Introduction

Most bacteria and archaea have an adaptive defense

system termed the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic

Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated sequence (Cas) genome

editing systems, which protect them from attack by phages, viruses,

plasmids and other foreign genetic materials (1,2).

With the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas system, recent advances in

genome editing technology hold great promise for improving the

environment, agriculture and human health (3-5).

The hallmark feature of CRISPR/Cas systems is the memory

acquisition of previous infections from mobile genetic elements

(MGEs) in the form of short sequences (spacers) incorporated into

the CRISPR array (6,7). The CRISPR array of adjacent regions

also consists of genes encoding Cas proteins. Cas proteins have a

notable role in CRISPR/Cas-driven immunity, including adaptation,

CRISPR RNA (crRNA) expression and interference (8,9).

More recently, the type VI CRISPR/Cas system, an

exclusively single-stranded RNA (ssRNA)-targeting platform, has

been developed (10,11). All the Cas13 subtype effectors are

functional crRNA-guided RNases with two definite and independent

catalytic centers. The pre-crRNA is processed by one catalytic

center and contains two R-X4-H motifs, termed higher

eukaryote and prokaryote nucleotide-binding (HEPN) domains,

responsible for the cleavage of ssRNA (12). The novel performance of Cas13

effectors has been used as a tool for targeting and manipulating

different RNAs, although practical applications of this technique

are still in their infancy (13-15).

Until recently, approaches for targeted cancer

therapy using small-molecule drugs and monoclonal antibodies have

become significant. However, certain complications of this

approach, such as off-target effects and the limited availability

of cancer-driven proteins, limit their broader application

(16,17). Furthermore, molecular analysis of

cancer using diagnostic methods is very expensive and is performed

using sophisticated equipment (18,19). To overcome these limitations of

cancer management, researchers are seeking a precise, efficient and

versatile platform for targeted cancer treatment (20,21).

CRISPR-mediated genetic manipulation has expanded

rapidly in recent years. RNA manipulation using the type VI

CRISPR/Cas13 system is a promising tool for cancer research,

diagnosis and therapy (22,23) (Fig.

1). Additionally, Cas13-based RNA detection and targeting

allows for the early monitoring of tumor markers from different

bodily fluids without the need for sophisticated instrumentation.

Furthermore, Cas13-based RNA editing offers significant prospects

for understanding drug resistance biology in addition to the

discovery of novel therapeutic targets (24). Cas13 can also be mutated to dead

Cas13 (dCas13), an RNA-binding effector that can be easily

programmed for novel tasks. dCas13 is formed from native Cas13 by

the mutation of its HEPN domain residues, which are involved in RNA

cleavage (25). dCas13 has

significant applications when bound to other proteins for cell

imaging in its living state, RNA interaction mapping, mRNA

splicing, RNA base editing, RNA methylation/demethylation and

blocking other RNA-binding proteins (26,27) (Fig.

1).

| Figure 1Some novel applications of Cas13 and

dCas13 in RNA targeting and editing. Activated Cas13 is employed

for different applications including disease therapeutics, RNA

knockdown, viral intervention, detection of biological agents,

loss-of-function screening and development of antimicrobials. The

RNA sequence can also be targeted by dCas13, which is catalytically

inactive and can be coupled to other proteins for the execution of

live cell RNA tracking and imaging, target mRNA

splicing/polyadenylation, single base editing,

methylation/demethylation of target RNA, RNA-binding protein

blocking and exploration of RNA-protein interactions. As an

example, for Cas representation, this figure shows the ternary

complex of LbuCas13a, downloaded from the PDB website https://www.rcsb.org/ (PDB ID: 5XWP) and was edited

using UCSF ChimeraX, version 1.8 (https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax). Cas13, Clustered

Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats-associated sequence

13; dCas13, dead Cas13; PDB, protein data bank. |

The present review summarizes the recent updates on

the CRISPR/Cas13 system in view of its structural, mechanistic and

novel applications in cancer management. In addition, the present

review will be helpful in understanding CRISPR/ Cas13-related novel

techniques that can be used as innovative tools for cancer

diagnostics and targeted therapeutics. Furthermore, some

limitations and future prospects must be addressed before this

RNA-editing tool can be used more efficiently.

Classification of the CRISPR/Cas system

The CRISPR/Cas system in bacteria and archaea uses

three stages to defend against viruses or other MGEs: Protospacer

acquisition, expression and target recognition (4,28).

In the first stage, a protospacer is incorporated in the host

CRISPR locus as spacers between crRNA repeats (29). In the next stage, the expression

of Cas proteins occurs and the spacers are transcribed as pre-crRNA

repeats (1,29,30). In the third stage, the interaction

between the target site of some invading viruses or other MGEs

(protospacers) occurs with the help of crRNA (spacers), leading to

genome cleavage (29,31). Most CRISPR/ Cas systems use a

sequence-specific protospacer adjacent motif adjacent to the

crRNA-specific site within the target genome to distinguish self

from foreign genetic elements (32).

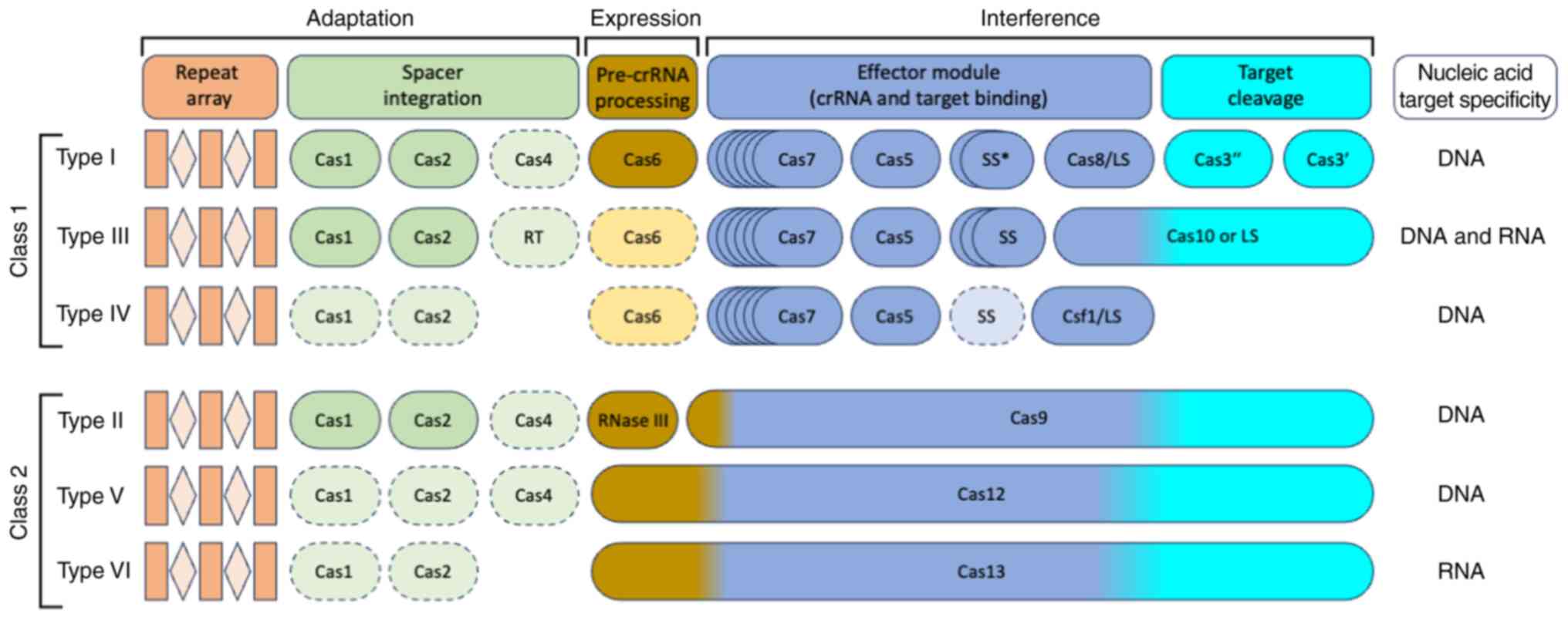

In recent years, the number and diversity of CRISPR/

Cas systems have significantly increased. The most updated

classification system for this genome editing tool consists of two

classes (class 1 and class 2), six types (type I to type VI) and 33

subtypes (33). The CRISPR/Cas

system classification is primarily based on the composition of the

Cas protein and the divergence of the sequence between the effector

modules (34,35). In the class 1 system, several

effector proteins are required for RNA-guided target cleavage.

However, only one RNA-guided endonuclease is required in class 2

systems to cleave foreign DNA/RNA sequences (34,36,37). The class 1 system of this genome

editing tool is divided into three types: Types I, III and IV,

while the class 2 system is classified as types II, V and VI

(34,38,39) (Fig.

2). In the type I system, the Cas3 signature gene is located at

the CRISPR/Cas locus; it encodes a large protein possessing

helicase activity to unwind RNA-DNA and DNA-DNA duplexes (40,41). The type II system is one of the

most well-known and widely used CRISPR/Cas systems, as only a

single multidomain protein targets and cleaves double-stranded DNA

(dsDNA) in this system (42,43). In the type III CRISPR/Cas system,

Cas10 acts as a signature gene that encodes a multidomain protein

for the target detection and cleavage of single-stranded DNA

(ssDNA) (44,45). The type IV CRISPR/Cas system has

no Cas nucleases and integrases as typically seen in other CRISPR

systems, but it does have CRISPR-associated splicing factor 1, and

deeper details about its function have yet to be explored (34,46). In the type V CRISPR/Cas system,

Cas12 acts as a signature gene, known as CRISPR from Prevotella and

Francisella 1 (Cpf1), C2c1 (class 2, candidate 1) or C2c3 (class 2,

candidate 3) proteins, that encodes the RuvC domain, which cleaves

both ssDNA and dsDNA (47,48).

The type VI CRISPR/Cas system contains Cas13 (C2c2), which encodes

the nucleotide binding domain (HEPN) of higher eukaryotes and

prokaryotes and can cleave ssRNA (49,50) (Fig.

2).

Type VI CRISPR/Cas system

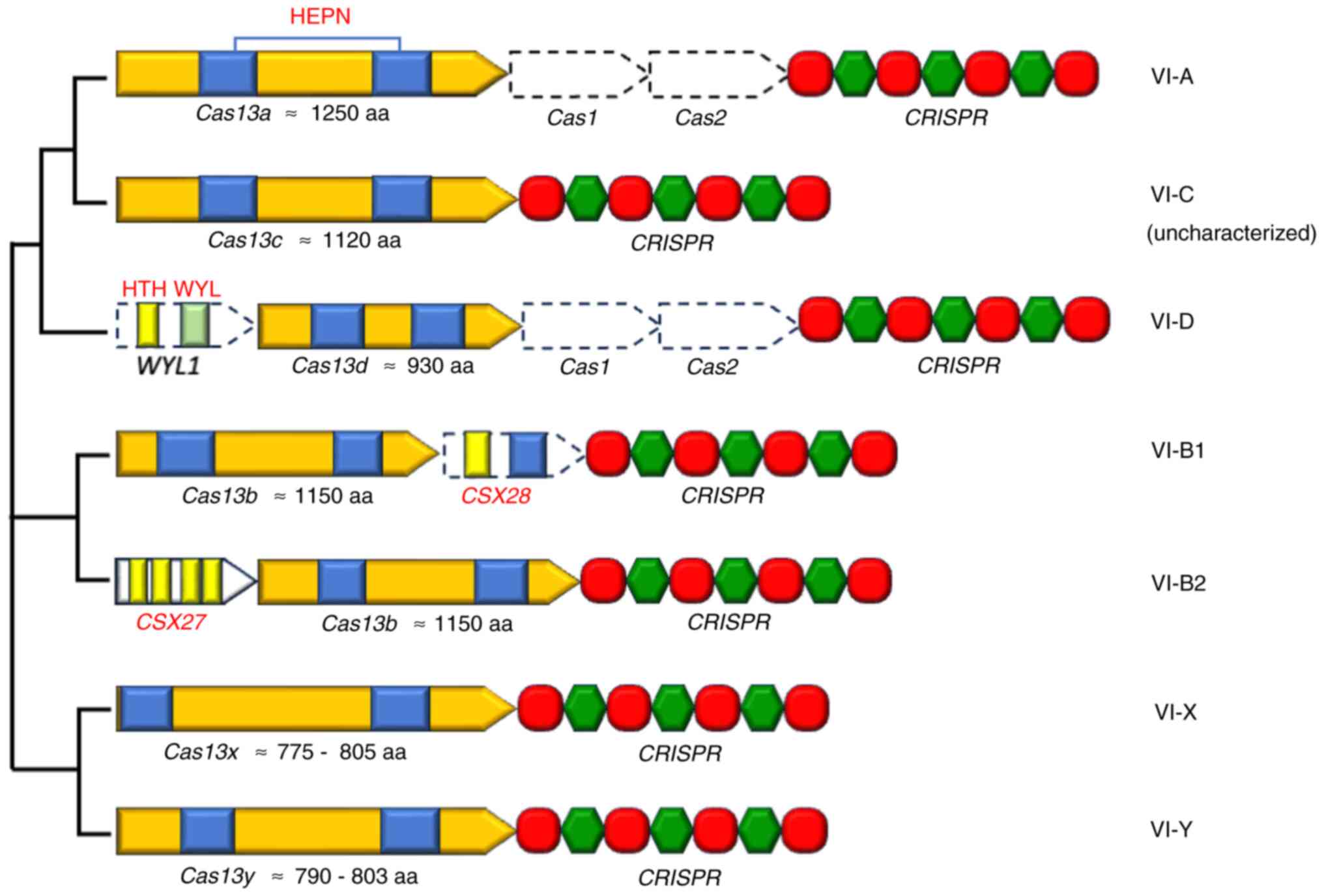

Cas13 is a single effector protein found in the type

VI CRISPR/ Cas system with the ability to process crRNA, recognize

invaders and trigger the immune system (25,51) (Figs.

1 and 2). To date, six

distinct type VI subtypes have been identified: VI-A to VI-D,

Cas13X and Cas13Y (39,52) (Fig.

3). The functional characterization of the VI-A, VI-B and VI-D

subtypes is now understood in more detail in relation to their

respective effectors compared with the other subtypes (53). However, there are other subtypes

of this system, such as Cas13e and Cas13i (54).

A single feature common to Cas13 proteins from

different subtypes is the shared inclusion of two HEPN domains

(39,55). This effector protein has a bilobed

shape, wherein RNA nuclease activity is attributed to one lobe and

RNA target recognition to the other. Cas13 can detect a target RNA

in a population of non-target RNAs with femtomolar sensitivity

(56). Binding of the target RNA

to Cas13 induces conformational changes in the nuclease lobe, which

contains two HEPN domains. This conformational change results in a

stable composite RNase pocket that mediates the cleavage of the

target RNA and bystander RNA (57-59), resulting in the inhibition of

invading DNA viruses (60,61).

The different subtypes of Cas effectors in the type VI CRISPR/Cas

system are elaborated below.

CRISPR/Cas13a

Cas13a, an effector of the VI-A CRISPR/ Cas system,

was previously termed class 2, candidate 2 (C2c2) and was first

discovered in 2015 using a computational pipeline by Shmakov et

al (62). In contrast to the

other CRISPR/Cas loci, the Cas1 and Cas2 genes are absent in the

type VI-A loci, but it does contain a CRISPR array along with a

Cas13 gene (Fig. 3). This CRISPR

array is notably unstructured and heterogeneous, with 35-39 bp

direct repeats (35,62). Cas13a is currently a

well-understood type VI effector protein with >1,000 amino

acids, and its primary structure lacks noticeable similarity with

other known Cas effectors (15,62,63). Based on cleavage preference and

non-cognate crRNAs, the currently recognized Cas13a orthologs are

distributed as either A-cleaving or U-cleaving (64,65). pre-crRNA maturation is not

essential for RNA interference; however, it can enhance activity by

releasing crRNA from the CRISPR array (64).

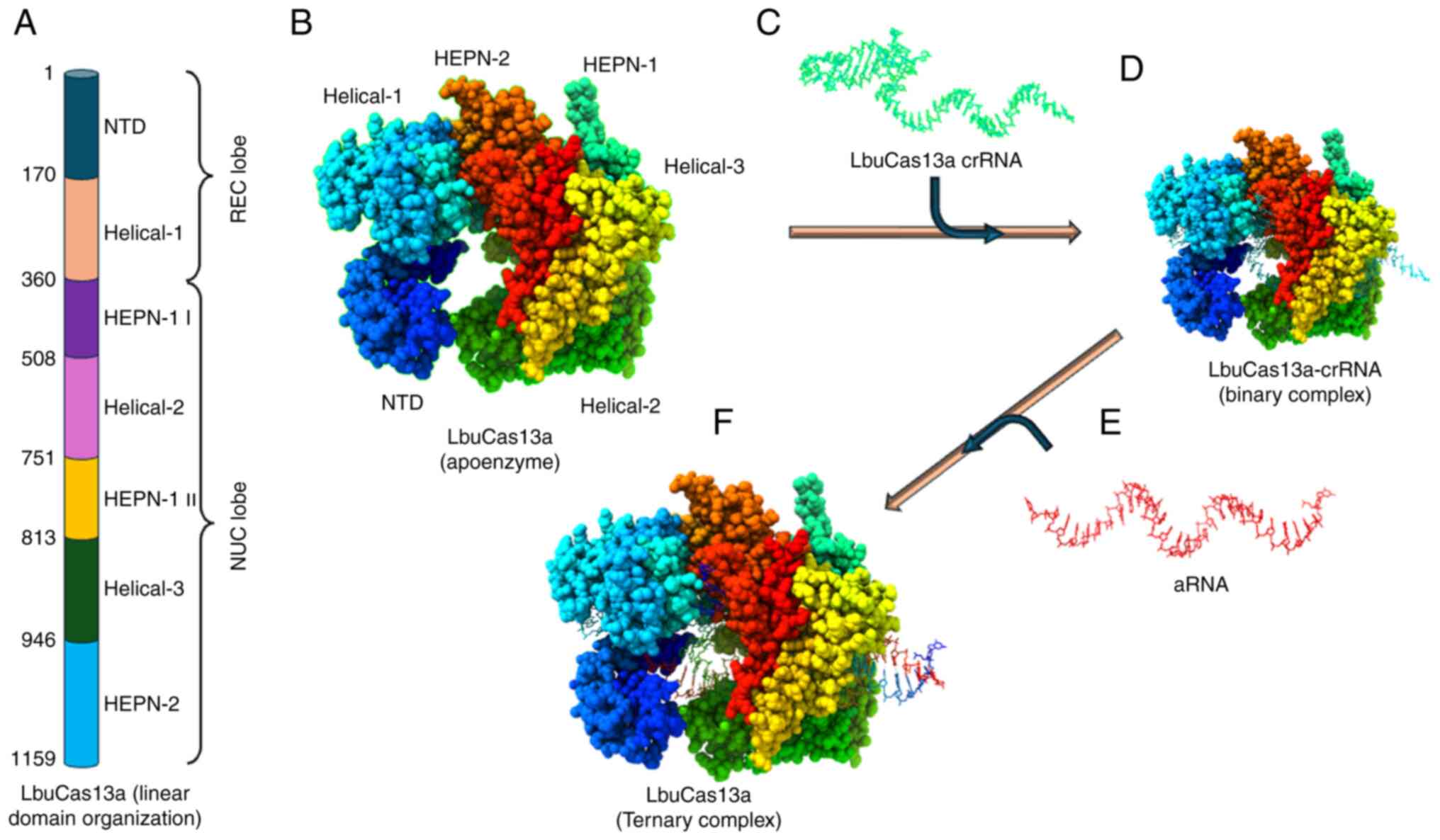

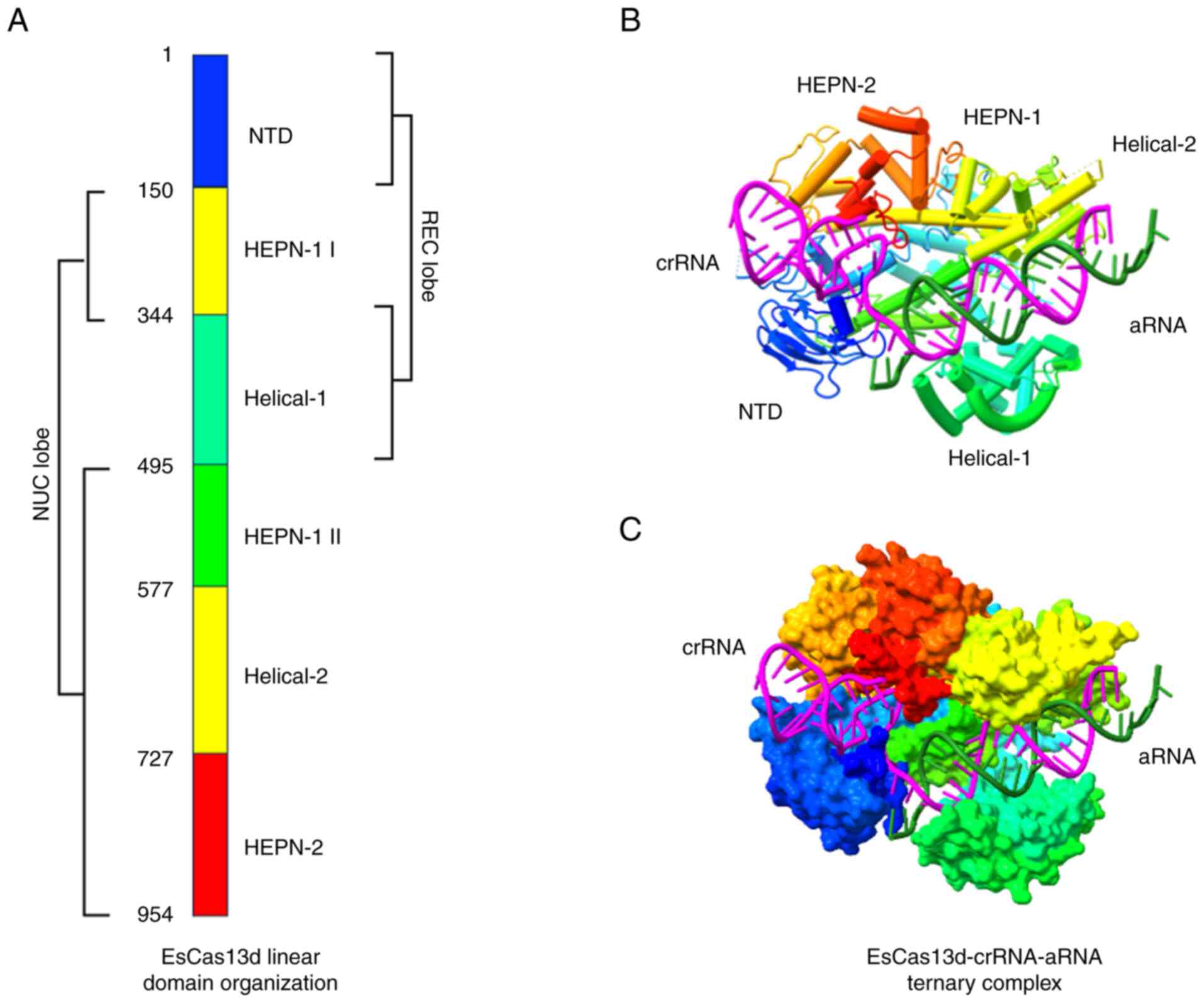

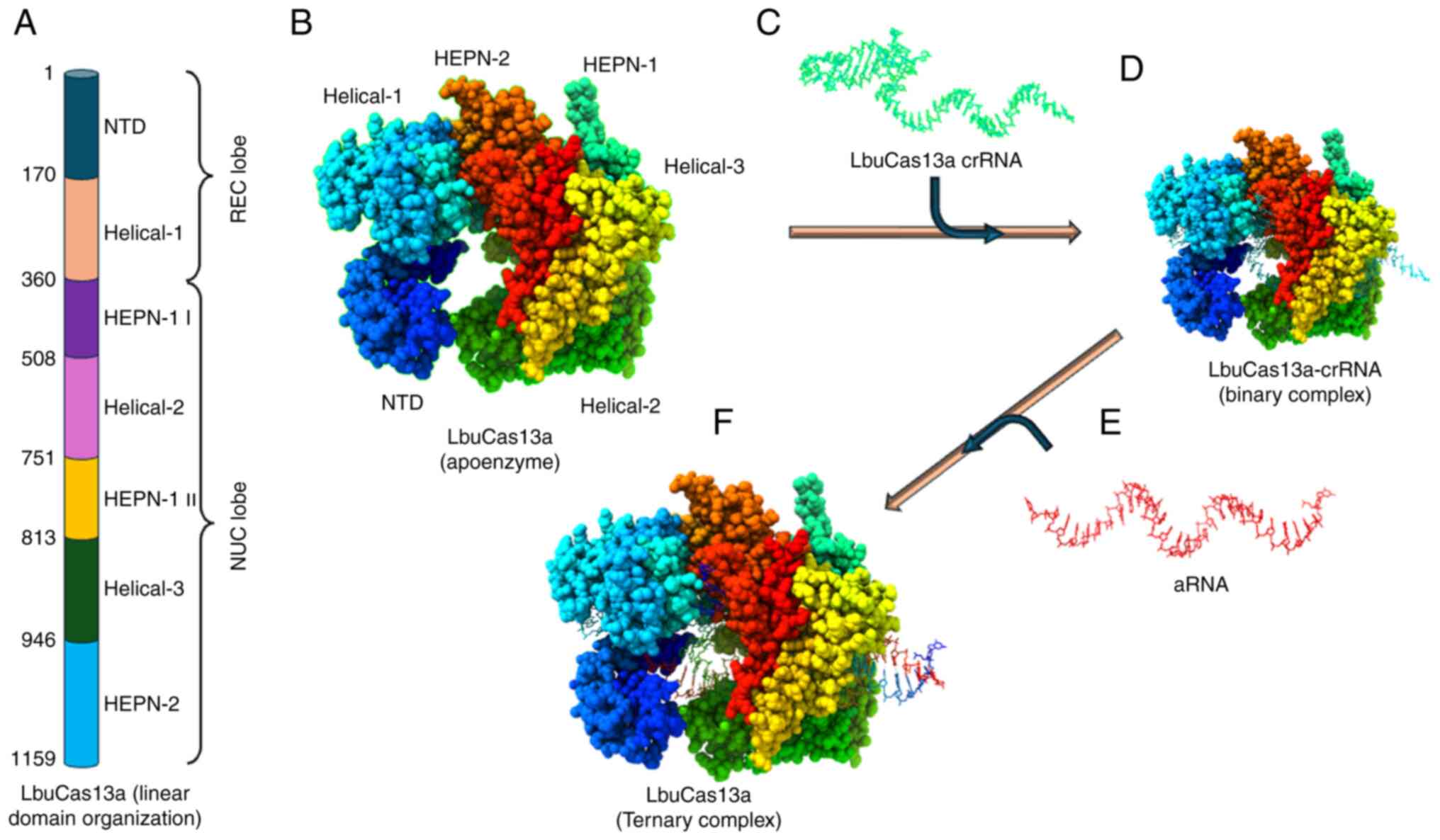

The domain organization of several Cas13a and crRNAs

in complex with activator RNA (aRNA) have been reported. Some

well-known examples include Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas13a

(LbaCas13a), Leptotrichia shahii Cas13a (66) and Leptotrichia buccalis

Cas13a (LbuCas13a) (51,65) (Fig.

4). Cas13a is predominantly α-helical, possessing a recognition

(REC) lobe and nuclease (NUC) lobe (Fig. 4A). However, the 3D structure

notably differs at the levels of architectural and domain

organization (51,65,66). The REC lobe consists of a strongly

basic cleft, which accommodates the repeat region of crRNA between

the N-terminal domain (NTD) and Helical-1 domain (Fig. 4C and D). The NUC lobe comprises

the HEPN-1, Helical-2, HEPN-2 and Helical-3 domains (Fig. 4A and B). The Helical-2 domain

divides HEPN-1 further into two distinct subdomains, HEPN-1I and

HEPN-1II (51,65). Cas13a undergoes a significant

conformational rearrangement upon crRNA binding and forms a compact

structure. This complex facilitates aRNA binding by closing the

crRNA-binding channel (51)

(Fig. 4E and F). In both

U-cleaving and A-cleaving Cas13a effectors, recognition of the

repeat region of the crRNA occurs in a sequence- and

structure-specific manner. It is well known that Cas13a is a single

effector protein performing the crRNA processing and interferences

steps without the help from other accessory proteins. For pre-crRNA

processing, critical catalytic residues have been identified for

all three Cas13a orthologs, but the A-cleaving LbaCas13a presents a

more detailed acid-base mechanism (51,65,66).

| Figure 4Basic structural features of type

VI-A CRISPR/Cas effectors. (A) Linear domain organization of

LbuCas13a, presenting different domains (REC and NUC lobes)

annotated with the corresponding amino acid number. (B) Cartoon

representation of the LbuCas13a apoenzyme. (C) Secondary structure

of LbuCas13a crRNA and its nucleotide sequence. (D) Binary

structure of the LbuCas13a-crRNA complex. (E) Secondary structure

of aRNA. (F) LbuCas13a-crRNA-aRNA ternary complex. The crystal

structure of LbuCas13a-crRNA-target RNA ternary complex was

downloaded from the PDB website https://www.rcsb.org/ (PDB ID: 5XWP) and was edited

using UCSF ChimeraX, version 1.8 (https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax). LbuCas13a,

Leptotrichia buccalis Cas13a; CRISPR, Clustered Regularly

Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; Cas, CRISPR-associated

sequence; HEPN, higher eukaryote and prokaryote nucleotide-binding;

REC, recognition; NUC, nuclease; crRNA, CRISPR RNA; aRNA, activator

RNA; PDB, protein data bank; NTD, N-terminal domain. |

Cas13a uses spacers with different sequence

identities and lengths (20-28 nucleotides) to successfully utilize

crRNAs (64,65). The 5′ region of the spacer is

hidden in the NUC lobe cavity in binary complex structures

(Fig. 4D) that are currently

known, and it adopts a deformed conformation stabilized by

significant interactions with the sugar-phosphate backbone

(51,65,66). The central portion of the spacer

surfaces out from the NUC lobe and passes through a groove created

between the NTD and Helical-2 domains (51,65,66). In Cas13a-crRNA binary complexes,

the center and 3′ region maintain an almost A-form helical

conformation; however, this is not apparent in all orthologs

(51,53).

The Cas13a functional aspects, including aRNA

binding, HEPN nuclease site activation and RNA interference, have

been well-studied. Sequence interrogation and propagation of the

crRNA spacer-aRNA duplex begins when a possible aRNA binds to the

central seed region of the crRNA (57,65). To further stabilize the duplex,

base pairing between aRNA and the remaining spacer is necessary

(57). Sequence interrogation and

propagation of the crRNA spacer-aRNA duplex eventually leads to

synergistic conformational changes in both crRNA and Cas13a, thus

forming a ternary complex with a fully active HEPN nuclease

position that is prepared to interfere with RNA (Fig. 4F). Exposure of the hidden

R-X4-H domain of the HEPN-1 region towards the exterior

shifts it closer to the R-X4-H domain in the HEPN-2

region, which activates the HEPN nuclease active site, permitting

interactions within the NUC duplex lobe and widening the binding

channel to accommodate the crRNA-aRNA duplex (51,57,65,66). The LbuCas13a binary complex and

its ternary complex provide the most pertinent insights into these

conformational changes (51).

The aRNA-bound spacer of crRNA in the ternary

complex of LbuCas13a approached a normal A-form helix (51,67). The duplex base pairs were mainly

in contact with the HEPN-1, Helical-2 and Helical-3 domains, while

they were bound inside the positively charged central channel of

the NUC lobe. LbuCas13a primarily interacts with nucleotides 7-15

(which often correspond to the seed area and portions of the HEPN

region), some nucleotides of spacer crRNAs and aRNA nucleotides

(51,53). A multitude of residues for spacer

interaction in LbuCas13a are important for ssRNA cleavage (51). The reason that Cas13a effectors

can employ spacers of >20 nucleotides with comparable efficacy

is because the duplex beyond the 24th base pair is situated outside

of the protein (51,68). Cas13a effectors cleave ssRNA

sequences in either cis or trans mode during RNA interference

(65,69,70). A groove on the protein surface

houses the HEPN active site, which is located away from the central

channel where the crRNA can bind with aRNA to form a crRNA-aRNA

complex. However, the catalytic centers of type II and V Cas

proteins are embedded within the proteins (51,65,66). For cleavage in trans, any RNA in

solution can readily approach the catalytic center; however, for

cleavage in cis, the effector-bound aRNA must be sufficiently

long.

The structure of the LbuCas13a ternary complex

demonstrated how RNA interacts with HEPN nuclease residues during

interference (Fig. 4F and G).

This interaction is performed by the nucleotide at the 5′ terminal

of aRNA swinging away from the crRNA-activator RNA duplex and being

inserted into the HEPN active center of the adjacent LbuCas13a

(65,71). An HEPN-1 β-hairpin stretches into

the main groove of the crRNA-aRNA duplex and contacts it through

some weak interactions and catches RNA in the immediate region of

the catalytic site (51,72). Its importance in capturing ssRNA

is demonstrated by the reduction in both trans and cis RNA

intrusion that result from interaction with the 5′ nucleotide of

aRNA (51).

CRISPR/Cas13b

In 2016, new computational procedures such as

position-specific iterative basic local alignment search tool and

hidden Markov models prediction, in addition to the ideas from

previous views and no firm requirement for cas1 and cas2

identification in this type, led to the discovery of Cas13b. Cas13b

consists of 1,100-1,200 amino acid effectors of type VI-B systems

(62,73). This subtype was found in bacteria

supported by other CRISPR/Cas systems, getting support from cas1

and cas2 genes. This suggests that the VI-B platform acquire

spacers in trans (73).

Type VI-B systems have several unique features: i)

The orientation of the processed mature crRNA is different from

that of the Cas13a and Cas13d crRNAs (73); ii) the size (36 nucleotides) of

crRNA direct repeat sequences (DRs) are all conserved; iii) the 5′

non-C and the 3′ NNA or NAN protospacer flanking sequences (PFSs)

limit the interference caused by Cas13b; iv) a small accessory

protein (~200 amino acids), either Csx27 or Csx28, controls the

interference of Cas13b; and v) ssRNA cleaves at the pyrimidine

base, preferring to cleave uracil. Csx28 boosts Cas13b-mediated

cleavage, which is routinely observed in subtype VI-B2 systems,

whereas Csx27 represses Cas13b-mediated cleavage. Csx27 is

infrequently present in subtype VI-B1 systems. Both accessory

proteins possess the potential to regulate orthogonal type VI-B

systems, thereby increasing their potential applications (73,74).

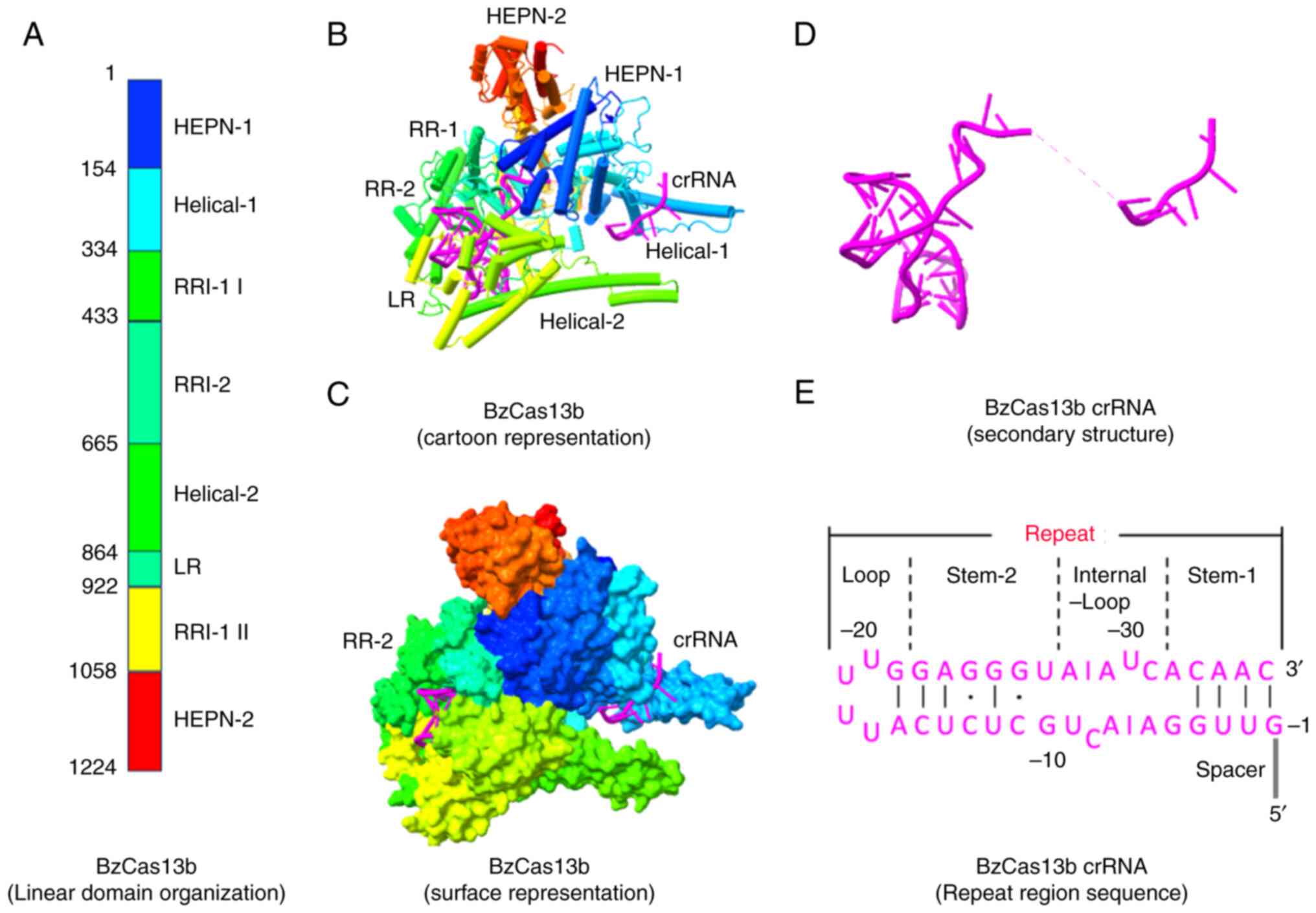

The general domain organization and mechanistic

action of Cas13b have recently been identified by determining the

structures of subtype VI-B1 Bergeyella zoohelcum (Bz)

(Fig. 5) and subtype VI-B2

Prevotella buccae (Pbu) Cas13b-crRNA binary complexes

(75-77). Cas13b adopts a distinct pyramidal

shape in both configurations with a positively charged central

cavity that holds the crRNA. The binary complex of Cas13b-crRNA

lacks a bilobed architecture, and its domain organization is

notably different from that of other type VI effectors (75,76). The two termini of the protein

consist of two domains, HEPN-1 and HEPN-2, placing the two

R-X4-H motifs relatively close to each other (Fig. 5B and C) (75,76). A sizable positively charged

channel connecting the solvent and the internal cavity was found at

the base of the pyramidal structures of both PbuCas13b and BzCas13b

(75,76). The Helical-1 and Helical-2 regions

surround this channel in BzCas13b and extend to resemble pincers

(Fig. 5B and C) (75). However, the purpose of these

pincers, which are specific to PbuCas13b, is not fully understood.

Cas13b recognizes its specific crRNA, resembling an L-shaped

architecture, with the 3′ segment of the spacer region and the bulk

of the repeat region protected inside the protein (75). The twisted hairpin loop (36

nucleotide repeat region) is almost perpendicular to the spacer

direction. The repeat region has four distinct subregions: Stem-1,

stem-2, internal loop and U-rich loop. Watson-Crick base pairing

and multiple H-bonds are responsible for maintaining intramolecular

contacts (75,76) Additionally, crRNAs have several

flipped nucleotides in their repeat regions. Except for HEPN-2,

crRNA interacts extensively with all Cas13b domains; the majority

of these interactions occur with the repeat region interacting

domain-2, which includes the lid and Helical-1 III (78).

The interactions between the repeat region of crRNA

and Cas13b stabilize the phosphate backbone of this RNA type, and

this interaction is based more on the crRNA structure than its

nucleotide sequence; however, this collaboration is

ortholog-specific (75,76). The spacer region of the crRNA in

BzCas13b is surrounded by different regions, such as the HEPN-1,

Helical-1 and repeat region domains on one side, and the Helical-2

domain on the other (75). Due to

the extreme spacer flexibility, the central region (nucleotides

9-15) is invisible (75). The

nucleotide sequence between 16-22 is in the surface groove near the

surface of the protein. The spacer orientation was modified in both

PbuCas13b and BzCas13b in relation to RR by preventing the initial

spacer nucleotide from moving, although this was achieved through

different sets of contacts (75).

This shows that for both Cas13b orthologs, effective activator RNA

binding and spacer trajectory determination depend on the proper

placement of the first spacer nucleotide. The lid protein domain

processes the pre-crRNA towards the downstream using tightly

conserved arginine and lysine residues (75,76). Nucleotide A(-37) was not

recognized by catalytic residues in a base-specific way (75).

A Cas13b-based computational model was analyzed by

studying the crystal structure of PbuCas13b complexed with

36-nucleotide direct repeat sequence and a 5-nucletide spacer at

1.6 Å and illustrated aRNA binding. According to this model, Cas13b

binds to crRNA and probes ssRNA at the spacer repeat

region-proximal (3′-end) (76).

If complementarity occurs, the HEPN-1 and Helical-2 domains open in

response to the initial binding of the potential aRNA to the crRNA

spacer, allowing the RNA to enter the positively charged core

cavity. Prior to full conformational activation of the bipartite

HEPN site, the remaining RNA sequence is scanned to complete

complementarity using the spacer (76). Nevertheless, the channel that has

been suggested as a pathway for aRNA to enter the central cavity is

absent from the structure of the BzCas13b-crRNA binary complex

(75,76). Furthermore, the narrower PbuCas13b

channel might not be open enough to maintain aRNA since the

interdomain linker connects the HEPN-1 and Helical-1 domains, which

probably prevents the HEPN-1 domain from moving as much.

Additionally, in both PbuCas13b and BzCas13b, the spacer 3′ region

is buried within the polypeptide chain. However, in the binary

molecule BzCas13b-crRNA, the 9-15 nucleotides traverse wide

solvent-reachable channel-like type VI-A systems (75). Accordingly, while tandem

mismatches are intolerant across the spacer, only one mismatch is

sufficient to eliminate PbuCas13a HEPN enzymatic activity (76). As a result, the spacer middle

region most likely probes aRNA first, with aRNA binding then moving

towards the spacer 5′ and 3′ ends.

CRISPR/Cas13c

The Cas13c subtype has not been well studied, mostly

due to its lower efficiency in RNA targeting and interference

compared with the other Cas13 subtypes (53). The Cas13c Fusobacterium

perfoetens ortholog is mostly used in the limited

investigations that have been conducted (79,80). Cas13c was initially discovered in

Fusobacterium and Clostridium using bioinformatics;

however, compared with the other Cas13 types, its functional

characterization is far less comprehensive. With ~1,120 amino

acids, this protein is identical to Cas13a in terms of locus and

crRNA structure. However, like Cas13b, it lacks an adaptation

module (Cas1 and Cas2). On the 5′ end of the crRNA, this subtype

displays a DR with a spacer size of 28-30 nucleotides (80).

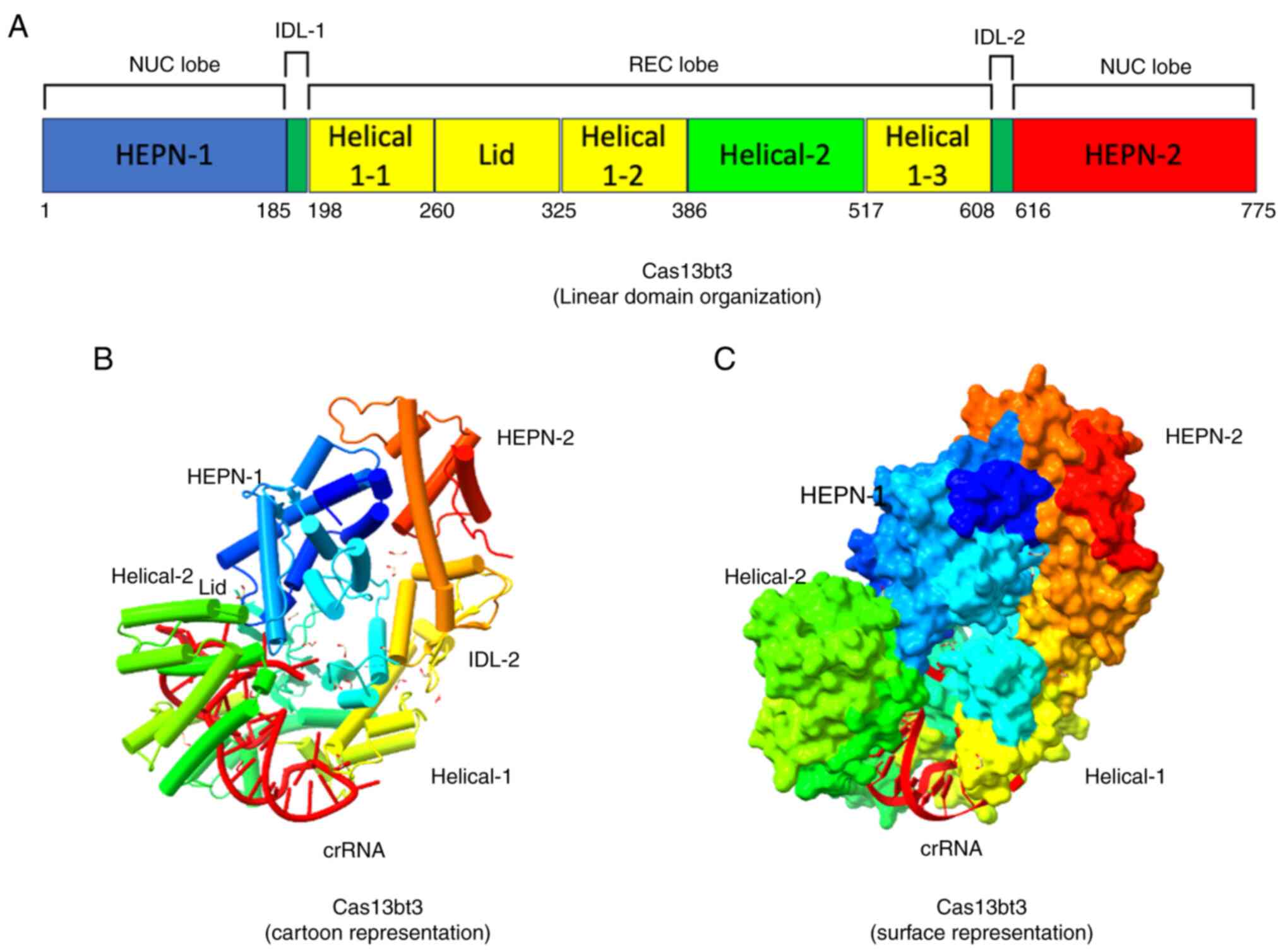

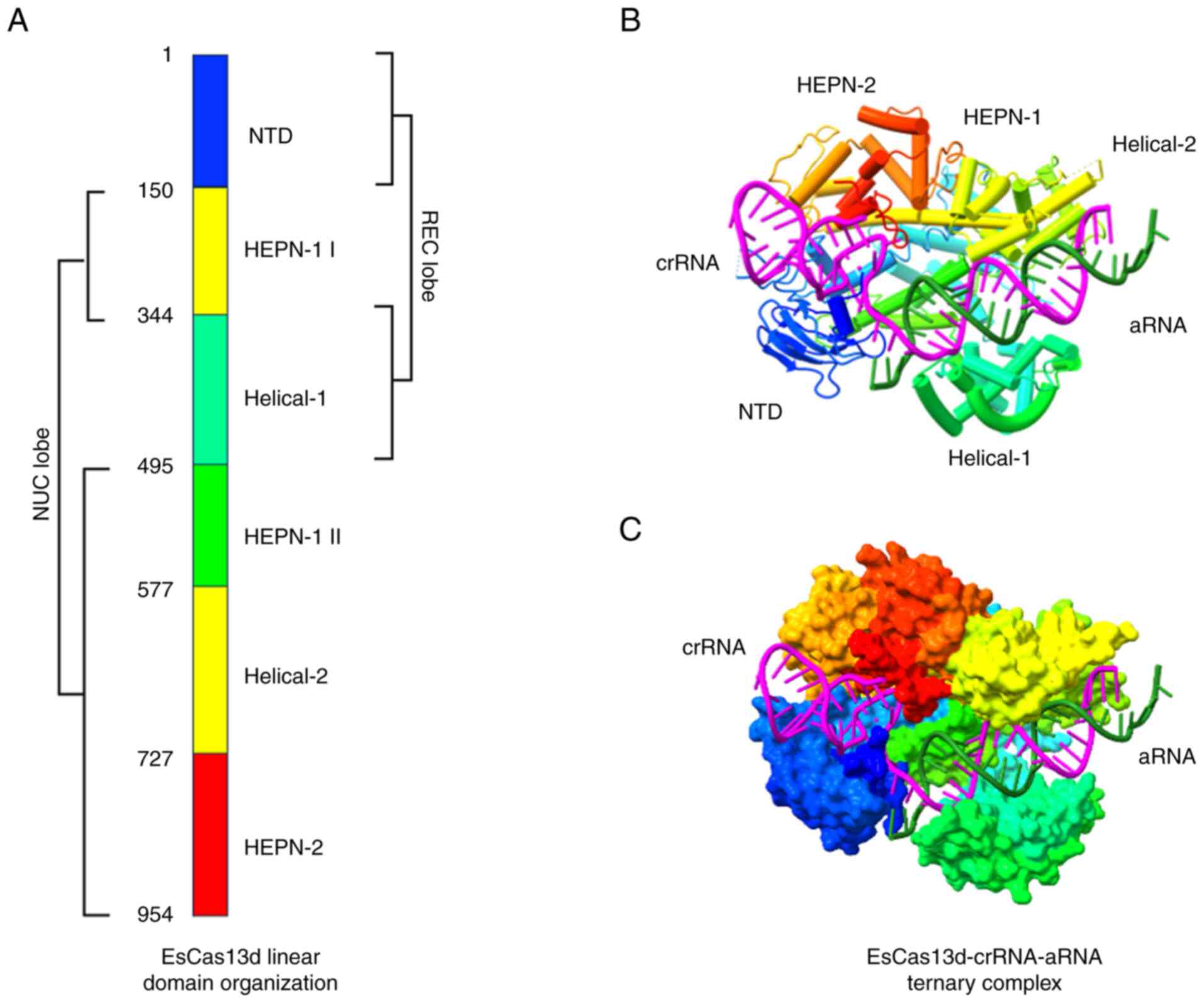

CRISPR/Cas13d

To date, Cas13d is the smallest type VI effector

with ~930 amino acids (10,11,81). Extending the search to smaller

effectors and refining the search tactics of earlier computational

pipelines led to the discovery of Cas13d (10,11,82). The core structure of Cas13d has

only a distant relationship with Cas13a or other type-VI effectors

outside the two HEPN domains (Fig.

3) (10,11,13). However, its ternary structure is

similar to that of Cas13a effectors (Fig. 6).

| Figure 6Diagrammatic representation of type

VI-D CRISPR/Cas effectors employing the EsCas13d-crRNA-aRNA ternary

complex. (A) Linear organization of EsCas13d showing the REC and

NUC lobes. (B) Cartoon representation of EsCas13d presenting the

position of crRNA (magenta) and aRNA (mountain green). (C) Surface

representation of EsCas13d. The crystal structure of EsCas13d

ternary complex was downloaded from the PDB website https://www.rcsb.org/ (PDB ID: 6E9F) and edited using

UCSF ChimeraX, version 1.8 (https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax). EsCas13d,

Escherichia coli Cas13d; CRISPR, Clustered Regularly

Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; Cas, CRISPR-associated

sequence; HEPN, higher eukaryote and prokaryote nucleotide-binding;

REC, recognition; NUC, nuclease; crRNA, CRISPR RNA; aRNA, activator

RNA; PDB, protein data bank; NTD, N-terminal domain. |

Ruminococcus and Eubacterium are two

benign gram-positive gut bacteria that are the source of the

majority of type VI-D CRISPR/Cas loci (10,11,83,84). Type VI-D loci are characterized by

notable divergence in locus organization and, in most cases, by the

absence of the Cas1 or Cas2 adaptation system in their immediate

proximity (Fig. 3) (10,11,85). For this effector, the repeat

section in the crRNA is highly conserved, with a stem containing an

A/U-rich loop (10,86). It has been observed that Cas13d

targets phage DNA rather than phage RNA, as assumed earlier, which

is consistent with other type VI systems (11,58).

The CRISPR array is processed by Cas13d and forms

mature crRNAs with a 5′-30 nucleotide repeat region (10,13). pre-crRNA processing tests

conducted in vitro have suggested that Cas13d does not

completely process the 3′ direct-repeat region. This results in

truncation, producing mature crRNAs with varying spacer lengths

(11). Overall, it is

hypothesized that Cas13d uses a base-catalyzed method to process

pre-crRNA in which the highly conserved basic residues of the

HEPN-2 domain are essential (13). Metal ions are not necessary;

however, their presence improves processing by increasing Cas13d

binding affinity for crRNA at lower Cas13d-crRNA ratios (13,75). Similar to other effectors of

Cas13, the Cas13d RNase potential is dependent on the availability

of Mg2+ ions and spacer-matching aRNA (10,11). With little secondary structure,

preference for uracil bases and no restrictions imposed by PFS,

Cas13d cleaves ssRNA sequences (10,11,77). Although strong collateral

non-specific RNase activity of Cas13d has been described in

vitro, no similar activity has been observed in mammalian cells

(10).

The cryo-electron microscopy structure of EsCas13d

in an apo-to-ternary state exhibits a bilobed presentation

(Fig. 6) (13,87,88). The Cas13d protein is composed of

five domains that are separated into two lobes: The NUC lobe is

composed of HEPN-1, Helical-2, Helical-1 and NTD domains, whereas

the REC lobe is composed of Helical-1 and NTD domains. The HEPN-1

domain functions as a hinge and structural scaffold that joins the

two lobes (13,75). Except for the Helical-1 domain of

Cas13a, all Cas13a domains have equivalents in the basic sequence

Cas13d (11). However, all five

protein segments are necessary for the enzymatic activity of Cas13d

due to their compact size (75).

Binding of crRNA leads to the stabilization of the REC segment and

portions of the HEPN-2 domain. This phenomenon also causes the

development of a positively charged area connecting the REC and NUC

domains (75). The spacer is

enclosed in an area composed of all protein segments other than the

N-terminus, and the repeat region of the crRNA is fastened within

the HEPN-1, HEPN-2 and NTD domains of this channel (13,75). Due to the small size of Cas13d, a

portion of the repeat region stem-loop protrudes into the solvent,

enabling truncation of the superfluous crRNA region in this area

(13). Cas13d forms extensive

contact with the crRNA repeat region, sugar-phosphate backbone and

nucleobases (13,75). Conserved base-specific contacts

are crucial for preserving the appropriate crRNA binding and

placement (13,75).

For ssRNA cleavage, the repeat region nucleotide

sequence of crRNA and its structure are important (13). The sugar-phosphate backbone plays

a major role in the interaction between Cas13d and the spacer

region, stabilizing its configuration and setting it up for aRNA

attachment (13,75). The spacer is reordered to create

an A-form RNA helix with aRNA upon engagement, eliminating most of

its prior interactions with Cas13d (75). Simultaneously, new contacts are

created between the crRNA spacer, aRNA and different domains of

Cas13d. Cas13d undergoes multiple conformational changes from

binary to ternary states, repositioning HEPN for ssRNA breakdown

and placing the target RNA in the channel (75). Strong associations exist between

aRNA binding and HEPN active-site activation. Partial

conformational rearrangement of Cas13d requires a minimum of 18

nucleotides with strict complementarity, half-maximum cleavage

activity requires 18-20 nucleotides and optimal cleavage activity

requires >21 nucleotides with complementarity (34,75). It was first considered that the

Cas13d crRNA spacer lacks a distinct seed region (75). Based on the available data, it

appears that a mismatch tolerance exists that is likely

ortholog-dependent, and a very mismatch-intolerant area inside the

central 3′ spacer nucleotides exists.

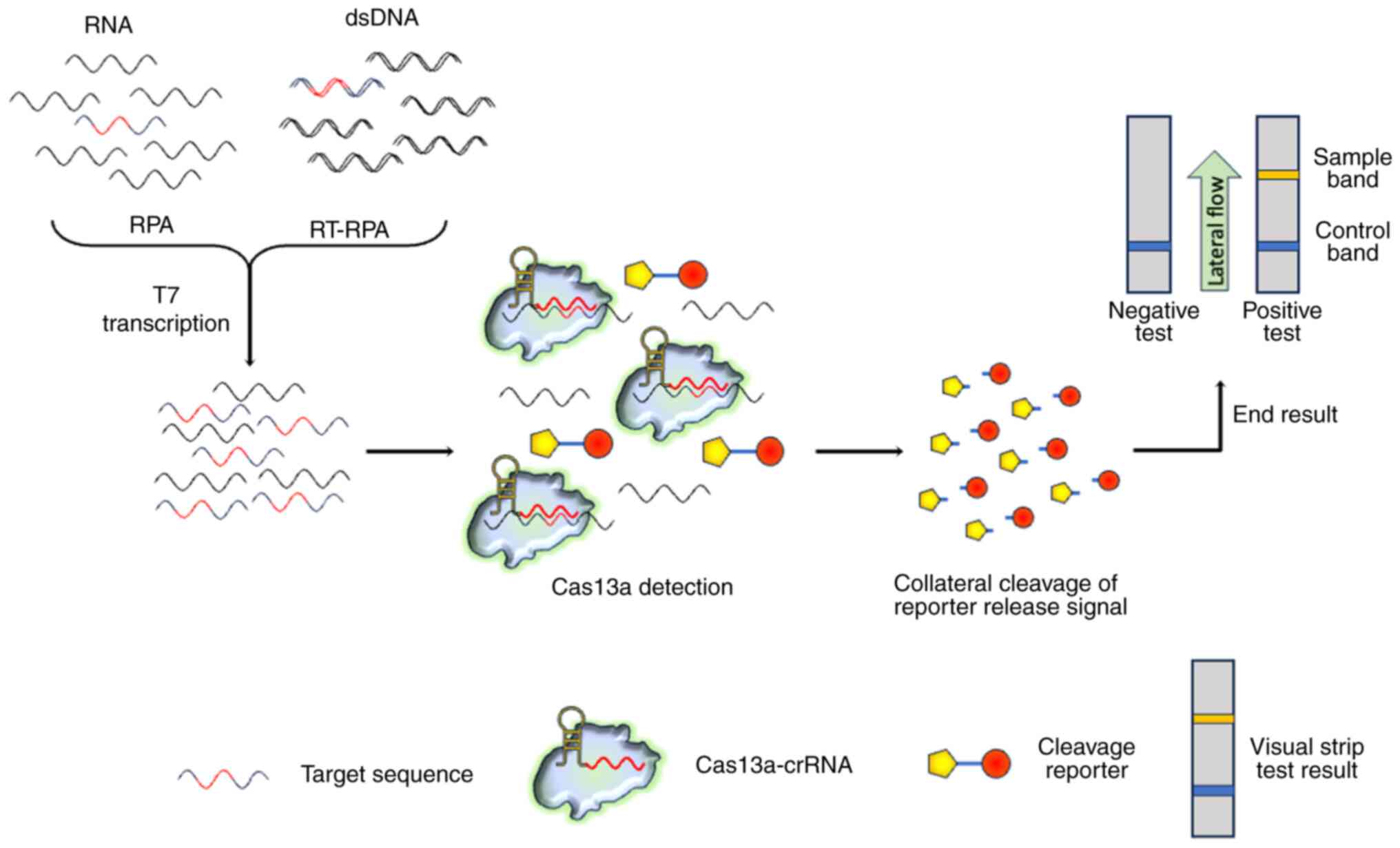

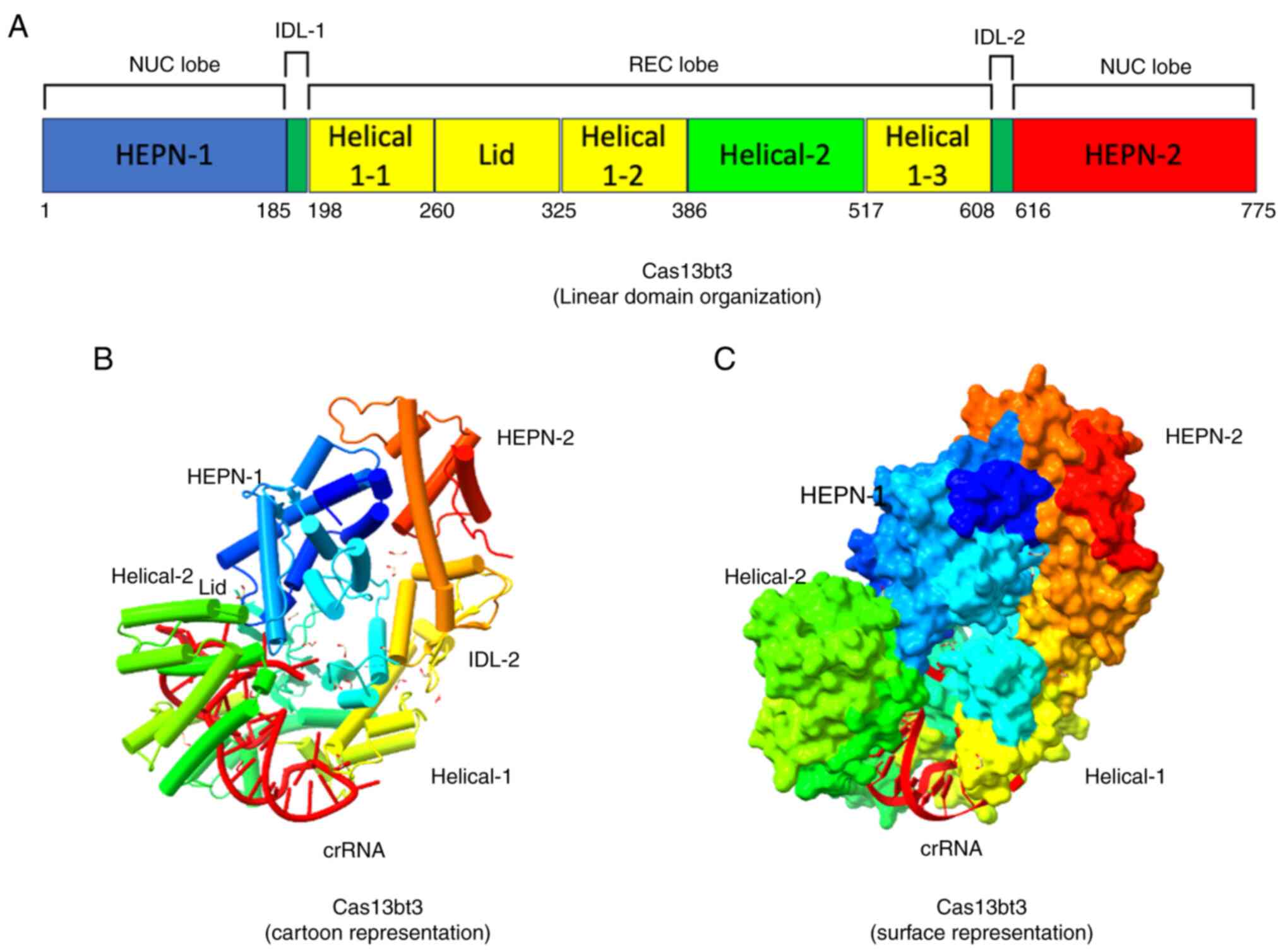

CRISPR/Cas13x and CRISPR/Cas13y

Cas13x (also known as Cas13bt3) and Cas13y have

been identified as subtypes of Cas13b. Using metagenomic data, a

recent study suggested additional categories of Cas13b exist, based

on clades of the derived phylogenetic tree (54,89). Undoubtedly, the effectiveness of

each subtype differs, depending on several factors. Being the

smallest Cas proteins, Cas13x and Cas13y have lengths between 775

and 800 amino acids, whereas the other Cas proteins have lengths

between 1,000 and 1,200 amino acids (52,85) (Fig.

7A). Furthermore, the corresponding single guide RNAs (sgRNAs)

differ fundamentally from one another in terms of sequence and

structure (for example, the sgRNA mounted by Cas13b has a spacer at

its 5′ end, whereas the sgRNA mounted by Cas13a has a spacer at its

3′ end) (55). Such CRISPR/Cas13

systems have been used for a number of purposes other than their

intended use in relatively recent times (71,90).

| Figure 7Structural features of the VI-X

CRISPR/Cas effector binary complex. (A) Linear domain organization

of Cas13bt3, presenting different domains (REC and NUC lobes)

annotated with corresponding amino acid numbers. (B) Cartoon

representation presenting the position of crRNA (red). (C) Surface

representation of Cas13bt3. The protein structure was downloaded

from the PDB website https://www.rcsb.org/ (PDB ID: 7VTI) and the binary

complex was edited using UCSF ChimeraX, version 1.8 (https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax). Cas13bt3,

Planctomycetota bacterium Cas13x; CRISPR, Clustered

Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; Cas,

CRISPR-associated sequence; HEPN, higher eukaryote and prokaryote

nucleotide-binding; REC, recognition; NUC, nuclease; crRNA, CRISPR

RNA; PDB, protein data bank. |

The VI-X and VI-Y families of bacteria produce all

known Cas13 orthologs. These orthologs originate from hypersaline

habitats, which lowers the possibility of preexisting immunity, as

observed in Cas9 and Cas12 orthologs that were found in pathogenic

bacterial samples that are closely related to humans (91). Additionally, to circumvent the

difficulty of delivering several large Cas13-based base editors

in vivo, Cas13x.1 has been truncated from amino acids 775 to

445 via structure-guided engineering. This allowed for the creation

of a minimum RNA base editor for C-to-U or A-to-I editing of a

variety of RNA loci in mammalian cells (52). Furthermore, it is anticipated that

in vivo RNA-editing-based research and therapeutic

applications will benefit from the use of these RNA editors with a

compact Cas13x.1 system (92-94). The summarized differences between

the various subtypes of the type VI CRISPR/Cas system are presented

in Table I.

| Table IComparison between different subtypes

of type VI CRISPR/Cas systems. |

Table I

Comparison between different subtypes

of type VI CRISPR/Cas systems.

|

Characteristics | VI-A | VI-B | VI-C | VI-D | VI-X | VI-Y |

|---|

| Cas effector | Cas13a | Cas13b | Cas13c | Cas13d | Cas13x | Cas13y |

| Size (no. of amino

acids) | ~1,250 | ~1,150 | ~1,121 | ~930 | ~775 | ~790 |

| Cas

architecture | REC and NUC

lobe | Pyramidal (binary

complex) | ND | REC and NUC

lobe | REC and NUC

lobe | ND |

| Location of

pre-crRNA processing | Helical-1 and

HEPN-2 domains | RRI-2 domain | ND | HEPN-2 domain | Not process | ND |

| Site of RNase

activity |

Surface-exposed |

Surface-exposed | ND |

Surface-exposed | ND | ND |

| Preference for

ssRNA cleavage | A- and U-cleaving

effectors | Pyrimidine base

(mostly U) | ND | U | ND | ND |

| Specificity | High | High | Unclear | High | High | High |

| Efficiency (for

KRAS), % | 57.5 | 62.9 | Low | >90.0 | >90.0 | >90.0 |

| Represented by

PFS | LwaCas13a | PspCas13b | FpCas13c | CasRx | Cas13x.1 | Cas13y.1 |

| 5′ non-G | 5′ non-C, 3′NAN or

NNA | ND | No

restrictions | No constraints | ND |

| Requirement of

small accessory proteins | None | Csx27 and

Csx28 | ND | WYL

domain-containing proteins | ND | ND |

| crRNA

orientation | 5′-3′ | 3′-5′ | ND | 5′-3′ | 3′-5′ | ND |

| crRNA repeat

length, nucleotides | Varies, 27-32 | 36 (short), 88

(long) | ND | 30 | 36 | ND |

| Repeat

architecture | Stem-loop | Distorted

stem-loop | ND | Stem-loop | ND | ND |

| Applications | RNA knockdown and

nucleic acid detection | RNA knockdown,

imaging and epigenetic engineering | Unclear | RNA knockdown,

imaging, epigenetic engineering and circular RNA screening | RNA knockdown and

epigenetic engineering | RNA knockdown |

Innovative applications of CRISPR/Cas13

platforms for the detection of tumor-related nucleic acids and

proteins

With great efficiency and precision, the

CRISPR/Cas13 system can be employed for targeted cancer therapy by

destroying and modifying the transcripts associated with

malignancy. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas13-based RNA editing is a

valuable choice for studying the biology of drug resistance

mechanisms, cancer research and the identification of new

therapeutic targets (22,23,95). Recently, the identification of

cancer-based RNAs, proteins and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from

liquid biopsy tests has been successfully performed using

Cas13-powered biosensors (96).

In vitro and in vivo Cas13 has also been utilized to

efficiently degrade a variety of cancer-associated RNAs.

Furthermore, a plethora of RNA-manipulation platforms based on the

CRISPR/Cas13 system have been engineered, providing a vital toolkit

for modeling, researching drug-resistance biology and identifying

new therapeutic targets in cancer (97-99). The adaptability of the Cas13

systems and their applications in tumor research, therapy and

diagnosis are discussed below. In addition, the benefits and

drawbacks of recent research and the promise of Cas13-based

techniques in the emerging fields of cancer treatment and diagnosis

are discussed.

Identification of different circulating

RNAs (cRNAs)

Compared with single RNA marker assessment, the

identification of numerous cRNAs in different biological samples

provides improved specificity and sensitivity for detecting the

initial stages of cancer (100-102). In this context, early-stage

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) detection has been performed by

identifying the expression levels of two mRNAs, epidermal growth

factor receptor (EGFR) and thyroid transcription factor-1, and four

micro (mi)RNAs (miR-17, miR-19b, miR-155 and miR-210), based on an

electrochemical biosensor provided by the CRISPR/Cas13 system

(23,103).

In one biosensor, a catalytic hairpin assay was

initiated by the collateral cleavage activity of Cas13, which

ultimately produced a current signal. The biosensor achieved high

sensitivity with a limit of detection (LOD) of 50 aM for RNA

detection, thus increasing the overall signal owing to the combined

effect of both the catalytic hairpin assay and collateral RNA

breakdown. The turnaround time was 36 min, and it was possible to

use a single biosensor chip 37 times continuously without any

sensitivity loss. Serum samples were obtained from four cohorts of

patients with NSCLC: 30 healthy individuals, 12 patients with

benign lung disease, 20 patients in the early stage (stages I-II)

of the disease and 55 patients in the late stage (stages III-IV) of

the disease. In total, six different RNA types from serum samples

were selected for disease evaluation. Of the 117 samples, 114 were

classified using this biosensor. Additionally, this platform

demonstrated 97.3% sensitivity and 95.2% specificity in

differentiating patients with NSCLC (stages I-IV) from non-cancer

populations, with 90% sensitivity and 95.2% specificity in

differentiating patients with initial-phase NSCLC (stages I and

II). Therefore, compared with reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR (RT-qPCR), the proposed biosensor offers more notable serum

sample discrimination. In this study, the detection cost was

estimated as $1.62 for each of the six RNAs; thus, multiple marker

analysis with this biosensor is reasonably priced (22). However, this method requires two

steps, which makes it less user friendly. Moreover, although the

biosensor can be reused, it cannot identify multiple RNAs

simultaneously. This lengthens the duration of multiple RNA

analysis. However, by improving the Cas13 platform for RNA

detection within the chip, a single-step technique could be

developed. This platform can also be coupled with a multichannel

biosensor. This research demonstrates that various RNAs in biopsy

samples can be analyzed by employing Cas13-based electrochemical

sensors to help diagnose cancer at the early stages. These precise

and sensitive biosensors can also be utilized to track clonal

evolution, therapeutic responses and tumor heterogeneity (22).

Identification of ctDNA

A promising marker for managing and diagnosing

cancer is the detection of ctDNA (104,105). The concept of CRISPR-based

diagnostics employing Cas13 was first presented by Zhang et

al (106). This approach can

be used in several applications, such as genotyping, the

identification of cancer-based alterations in DNA samples from

cellular extracts and the identification of harmful bacteria and

viruses (56).

For the rapid identification of RNA or DNA

sequences, the Specific High-Sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter

UnLOCKing (SHERLOCK) platform was engineered using a recombinase

polymerase amplification (RPA) system and collateral RNA breakdown

potential provided by Cas13 (107). SHERLOCK possesses a high

sensitivity and specificity for RNA and DNA identification

(Fig. 8). Cancer-related

BRAFV600E and EGFR-L858R mutations have been identified using the

SHERLOCK approach, and as few as 0.1% of mutant alleles were

identified in mock cell-free DNA samples (Table II) (56). The sensitivity of SHERLOCK is

comparable to those of qPCR and droplet digital PCR. In another

study on patients with NSCLC, liquid biopsy was used to identify

EGFR exon 19, EGFR-T790M and EGFR-L858R deletion changes in DNA

samples using fluorescence and readout techniques (108). The SHERLOCK approach was able to

significantly identify the mutant allele, even though in one

patient with the EGFR-T790M mutation, a 0.6% ratio of mutant

alleles in cell-free DNA was observed (108). SHERLOCK provides attomolar

sensitivity and single-base specificity for the detection of DNA

and RNA in clinical samples (97,109). This approach works well with

quick and easy techniques for the isolation of nucleic acids

(56). Additionally, each

SHERLOCK reagent costs less than $0.60 per test and can be utilized

in one-step reactions after freeze-drying (56). Moreover, orthogonal Cas13 enzymes

can identify several tumor-related nucleotide changes in a single

tube (108). A thorough

procedure that encompasses the LwCas13a enzyme purification step

has been previously suggested for the SHERLOCK assay (97). In conclusion, extremely sensitive

and specific ctDNA identification can be achieved at cheaper rates

without the need for complex instrumentation with Cas13-mediated

detection.

| Table IISummary of the different markers

present in various cancer types and their detection by the

CRISPR/Cas13-based approach. |

Table II

Summary of the different markers

present in various cancer types and their detection by the

CRISPR/Cas13-based approach.

| First author/s,

year | Cancer type | Sample used | Marker type and

target used | Method of

preamplification | Readout test,

sensitivity and assay time | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Tian et al,

2021 | Breast cancer | Cancer cell extract

and patient serum | miRNA (miR-17 and

miR-21) | Free of

amplification | Fluorescence, 100

aM and 60 min | (156) |

| Shan et al,

2019 | Breast cancer | Mock serum, cancer

cell extract and tumor tissue | miRNA (miR-17) |

Amplification-free | Fluorescence, 450

fM and 30 min | (14) |

| Zhou et al,

2021 | Breast cancer | Cancer cell extract

and mock serum | miRNA

(miR-10b) | Rolling circle

amplification | Colorimetric, 1 fM

and 120 min | (157) |

| Sha et al,

2021 | Breast cancer | Cancer cell

extract, mock serum and patient serum | miRNA (miR-17) | Amplification

free | Fluorescence, 1.33

fM and 125 min | (158) |

| Zhou et al,

2020 | Breast cancer | Cancer cell

extract | miRNA (miR-17) | Isothermal

exponential amplification | Electrochemilumi

nescence, 1 fM and 90 min | (112) |

| Cui et al,

2021 | Breast cancer | Mock serum | miRNA (miR-21) | Catalytic hairpin

assembly | Electrochemical,

2.6 fM and 150 min | (159) |

| Huang et al,

2020 | Breast cancer | Cancer cell extract

and mock serum | miRNA (miR-17) | Hyper-branching

rolling circle amplification | Fluorescence, 200

aM and 170 min | (160) |

| Abudayyeh et

al, 2016 | NSCLC | Mock serum | ctDNA (EGFR, L858R

and BRAF-V600E) | RPA and T7

transcription | Fluorescence, 0.1%

of mutant allele and 150 min | (25) |

| He et al,

2020 | NSCLC | Patient serum | Protein (serum

exosomal PD-L1) | T7 and RPA

transcription | Fluorescence, 10

particles/ml and 60 min | (120) |

| Gootenberg et

al, 2018 | NSCLC | Patient serum | ctDNA (EGFR-T790M,

EGFR L858R and EGFR exon 19 deletion) | T7 and RPA

transcription | Fluorescence

lateral-flow, 0.6% of mutant allele and 60-90 min | (108) |

| Sheng et al,

2021 | NSCLC | Patient serum | miRNA and mRNA

(miR-17, miR-19b, miR-155, miR-210 and TTF-1 and EGFR mRNAs) | Catalytic hairpin

assembly | Electrochemical, 50

aM and 36 min | (103) |

| Bruch et al,

2021 |

Medulloblastoma | - | miRNA (miR-19b and

miR-20a) |

Amplification-free | Electrochemical 10

nM (on-chip), 210 min | (114) |

| Bruch et al

2019 |

Medulloblastoma | Patient serum | miRNA (miR-19b and

miR-20a) |

Amplification-free | Electrochemical, 10

pM (off-chip), 2.2 nM (on-chip) and 210 min | (113) |

Identification of circulating miRNA

The identification of tumors at early stages by the

detection of circulating miRNAs represents an innovative strategy

for cancer diagnosis (110,111). The development of fast,

affordable, sensitive and targeted miRNA detection based on CRISPR

systems may help make cancer screening more common and enable early

detection. Compared with other CRISPR-associated enzymes utilized

in nucleic acid detection, Cas13 targets ssRNA directly and, when

activated, it demonstrates collateral ssRNA cleavage (15). Cas13 can be employed for RNA

detection without the need for reverse transcription or nucleic

acid amplification, as shown in Fig.

8. In this context, a one-step Cas13a-based miRNA detection

technique was designed to allow for amplification-free measurement

of miRNAs with a sensitivity of 450 fM and single-base specificity.

In this procedure, miR-17 was measured in the total RNA from mock

serum samples, cancer cell lines and tumor tissues from patients

with mammary cancer to highlight the potential of this

fluorescent-mediated technique (14). The Cas13-based approach showed a

potential increase in miR-17 levels in 18 out of 20 cancer tests,

and the results were comparable to those of RT-qPCR. According to

this study, tissue and liquid biopsy samples can be used to test

for cancer using the Cas13-based miRNA detection approach. To

improve the sensitivity of the original technique, Zhou et

al (112) developed several

novel biosensors based on this innovative approach (Table II).

A Cas13-mediated biosensor has been designed to

identify miR-19b and miR-20, which are elevated in patients with

medulloblastoma (113). In this

assay, the binding of miRNA-activates the Cas13 endonuclease. The

FAM-tagged reporter ssRNA is cleaved by active Cas13, leading to

the unbound washing out of glucose oxidase labeled with an anti-FAM

antibody. Glucose oxidase generates H2O2 in

electrochemical cells when the target miRNA is absent from the

sample. Consequently, the presence of the sample led to a decrease

in the signal. The instrument allowed the testing of 10 pM miR-19b

and miR-20a when the Cas13-based miRNA detection phase was carried

out outside the chip. Patients with medulloblastoma in both a full

remission state and a progressive state could be identified by the

biosensor. Furthermore, for the additional optimization of this

technique to achieve multiway detection, a new biosensor was

designed to simultaneously detect up to eight miRNAs (114). This led to the successful

detection of miR-20a and miR-19b of up to a10 nM range. These

studies demonstrated the role of Cas13-based electrochemical miRNA

sensors as potential tools for cancer diagnosis.

Detection of liquid biopsy proteins

Extracellular vesicles known as Exosomes are

released by various cell types including cancer cells (115). These vesicles are present in

bodily fluids such as saliva, blood and urine, and are composed of

lipids, proteins and nucleic acids. Exosomes are intriguing

candidates for liquid biopsy investigations in cancer diagnosis

(116). In particular, several

exosomal proteins have been identified for the identification of

cancer in its early stages, tracking the disease course and

estimating the prognosis (117,118).

Traditional protein analysis techniques, such as

mass spectrometry, ELISA and immunoblotting, require considerable

processing time, labor and expensive equipment. These techniques

also require several purification steps. New protein analysis

techniques have been developed to identify exosomal proteins,

including nanoplasmonic exosome sensors and flow cytometry.

However, these techniques are costly and require specialized

equipment (119). To overcome

these complications, RPA- and Cas13-mediated signaling has been

performed using DNA aptamer-based protein identification to

engineer an exosomal protein detection biosensor (120). This biosensor was devised to

identify exosomal programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), an important

biomarker for monitoring immune-based therapies. Exosomes were

extracted from the blood of patients using a mixture of antibodies.

The exosomes that were bound were mixed with DNA-based aptamers

that exclusively attached to PD-L1. After the unbound aptamers were

removed by washing, aptamers bound to PD-L1 were removed, and their

amplification was performed using RPA and T7 to produce RNAs. This

triggered Cas13a to break the reporter ssRNAs based on fluorescence

detection. This approach resulted in an LOD of 10 particles/ml, and

the detection range was notably more precise than that of ELISA for

identifying minute quantities of exosomal PD-L1. The researchers

followed a treatment plan with anti-PD-1 therapy for

non-progressive and progressive NSCLC. The PD-L1 levels were

examined in two groups of patients, and the biosensor verified that

only the progressive disease patient group showed a statistically

significant increase in exosomal PD-L1 expression.

In a different study, Chen et al (121) designed an immunosorbent assay

driven by Cas13 that could detect proteins at a femtomolar level

and was at least 100 times more sensitive than regular ELISA

testing. This technique is based on the idea that when a target

antigen is present in the sample, it attaches to a dsDNA sample and

adheres to the well via a sensing antibody. The dsDNA template is

transcriptionally transcribed by T7 to produce RNA copies, which

trigger Cas13 to break the ssRNA, a fluorescence-based reporter.

This procedure is called the CRISPR/Cas13a signal amplification

linked immunosorbent assay (CLISA). The detection range of CLISA is

very high, and the detection range for VEGF and IL-6 was shown to

be 0.81 and 2.29 fM, respectively (121) (Table II). According to these

experiments, tumor marker protein detection techniques with

Cas13-enhanced protein detection can be carried out quickly,

quantitatively, sensibly and specifically, without the requirement

for sophisticated equipment. By facilitating biopsy analysis for

tumor detection and therapeutic strategies, these techniques can

improve treatment outcomes and enable the initial stage of tumor

diagnosis.

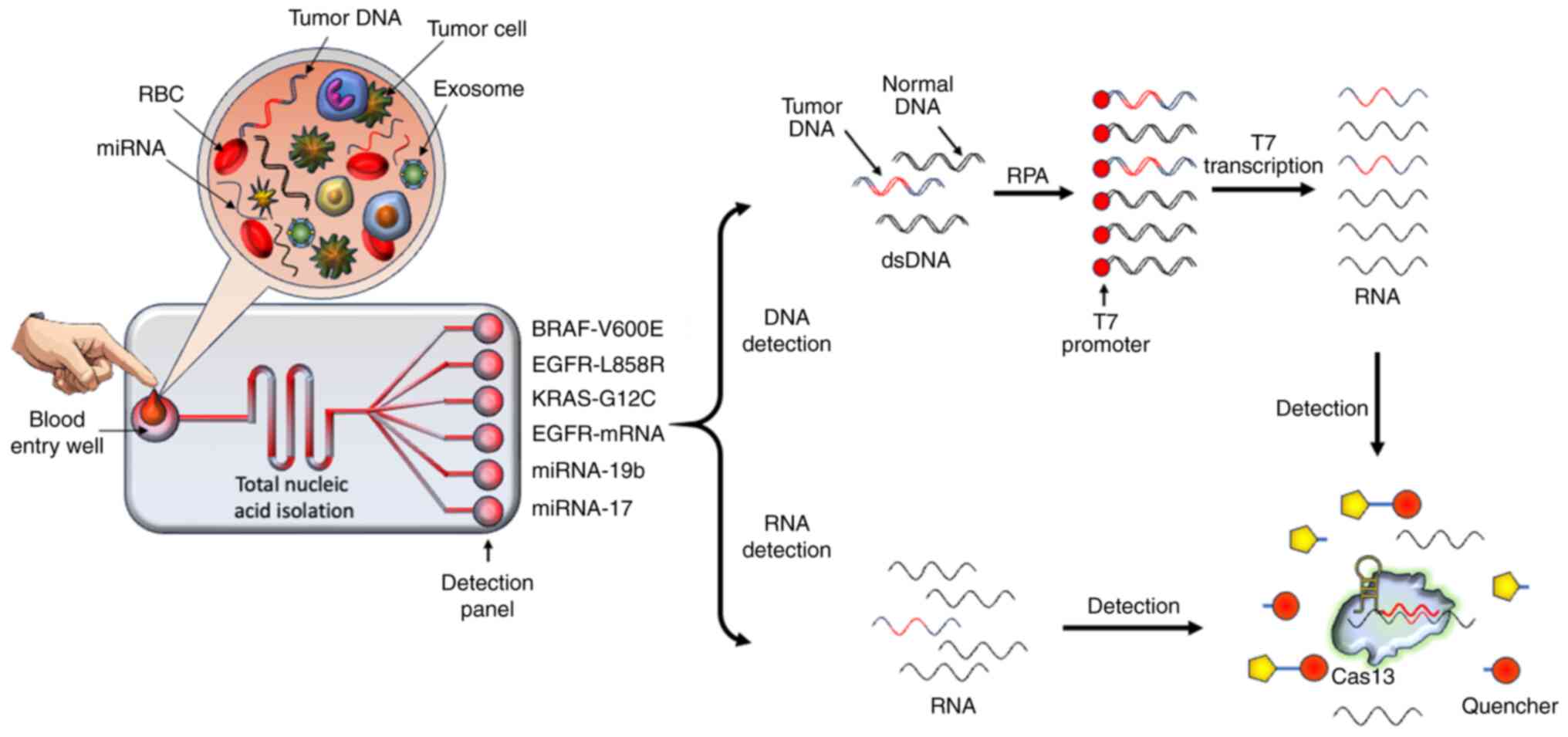

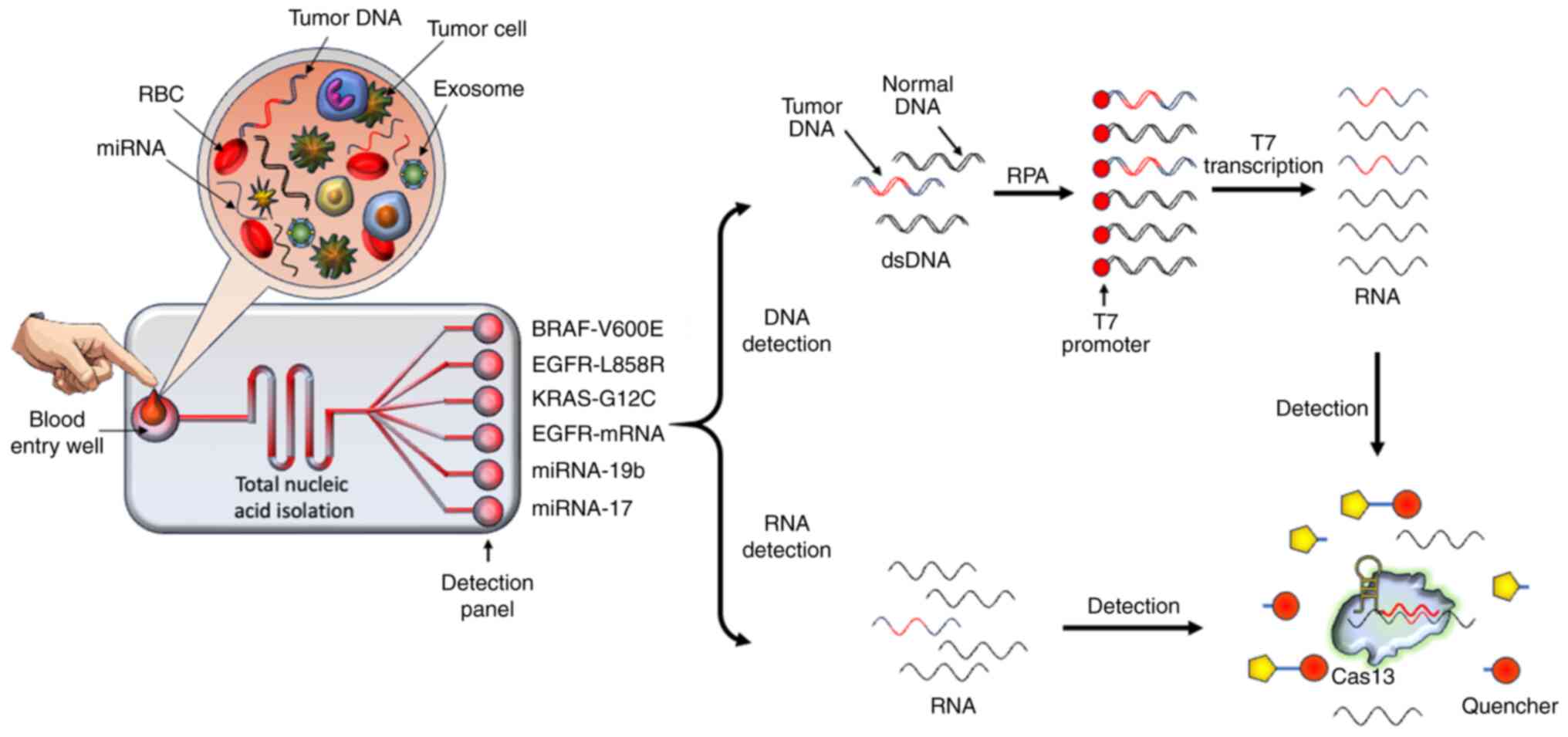

Although, the CRISPR/Cas13 system shows great

promise for cancer diagnostics, a fully integrated Cas13-based

biosensor has not yet been engineered. A multiplex hypothetical

biosensor for the diagnosis of NSCLC-based nucleic acid detection

has been proposed for future cancer detection (22) (Fig.

9). This biosensor can extract nucleic acids from whole blood,

which are then divided into multiple channels for detection by

Cas13 present in the detection panel of the biosensor. This

biosensor model was proposed to facilitate the initial detection of

cancer and to provide an overview of the response to treatment

therapy (22).

| Figure 9A proposed all-in-one Cas13-based

biosensor devise for future cancer diagnosis. As a microfluidic

sensor, the sample preparation and Cas13-based RNA and DNA

detection steps are integrated for initial-stage NSCLC diagnosis.

The patient's blood possesses cancer-derived cells, miRNAs,

circulating mRNAs, tumor DNAs and exosomes. In this proposed

device, the patient's blood sample is introduced into the entry

well directly. Following the quick nucleic acid isolation step, the

RNAs and DNAs flow within the channel and proceed to the detection

panel. In this panel, each well for detection contains reagents

needed to check for the NSCLC-based DNA mutation or RNA

quantification. Specific RNAs are targeted directly by Cas13, which

is activated in the presence of the CRISPR RNA spacer sequence. The

fluorescent reporter as well as target RNA are cleaved by the

activated Cas13. Additionally, cancer-associated DNAs are amplified

by RPA. After the addition of T7 promoter, the transcription of RPA

amplicons is performed. The mutation-based transcripts after

binding with Cas13 subsequently activate it, which concomitantly

cleaves the fluorescent reporter RNAs, thus providing a detectable

fluorescent signal. Cas13, CRISPR-associated sequence 13; NSCLC,

non-small cell lung cancer; miRNA, microRNA; RPA, recombinase

polymerase amplification; RBC, red blood cell; dsDNA,

double-stranded DNA. |

Delivery and expressional approaches of

CRISPR/Cas13 in cancer cells

The targeting of Cas13 expression in cancer cells

holds great promise; however, careful consideration of certain

factors such as off-target effects, immune response, tumor

heterogeneity and delivery challenges is crucial to maximize the

therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, Cas13-based cancer targeting can

be made safer by using delivery techniques that are specific to

tumor tissue or expression that is particular to cancer cells. Due

to the high specificity of Cas13, tumor-specific delivery

techniques and cancer cell-specific expression, studies employing

CRISPR/Cas13 for cancer cell targeting have been conducted without

causing harm to normal cells in vitro (122-124) or to normal tissues in

vivo (125,126). The safety of CRISPR-Cas13-based

RNA-targeting may be further enhanced using newly identified

anti-CRISPR inhibitors of Cas13a (127,128) for the optogenetic regulation of

Cas13 activity (129) or the

cancer tissue-specific activation of Cas13a enzymes (130). For the selective Cas13a-mediated

degradation of oncogenic mRNAs in cancer cells, Fan et al

(131) integrated tumor-specific

delivery, tumor-specific expression and laser-controlled release

techniques in a well-designed study. They coupled vascular

endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) monoclonal antibodies

with the lipid component of nanoparticles for tumor-specific

delivery since invasive bladder cancer has upregulated VEGFR2

expression (132). Cas13a was

expressed from human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), a

synthetic promoter unique to bladder cancer (133). Using a photothermal agent,

liposomes were released under laser control. By combining these

strategies, intelligent liposomes were installed in the bladder and

orthotopic bladder cancer tumors were effectively targeted

(131).

Using promoters unique to cancer cells is another

approach of cancer cell targeting. Gao et al (99) employed a decoy minimum promoter,

which is unique to nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), to express Cas13a

exclusively in cancer cells. It has been demonstrated that this

promoter only permits effective transcription when NF-κB, which is

upregulated in a number of malignancies, is present in high

concentrations (134-136). Gao et al (99) demonstrated that only the tumor

tissue expressed the Cas13a enzyme and that the target transcripts

were exclusively broken down in the tumor tissue, even though

adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) carrying Cas13a and crRNAs were

administered intravenously to numerous tissues (99).

Zhang et al (124) employed chemically-locked

nanoparticles containing plasmids encoding PD-L1-targeting crRNA

and Cas13a. Due to the low pH and high H2O2

concentration found in the tumor microenvironment, these

nanoparticles were engineered to only release the plasmids in tumor

tissues, and the Cas13a and crRNA-encoding plasmids were primarily

absorbed by cancer cells. Similarly, Jiang et al (125) ensured targeted delivery of

Cas13d/crRNA expression cassettes to the pancreas of orthotopic

tumor-bearing mice using a capsid-optimized AAV8. A study that used

the CRISPR-Cas13d technology to treat age-related macular

degeneration also found no in vivo harm (93). Together, these findings

demonstrate that the RNA-targeting CRISPR/Cas13 system is highly

precise and that both tumor tissue-specific viral and non-viral

delivery strategies, as well as expression unique to cancer cells,

can guarantee safety.

Pre-clinical and clinical applications of

CRISPR/Cas13 for the management of cancer

In addition to the detection of different tumor

related markers such as cRNAs, ctDNAs, circulating miRNAs and

proteins, the CRISPR/Cas13a system has also been used in real-world

clinical application for cancer therapy (22). By precisely identifying and

lowering the mRNA expression of oncogenes in cancer cells, the

CRISPR/Cas13a system has been used to stop tumor growth. This has

resulted in regulated incidental breakage and the induction of

programmed cell death in cancer cells (95). However, more research is necessary

to determine whether CRISPR/Cas13a, a potent RNA knockdown

technique, can be used in all types of cancer cells. The

pre-clinical and clinical applications of CRISPR/Cas13 system for

the management of different cancers is elaborated on below.

Pancreatic cancer

Due to its quick onset, low incidence of early

diagnosis, high surgical mortality rate and low cure rate,

pancreatic cancer has surpassed breast cancer; it is a very

challenging task to identify and treat pancreatic cancer and this

disease is expected to be the third leading cause of cancer-related

death in the United States (137,138). Due to the high mortality rate of

pancreatic cancer, effective novel therapeutic approaches are

desperately needed (122). A

mutant oncogene, known as Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene

homolog (KRAS), is the main cause of pancreatic cancer (139). One successful antitumor method

is to suppress the expression of the KRAS mutant at the mRNA level.

It is reported that the expression of mutant KRAS mRNA is markedly

reduced by the bacterial Cas13a protein and crRNA (25), demonstrating that the

CRISPR/Cas13a system can achieve up to 94% expressional knockdown.

In several KRAS-driven pancreatic cancer models, the Cas13a-crRNA

complex efficiently inhibits the KRAS-G12D mutation signaling

pathway, resulting in apoptosis and tumor growth inhibition both

in vitro and in vivo (140). This suggests that the CRISPR/

Cas13a system can be employed as a targeted therapy for patients

with pancreatic cancer harboring mutant KRAS (141). More notably, CRISPR/Cas13a

knockdown of KRAS-G12D can stop the growth of pancreatic cancer

cells, and CRISPR/Cas13a-mediated mRNA downregulation can cause

tumor cells to undergo apoptosis and cause marked tumor shrinkage

in vitro. Therefore, it can be concluded that the CRISPR/

Cas13a system is the most effective method for influencing the

efficient and focused suppression of carcinogenic mRNAs since it is

a flexible targeted therapeutic tool (22,142).

In a recent study, researchers employed an

innovative approach known as Cas13a Allele-Specific PCR Enzyme

Recognition (CASPER), an allele-specific PCR preamplification

technique, to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting

KRAS G12D with minimal DNA input (140). CASPER identified KRAS mutations

in DNA samples obtained from patients with pancreatic cancer by

ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration fluid; thus, implementing

this approach may be a versatile and reliable method for the

detection of point mutations in pancreatic cancer DNA samples.

Bladder cancer

Globally, bladder cancer is one of the most

prevalent cancer types, with a high incidence and recurrence rate

(143). This type of cancer had

a 5-year frequency of >1.7 million cases in 2020, making it the

sixth most common cancer worldwide (144). To the best of our knowledge, the

use of CRISPR/Cas13a-based therapeutic approaches for intravesical

instillation in bladder cancer is still unexplored, although

several experimental procedures have shown effectiveness in

enabling execution of CRISPR/Cas13a-based cellular functions. In

one study, the researchers used a CRISPR/Cas13a nanoplatform that

significantly reduced the expression of programmed death ligand 1

(PD-L1) after its intravesical instillation. The transmembrane

peptide, trans-activator of transcription and CRISPR/Cas13 were

genetically fused to generate the fusion protein, calpastatin

(CAST). Fluorinated chitosan (FCS), a transepithelial delivery

vehicle was assembled with CAST, which acted as a powerful

transmembrane RNA editor. The CAST-crRNAa/ FCS nanoparticles had

notable transepithelial properties and markedly reduced PD-L1

expression in tumor tissues when administered intravesically into

the bladder (145). The

researchers used a fenbendazole (FBZ) intravesical system to

increase immune activation in the tumor microenvironment. This

system was constructed by bovine serum albumin encapsulation and

FCS, which establishes FBZ as a potent chemo-immunological agent.

This nanoformulation method reorganized the immunological

microenvironment, synergistically decreased PD-L1 expression and

showed marked tumor cell death in a bladder cancer model. The study

suggested a possible synergistic treatment approach and revealed a

unique RNA editor nano-agent formulation. This strategy greatly

increased therapeutic efficacy and showed potential for the

clinical application of cancer perfusion therapies based on

CRISPR/Cas13 (145).

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is a common cancer that is a major

threat to women's health and is a major global public health issue.

Globally, there were 348,189 cervical cancer-related deaths and

661,021 new cases in 2022 (146). Multiple types of human

papillomavirus (HPV) have been linked to cervical cancer; however,

the primary causes are the high-risk HPVs, HPV16 and HPV18

(147). Cervical cancer is

largely caused by the E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which are encoded by

the HPV genome and lower the expression levels of the tumor

suppressor proteins, p53 and retinoblastoma. This results in

increased cell proliferation and decreased apoptosis, which

furthers the development of cervical cancer (148). Therefore, it is anticipated that

antiviral drugs that suppress the production of E6/E7 oncoproteins

will be used to treat cervical cancer. According to previous

research, the CRISPR/Cas13a system can efficiently and precisely

knockdown HPV16/18 E6/E7 mRNA (123). The HPV16 knockdown by the

CRISPR/Cas13a system markedly decreased tumor weight and volume in

a subcutaneous xenograft tumor growth model. According to the

aforementioned study, the ability of the CRISPR/Cas13a system to

target HPV E6/E7 mRNA may make it a viable treatment option for

cervical cancer linked to HPV.

Glioma

The most prevalent type of malignant brain cancer

is glioblastoma multiform (GBM), with an incidence rate of 3.23 per

100,000 population globally (149). Since there are several forms of

GBM and its prognosis is typically poor, research on its

therapeutic approach is especially crucial (150). The CRISPR/Cas13a system can kill

glioma cells that have upregulated EGFR VIII expression, a distinct

mutant subtype of EGFR observed in glioma. The CRISPR/Cas13a system

has been characterized by non-specific RNA cleavage, according to a

single-cell RNA sequencing investigation conducted on

U87-Cas13a-EGFR VIII cells (151). In addition, CRISPR/Cas13a has

been shown to inhibit glioma formation in intracranial tumors. In a

mouse tumor model, U87-F3-T3 cells expressing Cas13a prevented

glioma cells from proliferating and growing, demonstrating

CRISPR/Cas13a-based suppression (151).

Challenges and prospects

Understanding the scope and limitations of RNA

editing by the Cas13 system and avoiding potential errors are

crucial, although this system has numerous uses in clinical

diagnostics, scientific research and possible therapeutic

applications. For targeted RNA knockdown, high-fidelity Cas13

variants reduce the risk of unintentional collateral RNA

degradation. However, recent research has revealed unexpected

effects of expressing either Cas13 or gRNA alone. These unexpected

effects include off-target effects, intrinsic targeting of host RNA

and cellular toxicity (70). The

creation of an innovative Cas13 platform for a range of uses will

be made easier with an improved comprehension of these findings and

the underlying mechanisms.

The prospects to enhance the specificity and

minimize unintended RNA cleavage by the CRISPR/Cas13 system in the

near future may be challenging, which include different novel

approaches, such as i) optimizing the gRNA design: The new designs

of the gRNAs can significantly improve the targeting specificity

within cancer cells. This approach includes the chemical

modification of nucleotides and other structural alterations to

enhance the gRNA stability and reduce off-target effects. The

chemical modifications into gRNAs can enhance their binding

affinity and specificity for target RNA sequence (78); ii) use of high-fidelity Cas13

variants: The off-target effects of Cas13 can be further reduced by

using high-fidelity Cas13 variants. These variants are engineered

to have high specificity for their target RNA sequence (152); and iii) employment of

computational tools: The prediction and minimization of Cas13

off-target effects for potential gRNA-target interactions can be

advanced by computational tools and algorithms (153).

Additional challenges regarding the use of the

Cas13 system within the cells of interest include its delivery

options. The Cas13 system may have difficulty in penetrating

certain tissues or cell types (such as HeLa and 293T cells), which

limits its effectiveness. Off-target effects or unintended

consequences can raise ethical concerns, particularly in clinical

applications. Specifically, germline editing using this RNA editing

system raises ethical questions regarding the modification of

future generations. Despite these limitations, ongoing research is

addressing these challenges and exploring innovative approaches to

improve the specificity of the Cas13 RNA-editing strategy, enhance

its specificity and improve delivery approaches for potential

therapeutic applications.

Optimizing the delivery of CRISPR/Cas13 to cancer

cells is challenging but highly significant for enhancing its

therapeutic efficacy. Some novel strategies to improve the delivery

of CRISPR/Cas13 in target cells include: i) Viral vectors:

CRISPR/Cas13 components can be easily delivered by AAVs and

lentiviruses into target cells. These vectors can be modified to

target cancer cells specifically, ensuring efficient delivery and

expression of the CRISPR system (153); ii) nanoparticle-based delivery:

CRISPR/Cas13 components can also be delivered efficiently in target

cancer cells by utilizing nanoparticles, such as lipid

nanoparticles or polymer-based nanoparticles. These nanoparticles

can be engineered to target specific tumor cells, enhancing

specificity and reducing off-target effects (154); iii) cell-penetrating peptides

(CPPs): CPPs can facilitate the delivery of CRISPR/Cas13 components

into cancer cells by enhancing cellular uptake. These peptides can

be conjugated with CRISPR components to improve their intracellular

delivery (152); iv)

electroporation: This method involves applying an electric field to

cells to increase the permeability of the cell membrane, allowing

CRISPR/Cas13 components to enter the cells more effectively. It is

particularly useful for ex vivo applications, such as

modifying immune cells before reintroducing them into the patient

(155); and v) targeted delivery

systems: Developing targeted delivery systems that use ligands or

antibodies to recognize and bind to specific receptors on cancer

cells can enhance the precision of CRISPR/Cas13 delivery. This

approach minimizes off-target effects and maximizes therapeutic

impact (154). All these

strategies collectively contribute to a more effective and precise

delivery of CRISPR/Cas13 in cancer therapy, potentially leading to

improved treatment outcomes.

Furthermore, the prospects of Cas13 RNA-targeting

and editing approaches in the near future include the correction of

genetic defects, such as in cystic fibrosis, Huntington's disease

and sickle cell anemia, for proper disease management. In addition,

this system could be employed to target and destroy viral RNA to

combat viral infections, such as HIV and influenza, and emerging

viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2. Cas13-based diagnostic tools can be

developed for rapid and sensitive detection of genetic mutations,

pathogens and other biomarkers.

Conclusions

Since its discovery in 2016, the CRISPR/Cas13

platform has revolutionized the art of RNA-based diagnostics and

therapeutics, in addition to the fundamental study of RNA biology.

Cas13 is a potent gene targeting tool due to its ability to

precisely and efficiently target nearly any nuclear or cytoplasmic

RNA sequence. The potential of CRISPR/ Cas13 as a therapeutic

platform is further enhanced by its small size and inherent

flexibility. With its single-nucleotide accuracy and specificity,

the constantly growing CRISPR/ Cas13 toolset enables a wide variety

of RNA modifications. Safer treatments for a variety of illnesses

are made possible by the capacity to accurately modify RNAs,

including substitutions or nucleotide additions, without changing

DNA. However, the structural and biochemical aspects of the gene

editing strategies of the CRISPR/Cas13 system are still

insufficient to comprehend its thorough use in the clinical field.

The prospects to enhance the specificity and minimize unintended

RNA cleavage by the CRISPR/Cas13 system is highly significant but

challenging. These challenges can be circumvented by using new gRNA

designs, high-fidelity Cas13 variants and the employment of new

computational tools. Furthermore, optimizing the delivery

approaches of the CRISPR/Cas13 system into cancer cells may be

utilized by engineered nanoparticles, viral vectors, CPPs,

electroporation and other targeted delivery systems. We anticipate

that Cas13 technologies will continue to advance, opening

fascinating possibilities for RNA-based diagnostics, RNA-targeting

treatments and biological research.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization was conducted by KSA and AAK;

writing the original draft was conducted by KSA, AHR and AAK;

reviewing and editing the manuscript was conducted by KSA, AHR,

NMA, FMA, GhadahMA, GhadeerMA and AAK; data curation was conducted

by KSA, AHR, NMA, FMA, GhadahMA, GhadeerMA and AAK. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patent consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of

Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for

financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Funding

This study was supported by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and

Scientific Research at Qassim University (QU-APC-2025).

References

|

1

|

Marraffini LA: CRISPR-Cas immunity in

prokaryotes. Nature. 526:55–61. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Allemailem KS, Alsahli MA, Almatroudi A,

Alrumaihi F, Alkhaleefah FK, Rahmani AH and Khan AA: Current

updates of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing and targeting within

tumor cells: An innovative strategy of cancer management. Cancer

Commun (Lond). 42:1257–1287. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Piergentili R, Del Rio A, Signore F, Umani

Ronchi F, Marinelli E and Zaami S: CRISPR-Cas and its wide-ranging

applications: From human genome editing to environmental

implications, technical limitations, hazards and bioethical issues.

Cells. 10:9692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Allemailem KS, Almatroudi A, Rahmani AH,

Alrumaihi F, Alradhi AE, Alsubaiyel AM, Algahtani M, Almousa RM,

Mahzari A, Sindi AAA, et al: Recent updates of the CRISPR/ Cas9

genome editing system: Novel approaches to regulate its

spatiotemporal control by genetic and physicochemical strategies.

Int J Nanomedicine. 31:5335–5363. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Meng X, Wu TG, Lou QY, Niu KY, Jiang L,

Xiao QZ, Xu T and Zhang L: Optimization of CRISPR-Cas system for

clinical cancer therapy. Bioeng Transl Med. 8:e104742022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Heler R, Marraffini LA and Bikard D:

Adapting to new threats: The generation of memory by CRISPR-Cas

immune systems. Mol Microbial. 93:1–9. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Faure G, Shmakov SA, Yan WX, Cheng DR,

Scott DA, Peters JE, Makarova KS and Koonin EV: CRISPR-Cas in

mobile genetic elements: Counter-defence and beyond. Nat Rev

Microbiol. 17:513–525. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hille F, Richter H, Wong SP, Bratovič M,

Ressel S and Charpentier E: The biology of CRISPR-Cas: Backward and

forward. Cell. 172:1239–1259. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Van Der Oost J, Westra ER, Jackson RN and

Wiedenheft B: Unravelling the structural and mechanistic basis of

CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 12:479–492. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Konermann S, Lotfy P, Brideau NJ, Oki J,

Shokhirev MN and Hsu PD: Transcriptome engineering with

RNA-targeting type VI-D CRISPR effectors. Cell. 173:665–676.e14.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yan WX, Chong S, Zhang H, Makarova KS,

Koonin EV, Cheng DR and Scott DA: Cas13d is a compact RNA-targeting

type VI CRISPR effector positively modulated by a

WYL-domain-containing accessory protein. Mol Cell. 70:327–339.e5.