Traditionally, cancer is considered to originate

from genomic instability, whereas recent research has indicated

that epigenetic changes alone are sufficient to cause cancer

(1,2). The main forms of cancer therapy

available at present are surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy,

targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Tumor immunotherapy, which

targets tumor escape mechanisms, has both targetability and

long-lasting therapeutic effects. The immunotherapeutic modalities

that are mainly used at present are lysosomal virus therapy, cancer

vaccines, cytokine therapy, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell

therapy and immune checkpoint inhibition therapy (3). However, immunotherapy remains

expensive, lengthy and associated with off-target effects, posing

challenges in improving treatment efficiency (4).

Nanomaterials have emerged as promising therapeutic

agents for cancer because of their ability to improve efficacy,

high stability and specificity, capacity to control drug release

more precisely and the inherent therapeutic properties of certain

nanomaterials in response to stimuli (5-7).

Transition-metal NPs, which are derived from transition metals

(d-group elements), are particularly notable for their high

stability, modifiable properties and ability to participate in

multiple therapeutic modalities (8). In comparison with conventional tumor

immunotherapy, transition-metal NPs are highly targeted; moreover,

they are capable of combining multiple effects of chemistry, optics

and thermodynamics for treatment and can improve the

bioavailability and in vivo residence time of drugs

(9,10). Studies have suggested that

transition-metal NPs hold great potential in tumor immunotherapy;

however, their safety concerns and potential adverse effects

require cautious consideration. The present review focused on the

properties of transition-metal NPs, their advantages and

limitations in immunotherapy and their potential clinical

applications. Furthermore, it explored the feasibility of

categorizing such materials for future clinical practice.

Gold NPs (AuNPs). AuNPs are the most stable

transitionmetal NPs and show excellent stability, oxidation

resistance, biocompatibility and low toxicity, rendering them

suitable for biomedical applications (11). Notably, their tunable size and

shape allow for diverse functionalization, which is facilitated by

negatively charged surfaces that enable conjugation with

biologically active groups, such as amines and sulfhydryl groups

(11,12).

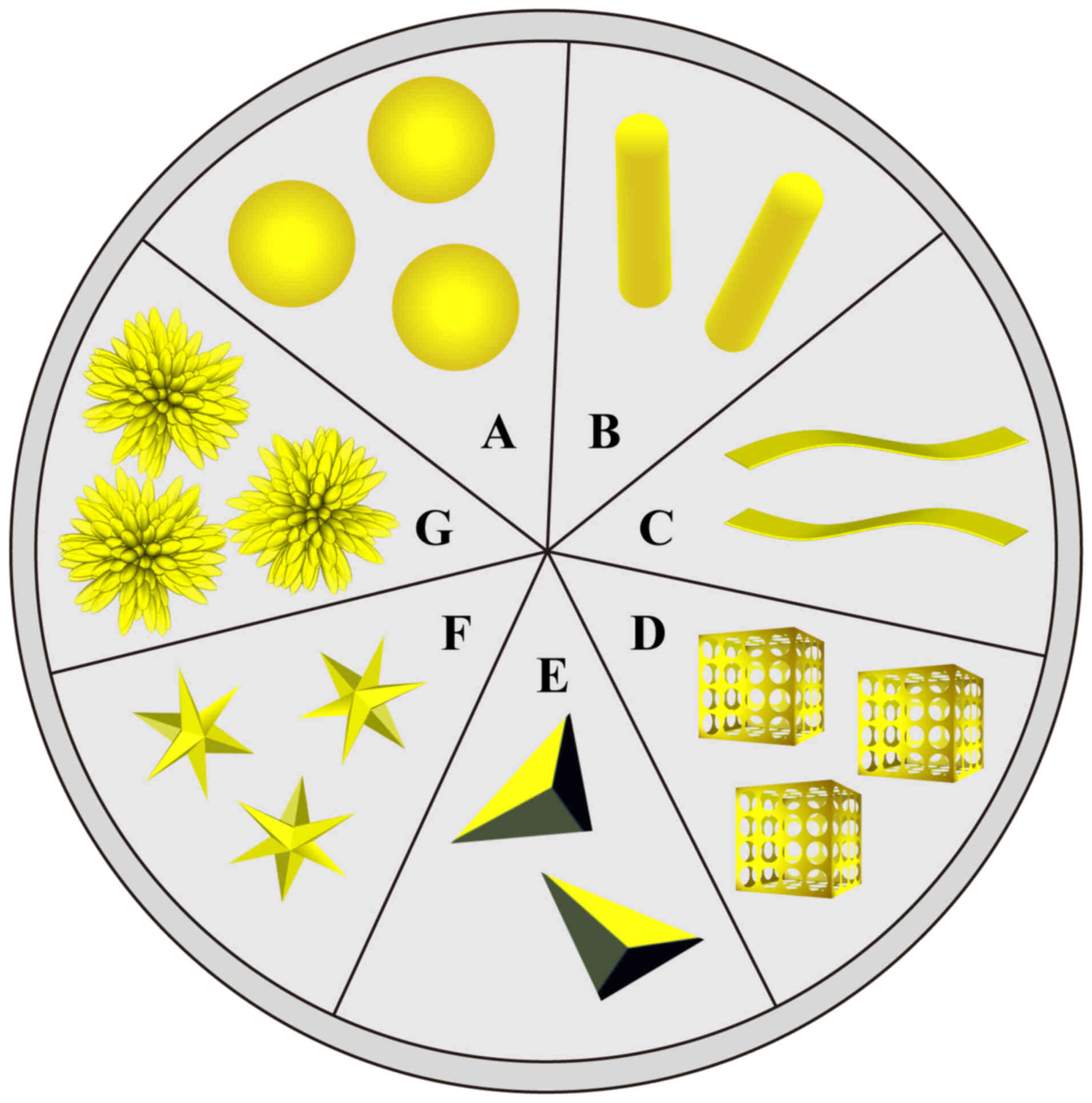

AuNPs can be classified on the basis of their

shapes, such as nanospheres, nanorods, nanoplates, nanocages,

nanotriangles, nanostars, nanoflowers and network dendrites, with

each shape showing a specific biomedical application (Fig. 1). AuNPs, particularly in nanoplate

or nanorod forms, have shown applications in imaging techniques

such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography

(CT) (13). Gold nanorods,

nanocages and nanoshells are considered excellent imaging NPs for

cancer therapy (14); for

example, an AuNP for CT imaging cancer therapy was studied by Wang

et al (15). AuNPs also

exhibit antimicrobial effects, possibly due to the surface charge,

with the surface modification between bacteria and AuNPs generating

reactive oxygen species (ROS). NPs also affect the cell membrane

permeability by disrupting intercellular communication (16). Bankar et al (17) have described the antibacterial

activity of network-dendritic AuNPs.

AuNPs are excellent drug carriers that can not only

carry small molecules but also transport large biomolecules through

different interactions, enabling drug release at the target

location (18). Additionally,

drug-loaded AuNPs can enhance drug accumulation and retention

(19). Gold nanospheres have a

uniform size, good tissue permeability and relatively simple

surface modifications, which are conducive to drug delivery

(20,21). Gold nanocages have hollow

interiors and porous structures, such that small molecules enter

the nanocages through the pores on the surfaces and are

encapsulated therein, which can be applied to the targeting area

(20).

In photothermal therapy (PTT), AuNPs convert light

into heat, thereby inducing high temperatures that cause

irreversible damage. Moreover, in vitro studies employing

tumor cell lines have confirmed that AuNPs can penetrate various

tumor cells, including lung, gastric and colorectal cancers, for

targeted therapy (22-24).

Despite these advantages, AuNPs should be used with

caution. The size, shape and surface properties of AuNPs are also

associated with their cytotoxicity. Additionally, modifications

such as PEGylation may induce toxicity (14). Exposure time and concentration

affect the cellular uptake of NPs and thus their cytotoxicity

(25).

AgNPs have attracted substantial attention because

of their nano-sized effects, surface properties and localized

surface plasmon resonance, making them valuable in antibiotics,

sensors and biomedical applications. Therefore, they have been

synthesized in various shapes to meet specific requirements

(26).

AgNPs have attracted growing interest in cancer

research because of their potential for next-generation diagnosis

and treatment, since they show broad anticancer effects by

inhibiting cancer cell growth and viability. AgNPs can induce

apoptosis and necrosis by generating ROS and damaging DNA (27). In vitro studies have shown

that AgNPs induce apoptosis by upregulating or downregulating gene

expression (28,29). They can also induce apoptosis by

altering key signaling pathways (30). Additionally, cancer cells treated

with AgNPs may experience cell cycle arrest (31). AgNPs inhibit tumor cell migration

and angiogenesis in vitro, indicating their possible role in

reducing distant metastasis (32). AgNPs can also be used to treat

cancer by coating them with polymers or by conjugating them with

drugs. Furthermore, because of their targeting ability and

biocompatibility, AgNPs show excellent anti-tumor efficacy and few

adverse reactions.

AgNPs inhibit tumor cell migration and invasion in a

concentration- and dose-dependent manner, which are critical

features for cancer development and progression (33,34). Although AgNPs have been shown to

inhibit tumor invasion, the underlying mechanism remains unknown.

One hypothesis suggests that AgNPs may reduce the production of

cytokines and growth factor proteins and inhibit the enzymatic

activity of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer cells (35).

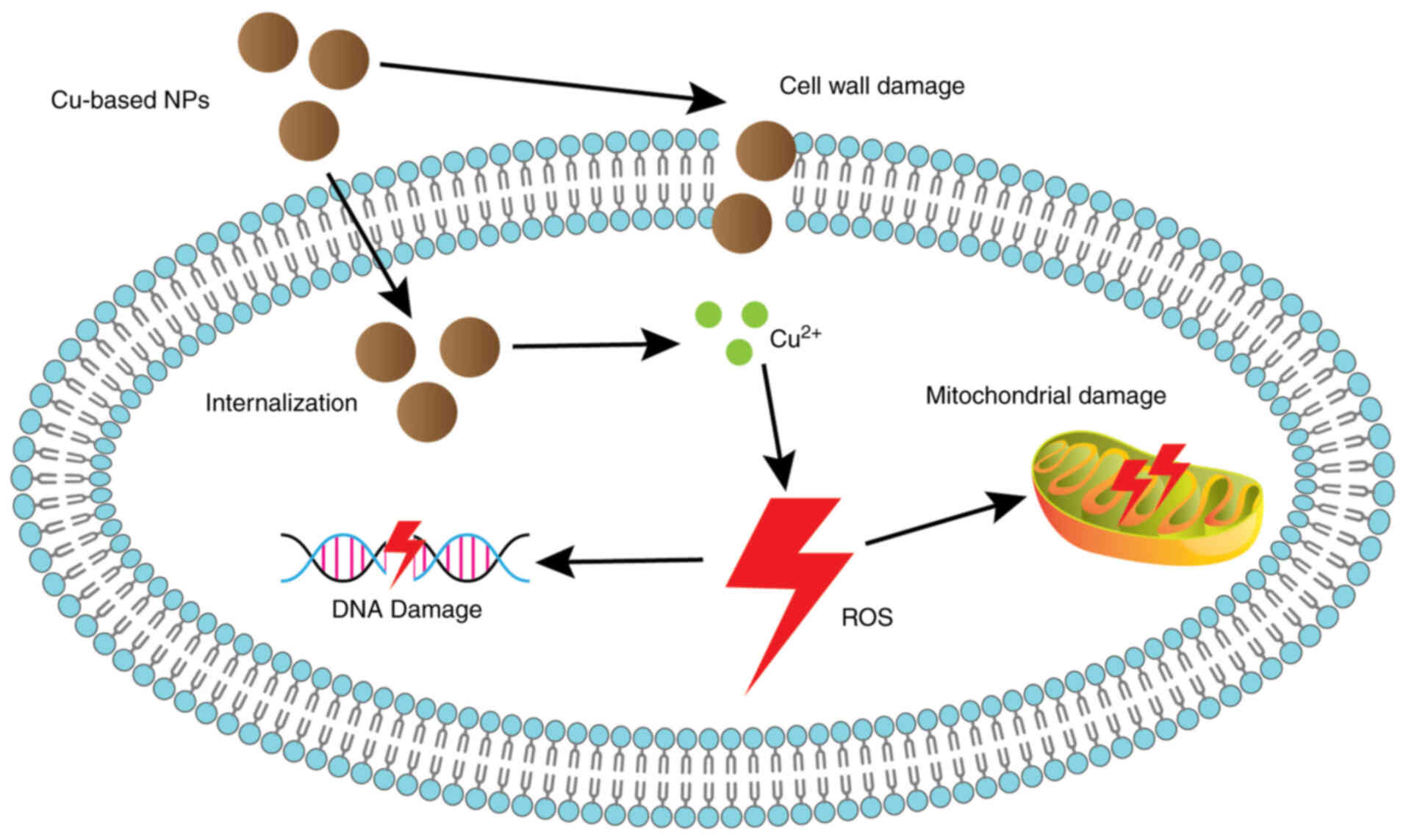

Cu-based NPs mainly include CuNPs, CuONPs and CuS

NPs. CuNPs are of interest owing to their unique physical and

chemical properties, high surface-to-volume ratio, low preparation

cost, low toxicity and good biocompatibility (36-38). Cu-based NPs exhibit antimicrobial

activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia

coli, Bacillus subtilis and Proteus vulgaris.

This antimicrobial property may be related to cell wall damage,

internalization of NPs into bacterial cells, Cu ion release, excess

ROS, oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and DNA damage

(Fig. 2) (39). CuNPs act as anti-tumor agents

through various cytotoxic mechanisms, including ROS production,

cell cycle blockade, DNA damage, apoptosis and autophagy and are

effective against a wide range of cancer cell lines (39-41). Woźniak-Budych et al

(42) demonstrated that

sulfobetaine-stabilized Cu(I) oxide NPs promoted the suppression of

cancer cell growth in a concentration-dependent manner in tumor

cell line models. Due to their large surface area, CuNPs facilitate

high-density surface ligand attachment, making them suitable drug

carriers for the controlled release of anticancer drugs during

tumor treatment (43,44). In tumor therapy, CuS is a

potential photothermal agent owing to its good photothermal effect.

Yuan et al (45) used CuS

NPs as photothermal agents and found that encapsulated CuS NPs can

be used for PTT combined with chemotherapy, achieving improved

results in late-stage combined anticancer therapy in

vivo.

However, the stable synthesis of CuNPs still remains

challenging at present because Cu is easily oxidized. The rapid

dissolution of nanodrugs may also involve the oxidation of CuO,

which increases the toxicity of CuONPs.

Owing to their magnetic properties, iron-based NPs

have been broadly used in MRI, photodynamic therapy (PDT)/PTT

combination therapy and immunotherapy (46). Iron-based NPs include FeNPs, iron

oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) and iron-based bimetallic NPs, of which

IONPs are the most widely used (47). IONPs are cheap to produce and are

biocompatible (47). Their large

surface area reduces the amount of drugs required and their toxic

effects on cells (48). They are

degraded into ferric ions in vivo and participate in

physiological iron homeostasis. In addition, an in vitro

study demonstrated the antagonistic effect of

Fe3O4 NPs on ROS accumulation, indicating

their ability to regulate oxidative stress and apoptosis (49,50). As ferromagnetic materials, IONPs

can be surface-modified to obtain superparamagnetic iron oxide

nanoparticles (SPIONs), ensuring uniform size and stability at the

desired pH. In addition, elevated iron levels induce the Fenton

reaction, which leads to an increase in ROS (51). When ROS production exceeds the

cellular clearance capacity, it leads to lipid peroxidation and DNA

damage, resulting in iron death, a mechanism that provides ideas

for disease treatment (51).

Since the upregulation of the dehydrogenase redox system in tumor

cells affects lipid peroxidation, Chen et al (52) designed a layered double hydroxide

nanoplatform co-loaded with the ferroptosis agent IONPs and the

dehydrogenase inhibitor small interfering RNA (siR). Evidence from

both in vitro and in vivo studies has confirmed that

this platform synergistically induces cancer cell death by

releasing IONPs and siR to enable the mass production of ROS while

accelerating the accumulation of lipid peroxidation (52).

IONPs can generate excess ROS and disrupt biofilms,

which opens up the possibility of antimicrobial therapy (53). In addition, IONPs can be used for

tissue repair (54). SPIONs are

capable of targeted drug delivery by binding to drugs and

biomolecules, localizing them to target sites and releasing them

through the action of a magnetic field.

IONPs can be used in PTT, PDT, hyperthermia therapy

and tumor immunotherapy of tumors owing to their magnetic and

superparamagnetic properties (55). In PTT, IONPs can act as

photo-absorbents (56). IONPs may

also be suitable as intensifiers for radiotherapy (57,58). In magnetic hyperthermia therapy,

IONPs are exposed to an alternating magnetic field and produce a

local heating effect, causing protein denaturation, cancer cell

apoptosis and tissue damage through high temperatures >42°C.

IONPs used in hyperthermia therapy must be defined in terms of size

and shape to obtain improved therapeutic effects (59). Magnetic hyperthermia therapy can

also be used as a stimulating agent in tumor immunotherapy

(60,61). IONPs are not only competent in

transporting tumor-specific antigens to dendritic cells (DCs) and T

cells, but also in treating tumors by inducing a shift in

macrophage polarization toward the M1 type and increasing ROS

production (62,63).

Nanoscale iron-based metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)

play an important role in biomedical engineering because of the

extensive porosity, surface area and chemical and thermal

stability, as well as their good biocompatibility and

biodegradability (64-66). Nanoscale iron-based MOFs are ideal

for drug delivery systems because of their unique properties and

their catalytic and redox activities make them suitable for use in

biosensors and electrochemical sensors. This catalytic activity has

been used in nano-catalytic medicine to generate ROS for cancer

treatment. Using in vitro and in vivo studies, Yang

et al (67) demonstrated

that an iron-containing metal-organic framework [MOF(Fe)]

nano-catalyst, acting as a peroxidase mimic, catalyzes the

generation of highly oxidizing•OH radicals in cancer cells and

amplifies oxidative damage in synergy with autophagy-inhibiting

drugs. Iron metal-phenolic networks have a specific range of

absorption peaks in the ultraviolet range and pH-responsiveness and

can be efficiently dissociated to release drugs under acidic

conditions (68). They are

capable of functional modification and can undergo the Fenton

reaction to induce ferroptosis. Luo et al (69) designed an integrated nanoplatform

called FCS/GCS that takes advantage of the properties of

metal-phenolic networks to enhance the anti-tumor effect; thus

nanoconjugates are degraded and released in the acidic tumor

microenvironment (TME) and the Fenton reaction can occur, which

induces ferroptosis in vitro and in vivo.

Cancer vaccines. Cancer vaccines act against cancer

by activating the innate cellular or humoral immune systems, with

most vaccines triggering the proliferation of CD8+ T

cells that specifically identify and eliminate cancer cells

(70,71). To date, three cancer vaccines have

been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) (72). Cancer nanovaccines,

whose antigens can be peptides, RNA, or DNA, are more flexible and

may elicit more robust immune responses. The simplest cancer

nanovaccine could be an antigen, an adjuvant, or even a

heterogeneous antigen in NPs with adjuvant properties (73). Currently, both therapeutic and

prophylactic vaccines against tumors are under investigation.

Metal ions are involved in several critical immune

processes in organisms; therefore, the application of

transition-metal NPs to tumor vaccines may promote effective

immunomodulation (74,75). NPs are modified to possess surface

properties similar to those of pathogens, thereby modulating the

interaction of the vaccine with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and

enhancing antigen immunogenicity (76). In addition, NPs can increase the

specificity of tumor vaccines and minimize harm to normal cells in

comparison with conventional tumor vaccines. Transition-metal-based

nanomaterials are often used as adjuvants and drug carriers in

tumor nanovaccines.

A lack of adjuvants in vaccinations often results in

weaker immune responses. Currently, Toll-like receptor (TLR)

agonists and stimulator of interferon genes (STING) agonists are

being studied as vaccine adjuvants (77,78). The human body has 10 different

TLRs, which are distributed on the extracellular and endosomal

membranes of immune cells and can induce the secretion of

cytokines, chemokines and type I interferons, thereby activating

the innate immune system and mediating the activation of acquired

immune responses (79,80). Shinchi et al (80) took into account the high affinity

of AuNPs for thiol-functionalized molecules, such as the TLR7

ligand and antigens and combined the small-molecule synthetic TLR7

ligand 2-methoxyethoxy-8-oxo-9-(4-carboxy benzyl)adenine (1V209)

and α-mannose co-immobilized on the surface of AuNPs, which served

as a potent adjuvant to enhance the activation of TLR7 on endosomal

membranes. STING is a transmembrane protein integrated within the

endoplasmic reticulum that activates type I interferons (81). The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-STING

pathway may act as an anti-tumor agent by inducing a

proinflammatory response dominated by type I interferons, which may

be a potential target for immunotherapy (82). Ding et al (83) designed a TME-responsive adjuvant

called MnOx nanospikes and prepared a vaccine using

ovalbumin (OVA) proteins as antigens to suppress primary and distal

tumor growth as well as tumor metastasis in vitro and in

vivo. In addition, a number of other cytokines with

immunostimulatory effects, such as IL-2, IL-1 and interferons, can

be used as adjuvants. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating

factor facilitates the attraction of DCs to the target site,

promotes DC maturation and facilitates antigen presentation

(84,85). Inorganic nanoadjuvants, which have

been found to enable the sustained release of antigens and

specifically increase the immune response, have also gained

widespread interest (86). Wang

et al (87) used human

tubercle bacillus-loaded Zn- and Mg-tricalcium phosphates as

adjuvants to boost the immune response and stimulate the secretion

of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, which markedly

inhibited the development of Lewis lung cancer cells in

vivo.

Transition-metal NPs can modulate their size and

shape to deliver antigens and adjuvants to specific tissues and

have been used as delivery carriers for cancer nanovaccines

(88,89). Vaccines that use AuNPs as carriers

exhibit high immunostimulatory activity (90). Zhang et al (91) studied multilayer polyelectrolytic

AuNPs with anionic poly I:C and antigenic peptides as nanocarriers,

which could induce more antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

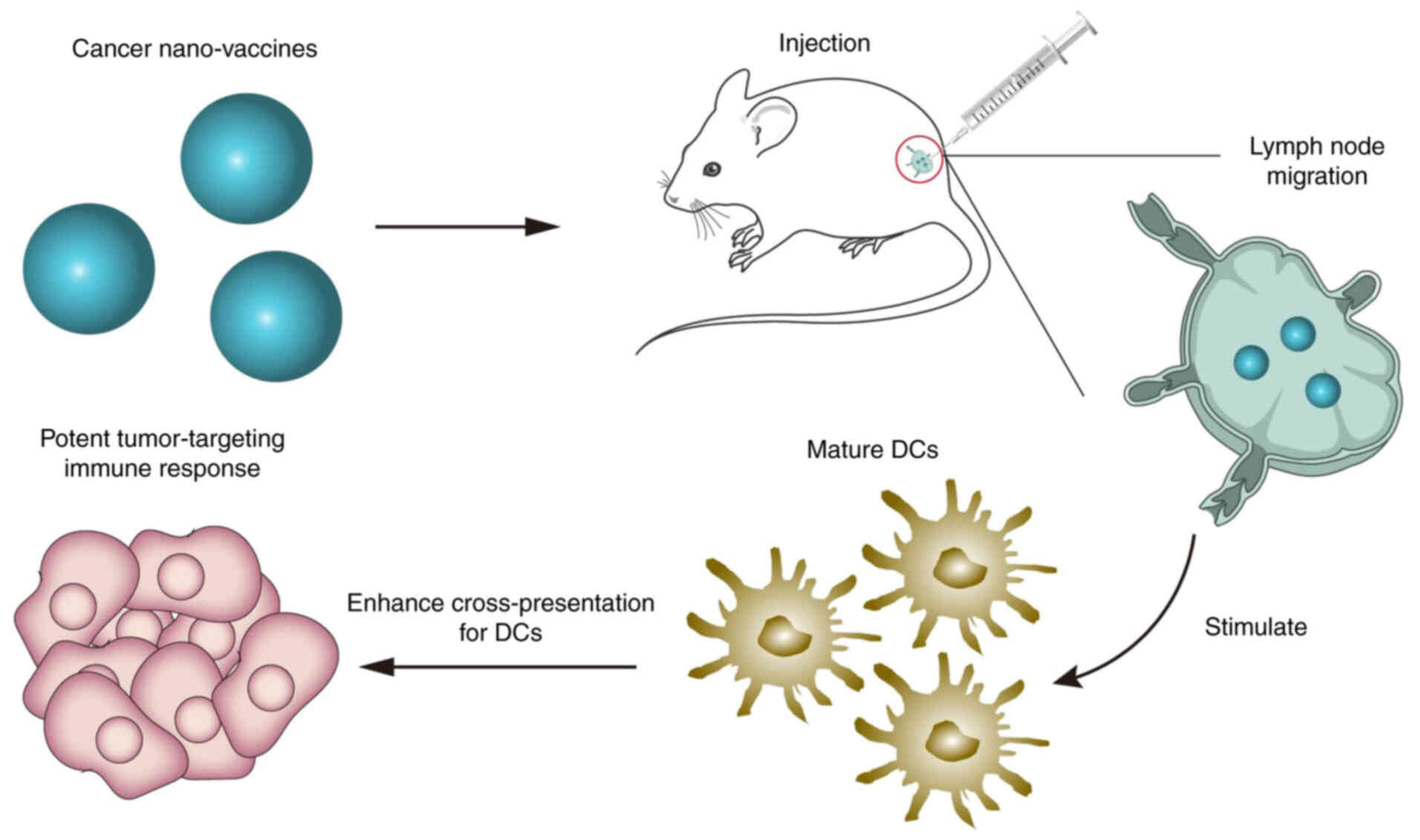

Zhao et al (92) prepared

a vaccine carrier containing Mn2+ ions and

meso-2,6-diaminopimelic acid (DAP) to encapsulate the OVA

antigen to form a cancer vaccine (Fig. 3). This vaccine could effectively

co-deliver OVA and DAP to the lymph nodes, stimulate the maturation

of DCs, enhance OVA cross-presentation to DCs and serve as a

prophylactic vaccine for B16-OVA melanoma tumors in

vivo.

Nanovaccines can also be integrated with other

immunotherapies to enhance their efficacy (73). Jin et al (93) developed polyethyleneimine modified

gold nanorods called GNRs-PEI. Subsequently, GNR-PEI/cyclic dimeric

guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate-laden macrophages

(GPc-RAWs) were injected into the tumor with simultaneous

introduction of a programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody.

This strategy inhibits tumor growth and metastasis through a

combination of tumor vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors in

vivo. Chen et al (94)

assembled an iron nano-adjuvant containing IONPs and STING agonists

that activated STING while forming a vaccine with OVA antigens to

induce long-lasting anti-tumor immunity and prevent postoperative

recurrence and distant metastasis in vivo by synergistic

treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.

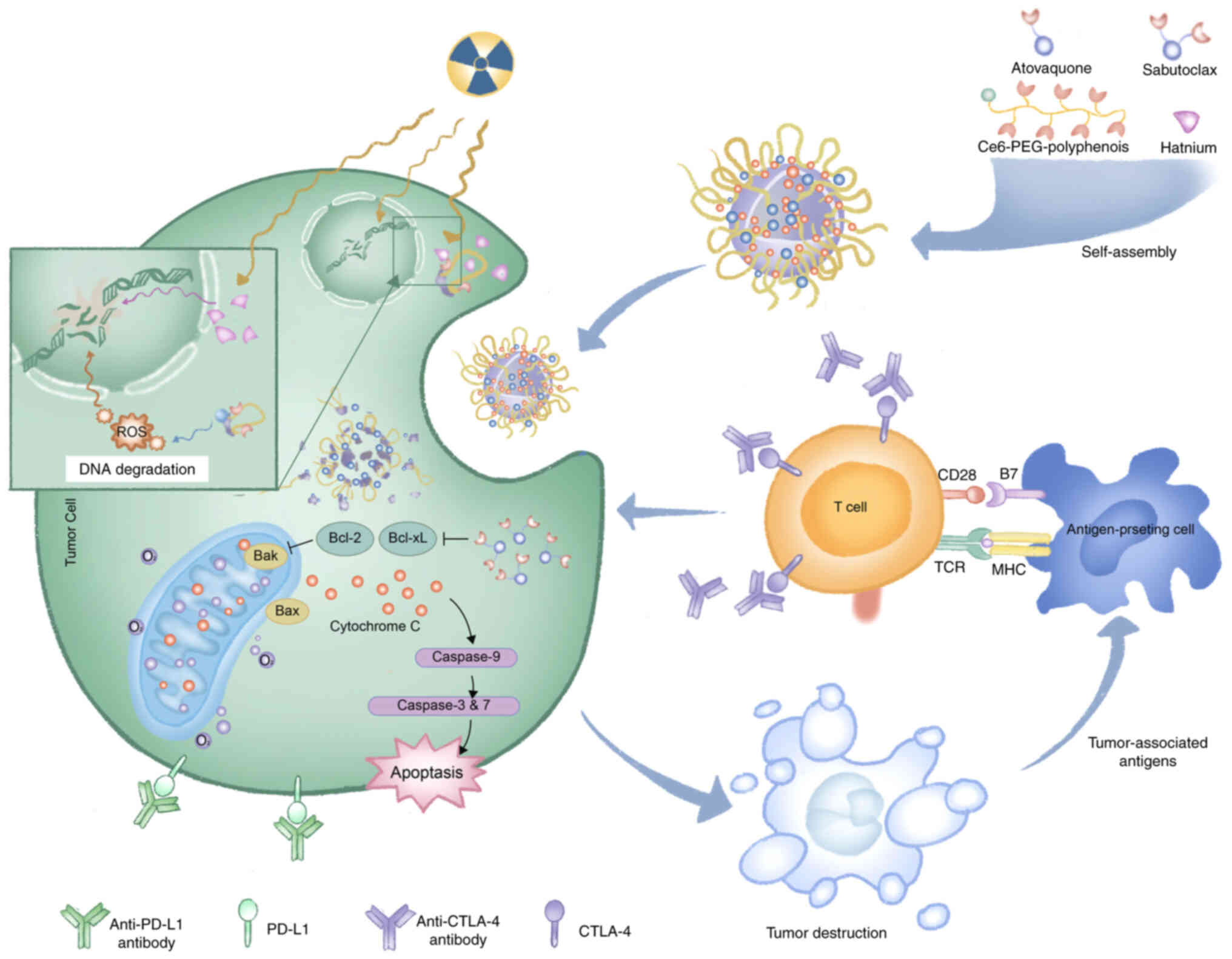

Immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer immunotherapies

promote immune system specificity against cancer. The blockade of

immune checkpoint programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic

T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) removes immune suppression,

enabling tumor clearance (95).

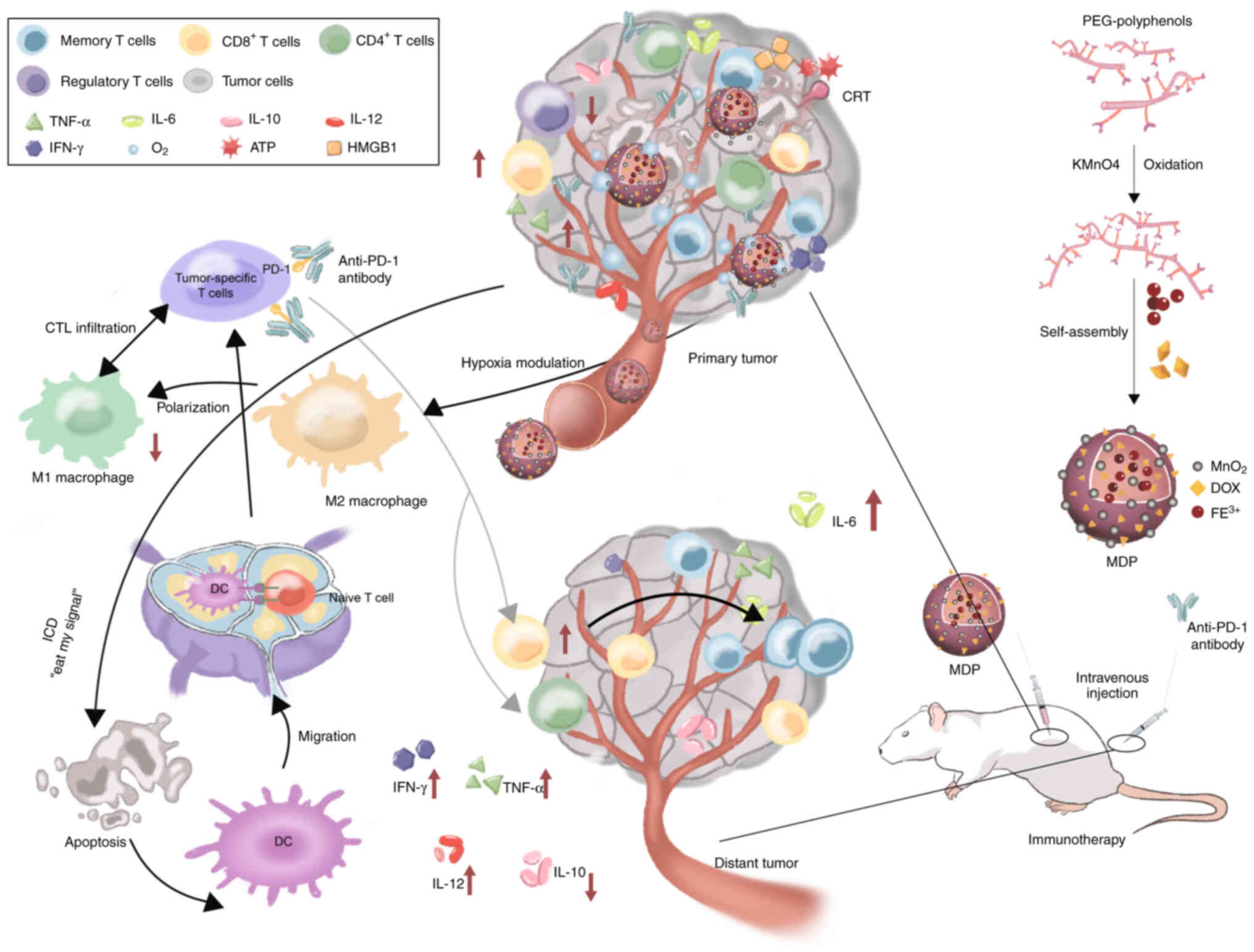

Nanometallic materials have become a hotspot in

research on checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Hybrid nanometallic

frameworks function as immunogenic cell death (ICD) inducers,

enhancing tumor sensitivity to immunotherapy. Researchers have

developed a phenolic ICD inducer to improve antigen generation,

tumor-specific T-cell infiltration and PD-1 checkpoint blockade,

stimulating anti-tumor immunity and generating significant abscopal

effects on distant tumors in vivo (Fig. 4) (96). Moreover, Sang et al

(97) developed metal-phenolic

network nanopumps to overcome resistance to combined

radiotherapy/anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapy. Evidence from both in

vitro and in vivo studies confirmed that these NPs

enhanced RT efficacy, alleviated hypoxia/induced apoptosis,

suppressed therapy-induced PD-L1 upregulation, effectively reversed

T-cell exhaustion and enabled immunotherapy for immunologically

non-responsive tumors (Fig.

5).

Immune checkpoint agonist antibodies. Immune cells

are stimulated by exogenous antigens to avoid autoimmunity and

tissue damage through regulation of costimulatory and

co-suppressive receptors, that is, the regulation of immune

checkpoints (98). Evidence

support the important role of the costimulatory pathway in

mediating anti-cancer immunity. The targets of immune agonist

antibodies are mainly the B7-CD28 and tumor necrosis factor

receptor (TNFR) families (98,99).

Typical costimulatory receptors of the B7-CD28

family are CD28 and inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS). CD28

activates downstream signaling after adhering to the ligands CD80

and CD86, driving T-cell function, proliferation and survival

(100). ICOS responds to ICOS

ligands to activate T cells and memory T cells. Thus, CD28 and ICOS

are potential targets for the development of therapeutic agonists

for tumor treatment (101,102). Chiang et al (103) reported an inherently therapeutic

fucoidan-dextran-based magnetic nanomedicine (IO@FuDex3)

combined with a checkpoint inhibitor and T-cell activators,

demonstrating in vivo that combining IONPs with anti-PD-L1

and agonist antibodies enhances the efficacy of immunotherapy.

The TNFR superfamily influences the maturation and

differentiation of B and T lymphocytes and is involved in

physiological processes such as apoptosis, inflammation and

autoimmunity (104). Six

receptors have been suggested to play major roles as immune

costimulators, namely, CD40, OX40, 4-1BB, CD27, GITR and CD30

(98). Among them, agonistic CD40

monoclonal antibody activates host APCs, especially DCs, thus

inducing anti-tumor T-cell responses, which are considered

promising for research (105).

Although nanomedicines targeting TNFR have been

investigated, nanomedicines based on transition-metal NPs targeting

TNFR are still lacking (106).

Overall, the use of immune checkpoint agonist antibodies

incorporating transition-metal NPs remains an area that requires

further exploration.

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT). ACT is a form of

treatment in which T cells are isolated from plasma or tumor

samples, expanded and activated in vitro, conditioned and

modified and injected back into the patient to activate the immune

system and suppress cancer (107-109). This method is based on the

principle of engineering T cells is to create T cells with

tumor-targeting structural domains, which enhances the specificity

of T-cell recognition in tumors (110,111). Due to the complexity and expense

of the natural activation process of T cells, the primary focus of

current research is the use of artificial antigen-presenting cells

(aAPCs), which mimic the function of APCs, to stimulate T cells to

initiate tumor-specific adaptive immunity (112). Nanoscale aAPCs have been

developed owing to their small size, low toxicity and low-dose

requirements (113,114).

PTT, which induces localized thermotherapy, is one

of the few NP-based therapies to enter clinical trials for cancer

and is expected to be applied synergistically with immunotherapy in

tumor treatment (120,121). Paholak et al (122) demonstrated that PTT mediated by

highly crystalline IONPs efficiently eliminated breast cancer stem

cells in a transformed model of triple-negative breast cancer,

thereby improving the long-term survival of patients with

metastatic breast cancer by inducing a systemic immune response

targeting distal cancer cells.

Nanoenzyme-based catalytic therapy is a novel

strategy for treating tumors; however, challenges such as hypoxia,

immunosuppression and insufficient endogenous

H2O2 levels in the TME limit the efficacy of

this strategy. Researchers have developed a trimetallic nanoenzyme

(Au@Pt@Rh) that exhibits endogenous peroxidase- and catalase-like

activities under acidic TME conditions. Au@Pt@Rh-activated

photothermal thermotherapy has also been shown to improve

peroxidase- and catalase-mimicking activity. By loading the

transforming growth factor-β inhibitor LY2157299, this nano-complex

successfully reprogrammed the immunosuppressive TME, alleviated

tumor hypoxia and generated highly toxic hydroxyl radicals (•OH)

(123).

Although PTT combined with immunotherapy shows

potential for tumor treatment, the toxicity of NPs and possible

damage to normal tissues from high temperatures and prolonged

irradiation remain to be addressed. Furthermore, considering the

effects of different temperatures on immune cells, the design of

specific strategies to maximize the effects of PTT and

immunotherapy requires further exploration.

PDT can induce an immune response and destroy tumor

tissues. PDT-mediated immunotherapy is a promising therapeutic

modality used to treat cancer. Duan et al developed

Zn-pyrophosphate NPs loaded with photosensitizer thermolipids

(ZnP@pyro) and found that ZnP@pyro PDT combined with anti-PD-L1

therapy eradicated primary breast tumors and generated systemic

tumor-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses to completely suppress

distant tumors. These results showed that NP-mediated PDT can

enhance immunotherapy by activating the innate and adaptive immune

systems in the TME (124).

Nevertheless, insufficient light-penetration depth remains an

unresolved limitation of PDT, posing a challenge to the clinical

translation of PDT and immune combination therapies.

Radiotherapy causes ionizing damage to tumor tissue

in an X-ray dose-dependent manner, with the maximum radiation dose

defined as the dose that causes no damage to adjacent normal tissue

(125). High-dose

hyperfractionated radiotherapy and radiotherapy sensitizers have

been investigated to enhance checkpoint blockade immunotherapy

(126). Ni et al

(127) reported two porous

Hf-based nMOFs that act as effective radioenhancers. More

importantly, in vitro and in vivo studies showed that

these nMOFs are capable of mediating low-dose radiotherapy in

combination with anti-PD-L1 treatment, which simultaneously treats

both local and distant tumors through a distant effect.

Nevertheless, further studies should explore these nMOFs in

relation to their therapeutic efficacy, toxic response and drug

design in terms of clinical transformation.

Conventional chemotherapy combined with metallic

nanomaterials is expected to synergistically inhibit tumor

progression, metastasis and recurrence. Xu et al (128) reported synergistic immunotherapy

for triple-negative breast cancer on the basis of the premise of

stimulating and promoting an ICD response using a transformable NP

that simultaneously delivered cisplatin, adjudin and WKYMVm. The

in vitro and in vivo results showed that the NP could

markedly inhibit primary tumor growth and lung metastasis and

enhance innate and adaptive anti-tumor immunity, resulting in

significant survival benefits.

To date, among transition-metal NPs, drugs that have

received FDA approval are mainly iron-based NPs, including INFed,

Dexferrum, Venofer, Feraheme, Injectafer, Monoferric, Feridex and

Ferrlecit (130,131). The main applications of these

iron-based NPs are in the treatment of iron-deficient anemia and

imaging (132).

Nanotherm® is an FDA-approved device with a SPION

formulation that causes apoptosis in cancer cells heated in a

high-frequency magnetic field (133). However, most transition-metal

NPs are not used clinically.

Clinical studies employing transition-metal NPs as

a therapeutic option for oncology patients have focused on

modalities such as chemotherapy and hyperthermia. Khoobchandani

et al (134) applied

AuNP-based Nano Swarna Bhasma to patients with stage IIIA or IIIB

breast cancer and found that the treatment group that received the

nanomedicine showed 100% clinical benefit in comparison with the

group that received standard of care treatment. Kumthekar et

al (135) employed

brain-penetrant RNA interference-based spherical nucleic

acid-containing AuNPs; they observed no treatment-related grade 4

or 5 toxicity after administration, while the presence of gold

accumulation in tumor-associated endothelial, macrophage and cancer

cells represented a potential strategy for the systemic treatment

of glioblastoma. In addition, drugs such as AuroLase and Magnablate

have been used in clinical trials for thermal ablation of cancer

(132).

Cancer immunotherapy has a promising future, in

which NPs have been tested in clinical trials related to cancer

vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Rojas et

al (136) developed mRNA

neoantigen vaccines in real time from surgically removed pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma tumors using uridine mRNA-lipoplex NPs. After

an 18-month follow-up period, patients who had T cells expanded by

the vaccine exhibited a longer median relapse-free survival than

those who did not have vaccine-expanded T cells. Alonso et

al (137) selected

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer patients who were unresponsive

to Bacillus Calmette-Guérin and applied

OncoTherad® nanomedicine for treatment and found that it

works by binding the TLR4 to activate the innate immune system and

reduce immune checkpoint molecules. In addition, Zhang et al

(138) found that ICIs combined

with nanomedicine chemotherapy inhibited the progression of

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Overall, most studies on cancer immunotherapy using

transition-metal NPs are in the preclinical stage and lack data

from clinical trials. The reasons for this worrisome state of

clinical transformation warrant further investigation.

Immunotherapy is affected by multiple factors such as off-target

toxicity, tissue heterogeneity, poor immune response durability and

adverse effects; often, only a limited number of patients respond

satisfactorily to immunotherapy (74). In addition, transition-metal NPs

face a number of challenges in drug delivery, release and

biodistribution and these factors directly determine their efficacy

in cancer treatment. Different routes of drug delivery are

associated with various biological barriers (139). Local delivery is more direct;

however, its invasiveness may pose other problems and local

delivery is limited by the site and type of cancer (140). Although systemic drug delivery

is more commonly used, it is influenced by a more complex set of

factors. During circulation, the NPs may be destabilized by shear

stress (141). Another challenge

is the absorption of NPs by the phagocytic cells in the

reticuloendothelial system (142). Different portals of entry often

allow NPs to target different cell populations and factors such as

the size, shape, charge and surface coating of transition-metal NPs

affect their biodistribution in vivo (89). The molecular mechanisms and

interactions between transition-metal NPs and biological systems

require further study. The heterogeneity of the TME and enhanced

permeability and retention in the human body lead to reduced

penetration of NPs and inhomogeneous tumor extravasation of NPs,

thus reducing their accumulation in the tumor.

The safety of transition-metal NPs in cancer

diagnosis and therapy is an important issue. Although previous

studies have demonstrated that transition-metal NPs can promote

anti-tumor immune responses in vivo (63), these materials have potential

safety risks. Immune responses to transition-metal NPs can also

cause inflammation and tissue damage (143,144). NPs can elicit allergic

reactions, limiting the feasibility and safety of repeated

administration (145). Oxidative

stress due to ROS imbalance is also a problem owing to the unique

ability of Cu-based NPs to generate ROS. In addition, long-term

accumulation of metal ions may lead to organ damage. Therefore,

future research should systematically evaluate both the short-term

immune responses and long-term toxicity of these nanomaterials.

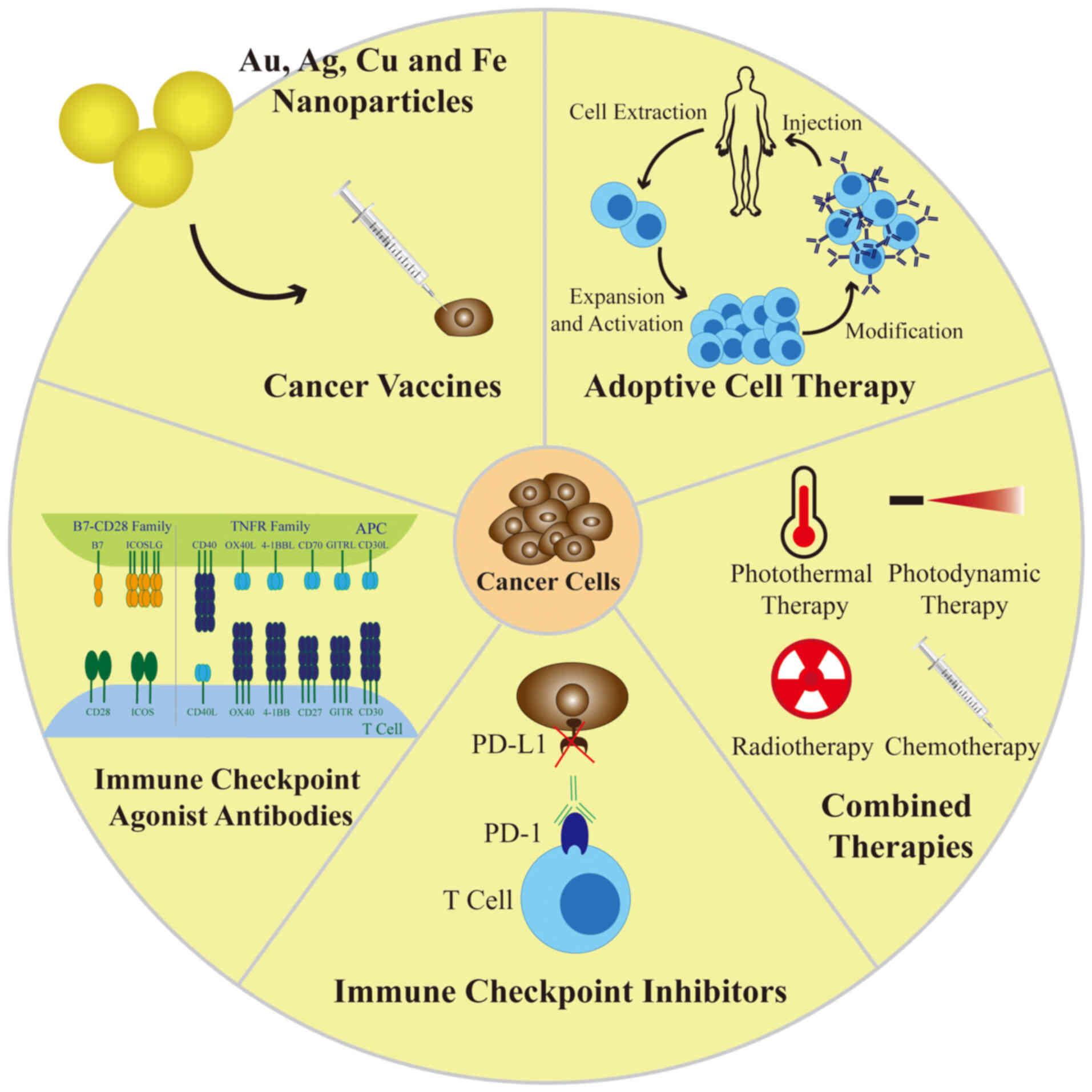

The present review critically analyzed the existing

applications and future potential of major transition-metal NPs in

cancer immunotherapy and a brief graphical summary of the review is

provided in Fig. 6. It began with

a detailed overview of the classification, properties, biomedical

roles and toxicity of major transition-metal NPs. The applications

of transition-metal NPs in tumor immunotherapies, including cancer

vaccines, ICIs, immune checkpoint agonist antibodies, ACT and

combination therapies, were then introduced. Finally, the current

status and challenges associated with clinical transformation were

discussed to provide ideas for subsequent clinical studies. To

provide a consolidated overview of biomedical applications, current

cancer research status and clinical transformation progress,

Table I presents a comparative

summary of transition metal NPs.

In conclusion, the efficacy and safety of

transition-metal NPs remain obstacles to clinical research

(153). Further research

regarding the design of NPs and their interactions in vivo

is required to improve specificity. Personalization of therapy for

different patient groups remains a challenge for clinical

transformation. In the future, systematic immunogenicity testing

combined with long-term clinical follow-up is recommended to

comprehensively evaluate the safety of metal-based materials.

Emerging technologies, such as single-cell transcriptomics and

spatial omics, may provide critical insights outlining how

nanoparticles reshape immune cell lineages and functions within the

TME, yielding a deeper mechanistic understanding. In addition, the

development of scalable manufacturing processes, demonstration of

batch-to-batch consistency and establishment of standardized

clinical-grade production workflows are essential steps toward

successful clinical translation. Transition-metal immunotherapy is

still in its infancy and much work remains to be conducted to make

the application of transition NPs in tumor immunotherapy a

reality.

Not applicable.

CS and YH were responsible for conceptualization.

ZD, ZC and CF were responsible for investigation. CF and YH were

responsible for project administration. CS and YH were responsible

for supervision. ZD and ZC were responsible for visualization. ZD

and ZC were responsible for writing the original draft. ZD, ZC, DX,

LX, CF, CS and YH were responsible for writing, reviewing and

editing. CS made a significant contribution to the manuscript

revision. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was funded by National Key R&D Program of

China (grant nos. 2023YFC2508601, 2023YFC2508604 and

2023YFC2508605), Tongji University Medicine-X Interdisciplinary

Research Initiative (grant no. 2025-0554-ZD-08), Shanghai Hospital

Development Center Foundation (grant nos. SHDC22025208 and

SHDC12024125), Clinical Research Foundation of Shanghai Pulmonary

Hospital (grant no. LYRC202401), The Innovation Team Project of the

Faculty of Chinese Medicine Science, Guangxi University of Chinese

Medicine (grant nos. 2023CX001 and 2024ZZA004) and Project for

Enhancing Young and Middle-aged Teacher's Research Basis Ability in

Colleges of Guangxi (grant no. 2025KY1124).

|

1

|

Zhang Y and Zhang Z: The history and

advances in cancer immunotherapy: understanding the characteristics

of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic

implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 17:807–821. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Parreno V, Loubiere V, Schuettengruber B,

Fritsch L, Rawal CC, Erokhin M, Győrffy B, Normanno D, Di Stefano

M, Moreaux J, et al: Transient loss of Polycomb components induces

an epigenetic cancer fate. Nature. 629:688–696. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chong G, Zang J, Han Y, Su R,

Weeranoppanant N, Dong H and Li Y: Bioengineering of nano

metal-organic frameworks for cancer immunotherapy. Nano Res.

14:1244–1259. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Surendran SP, Moon MJ, Park R and Jeong

YY: Bioactive Nanoparticles for cancer immunotherapy. Int J Mol

Sci. 19:38772018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bertrand N, Wu J, Xu X, Kamaly N and

Farokhzad OC: Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and

active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Adv Drug

Deliv Rev. 66:2–25. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R and Farokhzad

OC: Cancer nanomedicine: Progress, challenges and opportunities.

Nat Rev Cancer. 17:20–37. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

7

|

Zheng X, Wu Y, Zuo H, Chen W and Wang K:

Metal nanoparticles as novel agents for lung cancer diagnosis and

therapy. Small. 19:e22066242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhao W, Li A, Zhang A, Zheng Y and Liu J:

Recent advances in functional-polymer-decorated transition-metal

nanomaterials for bioimaging and cancer therapy. ChemMedChem.

13:2134–2149. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yang J and Zhang C: Regulation of

cancer-immunity cycle and tumor microenvironment by

nanobiomaterials to enhance tumor immunotherapy. Wiley Interdiscip

Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 12:e16122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu W, Song X, Jiang Q, Guo W, Liu J, Chu

X and Lei Z: Transition metal oxide nanomaterials: New weapons to

boost anti-tumor immunity cycle. Nanomaterials (Basel).

14:10642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Daniel MC and Astruc D: Gold

nanoparticles: Assembly, supramolecular chemistry,

quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology,

catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chem Rev. 104:293–346. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lee KX, Shameli K, Yew YP, Teow SY,

Jahangirian H, Rafiee-Moghaddam R and Webster TJ: Recent

developments in the facile bio-synthesis of gold nanoparticles

(AuNPs) and their biomedical applications. Int J Nanomed.

15:275–300. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hemalatha T, Prabu P, Gunadharini DN and

Gowthaman MK: Fabrication and characterization of dual acting oleyl

chitosan functionalised iron oxide/gold hybrid nanoparticles for

MRI and CT imaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 112:250–257. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Singh P, Pandit S, Mokkapati VRSS, Garg A,

Ravikumar V and Mijakovic I: Gold nanoparticles in diagnostics and

therapeutics for human cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 19:19792018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang R, Deng J, He D, Yang E, Yang W, Shi

D, Jiang Y, Qiu Z, Webster TJ and Shen Y: PEGylated hollow gold

nanoparticles for combined X-ray radiation and photothermal therapy

in vitro and enhanced CT imaging in vivo. Nanomedicine. 16:195–205.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Karthika V, Arumugam A, Gopinath K,

Kaleeswarran P, Govindarajan M, Alharbi NS, Kadaikunnan S, Khaled

JM and Benelli G: Guazuma ulmifolia bark-synthesized Ag, Au and

Ag/Au alloy nanoparticles: Photocatalytic potential, DNA/protein

interactions, anticancer activity and toxicity against 14 species

of microbial pathogens. J Photochem Photobiol, B. 167:189–199.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bankar A, Joshi B, Kumar AR and Zinjarde

S: Banana peel extract mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles.

Colloids Surf, B Biointerfaces. 80:45–50. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kumar CG, Poornachandra Y and Mamidyala

SK: Green synthesis of bacterial gold nanoparticles conjugated to

resveratrol as delivery vehicles. Colloids Surf, B Biointerfaces.

123:311–317. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cheng J, Gu YJ, Cheng SH and Wong WT:

Surface functionalized gold nanoparticles for drug delivery. J

Biomed Nanotechnol. 9:1362–1369. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li W, Cao Z, Liu R, Liu L, Li H, Li X,

Chen Y, Lu C and Liu Y: AuNPs as an important inorganic

nanoparticle applied in drug carrier systems. Artif Cells Nanomed

Biotechnol. 47:4222–4233. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kim DY, Kim M, Shinde S, Sung JS and

Ghodake G: Cytotoxicity and antibacterial assessment of gallic acid

capped gold nanoparticles. Colloids Surf, B Biointerfaces.

149:162–167. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lee KD, Nagajyothi PC, Sreekanth TVM and

Park S: Eco-friendly synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using

Inonotus obliquus and their antibacterial, antioxidant and

cytotoxic activities. J Ind Eng Chem. 26:67–72. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Naraginti S and Li Y: Preliminary

investigation of catalytic, antioxidant, anticancer and

bactericidal activity of green synthesized silver and gold

nanoparticles using Actinidia deliciosa. J Photochem Photobiol, B.

170:225–234. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Vijayakumar S, Vaseeharan B,

Malaikozhundan B, Gopi N, Ekambaram P, Pachaiappan R, Velusamy P,

Murugan K, Benelli G, Suresh Kumar R and Suriyanarayanamoorthy M:

Therapeutic effects of gold nanoparticles synthesized using Musa

paradisiaca peel extract against multiple antibiotic resistant

Enterococcus faecalis biofilms and human lung cancer cells (A549).

Microb Pathogen. 102:173–183. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Mironava T, Hadjiargyrou M, Simon M,

Jurukovski V and Rafailovich MH: Gold nanoparticles cellular

toxicity and recovery: Effect of size, concentration and exposure

time. Nanotoxicology. 4:120–137. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ziyu P and Haodong J: Controlled synthesis

of silver nanomaterials and their environmental applications. Prog

Chem. 35:1229–1257. 2023.

|

|

27

|

Huy TQ, Huyen PTM, Le AT and Tonezzer M:

Recent advances of silver nanoparticles in cancer diagnosis and

treatment. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 20:1276–1287. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mohamed AF, Nasr M, Amer ME, Abuamara TMM,

Abd-Elhay WM, Kaabo HF, Matar EER, El Moselhy LE, Gomah TA, Deban

MAE and Shebl RI: Anticancer and antibacterial potentials induced

post short-term exposure to electromagnetic field and silver

nanoparticles and related pathological and genetic alterations: In

vitro study. Infect Agent Cancer. 17:42022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yuan YG, Zhang S, Hwang JY and Kong IK:

Silver Nanoparticles potentiates cytotoxicity and apoptotic

potential of camptothecin in human cervical cancer cells. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2018:61213282018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Jeong JK, Gurunathan S, Kang MH, Han JW,

Das J, Choi YJ, Kwon DN, Cho SG, Park C, Seo HG, et al:

Hypoxia-mediated autophagic flux inhibits silver

nanoparticle-triggered apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. Sci

Rep. 6:216882016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yin M, Xu X, Han H, Dai J, Sun R, Yang L,

Xie J and Wang Y: Preparation of triangular silver nanoparticles

and their biological effects in the treatment of ovarian cancer. J

Ovarian Res. 15:1212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Noorbazargan H, Amintehrani S, Dolatabadi

A, Mashayekhi A, Khayam N, Moulavi P, Naghizadeh M, Mirzaie A,

Mirzaei Rad F and Kavousi M: Anti-cancer & anti-metastasis

properties of bioorganic-capped silver nanoparticles fabricated

from Juniperus chinensis extract against lung cancer cells. AMB

Express. 11:612021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Lu W and Kang Y: Epithelial-mesenchymal

plasticity in cancer progression and metastasis. Dev Cell.

49:361–374. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Meenakshisundaram S, Krishnamoorthy V,

Jagadeesan Y, Vilwanathan R and Balaiah A: Annona muricata assisted

biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles regulates cell cycle

arrest in NSCLC cell lines. Bioorg Chem. 95:1034512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Miranda RR, Sampaio I and Zucolotto V:

Exploring silver nanoparticles for cancer therapy and diagnosis.

Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 210:1122542022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Jia B, Mei Y, Cheng L, Zhou J and Zhang L:

Preparation of copper nanoparticles coated cellulose films with

antibacterial properties through one-step reduction. ACS Appl Mater

Interfaces. 4:2897–2902. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Luque-Jacobo CM, Cespedes-Loayza AL,

Echegaray-Ugarte TS, Cruz-Loayza JL, Cruz I, de Carvalho JC and

Goyzueta-Mamani LD: Biogenic synthesis of copper nanoparticles: A

systematic review of their features and main applications.

Molecules. 28:48382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Smith AM, Duan H, Rhyner MN, Ruan G and

Nie S: A systematic examination of surface coatings on the optical

and chemical properties of semiconductor quantum dots. Phys Chem

Chem Phys. 8:3895–3903. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Letchumanan D, Sok SPM, Ibrahim S, Nagoor

NH and Arshad NM: Plant-based biosynthesis of copper/copper oxide

nanoparticles: An update on their applications in biomedicine,

mechanisms, and toxicity. Biomolecules. 11:5642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Rehana D, Mahendiran D, Kumar RS and

Rahiman AK: Evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of

copper oxide nanoparticles synthesized using medicinally important

plant extracts. Biomed Pharmacother. 89:1067–1077. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mahmood RI, Kadhim AA, Ibraheem S,

Albukhaty S, Mohammed-Salih HS, Abbas RH, Jabir MS, Mohammed MKA,

Nayef UM, AlMalki FA, et al: Biosynthesis of copper oxide

nanoparticles mediated Annona muricata as cytotoxic and apoptosis

inducer factor in breast cancer cell lines. Sci Rep. 12:161652022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Woźniak-Budych MJ, Przysiecka Ł,

Maciejewska BM, Wieczorek D, Staszak K, Jarek M, Jesionowski T and

Jurga S: Facile synthesis of sulfobetaine-stabilized Cu2O

nanoparticles and their biomedical potential. ACS Biomater Sci Eng.

3:3183–3194. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wozniak-Budych MJ, Langer K, Peplinska B,

Przysiecka L, Jarek M, Jarzebski M and Jurga S: Copper-gold

nanoparticles: Fabrication, characteristic and application as drug

carriers. Mater Chem Phys. 179:242–253. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Tortella GR, Pieretti JC, Rubilar O,

Fernández-Baldo M, Benavides-Mendoza A, Diez MC and Seabra AB:

Silver, copper and copper oxide nanoparticles in the fight against

human viruses: progress and perspectives. Crit Rev Biotechnol.

42:431–449. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Yuan Z, Qu S, He Y, Xu Y, Liang L, Zhou X,

Gui L, Gu Y and Chen H: Thermosensitive drug-loading system based

on copper sulfide nanoparticles for combined photothermal therapy

and chemotherapy in vivo. Biomater Sci. 6:3219–3230. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang M, Wang W, Cui Y, Chu X, Sun B, Zhou

N and Shen J: Magnetofluorescent Fe3O4/carbon quantum dots coated

single-walled carbon nanotubes as dual-modal targeted imaging and

chemo/photodynamic/photothermal triple-modal therapeutic agents.

Chem Eng J. 338:526–538. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Frtús A, Smolková B, Uzhytchak M, Lunova

M, Jirsa M, Kubinová Š, Dejneka A and Lunov O: Analyzing the

mechanisms of iron oxide nanoparticles interactions with cells: A

road from failure to success in clinical applications. J Control

Release. 328:59–77. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Xuan S, Wang F, Lai JM, Sham KW, Wang YX,

Lee SF, Yu JC, Cheng CH and Leung KC: Synthesis of biocompatible,

mesoporous Fe(3)O(4) nano/microspheres with large surface area for

magnetic resonance imaging and therapeutic applications. ACS Appl

Mater Interfaces. 3:237–244. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang L, Wang Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Yin M, Li

J, Song H, Shi J, Ling D, Wang L, et al: Deciphering active

biocompatibility of iron oxide nanoparticles from their intrinsic

antagonism. Nano Res. 11:2746–2755. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Jin R, Lin B, Li D and Ai H:

Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for MR imaging and

therapy: Design considerations and clinical applications. Curr Opin

Pharmacol. 18:18–27. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Latunde-Dada GO: Ferroptosis: Role of

lipid peroxidation, iron and ferritinophagy. Biochim Biophys

Acta-Gen Subj. 1861:1893–1900. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Chen S, Yang J, Liang Z, Li Z, Xiong W,

Fan Q, Shen Z, Liu J and Xu Y: Synergistic functional nanomedicine

enhances ferroptosis therapy for breast tumors by a blocking

defensive redox system. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 15:2705–2713.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Cormode DP, Gao L and Koo H: Emerging

biomedical applications of enzyme-like catalytic nanomaterials.

Trends Biotechnol. 36:15–29. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Zhou C, Wang C, Xu K, Niu Z, Zou S, Zhang

D, Qian Z, Liao J and Xie J: Hydrogel platform with tunable

stiffness based on magnetic nanoparticles cross-linked GelMA for

cartilage regeneration and its intrinsic biomechanism. Bioact

Mater. 25:615–628. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ashraf N, Ahmad F, Da-Wei L, Zhou RB,

Feng-Li H and Yin DC: Iron/iron oxide nanoparticles: Advances in

microbial fabrication, mechanism study, biomedical, and

environmental applications. Crit Rev Microbiol. 45:278–300. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhou Z, Sun Y, Shen J, Wei J, Yu C, Kong

B, Liu W, Yang H, Yang S and Wang W: Iron/iron oxide core/shell

nanoparticles for magnetic targeting MRI and near-infrared

photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 35:7470–7478. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang X, Liu Z, Lou Z, Chen F, Chang S,

Miao Y, Zhou Z, Hu X, Feng J, Ding Q, et al: Radiosensitivity

enhancement of Fe3O4@Ag nanoparticles on human glioblastoma cells.

Artif Cell Nanomed Biotechnol. 46(Supp1): 975–984. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Zhong D, Zhao J, Li Y, Qiao Y, Wei Q, He

J, Xie T, Li W and Zhou M: Laser-triggered aggregated cubic

α-Fe2O3@Au nanocomposites for magnetic resonance imaging and

photothermal/enhanced radiation synergistic therapy. Biomaterials.

219:1193692019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Dennis CL and Ivkov R: Physics of heat

generation using magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia. Int J

Hyperthermia. 29:715–729. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Grauer O, Jaber M, Hess K, Weckesser M,

Schwindt W, Maring S, Wölfer J and Stummer W: Combined

intracavitary thermotherapy with iron oxide nanoparticles and

radiotherapy as local treatment modality in recurrent glioblastoma

patients. J Neurooncol. 141:83–94. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

61

|

Toraya-Brown S and Fiering S: Local tumour

hyperthermia as immunotherapy for metastatic cancer. Int J

Hyperthermia. 30:531–539. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Goldberg MS: Immunoengineering: How

nanotechnology can enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 161:201–204.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zanganeh S, Hutter G, Spitler R, Lenkov O,

Mahmoudi M, Shaw A, Pajarinen JS, Nejadnik H, Goodman S, Moseley M,

et al: Iron oxide nanoparticles inhibit tumour growth by inducing

pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization in tumour tissues. Nat

Nanotechnol. 11:986–994. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ge X, Wong R, Anisa A and Ma S: Recent

development of metal-organic framework nanocomposites for

biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 281:1213222022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Auer B, Telfer SG and Gross AJ: Metal

organic frameworks for bioelectrochemical applications.

Electroanalysis. 35:e2022001452023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Kim SN, Park CG, Huh BK, Lee SH, Min CH,

Lee YY, Kim YK, Park KH and Choy YB: Metal-organic frameworks,

NH(2)-MIL-88(Fe), as carriers for ophthalmic delivery of

brimonidine. Acta Biomater. 79:344–353. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Yang B, Ding L, Yao H, Chen Y and Shi J: A

metal-organic framework (MOF) fenton nanoagent-enabled

nanocatalytic cancer therapy in synergy with autophagy inhibition.

Adv Mater. 32:e19071522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Liu P, Shi X, Zhong S, Peng Y, Qi Y, Ding

J and Zhou W: Metal-phenolic networks for cancer theranostics.

Biomater Sci. 9:2825–2849. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Luo S, Ma D, Wei R, Yao W, Pang X, Wang Y,

Xu X, Wei X, Guo Y, Jiang X, et al: A tumor microenvironment

responsive nanoplatform with oxidative stress amplification for

effective MRI-based visual tumor ferroptosis. Acta Biomater.

138:518–527. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Farhood B, Najafi M and Mortezaee K: CD8+

cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J Cell

Physiol. 234:8509–8521. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Lin MJ, Svensson-Arvelund J, Lubitz GS,

Marabelle A, Melero I, Brown BD and Brody JD: Cancer vaccines: the

next immunotherapy frontier. Nat Cancer. 3:911–926. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Gupta M, Wahi A, Sharma P, Nagpal R, Raina

N, Kaurav M, Bhattacharya J, Rodrigues Oliveira SM, Dolma KG, Paul

AK, et al: Recent advances in cancer vaccines: Challenges,

achievements, and futuristic prospects. Vaccines (Basel).

10:20112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Musetti S and Huang L:

Nanoparticle-mediated remodeling of the tumor microenvironment to

enhance immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 12:11740–11755. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Li J, Ren H and Zhang Y: Metal-based

nano-vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Coord Chem Rev.

454:2143452022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Pradeu T and Vivier E: The discontinuity

theory of immunity. Sci Immunol. 1:AAG04792016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Duan X, Chan C and Lin W:

Nanoparticle-mediated immunogenic cell death enables and

potentiates cancer immunotherapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl.

58:670–680. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Yang Y, Huang CT, Huang X and Pardoll DM:

Persistent Toll-like receptor signals are required for reversal of

regulatory T cell-mediated CD8 tolerance. Nat Immunol. 5:508–515.

2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Hanson MC, Crespo MP, Abraham W, Moynihan

KD, Szeto GL, Chen SH, Melo MB, Mueller S and Irvine DJ:

Nanoparticulate STING agonists are potent lymph node-targeted

vaccine adjuvants. J Clin Invest. 125:2532–2546. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Kaur A, Baldwin J, Brar D, Salunke DB and

Petrovsky N: Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists as a driving force

behind next-generation vaccine adjuvants and cancer therapeutics.

Curr Opin Chem Biol. 70:1021722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Shinchi H, Yamaguchi T, Moroishi T, Yuki

M, Wakao M, Cottam HB, Hayashi T, Carson DA and Suda Y: Gold

nanoparticles coimmobilized with small molecule toll-like receptor

7 ligand and α-mannose as adjuvants. Bioconjugate Chem.

30:2811–2821. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Ishikawa H and Barber GN: STING is an

endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune

signalling. Nature. 455:674–678. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Motedayen Aval L, Pease JE, Sharma R and

Pinato DJ: Challenges and opportunities in the clinical development

of STING agonists for cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Med. 9:33232020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Ding B, Zheng P, Jiang F, Zhao Y, Wang M,

Chang M, Ma P and Lin J: MnOx nanospikes as nanoadjuvants and

immunogenic cell death drugs with enhanced antitumor immunity and

antimetastatic effect. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 59:16381–16384.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Slingluff CL Jr, Petroni GR, Olson WC,

Smolkin ME, Ross MI, Haas NB, Grosh WW, Boisvert ME, Kirkwood JM

and Chianese-Bullock KA: Effect of granulocyte/macrophage

colony-stimulating factor on circulating CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell

responses to a multipeptide melanoma vaccine: Outcome of a

multicenter randomized trial. Clin Cancer Res. 15:7036–7044. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, Tan G,

Bronte V and Borrello I: High-dose granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune

response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells.

Cancer Res. 64:6337–6343. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Behzadi M, Vakili B, Ebrahiminezhad A and

Nezafat N: Iron nanoparticles as novel vaccine adjuvants. Eur J

Pharm Sci. 159:1057182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Wang X, Li X, Onuma K, Sogo Y, Ohno T and

Ito A: Zn- and Mg- containing tricalcium phosphates-based adjuvants

for cancer immunotherapy. Sci Rep. 3:22032013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Shukla R, Bansal V, Chaudhary M, Basu A,

Bhonde RR and Sastry M: Biocompatibility of gold nanoparticles and

their endocytotic fate inside the cellular compartment: A

microscopic overview. Langmuir. 21:10644–10654. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Dobrovolskaia MA and McNeil SE:

Immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Nat

Nanotechnol. 2:469–478. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Tao Y, Ju E, Li Z, Ren J and Qu X:

Engineered CpG- antigen conjugates protected gold nanoclusters as

smart self-vaccines for enhanced immune response and cell imaging.

Adv Funct Mater. 24:1004–1010. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Zhang P, Chiu YC, Tostanoski LH and Jewell

CM: Polyelectrolyte multilayers assembled entirely from immune

signals on gold nanoparticle templates promote antigen-specific T

cell response. ACS Nano. 9:6465–6477. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Zhao H, Xu J, Li Y, Guan X, Han X, Xu Y,

Zhou H, Peng R, Wang J and Liu Z: Nanoscale coordination polymer

based nanovaccine for tumor immunotherapy. ACS Nano.

13:13127–13135. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Jin C, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Wang B and Hua P:

Combination of GNRs-PEI/cGAMP-laden macrophages-based photothermal

induced in situ tumor vaccines and immune checkpoint blockade for

synergistic anti-tumor immunotherapy. Biomater Adv. 133:1126032022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Chen F, Li T, Zhang H, Saeed M, Liu X,

Huang L, Wang X, Gao J, Hou B, Lai Y, et al: Acid-ionizable iron

nanoadjuvant augments STING activation for personalized vaccination

immunotherapy of cancer. Adv Mater. 35:e22099102023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Ljunggren HG, Jonsson R and Höglund P:

Seminal immunologic discoveries with direct clinical implications:

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine honours discoveries

in cancer immunotherapy. Scand J Immunol. 88:e127312018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Xie L, Wang G, Sang W, Li J, Zhang Z, Li

W, Yan J, Zhao Q and Dai Y: Phenolic immunogenic cell death

nanoinducer for sensitizing tumor to PD-1 checkpoint blockade

immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 269:1206382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Sang W, Zhang Z, Wang G, Xie L, Li J, Li

W, Tian H and Dai L: A triple-kill strategy for tumor eradication

reinforced by metal-phenolic network nanopumps. Adv Funct Mater.

32:21131682022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Mayes PA, Hance KW and Hoos A: The promise

and challenges of immune agonist antibody development in cancer.

Nat Rev Drug Discov. 17:509–527. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Lim SH, Beers SA, Al-Shamkhani A and Cragg

MS: Agonist antibodies for cancer immunotherapy: History, hopes and

challenges. Clin Cancer Res. 30:1712–1723. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Boomer JS and Green JM: An enigmatic tail

of CD28 signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2:a0024362010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Zhang Q and Vignali DA: Co-stimulatory and

co-inhibitory pathways in autoimmunity. Immunity. 44:1034–1051.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Yoshinaga SK, Whoriskey JS, Khare SD,

Sarmiento U, Guo J, Horan T, Shih G, Zhang M, Coccia MA, Kohno T,

et al: T-cell co-stimulation through B7RP-1 and ICOS. Nature.

402:827–832. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Chiang CS, Lin YJ, Lee R, Lai YH, Cheng

HW, Hsieh CH, Shyu WC and Chen SY: Combination of fucoidan-based

magnetic nanoparticles and immunomodulators enhances

tumour-localized immunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 13:746–754. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Locksley RM, Killeen N and Lenardo MJ: The

TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: Integrating mammalian biology.

Cell. 104:487–501. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Vonderheide RH and Glennie MJ: Agonistic

CD40 antibodies and cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 19:1035–1043.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Zhang Y, Zhao G, Chen YF, Zhou SK, Wang Y,

Sun YQ, Shen S, Xu CF and Wang J: Engineering nano-clustered

multivalent agonists to cross-link TNF receptors for cancer

therapy. Aggregate. 4:e3932023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Gupta J, Safdari HA and Hoque M:

Nanoparticle mediated cancer immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol.

69:307–324. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

June CH, Riddell SR and Schumacher TN:

Adoptive cellular therapy: A race to the finish line. Sci Transl

Med. 7:280ps72015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Krishna S, Lowery FJ, Copeland AR,

Bahadiroglu E, Mukherjee R, Jia L, Anibal JT, Sachs A, Adebola SO,

Gurusamy D, et al: Stem-like CD8 T cells mediate response of

adoptive cell immunotherapy against human cancer. Science.

370:1328–1334. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

June CH, O'Connor RS, Kawalekar OU,

Ghassemi S and Milone MC: CAR T cell immunotherapy for human

cancer. Science. 359:1361–1365. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Met Ö, Jensen KM, Chamberlain CA, Donia M

and Svane IM: Principles of adoptive T cell therapy in cancer.

Semin Immunopathol. 41:49–58. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Wang C, Sun W, Ye Y, Bomba HN and Gu Z:

Bioengineering of artificial antigen presenting cells and lymphoid

organs. Theranostics. 7:3504–3516. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Ichikawa J, Yoshida T, Isser A, Laino AS,

Vassallo M, Woods D, Kim S, Oelke M, Jones K, Schneck JP and Weber

JS: Rapid expansion of highly functional antigen-specific T cells

from patients with melanoma by nanoscale artificial

antigen-presenting cells. Clin Cancer Res. 26:3384–3396. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Zheng C, Zhang J, Chan HF, Hu H, Lv S, Na

N, Tao Y and Li M: Engineering nano-therapeutics to boost adoptive

cell therapy for cancer treatment. Small Methods. 5:e20011912021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Youn W, Ko EH, Kim MH, Park M, Hong D,

Seisenbaeva GA, Kessler VG and Choi IS: Cytoprotective

encapsulation of individual jurkat T cells within durable TiO2

Shells for T-cell therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 56:10702–10706.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Nie W, Wei W, Zuo L, Lv C, Zhang F, Lu GH,

Li F, Wu G, Huang LL, Xi X and Xie HY: Magnetic nanoclusters armed

with responsive PD-1 antibody synergistically improved adoptive

T-cell therapy for solid tumors. ACS Nano. 13:1469–1478. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Parkhurst MR, Riley JP, Dudley ME and

Rosenberg SA: Adoptive transfer of autologous natural killer cells

leads to high levels of circulating natural killer cells but does

not mediate tumor regression. Clin Cancer Res. 17:6287–6297. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Baruch EN, Berg AL, Besser MJ, Schachter J

and Markel G: Adoptive T cell therapy: An overview of obstacles and

opportunities. Cancer. 123:2154–2162. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Lin X, Li F, Gu Q, Wang X, Zheng Y, Li J,

Guan J, Yao C and Liu X: Gold-seaurchin based immunomodulator

enabling photothermal intervention and αCD16 transfection to boost

NK cell adoptive immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 146:406–420. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Kong C and Chen X: Combined photodynamic

and photothermal therapy and immunotherapy for cancer treatment: A

review. Int J Nanomedicine. 17:6427–6446. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Xiong Y, Rao Y, Hu J, Luo Z and Chen C:

Nanoparticle-based photothermal therapy for breast cancer

noninvasive treatment. Adv Mater. 37:e23051402025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Paholak HJ, Stevers NO, Chen H, Burnett

JP, He M, Korkaya H, McDermott SP, Deol Y, Clouthier SG, Luther T,

et al: Elimination of epithelial-like and mesenchymal-like breast

cancer stem cells to inhibit metastasis following

nanoparticle-mediated photothermal therapy. Biomaterials.

104:145–157. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Song G, Shao X, Qu C, Shi D, Jia R, Chen

Y, Wang J and An H: A large-pore mesoporous Au@Pt@Rh trimetallic

nanostructure with hyperthermia-enhanced enzyme-mimic activities

for immunomodulation-improved tumor catalytic therapy. Chem Eng J.

477:1471612023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Duan X, Chan C, Guo N, Han W, Weichselbaum

RR and Lin W: Photodynamic therapy mediated by nontoxic core-shell

nanoparticles synergizes with immune checkpoint blockade to elicit

antitumor immunity and antimetastatic effect on breast cancer. J Am

Chem Soc. 138:16686–16695. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Thariat J, Hannoun-Levi JM, Sun Myint A,

Vuong T and Gérard JP: Past, present, and future of radiotherapy

for the benefit of patients. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 10:52–60. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

126

|

Wardman P: Chemical radiosensitizers for

use in radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 19:397–417. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Ni K, Lan G, Chan C, Quigley B, Lu K, Aung

T, Guo N, La Riviere P, Weichselbaum RR and Lin W: Nanoscale

metal-organic frameworks enhance radiotherapy to potentiate

checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 9:23512018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Xu CF, Yu YL, Sun Y, Kong L, Yang CL, Hu

M, Yang T, Zhang J, Hu Q and Zhang Z: Transformable

nanoparticle-enabled synergistic elicitation and promotion of

immunogenic cell death for triple-negative breast cancer

immunotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 29:19052132019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

129

|

Liu Y, Qiao L, Zhang S, Wan G, Chen B,

Zhou P, Zhang N and Wang Y: Dual pH-responsive multifunctional

nanoparticles for targeted treatment of breast cancer by combining

immunotherapy and chemotherapy. Acta Biomater. 66:310–324. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

Bobo D, Robinson KJ, Islam J, Thurecht KJ

and Corrie SR: Nanoparticle-based medicines: A Review of

FDA-approved materials and clinical trials to date. Pharm Res.

33:2373–2387. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Fenton OS, Olafson KN, Pillai PS, Mitchell

MJ and Langer R: Advances in biomaterials for drug delivery. Adv

Mater. May 7–2018.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Anselmo AC and Mitragotri S: Nanoparticles

in the clinic: An update. Bioeng Transl Med. 4:e101432019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Huang Y, Hsu JC, Koo H and Cormode DP:

Repurposing ferumoxytol: Diagnostic and therapeutic applications of

an FDA-approved nanoparticle. Theranostics. 12:796–816. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Khoobchandani M, Katti KK, Karikachery AR,

Thipe VC, Srisrimal D, Dhurvas Mohandoss DK, Darshakumar RD, Joshi

CM and Katti KV: New approaches in breast cancer therapy through

green nanotechnology and nano-ayurvedic medicine - pre-clinical and

pilot human clinical investigations. Int J Nanomedicine.

15:181–197. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Kumthekar P, Ko CH, Paunesku T, Dixit K,

Sonabend AM, Bloch O, Tate M, Schwartz M, Zuckerman L, Lezon R, et

al: A first-in-human phase 0 clinical study of RNA

interference-based spherical nucleic acids in patients with

recurrent glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 13:eabb39452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Rojas LA, Sethna Z, Soares KC, Olcese C,

Pang N, Patterson E, Lihm J, Ceglia N, Guasp P, Chu A, et al:

Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in

pancreatic cancer. Nature. 618:144–150. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Alonso JCC, de Souza BR, Reis IB, de

Arruda Camargo GC, de Oliveira G, de Barros Frazão Salmazo MI,

Gonçalves JM, de Castro Roston JR, Caria PHF, da Silva Santos A, et

al: OncoTherad() (MRB-CFI-1) Nanoimmunotherapy: A promising

strategy to treat bacillus calmette-guérin-unresponsive

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Crosstalk among T-Cell CX3CR1,

immune checkpoints, and the toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:175352023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

138

|

Zhang G, Yuan J, Pan C, Xu Q, Cui X, Zhang

J, Liu M, Song Z, Wu L, Wu D, et al: Multi-omics analysis uncovers

tumor ecosystem dynamics during neoadjuvant toripalimab plus

nab-paclitaxel and S-1 for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A

single-center, open-label, single-arm phase 2 trial. EBioMedicine.

90:1045152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Blanco E, Shen H and Ferrari M: Principles

of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug