Biliary tract cancer (BTC) includes a spectrum of

invasive malignancies that arise from the bile duct epithelium. It

is relatively uncommon but highly heterogeneous, comprising

gallbladder cancer (GBC; which arises from the gallbladder or

cystic duct) and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA; which arises from the

intrahepatic, perihilar or distal biliary tree). BTC accounts for

<1% of all human types of cancer and ~3% of digestive system

tumors globally (1,2). In recent years, the incidence of BTC

has been increasing globally, particularly in Asian countries,

where it represents an important health problem (3,4).

Globally, adenocarcinoma accounts for ~90% of all BTC cases

(5,6). BTC is usually diagnosed at advanced

stage. The majority of patients with symptomatic BTC, such as those

presenting with biliary obstruction, have incurable tumors with

invasion of the surrounding organs, lymph nodes and distant

metastases, which results in poor prognoses (2,7).

At present, surgery remains the gold standard for treating

early-stage tumors; however, only a limited number of patients have

this opportunity (8,9). The 5-year overall survival rate of

BTC is <20% for patients from the United States of America and

Europe (10). Furthermore,

despite undergoing curative resection with a negative margin (R0),

BTC still have a high recurrence rate of >50% (8,9,11).

Gemcitabine-platinum chemotherapy is a recommended first-line

treatment for advanced BTC; however, its efficacy is not

satisfactory (12). The emergence

of targeted therapies and immunotherapies, such as Durvalumab and

Pembrolizumab, has revolutionized the treatment paradigm of

malignant tumors. Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy has been verified

to be effective in treating BTC (13-15). Investigating the key molecular

mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic targets for BTC is

imperative.

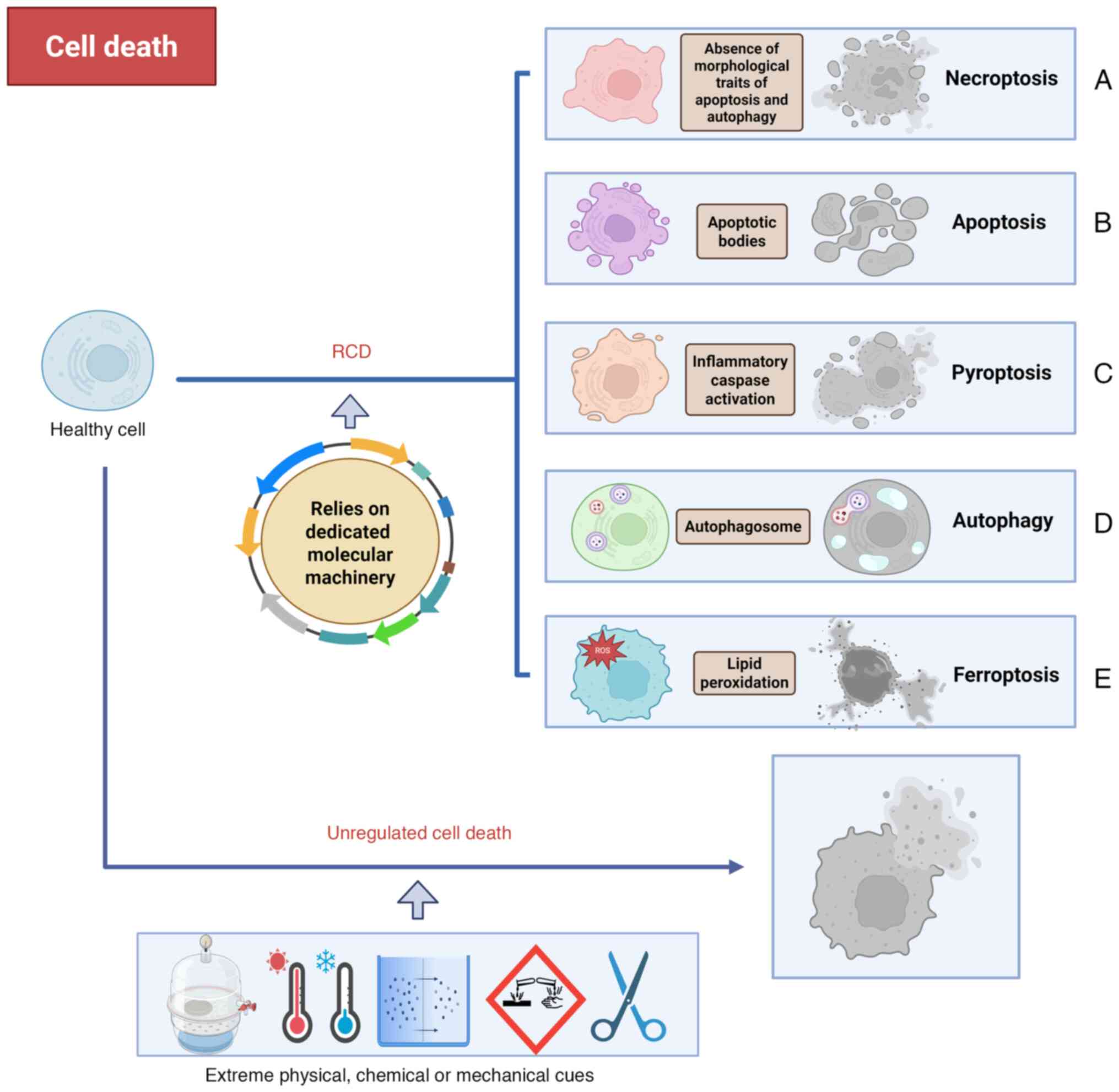

Cell death can occur either due to unregulated

causes or following a regulated process (Fig. 1) (16). Unregulated cell death is the

instantaneous demise of cells due to severe physical, chemical or

mechanical causes. Unlike unregulated cell death, regulated cell

death (RCD) is characterized by organized signaling cascades and

specific molecular mechanisms, suggesting that it can be controlled

(17). The process of RCD can be

influenced, either delayed or accelerated, through pharmacological

or genetic interventions. A study by Dixon et al (18) first proposed the notion of

'ferroptosis' in 2012 (19).

Ferroptosis is a new type of RCD, differing from necroptosis

(Fig. 1A) (20), apoptosis (Fig. 1B) (21), pyroptosis (Fig. 1C) (22) and autophagy (Fig. 1D) (23) in morphology, genetics and

biochemistry (24,25). As its name implies, ferroptosis is

an iron-dependent mechanism of cell death (26). Ferroptosis is triggered by lipid

peroxidation (LPO), which results from an imbalanced cellular

metabolism and redox homeostasis. The morphological evidence of

ferroptosis includes the presence of small mitochondria with

increased mitochondrial membrane densities, reduced or missing

mitochondrial crista, outer mitochondrial membrane rupture and a

normal nucleus (Fig. 1E)

(27,28). Ferroptosis is indicated to serve

an important pathophysiological role in the development and

occurrence of numerous diseases, such as ischemic heart disease and

acute kidney injury, but particularly in cancer (19,29). Non-small cell lung cancer,

hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer and

renal cell carcinoma are reported to be sensitive to ferroptosis

(30-34). Additionally, various ferroptosis

inducers, such as sorafenib, sulfasalazine and artemisinin,

demonstrate a mitigation of tumor progression (35). Due to the issue of drug

resistance, there is a growing interest regarding the potential of

targeting ferroptosis as a therapeutic strategy for malignancies

(36-38).

The present review aimed to provide a comprehensive

overview of the signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms of

ferroptosis, the research progress on ferroptosis in the occurrence

and development of BTC, and the potential application of

ferroptosis as a targeted therapy for BTC.

Following the first description of ferroptosis, a

form of non-apoptosis and iron-dependent RCD, in 2012, there has

been an increasing interest to investigate the process and

regulation of ferroptosis (39).

Previously, several studies investigated the mechanisms involved in

ferroptosis (40-42). The present study aimed to review

the core mechanisms of ferroptosis based on three aspects, namely

iron metabolism, lipid metabolism and antioxidant defense

systems.

Iron is one of the crucial minor elements for human

health, and the correct intracellular level of iron is

indispensable for a well-functioning metabolic balance (43). Iron is mainly obtained from

dietary intake, existing in two distinct oxidation states. These

are the divalent (Fe2+) and trivalent (Fe3+)

ions (44). The continuous

interconversion of Fe2+ and Fe3+ allows

iron-dependent cofactors, such as cytochrome P450s, to effectively

carry out their catalytic functions in various biological

processes, including nucleic acid synthesis as well as repair,

epigenetic regulation and cellular respiration (45). While in the Fe2+ state

or combined with a transporter protein, iron is primarily absorbed

in the duodenum and upper jejunum epithelial cells. The less

soluble Fe3+ ion must first be reduced to absorbable

ferrous Fe2+ and is then transported via divalent metal

transporter 1 (DMT1) into epithelial cells (46). Absorbed iron then either enters

the blood circulation via ferroportin (FPN) or is stored as

ferritin. Fe3+ is the primary form of iron in blood

circulation. FPN, encoded by the transporter solute carrier family

40 member 1 gene, is the only known iron-exporting protein in

mammalian cells. It is responsible for exporting Fe3+ to

the extracellular space (47).

Subsequently, multi-copper ferroxidases on the epithelial cell

membrane re-oxidize Fe2+ to Fe3+, which is

then bound by transferrin (TF) and transported in the plasma

(44). Lactotransferrin also

contributes positively to the regulation of iron absorption by

enhancing iron uptake, similar to TF (48). The majority of cells mainly obtain

non-heme iron through two primary pathways that involve TF-bound

iron uptake and non-TF-bound iron (NTBI) uptake. TF binds to

transferrin receptor (TFR)1 and forms endosomes through

clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Within cells, TF-bound iron

separates, and six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3

reduces Fe3+ to Fe2+, which then enters the

cytoplasm via DMT1 for subsequent use or storage as ferritin

(49,50). When there is an iron overload,

such as in hemochromatosis, excess iron surpasses the capacity of

TF, resulting in the increased circulation and uptake of NTBI

(forming an unstable iron pool) through transporters such as solute

carrier family 39 member 14 (51). The main repository for

intracellular iron is the ferritin dimer, consisting of ferritin

heavy and light chains. Nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)

increases iron levels by facilitating ferritin degradation

(52-54).

Ferroptosis relies on iron, as suggested by its

name. An elevated iron level in the body has a direct association

with the onset of ferroptosis (18). Excessive iron levels increase the

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to cell

dysfunction or death, tissue damage and diseases, such as human

leukocyte antigen-linked hemochromatosis and Friedreich ataxia

(44). An excessive accumulation

of iron can result in ferroptosis either through Fenton reactions

or by activating arachidonate lipoxygenases and cytochrome P450

oxidoreductase-mediated phospholipid peroxidation metabolism

(55,56). As an important step in

ferroptosis, the Fenton reaction involves the non-enzymatic

oxidation of organic compounds, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids

(PUFAs), into inorganic states by a mixture of hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) and Fe2+ (37). Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) is

the major neutralizing enzyme of phospholipid (PL) hydroperoxides

(OOHs; PLOOHs). GPX4 knockdown results in an accumulation of

PLOOHs, which induces an increase in lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis (57).

Uncontrolled LPO represents a key hallmark of

ferroptosis. A key initiation step of ferroptosis involves an

excessive oxidation of PUFA-PLs (19). The susceptibility of PUFAs to

peroxidation is attributed to their diallyl moieties (55). The magnitude of LPO is influenced

by both the abundance and distribution of PUFAs within

phospholipids (28). Arachidonic

acid (AA) and adrenic acid (AdA) serve as the primary LPO

substrates in ferroptosis. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family

member 4 (ACSL4) catalyzes the esterification of AA or AdA with

CoA, generating oxidizable AA- or AdA-CoA. Subsequently,

lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) facilitates the

PL remodeling of AA- or AdA-CoA and membrane

phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) into AA- or AdA-PE, anchoring it to

the cell or mitochondrial membranes (58). Conversely, acyl-CoA synthetase

long-chain family member 3 (ACSL3) and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1

(SCD1) confer cellular resistance to ferroptosis by catalyzing the

synthesis of monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) and the displacement

of PUFAs from plasma membrane phospholipids (55,59,60). Subsequently, 15-lipoxygenase (LOX)

then oxidizes AA-PE or AdA-PE to PL-PUFA-OOHs, which acts as a

ferroptosis signal (58).

However, 12-LOX can mediate the ACSL4-independent pathway of LPO

production via the p53/solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11)/12-LOX axis (61).

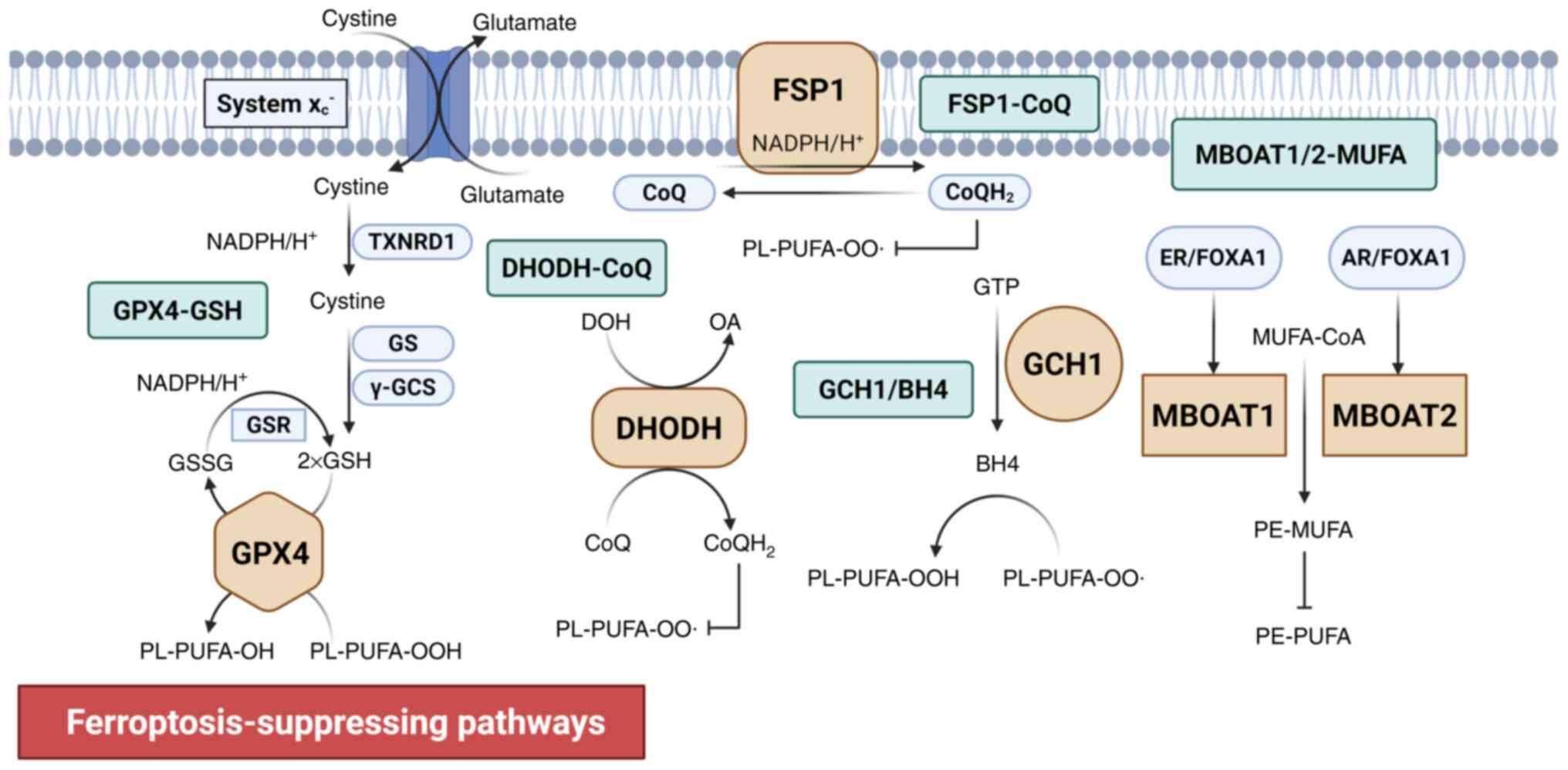

FSP1 is a GSH-independent ferroptosis suppressor,

acting in parallel to GPX4. When GPX4 is knocked out, FSP1 (also

known as apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondrial-associated protein

2) is activated as a compensatory antioxidant system. FSP1 is

located on the plasma membrane and uses NAD(P)H to reduce CoQ to

ubiquinol (CoQH2), which acts as an antioxidant by

binding to radicals. This neutralizes lipid peroxide free radicals

and blocks the propagation of LPO (66,67) (Fig.

2).

The GCH1-BH4 system is another important

GPX4-independent ferroptosis inhibitor. GCH1 prevents ferroptosis

via the synthesis of its metabolic derivatives, BH4 and

dihydrobiopterin (BH2), and lipid remodeling. GCH1 overexpression

selectively protects those PLs containing two PUFA chains from

degradation, which potentially has two simultaneous mechanisms: i)

Acting as an antioxidant that directly binds to radicals; and ii)

contributing to the synthesis of CoQ (68,69) (Fig.

2).

As PL-modifying enzymes, MBOAT1 and MBOAT2 function

as GPX4/FSP1-independent ferroptosis suppressors. MBOAT1 and 2

inhibit ferroptosis by remodeling PLs by selectively incorporating

MUFAs into lyso-PE. This increases the cellular MUFA-PE levels and

decreases the PUFA-PE levels (71). However, MBOAT1 and 2 function as

sex hormone-dependent regulators, and their transcription is

upregulated by androgen and estrogen receptors (71) (Fig.

2).

The TME serves pivotal roles in the initiation,

progression, metastasis and therapeutic resistance of tumors

(72-75). It is a dynamic interacting network

that is comprised of diverse cellular components, including

malignant cells, immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts and

endothelial cells, alongside acellular elements such as the

extracellular matrix, cytokines and metabolites (76). Ferroptosis engages in a complex

bidirectional crosstalk with the TME, particularly through

metabolic reprogramming and immunomodulation, which regulates BTC

malignancy and treatment responses (77,78).

Ferroptosis in malignant cells modulates antitumor

immunity within the TME through immunogenic signaling (79,80). Previous evidence indicates that

ferroptotic cancer cells release damage-associated molecular

patterns (DAMPs), a hallmark of immunogenic cell death (ICD), which

function as endogenous adjuvants to potentiate antitumor immunity

(81,82). As well as the classic DAMPs, such

as high mobility group protein 1 (83-85), adenosine triphosphate (86,87), calcium reticulum protein (84,86) and the recently identified

proteoglycan decorin (88),

ferroptotic cancer cells release immunomodulatory cytokines such as

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)

and interferon (IFN)-β, that contribute to the remodeling of the

TME (89). However, whether

ferroptosis is a classic form of ICD is still an ongoing scientific

debate (89). In addition, the

specific role of ferroptotic cancer cells in antitumor immunity is

also contradictory. A previous study demonstrates that tumor cell

competition for cystine compromises the function of CD8+ T cells

within the TME. Cystine deprivation triggers glutamate

accumulation, which potentiates CD36-mediated LPO (90). However, ferroptotic cells can

activate antitumor immunity by expressing

1-steaoryl-2-15-HpETE-sn-glycero-3-PE. This serves as a signal that

mediates phagocytosis by engaging Toll-like receptor 2 on

macrophages (91) and enhancing

the activities of natural killer cells (92).

Immune cells exhibit differential susceptibility to

ferroptosis within the TME, and their functional heterogeneity

enables distinct populations to either potentiate or suppress

ferroptosis in malignant cells (80). CD8+ T cells exhibit an increased

sensitivity to GPX4 inhibition compared with malignant cells,

resulting in a premature impairment of antitumor immunity prior to

notable tumor cell death (93).

However, these effector lymphocytes demonstrate relative resistance

to system Xc− inhibitors, such as sulfasalazine, as

inhibition of system Xc− did not affect T cell

proliferation and antitumor immune responses (94). Activated CD8+ T cells with high

expression levels of fatty acid transporter CD36 increases the risk

of LPO and ferroptosis (95).

Compared with tumor-derived CD8+ T cells, tumor-infiltrating

regulatory T cells (Tregs) typically have reduced levels of LPO,

suggesting that they are less prone to ferroptosis in the TME

(93). However, system

Xc− inhibitors rarely impair the viability of Tregs

(96). Tumor-associated

macrophages (TAMs) are one of the most abundant types of immune

cells in the TME and include the proinflammatory antitumor M1 and

anti-inflammatory protumor M2 types (97,98). The sensitivity of these two types

of cells to ferroptosis is different due to the high levels of

inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide-free radicals in

M1 type compared with M2 type TAMs (99). Another group of immune-suppressive

cells, namely myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), exhibit

notable resistance to ferroptosis, which is associated with the

upregulation of system Xc− and neutral ceramidase

N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase expression levels (100).

Metabolic reprogramming is a defining hallmark of

malignancy, triggering cancer metastasis, aggressiveness and

therapeutic resistance (101).

Remodeled metabolic environments and immunosuppressive environments

enable cancer cells to evade RCD (78). This metabolic reprogramming

extends beyond canonical adaptations such as the Warburg effect (in

which preferential glycolysis reduces mitochondrial ROS

generation), and includes the suppression of pyruvate

dehydrogenase, limiting the acetyl-CoA flux for PUFA biosynthesis,

which is critical for ferroptosis (102-104). Within the TME, MDSCs increase

immunosuppression through IL-6/JAK2/STAT3-mediated SLC7A11

upregulation, which depletes the extracellular cystine pools

(105). This metabolic

competition induces a GSH deprivation-induced ferroptosis in CD8+ T

cells, further inactivating antitumor immunity (90).

To resist ferroptosis, cancer cells use lipid

metabolic reprogramming as a defense strategy via two primary

mechanisms: i) PL membrane restructuring via the activation of the

sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1-SCD1 axis, replacing

oxidation-vulnerable PUFAs with MUFAs (106); and ii) mevalonate

pathway-derived antioxidant production, such as isopentenyl

pyrophosphate from cholesterol metabolism, which neutralizes lipid

peroxides (107,108). Iron homeostasis is also

inhibited through TFR1-mediated uptake and ferritin heavy chain

(FTH)-dependent storage, which reduces the levels of cytotoxic free

Fe2+ (109,110). Furthermore, gut

microbiota-derived metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids

(such as butyrate) and tryptophan metabolites (such as

indole-acrylic acid), also affect the TME and influence the

resistance of cancer cells to ferroptosis (111,112).

Epigenetic regulation is a heritable mechanism that

regulates the expression of genes through chemical modifications

without altering the DNA sequence. It primarily involves DNA

methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNA (ncRNA)-mediated

regulation and RNA methylation (113).

Several key genes are dynamically controlled by DNA

methylation. For example, in normal tissues, the core enzyme GPX4,

which is essential for eliminating lipid peroxides, has notably

reduced expression levels due to transcriptional repression caused

by the hypermethylation of CpG islands within its promoter region

compared with cancer tissues. This suppression increases cellular

susceptibility to ferroptosis (114-117). By contrast, the promoter of the

system Xc− light chain subunit SLC7A11 is frequently

hypomethylated, leading to its elevated expression levels (118,119). This enhances cystine uptake and

GSH synthesis, which inhibits ferroptosis. Furthermore,

hypermethylation of the FSP1 promoter results in a reduction to its

expression levels, which sensitizes cells to ferroptosis (120,121).

RNA methylation, the most abundant

post-transcriptional modification in eukaryotic mRNA, also

contributes to ferroptosis regulation. AlkB homolog 5 regulates

glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM) mRNA levels

though N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification

of GCLM and YTH m6A RNA binding protein-mediated decay

of GCLM, which regulates ferroptosis (122). Additionally,

methyltransferase-like protein 16 (METTL16) serves a role in

ferroptosis and tumorigenesis by catalyzing the m6A

modification of Sentrin/small ubiquitin-like modifier-specific

protease 3 mRNA and regulating the stability of lactotransferrin

(123).

Histone modifications serve an important role in

shaping chromatin structure. It exerts precise transcriptional

control over ferroptosis-associated genes, such as SLC7A11 and

ACSL3, and impacts gene expression and cancer development (124-126). p53 promotes the nuclear

translocation of a histone H2B monoubiquitylation (H2Bub1)

deubiquitinase, ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7), which

negatively regulates H2Bub1 levels. The interaction between p53 and

USP7 reduces the occupancy of H2Bub1 at the regulatory region of

SLC7A11, leading to transcriptional repression of SLC7A11and

enhancing the ferroptosis induction sensitivity of cells (125). Histone acetylation and

methylation also demonstrate bidirectional regulatory effects on

ferroptosis (126-129).

ncRNAs regulate the expression of

ferroptosis-associated genes via post-transcriptional regulation,

forming protein-RNA interaction networks. Specifically, microRNA

(miR)-137/miR-9 and miR-15a-5p promote ferroptosis by targeting

SLC7A11 and GPX4 mRNA, respectively (130,131), whereas miR-27a and miR-4717

exert anti-ferroptosis effects by targeting ACSL4 and NCOA4

(132,133). Long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) also

participate in ferroptosis regulation by acting as protein decoys,

chromatin modifiers or miRNA sponges (134,135).

Ferroptosis induction has emerged as a novel

strategy to overcome tumor therapy resistance (35,36). However, tumor cells establish

complex ferroptosis defense networks by remodeling immune-metabolic

environments, notably elevating the threshold for ferroptosis

initiation (78). The development

of this resistance limits the clinical application of

ferroptosis-inducing therapies (78). However, a series of innovative

strategies have been developed, providing a theoretical foundation

for designing effective treatments to circumvent resistance.

Recently identified, reversible palmitoylation modification of GPX4

is a key regulator of ferroptosis. The palmitoylation inhibitor

2-bromopalmitate notably enhances the antitumor efficacy of

ferroptosis inducers by inhibiting GPX4 palmitoylation (136). Furthermore, targeted protein

degradation represents an emerging therapeutic paradigm. The

GPX4-targeted autophagy-targeting chimera (GPX4-AUTAC), based on

selective autophagic degradation, induces ferroptosis and

demonstrates antitumor activity in vitro, in vivo and

in patient-derived organoids (137). In addition,

proteolysis-targeting chimeras that target GPX4/DHODH have also

been designed (138,139). The use of combination strategies

that target immune checkpoints alongside ferroptosis inducers are

also gaining attention (140).

Furthermore, the development of novel nanodrug delivery systems

offers additional approaches to overcome chemoresistance, such as

high-density lipoprotein nanoparticles with dual metabolic

disruption (selenium deprivation and LPO) (141) and antibody-targeted

nanoplatforms (such as Fe-MOF@Erastin@ Herceptin), which deliver

ferroptosis inducers (such as erastin) specifically to tumor cells

(142).

Ferroptosis is demonstrated to have therapeutic

potential in various types of cancer, including hepatocellular

carcinoma, lung carcinoma, lymphoma, pancreatic ductal carcinoma

and renal cell carcinoma (30-34). BTC is an uncommon type of

gastrointestinal malignancy that has a poor prognosis. In the early

stages of disease, surgical resection with negative margins can

effectively treat BTC (8,9). For unresectable and metastatic

disease, gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapies plus

immunotherapy (such as with Durvalumab or Pembrolizumab) are the

only preferred regimens approved by the National Comprehensive

Cancer Network (143,144). With the increasing number of

patients with BTC, investigating novel targets and alternative

options is crucial. Ferroptosis, which is considered to be one of

the most promising potential antitumor methods, can affect the

occurrence and development of BTC by regulating intracellular iron

and ROS levels, providing new treatment options for patients with

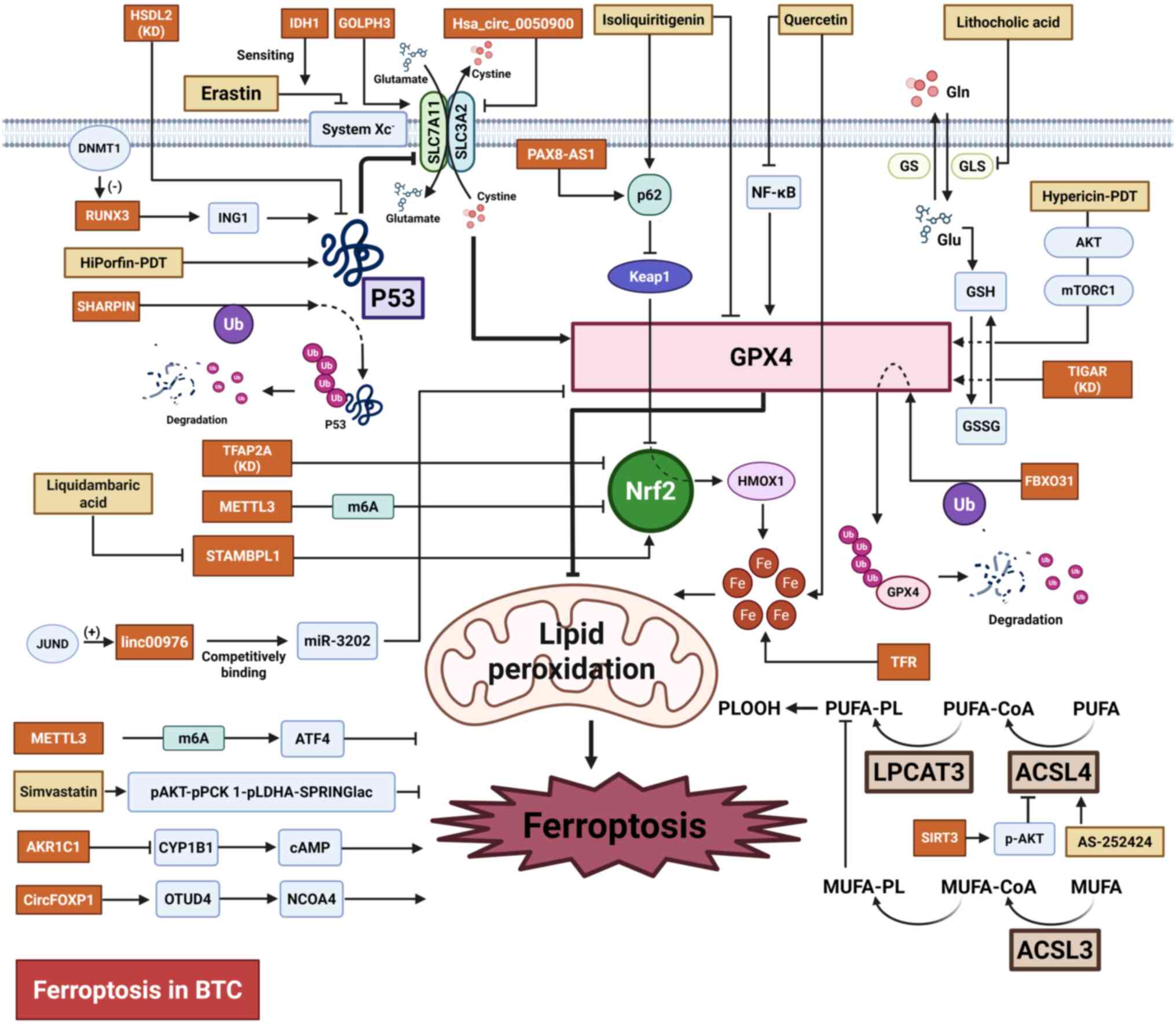

BTC (70,124,145). The following section primarily

concentrates on the advancements in ferroptosis-associated research

in BTC, including potential therapeutic targets, treatment options

and associated mechanisms (Table

I; Fig. 3).

TP53 is acknowledged as a classic tumor suppressor

gene, which serves important roles in controlling the cell cycle,

cell proliferation and cell death (146,147). TP53 serves a role in controlling

the susceptibility to ferroptosis via both transcription-dependent

and transcription-independent mechanisms (148). Shank-associated RH domain

interacting protein (SHARPIN) is a crucial part of the complex

responsible for activating the linear ubiquitin chain, which

inhibits ferroptosis through the p53/SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway

and promotes cell proliferation in CCA. Silencing the SHARPIN gene

results in the suppression of p53 ubiquitination and degradation,

as well as a decreased expression of SLC7A11, GPX4, superoxide

dismutase (SOD)-1 and SOD-2. Targeting SHARPIN may serve as a

potential strategy benefiting CCA treatment (149). Human hydroxysteroid

dehydrogenase-like 2 (HSDL2) is also a regulator of cancer

progression and lipid metabolism. Knocking down HSDL2 promotes CCA

progression by inhibiting ferroptosis through the p53/SLC7A11 axis

(150). As a member of

Runt-domain family, Runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) has

a reduced expression level in GBC. This downregulation, mediated by

promoter DNA hypermethylation, is notably associated with adverse

outcomes in patients with GBC. RUNX3 activates the transcription of

inhibitor of growth protein 1, which leads to the suppression of

SLC7A11 through a p53-dependent pathway and the induction of

ferroptosis (151). Golgi

phosphoprotein 3 also promotes CCA malignancy by inhibiting

ferroptosis through SLC7A11 upregulation (152). Additionally, TP53-induced

glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) is associated with

adverse outcomes and ferroptosis resistance in patients with

intrahepatic CCA (iCCA). TIGAR encodes an enzyme responsible

for regulating glycolysis and scavenging ROS. Knockdown of TIGAR

reduced the expression of GPX4, a key inhibitor of ferroptosis

(153). Furthermore, combining

TIGAR knockdown with cisplatin treatment synergistically induces a

notable increase in ferroptosis (153).

The transcription factor Nrf2 controls the

expression of genes involved in counteracting oxidative and

electrophilic stresses, which serves a role in regulating the

cellular antioxidant response (154,155). A study by Huang et al

(156) reports that

transcription factor activating enhancer-binding protein 2 α

(TFAP2A) may serve a role as a regulator of ferroptosis in GBC via

the Nrf2 signaling pathway. GBC cells exhibit elevated levels of

TFAP2A, compared with non-tumorigenic human intrahepatic bile duct

cells (H69), and knocking down TFAP2A lead to a decrease in GBC

cell proliferation, migration and invasion, as well as a decreased

expression of oxidative stress-associated genes, such as heme

oxygenase 1 and Nrf2. A study by Zheng et al (157) demonstrates high

methyltransferase-like 3 expression levels in cisplatin-resistant

iCCA cells compared with parental cells. This upregulation enhances

m6A modifications, leading to the inhibition of

ferroptosis and a resistance to cisplatin through the stabilization

of Nrf2 mRNA and an increase in the Nrf2 protein expression levels.

Additionally, overexpression of METTL16 in patients with CCA is

associated with poor prognosis. Mechanistically, METTL16 increases

the m6A modifications of activating transcription factor

4 (ATF4) mRNA, which increases the expression of ATF4 and

subsequently results in the suppression of ferroptosis (158).

At present, GPX4 is recognized as the only enzyme

with the ability to directly reduce complex phospholipid

hydroperoxide (159). Therefore,

GPX4, which is responsible for the efficient removal of

phospholipid hydroperoxides, is critical for cell survival

(160). When GPX4 fails to

effectively remove PLOOHs, there is an increase in LPO and

ferroptosis (57,161). GPX4 is also one of the important

adverse prognostic indicators in iCCA (162). A study by Lei et al

(163) demonstrates that JUND

enhances the transcription of linc00976, which promotes the

development of CCA and prevents ferroptosis by regulating the

miR-3202/GPX4 axis. F-box protein 31 (FBXO31) stimulates the

ubiquitination process of GPX4 and consequently promotes the

degradation of the GPX4 proteasome, which enhances the occurrence

of ferroptosis. Additionally, FBXO31-upregulated cancer stem

cell-like cells present enhanced sensitivity to cisplatin compared

with control cells (164). In

addition, lncRNA paired box 8-antisense RNA 1 binds to p62 and

activates Nrf2, which promotes GPX4 transcription and stabilizes

GPX4 mRNA by interacting with insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA

binding protein 3. This inhibits ferroptosis and promotes

resistance to gemcitabine and cisplatin. Treatment with JKE-1674 (1

μM), a GPX4 inhibitor, combined with gemcitabine (5

μM) and cisplatin (10 μM) exhibits an improved

antitumor potential in preclinical models of both subcutaneous

tumor and orthotopic mice models, compared with gemcitabine and

cisplatin therapy (165).

Previous studies reveal ACSL4 promotes ferroptosis

by catalyzing the esterification of long-chain PUFAs into PUFA-CoA,

which serve as substrates for LPO (166,167). Data from the Gene Expression

Omnibus and The Cancer Genome Atlas databases demonstrates that

there is a higher level of ACSL4 in CCA compared with normal

adjacent tissues. Additionally, ACSL4 levels are associated with

the prognosis of patients with CCA as well as the immune

infiltration in CCA (168).

Targeting the ACSL4 pathway may be an anti-cancer approach. A study

by Liao et al (169)

reveals that, via ACSL4-dependent lipid reprogramming, IFNγ from

cytotoxic T lymphocytes and AA from the TME induce tumor cell

ferroptosis. Furthermore, cancer cells that derive from migration

exhibit a higher ferroptosis sensitivity and PUFA lipid contents

compared with primary-tumor-derived cells. This supports the

possibility of targeting ferroptosis in the treatment of cancer

(170). Specific and targeted

inhibitors of ACSL4 with anti-ferroptosis function such as

AS-252424 have been screened and identified (171). In GBC, sirtuin 3 has tumor

suppressive effects through the induction of the expression of

ACSL4 and AKT-dependent ferroptosis, and inhibition of the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (172). Another member of the acyl-CoA

synthetase long chain family, ACSL3, synthesizes MUFAs that

suppress PUFAs peroxidation, which confers ferroptosis protection.

Furthermore, ACSL3 is an unfavorable prognostic biomarker in

patients with CCA and a mediator of ferroptosis resistance in CCA

cells. Therefore, ACSL3 may be a potential therapeutic target

(173).

Furthermore, several other factors potentially

regulate ferroptosis sensitivity. For example, circular

(circ)forkhead box protein P1 and Homo sapiens_circ_0050900

affect ferroptosis by interacting with OTU domain-containing

protein 4 and regulating SLC3A2, respectively (174,175). TFR modulates the ferroptosis

sensitivity of cells by regulating intracellular iron levels.

Additionally, TFR is also an adverse prognostic factor in patients

with iCCA (176). The regulatory

importance of the E26 transformation-specific variant 4-ALY/REF

export factor-pyruvate kinase M2 and Aldo-keto reductase family 1

member C1-cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1-cAMP axes

also warrant attention (177,178). Additionally, gut microbiotas

inhibit ferroptosis in iCCA by altering glutamine metabolism

through the regulation of the activin receptor-like kinase 5/NADPH

oxidase 1 axis (179).

Ferroptosis serves a role in the pathogenesis,

progression and treatment resistance of BTC. Furthermore,

accumulating evidence demonstrates that ferroptosis-associated

indicators are notably associated with patient prognosis and

represent potential prognostic biomarkers (Table II). Techniques such as RNA

sequencing and immunohistochemistry reveal elevated expression of

ferroptosis-associated markers, including ACSL3/4, SLC7A11 and

GPX4, in BTC tumor tissues compared with normal adjacent tissues,

which is notably associated with poorer clinical outcomes (168,173,176,180-183). By contrast, isocitrate

dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutations are associated with a more

favorable prognosis in BTC (183,184). In addition, other key

ferroptosis-associated markers, such as LPCAT3 and FSP1, are also

associated with prognosis in various solid tumors including ovarian

cancer and lung adenocarcinoma; however, their clinical validation

in BTC requires further investigation (185-192). Taken together, these

ferroptosis-associated indicators may serve as novel prognostic

markers for BTC, potentially offering a new perspective for precise

prognosis assessment and individualized treatment strategies.

Furthermore, integrating these indicators to establish

multi-parameter prognostic models may enhance the accuracy of

existing BTC prognostic assessment systems.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is currently

recognized as a viable complementary treatment in malignancies

(196). Accumulating evidence

demonstrates that TCM can notably enhance the chemosensitivity of a

patient, potentiate the antitumor efficacy of therapeutic agents

and mitigate treatment-associated adverse effects in cancer

management (197,198). Quercetin (QE), a flavonoid in

flowers, stems and leaves of various plants, possesses the ability

to impede the progression of breast and colon cancer by

interrupting the cell cycle (199,200). Previous studies demonstrate that

QE induces ferroptosis in iCCA cells by inhibiting the NF-κB

signaling pathway, which inhibits iCCA cell invasion (201,202). Isoliquiritigenin (ISL), also

known as 2',4',4-trihydroxychalcone, is also a type of flavonoid

and is extracted from the root of the liquorice plant. ISL induces

apoptosis and inhibits proliferation in tumors (203,204). A study by Wang et al

(205) reveals that ISL triggers

ferroptosis in GBC by activating the p62-Kelch-like ECH-associated

protein 1-Nrf2-haem oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) signaling pathway and

reducing the expression of GPX4. Silencing HMOX1 or increasing GPX4

expression levels decreases the susceptibility of GBC cells to

ISL-induced ferroptosis and enhances the survival of GBC cells

(205). Another naturally

occurring triterpenoid compound named liquidambaric acid (LCD) also

exhibits notable therapeutic potential. LCD can bind to and inhibit

signal transducing adaptor molecule binding protein like 1, which

stabilizes Nrf2 through de-ubiquitination, and notably enhances CCA

cell proliferation and migration while impeding ferroptosis

(206). Wu-Mei-Wan, a

long-utilized TCM formula, demonstrates potential efficacy as a

second-line GBC therapy. It enhances gemcitabine chemosensitivity

and induces ferroptosis through phosphorylated (p)-STAT3-mediated

transcriptional regulation of ferroptosis-associated targets,

downregulating GPX4, HIF-1α and FTH1, while upregulating ACSL4

(207).

At present, chemoimmunotherapy is the first-line

treatment option for BTC due to the durvalumab plus gemcitabine and

cisplatin in advanced BTC and KEYNOTE-966 studies (143,144). A study by Zhu et al

(208) reveals that, in

AKT-hyperactivated iCCA, the p-AKT-p-phosphoenolpyruvate

carboxykinase 1 (PCK1)-p-lactate dehydrogenase A-SPRINGlac axis is

a driver of ferroptosis resistance. This combines p-PCK1-mediated

glycolytic activation and mevalonate flux reprogramming. However,

simvastatin treatment effectively reverses this resistance,

underscoring its therapeutic potential for improving the

chemoimmunotherapy efficacy through ferroptosis sensitivity

(208).

In addition, metabolic products such as lithocholic

acid (LCA) are reagents involved in inhibiting tumorigenesis. A

study by Li et al (209)

reveals that LCA induces ferroptosis in GBC by suppressing

glutaminase-mediated glutamine metabolism, which may be a

tumor-suppressive mechanism with therapeutic potential.

PDT is a treatment modality that selectively

destroys tumor tissue through the light activation of

photosensitizers and release of ROS (210). The tumor-selective destruction

capacity of PDT minimizes damage to healthy tissues, which suggests

it may be a potential antitumor therapeutic strategy (211,212). The first-generation

photosensitizer-HiPorfin-mediated PDT promotes the apoptosis and

ferroptosis of CCA cells through the activation of the

p53/SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway (213). Furthermore, the

second-generation photosensitizer-Hypericin-mediated PDT induces

ferroptosis in CCA by inhibiting the AKT/mTORC1/GPX4 signaling

pathway (214). These findings

provide possible insights into individualized precision therapy for

CCA. Furthermore, combination strategies represent novel

therapeutic paradigms for BTC. Surufatinib (SUR), a multi-targeted

kinase inhibitor, has comparable clinical efficacy in patients with

advanced CCA compared with regorafenib, which is one of the

recommend regimens used for subsequent-line therapy of BTC

(12,215). Mechanistically, both SUR and PDT

induce ferroptosis through the upregulation of ACSL4 and

suppression of GPX4, and their effect is synergistically enhanced

during combination treatment (215). In addition, an integrated

nanotherapeutic platform known as CMArg@ Lip has been successfully

developed for combined PDT and gas therapy. This platform

encapsulates the photosensitizer, NO gas-generating agent and Nrf2

inhibitor with ROS-responsive liposomes, which enables it to

effectively address the challenges of tumor hypoxia and the

antioxidant microenvironment (216).

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent, LPO-driven form of

RCD, is a research focus in BTC therapeutics. Accumulating evidence

demonstrates marked vulnerability of BTC cells to ferroptosis,

unveiling novel avenues for targeted treatment. Despite promising

advances, challenges persist. While core ferroptosis pathways, such

as the GPX4-GSH axis and system Xc− regulation, are

delineated, the integrated regulatory network, particularly

crosstalk with metabolic reprogramming and TME interactions, is yet

to be fully elucidated. At present, clinically applicable

biomarkers for predicting ferroptosis sensitivity are lacking,

which hampers patient stratification. Furthermore, current

ferroptosis inducers, such as erastin analogs and RSL3 derivatives,

have limitations in tumor specificity, systemic toxicity and

pharmacokinetic profiles.

Future studies should prioritize the following: i)

Systematic investigations of ferroptosis synergism with immune

checkpoint inhibitors and molecular-targeted agents, using

multiomics approaches to decipher resistance mechanisms; ii)

development of integrated biomarker panels incorporating genetic,

epigenetic and microenvironmental features for precision patient

stratification; iii) therapeutic validation through physiologically

relevant platforms, including patient derived organoids, orthotopic

BTC models and humanized mouse systems simulating tumor-stroma

crosstalk; and iv) engineering of tumor-targeted nano-formulations,

such as the CMArg@Lip platform, to enhance the tumor-targeted

delivery of ferroptosis inducers while mitigating off-target

effects.

In summary, bridging mechanistic insights from

laboratory studies with rationally designed clinical trials

incorporating biomarker-driven enrollment may highlight ferroptosis

modulation as a potnetial therapeutic paradigm for BTC.

Not applicable.

RZ and YD contributed to literature searching and

screening, manuscript drafting and revision of the manuscript. SY

and HH contributed to the revision of the manuscript. FLi and FLiu

contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by 1.3.5 project for disciplines

of excellence (West China Hospital, Sichuan University; grant no.

ZYJC21046), 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence-Clinical

Research Incubation Project (West China Hospital, Sichuan

University; grant no. 2021HXFH001), China Telecom Sichuan Company

Biliary Tract Tumor Big Data Platform and Application Phase I

R&D Project (grant no. 312230752), National Natural Science

Foundation of China for Young Scientists Fund (grant no. 82303669),

Sichuan University-Sui Ning School-local Cooperation project (grant

no. 2022CDSN-18), and The Post-doctor Research Fund of West China

Hospital, Sichuan University (grant nos. ZYJC21046, 2021HXFH001 and

2024HXBH083).

|

1

|

Valle JW, Kelley RK, Nervi B, Oh DY and

Zhu AX: Biliary tract cancer. Lancet. 397:428–444. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Brindley PJ, Bachini M, Ilyas SI, Khan SA,

Loukas A, Sirica AE, The BT, Wongkham S and Gores GJ:

Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Torre LA, Siegel RL, Islami F, Bray F and

Jemal A: Worldwide burden of and trends in mortality from

gallbladder and other biliary tract cancers. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 16:427–437. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA;

WHO classification of tumours editorial board: The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Nakanuma Y and Kakuda Y: Pathologic

classification of cholangiocarcinoma: New concepts. Best Pract Res

Clin Gastroenterol. 29:277–293. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Roa JC, García P, Kapoor VK, Maithel SK,

Javle M and Koshiol J: Gallbladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

8:692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Vogel A, Bridgewater J, Edeline J, Kelley

RK, Klümpen HJ, Malka D, Primrose JN, Rimassa L, Stenzinger A,

Valle JW, et al: Biliary tract cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice

Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

34:127–140. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ruff SM, Cloyd JM and Pawlik TM: Annals of

surgical oncology practice guidelines series: Management of primary

liver and biliary tract cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 30:7935–7949.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Baria K, De Toni EN, Yu B, Jiang Z, Kabadi

SM and Malvezzi M: Worldwide incidence and mortality of biliary

tract cancer. Gastro Hep Adv. 1:618–626. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lamarca A, Edeline J and Goyal L: How I

treat biliary tract cancer. ESMO Open. 7:1003782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Benson AB, D'Angelica MI, Abrams T, Abbott

DE, Ahmed A, Anaya DA, Anders R, Are C, Bachini M, Binder D, et al:

NCCN Guidelines® insights: Biliary tract cancers,

version 2.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:694–704. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Harding JJ, Khalil DN, Fabris L and

Abou-Alfa GK: Rational development of combination therapies for

biliary tract cancers. J Hepatol. 78:217–228. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Palmieri LJ, Lavolé J, Dermine S, Brezault

C, Dhooge M, Barré A, Chaussade S and Coriat R: The choice for the

optimal therapy in advanced biliary tract cancers: Chemotherapy,

targeted therapies or immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther.

210:1075172020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lamarca A, Barriuso J, McNamara MG and

Valle JW: Molecular targeted therapies: Ready for 'prime time' in

biliary tract cancer. J Hepatol. 73:170–185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams

JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, Alnemri ES, Altucci L, Amelio I, Andrews

DW, et al: Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of

the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ.

25:486–541. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Koren E and Fuchs Y: Modes of regulated

cell death in cancer. Cancer Discov. 11:245–265. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An Iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Weinlich R, Oberst A, Beere HM and Green

DR: Necroptosis in development, inflammation and disease. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 18:127–136. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wyllie AH: Glucocorticoid-induced

thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease

activation. Nature. 284:555–556. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bergsbaken T and Cookson BT: Macrophage

activation redirects Yersinia-infected host cell death from

apoptosis to caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog.

3:e1612007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P

and Kroemer G: The molecular machinery of regulated cell death.

Cell Res. 29:347–364. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Dixon SJ and Stockwell BR: The role of

iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat Chem Biol.

10:9–17. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yang WS and Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis:

Death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 26:165–176. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

28

|

Liang D, Minikes AM and Jiang X:

Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular

signaling. Mol Cell. 82:2215–2227. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G and Tang D:

Broadening horizons: The role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 18:280–296. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gao GB, Chen L, Pan JF, Lei T, Cai X, Hao

Z, Wang Q, Shan G and Li J: LncRNA RGMB-AS1 inhibits HMOX1

ubiquitination and NAA10 activation to induce ferroptosis in

non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 590:2168262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects

against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology.

63:173–184. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Li J, Liu J, Zhou Z, Wu R, Chen X, Yu C,

Stockwell B, Kroemer G, Kang R and Tang D: Tumor-specific GPX4

degradation enhances ferroptosis-initiated antitumor immune

response in mouse models of pancreatic cancer. Sci Transl Med.

15:eadg30492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ding Y, Chen X, Liu C, Ge W, Wang Q, Hao

X, Wang M, Chen Y and Zhang Q: Identification of a small molecule

as inducer of ferroptosis and apoptosis through ubiquitination of

GPX4 in triple negative breast cancer cells. J Hematol Oncol.

14:192021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zou Y, Palte MJ, Deik AA, Li H, Eaton JK,

Wang W, Tseng YY, Deasy R, Kost-Alimova M, Dančík V, et al: A

GPX4-dependent cancer cell state underlies the clear-cell

morphology and confers sensitivity to ferroptosis. Nat Commun.

10:16172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Shen Z, Song J, Yung BC, Zhou Z, Wu A and

Chen X: Emerging strategies of cancer therapy based on ferroptosis.

Adv Mater. 30:e17040072018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Friedmann Angeli JP, Krysko DV and Conrad

M: Ferroptosis at the crossroads of cancer-acquired drug resistance

and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 19:405–414. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P and Vanden

Berghe T: Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell.

35:830–849. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Angeli JPF, Shah R, Pratt DA and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis inhibition: Mechanisms and opportunities. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 38:489–498. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mou Y, Wang J, Wu J, He D, Zhang C, Duan C

and Li B: Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: Opportunities and

challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 12:342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Tang D, Chen X, Kang R and Kroemer G:

Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell

Res. 31:107–125. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

41

|

Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ and Tang

D: Ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Autophagy. 17:2054–2081.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

42

|

Zeng F, Nijiati S, Tang L, Ye J, Zhou Z

and Chen X: Ferroptosis detection: From approaches to applications.

Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 62:e2023003792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Frey PA and Reed GH: The ubiquity of iron.

ACS Chem Biol. 7:1477–1481. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU and Andrews NC:

Balancing acts: Molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism.

Cell. 117:285–297. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Gonciarz RL, Collisson EA and Renslo AR:

Ferrous Iron-dependent pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 42:7–18.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J

and Jiang X: Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell

Res. 26:1021–1032. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Geng N, Shi BJ, Li SL, Zhong ZY, Li YC,

Xua WL, Zhou H and Cai JH: Knockdown of ferroportin accelerates

erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 22:3826–3836. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu J, Kang R and Tang D:

NEDD4L-mediated LTF protein degradation limits ferroptosis. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 531:581–587. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Alvarez SW, Sviderskiy VO, Terzi EM,

Papagiannakopoulos T, Moreira AL, Adams S, Sabatini DM, Birsoy K

and Possemato R: NFS1 undergoes positive selection in lung tumours

and protects cells from ferroptosis. Nature. 551:639–643. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Du J, Wang T, Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang X, Yu X,

Ren X, An Y, Wu Y, Sun W, et al: DHA inhibits proliferation and

induces ferroptosis of leukemia cells through autophagy dependent

degradation of ferritin. Free Radic Biol Med. 131:356–369. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Knutson MD: Non-transferrin-bound iron

transporters. Free Radic Biol Med. 133:101–111. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Song N, Zhang J, Zhai J, Hong J, Yuan C

and Liang M: Ferritin: A multifunctional nanoplatform for

biological detection, imaging diagnosis, and drug delivery. Acc

Chem Res. 54:3313–3325. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh

HJ III, Kang R and Tang D: Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by

degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 12:1425–1428. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW and

Kimmelman AC: Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo

receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 509:105–109. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M,

Shchepinov MS and Stockwell BR: Peroxidation of polyunsaturated

fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E4966–E4975. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yan B, Ai Y, Sun Q, Ma Y, Cao Y, Wang J,

Zhang Z and Wang X: Membrane Damage during ferroptosis is caused by

oxidation of phospholipids catalyzed by the oxidoreductases POR and

CYB5R1. Mol Cell. 81:355–369.e10. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Conrad M and Pratt DA: The chemical basis

of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 15:1137–1147. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S,

Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, et al: Oxidized

arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem

Biol. 13:81–90. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Magtanong L, Ko PJ, To M, Cao JY, Forcina

GC, Tarangelo A, Ward CC, Cho K, Patti GJ, Nomura DK, et al:

Exogenous monounsaturated fatty acids promote a

Ferroptosis-resistant cell state. Cell Chem Biol. 26:420–432.e9.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Tesfay L, Paul BT, Konstorum A, Deng Z,

Cox AO, Lee J, Furdui CM, Hegde P, Torti FM and Torti SV:

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 protects ovarian cancer cells from

ferroptotic cell death. Cancer Res. 79:5355–5366. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Chu B, Kon N, Chen D, Li T, Liu T, Jiang

L, Song S, Tavana O and Gu W: ALOX12 is required for p53-mediated

tumour suppression through a distinct ferroptosis pathway. Nat Cell

Biol. 21:579–591. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME,

Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji

AF, Clish CB, et al: Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by

GPX4. Cell. 156:317–331. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ingold I, Berndt C, Schmitt S, Doll S,

Poschmann G, Buday K, Roveri A, Peng X, Porto Freitas F, Seibt T,

et al: Selenium utilization by GPX4 is required to prevent

hydroperoxide-induced ferroptosis. Cell. 172:409–422.e421. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ursini F and Maiorino M: Lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic

Biol Med. 152:175–185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Dai C, Chen X, Li J, Comish P, Kang R and

Tang D: Transcription factors in ferroptotic cell death. Cancer

Gene Ther. 27:645–656. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M,

da Silva MC, Ingold I, Goya Grocin A, Xavier da Silva TN, Panzilius

E, Scheel CH, et al: FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis

suppressor. Nature. 575:693–698. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong

L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, et al:

The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit

ferroptosis. Nature. 575:688–692. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP Cyclohydrolase

1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 6:41–53. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Soula M, Weber RA, Zilka O, Alwaseem H, La

K, Yen F, Molina H, Garcia-Bermudez J, Pratt DA, Birsoy K, et al:

Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to canonical

ferroptosis inducers. Nat Chem Biol. 16:1351–1360. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee

H, Koppula P, Wu S, Zhuang L, Fang B, et al: DHODH-mediated

ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer.

Nature. 593:586–590. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Liang D, Feng Y, Zandkarimi F, Wang H,

Zhang Z, Kim J, Cai Y, Gu W, Stockwell BR and Jiang X: Ferroptosis

surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by

sex hormones. Cell. 186:2748–2764.e2722. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Lei G, Zhuang L and Gan B: The roles of

ferroptosis in cancer: Tumor suppression, tumor microenvironment,

and therapeutic interventions. Cancer Cell. 42:513–534. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

de Visser KE and Joyce JA: The evolving

tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic

outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 41:374–403. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan

V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI,

Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, et al: Understanding the tumor

immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med.

24:541–550. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Quail DF and Joyce JA: Microenvironmental

regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med.

19:1423–1437. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Elhanani O, Ben-Uri R and Keren L: Spatial

profiling technologies illuminate the tumor microenvironment.

Cancer Cell. 41:404–420. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Cui K, Wang K and Huang Z: Ferroptosis and

the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:3152024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Bhowmick S, Banerjee S, Shridhar V and

Mondal S: Reprogrammed immuno-metabolic environment of cancer: The

driving force of ferroptosis resistance. Mol Cancer. 24:1612025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Kim R, Taylor D, Vonderheide RH and

Gabrilovich DI: Ferroptosis of immune cells in the tumor

microenvironment. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 44:542–552. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Zheng Y, Sun L, Guo J and Ma J: The

crosstalk between ferroptosis and anti-tumor immunity in the tumor

microenvironment: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic controversy.

Cancer Commun (Lond). 43:1071–1096. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Demuynck R, Efimova I, Naessens F and

Krysko DV: Immunogenic ferroptosis and where to find it? J

Immunother Cancer. 9:e0034302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Fucikova J, Kepp O, Kasikova L, Petroni G,

Yamazaki T, Liu P, Zhao L, Spisek R, Kroemer G and Galluzzi L:

Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer

therapy. Cell Death Dis. 11:10132020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Wen Q, Liu J, Kang R, Zhou B and Tang D:

The release and activity of HMGB1 in ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 510:278–283. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zhao YY, Lian JX, Lan Z, Zou KL, Wang WM

and Yu GT: Ferroptosis promotes anti-tumor immune response by

inducing immunogenic exposure in HNSCC. Oral Dis. 29:933–941. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Han W, Duan X, Ni K, Li Y, Chan C and Lin

W: Co-delivery of dihydroartemisinin and pyropheophorbide-iron

elicits ferroptosis to potentiate cancer immunotherapy.

Biomaterials. 280:1213152022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

86

|

Wan C, Sun Y, Tian Y, Lu L, Dai X, Meng J,

Huang J, He Q, Wu B, Zhang Z, et al: Irradiated tumor cell-derived

microparticles mediate tumor eradication via cell killing and

immune reprogramming. Sci Adv. 6:eaay97892020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Efimova I, Catanzaro E, Van der Meeren L,

Turubanova VD, Hammad H, Mishchenko TA, Vedunova MV, Fimognari C,

Bachert C, Coppieters F, et al: Vaccination with early ferroptotic

cancer cells induces efficient antitumor immunity. J Immunother

Cancer. 8:e0013692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Liu J, Zhu S, Zeng L, Li J, Klionsky DJ,

Kroemer G, Jiang J, Tang D and Kang R: DCN released from

ferroptotic cells ignites AGER-dependent immune responses.

Autophagy. 18:2036–2049. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

89

|

Wiernicki B, Maschalidi S, Pinney J,

Adjemian S, Vanden Berghe T, Ravichandran KS and Vandenabeele P:

Cancer cells dying from ferroptosis impede dendritic Cell-mediated

Anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun. 13:36762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Han C, Ge M, Xing P, Xia T, Zhang C, Ma K,

Ma Y, Li S, Li W, Liu X, et al: Cystine deprivation triggers

CD36-mediated ferroptosis and dysfunction of tumor infiltrating

CD8+ T cells. Cell Death Dis. 15:1452024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

91

|

Luo X, Gong HB, Gao HY, Wu YP, Sun WY, Li

ZQ, Wang G, Liu B, Liang L, Kurihara H, et al: Oxygenated

phosphatidylethanolamine navigates phagocytosis of ferroptotic

cells by interacting with TLR2. Cell Death Differ. 28:1971–1989.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Kim KS, Choi B, Choi H, Ko MJ and Kim DH

and Kim DH: Enhanced natural killer cell anti-tumor activity with

nanoparticles mediated ferroptosis and potential therapeutic

application in prostate cancer. J Nanobiotechnology. 20:4282022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Drijvers JM, Gillis JE, Muijlwijk T,

Nguyen TH, Gaudiano EF, Harris IS, LaFleur MW, Ringel AE, Yao CH,

Kurmi K, et al: Pharmacologic screening identifies metabolic

vulnerabilities of CD8+ T cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 9:184–199.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

94

|

Arensman MD, Yang XS, Leahy DM,

Toral-Barza L, Mileski M, Rosfjord EC, Wang F, Deng S, Myers JS,

Abraham RT and Eng CH: Cystine-glutamate antiporter xCT deficiency

suppresses tumor growth while preserving antitumor immunity. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:9533–9542. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Xu S, Chaudhary O, Rodríguez-Morales P,

Sun X, Chen D, Zappasodi R, Xu Z, Pinto AFM, Williams A, Schulze I,

et al: Uptake of oxidized lipids by the scavenger receptor CD36

promotes lipid peroxidation and dysfunction in CD8+ T cells in

tumors. Immunity. 54:1561–1577.e7. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Xu C, Sun S, Johnson T, Qi R, Zhang S,

Zhang J and Yang K: The glutathione peroxidase Gpx4 prevents lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis to sustain Treg cell activation and

suppression of antitumor immunity. Cell Rep. 35:1092352021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Sica A and Mantovani A: Macrophage

plasticity and polarization: In vivo veritas. J Clin Invest.

122:787–795. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Biswas SK and Mantovani A: Macrophage

plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: Cancer as a

paradigm. Nat Immunol. 11:889–896. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Kapralov AA, Yang Q, Dar HH, Tyurina YY,

Anthonymuthu TS, Kim R, St Croix CM, Mikulska-Ruminska K, Liu B,

Shrivastava IH, et al: Redox lipid reprogramming commands

susceptibility of macrophages and microglia to ferroptotic death.

Nat Chem Biol. 16:278–290. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Zhu H, Klement JD, Lu C, Redd PS, Yang D,

Smith AD, Poschel DB, Zou J, Liu D, Wang PG, et al: Asah2 represses

the p53-Hmox1 axis to protect Myeloid-derived suppressor cells from

ferroptosis. J Immunol. 206:1395–1404. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Ždralević M, Vučetić M, Daher B, Marchiq

I, Parks SK and Pouysségur J: Disrupting the 'Warburg effect'

re-routes cancer cells to OXPHOS offering a vulnerability point via

'ferroptosis'-induced cell death. Adv Biol Regul. 68:55–63. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Amos A, Amos A, Wu L and Xia H: The

Warburg effect modulates DHODH role in ferroptosis: A review. Cell

Commun Signal. 21:1002023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Song X, Liu J, Kuang F, Chen X, Zeh HJ

III, Kang R, Kroemer G, Xie Y and Tang D: PDK4 dictates metabolic

resistance to ferroptosis by suppressing pyruvate oxidation and

fatty acid synthesis. Cell Rep. 34:1087672021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Dai Y, Cui C, Jiao D and Zhu X: JAK/STAT

signaling as a key regulator of ferroptosis: Mechanisms and

therapeutic potentials in cancer and diseases. Cancer Cell Int.

25:832025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Yi J, Zhu J, Wu J, Thompson CB and Jiang

X: Oncogenic activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling suppresses

ferroptosis via SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

117:31189–31197. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Garcia-Bermudez J, Baudrier L, Bayraktar

EC, Shen Y, La K, Guarecuco R, Yucel B, Fiore D, Tavora B,

Freinkman E, et al: Squalene accumulation in cholesterol

auxotrophic lymphomas prevents oxidative cell death. Nature.

567:118–122. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Warner GJ, Berry MJ, Moustafa ME, Carlson

BA, Hatfield DL and Faust JR: Inhibition of selenoprotein synthesis

by selenocysteine tRNA[Ser]Sec lacking isopentenyladenosine. J Biol

Chem. 275:28110–28119. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Qu L, He X, Tang Q, Fan X, Liu J and Lin

A: Iron metabolism, ferroptosis, and lncRNA in cancer: Knowns and

unknowns. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 23:844–862. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Zhang S, Xin W, Anderson GJ, Li R, Gao L,

Chen S, Zhao J and Liu S: Double-edge sword roles of iron in

driving energy production versus instigating ferroptosis. Cell

Death Dis. 13:402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

He Y, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Mertens RT, Cao Q,

Xu X, Guo K, Shi Q, Zhang X, Huo L, et al: Butyrate reverses

ferroptosis resistance in colorectal cancer by inducing

c-Fos-dependent xCT suppression. Redox Biol. 65:1028222023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Cui W, Guo M, Liu D, Xiao P, Yang C, Huang

H, Liang C, Yang Y, Fu X, Zhang Y, et al: Gut microbial metabolite

facilitates colorectal cancer development via ferroptosis

inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 26:124–137. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Cavalli G and Heard E: Advances in

epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature.

571:489–499. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Zhang X, Sui S, Wang L, Li H, Zhang L, Xu

S and Zheng X: Inhibition of tumor propellant glutathione

peroxidase 4 induces ferroptosis in cancer cells and enhances

anticancer effect of cisplatin. J Cell Physiol. 235:3425–3437.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Zhang X, Huang Z, Xie Z, Chen Y, Zheng Z,

Wei X, Huang B, Shan Z, Liu J, Fan S, et al: Homocysteine induces

oxidative stress and ferroptosis of nucleus pulposus via enhancing

methylation of GPX4. Free Radic Biol Med. 160:552–565. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Kim JW, Min DW, Kim D, Kim J, Kim MJ, Lim

H and Lee JY: GPX4 overexpressed non-small cell lung cancer cells

are sensitive to RSL3-induced ferroptosis. Sci Rep. 13:88722023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Lee J, You JH, Kim MS and Roh JL:

Epigenetic reprogramming of epithelial-mesenchymal transition

promotes ferroptosis of head and neck cancer. Redox Biol.

37:1016972020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Koppula P, Zhuang L and Gan B: Cystine

transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: Ferroptosis, nutrient

dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell. 12:599–620. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

119

|

Liu J, Xia X and Huang P: xCT: A critical

molecule that links cancer metabolism to redox signaling. Mol Ther.

28:2358–2366. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Pontel LB, Bueno-Costa A, Morellato AE,

Carvalho Santos J, Roué G and Esteller M: Acute lymphoblastic

leukemia necessitates GSH-dependent ferroptosis defenses to

overcome FSP1-epigenetic silencing. Redox Biol. 55:1024082022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Wang X, Kong X, Feng X and Jiang DS:

Effects of DNA, RNA, and protein methylation on the regulation of

ferroptosis. Int J Biol Sci. 19:3558–3575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Lv D, Zhong C, Dixit D, Yang K, Wu Q,

Godugu B, Prager BC, Zhao G, Wang X, Xie Q, et al: EGFR promotes

ALKBH5 nuclear retention to attenuate N6-methyladenosine and

protect against ferroptosis in glioblastoma. Mol Cell.

83:4334–4351.e4337. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Wang J, Xiu M, Wang J, Gao Y and Li Y:

METTL16-SENP3-LTF axis confers ferroptosis resistance and

facilitates tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol

Oncol. 17:782024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Wang Y, Hu J, Wu S, Fleishman JS, Li Y, Xu

Y, Zou W, Wang J, Feng Y, Chen J and Wang H: Targeting epigenetic

and posttranslational modifications regulating ferroptosis for the

treatment of diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:4492023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Wang Y, Yang L, Zhang X, Cui W, Liu Y, Sun

QR, He Q, Zhao S, Zhang GA, Wang Y and Chen S: Epigenetic

regulation of ferroptosis by H2B monoubiquitination and p53. EMBO

Rep. 20:e475632019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Ma M, Kong P, Huang Y, Wang J, Liu X, Hu

Y, Chen X, Du C and Yang H: Activation of MAT2A-ACSL3 pathway

protects cells from ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Free Radic Biol

Med. 181:288–299. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Li H, Liu W, Zhang X, Wu F, Sun D and Wang

Z: Ketamine suppresses proliferation and induces ferroptosis and

apoptosis of breast cancer cells by targeting KAT5/GPX4 axis.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 585:111–116. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Zhang X, Du L, Qiao Y, Zhang X, Zheng W,

Wu Q, Chen Y, Zhu G, Liu Y, Bian Z, et al: Ferroptosis is governed

by differential regulation of transcription in liver cancer. Redox

Biol. 24:1012112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Zille M, Kumar A, Kundu N, Bourassa MW,

Wong VSC, Willis D, Karuppagounder SS and Ratan RR: Ferroptosis in

neurons and cancer cells is similar but differentially regulated by

histone deacetylase inhibitors. eNeuro. 6:ENEURO.0263-18.20192019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Yadav P, Sharma P, Sundaram S, Venkatraman

G, Bera AK and Karunagaran D: SLC7A11/xCT is a target of miR-5096

and its restoration partially rescues miR-5096-mediated ferroptosis

and anti-tumor effects in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett.

522:211–224. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Deng SH, Wu DM, Li L, Liu T, Zhang T, Li

J, Yu Y, He M, Zhao YY, Han R and Xu Y: miR-324-3p reverses

cisplatin resistance by inducing GPX4-mediated ferroptosis in lung

adenocarcinoma cell line A549. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

549:54–60. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|