Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is defined as kidney

damage resulting from diabetes. In total, ~40% of patients with

diabetes will eventually develop DKD (1,2).

Moreover, with disease progression, patients with DKD experience a

decline in renal function, ultimately culminating in kidney failure

and end-stage kidney disease (3). Under the pathological condition of

DKD, metabolic dysregulation can trigger oxidative stress (4-7),

inflammatory cascades (8),

tubulointerstitial injury (9,10) and glomerular endothelial

dysfunction via fenestration alterations (11). Therefore, there is an urgent

requirement to fully understand the pathological changes in

different regions of DKD and explore effective diagnostic and

therapeutic approaches.

Metabolomics is an omics technology that enables the

comprehensive analysis of metabolites in organisms (12). Classic metabolomics methods focus

on identifying and quantifying metabolites, providing a global

metabolic pathway profile that captures systemic alterations under

physiological or pathological conditions (13,14). This enables the identification of

metabolic disparities across diverse sample cohorts (15,16). However, data obtained by these

methods lack information on the spatial distribution of metabolites

within tissues. This limitation has driven the development of

spatial metabolomics.

Spatial metabolomics is a technology developed over

the past two decades, and its application scope has been

continuously expanded in the last 5 years with the advancement of

technical methodologies (17,18). This technique integrates

metabolomics with spatial biology, offering a novel approach to

explore the heterogeneity of metabolites within tissue

microenvironments under disease conditions. Recent studies on

cancer types such as hepatocellular carcinoma have reported that

the spatial distribution patterns of immune cells can more

accurately predict diseases than gene expression levels alone

(19-22). This highlights the importance of

spatial location information in disease research. Currently,

spatial metabolomics has demonstrated great potential in several

fields, including neuroscience (23,24), microbiology (25), plant science (26), drug development (27) and clinical applications (28). Notably, the application of

spatial metabolomics in kidney research is still in its

developmental stage, with most existing studies concentrating on

the heterogeneity between the renal cortex and medulla (29-31).

The present review discusses the fundamental

principles and advantages of spatial metabolomics technology,

summarizing recent advancements in its application to metabolic

disorders in DKD. The focus is on characteristics associated with

carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism

and nucleic acid metabolism within cortical and medullary regions.

Finally, the review outlines potential future research directions,

aiming to provide valuable insights and contributions to

researchers in the fields of DKD and related pathophysiology.

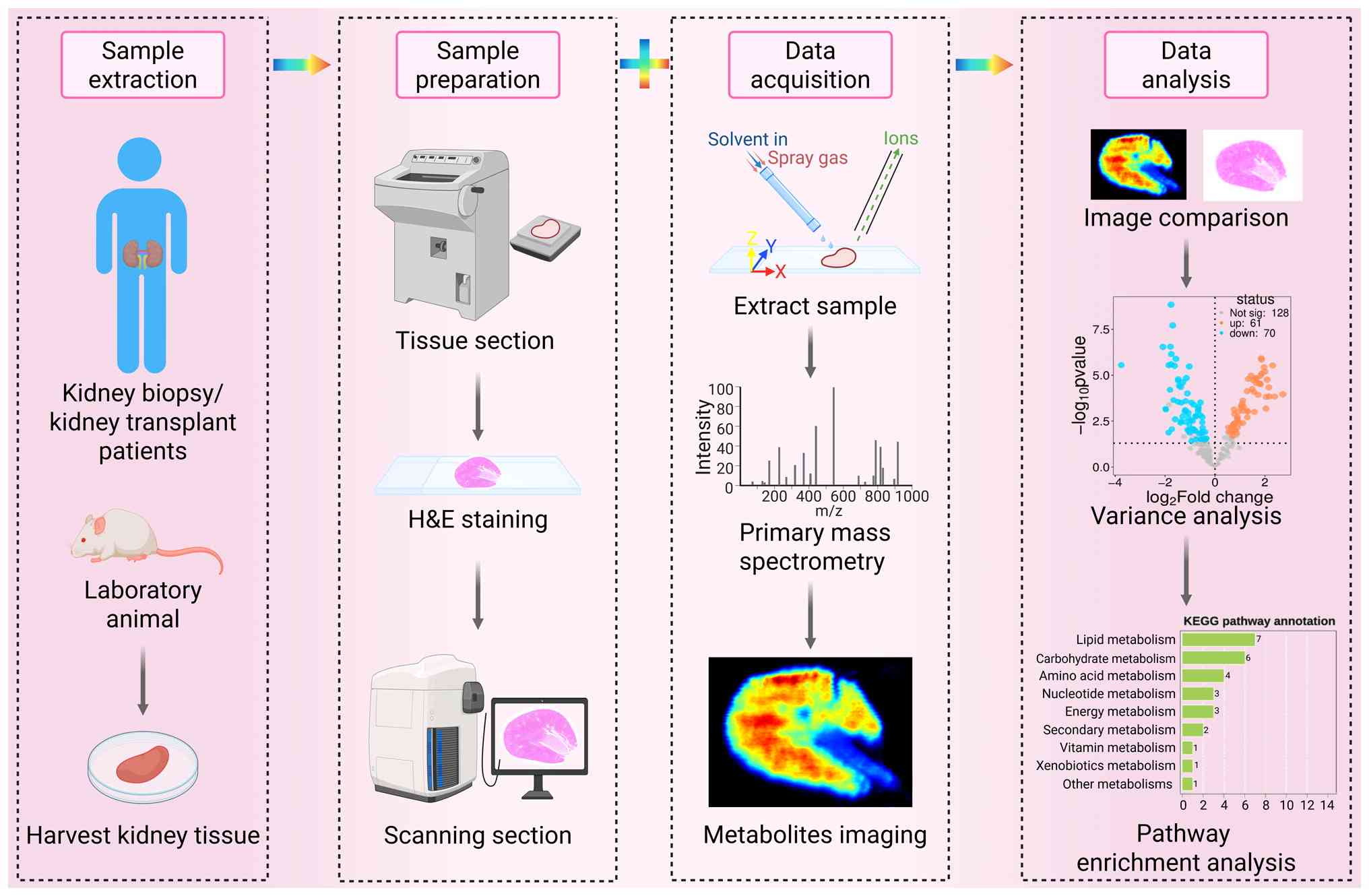

Spatial metabolomics represents a cutting-edge

technology that integrates mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) with the

principles of metabolomics. The fundamental working principle

involves employing specific ionization methods to ionize

metabolites present in tissue sections of samples (32). Currently, three primary

ionization techniques are widely utilized in spatial metabolomics:

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-MSI, desorption

electrospray ionization (DESI)-MSI and secondary ion (SIMS)-MSI

(33-38). These ionized metabolites are then

sent to a mass spectrometer for mass analysis, where they are

analyzed to obtain information on their mass-to-charge ratio. At

the same time, the spatial distribution images of metabolites in

the tissue sections are reconstructed by combining the mass

spectrometry data with the spatial coordinate information of the

tissue samples (32,39,40). To enable co-localization

analysis, previous studies spatially aligned consecutive kidney

sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin with MSI data (41,42) (Fig. 1).

The core advantage of spatial metabolomics is its

capability to resolve spatial information, enabling in situ

localization of metabolites within biological tissues. This is

particularly valuable in kidney research, where the average

cellular diameter is ~10 μm (43). MALDI-MSI boasts high sensitivity

and the capability to detect low-abundance metabolites, thus

occupying a dominant position in the field of spatial metabolomics.

Using MALDI-MSI with a spatial resolution of 20 μm, the

overall metabolic heterogeneity distribution from the cortex to the

medulla in DKD kidney sections can be clearly visualized, revealing

metabolic gradient changes in different functional regions under

disease conditions (31). By

contrast, employing a higher resolution of 5 μm with

MALDI-MSI and isotope labeling enables in situ,

cell-type-specific dynamic metabolic measurements, uncovering

cellular metabolism within the tissue structure (44). A key advantage of DESI-MSI is its

compatibility with fresh tissues, facilitating rapid detection of

clinical samples. Operating at room temperature and atmospheric

pressure, DESI-MSI requires no complex sample pretreatment

(45,46). With a typical spatial resolution

of 50-200 μm (47) and a

moderate detectable molecular weight range, it is more suitable for

imaging large tissue regions. This facilitates the investigation of

the pervasive metabolic landscape in advanced DKD, a condition

often characterized by extensive interstitial fibrosis. SIMS-MSI

operates under high-vacuum conditions and has stringent temperature

requirements. While SIMS-MSI achieves an ultra-high spatial

resolution of <1 μm, it has the narrowest detectable

molecular weight range among all the discussed techniques.

Nevertheless, it provides the highest spatial resolution among the

technologies addressed here, making it ideally suited for

single-cell metabolomics research (35,37). Therefore, the selection of an

appropriate spatial metabolomics technique for DKD research

necessitates a trade-off between its spatial resolution and

metabolite coverage. Future studies may integrate multiple

technologies to obtain more comprehensive metabolic information,

thereby enhancing our in-depth understanding of disease

mechanisms.

The kidney is a vital excretory and regulatory

organ, whose functions rely on the sophisticated structure and

division of labor between the renal cortex and medulla (48,49). The renal cortex, composed

primarily of abundant renal corpuscles and proximal tubules, is

principally responsible for blood filtration, reabsorption and

secretion of substances (50,51). By contrast, the renal medulla,

through the loops of Henle and collecting ducts, maintains internal

environmental homeostasis by regulating water-electrolyte balance

and urine concentration (52,53). Owing to these functional

distinctions between the two regions, there are notable differences

in their demand for and utilization of metabolites (54).

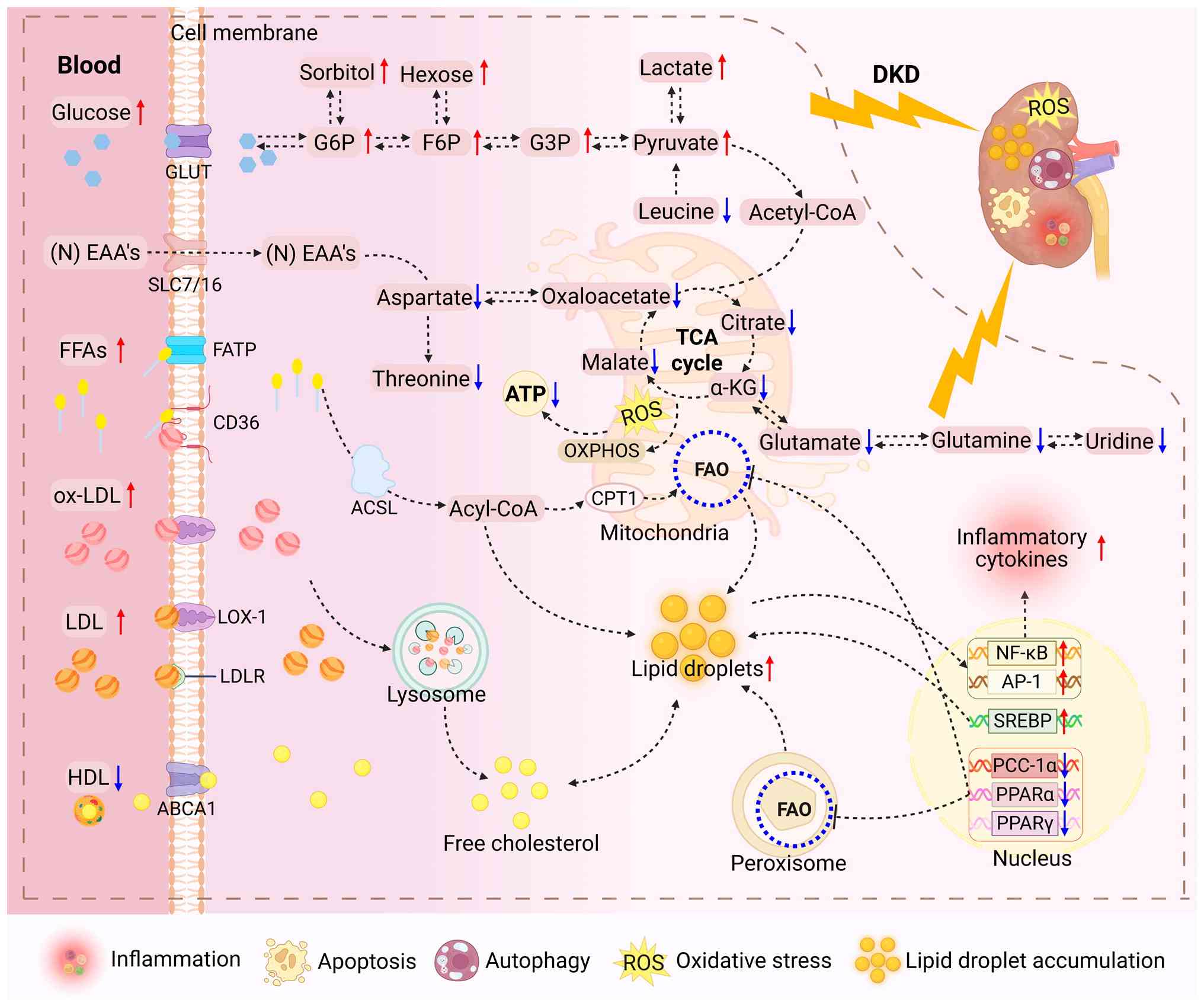

In the onset and progression of DKD, the

dysregulation of regional metabolic functions is particularly

critical, and metabolomics research provides an essential

technological approach for systematically elucidating its molecular

mechanisms (55,56). Classical metabolomics, through

the synergistic application of non-targeted metabolic profiling and

targeted metabolite quantification strategies, has systematically

constructed a comprehensive molecular map of the metabolic network

of the kidney (Fig. 2),

revealing ATP depletion driven by mitochondrial dysfunction,

imbalance of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates and

inhibition of fatty acid oxidation (FAO), which ultimately leads to

apoptosis, autophagy, oxidative stress and lipid droplet

accumulation (57,58). Therefore, the integration of

spatial metabolomics has enabled unprecedented precision in

regional metabolite localization (59,60).

A hyperglycemic environment can induce an imbalance

in energy metabolism homeostasis, characterized by mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming

(61,62). Notably, the renal medulla mainly

relies on glucose for energy (63,64). Previous research reported that

the levels of hexoses in the cortical tissue increased when male

C57BL/6J-Ins2Akita mice reached 17 weeks of age (65). When DKD rats were 24 and 28 weeks

old, respectively, the kidney glucose levels exhibited a marked

global increase, with particularly pronounced elevations observed

in the cortex region (31,66). By contrast, rats subjected to

prolonged feeding exhibited notably reduced glucose levels in the

renal medulla region (66).

However, it should be noted that these findings reflect the

complexity of metabolic heterogeneity across different regions and

time points. The discrepancies in glucose levels between the renal

cortex and medulla have led to varied interpretations of the

pathophysiological mechanisms of DKD, highlighting the necessity of

considering tissue specificity and its potential impacts on overall

disease progression when investigating metabolic alterations.

The distribution of TCA cycle intermediates also

exhibits spatial heterogeneity. Clinical studies have reported

that, compared with healthy controls, succinic acid and malic acid

are markedly reduced in kidney biopsies of patients with type 1

diabetes across several kidney regions, suggesting subclinical

mitochondrial dysfunction (67).

These spatial distribution abnormalities are highly congruent with

the global findings of classical metabolomics. In individuals with

DKD, enzymes involved in glycolytic, sorbitol, methylglyoxal and

mitochondrial pathways have been reported to exhibit reduced

expression and activity. Moreover, pyruvate kinase M2 demonstrates

marked decreases in both its transcriptional expression and

enzymatic activity (68). From

the perspective of metabolic pathways, the accumulation of TCA

cycle intermediates induces a burst of mitochondrial reactive

oxygen species, driving the progression of DKD (69,70). Table I consolidates information on

spatially resolved metabolic alterations in carbohydrate and TCA

cycle intermediates.

Classical metabolomics studies have systematically

characterized the systemic lipid metabolic dysregulation in DKD,

elucidating imbalances in cholesterol esterification, phospholipid

remodeling and triglyceride (TG) accumulation (71-73). Moreover, spatial metabolomics has

revealed notable regional variations in phospholipids and TGs in

DKD kidneys (66,74). Phospholipids are key components

of cell membranes and are associated with the pathogenesis of DKD

(75). Lysophosphatidic acid

(LPA), lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamine

(LPE) and lycerylphosphorylethanolamine (GPE) are all lipid

metabolites derived from phospholipids. In DKD model mice, the

levels of LPA, LPC, LPE and GPE in the cortex were reported to be

markedly elevated (65,76,77). Moreover, changes in the

phosphatidylcholine (PC)/phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) ratio have

been reported to have an impact on cellular processes associated

with health and disease (77).

In cardiovascular disease patients at risk of insulin resistance,

changes in the PC/PE ratio affect cellular processes related to

cardiovascular health and disease progression by regulating

inflammatory responses and the physiological state of

cardiomyocytes (78). Notably,

in db/db mice, the levels of PC/PE ratio in the cortex and medulla

showed opposite changes, indicating that metabolic responses in

different kidney regions during disease progression are both

complex and region-specific (66). TGs are subject to rapid turnover

and re-arrangement of fatty acids (FAs) (79). A recent spatial multi-omics study

of long-term DKD reported a marked accumulation of TG in the

medullary region (74).

Furthermore, in DKD rats at 24 weeks of age, renal cortical oleic

acid levels were elevated, whilst polyunsaturated FAs, including

linoleic acid, were markedly reduced (31).

Spatial metabolomics has advanced the understanding

of lipid changes in the kidneys of DKD to the level of proximal

tubular cells. Under physiological conditions, the kidney tubules

predominantly utilize FAs (64,80,81), and this utilization requires

carnitine as a carrier, facilitating the transport of long-chain

fatty acids into the mitochondria via the carnitine shuttle system

(82). Spatial metabolomics and

multi-omics analyses of human kidney samples reported that the

detection of acylcarnitines in cortical samples was insufficiently

sensitive (83). This

observation is consistent with the known downregulation of FAO in

chronic kidney disease, indicating impaired FAO in proximal tubular

cells of patients with kidney disease (84). Detailed lipid changes are

presented in Table II.

It should be noted that the inherent differences in

sample size, animal model selection and experimental methodologies

among the aforementioned studies may impose significant constraints

on the reproducibility and generalizability of the results.

Although spatial metabolomics has successfully revealed the

regional heterogeneity of lipid distribution in the kidney,

existing research is mostly confined to single-species models

(e.g., db/db mice and DKD rats). Moreover, the sample size used for

spatial metabolomics analysis is only up to 6 animals per group,

coupled with the lack of dynamic tracking data across different

disease stages. This may not only induce biases in interpreting the

causal relationship between lipid metabolic disorders and the

pathological progression of DKD, but may also hinder the accurate

reflection of the clinical metabolic characteristics of human DKD.

Therefore, future studies should prioritize optimizing experimental

designs by expanding sample sizes, diversifying animal models and

conducting dynamic monitoring across multiple disease stages, so as

to more comprehensively elucidate the metabolic response mechanisms

of distinct renal regions during DKD progression.

The dysregulation of amino acid metabolism in DKD is

not merely a consequence of renal dysfunction, but an active driver

of pathogenesis (85,86). Spatial metabolomics techniques

have revealed changes in amino acids in specific regions of the

kidney. In db/db mice, glutamate, spermine, taurine and spermidine

were notably reduced in both the cortex and medulla, whilst

histamine, putrescine and indoxyl sulfate markedly accumulated in

the cortex (66,87,88). Notably, spermidine has been

reported to exhibit multiple pharmacological effects, including

anti-aging, anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation and cardiovascular

protection (89-92). Sulfate is a protein-binding

gut-derived uremic toxin that has been reported to be closely

associated with podocyte loss in DKD (93). Our previous research demonstrated

that Tangshen formula can effectively decrease the concentration of

sulfate during the treatment of DKD (94). Furthermore, compared with that in

db/db mice, glutamate was reported to be similarly reduced in the

cortex and medulla of high-fat diet and STZ-induced DKD rats

(31,66). Additionally, glutamine,

aspartate, threonine and leucine/isoleucine were reported to be

markedly reduced (31,66,95). The heterogeneity of amino acid

and related metabolism in the cortex and medulla of DKD revealed by

spatial metabolomics is summarized in Table III.

Classic metabolomic studies have demonstrated that

after inducing diabetes in rats via injection of alloxan, the

levels of purine metabolites in their bodies are significantly

elevated, including uric acid (the end product of purine

metabolism) and metabolic intermediates such as xanthine,

hypoxanthine, adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and inosine (96-98). Notably, a large-scale clinical

metabolomics study, involving 4,503 healthy controls and 1,875

patients with DKD, reported that the levels of uracil in patients

with DKD were markedly reduced (99). These phenomena suggest unique

nucleic acid metabolic disturbances. However, to clarify their

local in situ distribution and pathological significance

within the kidney, spatial metabolomics is required.

Spatially resolved analyses have elucidated

compartment-specific nucleotide dysregulation, offering mechanistic

insights into DKD pathology (31,100). In db/db mice, the level of AMP,

a key intermediate in purine nucleotide metabolism, was reported to

be notably elevated across all renal regions (66). Moreover, in DKD rats, the levels

of AMP and guanosine monophosphate (GMP) were reported to be

markedly increased in the cortex, whilst they showed a decreasing

trend in the medulla (31).

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) integrates growth factor and

insulin signaling pathways to orchestrate critical cellular

processes, including cell proliferation, motility, survival,

protein synthesis, autophagy and transcriptional regulation

(101). In DKD, abnormal

activation of the mTOR pathway can mediate metabolic reprogramming,

with adenine reported to drive kidney pathological progression

through this pathway. Spatial metabolomics studies reveal that in

normal kidneys, adenine is primarily localized in the glomeruli and

vascular regions (102,103). However, in the pathology of

DKD, adenine diffusely increases throughout the entire tissue

section, particularly in the regions of sclerotic vessels, mildly

sclerotic glomeruli, atrophic renal tubules and areas of

interstitial inflammation (102). The importance of adenine in

rescue and targeted therapies has been elucidated using multimodal

omics approaches (104). As the

most abundant modified nucleoside in several RNA species,

pseudouridine has been recognized as a new biomarker demonstrating

better performance than creatinine in chronic kidney disease

stratification (105). Previous

studies have reported that diabetic mice exhibit relatively high

levels of pseudouridine in the cortex tissue (65). Table IV summarizes spatial

metabolomics research revealing dysregulation of nucleotide and

purine metabolism in kidneys of organisms with DKD.

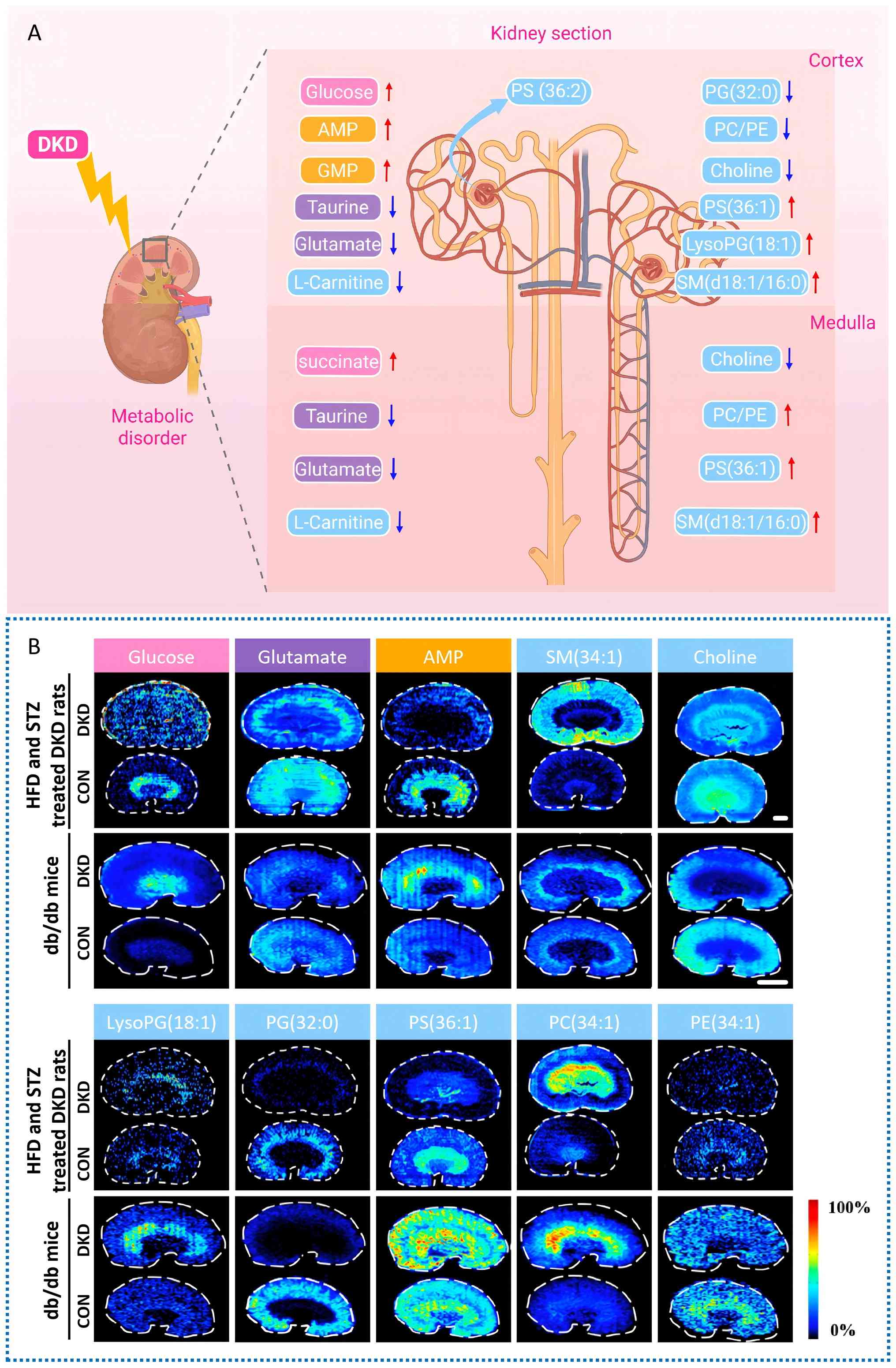

In-depth analyses of metabolic remodeling and

pathological mechanisms in the renal microenvironment is the

theoretical cornerstone for developing new targeted intervention

strategies for DKD. The present review systematically summarizes

the cutting-edge advancements in spatial metabolomics in this

field. Its core contribution lies in overcoming the limitations of

traditional global tissue analysis, revealing the fundamental

spatial heterogeneity of metabolic regulation along the

cortical-medullary axis and within specific pathological

structures. Synthesizing existing research findings, the metabolite

profiles in the renal cortex and medulla exhibit marked

region-specific dysregulation across multiple DKD animal models. In

the cortex region, the levels of glucose, AMP, GMP, PS(36:2),

PS(36:1), LysoPG(18:1) and SM(d18:1/16:0) are significantly

upregulated; concurrently, the levels of taurine, glutamate,

L-carnitine, PG(32:0), PC/PE and choline are notably downregulated.

In the medulla region, the levels of succinate, PS(36:1),

SM(d18:1/16:0) and PC/PE show significant elevation; meanwhile, the

levels of taurine, glutamate, L-carnitine and choline also display

a decreasing trend. Fig. 3

offers an intuitive visual overview and acts as a reference for

identifying regional or global metabolic targets in subsequent

targeted interventions. Metabolites exhibit similar or opposite

distribution and regional accumulation in different functional

areas of the kidney. These are key spatial details that traditional

tissue homogenate-based metabolomics cannot capture. Conventional

methods provide overall averages, masking contrasting trends across

anatomical regions. This obscures the true picture of metabolic

disorders.

The core value of spatial metabolomics lies in

addressing the 'where' and 'how' questions that conventional

techniques cannot resolve, thereby revealing the molecular

mechanisms and causal relationships driving pathological processes.

It is known that metabolic disorders disrupt cellular energy

homeostasis; for example, in the renal hyperglycemic environment,

the pentose phosphate, polyol and hexosamine pathways are

activated, leading to the local accumulation of toxic metabolites,

which in turn activate key signaling pathways and ultimately

trigger core pathological processes such as inflammation, oxidative

stress and fibrosis (106,107). However, classical metabolomics

cannot clearly illustrate in which region of the kidney these

metabolic disorders and signaling pathway activations occur, nor

how the spatial distribution of metabolites drives pathological

processes. This is where spatial metabolomics demonstrates its

unique value, and the research on endogenous adenine metabolism is

a prime example. The accumulation of adenine in specific regions

inhibits 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase whilst activating the

mTORC1-S6K signaling axis, thereby translating metabolic

dysregulation into typical pathological phenotypes such as cellular

hypertrophy and tissue fibrosis (108-111). By integrating spatial

metabolomics and spatial proteomics, research has reported that

metformin acts in the cortical-medullary outer zone, upregulating

nephrosis 2 and inhibiting IL-17 signaling (112). This specifically reverses

purine metabolic imbalance, thereby blocking glomerulosclerosis and

interstitial fibrosis (112).

This intuitively shows how the three-dimensional spatial coupling

of metabolism, transcription and proteins precisely remodels the

pathological microenvironment. Nevertheless, notably, knowledge

gaps remain regarding the regional dynamics of metabolites and the

precise mechanisms by which they promote renal pathology at the

molecular and cellular levels. The key direction for future

research should shift from current descriptive associations to

systematic functional validation and mechanistic exploration of

these spatially anchored metabolites.

As a pivotal methodology for investigating the

spatial distribution of metabolites in vivo, spatial

metabolomics is an indispensable component of spatial multi-omics

research. This technology not only provides a novel spatial

perspective for understanding DKD but also deepens the

comprehension of disease-specific metabolic processes. However, its

application in the field of DKD still faces several pressing

challenges that need to be addressed, for example: i) There are

limitations in technical sensitivity and resolution. Low-abundance

metabolites are prone to loss in imaging (113). Most existing studies only

localize metabolites to large anatomical regions, such as the

cortex or medulla, and they struggle to accurately depict the true

distribution of these metabolites within fine functional units,

such as glomeruli and specific tubular segments. If the resolution

is enhanced, the acquisition speed may consequently be reduced

(114). ii) The identification

and annotation of metabolites often lack sufficient precision. When

annotating metabolites, certain metabolites, such as isomers,

cannot be annotated with absolute certainty (17,115,116). iii) Data analysis and

interpretation present challenges. Crucial challenges exist in data

and signal processing, data comparability and the need for

optimization tailored to each tissue type (117). These challenges indicate that

engineers and researchers need to address the shortcomings to

provide more accurate spatial metabolic maps for the mechanistic

analysis of complex diseases such as DKD.

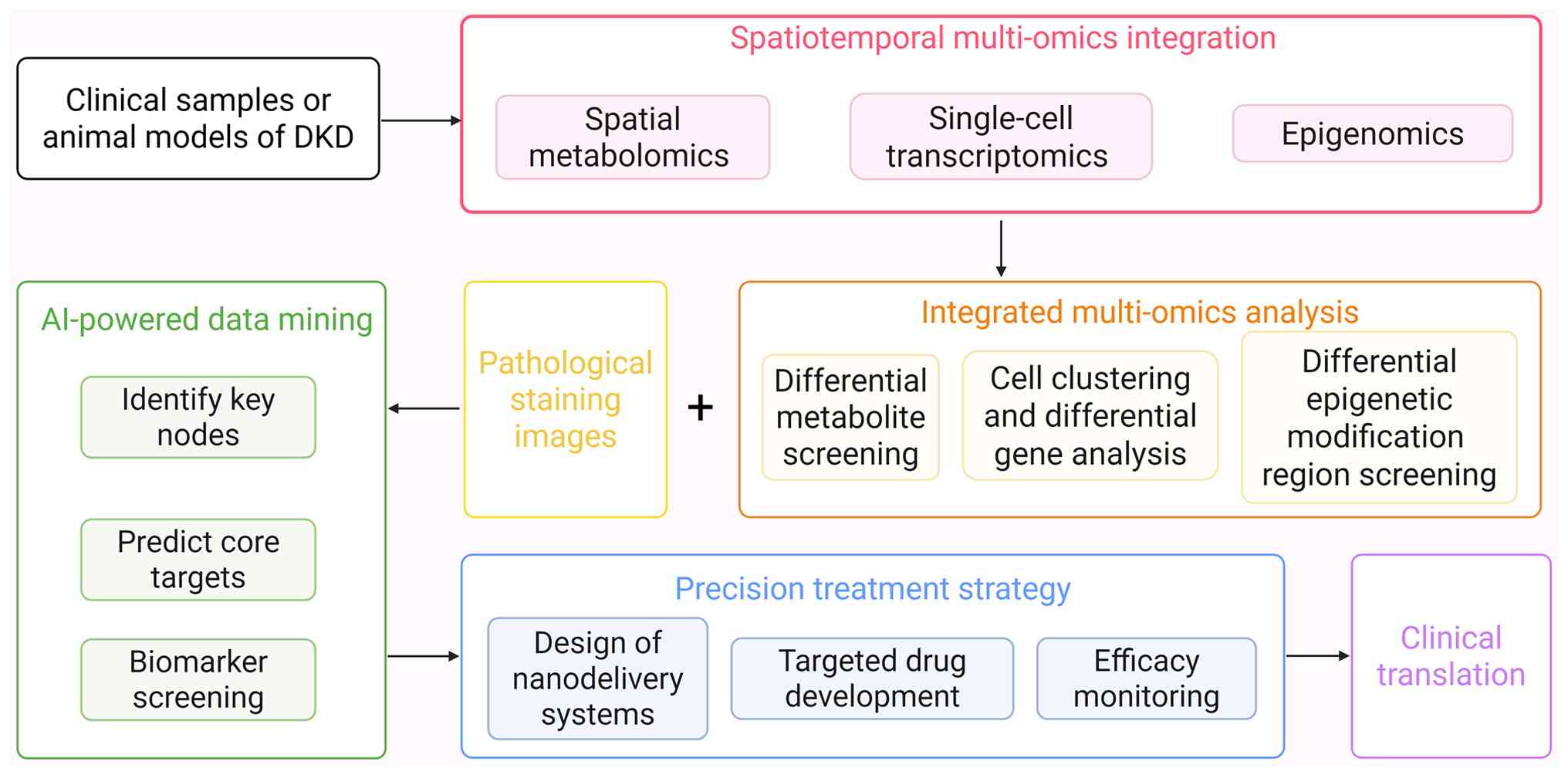

Moreover, spatial metabolomics can directly present

actual biochemical activities and functional metabolic outcomes,

offering new opportunities for DKD research: Firstly, applying

integrated spatial multi-omics to establish causal mechanisms. As

life science research progresses, single-omics approaches are

increasingly inadequate for comprehensively deciphering complex

biological processes. The integration of spatial metabolomics with

transcriptomics and proteomics has become more prevalent (118). By integrating data from spatial

metabolomics and spatial transcriptomics, researchers can associate

changes in metabolite levels with alterations in gene expression,

enabling a deeper exploration of the molecular mechanisms

underlying metabolic regulation (119). Secondly, targeted strategies

can address regional metabolic heterogeneity. This moves beyond

conventional treatment, enabling precision medicine. Spatial

metabolomics technology can assess changes in the distribution of

metabolites after drug intervention, effectively evaluate DKD

drugs, clarify the mechanism of drug treatment and monitor

treatment responses, thereby helping to further optimize treatment

regimens (31). By combining

nanotechnology with drug targeted delivery systems, precise

treatment can be implemented for specific regions of metabolic

heterogeneity (120). The

combined application of these technologies could provide new

possibilities for formulating personalized DKD treatment plans and

achieving accurate prognostic assessment for patients with DKD

(Fig. 4).

The present review systematically examines the

regional metabolic characteristics of DKD, and it highlights the

unique value of spatial metabolomics in elucidating the

pathological mechanisms of DKD. With continuous improvements in

spatial resolution and quantitative analytical techniques, this

technology is expected to serve a critical role in the precision

diagnosis and treatment of DKD. Future research may delve deeper

into the cellular level, focusing on elucidating the more refined

spatial localization and functional associations of specific

metabolites. With the continuous advancement of multi-center data

accumulation and clinical trial validation, region-specific

metabolites or key enzymes are expected to be translated into

reliable diagnostic biomarkers and intervenable therapeutic

targets. Such initiatives will enable the tailored development of

individualized therapies, ultimately boosting early diagnostic

efficiency and optimizing long-term outcomes for patients with

DKD.

Not applicable.

HL made substantial contributions to writing the

original draft, reviewing and editing the manuscript, acquiring

resources, conducting investigation, developing the

conceptualization and performing visualization. TZ participated in

reviewing and editing the manuscript, carrying out investigation,

securing funding acquisition and conceptualization. DF contributed

to reviewing and editing the manuscript, as well as

conceptualization. YL and BZ both took part in reviewing and

editing the manuscript, and visualization. WC and GM were involved

in visualization and investigation. JR made contributions to

writing the original draft and visualization. SD participated in

investigation and visualization. All authors have read and approved

the final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82374224), the Beijing Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. 7252270), the Noncommunicable Chronic

Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (grant no.

2023ZD0509306), National High Level Hospital Clinical Research

Funding (grant no. 2024-NHLHCRF-PY I-07) and National High Level

Hospital Clinical Research Funding (grant no.

2024-NHLHCRF-JBGS-ZH-01).

|

1

|

GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators: Global,

regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with

projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 402:203–234. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Joumaa JP, Raffoul A, Sarkis C, Chatrieh

E, Zaidan S, Attieh P, Harb F, Azar S and Ghadieh HE: Mechanisms,

biomarkers, and treatment approaches for diabetic kidney disease:

Current insights and future perspectives. J Clin Med. 14:7272025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Johansen KL, Gilbertson DT, Li SL, Li S,

Liu J, Roetker NS, Ku E, Schulman IH, Greer RC, Chan K, et al: US

renal data system 2023 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney

disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 83:A8–A13. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Vartak T, Godson C and Brennan E:

Therapeutic potential of pro-resolving mediators in diabetic kidney

disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 178:1139652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cleveland KH and Schnellmann RG:

Pharmacological targeting of mitochondria in diabetic kidney

disease. Pharmacol Rev. 75:250–262. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tuttle KR, Agarwal R, Alpers CE, Bakris

GL, Brosius FC, Kolkhof P and Uribarri J: Molecular mechanisms and

therapeutic targets for diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int.

102:248–260. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sharma V, Khokhar M, Panigrahi P, Gadwal

A, Setia P and Purohit P: Advancements, Challenges, and clinical

implications of integration of metabolomics technologies in

diabetic nephropathy. Clin Chim Acta. 561:1198422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rayego-Mateos S, Rodrigues-Diez RR,

Fernandez-Fernandez B, Mora-Fernández C, Marchant V, Donate-Correa

J, Navarro-González JF, Ortiz A and Ruiz-Ortega M: Targeting

inflammation to treat diabetic kidney disease: The road to 2030.

Kidney Int. 103:282–296. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Xu F, Jiang H, Li X, Pan J, Li H, Wang L,

Zhang P, Chen J, Qiu S, Xie Y, et al: Discovery of PRDM16-Mediated

TRPA1 induction as the mechanism for low Tubulo-interstitial

fibrosis in diabetic kidney disease. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e23067042024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liu D, Chen X, He W, Lu M, Li M, Zhang S,

Xie J, Zhang Y and Wang W: Update on the pathogenesis, diagnosis,

and treatment of diabetic tubulopathy. Integrat Med Nephrol Androl.

11:e23–00029. 2024.

|

|

11

|

Empitu MA, Rinastiti P and

Kadariswantiningsih IN: Targeting endothelin signaling in podocyte

injury and diabetic nephropathy-diabetic kidney disease. J Nephrol.

38:49–60. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Muthubharathi BC, Gowripriya T and

Balamurugan K: Metabolomics: Small molecules that matter more. Mol

Omics. 17:210–229. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou M, Sun W, Gao Y, Jiang B, Sun T, Xu

R, Zhang X, Wang Q, Xuan Q and Ma S: Metabolomic profiling reveals

interindividual metabolic variability and its association with

cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome risk. Cardiovasc Diabetol.

24:3152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Barovic M, Hahn JJ, Heinrich A, Adhikari

T, Schwarz P, Mirtschink P, Funk A, Kabisch S, Pfeiffer AFH, Blüher

M, et al: Proteomic and metabolomic signatures in prediabetes

progressing to diabetes or reversing to normoglycemia within 1

year. Diabetes Care. 48:405–415. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pereira PR, Carrageta DF, Oliveira PF,

Rodrigues A, Alves MG and Monteiro MP: Metabolomics as a tool for

the early diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic kidney disease. Med

Res Rev. 42:1518–1544. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Md Dom ZI, Moon S, Satake E, Hirohama D,

Palmer ND, Lampert H, Ficociello LH, Abedini A, Fernandez K, Liang

X, et al: Urinary Complement proteome strongly linked to diabetic

kidney disease progression. Nat Commun. 16:72912025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Alexandrov T: Spatial metabolomics and

imaging mass spectrometry in the age of artificial intelligence.

Annu Rev Biomed Data Sci. 3:61–87. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sharma K, Hansen J, Susztak K, Eberlin L,

Anderton CR, Alexandrov T and Iyengar R: Spatial metabolomics and

multiomics integration for breakthroughs in precision medicine for

kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. Oct 9–2025. View Article : Google Scholar : Epub ahead of

print. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Najumudeen AK and Vande voorde J: Spatial

metabolomics to unravel cellular metabolism. Nat Rev Genet.

26:2282025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Allam M and Coskun AF: Combining spatial

metabolomics and proteomics profiling of single cells. Nat Rev

Immunol. 24:7012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sun N, Krauss T, Seeliger C, Kunzke T,

Stöckl B, Feuchtinger A, Zhang C, Voss A, Heisz S, Prokopchuk O, et

al: Inter-organ cross-talk in human cancer cachexia revealed by

spatial metabolomics. Metabolism. 161:1560342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jia G, He P, Dai T, Goh D, Wang J, Sun M,

Wee F, Li F, Lim JCT, Hao S, et al: Spatial immune scoring system

predicts hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Nature.

640:1031–1041. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jiang X, Li T, Zhou Y, Wang X, Dan Z,

Huang J and He J: A new direction in metabolomics: Analysis of the

central nervous system based on spatially resolved metabolomics.

TrAC Trends Analytical Chemist. 165:1171032023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Miller A, York EM, Stopka SA,

Martínez-François JR, Hossain MA, Baquer G, Regan MS, Agar NYR and

Yellen G: Spatially resolved metabolomics and isotope tracing

reveal dynamic metabolic responses of dentate granule neurons with

acute stimulation. Nat Metab. 5:1820–1835. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dean DA, Klechka L, Hossain E, Parab AR,

Eaton K, Hinsdale M and McCall LI: Spatial metabolomics reveals

localized impact of influenza virus infection on the lung tissue

metabolome. mSystems. 7:e00353222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yu X, Liu Z and Sun X: Single-cell and

spatial multi-omics in the plant sciences: Technical advances,

applications, and perspectives. Plant Commun. 4:1005082023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Wang X, Zhang J, Zheng K, Du Q, Wang G,

Huang J, Zhou Y, Li Y, Jin H and He J: Discovering metabolic

vulnerability using spatially resolved metabolomics for antitumor

small molecule-drug conjugates development as a precise cancer

therapy strategy. J Pharm Anal. 13:776–787. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Bag S, Oetjen J, Shaikh S, Chaudhary A,

Arun P and Mukherjee G: Impact of spatial metabolomics on

immune-microenvironment in oral cancer prognosis: A clinical

report. Mol Cell Biochem. 479:41–49. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

He T, Lin K, Xiong L, Zhang W, Zhang H,

Duan C, Li X and Zhang J: Disorder of phospholipid metabolism in

the renal cortex and medulla contributes to acute tubular necrosis

in mice after cantharidin exposure using integrative lipidomics and

spatial metabolomics. J Pharm Anal. 15:1012102025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Qiu S, Wang Z, Wang X, Guo S, Cai Y, Xie

D, Hu Z, Wang S, Yang Q and Zhang A: Spatial metabolomics

identifies riboflavin metabolism as a therapeutic target of Huangqi

Guizhi Wuwu decoction in diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Chromatogr.

39:e702392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang Z, Fu W, Huo M, He B, Liu Y, Tian L,

Li W, Zhou Z, Wang B, Xia J, et al: Spatial-resolved metabolomics

reveals tissue-specific metabolic reprogramming in diabetic

nephropathy by using mass spectrometry imaging. Acta Pharm Sin B.

11:3665–3677. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Min X, Zhao Y, Yu M, Zhang W, Jiang X, Guo

K, Wang X, Huang J, Li T, Sun L and He J: Spatially resolved

metabolomics: From metabolite mapping to function visualizing. Clin

Transl Med. 14:e700312024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Tuck M, Grélard F, Blanc L and Desbenoit

N: MALDI-MSI towards multimodal imaging: Challenges and

perspectives. Front Chem. 10:9046882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kumar BS: Desorption electrospray

ionization mass spectrometry imaging (DESI-MSI) in disease

diagnosis: An overview. Anal Methods. 15:3768–3784. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yang S, Wang Z, Liu Y, Zhang X, Zhang H,

Wang Z, Zhou Z and Abliz Z: Dual mass spectrometry imaging and

spatial metabolomics to investigate the metabolism and

nephrotoxicity of nitidine chloride. J Pharm Anal. 14:1009442024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Song X, Zang Q, Li C, Zhou T and Zare RN:

Immuno-desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging

identifies functional macromolecules by using

Microdroplet-cleavable mass tags. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl.

62:e2022169692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lockyer NP, Aoyagi S, Fletcher JS, Gilmore

I, van der heide P, Moore KL, Tyler BJ and Weng LT: Secondary ion

mass spectrometry. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 4:322024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Coello Y, Jones AD, Gunaratne TC and

Dantus M: Atmospheric pressure femtosecond laser imaging mass

spectrometry. Anal Chem. 82:2753–2758. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen H, Durand S, Bawa O, Bourgin M,

Montégut L, Lambertucci F, Motiño O, Li S, Nogueira-Recalde U,

Anagnostopoulos G, et al: Biomarker identification in liver cancers

using desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

(DESI-MS) imaging: An approach for spatially resolved metabolomics.

Methods Mol Biol. 2769:199–209. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

He MJ, Pu W, Wang X, Zhong X, Zhao D, Zeng

Z, Cai W, Liu J, Huang J, Tang D and Dai Y: Spatial metabolomics on

liver cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Cancer

Cell Int. 22:3662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lakkimsetty SS, Weber A, Bemis KA, Stehl

V, Bronsert P, Föll MC and Vitek O: MSIreg: An R package for

unsupervised coregistration of mass spectrometry and H&E

images. Bioinformatics. 40:btae6242024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Zickuhr GM, Um IH, Laird A, Harrison DJ

and Dickson AL: DESI-MSI-guided exploration of metabolic-phenotypic

relationships reveals a correlation between PI 38:3 and

proliferating cells in clear cell renal cell carcinoma via

single-section co-registration of multimodal imaging. Anal Bioanal

Chem. 416:4015–4028. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wang G, Heijs B, Kostidis S, Rietjens RGJ,

Koning M, Yuan L, Tiemeier GL, Mahfouz A, Dumas SJ, Giera M, et al:

Spatial dynamic metabolomics identifies metabolic cell fate

trajectories in human kidney differentiation. Cell Stem Cell.

29:1580–1593.e7. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang G, Heijs B, Kostidis S, Mahfouz A,

Rietjens RGJ, Bijkerk R, Koudijs A, van der Pluijm LAK, van den

Berg CW, Dumas SJ, et al: Analyzing cell-type-specific dynamics of

metabolism in kidney repair. Nat Metab. 4:1109–1118. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lin J, Lin H, Li C, Liao N, Zheng Y, Yu X,

Sun Y and Wu L: Unveiling characteristic metabolic accumulation

over enzymatic-catalyzed process of Tieguanyin oolong tea

manufacturing by DESI-MSI and multiple-omics. Food Res Int.

181:1141362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Banerjee S, Wong AC, Yan X, Wu B, Zhao H,

Tibshirani RJ, Zare RN and Brooks JD: Early detection of unilateral

ureteral obstruction by desorption electrospray ionization mass

spectrometry. Sci Rep. 9:110072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Qi K, Wu L, Liu C and Pan Y: Recent

advances of ambient mass spectrometry imaging and its applications

in lipid and metabolite analysis. Metabolites. 11:7802021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Blanc T, Goudin N, Zaidan M, Traore MG,

Bienaime F, Turinsky L, Garbay S, Nguyen C, Burtin M, Friedlander

G, et al: Three-dimensional architecture of nephrons in the normal

and cystic kidney. Kidney Int. 99:632–645. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Li H, Li D and Humphreys BD: Chromatin

conformation and histone modification profiling across human kidney

anatomic regions. Sci Data. 11:7972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang SY and Mahler GJ: A glomerulus and

proximal tubule microphysiological system simulating renal

filtration, reabsorption, secretion, and toxicity. Lab Chip.

23:272–284. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Fan G, Jiang C, Huang Z, Tian M, Pan H,

Cao Y, Lei T, Luo Q and Yuan J: 3D autofluorescence imaging of

hydronephrosis and renal anatomical structure using

cryo-micro-optical sectioning tomography. Theranostics.

13:4885–4904. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hinze C, Karaiskos N, Boltengagen A,

Walentin K, Redo K, Himmerkus N, Bleich M, Potter SS, Potter AS,

Eckardt KU, et al: Kidney Single-cell transcriptomes predict

spatial corticomedullary gene expression and tissue osmolality

gradients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 32:291–306. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

53

|

Gao G, Sumrall ES, Pitchiaya S, Bitzer M,

Alberti S and Walter NG: Biomolecular condensates in kidney

physiology and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 19:756–770. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Ding Y, Zhao F, Hu J, Zhao Z, Shi B and Li

S: A conjoint analysis of renal structure and omics characteristics

reveal new insight to yak high-altitude hypoxia adaptation.

Genomics. 116:1108572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Gurung RL, Zheng H, Tan JLI, Liu S, Chan

C, Ang K, Tan C, Liu JJ, Subramaniam T, Sum CF and Lim SC:

Integrative metabolomic and proteomic analysis of diabetic kidney

disease progression with younger-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes

Obes Metab. 27:7454–7463. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Jiang X, Liu X, Qu X, Zhu P, Wo F, Xu X,

Jin J, He Q and Wu J: Integration of metabolomics and peptidomics

reveals distinct molecular landscape of human diabetic kidney

disease. Theranostics. 13:3188–3203. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Fan X, Yang M, Lang Y, Lu S, Kong Z, Gao

Y, Shen N, Zhang D and Lv Z: Mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming

in diabetic kidney disease. Cell Death Dis. 15:4422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Li S and Susztak K: Mitochondrial

dysfunction has a central role in diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 21:77–78. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Poorna R, Chen WW, Qiu P and Cicerone MT:

Toward Gene-correlated spatially resolved metabolomics with

fingerprint coherent Raman imaging. J Phys Chem B. 127:5576–5587.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Alexandrov T: Spatial metabolomics: From a

niche field towards a driver of innovation. Nat Metabolism.

5:1443–1445. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Zhang J, Wu T, Li C and Du J: A

glycopolymersome strategy for 'drug-free' treatment of diabetic

nephropathy. J Control Release. 372:347–361. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Luo A, Wang R, Gong J, Wang S, Yun C, Chen

Z, Jiang Y, Liu X, Dai H, Liu H and Zheng Y: Syntaxin 17

translocation mediated mitophagy switching drives

hyperglycemia-induced vascular injury. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e24149602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Rebelos E, Mari A, Oikonen V, Iida H,

Nuutila P and Ferrannini E: Evaluation of renal glucose uptake with

[18F] FDG-PET: Methodological advancements and metabolic

outcomes. Metabolism. 141:1553822023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Liu X, Du H, Sun Y and Shao L: Role of

abnormal energy metabolism in the progression of chronic kidney

disease and drug intervention. Ren Fail. 44:790–805. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhang G, Zhang J, DeHoog RJ, Pennathur S,

Anderton CR, Venkatachalam MA, Alexandrov T, Eberlin LS and Sharma

K: DESI-MSI and METASPACE indicates lipid abnormalities and altered

mitochondrial membrane components in diabetic renal proximal

tubules. Metabolomics. 16:112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Zhang X, Liu Y, Yang S, Gao X, Wang S,

Wang Z, Zhang C, Zhou Z, Chen Y, Wang Z and Abliz Z: Comparison of

local metabolic changes in diabetic rodent kidneys using mass

spectrometry imaging. Metabolites. 13:3242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zhang G, Liu L, Tamayo IM, De Leon NGP,

Vigers TB, Tommerdahl KL, Nelson RG, Ladd PE, Alexandrov T,

Birznieks C, et al: 406-P: Spatial metabolomics of human kidney

tissues reveal impaired tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle turnover in

type 1 Diabetes (T1D). Diabetes. 72:4062023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Qi W, Keenan HA, Li Q, Ishikado A, Kannt

A, Sadowski T, Yorek MA, Wu IH, Lockhart S, Coppey LJ, et al:

Pyruvate kinase M2 activation may protect against the progression

of diabetic glomerular pathology and mitochondrial dysfunction. Nat

Med. 23:753–762. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Hasegawa S and Inagi R: Harnessing

metabolomics to describe the pathophysiology underlying progression

in diabetic kidney disease. Curr Diab Rep. 21:212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Murphy DP, Wolfson J, Reule S, Johansen

KL, Ishani A and Drawz PE: A cohort study of sodium-glucose

cotransporter-2 inhibitors after acute kidney injury among Veterans

with diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 106:126–135. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wang Y, Liu T, Wu Y, Wang L, Ding S, Hou

B, Zhao H, Liu W and Li P: Lipid homeostasis in diabetic kidney

disease. Int J Biol Sci. 20:3710–3724. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Mitrofanova A, Merscher S and Fornoni A:

Kidney lipid dysmetabolism and lipid droplet accumulation in

chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 19:629–645. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Iizuka K: Commentary: Comprehensive

lipidome profiling of the kidney in early-stage diabetic

nephropathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:10153052022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Zhang YR, Piao HL and Chen D:

Identification of spatial specific lipid metabolic signatures in

Long-standing diabetic kidney disease. Metabolites. 14:6412024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Hao Y, Fan Y, Feng J, Zhu Z, Luo Z, Hu H,

Li W, Yang H and Ding G: ALCAT1-mediated abnormal cardiolipin

remodelling promotes mitochondrial injury in podocytes in diabetic

kidney disease. Cell Commun Signal. 22:262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Grove KJ, Voziyan PA, Spraggins JM, Wang

S, Paueksakon P, Harris RC, Hudson BG and Caprioli RM: Diabetic

nephropathy induces alterations in the glomerular and tubule lipid

profiles. J Lipid Res. 55:1375–1385. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

McCrimmon A, Corbin S, Shrestha B, Roman

G, Dhungana S and Stadler K: Redox phospholipidomics analysis

reveals specific oxidized phospholipids and regions in the diabetic

mouse kidney. Redox Biol. 58:1025202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Vianello E, Ambrogi F, Kalousová M,

Badalyan J, Dozio E, Tacchini L, Schmitz G, Zima T, Tsongalis GJ

and Corsi-Romanelli MM: Circulating perturbation of

phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) is

associated to cardiac remodeling and NLRP3 inflammasome in

cardiovascular patients with insulin resistance risk. Exp Mol

Pathol. 137:1048952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Wunderling K, Zurkovic J, Zink F,

Kuerschner L and Thiele C: Triglyceride cycling enables

modification of stored fatty acids. Nat Metab. 5:699–709. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Darshi M, Tumova J, Saliba A, Kim J, Baek

J, Pennathur S and Sharma K: Crabtree effect in kidney proximal

tubule cells via late-stage glycolytic intermediates. Iscience.

26:1064622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Hall AM: Protein handling in kidney

tubules. Nat Rev Nephrol. 21:241–252. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Panov AV, Mayorov VI, Dikalova AE and

Dikalov SI: Long-Chain and Medium-Chain fatty acids in energy

metabolism of murine kidney mitochondria. Int J Mol Sci.

24:3792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Li H, Li D, Ledru N, Xuanyuan Q, Wu H,

Asthana A, Byers LN, Tullius SG, Orlando G, Waikar SS and Humphreys

BD: Transcriptomic, epigenomic, and spatial metabolomic cell

profiling redefines regional human kidney anatomy. Cell Metab.

36:1105–1125.e10. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, Ko YA, Han SH,

Chinga F, Park AS, Tao J, Sharma K, Pullman J, et al: Defective

fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key

role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med. 21:37–46. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Li C, Gao L, Lv C, Li Z, Fan S, Liu X,

Rong X, Huang Y and Liu J: Active role of amino acid metabolism in

early diagnosis and treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Front

Nutr. 10:12398382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Liu L, Xu J, Zhang Z, Ren D, Wu Y, Wang D,

Zhang Y, Zhao S, Chen Q and Wang T: Metabolic homeostasis of amino

acids and diabetic kidney disease. Nutrients. 15:1842023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Linnan B, Yanzhe W, Ling Z, Yuyuan L,

Sijia C, Xinmiao X, Fengqin L and Xiaoxia W: In situ metabolomics

of metabolic reprogramming involved in a mouse model of type 2

diabetic kidney disease. Front Physiol. 12:7796832021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Han J, Li P, Sun H, Zheng Y, Liu C, Chen

X, Guan S, Yin F and Wang X: Integrated metabolomics and mass

spectrometry imaging analysis reveal the efficacy and mechanism of

Huangkui capsule on type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Phytomedicine.

138:1563972025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Castoldi F, Kroemer G and Pietrocola F:

Spermidine rejuvenates T lymphocytes and restores anticancer

immunosurveillance in aged mice. Oncoimmunology. 11:21468552022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zou D, Zhao Z, Li L, Min Y, Zhang D, Ji A,

Jiang C, Wei X and Wu X: A comprehensive review of spermidine:

Safety, health effects, absorption and metabolism, food materials

evaluation, physical and chemical processing, and bioprocessing.

Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 21:2820–2842. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Aihara S, Torisu K, Uchida Y, Imazu N,

Nakano T and Kitazono T: Spermidine from arginine metabolism

activates Nrf2 and inhibits kidney fibrosis. Commun Biol.

6:6762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Li X, Zhou X, Liu X, Li X, Jiang X, Shi B

and Wang S: Spermidine protects against acute kidney injury by

modulating macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activation and

mitochondrial respiration in an eIF5A hypusination-related pathway.

Mol Med. 28:1032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Jia M, Lin L, Xun K, Li D, Wu W, Sun S,

Qiu H and Jin D: Indoxyl sulfate aggravates podocyte damage through

the TGF-β1/Smad/ROS signalling pathway. Kidney Blood Press Res.

49:385–396. 2024.

|

|

94

|

Zhao T, Zhang H, Yin X, Zhao H, Ma L, Yan

M, Peng L, Wang Q, Dong X and Li P: Tangshen formula modulates gut

Microbiota and reduces gut-derived toxins in diabetic nephropathy

rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 129:1103252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Hejazi L, Sharma S, Ruiz A, Zhang G, Tucci

FC and Sharma K: Spatial metabolomics analysis by MSI-DeepPath

identifies key pathways in ZDF diabetic kidney disease model.

Diabetes. 72(Suppl 1): 400–P. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Varadaiah YGC, Sivanesan S, Nayak SB and

Thirumalarao KR: Purine metabolites can indicate diabetes

progression. Arch Physiol Biochem. 128:87–91. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Zubaidi SN, Wong PL, Qadi WSM, Dawoud EAD,

Hamezah HS, Baharum SN, Jam FA, Abas F, Moreno A and Mediani A:

Deciphering the mechanism of Annona muricata leaf extract in

alloxan-nicotinamide-induced diabetic rat model with 1H-NMR-based

metabolomics approach. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 260:1168062025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Shen XL, Liu H, Xiang H, Qin XM, Du GH and

Tian JS: Combining biochemical with (1)H NMR-based metabolomics

approach unravels the antidiabetic activity of genipin and its

possible mechanism. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 129:80–89. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Yuan Y, Huang L, Yu L, Yan X, Chen S, Bi

C, He J, Zhao Y, Yang L, Ning L, et al: Clinical metabolomics

characteristics of diabetic kidney disease: A meta-analysis of 1875

cases with diabetic kidney disease and 4503 controls. Diabetes

Metab Res Rev. 40:e37892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Jung I, Nam S, Lee DY, Park SY, Yu JH, Seo

JA, Lee DH and Kim NH: Association of succinate and adenosine

nucleotide metabolic pathways with diabetic kidney disease in

patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J.

48:1126–1134. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Mohandes S, Doke T, Hu H, Mukhi D, Dhillon

P and Susztak K: Molecular pathways that drive diabetic kidney

disease. J Clin Invest. 133:e1656542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Sharma K, Zhang GS, Hansen J, Bjornstad P,

Lee HJ, Menon R, Hejazi L, Liu JJ, Franzone A, Looker HC, et al:

Endogenous adenine mediates kidney injury in diabetic models and

predicts diabetic kidney disease in patients. J Clin Invest.

133:e1703412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Ragi N and Sharma K: Deliverables from

metabolomics in kidney disease: Adenine, new insights, and

implication for clinical Decision-making. Am J Nephrol. 55:421–438.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Drexler Y and Fornoni A: Adenine crosses

the biomarker bridge: From 'omics to treatment in diabetic kidney

disease. J Clin Invest. 133:e1740152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Hocher B and Adamski J: Metabolomics for

clinical use and research in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 13:269–284. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Efiong EE, Maedler K, Effa E, Osuagwu UL,

Peters E, Ikebiuro JO, Soremekun C, Ihediwa U, Niu J, Fuchs M, et

al: Decoding diabetic kidney disease: A comprehensive review of

interconnected pathways, molecular mediators, and therapeutic

insights. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 17:1922025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Sinha SK and Nicholas SB: Pathomechanisms

of diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Med. 12:73492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Huynh C, Ryu J, Lee J, Inoki A and Inoki

K: Nutrient-sensing mTORC1 and AMPK pathways in chronic kidney

diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 19:102–122. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Zhang J, Fuhrer T, Ye H, Kwan B,

Montemayor D, Tumova J, Darshi M, Afshinnia F, Scialla JJ, Anderson

A, et al: High-throughput metabolomics and diabetic kidney disease

progression: Evidence from the chronic renal insufficiency (CRIC)

study. Am J Nephrol. 53:215–225. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Hong YA and Nangaku M: Endogenous adenine

as a key player in diabetic kidney disease progression: An

integrated multiomics approach. Kidney Int. 105:918–920. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Demko J, Saha B, Takagi E, Manis A,

Richman P and Pearce D: Renal tubule mTORC2 deletion increases

gluconeogenesis and urinary glucose excretion. Physiology.

38:57350392023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Qiu S, Xie D, Guo S, Wang Z, Wang X, Cai

Y, Lin C, Yao H, Guan Y, Zhao Q, et al: Spatially segregated

multiomics decodes metformin-mediated function-specific metabolic

characteristics in diabetic kidney disease. Life Metabolism.

4:loaf0192025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Wu Q, Chu JL, Rubakhin SS, Gillette MU and

Sweedler JV: Dopamine-modified TiO2 monolith-assisted LDI MS

imaging for simultaneous localization of small metabolites and

lipids in mouse brain tissue with enhanced detection selectivity

and sensitivity. Chem Sci. 8:3926–3938. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Spraggins JM, Rizzo DG, Moore JL, Noto MJ,

Skaar EP and Caprioli RM: Next-generation technologies for spatial

proteomics: Integrating ultra-high speed MALDI-TOF and high mass

resolution MALDI FTICR imaging mass spectrometry for protein

analysis. Proteomics. 16:1678–1689. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Neumann EK, Migas LG, Allen JL, Caprioli

RM, Van de Plas R and Spraggins JM: Spatial metabolomics of the

human kidney using MALDI trapped ion mobility imaging mass

spectrometry. Anal Chem. 92:13084–13091. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Fu T, Oetjen J, Chapelle M, Verdu A,

Szesny M, Chaumot A, Degli-Esposti D, Geffard O, Clément Y,

Salvador A and Ayciriex S: In situ isobaric lipid mapping by

MALDI-ion mobility separation-mass spectrometry imaging. J Mass

Spectrom. 55:e45312020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Spatial Omics DataBase (SODB): Increasing

accessibility to spatial omics data. Nat Methods. 20:359–360. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Vandergrift GW, Veličković M, Day LZ,

Gorman BL, Williams SM, Shrestha B and Anderton CR: Untargeted

spatial metabolomics and spatial proteomics on the same tissue

section. Anal Chem. 97:392–400. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Abedini A, Levinsohn J, Klötzer KA,

Dumoulin B, Ma Z, Frederick J, Dhillon P, Balzer MS, Shrestha R,

Liu H, et al: Single-cell multi-omic and spatial profiling of human

kidneys implicates the fibrotic microenvironment in kidney disease

progression. Nat Genet. 56:1712–1724. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Chuang AE, Chen YL, Chiu HJ, Nguyen HT and

Liu CH: Nasal administration of polysaccharides-based nanocarrier

combining hemoglobin and diferuloylmethane for managing diabetic

kidney disease. Int J Biol Macromol. 282:1365342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|