Introduction

Intimate intercellular communication between breast

cancer (BC) cells and other cells in the surrounding

microenvironment exerts a significant influence on a number of key

processes, including primary tumor growth, metastasis evolution and

immune escape. In particular, the breast is a fat-rich organ and BC

development and progression are strongly influenced by the intimate

and highly vicious cycle between adipocytes, which act as endocrine

cells, and tumor cells (1). The

main methods of cell-to-cell communication are direct contacts

involving adhesion molecules and indirect contacts through

classical paracrine signaling mediated by secreted molecules

(2,3). Beyond the secretion of various

soluble factors (for example, leptin and adiponectin) (4-13),

adipocyte-derived EVs, a heterogeneous group of membrane-enclosed

structures, have emerged as an essential part of the adipocyte

secretome (14), acting as key

mediators of intercellular communication and contributing to

autocrine, paracrine and endocrine communication (15). Indeed, EVs are capable of

transferring a multitude of biological molecules, including

proteins, nucleic acids and lipids, which can subsequently alter

the biology of the recipient cells. In this situation, it has been

demonstrated that EVs derived from 3T3-L1 adipocytes, a widely used

in vitro model for white adipocytes, sustain proliferation,

migration and invasion and response to therapy in several cancer

cell lines through multiple mechanisms (16-21). For instance, melanoma cell lines

treated with adipocyte-derived EVs exhibit more aggressive

features, including elongated morphology and actin-rich membrane

profusion along with an increased cell migration in vitro

and lung colonization in vivo (18). Furthermore, it has been also

demonstrated that 3T3-L1-EV adipocytes promote lung cancer cell

invasion in vitro and in vivo through an increased

activity of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) (16). In another study, EVs derived from

3T3-L1 adipocytes were reported to: i) Promote the proliferation of

prostate cancer cells, ii) sustain their migratory capabilities and

iii) confer resistance to docetaxel. This is achieved through a

mechanism involving the Akt/hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1α)

axis, which is accompanied by enhanced glycolysis and ATP

production (17). The involvement

of the HIF-1α/von Hippel-Lindau axis in modulating the protumoral

effects of adipocyte-derived EVs has been also reported in

hepatocellular carcinoma (19).

In line with this evidence, our research group also found that

3T3-L1 adipocyte-derived EVs support BC cell proliferation, growth,

migration and invasion as well as their metastatic potential via

the induction of HIF-1α levels and activity (20).

The present study employed proteomic analysis to

gain deeper insights into the role of EVs in breast adiponcosis,

providing novel evidence on the role of adipocyte-derived EVs in

sustaining mitochondrial metabolism in BC cells through HIF-1α.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Dexamethasone, 3-Isobutyl-1-Methylxanthine and

bovine insulin were purchased from Merck KGaA. KC7F2 (cat. no.

S7946) from Selleck Chemicals LLC. Tumor susceptibility gene 101

(Tsg101; cat. no. MA1-23296) was purchased from Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. ALIX (cat. no. ab186429) and total OXPHOS (cat.

no. ab110411) cocktail was purchased from Abcam. CD81 (cat. no.

sc-166029); Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90; cat. no. sc-7947);

Calnexin (cat. no. sc-11397), HIF-1α (cat. no. sc-13515), TOM20

(cat. no. sc-17764), β-Actin (cat. no. sc-47778) and GAPDH (cat.

no. sc-166545) were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.

Cell cultures

Human MCF-7 (cat. no. HTB-22), ZR-75-1 (cat. no.

CRL-1500) and BT-474 (cat. no. HTB-20) BC epithelial cells and

murine 3T3-L1 (cat. no. CRL-1500) pre-adipocytes were acquired from

American-Type-Culture-Collection (ATCC) and cultured in accordance

with supplier specifications. MCF-7 and ZR-75-1 cells were cultured

in EMEM medium and RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

respectively, containing 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamine and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). BT-474

cells were cultured in ATCC Hybri-Care Medium supplemented with 10%

FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Every six months, cells were

authenticated by single tandem repeat analysis at our Sequencing

Core; morphology, doubling times and estrogen sensitivity and

tested for mycoplasma negativity (MycoAlert; Lonza Group Ltd.).

Isolation of extracellular vesicles

(EVs)

Isolation of 3T3-L1 adipocyte-derived

EVs

EVs were isolated from murine 3T3-L1 and 3T3-L1

adipocytes (3T3-L1A) conditioned media. Briefly, 3T3-L1 and 3T3-L1A

cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 24 h and EVs were

obtained from the resulting conditioned medium using differential

ultracentrifugation (20).

Isolation of normal weight (NW) and

overweight/obese (OW/Ob) EVs

EVs from serum samples of NW and OW/Ob female

patients with BC were isolated by the ExoQuick isolation agent

(System Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA, USA), following the

manufacturer's instructions (22). A total of 45 biological samples,

with an age range of 30-73 years for NW group and 36-83 years for

OW/Ob groups, were collected, between May 2016 and February 2020,

at the Department of Molecular Medicine and Medical Biotechnology,

University of Naples Federico II. The samples were stored at −80°C

until use. The study protocol was reviewed and approved (approval

no. 107/05) by the Ethics Committee of the University of Naples

Federico II (Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences).

Isolated EVs were stored at −80°C and characterized

by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Nanoparticle tracking

analysis (NTA) and immunoblotting. For TEM analysis, the

EV-containing aliquots were diluted in sterile NaCl 0.9% and then

added onto formvar-carbon coated grids (Electron Microscopy

Sciences, cat. no. FCF400-Cu). The grids were blotted dry at room

temperature. The imaging process was conducted using a Jeol JEM

1400 Plus transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo,

Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. NTA was

performed as previously reported (20). As storage at −80°C maintains EV

stability, with minimal changes in size, concentration and protein

content (23,24), these EVs were used in the

respective experiments reported in the current study.

Gene silencing transfection

Cells were transfected with small interfering

(si)HIF-1α silencer validated siRNA (cat. no. 4390824; ID s6541)

and with silencer select negative control (NC; cat. no. 4390843)

(Ambion; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), using

Lipofectamine® RNAi/MAX reagent (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manual instructions.

Specifically, 35×104 MCF-7 BC cells were transfected

with 50 pmol of both validated (si)HIF-1α silencer siRNA and

silencer select negative control and plated in 6-well plates. After

24 h, transfected cells were plated for mitotracker analysis

(35×104 cells in 6-well plates) and for seahorse

analysis (104 cells in XFe-96 well plates). Assays were

then performed as described.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot were performed as previously described

(25). Specifically, cell

extracts or EV lysates were obtained using RIPA buffer

(Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with protease inhibitor. 50 μg

of proteins, previously quantified by Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit

(cat. no. 23227; Thermo Fishers Scientific, Inc.) were resolved on

10% SDS polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose

membranes by using power blotter XL system (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with 5%

milk in tris-buffered saline for 1 h at room temperature, which was

followed by incubation overnight at 4°C in bovine serum albumin 5%

with primary antibodies. Specifically, anti-Tsg101 (cat. no.

MA1-23296; dilution 1:1,000); anti-ALIX (cat. no. ab186429;

dilution 1:1,000); total OXPHOS cocktail (cat. no. ab110411;

dilution 1:1,000); CD81 (cat. no. sc-166029; dilution 1:500); HSP90

(cat. no. sc-7947; dilution 1:500); Calnexin (cat. no. sc-11397;

dilution 1:1,000), HIF-1α (cat. no. sc-13515; dilution 1:200);

TOM20 (cat. no. sc-17764; dilution 1:1,000), β-Actin (cat. no.

sc-47778; dilution 1:10,000) and GAPDH (cat. no. sc-166545;

dilution 1:10,000) primary antibodies were used. IRDye 600 and

800CW Goat anti-Mouse or anti-Rabbit (LI-COR, Inc.) IgG secondary

antibodies were used at 1:15,000 dilution. Images were acquired

using Odyssey FC (LI-COR, Inc.) and ImageJ software was used to

quantify the band of interest (v.1.52a, NIH, USA).

Proteomic analysis

Filter-aided sample protocol (FASP)

digestion

The cells were lysed with RIPA buffer and the

protein digestion procedure was subsequently performed according to

the FASP method (26) using 10

kDa molecular cut-off microcon filters. According to the digestion

protocol, 50 μg of cell lysate was mixed with 10% SDS, 500

mM DTT, 1 M Tris HCl, pH 8.0 and incubated at 650 rpm for 10 min at

95°C. After incubation, the samples were allowed to reach to room

temperature and loaded onto the FASP filter. The protocol is

characterized by several distinct steps including two washes with

200 μl of 8M UREA (8 M UA, 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0)

and subsequent centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 20 min at room

temperature, followed by the addition of 50 μl of 50 mM

Iodioacetamide (IAA) and centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 20 min at

room temperature. After the alkylation reaction, two washes with 8M

UREA and two washes with 50 mM TEAB were performed. Enzymatic

digestion was then performed overnight at 37°C by adding 500 ng of

proteomics grade trypsin (MilliporeSigma) in 60 μl of 50 mM

TEAB buffer at pH 8.5.

SCX (strong cation exchange)

purification

The next day H2O (140 μl) was

added and the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min at

room temperature to collect 180-200 μl of digest. Then, 40

μl (corresponding to 10 μg of digested peptides) of

each extract were purified by StageTip SCX as described by

Rappsilber et al (27), to

remove detergent residues. Before proceeding with SCX purification,

tryptic digests were acidified with 360 μl of Wash B [80%

acetonitrile/0.5% formic acid (v/v)], to reduce the salt

concentration. Acidified tryptic peptides were then loaded onto

StageTips containing approximately 100 μg of a cation

exchange resin (Millipore Extraction Disks; MilliporeSigma) that

had before been conditioned with Wash A [20% acetonitrile/0.5%

formic acid (v/v)] and Wash B. After two washes with 50 μl

of Solution W2 and 50 μl of Solution W1, respectively, the

peptides were eluted by the addition of 10 μl of 500 mM

ammonium acetate-20% acetonitrile and were then diluted by adding

90 μl of 0.1% formic acid. Then, 1 μl of the purified

sample was used for preliminary liquid chromatography-tandem mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. Following the preliminary

injections, the final injections were performed. In particular, for

each biological replicate, three LC-MS/MS injections were performed

(technical replicate).

LC-MS/MS analysis

For peptide separation, the present study employed

an easy nlC-1000 chromatographic instrument coupled to an Exploris

480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For

LC-MS/MS analysis, samples were separated using a 14 cm, 75

μm i.d. column, packed in-house with 3 μm C18 silica

particles (Dr. Maisch HPLC GmbH). The peptides were eluted from the

column with a binary gradient of 140 min and a flow rate of 300

nl/min. The following mobile phases were used: Mobile phase A [2%

acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (v/v)] and mobile phase B [80%

acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (v/v)]. The peptide separation were

obtained at a flow rate of 300 nl/min as follows: From 0% B to 3% B

in 1 sec, from 3% B to 8% B in 40 min and from 42% B to 100% B in

13 min; the column was cleaned for 5 min with 100% B. The samples

were analyzed in Data Independent Acquisition (DIA) mode. The DIA

method included 60 windows (45 windows with an isolation window of

8 m/z, 10 windows with an isolation of 16 m/z and 5 windows with an

isolation of 28 m/z). Full MS scans were performed in the range

from 350 m/z up to 1,000 m/z with 60000 of resolution (AGC target

Custom; maximum injection time 50 and collision energy 25).

Statistical analysis of proteome

data

The RAW files were analyzed using the Spectronaut

software (version 13.0; Biognosys AG). The search was performed

with Direct DIA mode. Protein quantification was performed using

the following parameters: Active precursor filtering (it required

the precursor to be quantified in at least 20% of the runs);

imputation by run wise imputing, Major Group Top N (Max 10-Min 1).

Missing values at the protein quant level were 2006, averaging at

~111 proteins per sample (2.5%) and were handled in Spectronaut

using the following parameters: Active precursor filtering (it

required the precursor to be quantified in at least 20% of the

runs); imputation by run wise imputing. The resulting matrix, which

contained no missing values since already imputed in Spectronaut,

was then imported into Perseus (version 2.0.6.0;

Max-Planck-Gesellschaft) to perform the necessary statistical

analysis (28). The data were

transformed using a logarithmic scale (log2). Protein

quantities from technical replicates (separate LC-MS/MS injections)

were combined using the median value. Finally, the unpaired

two-sample t-test was used to assess the statistical significance

of protein abundances. Correction for multiple hypothesis testing

was permutation-based (FDR <0.05). The principal component

analysis (PCA) plot was generated by using the R packages (version

4.4.2; https://www.R-project.org/),

'Factoextra' (version 1.0.7, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra) and

'ggplot2' (version 3.5.2; https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org); 95% confidence limits

within the PCA plot were calculated using the function

'fviz_pca_ind' in the 'Factoextra' package.

Analysis of protein annotations

The resulting protein list was subjected to

different annotation tools for further in-depth analysis. For

functional makeup of the identified proteins Bionic Visualizations

Proteomaps was used (https://www.proteomaps.net). All de-regulated proteins

(39 upregulated and 59 downregulated) were used for the

analyses.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network construction

The PPI network of the candidate proteins was

generated using STRING version 12.0 (https://string-db.org/cgi/input?sessionId=bp7GGoXn66Fl&input_page_show_search=on).

Functional enrichment analysis

De-regulated proteins identified in MCF-7 cells

treated with 3T3-L1A-EVs were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) and

biological pathway enrichment analysis using FunRich tool

(http://www.funrich.org) against human FunRich

background database. P≤0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference and the GO results were ranked

by P-value. The top 10 significant pathways in the de-regulated

proteins were exhibited as bar charts. The same bioinformatics tool

was employed to construct a Venn diagram, with the objective of

evaluating the potential overlap between the identified

de-regulated proteins and EV proteins that have been previously

annotated in Vesiclepedia (version 5.1, http://www.microvesicles.org/) and Exocarta (version

3.1, http://www.exocarta.org/) databases.

Gene set enrichment analysis

(GSEA)

GSEA was performed using the Molecular Signatures

Database (MSigDB; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) to examine

the gene expression profiles of de-regulated proteins identified in

MCF-7 cells treated with 3T3-L1A-EVs. The analysis included

overlaps with GO categories: GO:BP (Biological Process), GO:CC

(Cellular Component) and GO:MF (Molecular Function). Results were

visualized using the ggplot2 package in R.

Pathway enrichment analysis

The analysis of signaling pathways in which

de-regulated proteins identified in MCF-7 cells treated with

3T3-L1A-EVs are involved was performed using the REACTOME free

online database (https://reactome.org/). The resulting data were

visualized in R using the ggplot2 package.

Seahorse XFe96 metabolic profile

analysis

By using XFe-96 well cell culture plates MCF-7,

ZR-75-1 and BT-474 cells were seeded in 150 μl of regular

growth medium for 24 h (104 cells/well). The next day, 2

μg/ml of 3T3-L1A-EVs were added to Exo-depleted medium

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 48 h. The real-time oxygen

consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular acidification rates

(ECAR) were assessed by using mito stress and glycolysis stress

assays, respectively (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The day prior to

assay a sensor cartridge was hydrated using Seahorse XF Calibrant

at 37°C for 1 h in a non-CO2 incubator. On the day of

the experiment, cells were in prewarmed XF assay media (10 mM

glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine to assess OCR levels; 2 mM

L-glutamine to measure ECAR levels and adjusted to pH 7.4) and

cells were maintained at 37°C for 1 h in a CO2-free

incubator. Then, 1.5 μM Oligomycin, 0.5 μM FCCP and

0.5 μM Rotenone/0.5 μM Antimycin A mix were

sequentially injected to measure mitochondrial activity. To assess

glycolytic activity 10 mM glucose, 1 μM Oligomycin and 50 mM

M2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) were sequentially injected. The data were

then normalized using the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay.

Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay

Trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 10%) was added to cells

(1 h at 4°C), then SRB dye was used (30 min; Acid Red 52; Merck

KGaA) and the cells washed two times with 1% acetic acid. The cells

were left to air dry for a minimum of 3 h. Finally, 10 mM Tris pH

8.8 solution was added and the absorbance measured at a wavelength

of 565 nm (Multiskan SkyHigh; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Determination of cellular ATP

levels

MCF-7 cells were plated in 1.5 ml of Exo-depleted

medium into 6 well-plates for 24 h (35×104 cells/well)

and the next day treated or not with the same amount (2

μg/ml) of EVs for 48 h. Intracellular ATP levels were

determined by using an ATP Assay Kit (cat. no. ab83355; Abcam) and

optical density (570 nm) was measured using a microplate reader

(Multiskan SkyHigh; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). ATP levels

were normalized to cell number.

Assessment of mitochondrial mass and

mitochondrial membrane potential

Cells were plated in 1.5 ml of regular growth medium

into 6 well-plates (35×104 cells/well) and the next day

were treated or not with 2 μg/ml of 3T3-L1A-EVs for 48 h in

Exo-depleted medium. At the end of the treatment, cells were

trypsinized and equally divided into two separate tubes. Each

aliquot was then incubated with a different probe

[MitoTracker® Deep Red FM or MitoTracker®

Orange CMTMRos (Thermo Fisher scientific, Inc.) 10 nM in PBS for

30-60 min at 37°C] to assess mitochondrial mass and membrane

potential, respectively, by FACS analysis (CytoFLEX Beckman,

Beckman Coulter, Inc.). For data analysis, manual gating was used

to remove debris and doublets and analysis was performed at

constant events (104) in each sample (Fig. S1). Data analysis was performed

using CytExpert Beckman Coulter software (version 2.4, Beckman

Coulter, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired

Student's t test for the comparison between two groups and one-way

ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test for the

comparison between multiple variables by using GraphPad Prism 8

(GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics) and the results were reported

as the mean ± SD or ± SEM, as indicated, of at least 3 independent

experiments, each performed in triplicate. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

3T3-L1A-derived EVs affect the proteomic

profile of BC cells

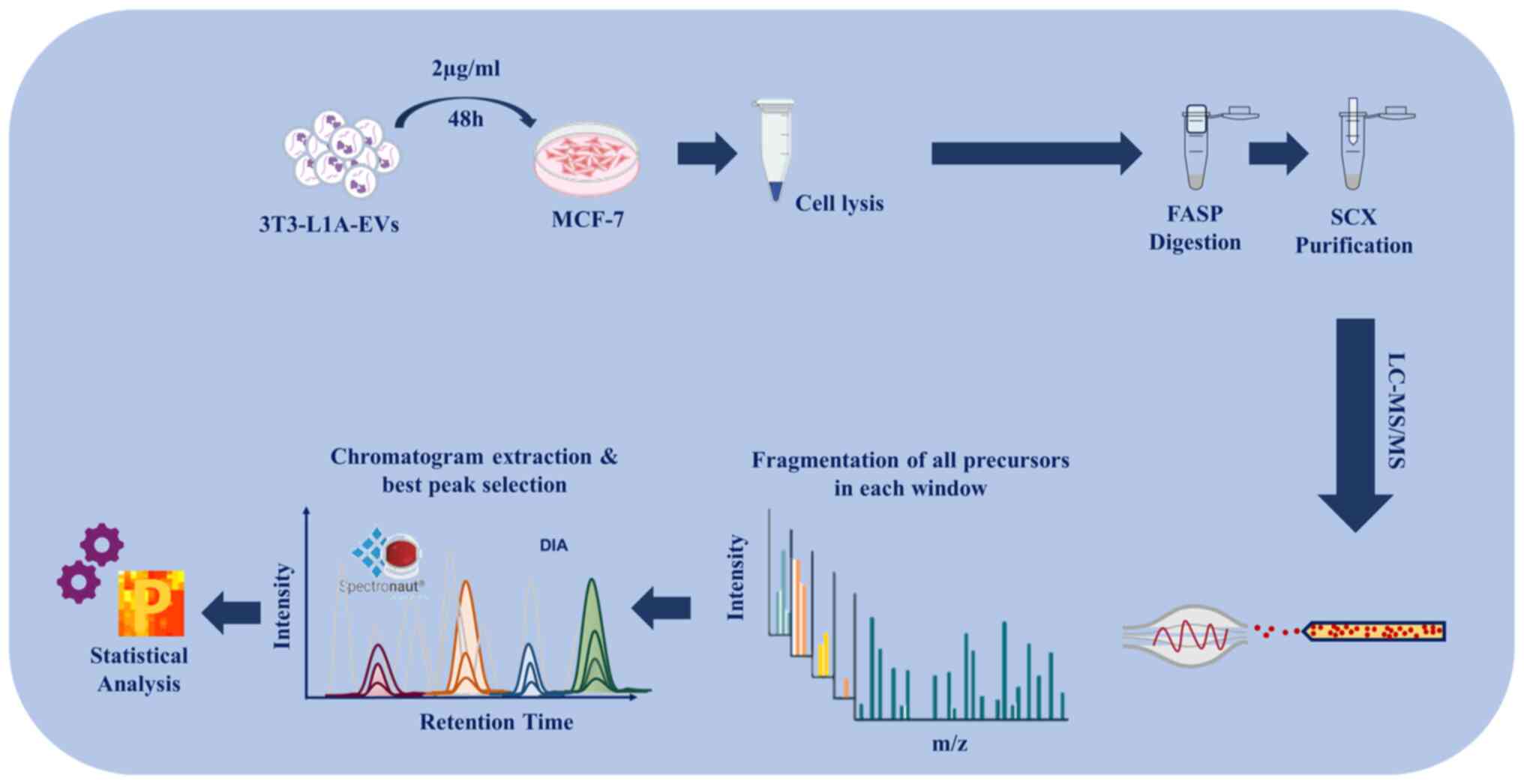

In order to evaluate the effect of EVs on the

proteomic profile of BC cells, the present study used stored and

fully characterized EVs, which had previously been isolated from

the conditioned media derived from 3T3-L1A cells, the most commonly

used in vitro model for white adipocytes (20). EVs were characterized by

transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Nanoparticle tracking

analysis (NTA) and immunoblotting. Specifically, TEM analysis

confirmed that EVs exhibited the characteristic oval or cup-shaped

morphology, enclosed within a lipid bilayer membrane (Fig. S2A) and the NTA analysis revealed

that the mode diameter remained consistently below 200 nm in all

isolated EVs (Fig. S2B).

Immunoblotting showed an enrichment of the EV hallmarks, including

Alix, CD81, Tsg101 and HSP90, while the negative marker Calnexin

was not detected in all isolated EVs (Fig. S2C). Estrogen receptor-positive

(ER+) MCF-7 BC cells were treated for 48 h with 2 μg/ml EVs

and then cells were subjected to LC-MS/MS, by using FASP protocol

and DIA. Raw data were analyzed by using Spectronaut and Perseus

(statistical analysis) software. A schematic diagram of the

experimental design of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

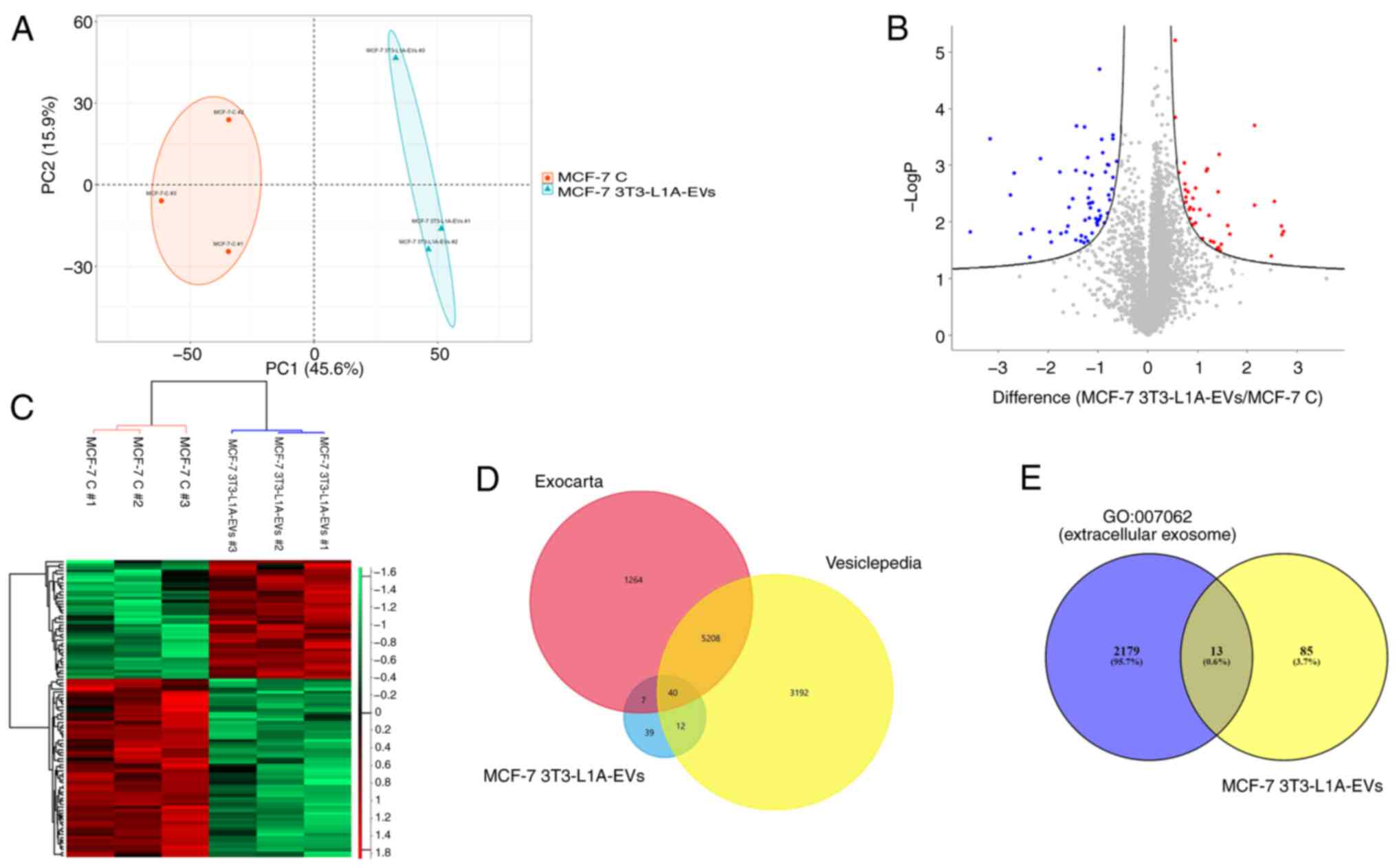

PCA indicated good reproducibility of the technical

replicates and injections demonstrating the different

two-dimensional distribution between the three replicates of each

sample (untreated and treated samples). Furthermore, the PCA

revealed that the EV-treated cells clustered separately from the

untreated cells, highlighting a significant difference in the

proteomes of the two different conditions (Fig. 2A). LC-MS/MS analysis allowed us to

identify 4,411 proteins (FDR <0.05). Prior to imputation, only

very few proteins were exclusively identified and quantified in

either one of the two conditions; in particular, syntenin-1,

ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 4 and vinexin were

exclusively identified in control MCF-7 cells, whereas

skin-specific protein 32 was exclusively detected in 3 analyses of

3T3-L1A-EV-treated MCF-7 cells. Among the proteins revealed by

LC-MS/MS analysis, 98 proteins were found to be differentially

expressed in 3T3-L1A-EV-treated MCF-7 cells, with a P≤0.05

(Table I). Of these, 39 proteins

were upregulated and 59 proteins downregulated, as reported in the

volcano plot (Fig. 2B). The

hierarchical cluster analysis confirmed the alteration in protein

levels between MCF-7 cells treated with 3T3-L1A-EVs and untreated

cells (Fig. 2C). In addition,

when the de-regulated proteins were compared with those identified

in the Vesiclepedia and Exocarta databases, it was found that 40 of

them could be attributed to vesicular origin (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the association of

the 98 differentially expressed proteins in 3T3-L1A-EVs-treated

MCF-7 cells were investigated with the 'extracellular exosome' gene

ontology (GO:0070062). It is notable that a total of 13 proteins

(gene names: PLG, APOD, PRKCA, CLIC1, SAMM50, HLA-B, GPRC5A,

GSTM2, PPIC, AASDHPPT, NEDD8, LAMTOR1 and VTN) were

found to be associated with the 'extracellular exosome' gene

ontology (Fig. 2E).

| Table IThe 98 de-regulated proteins

identified in the comparison MCF-7 3T3-L1A-EV treated cells vs.

untreated cells. |

Table I

The 98 de-regulated proteins

identified in the comparison MCF-7 3T3-L1A-EV treated cells vs.

untreated cells.

| Gene name | Fold change | Protein

descriptions |

|---|

| ATPIF1 | 6.6 | ATPase inhibitor,

mitochondrial |

| PLG | 6.5 | Plasminogen |

| USMG5 | 6.5 | Up-regulated during

skeletal muscle growth protein 5 |

| RABIF | 5.8 | Guanine nucleotide

exchange factor MSS4 |

| ANTXR2 | 5.6 | Isoform 4 of

Anthrax toxin receptor 2 |

| COX17 | 4.4 | Cytochrome c

oxidase copper chaperone |

| FBXO7 | 4.4 | F-box only protein

7 |

| AGPAT1 | 3.1 |

1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate

acyltransferase alpha |

| POLR2G | 3.1 | DNA-directed RNA

polymerase II subunit RPB7 |

| STAG2 | 2.8 | Cohesin subunit

SA-2; Isoform 2 of Cohesin subunit SA-2 |

| YARS2 | 2.7 | Tyrosine-tRNA

ligase, mitochondrial |

| MAP4K5 | 2.7 | Mitogen-activated

protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 5 |

| AFAP1 | 2.7 | Actin

filament-associated protein 1 |

| PRKCA | 2.7 | Protein kinase C

alpha type |

| BTF3 | 2.6 | Isoform 2 of

Transcription factor BTF3 |

| TUBGCP2 | 2.5 | Gamma-tubulin

complex component 2 |

| MRPL4 | 2.4 | 39S ribosomal

protein L4, mitochondrial |

| NSUN4 | 2.4 | 5-methylcytosine

rRNA methyltransferase NSUN4 |

| GEMIN6 | 2.3 | Gem-associated

protein 6 |

| PPM1H | 2.3 | Protein phosphatase

1H |

| TMEM38B | 2.2 | Trimeric

intracellular cation channel type B |

| IRF2BP1 | 2.1 | Interferon

regulatory factor 2-binding protein 1 |

| MPDU1 | 1.9 | Mannose-P-dolichol

utilization defect 1 protein |

| TBC1D23 | 1.9 | TBC1 domain family

member 23; Isoform 2 of TBC1 domain family member 23 |

| ACOT8 | 1.9 | Acyl-coenzyme A

thioesterase 8 |

| KRI1 | 1.9 | Protein KRI1

homolog |

| WDR6 | 1.9 | WD

repeat-containing protein 6 |

| PATL1 | 1.8 | Protein PAT1

homolog 1; Isoform 2 of Protein PAT1 homolog 1 |

| HLA-B | 1.8 | HLA class I

histocompatibility antigen, B-14 alpha chain |

| FHL3 | 1.8 | Four and a half LIM

domains protein 3 |

| CMC1 | 1.8 | COX assembly

mitochondrial protein homolog |

| ALG8 | 1.7 | Probable dolichyl

pyrophosphate Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 alpha-1,3-glucosyltransferase; |

| XIAP | 1.7 | E3

ubiquitin-protein ligase XIAP |

| TAPBP | 1.7 | Tapasin; Isoform 2

of Tapasin; Isoform 3 of Tapasin |

| DDX50 | 1.7 | ATP-dependent RNA

helicase DDX50 |

| IFI6 | 1.7 | Interferon

α-inducible protein 6 |

| PPP1R10 | 1.5 |

Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 1

regulatory subunit 10 |

| SUMO1 | 1.5 | Small

ubiquitin-related modifier 1; |

| SCRN3 | 1.5 | Secernin-3; Isoform

2 of Secernin-3 |

| PPIC | 0.6 | Peptidyl-prolyl

cis-trans isomerase C |

| NOP14 | 0.6 | Nucleolar protein

14 |

| CLIC1 | 0.6 | Chloride

intracellular channel protein 1 |

| PFDN6 | 0.6 | Prefoldin subunit

6 |

| HNRNPR | 0.6 | Heterogeneous

nuclear ribonucleoprotein R |

| RABGGTB | 0.6 | Geranylgeranyl

transferase type-2 subunit beta |

| JMJD6 | 0.6 | Bifunctional

arginine demethylase and lysyl-hydroxylase JMJD6 |

| RPP30 | 0.6 | Ribonuclease P

protein subunit p30; Isoform 2 of Ribonuclease P protein subunit

p30 |

| MRPL57 | 0.6 | Ribosomal protein

63, mitochondrial |

| COIL | 0.6 | Coilin |

| CRBN | 0.6 | Protein cereblon;

Isoform 2 of Protein cereblon |

| SAMM50 | 0.5 | Sorting and

assembly machinery component 50 homolog |

| CHRAC1 | 0.5 | Chromatin

accessibility complex protein 1 |

| CCDC175 | 0.5 | Coiled-coil

domain-containing protein 175 |

| NEDD8 | 0.5 | NEDD8 Ubiquitin

Like Modifier |

| LAMTOR1 | 0.5 | Regulator complex

protein LAMTOR1 |

| TOP2B | 0.5 | DNA topoisomerase

2-β; Isoform β-1 of DNA topoisomerase 2-β |

| MTIF2 | 0.5 | Translation

initiation factor IF-2, mitochondrial |

| SEMA4C | 0.5 | Semaphorin-4C |

| ZNF687 | 0.5 | Zinc finger protein

687; Isoform 2 of Zinc finger protein 687 |

| DERA | 0.5 |

Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase |

| CNOT3 | 0.5 | CCR4-NOT

transcription complex subunit 3 |

| DEGS1 | 0.5 | Sphingolipid

delta(4)-desaturase DES1 |

| ENOPH1 | 0.5 | Enolase-phosphatase

E1 |

| GOLM1 | 0.5 | Golgi membrane

protein 1; Isoform 2 of Golgi membrane protein 1 |

| RPL7L1 | 0.5 | 60S ribosomal

protein L7-like 1 |

| LAMTOR5 | 0.5 | Regulator complex

protein LAMTOR5 |

| GID8 | 0.4 | Glucose-induced

degradation protein 8 homolog |

| WDR3 | 0.4 | WD

repeat-containing protein 3 |

| CBX1 | 0.4 | Chromobox protein

homolog 1 |

| TPM1 | 0.4 | Isoform 10 of

Tropomyosin alpha-1 chain; Isoform 4 of Tropomyosin alpha-1

chain |

| GSKIP | 0.4 | GSK3-beta

interaction protein |

| RNPS1 | 0.4 | RNA-binding protein

with serine-rich domain 1 |

| UBQLN2 | 0.4 | Ubiquilin-2 |

| GPRC5A | 0.4 | Retinoic

acid-induced protein 3 |

| APOD | 0.4 | Apolipoprotein

D |

| TAF10 | 0.4 | Transcription

initiation factor TFIID subunit 10 |

| EIF1 | 0.4 | Eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 1 |

| GSTM2 | 0.4 | Glutathione

S-transferase Mu 2; Isoform 2 of Glutathione S-transferase Mu

2 |

| AASDHPPT | 0.4 |

L-aminoadipate-semialdehyde

dehydrogenase-phosphopantetheinyl transferase |

| NUP62 | 0.4 | Nuclear pore

glycoprotein p62 |

| NDUFAB1 | 0.4 | Acyl carrier

protein, mitochondrial |

| ESYT2 | 0.4 | Isoform 6 of

Extended synaptotagmin-2 |

| ARL1 | 0.4 | ADP-ribosylation

factor-like protein 1; Isoform 2 of ADP-ribosylation factor-like

protein 1 |

| ESYT1 | 0.3 | Isoform 2 of

Extended synaptotagmin-1 |

| LMBR1L | 0.3 | Protein LMBR1L |

| TAMM41 | 0.3 | Phosphatidate

cytidylyltransferase, mitochondrial |

| L3HYPDH | 0.3 |

Trans-L-3-hydroxyproline dehydratase |

| HAS1 | 0.3 | Hyaluronan synthase

1 |

| DAAM1 | 0.3 |

Disheveled-associated activator of

morphogenesis 1 |

| NECAB1 | 0.3 | N-terminal EF-hand

calcium-binding protein 1 |

| GTF2A1 | 0.2 | Transcription

initiation factor IIA subunit 1 |

| TMEM128 | 0.2 | Transmembrane

protein 128 |

| AURKA | 0.2 | Aurora kinase

A |

| MT-ND2 | 0.2 | NADH-ubiquinone

oxidoreductase chain 2 |

| C1QBP | 0.2 | Complement

component 1 Q subcomponent-binding protein, mitochondrial |

| TAGLN3 | 0.1 | Transgelin-3 |

| VTN | 0.1 | Vitronectin |

| ABRACL | 0.1 | Costars family

protein ABRACL |

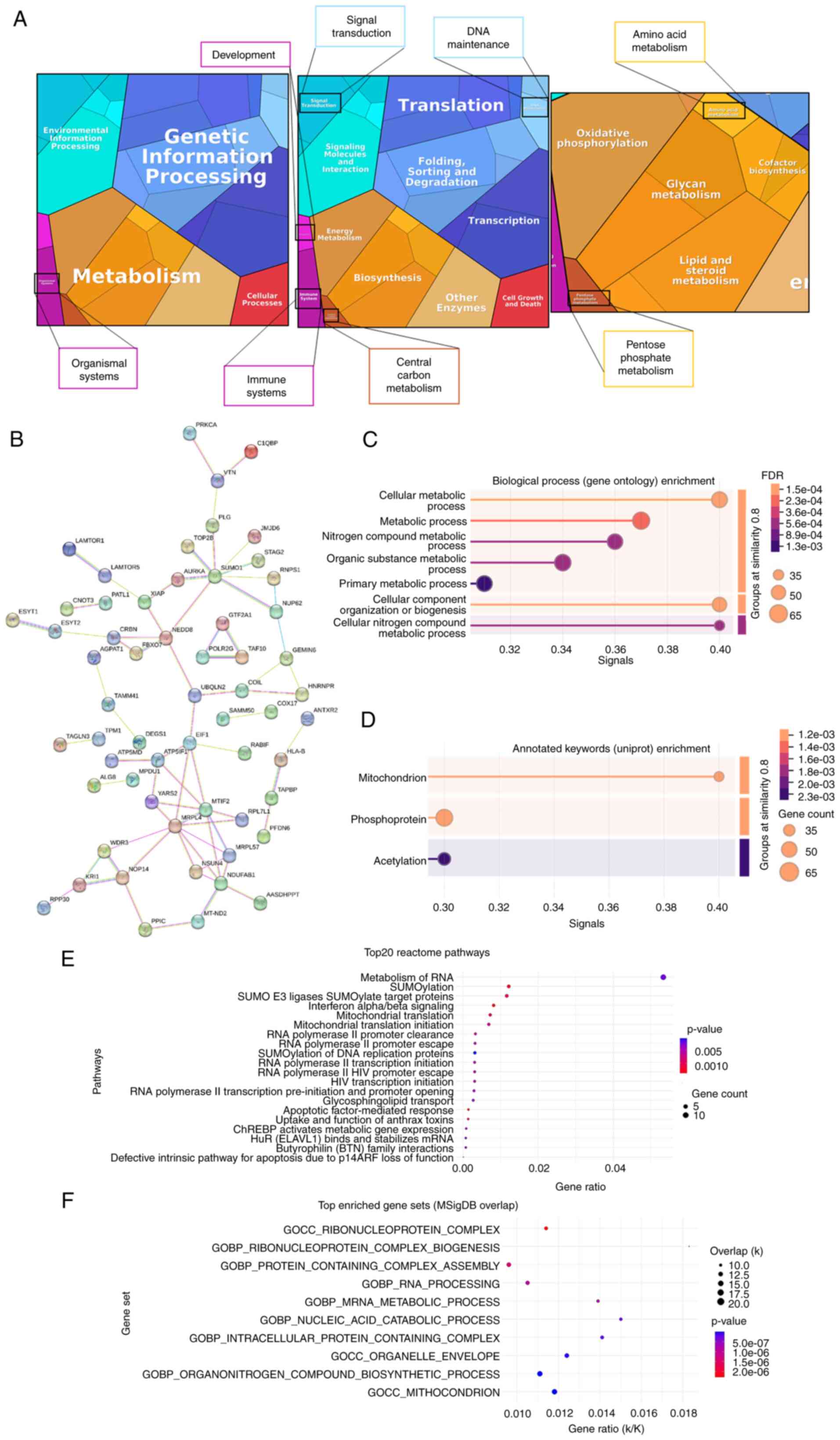

To investigate the biological significance of the 98

de-regulated proteins revealed by proteomic analysis, the proteome

of 3T3-L1A EV-treated MCF-7 cells was summarized into a proteomap

(29) (https://www.proteomaps.net), wherein each protein is

represented by a polygon which size is proportional to the

protein's abundance. Taking into account the protein fold

regulation, the present study gathered functional information

clustered in five categories: Genetic information processing

(blue), metabolism (orange), environmental information processing

(cyan), cellular processes (red) and organismal systems (pink)

(Fig. 3A). At the broadest level,

most proteins identified in EV-treated MCF-7 cells have been

assigned to the following biological processes: Genetic information

processing and metabolism, especially in terms of biosynthesis and

energy metabolism. In the category of metabolism, the de-regulated

proteins were involved into the oxidative phosphorylation,

lipid/steroid metabolism, glycan metabolism, cofactor biosynthesis,

amino acid metabolisms and pentose phosphate metabolism (Fig. 3A). The interactions of the 98

de-regulated proteins identified by proteomic analysis were

analyzed using the STRING software (https://string-db.org/cgi/input?sessionId=bAzNH23SoAwP&input_page_show_search=on).

The established network shown in Fig.

3B contained 98 nodes and MRLP4, MTIF2 and

NDUFAB1 had more degree of connection. Subsequently, a

functional enrichment analysis was conducted, which corroborated

the aforementioned findings. The 98 de-regulated proteins were

found to be involved in metabolic processes and in mitochondria. In

particular, cellular metabolic process (58 proteins; FDR: 0.0015),

cellular component organization or biogenesis (52 proteins; FDR

0.0018), cellular nitrogen compound metabolic process (37 proteins;

FDR 0.0046) and metabolic process (64 proteins; FDR 0.0021) were

among the first five biological processes (Fig. 3C). In addition, mitochondrion (18

proteins; FDR 0.0124) was the top subcellular localization

(Fig. 3D). In the Reactome

Pathway analysis (https://reactome.org/), the present study found

'Metabolism of RNA', 'SUMOylation', 'SUMO E3 ligases SUMOylate

target proteins', 'Interferon alpha/beta signaling', 'Mitochondrial

translation' and 'Mitochondrial translation initiation' among the

top five enrichment pathways ranked by P-value (Fig. 3E). Moreover, among the cellular

component GOs, 'mitochondrion' resulted the top enriched GO in the

Molecular Signatures Database analysis (MSigDB; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/; Fig. 3F), in term of overlap and P-value.

In order to conduct a more thorough investigation into the function

of the 98 de-regulated proteins identified in MCF-7 cells treated

with 3T3-L1A-EVs, the present study also conducted an evaluation of

their potential association with other GOs, including 'ATP

biosynthetic process', 'ADP metabolic process', 'response to

hypoxia' and 'glycolytic process'. No relevant associations were

found, except for NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 2, which

showed an association with 'ATP biosynthetic process' and 'response

to hypoxia' and for Acyl carrier protein, mitochondrial, which was

associated with 'ATP biosynthetic process' (data not shown).

The present study also used FunRich (http://www.funrich.org) platform to obtain GO

enrichments of the all de-regulated proteins. According to the

cellular component, the de-regulated proteins were clustered in

'mitochondrion' (21.2%), in 'nucleolus' (17.6%) and in 'cytoplasm'

(52.9%; Fig. S3A). In the

context of 'biological process', the investigated proteins were

markedly enriched in GOs such as 'protein modification' (2.1%),

'anti-apoptosis' (2.1%), 'lipid metabolism' (2.1%) and protein

metabolism' (13.4%; Fig. S3B).

Moreover, among the GO 'molecular functions' the de-regulated

proteins were mainly related to 'chaperone activity' (4.1%), a

family of proteins known to be regulators of metabolic processes

(30) (Fig. S3C).

Therefore, the present study sought to ascertain

whether 3T3-L1A-EVs might exert an influence on metabolism in BC

cells.

3T3-L1A-EVs support oxidative

phosphorylation of ER-positive BC cells

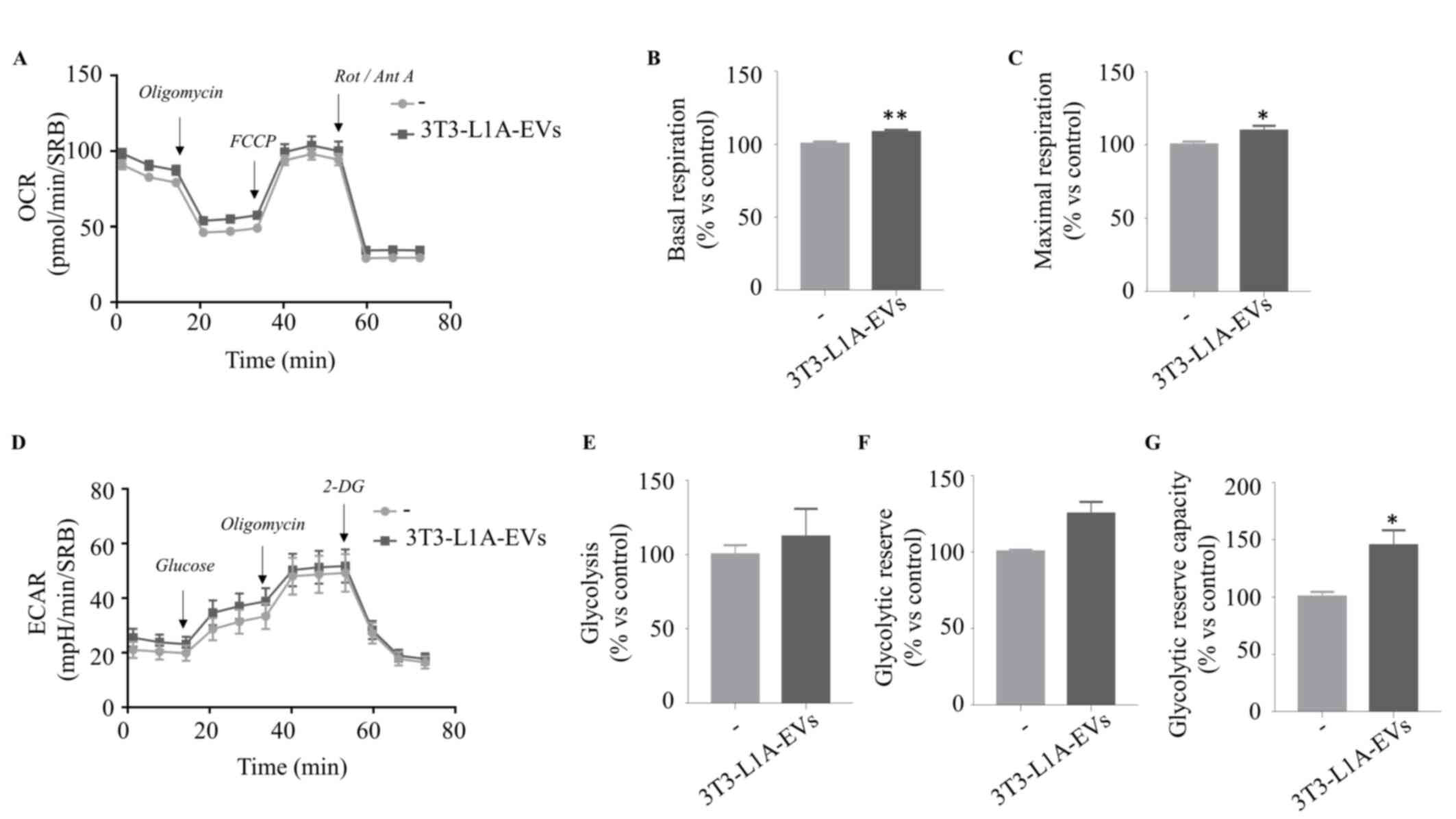

In order to validate the hypothesis that EVs

isolated from 3T3-L1 adipocytes can affect the metabolism of BC

cells, the present study investigated possible changes in the OCR

and the ECAR by using the Seahorse Extracellular Flux (XFe96)

Analyzer. OCR is a well-established indicator of mitochondrial

respiration rate because oxygen consumption by respiration is a

fundamental function of the mitochondria, mainly used in the

process of ATP production. Thus, the present study performed Mito

Stress Test that measures OCR levels in real time by sequential

injections of oligomycin, an inhibitor of ATP synthase (complex V),

carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), an

uncoupling molecule that disrupts the mitochondrial membrane

potential and a mixture of rotenone and antimycin A, inhibitors of

complex I and III, respectively (Fig.

4A). 3T3-L1A-EVs markedly increased basal (Fig. 4B) and maximal respiration

(Fig. 4C) of MCF-7 cells compared

with the control group. Meanwhile, by sequentially injecting a

saturating concentration of glucose, oligomycin and 2-DG, an

analogue of the glucose that inhibits glycolysis, ECAR, the release

of protons into the extracellular milieu generated by anaerobic

glycolysis, was estimated (Fig.

4D). The data showed that 3T3-L1A-EV treatment did not affect

glycolysis (Fig. 4E) or

glycolytic reserve (Fig. 4F), but

they markedly increased the glycolytic reserve capacity (Fig. 4G), which is the difference between

glycolytic capacity and glycolysis rate. It is noteworthy that the

glycolytic reserve is indicative of the capacity of cells to

enhance ATP production via glycolysis in response to stress or

other physiologically demanding circumstances. It was found that

pre-adipocyte-derived EVs (3T3-L1-EVs) had no detectable effects on

mitochondrial activity in MCF-7 cells (Fig. S4), further confirming previous

data that 3T3-L1-EVs failed to promote malignant features in BC

cells (20) and supporting the

notion that functional changes in tumor cells are specifically

driven by EVs from differentiated adipocytes.

To further support these findings, we also used two

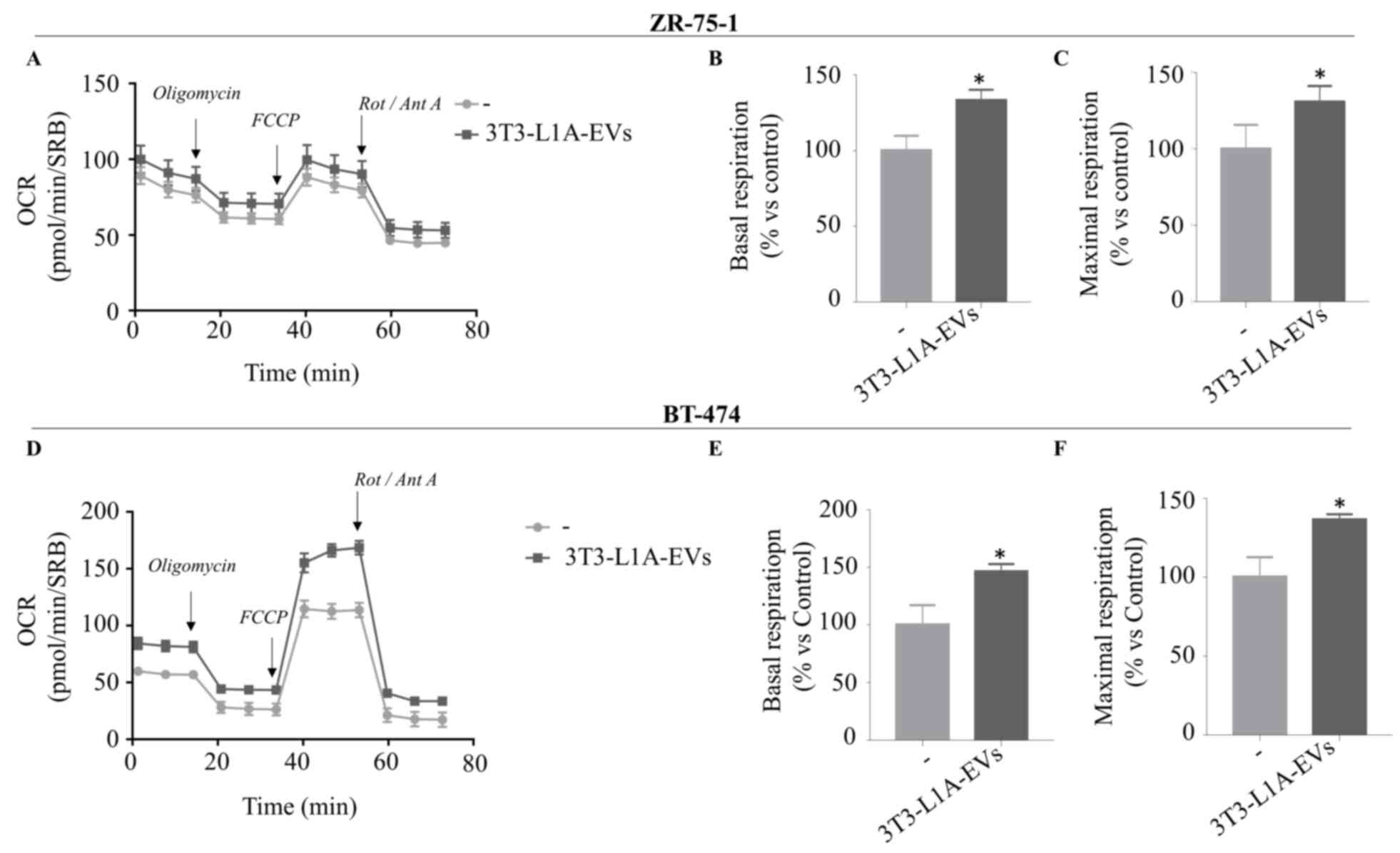

additional ER+ BC cell lines as ZR-75-1 (Fig. 5A-C) and BT-474 (Fig. 5D-F) and found that 3T3-L1A-EVs

affected mitochondrial respiration of both experimental models.

Therefore, EVs isolated from mature adipocytes may promote the

mitochondrial metabolism of BC cells, leading to an increase in

energy production in different cellular background.

As it is widely known that ATP production through

oxidative phosphorylation is markedly greater than that produced by

glycolysis alone, the present study also investigated the ATP

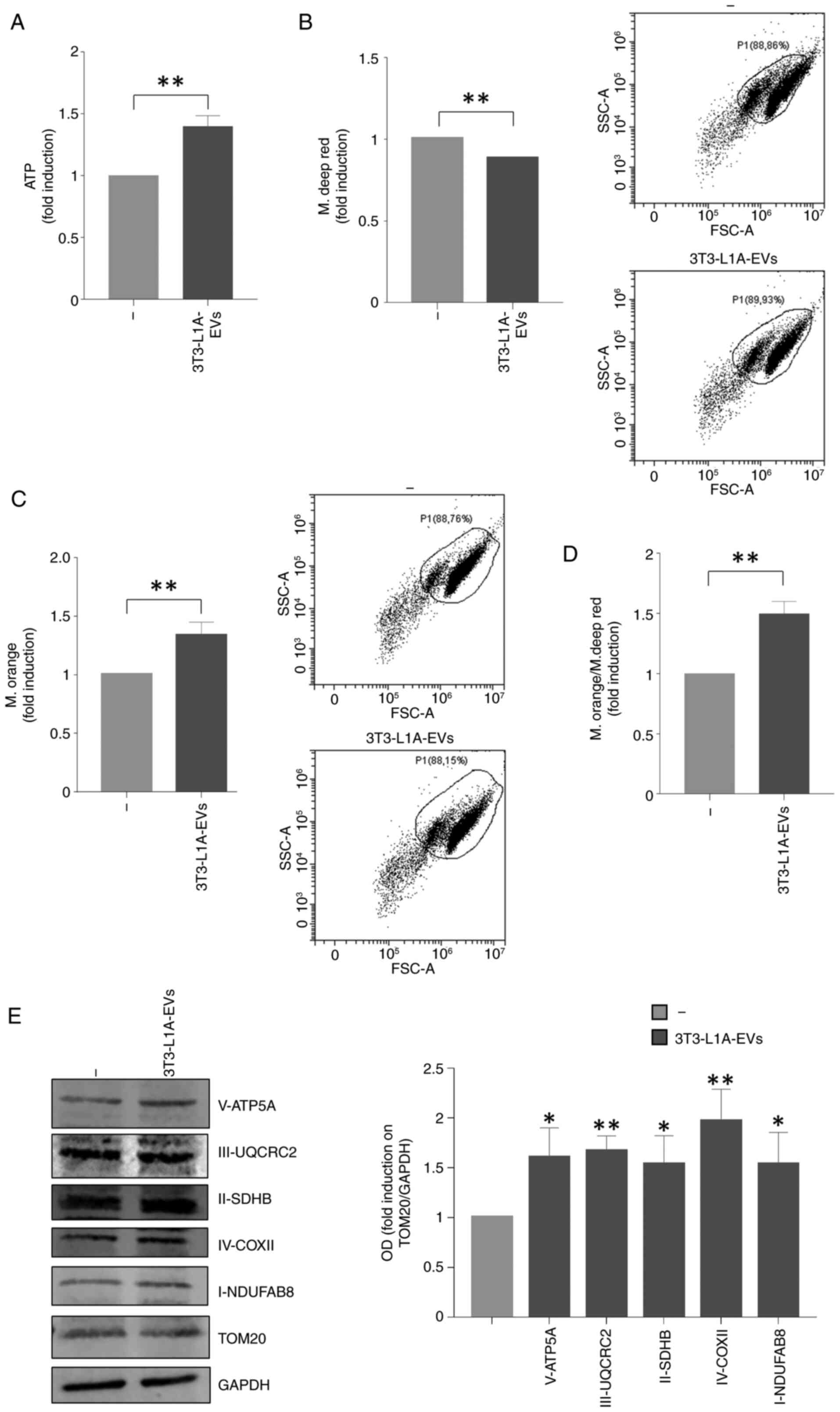

amounts in BC cells treated with 3T3-L1A-EVs. Notably, 3T3-L1A-EVs

enhanced the ATP production in MCF-7 BC cells (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the present study

investigated the mitochondrial phenotype of MCF-7 cells treated

with 3T3-L1A-EVs employing FACS analysis by using two different

dyes able to discriminate mitochondrial mass (MitoTracker Deep Red)

and mitochondrial membrane potential (MitoTracker Orange). There

was a slight reduction of mitochondrial mass along with a

significant increase in mitochondrial membrane potential in MCF-7

cells treated with 3T3-L1A-EVs compared with the control group

(Fig. 6B and C). Consequently,

the ratio of mitochondrial membrane potential/mitochondrial mass

confirmed elevated mitochondrial activity in MCF-7 EVs-treated

cells compared with the control group (Fig. 6D). In addition, an increase in

mitochondrial markers from Complexes I to V was observed in

EV-treated MCF-7 cells compared to control (Fig. 6E).

The aforementioned events confirmed the role of

3T3-L1A-EVs in regulating cell energy production by sustaining

mitochondrial function in BC cells.

HIF-1α is a potential mediator of the

effects of 3T3-L1A-EVs on BC cell metabolism

We have previously demonstrated that HIF-1α plays a

role in mediating the effects of 3T3-L1A-EVs on BC cell biology

(20). Indeed, treatment of BC

cells with 3T3-L1A EVs resulted in increased mRNA and protein

expression of HIF-1α as well as in an upregulation of well-known

HIF-1α target genes (such as VEGF, Ob, MMP-2,

MMP-9 and SERPINE1). Accordingly, inhibition of

HIF-1α activity using KC7F2, able to downregulate HIF-1α protein

synthesis and its transcriptional activity, or using a specific

siHIF-1α, resulted in the reversal of the promoting effects of

3T3-L1A-EVs on BC cell motility, invasion and metastasis (20). In light of these findings, the

present study sought to investigate the potential involvement of

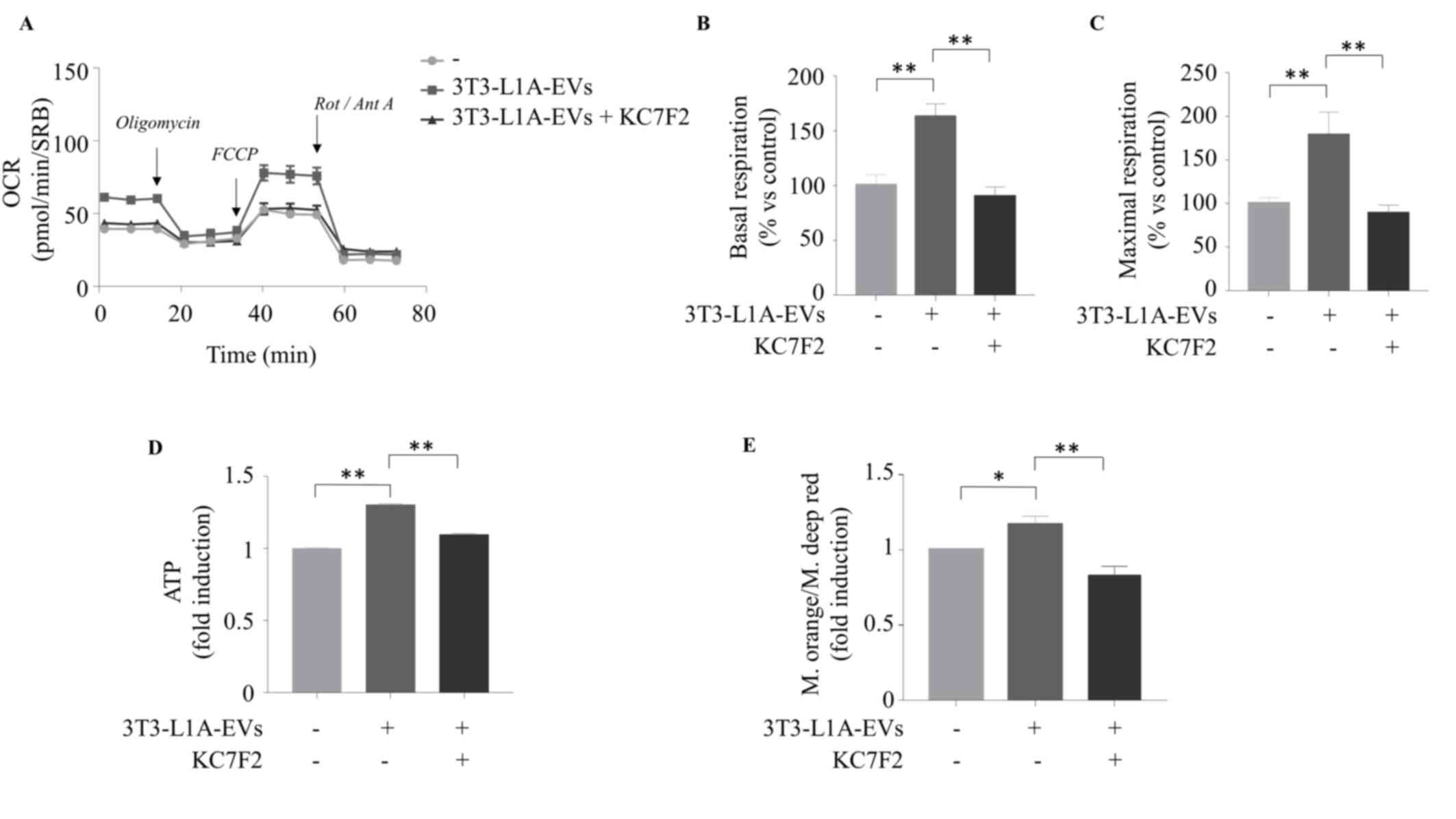

HIF-1α in mediating the metabolic effects of 3T3-L1-EVs. As a first

step, the specific HIF-1α inhibitor KC7F2 was used at 20 μM,

a concentration previously shown to be non-toxic both in

vitro and in vivo (20). It was found that the inhibition of

HIF-1α activity, using KC7F2, reversed the effects of 3T3-L1A-EVs

in increasing mitochondrial respiration in MCF-7 BC cells, which

exhibited levels comparable to those observed in the control group

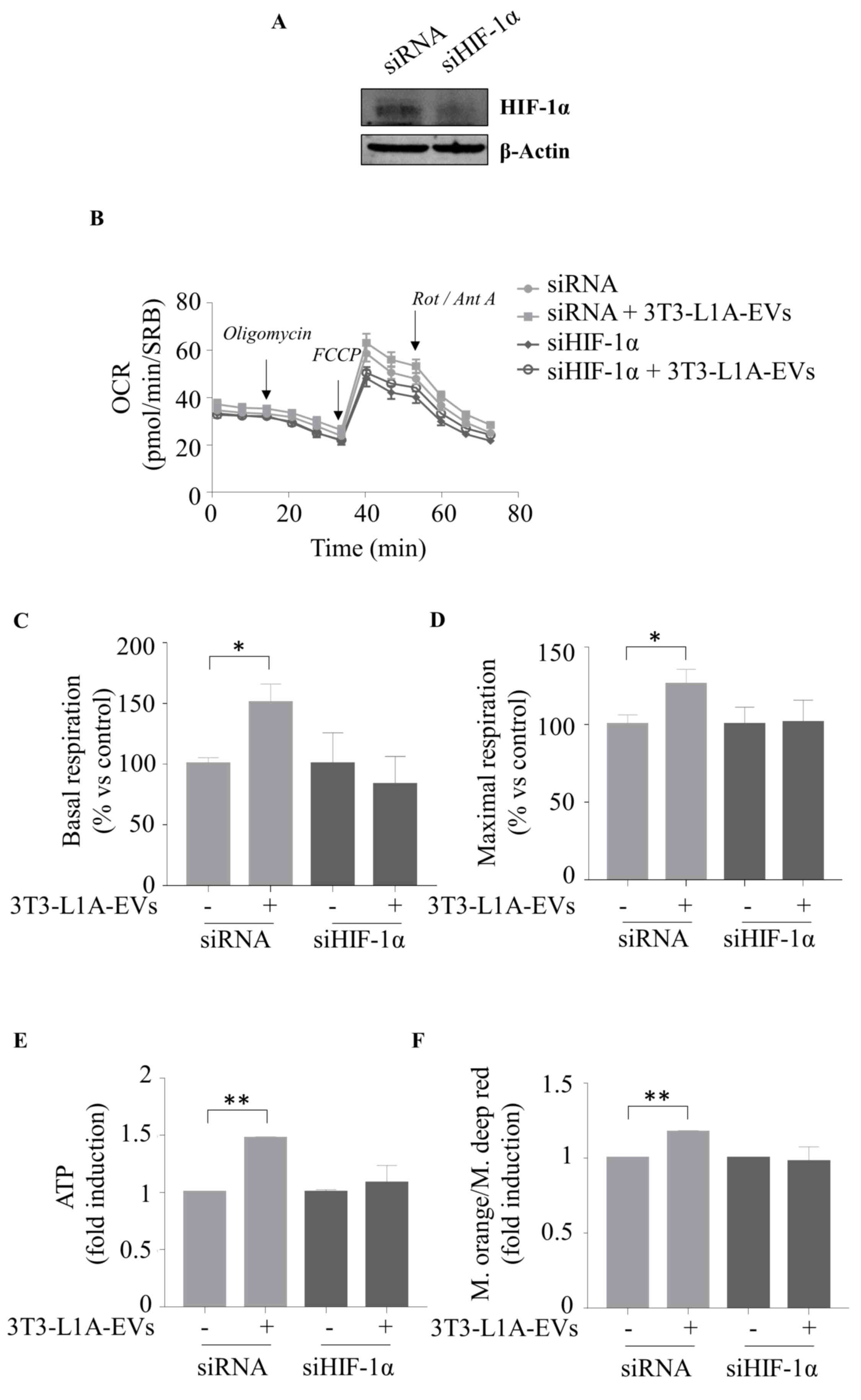

(Fig. 7A-C). Data were confirmed

by knocking down HIF-1α expression in MCF-7 BC cells (Fig. 8A-D). Specifically, HIF-1α

silencing (Fig. 8A) counteracted

3T3-L1A-EV-mediated effect on basal (Fig. 8C) and maximal (Fig. 8D) respiration. The aforementioned

data were further corroborated through an analysis of the ATP

levels conducted under the same experimental conditions.

Particularly, the specific blockade of HIF-1α activity (Fig. 7D and E) as well as its reduced

expression (Fig. 8E and F)

counteracted the ATP production and the mitochondrial activity

observed in MCF-7 cells when exposed to 3T3-L1A-EVs, further

supporting the potential involvement of HIF-1α in mediating the

effects of 3T3-L1A-EVs on BC cell metabolism.

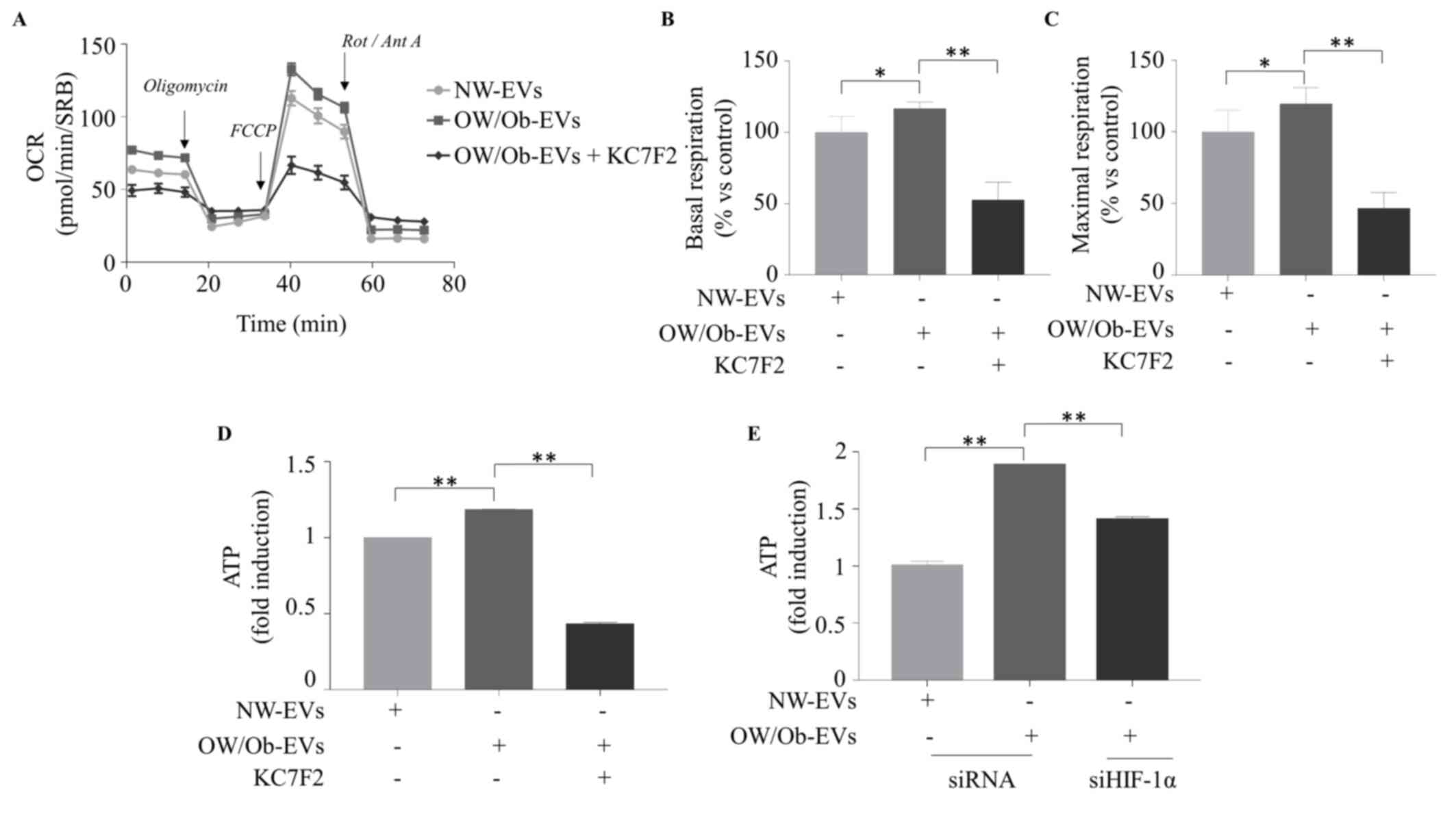

| Figure 7HIF-1α specific blockade inhibits

3T3L-1A-EV effects on cell metabolism and energy production. The

seahorse XF-e96 analyzer was used to assess the mitochondrial

metabolic profile of MCF-7 cells untreated (-) or treated with

3T3-L1A-EVs (2 μg/ml) for 48 h, in the presence or not of

HIF-1α specific inhibitor (KC7F2, 20 μM). (A) OCR flux and

histograms of different mitochondrial respiratory parameters (B)

basal and (C) maximal respiration. Data were analyzed using one-way

ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test and

represented as ± SEM of five biological replicates from three

independent experiments and normalized to protein content (SRB

assay). (D) ATP production; (E) ratio between mitochondrial

membrane potential and mitochondrial mass of MCF-7 cells untreated

(-) or treated with 3T3-L1A-EVs (2 μg/ml) for 48 h, in the

presence or not of HIF-1α specific inhibitor (KC7F2 20 μM).

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple

comparisons post hoc test and represented as ± SD of three

biological replicates from three independent experiments.

*P≤0.05; **P≤0.01. 3T3-L1A, murine 3T3-L1

adipocytes; EVs, extracellular vesicles; OCR, oxygen consumption

rates; SRB, sulforhodamine B; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide

p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; Rot, rotenone; Ant, Antimycin

A. |

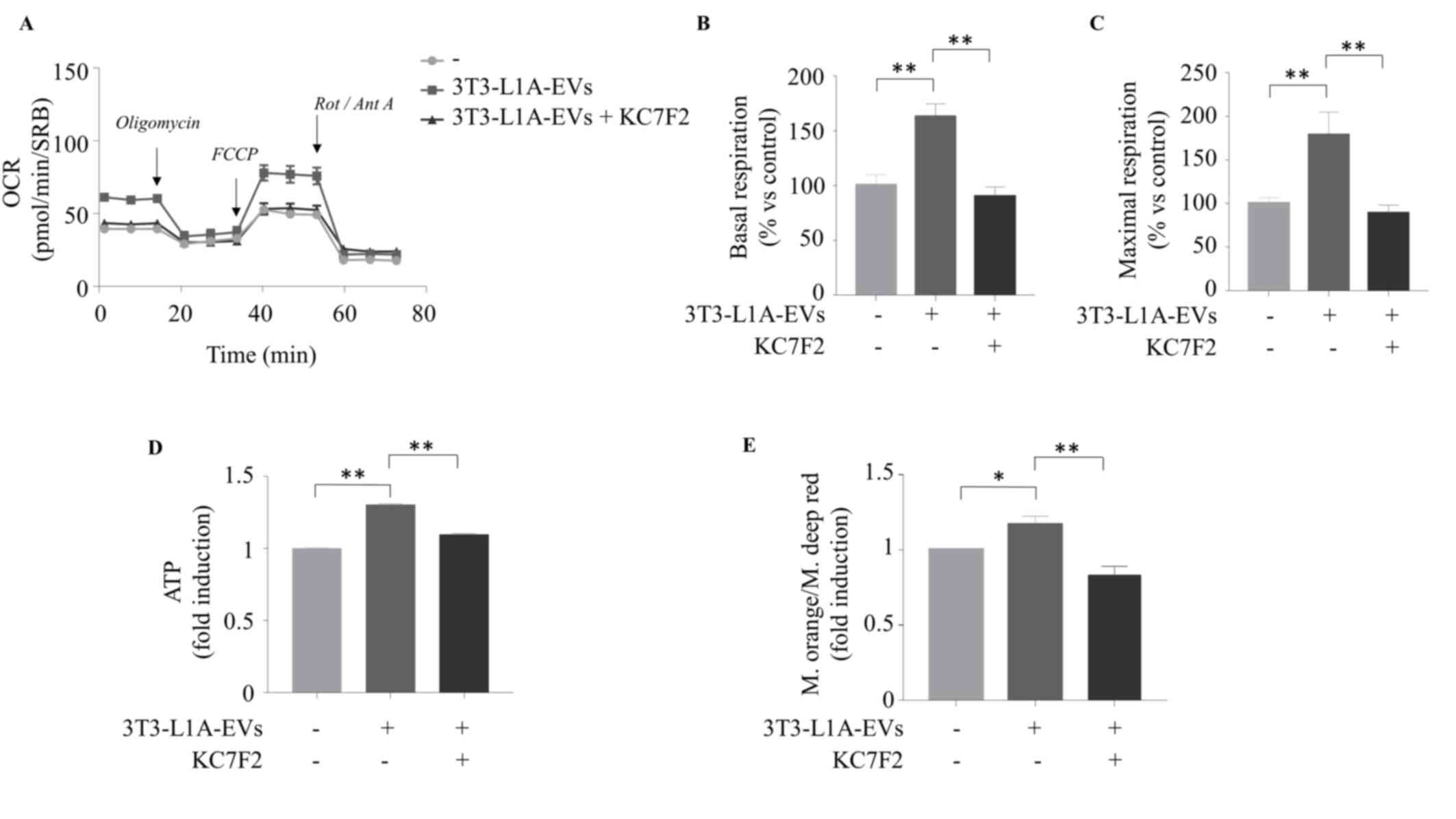

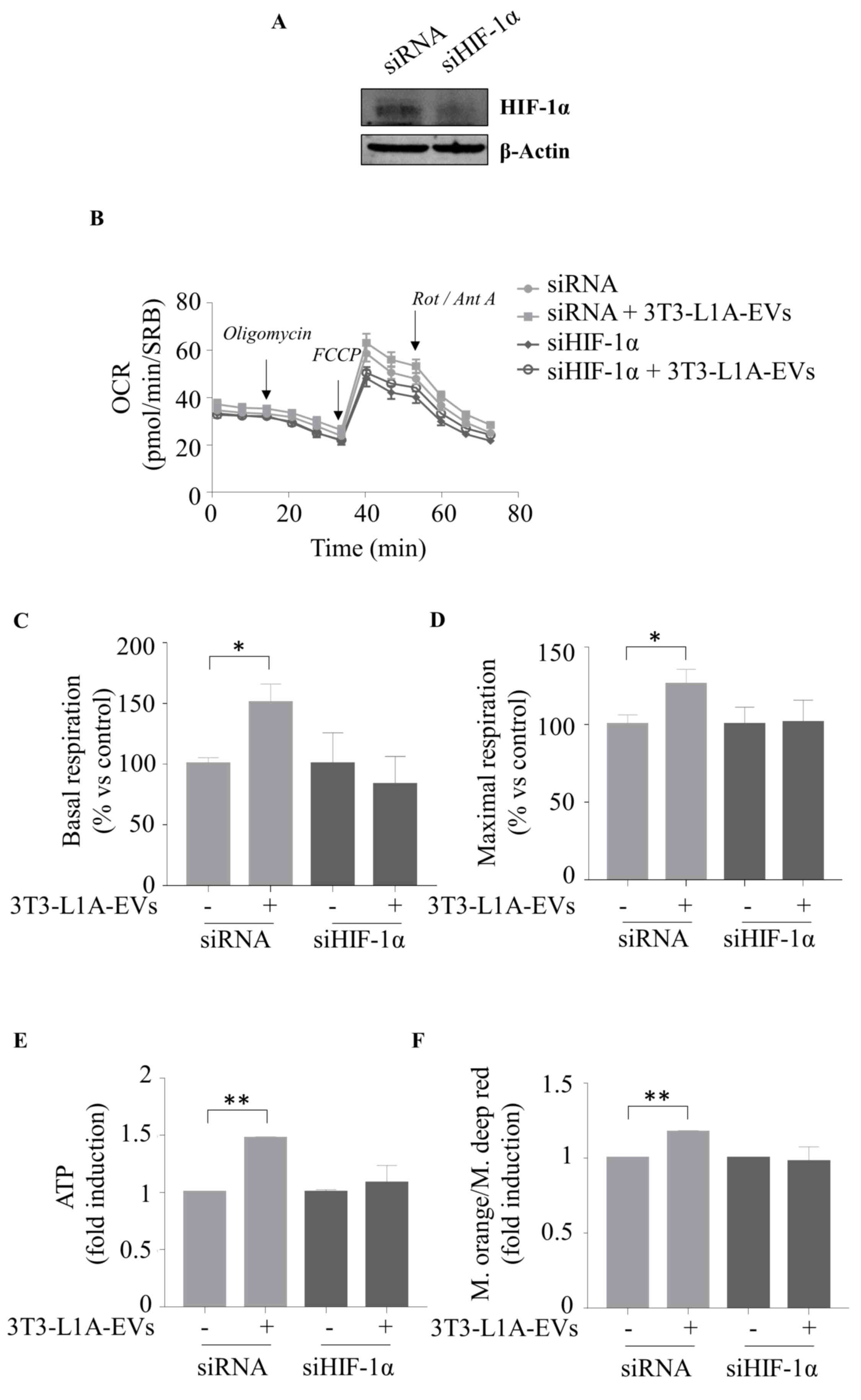

| Figure 8Silencing HIF-1α expression inhibits

3T3L-1A-EV effects on cell metabolism and energy production. (A)

Immunoblot analysis of HIF-1α in whole cell lysate of MCF-7 cells

transfected with negative control siRNA or siHIF-1α for 48 h.

β-Actin was used as a control of equal loading and transfer. The

seahorse XF-e96 analyzer was used to assess the mitochondrial

metabolic profile of MCF-7 cells untreated (-) or treated with

3T3-L1A-EVs (2 μg/ml) for 48 h, previously transfected for

48 h with either siRNA or with siHIF-1α. (B) OCR flux and

histograms of different mitochondrial respiratory parameters such

as (C) basal and (D) maximal respiration. Data were analyzed using

Student's t test and represented as ± SEM of five biological

replicates from two independent experiments and normalized to

protein content (SRB assay). (E) ATP production; (F) ratio between

mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial mass of MCF-7

cells transfected for 48 h with either siRNA or with siHIF-1α and

then untreated (-) or treated with 3T3-L1A-EVs (2 μg/ml) for

48 h. Data were analyzed using Student's t test and represented as

± SD of three biological replicates from two independent

experiments. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01. HIF-1α,

hypoxia inducible factor-1α; 3T3-L1A, murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes;

EVs, extracellular vesicles; si, small interfering; OCR, oxygen

consumption rates; SRB, sulforhodamine B; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide

p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; Rot, rotenone; Ant, Antimycin

A. |

EVs isolated from serum of obese patients

with BC promote mitochondrial metabolism and energy production in

MCF-7 cells via HIF-1α

Finally, in order to reproduce the findings within

the context of obesity, the present study used EVs that had been

isolated from the serum of NW and OW/Ob patients with BC and

characterized by TEM, NTA and immunoblotting as shown in Fig. S2D-F. It was found that EVs

derived from OW/Ob patients increased the basal and maximal

respiration of MCF-7 cells compared with the BC cells treated with

NW-EVs (Fig. 9A-C). Accordingly,

the OW/Ob-EVs enhanced the ATP production in BC cells (Fig. 9D). Of note, the HIF-1α inhibitor

KC7F2 abrogated the up-regulatory effects mediated by OW/Ob-EVs on

mitochondrial respiration and energy production (Fig. 9A-D). Furthermore, the enhanced

effects of OW/Ob-EVs on ATP production in MCF-7 cells were blocked

by a specific siHIF-1α (Fig.

9E).

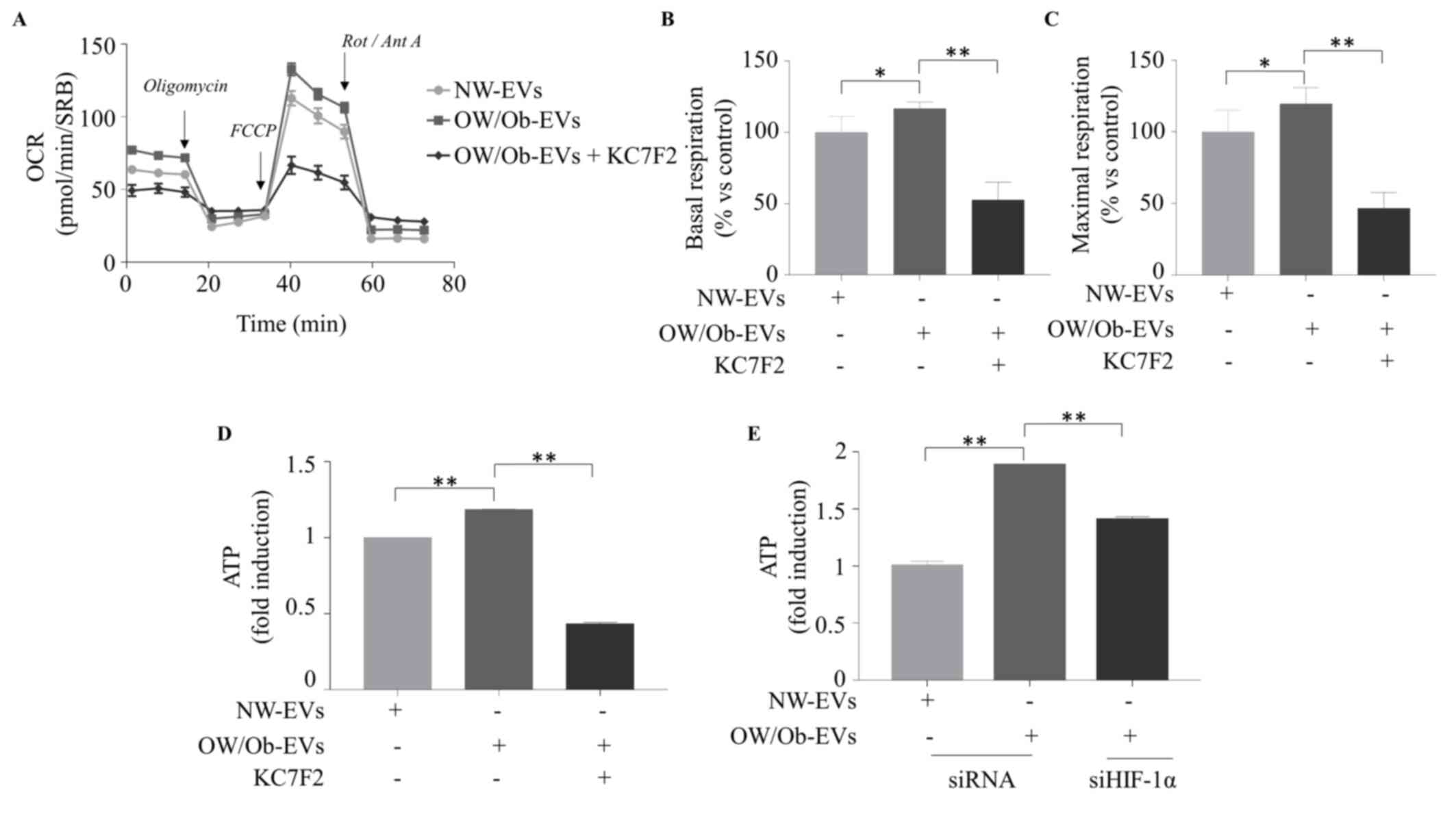

| Figure 9EVs derived from overweight/obese

patients with BC enhance mitochondrial phosphorylation and ATP

production in BC cells through HIF-1α. The seahorse XF-e96 analyzer

was used to assess the mitochondrial metabolic profile of MCF-7

cells treated with EVs (2 μg/ml) isolated from the serum of

NW and OW/Ob patients with BC for 48 h, in the presence or not of

HIF-1α specific inhibitor (KC7F2; 20 μM). (A) OCR flux and

histograms of different mitochondrial respiratory parameters such

as (B) basal (C) and maximal respiration are shown. Data were

analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post

hoc test and represented as ± SEM of five biological replicates

from two independent experiments and normalized to protein content

(SRB assay). ATP production in MCF-7 cells treated as indicated (D)

or transfected with siHIF-1α (E). Data were analyzed using one-way

ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test and

represented as ± SD of three biological replicates from two

independent experiments. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01.

EVs, extracellular vesicles; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor-1α;

NW, normal weight; OW/Ob, overweight/obese; OCR, oxygen consumption

rates; SRB, sulforhodamine B; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide

p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; Rot, rotenone; Ant, Antimycin

A. |

All these data supported the role of HIF-1α as a

potential mediator of the stimulatory effects of EVs on BC cell

metabolism.

Discussion

The complex and multifaceted interaction between

adipocytes and BC cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME)

exerts a profound influence on the development and progression of

BC. However, this dialogue has been largely confined to the various

factors secreted by adipose tissue, as well as adipokines,

cytokines and growth factors (4-13,31-33). Recently, EVs have been identified

as a component of the secretome of adipocytes and EV-mediated

effects represent a pivotal aspect of the dynamic TME. Although,

the majority of current studies focus on elucidating the cargo of

EVs or identifying genomic alterations induced by EVs in cancer

cells, there is still a gap in our knowledge regarding the

potential effects of EVs in modulating the metabolic phenotype of

BC cells. The present study described for the first time how EVs

derived from adipocytes may modify the proteomic profile of BC

cells. The findings demonstrated that these vesicles are able to:

i) Deregulate proteins associated with metabolic processes; ii)

switch the metabolic profile towards mitochondrial respiration; and

iii) enhance ATP production in BC cells. This occurs through a

mechanism involving HIF-1α.

It is now recognized that cells following the

malignant transformation into neoplastic cells rewire cellular

metabolism, essential to satisfy the demand of growth,

proliferation and progression (34-36). The defined metabolic hallmark of

tumor metabolism is aerobic glycolysis, accompanied by an increased

rate of lactate production, phenomenon known as the 'Warburg

effect' (37). Nevertheless,

cancer cells are capable of autonomously reprogramming their

metabolic pathways, enabling rapid adaptation to microenvironmental

changes and the fulfilment of increased bioenergetic demand

(38,39). Tumor-surrounding adipocytes

facilitate metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells by increasing

the availability of fatty acid and supporting beta-oxidation in

cancer cells. This provides an excess of substrate for the

production of ATP and the generation of lipid membranes (40-42). Studies have indicated that adipose

tissue can influence the mitochondrial metabolism of cancer cells

not only in close proximity through the secretion of substrates but

also via EVs (43-46). Particularly, it has been

demonstrated that the cargo of adipocyte-derived EVs may also

contain metabolites that can markedly impact the metabolism of

recipient cells, potentially contributing to cancer progression

(43-46). The present study demonstrated that

adipocyte-derived EVs altered the proteome of BC cells. Notably,

Proteomaps, STRING, REACTOME pathway, MsigDB and FunRich analyses

revealed that de-regulated proteins identified in the EV-treated

cells were highly enriched in GOs mainly related to mitochondrion,

protein metabolism, energy pathways and oxidoreductase activity.

Consequently, functional studies confirmed that adipocyte-derived

EVs enhanced mitochondrial respiration, a trait now regarded as a

hallmark of more aggressive cancers (47-49), in several ER-positive BC cells,

including MCF-7, ZR-75 and BT-474 cells. By contrast, no changes in

glycolysis were detected in the experimental conditions of the

present study. Furthermore, in agreement with these previously

reported data, the present study found that adipocyte-derived EVs

enhanced ATP production as a consequence of increased mitochondrial

activity, as evidenced by mitotracker analysis and the expression

of several mitochondrial markers.

Regarding obesity, a well-established risk factor

for BC, it has been extensively documented that the typical

enlarged adipocytes secrete a greater quantity of EVs that differ

in nature and size when compared with their NW counterparts. These

EVs have profound implications in the pathogenesis of several

malignancies, including breast, endometrial, prostate, colorectal

and melanoma (44-46,50-54). In this frame, our research group

identified a potential mechanism through which the

obesity-associated hormone leptin sustains exosome generation and

modifies the EV cargo in BC cells, thus supporting mitochondrial

metabolism in recipient epithelial tumor cells and macrophages

(52,55). Moreover, analysis of circulating

EV-derived miRNAs in patients with BC revealed a differential miRNA

profile within EVs in relation to a patient's body mass index and

allow the identification of let-7 as a potential obesity-related

miRNA whose downregulation may be associated with tumor progression

(22). It has been reported that

EVs derived from obese adipocytes influence the miRNome of BC cells

by altering their metabolic processes (45). Clement et al (44) conducted a comparative proteomic

analysis of EVs derived from adipocytes of lean and obese mice,

identifying the presence of proteins involved in fatty acid

oxidation (FAO). The horizontally transferred proteins, associated

with FAO, mitochondrial respiration and ATP production, remodel

melanoma metabolism and support aggressiveness. Furthermore, the

modulation of lipid metabolism induced by vesicles derived from

obese patients was also identified as a critical factor in the

development of ferroptosis and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer

cells (46). Consistent with this

evidence, the results of the present study revealed that EVs

isolated from the serum of OW/Ob patients with BC increased the

oxidative phosphorylation and the ATP production in BC cells

compared with those treated with EVs isolated from NW patients.

It has been widely reported that HIF-1α regulates

the expression of numerous genes involved in physiological and

pathological processes, including cell metabolism. Indeed, HIF-1α

is a transcription factor that plays a pivotal role in modulating

tumor metabolism in response to a low-oxygen environment.

Specifically, under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α is responsible for

regulating tumor cell metabolism towards glycolysis. This involves

the overexpression of glucose transporters (such as GLUT1 and GLUT

3) and glycolytic enzymes (such as hexokinase, phosphofructokinase,

aldolase, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase,

phosphoglycerate kinase, enolase, pyruvate kinase, lactate

dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase), which ultimately

results in an increased glucose uptake (56-60). In particular, HIF-1α is also

involved in the interactions between adipocytes and BC cells,

primarily by promoting lipolysis and free-fatty acid release in

adipocytes (61-63). This allows free fatty acid

transfer from the adipocyte to the BC cells, which then initiate

fatty acid metabolism in order to maintain high levels of ATP,

thereby supporting the growth and progression of the tumor

(41). Notably, since obesity is

characterized by adipose tissue hypoxia, HIF-1α expression and

activity resulted increased in obese conditions, with a consequent

release of pro-inflammatory signals (64-66). The present study demonstrated the

direct involvement of HIF-1α in the EV-enhanced effects on BC cell

metabolism. In particular, the pharmacological inhibition of HIF-1α

by using the cystamine compound KC7F2 or genetic inhibition by

employing a siHIF-1α counteracts the stimulatory effects of

adipocyte-derived EVs on the mitochondrial respiration and activity

as well as in the ATP energy production in BC cells. HIF-1α

inhibition was also able to reverse the effects of OW/Ob-EVs on BC

cell metabolic activity, further highlighting HIF-1α as a potential

target for therapeutic strategy in BC, especially in the context of

obesity.

In conclusion, the present study represented a

novel contribution to the growing body of evidence supporting the

involvement of EVs in the obesity-BC link. Investigation into the

function of adipocyte-derived EVs in educating BC cells towards a

more aggressive phenotype may facilitate the discovery of novel

biomarkers or innovative targets (for example, HIF-1α) that might

be involved in metabolic cancer vulnerability. Such discoveries

could then be employed for the purposes of a personalized

therapeutic approach in obese patients with BC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The mass spectrometry

proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange

Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset

identifier PXD059789.

Authors' contributions

LG, IB, CG and SC made substantial contributions to

the conception or design of the work, and drafted the article; LG,

IB and PDC contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or

interpretation of data for the work; MF and PDC contributed to the

acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of metabolism data; MG and

MSM performed, analyzed and intepreted the proteomic data; FG, GDN

and SP performed, analyzed and interpreted the flow-cytometry data;

DB, SA, MG and GA partecipated to the acquisition, analysis, or

interpretation of data from patients. All authors contributed to

revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the ethical

committee of University of Naples 'Federico II' (approval no.

107/05).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by BANDO PRIN 2017 grant no.

2017WNKSLR, PRIN 2022-European NextGenerationEU initiative under

the Italian Ministry of University and Research-M4C2-I1.1 (grant

no. 202239N8PR, CUP H53D23006360006) and PRIN PNRR 2022-European

NextGenerationEU initiative under the Italian Ministry of

University and Research as part of the PNRR-M4C2-I1.1 (grant no.

P2022YAKJY, CUP H53D23010120001) to I. Barone; PRIN 2022, European

NextGenerationEU initiative under the Italian Ministry of

University and Research M4C2-I1.1 (grant no. 2022AA4FTJ, CUP

H53D23006420006) to Giordano C; PRIN PNRR 2022-European

NextGenerationEU initiative under the Italian Ministry of

University and Research as part of the PNRR-M4C2-I1.1 (grant no.

P2022FK2J8, CUP H53D23010420001) to L. Gelsomino; AIRC Investigator

Grant no. 30782 to S. Catalano and grant no. 26246 to S. Andò. The

present study was also funded by the National Plan for NRRP

Complementary Investments grant no. PNC0000003, AdvaNced

Technologies for Human-centrEd Medicine (ANTHEM); POS RADIOAMICA

project funded by the Italian Minister of Health (CUP: grant no.

H53C22000650006); and POS CAL.HUB. RIA project funded by the

Italian Minister of Health (grant no. CUP H53C22000800006).

References

|

1

|

Ambrosio MR, Adriaens M, Derks K,

Migliaccio T, Costa V, Liguoro D, Cataldi S, D'Esposito V, Maneli

G, Bassolino R, et al: Glucose impacts onto the reciprocal

reprogramming between mammary adipocytes and cancer cells. Sci Rep.

14:246742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Dominiak A, Chelstowska B, Olejarz W and

Nowicka G: Communication in the cancer microenvironment as a target

for therapeutic interventions. Cancers (Basel). 12:12322020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhou JX, Taramelli R, Pedrini E,

Knijnenburg T and Huang S: Extracting intercellular signaling

network of cancer tissues using ligand-receptor expression patterns

from whole-tumor and single-cell transcriptomes. Sci Rep.

7:88152017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Andò S, Gelsomino L, Panza S, Giordano C,

Bonofiglio D, Barone I and Catalano S: Obesity, leptin and breast

cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Cancers

(Basel). 11:622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gelsomino L, Giordano C, Camera GL, Sisci

D, Marsico S, Campana A, Tarallo R, Rinaldi A, Fuqua S, Leggio A,

et al: Leptin signaling contributes to aromatase inhibitor

resistant breast cancer cell growth and activation of macrophages.

Biomolecules. 10:5432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Catalano S, Leggio A, Barone I, De Marco

R, Gelsomino L, Campana A, Malivindi R, Panza S, Giordano C,

Liguori A, et al: A novel leptin antagonist peptide inhibits breast

cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Mol Med. 19:1122–1132.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Barone I, Catalano S, Gelsomino L, Marsico

S, Giordano C, Panza S, Bonofiglio D, Bossi G, Covington KR, Fuqua

SA and Andò S: Leptin mediates tumor-stromal interactions that

promote the invasive growth of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res.

72:1416–1427. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Giordano C, Vizza D, Panza S, Barone I,

Bonofiglio D, Lanzino M, Sisci D, De Amicis F, Fuqua SA, Catalano S

and Andò S: Leptin increases HER2 protein levels through a

STAT3-mediated up-regulation of Hsp90 in breast cancer cells. Mol

Oncol. 7:379–391. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Devericks EN, Carson MS, McCullough LE,

Coleman MF and Hursting SD: The obesity-breast cancer link: A

multidisciplinary perspective. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 41:607–625.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Andò S, Naimo GD, Gelsomino L, Catalano S

and Mauro L: Novel insights into adiponectin action in breast

cancer: Evidence of its mechanistic effects mediated by ERα

expression. Obes Rev. 21:e130042020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mauro L, Naimo GD, Gelsomino L, Malivindi

R, Bruno L, Pellegrino M, Tarallo R, Memoli D, Weisz A, Panno ML

and Andò S: Uncoupling effects of estrogen receptor α on LKB1/AMPK

interaction upon adiponectin exposure in breast cancer. FASEB J.

32:4343–4355. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Naimo GD, Forestiero M, Paoli A, Malivindi

R, Gelsomino L, Győrffy B, Leonetti AE, Giordano F, Panza S,

Conforti FL, et al: ERα/LKB1 complex upregulates E-cadherin

expression and stimulates breast cancer growth and progression upon

adiponectin exposure. Int J Cancer. 153:1257–1272. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Naimo GD, Gelsomino L, Catalano S, Mauro L

and Andò S: Interfering role of ERα on adiponectin action in breast

cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 11:662020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hartwig S, De Filippo E, Göddeke S, Knebel

B, Kotzka J, Al-Hasani H, Roden M, Lehr S and Sell H: Exosomal

proteins constitute an essential part of the human adipose tissue

secretome. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 1867:1401722019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Durcin M, Fleury A, Taillebois E, Hilairet

G, Krupova Z, Henry C, Truchet S, Trötzmüller M, Köfeler H,

Mabilleau G, et al: Characterisation of adipocyte-derived

extracellular vesicle subtypes identifies distinct protein and

lipid signatures for large and small extracellular vesicles. J

Extracell Vesicles. 6:13056772017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang J, Wu Y, Guo J, Fei X, Yu L and Ma S:

Adipocyte-derived exosomes promote lung cancer metastasis by

increasing MMP9 activity via transferring MMP3 to lung cancer

cells. Oncotarget. 8:81880–81891. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fontana F, Anselmi M, Carollo E, Sartori

P, Procacci P, Carter D and Limonta P: Adipocyte-derived

extracellular vesicles promote prostate cancer cell aggressiveness

by enabling multiple phenotypic and metabolic changes. Cells.

11:23882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lazar I, Clement E, Dauvillier S, Milhas

D, Ducoux-Petit M, LeGonidec S, Moro C, Soldan V, Dalle S, Balor S,

et al: Adipocyte exosomes promote melanoma aggressiveness through

fatty acid oxidation: A novel mechanism linking obesity and cancer.

Cancer Res. 76:4051–4057. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu Y, Tan J, Ou S, Chen J and Chen L:

Adipose-derived exosomes deliver miR-23a/b to regulate tumor growth

in hepatocellular cancer by targeting the VHL/HIF axis. J Physiol

Biochem. 75:391–401. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

La Camera G, Gelsomino L, Malivindi R,

Barone I, Panza S, De Rose D, Giordano F, D'Esposito V, Formisano

P, Bonofiglio D, et al: Adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles

promote breast cancer cell malignancy through HIF-1α activity.

Cancer Lett. 521:155–168. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jafari N, Kolla M, Meshulam T, Shafran JS,

Qiu Y, Casey AN, Pompa IR, Ennis CS, Mazzeo CS, Rabhi N, et al:

Adipocyte-derived exosomes may promote breast cancer progression in

type 2 diabetes. Sci Signal. 14:eabj28072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Barone I, Gelsomino L, Accattatis FM,

Giordano F, Gyorffy B, Panza S, Giuliano M, Veneziani BM, Arpino G,

De Angelis C, et al: Analysis of circulating extracellular vesicle

derived microRNAs in breast cancer patients with obesity: A

potential role for Let-7a. J Transl Med. 21:2322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Aliakbari F, Stocek NB, Cole-André M,

Gomes J, Fanchini G, Pasternak SH, Christiansen G, Morshedi D,

Volkening K and Strong MJ: A methodological primer of extracellular

vesicles isolation and characterization via different techniques.

Biol Methods Protoc. 9:bpae0092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wu JY, Li YJ, Hu XB, Huang S and Xiang DX:

Preservation of small extracellular vesicles for functional

analysis and therapeutic applications: A comparative evaluation of

storage conditions. Drug Deliv. 28:162–170. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gelsomino L, Caruso A, Tasan E, Leonetti

AE, Malivindi R, Naimo GD, Giordano F, Panza S, Gu G, Perrone B, et

al: Evidence that CRISPR-Cas9 Y537S-mutant expressing breast cancer

cells activate Yes-associated protein 1 to driving the conversion

of normal fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell

Commun Signal. 22:5452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Murfuni MS, Prestagiacomo LE, Giuliano A,

Gabriele C, Signoretti S, Cuda G and Gaspari M: Evaluation of PAC

and FASP performance: DIA-Based quantitative proteomic Analysis.

Int J Mol Sci. 25:51412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rappsilber J, Mann M and Ishihama Y:

Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and

storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat Protoc.

2:1896–1906. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tyanova S, Temu T, Sinitcyn P, Carlson A,

Hein MY, Geiger T, Mann M and Cox J: The Perseus computational

platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat

Methods. 13:731–740. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liebermeister W, Noor E, Flamholz A,

Davidi D, Bernhardt J and Milo R: Visual account of protein

investment in cellular functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

111:8488–8493. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Binder MJ and Pedley AM: The roles of

molecular chaperones in regulating cell metabolism. FEBS Lett.

597:1681–1701. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Caruso A, Gelsomino L, Panza S, Accattatis

FM, Naimo GD, Barone I, Giordano C, Catalano S and Andò S: Leptin:

A heavyweight player in obesity-related cancers. Biomolecules.

13:10842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gelsomino L, Naimo GD, Malivindi R,

Augimeri G, Panza S, Giordano C, Barone I, Bonofiglio D, Mauro L,

Catalano S and Andò S: Knockdown of leptin receptor affects

macrophage phenotype in the tumor microenvironment inhibiting

breast cancer growth and progression. Cancers (Basel). 12:20782020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gelsomino L, Naimo GD, Catalano S, Mauro L

and Andò S: The emerging role of adiponectin in female

malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 20:21272019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Elia I and Haigis MC: Metabolites and the

tumour microenvironment: From cellular mechanisms to systemic

metabolism. Nat Metab. 3:21–32. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chae HS and Hong ST: Overview of cancer

metabolism and signaling transduction. Int J Mol Sci. 24:122022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Cantor JR and Sabatini DM: Cancer cell

metabolism: One hallmark, many faces. Cancer Discov. 2:881–898.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang J, Shay C, Saba NF and Teng Y: Cancer

metabolism and carcinogenesis. Exp Hematol Oncol. 13:102024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pavlova NN, Zhu J and Thompson CB: The

hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab.

34:355–377. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pham DV and Park PH: Tumor metabolic

reprogramming by adipokines as a critical driver of

obesity-associated cancer progression. Int J Mol Sci. 22:14442021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Balaban S, Shearer RF, Lee LS, van

Geldermalsen M, Schreuder M, Shtein HC, Cairns R, Thomas KC,

Fazakerley DJ, Grewal T, et al: Adipocyte lipolysis links obesity

to breast cancer growth: Adipocyte-derived fatty acids drive breast

cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancer Metab. 5:12017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Brown KA: Metabolic pathways in

obesity-related breast cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 17:350–363.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Müller G, Schneider M, Biemer-Daub G and

Wied S: Microvesicles released from rat adipocytes and harboring

glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins transfer RNA

stimulating lipid synthesis. Cell Signal. 23:1207–1223. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Clement E, Lazar I, Attané C, Carrié L,

Dauvillier S, Ducoux-Petit M, Esteve D, Menneteau T, Moutahir M, Le

Gonidec S, et al: Adipocyte extracellular vesicles carry enzymes

and fatty acids that stimulate mitochondrial metabolism and

remodeling in tumor cells. EMBO J. 39:e1025252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Liu S, Benito-Martin A, Pelissier Vatter

FA, Hanif SZ, Liu C, Bhardwaj P, Sethupathy P, Farghli AR, Piloco

P, Paik P, et al: Breast adipose tissue-derived extracellular

vesicles from obese women alter tumor cell metabolism. EMBO Rep.

24:e573392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang Q, Deng T, Zhang H, Zuo D, Zhu Q,

Bai M, Liu R, Ning T, Zhang L, Yu Z, et al: Adipocyte-derived

exosomal MTTP suppresses ferroptosis and promotes chemoresistance

in colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 9:e22033572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vander Heiden MG and

Kroemer G: Metabolic targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug

Discov. 12:829–846. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagés M,

Pestell RG, Sotgia F and Lisanti MP: Cancer metabolism: A

therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:11–31. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhou C, Huang YQ, Da MX, Jin WL and Zhou

FH: Adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles: Bridging the

communications between obesity and tumor microenvironment. Discov

Oncol. 14:922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Blandin A, Dugail I, Hilairet G, Ponnaiah

M, Ghesquière V, Froger J, Ducheix S, Fizanne L, Boursier J, Cariou

B, et al: Lipidomic analysis of adipose-derived extracellular

vesicles reveals specific EV lipid sorting informative of the

obesity metabolic state. Cell Rep. 42:1121692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gelsomino L, Barone I, Caruso A, Giordano

F, Brindisi M, Morello G, Accattatis FM, Panza S, Cappello AR,

Bonofiglio D, et al: Proteomic profiling of extracellular vesicles

released by leptin-treated breast cancer cells: A potential role in

cancer metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 23:129412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sakaue T, Dorayappan KDP, Zingarelli R,

Khadraoui W, Anbalagan M, Wallbillich J, Bognar B, Wanner R,

Cosgrove C, Suarez A, et al: Obesity-induced extracellular vesicles

proteins drive the endometrial cancer pathogenesis: Therapeutic

potential of HO-3867 and Metformin. Oncogene. 43:3586–3597. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Mathiesen A, Haynes B, Huyck R, Brown M

and Dobrian A: Adipose tissue-derived extracellular vesicles

contribute to phenotypic plasticity of prostate cancer cells. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:12292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Giordano C, Gelsomino L, Barone I, Panza

S, Augimeri G, Bonofiglio D, Rovito D, Naimo GD, Leggio A, Catalano

S and Andò S: Leptin modulates exosome biogenesis in breast cancer

cells: An additional mechanism in cell-to-cell communication. J

Clin Med. 8:10272019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liu Q, Guan C, Liu C, Li H, Wu J and Sun

C: Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha: A new strategy for

triple-negative breast cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother.

156:1138612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhi S, Chen C, Huang H, Zhang Z, Zeng F

and Zhang S: Hypoxia-inducible factor in breast cancer: Role and

target for breast cancer treatment. Front Immunol. 15:13708002024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Luo S, Jiang Y, Zheng A, Zhao Y, Wu X, Li

M, Du F, Chen Y, Deng S, Chen M, et al: Targeting hypoxia-inducible

factors for breast cancer therapy: A narrative review. Front

Pharmacol. 13:10646612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Liu ZJ, Semenza GL and Zhang HF:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and breast cancer metastasis. J Zhejiang

Univ Sci B. 16:32–43. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Infantino V, Santarsiero A, Convertini P,

Todisco S and Iacobazzi V: Cancer cell metabolism in hypoxia: Role

of HIF-1 as Key regulator and therapeutic target. Int J Mol Sci.

22:57032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yun Z, Maecker HL, Johnson RS and Giaccia

AJ: Inhibition of PPAR gamma 2 gene expression by the