Introduction

Liver cancer, the third leading cause of

cancer-associated death worldwide (1), with an estimated 865,269 new liver

cancer cases and 757,948 related deaths occurring worldwide in

2022, poses a significant public health challenge, especially in

China, where the 5-year survival rate was 12.1% from 1990 to 2021

(2). By 2040, liver cancer may

result in ~1.3 million fatalities worldwide (3,4).

The pathogenesis of liver cancer is associated with chronic

hepatitis infection, fatty liver disease, cirrhosis, long-term

exposure to carcinogens, such as aflatoxin, and excessive alcohol

consumption (5). Despite

advancements in the prevention, detection and treatment of liver

cancer, the majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages

of the disease (2). Treatment is

further hindered by challenges such as drug resistance and high

recurrence rates.

Sorafenib, the US Food and Drug

Administration-sanctioned multi-kinase inhibitor, is the sole

first-line systemic therapy for liver cancer. However, its

therapeutic efficacy remains limited (6). The SHARP trial (trial no.

NCT00105443) demonstrated that sorafenib could extend overall

survival by 2.8 months (7). In

addition, the majority of patients do not experience long-term

benefits due to the early onset of resistance to sorafenib. It has

also been reported that ~30% of patients benefit from sorafenib,

and resistance typically develops within 6 months (8). The mechanisms underlying sorafenib

resistance remain poorly understood. Given the limited efficacy of

the current treatment strategies, identifying novel therapeutic

targets and resolving sorafenib resistance are key for advancing

liver cancer therapy.

The direct effect of sorafenib on liver cancer cells

stems from ferroptosis induction rather than cell apoptosis

(9,10). Ferroptosis represents a form of

iron-dependent programmed cell death, which is triggered by lethal

lipid peroxidation (11,12). The morphological hallmarks of

ferroptosis include diminished mitochondrial cristae and atrophy

(11). Both iron chelators and

lipophilic antioxidants impede ferroptosis. Sensitivity to

ferroptosis can be augmented by excessive iron influx, either via

the interaction between transferrin and transferrin receptor or via

enhanced free iron availability resulting from selective ferritin

degradation, also known as ferritinophagy. Furthermore, impairments

in phospholipid peroxidases, particularly glutathione peroxidase 4

(GPX4) and the upstream cystine transporter solute carrier family 7

member 11 (SLC7A11), promote susceptibility to uncontrolled lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis (13). As a result, depleted glutathione

(GSH) fails to protect cells from oxidative stress and lipid

peroxidation. Therefore, the accumulation of free iron and lipid

peroxidation are hallmarks of ferroptosis. Sorafenib could directly

inhibit SLC7A11, thereby inhibiting GSH biosynthesis (8). Therefore, targeting ferroptosis may

offer a promising therapeutic strategy to overcome sorafenib

resistance.

Mitochondria exert pleiotropic functions in normal

physiology, including energy conversion, regulation of apoptosis,

biosynthetic metabolism and cellular proliferation (14,15). They also serve a key role in

stress sensing, environmental adaptation and tumorigenesis

(16). Additionally, mitochondria

are associated with tumor development, progression and resistance

to therapy via generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), thus

inducing genomic instability and modulating gene expression and

signaling pathways (17-21). Alterations in mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA) are associated with cell and metabolic consequences and

have been implicated in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of

several types of tumors (22).

Single-strand DNA-binding protein 1 (SSBP1), a homologue of

Escherichia coli SSB, serves key roles in mtDNA metabolism

and mtDNA replication via binding to single-stranded DNA (23,24). A study demonstrated that following

DNA damage, SSBP1 promptly localizes to double-strand DNA breaks

(DSBs) and is involved in DSB homology-directed repair (25). The aberrant expression of SSBP1 is

associated with several pathological conditions, including organ

dysfunction, neurodegenerative disease and cancer (26,27). Another study also showed that

SSBP1 knockout suppresses tumor cell proliferation, thus suggesting

that SSBP1 may serve as a potential therapeutic target for

glioblastoma (28). However, the

role of SSBP1 in liver cancer initiation, progression and sorafenib

resistance remains poorly understood. Therefore, the present study

aimed to investigate the effects of SSBP1 on mitochondrial

function, cell proliferation, migration and ferroptosis, as well as

the association between SSBP1 expression, sorafenib resistance and

patient prognosis. The present study aimed to determine whether

SSBP1 modulates sorafenib sensitivity via ROS-mediated ferroptosis

pathways, to identify a potential therapeutic target to overcome

drug resistance and improve patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of six male C57BL/6J mice (age, 8-10 weeks;

weight, 20-25 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory

Animal Technology Co., Ltd. All animal experiments were performed

according to international guidelines and approved by the Animal

Care and Use Committee of Tianjin Medical University (approval no.

TMUaMEC2024050; Tianjin, China). Animals were maintained under

specific-pathogen-free conditions (21-23°C; humidity, 60-65%;

light/dark cycle, 12:12 h; free access to food/water). A

diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced liver cancer mouse model was

established as previously described (29). Briefly, 2-week-old C57BL/6J mice

(weight, 8-12 g) were intraperitoneally administered 25 mg/kg body

weight DEN (cat. no. W610685; Energy Chemical) (Fig. S1A). When they reached 4 weeks of

age, mice were treated with weekly intraperitoneal injection of

CCl4 (5 ml/kg body weight, at a concentration of 10% in

olive oil) for a total of 20 times. Mice were monitored daily for

signs of distress and weighed three times/week. Abdominal

distension was assessed by palpation twice/week. Behavioral

parameters, including feeding efficiency and locomotor activity,

were recorded daily. At 24 weeks, all mice were euthanized via

inhalational exposure to CO2 (40% chamber volume/min) in

a sealed chamber, followed by confirmation of death through absence

of cardiac and respiratory function for 5 min. The humane endpoints

were defined as follows: i) Tumor volume >2×103

mm3; ii) tumor diameter >20 mm; iii) rapid or

continuous body weight loss >20% within 72 h; iv) tumor

ulceration or necrosis leading to skin rupture or persistent

exudation for >48 h and v) abdominal distension or ascites

burden >10% of body weight, exhibiting an appearance analogous

to that of a pregnant mouse compared with age-matched control mice.

Liver tissue samples were collected following euthanasia. Cancer

and adjacent paracancerous tissues were dissected, with the normal

adjacent tissues sampled at a distance of ≥0.5 cm from the tumor

margin to ensure clear distinction. All tissue samples were

immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen (−196°C) for subsequent

analyses.

Cells and transfection

Hep3B, HepG2, Huh7, Hepa1-6 and 293T cells were

obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The cells were

cultured in DMEM (cat. no. MA0212; Dalian Meilun Biology Technology

Co., Ltd.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

MN012103; Mengma (Tianjin) Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and 1%

antibiotics at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. A total

of 20 μg lentiCRISPRv2 (cat. no. 52961; Addgene, Inc.)

served as the core plasmid for constructing knockout-SSBP1 (for

both mouse and human sources), and H128

pLenti-EF1α-EGFP-3FLAG-PGK-Puro (HeYuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

for SSBP1 overexpression. Additionally, packaging plasmids (5

μg pMD2.G and 15 μg psPAX2, second-generation

lentiviral packaging plasmids) were purchased from Addgene, Inc.

The plasmids [sg-SSBP1 (sg, single-guide RNA),

5′-CACCGCAAGTGACTACCTGTAATAC-3′; sg-Ssbp1 (sg, single-guide RNA),

5′-CACCGGATAGTGAAGTATACCAAAT-3′; SSBP1-Flag, forward,

5′-CCGGAATTCATGTTTCGAAGACCTGTATTAC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCTGGATCCTTCCTCTTTGCTGTCTG-3′] or control plasmids, along with

packaging plasmids, were co-transfected into 293T cells

(5×105 cells/well) of a 6 well plate using

polyethyleneimine (cat. no. 408727; Sigma-Aldrich). The

transfection was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol

at 37°C for 6-8 h. medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS

(cat. no. MN012103; Mengma (Tianjin) Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Following incubation at 37°C for 24 and 48 h, viral particles were

collected and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. After

filtration, centrifugation was performed at 4°C for 2 h at 60,000 ×

g. At one day before infection, Hep3B, HepG2, Huh7, Hepa1-6 cells

were passaged into 6 well plates, and infection was performed when

the cell confluency reached 70%. Before infection, fresh complete

medium was added, 10-20 μl viral solution was introduced,

the plate was shaken to mix evenly and then incubated at 37°C.

After 8 h, the medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. At

48 h later, puromycin (2 μg/ml) was added for selection.

Following viral infection, Hep3B, HepG2, Huh7 and Hepa1-6 cells

were maintained in medium containing 2 μg/ml puromycin (cat.

no. P8230; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) to

establish stable cell lines with SSBP1 knockout and SSBP1

overexpression. The successful establishment of the aforementioned

cell lines was verified by western blotting.

Drugs

Sorafenib (cat. no. S1040; Selleck Chemicals) was

dissolved in DMSO to a final concentration of 10 mM/ml. Hep3B cells

were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1×105

cells/well and treated with 8 μM sorafenib for 12 h at

37°C.

Datasets and analysis

The Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular

Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) data-sets were retrieved from the National

Cancer Institute (NCI) Genomic Data Commons (30) (portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-LIHC, accession

no. phs000178), while the mitochondrial localization gene set was

sourced from MitoCarta3.0 (31)

(https://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta/mitocarta30-inventory-mammalian-mitochondrial-proteins-and-pathways).

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs), were identified using R

language (32) (version 3.6.2;

http://www.r-project.org/) with the criteria of

|log2 fold change (log2FC)|>1.0 (corresponding to a more than

2-fold absolute change in expression) and adjusted P-value <0.05

(to control for false discovery rate in multiple testing), and

analyzed with the Metascape online tool (33) (Metascape 3.5; https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1).

GSE14520 (34) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE14520),

GSE101685 (35) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE101685),

GSE151412 (36) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE151412)

and GSE62813 (37) (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE62813)

datasets were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology

Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) profiles (38) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and the relative

mRNA expression levels of SSBP1 and POLG (DNA polymerase gamma)

within these cohorts were analyzed. The expression patterns of

SSBP1 across TCGA in cancer were analyzed using the TIMER2.0

(39) (http://timer.cistrome.org/) and UALCAN (40) (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) analysis tools. The

effects of SSBP1 on the survival of patients with liver cancer and

those undergoing treatment with sorafenib were evaluated using the

Kaplan Meier Plotter online survival analysis tool (41) (https://kmplot.com/analysis/).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from tumor tissue or cells

using the TransZol Up RNA isolation reagent (cat. no. ET111-01-V2;

TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA with

the TransScriptII First Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (cat. no.

11120ES60; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), according to

the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR analysis was performed using

the SYBR Green PCR Mix (cat. no. 11200ES; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and targeted gene-specific primers

(Table SI). The thermocycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30

sec, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 10 sec, and

60°C for 30 sec. The relative mRNA expression levels were

calculated using the ΔΔCq method (42), while β-actin served as an internal

control. All primers were designed by NCBI and were synthesized by

Genewiz, Inc.

To measure the copy number of mtDNA, genomic DNA

extracted from liver cancer tissue or cells was quantified using

qPCR. The primer sequences used are presented in Table SII.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously

described (43). Briefly, total

protein was extracted from tumor tissue and cells using RIPA lysis

buffer (cat. no. WB3100; NCM Biotech; www.). The protein

concentration was determined using a BCA kit (cat. no. CW0014S;

Jiangsu CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd.) and equal amounts of protein (50

μg/lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by

electrotransferring onto a PVDF membrane (MilliporeSigma).

Following blocking with 10% skimmed milk powder solution for 2 h at

room temperature, the PVDF membrane was incubated with primary

antibodies against SSBP1 (anti-rabbit; cat. no. 12212-1-AP),

voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC; anti-rabbit; cat. no.

10866-1-AP; both 1:1,000; both Proteintech Group, Inc.), Flag

(anti-mouse; cat. no. F1804; Merck KGaA; 1:10,000), translocase of

the outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOM20; anti-rabbit; cat. no.

A19403; 1:5,000), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4; anti-rabbit; cat.

no. A11243), SLC7A11 (anti-rabbit; cat. no. A13685; both 1:1,000),

and β-actin (anti-rabbit; cat. no. AC026; 1:100,000; all from

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) at 4°C overnight. Following washing

with PBST (containing 0.1% Tween-20) three times (5 min each), the

membrane was incubated with the corresponding Peroxidase

AffiniPure™ Goat Anti-Mouse (cat. no. 115-035-003) and anti-Rabbit

IgG (H+L; cat. no. 111-035-003; both 1:10,000; both Jackson

ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) secondary antibodies at room

temperature for 1.5 h. The membrane was washed with PBST three

times and the immunoreactive signals were detected using the ECL

Western Blotting Detection Reagent (cat. no. CW0049M; Jiangsu CoWin

Biotech Co., Ltd.). The protein bands were scanned using the

MiniChemi 610 chemiluminescence imaging system (SinSage Technology,

Co., Ltd.) and relative intensity was semi-quantified by ImageJ

software (ImageJ 2.0; National Institutes of Health). β-actin

served as an endogenous control.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using MTT reagent (cat.

no. M8180; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), as

previously described (44).

Briefly, liver cancer cells were plated into 96 well plates at a

density of 3×103 cells/well and incubated either in the

presence or absence of sorafenib (8 μM). Following

incubation at 37°C for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively the culture

medium was replaced with 100 μl MTT reagent (0.5 mg/ml),

followed by incubation for 4 h at 37°C. Then, the purple formazan

was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Absorbance at a

wavelength of 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader

(45).

Colony formation assay

Liver cancer cells were seeded into 6-well plates at

a density of 1×103 cells/well in the presence or absence

of sorafenib (2.5 μM) at 37°C for ~2 weeks. Cells were

washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and

stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution (cat. no. G1064; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min, both at

room temperature. The colonies (>50 cells) were counted using

ImageJ software (ImageJ 2.0; National Institutes of Health) and

images were captured under a light microscope (magnification,

×40).

Transwell assay

The migration of liver cancer cells were assessed

using 24 well Transwell chambers. The upper and lower culture

compartments were separated by polycarbonate membranes with 8

μm pores (Corning, Inc.). The bottom chamber was filled with

DMEM (cat. no. MA0212; Dalian Meilun Biology Technology Co., Ltd.)

supplemented with 20% FBS (cat. no. MN012103; Mengma (Tianjin)

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) as a chemoattractant. A total of

5×104 cells in serum-free DMEM (were seeded into the

upper chamber and incubated at 37°C for 48 h in a humidified

incubator with 5% CO2. The cells that migrated to the

underside of the membrane were stained with 0.1% crystal violet

solution (cat. no. G1064; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 15 min at room temperature and images were captured

under a light microscope (magnification, ×40).

Wound healing assay

Liver cancer cells (Hep3B and Hepa1-6 cells) were

cultured in a 6 well plate until ~100% confluence and a scratch was

made. Following washing with PBS to remove detached cells, cells

were then cultured under serum-free conditions for 24 h. Images

were captured under a light microscope at 0 and 24 h to record the

changes in wound width (magnification, ×40). Wound distance was

expressed as ratio to the initial distance at 0 h.

Immunofluorescence staining

Mitochondrial morphology was evaluated using the

MitoTracker®-Red kit (cat. no. C1035; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, liver cancer cells cultured in cell chambers at 37°C were

treated in the presence or absence of sorafenib (8 μM, 12 h

at 37°C). Following washing with PBS, cells were incubated in

serum-free DMEM (cat. no. MA0212; Dalian Meilun Biology Technology

Co., Ltd.) supplemented with Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos (1:1,000) for

30 min at 37°C. After washing with PBS, 1 ml serum-free medium was

added to the cell chamber. A total of ≥8 randomly selected

fields/sample were observed under a laser confocal scanning

microscope (LSM-800; Carl Zeiss AG).

Mitochondrial mass determination

Following treatment with sorafenib (8 μM, 12

h at 37°C), cells were harvested and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5

min at room temperature. Following washing with PBS three times,

cells were incubated with the MitoTracker®-Red probe for

30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed three times with PBS and analyzed

using a 579 nm channel flow cytometer (BD FACSVerse; BD

Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software

(version 10.8.1; Tree Star, Inc.).

ROS analysis

ROS levels were measured using a DCFH-DA assay (cat.

no. S0035S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Liver cancer cells were seeded into 6

well plates at a density of 1×105 cells per well and

treated in the presence or absence of sorafenib (8 μM) at

37°C for 12 h. Cells were washed with PBS three times and the

fluorescence intensity was measured using a microplate reader, as

previously described (44). A

total of 1×104 cells/sample were analyzed on a BD

FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using an argon-ion laser

(15 mW) and an incident beam at 488 nm. Data analysis was performed

using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1; Tree Star, Inc.).

JC-1 assay

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was measured

using a JC-1 assay kit (cat. no. C2003S; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hep3B

cells were collected following centrifugation at 600 × g for 4 min

at room temperature and washed twice with PBS. Cells were incubated

with the JC-1 dye in the dark at 37°C for 20 min. Following gently

washing with PBS twice, the cells were analyzed using a BD

FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) to detect aggregates and

monomers. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software

(version 10.8.1; Tree Star, Inc.). MMP was calculated as the ratio

of the fluorescence intensity of aggregates to that of

monomers.

Cell death assay

Following centrifugation at 600 × g for 5 min at

room temperature, 5×105 Hep3B cells were collected and

washed twice with PBS. The cells were re-suspended in PBS and

stained with propidium iodide and Annexin (cat. no. C1067S;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) in the dark for 20 min. Cells

were washed with PBS and 1×104 cells/sample were

analyzed on a BD FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped

with a 15 mW argon-ion laser and an incident beam at 488 nm. Data

analysis was performed using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1; Tree

Star, Inc.). Cell death was calculated as the percentage of cells

positive for propidium iodide fluorescence (46).

Detection of lipid peroxidation

C11-BODIPY581/591 (5 μM; cat. no.

D3861; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to measure lipid

ROS levels. Hep3B cells seeded into glass-bottom cell culture

dishes at a density of 2×105 cells/ml, were treated with

sorafenib (8 μM, 12 h at 37°C) and incubated with

C11-BODIPY581/591 for 30 min at room temperature.

Following washing with PBS three times, ≥50 cells/group were

observed under a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG) and the

fluorescence intensity was measured using ImageJ software (ImageJ

2.0; National Institutes of Health). FITC/PE ratio was used to

determine lipid oxidation, and the mean ratio of each group was

normalized to that of the control.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS

software (version 26.0; IBM Corp.). All data are expressed as the

mean ± SD, and all experiments were repeated at least three times.

Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used for comparisons

between two groups when data passed normality and equal variance

test; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney test was used. For data that were

normally distributed containing >2 groups, one-way ANOVA was

used followed by Tukey's comparison post hoc test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

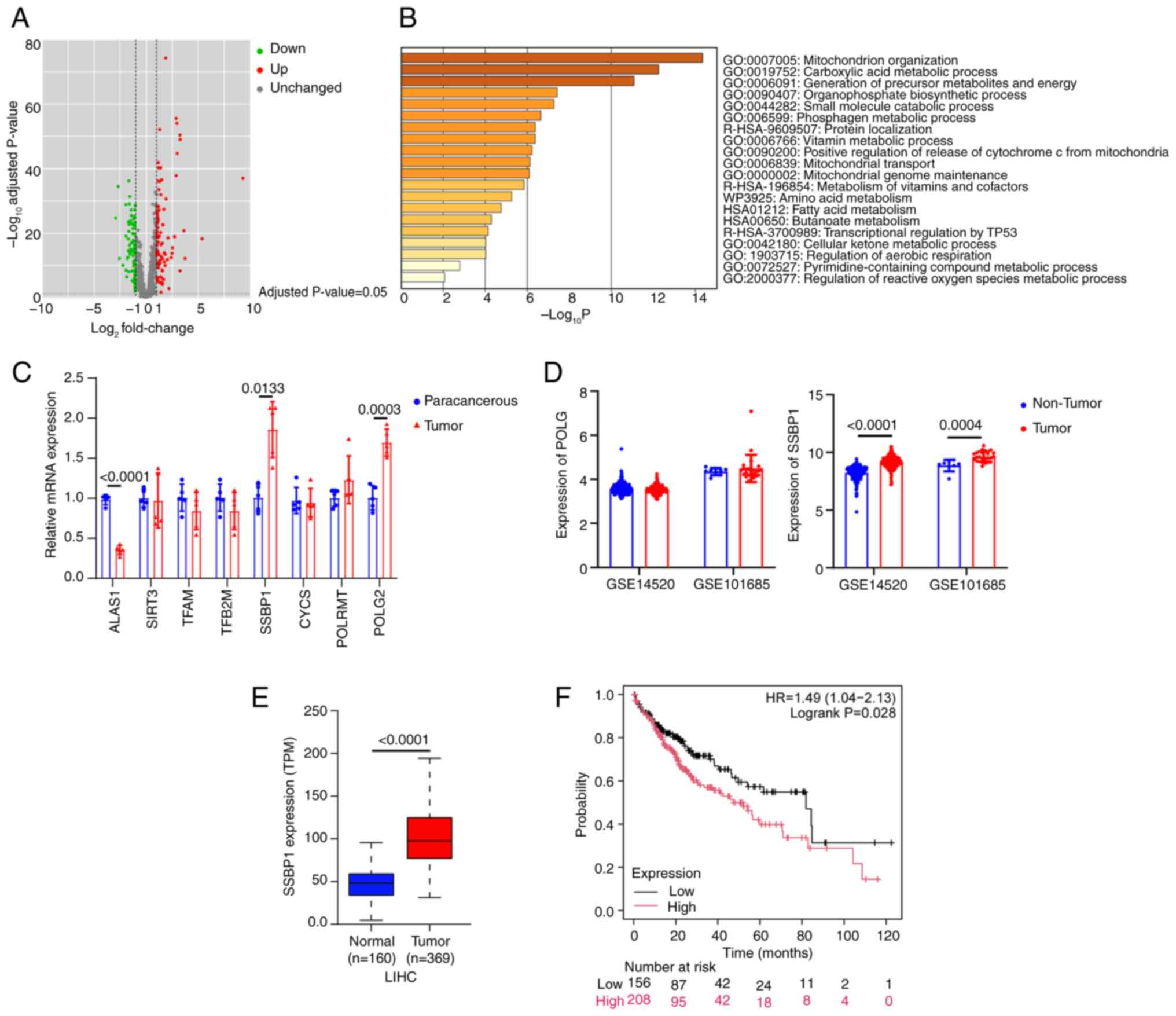

High SSBP1 expression is associated with

the progression and poor prognosis of liver cancer

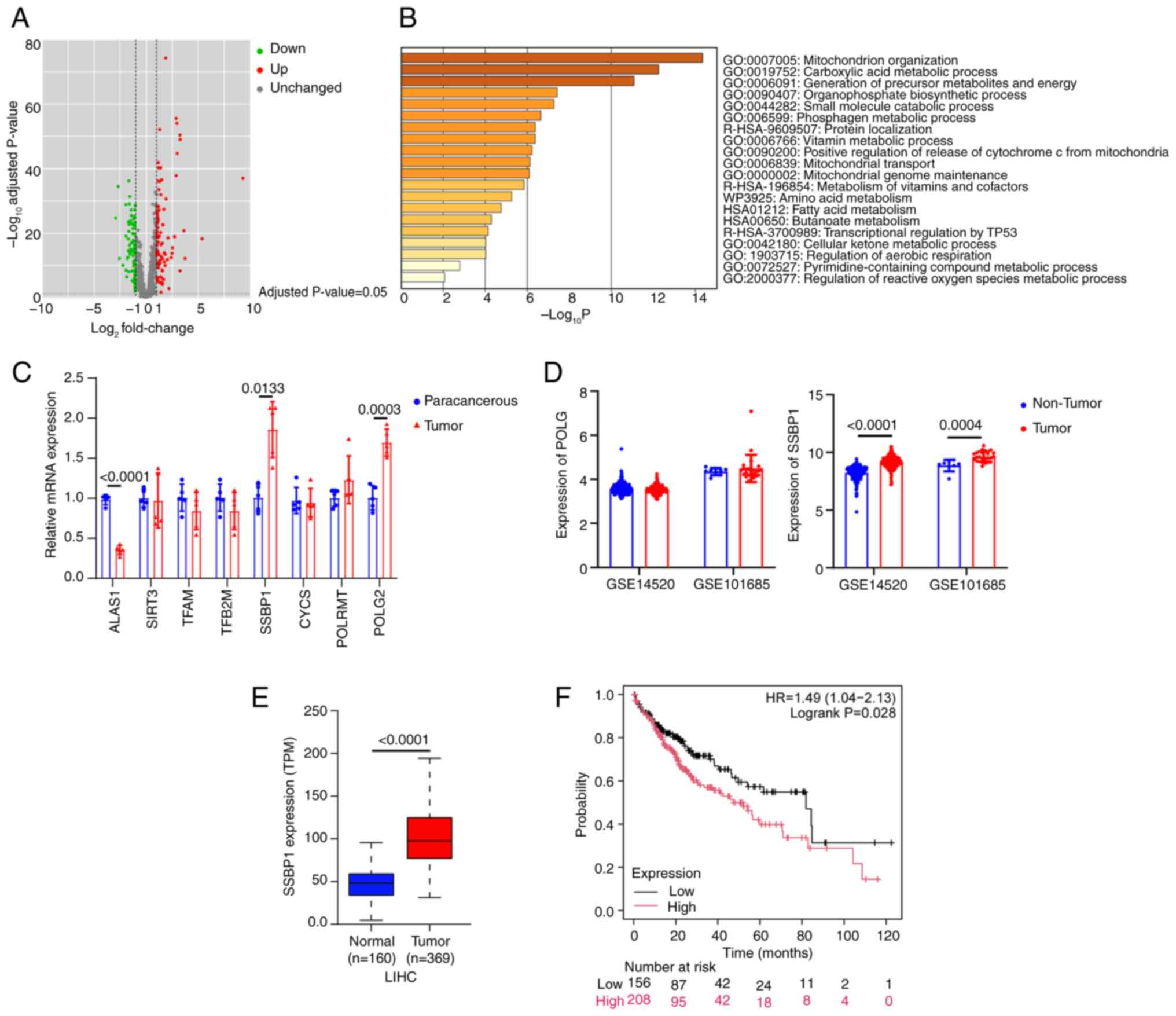

Among all mitochondrial-localized genes, 225 DEGs

were identified between liver cancer and normal tissue, including

85 up and 170 downregulated genes (Fig. 1A). To determine the main functions

of DEGs, the Metascape online tool was utilized. The analysis

revealed that the DEGs were primarily enriched in 'mitochondrion

organization' (Fig. 1B). Among 17

genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, eight genes, namely

ALAS1, SIRT3, TFAM, TFB2M, SSBP1, CYCS, POLRMT and POLG, were

significantly associated with liver cancer phenotypes within the

TCGA-LIHC datasets (data not shown). A DEN-induced liver cancer

mouse model was established and RT-qPCR showed that only SSBP1 and

POLG2 were upregulated, while ALAS1 was significantly downregulated

in tumors cells (Fig. 1C).

However, in the GEO datasets, the expression of SSBP1, but not

POLG, was markedly increased in liver cancer tissues compared with

adjacent non-cancerous tissue (Fig.

1D). SSBP1 was upregulated in numerous types of cancer tissues

compared with normal tissue (Fig.

S1B and C), thus suggesting that SSBP1 could serve a key role

in cancer, particularly in liver cancer (Fig. 1E). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

revealed that high SSBP1 expression was associated with poor

prognosis in liver cancer (Fig.

1F). Collectively, SSBP1 may be a potential biomarker for the

diagnosis and prognosis of liver cancer.

| Figure 1Integrated analysis of the expression

of SSBP1 in liver cancer. (A) Distribution of differential gene

expression levels after mapping mitochondrial-located genes

(MitoCarta3.0 list) onto the TCGA-LIHC dataset. (B) Enrichment

analysis using the R language. The gene sets ranking at the top

were predominantly implicated in mitochondrial organization and

biogenesis. (C) mRNA levels of mitochondrial biogenesis genes

(including ALAS1, SIRT3, TFAM, TFB2M, SSBP1, CYCS, POLRMT and POLG)

in liver cancer and paracancerous tissue (n=5). (D) Expression

profiles of POLG and SSBP1 in patients with liver cancer and

corresponding controls derived from the GSE14520 (tumor, n=225;

non-tumor, n=220) and GSE101685 datasets. (tumor, n=24; non-tumor,

n=8). (E) Transcriptional expression levels of SSBP1 in the

TCGA-LIHC dataset. (F) Association between SSBP1 expression and the

prognosis of liver cancer in the overall population (n=364) using

the Kaplan Meier Plotter online survival analysis tool. SSBP1,

single-stranded DNA binding protein 1; TCGA-LIHC, The Cancer Genome

Atlas liver hepatocellular carcinoma; ALAS1, aminolevulinic acid

synthase 1; SIRT3, sirtuin 3; TFAM, transcription factor A,

mitochondrial; TFB2M, transcription factor B2, mitochondrial; CYCS,

cytochrome c, somatic; POLRMT, RNA polymerase mitochondrial; POLG,

DNA polymerase γ; TPM, transcripts per million. |

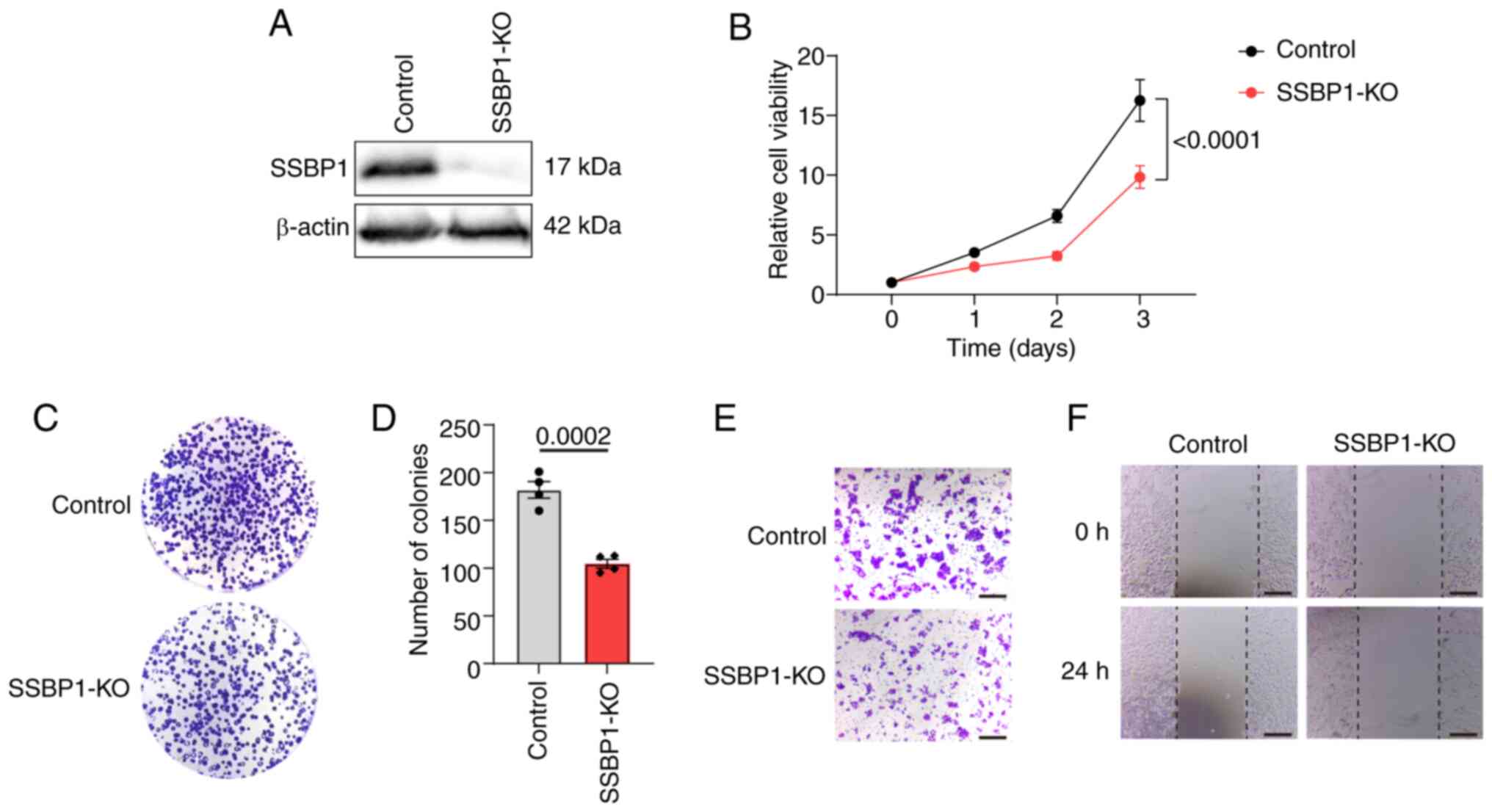

SSBP1 knockout inhibits liver cancer cell

proliferation and migration capacity

To investigate the effect of SSBP1 on the growth and

tumorigenesis of liver cancer, SSBP1 was knocked out using

independent lentiviral sgRNA. Western blot analysis demonstrated

that SSBP1 was successfully knocked out in the liver cancer cell

lines (Figs. 2A and S2A, G and J). MTT assay was employed to

monitor cell proliferation at 24 h intervals. Proliferation

capacity of SSBP1-knockout Hep3B cells was notably decreased

(Fig. 2B). Similarly, the number

of colonies formed by SSBP1-knockout Hep3B cells was significantly

decreased compared with control cells, consistent with the reduced

proliferation capacity observed in the MTT assay (Fig. 2C and D). To explore the effect of

SSBP1 on liver cancer cell migration, a Transwell assay was

performed. The loss of SSBP1 markedly decreased the migration of

Hep3B cells compared with the control group (Fig. 2E). Additionally, wound healing

assay was utilized to assess the migration ability of

SSBP1-knockout Hep3B cells. SSBP1 knockout significantly impaired

the motility of Hep3B cells compared with the control (Fig. 2F). The same results were observed

in Hepa1-6 (Fig. S2B-F), HepG2

(Fig. S2H and I) and Huh7 cells

(Fig. S2K and L).

SSBP1 overexpression promotes liver

cancer cell proliferation and migration capacity

As previously described, SSBP1 upregulation is

associated with most types of cancers (28). Therefore, the role of SSBP1 in

promoting liver cancer growth was investigated. Flag-tagged SSBP1

was overexpressed in liver cancer cell lines using a lentiviral

system and SSBP1 overexpression was validated using western blot

analysis (Figs. 3A and S3A). Compared with the control, the

proliferative capacity of SSBP1-overexpressing Hep3B cells was

significantly enhanced (Fig. 3B).

SSBP1 overexpression promoted the colony formation capacity of

Hep3B cells (Fig. 3C and D).

Transwell migration and wound healing assays demonstrated that

SSBP1 overexpression enhanced the migration potential of liver

cancer cells (Fig. 3E and F). The

same results were also obtained in HepG2 cells (Fig. S3B and C).

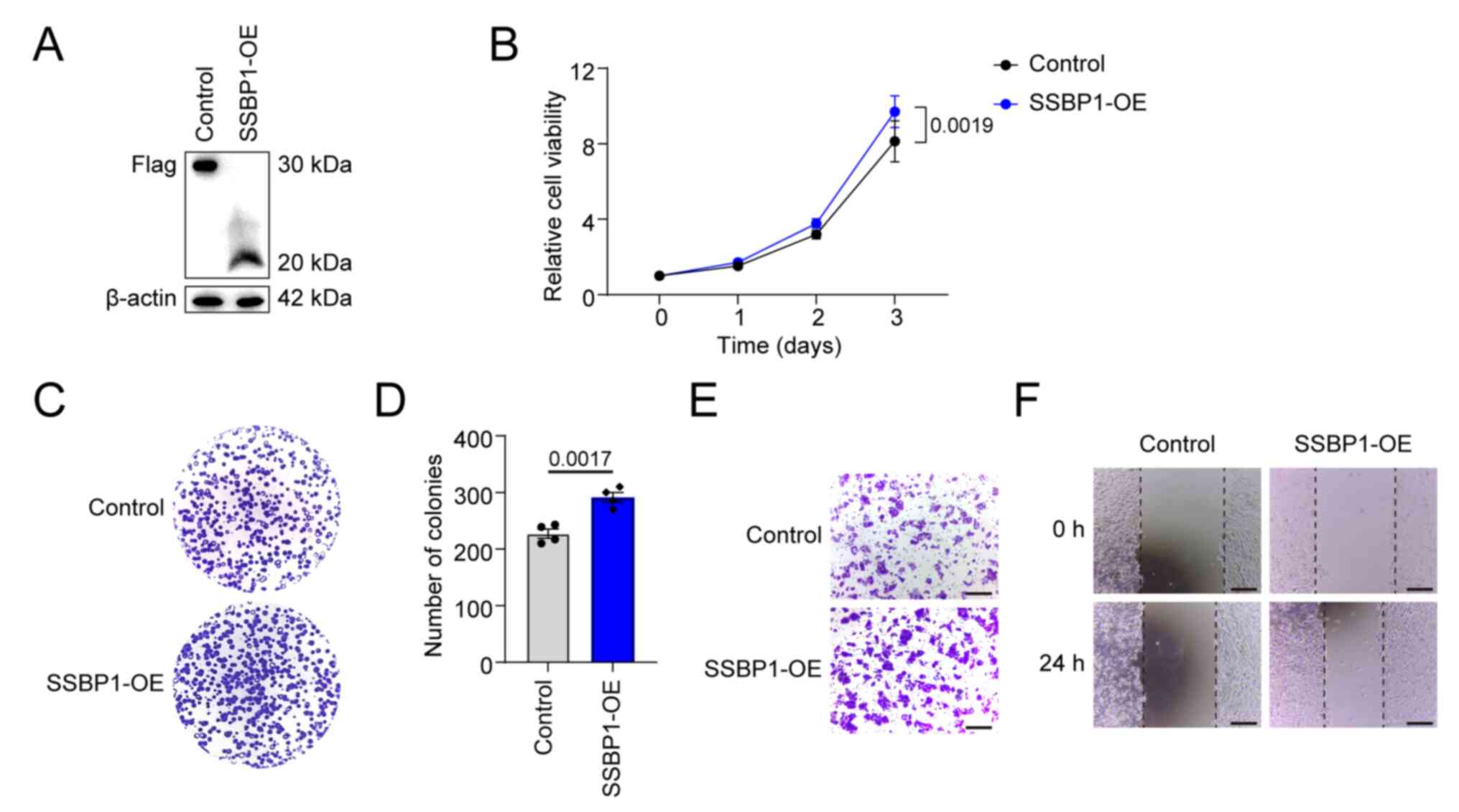

SSBP1 knockout inhibits mitochondrial

function

SSBP1 is a key mitochondrial protein; its abnormal

regulation affects mtDNA content, eventually leading to alterations

in mitochondrial function (27).

mtDNA copy number was elevated in liver cancer tissue (Fig. 4A). Concurrently, SSBP1

knockout in liver cancer cells decreased the number of mitochondria

while increasing their migration towards the nucleus (Fig. 4B and C). Additionally, the mtDNA

copy number was decreased (Fig.

4D). Western blot analysis indicated that SSBP1 knockout

diminished the expression of mitochondria-related proteins

(Fig. 4E). As mitochondria serve

as the primary source of cellular ROS generation (47), the accumulation of mitochondrial

ROS in Hep3B cells was evaluated. A significant increase in

mitochondrial ROS accumulation and a marked decrease in MMP were

observed in SSBP1-deficient cells (Fig. 4F-I). These results suggested that

SSBP1 knockout promoted mitochondrial damage in liver cancer

cells.

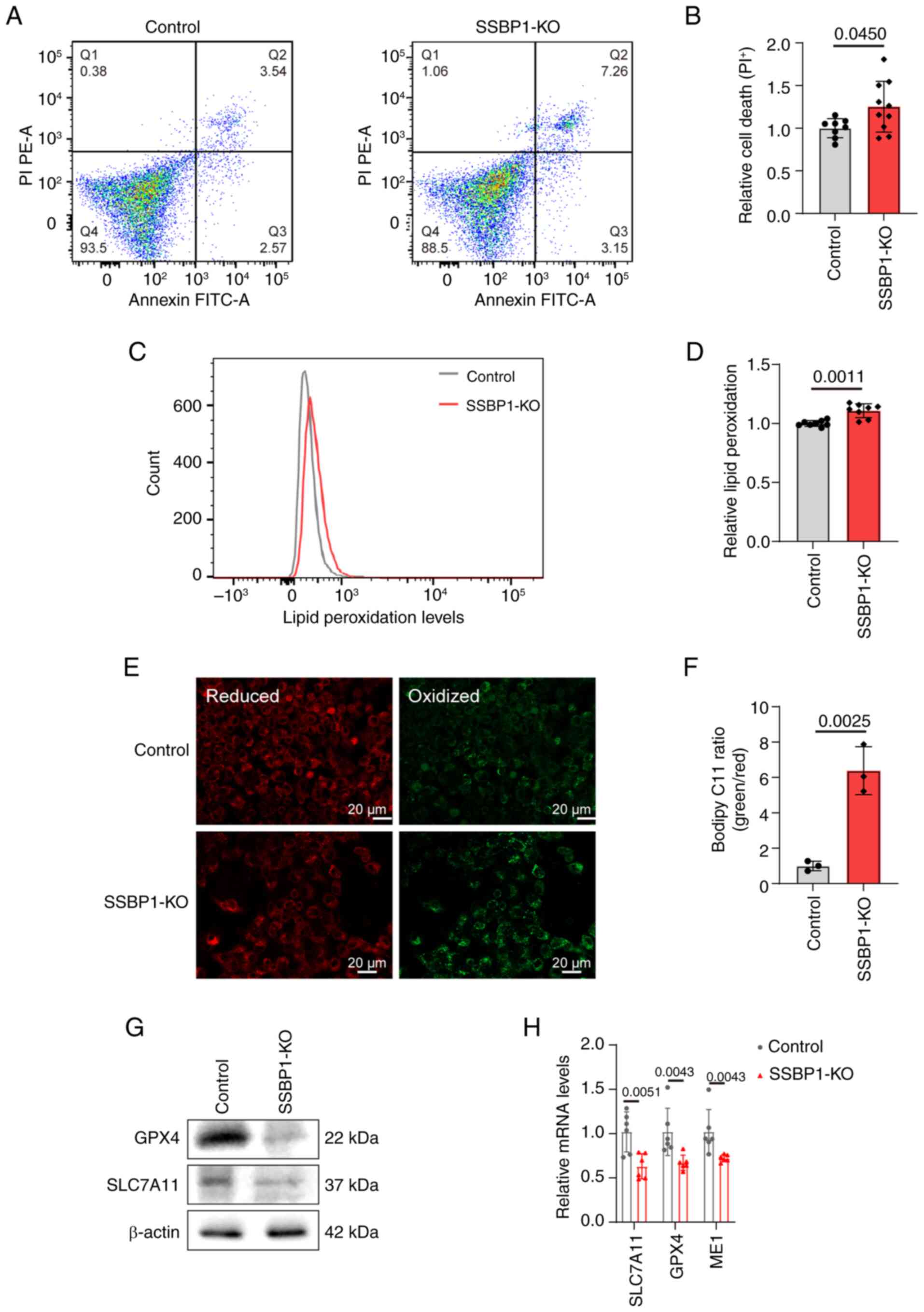

SSBP1 knockout triggers ferroptosis in

liver cancer cells

As aforementioned, the relative cell viability was

significantly decreased by SSBP1 deficiency. Therefore, the present

study aimed to investigate whether, in addition to impaired

proliferation, cell death also occurred. Flow cytometry showed that

SSBP1 deletion significantly increased the percentage of dead cells

compared with control cells (Fig.

5A-B). Among the various types of cell death, ferroptosis is

involved in the genesis and progression of liver cancer, with

mitochondria, where SSBP1 is located and which are crucial

energy-supplying organelles, serving a key role in this process

(27-29,44,48). Therefore, C11-BODIPY fluorescence

staining was employed to determine the extent of ferroptosis, and

the results revealed an increase in lipid peroxidation in

SSBP1-knockout Hep3B cells, confirming enhanced ferroptosis

(Fig. 5C-F). Consistently,

quantitative analysis showed that antioxidant genes (e.g., GPX4,

SLC7A11) were downregulated at both protein and mRNA levels in

SSBP1-deficient cells (Fig. 5G and

H), demonstrating that SSBP1 regulates liver cancer progression

via modulating ferroptosis. The same results were also observed in

HepG2 (Fig. S4A and B) and

Hepa1-6 cells (Fig. S4C).

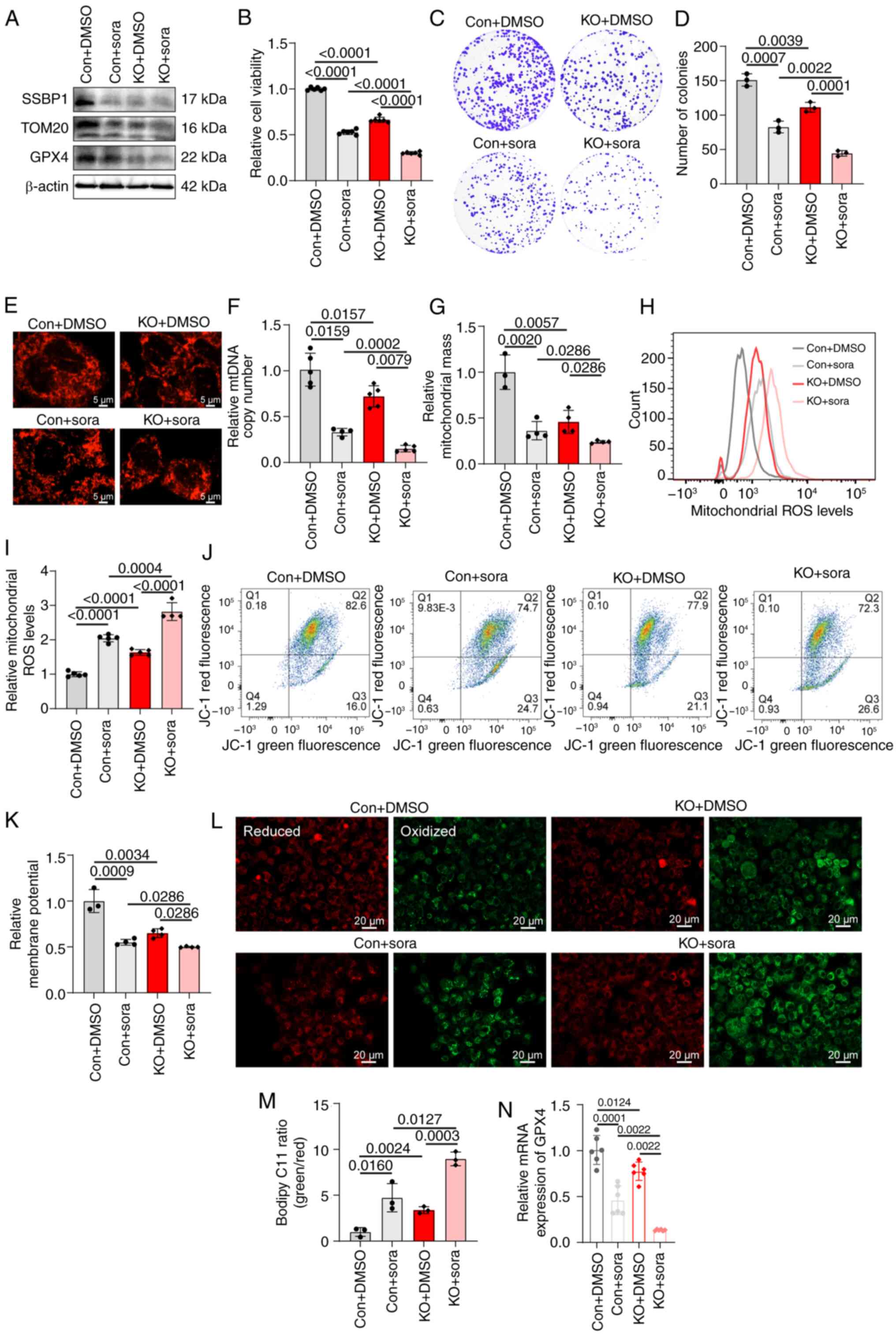

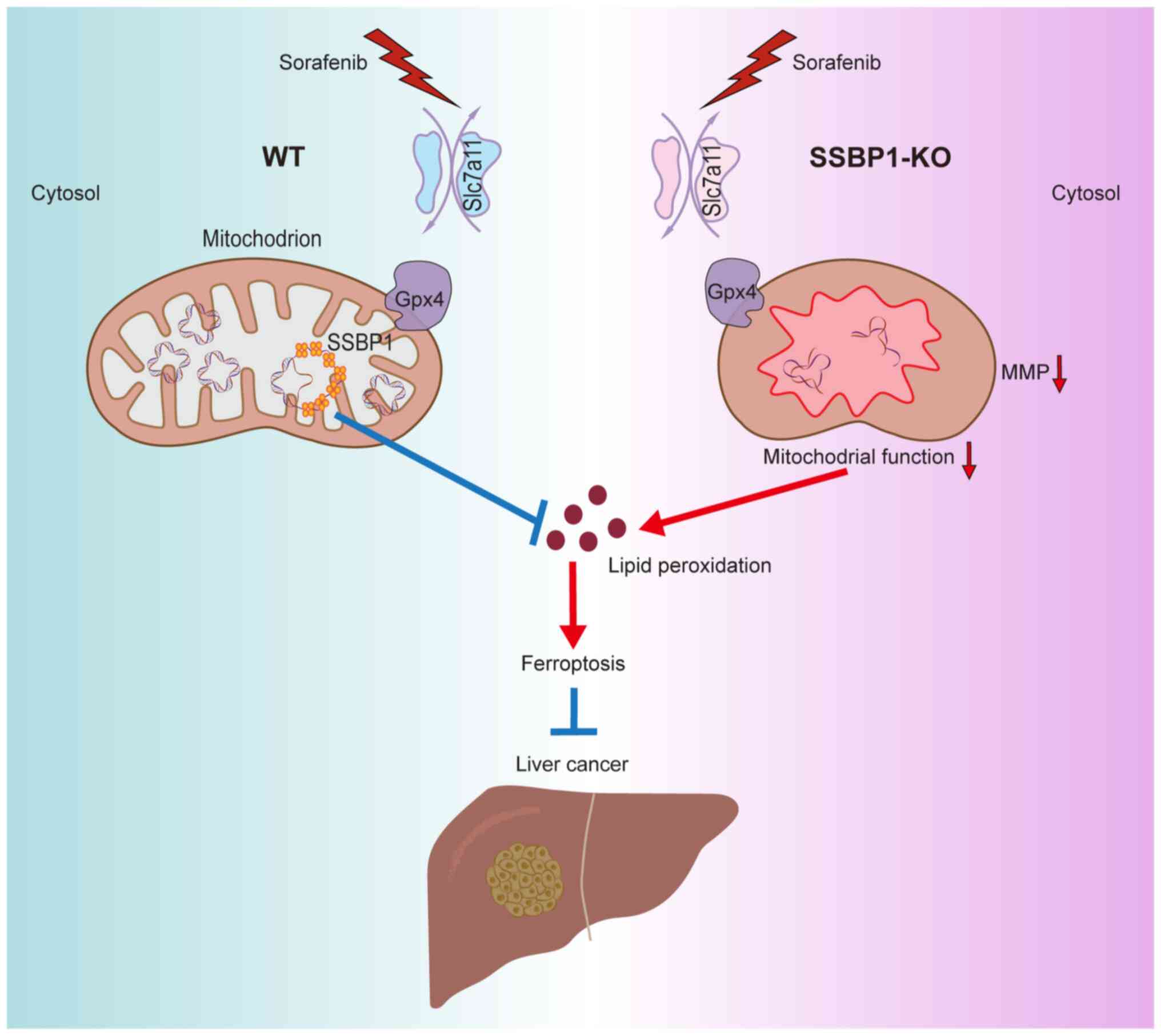

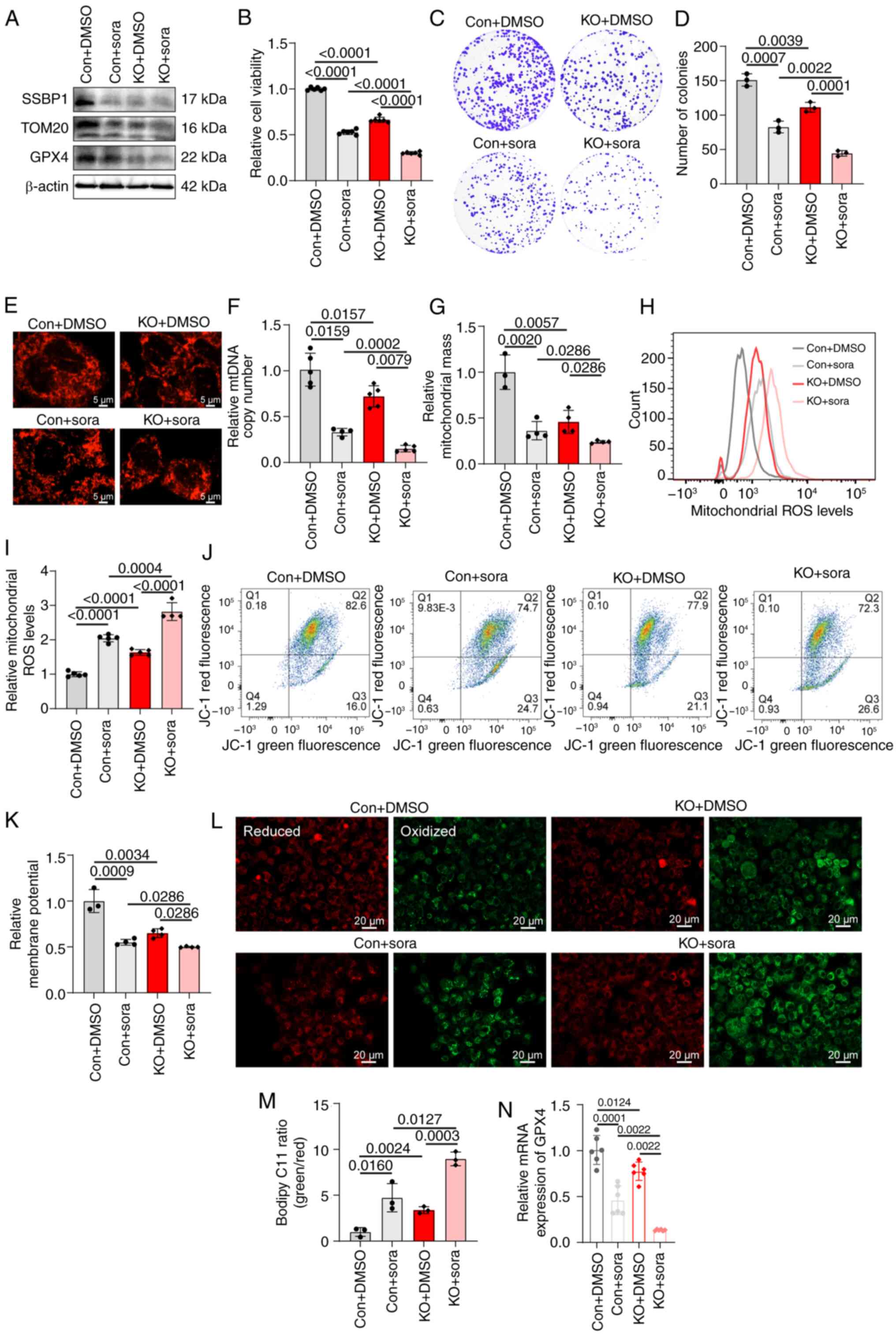

SSBP1 knockout enhances the sensitivity

of liver cancer cells to sorafenib

Based on the dual role of sorafenib as both a tumor

suppressor and inducer of ferroptosis in liver cancer (8), the present study explored the effect

of SSBP1 on sorafenib treatment. GEO datasets showed that when

liver cancer cells were treated with sorafenib, the expression of

SSBP1 notably decreased (Fig.

S5A), whereas SSBP1 was upregulated in sorafenib-resistant

cells compared with sorafenib-sensitive cells (Fig. S5B). In addition, high SSBP1

expression was associated with poor prognosis in sorafenib-treated

liver cancer (Fig. S5C).

Therefore, Hep3B cells were treated with sorafenib, and western

blot analysis showed that SSBP1 was markedly downregulated in these

cells (Fig. 6A). SSBP1 knockout

enhanced sorafenib-induced inhibition of clonogenicity and growth

inhibition (Fig. 6B-D).

Subsequently, the effect of SSBP1 deficiency on sorafenib treatment

in liver cancer was assessed. Following SSBP1 knockout, the mtDNA

copy number and mitochondrial mass of liver cancer cells were

markedly decreased following treatment with sorafenib (Fig. 6E-G). In addition, MitoTracker

staining indicated that mitochondrial fragmentation was enhanced

and mitochondria migrated closer to the nuclear periphery in

SSBP1-knockout liver cancer cells (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, treatment of

SSBP1-knockout liver cancer cells with sorafenib enhanced

intracellular ROS levels (Fig. 6H and

I) and decreased MMP compared with the control group (Fig. 6J and K). Lipid peroxidation levels

were markedly elevated, and the protein and mRNA expression of

ferroptosis-associated genes was reduced in Hep3B cells treated

with sorafenib (Fig. 6A and L-N).

In summary, SSBP1 deficiency enhanced the sensitivity of liver

cancer cells to sorafenib and may serve as a novel target for

overcoming sorafenib resistance (Fig.

7).

| Figure 6SSBP1 deficiency enhances the effect

of sora treatment. (A) Expression of SSBP1, TOM20 and GPX4 in Con

and SSBP1-KO Hep3B cells with or without sora treatment. (B) MTT

assay showed the relative viability of Con and SSBP1-KO Hep3B cells

with or without sora treatment (n=6). (C) Representative colony

formation assay showing proliferation capacity of Hep3B cells with

SSBP1 KO in the presence or absence of sora treatment. (D) Colony

formation capacity (n=3). (E) Immunofluorescence was performed to

detect the mitochondrial morphology in Hep3B cells following SSBP1

KO in the presence or absence of sora. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Magnification, ×630. (F) qPCR was used to analyze the mtDNA copy

number of Con and SSBP1-KO Hep3B cells with or without sora

treatment (n=4-5). Flow cytometry was employed to analyze (G)

mitochondrial mass (n=3-4) and (H) ROS levels (n=4-5) of Con and

SSBP1-KO Hep3B cells with or without sora treatment. (I) ROS levels

in Con and SSBP1-KO Hep3B cells with or without sora (n=4-5). (J)

Flow cytometry was performed to analyze (K) MMP of Control and

SSBP1-KO Hep3B cells with or without sora (n=3-4). (L) Fluorescence

images of C11-BODIPY-stained Hep3B cells. (M) Relative fluorescence

intensity was quantified by ImageJ software (n=3). Scale bar, 20

μm. Magnification, ×200. (N) mRNA expression of

ferroptosis-associated gene GPX4 in Con and SSBP1-KO Hep3B cells in

the presence or absence of sora (n=6). TOM20, translocase of the

outer mitochondrial membrane 20; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4;

SSBP1-KO, SSBP1 (single-stranded DNA binding protein 1) knockout;

mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; Con, control; sora, sorafenib. |

Discussion

Liver cancer poses a notable clinical challenge due

to the lack of early pathological indicators, which complicates

diagnosis (49). This, combined

with limited treatment options, contributes to high morbidity and

mortality rates (1-4). Furthermore, the efficacy of the

currently available treatment strategies remains unsatisfactory

(49). Therefore, the

identification of novel targets and biomarkers to improve the

clinical prognosis of patients with liver cancer is key. In the

present study, SSBP1 was identified as a promising therapeutic

target for liver cancer. SSBP1 was significantly upregulated in

tumor compared with adjacent healthy liver tissue. Analysis of TCGA

data revealed that patients with liver cancer with high SSBP1

expression displayed reduced overall survival. SSBP1, a

single-stranded DNA-binding protein, serves a key role in several

cellular processes including nuclear DNA replication, repair,

recombination, and mitochondrial genome maintenance. In cancer, its

expression and activity are typically altered, thus affecting tumor

cell proliferation and metastasis (24,25,28). Previous studies demonstrated that

SSBP1 is highly expressed in certain types of cancer (such as lung

adenocarcinoma) and involved in tumor occurrence and development

(49-52). However, the role of SSBP1 in liver

cancer remains unclear. Ohmori et al (53) cloned the single-stranded

DNA-binding protein in 1996, highlighting its key role in the

maximal expression of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

receptor and TSH-induced negative regulation, thus suggesting that

SSBP1 serves a potential role in cellular signaling regulation.

However, its function in liver cancer remains to be explored. The

present results showed that SSBP1 was highly expressed in tumor

compared with adjacent healthy liver tissues. TCGA dataset revealed

that patients with liver cancer highly expressing SSBP1 had

decreased overall survival, which was consistent with the research

findings of Yang et al (54) in lung adenocarcinoma. These

findings indicated that high SSBP1 expression may serve as a

potential indicator of poor prognosis. In terms of cell functions,

the results demonstrated that SSBP1 deficiency suppressed the

proliferation and migration of liver cancer cells, while SSBP1

overexpression displayed the opposite effects. These findings were

consistent with the known proliferative and metastasis-promoting

effects of SSBP1 on other types of cancer, which were verified in

liver cancer cell lines (28).

As a key regulator of the mitochondrial genome,

SSBP1 serves a role in maintaining mitochondrial function,

modulating metabolism and responding to DNA damage (55-57). Additionally, SSBP1 is involved in

the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (58). Comparative mitochondrial proteomic

analysis of patients with liver cancer provides insights for

exploring mitochondria-associated protein alterations in liver

cancer (59). A previous study

revealed that SSBP1 downregulation decreases mtDNA content and

perturbs mitochondrial energy function in glioblastoma cells

(43). In line with these

findings, elevated mtDNA copy number was recorded in liver cancer

tissue with high SSBP1 expression. In addition, SSBP1 knockout in

liver cancer cells decreased mitochondrial number, mtDNA copy

number and the levels of mitochondrial proteins, and increased

migration to the nucleus. Additionally, SSBP1-deficient cells

exhibited increased mitochondrial ROS levels and decreased MMP,

indicating mitochondrial damage. The aforementioned findings

aligned with those of previous studies supporting the role of SSBP1

in maintaining mitochondrial function and further highlighted the

role of SSBP1 in regulating mitochondrial function in liver cancer

cells (27,28). Mitochondria are considered the

primary source of intracellular ROS and serve a crucial role in

governing ferroptosis (44). To

investigate the potential association between SSBP1 and

ferroptosis, ferroptosis was assessed utilizing C11-BODIPY

fluorescence staining and by detecting the expression of

ferroptosis-related genes in liver cancer cells. Notably,

ferroptosis was significantly induced in liver cancer cells

following SSBP1 knockout. This finding was consistent with those of

previous studies indicating that SSBP1 regulates ferroptosis via

p53 signaling in glomerular podocyte injury (45,60). Overall, the aforementioned

findings demonstrate the mechanism underlying the effects of SSBP1

on regulating ferroptosis in liver cancer.

Inducing tumor cell death via pharmacological,

genetic and other interventional modalities is a fundamental

strategy for treating cancer (61). Numerous types of cell death have

been identified, including apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy and

ferroptosis (62). Ferroptosis is

characterized by uncontrolled lipid peroxidation. Therefore,

ferroptosis is considered a novel tumor-suppression mechanism

(63-65). As the liver is susceptible to

oxidative damage, ferroptosis has garnered increasing attention

within the realm of liver disease, particularly liver cancer

(44,48). Previous studies have primarily

focused on sorafenib-induced ferroptosis and its potential targets

both in vivo and/or in vitro (66-68). Although sorafenib is a

multi-kinase inhibitor that is considered the first-line systemic

therapy for patients with advanced liver cancer, drug resistance

can hamper its broad application (9). Therefore, it has been hypothesized

that genes that inhibit ferroptosis contribute to sorafenib

resistance (69). The present

study revealed that SSBP1 knockout markedly enhanced liver cancer

cell ferroptosis and concurrently inhibited cell proliferation when

combined with sorafenib treatment. In addition, mitochondrial

dysfunction and increased ROS levels induced by SSBP1 knockout may

collectively contribute to sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in liver

cancer. This implied that SSBP1 regulates ferroptosis sensitivity

through multiple pathways. On one hand, the burst of mitochondrial

ROS may directly initiate lipid peroxidation chain reactions. On

the other hand, mitochondrial dysfunction may promote the release

of mtDNA, thus activating the cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase)/STING

pathway and facilitating ferroptosis in liver cancer cells

(70). SSBP1 forms a complex with

heat shock factor 1 that translocates into the nucleus to regulate

mitochondrial protein import (71). Therefore, SSBP1 knockout could

disrupt the mitochondrial localization of GPX4, thus impairing GSH

redox cycling, a key antioxidant defense mechanism against lipid

peroxidation, and enhancing ferroptosis. Overall, the

aforementioned findings underscore the key role of SSBP1 in

modulating cell survival and response to therapy, underlining its

potential as a target for developing more effective treatment

strategies for liver cancer.

While the present study demonstrates that SSBP1

influences sorafenib efficacy via ferroptosis, it did not include

liver cancer specimens, and further studies are needed to

investigate the role of SSBP1 in other signaling pathways, which

may reveal broader therapeutic implications.

Overall, the mechanism by which SSBP1 regulates

tumor cell proliferation and sorafenib resistance in liver cancer

was elucidated. SSBP1 promoted the malignant progression of liver

cancer via suppressing ferroptosis. The present data provided novel

insights into the critical role of SSBP1 as a potential target for

liver cancer therapy.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZW and LZ conceived the study. SL, XY and HG

performed the experiments, analyzed data and wrote and revised the

manuscript. XH, DW, QZ, JX, JZ and LZ analyzed and interpreted

data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. SL,

LZ and ZW take responsibility for the integrity of data analysis.

ZW and LZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal

Care and Use Committee of Tianjin Medical University (approval no.

TMUaMEC2024050; Tianjin, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Scientific Research

Program of Tianjin Education Commission (Natural Science; grant no.

2023KJ037).

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li M, He H, Zhao X, Guan M, Khattab N,

Elshishiney G, You H and Hu Y: Trends in burden of liver cancer and

underlying etiologies in China, 1990-2021. Lancet Regional

Health-Western Pacific. 55:1013852025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O,

Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, Laversanne M, McGlynn KA and Soerjomataram I:

Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to

2040. J Hepatol. 77:1598–1606. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Villanueva A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 380:1450–1462. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Singal AG, Kanwal F and Llovet JM: Global

trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: Implications for

screening, prevention and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:864–884.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang H, Zhang W, Jiang L and Chen Y:

Recent advances in systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Biomark Res. 10:32022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard

P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A,

et al: Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J

Med. 359:378–390. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Guo L, Hu C, Yao M and Han G: Mechanism of

sorafenib resistance associated with ferroptosis in HCC. Front

Pharmacol. 14:12074962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R,

Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS,

et al: Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange

induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife.

3:e025232014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jurisic V, Bumbasirevic V, Konjevic G,

Djuricic B and Spuzic I: TNF-alpha induces changes in LDH isotype

profile following triggering of apoptosis in PBL of non-Hodgkin's

lymphomas. Ann Hematol. 83:84–91. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascon S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou Q, Meng Y, Li D, Yao L, Le J, Liu Y,

Sun Y, Zeng F, Chen X and Deng G: Ferroptosis in cancer: From

molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 9:552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fulda S, Galluzzi L and Kroemer G:

Targeting mitochondria for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov.

9:447–464. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wallace DC: Mitochondria and cancer. Nat

Rev Cancer. 12:685–698. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Eckl EM, Ziegemann O, Krumwiede L, Fessler

E and Jae LT: Sensing, signaling and surviving mitochondrial

stress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 78:5925–5951. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kasahara A and Scorrano L: Mitochondria:

From cell death executioners to regulators of cell differentiation.

Trends Cell Biol. 24:761–770. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Senft D and Ronai ZA: Regulators of

mitochondrial dynamics in cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 39:43–52.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kashatus JA, Nascimento A, Myers LJ, Sher

A, Byrne FL, Hoehn KL, Counter CM and Kashatus DF: Erk2

phosphorylation of Drp1 promotes mitochondrial fission and

MAPK-driven tumor growth. Mol Cell. 57:537–551. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bianchi NO, Bianchi MS and Richard SM:

Mitochondrial genome instability in human cancers. Mutat Res.

488:9–23. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang Y, Karakhanova S, Hartwig W, D'Haese

JG, Philippov PP, Werner J and Bazhin AV: Mitochondria and

mitochondrial ROS in cancer: Novel targets for anticancer therapy.

J Cell Physiol. 231:2570–2581. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Leao Barros MB, Pinheiro DDR and Borges

BDN: Mitochondrial DNA Alterations in Glioblastoma (GBM). Int J Mol

Sci. 22:58552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Arakaki N, Nishihama T, Kohda A, Owaki H,

Kuramoto Y, Abe R, Kita T, Suenaga M, Himeda T, Kuwajima M, et al:

Regulation of mitochondrial morphology and cell survival by

Mitogenin I and mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1760:1364–1372. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Oliveira MT and Kaguni LS: Functional

roles of the N- and C-terminal regions of the human mitochondrial

single-stranded DNA-binding protein. PLoS One. 5:e153792010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li Y, Bolderson E, Kumar R, Muniandy PA,

Xue Y, Richard DJ, Seidman M, Pandita TK, Khanna KK and Wang W:

HSSB1 and hSSB2 form similar multiprotein complexes that

participate in DNA damage response. J Biol Chem. 284:23525–23531.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zelinger L and Swaroop A: SSBP1 faux pas

in mitonuclear tango causes optic neuropathy. J Clin Invest.

130:62–64. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Wang Y, Hu L, Zhang X, Zhao H, Xu H, Wei

Y, Jiang H, Xie C, Zhou Y and Zhou F: Downregulation of

mitochondrial single stranded DNA binding protein (SSBP1) induces

mitochondrial dysfunction and increases the radiosensitivity in

Non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Cancer. 8:1400–1409. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Su J and Li Y, Liu Q, Peng G, Qin C and Li

Y: Identification of SSBP1 as a ferroptosis-related biomarker of

glioblastoma based on a novel mitochondria-related gene risk model

and in vitro experiments. J Transl Med. 20:4402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhang T, Cui Y, Wu Y, Meng J, Han L, Zhang

J, Zhang C, Yang C, Chen L, Bai X, et al: Mitochondrial GCN5L1

regulates glutaminase acetylation and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Clin Transl Med. 12:e8522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network:

Electronic address: wheeler@bcm.edu; Cancer Genome Atlas Research

Network: Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 169:1327–1341.23. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Rath S, Sharma R, Gupta R, Ast T, Chan C,

Durham TJ, Goodman RP, Grabarek Z, Haas ME, Hung WHW, et al:

MitoCarta3.0: An updated mitochondrial proteome now with

sub-organelle localization and pathway annotations. Nucleic Acids

Res. 49:D1541–D1547. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

32

|

Zhou X, Liu C, Zeng H, Wu D and Liu L:

Identification of a thirteen-gene signature predicting overall

survival for hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci Rep.

41:BSR202028702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M,

Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C and Chanda SK: Metascape

provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of

systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 10:15232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Roessler S, Jia HL, Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye

QH, Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS, Sun Z, Tang ZY, Qin LX, et al: A

unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor

relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer

Res. 70:10202–10212. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sun Q, Liu P, Long B, Zhu Y and Liu T:

Screening of significant biomarkers with poor prognosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma via bioinformatics analysis. Medicine

(Baltimore). 99:e217022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Vazquez Salgado AM, Preziosi ME, Yin D,

Holczbauer A, Zahm AM, Erez N, Kieckhaefer J, Ackerman D, Gade TP,

Kaestner KH, et al: In vivo screen identifies liver X receptor

alpha agonism potentiates sorafenib killing of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Gastro Hep Adv. 1:905–908. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

van Malenstein H, Dekervel J, Verslype C,

Van Cutsem E, Windmolders P, Nevens F and van Pelt J: Long-term

exposure to sorafenib of liver cancer cells induces resistance with

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, increased invasion and risk

of rebound growth. Cancer Lett. 329:74–83. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P,

Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH,

Sherman PM, Holko M, et al: NCBI GEO: Archive for functional

genomics data sets-update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D991–D995. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q,

Li B and Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48:W509–W514. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya

SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi B and Varambally

S: UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression

and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 19:649–658. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gyorffy B: Integrated analysis of public

datasets for the discovery and validation of survival-associated

genes in solid tumors. Innovation (Camb). 5:1006252024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Radenkovic S, Konjevic G, Gavrilovic D,

Stojanovic-Rundic S, Plesinac-Karapandzic V, Stevanovic P and

Jurisic V: pSTAT3 expression associated with survival and

mammographic density of breast cancer patients. Pathol Res Pract.

215:366–372. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hu X, Zhang P, Li S, Zhang J, Wang D, Wang

Z, Zhu L and Wang L: Mitochondrial GCN5L1 acts as a novel regulator

for iron homeostasis to promote sorafenib sensitivity in

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 22:5932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Scherbakov AM, Vorontsova SK, Khamidullina

AI, Mrdjanovic J, Andreeva OE, Bogdanov FB, Salnikova DI, Jurisic

V, Zavarzin IV and Shirinian VZ: Novel pentacyclic derivatives and

benzylidenes of the progesterone series cause anti-estrogenic and

antiproliferative effects and induce apoptosis in breast cancer

cells. Invest New Drugs. 41:142–152. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Radenkovic N, Milutinovic M, Nikodijevic

D, Jovankic J and Jurisic V: Sample preparation of adherent cell

lines for flow cytometry: Protocol optimization-our experience with

SW-480 colorectal cancer cell line. Indian J Clin Biochem.

40:74–79. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Hernansanz-Agustin P and Enriquez JA:

Generation of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria. Antioxidants

(Basel). 10:4152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sun K, Zhi Y, Ren W, Li S, Zhou X, Gao L

and Zhi K: The mitochondrial regulation in ferroptosis signaling

pathway and its potential strategies for cancer. Biomed

Pharmacother. 169:1158922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal

AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J and

Finn RS: Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:62021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Huang J and Xie ZF: Identification of

SSBP1 as a prognostic marker in human lung adenocarcinoma using

bioinformatics approaches. Math Biosci Eng. 19:3022–3035. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Li Q, Qu F, Li R, He X, Zhai Y, Chen W and

Zheng Y: A functional polymorphism of SSBP1 gene predicts prognosis

and response to chemotherapy in resected gastric cancer patients.

Oncotarget. 8:110861–110876. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Xu S, Feng Z, Zhang M, Wu Y, Sang Y, Xu H,

Lv X, Hu K, Cao J, Zhang R, et al: hSSB1 binds and protects p21

from ubiquitin-mediated degradation and positively correlates with

p21 in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 30:2219–2229.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ohmori M, Ohta M, Shimura H, Shimurat Y,

Suzuki K and Kohn LD: Cloning of the single strand DNA-binding

protein important for maximal expression and thyrotropin

(TSH)-induced negative regulation of the TSH receptor. Mol

Endocrinol. 10:1407–1424. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Yang X, Ma B, Liu Y, Zhou J, Guo J, Peng

Y, Bai Y, Wu J and Hu D: SSBP1 positively regulates RRM2, affecting

epithelial mesenchymal transition and cell cycle arrest in human

lung adenocarcinoma cells. Cell Signal. 127:1115522025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Morin JA, Cerron F, Jarillo J,

Beltran-Heredia E, Ciesielski GL, Arias-Gonzalez JR, Kaguni LS, Cao

FJ and Ibarra B: DNA synthesis determines the binding mode of the

human mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein. Nucleic

Acids Res. 45:7237–7248. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Richard DJ, Bolderson E, Cubeddu L,

Wadsworth RI, Savage K, Sharma GG, Nicolette ML, Tsvetanov S,

McIlwraith MJ, Pandita RK, et al: Single-stranded DNA-binding

protein hSSB1 is critical for genomic stability. Nature.

453:677–681. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Sykora P, Kanno S, Akbari M, Kulikowicz T,

Baptiste BA, Leandro GS, Lu H, Tian J, May A, Becker KA, et al: DNA

Polymerase beta participates in mitochondrial DNA repair. Mol Cell

Biol. 37:e00237–17. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang S, Guo H, Wang H, Liu X, Wang M, Liu

X, Fan Y and Tan K: A novel mitochondrial unfolded protein

response-related risk signature to predict prognosis, immunotherapy

and sorafenib sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Apoptosis.

29:768–784. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Ye Y, Huang A, Huang C, Liu J, Wang B, Lin

K, Chen Q, Zeng Y, Chen H, Tao X, et al: Comparative mitochondrial

proteomic analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma from patients.

Proteomics Clin Appl. 7:403–415. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wu WY, Wang ZX, Li TS, Ding XQ, Liu ZH,

Yang J, Fang L and Kong LD: SSBP1 drives high fructose-induced

glomerular podocyte ferroptosis via activating DNA-PK/p53 pathway.

Redox Biol. 52:1023032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Jurisic V, Bogdanovic G, Srdic T, Jakimov

D, Mrdjanovic J, Baltic M and Baltic VV: Modulation of TNF-alpha

activity in tumor PC cells using anti-CD45 and anti-CD95 monoclonal

antibodies. Cancer Lett. 214:55–61. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P

and Kroemer G: The molecular machinery of regulated cell death.

Cell Res. 29:347–364. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Li D, Wang Y, Dong C, Chen T, Dong A, Ren

J, Li W, Shu G, Yang J, Shen W, et al: CST1 inhibits ferroptosis

and promotes gastric cancer metastasis by regulating GPX4 protein

stability via OTUB1. Oncogene. 42:83–98. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

64

|

Li H, Yu K, Hu H, Zhang X, Zeng S, Li J,

Dong X, Deng X, Zhang J and Zhang Y: METTL17 coordinates

ferroptosis and tumorigenesis by regulating mitochondrial

translation in colorectal cancer. Redox Biol. 71:1030872024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Yuan S, Xi S, Weng H, Guo MM, Zhang JH, Yu

ZP, Zhang H, Yu Z, Xing Z, Liu MY, et al: YTHDC1 as a tumor

progression suppressor through modulating FSP1-dependent

ferroptosis suppression in lung cancer. Cell Death Differ.

30:2477–2490. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Lachaier E, Louandre C, Godin C, Saidak Z,

Baert M, Diouf M, Chauffert B and Galmiche A: Sorafenib induces

ferroptosis in human cancer cell lines originating from different

solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 34:6417–6422. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Li Y, Xia J, Shao F, Zhou Y, Yu J, Wu H,

Du J and Ren X: Sorafenib induces mitochondrial dysfunction and

exhibits synergistic effect with cysteine depletion by promoting

HCC cells ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 534:877–884.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Louandre C, Marcq I, Bouhlal H, Lachaier

E, Godin C, Saidak Z, Francois C, Chatelain D, Debuysscher V,

Barbare JC, et al: The retinoblastoma (Rb) protein regulates

ferroptosis induced by sorafenib in human hepatocellular carcinoma

cells. Cancer Lett. 356:971–977. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Guo M, Chen S, Sun J, Xu R, Qi Z, Li J,

Zhou L, Fang Y, Liu T and Xia J: PIP5K1A suppresses ferroptosis and

induces sorafenib resistance by stabilizing NRF2 in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Adv Sci (Weinh). e043722025. View Article : Google Scholar : Epub ahead of

print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zhao X, Yu M, Zhao Y, Zheng Y, Meng L, Du

K, Xie Z, Lv H, Zhang W, Liu J, et al: Circulating cell-free mtDNA

release is associated with the activation of cGAS-STING pathway and

inflammation in mitochondrial diseases. J Neurol. 269:4985–4996.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Tan K, Fujimoto M, Takii R, Takaki E,

Hayashida N and Nakai A: Mitochondrial SSBP1 protects cells from

proteotoxic stresses by potentiating stress-induced HSF1

transcriptional activity. Nat Commun. 6:65802015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|