Introduction

Sepsis, an infection-driven systemic inflammatory

response syndrome, poses a major global health challenge due to its

high incidence and mortality (1,2).

According to World Health Organization estimates, nearly 19 million

people develop sepsis annually and 20-30% succumb to severe

complications (2). In intensive

care units, mortality is up to 56%, making sepsis the third leading

cause of death worldwide (3,4).

Among complications, sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction (SIMD)

is especially common and carries the worst prognosis. A total of

~70% of septic patients experience impaired myocardial

contractility, decreased ejection fraction and arrhythmia. These

cardiac impairments often coincide with hypotension and lactic

acidosis, hastening circulatory collapse and multi-organ failure

(5-7).

SIMD arises from a multifactorial network of

inflammatory and oxidative processes. Pathogen-associated molecular

patterns (PAMPs) engage toll-like receptor (TLR)4 signaling through

MyD88 and TIR-domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-β,

thereby activating NF-κB and MAPKs (p38, JNK, ERK). This cascade

triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and

IL-1β (8). The cytokine surge,

in turn, stimulates NADPH oxidase to generate reactive oxygen

species (ROS), which induce lipid peroxidation and protein damage

(9). Oxidative stress further

compromises mitochondrial integrity, leading to decreased ATP

synthesis and the activation of caspase-3-mediated apoptosis.

Collectively, these events depress ejection fraction, promote

ventricular dilation and drive circulatory failure (8).

Current clinical management of SIMD follows the

Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines, focusing on fluid

resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics and vasopressors.

Inotropes or β-blockers may be used as adjunctive therapies, but

they typically yield only transient hemodynamic benefits and can

increase myocardial oxygen demand or provoke arrhythmia (5). Given the intertwined

inflammation-oxidation-mitochondria-apoptosis network in SIMD,

single-target drugs are unlikely to provide comprehensive

cardioprotection. However, natural products offer promising

multi-target interventions with low toxicity profiles (10). Traditional compounds such as

flavonoids, glycosides, alkaloids and saponins exhibit

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiapoptotic and

mitochondrial-restorative effects. Preclinical study demonstrates

their capacity to attenuate key aspects of SIMD pathology (10); for example, curcumin has been

found to have extensive cardiovascular protective effects by

regulating endothelial function (10).

To the best of our knowledge, a systematic synthesis

of how natural products counteract SIMD is lacking. The present

review therefore summarizes the clinical features and

pathophysiology of SIMD and the structure-activity-mechanism

relationships of major natural product classes. Furthermore, the

present study aimed to highlight the primary signaling pathways

involved and evaluate advanced delivery strategies that improve

bioavailability and representative compound binding to SIMD

targets. By offering an integrated framework, the present study

aimed to guide the development of novel multi-target therapeutic

agents, including dietary supplements and lead compounds, for SIMD

therapy.

Pathophysiology of SIMD

SIMD is a complex, dynamic process in which

overwhelming infection and systemic inflammation disrupt normal

cardiac function. Multiple interrelated mechanisms, including

dysregulated cytokine release, oxidative stress, mitochondrial

damage and impaired calcium handling, converge to depress

myocardial performance (5). A

comprehensive understanding of these pathways is key for accurate

diagnosis and designing targeted therapies (Fig. 1).

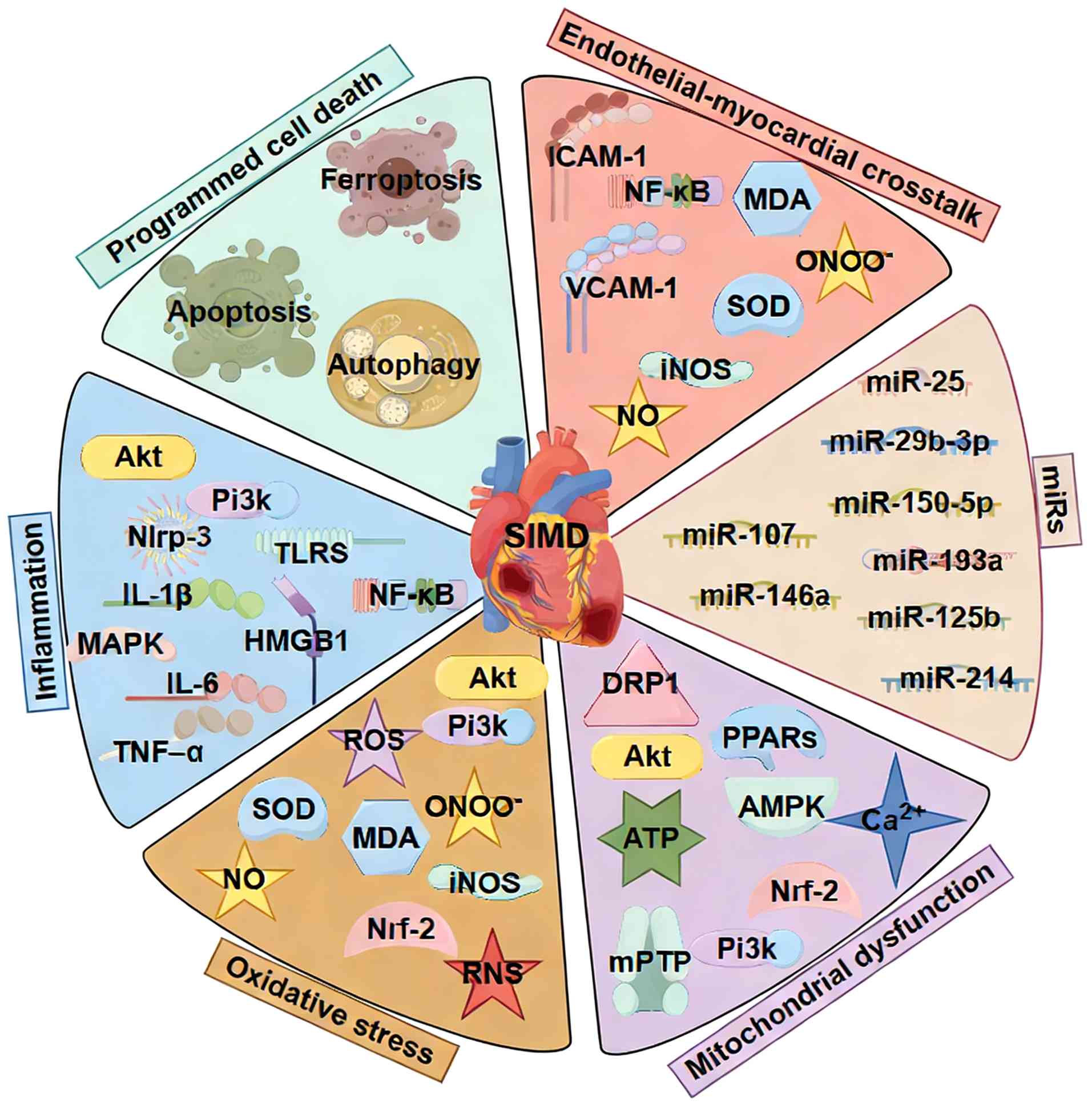

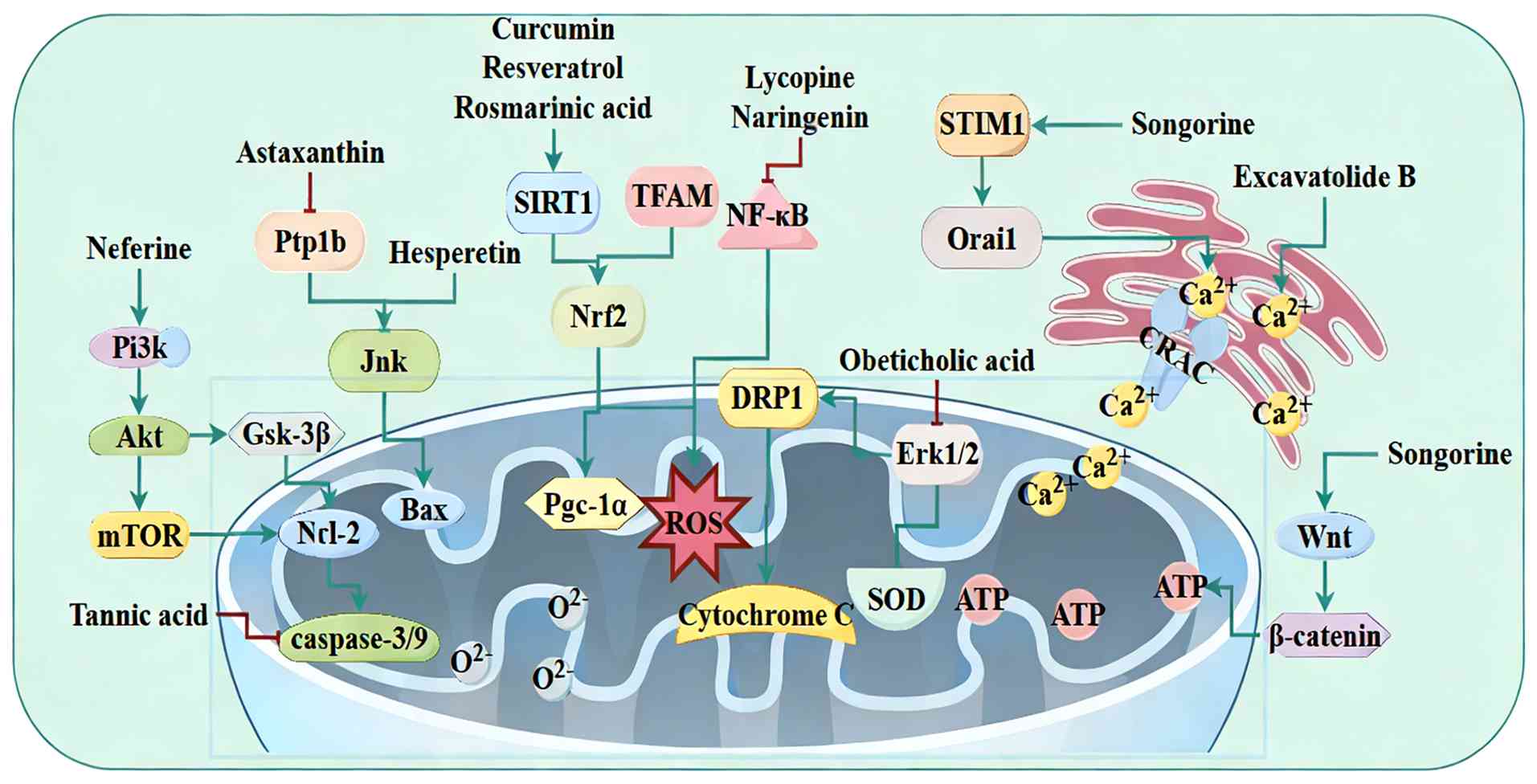

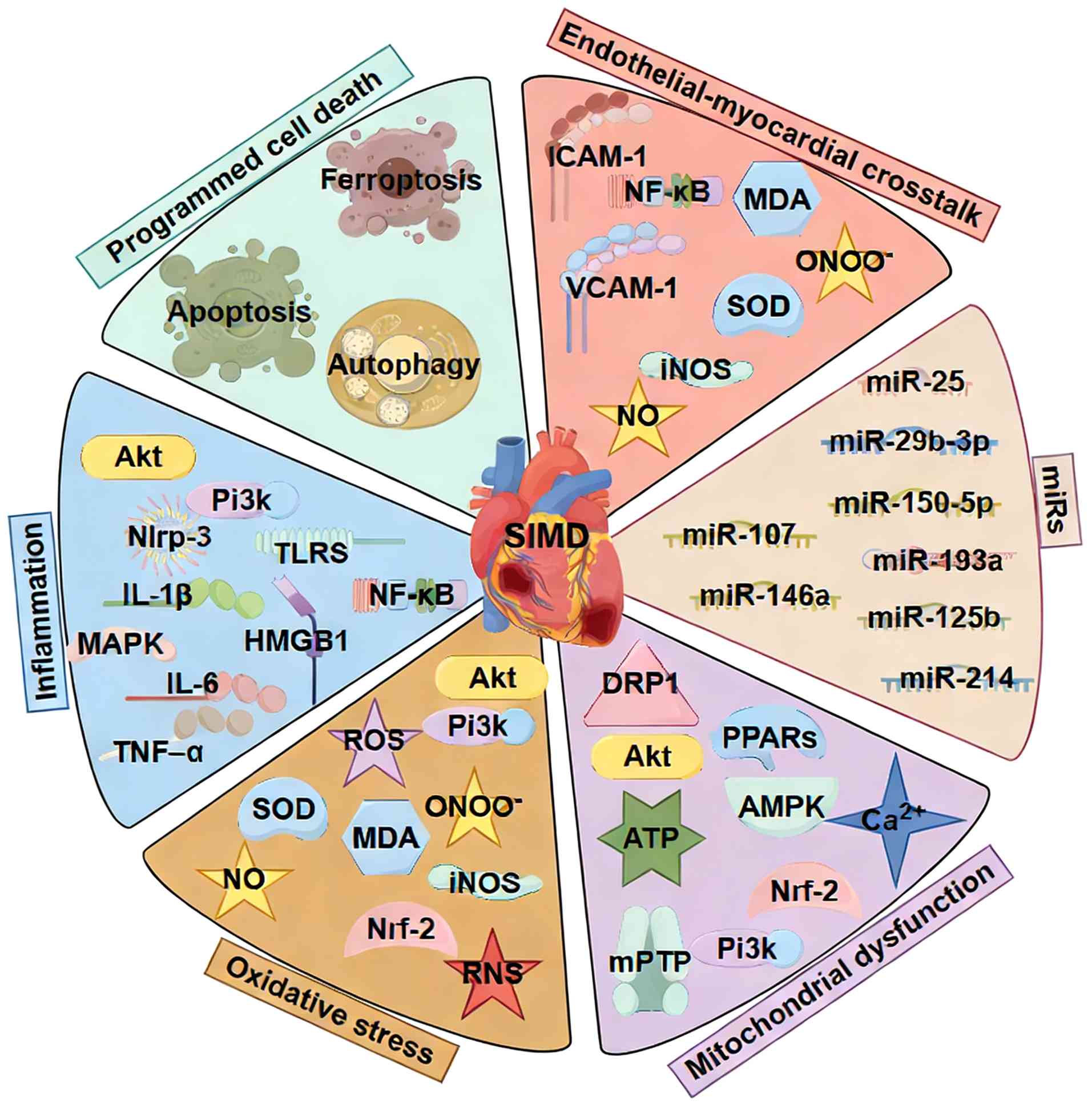

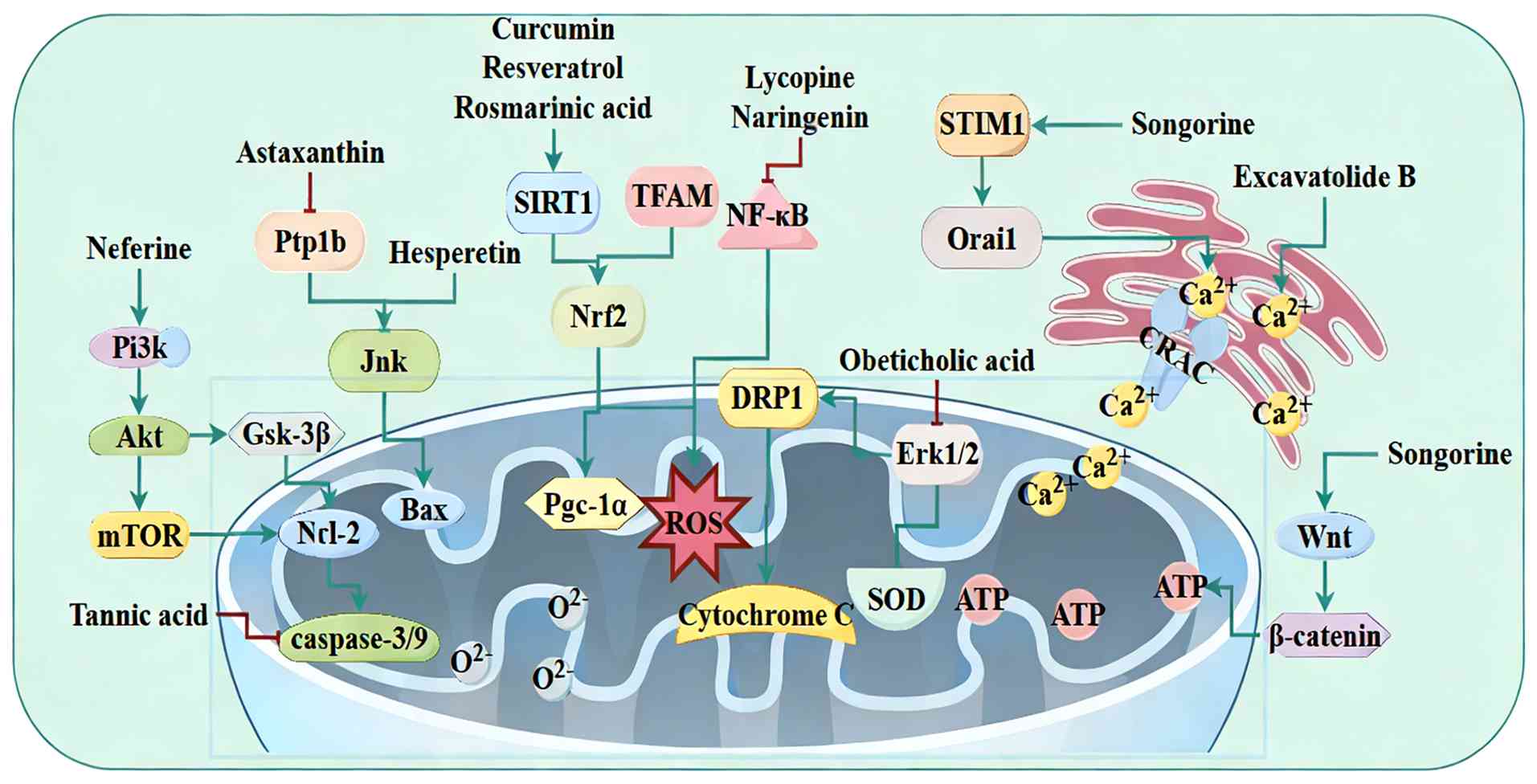

| Figure 1Pathophysiological mechanisms of

SIMD. This schematic illustrates the key interrelated pathways

(such as PI3K/Akt, NLRP3 and NF-κB) contributing to SIMD, including

dysregulated cytokine release, oxidative stress, mitochondrial

damage, impaired calcium handling and the regulatory roles of

specific. miRs. SIMD, sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction; miR,

microRNA HMGB, high mobility group box; TLRS, Toll like receptors;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA,

malondialdehyde; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; RNS,

reactive nitrogen species; DRP, dynamin-related protein; PPAR,

peroxisome proliferator activated-receptors; mPTP, mitochondrial

permeability transition pore. |

Clinical characteristics of SIMD

SIMD describes a transient, sepsis-associated

decline in myocardial function that can involve both the left and

right ventricles and may affect systolic and/or diastolic

performance (11). Many studies

define SIMD by a reversible decrease in left ventricular ejection

fraction (LVEF) accompanied by ventricular dilation and poor

response to fluid resuscitation or catecholamines (3,5,7).

However, because LVEF is load-dependent, it may not reliably

reflect contractile reserve during sepsis (12). Consequently, SIMD is now

recognized as a spectrum of load-independent myocardial depression

manifesting as left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction,

right ventricular dysfunction or a combination of both, often with

fluctuating hemodynamics (13).

Clinically, SIMD typically emerges within the first

hours to days of septic illness and presents with a heterogeneous

cardiac phenotype (14).

Systolic abnormalities range from decreased contractility to

ventricular dilation in certain patients (15), while diastolic dysfunction is

identified by altered filling parameters. Right ventricular

involvement is not uncommon and may exacerbate hemodynamic

instability (16). SIMD is often

reversible, although persistent dysfunction and worse outcomes

occur depending on sepsis severity, underlying comorbidities and

the level of hemodynamic support required (17). The clinical presentation may

evolve over time, with an initial high-output state potentially

progressing to a low-output phase, reflecting the interplay between

preload, afterload, myocardial depression and microcirculatory

redistribution (18). Thus, in

clinical practice, the diagnosis of SIMD relies on a comprehensive,

multi-faceted assessment. The typically involves confirming the

presence of sepsis, identifying otherwise unexplained myocardial

dysfunction, evidenced by new and often reversible

echocardiographic abnormality and associating these findings with

clinical signs of hemodynamic compromise, such as persistent

vasopressor dependency or objective evidence of tissue

hypoperfusion (14). While

elevated biomarkers such as cardiac troponins and natriuretic

peptides support the diagnosis by indicating myocardial injury or

stress, they are not standalone diagnostic criteria due to their

lack of specificity in the septic context (14).

Biomarkers of SIMD

Biomarkers of SIMD reflect diverse

pathophysiological domains, including direct myocardial injury,

ventricular wall stress, inflammatory remodeling and systemic

perfusion. It is crucial to note that most currently used

biomarkers are not specific to SIMD but indicate general myocardial

injury, stress, inflammation, or dysfunction. High-sensitivity

troponins I and T levels frequently rise in septic patients with

cardiac involvement, signaling myocardial injury rather than an

acute coronary syndrome. Troponin levels are associated with

illness severity and adverse outcomes (12,19), but their release in sepsis is

multifactorial, including demand ischemia, microvascular injury,

cytokine-mediated toxicity and catecholamine effects, underscoring

their lack of specificity for SIMD (19,20). B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP)

and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) increase

with myocardial wall stress and diastolic dysfunction and also

predict higher mortality (21,22). However, their variable

association with LVEF reduces their value as standalone markers of

intrinsic myocardial depression in SIMD (23).

Inflammatory and remodeling markers add prognostic

information beyond troponin and NPs. Soluble ST2 and galectin-3

rise in septic patients with myocardial involvement and are

associated with severity and adverse outcomes, reflecting ongoing

inflammation and fibrosis (24).

Similar to other markers, they are not specific to SIMD, and their

interpretation requires integration with imaging and clinical

context. Early injury markers such as heart-type fatty acid-binding

protein (H-FABP) may increase before troponin in certain cases,

offering potential for early risk stratification (25). Metabolic and perfusion markers,

including lactate, indicate global tissue hypoperfusion and shock

severity and thus complement cardiac-specific biomarkers in a

comprehensive hemodynamic assessment (26). Specific circulating microRNAs

(miRNAs or miRs) implicated in inflammatory and apoptotic pathways

(such as miR-21, miR-155 and miR-146a) represent a promising class

of biomarkers. They hold potential for more precise SIMD detection

and risk stratification but require prospective validation before

routine clinical use (27,28).

In summary, a multimodal strategy that integrates

biomarkers with load-independent echocardiographic measures and

detailed hemodynamic data is the most robust approach to defining

myocardial involvement, monitoring progression and guiding

management.

Pathology of SIMD

Programmed cell death

Cardiomyocyte loss in sepsis occurs through multiple

interrelated programmed cell death pathways (29). Apoptosis proceeds through

intrinsic mitochondrial pathways, where Bax and Bak mediate outer

mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and caspase activation, and

through endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways involving

glucose-regulated protein 78 kDa, CHOP and caspase-12 (30-32). Death receptor signaling via

TNF-R1 and FAS also contributes to caspase-8-mediated apoptosis.

Pharmacological modulation of these signals modestly improves

cardiac function in CLP (Cecum ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced

rats (33). Necroptosis, driven

by receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase RIPK1, RIPK3 and

MLKL (Mixed lineage kinase domain-like) MLKL, amplifies

inflammation and damages cardiomyocytes; inhibiting RIPK or MLKL

attenuates myocardial injury in CLP-induced septic mice (34). Pyroptosis, a lytic form of cell

death dependent on caspase-1-mediated gasdermin D (GSDMD) pore

formation, releases IL-1β and IL-18 and amplifies systemic

inflammation (35,36). Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent

form of lipid peroxidation, also contributes to cardiomyocyte

death; iron chelators and ferroptosis inhibitors lower ROS and

lipid peroxidation to preserve cardiac function in endotoxemia

(37,38). Autophagy plays a dual role in

SIMD. Moderate autophagic flux supports cell homeostasis and

cardiac resilience, but excessive or insufficient autophagy may

worsen injury (39).

Pharmacological induction of autophagy can restore homeostasis and

improve cardiac outcomes in septic rats (40).

Inflammation

Sepsis releases PAMPs and damage-associated

molecular patterns, which activate TLRs on cardiomyocytes,

fibroblasts and endothelial cells (ECs) (41). Except for TLR3, most TLR

signaling proceeds via the adaptor protein MyD88, activating

downstream effectors such as the MAPKs JNK, ERK1/2 and p38, as well

as the transcription factor NF-κB (42). This cascade drives production of

proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-12,

IL-17, IL-18) and chemokines such as CCL2/MCP-1 and CXCL8, which

recruit and activate immune cells (13,43-45). Activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome further amplifies IL-1β and IL-18 release, thereby

creating an inflammatory milieu that impairs cardiomyocyte

contractility by altering autophagy and lysosomal function

(46). High mobility group box

1) HMGB1 and extracellular histones released during sepsis impair

myocardial performance through TLR-dependent pathways, reinforcing

the inflammatory cascade (47).

Autonomic dysregulation also interacts with inflammation: Altered

adrenergic signaling can modulate cytokine production and

cardiomyocyte responsiveness, creating self-perpetuating feedback

loops that influence disease progression (48).

Oxidative stress

Alongside inflammation, sepsis triggers a surge of

ROS and nitrogen species (RNS) in cardiac tissue (49). ROS originate from electron leak

in mitochondrial complexes I-III and from NO-derived species such

as peroxynitrite (ONOO) (50).

Oxidative and nitrosative stress damage lipids, protein and DNA,

deplete antioxidants including superoxide dismutase, catalase and

glutathione, and disrupt calcium handling and

excitation-contraction coupling (51). NO produced by inducible nitric

oxide synthase (iNOS) contributes to myocardial depression, while

ONOO− nitrates tyrosine residues and further impairs

mitochondrial and contractile protein (52). This redox imbalance shifts

signaling toward proinflammatory pathways, creating a cycle that

worsens contractile dysfunction (53).

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondria are key for energy supply and cell

survival rate in SIMD (54).

Sepsis induces structural changes, swelling and cristae disruption,

alongside declines in oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis

(55). Excessive mitochondrial

fission, driven by the GTPase dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1),

fragments the organelle and worsens energy deficits, whereas

promoting fusion or mitophagy can maintain mitochondrial integrity

in LPS-induced mice (56). The

mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opens under

calcium overload, oxidative stress and ATP depletion, collapsing

membrane potential and releasing cytochrome c (57). Agents that prevent mPTP opening

or stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis improve mitochondrial

function and cardiac performance in septic rats (58). In SIMD, energy metabolism shifts

from fatty acid oxidation to glycolysis, decreasing ATP yield;

downregulation of lipid-oxidation regulators such as PPARs and α

subunit of peroxisome proliferators activated receptor-γ

coactivator-1 (PGC-1α exacerbates energetic failure (58). Additional mitochondrial insults

include mitochondrial DNA oxidation and impaired activity of

electron transport chain complexes II and IV, limiting ATP

production and contractile capacity (59). Restoring mitochondrial integrity

with targeted antioxidants and NAD+-boosting strategies

offers a promising therapeutic approach in SIMD (60).

Endothelial-myocardial crosstalk

ECs coordinate vascular tone, perfusion and

inflammation in the cardiovascular system (61). In sepsis, EC dysfunction

transforms the vascular bed into a source of injurious signals that

affect adjacent cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts and the

microcirculation (62). Under

inflammatory and oxidative stress, ECs activate TLRs, triggering

NF-κB and MAPK pathways and increasing production of ROS and RNS

(63). This pro-oxidant

environment impairs myocardial relaxation and contraction and

worsens microvascular perfusion. Upregulation of intercellular cell

adhesion molecule-1 vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) promotes

leukocyte trafficking into the myocardium, while degradation of the

glycocalyx increases vascular permeability, edema and microvascular

leakage, collectively decreasing oxygen delivery and substrate

availability to the heart (64,65). Emerging evidence supports

bidirectional communication between ECs and cardiomyocytes:

Endothelial-derived signals modulate cardiomyocyte function and

energy metabolism, while cardiomyocytes influence endothelial

behavior via paracrine pathways and hemodynamic feedback (66). For example, endothelial-derived

reactive species and altered NO signaling contribute to calcium

handling abnormality and energetic stress in cardiomyocytes

(67). Conversely, interventions

that dampen endothelial inflammation or NO production yield

downstream cardioprotective effects (68,69).

Role of miRNAs

Dysregulated miRNAs serve as key epigenetic

regulators and downstream effectors in the pathogenesis of SIMD

(70). These small non-coding

(nc)RNAs fine-tune gene expression post-transcriptionally,

predominantly by modulating central inflammatory and apoptotic

pathways.

Numerous miRNAs critically regulate the inflammatory

cascade in SIMD, primarily through targeting key components of the

NF-κB signaling pathway. Certain miRNAs serve as endogenous

negative feedback regulators to attenuate excessive inflammation.

For example, miR-146a and miR-125b dampen NF-κB activation and

subsequent pro-inflammatory cytokine production by targeting key

adaptor proteins IL-1 receptor-associated kinase) and TNF receptor

associated factor 6) (71,72). Similarly, miR-25 inhibits the

TLR4/NF-κB pathway by directly targeting PTEN (73) and miR-29b-3p suppresses

MAPK/NF-κB signaling by targeting FOXO3A (74). miR-335, although upregulated in

SIMD, appears to exert a net beneficial effect on inflammation and

injury when overexpressed, suggesting a complex, context-dependent

regulatory role (75).

Conversely, specific miRNAs exacerbate myocardial inflammation.

miR-193a, expression of which is enhanced via METTL3-mediated m6A

modification, promotes inflammation by targeting the anti-apoptotic

gene BCL2L2 (76). The

circROCK1/miR-96-5p/oxidative stress responsive kinase 1) pathway

also promotes myocardial injury and NF-κB activation (77). Furthermore, hsa-miR-23a-3p,

hsa-miR-3175 and hsa-miR-23b-3p are implicated in regulating NF-κB

signaling via histone deacetylase 7)/ACTN4 (A-actinin-4),

contributing to inflammatory damage (78).

Beyond inflammation, miRNAs determine cardiomyocyte

fate by fine-tuning apoptotic and other cell death pathways.

Multiple miRNAs confer cardioprotection by inhibiting pro-apoptotic

signals or enhancing survival pathways. These include miR-214,

which improves cardiac function and suppresses apoptosis (79). miR-21 inhibits apoptosis by

targeting programmed cell death 4) to activate the PI3K/Akt

pathway, as well as by directly regulating Bcl-2 and CDK6 (80). miR-150-5p alleviates apoptosis by

modulating Akt2 expression (80). miR-107 promotes cardiomyocyte

proliferation and inhibits apoptosis via the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway

(81,82). Regulatory networks involving long

(l)ncRNAs further augment this layer of control. For example, the

lncRNA KCNQ1OT1 serves as a competitive endogenous RNA to sponge

miR-192-5p, thereby upregulating the anti-apoptotic protein

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (83), while the lncRNA ZFAS1 protects

against apoptosis by sequestering miR-34b-5p to upregulate sirtuin

(SIRT)1 (84). Conversely,

detrimental miRNAs such as miR-208a-5p and miR-21-3p promote

apoptosis (85).

Additionally, miRNAs participate in specialized cell

death modalities and mitochondrial dysfunction associated with

SIMD. miR-383-3p has been shown to alleviate SIMD by inhibiting

ferroptosis via the activating transcription factor 4

(ATF)-CHOP-ChaC glutathione specific γ-glutamylcyclotransferase 1)

(86), whereas miR-194-5p

aggravates oxidative stress and apoptosis by targeting DUSP9

(87). The Xist/miR-7a-5p

pathway serves a key role in sepsis-induced mitochondrial

dysfunction. Inhibition of either Xist or miR-7a-5p upregulates the

key mitochondrial biogenesis factor PGC-1α, increases ATP

production, and decreases cardiomyocyte apoptosis, highlighting

their key role in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis (88,89).

Natural products against SIMD

The pathophysiology of SIMD is complex and

multifactorial. Interplay of cytokine storm, excessive generation

of ROS and RNS, mitochondrial dysfunction and dysregulated

endothelial-myocardial crosstalk collectively drive cardiomyocyte

apoptosis, ferroptosis and microcirculatory impairment.

Regulation of programmed cell death

Programmed cell death pathways implicated in SIMD

include apoptosis, pyroptosis, autophagy and ferroptosis. Natural

products can confer cardioprotection by either enhancing cell

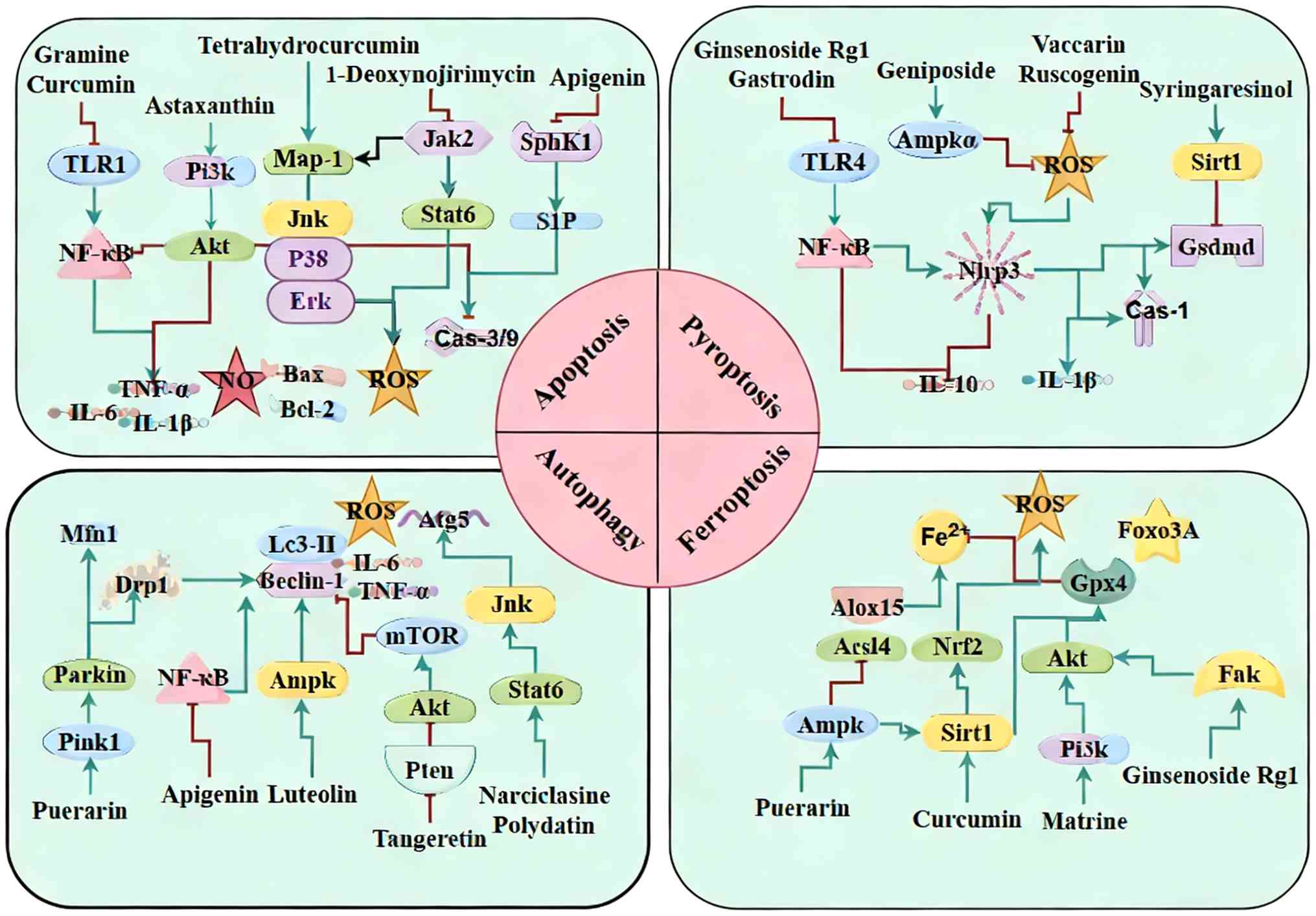

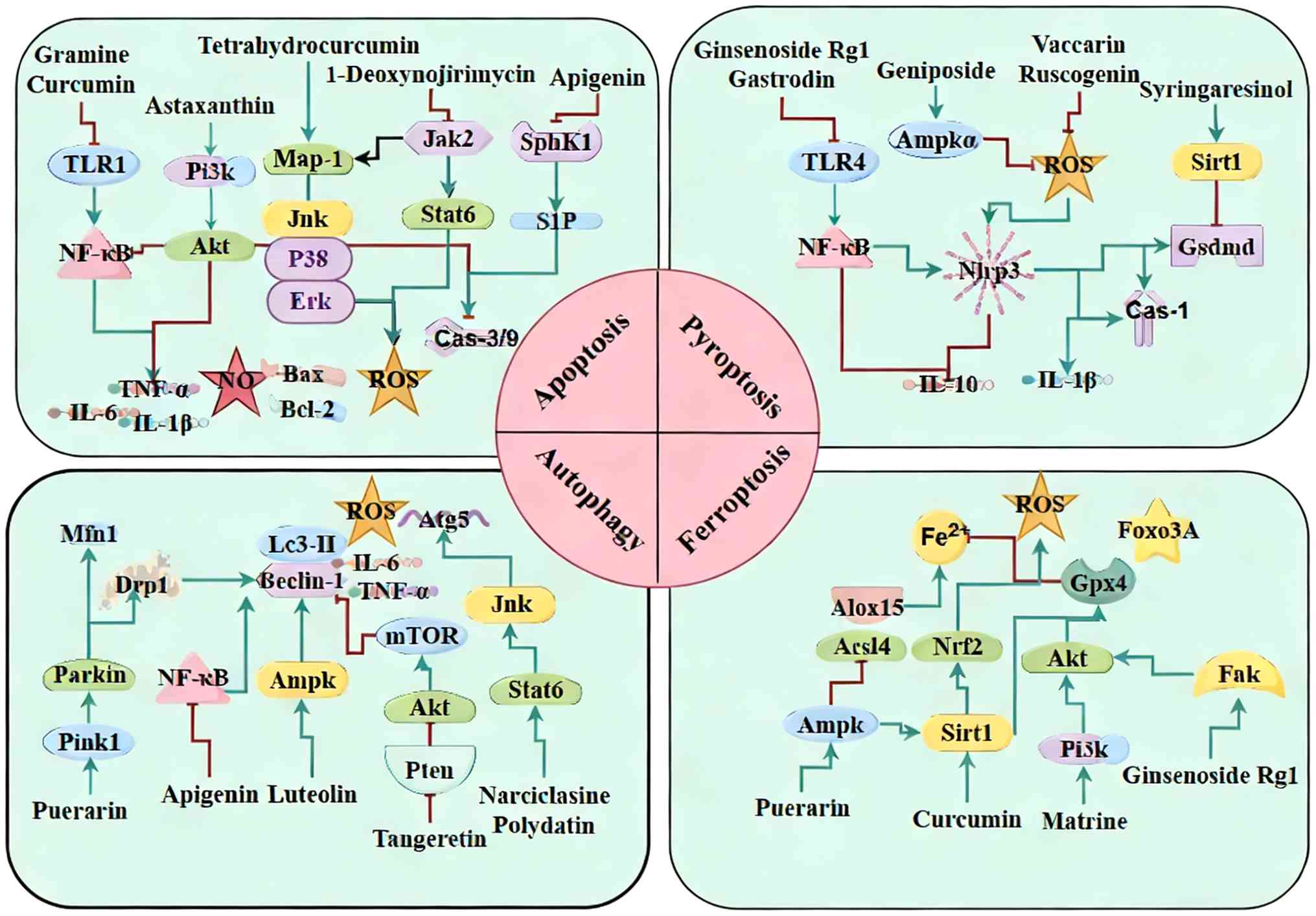

survival signals or inhibiting specific death pathways (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2Regulation of programmed cell death

by natural products in SIMD. Natural products attenuate SIMD

through suppression of pro-oxidant NF-κB/TLR signaling, modulation

of PI3K/Akt, AMPK/autophagy, TFEB, NLRP3/pyroptosis and mitophagy

pathways and restoration of GPX4-associated antioxidant defenses.

SIMD, sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction; TLR, Toll like

receptor; TFEB, T cell transcription factor EB; GPX, Glutathione

peroxidase; SphK, Sphingosine kinases; S1P, Sphingosine Kinase 1;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; MFN, mitofusin; SIRT, sirtuin 1;

GSDMD, gasdermin D; ALOX, arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase. |

Inhibition of apoptosis

Cardiomyocyte apoptosis is an early pathogenic event

in SIMD, contributing to amplified inflammation and progressive

cardiac dysfunction.

NF-κB, a master regulator of inflammation and

apoptosis, is a common target for numerous natural compounds that

also inhibit upstream TLR signaling. In CLP-induced septic mice,

compounds such as gramine, curcumin, andrographolide and berberine

suppress the TLR1/NF-κB axis, leading to lower TNF-α, IL-1β and NO

levels, decreased caspase-3 activation and apoptosis and restored

cardiac contractility, which translates into decreased mortality

(90-94). Notoginsenoside R1 activates the

PI3K/Akt pathway while concurrently inhibiting NF-κB, resulting in

suppressed caspase-3 activation and downregulated TNF-α and IL-1β

levels in both cardiomyocyte H9c2 and septic mice, thereby

attenuating inflammation and apoptosis (95,96).

The MAPK family also influences stress-induced

apoptosis. In LPS-challenged septic mice, tetrahydrocurcumin

upregulates mitogen activated protein kinase phosphatase 1),

suppresses ERK and JNK signaling and limits ROS production and

caspase-3-mediated apoptosis, preserving cardiac function (97). Astaxanthin similarly inhibits

ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK pathways while activating PI3K/Akt pathway,

resulting in lower serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and BNP, and reduced

myocardial injury and apoptosis in septic mice (98). Furthermore, 1-deoxynojirimycin

decreases ROS generation by inhibiting JAK2/STAT6 signaling,

thereby decreasing cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improving function

in septic mice (99).

Astragaloside IV protects against LPS-induced myocardial injury in

rats by inhibiting the JNK/Bax pathway, reducing levels of

caspase-3, CK-MB (Creatine kinase (CK-MB) and c-TnI (Cardiac

troponin I c-TnI) and increasing the Bcl-2/Bax ratio to mitigate

myocardial dysfunction (100).

In CLP-induced septic rats, apigenin inhibits the

Sphingosine kinase 1/sphingosine 1-phosphate) pathway, leading to

downregulation of cleaved caspase-3/-9 and Bax, upregulation of

Bcl-2, decreased serum CK-MB and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

levels, suppressed apoptosis and improved myocardial histology

(101). Gastrodin, tested in

CLP-induced septic mice and AC16 cardiomyocytes, modulates the

denticleless E3 ubiquitin protein ligase-homolog histone

acetyltransferase-driven ubiquitination-acetylation axis to promote

degradation of pro-caspase-3/-9 and Bax, thereby attenuating

apoptosis and alleviating myocardial damage (102).

Inhibition of pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of programmed

cell death triggered by inflammasome activation, characterized by

GSDMD-mediated pore formation and the release of IL-1β and IL-18

(103). In SIMD, pyroptosis not

only accelerates cardiomyocyte loss but also perpetuates a local

inflammatory cycle.

In CLP-induced septic mice, vaccarin and ruscogenin

attenuate myocardial injury by suppressing the NLRP3 inflammasome,

decreasing IL-1β and IL-18 release and limiting pyroptosis

(103,104). Artemisinin decreases NLRP3 and

caspase-1 expression in burned septic mice, lowers IL-1β and IL-18

mRNA in mouse monocytic macrophage leukemia RAW264.7 cells and

decreases neutrophil infiltration, thereby mitigating myocardial

damage (105). Similarly,

thymoquinone inhibits the NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β/IL-18 pathway,

downregulates p62 and c-TnT and upregulates IL-10, reducing

inflammation and pyroptosis in septic mice (106). Additionally, in LPS-challenged

septic mice, syringaresinol activates the endoplasmic reticulum

(ER)/SIRT1 pathway and suppresses NLRP3/GSDMD signaling to block

IL-1β and IL-18 release, significantly improving myocardial injury

(107). Both ginsenoside Rg1

and gastrodin inhibit the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling cascade,

downregulate Bax, upregulate Bcl-2 and restore cardiac function by

reducing pyroptosis (108,109). Nifuroxazide similarly targets

TLR4/NLRP3/IL-1β signaling to lower LDH and CK-MB levels, suppress

pyroptosis and protect myocardial function (110).

ROS also regulate NLRP3 activation. In LPS-induced

septic mice, carvacrol and emodin inhibit the ROS/NLRP3/GSDMD

pathway, decreasing IL-1β and IL-18 levels, which enhances survival

rate and restores cardiac function (111,112). Plumbagin also suppresses

ROS-mediated NLRP3/GSDMD signaling, decreases HMGB1, caspase-3 and

Bax expression and improves cardiac function through preventing

pyroptosis (113). Geniposide

downregulates neutrophil cytoplasmic factor 1 and suppresses the

AMPKα/ROS/NLRP3 pathway, leading to reduced ROS levels and improved

cardiac function and survival rate in septic mice (114). Finally, oxycodone markedly

improves EF and fractional shortening (FS), decreases levels of

ROS, c-TnI and CK-MB and activates the Nrf2/heme oxygenase (HO)-1

pathway to inhibit NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis, yielding notable

cardioprotective effects (115).

Autophagy

Autophagy is a key homeostatic process that removes

damaged organelles and proteins via lysosomal degradation. In

cardiomyocytes, it maintains mitochondrial quality, balances energy

metabolism and supports antioxidant defenses (39). In SIMD, autophagy exhibits a dual

role: Moderate activation clears dysfunctional mitochondria and

limits oxidative stress, whereas either excessive or insufficient

autophagic flux can exacerbate cell death and impair cardiac

function (116).

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway

induces autophagy. In CLP-induced septic mice, luteolin activates

AMPK pathway signaling, which increases LC3-II and Beclin-1

expression, enhances autophagic flux, improves LVEF and FS,

decreases levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and ROS, restores mitochondrial

architecture and inhibits apoptosis (116). Conversely, in CLP-induced

septic rats, tangeretin suppresses excessive autophagy by

inhibiting PTEN and activating the Akt/mTOR pathway. This lowers

serum levels of cardiac myosin light chain-1 (cMLC1), c-TnI, LDH

and (CK), alleviates oxidative stress and inflammation and

preserves myocardial function (117).

The NF-κB/TFEB (T cell transcription factor EBTFEB

pathway also regulates autophagy. In LPS-challenged septic mice,

apigenin inhibits NF-κB to decrease inflammation and oxidative

stress while upregulating TFEB and its downstream target genes such

as ATG5, lysosome-associated membrane protein 1), p62,

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3), vacuolar protein

sorting 11), thereby boosting autophagic flux. These combined

effects lower cardiac injury markers (CK, LDH, c-TnI, cMLC1),

improve survival rate and maintain cardiac function (118,119).

Mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) is key for

clearing damaged mitochondria. In LPS-stimulated H9c2

cardiomyocytes, puerarin upregulates Drp1 and mitofusin 1 to

preserve mitochondrial dynamics and activates the PINK1/Parkin

pathway, thereby reducing ROS, inhibiting apoptosis and restoring

cell viability (120).

Other natural compounds modulate autophagy through

alternative signaling nodes. In LPS-induced septic mice,

narciclasine and polydatin activate SIRT6 and JNK signaling, which

elevates LC3-II and Beclin-1 while lowering TNF-α and IL-6 levels,

thereby suppressing inflammation and attenuating myocardial injury

(121,122). Phlorizin modulates the

Hif-1α/BCL2 interacting protein 3) axis to promote Beclin-1

release, autophagosome formation and lysosomal degradation,

reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis, improving cardiac function

and enhancing survival rate (123).

Inhibition of ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of programmed

cell death characterized by glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)

inactivation, accumulation of lipid peroxides and iron overload

(37). In SIMD, inflammatory

disruption of iron homeostasis coupled with mitochondrial

dysfunction accelerates lipid peroxidation, triggering ferroptosis

and exacerbating cardiomyocyte injury (124). Consequently, targeting

antioxidant defenses, iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation

represents a promising therapeutic strategy.

The AMPK signaling axis serves a central role in

regulating ferroptosis. In LPS-induced septic mice, puerarin

activates AMPK to upregulate GPX4 and ferritin and downregulate

ACSL4 and the transferrin receptor (TFRC), reducing myocardial iron

content, lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis (124). Curcumin engages the AMPK/SIRT1

pathway to increase expression of GPX4, ferritin and translocase of

outer mitochondrial membrane 20 while decreasing levels of

Fe2+, MDA and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2,

thereby preventing ferroptotic cell death (125). Similarly, matrine activates

PI3K/Akt to enhance GPX4 and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio, reduce ACSL4 and

ROS and inhibit ferroptosis, improving cardiac performance

(126). Ginsenoside Rg1

stimulates FAK/Akt and upregulates FOXO3A, which decreases levels

of TNF-α, IL-1β and Fe2+ and increases Bcl-2,

collectively alleviating myocardial injury (127).

Direct inhibition of key lipid peroxidation enzymes

provides another mechanism to block ferroptosis. In LPS-stimulated

AC16 cardiomyocytes, resveratrol upregulates miR-149 and

downregulates HMGB1, decreasing Fe2+ accumulation and

lipid ROS to protect the myocardium (128). In CLP-induced septic mice,

narciclasine restores glutathione, downregulates TFRC and

upregulates GPX4 and HO-1, thereby inhibiting lipid peroxidation

and preserving cardiac function (129). Furthermore, resveratrol

activates the SIRT1/Nrf2 pathway to mitigate mitochondrial damage

and lipid peroxidation (130).

Arachidonic acid 15-lipoxygenase (ALOX15) is a key enzyme in lipid

peroxidation. Wogonin directly inhibits ALOX15, mitigating lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis in the myocardium (131). Quercetin also activates

PI3K/Akt to inhibit ALOX5-mediated lipid oxidation, restores GPX4

and glutathione (GSH) levels, lowers Fe2+ and ROS, and

suppresses myocardial inflammation and ferroptosis (132).

Collectively, natural products, such as flavonoids,

alkaloids and saponins, attenuate SIMD through diverse mechanisms.

These include suppression of pro-oxidant NF-κB/TLR signaling,

modulation of PI3K/Akt, AMPK/autophagy, TFEB, NLRP3/pyroptosis and

mitophagy pathways and restoration of GPX4-related antioxidant

defenses. For example, curcumin, resveratrol, and quercetin

concurrently inhibit apoptosis and pyroptosis, promote adaptive

autophagy and restrain ferroptosis. Similarly, astaxanthin,

apigenin and puerarin protect the myocardium through combined

activation of autophagy and inhibition of ferroptosis. This

multimodal pharmacological profile highlights the potential of

natural products to target the interconnected cell death networks

that drive SIMD.

Regulation of inflammation

Sepsis provokes a systemic inflammatory response

that contributes directly to myocardial injury. Endotoxins and

other PAMPs activate key signaling cascades, most notably the

TLR4/NF-κB, MAPK and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways, leading to the

release of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1)

and recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages into cardiac tissue.

The resulting inflammatory milieu impairs cardiomyocyte

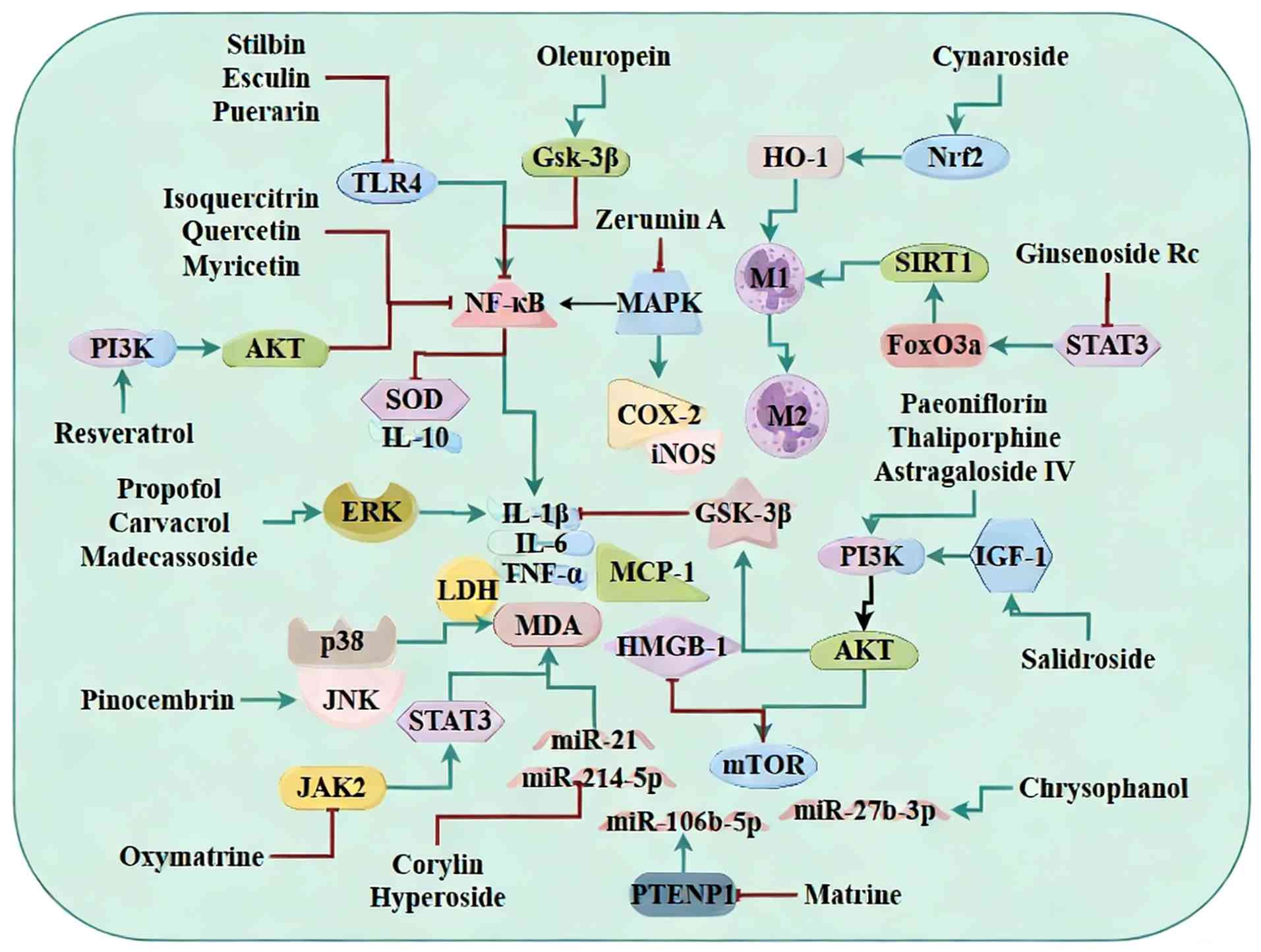

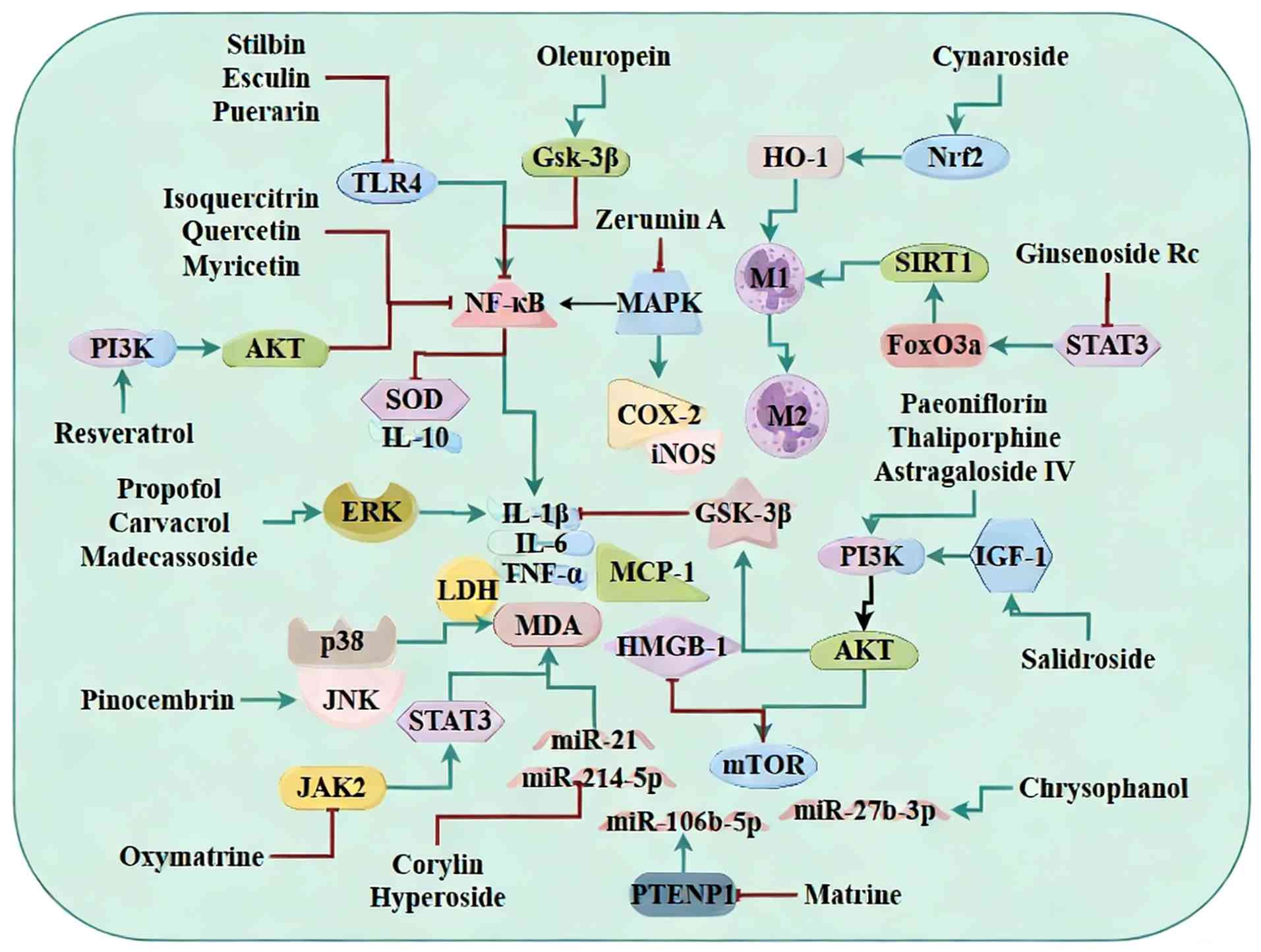

contractility and survival (Fig.

3).

| Figure 3Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of

natural products in sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction). Natural

products confer protection by inhibiting pro-inflammatory

TLR4/NF-κB and MAPK signaling cascades, activating the PI3K/Akt

survival pathway, modulating specific miR networks (miR-214-5p,

miR-21) and promoting the polarization of macrophages towards the

reparative M2 phenotype. TLR, toll-like receptor; miR, miRNA; GSK,

glycogen synthase kinase; HO, heme oxygenase; SIRT, sirtuin 1; COX,

cyclooxygenase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IGF, insulin

like growth factor; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCP, monocyte

chemotactic protein; MDA, malondialdehyde; HMGB, high mobility

group box. |

Inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway

Numerous flavonoids and other phytochemicals

suppress TLR4-driven NF-κB activation to decrease cytokine release

and improve cardiac function. In LPS-challenged septic mice,

isoquercitrin and quercetin inhibit NF-κB p65 phosphorylation,

lower TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 levels and significantly improve LVEF

and FS (133,134). Ciprofol similarly blocks NF-κB

activation in septic mice, decreasing levels of CK-MB, LDH, TNF-α

and IL-6 and restoring LVEF and FS (135). In CLP-induced septic rats,

astragaloside IV prevents NF-κB p65 phosphorylation, decreases

levels of LDH, CK-MB, IL-6, IL-1β and HMGB1 and enhances both

systolic and diastolic function as well as survival rate (136). Myricetin inhibits IκBα

degradation and NF-κB/p65 nuclear translocation in septic rats,

which lowers TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β and preserves cardiac function

(137,138). Similarly, naringin blocks NF-κB

nuclear translocation, decreases TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 levels and

enhanced superoxide dismutase activity while lowering MDA levels

and leads to improved cardiac performance in septic rats (139,140). Additionally, astilbin and

esculin both target the TLR4/NF-κB pathway to downregulate TNF-α,

IL-6 and MDA, correct QT prolongation and reduce the risk of

ventricular arrhythmia (141,142). Puerarin also inhibits

TLR4/NF-κB signaling in Langendorff-perfused hearts, decreasing

LDH, CK and TNF-α release and improving LV end-diastolic pressure

in septic rats (143). By

contrast, oleuropein activates the glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3

beta)/NF-κB pathway, decreases c-TnI, CK-MB, IL-6 and HMGB1 levels

and increases anti-inflammatory IL-10 levels, thereby protecting

cardiac function in septic rats (144).

Inhibition of MAPK-associated

pathways

The MAPK family intersects with NF-κB signaling to

amplify inflammation. In LPS-stimulated H9C2 cells, zerumin A

suppresses MAPK-mediated NF-κB activation, resulting in lower

levels of iNOS, ROS, COX-2, NO, MCP-1, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-1β and

higher IL-10 expression, which improves cell viability (145). In LPS-challenged septic mice,

propofol and carvacrol both inhibit ERK1/2 phosphorylation,

decrease IL-6 and TNF-α levels, alleviate myocardial injury and

enhance survival rate (146,147). Pinocembrin blocks the p38/JNK

MAPK pathway, decreasing myocarditis and arrhythmia risk in

LPS-induced septic rats (148).

Similarly, madecassoside inhibits ERK1/2 and p38 activation in

septic mice, delays arterial pressure decline and lowers TNF-α

levels, thereby mitigating tachycardia (149). Additionally, alisol B

23-acetate suppresses TLR4/NOX2 and p38/MAPK/ERK signaling,

decreasing IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α levels, which alleviates

myocardial injury and improves survival rate (150). In LPS-treated septic rats,

oxymatrine also inhibits the p38/MAPK/caspase-3 and JAK2/STAT3

pathways, decreases IL-1β and TNF-α levels and improves cardiac

function (151,152).

Activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway

The PI3K/Akt pathway exerts anti-inflammatory and

pro-survival effects in SIMD. In LPS-challenged septic mice,

astragaloside IV activates PI3K/Akt signaling to reduce LDH and

c-TnI levels, suppress myocardial inflammation and improve cardiac

performance (153).

Paeoniflorin and resveratrol also stimulate PI3K/Akt to decrease

levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, MCP-1, IFN-γ and iNOS, thereby

protecting against myocardial injury (154,155). In CLP-induced septic mice,

thaliporphine activates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway to decrease

levels of TNF-α, c-TnI and LDH and enhance LV function (156). Salidroside modulates the

IGF-1/PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway to decrease levels of CK, LDH, TNF-α,

IL-6 and IL-1β, thereby alleviating myocardial edema and

dysfunction (157).

miRNA-dependent anti-inflammatory

pathways

miRNAs have emerged as critical regulators of

myocardial inflammation in sepsis. For example, corylin improves

LPS-induced cardiac dysfunction in mice by downregulating

myocardial miR-214-5p, which attenuates inflammatory signaling

(158). In CLP-induced septic

mice, hyperoside exerts protective effects by suppressing the

sepsis-associated upregulation of miR-21, leading to decreased

myocardial inflammation (159).

Furthermore, matrine acts via the PTENP1/miR-106b-5p pathway to

inhibit proinflammatory pathways and enhance cardiomyocyte

viability, thereby improving cardiac function in CLP-induced mice

(160). Chrysophanol

downregulates miR-27b-3p and upregulates PPARγ, which suppresses

inflammatory cytokines and apoptotic proteins to repair CLP-induced

cardiac injury in mice (161).

Targeting macrophage polarization

Macrophage polarization strongly influences the

inflammatory milieu in SIMD. Pinostrobin inhibits TLR4/myeloid

differentiation protein-2 signaling in mouse monocytic macrophage

leukemia RAW264.7cells, decreasing expression of NO, prostaglandin

E2, TNF-α, IL-12, iNOS and COX-2, and improves heart rate and

survival rate in LPS-treated zebrafish (162). Cynaroside activates the

Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to lower IL-1β and TNF-α levels and promotes M2

macrophage polarization, thereby decreasing systemic inflammation

and protecting the myocardium in septic mice (163). Similarly, ginsenoside Rc

suppresses the STAT3/FoxO3a/Sirt1 pathway to limit M1

macrophage-mediated myocardial damage during sepsis (164).

Other anti-inflammatory agents

Several additional natural products exhibit potent

anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects in SIMD. In

LPS-induced septic mice, cyanidin lowers levels of LDH, CK, c-TnI,

TNF-α, IL-1β, MIP-2, MCP-1 and cMLC1, inhibits caspase-3 and PARP

cleavage and attenuates myocardial injury (165). Monotropein and baicalein

suppress TNF-α, IL-6, HMGB1 and iNOS/NO production while decreasing

MMP-2/9 and ROS levels to alleviate septic myocardial hypertrophy

and dysfunction (166,167). Paeoniflorin and honokiol

markedly decrease c-TnI, LDH, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β and raise IL-10

levels, improving cardiac contractility and enhancing survival rate

in CLP-induced septic mice (168,169). Similarly, dobutamine increases

serum levels of IL-10 and lowers c-TnI, NT-proBNP and H-FABP,

thereby enhancing survival rate in CLP-induced rats (170).

In LPS-challenged septic rats, magnolol corrects

hypotension and bradycardia by decreasing levels of iNOS, NO, TNF-α

and alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase) (171). Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate

also improves LV function by inhibiting expression of TNF-α, IL-6,

HMGB1, C-reactive protein, PCT (Procalcitonin (PCT), c-TnI/c-TnT

and BNP (172). Additionally,

micromeria congesta downregulates IL-2, caspase-3 and heat shock

protein (HSP)-27 to attenuate septic myocardial pathology (173). Naringenin and tubeimoside I

activate the SIRT3 or HIF-1α pathways to suppress IL-1β, IL-6 and

TNF-α, improving myocardial injury (174,175). Yohimbine blocks α2A-adrenergic

receptors at cardiac sympathetic terminals, promotes norepinephrine

release and decreases NO and TNF-α levels to alleviate cardiac

dysfunction in septic rats (176).

In summary, these natural products protect against

SIMD by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB and MAPK signaling, activating

PI3K/Akt, modulating miRNA networks and promoting macrophage M2

polarization. They collectively reduce proinflammatory cytokine

levels, limit inflammatory cell infiltration and improve cardiac

function and survival rate.

Regulation of oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is a key driver of cardiac injury

in SIMD. Inflammation, endotoxins and mitochondrial dysfunction

increase ROS/RNS levels, leading to lipid peroxidation, protein

carbonylation and DNA damage (49). These changes worsen contractile

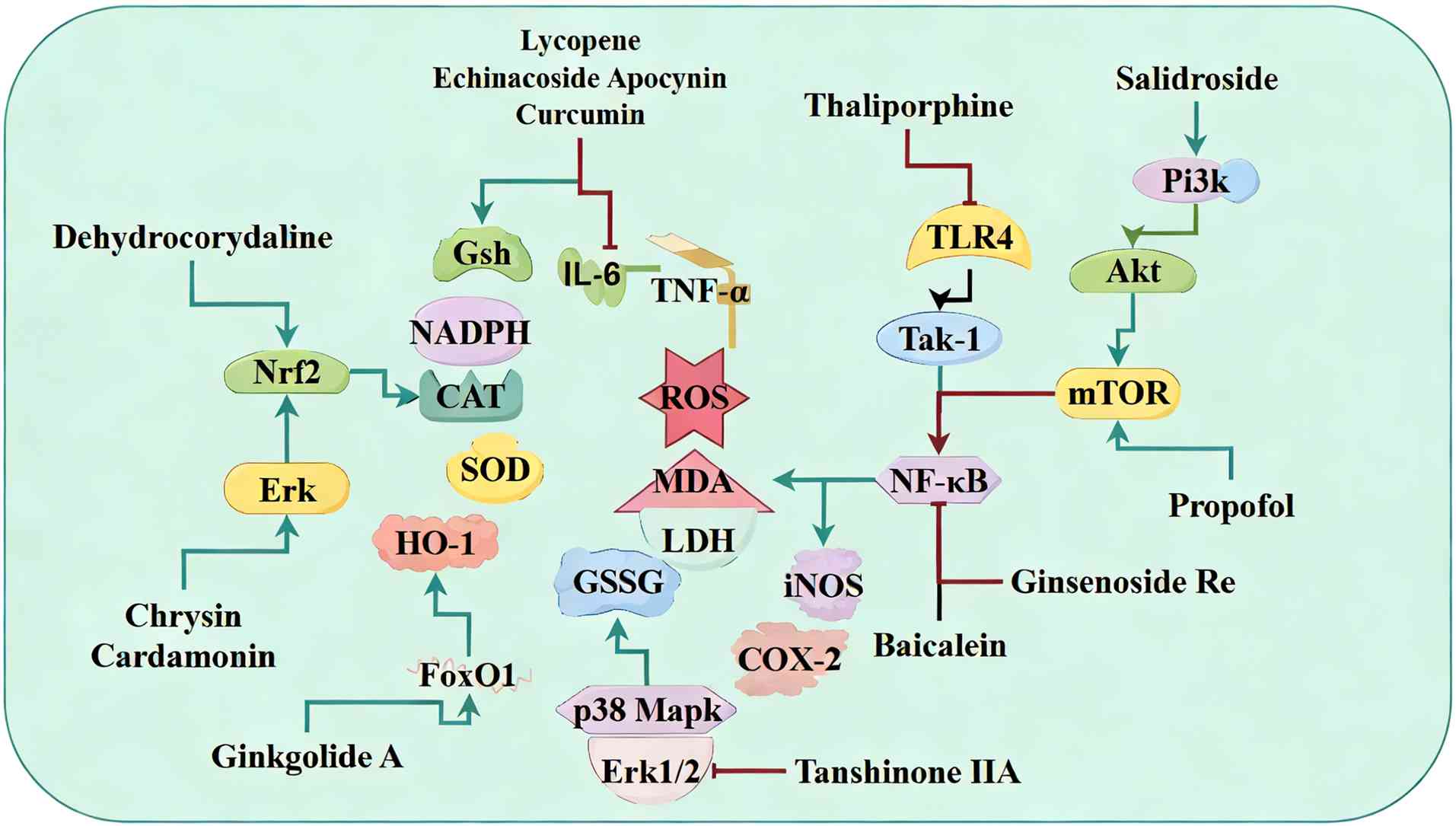

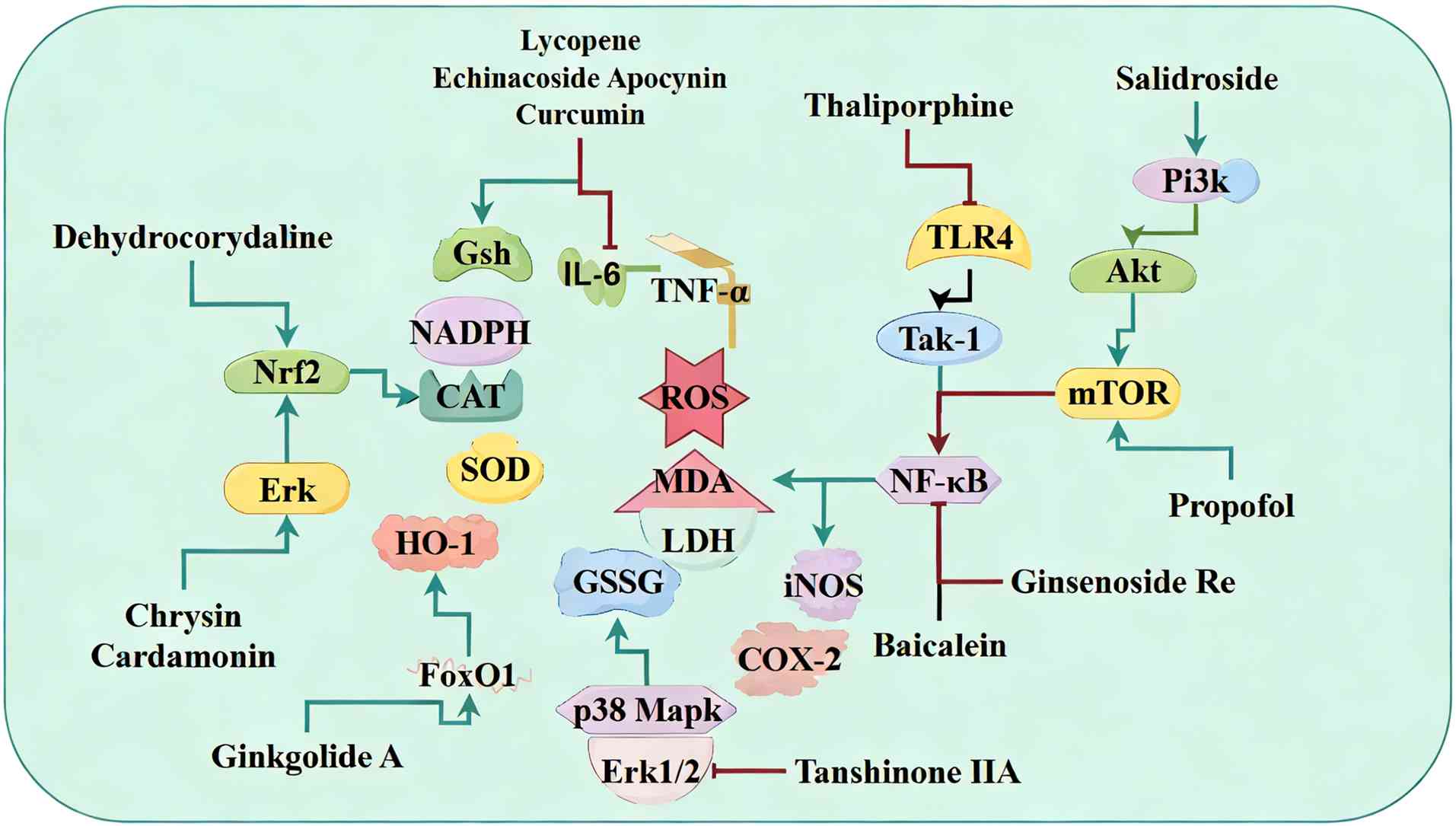

dysfunction and promote cardiomyocyte death (Fig. 4).

| Figure 4Modulation of oxidative stress by

natural products in sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction). Natural

products primarily enhance antioxidant defenses by activating

enzymes such as SOD, CAT and GSH-Px or by stimulating the Nrf2/HO-1

pathway. They also dampen proinflammatory signaling via NF-κB, TLR4

and ERK1/2-p38 MAPK signaling to reduce NOX2/iNOS-mediated ROS/RNS

production. SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; GSH-Px,

glutathione peroxidase; HO, heme oxygenase; TLR, Toll like

receptor; NOX, nitrogen oxide; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide

synthase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrogen

species; GSSG, glutathione oxidized; MDA, malondialdehyde; LDH,

lactate dehydrogenase; TAK, transforming growth factor-β-activated

kinase 1. |

Activation of antioxidant enzymes

Natural products directly enhance the activity of

endogenous antioxidant systems. In LPS-induced septic mice,

lycopene, echinacoside and apocynin lower myocardial ROS and MDA

levels while increasing NADPH oxidase and SOD activity (177-179). Similarly, rutin reduces CK,

LDH, MDA, ROS, TNF-α and IL-6 and increases SOD and catalase (CAT)

activity, thereby protecting cardiac structure and function

(180). In CLP-induced rats,

curcumin decreases plasma levels of ROS, c-TnI and MDA, restores

the GSH/oxidized glutathione (GSSG) ratio and enhances SOD activity

to improve LVEF and FS (181,182). Quercetin similarly upregulates

endothelial (e)NOS and maintains the GSH/GSSG balance, alleviating

hypotension and tachycardia in septic mice (183).

Activation of the Nrf2 pathway

The transcription factor Nrf2 orchestrates the

cellular antioxidant response. In LPS-challenged septic mice,

resveratrol activates Nrf2 to decrease myocardial ROS and increase

the expression of antioxidant genes (184). Chrysin and cardamonin engage

the ERK-Nrf2-HO-1 axis, upregulating HO-1 and SOD while lowering

levels of ROS, MDA, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, which improves cardiac

function (185,186). Dehydrocorydaline also triggers

the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, decreases levels of ROS, TNF-α and IL-1β and

restores SOD and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity, leading

to improved survival rate (187).

Regulation of the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB

pathway

NF-κB links inflammation with oxidative stress. In

LPS-treated septic rats, baicalein inhibits the NF-κB pathway to

decrease levels of iNOS, ROS and NO, improving blood pressure,

heart rate and survival rate (188,189). Thaliporphine also suppresses

the TLR4/transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1

(TAK1)/NF-κB pathway to lower myocardial NO, ROS, TNF-α and iNOS

levels and improve LV pressure-volume indices (190). Ginsenoside Re corrects the

iNOS/eNOS imbalance by inhibiting NF-κB signaling, thereby

reversing myocardial injury (191). In LPS-treated rats, salidroside

activates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway while inhibiting NF-κB, which

decreases levels of iNOS, COX-2 and ROS and improves cardiac

function (192). Propofol also

engages mTOR signaling to lower ROS and MDA levels and boosts SOD

activity, thereby reverse myocardial damage (193).

Other antioxidant agents

Additional natural products modulate oxidative

stress via unique pathways. In LPS-induced sepsis, ginkgolide A

activates FoxO1 and downstream effectors such as Kruppel-like

factor 15, thioredoxin 2), Notch1(Notch receptor 1), XBP1(X-box

binding protein 1), which upregulates antioxidant enzymes and

preserves mitochondrial function (194). Tanshinone IIA inhibits ERK1/2

and p38 MAPK phosphorylation, decreases NOX2 expression and lowers

MDA and ROS levels to alleviate cardiac dysfunction (195).

In summary, natural products primarily enhance

antioxidant defenses by activating enzymes such as SOD, CAT and

GSH-Px or by stimulating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. They also dampen

proinflammatory signaling via NF-κB, TLR4 and ERK1/2/p38 MAPK

pathways to reduce NOX2/iNOS-mediated ROS/RNS production. Through

simultaneous engagement of PI3K/Akt/mTOR and FoxO1 pathways, these

compounds preserve mitochondrial integrity and myocardial

contractility, thereby markedly improving SIMD outcomes and

survival rate.

Regulation of mitochondrial

dysfunction

Mitochondria serve not only as the energy source of

cardiomyocytes but also as a key hub for ROS production and the

regulation of programmed cell death (54). In SIMD, inflammatory mediators,

oxidative stress and impaired mitochondrial quality control cause

mitochondrial fragmentation, loss of membrane potential,

respiratory defects, diminished ATP synthesis and ultimately cell

death (55) (Fig. 5).

| Figure 5Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction

with natural products in SIMD. Natural products counteract SIMD by

engaging multiple mitochondrial-protective pathways, most notably

SIRT1/Nrf2, PI3K/Akt/mTOR and AMPK, and by promoting mitochondrial

biogenesis via PGC-1α/TFAM and UPRmt. SIMD, sepsis-induced

myocardial dysfunction; SIRT, sirtuin 1; PGC, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator; UPRmt, mitochondrial

unfolded protein response; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; PTP1B,

protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; DRP, dynamin-related protein 1; STIM, stromal

interaction molecule 1; CRAC, calcium release-activated

channels. |

Activation of Nrf-associated

pathways

Nrf pathways are key for maintaining mitochondrial

redox homeostasis. In LPS-induced septic mice, curcumin and

resveratrol upregulate PGC-1α and mitochondrial transcription

factor A (TFAM), inhibit DRP1-mediated excessive mitochondrial

fission and activate the SIRT1/Nrf2 pathway to normalize

mitochondrial morphology and respiration, thereby markedly

improving cardiac function (196,197). Rosmarinic acid similarly

preserves mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production by

triggering the SIRT1/Nrf2 pathway, resulting in decreased ROS

levels and enhanced survival rate (198). Songorine further boosts

Nrf1/TFAM signaling and promotes PGC-1α-Nrf2 interactions,

suppressing calcium release-activated channels) channel formation,

lowering mitochondrial ROS levels, restoring calcium homeostasis

and increasing contractile power (199).

Inhibition of AMPK-associated

pathways

Although AMPK often supports mitochondrial

homeostasis, certain stress contexts benefit from modulating its

downstream effectors. In LPS-stimulated H9C2 cells, hesperetin

upregulates Bcl-2, downregulates Bax and caspase-3/9 expression

through inhibiting JNK phosphorylation, thus preserving

mitochondrial membrane potential and decreasing apoptosis (200). In CLP-induced septic mice,

tannic acid attenuates ER stress and decreases expression of ROS,

Bax, cytochrome c and caspase-3/-9/-12, thereby safeguarding

mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes (201). Additionally, astaxanthin

inhibits the PTP1B/JNK pathway to maintain membrane potential and

limit ROS generation, which decreases cardiomyocyte apoptosis

(202). In LPS-challenged

septic mice, lycorine and naringenin activate AMPK and suppress

NF-κB signaling, together protecting cardiac function (203,204). Obeticholic acid blocks the

ERK1/2-DRP1 axis to prevent cytochrome c release and upregulates

GPX1 and SOD1/2, thereby restoring mitochondrial integrity

(205).

Activation of PI3K/Akt signaling

The PI3K/Akt pathway also contributes to

mitochondrial preservation. In LPS-induced septic rats, neferine

activates PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling to elevate the Bcl-2/caspase-3

ratio, decreases ROS levels and restores mitochondrial structure

and function, leading to improved myocardial performance (206). Ginsenoside Rg1 also engages the

recombinant purinergic receptor P2X to stimulate the Akt/GSK-3β

pathway, suppressing mitochondrial superoxide generation and

cytochrome c release, stabilizing calcium handling and enhancing

survival rate (207).

Other pathways

In LPS-treated septic mice, verbascoside promotes

mitochondrial biogenesis and morphological repair, thereby

improving cardiac function (208). Silibinin also decreases CCR2

levels and activates LXRα (Liver X receptors) signaling to dampen

inflammation and oxidative damage while improving mitochondrial

function (209,210). Additionally, chicoric acid

inhibits α-tubulin acetylation and NLRP3 inflammasome assembly,

indirectly restoring mitochondrial architecture and alleviating

myocardial injury (211).

Songorine also activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling to boost

mitochondrial biogenesis and suppress inflammation and apoptosis,

thereby improving LVEF and FS (212). Furthermore, excavatolide B

modulates intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ channels

to reverse calcium dysregulation and repair mitochondrial structure

in septic hearts (213).

Salvianolic acid B induces an ATF5-mediated mitochondrial unfolded

protein response (UPRmt), prevents excessive mitochondrial fission,

preserves membrane potential and significantly enhances contractile

function and mitochondrial ultrastructure (214).

In summary, natural products counteract SIMD by

engaging multiple mitochondrial-protective pathways, most notably

SIRT1/Nrf2, PI3K/Akt/mTOR and AMPK pathways, and by promoting

mitochondrial biogenesis via PGC-1α/TFAM and UPRmt. These

interventions preserve mitochondrial membrane potential, augment

ATP production, decrease ROS accumulation and suppress apoptosis,

collectively leading to substantial improvements in cardiac

function and survival rate in SIMD.

Regulation of endothelial-myocardial

crosstalk

ECs constitute the first line of defense in

maintaining microcirculatory stability and myocardial function

(61). In sepsis, endothelial

barrier dysfunction increases vascular permeability, tissue edema

and inflammatory cell infiltration, while endothelial-derived

cytokines and exosomes propagate injurious signals to

cardiomyocytes, exacerbating SIMD (63).

In LPS-induced septic mice, neohesperidin

dihydrochalcone markedly suppresses vascular hyperpermeability and

myocardial tissue damage. It decreases ROS production, preserves

mitochondrial membrane potential and enhances antioxidant defenses

(CAT, SOD, GSH) while lowering MDA levels (215). Mechanistically, it inhibits

phosphorylation of TAK1, ERK1/2 and NF-κB, stabilizes endothelial

junction protein and diminishes THP-1 monocyte adhesion and

infiltration (215). These

combined effects reinforce endothelial barrier function and

mitigate myocardial injury (215). In LPS-induced septic shock

rats, anisodamine restores hemodynamics and repairs the endothelial

glycocalyx, thereby decreasing myocardial damage (8). It lowers levels of lactate, IL-1β,

IL-6, TNF-α, CK, c-TnT, NT-proBNP, syndecan-1 and hyaluronic acid

via inhibition of NF-κB and NLRP3 signaling and activation of the

PI3K/Akt pathway (8). Moreover,

exosomes released by LPS-stimulated human umbilical vein ECs

transfer inflammatory and oxidative signals to the myocardium;

anisodamine attenuates these exosome-mediated effects, indicating

that it disrupts harmful endothelial-myocardial crosstalk to confer

cardioprotection in SIMD (216).

Classification and structure-activity

relationships

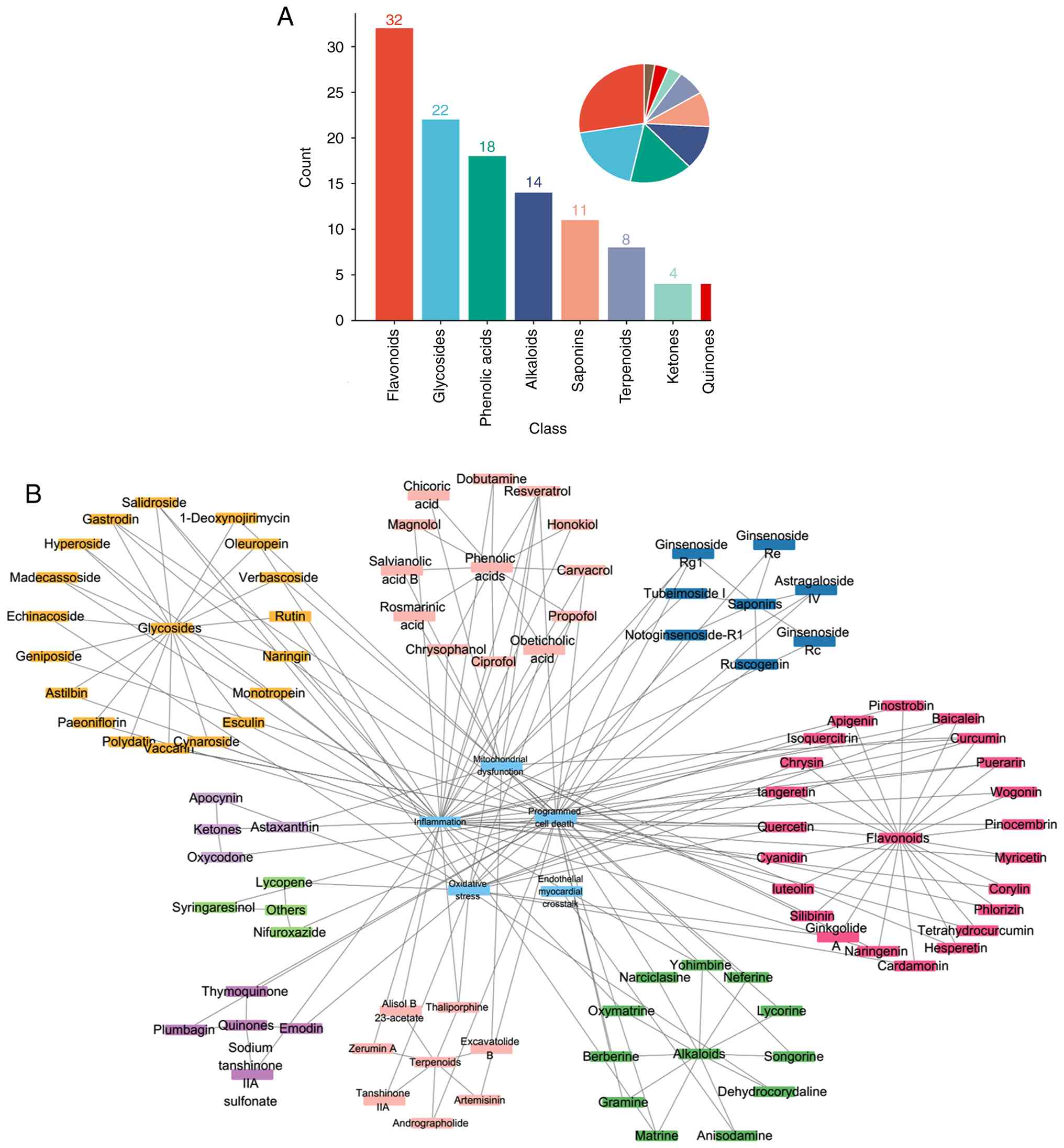

Natural products with efficacy against SIMD can be

divided into five major chemical classes: Flavonoids, glycosides,

phenolic acids, alkaloids and saponins (Fig. 6A). Notably, flavonoids and

glycosides account for approximately half of the identified

compounds. The prominent bioactivity of these classes is associated

with their characteristic chemical scaffolds. Specifically, the

presence of multiple hydroxyl (-OH) groups confers potent

antioxidant capacity by serving as hydrogen donors to directly

neutralize free radicals (217). Concurrently, conjugated double

bond systems (extended π-electron networks) enable electron

delocalization, which stabilizes antioxidant reaction intermediates

and facilitates key interactions with cellular signaling proteins

(kinases, transcription factors) (217). These combined physicochemical

properties underpin their broad-spectrum antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective activities observed in SIMD

models (Fig. 6B).

Flavonoids

Flavonoids share a characteristic C6-C3-C6

three-ring scaffold. Critical structural features include a C2-C3

double bond, hydroxyl groups at C3, C5 and/or C7 and a

catechol-type dihydroxy arrangement on the B-ring (positions 3',4')

(217). This configuration

maximizes electron delocalization and hydrogen-donating capacity,

explaining their strong radical scavenging activity and their

direct, Structure-activity relationship (SAR)-driven inhibition of

central pro-inflammatory signaling hubs such as NF-κB and MAPK

(218). Mechanistically,

flavonoids thereby modulate the TLR4/NF-κB pathway, NLRP3

inflammasome activation and MAPK pathways to lower proinflammatory

cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) and attenuate cardiomyocyte apoptosis

(219).

Glycosides

Glycosides consist of aglycone cores (flavonoid,

sesquiterpene or other scaffolds) linked to sugar moieties via O-

or C-glycosidic bonds. Glycosylation is a key SAR-modifying factor:

It markedly enhances aqueous solubility and pharmacokinetic

properties, improving tissue distribution and bioavailability

(220). Notable glycosides in

SIMD include isoquercitrin, paeoniflorin and salidroside. The sugar

units promote interactions with cell-surface receptors or

transporters, facilitate macrophage M2 polarization and improve

cardiomyocyte survival rate (220). Glycosides often retain and

enhance the anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties of

their parent aglycones, while also demonstrating distinct benefits

such as stabilizing mitochondrial membrane potential (220).

Phenolic acids

Phenolic acids feature an aromatic ring substituted

with ≥1 hydroxyl groups and a carboxyl group. The phenolic

hydroxyls are primary sites for antioxidant activity via hydrogen

atom transfer. The carboxyl group introduces an additional SAR

dimension, allowing coordination with metal ions or formation of

hydrogen bonds with target proteins (such as those involved in

redox signaling), thereby stabilizing mitochondrial function and

inhibiting NF-κB (221). In

SIMD rats, phenolic acids efficiently scavenge ROS, preserve

mitochondrial membrane potential, decrease intracellular

Ca2+ overload and mitigate cardiomyocyte necrosis and

apoptosis (128).

Alkaloids

Alkaloids contain ≥1 basic nitrogen atom within

heterocyclic or polycyclic scaffolds. Examples relevant to SIMD

include yohimbine and anisodamine. The basic nitrogen forms ionic

interactions with acidic residues in receptors or enzymes, thereby

modulating neurotransmitter release and inflammatory mediator

levels (222). In sepsis,

alkaloids often exhibit anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic

effects by blocking α2-adrenergic receptors or inhibiting the NLRP3

inflammasome, helping to preserve cardiomyocyte function (199).

Saponins

Saponins are composed of triterpene or steroid

aglycones linked to ≥1 sugar chains. This amphipathic structure

defines their unique SAR: Aglycone enables interactions with and

modulation of cell membrane properties and associated signaling

pathways, while the sugar chains confer water solubility and

influence pharmacokinetics (223). This structure allows saponins

to modulate membrane fluidity and receptor clustering, leading to

inhibition of caspase activation and decreased inflammatory

mediator release, thereby mitigating apoptosis in cardiomyocytes

(207).

Certain natural products display multi-target

actions across SIMD-relevant pathways, combining anti-inflammatory

and antioxidant effects with mitochondrial protection and

anti-apoptotic signaling. Notable multi-target compounds include

astragaloside IV, baicalein, carvacrol, curcumin, emodin,

ginsenoside Re, matrine, propofol, quercetin and resveratrol

(91,95,100,128,131). These agents exemplify the

potential of pleiotropic natural products to regulate inflammation,

oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and programmed cell

death in SIMD (Table SI).

Notable therapeutic targets in SIMD

Key signaling pathways in SIMD

Natural products exert protective effects in SIMD

by modulating multiple disease-associated pathways and molecular

targets. Their primary actions are divided into four categories:

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-cell death and mitochondrial

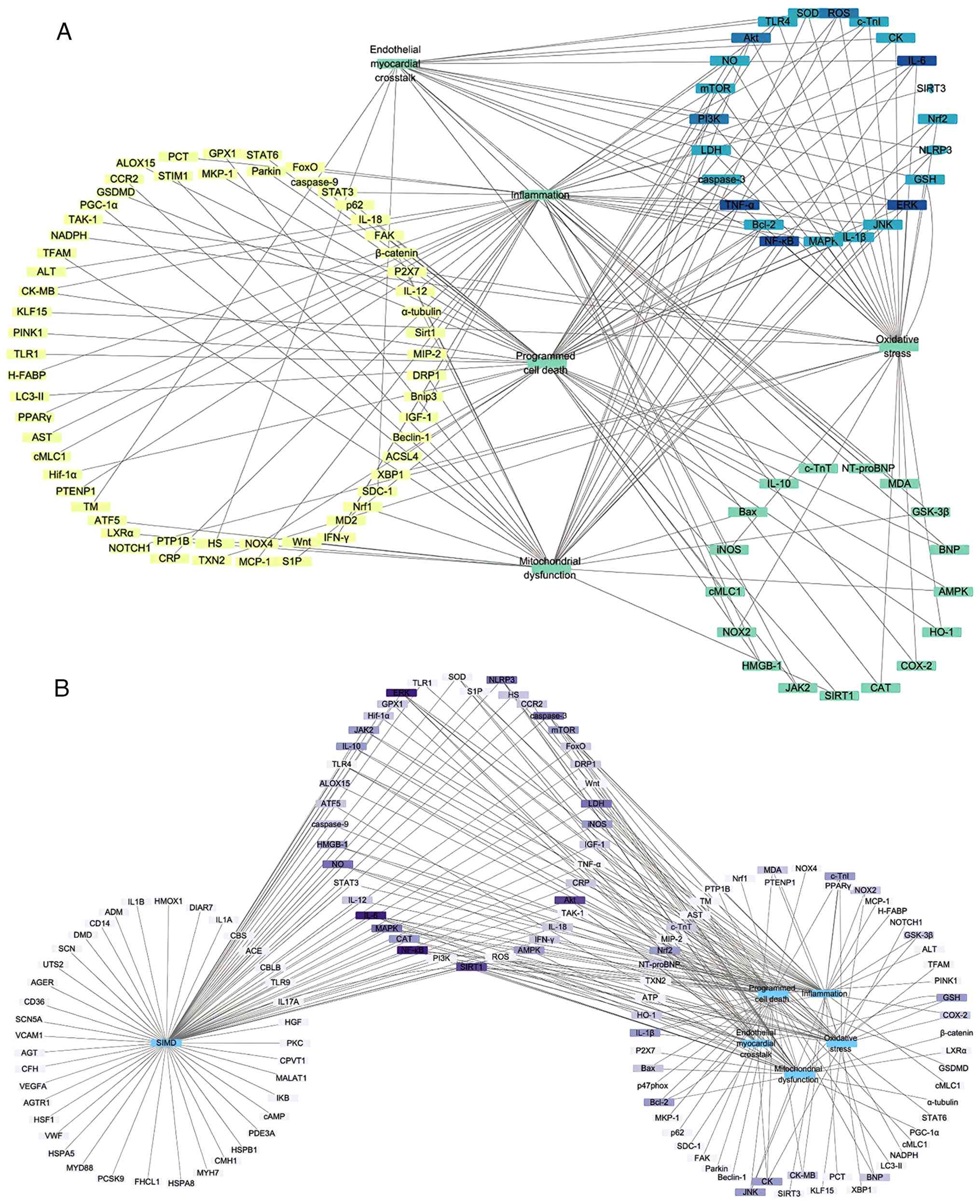

protection and repair (Fig. 7A).

Notable signaling cascades include NF-κB, the MAPK family, the

TLR4/MyD88 pathway, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Nrf2/HO-1 and the NLRP3

inflammasome.

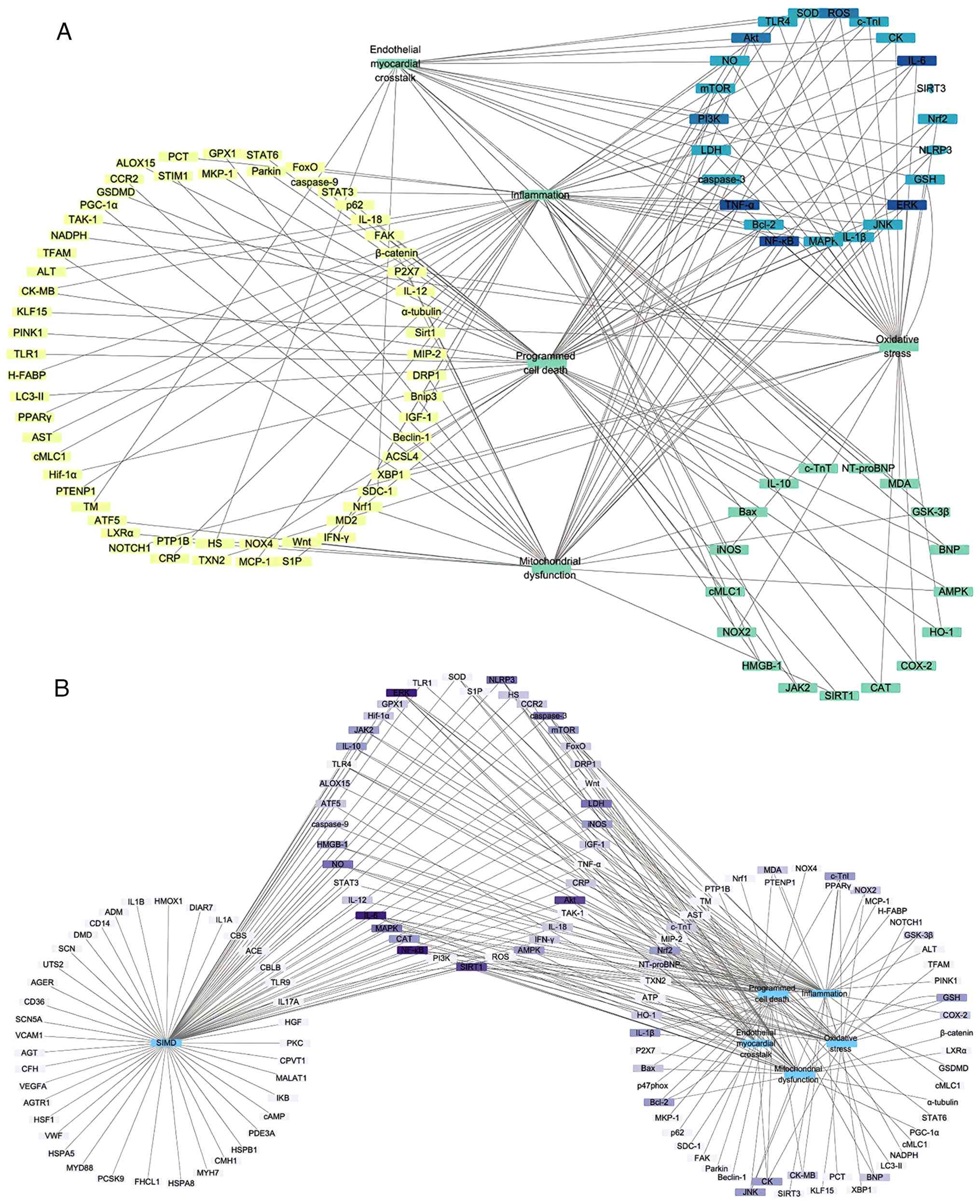

| Figure 7Notable therapeutic targets and

network pharmacology analysis in SIMD. (A) Primary actions of

natural products are categorized into anti-inflammatory,

antioxidant, anti-cell death and mitochondrial protection. Major

targeted signaling cascades include NF-κB, MAPK family, TLR4/MyD88,

PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Nrf2/HO-1 and the NLRP3 inflammasome. (B) Network

pharmacology comparison highlights high-frequency SIMD-associated

targets, such as iNOS (NOS2), NF-κB, MAPK members (JNK, ERK1/2),

PI3K/Akt/mTOR, NLRP3, SIRT1 and STAT3. SIMD, sepsis-induced

myocardial dysfunction; TLR, Toll like receptor; HO, heme

oxygenase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase ; SIRT, sirtuin

1. |

NF-κB serves as a key regulator of inflammation in

SIMD (224). In cardiomyocytes

and cardiac macrophages, LPS or endotoxin binding to TLR4/MyD88

activates the IKK complex, which phosphorylates and degrades IκBα.

This frees NF-κB (p65/p50) to enter the nucleus and upregulate

levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and iNOS, thereby amplifying local

inflammation and disturbing calcium homeostasis (225). As an upstream switch in early

SIMD, TLR4 recruits TIR domain containing adaptor protein/MyD88

adaptors following LPS engagement, propagating both NF-κB and MAPK

signaling and exacerbating myocardial injury (226,227).

The MAPK family, including p38, JNK, and ERK, also

governs myocardial stress responses, inflammation and death in SIMD

(228). p38 and JNK generally

promote inflammation and apoptosis, while ERK supports survival or

death depending on context (228). Overactivation of p38/JNK

triggers c-Jun and ATF-2, leading to caspase-3-mediated apoptosis

in SIMD (229). Nrf2/HO-1

provides the chief antioxidant defense. Under oxidative stress,

Nrf2 dissociates from Keap1, translocates to the nucleus and binds

antioxidant response elements to induce HO-1, NQO1 and other

protective genes (230). Excess

ROS in SIMD further damages membranes and amplifies NF-κB-driven

inflammation (231).

PI3K/Akt/mTOR and SIRT1/AMPK form core networks

that support cardiomyocyte survival and energy balance (232). PI3K activation leads to Akt

phosphorylation and mTOR signaling, which promotes protein

synthesis and restrains autophagy (233). SIRT1 deacetylates PGC-1α, p53

and NF-κB, coordinating mitochondrial biogenesis with

anti-inflammatory effects (234). AMPK senses low ATP levels and

works in concert with SIRT1 to maintain energy homeostasis

(235). In SIMD, these pathways

are typically downregulated, contributing to mitochondrial

dysfunction and cell death (124).

Finally, the NLRP3 inflammasome and ferroptosis

pathways drive inflammatory cell death in SIMD. NLRP3 assembly

activates caspase-1, leading to IL-1β maturation and pyroptosis

(236). Ferroptosis depends on

iron-catalyzed lipid peroxidation, with key regulators including

GPX4, acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and

nuclear receptor coactivator 4) (237).

Rather than acting on a single target, natural

products coordinate the aforementioned hubs to deliver combined

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-death and

mitochondrial-protective effects. Future studies should map the

spatiotemporal dynamics and crosstalk between these pathways to

guide the development of multitarget natural derivatives with

improved precision and synergy.

Network pharmacology comparison of

SIMD-associated targets

To evaluate how natural product targets align with

known SIMD genes, 'sepsis', 'myocardial injury', and 'myocardial

dysfunction' were in the Online Mendelian inheritance in Man and

GeneCards databases (8,10). This search yielded over 350

unique disease-associated genes, with 41 common targets (Fig. 7B). High-frequency targets

included iNOS (NOS2), NF-κB, MAPK family members (JNK, ERK1/2),

PI3K/Akt/mTOR, NLRP3, SIRT1 and STAT3.

Notably, certain predicted targets, such as VEGF,

cAMP, HSPs, Von Willebrand factor), MMP9 and PKC (Protein kinase

C), lack thorough experimental validation in SIMD. Conversely,

high-frequency targets such as NOX2, HO-1, GSK-3β, COX-2 and Nrf2

were not annotated as core SIMD targets in database queries. This

discrepancy may reflect annotation lags, limited natural

product-target interaction data and the inherent constraints of

network pharmacology analyses. Integrating network pharmacology

with systematic literature mining, multi-omics datasets and

experimental validation is essential to build a comprehensive

disease-drug-target network and inform the rational development of

new SIMD therapies.

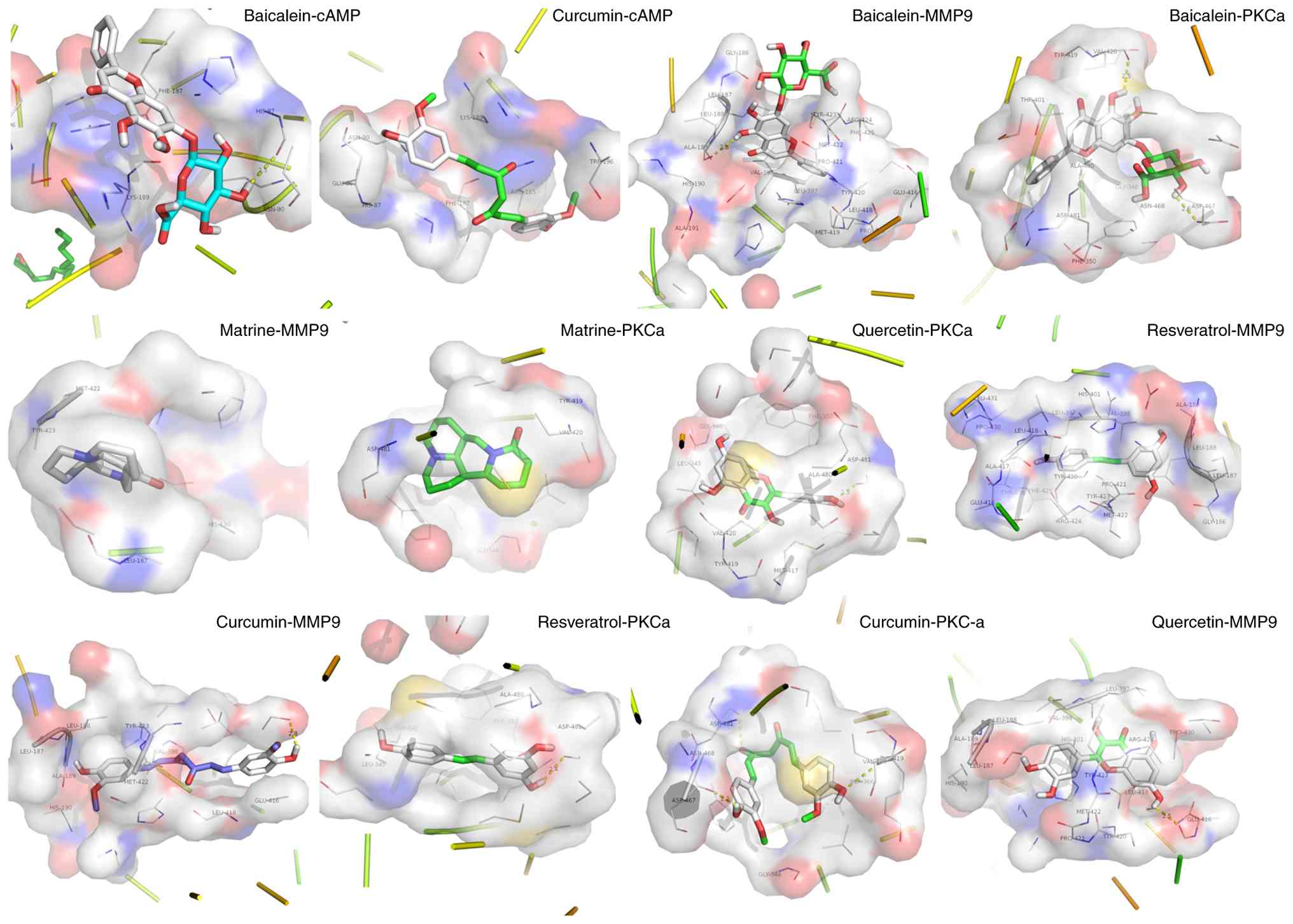

Docking of natural products to novel SIMD

targets

To identify additional molecular targets for

natural products in SIMD, molecular docking was performed for three

proteins not yet validated in vitro or in vivo:

cAMP-dependent protein kinase (cAMP), MMP9 and PKC). A total of

five representative ligands (baicalein, quercetin, curcumin,

matrine and resveratrol) were drawn in ChemDraw (14.0,

revvitysignals. com/products/research/chemdraw), energy-minimized

using the Molecular mechanics 2 force field, and docked to each

target with AutoDock Vina (1.1.2,

github.com/ccsb-scripps/AutoDock-Vina). The lowest-energy poses

exhibiting the most favorable orientations were selected for

analysis (238). All five

compounds bound tightly to both MMP9 and PKC, with calculated

binding energies <-8.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 8). Baicalein and curcumin also

demonstrated notable affinity for PKA, with binding energies

<-5.0 kcal/mol, suggesting potential direct modulation of this

kinase. Key interacting residues and hydrogen-bond contacts are

detailed in Table SII. These

findings indicate that multitarget natural products may exert

cardioprotective effects not only through established

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant pathways but also by directly

engaging cAMP-dependent protein kinase, MMP9 and PKC. This in

silico evidence lays the groundwork for experimental validation

of these novel interactions.

Novel formulations for natural product

therapeutics in SIMD

Although natural products offer multitarget synergy

against SIMD, their clinical translation is hampered by poor

solubility, low bioavailability and rapid clearance (239). Recent advances in formulation

science, including nanotechnology, supramolecular chemistry and

metal-organic coordination, provide new routes to improve delivery,

targeting and efficacy (240).

Metal-organic nanozymes

Self-assembled nanozymes that incorporate

metal-organic coordination combine drug delivery with enzyme-like

catalysis (239,240). For example, ceria

(CeO2) or iron oxide (Fe3O4)

nanoparticles mimic superoxide dismutase and catalase through

reversible Ce3+/Ce4+ or

Fe2+/Fe3+ redox cycling, efficiently

scavenging O2•- and H2O2 (241,242). By coordinating curcumin onto

ceria, researchers have created ceria-curcumin hybrids (CeCHs) that

exhibit dual SOD- and CAT-like activity in vitro (242). CeCHs neutralizes ROS, prevent

glutathione peroxidase 4-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes and

shift macrophages toward an M2 phenotype (243). In LPS- and CLP-induced septic

mice, CeCH decreases myocarditis and restores cardiac function

(243). Similarly, Brazilin-Ce

(IV) metal-organic nanoparticles inhibit IKKβ phosphorylation,

suppress NF-κB signaling and deliver strong anti-inflammatory and

cardioprotective effects in mice with myocardial infarction and

sepsis (244).

Polymeric and lipid-based

nanocarriers

Polymeric and lipid nanoparticles enhance the

stability, circulation time and tissue distribution of natural

products. Common polymers include poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid),

PVA (Polyvinyl alcohol) and chitosan. Liposomal systems, solid

lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and mesoporous silica nanoparticles also

serve as versatile carriers (245,246). In LPS-induced septic mice,

curcumin-loaded SLNs decrease IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β more

effectively than free curcumin, while boosting IL-10 levels. This

improvement is associated with stronger suppression of the

TLR2/TLR4/NF-κB pathway and decreased multi-organ injury (247). Nano-curcumin further enhances

mTOR pathway regulation and offers superior protection against

myocardial ultrastructural damage in SIMD mice compared with the

unformulated compound (248).

Cyclodextrin (CD)-based inclusion

complexes

CD hosts form non-covalent inclusion complexes with

hydrophobic drugs, improving their solubility and stability

(249,250). Hydroxypropyl-β-CD (HPβCD) and

methyl-β-CD (MβCD) are used (249). In neonatal mice with

LPS-induced sepsis, naringenin/HPβCD complexes more effective than

naringin in decreasing inflammatory cell infiltration in the lung,

heart, kidney and brain. They also lower TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6,

increase IL-10, catalase and SOD activity and decrease lipid

peroxidation and protein carbonylation, leading to improved

survival rate (251).

Quercetin/β-CD complexes extend plasma half-life of quercetin and

enhance myocardial accumulation in CLP-induced septic rats,

strengthening TLR4/NF-κB inhibition and improving cardiac function

(252). Chemical

derivatization, such as converting steviol glycosides into

isosteviol sodium salt, further boosts water solubility and, in

LPS-induced septic mice, enhances survival rate, multi-organ

function and reduces inflammation and macrophage infiltration

(253).

However, systematic pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics analyses, long-term toxicity studies and

validation in large-animal models remain outstanding needs.

Standardization of manufacturing methods, drug-loading efficiency

and in vivo kinetics is also required. Future efforts should

integrate multi-omics, high-resolution imaging and large-animal

models to optimize formulations, clarify dosing regimens, define

safety margins and accelerate clinical translation of these

advanced delivery systems.

Discussion

Sepsis ranks as the third leading cause of death

worldwide, affecting nearly 20 million people each year. A total of

40-60% of these patients develop SIMD, and their 28-day mortality

is ~3 times higher than that of patients without cardiac

involvement (11). This

underscores the urgent need for effective, low-toxicity treatments.

Natural products modulate key signaling networks, including

TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB, MAPKs (p38/JNK/ERK), the NLRP3 inflammasome,

PI3K/Akt/mTOR, SIRT1/AMPK and Nrf2/HO-1, to restore mitochondrial

membrane potential, maintain ATP production and decrease

inflammation, oxidative stress and cell death (207,217,220-222).

Multi-center randomized controlled trials indicate

that formulations such as Xuebijing injection can decrease 28-day

mortality and lower cardiac injury biomarkers (cTnI, NT-proBNP) and

inflammatory markers (PCT), indicating systemic and possible

myocardial protective effects (254,255). Similarly, the JinHong Formula

decreases mortality and improves organ function scores, potentially

through inhibition of inflammatory pathways such as IL-17 and TNF

(256). Other formulations,

including Dachaihu Tang and Shenfu injection, improve organ

dysfunction scores, microcirculation and inflammatory or

coagulation parameters (257,258). The alkaloid anisodamine has

decreases serum lactate and improves mortality in septic shock

(259,260). However, challenges remain. Most

trials did not specifically enroll patients with confirmed SIMD,

limiting direct conclusions about cardiac-specific efficacy.

Furthermore, notable heterogeneity exists in study designs, sample

size and the compositions of natural product formulations.

Additionally, pharmacokinetic challenges constrain the use of

natural products. Poor water solubility, low oral bioavailability

and rapid systemic clearance all decrease therapeutic impact. To

overcome these issues, researchers are developing novel

formulations, such as polymeric or lipid nanoparticles,

metal-organic frameworks, CD inclusion complexes, supramolecular

assemblies and chemical derivatives, to improve solubility,

stability, half-life and tissue targeting (261). Well-designed clinical trials

are essential to assess safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics

and real-world efficacy in patients with SIMD.

Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the

pathogenic network of SIMD is also needed. Extracellular vesicles

and their miRNA cargo mediate crosstalk between immune cells and

cardiomyocytes, regulating inflammation and apoptosis (262). Specific miRNAs fine-tune gene

networks that control survival, fibrosis and autophagy (263). Endothelial-myocardial

interactions, governed by adhesion molecules, inflammatory

mediators and the glycocalyx, critically influence microcirculatory

perfusion and cardiac stress responses (63,264). Mitochondria-endoplasmic

reticulum contacts sites serve as hubs for calcium homeostasis,

lipid metabolism and cell fate decisions (265,266). Additionally, emerging evidence

highlights the role of the gut-heart axis in SIMD (267). Sepsis-induced disruption of the

intestinal barrier leads to microbial translocation, systemic

dissemination of PAMPs and elevated levels of gut-derived

metabolites (267). This fuels

a persistent systemic inflammatory state and may contribute

directly to remote organ injury, including myocardial dysfunction

(267). Conversely, beneficial

microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, modulate

host immune responses and exert anti-inflammatory effects.

Interventions targeting the gut microbiota or its metabolites hold

promise for attenuating systemic inflammation and improving cardiac

outcomes in sepsis, presenting a novel therapeutic avenue for SIMD

(268). Thus, future efforts

should leverage single-cell sequencing, organoid models and

multi-omics approaches to build a comprehensive molecular map of

SIMD and natural product interventions. Such integrative studies

may identify new precision targets and accelerate the development

of optimized, multitarget natural therapies for clinical use.

In conclusion, the present study provides a

systematic overview of the structure-activity-mechanism

relationships between natural products and SIMD. The mechanisms

involve inhibition of the TLR4/MyD88-NF-κB/MAPK pathway and the

NLRP3 inflammasome and activation of antioxidant and anti-apoptotic

pathways, including PI3K/Akt/mTOR, SIRT1/AMPK and Nrf2/HO-1. The

present review also maps the association between natural product

classes and pharmacological activities and validated potential

compounds against new SIMD targets via network pharmacology and

molecular docking. Collectively, the present study clarified how

natural product structures are associated with SIMD pathology and

outlined a clear path from molecular design to clinical

translation. The present study provides a systematic theoretical

basis and practical avenues for multitarget natural product

interventions in SIMD, with implications for drug discovery and

clinical strategy advancement.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are

included in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

FT contributed to study design, performed the

literature review and drafted the manuscript. DL, SCZ and HMZ

performed the literature review. XWQ supervised the study. All

authors contributed to manuscript revision. All authors have read

and approved the final manuscript. FT and XWQ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

HO-1

|

heme oxygenase-1

|

|

PAMP

|

pathogen-associated molecular

pattern

|

|

PI3K

|

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

|

|

PKC

|

protein kinase C

|

|

SIMD

|

sepsis-induced myocardial

dysfunction

|

|

SIRT1

|

sirtuin 1

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding