Introduction

In the 1920s, the Nobel Prize winner Otto Warburg

observed a marked increase in glycolysis and enhanced lactate

production in tumor cells even when maintained in conditions of

high oxygen tension (termed Warburg effect), leading to widespread

concerns about the metabolic changes in human types of cancer

(1). Either as a consequence or as

a cause, alterations of cancer cell-intrinsic metabolism have been

considered as essential hallmarks of cancer. Among these metabolic

changes, de novo fatty acid biosynthesis was found elevated

in the majority of human types of cancer, such as prostate

(2), colorectal (3), ovarian (4), bladder (5), esophageal (6), gastric (7), lung (8), endometrial (9), breast (10) and soft tissue sarcomas (11). Fatty acid synthase (FASN) is

regarded as a key regulator of de novo fatty acid synthesis

and was widely found upregulated in a wide variety of human

malignancies and their pre-neoplastic lesions. Recent studies also

reveal that FASN is associated with the stage of cancer and

indicate a poor prognosis (12).

Thus, FASN could be considered as a reliable predictor of

recurrence and disease-free survival along with neo-plastic stage

(13). In vivo treatment

with inhibitors of FASN has been proven to lead to markedly

decreased survival in human cancer xenografts (14) and silencing of the FASN gene by

siRNA also inhibits cancer cell growth and ultimately induces

cancer cell apoptosis (15).

Therefore, agents that inhibit FASN and the de novo

fatty-acid synthesis pathways could be considered as novel

antitumor strategies.

Orlistat, an anti-obesity drug approved by the US

Food and Drug Administration, which possesses extremely low oral

bio-availability (16), exhibits

anti-proliferative and anti-tumor properties against prostate and

breast cancer cells due to its ability to block the lipogenic

activity of FASN (16), by acting

on the 2.3-A-resolution crystal structure of the thioesterase

domain of FASN (17). Orlistat

negatively influences FASN activity and has a significant effect on

the antitumor activity by inducing remarkable diversification such

as a complete G2-M phase loss, S-phase accumulation and the

emerging sub-G1 (apoptotic) cell increase, and repression of the

promoter activity of Her2/neu gene (18).

Ovarian cancer is the most common malignancy of the

female reproductive tract and is the leading cause of death from

gynecologic types of cancer; it is currently the fifth leading

cause of female cancer-related mortality (19). Finding a novel therapeutic approach

is essential since the 5-year survival rate of women with ovarian

cancer is low, despite the fact that significant progress has been

made in the therapy of this disease (20).

2-DE based proteomics has been shown to be a

powerful tool in rapidly profiling differentially expressed

proteins associated with a number of diseases (21–23).

In our study, we aimed to investigate the differential expression

in Orlistat-treated SKOV3 cells using a 2DE-MS-based proteomics

approach, in order to better understand the molecular mechanisms

underlying Orlistat-induced tumor repression. In total, more than

110 differentially expressed proteins were found altered between

Orlistat-treated and untreated SKOV3 cells, and subsequently 71

proteins were identified by MS analysis. Furthermore, we showed

that PKM2 was significantly down-regulated in Orlistat-treated

SKOV3 cells, which confirmed the antitumor properties of Orlistat,

indicating that Orlistat can be used as a novel adjuvant antitumor

agent for ovarian cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

The human epithelial serous cystadenocarcinoma cell

line SKOV3 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection

(ATCC, Rockville, MD). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s-modified

Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal calf serum

(Hyclone, USA), penicillin (107 U/l) and streptomycin (10 mg/l) at

37°C in a humidified chamber containing 5% CO2. Orlistat

was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). When the cells reached

50–70% confluency, the medium was replaced by a fresh culture

medium containing Orlistat. Control cells were cultured in a medium

containing an equal amount of DMSO instead of Orlistat. For 2-DE

analysis, SKOV3 cells were treated with 20 mM Orlistat for 4 days

and the media were changed every day. Cells were washed twice by

centrifugation in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and transferred

to sterile plastic tubes for storage at −80°C prior to use.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell growth and viability were assessed using an MTT

cell proliferation kit (Roche Applied Science). The cells were

seeded on 96-well microplates at 2.0x103/well. At 48, 72

and 96 h, the cells were treated with different concentrations of

Orlistat and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells were

subsequently incubated with 10 μl of MTT for 4 h, then the

media were removed and 150 μl DMSO were added. We put the

plate in a shaker before reading absorbance at 490-nm using a

microplate reader (3550-UV, Bio-Rad, USA), after 20 min of

incubation. The procedure was repeated three times with similar

results. The following formula was used to calculate the inhibition

rate of SKOV3 cell proliferation: (1-experimental group OD

value/negative control OD value) x 100%. Media-only treated

(untreated) cells were considered as the negative control

group.

2-DE and image analysis

Cells (1.3x108) were lysed in 1 ml lysis

buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 100 mM DTT, 0.2% pH

3.0–10.0 ampholyte, Bio-Rad, USA) containing protease inhibitor

cocktail 8340 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Samples were then kept

on ice and sonicated for six cycles of 10 sec, with each cycle

consisting of 5 sec sonication, followed by a 10 sec break. After

centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C, the supernatant was

collected and the protein concentrations determined using the DC

Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad). Protein samples (3 mg) were applied to

an immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strip (17 cm, pH 3.0–10.0 NL,

Bio-Rad) using a passive rehydration method. After 12–16 h of

rehydration, the strips were transferred to an isoelectric focusing

(IEF) cell (Bio-Rad) and focused for a total of 60,000 Vh. The

second dimension was performed using 12% equilibration. The gels

were stained using CBB R-250 (Merck, Germany) and scanned with a

Bio-Rad GS-800 scanner. Triplicate samples were analyzed at each

time point of treatment to ensure the reproducibility of analyses.

The maps were analyzed by PDQuest software Version 6.1 (Bio-Rad).

Each gel spot was normalized as a percentage of the total quantity

of all spots in that gel and evaluated in terms of OD. Only those

spots that changed consistently and significantly (>2.0-fold)

were selected for MS analysis.

In-gel digestion

In-gel digestion of proteins was carried out using

MS-grade Trypsin Gold (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, spots were cut out of the gel

(1–2 mm diameter) using a razor blade, and destained twice with 100

mM NH4HCO3/50% acetonitrile (ACN) at 37°C for

45 min in each treatment. Following dehydration and drying, the

gels were pre-incubated in 10–20 μl trypsin solution for 1

h. Samples were then added in adequate digestion buffer (40 mM

NH4HCO3/10% ACN) to cover the gels and

incubated overnight at 37°C. Tryptic digests were extracted using

MiliQ water initially, followed by extraction twice with 50% ACN/5%

trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for 1 h each time. The combined extracts

were dried in a vacuum concentrator at room temperature. The

samples were then subjected to MS analysis.

MALDI-Q-TOF analysis and protein

identification

Mass spectra were acquired using a quadrupole

time-of-flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester,

UK) with a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)

source (Micromass). Tryptic digests were dissolved in 5 μl

of 70% ACN/0.1% TFA, and then 1 μl of the digestion was

mixed with 1 μl saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid

(CHCA) in 50% ACN/0.5% TFA and spotted onto a 96-well target plate.

MS/MS was performed in a data-dependent mode in which the top ten

most abundant ions for each MS scan were selected for MS/MS

analysis. The MS/MS data were acquired and processed using the

MassLynx software (Micromass) and MASCOT was used to search the

database. Database searches were carried out using the following

parameters: database, Swiss-Prot; taxonomy, Homo sapien;

enzyme, trypsin; and allowance of one missed cleavage.

Carbamidomethylation was selected as a fixed modification and

oxidation of methionine was allowed to be variable. The peptide and

fragment mass tolerance were at 1 and 0.2 Da, respectively. The

data format selected was Micromass PKL and the instrument selected

was MALDI-Q-TOF. Proteins with probability-based MOWSE scores

exceeding their threshold (P<0.05) were considered to be

positively identified.

Western blot analysis

Collected cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM

Tris-base, 1.0 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1%

sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM PMSF) to extract all the proteins and

quantified by the DC protein assay Kit (Bio-Rad). Samples were

separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene

difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes

were blocked overnight with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 in 5%

skimmed milk at 4°C, and subsequently probed by the primary

antibodies: rabbit anti-PKM2 (diluted 1:500, Abcam, UK). Blots were

incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish

peroxidase for 2 h at room temperature. Target proteins were

detected by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Pharmacia

Biotech, Piscataway, USA), and β-actin was used as an internal

control.

Statistics

All quantitative data are recorded as the means ±

SD. Comparisons between two groups were performed by Student’s

t-test. Differences among multiple groups were assessed by one-way

ANOVA analysis. Relevance analysis of ordinal data was performed by

cross χ2 test. A statistically significant difference

was defined as p<0.05.

Results

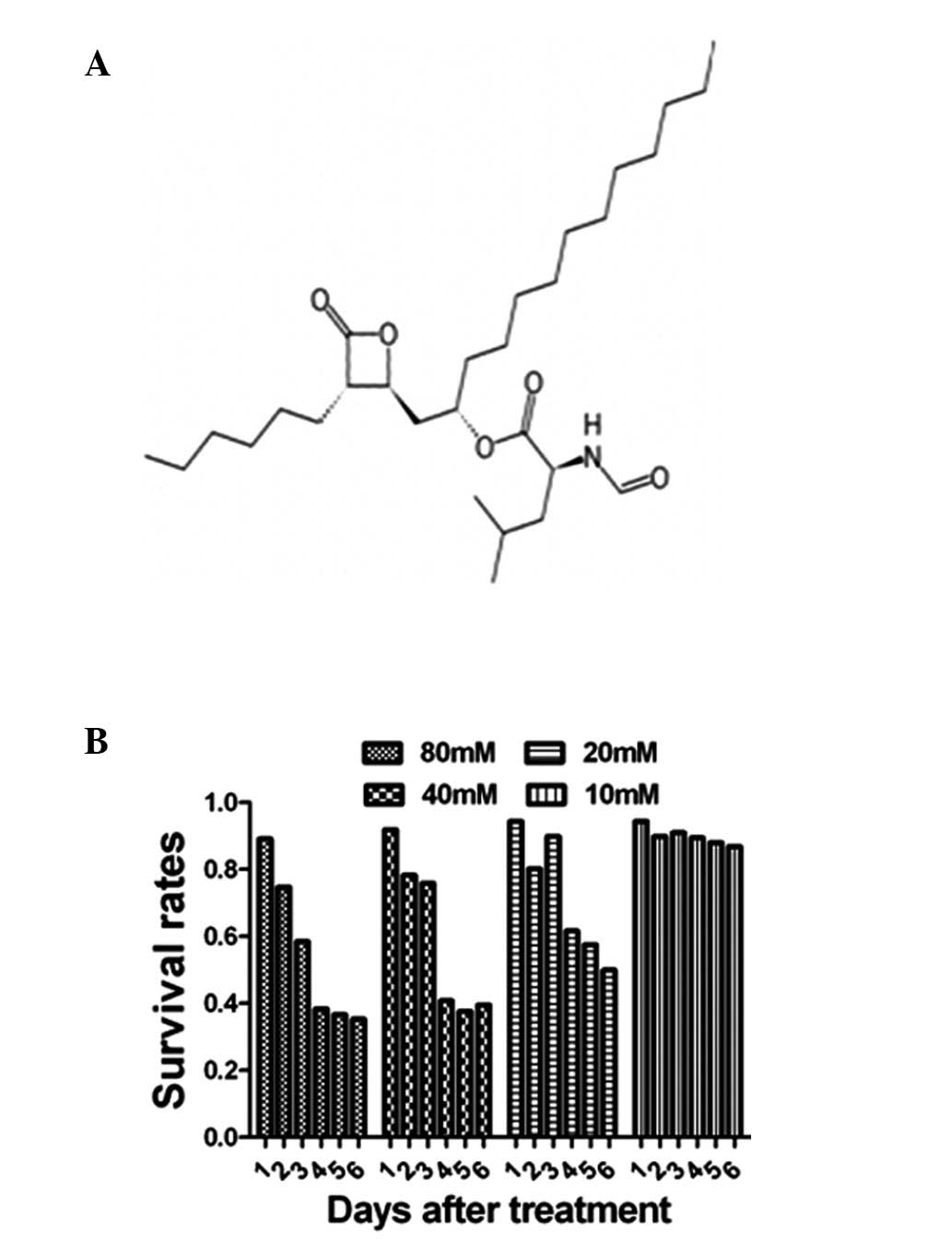

Proliferation activity of

Orlistat-treated SKOV3 cells

The proliferation activity of Orlistat-treated SKOV3

cells was examined using the MTT assays. MTT results showed that

the proliferation activity was suppressed by Orlistat in both a

dose- and duration-dependent manner, and the proliferation ratio

was decreased to 60% of the control value 96 h after treatment with

Orlistat when the drug concentration was 20 mM, as shown in

Fig. 1.

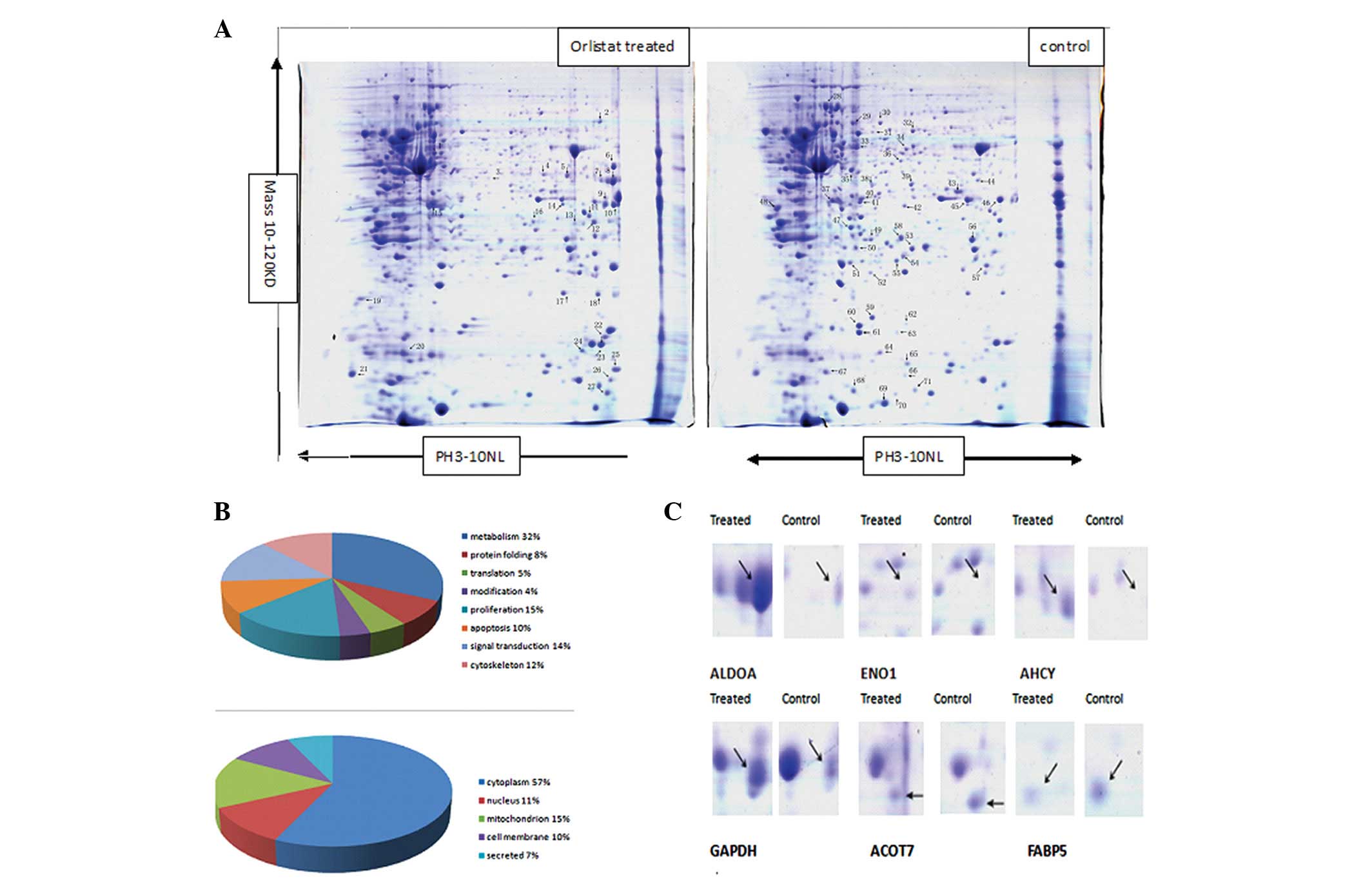

Proteomic analysis of Orlistat-treated

SKOV3 cell protein expression compared with the parental SKOV3

cells

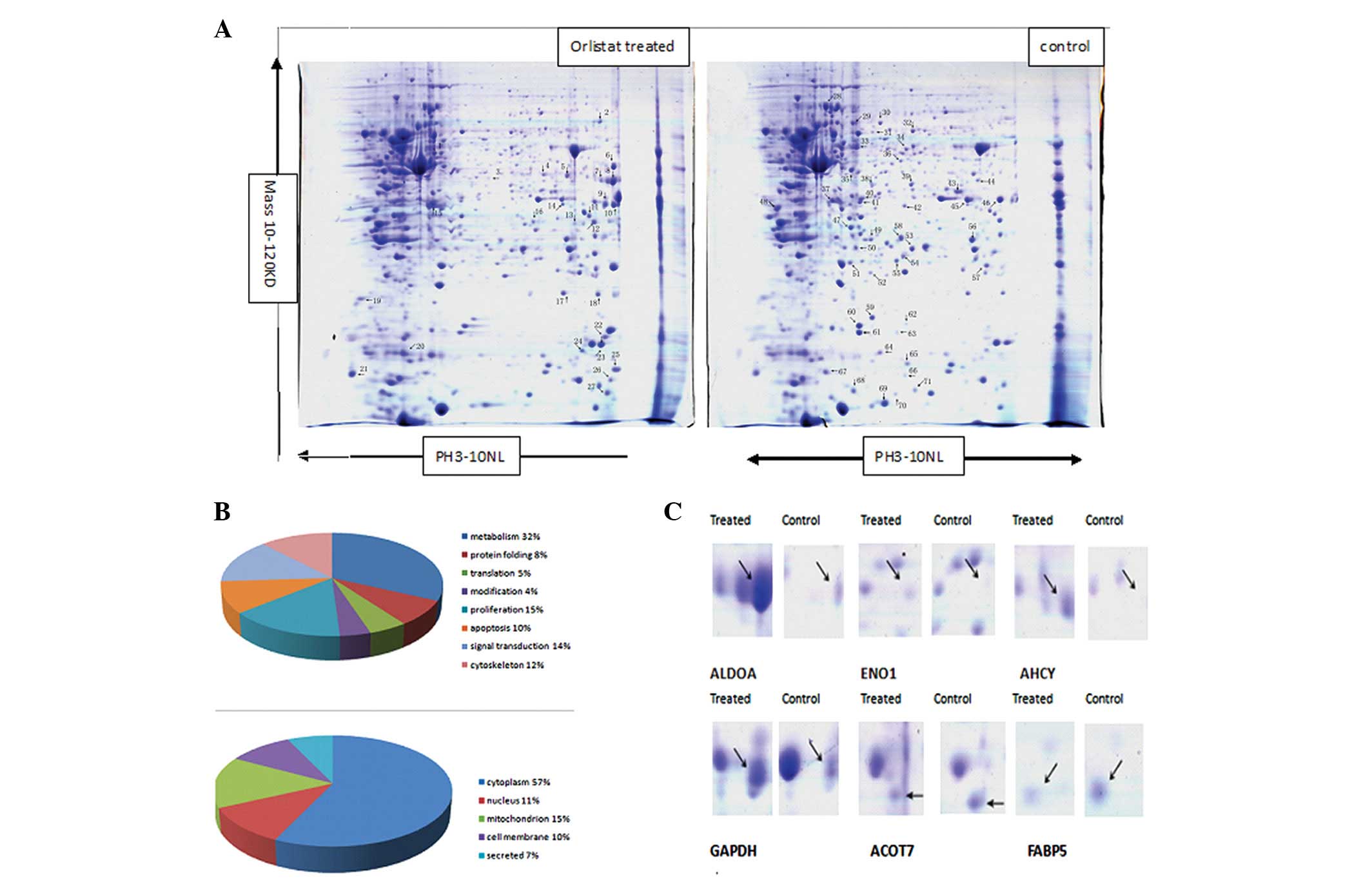

To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the

Orlistat-induced antitumor activity of SKOV3 cells, 2-DE based

proteomics was used to profile differentially expressed proteins in

SKOV3 cells treated with or without Orlistat. Image analysis was

performed using PDQuest 7.1 software. Representative 2-DE maps are

shown in Fig. 2. Approximately

1000–1100 protein spots were detected by CBB R-250 staining in a

single 2-DE gel. Each protein spot was normalized as a percentage

of the total intensity of all spots in the gel. By comparing 2-DE

patterns, differentially expressed proteins were defined as

statistically meaningful (p<0.05) based on both of the following

two criteria: i) intensity alterations of >2.0-fold (t-test,

p<0.05) and ii) observed in at least 3 individual experiments.

According to these criteria, a total of 111 spots were selected and

analyzed using MALDI-Q-TOF tandem mass spectrometry. A total of 71

proteins from the 111 spots were identified (Fig. 2). As different isoforms of a

protein might have distinct functions, each isoform/spot was

considered to be a single protein for analysis in our study.

| Figure 2Comparison of the protein expression

patterns between control and Orlistat-treated SKOV3 cells. (A)

Representative 2-D gel images of the human ovarian cancer cell line

SKOV3 treated with or without Orlistat. Total protein extracts were

separated on pH 3.0–10.0 nonlinear IPG strips in the first

dimension followed by 12% SDS-PAGE in the second dimension and

visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining. Seventy-one

differentially expressed spots (27 upregulated and 44 downregulated

in Orlistat-treated SKOV3 cells) were identified (as numbered).

Details for each numbered spot are reported in Table I. (B) Seventy-one identified

proteins were classified into 8 groups. These included metabolism

(32%), protein folding (8%), translation (5%), protein modification

(4%), cell proliferation (15%), apoptosis (10%), signal

transduction (14%) and cell cytoskeleton (12%). These proteins were

also found to be located in the cytoplasm (57%), nucleus (11%),

mitochondrion (15%), cell membrane (10%) or were secreted (12%).

(C) Enlargement of selected regions. Spots selected are ALDOA (Spot

8), ENO1 (Spot 3), AHCY (Spot 7), GAPDH (Spot 9), ACOT7 (Spot 44),

FABP5 (Spot 65). |

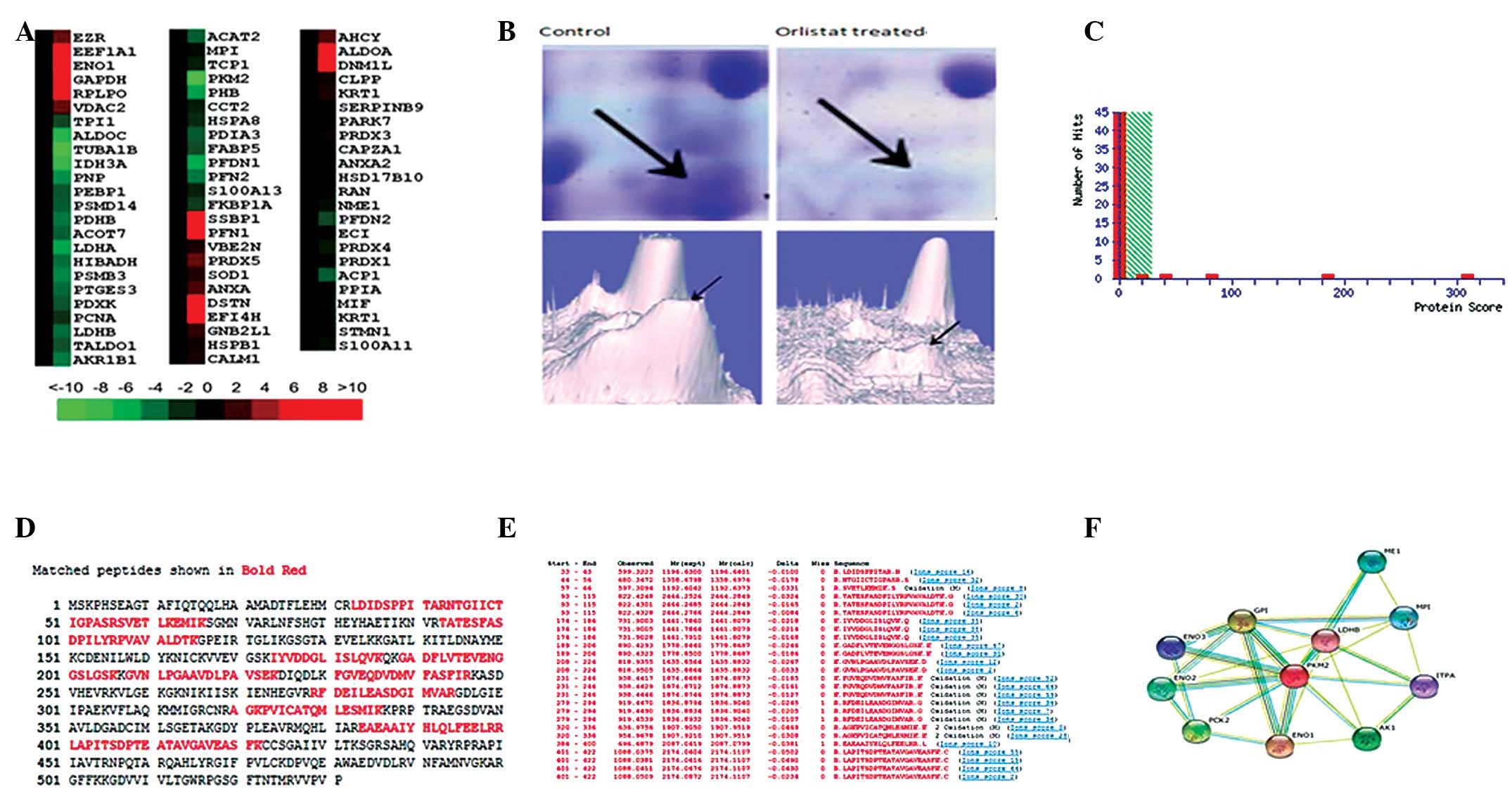

Protein identification and bioinformatics

analysis

In total, 71 spots with differential expression

levels were subjected to MS/MS analysis. The MS/MS data were

queried using the search algorithm MASCOT against the Expasy

protein sequence database. Proteins were identified based on a

number of criteria including PI, MW, the number of matched-peptides

and MOWSE score (Table I and

II).

| Table IProtein spots identified by

MALDI-Q-TOF. |

Table I

Protein spots identified by

MALDI-Q-TOF.

| Spot no. | Accession

no.b | Protein

namea | Gene name | Mwc | PIc | No. of peptide | Coverage (%) | Scored |

|---|

| Upregulated |

| 1 | P15311 | Ezrin | EZR | 69,484 | 5.94 | 5 | 6 | 133 |

| 2 | P68104 | Elongation factor

1-α 1 | EEF1A1 | 50,451 | 9.10 | 15 | 28 | 179 |

| 3 | P06733 | α-enolas | ENO1 | 47,481 | 7.01 | 8 | 18 | 57 |

| 4 | P04264 | Keratin, type II

cytoskeletal 1 | KRT1 | 66,170 | 8.15 | 3 | 3 | 68 |

| 5 | P50453 | Serpin B9 | SERPINB9 | 43,004 | 5.61 | 27 | 46 | 372 |

| 6 | O00429 | Dynamin-1-like

protein | DNM1L | 82,339 | 6.37 | 3 | 4 | 39 |

| 7 | P23526 |

S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase | AHCY | 48,255 | 5.92 | 16 | 24 | 86 |

| 8 | P04075 |

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | ALDOA | 39,851 | 8.30 | 56 | 68 | 723 |

| 9 | P04406 |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase | GAPDH | 36,201 | 8.57 | 27 | 55 | 400 |

| 10 | P22626 | 60S acidic

ribosomal protein P0 | RPLP0 | 37,464 | 8.97 | 12 | 41 | 238 |

| 11 | P45880 | Voltage-dependent

anion-selective channel protein 2 | VDAC2 | 32,060 | 7.49 | 10 | 29 | 91 |

| 12 | P63244 | Guanine

nucleotide-binding protein subunit β-2-like 1 | GNB2L1 | 35,511 | 7.60 | 12 | 52 | 101 |

| 13 | Q15056 | Eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 4H | EIF4H | 27,425 | 6.67 | 7 | 28 | 125 |

| 14 | P04083 | Annexin A1 | Annexin I | 38,918 | 6.57 | 7 | 12 | 45 |

| 15 | P52907 | F-actin-capping

protein subunit α-1 | CAPZA1 | 33,073 | 5.45 | 8 | 48 | 176 |

| 16 | Q16740 | Putative

ATP-dependent

Clp protease proteolytic subunit, mitochondrial | CLPP | 30,446 | 8.26 | 2 | 10 | 116 |

| 17 | P07355 | Annexin A2 | ANXA2 | 38,808 | 7.57 | 45 | 54 | 885 |

| 18 | Q99497 | Protein DJ-1 | PARK7 | 20,050 | 6.33 | 13 | 30 | 97 |

| 19 | P30048 |

Thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase,

mitochondrial | PRDX3 | 28,017 | 7.67 | 9 | 20 | 115 |

| 20 | P04792 | Heat shock protein

β-1 | HSPB1 | 22,826 | 5.98 | 6 | 37 | 48 |

| 21 | P62158 | Calmodulin | CALM1 | 16,827 | 4.09 | 6 | 30 | 84 |

| 22 | P60981 | Destrin | DSTN | 18,950 | 8.06 | 8 | 33 | 91 |

| 23 | P00441 | Superoxide

dismutase | SOD1 | 16,154 | 5.70 | 14 | 32 | 140 |

| 24 | P30044 | Peroxiredoxin-5,

mitochondrial | PRDX5 | 22,301 | 8.93 | 28 | 56 | 281 |

| 25 | Q04837 | Single-stranded

DNA-binding protein, mitochondrial | SSBP1 | 17,249 | 9.59 | 8 | 32 | 76 |

| 26 | P07737 | Profilin-1 | PFN1 | 15,216 | 8.44 | 9 | 57 | 135 |

| 27 | P61088 |

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 N | UBE2N | 17,184 | 6.13 | 7 | 36 | 42 |

| Downregulated |

| 28 | P11142 | Heat shock cognate

71 kDa protein | HSPA8 | 71,082 | 5.37 | 50 | 28 | 562 |

| 29 | P35232 | Prohibitin | PHB | 29,843 | 5.57 | 29 | 51 | 440 |

| 30 | P17987 | T-complex protein 1

subunit α | TCP1 | 60,819 | 5.80 | 28 | 37 | 170 |

| 31 | P30101 | Protein

disulfide-isomerase A3 | PDIA3 | 57,146 | 3.47 | 7 | 12 | 69 |

| 32 | P78371 | T-complex protein 1

subunit β | CCT2 | 57,794 | 6.01 | 36 | 49 | 446 |

| 33 | P14618 | Pyruvate kinase

isozymes M1/M2 | PKM2 | 58,470 | 7.96 | 26 | 36 | 309 |

| 34 | Q9BWD1 | Acetyl-CoA

acetyltransferase | ACAT2 | 41,838 | 6.47 | 12 | 41 | 86 |

| 35 | P34949 | Mannose-6-phosphate

isomerase | MPI | 47,196 | 5.62 | 2 | 7 | 38 |

| 36 | P09972 |

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase C | ALDOC | 39,830 | 6.41 | 13 | 15 | 205 |

| 37 | P68363 | Tubulin α-1B | TUBA1B | 50,804 | 4.94 | 35 | 41 | 513 |

| 38 | P50213 | Isocitrate

dehydrogenase (NAD) subunit α, mitochondrial | IDH3A | 40,022 | 6.47 | 22 | 49 | 152 |

| 39 | P37837 | Transaldolase | TALDO1 | 37,688 | 6.36 | 23 | 37 | 363 |

| 40 | P07195 | L-lactate

dehydrogenase B chain | LDHB | 36,900 | 5.71 | 12 | 41 | 86 |

| 41 | O00764 | Pyridoxal

kinase | PDXK | 35,308 | 5.75 | 18 | 42 | 175 |

| 42 | O00487 | 26S proteasome

non-ATPase regulatory subunit 14 | PSMD14 | 34,726 | 6.06 | 14 | 62 | 62 |

| 43 | P11177 | Pyruvate

dehydrogenase E1 component subunit β, mitochondrial | PDHB | 39,550 | 6.20 | 14 | 16 | 186 |

| 44 | O00154 | Cytosolic acyl

coenzyme A thioester hydrolase | ACOT7 | 42,454 | 8.85 | 13 | 25 | 177 |

| 45 | P15121 | Aldose

reductase | AKR1B1 | 36,230 | 6.51 | 40 | 11 | 62 |

| 46 | P00338 | L-lactate

dehydrogenase A chain | LDHA | 36,950 | 8.44 | 40 | 52 | 319 |

| 47 | P31937 |

3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase,

mitochondrial | HIBADH | 35,705 | 8.38 | 1 | 4 | 39 |

| 48 | P12004 | Proliferating cell

nuclear antigen | PCNA | 29,092 | 4.57 | 45 | 54 | 559 |

| 49 | Q06830 |

Peroxiredoxin-1 | PRDX1 | 22,324 | 8.27 | 2 | 18 | 60 |

| 50 | Q13162 |

Peroxiredoxin-4 | PRDX4 | 30,749 | 5.86 | 3 | 14 | 29 |

| 51 | P00491 | Purine nucleoside

phosphorylase | PNP | 32,325 | 6.45 | 4 | 5 | 35 |

| 52 | P30086 |

Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein

1 | PEBP1 | 21,158 | 7.01 | 36 | 62 | 432 |

| 53 | P60174 | Triosephosphate

isomerase | TPI1 | 26,938 | 6.45 | 15 | 57 | 136 |

| 54 | P49720 | Proteasome subunit

β type-3 | PSMB3 | 23,219 | 6.14 | 7 | 30 | 50 |

| 55 | Q15185 | Prostaglandin E

synthase 3 | PTGES3 | 18,971 | 4.35 | 6 | 18 | 90 |

| 56 | Q99714 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA

dehydrogenase type-2 | HSD17B10 | 27,134 | 7.66 | 42 | 73 | 632 |

| 57 | P62826 | GTP-binding nuclear

protein Ran | RAN | 24,579 | 7.01 | 4 | 18 | 19 |

| 58 | P42126 | Enoyl-CoA δ

isomerase 1, mitochondrial | ECI1 | 33,080 | 8.80 | 5 | 8 | 60 |

| 59 | P15531 | Nucleoside

diphosphate kinase A | NME1 | 17,309 | 5.83 | 19 | 59 | 192 |

| 60 | P62937 | Peptidyl-prolyl

cis-trans isomerase A | PPIA | 18,229 | 7.68 | 22 | 61 | 327 |

| 61 | P16949 | Stathmin | STMN1 | 17,292 | 5.76 | 18 | 24 | 608 |

| 62 | P24666 | Low molecular

weight phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase | ACP1 | 18,487 | 6.30 | 4 | 22 | 27 |

| 63 | Q9UHV9 | Prefoldin subunit

2 | PFDN2 | 16,695 | 6.20 | 1 | 9 | 46 |

| 64 | P62942 | Peptidyl-prolyl

cis-trans isomerase | FKBP1A | 12,000 | 7.88 | 3 | 27 | 26 |

| 65 | Q01469 | Fatty acid-binding

protein, epidermal | FABP5 | 15,497 | 6.60 | 9 | 37 | 90 |

| 66 | O60925 | Prefoldin subunit

1 | PFDN1 | 14,202 | 6.32 | 2 | 9 | 46 |

| 67 | P35080 | Profilin-2 | PFN2 | 15,378 | 6.55 | 18 | 30 | 179 |

| 68 | Q99584 | Protein

S100-A13 | S100A13 | 11,464 | 5.91 | 2 | 22 | 28 |

| 69 | P04264 | Keratin, type II

cytoskeletal 1 | KRT1 | 66,170 | 8.15 | 8 | 11 | 28 |

| 70 | P31949 | Protein

S100-A11 | S100A11 | 11,847 | 6.56 | 4 | 15 | 36 |

| 71 | P14174 | Macrophage

migration inhibitory factor | MIF | 12,639 | 7.74 | 16 | 17 | 366 |

| Table IIProteins identified to be involved in

the metabolic process. |

Table II

Proteins identified to be involved in

the metabolic process.

| Spot no. | Accession no. | Protein name | Average ratio | Subcellular

location | Main function |

|---|

| 3 | P06733 | α-enolas | 10.54 | Cell membrane | Glycolysis |

| 7 | P23526 |

S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase | 8.91 | Cytoplasm | Control of

methylations |

| 8 | P04075 |

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | 23.57 | Cytoplasm | Glycolysis and

gluconeogenesis |

| 9 | P04406 |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase | 4.72 | Cytoplasm | Glycolysis |

| 31 | P30101 | Protein

disulfide-isomerase A3 | 0.23 | Cytoplasm | Cysteine-type

endopeptidase activity |

| 33 | P14618 | Pyruvate kinase

isozymes M1/M2 | 0.08 | Cytoplasm | Glycolysis |

| 34 | Q9BWD1 | Acetyl-CoA

acetyltransferase | 0.22 | Cytoplasm | Acetyl-CoA

C-acetyltransferase activity |

| 35 | P34949 | Mannose-6-phosphate

isomerase | 0.73 | Cytoplasm | Mannose-6-phosphate

isomerase activity |

| 36 | P09972 |

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase C | 0.19 | Cytoplasm | Glycolysis and

gluconeogenesis |

| 38 | P50213 | Isocitrate

dehydrogenase (NAD) subunit α, mitochondrial | 0.17 | Mitochondrion | Tricarboxylic acid

cycle |

| 39 | P37837 | Transaldolase | 0.43 | Cytoplasm | Pentose-phosphate

pathway |

| 40 | P07195 | L-lactate

dehydrogenase B chain | 0.34 | Cytoplasm | (S)-lactate + NAD+=

pyruvate + NADH. |

| 43 | P11177 | Pyruvate

dehydrogenase E1 component subunit β, mitochondrial | 0.32 | Mitochondrion | Pyruvate

dehydrogenase (acetyl-transferring) activity |

| 44 | O00154 | Cytosolic acyl

coenzyme A thioester hydrolase | 0.37 | Mitochondrion | Fatty-acyl-CoA

binding |

| 45 | P15121 | Aldose

reductase | 0.31 | Cytoplasm | Catalytic

efficiencies |

| 46 | P00338 | L-lactate

dehydrogenase A chain | 0.23 | Cytoplasm | L-lactate

dehydrogenase activity |

| 47 | P31937 |

3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase,

mitochondrial | 0.33 | Mitochondrion |

3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase

activity |

| 51 | P00491 | Purine nucleoside

phosphorylase | 0.27 | Cytoplasm | Immune

response |

| 53 | P60174 | Triosephosphate

isomerase | 0.47 | Cytoplasm | Triose-phosphate

isomerase activity |

| 55 | Q15185 | Prostaglandin E

synthase 3 | 0.35 | Cytoplasm | Molecular

chaperone |

| 56 | Q99714 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA

dehydrogenase type-2 | 0.41 | Mitochondrion |

3-hydroxy-2-methylbutyryl-CoA

dehydrogenase activity |

| 58 | P42126 | Enoyl-CoA delta

isomerase 1, mitochondrial | 0.38 | Mitochondrion | Dodecenoyl-CoA

delta-isomerase activity |

| 65 | Q01469 | Fatty acid-binding

protein, epidermal | 0.27 | Cytoplasm | High specificity

for fatty acids |

The identified proteins were divided into various

groups based on their biological functions and subcellular

localization. This implicated roles in metabolism (32%), protein

folding (8%), translation (5%), protein modification (4%), cell

proliferation (15%), apoptosis (10%), signal transduction (14%) and

cell cytoskeleton (12%). The proteins were found to be located in

the cytoplasm (57%), nucleus (11%), mitochondrion (15%), cell

membrane (10%) or were secreted (12%) (Fig. 2). For a macroscopic presentation,

cluster maps and protein interaction and function networks were

generated using Cluster or the KEGG-based software tool Cytoscape,

respectively. Twenty-three proteins, accounting for 32% of the

proteins identified, were found to be associated with metabolism

regulation. The metabolism-regulating proteins were grouped in

different clusters. Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 were found to

show one of the most significant differences in expression between

SKOV3 cells treated with or without Orlistat. It was downregulated

more than 10-fold in SKOV3 cells treated with Orlistat compared to

those without Orlistat, and MS/MS analysis revealed 15 matched

peptides with 36% sequence coverage and a MOWSE score of 309

(Fig. 3).

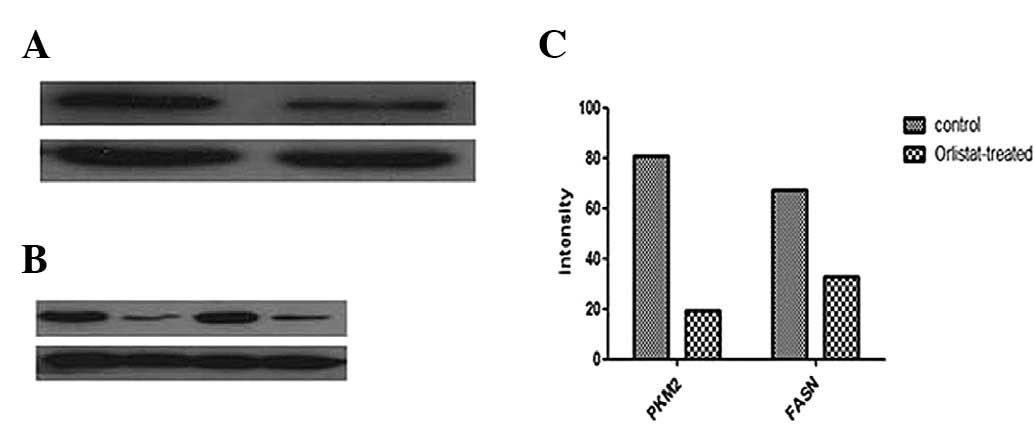

Proteomic validation of identified

proteins

The expression level of PKM2 was further validated

by western blotting. Consistent with the observations in 2-DE

analysis, PKM2 was downregulated in the Orlistat-treated SKOV3

cells compared with the parental SKOV3 cells. A similar change in

the expression level of FASN was detected in SKOV3 cells treated

with Orlistat (Fig. 5).

Discussion

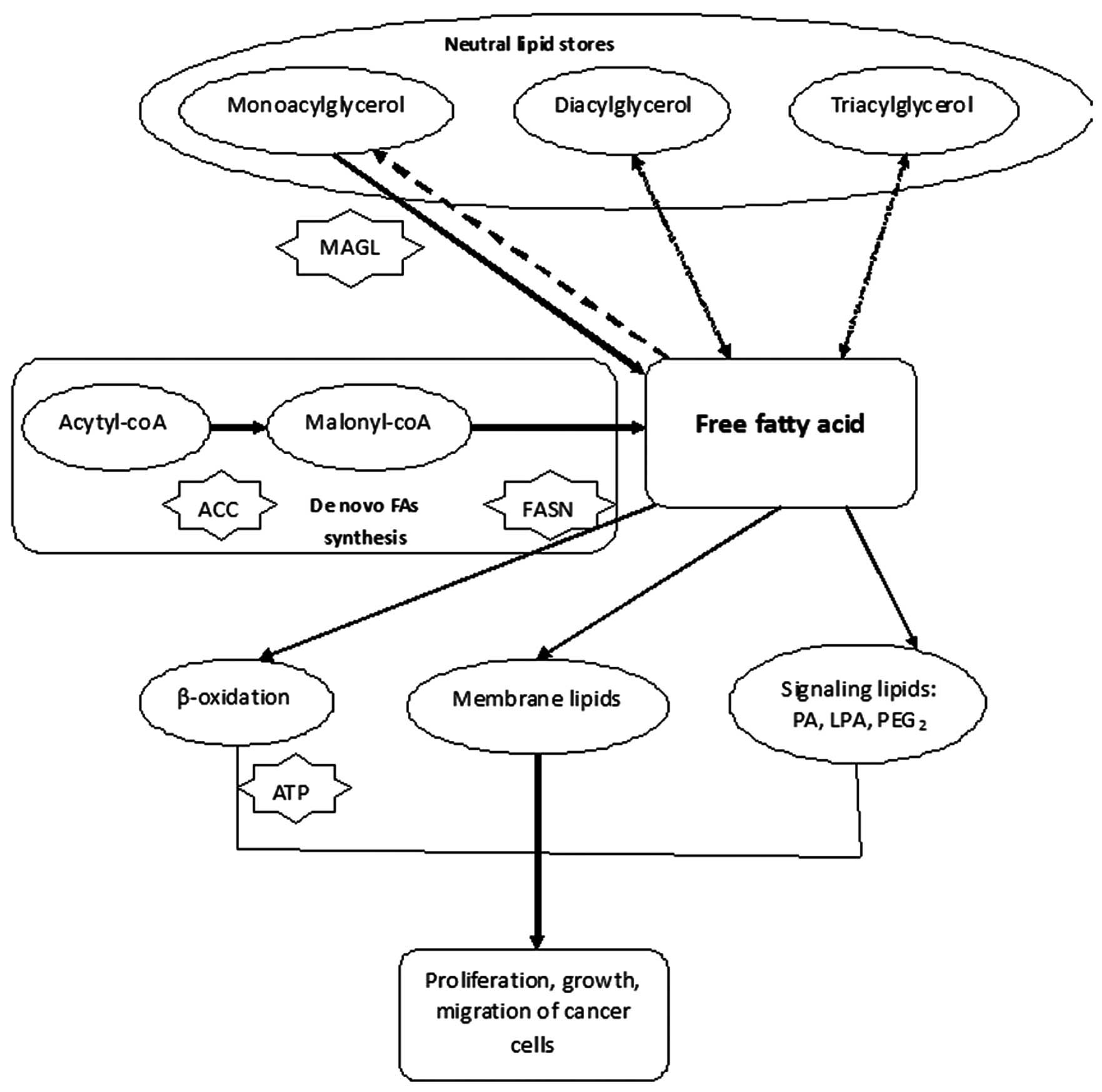

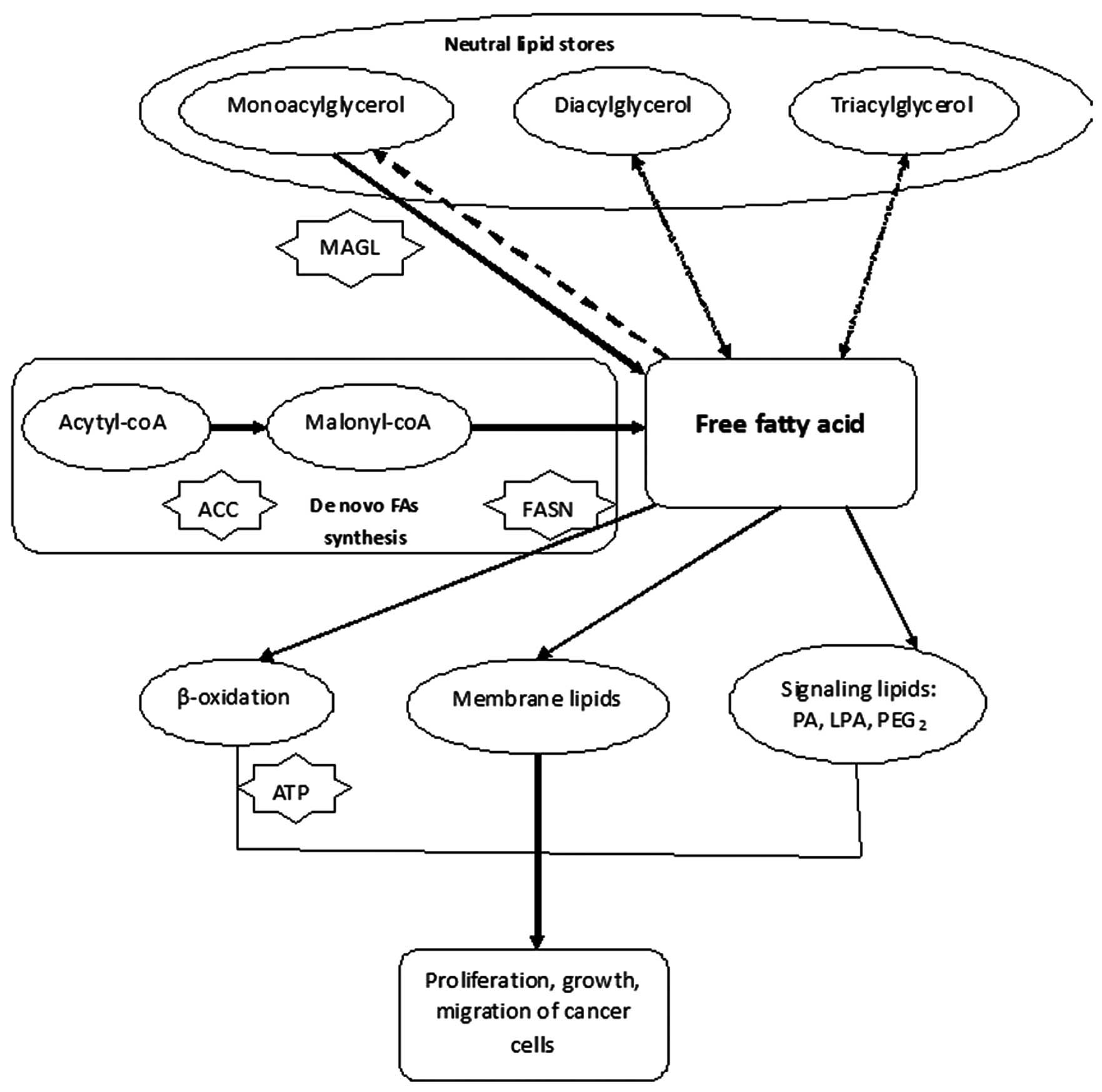

Altered expression of lipid metabolic enzymes is a

feature of various types of cancer, including those that develop in

ovarian tissues (24). Highly

proliferating cancer cells need to synthesize fatty acids de

novo to continually provide lipids for membrane production. The

synthesized fatty acids are also used for energy production through

β-oxidation and lipid modification of proteins (Fig. 4). FASN, one of the key enzymes

involved in de novo fatty-acid synthesis, was found to be

overexpressed in various human types of cancer, including prostate,

ovary, colon, and lung (25). FASN

has been found to be essential for ovarian cancer cell survival and

inhibition of FASN activity has been shown to have potential

chemo-preventive (26) and

therapeutic applications (27).

| Figure 4Free fatty acids can promote the

proliferation, growth and migration of cancer cells. FASN plays a

central role in regulation the synthesis of free fatty acids. So

inhibition of FASN and the de novo fatty-acid synthesis

pathways could be considered as novel strategies in antitumor

territory ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; FASN, fatty-acid synthase;

MAGL, monoacylglycerol lipase; PA, phosphatidic acid; LPA,

lysophosphatidic acid, and PGE2, prostaglandin E2, ATP, adenosine

5′-triphosphate. |

In this study, we found that treatment with

Orlistat, an inhibitor of FASN, promoted the apoptosis of SKOV3

cells (Fig. 1). We confirm the

inhibitory effect of Orlistat on FASN by western blot analysis

using the ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3) as a model, and we found

that FASN was 2-fold downregulated after treatment with Orlistat.

As shown in Fig. 5, we employed a

2-DE-based proteomics approach to annotate the altered proteins in

the SKOV3 cells prior to and following treatment with Orlistat. Our

proteomic analysis revealed a total of 71 differentially expressed

proteins, which were associated with cell metabolism, proliferation

and/or apoptosis.

Among them, Profilin 1, a member of the profilin

family, also known as PFN1, was ubiquitous and upregulated more

than 10-fold in SKOV3 cells after treatment with Orlistat. PFN1 was

found to be involved in multiple cell behaviors, such as cell

adhesion, growth, proliferation and signal transduction (34,35).

Moreover, 23 proteins were found differentially expressed related

to metabolism. Among them, pyruvate kinase (PK), a rate-limiting

enzyme during glycolysis, catalyzes the production of pyruvate and

adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and

adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) (28). Four mammalian PK isoenzymes (M1,

M2, L and R) were found in normal adult cells. By contrast, PKM2 is

found predominantly in the fetus as well as in tumor cells, where

the abundance of other isoforms of PK is low. PKM2 can exist in

either active tetramers or inactive dimers, but in tumor cells it

predominantly occurs in dimers with low activity (29). Cancer cells universally express the

M2 isoform of the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase (PKM2), and

previous studies have demonstrated that PKM2 expression is

necessary for aerobic glycolysis and cell proliferation in

vivo (28,30). Knockdown of PKM2 using RNA

interference significantly impairs cell growth in tissue culture,

inhibition of PKM2 with peptide aptamers inhibits cell

proliferation, and PKM2 expression is necessary for both aerobic

glycolysis and tumor growth in vivo (31,32).

It has been proven that the downregulation of PKM2 activity in

cancer cells aids in shunting key glycolytic intermediates toward

pathways where they, in turn, are utilized as precursors for lipid,

amino acid and nucleic acid synthesis. Therefore, the

downregulation of PKM2 activity provides a purposeful divergence

from catabolic metabolism aimed at energy production toward an

anabolic state aimed at providing the needed resources for rapid

cellular construction (33).

Research has also shown that PKM2 plays a general role in caspase-

and Bcl-independent apoptosis, thereby validating PKM2 as a

promising, generally relevant target for the development of

anticancer therapies with broad efficacy (34). In our study, PKM was downregulated

more than 10-fold, confirming our hypothesis that Orlistat has

antitumor abilities. Furthermore, significant downregulation of

PKM2 after treatment with Orlistat was confirmed in the ovarian

cancer cell line SKOV3 cells by western blot analysis.

In conclusion, using proteomic tools, we identified

71 differentially expressed proteins following Orlistat treatment

of ovarian cancer cells. The functions of the differentially

expressed proteins were correlated to apoptosis and/ or

anti-proliferation cellular processes. These results support the

hypothesis that Orlistat is a potential inhibitor of ovarian cancer

and can be used as a novel assistant antitumor agent, combined with

conventional surgical resection and chemotherapy.

Abbreviations:

|

2-DE

|

two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis;

|

|

MALDI-Q-TOF

|

matrix-assisted laser desorption

ionization quadrupole time-of-flight;

|

|

MOWSE

|

molecular weight search;

|

|

ALODA

|

aldolase A;

|

|

LDHA

|

L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain;

|

|

KPYM

|

pyruvate kinase muscle isozyme;

|

|

MS

|

mass spectrometry;

|

|

MTT

|

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide;

|

|

PI

|

propidium iodide;

|

|

CAPS

|

calcyphosine;

|

|

FAS

|

fatty-acid synthase

|

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the

National Key Basic Research Program (973 Program) of China

(2011CB910703).

References

|

1

|

Clemens MJ: Targets and mechanisms for the

regulation of translation in malignant transformation. Oncogene.

23:3180–3188. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bull JH, Ellison G, Patel A, et al:

Identification of potential diagnostic markers of prostate cancer

and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia using cDNA microarray. Br J

Cancer. 84:1512–1519. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rashid A, Pizer ES, Moga M, et al:

Elevated expression of fatty acid synthase and fatty acid synthetic

activity in colorectal neoplasia. Am J Pathol. 150:201–208.

1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gansler TS, Hardman W III, Hunt DA, et al:

Increased expression of fatty acid synthase (OA-159) in ovarian

neoplasms predicts shorter survival. Hum Pathol. 18:686–692. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gansler TS, Hardman W III, Hunt DA, et al:

Immunohistochemical expression and prognostic significance of FAS

and GLUT1 in bladder carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 23:335–339.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nemoto T, Terashima S, Kogure M, et al:

Overexpression of fatty acid synthase in oesophageal squamous cell

dysplasia and carcinoma. Pathobiology. 69:297–303. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kusakabe T, Nashimoto A, Honma K and

Suzuki T: Fatty acid synthase is highly expressed in carcinoma,

adenoma and in regenerative epithelium and intestinal metaplasia of

the stomach. Histopathology. 40:71–79. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Piyathilake CJ, Frost AR, Manne U, et al:

The expression of fatty acid synthase (FAS) is an early event in

the development and progression of squamous cell carcinoma of the

lung. Hum Pathol. 31:1068–1073. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pizer ES, Lax SF, Kuhajda FP, Pasternack

GR and Kurman RJ: Fatty acid synthase expression in endometrial

carcinoma: correlation with cell proliferation and hormone

receptors. Cancer. 83:528–537. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Alò PL, Visca P, Marci A, Mangoni A, Botti

C and Di Tondo U: Expression of fatty acid synthase (FAS) as a

predictor of recurrence in stage I breast carcinoma patients.

Cancer. 77:474–482. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pizer ES, Wood FD, Heine HS, Romantsev FE,

Pasternack GR and Kuhajda FP: Inhibition of fatty acid synthase

delays disease progression in a xenograft model of ovarian cancer.

Cancer Res. 56:189–193. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Alò PL, Visca P, Botti C, et al:

Immunohistochemical expression of human erythrocyte glucose

transporter and fatty acid synthase in infiltrating breast

carcinomas and adjacent typical/ atypical hyperplastic or normal

breast tissue. Am J Clin Pathol. 116:129–134. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Alò PL, Visca P, Framarino ML, et al:

Immunohistochemical study of fatty acid synthase in ovarian

neoplasms. Oncol Rep. 7:1383–1388. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Costello LC and Franklin RB: ‘Why do

tumour cells glycolyse?’: from glycolysis through citrate to

lipogenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 280:1–8. 2005.

|

|

15

|

De Schrijver E, Brusselmans K, Heyns W,

Verhoeven G and Swinnen JV: RNA interference-mediated silencing of

the fatty acid synthase gene attenuates growth and induces

morphological changes and apoptosis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells.

Cancer Res. 63:3799–3804. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Menendez JA, Vellon L and Lupu R:

Orlistat: From antiobesity drug to anticancer agent in Her-2/neu

(erbB-2)-overexpressing gastrointestinal tumors? Exp Biol Med

(Maywood). 230:151–154. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Pemble CW IV, Johnson LC, Kridel SJ and

Lowther WT: Crystal structure of the thioesterase domain of human

fatty acid synthase inhibited by Orlistat. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

14:704–709. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Knowles LM, Axelrod F, Browne CD and Smith

JW: A fatty acid synthase blockade induces tumor cell-cycle arrest

by down-regulating Skp2. J Biol Chem. 279:30540–30545. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J,

Murray T and Thun MJ: Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

58:71–96. 2008.

|

|

20

|

Raki M, Rein DT, Kanerva A and Hemminki A:

Gene transfer approaches for gynecological diseases. Mol Ther.

14:154–163. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu R, Li Z, Bai S, et al: Mechanism of

cancer cell adaptation to metabolic stress: proteomics

identification of a novel thyroid hormone-mediated gastric

carcinogenic signaling pathway. Mol Cell Proteomics. 8:70–85. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tong A, Wu L, Lin Q, et al: Proteomics

analysis of cellular protein alterations using a hepatitis B

virus-producing cellular model. Proteomics. 8:2012–2023. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu R, Wang K, Yuan K, et al: Integrative

oncoproteomics strategies for anticancer drug discovery. Expert Rev

Proteomics. 7:411–429. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Medes G, Thomas A and Weinhouse S:

Metabolism of neoplastic tissue. IV: A study of lipid synthesis in

neoplastic tissue slices in vitro. Cancer Res. 13:27–29.

1953.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Witkowski A, Joshi AK and Smith S:

Coupling of the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and lipoylation

pathways in mammalian mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 282:14178–14185.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chirala SS and Wakil SJ: Structure and

function of animal fatty acid synthase. Lipids. 39:1045–1053. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kuhajda FP, Jenner K, Wood FD, Hennigar

RA, Jacobs LB, Dick JD and Pasternack GR: Fatty acid synthesis: a

potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 91:6379–6383. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH,

et al: The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for

cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 452:230–233. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guminska M, Ignacak J, Kedryna T and

Stachurska MB: Tumor-specific pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 involved

in biochemical strategy of energy generation in neoplastic cells.

Acta Biochim Pol. 44:711–724. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mazurek S, Boschek CB, Hugo F and

Eigenbrodt E: Pyruvate kinase type M2 and its role in tumor growth

and spreading. Semin Cancer Biol. 15:300–308. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dombrauckas JD, Santarsiero BD and Mesecar

AD: Structural basis for tumor pyruvate kinase M2 allosteric

regulation and catalysis. Biochemistry. 44:9417–9429. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Spoden GA, Mazurek S, Morandell D, et al:

Isotype-specific inhibitors of the glycolytic key regulator

pyruvate kinase subtype M2 moderately decelerate tumor cell

proliferation. Int J Cancer. 123:312–321. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Steták A, Veress R, Ovádi J, Csermely P,

Kéri G and Ullrich A: Nuclear translocation of the tumor marker

pyruvate kinase M2 induces programmed cell death. Cancer Res.

67:1602–1608. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Janke J, Schlüter K, Jandrig B, et al:

Suppression of tumorigenicity in breast cancer cells by the

microfilament protein profilin 1. J Exp Med. 191:1675–1686. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wu N, Zhang W, Yang Y, et al: Profilin 1

obtained by proteomic analysis in all-trans retinoic acid-treated

hepatocarcinoma cell lines is involved in inhibition of cell

proliferation and migration. Proteomics. 6:6095–6106. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|