Alzheimer's disease (AD), the leading cause of

dementia, is characterized by irreversible cognitive decline. AD

currently affects ~55 million people globally, a number projected

to nearly triple by 2050 (1).

Despite its prevalence, no effective treatments or preventive

measures exist, and a comprehensive understanding of its

pathogenesis remains elusive (1-3).

The hallmarks of AD include extracellular amyloid β-protein (Aβ)

plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of

hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) (4). Aβ plaques disrupt inter-neuronal

communication (5) and trigger

neuroinflammation, while NFTs impair neuronal function by affecting

axoplasmic transport and disrupting the cytoskeleton (6). Therapeutic strategies targeting the

amyloid cascade or p-tau have yielded unsatisfactory clinical

outcomes, indicating the limitations of single-target therapies

(7). AD pathology also involves

other critical alterations, including neuronal loss, synaptic

dysfunction, oxidative stress and aberrant energy metabolism

(8-10), which interact synergistically to

drive disease progression. While the exact pathogenesis of AD is

not fully understood, emerging evidence implicates impaired

autophagic clearance as a key cellular mechanism in AD pathogenesis

(11) and as a significant

influence on its progression (12,13).

Autophagy, an essential intracellular degradation

pathway, plays a critical role in clearing damaged organelles and

protein aggregates (14-16). This process is significantly

impaired in AD (17),

manifesting as defects in autophagosome formation and maturation,

dysregulated lysosomal function and inefficient

autophagosome-lysosome fusion (18). These disruptions compromise the

clearance of Aβ and tau proteins, leading to the accumulation of

toxic species both inside and outside neurons, which in turn

amplifies neuronal injury and cell death (19,20). Autophagy dysfunction also

contributes to mitochondrial deficits, oxidative stress and chronic

neuroinflammation; it ultimately blocks energy production, disrupts

energy utilization and perturbs metabolic homeostasis, thereby

disturbing neuronal energy metabolism, impairing synaptic function

and promoting apoptosis (21).

Thus, strategies aimed at restoring autophagic activity have become

a major focus of AD therapeutic research (22).

Over the past few decades, mounting epidemiological

and clinical evidence has unequivocally established that regular

physical activity confers substantial benefits for the prevention

and management of various chronic diseases, particularly

cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes mellitus and certain

malignancies (for example, breast, colon and liver cancer)

(23-25). This evidence provides a framework

for developing non-pharmacological interventions in chronic disease

management. Beyond non-modifiable factors such as genetic

susceptibility (1), physical

inactivity is recognized as a significant modifiable risk factor

for AD, accounting for ~13% of cases worldwide (26,27). Clinical and preclinical evidence

shows that regular exercise not only reduces the risk of AD

incidence (28) but also

improves cognitive outcomes in patients with AD (29-32). Mechanistically, dysregulated

autophagy serves as a key pathogenic driver in AD, and exercise

modulates neurodegeneration by regulating autophagic pathways.

Reports have confirmed that physical activity significantly

promotes autophagic activation, alleviates cerebral

neuroinflammation and mitigates AD-related pathological damage in

human and animal models, such as transgenic mouse models of AD

(33,34). Thus, clarifying the molecular

signaling pathways underlying exercise-regulated autophagy in AD is

critical for elucidating the core mechanisms of exercise-based

interventions and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Although existing reviews have independently addressed the role of

autophagy in AD or the neuroprotective effects of exercise in AD, a

systematic overview of the mechanisms by which exercise modulates

autophagic signaling pathways to affect AD is lacking.

Clarification of this network pathway is required to translate

exercise-based interventions from basic research to clinical

practice in AD. The current review systematically explores the

recent research progress on how exercise influences the autophagy

signaling pathway in AD, emphasizing its core molecular mechanisms.

The review also assesses the potential synergy between exercise and

natural products in AD intervention, offering a theoretical

foundation and research direction for the future development and

clinical application of exercise-based AD-targeted

interventions.

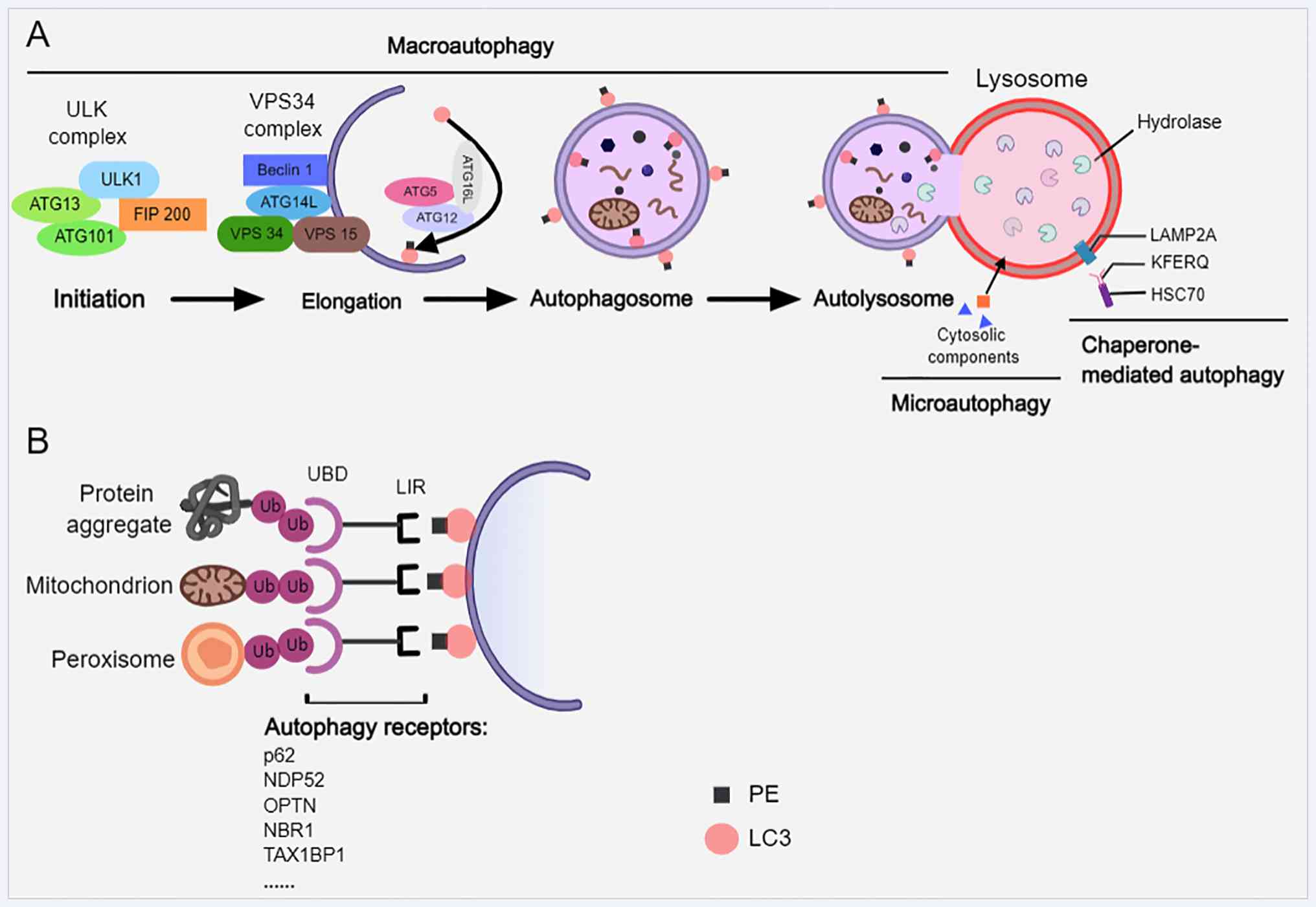

Neuronal autophagy is an essential intracellular

degradation system that mediates the delivery and breakdown of

cytoplasmic components within lysosomes (35,36). Autophagy is classified into three

forms based on the mechanisms of cargo delivery to lysosomes:

Macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy

(CMA) (19) (Fig. 1A). The initial step in

macroautophagy (commonly termed autophagy) is the formation of a

double-membrane vesicle known as the autophagosome (37). This process is regulated by a set

of highly conserved autophagy-associated proteins (ATGs) (36). The initial step involves the

activation of the UNC 51-like kinase (ULK) complex, consisting of

ULK1/2, ATG13, FAK family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa and

ATG101 (38,39). Subsequent phagophore nucleation

requires the class III PI3K complex, which includes vesicular

protein sorting 34 (VPS34), VPS15, beclin-1 and ATG14L (38). Phagophore expansion and

autophagosome maturation depend on two ubiquitin-like conjugation

systems: One results in the ATG5-ATG12-ATG16L complex that

facilitates membrane elongation, and the other conjugates

phosphatidylethanolamine to microtubule-associated protein 1 light

chain 3 (LC3), generating the lipidated form LC3-II that associates

with autophagosomal membranes (40). These steps are critical for

autophagosome biogenesis, cargo recognition and eventual fusion

with lysosomes to form autolysosomes (38).

By contrast, microautophagy involves the direct

engulfment of cytoplasmic material through lysosomal membrane

invagination (41). CMA, a

selective process, recognizes substrate proteins via the chaperone

heat shock cognate 70-kDa protein bearing a Kex2-Fer1-Endo U1-Qc-2

motif and translocates them into lysosomes through

lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP2A) (19,37,38). CMA deficiency has been linked to

exacerbated AD pathology (42).

Nutrient deprivation typically induces non-selective autophagy,

whereas selective autophagy targets damaged organelles such as

mitochondria and peroxisomes, as well as protein aggregates

(37,43) (Fig. 1B). Selective autophagy is

mediated by receptors such as p62, nuclear dot protein 52,

optineurin (OPTN), next to BRCA1 gene 1 and tax1 (human T-cell

leukemia virus type I) binding protein 1, which contain a

ubiquitin-binding domain and LC3 interaction region that connect

ubiquitinated cargo to the autophagic machinery (37,44,45).

Autophagic flux and the expression of

lysosome-associated proteins are significantly reduced in both

patients with AD and AD animal models (46). This dysregulation is hypothesized

to contribute to AD pathogenesis by impairing multiple steps in the

autophagy-lysosome pathway, from autophagosome formation to

lysosomal degradation (47). In

brains affected by AD, neuronal autophagy is disrupted at the

initiation phase, partly due to mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR) hyperactivation, which suppresses the ULK1 complex and

impedes autophagosome biogenesis (48,49). Moreover, mutations and the

downregulation of autophagy-related genes have been linked to AD.

For example, beclin-1 expression is markedly decreased in

AD-affected brains (50,51), and beclin-1-deficient microglia

in AD models have been reported to exhibit impaired phagocytosis

and reduced Aβ clearance (52).

LC3, a key autophagosomal membrane protein, shows altered

processing in AD, with reduced conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II,

thereby inhibiting autophagy initiation (53). Emerging evidence also implicates

non-canonical autophagic processes [e.g., LC3-associated

phagocytosis (LAP) and LC3-associated endocytosis (LANDO)] in AD

pathology, and this pathway has been discovered in microglia of the

brain and the central nervous system. LANDO deficiency exacerbates

neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits in AD mice (54,55). The mechanisms of LAP and LANDO

are distinct from those of autophagy (54). However, no current evidence

exists on how exercise affects these pathways. Therefore, the

present review will not elaborate further on these processes.

Lysosomal dysfunction further aggravates autophagic

impairment in AD. Decreased autolysosomal acidification occurs

prior to extracellular Aβ deposition (17), leading to defective proteolysis,

increased lysosomal membrane permeability (56,57) and impaired cathepsins, which are

lysosomal proteases essential in Aβ and tau clearance (58,59). Notably, Aβ accumulation both

results from and exacerbates lysosomal dysfunction, creating a

vicious cycle that promotes neurodegeneration (60). Restoring lysosomal function

enhances the clearance of Aβ and p-tau (57). The autophagy receptor

sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1/p62), which facilitates cargo delivery to

LC3, exerts protective effects in AD models by improving memory and

modulating autophagic activity (61,62).

Transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator

of autophagy-lysosomal biogenesis, plays a critical role in AD

(63-65). The activity of TFEB is inhibited

by mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1); however, TFEB-mediated endocytosis is

essential for mTORC1 activation and autophagy function (57,66). Oxidative stress also contributes

to AD progression by promoting the amyloidogenic processing of

amyloid precursor protein (APP) and tau hyperphosphorylation

(67). Reactive oxygen species

(ROS) accumulation damages mitochondria, leading to dysfunction

that triggers mitophagy, a selective autophagic process essential

for maintaining mitochondrial quality (45,68). Collectively, these disruptions in

the autophagy-lysosome pathway significantly exacerbate AD

pathology (63,69,70).

Considering the pivotal role that autophagy

dysfunction plays in the development of AD, restoring compromised

autophagic flux has become a promising approach for therapy. Among

the different interventions available, exercise is as a

non-pharmacological treatment that is safe, cost-effective and easy

to implement. Recent studies have reported the significant

potential of exercise to regulate autophagy and ameliorate AD

pathology (71,72). The subsequent sections focus on

the ways in which exercise serves as a potential modulator to

restore autophagic homeostasis in AD.

Exercise provides a multi-targeted physiological

intervention strategy to address the complex autophagy dysfunction

aforementioned. Preclinical studies have shown that exercise can

improve memory, promote neurogenesis, and enhance hippocampal

structure and synaptic plasticity in AD transgenic mouse models

[e.g., APP/presenilin 1 (PS1) and proline-301-serine (P301S)]

(73,74). Both human and animal studies have

shown that a wide range of physical activities, ranging from

low-intensity walking to high-intensity training, support cognitive

health (75,76). For example, adolescents

performing treadmill exercises demonstrated significant cognitive

improvements, particularly at moderate to high intensity exercise

(28).

In one study, 16 weeks of voluntary running

significantly improved autophagy dysfunction in mice with five

familial Alzheimer's disease mutations (5xFAD transgenic mice) and

exerted neuroprotective effects (77). Notably, more recent studies

demonstrated that moderate-intensity exercise was more effective in

modulating brain autophagy in AD models than low or high-intensity

exercise, whereas low-intensity exercise was associated with higher

AD risk, and very high intensity increased oxidative stress

(78-82). Aerobic exercise modalities, such

as treadmill running, voluntary wheel exercise and swimming, were

shown to specifically facilitate the autophagy-mediated clearance

of pathogenic proteins (82,83).

Exercise enhances autophagic activity through

multiple pathways. In APP/PS1 mice, 12 weeks of aerobic treadmill

exercise restored autophagy-lysosomal flux, increased autophagosome

numbers in the hippocampus and cortex, promoted Aβ clearance, and

improved cognitive performance (71,84,85). Similarly, extended treadmill

exercise reduced tau pathology in P301S mice, and autophagy was

shown to play a crucial role in tau degradation through a

ubiquitin-mediated mechanism (84,86). Exercise also upregulates the

expression of core autophagy-related proteins such as LC3-II and

beclin-1, as observed following both high intensity interval

training (HIIT) and moderate intensity continuous training (MICT)

(78). However, a separate

animal study reported no significant changes in LC3, p62 or

beclin-1 in whole hippocampal lysates after HIIT, suggesting that

HIIT has specific effects on brain regions or motor programs

(81).

In summary, preclinical studies consistently

confirmed that moderate-intensity exercise enhances autophagic

flux, particularly in the hippocampus of AD model mice, in a manner

associated with spatial memory improvement. These preclinical

findings underscore a bidirectional, functionally significant

relationship between exercise and autophagy in AD.

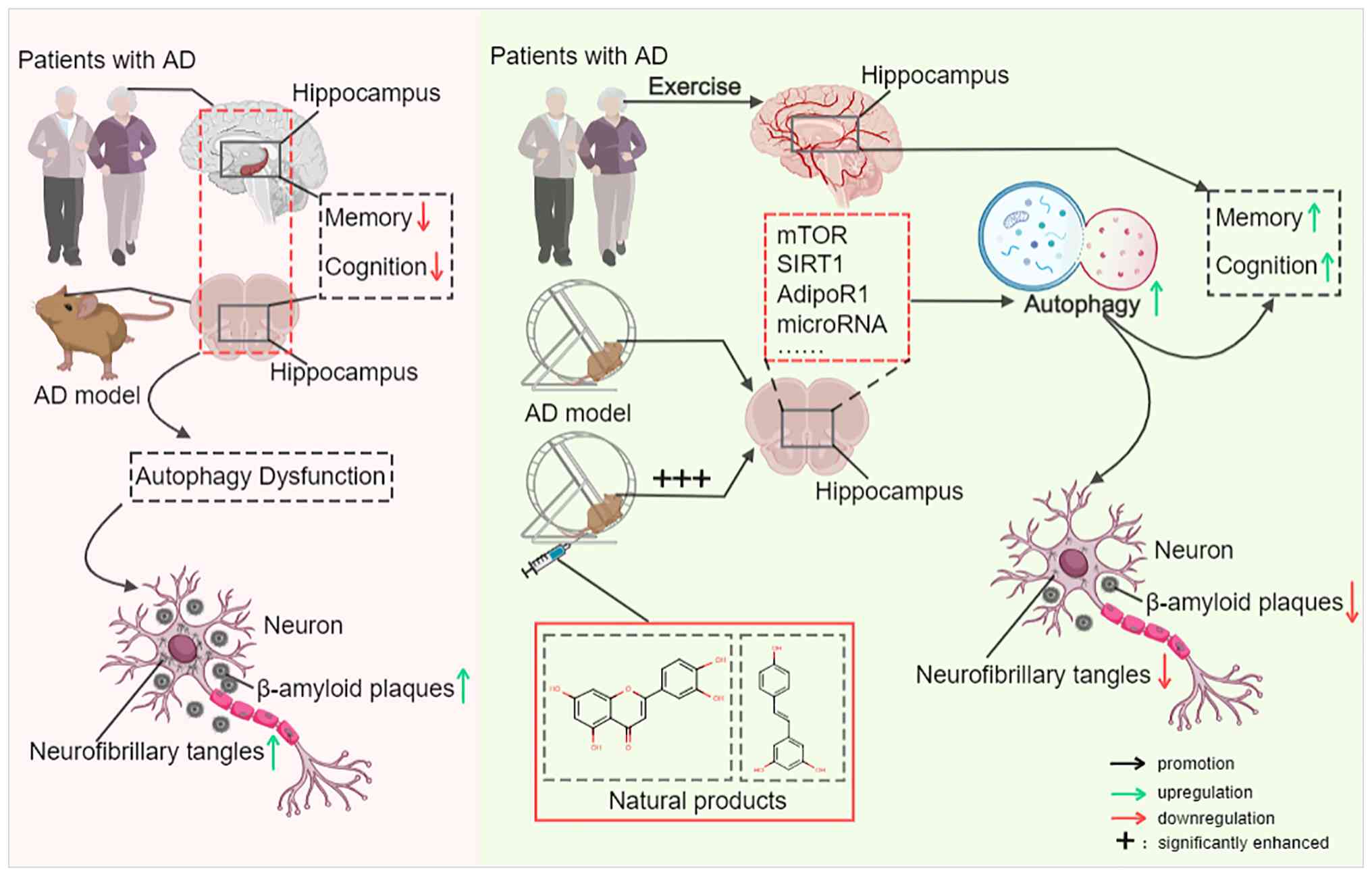

Exercise exerts neuroprotective effects against AD

primarily by restoring impaired autophagy flux, which serves as a

pivotal link between exercise-induced signaling activation and the

amelioration of AD-specific pathological phenotypes. A

well-orchestrated causal chain underpins this process. Exercise

triggers the activation of key signaling pathways [(mTOR, sirtuin 1

(SIRT1) and adiponectin (APN) receptor 1 (AdipoR1)] and the

modulation of microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs)/irisin, which in turn

corrects defects in autophagosome biogenesis, lysosomal function

and autophagosome-lysosome fusion. This restoration of

physiological autophagic flux directly enhances the clearance of

neurotoxic Aβ aggregates and p-tau, mitigates chronic

neuroinflammation, preserves mitochondrial integrity by improving

mitophagy and rescues synaptic dysfunction (87). In summary, these effects

alleviate neuronal damage and apoptosis, and ultimately improve

cognitive function in AD models and patients. Notably, the

regulatory effect of exercise on autophagy is not mediated by a

single mechanism but is achieved through complex crosstalk between

signaling pathways and a cooperative regulatory network. These

interactions have not been fully elucidated and analyzing them can

be helpful in understanding the overall neuroprotective effect of

exercise.

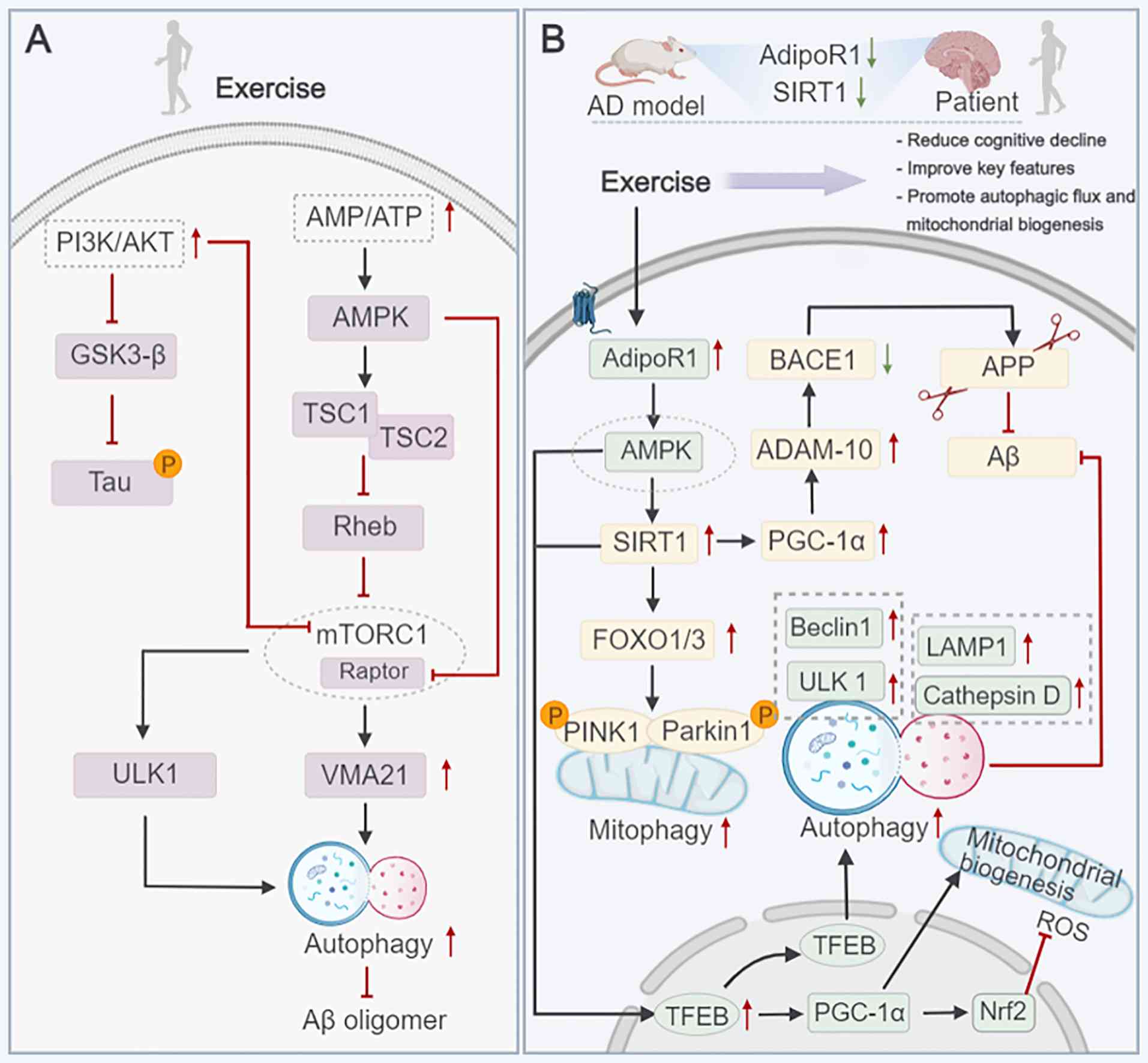

mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase within the

PI3K-related kinase family, plays a central role in regulating

multiple cellular processes. mTOR functions through two distinct

complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 (88), of which mTORC1 acts as a key

negative regulator of autophagy (89,90). Under nutrient-sufficient

conditions, active mTORC1 phosphorylates and inhibits the ULK1

complex, thereby suppressing the initiation of autophagy. mTORC1

activity is suppressed during nutrient deprivation or cellular

stress, leading to the ULK1-mediated induction of autophagy

(89).

In AD studies, analyses of animal and post-mortem

human brain tissue have shown that mTORC1 is often hyperactivated

(48,91). Preclinical research has

demonstrated that regulating mTOR expression can salvage autophagy

deficiency and enhance cognitive function in AD models [e.g.,

triple-transgenic (PS1m146v/APPswe/TauP301L) (3xTg)-AD mice]

(92). The post-exercise

activation of mTORC1 in the brains of experimental animals has also

been associated with improved learning and memory (93). Moreover, treadmill exercise in

neuron-specific enolase/human tau23 (NSE/htau23) transgenic mice

reduced glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) activity and tau

hyperphosphorylation by enhancing PI3K/AKT signaling, an effect

potentially mediated by AMPK activation and downstream mTORC1

inhibition (94) (Fig. 2A). Notably, this inhibition of

mTORC1 by exercise directly reversed the pathological suppression

of the ULK1 complex, restoring autophagosome formation and the

subsequent clearance of p-tau aggregates. Additionally, both HIIT

and MICT were reported to inhibit overactive PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling in the hippocampus, with HIIT displaying a more prominent

inhibitory effect. This signaling suppression, in turn, facilitated

autophagy flux and mitigated Aβ deposition, which were mediated by

augmented lysosomal acidification and enhanced cathepsin activity

(78).

Exercise increases neuronal energy demand by

increasing the AMP/ATP ratio and activating AMPK. This

energy-sensitive kinase promotes autophagy by phosphorylating both

tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)2 and TSC1, thereby enhancing the

inhibition of ras homolog enriched in brain, mTORC1 and raptor (a

core component of mTORC1), further inhibiting their activity

(95). Elevated AMPK

phosphorylation during exercise has been observed in the brains of

AD model animals (96).

Moreover, exercise-induced mTOR increased VMA21 expression in

APP/SP1 mice, contributed to the recovery of autolysosomal

function, reduced Aβ accumulation and improved cognitive impairment

(71) (Fig. 2A). Restoring autolysosomal

activity breaks the vicious cycle of Aβ accumulation and lysosomal

dysfunction in AD, ultimately reducing neuronal toxicity and

improving synaptic transmission.

SIRTs, a conserved family of nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide-dependent deacetylases known as 'longevity proteins',

comprise seven isoforms (SIRT1-SIRT7) (97). SIRT1, one of the most extensively

studied members, is highly expressed in the hippocampus and

prefrontal cortex, and its levels are significantly reduced in AD

(98). Previous studies have

shown that serum SIRT1 levels are reduced in patients with mild

cognitive impairment and AD, highlighting its potential as a

therapeutic target (98-101). Aerobic exercise has been shown

to mitigate cognitive decline, improve synaptic function, promote

neuronal survival and reduce Aβ accumulation in AD models by

activating the SIRT1 pathway (65,102). Similarly, resistance training

was reported to increase hippocampal and prefrontal SIRT1 activity

and alleviate tau pathology in AD mice (82). Recent studies demonstrated that

high-intensity training over 6 weeks increased PPARγ coactivator-1α

(PGC-1α) and SIRT1 activity in human skeletal muscle (101). Further animal experiments

indicated that 12 weeks of moderate-intensity treadmill training

inhibited the production of Aβ in NSE/APPsw transgenic mice by

upregulating SIRT1, enhancing PGC-1α expression, increasing a

disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 levels, and reducing β-secretase

1 (BACE1) (a rate-limiting enzyme in APP processing and Aβ

production) activity (103)

(Fig. 2B). This evidence

supports the critical role of SIRT1 in AD progression.

Exercise also counteracts impaired mitophagy in AD.

The PTEN-induced kinase 1-Parkin pathway, essential for

mitochondrial quality control, is potentiated by treadmill training

via the SIRT1-FOXO1/3 axis, enhancing mitophagy and mitochondrial

integrity (102,104-106). This SIRT1-mediated mitophagy

not only reduces oxidative stress by eliminating dysfunctional

mitochondria but also decreases Aβ aggregation by reducing

ROS-induced APP amyloidogenic processing, while preserving synaptic

function by maintaining mitochondrial energy supply. In a study

using SIRT1-inhibited model mice, researchers found that acute

wheel running for 1 h increased TFEB levels in the nuclei of the

cerebral cortex within 2-4 h. This increase was driven by an

upregulation of the AMPK-SIRT1 signaling pathway. Moreover, after 8

weeks of wheel running, TFEB levels were significantly increased in

the cortex, hippocampus and striatum. Exercise effectively

activated the autophagy-lysosomal pathway, enhancing lysosomal

function and biogenesis in the mouse brain (107). Further research indicated that

inhibiting SIRT1 did not prevent TFEB nuclear translocation,

suggesting that other mechanisms might contribute to

exercise-induced TFEB increases (Fig. 2B). Similar to SIRT1, SIRT3 has

also been implicated in mitophagy regulation (108). Single-nucleus RNA sequencing in

a clinical study showed the decreased expression of neuronal SIRT5

in patients with AD, suggesting its role in autophagy flux

(46). However, the effects of

exercise intensity on SIRT activation and the specific roles of

SIRT3 and SIRT5 in exercise-induced neuroprotection require further

investigation.

APN, a protein hormone secreted by adipose tissue,

acts through receptors, including AdipoR1, AdipoR2 and T-cadherin.

AdipoR1 is highly expressed in the brain, where it regulates energy

homeostasis, hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity

(109-111). Maintaining the APN metabolic

balance is increasingly recognized to be important in AD, with

reduced APN levels in patients with AD correlating with elevated

Aβ42 and p-tau in the cerebrospinal fluid and impaired

hippocampal function (111).

APN promotes hippocampal progenitor cell and Neuro2A

cell proliferation via AdipoR1 signaling, which suppresses GSK-3β

through p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and

phosphorylation at Ser-389, thereby supporting neurogenesis

(109). Impaired AdipoR1

expression has been reported in both patients with AD and AD animal

models (111,112). The activation of autophagy

through the AdipoR1/AMPK pathway exerts neuroprotective effects in

AD progression (113). Recent

studies have found that APN enhances autophagy through the

AdipoR1/AMPK/SIRT1 pathway, thereby promoting the clearance of Aβ

in APP/SP1 mice (114).

Notably, Aβ deposition and associated pathology were significantly

reduced in APP/PS1 mice after 12 weeks of moderate-intensity

aerobic intervention. These changes were related to improvements in

lysosomal function and the recovery of autophagy flux through the

AdipoR1/AMPK/TFEB signaling pathway (115). Specifically, AdipoR1 activation

by exercise-induced APN upregulation phosphorylates AMPK, which in

turn activates TFEB. TFEB nuclear translocation upregulates genes

involved in autophagosome formation (e.g., ULK1 and beclin-1) and

lysosomal function (e.g., LAMP1 and cathepsin D), thereby enhancing

the clearance of Aβ and p-tau, reducing neuroinflammation by

activating microglial autophagy and preserving synaptic plasticity

by maintaining neuronal energy metabolism (115). Thus, the translocation of the

TFEB nucleus is not only regulated by SIRT1, but also by AMPK.

Additionally, Aβ aggregation increases ROS levels, triggers

oxidative stress and disrupts mitochondrial autophagy. Exercise was

reported to promote the nuclear translocation of TFEB, increase the

expression of PGC-1α and nuclear factor e2-related factor 2,

improve mitochondrial autophagy, and thereby reduce mitochondrial

damage and neuronal death (65).

However, the mechanism by which exercise regulates AdipoR1 and the

complex signaling pathways of AdipoR1 require further preclinical

research.

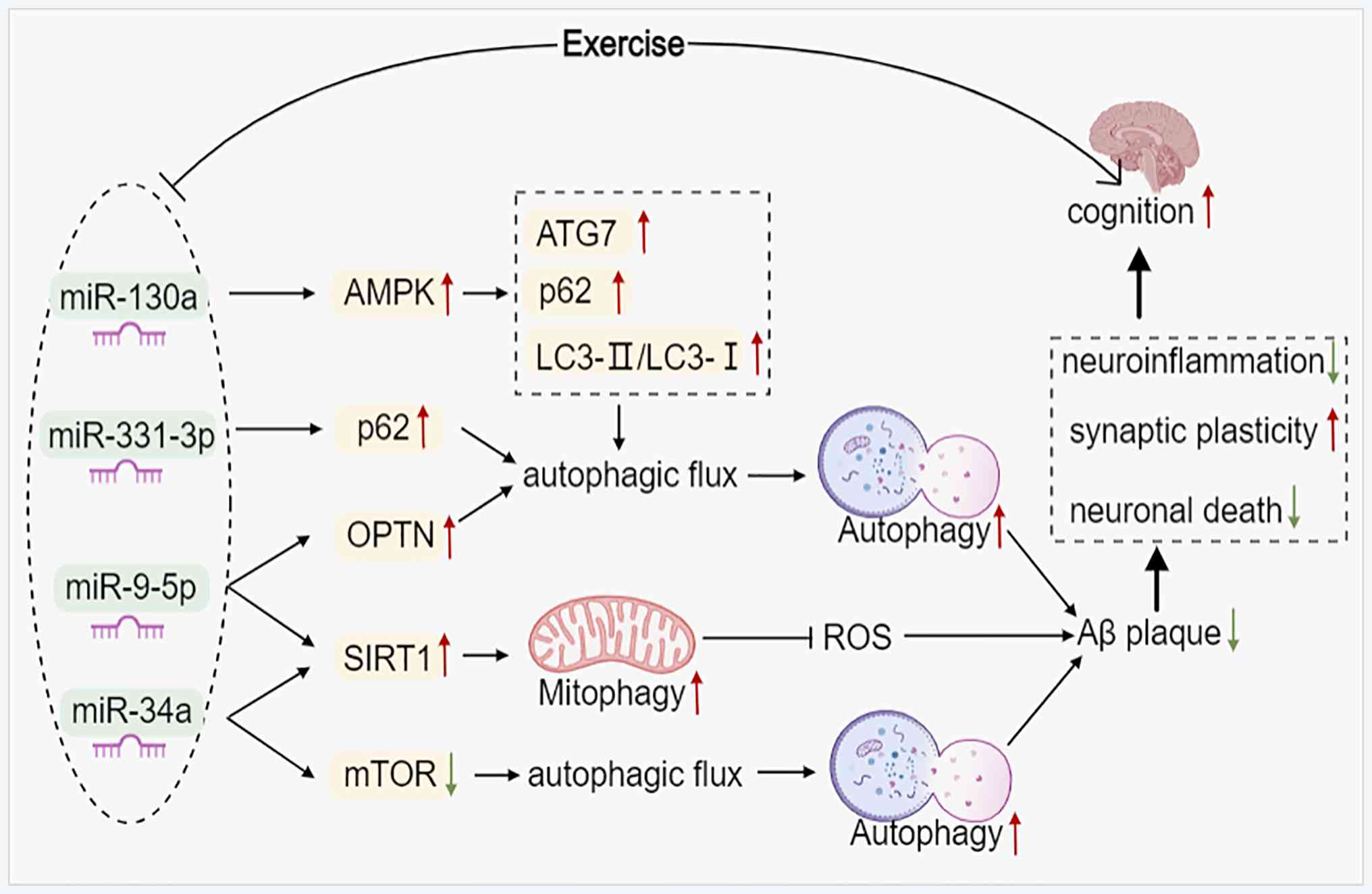

miRNAs are small endogenous non-coding RNAs that

post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression (116). The majority are highly

expressed in the nervous system and play important roles in

neuronal development, synaptic plasticity and the pathogenesis of

neurodegenerative diseases (117). In a previous study, clinical

data showed that miR-4763-3p was upregulated in the early stage of

AD compared with that in the healthy control group (118). A preclinical study has shown

that inhibiting miR-4763-3p can improve learning and memory

disorders in 3xTg-AD mice, accompanied by reduced

neuroinflammation, neuronal death and synaptic alterations

(118). miRNAs modulate

transcript stability and translation by binding to the 3'-UTR of

target mRNAs; their dysregulation can disrupt protein homeostasis,

leading to imbalances in Aβ production and clearance (119). Growing evidence indicates that

miRNA dysfunction contributes to impaired autophagy in AD, with

miRNAs indirectly influencing disease progression by regulating

autophagy (73,120).

Studies have begun to reveal the role of miRNAs in

exercise-induced autophagy in AD. For instance, miR-34a and miR-130

have been implicated in mediating the effects of exercise on

autophagic processes (121)

(Fig. 3). Swimming training was

reported to improve cognitive function and delay aging in rats by

counteracting miR-34a-mediated autophagic impairment and abnormal

mitochondrial dynamics (122).

Another study has shown that miR-34a-mediated autophagy may be

related to the activation of the SIRT1 signaling pathway and the

inhibition of mTOR signaling (123). Furthermore, cell experiments

using SH-SY5Y cells have identified miR-331-3p and miR-9-5p as

regulators of autophagy receptors, targeting SQSTM1/p62 and OPTN,

respectively. Overexpressing these miRNAs in SH-SY5Y cells impaired

autophagy flux and promoted Aβ plaque formation (124) (Fig. 3). Ginsenoside Rg1 treatment of

APP/PS1 mice activated miR-9-5p/SIRT1-mediated mitophagy,

alleviated mitochondrial dysfunction and effectively improved

cognitive function in AD mice (125). However, all these studies lack

a connection with exercise. A preclinical study showed that the

expression of miR-130a in aging rats (21 months) was significantly

downregulated compared with that in young rats (3 months). However,

voluntary wheel running (8 weeks) significantly increased the

expression of miR-130a, whereas the expression of autophagy-related

protein p62 decreased. The increase in the LC3II/LC3I ratio and the

expression of ATG7 reduced apoptosis in senescent rats. The

expression of p-AMPK increased, while SIRT1 remained unchanged,

suggesting that voluntary wheel running activates the AMPK

signaling pathway but not the SIRT1 pathway in aging rats (96). Additionally, D-gal-induced

SH-SY5Y cells showed results consistent with the animal experiments

(96). miRNA can activate

multiple signaling pathways, which may be related to the targeted

activation of upstream signaling molecules in various signaling

pathways. Therefore, more research on using miRNA as a potential

target for AD treatment, in which its comprehensive regulatory

network in exercise-regulated AD autophagy is analyzed, is

required.

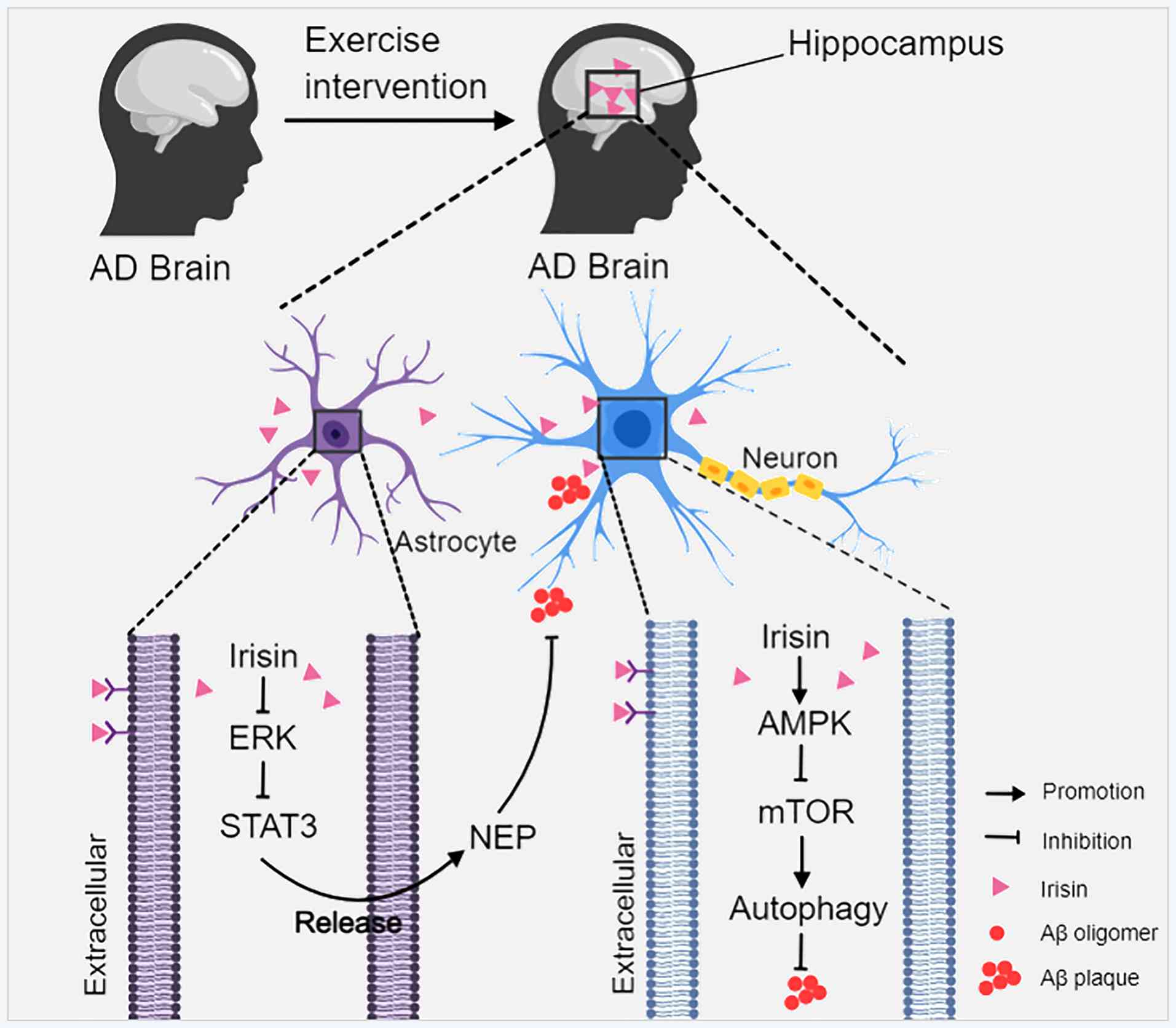

Irisin is a PGC-1α-dependent myokine that was

originally identified in skeletal muscle. Irisin is produced by the

proteolytic cleavage of the membrane protein fibronectin type III

structural domain-containing 5 protein (FNDC5) (126,127), is widely expressed in multiple

tissues and exhibits neuroprotective properties (128-130). Studies have reported decreased

levels of FNDC5/irisin in the hippocampus and cerebrospinal fluid

of patients with AD. Exercise-induced increases in irisin have been

shown to exert beneficial effects in AD models (127,131,132). A recent study demonstrated that

irisin suppressed Aβ aggregation by promoting the release of

enkephalin from astrocytes by inhibiting the ERK-STAT3 signaling

pathway (133). Research have

reported that exercise-induced irisin could regulate the AMPK

pathway by activating it and inhibiting mTOR, thereby increasing

autophagy and clearing amyloid proteins and toxic aggregates in the

brain (134-136) (Fig. 4). However, no experimental

evidence has verified that exercise regulates autophagy

dysregulation in AD by upregulating irisin. In addition, the miRNA

regulation of irisin may play an important role in the clinical

prevention and treatment of AD (128); however, relevant research data

are lacking. Therefore, this gap in the research field of

exercise-induced irisin autophagy in AD remains to be explored.

Given the complexity of AD pathology, single-target

therapies often fail in clinical trials. AD drug development

projects are targeting multiple mechanisms (1). Natural products derived from herbal

or dietary sources (e.g., curcumin, catechins and quercetin) have

shown favorable safety profiles and multi-target efficacy in

clinical studies focused on AD (137). For instance, quercetin and

curcumin have entered phase II clinical trials and have

significantly demonstrated improvements in cases of mild cognitive

impairment (1). These studies

highlight the essential role of natural products in treating AD.

Additionally, a number of studies have shown the effects of natural

products in regulating autophagy in AD (138-140). For instance, Esculentoside A is

a kind of triterpene saponin isolated from Phytolacca

esculenta that activates the autophagy pathway in an

AMPK-dependent manner, thereby promoting the clearance of p-tau and

alleviating cognitive decline in 3xTg-AD mice (138). Ginsenoside Rg2, a steroidal

glycoside derived from Panax ginseng, activates autophagy

via AMPK-dependent but mTOR-independent signaling pathways. This

activation facilitates the clearance of Aβ aggregates and enhances

cognitive function in 5xFAD transgenic mice (139). Notably, only a few studies have

focused on the synergistic effect of exercise and natural products

in the autophagy regulation of AD. Consequently, the following

review section will focus on representative natural products in AD

research. Their synergistic effects and underlying mechanisms in

regulating autophagy and alleviating AD pathology upon combination

with exercise will be systematically summarized.

Resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic compound

extracted from various plants (e.g., grapes and peanuts) (141), demonstrates antioxidant and

neuroprotective effects in vitro (142). Studies in AD models have shown

that resveratrol decreases Aβ aggregation and hippocampal toxicity,

promotes neurogenesis and mitigates hippocampal degeneration

(143-145). Clinical trials showed that

resveratrol sustainably decreased Aβ40 levels in the

cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of patients with AD, and that on

oral administration of high-dose resveratrol (500-1,000 mg/day) was

safe and well-tolerated (117,146). The therapeutic potential of

resveratrol in AD involves modulating AMPK-SIRT1-mediated autophagy

and miRNA-dependent pathways, as well as the direct activation of

autophagy via the mTOR signaling pathway, through which it

regulates tau hyperphosphorylation, neuroinflammation, BACE1

activity and Aβ accumulation (117). After 5 months of moderate to

vigorous exercise combined with resveratrol treatment (557

mg/kg/day, diet), the expression of autophagy-related markers

(LC3-I), lysosomal proteins (cathepsin B/D and LAMP2) and

ubiquitination markers (Ub1) was significantly reduced in 3xTg-AD

mice. The expression levels of p62 and SIRT1 proteins were

significantly increased, while the expression of AMPK was elevated

but not significantly different. These findings suggest that the

combination of exercise and resveratrol may synergistically enhance

autophagy via the AMPK-SIRT1 pathway, reduce Aβ oligomer levels,

decrease apoptosis and ultimately improve cognitive function

(147). However, differences in

the degree of AMPK-SIRT1 activation or that of other pathways,

cognitive improvements from different doses of resveratrol combined

with different exercise intensities, the impact of resveratrol

supplementation timing (such as before, after or simultaneously

with exercise) on bioavailability and synergistic effects, as well

as clinical trials, should all be explored in the future.

Luteolin, a natural flavonoid in a variety of

fruits, vegetables and herbs [e.g., honeysuckle (Lonicera

japonica) and Perilla (Perilla frutescens)] (148), confers significant

neuroprotection against glutamate-induced hippocampal neuronal

death (149). A clinical trial

of patients with AD showed that no dose-limiting toxicity occurred

when luteolin was administered at a dose of 100 mg/day (150). Preclinical studies have shown

that luteolin can improve cognitive function and protect AD neurons

by alleviating Aβ-induced oxidative stress, reducing mitochondrial

damage and alleviating neuroinflammation (148,151). In Aβ1-42

oligomer-induced AD mice, a combination of luteolin (100 mg/kg/day,

gavage) and 4 weeks of voluntary wheel exercise was more effective

than either treatment alone. This dual approach significantly

improved cognitive function, reduced Aβ accumulation and inhibited

microglial activation, thereby alleviating neuroinflammation. The

approach also enhanced autophagy activity in the hippocampus and

cortical regions, as indicated by a notable decrease in p-ULK1

protein expression and an increase in LC3II/LC3I expression in the

cerebral cortex. Notably, luteolin, exercise and their combination

each reduced p62 protein expression to varying degrees, although no

significant differences were observed among them (152). A recent study further confirmed

that luteolin combined with exercise could alleviate AD-related

cognitive impairment. Untargeted metabolomics was also used to

reveal the key role of autophagy in this combined mechanism

(153). In conclusion, further

research is warranted to elucidate how varying doses of luteolin

modulate its bioavailability and exert synergistic effects when

combined with distinct exercise intensities and supplementation

timing (before, after or during exercise). Additionally, more

robust clinical trials are necessary to investigate these

topics.

The combination of natural products and exercise

demonstrates synergistic potential in treating AD. Both resveratrol

and luteolin, two distinct types of natural products, have been

confirmed to possess neuroprotective effects and can modulate

autophagy pathways relevant to AD. Treatment of AD model mice with

either of the two natural products and exercise exerted effects

superior to individual interventions. This combined strategy more

significantly improves cognitive function, alleviates

neuroinflammation and reduces abnormal Aβ deposition.

In summary, the combined application of exercise and

natural products coordinated the regulation of autophagy processes

and pathological protein metabolism through multiple targets and

multiple pathways, and provides a promising intervention strategy

for preventing and treating AD. This combined protocol enhances the

autophagy-mediated neuroprotective cascade response, simultaneously

targeting multiple nodes of AD pathology, from the activation of

upstream signaling pathways to the clearance of downstream

pathological substrates, thereby avoiding the inherent limitations

of single-target interventions and achieving greater systemic

intervention efficacy.

AD is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder with

no curative treatments. Autophagy dysfunction is a key pathogenic

driver underlying the accumulation of neurotoxic Aβ aggregates,

p-tau, neuronal loss and synaptic impairment. The present review

systematically highlights current evidence demonstrating that

mild-to-moderate intensity physical exercise represents a safe,

cost-effective and multi-targeted non-pharmacological intervention

for AD (Table I; Fig. 5). Specifically, exercise restores

impaired autophagic flux in AD by modulating core signaling

pathways (mTOR, SIRT1 and AdipoR1), regulating miRNAs such as

miR-34a and miR-130a, and upregulating irisin. These regulatory

effects collectively enhance autophagosome biogenesis, improve

lysosomal function and promote autophagosome-lysosome fusion,

thereby facilitating the clearance of Aβ and p-tau, alleviating

neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction, and ultimately

ameliorating cognitive deficits in both preclinical AD models and

clinical settings. Additionally, combining exercise with natural

products (e.g., resveratrol and luteolin) exerts synergistic

neuroprotective effects by enhancing autophagy-mediated clearance

of pathological proteins, highlighting a promising multi-modal

intervention strategy for AD.

Despite this valuable insight, this review has

several specific limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First,

while the roles of key signaling pathways (mTOR, SIRT1 and AdipoR1)

in exercise-mediated autophagy regulation are summarized, molecular

crosstalk among these pathways (e.g., the AMPK-mTOR-SIRT1

regulatory axis) remains incompletely elucidated, and how exercise

coordinates these interconnected networks to fine-tune autophagic

flux demands the further integration of multi-omics data. Second,

this review did not address the potential regulation of

non-canonical autophagic pathways (e.g., LAP and LANDO) through

exercise due to limited existing experimental evidence. These

pathways have been implicated in AD pathology but remain a critical

knowledge gap in the field. Third, the miRNA regulatory network

underlying exercise-induced autophagy restoration remains

incompletely understood, with only a handful of miRNAs (e.g.,

miR-34a and miR-130a) characterized, and interactions between

miRNAs and irisin/FNDC5 in AD remain largely unvalidated. Fourth,

preclinical studies on combinations of exercise and natural

products are scope-limited, and data on the optimization of key

parameters are lacking, including natural product dosage, exercise

intensity and intervention timing (e.g., pre- or post-exercise

supplementation), which hinders the translation of these

synergistic effects into clinical practice. Finally, the current

evidence is predominantly derived from rodent models, and the

generalizability of these mechanisms to human AD populations,

particularly across different disease stages and genetic

backgrounds, remains to be fully established.

Future research should focus on novel, practical and

translationally relevant directions to address these gaps and

advance the field. Leveraging single-cell RNA sequencing and

spatial metabolomics to dissect cell-type-specific mechanisms of

exercise-regulated autophagy (e.g., in neurons, microglia and

astrocytes) will yield unprecedented insight into cell-cell

communication networks underlying neuroprotection. High-throughput

CRISPR screening can identify uncharacterized miRNAs or long

non-coding RNAs that link exercise and autophagy regulation,

facilitating the development of targeted nucleic acid-based

therapeutics (e.g., miRNA mimics or inhibitors) for combination

with exercise interventions. Large-scale stratified clinical trials

are urgently needed to establish personalized exercise

prescriptions, using peripheral biomarkers (e.g., serum irisin and

TFEB) to tailor exercise intensity, duration and modality for

individual patients with AD or high-risk populations. Integrating

network pharmacology and in vitro high-throughput assays to

identify shared molecular targets of natural products and exercise

(e.g., the AMPK-SIRT1-TFEB axis) will expedite the development of

combination preclinical strategies with optimized synergistic

efficacy. In addition, genetically engineered AD mouse models will

clarify the role of non-canonical autophagy (e.g., LAP and LANDO)

in exercise-mediated neuroprotection, filling a critical knowledge

gap in the current literature. Finally, exploring the long-term

sustainability of exercise-induced autophagy restoration and its

impact on AD progression (e.g., delaying conversion from mild

cognitive impairment to clinical AD) will provide critical evidence

to support the integration of exercise into routine clinical

care.

In summary, exercise is a potent intervention to

counteract autophagy dysfunction in AD, supported by preclinical

and clinical evidence of its neuroprotective effects. Addressing

the aforementioned limitations and pursuing innovative,

translationally focused research directions will further unravel

the mechanistic complexity of exercise-autophagy crosstalk and

enable the development of more effective, personalized strategies

for AD prevention and management. Given the current challenges in

AD drug development, integrating exercise alone or its combination

with natural products into clinical practice holds considerable

theoretical significance and potential for improving patient

outcomes.

WL and WW conducted the literature search, drafted

the manuscript and prepared the figures. YS, XL and YL drafted,

edited and revised the manuscript. XW and TT contributed to figure

design and edited the manuscript. XH and LZ commented on and edited

the manuscript, and provided substantial improvements. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is

not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present review was supported by the Chongqing Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. 2023NSCQ-MSX3083), the Outstanding

Youth Project of Department of Education of Hunan Province (grant

no. 24B1077) and the Chongqing Science and Health Joint Project

(grant no. 2026ZYYB027).

|

1

|

Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M,

Holstege H, Chételat G, Teunissen CE, Cummings J and van der Flier

WM: Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 397:1577–1590. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Reitz C, Pericak-Vance MA, Foroud T and

Mayeux R: A global view of the genetic basis of Alzheimer disease.

Nat Rev Neurol. 19:261–277. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Di Meco A, Curtis ME, Lauretti E and

Praticò D: Autophagy dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease:

Mechanistic insights and new therapeutic opportunities. Biol

Psychiatry. 87:797–807. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hardy J and Selkoe DJ: The amyloid

hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: Progress and problems on the

road to therapeutics. Science. 297:353–356. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

De Strooper B and Karran E: The cellular

phase of Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 164:603–615. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Iqbal K, Liu F and Gong CX: Tau and

neurodegenerative disease: The story so far. Nat Rev Neurol.

12:15–27. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tong BC, Wu AJ, Huang AS, Dong R,

Malampati S, Iyaswamy A, Krishnamoorthi S, Sreenivasmurthy SG, Zhu

Z, Su C, et al: Lysosomal TPCN (two pore segment channel)

inhibition ameliorates beta-amyloid pathology and mitigates memory

impairment in Alzheimer disease. Autophagy. 18:624–642. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

8

|

Nixon RA: Autophagy-lysosomal-associated

neuronal death in neurodegenerative disease. Acta Neuropathol.

148:422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tzioras M, McGeachan RI, Durrant CS and

Spires-Jones TL: Synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer disease. Nat

Rev Neurol. 19:19–38. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Butterfield DA and Halliwell B: Oxidative

stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat

Rev Neurosci. 20:148–160. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Deng Z, Dong Y, Zhou X, Lu JH and Yue Z:

Pharmacological modulation of autophagy for Alzheimer's disease

therapy: Opportunities and obstacles. Acta Pharm Sin B.

12:1688–1706. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lee JH and Nixon RA: Autolysosomal

acidification failure as a primary driver of Alzheimer disease

pathogenesis. Autophagy. 18:2763–2764. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P and Levine B:

Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse

diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 11:709–730. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Levine B and Kroemer G: Biological

functions of autophagy genes: A disease perspective. Cell.

176:11–42. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yu L, Chen Y and Tooze SA: Autophagy

pathway: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Autophagy. 14:207–215.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Kaushik S, Tasset I, Arias E, Pampliega O,

Wong E, Martinez-Vicente M and Cuervo AM: Autophagy and the

hallmarks of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 72:1014682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lee JH, Yang DS, Goulbourne CN, Im E,

Stavrides P, Pensalfini A, Chan H, Bouchet-Marquis C, Bleiwas C,

Berg MJ, et al: Faulty autolysosome acidification in Alzheimer's

disease mouse models induces autophagic build-up of Aβ in neurons,

yielding senile plaques. Nat Neurosci. 25:688–701. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Uddin MS, Stachowiak A, Mamun AA, Tzvetkov

NT, Takeda S, Atanasov AG, Bergantin LB, Abdel-Daim MM and

Stankiewicz AM: Autophagy and Alzheimer's Disease: From molecular

mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Front Aging Neurosci.

10:042018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nixon RA: The role of autophagy in

neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med. 19:983–997. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Palmer JE, Wilson N, Son SM, Obrocki P,

Wrobel L, Rob M, Takla M, Korolchuk VI and Rubinsztein DC:

Autophagy, aging, and age-related neurodegeneration. Neuron.

113:29–48. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Fang EF, Hou Y, Palikaras K, Adriaanse BA,

Kerr JS, Yang B, Lautrup S, Hasan-Olive MM, Caponio D, Dan X, et

al: Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses

cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci.

22:401–412. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Menzies FM, Fleming A, Caricasole A, Bento

CF, Andrews SP, Ashkenazi A, Füllgrabe J, Jackson A, Jimenez

Sanchez M, Karabiyik C, et al: Autophagy and neurodegeneration:

Pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Neuron.

93:1015–1034. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sharif K, Watad A, Bragazzi NL, Lichtbroun

M, Amital H and Shoenfeld Y: Physical activity and autoimmune

diseases: Get moving and manage the disease. Autoimmun Rev.

17:53–72. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zhu C, Ma H, He A, Li Y, He C and Xia Y:

Exercise in cancer prevention and anticancer therapy: Efficacy,

molecular mechanisms and clinical information. Cancer Lett.

544:2158142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Andersen LL: Health promotion and chronic

disease prevention at the workplace. Annu Rev Public Health.

45:337–357. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Halon-Golabek M, Borkowska A,

Herman-Antosiewicz A and Antosiewicz J: Iron Metabolism of the

skeletal muscle and neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci. 13:1652019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

López-Ortiz S, Pinto-Fraga J, Valenzuela

PL, Martín-Hernández J, Seisdedos MM, García-López O, Toschi N, Di

Giuliano F, Garaci F, Mercuri NB, et al: Physical exercise and

Alzheimer's disease: Effects on pathophysiological molecular

pathways of the disease. Int J Mol Sci. 22:28972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mahalakshmi B, Maurya N, Lee SD and

Bharath Kumar V: Possible neuroprotective mechanisms of physical

exercise in neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 21:58952020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sujkowski A, Hong L, Wessells RJ and Todi

SV: The protective role of exercise against age-related

neurodegeneration. Ageing Res Rev. 74:1015432022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

De la Rosa A, Olaso-Gonzalez G,

Arc-Chagnaud C, Millan F, Salvador-Pascual A, García-Lucerga C,

Blasco-Lafarga C, Garcia-Dominguez E, Carretero A, Correas AG, et

al: Physical exercise in the prevention and treatment of

Alzheimer's disease. J Sport Health Sci. 9:394–404. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fox FAU, Diers K, Lee H, Mayr A, Reuter M,

Breteler MMB and Aziz NA: Association between accelerometer-derived

physical activity measurements and brain structure: A

Population-based cohort study. Neurology. 99:e1202–e1215. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yau WW, Kirn DR, Rabin JS, Properzi MJ,

Schultz AP, Shirzadi Z, Palmgren K, Matos P, Maa C, Pruzin JJ, et

al: Physical activity as a modifiable risk factor in preclinical

Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 31:4075–4083. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cotman CW, Berchtold NC and Christie LA:

Exercise builds brain health: Key roles of growth factor cascades

and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 30:464–472. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kang J, Liu M, Yang Q, Dang X, Li Q, Wang

T, Qiu B, Zhang Y, Guo X, Li X, et al: Exercise training exerts

beneficial effects on Alzheimer's disease through multiple

signaling pathways. Front Aging Neurosci. 17:15580782025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Nixon RA and Rubinsztein DC: Mechanisms of

autophagy-lysosome dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25:926–946. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kaur J and Debnath J: Autophagy at the

crossroads of catabolism and anabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

16:461–472. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Nakatogawa H: Mechanisms governing

autophagosome biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:439–458. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Nazio F and Cecconi F: Autophagy up and

down by outsmarting the incredible ULK. Autophagy. 13:967–968.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Gui X, Yang H, Li T, Tan X, Shi P, Li M,

Du F and Chen ZJ: Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a

primordial function of the cGAS pathway. Nature. 567:262–266. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Li WW, Li J and Bao JK: Microautophagy:

Lesser-known self-eating. Cell Mol Life Sci. 69:1125–1136. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Bourdenx M, Martín-Segura A, Scrivo A,

Rodriguez-Navarro JA, Kaushik S, Tasset I, Diaz A, Storm NJ, Xin Q,

Juste YR, et al: Chaperone-mediated autophagy prevents collapse of

the neuronal metastable proteome. Cell. 184:2696–2714.e25. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kerr JS, Adriaanse BA, Greig NH, Mattson

MP, Cader MZ, Bohr VA and Fang EF: Mitophagy and Alzheimer's

disease: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends Neurosci.

40:151–166. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sulkshane P, Ram J, Thakur A, Reis N,

Kleifeld O and Glickman MH: Ubiquitination and receptor-mediated

mitophagy converge to eliminate oxidation-damaged mitochondria

during hypoxia. Redox Biol. 45:1020472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang Z, Yang X, Song YQ and Tu J:

Autophagy in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis: Therapeutic

potential and future perspectives. Ageing Res Rev. 72:1014642021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Deng P, Fan T, Gao P, Peng Y, Li M, Li J,

Qin M, Hao R, Wang L, Li M, et al: SIRT5-mediated desuccinylation

of RAB7A protects against Cadmium-induced Alzheimer's disease-like

pathology by restoring autophagic flux. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e24020302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Xie ZS, Zhao JP, Wu LM, Chu S, Cui ZH, Sun

YR, Wang H, Ma HF, Ma DR, Wang P, et al: Hederagenin improves

Alzheimer's disease through PPARα/TFEB-mediated autophagy.

Phytomedicine. 112:1547112023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Shafei MA, Harris M and Conway ME:

Divergent metabolic regulation of autophagy and mTORC1-early events

in Alzheimer's disease? Front Aging Neurosci. 9:1732017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang X and Jia J: Magnolol improves

Alzheimer's disease-like pathologies and cognitive decline by

promoting autophagy through activation of the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1

pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 161:1144732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang XW, Zhu XX, Tang DS and Lu JH:

Targeting autophagy in Alzheimer's disease: Animal models and

mechanisms. Zool Res. 44:1132–1145. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A,

Ojala J, Haapasalo A, Soininen H and Hiltunen M: Impaired autophagy

and APP processing in Alzheimer's disease: The potential role of

Beclin 1 interactome. Prog Neurobiol. 106-107:33–54. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

O'Brien CE and Wyss-Coray T: Sorting

through the roles of beclin 1 in microglia and neurodegeneration. J

Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 9:285–292. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Longobardi A, Catania M, Geviti A, Salvi

E, Vecchi ER, Bellini S, Saraceno C, Nicsanu R, Squitti R, Binetti

G, et al: Autophagy markers are altered in Alzheimer's disease,

dementia with lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia. Int J Mol

Sci. 25:11252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Peña-Martinez C, Rickman AD and Heckmann

BL: Beyond autophagy: LC3-associated phagocytosis and endocytosis.

Sci Adv. 8:eabn17022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Heckmann BL, Teubner BJW, Tummers B,

Boada-Romero E, Harris L, Yang M, Guy CS, Zakharenko SS and Green

DR: LC3-Associated Endocytosis facilitates β-Amyloid clearance and

mitigates neurodegeneration in murine Alzheimer's disease. Cell.

178:536–551.e14. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Udayar V, Chen Y, Sidransky E and Jagasia

R: Lysosomal dysfunction in neurodegeneration: Emerging concepts

and methods. Trends Neurosci. 45:184–199. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Chae CW, Yoon JH, Lim JR, Park JY, Cho JH,

Jung YH, Choi GE, Lee HJ and Han HJ: TRIM16-mediated lysophagy

suppresses high-glucose-accumulated neuronal Aβ. Autophagy.

19:2752–2768. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Qian XH, Ding GY, Chen SY, Liu XL, Zhang M

and Tang HD: Blood cathepsins on the risk of Alzheimer's disease

and related pathological biomarkers: Results from observational

cohort and mendelian randomization study. J Prev Alzheimers Dis.

11:1834–1842. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Almeida MF, Bahr BA and Kinsey ST:

Endosomal-lysosomal dysfunction in metabolic diseases and

Alzheimer's disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 154:303–324. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Mançano ASF, Pina JG, Froes BR and Sciani

JM: Autophagy-lysosomal pathway impairment and cathepsin

dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease. Front Mol Biosci.

11:14902752024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Cecarini V, Bonfili L, Gogoi O, Lawrence

S, Venanzi FM, Azevedo V, Mancha-Agresti P, Drumond MM, Rossi G,

Berardi S, et al: Neuroprotective effects of p62(SQSTM1)-engineered

lactic acid bacteria in Alzheimer's disease: A pre-clinical study.

Aging. 12:15995–16020. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Thal DR, Gawor K and Moonen S: Regulated

cell death and its role in Alzheimer's disease and amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 147:692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zheng X, Lin W, Jiang Y, Lu K, Wei W, Huo

Q, Cui S, Yang X, Li M, Xu N, et al: Electroacupuncture ameliorates

beta-amyloid pathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer

disease via a novel mechanism involving activation of TFEB

(transcription factor EB). Autophagy. 17:3833–3847. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Settembre C, Fraldi A, Medina DL and

Ballabio A: Signals from the lysosome: A control centre for

cellular clearance and energy metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

14:283–296. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Morais GP, de Sousa Neto IV, Marafon BB,

Ropelle ER, Cintra DE, Pauli JR and Silva A: The dual and emerging

role of physical exercise-induced TFEB activation in the protection

against Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Physiol. 238:954–965. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Nnah IC, Wang B, Saqcena C, Weber GF,

Bonder EM, Bagley D, De Cegli R, Napolitano G, Medina DL, Ballabio

A, et al: TFEB-driven endocytosis coordinates MTORC1 signaling and

autophagy. Autophagy. 15:151–164. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

67

|

Zhang J, Zhang Y, Wang J, Xia Y, Zhang J

and Chen L: Recent advances in Alzheimer's disease: Mechanisms,

clinical trials and new drug development strategies. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:2112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Dewanjee S, Chakraborty P, Bhattacharya H,

Chacko L, Singh B, Chaudhary A, Javvaji K, Pradhan SR, Vallamkondu

J, Dey A, et al: Altered glucose metabolism in Alzheimer's disease:

Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Free Radic

Biol Med. 193:134–157. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Chen WT, Lu A, Craessaerts K, Pavie B,

Sala Frigerio C, Corthout N, Qian X, Laláková J, Kühnemund M,

Voytyuk I, et al: Spatial transcriptomics and in situ sequencing to

study Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 182:976–991.e19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Martini-Stoica H, Xu Y, Ballabio A and

Zheng H: The Autophagy-lysosomal pathway in neurodegeneration: A

TFEB perspective. Trends Neurosci. 39:221–234. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wu JJ, Yu H, Bi SG, Wang ZX, Gong J, Mao

YM, Wang FZ, Zhang YQ, Nie YJ and Chai GS: Aerobic exercise

attenuates autophagy-lysosomal flux deficits by ADRB2/β2-adrenergic

receptor-mediated V-ATPase assembly factor VMA21 signaling in

APP-PSEN1/PS1 mice. Autophagy. 20:1015–1031. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

72

|

Bi SG, Yu H, Gao TL, Wu JJ, Mao YM, Gong

J, Wang FZ, Yang L, Chen J, Lan ZC, et al: Aerobic exercise

attenuates Autophagy-lysosomal flux deficits via β2-AR-Mediated

ESCRT-III Subunit CHMP4B in mice with human MAPT P301L. Aging Cell.

24:e701842025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Kou X, Chen D and Chen N: Physical

activity alleviates cognitive dysfunction of Alzheimer's disease

through regulating the mTOR signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci.

20:15912019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Li HY, Rong SS, Hong X, Guo R, Yang FZ,

Liang YY, Li A and So KF: Exercise and retinal health. Restor

Neurol Neurosci. 37:571–581. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Ungvari Z, Fazekas-Pongor V, Csiszar A and

Kunutsor SK: The multifaceted benefits of walking for healthy

aging: From Blue Zones to molecular mechanisms. Geroscience.

45:3211–3239. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Cassilhas RC, Tufik S and de Mello MT:

Physical exercise, neuroplasticity, spatial learning and memory.

Cell Mol Life Sci. 73:975–983. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Rocchi A, Yamamoto S, Ting T, Fan Y,

Sadleir K, Wang Y, Zhang W, Huang S, Levine B, Vassar R and He C: A

Becn1 mutation mediates hyperactive autophagic sequestration of

amyloid oligomers and improved cognition in Alzheimer's disease.

PLoS Genet. 13:e10069622017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Li X, He Q, Zhao N, Chen X, Li T and Cheng

B: High intensity interval training ameliorates cognitive

impairment in T2DM mice possibly by improving PI3K/Akt/mTOR

Signaling-regulated autophagy in the hippocampus. Brain Res.

1773:1477032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Chen J, Zhu T, Yang X, Yang Z, Shen M, Gu

B, Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Sun S, et al: Treadmill exercise

alleviates STING-mediated microglia pyroptosis and polarization via

activating mitophagy post-TBI. Free Radic Biol Med. 239:155–176.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Sun L, Wu L, Xu Z, Zeng W and Wang Y:

Running exercise alleviates depressive-like behaviors through the

activation of PINK1-Parkin mediated mitophagy in mice exposed to

chronic social defeat stress. Psychiatry Res. 352:1167142025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Zhang Y, Liao B, Hu S, Pan SY, Wang GP,

Wang YL, Qin ZH and Luo L: High intensity interval training induces

dysregulation of mitochondrial respiratory complex and mitophagy in

the hippocampus of middle-aged mice. Behav Brain Res.

412:1133842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Tan ZX, Dong F, Wu LY, Feng YS and Zhang

F: The beneficial role of exercise on treating Alzheimer's disease

by Inhibiting β-amyloid peptide. Mol Neurobiol. 58:5890–5906. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Gratuze M, Julien J, Morin F, Marette A

and Planel E: Differential effects of voluntary treadmill exercise

and caloric restriction on tau pathogenesis in a mouse model of

Alzheimer's disease-like tau pathology fed with Western diet. Prog

Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 79:452–461. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Xu L, Li M, Wei A, Yang M, Li C, Liu R,

Zheng Y, Chen Y, Wang Z, Wang K, et al: Treadmill exercise promotes

E3 ubiquitin ligase to remove amyloid β and P-tau and improve

cognitive ability in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. J Neuroinflammation.

19:2432022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Morais GP, de Sousa Neto IV, Veras ASC,

Teixeira GR, Paroschi LO, Pinto AP, Dos Santos JR, Alberici LC,

Cintra DEC, Pauli JR, et al: Chronic exercise protects against

cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model by enhancing

autophagy and reducing mitochondrial abnormalities. Mol Neurobiol.

62:12791–12810. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Ohia-Nwoko O, Montazari S, Lau YS and

Eriksen JL: Long-term treadmill exercise attenuates tau pathology

in P301S tau transgenic mice. Mol Neurodegener. 9:542014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Hussain MS, Agrawal N, Ilma B, M MR, Nayak

PP, Kaur M, Khachi A, Goyal K, Rekha A, Gupta S, et al: Autophagy

and cellular senescence in Alzheimer's disease: Key drivers of

neurodegeneration. CNS Neurosci Ther. 31:e705032025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Saxton RA and Sabatini DM: mTOR signaling

in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 168:960–976. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B and Guan KL:

AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of

Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 13:132–141. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Norwitz NG and Querfurth H: mTOR

Mysteries: Nuances and questions about the mechanistic target of

rapamycin in neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci. 14:7752020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Gourmaud S, Stewart DA, Irwin DJ, Roberts

N, Barbour AJ, Eberwine G, O'Brien WT, Vassar R, Talos DM and

Jensen FE: The role of mTORC1 activation in seizure-induced

exacerbation of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 145:324–339. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

92

|

Babygirija R, Sonsalla MM, Mill J, James

I, Han JH, Green CL, Calubag MF, Wade G, Tobon A, Michael J, et al:

Protein restriction slows the development and progression of

pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Commun.

15:52172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Watson K and Baar K: mTOR and the health

benefits of exercise. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 36:130–139. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Kang EB and Cho JY: Effect of treadmill

exercise on PI3K/AKT/mTOR, autophagy, and Tau hyperphosphorylation

in the cerebral cortex of NSE/htau23 transgenic mice. J Exerc

Nutrition Biochem. 19:199–209. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Deneubourg C, Ramm M, Smith LJ, Baron O,

Singh K, Byrne SC, Duchen MR, Gautel M, Eskelinen EL, Fanto M, et

al: The spectrum of neurodevelopmental, neuromuscular and

neurodegenerative disorders due to defective autophagy. Autophagy.

18:496–517. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

96

|

Shen K, Liu X, Chen D, Chang J, Zhang Y

and Kou X: Voluntary wheel-running exercise attenuates brain aging

of rats through activating miR-130a-mediated autophagy. Brain Res

Bull. 172:203–211. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Wątroba M and Szukiewicz D: The role of

sirtuins in aging and age-related diseases. Adv Med Sci. 61:52–62.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Wang J, Zhou F, Xiong CE, Wang GP, Chen

LW, Zhang YT, Qi SG, Wang ZH, Mei C, Xu YJ, et al: Serum sirtuin1:

A potential blood biomarker for early diagnosis of Alzheimer's

disease. Aging (Albany NY). 15:9464–9478. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Liu L, Dai WZ, Zhu XC and Ma T: A review

of autophagy mechanism of statins in the potential therapy of

Alzheimer's disease. J Integr Neurosci. 21:462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Surya K, Manickam N, Jayachandran KS,

Kandasamy M and Anusuyadevi M: Resveratrol mediated regulation of

hippocampal neuroregenerative plasticity via SIRT1 pathway in

synergy with wnt signaling: Neurotherapeutic implications to

mitigate memory loss in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis.

94(Suppl): S125–S140. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

101

|

Mehramiz M, Porter T, O'Brien EK,

Rainey-Smith SR and Laws SM: A potential role for Sirtuin-1 in

Alzheimer's disease: Reviewing the biological and environmental

evidence. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 7:823–843. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Zhao N, Xia J and Xu B: Physical exercise

may exert its therapeutic influence on Alzheimer's disease through

the reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction via

SIRT1-FOXO1/3-PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy. J Sport Health Sci.

10:1–3. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

103

|

Koo JH, Kang EB, Oh YS, Yang DS and Cho

JY: Treadmill exercise decreases amyloid-β burden possibly via

activation of SIRT-1 signaling in a mouse model of Alzheimer's

disease. Exp Neurol. 288:142–152. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Han R, Liu Y, Li S, Li XJ and Yang W:

PINK1-PRKN mediated mitophagy: Differences between in vitro and in

vivo models. Autophagy. 19:1396–1405. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

105

|

Pallanck LJ: Culling sick mitochondria

from the herd. J Cell Biol. 191:1225–1227. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Zhao N, Zhang X, Li B, Wang J, Zhang C and

Xu B: Treadmill exercise improves PINK1/Parkin-Mediated mitophagy

activity against Alzheimer's disease pathologies by upregulated

SIRT1-FOXO1/3 Axis in APP/PS1 mice. Mol Neurobiol. 60:277–291.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Huang J, Wang X, Zhu Y, Li Z, Zhu YT, Wu

JC, Qin ZH, Xiang M and Lin F: Exercise activates lysosomal

function in the brain through AMPK-SIRT1-TFEB pathway. CNS Neurosci

Ther. 25:796–807. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Tyagi A and Pugazhenthi S: A Promising

strategy to treat neurodegenerative diseases by SIRT3 Activation.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:16152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Khoramipour K, Chamari K, Hekmatikar AA,

Ziyaiyan A, Taherkhani S, Elguindy NM and Bragazzi NL: Adiponectin:

Structure, physiological functions, role in diseases, and effects

of nutrition. Nutrients. 13:11802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Bloemer J, Pinky PD, Govindarajulu M, Hong

H, Judd R, Amin RH, Moore T, Dhanasekaran M, Reed MN and

Suppiramaniam V: Role of adiponectin in central nervous system

disorders. Neural Plast. 2018:45935302018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Rehman IU, Park JS, Choe K, Park HY, Park

TJ and Kim MO: Overview of a novel osmotin abolishes abnormal

metabolic-associated adiponectin mechanism in Alzheimer's disease:

Peripheral and CNS insights. Ageing Res Rev. 100:1024472024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Ali T, Rehman SU, Khan A, Badshah H, Abid

NB, Kim MW, Jo MH, Chung SS, Lee HG, Rutten BPF and Kim MO:

Adiponectin-mimetic novel nonapeptide rescues aberrant neuronal

metabolic-associated memory deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Mol

Neurodegener. 16:232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Liu B, Liu J, Wang JG, Liu CL and Yan HJ:

AdipoRon improves cognitive dysfunction of Alzheimer's disease and

rescues impaired neural stem cell proliferation through

AdipoR1/AMPK pathway. Exp Neurol. 327:1132492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Sun F, Wang J, Meng L, Zhou Z, Xu Y, Yang

M, Li Y, Jiang T, Liu B and Yan H: AdipoRon promotes amyloid-β

clearance through enhancing autophagy via nuclear GAPDH-induced

sirtuin 1 activation in Alzheimer's disease. Br J Pharmacol.

181:3039–3063. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Jian Y, Yuan S, Yang J, Lei Y, Li X and

Liu W: Aerobic exercise alleviates abnormal autophagy in brain

cells of APP/PS1 mice by upregulating AdipoR1 levels. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:99212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Lu TX and Rothenberg ME: MicroRNA. J

Allergy Clin Immunol. 141:1202–1207. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Kou X and Chen N: Resveratrol as a natural

autophagy regulator for prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's

disease. Nutrients. 9:9272017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Qi W, Ying Y, Wu P, Dong N, Fu W, Liu Q,

Ward N, Dong X, Zhao RC and Wang J: Inhibition of miR-4763-3p

expression activates the PI3K/mTOR/Bcl2 autophagy signaling pathway

to ameliorate cognitive decline. Int J Biol Sci. 20:5999–6017.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Madadi S, Schwarzenbach H, Saidijam M,

Mahjub R and Soleimani M: Potential microRNA-related targets in

clearance pathways of amyloid-β: Novel therapeutic approach for the

treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Cell Biosci. 9:912019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Kou X, Chen D and Chen N: The regulation

of microRNAs in Alzheimer's sisease. Front Neurol. 11:2882020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|