Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common

malignancy and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality

worldwide (1). Several factors

contribute to GC initiation and progression, including

Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection, chronic gastritis and

genetic alterations (2,3). Despite its high incidence, GC is

often diagnosed at an advanced stage due to the non-specific nature

of its clinical symptoms. Consequently, late detection typically

leads to poor prognosis, with the 5-year survival rate remaining

<30% (4,5). This scenario underscores the urgent

need to identify novel therapeutic targets to enhance treatment

efficacy for GC.

The Eph receptor family, first identified in a human

hepatocellular carcinoma cell line known for erythropoietin

production, has been implicated in multiple types of cancer due to

its frequent upregulation in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)

screenings (6). For example,

ephrin-A1 is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and drives its

progression by promoting proliferation and invasion (7). Ephrin-B3 expression is upregulated

in glioma biopsies and promotes invasion of glioma cells (8). This discovery emerged during

research aimed at identifying novel tyrosine kinase receptors,

highlighting the significance of Eph receptors in oncogenic

processes (9). Ephrin-B2 (EFNB2),

a membrane-anchored ligand of the Eph family of RTKs (10), interacts with the EphB4 receptor

as part of the largest RTK subfamily. The EFNB2-EphB4 signaling

axis serves a key role in regulating cellular adhesion and

repulsion in diverse biological contexts (11,12). Furthermore, EFNB2 can function in

a cell-autonomous manner, independent of Eph receptor interactions,

and participates in complex signaling pathways, including the

AKT/mTOR and ERK pathways (13-15), thereby modulating various

physiological events. Notably, EFNB2 has been demonstrated to

regulate malignant progression in various tumor cells (15-18). For instance, EFNB2 is highly

expressed in pancreatic cancer, and facilitates proliferation,

migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer via activation of the

p53/p21 signaling axis (16).

Conversely, EFNB2 expression has been associated with good

prognosis in breast cancer, and is known to inhibit cell

proliferation and migration (17). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the role of EFNB2 in GC remains unclear and requires

further investigation.

Integrated genomic analysis has identified

dysregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in ~46% of GC cases

(19). This evolutionarily

conserved signaling pathway, frequently disrupted by component

mutations, regulates key cellular processes, including fate

determination, proliferation, differentiation, migration, apoptosis

and stemness maintenance (20-22). Under basal conditions, β-catenin

levels are tightly controlled by a destruction complex containing

GSK3β, which targets β-catenin for proteasomal degradation through

ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms (21). Upon pathway activation, stabilized

β-catenin is translocated into the nucleus, where it forms

transcriptional complexes with co-activators to modulate gene

expression programs, including c-myc controlling cell proliferation

and differentiation (21,22). Considering the potential roles of

EFNB2 and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in tumors, we hypothesized that

EFNB2 may regulate the malignant progression of GC through the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade.

The present study investigated the expression levels

of EFNB2 and its prognostic significance in patients with GC

through a comprehensive analysis of public databases and tissue

microarray (TMA)-based immunohistochemical (IHC) assessment. To

further elucidate the functional roles of EFNB2 in GC pathogenesis,

a series of cellular assays were carried out and murine models were

established to examine its regulatory effects on cellular

proliferation, apoptotic processes and cell cycle progression both

in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, CHIR99021 and

differentiation-inducing factor-3 (DIF-3) were employed to assess

whether the effects of EFNB2 were primarily mediated through the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

Various public online databases, including Gene

Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) (23), LinkedOmics (24), Kaplan-Meier Plotter (25), Tumor Immune Estimation Resource

(TIMER) (26) and Gene Expression

Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds), were used to

explore EFNB2 expression and prognosis, and perform associated

analyses. In GEPIA, the option 'Match TCGA normal and GTEx data'

was selected for EFNB2 expression analysis; the cutoff setting

'Cutoff-High versus Cutoff-Low: 30 versus 30' was employed for

survival analysis; and Spearman correlation analysis was performed

to assess the associations of EFNB2 with GSK3β, catenin β1 and MYC.

In Kaplan-Meier Plotter, the option 'Exclude GSE62254' was selected

for survival analysis (27).

Therefore, the analysis included datasets GSE14210, GSE15459,

GSE22377, GSE29272 and GSE51105 (28-32), with the cutoff set to 'Auto select

best cutoff'. Other parameters were left at the default.

Additionally, two GEO datasets (GSE13195 and GSE184336) were used

to compare the expression levels of EFNB2 and perform correlation

analyses (33,34).

Tissue samples

A commercial GC tissue microarray (cat. no.

HStmA180Su3) was purchased from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd.,

consisting of 96 GC tissues and 84 adjacent normal tissues (ANTs)

collected between December 2013 and September 2015. The mean age of

the patients was 59 years, with a range of 40-83 years. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Age ≥18 years, ii)

pathologically diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma; and iii)

underwent radical gastrectomy. The exclusion criteria included the

following: i) Underwent preoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy;

ii) pathological specimens unavailable; iii) mortality within 1

month following operation; and iv) refusal to participate in

follow-up. Levels of the tumor markers AFP, CEA, CA50, CA125, CA153

and CA199 were assessed in patients with GC 1-3 days prior to

surgery. Comprehensive clinical, pathological and follow-up data

were available for all participants, with the exception of 24

patients lacking HP infection data and 2 patients with missing HER2

expression data. The diagnosis and staging were examined based on

the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer

guidelines (35). Patients

underwent follow-up every 3-6 months, with a maximum follow-up of

60 months. Among the 96 cases, 67 patients died between June 2014

and March 2020, while the remaining 29 patients survived until the

end of the follow-up period. The clinicopathological

characteristics of the patients with GC are presented in Table I. Ethical approval for the present

study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the First

Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval no.

2024137; Hefei, China).

| Table IRelationship between EFNB2 expression

and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with gastric

cancer (n=96). |

Table I

Relationship between EFNB2 expression

and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with gastric

cancer (n=96).

| Parameters | Total, n | EFNB2

expression | P-value |

|---|

| Low, n (n=48) | High, n (n=48) |

|---|

| Age (years) | | | | 0.307 |

| <60 | 47 | 26 | 21 | |

| ≥60 | 49 | 22 | 27 | |

| Sex | | | | 0.811 |

| Female | 23 | 12 | 11 | |

| Male | 73 | 36 | 37 | |

| Helicobacter

pylori infection status | | | | 0.479 |

| Negative | 36 | 16 | 20 | |

| Positive | 36 | 19 | 17 | |

| Missing value | 24 | | | |

| Tumor location | | | | 0.128 |

| Cardia | 15 | 4 | 11 | |

| Gastric body | 15 | 9 | 6 | |

| Antrum | 66 | 35 | 31 | |

| Histological

grade | | | | 0.128 |

| G1 | 10 | 8 | 2 | |

| G2 | 38 | 17 | 21 | |

| G3 | 48 | 23 | 25 | |

| Tumor size

(cm) | | | | <0.001a |

| <4 | 48 | 35 | 13 | |

| ≥4 | 48 | 13 | 35 | |

| T stage | | | | 0.011a |

| T1-T2 | 25 | 18 | 7 | |

| T3-T4 | 71 | 30 | 41 | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | 0.369 |

| Negative | 28 | 16 | 12 | |

| Positive | 68 | 32 | 36 | |

| M stage | | | | 0.037a |

| M0 | 83 | 45 | 38 | |

| M1 | 13 | 3 | 10 | |

| TNM stage | | | | 0.004a |

| Ⅰ-Ⅱ | 46 | 30 | 16 | |

| Ⅲ-Ⅳ | 50 | 18 | 32 | |

| HER2 | | | | 0.130b |

| Negative | 87 | 45 | 42 | |

| Positive | 7 | 1 | 6 | |

| Missing value | 2 | | | |

H&E, IHC and TUNEL staining

H&E and IHC staining of human and mouse GC

tissues was conducted according to the standard procedures

previously described (36,37).

The sections were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C

overnight. The antibodies used were as follows: EFNB2 antibody

(1:500; cat. no. sc-398735; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.),

β-catenin antibody (1:500; cat. no. 51067-2-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) and Ki67 antibody (1:500; cat. no. ab15580; Abcam). The One

Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (cat. no. C1088; Beyotime

Biotechnology) was used according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Briefly, tumor sections were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at 25°C for 60 min and then washed three times

with PBS. The TUNEL reaction solution was prepared by mixing 5

μl TdT enzyme with 45 μl fluorescent labeling

solution. Each section was treated with 50 μl of the TUNEL

solution at 37°C for 60 min in the dark, and then washed three

times with PBS. Finally, the sections were mounted with one drop of

Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (1:1,000; cat. no. P0131;

Beyotime Biotechnology) at 37°C for 3 min and examined under an

inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). Three

random fields were captured for analysis. The percentage of Ki67 or

TUNEL-positive cells was calculated as the number of positive

cells/total number of cells per field.

TMA construction and IHC evaluation

A TMA of GC tissues and ANTs was constructed using

formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks (cat. no. HStmA180Su32;

Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd.) to evaluate the expression levels

of EFNB2. After IHC staining as described previously (36,37), TMA sections were scanned and

digitalized using the Panoramic MIDI system (3D Histech; 3DHISTECH,

Ltd.). IHC staining findings were independently assessed by two

senior pathologists who were blinded to the clinical outcomes of

the patients with GC. EFNB2 or β-catenin expression was quantified

using an integrated IHC score, which combined both staining

intensity and proportion (38,39). The samples were categorized into

two groups according to the median IHC score: The low and high

EFNB2 expression groups.

Cell culture and reagents

GC cell lines (MKN-45, AGS, MGC-803, BGC-823, and

HGC-27) and the normal gastric mucosa epithelial cell line (GES-1)

were obtained from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The

Chinese Academy of Sciences. lAGS cells were cultured in F12 medium

(HyClone; Cytiva). HGC-27 cells were cultured in DMEM (HyClone;

Cytiva). MKN-45, MGC-803, BGC-823 and GES-1 cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (HyClone; Cytiva). All media were supplemented

with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (MilliporeSigma). The cells were cultured

in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. For the

rescue experiments, cells in designated groups were treated at 37°C

for 24 h with either CHIR99021 (5 μM; MedChemExpress) to

activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade or DIF-3 (30

μM; MedChemExpress) to inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

cascade.

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA/sh) and plasmid

transfection

Transfection of GC cells was conducted using

Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

shRNAs, the negative control (NC) shRNA, overexpression plasmids

and empty vector were synthesized by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.

hU6-MCS-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin was used as the vector for

sh-EFNB2 and NC. The target sequence of EFNB2 shRNAs for AGS cells

was as follows: sh1-EFNB2, 5'-CGATTTCCAAATCGATAGTTT-3'; and

sh2-EFNB2, 5'-AGCAGACAGATGCACTATTAA-3'. A random sequence control

shRNA (5'-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3') was used as NC. For EFNB2

overexpression, HGC-27 cells were transfected with the

pcDNA3.1-EGFP-P2A-EFNB2-3FLAG plasmid utilizing

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Empty vector was used as a control for

overexpression experiments. The transfection protocol involved the

introduction of 10 μg of the designated plasmids into the

AGS or HGC-27 cells. GC cells were infected with the lentiviral

vector at 37°C for 48 h (MOI, 10). Following a 2-week selection

with 4 μg/ml puromycin (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.), the stable clones were kept in culture with a maintenance

dose of 2 μg/ml of puromycin (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.). After the 48-h transfection and subsequent 2-week

selection, the efficiency of EFNB2 knockdown or overexpression was

verified at the protein level.

Western blotting

Western blotting was conducted as previously

described (25-27). GES-1, MKN-45, AGS, MGC-803,

BGC-823 and HGC-27 cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer

(Beyotime Biotechnology). This buffer is formulated to prevent

protein degradation and preserve protein phosphorylation. The

details of the primary antibodies used were as follows: EFNB2

(1:1,000; cat. no. sc-398735; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.),

Bcl-2 (1:2,000; cat. no. ab182858; Abcam), Bax (1:2,000; cat. no.

ab32503; Abcam), CyclinD1 (1:1,000, cat. no. 2978; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), CDK4 (1:1,000; cat. no. 12790; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), GSK3β (1:5,000; cat. no. 82061-1-RR; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), phosphorylated (p-)GSK3β (Ser389; 1:1,000; cat. no.

14850-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), β-catenin (1:5,000; cat. no.

51067-2-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), c-myc (1:5,000; cat. no.

808451-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and β-actin (1:1,000; cat. no.

4970; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). After incubation with the

primary antibody at 4°C overnight, the membranes were incubated

with an HRP-labeled secondary antibody (1:5,000; cat. nos. ZB-5301

and ZB-5305; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and

visualized using a Tanon 5200 Multi-Imaging System (Tanon Science

and Technology Co., Ltd.).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and colony

formation assays

The protocols for the CCK-8 and colony formation

assays have been described in detail previously (16,26,27). CCK-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.)

was used to assess the proliferation of GC cells according to

manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, AGS or HGC-27 cells were seeded

into a 96-well plate at a density of ~4×103 cells/well.

The absorbance was evaluated at 450 nm using a microplate reader

(Tecan Group, Ltd.). For the colony formation assay, equal numbers

(500 cells/well) of GC cells were seeded into 6-well plates and

cultured in complete growth medium at 37°C. After 14 days of

incubation, colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min

and stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution (Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) for 30 min, both at room temperature. Images of the visible

colonies in each well were subsequently captured, and colonies were

quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.54k; National

Institutes of Health).

Cell migration and invasion assays

A Transwell chamber (8 μm pore size; Corning,

Inc.) precoated with Matrigel (1:8 dilution; BD Biosciences) at

37°C for 1 h was used for invasion assays, while a Transwell

chamber without Matrigel was employed for migration assays. For the

AGS cells (2×105 cells/well), serum-free F12 medium was

plated in the upper chamber, and F12 medium containing 20% FBS was

added to the lower chamber. For the HGC-27 cells (1×105

cells/well), serum-free DMEM was used in the upper chamber, and

DMEM with 20% FBS was used in the lower chamber. After 48 h of

incubation at 37°C, non-migratory cells were removed with a cotton

swab, while migratory cells were fixed and stained with 0.1%

crystal violet (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at room

temperature. The wells were examined under an Olympus IX70 light

microscope (Olympus Corporation), and cells were counted in at

least three randomly selected fields per well.

Flow cytometry

AGS and HGC-27 cells were cultured and harvested.

Apoptosis was detected using the APC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection

Kit with 7-AAD (cat. no. 640930; BioLegend, Inc.). Briefly, GC

cells were resuspended in 1X binding buffer at a density of

1×106 cells/ml and then incubated with 5 μl

annexin V-APC and 5 μl 7-AAD for 15 min at 25°C in the dark.

Samples were analyzed using a FACS Canto II flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences) and FlowJo v10.7.1 (BD Biosciences).

The cell cycle distribution was assessed by flow

cytometry after PI staining (cat. no. C1052; Beyotime

Biotechnology). Briefly, GC cells were fixed with 70% cold ethanol

on ice for 60 min. The cells were washed with PBS three times and

stained with PI solution in the dark for 30 min at 37°C. Finally,

the cell cycle distribution was analyzed using a FACS Canto II flow

cytometer (BD Biosciences). The percentages of cells in the

G0/G1, S and G2/M phases were

analyzed using ModFit LT 4.1 software (Verity Software House,

Inc.).

Nude mouse xenograft model

The Animal Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Anhui Medical University granted approval for this

protocol (approval no. LLSC20240221; Hefei, China). Female BALB/c

nude mice (5-6 weeks old; weight, 18-22 g) were obtained from

Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. A total

of 16 mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in

an air-conditioned room (22±2°C) with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle

and 60-65% relative humidity. The mice were provided with ad

libitum access to food and water. First, the encoder carried

out randomization using a random number table to assign mice into

four groups (n=4 per group). Each mouse was marked with an ear tag

for identification, and the correspondence between coded groups and

experimental groups was established. Second, without knowledge of

the tumor suspension assignments or mouse group identities, the

experimenters established the cell-derived xenograft (CDX) model.

HGC-27 cells stably transfected with either the empty vector or the

EFNB2 vector were inoculated subcutaneously into the groin of the

mice at a dose of 1×107 cells per mouse, suspended in

100 μl PBS. DIF-3 was administered via peritumoral

subcutaneous injection twice a week at a concentration of 50

μM and a dose of 100 μl per mouse. The control group

received PBS at the same frequency and dose. Animal welfare was

maximized, and pain and distress were minimized, while achieving

scientific research objectives. The humane endpoints used were as

follows: i) Body weight loss ≥20% of initial body weight; ii) tumor

volume exceeding 2,000 mm3; iii) tumor ulceration area

≥10 mm2; iv) detection of tumor metastasis to other

organs, such as the lungs; v) persistent vocalization, trembling or

self-mutilation behavior; and vi) inability to access food or water

autonomously, accompanied by signs of severe dehydration or

malnutrition. All mice in the present study were subjected to daily

health monitoring. Following the establishment of the subcutaneous

tumor-bearing models, this frequency was ensured to be no less than

twice daily to facilitate timely assessment of their condition.

Tumor size was measured with a vernier caliper every 3-4 days, and

the tumor volume was calculated using the following formula:

(Length × width2) × 0.5. A total of 28 days after

injection, mice were humanely euthanized via CO2

asphyxiation using a gradual-fill approach, with the gas introduced

at a rate of 30-50% of the chamber volume/min. Cervical dislocation

was subsequently performed to confirm death. Tumors were harvested

and weighed. All data were recorded according to the pre-assigned

identification numbers. The encoder and researchers jointly

unblinded the study by verifying the correspondence between the

codes and the actual group assignments. The harvested tumor tissues

were subsequently processed for histological staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS

Statistics 22.0 (IBM Corp.), while graphical representations were

generated with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (Dotmatics). Each experiment was

performed in at least triplicate, with data presented as the mean ±

SD. Q-Q plots and the Shapiro-Wilk test were used to assess the

normality of data. For the comparison of two groups, paired or

unpaired Student's t-tests were used when the continuous variable

satisfied the assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of

variance; the Mann-Whitney U test was used when the variable was

non-continuous or when these assumptions (normality and/or

homogeneity of variance) were violated. For comparisons among

multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test

was applied when the continuous variable satisfied the assumptions

of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance; otherwise, the

Kruskal-Wallis H test followed by Dunn's post hoc test was used.

The relationship between EFNB2 expression and clinicopathological

characteristics was examined using Pearson's χ2 test.

When the total sample size was ≥40 and at least one expected

frequency was between 1 and 5, Yates' continuity correction was

applied. Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier

approach, with significance determined by the log-rank test.

Multivariate analysis was conducted using the Cox proportional

hazards model. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

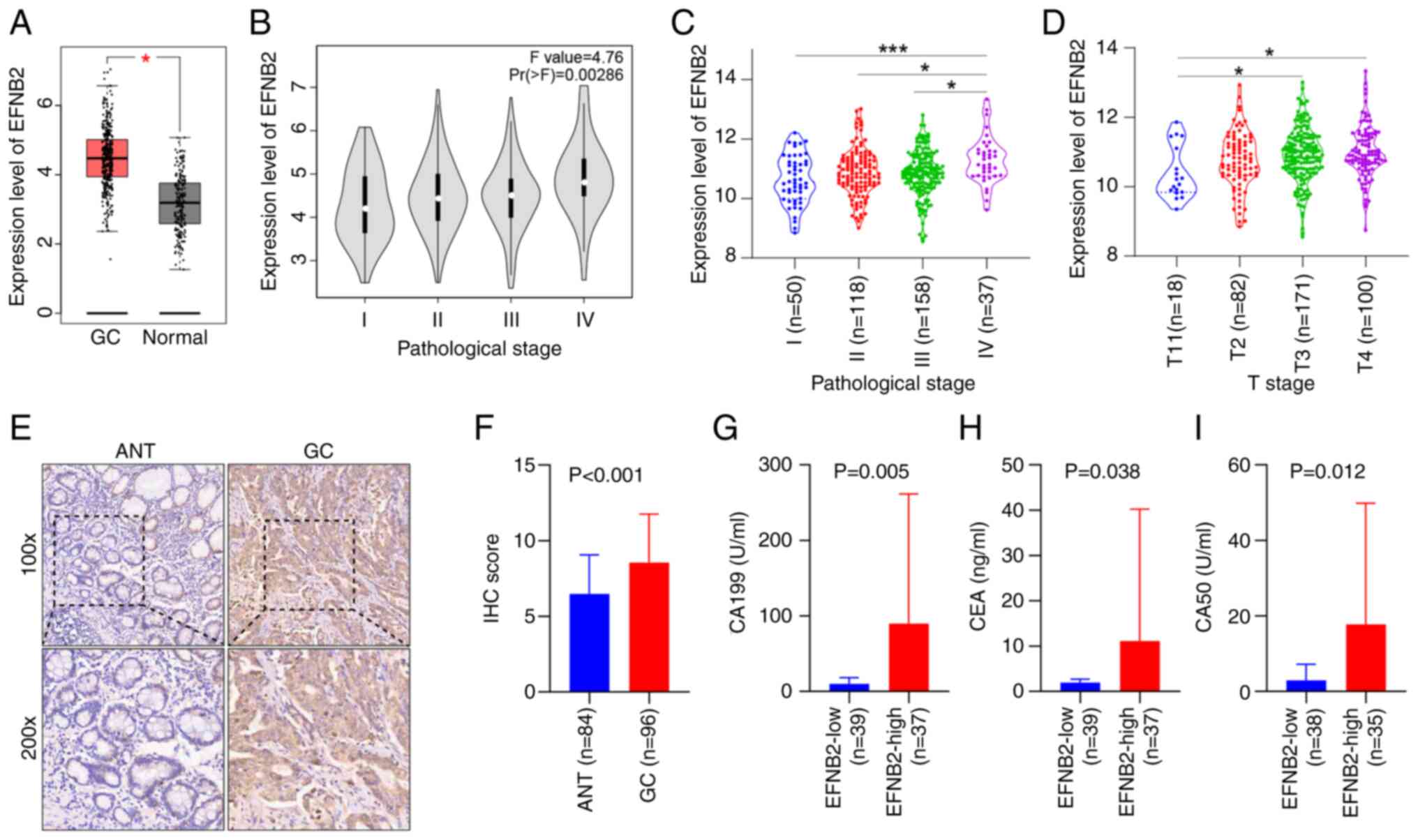

EFNB2 is highly expressed in GC tissues

and is associated with clinicopathologic characteristics

An analysis of EFNB2 expression across 33 cancer

types was performed using GEPIA, comparing tumor samples to

corresponding normal tissues from healthy individuals. Analysis

revealed that EFNB2 expression levels were increased in GC when

comparing 408 GC tissues and 211 normal tissues (Fig. 1A). EFNB2 exhibited abnormal

expression patterns in several solid malignancies, including colon

adenocarcinoma, esophageal carcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma

(Fig. S1A). Furthermore, the

independent GEO database analysis confirmed that EFNB2 was highly

expressed in GC tissues compared with ANTs or normal gastric mucosa

tissues (Fig. S1B and C).

Analysis of data from GEPIA and Linkedomics databases demonstrated

that the expression levels of EFNB2 increased with the progression

of GC staging (Fig. 1B and C).

EFNB2 expression levels were significantly increased in GC with

advanced T stages (T3 or T4) compared with earlier T stages (T1)

(Fig. 1D).

To further validate these observations, a TMA was

constructed for IHC analysis utilizing a total of 180 samples,

comprising 96 GC tissues and 84 ANTs. Analysis revealed elevated

expression levels of EFNB2 in GC tissues (Fig. 1E and F). Furthermore, EFNB2

expression levels were significantly associated with tumor size, T

stage, M stage and TNM stage. However, non-significant associations

were identified between EFNB2 expression and other clinical

parameters of patients with GC, including age, sex, HP infection,

tumor location, histological grade, lymph node metastasis and HER2

status (Table I). Additionally,

the high EFNB2 expression group exhibited increased levels of

specific tumor markers, including CA199, CEA and CA50 (Fig. 1G-I). However, no significant

differences in AFP, CA125 or CA153 levels were observed (Fig. S1D-F).

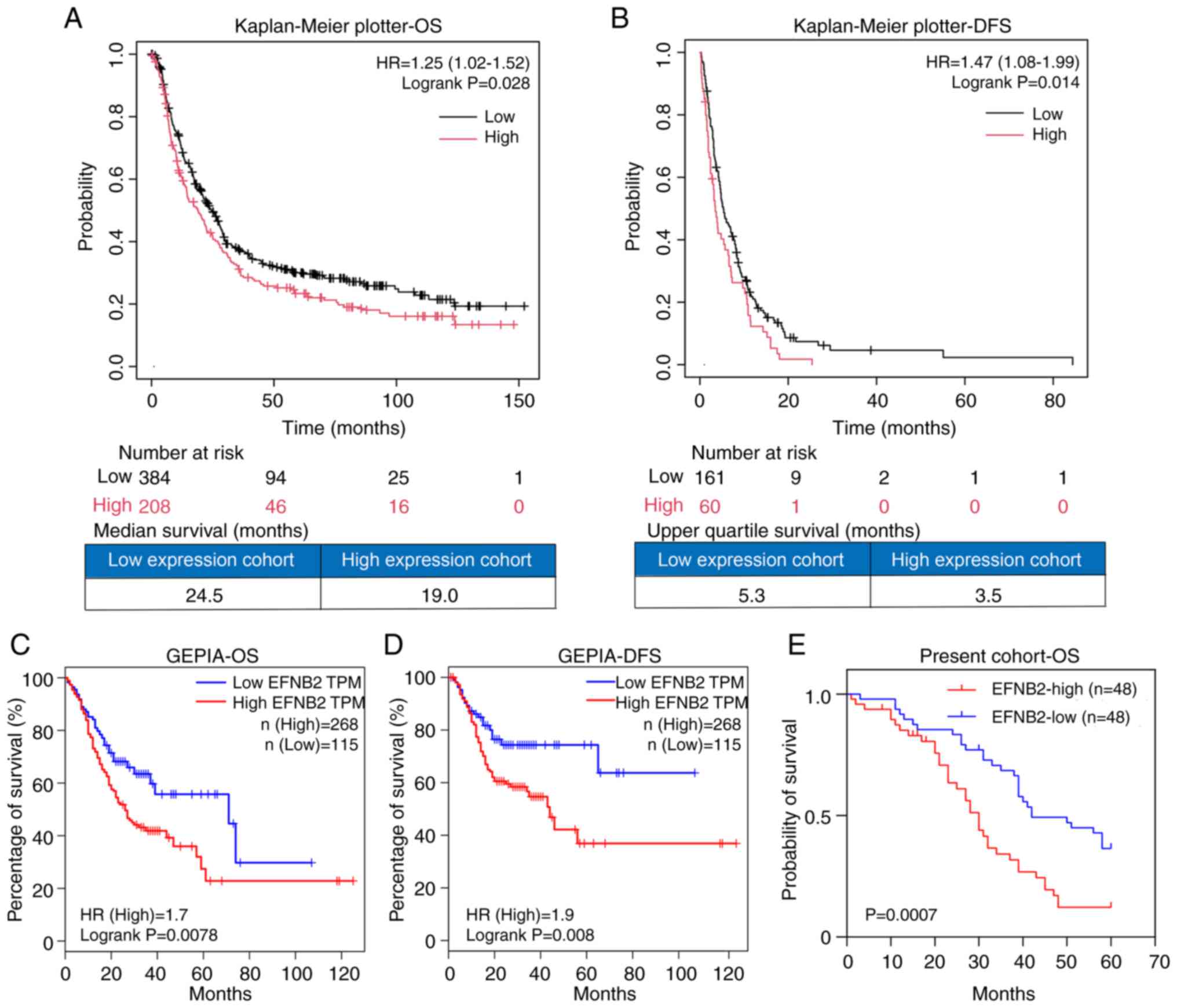

Upregulated EFNB2 expression is

associated with poor prognosis of patients with GC

Subsequently, public databases were used to

investigate the association between EFNB2 and the prognosis of

patients with GC. Analysis of data from the Kaplan-Meier plotter

demonstrated that EFNB2 expression was negatively associated with

overall survival (OS; n=592) and disease-free survival (DFS; n=221)

in patients with GC (Fig. 2A and

B). The EFNB2-high expression group exhibited a 1.25-fold

elevated risk of GC-related mortality compared with the low

expression group. Accordingly, the median OS was shorter in the

high-expression group (19.0 months) than in the low-expression

group (24.5 months) (Fig. 2A and

B). The EFNB2-high expression group exhibited a 1.47-fold

higher risk of relapse compared with the low expression group. The

upper quartile DFS times were 5.3 and 3.5 months for the low and

high expression groups, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly, analysis using

the GEPIA database (n=383) demonstrated that high EFNB2 expression

was significantly associated with worse overall prognosis and

shorter time to recurrence in patients with GC (Fig. 2C and D). Notably, analysis of the

GC cohort in the present study whose samples were included in the

TMA (n=96) verified that high EFNB2 expression was an adverse

factor for the overall prognosis of patients with GC (Fig. 2E). The median OS times of the low

and high expression groups were 42 and 30 months, respectively.

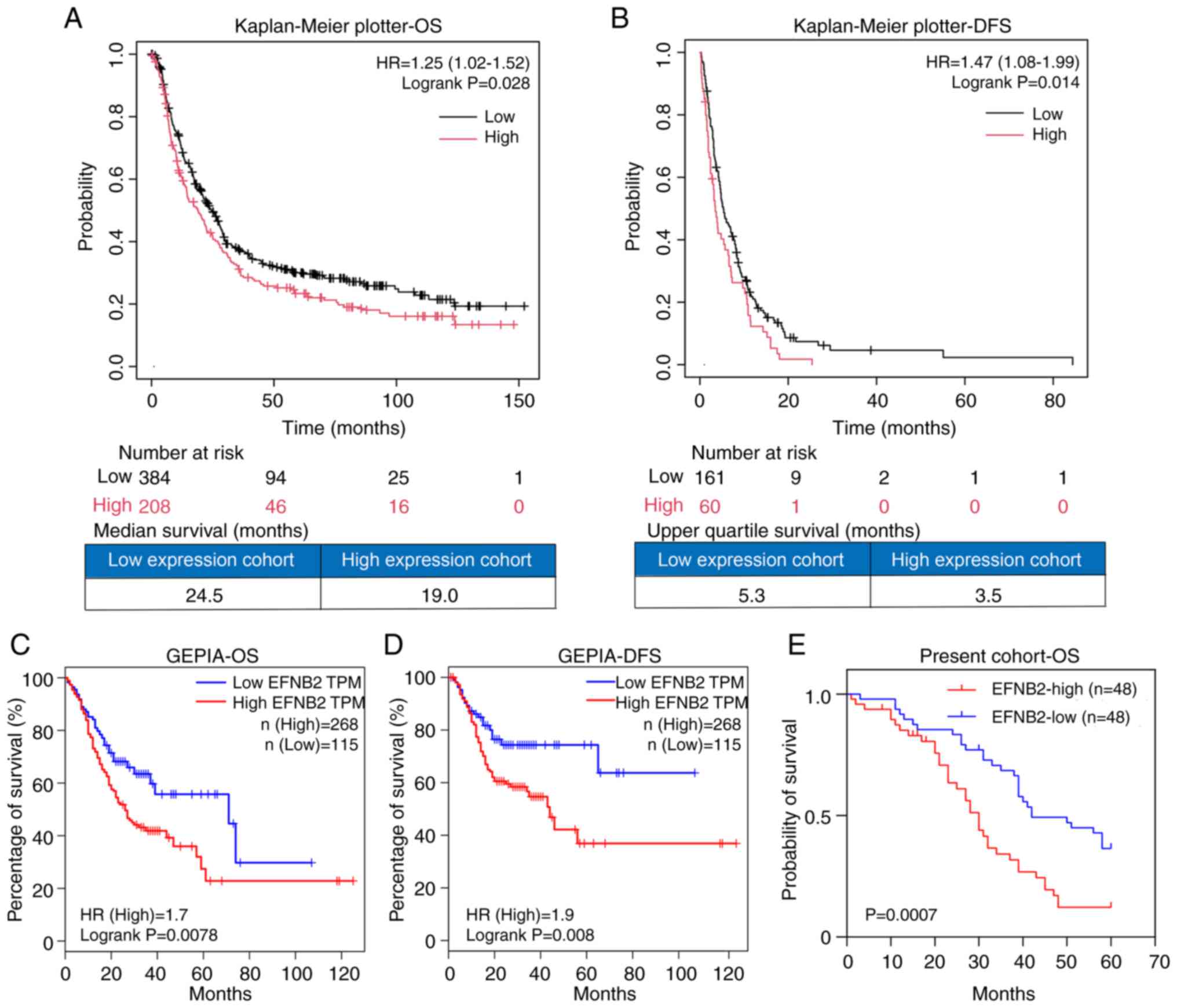

| Figure 2Upregulated EFNB2 expression is

associated with poor prognosis of patients with GC. The

Kaplan-Meier plotter demonstrated that EFNB2 was not only

associated with (A) OS (P=0.028), but also served as a negative

factor for (B) DFS in GC (P=0.014), when excluding the dataset

GSE62254. In the GEPIA database, the EFNB2-high expression group

exhibited shorter (C) OS and (D) DFS compared with the EFNB2-low

expression group, with the conditions set as 'Cutoff-High vs.

Cutoff-Low: 30 vs. 30' (P=0.0078 and 0.008, respectively). (E)

Analysis of the cohort of patients whose samples were included in

the tissue microarray (n=96) demonstrated that patients with GC

with high EFNB2 expression had a worse clinical outcome compared

with those with low EFNB2 expression (P=0.0007). OS, overall

survival; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; EFNB2,

ephrin-B2; GC, gastric cancer; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis; TPM, transcript per million. |

The univariate analysis revealed that EFNB2

expression, tumor size, T stage, M stage and TNM stage were

associated with the prognosis of patients with GC (Table II). These variables were

subsequently included in a Cox proportional hazards regression

model. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that only T stage

remained an independent adverse prognostic factor (Table II). Furthermore, subgroup

analysis of patients with GC demonstrated that high EFNB2

expression was associated with a worse prognosis in subgroups of

patients with the following characteristics: Age ≥60 years, male

sex, HP infection-positive, tumor location antrum, histological

G2-3 grade, T stage T3-T4, lymph node metastasis-positive, M stage

M0 and HER2-negative (Table

III; Fig. S2).

| Table IIUnivariate and multivariate analyses

for prognostic factors of gastric cancer. |

Table II

Univariate and multivariate analyses

for prognostic factors of gastric cancer.

| Parameters | Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (≥60 vs. <60

years) | 1.453

(0.896-2.355) | 0.130 | - | - |

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 1.113

(0.642-1.932) | 0.702 | - | - |

| Helicobacter

pylori infection (positive vs. negative) | 0.713

(0.413-1.229) | 0.223 | - | - |

| Tumor location

(cardia + gastric body vs. antrum) | 0.927

(0.549-1.565) | 0.776 | - | - |

| Histological grade

(G1 vs. G2-G3) | 1.151

(0.549-2.414) | 0.710 | - | - |

| Tumor size (≥4 vs.

<4 cm) | 2.315

(1.411-3.797) | 0.001a | 1.368

(0.687-2.726) | 0.373 |

| T stage (T1-T2 vs.

T3-T4) | 3.348

(1.695-6.614) | 0.001a | 2.385

(1.112-5.113) | 0.026a |

| Lymph node

metastasis (positive vs. negative) | 1.709

(0.971-3.008) | 0.063 | - | - |

| M stage (M0 vs.

M1) | 3.149

(1.687-5.880) | <0.001a | 1.731

(0.870-3.444) | 0.118 |

| TNM stage (I-II vs.

III-IV) | 2.813

(1.689-4.684) | <0.001a | 1.428

(0.741-2.751) | 0.287 |

| HER2 (positive vs.

negative) | 1.990

(0.851-4.651) | 0.112 | - | - |

| EFNB2 expression

(high vs. low) | 2.257

(1.381-3.689) | 0.001a | 1.300

(0.688-2.456) | 0.419 |

| Table IIIPrognostic relevance of EFNB2

expression in subgroups of patients with GC in which the worse

overall survival of patients with GC is significantly associated

with high EFNB2 expression. |

Table III

Prognostic relevance of EFNB2

expression in subgroups of patients with GC in which the worse

overall survival of patients with GC is significantly associated

with high EFNB2 expression.

| Subgroups | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age ≥60 years | 2.846 | 1.421-5.700 | 0.0032 |

| Male | 2.367 | 1.308-4.282 | 0.0044 |

| HP infection,

positive | 3.028 | 1.312-6.986 | 0.0094 |

| Tumor location,

antrum | 3.385 | 1.867-6.135 | <0.0001 |

| Histological grade,

G2-G3 | 2.825 | 1.639-4.868 | 0.0002 |

| T stage, T3-T4 | 2.166 | 1.261-3.719 | 0.0051 |

| Lymph node

metastasis, positive | 2.727 | 1.522-4.889 | 0.0008 |

| M stage, M0 | 2.493 | 1.381-4.500 | 0.0024 |

| HER2, negative | 2.548 | 1.465-4.433 | 0.0009 |

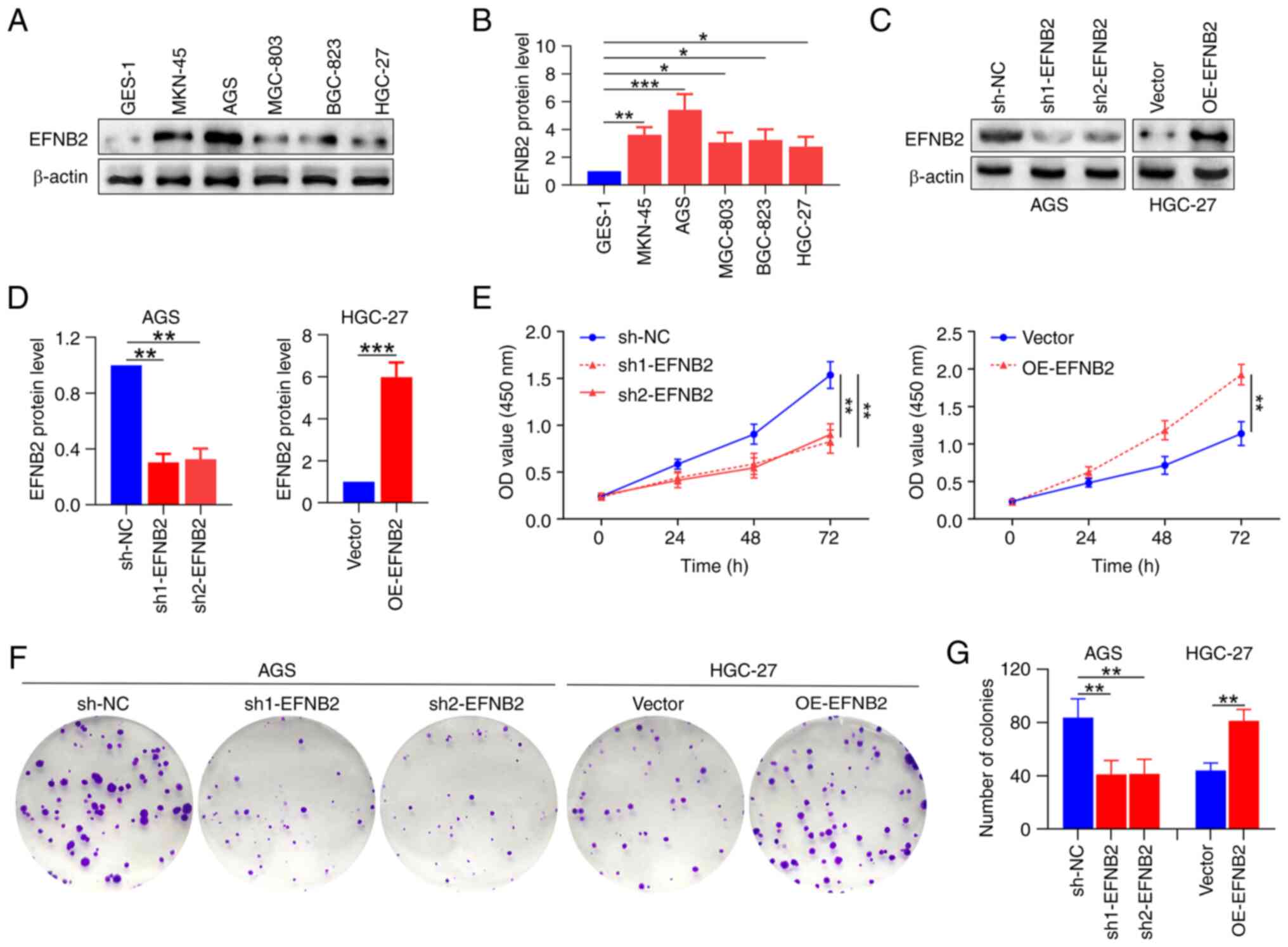

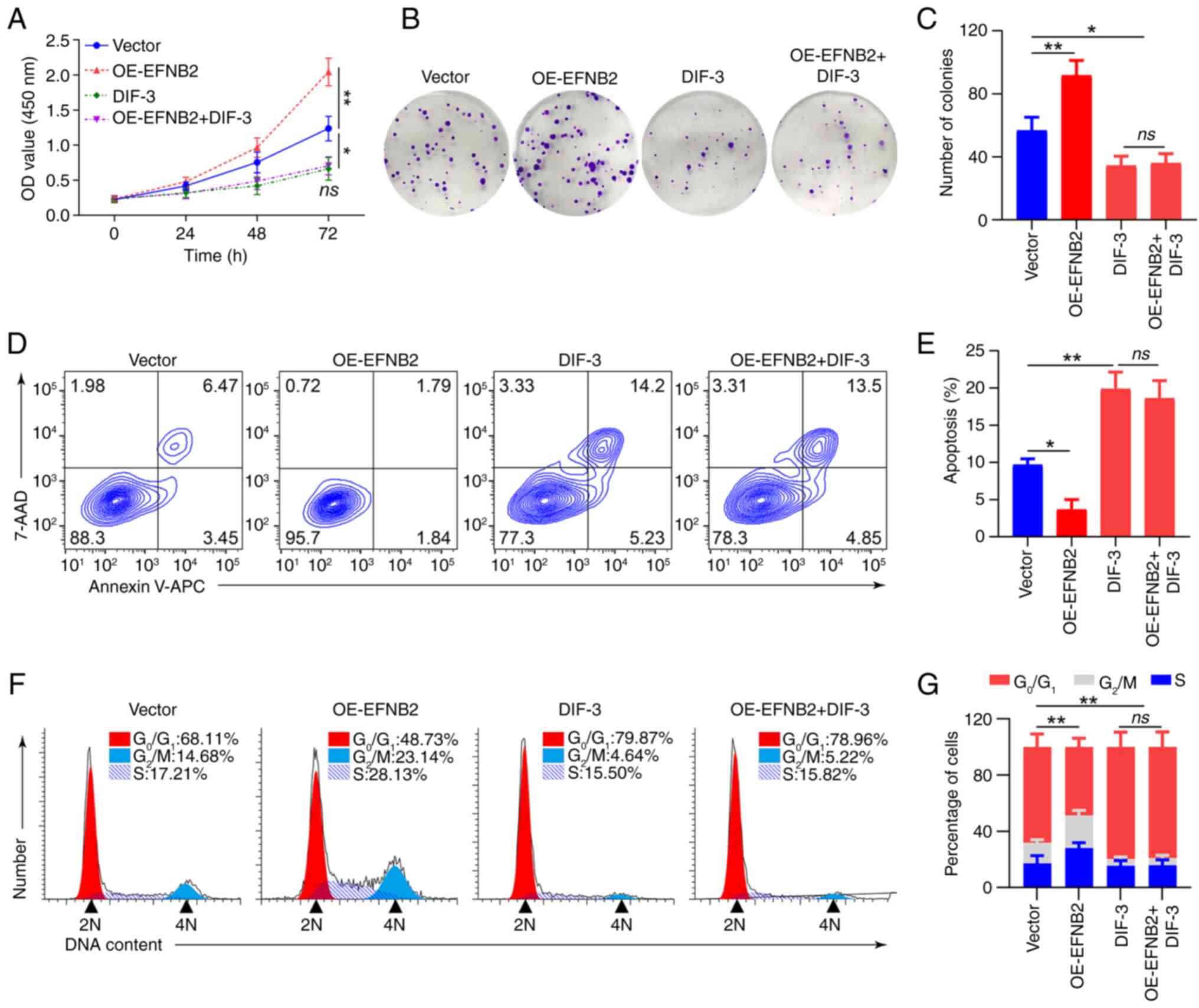

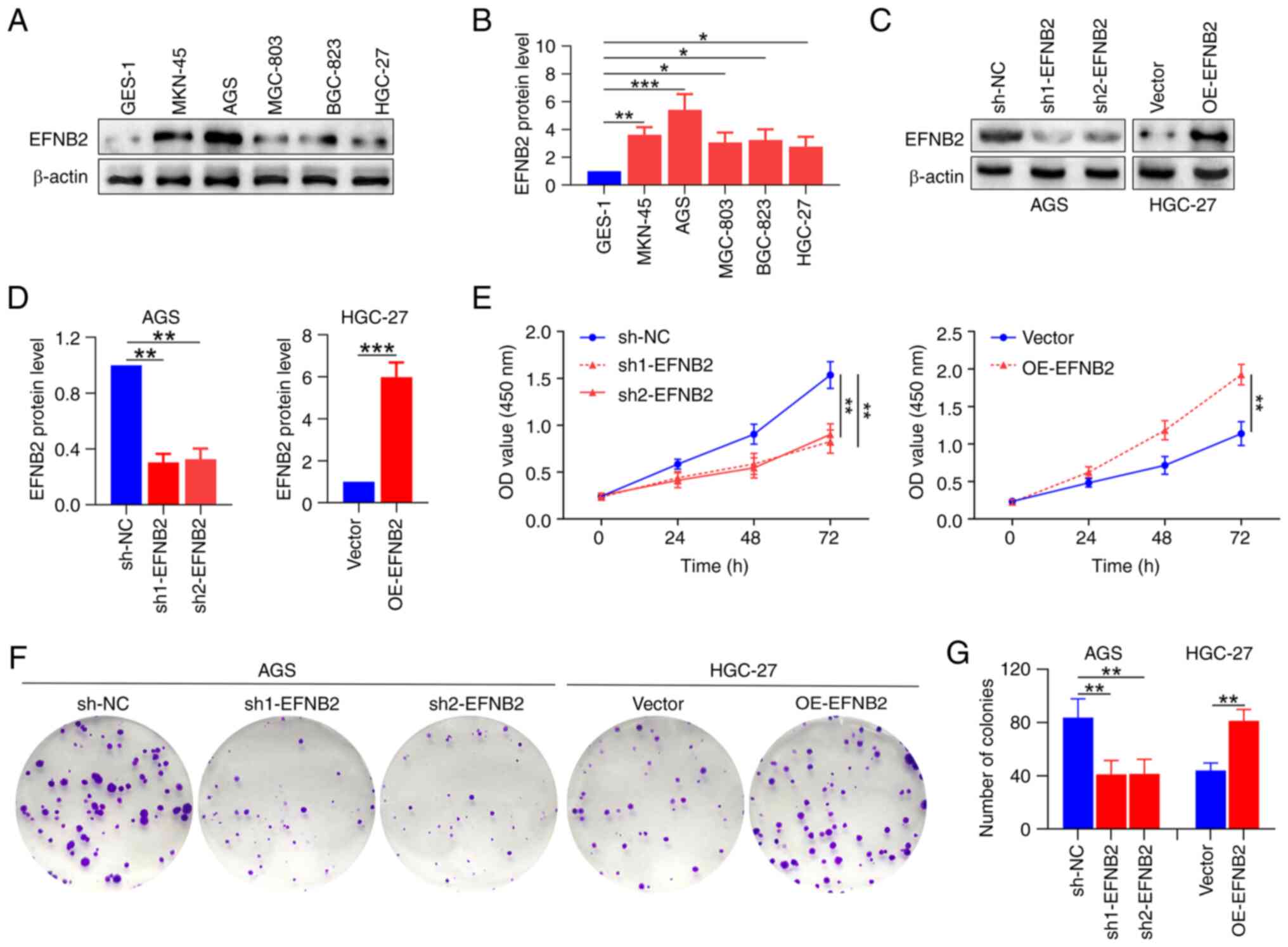

EFNB2 promotes proliferation, inhibits

apoptosis and alters the cell cycle distribution of GC cells in

vitro

To explore the roles of EFNB2 in GC cells, EFNB2

levels in various GC cell lines were measured. Compared with those

in human normal GES-1 cells, the expression levels of EFNB2 were

higher in multiple GC cell lines (Fig. 3A and B). For the subsequent

experiments, two cell lines were selected based on intrinsic EFNB2

expression levels: AGS cells (relatively high) and HGC27 cells

(relatively low). EFNB2 was then knocked down in the AGS cells and

overexpressed in the HGC27 cells using lentiviral transfection

(40). The successful stable

knockdown and overexpression of EFNB2 were verified at the protein

level (Fig. 3C and D). Analysis

of CCK-8 and colony formation assay data indicated that EFNB2

knockdown inhibited the proliferation and cell viability compared

with those in the NC group in AGS cells. Reciprocally, EFNB2

overexpression promoted these cellular properties in HGC-27 cells

(Fig. 3E-G). However, the

alteration of EFNB2 levels had a non-significant effect on cell

invasion and migration in GC cells (Fig. S3A-C). Additionally, analysis of

data from the TIMER database indicated that the infiltration of

CD8+ T cells and neutrophils in GC tissues was

negatively associated with EFNB2 expression levels, while a

non-significant relationship was found with the infiltration of

macrophages or dendritic cells (Fig.

S3D). These data indicated that EFNB2 serves a key role in the

malignant progression of GC.

| Figure 3EFNB2 promotes the proliferation and

viability of GC cells in vitro. (A) Representative western

blot bands. (B) Expression levels of EFNB2 were detected in

multiple GC cell lines and human GES-1 normal gastric mucosal

epithelial cells using western blotting (one-way ANOVA). (C)

Representative western blot bands. (D) The effects of EFNB2

knockdown and overexpression were verified by western blotting

(one-way ANOVA for AGS cells; unpaired Student's test for HGC-27

cells). (E) Cell Counting Kit-8 assays revealed the OD values at

450 nm after 0, 24, 48 and 72 h (one-way ANOVA). (F) Representative

colony formation assay images. (G) Colony formation was assessed by

counting the number of colonies in various groups (one-way ANOVA

for AGS cells; unpaired Student's test for HGC-27 cells). Data are

presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. GC, gastric

cancer; EFNB2, ephrin-B2; OD, optical density; OE, overexpression

vector; sh, short hairpin RNA; NC, negative control. |

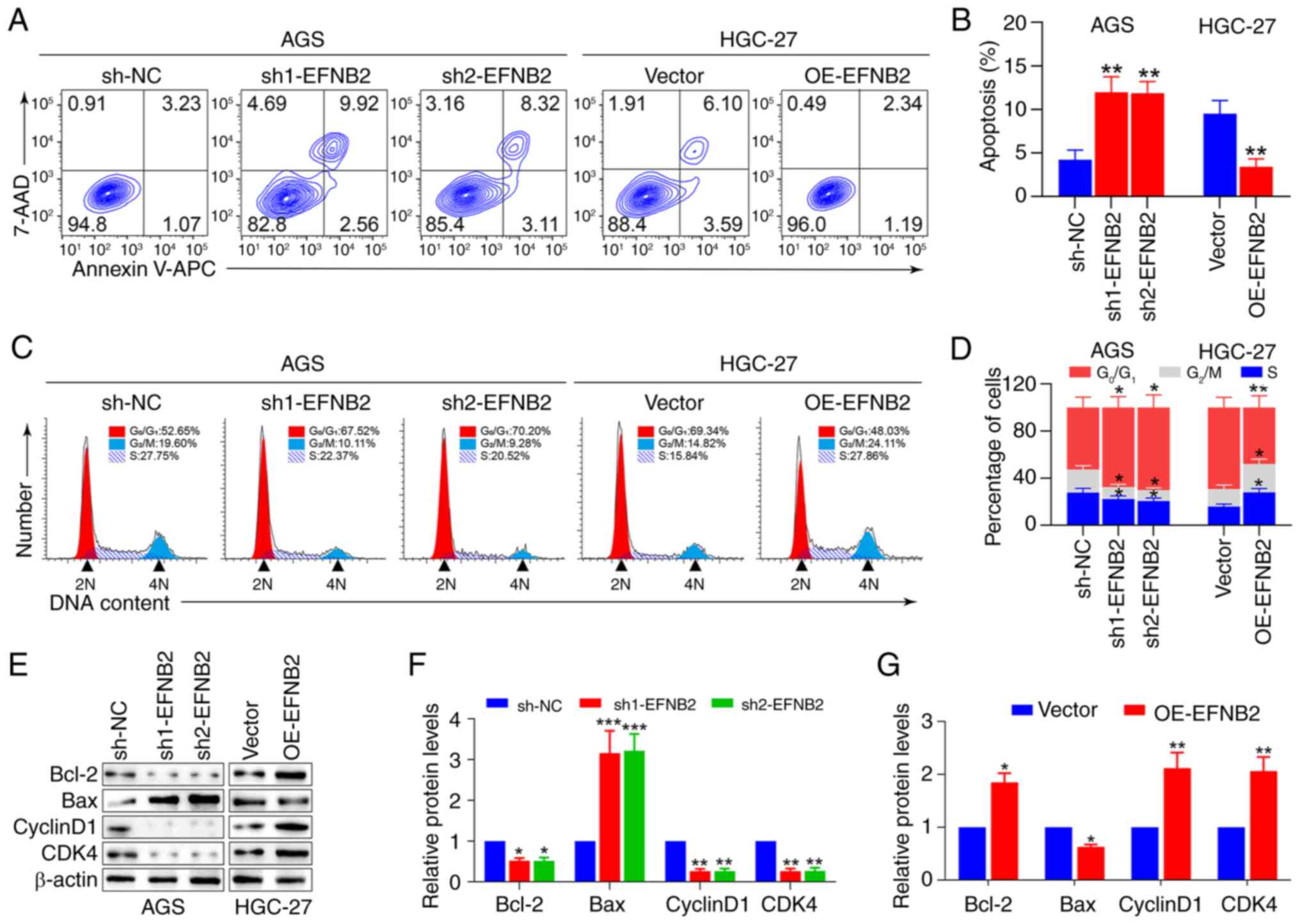

Apoptosis and cell cycle regulation were next

examined, as both are key factors influencing cell proliferation.

Flow cytometry and cell cycle analysis revealed that EFNB2

knockdown elevated the proportion of apoptotic cells and quiescent

period G0/G1 arrest, and decreased the

proportions of cells in the G2/M and S stages (Fig. 4A-D). Similarly, EFNB2

overexpression reduced the proportion of apoptotic cells and

quiescent period G0/G1 arrest, and increased

the proportions of cells in the G2/M and S stages

(Fig. 4A-D). Furthermore,

apoptosis-related and cell cycle-associated proteins were

evaluated. Analysis revealed that the expression levels of

anti-apoptosis factor Bcl-2 were decreased, whereas those of

pro-apoptosis protein Bax were elevated, and the levels of CyclinD1

and CDK4 were decreased following EFNB2 knockdown (Fig. 4E-G). Correspondingly, the level of

Bcl-2 was upregulated, while the level of Bax was downregulated,

and the expression levels of CyclinD1 and CDK4 were elevated

following EFNB2 overexpression (Fig.

4E-G). These findings indicated that EFNB2 facilitated cell

proliferation by reducing apoptosis and influencing the cell

cycle.

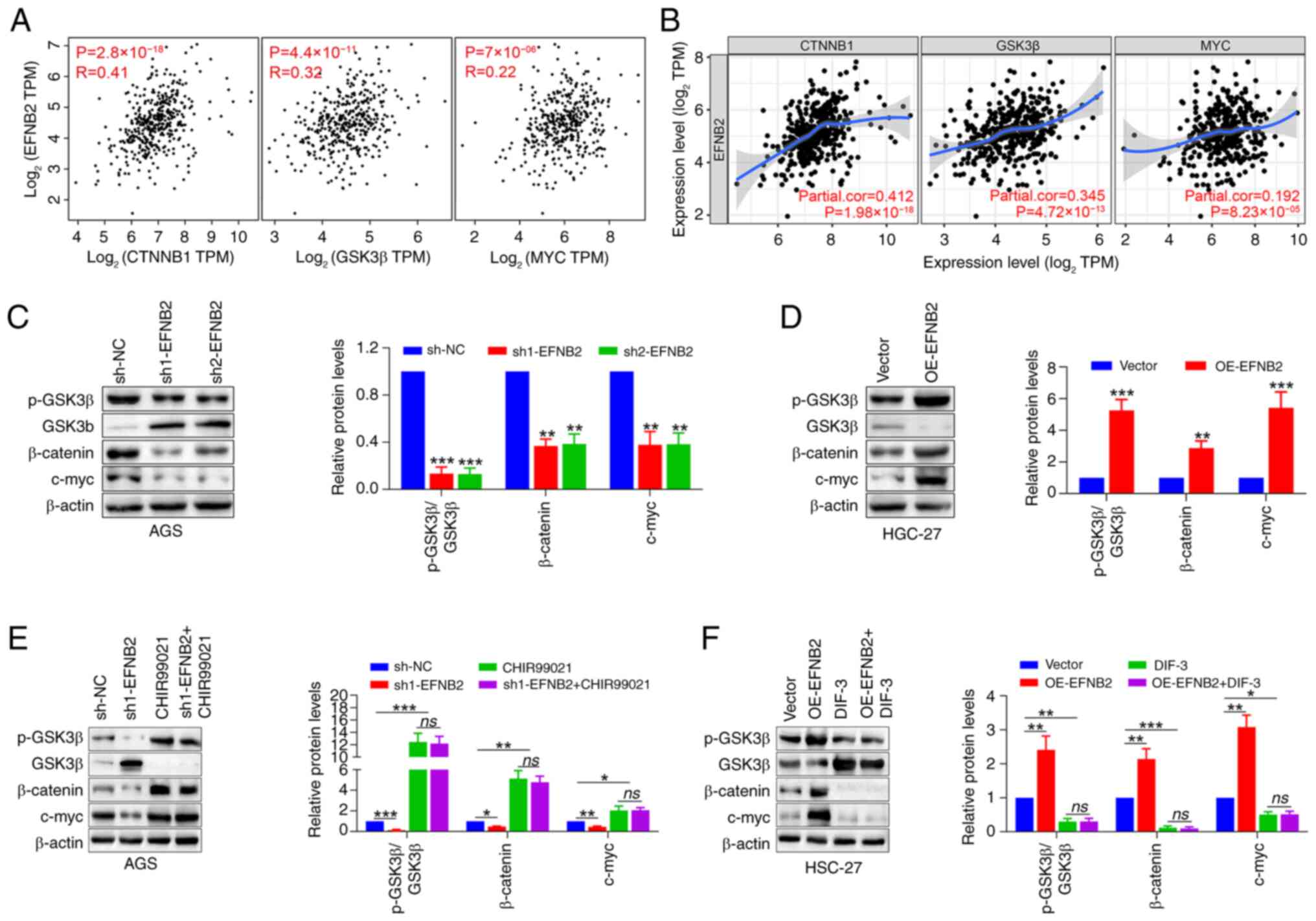

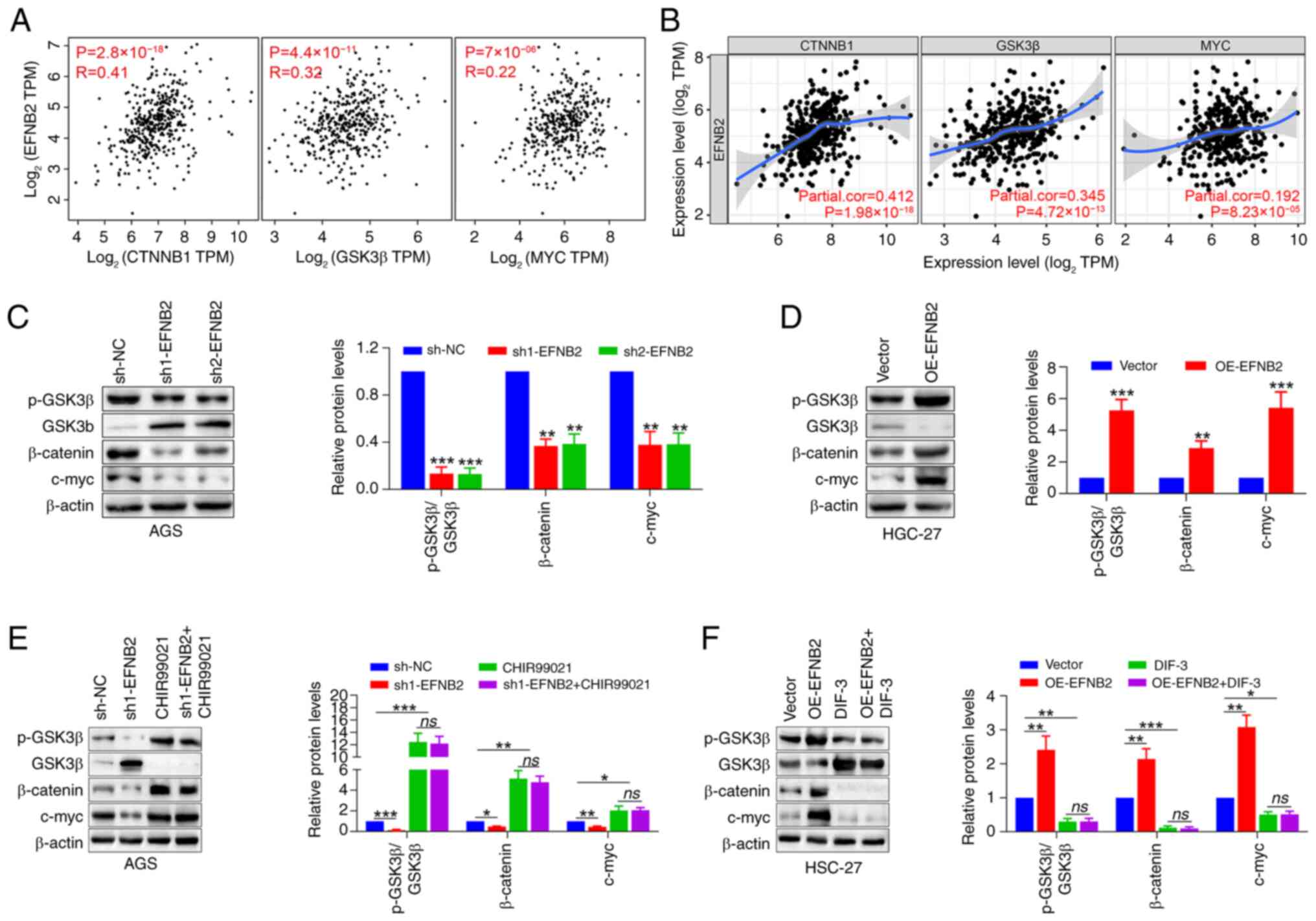

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is

responsible for EFNB2-mediated biological effects in GC cells

To further explore the potential mechanisms by which

EFNB2 promotes cell proliferation, the correlation modules of

public databases were explored. Data obtained from GEPIA and TIMER

databases demonstrated significant correlations between EFNB2

expression and the levels of GSK3β, catenin β1 and its downstream

effector MYC in GC (Fig. 5A and

B), suggesting EFNB2 may carry out a biological role via the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The independent GSE184336 dataset

(n=231) also confirmed the aforementioned associations (Fig. S3E). Emerging studies have

highlighted the frequent disruption of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway in GC, which is associated with aggressive tumor cell

proliferation and unfavorable outcomes (19,21,41). Subsequently, the changes in

Wnt/β-catenin pathway-associated proteins in response to modulated

EFNB2 expression were assessed. The findings demonstrated that

knockdown of EFNB2 decreased the p-GSK3β/GSK3β ratio, as well as

the protein levels of β-catenin and its downstream target c-myc

(Fig. 5C). Reciprocally, EFNB2

overexpression increased the p-GSK3β/GSK3β ratio and the expression

of β-catenin and downstream c-myc (Fig. 5D).

| Figure 5Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is

responsible for EFNB2-mediated biological effects in gastric cancer

cells. (A) Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis and (B)

Tumor Immune Estimation Resource databases were employed to explore

the transcriptional correlation between EFNB2 and CTNNB1, GSK3β and

downstream MYC (Spearman). Representative western blot bands and

semi-quantification of protein expression levels of p-GSK3β, GSK3β,

β-catenin and c-myc detected under the condition of EFNB2 (C)

knockdown and (D) overexpression (one-way ANOVA for AGS cells;

unpaired Student's test for HGC-27 cells). Representative western

blot bands and semi-quantification of protein expression levels in

the presence of (E) an agonist (CHIR99021) and (F) an inhibitor

(DIF-3) of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the EFNB2

knockdown or overexpression groups, respectively. Protein levels of

p-GSK3β, GSK3β, β-catenin and c-myc were detected by western

blotting (one-way ANOVA). Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 vs. sh-NC or vector group. ns, not

significant; NC, negative control; DIF-3, differentiation-inducing

factor-3; p-, phosphorylated; OE, overexpression vector; sh, short

hairpin RNA; CTNNB1, catenin β1; TPM, transcript per million;

EFNB2, ephrin-B2. |

Rescue experiments were conducted utilizing the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway agonist CHIR99021 and inhibitor

DIF-3. Western blotting revealed that CHIR99021 abolished the

inhibitory effect of EFNB2 knockdown on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway,

whereas DIF-3 abrogated the promoting effect of EFNB2

overexpression on this pathway (Fig.

5E and F). When the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was activated by

CHIR99021 or inhibited by DIF-3, EFNB2 lost its regulatory effect

on the pathway. Notably, DIF-3 eliminated the effects of EFNB2 on

proliferation, viability, apoptosis and cell cycle regulation in GC

cells (Fig. 6). These results

suggested that the biological functions of EFNB2 were dependent on

the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

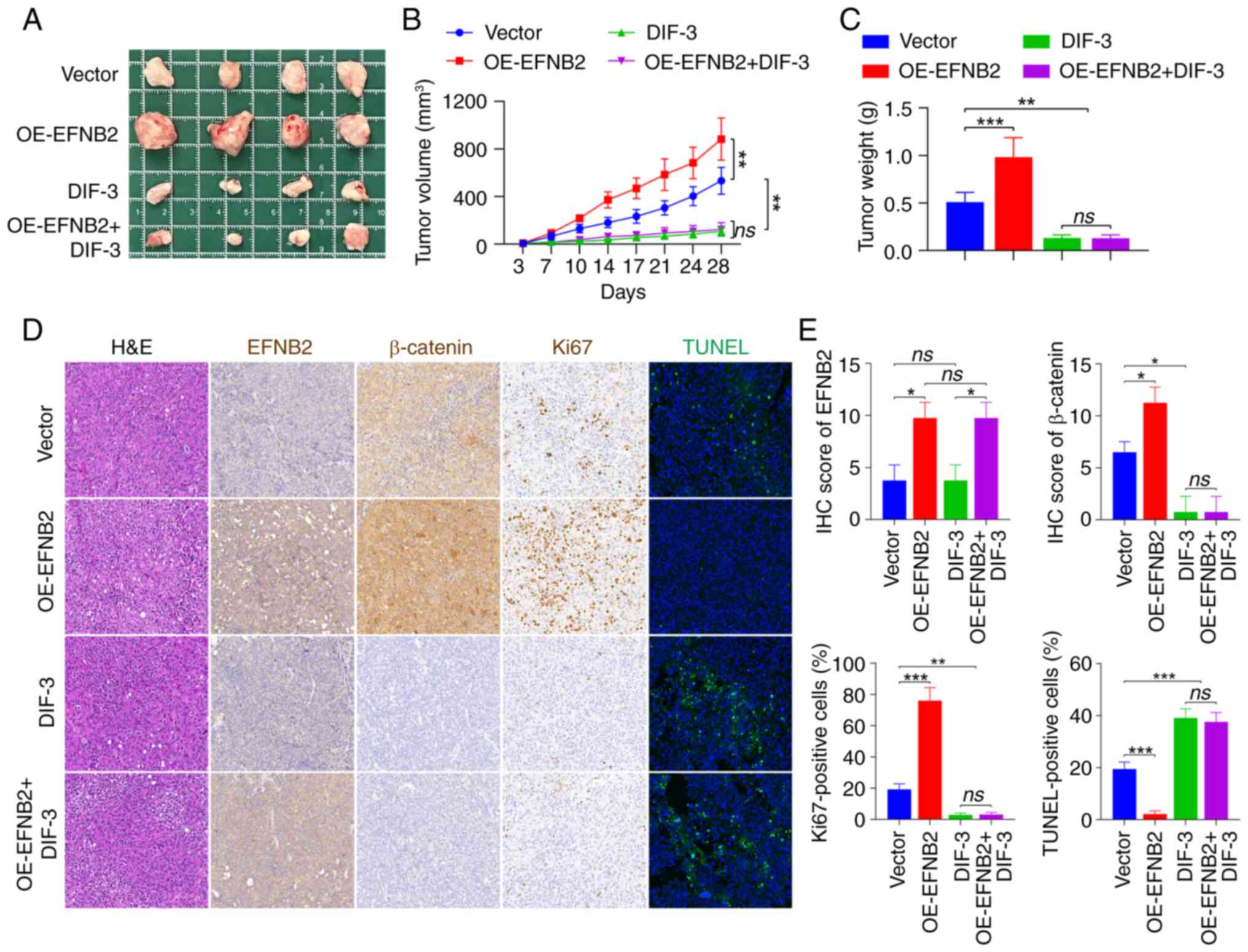

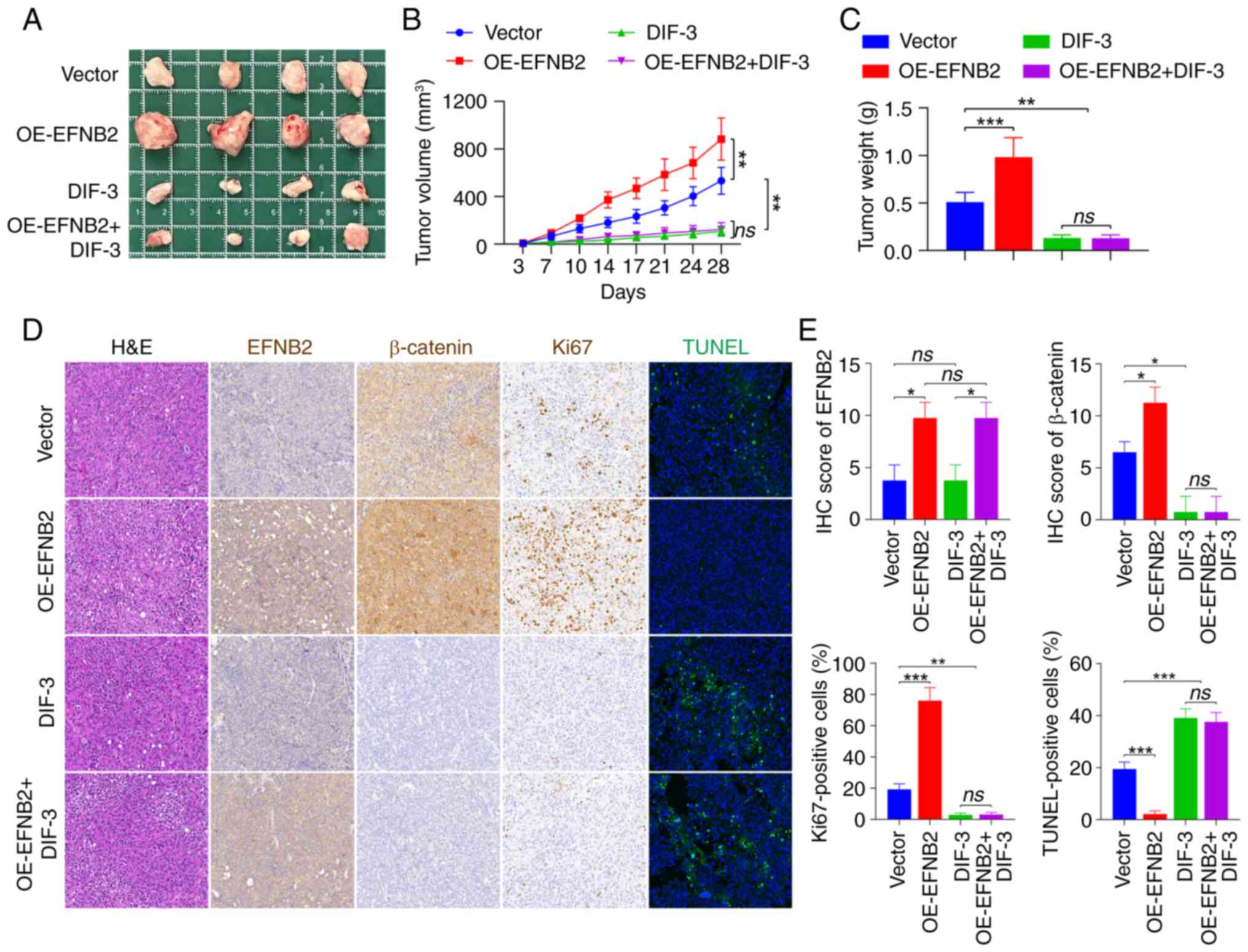

EFNB2 promotes the tumor growth of GC

through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in vivo

To further clarify whether elevated EFNB2 expression

could promote tumor growth in vivo, a CDX mouse model was

established by subcutaneously inoculating HGC-27 cell suspensions

into immunodeficient nude mice and tumor growth was monitored. At 4

weeks post-injection, the xenograft tumors of the EFNB2

overexpression group had a higher volume and weight compared with

those of the control group (Fig.

7A-C), suggesting that EFNB2 could effectively promote tumor

growth in vivo. Additionally, Wnt/β-catenin pathway

inhibitor DIF-3 successfully dampened GC progression and

counteracted the promoting effects of EFNB2 overexpression on tumor

growth in vivo (Fig.

7A-C). Subsequently, H&E and IHC staining were carried out

(Fig. 7D). The expression levels

of EFNB2 in xenograft tumors from CDX models in the EFNB2

overexpression group and the control group were assessed by IHC

staining (Fig. 7D and E). The

findings also demonstrated that DIF-3 abrogated the promoting

effect of EFNB2 overexpression on β-catenin (Fig. 7D and E). Furthermore, Ki67

staining was used to assess the proliferative state of tumor in

vivo. Compared with the control group, the proportion of

Ki67-positive cells in EFNB2 overexpression group was increased,

while DIF-3 eliminated the promoting effect of EFNB2 on

proliferation in CDX models (Fig. 7D

and E). TUNEL staining was used to evaluate the apoptotic

condition of tumors. The proportion of apoptosis was lower in the

EFNB2 overexpression group compared with the control group, while

DIF-3 reversed the inhibitory effect of EFNB2 on apoptosis in

vivo (Fig. 7D and E). These

data suggested that EFNB2 accelerated the tumor growth of GC via

the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in vivo.

| Figure 7EFNB2 promotes the tumor growth of

gastric cancer via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in

vivo. (A) Tumors from the immunodeficient nude mice in the four

experimental groups were excised and imaged. (B) Subcutaneous tumor

growth (mm3) was measured every 3-4 days following

various treatments (one-way ANOVA). (C) Excised tumor masses (g)

were weighed and compared across groups (one-way ANOVA). (D)

Histopathological evaluation of xenograft tumors included H&E

staining to examine tissue morphology, IHC analysis of EFNB2,

β-catenin and Ki67 expression, and TUNEL staining for apoptotic

cell evaluation. All images were captured at a magnification of

×200. (E) Quantification of IHC scores for EFNB2 and β-catenin, and

the percentage of positive cells for Ki67 and TUNEL staining

(Kruskal-Wallis H test for EFNB2 and β-catenin; one-way ANOVA for

Ki67 and TUNEL staining). Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. ns, not significant; EFNB2, ephrin-B2;

DIF-3, differentiation-inducing factor-3; OE, overexpression

vector; IHC, immunohistochemical. |

Discussion

The findings of the present study revealed a

significant upregulation of EFNB2 expression in GC tissues compared

with ANTs, which was inversely associated with patient prognosis,

as evidenced by analysis of multiple public databases and IHC

analysis of a TMA. Functional experiments indicated that EFNB2

knockdown suppressed cellular proliferation, induced apoptosis and

arrested cell cycle progression in vitro. By contrast,

overexpression of EFNB2 exhibited the opposite effect. Notably, the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was identified as a key mediator of

EFNB2-driven oncogenic processes in GC progression.

Accumulating clinical research supports EFNB2 as a

prognostic biomarker in multiple solid tumors (42-44). In head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma (HNSCC), increased EFNB2 expression has been identified

as an indicator of unfavorable clinical outcomes and reduced

therapeutic responsiveness (42).

Similarly, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), EFNB2

upregulation is inversely associated with patient survival

(43). Consistent with these

reports, the results of the present study demonstrated that

elevated EFNB2 expression was associated with a worse prognosis in

patients with GC. Notably, the consistent prognostic performance of

EFNB2 across different GC subgroups underscores its potential

clinical value in predicting the prognosis of patients with GC.

EFNB2 has emerged as a clinically relevant biomarker

across multiple malignancies, demonstrating distinct pathological

associations in various cancer types (42,43,45). In ESCC, transcriptional

upregulation of EFNB2 is associated with a family history of

esophageal cancer, advanced tumor stage and metastatic progression

(43). In HNSCC, elevated EFNB2

mRNA levels are largely found in human papillomavirus-negative

tumors arising from the oral cavity, especially in cases with

alcohol intake, TP53 mutations and EGFR amplification (42). In endometrial carcinoma, EFNB2

expression is associated with deep myometrial invasion >50%

(45). The present study

established a marked association between EFNB2 expression and

several GC parameters, including tumor size, T/M staging, TNM

classification and serum markers (CA199, CEA and CA50). However, no

statistically significant association with patient demographics

(age and sex), HP infection, tumor localization, histological

grade, nodal involvement and HER2 expression levels was observed.

Additionally, multivariate analysis demonstrated that only T stage

was an independent prognostic factor, while EFNB2 expression levels

did not reach statistical significance. These findings may be

attributed to the excessive number of variables included in the

analysis and the limited sample size, potentially leading to biased

estimates in the clinicopathological and prognostic assessments.

Future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate

these preliminary findings and obtain more reliable results.

Krusche et al (44) revealed that EFNB2 enhanced

perivascular invasion and proliferation in glioblastoma stem-like

cells by facilitating RhoA-mediated anchorage-independent

cytokinesis. In colorectal cancer with mutant p53, Alam et

al (15) reported that DNA

damage-induced EFNB2 reverse signaling contributed to

chemoresistance and promoted epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Conversely, EFNB2 could function as a tumor suppressor in specific

types of cancer. For instance, Magic et al (17) found that EFNB2 suppressed cell

proliferation and motility in vitro, and upregulated EFNB2

expression was associated with prolonged metastasis-free survival

in breast cancer. Similarly, Wang et al (46) observed that

EFNB2 decreased the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells.

The role of EFNB2 varies considerably with in different tumor

types, highlighting the need for further studies to fully

understand its complex functions.

The results of the present study indicated that

EFNB2 expression was significantly higher in GC cells and tissues,

and EFNB2 could increase cell survival and proliferation by

inhibiting apoptosis and accelerating the cell cycle. EFNB2

knockdown elevated Bax levels, while reducing Bcl-2 levels, whereas

EFNB2 overexpression exhibited the opposite effect. Bax and Bcl-2

are key regulators of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (39,47), functioning by accumulating in the

mitochondrial outer membrane to modulate its permeability (47). The balance between Bax-mediated

pro-apoptotic signals and Bcl-2-mediated anti-apoptotic signals is

important for maintaining cellular apoptosis homeostasis (40,47). Dysregulation of EFNB2 disturbed

the Bcl-2/Bax equilibrium, resulting in altered apoptotic activity.

EFNB2 downregulation decreased the levels of cell cycle-related

proteins CDK4 and CyclinD1, while EFNB2 overexpression increased

their expression. CyclinD1 and CDK4 serve a key role in the

G1-to-S-phase transition by forming a complex that

drives cell cycle progression, thereby fueling cellular

proliferation and tumor growth (48,49). Collectively, these alterations in

protein levels point to an underlying change in the proliferative

capacity of GC cells following EFNB2 dysregulation.

Previous studies have identified the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway as a key regulator in the progression of GC

(50-52) The nuclear translocation of

β-catenin activates multiple transcription factors, initiating

downstream signaling networks and driving the expression of

multiple proteins, including c-myc (51). Conversely, GSK3β serves a

counteracting role by phosphorylating β-catenin, which accelerates

its degradation and inhibits the transcriptional activity of

β-catenin target genes within the nucleus (52). Additionally, the oncogenic

transcription factor c-myc is dysregulated in >70% of different

types of human cancer, where it drives tumorigenesis by modulating

key cellular functions (53). As

a transcriptional regulator, it directly controls ~15% of genomic

targets, including key cell cycle components such as CyclinD1 and

CDK4, thereby orchestrating cellular proliferation, differentiation

and apoptosis (53). The present

study demonstrated that EFNB2 knockdown decreased the

phosphorylation of GSK3β, reduced β-catenin protein levels and

inhibited β-catenin-mediated c-myc expression, ultimately impairing

the proliferative capacity of GC cells. Conversely, EFNB2

overexpression exerted the opposite effects. EFNB2 could not only

regulate p-GSK3β levels but also directly influenced the levels of

total GSK3β. Although the opposite trends observed in GSK3β and

p-GSK3β levels further support the conclusions, the exact molecular

mechanism underlying these effects remains to be elucidated.

Rescue experiments offered additional evidence that

EFNB2 regulated GC cell proliferation, apoptosis and the cell cycle

via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. These in vitro

results were further validated using CDX murine models, which

substantiated the involvement of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in

EFNB2-mediated effects. Notably, although previous studies have

suggested that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is involved in GC metastasis

(54,55), the data in the present did not

reveal a notable effect of EFNB2 expression on the migration and

invasion of GC cells. This may be attributed to the involvement of

other signaling pathways that counteract the effects of the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway on migration and invasion. This observation

further underscores the complexity of the downstream signaling

networks of EFNB2, and the specific mechanisms involved require

further investigation.

In summary, the expression levels of EFNB2 were

higher in GC tissues compared with ANTs, and were associated with

an unfavorable clinical prognosis in patients with GC. EFNB2

effectively regulated cell proliferation, apoptosis and the cell

cycle in GC in vitro. Furthermore, EFNB2 promoted the tumor

growth and malignant progression of GC in vivo.

Mechanistically, EFNB2 exerted its oncogenic effects by activating

the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Consequently, EFNB2 may be a

potential molecular target for the treatment of GC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DD contributed to writing the original draft, data

visualization, experimental design and implementation. XW, RX, RL

and YZ contributed to experimental design and implementation, data

visualization, and writing, review and editing. ZW contributed to

supervision, project administration, and analysis and

interpretation of data. DD and ZW confirmed the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal procedures were carried out according to

the protocol approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the First

Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval no.

LLSC20240221; Hefei, China). The human tissue microarray was

purchased from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd. (HStmA180Su32)

after the approval of the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval no. 2024137; Hefei,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Scientific Research Fund

Project of Anhui Medical University (grant no. 2023xkj225) and Key

Natural Science Project of Anhui Provincial Universities (grant no.

2023AH053303).

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chen YC, Malfertheiner P, Yu HT, Kuo CL,

Chang YY, Meng FT, Wu YX, Hsiao JL, Chen MJ, Lin KP, et al: Global

prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection and incidence of

gastric cancer between 1980 and 2022. Gastroenterology.

166:605–619. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Onoyama T, Ishikawa S and Isomoto H:

Gastric cancer and genomics: Review of literature. J Gastroenterol.

57:505–516. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Qiu H, Cao S and Xu R: Cancer incidence,

mortality, and burden in China: A time-trend analysis and

comparison with the United States and United Kingdom based on the

global epidemiological data released in 2020. Cancer Commun (Lond).

41:1037–1048. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Guan WL, He Y and Xu RH: Gastric cancer

treatment: Recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol

Oncol. 16:572023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pasquale EB: Eph receptors and ephrins in

cancer: Bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer.

10:165–180. 2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Iida H, Honda M, Kawai HF, Yamashita T,

Shirota Y, Wang BC, Miao H and Kaneko S: Ephrin-A1 expression

contributes to the malignant characteristics of {alpha}-fetoprotein

producing hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 54:843–851. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nakada M, Drake KL, Nakada S, Niska JA and

Berens ME: Ephrin-B3 ligand promotes glioma invasion through

activation of Rac1. Cancer Res. 66:8492–8500. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hirai H, Maru Y, Hagiwara K, Nishida J and

Takaku F: A novel putative tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by the

eph gene. Science. 238:1717–1720. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Piffko A, Uhl C, Vajkoczy P, Czabanka M

and Broggini T: EphrinB2-EphB4 signaling in neurooncological

disease. Int J Mol Sci. 23:16792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rutkowski R, Mertens-Walker I, Lisle JE,

Herington AC and Stephenson SA: Evidence for a dual function of

EphB4 as tumor promoter and suppressor regulated by the absence or

presence of the ephrin-B2 ligand. Int J Cancer. 131:E614–E624.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Piffko A, Broggini T, Harms C, Adams RH,

Vajkoczy P and Czabanka M: Ligand-dependent and ligand-independent

effects of Ephrin-B2-EphB4 signaling in melanoma metastatic spine

disease. Int J Mol Sci. 22:80282021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Dai B, Shi X, Ma N, Ma W, Zhang Y, Yang T,

Zhang J and He L: HMQ-T-B10 induces human liver cell apoptosis by

competitively targeting EphrinB2 and regulating its pathway. J Cell

Mol Med. 22:5231–5243. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhong S, Pei D, Shi L, Cui Y and Hong Z:

Ephrin-B2 inhibits Aβ25-35-induced apoptosis by alleviating

endoplasmic reticulum stress and promoting autophagy in HT22 cells.

Neurosci Lett. 704:50–56. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Alam SK, Yadav VK, Bajaj S, Datta A, Dutta

SK, Bhattacharyya M, Bhattacharya S, Debnath S, Roy S, Boardman LA,

et al: DNA damage-induced ephrin-B2 reverse signaling promotes

chemoresistance and drives EMT in colorectal carcinoma harboring

mutant p53. Cell Death Differ. 23:707–722. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Zhu F, Dai SN, Xu DL, Hou CQ, Liu TT, Chen

QY, Wu JL and Miao Y: EFNB2 facilitates cell proliferation,

migration, and invasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via the

p53/p21 pathway and EMT. Biomed Pharmacother. 125:1099722020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Magic Z, Sandström J and Perez-Tenorio G:

Ephrin-B2 inhibits cell proliferation and motility in vitro and

predicts longer metastasis-free survival in breast cancer. Int J

Oncol. 55:1275–1286. 2019.

|

|

18

|

Zhang Y, Zhang R, Ding X and Ai K: EFNB2

acts as the target of miR-557 to facilitate cell proliferation,

migration and invasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by

bioinformatics analysis and verification. Am J Transl Res.

10:3514–3528. 2018.

|

|

19

|

Akhavanfar R, Shafagh SG, Mohammadpour B,

Farahmand Y, Lotfalizadeh MH, Kookli K, Adili A, Siri G and Eshagh

Hosseini SM: A comprehensive insight into the correlation between

ncRNAs and the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway in gastric cancer

pathogenesis. Cell Commun Signal. 21:1662023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Clevers H: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in

development and disease. Cell. 127:469–480. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Mirabelli CK, Nusse R, Tuveson DA and

Williams BO: Perspectives on the role of Wnt biology in cancer. Sci

Signal. 12:eaay44942019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lien WH and Fuchs E: Wnt some lose some:

Transcriptional governance of stem cells by Wnt/β-catenin

signaling. Genes Dev. 28:1517–1532. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C and

Zhang Z: GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression

profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:W98–W102.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Vasaikar SV, Straub P, Wang J and Zhang B:

LinkedOmics: Analyzing multi-omics data within and across 32 cancer

types. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:D956–D963. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Győrffy B: Survival analysis across the

entire transcriptome identifies biomarkers with the highest

prognostic power in breast cancer. Comput Struct Biotechnol J.

19:4101–4109. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu

JS, Li B and Liu XS: TIMER: A web server for comprehensive analysis

of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 77:e108–e110. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cristescu R, Lee J, Nebozhyn M, Kim KM,

Ting JC, Wong SS, Liu J, Yue YG, Wang J, Yu K, et al: Molecular

analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with

distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. 21:449–456. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kim HK, Choi IJ, Kim CG, Kim HS, Oshima A,

Michalowski A and Green JE: A gene expression signature of acquired

chemoresistance to cisplatin and fluorouracil combination

chemotherapy in gastric cancer patients. PLoS One. 6:e166942011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ooi CH, Ivanova T, Wu J, Lee M, Tan IB,

Tao J, Ward L, Koo JH, Gopalakrishnan V, Zhu Y, et al: Oncogenic

pathway combinations predict clinical prognosis in gastric cancer.

PLoS Genet. 5:e10006762009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Förster S, Gretschel S, Jöns T, Yashiro M

and Kemmner W: THBS4, a novel stromal molecule of diffuse-type

gastric adenocarcinomas, identified by transcriptome-wide

expression profiling. Mod Pathol. 24:1390–1403. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wang G, Hu N, Yang HH, Wang L, Su H, Wang

C, Clifford R, Dawsey EM, Li JM, Ding T, et al: Comparison of

global gene expression of gastric cardia and noncardia cancers from

a high-risk population in china. PLoS One. 8:e638262013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Busuttil RA, George J, Tothill RW,

Ioculano K, Kowalczyk A, Mitchell C, Lade S, Tan P, Haviv I and

Boussioutas A: A signature predicting poor prognosis in gastric and

ovarian cancer represents a coordinated macrophage and stromal

response. Clin Cancer Res. 20:2761–2772. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cheng L, Yang S, Yang Y, Zhang W, Xiao H,

Gao H, Deng X and Zhang Q: Global gene expression and functional

network analysis of gastric cancer identify extended pathway maps

and GPRC5A as a potential biomarker. Cancer Lett. 326:105–113.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lou S, Zhang J, Yin X, Zhang Y, Fang T,

Wang Y and Xue Y: Comprehensive characterization of tumor purity

and its clinical implications in gastric cancer. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:7825292022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

35

|

Fang C, Wang W, Deng JY, Sun Z, Seeruttun

SR, Wang ZN, Xu HM, Liang H and Zhou ZW: Proposal and validation of

a modified staging system to improve the prognosis predictive

performance of the 8th AJCC/UICC pTNM staging system for gastric

adenocarcinoma: A multicenter study with external validation.

Cancer Commun (Lond). 38:672018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu Q, Li Y, Niu Z, Zong Y, Wang M, Yao L,

Lu Z, Liao Q and Zhao Y: Atorvastatin (Lipitor) attenuates the

effects of aspirin on pancreatic cancerogenesis and the

chemotherapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine on pancreatic cancer by

promoting M2 polarized tumor associated macrophages. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 35:332016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Shen J, Cao B, Wang Y, Ma C, Zeng Z, Liu

L, Li X, Tao D, Gong J and Xie D: Hippo component YAP promotes

focal adhesion and tumour aggressiveness via transcriptionally

activating THBS1/FAK signalling in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 37:1752018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang Y, Liu Q, Liu J and Liao Q:

Upregulated CD58 is associated with clinicopathological

characteristics and poor prognosis of patients with pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 21:3272021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

39

|

Zhang Y, Liu Q, Yang S and Liao Q:

Knockdown of LRRN1 inhibits malignant phenotypes through the

regulation of HIF-1α/notch pathway in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 23:51–64. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhang Y, Zhang R, Luo G and Ai K: Long

noncoding RNA SNHG1 promotes cell proliferation through PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Cancer.

9:2713–2722. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Han R, Yang J, Zhu Y and Gan R: Wnt

signaling in gastric cancer: Current progress and future prospects.

Front Oncol. 14:14105132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Oweida A, Bhatia S, Hirsch K, Calame D,

Griego A, Keysar S, Pitts T, Sharma J, Eckhardt G, Jimeno A, et al:

Ephrin-B2 overexpression predicts for poor prognosis and response

to therapy in solid tumors. Mol Carcinog. 56:1189–1196. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ni Q, Chen P, Zhu B, Li J, Xie D and Ma X:

Expression levels of EPHB4, EFNB2 and caspase-8 are associated with

clinicopathological features and progression of esophageal squamous

cell cancer. Oncol Lett. 19:917–929. 2020.

|

|

44

|

Krusche B, Ottone C, Clements MP,

Johnstone ER, Goetsch K, Lieven H, Mota SG, Singh P, Khadayate S,

Ashraf A, et al: EphrinB2 drives perivascular invasion and

proliferation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Elife. 5:e148452016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Takai N, Miyazaki T, Fujisawa K, Nasu K

and Miyakawa I: Expression of receptor tyrosine kinase EphB4 and

its ligand ephrin-B2 is associated with malignant potential in

endometrial cancer. Oncol Rep. 8:567–573. 2001.

|

|

46

|

Wang L, Peng Q, Sai B, Zheng L, Xu J, Yin

N, Feng X and Xiang J: Ligand-independent EphB1 signaling mediates

TGF-β-activated CDH2 and promotes lung cancer cell invasion and

migration. J Cancer. 11:4123–4131. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

47

|

Peña-Blanco A and García-Sáez AJ: Bax, Bak

and beyond-mitochondrial performance in apoptosis. FEBS J.

285:416–431. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Tchakarska G and Sola B: The double

dealing of cyclin D1. Cell Cycle. 19:163–178. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Ziegler DV, Parashar K and Fajas L: Beyond

cell cycle regulation: The pleiotropic function of CDK4 in cancer.

Semin Cancer Biol. 98:51–63. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Koushyar S, Powell AG, Vincan E and Phesse

TJ: Targeting Wnt signaling for the treatment of gastric cancer.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:39272020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang

X, Zhou Z, Shu G and Yin G: Wnt/β-catenin signalling: Function,

biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 7:32022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Zhang Y and Wang X: Targeting the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J Hematol Oncol.

13:1652020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Madden SK, de Araujo AD, Gerhardt M,

Fairlie DP and Mason JM: Taking the Myc out of cancer: Toward

therapeutic strategies to directly inhibit c-Myc. Mol Cancer.

20:32021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Xue W, Yang L, Chen C, Ashrafizadeh M,

Tian Y and Sun R: Wnt/β-catenin-driven EMT regulation in human

cancers. Cell Mol Life Sci. 81:792024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wu C, Zhuang Y, Jiang S, Liu S, Zhou J, Wu

J, Teng Y, Xia B, Wang R and Zou X: Interaction between

Wnt/β-catenin pathway and microRNAs regulates

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer (review). Int J

Oncol. 48:2236–2246. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|