Liver cancer is the sixth most frequently diagnosed

cancer worldwide and the third most common cause of cancer-related

death, with ~906,000 new cases and 830,000 deaths worldwide in 2020

(1). In addition, the incidence

and mortality rates of liver cancer are generally higher in men

than in women (1). Hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) accounts for the largest proportion of cases among

all liver cancer types, is heterogeneous and imposes a large global

socio-economic burden (2). HCC

can occur either due to the dedifferentiation of hepatocytes or due

to the development of intrahepatic stem cells (3-5),

is characterized by difficulties in early detection, is prone to

metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis (6). The aggressiveness of HCC is closely

related to its degree of differentiation, microvascular

infiltration, intrahepatic metastases and satellite lesions, and

poorly differentiated HCC is associated with earlier recurrence and

poorer prognosis compared with well-differentiated HCC (7).

HCC therapy options include surgical excision, liver

transplantation, radiofrequency ablation and microwave ablation for

early-stage HCC (8-10). However, 40% of patients already

have advanced HCC when they are first diagnosed (11), resulting in limited treatment

options, and even radical treatment can still result in recurrence

or transformation within a short period, commonly within 1-3 years

(12). Although treatments with

multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been demonstrated to

prolong the overall survival (OS) of patients with HCC (13,14), drug resistance and side effects

limit the effect of TKIs (15,16).

The rise in immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and

breakthroughs in immunology studies have sparked an expanding

interest in cancer immunotherapy, especially in antibodies against

programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death

ligand 1 (PD-L1) (17). Anti-PD-1

drugs, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are efficient and

well-tolerated in patients with advanced HCC and are currently

recognized as second-line treatment options for patients with HCC

(18,19). A clinical study, IMBrave150,

revealed that atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) in combination with

bevacizumab (anti-vascular endothelial growth factor) was more

beneficial than sorafenib (SOR) in patients with advanced HCC, and

prolonged the median OS time of patients with unresectable HCC

(uHCC) (20,21). Compared with SOR, the combination

immunotherapy of durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) and tremelimumab

(anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4) administered in

the HIMALAYA study, which likely exerted antitumor effects by

activating T cells, exhibited an improved therapeutic effect for

uHCC (17,22). In addition, immunotherapy drugs

have the advantage that they do not need to be metabolized by the

liver, which marks a significant advancement in the management of

advanced HCC (23,24). Nevertheless, ICI therapy for HCC

still has shortcomings such as a low response rate, high tumor

tolerance to ICI therapy and multiple side effects (25-28), leading to the use of ICI therapy

in combination with various other therapies.

It has been confirmed that, during the development

and progression of HCC, the balance between regulatory cell death

(RCD) and cell survival serves a crucial function, and resistance

to apoptosis and evasion of cell death is one of the hallmarks of

HCC (29). Overcoming or delaying

TKI resistance increases tumor cell death (30,31), and inducing inflammatory forms of

cell death may enhance the tumor response to ICI treatment

(32). Therefore, cell death has

emerged as a popular research topic in the treatment of HCC.

Notably, considering that resistance to apoptotic RCD is a general

characteristic of cancer, non-apoptotic RCD (NARCD) serves a more

crucial role during the development of HCC and its response to

therapy (29). TKIs and ICIs are

both tightly associated with the regulation of NARCD pathways

(33,34).

At present, ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis

are three highly studied types of NARCD in HCC development and

treatment, and these influence the fate of cells in the liver

(35-40). There are some differences and

similarities among these three types of NARCD, and the key features

of ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis, including the

morphological and biochemical features, key regulators, and related

drugs are shown in Table I.

Furthermore, the roles of these NARCD pathways in the tumor

microenvironment (TME) and tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) are

gradually being recognized. Treatments targeting these NARCD

pathways in combination with TKI treatments (41-43) or ICI therapies (44-46) exhibit synergistically enhanced

anticancer activity compared with single treatment. Treatments

targeting these NARCD pathways could exert anticancer effects even

in cancer types resistant to TKIs and ICIs (34,47,48). Only a few patients exhibit a

response to TKI or ICI treatment alone, while triggering

ferroptosis, necroptosis or pyroptosis can alter this response

status and improve the response rate of therapy (32,49). Furthermore, ferroptosis,

pyroptosis and necroptosis, as three potential novel mechanisms of

immunogenic cell death (ICD) (50,51), have been suggested to transform

immune 'cold' tumors into immune 'hot' tumors, increasing the

sensitivity to ICI therapy, activating CD8+ T cell

adaptive immunity and maintaining durable immune memory so that the

body gains long-term antitumor immunity (52). Thus, ferroptosis, pyroptosis and

necroptosis are considered three novel potential therapeutic

targets to improve the treatment outcomes of HCC (49).

The present review first investigates the role of

ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis in the TME and TIME of HCC

and summarizes the related novel targets and signaling pathways.

Subsequently, the current status of targeting ferroptosis,

pyroptosis and necroptosis in combination with multiple HCC

treatment modalities is described. In particular, the potential

applications of targeting ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis

in combination with ICIs to enhance immune efficacy are

discussed.

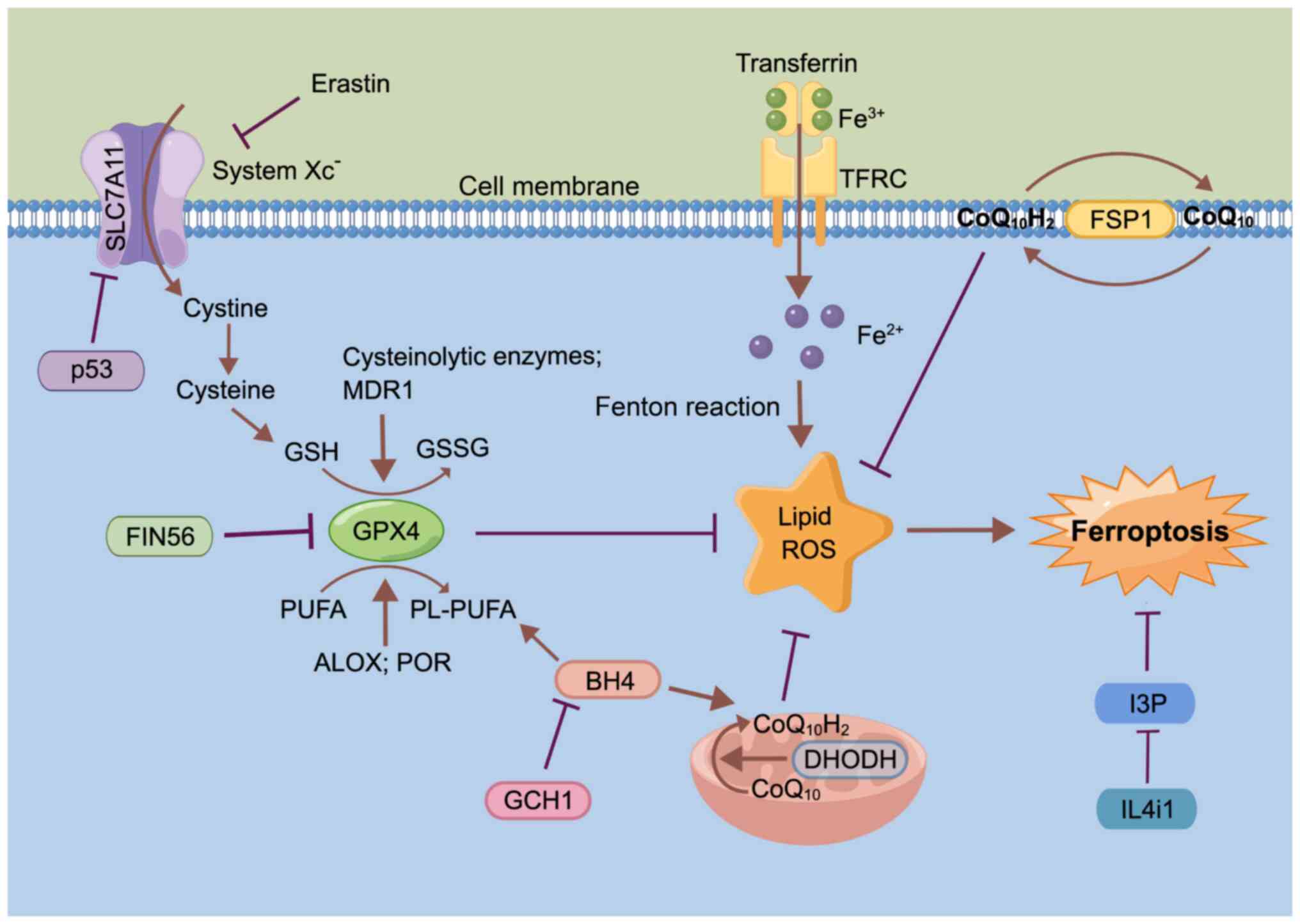

Originally conceptualized in 2012, ferroptosis is

considered a lipid peroxidation-driven, iron-dependent and

non-apoptotic form of cell death (53). Morphologically, the cellular

microstructure after ferroptosis is characterized by organelle

expansion, rupture of the plasma membrane and moderate chromatin

condensation, and the mitochondrial ultrastructure showing

abnormalities including contraction, fracture, enlargement of

cristae, increased membrane density and rupture of the outer

membrane (53-56). Mechanically, ferroptosis is driven

by iron-dependent phospholipid (PL) peroxidation, and regulated by

multiple cellular metabolic pathways, including redox homeostasis,

iron handling, mitochondrial activity, and metabolism of amino

acids, lipids and sugars (Fig. 1)

(53,57).

Unsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes, such as

polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), are mainly affected by lipid

peroxidation driven by free radicals (62). The key characteristic of PUFAs

driving ferroptosis is their ability to bind to PLs in membranes

upon PUFA activation (62).

Arachidonate lipoxygenase and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase act as

regulators of lipid peroxidation, mediating PUFA peroxidation to

promote ferroptosis (54,63).

GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4) acts as a key inhibitor of

ferroptosis and is regulated via several mechanisms. For example,

ferroptosis inducing 56 can induce degradation of GPX4 to induce

ferroptosis (Fig. 1) (64) or covalently binds to the

selenocysteine (Sec) site of GPX4 to induce GPX4 inactivation

(65). GSH depletion also

inactivates GPX4, and thus, drives ferroptosis, while both

GSH-related enzymes and the multidrug resistance protein 1, promote

GSH depletion (66,67). As research has progressed, a

number of novel ferroptosis-inducing mechanisms independent of GPX4

have been identified, such as ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 and

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibiting ferroptosis by producing

ubiquinol (CoQ10H2) in the cell cytomembrane

and inner mitochondrial membranes, respectively (68,69).

Mitochondria serve a diversified role in the process

of ferroptosis, iron metabolism and the oxidative phosphorylation

pathway, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly involved in

ferroptosis (70). It has been

demonstrated that the typical metabolic activities of the

mitochondria, including tricarboxylic acid cycle and electron

transport chain activities, are required for cellular lipid

peroxide production in ferroptosis induced by cysteine (Cys)

deprivation, but not in that induced by inhibiting GPX4 (57,71).

GTP cyclic hydrolase 1 improves ferroptosis

sensitivity by inhibiting generation of the antioxidant

tetrahydrobiopterin and increasing the abundance of

CoQ10H2 and PL-PUFA (73,74). IL-4-induced-1 stimulates

ferroptosis by inhibiting production of the metabolite

indole-3-pyruvate and limiting the activation of cytoprotective

gene expression programs (75).

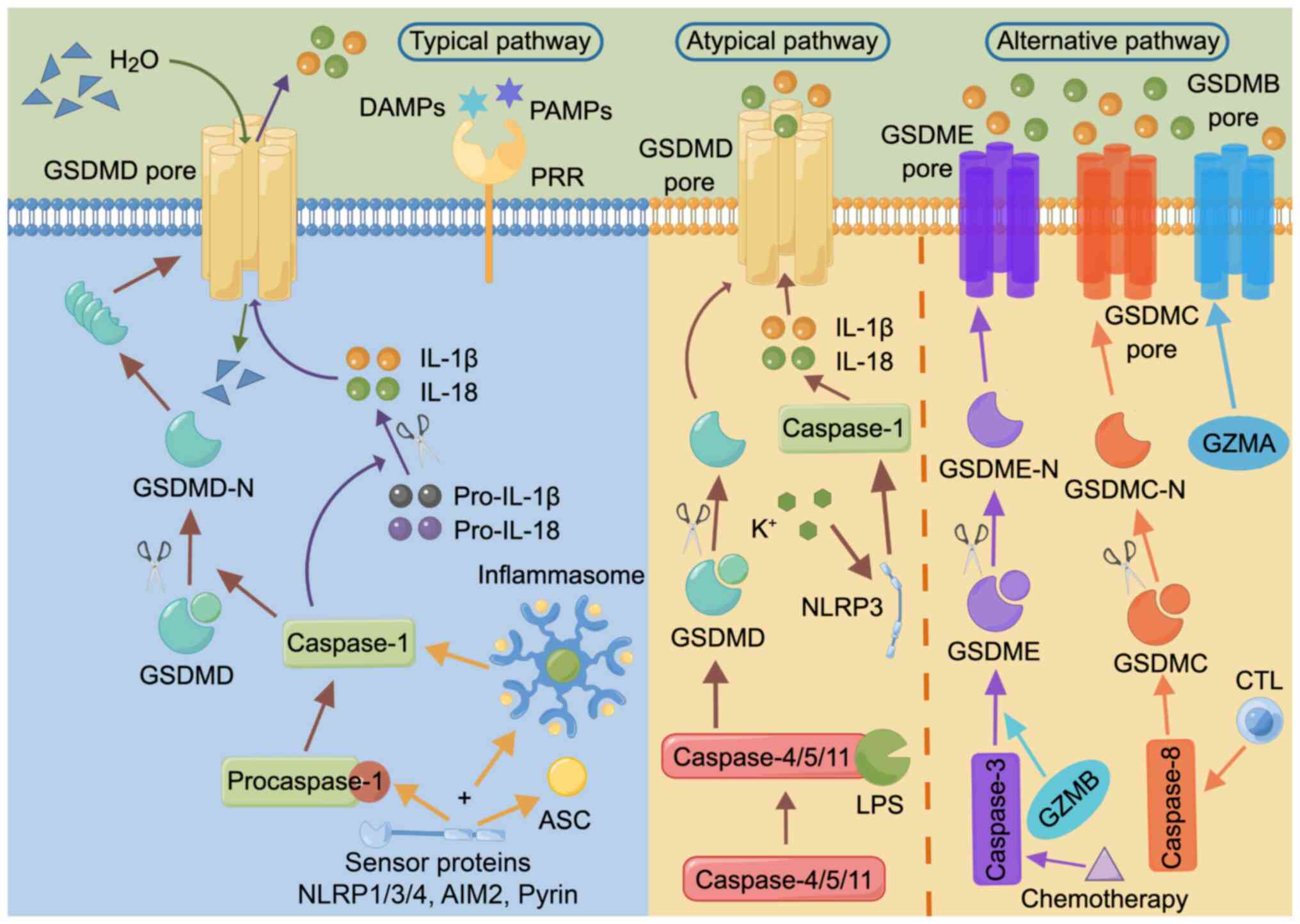

The typical pathway of pyroptosis is that, upon host

stimulation, GSDMD is cleaved by caspase-1, followed by

oligomerization and the formation of functional pores in the cell

membrane, leading to the release of inflammatory molecules such as

IL-1β and IL-18, disruption of osmotic pressure, water influx, and

thus, cell swelling, formation of membrane vesicles with

bubble-like protrusions (also known as scorch bodies) and plasma

membrane cleavage, and ultimately pyroptosis (80-83).

The atypical pathway of pyroptosis is a process not

reliant on inflammasome sensors, and involves the lytic apoptosis

of GSDMD cleaved by caspase-4/5/11 interacting with stimulators

such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The subsequently released

K+ activates NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain

containing 3 (NLRP3), which in turn activates caspase-1, and thus,

indirectly induces IL-1β and IL-18 production (84-86).

In addition, there are alternative pathways of

pyroptosis, such as via activated caspase-3/8, that can mediate the

cleavage of GSDME or GSDMC, releasing the N-terminal PFD and

eventually inducing pyroptosis (87-91). Alternatively, granzyme B from

lymphocytes induces pyroptosis by activating caspase-3 and

subsequent GSDME cleavage or by directly cleaving GSDME (92,93). Most GSDMs (except DFNB59) have an

N-terminal PFD and a C-terminal RD (81), and thus, also have the potential

to undergo cellular scorching, with GSDMB, GSDMC and GSDME being

the executors of cancer cell pyroptosis (CCP) (78). For example, GSDME can be cleaved

by small molecule kinase inhibitors or following the

chemotherapy-induced activation of caspase-3, resulting in

pyroptosis and the improvement of lung cancer and melanoma

treatments (87,94). GSDMC can be cleaved by caspase-8

to trigger CCP, including in lung and liver cancer (88). GSDMB can be cleaved directly by

granzyme A released from natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T

lymphocytes (CTLs) independently of caspases, contributing to the

necrosis of murine cancer cells (95).

In the induction of pyroptosis, inflammasomes are

oligomeric complexes composed of sensor proteins, bridging proteins

and effector caspases (96,97), and similarly serve as molecular

platforms for the activation of inflammatory caspases (97). Pattern recognition receptors

(PRRs) can act as sensor proteins, recognizing the relevant

molecular patterns that initiate inflammasome activation (98). Among them, NLRP1/3/4, absent in

melanoma 2 and pyrin can recruit the adapter apoptosis-associated

speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain and/or

pro-caspase-1 to assemble into inflammasomes and thereby activate

caspase-1, which in turn induces IL-1β and IL-18 processing

(99,100).

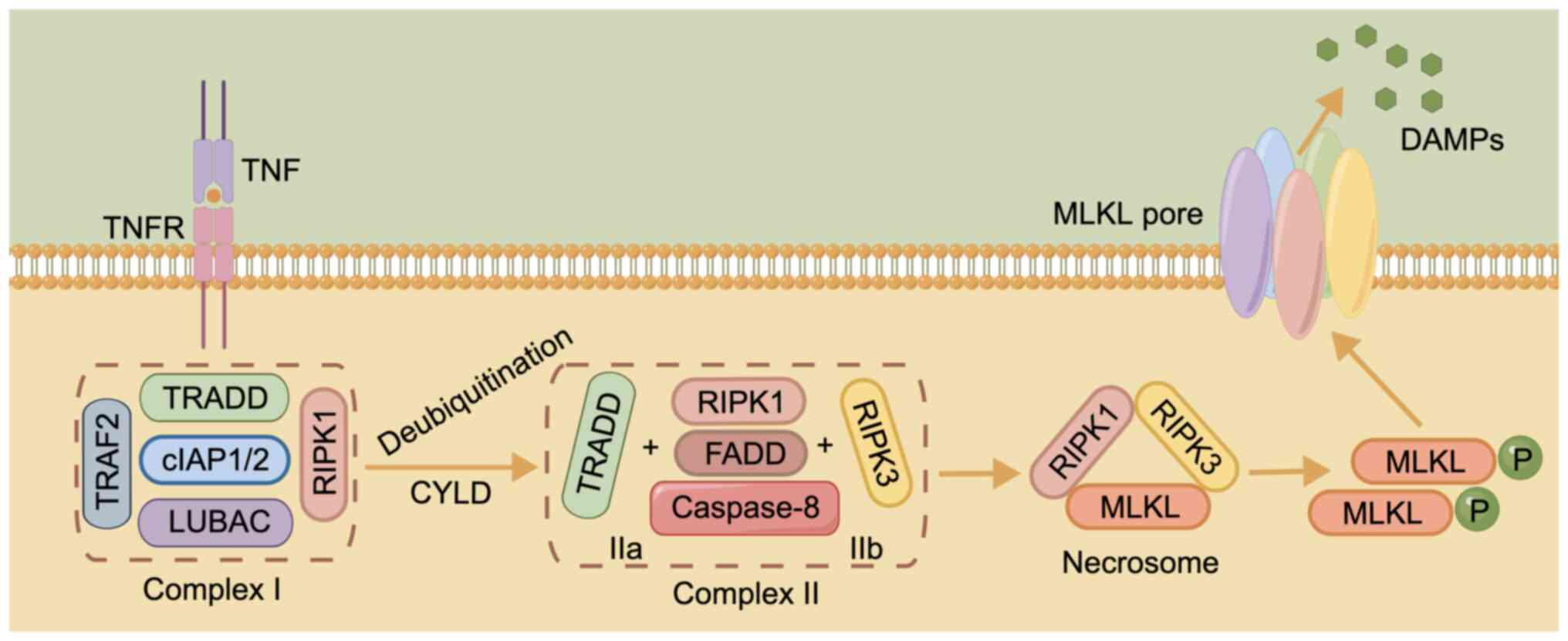

The initiation of necroptosis relies on specific

death receptors (DRs), including FAS, tumor necrosis factor

receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

(TRAIL) receptors TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2, or PRRs, such as toll-like

receptor (TLR)3, to recognize unfavorable signals from the intra-

and extracellular microenvironment (101). TNF is a major stimulus in

necroptosis, delivering cell death signals via binding to DRs

(102). This process is

associated with complex I, consisting of TNFR1-associated death

domain protein (TRADD), linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex,

TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), cellular inhibitor of

apoptosis protein (cIAP)1/2 and receptor-interacting protein kinase

(RIPK)1 (103). When

cylindromatosis deubiquitinates RIPK1, A20, ubiquitin-specific

peptidase (USP)21 or USP20, complex I becomes unstable, and TRADD

and RIPK1 are isolated and assembled with Fas-associated death

domain (FADD) protein and caspase-8 to form complex IIa, or RIPK3

replaces TRADD to form complex IIb with the other components

(104,105). Inactivation of caspase-8 and

cIAP induces the conversion of complex IIb into a necrosome,

triggering DR-induced necroptosis (106,107).

The necrosome is formed by binding of RIPK3 and

RIPK1 via the RIP homotypic-interacting motif (RHIM) domain at

first, followed by recruitment of mixed lineage kinase domain-like

pseudokinase (MLKL) after the formation of the complex (108). Phosphorylated MLKL, the main

executor of necroptosis, later oligomerizes and migrates to the

plasma membrane, damaging it and releasing potential

damage-associated molecular patterns to trigger necroptosis

(Fig. 3) (109,110). Another TLR containing RHIM, TIR

domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β enables direct

RHIM-dependent signaling, initiating necrosis via receptor

interacting protein 3 and MLKL (111). A recent study found that

extracellular osmotic pressure was also a stimulus for the

induction of necroptosis and that the activation of RIPK3 by the

Na+/H+ exchanger solute carrier family 9

member A1 increased the cytosolic pH, and this is a pathway that

does not depend on the RHIM structural domain to activate the

downstream effector MLKL (112).

As research regarding ferroptosis progresses, more

ferroptosis-related drugs and targets are being identified for HCC

treatment. As a type of TKI, SOR also induces ferroptosis to

augment anti-HCC benefits (113,114). Furthermore, SOR attenuates the

binding of beclin-1 to MCL1 by modulating the Src homology region 2

domain-containing phosphatase-1/STAT3 axis, whilst enhancing the

binding to SLC7A11 and thereby inhibiting system Xc-

activity (115). In addition,

glutaminase 2 exerts anti-HCC effects by depleting glutamine, and

thus, promoting ferroptosis (116). Using CRISPR screening,

phosphatidylserine-transfer RNA kinase depletion has been

identified to interfere with Sec and Cys synthesis, leading to GSH

depletion and GPX4 inactivation, thus inducing ferroptosis and

enhancing the sensitivity to targeted chemotherapy in HCC treatment

(117). The long non-coding RNA

HEPFA promotes erastin-induced ferroptosis by mediating the

destabilization of SLC7A11 through ubiquitination, causing its

depletion and the consequent accumulation of ROS and iron (118). In addition, suppressor of

cytokine signaling 2 can enhance the degradation of K48-linked

polyubiquitinated SLC7A11, and thus, promote ferroptosis to enhance

the sensitivity of HCC radiotherapy (119). Ferroptosis inducer erastin and

photosensitizer are ultrasonically treated with CD47-transfected

donor cells to form engineered exosomes to cause ferroptosis in HCC

and avoid phagocytosis by the mononuclear phagocyte system for

improved anticancer effects (120). In a previous study, since

arsenic trioxide (ATO) could induce ferroptosis, the therapeutic

effect of ATO was enhanced by the construction of arsenic-loaded

mimetic iron oxide nanoparticles, specifically magnetic

nanoparticles containing ATO that were camouflaged with HCC cell

membranes (121). In another

study, a novel cascade of copper-based nanocatalysts, which can

result in ferroptosis alone, also enhanced the HCC treatment

effects of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor meloxicam and SOR (122). It has also been reported that

the pH sensitivity of liposomal vesicles is enhanced following

incubation with amphiphilic dendrimers, thereby improving the

delivery of the anticancer drug SOR and the ferroptosis inducer

hemin in the acidic TME, synergistically treating the induction of

ferroptosis and apoptosis (123).

In addition to the previous understanding that SOR

induces the death of hepatoma cells, investigations have also

revealed that SOR could trigger ferroptosis in hepatic stellate

cells (HSCs), as demonstrated in an analysis of liver tissue HSCs

from patients with advanced fibrotic HCC treated with SOR

monotherapy (124,125). Liver fibrosis is a frequent

pathological process that numerous chronic liver diseases undergo

before progressing to cirrhosis and HCC, and the conversion of

quiescent, vitamin A-storing cells into proliferating, fibrotic

myofibroblasts by activated HSCs is a critical step in the

development of hepatic fibrosis; therefore, targeted removal of

HSCs is of great therapeutic significance (126). ELAV-like RNA binding protein 1,

zinc finger protein 36 and N6-methyladenosine can act as regulators

of SOR-induced ferroptosis in HSCs (124,125,127). In addition, artesunate reduces

hepatic fibrosis by triggering ferroptosis in activated HSCs

(128). Furthermore, SOR and

artesunate induce ferroptosis through different pathways, and their

combined use greatly improves the therapeutic effect in HCC

(128). With the rising

development of ICIs, SOR has often been used to assess the

effectiveness of ICIs in treating HCC, such as in the phase III

IMbrave150 and HIMALAYA trials, which demonstrated that the

efficacy of ICI combination therapy was comparable to or better

than that of SOR in patients with advanced HCC (21). Furthermore, clinical trials of

ICIs in combination with SOR (such as NCT03439891 and NCT02988440)

are underway and may provide novel perspectives on the

administration of ICIs in combination with TKIs.

Given the notable anticancer effect of SOR, there

has been an increasing number of studies on the association between

ferroptosis and SOR resistance in HCC. For instance, it has been

found that Yes1 associated transcriptional regulator

(YAP)/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) and

activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) drive resistance to SOR in

HCC by increasing SLC7A11 expression and preventing ferroptosis,

and knockdown of YAP/TAZ expression helped to overcome the SOR

resistance in HCC (30).

Additionally, in SOR-resistant HCC cells, ETS proto-oncogene 1

increases the transcription of microRNA (miR)-23a-3p, which could

directly target the 3'-untranslated region of acyl-CoA synthetase

long chain family member 4 (ACSL4), the key positive regulator of

ferroptosis (47). The

co-delivery of ACSL4 small interfering RNA and miR-23a-3p inhibitor

abolishes the SOR response (47).

Furthermore, metallothionein-1G has been found to facilitate SOR

resistance through inhibition of ferroptosis (129). The genetic and pharmacological

inhibition of MT-1G enhances the anticancer activity of SOR by

inducing ferroptosis of HCC cells (129). A novel photoactive SOR-ruthenium

(II) complex, is irradiated to reduce SOR resistance in HCC by

inducing ferroptosis and disrupting purine metabolism (31). It has also been found that

treatment of HCC with SOR induces macropinocytosis, which replaces

ferroptosis-depleted Cys, and thus, promotes resistance to SOR,

while amiloride can target micropinocytosis (130).

The proliferation of cancer cells depends on lactic

acid, which is produced following glucose consumption via aerobic

glycolysis to provide energy and is closely associated with

ferroptosis (131). For

instance, the glycolytic enzyme α-enolase 1 protects cancer cells

from ferroptosis by reducing mitochondrial iron accumulation

through inhibition of the iron regulatory protein 1/mitoferrin-1

pathway (132). Monocarboxylate

transporter 1 (MCT1)-mediated lactic acid uptake promotes ATP

production and AMP-activated protein kinase inactivation in HCC,

which in turn upregulates downstream stearoyl-coenzyme A

desaturase-1 to enhance the production of anti-ferroptosis

monounsaturated fatty acids (133). Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α also

drives resistance to ferroptosis in solid tumors by promoting

lactate production (134).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)

has long been known to influence tumor progression as a pivotal

regulator of the antioxidant response (135,136). Nuclear accumulation of NRF2 has

been found to activate ferroptosis-associated proteins, while

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), an adaptor of the

Cul3-ubiquitin E3 ligase complex, is responsible for the

degradation of NRF2; in turn, phosphorylated p62 binds Keap1 with

high affinity, thus targeting the p62/Keap1/NRF2 pathway increases

the anticancer activity of elastin and SOR, a process that is

facilitated by disulfiram/Cu (137-139). The GSH S-transferase

Z1/NRF2/GPX4 axis and the leukemia inhibitory factor

receptor/NF-κB/lipocalin-2 axis can also be targeted to promote

ferroptosis, thereby enhancing the sensitivity to SOR in HCC

treatment (140,141).

Necroptosis serves an important role in HCC

development. According to a previous study, the hepatic

microenvironment epigenetically shapes lineage commitment of liver

tumorigenesis, and abnormal activation of hepatocyte oncogenes can

lead to cholangiocarcinoma if adjacent hepatocytes undergo

necroptosis, but hepatocytes regulated by the same oncogenic

factors can develop into HCC cells if they are surrounded by

apoptotic hepatocytes (151).

Deletion of RIPK1, a central element of necroptosis, in hepatocytes

induces downregulation of TRAF2, leading to impaired caspase-8

activation and NF-κB activation; therefore, the

RIPK1/TRAF2/caspase-8 pathway has a notable influence on the

development of HCC (152). As

confirmed by a previous study, the NF-κB signaling pathway is an

important player in necroptosis (153). Apigetrin and deferasirox exert

anti-HCC effects by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway to

induce necroptosis (43,154). HSP90α has been found to bind

with the necrosome complex and promotes chaperone-mediated

autophagy degradation, which leads to necroptosis blocking and

results in SOR resistance (48).

The HSP90 inhibitor 17-allylamino demethoxygeldanamycin could

inhibit HSP90α activity and reverse SOR resistance in HCC by

activating necroptosis (48).

FADD, RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL are key signaling molecules in

necroptosis, and miR-675 could target FADD to induce necroptosis

and inhibit HCC progression via the RIPK3/MLKL axis (155), and rapamycin could induce HCC

cell necroptosis via the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway

(156). A recent study has found

that, as the liver progressively ages, necroptosis increases, which

in turn continuously exacerbates chronic liver inflammation, thus

exacerbating the HCC transition (157). This necroptosis-mediated liver

inflammation process may be prevented by β-carotene and

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (158,159). In addition, excess sorbitol

dehydrogenase (SORD) in HCC cells could inhibit tumor growth and

stemness by enhancing necroptosis signaling, and treatment with

human recombinant SORD controlled HCC cell growth and regulated

macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment (160). Nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) and

Linc00176 are also associated with HCC cell necroptosis, and

inhibition of NUPR1 with small compound ZZW-115 and deletion of

Linc00176 could induce necroptosis and exert anti-HCC effects

(161,162). In addition, connexin 32 has been

found to bind to Src and then mediate the inactivation of caspase 8

to trigger necroptosis in HCC cells, which could be used as an

anticancer target to enhance the function of necroptosis inducers

(163).

During the treatment of tumors, ferroptosis,

pyroptosis and necroptosis are closely associated with the immune

response (50,95,164). It has been found that

immunotherapy-activated CD8+ T cells could induce

ferroptosis of tumor cells by downregulating the expression of

SLC3A2 and SLC7A11, and ferroptosis inducers in combination with

checkpoint blockade synergistically enhanced antitumor efficacy

(164). Similarly,

CD8+ T cells have also been found to trigger tumor

clearance through activation of the GSDM granzyme axis to induce

pyroptosis (95,165), as have NK cells (93,95). Furthermore, necroptotic tumor

cells can release damage-associated molecular patterns such as heat

shock proteins, being more immunogenic than naïve tumor cells, to

activate the immune system with the participation of

CD8+ T cells, NK cells and dendritic cells (DCs)

(166-168), which may be related to the

activation of NF-κB (50).

Necrotic tumor cells, as well as fibroblast vaccination, contribute

to the induction of antitumor immunogenicity by necrotic apoptotic

cells (50,167,169), which enhances the antitumor

efficacy of ICI treatments (167).

The relationship between ferroptosis and the tumor

immune response is complicated. It has been demonstrated that

GPX4-associated ferroptotic hepatocyte death could cause a

HCC-suppressive immune response, characterized by a C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand 10-dependent infiltration of cytotoxic

CD8+ T cells that is counterbalanced by PD-L1

upregulation on tumor cells, as well as by a marked high mobility

group box 1-mediated myeloid derived suppressor cell (MDSC)

infiltration (170). A triple

combination of the ferroptosis-inducing natural compound withaferin

A, the C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 inhibitor SB225002 and

α-PD-1 contributed to improved treatment of HCC compared with

single treatment or dual combinations (170). In addition, inhibition of

phosphoglycerate mutase 1 promotes ferroptosis and downregulates

PD-L1 expression in HCC cells, further enhancing the infiltration

of CD8+ T cells, and thereby exerting antitumor effects

(36). Furthermore, TLR2 agonist

Pam3CSK4 could promote polarization of MDSCs into DCs and

macrophages and recovery of T cell function by downregulating the

expression of RUNX family transcription factor 1 (RUNX1), and TLR2

and RUNX1 may exert a regulatory effect on MDSCs by increasing ROS,

which is related to the ferroptosis pathway (171).

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), a key

tumor-infiltrating immune cell type in the TME, encourage tumor

invasion and metastasis by switching from the pro-inflammatory and

antitumor type M1 TAMs to the anti-inflammatory and pro-tumor type

M2 TAMs (172). Previous studies

have demonstrated that TAMs generally exhibit a pro-tumor phenotype

and inhibit CTLs by expressing PD-L1, thereby inducing immune

escape and tolerance (173-175). Inhibition of apolipoprotein C1

can reverse the M2 phenotype to the M1 phenotype in TAMs via the

ferroptosis pathway, enhancing the effect of anti-PD-1

immunotherapy and exerting anti-HCC effects (176). Injection of dextran chitosan

hydrogel can induce the repolarization of macrophages to the

M1-like phenotype, and promote the maturation and activation of

DCs, and combined treatment with PD-1 immunotherapy can effectively

treat the peritoneal dissemination of advanced HCC and malignant

ascites (37). A recent study

also revealed that inhibition of the heavy chain subunit from

system Xc- encoded by the SLC7A11 gene (xCT) could

induce ferroptosis of TAMs via the GPX4/ribonucleotide reductase

regulatory subunit M2 signaling pathway and inhibit M2-type

polarization via the suppressor of cytokine signaling

3/STAT6/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ pathway

(35). Furthermore, this xCT

inhibition-mediated macrophage ferroptosis increased PD-L1

expression in macrophages and improved the antitumor efficacy of

anti-PD-L1 therapy (35).

TKIs can remodel the TME of HCC and alter the

immunosuppressive microenvironment, which is closely connected to

pyroptosis, NK cells, T cells and regulatory T cells (177). Among them, SOR is a multi-target

kinase inhibitor that directly modulates immunity, causing HCC cell

death by inducing macrophage pyroptosis and activating cytotoxic NK

cells (41). A study has found

that the pyroptosis-score (PYS) could be used to assess the

prognosis of patients with HCC due to hepatitis B virus (HBV-HCC),

as a higher PYS in patients with HBV-HCC was associated with a

worse prognosis, and these patients were more likely to receive

anti-PD-L1 therapy (178). In

addition, a risk score model related to pyroptosis can be

constructed to predict the prognosis and immunological

characteristics of HCC (38).

The interaction of necroptosis and the immune

response is considered to be important in HCC development and

treatment because necroptosis is a primary cause of liver

inflammation and upregulates not only proinflammatory M1 TAMs, but

also proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, ultimately leading

to chronic liver disease (179).

However, a study has reported that RIPK3 is not expressed in

hepatocytes, and MLKL does not depend on RIPK3 alone to regulate

endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondrial Mg2+ dynamics

(108). Defective MLKL inhibits

mitochondrial Mg2+ absorption and ER Mg2+

release, and the resulting metabolic stress, in turn, induces

parthanatos [a form of ICD associated with antitumor immunity

(180)], activates anticancer

immune responses and increases the therapeutic impact of ICIs,

inhibiting HCC progression and immune escape (181). Similarly, RIPK3 defects in TAMs

activate PPAR and promote fatty acid metabolism, which in turn

induces the accumulation and polarization of M2 TAMs and ultimately

promotes HCC progression (182).

In addition, higher expression levels of RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL, are

associated with good prognosis in HCC and are especially positively

associated with CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in HCC

(183). However, monoclonal

antibodies targeting CD147 structural domain 1 can induce atypical

necroptosis independent of RIPK (184). Furthermore, both senescence and

SORD induce necroptosis in HCC cells and promote M1 TAM

polarization (157,160).

In conclusion, induction of ferroptosis, pyroptosis

and necroptosis is a novel avenue for killing HCC cells, providing

novel targets and signaling pathways for drug discovery, increasing

treatment effectiveness of immunotherapy, and possibly addressing

drug resistance. The combination of ferroptosis, pyroptosis and

necroptosis targets with ICIs may improve the therapeutic effect

and prognosis in patients with advanced HCC. However, some problems

still remain. First, although several compounds or drugs that

induce ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis have been

identified, clinical studies to assess their feasibility and safety

are lacking. Therefore, more research should be performed in the

future to improve the safety and personalized treatment options of

this treatment avenue. Second, clinical studies of novel drugs or

therapies for HCC are usually long and costly, which makes it

difficult to develop novel medicines and treatments based on

ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis. Third, the significance

and mechanisms of ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis in HCC

still need to be elaborated in further detail.

Not applicable.

RJL and XDY wrote the manuscript. RJL drew the

figures. SSY and ZWG participated in the conception of the

manuscript. XBZ and YSZ revised the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Fundamental Research

Funds for the Central Universities, Beijing University of Chinese

Medicine (grant no. 2021-JYB-XJSJJ-055), Beijing Traditional

Chinese Medicine 'Torch Inheritance 3+3 Project'-the Wang Pei

Famous Doctor Inheritance Workstation-Dongzhimen Hospital Branch

(grant no. 405120602) and 'Talent development program of Dongzhimen

Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine'.

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

|

|

2

|

Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, Eslahi M,

Ginsburg O, Lauby-Secretan B, Arbyn M, Basu P, Bray F and

Vaccarella S: Global estimates of incidence and mortality of

cervical cancer in 2020: A baseline analysis of the WHO global

cervical cancer elimination initiative. Lancet Glob Health.

11:e197–e206. 2023.

|

|

3

|

van Malenstein H, van Pelt J and Verslype

C: Molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma anno 2011.

Eur J Cancer. 47:1789–1797. 2011.

|

|

4

|

Park YN: Update on precursor and early

lesions of hepatocellular carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

135:704–715. 2011.

|

|

5

|

Trevisani F, Cantarini MC, Wands JR and

Bernardi M: Recent advances in the natural history of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 29:1299–1305. 2008.

|

|

6

|

Choi JY, Lee JM and Sirlin CB: CT and MR

imaging diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: Part I.

Development, growth, and spread: Key pathologic and imaging

aspects. Radiology. 272:635–654. 2014.

|

|

7

|

Komuta M: Histological heterogeneity of

primary liver cancers: Clinical relevance, diagnostic pitfalls and

the pathologist's role. Cancers (Basel). 13:28712021.

|

|

8

|

Berardi G, Igarashi K, Li CJ, Ozaki T,

Mishima K, Nakajima K, Honda M and Wakabayashi G: Parenchymal

sparing anatomical liver resections with full laparoscopic

approach: Description of technique and short-term results. Ann

Surg. 273:785–791. 2021.

|

|

9

|

Clavien PA, Lesurtel M, Bossuyt PM, Gores

GJ, Langer B and Perrier A; OLT for HCC Consensus Group:

Recommendations for liver transplantation for hepatocellular

carcinoma: An international consensus conference report. Lancet

Oncol. 13:e11–e22. 2012.

|

|

10

|

Pan T, Xie QK, Lv N, Li XS, Mu LW, Wu PH

and Zhao M: Percutaneous CT-guided radiofrequency ablation for

lymph node oligometastases from hepatocellular carcinoma: A

propensity score-matching analysis. Radiology. 282:259–270.

2017.

|

|

11

|

Cabibbo G, Enea M, Attanasio M, Bruix J,

Craxì A and Cammà C: A meta-analysis of survival rates of untreated

patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatology. 51:1274–1283. 2010.

|

|

12

|

Xing R, Gao J, Cui Q and Wang Q:

Strategies to improve the antitumor effect of immunotherapy for

hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 12:7832362021.

|

|

13

|

Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard

P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A,

et al: Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. New Engl J

Med. 359:378–390. 2008.

|

|

14

|

Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K,

Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park JW, Han G, Jassem J, et al: Lenvatinib

versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with

unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised phase 3

non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 391:1163–1173. 2018.

|

|

15

|

Reig M, Torres F, Rodriguez-Lope C, Forner

A, LLarch N, Rimola J, Darnell A, Ríos J, Ayuso C and Bruix J:

Early dermatologic adverse events predict better outcome in HCC

patients treated with sorafenib. J Hepatol. 61:318–324. 2014.

|

|

16

|

Chen S, Cao Q, Wen W and Wang H: Targeted

therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: Challenges and opportunities.

Cancer Lett. 460:1–9. 2019.

|

|

17

|

Greten TF, Lai CW, Li G and

Staveley-O'Carroll KF: Targeted and immune-based therapies for

hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 156:510–524. 2019.

|

|

18

|

El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi

TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling TH Rd, et al:

Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

(CheckMate 040): An open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose

escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 389:2492–2502. 2017.

|

|

19

|

Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S,

Ogasawara S, Palmer D, Verslype C, Zagonel V, Fartoux L, Vogel A,

et al: Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular

carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): A

non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 19:940–952.

2018.

|

|

20

|

Galle PR, Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Zhu AX,

Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb A, et al: Patient-reported

outcomes with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib in

patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave150):

An open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

22:991–1001. 2021.

|

|

21

|

Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR,

Ducreux M, Kim TY, Lim HY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, et al:

Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus

bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Hepatol. 76:862–873. 2022.

|

|

22

|

Kelley RK, Sangro B, Harris W, Ikeda M,

Okusaka T, Kang YK, Qin S, Tai DW, Lim HY, Yau T, et al: Safety,

efficacy, and pharmacodynamics of tremelimumab plus durvalumab for

patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Randomized

expansion of a phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol. 39:2991–3001.

2021.

|

|

23

|

Giannini EG, Aglitti A, Borzio M, Gambato

M, Guarino M, Iavarone M, Lai Q, Levi Sandri GB, Melandro F,

Morisco F, et al: Overview of immune checkpoint inhibitors therapy

for hepatocellular carcinoma, and the ITA.LI.CA cohort derived

estimate of amenability rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors in

clinical practice. Cancers (Basel). 11:16892019.

|

|

24

|

Greten TF, Abou-Alfa GK, Cheng AL, Duffy

AG, El-Khoueiry AB, Finn RS, Galle PR, Goyal L, He AR, Kaseb AO, et

al: Society for immunotherapy of cancer (SITC) clinical practice

guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 9:e0027942021.

|

|

25

|

Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron

AD, Kudo M, Okusaka T, Kobayashi M, Kumada H, Kaneko S, et al:

Phase Ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with

unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 38:2960–2970.

2020.

|

|

26

|

Wang Z, Wang Y, Gao P and Ding J: Immune

checkpoint inhibitor resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer

Lett. 555:2160382023.

|

|

27

|

Dolladille C, Ederhy S, Sassier M, Cautela

J, Thuny F, Cohen AA, Fedrizzi S, Chrétien B, Da-Silva A, Plane AF,

et al: Immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge after immune-related

adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 6:865–871.

2020.

|

|

28

|

Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X,

Li Z, Traugh N, Bu X, Li B, et al: Signatures of T cell dysfunction

and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med.

24:1550–1558. 2018.

|

|

29

|

Nyiramana MM, Cho SB, Kim EJ, Kim MJ, Ryu

JH, Nam HJ, Kim NG, Park SH, Choi YJ, Kang SS, et al: Sea hare

hydrolysate-induced reduction of human non-small cell lung cancer

cell growth through regulation of macrophage polarization and

non-apoptotic regulated cell death pathways. Cancers (Basel).

12:7262020.

|

|

30

|

Gao R, Kalathur RKR, Coto-Llerena M, Ercan

C, Buechel D, Shuang S, Piscuoglio S, Dill MT, Camargo FD,

Christofori G and Tang F: YAP/TAZ and ATF4 drive resistance to

Sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma by preventing ferroptosis.

EMBO Mol Med. 13:e143512021.

|

|

31

|

Lai Y, Lu N, Luo S, Wang H and Zhang P: A

photoactivated sorafenib-ruthenium(II) prodrug for resistant

hepatocellular carcinoma therapy through ferroptosis and purine

metabolism disruption. J Med Chem. 65:13041–13051. 2022.

|

|

32

|

Rosenbaum SR, Wilski NA and Aplin AE:

Fueling the fire: Inflammatory forms of cell death and implications

for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 11:266–281. 2021.

|

|

33

|

Hadian K and Stockwell BR: The therapeutic

potential of targeting regulated non-apoptotic cell death. Nat Rev

Drug Discov. 22:723–742. 2023.

|

|

34

|

Gao W, Wang X, Zhou Y, Wang X and Yu Y:

Autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in tumor

immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1962022.

|

|

35

|

Tang B, Zhu J, Wang Y, Chen W, Fang S, Mao

W, Xu Z, Yang Y, Weng Q, Zhao Z, et al: Targeted xCT-mediated

ferroptosis and protumoral polarization of macrophages is effective

against HCC and enhances the efficacy of the anti-PD-1/L1 response.

Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e22039732023.

|

|

36

|

Zheng Y, Wang Y, Lu Z, Wan J, Jiang L,

Song D, Wei C, Gao C, Shi G, Zhou J, et al: PGAM1 inhibition

promotes HCC ferroptosis and synergizes with anti-PD-1

immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e23019282023.

|

|

37

|

Meng J, Yang X, Huang J, Tuo Z, Hu Y, Liao

Z, Tian Y, Deng S, Deng Y, Zhou Z, et al: Ferroptosis-enhanced

immunotherapy with an injectable dextran-chitosan hydrogel for the

treatment of malignant ascites in hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 10:e23005172023.

|

|

38

|

Wang H, Zhang B, Shang Y, Chen F, Fan Y

and Tan K: A novel risk score model based on pyroptosis-related

genes for predicting survival and immunogenic landscape in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 15:1412–1444.

2023.

|

|

39

|

Peng YL, Wang LX, Li MY, Liu LP and Li RS:

Construction and validation of a prognostic signature based on

necroptosis-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One.

18:e2797442023.

|

|

40

|

Wang Y, Wang Y, Pan J, Gan L and Xue J:

Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in cancer: Crucial cell

death types in radiotherapy and post-radiotherapy immune

activation. Radiother Oncol. 184:1096892023.

|

|

41

|

Hage C, Hoves S, Strauss L, Bissinger S,

Prinz Y, Pöschinger T, Kiessling F and Ries CH: Sorafenib induces

pyroptosis in macrophages and triggers natural killer cell-mediated

cytotoxicity against hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology.

70:1280–1297. 2019.

|

|

42

|

Li Y, Yang W, Zheng Y, Dai W, Ji J, Wu L,

Cheng Z, Zhang J, Li J, Xu X, et al: Targeting fatty acid synthase

modulates sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib via

ferroptosis. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 42:62023.

|

|

43

|

Bhosale PB, Abusaliya A, Kim HH, Ha SE,

Park MY, Jeong SH, Vetrivel P, Heo JD, Kim JA, Won CK, et al:

Apigetrin promotes TNFα-induced apoptosis, necroptosis, G2/M phase

cell cycle arrest, and ROS generation through inhibition of NF-κB

pathway in Hep3B liver cancer cells. Cells. 11:27342022.

|

|

44

|

Wang Q, Wang Y, Ding J, Wang C, Zhou X,

Gao W, Huang H, Shao F and Liu Z: A bioorthogonal system reveals

antitumour immune function of pyroptosis. Nature. 579:421–426.

2020.

|

|

45

|

Xu C, Sun S, Johnson T, Qi R, Zhang S,

Zhang J and Yang K: The glutathione peroxidase Gpx4 prevents lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis to sustain Treg cell activation and

suppression of antitumor immunity. Cell Rep. 35:1092352021.

|

|

46

|

Wang W, Marinis JM, Beal AM, Savadkar S,

Wu Y, Khan M, Taunk PS, Wu N, Su W, Wu J, et al: RIP1 kinase drives

macrophage-mediated adaptive immune tolerance in pancreatic cancer.

Cancer Cell. 34:757–774.e7. 2018.

|

|

47

|

Lu Y, Chan YT, Tan HY, Zhang C, Guo W, Xu

Y, Sharma R, Chen ZS, Zheng YC, Wang N and Feng Y: Epigenetic

regulation of ferroptosis via ETS1/miR-23a-3p/ACSL4 axis mediates

sorafenib resistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 41:32022.

|

|

48

|

Liao Y, Yang Y, Pan D, Ding Y, Zhang H, Ye

Y, Li J and Zhao L: HSP90α mediates sorafenib resistance in human

hepatocellular carcinoma by necroptosis inhibition under hypoxia.

Cancers (Basel). 13:2432021.

|

|

49

|

Tang R, Xu J, Zhang B, Liu J, Liang C, Hua

J, Meng Q, Yu X and Shi S: Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis

in anticancer immunity. J Hematol Oncol. 13:1102020.

|

|

50

|

Aaes TL, Kaczmarek A, Delvaeye T, De

Craene B, De Koker S, Heyndrickx L, Delrue I, Taminau J, Wiernicki

B, De Groote P, et al: Vaccination with necroptotic cancer cells

induces efficient anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep. 15:274–287.

2016.

|

|

51

|

Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O,

Agostinis P and Vandenabeele P: Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in

cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:860–875. 2012.

|

|

52

|

Davola ME, Cormier O, Vito A, El-Sayes N,

Collins S, Salem O, Revill S, Ask K, Wan Y and Mossman K: Oncolytic

BHV-1 is sufficient to induce immunogenic cell death and synergizes

with low-dose chemotherapy to dampen immunosuppressive T regulatory

cells. Cancers (Basel). 15:12952023.

|

|

53

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012.

|

|

54

|

Tang D, Chen X, Kang R and Kroemer G:

Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell

Res. 31:107–125. 2021.

|

|

55

|

Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth

B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, Herbach N, Aichler M, Walch

A, Eggenhofer E, et al: Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator

Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol.

16:1180–1191. 2014.

|

|

56

|

Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius

E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A,

et al: ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular

lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 13:91–98. 2017.

|

|

57

|

Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis turns 10:

Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic

applications. Cell. 185:2401–2421. 2022.

|

|

58

|

Stockwell BR, Jiang X and Gu W: Emerging

mechanisms and disease relevance of ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol.

30:478–490. 2020.

|

|

59

|

Shah R, Shchepinov MS and Pratt DA:

Resolving the role of lipoxygenases in the initiation and execution

of ferroptosis. ACS Central Sci. 4:387–396. 2018.

|

|

60

|

Patel SJ, Protchenko O, Shakoury-Elizeh M,

Baratz E, Jadhav S and Philpott CC: The iron chaperone and nucleic

acid-binding activities of poly(rC)-binding protein 1 are separable

and independently essential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

118:e21046661182021.

|

|

61

|

Bloomer SA and Brown KE: Hepcidin and iron

metabolism in experimental liver injury. Am J Pathol.

191:1165–1179. 2021.

|

|

62

|

Zhang HL, Hu BX, Li ZL, Du T, Shan JL, Ye

ZP, Peng XD, Li X, Huang Y, Zhu XY, et al: PKCβII phosphorylates

ACSL4 to amplify lipid peroxidation to induce ferroptosis. Nat Cell

Biol. 24:88–98. 2022.

|

|

63

|

Zou Y, Li H, Graham ET, Deik AA, Eaton JK,

Wang W, Sandoval-Gomez G, Clish CB, Doench JG and Schreiber SL:

Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase contributes to phospholipid

peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 16:302–309. 2020.

|

|

64

|

Shimada K, Skouta R, Kaplan A, Yang WS,

Hayano M, Dixon SJ, Brown LM, Valenzuela CA, Wolpaw AJ and

Stockwell BR: Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals

metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 12:497–503.

2016.

|

|

65

|

Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P and Vanden

Berghe T: Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell.

35:830–849. 2019.

|

|

66

|

Cao JY, Poddar A, Magtanong L, Lumb JH,

Mileur TR, Reid MA, Dovey CM, Wang J, Locasale JW, Stone E, et al:

A genome-wide haploid genetic screen identifies regulators of

glutathione abundance and ferroptosis sensitivity. Cell Rep.

26:1544–1556.e8. 2019.

|

|

67

|

Hao S, Yu J, He W, Huang Q, Zhao Y, Liang

B, Zhang S, Wen Z, Dong S, Rao J, et al: Cysteine dioxygenase 1

mediates erastin-induced ferroptosis in human gastric cancer cells.

Neoplasia. 19:1022–1032. 2017.

|

|

68

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong

L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, et al:

The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit

ferroptosis. Nature. 575:688–692. 2019.

|

|

69

|

Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee

H, Koppula P, Wu S, Zhuang L, Fang B, et al: DHODH-mediated

ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer.

Nature. 593:586–590. 2021.

|

|

70

|

Liu Y, Lu S, Wu LL, Yang L, Yang L and

Wang J: The diversified role of mitochondria in ferroptosis in

cancer. Cell Death Dis. 14:5192023.

|

|

71

|

Gao M, Yi J, Zhu J, Minikes AM, Monian P,

Thompson CB and Jiang X: Role of mitochondria in ferroptosis. Mol

Cell. 73:354–363.e3. 2019.

|

|

72

|

Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T,

Hibshoosh H, Baer R and Gu W: Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated

activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 520:57–62. 2015.

|

|

73

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP cyclohydrolase

1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Central Sci. 6:41–53. 2020.

|

|

74

|

Soula M, Weber RA, Zilka O, Alwaseem H, La

K, Yen F, Molina H, Garcia-Bermudez J, Pratt DA and Birsoy K:

Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to canonical

ferroptosis inducers. Nat Chem Biol. 16:1351–1360. 2020.

|

|

75

|

Zeitler L, Fiore A, Meyer C, Russier M,

Zanella G, Suppmann S, Gargaro M, Sidhu SS, Seshagiri S, Ohnmacht

C, et al: Anti-ferroptotic mechanism of IL4i1-mediated amino acid

metabolism. Elife. 10:e648062021.

|

|

76

|

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y,

Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F and Shao F: Cleavage of GSDMD by

inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature.

526:660–665. 2015.

|

|

77

|

Cookson BT and Brennan MA:

Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol.

9:113–114. 2001.

|

|

78

|

Hou J, Hsu JM and Hung MC: Molecular

mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis in inflammation and

antitumor immunity. Mol Cell. 81:4579–4590. 2021.

|

|

79

|

Liu Z, Wang C, Yang J, Zhou B, Yang R,

Ramachandran R, Abbott DW and Xiao TS: Crystal structures of the

full-length murine and human gasdermin D reveal mechanisms of

autoinhibition, lipid binding, and oligomerization. Immunity.

51:43–49.e4. 2019.

|

|

80

|

Ding J, Wang K, Liu W, She Y, Sun Q, Shi

J, Sun H, Wang DC and Shao F: Pore-forming activity and structural

autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature. 535:111–116.

2016.

|

|

81

|

Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli

VG, Wu H and Lieberman J: Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes

pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature. 535:153–158.

2016.

|

|

82

|

Aglietti RA and Dueber EC: Recent insights

into the molecular mechanisms underlying pyroptosis and gasdermin

family functions. Trends Immunol. 38:261–271. 2017.

|

|

83

|

Fink SL and Cookson BT: Pillars article:

Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to

osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell Microbiol.

2006.8:1812–1825

J Immunol. 202:1913–1926. 2019.

|

|

84

|

Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O'Rourke K,

Anderson K, Warming S, Cuellar T, Haley B, Roose-Girma M, Phung QT,

et al: Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical

inflammasome signalling. Nature. 526:666–671. 2015.

|

|

85

|

Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande

Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, Newton K, Qu Y, Liu J, Heldens S, et al:

Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature.

479:117–121. 2011.

|

|

86

|

Yang D, He Y, Muñoz-Planillo R, Liu Q and

Núñez G: Caspase-11 requires the pannexin-1 channel and the

purinergic P2X7 pore to mediate pyroptosis and endotoxic shock.

Immunity. 43:923–932. 2015.

|

|

87

|

Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H,

Wang K and Shao F: Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through

caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature. 547:99–103. 2017.

|

|

88

|

Hou J, Zhao R, Xia W, Chang CW, You Y, Hsu

JM, Nie L, Chen Y, Wang YC, Liu C, et al: PD-L1-mediated gasdermin

C expression switches apoptosis to pyroptosis in cancer cells and

facilitates tumour necrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 22:1264–1275. 2020.

|

|

89

|

Rogers C, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Mayes L,

Alnemri D, Cingolani G and Alnemri ES: Cleavage of DFNA5 by

caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary

necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat Commun. 8:141282017.

|

|

90

|

Orning P, Weng D, Starheim K, Ratner D,

Best Z, Lee B, Brooks A, Xia S, Wu H, Kelliher MA, et al: Pathogen

blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin

D and cell death. Science. 362:1064–1069. 2018.

|

|

91

|

Sarhan J, Liu BC, Muendlein HI, Li P,

Nilson R, Tang AY, Rongvaux A, Bunnell SC, Shao F, Green DR and

Poltorak A: Caspase-8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit

pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

115:E10888–E10897. 2018.

|

|

92

|

Liu Y, Fang Y, Chen X, Wang Z, Liang X,

Zhang T, Liu M, Zhou N, Lv J, Tang K, et al: Gasdermin E-mediated

target cell pyroptosis by CAR T cells triggers cytokine release

syndrome. Sci Immunol. 5:eaax79692020.

|

|

93

|

Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Xia S, Kong Q, Li S, Liu

X, Junqueira C, Meza-Sosa KF, Mok TMY, Ansara J, et al: Gasdermin E

suppresses tumour growth by activating anti-tumour immunity.

Nature. 579:415–420. 2020.

|

|

94

|

Erkes DA, Cai W, Sanchez IM, Purwin TJ,

Rogers C, Field CO, Berger AC, Hartsough EJ, Rodeck U, Alnemri ES

and Aplin AE: Mutant BRAF and MEK inhibitors regulate the tumor

immune microenvironment via pyroptosis. Cancer Discov. 10:254–269.

2020.

|

|

95

|

Zhou Z, He H, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Su Y,

Wang Y, Li D, Liu W, Zhang Y, et al: Granzyme A from cytotoxic

lymphocytes cleaves GSDMB to trigger pyroptosis in target cells.

Science. 368:eaaz75482020.

|

|

96

|

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Gao W, Ding J, Li

P, Hu L and Shao F: Inflammatory caspases are innate immune

receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature. 514:187–192. 2014.

|

|

97

|

Deets KA and Vance RE: Inflammasomes and

adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 22:412–422. 2021.

|

|

98

|

Guo H, Callaway JB and Ting JP:

Inflammasomes: Mechanism of action, role in disease, and

therapeutics. Nat Med. 21:677–687. 2015.

|

|

99

|

Wang K, Sun Q, Zhong X, Zeng M, Zeng H,

Shi X, Li Z, Wang Y, Zhao Q, Shao F and Ding J: Structural

mechanism for GSDMD targeting by autoprocessed caspases in

pyroptosis. Cell. 180:941–955.e20. 2020.

|

|

100

|

Loveless R, Bloomquist R and Teng Y:

Pyroptosis at the forefront of anticancer immunity. J Exp Clin Canc

Res. 40:2642021.

|

|

101

|

Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap

P, Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA and Yuan J:

Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic

potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 1:112–119.

2005.

|

|

102

|

Frank D and Vince JE: Pyroptosis versus

necroptosis: Similarities, differences, and crosstalk. Cell Death

Differ. 26:99–114. 2019.

|

|

103

|

Choi ME, Price DR, Ryter SW and Choi AMK:

Necroptosis: A crucial pathogenic mediator of human disease. JCI

Insight. 4:e1288342019.

|

|

104

|

Lork M, Verhelst K and Beyaert R: CYLD,

A20 and OTULIN deubiquitinases in NF-κB signaling and cell death:

So similar, yet so different. Cell Death Differ. 24:1172–1183.

2017.

|

|

105

|

Priem D, van Loo G and Bertrand MJM: A20

and cell death-driven inflammation. Trends Immunol. 41:421–435.

2020.

|

|

106

|

Ye K, Chen Z and Xu Y: The double-edged

functions of necroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 14:1632023.

|

|

107

|

Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Kellert B,

Dimitrova DP, Langlais C, Hupe M, Cain K, MacFarlane M, Häcker G

and Leverkus M: cIAPs block Ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/caspase-8

containing intracellular cell death complex differentially

regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Mol Cell. 43:449–463. 2011.

|

|

108

|

Mompeán M, Li W, Li J, Laage S, Siemer AB,

Bozkurt G, Wu H and McDermott AE: The structure of the necrosome

RIPK1-RIPK3 core, a human hetero-amyloid signaling complex. Cell.

173:1244–1253.e10. 2018.

|

|

109

|

Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao

D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X and Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase

domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3

kinase. Cell. 148:213–227. 2012.

|

|

110

|

Kaczmarek A, Vandenabeele P and Krysko DV:

Necroptosis: The release of damage-associated molecular patterns

and its physiological relevance. Immunity. 38:209–223. 2013.

|

|

111

|

Kaiser WJ, Sridharan H, Huang C, Mandal P,

Upton JW, Gough PJ, Sehon CA, Marquis RW, Bertin J and Mocarski ES:

Toll-like receptor 3-mediated necrosis via TRIF, RIP3, and MLKL. J

Biol Chem. 288:31268–31279. 2013.

|

|

112

|

Zhang W, Fan W, Guo J and Wang X: Osmotic

stress activates RIPK3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis by increasing

cytosolic pH through a plasma membrane Na+/H+

exchanger. Sci Signal. 15:eabn58812022.

|

|

113

|

Coriat R, Nicco C, Chéreau C, Mir O,

Alexandre J, Ropert S, Weill B, Chaussade S, Goldwasser F and

Batteux F: Sorafenib-induced hepatocellular carcinoma cell death

depends on reactive oxygen species production in vitro and in vivo.

Mol Cancer Ther. 11:2284–2293. 2012.

|

|

114

|

Louandre C, Ezzoukhry Z, Godin C, Barbare

JC, Mazière JC, Chauffert B and Galmiche A: Iron-dependent cell

death of hepatocellular carcinoma cells exposed to sorafenib. Int J

Cancer. 133:1732–1742. 2013.

|

|

115

|

Huang CY, Chen LJ, Chen G, Chao TI and

Wang CY: SHP-1/STAT3-signaling-axis-regulated coupling between

BECN1 and SLC7A11 contributes to sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 23:110922022.

|

|

116

|

Suzuki S, Venkatesh D, Kanda H, Nakayama

A, Hosokawa H, Lee E, Miki T, Stockwell BR, Yokote K, Tanaka T and

Prives C: GLS2 is a tumor suppressor and a regulator of ferroptosis

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 82:3209–3222. 2022.

|

|

117

|

Chen Y, Li L, Lan J, Cui Y, Rao X, Zhao J,

Xing T, Ju G, Song G, Lou J and Liang J: CRISPR screens uncover

protective effect of PSTK as a regulator of chemotherapy-induced

ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 21:112022.

|

|

118

|

Zhang B, Bao W, Zhang S, Chen B, Zhou X,

Zhao J, Shi Z, Zhang T, Chen Z, Wang L, et al: LncRNA HEPFAL

accelerates ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating

SLC7A11 ubiquitination. Cell Death Dis. 13:7342022.

|

|

119

|

Chen Q, Zheng W, Guan J, Liu H, Dan Y, Zhu

L, Song Y, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Zhang Y, et al: SOCS2-enhanced

ubiquitination of SLC7A11 promotes ferroptosis and

radiosensitization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Differ.

30:137–151. 2023.

|

|

120

|

Du J, Wan Z, Wang C, Lu F, Wei M, Wang D

and Hao Q: Designer exosomes for targeted and efficient ferroptosis

induction in cancer via chemo-photodynamic therapy. Theranostics.

11:8185–8196. 2021.

|

|

121

|

Liu J, Li X, Chen J, Zhang X, Guo J, Gu J,

Mei C, Xiao Y, Peng C, Liu J, et al: Arsenic-loaded biomimetic iron

oxide nanoparticles for enhanced ferroptosis-inducing therapy of

hepatocellular carcinoma. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 15:6260–6273.

2023.

|

|

122

|

Tian H, Zhao S, Nice EC, Huang C, He W,

Zou B and Lin J: A cascaded copper-based nanocatalyst by modulating

glutathione and cyclooxygenase-2 for hepatocellular carcinoma

therapy. J Colloid Interface Sci. 607:1516–1526. 2022.

|

|

123

|

Su Y, Zhang Z, Lee LTO, Peng L, Lu L, He X

and Zhang X: Amphiphilic dendrimer doping enhanced ph-sensitivity

of liposomal vesicle for effective co-delivery toward synergistic

ferroptosis-apoptosis therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv

Healthc Mater. 12:e22026632023.

|

|

124

|

Zhang Z, Yao Z, Wang L, Ding H, Shao J,

Chen A, Zhang F and Zheng S: Activation of ferritinophagy is

required for the RNA-binding protein ELAVL1/HuR to regulate

ferroptosis in hepatic stellate cells. Autophagy. 14:2083–2103.

2018.

|

|

125

|

Zhang Z, Guo M, Li Y, Shen M, Kong D, Shao

J, Ding H, Tan S, Chen A, Zhang F and Zheng S: RNA-binding protein

ZFP36/TTP protects against ferroptosis by regulating autophagy

signaling pathway in hepatic stellate cells. Autophagy.

16:1482–1505. 2020.

|

|

126

|

Tsuchida T and Friedman SL: Mechanisms of

hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

14:397–411. 2017.

|

|

127

|

Shen M, Li Y, Wang Y, Shao J, Zhang F, Yin

G, Chen A, Zhang Z and Zheng S: N6-methyladenosine

modification regulates ferroptosis through autophagy signaling

pathway in hepatic stellate cells. Redox Biol. 47:1021512021.

|

|

128

|

Li ZJ, Dai HQ, Huang XW, Feng J, Deng JH,

Wang ZX, Yang XM, Liu YJ, Wu Y, Chen PH, et al: Artesunate

synergizes with sorafenib to induce ferroptosis in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 42:301–310. 2021.

|

|

129

|

Sun X, Niu X, Chen R, He W, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Metallothionein-1G facilitates sorafenib resistance

through inhibition of ferroptosis. Hepatology. 64:488–500.

2016.

|

|

130

|

Byun JK, Lee S, Kang GW, Lee YR, Park SY,

Song IS, Yun JW, Lee J, Choi YK and Park KG: Macropinocytosis is an

alternative pathway of cysteine acquisition and mitigates

sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 41:982022.

|

|

131

|

Byun JK: Tumor lactic acid: A potential

target for cancer therapy. Arch Pharm Res. 46:90–110. 2023.

|

|

132

|

Zhang T, Sun L, Hao Y, Suo C, Shen S, Wei

H, Ma W, Zhang P, Wang T, Gu X, et al: ENO1 suppresses cancer cell

ferroptosis by degrading the mRNA of iron regulatory protein 1. Nat

Cancer. 3:75–89. 2022.

|

|

133

|

Zhao Y, Li M, Yao X, Fei Y, Lin Z, Li Z,

Cai K, Zhao Y and Luo Z: HCAR1/MCT1 regulates tumor ferroptosis

through the lactate-mediated AMPK-SCD1 activity and its therapeutic

implications. Cell Rep. 33:1084872020.

|

|

134

|

Yang Z, Su W, Wei X, Qu S, Zhao D, Zhou J,

Wang Y, Guan Q, Qin C, Xiang J, et al: HIF-1α drives resistance to

ferroptosis in solid tumors by promoting lactate production and

activating SLC1A1. Cell Rep. 42:1129452023.

|

|

135

|

Ma Q: Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and

toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 53:401–426. 2013.

|

|

136

|

Sporn MB and Liby KT: NRF2 and cancer: The

good, the bad and the importance of context. Nat Rev Cancer.

12:564–571. 2012.

|

|

137

|

Ichimura Y, Waguri S, Sou YS, Kageyama S,

Hasegawa J, Ishimura R, Saito T, Yang Y, Kouno T, Fukutomi T, et

al: Phosphorylation of p62 activates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway during

selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 51:618–631. 2013.

|

|

138

|

Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects

against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology.

63:173–184. 2016.

|

|

139

|

Ren X, Li Y, Zhou Y, Hu W, Yang C, Jing Q,

Zhou C, Wang X, Hu J, Wang L, et al: Overcoming the compensatory

elevation of NRF2 renders hepatocellular carcinoma cells more

vulnerable to disulfiram/copper-induced ferroptosis. Redox Biol.

46:1021222021.

|

|

140

|

Wang Q, Bin C, Xue Q, Gao Q, Huang A, Wang

K and Tang N: GSTZ1 sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells to

sorafenib-induced ferroptosis via inhibition of NRF2/GPX4 axis.

Cell Death Dis. 12:4262021.

|

|

141

|

Yao F, Deng Y, Zhao Y, Mei Y, Zhang Y, Liu

X, Martinez C, Su X, Rosato RR, Teng H, et al: A targetable

LIFR-NF-κB-LCN2 axis controls liver tumorigenesis and vulnerability

to ferroptosis. Nat Commun. 12:73332021.

|

|

142

|

Hu J, Dong Y, Ding L, Dong Y, Wu Z, Wang

W, Shen M and Duan Y: Local delivery of arsenic trioxide

nanoparticles for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 4:282019.

|

|

143

|

Shangguan F, Zhou H, Ma N, Wu S, Huang H,

Jin G, Wu S, Hong W, Zhuang W, Xia H and Lan L: A novel mechanism

of cannabidiol in suppressing hepatocellular carcinoma by inducing

GSDME dependent pyroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6978322021.

|

|

144

|

Dai X, Sun F, Deng K, Lin G, Yin W, Chen

H, Yang D, Liu K, Zhang Y and Huang L: Mallotucin D, a clerodane

diterpenoid from croton crassifolius, suppresses HepG2 cell growth

via inducing autophagic cell death and pyroptosis. Int J Mol Sci.

23:142172022.

|

|

145

|

Shen Z, Zhou H, Li A, Wu T, Ji X, Guo L,

Zhu X, Zhang D and He X: Metformin inhibits hepatocellular

carcinoma development by inducing apoptosis and pyroptosis through

regulating FOXO3. Aging (Albany NY). 13:22120–22133. 2021.

|

|

146

|

Chen Z, He M, Chen J, Li C and Zhang Q:

Long non-coding RNA SNHG7 inhibits NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis by

targeting the miR-34a/SIRT1 axis in liver cancer. Oncol Lett.

20:893–901. 2020.

|

|

147

|

Kofahi HM, Taylor NGA, Hirasawa K, Grant

MD and Russell RS: Hepatitis C virus infection of cultured human

hepatoma cells causes apoptosis and pyroptosis in both infected and

bystander cells. Sci Rep. 6:374332016.

|

|

148

|

Wei Q, Zhu R, Zhu J, Zhao R and Li M:

E2-induced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome triggers pyroptosis

and inhibits autophagy in HCC cells. Oncol Res. 27:827–834.

2019.

|

|

149

|

Zhang Y, Yang H, Sun M, He T, Liu Y, Yang

X, Shi X and Liu X: Alpinumisoflavone suppresses hepatocellular

carcinoma cell growth and metastasis via NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. Pharmacol Rep. 72:1370–1382.

2020.

|

|

150

|

Wang F, Xu C, Li G, Lv P and Gu J:

Incomplete radiofrequency ablation induced chemoresistance by

up-regulating heat shock protein 70 in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Exp Cell Res. 409:1129102021.

|

|

151

|

Seehawer M, Heinzmann F, D'Artista L,

Harbig J, Roux PF, Hoenicke L, Dang H, Klotz S, Robinson L, Doré G,

et al: Necroptosis microenvironment directs lineage commitment in

liver cancer. Nature. 562:69–75. 2018.

|

|

152

|

Schneider AT, Gautheron J, Feoktistova M,

Roderburg C, Loosen SH, Roy S, Benz F, Schemmer P, Büchler MW,

Nachbur U, et al: RIPK1 suppresses a TRAF2-dependent pathway to

liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 31:94–109. 2017.

|

|

153

|

Hoesel B and Schmid JA: The complexity of

NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer.

12:862013.

|

|

154

|

Jomen W, Ohtake T, Akita T, Suto D, Yagi

H, Osawa Y and Kohgo Y: Iron chelator deferasirox inhibits NF-κB

activity in hepatoma cells and changes sorafenib-induced programmed

cell deaths. Biomed Pharmacother. 153:1133632022.

|

|

155

|

Harari-Steinfeld R, Gefen M, Simerzin A,

Zorde-Khvalevsky E, Rivkin M, Ella E, Friehmann T, Gerlic M,

Zucman-Rossi J, Caruso S, et al: The lncRNA H19-derived

MicroRNA-675 promotes liver necroptosis by targeting FADD. Cancers

(Basel). 13:4112021.

|

|

156

|

Zheng Y, Kong F, Liu S, Liu X, Pei D and

Miao X: Membrane protein-chimeric liposome-mediated delivery of

triptolide for targeted hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Drug

Deliv. 28:2033–2043. 2021.

|

|

157

|

Mohammed S, Thadathil N, Selvarani R,

Nicklas EH, Wang D, Miller BF, Richardson A and Deepa SS:

Necroptosis contributes to chronic inflammation and fibrosis in

aging liver. Aging Cell. 20:e135122021.

|

|

158

|

Hammerich L and Tacke F: Eat more carrots?

Dampening cell death in ethanol-induced liver fibrosis by

β-carotene. Hepatobil Surg Nutr. 2:248–251. 2013.

|

|

159

|

Zhao B, Lv X, Zhao X, Maimaitiaili S,

Zhang Y, Su K, Yu H, Liu C and Qiao T: Tumor-promoting actions of

HNRNP A1 in HCC are associated with cell cycle, mitochondrial

dynamics, and necroptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 23:102092022.

|

|

160

|

Lee SY, Kim S, Song Y, Kim N, No J, Kim KM

and Seo HR: Sorbitol dehydrogenase induction of cancer cell

necroptosis and macrophage polarization in the HCC microenvironment

suppresses tumor progression. Cancer Lett. 551:2159602022.

|

|

161

|

Lan W, Santofimia-Castaño P, Xia Y, Zhou

Z, Huang C, Fraunhoffer N, Barea D, Cervello M, Giannitrapani L,

Montalto G, et al: Targeting NUPR1 with the small compound ZZW-115

is an efficient strategy to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer

Lett. 486:8–17. 2020.

|

|

162

|

Tran DDH, Kessler C, Niehus SE, Mahnkopf

M, Koch A and Tamura T: Myc target gene, long intergenic noncoding

RNA, Linc00176 in hepatocellular carcinoma regulates cell cycle and

cell survival by titrating tumor suppressor microRNAs. Oncogene.

37:75–85. 2018.

|

|

163

|

Xiang YK, Peng FH, Guo YQ, Ge H, Cai SY,

Fan LX, Peng YX, Wen H, Wang Q and Tao L: Connexin32 activates

necroptosis through Src-mediated inhibition of caspase 8 in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 112:3507–3519. 2021.

|

|

164

|

Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijón M, Kennedy

PD, Johnson JK, Liao P, Lang X, Kryczek I, Sell A, et al:

CD8+ T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer

immunotherapy. Nature. 569:270–274. 2019.

|

|

165

|

Xi G, Gao J, Wan B, Zhan P, Xu W, Lv T and

Song Y: GSDMD is required for effector CD8+ T cell

responses to lung cancer cells. Int Immunopharmacol.

74:1057132019.

|

|

166

|

Yatim N, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Orozco S,

Schulz O, Barreira da Silva R, Reis e Sousa C, Green DR, Oberst A

and Albert ML: RIPK1 and NF-κB signaling in dying cells determines

cross-priming of CD8+ T cells. Science. 350:328–334. 2015.

|

|

167

|

Kang T, Huang Y, Zhu Q, Cheng H, Pei Y,

Feng J, Xu M, Jiang G, Song Q, Jiang T, et al: Necroptotic cancer

cells-mimicry nanovaccine boosts anti-tumor immunity with tailored

immune-stimulatory modality. Biomaterials. 164:80–97. 2018.

|

|

168

|

Snyder AG, Hubbard NW, Messmer MN, Kofman