Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) represents a

complex, chronic intestinal autoimmune disorder characterized by

enhanced gut permeability and dysregulated immune responses. This

multifactorial condition is driven by diverse influences, including

dietary factors, genetic predisposition and gut microbiome

composition IBD encompasses two primary subtypes: Ulcerative

colitis (UC), which manifests as superficial mucosal inflammation

confined to the colon and rectum, and Crohn's disease (CD),

characterized by transmural inflammation that can affect any

segment of the gastrointestinal tract (1). These debilitating conditions

predominantly affect young adults and adolescents, presenting with

severe clinical manifestations including abdominal pain, diarrhea,

malabsorption and systemic fatigue. Furthermore, IBD substantially

elevates the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) development and the

incidence rate of CRC in IBD is approximately 18% after 30 years

(2). However, the conventional

understanding of IBD pathogenesis as a simple triad of genetic

susceptibility, immune dysfunction and environmental triggers

fundamentally underestimates the dynamic complexity of molecular

communication networks that govern intestinal homeostasis. In this

review, a triadic regulatory network model was proposed that

emphasizes the interaction of host microRNAs (miRNAs), the gut

microbiome and immune pathways as an integrated system driving IBD

pathogenesis. Although recent genomic advances have identified over

250 genetic loci associated with IBD susceptibility (3), this reductionist approach fails to

address a critical paradox: Why do genetically identical

individuals exposed to similar environmental factors exhibit vastly

different disease trajectories and therapeutic responses?.

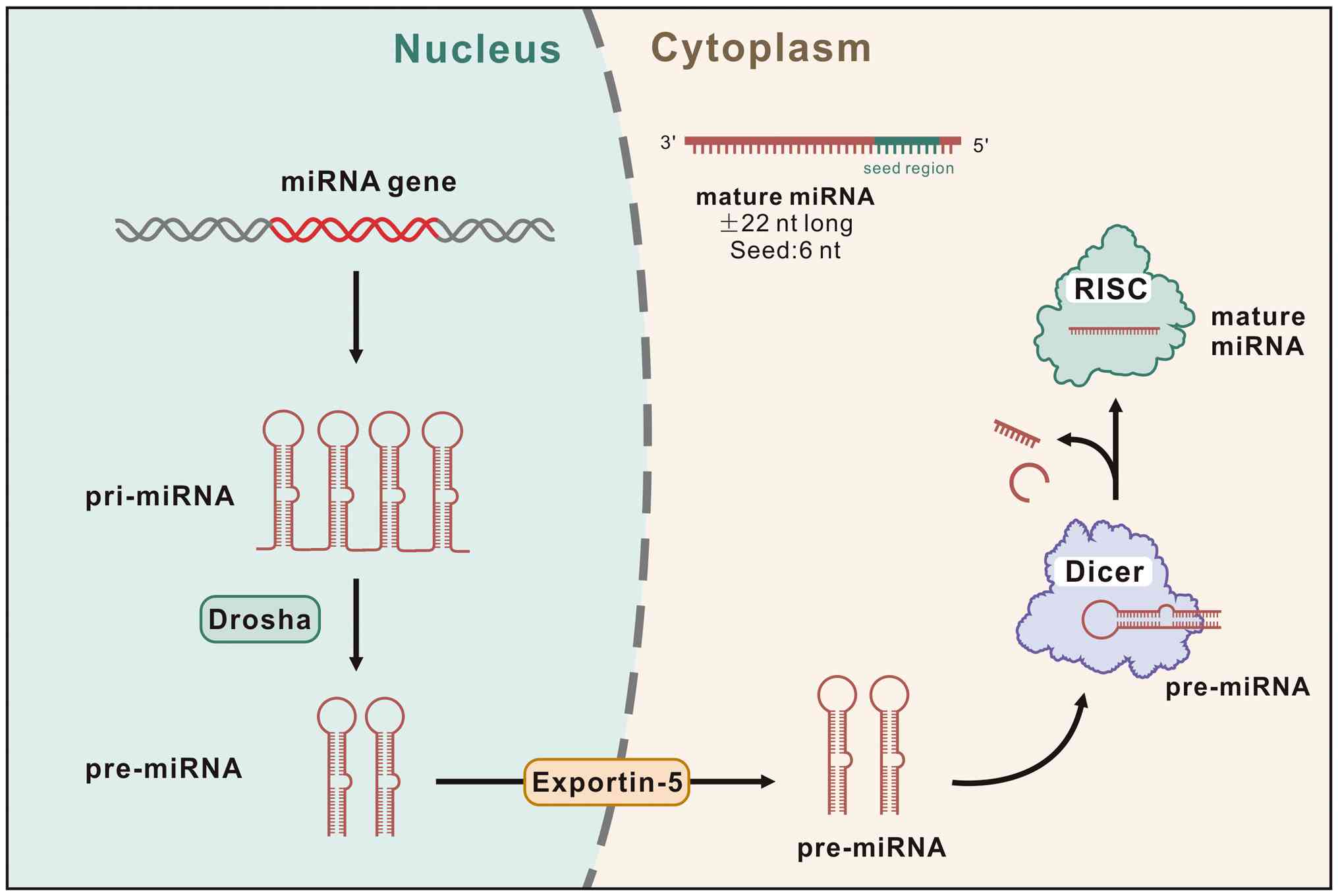

The emerging recognition of miRNAs as pivotal

regulatory molecules in IBD pathogenesis represents a paradigmatic

shift from static genetic determinism toward dynamic epigenetic

regulation. miRNAs are small, evolutionarily conserved, non-coding

RNA molecules of ~22 nucleotides in length that function as

post-transcriptional regulators. They exert their regulatory

effects by binding to complementary sequences within mRNA 3'

untranslated regions, thereby modulating protein synthesis and

influencing diverse biological processes (4) (Fig.

1). Consequently, miRNAs have emerged as critical molecular

determinants in IBD pathogenesis, possessing the unique ability to

simultaneously influence host immune function and the intestinal

microbial ecosystem (5).

Nevertheless, current miRNA research suffers from three fundamental

limitations that have hindered clinical translation: i) The

overwhelming focus on individual miRNA-target interactions while

ignoring systemic network effects; ii) the persistent separation of

host and microbial miRNA functions despite mounting evidence of

cross-kingdom regulation; and iii) the failure to account for

temporal dynamics and context-dependent miRNA functions.

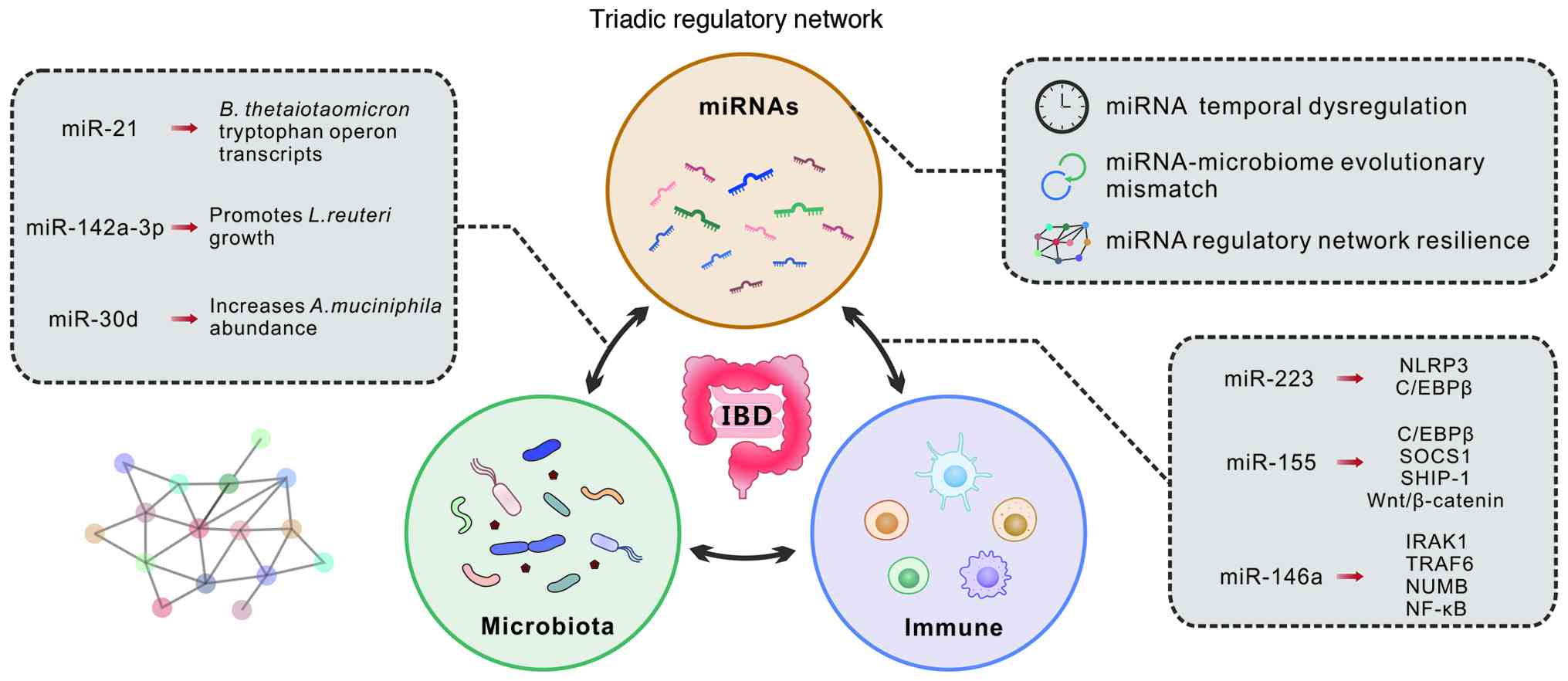

In this review, we propose a triadic regulatory

network hypothesis, which posits that IBD pathogenesis emerges from

dysregulated interactions within three interconnected regulatory

systems. The first involves host-intrinsic miRNA networks that

govern immune and epithelial cell functions (6). The second encompasses

microbiome-derived regulatory mechanisms, including bacterial

miRNAs and metabolite-mediated modulation of host miRNA expression

(7,8). The third comprises cross-kingdom

communication networks that facilitate bidirectional miRNA-mediated

dialogue between host and microbial communities (9). This framework challenges the

prevailing assumption that host and microbial regulatory systems

operate as independent entities. Instead, we propose that IBD

represents a failure of integrated cross-kingdom communication

rather than isolated host immune dysfunction. This perspective

fundamentally reframes therapeutic targeting from single-pathway

interventions toward network-based precision medicine. Such an

approach advances beyond current IBD therapies, which primarily

alleviate symptoms and suppress inflammation but fail to restore

the underlying regulatory balance governing host-microbiome

interactions (10).

Building upon this conceptual foundation, three

hypotheses may be derived that challenge current paradigms and

demand mechanistic innovation (Fig.

2). i) It may be hypothesized that temporal dysregulation of

miRNA expression cycles, rather than absolute expression levels,

represents the primary driver of IBD pathogenesis. For instance,

the microRNA miR-16 in the gut exhibits diurnal rhythmicity

in intestinal crypts, peaking and troughing over the day. This

rhythmic miR-16 expression helps coordinate epithelial

proliferation with feeding times, thereby maintaining mucosal

homeostasis (11). This

hypothesis challenges the current focus on static miRNA

quantification while emphasizing the potential importance of

circadian and ultradian rhythmic patterns that may be critical for

maintaining intestinal homeostasis. ii) It may be proposed that IBD

emerges from an evolutionary mismatch between rapidly evolving

dietary and lifestyle factors and the slower adaptation of ancient

miRNA-microbiome communication systems. This suggests that modern

environmental triggers disrupt co-evolved regulatory networks,

thereby explaining the rising IBD incidence in industrialized

populations (12). iii) It was

contended that current therapeutic failures may result not from

inadequate drug efficacy but from adaptive network reorganization,

wherein miRNA regulatory circuits undergo compensatory rewiring in

response to single-target interventions. This phenomenon is being

referred to as 'regulatory network resilience' and demands

fundamentally different therapeutic approaches. Furthermore,

specific miRNA signatures can effectively discriminate between UC

and CD phenotypes, monitor therapeutic responses and potentially

predict disease severity and long-term complications, including

colorectal carcinogenesis (13).

Despite extensive research, three critical

controversies remain unresolved and continue to impede clinical

progress. The cross-kingdom communication controversy persists

despite compelling evidence demonstrating host miRNA regulation of

bacterial gene expression. Intestinal epithelial cell miRNAs have

been shown to shape gut microbiota composition in colitis models,

and synthetic host miRNA mimics can alter specific bacterial

transcripts and growth in vitro (14). Nevertheless, the physiological

significance and therapeutic targetability of these interactions

remain actively debated, with conflicting reports attributing

observed effects to experimental artifacts rather than genuine

biological phenomena (15,16). Equally problematic is the

biomarker paradox. Although numerous studies have identified

promising miRNA biomarkers for diseases diagnosis, systematic

failures in clinical validation raise fundamental questions about

the stability, specificity and biological relevance of circulating

miRNAs as diagnostic tools (17,18). Perhaps most concerning is the

therapeutic translation gap. Despite promising preclinical results,

no miRNA-based therapeutics have yet reached clinical application

for IBD. In animal models, delivery of certain miRNAs such as

miR-146b or miR-26a mimics can attenuate intestinal inflammation

(19), underscoring their

therapeutic potential. However, translating these findings into

clinical practice faces major hurdles, including efficient delivery

of miRNA therapeutics to inflamed gut tissue, achieving precise

targeting specificity, and ensuring long-term safety and stability

in patients.

Rather than cataloguing individual miRNA-target

associations, this review examines miRNA-microbiome interactions as

a regulatory system and critically evaluates how its disruption

contributes to IBD. Three questions organize this review: What is

the mechanistic basis for bidirectional communication between host

miRNAs and gut microbiota? Why have single-target therapies largely

failed in clinical translation? And what obstacles must be overcome

to develop effective miRNA-based interventions? We propose that IBD

reflects a breakdown in host-microbiome communication, not merely

host immune dysregulation. This view suggests that restoring

regulatory balance across immune function, microbial ecology and

their molecular dialogue may prove more effective than suppressing

isolated pathways.

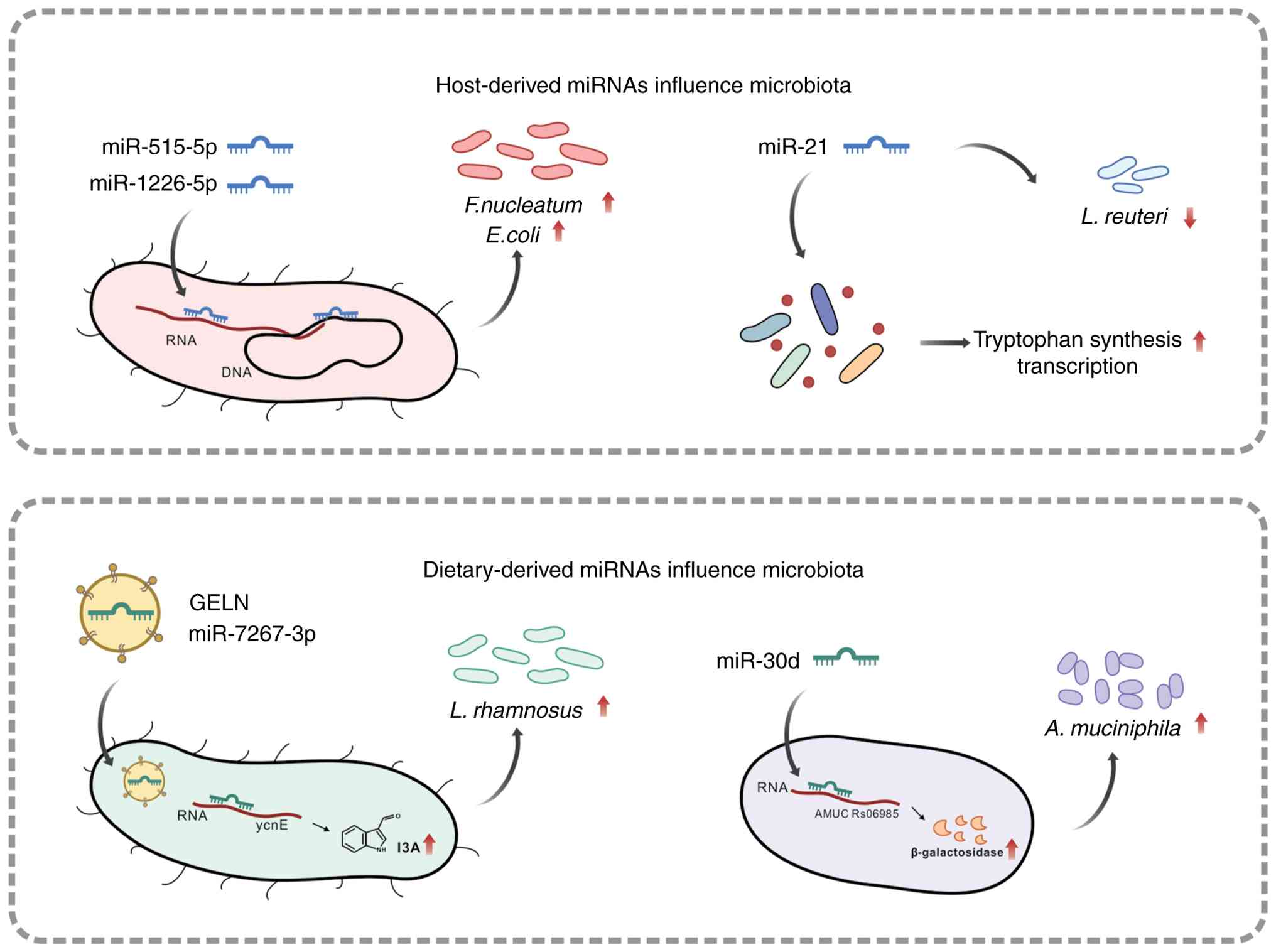

miRNAs have emerged as pivotal molecular mediators

orchestrating the complex bidirectional communication between host

cells and the gut microbiome. Host-derived miRNAs are actively

secreted into the intestinal lumen through multiple mechanisms,

including packaging within extracellular vesicles. Once in the

lumen, these miRNAs can traverse bacterial cell walls and directly

influence microbial gene expression patterns, subsequently reshape

the composition and functional activity of the microbiome. Studies

have shown that specific miRNAs, such as let-7b and miR-21 in feces

can directly regulate the composition and function of the

intestinal microbiota, increase its pro-inflammatory potential, and

further drive chronic inflammatory responses (20). A landmark study by Liu et

al (14) demonstrated that

fecal miRNA-mediated inter-species gene regulation facilitates host

control of the gut microbiota. miRNAs are abundant in mouse and

human fecal samples and are present within extracellular vesicles.

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) and Hopx-positive cells were

identified as the predominant fecal miRNA sources through

cell-specific loss of the miRNA-processing enzyme Dicer.

Critically, these miRNAs can enter bacteria such as

Fusobacterium nucleatum and Escherichia coli,

specifically regulate bacterial gene transcripts, and affect

bacterial growth. Confocal microscopy studies using

fluorescence-labeled (Cy3) miRNA mimics demonstrated that miRNAs

entered bacteria and co-localized with bacterial nucleic acids,

providing the temporal and spatial basis for bacterial gene

expression regulation. Several specific miRNAs have been identified

as regulators of bacterial growth: miR-515-5p elevated the

proportion of Fusobacterium nucleatum 16S rRNA/23S rRNA

transcripts, while miR-1226-5p upregulated the level of yegH mRNA

in Escherichia coli. Both miRNAs promoted the growth of

these bacteria, which have been implicated in colorectal cancer

development. IEC-miRNA-deficient (Dicer1ΔIEC) mice

exhibited uncontrolled gut microbiota and exacerbated colitis,

while wild-type fecal miRNA transplantation restored fecal microbes

and ameliorated colitis. Oral administration of synthetic miRNA

mimics affected specific bacteria in the gut, suggesting that

miRNAs may be used therapeutically to manipulate the microbiome for

disease treatment (14).

Conversely, this communication pathway operates bidirectionally, as

gut microbiota profoundly influences host miRNA expression

profiles. Studies utilizing germ-free mice colonized with

microbiota from pathogen-free mice revealed differential expression

of miRNAs in both the ileum and colon following colonization, with

specific miRNAs involved in intestinal cell communication, signal

transduction, and inflammatory responses (8). In the colon, the upregulated Abcc3

gene was identified as a potential target of miR-665, establishing

a mechanistic link between microbiota colonization and

miRNA-mediated gene regulation. Additionally, germ-free mice

display abnormally expressed miRNAs in the amygdala and prefrontal

cortex, with miR-182-5p, miR-183-5p, and miR-206-3p identified as

targets of gut microbiota influence, suggesting the involvement of

the microbiota-gut-brain axis in miRNA regulation (21). The gut microbiota regulates host

miRNA expression primarily through microbial metabolites, including

lipopolysaccharide (LPS), butyrate, bacterial amyloids, bile acids,

and tryptophan-derived indole compounds. Bacterial components like

LPS and flagellin trigger miR-146a expression in intestinal

epithelial cells through TLR4/MyD88 signaling, establishing a

direct molecular link between gut microbiota sensing and epithelial

gene regulation. Once induced, miR-146a dampens cytokine production

and promotes immune tolerance, essentially acting as a brake that

prevents the epithelium from overreacting to constant microbial

exposure (22). Short-chain

fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate and propionate, can

effectively regulate host miRNA expression through their activity

as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, thereby exerting a

profound influence on epithelial barrier integrity and immune

response modulation. Butyrate has been shown to alter the

expression of 44 miRNAs in human colon cancer cells, including

significant downregulation of the miR-106b family, which normally

targets the tumor suppressor p21. By inhibiting HDAC-mediated

histone deacetylation, butyrate increases chromatin accessibility

at target gene promoters, thereby modulating miRNA expression

profiles involved in intestinal homeostasis and carcinogenesis

(23). Another paradigmatic

example of this intricate regulatory mechanism is butyrate and

propionate, which impair key B cell functions via an epigenetic

mechanism. This mechanism involves HDAC inhibition at specific

miRNA host genes, leading to upregulation of miRNAs targeting Aicda

and Prdm1 and thereby suppressing the expression of Aicda and Prdm1

(24). This SCFAs-mediated

regulation of B cell class-switch DNA recombination and plasma cell

differentiation through miRNA modulation represents an important

mechanism by which the microbiome influences systemic immunity.

Bile acids, metabolized by both host and gut microbiota, have

emerged as important regulators of miRNA expression. The

transcriptional activity of farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a key bile

acid sensor, is modulated by miRNAs including miR-34a and miR-22,

which silence SIRT1 expression and thereby reduce FXR

transcriptional activity. Notably, FXR exhibits negative

autoregulation by inducing the transcription of miR-22,

establishing a feedback loop between bile acid signaling and miRNA

expression (25,26). Importantly, the gut microbiota

has been shown to regulate white adipose tissue inflammation and

obesity via a family of tryptophan-derived metabolite-associated

miRNAs, and microbial regulation of hippocampal miRNA expression

has implications for transcription of kynurenine pathway enzymes

(27,28). These findings collectively

establish that miRNA-mediated communication between the host and

gut microbiota represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism with

far-reaching implications for intestinal homeostasis, immune

function, and disease pathogenesis. Understanding these intricate

interactions provides new avenues for therapeutic intervention in

microbiome-related disorders.

To extend the triadic regulatory network framework,

additional emerging models that transcend traditional single-target

approaches may be considered. These hypotheses remain preliminary

but offer insights into dynamic regulatory ecosystems contributing

to IBD pathogenesis.

IBD pathogenesis may involve not only static

alterations in miRNA levels but also dysregulation of their

temporal rhythms (29). Emerging

evidence suggests that synchronized oscillations of miRNA

expression, aligned with circadian or ultradian cycles and feeding

patterns, are essential for maintaining intestinal homeostasis

(30). Preliminary data suggest

that disruptions in miRNA temporal dynamics, rather than changes in

absolute abundance, may drive microbiome dysbiosis and inflammation

(31-33). According to this perspective, the

normally rhythmic dialogue between host and microbiota, mediated by

periodic miRNA release and corresponding microbial responses,

becomes desynchronized in IBD. Although direct in vivo

evidence remains limited, early observations, including altered

circadian miRNA expression patterns in experimental models, support

this concept (34). Further

investigation is needed to determine whether restoration of proper

miRNA oscillations can reinstate the host-microbiome

equilibrium.

Emerging evidence indicates that miRNAs of dietary

or exogenous origin may influence host-microbe interactions

(35). The Exogenous miRNA

Integration Hypothesis proposes that dietary miRNAs, particularly

plant-derived miRNAs consumed in food, become functionally

integrated into host regulatory networks, thereby creating hybrid

regulatory circuits that evolved to sense and respond to

nutritional inputs (36). The

demonstration that orally administered miRNAs can alter gut

microbiota composition and ameliorate experimental colitis in

murine models provides initial evidence for this cross-kingdom

regulatory effect (37). This

mechanism may explain how modern processed diets, which are

depleted of natural miRNAs, could contribute to microbiome

dysbiosis and IBD development. However, this hypothesis remains

controversial, as conflicting studies question whether the dietary

miRNA effects observed in experimental systems reflect genuine

physiological integration or methodological artifacts. The

stability and bioavailability of exogenous miRNAs in the human

gastrointestinal tract remain under investigation and preliminary

findings require confirmation through independent studies employing

standardized protocols (38).

Resolution of this controversy will necessitate robust evidence,

including the detection of bioactive dietary miRNAs in human

intestinal samples and demonstration of their causal relationship

with microbiome alterations. Currently, the exogenous miRNA

hypothesis represents a compelling extension of the triadic network

model, suggesting that environmental miRNAs may constitute an

additional regulatory layer, although rigorous validation remains

essential.

The human gut microbiota consists of dense, diverse

bacterial communities where dominant groups like

Bacteroidales coexist through complex competitive and

cooperative interactions, utilizing specialized systems to break

down dietary polysaccharides and produce metabolites that influence

host health. These microbial communities undergo dynamic shifts

throughout life, with intense competition during early colonization

shaping which strains establish long-term residency, while factors

like diet, spatial niches, and interbacterial warfare through

toxins and secretion systems continuously sculpt community

composition and stability in the adult gut (39). The gut microbiome serves

essential physiological functions, including maintenance of mucosal

homeostasis, competitive exclusion of pathogenic microorganisms and

preservation of epithelial barrier integrity through regulation of

intercellular junction proteins. These functions are critical for

preventing microbial dysbiosis associated with gastrointestinal

disorders such as IBD (40).

Despite the fundamental importance of gut microbiota regulation,

the precise mechanisms through which host cells control microbial

community composition remain incompletely understood. Evidence from

Rothschild et al (41)

indicates that only 1.9 to 8.1% of microbiota variation can be

attributed to heritable genetic factors, suggesting that

non-genetic influences, including dietary patterns and epigenetic

modifications mediated through miRNA pathways, play predominant

roles in determining gut microbiome diversity. Recent research has

demonstrated that host cells can fundamentally reshape intestinal

microbiota composition through miRNA-mediated regulatory

mechanisms. Host-derived miRNAs can directly influence bacterial

growth dynamics, thereby modifying the microbial landscape within

the gut ecosystem. Host-derived miR-21 demonstrates the ability to

bind to diverse gut microbes and enhance tryptophan synthesis

transcripts, which subsequently regulate intestinal functions,

including immune response modulation and epithelial permeability

(42). Research by Liu et

al (14) has provided

evidence that fecal miRNAs can directly regulate bacterial gene

expression and influence microbial growth patterns within the

intestinal environment. Their investigations revealed that

miR-515-5p and miR-1226-5p can enter bacterial cells, co-localize

with bacterial nucleic acids and promote proliferation of

CRC-associated bacterial species, including Fusobacterium

nucleatum and Escherichia coli, through direct

modulation of gene expression profiles. Supporting evidence for the

role of miRNAs in host-microbiota interactions comes from

experimental studies demonstrating that genetic ablation of Dicer,

an essential enzyme for miRNA biogenesis, in IECs results in

profound alterations in intestinal microbiota composition and

increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced

experimental colitis in murine models. Specific host-produced

miRNAs can exert suppressive effects on microbial growth. For

example, the absence of CRC-associated miR-21 in knockout mice led

to excessive proliferation of intestinal Lactobacillus

species, while direct administration of human miR-21 demonstrated

inhibitory effects on Lactobacillus reuteri growth in

vitro (43). These findings

collectively underscore the importance of miRNAs in mediating

host-microbiota interactions and their potential for influencing

gut microbiota composition and functional capacity.

In addition to the well-established role of dietary

habits in shaping intestinal microbial communities, accumulating

evidence demonstrates that food-derived miRNAs significantly

contribute to gut microbiome formation and regulation.

Ginger-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (GELN) containing

bioactive miRNAs effectively mitigate DSS-induced experimental

colitis in mice by modulating intestinal microbial composition. In

this context, miR-7267-3p functions as a selective modulator that

promotes beneficial bacterial taxa, including

Lactobacillaceae and Bacteroidales S24-7, while

suppressing potentially pathogenic Clostridiaceae. This

miRNA exerts its effects by targeting monooxygenase-encoding genes

in Lactobacillus rhamnosus, thereby promoting bacterial

proliferation and increasing intracellular indole-3-carboxaldehyde

(I3A) levels in GELN-treated mice. Elevated I3A levels stimulate

IL-22 production, consequently strengthening the colonic mucus

barrier and enhancing gut barrier function (44). Additional evidence demonstrates

that miR-30d alleviates murine experimental autoimmune

encephalomyelitis by modulating gut microbiome composition,

specifically through promoting Akkermansia muciniphila

growth and enhancing bacterial lactase expression (45) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, oral

administration of miR-142a-3p mitigates DSS-induced colitis by

enhancing Lactobacillus reuteri populations, a key genus for

maintaining gut homeostasis. The beneficial effects of miR-142a-3p

are abolished by concurrent antibiotic treatment, indicating that

its therapeutic action is mediated through microbiome modulation

rather than direct anti-inflammatory effects on host cells

(46). The demonstrated effects

of dietary miRNAs on gut microbiota challenge the prevailing

assumption that miRNA-mediated regulation is exclusively

endogenous. These observations suggest that dietary miRNAs may

integrate into host regulatory networks to form hybrid regulatory

systems capable of sensing and responding to environmental

nutritional signals (47). This

mechanism potentially explains the contribution of modern processed

diets, which lack natural miRNAs, to microbiome dysbiosis and IBD

pathogenesis. Nevertheless, controversies regarding cross-kingdom

miRNA stability and biological activity persist, as conflicting

evidence precludes definitive determination of whether observed

effects constitute authentic regulatory mechanisms or experimental

artifacts. For example, controlled feeding studies in mice and

humans found no significant uptake of plant miRNAs like miR-168a

from a rice-containing diet, despite earlier claims of its presence

(48). An early study reported

that rice-derived miR-168a survived digestion, entered the murine

circulation, and downregulated hepatic LDLRAP1 (49), thereby increasing serum LDL,

widely cited as emblematic evidence of cross-kingdom miRNA

activity. However, subsequent independent studies in mice and

humans largely failed to detect meaningful dietary uptake or

gene-regulatory effects of miR-168a, indicating that such

cross-kingdom transfer is not robust under routine conditions and

remains contentious (50).

Resolution of these uncertainties requires the development of

standardized experimental protocols and implementation of

independent validation studies.

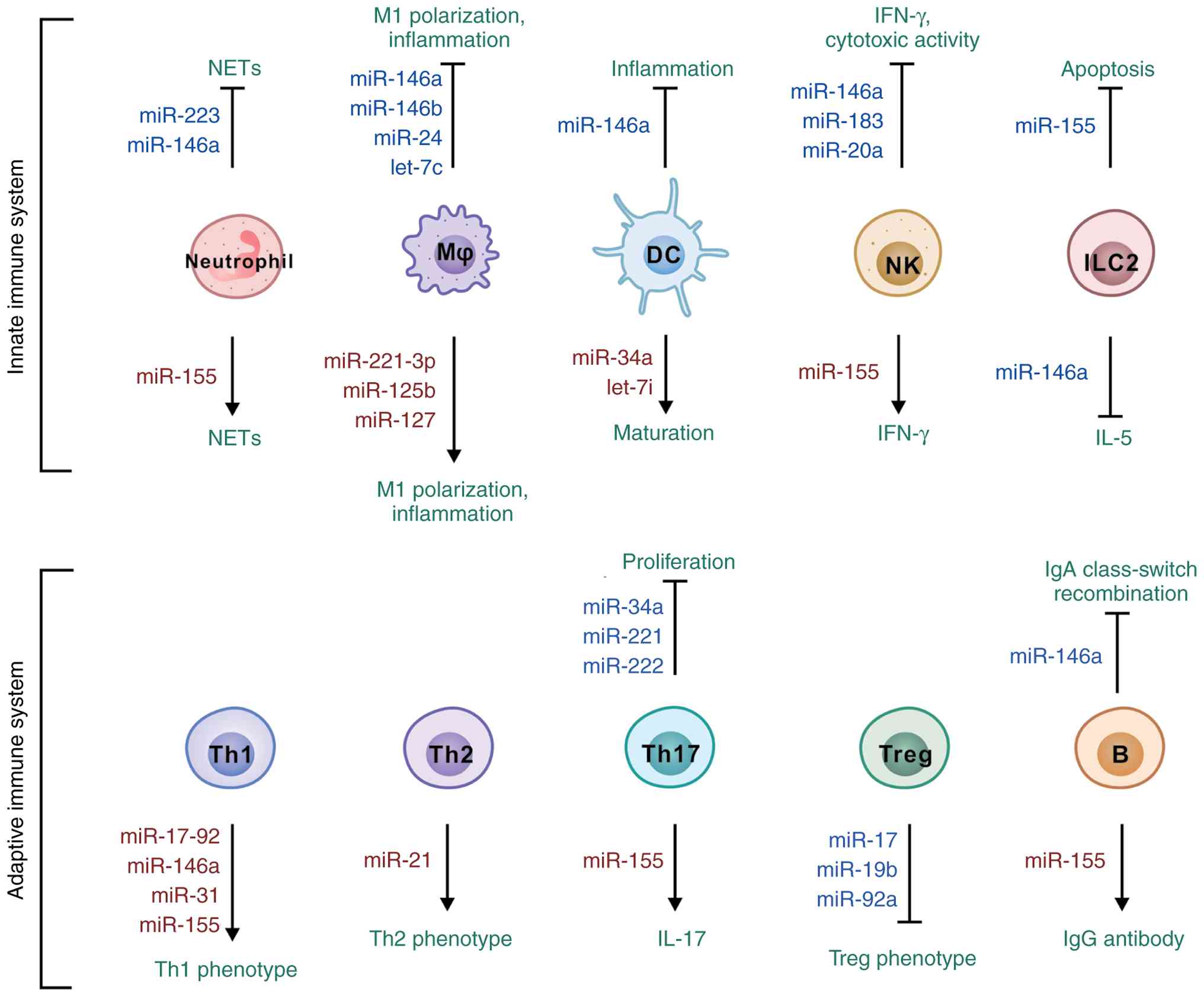

The innate immune system constitutes the primary

defense against pathogenic invasion, providing rapid,

broad-spectrum responses to diverse challenges while engaging in

bidirectional crosstalk with adaptive immunity. Innate immune

responses are regulated through intricate signaling networks, with

specific miRNAs functioning as molecular switches that govern

immune homeostasis. Mast cells and eosinophils represent critical

effector populations in innate immunity whose functional responses

are tightly regulated by specific miRNAs. miR-221/222 are markedly

upregulated following mast cell activation (51). These miRNAs modulate cell cycle

progression. Upon IgE-antigen stimulation, miR-221 enhances mast

cell adhesion, migration, degranulation, and cytokine production,

with these effects mediated through transcriptional remodeling of

cytoskeletal components and increased cortical actin accumulation

(52). In eosinophils, miR-223

plays a dual regulatory role governing both proliferation and

differentiation. miR-223 expression increases progressively during

eosinophilopoiesis, with targeted deletion resulting in

hyperproliferative eosinophil progenitors and delayed CCR3

expression (53). miR-223 has

emerged as a particularly significant biomarker for IBD and robust

evidence supports its potent anti-inflammatory properties through

multiple mechanisms (54). This

miRNA alleviates intestinal inflammation in murine models by

suppressing the NOD-like receptor (NLR) family pyrin domain

containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome (55). miR-223-deficient mice develop

more severe colitis with enhanced NLRP3 inflammasome activation,

whereas therapeutic administration of miR-223 mimics ameliorates

disease severity (55,56). Furthermore, miR-223 regulates

intestinal immune cell activity, as evidenced by the

pro-inflammatory phenotype of immune cells from miR-223-deficient

mice. Mechanistically, miR-223 directly targets CCAAT/enhancer

binding protein (C/EBP)β mRNA to suppress pro-inflammatory gene

expression in intestinal dendritic cell (DC)s and macrophages

(57). Moreover, miR-223 exerts

an anti-inflammatory effect by limiting calcium influx and

mitochondrial ROS production in neutrophils to suppress

IL-18-induced neutrophil extracellular trap (NET)s formation, while

its exosomal transfer further reduces IL-18 production in

macrophages, collectively restraining inflammatory amplification

(58). These findings highlight

the therapeutic potential of miR-223 in modulating intestinal

inflammation. By contrast, miR-155 functions as a pro-inflammatory

miRNA with a crucial role in mucosal immune homeostasis. miR-155 is

upregulated in IBD and drives intestinal inflammation by

suppressing SHIP-1, which unleashes AKT signaling and

pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Blocking miR-155 restores SHIP-1

levels and effectively dampens the inflammatory cascade in

experimental colitis (59).

Further research has revealed miR-155 enhances the survival of

activated innate lymphoid cell type 2 (ILC2) by preventing

apoptosis, thereby sustaining type-2 immune responses during

alarmin stimulation or helminth infection (60). miR-155 further promotes

IL-33-induced ILC2 proliferation (61) and maintains IFN-γ expression in

natural killer (NK) cells (62).

In neutrophils, miR-155 drives NET formation through upregulation

of peptidylarginine deiminase 4, whereas miR-223 exerts opposing

effects (63,64). In IBD murine models, activated

myeloid cells produce miR-155 through NF-κB-regulated pathways,

triggering pro-inflammatory responses during early phases of the

inflammatory cascade. Subsequently, miR-146a, an inducible

anti-inflammatory miRNA, is transcriptionally activated by NF-κB

following exposure to LPS, TNFα, or IL-1β. It then targets IL-1

receptor associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and TNF receptor associated

factor 6 (TRAF6) to dampen the very signaling cascade that

triggered its expression, forming a negative feedback loop that

fine-tunes innate immune responses (65). Delivering miR-146a via

extracellular vesicles effectively reduces colonic damage,

inflammatory cytokines, and disease severity in experimental

colitis models (66). Indeed,

miR-146a is widely recognized for its potent anti-inflammatory

effects within the innate immune system through multiple

mechanisms. miR-146a inhibits ILC2 proliferation and function,

resulting in reduced IL-5 secretion in murine models (67). Additionally, miR-146a reduces NET

formation processes associated with chronic inflammatory conditions

in experimental murine models (68). miR-146a decreases IFN-γ

expression in human NK cells (69) and reduces major

histocompatibility complex class II and pro-inflammatory cytokine

expression, including IL-6, in human and murine DCs and macrophages

(70). miR-146b plays a

particularly crucial role in regulating macrophage polarization

within the intestinal microenvironment (71). miR-146b is downregulated in

DSS-induced colitis and LPS-stimulated macrophages, exerting

inhibitory effects by suppressing fibrinogen-like 2 (FGL2), an

activator of p38-MAPK, NLRP3 and NF-κB-p65 signaling (72). Through FGL2 inhibition, miR-146b

reduces M1 macrophage polarization and inflammatory responses in

vitro and attenuates intestinal damage in IBD models in

vivo. Furthermore, IL-10 stimulation enhances miR-146b

expression in immune cells, whereas IL-10-deficient macrophages

exhibit reduced miR-146b levels. Mechanistically, miR-146b targets

interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) mRNA to suppress bacterial

toxin-induced IRF5 protein synthesis and pro-inflammatory

macrophage polarization. Current evidence indicates that regulation

of pro-inflammatory macrophage activity within intestinal tissues

is primarily governed by the IL-10-miR-146b-IRF5 regulatory axis

(71). miR-150 modulates NK cell

maturation via c-Myb targeting and PI3K-AKT pathway suppression

(69). miR-150-deficient mice

exhibit decreased TGF-β levels, resulting in impaired

intraepithelial lymphocyte production and differentiation (73). Distinct miRNA expression patterns

characterize M1- and M2-polarized macrophages in human and murine

systems. miR-155 drives macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory M1

phenotype during colitis by suppressing C/EBPβ and SOCS1, which

fuels intestinal inflammation and worsens IBD pathology. Knocking

out miR-155 shifts the balance toward anti-inflammatory M2

macrophages, dampening immune cell infiltration and protecting

against colitis (74).

miR-221-3p modulates inflammatory responses in TLR4-activated

M2-macrophages by targeting Janus kinase (JAK)3. Aberrant

miR-221-3p expression impairs anti-inflammatory responses and

promotes M2-to-M1 phenotypic transition (75). Similarly, miR-125b (76) and miR-127-3p (77) facilitate polarization toward the

M1 inflammatory phenotype. Conversely, let-7c has been shown to

promote polarization toward the M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype in

macrophages. let-7c overexpression decreases M1 markers (inducible

nitric oxide synthase, IL-12) while increasing M2 markers folate

receptor-β through C/EBPδ and p21-activated kinase 1 suppression

(78). Beyond these extensively

characterized miRNAs, numerous additional miRNAs have been

identified as important modulators of innate immune cell

maturation, specialization and proliferation. For instance, miR-183

have been demonstrated to suppress NK cell cytotoxicity by

targeting cell surface proteins (79). Additionally, miR-34a (80) and let-7i (81) have been identified as promoters

of DC activation and maturation in human and murine systems,

respectively. These findings demonstrate the diverse regulatory

roles of miRNAs in innate immunity under physiological and

pathological conditions.

The development and function of the intestinal

adaptive immune system are governed by intricate signaling networks

that play fundamental roles in the differentiation and maturation

of various adaptive immune cell populations, including T cells and

B cells (5). These critical

processes are extensively modulated by host miRNAs within the

intestinal microenvironment. Dysregulation of these regulatory

miRNAs can result in profound immune dysfunction and potentially

trigger autoimmune pathological processes (82). Notably, miRNAs demonstrate

remarkable versatility in their regulatory capacity, simultaneously

managing multiple facets of adaptive immune system function.

Previous research has established that CD is predominantly

associated with T helper (Th)1-mediated immune responses, whereas

UC is primarily driven by Th2-mediated inflammatory processes

(1). Intestinal miRNAs exert a

profound influence on CD4+ T-cell differentiation patterns in IBD

pathogenesis. miR-17~92 enhances Th1 phenotypic commitment through

IFN-γ upregulation (83).

miR-17~92-deficient T cells failed to provoke severe colitis when

transferred into Rag2−/− mice, showing markedly reduced

weight loss and colon inflammation compared to wild-type controls.

This impaired pathogenicity resulted from diminished Th17

differentiation and decreased IL-17A production by the knockout

cells (84). miR-155

overexpression enhances Th1 differentiation, whereas its knockdown

reduces CD4+ T-cell migration to colonic sites and promotes Th2

differentiation (85). And

miR-31 induces Th1-type inflammation by suppressing IL-25 in the

colon, thereby promoting IL-12/23-driven Th1/Th17 immune responses

in colitis (86). Furthermore,

it is worth noting that miR-146a can enhance Th1-mediated

inflammation by promoting Th1 differentiation through

post-transcriptional upregulation of the T-bet pathway and

increasing key pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in

atherosclerosis (87). miR-124

suppresses Th2 responses by shifting the Th1/Th2 balance toward Th1

through an IL-6R-dependent pathway (88). Conversely, miR-21 plays a crucial

role in modulating Th2 responses by negatively regulating

pro-inflammatory signals, thus contributing to the resolution of

inflammation (89). miR-21

promotes Th2 differentiation by increasing Gata3 expression and

decreasing Sprouty1 levels, acting as a key target of Bcl6 and

enhancing Th2 responses in both conventional and Treg cells

(90). miR-21-deficient mice

exhibit elevated Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, CXCL9) and reduced Th2

mediators (IL-4, CCL17) (91).

Similarly, miR-29 suppresses Th1 differentiation by targeting the

transcription factor T-bet (92,93). miRNAs sustain inflammatory

responses by reinforcing T-cell activation and maintaining their

pathogenic states. In psoriasis, miR-210 promotes Th17 and Th1

differentiation while blocking Th2 responses in CD4+ T cells

through direct targeting of STAT6 and LYN, shifting the immune

balance toward pathogenic inflammation (94). miR-24 displays distinct

regulatory patterns compared to other miRNAs. It facilitates Th1,

Th17, and iTreg differentiation while simultaneously suppressing

Th2 responses by targeting an unconventional site in IL-4 mRNA: one

nucleotide downstream of the stop codon, where the 3' end of miR-24

binds sequences that extend into the IL-4 coding region. This

contrasts sharply with its cluster partners miR-23 and miR-27,

which broadly inhibit multiple T cell lineages. miR-24 can

counteract their suppressive effects, likely by targeting Smad7, a

negative regulator of TGF-β signaling, which enhances the

differentiation of TGF-β-dependent T cell populations (95). In chronic inflammation, miR-148a

becomes upregulated in repeatedly activated Th1 cells and promotes

their survival by suppressing Bim, a pro-apoptotic protein.

Therapeutic blockade of miR-148a using antagomirs selectively

eliminates these pathogenic Th1 cells from inflamed tissues while

sparing protective memory T cells, offering a targeted approach for

treating chronic inflammatory diseases (96).

The development and function of Th17 cells serve as

crucial modulators in maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis and

these processes can be significantly influenced by local microbiota

and miRNAs (97). miR-155

promotes IL-17 production in Th17 cells (98) but does not enhance TGF-β and

IL-10 release in regulatory T cells (Tregs), despite being

regulated by the Treg-specific transcription factor Foxp3 (99). Targeted inhibition of miR-155

alleviates DSS-induced colitis by modulating Th17-mediated

inflammation (100).

Furthermore, intestinal miR-155 enhances DC cytokine production,

driving Th17 cell differentiation and immune responses associated

with autoimmune disorders (101). Conversely, miR-155 silencing

reduces Th17 cells and inflammatory cytokines to suppress mucosal

immunity and alleviate colitis (102). miR-34a suppresses Th17-mediated

inflammation by directly targeting IL-6R and IL-23R to limit Th17

differentiation and expansion while also blocking CCL22-dependent

Th17 recruitment to the colonic epithelium (103). miR-221 and miR-222 modulate

Th17 activity downstream of IL-23 signaling by targeting MAF and

IL-23R, thereby limiting Th17 expansion. Reduced expression of

either miRNA increases intestinal susceptibility in murine models,

consistent with IL-23 pathway suppression (104,105). miR-125a suppresses Th1/Th17

differentiation and cytokine production by targeting E26

transformation specific-1, transcription factor in CD4+ T cells.

Its downregulation in IBD mucosa and exacerbation of

trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in miR-125a-deficient

mice demonstrate its essential role in mucosal homeostasis

(106). Additionally, miR-146a

(107,108) and miR-106a (109) suppress Th17-cell

differentiation and cytokine secretion, particularly IL-17, in the

gastrointestinal tract. TNFα drives miR-106a expression in IBD,

which suppresses IL-10 production and impairs regulatory T cell

function. Genetic deletion of miR-106a attenuates intestinal

inflammation by restoring Treg suppressive capacity and reducing

pathogenic Th1 and Th17 responses (110).

Intestinal miRNAs also serve as critical regulators

of Treg differentiation and maturation. miR-10a, an miRNA highly

expressed in Tregs, is activated by TGF-β and vitamin A

derivatives. miR-10a suppresses mRNA expression of Ncor2 and Bcl6

in intestinal Peyer's patches, preventing inducible Treg conversion

to follicular helper T cells (Tfh). miR-10a also dampens DC

activation by directly targeting IL-12/IL-23p40 and NOD2, thereby

reducing the cytokine signals that drive inflammatory T cell

responses. It also directly suppresses Th1 and Th17 differentiation

in CD4+ T cells while leaving Th2 function intact, positioning it

as a key brake on intestinal inflammation (83,111). Paradoxically, CD4+ T cells from

miR-10a-deficient mice exhibit reduced susceptibility to

DSS-induced colitis, as miR-10a limits IL-10 production by

repressing Prdm1, the gene encoding Blimp1 (112). Beyond transcriptional control,

miR-10a constrains Treg suppressive capacity by targeting Uqcrq, a

component of mitochondrial complex III essential for oxidative

phosphorylation, as well as amphiregulin, a molecule critical for

epithelial repair. Treg-specific deletion of miR-10a enhances both

suppressive function and barrier protection, resulting in

attenuated colitis in experimental models (113). The miR-17~92 cluster of miRNAs,

known for its oncogenic activity, enhances T cell-dependent humoral

immunity by promoting Tfh development in germinal centers (114). Within this cluster, miR-17 and

miR-19b augment pro-inflammatory Th1 responses while impairing Treg

differentiation in murine models (115). Additionally, miR-92a promotes

Th17 differentiation and suppresses Treg development by inhibiting

Foxo1 (116). Beyond T cells,

intestinal B cells contribute to miRNA-mediated regulation in

adaptive immunity. B-cell miRNAs exhibit stage-specific expression,

enabling subset classification based on distinct expression

profiles (117). miR-150

controls pro-B to pre-B cell transition and its deficiency enhances

B1 cell-mediated immunity through c-Myb upregulation (118). miR-155 promotes pathogenic IgG

autoantibody production by lowering the activation threshold in B

cells, thereby enhancing their ERK signaling, proliferation, and

class-switch responses (119).

And miR-146a restrains IgA class-switch recombination by

suppressing Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 in B cells, thereby limiting IgA

production and preventing IgA-driven immunopathology (120) (Fig. 4). In brief, the emerging picture

of miRNA regulation in immune responses reveals that traditional

binary classifications of miRNAs as being pro- or anti-inflammatory

inadequately represent the dynamic nature of immune regulation.

Accumulating evidence indicates that miRNAs function as molecular

switches redirecting regulatory networks between functional states

rather than modulating individual pathways. This context-dependent

behavior explains the apparent contradictions in miRNA function

studies and suggests that therapeutic interventions should target

network states rather than individual miRNAs.

miRNAs exhibit distinctive tissue-specific

expression patterns and can be extracted from diverse biological

tissues, including pulmonary tissues, through advanced RNA

sequencing methodologies (121). These small regulatory molecules

participate in post-transcriptional gene regulation by binding with

sequence complementarity to mRNA molecules, thereby modulating

protein translation (122). The

primary regulatory mechanisms of miRNAs include suppression of

target mRNA translation and reduction of mRNA stability, which

collectively decrease the final protein output from specific mRNA

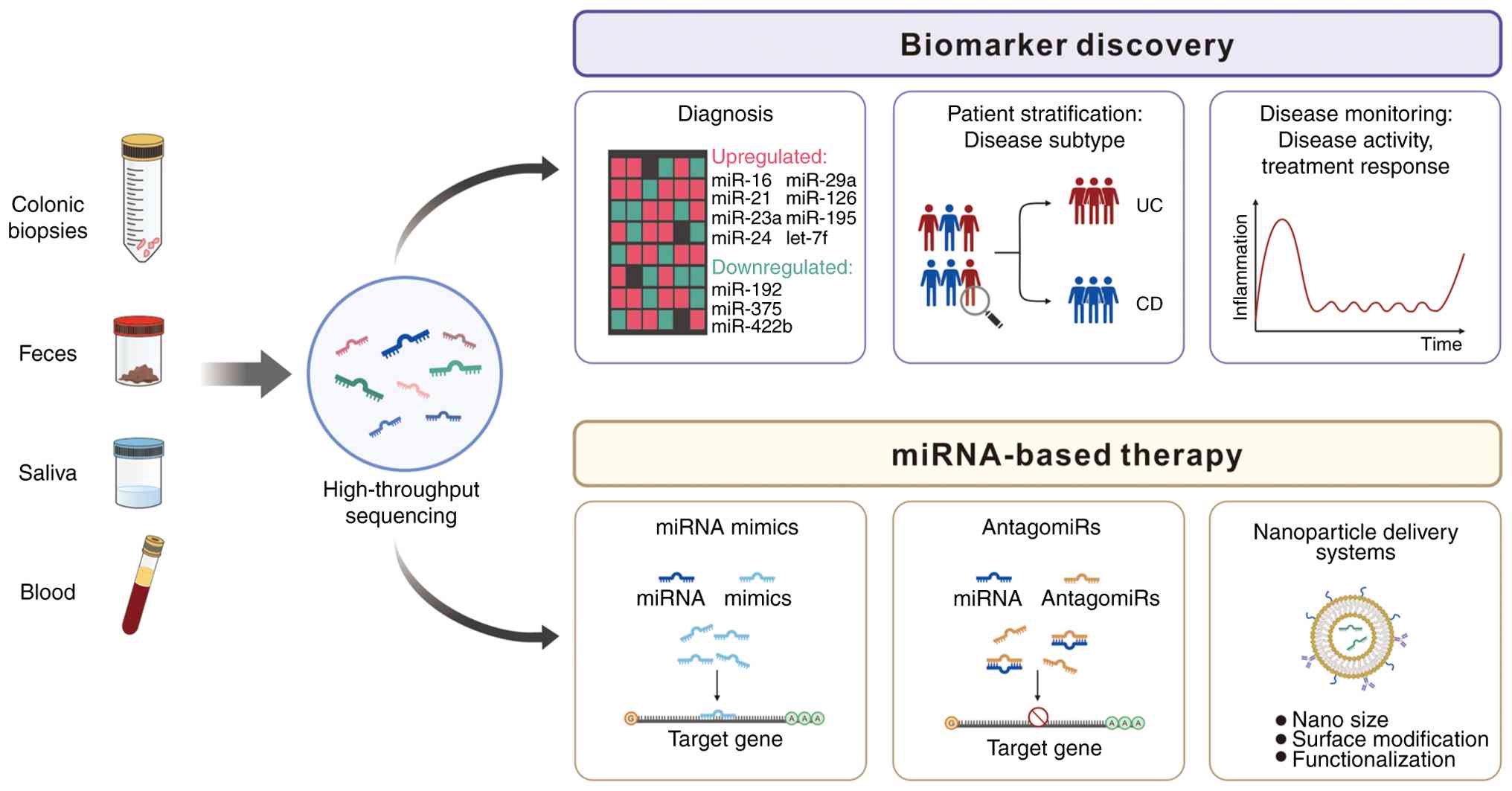

transcripts. With the revolutionary development of miRNA microarray

technologies and high-throughput RNA sequencing platforms, miRNAs

have been identified in stable forms not only within human

peripheral blood but also in various bodily fluids, including

saliva, urine and fecal samples (123,124). This inherent stability renders

miRNAs suitable as biomarkers for non-invasive liquid biopsy-based

diagnostic strategies, particularly for cancer detection and

monitoring (125).

A pioneering investigation of miRNA alterations in

patients with IBD identified 11 differentially expressed miRNAs in

patients with UC compared to healthy controls. miR-16, miR-21,

miR-29a and several other miRNAs exhibited elevated expression

levels, whereas miR-192, miR-375 and other miRNAs demonstrated

reduced expression in gut-related immune dysregulation (129,130). Subsequent studies have further

characterized the complex changes in miRNA expression profiles in

patients with IBD. miR-21 levels are elevated in UC compared to

both controls and CD, with expression localized to lamina propria

cells including macrophages and T cell subsets. miR-126 is

upregulated in UC and specifically expressed in endothelial cells,

likely reflecting increased vascularization in inflamed tissue

(131). It is worth noting that

miR-21 promotes colitis progression and drives abnormal

angiogenesis in CD by suppressing PTEN and activating the

PI3K/AKT/VEGF pathway. Blocking miR-21 with antagonists reduces

inflammation and restores normal vascular development in

experimental colitis models (132). And miR-155 levels spike in CD

patients who develop intestinal strictures, directly driving the

fibrotic process. It works by suppressing HBP1, which unleashes

Wnt/β-catenin signaling and triggers excessive collagen deposition

in the gut wall (133). Several

dysregulated miRNAs have emerged as potential biomarkers for

distinguishing between CD and UC in both colonic tissue biopsies

and non-invasive biological samples, including peripheral blood and

fecal specimens (134). The

persistent failure of miRNA biomarkers to achieve clinical

validation despite extensive research reveals fundamental

limitations in current conceptual frameworks. Accumulating evidence

suggests that static miRNA expression levels are insufficient for

disease diagnosis. Instead, IBD development appears to result from

altered temporal patterns and impaired regulatory responses to

environmental factors. This perspective explains why static

measurements fail in clinical validation and suggests that

diagnostic approaches must assess miRNA regulatory capacity rather

than absolute expression levels. Furthermore, the assumption that

specific miRNA profiles directly correlate with disease activity

overlooks confounding effects of medication (135), diet (136) and microbiome composition

(137), variables that may

contribute more variance to miRNA expression than disease pathology

itself (138).

Microbiome-derived nucleic acids are present in

detectable trace amounts in various human biological fluids,

including saliva, stool, peripheral blood and plasma, suggesting

their substantial potential as novel biomarkers for disease

diagnosis and monitoring (139-141). The gut microbiome's profound

influence on the host transcriptome represents an expanding area of

diagnostic research, with investigations focusing on

microbiota-derived miRNAs, although the molecular mechanisms

underlying these interactions remain elusive (138,142). Experimental evidence

demonstrates that the intestinal microbiota influences host miRNA

expression through multiple regulatory pathways. For instance,

specific pathogen-free-colonized mice exhibit altered miRNA

expression levels in ileal and colonic tissues compared to

germ-free controls (143). DNA

microarray and miRNA expression analysis, combined with

computational modeling, have identified that miRNA-665 suppresses

ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3, a gene involved in

endogenous toxin metabolism and cellular detoxification (144). Additionally, miR-107 was

downregulated by gut microbiota in immune cell populations,

including DCs and macrophages, affecting MyD88 and NF-κB signaling

pathways (145). Given that

miR-107 specifically targets the IL-23p19 gene, it is hypothesized

to modulate immune homeostasis and inflammatory balance. These

findings suggest that the intestinal microbiota possesses the

capacity to regulate host gene expression through sophisticated

alterations of the host's miRNA expression profile (145).

The gut microbiome's surveillance against pathogens

and tissue damage relies on pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)

that detect pathogen-associated and damage-associated molecular

patterns through two main families: membrane-bound TLRs and

cytosolic NLRs (146). TLRs

exhibit predominant or selective expression in specific cellular

lineages, including immune cells (lymphocytes, DCs, macrophages and

neutrophils) and non-immune cells (IECs and fibroblasts) (147). Upon ligand activation, TLRs and

NLRs engage adapter proteins to trigger signaling cascades through

NF-κB, IRFs, and MAPKs that regulate transcription of

pro-inflammatory molecules, growth factors, and cytokines (148), pathways frequently dysregulated

in IBD. The NLR family gene NOD2, mapped to chromosome 16q12.1,

represents the first identified genetic susceptibility locus for CD

and constitutes the first genetic determinant definitively

associated with adult-onset IBD. NOD2 is expressed in various

immune cell populations, including DCs, macrophages, monocytes and

specialized Paneth cells, and its discovery has underscored the

significance of PRR signaling pathways as potential therapeutic

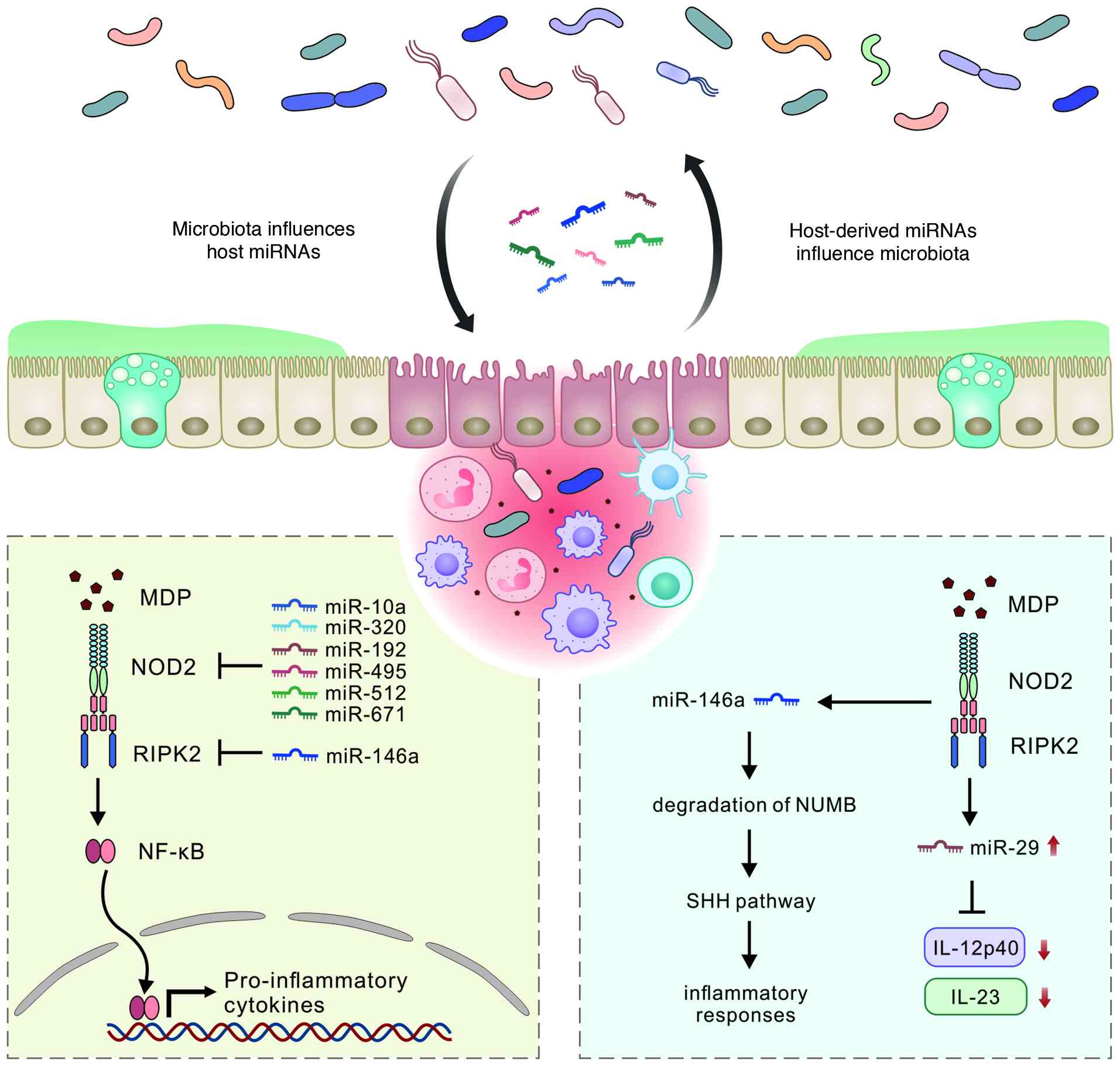

targets for IBD and related inflammatory conditions. miRNAs play

crucial regulatory roles in modulating PRR signaling pathways and

are increasingly considered as promising therapeutic targets for

IBD intervention. miRNAs modulate NOD2 expression, thereby

initiating complex cascades of inflammatory responses within

intestinal tissues. Research has demonstrated that miRNAs regulate

autophagy-related genes including NOD2, ATG16L1, and IRGM, which

converge on autophagy pathways critical for IBD pathogenesis.

Specifically, miR-30c and miR-130a are upregulated in enterocytes

upon NF-κB activation during AIEC infection, resulting in decreased

ATG5 and ATG16L1 levels, impaired autophagy, and increased

intracellular AIEC burden with escalated inflammatory responses

(5). miR-146a, a highly

conserved anti-inflammatory miRNA, restrains colitis by directly

targeting RIPK2 in myeloid cells, thereby weakening NOD2

inflammatory signaling and reducing production of IL-17 inducing

cytokines in the colon. When miR-146a is absent, RIPK2 driven

signaling becomes exaggerated, amplifies the IL-17 inflammatory

axis, and leads to more severe colonic inflammation (149). miR-146a functions in γδ-T cells

as a thymus imprinted brake that targets NOD1 and limits their

shift toward IFN-γ production and IL-17 plus IFN-γ multifunctional

states under inflammation (150). Furthermore, miR-146a regulates

multiple genetic networks in IBD, and its deficiency worsens

symptoms in a mouse model, while mimics alleviate the disease,

highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target (151). Additional miRNAs, including

miR-10a, miR-512, miR-320, miR-192, miR-495 and miR-671, directly

target NOD2 expression and suppress the release of inflammatory

cytokines. The expression of these regulatory miRNAs is

dysregulated in patients with IBD, highlighting their roles in

disease pathogenesis (126).

miR-122 exerts a protective effect against intestinal epithelial

injury by targeting and suppressing NOD2, thereby inhibiting NF-κB

activation and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine release.

Downregulation of miR-122 in CD patients likely contributes to

uncontrolled intestinal inflammation and disease progression

(152). Conversely, NOD2

signaling also regulates miRNA expression. NOD2 activation enhances

miR-29 expression in DCs, which subsequently regulates multiple

immune mediator pathways. NOD2 is essential for induction of the

entire miR-29 family (including miR-29a, miR-29b and miR-29c),

either independently or in conjunction with TLR2 or TLR5 signaling.

miR-29 overexpression reduces IL-12p40/IL-23 expression and

mitigates Th17 cells responses (153,154). NOD2 signaling enhances the

expression of miR-146a, which targets the NUMB gene to relieve its

suppression of Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling (Fig. 5). This cross-talk between NOD2,

miR-146a, and SHH signaling contributes to the amplification of

inflammatory responses in IBD (155). TLR4, an endotoxin recognition

receptor expressed on both immune cells and IECs, is

translationally suppressed by miRNA let-7i, whereas miR-21

indirectly modulates TLR4 signaling by targeting downstream

components of the MyD88/NF-κB pathway (20). The expression of TLR2, which

detects gram-positive bacterial components and is expressed

predominantly in immune cells and colonic epithelial cells

(40), is downregulated by

miR-195 in THP-1 macrophages polarized to the pro-inflammatory M1

phenotype, impacting immune responses and inflammatory signaling

pathways (156). miR-149,

recognized for its anti-inflammatory properties, is associated with

IBD pathogenesis. Its expression levels are reduced in the

peripheral blood of patients with CD. miR-149 mitigates TLR-induced

inflammation and cytokine production through targeted suppression

of the MyD88 signaling adapter and NF-κB pathway (157). Collectively, these

investigations highlight the roles of PRR signaling from IEC and

myeloid cell populations in mediating responses to intestinal

injuries or microbial infections. These findings also indicate the

therapeutic potential of targeting specific miRNAs in clinical

scenarios characterized by inadequate or dysregulated immune

responses, such as those observed in IBD pathogenesis. Beyond their

involvement in PRR signaling regulation, miRNAs are involved in

transcriptional modulation of cytokine expression following PRR

activation and in subsequent signal transduction cascades that

activate both innate and adaptive immune response systems. The

bidirectional regulatory relationships between miRNAs and PRR

signaling pathways reveal that IBD pathogenesis cannot be explained

by traditional linear inflammatory models. Accumulating evidence

suggests that IBD results from the failure of adaptive regulatory

networks to maintain homeostasis in the face of environmental

challenges, rather than from aberrant activation of individual

inflammatory pathways. This perspective explains why

anti-inflammatory therapeutics provide temporary symptom relief but

fail to achieve long-term remission: They suppress inflammatory

outputs without restoring regulatory network function. Furthermore,

the observation that identical genetic variants (e.g., NOD2

mutations) can result in different clinical phenotypes suggests

that therapeutic efficacy depends on the restoration of network

adaptability rather than the correction of specific molecular

defects (158,159).

miRNAs are being investigated for their potential

as non-invasive biomarkers for predicting disease progression and

monitoring therapeutic responses in patients with IBD. Patients

with active UC show distinct expression profiles of multiple miRNAs

compared to healthy controls, with miR-21-5p, miR-16-5p and

additional miRNAs showing elevated expression in the feces samples,

while miR-141 and other selected miRNAs exhibited reduced

expression in the biopsy samples, consistent with previous reports

(134,160). Fecal miRNA profiling has

demonstrated distinctly different composition in IBD patients, with

miR-16-5p showing significantly increased expression both in UC and

CD patients, while miR-21-5p elevation was specifically observed in

UC patients (161). Additional

studies have identified miR-223 and miR-1246 present at high levels

in the stool of subjects with active IBD (162). Comprehensive fecal miRNA

analysis in CD identified 17 significantly altered miRNAs including

upregulation of miR-16-5p, miR-142-5p, miR-223-3p, miR-15a-5p, and

miR-27a-3p, as well as downregulation of miR-10b-5p, miR-192-5p,

miR-10a-5p, miR-375, and miR-200a-3p (163). Consequently, several miRNAs

have emerged as diagnostic indicators for differentiating between

UC and CD in colonic tissue biopsies and non-invasive samples,

including peripheral blood, fecal specimens and saliva. A colon

biopsy-based study in patients with IBD identified a diagnostic

panel consisting of miR-19a, miR-21, miR-31, miR-146a and miR-375

as potential biomarkers for distinguishing between CD and UC

(164). Peck et al

(165), using NGS, demonstrated

that a combination of miR-31-5p, miR-215, miR-223-3p, miR-196b-5p

and miR-203 could categorize CD patients based on disease behavior,

independent of inflammatory status. miRNA expression profiling in

quiescent CD patients vs. healthy controls revealed site-specific

differences across intestinal segments. In healthy tissue, the

terminal ileum exhibited elevated expression of miR-31-5p compared

to sigmoid colon (166).

Additionally, nine miRNAs showed differential expression driven by

both disease status and anatomical location, targeting

immunoregulatory genes including NOD2 and IL6ST. These observations

support the hypothesis that miRNAs may modulate

inflammation-related gene expression through different mechanisms

in IBD subtypes and anatomical locations (167,168). Recent pediatric IBD studies

identified miR-29 as a distinguishing feature, with elevated ileal

miR-29 levels strongly predictive of severe inflammation and

stricturing behavior in treatment-naive pediatric CD patients

(169). Pediatric patients with

elevated miR-29 exhibited significantly lower Paneth cell counts,

increased inflammation scores, and reduced levels of PMP22,

indicating that miR-29 upregulation is associated with inflammation

and Paneth cell loss. Another study identified miR-223 as a serum

biomarker for IBD diagnosis, with elevated levels in patients with

IBD compared to healthy controls (168). This miRNA correlated positively

with disease activity measures in both patients with CD and UC, and

exhibited stronger correlations with disease activity parameters in

CD than conventional inflammatory markers such as the erythrocyte

sedimentation rate and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

(170). A serum miRNA signature

has been identified that not only indicates the development of

colitis but also discriminates between inflammations of various

origins, predicting UC with 83.3% accuracy (171). Recent innovations in biomarker

discovery have revealed that extracellular vesicle (EV)-associated

miRNAs can be dynamically modulated by diagnostic ultrasound, with

miR-942-5p showing strong induction in higher grade intestinal

inflammation and correlation with clinical activity in CD (172). Studies on extracellular

vesicle-derived miRNAs have demonstrated that miR-181b-5p and

miR-200b-3p play crucial roles in host-microbe interactions in

colitis, with miR-181b-5p transplantation inhibiting M1 macrophage

polarization and promoting M2 polarization to reduce inflammation

(173).

Beyond their utility in monitoring disease activity

in clinical practice, miRNAs also demonstrate potential as

predictors of therapeutic response to various treatment modalities.

In a study of patients with severe UC, Morilla et al

(174) identified 15 miRNAs

associated with responsiveness to corticosteroid therapy in

patients with refractory disease, indicating the potential of

miRNAs as predictive biomarkers for treatment response in IBD

management. A validation study identified five candidate serum

miRNAs (miR-126, let-7c, miR-146a, miR-146b, and miR-320a)

associated with clinical response and mucosal inflammation in

pediatric IBD patients, demonstrating their potential as

pharmacodynamic and response monitoring biomarkers (175). In a study involving pediatric

patients with IBD (including 17 cases of CD and 2 cases of UC)

treated with either prednisone or infliximab therapy, the

expression levels of miR-146a, miR-320a and miR-146b decreased with

both therapeutic interventions, correlating with reduced

inflammatory responses. By contrast, miR-486 responded to

prednisone treatment but showed no response to infliximab therapy,

illustrating the diversity in miRNA responses to different

therapeutic modalities (160).

Serum levels of miR-146a, miR-146b, miR-320a, miR-126, and let-7c

change when pediatric IBD patients respond to anti-TNF-α or

glucocorticoid therapy. These same miRNAs run high in inflamed gut

tissue, making them promising candidates for tracking disease

activity without repeated colonoscopies (175). It is noteworthy that miRNA

biomarkers haven't reached clinical use so far because we've been

approaching the problem wrong. Diseases like IBD emerge from

dysfunctional regulatory networks, yet we keep measuring static

molecular snapshots. This is why biomarker studies repeatedly fail

validation. The solution is to test how these networks respond to

standardized challenges like dietary shifts or controlled immune

stimulation, similar to how glucose tolerance tests assess diabetes

by measuring functional capacity rather than resting blood sugar.

While miRNA expression profiles show real potential for

distinguishing UC from CD and predicting treatment response, the

field needs to identify IBD-specific signatures and evaluate their

therapeutic value. But the critical shift must be from static

measurements to dynamic assessments that capture the temporal

complexity and network dysfunction underlying IBD pathogenesis.

miRNAs are emerging as therapeutic agents due to

their ability to regulate multiple gene targets within biological

networks (19). Several miRNAs,

including miR-29 and miR-126, show therapeutic potential in IBD

treatment by modulating inflammatory pathways that share

mechanistic similarities with approved biological drugs. miR-29

suppresses IL-23 production (153) while miR-126 inhibits leukocyte

adhesion through vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 regulation

(176). Additionally, miR-155

antagomirs suppress proteins within the JAK signaling cascade

(177), resembling the

therapeutic effects of JAK inhibitors currently employed in UC

treatment. Two principal strategies have emerged for therapeutic

miRNA intervention: i) Inhibiting upregulated pathogenic miRNAs

using antagomirs; and ii) replacing downregulated beneficial miRNAs

with synthetic mimics. Both strategies have demonstrated

encouraging outcomes in preclinical IBD animal models and in

vitro cellular systems, although clinical evidence from human

studies remains limited.

miR-155 represents a particularly promising

therapeutic target in IBD treatment, as its expression is

significantly elevated in inflamed IBD mucosal tissues. Targeted

inhibition of miR-155 shows substantial promise as an

anti-inflammatory strategy by blocking the miR-155/NF-κB signaling

axis, thereby suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and

modulating aberrant Th17-cell maturation (178). Similarly, TNF-α-driven miR-122a

upregulation in intestinal epithelium promotes occludin mRNA

degradation and barrier dysfunction in IBD. Anti-sense

oligonucleotide-mediated miR-122a suppression prevents this

pathogenic cascade, maintaining occludin expression and barrier

integrity in both in vitro and in vivo models

(179). Rawat et al

(180,181) demonstrated that miR-200c-3p

expression increases rapidly in intestinal epithelial cells during

inflammation, where IL-1β triggers its upregulation and subsequent

degradation of occludin mRNA through direct binding to the 3'UTR

region. This process disrupts tight junction integrity and elevates

intestinal permeability in both ulcerative colitis patients and

experimental colitis models. Blocking miR-200c-3p with antagomirs

restores occludin expression and prevents colitis progression,

suggesting this microRNA represents a promising therapeutic target

for preserving the intestinal barrier in IBD (180,181). Furthermore, targeted inhibition

of specific miRNAs could serve as innovative therapeutic approaches

for restoring compromised intestinal epithelial barrier function in

IBD (182). The role of

miR-146a in IBD presents a complex regulatory paradigm that

requires careful consideration. This miRNA is upregulated in

inflamed intestinal regions of patients with UC (183). However, conflicting data exist

regarding the precise roles of miR-146a/b in intestinal

inflammation. Certain studies suggest a pro-inflammatory role for

miR-146a (184), while others

demonstrate a regulatory role for miR-146b in facilitating

macrophage transition from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory

M2 polarization (185). This

contradictory evidence highlights the need for comprehensive

research to clarify miR-146 family member functions within the

intestinal microenvironment and optimize the balance between their

anti-inflammatory roles and mucosal barrier function regulation for

potential IBD therapeutic applications (178).

Intestinal fibrosis in IBD results from

fundamentally dysregulated tissue repair processes that lead to

excessive extracellular matrix deposition and pathological tissue

remodeling (186). This

complication affects approximately half of patients with CD and

frequently causes intestinal strictures requiring surgical

intervention. It is now recognized as a self-perpetuating

pathological process that persists independently of ongoing

inflammation (186). From a

clinical perspective, precise biomarkers for fibrosis detection and

effective antifibrotic therapies remain critically absent. Emerging

evidence has begun to elucidate the roles of miRNAs in fibrotic

processes across various organ systems, including the

gastrointestinal tract (187).

Although the involvement of miRNAs in IBD-related inflammation has

been increasingly well-characterized, their specific contributions

to intestinal fibrosis remain incompletely understood.

Nevertheless, miRNAs have demonstrated substantial potential as

both profibrotic and antifibrotic regulatory molecules,

representing promising targets for the diagnosis, prevention and

treatment of pathological fibrogenesis (178). miR-155-5p is particularly

implicated in IBD-associated fibrogenesis, especially in CD, where

its expression correlates inversely with E-cadherin levels and

significantly contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT). This miRNA is more abundant in CD tissues with fibrotic

strictures. Through targeted inhibition of HMG-box transcription

factor 1 (HBP1), it activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway,

thereby increasing the expression of fibrosis-associated markers.

In murine models, miR-155 mimics effectively induce fibrotic

changes, whereas specific inhibitors significantly attenuate

fibrosis development, establishing miR-155 as a promising

therapeutic target for IBD-associated fibrosis (188). Conversely, in vitro

studies demonstrate that miR-200b effectively ameliorate

TGF-β1-induced intestinal fibrosis through targeted suppression of

zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) and ZEB2 transcription

factors. Therapeutic delivery of miR-200b-containing microvesicles

(miR-200b-MVs) significantly alleviates intestinal fibrosis by

inhibiting pathological EMT (189). Similarly, miR-29b functions

through direct downregulation of collagen synthesis pathways while

simultaneously upregulating MCL-1 expression, which subsequently

inhibits intestinal fibrosis development (190). Additionally, miR-130a-3p mimics

effectively reverse the pathological effects of hsa_circRNA_102610,

suggesting that exogenous miR-130a-3p may inhibit profibrogenic

signaling through targeted suppression of hsa_circRNA_102610

(191). However, substantially

more research is required to comprehensively elucidate

profibrogenic miRNA networks and develop effective anti-miRNA

therapeutic strategies for IBD-associated fibrosis.

The consistent inability to translate promising

preclinical miRNA therapeutics into clinical applications indicates

a fundamental misunderstanding of therapeutic targeting strategies

in complex diseases. Accumulating evidence suggests that

therapeutic interventions targeting individual miRNAs invariably

induce compensatory network reorganization that not only negates

therapeutic benefits but may also generate novel pathological

states. This phenomenon provides an explanation for the systematic

failure of single-target miRNA therapeutics in clinical

translation, despite encouraging preclinical outcomes. Rather than

targeting individual miRNAs, therapeutic strategies should

prioritize the restoration of network adaptability through

coordinated modulation of multiple regulatory nodes while

maintaining the system's homeostatic capacity. Furthermore, the

observation that identical miRNA perturbations can elicit opposing

effects in different cellular contexts indicates that therapeutic

efficacy depends on restoring context-specific responsiveness

rather than achieving predetermined molecular endpoints.

The development of sophisticated miRNA-based

diagnostic tools for IBD possesses substantial potential to improve

the accuracy and efficiency of disease diagnosis and monitoring.

miR-21 has emerged as a promising diagnostic biomarker for

differentiating UC from CD. Both RT-qPCR and quantitative in

situ hybridization (qISH) consistently demonstrate

significantly elevated miR-21 expression in UC compared to CD

tissue samples. These findings indicate that miR-21 functions not

merely as a nonspecific inflammatory marker but is specifically

associated with the distinct immunopathological processes

underlying UC pathogenesis.

Detailed qISH analysis has revealed complex spatial

distribution patterns of miR-21 expression, with predominant

localization in inflamed lamina propria cell populations and

specific epithelial cell subsets within architecturally compromised

crypts, suggesting a multifaceted role for miR-21 in UC

pathophysiology (192). This

spatial heterogeneity reveals a fundamental limitation in current

diagnostic approaches: The assumption that homogenized tissue

measurements or systemic biomarker levels can accurately represent

the spatially organized pathological processes characterizing IBD.

Additionally, specific miRNAs, including miR-144, miR-519 and

miR-211 have been recognized as significant modulators of gut

microbiota composition and potential diagnostic indicators for CD,

as demonstrated through comprehensive studies in adult patients

(193). However, utilizing

microbiome-modulating miRNAs as diagnostic tools presents a

conceptual paradox: If these miRNAs actively shape the microbial

environment influencing disease pathogenesis, their stability and

reliability as diagnostic indicators remain questionable.

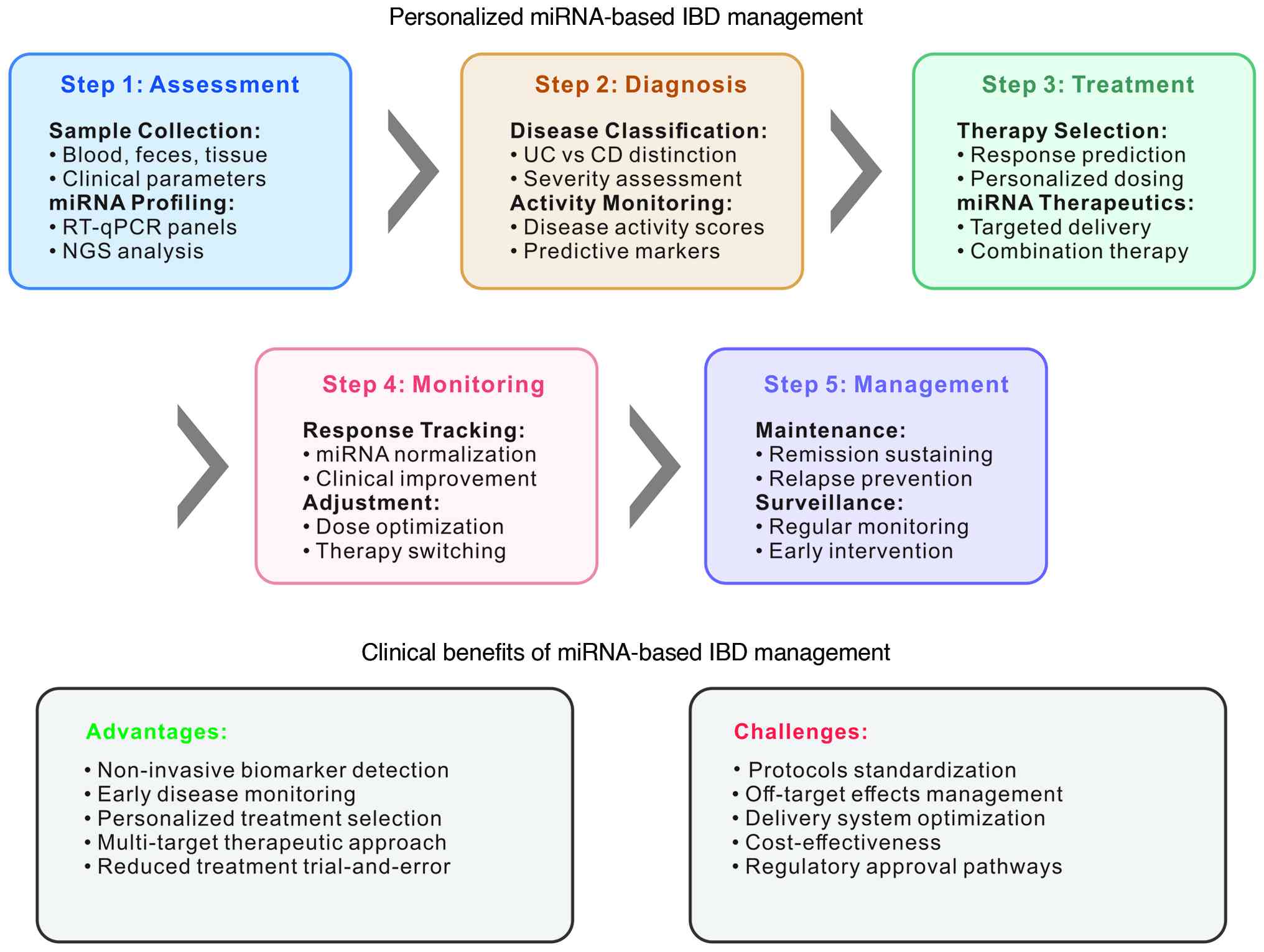

The integration of advanced bioinformatics

approaches with high-throughput sequencing technologies has

facilitated the development of sophisticated miRNA signature

panels, offering enhanced diagnostic accuracy compared to

individual miRNA biomarkers. These multi-miRNA panels demonstrate

improved sensitivity and specificity for IBD subtype

differentiation while providing prognostic information regarding

disease severity and therapeutic response potential. Machine

learning approaches, particularly penalized support vector machines

and random forest algorithms, have been successfully applied to

analyze peripheral blood miRNA signatures, achieving classification

accuracy of 97% for distinguishing CD from UC using a sparse model

of 16 distinct miRNAs (194).

Neural network analysis combining data from 9 miRNA candidates with

five clinical factors achieved 93% accuracy in discriminating

responders to steroids from non-responders in acute severe UC

(174). The growing use of

advanced computational methods to combine multi-omics information

such as microbiome, genomics, and metabolomics is paving the way

for precision medicine in IBD, enabling more accurate prediction of

treatment responses and the discovery of meaningful biomarkers.

However, the increasing complexity of these panels paradoxically

reduces their clinical utility by creating systems that exceed the

practical requirements for routine clinical implementation and

complicate biological interpretation. The persistent discrepancy

between diagnostic potential and clinical implementation reveals a

fundamental misalignment between technological capabilities and

clinical requirements. Effective IBD diagnostics should focus on

assessing regulatory network function rather than static molecular

signatures. Instead of measuring absolute miRNA levels, diagnostic

tools should evaluate the dynamic responsiveness of miRNA

regulatory networks to standardized physiological challenges,

thereby providing functional assessments of regulatory capacity.

This approach would help differentiate patients with intact

regulatory networks, who may respond favorably to targeted

interventions, from those with compromised network function and

requiring more comprehensive therapeutic strategies. Furthermore,

diagnostic tools must incorporate temporal measurements to capture

disease progression patterns and therapeutic response dynamics,

accounting for the inherently dynamic nature of IBD pathogenesis

(Fig. 6).

Targeting miRNAs for IBD therapeutic applications

represents a promising yet challenging approach requiring

consideration of multiple complex factors. Synthetic miRNA mimics

designed to replicate beneficial endogenous miRNAs and specific

antagomiRs engineered to suppress pro-inflammatory miRNAs may offer

innovative therapeutic strategies without significantly increasing

treatment-related toxicity. However, off-target gene repression

mediated by miRNA-based molecules, resulting from partial sequence

complementarity with non-target mRNAs, can potentially cause

unintended clinical toxicity (195). The specific biological effects

of individual miRNAs and particular microbiota species on

inflammatory processes and carcinogenesis remain incompletely

characterized and require further investigation before clinical

translation (196).

Additionally, the dynamic nature of the microbiota composition and

the long-term consequences of microbiota modulation on miRNA

expression profiles warrant careful consideration in therapeutic

development (197). Critical

translational challenges include developing efficient, targeted

delivery systems capable of ensuring tissue-specific miRNA delivery

while minimizing systemic exposure and adverse effects (198). The stability of therapeutic

miRNAs in biological fluids and their bioavailability at target