Prostate cancer (PCa) is among the most prevalent

malignancies in males globally and has emerged as a notable public

health concern (1). The

pathophysiology of PCa is intricate and early-stage symptoms often

go undetected; however, as the condition progresses, it may

markedly affect the prognosis of patients and treatment efficacy

(2,3). Androgen pathway inhibitors and

chemotherapeutic medicines act as first-line therapeutic options

for PCa, while prostate-specific antigen testing, multi-parametric

magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission

tomography-computed tomography imaging function as first-line

diagnostic techniques, considerably enhancing the survival rates

and prognosis of patients. Despite advancements in medical

technology and the growing complexity of diagnostic and therapeutic

approaches for PCa, the treatment and prognosis remain poor due to

delayed diagnosis, postoperative recurrence, complications,

complexities in treatment and resistance (4-6).

For example, the effectiveness of non-selective immune checkpoint

inhibitor therapy in patients remains ambiguous and its application

in the early stages of treatment-resistant clones may promote the

emergence of highly cross-resistant clones, thereby diminishing the

clinical efficacy of subsequent androgen pathway inhibitor therapy

(7). Thus, further investigations

are required, to determine the specific pathophysiology of PCa and

identify novel treatment targets that may improve patient

prognoses.

In ~1980, researchers demonstrated that copper may

be associated with programmed cell death (8). In 2022, Tsvetkov et al

(9) highlighted a novel mechanism

of copper-induced cell death; namely, cuproptosis (9). The results of this previous study

provided novel insights into the role of copper in tumor growth.

Cuproptosis is an emerging form of cell death in PCa, with evidence

suggesting that it suppresses tumor progression. Inducing

cuproptosis or modulating cuproptosis-related genes (CRGs) may

exhibit potential as novel anti-cancer therapies. Thus, further

investigations are required to determine the specific processes

associated with cuproptosis and the potential role it may play in

PCa.

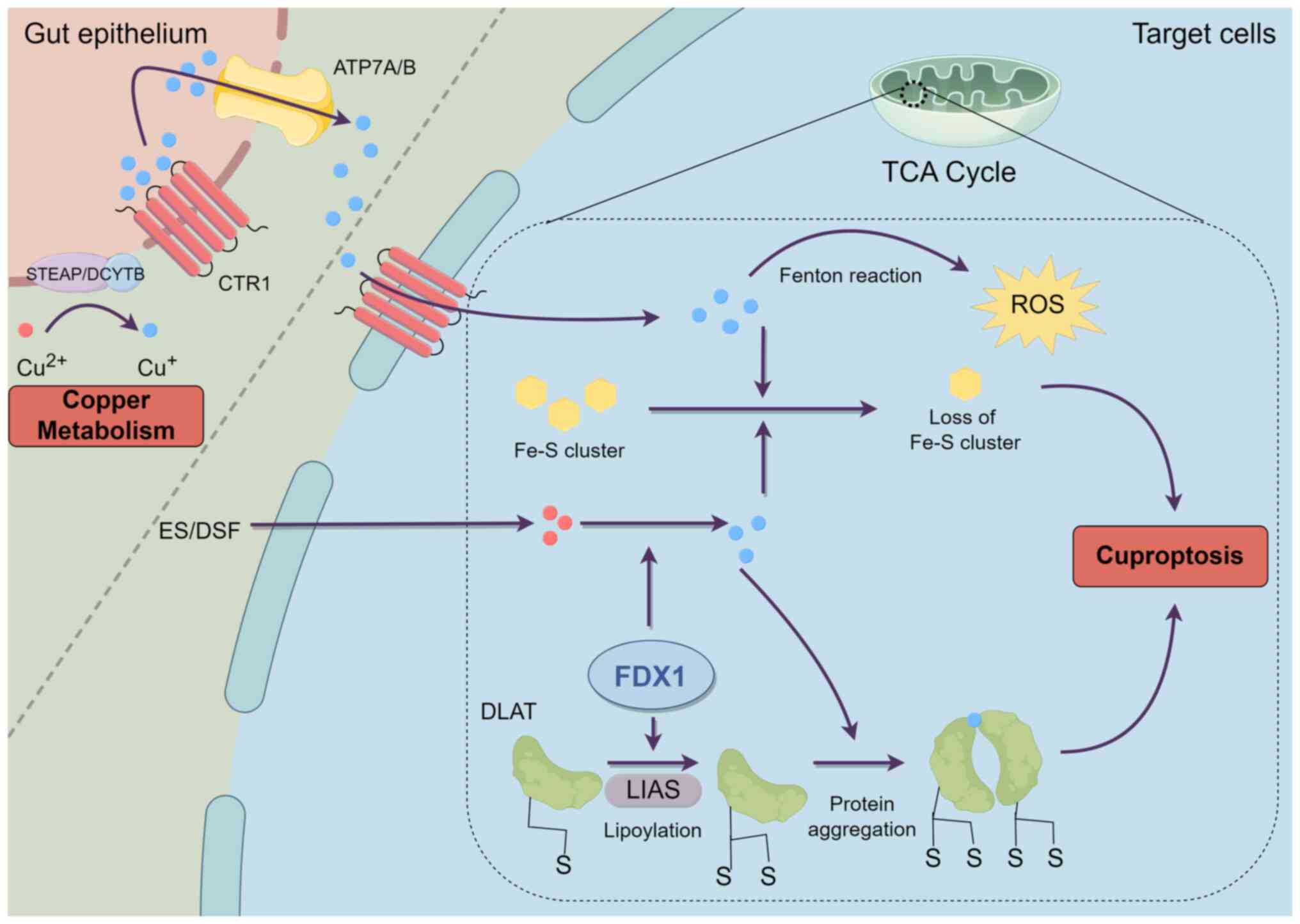

However, excessive accumulation of intracellular

copper ions may be harmful to cells (26). Results of a previous study

(27) indicated that excessively

high copper levels promote the generation of reactive oxygen

species (ROS), resulting in oxidative stress and DNA damage that

may lead to cell death. Alterations in the valence state of copper

ions result in harm to bio-organic molecules, including proteins,

nucleic acids and lipids. These alterations may disrupt the

production of iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters; thus, impacting enzyme

activity (28). Excess copper

ions associate with the lipoylated constituents of the

tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) within mitochondria. Ferredoxin 1

(FDX1), a member of the ferredoxin protein family, co-regulates the

proteolipoylation of proteins, such as dihydrolipoic acid

S-acetyltransferase (DLAT) and lipoic acid synthetase (LIAS). FDX1

reduces Cu2+ to Cu+, which exhibits higher

levels of toxicity. This ion subsequently binds to lipoylated

proteins, causing DLAT aggregation, resulting in proteotoxic stress

and cellular apoptosis. Moreover, Cu+ may destabilize

the architecture of Fe-S cluster proteins and impede the synthesis

of Fe-S proteins, which are integral to mitochondrial stability.

The depletion of Fe-S cluster proteins markedly compromises

cellular metabolic functions and energy maintenance, leading to an

escalation of oxidative free radicals and the production of ROS,

thereby increasing cytotoxicity and culminating in cell death

(Fig. 1). In addition, FDX1 and

LIAS may be affected by cuproptosis, resulting in reduced

expression (9,29,30). Thus, the homeostatic management of

copper is crucial to avert cytotoxicity and sustain overall health.

Notably, the processes and attributes of cuproptosis may exhibit

potential in the treatment of specific disorders.

The identification of cuproptosis has offered novel

insights into the initiation and advancement of tumor pathologies.

Copper participates in the biological mechanisms of tumor

proliferation and migration during the initial stages, activating

metastasis-associated enzymes and signaling pathways to facilitate

the spread of cancer (26).

Notably, it binds to and activates critical molecules within

various tumor signaling pathways (31,32), thereby influencing cancers

directly or indirectly, and is intricately associated with the

regulation of anti-tumor immunity (33). Moreover, copper directly

influences or indirectly modifies the activity of key components,

such as the Notch system; thus, affecting tumor angiogenesis,

metabolism and inflammatory response (34). Copper also plays a key role in

cancer cell proliferation (35)

and results of a previous study (36) revealed that metallothionein, which

is associated with copper storage, was markedly diminished in tumor

tissues. Collectively, these results suggest that the capacity of

cancer cells for regulating copper levels may be compromised.

Moreover, copper facilitates angiogenesis, which is intricately

associated with the advancement of malignant tumors (37,38). Results of previous studies

(39-41) demonstrate that copper may activate

numerous angiogenic factors and stabilize nuclear hypoxia-inducible

factor-1, thereby augmenting the expression of pro-angiogenic

factors. In addition, copper facilitated angiogenesis in numerous

in vitro and in vivo models, whereas copper chelators

inhibited tumor angiogenesis (42). Results of a further previous study

(43) revealed that increased

copper concentrations in tumor cells facilitated tumor

angiogenesis, resulting in tumor advancement and spread.

Consequently, increased copper concentrations may facilitate tumor

development and progression. Excess copper levels may lead to

cytotoxicity and trigger cuproptosis, which suppress tumor

progression. Notably, excess copper-induced cuproptosis may exert

inhibitory effects in numerous types of cancer (44). Copper exerts a dual influence on

tumors and their metabolism, facilitating tumor cell proliferation

and differentiation, while simultaneously suppressing proliferation

and triggering apoptosis. This phenomenon is intricately associated

with its biochemical characteristics and the complex tumor

microenvironment (45).

Elevated copper concentrations in PCa cell tissues

are a hallmark of patients with PCa (46), as demonstrated using in

vitro cell line studies (47-49) and a xenograft mouse model

(49,50). Notably, patients with PCa exhibit

higher than expected serum copper levels (51-53) and elevated serum copper levels may

be associated with a poor prognosis in patients with PCa (54). The RNA interference-mediated

knockdown of CTR1 decreased copper ion absorption in PCa cells,

resulting in the substantial inhibition of tumor growth (50). Collectively, these findings

highlighted the role that increased copper ion concentrations may

play in sustaining the biological processes of PCa cells, while

diminished copper ion levels may fail to support the physiological

functions of tumor cells.

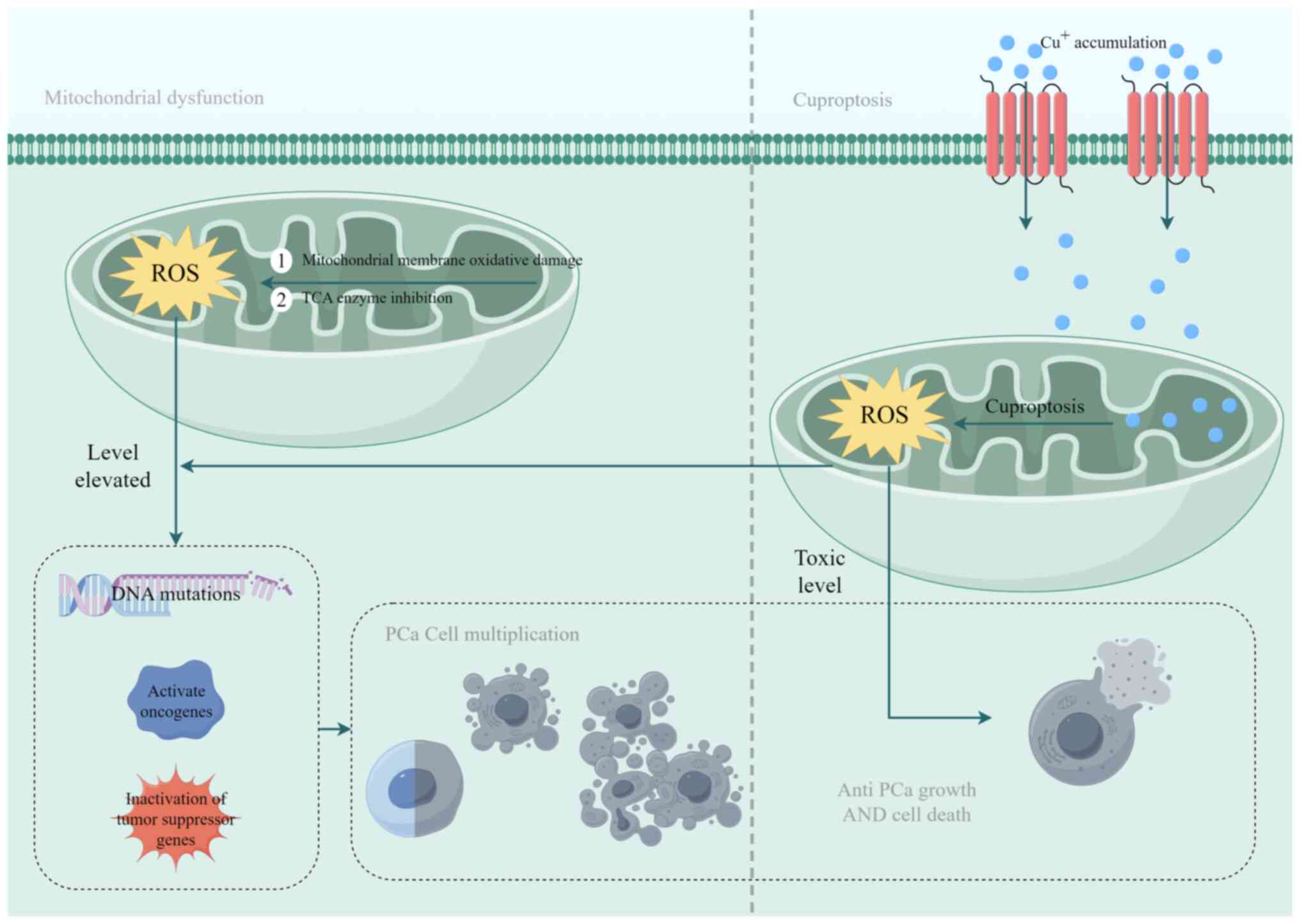

Mitochondrial dysfunction is pivotal for

cuproptosis, resulting in oxidative damage to the mitochondrial

membrane and compromised enzyme performance in the TCA cycle

(29). By contrast, excessive

copper accumulation in cellular mitochondria initiates cuproptosis

(68), producing substantial

amounts of ROS. During PCa progression, ROS levels are increased in

PCa cells (69), resulting in DNA

mutations, oncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene

inactivation. This cascade facilitates malignant cell

transformation and the activation of stress-responsive survival

pathways, thereby exacerbating the aberrant proliferation of PCa

cells (70). In addition, the

process of cuproptosis generates ROS, further advancing PCa

progression (71). Notably, a

requisite level of ROS is essential for tumor cell growth and DNA

mutation; however, severe oxidative stress may deplete the

capabilities of the antioxidant system, resulting in apoptosis

(72). In cuproptosis, ROS are

continuously generated, leading to toxic concentrations in PCa

cells and notable effects on tumor growth. Results of previous

studies (73-75) indicate that the excessive creation

and accumulation of ROS are employed to impede PCa progression.

Moreover, soy isoflavones, such as genistein and soy glycosides,

may elevate copper concentrations in PCa cells through mobilizing

endogenous copper and disrupting the expression of copper

transporter protein genes, CTR1 and ATP7A, in cancer cells. This

process subsequently induced high levels of ROS production,

ultimately resulting in apoptosis in PCa cells (76). Moreover, curcumin analogs

(77) and felicidin (78) exhibit analogous mechanisms of

action to impede PCa cell proliferation. Results of a previous

study (79) reveal that

alterations in the ATP7B gene inhibits the regulation of copper ion

distribution in vivo, resulting in increased copper levels

in PCa cells. Similarly, ATP7B protein levels were markedly

enhanced in docetaxel-resistant PCa cell lines, resulting in

diminished intracellular copper levels. Notably, these levels may

be promoted through silencing ATP7B expression or using a

combination of disulfiram and copper to enhance intracellular

copper concentrations (80). This

modified intra- and extracellular copper distribution results in a

substantial inhibitory effect on PCa growth, which may be

associated with the excessive production of ROS due to copper ion

carriers entering PCa cells, as well as antioxidant deficiencies

present in these cells (79).

Results of a previous study (81)

highlight a reciprocal interaction between cuproptosis and

copper-induced oxidative stress. The accumulation of ROS may

facilitate the progression of PCa and exert an inhibitory effect on

it. Cuproptosis may induce excessive ROS production to promote

tumor cell death; however, investigations surrounding this dual

mechanism are limited (Fig. 2).

The specific impact of cuproptosis on PCa requires further

validation through relevant experiments to elucidate the mechanism

underlying cuproptosis in the context of PCa development.

Copper participates in tumor metabolism and promotes

tumor progression. Notably, copper is associated with the

progression and spread of PCa (82,83) and it also facilitates tumor

angiogenesis (37,38). Angiogenesis markedly contributes

to the progression and metastasis of PCa (84), primarily driven by angiogenic

factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast

growth factor, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) and interleukin

(85). Results of a previous

study (79) reveal that a

reduction in copper levels diminishes HIF activity and obstructed

tumor angiogenesis. Moreover, restrictions in angiogenesis may

limit PCa progression (86).

Copper chelators may also diminish intracellular copper ion

concentrations and lower copper bioavailability, thereby reducing

copper-induced angiogenesis (42). Therefore, lowering copper

concentrations to impede tumor angiogenesis may mitigate tumor

advancement.

Complexities in lipid metabolism may contribute to

carcinogenesis and disease progression. Results of a previous study

(87) reveal that disturbances in

lipid metabolism are associated with disease advancement and the

development of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). In

addition, cholesteryl esters (CE) are excessively accumulated in

high-grade PCa and metastatic sites (88). The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

plays an important role in the metastasis of PCa and the depletion

of CE markedly obstructs Wnt3a secretion through reducing

unsaturated fatty acid levels, which inhibit the activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and restrict the acylation of

Wnt3a, thereby inhibiting the metastasis of PCa (89). Copper ions also activate the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, resulting in augmented cancer stem

cell characteristics and increased resistance to numerous therapies

(90). Elevated serum copper

levels may be associated with increased serum total cholesterol and

HDL cholesterol levels, as well as a heightened risk of

dyslipidemia characterized by high serum total cholesterol and LDL

cholesterol (91). Results of

previous studies (92,93) reveal that zebrafish and grass carp

exhibit elevated copper concentrations in their livers when

subjected to excess copper, resulting in increased lipid

accumulation and levels of triglycerides. These findings indicate

that alterations in copper levels, particularly in excess, may

influence the progression of PCa by affecting lipid metabolism and

signaling system activity; however, further molecular or animal

studies are required to validate these mechanisms.

In conclusion, the mechanisms underlying cuproptosis

in PCa primarily encompass oxidative stress, intracellular copper

distribution, angiogenesis and lipid metabolism dysregulation.

Further investigations into these mechanisms may facilitate a

deeper comprehension of cuproptosis in PCa and aid in identifying

potential therapeutic targets.

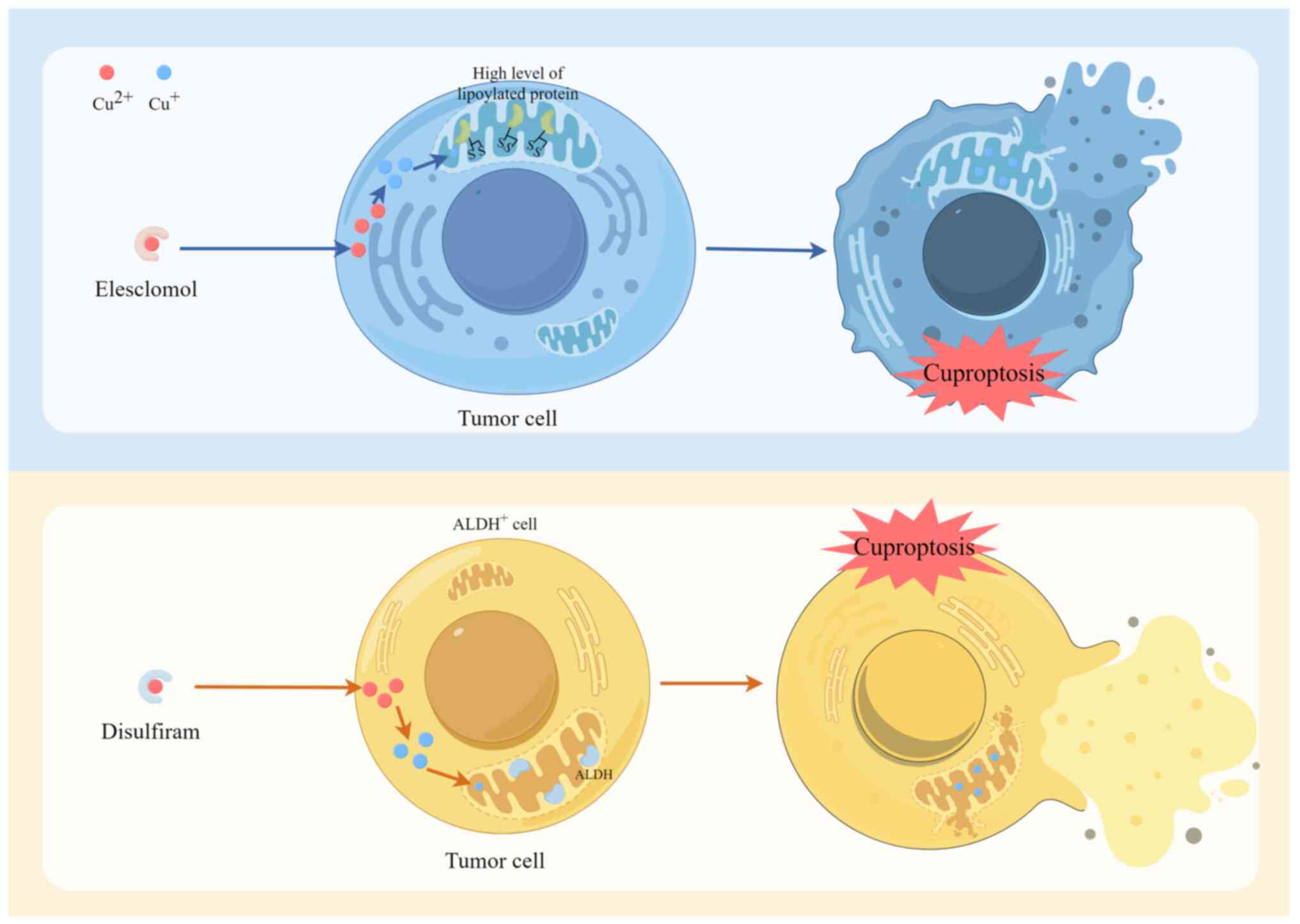

Elesclomol (ES) is a copper ion transporter that

facilitates the entry of copper ions into cells, often targeting

mitochondria. The entry of copper into cells leads to the

accumulation of ROS, consequently impeding tumor growth. In cancer

therapy, ES may leverage its capacity to produce cuproptosis to

eliminate malignant cells. Disulfiram (DSF) functions as a copper

ion transporter through binding to copper ions and facilitating

entry into the cell. Notably, DSF has previously been investigated

for the treatment of specific types of cancer, particularly those

with elevated levels of lipoylated proteins (94). The two aforementioned copper ion

carriers have been extensively researched for their ability to

carry Cu2+ into cells or mitochondria to facilitate

copper-dependent cell death (Fig.

3). Copper exerts a multifaceted impact on PCa growth and

proliferation; however, results of in vitro studies

(61,62) consistently demonstrate that ES

diminishes PCa cell viability via a reduction in FDX1 expression

levels. Moreover, ES promotes keratin formation in tumor cells,

inhibits autophagy in PCa via the DLAT/mammalian target of

rapamycin pathway and enhances sensitivity to docetaxel and

paclitaxel chemotherapy (95). In

addition, DSF compounds combined with copper have demonstrated

efficacy in breast cancer treatment through downregulating the

expression of the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) associated

with human chromosome 10 deletion and activating protein kinase B

(AKT) signaling. This indicates a potential for combination therapy

utilizing phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT inhibitors

(96). Results of further

previous studies (97,98) reveal that PCa may involve the same

PTEN and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways for targeted therapy,

highlighting that these pathways may inhibit PCa progression.

However, previous investigations focused on the role of PTEN and

PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in PCa progression remain limited.

Moreover, ES may exhibit potential in the treatment

of PCa. Results of a previous study (99) revealed that DSF may inhibit the

proliferation of PCa cell lines and this mechanism may be mediated

by other pharmacological agents or specific sensitizers, such as

copper (100). Thus, copper may

be used to suppress the growth of PCa cells (49,101), ultimately improving the survival

rate of patients (80).

Collectively, these results revealed that although

copper ion carrier-induced cell death is a key form of cell death,

few studies have confirmed the efficacy in PCa using in

vitro investigations. Results of previous research demonstrated

that several substances may elevate intracellular copper ion

concentrations, including the aforementioned copper ion carriers,

copper ion compounds and several copper chelators that inhibit the

increase in copper ion levels. Triethylenetetramine dihydrochloride

(102), 8-hydroxyquinoline

(103), penicillamine (104), methanobactin (105), Bathocuproine disulphonate

(106) and choline

tetrathiomolybdate (107) are

key compounds that regulate intracellular copper ion

concentrations, thereby facilitating or obstructing copper

ion-associated biological functions. The aforementioned drugs are

theoretically capable of stimulating cell proliferation; however,

no previous investigations have been undertaken regarding

cuproptosis in PCa. Preliminary experiments should be performed to

substantiate this hypothesis and to aid in the development of novel

cuproptosis-associated therapies.

A reduction in glutathione (GSH), a natural chelator

of intracellular copper ions, results in an elevation of

intracellular copper concentration, ultimately culminating in cell

death (9). In healthy prostate

cells, GSH neutralizes ROS produced by increased copper ion levels

from copper ion carriers; thus, providing an antioxidant effect and

reducing sensitivity to ROS. Conversely, PCa cells possess

diminished levels of GSH and are deficient in antioxidants,

rendering them susceptible to ROS generated by copper ion carriers.

Subsequently, this may result in PCa cell mortality (79). In addition, elevated copper

concentrations facilitate tumor angiogenesis and disrupt lipid

metabolism. Steroid-based compounds impede PCa progression through

the inhibition of CTR, thereby decreasing copper absorption by PCa

cells and mitigating the proliferative effects of copper. These

results indicate that the aforementioned compounds may represent

innovative anticancer agents targeting anti-copper therapy

(35). Results of a further study

(108) reveal that the pro-drug,

gamma-glutamyl transferase-activated prochelator releasing

dithiocarbamate (GGTDTC), is activated by gamma-glutamyl

transferase (GGT) in PCa cells. The release of dithiocarbamate

(DTC), which chelates with copper ions to form a Cu-DTC complex, is

highly toxic and promotes PCa cell death by triggering oxidative

stress to generate large amounts of ROS. Ultimately, this

interferes with protein ubiquitination. In PCa cells, GGT is often

overexpressed and the concentration of copper ions is high. In

addition, GGT exhibits a decreased antioxidant capacity, leading to

metabolic disorders. This compound is more selective to cancer

cells and therefore less toxic to non-tumor cells. In addition, GGT

exhibits improved selectivity (108). Thus, the use of copper

chelators, in addition to elevated copper ion concentrations that

mediate cuproptosis and impede tumor advancement, may diminish

intracellular copper levels and initiate cuproptosis. These

compounds may be used to leverage the highly toxic characteristics

of copper-chelator complexes, which may further inhibit tumor

progression to some degree. However, the specific mechanisms remain

to be fully elucidated.

Nanotechnology facilitates the targeted delivery of

copper ions to tumor sites via modifying responsive groups that

coordinate with copper compounds. This process enhances the

concentration of copper ions within tumor cells, leading to the

toxic oligomerization of lipoylated proteins and the degradation of

Fe-S cluster proteins. This ultimately induces cuproptosis in tumor

cells and produces a therapeutic effect against cancer (109). Researchers presented a novel

nanoparticle, DCM@GDY-CuMOF@DOX, capable of releasing

Cu+ in the presence of GSH, ultimately facilitating the

onset of cuproptosis (110).

Concurrently, doxorubicin (DOX) generates high levels of hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2), which, when catalyzed by

Cu+, is transformed into cytotoxic ROS via a Fenton-like

reaction. Notably, this process induces cancer cell death. ROS

produced via this method may trigger apoptosis, resulting in

oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial impairment. By contrast to

the administration of DOX alone, nanoparticles enveloped within the

PCa cell membranes (DU145 cell membrane; DCM) exhibit isotypic

targeting capabilities, allowing them to specifically identify and

target identical PCa cells. This process may diminish the

likelihood of non-specific targeting during blood circulation. The

non-specific adsorption and elimination in the bloodstream extend

circulation time within the body, thereby minimizing toxicity to

healthy tissues and enhancing the precision of targeting PCa cells

for treatment. Haemolysis experiments, histopathological

assessments and serum biochemical analyses demonstrated that

nanoparticles did not induce notable damage to healthy cells and

tissues; however, they did exhibit targeting capabilities and

biocompatibility. Thus, these may exhibit potential in clinical

practice (110). Results of a

previous study (111)

demonstrate that cuprous oxide nanoparticles (CONPs) selectively

inhibited the proliferation of CRPC cells. Toxicological

investigations revealed that CONPs elevate copper demand and uptake

capacity and induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer

cells. In addition, CONPs suppressed stem cell properties and the

Wnt signaling pathway and exhibited minimal effects on healthy

prostate epithelial cells. Moreover, Cu(DDC)2

nanoparticles facilitate the transport of Cu2+ into

cells, elevate intracellular copper levels and mediate the

apoptosis of paclitaxel-resistant PCa cells (112). These nanoparticles facilitated

tumor site-specific accumulation and induce cuproptosis through

loading copper ions and employing a responsive release mechanism,

offering a novel, targeted and biocompatible therapeutic

alternative for PCa treatment.

Moreover, liposomal copper (LpCu) effectively

transports copper ions into PCa cells via encapsulating copper

salts within liposomes. PCa cells treated with LpCu exhibit

metabolic toxicity comparable with that of free copper salts,

indicated by increased intracellular copper levels and increased

levels of ROS, apoptosis and necrosis (113). Specific steroid-based compounds

form complexes with copper ions, diminishing the concentration of

free copper ions within the cell. Thus, the influx of copper ions

into PCa cells via CTR1 is reduced, effectively impeding copper

absorption by PCa cells and disrupting their biosynthesis to

inhibit PCa cell proliferation (35).

Surgery remains the primary treatment option for

localized PCa and androgen deprivation therapy is effective for

patients with biochemically recurrent and metastatic

hormone-sensitive PCa. However, resistance and progression to CRPC

may still occur, along with suboptimal therapeutic outcomes

following chemotherapy and immunotherapy (54). At present, research is focused on

the role of cuproptosis in malignancies, to determine the effects

on cell growth and the specific underlying mechanisms.

Cuproptosis affects treatment resistance and

contributes to the management of PCa. Notably, enzalutamide

augments the susceptibility of CRPC cells to copper ion carriers

and improves treatment efficacy through facilitating

copper-dependent cell death. This combination therapy efficiently

suppresses the proliferation of CRPC cells and reverses the

resistance of enzalutamide-resistant cells both in vitro and

in vivo (43). By

contrast, enzalutamide-resistant PCa cells demonstrate high levels

of resistance to cuproptosis and the alteration of NUDT21 activity

or the addition of PDHA improve the effectiveness of the copper

ionophore, potentially leading to treatment resistance in PCa

(67). Results of a further

previous study revealed that a combination of disulfiram and copper

led to a notable reduction in the expression of ATP7B and the

elevation of intracellular copper levels in PCa cell lines,

rendering resistant cells sensitive to the growth-inhibitory and

apoptotic effects of docetaxel (80). Results of both in vivo and

in vitro studies demonstrate that a combination of DSF and

copper markedly reduces cell proliferation and the induction of

apoptosis, indicative of the increased antitumor efficacy of

docetaxel (80). Moreover, DSF

and copper directly interact with ATP7B, leading to the

downregulation of its downstream proteins, including copper

metabolism MURR1 Domain containing 1, α-clusterin and S-phase

kinase associated protein 2. Simultaneously, DSF and copper promote

upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 thus inhibiting

tumor growth (80). Results of a

previous study (95) reveal that

a combination of ES and CuCl2 (ES-Cu) effectively

induces copper-mediated cytotoxicity in PCa cells, inhibits

autophagy via DLAT upregulation and subsequently promotes cell

retention in the G2/M phase, thereby augmenting the

chemotherapeutic efficacy of docetaxel. In vivo experiments

further demonstrate that the combination of ES-Cu and docetaxel

markedly suppresses tumor growth in a PCa transplantation model

using nude mice, where tumor proliferation was markedly inhibited

(95). Collectively, these data

indicated that copper-induced cell death may impact the sensitivity

of PCa to pharmacological agents.

Complanatoside A (CA) is a flavonoid derived from

the Traditional Chinese Medicine, Semen Astragali

Complanati. Results of a previous study (114) reveal that CA downregulates the

expression of the copper efflux-associated protein, ATOX1, promotes

the accumulation of intracellular copper ions, inhibits

mitochondrial activity and induces copper-mediated cell death.

Notably, this agent markedly suppresses the proliferation, invasion

and growth of PCa cells both in vivo and ex vivo,

with no notable damage to major organs in experimental animal

models (114). Nuclear

factor-activated T cell 5 (NFAT5) is a transcription factor that

activates T cells and plays a key role in cellular stress response,

immunological response and cell proliferation. Results of previous

study revealed that NFAT5 acts as a target gene of microRNA

(miR)-206 through bioinformatics analysis and database predictions.

In addition, results of a previous study (115) reveal that the long-chain

non-coding RNA (lncRNA), AP000842.3, acts as a target gene of

miR-206, functioning as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) that

modulates the expression levels of NFAT5. Thus, this lncRNA affects

the sensitivity of PCa cells to copper death inducers. In cellular

experiments, NFAT5 knockdown markedly increases the sensitivity of

PCa cells to copper-induced cytotoxicity and this was highlighted

by elevated intracellular copper ion concentrations and reduced ROS

levels (115). Therefore, the

interaction of lncRNA AP000842.3 with miR-206 may play a key role

in regulating NFAT5 expression. Notably, this regulatory mechanism

may be partly dependent on miR-206, providing a novel potential

target for PCa diagnosis and treatment (115).

Resveratrol, a polyphenol compound mainly located in

red grapes and pomegranates, is an antioxidant that inhibits PCa

cells through interacting with copper ions. This process

contributes to the redox of copper ions and the generation of ROS,

leading to an increase in intracellular oxidative stress and

interference with intracellular signaling pathways, such as MAPK,

PI3K/Akt and NF-κB pathways. Moreover, results of a this study

(116) reveal that resveratrol

inhibits cell cycle progression, thus inhibiting PCa cell

proliferation. This compound also activates key intracellular

apoptotic signaling pathways, such as the mitochondrial pathway and

death receptor pathway, to promote the apoptosis of PCa cells. By

contrast, copper ion chelation reverses the anticancer effects of

resveratrol, further confirming the key role of copper ions in the

action of resveratrol. In addition, the observed elevation of

copper ions may facilitate their absorption and storage, promoting

the harmful effects of resveratrol through the upregulation of the

copper transporter protein, CTR (116). Collectively, results of these

investigations indicated that copper and copper-induced

cytotoxicity may serve as viable therapeutic approaches for the

treatment of PCa.

Despite the limited number of studies on cuproptosis

in PCa, previous studies revealed that CRGs may act as novel

therapeutic targets, playing a key role in the progression of PCa

(Table II). Moreover,

cuproptosis may be associated with key predictors of PCa,

exhibiting potential as a novel indicator of the prognosis of

patients with PCa and their responsiveness to treatment (Table III).

Irrespective of the trajectory of predictive

modeling, research is focused on the development of novel molecular

instruments for prognostic evaluation and clinical decision-making

in PCa. Cuproptosis-based prognostic models exhibit efficacy in

predicting outcomes of patients with PCa; however, the recurrence

prediction mediated by CDI surpasses that of the cuproptosis-based

prognostic models (123). CRLs

obtained from bioinformatics analysis not only aid in the

establishment of a prognostic prediction model for patients with

PCa, but also the results of cellular experiments reveal that the

knockdown of CRLs, particularly AC106820.5, may inhibit the

proliferation, migration and invasive capabilities of PCa cells

(127). Collectively, these data

illustrate that bioinformatics analyses may be used to identify

potential therapeutic targets in the treatment of PCa. Notably, the

aforementioned models may also be used to predict responsiveness to

immunotherapy, leading to the development of personalized treatment

options that improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

The redox activity of copper represents a dual

purpose in cellular viability; for example, it acts as a crucial

cofactor for enzymes that facilitate vital physiological processes

in cellular metabolism and may induce oxidative stress and cell

death when present in excess (131,132). The initial discovery of

cuproptosis elucidated the association between copper-induced cell

death and mitochondrial metabolism, thus furthering investigations

in copper biology and offering novel insights for future

investigations into cell death pathways. In PCa, increased copper

concentrations and a disruption of copper transporters result in

the accumulation of copper ions within tumor cells, facilitating

the initiation of cuproptosis. The activation of cuproptosis

facilitates the elimination of surplus copper ions, mitigates

cellular damage resulting from copper metabolism disorders and

suppresses the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of PCa cells,

thereby inhibiting tumor progression induced by copper metabolism

disorders. However, further investigations are required to

determine the specific underlying mechanisms.

In recent years, cuproptosis has become a novel

focus within PCa research, demonstrating potential in various

tumors to markedly impact the proliferation, invasion and

metastasis of tumor cells. Despite novel insights into the role of

cuproptosis in PCa, this field of study exhibits certain

limitations. Cuproptosis may inhibit the progression of PCa;

however, PCa requires elevated copper levels for its physiological

functions. In addition, FDX1 expression in PCa cells remains low to

prevent the initiation of cuproptosis. Androgens may enhance the

transcriptional levels of CTR1, ATP7B and STEAP in PCa cells via

androgen receptor activation, thereby increasing copper uptake and

facilitating PCa progression (49). Moreover, the hypothesis regarding

increased copper demand in PCa and the approaches to alleviate

levels of toxicity remain ambiguous and the specific molecular

mechanisms underlying cuproptosis have yet to be fully elucidated.

Thus, further investigations should focus on the specific signaling

pathways and regulatory mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

Notably, these processes may include the accumulation of copper

ions in PCa cells, the functions of pivotal proteins and the

activation of signaling pathways associated with the onset of

cuproptosis. To date, previous research has focused on CRGs and

CRLs and the use of bioinformatics analyses, predictive model

development and in vitro experimentation. The aforementioned

studies have primarily utilized public databases for analysis,

which may result in limitations in the validity of studies, through

large-scale clinical samples and a lack of investigation into

clinical applications. Thus, further investigations should focus on

the use of genetic analysis of clinical samples to validate prior

findings and inform subsequent studies. Notably, the AlphaFold

(https://deepmind.google/science/alphafold/) suite of

tools constitutes a robust, integrated platform for structural

prediction. It is used to accurately predict the structures of

proteins interacting with various biomolecules (133). Thus, the development of novel

prediction models using AlphaFold 3 tools may further the

understanding of PCa at the molecular level and aid in the

identification of additional therapeutic targets. Further

investigations into drug sensitivity may lead to the development of

novel therapeutic targets, while analyses of immune cells inside

the tumor microenvironment may clarify the role of cuproptosis in

modulating their activity and the potential impact on tumor

proliferation and metastasis. Moreover, a multidisciplinary

research approach is required to elucidate the specific role of

cuproptosis in PCa, thereby establishing a foundation for the

advancement of novel therapies aimed at enhancing the prognosis and

quality of life of patients.

In conclusion, the present review article

demonstrated that cuproptosis may exhibit potential in the

treatment of PCa. Notably, copper-based nanomedicines, as well as

traditional copper ion carriers and chelators, may elicit more

potent anti-tumor effects. Additional investigations into the

transformation of conventional pharmaceuticals into nanoparticles,

alongside additional clinical trials, may aid in the development of

a novel therapeutic approach. However, these trials should be

preceded by a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms

underlying copper metabolism and cuproptosis, aiming to determine

distinct interactions between copper and the tumor

microenvironment, as well as immune responses, which are essential

for drug design and efficacy prediction. Notably, the

identification of cuproptosis has prompted extensive investigations

into novel treatment options for PCa and this newly recognized

mechanism of regulatory cell death may contribute to theoretical

advancements and practical implementations in the field.

Not applicable.

ZL was responsible for writing the original draft,

reviewing and editing, project administration, supervision and

conceptualization. YC was responsible for writing the original

draft, reviewing and editing, supervision and visualization. KZ was

responsible for writing the original draft, supervision and

conceptualization. ZC was responsible for writing the original

draft and resources. YY was responsible for funding acquisition,

supervision, project administration, writing, reviewing and

editing. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 81503589, 81973866 and 82474520),

the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (grant no.

2022NSFSC0684) and the Sichuan Provincial Administration of

Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Research

Special Fund Project (grant no. 2021ZD016).

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel DA, O'Neil ME, Richards TB, Dowling

NF and Weir HK: Prostate cancer incidence and survival, by stage

and race/ethnicity - United States, 2001-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal

Wkly Rep. 69:1473–1480. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang Z, Garzotto M, Davis EW II, Mori M,

Stoller WA, Farris PE, Wong CP, Beaver LM, Thomas GV, Williams DE,

et al: Sulforaphane bioavailability and chemopreventive activity in

men presenting for biopsy of the prostate gland: A Randomized

controlled trial. Nutr Cancer. 72:74–87. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Tilki D, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van

den Broeck T, Brunckhorst O, Darraugh J, Eberli D, De Meerleer G,

De Santis M, Farolfi A, et al: EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG

guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II-2024 update: Treatment of

relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 86:164–182.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E,

Van den Broeck T, Brunckhorst O, Darraugh J, Eberli D, De Meerleer

G, De Santis M, Farolfi A, et al: EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG

guidelines on prostate cancer-2024 update. Part I: Screening,

diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol.

86:148–163. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gillessen S, Bossi A, Davis ID, de Bono J,

Fizazi K, James ND, Mottet N, Shore N, Small E, Smith M, et al:

Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer. Part I:

Intermediate-/high-risk and locally advanced disease, biochemical

relapse, and side effects of hormonal treatment: Report of the

advanced prostate cancer consensus conference 2022. Eur Urol.

83:267–293. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

7

|

Sandhu S, Moore CM, Chiong E, Beltran H,

Bristow RG and Williams SG: Prostate cancer. Lancet. 398:1075–1090.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Halliwell B and Gutteridge JM: Oxygen

toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem

J. 219:1–14. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon

M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, Rossen J, Joesch-Cohen L, Humeidi R,

Spangler RD, et al: Copper induces cell death by targeting

lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 375:1254–1261. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Francque SM, Marchesini G, Kautz A,

Walmsley M, Dorner R, Lazarus JV, Zelber-Sagi S, Hallsworth K,

Busetto L, Frühbeck G, et al: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A

patient guideline. JHEP Rep. 3:1003222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mason KE: A conspectus of research on

copper metabolism and requirements of man. J Nutr. 109:1979–2066.

1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dancis A, Roman DG, Anderson GJ,

Hinnebusch AG and Klausner RD: Ferric reductase of Saccharomyces

cerevisiae: molecular characterization, role in iron uptake, and

transcriptional control by iron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

89:3869–3873. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Georgatsou E, Mavrogiannis LA, Fragiadakis

GS and Alexandraki D: The yeast Fre1p/Fre2p cupric reductases

facilitate copper uptake and are regulated by the copper-modulated

Mac1p activator. J Biol Chem. 272:13786–13792. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Guan D, Zhao L, Shi X, Ma X and Chen Z:

Copper in cancer: From pathogenesis to therapy. Biomed

Pharmacother. 163:1147912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Boyd SD, Ullrich MS, Skopp A and Winkler

DD: Copper sources for Sod1 activation. Antioxidants (Basel).

9:5002020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Luza SC and Speisky HC: Liver copper

storage and transport during development: Implications for

cytotoxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 63:812S–820S. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Pufahl RA, Singer CP, Peariso KL, Lin SJ,

Schmidt PJ, Fahrni CJ, Culotta VC, Penner-Hahn JE and O'Halloran

TV: Metal ion chaperone function of the soluble Cu(I) receptor

Atx1. Science. 278:853–856. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Heaton DN, George GN, Garrison G and Winge

DR: The mitochondrial copper metallochaperone Cox17 exists as an

oligomeric, polycopper complex. Biochemistry. 40:743–751. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gromadzka G, Tarnacka B, Flaga A and

Adamczyk A: Copper dyshomeostasis in neurodegenerative

diseases-therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci. 21:92592020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

La Fontaine S and Mercer JFB: Trafficking

of the copper-ATPases, ATP7A and ATP7B: Role in copper homeostasis.

Arch Biochem Biophys. 463:149–167. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lutsenko S, LeShane ES and Shinde U:

Biochemical basis of regulation of human copper-transporting

ATPases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 463:134–148. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lutsenko S, Bhattacharjee A and Hubbard

AL: Copper handling machinery of the brain. Metallomics. 2:596–608.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lutsenko S: Copper trafficking to the

secretory pathway. Metallomics. 8:84–852. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Csiszar K: Lysyl oxidases: A novel

multifunctional amine oxidase family. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol

Biol. 70:1–32. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pierson H, Yang H and Lutsenko S: Copper

transport and disease: What can we learn from organoids? Annu Rev

Nutr. 39:75–94. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen L, Min J and Wang F: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct

Tar. 7:3782022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Gaetke LM and Chow CK: Copper toxicity,

oxidative stress, and antioxidant nutrients. Toxicology.

189:147–163. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang Z, Jin D, Zhou S, Dong N, Ji Y, An P,

Wang J, Luo Y and Luo J: Regulatory roles of copper metabolism and

cuproptosis in human cancers. Front Oncol. 13:11234202023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tang D, Chen X and Kroemer G: Cuproptosis:

A copper-triggered modality of mitochondrial cell death. Cell Res.

32:417–418. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sun L, Zhang Y, Yang B, Sun S, Zhang P,

Luo Z, Feng T, Cui Z, Zhu T, Li Y, et al: Lactylation of METTL16

promotes cuproptosis via m(6)A-modification on FDX1 mRNA in gastric

cancer. Nat Commun. 14:65232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xie J, Yang Y, Gao Y and He J:

Cuproptosis: Mechanisms and links with cancers. Mol Cancer.

22:462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Feng Q, Huo C, Wang M, Huang H, Zheng X

and Xie M: Research progress on cuproptosis in cancer. Front

Pharmacol. 15:12905922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu WQ, Lin WR, Yan L, Xu WH and Yang J:

Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in cancer immunity and therapy.

Immunol Rev. 321:211–227. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Nowell CS and Radtke F: Notch as a tumour

suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 17:145–159. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xie F and Peng F: Reduction in copper

uptake and inhibition of prostate cancer cell proliferation by

novel steroid-based compounds. Anticancer Res. 41:5953–5958. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Si M and Lang J: The roles of

metallothioneins in carcinogenesis. J Hematol Oncol. 11:1072018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Baldari S, Di Rocco G and Toietta G:

Current biomedical use of copper chelation therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

21:10692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ilyechova EY, Bonaldi E, Orlov IA,

Skomorokhova EA, Puchkova LV and Broggini M: CRISP-R/Cas9 mediated

deletion of copper transport genes CTR1 and DMT1 in NSCLC cell line

H1299. Biological and pharmacological consequences. Cells.

8:3222019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shao S, Si J and Shen Y: Copper as the

target for anticancer nanomedicine. Adv Ther. 2:2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/adtp.201800147.

|

|

40

|

Li Y: Copper homeostasis: Emerging target

for cancer treatment. IUBMB Life. 72:1900–1908. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lelièvre P, Sancey L, Coll JL, Deniaud A

and Busser B: The multifaceted roles of copper in cancer: A trace

metal element with dysregulated metabolism, but also a target or a

bullet for therapy. Cancers (Basel). 12:35942020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li S, Zhang J, Yang H, Wu C, Dang X and

Liu Y: Copper depletion inhibits CoCl2-induced aggressive phenotype

of MCF-7 cells via downregulation of HIF-1 and inhibition of

Snail/Twist-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Rep.

5:124102015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gao X, Zhao H, Liu J, Wang M, Dai Z, Hao

W, Wang Y, Wang X, Zhang M, Liu P, et al: Enzalutamide sensitizes

castration-resistant prostate cancer to copper-mediated cell death.

Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e24013962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang Y, Chen Y, Zhang J, Yang Y, Fleishman

JS, Wang Y, Wang J, Chen J, Li Y and Wang H: Cuproptosis: A novel

therapeutic target for overcoming cancer drug resistance. Drug

Resist Update. 72:1010182024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Ge EJ, Bush AI, Casini A, Cobine PA, Cross

JR, DeNicola GM, Dou QP, Franz KJ, Gohil VM, Gupta S, et al:

Connecting copper and cancer: From transition metal signalling to

metalloplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 22:102–113. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

46

|

Stanislawska IJ, Figat R, Kiss AK and

Bobrowska-Korczak B: Essential elements and isoflavonoids in the

prevention of prostate cancer. Nutrients. 14:12252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cater MA and Haupt Y: Clioquinol induces

cytoplasmic clearance of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis

protein (XIAP): Therapeutic indication for prostate cancer. Biochem

J. 436:481–491. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chen D, Cui QC, Yang H, Barrea RA, Sarkar

FH, Sheng S, Yan B, Reddy GP and Dou QP: Clioquinol, a therapeutic

agent for Alzheimer's disease, has proteasome-inhibitory, androgen

receptor-suppressing, apoptosis-inducing, and antitumor activities

in human prostate cancer cells and xenografts. Cancer Res.

67:1636–1644. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Safi R, Nelson ER, Chitneni SK, Franz KJ,

George DJ, Zalutsky MR and McDonnell DP: Copper signaling axis as a

target for prostate cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 74:5819–5831.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Cai H, Wu JS, Muzik O, Hsieh JT, Lee RJ

and Peng F: Reduced 64Cu uptake and tumor growth inhibition by

knockdown of human copper transporter 1 in xenograft mouse model of

prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 55:622–628. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Saleh SAK, Adly HM, Abdelkhaliq AA and

Nassir AM: Serum levels of selenium, zinc, copper, manganese, and

iron in prostate cancer patients. Curr Urol. 14:44–49. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kaba M, Pirincci N, Yuksel MB, Gecit I,

Gunes M, Ozveren H, Eren H and Demir H: Serum levels of trace

elements in patients with prostate cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

15:2625–2629. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ozmen H, Erulas FA, Karatas F, Cukurovali

A and Yalcin O: Comparison of the concentration of trace metals

(Ni, Zn, Co, Cu and Se), Fe, vitamins A, C and E, and lipid

peroxidation in patients with prostate cancer. Clin Chem Lab Med.

44:175–179. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wu J, He J, Liu Z, Zhu X, Li Z, Chen A and

Lu J: Cuproptosis: Mechanism, role, and advances in urological

malignancies. Med Res Rev. 44:1662–1682. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Baszuk P, Marciniak W, Derkacz R,

Jakubowska A, Cybulski C, Gronwald J, Dębniak T, Huzarski T,

Białkowska K, Pietrzak S, et al: Blood copper levels and the

occurrence of colorectal cancer in Poland. Biomedicines.

9:16282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Baltaci AK, Dundar TK, Aksoy F and

Mogulkoc R: Changes in the serum levels of trace elements before

and after the operation in thyroid cancer patients. Biol Trace Elem

Res. 175:57–64. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Jin Y, Zhang C, Xu H, Xue S, Wang Y, Hou

Y, Kong Y and Xu Y: Combined effects of serum trace metals and

polymorphisms of CYP1A1 or GSTM1 on non-small cell lung cancer: A

hospital based case-control study in China. Cancer Epidemiol.

35:182–187. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Aubert L, Nandagopal N, Steinhart Z,

Lavoie G, Nourreddine S, Berman J, Saba-El-Leil MK, Papadopoli D,

Lin S, Hart T, et al: Copper bioavailability is a KRAS-specific

vulnerability in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 11:37012020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Lener MR, Scott RJ, Wiechowska-Kozlowska

A, Serrano-Fernández P, Baszuk P, Jaworska-Bieniek K, Sukiennicki

G, Marciniak W, Muszyńska M, Kładny J, et al: Serum concentrations

of selenium and copper in patients diagnosed with pancreatic

cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 48:1056–1064. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Pavithra V, Sathisha TG, Kasturi K,

Mallika DS, Amos SJ and Ragunatha S: Serum levels of metal ions in

female patients with breast cancer. J Clin Diagn Res. 9:BC25–BC27.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yang L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Jiang P, Liu F

and Feng N: Ferredoxin 1 is a cuproptosis-key gene responsible for

tumor immunity and drug sensitivity: A pan-cancer analysis. Front

Pharmacol. 13:9381342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yang L, Tang Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Jiang P,

Liu F and Feng N: Comprehensiveness cuproptosis related genes study

for prognosis and medication sensitiveness across cancers, and

validation in prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 14:95702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Yang Q, Zeng S and Liu W: Roles of

cuproptosis-related gene DLAT in various cancers: A bioinformatic

analysis and preliminary verification on pro-survival autophagy.

PeerJ. 11:e150192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Li C, Xiao Y, Cao H, Chen Y, Li S and Yin

F: Cuproptosis regulates microenvironment and affects prognosis in

prostate cancer. BIOL Trace Elem Res. 202:99–110. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Xiao S and Lou W: Integrated analysis

reveals a potential cuproptosis-related ceRNA axis

SNHG17/miR-29a-3p/GCSH in prostate adenocarcinoma. Heliyon.

9:e215062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Zhang D, Wang T, Zhou Y and Zhang X:

Comprehensive analyses of cuproptosis-related gene CDKN2A on

prognosis and immunologic therapy in human tumors. Medicine

(Baltimore). 102:e334682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Lin SC, Tsai YC, Chen YL, Lin HK, Huang

YC, Lin YS, Cheng YS, Chen HY, Li CJ, Lin TY and Lin SC:

Un-methylation of NUDT21 represses docosahexaenoic acid

biosynthesis contributing to enzalutamide resistance in prostate

cancer. Drug Resist Update. 77:1011442024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Tang D, Kroemer G and Kang R: Targeting

cuproplasia and cuproptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

21:370–388. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P and Victor

VM: Role of ROS and RNS sources in physiological and pathological

conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016:12450492016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Han C, Wang Z, Xu Y, Chen S, Han Y, Li L,

Wang M and Jin X: Roles of reactive oxygen species in biological

behaviors of prostate cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2020:12696242020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Liu Y, Chen A, Wu Y, Ni J, Wang R, Mao Y,

Sun N and Mi Y: Identification of mitochondrial carrier homolog 2

as an important therapeutic target of castration-resistant prostate

cancer. Cell Death Dis. 16:702025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Khandrika L, Kumar B, Koul S, Maroni P and

Koul HK: Oxidative stress in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett.

282:125–136. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Baohai X, Shi F and Yongqi F: Inhibition

of ubiquitin specific protease 17 restrains prostate cancer

proliferation by regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

(EMT) via ROS production. Biomed Pharmacother. 118:1089462019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Lee W, Kim KY, Yu SN, Kim SH, Chun SS, Ji

JH, Yu HS and Ahn SC: Pipernonaline from Piper longum Linn. induces

ROS-mediated apoptosis in human prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 430:406–412. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Kim SH, Kim KY, Yu SN, Park SG, Yu HS, Seo

YK and Ahn SC: Monensin induces PC-3 prostate cancer cell apoptosis

via ROS production and Ca2+ homeostasis disruption. Anticancer Res.

36:5835–5843. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Farhan M, El Oirdi M, Aatif M, Nahvi I,

Muteeb G and Alam MW: Soy isoflavones induce cell death by

copper-mediated mechanism: Understanding its anticancer properties.

Molecules. 28:29252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Alhasawi M, Aatif M, Muteeb G, Alam MW,

Oirdi ME and Farhan M: Curcumin and its derivatives induce

apoptosis in human cancer cells by mobilizing and redox cycling

genomic copper ions. Molecules. 27:74102022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Farhan M, Rizvi A, Ali F, Ahmad A, Aatif

M, Malik A, Alam MW, Muteeb G, Ahmad S, Noor A and Siddiqui FA:

Pomegranate juice anthocyanidins induce cell death in human cancer

cells by mobilizing intracellular copper ions and producing

reactive oxygen species. Front Oncol. 12:9983462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Denoyer D, Pearson HB, Clatworthy SA,

Smith ZM, Francis PS, Llanos RM, Volitakis I, Phillips WA, Meggyesy

PM, Masaldan S and Cater MA: Copper as a target for prostate cancer

therapeutics: copper-ionophore pharmacology and altering systemic

copper distribution. Oncotarget. 7:37064–37080. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Song L, Nguyen V, Xie J, Jia S, Chang CJ,

Uchio E and Zi X: ATPase copper transporting beta (ATP7B) is a

novel target for improving the therapeutic efficacy of docetaxel by

disulfiram/copper in human prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther.

23:854–863. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Vo T, Peng TY, Nguyen TH, Bui TNH, Wang

CS, Lee WJ, Chen YL, Wu YC and Lee IT: The crosstalk between

copper-induced oxidative stress and cuproptosis: A novel potential

anticancer paradigm. Cell Commun Signal. 22:3532024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Onuma T, Mizutani T, Fujita Y, Yamada S

and Yoshida Y: Copper content in ascitic fluid is associated with

angiogenesis and progression in ovarian cancer. J Trace Elem Med

Biol. 68:1268652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Oliveri V: Selective targeting of cancer

cells by copper ionophores: An overview. Front Mol Biosci.

9:8418142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Melegh Z and Oltean S: Targeting

angiogenesis in prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 20:26762019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Ioannidou E, Moschetta M, Shah S, Parker

JS, Ozturk MA, Pappas-Gogos G, Sheriff M, Rassy E and Boussios S:

Angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic treatment in prostate cancer:

mechanisms of action and molecular targets. Int J Mol Sci.

22:99262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Fang J, Ding M, Yang L, Liu LZ and Jiang

BH: PI3K/PTEN/AKT signaling regulates prostate tumor angiogenesis.

Cell Signal. 19:2487–2497. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Marin-Aguilera M, Pereira MV, Jimenez N,

Reig Ò, Cuartero A, Victoria I, Aversa C, Ferrer-Mileo L, Prat A

and Mellado B: Glutamine and cholesterol plasma levels and clinical

outcomes of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate

cancer treated with taxanes. Cancers (Basel). 13:49602021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Yue S, Li J, Lee SY, Lee HJ, Shao T, Song

B, Cheng L, Masterson TA, Liu X, Ratliff TL and Cheng JX:

Cholesteryl ester accumulation induced by PTEN loss and PI3K/AKT

activation underlies human prostate cancer aggressiveness. Cell

Metab. 19:393–406. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Lee HJ, Li J, Vickman RE, Li J, Liu R,

Durkes AC, Elzey BD, Yue S, Liu X, Ratliff TL and Cheng JX:

Cholesterol esterification inhibition suppresses prostate cancer

metastasis by impairing the wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol Cancer Res.

16:974–985. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Liu YT, Chen L, Li SJ, Wang WY, Wang YY,

Yang QC, Song A, Zhang MJ, Mo WT, Li H, et al: Dysregulated

Wnt/β-catenin signaling confers resistance to cuproptosis in cancer

cells. Cell Death Differ. 31:1452–1466. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Song X, Wang W, Li Z and Zhang D:

Association between serum copper and serum lipids in adults. Ann

Nutr Metab. 73:282–289. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Pan YX, Zhuo MQ, Li DD, Xu YH, Wu K and

Luo Z: SREBP-1 and LXRα pathways mediated Cu-induced hepatic lipid

metabolism in zebrafish Danio rerio. Chemosphere. 215:370–379.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Xu YC, Xu YH, Zhao T, Wu LX, Yang SB and

Luo Z: Waterborne Cu exposure increased lipid deposition and

lipogenesis by affecting Wnt/β-catenin pathway and the beta-catenin

acetylation levels of grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella. Environ

Pollut. 263(Pt B): 1144202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Yang L, Yang P, Lip GYH and Ren J: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in cardiovascular disease therapeutics.

Trends Pharmacol Sci. 44:573–585. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wen H, Qu C, Wang Z, Gao H, Liu W, Wang H,

Sun H, Gu J, Yang Z and Wang X: Cuproptosis enhances docetaxel

chemosensitivity by inhibiting autophagy via the DLAT/mTOR pathway

in prostate cancer. FASEB J. 37:e231452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Zhang H, Chen D, Ringler J, Chen W, Cui

QC, Ethier SP, Dou QP and Wu G: Disulfiram treatment facilitates

phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition in human breast cancer cells

in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 70:3996–4004. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Bergez-Hernandez F, Irigoyen-Arredondo M

and Martinez-Camberos A: A systematic review of mechanisms of PTEN

gene down-regulation mediated by miRNA in prostate cancer. Heliyon.

10:e349502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Marques RB, Aghai A, de Ridder CMA,

Stuurman D, Hoeben S, Boer A, Ellston RP, Barry ST, Davies BR,

Trapman J and van Weerden WM: High efficacy of combination therapy

using PI3K/AKT inhibitors with androgen deprivation in prostate

cancer preclinical models. Eur Urol. 67:1177–1185. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Lin J, Haffner MC, Zhang Y, Lee BH,

Brennen WN, Britton J, Kachhap SK, Shim JS, Liu JO, Nelson WG, et

al: Disulfiram is a DNA demethylating agent and inhibits prostate

cancer cell growth. Prostate. 71:333–343. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

100

|

Iljin K, Ketola K, Vainio P, Halonen P,

Kohonen P, Fey V, Grafström RC, Perälä M and Kallioniemi O:

High-throughput cell-based screening of 4910 known drugs and

drug-like small molecules identifies disulfiram as an inhibitor of

prostate cancer cell growth. Clin Cancer Res. 15:6070–6078. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Tesson M, Rae C, Nixon C, Babich JW and

Mairs RJ: Preliminary evaluation of prostate-targeted radiotherapy

using 131I-MIP-1095 in combination with radiosensitising

chemotherapeutic drugs. J Pharm Pharmacol. 68:912–921. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Castoldi F, Hyvonen MT, Durand S,

Aprahamian F, Sauvat A, Malik SA, Baracco EE, Vacchelli E, Opolon

P, Signolle N, et al: Chemical activation of SAT1 corrects

diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Cell Death Differ. 27:2904–2920.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Vetrik M, Mattova J, Mackova H, Kucka J,

Pouckova P, Kukackova O, Brus J, Eigner-Henke S, Sedlacek O, Sefc

L, et al: Biopolymer strategy for the treatment of Wilson's

disease. J Control Release. 273:131–138. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Mao L, Huang CH, Shao J, Qin L, Xu D, Shao

B and Zhu BZ: An unexpected antioxidant and redox activity for the

classic copper-chelating drug penicillamine. Free Radic Biol Med.

147:150–158. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Kenney GE and Rosenzweig AC: Chemistry and

biology of the copper chelator methanobactin. ACS Chem Biol.

7:260–268. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

106

|

Lenartowicz M, Moos T, Ogorek M, Jensen TG

and Moller LB: Metal-dependent regulation of ATP7A and ATP7B in

fibroblast cultures. Front Mol Neurosci. 9:682016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Lee K, Briehl MM, Mazar AP,

Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Glinsmann-Gibson B, Rimsza LM and

Tome ME: The copper chelator ATN-224 induces

peroxynitrite-dependent cell death in hematological malignancies.

Free Radic Biol Med. 60:157–167. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Bakthavatsalam S, Sleeper ML, Dharani A,

George DJ, Zhang T and Franz KJ: Leveraging γ-Glutamyl transferase

to direct cytotoxicity of copper dithiocarbamates against prostate

cancer cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 57:12780–12784. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Wei C and Fu Q: Cell death mediated by

nanotechnology via the cuproptosis pathway: A novel horizon for

cancer therapy. VIEW-CHINA. 4:202300012023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Xie W, Zhang Y, Xu Q, Zhong G, Lin J, He

H, Du Q, Tan H, Chen M, Wu Z, et al: A Unique approach: biomimetic

graphdiyne-based nanoplatform to treat prostate cancer by combining

cuproptosis and enhanced chemodynamic therapy. Int J Nanomedicine.

19:3957–3972. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Wang Y, Yang QW, Yang Q, Zhou T, Shi MF,

Sun CX, Gao XX, Cheng YQ, Cui XG and Sun YH: Cuprous oxide

nanoparticles inhibit prostate cancer by attenuating the stemness

of cancer cells via inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway. Int J

Nanomedicine. 12:2569–2579. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Chen W, Yang W, Chen P, Huang Y and Li F:

Disulfiram copper nanoparticles prepared with a stabilized metal

ion ligand complex method for treating drug-resistant prostate

cancers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 10:41118–41128. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Wang Y, Zeng S, Lin TM, Krugner-Higby L,

Lyman D, Steffen D and Xiong MP: Evaluating the anticancer

properties of liposomal copper in a nude xenograft mouse model of

human prostate cancer: Formulation, in vitro, in vivo, histology

and tissue distribution studies. Pharm Res. 31:3106–3119. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Zhao Y, Wang R, Hu C, Wang Y, Li Z, Yin D

and Tan S: Complanatoside A disrupts copper homeostasis and induces

cuproptosis via directly targeting ATOX1 in prostate cancer.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 496:1172572025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Zhou G, Chen C, Wu H, Lin J, Liu H, Tao Y

and Huang B: LncRNA AP000842.3 triggers the malignant progression

of prostate cancer by regulating cuproptosis related gene NFAT5.

Technol Cancer Res Treat. 23:153303382412555852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Farhan M: Cytotoxic activity of the red

grape polyphenol resveratrol against human prostate cancer cells: A

molecular mechanism mediated by mobilization of nuclear copper and

generation of reactive oxygen species. Life (Basel).

14:6112024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Wang X, Chen X, Xu C, Zhou W and Wu D:

Identification of cuproptosis-related genes for predicting the

development of prostate cancer. Open Med (Wars). 18:202307172023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Cheng B, Tang C, Xie J, Zhou Q, Luo T,

Wang Q and Huang H: Cuproptosis illustrates tumor micro-environment

features and predicts prostate cancer therapeutic sensitivity and

prognosis. Life Sci. 325:1216592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Jin L, Mei W, Liu X, Sun X, Xin S, Zhou Z,

Zhang J, Zhang B, Chen P, Cai M and Ye L: Identification of

cuproptosis-related subtypes, the development of a prognosis model,

and characterization of tumor microenvironment infiltration in

prostate cancer. Front Immunol. 13:9740342022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Wang H, Xie M, Zhao Y and Zhang Y:

Establishment of a prognostic risk model for prostate cancer based

on Gleason grading and cuprotosis related genes. J Cancer Res Clin

Oncol. 150:3762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Yao K, Zhang R, Li L, Liu M, Feng S, Yan

H, Zhang Z and Xie D: The signature of cuproptosis-related immune

genes predicts the tumor microenvironment and prognosis of prostate

adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 14:11813702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Zhang J, Jiang S, Gu D, Zhang W, Shen X,

Qu M, Yang C, Wang Y and Gao X: Identification of novel molecular

subtypes and a signature to predict prognosis and therapeutic

response based on cuproptosis-related genes in prostate cancer.

Front Oncol. 13:11626532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Ma S, Xu M, Zhang J, Li T, Zhou Q, Xi Z,

Wang Z, Wang J and Ge Y: Analysis and functional validations of

multiple cell death patterns for prognosis in prostate cancer. Int

Immunopharmacol. 143(Pt 1): 1132162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Cheng X, Zeng Z, Yang H, Chen Y, Liu Y,

Zhou X, Zhang C and Wang G: Novel cuproptosis-related long

non-coding RNA signature to predict prognosis in prostate

carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 23:1052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Ma Z, Liang H, Cui R, Ji J, Liu H, Liu X,

Shen P, Wang H, Wang X, Song Z and Jiang Y: Construction of a risk

model and prediction of prognosis and immunotherapy based on

cuproptosis-related LncRNAs in the urinary system pan-cancer. Eur J

Med Res. 28:1982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Jiang S, Li Z, Dou R, Lin Z, Zhang J,

Zhang W, Chen Z, Shen X, Ji J, Qu M, et al: Construction and

validation of a novel cuproptosis-related long noncoding RNA

signature for predicting the outcome of prostate cancer. Front

Genet. 13:9768502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Zhong H, Lai Y, Ouyang W, Yu Y, Wu Y, He

X, Zeng L, Qiu X, Chen P, Li L, et al: Integrative analysis of

cuproptosis-related lncRNAs: Unveiling prognostic significance,

immune microenvironment, and copper-induced mechanisms in prostate

cancer. Cancer Pathog Ther. 3:48–59. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

128

|

Ren L, Yang X, Wang W, Lin H, Huang G, Liu

Z, Pan J and Mao X: A cuproptosis-related LncRNA signature:

Integrated analysis associated with biochemical recurrence and

immune landscape in prostate cancer. Front Genet. 14:10967832023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Yu Z, Deng H, Chao H, Song Z and Zeng T:

Construction of a cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature to predict

biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. Oncol Lett. 28:5262024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

Lu Y, Wu J, Li X, Leng Q, Tan J, Huang H,

Zhong R, Chen Z and Zhang Y: Cuproptosis-related lncRNAs emerge as

a novel signature for predicting prognosis in prostate carcinoma

and functional experimental validation. Front Immunol.

15:14711982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Nyvltova E, Dietz JV, Seravalli J,

Khalimonchuk O and Barrientos A: Coordination of metal center

biogenesis in human cytochrome c oxidase. Nat Commun. 13:36152022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Xue Q, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D, Liu J

and Chen X: Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy.

Autophagy. 19:2175–2195. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J, Evans R,

Green T, Pritzel A, Ronneberger O, Willmore L, Ballard AJ, Bambrick

J, et al: Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular

interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature. 630:493–500. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|