp16 deletion

significantly reduces CLPs (76), highlighting a role for H2A

ubiquitination in early lymphopoiesis. Similarly, the

ubiquitination of H2BK120ub, catalyzed by the RNF20/RNF40 complex

and removed by the SAGA-associated deubiquitinase USP22, is

essential for CSR by facilitating DNA double-strand break repair

during activation (77,78). Rnf20 or Rnf40

knockdown diminishes H2Bub levels and impairs CSR in CH12 cells

(78), and the conditional

deletion of Usp22 in pre-B-cells disrupts classical

non-homologous end joining and antigen-specific IgG1 production

without affecting early B-cell development in the BM and periphery

(77). In summary, these

findings demonstrate that histone ubiquitination is particularly

critical for DNA repair processes during antigen-driven B-cell

differentiation.

Previous studies have delineated stage-specific

miRNA networks governing B-cell biology. For example, miR-181 and

the miR-17-92 cluster promote early B-cell development (79,80). By contrast, the constitutive

expression of miR-150 and miR-34a blocks pro-B-cell to pre-B-cell

transition. Mechanistically, miR-150 and miR-34a interfere with

early B-cell development by targeting the transcription factors,

C-Myb and Foxp1, respectively (81,82). Moreover, studies have

demonstrated that the miR-212/132 cluster regulates immunoglobulin

gene rearrangement by directly targeting Sox4 mRNA (83).

During peripheral maturation, transitional B-cells

differentiate into splenic follicular or marginal zone (MZ) B-cell

subsets. miR-146a deficiency in murine models causes selective

depletion of MZ B-cells via Numb-mediated inhibition of Notch2

signaling (84). A complex

network of cytokines (such as IL-6, IL-21 and BAFF) and

transcription factors (such as Bcl6, Blimp-1 and IRF4) regulates GC

responses and antibody affinity maturation (54,55). miR-155 regulates GC reactions and

IgG1+ B-cell differentiation by modulating cytokine

production and targeting multiple genes, including the

transcription factor PU.1 (85,86). Another critical regulator is

miR-142, which plays a pivotal role in B-cell homeostasis.

miR-142-deficient mice develop immunoproliferative disorders

characterized by an expansion of MZ B-cells and a reduction in B1

B-cells, partly due to the derepression of BAFF (87). Collectively, these findings

underscore the intricate miRNA-mediated networks that ensure proper

B-cell lineage specification, function and immune competence.

In B-cell development and differentiation, lncRNAs

have emerged as key regulatory nodes (88). Numerous lncRNAs display

stage-specific expression from hematopoietic stem cells to mature

B-cells, plasma cells and memory B-cells (88,89). Expression profiling across

developmental stages reveals thousands of lncRNAs associated with

proliferation, V(D)J recombination, maturation and immune memory

formation (90,91). Early B-cells exhibit IgH

locus-associated lncRNAs enriched at topologically associating

domain anchors and enhancers, suggesting roles in 3D genome

organization and antibody repertoire diversification (92,93). Moreover, lncRNA-CSRIgA

promotes the recruitment of regulatory proteins to a proximal

CTCF-binding site, thereby reshaping chromosomal interactions

within the topologically associated domain

(TADlncCSRIgA) and long-range contacts with the 3' RR

super-enhancer, ultimately facilitating CSR to IgA (93). LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2 are required

for HSC self-renewal and differentiation; their knockdown in stem

and progenitor cells (Sca-1+) impairs commitment to the

B-cell lineage (94).

Furthermore, XIST is necessary for the sustained silencing of a set

of X-linked immune-related genes (such as TLR7) in B-cells; XIST

depletion reactivates these loci and drives differentiation of

CD11c+ atypical memory B-cells implicated in the

pathogenesis of SLE (95).

The emergence of autoreactive B-cells and their

secreted autoantibodies during B-cell development and

differentiation drives the onset of autoimmune diseases, primarily

including SLE, RA, primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS), multiple

sclerosis (MS) and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Emerging

evidence suggests that epigenetic dysregulation in B-cells

contributes to aberrant B-cell development and differentiation,

thereby promoting autoimmune pathogenesis (summarized in Table SI).

SLE is a chronic, relapsing-remitting systemic

autoimmune disease characterized by immune dysregulation (96). B-cells, as the main source of

pathogenic autoantibodies, play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis

of SLE (97). The low

concordance rate of SLE among monozygotic twins indicates that

epigenetic regulation is critically involved in the development of

SLE (98). In recurrent SLE twin

pairs, interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in B-cells exhibit

hypomethylation, whereas key upstream regulators such as TNF

and EP300 are hypermethylated (98). Similarly, the persistent

hypomethylation of CpG sites within ISGs has been observed in SLE

patient B-cells (99). Fali

et al (100) reported

that DNA hypomethylation in SLE B-cells leads to the overexpression

of HRES1/p28, being associated with disease activity. Furthermore,

compared with healthy children and adult patients with SLE, B-cells

from pediatric patients with SLE display a distinctive chromatin

accessibility landscape, with increased accessibility at non-coding

genomic regions that regulate inflammatory activation, indicating

that epigenetic dysregulation-induced aberrant expression of

regulatory elements controlling B-cell activation plays a critical

role in the pathogenesis of pediatric SLE (101). In a murine model, the adoptive

transfer of B-cells treated with a DNMT1 inhibitor into syngeneic

mice resulted in increased antinuclear antibody production

(102). Conversely, the

deficiency of the demethylases Tet2 and Tet3 leads to

hyperactivation of lymphocytes and spontaneous SLE-like

autoimmunity (103).

Mechanistically, Tet2 and Tet3 remove methylation marks and

cooperate with HDAC1/2-mediated deacetylation to suppress

Cd86 expression upon self-antigen engagement, thereby

preventing excessive autoreactive B-cell activation (103). Collectively, these studies

demonstrate that alterations in B-cell DNA methylation are closely

linked to the pathogenesis of SLE.

In addition to DNA methylation, the dysregulation of

histone methylation and acetylation critically contributes to the

pathogenesis of SLE. During B-cell activation, T-helper

cell-derived co-stimulatory signals upregulate the histone

demethylases KDM4A and KDM4C, coincident with global reductions in

H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 levels (104). These demethylases cooperate

with NF-κB p65 to target and activate WDR5, which mediates H3K4

methylation at cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKN) gene

loci, thereby restraining excessive B-cell proliferation (104). In B-cells from patients with

SLE, the downregulation of KDM4A/C and WDR5,

accompanied by reduced CDKN expression, is associated with

heightened B-cell activation and proliferation (104). Moreover, in a previous study,

the overexpression of the HMT EZH2 was observed in peripheral blood

B-cells and leukocytes from patients with SLE (105). The inhibition of EZH2 with

3-deazaneplanocin A in MRL/lpr mice reduced splenocyte H3K27me3

levels, attenuated anti-dsDNA antibody production and ameliorated

lupus-like pathology (105).

Compared with healthy donors, B-cells from patients with SLE

exhibit the hypoacetylation of histones H3 and H4 (106). The expression and enzymatic

activity of the histone deacetylases HDAC6 and HDAC9 are markedly

upregulated in B-cells from MRL/lpr mice relative to control mice

(107). Moreover, the loss of

histone acetyltransferase activity from a single Ep300

allele in mouse B-cells leads to the development of an autoimmune

disease that closely resembles the pathological features of SLE

(108). In the area of

chromatin remodeling, the literature search performed for the

present review identified no available studies to date that have

reported alterations in chromatin-remodeling complexes in B-cells

and their associations with SLE and other autoimmune diseases.

Further investigations in this area are thus warranted (7).

The dysregulated expression of miRNAs in B-cells

also contributes to autoimmune pathogenesis. In patients with SLE,

B-cells exhibit a decreased expression of Lyn, a critical negative

regulator of B-cell activation (109). miR-30a specifically targets Lyn

mRNA through the binding to the 3' untranslated region (3'-UTR),

and the observed upregulation of miR-30a in SLE B-cells is strongly

associated with a decreased expression of Lyn and subsequent B-cell

hyperactivation (109). EBF1

promotes B-cell activation and proliferation via the activation of

the AKT signaling pathway. However, miR-1246 counteracts this

process by interacting with the 3'-UTR of EBF1 mRNA to mediate its

degradation (110). In SLE

B-cells, the abnormal activation of AKT-p53 signaling downregulates

miR-1246, thereby enhancing EBF1 expression and exacerbating B-cell

activation (110). In MRL/lpr

mice, miR-7 is upregulated and targets PTEN to down-modulate the

PTEN/AKT pathway, thereby driving spontaneous GC formation and the

generation of autoreactive antibody-secreting PCs (111). B6.Sle123 mice, a spontaneous

genetic model of SLE, exhibit an increased expression of miR-21 in

both B- and T-cells, which regulates cellular proliferation and

apoptosis (112). Notably, the

in vivo silencing of miR-21 using tiny seed-targeting LNA

significantly ameliorates splenomegaly, a hallmark autoimmune

manifestation in these mice (112). Research on B/W lupus mice has

revealed elevated miR-15a levels in B-10 cells, being associated

with autoantibody titers (113). Moreover, mice with the

lymphocyte-specific overexpression of the miR-17-92 cluster develop

spontaneous autoimmune manifestations. Mechanistically, the

miR-17-92 cluster drives lymphocyte proliferation and breaks

self-tolerance by directly repressing the pro-apoptotic protein Bim

and the tumor suppressor, PTEN (114).

RA is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder

characterized by progressive synovial inflammation, cartilage

degradation and bone erosion, primarily affecting diarthrodial

joints (115,116). As one of the most prevalent

inflammatory arthropathies, RA affects ~0.5-1% of the global

population (116). Synovial

tissue samples from patients with RA demonstrate prominent

infiltration of B-cells and PCs. Notably, approximately 80% of

patients with well-established RA exhibit characteristic

autoantibodies, such as anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and

rheumatoid factor, highlighting the pivotal role of B-cell-mediated

immunity in the pathogenesis of RA (117).

In an epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) on

patients with RA, 64 differentially methylated CpG sites and six

dysregulated biological pathways were consistently identified in

B-cells across three different replication cohorts (118). Among these, the key B-cell

activation gene CD1C exhibited significant hypermethylation

in B-cells from RA patients (118). B-cells from patients with

early-stage RA also exhibit a decreased expression of DNMT1 and

DNMT3A, concomitant with a global decrease in DNA methylation

(119). Methotrexate (MTX)

treatment partially reversed these epigenetic alterations by

restoring DNMT1 and DNMT3A expression in B-cells (119). In the proteoglycan-induced

arthritis (PGIA) murine model, the promoter hypomethylation-driven

Zbtb38 overexpression in B-cells promotes the progression of

arthritis by suppressing IL-1 receptor 2 expression and inhibiting

key anti-inflammatory pathways (120). Conversely, the administration

of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-azacytidine (AzaC) has

been shown to ameliorate autoimmune arthritis in PGIA mice by

downregulating AID in B-cells, impairing CSR and GC responses, and

reducing IgG1 production (121). As demonstrated in a previous

study, compared with healthy controls, the expression of class I

HDACs was significantly decreased in peripheral blood mononuclear

cells from patients with RA, whereas nuclear HAT activity was

markedly increased (122). This

imbalance resulted in increased acetylation of histone H3 and

upregulation of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby

contributing to the pathogenesis of RA (122).

The dysregulated expression of miRNAs in B-cells

further contributes to the development of RA. In a previous study,

small RNA sequencing revealed the differential expression of 27

miRNAs in B-cells from patients with RA in remission following

treatment with MTX, compared to the healthy controls. The predicted

targets of these miRNAs were enriched in pathways governing B-cell

activation, differentiation, and BCR signaling (123). Compared with healthy controls,

miR-155 (an essential regulator of GC and PC differentiation) is

markedly upregulated in peripheral blood B-cells from patients with

RA (124). In synovial tissue,

miR-155 expression inversely correlates with the transcription

factor PU.1. The inhibition of endogenous miR-155 in RA B-cells

restores PU.1 levels and reduces autoantibody production (124). A high expression of miR-155 has

also been observed in CD14+ synovial cells, where it

downregulates the anti-inflammatory phosphatase SHIP-1 and promotes

the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (125). Conversely, miR-155 inhibition

in RA CD14+ synovial cells has been shown to decrease

TNF-α secretion (125).

Moreover, the genetic deletion of miR-155 prevents collagen-induced

arthritis in mice, identifying miR-155 as a potential therapeutic

target in RA (125).

pSS is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease

characterized by the lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands,

resulting in inflammation and tissue destruction of the salivary

and lacrimal glands, and clinically manifesting as xerostomia (dry

mouth) and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes) (126). Beyond classic exocrine

involvement, pSS often presents with systemic complications,

including interstitial lung disease, renal tubular acidosis,

peripheral neuropathy, as well as hematological abnormalities, such

as cytopenias and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, reflecting

its complex immunopathogenesis (127,128). Emerging evidence implicates

epigenetic dysregulation and B-cell hyperactivity with autoantibody

production as key drivers of pSS. For example, anti-SSA/Ro

antibodies are detected in ~33-74% of cases, and anti-SSB/La

antibodies are detected in 23-52% of cases (128).

Epigenome-wide analyses have demonstrated that DNA

methylation changes in peripheral B-cells of patients with pSS far

exceed those observed in T-cells, with genes involved in B-cell

signaling, inflammation and autoimmunity exhibiting significant

methylation alterations (129).

Specifically, ISGs, including PARP9, IFI44L and

MX1 are markedly hypomethylated in B-cells of patients with

pSS, being associated with their transcriptional upregulation and

B-cell expansion (129,130). In a genome-wide DNA methylation

study of labial salivary gland biopsies, 7,820 differentially

methylated sites associated with disease status were identified,

5,699 hypomethylated and 2,121 hypermethylated, and enrichment

analysis revealed that genes crucial for B-cell differentiation and

function (such as SPI1, CD19, CD79B,

PTPRCAP and TNFRSF13B) were predominantly

hypomethylated, highlighting the pivotal role of B-cell DNA

methylation alterations in pSS (131). Furthermore, in another study,

active histone marks, including H3K4me2, H3K4me3, H3K36me3, H3K9ac

and H3K27ac, were shown to be significantly enriched at promoters

and enhancers harboring Sjögren's syndrome risk variants in B-cells

from patients with pSS, suggesting that epigenetic mechanisms

contribute to the regulation of these promoters and enhancers

(132).

The transcriptome sequencing of B-cell subsets from

patients with pSS has revealed the significant upregulation of the

lncRNA LINC00487 in CD38+IgD+

(immature B-cells), CD38−IgD+ (Bm1 cells),

CD38highIgD+ (pre-GC B-cells) and

CD38±IgD− (MBCs) subsets, with

LINC00487 expression levels being positively associated with

the clinical disease activity score (133). Furthermore, in a previous

study, comparative miRNA expression profiling revealed significant

disparities between B- and T-cells in patients with pSS. Peripheral

B-cells from patients with pSS exhibited the significant

dysregulation of 24 miRNAs, with 11 upregulated and 13

downregulated miRNAs, compared to the healthy controls (134). In both discovery and

independent replication cohorts, miR-30b-5p, miR-222-3p,

miR-19b-3p, miR-26a-5p, and miR-378a-3p were consistently

dysregulated (134). Notably,

miR-30b-5p targets the 3'-UTR of BAFF, and its downregulation in

pSS B-cells is associated with BAFF overexpression (134). Elevated BAFF levels have also

been observed in salivary gland-infiltrating B-cells (135). Collectively, these studies

highlight the critical contribution of non-coding RNA dysregulation

in the B-cell-mediated pathogenesis of pSS.

MS is a chronic immune-mediated demyelinating

disorder of the central nervous system (CNS), characterized by

inflammatory lesions, axonal damage and progressive neurological

disability (136,137). Accumulating evidence over the

past decade has demonstrated that B-cells play a pivotal role in

the pathogenesis of MS by producing autoantibodies, presenting

antigens, and secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby

exacerbating damage to the CNS (138,139). An abnormal cytokine profile has

been observed in B-cells from patients with MS, with activated

B-cells exhibiting the excessive production of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, including TNF-α, lymphotoxin and granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor (140,141). Moreover, clinical trials of

B-cell-depleting therapies in relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) have

yielded strikingly positive outcomes, further underscoring the

contribution of B-cells to disease activity (142).

The genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of

T-cells, monocytes and B-cells from patients with RRMS, secondary

progressive MS and healthy controls has revealed a preponderance of

differentially methylated positions (DMPs) in B-cells (143). These DMPs are predominantly

located within genes associated with lymphocyte signaling pathways

(143). In a previous study on

patients with RRMS in remission under various treatments, the

analysis of CD19+ B-cell methylomes identified a large

hypermethylated region encompassing the transcriptional start site

of the lymphotoxin-α (LTA) locus (144). Additionally, four MS-associated

loci, including SLC44A2, LTBR, CARD11 and

CXCR5, exhibited significant methylation changes (144), suggesting that B-cell-specific

DNA methylation, particularly at the LTA locus, may

contribute to the pathogenesis of MS. Moreover, in another study,

an integrative analysis of MS immune-cell GWAS data and

histone-modification profiles revealed that MS genetic risk loci in

B-cells are enriched at active enhancers and promoters marked by

H3K4me1, H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, indicating that MS genetic risk

associations preferentially localize to active enhancer and

promoter regions (145).

The dysregulated expression of miRNAs in B-cells

also influences the progression of MS. In a previous study, the

transcriptomic analyses of peripheral B-cells from untreated

patients with MS revealed the marked downregulation of IRF1

and CXCL10; the suppression of the IRF1/CXCL10 axis may

foster a pro-survival phenotype in these cells (146). Mechanistically, the

upregulation of miR-424 in B-cells of patients mediates the

downregulation of IRF1 and CXCL10 (146). In RRMS lymphocyte subsets,

purified CD19+ B-cells exhibit an increased expression

of miR-497 alongside decreased levels of miR-92, miR-153, miR-135b,

miR-422a and miR-189 relative to healthy volunteers (147). A comprehensive expression

analysis of 1,059 miRNAs in B-cells from healthy volunteers,

treatment-naïve patients with RRMS and natalizumab-treated patients

with RRMS identified 49 differentially expressed miRNAs in

untreated patients compared to healthy volunteers, including

miR-25, miR-19b, miR-106b, miR-93 and miR-181a (148). Target prediction and pathway

analyses indicated that these miRNAs predominantly regulate B-cell

receptor signaling pathway, PI3K pathway, and PTEN pathway

(148). Notably, natalizumab

treatment upregulated 10 miRNAs, including miR-106b, miR-19b and

miR-191 (148). Furthermore,

hyperactivated B-cells in MS secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines,

including TNF-α and lymphotoxin. The elevated expression of miR-132

in these cells enhances TNF-α and lymphotoxin production by

inhibiting SIRT1 activity (149).

T1DM is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized

by the immune-mediated destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic

β-cells, culminating in absolute insulin deficiency (150). Although T-cells have

traditionally been considered the primary mediators of pancreatic

tissue injury, accumulating evidence indicates that B-cells also

contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of T1DM (151). To investigate the influence of

B-cell epigenetic factors on the progression of T1DM, a genome-wide

DNA methylation study was performed on purified B-cells from three

pairs of monozygotic twins discordant for T1DM and six pairs of

unaffected monozygotic twins. This analysis identified 88 CpG sites

with altered methylation in B-cells from the T1DM-affected twins

(152). Functional enrichment

analysis revealed that genes harboring these differentially

methylated sites are predominantly involved in immune-response

pathways (152). In a separate

investigation involving 52 pairs of monozygotic twins discordant

for T1DM, methylation profiling at 406,365 CpG sites in B-cells,

monocytes, and CD4+ T-cells uncovered multiple

cell-type-specific differentially variable positions (DVPs) related

to cell-cycle control and metabolic processes in the T1DM-affected

twins compared with their healthy co-twins and unrelated healthy

controls (153). Notably,

significant DVPs were observed at loci encoding the B-cell

transcriptional regulators NRF1 and FOXP1, highlighting a postnatal

role for DNA methylation in the pathogenesis of T1DM (153). Compared with healthy controls,

peripheral blood lymphocytes from individuals with T1D have been

shown to exhibit a significant increase in H3K9me2 at genes

involved in autoimmune and inflammatory pathways (154). These findings indicate that

altered histone methylation at key genomic loci in lymphocytes is

associated with T1DM (154).

Complementary studies in murine models have demonstrated that the

diabetes-protective Idd9.3 locus encodes miRNA-34a, which

impairs B-cell development and maturation by targeting the core

regulatory factor Foxp1, thereby conferring resistance to the onset

of T1DM (155).

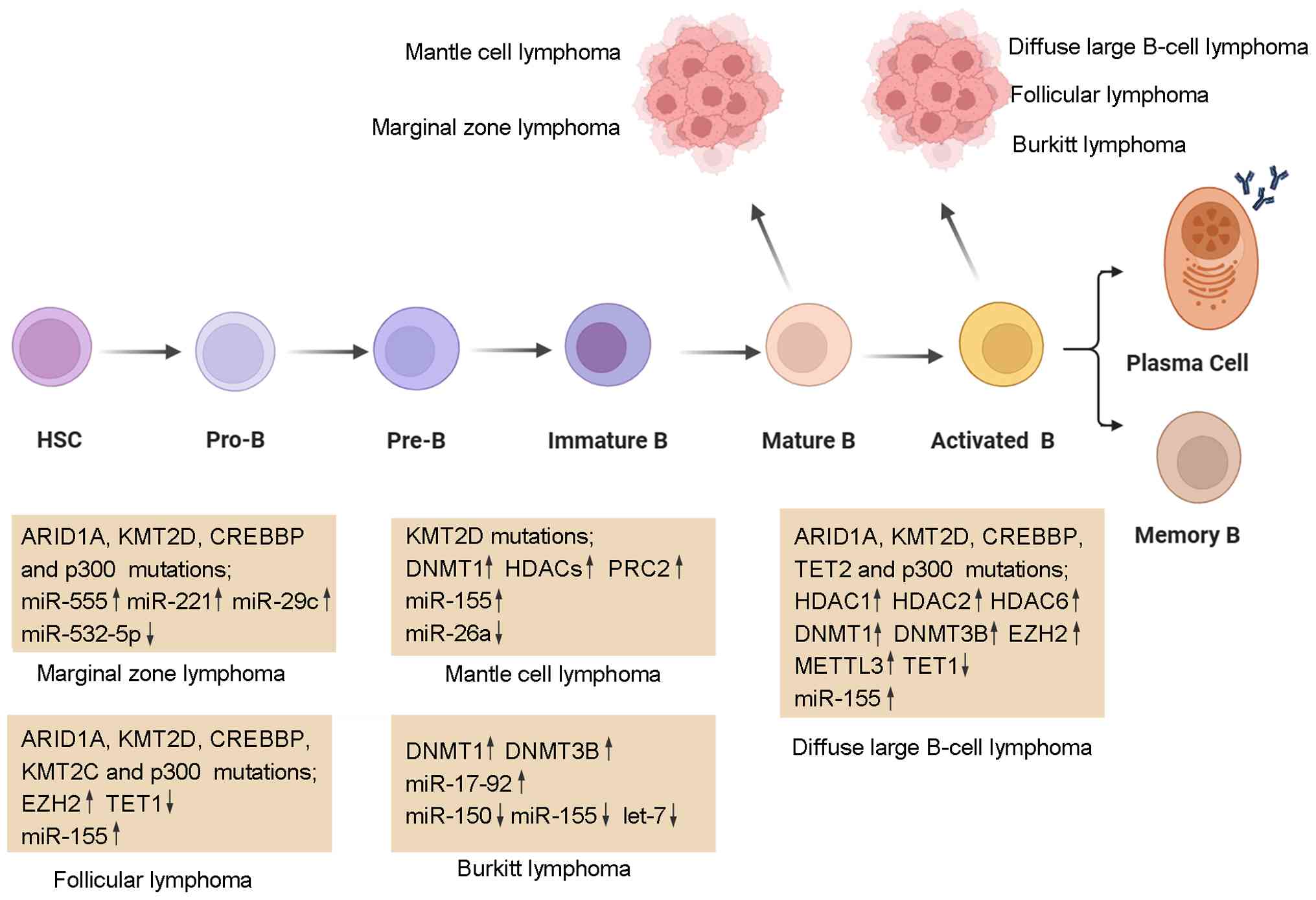

B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) is a highly

heterogeneous malignancy originating from B-cells and accounts for

~85-90% of all lymphoma cases (6). Based on the cell of origin,

molecular characteristics and clinical behavior, B-NHL can be

classified into several distinct subtypes, including DLBCL, FL,

MCL, Burkitt lymphoma (BL) and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL). The

present review focuses on the role of dysregulated epigenetic

mechanisms in the pathogenesis and progression of B-NHL

(illustrated in Fig. 3). The

roles of dysregulated epigenetic enzymes in B-NHL are summarized in

Table SII.

DLBCL is the most common and aggressive subtype of

B-NHL, representing ~30-40% of all B-NHL cases (156,157). Gene expression profiling

further stratifies DLBCL into GC B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL, activated

B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL and unclassified groups (158). Loss-of-function mutations in

the SET domain of histone lysine N-methyltransferase 2D (KMT2D)

represent the most frequent epigenetic abnormality in DLBCL,

occurring in ~30-40% of cases (159,160). Mechanistically, KMT2D

deficiency impairs H3K4 methylation and dysregulates the expression

of specific gene sets, including those involved in JAK-STAT,

Toll-like receptor, CD40 and BCR signaling pathways, as well as

tumor suppressors, such as SOCS3, TNFRSF14 and

TNFAIP3 (161).

Consequently, KMT2D mutations promote malignant B-cell

proliferation by disrupting the coordinated activation of B-cell

signaling cascades and the expression of anti-oncogenic regulators

(161). Furthermore,

loss-of-function mutations in the histone acetyltransferases CREBBP

and p300 are found in ~40% of DLBCL cases (159,162). These mutations reduce the

acetylation of BCL6 and p53, thereby perturbing BCL6 inactivation

and p53-mediated tumor suppression and enhancing tumor cell

resistance to DNA damage (163). The overexpression of the HDACs,

HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC6, together with global H4 hypoacetylation,

also contributes to transcriptional repression (164). In particular, HDAC6 plays a

critical role in coping with proteotoxic stress by regulating the

acetylation-dependent stability of the HSP90 and mediating the

binding of misfolded proteins to the dynein motor for transport to

aggresomes (165-167).

Dysregulated DNA methylation further contributes to

the pathogenesis of DLBCL. DNMT1 and DNMT3B are overexpressed in

DLBCL, and are associated with an advanced clinical stage,

therapeutic resistance, and, specifically for DNMT3B, significantly

shorter overall survival and progression-free survival (168). Research has demonstrated that

DNMT1 modulates cell-cycle progression and DNA replication, as

DNMT1 knockdown in GCB-DLBCL cell lines markedly suppresses the

expression of CDK1, CCNA2, E2F2, PCNA,

RFC5 and POLD3 (169). By contrast, the DNA demethylase

TET2 functions as a tumor suppressor and harbors loss-of-function

mutations in DLBCL (170).

Murine models demonstrate that the knockout of Tet1 and

Tet2 promotes the development of DLBCL (171,172). Moreover, transcriptional

downregulation of TET1 has been observed in patients with

DLBCL and FL (173). EZH2, the

catalytic subunit of PRC2, is overexpressed in >70% of

aggressive B-cell lymphomas and is associated with high

proliferation rates (174).

Furthermore, gain-of-function mutations of EZH2 (most frequently at

Y641 and A677) are predominate in GC-type DLBCL and FL (175). Moreover, a mutation of EZH2

promotes the growth of GC-type DLBCL by recruiting PRC2 to silence

PRDM1 (176).

Recent evidence has also highlighted dysregulated

RNA methylation and miRNAs in DLBCL. The

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) 'writer'

METTL3 and global m6A levels are upregulated in DLBCL

tissues and cell lines, and METTL3 knockdown inhibits proliferation

by reducing m6A modification of pigment

epithelium-derived factor mRNA, thereby impairing DLBCL progression

(177). The miR-17-92 cluster

is overexpressed in DLBCL and FL. Mechanistically, overexpressed

miR-17-92 cooperates with c-MYC to promote B-cell lymphoma growth

by enhancing lymphoma cell proliferation and suppressing apoptosis

(178,179). In a previous study, the

analysis of miRNA profiles from 58 DLBCL cases revealed that,

compared to normal tissues, miR-155, miR-210, miR-106a, and

miR-17-5p were significantly upregulated, whereas miR-95, miR-150,

miR-139, miR-145, miR-149, miR-328, miR-10a, miR-99a, miR-320,

miR-151 and let-7e were downregulated (180). Notably, miR-155 plays a crucial

role in the pathogenesis of DLBCL by inhibiting apoptosis and

promoting cell proliferation through the activation of the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway (181).

FL, the second most common subtype of B-NHL,

accounts for ~25% of all B-NHL cases. FL originates from GC B-cells

and is characterized by the t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation, which leads

to the overexpression of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2

(182). Among the KMT2 family

members, KMT2D and KMT2C have been implicated in the pathogenesis

of FL (183,184). Of note, ~72% of patients with

FL harbor KMT2D mutations, the majority of which are nonsense or

frameshift alterations resulting in reduced KMT2D protein

expression (183). In addition,

gain-of-function mutations in EZH2 are observed in ~7.2% of FL

cases (185). Mechanistically,

mutant EZH2 drives FL initiation by epigenetically reprogramming

B-cells and remodeling the immune microenvironment: It promotes the

follicular dendritic cell (FDC)-mediated replacement of T-cell

help, thereby facilitating the gradual expansion of GC B-cells

(186). CREBBP is also

recurrently mutated in over 50% of FL cases (163). In a Bcl2-overexpressing

mouse model, GC-specific Crebbp deletion accelerates FL

development (187). Mutations

in the SWI/SNF complex subunit ARID1A reduce RUNX3

expression, resulting in decreased RUNX3/ETS1-driven FAS

transcription (188). The

consequent downregulation of FAS renders FL cells resistant to FAS

ligand-induced apoptosis (188). The comparative profiling of

miRNA expression in FL and DLBCL vs. normal lymph nodes has

revealed the overexpression of miR-155, miR-106a, miR-149, miR-210

and miR-139 in both malignancies. Notably, miR-20a/b and miR-194

are selectively upregulated in FL; these miRNAs enhance tumor cell

proliferation and survival by targeting CDKN1A and

SOCS2, respectively (189).

Epigenetic dysregulation also plays a pivotal role

in the pathogenesis of MCL. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling

has revealed highly heterogeneous methylation patterns in MCL tumor

tissues compared with normal lymphoid counterparts. Specifically,

WNT pathway inhibitors and several tumor suppressor genes show

significant hypermethylation (195). Moreover, DNMT1 is upregulated

in MCL, and treatment with arsenic trioxide inhibits WNT/β-catenin

signaling and reduces DNMT1 levels, thereby inducing apoptosis and

attenuating proliferation in MCL cell lines (196). Hypomethylation within the

downstream region of the SOX11 oncogene has been identified

in MCL tumors, suggesting that epigenetic mechanisms may regulate

SOX11 expression (197).

Histone modifications further contribute to MCL

biology. HDACs are overexpressed in MCL, and pharmacologic HDAC

inhibition induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in these cells

(198,199). KMT2D is among the most

frequently mutated genes in both DLBCL and MCL (200). Loss-of-function KMT2D mutations

reduce H3K4 methylation and drive neoplastic proliferation in MCL

(201). Furthermore, the PRC2

complex is overexpressed in MCL cell lines, promoting tumor-cell

proliferation and survival by epigenetically silencing the

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene CDKN2B (202).

miRNAs provide an additional layer of epigenetic

regulation in MCL. A study of the miRNA expression profiles in 30

patients with MCL revealed that, compared to normal B-cells, 18

miRNAs were significantly downregulated and 21 miRNAs were

significantly upregulated in MCL tissues (203). Notably, miR-142-3p/5p,

miR-29a/b/c and miR-150 were significantly downregulated, whereas

miR-155 and miR-124a were markedly upregulated (203). A separate study reported that

miR-26a, miR-31, miR-27b and miR-148a were significantly

downregulated, whereas miR-370, miR-617 and miR-654 were

upregulated in MCL tissues compared to reactive lymphoid tissues.

Notably, MAP3K2 (a predicted target of miR-26a) was upregulated in

MCL tissues and plays a crucial role in the activation of the

alternative NF-κB pathway (204).

BL is a GC-derived B-NHL, accounting for ~1-5% of

all NHL cases. BL is characterized by MYC dysregulation secondary

to chromosomal translocations such as t(8;14) (q24;q32). Overexpression of DNA

methyltransferases DNMT1 and DNMT3B has been observed in primary BL

specimens, and treatment of BL cell lines with the DNMT inhibitor

5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine significantly inhibits cellular

proliferation by reducing the protein levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3B

(205). miR-155 expression is

significantly downregulated in BL, where it binds to the 3'-UTR of

AID mRNA, promoting its degradation and thereby suppressing

AID-mediated MYC-IGH translocations (206). miR-150 is also downregulated in

BL and directly targets c-Myb and Survivin (207). The re-expression of miR-150 in

the Raji cell line has been shown to diminish cell proliferation,

suggesting that miR-150 may serve as a potential therapeutic target

of BL (207). Compared with

other types of NHL, BL exhibits the upregulation of the miR-17-92

cluster and the downregulation of let-7 family miRNAs, miR-146a,

miR-155 and the miR-29 family (208). In addition, reduced levels of

let-7 family, miR-132, miR-125b-1 and miR-154 contribute to

increased expression of MYC and other oncogenes in BL (209).

MZL accounts for ~5-15% of all B-NHL. It can be

subdivided into three distinct subtypes: Extranodal marginal zone

lymphoma (EMZL), splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) and nodal

marginal zone lymphoma (NMZL) (210). EMZL represents >60% of MZL

cases and is associated with chronic inflammation triggered by

autoimmune disorders or infectious agents. This subtype is

characterized by recurrent genetic translocations, including

t(11;18)(p21;q21) in API2-MALT1, t(14;18)(p32;q21) in IGH-MALT1 and

t(1;14) (p22;q32) in BCL10-IGH, which

collectively drive transcriptional dysregulation of BCL10,

MALT1 and FOXP1 (211-213). By contrast, these

translocations are not detected in NMZL and SMZL (210). However, NMZL and SMZL share

recurrent somatic mutations in KMT2D, NOTCH2, PTPRD, TNFAPI3

and KLF2 (214).

Epigenetic alterations play a critical role in the

pathogenesis of MZL. In SMZL, frequent mutations occur in chromatin

regulators, such as KMT2D, ARID1A, p300 and CREBBP (215). The genome-wide methylation

profiling of SMZL has revealed hypermethylation and the

transcriptional silencing of multiple tumor suppressors

(KLF4, DAPK1, CDKN1C, CDKN2D and

CDH1/2) alongside hypomethylation and overexpression of

oncogenes in the NF-κB, AKT/PI3K, BCR and IL-2 signaling pathways

(216). Compared with reactive

lymphoid hyperplasia, NMZL exhibits the upregulation of miR-555,

miR-221 and miR-29c, and the downregulation of miR-532-5p.

Predicted targets of miR-555 and miR-221 include CD10 and LMO2,

respectively, whereas miR-532-5p targets BCR-related kinases, such

as SYK and LYN, the overexpression of which is associated with

enhanced tumor cell proliferation (217).

Epigenetic modifications are dynamic and

reversible, and serve as valuable biomarkers in B-cell-mediated

autoimmune diseases and lymphomas (summarized in Table SIII). Alterations in DNA

methylation, histone modification and non-coding RNAs contribute to

disease classification, prognosis and to the prediction of the

therapeutic response (218). In

SLE, B-cells exhibit global hypomethylation, particularly at

interferon-related genes such as IFI44L, PARP9 and MX1, which are

strongly associated with disease activity (219). Additional regulators involved

in inflammatory and chromatin networks also display aberrant

epigenetic states (220). In

patients with SLE, defective DNA methylation in B-cells leads to

the overexpression of the endogenous retrovirus HRES1/p28, with the

dysregulation of the Erk/DNMT1 signaling pathway and autocrine IL-6

signaling playing key roles (100). Notably, intervention with

anti-IL-6 receptor antibodies can restore DNA methylation and

effectively suppress HRES1/p28 expression, providing a novel

therapeutic strategy for the disease. At the miRNA level, miR-30a

upregulation promotes B-cell activation by suppressing Lyn

(109), whereas reduced

miR-1246 increases EBF1 expression and enhances AKT signaling,

promoting B-cell activation and proliferation (110). In pSS, B-cells display

widespread methylome and transcriptome dysregulation affecting

inflammatory and B-cell signaling pathways, including ISGs; the

hypomethylation of PARP9, IFI44L and MX1 is associated with B-cell

expansion (221,222). The downregulation of miR-30b-5p

contributes to the excess expression of BAFF.

In RA, EWAS analyses have identified multiple

differentially methylated loci with biomarker potential (223). Early-stage RA is characterized

by decreased DNMT1/3A expression and global hypomethylation, while

MTX may partially restore methylation patterns and predict

treatment response (119). The

upregulation of miR-155 enhances autoantibody production by

suppressing PU.1, contributing to pathogenic B-cell responses

(124). In MS, B-cell

methylation alterations are prominent. Patients with RRMS exhibit

differential methylation, including the hypermethylation of the

IL2RA promoter and changes at SLC44A2, LTBR, CARD11, and CXCR5,

implicating epigenetic regulation in disease susceptibility and

progression (224). Upregulated

miR-424 suppresses the IRF1-CXCL10 pathway and promotes a survival

phenotype, whereas miR-132 enhances TNF-α and lymphotoxin

expression by targeting SIRT1, strengthening inflammatory B-cell

responses (146,149).

Recent studies have identified two prognostic

molecular signatures in DLBCL: A six-gene m6A regulator

signature (ALKBH5, FMR1, HNRNPC, RBM15B, YTHDC2 and YTHDF1) and an

eight-gene mitochondria-related signature (PCK2, PUSL1, ACP6, PDK4,

ALDH4A1, C15orf61, THNSL1 and COX7A1) (225,226). Both signatures demonstrated

potent prognostic performance, stratifying patients into high- and

low-risk groups with distinct survival patterns, immune

infiltration characteristics, and predicted responses to

immunotherapy. These findings underscore the prognostic relevance

of m6A regulation and mitochondrial metabolism in DLBCL,

and provide promising biomarkers for precision risk assessment and

therapeutic guidance. The overexpression of DNMT3B predicts a poor

survival, whereas the loss of TET2 disrupts AID-mediated DNA

demethylation in GC B-cells, resulting in aberrant DNA

hypermethylation that alters gene regulation and promotes

lymphomagenesis (168,227).

In FL, gain-of-function EZH2 mutations (such as

Y641) reprogram GC B-cells by reducing their dependence on

T-follicular helper cells, promoting centrocyte survival and slow

expansion within FDC networks, thereby establishing an aberrant

immunological niche that underlies indolent tumor growth (186). Concurrently, the epigenetic

dysregulation of GC B-cells through mutations in KMT2D and CREBBP

perturbs transcriptional programs controlling proliferation,

differentiation and microenvironment interactions, contributing to

malignant transformation and immune niche remodeling (228). Collectively, these epigenetic

alterations highlight critical mechanisms by which GC B-cells

evolve into FL and provide potential targets for

microenvironment-focused therapeutic strategies. In MCL,

integrative DNA methylome analyses reveal widespread epigenetic

heterogeneity with hypermethylation of B-cell-unrelated regions and

recurrent hypomethylated differentially methylated regions

associated with SOX11, suggesting that epigenetic

reprogramming of distal regulatory elements contributes to

tumorigenesis and clinical behavior (197).

Epigenetic regulatory pathways provide multiple

druggable targets for B-cell-associated autoimmune diseases and

B-cell lymphomas, and several inhibitors have already entered

clinical use or advanced stages of clinical development (summarized

in Table SIII). Mutations in

EZH2 are observed in ~22% of GC-derived lymphomas, including FL and

DLBCL (175). The FDA-approved

EZH2 inhibitor, tazemetostat, has demonstrated clinical activity in

patients with EZH2 mutant relapsed or refractory FL

(229,230). An open-label, single-arm, phase

II clinical trial reported that oral tazemetostat administered at

800 mg twice daily achieved an objective response rate of 69% in

the EZH2 mutant cohort vs. 35% in the EZH2 wild-type

cohort (230). Moreover, in

GC-DLBCL cases that are insensitive to EZH2 inhibition, combination

therapeutic approaches targeting compensatory pathways, for

example, the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, have shown promise

in preclinical models (231).

KMT2D loss-of-function mutations represent another major alteration

in GC-derived lymphomas (159).

Haploinsufficiency of KMT2D disrupts H3K4 methylation at

enhancers, resulting in global impairment of enhancer activity and

consequent dysregulation of genes involved in differentiation and

immune regulation (161).

Preclinical studies have shown that pharmacological inhibition of

members of the KDM5 family of H3K4 demethylases, which functionally

antagonize KMT2D, can restore H3K4 methylation levels and suppress

tumor growth in KMT2D-mutant models (232). However, as KDM5 family members

exhibit significant functional redundancy, therapeutic efficacy may

require the simultaneous inhibition of multiple paralogs (232). CREBBP alterations impair

histone acetylation at enhancers and promoters that regulate genes

involved in immune responses and cellular differentiation (233). Mechanistic analyses have

indicated that CREBBP loss creates a dependency on class I histone

deacetylase activity, notably HDAC3 (233). The selective inhibition of

HDAC3 reverses the epigenetic reprogramming induced by CREBBP

mutations, restores the expression of tumor-suppressor and

antigen-presentation genes, and demonstrates anti-B-cell lymphoma

activity in preclinical models (233,234). In addition, combination

regimens pairing the pan-HDAC inhibitor vorinostat with rituximab

(a monoclonal antibody targeting CD20) have improved outcomes in

patients with B-cell lymphoma (235). Moreover, in vitro

research has demonstrated that the PRC2 inhibitor, pyrroloquinoline

quinone, exerts potent inhibitory effects on the proliferation of

B-cell lymphoma cells (236).

The aberrant expression of HDACs plays a crucial

role in the development of autoimmune diseases, and inhibitors

targeting HDACs have shown immense promise in the treatment of

these disorders (237,238). Compared with age-matched

control mice, MRL/lpr lupus model mice exhibit an elevated

expression and activity of HDAC6 and HDAC9 during both the early

and late stages of disease (107). Preclinical studies have

demonstrated that the HDAC6-selective inhibitor, ACY-738, suppress

multiple B-cell activation pathways, reduces PC formation and

attenuates GC responses in lupus-prone mice (238,239). Treatment with the DNMT

inhibitor, 5'-azacytidine, an FDA-approved anticancer agent,

induces hypomethylation of the Ahr gene, downregulates

Aicda expression, attenuates GC responses and diminishes

IgG1 production, ultimately leading to marked amelioration of

RA-like disease in mice (121).

Taken together, these findings establish a strong rationale for

developing novel epigenetic therapies in autoimmune diseases and

lymphomas.

B-cells allow response against a large number of

antigens from various pathogens and confer the important feature of

immune memory. Extensive research has shown that DNA methylation,

post-translational histone modifications, and miRNAs together

constitute the epigenetic landscape governing B-cell

differentiation and function. Technological advances, particularly

in single-cell transcriptomics, whole-genome bisulfite sequencing

and next-generation sequencing, have greatly deepened our

understanding of these regulatory mechanisms during B-cell

development and differentiation. Specifically, distinct B-cell

subsets exhibit dynamic epigenetic profiles, while immature B-cells

display genome-wide DNA hypermethylation and histone deacetylation,

whereas activated B-cells exhibit elevated histone lysine

methylation. Dysregulation of epigenetic modifications frequently

contributes to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases and

lymphomas.

Over the past decades, high-throughput sequencing

approaches have provided extensive insights into the mechanisms

through which epigenomic dysregulation contributes to

B-cell-mediated autoimmunity and lymphomagenesis. Aberrant DNA

methylation patterns, altered histone-modifying enzyme activities,

and imbalances in miRNA and lncRNA expression act in concert to

promote autoreactive B-cell expansion, pathogenic autoantibody

production and pro-inflammatory cytokine release, thereby

facilitating malignant transformation. Unlike irreversible genetic

mutations, epigenetic modifications are reversible and thus

represent attractive therapeutic targets. Preclinical and clinical

evidence demonstrates that selective inhibitors targeting these

epigenetic enzymes, such as EZH2 inhibitors, KDM5 inhibitors,

HDAC3/HDAC6 inhibitors and DNMT inhibitors, can restore normal

epigenetic landscapes, suppress malignant B-cell proliferation,

attenuate autoimmune responses, and improve disease outcomes

(121,229,232,234). Moreover, combination strategies

that integrate epigenetic modulators with chemotherapeutic agents

or therapies targeting compensatory pathways further enhance

therapeutic efficacy and overcome resistance mechanisms (231,240). These findings collectively

provide a strong rationale for the continued development and

clinical translation of epigenetic therapies, highlighting their

promise as precision interventions for both B-cell malignancies and

autoimmune disorders.

The pathogenesis of B-cell-derived autoimmune

diseases and lymphomas involves complex interactions among genetic,

epigenetic and microenvironmental factors. Although significant

progress has been made in elucidating epigenetic contributions,

further studies are required to define the precise molecular events

that drive disease initiation and progression. Future efforts

integrating multi-omics analyses, single-cell sequencing and

spatial epigenomics will be critical for elucidating these

mechanisms. Moreover, the identification of reliable biomarkers is

essential for early diagnosis and the development of targeted

therapies. The comprehensive characterization of B-cell epigenetic

landscapes using high-throughput technologies will accelerate

biomarker discovery and facilitate personalized treatment

strategies in B-cell autoimmune diseases and lymphomas.

Not applicable.

YL, YG and JZ wrote the manuscript. RR provided the

overall concept and framework of the manuscript and revised it. All

authors have read and agreed to the published version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Gansu Province University

Teacher Innovation Fund Project (grant no. 2025A-052), the Youth

Science Fund of Lanzhou Jiaotong University (grant no. 1200061323),

Peking University Medicine Sailing Program for Young Scholars'

Scientific and Technological Innovation (grant no.

BMU2025YFJHPY035), and the Fundamental Research Funds for Central

Universities.

|

1

|

Pieper K, Grimbacher B and Eibel H: B-cell

biology and development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 131:959–971. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hardy RR, Kincade PW and Dorshkind K: The

protean nature of cells in the B lymphocyte lineage. Immunity.

26:703–714. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jensen CT, Strid T and Sigvardsson M:

Exploring the multifaceted nature of the common lymphoid progenitor

compartment. Curr Opin Immunol. 39:121–126. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Suan D, Sundling C and Brink R: Plasma

cell and memory B cell differentiation from the germinal center.

Curr Opin Immunol. 45:97–102. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kaliman P: Epigenetics and meditation.

Curr Opin Psychol. 28:76–80. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Silkenstedt E, Salles G, Campo E and

Dreyling M: B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Lancet. 403:1791–1807.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mu S, Wang W, Liu Q, Ke N, Li H, Sun F,

Zhang J and Zhu Z: Autoimmune disease: A view of epigenetics and

therapeutic targeting. Front Immunol. 15:14827282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ghafouri-Fard S, Khoshbakht T, Hussen BM,

Taheri M and Jamali E: The emerging role non-coding RNAs in B

cell-related disorders. Cancer Cell Int. 22:912022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sermer D, Pasqualucci L, Wendel HG,

Melnick A and Younes A: Emerging epigenetic-modulating therapies in

lymphoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 16:494–507. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gamarra N and Narlikar GJ: Collaboration

through chromatin: Motors of transcription and chromatin structure.

J Mol Biol. 433:1668762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zheng H and Xie W: The role of 3D genome

organization in development and cell differentiation. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 20:535–550. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zaret KS: Pioneer Transcription factors

initiating gene network changes. Annu Rev Genet. 54:367–385. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Klemm SL, Shipony Z and Greenleaf WJ:

Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat Rev

Genet. 20:207–220. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chiarella AM, Lu D and Hathaway NA:

Epigenetic control of a local chromatin landscape. Int J Mol Sci.

21:9432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nodelman IM and Bowman GD: Biophysics of

chromatin remodeling. Annu Rev Biophys. 50:73–93. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tan T, Shi P, Abbas MN, Wang Y, Xu J, Chen

Y and Cui H: Epigenetic modification regulates tumor progression

and metastasis through EMT (review). Int J Oncol. 60:702022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lorch Y and Kornberg RD:

Chromatin-remodeling for transcription. Q Rev Biophys. 50:e52017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tanny JC: Chromatin modification by the

RNA polymerase II elongation complex. Transcription. 5:e9880932014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Moore LD, Le T and Fan G: DNA methylation

and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 38:23–38. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

López-Moyado IF, Ko M, Hogan PG and Rao A:

TET enzymes in the immune system: From DNA demethylation to

immunotherapy, inflammation, and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol.

42:455–488. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gigek CO, Chen ES and Smith MA:

Methyl-CpG-binding protein (MBD) family: Epigenomic read-outs

functions and roles in tumorigenesis and psychiatric diseases. J

Cell Biochem. 117:29–38. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kouzarides T: Chromatin modifications and

their function. Cell. 128:693–705. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Shvedunova M and Akhtar A: Modulation of

cellular processes by histone and non-histone protein acetylation.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 23:329–349. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sabari BR, Zhang D, Allis CD and Zhao Y:

Metabolic regulation of gene expression through histone acylations.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 18:90–101. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

25

|

Jambhekar A, Dhall A and Shi Y: Roles and

regulation of histone methylation in animal development. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 20:625–641. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mattiroli F and Penengo L: Histone

ubiquitination: An integrative signaling platform in genome

stability. Trends Genet. 37:566–581. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Oss-Ronen L, Sarusi T and Cohen I: Histone

mono-ubiquitination in transcriptional regulation and its mark on

life: Emerging roles in tissue development and disease. Cells.

11:24042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lim PS, Li J, Holloway AF and Rao S:

Epigenetic regulation of inducible gene expression in the immune

system. Immunology. 139:285–293. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Su N, Yu X, Duan M and Shi N: Recent

advances in methylation modifications of microRNA. Genes Dis.

12:1012012023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Saliminejad K, Khorram Khorshid HR,

Soleymani Fard S and Ghaffari SH: An overview of microRNAs:

Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J Cell

Physiol. 234:5451–5465. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Nguyen TA, Park J, Dang TL, Choi YG and

Kim VN: Microprocessor depends on hemin to recognize the apical

loop of primary microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:5726–5736. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wilson RC, Tambe A, Kidwell MA, Noland CL,

Schneider CP and Doudna JA: Dicer-TRBP complex formation ensures

accurate mammalian MicroRNA biogenesis. Mol Cell. 57:397–407. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fareh M, Yeom KH, Haagsma AC, Chauhan S,

Heo I and Joo C: TRBP ensures efficient Dicer processing of

precursor microRNA in RNA-crowded environments. Nat Commun.

7:136942016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bartel DP: Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell.

173:20–51. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Abdelfattah AM, Park C and Choi MY: Update

on non-canonical microRNAs. Biomol Concepts. 5:275–287. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Fabian MR, Sonenberg N and Filipowicz W:

Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev

Biochem. 79:351–379. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Coyle MC and King N: The evolutionary

foundations of transcriptional regulation in animals. Nat Rev

Genet. 26:812–827. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen LL and Kim VN: Small and long

non-coding RNAs: Past, present, and future. Cell. 187:6451–6485.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Winkle M, Kluiver JL, Diepstra A and van

den Berg A: Emerging roles for long noncoding RNAs in B-cell

development and malignancy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 120:77–85.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Carninci P,

Carpenter S, Chang HY, Chen LL, Chen R, Dean C, Dinger ME,

Fitzgerald KA, et al: Long non-coding RNAs: Definitions, functions,

challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:430–447.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL and Huarte M:

Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological

functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:96–118. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Gail EH, Healy E, Flanigan SF, Jones N, Ng

XH, Uckelmann M, Levina V, Zhang Q and Davidovich C: Inseparable

RNA binding and chromatin modification activities of a