Sepsis is a life-threatening syndrome resulting from

a dysregulated host response to infection, which can progress to

multiple organ dysfunction syndrome with a mortality rate

approaching 40% (1,2). Immune homeostasis plays a pivotal

role in the complex pathophysiology of sepsis and is directly

linked to clinical outcomes. Sepsis disrupts immune balance,

leading to a state of immunosuppression. The mechanisms underlying

this immune dysregulation are multifactorial, including excessive

anti-inflammatory cytokine release, abnormal apoptosis of immune

effector cells, over-proliferation of immunosuppressive cells and

upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules (3). Sepsis inflicts extensive damage to

multiple organs, including the kidneys, liver, lungs, circulatory

system, gastrointestinal tract, blood and central nervous system.

Among these, the kidneys are often the first organs affected during

sepsis (4). Acute kidney injury

(AKI), one of the most common and severe complications of sepsis,

occurs in >50% of sepsis cases and is associated with

significantly increased mortality (5). In sepsis, the kidneys undergo a

series of alterations, including hemodynamic changes,

microcirculatory dysfunction, endothelial injury, inflammatory

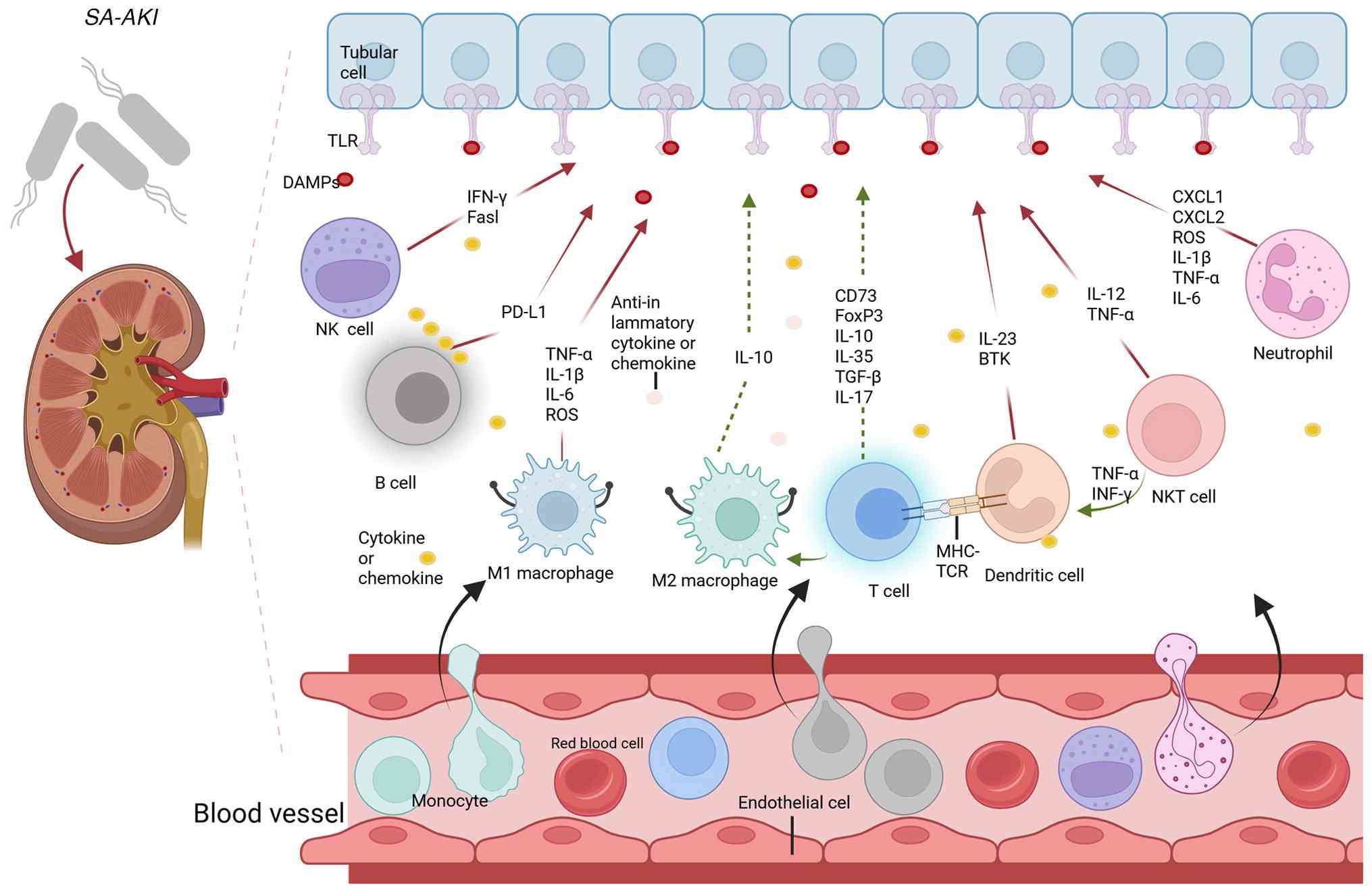

responses, oxidative stress and direct tubular damage (6). Furthermore, immune responses driven

by various immune cells, such as macrophages, neutrophils,

dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, natural killer T

(NKT) cells, B cells and T cells, play a pivotal role in the

development and progression of sepsis-associated AKI (SA-AKI)

(Fig. 1). Damage-associated

molecular patterns (DAMPs) are recognized by Toll-like receptors

(TLRs), activating immune cells and initiating an inflammatory

cascade (7). Upon sensing damage

signals, innate immune cells not only help control tissue injury

but also initiate adaptive immune responses. These immune cells

synergistically contribute to the onset, progression and

persistence of disease. In sepsis, immune cell roles differ between

the early hyperinflammatory phase and the later immunosuppressive

phase. The early phase is characterized by a pro-inflammatory

response marked by a cytokine storm. Following this excessive

inflammation, patients either gradually recover or transition into

a state of persistent immunosuppression, characterized by immune

cell exhaustion (8-16); key features of this progression

are summarized in Table I.

However, the roles of mast cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)

in SA-AKI remain insufficiently studied, and their exact mechanisms

are still unclear (Fig. 1).

Therefore, precise targeting of immune cells may offer a promising

strategy for preventing and treating SA-AKI.

Under physiological conditions, the kidneys harbor a

notable population of resident macrophages from birth. These

macrophages primarily include those derived from yolk sac erythroid

progenitors, fetal liver erythroid progenitors and hematopoietic

stem cells (17). During early

embryogenesis, yolk sac-derived macrophages play a predominant role

(18). In adulthood, macrophage

populations are sustained through two distinct mechanisms: The

self-renewal of fetal liver erythroid progenitor-derived and

hematopoietic stem cell-derived macrophages and the replacement of

macrophages by monocyte-derived cells (17). Kidney resident macrophages (KRMs)

and recruited macrophages perform distinct functions within the

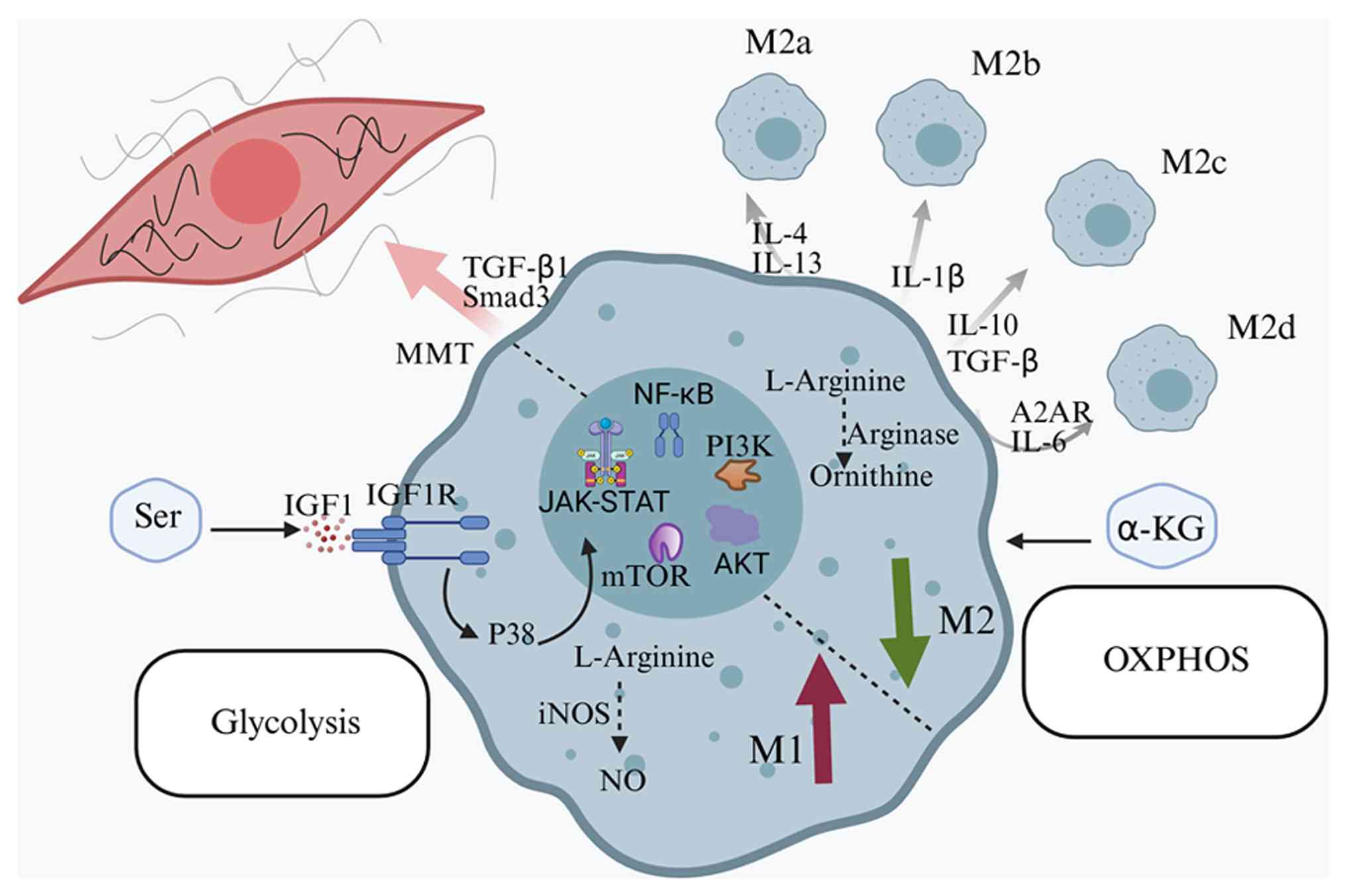

kidney. In the context of SA-AKI, macrophages play a pivotal role

in driving both injury and repair through a complex interplay of

polarization, metabolic reprogramming and signaling pathways, as

summarized in Fig. 2.

As tissue-resident immune cells, KRMs are essential

for maintaining normal kidney function. These macrophages are

complex, highly adaptable renal resident mononuclear phagocytes

with diverse functions, which originate from the yolk sac during

early embryogenesis and persist in the kidney throughout

development (19,20). KRMs help maintain systemic

homeostasis through various mechanisms, such as clearing cellular

debris, modulating local inflammation and promoting tissue repair

(21). In adult tissues, KRMs

possess self-renewal capabilities with minimal input from

peripheral blood, helping sustain renal homeostasis, monitor the

immune microenvironment, promote angiogenesis and mitigate AKI.

Following kidney injury, KRMs aid in tissue repair and regeneration

(22). Additionally, KRMs can

reduce renal injury by selectively inhibiting interleukin (IL)-6

production from endothelial cells through IL-1 receptor antagonist

expression (23). Furthermore,

KRMs regulate renal sympathetic nerve activity, influencing salt

and water balance and further promoting renal function recovery

(24).

In SA-AKI, monocyte recruitment is a critical

pathophysiological event. This process involves multiple mechanisms

that synergistically contribute to uncontrolled inflammation and

exacerbated renal injury. These mechanisms include the release of

chemoattractants, expression of adhesion molecules, activation of

inflammatory cascades and microcirculatory dysfunction (25). During sepsis, renal tubular

epithelial cells upregulate the expression of C-C motif ligand

chemokine 2 (CCL2) at both the mRNA and protein levels through the

combined actions of chemokine receptors CCR2 and C-X3-C motif

chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1); this upregulation drives monocyte

chemotaxis (26). Moreover, the

endothelial glycocalyx, produced by vascular endothelial cells,

undergoes degradation during sepsis due to inflammatory responses

and oxidative stress. The glycocalyx, a critical component of the

vascular endothelial barrier, when damaged, increases vascular

permeability, facilitating the contact and adhesion of monocytes to

endothelial cells (27).

Monocytes infiltrating the kidney can differentiate into M1 or M2

macrophages, exerting pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory

effects, respectively. Notably, a specific monocyte subset, such as

Ly6Chigh monocytes, strongly adheres to the renal vascular wall in

a CX3CR1-dependent manner during the early stages of sepsis. This

subset plays a protective role via CX3CR1-dependent adhesion

mechanisms (28).

Sepsis is primarily induced by lipopolysaccharide

(LPS) released from Gram-negative bacteria. LPS binds to TLRs on

renal cells, triggering the release of DAMPs (29). These molecules act as endogenous

'danger signals', recognized by receptors on macrophages, leading

to their activation. This activation results in the extensive

release of inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α

(TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-6 and the chemoattractant CCL2, initiating a

cytokine storm and exacerbating renal inflammatory injury (30,31). Macrophages exhibit high

plasticity and can polarize into distinct phenotypes, typically

classified as M1 and M2. M1 macrophages primarily contribute to

inflammation by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as

TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), driving

inflammation and tissue damage. By contrast, M2 macrophages are

involved in tissue repair and inflammation resolution (32). Thus, modulation of macrophage

polarization represents a potential strategy for alleviating renal

injury in SA-AKI. Macrophage polarization is a dynamic process and

excessive suppression of M1 polarization may impair pathogen

clearance, hindering tissue healing. Conversely, overactivation of

M2 macrophages can lead to immunosuppression, increasing infection

risk (33,34). Therefore, precise regulation of

the M1/M2 balance is critical to avoid adverse outcomes.

Macrophage metabolic reprogramming plays a pivotal

role in SA-AKI. During sepsis, macrophages undergo significant

metabolic changes to support the inflammatory response and cellular

survival (35). This

reprogramming involves a shift from fatty acid oxidation (FAO) to a

dual reliance on glycolysis and FAO. M1 macrophages predominantly

utilize aerobic glycolysis to rapidly initiate immune responses,

while M2 macrophages rely on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to

exert anti-inflammatory effects and prevent tissue damage (36). In the early stages of sepsis,

macrophages activate the AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR)/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α signaling pathway, which

enhances glycolytic enzyme activity and suppresses the

tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, initiating glycolysis to generate

ATP, supporting cell survival and pro-inflammatory responses

(35). However, excessive

glycolysis can induce immunosuppression, impairing host defense and

immune function. This immunosuppressive state is characterized by

pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-6 and CCL2) and

T-cell-recruiting chemoattractants, as well as anti-inflammatory

cytokines (such as IL-4, IL-10) (37). Nevertheless, this metabolic shift

can impair mitochondrial function and reduce ATP production.

Limiting glycolysis can mitigate the inflammatory response

(38,39). While the transition from OXPHOS

to aerobic glycolysis is essential for renal survival in early

sepsis, failure to restore OXPHOS in the later stages may result in

persistent inflammation and renal fibrosis (35). During the late inflammatory

phase, cells activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ

coactivator 1α and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 through

mediators such as sirtuin (Sirt)6, signal transducer and activator

of transcription 3 (STAT3) and sirtuin 1, promoting a metabolic

shift back to OXPHOS. Restoration of OXPHOS stimulates

mitochondrial biogenesis, generates ATP and exerts

anti-inflammatory effects, promoting renal function recovery

(35). Additionally, lactate, a

key metabolite in macrophage metabolism, influences the macrophage

phenotype through lactylation, further impacting disease

progression (40).

Amino acid metabolism, which regulates macrophage

activation, is one of the earliest metabolic alterations during

macrophage polarization. Arginine, glutamine and serine metabolism

play pivotal roles in this process (41). Arginine catabolism regulates

macrophage activation primarily through inducible nitric oxide

synthase (iNOS) and arginase 1 (Arg1). iNOS, predominantly

expressed in M1 macrophages, catalyzes the synthesis of nitric

oxide and L-citrulline from arginine. Nitric oxide, a ROS, helps M1

macrophages combat pathogen invasion (40-42). By contrast, Arg1, highly

expressed in M2 macrophages, catalyzes the hydrolysis of arginine

into urea and L-ornithine. The metabolites of L-ornithine,

including polyamines and proline, influence macrophage

proliferation and collagen synthesis (42-44). A distinctive feature of M2

macrophages is their increased glutamine metabolism, with one-third

of the carbon in TCA cycle metabolites of M2 macrophages derived

from glutamine. Glutaminolysis generates α-ketoglutarate (α-KG),

which enhances M2 macrophage activation and governs metabolic

reprogramming through Jmjd3-dependent regulation. Additionally,

α-KG, via a prolyl hydroxylase-dependent mechanism, inhibits the

NF-κB pathway, thereby limiting M1 macrophage activation and

modulating IKKβ activity (45).

Serine metabolism also plays a pivotal role in macrophage

functional polarization. It has been shown that serine metabolism

suppresses insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) transcription by

increasing the promoter abundance of H3K27me3 through

S-adenosylmethionine. Deficiency in serine metabolism alters M1

macrophage polarization and modulates Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT1

signaling via IGF1-dependent p38 activation (46).

In conclusion, during SA-AKI, macrophage metabolic

reprogramming may be a critical component of the host defense

response. However, specific regulatory strategies require further

investigation to precisely modulate macrophage metabolism for

therapeutic purposes.

NF-κB is a dimeric transcription factor composed of

five protein family members and is present in nearly all human

cells (47); it plays a critical

role in inflammation and immunity by regulating the expression of a

broad range of chemoattractants, cytokines, transcription factors

and regulatory proteins (47).

The binding of LPS to its receptor, TLR4, on macrophages activates

the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)-dependent

signaling pathway. This pathway activates the IKK complex, which

phosphorylates IκB proteins, leading to their ubiquitination and

proteasomal degradation. Degradation of IκB releases NF-κB dimers,

such as p50/RelA (p65), allowing their translocation to the nucleus

(48). Within the nucleus, NF-κB

binds to specific κB sites on DNA via its Rel homology domain,

promoting the transcription of inflammatory genes, including TNF-α

and IL-1β, thereby amplifying the inflammatory response (48). The NF-κB pathway interacts

extensively with other signaling pathways. For instance, the

PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating

macrophage polarization (49).

Moreover, complex regulatory interactions exist between NF-κB and

pathways such as the MAPK and STAT pathways.

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a critical

cascade that governs various cellular processes, including growth,

proliferation, survival, metabolism and migration (50). A study has shown that LPS-induced

activation of TLR4 in macrophages triggers the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway, leading to the production of muscle-type pyruvate kinase

isozyme, which then facilitates the acetylation of high mobility

group box 1 (HMGB1). Acetylated HMGB1 promotes LPS uptake by

macrophages and inhibits macrophage apoptosis (51). This pathway is also essential for

regulating macrophage polarization towards M1 or M2 phenotypes.

Androulidaki et al (52)

demonstrated that AKT1 modulates macrophage polarization upon LPS

stimulation. AKT1 deficiency promotes M1 polarization, while AKT2

deficiency favors M2 polarization. For instance, Aquaporin 1 has

been shown to mitigate SA-AKI by promoting M2 polarization via the

PI3K/AKT pathway (53,54).

The JAK/STAT pathway is a key mechanism in cell

communication, enabling cells to respond to external stimuli

(55); it plays a critical role

in various physiological and pathological processes, including cell

proliferation, metabolism, immune response and inflammation

(55). During sepsis, the

release of large quantities of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as

TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β) activates the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

Activated STAT proteins translocate to the nucleus, driving the

transcription of additional inflammatory mediators, thus amplifying

the inflammatory response and contributing to kidney damage

(56,57). STAT inhibitors can effectively

reduce inflammation by restoring the CD11blowF4/80high macrophage

population, which exhibits potential anti-inflammatory properties,

thus protecting the kidneys from injury (58). For example, curcumin has been

demonstrated to alleviate inflammation and apoptosis by modulating

the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, mitigating SA-AKI (59).

The JAK/STAT pathway also regulates immune cell

function. In sepsis, this pathway influences macrophage activation

and differentiation, enabling macrophages to produce inflammatory

cytokines through receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein

kinase and the NLRP3 inflammasome, thus impacting the intensity and

duration of the immune response (51,56). For instance, mesenchymal stem

cells (MSCs) with upregulated heme oxygenase-1 expression can

ameliorate SA-AKI by activating the JAK/STAT3 pathway (60). Moreover, blocking TLR4/TNF1 can

promote a phenotypic shift of M1 macrophages towards the M2

phenotype by inhibiting STAT1/STAT3 expression and increasing

Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 expression (61). Acyl-CoA thioesterase 11, an

IL-1β-associated gene involved in fatty acid metabolism, promotes

the accumulation of fatty acids, such as eicosatetraenoic acid (EA)

and stearic acid, within macrophages (62). This accumulation inhibits

JAK/STAT signaling activation via palmitoylation of interferon-γ

(IFN-γ) receptor 2 at the C261 site (62). Eicosatetraenoic acid has also

been shown to alleviate sepsis-associated organ damage via the same

pathway (62). Additionally,

macrophages expressing the chemokine CCL5 activate several pathways

related to immune and inflammatory responses, including

IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, TGF-β signaling and inflammatory

responses, recruiting neutrophils and exacerbating SA-AKI (63). In summary, the JAK/STAT signaling

pathway plays a complex role in the pathophysiology of SA-AKI. By

regulating inflammatory responses, immune modulation and apoptosis,

this pathway contributes to the initiation and progression of renal

injury. Thus, targeting the JAK/STAT pathway may offer novel

therapeutic strategies for SA-AKI.

Accumulative evidence suggests that the M1/M2

dichotomy does not fully encompass the complex behaviors and

functions of macrophages in vivo (26,64,65). Macrophages may exhibit multiple

phenotypes and even co-express both M1 and M2 markers

simultaneously. For example, macrophages can display mixed M1/M2

phenotypes, which are essential for regulating the assembly and

structure of the extracellular matrix (66). Additionally, M2 macrophages

represent not a single phenotype but several subtypes, including

M2a, M2b, M2c and M2d, each characterized by distinct surface

markers, cytokine secretion profiles and immune effector functions

(67,68). M2a and M2b macrophages are

particularly prevalent in renal tissue. M2a macrophages, typically

induced by IL-4 or IL-13, express high levels of Arg1 and the

mannose receptor and are primarily involved in wound healing,

fibrosis and allergic responses (67). M2b macrophages, stimulated by

immune complexes or IL-1β, exhibit immunomodulatory and

anti-inflammatory effects. These cells produce anti-inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-10, while also secreting pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, thereby participating in immune

complex-mediated diseases (69).

In the later stages of sepsis, promoting the M2b macrophage

phenotype may help maintain immune homeostasis and facilitate

tissue healing. However, the activity of M2b macrophages must be

precisely regulated to prevent exacerbation of inflammation or

suppression of immune responses. M2c macrophages, induced by IL-10

or TGF-β, are primarily involved in immunosuppression and tissue

remodeling. They express surface markers such as CD163 and signal

regulatory protein α (SIRPα) (67,68). M2d macrophages, induced by

adenosine A2A receptor agonists or IL-6, play a major role in tumor

angiogenesis and immunosuppression (67). Future research should focus on

investigating M2 macrophage subtypes and their specific functions

in SA-AKI, providing a theoretical foundation for more targeted

therapies.

Fibrosis, a common pathological feature of chronic

disorders, is characterized by excessive activation of

myofibroblasts and abnormal deposition of extracellular matrix in

tissues (70). Macrophages can

directly transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts via MMT, promoting

renal fibrosis (71,72). Recently, MMT has been recognized

as a novel source of myofibroblasts and plays a critical role in

fibrotic processes across multiple organs. The regulatory

mechanisms underlying MMT remain incompletely understood, but the

TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling cascade is the most extensively studied

pathway (73,74). Although no direct evidence

currently links MMT to SA-AKI, a study has confirmed increased

expression of TGF-β R2 and phosphorylated Smad3 in the kidneys of

septic mice (75). Given the

critical role of the TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway in MMT, it is

hypothesized that MMT may contribute to the development and

progression of renal fibrosis following SA-AKI. Therapeutic

strategies targeting MMT hold promise for improving the long-term

prognosis of SA-AKI, although further experimental validation is

needed.

Catalytic nanoparticles offer a promising

alternative to conventional anti-infective therapies by modulating

innate immune responses and engineering macrophages for

immunotherapy, thus providing innovative treatment options for

infectious diseases such as sepsis. For example,

ultrasound-responsive piezoelectric catalytic nanoparticles enhance

macrophage-mediated antibacterial phagocytosis and bactericidal

activity through intracellular piezoelectric catalysis (76). Bone marrow-derived macrophages

co-cultured with these piezoelectric nanoparticles form

piezoelectric macrophages, which, upon activation via ultrasound

irradiation, can be utilized in adoptive cell therapy. This

approach has proven effective against immunosuppressive bacterial

infections, including sepsis (76). However, challenges remain in

targeting these piezoelectric nanomaterials to macrophages and

kidneys, as they are typically non-degradable and considered

biologically inert, necessitating further investigation into their

long-term effects and biosafety. Another novel nanoparticle

modulates metabolic reprogramming in macrophages to mitigate the

septic cytokine storm (77).

Additionally, engineered apoptotic extracellular vesicles derived

from macrophages can alleviate symptoms in septic patients by

clearing toxins and regulating inflammatory responses (78). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

(NAD+), an immunomodulator, shows promise for sepsis

treatment. Co-incubation of LPS-activated macrophages with

NAD+-loaded lipid nanoparticles not only reduces the

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS by macrophages but

also enhances their viability (79). Moreover, nanoparticles formed by

coordination between Ce3+ and astragalin (CeAst

nanoparticles), encapsulated with macrophage membranes and modified

with a kidney-targeting peptide, form the CeAst@MK system. This

nanoplatform enables precise kidney targeting and promotes M2

macrophage polarization (80).

The CeAst@MK system exhibits excellent biocompatibility and in

vivo safety, indicating notable potential for clinical

translation. A novel system of mannose-conjugated, PEGylated

graphene oxide nanoparticles loaded with a sesquiterpene lactone

(GMO@ GO@PEG@MAN) not only targets the kidneys but also binds to

macrophages and promotes the transition from M1 to M2 macrophages

(81). Given the promising

outcomes of these macrophage-based therapies in sepsis treatment,

they hold notable potential for managing SA-AKI. Ongoing

optimization of therapeutic strategies, deeper exploration of

underlying mechanisms and enhanced clinical translational research

are expected to improve the prognosis of patients with SA-AKI. As

an emerging therapeutic approach, macrophage-based therapy shows

broad potential in SA-AKI management. Through continuous refinement

of treatment strategies and further investigation into its

mechanisms, new avenues for improving patient outcomes in SA-AKI

are anticipated.

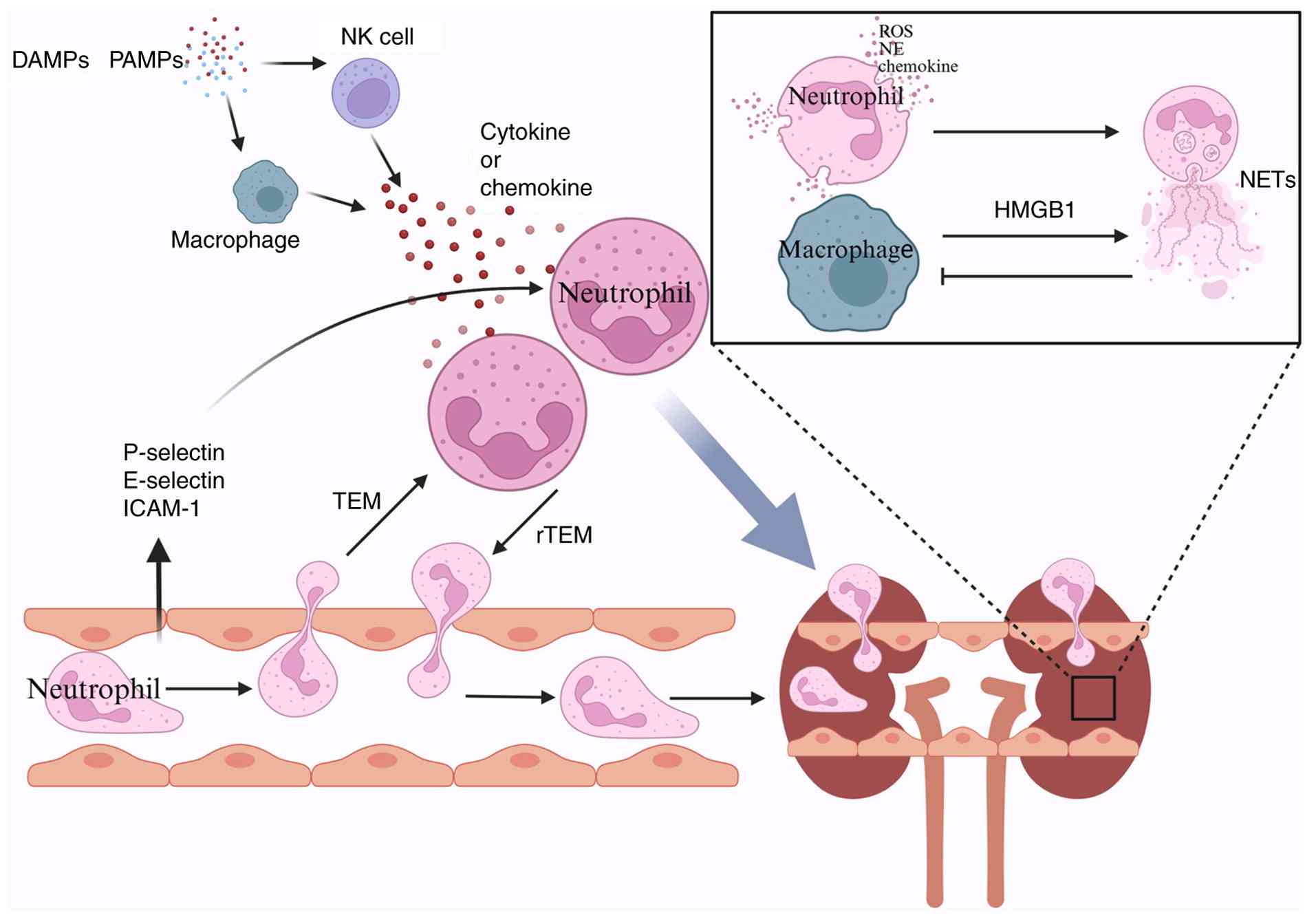

Neutrophils are a critical component of the first

line of defense against invading microorganisms, playing a key role

in infection control and the mediation of inflammatory responses

(Fig. 3). Neutrophils constitute

~70% of the total white blood cell count in circulation, making

them the most abundant type of leukocyte. However, under normal

physiological conditions, the number of neutrophils in the kidney

is relatively low. Neutrophils primarily function in immune

surveillance, clearing small quantities of pathogens or cellular

debris that enter the kidney (82); they are typically maintained in a

non-activated state to prevent unnecessary damage to renal tissues

(82). In sepsis, excessive

neutrophil activation can lead to an uncontrolled inflammatory

response. Analysis of the large MIMIC-IV database has shown that an

elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte-to-platelet ratio is strongly

associated with an increased risk and severity of SA-AKI (83), indicating a notable role for

neutrophils in the pathophysiology of SA-AKI. Similar to

macrophages, neutrophils display phenotypic heterogeneity, with N1

neutrophils being pro-inflammatory and N2 neutrophils being

anti-inflammatory (84).

Neutrophils isolated from the kidneys of cecal ligation and

puncture (CLP) mice exhibit a CD11bhigh, CD54high and CD95high

profile, indicating an N1 phenotype (85,86). Upon LPS stimulation, CD54

expression on neutrophils increases, which correlates with enhanced

phagocytosis and ROS production (87).

During SA-AKI, significant neutrophil recruitment

and infiltration occur in the kidneys. Sepsis triggers a systemic

inflammatory response, leading to endothelial cell activation and

upregulation of various adhesion molecules, such as P-selectin,

E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (88). These adhesion molecules interact

with ligands on the neutrophil surface, promoting neutrophil

adhesion from the circulation to the renal vascular endothelium and

their subsequent migration into renal tissue (88). Additionally, one study indicated

that the release of DAMPs and pathogen-associated molecular

patterns activates monocytes/macrophages and DCs, leading to the

secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which

initiate neutrophil recruitment into renal tissue (89-91). Other research has highlighted a

sharp increase in classical pro-inflammatory chemokines and

cytokines, such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)1 and CXCL2,

during SA-AKI (88,89). Neutrophils follow the CXCL1

and/or CXCL2 gradient to the sites of infection and uncontrolled

levels of these chemokines may enhance tissue damage by

over-activating neutrophils (92,93). Once recruited to the kidneys,

neutrophils primarily accumulate around microvessels, with

subsequent infiltration into the renal tubulointerstitium (94). Upon tissue infiltration,

neutrophils are further activated, releasing inflammatory mediators

such as ROS, proteases (such as neutrophil elastase) and cytokines

(95). Excessive ROS production

plays a key role in sepsis and SA-AKI, causing direct damage to

renal tubular epithelial cells through lipid peroxidation, protein

denaturation and DNA damage (96). Neutrophil elastase degrades the

extracellular matrix, disrupting the structural integrity of renal

tissue (97). In contrast to

most studies that rely on reducing systemic neutrophil counts or

inflammatory cytokines, one study demonstrated that renal injury

during systemic inflammation was not significantly alleviated after

specifically targeting neutrophil recruitment into the kidney. This

finding suggests that the uncontrolled systemic inflammatory

response, rather than local neutrophil recruitment into the kidney,

dominates the pathogenesis of kidney injury in SA-AKI. However, the

authors of this study also acknowledged the limitation that the

specific mechanisms by which individual circulating proinflammatory

mediators contribute to renal injury remain to be elucidated

(98). This study likely focuses

on the role of circulating inflammatory mediators in the early

stages of the disease, whereas other studies emphasize the local

effects of neutrophils in the kidneys during disease progression.

Moreover, neutrophils recruited to sites of inflammation often

undergo apoptosis. Insufficient clearance of apoptotic neutrophils

can result in the persistence and worsening of inflammation

(99). In patients with SA-AKI,

peripheral blood mononuclear cells express high levels of the

anti-phagocytic signal, involving leukocyte surface antigen CD47

and SIRPα. This signal facilitates the clearance of apoptotic

neutrophils, promoting the resolution of inflammation and repair of

tissue injury (100).

Neutrophil metabolic reprogramming refers to the

adjustment of metabolic pathways in response to physiological or

pathological conditions. Typically, neutrophils utilize multiple

metabolic pathways, including glycolysis (101), the pentose phosphate pathway

(PPP) and FAO, to support immune functions such as chemotaxis, ROS

production, neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation and

degranulation (102). Under

normal conditions, glycolysis serves as the primary energy source.

However, in inflammatory or tumor microenvironments, neutrophils

may shift to alternative metabolic pathways, such as FAO, to

sustain effector functions. A study has shown that during sepsis,

levels of glycolysis, PPP and fatty acid amide hydrolase are

elevated in neutrophils (103).

2-deoxy-D-glucose alleviates excessive inflammatory responses by

enhancing neutrophil recruitment, highlighting the link between

metabolic regulation and infection/inflammation (104). Furthermore, during the acute

phase of sepsis, the long non-coding RNA GSEC (containing a

G-quadruplex sequence) is upregulated in sepsis-induced

neutrophils, enhancing the transcription and translation of

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 mRNA, which

promotes neutrophil glycolysis and the production of inflammatory

cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 (35). Thus, neutrophil metabolic

reprogramming in SA-AKI likely contributes to the increased release

of ROS, NETs and other factors, exacerbating disease progression.

This process represents an interesting area for future

investigation in SA-AKI.

Additionally, NETs play a notable role in the

development of SA-AKI. NETs are web-like structures composed of

DNA, histones and antimicrobial proteins, released by activated

neutrophils (105). The

formation of NETs is regulated by the pore-forming protein

gasdermin D and depends on NADPH oxidase and neutrophil elastase

activity (106). NETs can

suppress macrophage phagocytosis, leading to persistent

inflammation and tissue damage. Inhibiting NET formation may

alleviate SA-AKI by restoring the infiltration and survival of

GAS6+ macrophages, promoting the clearance of damaged

cells and the resolution of inflammation (107). However, while NETs provide a

fibrous scaffold to entangle bacteria or pathogens, excessive

activation of NETs can worsen inflammation and tissue injury

(108). Furthermore, prolonged

disturbances in the pro-/anti-inflammatory balance lead to

pathogenic NET formation, which is a hallmark of systemic

inflammatory response syndrome (107). NETs can exacerbate kidney

damage by releasing cytokines and histones. Histones within NETs

directly damage renal tubular epithelial cells (109), while the DNA component can

activate the complement system (110), thereby intensifying the

inflammatory response. Notably, defective NET formation has been

shown to be protective in SA-AKI models (111).

Neutrophils do not remain fixed at the site of

inflammation; they can exit via a process known as rTEM (112,113), in which neutrophils move back

across the endothelium from the interstitial space into the

bloodstream. This re-migration occurs through interactions between

neutrophil surface molecules, such as β2 integrins, and

corresponding ligands on vascular endothelial cells, with

regulation by various cytokines and chemoattractants. rTEM plays a

dual role: On the one hand, it may help reduce local inflammatory

damage by decreasing neutrophil numbers in the affected tissue

(114), while on the other

hand, activated neutrophils re-entering the circulation can carry

inflammatory mediators, releasing them into the bloodstream and

potentially causing remote organ damage (115). For example, one study showed

that extracellular vesicles derived from endothelial cells

exacerbate remote lung injury by promoting rTEM (116). It is plausible that rTEM also

contributes significantly to SA-AKI, warranting further

investigation.

Additionally, neutrophil gelatinase-associated

lipocalin (NGAL) is crucial in the pathogenesis and progression of

SA-AKI. NGAL functions as a notable renal growth factor,

facilitating the differentiation of renal progenitor cells into

renal tubular epithelial cells (117). During the initial stages of

AKI, NGAL is upregulated in a compensatory manner to promote

tubular repair and regeneration (117). NGAL, primarily secreted by

neutrophils, is also produced by endothelial cells upon stimulation

by TNF-α, LPS and IL-1β (118).

After the kidney sustains ischemic, septic or nephrotoxic injury,

it releases large amounts of NGAL into both urine and serum. Thus,

NGAL is considered a promising early biomarker for SA-AKI (119-122). Beyond serving as an early

diagnostic biomarker, serum and urine NGAL can predict the

progression of AKI to CKD in patients with SA-AKI (123).

Numerous innovative nanotechnology-based therapies

targeting neutrophils have been developed. In diseases associated

with neutrophil infiltration, neutrophils serve not only as

therapeutic targets but also as ideal carriers for targeted drug

delivery (124). For example, a

targeted nanodrug delivery platform, Ac-PGP (a peptide sequence

that targets the CXCR2 receptor on neutrophils)-tetrahedral

framework nucleic acid (tFNA), utilizes tFNA and a neutrophil

hitchhiking mechanism (125).

DNA-based nanorobots have also been employed to target, load and

modulate neutrophils for precise drug delivery and

anti-inflammatory effects (125,126). Ly6G nanoparticles loaded with a

selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor can effectively suppress

the release of cytokines and chemoattractants from activated

neutrophils, preventing organ damage caused by excessive neutrophil

accumulation and migration (127). Additionally, nanomaterials

loaded with astragaloside IV, a natural compound with

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, can precisely target

neutrophils and inhibit NET formation, mitigating sepsis-induced

inflammatory responses and organ damage (128). Similarly, nanomaterials loaded

with Coenzyme Q10, an antioxidant, significantly enhance kidney

delivery efficiency, offering a new approach to alleviating kidney

damage (129). Nanozymes,

nanomaterials with enzyme-like activities, also play a vital role

in SA-AKI treatment by catalyzing specific biochemical reactions

and protecting the kidneys through mechanisms such as scavenging

excess ROS and modulating inflammatory signaling pathways (130). Neutrophil-targeted nanodrug

delivery systems provide novel strategies for SA-AKI treatment by

enabling precise intervention in neutrophil-mediated kidney injury,

optimizing nanocarrier design and facilitating clinical

translation.

Although studies targeting neutrophil-mediated

injury pathways have shown promising results, neutropenia remains a

high-risk condition in critically ill septic patients (131). Compared with non-neutropenic

patients, severe sepsis triggers a distinct inflammatory response

in neutropenic patients (131).

Levels of IL-6, IL-8 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

(CSF) are significantly elevated in neutropenic septic patients and

are independently associated with an increased risk of AKI

(131). Therefore, the

development of therapeutic strategies targeting neutrophils must be

carefully balanced to avoid excessive suppression of their

functions, which could impair renal repair.

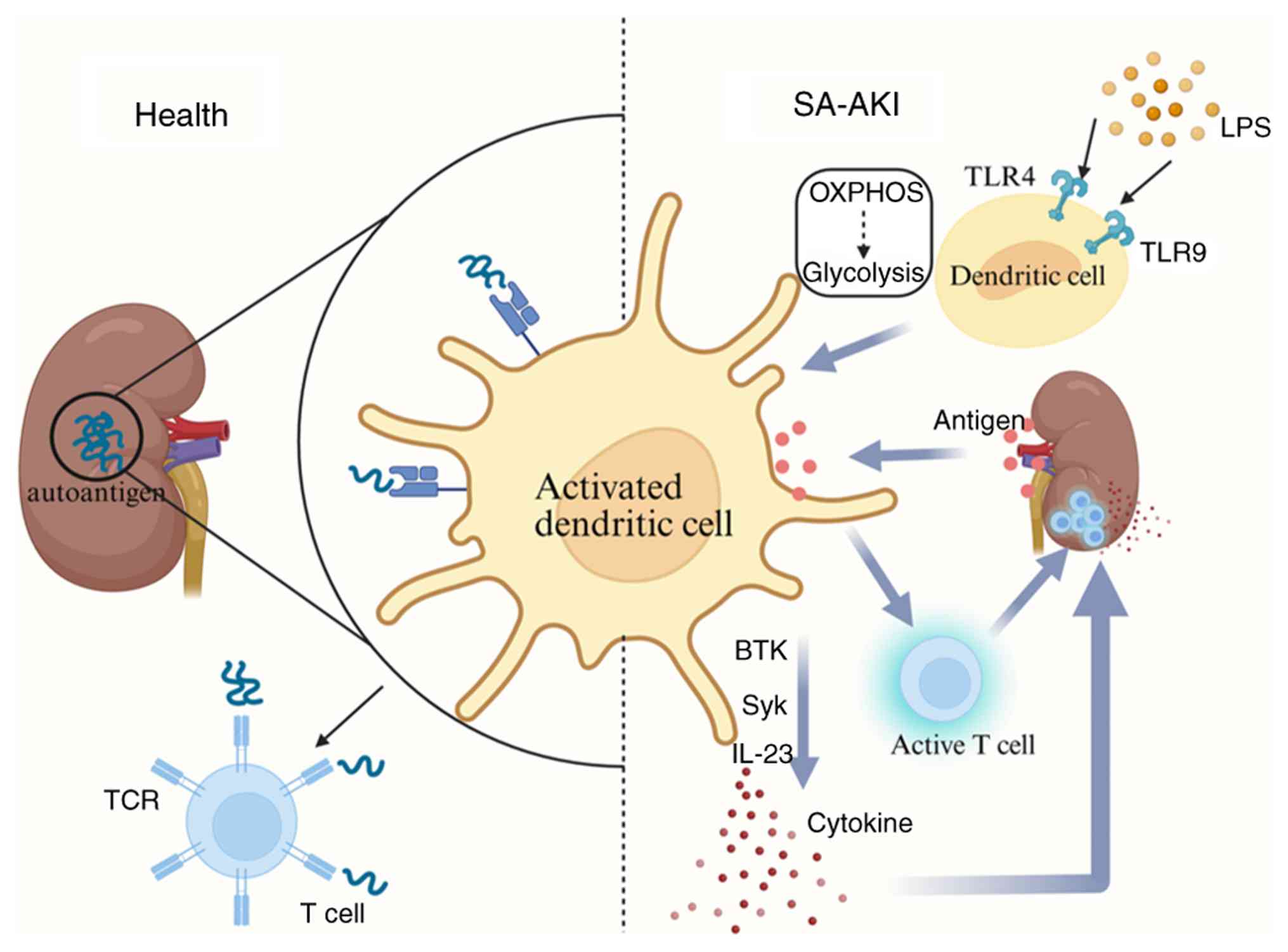

DCs, the most abundant resident leukocytes in the

kidney, play a critical role in renal immunity by forming a

sophisticated immune sentinel system that continuously monitors the

tubulointerstitial compartment (132) (Fig. 4). Under normal physiological

conditions, DCs primarily maintain immune tolerance and prevent

autoimmune responses (133);

they constantly sample and present autoantigens and

low-molecular-weight antigens from the glomeruli and tubules to T

lymphocytes, thereby promoting T cell tolerance and preventing

attacks on renal tissues (133,134). Additionally, DCs have the

capacity to recognize and clear apoptotic cells and debris,

preventing excessive activation of inflammatory responses (133). However, under pathological

conditions, DCs undergo notable changes. Upon recognition of DAMPs,

DCs undergo metabolic reprogramming, shifting from OXPHOS to

glycolysis to generate an immunogenic response (135). This metabolic shift is

accompanied by phenotypic maturation, enabling DCs to specialize in

T cell stimulation and activate innate immune cells (136). Mature DCs then migrate to

inflamed tissues and lymph nodes, enhancing their

antigen-presenting capacity by upregulating major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and T cell

co-stimulatory proteins on their cell membranes, thus facilitating

T cell activation and initiating an immune response (137,138).

DCs play an even more critical role in sepsis, where

they modulate the adaptive immune response to infection by

producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that guide

lymphocyte activation and lineage commitment (139). DCs may also mediate T cell

infiltration into the kidney, initiating inflammatory responses

that contribute to the onset and progression of SA-AKI, potentially

through antigen uptake from peritubular capillaries (139). DCs mediate the link between

TLRs and sepsis. TLR4 and TLR9, key members of the TLR family, are

closely associated with sepsis-induced inflammatory responses. TLR4

serves as the cellular receptor for LPS on the DC surface; the

binding of LPS to TLR4 activates downstream signaling pathways,

leading to the activation of NF-κB, a transcription factor that

regulates gene expression during LPS-induced inflammatory responses

in both kidney damage and sepsis (140). Triggered by endogenously

released mitochondrial DNA during sepsis, TLR9 activates DCs. The

activated DCs then produce IL-23, which induces γδ T cells to

produce IL-17A, thereby promoting the development of SA-AKI

(141). Based on these

mechanisms, developing specific inhibitors targeting TLR4 or TLR9

could be an effective strategy to mitigate the progression of the

inflammatory cascade in SA-AKI (140). Furthermore, LPS activates TLR4

signaling through two distinct pathways: Via the plasma membrane

through the Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter protein

(TIRAP)-MyD88 adapter complex and via endosomes through the

TRIF-related adaptor molecule-Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing

adapter inducing IFN-β (TRAM-TRIF) adapter complex. In DCs, the

p110δ subunit of PI3K acts as a key mediator, promoting the

transition of TLR4 signaling from the pro-inflammatory

TIRAP-MyD88-dependent phase to the anti-inflammatory

TRAM-TRIF-dependent phase (142). Therefore, using DCs as vehicles

through genetic modification or drug delivery approaches to enhance

the anti-inflammatory effects of the p110δ subunit presents a

promising therapeutic strategy for SA-AKI.

In addition to TLR4 and TLR9-related mechanisms, DCs

influence the progression of SA-AKI through the release of

inflammatory cytokines, a process regulated by the spleen tyrosine

kinase (Syk) signaling pathway (143). Inhibition of Syk signaling has

been shown to limit the inflammatory cascade in SA-AKI (144). Concurrently, research has

identified that activation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) in DCs

leads to a significant increase in biochemical markers associated

with subacute kidney injury. During the onset of SA-AKI, BTK is

activated in DCs, neutrophils and B cells, and inhibiting BTK

signaling improves renal function following AKI (145). Therefore, inhibiting both the

Syk and BTK signaling pathways in innate immune cells may serve as

an effective strategy to attenuate the progression of the

inflammatory cascade in SA-AKI.

Mast cells are granule-rich immune cells distributed

throughout the body, particularly in areas commonly exposed to

microbes, such as mucosal tissues, skin and connective tissues

(150). These cells interact

with pathogens through surface and intracellular receptors,

including pattern recognition receptors, bacterial toxin receptors,

antimicrobial peptides, complement proteins and Fc receptors

(151). While mast cells are

traditionally associated with allergic reactions, atopic asthma and

other IgE-mediated allergic diseases (152), studies have highlighted their

broader immunomodulatory roles. These include enhancing host

resistance in certain bacterial or parasitic infection models and

even providing defense against specific animal venoms (152). This functional diversity is

especially evident in sepsis. In the early stages of infection,

mast cells activate neutrophils by releasing IL-6 and suppressing

TNF, thereby enhancing their bactericidal activity (150,153-156). However, in severe sepsis,

excessive mast cell activation exacerbates the systemic

inflammatory response and increases mortality. Despite this, in

models of sepsis and ischemia-reperfusion injury, mast cells can

modulate TNF levels through the release of anti-inflammatory

mediators, such as protease 4 (a homolog of mouse mast cell

protease), which suppresses neutrophil overactivation, reduces

inflammation and mitigates renal impairment (152,157). In the context of kidney

disease, mast cells display a dual role. In anti-glomerular

basement membrane antibody-induced glomerulonephritis, mast cells

reduce glomerular injury by initiating repair mechanisms (158). By contrast, in

cisplatin-induced AKI, mast cells exacerbate the condition through

a TNF-dependent pathway (159).

While the specific role of mast cells in SA-AKI remains unclear,

existing evidence suggests their potential importance. Mast cells

may combat infection via rapid inflammatory responses and influence

disease progression through immunomodulation. Current understanding

of this mechanism largely relies on non-sepsis models, such as

cisplatin-induced and ischemia-reperfusion injury models. However,

the unique immune microenvironment in sepsis may alter the

manifestation of these mechanisms, and their direct role in SA-AKI

requires further validation.

Given the complex and diverse roles of mast cells,

future multicenter, large-scale clinical studies are urgently

needed. These studies should focus on the specific association

between mast cells and SA-AKI and further elucidate their

immunoregulatory functions, repair mechanisms and interactions with

the renal microenvironment. Such investigations are expected to

provide novel insights and therapeutic strategies for the treatment

of SA-AKI.

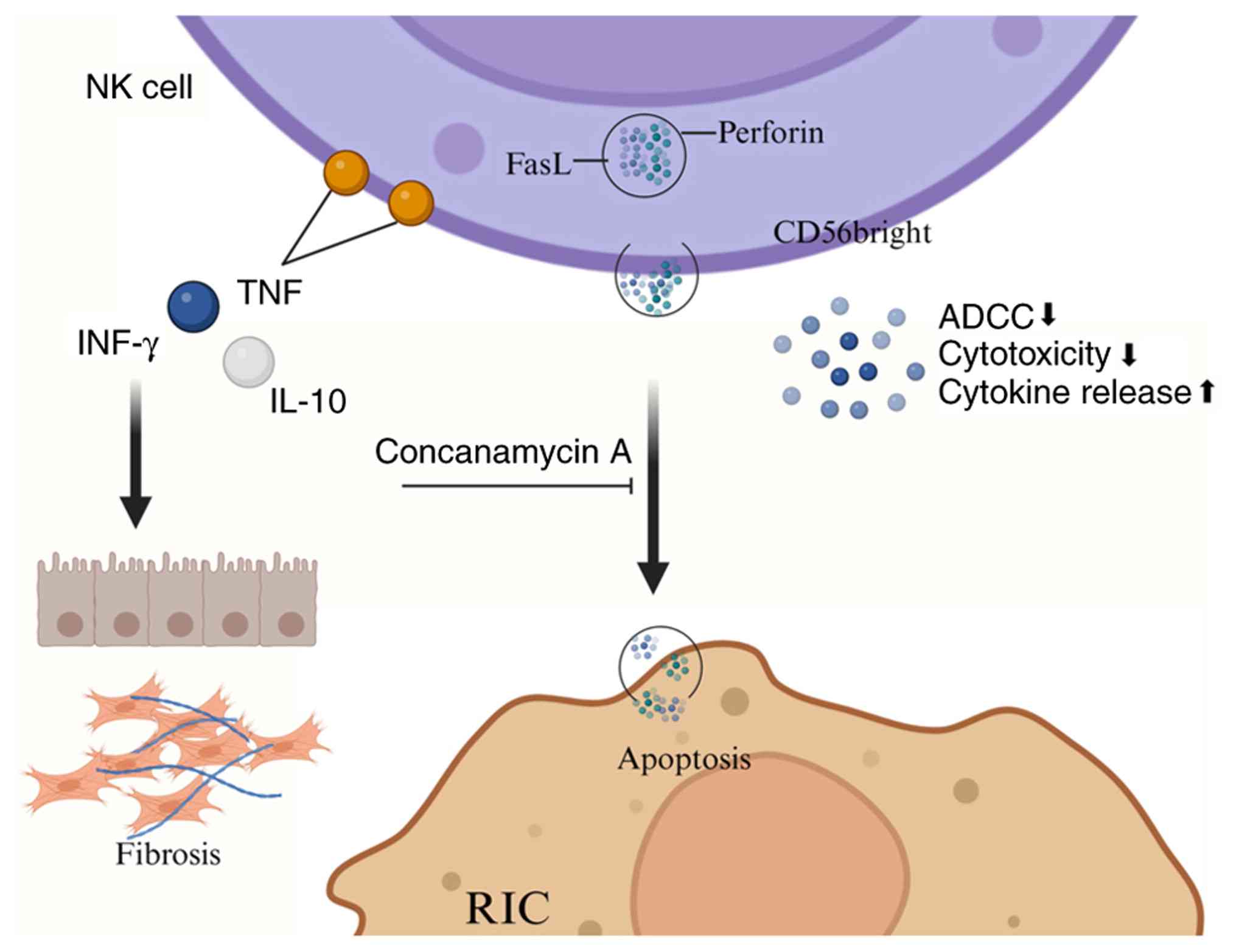

NK cells are large granular lymphocytes derived from

the bone marrow, constituting ~15% of all circulating lymphocytes.

Fig. 5 provides a schematic

overview of the roles and mechanisms of NK cells in the

pathogenesis of SA-AKI. As vital components of the innate immune

system, NK cells are capable of directly lysing tumor cells and

other target cells (160,161); however, their function is

dualistic. While NK cells are critical for immune defense,

excessive activation may result in attacks on normal cells, leading

to shock and multiple organ failure (MOF) (162). The mechanisms of NK cell action

manifest in two primary ways: i) Direct cytolysis via azurophilic

granules within the cytoplasm; and ii) the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFNs and TNF, to modulate the

activities of other immune cells (160,163). The activity of NK cells is

regulated by a balance of activating and inhibitory receptors on

their surface. Most healthy cells express MHC class I molecules,

which deliver inhibitory signals that suppress NK cell activity

(164). In humans, NK cells are

typically divided into two subsets: i) CD56bright NK cells,

predominantly found in lymphoid organs; and ii) CD56dim NK cells,

which are mainly located in peripheral blood. CD56bright NK cells

primarily exert immunoregulatory functions through cytokine

secretion, while CD56dim NK cells exhibit potent cytotoxic

capabilities (165,166). Notably, CD56bright NK cells

often express tissue-resident markers in the healthy kidney and may

play a key role in renal defense against infections (167). However, in patients with renal

fibrosis and chronic kidney disease (CKD), a substantial number of

CD56bright NK cells accumulate in the renal tubulointerstitium,

where they produce IFN-γ and contribute to the progression of renal

fibrosis (168). In the context

of SA-AKI, targeted treatment strategies could be developed based

on the distinct characteristics of these NK cell subsets. For

example, the cytotoxic function of CD56dim NK cells could be

harnessed to clear damaged cells, while the activity of CD56bright

NK cells could be modulated to prevent excessive inflammatory

responses. Furthermore, NK cells produce a wide range of cytotoxic

effector molecules, including Fas ligand (FasL) and perforin.

Notably, stimulation with bacterial components such as LPS leads to

a significant increase in the proportion of perforin-positive cells

(169,170). Stimulated human

CD56+ NK cell subsets can damage intrinsic renal cells,

including renal tubular epithelial cells and glomerular endothelial

cells. Inhibition of the perforin-mediated pathway with

concanamycin A can reduce the cytotoxicity of CD56+ NK

cells against glomerular endothelial cells (169,171).

In sepsis-related research, a decrease in human NK

cell counts has been observed within 1 day of sepsis onset, which

increases the risk of hospital-acquired infections and

sepsis-related complications (168). Additionally, NK cell function

is impaired in critically ill septic patients, accompanied by

reduced cytokine secretion (172). A further study has indicated

that lower levels of NK cells and other immune cells elevate

mortality risk in septic patients, whereas those with higher NK

cell levels tend to have longer survival times (173). A case report described a

patient with pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma who developed sepsis

and showed a poor response to conventional therapy. Following NK

cell infusion therapy, the patient's infection markers initially

decreased but later increased. While the long-term efficacy of NK

cell therapy requires further investigation, optimizing treatment

regimens holds promise for improving NK cell survival and

therapeutic outcomes (174).

The aforementioned case report suggests that NK cell therapy can

enhance patient physical function, increase cytokine levels with

antitumor activity and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines; it also

provides insights for SA-AKI treatment: Monitoring NK cell count

and function during therapy and selecting the appropriate timing

for intervention. For instance, administering appropriate

stimulation or supplementation before NK cell numbers severely

decline may enhance treatment efficacy, whereas restoring function

is necessary if NK cell activity is already impaired. Future

research should focus on optimizing NK cell treatment strategies,

including selecting suitable cell sources and determining the

optimal infusion doses and frequencies, to improve their survival

and efficacy in SA-AKI treatment.

In addition to NK cells, NKT cells represent a

unique subset of immune cells that exhibit characteristics of both

T cells and NK cells. As innate lymphocytes bridging innate and

adaptive immune responses, NKT cells are present in extremely low

numbers in the blood, accounting for <0.1% of human peripheral

blood mononuclear cells (175).

Based on the variability of the T cell receptor (TCR) chain, NKT

cells can be classified into two types: Type I (iNKT cells) and

type II (vNKT cells) (174,176). Among these, iNKT cells are the

predominant subtype in humans, expressing the Va-24 and Ja-18

chains; they differentiate into mature iNKT cells upon recognition

of glycolipid antigens presented by CD1d molecules (177). Furthermore, various cytokines

secreted by iNKT cells play a potent regulatory role in the

maturation of DCs, positioning iNKT cells as a critical link

between innate and adaptive immunity (177). A reciprocal regulatory

relationship exists between iNKT and vNKT cells, with vNKT cells

suppressing iNKT cell-mediated inflammatory responses. This

interaction may influence disease progression during the onset and

development of SA-AKI. Therefore, in treating SA-AKI, it is

essential to consider not only the overall status of NKT cells but

also the interactions between different subsets (178,179). Like NK cells, NKT cells express

activating receptors, inhibitory receptors and cytokine receptors

(such as IL-12 and TNF-α receptors) (167); they also possess the NK1.1

antigen and an intermediate TCR (171). NKT cells recognize lipids and

glycolipids presented by CD1d molecules (180) and can be activated through TCR

engagement, exhibiting potent cytotoxic functions and directly

participating in the clearance of infectious agents (167). This dual functionality provides

a more comprehensive perspective for understanding the

pathophysiology of SA-AKI and offers potential therapeutic

targets.

The role of iNKT cells in immune functions is

multifaceted. On the one hand, a study has demonstrated that iNKT

cells can mediate macrophage inflammatory responses to pathogenic

microorganisms by regulating macrophage quantity and phenotype,

optimizing immune factor release, enhancing host defense capacity

and improving macrophage killing efficiency (181). On the other hand, research on

sepsis has revealed that iNKT cells exacerbate the inflammatory

response during the early stages of sepsis, worsening its severity.

iNKT cell-deficient mice exhibit a certain level of protection

against sepsis (182), whereas

CD1-deficient mice, lacking both iNKT and vNKT cells, do not show

this protective effect (183).

During the development of AKI, NKT cells are known to highly

express inflammatory regulators, modulating the production of

cytokines involved in injury and complement activation, indicating

their involvement in AKI pathogenesis through inflammatory

mechanisms (184). SA-AKI can

lead to MOF, including AKI (167,185). Upon stimulation by cytokines or

bacterial components, NKT cells are activated. Similar to NK cells,

they can damage renal tubular epithelial cells via the TNF-α/FasL

system and injure vascular endothelial cells through a

perforin-mediated pathway. These independent mechanisms contribute

to the induction of SA-AKI (171). Relevant studies support this

view: In patients with SA-AKI undergoing continuous renal

replacement therapy (CRRT), the expression of perforin in

CD56+ NK cells and CD56+ T cells (that is,

NKT cells) is elevated, with FasL expression significantly

upregulated in these CD56+ T cells (167,169). This suggests that both the

TNF-α/FasL system and perforin play critical roles in the

progression of SA-AKI. Future strategies for SA-AKI treatment could

focus on regulating NKT cell activation. Additionally, this

phenomenon suggests that CRRT may be linked to NKT cell activation.

Subsequent therapeutic approaches could consider combining CRRT

with treatments targeting NKT cells to enhance CRRT efficacy and

improve the prognosis of patients with SA-AKI by modulating NKT

cell activation.

ILCs are critical components of the innate immune

system, playing essential roles in immune responses, inflammation

and tissue healing (186).

Although ILCs lack lineage-specific surface markers or antigen

receptors typical of other immune cells, they are critical for

maintaining protective immunity, homeostasis and inflammatory

responses (187). The role of

ILCs in the kidney is becoming increasingly recognized, with

evidence suggesting their involvement in immune surveillance,

homeostasis maintenance and disease progression within the kidney

(188). Despite their lack of

antigen-specific reactivity, ILCs share key transcriptional

regulators with T lymphocytes and possess the ability to produce

cytokines (189). ILCs are

classified into three main subsets: Group 1 ILCs (ILC1s), group 2

ILCs (ILC2s) and group 3 ILCs (ILC3s), each functionally associated

with Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells, respectively (190). Among these, ILC2-derived

cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, play a key role in driving

macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype (191). As aforementioned, appropriate

M2 macrophage activation is essential for ameliorating SA-AKI.

Kidney-resident ILC2s express receptors for IL-25

(IL-17RB) and IL-33 (T1/ST2), which, when activated by their

respective cytokines, promote ILC2 expansion in vivo

(192). While ILC2s exert

protective effects in the kidney, their impact depends on renal

IL-33 levels. During kidney injury and disease, IL-33, released

from vascular endothelial cells and/or renal tubular epithelial

cells, activates kidney-resident ILC2s (193). Studies on ILC2 function have

shown varying results. For instance, Akcay et al (194) found that recombinant IL-33

exacerbated AKI in a cisplatin-induced model by promoting

CD4+ T cell-mediated CXCL1 production. However, soluble

ST2, which neutralizes IL-33, reduced the severity of AKI. This

suggests that in cisplatin-induced AKI, IL-33 aggravates kidney

damage by activating the ST2 signaling pathway and promoting

inflammation. Conversely, Cao et al (195) observed that in an

ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI model, IL-33 pretreatment improved

renal injury by activating ILC2s, promoting M2 macrophage

polarization and aiding renal function recovery. These studies

indicate that the role of IL-33 in AKI is context-dependent,

influenced by factors such as the type of injury, inflammatory

environment and immune cell composition. The role of ILC2s in

SA-AKI remains unclear. Unlike non-infection-induced AKI, SA-AKI

pathogenesis is more complex and it is uncertain whether IL-33

activates ILC2s through similar mechanisms. However, a study has

shown that during sepsis, plasma IL-33 levels are significantly

elevated in young mice, promoting the egress of ILC2s from the bone

marrow. This alteration may affect the accumulation and function of

ILC2s in the kidney (196).

Therefore, when studying the functions of ILC2s in SA-AKI, factors

such as the experimental model and conditions must be carefully

considered. Further research into the specific signaling pathways

activated by IL-33 in different AKI models, along with the roles of

ILC2s in these pathways, could provide a theoretical foundation for

developing more effective therapeutic strategies for SA-AKI.

Research on the role of ILCs in SA-AKI is still

limited and their precise mechanisms of action are not fully

understood. Given the preliminary evidence supporting the

involvement of ILCs in other types of AKI, further investigation

into the functions and mechanisms of ILC subsets in SA-AKI is

crucial for advancing our understanding and treatment of this

condition.

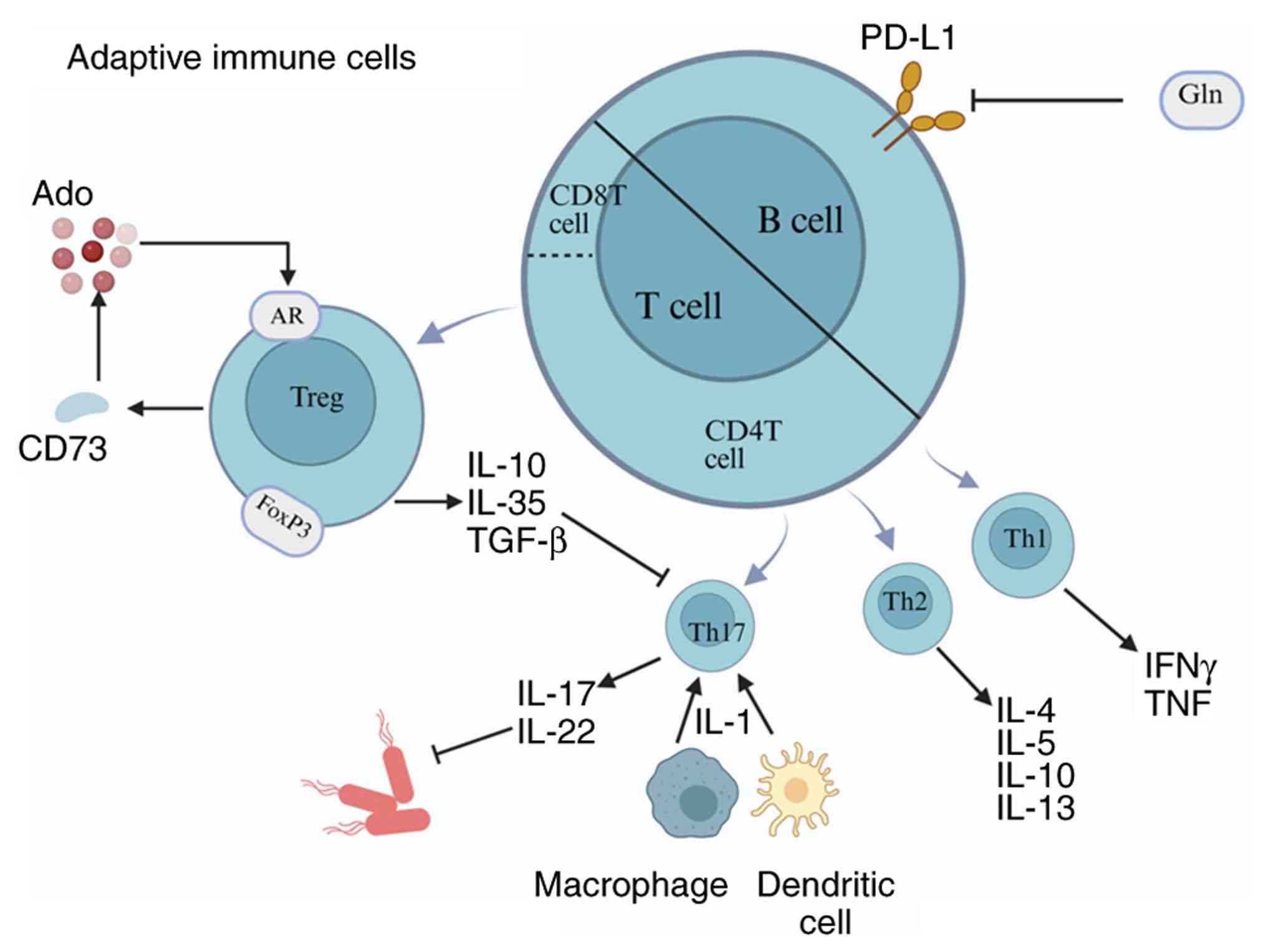

B cells, a key subset of lymphocytes, play an

essential role in the immune response. As summarized in Fig. 6, B cells produce antibodies,

presenting antigens and secreting cytokines, thereby mediating both

adaptive and innate immune responses, maintaining immune balance

and renal homeostasis (197).

However, due to their pathogenic role in organ transplantation and

autoimmune diseases, B cells are considered to have detrimental

effects in AKI (198). In a

cisplatin-induced AKI model, Inaba et al (199) observed that renal B cells were

a significant source of CCL7, promoting the recruitment of

neutrophils and monocytes to the injured kidney and exacerbating

AKI severity. Similarly, in a study of unilateral ureteral

obstruction-induced AKI, Han et al (200), found that early accumulation of

B cells in the kidney accelerated the mobilization and infiltration

of monocytes/macrophages, aggravating fibrosis induced by AKI.

Clinical studies on SA-AKI have shown an association between the

plasma lymphocyte ratio and renal function, with 1 study revealing

that septic patients who recovered renal function had fewer B

lymphocytes at hospital admission (201). Sepsis increases the expression

of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on B lymphocytes. Programmed

cell death protein 1 (PD-1) impairs immunity by inducing apoptosis,

inhibiting T-cell activation, increasing IL-10 production and

rendering T cells unresponsive while reducing their cytokine

secretion, leading to T-cell exhaustion. Glutamine administration

has been shown to reduce the expression of PD-1/PD-L1 on B cells,

alleviating kidney damage (202).

Under normal physiological conditions, T cells play

a pivotal role in maintaining renal immune homeostasis (203) (Fig. 6); they regulate immune responses,

preventing autoimmune reactions and excessive inflammation, thereby

protecting the kidneys from damage. T cells continuously monitor

renal tissues, identifying and eliminating potential pathogens or

abnormal cells to preserve kidney health (204). Following the onset of SA-AKI, T

cells, as key immune cells combating pathogen infections, play a

decisive role in the pathogenesis and progression of the

disease.

T cell subsets exert distinct immunomodulatory

functions in the kidneys. T lymphocytes can be classified into two

major subsets: CD4+ Th cells and CD8+ T

cells. Th cells are further divided into Th1, Th2 and Th17 subsets.

Th1 cells primarily produce IFN-γ and TNF-α, exerting

pro-inflammatory effects. Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and

IL-13 (205), predominantly

mediating anti-inflammatory effects. Th17 cells mainly produce

IL-17 and IL-22 (206). After

kidney injury, IL-1 secreted by renal DCs and macrophages promotes

the differentiation and activation of Th17 cells (207). Th17 cells infiltrate the renal

parenchyma during murine AKI, defend against extracellular

pathogens through the production of their signature cytokine IL-17

and play a pivotal role in promoting autoimmune diseases and tissue

inflammation (208).

In sepsis, lymphocyte dysfunction occurs not only

in peripheral blood cells but also in target organs (219). T cell priming is regulated by a

balance of positive and negative co-stimulatory molecules, with

imbalances in these molecules (also known as immune checkpoint

molecules) being closely linked to immune dysfunction (220). A common feature of

sepsis-associated immunosuppression is impaired lymphocyte function

and increased expression of inhibitory checkpoint molecules such as

PD-1. Activation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway by lactate can induce

immunosuppression by promoting lymphocyte apoptosis in SA-AKI.

Blocking the lactate receptor or PD-1/PD-L1 can restore lymphocyte

function and alleviate kidney damage (221). Additionally, MSCs can restore

the balance between Th17 and Treg cells via the galectin-9/T-cell

immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing molecule-3 pathway,

reduce inflammatory cell infiltration and reestablish the

equilibrium between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory

responses, thus improving SA-AKI (222). Dysregulation of T cells can

also lead to the abnormal release of immunomodulatory molecules,

such as excessive inflammatory cytokines, exacerbating tissue

inflammatory injury. In this context, glutamine has been shown to

alleviate SA-AKI by balancing T cell polarization and reducing T

cell apoptosis (223). Given

the imbalance in T cell subsets in patients with SA-AKI, future

therapeutic strategies should aim to selectively expand protective

T lymphocyte subsets or suppress damaging T cell subsets.

Several potential therapeutic targets related to T

cells in SA-AKI have been identified. In addition to α7nAChR

agonists, MSCs and anti-PD-L1 antibodies, recombinant human soluble

thrombomodulin (rTM), a single-transmembrane, multi-domain

glycoprotein receptor for thrombin, has emerged as a promising

candidate (224). rTM not only

reduces the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and

chemoattractants induced by LPS, thereby decreasing leukocyte

infiltration into the kidneys, but also mitigates kidney damage by

reducing the accumulation of CD4+ T cells,

CD11c+ cells and F4/80+ cells in SA-AKI. This

effect is mediated through enhanced phosphorylation of c-Jun, which

diminishes cytokine production and apoptosis signaling (224). Additionally, CD28 plays a role

in regulating TNF-α and IL-10 homeostasis, influencing the

expression of chemoattractants. Through the CD28 pathway, T cells

modulate renal function during sepsis (225).

In addition to therapeutic targets, certain T

cell-related biomarkers may serve as predictors for SA-AKI. Ma

et al (226)

demonstrated that T cell knock-out mice exhibit reduced

inflammatory cytokine secretion in renal tissue after LPS injection

and that T cell suppression alleviates sepsis-induced inflammation

and kidney damage. Therefore, T cell hyperactivation or

upregulation could serve as a biomarker for worsening SA-AKI, and

therapies targeting T cells or blocking receptors for inflammatory

cytokine secretion may offer benefits in treating SA-AKI (226). Elevated plasma levels of IL-10

and soluble CD25 (a marker of Treg cells) in patients with SA-AKI

may also serve as novel biomarkers (227). Moreover, ATP content in

CD4+ T cells (ATP_CD4) has been shown to correlate with

survival in sepsis patients. Low ATP_CD4 levels at 48 h post-onset

may indicate a higher likelihood of complete renal recovery, making

it a potential prognostic indicator (228).

Future research should focus on elucidating the

mechanisms of T cells in SA-AKI, including interactions among

different subsets and signaling pathways. Integrating the

regulation of immune checkpoint molecules, MSCs application,

exploration of potential therapeutic targets and the development of

biomarkers will contribute to the formulation of comprehensive

treatment strategies to improve the prognosis of patients with

SA-AKI.

Although treatment for SA-AKI significantly

alleviates the complex inflammatory response within the kidney, the

potential for persistent adverse effects following treatment

warrants attention. Even after the acute phase of AKI resolves,

renal injury may result in permanent nephron loss or maladaptive

repair, ultimately leading to CKD or accelerating the progression

of pre-existing CKD (229).

Furthermore, sepsis-induced immunosuppression represents a

prolonged and complex state of immune dysfunction. Even after the

acute inflammatory response is controlled, the immune system may

remain dysregulated, increasing the risk of subsequent infections

and abnormal responses during tissue healing (16). Additionally, sepsis often

involves multiple organs, leading to intricate organ-organ

interactions (230). AKI can

modulate the function of other vital organs through inter-organ

crosstalk. TNF-α and IL-1, key mediators of renal injury, also play

central roles in the pathophysiology of cardiac dysfunction during

sepsis (231). During SA-AKI,

renal injury not only triggers immune responses in lung tissue,

including monocyte, neutrophil and CD8+ T cell

infiltration, but also increases inflammatory cytokine production

and activates immune cells that impair intestinal barrier function

and increase permeability. Intestinal hyperpermeability is a common

factor exacerbating renal failure (232). These complex interactions

suggest that dysfunction in organs beyond the kidney may persist or

worsen, adversely impacting renal recovery. Therefore, the

therapeutic strategy for SA-AKI should focus not only on mitigating

renal inflammation but also on addressing the potential for

long-term adverse effects following treatment.

The present review systematically summarized the

mechanisms of various immune cells in SA-AKI and discussed

potential therapeutic strategies, encompassing both innate and

adaptive immunity and introducing innovative approaches such as

nanotechnology and cell therapy. However, several limitations

remain. First, some mechanistic studies cited in the present review

are based on non-septic AKI models (such as cisplatin-induced or

ischemia-reperfusion injury), which, while simulating certain

pathological features of kidney injury, differ significantly from

the immune microenvironment of patients with sepsis.

Sepsis-specific phenomena, such as immunoparalysis and endotoxin

tolerance, are difficult to replicate fully in these models,

limiting the direct applicability of their findings to SA-AKI.

Second, the roles of certain immune cells (such as mast cells and

ILCs) in SA-AKI are still discussed primarily through inference or

indirect evidence, particularly concerning their specific functions

in sepsis. Further experimental validation using sepsis-specific

models is necessary to confirm these roles. Finally, while the

present review has introduced various novel therapeutic strategies

based on nanotechnology and cell therapy, the application of these

strategies in treating SA-AKI remains challenging. Most

nanomaterials lack clinical evaluations for long-term safety and

biocompatibility. Although some animal studies have shown positive

results, the human immune system's response to nanomaterials may

differ. Additionally, targeted therapies for the kidneys require

further research. The stability of the preparation process and

quality control in the clinical translation of nanomaterials are

also key factors affecting long-term safety. Therefore, long-term

safety testing and large-scale clinical studies are needed to

ensure the sustainability and reliability of these treatments. In

conclusion, future research should focus on the development and

application of sepsis-specific animal models, enhance

spatio-temporal analysis of the dynamic functions of immune cells

and promote the translation of basic research into clinical

applications, ultimately providing a more reliable foundation for

precision immunotherapy in SA-AKI.

Not applicable.

LX, WJ, JY and RZ wrote the main manuscript text.

LS and JW modified the details of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All of the authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

We sincerely thank Dr Keran Shi (Department of

Critical Care Medicine, The Yangzhou Clinical College of Xuzhou

Medical University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu 225001, P.R. China), Dr

Yuanjin Pan (Department of Critical Care Medicine, Northern Jiangsu

People's Hospital Affiliated to Yangzhou University, Yangzhou,

Jiangsu 225001, P.R. China), Dr. Yuchen Wang (Department of

Critical Care Medicine, The Yangzhou Clinical College of Xuzhou

Medical University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu 225001, P.R. China) and Dr

Luanluan Li (Department of Critical Care Medicine, Northern Jiangsu

People's Hospital Affiliated to Yangzhou University, Yangzhou,

Jiangsu 225001, P.R. China) for their continuous encouragement and

valuable insights during the preparation of this review. Their

constructive suggestions and enthusiastic support not only

alleviated the challenges encountered during the writing process

but also inspired us to refine the content with greater depth and

precision.

This work was supported by grants from Health and Wellness

Development and Promotion Project (grant no. QS-XFGCJWZZ-0062);

National Key Clinical Specialty, Financial Appropriations of

National [grant no. 176.(2022)]; Flagship Institution of Chinese

and Western Medicine Coordination, Financial Appropriations of

National (grant no. Jiangsu 60(2023)]; Jiangsu Provincial Medical

Key Discipline Cultivation Unit (grant no. JSDW20221); Yangzhou

Social Development Project (grant no. YZ2023105); Special

Scientific Research Fund of Yangzhou Health Commission (grant no.

2023-1-02) and Management Project of Northern Jiangsu People's

Hospital (grant no. YYGL202306).

|

1

|

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW,

Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche

JD, Coopersmith CM, et al: The third international consensus

definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA.

315:801–810. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Seymour CW, Kennedy JN, Wang S, Chang CH,

Elliott CF, Xu Z, Berry S, Clermont G, Cooper G, Gomez H, et al:

Derivation, validation, and potential treatment implications of

novel clinical phenotypes for sepsis. JAMA. 321:2003–2017. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Liu D, Huang SY, Sun JH, Zhang HC, Cai QL,

Gao C, Li L, Cao J, Xu F, Zhou Y, et al: Sepsis-induced

immunosuppression: Mechanisms, diagnosis and current treatment

options. Mil Med Res. 9:562022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang D, Sun T and Liu Z: Sepsis-associated

acute kidney injury. Intensive Care Res. 3:251–258. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS,

Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, et al:

Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: A multinational,

multicenter study. JAMA. 294:813–818. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Balkrishna A, Sinha S, Kumar A, Arya V,

Gautam AK, Valis M, Kuca K, Kumar D and Amarowicz R:

Sepsis-mediated renal dysfunction: Pathophysiology, biomarkers and

role of phytoconstituents in its management. Biomed Pharmacother.

165:1151832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lee K, Jang HR and Rabb H: Lymphocytes and

innate immune cells in acute kidney injury and repair. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 20:789–805. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gao X, Cai S, Li X and Wu G:

Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: Mechanisms, biomarkers and

immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 16:15771052025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang Z and Wang Z: The role of macrophages

polarization in sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Front Immunol.

14:12094382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kwok AJ, Allcock A, Ferreira RC,

Cano-Gamez E, Smee M, Burnham KL, Zurke YX; Emergency Medicine

Research Oxford (EMROx); McKechnie S, Mentzer AJ, et al:

Neutrophils and emergency granulopoiesis drive immune suppression

and an extreme response endotype during sepsis. Nat Immunol.

24:767–779. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Qi X, Yu Y, Sun R, Huang J, Liu L, Yang Y,

Rui T and Sun B: Identification and characterization of neutrophil

heterogeneity in sepsis. Crit Care. 25:502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhao F, Xiao C, Evans KS, Theivanthiran T,

DeVito N, Holtzhausen A, Liu J, Liu X, Boczkowski D, Nair S, et al:

Paracrine Wnt5a-β-catenin signaling triggers a metabolic program

that drives dendritic cell tolerization. Immunity. 48:147–160.e7.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Flohé SB, Agrawal H, Schmitz D, Gertz M,

Flohé S and Schade FU: Dendritic cells during polymicrobial sepsis

rapidly mature but fail to initiate a protective Th1-type immune

response. J Leukoc Biol. 79:473–481. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tang J, Shang C, Chang Y, Jiang W, Xu J,

Zhang L, Lu L, Chen L, Liu X, Zeng Q, et al: Peripheral

PD-1+NK cells could predict the 28-day mortality in

sepsis patients. Front Immunol. 15:14260642024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nascimento DC, Viacava PR, Ferreira RG,

Damaceno MA, Piñeros AR, Melo PH, Donate PB, Toller-Kawahisa JE,

Zoppi D, Veras FP, et al: Sepsis expands a CD39+

plasmablast population that promotes immunosuppression via

adenosine-mediated inhibition of macrophage antimicrobial activity.

Immunity. 54:2024–2041.e8. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kox M, Bauer M, Bos LDJ, Bouma H, Calandra

T, Calfee CS, Chousterman BG, Derde LPG, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ,

Gómez H, et al: The immunology of sepsis: Translating new insights

into clinical practice. Nat Rev Nephrol. 22:30–49. 2026. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Dick SA, Wong A, Hamidzada H, Nejat S,

Nechanitzky R, Vohra S, Mueller B, Zaman R, Kantores C, Aronoff L,

et al: Three tissue resident macrophage subsets coexist across

organs with conserved origins and life cycles. Sci Immunol.

7:eabf77772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bell RMB and Conway BR: Macrophages in the

kidney in health, injury and repair. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol.

367:101–147. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zimmerman KA, Yang Z, Lever JM, Li Z,

Croyle MJ, Agarwal A, Yoder BK and George JF: Kidney resident

macrophages in the rat have minimal turnover and replacement by

blood monocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 321:F162–F169. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cheung MD, Erman EN, Moore KH, Lever JM,

Li Z, LaFontaine JR, Ghajar-Rahimi G, Liu S, Yang Z, Karim R, et

al: Resident macrophage subpopulations occupy distinct

microenvironments in the kidney. JCI Insight. 7:e1610782022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhao J, Andreev I and Silva HM: Resident

tissue macrophages: Key coordinators of tissue homeostasis beyond

immunity. Sci Immunol. 9:eadd19672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Qu Z, Chu J, Jin S, Yang C, Zang J, Zhang

J, Xu D and Cheng M: Tissue-resident macrophages and renal