Introduction

Glioma is the most common malignant tumor within the

central nervous system, constituting ~80% of primary brain tumors

(1). Patients with glioblastoma

multiforme have a median survival of ≤15 months (2). Current treatment modalities for

glioma include conventional approaches such as surgical resection,

pharmacological interventions and chemotherapy, as well as emerging

therapies such as immunotherapy and proton therapy. However,

despite technical advancements in these methods, they have not

markedly improved patient survival periods (3-5).

Notably, the propensity of gliomas for local invasion and

metastasis within brain tissue complicates radical resection and

effective local radiotherapy, consequently yielding suboptimal

treatment outcome. Hence, there is an urgent need to elucidate the

molecular mechanisms driving glioma invasion and local metastasis

whilst developing effective therapeutic interventions.

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1), the rate-limiting

enzyme in fatty acid synthesis, catalyzes the conversion of

acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA (6). As

acetyl-CoA is also a key cofactor for histone acetyltransferases,

ACC1 indirectly influences protein acetylation (7). Elevated ACC1 expression in liver

cancer has been associated with enhanced tumor metastasis via

increased fatty acid synthesis (8). Conversely, ACC1 deficiency in breast

cancer has been associated with invasion and metastasis, attributed

to elevated acetyl-CoA levels that promote protein acetylation and

the upregulation of metastasis-associated gene transcription

(7). These findings suggest that

the role of ACC1 in tumor development exhibits tissue

heterogeneity, likely influenced by signaling pathways triggered by

its regulated metabolites within distinct tissue environments.

Thus, unraveling the underlying regulatory mechanisms of ACC1 may

provide valuable insights into glioma progression.

Our unpublished data demonstrated that ACC1

knockdown promoted U251 glioma cell proliferation, as revealed by

cell density assessment based on phase-contrast images, cell

counting and real-time cell analysis (RTCA). However, MTT assays

revealed lower readouts in ACC1-knockdown cells compared with

controls (Wang et al, unpublished data), suggesting a

discrepancy between assays. Therefore, we hypothesized that MTT may

not accurately reflect ACC1-knockdown cell proliferation.

Furthermore, as MTT relies on succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)

activity to reduce MTT to formazan (9), we hypothesized that ACC1 knockdown

may inhibit SDH activity in glioma cells.

SDH, a mitochondrial complex II enzyme crucial for

electron transport, serves a role in regulating reactive oxygen

species (ROS) levels. Decreased SDH activity has been associated

with elevated ROS and tumor progression in several cancers

(10-12). Increased ROS can activate

signaling pathways that promote cell proliferation, migration and

invasion (13-16). Redox imbalance is also implicated

in glioma progression (17).

The present study aimed to comprehensively

investigate the role of ACC1 in modulating proliferation, migration

and invasion of glioma cells and its clinical relevance. To achieve

this, ACC1 overexpression and knockdown models were employed across

four glioma cell lines (U87, U251, T98G and LN229), and phenotypes

were assessed via functional assays. Based on the observed cell

line-specific responses, U251 cells were selected for mechanistic

studies focusing on regulation of the SDH-ROS axis, DNA

methyltransferase (DNMT)-mediated epigenetic modifications, and

P300-acetyl-CoA crosstalk, validated by inhibitors and small

interfering RNA (siRNA). Clinical correlation was analyzed using

tissue microarray immunohistochemistry and public datasets.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

The human glioma cell line, U87 MG ATCC (GCPC096821,

glioblastoma of unknown origin), was purchased from Shanghai

Genechem Co., Ltd; U251 (SCSP-559) and T98G (SCSP-5274) cells were

purchased from the China Infrastructure of Cell Line Resources,

Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical

Sciences; and LN229 (CBP60302) cells were purchased from Nanjing

Cobioer Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All the cell lines used in the

present study were verified by short tandem repeat analysis,

confirming their identity and purity. U87, U251 and T98G cells were

cultured in MEM (cat. no. SH30024.01; HyClone™; Cytiva)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Shanghai XP BioMed

Ltd.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). LN229 cells were cultured in DMEM

(cat. no. 10-013-CV; Corning, Inc.) with the same supplements. All

cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2

incubator and passaged at 80-90% confluence. N-acetyl-cysteine

(NAC) was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (cat.

no. S0077). Azacitidine (Aza) (cat. no. S1782) and C646 (cat. no.

S7152) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. Drug treatments were

performed as follows: NAC (5 mM), Aza (4 μM) and C646 (5

μM) were applied to cells for 48 h at 37°C under standard

culture conditions.

Transfection

The human ACACA plasmid and vector plasmid were

purchased from GeneCopoeia, Inc. Pre-packaged lentiviral particles

for human ACACA knockdown [short hairpin (sh)ACC1] and its scramble

negative control (NC), as well as siRNA targeting P300 and its

siNC, were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. siRNA and

shRNA sequences are listed in Table

SI.

Plasmid and siRNA transfections were performed using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (cat. no. 11668019; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Briefly, for U87 cells, 1 μg ACACA or vector

plasmid DNA was complexed with the transfection reagent, whereas

U251 cells were transfected with 20 μM siP300 or siNC. The

complexes were applied to respective cells cultured in 6-well

plates. Transfection mixtures were incubated with cells at 37°C for

6 h, after which the medium was replaced with fresh complete

medium. Functional assays were conducted 48 h post-transfection to

assess phenotypic effects.

For lentiviral transduction, commercially provided

lentiviral particles (third generation system, titer:

1×108 TU/ml) were thawed on ice. U251, T98G and LN229

cells were incubated with lentiviruses at a multiplicity of

infection of 4 in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene for 24 h

at 37°C. The viral suspension was then replaced with fresh complete

medium. To establish stable cell lines, transduced cells underwent

selection with 2 μg/ml puromycin starting 72 h

post-transduction for 3 days. Surviving cells were maintained in

medium containing 1 μg/ml puromycin. All subsequent

experiments were performed post-selection.

Western blotting

U87, U251, T98G and LN229 cells were lysed in RIPA

buffer (cat. no. AR0105; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.)

containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. AR1182; Wuhan

Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.), 1% PMSF (cat. no. P0100,

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and 5%

phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. 4906845001; Roche

Diagnostics). Protein concentration was quantified using a BCA

assay (cat. no PC0020; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.). A total of 30 μg protein per sample was

separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and transferred to PVDF membranes

(cat. no. IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). Membranes were

blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (cat. no. D8340; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 1 h and

incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against the

following targets: ACC1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 4190), cyclin D1

(1:1,000; cat. no. 2922), p21 (1:1,000; cat. no. 2947), DNMT1

(1:1,000; cat. no. 5032), histone H3 acetylation at lysine 9

(H3K9ac; 1:1,000; cat. no. 9649) and H3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 4499)

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cyclin B1 (1:1,000;

cat. no. 55004-1-AP), SDHA (1:2,000; cat. no. 14865-1-AP), SDHB

(1:1,000; cat. no. 10620-1-AP), fatty acid synthase (FASN; 1:2,000;

cat. no. 10624-2-AP) and β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. 20536-1-AP)

purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc.; and fibronectin (1:1,000;

cat. no. WL03677), vimentin (1:500; cat. no. WL01960), plasminogen

activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1; 1:1,000; cat. no. WL01486), P300

(1:1,000; cat. no. WL01307), sterol regulatory element-binding

protein 1 (SREBP1; 1:1,000; cat. no. WL02093) and GAPDH (1:1,000;

cat. no. WL01114) from Wanleibio Co., Ltd. Membranes were then

incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies

(1:5,000; cat. no. bs-0295G-HRP; BIOSS) at room temperature for 1

h. Signals were detected using an ECL substrate (cat. no. PE0010;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and images

were captured using an Amersham Imager 600 system (Cytiva). Band

density semi-quantification was performed using ImageJ software

(version v1.8.0.345; National Institutes of Health).

Transwell migration and invasion

assays

For migration assays, U87, U251, T98G and LN229

cells (2×104 cells) in 200 μl serum-free MEM

(U87, U251 and T98G cells) or DMEM (LN229 cells) were seeded into

the upper chambers of Transwell inserts. The lower chambers

contained 600 μl corresponding medium with 10% FBS. For

invasion assays, inserts were pre-coated with 100 μl

Matrigel (cat. no. 354262; Corning, Inc.) diluted 1:3 in

corresponding serum-free medium. To ensure consistency in Matrigel

coating, standardized protocols recommended by the manufacturer

were followed, including pre-cooling plates to 4°C, dilution with

ice-cold medium and incubation at 37°C for 1 h (18). Additionally, when adding Matrigel,

the culture plate was placed in a tray equipped with a spirit level

to ensure a level surface for sample addition. After 24 h

incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator,

non-migrated/non-invaded cells remaining on the upper surface of

the membrane were removed. Migrated/invaded cells that adhered to

the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 10 min and stained with crystal violet (cat.

no. C0121; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 5 min at room

temperature. Cells were counted using an inverted optical

microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ts2; Nikon Corporation) equipped with a

digital camera (DS-Fi1c; Nikon Corporation).

Wound-healing assay

U87, U251, T98G and LN229 cells were seeded in a

6-well plate until ~90% confluency was reached in complete medium

containing 10% FBS. Uniform linear scratches were created by gently

dragging a sterile 200 μl pipette tip across the cell

monolayer in a single, consistent motion. Detached cells and debris

were then removed by washing the monolayer three times with PBS.

The medium was then replaced with low-serum medium (2% FBS in MEM

for U87/U251/T98G or DMEM for LN229). Immediately after scratching,

the initial scratch width was visualized under a microscope (Nikon

Eclipse Ts2; Nikon Corporation) to ensure consistency. After 24 and

48 h of culture in low-serum conditions, images of the cells were

captured under a microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ts2; Nikon Corporation).

Cell migration was assessed by calculating the proportion of the

area occupied by migrated cells within the scratch region relative

to the initial scratch area.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from U87, U251, T98G and LN229 cells was

extracted using TRIzol™ reagent (cat. no. 15596018; Invitrogen™;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and reverse transcribed into cDNA

using the All-In-One 5X RT MasterMix with AccuRT Genomic DNA

Removal Kit (cat. no. G492; Applied Biological Materials Inc.)

under the following conditions: 42°C for 2 min (gDNA removal),

followed by 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 min

(cDNA synthesis). qPCR was performed using the BlasTaq™ 2X qPCR

MasterMix with SYBR-like dye (cat. no. G891; Applied Biological

Materials Inc.) on a QuantStudio™ Dx Real-Time PCR Instrument

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the

following thermocycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min; followed by 40

cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min; and final

dissociation at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Relative mRNA

expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(19). Primer sequences are

listed in Table SII. Primers for

DNMT1/3A/3B, SDHA/B/C/D, P300 and GAPDH were purchased from

GenScript Biotech Corporation.

SDH enzyme activity assay

SDH activity was measured using the Complex II

Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit (cat. no. ab109908; Abcam),

according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of

8×106 U251 cells were used per assay. Samples were

normalized to protein content determined using a BCA assay.

Absorbance was measured at 600 nm using a microplate reader

(Multiskan Spectrum; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Cellular ROS measurement

U251 cells were harvested and stained with 10

μM dihydroethidium (cat. no. KGA7502; Jiangsu KeyGen Biotech

Co., Ltd.) in serum-free medium for 30 min at 37°C in the dark,

with gentle mixing every 5 min. Cells were washed with PBS and

fluorescence of the oxidized DHE-nucleic acid adduct was measured

using the FL2 channel (585/42 nm bandpass filter) on a flow

cytometer (BD FACSCalibur™; BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed

using FlowJo software (version v10.8; BD Biosciences).

Acetyl-CoA measurement

Cellular acetyl-CoA levels were measured using the

Acetyl-Coenzyme A Assay Kit (cat. no. MAK039; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of

8×106 U251 cells were used per assay. Cell lysates were

deproteinized with perchloric acid, neutralized with potassium

bicarbonate and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

Acetyl-CoA levels in the supernatant were determined using

fluorescence (excitation 535 nm, emission 587 nm) using the

SpectraMax Gemini EM Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices,

LLC).

Methylation-specific PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted using the

EasyPure® Genomic DNA Kit (cat. no. EE101; TransGen

Biotech Co., Ltd.) and bisulfite-converted using the EpiArt DNA

Methylation Bisulfite Kit (cat. no. EM101; Vazyme Biotech Co.,

Ltd.). The SDHB promoter region was amplified using

methylation-specific primers and the BlasTaq™ 2X qPCR Master Mix

with SYBR-like dye (cat. no. G891; Applied Biological Materials

Inc.) under the following thermocycling conditions: 95°C for 5 min;

followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 72°C

for 45 sec; and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Unconverted DNA

was used as a loading control. PCR products were separated on a 2%

agarose gel and visualized using a UVIpro gel imaging system with

UVIband software v2.9.0 (UVItec Ltd.). Primers for the

methylated/unmethylated SDHB promoter regions were purchased from

GenScript Biotech Corporation. Primer sequences are listed in

Table SII.

Immunohistochemical staining

A commercially pre-fixed glioma tissue microarray

(cat. no. HBraG149Su01; Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd.),

containing 123 evaluable samples from an original cohort of 149

samples, was used. Samples were excluded due to incomplete tissue

integrity during microarray production or detachment during

staining. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated through xylene

twice (10 min each) and graded alcohols (100, 90, 80 and 60%; 5 min

each), then subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval in citrate

buffer (pH 6.0) at 100°C for 10 min using a water bath. Retrieval

was followed by washing in PBS. Endogenous peroxidase activity was

blocked with 3% H2O2 for 10 min at room

temperature, and cell membranes were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton

X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Sections were blocked

with 10% goat serum (cat. no. C0265; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1 h, then incubated with

ACC1 antibodies (1:300; cat. no. 67373-1-Ig; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) at 4°C overnight. The ready-to-use HRP-conjugated universal

anti-rabbit/mouse IgG secondary antibody [cat. no. GK500705;

Genetech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.] was applied and incubated at room

temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, antigen detection was performed

using the DAB chromogen substrate (components A and B of the

GK500705 kit mixed at a 1:1 ratio) for 1 min. Nuclei were

counterstained with hematoxylin (cat. no. C0107; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) at room temperature for 2 min. Whole-slide

scanning of the tissue microarray was conducted using the

Pannoramic DESK scanner (3DHISTECH, Ltd.), with the results viewed

using CaseViewer 2.4 software (3DHISTECH, Ltd.), and

semi-quantitative analysis of ACC1 expression was performed using

Aipathwell v2 software (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.).

Public database analysis

Transcriptomics data from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/)

glioblastoma cohort (TCGA-GBM) were analyzed via the UALCAN portal

(http://ualcan.path.uab.edu). Proteomics

data were obtained from the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis

Consortium (CPTAC) dataset PDC000204 (https://pdc.cancer.gov/pdc). Additionally,

transcriptomics and clinical data from three Chinese Glioma Genome

Atlas (CGGA) datasets (mRNA_array_301, mRNAseq_325, mRNAseq_693)

were accessed through the CGGA portal (http://www.cgga.org.cn).

Additional experimental methods

Additional experimental methods associated with the

supplementary figures of the present study are detailed in Data S1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics). Data from three independent experimental

repeats are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Unpaired

Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc

test were used for group comparisons. Spearman's correlation was

applied for correlation analyses. For recurrence risk assessment of

CGGA datasets, univariate Cox proportional hazards regression

analysis was performed to determine the association between ACC1

expression levels (dichotomized as high/low) and recurrence risk.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

ACC1 knockdown promotes proliferation,

migration and invasion of glioma cells and selectively inhibits SDH

in U251 cells

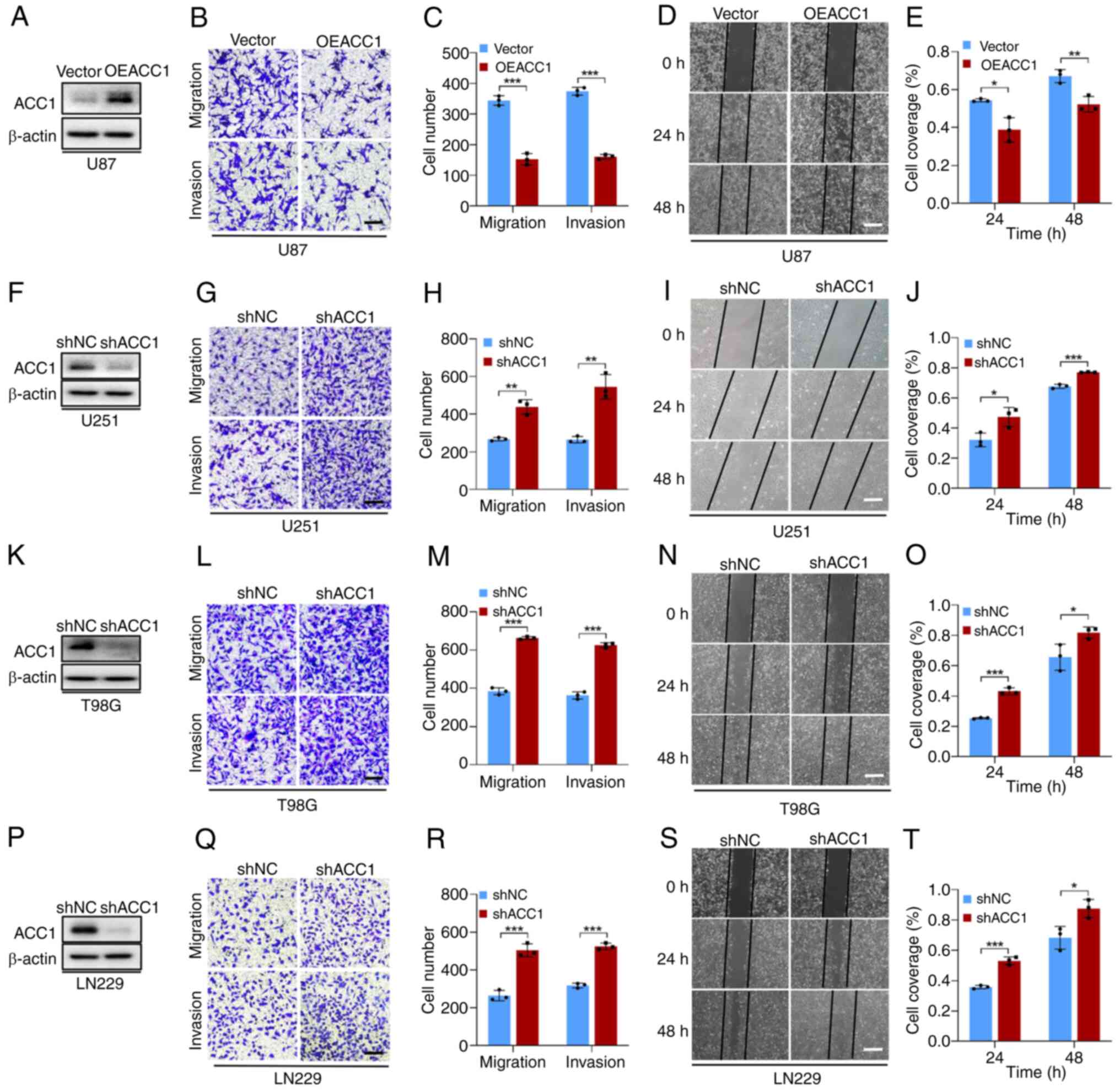

To assess the role of ACC1 in glioma, its protein

expression in four glioma cell lines was first evaluated (Fig. S1A). U87 cells, demonstrating the

lowest ACC1 expression compared with the other cell lines, were

selected for plasmid-mediated overexpression (Fig. 1A). U251, T98G and LN229 cells,

with comparably higher ACC1, underwent lentiviral knockdown

(Fig. 1F, K and P). ACC1

overexpression in U87 cells significantly decreased cell migration

and invasion compared with the control (Fig. 1B-E), whilst ACC1 knockdown

significantly increased these behaviors in U251 (Fig. 1G-J), T98G (Fig. 1L-O) and LN229 (Fig. 1Q-T) cells.

Proliferation analyses revealed a cell line-specific

pattern. MTT assays demonstrated that, compared with controls, ACC1

overexpression significantly inhibited U87 cell proliferation

(Fig. S1B) and ACC1 knockdown

significantly increased proliferation in T98G and LN229 cells

(Fig. S1D and E). By contrast,

ACC1 knockdown in U251 was associated with a significant reduction

in cell proliferation (Fig.

S1C), initially suggesting growth suppression. However, this

finding contradicted multiple independent lines of evidence.

Specifically, microscopic observation of cell density, manual cell

counts and RTCA (detailed methods in Data S1; Fig. S1F-H), together with colony

formation assays (Fig. S1I and

J), cell cycle progression assays (Fig. S1K-N) and 3D tumor-sphere

formation assays (Fig. S1O and

P) consistently demonstrated that ACC1 knockdown significantly

promoted U251 cells proliferation in comparison with controls.

Supporting this, RT-qPCR revealed that ACC1 modulation influenced

SDH subunit transcript levels specifically in U251 cells (Fig. S2B), with no significant changes

observed in the other glioma cell lines (Fig. S2A, C and D). Moreover, western

blot analysis demonstrated that the protein levels of SDHA and

SDHB, the most abundantly expressed subunits of the SDH complex

(20), were significantly reduced

in U251 cells following ACC1 knockdown compared with controls

(Fig. S2E-L), indicating a cell

line-specific regulatory effect.

Taken together, the aforementioned findings indicate

that the reduced proliferation rate observed in U251 cells upon

ACC1 knockdown was due to SDH suppression rather than impaired

proliferation. Given the consistent phenotype of enhanced

proliferation, migration and invasion, along with the unique

metabolic response to ACC1 silencing, U251 cells were selected for

further mechanistic studies. However, additional studies are

warranted to elucidate ACC1-related pathways in other glioma cell

lines.

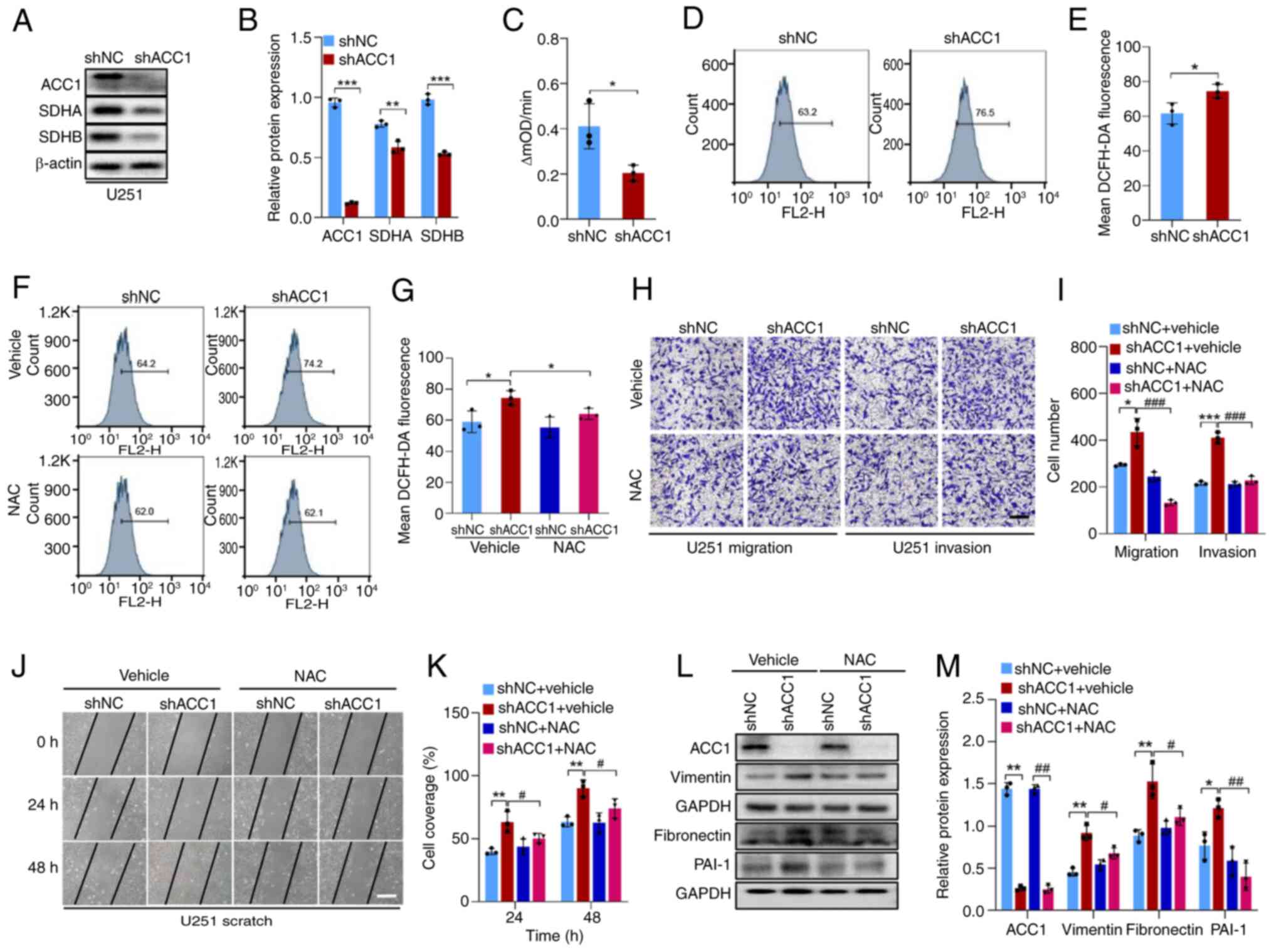

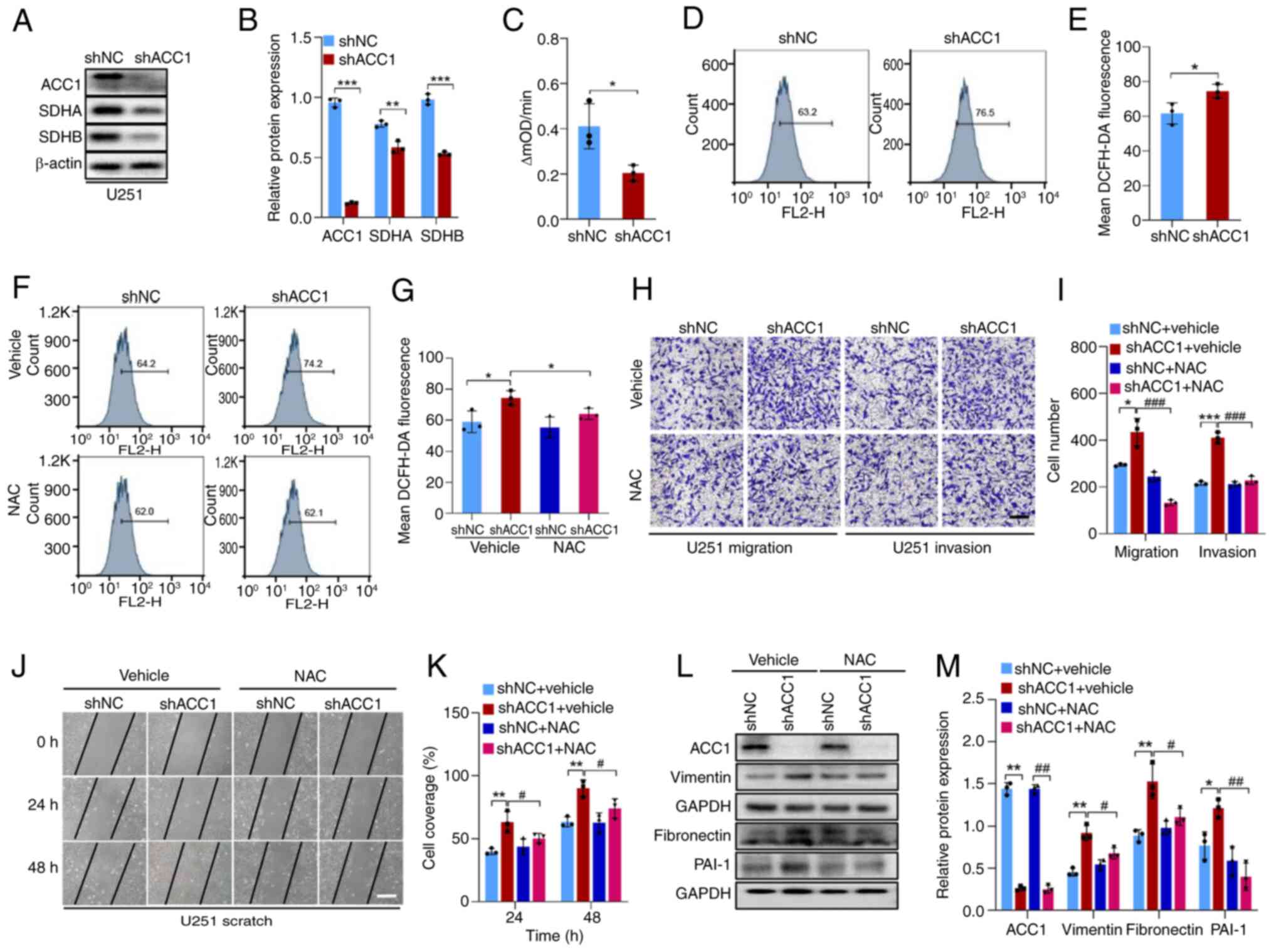

ACC1 knockdown promotes migration and

invasion of U251 cells by increasing ROS levels

Due to the well-established association between SDH

inhibition and ROS generation (21), the present study aimed to assess

whether the downregulation of ACC1 facilitates glioma cell

migration and invasion by stimulating ROS production through SDH

inhibition. To address this, a series of experiments were

performed, and the experimental results demonstrated that, compared

with controls, ACC1 knockdown significantly decreased SDHA and SDHB

protein levels (Fig. 2A and B)

and SDH enzyme activity (Fig.

2C), leading to significantly elevated intracellular ROS levels

(Fig. 2D and E). Application of 5

mM NAC (Fig. S3A), a free

radical scavenger (22),

effectively prevented the ACC1 knockdown-induced upregulation of

intracellular ROS (Fig. 2F and

G). Moreover, Transwell (Fig. 2H

and I) and wound healing assays (Fig. 2J and K) demonstrated that NAC at

least partially reversed ACC1 knockdown-induced cell migration and

invasion. Western blot results also revealed that NAC application

prevented ACC1 knockdown-induced upregulation of migration-related

markers, fibronectin and vimentin, and the invasion-related marker

PAI-1 (Fig. 2L and M). Moreover,

rescue experiments were performed by reintroducing ACC1 into ACC1

knockdown cells (shACC1 + OEACC1). The findings revealed that,

compared with in the shACC1 + vector group, ACC1 overexpression

significantly attenuated the enhanced cell migration, invasion and

ROS elevation (Fig. S4). These

findings suggest that knockdown of ACC1 promotes the migration and

invasion of U251 cells by increasing intracellular ROS levels

induced by SDH inhibition.

| Figure 2KD of ACC1 in U251 cells promotes

cell migration and invasion by down-regulating SDH and thus

elevating ROS level. (A) WB of ACC1, SDHA and SDHB after ACC1 KD.

(B) Semi-quantification of ACC1, SDHA and SDHB protein levels after

ACC1 KD. (C) Quantification of SDH activity following ACC1 KD. (D)

Flow cytometric analysis of ROS after ACC1 KD. (E) Quantification

of cellular ROS fluorescence signals after ACC1 KD. (F) Flow

cytometric analysis of ROS after NAC treatment. (G) Quantification

of cellular ROS fluorescence signals after NAC treatment. (H)

Images of Transwell migration and invasion assays after NAC

treatment. (I) Quantification of Transwell migration/invasion assay

findings after NAC treatment. (J) Wound-healing images of cells

after NAC treatment. (K) Quantification of wound-healing assay

after NAC treatment. (L) WB of ACC1, vimentin, fibronectin and

PAI-1 after NAC treatment. (M) Semi-quantification of ACC1,

fibronectin, vimentin and PAI-1 protein levels after NAC treatment.

Scale bars, 100 μm. Error bars represent the mean ± standard

deviation from three independent experiments.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. #P<0.05;

##P<0.01; ###P<0.001. ACC1, acetyl-CoA

carboxylase 1; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; ROS, reactive oxygen

species; NAC, N-acetyl-cysteine; PAI-1, plasminogen activator

inhibitor-1; sh, short hairpin; NC, negative control; OD, optical

density; WB, western blotting; KD, knockdown. |

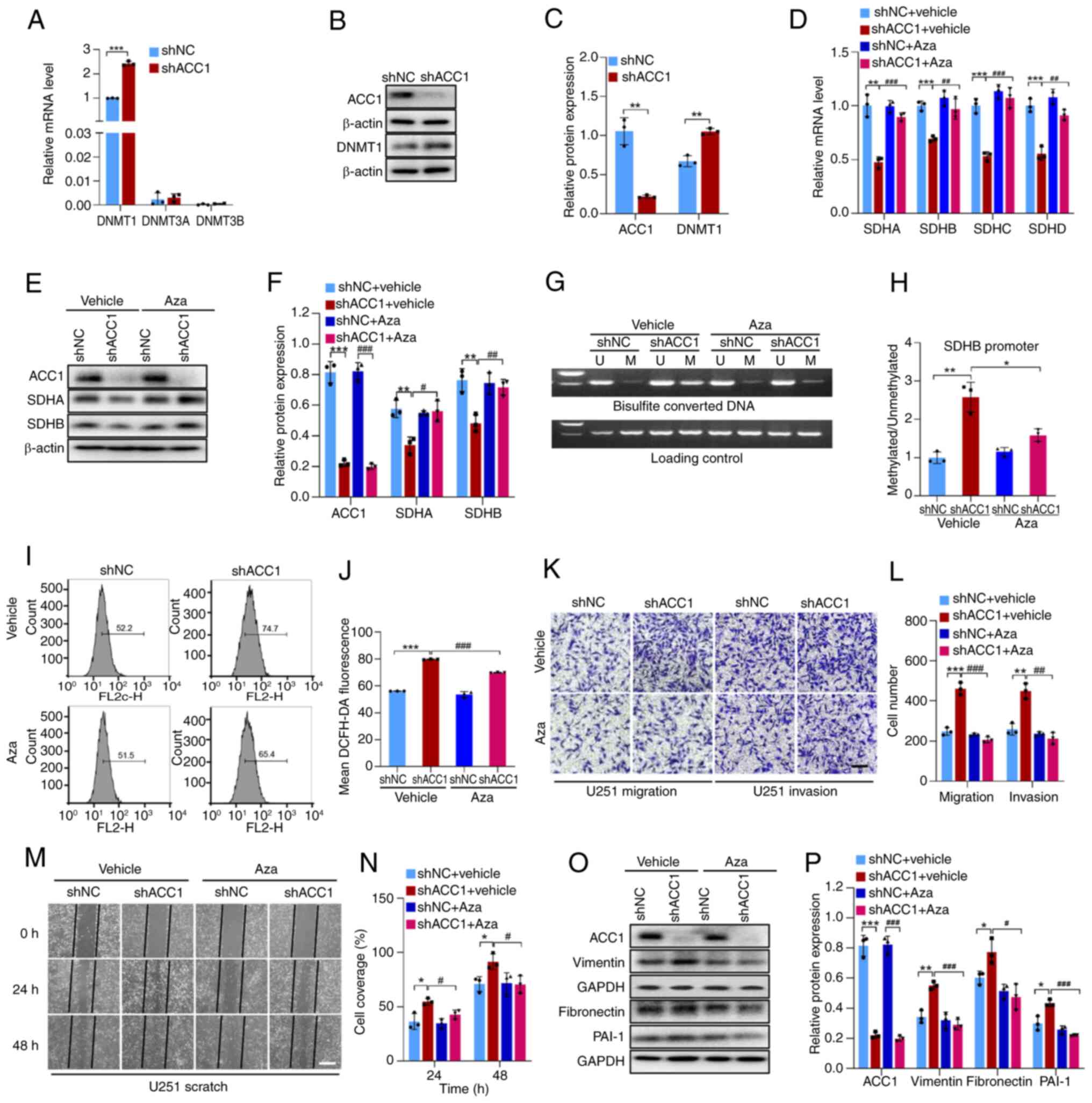

Increased DNMT1 expression leads to SDH

hypermethylation and ROS upregulation

The primary mechanism underlying gene transcription

inhibition involves DNA methylation, which is mediated by DNMTs

(23). The DNMT family consists

of DNMT1/2/3A/3B/3L (24), with

DNMT2 primarily targeting transfer RNA methylation (25) and DNMT3L lacking catalytic

activity (26). DNMT1/3A/3B are

the main mediators of DNA methyltransferase activity in vivo

(27). Analysis of TCGA database

revealed upregulation of DNMT1/3A/3B mRNA levels in glioma tissues,

compared with in normal tissues (Fig. S5A-C). This trend is consistent

with the elevated protein expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3A observed

in the CPTAC database (28),

although DNMT3B data was unavailable (Fig. S5D and E). CPTAC data also

revealed that all four subunits of SDH (SDHA-D) are downregulated

in glioma tissue compared with in normal tissue (Fig. S5F-I), which is by contrast to the

upregulation of DNMTs. This opposing expression pattern suggests a

possible inverse association between DNMT and SDH levels in

gliomas.

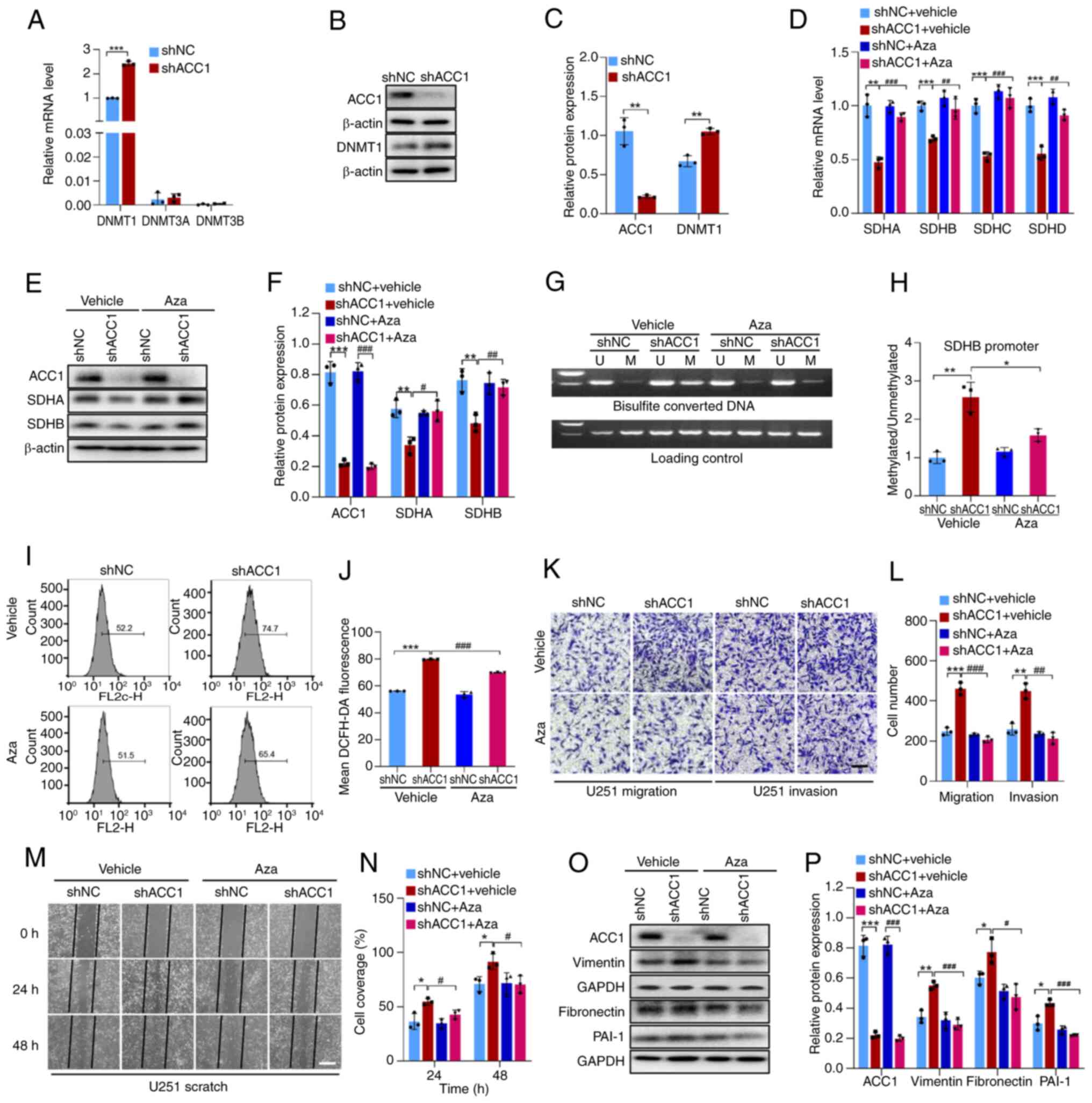

RT-qPCR analysis revealed that, in U251 cells, DNMT1

was predominantly expressed, whereas DNMT2 and DNMT3 exhibited very

low expression levels. Moreover, ACC1 knockdown significantly

increased DNMT1 expression compared with that of controls (Fig. 3A-C). To further evaluate whether

ACC1 knockdown reduces SDH levels by promoting its methylation,

thereby increasing ROS levels to promote cell migration and

invasion, the DNMT inhibitor Aza was utilized to inhibit DNMT

activity and reduce methylation levels. In comparison with

controls, treatment with 4 μM Aza, a concentration that was

demonstrated to not affect cell viability (Fig. S3B), significantly reduced SDH

downregulation caused by ACC1 knockdown (Fig. 3D-F) and hypermethylation of the

SDHB promoter (Fig. 3G and H),

and significantly attenuated the ACC1 knockdown-induced increase in

ROS and cell migration/invasion (Fig.

3I-P). These results collectively indicate that ACC1 knockdown

upregulates DNMT1, leading to the downregulation of SDH, the

increase of ROS levels, and ultimately the promotion of U251 cell

migration and invasion.

| Figure 3KD of ACC1 in U251 cells increases

DNMT1 expression, leading to hypermethylation of SDH and subsequent

upregulation of ROS levels. (A) RT-qPCR of DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B

mRNA levels after ACC1 KD. (B) WB of ACC1 and DNMT1 after ACC1 KD.

(C) Semi-quantification of ACC1 and DNMT1 protein levels after ACC1

KD. (D) RT-qPCR of SDHA, SDHB, SDHC and SDHD mRNA levels after

treatment with Aza. (E) WB of ACC1, SDHA and SDHB after Aza

treatment. (F) Semi-quantification of ACC1, SDHA and SDHB protein

levels after Aza treatment. (G) Methylation-specific PCR of SDHB

promoter methylation after Aza treatment. (H) Semi-quantification

of SDHB promoter methylation levels after Aza treatment. (I) Flow

cytometric analysis of ROS after Aza treatment. (J) Quantification

of cellular ROS fluorescence signals after Aza treatment. (K)

Images of Transwell migration and invasion assays after Aza

treatment. (L) Quantification of Transwell migration/invasion

assays after Aza treatment. (M) Wound-healing images after Aza

treatment. (N) Wound-healing assay quantification after Aza

treatment. (O) WB of ACC1, vimentin, fibronectin and PAI-1 after

Aza treatment. (P) Semi-quantification of ACC1, vimentin,

fibronectin and PAI-1 protein levels after Aza treatment. Scale

bars, 100 μm. Error bars represent the mean ± standard

deviation from three independent experiments.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. #P<0.05;

##P<0.01; ###P<0.001. ACC1, acetyl-CoA

carboxylase 1; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; SDH, succinate

dehydrogenase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; Aza, azacitidine; PAI-1,

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; U, unmethylated; M, methylated;

WB, western blotting; KD, knockdown; sh, short hairpin; NC,

negative control. |

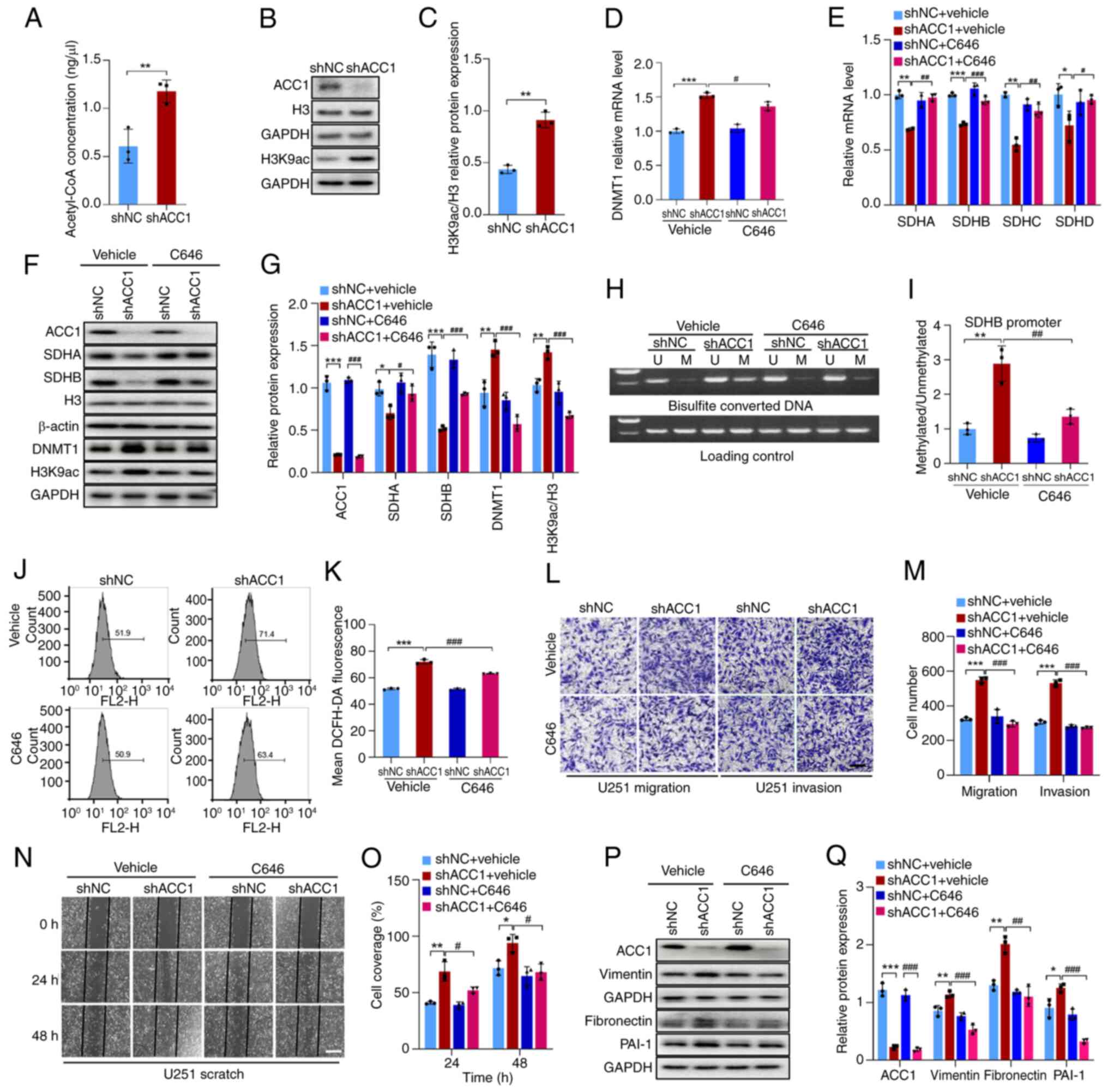

ACC1 knockdown increases histone

acetylation by elevating Acetyl-CoA, leading to DNMT1

upregulation

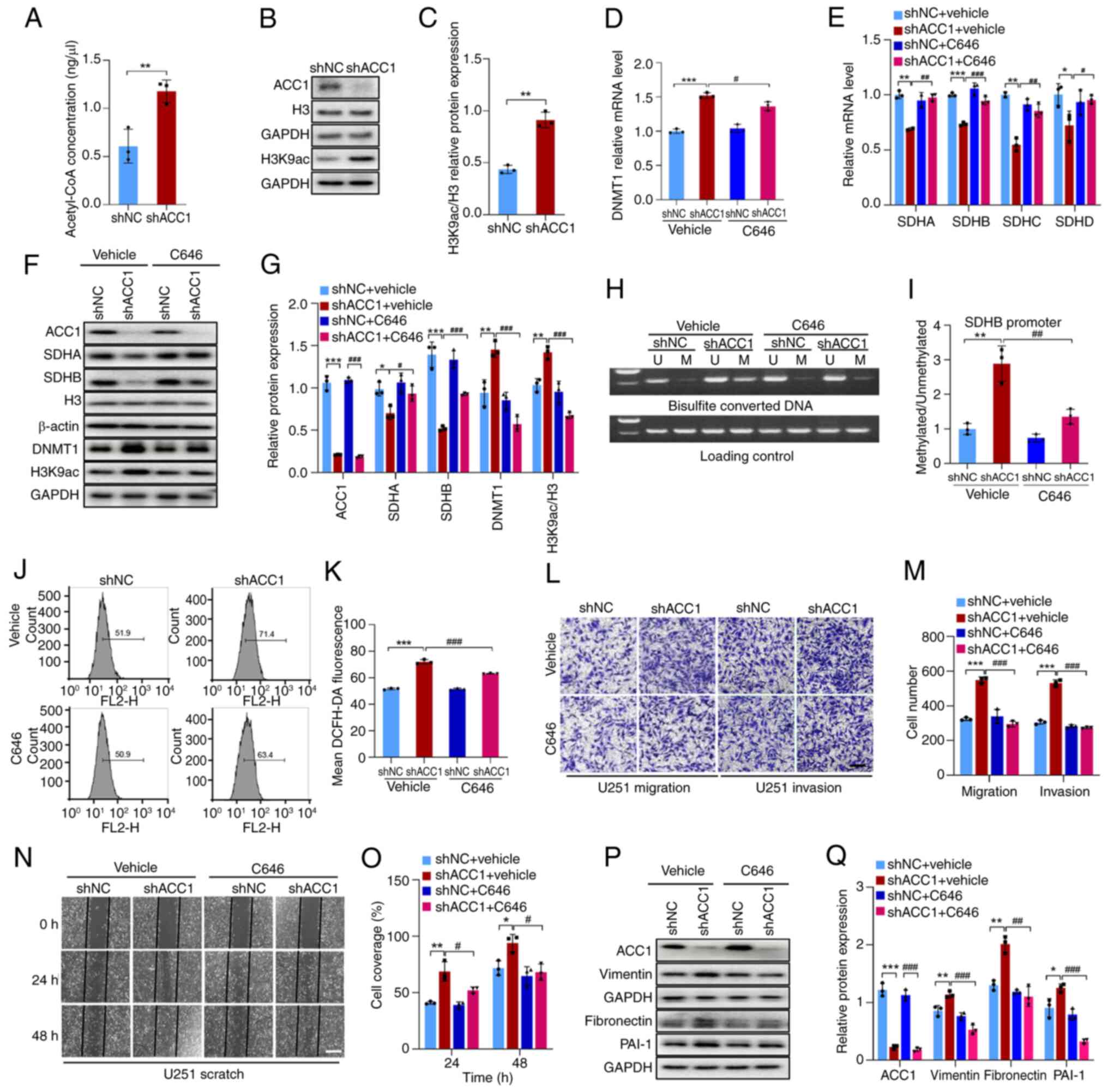

As ACC1 influences protein acetylation by modulating

acetyl-CoA levels (29), we

hypothesized that the upregulation of DNMT1 upon ACC1 knockdown may

be associated with this phenomenon. The results of the present

study revealed that, compared with controls, knockdown of ACC1

significantly increased acetyl-CoA levels (Fig. 4A) and promoted H3K9ac expression

(Fig. 4B and C). Notably, the

knockdown of ACC1 did not significantly reduce the intracellular

level of fatty acids compared with the control (Fig. S6A). SREBP1, encoded by the sterol

regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1 (SREBF1) gene, is

a key regulator of lipid metabolism that can activate the

transcription of fatty acid synthesis-related genes such as FASN,

thereby maintaining cellular fatty acid homeostasis (30). The results demonstrated that,

compared with controls, ACC1 knockdown significantly upregulated

both SREBF1 (Fig. S6B and C) and

FASN mRNA levels (Fig. S6D), as

well as SREBP1 and FASN protein levels (Fig. S6E and F). This suggests a

compensatory enhancement of fatty acid synthesis to counteract the

reduction caused by ACC1 depletion, ultimately preserving cellular

fatty acid balance. As this compensatory mechanism maintains fatty

acid levels, the phenotypic changes observed after ACC1 knockdown

may be driven by alterations in histone acetylation rather than

disruptions in fatty acid metabolism.

| Figure 4KD of ACC1 induces histone

acetylation via acetyl-CoA elevation, resulting in DNMT1

upregulation. (A) Fluorometric assay of acetyl-CoA levels after

ACC1 KD. (B) WB of ACC1, H3K9ac and H3 after ACC1 KD. (C)

Semi-quantification of H3K9ac/H3 protein levels after ACC1 KD. (D)

RT-qPCR of DNMT1 mRNA levels after treatment with C646. (E) RT-qPCR

of SDHA, SDHB, SDHC and SDHD mRNA levels after treatment with C646.

(F) WB of ACC1, SDHA, SDHB, H3, DNMT1 and H3K9ac after treatment

with C646. (G) Semi-quantification of ACC1, SDHA, SDHB, DNMT1 and

H3K9ac/H3 protein levels after treatment with C646. (H)

Methylation-specific PCR of SDHB promoter methylation after

treatment with C646. (I) Semi-quantification of SDHB promoter

methylation level after treatment with C646. (J) Flow cytometric

analysis of ROS after treatment with C646. (K) Quantification of

cellular ROS fluorescence signals after treatment with C646. (L)

Images of Transwell migration/invasion assays after treatment with

C646. (M) Quantification of Transwell migration/invasion assays

after treatment with C646. (N) Wound-healing images after treatment

with C646. (O) Wound-healing assay quantification after treatment

with C646. (P) WB of ACC1, vimentin, fibronectin and PAI-1 after

treatment with C646. (Q) Semi-quantification of ACC1, vimentin,

fibronectin and PAI-1 protein levels after treatment with C646.

Scale bars, 100 μm. Error bars represent the mean ± standard

from three independent experiments. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

#P<0.05; ##P<0.01;

###P<0.001. ACC1, acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1; DNMT, DNA

methyltransferase; H3K9ac, histone H3 acetylation at lysine 9; SDH,

succinate dehydrogenase; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1;

U, unmethylated; M, methylated; WB, western blotting; KD,

knockdown; sh, short hairpin; NC, negative control. |

To further evaluate whether increased histone

acetylation leads to the upregulation of DNMT1, C646 was utilized

to inhibit histone acetylation. A total of 5 μM C646

(Fig. S3C) effectively reduced

histone acetylation levels (Fig. 4F

and G), prevented the upregulation of DNMT1 induced by ACC1

knockdown (Fig. 4D, F and G) and

subsequently reversed the effects of ACC1 knockdown on SDH, ROS

levels and migration/invasion (Fig.

4E-Q). These findings suggest that knockdown of ACC1 promotes

histone acetylation by increasing acetyl-CoA levels, which

subsequently upregulates the expression of DNMT1. Consequently,

hypermethylation of SDH promoter inhibits SDH expression, leading

to increased ROS production and ultimately facilitating cell

migration and invasion.

ACC1 elevates DNMT1 expression through

P300 interaction

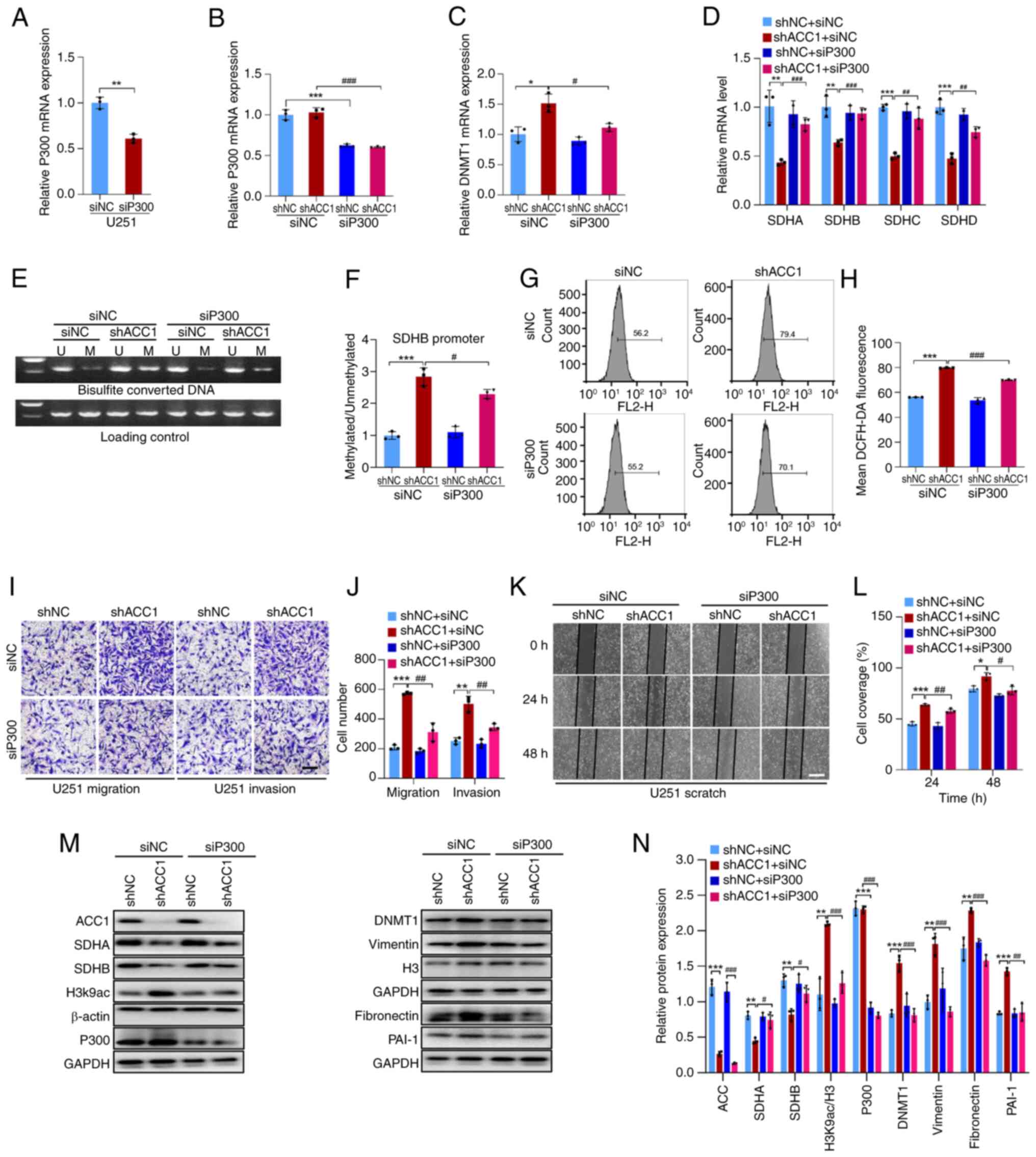

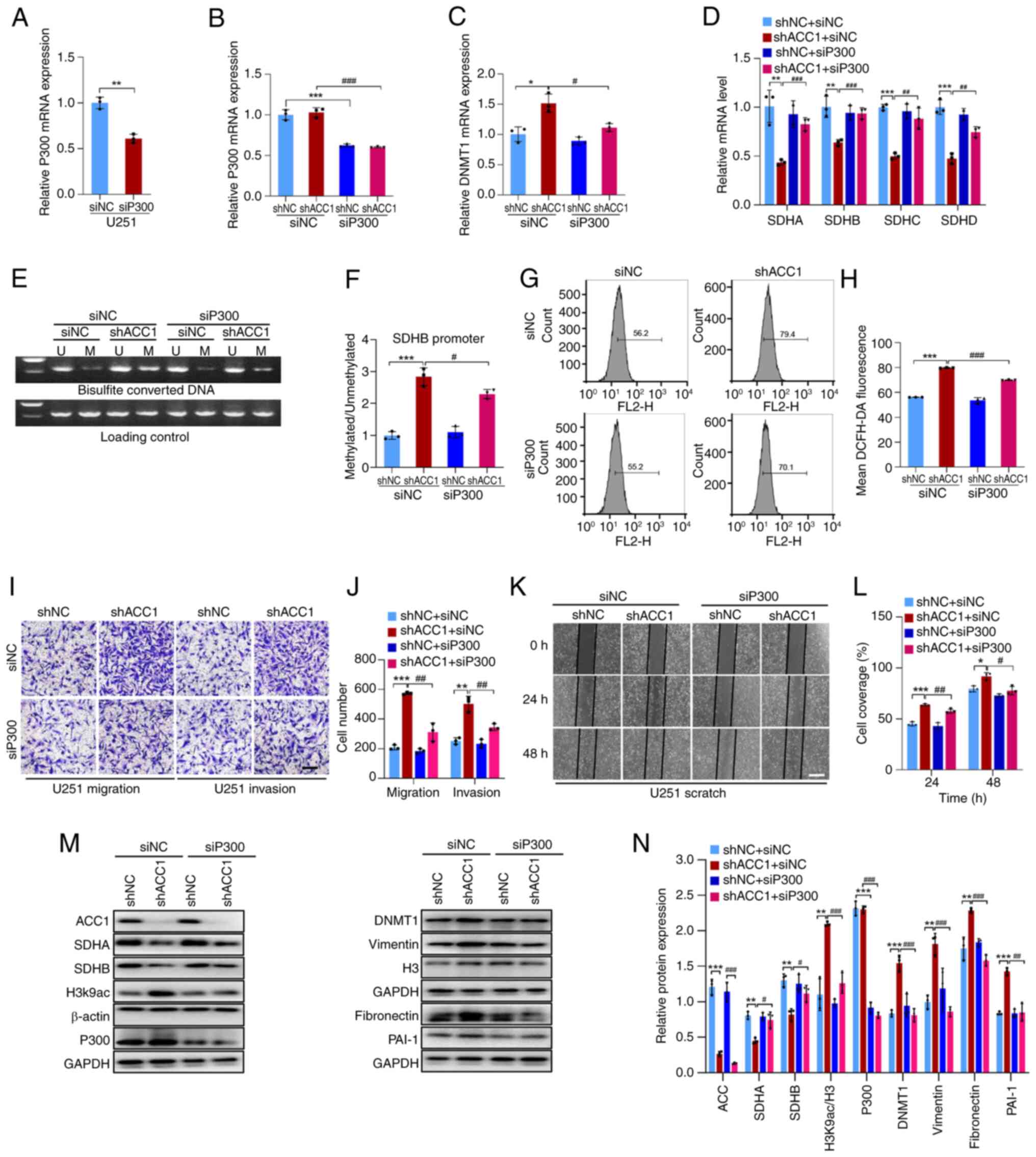

To assess the involvement of P300 in the

upregulation of DNMT1 induced by ACC1 knockdown, siRNA was utilized

to interfere with P300 expression (Fig. 5A, B, M and N). Compared with in

cells with ACC1 knockdown alone (shACC1 + siNC), the silencing of

P300 in ACC1 knockdown cells (shACC1 + siP300) significantly

reduced the ACC1 knockdown-induced increase in DNMT1 expression

(Fig. 5C, M and N). Additionally,

compared with shACC1 + siNC, interference with P300 (shACC1 +

siP300) restored SDH expression (Fig.

5D, M and N) and reduced SDHB promoter methylation (Fig. 5E and F). Compared with shACC1 +

siNC, P300 knockdown (shACC1 + siP300) also attenuated the

increased ROS and enhanced migration/invasion observed upon ACC1

knockdown (Fig. 5G-N). Overall,

the results indicate that ACC1 knockdown enhances the availability

of substrates for P300 by elevating acetyl-CoA levels, resulting in

increased DNMT1 expression, SDH hypermethylation and elevated ROS

levels, which ultimately promotes cell migration and invasion.

| Figure 5KD of ACC1 in U251 cells elevates

DNMT1 expression via P300. (A) RT-qPCR of P300 mRNA after siP300

transfection in wild-type U251 cells. (B) RT-qPCR of P300 mRNA

after siP300 transfection in ACC1 KD cells. (C) RT-qPCR of DNMT1

mRNA after siP300 transfection. (D) RT-qPCR of SDHA, SDHB, SDHC and

SDHD mRNA after siP300 transfection. (E) Methylation-specific PCR

of SDHB promoter methylation after siP300 transfection. (F)

Semi-quantification of SDHB promoter methylation levels after

siP300 transfection. (G) Flow cytometric analysis of ROS after

siP300 transfection. (H) Quantification of cellular ROS

fluorescence signals after siP300 transfection. (I) Images of

Transwell migration/invasion assays after siP300 transfection. (J)

Quantification of Transwell migration/invasion assays after siP300

transfection. (K) Wound-healing images after siP300 transfection.

(L) Wound-healing assay quantification after siP300 transfection.

(M) WB of ACC1, SDHA, SDHB, H3K9ac, P300, DNMT1, vimentin, H3,

fibronectin and PAI-1 after siP300 transfection. (N)

Semi-quantification of ACC1, SDHA, SDHB, H3K9ac/H3, P300, DNMT1,

vimentin, fibronectin and PAI-1 protein levels after siP300

transfection. Scale bars, 100 μm. Error bars represent the

mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. #P<0.05;

##P<0.01; ###P<0.001. ACC1, acetyl-CoA

carboxylase 1; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; SDH, succinate

dehydrogenase; si, small interfering; U, unmethylated; M,

methylated; ROS, reactive oxygen species; H3K9ac, histone H3

acetylation at lysine 9; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1;

WB, western blotting; KD, knockdown; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; sh, short hairpin; NC, negative

control. |

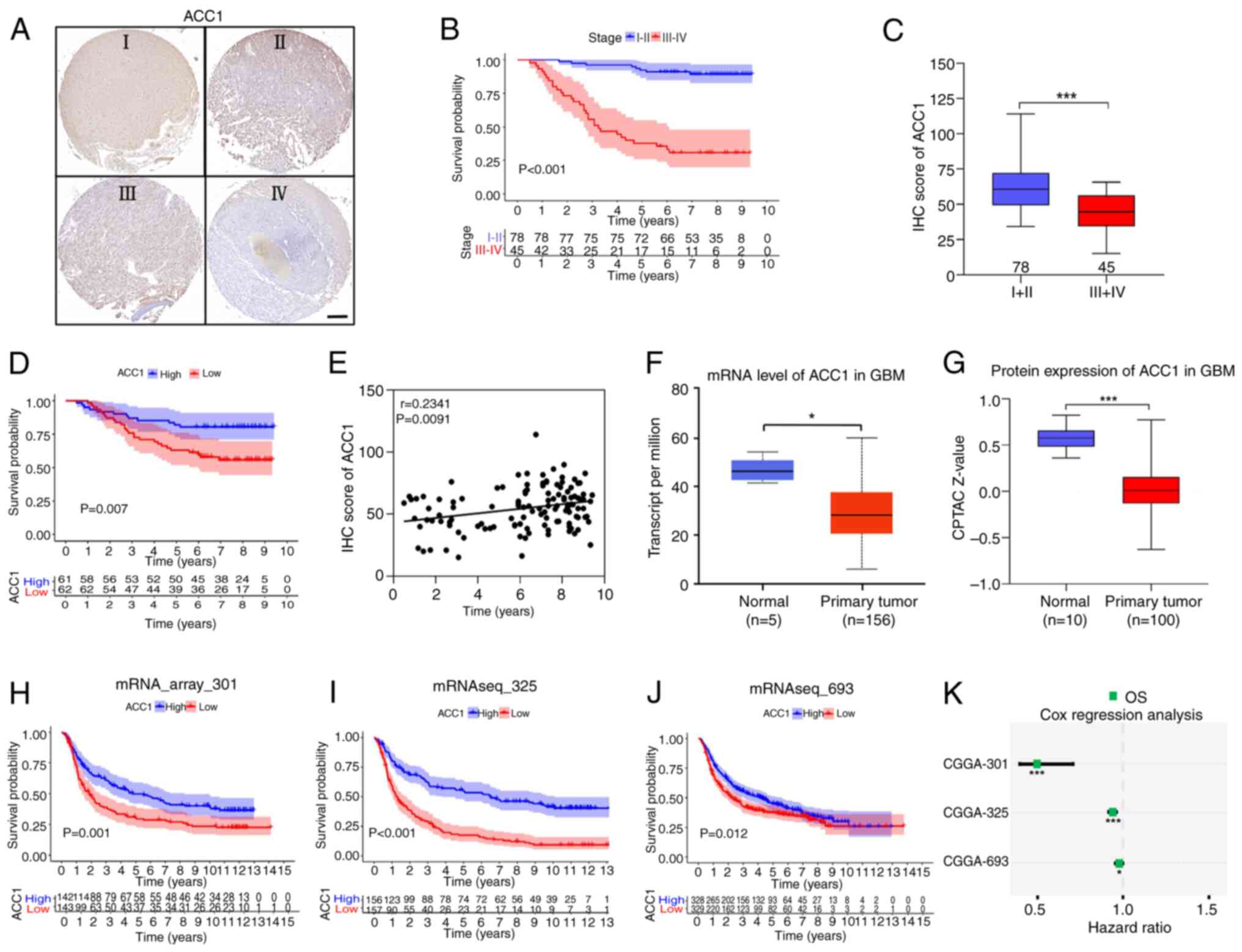

Low ACC1 expression is associated with

poor prognosis in patients with glioma

To further assess the association between ACC1

levels and the prognosis of patients with glioma,

immunohistochemical staining of ACC1 was performed using a glioma

tissue microarray (Fig. 6A).

Analysis of clinical data indicated a significant reduction in

overall survival (OS) among patients with grades III-IV glioma,

compared with those with grades I-II (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, evaluation based

on immunohistochemistry scores revealed significantly lower ACC1

levels in tumor tissues from patients with grades III-IV glioma

compared with those with grades I-II (Fig. 6C). Notably, patients exhibiting

low ACC1 expression experienced significantly worse OS outcomes

compared with those with high ACC1 expression (Fig. 6D), with a positive correlation

observed between survival time and ACC1 expression levels (Spearman

r=0.2341; P=0.0091; Fig. 6E).

Moreover, data from TCGA (Fig.

6F) and CPTAC databases (Fig.

6G) corroborated the downregulation of ACC1 in glioma tissues

compared with in normal tissues (28). Finally, analysis of three datasets

from the CGGA (31) database

(mRNA_array_301, mRNAseq_325 and mRNAseq_693) revealed that

patients with glioma with low ACC1 expression exhibited worse OS

(Fig. 6H-J) and were at a higher

risk of recurrence, compared with those with high ACC1 expression

(Fig. 6K). In summary, the

aforementioned findings highlight the association between low ACC1

expression and adverse outcomes in patients with glioma.

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate the

multifaceted role of ACC1 in glioma progression, impacting

proliferation, migration, invasion and prognosis. The study first

assessed ACC1 expression across four glioma cell lines, revealing a

differential pattern: U87 cells demonstrated lower ACC1 levels,

whilst U251, LN229 and T98G cells exhibited higher expression. This

pattern closely mirrored the ACC1 mRNA levels observed in U87,

U251, T98G and LN229 cells, according to the Cancer Cell Line

Encyclopedia database (32).

However, abnormal SDH activity was observed exclusively in U251

cells. To further explore the mechanism underlying this

specificity, the research focused on the molecular characteristics

of U251 cells.

Understanding glioma cell origin, classification and

heterogeneity of glioma cells is essential for both research and

therapy. Although U87, U251, T98G and LN229 are all World Health

Organization grade IV glioma cell lines derived from astrocytic

transformation, they originate from patients with diverse ethnic

backgrounds, ages, sexes and tumor locations, resulting in distinct

genetic backgrounds and molecular characteristics (33,34). According to TCGA classification,

U251 and LN229 belong to the classical subtype, whilst U87 and T98G

represent the mesenchymal subtype, with notable differences in gene

expression profiles and signaling pathway activity (35). Morphologically, U251 and T98G

exhibit fibroblast-like characteristics, whereas U87 and LN229

display more epithelial-like features, further illustrating the

phenotypic diversity among glioma cells (33). In this context, the finding that

ACC1 knockdown reduced SDH expression specifically in U251 cells

highlights this intrinsic heterogeneity and underscores the

importance of molecular subtyping and precise diagnostic strategies

in glioma.

SDH activity is associated with ROS levels in

several cancers. SDH mutations increase ROS and promote tumor

development in paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma (11) and gastrointestinal stromal tumors

(12). Redox imbalance is also

implicated in glioma progression (17). Elevated ROS levels have been

reported to drive glioma stem cell proliferation (36) and enhance the proliferation and

migration/invasion in glioma cell lines (37,38). Our previous findings demonstrated

that ACC1 knockdown in U251 cells increases ROS and promotes

migration/invasion via ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Wang et al,

unpublished data). The results of the current study further support

the importance of ROS in glioma pathogenesis.

Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation and

histone modifications, serve crucial roles in cancer progression,

including in glioma (39).

Elevated histone acetylation has been reported to promote invasion

and metastasis across several tumors, including glioma (40). The dynamic balance of histone

acetylation and deacetylation modulates DNMT1 activity, a key

regulator of epigenetic processes, as supported by multiple studies

(41-45). Specifically, the histone

acetyltransferase P300 directly interacts with the DNMT1 promoter,

enhancing chromatin acetylation and DNMT1 gene transcription

(46). Furthermore, P300

functions as a critical transcriptional regulator of DNMT1, as

highlighted by its role in cancer progression, as demonstrated by

Li et al (46) in breast

cancer. In U251 glioma cells, the present study demonstrated that

suppressing ACC1 increased the levels of acetyl-CoA, consequently

promoting protein acetylation catalyzed by histone

acetyltransferases, including that of P300. This is likely to

induce increased histone acetylation, potentially reshaping gene

expression profiles and fueling glioma advancement. Additionally,

this may enhance the binding affinity of P300 to the DNMT1

promoter, resulting in increased DNMT1 acetylation, elevated DNMT1

expression and subsequent epigenetic modifications. Moreover,

recent studies have highlighted the role of DNMT1-mediated

hypermethylation of the SDHB promoter in reducing SDHB expression,

which, in turn, is associated with elevated levels of ROS and

contributes to adrenal cortical dysfunction (47). In line with this, the findings of

the present study in U251 glioma cells suggest that increased DNMT1

expression induces hypermethylation of the SDH promoter. This

epigenetic modification elevates ROS levels, fostering U251 glioma

cell migration and invasion.

Furthermore, the in vitro results in the

present study demonstrate that ACC1 knockdown promoted glioma cell

migration and invasion, suggesting a role for ACC1 in glioma

progression. This finding aligned with that of the clinical tissue

microarray analysis, which revealed that lower ACC1 expression was

associated with a worse prognosis in patients with glioma. This was

further supported by survival data from the CGGA database.

Together, these results indicate that ACC1 may serve as a potential

prognostic marker in glioma. Moreover, analysis of the CPTAC glioma

dataset revealed consistent downregulation of all SDH subunits in

high-grade gliomas, suggesting that SDH suppression is a common

feature of aggressive glioma phenotypes. This is consistent with

previous studies linking reduced SDH expression with poor prognosis

in patients with high-grade gliomas (20). However, as ACC1 knockdown was

associated with SDH reduction specifically in U251 cells in the

present study, SDH levels and their association with ACC1

expression in patient tissues were not evaluated, leaving the

clinical relevance and subtype-specific significance of this

relationship uncertain. These findings highlight the need for

further clinical validation to determine whether SDH dysregulation

contributes to ACC1-mediated glioma progression across distinct

glioma subtypes.

Notably, despite adherence to standardized

protocols, the present study was unable to establish a stable

orthotopic xenograft model using U251 cells, and this limitation

precluded in vivo validation of the in vitro

findings. Therefore, future studies should employ patient-derived

xenograft models to evaluate the physiological relevance of the

results of the present study.

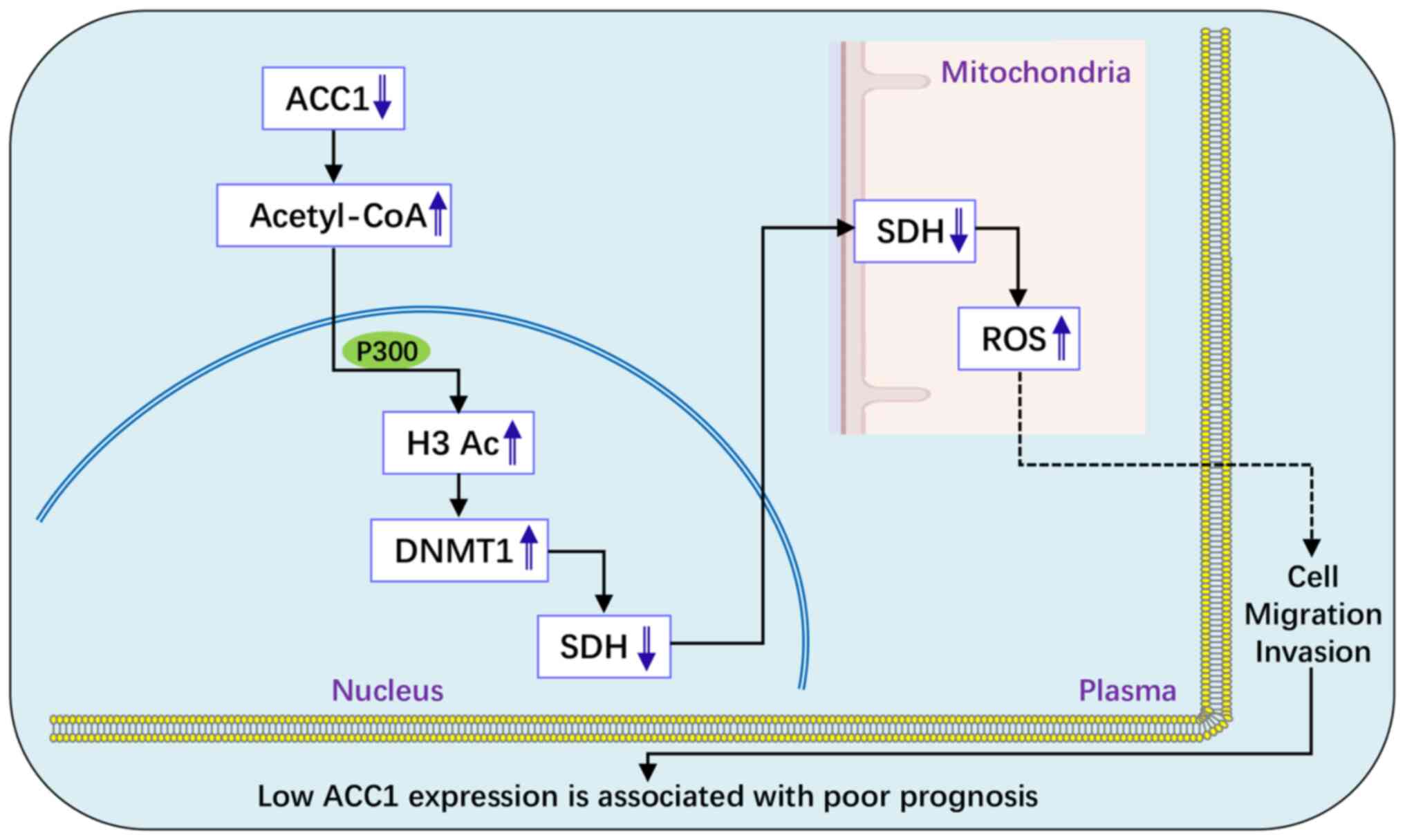

In conclusion, the results of the present study

demonstrated that low ACC1 expression is associated with poor

prognosis in patients with glioma and that ACC1 knockdown enhances

glioma cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Specifically, in

U251 cells, ACC1 knockdown promotes migration and invasion through

the acetyl-CoA/P300/DNMT1/SDH/ROS pathway (Fig. 7). These findings highlight ACC1 as

a potential therapeutic target and underscore the need for

personalized treatment strategies for patients with glioma.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated from this study are available

upon request from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XXW, YW, YZL and BSZ conceived and designed the

study. XXW and YW performed the investigation and data analysis.

XXW, WLZ, WQY and JPT conducted the experiments and bioinformatics

analysis. YZL and BSZ supervised the research. XXW and YZL drafted

the manuscript. XXW and YZL confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors edited, read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethics approval for the glioma tissue microarray was

obtained by Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd. (approval no. SHYJS-C

P-1801018).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors that they have declare no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81973988), the Henan

Key Laboratory of Neurorestoratology Foundation (grant no.

HNSJXF-2021-014) and the Henan Plan of the Medical Science and

Technology Research (grant no. LHGJ20230519).

References

|

1

|

Lapointe S, Perry A and Butowski NA:

Primary brain tumors in adults. Lancet. 392:432–446. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Delgado-López PD and Corrales-García EM:

Survival in glioblastoma: A review on the impact of treatment

modalities. Clin Transl Oncol. 18:1062–1071. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Khasraw M and Lassman AB: Advances in the

treatment of malignant gliomas. Curr Oncol Rep. 12:26–33. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lucke-Wold B, Rangwala BS, Shafique MA,

Siddiq MA, Mustafa MS, Danish F, Nasrullah RMU, Zainab N and Haseeb

A: Focus on current and emerging treatment options for glioma: A

comprehensive review. World J Clin Oncol. 15:482–495. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Duzan A, Reinken D, McGomery TL, Ferencz

NM, Plummer JM and Basti mM: Endocannabinoids are potential

inhibitors of glioblastoma multiforme proliferation. J Integr Med.

21:120–129. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hunkeler M, Hagmann A, Stuttfeld E, Chami

M, Guri Y, Stahlberg H and Maier T: Structural basis for regulation

of human acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Nature. 558:470–474. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Rios Garcia M, Steinbauer B, Srivastava K,

Singhal M, Mattijssen F, Maida A, Christian S, Hess-Stumpp H,

Augustin HG, Müller-Decker K, et al: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

1-dependent protein acetylation controls breast cancer metastasis

and recurrence. Cell Metab. 26:842–855.e5. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ye B, Yin L, Wang Q and Xu C: ACC1 is

overexpressed in liver cancers and contributes to the proliferation

of human hepatoma Hep G2 cells and the rat liver cell line BRL 3A.

Mol Med Rep. 19:3431–3440. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Garn H, Krause H, Enzmann V and Drössler

K: An improved MTT assay using the electron-coupling agent

menadione. J Immunol Methods. 168:253–256. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Owens KM, Aykin-Burns N, Dayal D, Coleman

MC, Domann FE and Spitz DR: Genomic instability induced by mutant

succinate dehydrogenase subunit D (SDHD) is mediated by O2(-•) and

H2O2. Free Radic Biol Med. 52:160–166. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Turchini J and Gill AJ: Morphologic clues

to succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) deficiency in pheochromocytomas

and paragangliomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 44:422–424. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Neppala P, Banerjee S, Fanta PT, Yerba M,

Porras KA, Burgoyne AM and Sicklick JK: Current management of

succinate dehydrogenase-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

Cancer Metastasis Rev. 38:525–535. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rani V, Deep G, Singh RK, Palle K and

Yadav UC: Oxidative stress and metabolic disorders: Pathogenesis

and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci. 148:183–193. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chang H, Li J, Qu K, Wan Y, Liu S, Zheng

W, Zhang Z and Liu C: CRIF1 overexpression facilitates tumor growth

and metastasis through inducing ROS/NFκB pathway in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 11:3322020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Checa J and Aran JM: Reactive oxygen

species: Drivers of physiological and pathological processes. J

Inflamm Res. 13:1057–1073. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sarmiento-Salinas FL, Perez-Gonzalez A,

Acosta-Casique A, Ix-Ballote A, Diaz A, Treviño S, Rosas-Murrieta

NH, Millán-Perez-Peña L and Maycotte P: Reactive oxygen species:

Role in carcinogenesis, cancer cell signaling and tumor

progression. Life Sci. 284:1199422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhou Y, Wang L, Wang C, Wu Y, Chen D and

Lee TH: Potential implications of hydrogen peroxide in the

pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies of gliomas. Arch Pharm Res.

43:187–203. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kleinman HK and Martin GR: Matrigel

basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Semin Cancer

Biol. 15:378–386. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sharpe MA, Ismail N and Baskin DS:

Metabolic sculpting of the mitochondria, cell signaling and the

cancer phenotype. Transl Cancer Res. 6:S182–S188. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhang W and Lang R: Succinate metabolism:

A promising therapeutic target for inflammation,

ischemia/reperfusion injury and cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol.

11:12669732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zafarullah M, Li WQ, Sylvester J and Ahmad

M: Molecular mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine actions. Cell Mol Life

Sci. 60:6–20. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Suzuki mM and Bird A: DNA methylation

landscapes: Provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet.

9:465–476. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bestor T, Laudano A, Mattaliano R and

Ingram V: Cloning and sequencing of a cDNA encoding DNA

methyltransferase of mouse cells. The carboxyl-terminal domain of

the mammalian enzymes is related to bacterial restriction

methyltransferases. J Mol Biol. 203:971–983. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ashapkin VV, Kutueva LI and Vanyushin BF:

Dnmt2 is the most evolutionary conserved and enigmatic cytosine DNA

methyltransferase in eukaryotes. Genetika. 52:269–282. 2016.In

Russian. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liao HF, Tai KY, Chen WS, Cheng LC, Ho HN

and Lin SP: Functions of DNA methyltransferase 3-like in germ cells

and beyond. Biol Cell. 104:571–587. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Robertson KD, Uzvolgyi E, Liang G,

Talmadge C, Sumegi J, Gonzales FA and Jones PA: The human DNA

methyltransferases (DNMTs) 1, 3a and 3b: Coordinate mRNA expression

in normal tissues and overexpression in tumors. Nucleic Acids Res.

27:2291–2298. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chandrashekar DS, Karthikeyan SK, Korla

PK, Patel H, Shovon AR, Athar M, Netto GJ, Qin ZS, Kumar S, Manne

U, et al: UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis

platform. Neoplasia. 25:18–27. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wu J, Singh K, Shing V, Gupta A, Arenberg

BC, Huffstutler RD, Lee DY and Sack MN: Mitochondrial fatty acid

oxidation regulates monocytic type I interferon signaling via

histone acetylation. Sci Adv. 11:eadq93012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Eberlé D, Hegarty B, Bossard P, Ferré P

and Foufelle F: SREBP transcription factors: Master regulators of

lipid homeostasis. Biochimie. 86:839–848. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhao Z, Zhang KN, Wang Q, Li G, Zeng F,

Zhang Y, Wu F, Chai R, Wang Z, Zhang C, et al: Chinese glioma

genome atlas (CGGA): A comprehensive resource with functional

genomic data from Chinese glioma patients. Genomics Proteomics

Bioinformatics. 19:1–12. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jané-Valbuena J,

Kryukov GV, Lo CC, McDonald ER III, Barretina J, Gelfand ET,

Bielski CM, Li H, et al: Next-generation characterization of the

cancer cell line encyclopedia. Nature. 569:503–508. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Vitale AM, D'Amico G, Santonocito R,

Spinnato G, Di Marco M, Scalia F, Campanella C, Tringali G, Giusti

I, Dolo V, et al: An overview of glioblastoma multiforme in vitro

experimental models. J Biol Res. 6:1982024.

|

|

34

|

Hong X, Chedid K and Kalkanis SN:

Glioblastoma cell line-derived spheres in serumcontaining medium

versus serum-free medium: A comparison of cancer stem cell

properties. Int J Oncol. 41:1693–1700. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hernández-Vega AM, Del Moral-Morales A,

Zamora-Sánchez CJ, Piña-Medina AG, González-Arenas A and

Camacho-Arroyo I: Estradiol induces epithelial to mesenchymal

transition of human glioblastoma cells. Cells. 9:19302020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yuan S, Lu Y, Yang J, Chen G, Kim S, Feng

L, Ogasawara M, Hammoudi N, Lu W, Zhang H, et al: Metabolic

activation of mitochondria in glioma stem cells promotes cancer

development through a reactive oxygen species-mediated mechanism.

Stem Cell Res Ther. 6:1982015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu L, Wang F, Xu J and Chen Z: PTPN2

induced by inflammatory response and oxidative stress contributed

to glioma progression. J Cell Biochem. 120:19044–19051. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chiu WT, Shen SC, Chow JM, Lin CW, Shia LT

and Chen YC: Contribution of reactive oxygen species to

migration/invasion of human glioblastoma cells U87 via

ERK-dependent COX-2/PGE2 activation. Neurobiol Dis.

37:118–129. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Recillas-Targa F: Cancer epigenetics: An

overview. Arch Med Res. 53:732–740. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fan Y, Peng X, Wang Y, Li B and Zhao G:

Comprehensive analysis of HDAC family identifies HDAC1 as a

prognostic and immune infiltration indicator and HDAC1-related

signature for prognosis in glioma. Front Mol Biosci. 8:7200202021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tan HH and Porter AG: p21(WAF1) negatively

regulates DNMT1 expression in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 382:171–176. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Peng L, Yuan Z, Ling H, Fukasawa K,

Robertson K, Olashaw N, Koomen J, Chen J, Lane WS and Seto E: SIRT1

deacetylates the DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) protein and alters

its activities. Mol Cell Biol. 31:4720–4734. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Harada T, Ohguchi H, Grondin Y, Kikuchi S,

Sagawa M, Tai YT, Mazitschek R, Hideshima T and Anderson KC: HDAC3

regulates DNMT1 expression in multiple myeloma: Therapeutic

implications. Leukemia. 31:2670–2677. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Du Z, Song J, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Guda K, Yang

S, Kao HY, Xu Y, Willis J, Markowitz SD, et al: DNMT1 stability is

regulated by proteins coordinating deubiquitination and

acetylation-driven ubiquitination. Sci Signal. 3:ra802010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kishikawa S, Ugai H, Murata T and Yokoyama

KK: Roles of histone acetylation in the Dnmt1 gene expression.

Nucleic Acids Res. Suppl:209–210. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Li Z, Wang P, Cui W, Yong H, Wang D, Zhao

T, Wang W, Shi M, Zheng J and Bai J: Tumour-associated macrophages

enhance breast cancer malignancy via inducing ZEB1-mediated DNMT1

transcriptional activation. Cell Biosci. 12:1762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Mateska I, Witt A, Hagag E, Sinha A,

Yilmaz C, Thanou E, Sun N, Kolliniati O, Patschin M, Abdelmegeed H,

et al: Succinate mediates inflammation-induced adrenocortical

dysfunction. Elife. 12:e830642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|