Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) persists as a foremost

contributor to global morbidity and mortality, posing a pervasive

disease burden that critically undermines population health metrics

(1). Atherosclerosis (AS),

serving as the pathological foundation and primary etiology of CVD,

manifests as a chronic vascular disorder characterized by

lipid-laden arterial wall deposition coupled with persistent

oxidative stress and inflammatory responses (2,3).

The pathogenesis of AS involves multiple processes: endothelial

dysfunction, lipoprotein retention, macrophage activation,

inflammatory cytokine release, oxidized low density lipoprotein

(ox-LDL)-driven foam cell formation and vascular smooth muscle cell

migration. Oxidative stress plays a central role by impairing

endothelial function, promoting ox-LDL accumulation, and enhancing

foam cell formation, collectively accelerating plaque development

(4). These molecular

interactions synergistically drive plaque instability through

matrix metalloproteinase activation and fibrous cap attenuation.

Preserving redox balance therefore represents a critical

therapeutic strategy for decelerating atherogenesis and sustaining

vascular homeostasis.

Under pathophysiological stress, the excessive

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that surpasses the

endogenous antioxidant capacity perturbs redox homeostasis, thereby

inducing oxidative modifications to cellular nucleic acids,

proteins, and lipids, which culminate in multi-level tissue damage

(5). Substantial evidence

identifies vascular endothelial dysfunction as the seminal event in

atherosclerotic pathogenesis (6). Under physiological conditions, the

vascular endothelium sustains homeostatic balance via orchestrated

regulation of vasomotor tone, thrombotic homeostasis, and selective

permeability. During atherosclerotic initiation, ROS-driven

oxidative stress disrupts this equilibrium, manifesting as: i)

Structural barrier compromise, ii) loss of thromboresistant

capacity, and iii) transition to pro-inflammatory phenotype

(7). This pathognomonic triad

perpetuates a vicious cycle of endothelial activation,

subendothelial lipoprotein retention, and vascular remodeling that

drives atherosclerotic plaque progression.

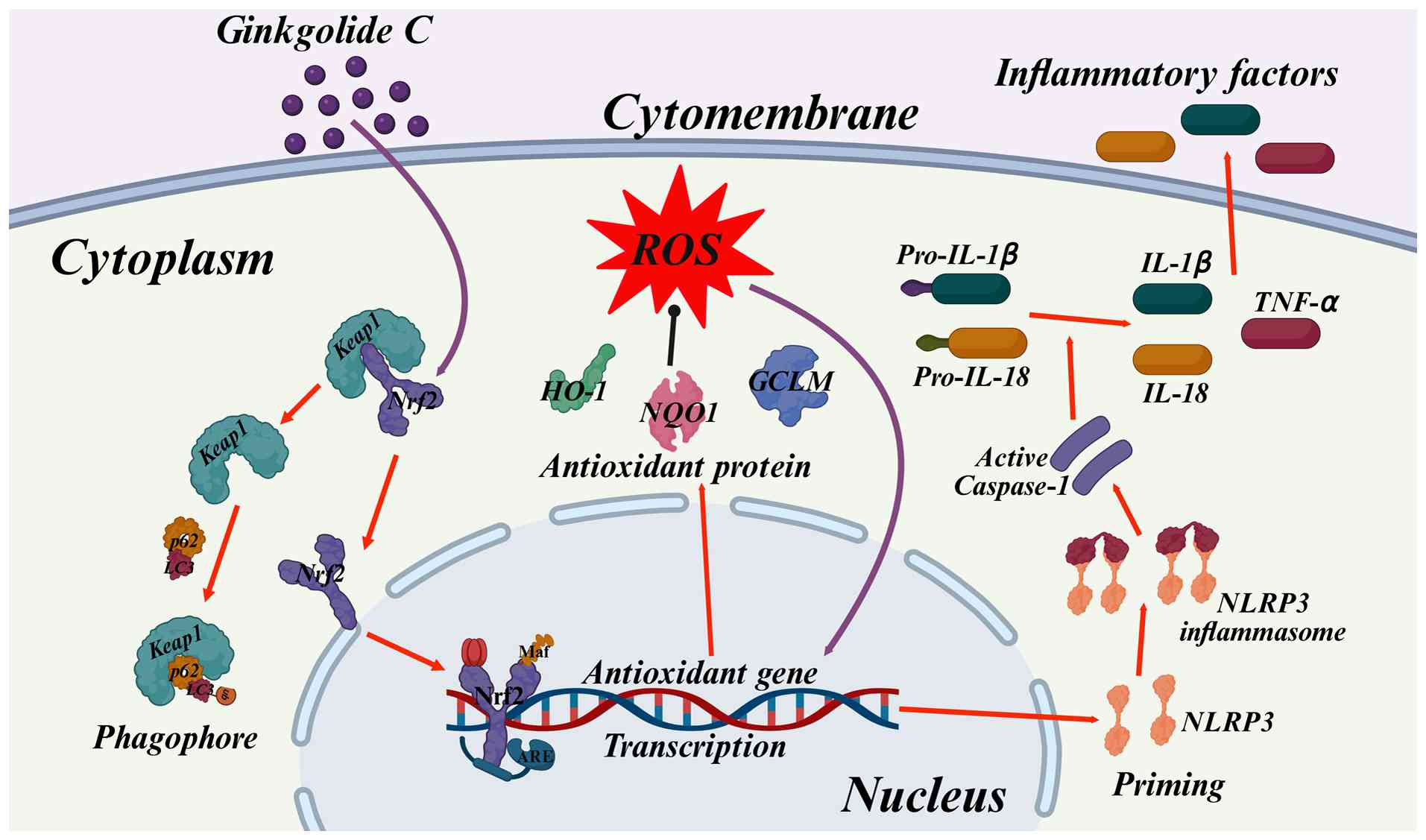

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2),

the key transcriptional regulator of cellular redox balance,

coordinates intrinsic antioxidant mechanisms to neutralize

ROS-driven oxidative damage (8).

Vascular endothelium employs tonic Nrf2 signaling to mediate

oxidation-sensitive activation, orchestrating cytoprotective

transcriptional programs through redox-responsive gene networks.

Nrf2 deficiency dysregulates adaptive redox homeostasis, amplifying

free radical flux and compromising reparative angiogenesis via

blunted endothelial tip cell specification and dysfunctional

angiocrine signaling (9). Under

redox homeostasis, Keap1 orchestrates Nrf2 cytoplasmic retention by

directing constitutive ubiquitination-proteasome turnover, thereby

enforcing Nrf2 transcriptional dormancy. Electrophilic stress

initiates redox-gated conformational switches within the Keap1-Nrf2

axis via cysteine sensor modification, uncoupling ubiquitin ligase

activity while liberating Nrf2 for nuclear import. Nrf2 forms

heterodimers with small Maf proteins in the nucleus, activating the

expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone

oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) and glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier

subunit (GCLM) through binding to antioxidant response elements

(ARE) (10,11). This regulated genetic response

orchestrates a reduction in ROS production, a bolstering of free

radical scavenging capacity, and a stabilization of the

intracellular redox state, thereby attenuating oxidative tissue

damage.

The Nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome

serves as a molecular signaling nexus that integrates

stress-activated pathways with inflammatory cascades, functionally

linking canonical pyroptosis to atherosclerotic pathogenesis

through regulated secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (12). Excessive ROS act as potent

activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering its

oligomerization through protein-protein interactions to form the

NLRP3-ASC-pro-cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase (Caspase-1)

supramolecular complex (13).

Activated Caspase-1 subsequently cleaves pro-Interleukin-1β (IL-1β)

and pro-Interleukin-18 (IL-18) into their biologically active

forms, driving the secretion of these inflammatory mediators while

simultaneously inducing cellular osmotic imbalance through

gasdermin-D-mediated membrane pore formation (14). This dual mechanism mediates the

execution of distinctive pyroptotic events-cellular swelling,

plasma membrane rupture, and release of cytoplasmic contents-the

dissemination of which, as damage-associated molecular patterns,

thereby potentiates inflammatory responses. The cyclical interplay

between ROS overproduction, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and

persistent inflammation establishes a self-perpetuating vicious

cycle that exacerbates vascular endothelial dysfunction and plaque

instability in AS (15).

Therapeutic strategies targeting ROS-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome

activation demonstrate significant potential to disrupt this

deleterious cycle, thereby attenuating inflammatory burden and

ameliorating atherosclerotic progression.

Ginkgo biloba L. (Ginkgoaceae; MPNS-verified)

a unique tree species native to China, is valued for its

neuroprotective properties in addressing cardio-cerebrovascular

diseases and neurological disorders (16). Contemporary pharmacological

research has elucidated the multifaceted pharmacodynamics of foliar

extracts, demonstrating their capacity to confer dose-dependent

cardioprotection, modulate neurovascular homeostasis, and suppress

neoplastic proliferation (17).

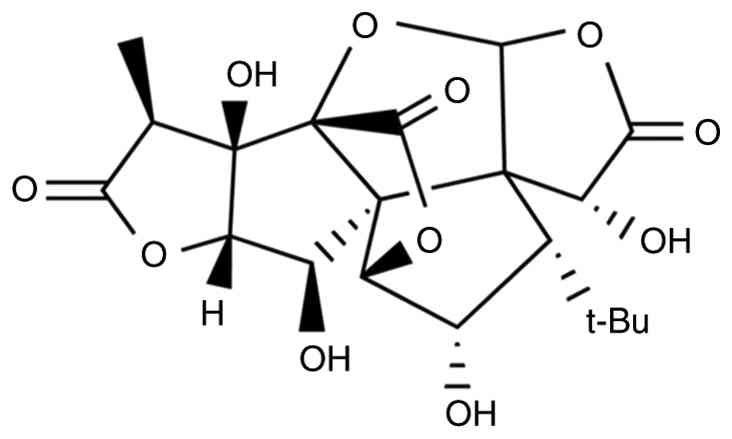

Of particular scientific interest is ginkgolide C (GC) (Fig. 1), a unique terpenoid trilactone

isolated from Ginkgo biloba leaves characterized by its

distinctive pentacyclic structure. Previous studies have

characterized GC as a pleiotropic therapeutic agent, demonstrating

potent anti-inflammatory efficacy and the capacity to confer

multi-organ protection in experimental models of cardiac and

cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury (18,19). Atherosclerotic progression is

increasingly recognized as a critical pathogenic link between

ischemic events and cerebral/cardiovascular comorbidities, driven

by interconnected pathways of endothelial dysfunction and amplified

oxidative stress (20). However,

the potential of GC to mitigate atherosclerotic lesions through

suppression of ROS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and

subsequent attenuation of inflammatory cascades remains

experimentally unestablished.

The present study aimed to elucidate the

anti-atherosclerotic mechanisms of GC through a combined

experimental approach both in vivo and in vitro,

focusing specifically on its dual-pathway regulatory activity. The

experimental findings demonstrated that GC ameliorates

atherosclerotic pathology through endothelial Nrf2 pathway

activation, which coordinates upregulation of antioxidant defense

proteins, suppression of ROS generation and sequential inhibition

of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly, ultimately attenuating

pro-inflammatory cytokine production and inflammatory cascade

propagation.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

GC (PubChem CID: 161120) and Atorvastatin (AVT;

PubChem CID: 60823) were commercially acquired from

MilliporeSigma-Aldrich. Anti-NLRP3 (cat. no. 15101S) was obtained

from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Anti-Nrf2 (cat. no.

16396-1-AP) was obtained from Proteintech Group, Inc. Anti-HO-1

(cat. no. PAA584Hu01), anti-NOQ1 (cat. no. PAL969Hu01), anti-GCLM

(cat. no. PAB038Hu01), anti-Caspase-1 (cat. no. PAB592Hu01),

anti-β-actin (cat. no. PAB340Mi01) and anti-histone (cat. no.

PAS091Ge01) antibodies were obtained from Cloud-Clone Corp. The

following analytical-grade materials were commercially sourced from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology: BCA protein quantification

kits (cat. no. P0010S), PVDF western blot membranes (cat. no.

FFP28), SDS-PAGE electrophoresis systems (cat. no. PG012) and ECL

Plus chemiluminescence substrates (cat. no. P0018M).

Randomization and blinding

procedures

Randomization was applied to animal/cell grouping,

and blinding was strictly maintained during data collection and

analysis to minimize potential bias and ensure experimental

objectivity.

Animal experiments

A total of 6 4-6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice weighing

14-16 g and 30 Apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) male

mice weighing 14-16 g were obtained from Huazhong Agricultural

University and Guangdong Yaokang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.,

respectively. All animals were maintained under standardized

laboratory conditions. Ambient temperature was regulated at

20-25°C, relative humidity was stabilized at 40-60%, and a 12-h

photocycle was enforced. A certified rodent diet and water were

provided ad libitum. All experimental procedures strictly

adhered to the Ethics Committee of the Shandong Provincial Hospital

Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (approval no.

2022-661; Jinan, China).

Mice were randomized into 6 groups (n=6/group):

control group, AS model group, 2.5 mg/kg AVT group, and 12, 24, 48

mg/kg GC groups. ApoE−/− mice used for AS modeling, AVT

and GC treatment underwent disease induction through three

sequential interventions: Initial preconditioning via a single

cholecalciferol injection (300,000 IU/kg in 0.2 ml saline),

followed by 16 weeks of high-fat/high-cholesterol diet (40% of

calories from fat), and culminating in a final intraperitoneal

administration of vitamin D3 (100,000 IU/kg). Control

mice were maintained on standard chow and purified water under

controlled environmental conditions (22±1°C, 55±5% humidity, 12-h

light cycle) throughout the study. After confirming successful AS

development, daily tail vein injections of AVT or GC were

administered continuously for 7 days to the AVT or GC groups. At

the end of the experiment, euthanasia was performed by an

intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of sodium pentobarbital

(150 mg/kg). Death was confirmed by the cessation of heartbeat and

respiration, assessed by visual inspection and palpation.

Plaque assessment

After 24-h fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C,

aortic root specimens were dehydrated in 30% sucrose and embedded

in OCT compound in the coronal orientation. Serial

10-μm-thick sections were obtained along the aortic valve

axis using a cryostat. For analysis, 10 representative sections

were stained with Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich) for lipid visualization

or with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for structural assessment.

Plaque areas were quantified in ImageJ software (version 1.8.0;

National Institutes of Health) applying standardized threshold

parameters.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

observation

Aortic root specimens were primarily fixed with 3%

glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer (Ph 7.2) for 48-72 h, followed

by thorough PBS rinsing and subsequent graded ethanol dehydration.

Following embedding and polymerization in Epon 812 resin, tissue

blocks were subjected to ultrathin sectioning. Sections of 90 nm

thickness, prepared with an ultramicrotome equipped with a diamond

knife, were imaged using a Hitachi H-800 TEM at an acceleration

voltage of 80 kV to assess ultrastructural details.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

IF analysis cellular localization of Nrf2 and NLRP3

was assessed through IF. Fixed cells (pre-cooled methanol, −20°C,

10 min) underwent triple PBS washing (5 min each, pH 7.4) followed

by non-specific binding blockade with 3% BSA (MilliporeSigma)/0.1%

Tween-20 (1 h, RT). Primary antibodies included anti-Nrf2 (1:200;

cat. no. ab62352; Abcam) and anti-NLRP3 (1:500; cat. no. ab263899;

Abcam). Corresponding Secondary antibodies (1:500; cat. nos.

ab205718 and ab97051 Abcam) were purchased from Abcam. Nuclear

visualization employed DAPI staining (0.1 μg/ml PBS; 5 min;

cat. no. ab285390; Abcam). Confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP8, 40x

oil lens, NA 1.30) captured images using LAS X 3.7.4 with

standardized 358/461 nm excitation/emission and z-axis imaging

(1-μm intervals).

Serum lipid quantification

Blood samples were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 20

min at 4°C, followed by a 1:1 dilution of the resulting supernatant

with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Total cholesterol (TC),

triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were tested using a

Beckman DXC700au system (NIST SRM 1951c-calibrated) with endpoint

analysis at 500 nm under standardized conditions (37±0.2°C, <3%

intra-assay CV).

Cell experiments

Primary mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAECs) were

obtained through enzymatic digestion of thoracic aortas isolated

aseptically from 8-12-week-old mice. Following the removal of

adventitial tissue and longitudinal incision, vessels were

enzymatically digested with collagenase I (1 mg/ml) at 37°C for

15-20 min. Digested cells were filtered through 40-μm

strainers and plated onto gelatin-coated dishes in

endothelial-specific medium (10% FBS; 30 μg/ml ECGS; 100

μg/ml heparin; all from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Cellular purity was enhanced through differential adhesion

(three sequential 30-min platings at 37°C, 5% CO2).

Cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and

1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Cultures were kept at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere

with 95% humidity in a tri-gas incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). To simulate atherosclerotic inflammatory responses,

confluent monolayers were sequentially challenged with ox-LDL (100

μg/ml, 12 h).

The cells were randomized into 5 groups (n=3/group):

control group, cells in DMEM without ox-LDL stimulation; Model

group, cells treated with ox-LDL stimulation; GC group, cells

pretreated with GC (1, 10, 100 μM) for 24 h prior to ox-LDL

co-stimulation.

Cell viability

The assessment of cell viability was performed using

the MTT reduction method. Interventions were performed upon the

cells reaching a density of 5,000 cells per well. Following

experimental interventions, the culture medium was replaced with 5

mg/ml MTT solution and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Subsequently, the

supernatant was carefully removed, and the formazan crystals were

solubilized in DMSO under 300 rpm orbital agitation for 15 min. The

optical density at 490 nm was recorded with a microplate reader and

normalized relative to the control group.

ROS assay

ROS levels were measured via

2',7'-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA; Abcam). Cells

(1×105 cells/well) in 6-well plates were incubated with

10 μM DCFDA at 37°C for 20 min. Fluorescence images were

captured with a fluorescence microscope (BD Biosciences), and ROS

fluorescence intensity was analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software

(version 6.0; Media Cybernetics Inc.).

Detections of inflammatory factors and

oxidative stress factors

IL-1β, IL-18 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α

concentrations in serum and cell culture supernatants were

determined by ELISA kits (IL-1β, cat. no. 88-7013A-88; IL-18, cat.

no. KMC0181; TNF-α, cat. no. BMS607-3; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions. The levels of

superoxide dismutase (SOD; cat. no. A001-3), malondialdehyde (MDA;

cat. no. A003-1), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; cat. no. A020-2),

creatine kinase (CK; cat. no. A032-1-1), catalase (CAT; cat. no.

A007-1-1), glutathione (GSH; cat. no. A006-2-1) and NADPH (cat. no.

A115-1-1) in serum and cell culture supernatants were detected by

chemical kits of Nanjing Jiancheng Engineering Institute.

TUNEL staining

DNA fragmentation in individual cells was detected

by TUNEL staining with a fluorescence kit (Roche Diagnostics).

Following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (20 min) and

permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 (10 min) at room

temperature, MAECs on coverslips were subjected to TUNEL assay by

incubation with the reagent at 37°C for 60 min. Fluorescent signals

were visualized and recorded with an Olympus FV3000 confocal

microscopy system.

Western blot analysis for Nrf2, NLRP3,

HO-1, NQO1, GCLM and Caspase-1 expression levels in MAECs

Total protein quantification was performed using BCA

assay. Subcellular fractionation was conducted with a

Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Protein Isolation Kit (cat. no. P1250; Applygen

Technologies, Inc.) following established protocols. Protein

samples (50 μg) underwent SDS-PAGE (10% gel) electrophoresis

and subsequent PVDF membrane transfer. Membranes were blocked with

5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, then incubation with

primary antibodies (1:800 dilution) targeting Nrf2, NLRP3, HO-1,

NQO1, GCLM and total Caspase-1 at 37°C for 4 h. Membranes were

subsequently probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

diluted at 1:1,000. Specific signals were visualized with ECL Plus

reagent and quantified via densitometry using a Bio-Rad Gel Imaging

System and Quantity One software (version 5.0; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

Total protein quantification was determined via BCA

assay. Nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation employed the

nuclear-cytoplasmic protein isolation kit (cat. no. P1250; Applygen

Technologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A

total of 50 μg protein samples were separated through

SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes. After 5% skim

milk blocking, membranes were probed with primary antibodies

(Nrf2/NLRP3/HO-1/NQO1/GCLM/Caspase-1; 1:800) at 37°C (4 h),

followed by HRP-secondary antibodies (1:1,000). Chemiluminescent

detection was performed with ECL Plus reagent, followed by

densitometric analysis of the bands using the Quantity One software

(version 5.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) imaging system.

Statistical analysis

Triplicate experimental data are expressed as the

mean ± SD. Intergroup comparisons were assessed through one-way

ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc adjustment (GraphPad Prism version

5.0; Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant significance.

Results

GC alleviates atherosclerotic

pathological damage in AS model mice

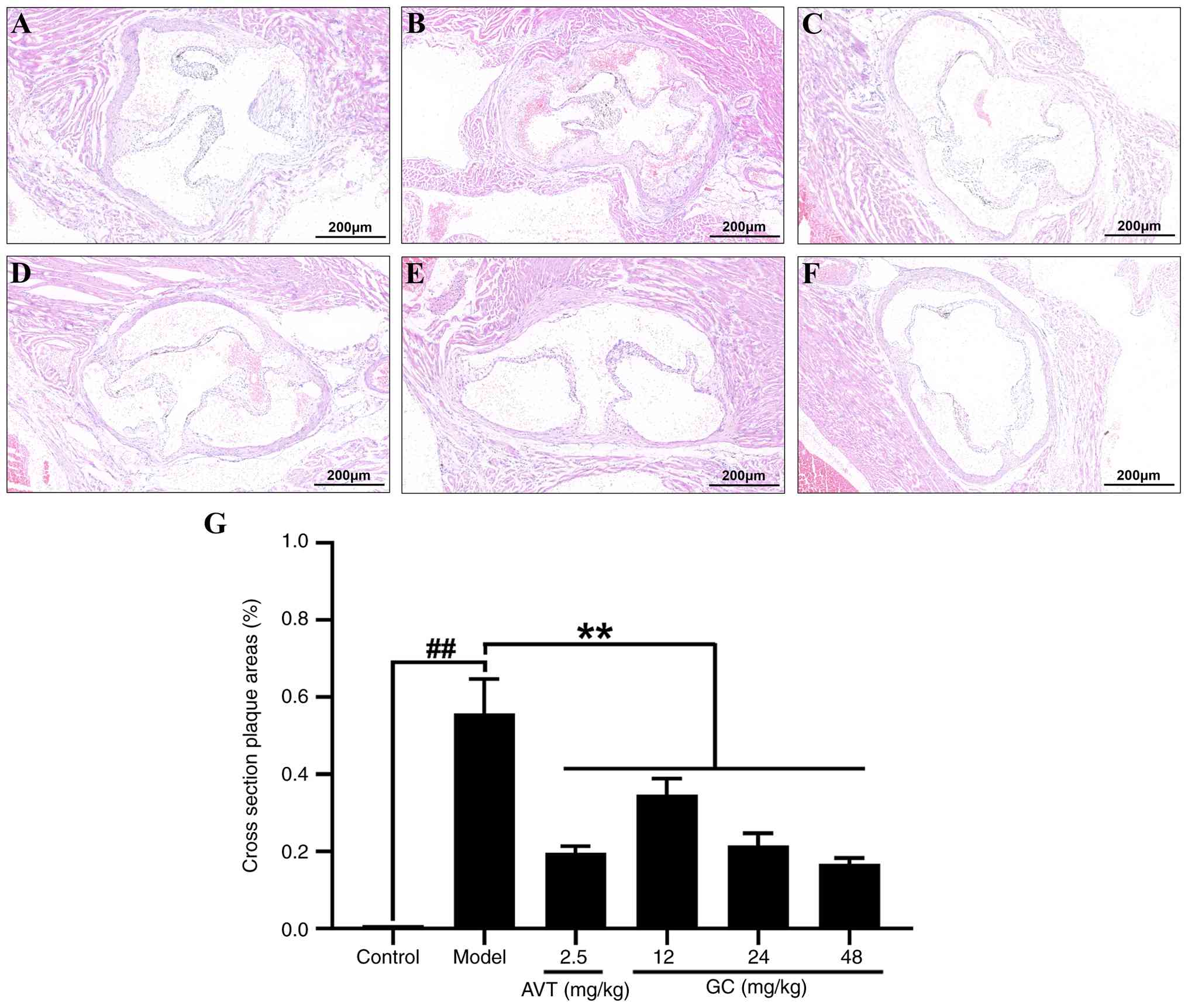

To observe the histopathological changes in the

aortic root following atherosclerotic injury, H&E staining was

performed. As depicted in Fig.

2A, aortic sections from the control group demonstrated a

well-defined trilaminar architecture: The tunica intima was lined

by a continuous endothelial monolayer; the tunica media showed

regularly arranged, wavy elastic fibers interspersed with smooth

muscle cells; and the tunica adventitia was composed of loose

connective tissue. No pathological alterations such as lipid

deposition, foam cell formation, inflammatory infiltration, luminal

disruption, or vascular wall thickening were observed. In the model

group (Fig. 2B), marked intimal

thickening was observed, featuring foam cells (vacuolated

cytoplasm), cholesterol clefts, inflammatory infiltration, and

fibrous caps overlying lipid cores. The tunica media showed

fragmented elastic fibers with reduced smooth muscle cells, while

the adventitia presented neovascularization and chronic

inflammation, accompanied by a narrowed and irregular lumen. In 2.5

mg/kg AVT group (Fig. 2C) and

12, 24, 48 mg/kg GC groups (Fig.

2D-F), the aortic intima displayed a significant decrease in

pathological thickening with parallel reductions in atherosclerotic

plaque deposition (Fig. 2G).

GC reduces atherosclerotic lipid

deposition in AS model mice

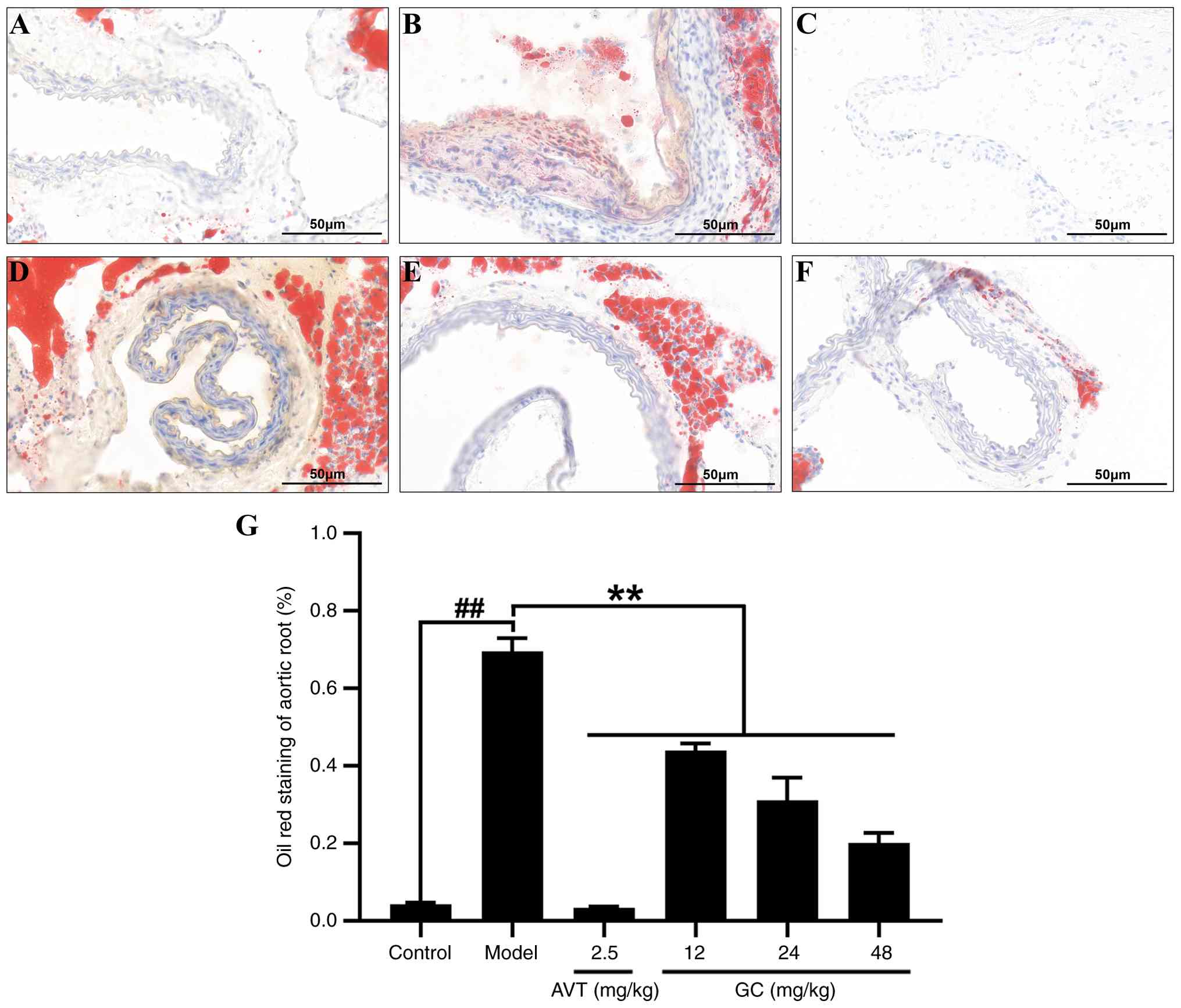

To investigate the effect of GC on lipid deposition

and examine its impact on plaque characteristics following

atherosclerotic injury, Oil Red O staining was performed. As shown

in Fig. 3A, the control group

exhibited no Oil Red O-positive red signals in any aortic wall

layers (intima, media, adventitia), with only physiological lipid

staining observed in periadventitial adipose tissue. The luminal

surface appeared smooth without lipid droplet adhesion, indicating

no pathological lipid deposition. By contrast, the model group

displayed bright red mass-like lipid deposits (plaque lipid cores)

in the aortic sinus and subintimal regions, accompanied by diffuse

punctate red infiltration (early lipid infiltration) at plaque

margins. Strongly positive lipid halos surrounded cholesterol

clefts in some areas, suggesting lipid metabolic disturbances and

extensive foam cell aggregation (Fig. 3B). However, Oil Red O staining

demonstrated a reduction in lipid core size, significant

attenuation of red-positive deposition area, and faded lipid halos

surrounding cholesterol clefts, indicative of ameliorated lipid

metabolic dysregulation and enhanced plaque stability after

treatment of 2.5 mg/kg AVT (Fig.

3C) and 12, 24, 48 mg/kg GC (Fig. 3D-F). Quantitative analysis of

atherosclerotic plaque area based on oil red O staining is

demonstrated in Fig. 3G.

GC reduces blood lipid levels in AS model

mice

The result in Table

I showed that the blood lipid levels in model group were

markedly changed (TG: 5.58±0.26 mM; TC: 41.59±5.49 mM; LDL-C:

16.14±2.41 mM and HDL-C: 1.46±0.24 mM, all P<0.01 vs. control

group). 2.5 mg/kg AVT and 12, 24, 48 mg/kg GC significantly

improved the blood lipid levels (all P<0.01 vs. model group).

The findings revealed that GC exhibited hypolipidemic effects and

attenuated atherosclerotic development.

| Table IEffect of GC on serum lipid levels in

atherosclerosis model mice. |

Table I

Effect of GC on serum lipid levels in

atherosclerosis model mice.

| Group | Dose (mg/kg) | TG (mM) | TC (mM) | LDL-C (mM) | HDL-C (mM) |

|---|

| Control | | 1.39±0.26 | 3.63±0.17 | 1.50±0.33 | 4.97±0.64 |

| Model | | 5.58±0.26b | 41.59±5.49b | 16.14±2.41b | 1.46±0.24b |

| AVT | 2.5 | 1.53±0.36a | 16.51±4.14a | 1.67±0.62a | 3.96±0.60a |

| GC | 12 | 3.47±0.25a | 26.45±2.18a | 5.52±1.48a | 2.72±0.84a |

| 24 | 2.71±0.39a | 17.83±2.00a | 4.30±1.51a | 3.26±0.34a |

| 48 | 1.67±0.54a | 11.75±1.23a | 2.37±1.03a | 4.44±0.54a |

GC improves atherosclerotic

ultrastructural changes in AS model mice

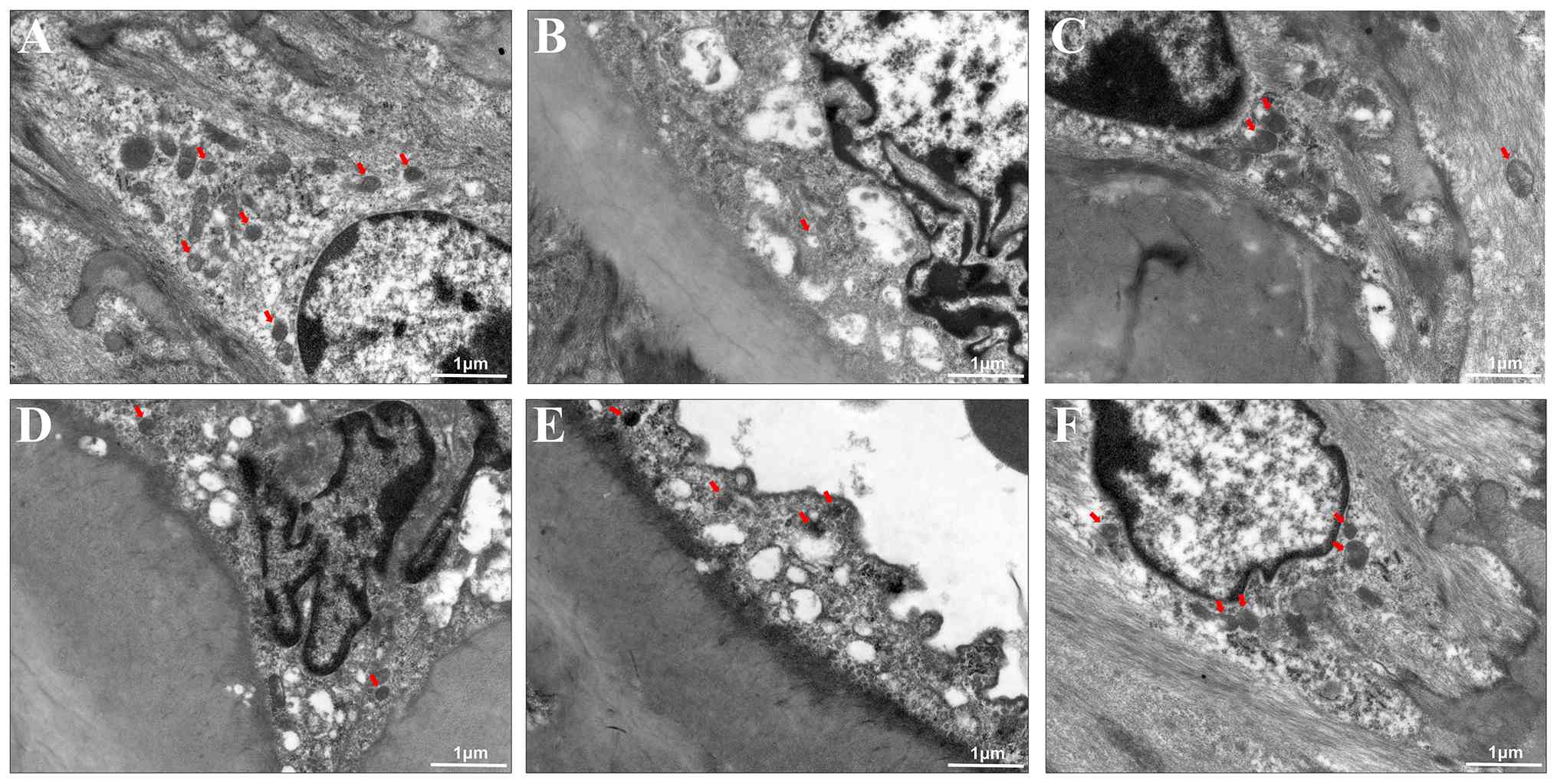

Additionally, ultrastructural changes induced by GC

were analyzed by TEM. In control group, the endothelial cells

formed a continuous monolayer with intact tight junctions; the

medial smooth muscle cells were densely packed with contractile

myofilaments and surrounded by orderly arranged elastic fibers; the

extracellular matrix showed no lipid droplet deposition,

inflammatory infiltration, or structural disruption (Fig. 4A). However, in the model group,

endothelial disruption with lipid deposition, smooth muscle foam

cell transformation (marked by contractile myofilament loss and

lipid droplet-induced organelle compression), and elastic fiber

fragmentation were prominently observed. Concurrently,

extracellular collagen disorganization and cholesterol crystal

deposition synergistically drove plaque instability (Fig. 4B). The results in Fig. 4C-F revealed that 2.5 mg/kg AVT

and 12, 24, 48 mg/kg GC significantly improved the endothelial

continuity restoration, smooth muscle contractile phenotype

reconstruction (marked by myofilament regeneration and lipid

droplet clearance), and elastic-collagen reorganization in the

extracellular matrix. Plaque cholesterol crystal dissolution with

attenuated inflammatory infiltration indicates GC effectively

reversed core pathological cascades of AS.

GC upregulates the expression levels of

Nrf2 and its downstream antioxidant proteins HO-1, NQO1 and GCLM in

AS model mice

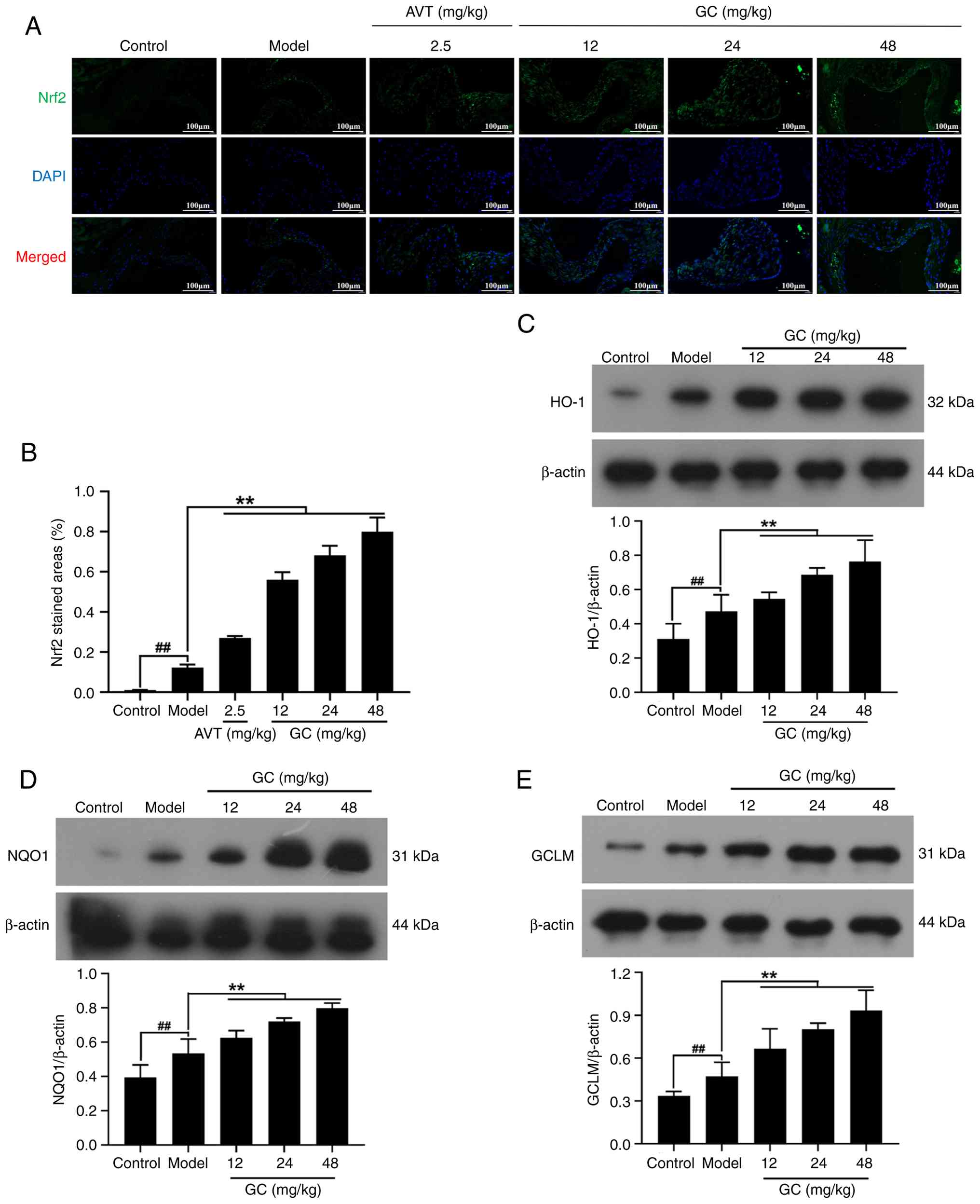

As shown in Fig. 5A

and B through IF analysis, Nrf2 expression demonstrated

relatively low baseline levels in the control group. The model

group exhibited marginal elevation in Nrf2 expression compared with

the control group. However, GC administration at doses of 12, 24

and 48 mg/kg induced significant upregulation of Nrf2 expression

levels (all P<0.01 vs. model group). Moreover, 2.5 mg/kg AVT

slightly elevated the expression of Nrf2 (P<0.01 vs. model

group). Furthermore, baseline expression levels of HO-1, NQO1 and

GCLM were markedly diminished in the control group. While the model

group demonstrated modest elevation of these antioxidant markers

relative to controls, 12, 24, 48 mg/kg GC produced statistically

significant inductions in HO-1, NQO1 and GCLM expression (Fig. 5C-E; all P<0.01 vs. model

group).

GC downregulates the expression levels of

NLRP3 and its downstream Caspase-1

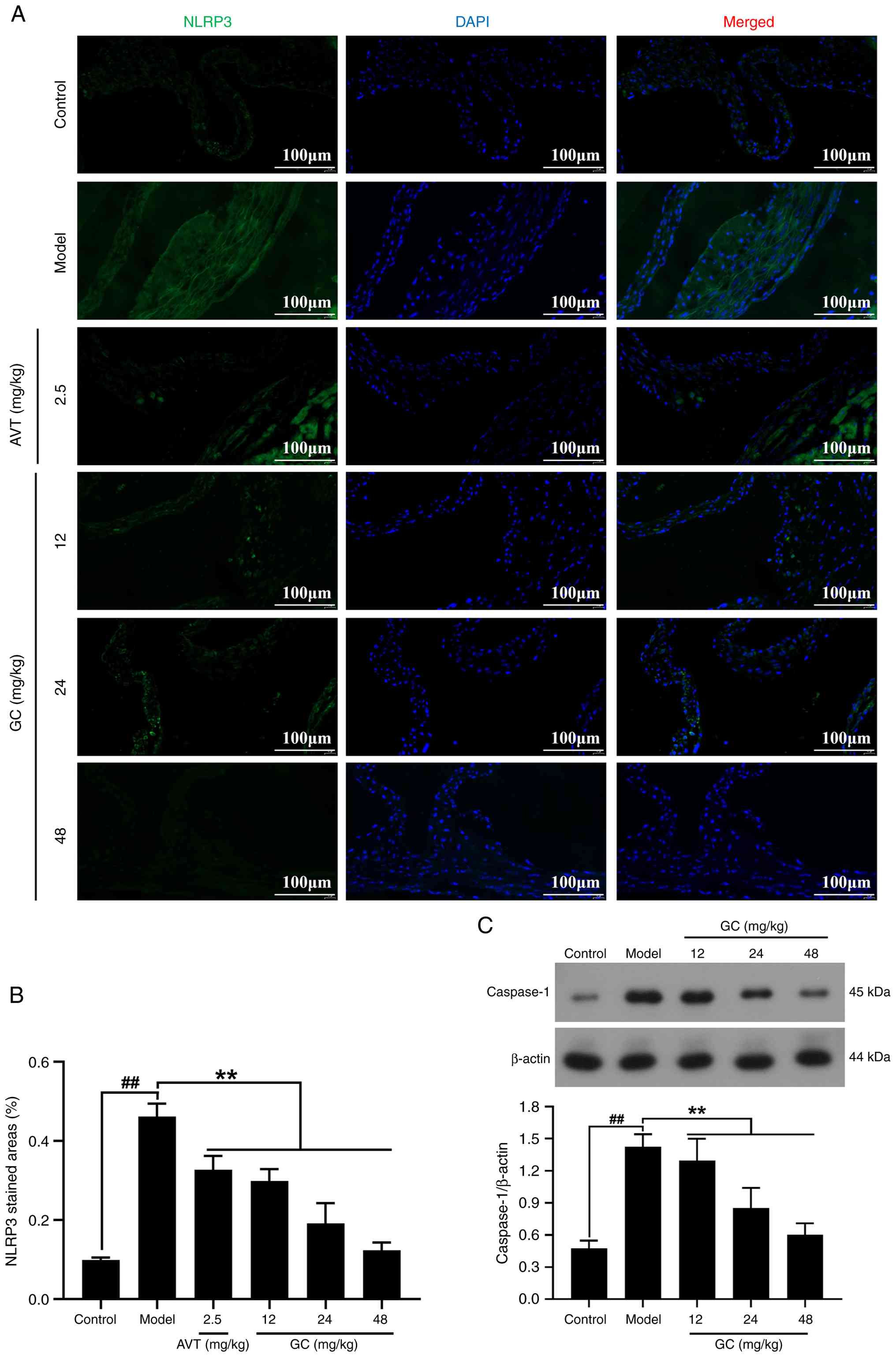

As demonstrated in Fig. 6A-C, pathological activation of

NLRP3 inflammasome components was significantly elevated in the

model group, showing significant upregulation of both NLRP3 and

Caspase-1. Conversely, GC treatment at ascending doses (12, 24, 48

mg/kg) exhibited progressive suppressions of NLRP3 and Caspase-1

(all P<0.01 vs. model group).

GC inhibits oxidative stress and

inflammatory damage in AS model mice

Next, the effect of GC on the expression of

inflammatory cytokines was further investigated in the serum of AS

model mice. As revealed in Table

II, the levels of IL-1β, IL-18 and TNF-α in the control group

were low. After modeling, the levels of IL-1β, IL-18 and TNF-α

increased to 361.85±62.80 pg/ml, 96.41±8.10 pg/ml, 97.90±6.64

pg/ml, respectively (all P<0.01 vs. control group). However, 2.5

mg/kg AVT and 12, 24, 48 mg/kg GC could dose-dependently reduced

the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-18 and TNF-α (all P<0.01 vs.

model group).

| Table IIEffect of GC on serum inflammatory

cytokines in atherosclerosis model mice. |

Table II

Effect of GC on serum inflammatory

cytokines in atherosclerosis model mice.

| Group | Dose (mg/kg) | IL-1β (pg/ml) | IL-18 (pg/ml) | TNF-α (pg/ml) |

|---|

| Control | | 29.28±3.14 | 16.24±1.05 | 6.30±1.50 |

| Model | |

361.85±62.80b | 96.41±8.10b | 97.90±6.64b |

| AVT | 2.5 |

104.85±10.95a | 59.46±6.90a | 33.04±6.82a |

| GC | 12 |

133.27±18.50a | 57.47±2.07a | 40.35±3.55a |

| 24 | 84.12±12.52a | 28.25±8.88a | 35.27±3.80a |

| 48 | 38.01±4.01a | 17.52±2.27a | 24.39±6.21a |

As demonstrated in Table III, the levels of SOD, MDA,

LDH, CK, CAT, GSH and NADPH in the control group were 156.49±13.59

U/ml, 1.39±0.18 nM, 3513.01±663.44 U/l, 0.34±0.10 U/ml, 9.78±1.21

U/ml, 267.07±22.48 μM and 4.07±0.20 μM, respectively.

After modeling, the cohort exhibited significant reductions in

antioxidant defense markers (SOD, CAT and GSH) concomitant with

significant elevations in oxidative stress indicators (MDA, LDH and

CK) and NADPH generation (all P<0.01 vs. control group). 2.5

mg/kg AVT and 12, 24, 48 mg/kg GC significantly upregulated SOD,

CAT and GSH while downregulating MDA, LDH, CK and NADPH, with all

changes reaching statistical significance (P<0.05 vs. model

group).

| Table IIIEffect of GC on antioxidant enzymes

in atherosclerosis model mice. |

Table III

Effect of GC on antioxidant enzymes

in atherosclerosis model mice.

| Group | Control | Model | AVT | GC |

|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) | | | 2.5 | 12 | 24 | 48 |

| SOD (U/ml) | 156.49±13.59 | 47.66±9.25b | 82.01±4.51a | 93.69±9.46a | 101.95±6.02a | 133.82±5.59a |

| MDA (nM) | 1.39±0.18 | 8.10±0.60b | 4.48±0.34a | 4.20±0.67a | 3.29±0.63a | 2.37±0.26a |

| LDH (U/l)

3,513.01±663.44 |

9,953.69±510.21b |

4,724.05±641.13a |

6,460.10±728.44a |

5,125.62±239.46a |

4,242.19±692.69a |

| CK (U/ml) | 0.34±0.10 | 1.37±0.22b | 0.55±0.06a | 0.89±0.14a | 0.60±0.10a | 0.48±0.05a |

| CAT (U/ml) | 9.78±1.21 | 2.64±1.16b | 6.10±0.73b | 5.54±0.78a | 6.50±1.23a | 7.77±1.28a |

| GSH

(μM) | 267.07±22.48 | 79.55±15.10b | 129.25±6.20b |

133.67±21.23a |

181.02±19.21a |

219.30±15.46a |

| NADPH

(μM) | 4.07±0.20 | 8.20±0.25b | 5.48±0.39b | 5.90±0.39a | 4.45±0.40a | 4.10±0.73a |

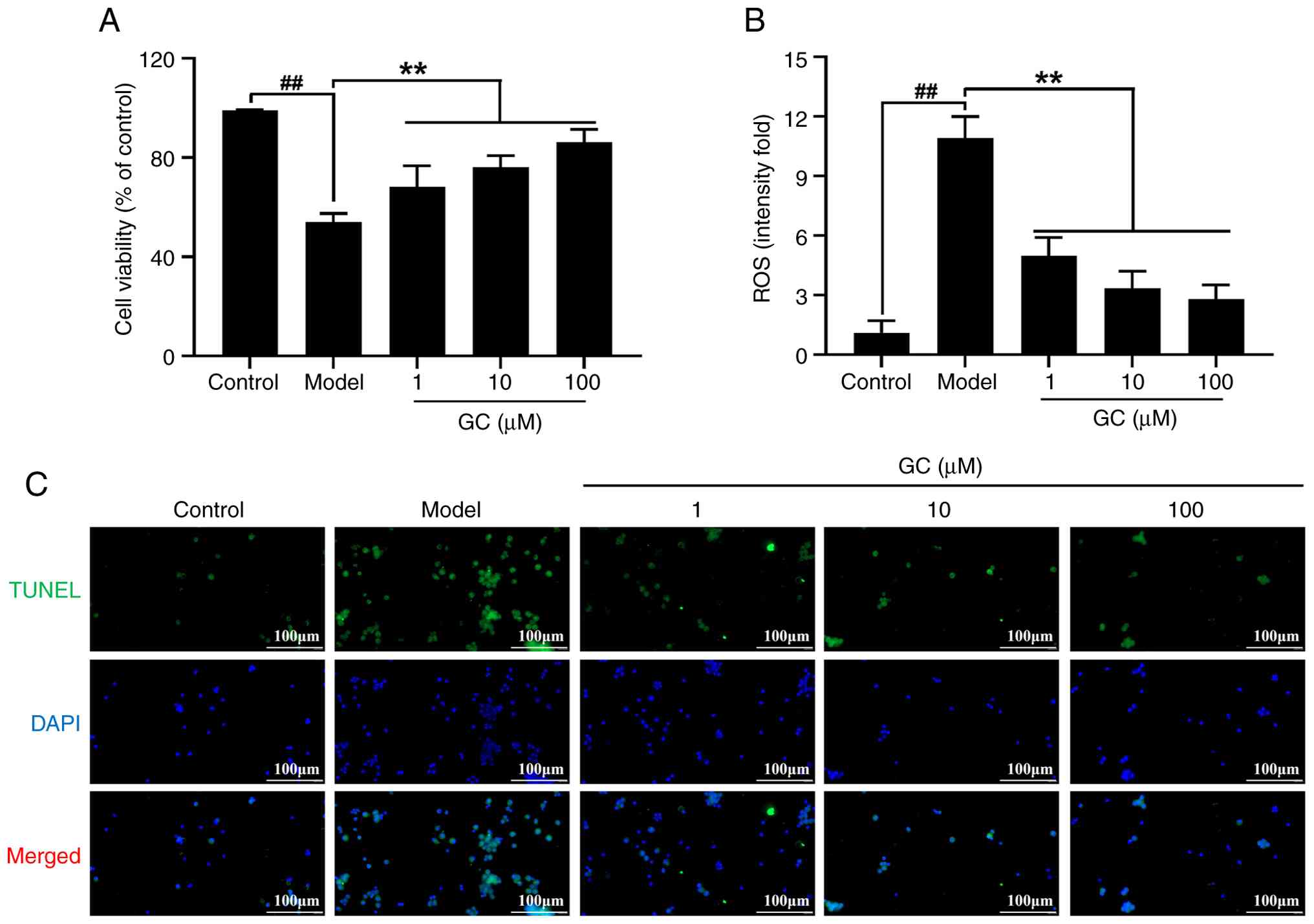

GC promotes cell survival, suppresses ROS

generation, and inhibits apoptosis in ox-LDL-stimulated MAECs

As shown in Fig.

7A, ox-LDL-treated MAECs exhibited a significant reduction in

cell viability (54.08±3.36%; P<0.01 vs. control group) as

determined by MTT assay. Treatment of GC (1, 10, 100 μM)

demonstrated dose-responsive enhancement of MAECs viabilities

(68.11±8.67%, 76.05±4.71%, 86.19±5.11%, P<0.01 vs. model

group).

Then, DCFDA was used for determining the level of

ROS in MAECs (Fig. 7B). In

contrast to the marked increase observed in ox-LDL-treated groups,

ROS levels in the control group were substantially lower. In

contrast to the model group, GC treatment at 1, 10 and 100

μM significantly reduced ROS levels (all P<0.01).

TUNEL staining result in Fig. 7C indicated that minimal apoptosis

in control group, whereas the model group exhibited significant

apoptotic cells. Treatment with 1, 10 and 100 μM GC markedly

reduced apoptosis.

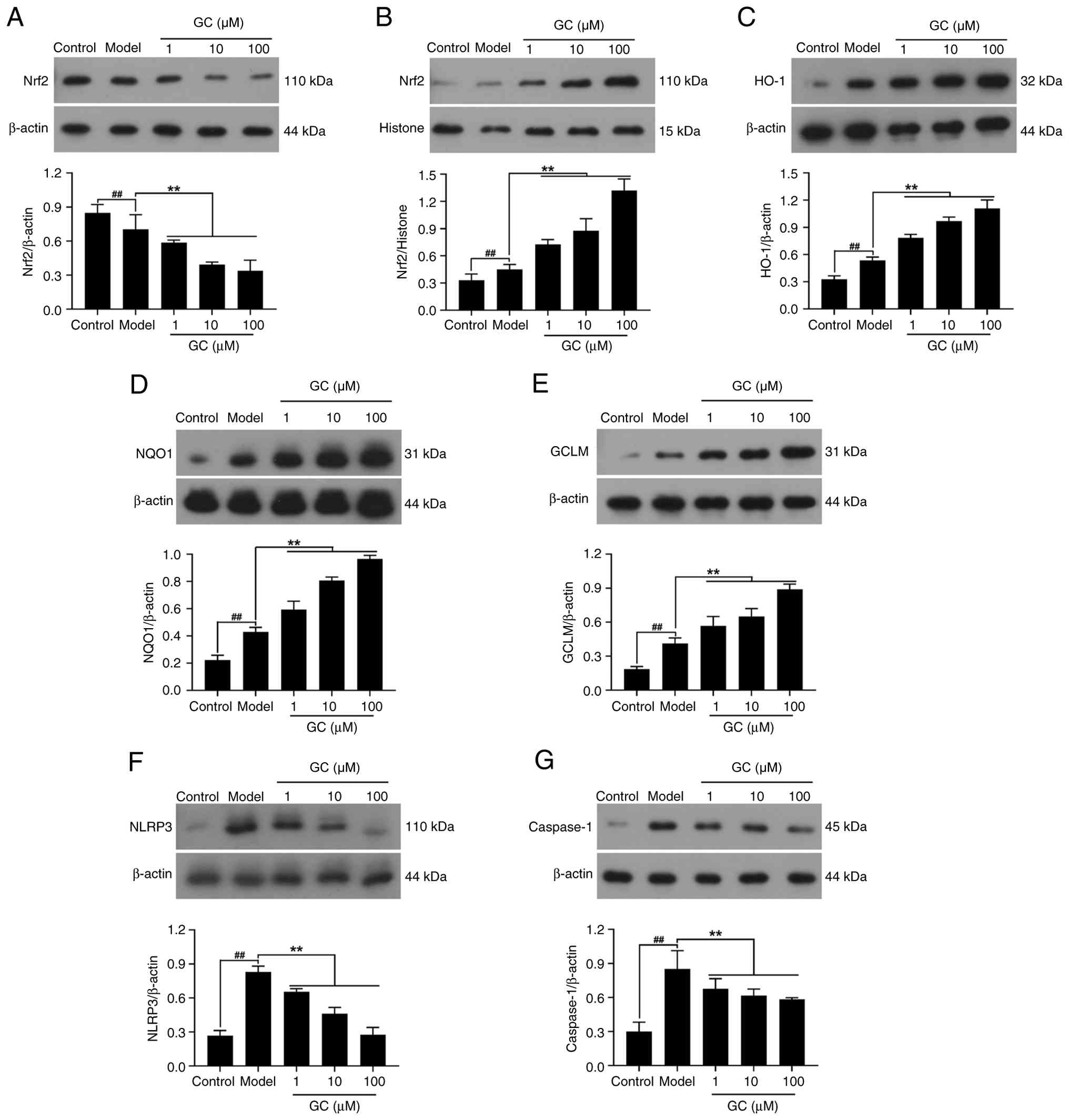

GC enhances Nrf2 nuclear translocation

with upregulation of HO-1/NQO1/GCLM, while suppressing

NLRP3/Caspase-1 expression

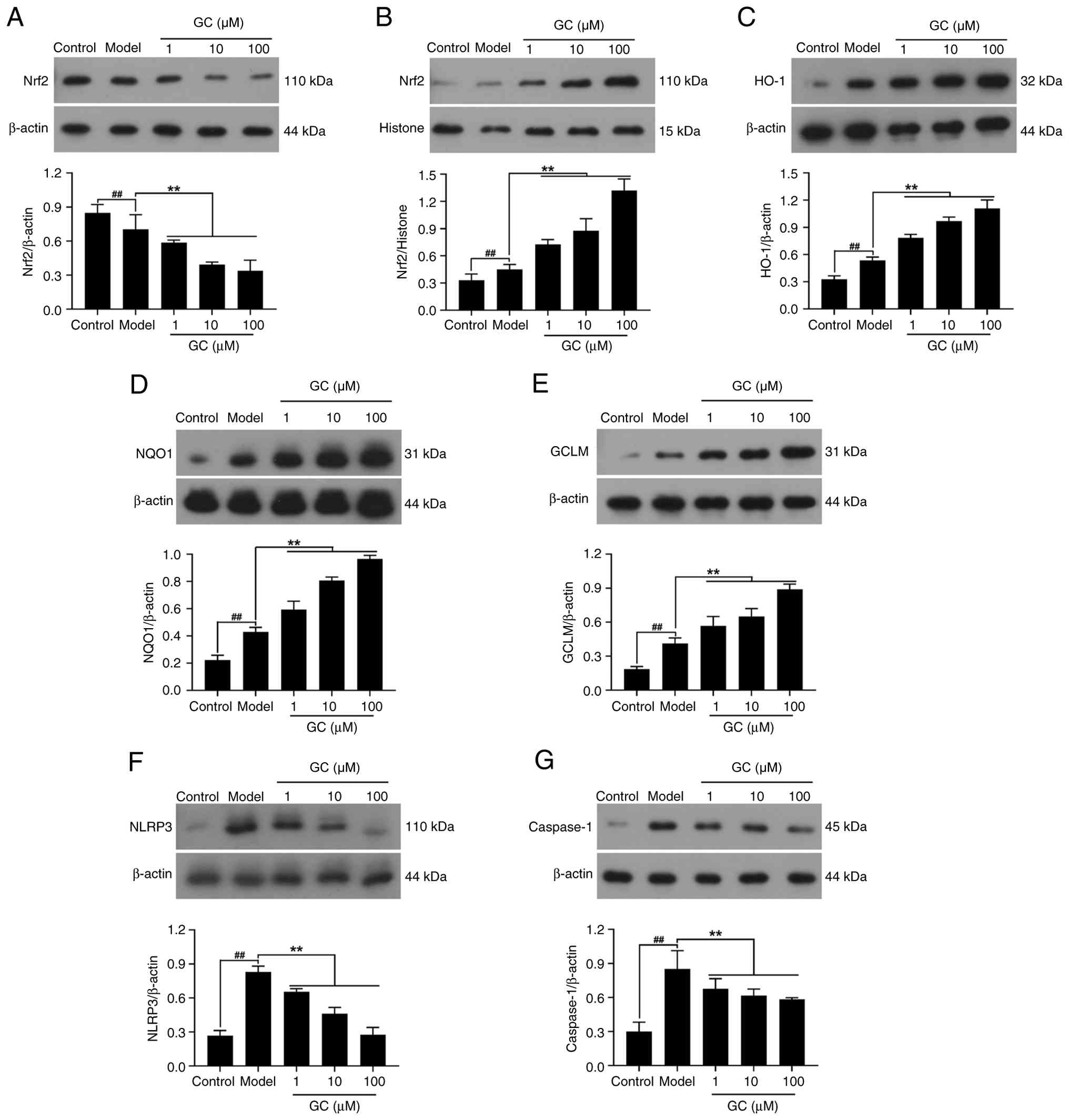

As revealed in Fig.

8A and B, Nrf2 was primarily localized in the cytoplasm with

barely detectable nuclear levels in control cells. By contrast,

ox-LDL stimulation promoted its nuclear translocation. However, GC

(1, 10, 100 μM) significantly enhanced the

cytoplasmic-to-nuclear translocation of Nrf2. Therefore, GC

significantly activated the Nrf2 signaling pathway, with increased

cytoplasmic-to-nuclear translocation of Nrf2 leading to

upregulation of HO-1, NQO1 and GCLM expression levels (Fig. 8C-E). The results in Fig. 8F and G showed that ox-LDL

stimulation notably upregulated the expression of NLRP3 and

Caspase-1. Whereas treatment of 1, 10 and 100 μM GC

demonstrated dose-dependent suppression of NLRP3/Caspase-1 cascade

activation.

| Figure 8Effect of GC on expression levels of

Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, GCLM, NLRP3 and Caspase-1 in oxidized-low density

lipoprotein stimulated mouse aortic endothelial cells. (A-G)

Western blot was applied to quantify the expression levels of (A)

cytoplasmic Nrf2, (B) nuclear Nrf2, (C) HO-1, (D) NQO1, (E) GCLM,

(F) NLRP3 and (G) Caspase-1. Results were expressed as

protein/reference protein ratio. Data are expressed as the mean ±

SD. ##P<0.01 vs. control group;

**P<0.01 vs. model group. GC, ginkgolide C; Nrf2,

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1, heme

oxygenase-1; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1; GCLM,

glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit; NLRP3, Nod-like

receptor protein 3. |

GC also improves antioxidant capacity and

suppresses inflammatory reaction in ox-LDL-stimulated MAECs

Results were consistent with in vivo

experiments (Tables IV and

V). ox-LDL exposure triggered

concurrent elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-18

and TNF-α) and oxidative markers (MDA, LDH, CK and NADPH),

paralleled by significant depletion of antioxidant defenses (SOD,

CAT and GSH) (all P<0.01 vs. control). However, 1, 10, and 100

μM GC could significantly improve the inflammatory response

and oxidative stress damage induced by ox-LDL.

| Table IVEffect of GC on the supernatant

inflammatory cytokines of oxidized-low density lipoprotein

stimulated mouse aortic endothelial cells. |

Table IV

Effect of GC on the supernatant

inflammatory cytokines of oxidized-low density lipoprotein

stimulated mouse aortic endothelial cells.

| Group | Dose

(μM) | IL-1β (pg/ml) | IL-18 (pg/ml) | TNF-α (pg/ml) |

|---|

| Control | | 1.80±0.53 | 11.73±2.90 | 6.94±1.47 |

| Model | |

1,085.96±135.24b |

121.00±19.23b |

588.98±111.82b |

| GC | 1 |

509.94±113.03a | 34.43±5.09a |

245.31±20.99a |

| 10 |

252.86±39.04a | 21.12±6.34a |

169.81±33.94a |

| 100 |

105.53±13.05a | 12.27±1.34a | 65.90±9.20a |

| Table VEffect of GC on antioxidant enzymes

of oxidized-low density lipoprotein stimulated mouse aortic

endothelial cells. |

Table V

Effect of GC on antioxidant enzymes

of oxidized-low density lipoprotein stimulated mouse aortic

endothelial cells.

| Group | Control | Model | GC |

|---|

| Dose

(μM) | | | 1 | 10 | 100 |

| SOD (U/mg pro) | 296.04±24.49 |

129.08±23.70b | 206.48±7.53a | 241.78±8.70a |

273.96±18.58a |

| MDA (nM/mg

pro) | 6.18±0.24 | 21.87±0.71b | 15.91±1.66a | 11.53±3.93a | 9.39±1.77a |

| LDH (U/l) | 702.27±38.14 |

1,257.27±212.96b |

1,022.00±83.18a |

891.48±38.90a |

805.04±66.59a |

| CK (U/mg pro) | 0.40±0.35 | 1.45±0.28b | 1.01±0.41a | 0.95±0.38a | 0.83±0.21a |

| CAT (U/ml) | 7.80±2.06 | 0.97±0.05b | 2.38±0.58a | 4.08±0.71a | 6.17±0.38a |

| GSH (mg/g pro) | 3.76±1.05 | 1.57±0.42b | 2.45±0.41a | 2.74±0.30a | 3.22±0.19a |

| NADPH

(μM) | 9.72±2.52 | 34.60±4.18b | 23.62±3.17a | 16.51±0.54a | 12.19±3.33a |

The data demonstrate a significant dual benefit of

GC: It conferred a dose-dependent enhancement in oxidative stress

tolerance concurrent with a suppression of inflammation. This

effect, achievable through the potential activation of endogenous

pathways such as Nrf2, highlights GC's role in simultaneously

addressing two key pathological processes.

Discussion

CVDs remain the globally predominant cause of

mortality, with AS serving as a central pathological driver

(21). AS manifests as a

multifactorial vascular pathology originating from disrupted

endothelial homeostasis, clinically characterized by impaired

vasomotor regulation, dyslipidemia, oxidative stress and chronic

inflammatory cytokine activation (22,23). Exacerbated oxidative stress

induces pathological ROS overproduction, elevating oxidative

derivatives and provoking systemic oxidative damage. Subsequent

pathological ROS accumulation directly activates the NLRP3

inflammasome, thereby potentiating proinflammatory cascades that

exacerbate atherosclerotic lesion progression (24). Crucially, Nrf2, serving as a

master regulator of redox homeostasis, negatively modulates NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated inflammation through redox-sensitive

suppression of ROS-mediated signaling pathways (25). This mechanistic framework

supports the author's hypothesis that GC attenuates atherosclerotic

injury via Nrf2 activation-mediated ROS inhibition, consequently

attenuating NLRP3 inflammasome activation and reducing

atherosclerotic plaque progression.

Ginkgo biloba, a monotypic genus in the

family Ginkgoaceae and the sole extant species of this lineage, is

recognized as a 'living fossil' that occupies a pivotal node in

plant evolutionary history (26,27). Modern pharmacological research

demonstrates that the biological activity of Ginkgo biloba

leaf extracts predominantly originates from its characteristic

secondary metabolites, specifically terpene lactones (6%) and

flavonoid glycosides (24%) as principal active components. The

latter category encompasses specific compounds such as ginkgolides

A/B/C/J and bilobalide, whose unique diterpene trilactone molecular

structure confers multi-target pharmacological activities (28). Guided by cumulative preclinical

evidence, GC was designated as the lead therapeutic candidate.

Experimental investigations employing in vitro and in

vivo models have established that both isolated constituents

manifest concentration-dependent cytoprotective efficacy against

ischemia-reperfusion pathophysiology in both myocardial and

cerebral compartments (18,19). The pathophysiological continuum

of AS, constituting the common etiological substrate for

cardio-cerebrovascular disorders, is mechanistically underpinned by

dysregulated endothelial homeostasis, pathogenic leukocyte

recruitment, and atheroma destabilization, pathobiological

processes intrinsically linked to redox imbalance and dysregulated

proinflammatory signaling pathways (29,30). Leveraging GC's multifaceted

anti-inflammatory pharmacodynamics and multiphasic vascular

protective actions, the present investigation systematically

interrogates the compound's interactome within AS pathobiology,

with dual objectives: i) Characterization of bioactive effector

moieties governing its therapeutic efficacy, and ii) comprehensive

mapping of pleiotropic therapeutic modalities encompassing atheroma

stabilization, endothelial homeostatic restoration, and

immunomodulatory microenvironment remodeling.

Of particular note is the atherogenic diet-fed

ApoE−/− mouse model employed in the present study, which

allowed for the evaluation of GC interventions under controlled,

dose-escalating conditions. The experimental approach integrated

serum lipid profiling, histological examination of plaques, and

ultrastructural visualization via electron microscopy.

Pathophysiologically, atherogenesis is widely understood to be

initiated by dyslipidemia, wherein LDL-C undergoes oxidative

modification to ox-LDL, triggering endothelial activation,

inflammatory recruitment, and foam cell formation-central events in

plaque development (31,32). Epidemiological observations

consistently link hypercholesterolemia with increased

cardiovascular risk, whereas HDL-C is recognized for its protective

role via reverse cholesterol transport (33). In light of these established

mechanisms, the lipid-modulating effects observed following GC

intervention provide a substantive basis for discussing its

potential therapeutic mechanism. The results suggest that GC may

exert a dual regulatory influence, not only reducing atherogenic

lipids but also promoting functional HDL activity, thereby

contributing to the restoration of lipid homeostasis. This

positions GC as a candidate for further investigation into its role

in modulating key pathways involved in AS progression. Notably, the

pleiotropic modulation of both pro-atherogenic lipoprotein

suppression and reverse cholesterol transport enhancement suggests

GC's unique position in contemporary anti-atherosclerotic

therapeutic strategies, potentially bridging current gaps in

targeting complex lipid flux dysregulation. In the present study,

GC was administered for only 7 days in a murine model of

atherosclerotic lesions, yet AS is a chronic, long-term disease

process. Whether GC can be sustainably used or possesses the

potential to reverse atherosclerotic lesions remains unclear.

Consequently, future studies are needed to systematically evaluate

extended GC treatment regimens (for example, 6-12 weeks) to

characterize its pharmacodynamic effects on plaque stabilization

and regression.

The multifaceted antiatherogenic profile of GC

warrants particular attention in the context of current therapeutic

challenges. Rather than focusing solely on lipid reduction, GC

appears to concurrently address plaque stabilization through

collagenous cap preservation and endothelial restoration, as

reflected in histopathological and ultrastructural observations.

This suggests a synergistic mechanism that targets multiple

pathological pathways-lipid retention, inflammatory signaling, and

extracellular matrix degradation-which collectively contribute to

atherosclerotic progression (34). Such a multiphasic therapeutic

approach may offer distinct advantages over conventional

monotherapeutic strategies, particularly in its ability to

intervene at both early and advanced stages of the disease

(35). By reinforcing plaque

microstructure and reducing lipid core vulnerability, GC holds

potential clinical utility in managing high-risk plaques,

especially in cases where statin therapy alone fails to mitigate

persistent inflammatory risks. The convergence of these mechanisms

supports GC's promise as a multimodal agent, meriting further

investigation into its translational application in complex

atherosclerotic disease.

The antioxidant properties of GC and their

implications for AS management merit further discussion within the

broader context of redox imbalance in CVD. Oxidative stress,

characterized by disrupted redox homeostasis, plays a

well-established role in driving endothelial dysfunction and plaque

instability, largely through the persistent generation of ROS and

subsequent lipid peroxidation (36). In this regard, GC appears to

modulate key components of the oxidative cascade, influencing both

the initiation and propagation of oxidative damage. Its potential

to enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses while simultaneously

mitigating peroxidative processes suggests a biphasic mechanism

that may effectively disrupt the ROS-lipid oxidation-inflammatory

axis, a critical pathway in AS progression. Notably, such a

multitarget antioxidant strategy differs from conventional

approaches by addressing oxidative stress at multiple levels, not

only scavenging free radicals but also promoting enzymatic

homeostasis (37). This may

offer a more sustainable and physiologically integrated means of

reducing oxidative injury in vascular tissues. Furthermore, the

potential involvement of the Nrf2 pathway, as inferred from

indirect evidence, hints at epigenetically mediated enhancement of

cellular antioxidant capacity, positioning GC as a modulator of

redox signaling beyond mere scavenging activity. Such pleiotropic

regulation could be particularly relevant in clinical settings

involving high residual oxidative stress, such as statin-resistant

or advanced atherosclerotic cases, where monotherapeutic

antioxidant strategies have shown limited success (38). These mechanistic insights

encourage further investigation into GC's translational potential

for preventing oxidative stress-driven cardiovascular events.

The central role of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in

maintaining cellular redox homeostasis provides a compelling

framework for discussing antioxidant-based interventions in AS. As

a key transcriptional regulator, Nrf2 responds to oxidative stress

by translocating to the nucleus and binding to ARE, thereby

orchestrating the expression of cytoprotective genes (39,40). This mechanism enables a

coordinated upregulation of endogenous defenses, which has

attracted interest as a therapeutic strategy in vascular diseases

driven by oxidative injury (41). Within this context, GC appears to

engage the Nrf2-ARE axis, suggesting a capacity to modulate

oxidative signaling beyond simple antioxidant scavenging. By

potentially enhancing multiple defense mechanisms, such as

HO-1-mediated detoxification, NQO1-regulated redox cycling and

glutathione biosynthesis, GC may reinforce antioxidant capacity

across cellular compartments, offering a more integrated approach

to managing redox imbalance in AS.

Such multi-level regulation could be particularly

advantageous in resolving the spatial and compositional

heterogeneity of oxidative stress within atherosclerotic plaques

(42,43). Unlike conventional monofunctional

antioxidants, the potential epigenetic influence of GC on Nrf2

signaling may enable sustained modulation of redox homeostasis,

positioning it as a candidate for addressing complex clinical

scenarios, including statin-resistant cases where persistent

oxidative stress contributes to residual cardiovascular risk. These

considerations underscore the relevance of further exploring GC's

role in targeting the interplay between oxidative stress, lipid

metabolism and inflammation, key drivers of plaque progression and

vulnerability.

The therapeutic strategy of concurrently targeting

the NLRP3 inflammasome and potentiating the Nrf2 pathway represents

a promising direction in AS research, particularly for disrupting

the self-perpetuating cycle of oxidative stress, inflammation and

lipid dysregulation (29,44).

GC's putative dual modulation of these pathways suggests a capacity

to intervene at multiple nodal points within the atherogenic

cascade, not only by potentially mitigating oxidative triggers via

Nrf2-mediated mechanisms but also by suppressing downstream

inflammasome activation and cytokine release. Such an integrated

approach may effectively uncouple the ROS-inflammation-lipid

deposition triad, which is central to plaque progression and

destabilization.

By simultaneously addressing oxidative insult and

inflammatory amplification, GC could offer a therapeutic advantage

over agents that target only single components of this pathogenic

network. This may be especially relevant in advanced

atherosclerotic lesions, where metabolic dysfunction and chronic

inflammation coexist. The ability to stabilize plaque phenotype by

modulating endothelial activation and attenuating leukocyte

recruitment further highlights its potential vascular-protective

role (45). From a clinical

perspective, this bifunctional anti-inflammatory and antioxidant

profile may hold particular value in managing complex patient

subsets, such as those with pyroptosis-prone plaques or inadequate

responses to conventional lipid-lowering therapy, underscoring the

need for further investigation into its translational applicability

(46,47).

Collectively, this investigation mechanistically

demonstrates GC-mediated cytoprotection against AS through

Nrf2-dependent redox homeostasis modulation, concomitantly

attenuating NLRP3 inflammasome activation and downstream

pro-inflammatory effector signaling (Fig. 9). These findings establish a

preclinical rationale for advancing Ginkgo biloba bioactive

constituents as multi-mechanistic therapeutics in atherosclerotic

CVD management.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RZ conducted investigation, formal analysis,

conceptualization, developed methodology, acquired funding, curated

and visualized data, wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. The

author read and approved the final version of the manuscript. RZ

confirms the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to

Shandong First Medical University (approval no. 2022-661; Jinan,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

|

1

|

Boffa MB and Koschinsky ML: Lipoprotein(a)

and cardiovascular disease. Biochem J. 481:1277–1296. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lusis AJ: Atherosclerosis. Nature.

407:233–241. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hassan HA, Ahmed HS and Hassan DF: Free

radicals and oxidative stress: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets.

Hum Antibodies. 32:151–167. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Aleksandrowicz M, Konop M, Rybka M,

Mazurek Ł, Stradczuk-Mazurek M, Kciuk M, Bądzyńska B, Dobrowolski L

and Kuczeriszka M: Dysfunction of microcirculation in

atherosclerosis: Implications of nitric oxide, oxidative stress,

and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 26:64672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Batty M, Bennett MR and Yu E: The role of

oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Cells. 11:38432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jakubowski H and Witucki Ł: Homocysteine

metabolites, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease.

Int J Mol Sci. 26:7462025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhu L, Liao Y and Jiang B: Role of ROS and

autophagy in the pathological process of atherosclerosis. J Physiol

Biochem. 80:743–756. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Howden R: Nrf2 and cardiovascular defense.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013:1043082013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel

SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K and Valko M: Reactive oxygen species,

toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and

aging. Arch Toxicol. 97:2499–2574. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mimura J and Itoh K: Role of Nrf2 in the

pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Free radical biology &

medicine. 88:221–232. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

O'Rourke SA, Shanley LC and Dunne A: The

Nrf2-HO-1 system and inflammaging. Front Immunol. 15:14570102024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Grebe A, Hoss F and Latz E: NLRP3

Inflammasome and the IL-1 pathway in atherosclerosis. Circ Res.

122:1722–1740. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang K, Liu H, Sun W, Guo J, Jiang Z, Xu S

and Miao Z: Eucalyptol alleviates avermectin exposure-induced

apoptosis and necroptosis of grass carp hepatocytes by regulating

ROS/NLRP3 axis. Aquat Toxicol. 264:1067392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fu J and Wu H: Structural mechanisms of

NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation. Annu Rev Immunol.

41:301–316. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tall AR and Bornfeldt KE: Inflammasomes

and atherosclerosis: A mixed picture. Circ Res. 132:1505–1520.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hort J, Duning T and Hoerr R: Ginkgo

biloba Extract EGb 761 in the treatment of patients with mild

neurocognitive impairment: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis

Treat. 19:647–660. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Boateng ID: Ginkgols and bilobols in

Ginkgo biloba L. A review of their extraction and bioactivities.

Phytother Res. 37:3211–3223. 2023. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang R, Han D, Li Z, Shen C, Zhang Y, Li

J, Yan G, Li S, Hu B, Li J and Liu P: Corrigendum: Ginkgolide C

alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced inflammatory

injury via inhibition of CD40-NF-κB pathway. Front Pharmacol.

15:14925202024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li B, Zhang B, Li Z, Li S, Li J, Wang A,

Hou J, Xu J and Zhang R: Ginkgolide C attenuates cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion-induced inflammatory impairments by

suppressing CD40/NF-κB pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 312:1165372023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Emanueli C, Schmidt AM and Golledge J:

Unveiling intriguing links between limb ischemia, systemic

inflammation, and progressive atherosclerosis: A tangled and

interconnected web. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 43:907–909.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tasouli-Drakou V, Ogurek I, Shaikh T,

Ringor M, DiCaro MV and Lei K: Atherosclerosis: A comprehensive

review of molecular factors and mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci.

26:13642025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang X, Shen Y, Shang M, Liu X and Munn

LL: Endothelial mechanobiology in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res.

119:1656–1675. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang DR, Wang MY, Zhang CL and Wang Y:

Endothelial dysfunction in vascular complications of diabetes: A

comprehensive review of mechanisms and implications. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15:13592552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

He B, Nie Q, Wang F, Wang X, Zhou Y, Wang

C, Guo J, Fan X, Ye Z, Liu P and Wen J: Hyperuricemia promotes the

progression of atherosclerosis by activating endothelial cell

pyroptosis via the ROS/NLRP3 pathway. J Cell Physiol.

238:1808–1822. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang B, Yu J, Bao L, Feng D, Qin Y, Fan

D, Hong X and Chen Y: Cynarin inhibits microglia-induced pyroptosis

and neuroinflammation via Nrf2/ROS/NLRP3 axis after spinal cord

injury. Inflamm Res. 73:1981–1994. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lin J, Sun X and Yang L: Effects and

safety of Ginkgo biloba on depression: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 15:13640302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fang WH, Bonavida V, Agrawal DK and

Thankam FG: Hyperlipidemia in tendon injury: Chronicles of

low-density lipoproteins. Cell Tissue Res. 392:431–442. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Silva H and Martins FG: Cardiovascular

activity of Ginkgo biloba-An insight from healthy subjects. Biology

(Basel). 12:152022.

|

|

29

|

Kong P, Cui ZY, Huang XF, Zhang DD, Guo RJ

and Han M: Inflammation and atherosclerosis: Signaling pathways and

therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1312022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Weber C, Habenicht AJR and von

Hundelshausen P: Novel mechanisms and therapeutic targets in

atherosclerosis: Inflammation and beyond. Eur Heart J.

44:2672–2681. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang S, Hong F, Ma C and Yang S: Hepatic

lipid metabolism disorder and atherosclerosis. Endocr Metab Immune

Disord Drug Targets. 22:590–600. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lubrano V, Ndreu R and Balzan S: Classes

of lipid mediators and their effects on vascular inflammation in

atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 24:16372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bu LL, Yuan HH, Xie LL, Guo MH, Liao DF

and Zheng XL: New dawn for atherosclerosis: Vascular endothelial

cell senescence and death. Int J Mol Sci. 24:151602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Pintó X, Fanlo M, Esteve V and Millán J:

Remnant cholesterol, vascular risk, and prevention of

atherosclerosis. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 35:206–217.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gaggini M, Gorini F and Vassalle C: Lipids

in atherosclerosis: Pathophysiology and the role of calculated

lipid indices in assessing cardiovascular risk in patients with

hyperlipidemia. Int J Mol Sci. 24:752022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Dabravolski SA, Churov AV, Beloyartsev DF,

Kovyanova TI, Lyapina IN, Sukhorukov VN and Orekhov AN: The role of

NRF2 function and regulation in atherosclerosis: An update. Mol

Cell Biochem. 480:3935–3949. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jomova K, Alomar SY, Valko R, Liska J,

Nepovimova E, Kuca K and Valko M: Flavonoids and their role in

oxidative stress, inflammation, and human diseases. Chem Biol

Interact. 413:1114892025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yan Q, Liu S, Sun Y, Chen C, Yang S, Lin

M, Long J, Yao J, Lin Y, Yi F, et al: Targeting oxidative stress as

a preventive and therapeutic approach for cardiovascular disease. J

Transl Med. 21:5192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang Z, Dai Y, Xiao Y and Liu Q:

Protective effects of catalpol on cardio-cerebrovascular diseases:

A comprehensive review. J Pharm Anal. 13:1089–1101. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Han H, Zhang G, Zhang X and Zhao Q:

Nrf2-mediated ferroptosis inhibition: A novel approach for managing

inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology. 32:2961–2986. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Meng T, Li X, Li C, Liu J, Chang H, Jiang

N, Li J, Zhou Y and Liu Z: Natural products of traditional Chinese

medicine treat atherosclerosis by regulating inflammatory and

oxidative stress pathways. Front Pharmacol. 13:9975982022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Huang Z, Wu M, Zeng L and Wang D: The

beneficial role of Nrf2 in the endothelial dysfunction of

atherosclerosis. Cardiol Res Pract. 2022:42877112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Pfefferlé M and Vallelian F: Transcription

factor NRF2 in shaping myeloid cell differentiation and function.

Adv Exp Med Biol. 1459:159–195. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhang XN, Yu ZL, Chen JY, Li XY, Wang ZP,

Wu M and Liu LT: The crosstalk between NLRP3 inflammasome and gut

microbiome in atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Res. 181:1062892022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Tanase DM, Valasciuc E, Gosav EM, Ouatu A,

Buliga-Finis ON, Floria M, Maranduca MA and Serban IL: Portrayal of

NLRP3 inflammasome in atherosclerosis: Current knowledge and

therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci. 24:81622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang H and Dhalla NS: The role of

Pro-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular

disease. Int J Mol Sci. 25:10822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Asemi R, Omidi Najafabadi E, Mahmoudian Z,

Reiter RJ, Mansournia MA and Asemi Z: Melatonin as a treatment for

atherosclerosis: Focus on programmed cell death, inflammation and

oxidative stress. J Cardiothorac Surg. 20:1942025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|