Introduction

Autoimmune diseases, once considered rare, now

affect a substantial proportion of the global population and arise

from a breakdown of immune tolerance, whereby adaptive and innate

responses fail to discriminate self from non-self (1). While inherited risk loci explain

part of disease susceptibility, mounting evidence implicates

epigenetic mechanisms, heritable yet reversible changes in gene

regulation, including DNA methylation, histone modifications and

non-coding RNAs, as key determinants of pathogenic immune programs

(2,3). These mechanisms are metabolically

gated: The one-carbon (folate) network supplies methyl groups for

DNA and histone methylation, thereby coupling nutrient status to

chromatin state and immune function (4). This metabolic-epigenetic axis

carries out a central role in integrating environmental factors,

nutrition and cellular stress responses, thereby shaping

immune-system development across the lifespan.

Within this network, methylenetetrahydrofolate

reductase (MTHFR) reduces 5,10-methylene-THF to 5-methyl-THF,

enabling remethylation of homocysteine to methionine and sustaining

S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor. Common

MTHFR variants 677C>T and 1298A>C lower enzymatic flux

to varying degrees and, particularly under low folate conditions,

are associated with hyperhomocysteinemia and reduced methylation

capacity (5-8). Beyond genetics, emerging research

indicates that MTHFR itself is subject to epigenetic

regulation (promoter methylation, chromatin context, microRNAs and

lncRNAs) (9-12), positioning the enzyme both as a

modulator and as a target within the metabolism-epigenome

interface. This dual role underscores why MTHFR alterations

can propagate broadly across the immune, vascular and neurological

systems, especially in environments of chronic inflammation or

increased methylation demand.

The research landscape shows convergent epigenetic

phenotypes across immune-mediated conditions, for example, synovial

and T-cell hypomethylation in rheumatoid arthritis (RA),

interferon-driven signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE),

mucosal (and saliva-detectable) alterations in celiac disease (CeD)

and therapy-responsive methylomes in multiple sclerosis (MS)

(2,3,13,14). These findings are consistent with

constraints on methyl-group availability and inflammation-linked

suppression of the methylation machinery (2,3).

Yet key controversies remain. First, associations between

MTHFR variants and autoimmunity are heterogeneous across

ancestries and clinical phenotypes and appear conditional on

environmental factors (dietary folate/B-vitamin status) and

medications (such as methotrexate; MTX) (5-8).

Second, the direction of causality is debated: Epigenetic

abnormalities may be primary drivers, secondary consequences of

inflammation and treatment or both and locus-resolved evidence in

primary immune cells for MTHFR regulation is still limited.

Moreover, the majority of existing studies examine isolated

components of the pathway (2,15-17), highlighting the need for

integrative analyses that jointly evaluate genetic variants,

methylation capacity, inflammatory signaling and nutrient

availability.

The present review synthesizes current literature on

the folate-MTHFR-SAM axis as a modulator of epigenetic

stability in autoimmune disease. Specifically, the present review

i) summarizes epigenetic regulation of MTHFR (DNA

methylation, histone marks and non-coding RNAs); ii) outlines

one-carbon biochemistry and gene-nutrient interactions that tune

methylation capacity; iii) integrates disease-specific epigenomic

findings across RA, SLE, MS, CeD and fibromyalgia (FM); and iv)

discusses translational implications for biomarkers and

nutritionally informed or epigenetic adjuncts to immunotherapy. The

present review highlights areas of agreement and active debate and

delineates priorities for cell type-resolved and mechanism-anchored

studies. By doing so, the present review aims to bridge molecular

insights relevant to autoimmune diseases, emphasizing how

folate-dependent epigenetic regulation can contribute both to

disease-risk stratification and to the development of personalized

therapeutic strategies.

Literature search

For the present review, a literature search was

performed in the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and PubMed Central

(PMC) (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

databases using topics and subtopics associated with the role of

one-carbon metabolism (such as MTHFR, folate and homocysteine),

epigenetic mechanisms (such as DNA methylation and histone

modification) and their impact on autoimmune diseases such as RA,

SLE, MS, cEd and FM. The reviewed publications included mechanistic

studies, clinical trials and systematic reviews involving human

subjects that report relevant findings on direct epigenetic

evidence (such as DNA methylation levels), biochemical markers or

clinical outcomes associated with disease activity and therapeutic

response.

Folates

History and discovery

In 1931, studies investigating anemia during

pregnancy identified nutritional deficiency as a key etiological

factor. Experimental work by Wills and Stewart (18) demonstrated that supplementation

with yeast extract (Marmite®) or animal protein could

reverse severe anemia in animal models. These findings led to the

identification of an unknown nutritional factor distinct from

vitamin B2, called the 'Wills factor', which was later

recognized as folate (18-21).

In 1941, Mitchell et al (21) published the first study

describing the concentration of folic acid, a compound named after

the Latin word folium (leaf). Their study revealed that folic acid

was capable of promoting the proliferation of Lactobacillus

casei, Lactobacillus delbreuckii and Streptococcus

lactis. The isolation of the pure, crystalline form of folic

acid (pteroglutamic acid) was first achieved by Robert Stokstad and

Lederle Laboratories in 1943. This achievement was notable because

it enabled researchers to study the characteristics and properties

of the compound. The utilization of folic acid-fermenting

microorganisms was instrumental in achieving this goal (22).

In 1945, Angier et al (23) determined that the chemical

synthesis of pteroglutamic acid from liver samples (21). This development represented a

pivotal shift in the management of megaloblastic anemias due to the

ability to produce folic acid on a large scale for clinical use

(23).

Although early research on folic acid focused on

treating a specific form of anemia, Kumar (24), was the first to identify key

elements of folic acid metabolism associated with acute

lymphoblastic leukemia in children. This work and its broader

implications have been discussed by Kumar et al (24). Despite recognition of the

essential roles of folate in DNA synthesis and neural tube defect

prevention, its metabolic pathway remained poorly characterized. In

1971, Kutzbach and Stokstad (25) isolated and described the enzyme,

MTHFR, for the first time. The enzyme was found to be subject to

allosteric regulation by SAM, associating it with methionine

metabolism, DNA synthesis, cardiovascular disease and neural tube

defects.

In 1973, Tamura and Stokstad (26) evaluated the bioavailability of

naturally occurring folates compared with five synthetic

derivatives. They observed increased bioavailability for synthetic

folates compared with food sources such as liver, yeast, banana,

orange juice and lettuce. Based on advancements in folate

metabolism research, in 1980, scientists described the 'folate

trap', a phenomenon in which the enzyme methionine synthase (MTR),

in the absence of its cofactor (vitamin B12), is unable

to convert homocysteine into methionine. This traps folate in its

5-methyltetrahydrofolate form and inhibits purine and thymidine

synthesis for DNA, even when folate levels are sufficient (27).

In 1990, Frosst et al (28) identified a C677T polymorphism in

the MTHFR gene that reduced enzyme activity and altered

folate concentrations. Epidemiological evidence accumulated since

the discovery of folate, its sources and bioavailability has served

as a foundation for translating knowledge into preventive and

therapeutic public health strategies. Efforts to fortify food

products with synthetic folic acid have been implemented in several

countries, including the United States, Canada, Argentina, Chile

and others across Europe and Latin America (29). These initiatives have led to

substantial reductions in the prevalence of neural tube defects in

newborns, with decreases ranging from ~25 to >60%, depending on

the country and the specifics of program implementation (13,29). Despite these successes, some

populations may exceed recommended folate intake, underscoring the

importance of careful monitoring. Conversely, countries such as

Mexico and Colombia lack comprehensive surveillance and monitoring

systems to evaluate the impact of mandatory folic acid

fortification on population health (29-31).

Chemical structure

During its discovery, folic acid was assigned

multiple names. One of the most widely recognized designations is

folic acid, although it is more commonly referred to as vitamin

B9 or folate (32-34). The term folate refers to a family

of molecules with similar chemical structures that exert beneficial

effects in various health conditions, ranging from anemia to

cardiovascular diseases, cancer and inflammatory processes

(29,35). The chemical structure of folic

acid (C19H19N7O6) serves as the foundation for the diverse chemical

forms of folates. The structural components of folates can be

categorized as follows: i) A heterocyclic pterin structure in

oxidized or reduced form, consisting of a pyrimidine ring, a

pyrazine ring and a methyl-group at carbon 6 that serves as a

bridge for acid linkage; ii) p-aminobenzoic acid; and iii) a mono

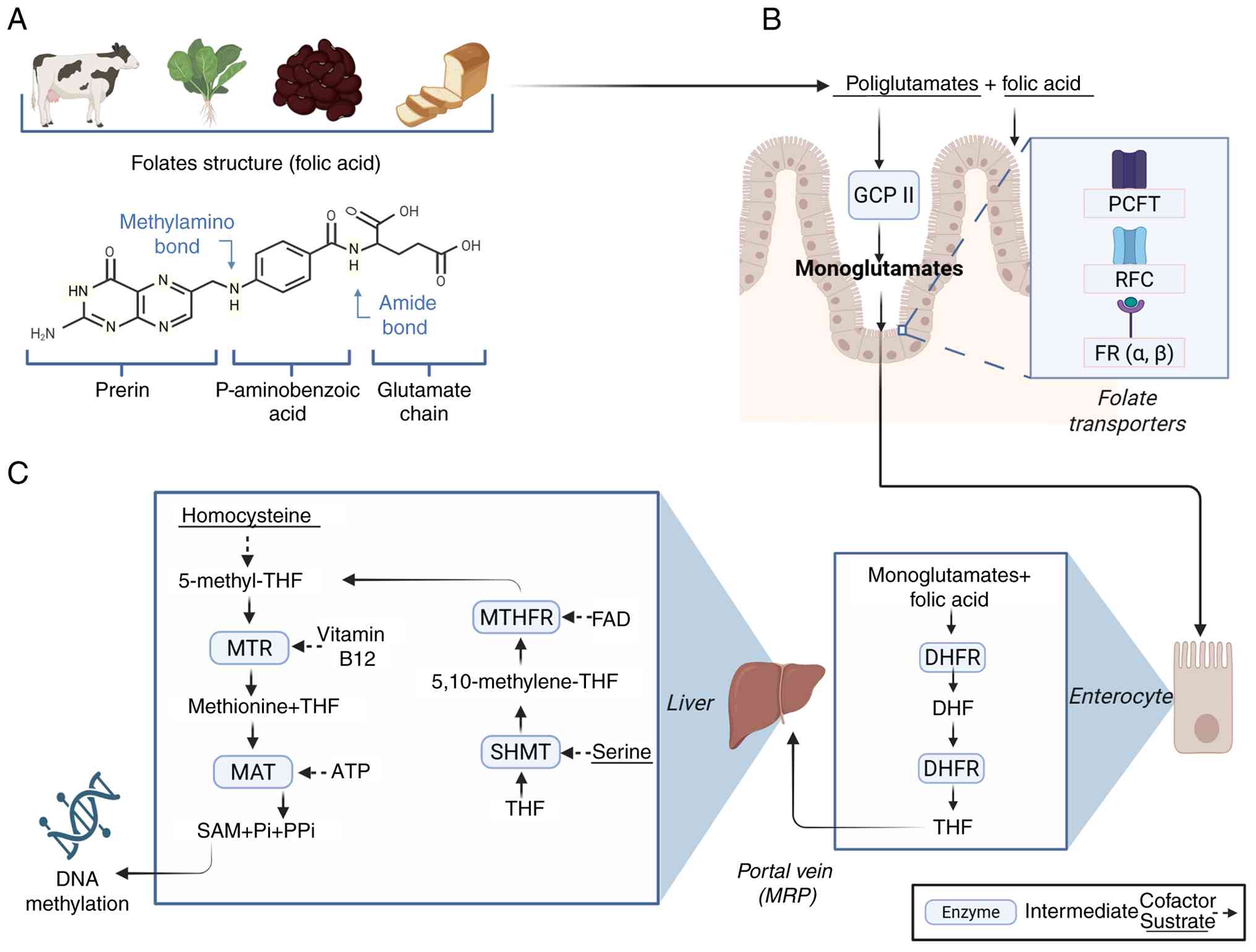

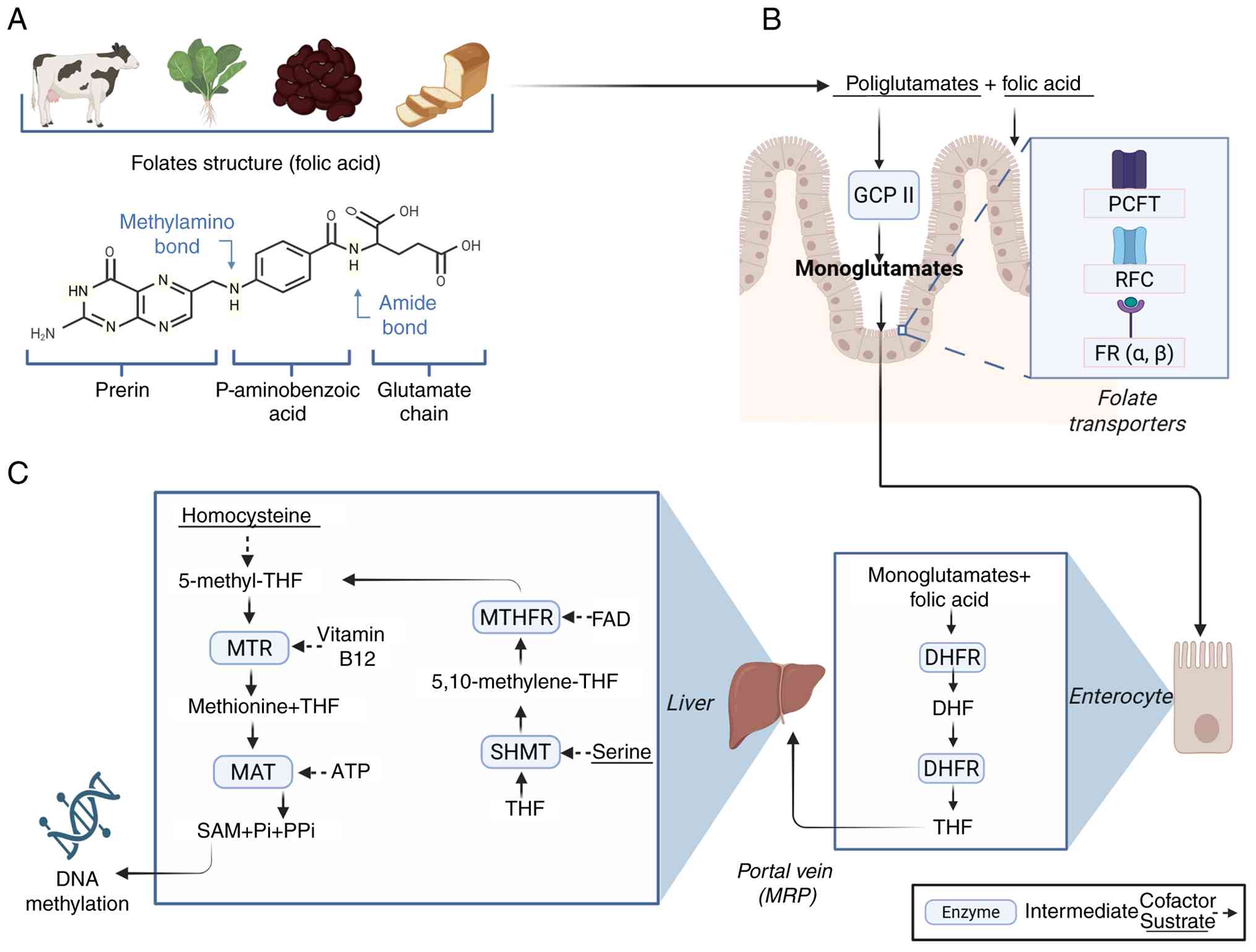

or polyglutamate chain of variable length (Fig. 1A).

| Figure 1(A) Dietary sources of folate and

general structure. Dietary folates, comprising three main

components (pterin, p-aminobenzoic acid and a glutamate

chain), are ingested as polyglutamates and hydrolyzed to

monoglutamates by the enzyme GCPII in the intestinal brush border.

(B) Intestinal absorption of folate. Folate uptake occurs through

transporters located in enterocytes, primarily the PCFT and the

RFC, as well as through FRα/FRβ present in other cell types. (C) In

folate metabolism, within intestinal cells, folate is sequentially

reduced by DHFR to DHF and ultimately to its active form, THF. THF

is transported to 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-MTHF) by

serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) and subsequently reduced by

the FAD-dependent enzyme MTHFR to 5-methylenetetrahydrofolate

(5-MTHF). The latter donates its methyl group to homocysteine to

regenerate methionine, in a reaction catalyzed by MTR that requires

vitamin B12. Methionine is then converted by MAT into

SAM, the universal methyl donor, in an ATP-dependent process. This

sequence associates folate metabolism with methylation reactions

that are key for nucleotide synthesis and epigenetic regulation.

GCPII, glutamate carboxypeptidase II; PCFT, proton-coupled folate

transporter; RFC, reduced folate carrier; FR, folate receptor;

DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; THF, tetrahydrofolate; 5,10-MTFH,

5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; SHMT, serine

hydroxymethyltransferase; MTR, methionine synthase; MAT, methionine

adenosyltransferase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine. |

A carbon unit may be associated with either the

pterin or the p-aminobenzoic ring, or with both. The classification

of folates depends on the oxidation state of the pterin and carbon

unit, as well as the polyglutamylation state. Consequently, folate

derivatives such as dihydro, tetrahydro, methyl and formyl forms

are expected, invariably conjugated with p-aminobenzoyl-glutamate

as mono-, di-, tri- or polyglutamates (36-38).

This group of compounds, associated with

water-soluble-B complex vitamins, cannot be synthesized by

mammalian cells; therefore, dietary intake is essential, either for

natural sources (tetrahydrofolate, THF) or synthetic

supplementation (folic acid) (31). In total, ~150 biochemical

derivatives with metabolic activity have been described, among

which tetrahydrofolates are the most relevant due to their roles in

DNA and RNA synthesis, cell division, methylation reactions and as

cofactors in multiple metabolic pathways (30,36).

Folic acid, the most oxidized and stable form of

folate, is reduced by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) at nitrogen 8

to produce dihydrofolate (DHF). Further reduction at nitrogen 5

yields THF, the active form of the vitamin that functions as a

coenzyme (Fig. 1). THF accepts

carbon atoms at nitrogen positions 5 and 10, generating cofactor

derivatives with specific physiological functions: 5-methyl-THF,

5,10-methyl-THF, 10-formyl-THF and 5-formyl-THF (37).

THF is the principal dietary form of folate in the

body, acting as a carrier in one-carbon cycle biosynthesis. Its

derivative, 5-methyl-THF, is the predominant active form of folate

in blood and supports the conversion of methionine to SAM for

methylation processes. Folic acid, a synthetic and fully oxidized

compound used in supplementation and food fortification, requires

hepatic DHFR for biological activity. By contrast, folinic acid can

yield 5,10-methyl-THF or 5-methyl-THF without requiring DHFR,

making it particularly useful for counteracting the effects of

chemotherapeutic agents (38,39).

The metabolic reactions of folate and its

derivatives are closely associated with the one-carbon cycle and

subject to feedback regulation, emphasizing the generation of

methyl groups that influence epigenetic modifications (36). In addition, folate intermediates

participate in the synthesis of purines, pyrimidines and

methionine, in the interconversion of serine to glycine and in the

catabolism of the latter (40).

Dietary sources

In mammals, the main source of folate comes from

dietary intake. Folate is a component of various food groups,

including vegetables, cereals, fruits and foods of animal origin

(Table I). It can also be

produced as a metabolite by the intestinal microbiota from

different phyla such as bacteroidetes, fusobacteria, proteobacteria

and actinobacteria (41-44).

| Table INatural foods rich in folate and

industrialized foods fortified with folic acid. |

Table I

Natural foods rich in folate and

industrialized foods fortified with folic acid.

| Food | Folate

(μg/100 g) | Scientific

source |

|---|

| Cooked beef

liver | 290 | USDA |

| Raw spinach | 194 | USDA |

| Cooked lentils | 181 | USDA |

| Cooked white

beans | 172 | BEDCA |

| Cooked

broccoli | 108 | USDA |

| Cooked turnip

greens | 106 | FAO/INFOODS |

| Avocado | 81 | USDA |

| Cooked pork

kidney | 77 | BEDCA |

| Roquefort

cheese | 50 | BEDCA |

| Cooked egg | 25 | FAO/INFOODS |

| Fortified breakfast

cereal | 150-400 | USDA |

| Enriched wheat

pasta | 100-150 | BEDCA |

| Enriched white

bread | 120 | USDA |

| Fortified corn

flour | 80-120 | FAO/INFOODS |

| Enriched white

rice | 90-110 | USDA |

Bioavailability and intestinal

absorption

In mammals, the main source of folate is dietary

intake. Folate is abundant in various food groups, including

vegetables, cereals, fruits and foods of animal origin, and it may

also be produced as a metabolite by the intestinal microbiota. Once

ingested, the efficiency with which folate becomes available for

metabolic reactions depends not only on its chemical form but also

on how it is processed and absorbed in the body. Dietary folates

are typically present as polyglutamates, which are chemically

labile and can be lost during food processing and cooking.

Depending on the food type and preparation, losses can range from

20-60% in vegetables and 30-70% in cereals (45). The bioavailability of folate

refers to the proportion that is absorbed and available for

metabolic reactions or storage. Thus, foods may be rich in folate

yet exhibit low bioavailability (46,47).

The bioavailability of dietary folates can be

compromised by several factors: i) Incomplete release of the

molecule from the original food matrix; ii) degradation of the

molecule within the gastrointestinal tract; and iii) incomplete

hydrolysis of the molecule due to the presence of other dietary

components, such as fatty acids. Additionally, individual

characteristics (such as sex and genetic variations), folate stores

and the availability of other nutrients (vitamin C, vitamin

B12, vitamin B6, niacin, riboflavin or

choline) influence the bioavailability of both dietary and

synthetic folate (46).

Folate absorption primarily occurs in the proximal

segments of the small intestine, the duodenum and jejunum, where an

acidic environment facilitates folate transport (48-50). Dietary polyglutamates undergo

hydrolysis at the intestinal brush border through the action of

glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII), converting them into

monoglutamates that can be absorbed in a manner similar to

synthetic folic acid (48,49). Due to the charge and hydrophilic

nature of the molecule, passive diffusion across cell membranes is

inefficient (50). Reduced

folate carriers (RFCs) serve as the main transporters mediating

systemic folate metabolism (50,51). In addition, dietary folates are

absorbed primarily via proton-coupled folate transporters (PCFTs),

which are located mainly in the upper gastrointestinal tract and in

certain tumors (Fig. 1B)

(48,50,52). Folate receptors (FRα and FRβ)

located in the cell membrane possess a glycosylphosphoinositol

anchor and mediate endocytosis of folate at neutral or slightly

acidic pH (50,51). Across the basolateral membrane,

folates are subsequently transported into the vascular system via

ABCC proteins, particularly ABCC3 (50).

Folate metabolism

The transformation of dietary folate into its active

monoglutamate form requires the action of the enzyme GCPII, located

on the intestinal brush border. GCPII catalyzes the hydrolysis of

folate, generating monoglutamate, which is then internalized by

PCFT within enterocytes. After absorption, DHFR sequentially

reduces monoglutamate to DHF and then to 5-methyl-THF. The

resulting metabolite is exported via the portal vein through

interacting with multidrug resistance proteins until it enters the

bloodstream and reaches tissues, where it is taken up by the RFC

system or by folate receptors. Once inside cells, folate is

converted to polyglutamate forms within tissues, while its active

form is primarily metabolized in the liver (53,54).

5-methyl-THF enters cells via transporters or

receptors. Inside the cell, it participates in the remethylation of

homocysteine to methionine through the activity of MTR and its

cofactor vitamin B12. Methionine is subsequently

converted by methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) into SAM, the

universal methyl donor for DNA methylation (Fig. 1C). Following methyl group

donation, SAM is converted to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), which

is then hydrolyzed by SAH hydrolase into homocysteine and adenosine

(55). To maintain balanced

production of bioactive folate metabolites, interconversion occurs

at both the mitochondrial and cytosolic levels. This process

involves the cytosolic enzyme serine hydroxymethyltransferase

(SHMT1), which catalyzes the conversion of serine to glycine and

transfers a one-carbon unit to THF to form

5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate. The mitochondrial isoform (SHMT2)

catalyzes the reverse reaction, synthesizing serine from glycine.

The newly formed serine serves as a feedback substrate in the

metabolic pathways for thymidylate and methionine synthesis and

supports DNA methylation (56).

These reactions underscore the close interconnection

between folate metabolism, the one-carbon cycle and methionine

metabolism. The capacity of folate to accept and donate methyl

groups is fundamental to epigenetic regulation, influencing gene

expression and protein synthesis through methylation processes

(54). MTX, the primary

treatment for inflammatory autoimmune diseases such as RA and MS,

acts as a folate antagonist. It directly inhibits folate metabolism

and indirectly disrupts associated pathways, including purine and

pyrimidine synthesis. Within these pathways, folate-derived

metabolites such as 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-THF) and

10-formyl-THF carry out essential roles. MTX inhibits key enzymes

of folate metabolism, including DHFR, thymidylate synthase, MTHFR

and SHMT (57,58).

In addition to these pharmacological effects, MTX

interacts with genetic variants in the MTHFR gene (C677T and

A1298C), which independently reduce biologically active folate

levels and elevate homocysteine concentrations. These alterations

contribute to gastrointestinal and hematologic toxicity,

inflammation, oxidative stress and increased cardiovascular risk.

Therefore, maintaining adequate levels of biologically active

folate is essential to preserve cellular homeostasis, support

methylation-dependent processes and minimize systemic dysfunction

across multiple organ systems (59).

Normal values and clinical evaluation of

folate status

Alterations in folate concentration have been

associated with various health complications due to the essential

role of folate in DNA replication, cell proliferation and growth.

This has led to widespread implementation of supplementation and

fortification programs in staple foods across several countries

(60). The prevailing scientific

consensus indicates that high folate intake does not adversely

affect healthy individuals. However, in individuals with

preexisting neoplastic conditions, excessive intake, particularly

of synthetic folic acid, may increase cancer risk, although this

relationship remains to be fully elucidated (61). The erythrocyte folate

concentrations (RBC folate) are considered a stable and reliable

long-term indicator of folate status, as it reflects intracellular

stores, whereas plasma folate concentrations are more transient and

influenced by recent dietary intake. Similarly, analysis of plasma

homocysteine concentrations also facilitates the identification of

disturbances in the methylation cycle (Table II) (62-64).

| Table IIReference concentrations of folate in

serum and erythrocytes (62). |

Table II

Reference concentrations of folate in

serum and erythrocytes (62).

A, Serum or plasma

folate concentration

|

|---|

| Concentration,

ng/ml (nmol/l) | Interpretation |

|---|

| >20 (45.3) | Elevated |

| 6-20

(13.5-45.3) | Normal range |

| 3-5.9

(6.8-13.4) | Possible

deficiency |

| <3

(<6.8) | Deficiency |

|

| B, Erythrocyte

folate concentrations |

|

| Concentration ng/ml

(nmol/l) | Interpretation |

|

| >140

(>317.5) | Elevated |

| 100-140

(226.5-317.5) | Normal range |

| <100

(<226.5) | Possible

deficiency |

Recommended daily intake (RDI)

Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

established the mandatory fortification of all enriched cereal

grain products with folic acid in 1996, full implementation,

providing 140 μg per 100 g of product, was achieved in 1998

(65). Subsequently, in 2016,

the FDA issued a voluntary recommendation for the fortification of

cornmeal. In the United States, the primary dietary sources of

folate include enriched grain products, fortified cornmeal,

ready-to-eat cereals containing 100-400 μg per serving and

adult supplements providing 400-800 μg of folic acid

(66).

Folate requirements depend on age and

physiological status, particularly in women and adolescents of

reproductive age

The RDI is defined as the amount of nutrients

necessary to meet the nutritional needs of 97-98% of the healthy

population. For folate, the average recommended intake is expressed

as micrograms (μg) of dietary folate equivalents (DFE). For

adults, the recommended amount is 400 μg per day (Table III) (67,68).

| Table IIIRecommended daily intake of folate by

age group and physiological condition. |

Table III

Recommended daily intake of folate by

age group and physiological condition.

| Age

group/condition | Daily

recommendation (μg DFE per day)a |

|---|

| Infants 0-6

months | 65 |

| Infants 7-12

months | 80 |

| Children 1-3

years | 150 |

| Children 4-8

years | 200 |

| Children 9-13

years | 300 |

| Adolescents 14-18

years (men) | 400 |

| Adolescents 14-18

years (women) | 400 |

| Adults (≥19

years) | 400 |

| Pregnancy | 600 |

| Lactation | 500 |

The MTHFR: Genetics and

regulation

Genomic location and structure

MTHFR is located on chromosome 1p36.22 and

spans ~20.3 kb, comprising 12 exons in the human genome. Its

promoter is GC-rich and TATA-less, containing Sp1, AP-1, AP-2 and

CAAT elements consistent with housekeeping-type regulation.

Multiple transcription start sites and alternative splicing events

generate two protein isoforms (70 and 77 kDa) and heterogeneous

mRNA 5' and 3'untranslated regions (UTRs), reflecting complex

transcriptional control. Predicted and observed protein lengths

across transcripts range from 656 to 700 amino acids (69-71). The gene encodes MTHFR, a

cytosolic flavoprotein that catalyzes the reduction of

5,10-methylene-THF to 5-methyl-THF, thereby associating the folate

and methionine cycles. Human MTHFR contains an N-terminal catalytic

domain that binds FAD and the folate substrate, and a C-terminal

regulatory domain that binds SAM to mediate allosteric inhibition.

Phosphorylation of N-terminal residues further sensitizes the

enzyme to SAM-dependent feedback (72-74). At the genetic level, two common

functional polymorphisms, C677T (rs1801133) and A1298C (rs1801131),

are widely studied for their effects on enzyme thermolability and

folate/homocysteine status. By contrast, rare truncating or severe

missense variants across catalytic or regulatory domains underlie

classical MTHFR deficiency (75-77).

Epigenetic regulation of MTHFR (DNA

methylation, histone marks and non-coding RNAs)

Expression of the MTHFR gene is finely

controlled by multiple epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA

methylation, histone modifications and non-coding RNAs.

Functionally, MTHFR bridges one-carbon metabolism with the

epigenome by generating 5-methyl-THF for methionine remethylation

and SAM synthesis, thereby determining the methyl-group supply

available for DNA and histone methyltransferases. Evidence shows

that MTHFR acts both as a modulator and a target of

epigenetic regulation: Promoter DNA methylation, chromatin state

and non-coding RNAs can alter its expression, while reduced MTHFR

activity, whether genetic or epigenetic, reduces SAM levels,

limiting methyltransferase capacity and favoring hypomethylation at

methylation-sensitive loci. The result is a metabolic-epigenetic

feedback loop in which folate flux and chromatin control

co-regulate each other (78,79).

The first regulatory layer involves DNA methylation,

the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases (typically in CpG

promoter regions), which generally represses gene transcription. In

MTHFR, promoter methylation modulates expression in a tissue

and context-dependent manner. For example, in sperm DNA from men

with idiopathic infertility, a case-control study reported

MTHFR promoter hypermethylation in 45% (41/94) of cases vs.

15% (8/54) of fertile controls, with higher methylation levels in

the oligozoospermic subgroup (80). These findings illustrate that

absolute percentages vary widely by CpG site, tissue and

methodology, and that direct data from autoimmune cohorts remain

scarce (81-83).

A second regulatory layer involves histone

post-translational modifications, such as acetylation (for example

H3K9ac) or methylation (for example H3K9me3 and H3K27me3), which

remodel chromatin to activate or repress transcription. This

process is highly sensitive to the metabolic state. During

2-acetylaminofluorene-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats,

MTHFR expression is downregulated early; concomitant

promoter-level increases in repressive marks (H3K27me3 gain and

H3K18ac loss) were also observed in the associated methylation gene

Mat1a, while MTHFR repression was mechanistically

associated with miR-22 and miR-29b (84). Models of folate stress likewise

show global reductions in H3K27 and H3K9 methylation, consistent

with SAM limitation (85). In

acute myeloid leukemia cells, reduced MTHFR function, whether due

to polymorphisms or pharmacologic inhibition, decreases

intracellular SAM, leading to loss of the repressive histone marks

H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 and de-repression of transcription factors

such as SPI1 (85). In

neuronal (SH-SY5Y) cell models, MTHFR acts as a metabolic buffer:

Excessive folate disturbs histone-modifying enzyme expression and

shifts the H3K4me3/H3K9me2 balance (86,87). These effects are markedly

amplified when MTHFR is deficient, emphasizing its role in

safeguarding the epigenome against nutrient fluctuations (86-87).

A third regulatory layer involves non-coding RNAs.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) bind mRNA to inhibit translation and can

modulate MTHFR expression. For instance, miR-22-3p and

miR-149-5p bind the 3'UTR of MTHFR mRNA, and under folate

deficiency, their upregulation suppresses MTHFR protein, further

restricting one-carbon flux. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) can

also guide chromatin modifiers: The lncRNA HOTAIR, for example,

recruits protein complexes to the MTHFR promoter in

esophageal cancer cells, depositing repressive H3K27me3 marks and

silencing transcription (88-91).

While the majority of direct evidence of

MTHFR epigenetic regulation derives from reproductive and

cancer models, autoimmune contexts offer a compelling rationale for

analogous studies in immune cells. Both RA and SLE exhibit

pronounced DNA-methylation defects in T cells (such as

hypomethylation of type-I-interferon-stimulated genes such as

IFI44L) and show responsiveness to SAM-linked chromatin

mechanisms. These parallels make MTHFR-centered regulation a

plausible contributor in autoimmune pathogenesis and a promising

target for future cell-specific investigations (92-94).

The biochemical axis: One-carbon

metabolism

One-carbon metabolism, SAM and

homocysteine

The one-carbon network integrates the folate and

methionine cycles to supply methyl groups for biosynthesis and

epigenetic regulation. Folate coenzymes carry and transform

one-carbon units primarily derived from serine and glycine. MTHFR

catalyzes the reduction of 5,10-methylene-THF to 5-methyl-THF,

which donates a methyl group to homocysteine via MTR (a vitamin

B12-dependent enzyme) to regenerate methionine.

Methionine is subsequently adenylated by MAT to form SAM, the

universal methyl donor utilized by DNA, RNA and histone

methyltransferases.

After methyl transfer, SAH is formed and hydrolyzed

by adenosylhomocysteinase (AHCY) into homocysteine and adenosine,

thereby removing a potent inhibitor of methyltransferases.

Consequently, the SAM:SAH ratio serves as a proximate index of

cellular methylation capacity. In the liver and kidney, an

alternative remethylation pathway involves betaine-homocysteine

methyltransferase (BHMT), while homocysteine can also leave the

cycle through transsulfuration, catalyzed by cystathionine

β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase, to generate cysteine and

glutathione. Collectively, these reactions couple nutrient status

to epigenetic regulation via SAM production and SAH clearance

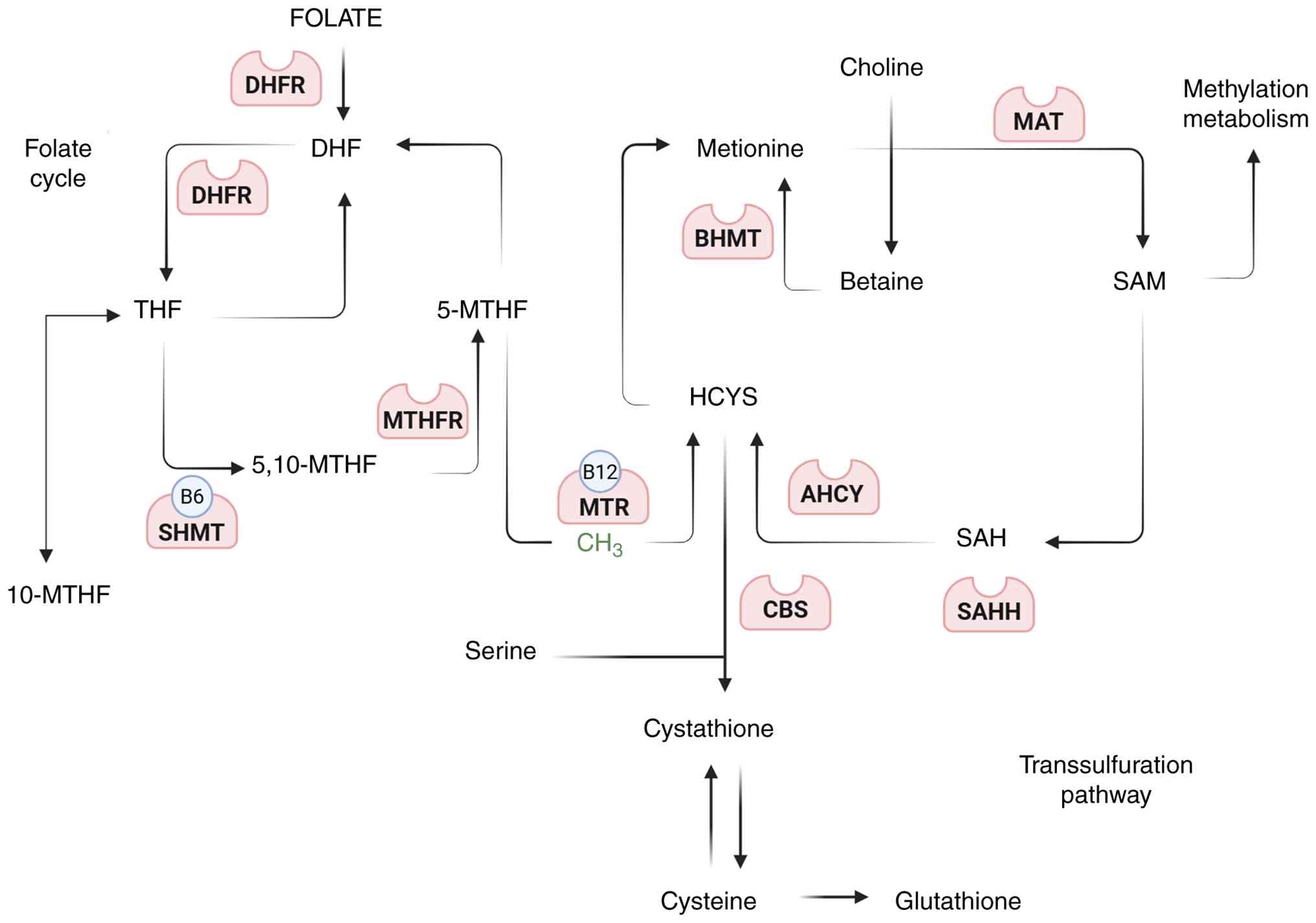

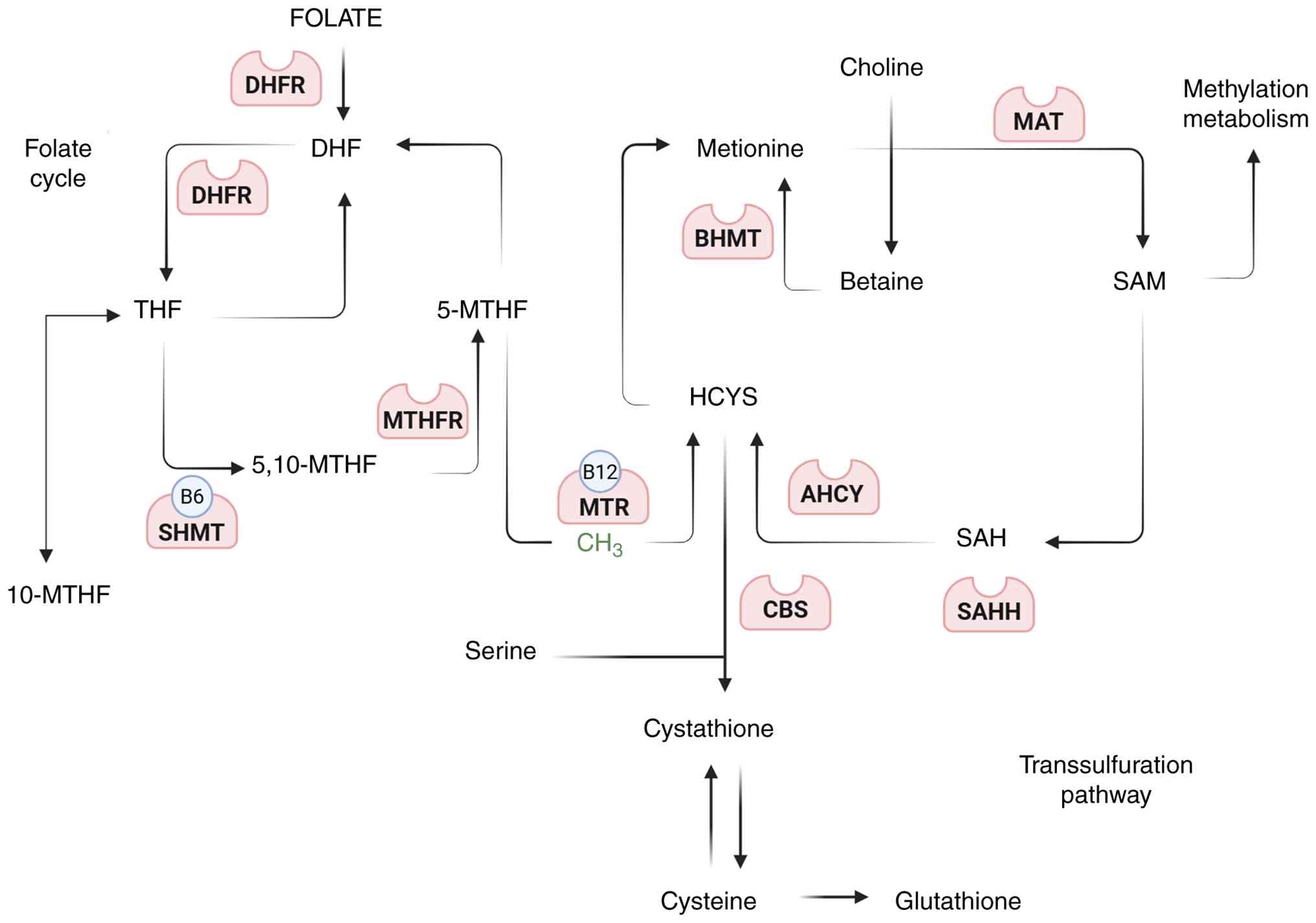

(Fig. 2) (95-99).

| Figure 2Schematic representation of the

folate and methionine cycles illustrating their interconnection

with one-carbon metabolism, methylation reactions and

transsulfuration. Dietary folate is initially reduced to DHF and

THF by DHFR. THF is converted to 5,10-MTHF by SHMT (a vitamin

B6-dependent enzyme) and subsequently reduced to 5-MTHF

by MTHFR. 5-MTHF donates a methyl group to Hcy via MTR (a vitamin

B12-dependent enzyme), thereby regenerating methionine.

Methionine is then converted to SAM by MAT. SAM serves as the

universal methyl donor for DNA, RNA, protein and lipid methylation.

Following methyl donation, SAM is converted to SAH, which is

hydrolyzed by AHCY to Hcy. Homocysteine can be remethylated by BHMT

using betaine as a methyl donor or diverted into the

transsulfuration pathway via CBS to generate cystathionine,

cysteine and ultimately glutathione. This pathway highlights the

biochemical integration of folate status, methylation potential and

redox homeostasis (97-99). DHR, dihydrofolate; THF,

tetrahydrofolate; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; 5,10-MTHF;

5,10-methylene-THF, SHMT, serine hydroxymethyltransferase; 5-MTHF,

5-methyl-THF; 5-MTHF, 5-methyl-THF; MTHFR,

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; Hcy, homocysteine; MTR,

methionine synthase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; MAT, methionine

adenosyltransferase; SAH; S-adenosylhomocysteine; AHCY,

adenosylhomocysteinase; BHMT, betaine-homocysteine

methyltransferase; CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; SAHH,

S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. |

A fundamental biochemical principle is that SAH

inhibits the majority of methyltransferases with low-micromolar

inhibition constants (Ki). Accumulation of SAH, or a reduction in

SAM, thus constrains DNA and histone methylation even when

substrate (cytosine or lysine) is available. Manipulating AHCY

activity or methionine flux can therefore alter global methylation

states. This inhibitory 'SAH brake' explains why the SAM:SAH ratio,

rather than SAM alone, more accurately reflects methylation

capacity in cells and tissues (98,100,101).

In humans, the MTHFR C677T variant decreases

enzymatic activity and interacts with folate status to influence

genomic DNA methylation and homocysteine levels, with the lowest

methylation observed in TT homozygotes under low-folate conditions.

In mice, MTHFR deficiency decreases SAM, increases SAH and reduces

global DNA methylation, directly associating impaired MTHFR flux to

a hypomethylated genome (102,103). Dietary interventions further

demonstrate causal control of leukocyte methylation by one-carbon

nutrients. Randomized and longitudinal studies have shown that

folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation modify DNA

methylation profiles, both globally and at specific loci,

consistent with enhanced methyl-group availability for

DNMT-mediated reactions (104-106). Epigenome-wide analyses of

habitual folate and B12 intake corroborate these

associations. Although the magnitude and direction of methylation

change are locus-specific, the collective evidence supports

nutrient-sensitive modulation of the blood methylome through the

folate-MTHFR-SAM axis (104-106).

Finally, plasma homocysteine serves as a clinically

accessible marker of one-carbon imbalance. Elevated concentrations

often indicate insufficient folate or vitamin B12

intake, or reduced MTHFR or MTR activity, and are typically

accompanied by a low SAM:SAH ratio and reduced methylation

potential. In hepatic and renal tissues, BHMT provides a

compensatory remethylation pathway that becomes particularly

relevant when folate-dependent remethylation is limited,

underscoring tissue-specific buffering within the one-carbon

network. These biochemical relationships demonstrate that folate

availability and MTHFR activity define the upper limit for DNA and

histone methylation, providing a mechanistic bridge to the

epigenetic phenotypes described in autoimmune diseases (95-97,99).

Crosstalk with inflammatory and

immunological pathways

Epigenetic regulation intersects immune function

through the one-carbon network that maintains cellular methylation

potential in leukocytes. DNA methylation at promoters and

enhancers, together with SAM-dependent histone methylation,

regulates cytokine programs and lineage stability. Because both

processes depend on the folate-MTHFR-SAM axis and are inhibited by

SAH, immune activation is tightly associated with one-carbon flux

(107,108).

In RA, inflammatory signaling actively suppresses

the methylation machinery. IL-1 rapidly downregulates DNMT1 and

DNMT3A in synovial fibroblasts at picogram concentrations, a change

associated with DNA hypomethylation and sustained inflammatory gene

expression. In SLE, oxidative stress inhibits ERK signaling in

CD4+ T cells, decreases DNMT1 expression and induces

promoter demethylation with aberrant overexpression of normally

silenced genes, thus mechanistically associating inflammatory

stress to erosion of the T-cell methylome (109-111).

Beyond T and stromal compartments, innate immune

cells can also rely on one-carbon-supported SAM to mount

proinflammatory responses. Upon LPS stimulation, macrophages

upregulate serine synthesis and one-carbon metabolism, fueling

epigenetic reprogramming that licenses IL-1β expression.

Inhibition of serine metabolism, in turn, blunts IL-1β production

both in vitro and in vivo. Complementing these

disease-specific examples, epigenome-wide studies in type 1

diabetes (T1D) have demonstrated methylation abnormalities in

immune effector cells (CD4+ T cells, B cells and

monocytes), underscoring that immune epigenomes are broadly

sensitive to both inflammatory context and metabolic state

(112,113).

Converging evidence associates folate status and

homocysteine to inflammatory tone. Folate deficiency increases

oxidative and nitrosative stress, activating NF-κB, while

homocysteine triggers NF-κB activation and IL-6/IL-1β production in

vascular and myeloid cells, biochemical routes through which

impaired remethylation amplifies inflammation. In

macrophage-lineage cells, experimental folate restriction enhances

proinflammatory responses, consistent with a model in which limited

methyl-donor availability constrains methyltransferase activity and

shifts signaling toward activation (114,115).

Collectively, these findings support a bidirectional

feedback loop: Inflammatory cues (such as IL-1 and oxidative

stress) suppress DNMT expression and activity, eroding genomic

methylation, while low folate or MTHFR-limited flux and the

resulting homocysteine/SAM:SAH imbalance promote oxidative and

NF-κB signaling. Together, these mechanisms stabilize a

proinflammatory, hypomethylated epigenetic state within immune

tissues. This mechanistic crosstalk provides the biochemical bridge

associating nutrient status and MTHFR activity to the

immune-epigenetic phenotypes observed across RA, SLE, T1D and other

immune-mediated diseases (107,108,111,116-118).

MTHFR-mediated epigenetic

dysregulation in autoimmune diseases

RA

RA is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder

characterized by persistent synovitis, pannus formation and

extra-articular manifestations. Superimposed on this pathogenetic

framework is a robust epigenetic component. Drug-naïve patients

already exhibit disease-associated DNA-methylation differences in

circulating T-cell subsets and synovial tissue, including global

hypomethylation in early disease and cell-type-specific changes

across naïve and memory CD4+ lineages (119,120). In synovial fibroblasts,

proinflammatory cues directly impair methylation capacity: IL-1

rapidly downregulates DNMT1 and DNMT3A/3B expression and activity,

promoting demethylation and stable activation of inflammatory gene

programs (116).

At the gene level, methylation alterations converge

on RA-relevant loci. Hypomethylation at the TNF locus

associates with increased expression and, importantly, predicts

response to biological therapies in clinical cohorts (121). An additional chromatin study in

synovial fibroblasts reveal histone-methylation/STAT3 crosstalk

controlling IL-6-driven effector genes, underscoring how

methyl-donor availability and chromatin state co-regulate cytokine

programs (122).

Regulatory-T-cell instability also arises through epigenetic

mechanisms: Patients with RA exhibit reduced FOXP3

expression and insufficient demethylation of the FOXP3 TSDR,

while MTX therapy can restore Treg function by demethylating a

FOXP3 enhancer, associating pharmacologic intervention to

methylome repair (123,124).

Biochemically, these patterns align with one-carbon

control. The folate-MTHFR-SAM axis determines the methyl-group

supply for DNMTs. Common MTHFR variants (C677T and A1298C)

and low folate levels reduce SAM and increase SAH, limiting

methyltransferase capacity. Consistently, baseline leukocyte DNA

methylation (including global indices) predicts MTX non-response in

early RA, while multiple cohorts reveal methylation signatures

associated with MTX response, pointing to a pharmaco-epigenetic

interface between folate metabolism and RA therapy (125-127). Preliminary evidence further

suggests MTHFR variants may modulate anti-TNF responses in

an allele-dose manner, although results remain population-specific

(128). Overall, folate status,

MTHFR genotype and DNMT activity appear to co-determine the

epigenetic tone of RA tissues and the likelihood of therapeutic

control (129).

SLE

SLE is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes

widespread inflammation and tissue damage affecting the skin,

joints, kidneys, brain, lungs and heart. A defining molecular

hallmark is global DNA hypomethylation in lymphocytes, especially

CD4+ T cells, which associates with disease activity and

stabilizes a type-I-interferon-driven program. Among

interferon-stimulated genes, IFI44L promoter hypomethylation

is exceptionally consistent and has emerged as a diagnostic

biomarker across tissues (130). Mechanistically, SLE T cells

exhibit reduced DNMT1 (maintenance methyltransferase) and

dysregulated DNMT3A/3B, partly due to oxidative-stress mediated

inhibition of ERK signaling, directly associating inflammatory

stress to methylome erosion (131,132).

This enzymatic deficit is compounded by a

one-carbon bottleneck. MTHFR activity is essential for generating

SAM, the universal methyl donor for all DNMTs. Polymorphic

depression of MTHFR activity (such as C677T) and

folate/B12 insufficiency favor hyperhomocysteinemia and

a low SAM:SAH ratio, both of which inhibit methyltransferases.

Meta-analyses confirm associations between MTHFR C677T and

SLE susceptibility; in SLE cohorts, the 677TT genotype and elevated

homocysteine levels associate with subclinical atherosclerosis,

emphasizing the clinical consequences of impaired remethylation

(133,134).

Functionally, SLE exhibits promoter hypomethylation

and overexpression of proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6,

particularly in T cells and affected tissues) alongside IL-17 axis

activation. Conversely, tolerance-maintaining pathways become

epigenetically repressed, such as IL-2 transcriptional silencing

and FOXP3 locus instability, where insufficient TSDR

demethylation undermines Treg stability (135,136). Altogether, this evidence

positions the MTHFR-SAM-DNMT axis at the core of SLE

immunoepigenetics: Metabolic constraint yields methylation defects

that hardwire the interferon-skewed, proinflammatory state. The

reversible nature of DNA methylation underscores its diagnostic and

therapeutic potential, motivating interventions that restore

one-carbon flux or target epigenetic writers and erasers (130).

MS

MS is a chronic, immune-mediated neurodegenerative

disorder of the central nervous system, characterized by

demyelination, axonal injury and progressive neurological

impairment (137). Epigenetic

deregulation contributes to its pathogenesis by promoting a

proinflammatory phenotype in peripheral immune cells. Cell-sorted

studies have revealed widespread methylation shifts in T cells and

monocytes, including reproducible changes in CD8+ T

cells and distinct profiles relative to CD4+ subsets,

indicative of compartment-specific immune methylome remodeling

(138-141). These patterns are clinically

dynamic: Both global and locus-specific methylation signals

associate with disability scores and can be modified by

disease-modifying therapies, highlighting the plasticity of the MS

methylome (138,139). In line with immune

polarization, proinflammatory pathways (Th1/Th17) and regulatory

circuits (Treg networks) represent methylation-sensitive axes in MS

(140,141). Central nervous system tissue

analyses further reveal lesion-associated methylation changes

affecting myelin biology and glial programs, associating epigenetic

remodeling to demyelination and repair potential (137).

These epigenetic alterations are biochemically

associated with one-carbon metabolism. The folate-MTHFR-SAM axis

supplies the methyl donor required by DNMTs. Across cohorts, plasma

homocysteine levels are elevated in MS (with folate and

B12 largely unchanged), consistent with impaired

methyl-group homeostasis and a reduced SAM:SAH ratio. Associations

between MTHFR C677T and MS vary across populations, some

case-control studies identify risk signals, while others do not,

supporting a 'substrate-limitation' model where genetic

predisposition interacts with B-vitamin status to constrain DNMT

activity and stabilize a proinflammatory methylation landscape

(7,142,143).

Several agents modulate immune cell methylomes.

Dimethyl fumarate induces coordinated DNA methylation changes in

circulating leukocytes (including CD4+ T cells and

monocytes), while interferon-β produces targeted,

cell-type-specific methylation shifts, demonstrating that

MS-relevant epigenetic programs are reversible and may be corrected

in tandem with the restoration of one-carbon flux (138,144-146).

CeD

CeD is an autoimmune enteropathy triggered by

dietary gluten in genetically susceptible individuals carrying

HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 haplotypes (147). Beyond its genetic

predisposition, CeD exhibits distinctive DNA methylation

alterations in intestinal mucosa and saliva, revealing the

importance of gene-environment interactions mediated by epigenetic

mechanisms (147-149). Genome-wide studies demonstrate

differential methylation within the HLA region, partly independent

of genotype, and tissue-specific analyses confirm mucosal

remodeling (148). Remarkably,

saliva methylation profiles associate with intestinal patterns,

supporting their potential as non-invasive biomarkers (150).

A compelling mechanistic explanation arises from

the interplay between intestinal pathology and one-carbon

metabolism. Untreated CeD leads to villous atrophy, causing

malabsorption of key nutrients, including folate, thereby

disrupting the MTHFR-dependent remethylation cycle. Common

MTHFR variants may further impair this pathway. Consistent

with this model, hyperhomocysteinemia is frequently observed at

diagnosis and typically improves with a gluten-free diet; however,

in patients with MTHFR variants, elevated homocysteine may

persist despite supplementation. At the tissue level, global

hypomethylation signals, such as LINE-1 hypomethylation, have been

identified in CeD-associated intestinal mucosa, consistent with

substrate limitation of SAM-dependent methylation (151).

This convergence of factors constrains SAM

synthesis, limiting DNMT activity and thereby compromising

maintenance of the methylome. It provides a biochemical explanation

for the epigenetic alterations observed in CeD (152-154). The resulting model establishes

a mechanistic cascade associating dietary triggers (gluten),

intestinal injury (malabsorption), metabolic disruption

(folate/MTHFR deficiency) and epigenetic dysregulation (SAM/DNMTs

imbalance). Clinically, residual folate insufficiency has been

documented even in treated cohorts, emphasizing the need to ensure

methyl-donor adequacy. Methylation profiles, including saliva-based

assays, may assist in diagnosis, monitoring and assessment of

dietary adherence (148,153,154).

FM

Although FM is not a classical autoimmune disease,

it consistently presents with epigenetic abnormalities intersecting

immune and neuroendocrine pathways. Genome-wide and

candidate-region studies reveal global DNA hypomethylation and

locus-specific changes in peripheral blood, enriched for

stress-response, immune-inflammatory and central-sensitization

pathways. These alterations, replicated across independent cohorts,

involve disease-relevant loci such as COMT and BDNF

(155-160).

Mechanistically, these epigenetic findings align

with one-carbon metabolism. A 'substrate-limitation' model in FM is

supported by elevated homocysteine levels observed in FM/chronic

fatigue syndrome cohorts, by associations between symptoms and the

MTHFR C677T (rs1801133) variant, and by gene-environment

interactions showing that rs1801133 modifies the effect of physical

activity on fatigue. Together, these findings indicate that genetic

variation and B-vitamin status can limit SAM availability and

consequently DNMT activity (161-163).

The translational implications are direct. Blood

methylation panels already demonstrate diagnostic and prognostic

potential. Clinical trials further provide proof-of-concept:

Vitamin B12 supplementation markedly improves symptom

severity and anxiety in patients with FM, consistent with

restoration of one-carbon flux and normalization of

methylation-dependent pathways. Similarly, folate and

B12 supplementation have been shown to enhance leukocyte

and mucosal DNA methylation in colorectal adenoma cohorts,

confirming that methyl-donor interventions can modulate the human

methylome. Despite heterogeneity and modest sample sizes, these

findings establish a functional association between nutrient

availability, MTHFR-dependent SAM synthesis and epigenetic

control, underscoring the rationale for larger, mechanistically

informed intervention studies (106,164,165).

These disease-specific epigenetic and metabolic

patterns, encompassing RA, SLE, MS, CeD and FM, are summarized in a

comparative framework (Table

IV), providing an integrated overview of autoimmune diseases

and related disorders.

| Table IVEpigenetic and metabolic comparison

of autoimmune and associated disorders, a summary of converging

evidence associating one-carbon metabolism dysregulation to

epigenetic alterations, particularly DNA hypomethylation, across

autoimmune and associated disorders. |

Table IV

Epigenetic and metabolic comparison

of autoimmune and associated disorders, a summary of converging

evidence associating one-carbon metabolism dysregulation to

epigenetic alterations, particularly DNA hypomethylation, across

autoimmune and associated disorders.

| Feature | RA | SLE | MS | CeD | FM |

|---|

| Primary

pathophysiology | Chronic systemic

autoimmune disorder characterized by persistent joint inflammation

(synovitis). | Systemic autoimmune

disease-causing widespread inflammation and multi-organ

damage. | Immune-mediated

neurodegenerative disorder of the CNS causing demyelination. | Autoimmune

enteropathy triggered by gluten, resulting in villous intestinal

malabsorption. | Neuro-sensory

disorder with chronic pain and fatigue; not a classical autoimmune

disease but involves immune dysregulation. |

| Key epigenetic

signature | Global

hypomethylation in early diseases and cell-type specific

changes. | Global DNA

hypomethylation in lymphocytes (especially CD4+ T cells)

as a defining molecular hallmark. | Widespread, dynamic

methylation shifts in T cells and monocytes. | Altered DNA

methylation in intestinal mucosa and saliva; hypomethylation in the

HLA region. | Global DNA

hypomethylation in peripheral blood, involving stress and

pain-regulation pathways. |

| Affected

cells/tissues | CD4+ T

cells, synovial fibroblasts, circulating leukocytes. | CD4+ T

cells, lymphocytes. |

CD4+/CD8+ T cells,

monocytes, CNS tissue. | Intestinal

epithelium/mucosa, saliva. | Peripheral blood

leukocytes. |

| Role of one-carbon

metabolism | MTHFR

variants and low folate reduce SAM levels, impairing methylation.

Methylation status predicts response to MTX. | MTHFR

variants (C677T) increase susceptibility. Low folate/B12

leads to a reduced SAM:SAH ratio, inhibiting methylation. | Elevated

homocysteine indicates impaired methyl-group metabolism. A

'substrate-limitation' model has been proposed. | Gluten-induced

malabsorption causes folate deficiency, leading to

hyperhomocysteinemia and limited SAM availability for

methylation. | Elevated

homocysteine and symptom association with the MTHFR C677T

support a 'substrate-limitation' model. |

| Key genes and

pathways | TNF,

IL-6, FOXP3 (Treg stability). | IFI44L

(biomarker), IL-6, IL-17, IL-2, FOXP3

(Treg stability). | Th1/Th17

proinflammatory programs, Treg networks, myelin-associated

genes. | HLA region,

RNF5. | Stress-response

genes (COMT, BDNF), immune-inflammatory

pathways. |

| Clinical

implications | TNF

methylation predicts biological response; methylation profiles

predict MTX response. | IFI44L

hypomethylation serves as a diagnostic biomarker; restoration of

one-carbon flux is a potential therapy. | Methylation

patterns associate with disability and are modified by treatments

(for example dimethyl fumarate), suggesting therapeutic

targets. | Saliva methylation

profiles may serve as non-invasive biomarkers; diet and folate

status are key for management. | Blood methylation

panels show diagnostic potential; B-vitamin supplementation has

demonstrated clinical benefits. |

Clinical implications and therapeutic

potential

Dietary interventions and folate

supplementation

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the

dose-response relationship between folate intake and changes in

blood biomarkers. The review included 120 clinical trials in

healthy participants with study durations ranging from 3 to 144

weeks. Doses of 375-570 μg/day produced a 1.7-fold increase

in erythrocyte folate concentrations relative to baseline (95% CI,

1.66-1.93), reaching normalization by week 36. The analysis

reported moderate heterogeneity among studies (posterior predictive

interval=1.37-2.34) (166).

Individuals carrying the MTHFR C677T TT

genotype (homozygous mutant) exhibit lower folate and higher

homocysteine concentrations, often presenting with fatigue,

irritability and megaloblastic anemia. By contrast, those with the

MTHFR A1298C CC genotype (homozygous mutant) tend to have

higher folate concentrations without overt clinical symptoms,

although vitamin B12 deficiency may be masked (63).

In RA, methotrexate, a folate antagonist with

gastrointestinal toxicity, is a cornerstone therapy. Meta-analytic

data indicate that folic or folinic acid supplementation <5

mg/day reduces gastrointestinal adverse effects by 79% (odds

ratio=0.21; 95% CI, 0.10-0.44) but does not notably modify disease

activity as measured by tender-joint count (167).

Conversely, in SLE, methyl-donor-rich diets or

folic acid supplementation have been proposed to modulate

epigenetic mechanisms underlying proinflammatory gene expression.

Experimental evidence has demonstrated that folic acid can

epigenetically silence the IRF5 gene, a key driver of TNF-α

synthesis and suppress type I and III interferon pathways, both

commonly overexpressed in SLE (168).

In MS, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis

assessed folate metabolism and epigenetic implications. No notable

differences were found in folate levels between patients and

controls (weighted mean difference [WMD]=0.00 μg/l; 95%

CI,−0.01 to 0.01; I2=0%). However, homocysteine levels

were notably increased in MS (WMD=2.47 μmol/; 95% CI, 0.40

to 4.55; I2=92%), suggesting a potential association

between altered one-carbon metabolism, inflammation and disease

activity (169).

Patients with CeD frequently exhibit low folate

concentrations due to persistent enteropathy, inadequate adherence

to a gluten-free diet or consumption of non-fortified gluten-free

products. Consequently, management strategies should emphasize a

well-planned gluten-free diet, folic acid supplementation,

nutritional education and the fortification of gluten-free foods

(170).

In FM, low dietary folate intake has been inversely

associated with disease severity. A study using the Fibromyalgia

Impact Questionnaire-Revised reported a negative association

between dietary folate intake and symptom burden (r=-0.250;

P=0.017) (171). This

relationship likely reflects the role of folate in neurotransmitter

synthesis, epigenetic regulation, DNA methylation and the

modulation of inflammation and oxidative stress (172).

Therapeutic strategies based on

epigenetic modulation

A meta-analysis of intervention studies (folic acid

supplementation, fortified foods and natural folate sources) in

individuals stratified by MTHFR C677T genotype included six

randomized controlled trials and four quasi-experimental studies,

each lasting ≥4 weeks and using doses of 400-1,670 μg DFE.

Homozygous TT carriers displayed higher baseline homocysteine and

lower folate concentrations compared with CT and CC genotypes.

Following supplementation, homocysteine levels decreased across all

genotypes; however, serum folate increases were smaller among TT

carriers. These data highlight a persistent biochemical

vulnerability in individuals with reduced MTHFR activity.

Populations of Asian and Latin American ancestry carrying the TT

genotype may require higher daily folate intakes, direct

supplementation with 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), prolonged

interventions and/or combined B-vitamin therapy (173).

Genotype-specific differences in folate and

homocysteine metabolism have implications for methylation-dependent

regulatory pathways. Given the central role of folate in one-carbon

metabolism, optimizing folate status in TT carriers could enhance

epigenetic stability, particularly in tissues sensitive to

methylation imbalance (174).

Limitations and future perspectives

The main strength of the present review is its

comprehensive integration of the biological mechanisms associating

one-carbon metabolism and epigenetic regulation in autoimmune

diseases, which contributes to the literature, as, to the best of

our knowledge, few studies have synthesized these complex

interactions. However, it is important to note that the analysis of

the present review focused primarily on the folate-dependent

pathway, which constitutes a limitation because it excludes other

nutrients involved in epigenetic regulation, such as choline,

serine and vitamins B12 and B6, all of which

participate in SAM availability and overall methylation capacity

(175,176).

Current evidence also poses challenges due to the

heterogeneity of study designs and methodologies. Several studies

rely on small cohorts that do not stratify participants by folate

level or MTHFR genotype and employ disparate methods to

quantify DNA methylation (for example, global, LINE-1 or

locus-specific promoter assays) (177-182). These methodological differences

hinder the ability to compare findings and to draw firm conclusions

regarding the mechanisms associating methylation changes to

autoimmune diseases. In addition, the predominance of

cross-sectional designs limits the capacity to determine causality

between folate deficiency and disease progression.

Future research must move beyond associations

toward establishing causality. This requires longitudinal,

multi-omics studies that integrate genomics, epigenomics and

metabolomics in disease-specific cohorts. Such approaches will

enable the identification of more precise molecular markers of

one-carbon metabolism dysfunction and its relationship to immune

regulation. Once improved definition of these mechanisms are

established, the next step should involve targeted interventions.

Clinical trials are needed to determine whether restoring

methylation capacity, through folate supplementation or strategies

that increase SAM availability, actually reduces inflammatory

phenotypes. Ultimately, the goal is to validate sensitive

biomarkers that support the development of personalized prevention

and treatment strategies tailored to the genotype of each

patient.

Conclusions

The MTHFR-folate axis represents a pivotal

intersection between metabolism, immune homeostasis and epigenetic

regulation in autoimmune diseases. Genetic and environmental

perturbations affecting this axis have been consistently associated

with epigenetic alterations underlying the pathophysiology of RA

and SLE. By contrast, evidence regarding MS, CeD and FM remains

heterogeneous and warrants further clarification. Importantly, this

axis not only influences DNA and histone methylation but also

modulates inflammatory signaling and cellular stress responses,

highlighting its potential as both a biomarker and a therapeutic

target.

Future research should prioritize clinical trials

that integrate genetic background, nutritional status, inflammatory

load and emerging biomarkers, such as homocysteine levels and the

SAM:SAH ratio, while evaluating the effects of targeted nutritional

interventions involving folic acid and vitamin B12.

Complementary studies using primary immune cells and

tissue-specific models are essential to elucidate how

MTHFR-related methylation changes translate into functional

dysregulation of the immune system. This integrative approach will

facilitate the characterization of disease-specific epigenetic and

metabolomic profiles, supporting the development of personalized,

mechanism-based therapeutic strategies in autoimmune

conditions.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

PMNR, RFBS, FJTH and HRCG contribute to

conceptualization; PMNR and RFBS contributed to investigation; JFMV

contributed to project administration; FJTH, HRCG, JHB and JFV

contributed to supervision; FJTH, HRCG, JHB, COHR, SRDLS and JFMV

contributed to validation; PPMNR, RFBS and FJTH contributed to

visualization; PMNR and RFBS contributed to writing of the original

draft; FJTH, HRCG, JHB, COHR, SRDLS and JFMV contributed to review

and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data authentication not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

|

1

|

Song Y, Li J and Wu Y: Evolving

understanding of autoimmune mechanisms and new therapeutic

strategies of autoimmune disorders. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

9:2632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Danieli MG, Casciaro M, Paladini A,

Bartolucci M, Sordoni M, Shoenfeld Y and Gangemi S: Exposome:

Epigenetics and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 23:1035842024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gurugubelli KR and Ballambattu VB:

Perspectives on folate with special reference to epigenetics and

neural tube defects. Reprod Toxicol. 125:1085762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Souza LL, da Mota JCNL, Carvalho LM,

Ribeiro AA, Caponi CA, Pinhel MAS, Costa-Fraga N, Diaz-Lagares A,

Izquierdo AG, Nonino CB, et al: Genome-wide impact of folic acid on

DNA methylation and gene expression in lupus adipocytes: An in

vitro study on obesity. Nutrients. 17:10862025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lu M, Peng K, Song L, Luo L, Liang P and

Liang Y: Association between Genetic polymorphisms in

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and risk of autoimmune

diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Markers.

2022:45681452022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tsai TY, Lee TH, Wang HH, Yang TH, Chang

IJ and Huang YC: Serum Homocysteine, Folate, and vitamin

B12 levels in patients with systemic lupus

Erythematosus: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Am Coll Nutr.

40:443–453. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Dardiotis E, Arseniou S, Sokratous M,

Tsouris Z, Siokas V, Mentis AA, Michalopoulou A, Andravizou A,

Dastamani M, Paterakis K, et al: Vitamin B12, folate, and

homocysteine levels and multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. Mult

Scler Relat Disord. 17:190–197. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nomair AM, Abdelati A, Dwedar FI, Elnemr

R, Kamel YN and Nomeir HM: The impact of folate pathway variants on

the outcome of methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis

patients. Clin Rheumatol. 43:971–983. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Crider KS, Yang TP, Berry RJ and Bailey

LB: Folate and DNA methylation: A review of molecular mechanisms

and the evidence for Folate's role. Adv Nutr. 3:21–38. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Coppedè F, Denaro M, Tannorella P and

Migliore L: Increased MTHFR promoter methylation in mothers of Down

syndrome individuals. Mutat Res. 787:1–6. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sun H, Song K, Zhou Y, Ding JF, Tu B, Yang

JJ, Sha JM, Zhao JY, Zhang Y and Tao H: MTHFR epigenetic

derepression protects against diabetes cardiac fibrosis. Free Radic

Biol Med. 193:330–341. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Prasad S, Adivikolanu H, Banerjee A,

Mittal M, Lemos JRN, Mittal R and Hirani K: The role of microRNAs

and long non-coding RNAs in epigenetic regulation of T cells:

Implications for autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 16:16958942025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nuermaimaiti K, Li T, Li N, Shi T, Liu W,

Abulaiti P, Abulaihaiti K and Gao F: Vitamin and trace elements

imbalance are very common in adult patients with newly diagnosed

Celiac disease. Sci Rep. 15:283152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fusco R, Siracusa R, D'Amico R, Peritore

AF, Cordaro M, Gugliandolo E, Crupi R, Impellizzeri D, Cuzzocrea S

and Di Paola R: Melatonin plus folic acid treatment ameliorates

reserpine-induced fibromyalgia: An evaluation of pain, oxidative

stress, and inflammation. Antioxidants (Basel). 8:6282019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nielsen HM and Tost J: Epigenetic Changes

in Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases. Epigenetics: Development

and Disease. Kundu TK: 61. Springer; Netherlands, Dordrecht: pp.

455–478. 2013

|

|

16

|

Surace AEA and Hedrich CM: The role of

epigenetics in autoimmune/inflammatory disease. Front Immunol.

10:15252019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Funes SC, Fernández-Fierro A,

Rebolledo-Zelada D, Mackern-Oberti JP and Kalergis AM: Contribution

of Dysregulated DNA methylation to autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci.

22:118922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wills L and Stewart A: Experimental anæmia

in monkeys, with special reference to macrocytic nutritional

anæmia. Br J Exp Pathol. 16:444–453. 1935.

|

|

19

|

Bastian H: Lucy Wills (1888-1964): The

life and research of an adventurous independent woman. J R Coll

Phys Edinb. 38:89–91. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Viswanathan M, Urrutia RP, Hudson KN,

Middleton JC and Kahwati LC: Folic acid supplementation to prevent

neural tube defects: Updated evidence report and systematic review

for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 330:460–466. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Mitchell HK, Snell EE and Williams RJ:

Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 63, 1941: The

concentration of 'folic acid' by Herschel K. Mitchell, Esmond E.

Snell, and Roger J. Williams. Nutr Rev. 46:324–325. 1988.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rosenberg IH: A history of the isolation

and identification of folic acid (folate). Ann Nutr Metab.

61:231–235. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Angier RB, Boothe JH, Hutchings BL, Mowat

JH, Semb J, Stokstad EL, Subbarow Y, Waller CW, Cosulich DB,

Fahrenbach MJ, et al: Synthesis of a compound identical with the L.

casei factor isolated from liver. Science. 102:227–228. 1945.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kumar Upadhyay A, Prakash A, Kumar A, Jena

S, Sinha N and Sharma S: Dr. Sidney Farber (1903-1973): Founder of

pediatric pathology and the father of modern chemotherapy. Cureus.

16:e682862024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kutzbach C and Stokstad ELR: Mammalian

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Partial purification,

properties, and inhibition by S-adenosylmethionine. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 250:459–477. 1971. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tamura T and Stokstad ELR: The

availability of food folate in man. Br J Haematol. 25:513–532.

1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Castillo LF, Pelletier CM, Heyden KE and

Field MS: New insights into folate-vitamin B12 interactions. Annu

Rev Nutr. 45:23–39. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P,

Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, Boers GJ, den Heijer M, Kluijtmans LA,

van den Heuvel LP, et al: A candidate genetic risk factor for

vascular disease: A common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate

reductase. Nat Genet. 10:111–113. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Loperfido F, Sottotetti F, Bianco I, El

Masri D, Maccarini B, Ferrara C, Limitone A, Cena H and De Giuseppe

R: Folic acid supplementation in European women of reproductive age

and during pregnancy with excessive weight: A systematic review.

Reprod Health. 22:132025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Arynchyna-Smith A, Arynchyn AN, Kancherla

V, Anselmi K, Aban I, Hoogeveen RC, Steffen LM, Becker DJ,

Kulczycki A, Carlo WA and Blount JP: Improvement of serum folate

status in the US women of reproductive age with fortified iodised

salt with folic acid (FISFA study). Public Health Nutr.

27:e2182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Quinn M, Halsey J, Sherliker P, Pan H,

Chen Z, Bennett DA and Clarke R: Global heterogeneity in folic acid

fortification policies and implications for prevention of neural

tube defects and stroke: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine.

67:1023662023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

He Q and Li J: The evolution of folate

supplementation-from one size for all to personalized, precision,

poly-paths. J Transl Int Med. 11:128–137. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Scaglione F and Panzavolta G: Folate,

folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are not the same thing.

Xenobiotica. 44:480–488. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hoffbrand AV and Weir DG: The history of

folic acid. Br J Haematol. 113:579–589. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mishra VK, Rodriguez-Lecompte JC and Ahmed

M: Nanoparticles mediated folic acid enrichment. Food Chem.

456:1399642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wusigale and Liang L: Folates: Stability

and interaction with biological molecules. J Agric Food Res.

2:1000392020.

|

|

37

|

Siatka T, Mát'uš M, Moravcová M, Harčárová

P, Lomozová Z, Matoušová K, Suwanvecho C, Kujovská Krčmová L and

Mladěnka P: Biological, dietetic and pharmacological properties of

vitamin B9. NPJ Sci Food. 9:302025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Erşan S, Chen Y and Park JO: Comprehensive

profiling of folates across polyglutamylation and one-carbon

states. Metabolomics. 21:712025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yang M, Wang D, Wang X, Mei J and Gong Q:

Role of folate in liver diseases. Nutrients. 16:18722024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Revuelta JL, Serrano-Amatriain C,

Ledesma-Amaro R and Jiménez A: Formation of folates by