Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents one of the most

common malignancies worldwide. Every year, >1.3 million people

are diagnosed with CRC globally, of which ~0.7 million succumb to

this disease (1). Only ~50% of

patients with CRC survive for 5 years after diagnosis in Europe

(2), despite some improvements

being made in early diagnosis and systemic therapies. The

pathogenesis and progression of CRC is a complex process, and the

potential mechanism remains unclear.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of

non-encoding RNAs, which are >200 nucleotides long. Recent

research has indicated that numerous lncRNAs serve an important

role in the majority of physiological and pathological processes,

including embryonic stem cell self-renewal, carcinogenesis and

cancer metastasis (3,4). In addition, lncRNAs function as

oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, which participate in CRC

tumorigenesis and progression. For example, Xu et al

(5) demonstrated that the lncRNA

microRNA (miRNA/miR)-17-92a-1 cluster host gene (MIR17HG) drove

tumor development and metastasis in CRC cells by enhancing the

expression of NF-κB/RELA. In addition, HOX transcript antisense RNA

has been revealed to enhance CRC cell migration and drug resistance

via a miR-203a-3p-dependent Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

(6). As an oncogene, the lncRNA

H19 has been shown to accelerate cell proliferation and

metastasis in CRC by acting on Wnt signaling (7).

Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) are a subgroup of

ncRNAs that are 60-300 nucleotides in length, which contribute to

tumorigenesis and metastasis in diverse types of human cancer. Most

snoRNAs are encoded in the introns of snoRNA host genes (SNHGs)

(8). Specifically, there are

numerous SNHGs associated with CRC carcinogenesis and progression;

for example, SNHG7 has been shown to be overexpressed in CRC tumor

tissues (TTs) compared with its expression in adjacent

non-cancerous tissues (ANTs). This high expression has been

revealed to be related to aggressive pathological characteristics,

such as tumor size, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, distant

metastasis and poor survival (9,10).

Located on chromosome 8q21.1, SNHG22 is 2,157 nucleotides

long (11). Previous studies have

reported that SNHG22 contributes to cell growth, migration,

invasion and chemotherapy resistance in epithelial ovarian

carcinoma (EOC), papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and breast cancer

(12-14). Notably, in these three types of

cancer, SNHG22 expression was revealed to be upregulated in TTs

compared with that in ANTs, thus indicating its association with

poor prognosis. To the best of our knowledge, the biological role

and expression patterns of SNHG22 have not been examined in human

CRC.

The present study investigated SNHG22 expression in

adenoma and CRC tissues, and evaluated its clinical significance.

Furthermore, the biological behaviors of SNHG22 were explored in

CRC cell lines in vitro and in vivo. The present

study also investigated the mechanisms underlying the pro-oncogenic

effects of SNHG22 on CRC.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples and cell lines

A total of 93 paired CRC TTs and matched ANTs were

collected from patients who had undergone surgery between January

2012 and October 2012 (Zhengzhou cohort). Additional fresh

specimens were collected from patients with colorectal adenoma

(CRA) (n=33) who had undergone colonoscopy. The CRA or CRC

diagnoses were based on histopathological evaluation using the 7th

edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system

(15). All specimens were quickly

snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until required.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou

University (approval no. 2011110402; Zhengzhou, China). Patients

with any history of other types of cancer, and who had received

preoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy were excluded. The

clinical characteristics of all patients are listed in Table SI.

Human colon cancer cell lines (Caco2, LS174T, LoVo,

SW480, SW620) and a CRC cell line (HT-29) were all obtained from

the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The cells were

maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5%

CO2). The FHC human normal colon epithelial cell line

was purchased from Mingzhou Company (cat. no. MZ-0713) and was

cultured in 90% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 20% FBS. All

cells tested negative for mycoplasma contamination and this result

was verified by short tandem repeat fingerprinting before use.

Cell transfection

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against SNHG22 (si#1

and si#2) or E2F transcription factor 3 (E2F3) (siE2F3), and the

overexpression vectors pcDNA3.1/Control (Vector), pcDNA3.1/SNHG22

(SNHG22) and pcDNA3.1/E2F3 (E2F3) were purchased from Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd.. A non-targeting sequence was used as the

negative control (siNC; Shanghai GenePharma Co. Ltd.). The miRNA

mimics, inhibitor and negative controls (NC mimic and NC inhibitor)

were purchased from Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.. For the in

vivo experiments, vectors containing short hairpin RNAs

(shRNAs) targeting SNHG22 (shSNHG22, i.e., sh#1 and sh#2) or a

non-targeting sequence (shNC) were subcloned into Lv5 lentiviruses

(Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) and infected into LoVo cells to

generate Lv-sh#1 and Lv-sh#2. For LoVo cells infection, cells

(5×104 cell/well) were cultured for 24 h, and then

recombinant lentivirus in serum-free growth medium was added at a

multiplicity of infection of 50 at 37°C for 2 days. For transient

transfection, Caco2, LS174T and LoVo cells (3×104

cell/well) in 6-well plates were transfected with vectors/sequences

at a concentration of 20 µg/ml at 37°C. After culturing for

24 h, cells were harvested for subsequent experiments. Transfection

experiments were conducted with Lipofectamine® 3000

transfection reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. All the

aforementioned sequences are shown in Table SII.

Cell proliferation

Cell proliferation was detected using Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The cells were transfected with the

indicated vectors or sequences, and then cultured in a 96-well

plate for 1, 2, 3 and 4 days after transfection. Subsequently, ~10

µl CCK-8 reagent was added per well, and incubated at 37°C

for 2 h in a 5% CO2 humidified chamber. The absorbance

was measured at 490 nm in each well using a microplate reader

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The experiment was repeated at least

three times.

Flow cytometry

Cell cycle distribution was detected using flow

cytometry. After the CRC cells had been harvested and washed, cells

were detected with a Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis Kit (cat.

no. C1052M; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Apoptosis was detected using an Annexin

V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide (PI)-Apoptosis

Detection kit [MultiSciences (Lianke) Biotech Co., Ltd.]. CRC cells

(5×104/well) were seeded and resuspended in 12-well

plates, and Annexin V-FITC (5 µl/well) and PI (100

µl/well) were added to each reaction system for 6 min.

Immediately after staining, flow cytometric assays were conducted

using a flow cytometer (EPICS; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Analysis of

flow cytometry results was conducted using FlowJo software7.6.1

(FlowJo, LLC).

Wound scratch assay

Cell migration was determined using a wound scratch

assay. Briefly, 1×106 transfected cells/well were seeded

into a 24-well plate. When cells reached 100% confluence, a sterile

20-µl pipette tip was used to produce a clear line in the

wells. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the

cells were grown in serum-free medium at 37°C for 24 h. Under a

light microscope, images of the cells were captured to record the

wound width at 0 h and more images were captured after 24 h. The

migration distance was determined as the distance covered between 0

and 24 h.

Cell migration and invasion assay

Cell migration and invasion were examined using

Transwell inserts (pore size, 8.0 µm) pre-coated without

(for migration) or with (for invasion) Matrigel (on ice for 1 h; BD

Biosciences). Briefly, 2×105/well transfected cells in

200 µl serum-free medium were suspended in the upper

chamber, and the lower chamber was filled with 700 µl medium

containing 15% FBS. After 24 h at 37°C in an atmosphere containing

5% CO2, the membranes in the lower chamber were fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h and stained with

crystal violet for 18 min. After washing with PBS, images of the

cells on the membrane were captured under a light microscope in

five randomly selected fields per sample.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues and

exponentially growing cells using TRIzol® (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA were

separated using the PARIS Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (1,000 ng) using a reverse

transcriptase cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

according to manufacturer's protocol. mRNA expression levels were

measured using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) on the CFX96 sequence detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 sec,

followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 30 sec,

dissociation at 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min and 95°C for 15

sec. The primer sequences are shown in Table SII. The RT-qPCR data were

calculated using the comparative threshold cycle

(2−ΔΔCq) method with β-actin and U6 as the internal

controls (16).

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted from cells and tissues

using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

concentration of each protein was determined using a BCA protein

assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently,

equal amounts of cell lysates (20 µg) were separated by

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10%

gels, and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes

(MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked with TBS-3% Tween-20

containing 5% skim milk at room temperature for 24 h and blotted

with a primary antibody against E2F3 (cat. no. ab50917; 1:2,000;

Abcam) at 4°C for 16 h. Subsequently, membranes were incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000;

cat. no. ab205718; Abcam) on room temperature for 2 h. After

washing, immunoreactive bands were detected using chemiluminescence

(Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). β-actin (cat. no. ab8227;

1:10,000; Abcam) was used as the loading control. Protein

expression levels were semi-quantified by normalization against

β-actin using ImageJ (version 1.36; National Institutes of

Health).

Luciferase reporter assay

The predicted binding sites of miR-128-3p with the

SNHG22 3′ untranslated region (UTR) or E2F3 3′UTR

were obtained from starBase v3.0 (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/). The mutant (mut)

SNHG22 and E2F3 3′ UTR luciferase reporter vectors

were constructed using a Mutagenesis Kit (Qiagen, Inc.). The

wild-type (wt) and mut sequences were each cloned into a psiCHECK2

vector (Promega Corporation). CRC cells (1×103/well) and

293T cells (1×103/well; American Type Culture

Collection) in 96-well plates were co-transfected with wt/mut

plasmid and miR-128-3p or NC (50 µm) using Lipofectamine

RNAiMAX (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After 36-h

transfection at 4°C, the cells were collected and tested using a

dual-luciferase assay system (Promega Corporation) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. pRL-TK was used as the internal

control.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

RIP was performed using an EZ-Magna RIP Kit

(MilliporeSigma) and an anti-Argonaute-2 (Ago2) antibody (cat. no.

ab32381; Abcam). CRC cells (2×107) were lysed in RIP

buffer and centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. The cell

lysates were incubated with magnetic beads (100 µl)

conjugated with the anti-Ago2 antibody (cat. no. ab32381; Abcam) or

immunoglobulin G (cat. no. ab104155; Abcam) for 3 h. After

extensive washing using an elution buffer at 65°C for 10 min, the

purified RNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR.

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the

Committee of the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Zhengzhou

University (approval no. 20180376). A total of 15 male BALB/c nude

mice (age, 4 weeks; weight, 14-16 g; Shanghai Experiment Animal

Centre) were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and

randomly subdivided into three subgroups. LoVo cells that had been

stably infected with Lv-shNC, Lv-sh#1 and Lv-sh#2 vectors were

harvested, and 6×106 cells were injected subcutaneously

into the dorsal flank region of each mouse. Tumor growth was

measured every 5 days, and was calculated using the following

formula: Volume=(width2 × length)/2. Euthanasia was

performed by intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg pentobarbital

(17). Subsequently, the weight

of each tumor was evaluated, and the tumor samples were processed

for RT-qPCR, western blotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC). The

present study was carried out according to the National Institutes

of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

(18).

Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and

IHC

The tumors from the nude mice were fixed in 10%

paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 12 h, and then dehydrated in different

concentrations of ethanol, permeabilized using xylene and embedded

in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were then sliced

(0.5 µm), rehydrated, and were stained with HE at 4°C for 10

min and sealed with neutral gum. For IHC assessment of E2F3 and

Ki-67 in colorectal tumor tissues from the nude mice, the DAKO

Envision system (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was used.

Briefly, after paraffin-embedded sections of tumor tissues were

heated at 60°C, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies

against E2F3 (1:200; cat. no. ab50917; Abcam) and Ki-67 (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab279653; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Then, the sections were

incubated with biotin-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1,000; cat.

no. ab205718; Abcam) at 37°C for 20 min. Under a light microscope,

IHC staining scores for E2F3 were obtained by multiplying the

intensity (0, negative; 1, low; 2, medium; and 3, high) with the

extent of staining (0, 0%; 1, 0-10%; 2, 10-50%; 3, 50-75%; 4,

>75%); the final scores were between 0-12. For evaluation of

Ki67, the number of positive cells was calculated in three

representative areas of high staining.

Bioinformatics and statistical

analyses

lncLocator (19)

was used to analyze lncRNA subcellular locations. CPAT (http://lilab.research.bcm.edu/cpat/index.php) and

LNCipedia (https://lncipedia.org) were used to

analyze the protein coding probability. The online tools TargetScan

(http://www.targetscan.org/), miRwalk

(http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de), miRTarbase

(http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/index.html), miRDB

(http://www.mirdb.org/), and starBase (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/index.php)

were used to analyze potential target genes of miR-128-3p. Analysis

of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-colon adenocarcinoma

(COAD) (n=267) was conducted using starBase and UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html)

online tools. All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation from triplicate experiments. Regarding comparisons,

Student's t-test (two groups) or one-way ANOVA with Scheffe test

(multiple groups) was conducted as appropriate. To compare SNHG22

expression levels in TT, ANT and CRA samples, paired samples were

analyzed using a paired Student's t-test and independent samples

were analyzed using unpaired Student's t-tests, after which, a

Bonferroni correction was applied. To compare E2F3 and Ki-67

staining scores in mice tumor samples, Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's

post hoc test was used. Correlations were calculated using

Spearman's correlation analysis. The survival curves were

constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and were analyzed using

the log-rank test. Crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox proportional

hazards modeling. Potential confounders were included in the

multivariate analysis at a significance level of P<0.15, as

determined by univariate analysis. All statistical analyses were

conducted using the PASW Statistics 19.0 software program (SPSS,

Inc.) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad, Inc.). P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

SNHG22 is upregulated in CRC tissues and

cell lines, and is associated with poor prognosis in patients with

CRC

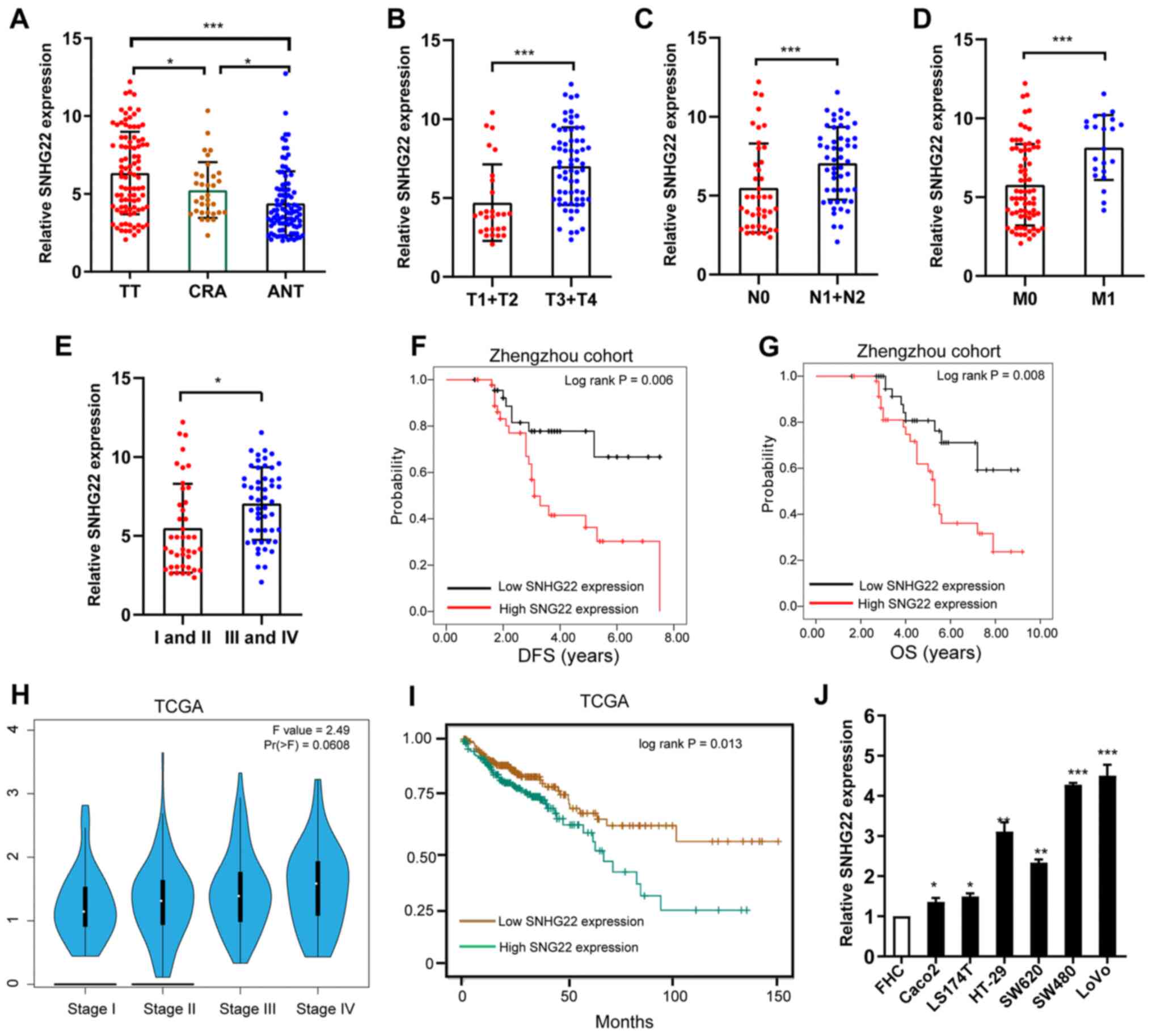

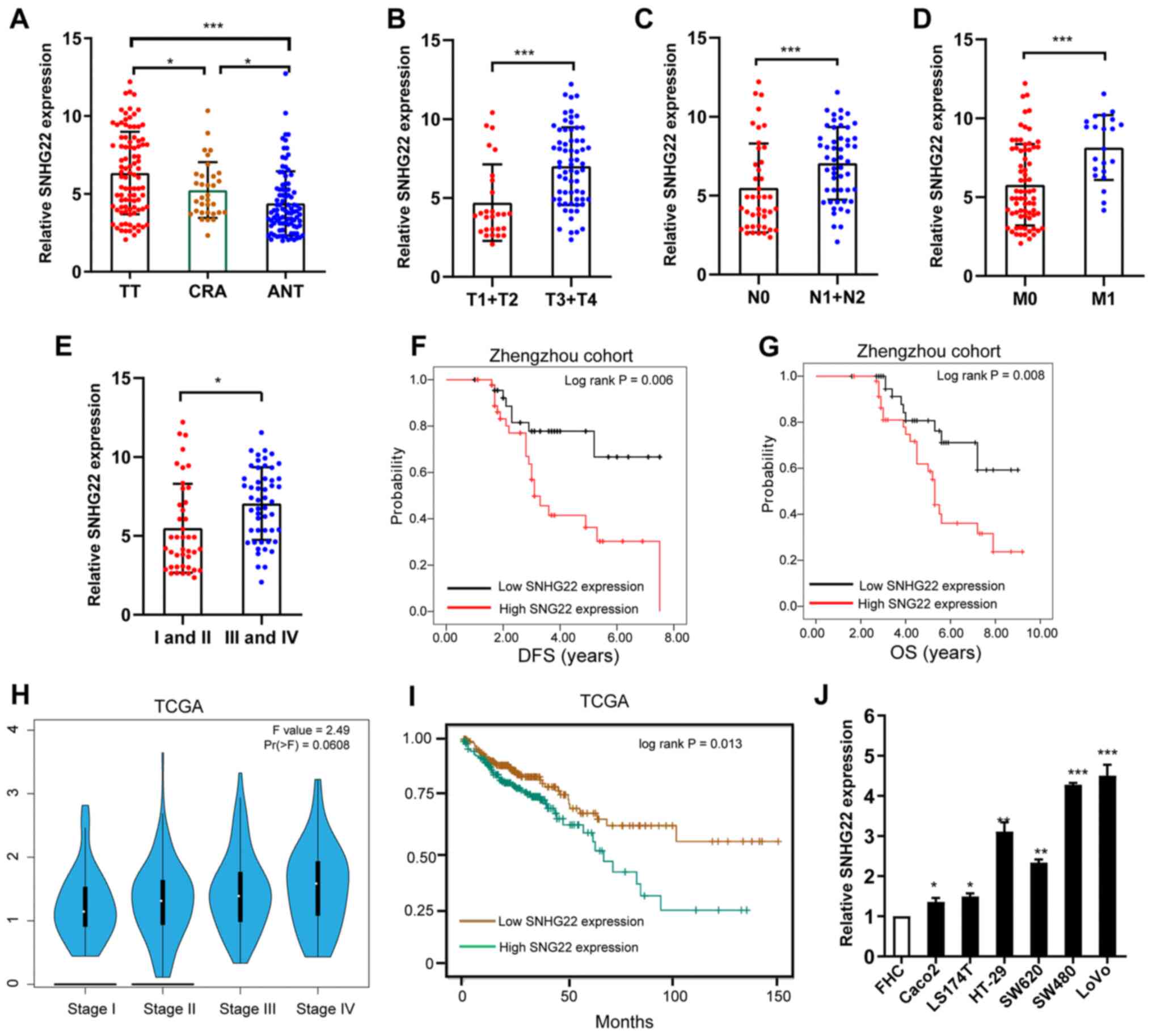

To investigate SNHG22 expression levels in CRC,

RT-qPCR analysis was performed to examine SNHG22 levels in TT and

ANT colorectal samples (n=93 pairs) and human CRA samples (n=32).

SNHG22 expression was significantly higher in TTs compared with

that in CRA tissues and ANTs (Fig.

1A). Additionally, high SNHG22 expression was significantly

associated with advanced T stage (Fig. 1B), lymph node metastasis (Fig. 1C), distant metastasis (Fig. 1D), advanced clinical stage

(Fig. 1E), and poor disease-free

survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) (Fig. 1F and G). Data from TCGA confirmed

these results (Fig. 1H and I).

Multivariate Cox regression analysis validated high SNHG22

expression as a predictor of poor DFS (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.04-2.71)

and OS (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.02-2.06; Table I). High SNHG22 expression was also

confirmed in the CRC cell lines (LS174T, LoVo, Caco2, SW480, HT-29

and SW620) compared with that in the FHC cell line (Fig. 1J). These results indicated that

SNHG22 was highly expressed in CRC tissues and cell lines, and may

be associated with poor survival in CRC. Furthermore, the coding

potential of SNHG22 was calculated using CPAT and LNCipedia; the

results revealed that SNHG22 had very low coding probability, thus

indicating that it may be a ncRNA (Fig. S1).

| Figure 1Differential expression of SNHG22 in

CRC tissues and cell lines. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression

levels of SNHG22 in TTs (n=93), ANTs (n=93) and CRA (n=33) colon

tissues. Differential expression of SNHG22 in CRC tissues was

analyzed according to (B) T stage, (C) node status, (D) distant

metastasis and (E) TNM stage. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of

SNHG22 expression and (F) DFS and (G) OS in patients with CRC. (H)

Expression of SNHG22 in patients with CRC split according to TNM

stage in TCGA-COAD dataset. (I) OS in patients with CRC in

TCGA-COAD dataset. (J) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression levels of

SNHG22 in CRC cell lines and the FHC cell line, a human normal

colon epithelial cell line. Data are presented as the mean ± SD

from triplicate experiments. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 as indicated or

vs. FHC. ANT, adjacent non-cancerous tissue; COAD, colorectal

adenocarcinoma; CRA, colorectal adenoma; CRC, colorectal cancer;

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; SNHG22, small nucleolar RNA host

gene 22; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis;

TT, tumor tissue. |

| Table ICox proportional hazards regression

models for overall and recurrence-free survival among patients with

colorectal cancer. |

Table I

Cox proportional hazards regression

models for overall and recurrence-free survival among patients with

colorectal cancer.

| Parameter | Univariate analysis

| Multivariate

analysis

|

|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Disease-free

survival | | | | |

| Location, rectum

vs. colon | 1.98

(0.85-4.60) | 0.112 | 1.67

(0.71-3.90) | 0.237 |

| T stage, T3-4 vs.

T1-2 | 2.13

(1.05-4.30) | 0.035 | 1.66

(1.02-2.70) | 0.041 |

| Node involvement,

yes vs. no | 2.35

(1.07-5.13) | 0.033 | 1.27

(1.00-1.61) | 0.048 |

| M stage, M1 vs.

M0 | 2.56

(1.23-5.33) | 0.012 | 1.51

(1.04-2.20) | 0.031 |

| Tumor

differentiation, poor vs. well + moderate | 1.49

(0.95-2.34) | 0.084 | 1.14

(0.88-1.48) | 0.321 |

| CEA, ≥5 vs. <5

ng/ml | 1.40

(0.68-2.86) | 0.362 | | |

| Margin, positive

vs. negative | 1.32

(0.61-2.84) | 0.483 | | |

| Chemotherapy, yes

vs. no | 1.34

(0.57-3.15) | 0.501 | | |

| SNHG22, high vs.

low | 2.47

(1.13-5.41) | 0.023 | 1.68

(1.04-2.71) | 0.034 |

| Overall

survival | | | | |

| Location, rectum

vs. colon | 2.19

(1.01-4.75) | 0.047 | 1.81

(0.83-3.96) | 0.138 |

| T stage, T3-4 vs.

T1-2 | 1.59

(1.00-2.53) | 0.050 | 1.33

(0.97-1.82) | 0.077 |

| Node involvement,

yes vs. no | 1.91

(1.12-3.26) | 0.018 | 1.57

(1.06-2.33) | 0.025 |

| M stage, M1 vs.

M0 | 1.98

(1.24-3.15) | 0.004 | 1.49

(1.08-2.05) | 0.014 |

| Tumor

differentiation, poor vs. well + moderate | 1.39

(0.66-2.93) | 0.395 | | |

| CEA, ≥5 vs. <5

ng/ml | 1.06

(0.54-2.09) | 0.868 | | |

| Margin, positive

vs. negative | 0.97

(0.45-2.08) | 0.930 | | |

| SNHG22, high vs.

low | 2.21

(1.08-4.55) | 0.031 | 1.45

(1.02-2.06) | 0.039 |

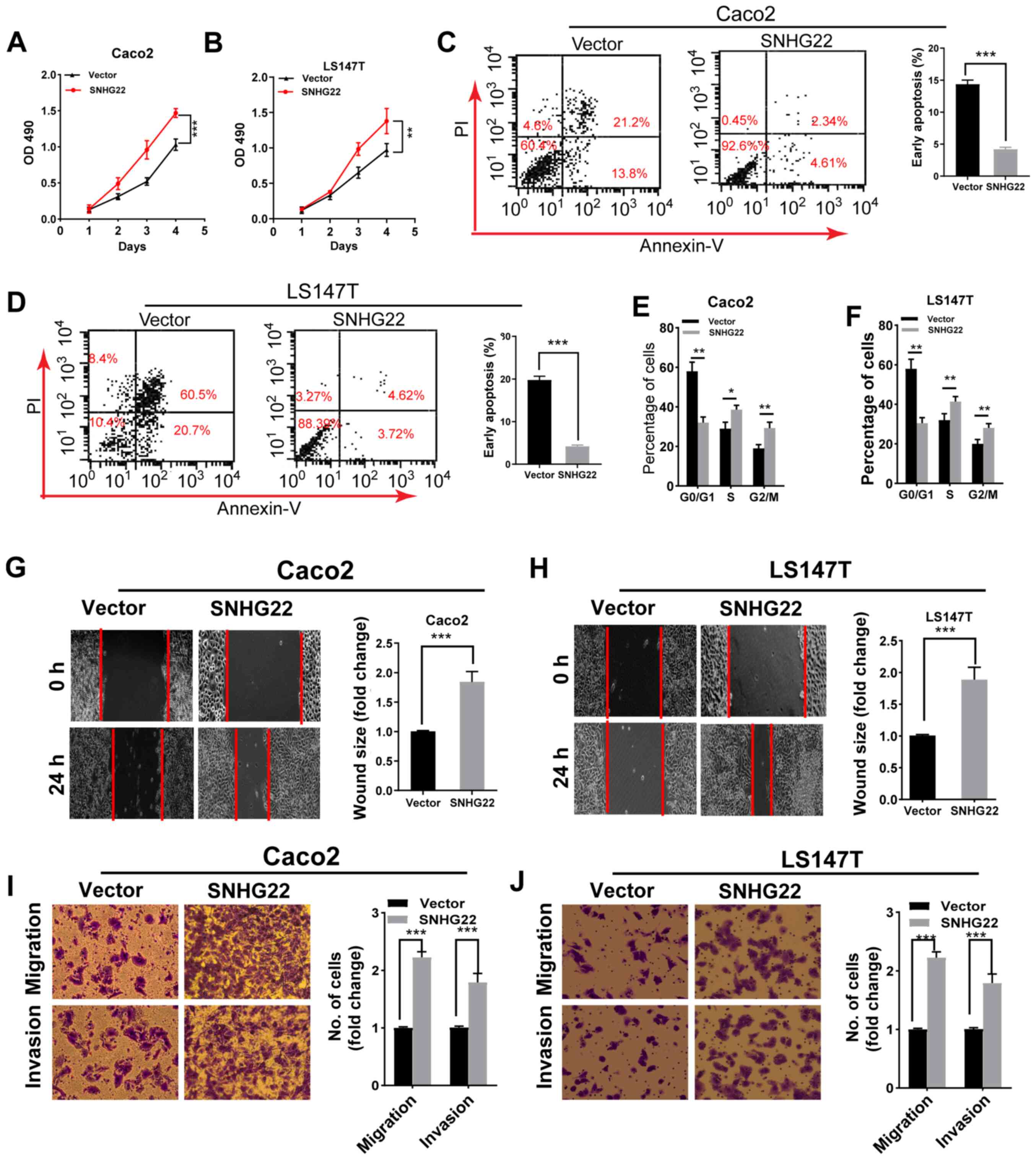

Overexpression of SNHG22 stimulates CRC

cell proliferation, apoptosis resistance, migration, and invasion

in vitro

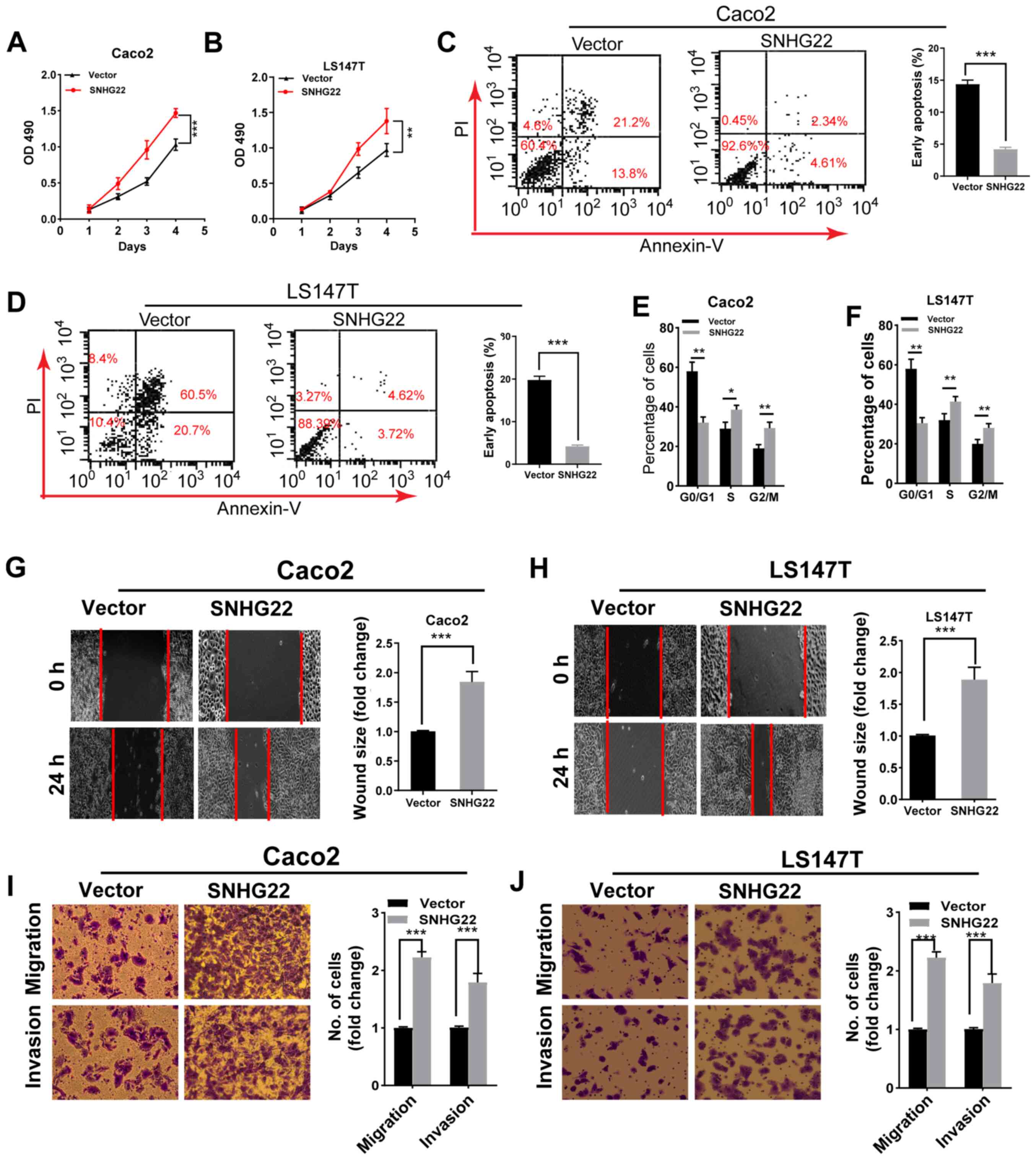

To investigate the role of SNHG22 in the progression

of CRC cells, gain-of-function experiments were performed using the

Caco2 and LS174T cell lines because both cell lines had low SNHG22

expression levels. SNHG22 expression was significantly enhanced

after the cells had been transfected with the SNHG22 vector

(Fig. S2A). Functionally,

upregulating SNHG22 expression promoted the proliferation,

G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis resistance of both cell

lines (Figs. 2A-F and S2B). Furthermore, the wound scratch and

Transwell assays demonstrated a marked enhancement in the migratory

and invasive ability of SNHG22-overexpressing cells (Fig. 2G-J). These data indicated that

SNHG22 overexpression may promote CRC cell proliferation, apoptosis

resistance, migration and invasion.

| Figure 2Overexpression of SNHG22 promotes

colorectal cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis resistance,

migration and invasion in vitro. Cell Counting Kit-8 assay

analysis of the proliferative ability of (A) Caco2 and (B) LS147T

cells transfected with the indicated vectors. Flow cytometric

analysis of the (C and D) apoptotic rates and (E and F) cell cycle

progression of Caco2 and LS147T cells transfected with the

indicated vectors. Wound scratch analysis of the migration of (G)

Caco2 and (H) LS147T cells transfected with the indicated vectors

(magnification, ×200). Transwell assay analysis of the migration

and invasion of (I) Caco2 and (J) LS147T cells transfected with the

indicated vectors (magnification, ×200). Data are presented as the

mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. NC, negative

control; OD, optical density; PI, propidium iodide; SNHG22, small

nucleolar RNA host gene 22. |

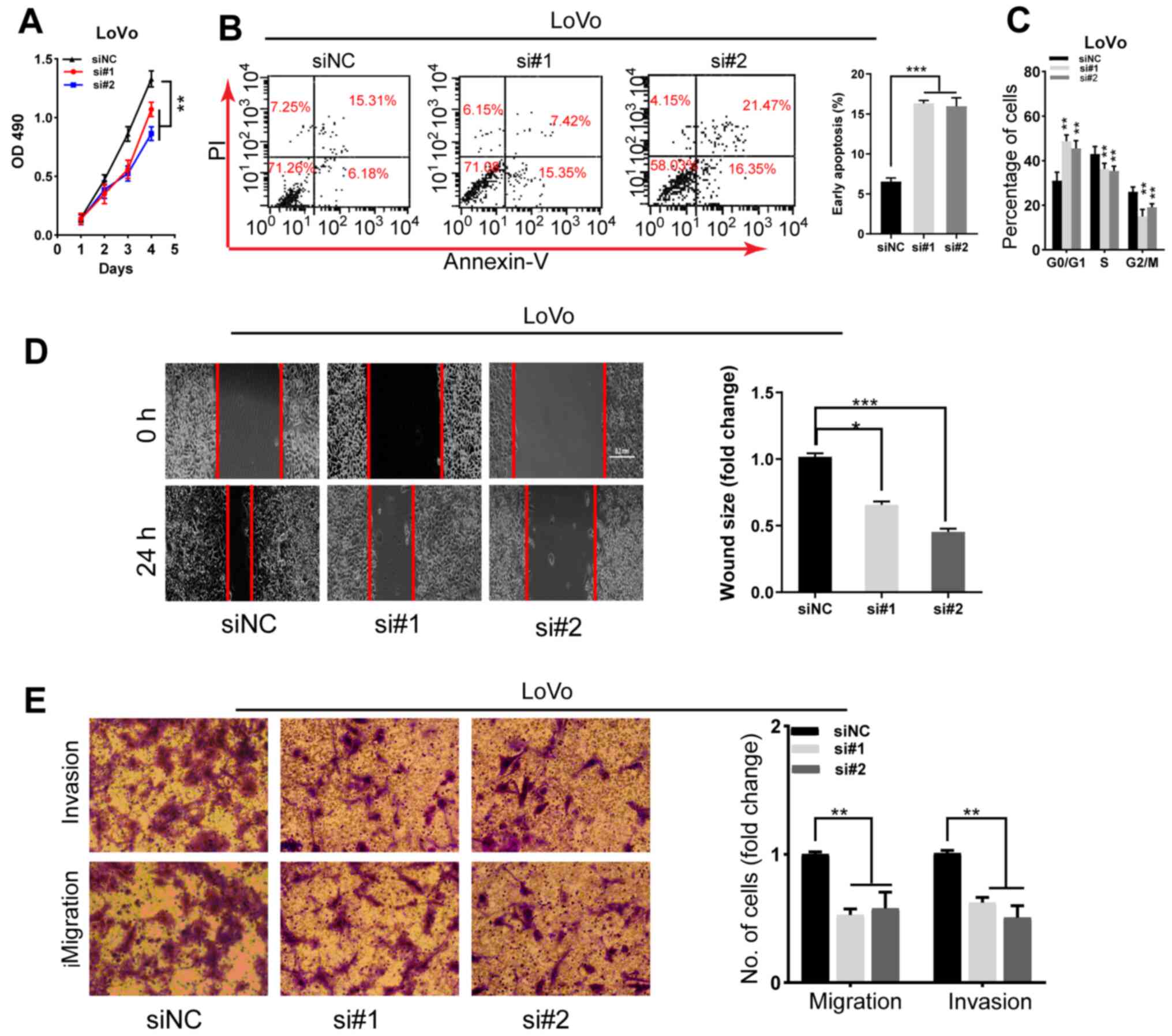

Knockdown of SNHG22 inhibits CRC cell

proliferation, apoptosis resistance, migration, and invasion in

vitro

To determine whether silencing SNHG22 would affect

CRC cell biological function, two parallel siRNAs targeting SNHG22

(i.e., si#1 and si#2) were used for the knockdown experiments.

RT-qPCR confirmed the knockdown efficiency of both siRNAs in the

LoVo cell line (Fig. S3A). The

results of CCK-8 assay and flow cytometry demonstrated a marked

decrease in LoVo cell proliferation, G2/M phase arrest

and apoptosis resistance in cells with SNHG22 knockdown (Figs. 3A-C and S3B). Furthermore, the wound scratch and

Transwell assays indicating that silencing SNHG22 attenuated LoVo

cell migratory and invasive ability (Fig. 3D and E). These data indicated that

knocking down SNHG22 may inhibit CRC cell proliferation, migration

and invasion.

| Figure 3Knockdown of SNHG22 inhibits

colorectal cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis resistance,

migration and invasion in vitro. (A) Cell Counting Kit-8

assay analysis of the proliferative ability of LoVo cells after

transfection with the indicated sequences. Flow cytometric analysis

of the (B) apoptotic rates and (C) cell cycle progression of LoVo

cells after transfection with the indicated sequences. (D) Wound

scratch analysis of the migration of LoVo cells after transfection

with the indicated sequences (magnification, ×200). (E) Transwell

invasion assay analysis of the invasion of LoVo cells after

transfection with the indicated sequences (magnification, ×200).

Data are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 as indicated or vs. siNC. NC, negative

control; OD, optical density; PI, propidium iodide; si, small

interfering; SNHG22, small nucleolar RNA host gene 22. |

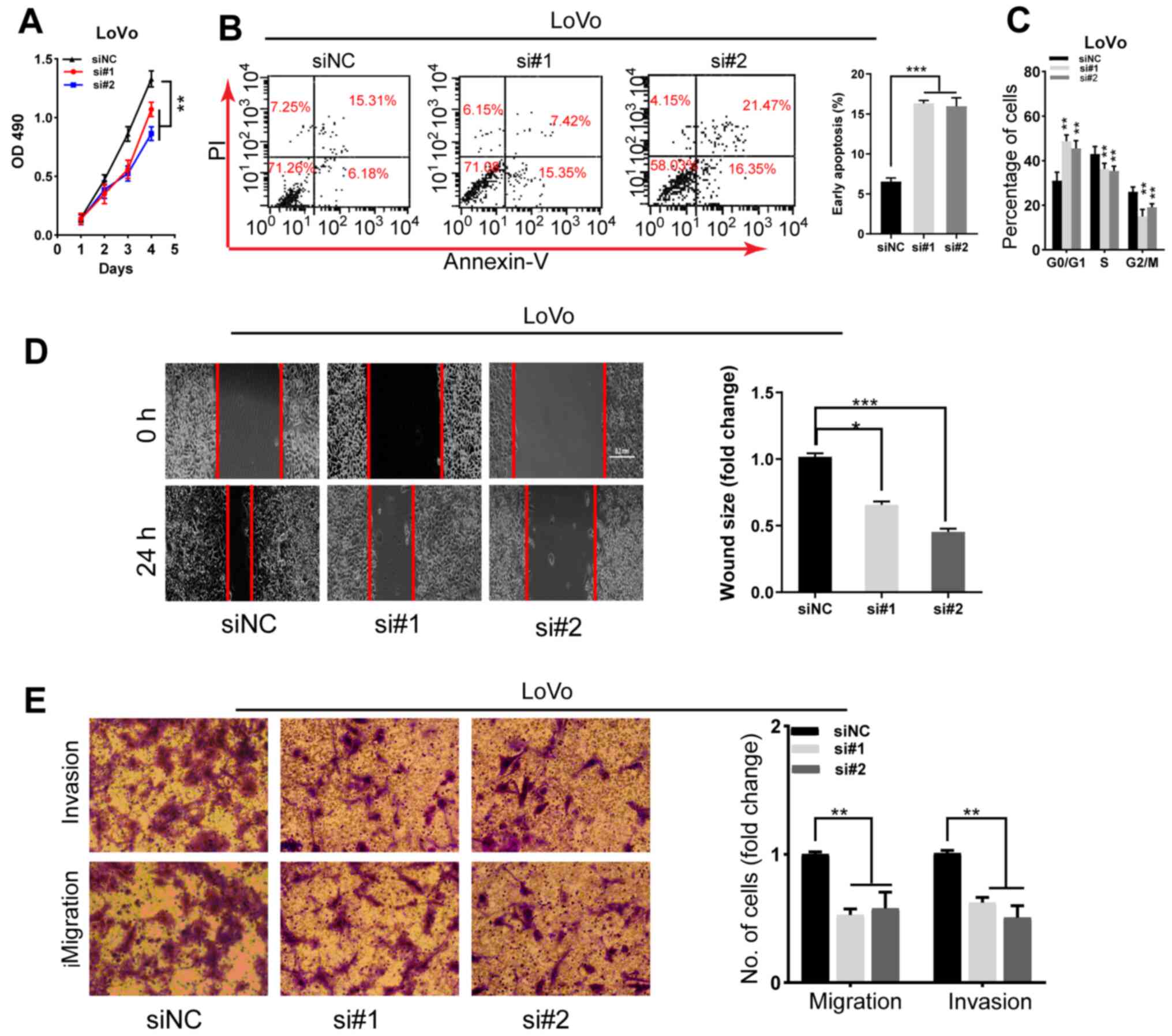

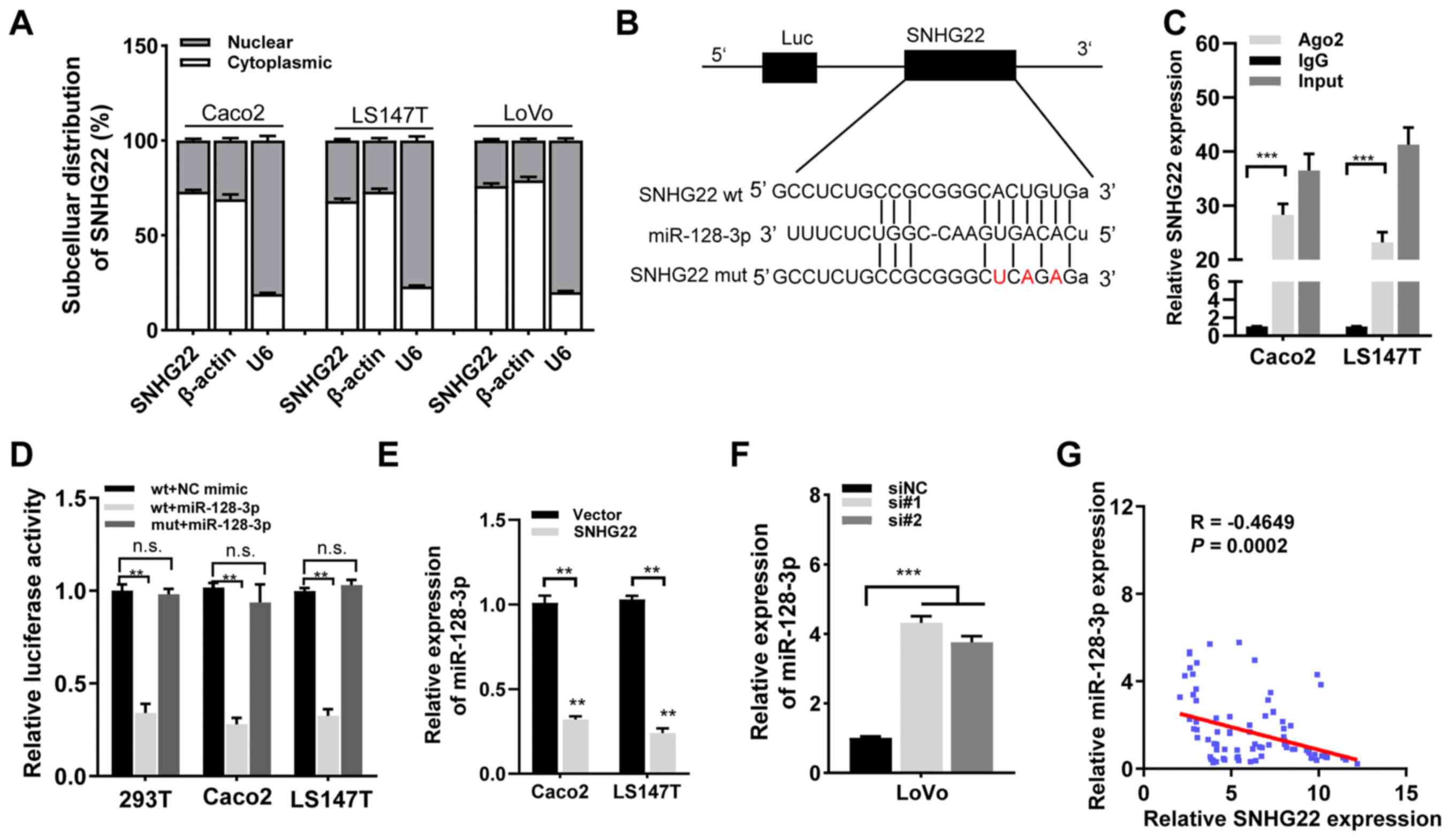

SNHG22 functions as a competing

endogenous RNA (ceRNA) to regulate miR-128-3p expression in CRC

cells

As the subcellular localization of lncRNAs can

indicate their function, the results from lncLocator (19) demonstrated that SNHG22 was

preferentially localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. S4). Subsequent cellular

fractionation experiments confirmed this in CRC cells (Caco2,

LS174T and LoVo; Fig. 4A). The

starBase v3.0 findings indicated that SNHG22 contains complementary

binding sites to miR-128-3p seed regions (Fig. 4B). To test this hypothesis, RIP

experiments were performed with anti-Ago2 in Caco2 and LS174T

cells, and observed enrichment of SNHG22 with the Ago2 antibody was

detected (Fig. 4C), indicating

that SNHG22 had complementary binding sites to miR-128-3p and

directly bound to miR-128-3p. To explore whether SNHG22 is

regulated by miR-128-3p, dual-luciferase reporter plasmids were

constructed containing wt or mut putative binding sites of SNHG22

transcripts. Luciferase activity was markedly reduced in 293T cells

that had been co-transfected with SNHG22 wt and miR-128-3p mimic

compared with those transfected with SNHG22 wt and NC mimic.

However, no statistical changes in luciferase activity were

observed in cells transfected with the mut reporter. These results

were confirmed in the Caco2 and LS174T cell lines (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, RT-qPCR revealed

that SNHG22 overexpression significantly decreased miR-128-3p

expression levels in CRC cells, whereas silencing SNHG22 enhanced

miR-128-3p expression (Fig. 4E and

F). SNHG22 expression had a significant inverse relationship

with miR-128-3p expression in human CRC tissues from the Zhengzhou

cohort (Fig. 4G). These findings

demonstrated that SNHG22 may act as a miR-128-3p sponge in CRC.

| Figure 4SNHG22 functions as a competing

endogenous RNA to regulate miR-128-3p expression in CRC. (A)

Subcellular localization of SNHG22 in CRC cell lines (Caco2, LS147T

and LoVo). β-Actin and U6 served as cytoplasmic and nuclear

localization markers, respectively. (B) Predicted binding sites of

miR-128-3p to the SNHG22 sequence. (C) RNA immunoprecipitation

assay was performed with an antibody against Ago2 or IgG in Caco2

and LS147T cell lines. (D) Luciferase activity of 293T, Caco2 and

LS147T cell lines co-transfected with miR-128-3p mimic (or NC

mimic) and luciferase reporters containing SNHG22 wt or SNHG22 mut

transcript was analyzed. (E and F) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR analysis of the expression levels of

miR-128-3p in CRC cells after transfection with the indicated

vectors and sequences. (G) Negative correlation between SNHG22 and

miR-128-3p expression in human CRC tissues from the Zhengzhou

cohort (Spearman's correlation analysis; R=-0.4649, P=0.002). Data

are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Ago2, Argonaute2;

CRC, colorectal cancer; EV, empty vector; miR, microRNA; mut,

mutant; NC, negative control; n.s., not significant; si, small

interfering; SNHG22, small nucleolar RNA host gene 22; wt,

wild-type. |

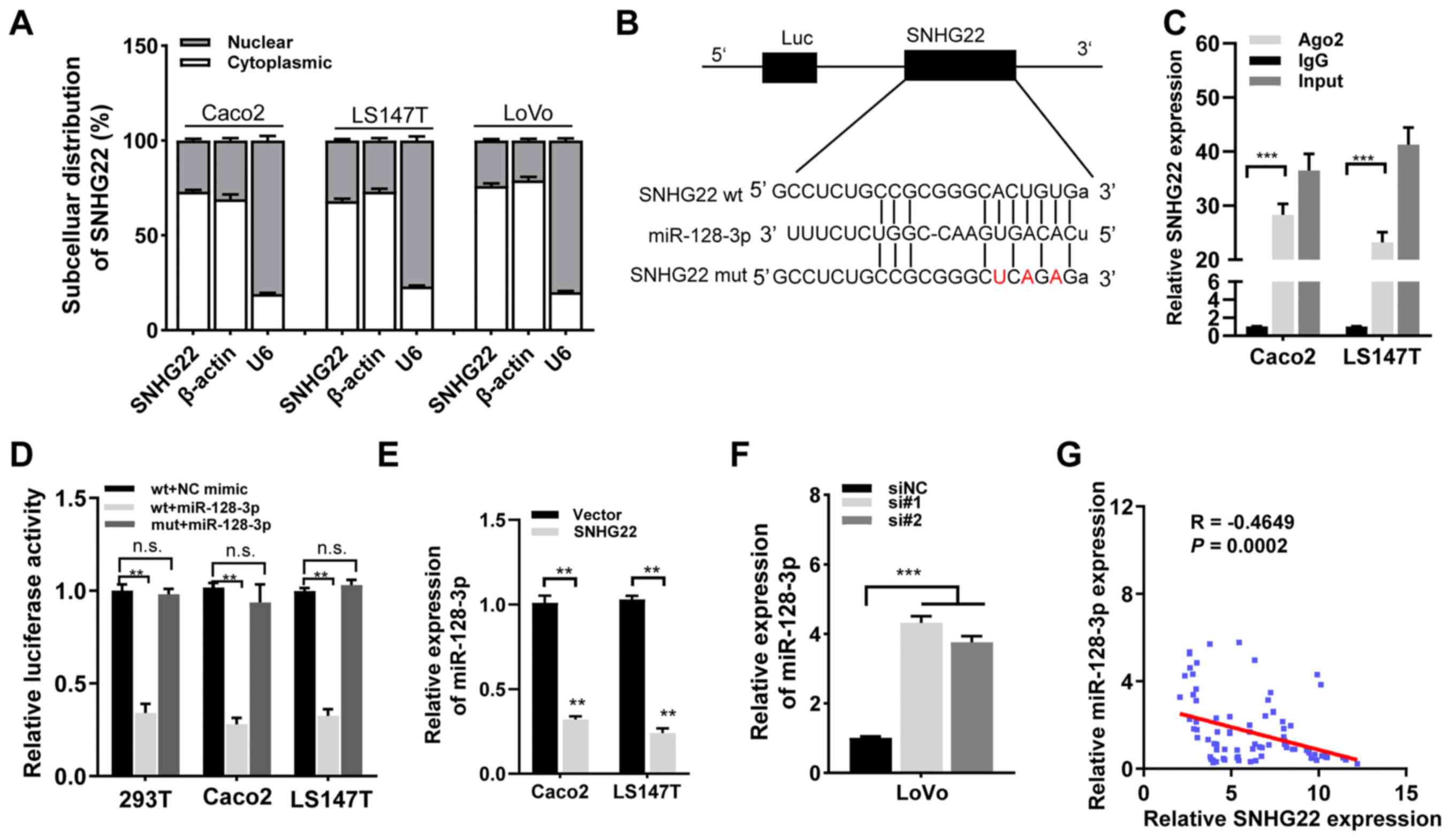

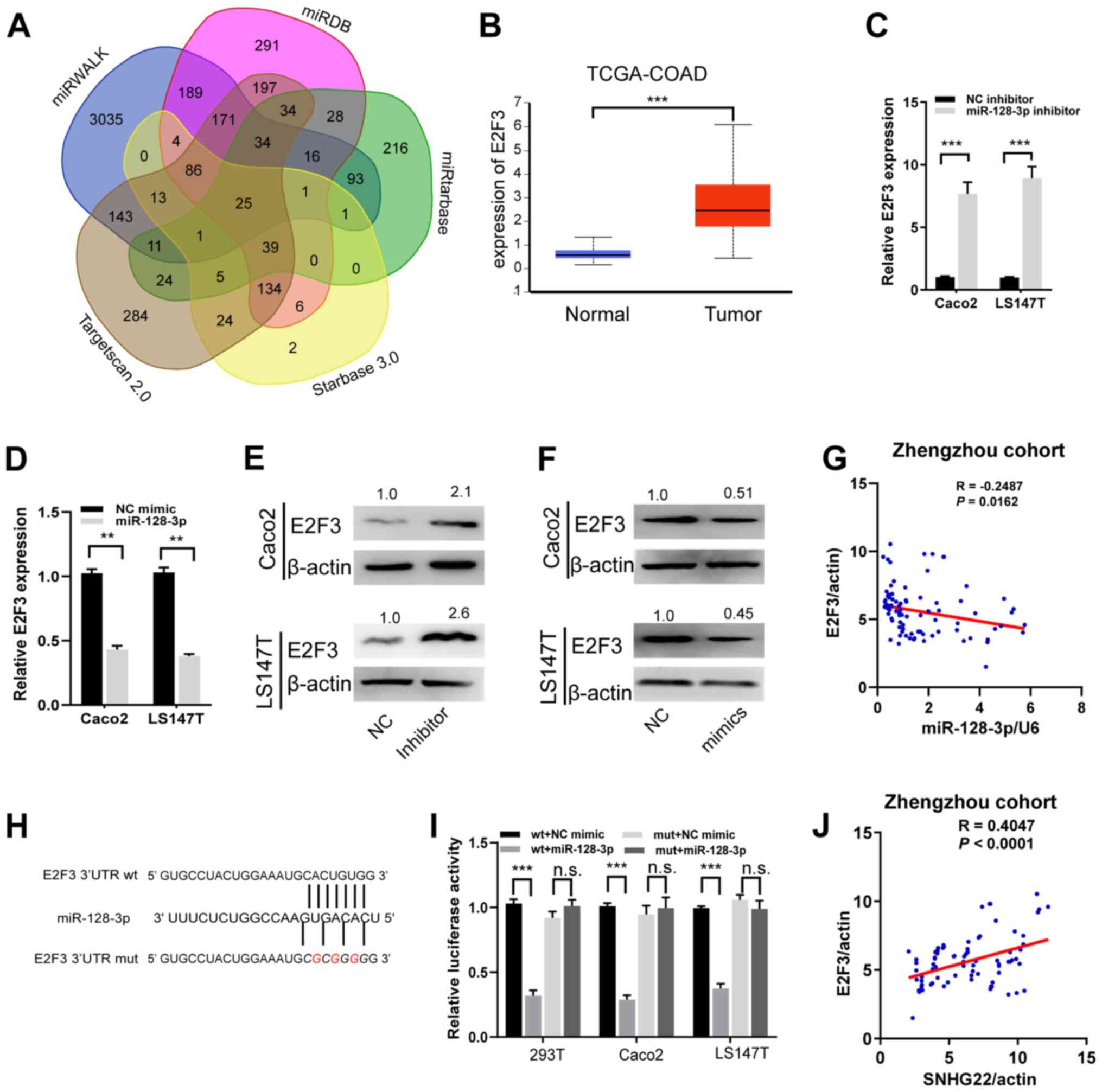

miR-128-3p targets and regulates

E2F3

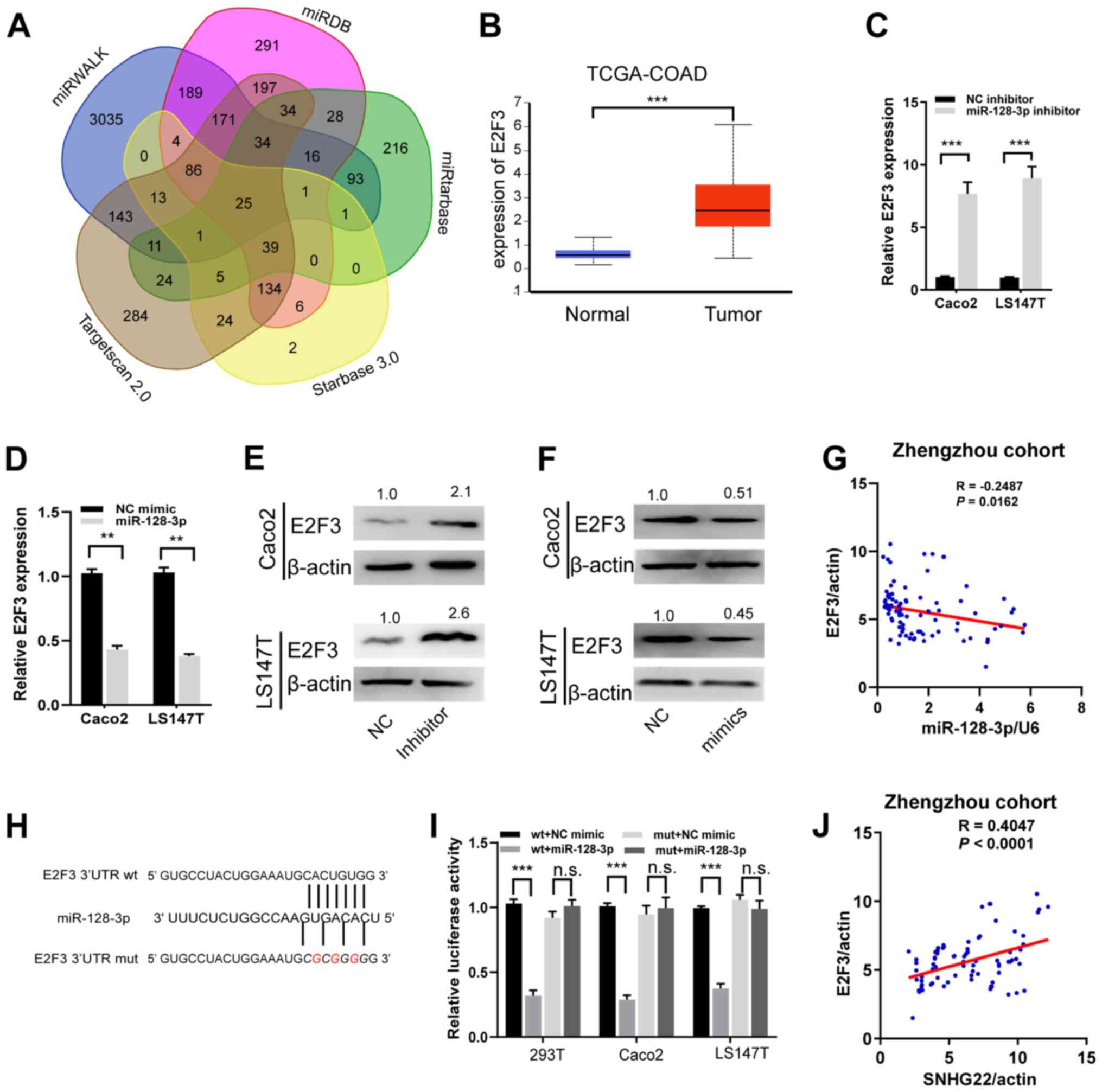

Five independent algorithmic programs were used to

define putative targets of miR-128-3p, and identified 25 common

predicted targets (Fig. 5A).

Among these, E2F3 was selected because TCGA-COAD data indicated

that E2F3 can enhance CRC progression and may be associated with

tumor (Figs. 5B, and S5A and B). After successfully

transfecting miR-128-3p mimics and inhibitor into CRC cells

(Fig. S5C and D), it was

revealed that miR-128-3p overexpression markedly decreased the mRNA

and protein expression levels of E2F3 in Caco2 and LS174T cells,

whereas silencing miR-128-3p enhanced the expression levels of E2F3

(Fig. 5C-F). Moreover, Spearman's

correlation analysis identified a significant inverse relationship

between the expression levels of E2F3 mRNA and miR-128-3p in human

CRC tissues from the Zhengzhou cohort (Fig. 5G). To determine if E2F3 is an

authentic target of miR-128-3p, luciferase reporter gene constructs

were generated wherein the E2F3 3′UTR sequences were fused with the

Renilla luciferase coding sequence (Fig. 5H). The upregulation of miR-128-3p

significantly decreased the luciferase activity of the E2F3 wt

3′UTR. (Fig. 5I). Nevertheless,

altering miR-128-3p expression had no significant effects on the

mut construct (Fig. 5I). In

addition, E2F3 mRNA expression had a meaningful positive

relationship with SNHG22 in human CRC tissues from the Zhengzhou

cohort (Fig. 5J). These data

suggested that E2F3 could be a direct target of miR-128-3p in CRC

cells.

| Figure 5miR-128-3p targets and regulates

E2F3. (A) A Venn diagram showing the number of genes identified as

potential targets of miR-128-3p. (B) Expression levels of E2F3 in

tumor and unmatched normal tissues in TCGA-COAD dataset. (C and D)

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and (E and F) western blot

analysis of the mRNA and protein expression levels of E2F3 in Caco2

and LS147T cells after transfection with the indicated sequences.

Protein expression levels were semi-quantified by normalization

against β-actin with ImageJ. (G) A significant inverse association

was detected between miR-128-3p and E2F3 mRNA expression in human

CRC tissues from the Zhengzhou cohort (R=−0.2487, P=0.016). (H)

miR-128-3p putative binding sites and corresponding mut sequence of

E2F3. (I) Dual-luciferase reporter assays in CRC cell lines

co-transfected with miR-128-3p mimic and luciferase reporters

containing wt or mut E2F3 transcripts. The relative luciferase

activity was normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity.

(J) A positive correlation between SNHG22 and E2F3 expression in

human CRC tissues from Zhengzhou cohort (R=−0.4047, P<0.001).

Data are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. COAD, colon

adenocarcinoma; CRC, colorectal cancer; E2F3, E2F transcription

factor 3; miR, microRNA; mut, mutant; NC, negative control; n.s.,

not significant; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; UTR, untranslated

region; wt, wild-type. |

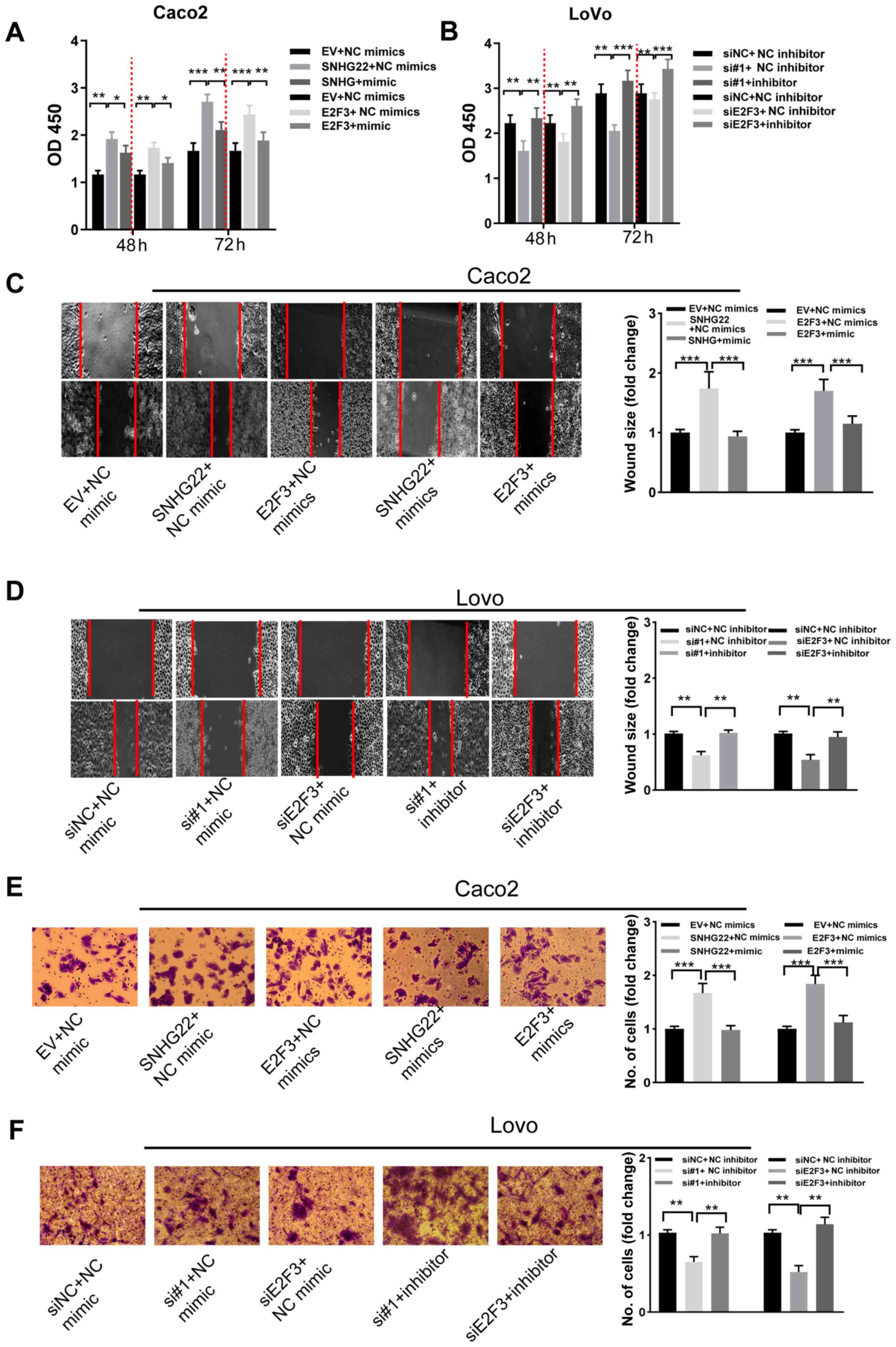

SNHG22 exerts its function by inhibiting

the miR-128-3p/E2F3 axis in CRC cells

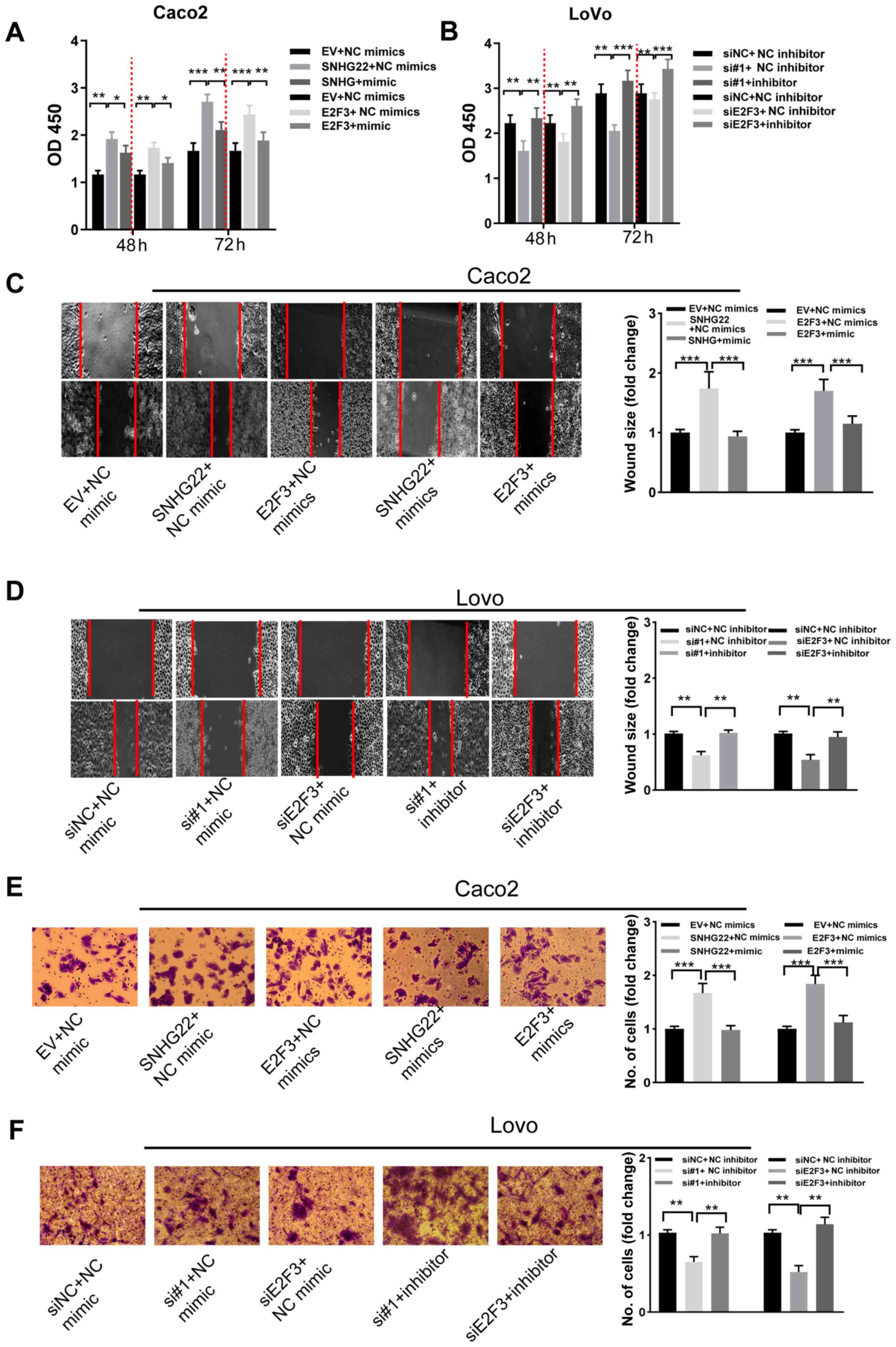

Functional rescue experiments were performed to

examine whether the miR-128-3p/E2F3 axis mediates the biological

roles of SNHG22 in CRC cells. The results of RT-qPCR analyses

confirmed the transfection efficiencies of E2F3 overexpression and

siRNA vectors in CRC cells (Fig. S6A

and B). SNHG22 or E2F3 overexpression stimulated Caco2 cell

proliferation, apoptosis resistance, migration and invasion,

whereas upregulating miR-128-3p reversed these effects. By

contrast, knocking down SNHG22 or E2F3 significantly weakened the

LoVo cell malignant phenotype; nevertheless, these inhibitory

effects were attenuated by co-transfection with miR-128-3p

inhibitors (Figs. 6A-F, and

S6C and D). These results

indicated that the miR-128-3p/E2F3 axis reversed the stimulatory

effects of SNHG22 on the proliferative, migratory and

invasive capacity of CRC cells.

| Figure 6SNHG22 exerts its function by

inhibiting the miR-128-3p/E2F3 axis in CRC cells. Cell Counting

Kit-8 assay analysis of the proliferative ability of (A) Caco2 and

(B) LoVo cells after transfection with the indicated vectors and

sequences. Wound scratch analysis of the migratory ability of (C)

Caco2 and (D) LoVo cells after transfection with the indicated

vectors and sequences (magnification, ×200). Transwell assay

analysis of the invasive ability of (E) Caco2 and (F) LoVo cells

after transfection with the indicated vectors and sequences

(magnification, ×200). Data are presented as the mean ± SD from

triplicate experiments. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. E2F3, E2F

transcription factor 3; EV, empty vector; miR, microRNA; NC,

negative control; OD, optical density; si, small interfering;

SNHG22, small nucleolar RNA host gene 22. |

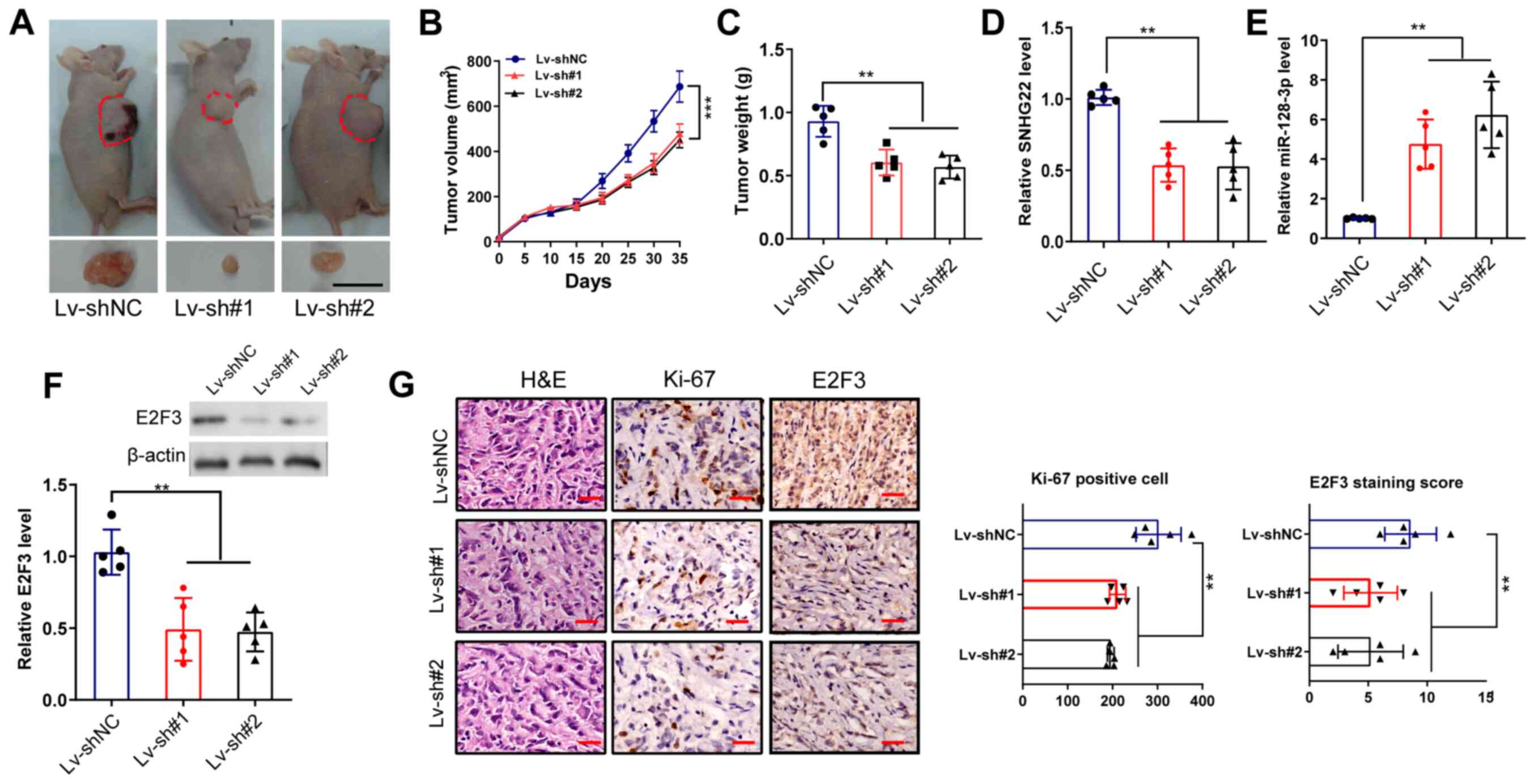

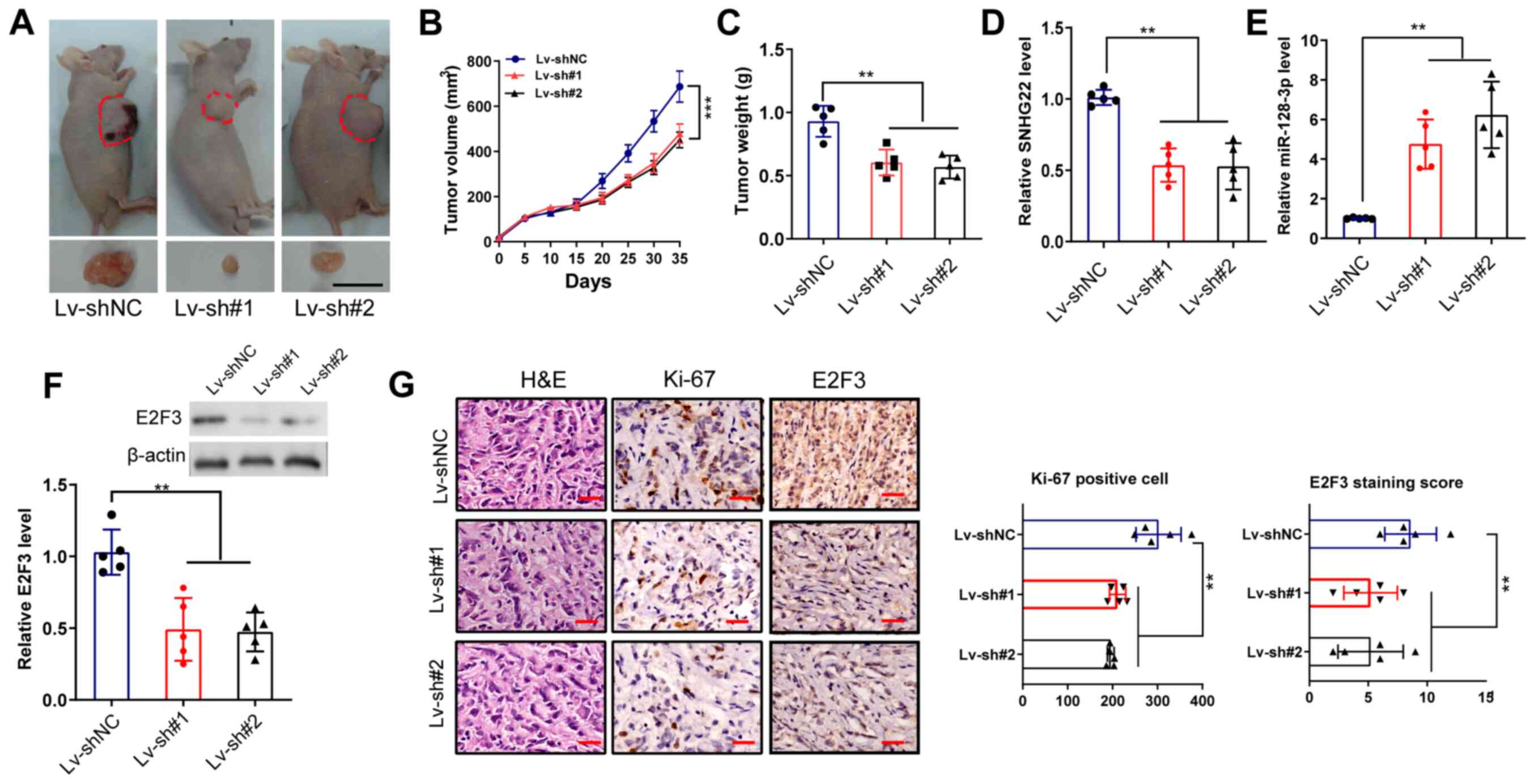

Knockdown of SNHG22 inhibits CRC tumor

xenograft growth in vivo

A tumor xenograft assay was performed to confirm the

roles of SNHG22 in CRC growth in vivo. As shown in Fig. 7A-C, compared with in the Lv-shNC

group, the tumor size, volume and weight in mice in the Lv-sh#1 and

Lv-sh#2 groups were markedly reduced (P<0.01). Furthermore,

RT-qPCR verified the decreased expression levels of SNHG22 and

E2F3, and the increased expression levels of miR-128-3p in tumors

from the Lv-sh#1 and Lv-sh#2 groups compared with those in the shNC

group (Fig. 7D-F).

Immunohistochemistry showed that tumors from the Lv-sh#1 and

Lv-sh#2 groups had decreased expression levels of Ki-67 and E2F3

staining compared with those in tumors from the shNC group

(Fig. 7G).

| Figure 7Knockdown of SNHG22 inhibits tumor

xenograft growth of CRC in vivo. (A) LoVo cells were

inoculated in BALB/c nude mice (n=5/group) to establish

subcutaneous xenograft tumors, and images of the dissected tumors

were captured. Scale bar, 10 mm. Effects of SNHG22 knockdown in

LoVo cells on (B) tumor volume and (C) tumor weight in the

subcutaneous xenograft mouse models. (D and E) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and (F) western blot analysis of the

expression levels of SNHG22, miR-128-3p and E2F3 in the

subcutaneous xenograft mouse models. (G) Immunohistochemical

analysis of the expression levels of Ki-67 and E2F3 in the

subcutaneous xenograft mouse models. Scale bar, 100 µm. Data

are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. E2F3, E2F

transcription factor 3; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; Lv, lentivirus;

miR, microRNA; NC, negative control; sh, short hairpin; SNHG22,

small nucleolar RNA host gene 22. |

Discussion

Accumulating evidence has recently revealed that the

dysregulation of lncRNAs serves an essential role in the

development and invasion of human cancer, including CRC (20,21). The present study revealed that

SNHG22 expression was significantly elevated in CRC tissues

and cell lines. High levels of SNHG22 expression were

significantly associated with unfavorable clinicopathological

characteristics and worse survival in patients with CRC.

Functionally, ectopic SNHG22 overexpression drove proliferation,

apoptosis resistance, migration and invasion in CRC cell lines.

Knocking down SNHG22 inhibited xenograft tumor growth in

vivo. The present study confirmed that SNHG22 performed

its tumor-promoting function by sponging miR-128-3p, and enhancing

the expression and activity of E2F3. To the best of our knowledge,

the present results are the first to clarify that SNHG22

acts as an oncogene in CRC, and that it may be used as a potential

therapeutic target for this disease.

The current anatomically based TNM staging system

cannot precisely distinguish the risk of recurrence/distant

metastasis in patients with CRC; therefore, it is essential to

identify novel prognostic biomarkers. The dysregulation of lncRNAs

in various human tumors is associated with excellent or poor

survival, thus making them promising prognostic biomarkers

(22,23). For example, SNHG7

expression has been reported to be enhanced in CRC tissues compared

with that in non-cancerous tissues, and this high expression was

related to aggressive pathological characteristics, such as TNM

stage, lymphatic metastasis and distant metastasis, as well as poor

prognosis (9,10). The upregulation of Pvt1 oncogene

has also been reported to indicate poor survival in several types

of cancer, including CRC (23).

Some researchers have reported upregulated SNHG22 expression

in EOC, PTC and clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and high

SNHG22 expression may indicate poor prognosis in these three

human malignancies (12,14,24). The present study first explored

the expression patterns of SNHG22 in CRC TTs and ANTs, and

in CRA tissues, and revealed that SNHG22 expression was

upregulated in the order of ANTs > CRA tissues > TTs. High

SNHG22 expression levels were associated with advanced T

stage, node involvement, metastasis and poor survival in patients

with CRC. Therefore, SNHG22 may serve as an independent

prognostic indicator in patients with CRC.

As an oncogene, SNHG22 may serve critical

roles in tumor advancement processes; for example, it was shown to

be highly expressed in EOC, and to stimulate EOC cell

proliferation, invasion and chemotherapy resistance by sponging

miR-2467 to facilitate galectin-1 expression in EOC cells (11). Fang et al (13) observed that, in breast cancer,

SNHG22 facilitated tumor progression by sequestering

miR-324-3p and subsequently upregulating SDS3 homolog, SIN3A

corepressor complex component. The present study also examined the

effects of SNHG22 on the phenotype of CRC cells, and revealed that

SNHG22 promoted CRC cell proliferation, apoptosis resistance,

invasion and migration in vitro. Knocking down SNHG22 in

vivo inhibited xenograft tumor growth. All these results

implicate SNHG22 as a possible critical oncogenic lncRNA in

CRC.

Most cytoplasmic lncRNAs exert their regulatory

effects on gene expression by functioning as ceRNAs, regulating

miRNAs by competitively binding their target sites on

protein-coding mRNA molecules (25,26). For example, acting as a ceRNA,

MIR17HG has been reported to base its biological behaviors on a

sequence-specific interaction with miR-17-5p, thereby augmenting

the biological roles of mRNA targets (5). Chen et al (27) reported that the lncRNA

up-regulated in colorectal cancer liver metastasis promoted the

invasion of CRC cell lines by sponging miR-215. Based on

bioinformatics analyses and experimental assays, the present study

demonstrated that SNHG22 was preferentially localized to the

cytoplasm. Furthermore, it was confirmed that SNHG22 could

sponge miR-128-3p in CRC, and the dual-luciferase reporter assay

indicated that SNHG22 may interact with miR-128-3p and hinder its

biological roles. miR-128-3p has been reported to function as a

tumor suppressor in several types of human cancer (28-32), and may be involved in cell

proliferation, the cell cycle and chemosensitivity. It has been

suggested that miR-128-3p may enhance the chemosensitivity of

oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells by targeting BMI1 proto-oncogene,

polycomb ring finger and ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 5

(30). Moreover, nanocomplexes

loaded with miR-128-3p elevated chemotherapy roles through dual

targeting, and silencing PI3K-AKT and MEK-ERK pathway activity in

CRC cell lines (29).

As a ceRNA, the function of lncRNAs depends on the

miRNA target gene. Using five online databases, E2F3 was

predicted as a potential target of miR-128-3p. This hypothesis was

validated with luciferase reporter assays. The results revealed

that miR-128-3p overexpression inhibited the E2F3 wt 3′UTR

luciferase activity, but did not change that of the E2F3 mut

3′UTR. Furthermore, miR-128-3p overexpression inhibited E2F3 mRNA

and protein expression levels, whereas silencing miR-128-3p

elevated them, suggesting that E2F3 could be a direct target

of miR-128-3p in CRC cells. Further functional rescue experiments

validated the hypothesis that SNHG22 may regulate CRC

proliferation and invasion by competitively sponging miR-128-3p and

restoring E2F3 activity. Recent studies have revealed that

E2F3 may serve an essential role in regulating human cancer cell

proliferation, apoptosis and chemosensitivity (33,34).

In conclusion, the results of the present study

revealed that, as an oncogenic lncRNA in CRC, SNHG22 was

upregulated and related to poor survival in patients with CRC.

Functional and mechanistic analyses demonstrated that SNHG22

promoted CRC tumorigenesis and metastasis by sponging miR-128-3p,

leading to elevated expression of E2F3. These findings may provide

novel insights into the development of therapeutics for CRC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request or from the TCGA repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/.

Authors' contributions

LFZ, JNY, CFW and XYD conceived and designed the

present study. JNY, YLL, HNZ and XYD performed the experiments.

JNY, CFW, XYD and YZZ analyzed and interpretated the data. JNY, CFW

and LFZ wrote, reviewed and/or revised the manuscript. JNY and LFZ

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study involving human tissues was

approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University (approval

no. 2011110402). All patients provided written informed consent

prior to their inclusion within the study. The research has been

carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association

Declaration of Helsinki. All animal experiments were approved by

the Committee of the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Zhengzhou

University (approval no. 20180376).

Patient consent for publication

All patients included in the present study have

provided consent for both participation and publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

EOC

|

epithelial ovarian carcinoma

|

|

PTC

|

papillary thyroid cancer

|

|

lncRNA

|

long non-coding RNA

|

|

snoRNA

|

small nucleolar RNA

|

|

SNHG

|

small nucleolar RNA host gene

|

|

siRNA

|

small interfering RNA

|

|

UTR

|

untranslated region

|

|

mut

|

mutant

|

|

RIP

|

RNA immunoprecipitation

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

TT

|

tumor tissue

|

|

ANT

|

adjacent non-cancerous tissue

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

DFS

|

disease-free survival

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

ceRNA

|

competing endogenous RNA

|

|

HR

|

hazard ratio

|

|

CI

|

confidence interval

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP,

Francisci S, Baili P, Pierannunzio D, Trama A, Visser O, Brenner H,

Ardanaz E, et al: Cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007 by country

and age: Results of EUROCARE-5-a population-based study. Lancet

Oncol. 15:23–34. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

He Q, Long J, Yin Y, Li Y, Lei X, Li Z and

Zhu W: Emerging roles of lncRNAs in the formation and progression

of colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 9:15422020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Luo Y, Yang J, Yu J, Liu X, Yu C, Hu J,

Shi H and Ma X: Long non-coding RNAs: Emerging roles in the

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Front Oncol. 10:482020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Xu J, Meng Q, Li X, Yang H, Xu J, Gao N,

Sun H, Wu S, Familiari G, Relucenti M, et al: Long noncoding RNA

MIR17HG promotes colorectal cancer progression via miR-17-5p.

Cancer Res. 79:4882–4895. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Xiao Z, Qu Z, Chen Z, Fang Z, Zhou K,

Huang Z, Guo X and Zhang Y: LncRNA HOTAIR is a prognostic biomarker

for the proliferation and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer via

miR-203a-3p-mediated Wnt/ß-catenin signaling pathway. Cell Physiol

Biochem. 46:1275–1285. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ding D, Li C, Zhao T, Li D, Yang L and

Zhang B: LncRNA H19/miR-29b-3p/PGRN axis promoted

epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colorectal cancer cells by

acting on Wnt signaling. Mol Cells. 41:423–435. 2018.

|

|

8

|

Williams GT and Farzaneh F: Are snoRNAs

and snoRNA host genes new players in cancer? Nat Rev Cancer.

12:84–88. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Shan Y, Ma J, Pan Y, Hu J, Liu B and Jia

L: LncRNA SNHG7 sponges miR-216b to promote proliferation and liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer through upregulating GALNT1. Cell

Death Dis. 9:7222018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Li Y, Zeng C, Hu J, Pan Y, Shan Y, Liu B

and Jia L: Long non-coding RNA-SNHG7 acts as a target of miR-34a to

increase GALNT7 level and regulate PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in

colorectal cancer progression. J Hematol Oncol. 11:892018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, Otsuki T,

Sugiyama T, Irie R, Wakamatsu A, Hayashi K, Sato H, Nagai K, et al:

Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length

human cDNAs. Nat Genet. 36:40–45. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhang PF, Wu J, Luo JH, Li KS, Wang F,

Huang W, Wu Y, Gao SP, Zhang XM and Zhang PN: SNHG22 overexpression

indicates poor prognosis and induces chemotherapy resistance via

the miR-2467/Gal-1 signaling pathway in epithelial ovarian

carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 11:8204–8216. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Fang X, Zhang J, Li C, Liu J, Shi Z and

Zhou P: Long non-coding RNA SNHG22 facilitates the malignant

phenotypes in triple-negative breast cancer via sponging miR-324-3p

and upregulating SUDS3. Cancer Cell Int. 20:2522020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Gao H, Sun X, Wang H and Zheng Y: Long

noncoding RNA SNHG22 increases ZEB1 expression via competitive

binding with microRNA-429 to promote the malignant development of

papillary thyroid cancer. Cell Cycle. 19:1186–1199. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG,

Greene F and Trotti A: AJCC cancer staging handbook. 7th edition.

Springer; New York, NY: 2010

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Du Y, Wei N, Hong J and Pan W: Long

non-coding RNASNHG17 promotes the progression of breast cancer by

sponging miR-124-3p. Cancer Cell Int. 20:402020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

National Research Council (US) Committee

for the Update of the Guide for the Care and use of Laboratory

Animals: Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. 8th

edition. National Academies Press (US); Washington, DC: 2011

|

|

19

|

Cao Z, Pan X, Yang Y, Huang Y and Shen HB:

The lncLocator: A subcellular localization predictor for long

non-coding RNAs based on a stacked ensemble classifier.

Bioinformatics. 34:2185–2194. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lan Y, Xiao X, He Z, Luo Y, Wu C, Li L and

Song X: Long noncoding RNA OCC-1 suppresses cell growth through

destabilizing HuR protein in colorectal cancer. Nucleic Acids Res.

46:5809–5821. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang Y, Lu JH, Wu QN, Jin Y, Wang DS, Chen

YX, Liu J, Luo XJ, Meng Q, Pu HY, et al: LncRNA LINRIS stabilizes

IGF2BP2 and promotes the aerobic glycolysis in colorectal cancer.

Mol Cancer. 18:1742019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wang D, Zhang H, Fang X, Zhang X and Liu

H: Prognostic value of long non-coding RNA GHET1 in cancers: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 20:1092020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Xiao M, Feng Y, Liu C and Zhang Z:

Prognostic values of long noncoding RNA PVT1 in various carcinomas:

An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cell Prolif.

51:e125192018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yang W, Zhang K, Li L, Ma K, Hong B, Gong

Y and Gong K: Discovery and validation of the prognostic value of

the lncRNAs encoding snoRNAs in patients with clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 12:4424–4444. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Li M, Bian Z, Jin G, Zhang J, Yao S, Feng

Y, Wang X, Yin Y, Fei B, You Q and Huang Z: LncRNA-SNHG15 enhances

cell proliferation in colorectal cancer by inhibiting miR-338-3p.

Cancer Med. 8:2404–2413. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yan J, Jia Y, Chen H, Chen W and Zhou X:

Long non-coding RNA PXN-AS1 suppresses pancreatic cancer

progression by acting as a competing endogenous RNA of miR-3064 to

upregulate PIP4K2B expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:3902019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen DL, Lu YX, Zhang JX, Wei XL, Wang F,

Zeng ZL, Pan ZZ, Yuan YF, Wang FH, Pelicano H, et al: Long

non-coding RNA UICLM promotes colorectal cancer liver metastasis by

acting as a ceRNA for microRNA-215 to regulate ZEB2 expression.

Theranostics. 7:4836–4849. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhao J, Li D and Fang L: MiR-128-3p

suppresses breast cancer cellular progression via targeting LIMK1.

Biomed Pharmacother. 115:1089472019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Liu X, Dong C, Ma S, Wang Y, Lin T, Li Y,

Yang S, Zhang W, Zhang R and Zhao G: Nanocomplexes loaded with

miR-128-3p for enhancing chemotherapy effect of colorectal cancer

through dual-targeting silence the activity of PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK

pathway. Drug Deliv. 27:323–333. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Liu T, Zhang X, Du L, Liu X, Tian H, Wang

L, Li P, Zhao Y, Duan W, Xie Y, et al: Exosome-transmitted

miR-128-3p increase chemosensitivity of oxaliplatin-resistant

colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 18:432019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li X, Lv X, Li Z, Li C, Li X, Xiao J, Liu

B, Yang H and Zhang Y: Long noncoding RNA ASLNC07322 functions in

VEGF-C expression regulated by smad4 during colon cancer

metastasis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 18:851–862. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Fu C, Li D, Zhang X, Liu N, Chi G and Jin

X: LncRNA PVT1 facilitates tumorigenesis and progression of glioma

via regulation of MiR-128-3p/GREM1 axis and BMP signaling pathway.

Neurotherapeutics. 15:1139–1157. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wang H, Wang L, Zhang S, Xu Z and Zhang G:

Downregulation of LINC00665 confers decreased cell proliferation

and invasion via the miR-138-5p/E2F3 signaling pathway in NSCLC.

Biomed Pharmacother. 127:1102142020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Chen J, Liu X, Xu Y, Zhang K, Huang J, Pan

B, Chen D, Cui S, Song H, Wang R, et al: TFAP2C-activated MALAT1

modulates the chemoresistance of docetaxel-resistant lung

adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 14:567–582. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|