Introduction

From 1990 to 2017, the incidence of pancreatic

cancer has increased (age-standardized incidence rate, 5.0/100,000

person-years in 1990 to 5.7 in 2017), positioning it among the most

lethal types of human malignancy, largely due to its poor prognosis

(1). Although progress has been

made in contemporary medical practices, the 5-year survival rate

for this disease has improved marginally, rising from <5% in

1990 to ~10% by 2021 (2). This

limited survival benefit is primarily associated with delayed

detection, as a majority of patients are diagnosed at a later stage

of the disease. In cases where early diagnosis is achieved, ~20% of

individuals meet the criteria for surgical resection. For those who

undergo surgery, the 5-year survival rate may increase to ~25%

(3). As the risk of pancreatic

cancer is associated with aging, the prevalence of the disease is

projected to escalate in response to the global aging trend

(4). Anatomically, the pancreas

is connected to the gastrointestinal system via the pancreatic

duct, which facilitates the retrograde movement of intestinal

microorganisms into the pancreatic ductal system. This microbial

translocation and resulting dysbiosis may contribute to sustained

inflammatory responses, offering a potential explanation for the

higher frequency of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in the

pancreatic head compared with its body or tail (5). The gut microbiota, a complex and

essential component of the human organism, comprises

>1×1014 microbial cells (6). Certain bacteria-associated

metabolites, such as nitrosamines, may modulate the immune

landscape and influence resistance to treatment, thereby serving a

role in the development and progression of pancreatic cancer

(7).

The circadian clock is a conserved molecular

feedback loop that regulates signaling pathways, controlling cell

metabolism and immune function (8). Disruption of circadian rhythms

leads to misalignment between external signals and the internal

clock, resulting in metabolic dysregulation (9). A previous study has revealed

circadian rhythm dysfunction in PDAC, which is associated with

tumor progression and poor prognosis (10). Additionally, the gut microbiome

exhibits circadian variations (11). For example, enteric

Enterobacteriaceae in the gastrointestinal tract are sensitive to

melatonin, a neurohormone secreted into the gastrointestinal lumen,

and exhibit circadian patterns of aggregation and motility

(12). Disruption of circadian

rhythms alters the gut microbiota and its metabolites, thereby

promoting cancer development (13). Therefore, circadian rhythm

disturbances may contribute to the development of pancreatic cancer

by affecting the gut microbiota and its metabolites. Previous

reviews have primarily focused on the association between either

circadian rhythms or the gut microbiota and pancreatic cancer

(14,15). To the best of our knowledge,

however, a comprehensive discussion linking circadian rhythm, gut

microbiota and pancreatic cancer has been lacking. The present

review aimed to summarize the impact of circadian rhythm disruption

on the gut microbiota and its metabolites and discuss microbiota

associated with pancreatic cancer, exploring how microbiota and

metabolites influence pancreatic cancer progression. The aim of the

present study is to enhance understanding and application of gut

microbiota in the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Methods

PubMed (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Web of Science

(clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-referencing/web-of-science/)

databases were searched from inception to October 2025 for relevant

literature, with the language restricted to English. The search

strategy focused on the association between circadian rhythm, gut

microbiota and pancreatic cancer. Key words included 'circadian

rhythm', 'circadian disruption', 'gut microbiota', 'microbial

metabolites', 'pancreatic cancer', 'pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma', as well as mechanism-related terms such as 'LPS',

'SCFAs', 'immune suppression', and 'TLRs'.

The present study included original studies

(including in vitro and in vivo experiments, animal

studies, clinical observations and trials) that explored the

association between pancreatic cancer, circadian rhythm disruption,

gut microbiota and their metabolites, immune regulation, tumor

microenvironment, gut-pancreas axis or microbiota-mediated drug

resistance. In addition, high-quality review articles were used to

supplement background information and theoretical frameworks.

Excluded studies included those not clearly

involving the mechanisms of circadian rhythm or gut microbiota in

non-pancreatic cancer research, non-English publications,

conference abstracts, non-peer reviewed preprints, incomplete case

reports and commentaries or editorials with low relevance to the

review topic.

A total of two authors independently conducted the

initial screening and full-text review of all retrieved articles.

Disagreements were resolved through discussion, with arbitration by

a third reviewer when necessary.

The present review did not conduct a meta-analysis

due to substantial heterogeneity between the included studies in

terms of study populations, exposure assessment and outcome

definitions, as well as partial overlap among cohorts. Under such

conditions, a quantitative synthesis may lead to inappropriate

weighting or potential double-counting of results. The present

study extracted and reported the effect sizes and corresponding

uncertainty measures from the original publications, including odds

ratio (OR), hazard ratios (HRs), standardized incidence ratios

(SIRs), areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve

(AUROCs), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), as well as the study

designs and population characteristics for each study.

Disruption of circadian rhythm and

pancreatic cancer risk

Sleep disorders include conditions such as insomnia,

narcolepsy and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (16). Engaging in shift work, which

requires activity during usual sleep periods, can disturb circadian

rhythms (17). As reported by

the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 2019, such

circadian disruption is associated with elevated cancer risk

(17). Gu et al (18) suggested that residents of the

western regions of the United States, where there is a temporal

discrepancy between natural sunlight exposure and internal

biological clocks, may face an increased likelihood of circadian

rhythm misalignment. This misalignment is a potential contributor

to the development of diseases such as pancreatic cancer (18). In a study by Parent et al

(19), data from 3,137 male

patients with cancer patients were analyzed, revealing that those

with a history of night shift employment exhibited a notably higher

risk of pancreatic cancer (OR: 2.27, 95% CI: 1.24-4.15), although

no significant association was observed between cancer risk and the

total duration of night shift work. Moreover, findings from a Cox

proportional hazards model based on 464,371 individuals indicate

that those residing in areas with increased nighttime light

exposure have a 27% greater risk of developing PDAC compared with

individuals exposed to lower levels of night lighting (HR: 1.24,

95% CI: 1.03-1.49) (20).

Additionally, Mendelian randomization analysis by Titova et

al (21) demonstrated that a

genetic tendency toward shorter sleep duration is associated with a

heightened risk of pancreatic cancer (OR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.32-3.62).

In the US National Institutes of health-American association of

retired persons diet and health study prospective cohort, nighttime

light exposure assessed by satellite remote sensing was positively

associated with PDAC incidence, with the with individuals in the

highest exposure quartile having an increased risk of PDAC compared

with those in the lowest quartile (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.03-1.49; male,

HR 1.21, 95% CI 0.96-1.53; female, HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.94-1.75),

suggesting that environmental circadian disruption may promote PDAC

development (20). A

case-control study from Canada based on 3,137 male patients with

cancer showed that those who had ever worked night shifts had a

notably increased risk of pancreatic cancer (adjusted OR 2.27, 95%

CI 1.24-4.15), and this association is not increased by longer

cumulative duration of night shift work, suggesting that the

exposure is more important than duration (19). Using a German health insurance

database, a case-control study with propensity score matching

included 37,161 gastrointestinal cancer cases and an equal number

of controls; having a recorded sleep disorder in the year before

diagnosis was associated with an increased overall odds of

gastrointestinal cancer (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.08-1.34), and

site-specific analyses suggested higher odds for pancreatic cancer

in the year preceding diagnosis, supporting a short-term

association between sleep disorders and cancer that may reflect

bidirectional interactions between circadian disruption and early

tumorigenesis (22). An

ecological analysis using longitude position within a time zone as

a proxy for social jetlag covered 607 counties across 11 US states

and showed that moving from the eastern to the western edge of the

same time zone was associated with higher age-standardized

incidence rates for overall malignancy and several site-specific

cancers (risk gradients evaluated/5 degrees of longitude and

remaining significant after multiple-comparison adjustments);

although a distinct estimate for pancreatic cancer was not

significant, this general pattern supports incorporating circadian

disruption into etiological frameworks for pancreatic cancer

(18). By contrast with the

aforementioned positive signals, a meta-analysis pooling data from

>8.4 million individuals across prospective and case-control

studies found no significant increase in overall pancreatic cancer

risk when comparing ever vs. never night shift work (pooled OR

1.007, 95% CI 0.910-1.104; pancreatic cancer k=6; heterogeneity

I2 3.2%), suggesting that discrepancies between studies

may reflect differences in exposure metrics, occupational

composition and confounding control, highlighting the need for more

objective circadian measures to identify high-risk groups (23). Mendelian randomization analysis

indicates that genetic predisposition to short sleep is associated

with higher pancreatic cancer risk (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.32-3.62),

whereas genetic predisposition to long sleep is associated with

lower risk (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.25-0.79), but these associations are

not significant after multiple testing correction and not

replicated in external two-sample analyses, implying that the

causal role of sleep duration in PDAC requires larger samples and

stronger instruments for confirmation (21).

In sum, epidemiological signals linking circadian

disruption to pancreatic cancer are modest and heterogeneous.

Across cohorts, satellite-derived light at night shows small excess

risks (highest vs. lowest exposure HR, 1.2-1.3), single

case-control estimates for ever night shift work can be larger (OR

~2.3), whereas meta-analytic pooling under mixed exposure

definitions demonstrate a pooled OR close to 1.0, indicating no

clear overall association. Mendelian randomization analysis

(21) using genetic variants as

proxies for short sleep suggest risk but does not withstand

multiple-testing and lacks replication. Heterogeneity may reflect

exposure misclassification, occupational mix and incomplete control

of smoking, adiposity and diabetes, and short-term elevations in

sleep disorder diagnoses before cancer raise the possibility of

reverse causation. Clinically, these data support pragmatic

mitigation of circadian misalignment and incorporation of objective

circadian metrics into risk stratification, using study designs

that account for the induction and latency period between exposure

and cancer diagnosis to clarify timing; peri-therapeutically,

actigraphy-guided light and sleep alignment may be piloted

alongside standard care to test whether circadian calibration

improves treatment tolerance and clinical outcomes.

Circadian regulation of gut barrier

microbiota and immunity in pancreatic cancer

The circadian clock is a multilayered temporal

control system that synchronizes daily oscillations of the

gastrointestinal barrier, immune response and metabolic pathways

(24). Multiple studies indicate

that disruption of host circadian rhythms reshapes both the

composition and rhythmicity of the gut microbiota, alters systemic

exposure to key microbial metabolites such as lipopolysaccharide

(LPS) and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), promotes chronic

inflammation and immune imbalance within the tumor microenvironment

and influences pancreatic cancer phenotypes (24,25). Conversely, selected microbial

metabolites (such as SCFAs, acetate, propionate and butyrate)

modulate core clock machinery in the host, which implies a

bidirectional loop (26).

Host clock disruption reshapes microbiota

and compromises the barrier in pancreatic cancer

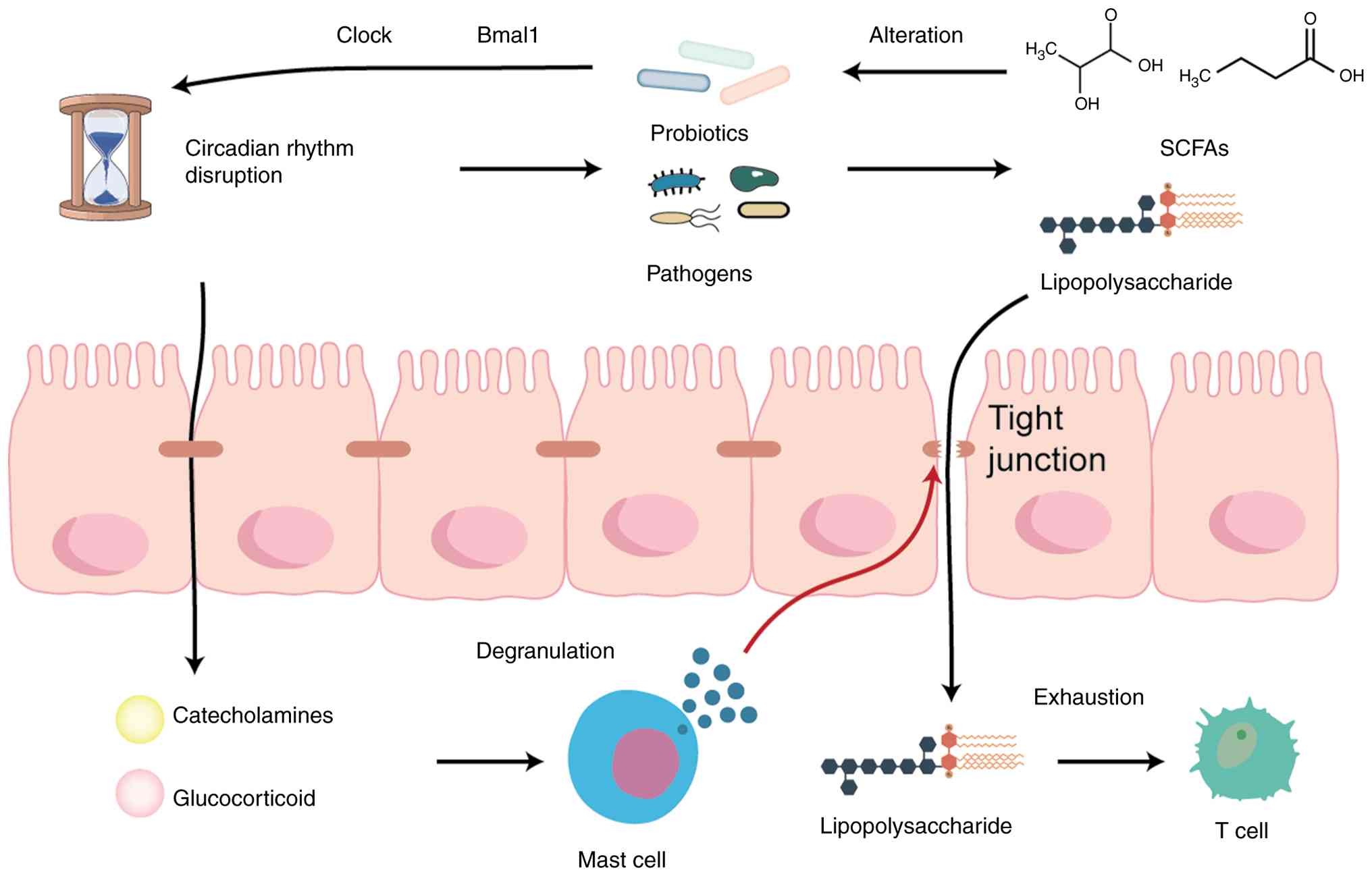

Circadian rhythm disturbances may influence

pancreatic cancer through alterations in the gut microbiome

(Fig. 1). In mice, deletion of

the core clock gene BMAL1 abolishes the diurnal oscillation of the

phylum Bacteroidetes and decreases its absolute abundance relative

to controls, indicating that host clock genes directly shape

microbial rhythmicity and abundance structure (24). On a broader scale, the gut

microbiota as a whole exhibits marked daily oscillations. Disrupted

feeding rhythms and experimental jet lag disturb these oscillations

and produce transferable metabolic imbalance, demonstrating that

behavioral and environmental cues act through the microbiota to

influence host metabolic outcomes (25). Evidence linking the upper

gastrointestinal microbiome with pancreatic cancer comes from study

of duodenal fluid and bile (22). In a prospective cohort, patients

with PDAC who have shorter survival show enrichment of oral and

opportunistic taxa in duodenal fluid, especially members of

Fusobacteria and the genus Rothia, suggesting that upstream

dysbiosis is associated with poor prognosis (22). Patients with severe obstructive

sleep apnea have significantly higher fecal Fusobacterium levels

and its abundance is positively associated with the apnea hypopnea

index (AHI) (27). This suggests

that sleep fragmentation and intermittent hypoxia selectively

enrich proinflammatory taxa, a feature that may be shared with the

unfavorable pancreatic tumor microenvironment (in linear

regression, AHI is positively associated with the relative

abundance of Fusobacterium, β=0.538) (27).

Circadian imbalance also directly impairs the

intestinal epithelial barrier. Both genetic clock disruption and

environmental light and dark phase misalignment increase epithelial

permeability, facilitate endotoxin translocation and trigger

systemic inflammatory responses, thereby creating an anatomical

route for gut-derived molecules to enter the circulation (28). Classical sleep deprivation model

further shows that progressively sleep restricted rats develop

cultivable bacteria in tissue that is normally sterile, which

supports translocation of microbes and their components across

compromised barriers (29).

Human study demonstrates that partial nocturnal sleep loss raises

circulating norepinephrine and epinephrine levels, reflecting

heightened sympathetic activity that is associated with

inflammatory susceptibility (30). At the mucosal level, mast cell

tryptase activates epithelial protease-activated receptor 2 to

increase paracellular permeability, providing a cellular basis for

stress-induced tight junction disruption and barrier leak (31). These barrier and inflammatory

alterations align with pancreatic tumor biology. In a mouse model

of PDAC, increased gut permeability elevates LPS levels in both the

circulation and tumor tissue. The rise in LPS coincides with T cell

infiltration while simultaneously inducing T cell exhaustion and

loss of effector function, together establishing an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (P<0.05) (32).

Bidirectional coupling of microbial

metabolites and the host clock in pancreatic cancer

Circadian disruption due to sleep disorders alters

the microbial metabolic profile. Patients with severe obstructive

sleep apnea show notably higher plasma D lactate levels, along with

enrichment of proinflammatory gut taxa, suggesting that microbially

derived lactate stereoisomers may serve as surrogate indicators of

systemic metabolic stress (27).

In mice, fecal microbiota transplantation from sleep deprived

donors to healthy recipients reproduces colonic dysbiosis

characterized by increased Aeromonas and endotoxins in serum

and colon, and reduced butyrate levels, which indicates that

circadian disruption drives inflammatory phenotypes through

transferable microbe and metabolite consortia (33). In the aforementioned

transplantation model, melatonin supplementation reverses

dysbiosis, restores canonical butyrate producers including the

Ruminococcaceae NK4A136 (an uncultured Ruminococcaceae clade)

group, the Eubacterium xylanophilum group, Ruminococcus 1 and

Ruminococcaceae A2, and alleviates inflammation. These findings

imply that circadian signals improve host inflammatory status by

rebuilding butyrate-producing niches (33). Functionally, SCFAs, especially

butyrate, regulate immune cell and tumor cell phenotypes through G

protein-coupled receptors and histone deacetylase pathways. SCFAs

serve as metabolic substrates and epigenetic regulators and show

anti-inflammatory and antitumor potential in cancer (26).

LPS, a Gram-negative cell wall component, is a key

metabolite-associated mediator that links microbial rhythm

disruption to systemic inflammation (28). LPS traverses the injured

intestinal barrier and activates mucosal and systemic immunity,

driving chemotaxis, adhesion molecule expression and cytokine

cascades that provide sustained stimuli for immune exhaustion and

fibrosis in pancreatic tumors (32). Endotoxin exposure and host

responses show clear diurnal features. In healthy volunteers, fever

and neuroendocrine responses to low dose endotoxin depend on time

of day, indicating that human systemic sensitivity to LPS varies

across the circadian cycle (34). At the cellular level, mRNA

expression of several toll-like receptors (TLRs), including TLR4,

oscillates in splenic adherent immune cells over the 24-h cycle.

LPS given at different times of day elicits distinct cytokine

profiles, indicating that innate immune recognition is under

circadian clock control (35).

Consistently, the macrophage clock modulates LPS-induced NF-κB

signaling and cytokine production through BMAL1 and microRNA (miRNA

or miR)-155, imparting temporal specificity to endotoxin responses

(36). Barrier dysfunction

caused by circadian disruption increases exposure to

microbiota-derived LPS in the circulation (28,37). In a light shift model, microbial

community structure and function are altered, with enrichment of

pathways involved in LPS biosynthesis, which suggests rhythm

disturbance may both increase endotoxin supply and modify host

responsiveness (38). Taken

together, these observations indicate that the circadian clock

interfaces with gut-derived LPS signaling in the pancreatic cancer

microenvironment through regulation of epithelial permeability and

time selective responsiveness of innate TLR4 pathways. The

coexistence of dysbiosis and circadian misalignment may intensify

immunosuppression in PDAC and confer temporal sensitivity to

immunotherapy strategies such as PD-1 and PD-L1 blockade (39,40).

Microbial metabolites feed back onto host clock

genes. Dietary choline is converted by gut microbes to

trimethylamine and oxidized in the liver to trimethylamine N-oxide

(TMAO) (41). In endothelial

cell models in vitro, TMAO upregulates circadian locomotor

output cycles kaput (CLOCK) and brain and muscle ARNT-like 1

(BMAL1) and modulates cell proliferation rhythms by coupling with

long non-coding RNA and MAPK pathways, which suggests that certain

metabolites remodel peripheral clocks (41,42). In summary, circadian disruption

shapes a pancreatic tumor microenvironment in which proinflammatory

immunity coexists with immune exhaustion through alteration of

butyrate-producing niches and increased endotoxin exposure.

Metabolites such as butyrate and TMAO influence host clock gene

networks through receptor-mediated and epigenetic pathways. This

bidirectional coupling provides tractable entry points for

mechanistic studies and intervention strategies (26,41).

Evidence across genetic, behavioral and clinical

models supports a coherent chain from host clock disruption to

dysbiosis, barrier leak and time-dependent immune dysfunction in

pancreatic cancer. Loss of microbial rhythmicity following BMAL1

deletion (24) coincides with

community shifts in humans, including enrichment of oral taxa in

proximal gut among short-survival PDAC cases with measurable

α-diversity decrease and β-diversity separation (22). Sleep fragmentation and

intermittent hypoxia show a proinflammatory effect on fecal

communities, exemplified by a positive association between AHI and

Fusobacterium abundance in regression analyses (β=0.538) (27). Independent lines of evidence

indicate barrier compromise and systemic activation, with partial

sleep loss elevating catecholamine levels (30) and PDAC models linking increased

permeability with higher circulating and intratumoral LPS alongside

T cell infiltration with functional exhaustion (32). Metabolite-clock crosstalk is

bidirectional, as butyrate depletion and enrichment of LPS pathway

are associated with circadian misalignment (38), while TMAO upregulates CLOCK and

BMAL1 in vitro (41), and

melatonin restores canonical butyrate producers following dysbiosis

transfer (33). These

observations support clinical frameworks that integrate objective

circadian phenotyping with multi-site microbiome and metabolite

readouts, and pilot peri-therapeutic ecological calibration and

time-informed immunotherapy scheduling to test translatability

(40).

Gut microbiota and pancreatic cancer

The gut microbiota is a complex and finely balanced

ecosystem, constituting the largest microbial community in the

human body. It serves essential roles in protecting the host from

infection, aiding digestion and regulating the immune system

(43). Dysbiosis, or imbalance

in the gut microbiota, is associated with a number of diseases,

particularly metabolic disorders, including obesity, type 2

diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome.

Gut microbiota can reach the pancreas through the circulatory

system and pancreatic ducts, suggesting a potential involvement in

pancreatic pathophysiology (44). Antibiotic-mediated depletion of

gut microbiota in mice increases the number of anti-tumor T cells

[such as T helper (Th)1 and type 1 cytotoxic T cells], reduce

pro-tumor cell populations (such as IL-17A and IL-10-producing T

cells) and enhance the infiltration of effector T cells into

pancreatic tumors, thereby boosting the immune system capacity to

combat pancreatic cancer (45).

These findings highlight the role of gut microbiota in modulating

pancreatic cancer development through immune regulation, though the

exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

Role of gut microbiota in pancreatic

cancer development

Heliobacter pylori

Meta-analysis has demonstrated a notable association

between serum positivity for H. pylori and an increased risk

of pancreatic cancer, although no significant association was

identified specifically for positivity with the

cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) strain (pooled adjusted OR,

1.38, 95% CI 1.08-1.75) (46).

These findings indicate that the effect of H. pylori

infection on pancreatic cancer risk may depend on bacterial strain

variation. Schulte et al (47) showed that individuals infected

with CagA− H. pylori strains exhibit a notably

elevated risk of developing pancreatic cancer (OR 1.30; 95% CI

1.02-1.65), whereas those with CagA+ strains exhibit a

reduced risk (OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.67-0.91). Consistent with these

results, a meta-analysis involving 3,033 participants found a

significant yet modest association between H. pylori

infection and pancreatic cancer incidence. However, the

aforementioned analysis did not reveal a significant association

between the presence of CagA+ strains and the occurrence

of pancreatic cancer (overall pooled OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.22-1.77),

and this association persisted when the analysis was restricted to

the studies of higher methodological quality, defined as those

scoring ≥6 on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (high-quality subset OR

1.28, 95% CI 1.01-1.63). By contrast, the subgroup analysis limited

to CagA+ strains did not show a significant association

with pancreatic cancer (OR 1.42, 95% CI 0.79-2.57) (48). The aforementioned studies suggest

that the risk of pancreatic cancer may vary depending on the

specific strain of H. pylori, although further investigation

is needed to define the relationship (47). Beyond H. pylori strains,

the ABO genotype may also play a role in this process. ABO blood

group antigens are expressed in the gastrointestinal epithelium and

influence H. pylori adhesion, thereby regulating gastric and

pancreatic secretion functions, which may impact pancreatic

carcinogenesis related to dietary and smoking-associated

nitrosamine exposure, thus influencing pancreatic cancer risk

(49). H. pylori damages

the gastric mucosa, leading to the formation of gastric ulcers.

Gastric ulcers are typically associated with hypochlorhydria,

creating an environment conducive to the accumulation of nitrites

(50), which are carcinogenic

and increase the risk of pancreatic cancer (51). This may explain why patients with

untreated gastric ulcer face a heightened risk of pancreatic

cancer. During years 3-38 of follow-up after ulcer diagnosis, the

SIR was 1.20 (95% CI 1.10-1.40); at 15 years of follow-up, the SIR

was 1.50 (95% CI 1.10-2.10); and 20 years after gastric resection,

the SIR was 2.10 (95% CI 1.40-3.10) (52). Alcohol consumption may also play

a role in H. pylori-induced pancreatic cancer, as infection

with H. pylori may increase pancreatic cancer risk in

low-alcohol consumers (overall adjusted OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.75-2.09;

never smokers-adjusted OR 3.81, 95% CI 1.06-13.63; low-alcohol

consumers-adjusted OR 2.13, 95% CI 0.97-4.69) (53).

Fusobacterium

A cohort study detected Fusobacterium DNA in

pancreatic cancer tissue and linked its presence to poor prognosis;

patients with Fusobacterium-positive tumors show

significantly shorter survival, supporting its potential as an

adverse prognostic biomarker (multivariable HR for overall

mortality 2.57, 95% CI 1.01-6.58; multivariable HR for

cancer-specific mortality 2.16, 95% CI 1.02-4.59) (54). Mechanistically, mouse and human

data indicate that intratumoral Fusobacterium nucleatum

augments chemokine signaling and recruits granulocytes, thereby

intensifying inflammatory conditions and promoting pancreatic

cancer progression; activation of CXCL1 and its receptor CXCR2 is a

key pathway (tumor tissue detection rate 15.5%) (55). Upstream sources may involve the

upper gastrointestinal tract: Duodenal fluid analysis has shown

that show enrichment of Fusobacteria and oral taxa such as Rothia

in short-survival patients, suggesting oral-gut translocation and

dysbiosis of the upper gut as a microbial reservoir for pancreatic

colonization (discovery cohort n=308 with PDAC n=74; enrichment

determined by differential abundance testing) (56). Intratumoral bacteria typically

localize intracellularly within immune and cancer cells, a

distribution that may facilitate immune evasion and direct

crosstalk with host signaling networks (57). The pancreatic cancer microbiome

induces suppression of innate and adaptive immunity, including

polarization of tumor-associated macrophages toward

immunosuppressive states and inhibition of T cell activation,

thereby creating a niche favorable for pro-inflammatory colonizers

such as Fusobacterium (antibiotic-mediated microbial

depletion significantly decreases orthotopic tumor growth and

myeloid suppressor populations and increases

CD4+/CD8+ T cell infiltration) (58). The detection rate of F.

nucleatum in pancreatic cancer is associated with prognosis and

immune escape, further supporting its feasibility as an

intervention target (59).

Veillonella and Streptococcus

A multi-center fecal metagenomic study developed

specific pancreatic cancer classification models in which

oral-associated genera including Veillonella and

Streptococcus repeatedly emerge as discriminative features

and retain stable performance in independent validation,

underscoring their key roles in disease-associated communities

(fecal metagenomic classifier AUROC up to 0.84; combination with

CA19-9 increases AUROC to 0.94; external disease-specificity tested

in 25 datasets at 90% specificity with low false-positive rates)

(60). An independent Israeli

amplicon-based study similarly reported increased relative

abundance of Veillonellaceae and Akkermansia in feces

from patients with pancreatic cancer, along with depletion of

families common in healthy controls such as Clostridiaceae,

Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, and achieved an

AUC of 82.5% for distinguishing patients with pancreatic cancer

from healthy controls (61). A

prospective Chinese fecal study further showed decreased overall α

diversity and enrichment of inflammation-related functions such as

LPS biosynthesis, and highlighted associations between

Streptococcus and intestinal bile factors, suggesting

potential interactions between altered bile dynamics and expansion

of oral taxa (62). Multi-site

sampling combined with fluorescence in situ hybridization

(FISH) confirms that characteristic oral-gut taxa can be detected

in pancreatic tumor tissue in situ, strengthening the

biological continuity between oral-gut sources and pancreatic

colonization (60).

Akkermansia muciniphila and

butyrate-associated commensal organisms

Metagenomic analysis of long-term survivors has

revealed enrichment of commensal organisms associated with

antitumor immunity, most notably Faecalibacterium

prausnitzii and A. muciniphila, relative to typical

pancreatic cancer cases; both taxa are associated with favorable

responses to immunotherapy in other types of malignancy, suggesting

they may modulate pancreatic cancer progression by promoting

antitumor immunity (significant enrichment of F. prausnitzii

and A. muciniphila reported with metagenomic testing)

(63). A cross-cohort stool and

tissue study identified Akkermansia as a recurrent feature in

diagnostic models, with in-tumor validation by FISH, consistent

with potential migration from the gut and niche adaptation within

the pancreas (fecal AUROC up to 0.84, rising to 0.94 with CA19-9)

(60). Concordant with Israeli

amplicon data, pancreatic cancer cohorts frequently show higher

levels of Akkermansia and Veillonellaceae alongside decreased

levels of Ruminococcaceae and other butyrate-associated families, a

directional shift aligned with perturbations in mucosal barrier

integrity, SCFA homeostasis and immune regulation (AUC 82.5% for a

taxa-based classifier) (61). At

the tissue level, the intratumoral microbiome is coupled with the

host immune landscape; tumors from long-term survivors harbor more

diverse microbial networks that are associated with features of T

cell activation, including increased intratumoral CD3+

and CD8+ T cell infiltration and higher numbers of

granzyme B-positive cytotoxic T cells, providing histological

support for the hypothesis that butyrate-associated commensal

organisms shape antitumor immunity via metabolic and

antigen-presentation pathways (64). Systemically, immunosuppression

driven by the pancreatic cancer microbiome is partially reversed by

microbiota depletion, in line with the enrichment of beneficial

commensal organisms in long-term survivors and supporting

microbiome-based strategies to improve antitumor immune responses

(antibiotics decrease tumor burden and reprogram myeloid/T cell

compartments) (58).

Porphyromonas gingivalis and oral-gut

translocation

Oral pathobionts are associated with pancreatic

cancer (60,65). Mechanistically, P.

gingivalis can colonize pancreatic tumors and accelerate the

growth of orthotopic and ectopic pancreatic cancer by inducing

tumor-associated neutrophils to secrete neutrophil elastase,

thereby establishing a neutrophil-dominated pro-inflammatory

microenvironment (65).

Detection of this oral pathogen in both tumor tissue and the oral

cavity reinforces the anatomical route for oral-gut translocation

and distal colonization, and implies that periodontal disease

control may have practical relevance for pancreatic cancer

prevention and peri-therapeutic management (65). Elevated intratumoral microbial

loads coexisting with immune suppression may provide a niche that

permits the persistence of oral taxa, consistent with findings that

microbial depletion activates antitumor immunity and restrains

tumor growth (58). Moreover,

multi-site sequencing and ISH confirm that characteristic gut and

oral bacteria can be directly visualized within pancreatic tissue,

providing anatomical evidence for the involvement of oral microbes

in pancreatic cancer progression (fecal classifier AUROC up to 0.84

with tissue-level FISH validation in a subset) (60).

Microbial communities within the

pancreas

In the context of pancreatic cystic lesions,

intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) is reported as a

potential precursor to invasive pancreatic cancer (66). Notably, in patients with IPMN

with high-grade dysplasia and cancer, bacterial 16S rDNA copy

numbers and IL-1β protein levels in cystic fluid are significantly

higher compared with patients with non-IPMN pancreatic cystic

neoplasm (16S rDNA geometric mean 17.7-fold higher in IPMN with

high-grade dysplasia vs. IPMN with low-grade dysplasia; IL-1β

103.2-fold higher) (66). This

suggests that an increase in intra-pancreatic bacteria may be

associated with pancreatic cancer pathogenesis. Riquelme et

al (64)demonstrated that

pancreatic tissue from long-term survival patients with PDAC

exhibit notably higher α-diversity in their pancreatic microbiomes.

Additionally, specific microbial taxa (Pseudoxanthomonas,

Streptomyces, Saccharopolyspora and Bacillus clauii) within

the tumor microbiome are significantly associated with prolonged

survival (64). These findings

indicate that not only do specific microbial communities exist

within pancreatic cancer tissue, but they also exhibit distinct

patterns depending on the disease state. The pancreatic duct and

the intestine are anatomically connected, with interactions between

the pancreas and the gut facilitated by the pancreatic duct. FISH

with 16S rRNA probes and quantitative PCR results indicate that the

bacterial population in the pancreas of patients with pancreatic

cancer is 1,000 times higher than that in healthy pancreatic tissue

(67). Certain bacteria migrate

through the pancreatic duct and accumulate in pancreatic cancer

tissue (67). In the adult gut

microbiome, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are dominant, while

Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and

Verrucomicrobia are present at lower levels (68). However, in the gut microbiota of

patients with pancreatic cancer, the relative abundance of

Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria

and Verrucomicrobia is notably increased. Correspondingly,

an abnormal increase in Proteobacteria is also detected in

the pancreatic microbiota of these patients, with the abundance of

Proteobacteria associated with pancreatic cancer progression

(58). These findings suggest

that the gut microbiota influences the abundance of microbial

communities within the pancreas and may serve a role in the

development of pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, the microbial

communities within pancreatic cancer tissue selectively activate

TLRs, triggering immune tolerance responses that contribute to

immune evasion in pancreatic cancer (69). For examples, the abundance of

B. pseudolongum in both pancreatic cancer tissue and the gut

of patients with PDAC is increased. The cell-free extracts of B.

pseudolongum selectively activate TLR2 and TLR5, promoting

macrophage polarization and subsequent secretion of

immune-suppressive cytokines, such as IL-10, which provide immune

protection for the tumor (58).

In addition, the presence of Gammaproteobacteria in pancreatic

cancer tissue has been reported (70). These bacteria secrete enzymes,

such as cytosine deaminase, which convert gemcitabine, a

chemotherapeutic agent used for PDAC, into its inactive form,

2',2'-difluorodeoxyuridine (70). This results in the development of

gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic tumors, which is reversed by

ciprofloxacin treatment (70).

Moreover, H. pylori DNA is detected in 75% of pancreatic

tissue samples and 60% of duodenal samples from patients with

exocrine pancreatic cancer. This suggests H. pylori may be

transmitted from the digestive tract to the pancreas, potentially

promoting the development of pancreatic cancer and chronic

pancreatitis (71). H.

pylori stimulates pancreatic cancer cells to secrete IL-8,

VEGF, NF-κB, activator protein 1 and serum response element, which

enhance immune responses, angiogenesis and promote cancer cell

proliferation and survival (72). Additionally, F. nucleatum,

a bacterium associated with periodontal disease, has been detected

in pancreatic cancer tissue (prevalence, 8.8%) (54). Patients with Fusobacterium

positivity have notably higher cancer-specific mortality rates,

suggesting that the presence of Fusobacterium in pancreatic tissue

is independently associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic

cancer (54).

Collectively, oral-gut pathobionts expand along the

oral/duodenal/pancreatic continuum and align with adverse

phenotypes (56). Intratumoral

Fusobacterium is associated with shorter survival after adjustment

for clinical covariates, with HR of ~2 two, and tumor positivity is

observed in a minority of cases, suggesting a high-risk microbial

subset rather than a ubiquitous marker (54). H. pylori shows

strain-contingent signals, with pooled ORs for seropositivity in

the range of 1.3-1.5, a higher risk with CagA-negative strains near

1.30 and a lower risk with CagA-positive strains near 0.78

(47). Long-term gastric ulcer

carries standardized incidence ratios between 1.2 and 2.1 across

latency windows, consistent with nitrosation-associated pathways

that may intersect with pancreatic carcinogenesis (52). Diagnostic modeling adds

convergent support (60). Stool

classifiers that elevate oral taxa such as Veillonella and

Streptococcus have AUC values near 0.84 and approach 0.94

when combined with CA19-9, with external disease specificity

maintained at high specificity thresholds (60), while an independent amplicon

study reports an AUC near 0.825 (61). By contrast, commensal organisms

linked to barrier integrity and immune tone, including

Akkermansia and butyrate-associated families, concentrate in

long-survivor networks and track with T cell-active tissue states

(64).

These findings suggest complementary avenues for

translation. Biomarker development may use stool or tumor microbial

signatures together with clinical markers such as CA19-9 to support

risk stratification and prognostic assessment across settings

(60). In parallel,

peri-therapeutic ecological modulation can be tested through

mechanism-guided hypotheses, including inhibition of the CXCL1 and

CXCR2 chemokine axis to limit neutrophil recruitment (55), reprogramming of macrophages

through TLR-based signaling (58) and mitigation of microbe-mediated

drug metabolism (70). However,

most available studies are associative and sensitive to sampling

site and batch structure, and effect estimates vary with exposure

definitions and host context. More persuasive mechanistic

inferences require converging evidence that traces microbial

sources to in-tumor localization, delineates immune consequences

and demonstrates reversibility under intervention, accompanied by

clear reporting of effect sizes and heterogeneity to clarify

magnitude and generalizability.

Hepatitis viruses and pancreatic cancer

Patients with chronic liver disease associated with

hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) commonly

exhibit marked disturbances of the gut microbiota (73). Epidemiological evidence indicates

that chronic HBV/HCV infection is associated with an increased risk

of pancreatic cancer, positioning viral hepatitis as a key link

between gut microbiota alterations and pancreatic cancer

progression (74).

HBV and HCV, is a leading cause of death due to

viral hepatitis (75). HBV and

HCV are not only detected in the liver but also in extrahepatic

tissue such as the pancreas (76). For example, Yoshimura et

al (77) demonstrated

hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity in the pancreatic

tissue of patients with pancreatic lesions, and electron microscopy

reveals structures resembling HBV core particles in both the

nucleus and cytoplasm. Jin et al (78) demonstrated that HBsAg and HBcAg

are expressed in both pancreatic cancer tissue (21%, 34/162) and

non-tumorous pancreatic tissue (29%, 47/162) and that both HBsAg

and HBcAg are significantly associated with the occurrence of

chronic pancreatitis (78). The

aforementioned study also revealed the presence of the S, C, and X

genes of HBV in pancreatic cancer (20%, 6/30) and non-cancerous

pancreatic tissue samples (26.9%, 7/26). Notably, HBV DNA and

anti-HBc antibody positivity are significantly higher in patients

with pancreatic cancer compared with healthy controls (78). Taranto et al (79) suggested that mild pancreatic

injury, indicated by elevated pancreatic amylase levels, may occur

during the early stages of acute viral hepatitis. Chronic HBV

infection and the presence of HBsAg notably increase the risk of

pancreatic cancer (80).

Similarly, Iloeje et al (81) found that chronic HBV infection

may be associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer, with

a notably higher risk in HBsAg-positive patients with HBV DNA ≥300

copies/ml, compared with those with HBV DNA <300 copies/ml.

Additionally, the rate of synchronous liver metastasis in

HBsAg-positive patients and those with chronic HBV infection is

significantly lower than in HBsAg-negative patients and non-HBV

infection groups, suggesting that HBV infection may influence the

occurrence of liver metastasis and serve as an independent

prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer (82). Given the higher detectability of

HBV DNA in patients with pancreatic cancer, this suggests a

potential role of latent HBV infection in pancreatic cancer

progression. Latent HBV infection may not only serve as a reservoir

for HBV following HBsAg clearance but could also trigger a mild yet

prolonged necrotic inflammatory process, promoting the development

of pancreatic cancer (78). A

meta-analysis has shown that HBsAg positivity is associated with an

increased risk of pancreatic cancer, while anti-HBc positivity also

suggests an elevated risk, though the findings are not

statistically significant, indicating the need for further studies

to clarify the association between chronic HBV infection and

pancreatic cancer (83). Beyond

HBV and HCV, torque teno virus (TTV), a liver-tropic virus first

isolated from a patient with acute post-transfusion hepatitis in

1997, is considered a pathogenic factor in acute hepatitis

(84). TTV has been detected not

only in the liver but also in the pancreas: TTV DNA has been found

in patients with unexplained hepatitis who later develop pancreatic

cancer, suggesting a potential link between TTV and pancreatic

cancer (85). However, further

research is needed to confirm this association (85).

The role of hepatitis viruses in pancreatic cancer

development may be associated with inflammation, as HBsAg and HBcAg

positivity in pancreatic tissue significantly increases the

incidence of chronic pancreatitis (78). Following liver transplantation,

pancreatic inflammation occurs is often associated with acute HBV

infection in the transplanted liver (86), supporting the hypothesis that HBV

may induce pancreatic cancer through inflammatory mechanisms.

Additionally, a previous study suggests a notable interaction

between a history of diabetes and chronic HBV infection, further

increasing the risk of PDAC (80). There is a higher incidence of

latent HBV infection in diabetic patients compared with healthy

controls, which may be linked to the high incidence of primary

hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients (87). The pathogenesis of type 2

diabetes also involves pancreatitis (88), supporting the potential role of

HBV in promoting pancreatic cancer through inflammation. Moreover,

hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) expression upregulates ErbB4 and

TGF-α expression, activating the PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and ERK signaling

pathways, thereby promoting the proliferation and invasion of

pancreatic cancer cells. Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway

reverses the effects of HBx in PDAC cell lines (89). Therefore, HBx may promote

pancreatic cancer progression by modulating these pathways

(89).

Mechanisms of gut microbiota-mediated

pancreatic cancer progression

Microbial-induced inflammatory

pathways

Pancreatic inflammation serves a key role in the

development of pancreatic cancer, with evidence indicating a

significantly higher risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with

chronic pancreatitis (90).

Increasing evidence suggests that microbial infection contributes

to the progression of pancreatitis (91,92). Dysbiosis in the gastrointestinal

microbiota leads to the proliferation of harmful bacteria, which

disrupt the epithelial barrier, allowing pathogenic bacteria to

migrate to the pancreas. The colonization of these harmful bacteria

in the pancreas triggers pancreatic inflammation (92). Serra et al (93) showed that Gram-negative bacteria

contribute to the promotion of tumor-associated inflammatory

responses.

The pro-inflammatory effects of microbes involve

pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and their associated signaling

molecules. NOD-like receptors (NLRs), which are cytosolic PRRs,

activate NF-κB signaling pathways upon recognition of

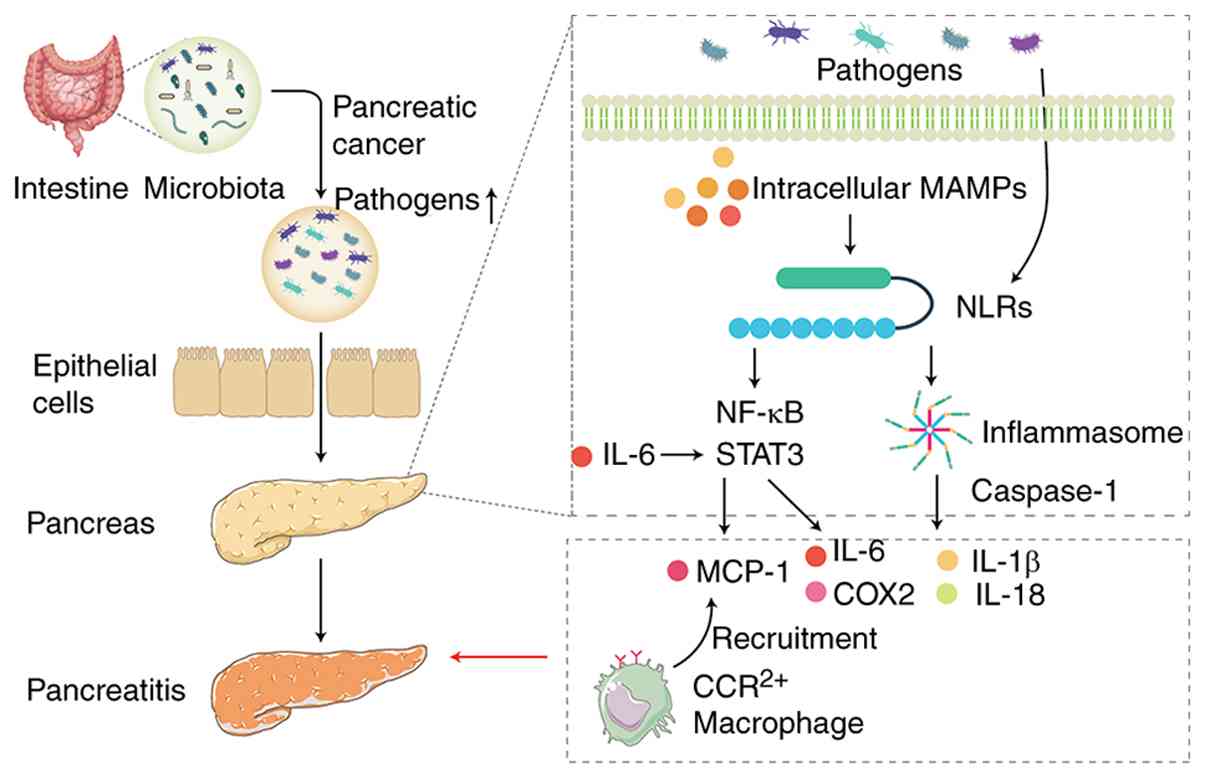

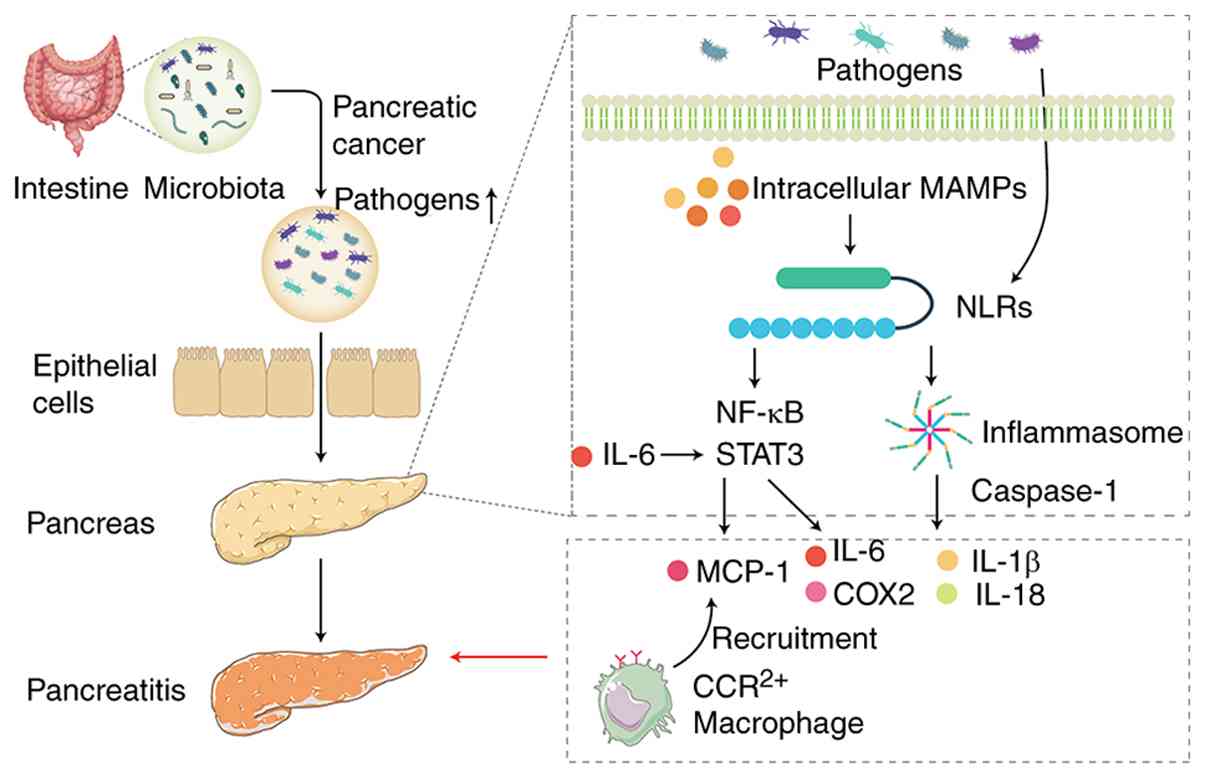

microbial-associated molecular patterns (Fig. 2). This activation not only

triggers NF-κB signaling but also promotes inflammasome formation

(94). One of the key components

of activated inflammasomes is caspase-1, which facilitates the

cleavage and maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as

IL-1β and IL-18 (95).

Inflammasomes are key regulators of the host defense against

pathogen invasion and maintaining intestinal microbial balance.

Mice lacking NLRs exhibit alterations in gut microbiota and

microbial dysbiosis, which leads to the development of inflammatory

disease (96). Mice with NOD1,

Nlrp3 or caspase-1 knockout show reduced acute pancreatitis induced

by cerulein, indicating the key role of inflammasomes in the

promotion of pancreatitis (97).

Moreover, NOD1 responds to gut microbiota and promotes the

activation of NF-κB and STAT3. Activation of these pathways

enhances the production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

(MCP-1), which recruits C-C chemokine receptor type 2-posotive

(CCR2+) inflammatory cells to the pancreas, thereby

initiating pancreatitis (98).

STAT3 is a key participant in pancreatitis and is activated in

cerulein-challenged mice. In wild-type mice, STAT3 activation is

transient and returns to baseline as the pancreas recovers from

cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. However, in KC mice (mice with

KRAS mutations in pancreatic epithelial cells), STAT3 activation

persists due to the recruitment of myeloid cells, which secrete

IL-6, activating STAT3 in the pancreas (99,100). Persistent STAT3 activation

promotes the expression of cytokines, chemokines and other

mediators, such as IL-6 and COX2, further driving pancreatic cancer

progression (100,101). Additionally, STAT3 induces the

expression of MMP-7, which facilitates tumor metastasis (99). Germ-free mice exhibit fewer

gastrointestinal malignancies, potentially due to decreased

tumor-associated inflammation (102). This anti-tumor effect was also

confirmed in mice treated with antibiotics to decrease

gastrointestinal microbiota (102). Although the aforementioned

studies have not been verified in pancreatic cancer models, similar

evidence suggests that antibiotic-induced gut sterilization

alleviates acute pancreatitis (91).

| Figure 2Microbial infection and inflammatory

pathways in pancreatitis and cancer development. Dysbiosis of the

gut microbiota leads to the proliferation of harmful bacteria,

disrupting the intestinal epithelial barrier and allowing

pathogenic bacteria to migrate to the pancreas, triggering an

inflammatory response. NLRs activate the NF-κB signaling pathway

and promote inflammasome formation following recognition of MAMPs.

A key component of inflammasomes, caspase-1, facilitates the

maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18,

exacerbating the inflammatory response. NOD1 responds to gut

microbiota and activates the NF-κB and STAT3 pathways, leading to

the production of MCP-1, which recruits CCR2+

inflammatory cells to the pancreas. Persistent activation of STAT3

promotes the production of cytokines and chemokines such as IL-6

and COX2. Figure created using Adobe Illustrator 2025 (Adobe,

Inc.). MAMP, microbial-associated molecular pattern; NLR, Nod-like

receptor; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; CCR, C-C

chemokine receptor. |

Gut microbiota regulation of the immune

system in pancreatic cancer

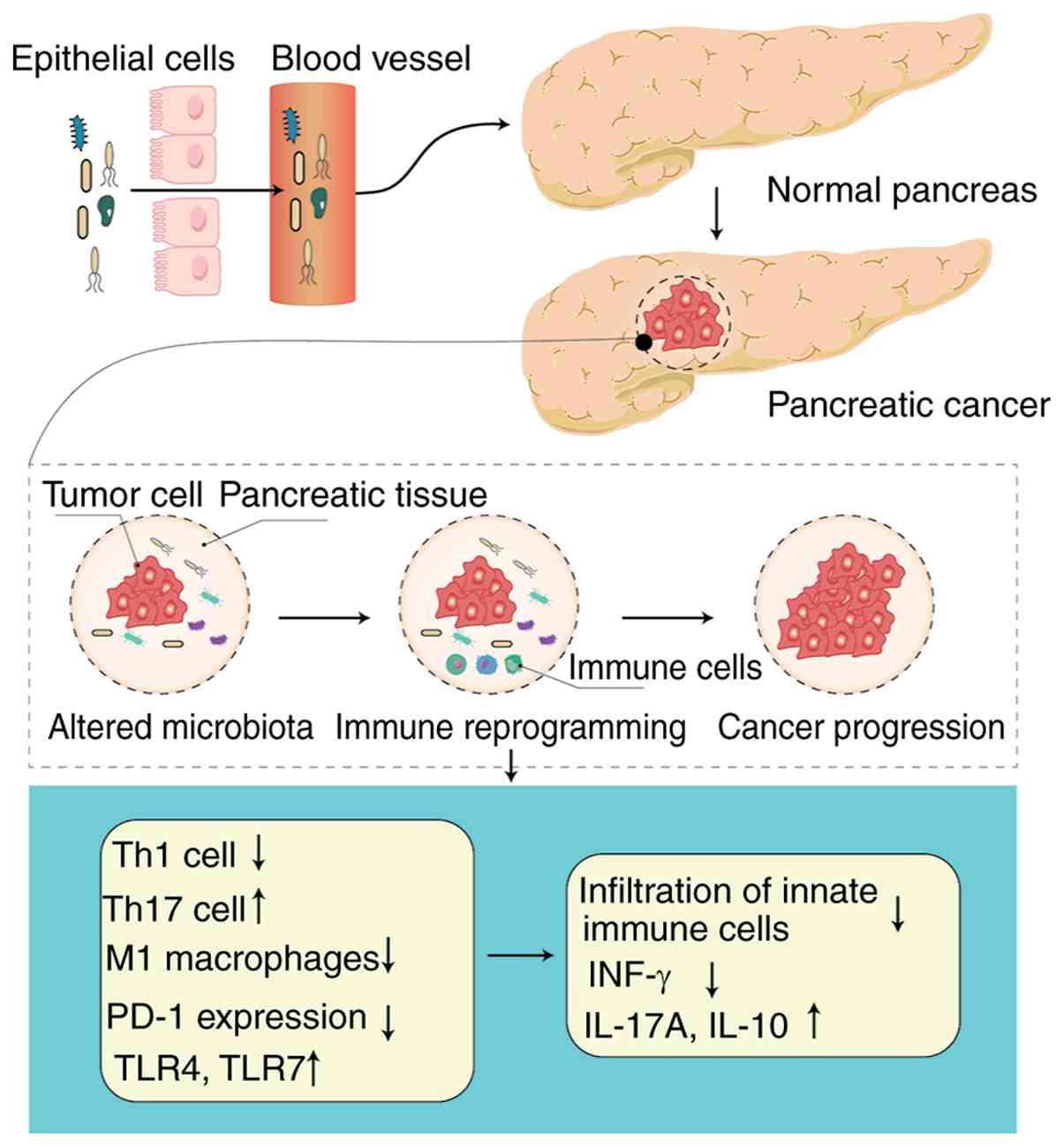

Changes in the gut microbiota present within

pancreatic cancer tissue contribute to immune suppression within

the tumor microenvironment (Fig.

3). Pushalkar et al (58) demonstrated that administering

oral antibiotics to eliminate gut microbiota effectively inhibits

tumor progression. However, this effect is not observed in

recombination activating gene 1 (Rag1) knockout mice, suggesting

that the immune system is essential for gut microbiota-mediated

regulation of tumor development (45). Furthermore, depletion of gut

microbiota led to a marked increase in T cells producing IFN-γ,

while the populations of T cells secreting IL-17A and IL-10 are

notably decreased (45). In the

pancreatic cancer tumor microenvironment, the Th2/Th1 ratio is

considered an independent prognostic marker for patient survival. A

decrease in this ratio is associated with notably prolonged overall

survival (103). This suggests

that the removal of gut microbiota inhibits tumor growth by

increasing Th1 responses and decreasing Th17 and regulatory T cell

responses. Thomas et al (104) investigated the effects of

microbiota depletion in KrasG12D/PTENlox/+

mice, showing that microbiota-depleted mice exhibit fewer poorly

differentiated tumors. Furthermore, in a xenograft model of PDAC in

non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD-SCID)

mice, tumor growth is inhibited in microbiota-depleted mice

compared with microbiota-intact controls (104). The aforementioned study also

observed a notable increase in CD45+ immune cells within

PDAC xenografts derived from mice subjected to gut microbiota

depletion, implying intestinal microbiota may contribute to the

suppression of innate immune responses (104). Pushalkar et al (58) demonstrated that in KC mice (Kras;

p48Cre), the decrease in gut microbiota resulted in

diminished infiltration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells within

tumor tissues. This microbial alteration also facilitates the

polarization of tumor-associated macrophages toward the

pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and supports the differentiation of

CD4+ Th cells toward the Th1 subtype. Additionally,

microbiota depletion leads to a significant rise in the expression

of PD-1 on effector T cells (58). Fecal bacteria from PDAC mice

inhibit the tumor-protective effects observed in

microbiota-depleted KC mice, whereas fecal bacteria from normal

mice do not have this effect (58). The immunosuppressive effects of

PDAC-associated bacterial extracts are abolished in macrophages

lacking TLR signaling (58).

These observations indicate that manipulating the gut microbiota

may affect the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

and they offer strong evidence for the role of gut microbes in

reprogramming immune responses through TLR signaling pathways. TLRs

are well-studied PRRs that detect pathogen- and damage-associated

molecular patterns (DAMPs). When TLR activation is not properly

regulated, it may result in impairments in immune function

(105). Following activation,

TLRs recruit signaling molecules such as MyD88 or

TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF), further

activating the NF-κB and MAPK pathways. In patients with pancreatic

cancer and mouse models, the expression of TLR4 and TLR7 is

upregulated (106,107). The upregulated TLRs bind to

DAMPs, promoting immune cell release of inflammatory mediators,

which alter the tumor microenvironment and promote pancreatic

cancer progression (106).

Blocking MyD88 can inhibit the immunosuppressive effects of

fecal-derived extracts from KC mice, evidenced by the activation of

CD4+ T cells and the upregulation of immune mediators

such as lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), CD44, TNF

and IFN-γ (58,107). These data support the

hypothesis that gut microbiota mediates immune suppression and

promotes tumor proliferation via TLRs, particularly TLR2 and TLR5

pathways and downstream MyD88 signaling.

Regulation of pancreatic cancer by

microbial metabolites

SCFAs and pancreatic cancer

Microbes are key regulators of metabolic processes

and studies have shown that microbial metabolites can impact both

gut and systemic homeostasis, thereby influencing tumorigenesis

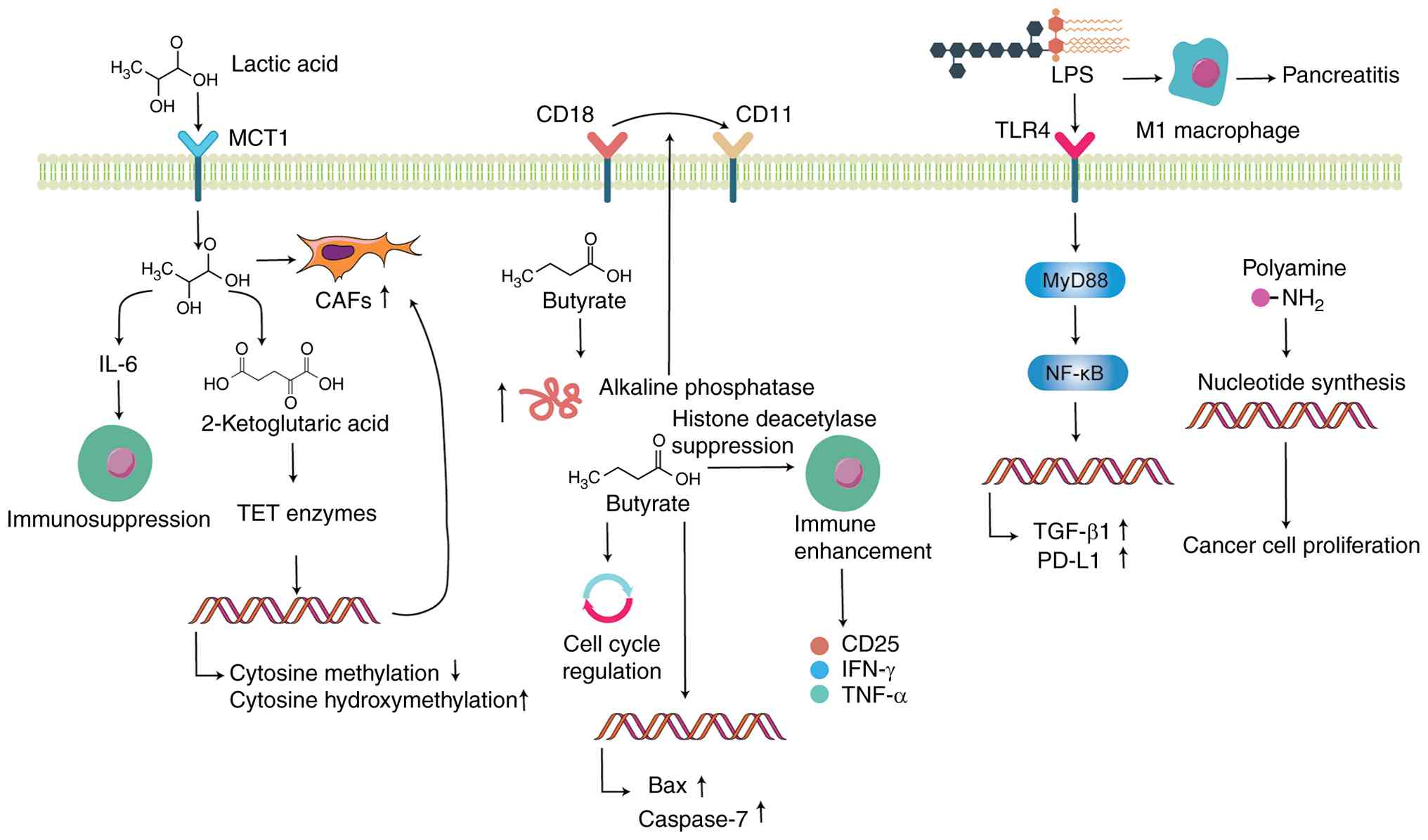

(62,108) (Fig. 4). Evidence has outlined the

primary categories of microbial metabolites and their potential

association with pancreatic cancer (Table I) (110-115,117-119,123). Among these metabolites, SCFAs

are a key group generated by the fermentation of indigestible

carbohydrates through gut microbial activity (109). These include lactate, acetate

and butyrate. Data obtained through single-cell RNA sequencing have

identified a negative association between lactate metabolism

markers and anti-tumor immune responses, along with disruptions in

immune cell infiltration patterns (109). By contrast, these markers have

shown a positive association with signaling pathways that support

tumor progression (109).

Furthermore, the elimination of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), a

key enzyme governing lactate production in pancreatic cancer cells,

enhances the activity of CD8+ T cells involved in

anti-tumor immunity and improves the overall effectiveness of

immunotherapy (109). A similar

study (110) suggested that

increased LDHA expression in the tumor microenvironment of PDAC is

a poor prognostic factor for patients with PDAC. In a mouse model

of PDAC enriched with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), LDHA

depletion inhibits tumor growth (110). The aforementioned study also

found that lactate is taken up by CAFs via monocarboxylate

transporter 1, promoting CAF proliferation. Additionally, lactate

upregulates IL-6 expression in CAFs, which suppresses immune cell

activity (110).

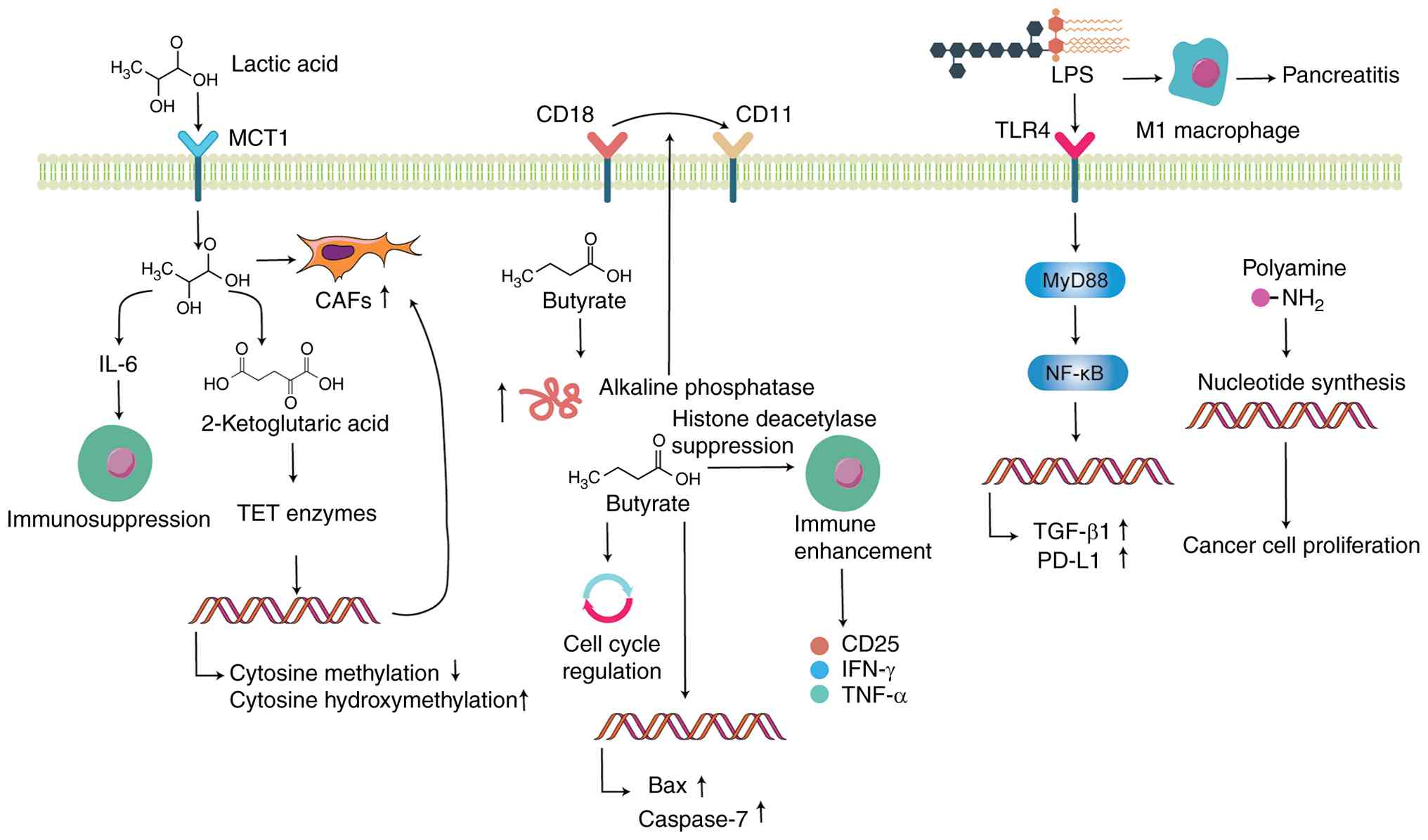

| Figure 4Gut microbiota metabolites and

pancreatic cancer progression. Lactic acid, a short-chain fatty

acid, is absorbed by CAFs via MCT1, promoting CAF proliferation and

upregulating IL-6 expression, which suppresses immune cell activity

and enhances CAF formation via α-ketoglutarate-dependent TET

enzymes. Butyrate increases alkaline phosphatase activity,

facilitating the conversion of CD18 to CD11 cells. Additionally,

butyrate inhibits the cell cycle progression, increases the

expression of pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and caspase-7 and

suppresses pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Butyrate enhances

immune cell activity and stimulates the production of immune

factors such as CD25, IFN-γ and TNF-α. LPS, via the

TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, elevates the production of

PD-L1 and TGF-β1 in tumor cells, promoting pancreatic cancer

progression. LPS promotes M1 polarization of macrophages,

contributing to pancreatic inflammation. Polyamines drive tumor

proliferation by promoting the synthesis of purine and pyrimidine

nucleotides. Figure created using Adobe Illustrator 2025 (Adobe,

Inc.). CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; MCT, monocarboxylate

transporter; TET, 10-11 translocation; LPS, lipopolysaccharide;

TLR, toll-like receptor. |

| Table IMicrobial metabolites and their

associations with pancreatic cancer progression. |

Table I

Microbial metabolites and their

associations with pancreatic cancer progression.

| Authors, year | Metabolite | Model |

Effect/mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kitamura et

al, 2023 | Lactic acid | CAF-rich murine

PDAC | CAFs take up

lactate and promote their own proliferation via the TCA cycle;

lactate stimulates CAFs to express IL-6 and inhibits the activity

of cytotoxic immune cells | (110) |

| Bhagat et

al, 2019 | | PDAC cells with

CAFs | Lactate stimulates

the production of α-KG in MSCs, activating TET enzyme, which

decreases cytosine methylation and increases hydroxymethylation,

promoting MSC differentiation into CAFs and boosting PDAC

invasiveness | (111) |

| Mullins et

al, 1991 | Butyrate | HPAF cell line | Increased alkaline

phosphatase activity notably promotes the transition of CD18 to

CD11 cells, facilitates the differentiation of pancreatic cancer

cell lines and inhibits the proliferation and invasion of PDAC

cells | (112) |

| Pellizzaro et

al, 2008 | | MIA PaCa-2

cells | Arrests the cell

cycle at G0/G1 and G2/M phases, upregulates pro-apoptotic proteins

Bax and caspase-7, downregulates angiogenesis-associated proteins

VEGF-A165 and VEGF-D and inhibits proliferation of pancreatic

cancer cells | (113) |

| Kanika et

al, 2015 | Sodium

butyrate | Wistar rat | Inhibits

L-arginine-induced pancreatic fibrosis and pancreatic injury | (114) |

| Luu et al,

2021 | Valerate and

butyrate | CTLs and CAR T

cells | Inhibits the

activity of class I histone deacetylase, enhances the

anti-pancreatic cancer tumor activity of CTLs and CAR T cells,

increases the expression of effector molecules such as CD25, IFN-γ

and TNF-α | (115) |

| Sivam et al,

2023 |

Lipopolysaccharide | PDAC cells and RAW

264.7 macrophages | Promotes the

activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, increases the expression of IL-1β

and TNF-α, facilitates the formation of a pro-inflammatory

microenvironment and enhances the survival of PDAC cells | (117) |

| Peng et al,

2023 | | C57BL/6J mouse | Promotes macrophage

M1 polarization and exacerbates pancreatitis via the MLKL/CXCL10

pathway | (118) |

| Sun et al,

2018 | | Sprague-Dawley

rat | Increases TGF-β1

production by activating the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway,

promoting the development of chronic pancreatitis | (119) |

| Mendez et

al, 2020 | Polyamine | KPC mouse | Metabolic pathways

associated with polyamine biosynthesis are upregulated in the gut

microbiota of PDAC mice and mice with PanIN show increased serum

polyamine levels | (123) |

Lactate induces the production of α-ketoglutarate

in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). This activates 10-11

translocation enzymes, resulting in decreased DNA methylation and

increased hydroxymethylation, an epigenetic modification that

promotes MSC differentiation into CAFs, contributing to the

invasive behavior of PDAC (111). Butyrate enhance alkaline

phosphatase activity and facilitates the transformation of CD18

into CD11 cells, which contributes to the differentiation of

pancreatic cancer cell lines and suppression of PDAC cell

proliferation and invasion (112). Moreover, a butyrate compound

conjugated with hyaluronic acid induces cell cycle arrest at both

the G0/G1 and G2/M phases. This compound also promotes the

expression of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and caspase-7,

while concurrently reducing the levels of angiogenesis-associated

factors including VEGF-A165 and VEGF-D, thereby inhibiting the

proliferation of the MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cell line

(113). In a study by Ren et

al (62), gut microbiota

profiles of patients with pancreatic cancer and healthy controls

were compared using MiSeq sequencing. The results indicated a

higher abundance of pathogenic and LPS-producing bacteria in

patients with pancreatic cancer patients, whereas levels of

beneficial microbes, including butyrate-producing species and

probiotics, are diminished (62). These findings are in line with

the research by Kanika et al (114), who reported that sodium

butyrate, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, decreases pancreatic

fibrosis and injury induced by L-arginine in Wistar rats.

Additionally, an in vitro study (115) has shown that treating cytotoxic

T lymphocytes and chimeric antigen receptor T cells with pentanoate

and butyrate can enhance their anti-tumor functions against

pancreatic cancer. This is achieved through inhibition of class I

histone deacetylase activity and upregulation of effector molecules

such as CD25, IFN-γ and TNF-α (115). The aforementioned studies

suggest that different SCFA components may have distinct effects on

pancreatic cancer. Future research should focus on modulating the

gut microbiota, such as decreasing levels of lactate-producing

microbes and increasing levels of butyrate-producing microbes, to

regulate pancreatic cancer progression. However, further

experimental studies are needed.

Role of LPS in pancreatic cancer

LPS, a notable component of the outer membrane of

Gram-negative bacteria, is released into the surrounding

environment under the action of antibiotics or host immune cells

(116). In a co-culture system

involving PDAC cells and macrophages (RAW 264.7), stimulation with

LPS activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. This leads to elevated

expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, which

contribute to the formation of a pro-inflammatory tumor

microenvironment and enhanced PDAC cell survival (117). Notably, this effect is

mitigated by MCC950, a selective inhibitor of the NLRP3

inflammasome (117). Peng et

al (118) established an

acute pancreatitis model in C57BL/6J mice using cerulein combined

with LPS. The results showed a marked increase in the expression of

mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) and phosphorylated

MLKL in pancreatic acinar cells, accompanied by a rise in M1-type

macrophage polarization. Disruption of MLKL or neutralization of

the chemokine CXCL10 decreases M1 macrophage polarization and

alleviates the severity of acute pancreatitis in cerulein and

LPS-induced acute pancreatitis C57BL/6J mice (118). Additionally, LPS has been shown

to enhance the production of TGF-β1 via the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB

signaling pathway, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of

chronic pancreatitis (119). In

PDAC tissue, LPS also upregulates PD-L1 expression through the same

TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway, facilitating tumor immune escape

mechanisms (40). The

aforementioned studies indicate that LPS promotes macrophage M1

polarization and contributes to the formation of an inflammatory

pancreatic microenvironment, which accelerates the progression of

pancreatic cancer, primarily via the NLRP3 inflammasome,

MLKL/CXCL10 pathway and TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling.

Polyamines in pancreatic cancer

progression

Polyamines are small polycationic molecules that

serve various biological roles, including gene regulation, stress

resistance and cell proliferation and differentiation (120). Polyamines promote synthesis of

purine and pyrimidine nucleotides by providing amino groups, which

supports rapid cell proliferation, making them potential biomarkers

for tumor progression (121).

The gut microbiota is associated with polyamine concentrations and

serves an essential role in regulating human gut polyamine levels

(122). In PDAC mice, notable

upregulation of the metabolic pathways associated with polyamine

biosynthesis in the gut microbiota is observed (123). Serum analysis shows increased

polyamine concentrations in mice with pancreatic intraepithelial

neoplasia, even without observable tumors (123). The aforementioned study also

detected Lactobacillus in the gut microbiota of 4-month-old

LSL-KrasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53R172H/+; Pdx1-Cre)

mice and metabolomic analysis demonstrates an association between

Lactobacillus and polyamine metabolism (123). This confirms the role of

polyamines as microbial metabolites in promoting pancreatic cancer

progression. Similar finding has been reported in gastric cancer,

where H. pylori regulates polyamine metabolism to facilitate

tumor progression (124). The

aforementioned studies suggest that gut microbiota imbalances, such

as an increase in Lactobacillus, promote polyamine

synthesis, thereby serving a notable role in pancreatic cancer

progression. Future research should focus on the inhibition of

polyamine metabolism and its association with pancreatic cancer to

enhance microbiota modulation strategies for pancreatic cancer

therapy.

Extracellular polymeric substance

(EPS)

In the clinical context of malignant biliary

obstruction due to pancreatic cancer, intraductal drains and stents

provide artificial surfaces that facilitate microbial adhesion and

colonization (125). These

conditions promote production of EPS and subsequent biofilm

formation. EPS, which comprises polysaccharides, protein and

extracellular DNA (eDNA), constitute the structural and functional

core of biofilms (126). This

matrix governs adhesion, antimicrobial tolerance, immune evasion

and mechanical stability, thereby influencing the control of

jaundice, the incidence of cholangitis and the timing and efficacy

of systemic anticancer therapy (127,128). Before and after surgery, as

well as during palliative treatment, >60% of pancreatic cancer

cases arise in the pancreatic head, invade the bile duct and

produce obstructive jaundice that necessitates endoscopic

transpapillary stent placement (129). Multispecies communities and

matrix-like EPS deposits emerge rapidly within the stent lumen.

These changes form the pathological basis for stent re-occlusion

and infection (129). Biliary

stents retrieved from malignant obstruction associated with

pancreatic cancer demonstrate that proteins and polysaccharides are

the predominant, quantifiable components of the biofilm matrix.

This implies a material basis linking EPS burden to stent failure

(130). Metagenomic and

culture-based investigation further shows that among patients

undergoing pancreatic surgery or stent placement, biofilms within

biliary stents are enriched with bacteria of oral and intestinal

origin and contain gene clusters associated with biofilm formation

and antimicrobial resistance (125). These findings indicate that

diverse microorganisms in the biliary environment rely on EPS for

adhesion, cooperative community behavior and drug tolerance

(125). Consistent with these

results, prospective cohort data show that plastic biliary stents

are almost invariably colonized by bacterial and fungal biofilms

with broad resistance spectra (131). This suggests that systemic

antimicrobial therapy alone is unlikely to eradicate organisms

embedded within biofilms, a limitation associated with the barrier

function of EPS (131). With

regard to clinical outcomes, in patients with gastrointestinal

malignancy complicated by malignant biliary obstruction, the

presence of cholangitis before percutaneous or endoscopic biliary

drainage is associated with notably worse overall survival. This

association indicates that biofilm-associated infection narrows the

therapeutic window for systemic treatment in pancreatic cancer,

with EPS-mediated barriers to both antimicrobials and host defenses

as key etiological factors (132). Within EPS, polysaccharides and

proteins crosslink through electrostatic and hydrophobic

interactions to form a three-dimensional network. This network

confers high viscoelasticity and low permeability, limits bacterial

detachment under bile flow shear and restricts the diffusion of

bile acids, antibiotics and complement. The resulting

physicochemical shield provides the microscopic basis for biliary

stent re-occlusion (133).

eDNA, a key scaffold component of EPS, binds multivalent cations

and cationic antimicrobial peptides, thereby depleting local

divalent ions. This upregulates bacterial membrane modification

pathways and increases the minimum inhibitory concentrations of

aminoglycosides and cationic peptides by several-fold (134). This chemical antagonism has

been demonstrated in vitro and may explain the persistence

of biofilm-associated resistance in clinical settings (134). In a polymicrobial in

vitro model, exogenous DNase alone or in combination with

protease markedly weakens biofilm structure, decreases colony

viability and improves antibiotic penetration (135). These findings suggest that

enzymatic strategies targeting EPS degradation may serve as

intrastent or locally irrigated adjuncts for infection associated

with biliary stents in pancreatic cancer. Nevertheless, biliary

safety and pharmacokinetics require clinical validation (136). Beyond common members of

Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci, biliary stent biofilms may

accumulate oral streptococci and actinomycetes (125). Features of the biofilm

microbiota, such as polymicrobial community structure, dominance of

taxa including Streptococcus anginosus, Escherichia

coli and Enterococcus faecalis, and enrichment of

biofilm and antimicrobial resistance genes, are associated with

time to re-occlusion, which provides new evidence to support

individualized stent management and materials science-based

improvements in patients with pancreatic cancer (137).

Taken together, biliary obstruction resulting from

pancreatic cancer and the use of drainage devices supply a stable

substratum for microbial adhesion. EPS-driven biofilms exert system

level effects on infection, re-occlusion, limit the access of host

immune cells and soluble mediators to the stent surface and

surrounding tissue, and alter drug permeability. These phenomena

define a strategic bridge between device management in the biliary

tract and the overall effectiveness of comprehensive therapy for

pancreatic cancer.

Gut microbiota and chemotherapy

resistance in pancreatic cancer

Surgical resection followed by adjuvant

chemotherapy is the preferred treatment strategy for early-stage

pancreatic cancer. However, drug resistance to chemotherapy notably

contributes to poor clinical prognosis (138). Gemcitabine is the first-line

chemotherapy drug for patients with pancreatic cancer not eligible

for surgical resection (139).

Evidence (70) has shown that

certain bacteria, such as Gammaproteobacteria including

Escherichia coli, in pancreatic tissue contribute to drug

resistance by expressing long-form cytidine deaminase. This enzyme

converts gemcitabine (2,2-difluorodeoxycytidine) into its inactive

form (2,2-difluorodeoxyuridine), thereby leading to drug resistance

(70). This finding is

consistent with research by Bengala et al (140), which reported that high

expression of cytidine deaminase (CDA) in patients with advanced

pancreatic cancer is associated with significantly higher rates of

early disease progression and shorter overall survival. In

addition, Mycoplasma hyorhinis infection is implicated in

various types of cancer in humans, including gastric and colon

carcinoma, esophageal and lung cancers, breast cancer and gliomas

(141). Gemcitabine is

converted into its inactive form in tumor cell extracts from M.

hyorhinis-infected cells (142). Furthermore, the use of cytidine

deaminase inhibitors restores the activity of gemcitabine in these

cells, indicating that M. hyorhinis produces mycoplasma

cytidine deaminase, which facilitates the metabolism of gemcitabine

(142). Weniger et al

(143) discovered that

gemcitabine therapy improved progression-free survival in patients

with pancreatic cancer negative for Klebsiella pneumoniae,

but no significant improvement was observed in patients positive

for this bacterium. Additionally, the use of quinolone antibiotics

in K. pneumoniae-positive patients notably improved their

overall survival. These findings suggest that K. pneumoniae