Introduction

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) are rare, heterogeneous

neoplasms derived from primordial germ cells (PGCs). While they

typically develop in the gonads, they can also arise in

extragonadal midline locations, particularly in children (1). Diagnosis often involves imaging

studies and evaluation of serum markers, including α-fetoprotein,

β-human chorionic gonadotropin and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

(2). GCTs account for ~3% of

childhood cancers (3) and

represent ~11% of adolescent cancer cases diagnosed post-puberty

(4). In adults, although GCTs

represent only ~1% of cancers, they are the most common testicular

cancer in young adults (5) and

account for 20-25% of all ovarian neoplasms (6).

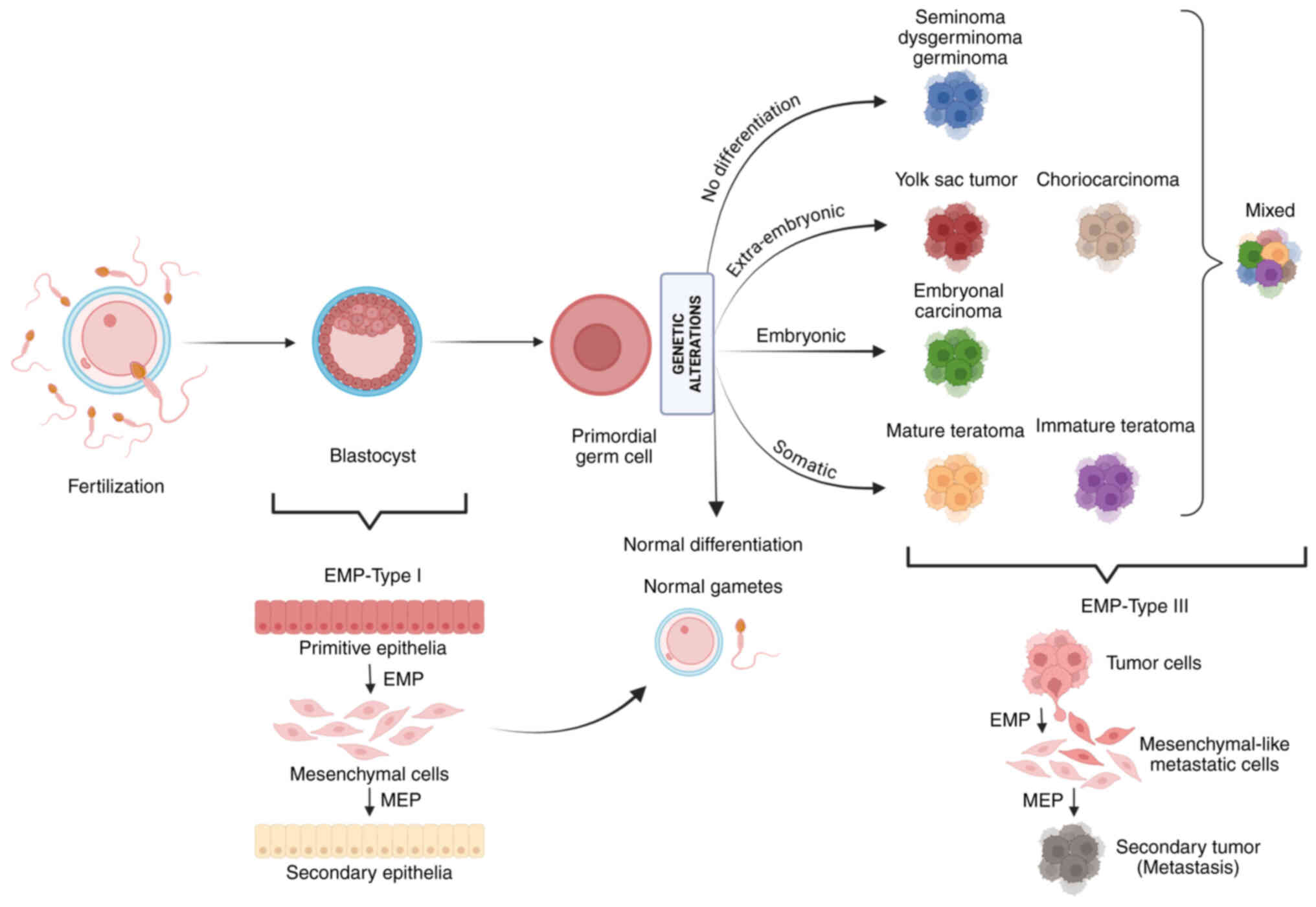

The diverse histologies observed in GCTs arise from

the totipotent nature of PGCs and the specific differentiation

stage at which genetic alterations occur (7). According to Teilum's classification,

germinomas, known as seminomas (SEs) in the testes and

dysgerminomas in the ovaries, are undifferentiated cells with

pluripotent features that originate directly from PGCs (Fig. 1). Embryonal carcinomas (ECs) arise

after early embryonic differentiation and can develop into to a

variety of histological subtypes. When ECs follow an embryonic

developmental pathway, they may differentiate into teratomas (TEs),

which contain tissues derived from all three germ layers: Endoderm,

mesoderm and ectoderm. Conversely, if cells undergo extra-embryonic

differentiation, they may give rise to yolk sac tumors (YSTs),

characterized by extra-embryonic mesoblast overgrowth, or

choriocarcinomas (CC), which display trophoblastic differentiation

(7,8). Non-germinomatous GCTs are generally

more aggressive than germinomas, exhibiting increased proliferation

and a higher metastatic potential (9,10).

By contrast, germinomas are associated with a more favorable

prognosis due to their high sensitivity to chemotherapy and

radiotherapy (11).

Surgical resection is typically the first-line

treatment for GCTs (7); however,

systemic therapy is generally required for disease control.

Etoposide- and cisplatin-based chemotherapy has remained the

standard of care for >4 decades, despite the associated toxicity

(12). Cisplatin remains the

cornerstone of treatment, achieving cure rates of 80-90% (13,14). Nonetheless, ~30% of patients show

an incomplete response or develop resistance to cisplatin, leading

to poor clinical outcomes and reduced survival (14,15). Alternative treatments demonstrate

response rates of only 20-40%, with median survival times of ~6-8

months (16).

The biology of cisplatin resistance is

multifactorial (17) and has been

linked to several molecular alterations, including changes in tumor

protein p53, mouse double minute 2 homolog (12), DNA methylation patterns (18), dysregulation of the

platelet-derived growth factor receptor β/AKT signaling pathway

(19) and overexpression of ERBB4

oncogenic EGFR-like receptor (20). These resistance mechanisms are

often categorized into four types: Pre-target (before DNA-binding);

on-target (related to DNA-cisplatin adducts); post-target (cell

death signaling pathways induced by cisplatin-mediated DNA damage);

or off-target (involving pathways not directly linked to

cisplatin-induced signals) (20).

Therefore, comprehensive investigations into these resistance

mechanisms are essential for identifying novel treatment

strategies.

Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity (EMP) has emerged

as a key hallmark of cancer, particularly in its role as a driver

of metastasis and chemoresistance (21). EMP is a process characterized by a

series of molecular and morphological alterations, accompanied by

the expression of specific markers, leading to the suppression of

epithelial cell characteristics. During EMP, cells acquire

mesenchymal properties, adopting a more malignant phenotype with

enhanced invasion, migration and dissemination capabilities

(22,23). However, given the paucity of

studies investigating the association between EMP and cisplatin

resistance in GCTs, the present review was conducted to compile and

discuss the available evidence.

Unraveling the mechanisms and implications

of EMP

EMP was initially described as

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process in which cells

were considered to exist in one of two distinct states, namely an

epithelial or mesenchymal phenotype (24). Subsequently, the concept of EMT

was redefined as a reversible and transient process, applicable to

diverse contexts, and thus renamed EMP (25,26). A further study revealed that the

cells can adopt intermediate or hybrid phenotypes, known as partial

EMP, displaying characteristics of both epithelial and mesenchymal

cells (27). At present, it is

widely accepted that these hybrid states are prevalent in the tumor

microenvironment (TM), where not all cells complete the full EMP

process, meaning they may never fully acquire a mesenchymal

phenotype (27).

Epithelial cells are tightly organized with minimal

surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM); their distinct

characteristics are defined by structural components such as tight

junctions, adherens junctions, desmosomes and gap junctions, which

maintain strong cell-to-cell adhesion and tissue integrity

(28). These junctions are

responsible for maintaining both structural and functional

integrity. Specifically, they firmly hold cells in place and

prevent individual cell displacement. These cell-to-cell

interactions involve E-cadherin (CDH1)-mediated junctions and

desmosomes, as well as cell-ECM interactions mediated by integrins

and other molecules. Together, these interactions confer polarity

to epithelial cells with distinct basal and apical functions

(29). The polarity of epithelial

cells is maintained by tight junctions, which create distinct

apical and basal regions and form an effective barrier. This

barrier regulates the passage of molecules and ions, thus

preserving cell polarity. Adherens junctions, which are mediated by

the transmembrane protein CDH1, serve to provide robust

cell-to-cell adhesion by connecting to actin filaments, thereby

ensuring structural stability (29). Desmosomes function as anchors for

cells by interacting with intermediate filaments (30). Additionally, gap junctions,

composed of connexins, facilitate direct intercellular

communication. Together, these structures promote the integrity and

cohesion of epithelial tissue, with key markers including CDH1,

desmoplakin, cytokeratins, claudins and occludins (31).

In contrast to epithelial cells, mesenchymal cells

display reduced intercellular adhesion and lack apical-basal

polarity. These cells interact with ECM components through

integrins at focal adhesion sites, enabling cell movement. The

cells also feature a cytoplasm rich in vimentin (VIM) filaments, a

mesodermal marker, and form irregular structures with enhanced

migratory capacity. Other expressed markers include N-cadherin

(CDH2), smooth muscle α-actin (α-SMA), fibroblast-specific protein

1 (FSP-1), fibronectin (FN1), type I collagen (COL1A1) and matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs) (32).

During EMP, epithelial cells lose cellular polarity

by downregulating the expression of cytokeratins and adhesion

molecules, such as CDH1. Concurrently, the expression of

mesenchymal markers, such as α-SMA, FSP-1, VIM, CDH2, FN1, COL1A1

and MMPs, is upregulated. Cells with polyhedral morphologies begin

to adopt a fibroblast-like morphology (28). This transition is accompanied by

enhanced migratory and invasive capacities, resistance to apoptosis

and increased production of ECM components (32).

EMP can be triggered in various biological contexts

by diverse signaling molecules. These molecules trigger distinct

signaling pathways, ultimately activating a specific set of

transcription factors (TFs), often referred to as 'master

regulators' of EMP. These include members of the Snail family

(Snail1 and Snail2/Slug), the zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox

proteins (Zeb1 and Zeb2) and the Twist family (Twist1 and Twist2).

These TFs suppress the expression of epithelial markers and

activate mesenchymal markers (33).

EMP is categorized into three types. EMP type 1 has

been associated with a variety of physiological processes,

particularly during embryogenesis (Fig. 1), where it plays a key role in the

migration and differentiation of cells that form the germ layers

(34). These germ layers are the

origin of tissue and organ development. EMP type 1 has been

demonstrated to be non-aggressive and non-invasive; it has been

shown to be essential for the proper functioning of physiological

processes, including organ and tissue formation, placenta

development and embryo implantation (35). EMP type 1 is also involved in the

formation of melanocytes from the neural crest, which is essential

for pigmentation (22).

EMP type 2 plays an important role in tissue

regeneration and fibrosis, including conditions such as renal and

pulmonary fibrosis, and can be categorized into physiological

(tissue regeneration) and pathological (persistent fibrosis)

processes (36). In its

physiological form, cells mobilize into fibroblast-like phenotypes,

facilitating tissue repair after trauma (37). This regenerative phase is linked

to the inflammatory response, which subsides once inflammation is

resolved, as observed in wound healing and tissue regeneration

(37). However, when inflammation

persists, physiological EMP type 2 can progress to a pathological

state (31), contributing to

chronic fibrosis and organ damage, as observed in the kidney and

liver (38). This process is

driven by inflammatory cells and fibroblast-like cells, which

release various inflammatory signals (39) and contribute to a collagen-rich

ECM. Protein markers, such as VIM, serve as molecular targets to

identify signs of persistent inflammation that may progress to a

chronic state, thereby establishing a link with EMP type 2

(38).

EMP type 3 is closely linked to cancer progression,

underscoring the importance of studies exploring the connection

between EMP and tumor dissemination (Fig. 1). Such studies can provide an

understanding of the molecular mechanisms influencing signaling

pathways that regulate EMP activation or its inhibition (40,41), potentially informing novel

therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, identifying specific markers

associated with EMP is essential for understanding a tumor's

metastatic potential, improving patient survival predictions and

developing targeted therapies for treatment-resistant cancer

(42).

The acquired plasticity of cancer cells through EMP

has been widely documented across various cancer types and is

strongly associated with resistance to cisplatin (43,44). In the following sections, key

studies are reviewed that explore the role of EMP markers in GCTs,

focusing on their involvement in cisplatin resistance, drawing

insights from both in vitro and in vivo models.

EMP analysis in vitro models of

GCTs

Different cell lines, whose characteristics are

presented in Table I, have been

used to investigate the molecular mechanisms, genetic alterations

and therapeutic responses in GCTs. Most cell lines have been

isolated from the testes of adult individuals (aged 22 years or

older). Cell lines representing the various histological types of

GCTs from children and adolescents are scarce or unavailable,

except for choriocarcinoma cell lines from fetal placentas. This

lack of pediatric and adolescent cell lines significantly hinders

research and molecular studies. Next, the present study will review

key studies that have used GCT cell lines to research biomarkers

and therapeutic targets, offering insights into future therapeutic

strategies.

| Table ICharacteristics of human germ cell

tumor cell lines. |

Table I

Characteristics of human germ cell

tumor cell lines.

| Cell lines | Primary tissue | Sex | Age, years | Histologies |

|---|

| NTERA-2 | Testis | Male | 22 | Embryonal

carcinoma |

| 2102EP | Testis | Male | 23 | Embryonal

carcinoma |

| 1777N Rpmet | Testisa | Male | 25 | Embryonal

carcinoma |

| NCCIT | Mediastinum | Male | 24 | Embryonal

carcinoma |

| 833KE | Abdomen | Male | 19 | Embryonal

carcinoma |

| BeWo | Placenta | Male | Fetus |

Choriocarcinoma |

| JAR | Placenta | Male | Fetus |

Choriocarcinoma |

| JEG3 | Placenta | Male | Fetus |

Choriocarcinoma |

| TCam-2 | Testis | Mal | 35 | Seminoma |

| SEM-1 | Mediastinum | Male | 58 | Seminoma |

| GCT27 | Testis | Male | NI | Teratoma |

| SuSa | Testis | Male | 46 | Teratoma |

| NOY-1 | Ovary | Female | 28 | Yolk sac tumor |

| H12.1 | Testis | Male | 19 | Mixed (embryonal

carcinoma and teratoma) |

| 1411HP | Testisb | Male | 17 | Mixed (embryonal

carcinoma and yolk sac tumor) |

ECM remodeling and its role in tumor

behavior

Both normal and transformed mesenchymal and

epithelial cells rely on ECM proteins for growth and

differentiation in vitro. These proteins play a key role in

processes such as motility, wound healing and tumor metastasis,

mechanisms that are closely linked to EMP. In teratoma cell

culture, cells secrete adhesion proteins such as vitronectin, FN1,

laminin and type IV collagen (45). In human GCTs, differentiated cells

in low-density cultures produce FN1 in a differentiation-dependent

manner, with less differentiated cells exhibiting decreased FN1

synthesis (46).

In this regard, some studies indicate that

modulation of those ECM proteins influences cell adhesion,

plasticity and invasion capacity in vitro (47,48). In BeWo cells, the heme oxygenase-1

(HMOX1) gene, which is upregulated in various tumor types,

has been shown to increase adhesion by modulating laminin and FN1.

This process, dependent on peroxidasin homolog, a cell surface

peroxidase, occurs at both the gene level and HMOX1 protein level

(Table II) (47). Therefore, the protein network

activated by HMOX1 influences key cellular functions, such as

adhesion, signaling and transport, supporting tumor growth and

dissemination (47).

| Table IIAssociation between EMP and

resistance in different germ cell tumor cell lines. |

Table II

Association between EMP and

resistance in different germ cell tumor cell lines.

A, Embryonal

carcinoma

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Cell lines | Association with

EMP | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pulzová et

al, 2021 | 1777N and

Rpmet | Cell adhesion

remodeling. | (48) |

| Liu et al,

2022 | NCCIT | Long non-coding RNA

LINC00313I is upregulated in TGCT tissues. Moreover,

LINC00313I-silencing is associated with decreased migration and

invasion in the NCCIT cell line. Potential inhibitor:

Panobinostat. | (66) |

| Abada et al,

2014 | NTERA-2 | Cisplatin triggers

differentiation which leads to resistance. This process is linked

with reduced expression of NANOG and POU5F1 and

increased NES, STMN2 and FN1. | (81) |

| Wu et al,

2012 | NCCIT and

NTERA-2 | Hypoxia reduces

levels of POU5F1 protein which triggers drug resistance.

SENP1 can normalize POU5F1 levels. Potential inhibitor:

SENP1. | (64) |

| Koch et al,

2003 | NTERA-2, 2102 EP

and NCCIT | Hypoxia reduces

drug cytotoxicity. Potential inhibitor: Erythropoietin. | (65) |

|

| B,

Choriocarcinoma |

|

| First author,

year | Cell lines | Association with

EMP | (Refs.) |

|

| Tauber et

al, 2010 | BeWo | High expression of

HMOX1 gene and ECM remodeling. | (47) |

| Butler et

al, 2009 | BeWo | Increased ILK,

along with the expression of p-AKT and SNAIL proteins. | (53) |

| Ng et al,

2011 | BeWo | Increased invasive

capacity with increased TWIST and decreased

CDH1. | (55) |

| Iwaki et al,

2004 | BeWo | Hypoxia increases

mRNA levels of fibronectin domains and integrin α-5,

but not integrin α-1. | (62) |

| DaSilva-Arnold

et al, 2019 | BeWo | Overexpression of

ZEB2 changes the morphology of BeWo and JEG-3 cells towards

a mesenchymal phenotype and promotes a gene expression profile

consistent with EMP. | (58) |

| Xu et al,

2022 | JEG3 | High expression of

HIF-1α is found. HIF-1α depends on DEC1 to trigger EMP by

β-catenin signaling. Potential inhibitor: DEC1 inhibitors. | (61) |

| Zhang et al,

2024 | BeWo and JAR | Transcription

factor TWIST1 is found to be upregulated compared with a

normal extravillous trophoblast cell line. | (56) |

| Tian et al,

2015 | JAR and JEG-3 | Overexpression of

HIF-1α depends on NOTCH signaling to promote EMP. Potential

inhibitor: DAPT. | (60) |

| Xue et al,

2020 | JAR JEG-3 | Forskolin promotes

invasion, migration, vasculogenic-like network formation and

NOTCH-1-mediated EMP. | (63) |

|

| C, Seminoma |

|

| First author,

year | Cell lines | Association with

EMP | (Refs.) |

|

| Teveroni et

al, 2022 | SEM-1 | PTTG1

depends on ZEB1 to repress CDH1. This cooperation

facilitates cell invasion and cell growth. | (59) |

|

| D, Various cell

lines |

|

| First author,

year | Cell lines | Association with

EMP | (Refs.) |

|

| Skowron et

al, 2022 | TCam-2, 2102EP, JAR

and GCT72 | ECM remodeling

promotes migration and invasion. Secreted collagen I/IV and

fibronectin causes decreased sensitivity to cisplatin. | (50) |

The EC 2102EP cell line, derived from a primary

tumor, and 1777NRpmet, a differentiated EC cell line with immature

teratoma features derived from a metastatic tumor, were analyzed in

a previous study, revealing increased expression of tyrosine

3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein β and

γ polypeptide, caldesmon 1, filamin A, VIM and vinculin

genes in 1777NRpmet compared with the primary tumor, while

PARK7 expression decreased (48). These findings suggest a role for

cell adhesion remodeling and ECM crosslinking in testes invasion,

EMP and metastasis (48).

ECM remodeling has also been observed in

cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines, characterized by

elevated expression of the collagen type VI α 3 chain gene.

Furthermore, these cells demonstrated increased chemoresistance

when cultured on collagen IV-coated dishes (49). Similarly, co-culture of GCT cell

lines with TM cells has shown an interplay, where exposure to

TM-secreted components such as collagen I/IV and FN1 decreased

sensitivity to cisplatin (50).

These studies demonstrate that several factors contribute to the

critical role of ECM remodeling and adhesion molecules in

triggering cell plasticity, cisplatin resistance and tumor cell

survival.

Beyond ECM proteins, their interaction with other

cell components, such as integrins and their signaling pathways,

has also been implicated in the EMP process and treatment

resistance (51,52). Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is

related to adhesion to the extracellular environment, transduction

signaling, and interaction with β-catenin (CTNNB1) and cytoskeletal

proteins. BeWo cells exhibit increased ILK activity during the

differentiation process, along with the expression of

phosphorylated AKT and SNAIL proteins (53).

During EMP, dynamic alterations occur not only in

ECM-cell interactions but also in cell-cell adhesion, modulating

adhesion and structural proteins. In this setting, CDH2 is

upregulated while CDH1 is downregulated, a mechanism that plays a

crucial role in malignancies, favoring tumor cell metastasis and

migration. Upregulation of CDH1 may be linked to decreased

migratory ability in cancer cells and increased sensitivity to cell

death, likely due to the inhibition of the EMP process (43). These changes are widely associated

with TFs such as TWIST, ZEB1/2 and SNAIL/SLUG (54).

EMP and transcriptional regulation

EMP is governed by specific EMP TFs that orchestrate

transcriptional reprogramming to promote the loss of epithelial

traits and acquisition of mesenchymal properties.

Expression of TWIST and CDH1 genes was

previously evaluated in BeWo cells during differentiation and

fusion (55). This

differentiation process was accompanied by an increase in

TWIST expression and a decrease in CDH1 expression,

even in the presence of exogenous TWIST expression. However,

differentiation failed when TWIST was knocked down.

Moreover, treatment with 8-Br-cAMP increased TWIST levels.

This demonstrates the role of these molecules in the

differentiation and invasive capacity promoted in the EMP process

(55). A study on gestational

trophoblastic disease evaluated the expression and influence of

TWIST1 gene silencing in the CC BeWo and JAR cell lines

(56). It was revealed that this

TF was upregulated, and its knockout significantly inhibited the

proliferation, migration and invasion of these cells. Additionally,

protein analysis revealed that silencing of the TWIST1 gene led to

increased expression of CDH1 and decreased expression of CDH2 and

VIM. Thus, TWIST1 silencing promotes an epithelial

phenotype, inhibiting EMP and malignant behavior (56). Furthermore, increased TWIST

protein expression was observed in cisplatin-resistant ovarian

cancer cell lines (57).

In the CC BeWo and JEG-3 cell lines, overexpression

of ZEB2 enhanced cell migration and invasion capabilities.

Alongside ZEB2 upregulation, changes were observed in gene

expression, cell morphology and protein levels (58). At the gene expression level,

alterations occurred in EMP markers, though some divergence was

noted among cell clones. Additionally, JEG-3 clones overexpressing

ZEB2 exhibited differential gene expression of other EMP

markers, such as decreased SNAIL and increased SLUG

and TWIST1, distinct from BeWo clones. This suggests that

ZEB2 overexpression activates cell-specific downstream

pathways to promote EMP. Lastly, protein expression of EMP markers

was more pronounced in BeWo cells than that in JEG-3 cells

(58).

Our group investigated the role of EMP TF

SLUG in GCTs (21). The

analysis revealed distinct expression profiles of EMP markers

across different histologies. SEs exhibited lower expression of EMP

markers, while ECs and mixed GCTs showed higher expression.

SNAIL and SLUG displayed varying expression levels in

each histology, and patients with lower SLUG expression had

a longer median progression-free survival time. Furthermore,

integrated analyses showed that patients expressing low levels of

both factors (SNAILlowSLUGlow) had a

higher progression-free survival rate compared to those with high

expression of both TFs

(SNAILhighSLUGhigh) (21).

The role of EMP mediators in enhancing invasiveness

is evident across various GCT types, potentially involving

different molecular pathways. In human SE, Securin (PTTG1)

has been identified as an EMP mediator. This gene promotes

invasiveness by expressing MMP2 protein, which facilitates

migration and invasion (59). In

the SE SEM-1 cell line, PTTG1 relies on ZEB1 to

exhibit invasion and cell growth features, and to form an axis that

represses CDH1 expression. Additionally, database analysis

shows that in seminoma tumors, where PTTG1 is more localized in the

nucleus compared with the non-seminoma subtype, CDH1

expression is significantly lower than that observed in

non-seminomas (59). Based on

these observations, the PTTG1-ZEB1-CDH1 axis appears

particularly relevant in SEs compared with NGGCTs (59). However, further research is needed

to elucidate the specific mechanisms through which these mediators

influence tumor progression and response to treatment.

Hypoxia, long non-coding RNAs and

emerging mechanisms

In addition to differentiation-related pathways,

external environmental factors, such as hypoxia, influence

resistance mechanisms and EMP in GCTs. The role of Notch receptor

(NOTCH) signaling was previously investigated in CC, focusing on

how it links hypoxia to EMP (60). Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible

factor 1-α (HIF-1α) protein in JAR and JEG-3 cell lines reduced the

expression of epithelial markers (CDH1, Cytokeratin 18 and

Cytokeratin 19) while enhancing cell migration and invasiveness.

HIF-1α overexpression was positively correlated with NOTCH1 and

Hairy and enhancer of split-1 proteins. Inhibiting NOTCH1 with

N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl

ester reversed the EMP changes, increasing CDH1, CK18 and CK19,

while reducing the activities of MMP2 and MMP9. Thus, HIF-1α

promotes CC metastasis through EMP via the NOTCH signaling pathway

(60).

Moreover, JEG-3 cells exhibit higher HIF-1α protein

expression compared with control chorionic trophoblast cells.

Knocking down HIF-1α decreases cell proliferation and

migration. Additionally, it is associated with reduced cell

invasion, increased CDH1, and decreased VIM and

α-SMA, thereby suppressing EMP. HIF-1α has been shown

to modulate deleted in esophageal cancer 1 (DEC1). However,

when DEC1 is overexpressed, it partially reverses the

effects of HIF-1α knockdown, indicating that both

HIF-1α and DEC1 regulate EMP mediators (VIM, α-SMA

and Wnt/CTNNB1 signaling) (61).

In one study using BeWo cells and the early placenta, hypoxic

conditions induced higher mRNA levels of genes encoding FN1 domains

and integrin α-5 compared with normoxic conditions, while the

levels of integrin α-1 mRNA decreased (62).

Hypoxia is also associated with vasculogenic mimicry

(VM), a process whereby cancer cells form tubular channels

mimicking blood vessels. These cells may undergo EMP to exhibit an

endothelial-like phenotype, enhancing tumor aggressiveness and

facilitating metastasis (63). In

this context, in a previous study, JAR and JEG-3 cells treated with

forskolin, a cAMP activator, exhibited increased VM, migration and

invasive capacity. These cells produced MMP2 and MMP9 at both the

gene and protein levels, increasing the expression of mesenchymal

markers via NOTCH1 signaling. NOTCH1 signaling can be triggered

under hypoxic conditions and is linked to EMP markers (63).

In GCTs, hypoxia reduces POU5F1 protein levels in EC

cells, contributing to cisplatin resistance. However,

overexpression of the sentrin-specific peptidase 1 (SENP1)

gene normalizes POU5F1 protein levels and restores drug sensitivity

(64). Similarly, in EC NTERA-2,

2102EP and NCCIT cell lines exposed to cisplatin under hypoxic and

normoxic conditions, cisplatin was less effective under hypoxia.

Hypoxic cells displayed a higher IC50

(NCCIT>2102EP>NTERA-2), indicating that hypoxia reduces

cytotoxicity not only for cisplatin but also for other drugs,

suggesting it is not exclusively linked to cisplatin resistance in

GCTs (65).

Another factor associated with EMP is long

non-coding RNAs, such as SPRY4, LINC00467 and

LINC00313, which regulate gene expression. LINC00313

was found to be upregulated in TGCT cells, serving as a good

biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis. In silico analyses

revealed that LINC00313 was associated with lower immune

cell infiltration (CD4+, CD8+ and dendritic

cells) and an altered immune microenvironment (66). In vitro studies

demonstrated that LINC00313 promotes migration and invasion,

and acts as an EMP mediator by upregulating VIM, ZEB1, SNAIL,

CTNNB1 and CDH2 proteins, potentially through microRNA

(miRNA/miR)-138-5p, miR-150-5p, miR-204-5p and miR-205-5p (66). Moreover, long non-coding RNAs are

reportedly involved in cisplatin resistance in other tumors

(43). Thus, targeting

LINC00313 could be a promising strategy to overcome

cisplatin resistance by inhibiting EMP, thereby reducing cancer

cell proliferation, migration and invasion.

Despite the scarcity of studies exploring these

associations, research on EMP markers in GCT cell lines, primarily

BeWo, JAR and JEG-3 (53-56,58,63), has focused on differentiation,

invasion and EMP in pregnancy-related phenomena rather than GCTs.

Even fewer studies have evaluated EMP in GCTs and its association

with cisplatin resistance. In summary, various GCT cell lines have

provided valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying

EMP. ECM remodeling, integrin signaling and dynamic regulation of

key TFs, such as TWIST, ZEB1 and SLUG are

critical drivers of EMP and tumor progression. However, the limited

availability of pediatric and adolescent GCT cell lines poses a

significant challenge to understanding the EMP mechanisms in these

populations. Additionally, external factors, such as hypoxia and

long non-coding RNAs, add complexity to the regulation of EMP and

chemoresistance in GCTs.

EMP pathway intersections underlying

cisplatin resistance

As aforementioned, cisplatin resistance mechanisms

can be classified as pre-target, on-target, post-target and

off-target (20). A comparison

between NTERA-2 cells and their resistant counterparts, NTERA-2R

cells, reveals similar behavior in drug uptake, efflux and

DNA-binding. However, the resistant lineage exhibits alterations in

cell cycle regulation and cell death response. These findings

suggest that resistance mechanisms in NTERA-2R are less related to

DNA binding and damage induction, and more associated with cellular

responses to this damage, implicating post-target or off-target

mechanisms (13). Supporting this

hypothesis, our group demonstrated that NTERA-2R cells showed

upregulation of DNA repair-related genes (O-6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase; complex subunit, DNA damage recognition and

repair factor; and DNA polymerase delta 4, accessory subunit)

compared with NTERA-2 cells (Table

III). This overexpression was accompanied by more aggressive

cellular behaviors, such as increased proliferation, colony

formation and migration. As expected, NTERA-2R cells exhibited a

lower rate of apoptosis following cisplatin treatment compared with

NTERA-2 cells. However, combining the proteasome inhibitor MG-132

with cisplatin made the apoptosis rate of the two cell lines

comparable, highlighting a potential combinatorial strategy to

overcome cisplatin resistance (67).

| Table IIIAdditional molecular mechanisms of

resistance observed in germ cell tumors. |

Table III

Additional molecular mechanisms of

resistance observed in germ cell tumors.

| First author,

year | Cell lines | Association with

resistance | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Lengert et

al, 2022 | NTERA-2 and

NTERA-2R | DNA repair genes

increased: MGMT, XPC and POLD4. Potential

inhibitor: Proteasome inhibitor (MG-132). | (67) |

| Fichtner et

al, 2022 | NTERA-2R, NCCIT-R

and 2102EP-R | Upregulated

proteins ANXA1, TAGLN, COL1A1 and VIM. Upregulated protein ANXA1;

downregulated COL1A1. Upregulated protein ANXA1; downregulated

TAGLN and VIM. | (14) |

| Cardoso et

al, 2024 | NTERA-2R | Cisplatin treatment

increased FN1, VIM, ACTA2, COL1A1,

TGF-β and SLUG. | (21) |

| Schmidtova et

al, 2019 | NTERA-2 | Increase in

ALDH1A1, ALDH1A3 and NANOG. Decrease in

ALDH1A2 and ALDH1B1. Decreased proteins NANOG and

SOX2. | (73) |

| Schmidtova et

al, 2019 | NCCIT-R | Increase in

ALDH1A2, ALDH1A3, NANOG and CD133. No

protein expression changes. Potential inhibitor: ALDH inhibitor

(Disulfiram). | (73) |

| Miranda-Gonçalves

et al, 2021 | NCCIT-R | Increased

VIRMA. | (90) |

| Port et al,

2011 | NTERA-2R, NCCIT-R

and 2102EP-R | Upregulation of

hsa-miR-10b and hsa-miR-512-3p. | (91) |

| Lobo et al,

2020 | NTERA-2R | Increased

expression of genes HDAC8, 9 and 11. Only HDAC11

protein was significantly expressed. Potential inhibitor: HDAC

inhibitors (Belinostat and Panobinostat). | (17) |

| Schmidtova et

al, 2020 | NOY-1-R | Increase of CD133,

ABCG2 and ALDH3A1. Reduced gene and promoter methylation. Increased

expression of ALDH1A3. accompanied by higher ALDH enzymatic

activity. | (74) |

| Roška et al,

2020 | H12.1D | Upregulated

TRIB3; IGFBP2, NANOG, POU5F1 and SOX2 genes

downregulated. | (75) |

| Schmidtova et

al, 2021 | TCam-2R and

NCCIT-R | Increased gene and

protein expression of β-catenin. | (84) |

| Schmidtova et

al, 2021 | NTERA-2R | Decreased β-catenin

and cyclin D1 expression levels. Potential inhibitor: Wnt/β-catenin

inhibitor (PRI-724). | (84) |

| Funke et al,

2023 | JAR-R and

2102EP-R | Overexpression of

NAE1. Potential inhibitor: NAE1 inhibitor (MLN4924). | (88) |

| Skowron et

al, 2020 | TCam-2, 2102EP,

NCCIT and JAR | Increased gene and

protein CDK4/CDK4; CDK6/CDK6 expression weak or absent. Potential

inhibitor: CDK4/6 inhibitors (palbociclib and ribociclib). | (92) |

| Noel et al,

2010 | 833K-R, Susa-R and

GCT27-R | Upregulation of

CCND1. | (93) |

Regarding DNA repair-related protein expression, a

study involving NTERA-2, NCCIT and 2102EP cell lines, and their

resistant counterparts, revealed deregulated proteins in at least

two resistant cell lines. These included downregulation of

cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase, alongside

upregulation of annexin A1 (ANXA1), L-LDH A chain and

NADPH-adrenodoxin oxidoreductase. Additionally, transgelin (TAGLN)

was upregulated in NTERA-2R cells but downregulated in 2102EP-R

cells, while COL1A1 and VIM showed contrasting expression patterns,

being upregulated in NTERA-2R cells but downregulated in NCCIT-R

and 2102EP-R cells, respectively (Table III). Among these proteins,

ANXA1, TAGLN, COL1A1 and VIM are associated with EMP in GCTs or

other cancer types (68-70). Gene enrichment analysis detected

DNA repair-associated proteins across all resistant lineages, but

an EMP gene set was detected in NTERA-2R cells. These results

further corroborate the association of cisplatin resistance and EMP

in GCTs (14).

Our group also evaluated EMP markers in NTERA-2 and

NTERA-2R cells through mRNA quantification, with some findings

confirmed at the protein level. After 72 h of cisplatin treatment,

mRNA levels of FN1, VIM, α smooth muscle actin,

COL1A1, TGF-β and SLUG were higher in

resistant cells compared with those in parental cells (Table III) (21). Additionally, CDH1 and its

corresponding protein exhibited an increasing trend in NTERA-2R,

while CDH2 and its protein displayed a decreasing trend

(21). No differences were

observed in SNAIL expression levels (21). Together, the findings suggest that

EMP may be involved in chemoresistance (21).

Upregulation of cancer stem cell (CSC) markers is a

well-documented phenomenon in chemoresistant solid tumors, with

aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) as a key marker (71,72). However, in GCTs, this upregulation

is not always consistent. A comparative study of

cisplatin-sensitive NTERA-2 cells and their resistant counterpart

(NTERA-2R) revealed increased gene expression levels of aldehyde

dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 (ALDH1A1), ALDH1A3

and NANOG, alongside decreased levels of ALDH1A2 and

ALDH1B1 in the resistant NTERA-2 cells. However, NANOG and

SOX2 protein levels were decreased in the NTERA-2R cells. In

another EC cell line, NCCIT-R, ALDH1A2, ALDH1A3,

NANOG and prominin-1 (CD133) levels were

increased, but protein levels showed no significant changes

(Table III). Moreover,

treatment with the ALDH inhibitor disulfiram reduced cell

viability, which was potentiated by combined cisplatin treatment.

This combination also reduced the viability of resistant cells in a

3D spheroid model (73).

Similarly, CSC markers were evaluated in an ovarian

YST cell line (NOY-1) and its cisplatin-resistant variant

(NOY-1-R). The resistant cells exhibited increased protein

expression of CD133, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (JR

Blood Group) (ABCG2) and ALDH3A1. This upregulation was associated

with reduced gene promoter methylation, increased expression of

ALDH1A3 and higher ALDH enzymatic activity (Table III). These findings underscore

the potential role of the ALDH protein family in cisplatin

resistance in refractory YST and suggest cross-resistance to ALDH

inhibitors in cisplatin-resistant GCTs (74).

Pluripotency markers have also been examined in

cisplatin-sensitive cell lines (H12.1, 2102EP and NTERA-2) and

their resistant counterparts (H12.1D, 1411HP and 1777NRpmet).

Several genes related to pluripotency, cell metabolism,

proliferation and migration were identified. Upregulated genes

included PCP4, tribbles pseudokinase 3 (TRIB3),

ID2 and SLC40A1, while downregulated genes included

insulin like growth factor binding protein 2 (IGFBP2),

L1TD1, NANOG, POU5F1 and SOX2 (75) (Table III). Among these, TRIB3

(76), IGFBP2 (77), NANOG (78), POU5F1 (79) and SOX2 (80) are associated with EMP-related

processes.

Signaling pathways related to differentiation can

modulate FN1 expression in cisplatin-resistant NTERA-2 cells. In a

previous study, cisplatin treatment reduced the expression of the

TFs NANOG and POU5F1, which maintain the

undifferentiated state, while promoting expression of

differentiation markers, such as nestin (NES), Stathmin-2

(STMN2) and FN1. Cells that did not downregulate

NANOG and POU5F1 failed to develop resistance to

cisplatin. Overexpression of NANOG prevented

cisplatin-induced resistance, indicating a link between cellular

differentiation and drug resistance (81).

The Wnt/CTNNB1 signaling pathway is known to play a

role in GCTs (82,83). The effects of Wnt/CTNNB1 signaling

pathway inhibition using PRI-724 were evaluated in GCT cell lines

(NTERA-2, JEG-3, TCam-2 and NCCIT) and their resistant variants

(NTERA-2R, JEG-3-R, TCam-2-R and NCCIT-R). Gene and protein

expression levels of CTNNB1 and cyclin D1 were increased in

TCam-2-R and NCCIT-R cells but decreased in NTERA-2R cells.

Treatment with PRI-724 induced pro-apoptotic effects (activation of

caspases 3/7) in all cell lines, indicating that the Wnt/CTNNB1

pathway contributes to resistance (84).

EMP can be regulated by post-translational

modifications (85), which are

known to influence cancer aggressiveness and cisplatin resistance

in tumors (86,87). One such process is neddylation,

which involves conjugation of the ubiquitin-like molecule NEDD8 to

a target protein, altering its stability, function or subcellular

localization. Neddylated proteins may undergo degradation via the

ubiquitin-proteasome system, and aberrant degradation of tumor

suppressor proteins through this pathway can contribute to

carcinogenesis (88,89).

A genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 screen showed

upregulation of NEDD8-activating enzyme E1 subunit 1 (NAE1)

gene in cisplatin-resistant colonies of JARMPHv2/SAMv2 and

2102EPMPHv2/SAMv2 cell lines. Inhibition of neddylation with

MLN4924 sensitized these cells to cisplatin, resulting in

apoptosis, G2/M cell cycle arrest, γH2AX/p27

accumulation and differentiation into mesoderm/endoderm lineages in

TGCT cells, while fibroblasts remained unaffected (88). NAE1 inhibition has also been

evaluated in ovarian cancer, in which, both in vivo and

in vitro, exposure to this inhibitor augmented cisplatin

activity, showing synergetic capacity, and even resensitized

cisplatin-resistant cells/tumors. The drug caused stabilization of

NEDD8, and it also promoted apoptosis induced by oxidative stress

(86).

Epigenetic alterations, particularly in RNA, have

been studied, with N6-methyladenosine (m6A) being the most common

mRNA modification. In GCTs, the protein levels of m6A writer

complex vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA) were

higher in cisplatin-resistant NCCIT-R cells compared with those in

NCCIT cells (88). Knockdown of

VIRMA reduced m6A abundance, increased cisplatin sensitivity, and

decreased cell viability, tumor cell proliferation, migration and

invasion in NCCIT cells (90).

miRNA expression was also evaluated in the NTERA-2,

NCCIT and 2102EP cell lines, and their cisplatin-resistant

counterparts (NTERA-2R, NCCIT-R and 2102EP-R). Differentially

expressed miRNAs included hsa-miR-10b and hsa-miR-512-3p, which

were both upregulated 2-3-fold in all resistant cell lines.

Notably, hsa-miR-10b was implicated in breast cancer invasion and

metastasis (91).

Histone deacetylases (HDACs), which regulate

chromatin accessibility, were investigated in GCT cell lines.

Differential expression of HDACs, including HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC7,

was observed. TCam-2 cells displayed lower histone expression. In

NTERA-2R cells, significant gene-level expression of HDAC8,

HDAC9 and HDAC11 was observed. However, only HDAC11 showed

significant protein expression. Treatment with HDAC inhibitors,

such as belinostat and panobinostat, reduced cell viability in a

time- and dose-dependent manner, inducing cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis. Pre-treatment with non-toxic doses of belinostat

enhanced cisplatin sensitivity (17).

Cell cycle dysregulation was also analyzed in

TGCTs. Gene and protein analysis revealed high expression of

CDK4/CDK4 in TCam-2, 2102EP, NCCIT and JAR cell lines,

whereas CDK6/CDK6 expression was weak or absent (Table III). Treatment with CDK4/6

inhibitors (palbociclib and ribociclib) reduced cell viability and

induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, suggesting these

inhibitors as potential therapeutic options for both

cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant GCTs (92). Cisplatin resistance was associated

with cyclin D1 (CCND1) upregulation in resistant cell lines

(833K-R, Susa-R and GCT27-R), encoding cyclin D1, a protein

involved in G1/S cell cycle transition. Knockdown of

CCND1 reduced cell viability and increased cell death

following cisplatin treatment (93).

Cisplatin-resistant GCT cell lines exhibit

alterations across multiple biological processes, including DNA

repair (94), CSC markers

(95), post-translational

modifications, epigenetic changes (85), epitranscriptomic alterations and

cell cycle dysregulation (96).

This current review focuses on how these processes converge on EMP,

either as drivers or consequences, providing potential therapeutic

targets for treatment.

Despite valuable insights from available studies,

critical limitations must be acknowledged. Much of the data on EMP

in GCTs are derived from choriocarcinoma-derived cell lines (BeWo,

JAR and JEG-3), which, although informative, primarily model

placental development and pregnancy-related pathologies rather than

non-gestational GCTs. This limits the translatability of findings

to the broader spectrum of GCTs, especially those in pediatric and

adolescent populations. Moreover, few studies have directly

investigated the association between EMP and cisplatin resistance

in GCTs, leaving gaps in understanding how these processes

intersect and contribute to treatment failure. The reliance on

limited in vitro models and the scarcity of cell lines

representing various histological subtypes and age groups further

constrain generalizability. Future research should focus on

developing and characterizing additional GCT models, particularly

from pediatric cases, and integrating EMP-related mechanisms with

chemoresistance pathways to uncover clinically relevant

targets.

EMP analysis in in vivo models of

GCTs

Although recent studies have focused on elucidating

key insights into plasticity, to the best of our knowledge, few

studies demonstrate a specific association between animal

experimentation, GCT cellular models and cisplatin resistance. It

is evident that numerous studies are limited to standardizing

cellular models for xenografts or developing animal models that

best represent neoplasia development. These efforts are intended to

facilitate future detection in humans through patient-derived

xenograft (PDX) models (Fig. 2).

Therefore, in this section, the present study will discuss markers

of cellular plasticity and approaches in cisplatin resistance

models in GCTs.

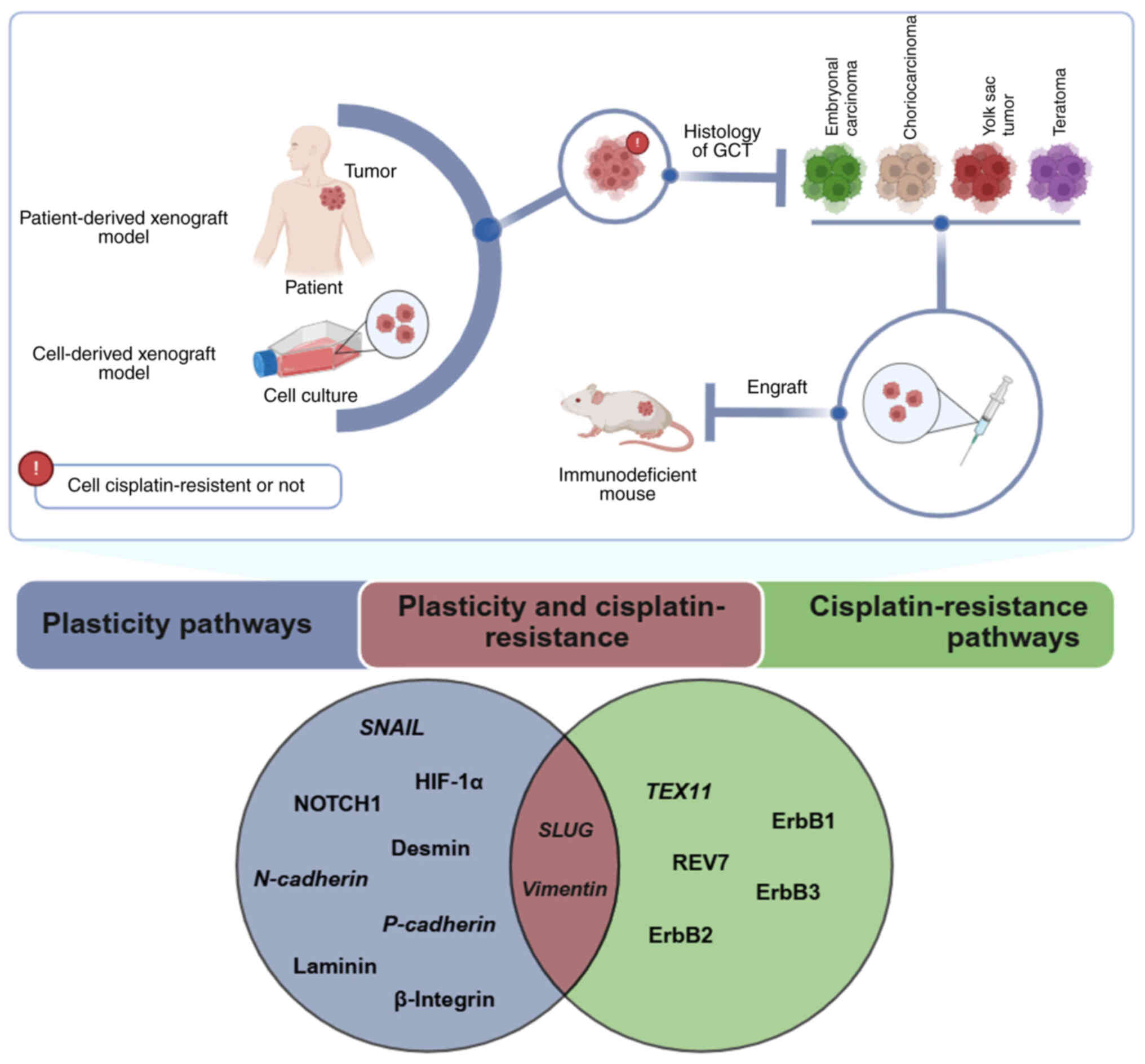

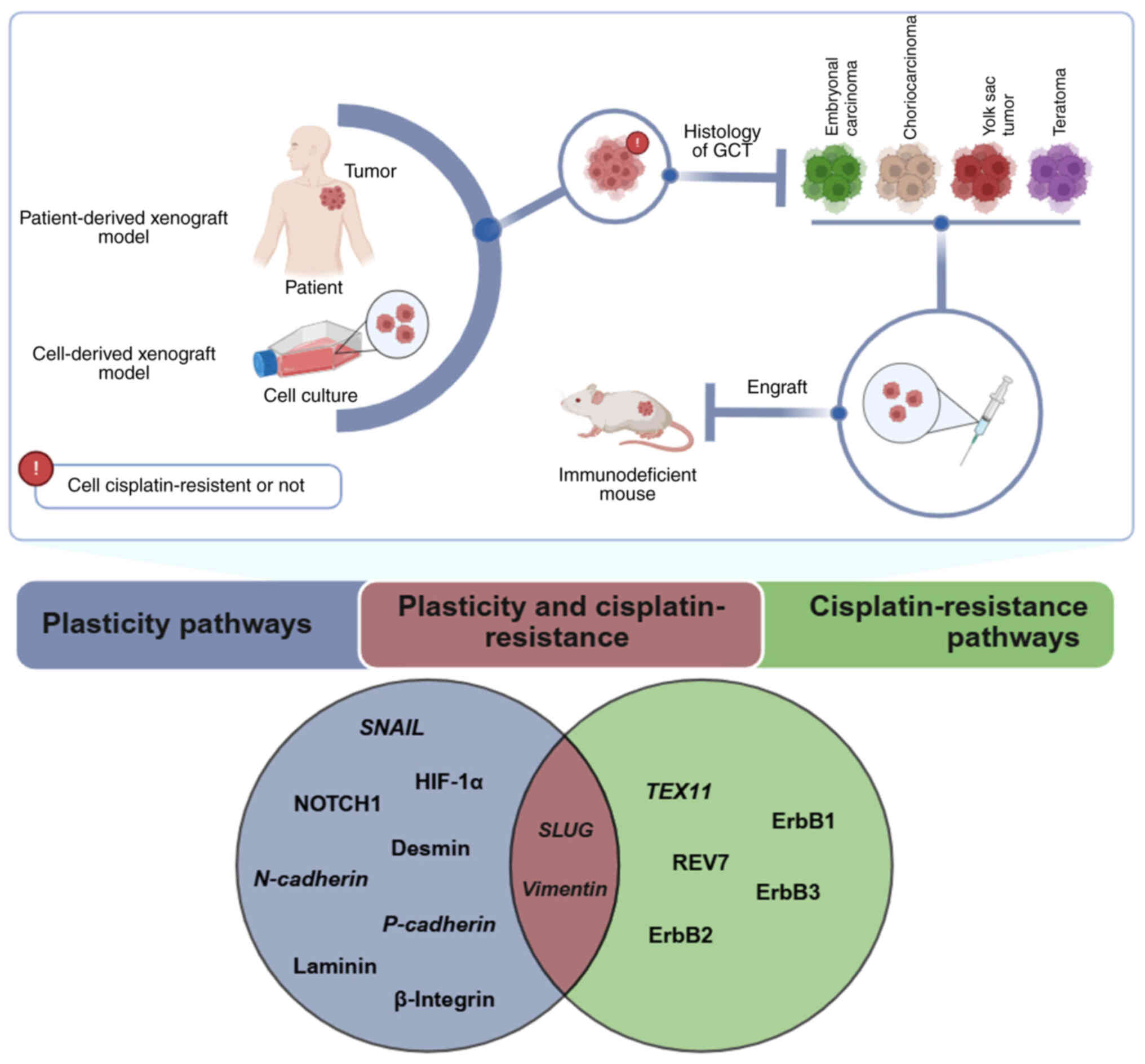

| Figure 2Overview of in vivo GCT models

and key findings on plasticity and cisplatin resistance. Cellular

plasticity pathways, shown in blue, include the genes SNAIL,

SLUG, HIF-1α, N-cadherin and P-cadherin and the

proteins NOTCH1, desmin, laminin and β-integrin. Cisplatin

resistance pathways, in green, involve the TEX11 gene and

the proteins REV7, ErbB1, ErbB2 and ErbB3. SLUG and

vimentin genes are the only plasticity markers linked to

cisplatin resistance in GCTs (in brown). Created in BioRender.

Pinto, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z54o788. GCT, germ cell tumor;

HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α; TEX11,

testis-expressed 11; REV7, reversionless 7. |

Markers of cellular plasticity in

GCTs

Most studies on cellular plasticity in GCTs focus

on key TFs, proteins expressed during this phenotypic transition in

differentiating cells, and splice variants linked to tumor

angiogenesis directly associated with plasticity proteins. The lack

of data connecting animal experimentation, GCT cellular models and

cisplatin resistance can be attributed primarily to experimental

limitations and notable differences between human and animal tumors

(97).

In murine EC stem cells, commonly used in

vivo experiments, the cytoskeleton initially expresses VIM,

followed by keratin polypeptides after differentiation (97). By contrast, human EC cells exhibit

a divergent pattern of gene expression, initially producing keratin

polypeptides and subsequently undergoing spontaneous or induced

differentiation, resulting in the expression of VIM and other

intermediate filaments, including neurofilaments (97). For this reason, studies have used

xenograft models to address these differences, as discussed

below.

Species differences were evident in a study of

xenografts of human teratocarcinoma NTERA-2 and 2102EP cells in

nude mice, which produced solid tumors (97). Using a polyclonal antibody for

human epidermal keratin raised in rabbits and three monoclonal

antibodies for specific keratin polypeptides (AE-1, AE-3 and

RGE53), researchers analyzed intermediate filament protein

expression (97). The results

showed that tumors derived from NTERA-2 reacted with all keratin

antibodies and exhibited positive cells for neurofilaments and

mesenchymal areas containing VIM and desmin. By contrast,

2102EP-derived tumors expressed only keratin polypeptides. These

findings demonstrated differences in intermediate filament

expression between human and murine teratocarcinomas (97).

An important aspect of plasticity is the role of

TFs such as HIF-1α and SNAIL (98). HIF-1α has therapeutic potential in

cases where chemotherapy has been unsuccessful, as elevated HIF-1α

levels have been observed in CC. Positive HIF-1α expression is

correlated with NOTCH1 in CC cell lines, suggesting that

HIF-1α-induced plasticity depends on NOTCH1 signaling (98). Reduction of endogenous NOTCH1

signaling was associated with disruption of plasticity, while its

activation was linked to increased invasion and metastasis in cells

overexpressing HIF-1α in in vivo models of CC. Thus, NOTCH1

is directly related to invasion and metastasis in CC, and its

inhibition may be a promising therapeutic target by limiting

invasion and metastasis through suppression of plasticity (98).

Another TF, SNAIL, has been found to be strongly

associated with plasticity. Evidence shows that both SNAIL and SLUG

are present in the germ cells of normal human testes, similar to

observations in mice (99,100).

Positive regulation of SNAIL has been associated with the induction

of metastasis and poor prognosis, while its silencing suppresses

tumor growth and invasiveness in breast cancer (101). Although negative regulation of

SNAIL has been observed in CC cells treated with a NOTCH1

inhibitor, this evaluation was conducted only in vitro

(98).

Studies have analyzed the direct or indirect

presence of proteins characteristic of the mesenchymal phenotype in

in vivo models, such as CDH2, laminin and integrin β-1

(102,103). Through the mating of mice with

recessive and null N- or P-cadherin mutations, pluripotent

embryonic stem cells generated in vitro underwent

differentiation in vivo into TEs (102). The results showed that the

differentiation and histogenesis occurred within the TEs, as cells

lacking N- and P-cadherin exhibited predominantly adherent

structures and significant qualitative and quantitative

differentiation. Although the cells were inoculated near the

animals' lymph nodes, none metastasized or caused mortality in the

host, with the studies noting that some cells likely still

expressed CDH1 (102).

Furthermore, a study using syngeneic 129/Sv male

mice examined the impact of the absence of integrin β-1, a protein

involved in recognizing various laminins and collagen IV, on

teratoma development. Absence of integrin β-1 was found to be

efficient for analysis compared with TEs derived from wild-type

cells (103). Two stem cell

lines, D3 (wild-type) and G201 (integrin β-1-deficient via double

knockout of the integrin gene), were inoculated into the mice.

After 21 days, tumors were surgically collected. The results showed

that animals inoculated with the deficient cell line produced 90%

fewer TEs compared with the wild-type, with abundant epithelial

cells but losses in cuboidal shape, irregular layer arrangement and

reduced fluorescence in laminin α-1 staining (103). The mutant epithelial cells

exhibited a partially widened basal membrane, loop formation and

multilayered cells. Additionally, selective negative regulation of

laminin-1 was observed, indicating a loss of molecular contacts

with cellular receptors and aberrant structural characteristics

(103).

It was demonstrated that F9 mouse EC cells have

higher affinity for FN1 than for laminin in terms of attachment and

dissemination in the animal organism. Laminin is predominantly

found in the pulmonary matrix, while FN1 is found in the liver.

Thus, the low affinity of these cells for laminin in the lung

caused their rapid elimination from that organ. These results were

obtained from a study evaluating cell migration after injection

into the tail vein of mice, showing that the tumor cell adhesion to

organs is necessary but not sufficient for metastasis (104).

A key driver of tumor growth and metastasis is high

vascularization due to angiogenesis (105). The splice variant FN1B

stands out as a specific biomarker of angiogenesis expressed around

new blood vessels in various human cancer types, such as

glioblastoma and small cell lung cancer. Through culturing mouse

embryonal teratocarcinoma cells and inoculating them into

4-week-old female mice, a study observed via microPET imaging, that

FN1B serves as a promising biomarker for microPET imaging

targeting (105).

Taken together, these studies provide significant

insights into the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying

plasticity in GCTs, particularly through in vivo models and

characterization of key proteins, TFs and angiogenesis-related

biomarkers. However, distinct differences in intermediate filament

expression between human and murine tumors, as well as limited

exploration of species-specific pathways, highlight the complexity

of translating findings across models. Moreover, while substantial

progress has been made in linking plasticity to invasion and

metastasis, the role of plasticity in treatment resistance,

particularly to cisplatin, remains insufficiently understood.

Bridging this knowledge gap will require integrating advanced

experimental approaches focusing on the interplay between

plasticity mechanisms and therapeutic responses, ultimately paving

the way for more precise and effective treatments for GCTs.

Approaches in cisplatin resistance

models

Several studies on resistance have focused on

demonstrating cisplatin resistance in in vivo models,

particularly in PDX models. However, some of these studies

investigated this phenomenon in tumor types other than GCTs, such

as ovarian (106,107), lung (108,109), liver (110,111), colorectal (112), gastric (113,114) and brain (115) cancer. Thus, the primary

objective of these studies was to characterize cisplatin

resistance, analyze genes, proteins and signaling pathways involved

in chemoresistance, compare different drugs associated with

chemoresistance and establish new targeted drugs for treatment.

Nevertheless, few studies have explored the interaction between

cisplatin resistance and plasticity, as highlighted below.

A notable study examined the association between

plasticity and treatment resistance, using a novel cyclic peptide,

MTI-101, in synergy with cisplatin in lung cancer (109). In vivo data indicated

that the treatment increased CDH1 and decreased VIM expression,

suggesting that chronic treatment with MTI-101 could reduce

metastatic disease (109).

Despite these notable results, a direct association between

cisplatin resistance, plasticity and GCT models was not observed. A

similar observation was reported using zebrafish xenografts to

evaluate the therapeutic benefits of cisplatin and valproic acid in

patient-derived laryngeal cancer cell lines (116). Evidence highlighted that the

RK45 cell line activated genes associated with the epithelial

phenotype. Following treatment with both chemotherapeutics,

upregulation of CDH1, which encodes CDH1, and its placental

form, CDH3, was observed (116). Additionally, negative regulation

of the TFs ZEB1 and FGFR1, genes that induce

plasticity progression and may be associated with the weak response

of RK33 cells to the combination of cisplatin and valproic acid

drugs, was noted. Meanwhile, the RK33 cell line exhibited

upregulation of mesenchymal phenotype genes, such as VIM (116).

Some studies have explored cisplatin resistance in

xenograft models using GCT cell lines. An in vivo model

utilizing the GCT NTERA-2 cell line, including both the parental

and cisplatin-resistant strains, was employed to evaluate drug

sensitivity. It was reported that both cell lines were sensitive to

the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor guadecitabine, suggesting that

this agent may offer a potential therapeutic alternative for

patients with cisplatin-resistant GCTs. This finding highlights the

potential of epigenetic therapies in overcoming resistance and

improving treatment outcomes for these patients (117). The same cell line, NTERA-2, was

used to investigate the effects of cholecalciferol (inactive form

of vitamin D) and 1,25(OH)2D3 on cisplatin

treatment in an in vivo xenotransplantation mouse model,

using tumor growth and tumor size as endpoints. In contrast to the

findings with guadecitabine, treatment with the active form of

vitamin D showed no antitumor activity in vivo (118).

Beyond the use of xenograft models derived from

established cell lines, research has focused on developing PDX

models. These PDX models preserve essential characteristics of

original patient tumor cells, including maintaining high genetic

and transcriptional stability. Importantly, key mutations present

in primary tumors have been shown to remain consistent across

successive PDX passages (119,120). PDX models show greater

similarity to human tumors compared with cell lines. Analyses of

cisplatin resistance in PDX have shown results resembling those

observed in the corresponding patient, highlighting the superiority

of PDX models in predicting drug response (119).

A xenograft model of TGCT derived from a patient

with cisplatin resistance was used to evaluate potential

therapeutic strategies. The findings revealed the efficacy of short

interfering RNA targeting testis-expressed 11 (TEX11), a

gene significantly upregulated in the tumor. TEX11, known

for its role in meiosis, was implicated in promoting resistance to

cisplatin by inhibiting cisplatin-induced double-strand DNA

breakage. These results highlight TEX11 as a promising

therapeutic target for addressing cisplatin-resistant TGCTs

(121). Additionally,

reversionless 7 gene (REV7) deficiency is involved in DNA

damage repair, cell cycle regulation and gene expression, and it

sensitized cisplatin-resistant tumors in vivo. This was

observed in a tumor xenograft of a GCT (testicular EC) in SCID mice

(122). Thus, these studies

underscore the potential of targeting key molecular players, such

as TEX11 and REV7, in overcoming cisplatin resistance

in TGCTs.

A xenograft model was established in

immunodeficient mice using cisplatin-resistant cells derived from a

previously cisplatin-sensitive YST of a patient with ovarian

cancer. This model provided insights into the association between

CSC markers and cisplatin resistance (increased expression of

CD133, ALDH3A1 and ABCG2), underscoring potential targets to

address chemoresistance (74).

In the context of PDX models for GCTs, primary

choriocarcinoma tumors were implanted in mice to evaluate the

expression of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases and

assess the effects of their inhibitors (123). The ErbB family is associated

with tumor progression, correlating with worse prognosis and

resistance to conventional therapies (123). ErbB receptors are naturally

expressed in tissues of epithelial, mesenchymal and neuronal origin

(123). However, members of the

ErbB family (ErbB1, ErbB2 and ErbB3) exhibit distinct expression

patterns in tumors, such as CC, EC and YST (120). Specifically, ErbB1 is

upregulated in CC, ErbB2 is highly expressed in EC, and elevated

levels of ErbB3 are observed in CC, EC and YST (120). Therapeutic inhibition of these

markers has shown that targeting a single ErbB family member is

insufficient to disrupt tumor growth, as compensatory pathway

reactivation contributes to resistance against ErbB-targeted

therapies (120,124).

Despite studies identifying important pathways

associated with cisplatin resistance or sensitivity in GCTs, little

information addresses plasticity. To address this gap, our research

group conducted a study analyzing the expression of SLUG, a key

plasticity TF, in both parental and cisplatin-resistant xenograft

tumors (21). Parental and

cisplatin-resistant NTERA-2 cells were inoculated into athymic

mice, and significant upregulation of VIM and SLUG

expression was observed. This suggests that SLUG may serve

as an important TF for linking plasticity and cisplatin resistance

in GCTs (21). While this study

offers insights into the mechanisms of plasticity and cisplatin

resistance, murine models do not fully reflect the complexity of

human tumors. This is particularly due to species-specific

differences in gene expression and treatment response. However, a

deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying EMP and

drug resistance presents a promising avenue for the development of

innovative therapeutic strategies tailored to target TGCTs, thereby

opening new avenues for more effective and personalized

treatments.

Potential inhibitors targeting EMP

Inhibitors targeting EMP have become a key strategy

in combating cancer progression, metastasis and treatment

resistance. By modulating key signaling pathways and molecular

markers associated with plasticity, these inhibitors offer a

promising approach to mitigating the aggressive behavior of tumors

(125).

In JEG-3 cells, cyclosporin-A (CsA) was shown to

promote invasion through reduced CDH1 expression via the EGFR/ERK

signaling pathway. This effect was counteracted by U0126, an ERK

pathway inhibitor, demonstrating its ability to suppress

EMP-related invasive behavior (126). Similarly, the

phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor rolipram has been highlighted

as a potential therapeutic agent. Rolipram effectively reduced

migration and invasion in JEG-3 and JAR cells by modulating EMP

markers at the mRNA and protein levels, including decreased

expression levels of MMP9 and TIMP1, and increased expression of

CDH1, positioning PDE4 inhibitors as promising candidates for

modulating EMP in cancer therapy (127,128). Thus, CsA and PDE4 inhibitors

demonstrate significant impacts on EMP and invasive behavior in

cancer cells.

Further advancements in overcoming cisplatin

resistance in GCTs include the use of monanchocidin A (MonA), an

alkaloid compound with antitumor properties. MonA demonstrated the

ability to downregulate VIM isoforms, suppress migration and alter

cell morphology in cisplatin-resistant NCCIT-R cells, suggesting

its potential role in addressing EMP-related resistance mechanisms

(129). Additionally,

panobinostat, an HDAC inhibitor, has shown potential as an

inhibitor of LINC00313, a long non-coding RNA linked to EMP

mediation. Although its effects on specific EMP markers require

further study, panobinostat represents a promising avenue for

therapeutic exploration (65).

These inhibitors hold considerable promise for further

investigation as potential therapeutic agents for GCT treatment,

particularly for addressing EMP-driven cisplatin resistance, a

critical unmet clinical need.

Insights from clinical trials in non-GCT

malignancies

To date, to the best of our knowledge, clinical

trials targeting EMP pathways in GCTs remain unavailable. However,

investigations into EMP-related targets in other malignancies

provide valuable insights. For instance, andecaliximab, a

monoclonal antibody inhibiting MMP9, a key EMP player, has

demonstrated manageable safety profiles and varying efficacy in

advanced cancer types, such as gastric and pancreatic

adenocarcinoma (130,131). In pancreatic adenocarcinoma,

combinations with chemotherapy regimens, such as gemcitabine and

nab-paclitaxel, achieved a progression-free survival time of 7.8

months and an objective response rate of 44.4%. In advanced gastric

cancer, one study evaluated andecaliximab as monotherapy and in

combination with nivolumab, showing a manageable safety profile and

clinical activity, with a median progression-free survival time of

1.4 and 4.6 months for monotherapy and combination therapy,

respectively (132). Another

study assessing andecaliximab combined with nivolumab in pretreated

metastatic gastric cancer reported a favorable safety profile but

no significant improvement in survival outcomes compared with

nivolumab alone (133). A phase

I study combining sapanisertib with ziv-aflibercept, a VEGF

inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors, demonstrated a

disease control rate of 78%, with 74% achieving stable disease and

4% achieving a confirmed partial response (134).

Additionally, PRT543, an inhibitor of protein

arginine methyltransferase 5, which downregulates NOTCH1 and MYB

signaling, achieved a clinical benefit rate of 57% and a median

progression-free survival time of 5.9 months in adenoid cystic

carcinoma (135). Furthermore,

chidamide, an HDAC inhibitor, demonstrated anti-NOTCH1 activity and

clinical efficacy in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia,

suggesting its utility in EMP-related pathways (136). Moreover, the combination of

bevacizumab, an antiangiogenic agent targeting VEGF, and

bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor that suppresses HIF-1α

transcriptional activity, demonstrated clinical activity in a phase

I trial involving patients with advanced malignancies. Among the 91

patients treated, 12% achieved either a partial response or stable

disease lasting ≥6 months, highlighting the potential of dual

targeting of angiogenesis and HIF-1α in overcoming resistance to

antiangiogenic therapy (137).

These findings highlight the potential of EMP-targeting strategies

in broader oncology contexts and underscore the need to explore

their therapeutic value in GCTs, where emerging evidence suggests a

role for EMP in treatment resistance.

To offer a comprehensive summary and highlight

connections between all topics discussed in this review, Fig. 3 provides a graphical

representation synthesizing the key aspects of the article.

![Graphical representation of EMP

markers, cisplatin resistance and potential inhibitors across GCT

histologies. This figure illustrates the histologies studied both

in vivo and in vitro, including those related to

cisplatin resistance and the status of potential inhibitors for

targeted therapy. Red circles indicate association with cisplatin

resistance. Created in BioRender. Pinto, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/x70i558.EMP,

epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity; GCT, germ cell tumor; CCND1,

cyclin D1; ErbB, ErbB family; CD133, prominin-1; ALDH3A1, aldehyde

dehydrogenase 3 family member A1; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette

subfamily G member 2; TRIB3, Tribbles pseudokinase 3; IGFBP2,

insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2; NANOG, homeobox

protein NANOG; POU5F1, POU class 5 homeobox 1; SOX2, SRY-related

HMG-box 2; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; VIRMA, Vir-like M6A

methyltransferase associated; ACTA2, actin alpha 2; COL1A1, type I

collagen; FN1, fibronectin; HDAC, histone deacetylase; POLD4, DNA

Polymerase Delta 4, Accessory Subunit; TGF-β, transforming growth

factor beta; VIM, vimentin; XPC, XPC complex subunit, DNA damage

recognition and repair factor; NES, nestin; STMN2, stathmin-2;

REV7; reversionless 7; has-miR, Homo sapiens microRNA; ANXA1,

annexin A1; TAGLN, Transgelin; TEXT11, testis-expressed 11;

LINC003131, long intergenic non-coding RNA; PTTG1, pituitary

tumor-transforming gene 1; DAPT,

N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl

ester; MLN4924, pevonedistat; MG-132, proteasome inhibitor; PDE4,

phosphodiesterase 4; SENP1, SUMO specific peptidase 1; ILK,

integrin linked kinase; SNAIL, snail family transcriptional

repressor 1; TWIST1, Twist-related protein 1; NAE1, NEDD8

activating enzyme E1 subunit 1; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1

Subunit Alpha ; ZEB2, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2; HMOX1,

heme oxygenase 1; NOTCH1, notch receptor 1.](/article_images/ijo/67/6/ijo-67-06-05811-g02.jpg) | Figure 3Graphical representation of EMP

markers, cisplatin resistance and potential inhibitors across GCT

histologies. This figure illustrates the histologies studied both

in vivo and in vitro, including those related to

cisplatin resistance and the status of potential inhibitors for

targeted therapy. Red circles indicate association with cisplatin

resistance. Created in BioRender. Pinto, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/x70i558.EMP,

epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity; GCT, germ cell tumor; CCND1,

cyclin D1; ErbB, ErbB family; CD133, prominin-1; ALDH3A1, aldehyde

dehydrogenase 3 family member A1; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette

subfamily G member 2; TRIB3, Tribbles pseudokinase 3; IGFBP2,

insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2; NANOG, homeobox

protein NANOG; POU5F1, POU class 5 homeobox 1; SOX2, SRY-related

HMG-box 2; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; VIRMA, Vir-like M6A

methyltransferase associated; ACTA2, actin alpha 2; COL1A1, type I

collagen; FN1, fibronectin; HDAC, histone deacetylase; POLD4, DNA

Polymerase Delta 4, Accessory Subunit; TGF-β, transforming growth

factor beta; VIM, vimentin; XPC, XPC complex subunit, DNA damage

recognition and repair factor; NES, nestin; STMN2, stathmin-2;

REV7; reversionless 7; has-miR, Homo sapiens microRNA; ANXA1,

annexin A1; TAGLN, Transgelin; TEXT11, testis-expressed 11;

LINC003131, long intergenic non-coding RNA; PTTG1, pituitary

tumor-transforming gene 1; DAPT,

N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl

ester; MLN4924, pevonedistat; MG-132, proteasome inhibitor; PDE4,

phosphodiesterase 4; SENP1, SUMO specific peptidase 1; ILK,

integrin linked kinase; SNAIL, snail family transcriptional

repressor 1; TWIST1, Twist-related protein 1; NAE1, NEDD8

activating enzyme E1 subunit 1; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1

Subunit Alpha ; ZEB2, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2; HMOX1,

heme oxygenase 1; NOTCH1, notch receptor 1. |

Conclusion

The present review highlights several critical gaps

in the current understanding of EMP and its association with

cisplatin resistance in GCTs. A major limitation is the scarcity of

studies directly investigating EMP-associated cisplatin resistance

in GCTs, with most research focusing separately on EMP or

resistance mechanisms rather than their interplay. Additionally,

while in vitro studies using GCT cell lines have provided

some insights, there is a notable lack of in vivo research

exploring the connection between plasticity and resistance in GCTs.

These findings underscore the necessity for integrated studies that

combine both EMP and resistance mechanisms to enhance our

comprehension of the molecular mechanisms involved. Advancing

research in this area could lead to the identification of novel

therapeutic targets, ultimately improving outcomes for the 30% of

patients with GCT who have a poor prognosis or experience treatment

failure. To address the current knowledge gap, future research

should focus on longitudinal analysis of EMP markers in patient

cohorts, exploring the intricate association between plasticity

mechanisms and therapeutic responses. This will help validate their

prognostic utility and pave the way for developing more effective

and personalized treatments for GCTs.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ESDBG, TMDS, ALPO, AFSPB, IIVC, LS, LFL, MNR and

MTP contributed to the conception, design, literature search and

analysis of the study. ESDBG, TMDS, ALPO, AFSPB, IIVC, LS and MNR

drafted and wrote the manuscript. ESDBG, TMDS and AFSPB prepared

the figures. MTP supervised the review, critically evaluated and

revised the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work artificial

intelligence tools were used to translate the language of the

manuscript and, subsequently, the authors revised and edited the

content translated by the artificial intelligence tools as

necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of

the present manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the São Paulo State Research Support

Foundation, Brazil (grant no. 2019/07502-8) and the Researcher

Support Program from Barretos Cancer Hospital.

References

|

1

|

Oosterhuis JW and Looijenga LHJ: Human

germ cell tumours from a developmental perspective. Nat Rev Cancer.

19:522–537. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Drozynska E, Bien E, Polczynska K,

Stefanowicz J, Zalewska-Szewczyk B, Izycka-Swieszewska E,

Ploszynska A, Krawczyk M and Karpinsky G: A need for cautious

interpretation of elevated serum germ cell tumor markers in

children. Review and own experiences. Biomark Med. 9:923–932. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lopes LF, Sonaglio V, Ribeiro KCB,

Schneider DT and de Camargo B: Improvement in the outcome of

children with germ cell tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 50:250–253.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Veneris JT, Mahajan P and Frazier AL:

Contemporary management of ovarian germ cell tumors and remaining

controversies. Gynecol Oncol. 158:467–475. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Trabert B, Chen J, Devesa SS, Bray F and

McGlynn KA: International patterns and trends in testicular cancer

incidence, overall and by histologic subtype, 1973-2007. Andrology.

3:4–12. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Smith HO, Berwick M, Verschraegen CF,

Wiggins C, Lansing L, Muller CY and Qualls CR: Incidence and

survival rates for female malignant germ cell tumors. Obstet

Gynecol. 107:1075–1085. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shaikh F, Murray MJ, Amatruda JF, Coleman

N, Nicholson JC, Hale JP, Pashankar F, Stoneham SJ, Poynter JN,

Olson TA, et al: Paediatric extracranial germ-cell tumours. Lancet

Oncol. 17:e149–62. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Teilum G: Ovarian Cancer. Gentil F and

Junqueira AC: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 1968,

Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-87755-1.

|

|

9

|

Yao X, Zhou H, Duan C, Wu X, Li B, Liu H

and Zhang Y: Comprehensive characteristics of pathological subtypes

in testicular germ cell tumor: Gene expression, mutation and

alternative splicing. Front Immunol. 13:10964942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kobayashi K, Saito T, Kitamura Y,

Nobushita T, Kawasaki T, Hara N and Takahashi K: Oncological

outcomes in patients with stage I testicular seminoma and

nonseminoma: Pathological risk factors for relapse and feasibility

of surveillance after orchiectomy. Diagn Pathol. 8:572013.