Introduction

Cancer is a paramount societal, public health and

economic challenge in the twenty-first century, accounting for

nearly 16.8% of global deaths (one in six deaths) and 22.8% of

deaths attributable to non-communicable diseases (1). The disease is responsible for 3 in

10 premature deaths from non-communicable diseases worldwide (30.3%

among individuals aged 30-69 years), ranking amongst the three

principal causes of mortality within this demographic across 177 of

183 nations (2). In the United

States in 2025, there will be ~2,041,910 new cancer diagnoses,

equating to ~5,600 cases daily (3). Oncological research has

predominantly focused on intrinsic characteristics of neoplastic

cells, with comparatively limited attention to extracellular

stromal components. The extracellular matrix (ECM) constitutes a

crucial element of tumor stroma. Alterations in ECM protein

expression represent significant mechanisms influencing tumor cell

proliferation, migration and invasion, with Fibulin2 serving as a

typical protein. Even intracellular modifications in Fibulin2

expression may have a substantial impact on the ECM due to the

secretory properties of Fibulin2. Furthermore, Fibulin2 is

considered to be a promising biomarker in multi-tumor research

contexts (4-7).

Fibulin2 was initially characterized by Pan et

al (8), who identified it in

a murine fibroblast cDNA library using the Fibulin1 cDNA probe.

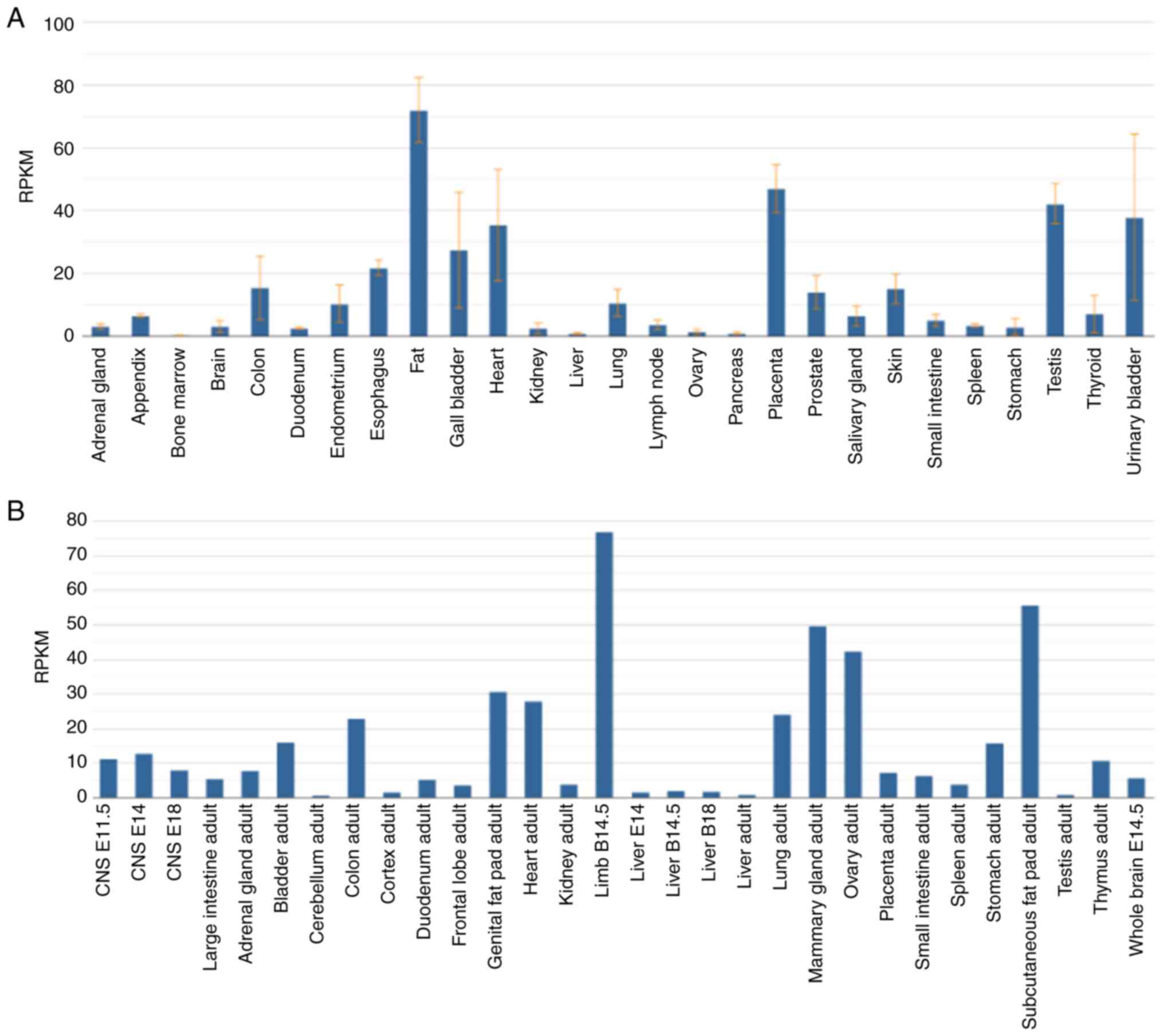

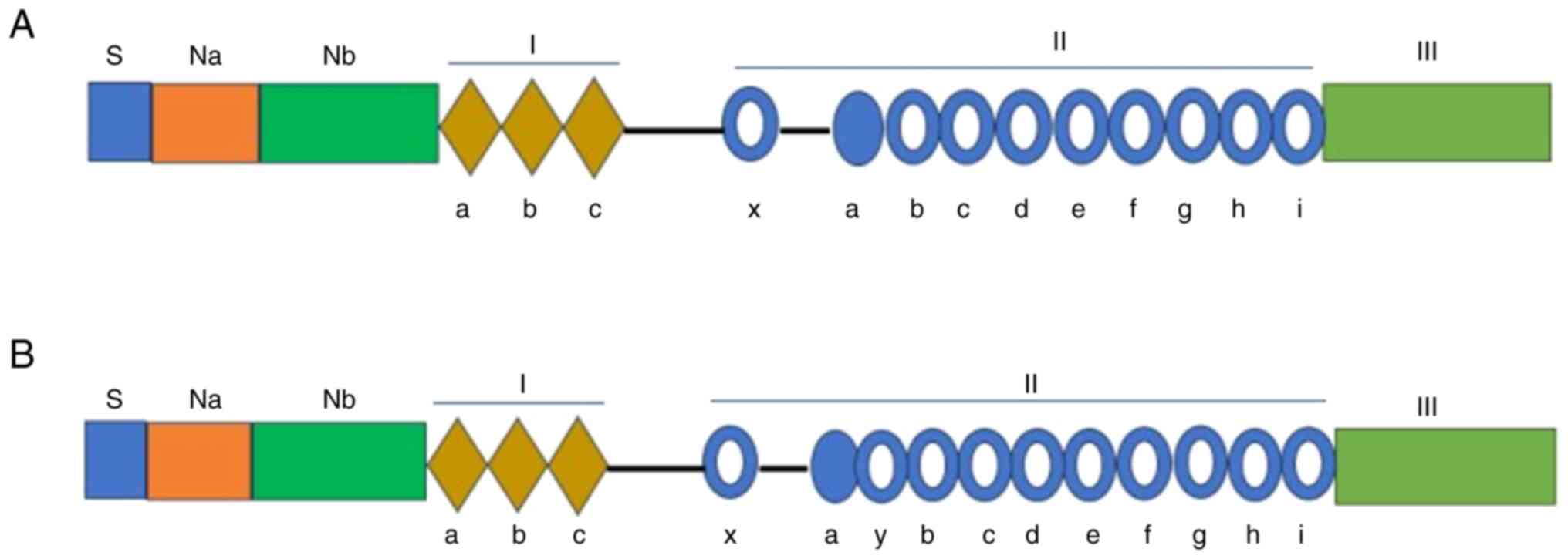

Fibulin2 is expressed in humans and mice (Fig. 1A and B). In human physiology,

Fibulin2 is highly expressed in cardiac tissue, placenta, testes

and the urinary bladder, but expressed at low levels in brain

tissue, splenic parenchyma and bone marrow (Fig. 1A). Fibulin2 exhibits aberrant

expression across malignancies of diverse organs (9), such as colorectal cancer (4) and lung cancer (10). The protein structures of human and

murine Fibulin2 exhibit remarkable homology (8,11)

(Fig. 2A and B), providing a

robust theoretical basis for using murine cellular systems and

animal models as surrogates for human studies in oncological

research. In the Na, I, II and III domains, the amino acid sequence

identity is ~90%, whereas the Nb domain shows only 62% sequence

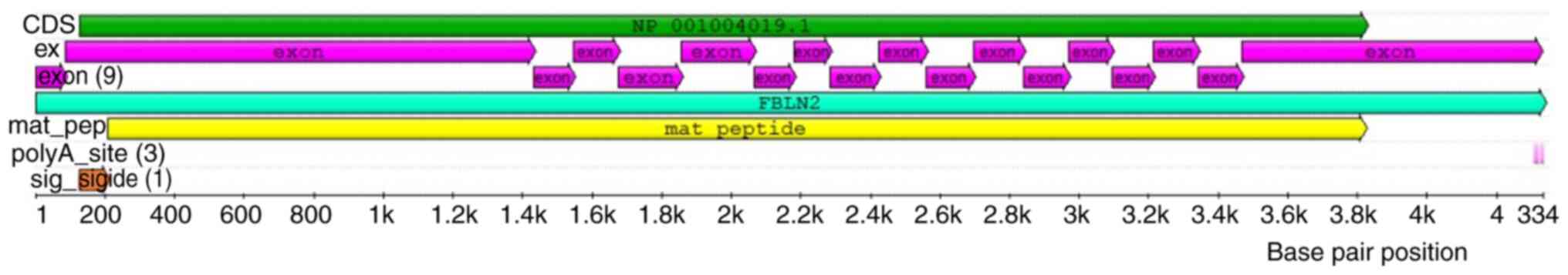

identity (8,11). Human Fibulin2 contains 18 exons

(11) (Fig. 3), while mouse Fibulin2 contains 17

exons (8). Surface plasmon

resonance and/or solid-phase microplate analyses have shown that

Fibulin2 has high binding affinity for Perlecan (12,13), laminin5 (14,15), Fibronectin (16), collagen XVIII (17), Aggrecan, Versican, Brevican lectin

domains (18), the C-terminal

region V of Perlecan (19), and

the short arms of Laminin-5 and Laminin-1 (20), which helps maintain the ECM

(21). Consequently, ECM

stabilization mediated by Fibulin2 represents a pivotal mechanism

underlying tumor suppression.

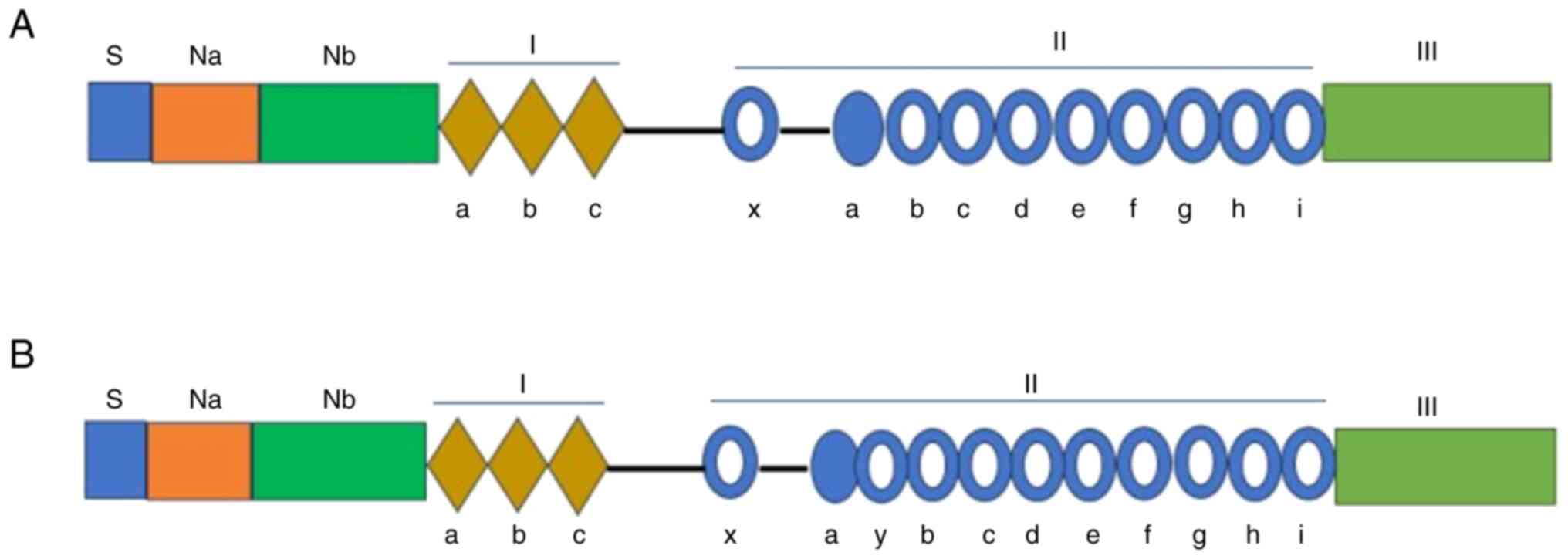

| Figure 2Protein structure of human Fibulin2

and mouse Fibulin2. (A) Diagram of the protein domains of human

Fibulin2 starting with the S, Na and Nb subdomains, followed by

domain I, II and III. Diamonds indicate anaphylatoxin-like motifs

in domain Ⅰ. Solid circles represent EGF-like repeats, while those

depicted as hollow rounds contain the consensus sequence for

calcium binding. (B) Diagram of the protein domains of mouse

Fibulin2 showing that the Fibulin2 protein comprises S, Na, Nb, I,

II and III domains. At the N-terminus are domains Na and Nb, which

span 408 amino acids, and include the 'Na' subdomain containing 22

cysteines and the 'Nb' subdomain devoid of cysteine. Domain I

consists of three anaphylatoxin-like motifs. Domain II encompasses

11 EGF-like repeats, all of which except IIa possess a consensus

sequence for calcium binding. Domain I is connected via a

50-amino-acid linker segment to the first EGF module (IIx) of

domain II, which is followed by another 34-amino-acid linker

segment and then 10 EGF modules. Domain III is depicted as a light

green box. Na, N-terminal cysteine-rich; Nb, N-terminal

cysteine-free; S, signal peptide. |

Nevertheless, Fibulin2 does not universally exert

inhibitory effects across all malignancies; rather, it acts as a

promoter in certain neoplastic contexts. For instance, increased

Fibulin2 expression inhibits cell proliferation in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma (22), Kaposi's sarcoma

(23) and breast cancer (24). Conversely, suppression of Fibulin2

expression effectively attenuates lung adenocarcinoma progression

(10). Therefore, the present

review summarizes the diverse roles of Fibulin2 across various

malignancies, while examining underlying mechanisms, alongside

comprehensive analysis of the potential of Fibulin2 as a biomarker.

Regarding the mechanistic influence of Fibulin2 on tumor

development and its utility as a tumor marker, several critical

issues persist. The mechanisms governing Fibulin2 function across

numerous malignancies require further elucidation. The role and

mechanistic basis of the effects of Fibulin2 on tumor stroma remain

poorly understood. Furthermore, its clinical application as a

biomarker is not yet mature. Therefore, the present overview

provides guidance for the clinical translation of Fibulin2 as both

a therapeutic target and predictive marker in oncological

diseases.

Summary of the mechanisms and roles of

Fibulin2

Fibulin2 acts as an upstream regulator of the

Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma and the TGF-β/

Smad2/TGFB induced factor homeobox 2 (TGIF2) pathway or β-catenin

in gastric cancer (25-27). Differences in Fibulin2 expression

between tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues lead to the

activation of these pathways (25,26). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the factors causing altered Fibulin2 expression in liver

and gastric cancer, as well as its upstream regulators, remain

unclear. In p53-null immortalized mouse keratinocytes and

RasV12-transformed mouse keratinocytes, which are skin cancer

models, Fibulin2 is regulated by the upstream molecule Integrin

α3β1 (28). Changes in

Fbln2 expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells alter the

expression of downstream Integrin genes, including Itga1,

Itga2, Itga10 and Itgb1 (10). A reciprocal regulatory

relationship may exist between Fibulin2 and certain Integrin

proteins, which warrants further investigation. In nasopharyngeal

carcinoma, Fbln2 acts as an upstream inhibitor of

VEGF-165, VEGF-189 and MMP-2. The upstream

factors regulating Fbln2 expression in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma remain to be elucidated (22). Given that Fibulin2 is a secreted

protein, it likely exerts autocrine or paracrine effects on its

producing cells or neighboring cells, potentially binding to

receptors such as Integrin proteins to establish feedback loops.

However, such feedback mechanisms have not received sufficient

attention in current tumor-related studies, and further research is

needed to demonstrate their existence across various tumor types.

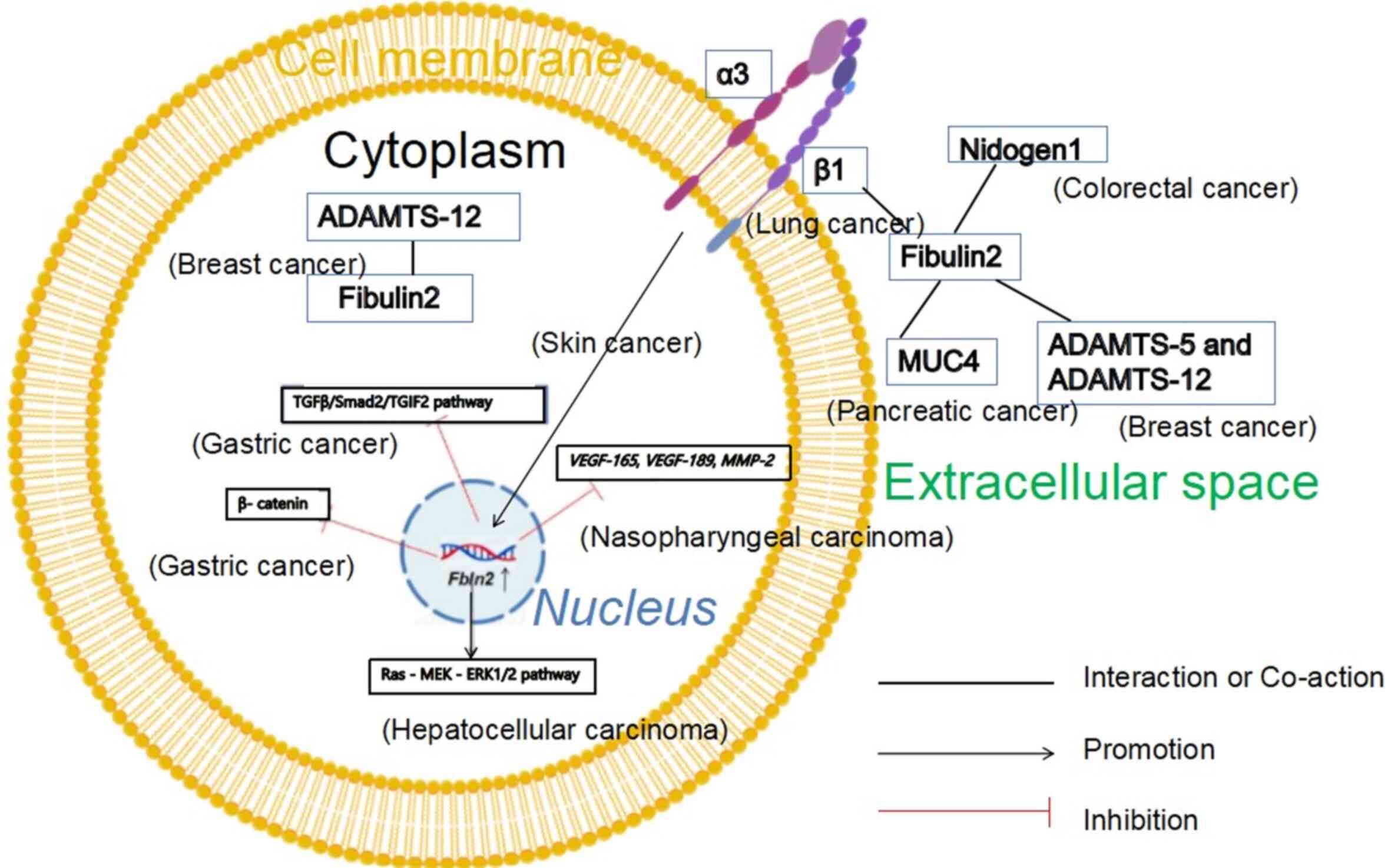

In the extracellular space, Fibulin2 interacts with multiple

proteins: Integrin β1 in non-small cell lung cancer (29), a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS)-5 and ADAMTS-12 in breast

cancer (30), Nidogen1 in

colorectal cancer (CRC) (31),

and mucin 4 (MUC4) in pancreatic cancer (32). These are protein-protein

interactions rather than upstream-downstream regulatory

relationships (Fig. 4). In breast

cancer, ADAMTS-5 cleaves Fibulin2, and this role can be inhibited

by ADAMTS-12 (30). Differences

in mechanisms of Fibulin2 regulating tumor development across tumor

types are shown in Table I.

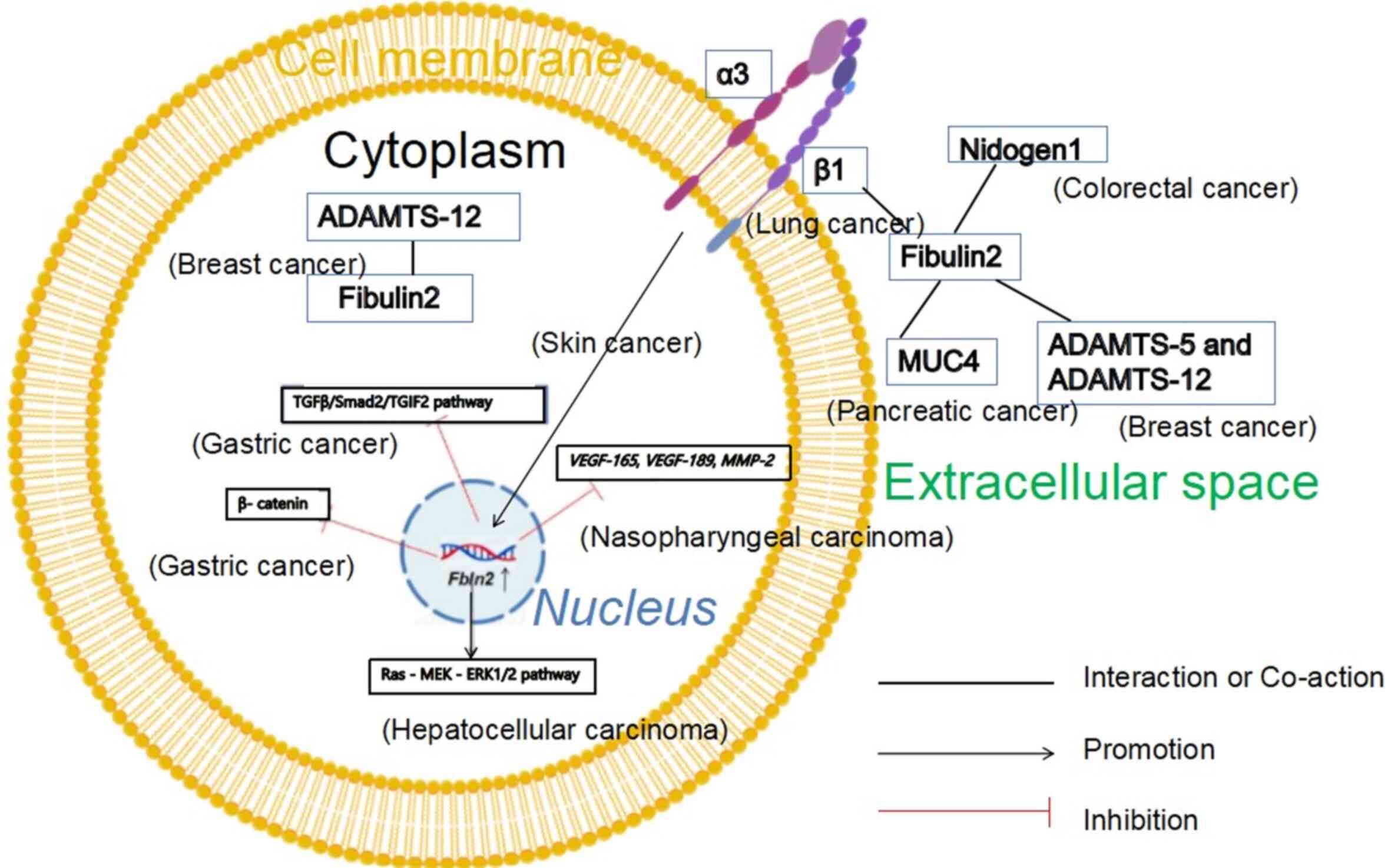

| Figure 4Mechanistic roles of Fibulin2 in

various tumors. The yellow circle denotes the phospholipid bilayer,

and the small blue circle inside represents the nucleus. Solid

lines indicate an interaction or co-action relationship between

molecules. Arrow-headed lines represent a positive promoting

relationship between molecules, and red lines denote an inhibitory

relationship between molecules. Overexpression of Fbln2 in

gastric cancer cells results in diminished expression of β-catenin,

phosphorylated-Smad2 and TGIF2 in the TGF-β/Smad2/TGIF2 pathway. In

liver cancer cells, overexpression of Fbln2 activates the

Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 pathway. In nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells,

overexpression of Fbln2 leads to decreased expression of

VEGF-165, VEGF-189 and MMP-2. Overexpression

of ADAMTS-12 and Fibulin2 in breast cancer cells can inhibit tumor

development. Fibulin2 and Integrin β1 exhibit partial

colocalization near the cell membrane in non-small cell lung cancer

tissue sections. As secreted proteins, Fibulin2 and Nidogen1

collectively promote the development of CRC. The interaction

between MUC4 and Fibulin2 promotes the development of pancreatic

cancer. ADAMTS-5, ADAMTS-12 and Fibulin2 are secreted proteins. In

breast cancer, ADAMTS-5 cleaves Fibulin2, and this role can be

inhibited by ADAMTS-12. BioGDP.com was

used to generate figures (https://biogdp.com/?tg=CFXL). ADAMTS, a disintegrin

and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs; MUC4, mucin 4;

TGIF2, TGFB induced factor homeobox 2. |

| Table IDifferences in mechanisms of Fibulin2

regulating tumor development across tumor types. |

Table I

Differences in mechanisms of Fibulin2

regulating tumor development across tumor types.

A, Pro-carcinogenic

|

|---|

| First author/s,

year | Tumor type | Mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Baird et al,

2013 | Lung

adenocarcinoma | Fbln2

promotes the adhesion of tumor cells to type I collagen and the

expression of Itga1, Itga2, Itga10 and

Itgb1 | (10) |

| Vaes et al,

2021 | CRC | Fibulin2 and

Nidogen1 jointly promote tumor development | (31) |

| Hu et al,

2023 | Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Fibulin2

facilitates the activation of the Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 signaling

pathway | (25) |

| Missan et

al, 2014 |

Immortalized/transformed

keratinocytes | Fibulin2 expression

is regulated by Integrin α3β1 | (28) |

|

| B,

Anti-carcinogenic |

|

| First author/s,

year | Tumor type | Mechanism | (Refs.) |

|

| Law et al,

2012 | Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma | Fbln2

inhibits the expression of VEGF-165, VEGF-189 and

MMP-2 | (22) |

| Ma et al,

2019 | Gastric cancer | Fibulin2

downregulates β-catenin and its downstream c-myc and cyclin D1 | (26) |

| Zhou et al,

2025 | Gastric cancer | Fibulin2 inhibits

the TGF-β/Smad2-TGIF2 pathway | (27) |

| Senapati et

al, 2012 | Pancreatic

cancer | MUC4 interacts with

Fibulin2, disrupting the intact BM and promoting tumor

development | (32) |

| Fontanil et

al, 2017; Fontanil et al, 2014 | Breast cancer | Fibulin2 and

ADAMTS-12 jointly inhibit tumor development; ADAMTS-5 cleaves

Fibulin2, promoting tumor development | (30,80) |

Roles and mechanisms of Fibulin2 in

promoting various tumor types

In the enteric nervous system of patients with

colorectal carcinoma, Ndrg4 expression is absent or markedly

reduced (33), while enteric

nerve cells concurrently secrete higher levels of Fibulin2.

Fibulin2 and Nidogen1 promote human colorectal carcinoma cell

proliferation and migration. A study substantiated its conclusions

by stimulating cells with Fibulin2 and Nidogen1 proteins, then

assessing cell proliferation and migration (31). However, the study failed to

demonstrate the isolated effects of Fibulin2 on CRC cells and

mechanisms (31). In an

experiment investigating subcutaneous tumor formation in lung

adenocarcinoma, tumors were generated in mice by injecting tumor

cells in PBS subcutaneously into the right flank. Tumors formed by

Fbln2-knockdown cells exhibited reduced size, weight and

tissue consistency compared with those formed by normal cells

(10). In vitro

experiments revealed that Fbln2-knockdown cells, compared

with normal cells, exhibited markedly attenuated type I collagen

adhesion capacity alongside markedly reduced tumor cellular

pseudopodia (10). Itga1,

Itga2, Itga10 and Itgb1 were notably reduced

following Fbln2 depletion in lung adenocarcinoma cells

(10). These genes encode

Integrin proteins α1β1, α2β1, α10β1 and α11β1, respectively, which

can bind to collagen (34). In

summary, Fibulin2 is closely associated with other ECM proteins in

lung adenocarcinoma. Aberrant Fibulin2 expression leads to abnormal

changes of other ECM proteins such as integrin proteins and

collagen (10).

Immunohistochemistry revealed Fibulin2 upregulation in lung cancer

tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues. In vitro

validation relied exclusively on Fbln2 knockdown.

Incorporating overexpression experiments would enhance

methodological rigor (10). In

p53-null immortalized mouse keratinocytes and RasV12-transformed

mouse keratinocytes, knockdown of Fbln2 diminished cell

invasion; however, subcutaneous injection of Fbln2-knockdown

cells failed to produce a notable reduction in tumor growth volume

compared with controls (28).

Fibulin2 expression was regulated by Integrin α3β1 and promoted the

invasion of immortalized/transformed keratinocytes (28). The research was limited by overly

simplistic mechanistic exploration, necessitating further

investigation of more specific mechanisms. In mouse non-small cell

lung cancer tissue sections, ECM-expressed Fibulin2 interacts with

cell membrane-expressed Integrin β1. The interaction between

Integrin β1 and Fibulin2 mediates tumor cellular adhesion to the

ECM while conferring chemotherapy drug resistance (29). The study employed

immunofluorescence double-labeling experiments to demonstrate

partial colocalization of Integrin β1 and Fibulin2, subsequently

inferring disease mechanisms (29). Additional experiments are

necessary, including experiments verifying whether Integrin β1 is a

receptor of Fibulin2 and assessing its impact on tumors. In human

hepatocellular carcinoma cells, Fibulin2 promotes carcinoma cell

proliferation while inhibiting apoptosis through Ras-MEK-ERK1/2

signaling pathway activation (25). In in vitro experiments on

liver cancer cells, Fbln2 knockdown and overexpression were

performed, and the expression changes of key proteins in the

Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 signaling pathway were detected by western blotting

(WB) (25). Fibulin2 exerts

tumor-promoting effects in both in vitro and in vivo

experiments (25). However, this

merely establishes an association between Fibulin2 and the

Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 signaling pathway rather than a direct regulatory

relationship, as indirect mechanisms may exist. Future research

could use glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down to further

verify the direct interactions between Fibulin2 and these pathway

proteins. Fibulin2 expression alterations within neoplastic tissues

and corresponding modifications in tumor cell proliferation,

migration and invasion (demonstrating the pro-carcinogenic

properties of Fibulin2) are shown in Table II.

| Table IIChanges in Fibulin2 expression in

tumor tissue and changes in tumor cell proliferation, migration and

invasion (Fibulin2 exerts a pro-carcinogenic effect). |

Table II

Changes in Fibulin2 expression in

tumor tissue and changes in tumor cell proliferation, migration and

invasion (Fibulin2 exerts a pro-carcinogenic effect).

| First author/s,

year | Tumor | Tumor vs. non-tumor

tissue | Fibulin2

expression | Proliferation | Migration | Invasion | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Vaes et al,

2021 | CRC | Carcinoma vs.

paracarcinoma | Upregulated | Increased after

Nidogen1 and Fibulin2 stimulation | Increased after

Nidogen1 and Fibulin2 stimulation | | (31) |

| Baird et al,

2013 | Lung

adenocarcinoma | Carcinoma vs.

paracarcinoma | Upregulated | Decreased after

knockdown of Fbln2 | Decreased after

knockdown of Fbln2 | Decreased after

knockdown of Fbln2 | (10) |

| Hu et al,

2023 | Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Carcinoma vs.

paracarcinoma | Upregulated | Decreased after

knockdown of Fbln2; increased after overexpression of

Fbln2 | | | (25) |

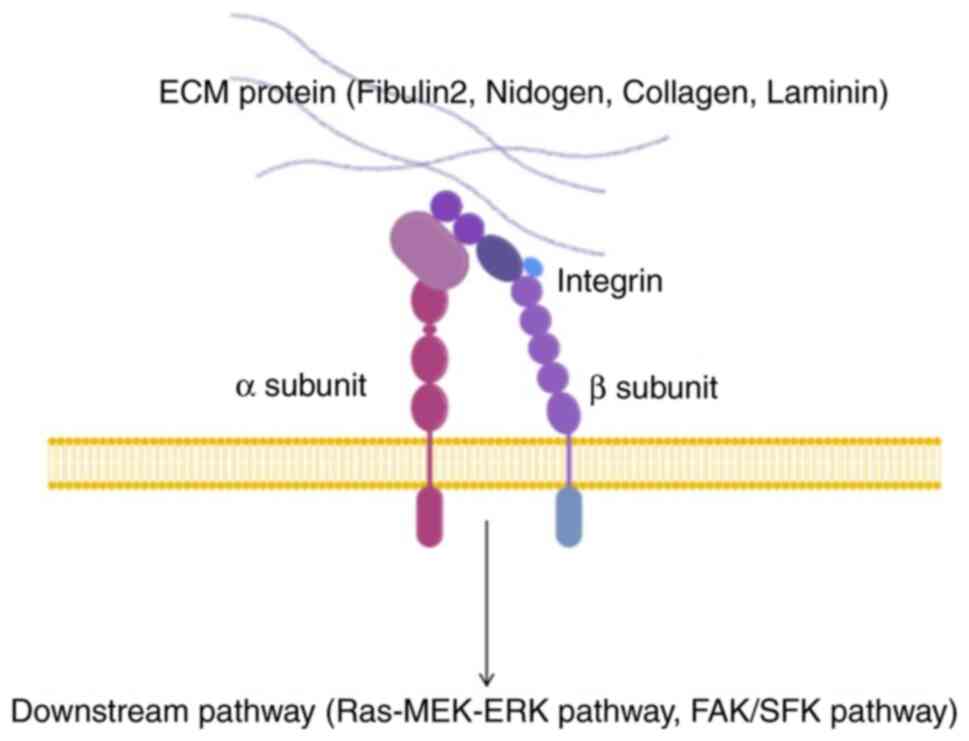

Fibulin2 is associated with Integrin proteins in

mechanistic investigations of lung adenocarcinoma (10), non-small cell lung carcinoma

(29), p53-null immortalized

murine keratinocytes and RasV12-transformed murine keratinocytes

(28). In a hepatocellular

carcinoma study, the authors did not study Integrin proteins

(25), the Ras-MEK-ERK1/2

signaling pathway constitutes a crucial downstream pathway of

Integrin according to previous investigations (35-37). Integrins, as principal ECM

cell-surface receptors, represent essential mediators of cellular

communication with the tumor microenvironment (TME) (35,38,39). Integrins comprise a family of 24

heterodimeric receptors (40).

Integrins consist of two subunits: α and β subunits, which have

extensive extracellular domains and short cytoplasmic domains

(41,42). These interact with ECM proteins

outside the cell membrane while connecting to downstream pathways,

including the Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 and FAK/SFK pathways in the cytoplasm

(35). When ECM protein,

including Fibulin2, Nidogen, Collagen and Laminin, or Integrin

expression is altered, fibrosis or remodeling can change tissue

stiffness, and downstream Integrin pathways such as the

Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 and FAK/SFK pathways may be activated, affecting

tumor migration, invasion and proliferation (35,43,44) (Fig.

5).

Limitations

Most studies examining the tumor-promoting functions

of Fibulin2 are simplistic. Future research may include additional

experiments to enhance persuasiveness. Furthermore, other factors

impact future drug development. For example, studies have used

immortalized cell lines such as the HCT116 and Caco-2 human CRC

cell lines (31), and mouse

models such as nude mice subcutaneously injected with SNU398 cells

(25). These models differ

substantially from primary cells and the human body, potentially

leading to the failure of related drugs in human applications.

Inferring disease mechanisms solely from protein spatial

associations, exemplified by partial Integrin β1 and Fibulin2

colocalization in lung carcinoma tissue sections (29), may fail to establish causative

relationships, resulting in ineffective therapeutic targets.

Focusing on single signaling pathways, such as the Ras-MEK-ERK1/2

signaling cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma (25), while disregarding other potential

pathways, may lead to compensatory pathway activation and

therapeutic resistance after single-target inhibition, thereby

limiting the applicability of conclusions. To the best of our

knowledge, the impact of changes in Fibulin2 expression on tumor

stroma activity [which depends on cancer-associated fibroblasts

(CAFs)] has not been investigated. Tumor stromal activity and

changes in CAF properties substantially influence tumor

development. In advanced-stage malignancies, activated stroma

promotes further genetic and epigenetic alterations in carcinoma

cells (45-47) while supporting carcinoma

progression (48). CAFs are one

of the cell types in the TME. CAFs exhibit proliferative, migratory

and high secretory activities (49,50). Due to their altered morphology

[multispindled rather than single-spindled (51)] and Acta2 and prolyl

endopeptidase expression, CAFs are frequently referred to as

myofibroblasts (50). CAFs

secrete ECM factors, including tenascin, periostin, secreted

protein acidic and rich in cysteine, and collagens (51-58). The expression levels of MMPs and

other enzymes that degrade and metabolize the ECM are increased in

CAFs, enabling cell penetration through the ECM (59-61). CAFs also secrete high levels of

growth factors, cytokines and chemokines, promoting intrinsic

malignant hallmarks of carcinoma cells through autocrine and

paracrine mechanisms (62). In

these studies where Fibulin2 had a tumor-promoting effect (10,25,28,31), while Fibulin2 was secreted by

tumor cells and acted on the stroma, it remained unclear how the

stroma reciprocally affects tumor cells. Whether tumor cell

secretion of Fibulin2 impacts CAFs requires further

exploration.

Roles and mechanisms of Fibulin2 in

inhibiting various tumor types

Alterations in Fibulin2 expression in tumor tissues

and corresponding changes in tumor cell proliferation, migration

and invasion (demonstrating the anti-carcinogenic properties of

Fibulin2) are summarized in Table

III. In human gastric cancer, Fibulin2 expression in malignant

tissues is reduced compared with that in adjacent normal tissues,

and is negatively associated with β-catenin (26). β-catenin is a bifunctional protein

with both cell adhesion and signal transduction activities, and was

initially identified through a study of the cell adhesion molecule

E-cadherin (63). β-catenin is an

essential component of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, serving

a pivotal role in gastric carcinoma pathogenesis and progression

(64). A study has established

direct or indirect regulatory relationships between the Fibulin

family and β-catenin, with both substantially influencing gastric

carcinoma development (65).

β-catenin is typically localized in the cytoplasm, with its

expression suppressed through ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated protein

degradation (66). Following

construction of Fbln2 overexpression plasmids and

transfection of them into AGS and SGC-790 human gastric cancer cell

lines, WB analysis has confirmed that Fibulin2 overexpression

downregulated β-catenin and its downstream c-myc and cyclin D1,

thereby inhibiting the proliferation of gastric cancer cells

(26). Immunohistochemistry

demonstrated downregulation of Fibulin2 in gastric cancer tissues

compared with adjacent normal tissues (26). In vitro validation relied

exclusively on Fbln2 overexpression, and incorporation of

knockdown experiments would enhance methodological rigor (26). Another study has confirmed that

reduced Fibulin2 expression in gastric carcinoma tissues promotes

tumor cell proliferation and metastasis through activation of the

TGF-β/Smad2/TGIF2 pathway (27).

The study used normal and Fbln2-knockdown human gastric

cancer cell lines for RNA sequencing, demonstrating upregulation of

the TGF-β signaling pathway in Fbln2-knockdown gastric

cancer cells (27). Following

Fbln2 knockdown and overexpression in gastric carcinoma

cells, WB analysis revealed corresponding increases and decreases

in Smad2 and TGIF2 phosphorylation (27). Addition of TGF-β signaling pathway

inhibitor reversed these expression changes (27). The specific mechanism by which

decreased Fbln2 expression in cells alters the activity of

the TGF-β pathway requires further exploration. This establishes an

association rather than a direct regulatory relationship between

Fibulin2 and the TGF-β/Smad2/TGIF2 pathway, as indirect mechanisms

cannot be excluded. Future research could use GST pull-down to

demonstrate direct interactions between Fibulin2 and pathway

proteins.

| Table IIIChanges in Fibulin2 expression in

tumor tissue and changes in tumor cell proliferation, migration and

invasion (Fibulin2 exerts an anti-carcinogenic effect). |

Table III

Changes in Fibulin2 expression in

tumor tissue and changes in tumor cell proliferation, migration and

invasion (Fibulin2 exerts an anti-carcinogenic effect).

| First author/s,

year | Tumor | Tumor vs. non-tumor

tissue | Fibulin2

expression | Proliferation | Migration | Invasion | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Law et al,

2012 | Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma | Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma biopsy tissue vs. non-tumor tissue | Downregulated | Decreased after

Fbln2s overexpression | Decreased after

Fbln2s overexpression | Decreased after

Fbln2s overexpression | (22) |

| Ren et al,

2016 | Glioma | | | Decreased after

Fibulin2 overexpression | Decreased after

Fibulin2 overexpression | Decreased after

Fibulin2 overexpression | (7) |

| Zhang et al,

2020 | Breast cancer | | | Decreased after

Fibulin2 overexpression | Decreased after

Fibulin2 overexpression | Decreased after

Fibulin2 overexpression | (24) |

| Alcendor et

al, 2011 | Kaposi's

sarcoma | Carcinoma tissue

vs. paracarcinoma tissue | Downregulated | | | | (23) |

| Ma et al,

2019 | Gastric cancer | Carcinoma tissue

vs. paracarcinoma tissue | Downregulated | Decreased after

Fibulin2 overexpression | | | (26) |

Kaposi's sarcoma, which originates from human

vascular endothelial cells, is characterized by vascular

proliferation caused by HIV infection of endothelial cells

(23). In cutaneous microvascular

endothelial cells after 10 days of infection, Fibulin2 protein and

mRNA expression are decreased by 50- and 26-fold, respectively.

Simultaneously, mRNA levels of the ECM-binding partners fibronectin

and tropoelastin are decreased 5- and 25-fold, respectively. This

weakens the binding of Fibulin2 to ECM proteins, including

fibronectin and tropoelastin, compromising basement membrane (BM)

stability and promoting tumor progression (23). Fibronectin is crucial for numerous

cell functions, including migration, proliferation and

differentiation (67).

Transcriptional downregulation of fibronectin has been associated

with highly metastatic breast carcinoma cells in murine models

(68). Tropoelastin is the

soluble precursor of elastin, inducible by ultraviolet irradiation

and degradable by MMP-12 (69).

Loss of tropoelastin causes developmental tissue disorders,

including aneurysms, atherosclerosis and reduced skin elasticity

(70). Tropoelastin and

fibronectin are essential ECM proteins critical for wound healing

(71). The study investigating

Kaposi's sarcoma failed to establish causative relationships

between Fibulin2 alterations and changes in fibronectin or

tropoelastin (23). Future

research should include cellular Fbln2 knockdown and

overexpression for validation.

In astrocytoma research, U251 cells (a human glioma

cell line) exhibited reduced migration and invasion following

Fibulin2 overexpression. The conclusion that Fibulin2 inhibits

astrocytoma was confirmed by comparing Fbln2-overexpressing

U251 cells with negative controls transfected with empty vectors

(7). A previous study revealed

that across different astrocytoma grades, Fibulin2 inhibits tumor

development (7). The authors

suggested an ECM-stabilizing function of Fibulin2; however,

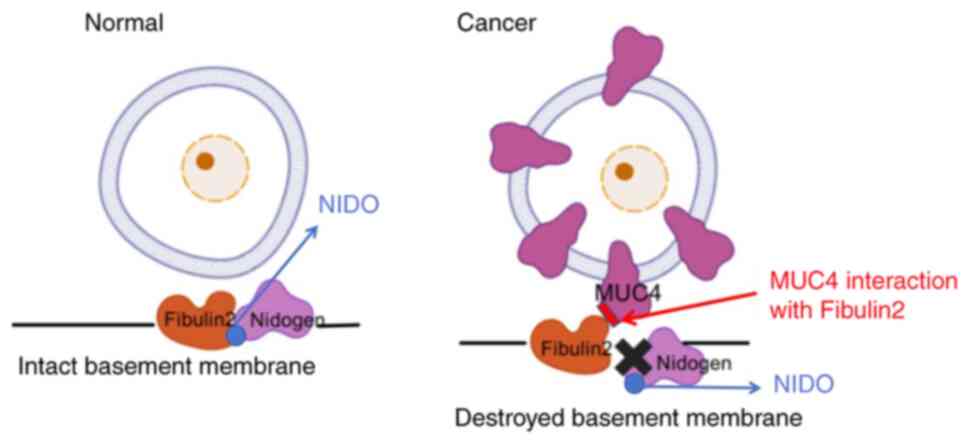

experimental verification is required (7). During pancreatic carcinoma

development, MUC4 protein expression is markedly upregulated on

pancreatic carcinoma cell surfaces and MUC4 binds to Fibulin2

(32). This binding interferes

with the normal interaction between Fibulin2 and the G1 domain of

Nidogen (NIDO), disrupting BM integrity (32) (Fig.

6). Tumor cells consequently breach the BM more readily,

facilitating invasion and metastasis. In pancreatic cancer tissue

sections, immunofluorescence double-labeling experiments have shown

colocalization of MUC4 and Fibulin2 (32). However, immunofluorescence

double-labeling experiments merely suggest potential connections

between these proteins and do not convincingly demonstrate the

roles of MUC4 and Fibulin2 in pancreatic carcinoma (32). Future studies may use conditional

knockout of MUC4 and Fibulin2 in murine models for further

validation. Additionally, numerous previous articles and reviews

have erroneously characterized Fibulin2 as an oncogenic protein in

pancreatic carcinoma when citing the conclusions of this study

about pancreatic carcinoma. The original study provides no evidence

to suggest that Fibulin2 promotes pancreatic carcinoma metastasis

and invasion (32).

Breast carcinoma is a prevalent malignancy in women

with a high incidence (72). In a

breast carcinoma study, transfection of Fbln2 plasmids into

human breast carcinoma cell lines reduced tumor cell migration and

invasion compared with those of negative control lentiviral vector

groups (24). Fibulin2 expression

is reduced in breast carcinoma tissues compared with adjacent

normal tissues (73). Knockdown

of Fbln2 is associated with disruption of the type IV

collagen sheath surrounding breast cells in vitro (74); Ibrahim et al (74) hypothesized that its downregulation

may be associated with BM disruption and early invasion. However,

the BM composition is complex, precluding exclusion of compensation

by other Fibulin family members (such as Fibulin1 and Fibulin5) or

ECM proteins, which requires demonstration (75). A study involving 272 patients with

breast carcinoma from a Norwegian hospital found a positive

association between elevated perivascular Fibulin2 expression in

breast carcinoma and survival rates (76). Elevated Fibulin2 expression was

associated with luminal breast carcinoma, pronounced elastic tissue

hyperplasia in the tumor stroma and favorable prognosis, while

reduced expression was associated with the basal-like phenotype,

triple-negative breast carcinoma, interval breast carcinoma,

vascular invasion and poor prognosis (76). The study lacked mechanistic

exploration and only reported observed associations.

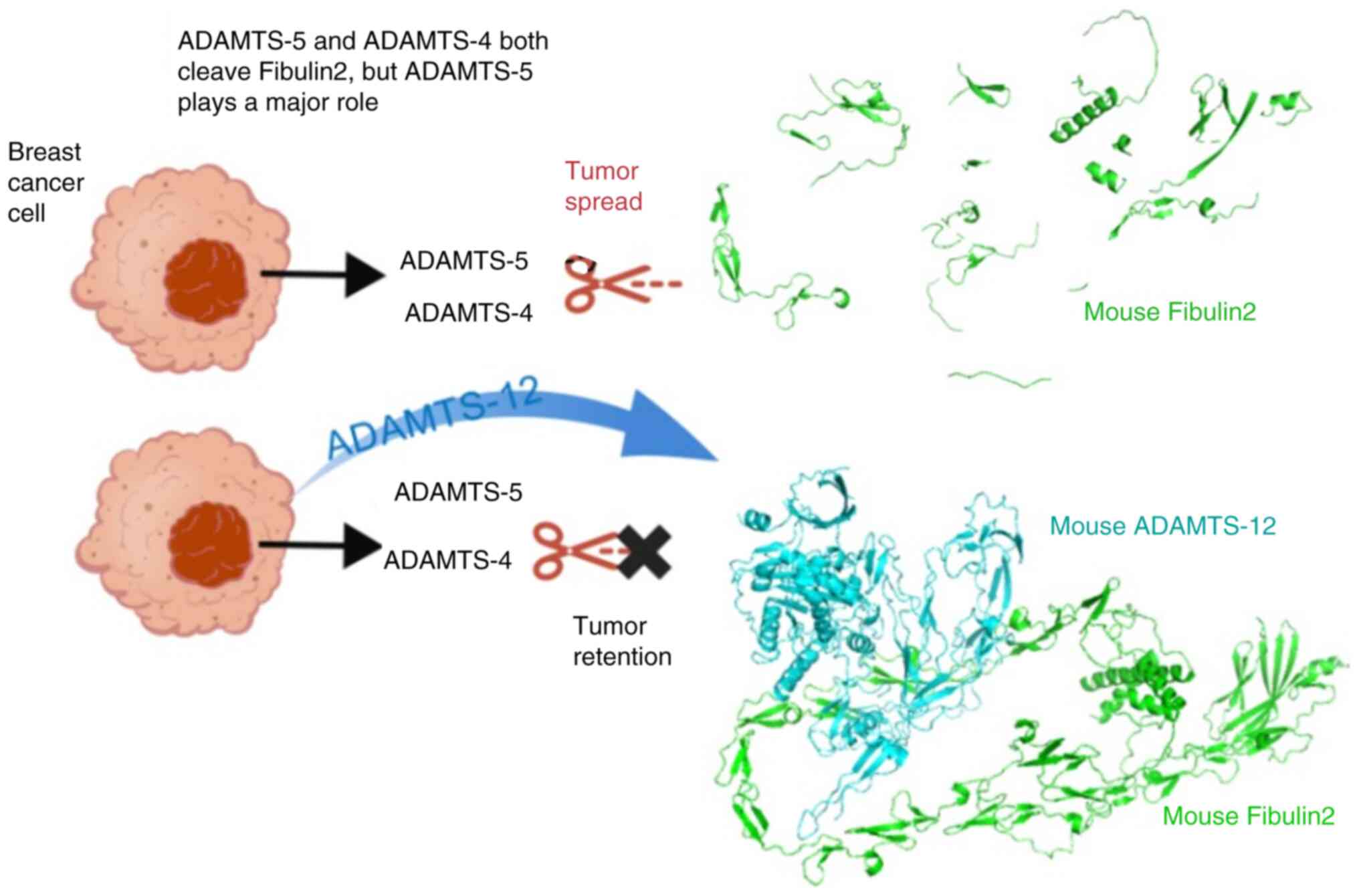

The TME is currently being investigated as a novel

therapeutic target for cancer. ADAMTS is secreted by carcinoma and

stromal cells, potentially modifying the TME through various

mechanisms, thereby promoting or inhibiting tumors (77). ADAMTS-12 is a secreted

metalloproteinase that has functions in tissue remodeling and cell

migration or adhesion (78,79). In 293-EBNA cells, yeast two-hybrid

screening and co-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that

the carboxyl-terminal region of Fibulin2 interacts with the spacer

region of ADAMTS-12 (80). When

Fibulin2 and ADAMTS-12 were concurrently overexpressed in breast

cancer cells, they reduced cell invasion and migration in

vitro, inhibited cell migration on relevant matrices, decreased

mammosphere unit formation, and suppressed tumor growth in

vivo (80). Fibulin2 and

ADAMTS-12 expression in breast cancer tissue was negatively

associated with histopathological tumor stage, with patients

exhibiting the best prognosis when both were highly expressed

(80). ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 are

members of the ADAMTS secreted metalloproteinase family (81). A previous study has indicated that

both ADAMTS-5 and Fibulin2 are expressed in the stromal and

epithelial components of breast cancer tissue, with

immunofluorescence double staining showing partial colocalization

(30). ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5,

predominantly ADAMTS-5, can specifically cleave Fibulin2, enhancing

breast carcinoma cell migration and invasion, while increasing the

tumorigenic potential (30)

(Fig. 7). The study compared the

invasion of breast cancer cell lines with simultaneous

overexpression of ADAMTS-5 and Fibulin2, breast cancer cell lines

with overexpression of ADAMTS-5 or Fibulin2 alone and the control

group (30). The invasion

capacity of MCF-7 cells was increased by the simultaneous

overexpression of Fibulin-2 and ADAMTS-5 compared with the control

group and overexpression of Fibulin2 alone (30). However, the invasion capacity of

MCF-7 cells was decreased by the simultaneous overexpression of

Fibulin-2 and ADAMTS-5 compared with overexpression of ADAMTS-5

alone (30). ADAMTS-5-mediated

Fibulin2 degradation is inhibited by ADAMTS-12 (Fig. 7) (30). However, in vivo experiments

only showed partial colocalization of ADAMTS-5 or ADAMTS-12 with

Fibulin2 via immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry, which is

insufficient to establish their relationship with breast cancer

(30). Future research using

conditional gene-knockout mice to substantiate the relationship

between these proteins and breast cancer would be more compelling.

When mammary fibroblasts are cultured in medium containing excess

Fibulin2 and ADAMTS-5, the expression levels of α-smooth muscle

actin (α-SMA) increase. Stimulation with excess Fibulin2 alone can

also increase α-SMA expression levels, as observed by WB (the

authors did not conduct statistical analysis), indicating that

Fibulin2 promotes breast fibroblast activation (30). Breast fibroblasts are a key

component of the tumor stroma (82). This indicates that changes in

Fibulin2 expression in breast cancer cells can activate stromal

fibroblasts and potentially drive their differentiation into CAFs,

a phenomenon closely related to the secretory properties of

Fibulin2 (30). Similar

mechanisms may occur in other tumor types; however, they have

received limited attention to date and warrant further

investigation.

Due to the opposing roles of different ADAMTS

subtypes in breast cancer, developing highly specific inhibitors

that selectively block the tumor-promoting activities of ADAMTS

subtypes without affecting their potential tumor-suppressive

effects remains challenging. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting

aggrecanases, including ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5, have advanced to a

phase III clinical trial for orthopedic applications (83). This provides valuable insights for

the development of ADAMTS-targeted therapeutics for breast cancer

treatment.

Cancer progression is accompanied by uncontrolled

tumor growth, local invasion and metastasis; processes that depend

heavily on the proteolytic activities of multiple MMPs. These

enzymes affect tissue integrity by degrading ECM components such as

Fibulin2 (84). In a

nasopharyngeal carcinoma study involving samples from 30 patients,

Fbln2 levels in carcinoma tissues substantially exceeded

those in normal tissues, as detected by gene chip technology

(22). In nasopharyngeal cancer

cell lines, overexpression of Fbln2s, which encodes the

short isoform of Fibulin2, downregulated the expression levels of

VEGF-165, VEGF-189 and MMP-2 compared with

those in the control group (22).

Sustained angiogenesis is indispensable for both tumor growth and

metastasis (85). MMP-2 is an

effective gelatinase capable of cleaving protein components of the

ECM and is involved in the invasion and metastasis process of tumor

cells (86). Evidence has

indicated that Fibulin2 is cleaved by MMP-2 (87), and inhibits nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cell migration and invasion by strictly regulating

MMP-2 expression (22).

However, the study could not establish a direct regulatory

relationship between Fbln2 and VEGF-165,

VEGF-189 or MMP-2, because there may be unknown

molecules or signaling pathways mediating the interaction between

Fbln2 and VEGF-165, VEGF-189 or MMP-2.

WB analysis of osteosarcoma cell line lysates has indicated

multiple Fibulin2 fragments (87). Gelatinase MMP-2 facilitates

Fibulin2 degradation through MMP-dependent mechanisms in

osteosarcoma cell lines (87).

Following addition of an MMP-2 inhibitor to the cell culture

medium, WB indicated no change in the cleaved Fibulin2 fragments,

indicating that unidentified mechanisms require exploration

(87). This study using an

osteosarcoma cell line relied entirely on in vitro

experiments, and in vivo experiments are required for

verification, as the in vivo environment is more complex

than the in vitro cell culture environment (87).

Most documented MMP inhibitors exhibit non-specific

binding and have diminished efficacy, attributable to their

pronounced sequence homology with other MMPs (88). To date, no effective MMP inhibitor

has successfully completed clinical trials and secured regulatory

approval from the Food and Drug Administration for tumor treatment

(84,88).

Limitations

Studies on the tumor-inhibitory effect of Fibulin2

predominantly focus on preserving BM structural integrity (7,32,74). Few studies have investigated the

mechanisms of interaction between Fibulin2 and classical signaling

pathways. Only the association among Fibulin2, β-catenin and the

TGF-β/Smad2/TGIF2 pathways has been demonstrated in gastric cancer

studies (26,27). An intricate association exists

between the β-catenin and TGF-β signaling pathways and the

aforementioned Integrins (89,90). Whether Fibulin2 indirectly

regulates the β-catenin and TGF-β/Smad2/TGIF2 pathways through

Integrins warrants comprehensive investigation. Some methodological

considerations profoundly impact future pharmaceutical development

efforts. For example, the use of established cell lines, such as

the HGC27 and MKN28 cell lines, to study gastric cancer fails to

replicate the complexity of primary cells isolated from living

tissues (27). Inferring causal

relationships in disease mechanisms based solely on gene or protein

expression associations or simultaneous alterations, exemplified by

MUC4 and Fibulin2 in pancreatic cancer (32), and simultaneous changes in

Fibulin2, fibronectin and tropoelastin in Kaposi's sarcoma

(23), may result in ineffective

drug targets. Focusing on signaling pathways, such as the

TGF-β/TGIF2 pathway in gastric cancer (27), while disregarding other potential

pathways, may lead to therapeutic resistance due to the activation

of compensatory pathways following single-target inhibition. The

role of tumor stroma in inhibiting or promoting tumors is

associated not only with signaling pathway activation but is also

closely associated with stromal cells, such as the activity or

senescence state of fibroblasts (91). Secretion of growth factors with

inhibitory functions by non-activated fibroblasts (92) or upregulation of the tissue

inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) family are potential

mechanisms by which tumor stroma suppresses neoplastic progression

(93,94). Notably, both MMPs and the

previously discussed ADAMTS are strictly regulated by TIMPs in

normal tissues (95,96). Expression of TIMP family proteins

in fibroblasts governs ECM structural organization and stromal cell

architecture (97). These

proteins function as endogenous negative regulators of MMP

activity, and numerous malignancies exhibit aberrant TIMP and/or

MMP expression patterns (93,98-99). Loss or reduction of TIMP

expression leads to enhanced MMP functionality, facilitating

stromal activation and subsequent tumor progression (100,101). TIMP overexpression attenuates

tumorigenesis, growth, angiogenesis and metastasis in some cancer

types, such as pancreatic cancer (94). Whether altered Fibulin2 expression

in tumor cells influences fibroblast activity and stromal TIMP

family expression requires further elucidation.

Fibulin2 as a biomarker for tumors

Studies on Fibulin2 as a biomarker are summarized

in Table IV. For case-control

studies involving human populations in Table IV, according to the 2011 Evidence

Hierarchy of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine, the

evidence level of most studies was 4 (102).

| Table IVFibulin2: A potential biomarker in

tumors and other diseases. |

Table IV

Fibulin2: A potential biomarker in

tumors and other diseases.

| First author/s,

year | Disease | Source | Expression | Comparison/

evidence level | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ren et al,

2016 | Astrocytoma | Human

astrocytomas | Downregulation | Grades II/III/IV

vs. grade I/4 | (7) |

| Whiteaker et

al, 2007 | Breast cancer | Mouse plasma | Upregulation | Breast cancer mouse

vs. normal mice | (103) |

| Ibrahim et

al, 2020 | HCM | Human serum | Upregulation | Patients with HCM

vs. healthy individuals/4 | (107) |

| Sofela et

al, 2021; Sofela et al, 2021 | Meningioma | Human plasma | Upregulation | Grade II vs. grade

I/4 | (5,6) |

| Li et al,

2022 | Infection | Human plasma | Upregulation | Patients with

infection vs. healthy individuals/3 | (108) |

| Knittel et

al, 1999 | Liver fibrosis | Rat liver

myofibroblasts | Upregulation | Liver stellate

cells vs. liver myofibroblasts | (109) |

| Setiawati et

al, 2024 | Meningioma | Human tumor

tissue | Fibulin2 expression

was elevated in patients <50 years old or exhibiting high

histopathological grading | High vs. low

Fibulin2 expression/4 | (106) |

| Klingen et

al, 2021 | Breast cancer | Human breast cancer

tissue | Diminished Fibulin2

expression in perivascular regions was associated with attenuated

survival outcomes | High vs. low

Fibulin2 expression/4 | (76) |

| WalyEldeen et

al, 2024 | Breast cancer | Human breast cancer

mRNA data | High Fbln2

mRNA expression was associated with favorable prognosis in

relatively early breast cancer, with contrary associations observed

in relatively late lesions | High vs. low

Fbln2 expression/4 | (105) |

| Takakura et

al, 2023 | Advanced CRC | Human serum | Fibulin2 expression

was increased in recurrent and advanced CRC | Patients with

advanced CRC vs. healthy individuals/4 | (4) |

| Ibrahim et

al, 2018 | Breast cancer | Human breast cancer

tissue | Higher Fbln2

mRNA expression was associated with improved survival in low and

intermediate grade breast cancer, exhibiting contrary associations

in high-grade breast cancer | High vs. low

Fbln2 expression/4 | (74) |

| Avsar et al,

2019 | Lung cancer | Human blood | Downregulation | Patients with lung

cancer vs. healthy individuals/4 | (104) |

Fibulin2 as a marker to distinguish

patients with tumors from normal populations

In breast cancer mouse models, Fibulin2 expression

in plasma was substantially higher than that in normal mice,

indicating its potential as a plasma biomarker (103). The study used mice rather than

humans as research subjects. Due to species differences, the

effectiveness of the marker in humans requires verification,

limiting the applicability of the conclusions. Using liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and label-free

quantitative methods, differences in Fibulin2 expression have been

detected in the sera of patients with advanced colon cancer and

healthy individuals. Fibulin2 is a diagnostic marker for advanced

colon cancer (4). The sample

sizes for the patient and normal control groups were only 8 and 10,

respectively, in the study investigating advanced colon cancer,

representing inadequate sample sizes (4). Consequently, the cohort lacks

representativeness, predisposing it to false positives or false

negatives. Future research should expand the sample size to enhance

the robustness of the conclusions. In a study on patients with lung

cancer, Fbln2 gene expression levels of the enriched

epithelial cells of peripheral blood lymphocytes were found to be

decreased ~2-fold in patients with metastatic and non-metastatic

lung cancer compared with healthy controls (104). Fbln2 is a potential

biomarker to distinguish patients with lung cancer from healthy

controls (104).

Fibulin2 as a marker to distinguish

different grades of tumors

Surgical specimens of astrocytomas have been

analyzed using LC-MS/MS, WB and reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR, revealing that Fibulin2 was downregulated in grade II/III/IV

astrocytomas compared with grade I astrocytomas, with negative

expression being associated with advanced clinical stages (7). The sample sizes of patients with

different grades of glioma were only 5 each, representing small

sample sizes that may reduce diagnostic accuracy. Fibulin2

expression in the plasma of patients with grade II meningioma is

higher than that in grade I patients, indicating that Fibulin2 is a

potential marker to distinguish between patients with grade II and

I meningioma (5,6).

Fibulin2 as a marker to predict the

prognosis of patients

In studies of Fibulin2 as a marker to predict the

prognosis of patients (74,105), comprehensive analysis of human

sample data from multiple databases yielded information on patients

with breast cancer, including their stages, molecular subtypes and

treatment conditions. Based on the Kaplan-Meier plotter dataset,

after chemotherapy, high Fbln2 expression was associated

with improved overall survival in Her2− patients. In

grade 2 patients (including those after chemotherapy/hormonal

therapy), unstratified patients with breast cancer,

Her2− patients, Luminal− patients and

estrogen receptor+ patients after chemotherapy, high

Fbln2 expression was associated with improved

recurrence-free survival. Conversely, in grade 3 patients, low

Fbln2 expression was associated with improved overall

survival. In Her2+ patients, estrogen

receptor− patients and grade 3 patients, low

Fbln2 expression was associated with improved

recurrence-free survival. Analysis of sample data from patients

with breast cancer with different molecular subtypes in The Cancer

Genome Atlas dataset revealed that in Luminal B patients, low

Fbln2 expression was associated with improved overall

survival. In Her2+ patients, high Fbln2

expression was associated with improved overall survival (105). Another study used the

Kaplan-Meier plotter dataset to collect the mRNA expression and

survival data of patients with breast cancer, analyzing the

association between Fbln2 expression and prognosis in

different subgroups (74). In

patients with lymph node-negative and intermediate-grade breast

cancer, high Fbln2 mRNA expression was associated with

improved distant metastasis-free survival compared with that of

patients with low expression. By contrast, in patients with

high-grade breast cancer, the opposite was true: Elevated

Fbln2 mRNA expression was associated with poorer prognosis

than low expression (74). The

conclusions of both studies were derived from database analyses

(74,105). However, samples from public

databases are prone to heterogeneity, so clinical validation of

their findings is necessary. In a study analyzing human meningioma

tissue samples, high-grade histopathology was associated with

elevated Ki-67 and Fibulin2 expression. The higher the histological

grade of meningioma was based on histopathology, the poorer the

prognosis of patients. Higher grades were associated with increased

risks of recurrence, progression and mortality. The younger age

group (<50 years) exhibited higher Fibulin2 expression than the

older age group (>50 years). Fibulin2 expression exhibited an

association with age and histopathological grading (106). The sample sizes for low-grade

and high-grade gliomas were both 25, representing relatively small

cohorts. Furthermore, as the study was a cross-sectional study, it

could not determine whether elevated Fibulin2 expression was the

cause or consequence of increased meningioma grading.

Fibulin2 as a marker in non-tumor

diseases

In a study examining patients with hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy (HCM), serum Fibulin2 expression in patients with

HCM markedly exceeded that of normal individuals, suggesting that

Fibulin2 may be beneficial for HCM diagnosis (107). This retrospective study included

95 consecutive patients with obstructive HCM eligible for septal

myectomy surgery. However, HCM has numerous subtypes, with sampling

limited to specific subtypes, introducing bias that affects the

generalizability of the conclusions to HCM overall. In a study

examining patients with infections, plasma Fibulin2 expression in

patients with infections was higher than that in normal individuals

(108). All patients in the

study were from the emergency department, and the disease types

included were limited, leading to selection bias in the study

population. The applicability of the conclusions supporting

Fibulin2 as a clinical diagnostic marker for infection remains

limited. Immunohistochemical expression of Fibulin2 distinguishes

liver stellate cells from liver myofibroblasts after liver injury,

suggesting that liver myofibroblasts are a unique cell population

involved in matrix production during liver fibrosis caused by

chronic liver injury (109).

Differences in Fibulin2 expression have been observed between liver

stellate cells and liver myofibroblasts in normal livers, livers

with acute damage and livers with chronic damage (109). This study provides a novel

marker for researchers to label liver myofibroblasts in related

research, although its application remains limited to basic

research. Future research should explore whether Fibulin2 can be

translated into a clinical diagnostic marker for liver-related

diseases based on this finding.

Challenges and limitations of clinical

translation

Although Fibulin2 shows considerable potential as a

therapeutic target and biomarker, several challenges and

limitations remain. Addressing these impediments is crucial for

successful clinical translation.

Mechanisms of Fibulin2 in tumors are not

fully understood

Currently, studies on Fibulin2 receptors remain

limited. In infected bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, Fibulin2

binds to the transmembrane receptor Notch2 (110). In a rat model of neuropathic

pain, Fibulin2 expression in the spinal dorsal horn was upregulated

(111). Fibulin2 specifically

binds to the B1a subunit of γ-aminobutyric acid B receptor,

inhibiting its activity and thereby exacerbating pain (111). Following multiple sclerosis,

Fibulin2 suppresses oligodendrocyte generation through Notch

pathway activation (112). In

tumor research, Integrin proteins have been demonstrated to be

receptors of Fibulin2 (29). The

mechanistic evidence in numerous studies exhibits

oversimplification (10,22,28,29). These studies predominantly involve

Fbln2 knockdown or overexpression, followed by detection of

expression changes in specific key proteins in vitro. Other

studies primarily encompass influencing the alteration of the BM

(7,32,74). The impact of Fibulin2 on

neoplastic processes is complex, requiring further investigation

into more comprehensive mechanistic pathways. This would facilitate

the design of precision-targeted pharmaceuticals against

disease-associated molecular targets.

Side effects and toxicities

Due to the complexity of the function of Fibulin2,

targeting Fibulin2 may induce various adverse effects and

toxicities. Beyond its role in tumors, Fibulin2 serves a pivotal

role in maintaining tissue integrity (74,75,113), regulating fibrosis and immunity

(114-120), and supporting tissue development

and repair (121-126). For example, Fibulin2-deficient

mouse pups developed blisters, demonstrating that Fibulin2

deficiency during development could cause BM rupture. However,

adult Fibulin2-deficient mice exhibited no blisters, likely due to

compensatory mechanisms mediated by other ECM components (75,113). Reduced Fbln2 expression

disrupts sheath formation in the mammary epithelium and

downregulates Integrin β1 expression, compromising BM integrity.

Fibulin2 serves a crucial role in stabilizing the BM structure of

the mammary epithelium (74). The

Fibulin2 protein exhibits close associations with fibrosis. By

establishing cardiac hypertrophy models in Fibulin2 homozygous and

wild-type mice via angiotensin II infusion, Fibulin2 knockout has

been shown to inhibit myocardial fibrosis via H&E staining,

Masson staining and immunohistochemistry analysis (114). This finding was corroborated by

observations that Fbln2 reduced fibrosis markers in primary

cardiomyocyte fibroblasts from Fibulin2 homozygous and wild-type

mice stimulated with TGF-β1 (114). Consistent results were obtained

when establishing myocardial infarction models in Fibulin2

homozygous and wild-type mice: The survival rate of Fibulin2

homozygous mice was higher than that of wild-type mice (115). A 5-day mouse model of skin

injury revealed markedly elevated Fibulin2 expression in mice with

skin injuries compared with normal mice, as detected by nucleic

acid analysis and immunofluorescence (116). Unilateral ureteral obstruction

leads to renal fibrosis. Immunofluorescence staining in mice after

7 days of unilateral ureteral obstruction showed higher Fibulin2

expression compared with that in normal mice (117). After establishing a liver

fibrosis model in rats, immunofluorescence revealed higher Fibulin2

expression in rats with liver fibrosis compared with normal rats

(118). Fibulin2 is upregulated

in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (119). Fibulin2 inhibition suppresses

α-SMA, collagen type Iα1 and fibronectin expression in human lung

fibroblast-derived MRC-5 cells (119). Fibulin2 influences immune

function, with reduced levels being associated with immune

impairment after bone trauma (120). In terms of tissue development

and repair, Fibulin2 is a key mediator of the neurogenic effect of

TGF-β1 on adult neural stem cells (121). Fibulin2-mediated TGF-β signaling

in astrocyte extracellular vesicles promotes synapse formation

(122). During myoblast

differentiation, Fbln2 expression is upregulated, and

Fbln2 is indispensable for myoblast differentiation

(123-125). Fibulin2 regulates smooth muscle

cell migration during blood vessel wall repair (126).

Consequently, the functions of Fibulin2 exhibit

extraordinary complexity. Although targeting of Fibulin2 has

therapeutic potential in tumor treatment, it may cause

immunosuppression (120),

disrupt the balance between ECM production and degradation, and

induce severe complications such as excessive collagen deposition

and fibrosis (114-119).

Clinical translation challenges

To the best of our knowledge, currently, there are

no clinical studies on Fibulin2 as a therapeutic target. Existing

clinical studies related to Fibulin2 only focus on its use as a

marker (5,6,7,107,108). The clinical translation of

Fibulin2-targeted drugs for cancer treatment faces numerous

obstacles, although current research has not yet reached this

stage. Beyond the aforementioned incomplete understanding of

mechanisms, there are substantial challenges in clinical drug

trials themselves. The following issues are similarly prevalent in

the research and development of oncology drugs. For example,

determining the optimal dosing and regimens for targeted drugs is

challenging due to their narrow therapeutic window and potential

toxicity (127). Careful dose

escalation studies and monitoring of adverse reactions are

necessary. Additionally, for combination therapies involving

targeted drugs and other anticancer drugs, synergistic dose

regimens need to be determined. Establishing appropriate clinical

trial endpoints and efficacy measures is quite complex, as

traditional endpoints such as overall survival and progression-free

survival may inadequately reflect the therapeutic effects and

potential long-term implications of targeted drugs (128). Determining the optimal

combination, sequence and potential interactions between treatments

is challenging. Extensive preclinical and clinical studies are

necessary to evaluate synergistic effects, additional benefits or

potential antagonistic interactions of treatments to maximize

therapeutic efficacy.

Challenges in the clinical application of

markers

Biomarkers should meet strict criteria to ensure

concordance between measured and actual physiological values,

including accuracy, precision, sensitivity, reproducibility,

stability (129,130), specificity, dynamics,

detectability and minimal invasiveness (131). Fibulin2 exhibits significant

expression differences across distinct stages of tumor development

and between normal and diseased conditions (4,5,6,7,103). Fibulin2 is also a potentially

effective biomarker in studies of infection and fibrosis (108,109). However, numerous studies are

limited by inadequate sample sizes. Furthermore, Fibulin2 can serve

as a marker in studies on different diseases, and thus, does not

meet the specificity criteria for a marker. Its low specificity

fundamentally hinders the clinical utility of Fibulin2 as a single

biomarker. In breast cancer, meningioma, infection and HCM,

Fibulin2 in human serum samples is detected using ELISA (5,103,107,108). ELISA has considerable

advantages, including high sensitivity, high specificity (132) and the ability to analyze

multiple samples simultaneously within short timeframes (133). This ensures practical

feasibility and convenience for large-scale screening programs and

facilitates high-throughput sample processing (133). However, its inherent limitations

include lengthy sample pretreatment and purification procedures,

unsuitability for rapid detection, high cost, lack of real-time

detection capabilities (134),

and the need for a relatively large sample volume (100-200

µl) (135). As a

biomarker, Fibulin2 should not merely aid in staging disease

progression or pathological exclusion but also provide therapeutic

guidance. This requires that Fibulin2 demonstrates systematic

changes corresponding to dynamic disease progression. Most studies

so far have not conducted comprehensive dynamic monitoring.

Future perspectives of clinical

translation

Emerging Fibulin2-targeted therapies

At present, there is a lack of pharmaceutical

investigations targeting Fibulin2 for tumor treatment. A key

contributing factor to this scarcity is the multifaceted complexity

of its biological functions as aforementioned. Fibulin2-directed

therapeutic interventions may induce considerable toxicity and

adverse sequelae (74,75,113-126). Next-generation small-molecule

inhibitors, novel monoclonal antibodies, ligand traps, gene

editing, RNA interference technologies, nanomaterials and

peptide-based therapies are emerging targeted treatments in cancer.

Beyond the need to further elucidate the mechanistic basis of the

role of Fibulin2 in tumors, the strategic application of these

emerging technologies in prospective Fibulin2-targed drugs will

prove instrumental in enhancing therapeutic specificity and potency

while reducing adverse effects.

Combining other therapies with

Fibulin2-targeted therapies

Integrating Fibulin2-targeted treatment with other

modalities is a strategic approach to enhance antitumor efficacy

and circumvent resistance mechanisms. For example, synergistic

combinations with immunotherapeutic agents, particularly immune

checkpoint inhibitors (such as anti-programmed cell death protein 1

and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4), show promise

by reactivating antitumor immune responses by reducing

immunosuppression (136,137). Combining Fibulin2-targeted

treatment with adoptive cell therapy, such as chimeric antigen

receptor-T cells, may enhance cellular persistence and

effectiveness (138).

Co-administering signaling pathway inhibitors with

Fibulin2-targeted treatment helps attenuate parallel signaling

pathways, thereby blocking the compensatory mechanisms exploited by

malignant cells. This strategy aims to enhance comprehensive

antitumor activity and delay drug resistance. Integrating

Fibulin2-targeted treatment with traditional chemotherapy and

radiotherapy increases tumor susceptibility to these treatments.

Concomitant use of epigenetic modulators can enhance therapeutic

responsiveness by systematically reprogramming the TME, which is

effective in addressing epigenetic changes that promote cancer

progression (139).

Combining Fibulin2 with other

markers

Given the limited specificity of Fibulin2 as a

single biomarker, integrating multiple biomarkers is advantageous

to address this limitation. While there are currently no reports on

the use of Fibulin2 in combination with other markers for tumor

detection, the use of microRNAs (miRNAs) and other proteins as

combined markers for early-stage cancer diagnosis has demonstrated

the considerable potential of combined marker detection, offering

valuable insights for combining Fibulin2 with other markers

(140,141). For example, Yu et al

(140) described a multi-marker

diagnostic method for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, using α

fetoprotein and miRNA-125b as combined markers to simultaneously

improve diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Yuan et al

(141) proposed a new

combination of circulating miRNAs and plasma protein biomarkers for

pancreatic cancer diagnosis. These combined indicators exhibited

higher specificity in distinguishing pancreatic cancer from other

gastrointestinal cancers than CA19-9 and individual indicators

(141). Combining Fibulin2 with

other markers such as miRNAs for early cancer screening, diagnosis

and prognosis may enhance specificity compared with using Fibulin2

alone. The introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine

learning can facilitate the identification of novel potential

combined biomarkers. AI algorithms excel in analyzing and

identifying unique combinations of gene mutations and using

large-scale genomic databases to identify cancer-specific markers

(142).

Improvements in traditional ELISA

detection methods

The quantification of Fibulin2 in serum and plasma

is performed using traditional ELISA. ELISA detection requires

air-conditioned laboratories, refrigeration facilities for

chemicals and reagents, a reliable power supply,

precision-calibrated equipment, and highly trained personnel

(135). Some laboratories or

hospitals still lack access to affordable infrastructure for these

complex diagnostic tests. To address these deficiencies,

laboratories worldwide have evaluated and implemented various

modified forms of ELISA. These innovative ELISA formats have

greater potential for clinical translation due to their low cost,

short detection time, portability and reduced reagent needs

(143-146). For example, microfluidic-based

ELISA, paper-ELISA and aptamer-ELISA can mitigate the limitations

of traditional ELISA to some extent (143-146).

Conclusion

The oncogenic or suppressive effects of altered

Fibulin2 expression in malignant cells vary markedly across diverse

tumors. The contributing factors include distinct mechanisms,

including the activation of different signaling pathways and the

complex relationships with BM or other ECM proteins, tumor

development stage, species and tumor origin. Although current

mechanistic studies help clarify aspects of pathogenic processes,

several outstanding issues remain to be resolved. These include

validating the upstream and downstream molecules of Fibulin2,

confirming the existence of feedback loops, exploring alternative

pathways, and clarifying the relationship between Fibulin2 and

stromal fibroblasts. These considerations are crucial to improve

the safety and effectiveness of future relevant drug research. The

use of Fibulin2 alone as a marker for tumor diagnosis or staging

remains not well-established. Future research should further

explore methods to enhance specificity, such as identifying novel

and specific markers to be used in combination with Fibulin2 as a

dual-marker system.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YY completed most of the work, wrote the original

draft and created illustrations. ZW wrote and revised the article,

and collected the literature. LW revised the article and collected

the literature. JF reviewed and edited the manuscript, provided

resources, and acquired funding. ZL supervised the study, edited

and reviewed the manuscript, was involved in project

administration, and acquired funding. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

CAF

|

cancer-associated fibroblast

|

|

ECM

|

extracellular matrix

|

|

BM

|

basement membrane

|

|

TIMP

|

tissue inhibitor of

metalloproteinases

|

|

WB

|

western blotting

|

|

ADAMTS

|

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

with thrombospondin motifs

|

|

AI

|

artificial intelligence

|

|

HCM

|

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the Key Research

and Development Program of Sichuan Province (grant no.

2023YFQ0009), the Chongqing Municipality Science-Health Joint

Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project (grant no.

2023DBXM010), and the Sichuan Provincial Central Government-Guided

Local Science and Technology Development Special Project (grant no.

2023ZYD0288).

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E and

Soerjomataram I: The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a

leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 127:3029–3030.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung

H and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 75:10–45.

2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Takakura D, Ohashi S, Kobayashi N,

Tokuhisa M, Ichikawa Y and Kawasaki N: Targeted O-glycoproteomics

for the development of diagnostic markers for advanced colorectal

cancer. Front Oncol. 13:11049362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sofela AA, Hilton DA, Ammoun S, Baiz D,

Adams CL, Ercolano E, Jenkinson MD, Kurian KM, Teo M, Whitfield PC,

et al: Fibulin-2: A novel biomarker for differentiating grade II

from grade I meningiomas. Int J Mol Sci. 22:5602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sofela AA, McGavin L, Whitfield PC and

Hanemann CO: Biomarkers for differentiating grade II meningiomas

from grade I: A systematic review. Br J Neurosurg. 35:696–702.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ren T, Lin S, Wang Z and Shang A:

Differential proteomics analysis of low- and high-grade of

astrocytoma using iTRAQ quantification. Onco Targets Ther.

9:5883–5895. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pan TC, Sasaki T, Zhang RZ, Fässler R,

Timpl R and Chu ML: Structure and expression of fibulin-2, a novel

extracellular matrix protein with multiple EGF-like repeats and

consensus motifs for calcium binding. J Cell Biol. 123:1269–1277.

1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang H, Hui D and Fu X: Roles of

Fibulin-2 in carcinogenesis. Med Sci Monit.

26:e9180992020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Baird BN, Schliekelman MJ, Ahn YH, Chen Y,

Roybal JD, Gill BJ, Mishra DK, Erez B, O'Reilly M, Yang Y, et al:

Fibulin-2 is a driver of malignant progression in lung

adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 8:e670542013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang RZ, Pan TC, Zhang ZY, Mattei MG,

Timpl R and Chu ML: Fibulin-2 (FBLN2): Human cDNA sequence, mRNA

expression, and mapping of the gene on human and mouse chromosomes.

Genomics. 22:425–430. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Brown JC, Sasaki T, Göhring W, Yamada Y

and Timpl R: The C-terminal domain V of perlecan promotes beta1

integrin-mediated cell adhesion, binds heparin, nidogen and

fibulin-2 and can be modified by glycosaminoglycans. Eur J Biochem.

250:39–46. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hopf M, Göhring W, Kohfeldt E, Yamada Y

and Timpl R: Recombinant domain IV of perlecan binds to nidogens,

laminin-nidogen complex, fibronectin, fibulin-2 and heparin. Eur J

Biochem. 259:917–925. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sasaki T, Göhring W, Mann K, Brakebusch C,

Yamada Y, Fässler R and Timpl R: Short arm region of laminin-5

gamma2 chain: Structure, mechanism of processing and binding to

heparin and proteins. J Mol Biol. 314:751–763. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Talts JF, Andac Z, Göhring W, Brancaccio A

and Timpl R: Binding of the G domains of laminin alpha1 and alpha2

chains and perlecan to heparin, sulfatides, alpha-dystroglycan and

several extracellular matrix proteins. EMBO J. 18:863–870. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sasaki T, Wiedemann H, Matzner M, Chu ML

and Timpl R: Expression of fibulin-2 by fibroblasts and deposition

with Fibronectin into a fibrillar matrix. J Cell Sci. 109(Pt 12):

2895–2904. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sasaki T, Fukai N, Mann K, Göhring W,

Olsen BR and Timpl R: Structure, function and tissue forms of the

C-terminal globular domain of collagen XVIII containing the

angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin. EMBO J. 17:4249–4256. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Olin AI, Mörgelin M, Sasaki T, Timpl R,

Heinegård D and Aspberg A: The proteoglycans aggrecan and Versican

form networks with fibulin-2 through their lectin domain binding. J

Biol Chem. 276:1253–1261. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Friedrich MV, Göhring W, Mörgelin M,

Brancaccio A, David G and Timpl R: Structural basis of

glycosaminoglycan modification and of heterotypic interactions of

perlecan domain V. J Mol Biol. 294:259–270. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Utani A, Nomizu M and Yamada Y: Fibulin-2

binds to the short arms of laminin-5 and laminin-1 via conserved

amino acid sequences. J Biol Chem. 272:2814–2820. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

de Vega S, Iwamoto T and Yamada Y:

Fibulins: Multiple roles in matrix structures and tissue functions.

Cell Mol Life Sci. 66:1890–1902. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Law EW, Cheung AK, Kashuba VI, Pavlova TV,

Zabarovsky ER, Lung HL, Cheng Y, Chua D, Kwong DLK, Tsao SW, et al:

Anti-angiogenic and tumor-suppressive roles of candidate

tumor-suppressor gene, Fibulin-2, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Oncogene. 31:728–738. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Alcendor DJ, Knobel S, Desai P, Zhu WQ and

Hayward GS: KSHV regulation of fibulin-2 in Kaposi's sarcoma:

Implications for tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 179:1443–1454. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang X, Duan L, Zhang Y, Zhao H, Yang X

and Zhang C: Correlation of Fibulin-2 expression with

proliferation, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Oncol

Lett. 20:1945–1951. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hu X, Liu T, Li L, Gan H, Wang T, Pang P

and Mao J: Fibulin-2 facilitates malignant progression of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Turk J Gastroenterol. 34:635–644. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ma H, Lian C and Song Y: Fibulin-2

inhibits development of gastric cancer by downregulating β-catenin.

Oncol Lett. 18:2799–2804. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhou M, Mao X, Shen K, Zhan Q, Ni H, Liu

C, Huang Z and Li R: FBLN2 inhibits gastric cancer proliferation

and metastasis via the TGFβ/TGIF2 pathway. Pathol Res Pract.

269:1558992025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Missan DS, Chittur SV and DiPersio CM:

Regulation of fibulin-2 gene expression by integrin α3β1

contributes to the invasive phenotype of transformed keratinocytes.

J Invest Dermatol. 134:2418–2427. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang MR, Chen RJ, Zhao F, Zhang HH, Bi QY,

Zhang YN, Zhang YQ, Wu ZC and Ji XM: Effect of Wenxia Changfu

formula combined with cisplatin reversing non-small cell lung

cancer cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance. Front Pharmacol.

11:5001372020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fontanil T, Álvarez-Teijeiro S, Villaronga

MÁ, Mohamedi Y, Solares L, Moncada-Pazos A, Vega JA, García-Suárez

O, Pérez-Basterrechea M, García-Pedrero JM, et al: Cleavage of

Fibulin-2 by the aggrecanases ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 contributes to

the tumorigenic potential of breast cancer cells. Oncotarget.

8:13716–13729. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Vaes N, Schonkeren SL, Rademakers G,

Holland AM, Koch A, Gijbels MJ, Keulers TG, de Wit M, Moonen L, Van

der Meer JRM, et al: Loss of enteric neuronal Ndrg4 promotes

colorectal cancer via increased release of Nid1 and Fbln2. EMBO

Rep. 22:e519132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Senapati S, Gnanapragassam VS, Moniaux N,

Momi N and Batra SK: Role of MUC4-NIDO domain in the MUC4-mediated

metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 31:3346–3356.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

33

|