Introduction

The human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

(HER2)-positive subtype accounts for 15-20% of breast cancer cases

and is characterized by aggressive nature and poor clinical

outcomes (1). Over the past two

decades, the implementation of HER2-targeted therapeutics,

including monoclonal antibodies, small molecule tyrosine kinase

inhibitors and antibody-drug conjugates such as trastuzumab

emtansine and trastuzumab deruxtecan, has markedly improved patient

outcomes in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (2). In the metastatic setting, these

therapeutic advances are associated with a median overall survival

exceeding 50 months, as demonstrated by clinical trials and

real-world studies conducted in North America and Europe (3-5).

Despite advances in HER2-targeted therapies, approximately 15-24%

of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer develop metastatic

disease, highlighting a persistent risk of disease progression

(6). Therapeutic resistance

remains a major limitation, underscoring the need for more

effective and durable therapeutic strategies (2,7).

In breast cancer, cancer stem cells (CSCs)

constitute a distinct subpopulation characterized by self-renewal

capacity, multilineage differentiation potential and resistance to

standard chemotherapy. These cells are commonly defined by specific

phenotypic markers, most notably a

CD44high/CD24low surface profile and elevated

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) activity, both of which are

associated with tumor initiation, progression, metastasis and poor

clinical outcomes (8-10). HER2-positive breast cancer

exhibits pronounced tumor heterogeneity and biological complexity,

typically harboring increased CSC-like populations, which actively

contribute to resistance mechanisms (11,12). In these resistant tumors, CSCs

exhibit increased activation of survival pathways, including

PI3K/AKT and Notch signaling, and CSC characteristics are further

promoted by HER2/HER3-mediated signaling, creating a

self-reinforcing cycle of resistance (13). Consequently, simultaneously

targeting HER2/HER3 signaling and CSC pathways may offer an

effective strategy to overcome trastuzumab resistance.

Recently, drug repurposing, which involves

identifying novel anticancer indications for existing

non-oncological agents, has emerged as a rational and

cost-effective strategy in therapeutic development (14). Disulfiram, an ALDH inhibitor that

targets CSC-like properties, has also been shown to inhibit HER2

signaling through proteasome inhibition and copper-dependent

oxidative stress (15,16), and is being evaluated in a Phase

II trial with copper in metastatic breast cancer (trial no.

NCT03323346). Metformin, a widely used antidiabetic agent, improves

clinical and pathological responses when combined with neoadjuvant

doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by a taxane, in breast

cancer (trial no. NCT04170465) (17) and shows potential survival

benefits in the HER2-positive subgroup in the large-scale MA.32

Phase III trial (trial no. NCT01101438) (18). Together, findings suggest that

disulfiram and metformin are promising drug repurposing candidates

for breast cancer therapy.

Ebastine is a second-generation antihistamine with

favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles, including high oral

bioavailability, minimal central nervous system (CNS) penetration

and low systemic toxicity (19,20). Although primarily used for

allergic conditions, recent in vitro and in vivo

preclinical studies have shown its antitumor potential in various

types of cancer through diverse mechanisms such as EZH2 (enhancer

of zeste homolog 2) inhibition, autophagy induction and suppression

of angiogenesis (21-23). Our previous study demonstrated

that ebastine suppresses metastatic progression in triple-negative

breast cancer by targeting focal adhesion kinase, leading to

inhibition of STAT3/ERK signaling and decreased CSC-like properties

(22). These findings highlight

the potential of ebastine as a multi-targeted anticancer, agent

although its mechanism of action in the context of HER2-positive

breast cancer remains to be fully elucidated. The present study

investigated the potential of ebastine to overcome trastuzumab

resistance by targeting HER2/HER3 heterodimerization and CSC-like

properties in vitro and evaluated its antitumor efficacy

in vivo using a trastuzumab-resistant xenograft model.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Ebastine was purchased from Selleck Chemicals.

Propidium iodide (PI), Triton X-100 and DMSO were obtained from

Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA). Phosphatase and protease inhibitor

cocktail tablets were obtained from Roche Applied Sciences. RNase A

was purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Primary antibodies were as follows: Ki-67 (cat. no. ab16667), CD31

(cat. no. ab28364), ALDH1A1 (Abcam; cat. no. ab52492), Bcl-2

(Abcam; cat. no. ab692) and CD44 (all Abcam; cat. no. ab254530);

HER2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 2165), HER3 (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 12708), phosphorylated

(p-)HER2 (Y1221/1222; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no.

2243), p-HER3 (Y1289; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no.

2842), Akt (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 9272), p-Akt

(S473; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 4060), PARP (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 9542), cleaved PARP (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 5625), caspase-3 (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 7148), -7 (Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 12827) and -8 (Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 4790), cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 9664), -7 (Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.; cat. no. 8438) and -8 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat.

no. 9496), Bax (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 2772) and

vimentin (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 5741);

anti-intracellular domain (ICD) HER2 clone 4B5 (Ventana Medical

Systems; cat. no. 790-4493) and GAPDH (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. MA5-15738). Secondary antibodies

included HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.;

cat. no. 1721011) and anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.;

cat. no. 1706515), as well as Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat.

no. A-11037), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. A-11008),

Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. A-11032) and Alexa Fluor

488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. A-11001).

Breast cancer cell lines

The human breast cancer cell lines SKBR3, BT474,

MDA-MB-453 (American Type Culture Collection) and JIMT-1 (Leibnitz

Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell

Cultures GmbH) were cultured in DMEM, MEM or RPMI-1640 (all

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. All cell

lines were passaged for <6 months and were authenticated by

short tandem repeat profiling performed by Macrogen, Inc. The study

design is summarized in Fig.

S1.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the CellTiter

96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS)

according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega Corporation).

The quantity of formazan product was determined by measuring

absorbance at 490 nm using a SpectraMax® 190 microplate

reader (Molecular Devices LLC).

Sub-G1 analysis and Annexin V/PI

assay

For cell cycle analysis, JIMT-1, MDA-MB-453, SKBR3

and BT474 cells were fixed with pre-chilled 95% ethanol containing

0.5% Tween-20 at 4°C for 24 h, then incubated with PI and RNase A

(both 50 μg/ml) at room temperature for 30 min. Apoptotic

cell death was determined as the sum of early apoptotic (Annexin

V+/PI−) and late apoptotic (Annexin

V+/PI+) populations, using the FITC Annexin V

Apoptosis Detection kit (BD Biosciences), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Stained cells were analyzed by flow

cytometry using a BD LSRFortessa™ X-20 Cell Analyzer (BD

Biosciences), and BD FACSDiva™ software (version 8.0.1; BD

Biosciences).

Aldefluor-positivity assay and

CD44high/CD24low staining

An Aldefluor™ assay kit (Stemcell Technologies,

Inc.) was used to assess ALDH1 activity, according to the

manufacturer's instructions. BT474 and SKBR3 cells were incubated

for 45 min at 37°C in Aldefluor assay buffer containing the ALDH

substrate BODIPY-aminoacetaldehyde (1 μM/0.5x106

cells). The ALDH1-specific inhibitor diethylamino-benzaldehyde (50

mM) was used to define the baseline Aldefluor fluorescence. For

CD44/CD24 analysis, cells (1x106) were immunostained at

4°C for 30 min with FITC-conjugated anti-CD24 (cat. no. 555427),

PE-conjugated anti-CD44 (BD Biosciences; cat. no. 555479),

FITC-(cat. no. 553456) or PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (all 1:50;

all BD Biosciences; cat. no. 555749), followed by flow cytometric

analysis using a BD LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using BD

FACSDiva software (version 8.0.1; BD Biosciences).

Immunoblot analysis

JIMT-1, SKBR3 and BT474 cells were lysed in cold

lysis buffer [0.5% Triton X-100, 30 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH

7.4)] containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail

tablets. The supernatant was collected following centrifugation

(14,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min), and protein concentrations were

quantified using a Quick Start™ Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein (25 μg/lane)

were separated by SDS-PAGE using 8-15% gradient gels and

transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5%

skimmed milk for 30 min at room temperature and incubated overnight

at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in 5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA; cat. no. A7906-100G) as follows: HER2 (1:2,000), p-HER2

(1:1,000), HER3, p-HER3, Akt, p-Akt, PARP, cleaved PARP, caspase-3,

-7 and -8, cleaved caspase-3, -7 and -8, Bcl-2, Bax (all 1:2,000)

or GAPDH (1:3,000). Following washing with 1X PBST, membranes were

incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (1:3,000-1:10,000; cat.

no. 1721011) or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:3,000-1:5,000;

both Bio-Rad Laboratories, cat. no. 1706515) for 1 h at room

temperature. Signal intensity was detected using a

Chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on X-ray

film (AGFA HealthCare) and quantified using AlphaEaseFC software

(version 4.0.0; Alpha Innotech).

Immunoprecipitation assay

A Dynabeads™ Protein G Immunoprecipitation kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was used to evaluate

protein-protein interactions according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Cells were lysed in Pierce® IP lysis

buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with

phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails. The supernatant was

collected by centrifugation (14,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min) and

equal amounts (1,000 μg) were incubated with 10 μg

anti-HER2 antibody conjugated to Dynabeads Protein G at 4°C

overnight. The protein complexes were eluted by boiling the beads

in a mixture of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and elution buffer (1:1),

followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described above.

Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

CETSA was performed to evaluate the direct

engagement of ebastine with endogenous HER2. 293T (American Type

Culture Collection) cells were cultured overnight at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, and treated with

either DMSO (vehicle) or 30 μM ebastine for 1 h at 37°C.

Cells were harvested, resuspended in PBS containing protease and

phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Science) and

aliquoted into PCR tubes. Samples were heated at 45-63°C for 3 min

using a thermal cycler, followed by cooling at room temperature for

3 min. The heated cells were lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles

consisting of freezing in liquid nitrogen (-196 °C) for 3 min

followed by thawing at room temperature for 1 min, and soluble

fractions were obtained by centrifugation (14,000 × g at 4°C for 20

min). Supernatants were collected and analyzed by immunoblotting

using anti-HER2 antibody, as aforementioned.

Mammosphere formation assay

BT474 (5x104/ml) and JIMT-1 cells

(1.5x104/ml) were plated in ultra-low attachment dishes

and cultured under serum-free suspension conditions in HuMEC basal

serum-free medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 5

days (BT474) or 8 days (JIMT-1) supplemented with B27 (1:50,

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 20 ng/ml human EGF and

basic fibroblast growth factor (both Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 1%

antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat.

no. 15240-062), 4 μg/ml heparin and 15 μg/ml

gentamycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The number

and volume of mammospheres were assessed using an inverted light

microscope, CKX53 (Olympus Corporation), and calculated using the

formula: Volume=(4/3) × π × r3, where r is the

radius.

Animals and in vivo xenograft

experiment

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance

with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and

approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

(approval no. KOREA-2021-0070-C1) of Korea University College of

Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea. Female BALB/c nude mice (age, 5

weeks; n=10; initial body weight, 16-17 g) were purchased from NARA

Biotech, housed under standard specific pathogen-free conditions

(temperature, 22±2°C; humidity, 50±10%; 12-h light/dark cycle) and

acclimated for 1 week with free access to food and water. JIMT-1

cells (3.5x106) were inoculated into the fourth mammary

fat pads of the mice. When the mean tumor volume reached 100

mm3, mice were randomized into two groups (n=5/group)

and administered either a solvent control (DMSO/corn oil, 1:9) or

ebastine (20 mg/kg body weight/day) via intraperitoneal injection

every other day for 46 days. Tumor volume and body weight were

measured twice/week. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula:

Volume=(length × width2)/2. At study termination, the

largest tumor measured 14.42 mm in diameter with a volume of

1,873.55 mm3, which was within the tumor-size limits

permitted by the approved IACUC protocol. Mice were euthanized

using a gradual-fill CO2 method, starting at an initial

concentration of 20% CO2 and gradually increasing to 70%

CO2, followed by cervical dislocation to ensure complete

euthanasia, in accordance with the IACUC-approved protocol. Death

was confirmed by the absence of respiration and heartbeat.

Molecular modeling and docking

analysis

Molecular docking studies were performed using

publicly available platforms for protein-ligand virtual screening,

including GalaxySagittarius (galaxy.seoklab.org/), DockThor (dockthor.lncc.br/) and CB-Dock2 (cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/). Following completion

of the docking simulations, 2D and 3D visualization of

protein-ligand interactions, along with predicted binding

affinities and binding energies, was performed using UCSF Chimera

1.16 (cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/) and BIOVIA

Discovery Studio 2021 (discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download/).

Serum biochemistry for liver and renal

injury biomarkers

At the time of sacrifice, blood samples (0.5-1.0 ml)

were collected from each animal, and serum was obtained by

centrifugation at 1,100 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Serum biochemical

markers of liver and renal function, including aspartate

aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total

bilirubin (TBL), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, were

evaluated using a serum biochemistry profiling service by DKKorea

Inc.

Immunohistochemistry with apoptosis

in-situ localization (TUNEL)

Tumors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 24 h and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections (5

μm thickness) were mounted on positively charged glass

slides, deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through a graded

ethanol series to water. For antigen retrieval, sections were

boiled in citric acid buffer (pH 6.0) at ~95-100°C for 20 min. The

sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies

diluted in antibody diluent [Ki-67, CD31, HER2, 4B5, HER3, ALDH1A1,

CD44 (all 1:100) and vimentin (1:300)], followed by incubation with

Alexa Fluor® 488- or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies

at room temperature for 2 h. Slides were mounted with ProLong™ Gold

Antifade Reagent with DAPI at room temperature for 1 h. In

situ TUNEL assays were performed on tissue sections using a

TUNEL kit (Roche Applied Sciences; cat. no. 11684795910), according

to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, sections were

incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture at 37°C for 1 h, and

fluorescence signals were evaluated in at least five randomly

selected fields of view per section. All images were acquired using

a confocal microscope, and fluorescence intensity was analyzed

using the histogram tool in ZEN Blue software (version 3.2; Carl

Zeiss Microscopy GmbH).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining

Organs (kidney, liver and lung) were excised, fixed

in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature for 24-48 h,

embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4 μm thickness.

Sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded

ethanol to water, and stained with hematoxylin for 3 min followed

by eosin for 1 min at room temperature, followed by dehydration,

clearing and mounting. H&E-stained sections were examined under

a light microscope to assess histopathological abnormality.

Whole-slide images were acquired using a slide scanner (Axio Scan,

Z1; Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH), and digital images were used for

histopathological evaluation and quantitative analysis.

Public datasets and bioinformatics

analysis

For survival analyses, mRNA expression data and

clinical information of patients with breast cancer were obtained

from the UCSC Xena TCGA-BRCA cohort (tcga.xenahubs.net; dataset IDs:

TCGA.BRCA.sampleMap/HiSeqV2 and TCGA.BRCA.

sampleMap/BRCA_clinicalMatrix) (24) and the GENT2 database (gent2.appex.kr/gent2/; GEO-derived; GPL570 and GPL96)

(25). Patients were stratified

into high- and low-expression groups based on the median expression

of each gene (TCGA: CD44=13.023, ALDH1A1=8.5464, ERBB2=12.707; GEN

T2: CD4 4 =9.894818, A LDH1A1=7.870365, ERBB2=9.210671). Survival

regression curves were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software

(Dotmatics) and overall survival was analyzed for up to 200 months

using the log-rank test.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0

statistical software (Dotmatics). All data are presented as the

mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Statistical

comparisons were performed using unpaired Student's t-test or one-

or two-way ANOVA. For multiple group comparisons, the Bonferroni

post hoc test was applied. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient

was calculated to determine the association between ALDH1A1 and

CD44 expression in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Ebastine induces apoptosis in

trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer cells

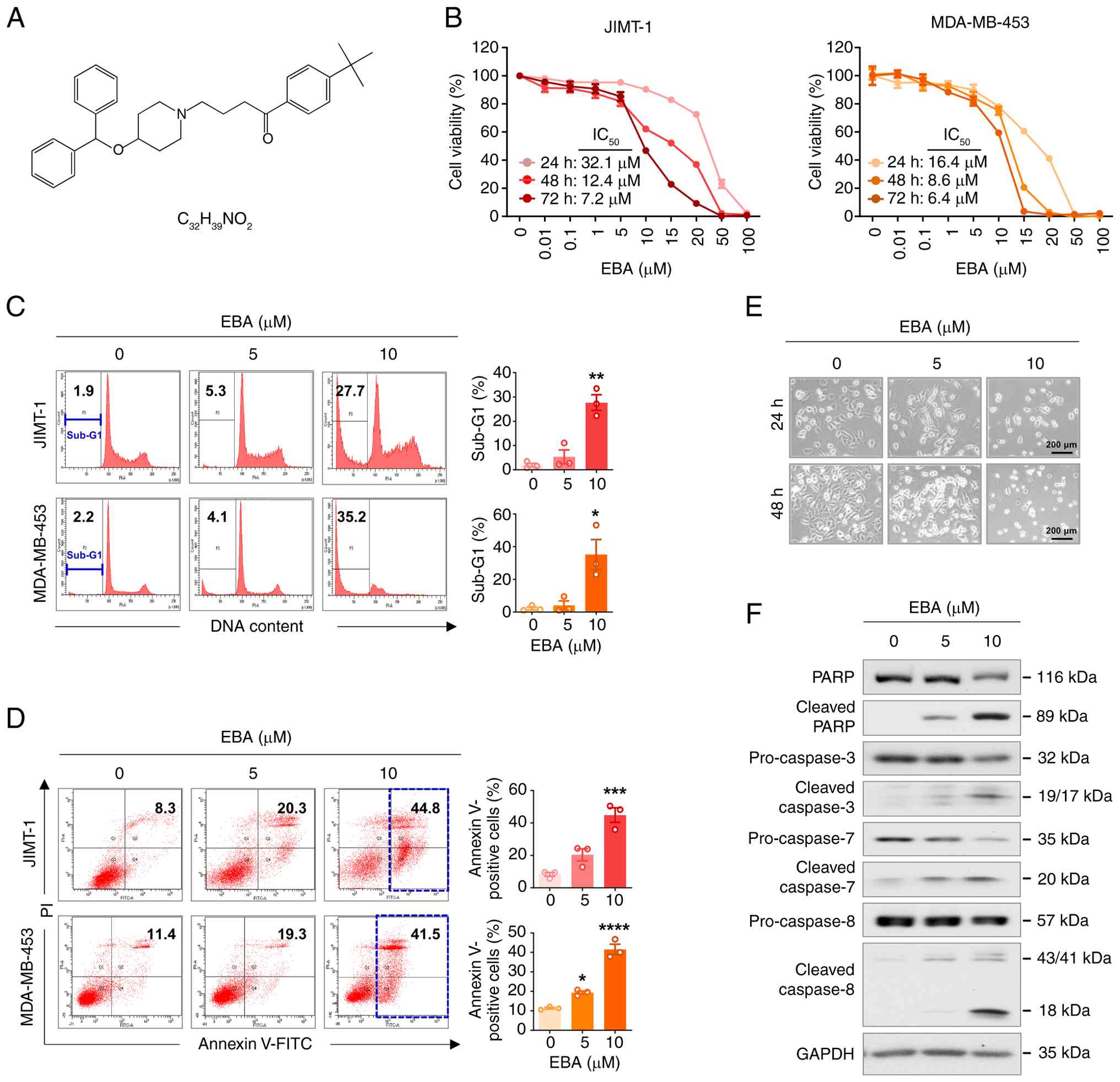

Ebastine is a piperidine derivative containing a

diphenylmethoxy group, connected via a butan-1-one chain to a

4-tert-butylphenyl group. This structural configuration enhances

membrane permeability and metabolic stability (Fig. 1A) (19,26). To evaluate its therapeutic

potential in overcoming trastuzumab resistance, the present study

examined whether ebastine inhibited the viability of HER2-positive

breast cancer cells with established trastuzumab resistance. The

JIMT-1 cell line, derived from a patient with intrinsic resistance

to trastuzumab, and the MDA-MB-453 cell line, established from the

pleural effusion of a patient with metastatic breast cancer and

known to be insensitive to trastuzumab, were used as representative

models (27-29). Compared with

trastuzumab-sensitive BT474 and SKBR3 cells, these resistant lines

showed notably lower basal HER2/HER3 expression and

phosphorylation, consistent with their decreased responsiveness to

trastuzumab (Fig. S2).

Ebastine (0-100 μM, 24-72 h) decreased

viability in JIMT-1 and MDA-MB-453 cells in a time- and

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B).

To determine whether this inhibition was associated with apoptosis,

the present study performed DNA content analysis to quantify the

sub-G1 population. A significant accumulation of HER2-positive

breast cancer cells in the sub-G1 phase was occurred following

ebastine treatment (10 μM, 48 h, Fig. 1C). Ebastine treatment led to an

increase in early and late apoptotic JIMT-1 and MDA-MB-453 cells

(Fig. 1D). Consistent with these

findings, ebastine-treated JIMT-1 cells exhibited characteristic

morphological features of apoptosis, including nuclear

condensation, cytoplasmic shrinkage and detachment from the culture

substrate (Fig. 1E).

Mechanistically, ebastine-induced apoptosis involved caspase

activation, evidenced by the cleavage of caspase-8 and activation

of executioner caspases-3, -7, and -8 (Fig. 1F). Notable PARP cleavage

indicated that cell death occurred through a caspase-dependent

pathway.

The present study evaluated the effect of ebastine

on trastuzumab-sensitive HER2-positive breast cancer BT474 and

SKBR3 cells. Ebastine (0-100 μM, up to 72 h) decreased cell

viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. S3A and B). The apoptotic features

included notable morphological changes (Fig. S3C), a marked increase in the

sub-G1 population (Fig. S3D),

and an elevated proportion of Annexin V-positive cells (Fig. S3E) following ebastine treatment

(5-10 μM, 48 h). These effects coincided with activation of

caspases-3 and -7, increased PARP cleavage (Fig. S3F and G) and increased p18Bax

levels without altering Bcl-2 expression (Fig. S3H and I).

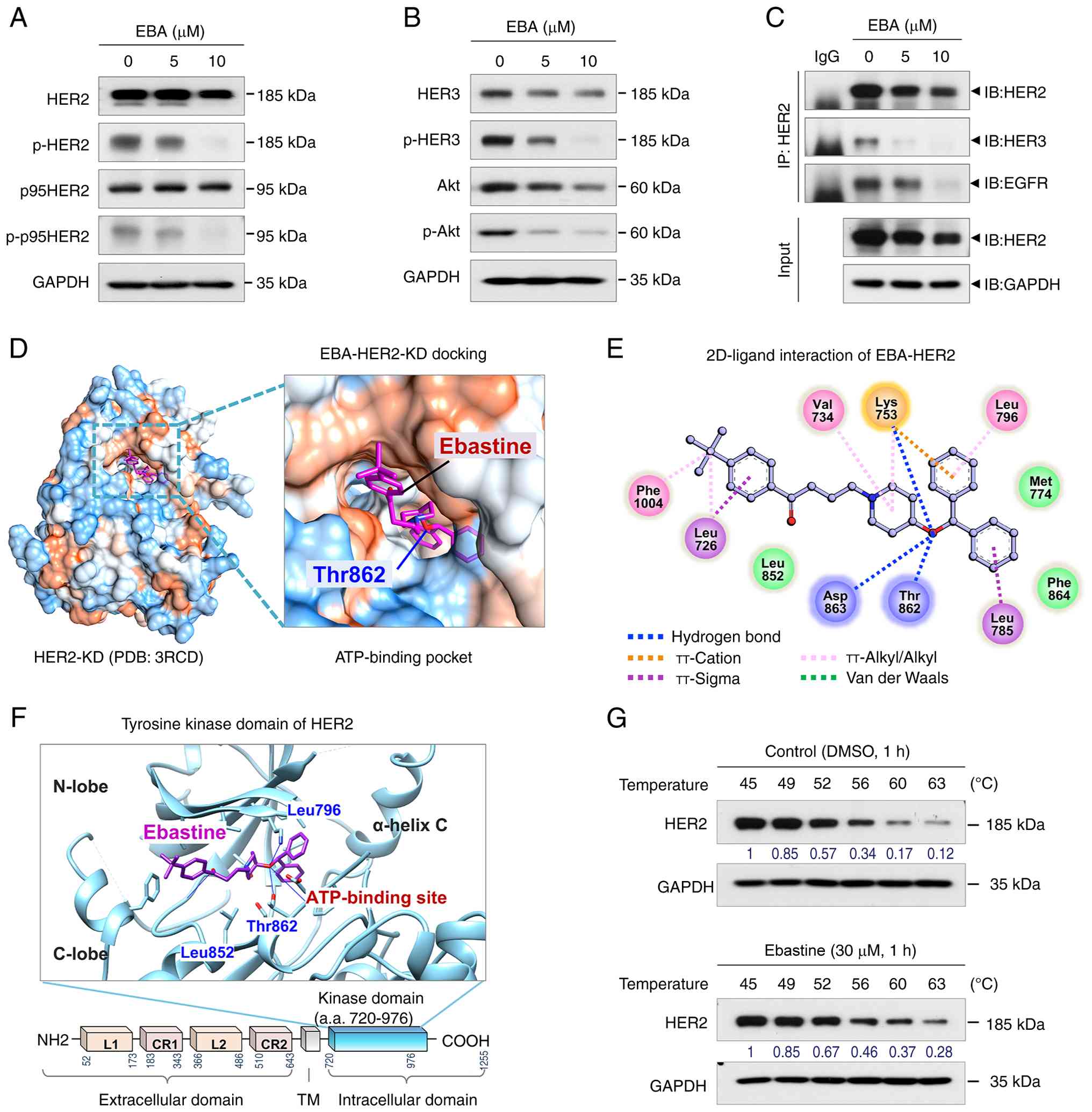

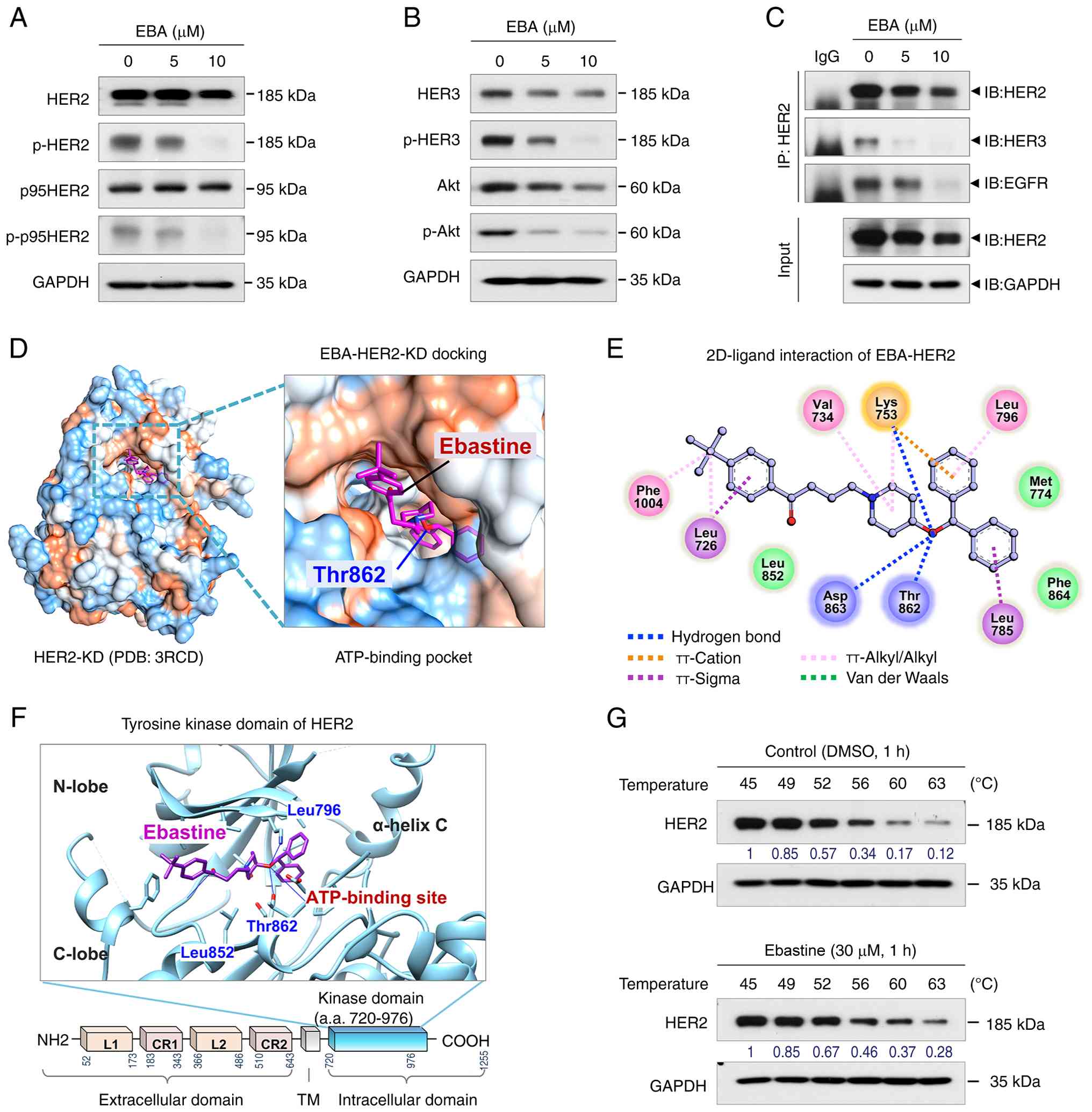

Ebastine downregulates HER2/HER3 and

truncated-p95HER2

Trastuzumab resistance is primarily driven by HER2,

HER3 and the truncated isoform p95HER2, which maintain pro-survival

PI3K/AKT signaling through persistent HER2/HER3 heterodimerization

(30). Ebastine (5-10 μM,

48 h) notably decreased total and p-HER2 (Y1221/1222), as well as

HER3 and p-HER3 (Y1289) in JIMT-1 (Fig. 2A and B) cells. p95HER2, which

lacks the extracellular domain required for trastuzumab binding,

retains HER2 kinase activity and contributes to therapeutic

resistance (31,32). Ebastine also downregulated

cleaved p95HER2 and suppressed the expression of AKT and p-AKT

(Fig. 2A and B). Since AKT

functions downstream of the HER2/HER3 signaling pathway, the

present study examined its phosphorylation status as an indicator

of downstream signaling (33,34). Immunoprecipitation analysis using

anti-HER2 revealed that ebastine substantially impaired the

heterodimerization of HER2 with both HER3 and EGFR (Fig. 2C). Similarly, in

trastuzumab-sensitive BT474 and SKBR3 cells, ebastine decreased the

phosphorylation of HER2, HER3, and p95HER2, leading to decreased

AKT activation (Fig. S4). The

present study performed molecular docking simulation to determine

whether this was due to the binding of ebastine to HER2 (Fig. 2D-F). Docking studies using the

crystal structure of the HER2 kinase domain retrieved from the

Protein Data Bank revealed that ebastine fit into the ATP-binding

pocket near the hinge region between the N- and C-lobe of the

tyrosine kinase domain (Fig. 2D and

F). This interaction was stabilized by three hydrogen bonds,

several π-interactions and hydrophobic contacts. Ebastine formed

hydrogen bonds with key residues within the ATP-binding site of

HER2-KD (HER2 kinase domain), including Thr862, Asp863 and Lys753

and a π-cation interaction occurred between the active site residue

Lys753 and a phenyl ring of ebastine (Fig. 2E). To validate this predicted

interaction, CETSA was performed using 293T cells. Ebastine (30

μM, 1 h) markedly enhanced the thermal stability of

endogenous HER2 compared with DMSO-treated controls. In

DMSO-treated samples, the soluble fraction of HER2 was largely lost

at temperatures >60°C, whereas ebastine-treated cells

demonstrated detectable HER2 up to ~63°C (Fig. 2G). These results indicated that

ebastine stabilized HER2 in cells, supporting the hypothesis of a

physical interaction between the proteins. Collectively, molecular

docking and CETSA data suggested that ebastine may interact with

the HER2 kinase domain and was associated with decreased HER2

phosphorylation, which may overcome trastuzumab resistance in

HER2-positive breast cancer.

| Figure 2EBA downregulates HER2, p95HER2, HER3

and AKT expression. (A) Immunoblot analysis of HER2, p95HER2 and

p-HER2 (Y1221/1222) in JIMT-1 cells treated with EBA for 48 h. (B)

Immunoblot analysis of HER3, p-HER3 (Y1289), AKT and p-AKT

following treatment with EBA (48 h) in JIMT-1 cells. (C) Immunoblot

analysis of HER2, HER3 and EGFR following IP with anti-HER2

antibody in JIMT-1 cells treated with EBA. In silico

molecular docking of EBA with the crystal structure of HER2-KD. (D)

Surface map of lipophilic and hydrophilic properties at the

ATP-binding site of HER2-KD (red, hydrophobic; blue, hydrophilic).

(E) 2D interaction diagram showing intermolecular interactions

between EBA and HER2-KD. Key amino acid residues within the binding

pocket are shown. (F) Predicted binding pose of EBA (purple stick

model) within the tyrosine kinase domain of HER2 (blue ribbon). (G)

293T cells were treated with DMSO or EBA for 1 h at 37°C, followed

by heating for 3 min. Soluble fractions were collected following

centrifugation and analyzed by immunoblotting using an anti-HER2

antibody. EBA, ebastine; p-, phosphorylated; IP,

immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblotting; KD, kinase domain PCB,

protein complex binding; TM, transmembrane; a.a., amino acid. |

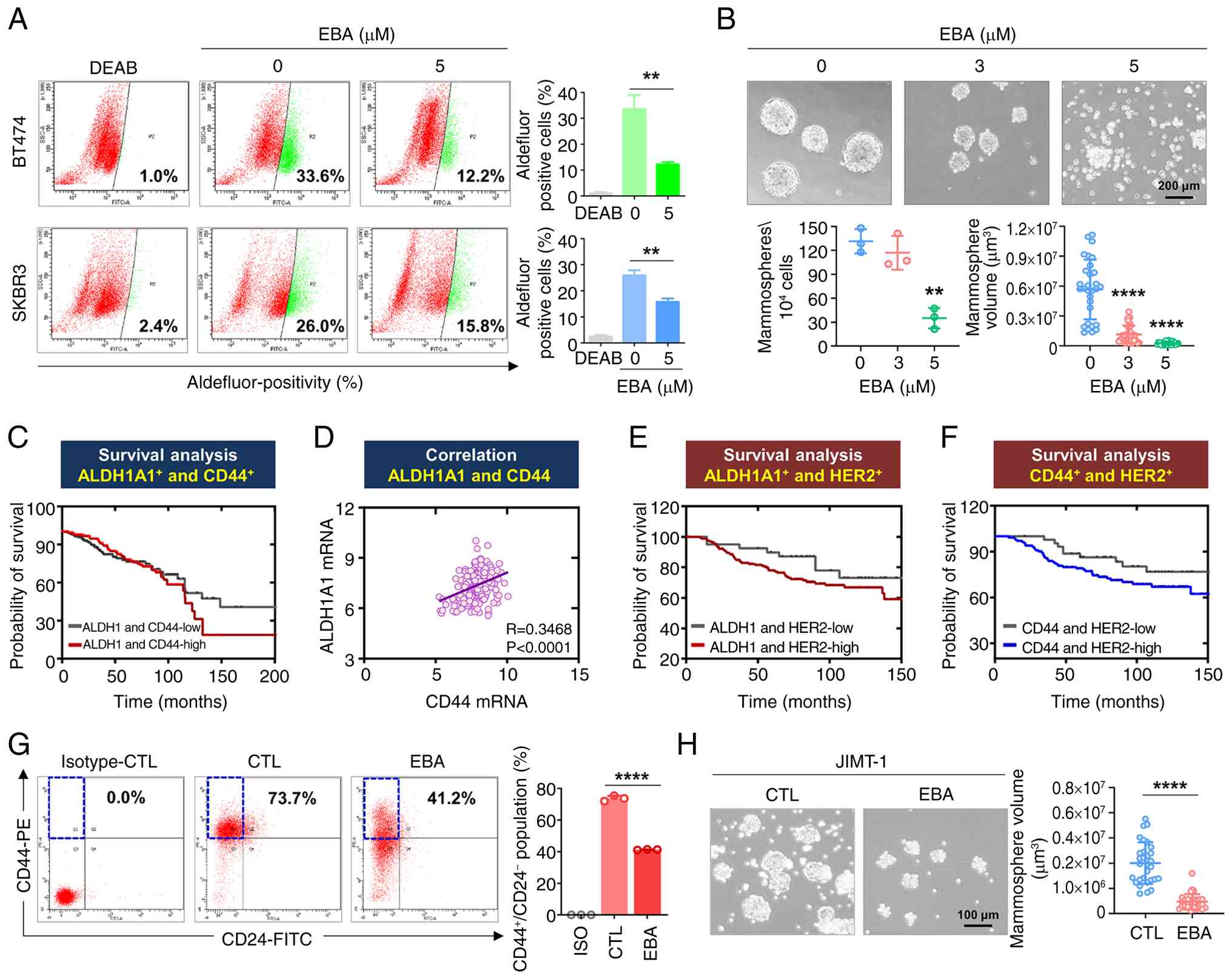

Ebastine targets breast CSC (BCSC)-like

properties in HER2-positive breast cancer

BCSCs are defined by their self-renewal and

tumor-initiating capacity and characterized by distinct molecular

markers and functional attributes (35). ALDH1, a detoxifying enzyme for

intracellular aldehydes, contributes to maintaining the stem-like

state in tumor cells with activated cancer hallmarks (10). HER2-positive breast cancer

exhibits the highest ALDH1 activity among all subtypes (15). Ebastine significantly decreased

ALDH1 activity in BT474 and SKBR3 cells (Fig. 3A). To evaluate self-renewal, the

present study performed 3D mammosphere assay, which functionally

assess the tumor-initiating potential of BCSCs (36). Ebastine significantly decreased

mammosphere number and volume in BT474 cells (P<0.01, Fig. 3B), indicating impaired

self-renewal.

The CD44high/CD24low phenotype

marks a CSC-like population in breast cancer and is associated with

increased invasiveness, a key feature of early metastasis (10,37). Tumorigenesis can be initiated by

a limited number of cells, requiring ~500 Aldefluor-positive cells

or 20 ALDH+/CD44+/CD24− cells

(10). Kaplan-Meier analysis

showed that patients with breast cancer with high expression of

ALDH1A1 and CD44 had a shorter overall survival (Fig. 3C). Gene expression analysis of

GENT2 dataset showed a significant positive correlation between

CD44 and ALDH1A1 in patients with HER2-high breast cancer (Fig. 3D). High expression of either

ALDH1A1 (Fig. 3E) or CD44

(Fig. 3F) was associated with

poor prognosis in this HER2-overexpressing patient group. These

findings indicated that CSC markers were clinically associated with

poor outcomes in patients with HER2 overexpression, supporting the

mechanistic relevance of ebastine CSC-targeting effects observed

in vitro. CD44-associated gene expression is positively

associated with trastuzumab response, suggesting CD44 as a

potential biomarker (38).

Ebastine treatment significantly decreased the

CD44high/CD24low stem-like population

(Fig. 3G) and impaired

mammosphere formation in trastuzumab-resistant JIMT-1 cells

(Fig. 3H), demonstrating that

ebastine effectively targeted CSC-like properties in

trastuzumab-resistant contexts.

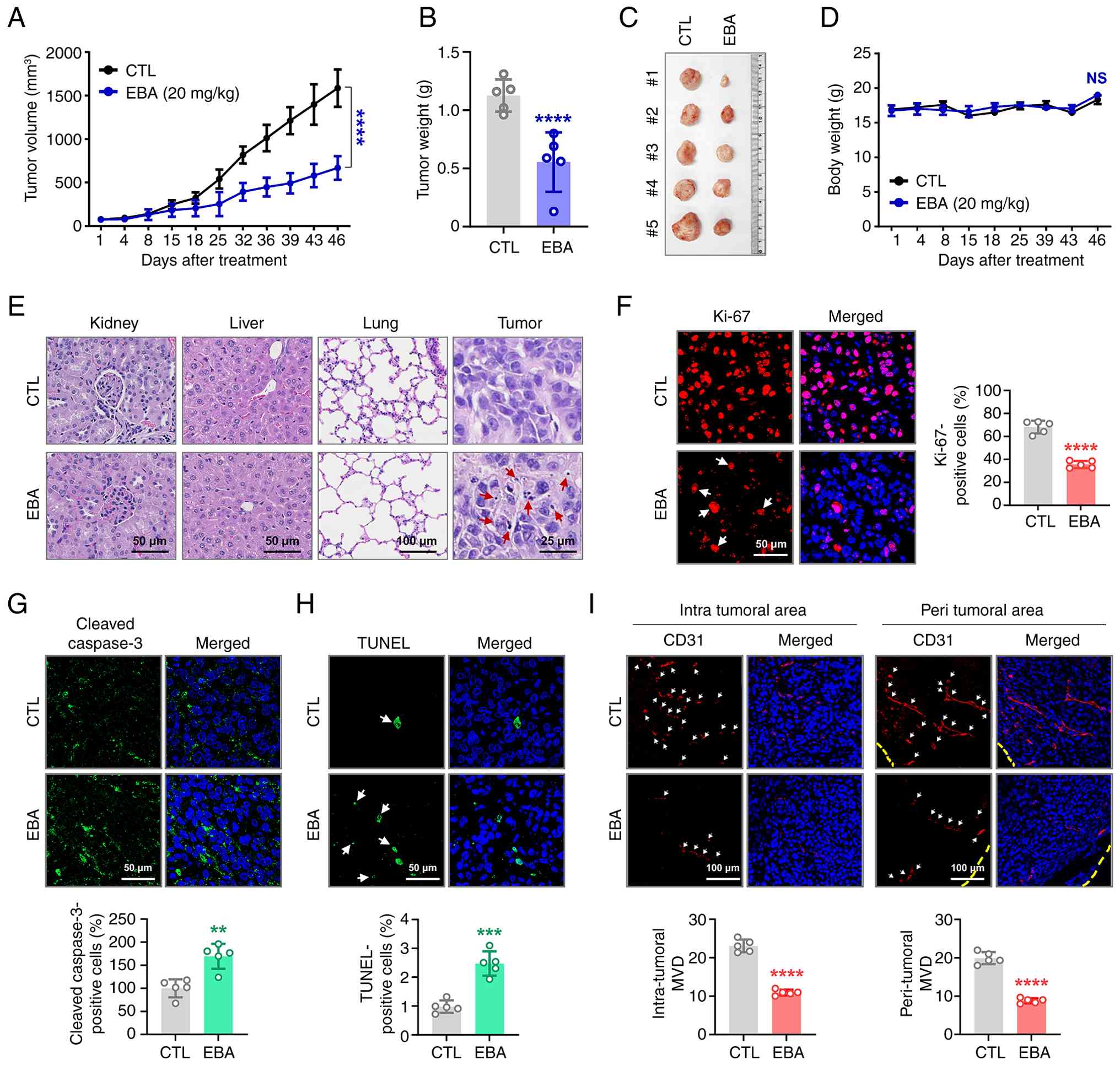

Ebastine exerts anti-tumor activity in

trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer in vivo

To assess the physiological relevance of the in

vitro findings, the present study established a

trastuzumab-resistant JIMT-1 xenograft model to evaluate the

antitumor effect of ebastine in vivo (Fig. 4A). When tumor volumes reached ~50

mm3, mice were administered ebastine (20 mg/kg, every

other day) or vehicle control. At day 46, ebastine led to a

significant suppression of tumor volume (Fig. 4A) and tumor weight (Fig. 4B and C), without affecting body

weight (Fig. 4D).

Histopathological examination using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining revealed no observable abnormality in the kidney, liver or

lung tissue of ebastine-treated mice compared with controls. Tumor

tissue from the ebastine-treated group exhibited a notable number

of cells with nuclear condensation and fragmentation, indicative of

treatment-induced apoptosis (Fig.

4E). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed a significant

reduction in the Ki-67 proliferation index following ebastine

treatment (Fig. 4F), supporting

its antiproliferative activity. Apoptosis induction was evidenced

by a significant increase in DNA fragmentation, as determined by

the in situ TUNEL assay (Fig.

4H), accompanied by enhanced caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 4G). The antiangiogenic potential

of ebastine was assessed by quantifying microvessel density using

the endothelial marker CD31. A significant decrease in the number

of CD31-positive microvessels was observed in both intratumoral and

peritumoral (Fig. 4I) regions

following ebastine treatment.

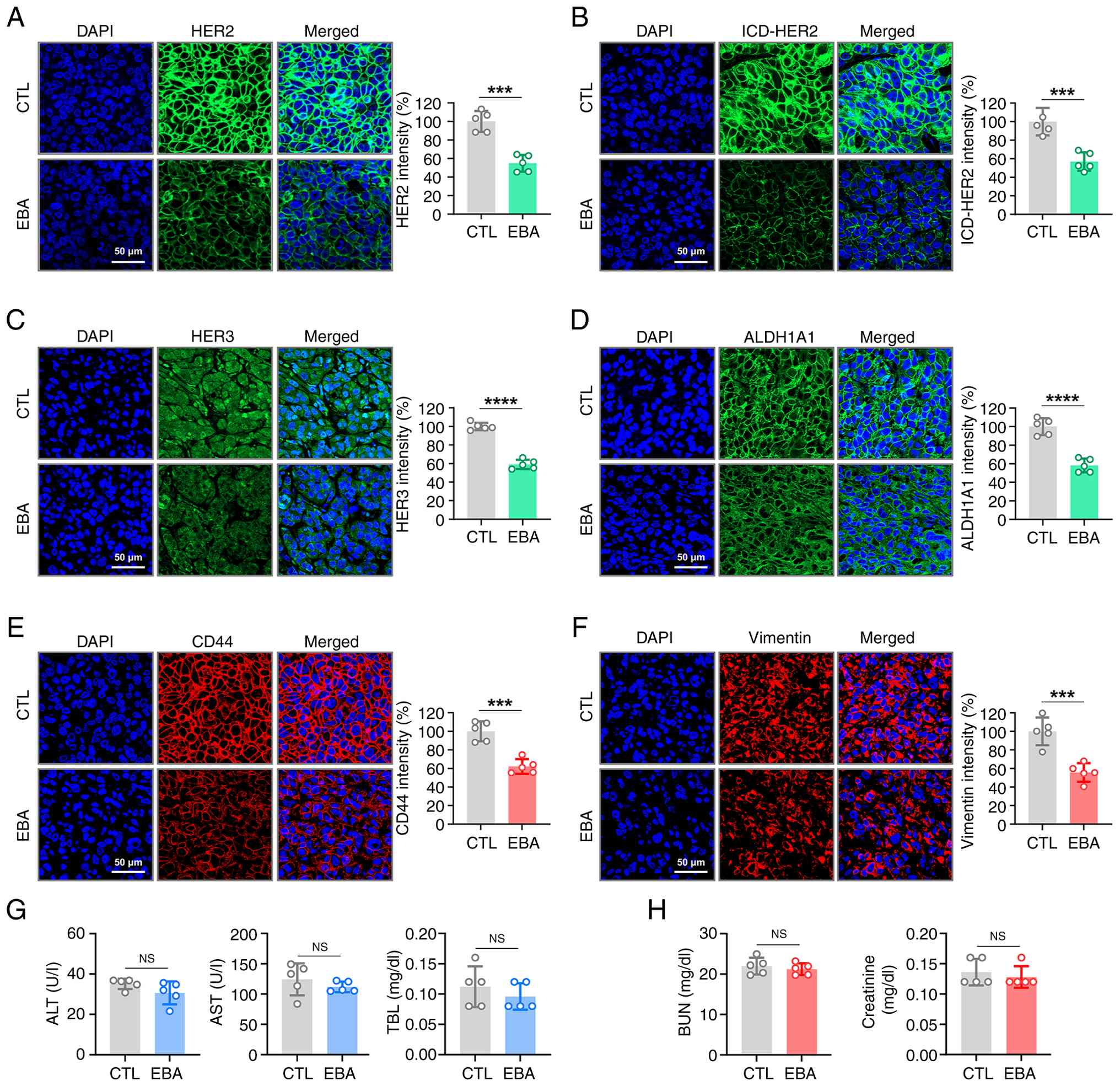

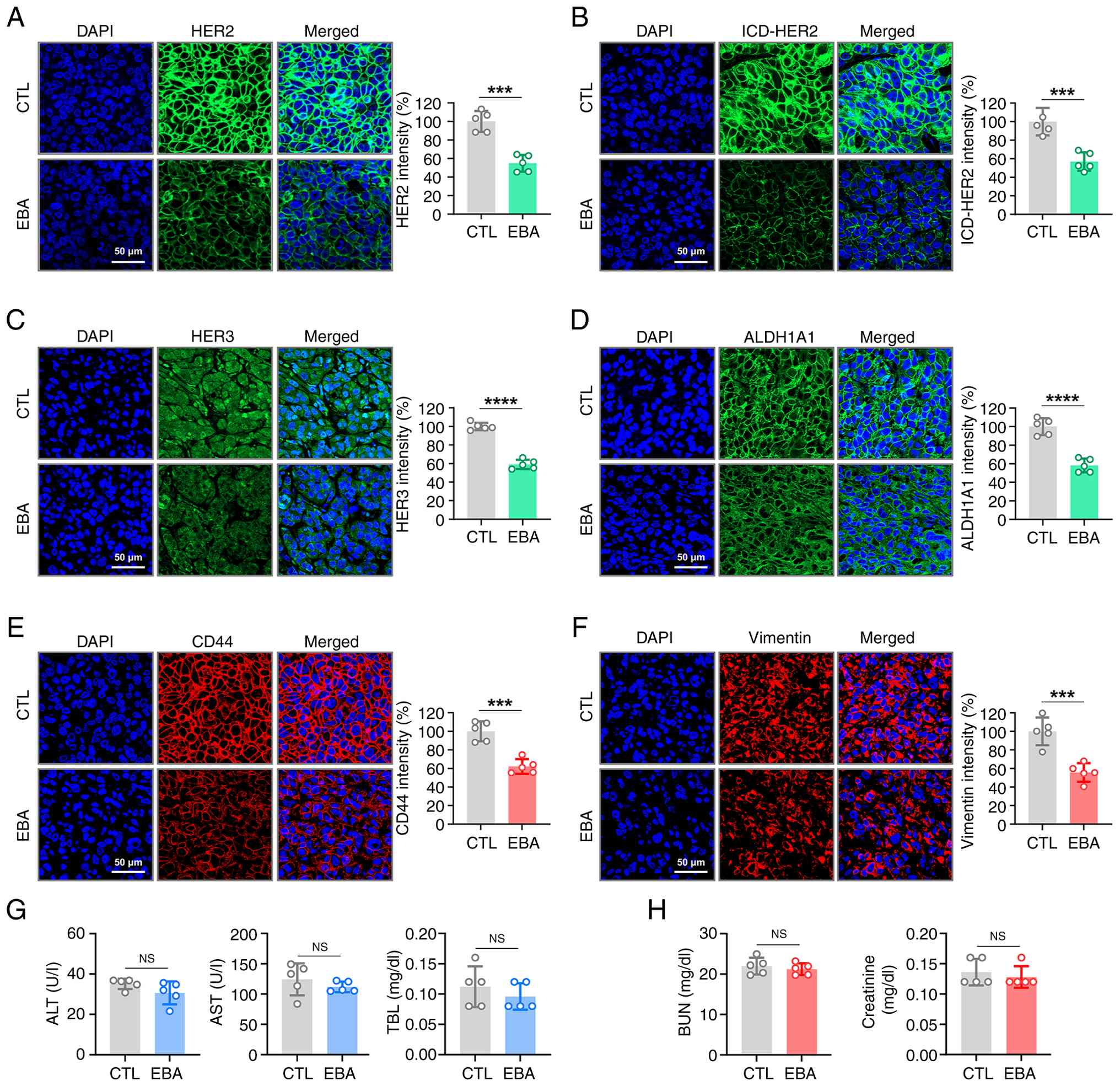

Ebastine downregulates HER2/HER3

expression and CSC-associated markers in vivo

To validate the in vitro observations, the

present study examined the expression of full-length HER2, ICD-HER2

and HER3 in trastuzumab-resistant xenograft tumors using

immunohistochemistry. The present study assessed ICD-HER2

expression with 4B5, an FDA-approved antibody that specifically

recognizes an epitope within the HER2 intracellular domain. Tumors

from ebastine-treated mice exhibited significantly decreased

expression of full-length HER2 (Fig.

5A), ICD-HER2 (Fig. 5B) and

HER3 (Fig. 5C) relative to

control tumors. Consistent with the in vitro abrogation of

the CSC-like phenotype, ebastine administration significantly

decreased the expression of ALDH1A1 (Fig. 5D) and CD44 (Fig. 5E) in tumor tissues. Expression of

the mesenchymal marker vimentin was also significantly decreased in

the ebastine-treated group (Fig.

5F).

| Figure 5EBA downregulates HER2, ICD-HER2,

HER3, ALDH1A1, CD44 and vimentin in JIMT-1 xenograft tumors.

Immunofluorescence staining of JIMT-1 xenograft tumor tissue for

(A) full-length HER2 (green), (B) ICD-HER2 (green) and (C) HER3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of (D) ALDH1A1 (green) and (E) CD44

(red) in tumor tissue. (F) Tumor sections were immunostained for

vimentin (red). Magnification, x500. Fluorescence intensities were

quantified. Serum biochemical analysis for (G) liver and (H) kidney

function in EBA-treated or CTL mice (n=5). Serum levels of ALT,

AST, TBL, BUN and creatinine were assessed.

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ALT, alanine

aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea

nitrogen; EBA, ebastine; ICD, intracellular domain; ALDH, aldehyde

dehydrogenase; CTL, control; NS, not significant. |

Ebastine exhibits no significant

hepatotoxicity or nephrotoxicity in vivo

To evaluate the potential hepatotoxicity of

ebastine, serum samples from treated mice were analyzed for AST,

ALT and TBL. No significant alterations were detected in these

hepatic toxicity markers (Fig.

5G). BUN and creatinine levels, key indicators of renal

function, remained within the normal range (Fig. 5H). These biochemical results

indicated that ebastine did not cause hepatic or renal dysfunction,

even at doses that produce anticancer efficacy.

Discussion

Repurposing existing drugs for new therapeutic

indications has attracted attention in oncology as a cost-effective

and time-efficient alternative to traditional drug development

(14,39,40). As these agents already possess

established safety and pharmacokinetic profiles, they can be more

rapidly transitioned into clinical use, offering a practical

strategy to address issues such as treatment resistance and tumor

heterogeneity (14,40). The present study investigated the

anticancer potential of ebastine, an FDA-approved second-generation

antihistamine, in the context of trastuzumab-resistant

HER2-positive breast cancer. First-generation antihistamines, such

as diphenhydramine, often cause CNS side effects due to their

ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (41). By contrast, ebastine has minimal

CNS penetration, high oral bioavailability and low toxicity, making

it more suitable for long-term use (19,42). These advantages highlight its

potential as a safe and effective anticancer agent for drug

repurposing in oncology.

In ebastine, the diphenylmethoxy-substituted

piperidine and 4-tert-butylphenyl group enhance flexibility and

hydrophobic interactions at protein binding sites. Docking

simulations showed that ebastine fit into the ATP-binding pocket of

the HER2 kinase domain. Its aromatic rings form π-π and π-cation

interactions, while the piperidine group forms hydrogen bonds with

key residues such as Thr862, Asp863 and Lys753. This interaction

likely facilitates the stable binding of ebastine to HER2, notably

downregulating p-HER2 and HER3, as well as trastuzumab

resistance-associated p95HER2. This results in the disruption of

HER2/HER3 and HER2/EGFR heterodimerization, a key mechanism

underlying persistent downstream signaling in HER2-positive tumors

refractory to standard therapy. Trastuzumab and HER2-targeted

tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; such as lapatinib, neratinib and

tucatinib) differ mechanistically, with trastuzumab targeting the

extracellular HER2 domain and TKIs inhibiting intracellular kinase

activity, however, these agents typically share common mechanisms

of therapeutic resistance (43).

A notable mechanism involves HER2/HER3 heterodimerization, where

HER3, despite lacking intrinsic kinase function, serves as a potent

co-activator by recruiting PI3K to its docking sites. This

interaction activates downstream PI3K/AKT signaling, enabling tumor

cells to bypass HER2-targeted inhibition (2,43). Additionally, genetic alterations

such as activating mutations in PIK3CA or loss of PTEN limit the

efficacy of these targeted agents (44).

To evaluate the in vivo relevance of the

present findings, a trastuzumab-resistant xenograft model was

established using JIMT-1 cells, which were originally derived from

a patient exhibiting intrinsic resistance to trastuzumab (27). Notably, JIMT-1 cells display

resistance not only to trastuzumab but also to numerous

HER2-targeted TKIs (45),

rendering them a representative preclinical model for studying

refractory HER2-positive breast cancer. In the xenograft model,

ebastine treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the

expression of full-length HER2, ICD-HER2 and HER3 within tumor

tissues, further substantiating its ability to interfere with key

therapeutic resistance pathways.

As a transmembrane receptor for hyaluronic acid,

CD44 binds to its polymerized form, contributing to the formation

of a physical barrier that obscures HER2 and diminishes the

efficacy of HER2-targeted antibody therapy (46). CD44 is notably overexpressed in

HER2-positive breast cancer cells exhibiting trastuzumab resistance

compared with sensitive cell lines (47). Consistently, the

trastuzumab-resistant cell line JIMT-1 exhibited a high proportion

(~50%) of CD44high/CD24low cells, compared

with the low frequencies observed in sensitive cell lines such as

SKBR3 (0.03%) and BT474 (0.36%) in our previous studies (15,47). Suppression of CD44 enhances

trastuzumab sensitivity and decreases the invasive behavior and

anchorage-independent proliferation of resistant cells (38). Furthermore, CD44 activates Rho

GTPases, PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways, which

collectively promote cell survival, proliferation and invasion,

thereby contributing to the aggressive phenotype of tumor cells

(48,49). In this context, ebastine

treatment significantly decreased the

CD44+/CD24− subpopulation in vitro and

decreased CD44 expression in trastuzumab-resistant JIMT-1 xenograft

tumors in vivo, highlighting its potential to overcome

resistance by targeting CD44. In parallel, ebastine also

effectively attenuated stem-like phenotypes in HER2-positive breast

cancer by decreasing ALDH1 enzymatic activity and impairing the

mammosphere-forming capacity. Elevated expression of ALDH1A1 and

CD44 is associated with shorter overall survival and poor prognosis

in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer, highlighting their potential

as biomarkers for trastuzumab resistance. These findings indicate

that ebastine may improve therapeutic outcomes by targeting

CD44+/ALDH1+ stem-like tumor populations.

Vimentin, a key indicator of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition, promotes tumor progression in breast cancer by

enhancing cell plasticity and motility through cytoskeletal

remodeling (50,51). Vimentin is frequently upregulated

in aggressive breast cancer subtypes, such as triple-negative

breast cancer, and is highly expressed in HER2-positive breast

cancer exhibiting resistance to trastuzumab (52,53). Its expression is associated with

the acquisition of stem-like characteristics, including the

CD44+/CD24− phenotype (54,55). In addition to its role in

promoting stemness, vimentin enhances endothelial cell motility and

structural organization and promotes tumor angiogenesis by

regulating VEGF-dependent signaling pathways (56,57). Although HER2 is typically

associated with an epithelial phenotype, the trastuzumab-resistant

JIMT-1 cell line exhibits mesenchymal features marked by elevated

vimentin expression during tumor progression. Here, ebastine

administration markedly decreased vimentin levels, which may

contribute to suppression of tumor angiogenesis and growth in

vivo.

Although HER2-targeted TKIs effectively inhibit

HER2 signaling, several studies have reported that TKI exposure can

enrich CSC-like populations (58-60). For example, lapatinib has been

shown to increase mammosphere formation in HER2-overexpressing

breast cancer cells, suggesting CSC enrichment (58,61). By contrast, the present data

showed that ebastine decreased ALDH activity and the

CD44high/CD24low fraction and impaired

mammosphere formation, indicating suppression of CSC-like traits.

Several drug-repurposing candidates, including disulfiram,

metformin and niclosamide, have also been explored for their

potential to modulate CSC characteristics by targeting pathways

involved in self-renewal, metabolism and therapeutic resistance

(14,61,62). Disulfiram exerts its anticancer

and CSC-suppressive effects primarily via ALDH inhibition and

proteasome-mediated cytotoxic mechanisms (15,16,63). However, disulfiram has limited

clinical success because its anticancer activity is highly

copper-dependent, resulting in unstable and inconsistent

therapeutic efficacy in vivo (64,65). By contrast, ebastine offers

advantages for drug repurposing due to its metal-independent

mechanisms, stable pharmacokinetic profile and predictable

formation of the active metabolite carebastine (19,66). Metformin is a promising drug

repurposing candidate because it has a long-established safety

profile and low cost, while exerting anticancer effects partly via

AMPK activation, mitochondrial complex I inhibition and suppression

of CSCs (67,68). Although metformin downregulates

HER2 expression through inhibition of the mTOR effector p70S6K1

(69), evidence for its direct

targeting of HER2 signaling remains limited, whereas ebastine

decreases both full-length HER2 and p95HER2 expression and

modulates key signaling nodes associated with trastuzumab

resistance. Niclosamide suppresses key oncogenic pathways,

including Wnt/β-catenin and STAT3 signaling, demonstrating broad

antitumor potential. However, its poor oral bioavailability

necessitates the use of salt forms, prodrugs or nano-based delivery

systems to achieve adequate systemic exposure (61,70). By contrast, ebastine shows high

oral bioavailability, predictable pharmacokinetics and reliable

in vivo exposure, making it a more practical and clinically

feasible option for drug repurposing (19,26,66).

Ebastine may offer strategic therapeutic advantages

by concurrently attenuating the HER2/HER3 signaling pathway, one of

the key drivers of trastuzumab resistance, and suppressing

CSC-associated phenotypes, thereby exhibiting multifaceted

anticancer activity. Taken together, the present findings

demonstrate that ebastine inhibited HER2 kinase activation and

HER2/HER3 heterodimerization, induced caspase-mediated apoptosis

and downregulated CSC-associated markers such as CD44, ALDH1 and

vimentin, supporting its potential as a promising drug-repurposing

candidate for trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast

cancer.

While the present study provided evidence that

ebastine inhibited HER2 signaling and overcomes trastuzumab

resistance, it has several limitations. Although the molecular

docking and CETSA results support a cellular interaction between

ebastine and HER2, these findings do not constitute definitive

biochemical evidence of direct HER2 inhibition. Additional

biochemical and biophysical analyses, such as in vitro

kinase assay, surface plasmon resonance and isothermal titration

calorimetry, are required to confirm direct binding and quantify

binding affinity. Furthermore, site-directed mutagenesis of key

residues (Lys753, Thr862 and Asp863) will be necessary to validate

the predicted binding sites. Future studies should also focus on

evaluating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of

ebastine in tumor-bearing models, exploring its combinatorial

efficacy with trastuzumab or HER2-targeted tyrosine kinase

inhibitors and conducting early-phase clinical investigations to

assess its translational potential. Collectively, these approaches

are essential to elucidate the molecular mechanism of the

ebastine-HER2 interaction and facilitate its clinical development

as a repurposed anticancer agent.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

EJ, YJK, JYK and JHS conceived and designed the

study. EJ, DK, JS, SL, DL, SK, KL, YJK and JYK performed the

experiments. EJ, DK, JS, MP, SK, SP, YKK, KDN, YJK and JYK analyzed

the data. EJ, YJK and JYK wrote the manuscript. JYK and JHS confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were performed in strict

accordance with institutional guidelines and were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Korea University

College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea (approval no.

KOREA-2021-0070-C1; approved on May 23, 2022). All procedures were

conducted in compliance with the Animal Research: Reporting of

In Vivo Experiments guidelines and relevant national

regulations for the care and use of laboratory animals. The study

did not involve human participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Korea Health Technology

R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development

Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic

of Korea (grant no. HR20C0021), the National Research Foundation

funded by the Korean government (grant nos. 2021R1A2C2009723,

2023R1A2C3004010, RS-2024-00342677, RS-2025-02634306 and

RS-2025-00558356), a Korea University Guro Hospital Grant (grant

no. O2411391) and the Brain Korea 21 Plus Program (grant no.

T2024656).

References

|

1

|

Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ,

Ullrich A and McGuire WL: Human breast cancer: Correlation of

relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene.

Science. 235:177–182. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Swain SM, Shastry M and Hamilton E:

Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer: Advances and future

directions. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 22:101–126. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, Ro J,

Semiglazov V, Campone M, Ciruelos E, Ferrero JM, Schneeweiss A,

Heeson S, et al: Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in

HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 372:724–734.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Xu L, Xie Y, Gou Q, Cai R, Bao R, Huang Y

and Tang R: HER2-targeted therapies for HER2-positive early-stage

breast cancer: present and future. Front Pharmacol. 15:14464142024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhu K, Yang X, Tai H, Zhong X, Luo T and

Zheng H: HER2-targeted therapies in cancer: A systematic review.

Biomark Res. 12:162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sánchez-Lorenzo L, Bachiller A, Gea C and

Espinós J: Current management and future perspectives in metastatic

HER2-positive breast cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 40:1515542024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Arteaga CL and Engelman JA: ERBB

receptors: From oncogene discovery to basic science to

mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 25:282–303. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chu X, Tian W, Ning J, Xiao G, Zhou Y,

Wang Z, Zhai Z, Tanzhu G, Yang J and Zhou R: Cancer stem cells:

Advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:1702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pattabiraman DR and Weinberg RA: Tackling

the cancer stem cells-what challenges do they pose? Nat Rev Drug

Discov. 13:497–512. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E,

Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG,

Liu S, et al: ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human

mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell

Stem Cell. 1:555–567. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Shah D and Osipo C: Cancer stem cells and

HER2 positive breast cancer: The story so far. Genes Dis.

3:114–123. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Duru N, Fan M, Candas D, Menaa C, Liu HC,

Nantajit D, Wen Y, Xiao K, Eldridge A, Chromy BA, et al:

HER2-associated radioresistance of breast cancer stem cells

isolated from HER2-negative breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res.

18:6634–6647. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Korkaya H and Wicha MS: HER2 and breast

cancer stem cells: More than meets the eye. Cancer Res.

73:3489–3493. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xia Y, Sun M, Huang H and Jin WL: Drug

repurposing for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

9:922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kim JY, Cho Y, Oh E, Lee N, An H, Sung D,

Cho TM and Seo JH: Disulfiram targets cancer stem-like properties

and the HER2/Akt signaling pathway in HER2-positive breast cancer.

Cancer Lett. 379:39–48. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen D, Cui QC, Yang H and Dou QP:

Disulfiram, a clinically used anti-alcoholism drug and

copper-binding agent, induces apoptotic cell death in breast cancer

cultures and xenografts via inhibition of the proteasome activity.

Cancer Res. 66:10425–10433. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Serageldin MA, El-Bassiouny NA, El-Kerm Y,

Aly RG, Helmy MW, El-Mas MM and Kassem AB: A randomized controlled

study of neoadjuvant metformin with chemotherapy in nondiabetic

breast cancer women: The METNEO study. Br J Clin Pharmacol.

90:3160–3175. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Goodwin PJ, Chen BE, Gelmon KA, Whelan TJ,

Ennis M, Lemieux J, Ligibel JA, Hershman DL, Mayer IA, Hobday TJ,

et al: Effect of metformin vs placebo on invasive disease-free

survival in patients with breast cancer: The MA.32 randomized

clinical trial. JAMA. 327:1963–1973. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Roberts DJ: A preclinical overview of

ebastine. Studies on the pharmacological properties of a novel

histamine H1 receptor antagonist. Drugs. 52(Suppl 1): S8–S14. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Noveck RJ, Preston RA and Swan SK:

Pharmacokinetics and safety of ebastine in healthy subjects and

patients with renal impairment. Clin Pharmacokinet. 46:525–534.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li Q, Liu KY, Liu Q, Wang G, Jiang W, Meng

Q, Yi Y, Yang Y, Wang R, Zhu S, et al: Antihistamine drug ebastine

inhibits cancer growth by targeting polycomb group protein EZH2.

Mol Cancer Ther. 19:2023–2033. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Seo J, Park M, Ko D, Kim S, Park JM, Park

S, Nam KD, Farrand L, Yang J, Seok C, et al: Ebastine impairs

metastatic spread in triple-negative breast cancer by targeting

focal adhesion kinase. Cell Mol Life Sci. 80:1322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pan Z, Li SJ, Guo H, Li ZH, Fei X, Chang

SM, Yang QC and Cheng DD: Ebastine exerts antitumor activity and

induces autophagy by activating AMPK/ULK1 signaling in an

IPMK-dependent manner in osteosarcoma. Int J Biol Sci. 19:537–551.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Comprehensive

molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 490:61–70.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Park SJ, Yoon BH, Kim SK and Kim SY:

GENT2: An updated gene expression database for normal and tumor

tissues. BMC Med Genomics. 12(Suppl 5): S1012019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wiseman LR and Faulds D: Ebastine. a

review of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in

the treatment of allergic disorders. Drugs. 51:260–277. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tanner M, Kapanen AI, Junttila T, Raheem

O, Grenman S, Elo J, Elenius K and Isola J: Characterization of a

novel cell line established from a patient with Herceptin-resistant

breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 3:1585–1592. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Vranic S, Gatalica Z and Wang ZY: Update

on the molecular profile of the MDA-MB-453 cell line as a model for

apocrine breast carcinoma studies. Oncol Lett. 2:1131–1137. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Park M, Jung E, Park JM, Park S, Ko D, Seo

J, Kim S, Nam KD, Kang YK, Farrand L, et al: The HSP90 inhibitor

HVH-2930 exhibits potent efficacy against trastuzumab-resistant

HER2-positive breast cancer. Theranostics. 14:2442–2463. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang ZH, Zheng ZQ, Jia SC, Liu SN, Xiao

XF, Chen GY, Liang WQ and Lu XF: Trastuzumab resistance in

HER2-positive breast cancer: Mechanisms, emerging biomarkers and

targeting agents. Front Oncol. 12:10064292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chandarlapaty S, Scaltriti M, Angelini P,

Ye Q, Guzman M, Hudis CA, Norton L, Solit DB, Arribas J, Baselga J

and Rosen N: Inhibitors of HSP90 block p95-HER2 signaling in

trastuzumab-resistant tumors and suppress their growth. Oncogene.

29:325–334. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Yang M, Li Y, Kong L, Huang S, He L, Liu

P, Mo S, Lu X, Lin X, Xiao Y, et al: Inhibition of DPAGT1

suppresses HER2 shedding and trastuzumab resistance in human breast

cancer. J Clin Invest. 133:e1644282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Baselga J and Swain SM: Novel anticancer

targets: Revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3. Nat Rev Cancer.

9:463–475. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gajria D and Chandarlapaty S:

HER2-amplified breast cancer: Mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance

and novel targeted therapies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther.

11:263–275. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Korkaya H, Paulson A, Iovino F and Wicha

MS: HER2 regulates the mammary stem/progenitor cell population

driving tumorigenesis and invasion. Oncogene. 27:6120–6130. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Oh E, Kim YJ, An H, Sung D, Cho TM,

Farrand L, Jang S, Seo JH and Kim JY: Flubendazole elicits

anti-metastatic effects in triple-negative breast cancer via STAT3

inhibition. Int J Cancer. 143:1978–1993. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Idowu MO, Kmieciak M, Dumur C, Burton RS,

Grimes MM, Powers CN and Manjili MH: CD44(+)/CD24(-/low) cancer

stem/progenitor cells are more abundant in triple-negative invasive

breast carcinoma phenotype and are associated with poor outcome.

Hum Pathol. 43:364–373. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Boulbes DR, Chauhan GB, Jin Q,

Bartholomeusz C and Esteva FJ: CD44 expression contributes to

trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Breast

Cancer Res Treat. 151:501–513. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pushpakom S, Iorio F, Eyers PA, Escott KJ,

Hopper S, Wells A, Doig A, Guilliams T, Latimer J, McNamee C, et

al: Drug repurposing: Progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat

Rev Drug Discov. 18:41–58. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Armando RG, Mengual Gómez DL and Gomez DE:

New drugs are not enough-drug repositioning in oncology: An update.

Int J Oncol. 56:651–684. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Simons FER and Simons KJ: H1

antihistamines: Current status and future directions. World Allergy

Organ J. 1:145–155. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hurst M and Spencer CM: Ebastine: An

update of its use in allergic disorders. Drugs. 59:981–1006. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Schlam I, Tarantino P and Tolaney SM:

Overcoming resistance to HER2-directed therapies in breast cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 14:39962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Berns K, Horlings HM, Hennessy BT,

Madiredjo M, Hijmans EM, Beelen K, Linn SC, Gonzalez-Angulo AM,

Stemke-Hale K, Hauptmann M, et al: A functional genetic approach

identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab

resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 12:395–402. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pourjamal N, Yazdi N, Halme A, Joncour VL,

Laakkonen P, Saharinen P, Joensuu H and Barok M: Comparison of

trastuzumab emtansine, trastuzumab deruxtecan, and disitamab

vedotin in a multiresistant HER2-positive breast cancer lung

metastasis model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 41:91–102. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Pályi-Krekk Z, Barok M, Isola J, Tammi M,

Szöllosi J and Nagy P: Hyaluronan-induced masking of ErbB2 and

CD44-enhanced trastuzumab internalisation in trastuzumab resistant

breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 43:2423–2433. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kim YJ, Sung D, Oh E, Cho Y, Cho TM,

Farrand L, Seo JH and Kim JY: Flubendazole overcomes trastuzumab

resistance by targeting cancer stem-like properties and HER2

signaling in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 412:118–130.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Chen C, Zhao S, Karnad A and Freeman JW:

The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: Therapeutic

implications. J Hematol Oncol. 11:642018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ouhtit A, Rizeq B, Saleh HA, Rahman MM and

Zayed H: Novel CD44-downstream signaling pathways mediating breast

tumor invasion. Int J Biol Sci. 14:1782–1790. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Berr AL, Wiese K, Dos Santos G, Koch CM,

Anekalla KR, Kidd M, Davis JM, Cheng Y, Hu YS and Ridge KM:

Vimentin is required for tumor progression and metastasis in a

mouse model of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 42:2074–2087.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Grasset EM, Dunworth M, Sharma G, Loth M,

Tandurella J, Cimino-Mathews A, Gentz M, Bracht S, Haynes M, Fertig

EJ and Ewald AJ: Triple-negative breast cancer metastasis involves

complex epithelial-mesenchymal transition dynamics and requires

vimentin. Sci Transl Med. 14:eabn75712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Winter M, Meignan S, Völkel P, Angrand PO,

Chopin V, Bidan N, Toillon RA, Adriaenssens E, Lagadec C and Le

Bourhis X: Vimentin promotes the aggressiveness of triple negative

breast cancer cells surviving chemotherapeutic treatment. Cells.

10:15042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Li F, Zhang L, Feng F, Zheng K, Li Y, Wang

T and Ren G: Livin participates in resistance to trastuzumab

therapy for breast cancer through ERK1/2 and AKT pathways and

promotes EMT-like phenotype. RSC Adv. 8:28588–28601. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Liu S, Cong Y, Wang D, Sun Y, Deng L, Liu

Y, Martin-Trevino R, Shang L, McDermott SP, Landis MD, et al:

Breast cancer stem cells transition between epithelial and

mesenchymal states reflective of their normal counterparts. Stem

Cell Reports. 2:78–91. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Usman S, Waseem NH, Nguyen TKN, Mohsin S,

Jamal A, Teh MT and Waseem A: Vimentin Is at the heart of

epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) mediated metastasis.

Cancers (Basel). 13:49852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

van Beijnum JR, Huijbers EJM, van Loon K,

Blanas A, Akbari P, Roos A, Wong TJ, Denisov SS, Hackeng TM,

Jimenez CR, et al: Extracellular vimentin mimics VEGF and is a

target for anti-angiogenic immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 13:28422022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Dave JM and Bayless KJ: Vimentin as an

integral regulator of cell adhesion and endothelial sprouting.

Microcirculation. 21:333–344. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Shah D, Wyatt D, Baker AT, Simms P,

Peiffer DS, Fernandez M, Rakha E, Green A, Filipovic A, Miele L and

Osipo C: Inhibition of HER2 increases JAGGED1-dependent breast

cancer stem cells: Role for membrane JAGGED1. Clin Cancer Res.

24:4566–4578. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Hangauer MJ, Viswanathan VS, Ryan MJ, Bole

D, Eaton JK, Matov A, Galeas J, Dhruv HD, Berens ME, Schreiber SL,

et al: Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4

inhibition. Nature. 551:247–250. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Huang WC, Hung CM, Wei CT, Chen TM, Chien

PH, Pan HL, Lin YM and Chen YJ: Interleukin-6 expression

contributes to lapatinib resistance through maintenance of stemness

property in HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Oncotarget.

7:62352–62363. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Kim JH, Park S, Jung E, Shin J, Kim YJ,

Kim JY, Sessler JL, Seo JH and Kim JS: A dual-action

niclosamide-based prodrug that targets cancer stem cells and

inhibits TNBC metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120:e23040811202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ajmeera D and Ajumeera R: Drug

repurposing: A novel strategy to target cancer stem cells and

therapeutic resistance. Genes Dis. 11:148–175. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Kim JY, Lee N, Kim YJ, Cho Y, An H, Oh E,

Cho TM, Sung D and Seo JH: Disulfiram induces anoikis and

suppresses lung colonization in triple-negative breast cancer via

calpain activation. Cancer Lett. 386:151–160. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Kannappan V, Ali M, Small B, Rajendran G,

Elzhenni S, Taj H, Wang W and Dou QP: Recent advances in

repurposing disulfiram and disulfiram derivatives as

copper-dependent anticancer agents. Front Mol Biosci. 8:7413162021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Cvek B: The promiscuity of disulfiram in

medicinal research. ACS Med Chem Lett. 14:1610–1614. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Vincent J, Liminana R, Meredith PA and

Reid JL: The pharmacokinetics, antihistamine and

concentration-effect relationship of ebastine in healthy subjects.

Br J Clin Pharmacol. 26:497–502. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Rocha GZ, Dias MM, Ropelle ER,

Osório-Costa F, Rossato FA, Vercesi AE, Saad MJ and Carvalheira JB:

Metformin amplifies chemotherapy-induced AMPK activation and

antitumoral growth. Clin Cancer Res. 17:3993–4005. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Saini N and Yang X: Metformin as an

anti-cancer agent: Actions and mechanisms targeting cancer stem

cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 50:133–143. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C and

Menendez JA: The antidiabetic drug metformin suppresses HER2

(erbB-2) oncoprotein overexpression via inhibition of the mTOR

effector p70S6K1 in human breast carcinoma cells. Cell Cycle.

8:88–96. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Tan M, Ye W, Liu Y, Chen X, Huttad L, Chua

MS and So S: Niclosamide prodrug enhances oral bioavailability and

efficacy against hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting vasorin-TGFβ

signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 182:5517–5535. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|