Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of

cancer-related death in men and women (1). Up to 85% of patients are diagnosed at

an advanced stage when the tumor is unresectable because of

infiltration of local arteries or distant metastasis (2). Gemcitabine has been the standard of

care for the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer based on a

randomized trial showing an improvement in the one-year survival

with gemcitabine compared to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (3). Although well-tolerated, the efficacy

of gemcitabine is modest, with reported response rates (RR) of 10%

and median survival of less than 7 months (3). The combination of gemcitabine with a

variety of cytotoxic and targeted agents has generally shown no

significant survival advantage as compared to gemcitabine alone

(4). Some studies have suggested a

significant benefit in overall survival (OS) and progression-free

survival (PFS) associated with gemcitabine-based cytotoxic

combinations in patients with good performance status (5,6). An

impressive efficacy and longer median OS of 10.2 months was first

reported in a phase II study in patients with advanced pancreatic

cancer under treatment with the combination regimen FOLFIRINOX

(oxaliplatin, irinotecan, 5-FU and leucovorin) (7). Subsequently, FOLFIRINOX was compared

to gemcitabine in a randomized phase III trial in patients with

advanced pancreatic cancer (8).

This study confirmed statistically significant and clinically

relevant improvements in OS (11.1 vs. 6.8 months), PFS (6.4 vs. 3.3

months) and RR (31.6 vs. 9.4%) with FOLFIRINOX compared to

gemcitabine alone. Because of significant higher grade 3 and 4

toxicities (mostly neutropenia, diarrhea, febrile neutropenia,

thrombocytopenia, sensory neuropathy) with FOLFIRINOX and the

limited survival time of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer,

biomarkers allowing a better patient selection are required.

Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess clinical (age, body

mass index, gender), histopathological [histology, grading, tumor

location, T-stage, levels of carboanhydrase 19.9 (CA19.9) and

carcinoembryogenic antigen (CEA), p53 and Ki67 expression]

parameters of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with

FOLFIRINOX and their association with response to treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design and assessment of

response

We conducted a retrospective review of all patients

with either primarily locally advanced, metastatic or recurrent

unresectable pancreatic cancer treated with FOLFIRINOX at our

department between October, 2010 and November, 2012. We evaluated

patient and tumor characteristics such as gender, age, age adapted

body mass index (BMI), performance status, T-stage according to the

TNM classification, initial tumor localization (the head vs. the

body, tail or the papilla of the pancreas) and primary metastases

(hepatic, peritoneal, pulmonal) or localization of relapse (local

vs. visceral metastasis) based on review of the patients’ medical

records. Response was assessed by review of the patients imaging

studies according to RECIST criteria as complete (CR), partial

response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) as

well as by tumor marker response of CA19.9 (9). Thus, a decrease or increase in CA19.9

by 50% compared to baseline after treatment was classified as PR or

PD, respectively. The objective response rate was defined as the

percentage of patients with CR and PR. The disease control rate was

defined as the percentage of patients with CR, PR and SD (Table I).

| Table I.Demographic and baseline

characteristics of all the patients. |

Table I.

Demographic and baseline

characteristics of all the patients.

| Characteristics | |

|---|

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Male | 24 (49) |

| Female | 25 (51) |

| Age, years | |

| Median | 62 |

| Range | 42–76 |

| BMI | |

| Median | 22.3 |

| Range | 17.2–34.8 |

| ECOG performance

score 0, no. (%) | 49 (100) |

| Histology, no.

(%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 42 (95.5) |

| Giant cell

carcinoma | 1 (2.3) |

| Adenosquamous

carcinoma | 1 (2.3) |

| No histology | 5 (10) |

| Grading | |

| 2 | 28 (65.1) |

| 3 | 15 (34.9) |

| Pancreatic tumor

localization, no. (%) | |

| Head | 24 (49.0) |

| Body | 7 (14.3) |

| Tail | 16 (32.7) |

| Papilla vateri | 2 (4.1) |

| T-stage | |

| 2 | 3 (6.7) |

| 3 | 26 (57.8) |

| 4 | 16 (35.6) |

| Non-metastatic

disease, no. (%) | 6 (12.2) |

| Metastatic disease,

no. (%) | 28 (57.1) |

| Metastatic sites | |

| Liver | 15 (53.6) |

|

Liver/peritoneum | 8 (28.6) |

| Lung | 4 (14.3) |

| Liver/lung | 4 (14.3) |

| Relapsed disease,

no (%) | 15 (30.6) |

| Locoregional | 1 (6.7) |

| Visceral (liver,

lung, periteonal) | 7 (46.7) |

| Locoregional and

visceral | 7 (46.7) |

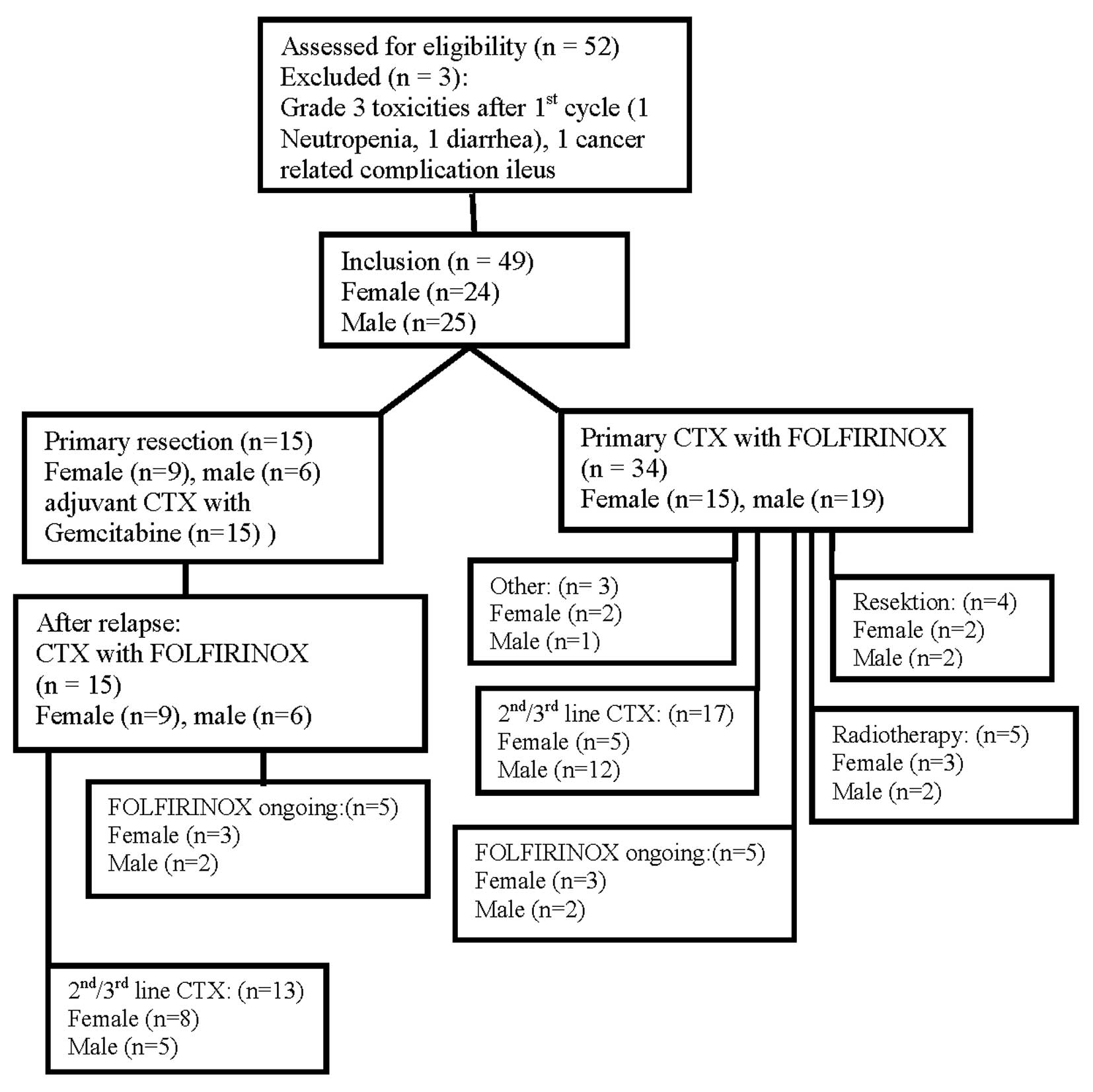

Treatment

Full dose FOLFIRINOX consisted of oxaliplatin 85

mg/m2 over 3 h, followed by irinotecan 180

mg/m2 over 90 min and leucovorin 400 mg/m2

over 2 h, followed by 5-FU 400 mg/m2 as a bolus and

2,400 mg/m2 as a 46 h continuous infusion. Dose

modifications due to toxicity were made according to the discretion

of the treating physician. Treatment was discontinued in case of

unacceptable toxicity, progression of disease or pursuit of

alternative therapies including surgical resection or radiotherapy

for locally advanced disease (Fig.

1).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for Ki67 and p53

protein was performed using the antibodies monoclonal mouse

anti-human Ki67 (clone MIB-1, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at a working

dilution of 1:500 and monoclonal mouse anti-human p53 (clone DO-7,

Dako) at a working dilution of 1:200 on routinely formalin-fixed

paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue, using a standardized automated

platform (AutostainerPlus, Dako) in combination with Envision

polymer detection system (Dako). Archival FFPE sections (3

μm) were deparaffinized in combination with heat-induced

epitope retrieval (HIER) at 98°C for 40 min in antigen retrieval

buffer pH 9.0 (Dako) in a PT Link™-module (Dako). Endogenous

peroxidase blocking was carried out for 10 min with 3%

H2O2 in absolute methanol and normal serum

was applied. Primary antibodies and detection reagents were

incubated at RT for 30 min and after several washes detection was

performed using EnvisionFlex™ detection system, followed by

chromogenic visualisation with diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 10 min.

Nuclear counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin. Assessment

of Ki67 and p53 staining was performed according to the

recommendations of the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer working

group (10). At least three

high-power (×40 objective) fields and clear hot spots were selected

to represent the spectrum of staining seen and 100 cancer cells

were evaluated.

CA19.9 and CEA measurement

CA19.9 and CEA measurements were carried out at a

certified laboratory associated with the hospital by an

electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim,

Germany). The upper limit normally used for CA19.9 was 37 U/ml and

for CEA 3.5 μg/l. Serum levels of CA19.9 and CEA were

measured before therapy and every second week during therapy.

Statistics

Baseline and clinicopathological characteristics

were summarized as median and range for continuous variables and as

absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables.

Comparisons in regard to gender and therapy response were either

performed with the Kruskal-Wallis, the Mann-Whitney U or the

χ2 test. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate

statistical significance. Tumor markers were correlated with each

other using Spearman rank correlation coefficient. A multivariate

logistic regression model was performed to assess the joint effect

of gender, age and clinical variables such as tumor stage, line of

treatment (primary treatment vs. treatment in the relapsed stage)

and biomarkers such as Ki67 and p53 on the response rate. OS and

PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method together with the

log-rank test. As survival measures, median and 95% confidence

intervals are given.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

Between October 2010 and November 2012 a total of 52

patients with either locally advanced non-metastatic (n=6),

metastatic (n=31) or relapsed unresectable pancreatic cancer after

initial resection (n=15) were treated with FOLFIRINOX at our

department (Fig. 1). Two patients

discontinued CTX after the first application due to grade 3

toxicities (1 febrile neutropenia, 1 diarrhea) or cancer related

complications (1 patient with ileus) and therefore were excluded

from our analysis. Thus, a total of 49 patients could finally be

included in our study. Demographic and tumor parameters were

equally distributed between both genders (Table II). Although female patients showed

higher numbers of metastatic tumors (15 vs. 13) and no locally

advanced non-metastatic tumors before treatment compared to males

(0 vs. 6 months) (p=0.095), they were characterized by significant

higher levels of CA19.9 (p=0.037) and CEA (p=0.05).

| Table II.Demographic and baseline

characteristics of female vs. male patients. |

Table II.

Demographic and baseline

characteristics of female vs. male patients.

|

Characteristics | Female (n=24) | Male (n=25) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | | | |

| Median | 61 | 63 | 0.603 |

| Range | 42–73 | 45–76 | |

| BMI | | | |

| Median | 22.3 | 22.9 | 0.379 |

| Range | 17.2–34.8 | 17.3–30-7 | |

| Level of

carbohydrate antigen 19.9 | | | |

| Median | 2494 | 185 | 0.037 |

| Range | 0–140241 | 0–32266 | |

| Level of

carcinoembryogenic antigen | | | |

| Median | 10.4 | 5.7 | 0.05 |

| Range | 2–363 | 2–306 | |

| Level of Ki-67

positive cancer cells (%) | | | |

| Median | 30 | 20 | 0.457 |

| Range | 1–80 | 1–70 | |

| Level of mutant p53

cancer cells (%) | | | |

| Median | 30 | 1 | 0.147 |

| Range | 1–100 | 0–90 | |

| Histology, no.

(%) | | | |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 22 (100) | 20 (90.9) | 0.351 |

| Giant cell

carcinoma | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Adenosquamous

carcinoma | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Grading | | | |

| 2 | 14 (63.6) | 14 (66.7) | 0.835 |

| 3 | 8 (36.4) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Pancreatic tumor

location, no. (%) | | | |

| Head | 12 (50) | 12 (48.0) | 0.946 |

| Body | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Tail | 7 (29.2) | 9 (36.0) | |

| Papilla

Vateri | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.0) | |

| T-stage | | | |

| 2 | 1 (4.8) | 2 (8.3) | 0.063 |

| 3 | 16 (76.2) | 10 (41.7) | |

| 4 | 4 (19) | 12 (50.0) | |

| Non-metastatic

disease, no. (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Metastatic disease,

no. (%) | 15 (62.5) | 13 (52.0) | |

| Metastatic sites,

no. (%) | | | |

| Liver | 9 (60.0) | 6 (46.2) | 0.466 |

|

Liver/peritoneum | 4 (26.7) | 4 (30.7) | |

| Lung | 2 (13.3) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Liver/lung | 3 (20.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Relapsed disease,

no (%) | 9 (37.5) | 6 (24.0) | 0.629 |

| Locoregional | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Visceral (liver,

lung, periteonal) | 4 (44.4) | 3 (50.0) | |

|

Locoregional/visceral | 4 (44.4) | 3 (50.0) | |

Efficacy of FOLFIRINOX in the whole study

population and according to gender

Based on the imaging studies of the patients as well

as tumor marker response we confirmed a PR and SD in 27 (55.1%) and

7 (14.3%) patients, respectively. There were no complete remissions

(CR). Fifteen out of 49 patients (30.6%) patients did not respond

to a CTX with FOLFIRINOX and were classified as PD (Table III). When response rates were

analyzed according to gender, a significantly higher objective

response rate, defined as patients with either CR or PR, of 75 vs.

36% (p=0.004) as well as a higher disease control rate defined as

patients with either PR or SD of 91.7 vs. 48% (p=0.001) was seen in

female patients compared to male patients (Table III). The predictive effect of

gender on the response rate remained statistically significant

(p=0.041) in the multivariate logistic regression analysis

adjusting for age, tumor stage, line of treatment, Ki67 and p53.

Two female patients with metastatic disease as well as 2 male

patients with locally advanced disease were able to undergo

resection (Fig. 1).

| Table III.Response rates in all patients and in

patients allocated according to gender (female vs. male). |

Table III.

Response rates in all patients and in

patients allocated according to gender (female vs. male).

| Variable | Total (n=49) | | |

|---|

| Response, no.

(%) | | | |

| CR | 0 (0) | | |

| PR | 27 (55.1) | | |

| SD | 7 (14.3) | | |

| PD | 15 (30.6) | | |

| Rate of disease

control (PR + SD) | | | |

| No. (%) | 34 (69.4) | | |

|

| Variable | Female (n=24) | Male (n=25) | P-value |

|

| Response, no.

(%) | | | |

| PR | 18 (75) | 9 (36) | 0.004 |

| SD | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12) | |

| PD | 2 (8.3) | 15 (52) | |

| Rate of disease

control (PR + SD) | | | |

| No. (%) | 22 (91.7) | 12 (48) | 0.001 |

Efficacy of FOLFIRINOX in primarily

treated and relapsed pancreatic carcinomas

Disease control rates in the whole study population

did not differ significantly when RRs were assessed in untreated

patients compared to patients after surgical resection and

treatment in the relapsed stage (70.6 vs. 66.7%). However, when

patients were analyzed according to gender and line of treatment,

in women FOLFIRINOX caused a disease control rate of 100% in the

first-line setting compared to 77.8% in the relapsed stage

(p=0.057). Male patients showed a significantly lower disease

control rate of 47.4% after first-line treatment than females

(p=0.001). Their response rates in first-line and treatment in the

relapsed stage (50%) did not differ (p=0.670) (Table IV).

| Table IV.Efficacy of FOLFIRINOX in primary and

relapsed pancreatic carcinomas. |

Table IV.

Efficacy of FOLFIRINOX in primary and

relapsed pancreatic carcinomas.

| Primary

treatment | All patients

(n=34) | | P-value |

|---|

| Response, no.

(%) | | | |

| PR+SD | 24 (70.6) | |

| PD | 10 (29.4) | |

|

| Female (n=15) | Male (n=19) | |

|

| Response, no.

(%) | | | |

| PR+SD | 15 (100) | 9 (47.4) | 0.001 |

| PD | 0 (0) | 10 (52.6) | |

|

| Treatment relapsed

stage | All patients

(n=15) | | P-value |

|

| Response, no.

(%) | | | |

| PR+SD | 10 (66.7) | |

| PD | 5 (33.3) | |

|

| Female (n=9) | Male (n=6) | |

|

| Response, no.

(%) | | | |

| PR+SD | 7 (77.8) | 3 (50) | 0.064 |

| PD | 2 (22.2) | 3 (50) | |

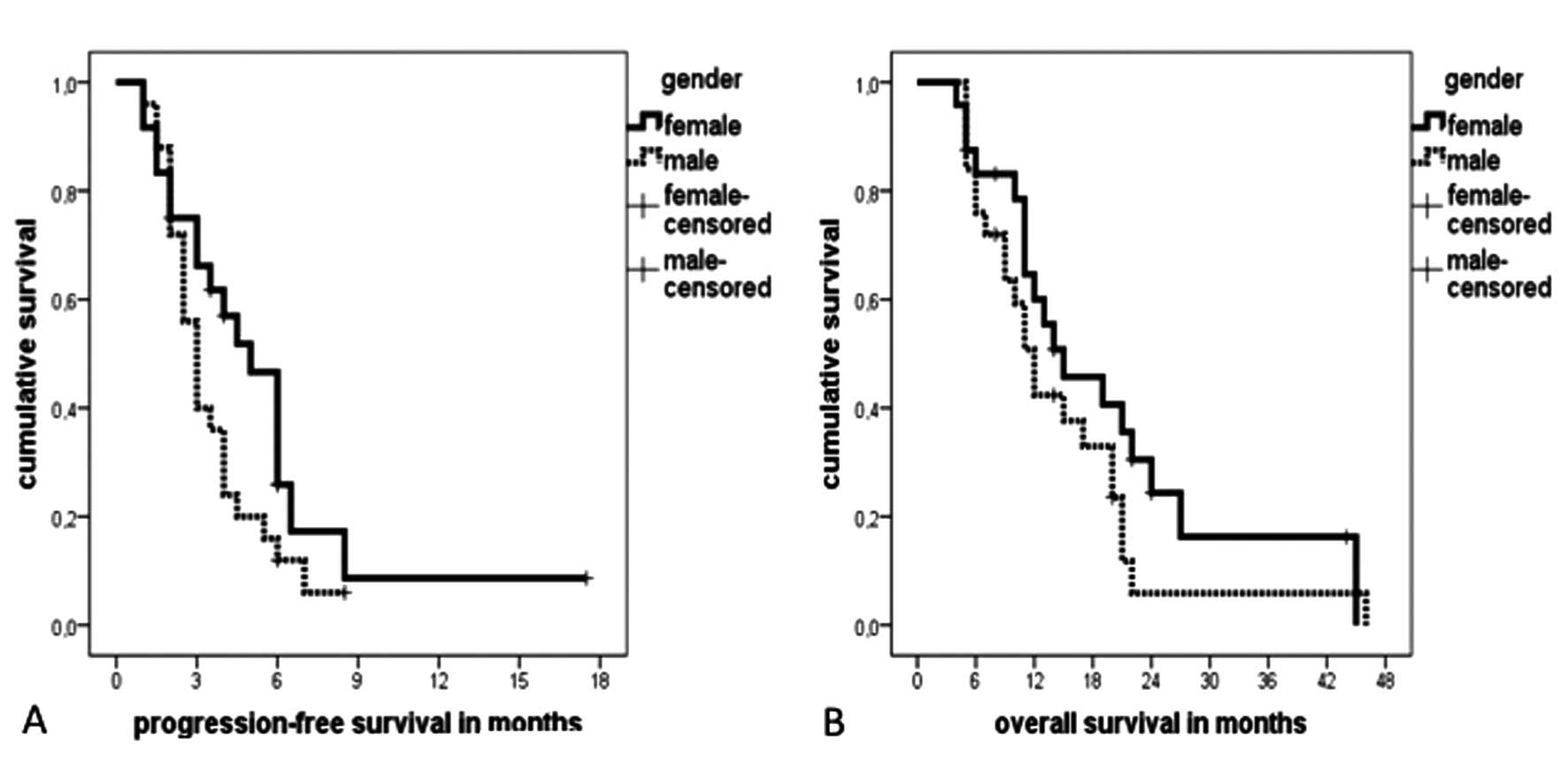

Progression-free and overall

survival

Survival data are shown in Table V and Fig. 2. For the entire cohort of patients

the median PFS was 3.5 months (95% CI, 2.7–4.3 months) with a

median OS of 13 months (95% CI, 9.4–16.6 months). Despite

significantly higher response rates, female patients showed only a

tendency towards a longer median PFS of 5 months compared to 3

months in male patients (p=0.09) (Fig.

2A). The median OS did not significantly differ between female

(15 months, 95% CI, 6.5–23.5 months) and male patients (12 months,

95% CI, 9.7–14.3 months) (p=0.20) (Fig. 2B).

| Table V.Median progression-free and overall

survival. |

Table V.

Median progression-free and overall

survival.

| Progression-free

survival median, months (95% CI) | Overall survival

median, months (95% CI) |

|---|

| Overall study

population | | |

| All patients

(n=49) | 3.5 (2.7–4.3) | 13 (9.4–16.6) |

| Female

(n=25) | 5.0 (3.6–6.4) | 15 (6.5–23.5) |

| Male (n=24) | 3.0 (2.4–3.6) | 12 (9.7–14.3) |

| Primary

treatment | | |

| All patients

(n=34) | 4.0 (2.7–5.3) | 11 (9.9–12.0) |

| Female

(n=15) | 5.0 (3.5–6.5) | 11 (9.3–12.7) |

| Male (n=19) | 3.0 (2.3–3.7) | 11 (1.3–8.4) |

| Treatment relapsed

stage | | |

| All patients

(n=15) | 3.0 (1.6–4.4) | 21 (19.1–22.9) |

| Female (n=9) | 3.5 (2.0–5.0) | 22 (19.1–24.9) |

| Male (n=6) | 2.0 (n.a.) | 20 (12.8–27.2) |

Clinicopathological characteristics and

their association with response to treatment with FOLFIRINOX

There was no significant associations of either age,

BMI, serum levels of CA19.9 and CEA or expression of p53 and Ki67

in pancreatic tumors with response to FOLFIRINOX (Table VI). However, tumors of patients

with PR to FOLFIRINOX showed a tendency towards a higher expression

of Ki67 and p53 as well as higher levels of CA19.9 compared to

resistant tumors. In univariate analysis CA19.9 levels were

significantly associated with the expression of Ki67 (p=0.017,

r=0.39) (data not shown).

| Table VI.Clinicopathological characteristics

and their association with response to treatment with

FOLFIRINOX. |

Table VI.

Clinicopathological characteristics

and their association with response to treatment with

FOLFIRINOX.

| Variable | PR | PD | P-value |

|---|

| Ki-67 expression

(%) | | | |

| Median | 25 | 17.5 | 0.328 |

| Range | 1–80 | 1–70 | |

| Mutant p53

expression (%) | | | |

| Median | 20 | 5.5 | 0.422 |

| Range | 0–100 | 1–90 | |

| Level of

carbohydrate antigen 19.9 | | | |

| Median | 1612 | 1322 | 0.529 |

| Range | 1–140241 | 0–32266 | |

| Level of

carcino-embroygenic antigen | | | |

| Median | 7 | 7.45 | 0.752 |

| Range | 2–363 | 2–306 | |

| Age, years | | | |

| Median | 61 | 63 | 0.783 |

| Range | 42–73 | 46–69 | |

| Body mass

index | | | |

| Median | 21.8 | 23 | 0.312 |

| Range | 17.2–30.7 | 18.2–30.7 | |

Discussion

Most patients with pancreatic cancer are either

unresectable at diagnosis or will suffer from a relapse after

initial surgery, resulting in a 5-year OS of 6% (11). The median OS of patients with

advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer is 6 months with most

chemotherapeutic options (4).

Treatment with FOLFIRINOX has offered a new option for patients

with advanced pancreatic cancer and a good performance status

(8). However, it was reported that

a considerable percentage of patients, up to 50%, treated with

FOLFIRINOX experienced grade 3 and 4 toxicities (7,8).

Understanding the features that determine response or resistance to

this chemotherapy regimen could permit the selection of the most

suitable patients for treatment with FOLFIRINOX. Thus, in our

study, we evaluated clinical and histological markers and their

associations with response to FOLFIRINOX.

The objective response rate, defined as the

percentage of patients with CR and PR, was slightly higher (55.1%)

in our overall study population compared to the 32% reported by

Conroy et al (8). This

might be explained by the fact that in our highly selected study

population all patients (100%) exhibited an ECOG performance status

(PS) 0 whereas the majority (61%) of patients in the historical

group of Conroy et al had an ECOG PS 1. Higher response

rates of 45% compared to the historical data of Conroy et al

were also obtained in another retrospective analysis performed by

Gunturu et al (12). This

study population also consisted of a higher percentage of patients

(69%) with an ECOG PS 0. The percentage of patients with SD

reported by Conroy et al was higher compared to our study

population (39 vs. 14.3%). Therefore, a similar disease control

rate, defined as percentage of patients with CR, PR or SD, could be

seen in our study compared to historical data (69.4 vs. 70%)

(8).

When RRs were assessed according to gender a highly

significant difference in response to FOLFIRINOX could be seen

between the female and male treatment groups. As shown in Table III, there was a significant higher

percentage of female patients with PR (75%) compared to males (36%)

(p=0.004) leading to a significantly (p=0.001) higher disease

control rate in female patients (91.7 vs. 48.0%). To our knowledge,

this is the first study reporting different response rates to CTX

according to gender in patients with pancreatic cancer. Although we

could see a tendency towards a longer median PFS in female patients

(5 months) compared to males (3 months) (p=0.099) significantly

higher response rates did not cause a significant difference in the

median OS between female and male patients (15 vs. 12 months)

(p=0.200) (Table V, Fig. 2). This might be explained by the

small sample size as well as the fact, that there was a higher

number of locally advanced non-metastatic tumors in male patients

compared to females (6 vs. 0) (p=0.095) (Table II). Patients with locally advanced

pancreatic tumors are known to have a longer median OS of 15.7

months than patients with metastatic pancreatic tumors (9.5 months)

(7). Thus, the higher number of

locally advanced pancreatic tumors in male patients might have

nullified the benefit of higher response rates in female patients.

Retrospective analyses should be viewed with caution and causes for

the improved RR to FOLFIRINOX in the female study population remain

speculative. Demographic and baseline disease characteristics were

well-balanced and did not differ significantly between the female

and male group in our study. CA19.9 is the most extensively studied

and validated biomarker for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer

(13). Despite its limitations as

false negative results in sialyl Lewis negative individuals and

false positive elevation in the presence of obstructive jaundice

CA19.9 serum levels as well as a reduction in CA19.9 levels during

treatment have prognostic and predictive value (13). It has been reported that patients

with pretreatment levels lower than median showed a better tumor

response to neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy with 5-FU or adjuvant CTX

with gemcitabine (14,15). There are no data so far regarding

the predictive value of pretreatment levels of CA19.9 and response

to CTX with FOLFIRINOX. In our patients serum levels of CA19.9

(p=0.037) and CEA (0.05) were significantly higher in female

patients compared to males (Table

II). There was a tendency of higher serum levels of CA19.9

(median 1,612 vs. 1,322 U/ml) in tumors of objective responders

(PR) compared to patients with PD (Table V). However, the difference did not

reach significance probably because of the limited sample size.

While an association of response to CTX and the rate of Ki67 in

breast cancer as well some gastrointestinal cancers has been

reported, data in pancreatic cancer for Ki67 as a potential

predictive marker for response CTX cancer are lacking (16–19).

The proliferation rate of tumor cells as defined by Ki67 was higher

in responders vs. non-responders (median 25.0 vs. 17.5% positive

cells) in our patients. In univariate analysis of our cohort,

CA19.9 serum levels were significantly associated with the

expression of Ki67 in univariate analysis (p=0.017, r=0.39, data

not shown).

Despite its central role in the control of

apoptosis, senescence and cell cycle arrest, the tumor suppressor

protein p53 remains an enigma for its possible role in predicting

response to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Mutant p53 proteins

generally have an increased stability and accumulate in the nucleus

of tumor cells and may be detectable by immunohistochemistry. It is

believed that this is a consequence of the inactive p53 mutant

protein not inducing the MDM2 protein required to target its own

degradation (20). The status of

p53 is associated with cancer cell resistance to various

chemotherapeutics (21,22). Wild-type p53 is thought to render

tumors more sensitive to treatment by the induction of apoptosis,

and p53 inactivation may lead to resistance to treatment. However,

because p53 is also responsible for prolonged cell cycle arrest

after chemotherapy-induced genetic damage, it is expected to

facilitate DNA repair in the absence of an apoptotic response.

Therefore tumors that inactivate p53 might be less capable of DNA

repair and more sensitive to a DNA damage-induced mitotic

catastrophe as reported in gastric cancer (23). In our cohort of patients p53

staining was increased in responders as compared to non-responders

(20.0 vs. 5.5% positive cells, Table

VI), although this difference was not statistically

significant. The role of p53 in predicting response to FOLFIRINOX

in pancreatic cancer patients will have to be studied in a larger

cohort of patients.

The results of our study indicate, that female

gender could positively predict response to FOLFIRINOX in patients

with advanced pancreatic cancer. The predictive value of serum

levels of CA19.9 and expression of p53 and Ki67 in advanced

pancreatic tumors require further substantiation.

Abbreviations:

|

CTX

|

chemotherapy

|

|

BMI

|

body mass index

|

|

PR

|

partial remission

|

|

SD

|

stable disease

|

|

PD

|

progressive disease

|

|

APC

|

advanced pancreatic cancer

|

|

CEA

|

carcinoembryogenic antigen

|

|

CA19.9

|

carboanhydrase 19.9

|

References

|

1.

|

Siegel R, Naishadham D and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 62:10–29. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2.

|

Lefebvre AC, Maurel J, Boutreux S, et al:

Pancreatic cancer: incidence, treatment and survival trends - 1175

cases in Calvados (France) from 1978 to 2002. Gastroenterol Clin

Biol. 33:1045–1051. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Burris HA III, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et

al: Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine

as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a

randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 15:2403–2413. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Di Marco M, Di Cicilia R, Macchini M, et

al: Metastatic pancreatic cancer: is gemcitabine still the best

standard treatment? (Review). Oncol Rep. 23:1183–1192.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, et al:

Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine

plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J

Clin Oncol. 27:5513–5518. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al:

Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in

patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the

National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin

Oncol. 25:1960–1966. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7.

|

Conroy T, Paillot B, Francois E, et al:

Irinotecan plus oxaliplatin and leucovorin-modulated fluorouracil

in advanced pancreatic cancer - a Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of the

Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer study. J

Clin Oncol. 23:1228–1236. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8.

|

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al:

FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N

Engl J Med. 364:1817–1825. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et

al: New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid

tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer,

National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer

Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92:205–216. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10.

|

Dowsett M, Nielsen TO, A’Hern R, et al:

Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: recommendations from the

International Ki67 in Breast Cancer working group. J Natl Cancer

Inst. 103:1656–1664. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn

A, Marchesi F and Capocaccia R; EUROCARE-4: Survival of cancer

patients diagnosed in 1995–1999 Results and commentary. Eur J

Cancer. 45:931–991. 2009.

|

|

12.

|

Gunturu KS, Yao X, Cong X, et al:

FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer:

single institution retrospective review of efficacy and toxicity.

Med Oncol. 30:3612013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Ballehaninna UK and Chamberlain RS: The

clinical utility of serum CA 19-9 in the diagnosis, prognosis and

management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An evidence based

appraisal. J Gastrointest Oncol. 3:105–119. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Micke O, Bruns F, Kurowski R, et al:

Predictive value of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 in pancreatic cancer

treated with radiochemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

57:90–97. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Humphris JL, Chang DK, Johns AL, et al:

The prognostic and predictive value of serum CA19.9 in pancreatic

cancer. Ann Oncol. 23:1713–1722. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Fasching PA, Heusinger K, Haeberle L, et

al: Ki67, chemo-therapy response, and prognosis in breast cancer

patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment. BMC Cancer. 11:4862011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Zhang GC, Qian XK, Guo ZB, et al:

Pre-treatment hormonal receptor status and Ki67 index predict

pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant trastuzumab/taxanes but

not disease-free survival in HER2-positive breast cancer patients.

Med Oncol. 29:3222–3231. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18.

|

Carlomagno C, Pepe S, D’Armiento FP, et

al: Predictive factors of complete response to neoadjuvant

chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. Oncology.

78:369–375. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Ressiot E, Dahan L, Liprandi A, et al:

Predictive factors of the response to chemoradiotherapy in

esophageal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 32:567–577. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Soussi T: p53 alterations in human cancer:

more questions than answers. Oncogene. 26:2145–2156. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Sax JK and El-Deiry WS: p53 downstream

targets and chemo-sensitivity. Cell Death Differ. 10:413–417. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22.

|

Bertheau P, Espie M, Turpin E, et al: TP53

status and response to chemotherapy in breast cancer. Pathobiology.

75:132–139. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Bataille F, Rummele P, Dietmaier W, et al:

Alterations in p53 predict response to preoperative high dose

chemotherapy in patients with gastric cancer. Mol Pathol.

56:286–292. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|