Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents one of the most

prevalent malignancies of the digestive tract. In 2020, CRC emerged

as the third most diagnosed cancer worldwide and ranked second

among global cancer mortality factors (1). Due to its insidious onset, most CRC

patients present with advanced-stage disease at initial diagnosis,

which limits opportunities for curative interventions such as

surgical resection and local ablation (2). Consequently, the development and

establishment of efficient multimodal therapeutic strategies have

emerged as a research hotspot globally.

Current therapeutic modalities for CRC primarily

encompass surgical resection, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and

targeted therapy, which have demonstrably provided symptomatic

relief, prolonged survival and improved the life quality of

patients. However, adjuvant pharmacological treatment regimens for

CRC, using chemotherapeutic agents such as irinotecan

hydrochloride, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin and cetuximab,

frequently induce irreversible damage to normal tissues and organs,

accompanied by severe adverse reactions and toxic side effects

(3). For instance, 5-FU

administration may precipitate severe gastrointestinal reactions

that exacerbate mucosal damage and related symptomatology (4). In addition, the emergence of drug

resistance to cetuximab has progressively become a major clinical

challenge requiring urgent attention (5). Therefore, developing effective yet

low-toxicity therapeutic agents for CRC may constitute a pivotal

strategy to enhance overall treatment efficacy.

Recent researches have elucidated that the

pathogenesis of CRC involves the dysregulation of a number of

cascading signaling pathways, including signal transducer and

activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), transforming growth factor-β

(TGF-β), phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase (PI3K/Akt) and

Wnt/β-catenin, characterized by aberrant silencing or activation of

specific targets (6). However,

current pharmacological interventions for CRC predominantly focus

on single-target therapies. While acknowledging the clinical

efficacy of specific single-target agents in CRC management (such

as immune checkpoint inhibitors), monotherapy targeting individual

signaling cascades or biological markers generally fail to achieve

optimal therapeutic outcomes. Naturally derived phytochemicals

exhibit marked advantages in modulating signal transduction

cascades through multi-target, multi-pathway and multi-effect

mechanisms, thereby enhancing treatment efficacy and quality of

life in CRC patients while effectively preventing recurrence and

potentiating targeted drug performance (7). Notable examples include paclitaxel,

the first plant-derived chemotherapeutic agent and camptothecin,

another plant-based antineoplastic alkaloid, have shown promising

clinical applications. These instances underscore the growing

significance of natural product-derived chemicals in anticancer

drug discovery and research.

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress-induced

damage are closely implicated in the initiation and progression of

CRC. Under physiological conditions, the balanced production of

reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their elimination by endogenous

antioxidants maintains the body's oxidative-antioxidant

equilibrium. However, during pathological states, various

environmental and endogenous stressors stimulate excessive ROS

generation, disrupting this equilibrium and triggering oxidative

stress. The resultant oxidative stress induces macromolecular

oxidation of proteins, lipids and DNA/RNA, leading to lipid

peroxidation of biomembranes, denaturation of intracellular

proteins and enzymes and DNA damage. These alterations compromise

intestinal mucosal barrier integrity, ultimately promoting mucosal

injury, colitis and colorectal carcinogenesis (8,9).

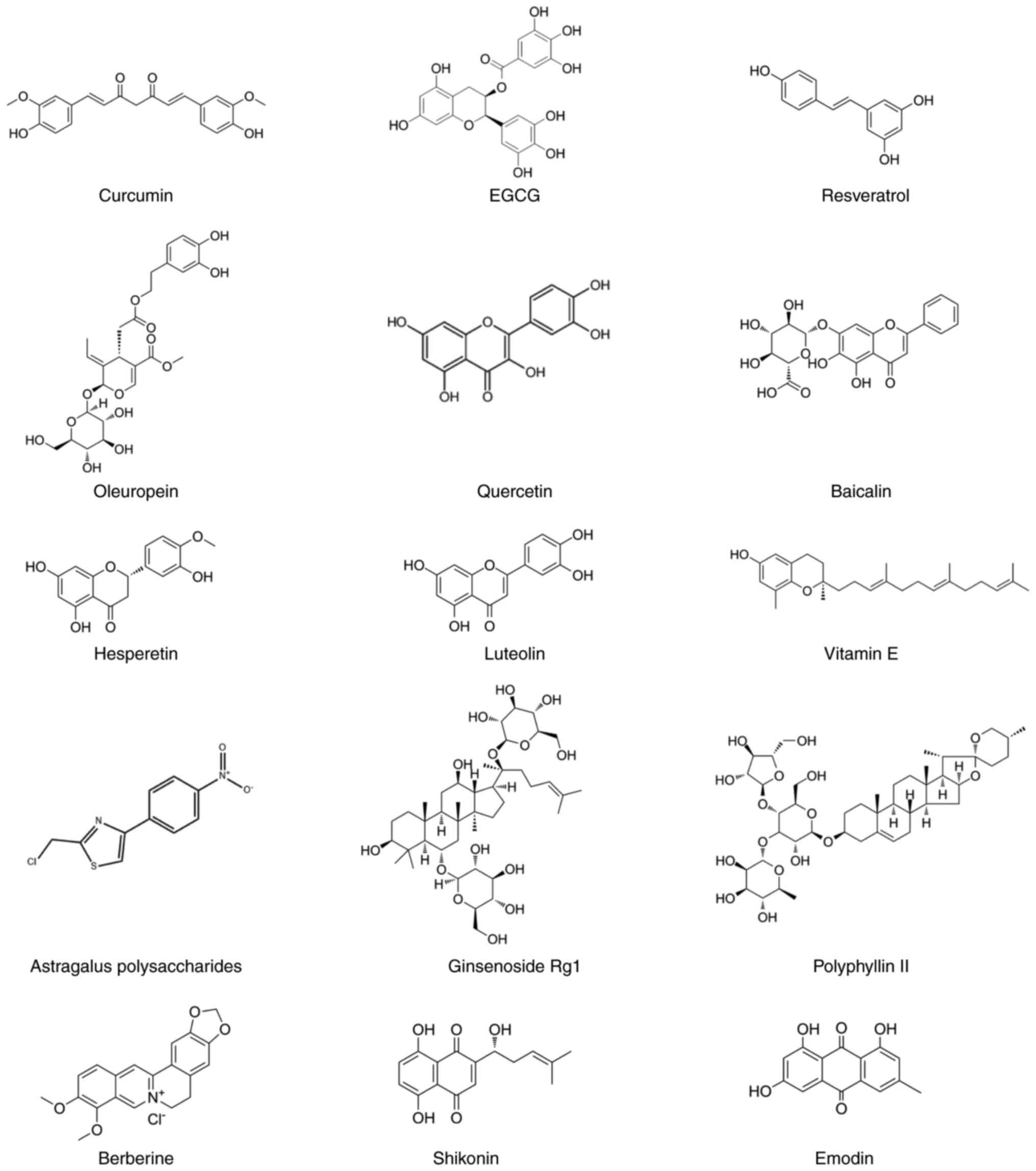

Over the past decade, numerous plant-based

antioxidants (PBAs) with anticancer properties have been

identified, such as curcumin and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)

(10). Chemically, PBAs under

investigation for CRC therapy comprise diverse structural classes

including phenolics, polysaccharides, alkaloids and terpenoids

(Fig. 1). While these monomer

compounds have demonstrated promising antitumor activities in

epidemiological, in vitro and preclinical studies across

various malignancies, their combinatorial application in CRC

chemotherapy remains underexplored and the precise synergistic

antitumor mechanisms remain incompletely elucidated (11). As oncology enters the era of

precision medicine, effective integration of research on PBAs

against CRC to maximize their therapeutic potential represents an

urgent priority in fundamental research.

The present review elucidated the preventive and

therapeutic effects of PBAs on the occurrence and progression of

CRC from the foundational cellular mechanisms and clinical

research. Various types of PBAs play roles by regulating the

signaling pathways related to CRC and modulating the expression of

target genes involved in these pathways. Rather than focusing

solely on a class of plant compounds or herbal medicines that

modulate the gut microbiota of CRC (12,13), the present review comprehensively

detailed the classification and therapeutic effects of various

plant-derived antioxidant monomer components with anti-CRC

properties. The present review also provided a more comprehensive

theoretical basis for further understanding of the molecular

mechanism of PBAs in the treatment of CRC. Additionally, there are

few clinical studies on the prevention and treatment of CRC using

PBAs and they are still facing bioavailability and safety problems.

Different drug delivery strategies and individualized treatment

concepts have been developed and the present review highlighted and

emphasized the limitations and challenges of current progress. It

requires further investigation to explore and promote the efficacy

of PBAs in CRC.

Foundational mechanisms of plant-based

antioxidants

Antioxidant and redox homeostasis

The mutation and transformation of normal tissue

cells into cancerous cells can be triggered by the accumulation of

free radicals during early stages, with oxygen-derived free

radicals subsequently participating in cancer progression. Free

radicals produced by Enterococcus bacteria in the colon may

directly induce colonic DNA mutations, thereby contributing to CRC

development (14). Oxidative

stress is widely thought to promote intestinal epithelial cell

damage by inducing genetic instability, specific gene alterations

and aberrant methylation, creating opportunities for colorectal

carcinogenesis. Excessive ROS generation triggers tissue or

intracellular oxidative stress, further inducing oxidative DNA

damage. Increased DNA damage stimulates the uptake of

ω-polyunsaturated fatty acids as a compensatory response (15). Concurrently, ROS activates both

intrinsic mitochondrial-mediated and extrinsic death

receptor-mediated apoptosis pathways, thereby promoting CRC

initiation and progression (16).

Gingerol (6-Shogaol, 20 mg/kg/day, orally), compared

with the control group [a mouse colorectal adenoma model induced by

Azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)], reportedly

demonstrates significant antioxidant stress effects by reducing

levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α),

lipid peroxidation, myeloperoxidase (MPO) and nitric oxide (NO),

while markedly enhancing activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD),

catalase (CAT) and glutathione (GSH) (17). These effects collectively promote

redox homeostasis restoration in colonic tissues. Curcumin

activates intracellular redox reactions to induce ROS generation,

which upregulates apoptotic receptors on tumor cell membranes. In

addition, curcumin enhances the expression and activity of p53, a

tumor suppressor that inhibits proliferation and promotes

apoptosis. This compound also potently inhibits NF-κB and COX-2

activities, both linked to overexpression of anti-apoptotic genes

such as Bcl-2. Curcumin further attenuates pro-survival PI3K

signaling while increasing mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)

expression, stimulating endogenous ROS production, which may

activate a ROS/KEAP1/NRF2/miR-34a/b/c cascade to suppress

colorectal cancer metastasis (18).

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory

effects

Colitis-associated CRC (CAC) is now understood to

develop from chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (19). During early intestinal

inflammation and mucosal barrier disruption, luminal microbial

antigens trigger immune cell chemotaxis to the colonic mucosa.

These infiltrating cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines

including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), establishing

a chronic inflammatory microenvironment. Concurrently,

immune-derived reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, such as inducible

nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), induce colonic epithelial DNA damage

(20). Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)

serves as a master regulator of inflammatory mediator production,

with its hyperactivation critical for maintaining colonic

inflammation and promoting epithelial dysplasia (21). Upon activation, inhibitors of

NF-κB (IκBs) undergo phosphorylation and degradation, releasing the

p65 subunit for nuclear translocation and pro-inflammatory gene

transcription (22). To

investigate the effect of Berberine (BBR) on intestinal

inflammatory response in AOM/DSS-induced CAC mice, BBR (daily

gavage of 100 mg/kg) markedly decreased the colonic levels of TNF

α, IL-6 and IL-1β compared with the CAC group (daily gavage of 100

μl PBS). Furthermore, compared with the CAC group, the

zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), occludin and mucin-2 (MUC-2) mRNAs were

markedly upregulated in response to BBR (23). These results indicated that BBR

could improve colitis symptoms and epithelial injury in inflamed

mucosa, inhibiting CAC development. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a

pathogen recognition receptor expressed in colonic epithelia and

lamina propria immune cells, activates downstream inflammatory

pathways that exacerbate IBD-associated inflammation and

tumorigenesis (24). Compared

with the control group (constituting AOM/DSS-induced CAC mouse

model), Rosmarinic acid (30 mg/kg/day; orally) markedly decreased

83.3% of the polypoid tumor number and inhibited COX-2 and iNOS

protein levels in vivo. Furthermore, Rosmarinic acid (25

μM) competitively antagonizes TLR4, blocking NF-κB and STAT3

activation in HCT116 cells and HT29 cells exposed to the

inflammatory microenvironment (25). This suppression reduces

inflammatory mediator levels and confers chemo-preventive effects

against CAC.

The intestine constitutes the most significant

component of the human immune system, making the modulation of

intestinal immune status to restore homeostasis a promising

therapeutic approach for treating IBD and preventing CAC

development. During intestinal inflammation, myeloid-derived

suppressor cells (MDSCs) are recruited and activated in gut

tissues, where they suppress dendritic cell antigen

uptake/processing and subsequent CD4+ T cell

proliferation/activation. This impairment compromises pathogen

clearance at bacterial penetration sites, perpetuating chronic

inflammatory stimuli (26). The

resultant shift from acute to chronic inflammation creates a

permissive microenvironment for tumor initiation.

Madecassic acid (MA), a triterpenoid compound

isolated from Centella asiatica, blocks MDSC migration by

inhibiting γδT17 cell activation and related chemokine expression.

Compared with the control group (AOM/DSS mouse model) and the

positive control group (5-amino-o-hydroxybenzoic acid, 5-ASA; 75

mg/kg/day, orally), orally administrated of MA (25 mg/kg/day) can

markedly weaken the severity of CAC and reduce the incidence of

tumors and 5-ASA only delays the progression of tumors (27). This intervention enhances

antitumor immunity and suppresses CAC progression. Curcumin (20

μM) exerts dual actions by inducing CT26 tumor cell

apoptosis and heat shock protein 70 expression while recruiting

CD3+ T cells and F4/80+ macrophages to

inhibit CRC growth (28). In

addition, tumors from curcumin-treated rats (750 μg/kg, i.p.

on days 21 and 26) were infiltrated with numerous activated

lymphocytes, compared with the control group (untreated). The

proteome alterations showed that curcumin suppresses Foxp3

expression while enhancing type II interferon production, skewing T

cell differentiation toward Th1 phenotype and counteracting tumor

immune evasion (29).

Cell cycle and apoptosis regulation

Dysregulation of cell cycle progression represents a

critical mechanism underlying uncontrolled proliferation and

malignant transformation of tumor cells, with aberrant activation

of cell cycle checkpoints playing a pivotal role in this process.

Overexpression of Cyclin D1 and Cyclin B1, key rate-limiting

regulators for G1/S and G2/M phase

transitions, respectively, disrupts cellular proliferation control,

impairs differentiation and facilitates oncogenic progression

(30). Consequently, targeted

cell cycle arrest has emerged as a promising therapeutic avenue for

cancer cell elimination. EGCG has been shown to downregulate mRNA

expression of several cell cycle-related genes while enhancing

expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and

apoptosis-associated death receptor 5 (31). Disrupted apoptotic processes

compromise the equilibrium between apoptosis and proliferation in

colonic epithelial cells, ultimately contributing to CRC

development. It demonstrates that various PBAs exert anti-apoptotic

effects via mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways, primarily by

modulating the expression of cysteine-aspartic acid protease

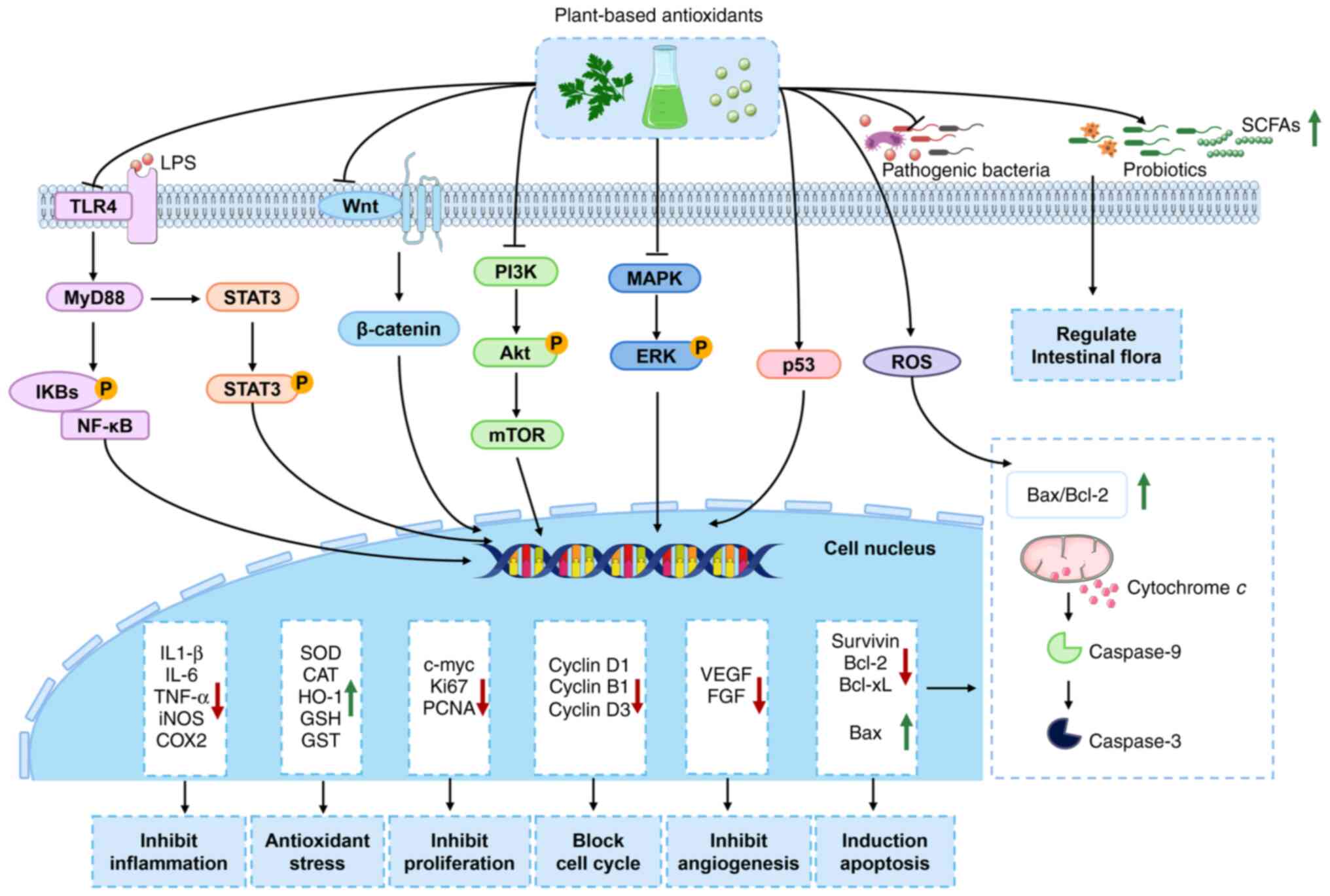

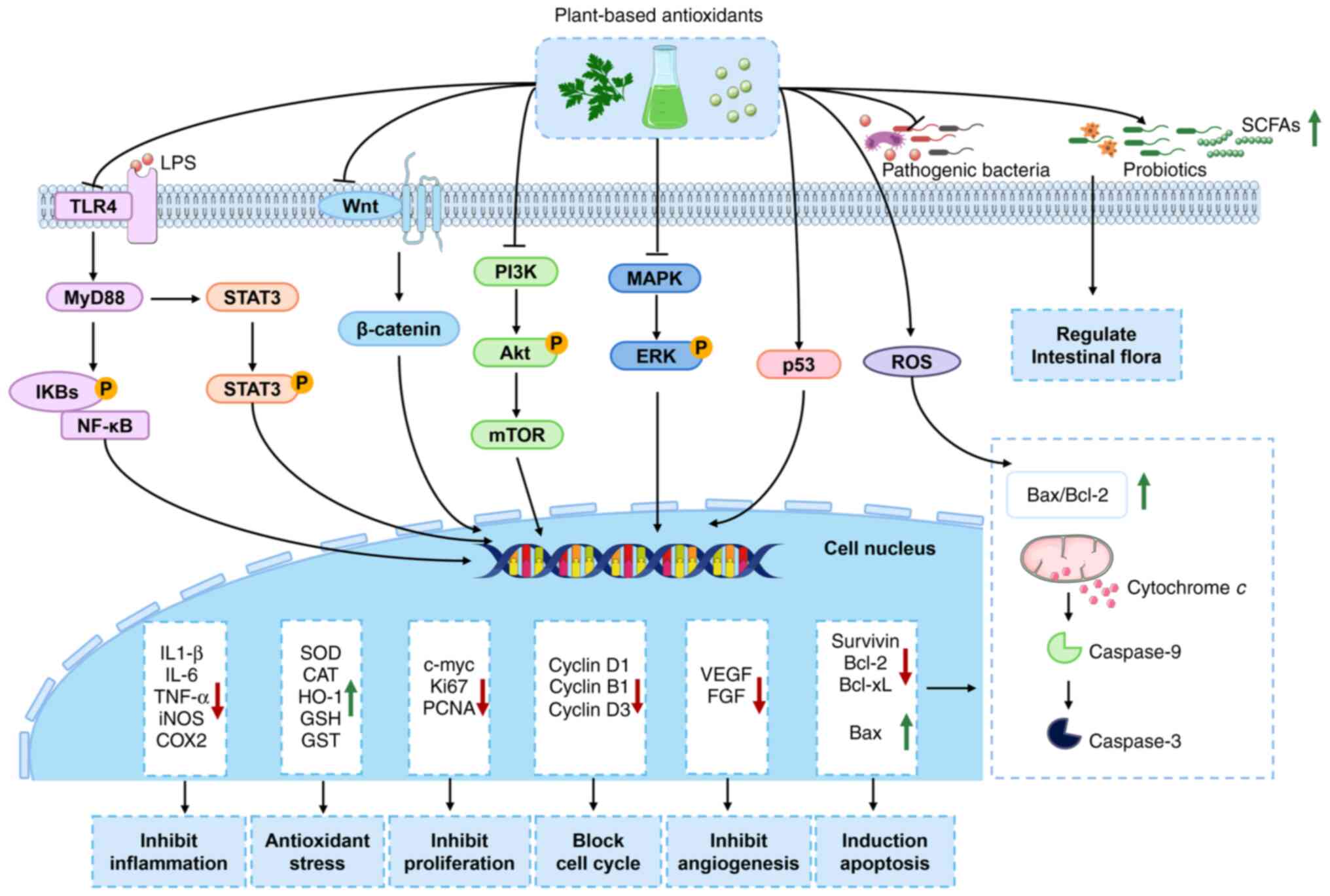

(caspase) family members and Bcl-2 family proteins (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2Signaling pathway diagram

illustrating the mechanisms of plant-based antioxidants against

CRC. Plant-based antioxidants exhibit significant efficacy in the

prevention and treatment of CRC. Its molecular mechanisms of action

encompass multi-targets, including NF-κB, TLR4, Wnt/β-catenin,

PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways, which suppress chronic

inflammation, alleviate oxidative stress, inhibit cell

proliferation and angiogenesis, induce cell apoptosis and cell

cycle arrest and regulate gut microbiota composition. CRC,

colorectal cancer; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B; TLR4, toll-like

receptor 4; PI3K/Akt, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase;

MAPK/ERK, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular

signal-regulated kinase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IKBs, inhibitors

of NF-κB; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription

3; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; ROS, reactive oxygen

species; SCFAs, short chain fatty acids; iNOS, inducible nitric

oxide synthase; COX2, cyclooxygenase-2; SOD, superoxide dismutase;

CAT, catalase; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; GSH, glutathione; GST,

glutathione S-transferase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth

factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor. |

The cell viability assay showed that curcumin

analogue, MS13 (1,5-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien

e-3-one) has a greater cytotoxicity effect on SW480

(EC50: 7.5±2.8 μM) and SW620 (EC50:

5.7±2.4 μM), compared with curcumin (SW480, EC50:

30.6±1.4 μM) and SW620, EC50: 26.8±2.1

μM). Subsequent analysis indicated that MS13 induced

apoptosis by enhancing caspase-3 activity while reducing Bcl-2

protein levels, thereby suppressing CRC cell growth (32). Furthermore, a significant

proportion of these phytochemicals activate mitochondrial apoptosis

by targeting aberrant signaling cascades within cancer cells,

including the PI3K/Akt, MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase

(ERK) and p38 MAPK pathways (Fig.

2). In addition, it has been established that EGCG inhibits

tumor cell growth and apoptosis through the PI3K-Akt-Cyclin D1 and

p53 signaling axes. Its pro-apoptotic mechanism also involves

suppression of fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein-mediated Jun

N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling, leading to increased BAX/Bcl-2

ratio (31). These findings

collectively underscore the multi-targeted therapeutic potential of

PBAs in CRC management through coordinated regulation of

apoptosis-related proteins and oncogenic signaling networks.

Epigenetic modifications and miRNA

regulation

Recent investigations have elucidated the biological

activities of EGCG in inhibiting DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) and

microRNA expression, which play pivotal roles in cancer

therapeutics (31). EGCG

reportedly suppresses DNMT activity via radical scavenging and

antioxidant mechanisms, leading to demethylation and upregulated

expression of tumor suppressor genes P16 and P21,

ultimately inducing apoptosis and inhibiting tumorigenesis.

Notably, treatment of EGCG (20 μg/ml) to head and neck

cancer cell lines markedly reduced DNMT activity to 60% in SCC-1

and 80% in FaDu cells. An in vivo study demonstrated that

administration of EGCG (0.5%, w/w) inhibited tumor growth in

xenografts in nude mice (80%) compared with non-EGCG-treated

controls (33).

During the progression of IBD, numerous miRNAs

exhibit altered expression patterns and regulate the expression of

related tumor suppressor genes and proto-oncogenes, exerting

pro-carcinogenic effects by disrupting intestinal homeostasis.

Substantial evidence supports the association between CAC and

inflammation-induced aberrant miRNA expression. Pristimerin, a

natural triterpenoid compound isolated from Celastraceae

plants, alleviates intestinal inflammation symptoms in DSS-induced

colitis models through intraperitoneal injection of 0.4 mg/kg daily

for 5 days compared with the untreated model mice (34). This effect is mediated by

inhibiting intestinal miRNA-155 expression and suppressing the

NF-κB signaling pathway. Resveratrol, a naturally occurring

stilbene compound, has been reported to markedly inhibit LoVo and

SW480 cell viability by 50% at the concentration of 50 μM.

Compared with control groups, Resveratrol treatment led to

increased miR-769-5p expression and decreased MSI1 expression in

CRC cells (35). This indicates

that Resveratrol inhibits CRC cell proliferation and migration by

activating the miR-769-5p/MSI1 pathway. The aforementioned studies

overlap in their assertion that PBAs can attenuate intestinal

inflammation and suppress CRC by targeting miRNAs, highlighting the

need for developing more miRNA-targeted small molecule therapeutics

to expand clinical treatment options.

Gut microbiota regulation

CRC patients exhibit marked alterations in gut

microbiota composition and distribution, characterized by reduced

beneficial bacteria and increased pathogenic species. Pathogens

such as Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium,

Streptococcus and Enterococcus promote colorectal

carcinogenesis by secretion of oncogenic metabolites that induce

DNA damage, amplify inflammation and activate proliferative

signaling pathways (36).

Conversely, probiotics and their metabolites (such as short-chain

fatty acids, SCFAs) exert chemopreventive effects via

anti-mutagenesis, proliferation suppression, apoptosis induction,

mucosal barrier enhancement, inflammatory microenvironment

modulation and immune activation (37,38). Gut microbiota can produce ROS or

stimulate intestinal epithelial cells to produce ROS, thereby

promoting tumorigenesis and development (39).

PBAs have shown promise in alleviating gut dysbiosis

in CRC animal models. Compared with the NC group, an AOM/DSS

induced CRC model group (PBS, 150 mg/kg/day) exhibited a marked

reduction in colon length and an obvious increase in tumor count,

while the curcumin treatment groups (CRC-Cur, 150 mg/kg/day)

increased the length of the colon and markedly reduced the number

of tumors. The intestinal flora and intestinal metabolites analysis

showed that curcumin educed harmful bacteria (such as

Ileibacterium, Monoglobus and Desulfovibrio)

and increased the abundance of Clostridia_UCG-014,

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in AOM/DSS-induced

CRC model mice (40). Patchouli

essential oil (40 mg/kg/day) markedly reduced the number of polyps

(47.14±15.66) compared with the control group (vehicle 0.5%

carboxymethyl cellulose + 1% DMSO, 81.86±12.36) in

ApcMin/+ mice while enhancing intestinal barrier

integrity and alleviating the inflammatory microenvironment. This

effect was associated with decreased abundance of pathogenic

bacteria (Desulfovibrio, Mycoplasma genitalium and

Clostridium difficile) and elevated fecal SCFAs, which

upregulated SCFA receptors (GPR41, GPR43 and GPR109a) and

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression (41). Compared with a dextran sulfate

sodium (DSS)-induced colitis group (daily gavage of PBS for 3 weeks

with 2.5% DSS in drinking water for the last 6 days), an EGCG group

(50 mg/kg) altered the gut microbiome of DSS-treated mice by

increasing Akkermansia abundance and butyrate production.

The alteration of gut microbiome further promotes anti-inflammatory

effects and colonic barrier integrity (42). Current research on plant-based CRC

prevention has mainly focused on microbiota modulation and

metabolite production, with little emphasis on host-microbiota

crosstalk mechanisms involving antitumor immunity and epithelial

cell signaling. Accordingly, further investigations are warranted

to elucidate these interactive pathways.

Unique anti-tumor effects of key plant-based

antioxidants in CRC

Polyphenols

Curcumin

Curcumin, derived from the rhizome of Curcuma

longa (turmeric), exhibits diverse biological activities

including anti-cancer, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral,

antioxidant, anti-aging, anti-diabetic and cardiovascular

protective properties (43).

Systematic meta-analyses show that curcumin has therapeutic

potential for CRC, improves survival rates and enhances quality of

life (44-46). Curcumin targets proliferating

cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) within CRC premalignant adenoma and

early-stage cancer tissues. Curcumin decreases the proportion of

proliferating CSCs by direct binding to NANOG, thereby inhibiting

tumor development (47).

Moreover, Curcumin can inhibit CRC growth by inducing ferroptosis

via regulation of p53 and SLC7A11/glutathione/GPX4 axis (48). Combining curcumin (50 μM)

and metformin (40 μM) markedly suppresses the migration

ability of HCT116 cells and promote ROS-induced cell death

(49), which provides a potential

option for CRC treatment. Overall, these findings indicate that

curcumin plays an effective adjunct therapy for CRC on a number of

molecular targets. However, its low bioavailability and rapid

metabolism limit its clinical translation (46). Addressing these challenges through

more studies, determining effective doses and improving

formulations to enhance absorption is essential.

EGCG

The anti-cancer mechanisms of EGCG encompass

angiogenesis inhibition, induction of tumor cell death and

suppression of tumor growth.

EGCG downregulates the expression of HIF-1α, HIF-1β

and VEGF in CRC cells, reducing tumor vascular density and

effectively controlling tumor cell metastasis while inhibiting the

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (31).

Furthermore, EGCG inhibits CRC cell proliferation and induces

apoptosis by blocking the activation of the receptor tyrosine

kinases family members EGFR, IGF-1R and VEGFR2 (50). In the Caco-2 cell line, EGCG (15

μM) downregulates the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 through

a NOX1/EGFR signaling pathway-dependent mechanism, while directly

inhibiting the enzymatic activity of MMPs, thereby effectively

suppressing tumor cell invasion and metastasis (51). A fibril composed of EGCG and

lysozyme (EGCG-LYS) demonstrated excellent siRNA delivery

efficiency in in vitro experiments. It could effectively

silence the expression of circMAP2K2 (hsa_circRNA_102415), thereby

inhibiting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like

phenotype generated by circMAP2K2 through the protease-mediated

PCBP1/GPX1 axis, inhibiting the activated AKT/GSK3β signaling

pathway and achieving the goal of inhibiting the proliferation and

metastasis of gastric cancer cells, which provides a new tool for

the treatment of gastric cancer (52). Collectively, these findings

demonstrate that EGCG effectively alleviates tumor angiogenesis and

metastasis.

Apoptosis, a programmed cellular protective

mechanism, represents the primary pathway for eliminating tumor

cells through the induction of their programmed death. EGCG induces

apoptosis in gastrointestinal tumor cells in a dose-dependent

manner without affecting normal cell growth and it triggers cancer

cell death through a number of pathways (31). Specifically, EGCG enhances the

translocation of cytochrome c from the mitochondrial inner

membrane to the cytoplasm, inhibits ATP synthesis, disrupts

mitochondrial membrane potential, activates caspase cascades and

promotes tumor cell apoptosis (53). Moreover, treatment with 10

μg/ml EGCG for 24 h induced apoptosis and markedly

suppressed the proliferation in CACO-2 and CW-2 cells. The miRNA

analysis showed that the expression of hsa-miR-187-5p in CW-2 cells

was markedly downregulated following EGCG treatment (54). An in vitro dosage of 6

μM EGCG has an initial antagonistic effect on oxaliplatin

cytotoxicity and increases the sensitivity of HCT116 and HT29 cells

to subsequent oxaliplatin administration, which provides an

adjunctive treatment for CRC with lower and safer doses of EGCG

(55). EGCG also inhibits gastric

cancer cell proliferation by targeting STAT3 to inhibit M2

macrophages polarization induced by PLXNC1-mediated exosomes

(56). In an in vivo

study, mice received intraperitoneal injections of EGCG at a dose

of 50 μg/kg (0.1 ml) developed markedly smaller tumors than

the control group treated with 0.1 ml PBS alone (54). While EGCG primarily antagonizes

gastrointestinal tumors by inducing tumor cell apoptosis, the

methods of triggering such apoptosis are complex and diverse, with

a number of underlying mechanisms remaining unclear. Elucidating

the molecular mechanisms of tumor apoptosis represents one of the

significant future directions in cancer research to more

effectively induce this process. Furthermore, EGCG can be

administered orally or injected with an acceptable safety profile

and its safe dose of antitumor effects still needs more

reports.

Resveratrol

Resveratrol exerts multi-faceted effects on CRC

through various mechanisms, including suppression of cell

proliferation, inhibition of metastasis, induction of apoptosis,

stimulation of autophagy, modulation of immune responses,

alleviation of inflammation, regulation of gut microbiota and

enhancement of other anticancer drug efficacy (57). The expression of pro-inflammatory

cytokine tumor necrosis factor-β and its receptor activates nuclear

transcription factor NF-κB, which participates in CRC cell growth

and proliferation. Compared with HCT116 and SW480 cells in the

control groups, resveratrol (5 μM) suppressed the cancer

cell proliferation with the regulation of β1-integrin/FAK/p65-NF-kB

pathway and cyclin D1-signaling. CRC cells treated with resveratrol

markedly inhibited β1-integrin expression and reduced the

distribution of β1-integrin receptors on the cell surface (58). In addition, high concentration

(>10 μM) of resveratrol disrupted interactions between

CRC cells and stromal cells within the multicellular tumor

microenvironment, triggering apoptosis through promoting

hyperacetylation of p53 and FOXO3a as post-translational substrates

of Sirt-1 in the CRC tumor microenvironment (59). Furthermore, resveratrol markedly

reduced serine/threonine kinase 1/2/3 (Akt1/2/3) phosphorylation,

downregulated bone morphogenetic protein expression via PI3K/Akt

signaling inhibition, upregulated STATB2 to promote Bax-Caspase 3/9

apoptotic pathway protein expression in HCT116 cells and induced

CRC cell apoptosis (60).

Oxidative stress has been established as a

pro-carcinogenic factor and resveratrol alleviates oxidative stress

by up-regulating antioxidant enzymes. Reports suggest that

resveratrol achieves therapeutic efficacy by inhibiting SOD

activity or activating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant signaling

pathways, thereby suppressing oxidative stress in CRC. Resveratrol

(10 μmol/l) was found to activate Nrf2 and Sirt-1 to

regulate cellular oxidation, reducing 5-FU-induced oxidative stress

damage in normal cells at a 5 μg/ml concentration,

demonstrating a dose-response relationship (61). Furthermore, in a murine

cardiotoxicity model established via intraperitoneal injection of

5-FU at 15, 30 and 60 mg/kg, resveratrol was found to attenuate

myocardial cell toxicity induced by 5-FU, showing potential in

mitigating cardiac damage associated with long-term high-dose 5-FU

treatment for CRC (62).

Sprague-Dawley rats that received oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg/day,

cumulative dose: 6 mg/kg, i.p.) and oral resveratrol (7.14

mg/kg/day) was found not to develop mechanical allodynia or

hypersensitivity, which inhibited upregulation of NF-κB, TNF-α,

AIF3 and excitatory neuronal promoter c-fos, while increasing

expression of Nrf2, NQO-1, HO-1 and Sirt1. This combination

restored the GSH/GSSG ratio, preventing and antagonizing

chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathic pain (63).

Oleuropein

Oleuropein represents one of the primary phenolic

compounds in olive leaf extracts. It has demonstrated that

oleuropein exerts protective effects in acetic acid-induced

ulcerative colitis in rats by inhibiting the production of

intestinal inflammatory factors (64). There were three groups: Normal

control, positive control (ulcerative colitis and untreated) and

oleuropein group (treated with intrarectal oleuropein at a dose of

350 mg/kg). Compared with the positive control group, oleuropein

resulted in a significant reduction of MPO and NO levels and

increased SOD, CAT and GPX levels in colon tissues. Moreover, the

expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α,

IL-10, COX-2, iNOS and NF-κB) were also decreased in the oleuropein

group. In the intestinal tissues of rats treated with oleuropein,

expression of the pro-apoptotic gene Bcl-2-associated X protein was

reduced, while the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 was

upregulated. These findings indicate that oleuropein alleviates

inflammation by suppressing aberrant apoptosis of intestinal

cells.

Flavonoids

Flavonoids represent a class of plant secondary

metabolites characterized by a basic structure comprising two

benzene rings interconnected via a three-carbon bridge,

establishing a C6-C3-C6 configuration (65). Baicalin, a natural flavonoid, has

been found to possess remarkable anti-CRC properties. Studies have

revealed its capacity (at 100 μg/ml) to induce cell cycle

G1 phase arrest in CRC cells, promote p53-independent

apoptosis and suppress both endogenous and exogenous TGF-β1-induced

EMT via inhibition of the TGF-β/Smad pathway (66). In an in vivo test,

orthotopic transplanted colon tumor model mice were randomly

divided into negative control, positive control (25 mg/kg of 5-FU),

low dose group (100 mg/kg of baicalin) and high dose group (200

mg/kg baicalin), respectively. The low-dose baicalin group

exhibited markedly tumor inhibition rates (ratios of average tumor

size of treated groups and negative control group) compared with

those in both positive control and high-dose baicalin groups.

Hesperetin, a flavonoid primarily derived from citrus fruits, has

been reported to prevent DSS-induced colitis. The mice were

randomly divided into four groups: control group, DSS group,

hesperetin treated group (20 mg/kg, injected daily

intraperitoneally) and DSS with hesperetin treated group (20 mg/kg,

injected daily intraperitoneally). The DSS group showed a lower

weight and colon length compared with the control group, while

these changes were rescued by hesperetin treatment. Hesperetin

enhances intestinal expression of ZO-1, occludin and MUC-2, while

reducing TNF-α, IL-6, IL-18, HMGB1 and IL-1β levels to exert

intestinal protective effects (67). Further investigation revealed

hesperetin's ability to decrease expression of receptor-interacting

protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like

protein (MLKL), two critical mediators of necroptosis pathways,

suggesting its capacity to ameliorate DSS-induced intestinal

inflammation through suppression of the RIPK3/MLKL necroptosis

signaling cascade (67). This

anti-inflammatory action preserves intestinal barrier homeostasis

and inhibits intestinal tissue carcinogenesis driven by persistent

inflammatory stimuli. Moreover, 50 or 100 mg/kg of luteolin has

been found to markedly attenuate DSS-induced murine colitis

symptoms compared with a DSS group, primarily by inhibiting JNK1/2,

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)

signaling, NF-κB and STAT3 pathways to exert anti-inflammatory,

anti-apoptotic and anti-autophagic effects for colonic homeostasis

restoration (68).

Vitamins

Defects in intestinal mucosal antioxidant defense

constitute the initiating factor in the pathogenesis of IBD, with

oxidative imbalance in the intestinal mucosa further associated

with disease activity and progression. Reduced plasma levels of

vitamins A, E and β-carotene, coupled with decreased antioxidant

enzyme activity in the intestinal mucosa, correlate with IBD

severity and may serve as indicators of disease activity (69). Notably, vitamin E (δ-tocotrienol),

a natural antioxidant, protects phagocytes and surrounding tissues

from oxidative assault by free radicals generated from neutrophils

and macrophages (70). This

compound inhibits the elevation of free radicals produced during

lipid and lipoprotein oxidative damage in IBD.

Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides, complex carbohydrate macromolecules

formed through condensation and dehydration of a number of

monosaccharide units, have recently attracted significant interest

in their anti-CRC effects. Tao et al (71) investigated the anti-tumor

activities of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides,

Astragalus polysaccharides and Lentinus edodes

polysaccharides with varying molecular weights using a zebrafish

xenograft model. Compared with the model group (inhibition

0±5.09%), the results indicated that all three polysaccharides

inhibited the growth of HT29 cells in the xenograft model, with

Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides (250 μg/ml)

exhibiting the most significant inhibitory effect on CRC

(67.91±1.69%). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway

enrichment analysis suggested that their primary mechanisms may

involve immunomodulation and induction of apoptosis.

Astragalus polysaccharides, a major bioactive component in

Astragalus membranaceus, primarily consist of arabinose,

galactose, glucose, xylose and mannose (72). Compared with the AOM/DSS control

group, in vivo studies revealed that middle doses (200

mg/kg) of Astragalus polysaccharides effectively improved

CD8+ T cell function through modulation of the

STAT3/Gal-3/LAG3 pathway to inhibit CRC development (73). These findings suggest that

Astragalus polysaccharides may exert anti-CRC effects as a

novel strategy for future clinical development of natural

anti-tumor drugs.

Saponins

Ginsenoside Rg1, a bioactive component derived from

the traditional Chinese medicine Panax ginseng, exerts

therapeutic effects via modulation of various metabolic pathways of

the gut microbiota, primarily by enhancing tryptophan metabolite

levels to influence microbial tryptophan metabolism, thereby

alleviating intestinal inflammation (74). Polyphyllin, a natural steroidal

saponin derived from the traditional Chinese medicine Paris

polyphylla, encompasses compounds such as Polyphyllin I, II, VI

and VII, demonstrating significant anti-tumor, antimicrobial,

antioxidant, sedative, analgesic, hemostatic, immunomodulatory and

organ-protective effects, with particularly notable anti-tumor

activities (75). Li et al

(76) found that the percentages

of the apoptotic cells for HCT116 cells increased from 4.7-35.2% in

the control group and the Polyphyllin II treated group (4

μM) and for SW620 cells from 4.6-27.3% in the control group

and the Polyphyllin II treated group. In vivo study showed

Polyphyllin II (0.5 or 1 mg/kg, i.p. once every 3 days) suppressed

HCT116 tumor growth in nude mice. Further mechanism study revealed

that Polyphyllin II markedly induced G2/M-phase cell

cycle arrest and apoptosis and reduced the expression levels of

phosphorylated (p-)PI3K, p-Akt and p-mTOR in HCT116 and SW620

cells, promoting the expression of autophagy-related protein

LC3B-II. Further increases in LC3B-II expression were observed upon

treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, indicating that

Polyphyllin II induces tumor cell autophagy by inhibiting the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Moreover, Polyphyllin II was found

to induce tumor cell apoptosis by suppressing the Janus kinase

2/signal transducer and activator of STAT3 signaling pathway,

exerting anti-CRC effects (76).

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are organic compounds containing one or

more basic nitrogen atoms arranged in cyclic structures. Berberine,

also known as berberrubine, is a quaternary ammonium isoquinoline

alkaloid isolated from the traditional Chinese medicine

Coptischinensis, demonstrating diverse biological activities

including anti-tumor, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory,

cholesterol-lowering, anti-diabetic, anti-obesity and

anti-microbial properties (77).

Its anti-cancer effects and mechanisms have been extensively

studied, establishing it as a potential anti-cancer drug candidate.

It has been reported that berberine alleviates AOM/DSS-induced

intestinal barrier damage in mice, thereby reducing microbial

invasion (78). In the AOM/DSS

mice model, berberine was daily administered with a dose of 50 and

100 mg/kg and aspirin was the positive control. Compared with the

AOM/DSS model group, berberine markedly reduced the number and load

of tumors in mice. Furthermore, berberine suppressed inflammation

and CRC development by increasing the abundance of short-chain

fatty acid-producing bacteria and decreasing pathogenic bacterial

populations (78). By reshaping

the gut microbiota composition, berberine increased the expression

of occludin and ZO-1, inhibited the activation of the

p-NF-κB/p-STAT3 pathway, consequently impeding colorectal

adenocarcinoma progression. Berberine's restorative mechanisms

against oxidative stress-induced DNA damage have been demonstrated

across murine models. In adenovirus-infected AOM/DSS mice

administered with 28 mg/kg berberine for 5 weeks, berberine

enhanced Dicer expression and reduced IL-6 expression, mitigating

intestinal injury (79).

Collectively, these findings indicate that berberine suppresses CRC

progression by reducing inflammation-related chemotactic factors,

enhancing antioxidant radical scavenging capacity and repairing DNA

damage.

Terpenoids

Terpenoids represent a class of compounds composed

of five-carbon isoprene units (C5H8),

categorized based on the number of isoprene units into

monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, diterpenes, sesterterpenes,

triterpenes, tetraterpenes and polyterpenes (80). Zingiberene, a sesquiterpene

compound and the primary constituent of ginger essential oil,

exhibits anti-cancer, antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory

and anti-angiogenic activities. In the aberrant crypt focus (ACF)

rat model induced with 1.2 Dimethylhydrazine (DMH) at a 20 mg/kg

dose, the experimental treatment group (DMH + Zingiberene at a 300

mg/kg concentration) showed decreased amount of AC in the distal

region compared with the positive induction control group (81). It also has shown that zingiberene

demonstrates specific activity against HT-29 cells with minimal

effects on non-cancerous cells. It promotes the formation of

autophagosomes in tumor cells, increasing LC3-II expression and

decreasing p62 expression to induce autophagy (82).

Quinones

There has been burgeoning research interest in the

potential of various plant-based quinone bioactive compounds for

CRC drug development due to their promising therapeutic efficacy.

Shikonin, a naphthoquinone component primarily sourced from the

traditional Chinese medicinal herb

Lithospermumerythrorhizon, activates ROS-mediated

endoplasmic reticulum stress to notably inhibit HCT116 cell

proliferation. In addition, 1.5 μM shikonin markedly

inhibited the HCT116 cell colonies compared with the control group.

In the HCT116 xenograft mouse model, a dose of 3 mg/kg (i.p.)

shikonin effectively inhibited tumor growth by 52.3% in

vivo. Moreover, shikonin downregulates Bcl-2 expression and

activates cleavage of caspase3/9 and PARP to induce apoptosis

(83). Emodin is a natural

anthraquinone compound with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and

anti-tumor properties. In AOM/DSS-induced models, emodin (50 mg/kg)

reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells, expression of cytokines

and pro-inflammatory enzymes in the tumor microenvironment while

enhancing CD3+ T lymphocyte levels. In addition, emodin

decreased viability, migration and fibroblast-induced invasion

capacity of SW-620 and HCT116 cells in vitro (84).

Current challenges and progress in clinical

research

PBAs have shown promising therapeutic effects in CRC

cell lines and animal models. Several clinical trials investigating

the prevention and treatment of CRC with PBAs have been conducted

(Table I). Carroll et al

(85) assessed the effects of

oral curcumin (2 g/day or 4 g/day for 30 days) on PGE2 within ACF

in a nonrandomized, open-label clinical trial. Colonoscopy revealed

no significant ACF reduction in the 2 g/day group, whereas the 4

g/day group showed a 40% reduction. Cruz-Correa et al

(86) evaluated the regress

adenomas effects of curcumin (480 mg/day) and quercetin (20 mg/day)

in 5 post-colectomy familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients.

Colonoscopy demonstrated a 60.4% reduction in polyp number and a

50.9% decrease in size compared with baseline. While this study

showed prominent therapeutic effects, a subsequent larger trial

involving 44 FAP patients found no significant differences in polyp

number or size (87). Panahi

et al (88) assessed the

effects of curcumin in 67 stage III CRC patients with chemotherapy

after the surgery. The results demonstrated that 8-week

curcuminoids capsules (500 mg daily) improved erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR) and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels,

while also enhancing the quality of life in stage III CRC patients

Compared with the control group taking placebo capsules. The effect

of curcumin on the prognosis of CRC patients remains unclear.

Several completed clinical trials (NCT02439385, NCT01490996 and

NCT01948661) are expected to provide further elucidation upon

publication of their results.

| Table IClinical researches of PBAs. |

Table I

Clinical researches of PBAs.

| First author/s,

year | Type of PBA | Type of study | Patients | Group | Outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Carroll et

al, 2011 | Curcumin | Open-label

trial | 44 eligible smokers

with 8 or more ACF on screening colonoscopy | 2 g/day or 4 g/day

for 30 days | No significant ACF

reduction in the 2 g/day group, 40% reduction in ACF number in the

4 g/day group | (85) |

| Cruz-Correa et

al, 2006 | Curcumin | Single-arm

trial | 5 post-colectomy

FAP patients | Curcumin (480

mg/day) and quercetin (20 mg/day) | 60.4% reduction in

polyp number and 50.9% decrease in size compared with baseline | (86) |

| Cruz-Correa et

al, 2018 | Curcumin | Randomized

controlled trial | 44 FAP patients who

had not undergone colectomy | Curcumin (1,500 mg

orally, twice per day) or identical-appearing placebo capsules for

12 months | No significant

difference in mean polyp size between the curcumin group and the

placebo group | (87) |

| Panahi et

al, 2021 | Curcumin | Randomized

controlled trial | 67 stage III CRC

patients with chemotherapy after the surgery | Treatment group

receiving curcuminoids capsules (500 mg/day) (n=36), or the control

group taking placebo capsules (n=36) for 8 weeks | A significant

change in CRP and ESR in treatment group. A significant improvement

in functional and global quality of life in treatment group | (88) |

| Patel et al,

2010 | Resveratrol | Single-arm

trial | 20 CRC patients

before surgical resection | 0.5 or 1g daily for

8 days | 5% reduction in

tumor cell proliferation | (89) |

| Seufferlein et

al, 2022 | EGCG | Randomized

controlled trial | 1,001 patients with

colon adenomas | EGCG (150 mg/day)

or placebo groups over 3 years | No significant

difference in adenoma rate between the EGCG group and the placebo

group | (90) |

| Sinicrope et

al, 2021 | EGCG | Randomized

controlled trial | 39 patients with at

least 5 rectal ACF | EGCG (780 mg/day)

or placebo groups over 6 months | No significant

differences in ACF number, total ACF burden and adenoma

recurrence | (91) |

| Bonelli et

al, 2013 | Vitamin | Randomized

controlled trial | 411

post-polypectomy patients | Active compound

(200 μg selenium, 30 mg zinc, 2 mg vitamin A, 180 mg vitamin

C, 30 mg vitamin E) or a placebo daily for 5 years | 39% reduction of

the risk of recurrence in the intervention group Compared with the

placebo group | (92) |

| Oliai Araghi et

al, 2019 | Vitamin | Randomized

controlled trial | 2,524 Participants

aged 65 years and over with an elevated homocysteine Level | Folic acid (400

μg/day) and vitamin B12 (500 μg/day) vs. placebo over

2 to 3 years | Vitamin B12 were

markedly associated with a higher risk of CRC | (93) |

| Greenberg et

al, 1994 | Vitamin | Randomized

controlled trial | 864 patients who

had at least one histologically confirmed adenoma removed from the

large bowel | Beta carotene (25

mg daily); vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 mg daily); or

the beta carotene plus vitamins C and E; placebo | There was no

evidence that either beta carotene or vitamins C and E reduced the

incidence of adenomas | (94) |

| Gaziano et

al, 2009 | Vitamin | Randomized

controlled trial | 14,641 male

physicians aged 50 years or older | 400 IU of vitamin E

every other day and 500 mg of vitamin C daily; placebo | Neither vitamin E

nor vitamin C had a significant effect on CRC incidence | (95) |

| Wang et al,

2012 | Vitamin | Randomized

controlled trial | 816 CRC patients

and 815 controls | Dietary intakes of

vitamin C and vitamin E were assessed by a PC-assisted interview

regarding 148 food items | Intake of vitamin C

and vitamin E were not related to CRC risk in either men or

women | (96) |

| Ng et al,

2019 | Vitamin | Randomized

controlled trial | 139 patients with

advanced or metastatic CRC | mFOLFOX6 plus

bevacizumab chemotherapy every 2 weeks and either high-dose vitamin

D3 (n=69) or standard-dose vitamin D3 (n=70) daily | No significant

improvement in progression-free survival between high-dose and

standard-dose groups | (97) |

| Chen et al,

2020 | Berberine | Randomized

controlled trial | 553 participants

who had colorectal adenomas that had undergone complete

polypectomy | Berberine (0.3 g

twice daily) or placebo | Lower adenoma

recurrence in the berberine group vs. the placebo group | (98) |

Patel et al (89) enrolled 20 CRC patients who

received 0.5 g or 1.0 g/day resveratrol for 8 days before surgery

intervention. Post-intervention tissue analysis revealed a 5%

reduction in tumor cell proliferation. Further clinical trials

(NCT00256334 and NCT00433576) have been conducted, with the results

eagerly expected.

Seufferlein et al (90) investigated EGCG's preventive

effects on CRC, with 1,001 colon adenoma patients randomized to

EGCG (150 mg/day) or placebo groups. At 3 years, colonoscopy showed

adenoma recurrence rates of 55.7% (placebo) vs. 51.1% (EGCG), with

no statistical significance. Sinicrope et al (91) also studied EGCG's effects on 39

patients with 35 rectal ACFs, with no significant

differences in ACF number, total ACF burden and adenoma recurrence

observed. Several clinical trials (NCT02891538 and NCT01360320)

investigating the preventive effects of EGCG have been completed,

though their results remain unpublished.

The clinical evidence regarding vitamin

supplementation for CRC prevention remains contradictory. Bonelli

et al (92) demonstrated

in a double-blind randomized trial that vitamins A, C and E could

markedly reduce intestinal adenoma recurrence in patients with

prior polypectomy. However, Oliai et al (93) reported that vitamin B12 could

potentially increase risk of CRC. A number of relevant clinical

trials have demonstrated no significant effects of vitamins on CRC

outcomes. In Greenberg et al's study (94) of 864 adenoma patients, vitamin C

and E supplementation showed no difference in adenoma incidence

compared with placebo groups. Gaziano et al's large-scale

trial (95) involving 14,641 male

physicians found no effect of vitamin E and C on CRC incidence.

Similarly, Wang et al (96) analyzed antioxidant vitamin C and E

intake in 816 CRC patients vs. 815 controls, showing no association

with cancer risk. Ng et al (97) evaluated vitamin D3 supplementation

in advanced/metastatic CRC, revealing no significant improvement in

progression-free survival (PFS) between high-dose and standard-dose

groups. Ongoing clinical trials (NCT02969681, NCT01574027,

NCT00905918 and NCT02603757) are currently underway, whose findings

are expected to further clarify the role of vitamins in CRC.

A multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled

trial has demonstrated berberine's efficacy in CRC prevention. In

this study, Chen et al (98) enrolled 1,108 patients with

colorectal adenomas, which were randomly allocated to the berberine

group (n=553, 0.3 g twice daily) and placebo group (n=555).

Colonoscopy evaluation after a 2-year's follow-up revealed lower

adenoma recurrence in the berberine group (n=155, 36%) compared

with the placebo group (n=216, 47%). These results warrant

validation through ongoing clinical trials (NCT03281096,

NCT02226185 and NCT03333265).

Despite the potential anticancer effects

demonstrated in preclinical studies, PBAs have not shown clear

clinical benefits in CRC and their clinical translation faces a

number of challenges. Indeed, low bioavailability is a critical

limiting factor. For example, bioavailability of oral curcumin is

<1% (99), with resulting

concentrations in plasma much lower than the doses in vitro.

Second, the core roles of PBAs in CRC remain unclear. While current

research reveals a number of anti-tumor mechanisms (gene

expression, signaling pathways and epigenetics) of PBAs in CRC, the

heterogeneity across models (cell lines, animal species) and

differences between models and human obscure the core mechanisms.

Third, clinical trial design requires optimization. Dose selection

lacks standardization: Carroll et al (85) found efficacy with 4 g/day

curcumin, whereas a larger trial by Cruz-Correa et al

(87) showed no benefit at 480

mg/day, highlighting the need for pharmacokinetic-guided

individualized dosing. Moreover, the influence of patient

heterogeneity on the anticancer effects of PBAs warrants further

confirmation. For example, genetic backgrounds of FAP patients may

affect curcumin response (86,87).

Directions for future research

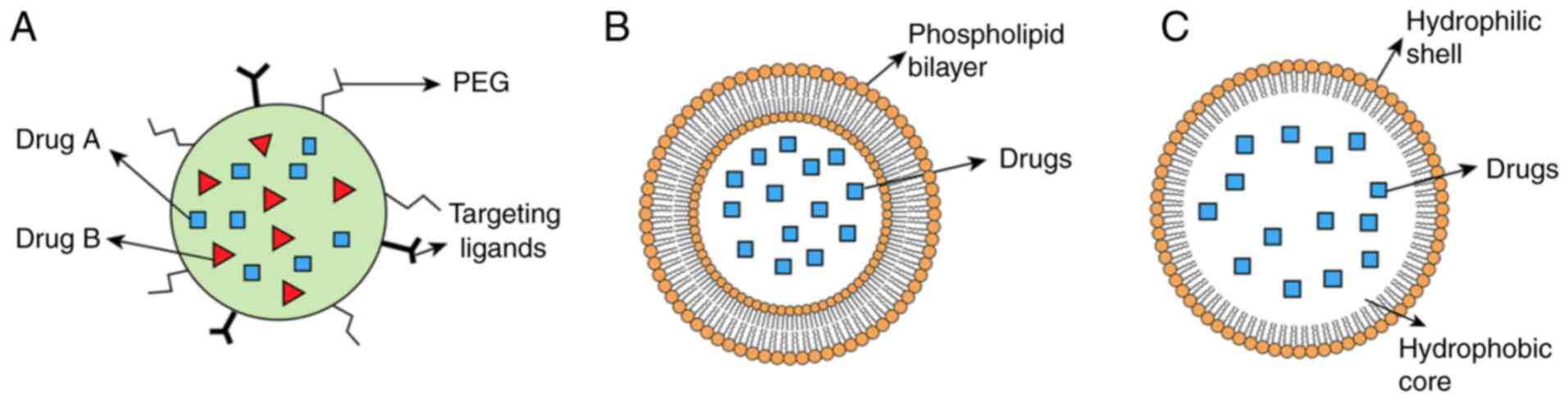

Improving bioavailability represents the central

goal for clinical translation of PBAs. Nano-drug delivery system

has become a research focus in the context of PBAs given its

ability to improve drug solubility, prolong circulation time and

enhance tumor targeting (100,101). Currently, nanoparticles, nano

micelles and liposomes are relatively reliable nano-drug delivery

systems to improve the bioavailability of PBAs (Fig. 3).

Nanoparticles are generally classified into three

classes: Inorganic, organic and carbon-based. Various strategies

such as surface modification of nanoparticles with synthetic

polymer polyethylene glycol (PEG) can improve the water solubility

of nanoparticles (101). Zhang

et al (102) developed

erythrocyte membrane-coated resveratrol nanoparticles modified with

PCL-PEG, markedly prolonging half-life of resveratrol. Sun et

al (103) designed

PEG-modified amphiphilic cyclodextrin nanoparticles for co-delivery

of ginsenoside and quercetin, enhancing duration of drug in CRC

models. In addition, designing nanoparticles according to the

characteristics of PBAs represents an effective way to improve

bioavailability.

Nanomicelles, self-assembled amphiphilic polymer

structures, feature a hydrophilic shell to enhance pharmacokinetics

and a hydrophobic core to encapsulate the drug and control release

(104). Ran et al

(105) encapsulated ginsenoside

compound K in nanomicelles fabricated via ultrasonic self-assembly

of O-carboxymethyl chitosan, N-isopropylacrylamide and

thermoresponsive IR820. The nanomicelles markedly improved water

solubility and bioavailability of ginsenoside. Zhu et al

(106) incorporated silybin into

Soluplus-PVPVA nanomicelles, enhancing the pharmacokinetics of

silybin.

Liposomes are biocompatible and biodegradable

spherical vesicles with hydrophilic cores and lipid bilayers

(107). These structures serve

as effective carriers for the delivery of PBAs. Notably, curcumin

liposomes exhibit improved solubility and anticancer activity

against CRC cell lines (82,108), with clinical studies confirming

safety and tolerability in CRC patients (109).

Developing nano-drug delivery systems combining

PBAs with chemotherapeutics is another direction of further

research. Curcumin can reportedly reverse the resistance of CRC

cell lines to 5-FU, irinotecan and oxaliplatin through a number of

mechanisms (110,111). Quercetin can synergistically

enhance the killing effect of doxorubicin, 5-FU and oxaliplatin on

CRC cells (112-114). Rutin can alleviate

ensartinib-induced hepatotoxicity (115). Howells et al (116) conducted a study of 28 patients

with metastatic CRC receiving either FOLFOX alone or FOLFOX

combined with curcumin. The results showed that the curcumin-FOLFOX

combination exhibited favorable safety and superior clinical

outcomes compared with FOLFOX. Therefore, the combination of PBAs

and chemotherapeutic drugs may enhance the therapeutic effect of

chemotherapeutic drugs and appropriate nano-drug delivery systems

can further improve the utilization and targeting of drugs. Sen

et al (117) developed a

liposome containing both apigenin and 5-FU, which demonstrated

improved anti-tumor effects than 5-FU. Liu et al (118) designed a nanoparticle loaded

with irinotecan and quercetin with Conatumumab modified to target

CRC cells, with the nanoparticle yielding improved anti-tumor

effects without systemic toxicity.

Personalized treatment involving PBAs in CRC will

contribute to its clinical translation. First, the mechanism

underlying the efficacy of different PBAs in treating CRC needs to

be elucidated. Integrating single-cell sequencing or spatial

transcriptome technology will help to identify the core targets of

specific cell subsets (119).

The core targets can subsequently be harnessed to identify

populations that benefit from PBAs or those for whom they are

unsuitable. For instance, microsatellite-stable CRC cell lines are

more sensitive to curcumin (120), while EGCG may restore

TCF4-chromatin interactions and activate the Wnt pathway in

p53-mutant models, paradoxically promoting tumorigenesis (121). Thus, microsatellite-stable CRC

patients could be potential beneficiaries of curcumin, while EGCG

should be avoided in patients with p53 mutations. Future efforts

should focus on integrating molecular subtyping and biomarkers to

identify the potential population, thereby advancing the clinical

application of PBAs in CRC treatment.

Conclusion

CRC remains a formidable global health challenge,

with conventional therapies often limited by toxicity, drug

resistance and poor patient compliance. PBAs, characterized by

their multi-target, multi-pathway mechanisms, have emerged as

promising candidates for CRC prevention and treatment. Preclinical

studies highlight their ability to modulate oxidative stress,

inflammation, apoptosis, epigenetic dysregulation and gut

microbiota imbalance; key drivers of CRC pathogenesis. Compounds

such as curcumin, EGCG, resveratrol and berberine demonstrate

pleiotropic effects, including chemo-sensitization, immune

modulation and synergy with conventional therapies. Notably, these

natural agents mitigate chemotherapy-induced toxicity while

enhancing therapeutic efficacy, underscoring their potential as

adjunctive or alternative treatments.

However, clinical translation faces significant

hurdles and clinical efficacy from limited phase I/II trials. Low

bioavailability, inconsistent clinical outcomes and heterogeneous

patient responses remain critical barriers. In this regard, while

curcumin exhibits dose-dependent adenoma reduction in trials, its

poor absorption limits clinical utility. Similarly, EGCG and

vitamin supplementation trials revealed mixed results, emphasizing

the need for optimized trial designs, standardized dosing and

biomarker-driven patient stratification. Advances in nano-drug

delivery systems, such as nanoparticles, liposomes and

nanomicelles, offer promising solutions to enhance solubility,

stability and tumor targeting. Combinatorial strategies integrating

PBAs with chemotherapeutics (such as FOLFOX-curcumin) further

demonstrate improved safety and efficacy, warranting expanded

clinical exploration.

Future research should prioritize elucidating core

mechanisms through advanced technologies such as single-cell

sequencing and spatial transcriptomics, enabling precise

identification of molecular targets and responsive patient

subgroups. Personalized approaches, informed by CRC molecular

subtypes (such as microsatellite stability, p53 status), will

refine therapeutic applications. In addition, deeper investigations

into gut microbiota-PBAs crosstalk and host-microbe interactions

may unlock novel preventive and therapeutic avenues.

In conclusion, PBAs represent a versatile and

sustainable frontier in CRC management. While challenges persist,

interdisciplinary innovations in drug delivery, mechanism

elucidation and precision medicine are key to unlocking their full

clinical potential, ultimately bridging the gap between traditional

phytotherapy and modern oncology.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, investigation and writing the

original draft was by DF, HF, KY, YW, BN and XL. DF, HF, KY, YW, BN

and XL were responsible for writing, review and editing. DF, HF,

KY, YW, BN and XL were responsible for visualization. DF, HF and XL

were responsible for supervision. HF, XL and DF were responsible

for project administration. Data authentication is not applicable.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82303765) and the Beien funding from

the Bethune Charitable Foundation (grant no. bnmr-2023-004).

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Patel SG, Karlitz JJ, Yen T, Lieu CH and

Boland CR: The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: A

comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology,

risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 7:262–274. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chen EX, Jonker DJ, Loree JM, Kennecke HF,

Berry SR, Couture F, Ahmad CE, Goffin JR, Kavan P, Harb M, et al:

Effect of combined immune checkpoint inhibition vs best supportive

care alone in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: The

Canadian Cancer Trials Group CO.26 Study. JAMA Oncol. 6:831–838.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hudita A, Radu IC, Galateanu B, Ginghina

O, Herman H, Balta C, Rosu M, Zaharia C, Costache M, Tanasa E, et

al: Bioinspired silk fibroin nano-delivery systems protect against

5-FU induced gastrointestinal mucositis in a mouse model and

display antitumor effects on HT-29 colorectal cancer cells in

vitro. Nanotoxicology. 15:973–994. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Georgiou A, Stewart A, Vlachogiannis G,

Pickard L, Valeri N, Cunningham D, Whittaker SR and Banerji U: A

phospho-proteomic study of cetuximab resistance in

KRAS/NRAS/BRAF(V600) wild-type colorectal cancer. Cell Oncol

(Dordr). 44:1197–1206. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li Q, Geng S, Luo H, Wang W, Mo YQ, Luo Q,

Wang L, Song GB, Sheng JP and Xu B: Signaling pathways involved in

colorectal cancer: Pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:2662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang Y, Liu M, Jafari M and Tang J: A

critical assessment of Traditional Chinese Medicine databases as a

source for drug discovery. Front Pharmacol. 15:13036932024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sies H, Mailloux RJ and Jakob U:

Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

25:701–719. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Porter RJ, Arends MJ, Churchhouse AMD and

Din S: Inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer:

Translational risks from mechanisms to medicines. J Crohns Colitis.

15:2131–2141. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Naeem A, Hu P, Yang M, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhu

W and Zheng Q: Natural products as anticancer agents: Current

status and future perspectives. Molecules. 27:83672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yang H, Yue GGL, Leung PC, Wong CK and Lau

CBS: A review on the molecular mechanisms, the therapeutic

treatment including the potential of herbs and natural products,

and target prediction of obesity-associated colorectal cancer.

Pharmacol Res. 175:1060312022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Bu F, Tu Y, Wan Z and Tu S: Herbal

medicine and its impact on the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 13:10960082023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ding Y and Yu Y: Therapeutic potential of

flavonoids in gastrointestinal cancer: Focus on signaling pathways

and improvement strategies (Review). Mol Med Rep. 31:1092025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Janney A, Powrie F and Mann EH:

Host-microbiota maladaptation in colorectal cancer. Nature.

585:509–517. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zińczuk J, Maciejczyk M, Zaręba K,

Pryczynicz A, Dymicka-Piekarska V, Kamińska J, Koper-Lenkiewicz O,

Matowicka-Karna J, Kędra B, Zalewska A and Guzińska-Ustymowicz K:

Pro-Oxidant enzymes, redox balance and oxidative damage to

proteins, lipids and DNA in colorectal cancer tissue. is oxidative

stress dependent on tumour budding and inflammatory infiltration?

Cancers (Basel). 12:16362020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Monticelli S and Cejka P: DNA sensing and

repair systems unexpectedly team up against cancer. Nature.

625:457–458. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ajeigbe OF, Maruf OR, Anyebe DA, Opafunso

IT, Ajayi BO and Farombi EO: 6-shogaol suppresses AOM/DSS-mediated

colorectal adenoma through its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory

effects in mice. J Food Biochem. 46:e144222022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Liu C, Rokavec M, Huang Z and Hermeking H:

Curcumin activates a ROS/KEAP1/NRF2/miR-34a/b/c cascade to suppress

colorectal cancer metastasis. Cell Death Differ. 30:1771–1785.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sun R, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Tang T, Cao Y,

Yang L, Tian Y, Zhang Z, Zhang P and Xu F: Temporal and spatial

metabolic shifts revealing the transition from ulcerative colitis

to colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e24125512025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bardelčíková A, Šoltys J and Mojžiš J:

Oxidative stress, inflammation and colorectal cancer: An overview.

Antioxidants (Basel). 12:9012023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Mandal M, Mamun MAA, Rakib A, Kumar S,

Park F, Hwang DJ, Li W, Miller DD and Singh UP: Modulation of

occludin, NF-κB, p-STAT3, and Th17 response by DJ-X-025 decreases

inflammation and ameliorates experimental colitis. Biomed

Pharmacother. 185:1179392025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Li Q, Chen Y, Zhang D, Grossman J, Li L,

Khurana N, Jiang H, Grierson PM, Herndon J, DeNardo DG, et al:

IRAK4 mediates colitis-induced tumorigenesis and chemoresistance in

colorectal cancer. JCI Insight. 4:e1308672019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang M, Ma Y, Yu G, Zeng B, Yang W, Huang

C, Dong Y, Tang B and Wu Z: Integration of microbiome, metabolomics

and transcriptome for in-depth understanding of berberine

attenuates AOM/DSS-induced colitis-associated colorectal cancer.

Biomed Pharmacother. 179:1172922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Burgueño JF, Fritsch J, González EE,

Landau KS, Santander AM, Fernández I, Hazime H, Davies JM,

Santaolalla R, Phillips MC, et al: Epithelial TLR4 Signaling

Activates DUOX2 to induce microbiota-driven tumorigenesis.

Gastroenterology. 160:797–808.e6. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Jin BR, Chung KS, Hwang S, Hwang SN, Rhee

KJ, Lee M and An HJ: Rosmarinic acid represses colitis-associated

colon cancer: A pivotal involvement of the TLR4-mediated

NF-κB-STAT3 axis. Neoplasia. 23:561–573. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hernández-Rocha C, Turpin W, Borowski K,

Stempak JM, Sabic K, Gettler K, Tastad C, Chasteau C, Korie U,

Hanna M, et al: After surgically induced remission, Ileal and

colonic mucosa-associated microbiota predicts crohn's disease

recurrence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 23:612–620.e10. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yun X, Zhang Q, Fang Y, Lv C, Chen Q, Chu

Y, Zhu Y, Wei Z, Xia Y and Dai Y: Madecassic acid alleviates

colitis-associated colorectal cancer by blocking the recruitment of

myeloid-derived suppressor cells via the inhibition of IL-17

expression in γδT17 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 202:1151382022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kuo IM, Lee JJ, Wang YS, Chiang HC, Huang

CC, Hsieh PJ, Han W, Ke CH, Liao ATC and Lin CS: Potential

enhancement of host immunity and anti-tumor efficacy of nanoscale

curcumin and resveratrol in colorectal cancers by modulated

electro-hyperthermia. BMC Cancer. 20:6032020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Pouliquen DL, Malloci M, Boissard A, Henry

C and Guette C: Proteomes of residual tumors in curcumin-treated

rats reveal changes in microenvironment/malignant cell crosstalk in

a highly invasive model of mesothelioma. Int J Mol Sci.

23:137322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Montalto FI and De Amicis F: Cyclin D1 in

cancer: A molecular connection for cell cycle control, adhesion and

invasion in tumor and stroma. Cells. 9:26482020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Alam M, Gulzar M, Akhtar MS, Rashid S,

Zulfareen Tanuja, Shamsi A and Hassan MI:

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate therapeutic potential in human diseases:

Molecular mechanisms and clinical studies. Mol Biomed. 5:732024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ismail NI, Othman I, Abas F, H Lajis N and

Naidu R: The curcumin analogue, MS13

(1,5-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadiene-3-one), inhibits

cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in primary and metastatic

human colon cancer cells. Molecules. 25:37982020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Agarwal A, Kansal V, Farooqi H, Prasad R

and Singh VK: Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), an active phenolic

compound of green tea, inhibits tumor growth of head and neck

cancer cells by targeting DNA hypermethylation. Biomedicines.

11:7892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tian M, Peng S, Wang S, Li X, Li H and

Shen L: Pristimerin reduces dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis

in mice by inhibiting microRNA-155. Int Immunopharmacol.

94:1074912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu H, Zhang L, Hao L and Fan D:

Resveratrol inhibits colorectal cancer cell tumor property by

activating the miR-769-5p/MSI1 pathway. Mol Biotechnol.

67:1893–1907. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wang Z, Dan W, Zhang N, Fang J and Yang Y:

Colorectal cancer and gut microbiota studies in China. Gut

Microbes. 15:22363642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chattopadhyay I, Dhar R, Pethusamy K,

Seethy A, Srivastava T, Sah R, Sharma J and Karmakar S: Exploring

the role of gut microbiome in colon cancer. Appl Biochem

Biotechnol. 193:1780–1799. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Liu P, Wang Y, Yang G, Zhang Q, Meng L,

Xin Y and Jiang X: The role of short-chain fatty acids in

intestinal barrier function, inflammation, oxidative stress, and

colonic carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Res. 165:1054202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Su ACY, Ding X, Lau HCH, Kang X, Li Q,

Wang X, Liu Y, Jiang L, Lu Y, Liu W, et al: Lactococcus lactis

HkyuLL 10 suppresses colorectal tumourigenesis and restores gut

microbiota through its generated alpha-mannosidase. Gut.

73:1478–1488. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Deng W, Xiong X, Lu M, Huang S, Luo Y,

Wang Y and Ying Y: Curcumin suppresses colorectal tumorigenesis

through restoring the gut microbiota and metabolites. BMC Cancer.

24:11412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Leong W, Huang G, Liao W, Xia W, Li X, Su

Z, Liu L, Wu Q, Wong VKW, Law BYK, et al: Traditional Patchouli

essential oil modulates the host's immune responses and gut

microbiota and exhibits potent anti-cancer effects in Apc(Min/+)

mice. Pharmacol Res. 176:1060822022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Wu Z, Huang S, Li T, Li N, Han D, Zhang B,

Xu ZZ, Zhang S, Pang J, Wang S, et al: Gut microbiota from green

tea polyphenol-dosed mice improves intestinal epithelial

homeostasis and ameliorates experimental colitis. Microbiome.

9:1842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Urošević M, Nikolić L, Gajić I, Nikolić V,

Dinić A and Miljković V: Curcumin: biological activities and modern

pharmaceutical forms. Antibiotics (Basel). 11:1352022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Weng W and Goel A: Curcumin and colorectal

cancer: An update and current perspective on this natural medicine.

Semin Cancer Biol. 80:73–86. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

López-Gómez L and Uranga JA: Polyphenols

in the prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer: A systematic

review of clinical evidence. Nutrients. 16:27352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Neira M, Mena C, Torres K and Simón L: The

potential benefits of curcumin-enriched diets for adults with

colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Antioxidants (Basel).

14:3882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|