Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor

among women worldwide (1). In

clinical practice, immunohistochemical results are often used to

define the four breast cancer subtypes, including luminal A,

luminal B, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-enriched

and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (2). Luminal A is characterized by high

expression of the estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor

(PR) as well as low expression of Ki67 and is HER2-negative,

indicating slower cell growth and improved prognosis. Luminal B

tumors are ER-positive and PR-positive, but they can be either

HER2-positive or HER2-negative. They exhibit higher levels of Ki67,

which indicates faster cell growth. HER2-enriched cancer is

ER-negative and PR-negative and exhibits high Ki67 levels,

indicating that the tumor is highly aggressive. TNBC lacks the

expression of HER2, ER and PR, and is clinically recognized as the

most therapeutically recalcitrant breast cancer subtype (3). Due to the notable invasiveness and

high recurrence and metastasis rates of TNBC, chemotherapy

resistance often develops during treatment, leading to a poor

prognosis following conventional chemotherapy (4). Consequently, it is essential to

further develop effective antitumor drugs with low toxicity that

can reverse drug resistance.

Autophagy is a cellular biological process in which

cells degrade dysfunctional organelles or unnecessary components

through autophagosomes, subsequently recycling the nutrients for

their growth (5). Previous

research has identified autophagy as a promising therapeutic target

in the treatment of cancer, and an increasing body of evidence

supports that blocking autophagy can effectively inhibit the growth

and progression of advanced tumors (6,7).

In recent years, research has focused on targeting the various

pathways involved in tumor progression, including the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

and cyclin D/CDK/retinoblastoma protein pathways (8,9).

In this respect, autophagy inhibition has been demonstrated to

enhance chemotherapeutic responsiveness.

Research indicates that metastatic cell lines have

higher levels of basal autophagy compared with non-metastatic cell

lines, suggesting that autophagy may enhance the invasiveness of

tumor cells (10,11). High expression of

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) has been

linked to tumor progression and poor outcomes in TNBC,

demonstrating its potential as a prognostic biomarker for this

disease (10). Furthermore, the

knockout of autophagy-related genes, specifically LC3, has been

shown to inhibit autophagy, leading to a marked decrease in cell

proliferation, colony formation and migratory/invasive

capabilities, while also promoting apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cell

lines (12). Overall, autophagy

is essential for the survival of tumor cells (8). At present, the only autophagy

inhibitors available for clinical application are chloroquine (CQ)

and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ). However, these agents are associated

with retinotoxicity and cardiotoxicity (13). Therefore, it is essential to

further search for autophagy inhibitors with low toxicity that

exhibit enhanced specificity.

Immune checkpoint molecules play a key role in the

antitumor immune response. Cancer cells frequently exploit these

mechanisms to evade immune surveillance, thereby facilitating

cancer progression and contributing to treatment resistance

(14). Immune checkpoint

inhibitors regulate the TME through various mechanisms to exert

their anticancer effects. With the development of cancer

immunotherapy, targeting programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) or

programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathways can enhance antitumor

immune activity and inhibit cancer cell proliferation (9). However, the low response rate of

antitumor immunotherapy limits its efficacy (15). Furthermore, autophagy is a

critical factor in tumor immunotherapy and interacts with immune

cells to regulate therapeutic effects (16). Autophagy has been demonstrated to

play a notable role in T cell activation and memory

differentiation, and it can influence the immunogenicity of tumor

cell death (17,18). In summary, cytoprotective

autophagy and the immunosuppressive TME have been recognized as

notable barriers. Consequently, the development of novel drugs that

inhibit autophagy and possess immunomodulatory effects, or the use

of multi-drug combinations, may further enhance therapeutic

efficacy.

Inhibiting autophagy while modulating the antitumor

immune response holds potential for effective tumor suppression.

Small molecule compounds have demonstrated advantages for

tumor-targeting therapy. These small molecule compounds can be

easily modified to become more suitable for clinical needs, and

their synthesis cost is low and easy to promote, which makes them

hot spots in the current research of tumor-targeting therapy

(9,19). LLY-507, a selective small-molecule

inhibitor of SET and MYND domain-containing protein 2 (SMYD2), has

been extensively validated for its mechanism of action and

antitumor properties. LLY-507 exhibits submicromolar potency

against SMYD2 in various cancer cell lines (such as esophageal

squamous carcinoma, bladder carcinoma gastric cancer cell lines) by

occupying the peptide-binding groove of SMYD2 (20-23). However, the impact of LLY-507

derivatives and their synthetic intermediates on tumor cell

autophagy and immune modulation remains unexplored.

In the present study, a series of LLY-507

derivatives, including 26 intermediates, were screened. Through the

mRFP-GFP-LC3 fluorescence tandem assay, CYTO-ID assay,

monodansylcadaverine (MDC) staining and protein-level detection of

LC3, the intermediate compound FZU-0045-053 (053) in the synthesis

process of LLY-507 derivatives was preliminarily screened as having

autophagy-regulating effects on breast cancer cells. To capture the

spectrum of breast cancer heterogeneity, two representative cell

lines were selected: MDA-MB-231 as a triple-negative

(ER−/PR−/HER2−) basal-like subtype

and MCF-7 as a hormone receptor-positive

(ER+/PR+) luminal subtype. This dual-model

system provides a critical platform for mechanistic studies, drug

discovery and personalized therapy development by encompassing both

treatment-responsive and therapy-resistant phenotypes. At the

cellular level, the effects of compound 053 on key autophagy

markers were validated to elucidate its regulatory mechanism on

autophagy in breast cancer cells. Apoptosis and proliferation

assays were used to verify whether the combination of 053 and

chemotherapy drugs could reverse chemotherapy resistance. The PD-L1

levels of tumor cells and the co-stimulatory or co-inhibitory

molecules on the surface of T cells were detected to evaluate the

effect of compound 053 on the immune response. Additionally, an

MDA-MB-231 xenograft model was established to evaluate the

antitumor and autophagy-regulating effects of 053± gemcitabine

(GEM). The 4T1 xenograft model was established to assess the

antitumor and immune-modulating effects of 053± GEM.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Compound 053 was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 10

mM stock solution. CQ (cat. no. C129284) was purchased from

Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. and dissolved in

DMSO to prepare a 10 mM stock solution. Rapamycin (RAPA; cat. no.

HY-10219) was purchased from MedChemExpress and dissolved in DMSO

to prepare a 10 mM stock solution. Adriamycin (ADM; cat. no.

HY-15142A; MedChemExpress) was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 10 mM

stock solution. GEM (cat. no. HY-17026; MedChemExpress) was

dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 100 mM stock solution. Paclitaxel

(PTX; cat. no. HY-B0015; MedChemExpress) was dissolved in DMSO to

prepare a 100 mM stock solution. Cisplatin (DDP; cat. no. HY-17394;

MedChemExpress) was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 100 mM stock

solution. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU; cat. no. HY-90006; MedChemExpress)

was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 100 mM stock solution.

Synthesis of compound 053

The synthesis, detailed synthetic procedure and

characterization of compound 053 are described in Data S1.

Cells and cell culture

The breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 (cat. no.

KGG3332-1), MDA-MB-231 (cat. no. KGG3220-1) and 4T1 (cat. no.

KGG2224-1) (all from Nanjing Kaiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were

cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no. L210KJ; Shanghai Yuanpei

Biotech Co., Ltd.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

cat. no. A0050-3110; Cegrogen Biotech GmbH) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. MA0110; Dalian Meilun Biology

Technology Co., Ltd.).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (primary cells

isolated from human blood) were obtained in accordance with the

regulations established by The Ethics Committee of Fujian

Provincial Cancer Hospital (Fuzhou, China; approval no.

K2023-305-01) and with the informed consent of the participants.

Blood samples were collected at the Fujian Provincial Key

Laboratory of Tumor Biotherapy, Clinical Oncology School of Fujian

Medical University, Fujian Cancer Hospital (Fuzhou, China). All

participants were women, ranging in age from 25 to 40 years. The

blood sample collection period extended from September 2023 to

August 2024. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria for participants

consisted of healthy adults without major diseases. CD3 (10

μg/ml; cat. no. T210; Takara Bio, Inc.) was used to coat 1

well of a 6-well plate overnight at 4°C. A total of 4 ml peripheral

blood was drawn from healthy individuals, and after removing the

serum, it was diluted with PBS. The mixture was slowly added to a

centrifuge tube containing 4 ml Ficoll Paque PREMIUM (cat. no.

17544202; Cytiva) and centrifuged at 800 × g with an acceleration

of 8 and a deceleration of 0 for 20 min at room temperature. The

middle white membrane layer was collected and washed twice with

PBS. The cells were resuspended in X-VIVO 15™ culture medium (cat.

no. 04-418Q; Lonza Group, Ltd.), which contained 10% FBS, 0.5

μg/ml interleukin-2 (cat. no. GMP-11848-HNAE; Beijing Sino

Technology Co. Ltd.) and 0.25 μg/ml interferon-γ (IFN-γ;

cat. no. 11725-HNAS; Beijing Sino Technology Co. Ltd.). The cell

mixture was transferred to the CD3-coated plate, and 25

μl/ml CD3/CD28 (cat. no. 10971; Stemcell Technologies, Inc.)

was added. The cell culture conditions were a constant temperature

of 37°C and a gaseous environment of 5% CO2.

mRFP-GFP-LC3 fluorescence tandem

assay

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with the

pGMLV-CMV-RFP-GFP-hLC3-Puro lentivirus (cat. no. GM-0220LV05-1;

GemPharmatech Co., Ltd.) and were subsequently designated as MCF-7

GFP/RFP-LC3B and MDA-MB-231 GFP/RFP-LC3B, respectively. After

adding viral supernatant at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10

for MDA-MB-231 cells and MOI of 30 for MCF-7 cells, as well as 2

μg/ml polybrene (cat. no. C0351; Beyotime Biotechnology) for

a co-incubation of 24 h, the medium was replaced with fresh

complete medium. At 72 h post-viral transduction, 2 μg/ml

puromycin was added to the cells and selection was continued for 2

weeks until all cells in the untransduced control group had died,

after which subsequent experiments were conducted. Untransfected

wild-type (WT) cells, MCF-7 WT and MDA-MB-231 WT, served as

controls. As shown in Fig. S1A and

B, after treatment with RAPA (10 μM) for 24 h to induce

autophagy, clear red and green fluorescence signals were observed

in the MCF-7 GFP/RFP-LC3B and MDA-MB-231 GFP/RFP-LC3B cells under

fluorescence microscopy. By contrast, no significant fluorescence

was detected in the control groups (MCF-7 WT and MDA-MB-231 WT).

This demonstrated the successful establishment of stable cell lines

expressing pGMLV-CMV-RFP-GFP-hLC3-Puro.

Next, MCF-7 GFP/RFP-LC3B or MDA-MB-231 GFP/RFP-LC3B

cells (~1×104/well) were seeded into 24-well plates,

which contained microscope cover glasses and cultured at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells were

then treated with 053 (5 μM), CQ (30 μM), RAPA (10

μM) or RAPA combined with CQ or 053 for 24 h. Microscope

cover glasses containing cells were washed three times with PBS and

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature,

washed three more times with PBS for 5 min each, air-dried and

overlaid on slides dripped with DAPI anti-fluorescence attenuation

sealer. The slides were observed and images were captured using an

Olympus inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). The

level of fluorescence was analyzed using ImageJ (1.8.0.1; National

Institutes of Health) software.

CYTO-ID assay

MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells (~5×104/well)

were cultured in 24-well plates for 24 h, treated with RAPA (10

μM), CQ (30 μM) or 053 (0, 0.5, 2.5 or 5 μM)

for 24 h and stained with CYTO-ID® Autophagy detection

kit 2.0 (cat. no. ENZ-KIT175-0200; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.). The

CYTO-ID staining was observed and images were captured by inverted

fluorescence microscope or detected by flow cytometry (MoFlo XDP;

Beckman Coulter Ltd.). FlowJo software (v10.8.1; BD Biosciences)

was used for analysis.

MDC staining

MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells (~1×105/well)

were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Next, cells were

treated with 5 μM 053 and 30 or 60 μM CQ for 24 h.

The cells were stained according to the MDC Staining Assay Kit

(cat. no. C3018M; Beyotime Biotechnology) and detected by flow

cytometry (MoFlo XDP). FlowJo software was used for analysis.

Brightfield microscopy

MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells (~1×105/well)

were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Next, cells were

treated with different concentrations of 053 (0, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20

μM) for 24 h. Micrographs were obtained using an inverted

fluorescence microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy

MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells (~1×105/well)

were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Next, cells were

treated with 5 μM 053 for 24 h. The cells were collected,

washed once with PBS and then resuspended in 2.5% glutaraldehyde

and fixed at 4°C for 24 h. After gradual dehydration with ethanol,

the cells were treated with acetone for 10 min, followed by

treatment with a mixture of epoxy resin and acetone. Finally, the

samples were embedded in resin and subjected to ultrathin

sectioning at a thickness of 60 nm. The sections were stained with

uranyl acetate for 15 min at room temperature, washed twice with

distilled water and subsequently stained with lead citrate for 5

min at room temperature. After a final thorough wash with ultrapure

water, the samples were observed and imaged under the transmission

electron microscope. Images were observed and captured using a FEI

Tecnai 12 BioTwin transmission electron microscope (FEI; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Cell viability

MDA-MB-231 or 4T1 cells (~2×103/well)

were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After which, the

cells were treated with 053 (0, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20 μM), 10

μM docetaxel (DOC), 50 μM DDP, 80 μM GEM, 0.1

μM PTX or 50 μM 5-fluoro-2,4-pyrimidinedione (5-FU)

alone or combined with 053 (5 μM) for 24 h. The CellTiter

96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (cat.

no. G3581; Promega Corporation) was used to detect cell growth

inhibition activity. Finally, the absorbance at 490 nm was measured

using a microplate reader (Corona Electric Co., Ltd.). T cells

(~2×103/well) were seeded into 96-well plates, and

treated with 053 (0, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20 μM) for 24 h.

T cells were co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells at a

1:1 ratio, both of which were treated with 053 (0, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20

μM) for 24 h. The ATP Detection Assay Kit (cat. no. S0026;

Beyotime Biotechnology) was used to evaluate T cell proliferation,

and the relative light unit values were measured using a

luminometer.

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the

effects of compound 053, CQ or RAPA on the protein levels of LC3,

p62, mTOR, phosphorylated (p-)mTOR, AKT and p-AKT. Western blot

analysis was also conducted to assess the effects of compound 053,

ADM, GEM and CQ on the protein levels of co-stimulatory and

co-inhibitory molecules on the surface of T cells. Total proteins

were extracted from cells with RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. PC101;

Shanghai Epizyme Biopharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.; Ipsen

Pharma) and the BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. P0012; Beyotime

Biotechnology) was used for protein quantification. Equal amounts

of protein (30 μg) were separated on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel

(cat. no. PG113; Shanghai Epizyme Biopharmaceutical Technology Co.,

Ltd.; Ipsen Pharma) and transferred to a nitrocellulose transfer

membrane (cat. no. 66485; Pall Corporation). The membrane was

blocked by 5% w/v non-fat dry milk at room temperature for 1 h and

incubated with the LC3B (cat. no. 83506; 1:1,000), p62 (cat. no.

88588; 1:1,000), AKT (cat. no. 4691; 1:1,000), p-AKT (cat. no.

9271; 1:1,000), p-mTOR (cat. no. 5536; 1:1,000), mTOR (cat. no.

2983; 1:1,000), T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing

protein 3 (TIM3; cat. no. 45208; 1:1,000), programmed cell death

protein 1 (PD-1; cat. no. 86163; 1:1,000), V-domain immunoglobulin

suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA; cat. no. 54979; 1:1,000),

CD40 ligand (CD40L; cat. no. 15094; 1:1,000) (all from Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), tumor necrosis factor receptor

superfamily, member 4 (OX40; cat. no. ab264466; 1:1,000; Abcam) and

tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 9 (4-1BB; cat.

no. ab68185; 1:1,000; Abcam) antibodies overnight at 4°C. After

washing the primary antibody away with 1X TBST (0.1% Tween-20), the

membrane was incubated with the secondary antibody goat anti-mouse

IgG (HRP conjugated; 1:10,000; cat. no. LF101; Shanghai Epizyme

Biotech Co., Ltd.) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (HRP conjugated;

1:10,000; cat. no. LF102; Shanghai Epizyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 1

h at room temperature. The chemiluminescence detection was

ultimately performed using a FluorChem E digital darkroom system

(Bio-Techne).

Apoptosis assay

MDA-MB-231 cells (~1×105/well) were

seeded into 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The commonly used

concentrations of DOC in in vitro cell experiments range

from 0 to 10 μM (24,25). Short-term high doses are used to

observe rapid cytotoxicity or changes in signaling pathways.

Experiments with sensitive cell lines (Luminal) typically use

50-100 nM, while invasive cell lines (TNBC) typically use 1-10

μM (26). Clinically,

intravenous injections of 75-100 mg/m2 DOC are

administered, which require individualized adjustment. Clinical

doses for the Luminal-type are typically 75 mg/m2,

recommended clinical doses for the HER2-positive type are 75-100

mg/m2 and high-dose 100 mg/m2 is used for

TNBC (27,28). In the present study, the cells

were treated with 053 (0, 5 or 10 μM), DOC (10 μM),

DDP (50 μM), GEM (80 μM), PTX (0.1 μM) and

5-FU (50 μM) alone or combined with 053 (5 μM) for 24

h. Subsequently, the cells were collected and washed with Annexin

V-FITC binding buffer (cat. no. C1062S; Beyotime Biotechnology)

twice, resuspended with staining solution containing 5 μl

Annexin V-FITC and 5 μl PI (cat. no. C1062S; Beyotime

Biotechnology) and incubated for 30 min in the dark. Finally, cell

apoptosis was assessed using flow cytometry (MoFlo XDP). FlowJo

software was used for analysis.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells (~1×105/well)

were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After which, the

cells were treated with different concentrations of 053 (0, 2.5, 5

or 10 μM) for 24 h. A ROS Assay Kit (cat. no. CM-H2DCFDA;

Beyotime Biotechnology) was used to detect intracellular ROS level

of cells, and fluorescence was measured using a flow cytometer

(MoFlo XDP). FlowJo software was used for analysis.

Multi-color flow cytometry assay

MDA-MB-231 or 4T1 cells (~1×105/well)

were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After which, the

cells were treated with different concentrations of 053 (0, 5 and

10 μM) for 24 h. Next, MDA-MB-231 or 4T1 cells were

collected for PD-L1/B7-H1-PE (cat. no. 10084-R312-P; 1:25; Beijing

Sino Technology Co. Ltd) antibody labelling. T cells

(~1×105/well) were seeded into 6-well plates and treated

with concentrations of 053 (0, 5 and 10 μM) for 24 h. T

cells were co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells at a 1:1 ratio, both

of which were treated with 053 (0, 5 or 10 μM) for 24 h.

Treated T cells were collected for CD3-BV650 (cat. no. A07749;

1:25; Beckman Coulter, Inc.), CD4-APC-H7 (cat. no. 737660; 1:25;

Beckman Coulter, Inc.), CD8-PE-CY7 (cat. no. 6604728; 1:25; Beckman

Coulter, Inc.), IFN-γ-FITC (cat. no. 11-7319-82; 1:25; eBioscience;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), Granzyme B-FITC (cat. no. 560211;

1:25; BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences), PD-1-BV421 (cat. no. 564323;

1:25; BD Biosciences), TIM3-RB705 (cat. no. 570584; 1:25; BD

Biosciences), OX-40-RB705 (cat. no. 757846; 1:25; BD Biosciences),

4-1BB-RY603 (cat. no. 759418; 1:25; BD Biosciences) and inducible

T-cell Co-stimulator (ICOS-R718; cat. no. 751854; 1:25; BD

Biosciences) antibody labeling. Finally, after incubating for 30

min at room temperature in the dark, the assay was performed using

flow cytometry (MoFlo XDP). FlowJo software was used for analysis.

The flow cytometry gating strategy involved labelling T cells with

CD3 to assess the expression of PD-1, TIM3, OX-40, 4-1BB and ICOS

on the surface of T cells. CD3+ T cells were then

separated into CD3+CD8+ T cells or

CD3+CD4+ T cells, then IFN-γ and granzyme B

were detected.

In vivo xenograft experiment

A total of 24 BALB/cJ female nude mice (age, 5-6

weeks; weight, 16-20 g) and 24 BALB/c female mice (age, 5-6 weeks;

weight, 10-14 g) were purchased from GemPharmatech Co. Ltd. and

housed in a specialized pathogen-free environment (20-25°C;

humidity, 40-60%; 12-h light/dark cycle and ad libitum

access to food and water). Animals were checked daily and any

animal found unexpectedly to be moribund, cachectic or unable to

obtain food or water was sacrificed. However, no such cases

occurred during the present study. The in vivo mouse study

procedure was performed according to The Laboratory Animal Ethics

Committee of The College of Biological Sciences and Engineering,

Fuzhou University (Fuzhou, China; approval no. 2022-SG-022). In

strict compliance with animal welfare guidelines, the tumor burden

was maintained within ethical limits: Tumor weight did not exceed

10% of the mouse body weight (10% indicates: subcutaneous tumors on

the backs of 25 g mice reached a diameter of ~17 mm), the average

tumor diameter remained under 20 mm and the tumor volume was kept

below 2,000 mm3. After 7 days, when the mice had

acclimatized to the new environment, 5×106 MDA-MB-231

cells were injected subcutaneously into the left hindlimbs of

BALB/cJ nude mice and 2×106 4T1 cells were injected

subcutaneously into the left hindlimbs of BALB/c mice. When the

tumor volume measured ~100 mm3 (7 days, recorded as day

0), mice were randomly divided into the following four groups

(n=5/group): i) PBS (control); ii) 053; iii) GEM; and iv) 053+ GEM.

During the experiment, the health and behavior of the mice were

monitored daily. Following tumor formation, intravenous injections

via the tail vein were administered every 3 days at a dosage of 150

μl per mouse for a period of 3 weeks, totaling 7 injections.

The administered agents consisted of normal saline, 053 (10 mg/kg),

GEM (10 mg/kg) or a combination of 053 (5 mg/kg) and GEM (5 mg/kg).

The body weight, tumor length and width were measured every 3 days,

and the tumor volume was calculated according to the formula: Tumor

volume=(longest diameter × shortest diameter2)/2. At the

end of the study (21 days post-injection), mice were euthanized

following deep anesthesia using isoflurane (5% for induction, 2%

for maintenance). CO2 inhalation was used to complete

euthanasia at a displacement rate of 30-70% of the chamber volume

per min. Following euthanasia by carbon dioxide inhalation,

cervical dislocation was performed to confirm death (evidenced by a

visible gap between the skull and the spine), and death was further

verified by the absence of respiration. After euthanasia, the

tumors, heart, liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys were excised and

immediately placed in either 4% paraformaldehyde or tissue

preservation solution (cat. no. HY-K6010; MedChemExpress), followed

by storage at 4°C for subsequent analysis. All mice were euthanized

at the planned end of the experiment.

Tumor tissue was transferred to an Eppendorf tube

and cut into small fragments. Tumor tissue digestion solution (cat.

no. abs50090-10T; Absin Bioscience Inc.) was then added for

digestion into a single-cell suspension. After which, the

single-cell suspension was slowly added to a centrifuge tube

containing 4 ml Ficoll Paque PREMIUM and centrifuged at 2,000 × g

with an acceleration of 8 and a deceleration of 0 for 20 min at

room temperature. The middle white membrane layer was collected and

washed twice with PBS, followed by labeling with Fixable Viability

Stain 510 (FVS510; cat. no. 564406; 1:1,000), CD45-APC-CY7 (cat.

no. 557659; 1:25), CD3-APC (cat. no. 565643; 1:25), CD4-BV605 (cat.

no. 563151; 1:25), CD8a-PE-CY7 (cat. no. 552877; 1:25), PD-1-BV421

(cat. no. 748268; 1:25), TIM3-BV650 (cat. no. 747623; 1:25),

OX-40-BV605 (cat. no. 740545; 1:25), ICOS-BB515 (cat. no. 565880;

1:25) and 4-1BB-BV421 (cat. no. 740033; 1:25) (all from BD

Biosciences). The tumor cells at the bottom were collected and

washed twice with PBS, followed by labeling with FVS510 and PD-L1

(cat. no. 758168; 1:25; BD Biosciences). The assay was performed

using flow cytometry (MoFlo XDP). FlowJo software was used for

analysis. The flow cytometry gating strategy used FVS510 to

identify the viable tumor cell population and detect PD-L1

expression. Viable lymphocyte populations were identified using

FVS510 and CD45, followed by CD3 marking of T cells to detect the

expression of PD-1, TIM3, OX-40, 4-1BB and ICOS on the surface of T

cells and further detection of the proportions of

CD3+CD8+ T cells and

CD3+CD4+ T cells.

Biological tissue sections test

Tissues including major organs and tumors were

collected from mouse xenograft models and fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h, followed by paraffin embedding.

Sections (5 μm) were prepared from the paraffin-embedded

blocks, dewaxed in xylene and immersed in EDTA antigen retrieval

buffer. Subsequently, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was

performed. The sections were stained with 1% hematoxylin for 5 min

at room temperature, treated with 1% acid alcohol for 45 sec and

then counterstained with eosin for 2 min at room temperature. After

dehydration through a graded series of ethanol (70, 85, 95 and

100%), the sections were cleared in xylene and finally mounted with

neutral resin. The results were observed under an optical

microscope.

For immunohistochemical detection, paraffin-embedded

sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through a graded

ethanol series. For antigen retrieval, the sections were heated in

citrate buffer at 100°C for 10 min. For the detection of

intracellular epitopes (Ki67/LC3/p62), permeabilization was first

performed with 0.1% Triton X-100 (20 min, room temperature),

followed by quenching of endogenous peroxidase activity with 3%

H2O2 (20 min, room temperature). The sections

were then blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature and

subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies: Anti-Ki67 antibody (cat. no. GB111499-100; 1:1,000;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd), anti-LC3 antibody (cat. no.

81004-1-RR; 1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc), anti-p62 antibody

(cat. no. GB11239-1-100; 1:1,000; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd), anti-PD-L1 antibody (cat. no. GB150059-100; 1:1,000; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd), anti-PD-L2 antibody (cat. no.

27406-1-AP; 1:4,000; Proteintech Group, Inc), anti-CD3 antibody

(cat. no. GB11014-100; 1:1,000; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd), anti-CD4 antibody (cat. no. GB11064-100; 1:1,000; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd), anti-CD8 antibody (cat. no.

GB11068; 1:1,000; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd),

anti-4-1BB/CD137 antibody (cat. no. A2025; 1:200; ABclonal Biotech

Co., Ltd), anti-CD134/OX40 antibody (cat. no. 32621-1-AP; 1:500;

Proteintech Group, Inc), anti-PD1 antibody (cat. no. GB153744-100;

1:400; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd) and anti-TIM3 antibody

(cat. no. 11872-1-AP; 1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc).

Subsequently, the samples were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. GB23303; 1:5,000; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat.

no. GB23301; 1:5,000; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd) at 37°C

for 1 h. Following this, staining was performed with DAB chromogen

for 15 min (cat. no. G1211; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd),

and hematoxylin was used as a counterstain for 3 min at room

temperature. Finally, dehydration was conducted using a graded

ethanol series, followed by immersion in xylene, and mounting with

neutral balsam. The results were observed under an optical

microscope.

Following permeabilization with Proteinase K (20

μg/ml; 37°C, 20 min), TUNEL assay was performed using the

commercial kit (cat. no. G1501; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sections

were then directly mounted with an antifade mounting medium

containing DAPI (cat. no. P0126; Beyotime Biotechnology). All

section images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (Dotmatics) or FlowJo

software (v10.8.1; BD Biosciences) were used for data analysis. All

results are expressed as the mean ± standard error. Statistical

significance was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance and

post hoc comparisons were performed using Dunnett's multiple

comparisons test to compare all experimental groups against a

single control group, while controlling the family-wise error rate

under multiple testing conditions. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Preliminary characterization of compound

053 on autophagy regulatory function

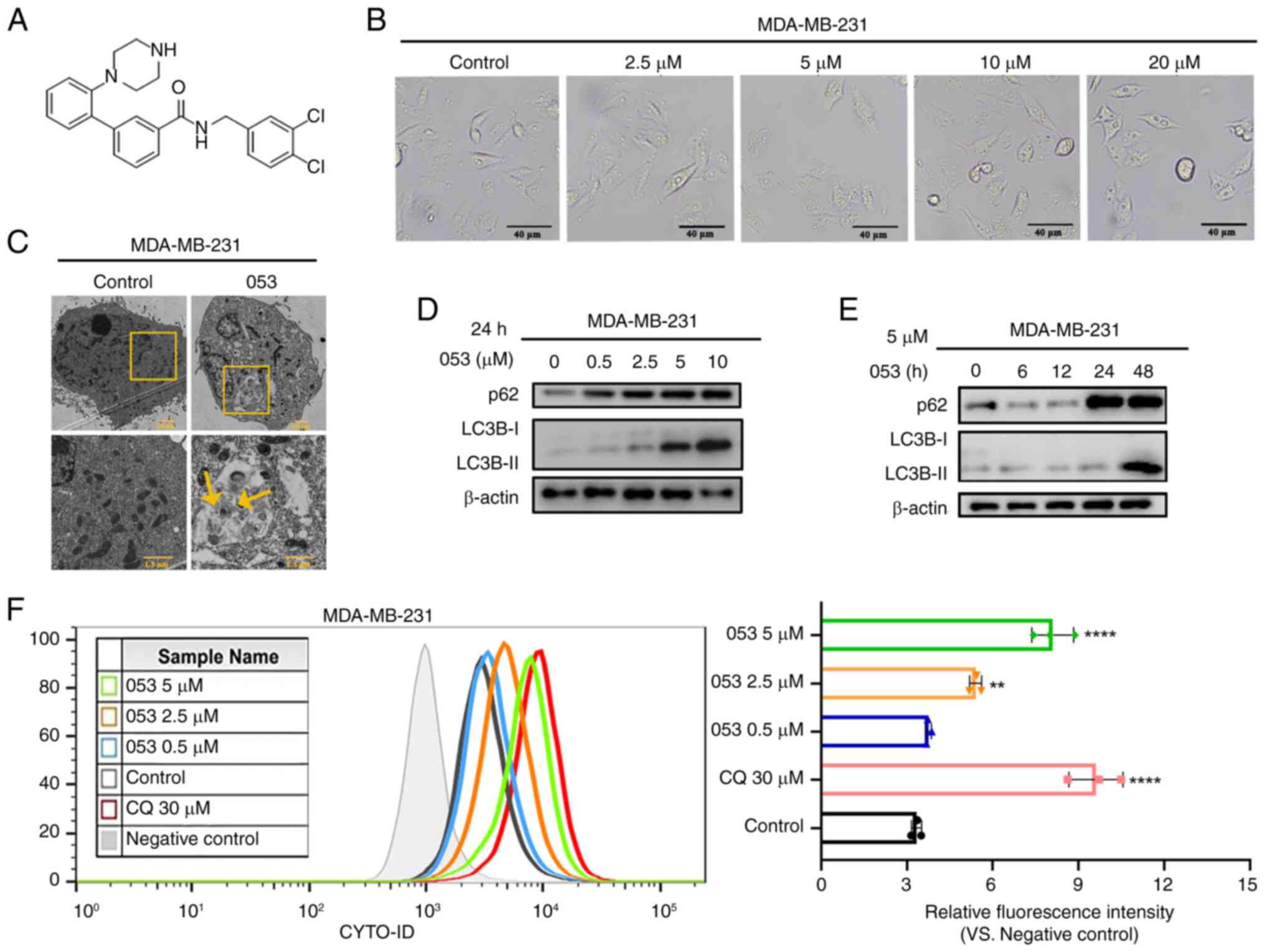

The structural formula of compound 053 is shown in

Fig. 1A. The preliminary

investigation was conducted using the tandem mRFP-GFP-LC3B reporter

system. During autophagosome-lysosome fusion, only red fluorescence

was detectable as the acidic lysosomal environment quenches GFP

fluorescence while mRFP remains stable. When autophagy was

inhibited, cytoplasmic yellow fluorescence of mRFP-GFP-LC3B was

observed, resulting from co-localization of mRFP and GFP signals

due to impaired autophagosome-lysosome fusion. In 053-treated MCF-7

cells, the number of GFP/mRFP-labeled LC3B puncta was significantly

increased compared with control, with both the 053- and CQ-treated

groups exhibiting enhanced yellow fluorescence, suggesting that

compound 053 may regulate the autophagic process in breast cancer

cells (Fig. S1C and D). The

synthesis, detailed synthetic procedure and characterization of

compound 053 are described in Data S1 (Figs. S2-S14).

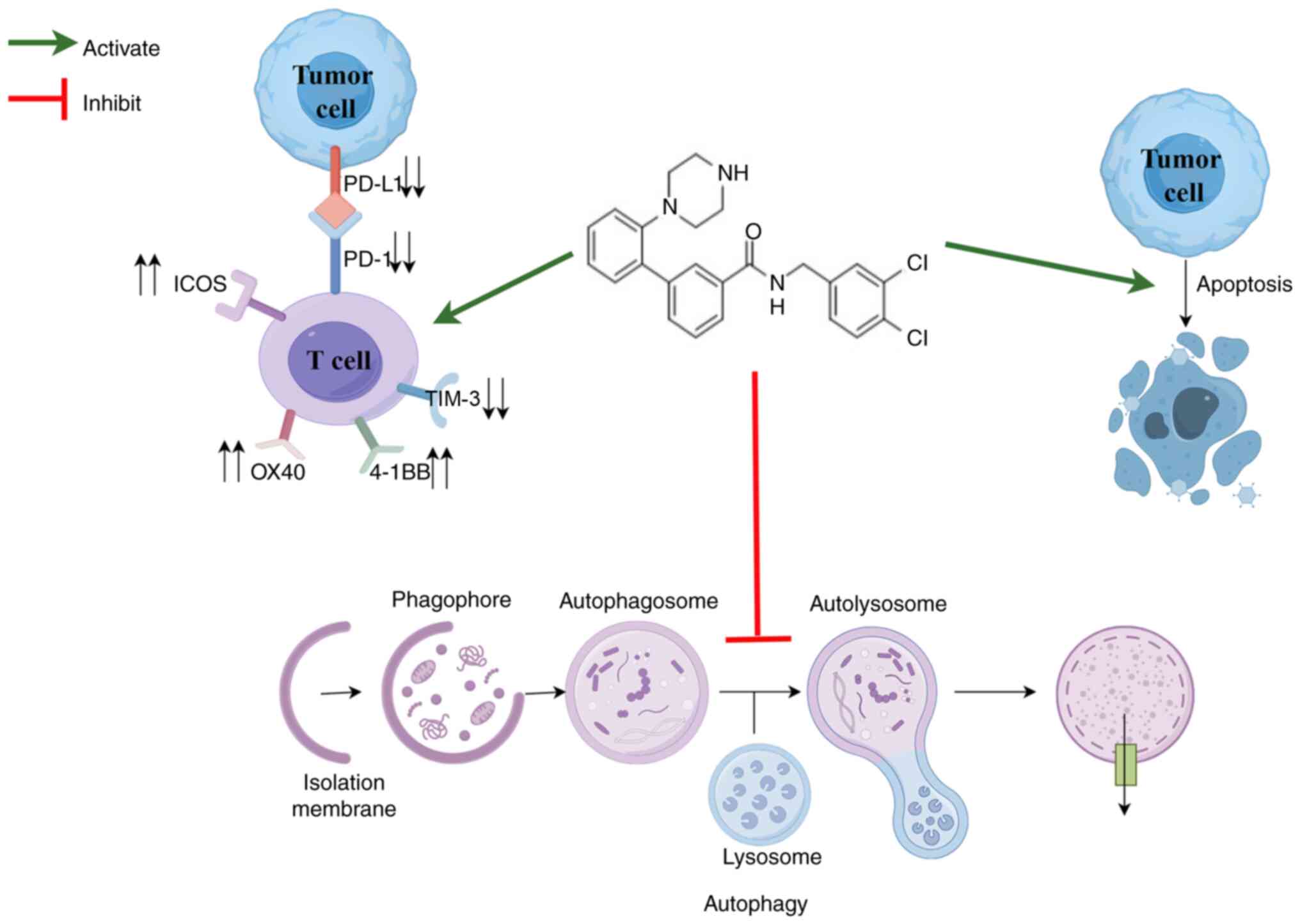

| Figure 1Compound 053 inhibits late autophagy

in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Chemical structural formula of 053. The

relative molecular mass of 053 is 440.37 g/mol. (B) Representative

microscope images of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with different

concentrations of 053 (0-20 μM) for 24 h. Scale bar, 40

μm. (C) Internal structure of MDA-MB-231 cells under

transmission electron microscopy after treatment with 5 μM

053 for 24 h. The lower image is a magnified view of the yellow box

in the image above. Scale bar, 1.5 μm. (D) Protein levels of

p62 and LC3B-Ⅰ/Ⅱ in MDA-MB-231 cells were analyzed by western

blotting after treatment with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h. (E)

MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 5 μM 053 for different

times (0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h), and the protein levels of p62 and

LC3B-Ⅰ/Ⅱ were analyzed by western blotting. (F) Flow cytometry was

used to detect the fluorescence intensity of autophagy-related

vesicles stained with CYTO-ID in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were

treated with 053 (0-5 μM) or CQ (30 μM) for 24 h. The

bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence

intensity. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3). Statistical

significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's

multiple comparisons test to compare all experimental groups

against a single control group. **P<0.01 and

****P<0.0001 vs. Control. 053, FZU-0045-053;

p62/SQSTM1, sequestosome 1; LC3B, microtubule-associated protein

1A/1B-light chain 3B; CQ, chloroquine. |

Similar to CQ, compound 053 inhibits late

autophagy in breast cancer cells

In the present study, the effects of compound 053 on

the MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines were examined to

facilitate a comparative analysis of their regulatory impacts. In

the cell morphology analysis, it was found that with increased 053

concentration, cytoplasmic vacuolization was induced in MDA-MB-231

cells with the appearance of a large number of vesicles, which was

accompanied by a reduction of the cell volume (Fig. 1B), suggesting that 053 may

regulate autophagic flux while promoting apoptosis. To further

demonstrate that 053 regulates autophagy, ultrastructural studies

were performed. Compared with the control group, the number of

vacuoles was increased in 053-treated MDA-MB-231 cells, and

autophagic vesicles formed in the cytoplasm contained recognizable

double-membrane structures and undegraded cargo (Fig. 1C).

LC3B-I/II is a protein marker that is intricately

related to the autophagy process and has been used to monitor

autophagy (29). The adaptor

protein p62 connects autophagosomes to their substrates and serves

as a molecular regulator in the process of cellular autophagy.

Elevated levels of p62 typically reflect the blockage of autophagic

flux (30). In addition, the

accumulation of autophagosomes may be associated with the

activation of autophagy or the suppression of late-stage autophagy.

Therefore, the protein levels of p62 were detected using western

blotting to clarify the role of 053 in the regulation of autophagy.

The results showed that the protein levels of p62 and LC3B-II

exhibited an increase in a manner that was both time- and

concentration-dependent following the application of 053 to

MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 1D and

E).

The CYTO-ID probe labels vacuoles associated with

the autophagy pathway, whereby the green dye typically accumulates

in spherical vacuoles around the nucleus. CQ, a late-stage

autophagy inhibitor, primarily inhibits autophagy by blocking the

fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes (31). To further explore the role of 053

in the regulation of autophagy in both cell lines, CYTO-ID staining

was conducted, followed by quantitative analysis using flow

cytometry. The fluorescence intensity of CYTO-ID in MDA-MB-231

cells was gradually enhanced with increasing 053 concentration

(Fig. 1F). Treatment of MCF-7

cells with 053 significantly increased vesicle accumulation, while

p62 and LC3B-II protein levels exhibited time- and

concentration-dependent elevation (Fig. S15A-D). Concurrently, CYTO-ID

fluorescence intensity progressively increased with increasing 053

concentrations (Fig. S15E).

These results demonstrated that compound 053 shares similar effects

with CQ in promoting the accumulation of acidic autophagic vesicles

and upregulating autophagy-related proteins (particularly p62 and

LC3B-II) in breast cancer cells. These findings indicate that 053

likely suppresses late-stage autophagy by blocking autophagic flux,

rather than inducing autophagy.

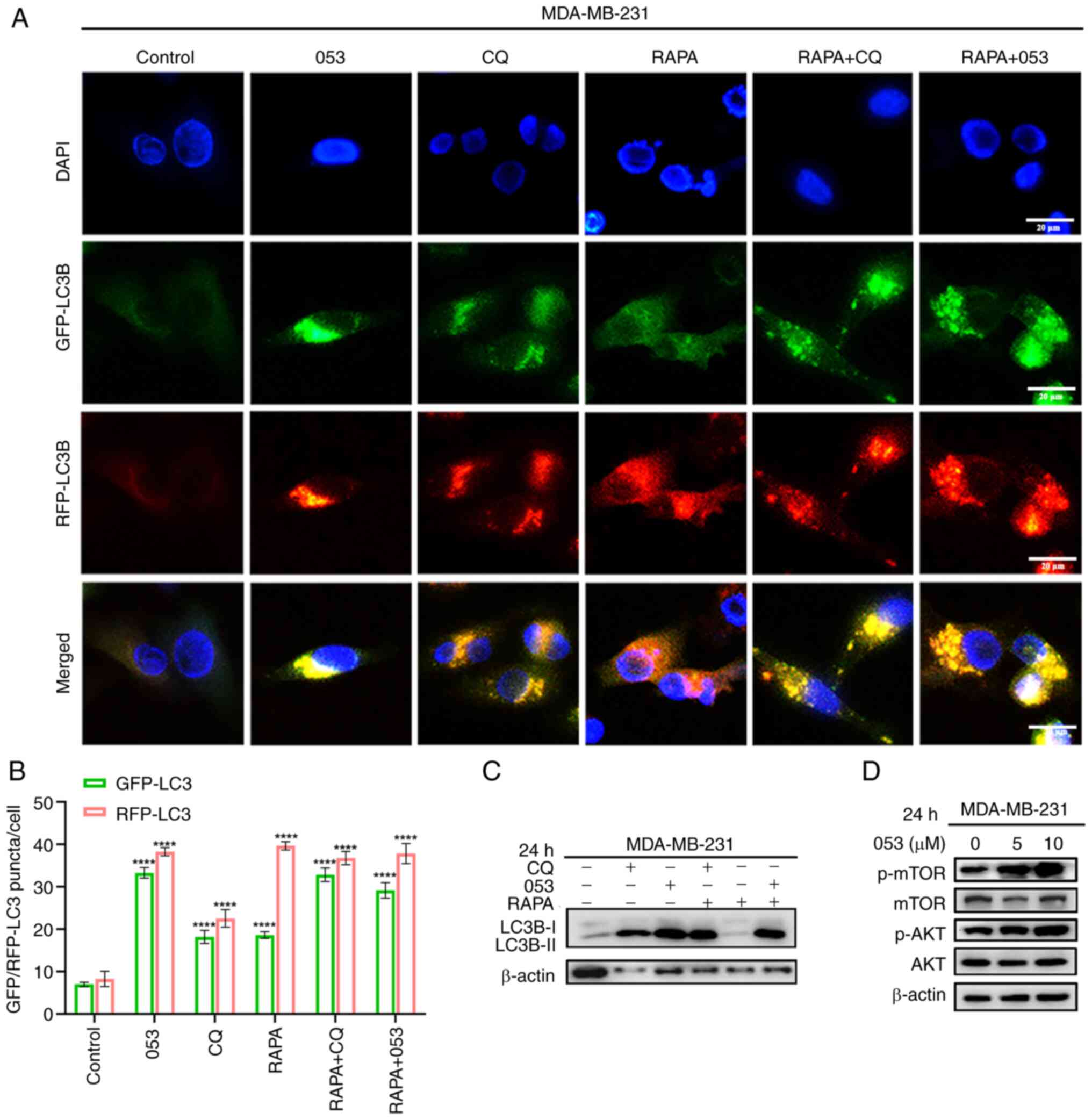

To confirm the effect of 053 on autophagic flux, the

tandem mRFP-GFP-LC3B reporter gene was used for observation. The

results demonstrated that both red and green fluorescence were

enhanced by the action of 053 and CQ compared with the control

group, and the yellow fluorescence was further enhanced by the

co-localized superposition of red and green fluorescence. By

contrast, the GFP fluorescence signal was weakened by the use of

the autophagy inducer RAPA alone, and only red fluorescence could

be detected by the superposition of red and green fluorescence,

which indicated that RAPA-induced autophagy accelerated autophagic

flux (Figs. 2A, B, S16A and S16B). Thus, it is evident that

053, similarly to CQ, may disrupt the autophagic flux by blocking

the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes at a late stage, leading

to the accumulation of autophagosomes rather than inducing

autophagy.

To further confirm that 053 is a late-stage

autophagy inhibitor that functions similarly to CQ, western

blotting was used to analyze the protein levels of LC3B in both

cell lines following treatment with 053, CQ and RAPA. It was found

that treatment with 053 or CQ alone increased the protein level of

LC3B-II in cells, while the autophagy inducer RAPA did not increase

the protein level of LC3B-II. This indicated that the efficiency of

autophagic lysosomal degradation was not affected by RAPA treatment

at this time, and that LC3B-II levels did not increase even when

autophagy was activated. However, when 053 or CQ was combined with

RAPA, LC3B-II protein resumed accumulation (Figs. 2C and S16C). The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling

pathway has been demonstrated to be a key pathway in the cellular

regulation of autophagy (32). It

was further verified whether the inhibitory effect of 053 on

autophagy in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells was associated with the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Notably, 053 specifically promoted

the phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR in MDA-MB-231 cells, while not

influencing the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in MCF-7 cells

(Figs. 2D and S16D). In conclusion, these results

suggested that 053 is a late autophagy inhibitor similar to CQ,

which may inhibit autophagy by blocking the fusion of

autophagosomes and lysosomes. The inhibitory effect of 053 on

autophagy in MDA-MB-231 cells is associated with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway.

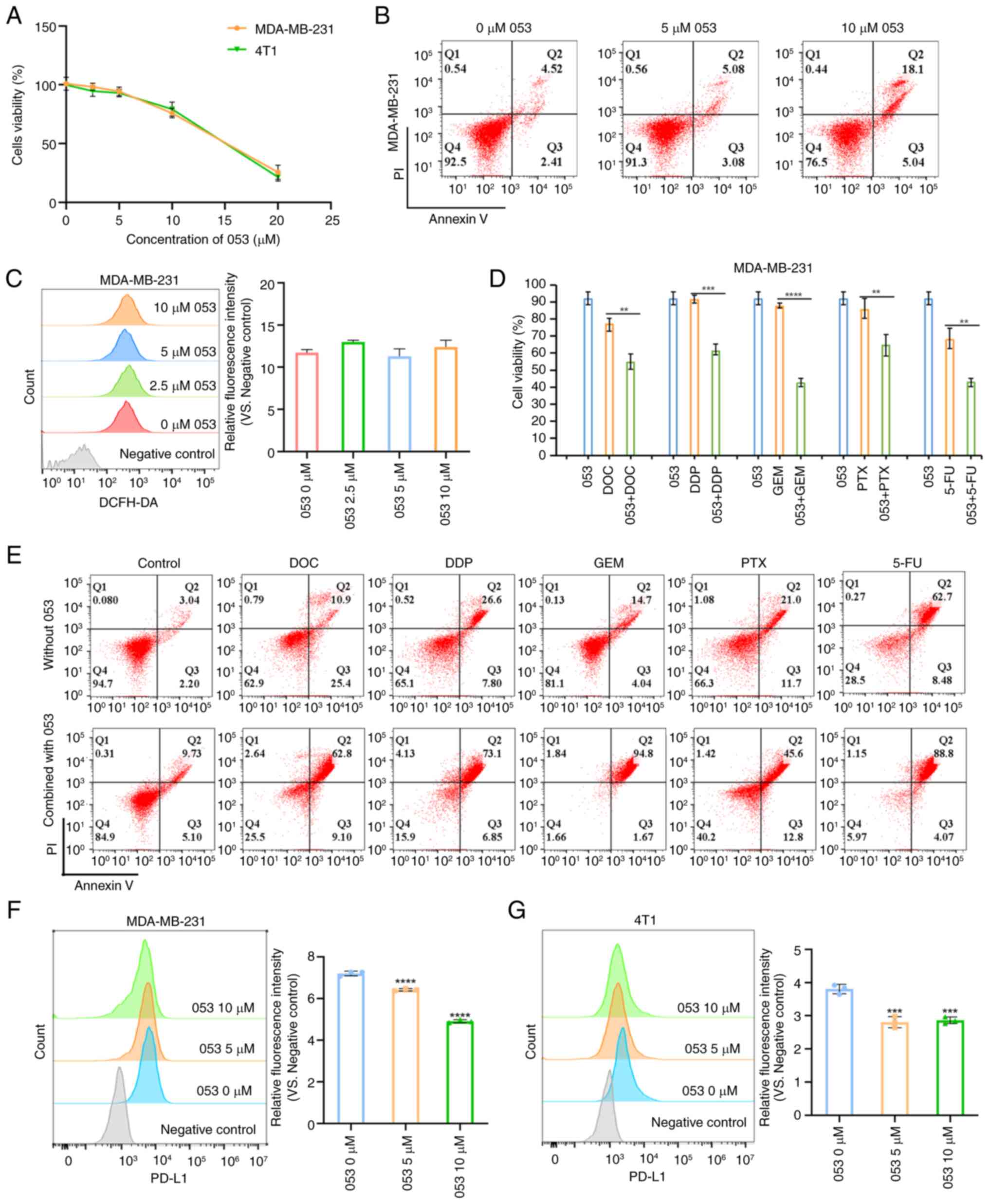

Compound 053 enhances chemosensitivity

and downregulates PD-L1 expression in breast cancer cells

Initially, the effect of compound 053 on the

viability of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells was evaluated using the

CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution assay. As shown in

Figs. 3A and S17A, the results revealed that compound

053 significantly decreased the viability of 4T1, MDA-MB-231 and

MCF7 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, the effect of

compound 053 on apoptosis in breast cancer cells was assessed using

the Annexin-V/PI assay and it was discovered that 053 could also

induce apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner (Figs. 3B and S17B). To further investigate whether

the apoptosis and autophagy inhibition induced by 053 was

associated with intracellular ROS production, the effect of 053 on

ROS levels in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells was assessed using a

DCFH-DA probe. As shown in Figs.

3C and S17C, compound 053

did not alter ROS levels in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, suggesting

that the apoptosis and autophagy inhibition mediated by 053 is not

associated with ROS levels in breast cancer cells. These findings

suggest that as the concentration of 053 increased, it inhibited

the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, while also

inducing apoptosis.

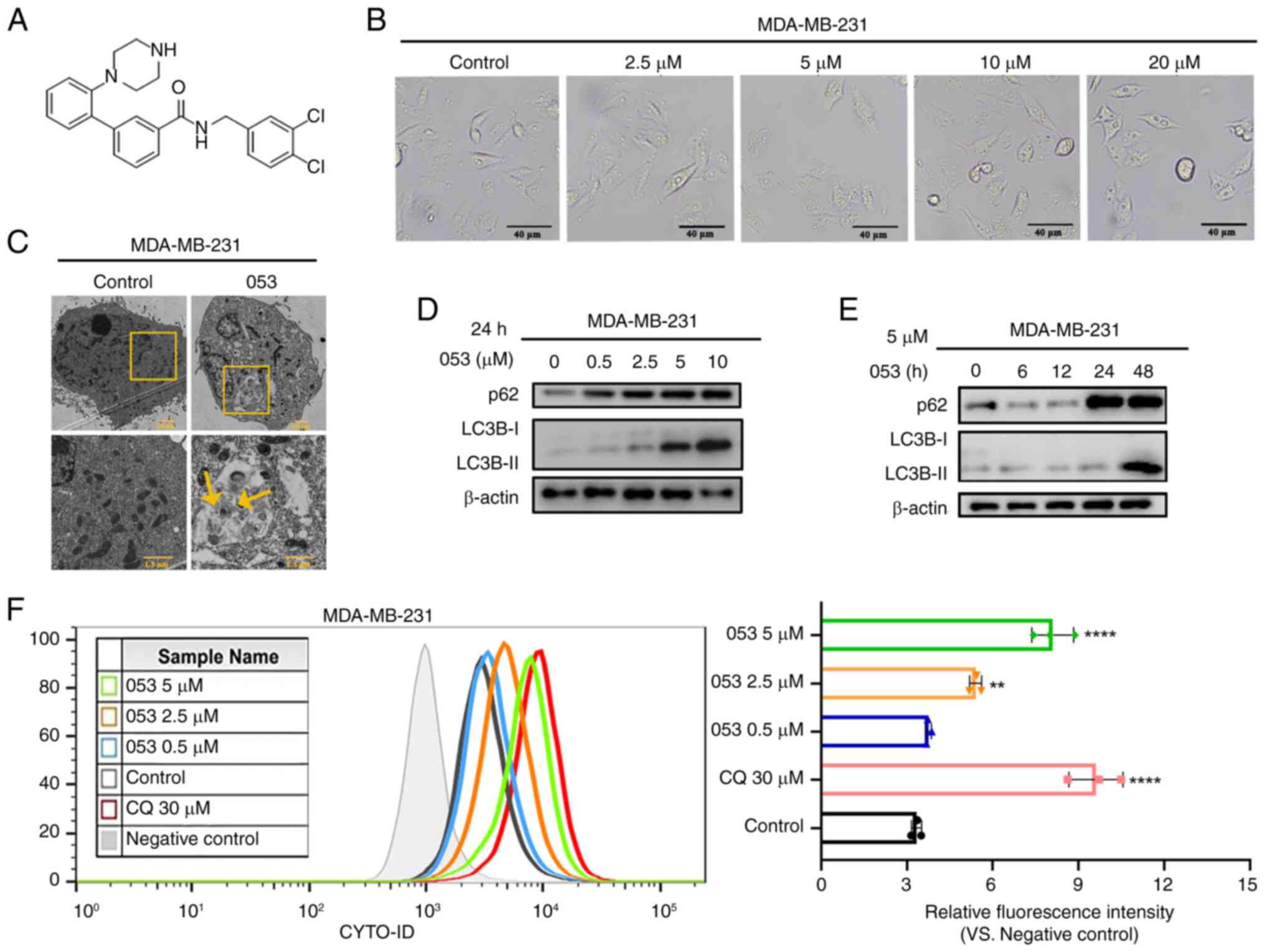

| Figure 3Compound 053 induces apoptosis and

downregulates PD-L1 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) CellTiter

96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay was

used to determine the proliferation of 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cells

treated with 053 (0-20 μM) for 24 h. (B) The apoptosis of

MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h

was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) The ROS levels in MDA-MB-231

cells after treatment with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h was

analyzed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows quantitative

analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. Data are presented as

mean ± SEM (n=3). Statistical significance was determined by

one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test to

compare all experimental groups against a single control group. (D)

CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation

detection of MDA-MB-231 cell viability when treated with 053 (5

μM), DOC (10 μM), DDP (50 μM), GEM (80

μM), PTX (0.1 μM) and 5-FU (50 μM) treated

alone, or the effect of 053 combined with chemotherapy drugs on the

viability of MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h treatment. Data are

presented as mean ± SEM (n=4). Statistical significance was

determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple

comparisons test to compare all experimental groups against a

single control group. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. (E)

Apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 cells was detected by flow cytometry, cells

were treated with 053 (5 μM), DOC (10 μM), DDP (50

μM), GEM (80 μM), PTX (0.1 μM) and 5-FU (50

μM) or 053 in combination with chemotherapy drugs for 24 h.

(F) Flow cytometry was used to detect PD-L1 surface expression on

MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h. The

bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence

intensity. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3). Statistical

significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's

multiple comparisons test to compare all experimental groups

against a single control group. ****P<0.0001 vs. 0

μM 053. (G) Flow cytometry was used to detect surface

expression on 4T1 cells treated with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h.

The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence

intensity. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3). Statistical

significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's

multiple comparisons test to compare all experimental groups

against a single control group. ***P<0.001 vs. 0

μM 053. 053, FZU-0045-053; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

DOC, docetaxel; DDP, cisplatin; GEM, gemcitabine; PTX, paclitaxel;

5-FU, 5 -fluorouracil; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1. |

Autophagy inhibition has been shown to enhance

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis and suppress tumor cell

proliferation, while also serving as a key mechanism of

chemoresistance (11).

Previously, it was demonstrated that compound 053 can inhibit

late-stage autophagy. Therefore, its effect on the chemosensitivity

of MDA-MB-231 cells was further investigated. Initially, the impact

of compound 053 in combination with conventional breast cancer

chemotherapeutic agents, including PTX, DDP, DOC, GEM and 5-FU, was

assessed. Cell viability assay revealed that the combination of 053

and chemotherapeutic agents more effectively reduced the survival

rate of MDA-MB-231 cells compared with treatment with either 053 or

the chemotherapeutic agents alone (Fig. 3D). The Annexin V/PI assay revealed

that 053 combined with chemotherapeutic drugs significantly

enhanced apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells compared with chemotherapy

alone (Fig. 3E). In conclusion,

compound 053 significantly enhanced the chemosensitivity of

MDA-MB-231 cells by inhibiting autophagy.

It has been reported that PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1

can be regulated by autophagy in various types of cancer (33). Tumor cells evade immune

surveillance by upregulating the expression of PD-L1. PD-L1

expression in 053-treated MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells was examined

using flow cytometry and western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3F and G, 053 treatment

significantly downregulated the expression of PD-L1 on the surface

of MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells compared with the control group. In

conclusion, 053 could negatively regulate the expression of PD-L1

on the surface of MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells.

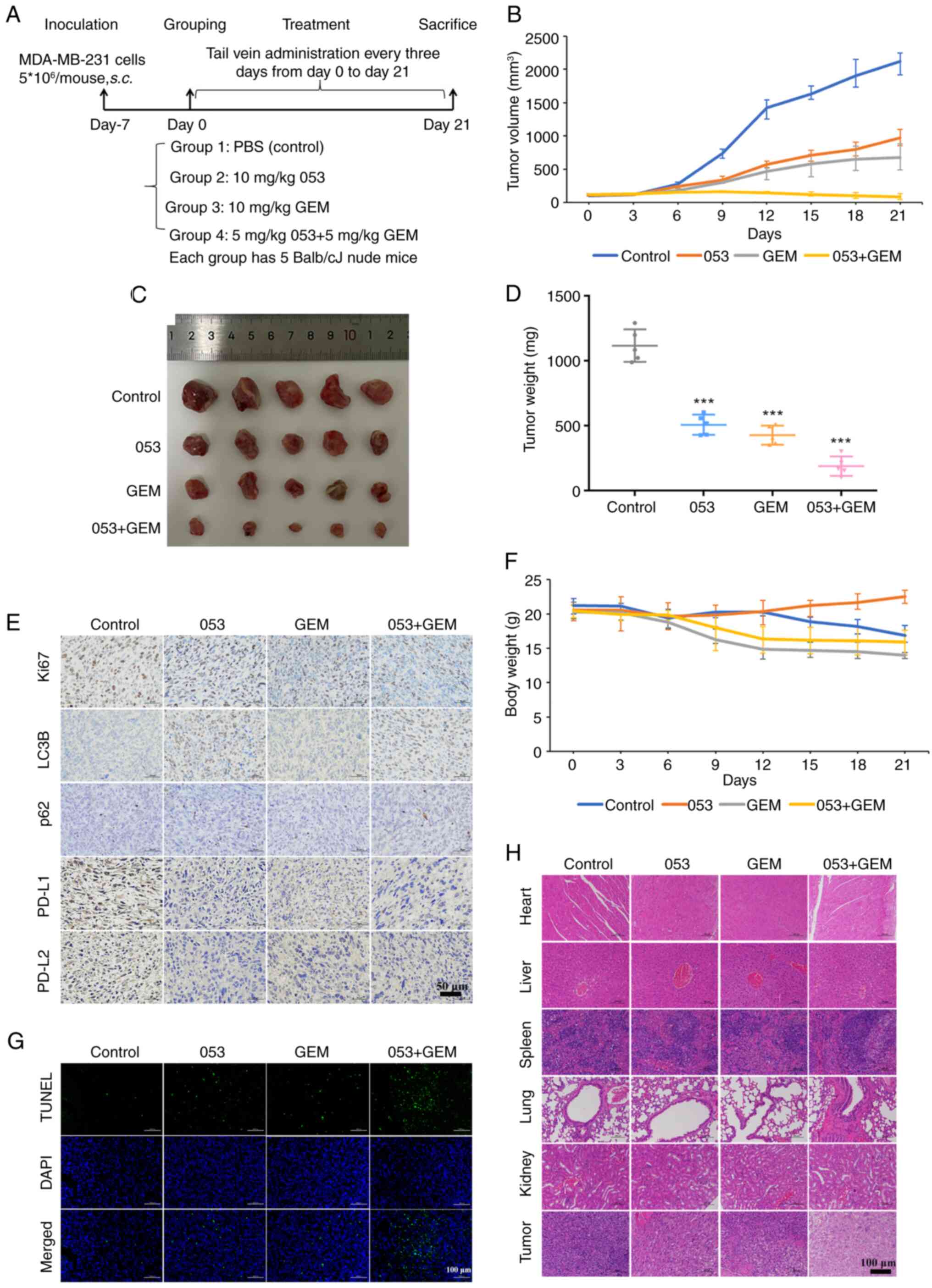

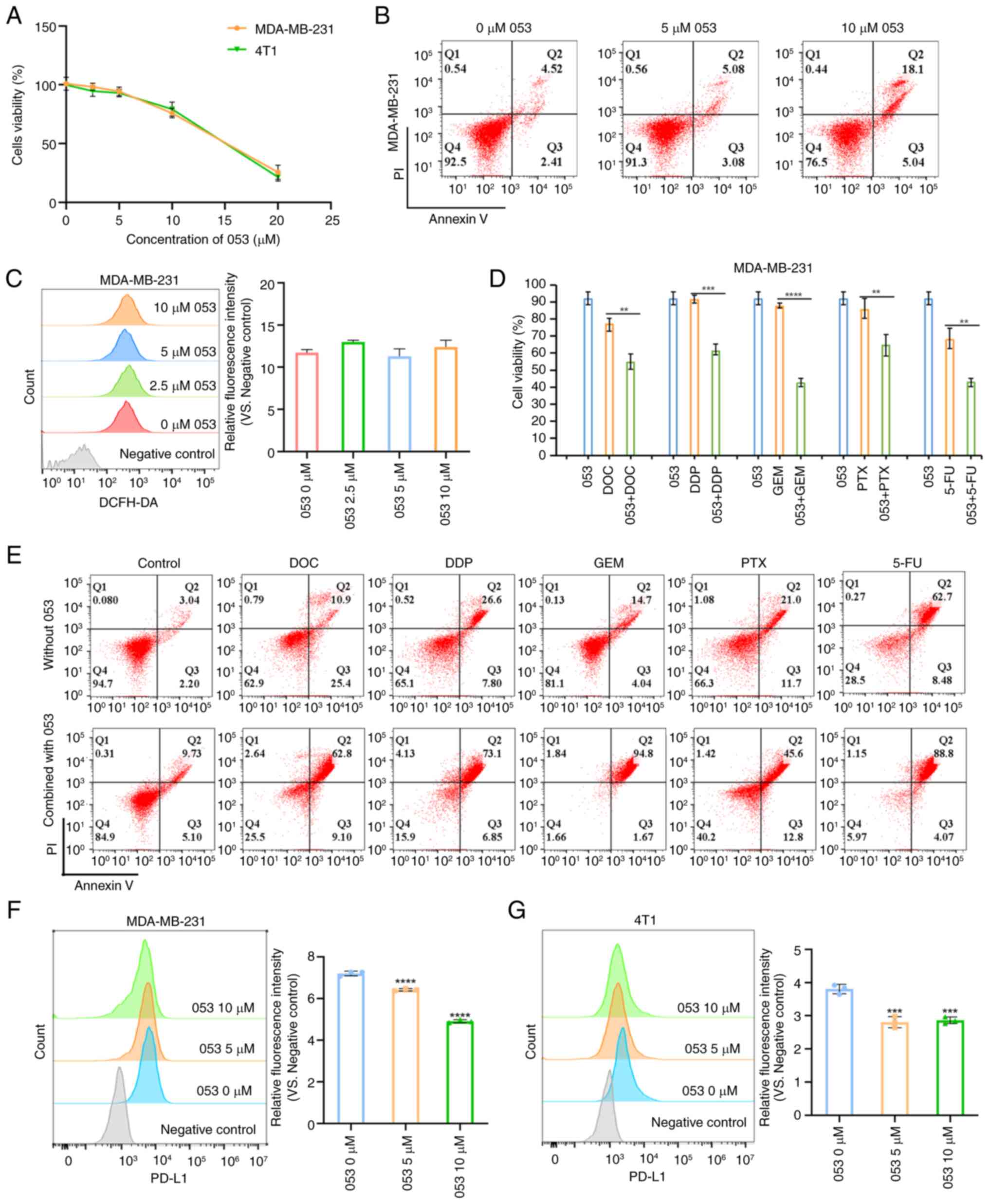

Compound 053 enhances the in vivo

antitumor effect of GEM by inhibiting autophagy in the MDA-MB-231

xenograft nude mouse model

To more accurately simulate the in vivo

effects of compound 053, a BALB/cJ nude mouse model for MDA-MB-231

breast cancer xenografts was established. After tumor formation,

mice were injected with saline, 053 (10 mg/kg), GEM (10 mg/kg) or a

combination of 053 (5 mg/kg) and GEM (5 mg/kg) via tail vein

injection every 3 days for 3 weeks (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B-D, the tumor size and weight in

the control group of the nude mouse xenograft model continued to

increase, while tumor growth in the drug-treated groups was

inhibited to varying degrees. Notably, the tumor growth in the nude

mouse xenograft model treated with the combination of 053 and GEM

was the slowest and thus this treatment exhibited the most

significant antitumor effect. As shown in Fig. 4E and G, immunohistochemical and

immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissues from the nude mouse

xenograft model revealed that, compared with the saline-treated

group (control), 053 treatment alone reduced Ki67 expression and

increased TUNEL expression in tumors, while the combination of 053

and GEM further decreased Ki67 expression and elevated TUNEL

expression. Subsequently, the antitumor effect of 053 was further

confirmed by analyzing H&E-stained tumor tissues. As shown in

Fig. 4H, the tumor tissues in the

control group showed almost no cell necrosis or apoptosis, whereas

the 053- and GEM-treated groups displayed extensive cell shrinkage

and apoptotic nuclei, and the tumor tissues in the 053- and

GEM-combined treatment group exhibited the most severe cell damage.

More notably, immunohistochemical staining of the tumor tissues

also showed that, compared with the control group, 053 alone or in

combination with GEM significantly increased the expression of LC3B

and p62 in the tumor tissues (Fig.

4E). As previously demonstrated, it was confirmed that 053 can

negatively regulate the expression of PD-L1in MDA-MB-231 cells

in vitro. Therefore, the expression of PD-L1 in the tumor

tissues of a nude mouse xenograft model was further tested using

immunohistochemical staining. Notably, treatment with 053 alone or

in combination with GEM reduced the expression of PD-L1 in tumor

tissues compared with the control group (Fig. 4E). All the aforementioned results

indicated that 053 can effectively inhibit the autophagy of tumor

cells in vivo, and the combination treatment with GEM

significantly enhances the antitumor effect.

| Figure 4Compound 053 enhances the therapeutic

effect of GEM by inhibiting autophagy in the MDA-MB-231 xenograft

model. (A) Mouse treatment plan. (B) The tumor size was measured

with a caliper every 3 days and the volume was calculated (n=5).

(C) Tumor morphology of mouse removed at 21 days of treatment. (D)

The tumors were removed and weighed at 21 days of treatment. Data

are presented as mean ± SEM (n=5). Statistical significance was

determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple

comparisons test to compare all experimental groups against a

single control group. ***P<0.001 vs. Control. (E)

Protein levels of Ki67, LC3B, p62, PD-L1 and PD-L2 were detected

using immunohistochemical staining in tumor tissues of mice after

21 days of treatment. Nuclei are localized in blue and target

proteins are localized in brown. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Body

weight was measured every 3 days. (G) The TUNEL assay was used to

evaluate DNA fragmentation in mouse tumor tissues after 21 days of

treatment. Blue fluorescence indicates nuclear staining (DAPI),

while green fluorescence specifically labels DNA breaks associated

with apoptosis. Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) H&E staining of

tumor tissues and major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs and

kidneys) of mice after 21 days of treatment. Nuclei are blue-purple

and cytoplasm is red. Scale bar, 100 μm. 053, FZU-0045-053;

GEM, gemcitabine; LC3B, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light

chain 3B; p62/SQSTM1, sequestosome 1; PD-L1/2, programmed

death-ligand 1/2. |

In addition, there was no significant decrease in

body weight in the 053-treated mice compared with the other

treatment groups during the treatment period (Fig. 4F). The major organs (heart, liver,

spleen, lungs and kidneys) of the treated mice were further

examined using H&E staining. As shown in Fig. 4H, no obvious organ damage or

inflammatory lesions were observed in mice treated with 053.

However, mice treated with GEM showed mild inflammation in the

liver, irregular arrangement of alveolar epithelial cells, diffuse

alveolar damage and interstitial edema. These results indicate that

053 exhibits greater biosafety in mice compared with the

conventional chemotherapeutic agent GEM. In summary, 053 exhibits

high biosafety in vivo and enhances the antitumor effect by

inhibiting autophagy in tumor cells while negatively regulating the

expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues.

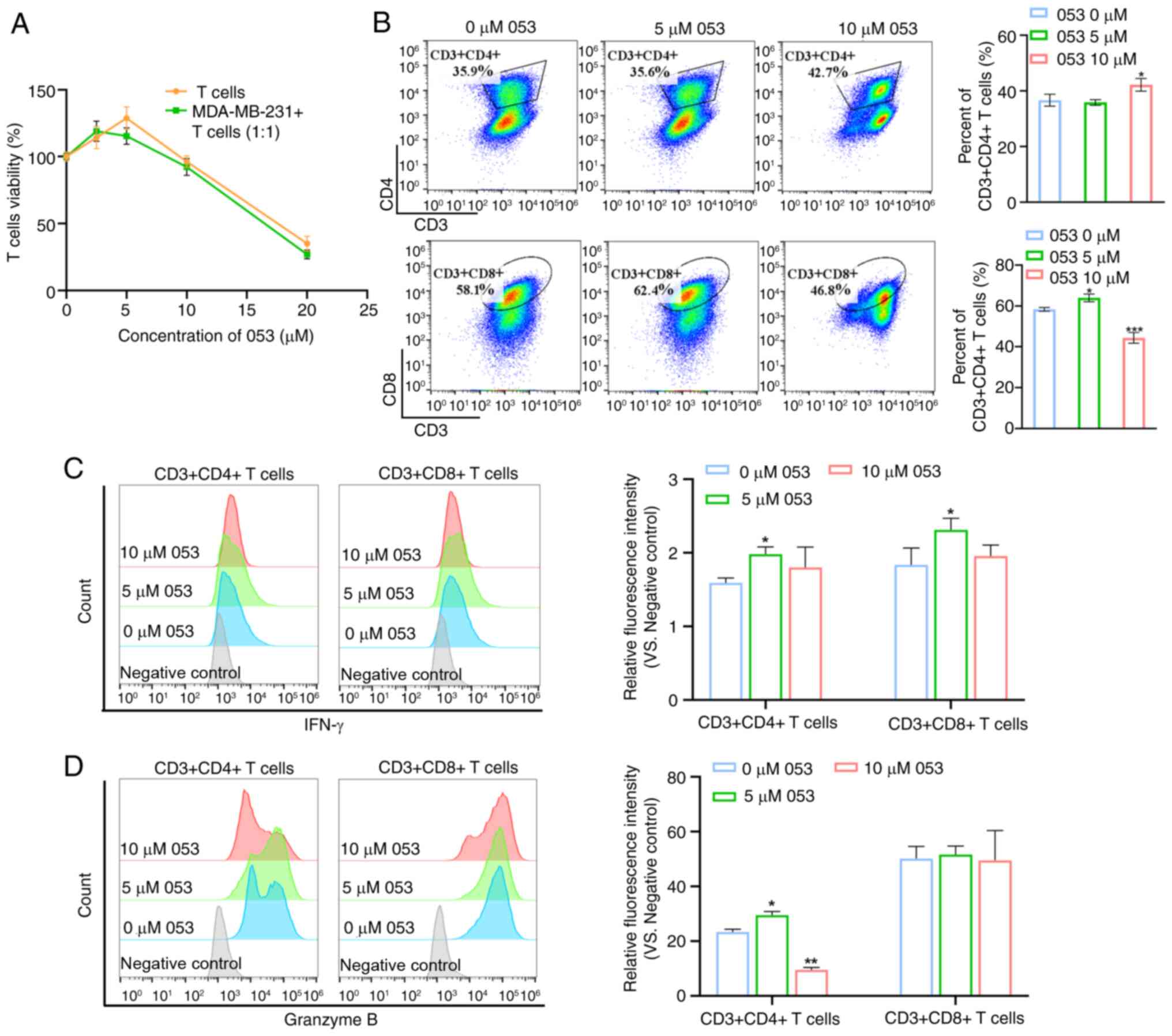

Compound 053 promotes T cell activation

and proliferation by regulating co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory

molecules on the surface of T cells

The dose-response experiments demonstrated that low

dose 053 (0-5 μM) promoted T cell proliferation, while

higher concentrations (>5 μM) induced cytotoxicity.

Notably, this biphasic effect was replicated in the T cell-tumor

cell (MDA-MB-231) co-culture system, indicating that 5 μM

053 optimally activated T cell expansion in both isolated and

tumor-associated environments (Fig.

5A). Therefore, it was hypothesized that compound 053 exhibits

immunomodulatory potential. Subsequently, it was observed that

treatment with 5 μM 053 did not alter the proportion of

CD4+ T cells but slightly increased the proportion of

CD8+ T cells. Notably, treatment with 10 μM 053

reduced the proportion of CD8+ T cells, while increasing

the proportion of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5B). Activated CD4+ T

cells and CD8+ T cells secrete a range of cytokines

involved in inflammatory responses and immunomodulation. As shown

in Fig. 5C and D, using flow

cytometry it was found that 5 μM 053 promoted the expression

of IFN-γ and Granzyme B in T cells, but 10 μM 053

downregulated the expression of IFN-γ and Granzyme B in T cells,

which was due to the toxicity of high concentrations of compound

053 to T cells.

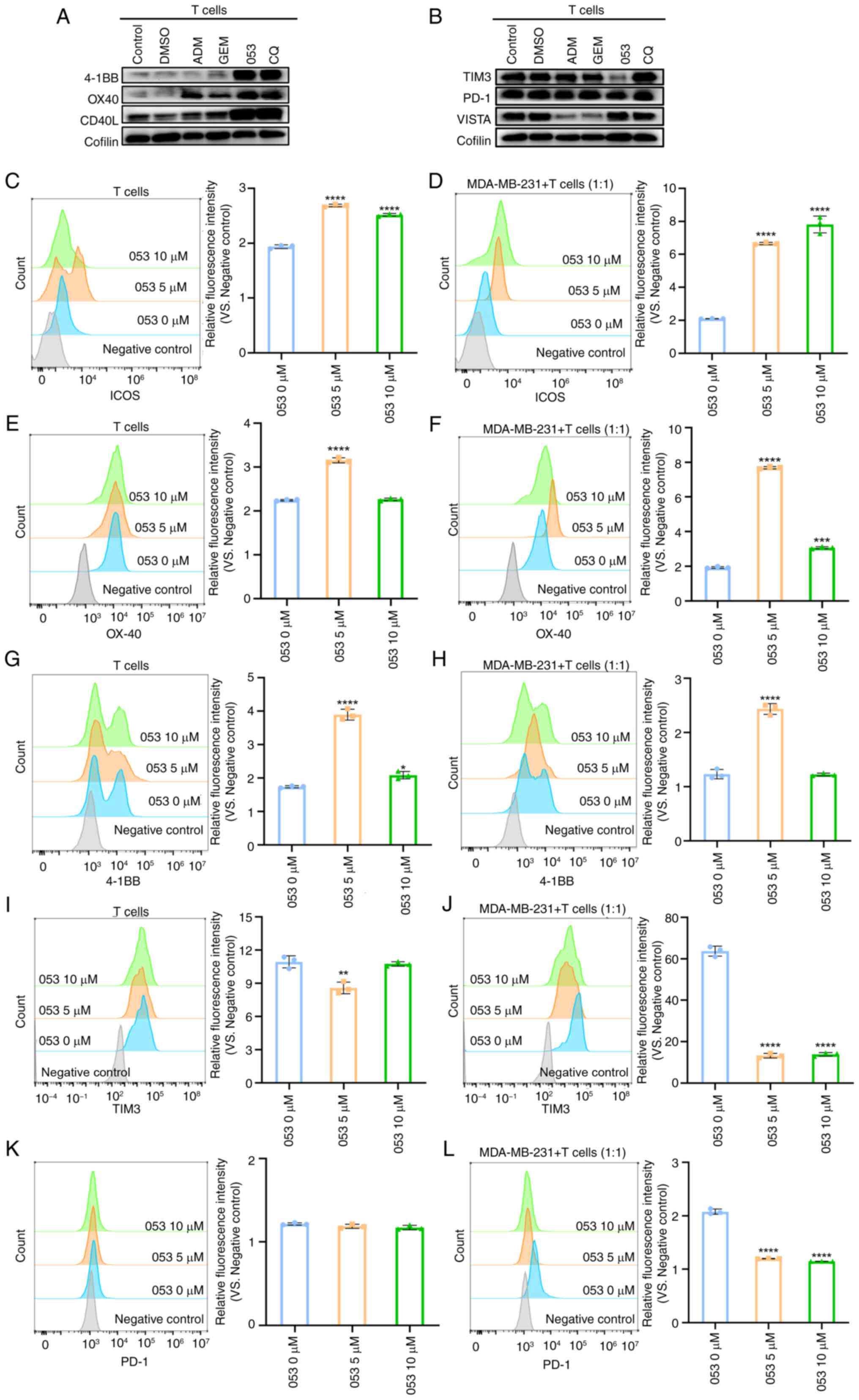

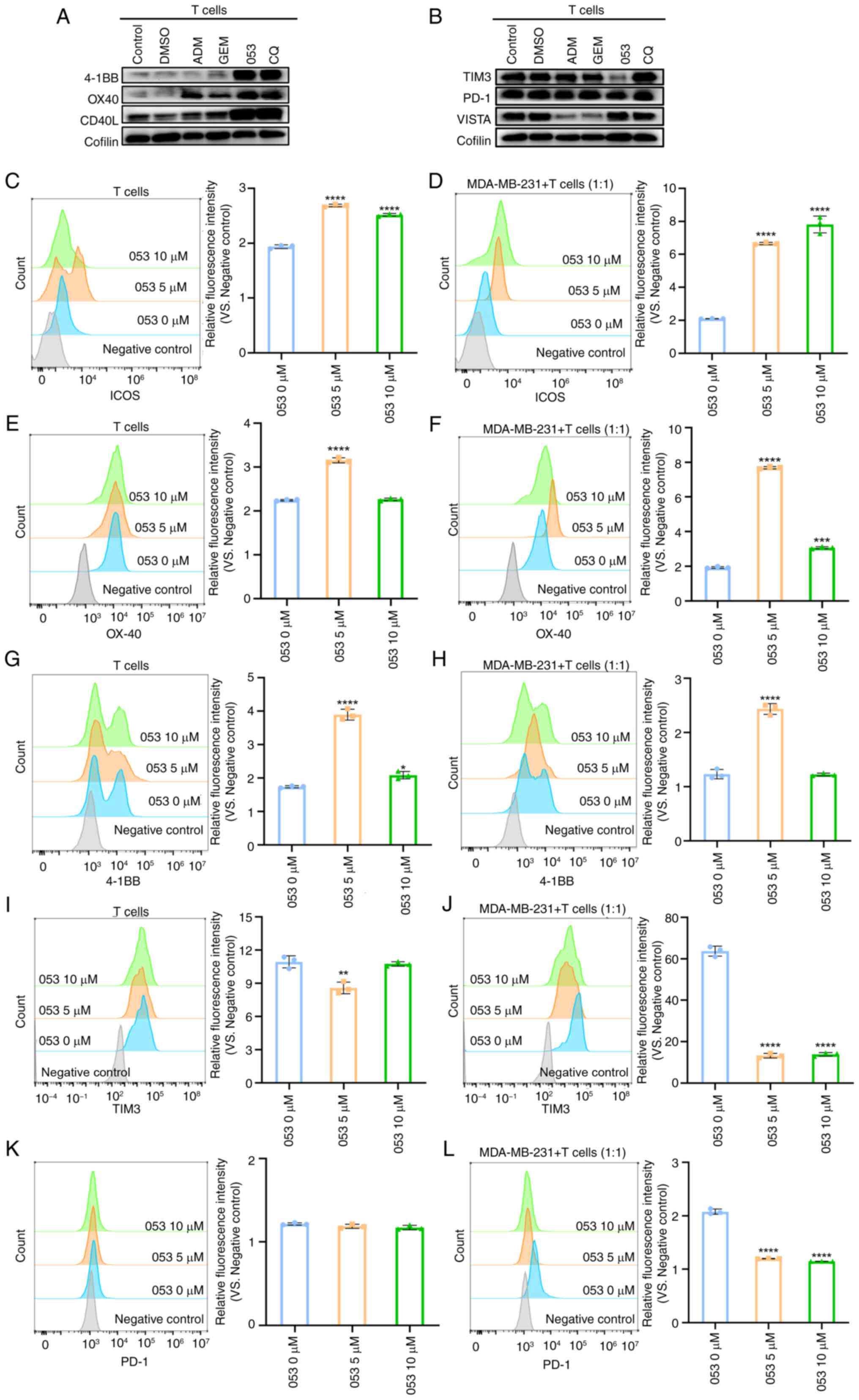

Co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of T cells,

such as 4-1BB, OX-40 and CD40L, transmit positive signals by

binding to their respective ligands, thereby promoting T cell

activation and participation in subsequent immune responses

(34). By contrast, co-inhibitory

molecules on the surface of T cells, such as TIM3, PD-1 and VISTA,

downregulate or terminate T cell activation and proliferation by

transmitting inhibitory signals (35). Western blotting was performed to

evaluate the effects of compound 053, ADM, GEM and CQ on the

protein levels of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules on the

surface of T cells. As shown in Fig.

6A and B, it was found that compound 053 (5 μM)

upregulated the expression levels of 4-1BB, CD40L and OX-40, while

they decreased the levels of TIM3 on the surface of T cells.

However, treatment with 053 did not alter the expression level of

PD-1 and VISTA on the surface of T cells, and the levels of TIM-3,

VISTA and PD-1 in the CQ group also appeared unchanged. Flow

cytometry further validated that 053 (0-10 μM) treatment

upregulated co-stimulatory molecules (4-1BB, ICOS and OX-40) and

downregulated inhibitory markers (TIM-3) in T cells cultured alone

or with MDA-MB-231 cells, with optimal effects at 5 μM

(Fig. 6C-J). When T cells were

treated with compound 053 in a monoculture system, the expression

level of PD-1 remained unchanged. However, when 053 was applied to

a co-culture system of T cells and MDA-MB-231 cells, it

downregulated the surface expression of PD-1 on T cells (Fig. 6K and L). In conclusion, compound

053 regulated the activation and proliferation of T cells by

downregulating the co-inhibitory molecules TIM3 and PD-1, and

upregulating the co-stimulatory molecules 4-1BB, OX40, CD40L and

ICOS to promote immune responses.

| Figure 6Compound 053 modulates co-stimulatory

and co-inhibitory molecules on T cell surfaces. (A) The protein

levels of 4-1BB, OX40 and CD40L after 5 μM ADM, GEM (80

μM), 053 (5 μM) or CQ (30 μM) treatment were

analyzed by western blotting. (B) The protein levels of TIM3, PD-1

and VISTA after 5 μM ADM, GEM (80 μM), 053 (5

μM) or CQ (30 μM) treatment were analyzed by western

blotting. (C) After T cells were treated with 053 (0-10 μM)

for 24 h, ICOS expression on T cell surfaces was analyzed by flow

cytometry. The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative

fluorescence intensity. (D) T cells were co-cultured with

MDA-MB-231 cells at a 1:1 ratio and treated with 053 (0-10

μM) for 24 h, followed by flow cytometric analysis of ICOS

expression on T cell surfaces. The bar graph shows quantitative

analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. (E) After T cells were

treated with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h, OX-40 expression on T

cell surfaces was analyzed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows

quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. (F) T

cells were co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells at a 1:1 ratio and

treated with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h, followed by flow

cytometric analysis of OX-40 expression on T cell surfaces. The bar

graph shows quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence

intensity. (G) After T cells were treated with 053 (0-10 μM)

for 24 h, 4-1BB expression on T cell surfaces was analyzed by flow

cytometry. The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative

fluorescence intensity. (H) T cells were co-cultured with

MDA-MB-231 cells at a 1:1 ratio and treated with 053 (0-10

μM) for 24 h, followed by flow cytometric analysis of 4-1BB

expression on T cell surfaces. The bar graph shows quantitative

analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. (I) After T cells were

treated with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h, TIM3 expression on T

cell surfaces was analyzed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows

quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. (J) T

cells were co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells at a 1:1 ratio and

treated with 053 (0-10 μM) for 24 h, followed by flow

cytometric analysis of TIM3 expression on T cell surfaces. The bar

graph shows quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence

intensity. (K) After T cells were treated with 053 (0-10 μM)

for 24 h, PD-1 expression on T cell surfaces was analyzed by flow

cytometry. The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative

fluorescence intensity. (L) T cells were co-cultured with

MDA-MB-231 cells at a 1:1 ratio and treated with 053 (0-10

μM) for 24 h, followed by flow cytometric analysis of PD-1

expression on T cell surfaces. The bar graph shows quantitative

analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. Data are presented as

mean ± SEM (n=3). Statistical significance was determined by

one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test to

compare all experimental groups against a single control group.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. 0

μM 053. 053, FZU-0045-053; ADM, adriamycin; 4-1BB, tumor

necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9; OX40, tumor necrosis

factor receptor superfamily member 4; CD40L, CD40 ligand; ICOS,

inducible T-cell co-stimulator; PD-1, programmed cell death protein

1; TIM3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3;

VISTA, V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation; GEM,

gemcitabine; CQ, chloroquine. |

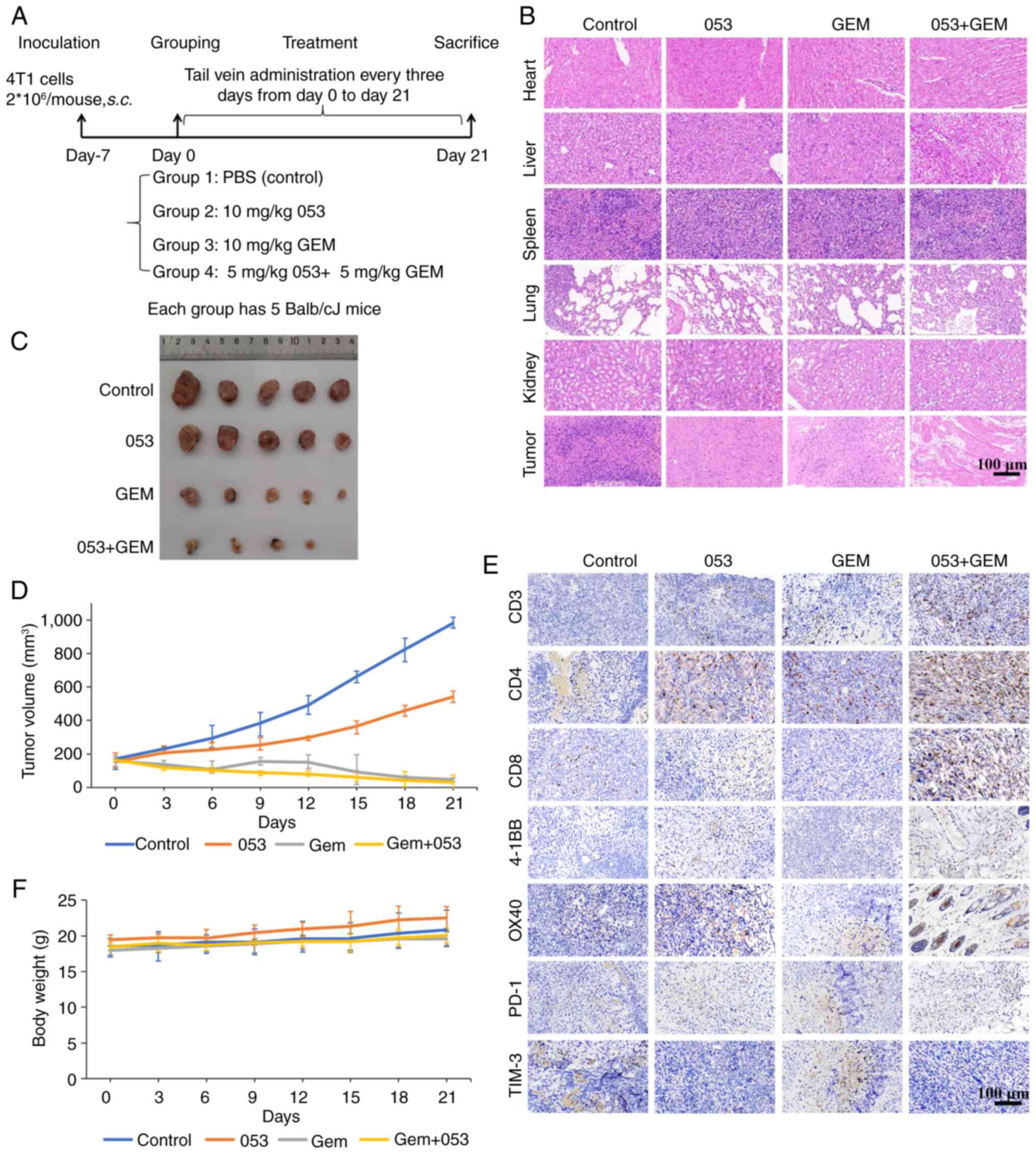

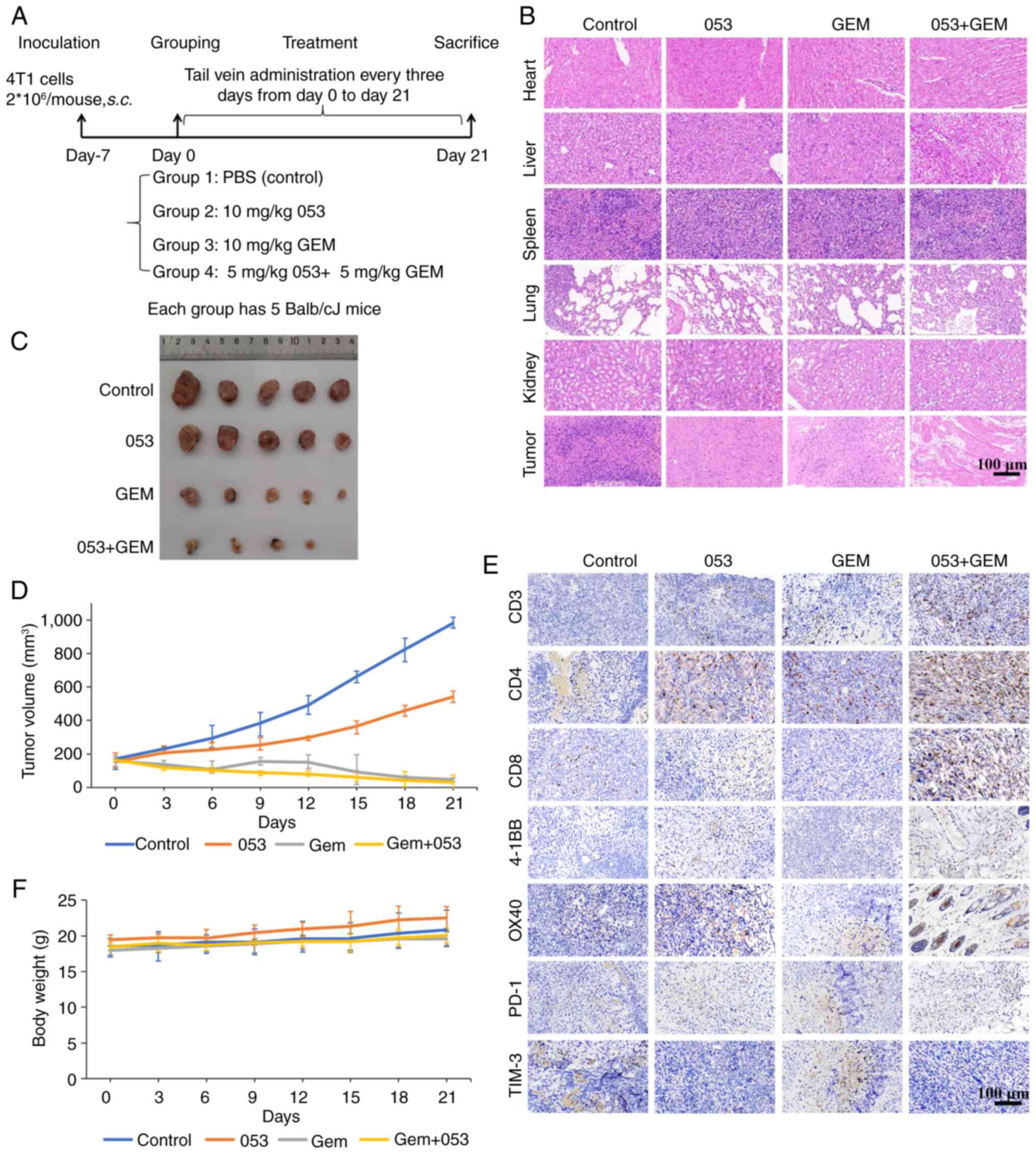

Compound 053 enhances the in vivo

antitumor efficacy of GEM by modulating co-stimulatory and

co-inhibitory molecules on tumor-infiltrating T cells in the 4T1

xenograft model

To more accurately simulate the in vivo

antitumor effects of compound 053 through immunomodulation, a

BALB/c mouse 4T1 breast cancer xenograft model was established.

After tumor formation, mice were injected via the tail vein with

saline, 053 (10 mg/kg), GEM (10 mg/kg) or a combination of 053 (5

mg/kg) and GEM (5 mg/kg) every 3 days for 3 weeks (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 7C and D, consistent with the trends

observed in the previously described nude mouse xenograft model,

tumor growth was inhibited to varying degrees in the drug-treated

groups compared with the control group. Notably, the combination

treatment of 053 and GEM exhibited the slowest tumor growth

(Fig. 7C and D). In addition,

there was no significant decrease in body weight in the mice

treated with 053 compared with the other treatment groups (Fig. 7F). H&E staining was used for

the histological examination of major organs in mice, and no

significant detrimental effects were observed at the therapeutic

dose of 053 (Fig. 7B).

Subsequently, analysis of the H&E staining of the tumor

tissues, which was also consistent with the trend observed in the

aforementioned nude mouse xenograft model, revealed that the 053

and GEM-treated groups exhibited extensive cell atrophy and nuclear

apoptosis compared with the control group, with the tumor tissues

of the 053 and GEM combination treatment group showing the most

severe cell damage (Fig. 7B). In

addition, immunohistochemical analysis of the tumors revealed that

053 increased the levels of CD3, CD4, CD8, 4-1BB and OX-40 in the

tumor tissues, while the levels of PD-1 and TIM3 were reduced,

particularly when 053 was combined with GEM (Fig. 7E).

| Figure 7Compound 053 enhances the in

vivo antitumor effect of GEM in the 4T1 xenograft model. (A)

Mouse treatment plan. (B) H&E staining of heart, liver, spleen,

lung and kidney. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Tumor morphology of

mouse removed at 21 days of treatment. (D) The tumor size was

measured with a caliper every 3 days and the volume was calculated

(n=5). (E) Protein levels of CD3, CD4, CD8, 4-1BB, OX40, PD-1 and

TIM3 were detected using immunohistochemical staining in tumor

tissues of mice after 21 days of treatment. Nuclei are localized in

blue and target proteins are localized in brown. Scale bar, 100

μm. (F) Body weight was measured every 3 days (n=5). 053,

FZU-0045-053; GEM, gemcitabine; 4-1BB, tumor necrosis factor

receptor superfamily member 9; OX40, tumor necrosis factor receptor

superfamily member 4; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; TIM3,

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3. |

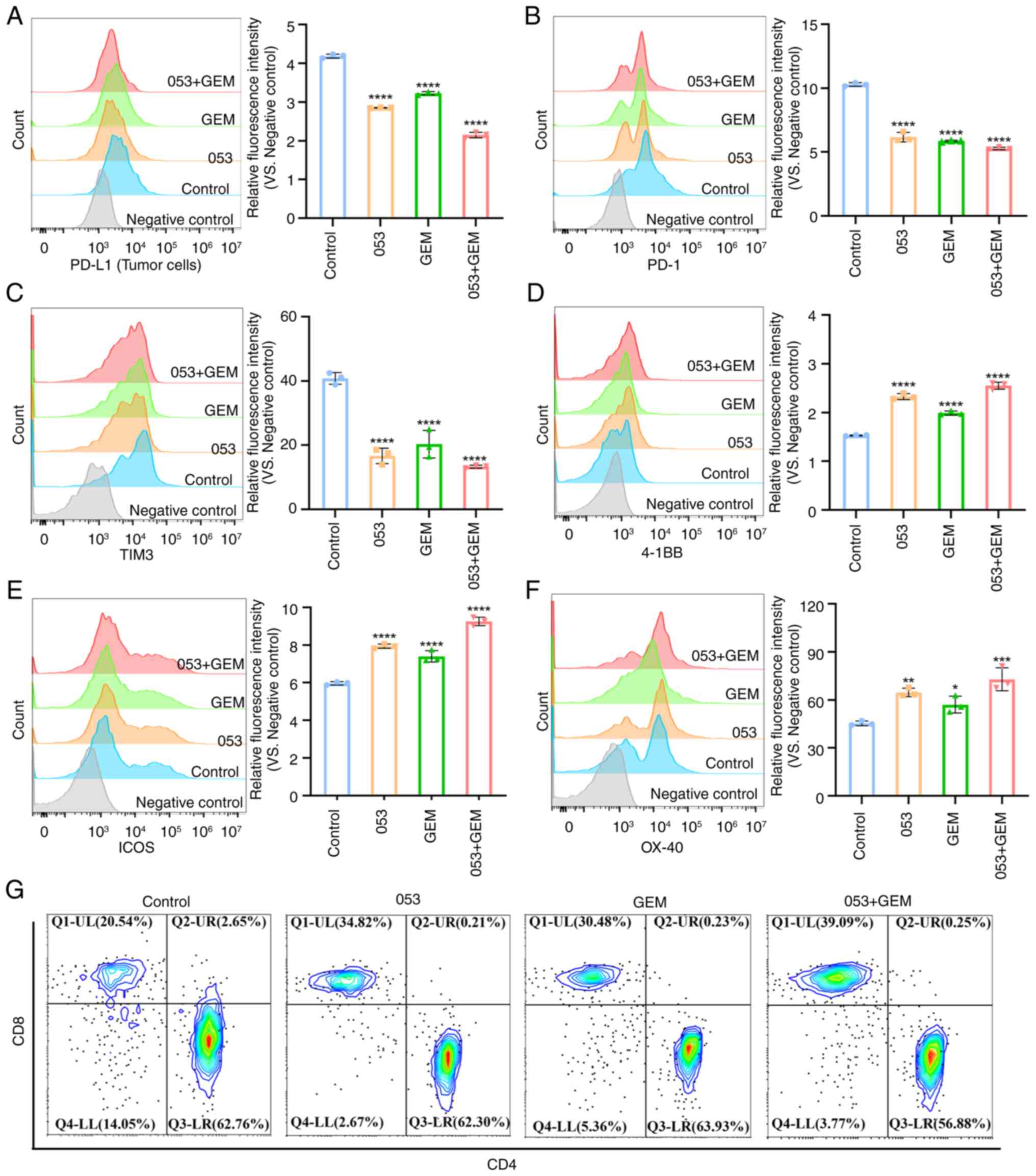

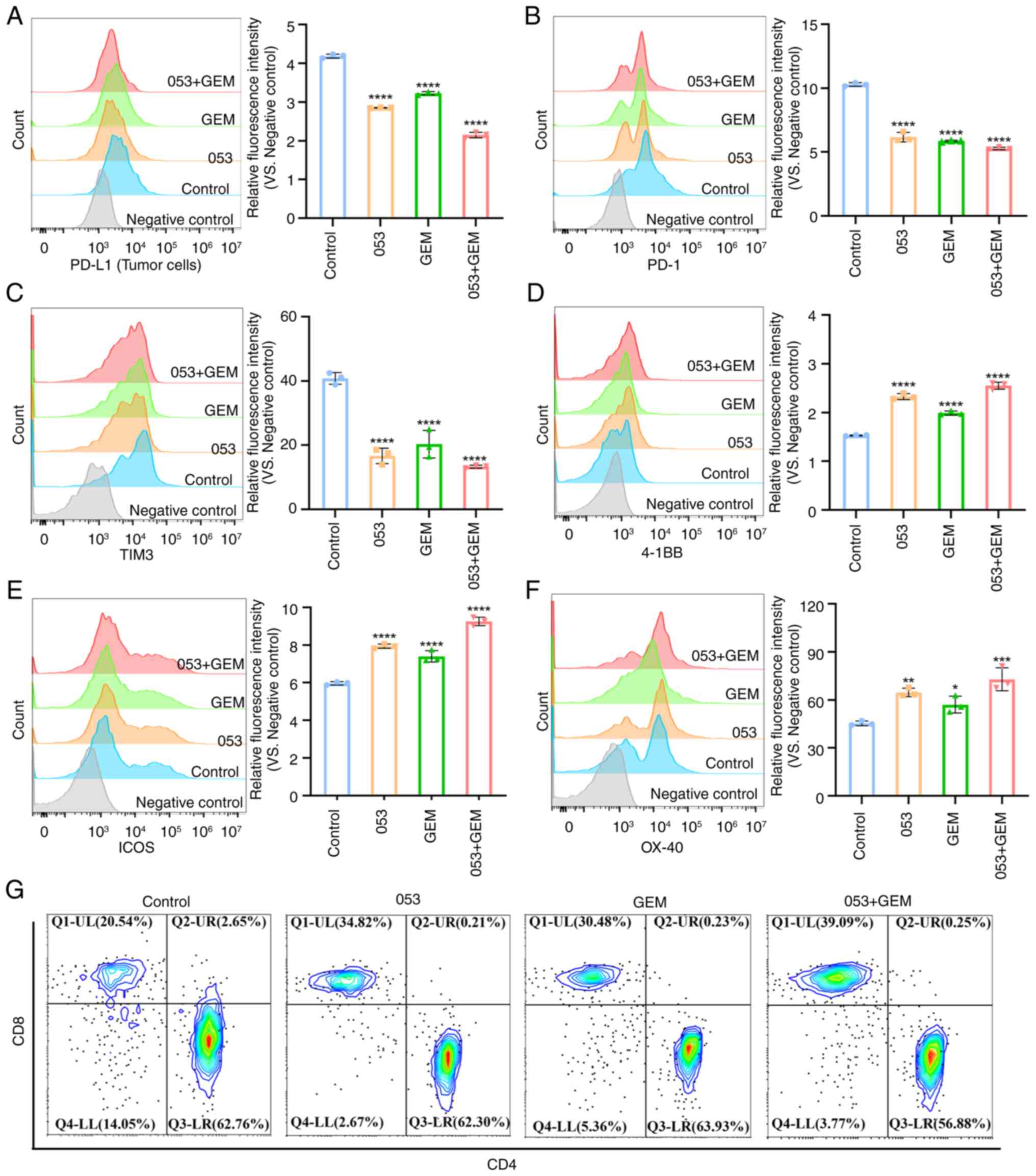

Subsequently, tumor tissues were digested into

single-cell suspensions and tumor cells were separated from

lymphocytes using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Flow

cytometric analysis revealed that both the 053 monotherapy group

and the 053+ GEM combination therapy group showed reduced PD-L1

expression on tumor cells (Fig.

8A). As shown in Fig. 8B-F,

flow cytometric analysis further validated the aforementioned

findings, demonstrating that both the 053 monotherapy group and the

053+ GEM combination therapy group exhibited increased expression

of co-stimulatory molecules (4-1BB, ICOS and OX-40) on

tumor-infiltrating T cells, along with decreased expression of

co-inhibitory molecules (PD-1 and TIM-3). Moreover, flow cytometric

analysis revealed an increase in the proportion of

tumor-infiltrating CD3+CD8+ T cells in both

the 053 monotherapy group and the 053+ GEM combination therapy

group, rising from 20.54 to 34.82 and 39.09% (Fig. 8G). Notably, the combination

therapy group showed more pronounced effects than monotherapy. In

summary, these findings demonstrate that compound 053 downregulates

PD-L1 expression on tumor cells while modulating co-stimulatory and

co-inhibitory molecules on tumor-infiltrating T cells. This dual

mechanism promotes T cell activation and proliferation, enhances

effector functions and increases cytotoxic CD8+ T cell

infiltration in tumor tissues, ultimately potentiating its

antitumor efficacy.

| Figure 8Compound 053 modulates PD-L1 on tumor

cells and co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory molecules on

tumor-infiltrating T cells in the 4T1 xenograft model. (A) Flow

cytometry was performed to analyze PD-L1 surface expression on

tumor cells. The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative

fluorescence intensity. (B) PD-1 expression on tumor-infiltrating T

cells surfaces was analyzed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows

quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. (C) TIM3

expression on tumor-infiltrating T cells surfaces was analyzed by

flow cytometry. The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of

relative fluorescence intensity. (D) 4-1BB expression on

tumor-infiltrating T cells surfaces was analyzed by flow cytometry.

The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence

intensity. (E) ICOS expression on tumor-infiltrating T cells

surfaces was analyzed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows

quantitative analysis of relative fluorescence intensity. (F) OX-40

expression on tumor-infiltrating T cells surfaces was analyzed by

flow cytometry. The bar graph shows quantitative analysis of

relative fluorescence intensity. Data are presented as mean ± SEM

(n=3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA

followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test to compare all

experimental groups against a single control group.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. 0

μM 053. (G) Flow cytometry was used to analyze the

differentiation of CD3+CD4+ T cells and

CD3+CD8+ T cells. 053, FZU-0045-053; 4-1BB,

tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9; OX40, tumor

necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 4; ICOS, inducible

T-cell co-stimulator; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; TIM3,

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3; GEM,

gemcitabine; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1. |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, CQ/HCQ is the only

clinically approved autophagy inhibitor. However, its efficacy

remains unsatisfactory in current clinical trials for various

cancer types (13,36). Consequently, there is a need to

develop additional autophagy modulators with novel antitumor

potential. Different autophagy inhibitors target different stages

of autophagy. For example, CQ and Bafilomycin A1 primarily inhibit

the final stage of autophagy by blocking autophagosome-lysosome

fusion, leading to the accumulation of autophagic vesicles in

cells, while 3-methyladenine mainly inhibits early autophagy by

preventing autophagosome formation (31,37,38). Among the more common autophagy

inhibitors that block the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes,

CQ was selected as a positive control in the present study.

Research indicates that CQ increases the levels of LC3-II and p62

proteins, enhances autophagosome formation and promotes apoptosis,

pretreatment with RAPA mitigates these effects (39). Notably, the present study found

that both 053 and CQ treatments increased the levels of LC3B-II and

p62 proteins, as well as increased the accumulation of acidic

autophagosomes. Consequently, we hypothesized that 053, similar to

CQ, may be a late autophagy inhibitor. Subsequently, it was

investigated whether 053 affects the fusion of autophagosomes and

lysosomes using a tandem mRFP-GFP-LC3B reporter gene assay. The

results showed that both 053 and CQ enhanced yellow fluorescence

following co-localization stacking. Consequently, it was speculated

that 053, similar to CQ, disrupts autophagic flux at late stages by

blocking autophagosome-lysosome fusion, which leads to the

accumulation of autophagosomes. It has been reported that autophagy

can be regulated through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, and

the inhibition of this pathway downregulates p62 expression in

breast cancer cells, thereby inducing autophagy (9). Additionally, the natural product

astragaloside II overcomes DDP resistance in hepatocellular

carcinoma cells by inactivating autophagy through the enhancement

of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (32). The results of the present study

also suggest that 053 inhibits autophagy by activating the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in MDA-MB-231 cells. However, no

significant activation of this pathway was observed in MCF-7 cells.

It has been reported that autophagy regulators can modulate

autophagy through both mTOR-dependent and mTOR-independent pathways

(40). Therefore, we hypothesize

that the autophagy-regulating effect of 053 on MCF-7 cells may not

be dependent on the AKT/mTOR pathway.

Research indicates that the development of

multidrug resistance frequently results from prolonged chemotherapy

regimens. Additionally, the suppression of autophagy has been

demonstrated to improve the effectiveness of chemotherapy, targeted

therapies and immunotherapies, thereby enhancing antitumor

responses (41). Consequently,

after confirming that 053 is an autophagy inhibitor, the present

study further investigated whether 053 enhances the sensitivity of

chemotherapeutic agents by inhibiting autophagy. The results showed

that 053 treatment alone induced tumor cell apoptosis in a time-

and concentration-dependent manner, and the combination of 053 with

chemotherapeutic agents had a significant synergistic effect,

further inducing apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Furthermore, in

the MDA-MB-231 xenograft nude mouse model, 053 treatment alone

induced apoptosis and inhibited autophagy in tumor cells, resulting

in a certain antitumor effect, and the antitumor effect was more

pronounced when 053 was combined with the chemotherapeutic agent

GEM. High levels of ROS have been reported to increase

autophagosome formation and damage in cells (42). However, the results of the present

study were inconsistent with this finding, as 053 did not affect

ROS levels in tumor cells, suggesting that 053 does not depend on

the ROS pathway to regulate autophagy and apoptosis in breast

cancer cells.

The expression of PD-L1 is related to autophagy

mediated by LC3 and p62. There is a strong negative correlation

between p62 and PD-L1 (9).

Notably, the present study demonstrated that compound 053 inhibited

autophagy in tumor cells by increasing the protein levels of LC3-II

and p62, while simultaneously downregulating PD-L1 expression.

Research has shown that knocking out the autophagy-related gene

Rb1cc1 in tumor cells to inhibit autophagy increases TNFα-mediated

T cell killing of tumor cells and enhances the efficacy of immune

checkpoint blockade in mouse tumor models (43). Immune checkpoint blockade in tumor

immunotherapy has been reported to enhance antitumor T-cell

responses through anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-L1 therapy

(20). T cell co-stimulation is

mediated by immunoregulatory molecules (CD28, CD40L, CD30, OX40 and

4-1BB) expressed on T lymphocytes, while co-inhibitory receptors

(PD-1, CTLA-4, VISTA and TIM3) induce T cell dysfunction and

abrogate antitumor immunity (9,19,34,35). The results of the in vivo

and in vitro experiments in the present study showed that

053 upregulated the expression levels of 4-1BB and OX-40 while

decreasing the levels of PD-1 and TIM-3 on the surface of T cells,

and the effect was more pronounced when 053 was combined with GEM

in vivo. Furthermore, autophagy deficiency leads to the

accumulation of cytoplasmic DNA (such as the release of

mitochondrial DNA), blocking STING degradation and promoting the

secretion of type I interferons and pro-inflammatory factors

through the cGAS/STING pathway, which enhances CD8+ T

cell infiltration (44,45). The results of the present study

further indicated that compound 053 upregulated the expression of

IFN-γ and Granzyme B in T cells, thereby promoting T cell

activation and proliferation. In the 4T1 xenograft model, treatment

with 053 significantly enhanced the infiltration of CD8+

T cells into tumor tissues. IRGQ-mediated autophagy inhibition can

reduce the degradation of MHC class I molecules, enhance tumor

antigen presentation and promote T cell recognition (46). This aligns with the findings of

the present study in which compound 053 not only inhibited tumor

cell autophagy but also exhibited immunostimulatory properties.

Therefore, the regulatory effect of autophagy deficiency in tumor

cells on immune responses is likely secondary. However, the

mechanistic link between autophagy inhibition and immune regulation

in the present study still needs further validation, such as

knocking out key autophagy genes in TNBC cells to explore whether

053 has similar immune regulatory effects.

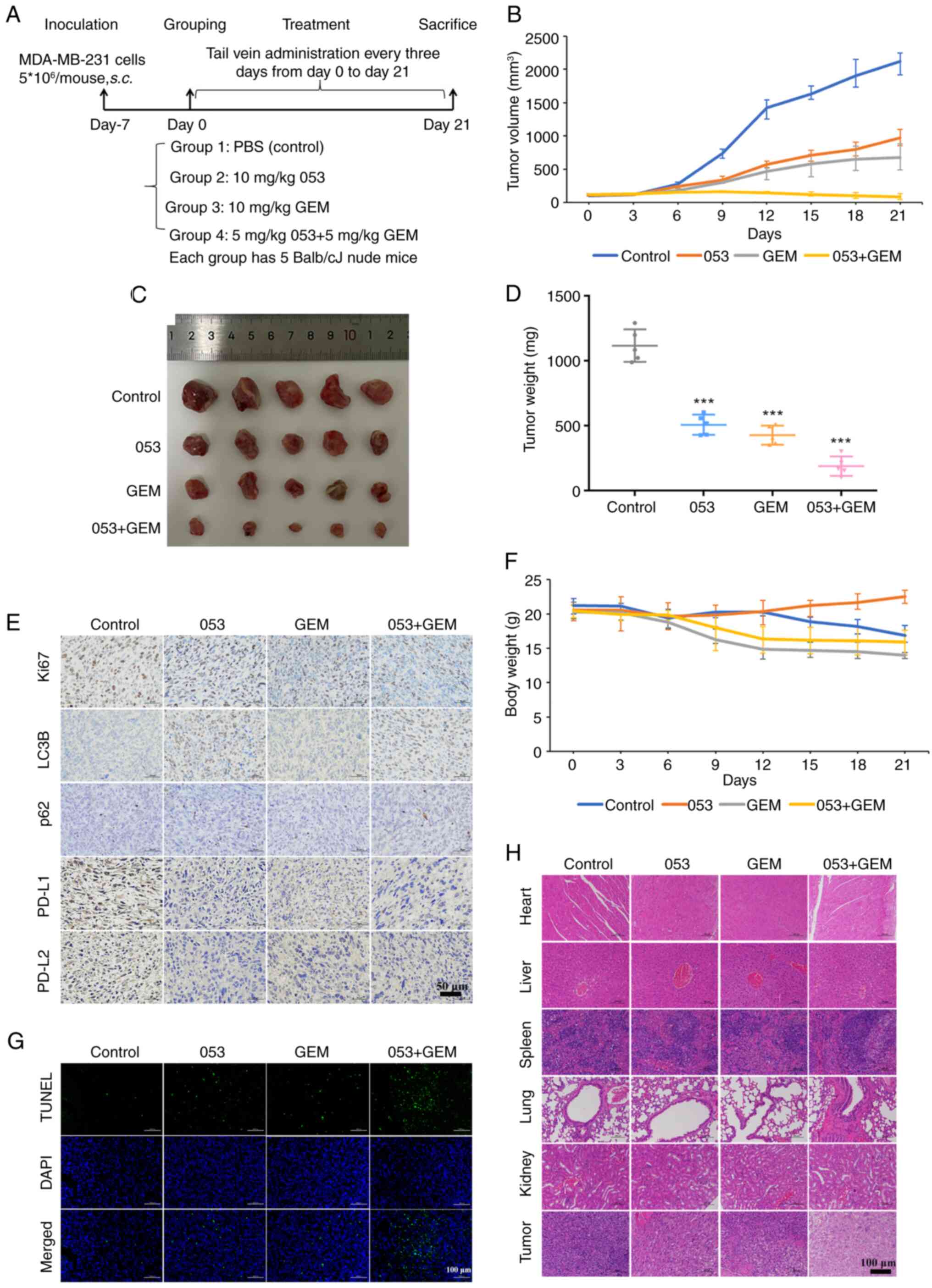

In conclusion, in the present study, small molecule

compounds were selected to investigate their modulatory effects on

autophagy and immune responses in tumor. Notably, the results

showed that the small molecule compound 053 not only inhibited

autophagy but also downregulated the expression of PD-L1 while

promoting the activation and proliferation of T cells by regulating

co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules on the surface of T

cells (Fig. 9). This compound

activated antitumor immunity while inhibiting autophagy, blocking

the self-protective mechanisms of tumor cells under chemotherapy

stress, thereby enhancing their sensitivity to treatment. For

difficult-to-treat subtypes of breast cancer, such as TNBC, this

compound may fill the gap in existing immunotherapy resistance,

providing a novel strategy to overcome resistance to traditional

treatments. Future research should further explore the interaction

between key pathways regulating breast cancer autophagy and the

immune microenvironment. Additionally, investigating the in

vivo efficacy of 053 in metastatic lesions and its ability to

reverse resistance, as well as verifying whether the combination of

053 with chemotherapy drugs or immune checkpoint inhibitors can

improve efficacy, could provide new therapeutic strategies for

multi-target intervention in breast cancer. However, the present

study has certain limitations as it only examined the autophagy

inhibition and immune-promoting effects of compound 053 on breast

cancer cells. To further elucidate the mechanistic relationship

between 053-induced autophagy inhibition and immunomodulation and

to determine whether its immune effects are secondary consequences

or independent mechanisms, genetic knockout of key autophagy genes

in TNBC cells should be performed.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JL developed the framework of the study; JL,YY,

LuC, FC and HZ performed the experiments, investigation and

analyzed the data; JL and YY were responsible for drafting the

initial manuscript; JL, SC, PQ, YL, LiC and YS interpreted the data

and wrote and revised the manuscript; HC and QL designed and

supervised the study, interpreted the data and wrote and revised

the manuscript; JL, HC and QL confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The in vivo mouse study procedures were

performed in accordance with the regulations of the Laboratory

Animal Ethics Committee of the College of Biological Sciences and

Engineering, Fuzhou University (Fuzhou, China; approval no.

2022-SG-022). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from

healthy individuals in compliance with the regulations set forth by

the Ethics Committee of Fujian Cancer Hospital (Fuzhou, China;

approval no. K2023-305-01). This process included obtaining

informed consent documents (approval no. 1.0, 2023.8.18).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82374081), Joint Funds for the

Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province, China (grant

nos. 2023Y9406 and 2021Y9209), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian

(grant no. 2024J011065), Major Scientific Research Program for

Young and Middle-aged Health Professionals of Fujian Province,

China (grant no. 2022ZQNZD008), High-level Talents Training Project

of Fujian Cancer Hospital (grant nos. 2022YNG04 and 2023YNG02) and

The Fuzhou University Testing Fund of Precious Apparatus (grant no.

2024T019).

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

|

|

2

|

Xiong X, Zheng LW, Ding Y, Chen YF, Cai

YW, Wang LP, Huang L, Liu CC, Shao ZM and Yu KD: Breast cancer:

Pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

10:492025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Obidiro O, Battogtokh G and Akala EO:

Triple negative breast cancer treatment options and limitations: