Introduction

Obesity prevalence continues to rise globally, with

>1.9 billion adults classified as overweight and >650 million

classified as obese, according to the latest World Health

Organization reports (1). Obesity

is a key risk factor for numerous chronic diseases, including type

2 diabetes mellitus (2),

cardiovascular diseases (3) and

osteoarthritis (4). Obesity leads

to insulin resistance, which can progress to type 2 diabetes

(2). The excess fat tissue alters

metabolic processes, increasing the production of pro-inflammatory

cytokines and free fatty acids, which in turn impair insulin

signaling (2). Obesity also

elevates the risk of cardiovascular diseases. The excess adipose

tissue increases the workload of the heart, raises the blood

pressure and contributes to the buildup of plaque in the arteries

(3). Furthermore, obesity is

linked to a higher incidence of osteoarthritis, as the excess

weight puts additional stress on joints, causing cartilage

degradation and inflammation (4).

The global economic burden of obesity is enormous, with healthcare

costs related to obesity-related diseases increasing in both

developed and developing nations (5).

BC stands out as a leading cause of cancer-related

mortality among women globally. In 2020 alone, there were ~2.3

million new cases diagnosed, accounting for a significant

proportion of all cancer cases (6). The impact of BC extends beyond

physical health, affecting psychological wellbeing and the quality

of life (6). The diagnosis of BC

often leads to heightened anxiety, depression and body image issues

(7). Conventional treatments,

including surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, while

effective in numerous cases, are associated with a range of side

effects. These can include lymphedema, fatigue, nausea, hair loss

and, in some instances, long-term organ damage (8). The economic costs of BC treatment

are also substantial, including direct medical expenses as well as

indirect costs due to lost productivity (9). Despite advances in early detection

and treatment, certain subtypes of BC, such as triple-negative BC

(TNBC), remain particularly aggressive and challenging to treat,

with limited targeted therapies available (10).

Recent research has begun to unravel the complex

relationship among obesity, chronic breast inflammation and BC

development (11).

Epidemiological studies have established a clear association

between obesity and an increased risk of BC, particularly in

postmenopausal women (11,12).

The mechanisms underlying this link are multifaceted. Adipose

tissue in the breast is not inert; it actively secretes a variety

of inflammatory mediators. These include cytokines such as IL-6 and

TNF-α, which create a pro-inflammatory microenvironment (13). Chronic inflammation is now

recognized as a key driver of carcinogenesis. Persistent low-grade

inflammation leads to DNA damage through the production of reactive

oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species (13). Inflammatory cells also secrete

growth factors and angiogenic factors, promoting cell proliferation

and the formation of new blood vessels to supply growing tumors

(13). Emerging evidence suggests

that specific signaling pathways, such as the NF-κB pathway, are

activated in obese breast tissue (14). This pathway regulates the

expression of genes involved in cell survival, proliferation and

immune responses (14).

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) upregulation in obese breast tissue

results in increased prostaglandin E2 levels, which suppress

apoptosis and induce DNA damage (15). Furthermore, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway is often dysregulated in obesity-related BC (16). This pathway is critical for the

regulation of cell proliferation and metabolism, and its activation

can lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation and resistance to cell

death (16).

The present review aims to comprehensively explore

the molecular mechanisms that connect obesity, chronic breast

inflammation and breast carcinogenesis. By delving into the latest

research findings from PubMed-listed studies (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), the present

review aims to provide a detailed understanding of how

obesity-induced inflammation contributes to the development and

progression of BC. The search strategy employed the following key

words and Boolean operators: ('obesity' OR 'adiposity') AND

('chronic inflammation' OR 'breast inflammation') AND ('breast

cancer' OR 'breast carcinogenesis') AND ('molecular mechanisms' OR

'signaling pathways'). Articles published in English between 2013

and 2025 were included, with priority given to meta-analyses,

systematic reviews and high-impact original research. The clinical

implications of these molecular insights are also discussed,

focusing on novel diagnostic approaches, biomarkers for early

detection and risk assessment, and innovative prevention and

treatment strategies tailored to the obese population. Furthermore,

the present review aims to identify gaps in the current knowledge

and propose future research directions, such as long-term

intervention studies and the exploration of personalized medicine

approaches based on the obese inflammatory phenotype in patients

with BC. The ultimate goal is to enhance the prevention, early

detection and treatment of BC in the context of the obesity

epidemic, improving outcomes for this vulnerable patient population

and reducing the global burden of BC.

Obesity and BC epidemiology

Obesity represents a significant global health

challenge and is a well-established modifiable risk factor for

postmenopausal BC, while its association with premenopausal BC risk

appears more complex (17-19).

Furthermore, a substantial body of evidence has demonstrated that

obesity adversely impacts prognosis and treatment outcomes across

various BC subtypes, contributing to cancer-related mortality

(20-22). This section synthesizes key

epidemiological findings on the relationships among obesity, BC

risk, prognosis and treatment response (Table SI).

Obesity as a risk factor for BC

development

Numerous large-scale epidemiological studies have

demonstrated that an elevated BMI increases the risk of developing

postmenopausal BC (19,23) (Table SI). A secondary analysis of the

Women's Health Initiative (WHI) observational study revealed a

clear positive association between higher BMI and increased risk of

invasive postmenopausal BC (18).

Crucially, Ladoire et al (21) demonstrated that even among

postmenopausal women with a normal BMI, higher levels of body fat

were independently associated with an increased BC risk, suggesting

that adiposity itself, beyond BMI classification, is a critical

factor. The risk appears to be further amplified by metabolic

dysfunction. Agnoli et al (12) found that metabolic syndrome, a

cluster of conditions often associated with obesity (including

hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and central

adiposity), conferred an elevated risk of BC in postmenopausal

women compared with that of those without metabolic syndrome. The

underlying mechanisms linking obesity to carcinogenesis involve

chronic low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress (24). Dias et al (24), in a nested case-control study

within the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cohort, provided evidence that

systemic low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress biomarkers

were associated with an increased risk of invasive postmenopausal

BC, suggesting that these inflammatory and oxidative processes may

mechanistically link obesity to breast carcinogenesis by promoting

genomic instability and epithelial cell proliferation. Kabat et

al (19) further investigated

metabolic phenotypes, suggesting that specific obesity-related

metabolic disturbances contribute to BC risk beyond overall

adiposity. Recent data from the WHI reported by Chlebowski et

al (25) reinforced these

findings, revealing higher BC incidence and mortality rates among

postmenopausal women with obesity or metabolic syndrome compared

with those without these conditions. The relationship between

obesity and premenopausal BC risk appears inconsistent, with some

studies suggesting a lower risk in women with a higher BMI,

possibly due to hormonal modulation (19,23).

Impact of obesity on BC prognosis and

outcomes

Beyond increasing BC incidence, obesity is strongly

linked to poorer prognosis in women diagnosed with BC compared with

that of non-obese counterparts, affecting disease-free survival

(DFS) and overall survival (OS) (21,25-27) (Table SI). Ladoire et al

(21), in a pooled analysis of

two large French randomized trials, reported that obese women (BMI

≥30 kg/m2) with node-positive BC had worse DFS and OS

compared with non-obese patients. This adverse prognostic effect

was particularly pronounced in hormone receptor-positive

(HoR+) disease. Analysis of the CALGB 9741 trial by

Ligibel et al (22)

confirmed that a higher BMI was associated with increased

recurrence and mortality risks in women with node-positive BC,

especially within the luminal A subtype as defined by the PAM50

gene expression assay. Widschwendter et al (26), analyzing the SUCCESS A trial

focusing on high-risk early BC (EBC), also found that obesity was

an independent negative prognostic factor for DFS, OS and distant

DFS. Gennari et al (27)

reported that obese patients with high-risk EBC treated with

adjuvant chemotherapy had shorter DFS and OS times compared with

normal-weight patients. Biganzoli et al (28) observed distinct recurrence

dynamics based on baseline BMI, with obese patients showing a

persistently elevated recurrence risk over time compared with

non-obese patients.

However, the prognostic impact appears to vary by BC

subtype. While consistently negative in HoR+ disease,

some studies suggest a potentially less detrimental or even neutral

effect in HER2+ BC or TNBC (26,29). Widschwendter et al

(26) noted that the negative

impact of obesity was significant in HoR+ disease but

not in TNBC within their cohort. Studies continue to explore these

nuances. Lammers et al (29) specifically investigated

HoR+ BC, confirming that a higher BMI was associated

with worse prognosis in this HoR+ patient subgroup

(n=3,521; 78% of the study cohort). Furthermore, obesity may

influence tumor biology and dissemination; Tzschaschel et al

(30) found an association

between obesity and increased detection of circulating tumor cells

in patients with EBC, potentially indicating a mechanism for worse

outcomes. Tangalakis et al (31) suggested that obesity might not

significantly influence the management or outcomes of advanced BC

in elderly patients, highlighting the context-dependency of the

effects of obesity.

Obesity is generally linked to worse prognosis in

HoR+ BC; however, its impact on TNBC remains debated

(32-35). A secondary analysis of the

SUCCESS-A trial indicated that BMI ≥30 kg/m2 did not

significantly influence DFS or OS in the TNBC subgroup [n=769;

hazard ratio (HR), 1.12; 95% CI, 0.82-1.53] (32). Conversely, metabolomics studies

have identified obesity-associated lipid-peroxidation products,

particularly 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), as activators of the

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) cytoprotective

axis in TNBC cells, promoting doxorubicin and carboplatin

resistance (33-35). Integration of these contradictory

data suggests that the prognostic neutrality of obesity in early

TNBC cohorts may not extend to tumors with high 4-HNE/Nrf2

signaling, a hypothesis requiring prospective validation.

Obesity, treatment response and

interventions

Obesity can modulate the efficacy of BC therapies

and influence treatment-related side effects (36). Studies in the neoadjuvant and

adjuvant settings suggest differential responses based on BMI

(35-37). Di Cosimo et al (36), in an exploratory analysis of the

NeoALTTO trial, observed that obese patients with HER2+

BC had lower rates of pathological complete response following dual

HER2-targeted therapy plus chemotherapy compared with normal-weight

patients. An analysis of the ALTTO trial by Martel et al

(37) also indicated that a

higher BMI was associated with worse outcomes in patients with

HER2+ EBC treated with adjuvant trastuzumab-based

therapy, particularly in terms of DFS. Similarly, sub-analysis of

the APHINITY trial (pertuzumab and trastuzumab) by Dauccia et

al (38) revealed that a

higher BMI was associated with an increased risk of invasive DFS

(IDFS) events in HER2+ EBC, specifically among

node-positive patients, consistent with the subgroup analysis of

patients with HER2− early BC with node-positive disease,

showing an increased risk of IDFS events with higher BMI.

Weight gain during treatment is another concern.

Sedjo et al (39)

documented significant weight gain among overweight and obese BC

survivors prior to enrolling in a weight-loss intervention study.

Mutschler et al (40)

demonstrated that weight gain during adjuvant chemotherapy was an

independent negative prognostic factor for DFS in patients with

high-risk EBC. Conversely, intentional weight loss may improve

outcomes (41,42). Goodwin et al (41) conducted the LISA trial, a

randomized study showing that a telephone-based weight loss

intervention was feasible and effective in reducing weight among

postmenopausal women receiving adjuvant letrozole for BC. While

LISA was not powered for survival endpoints, it established the

principle of intervention feasibility. Babatunde et al

(42) demonstrated that a dietary

and physical activity intervention successfully reduced chronic

inflammation markers in obese African-American women, a group at

heightened risk of obesity-related BC. The impact of obesity

extends to survivorship issues; Inglis et al (43) linked excess body weight in BC

survivors to increased cancer-related fatigue, systemic

inflammation and adverse serum lipid profiles. Furthermore,

Kiecolt-Glaser et al (44)

demonstrated that obesity, alongside chemotherapy, was associated

with lower primary vaccine responses (reduced anti-typhoid Vi IgG

titers) in BC survivors, underscoring obesity-related immune

suppression. Analyses have also explored how obesity might

influence specific treatments. Poggio et al (45), analyzing the GIM2 trial, reported

that the benefit of dose-dense adjuvant chemotherapy on

disease-free survival did not differ significantly between obese

(BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and non-obese patients with early BC

(P=0.17), indicating no evidence for schedule-specific

BMI-dependent efficacy in that cohort. Meanwhile, Biganzoli et

al (46), examining the SOLE

trial, observed that obese patients receiving extended letrozole

had a shorter disease-free survival than non-obese patients,

indicating BMI-related prognostic divergence during prolonged

endocrine therapy. Macis et al (47) explored adiponectin as a potential

mediator of the obesity-BC risk relationship.

In conclusion, epidemiological evidence robustly

establishes obesity as a risk factor for postmenopausal BC

development and a negative prognostic factor impacting survival

outcomes across various BC subtypes, particularly HoR+

disease (Table SI). Obesity also

influences treatment efficacy, potentially contributing to reduced

response rates in neoadjuvant settings and worse survival outcomes

in adjuvant settings, while also exacerbating treatment-related

toxicities and survivorship issues (41,42). These findings underscore the

critical importance of addressing obesity within comprehensive BC

prevention and management strategies. Further research is required

to fully elucidate subtype-specific effects and optimize weight

management interventions to improve BC outcomes (47).

Molecular mechanisms linking obesity to

BC

Adipose expansion in obesity orchestrates a

protumorigenic milieu: Hypertrophic adipocytes release excess

leptin and reduced adiponectin, skewing signaling toward Janus

kinase 2 (JAK2)/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation, while insulin

resistance-driven hyperinsulinemia amplifies insulin-like growth

factor-1 (IGF-1)-mediated mitogenesis (48-50). Concurrently, dying adipocytes

recruit M1 macrophages that form crown-like structures (CLS) and

secrete IL-6 and TNF-α, sustaining NF-κB and MAPK loops, which

promote DNA damage, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and

angiogenesis (51,52). These intertwined adipokine,

metabolic and inflammatory circuits, including leptin-STAT3,

insulin-PI3K/AKT/mTOR and TNF-α/IL-6-driven NF-κB activation, are

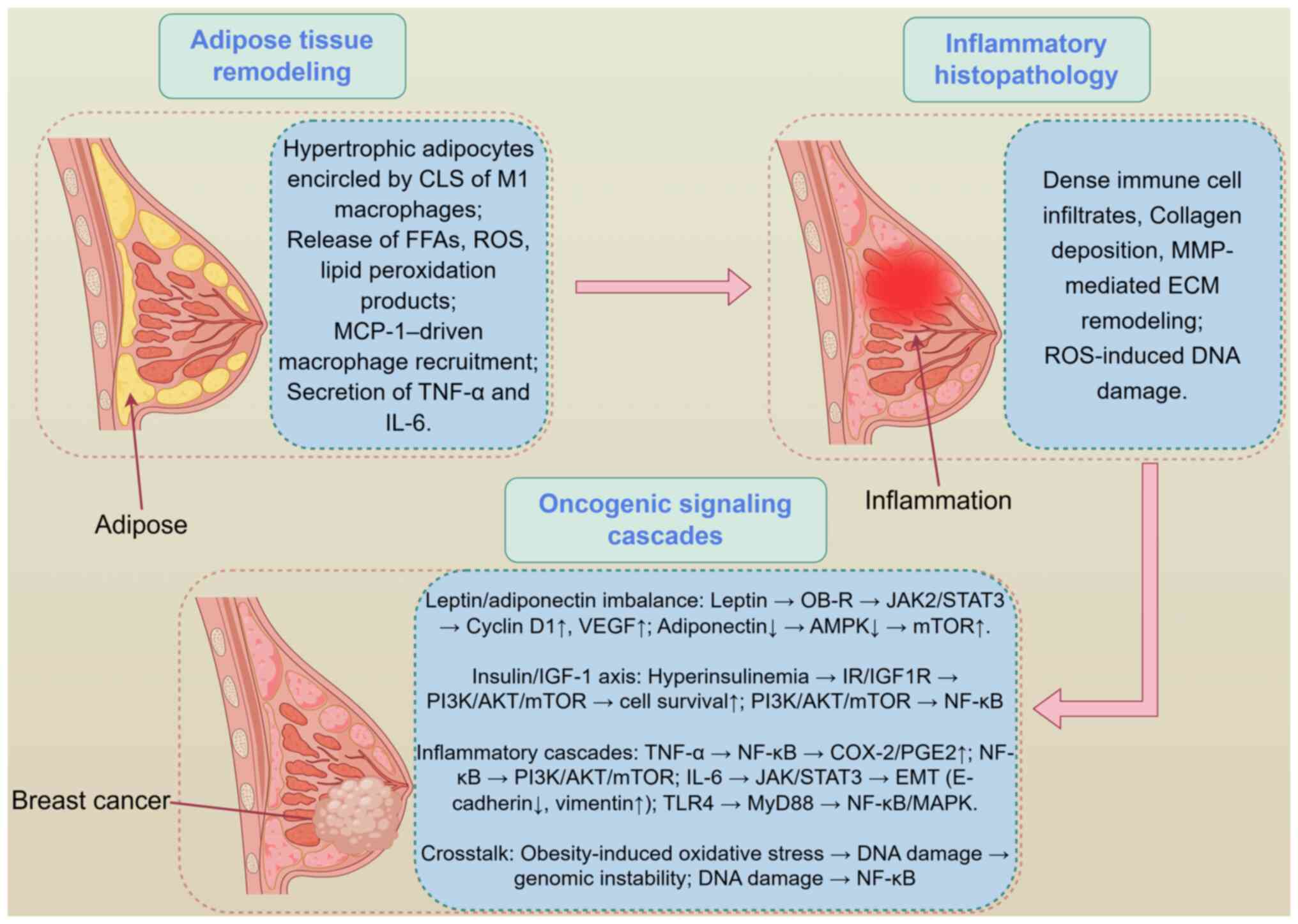

schematically shown in Fig. 1

(48-52), which illustrates obesity-induced

breast tissue inflammation, CLS formation and downstream

protumorigenic signaling cascades.

| Figure 1Obesity-induced molecular events and

chronic breast inflammation. By Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com/static/index.html#/; 2.0

version; ID: RSAYO3b3b5). AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CLS,

crown-like structures; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; ECM, extracellular

matrix; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; FFA, free fatty

acids; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; IGF1R, IGF-1 receptor;

IR, insulin receptor; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; MCP-1, monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1; MyD88, myeloid differentiation primary

response 88; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

TLR4, toll-like receptor 4. |

Adipokines and their roles

Leptin

The levels of leptin, predominantly produced by

adipose tissue, are elevated in obese individuals (48). Leptin binds to its receptor OB-R,

which is expressed in various tissues, including breast tissue

(48). The activation of leptin

signaling pathways promotes BC development and progression through

the JAK-STAT and PI3K-Akt pathways. Specifically, leptin activates

JAK2, leading to STAT3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation,

which promotes cell proliferation and angiogenesis (48,49). Leptin also activates the PI3K-Akt

pathway, reducing apoptosis and stimulating mTOR-dependent cell

proliferation (50).

In breast epithelial cells, insulin receptor

substrate 1/2 (IRS-1/2) phosphorylation constitutes a shared

regulatory node that integrates leptin-activated JAK2/STAT3

signaling with the insulin resistance-driven PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis

(53). Leptin induces

JAK2-dependent phosphorylation of IRS-1 on Tyr608 and Ser307, which

impairs insulin-receptor signaling and promotes compensatory

hyperinsulinemia (53).

Conversely, chronic hyperinsulinemia leads to phosphorylation of

IRS-1/2 on additional serine residues (Ser612 and Ser636) via

mTOR/ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1 feedback loops, further

amplifying PI3K/AKT/mTOR activity (54). This bidirectional crosstalk

creates a feed-forward circuit in which leptin-driven JAK2/STAT3

signaling exacerbates insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia in

turn heightens leptin sensitivity, jointly accelerating breast

epithelial proliferation (55).

Adiponectin

Adiponectin, another important adipokine secreted by

adipose tissue, has antitumor properties (56). Adiponectin binds to its receptors

adiponectin receptor (AdipoR)1 and AdipoR2 on the surface of cells,

including breast cells, and activates the AMP-activated protein

kinase (AMPK) pathway (56). AMPK

is an energy-sensing enzyme that regulates cellular metabolism.

Activation of AMPK by adiponectin leads to a series of downstream

effects that inhibit cell proliferation and promote apoptosis

(57). Conversely,

gene-expression profiling has revealed increased adiponectin

signaling in aggressive Claudin-low and mesenchymal-type BCs,

indicating that adiponectin function may be context-dependent

rather than adiponectin being universally protective (58). However, adiponectin levels are

decreased in obesity, impairing these protective effects and

potentially contributing to BC development (59).

Insulin resistance and

hyperinsulinemia

Obesity is closely associated with insulin

resistance, characterized by reduced cellular responsiveness to

insulin (60). This condition is

driven by hypertrophic adipose tissue that secretes

pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, thereby

promoting chronic inflammation (60). These cytokines interfere with

insulin signaling by activating the NF-κB pathway, leading to the

expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling proteins that

inhibit IRS signaling (61).

Additionally, lipotoxicity from excess free fatty acids generates

diacylglycerols and ceramides, which activate protein kinase C

isoforms and impair insulin receptor (IR) and IRS function through

serine phosphorylation (62).

Oxidative stress further exacerbates insulin resistance by damaging

insulin signaling components (62).

Insulin resistance leads to hyperinsulinemia, which

can affect breast cells (63).

Insulin binds to IRs on breast cells, activating the PI3K-Akt-mTOR

pathway (63). This promotes cell

proliferation and survival by stimulating protein and lipid

synthesis and inhibiting apoptosis (63). Hyperinsulinemia also enhances the

activity of the IGF pathway. Insulin can bind to IGF-1 receptors

with lower affinity, but high insulin levels can amplify

growth-promoting signals through crosstalk between insulin and IGF

pathways (64). These activated

pathways synergistically promote cell proliferation, survival and

transformation, increasing the BC risk (64).

Inflammatory mediators from adipose

tissue

In summary, obesity drives BC development and

progression through molecular mechanisms such as adipokine

dysregulation (for example, elevated leptin levels and reduced

adiponectin levels), insulin resistance and compensatory

hyperinsulinemia, and chronic inflammation mediated by cytokines

such as IL-6 and TNF-α (19,63). Understanding these mechanisms is

crucial for developing targeted prevention and treatment strategies

for BC in obese individuals.

TNF-α and IL-6 levels are markedly elevated in obese

mammary fat (65,66). TNF-α promotes cell survival via

PI3K/Akt-dependent upregulation of Bcl-2 (65) and induces COX-2 transcription

(66). IL-6 triggers JAK/STAT3

phosphorylation, driving VEGF secretion and EMT (51). Conversely, local delivery or

adipocyte-derived IL-4/IL-13 can polarize macrophages toward an

anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, which downregulates TNF-α and IL-6,

and attenuates NF-κB signaling, and thereby limits obesity-driven

epithelial proliferation (51,52). The canonical NF-κB and MAPK

cascades activated by these cytokines are described in the section

on molecular pathways in chronic breast inflammation, where they

are examined specifically within the chronically inflamed breast

microenvironment.

Role of non-coding RNAs in

obesity-related BC

Emerging evidence has highlighted the critical role

of non-coding RNAs, particularly long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), in

mediating obesity-driven breast inflammation and carcinogenesis

(67,68). The lncRNA HOX transcript antisense

RNA (HOTAIR) is upregulated in breast adipose tissue of obese

individuals and promotes tumor progression by recruiting

chromatin-modifying complexes that silence tumor suppressor genes

(67). In obese mouse models,

HOTAIR overexpression is associated with enhanced NF-κB and STAT3

signaling, driving pro-inflammatory cytokine production and

macrophage polarization towards an M2 tumor-promoting phenotype

(68).

Pre-clinical proof-of-concept studies have indicate

that antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting the

obesity-upregulated lncRNA HOTAIR can blunt tumor growth in murine

BC models (58,69). Gupta et al (69) first demonstrated that HOTAIR

recruits polycomb repressive complex 2 to silence

metastasis-suppressor loci; when HOTAIR was knocked down with

2'-O-methyl gapmer ASOs (25 mg kg−1; intraperitoneal;

twice weekly for 3 weeks), orthotopic 4T1 mammary tumors grew 45%

more slowly and exhibited a 60% reduction in pulmonary metastatic

foci (P<0.01) compared with those of control mice treated with

scrambled antisense oligonucleotides. In high-fat diet-induced

obese MMTV-PyMT mice, the same regimen decreased mammary tumor

multiplicity and lowered IL-6 and TNF-α protein levels in

peritumoral adipose tissue, indicating that HOTAIR blockade can

simultaneously restrain tumor progression and dampen obesity-driven

inflammation (58). RNA

sequencing (RNA-seq) of liver and kidney samples collected at

necropsy revealed no significant off-target transcriptomic

perturbations, and serum chemistry profiles remained within normal

limits, suggesting an acceptable acute-toxicity window (32). While these data are confined to

rodent systems and lack chronic-dosing or formal immunogenicity

analyses, they provide the first direct evidence that

pharmacological inhibition of HOTAIR can reverse obesity-promoted

mammary tumorigenesis and adipose inflammation, providing a

mechanistic rationale for future Good Laboratory Practice

toxicology and dose-finding studies (32).

RNA-seq analysis of mammary tissue from ASO-treated

obese mice revealed minimal off-target transcriptomic perturbations

beyond the intended HOTAIR network, with no significant toxicity in

liver or kidney function tests (70). To further assess systemic safety,

RNA-seq was also performed on liver and kidney tissues collected at

necropsy; these datasets showed no significant off-target gene

expression changes compared with scrambled-ASO controls, supporting

the specificity of the HOTAIR-targeting approach (70). However, comprehensive

organ-specific toxicity studies and assessments of immune

activation (for example, complement activation) remain pending,

highlighting the need for rigorous safety evaluations before

clinical translation (71).

Obesity-mediated tumor immune

microenvironment (TIME) remodeling

In addition to myeloid-derived suppressor cell

(MDSC) expansion via leptin/IL-6-JAK/STAT3 signaling, obesity

directly enforces T-cell exhaustion in breast tissue (72). Single-cell RNA-seq of mammary

tumors from high-fat diet-fed MMTV-PyMT mice revealed a 2.3-fold

increase in programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)+

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3+

CD8+ T cells vs. lean controls, accompanied by reduced

granzyme-B secretion (P<0.01) (72). Analogously, peripheral blood of

obese post-menopausal women (BMI ≥35 kg m−2) harbored

significantly higher exhausted T cell frequencies (PD-1+

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4+) that were

correlated with elevated serum leptin levels (r=0.62; P=0.003)

(73). These findings demonstrate

that obesity promotes the expansion of immunosuppressive myeloid

cells and concurrently impairs cytotoxic T-cell function, thereby

facilitating immune escape during early breast carcinogenesis.

Chronic breast inflammation and BC

Obesity-driven CLS formation, macrophage

infiltration and sustained TNF-α/IL release establish a

protumorigenic breast microenvironment (66,74,75). Histological immune clustering,

oxidative DNA damage and extracellular matrix remodeling converge

on NF-κB and MAPK activation, accelerating carcinogenesis (as

schematically outlined in Fig. 1,

which integrates these obesity-driven inflammatory and molecular

events into a unified protumorigenic framework).

Definition and characteristics of chronic

breast inflammation Histological features

Chronic breast inflammation is characterized by

immune cell infiltrates, including macrophages and lymphocytes,

often forming clusters around adipocytes or within the stromal

compartments (74). This

condition is associated with fibrosis and tissue remodeling,

leading to the deposition of extracellular matrix components such

as collagen and the activation of fibroblasts. These changes alter

breast tissue architecture, with activated fibroblasts depositing

extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen, thereby forming

fibrotic bands and replacing normal glandular tissue with dense

fibrous tissue (76). Proteolytic

enzymes such as MMPs are also activated, facilitating cell

migration and potentially promoting cancer cell dissemination

(77).

Causes of chronic breast inflammation in

the context of obesity

Obesity contributes to chronic breast inflammation

through several mechanisms. Adipocyte death is a key factor. In

obese individuals, the increased size of adipocytes can lead to

hypoxia and cell death. The dead adipocytes trigger an inflammatory

response, with infiltration of macrophages and the formation of CLS

around dead adipocytes (78).

These CLS are composed of macrophages encircling a necrotic core of

dead adipocytes and are associated with the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines (78).

Additionally, lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress serve

significant roles in amplifying local inflammation and promoting

DNA damage within the obese breast tissue microenvironment

(66). The excessive accumulation

of lipids in obese breast tissue can lead to the generation of ROS

and lipid peroxidation products. These oxidative stress-related

molecules can damage cellular components, including DNA, proteins

and lipids, and activate inflammatory signaling pathways, further

exacerbating the inflammatory response in the breast tissue

(79).

Molecular pathways in chronic breast

inflammation-induced carcinogenesis

NF-κB pathway activation

The NF-κB pathway is a central player in the

inflammatory response and is frequently activated in chronic breast

inflammation (75). Inflammatory

mediators, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which are produced by immune

cells in the inflamed breast tissue, can activate the NF-κB pathway

(75). Upon activation, NF-κB

translocates to the nucleus and regulates the transcription of

numerous genes involved in cell survival, proliferation and

inflammation. For example, NF-κB activation leads to the increased

expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL,

promoting cell survival. NF-κB activation also upregulates cyclin

D1 and other cell cycle-promoting genes, driving cell proliferation

(75). Furthermore, NF-κB induces

the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines,

creating a self-sustaining inflammatory loop that contributes to

the development of a tumor-promoting microenvironment (75).

MAPK pathway activation

The MAPK pathway is another critical signaling

pathway involved in chronic breast inflammation-induced

carcinogenesis (80). There are

several types of MAPK pathways, including the ERK, JNK and p38

kinase pathways. In chronic breast inflammation, these pathways can

be activated by various stimuli, such as growth factors, cytokines

and oxidative stress (80). For

instance, ERK activation can be triggered by growth factors

released from inflammatory cells, leading to the phosphorylation

and activation of transcription factors such as Elk-1 and c-Fos,

which promote cell proliferation and differentiation (81). JNK and p38 pathways are often

activated in response to stress signals, including oxidative stress

and inflammatory cytokines. Their activation results in the

phosphorylation of transcription factors such as c-Jun and

activating transcription factor-2, which regulate the expression of

genes involved in cell survival, apoptosis and inflammation

(82). The activation of MAPK

pathways can lead to changes in breast cell behavior, such as

increased proliferation, migration and invasion, which are

hallmarks of cancer development (80-82).

Toll-like receptor (TLR)

signaling

TLRs are pattern recognition receptors that serve a

crucial role in the innate immune response (83). During chronic breast inflammation,

TLRs in breast tissue can be activated by various endogenous

ligands released from damaged cells or by pathogens (83). For example, TLR4 can be activated

by saturated fatty acids, the levels of which are elevated in the

breast tissue of obese individuals (83). Once activated, TLRs initiate

downstream signaling cascades, such as the MyD88-dependent pathway,

leading to the activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways. This results

in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines,

amplifying the inflammatory response in the breast tissue (83). The chronic activation of TLR

signaling can create a prolonged inflammatory state, which

contributes to DNA damage, genomic instability and the promotion of

carcinogenesis (84).

Additionally, TLR signaling can also influence the TIME by

modulating the function and recruitment of immune cells,

potentially facilitating tumor immune evasion and progression

(85).

In summary, chronic breast inflammation,

particularly in the context of obesity, contributes to breast

carcinogenesis through various molecular pathways, including the

NF-κB, MAPK and TLR signaling pathways. These pathways drive the

development of a tumor-promoting microenvironment, characterized by

increased cell survival, proliferation and inflammation, thereby

increasing the risk of BC. Understanding these mechanisms provides

insights into potential therapeutic targets for the prevention and

treatment of BC in individuals with chronic breast

inflammation.

Interplay between obesity-related factors

and chronic breast inflammation in carcinogenesis

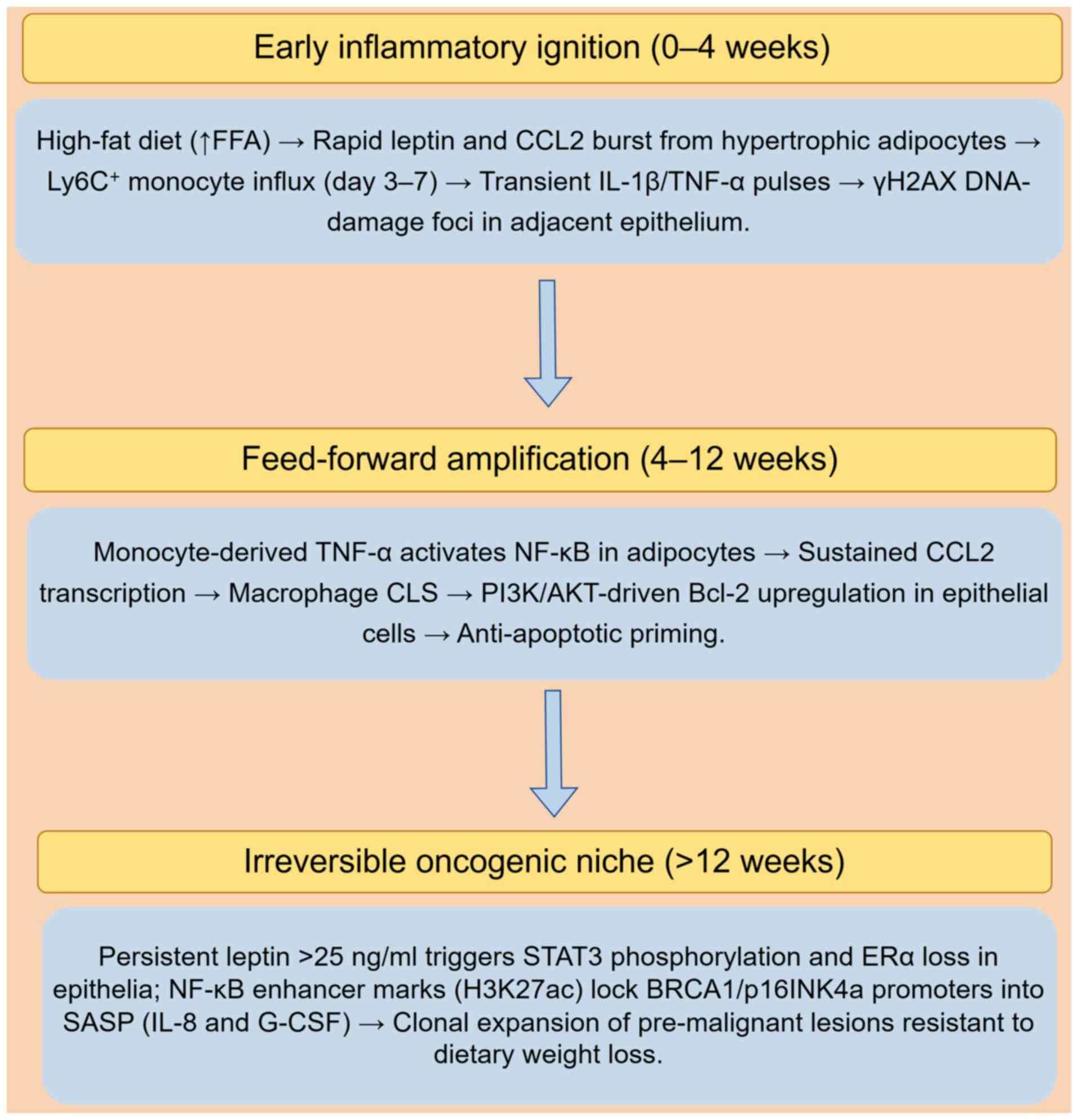

Dynamic, time-resolved crosstalk among adipocytes,

immune cells and epithelia converts obesity-associated inflammation

from a reversible stress into an irreversible oncogenic driver

(86). This section delineates

the sequential ignition, amplification and commitment phases that

precede malignant transformation, emphasizing dynamic feed-forward

loops, circadian regulation and epigenetic memory. Rather than

merely outlining isolated signaling events, it integrates temporal

and contextual dynamics to provide a more mechanistic understanding

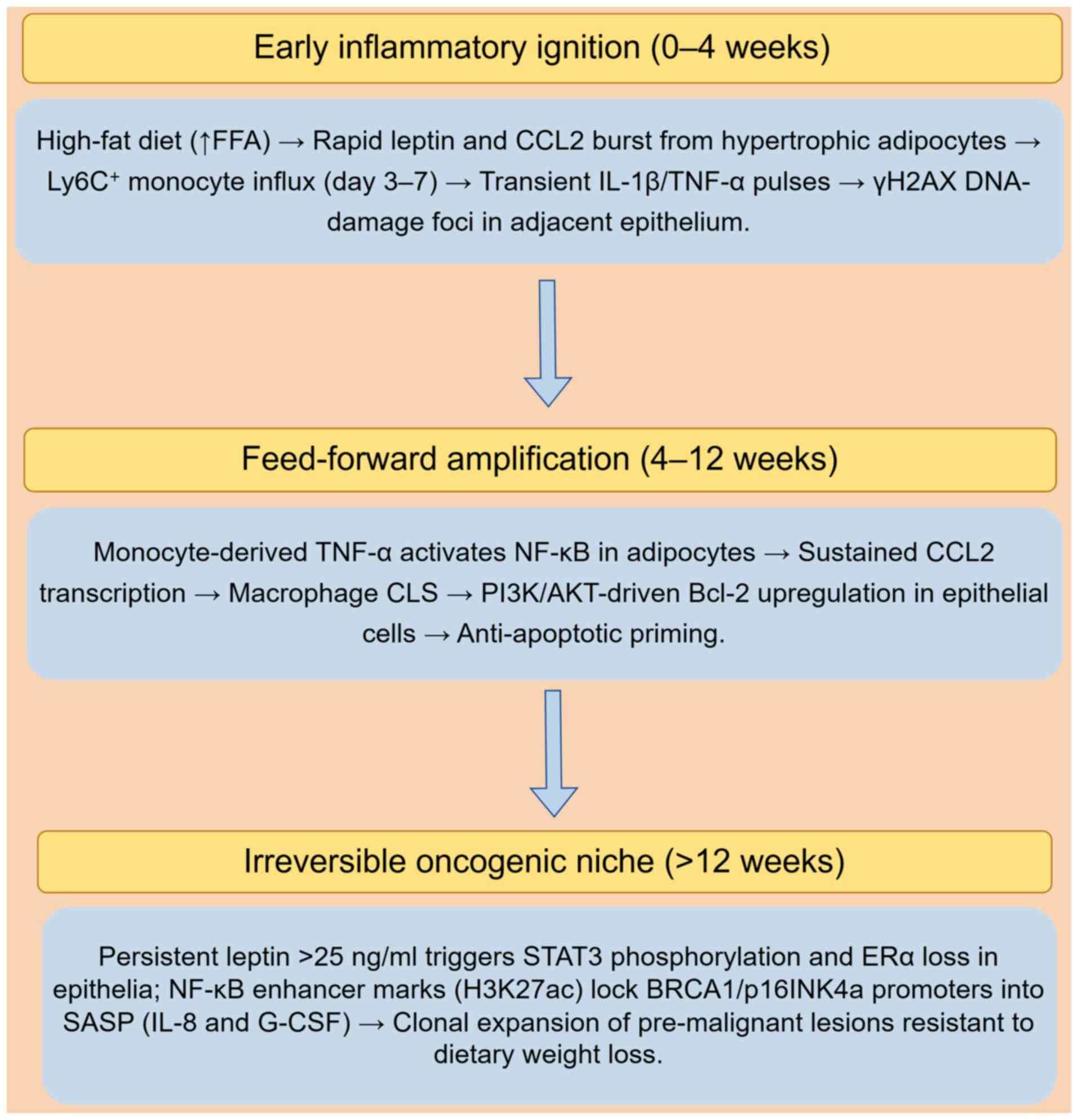

of obesity-driven breast carcinogenesis (Fig. 2). Notably, the time-resolved

sequence summarized in Fig. 2 is

derived exclusively from ovariectomized (postmenopausal) MMTV-PyMT

mice and short-term explants of breast adipose tissue from obese

postmenopausal women (23,87,88).

| Figure 2Time-resolved crosstalk in the obese

breast microenvironment during early carcinogenesis. By Figdraw

(https://www.figdraw.com/static/index.html#/; 2.0

version; ID: UAAWW758ae). The depicted adipocyte-immune

interactions and epigenetic reprogramming events are primarily

derived from high-fat diet-fed, ovariectomized (postmenopausal)

murine mammary tissue models and ex vivo explants from obese

postmenopausal women. γH2AX, phosphorylated histone H2AX; CCL2, C-C

motif chemokine ligand 2; CLS, crown-like structures; ERα, estrogen

receptor α; FFA, free fatty acids; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony

stimulating factor; H3K27ac, histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation;

Ly6C, lymphocyte antigen 6C; SASP, senescence-associated secretory

phenotype. |

Early inflammatory ignition (0-4

weeks)

High-fat feeding in MMTV-PyMT mice rapidly (within 7

days) elevates mammary C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and

leptin secretion, leading to lymphocyte antigen 6C-positive

monocyte influx that precedes CLS formation (87). Single-cell RNA-seq time-courses

reveal that these monocytes transiently express IL-1β and TNF-α at

day 7, coinciding with phosphorylated histone H2AX DNA-damage foci

in adjacent epithelial cells (86). In human breast tissue explants

from obese women (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), a similar early

cytokine switch (IL-1β to IL-6) has been observed within 6 days

ex vivo, supporting the translational relevance (23).

Feed-forward amplification (4-12

weeks)

During this amplification phase, NF-κB activation in

adipocytes further amplifies CCL2 transcription, establishing a

self-sustaining macrophage retention loop (88). Simultaneously, monocyte-derived

TNF-α activates NF-κB in adipocytes, further reinforcing this

feed-forward inflammatory cycle (88). Concomitant PI3K/AKT signaling in

epithelial cells upregulates anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, rendering cells

resistant to physiological clearance (65). This feed-forward circuit is unique

to the obese state; in lean controls, macrophage numbers plateau

after day 7 and do not sustain NF-κB activity (86).

Irreversible oncogenic niche transition

(>12 weeks)

After chronicity, transient NF-κB pulses are

replaced by stable enhancer histone marks (histone H3 lysine 27

acetylation) at BRCA1 and p16INK4a promoters, locking

cells into a senescence-associated secretory phenotype that

continuously secretes IL-8 and granulocyte-colony stimulating

factor (88). Obesity-specific

miR-155 elevation persists even upon in vitro adipocyte

dedifferentiation, indicating a cell-autonomous memory transferable

to epithelial cells via exosomal cargo (89). Multiphoton intravital microscopy

demonstrates that CD68+ macrophages form periductal

niches that expand clonally once circulating leptin exceeds 25 ng

ml−1; epithelial cells within these niches exhibit STAT3

phosphorylation and loss of estrogen receptor α expression, changes

that do not regress after 8 weeks of dietary weight loss (90), signifying an irreversible

commitment to oncogenesis.

Clinical implications

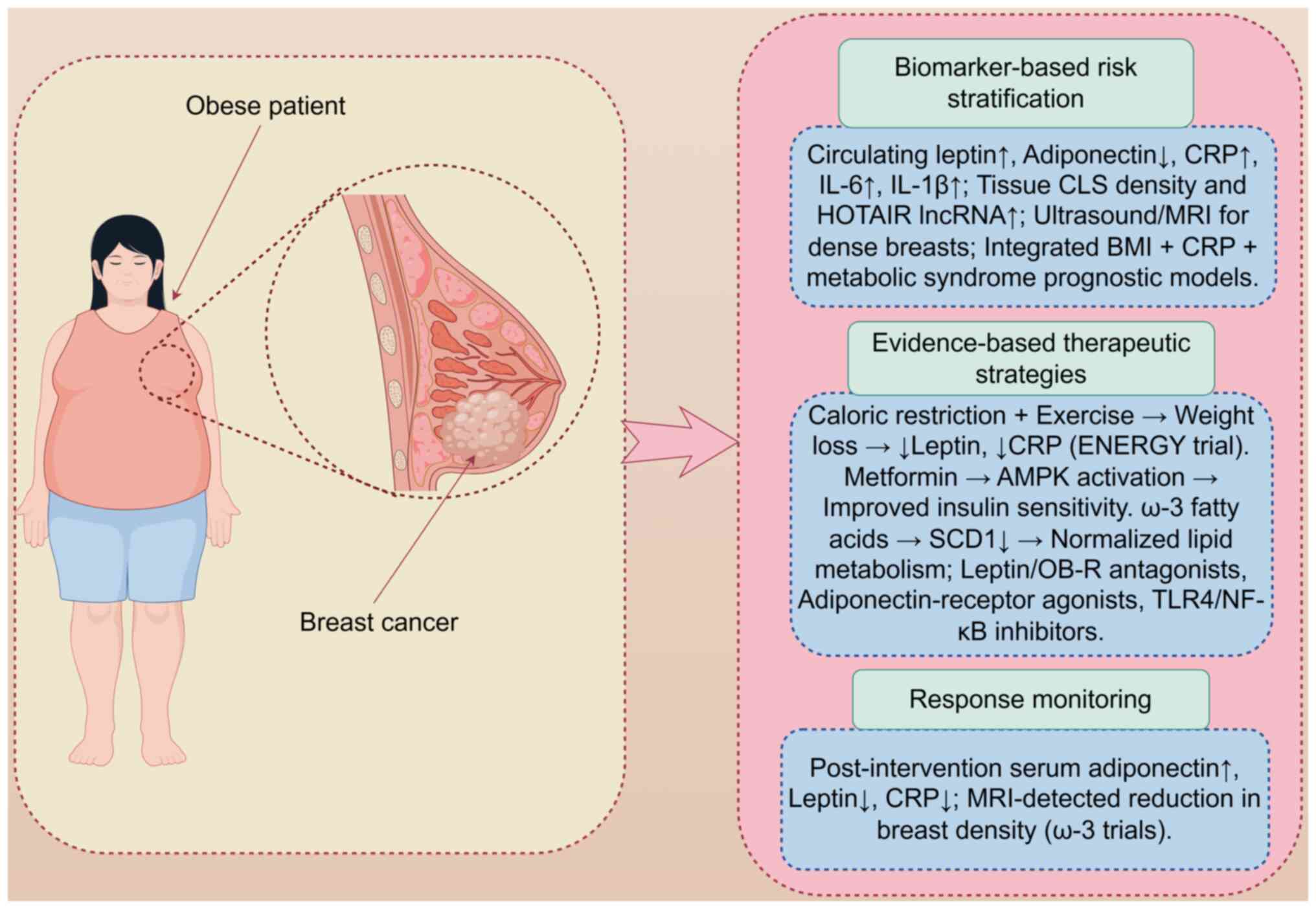

Composite models combining elevated leptin, CRP and

IL-6 levels, and MRI-detected breast density outperform

single-parameter risk prediction (91-93). Lifestyle caloric restriction,

metformin-mediated AMPK activation and high-dose ω-3 fatty acids

reduce systemic inflammation and tumor-promoting signaling;

therapeutic monitoring via serial assessment of these biomarker

trajectories can track intervention efficacy and disease

progression (Fig. 3). Fig. 3 illustrates an integrated clinical

approach for obese patients with BC, encompassing risk

stratification using composite biomarkers and imaging, targeted

interventions including lifestyle modifications and

pharmacotherapy, and continuous monitoring of biomarker dynamics to

optimize outcomes (91,94,95).

Diagnosis

Biomarkers for the prediction of BC

risk in obese patients with chronic breast inflammation

In obese patients with chronic breast inflammation,

several biomarkers show promise in predicting BC risk. Adipokines

are a key focus. Leptin, the levels of which are elevated in

obesity, is linked to BC risk, and promotes cell proliferation and

inhibits apoptosis via pathways such as the JAK-STAT and PI3K-Akt

pathways (96). Conversely,

adiponectin levels are reduced in obesity, and adiponectin has

anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects. Lower adiponectin

levels are associated with an increased risk of BC (97).

Inflammatory markers are also crucial. CRP, a

marker of systemic inflammation, is positively associated with BC

risk in obese postmenopausal women (91). Elevated CRP levels are linked to

shorter DFS (91). Similarly,

IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α are upregulated in obese breast tissue. These

cytokines induce DNA damage through ROS production and promote a

tumor-supportive microenvironment (92).

Imaging techniques for the detection

of BC in obese individuals

Obesity poses challenges for traditional

mammography. The increased breast density and volume can obscure

tumors, reducing the sensitivity of mammography (98). Alternative imaging modalities are

being explored (98). Ultrasound

is useful for distinguishing between cystic and solid masses.

Ultrasound offers real-time imaging and avoids radiation exposure.

However, its sensitivity decreases for smaller tumors (99). MRI shows higher sensitivity than

traditional mammography in detecting BC in obese patients. MRI

provides detailed soft tissue contrast and can identify multiple

tumors. Despite its advantages, MRI is costly and may yield

false-positive results, requiring further confirmation (93).

Prognosis

Impact of obesity and chronic breast

inflammation on BC prognosis

Obesity impacts BC prognosis. Obese patients with

BC often have poorer OS rates compared with normal-weight patients.

They tend to present with higher tumor grades, larger tumor sizes

and increased lymph node involvement (100). Obesity-related inflammation

promotes tumor progression and metastasis (101). Additionally, compared with their

non-obese counterparts, obese patients are more likely to develop

resistance to endocrine therapy and chemotherapy (102).

Molecular mechanisms related to obesity and

inflammation influence prognosis. The chronic inflammatory state in

obese patients leads to elevated levels of pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. These cytokines activate

signaling pathways that promote cell proliferation, inhibit

apoptosis and enhance angiogenesis (52). The dysregulated adipokines leptin

and adiponectin also contribute to a poorer prognosis in obese

patients compared with their non-obese counterparts by creating a

tumor-supportive microenvironment (52). Furthermore, obesity-associated

insulin resistance and elevated IGF-1 levels are linked to

increased tumor recurrence and mortality (103).

Prognostic models incorporating

obesity-related and inflammatory factors

Prognostic models that integrate obesity-related

and inflammatory factors are being developed to better predict BC

outcomes. These models incorporate clinical data such as BMI, waist

circumference and metabolic markers (94). They also include levels of

inflammatory cytokines such as CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α. Laforest et

al (95) have shown that

combination of these factors improves the accuracy of prognosis

prediction. For instance, a model incorporating BMI and CRP levels,

along with components of metabolic syndrome such as waist

circumference, hypertension, dyslipidemia and insulin resistance,

demonstrated better predictive performance for disease recurrence

and survival compared with models using single factors (93). However, validation across diverse

patient populations is needed to ensure reliability and

applicability. Further research is ongoing to refine these models

and enhance their clinical utility (91).

Therapeutic strategies for obesity

management in BC

The established link between obesity and adverse BC

outcomes necessitates evidence-based therapeutic strategies

targeting weight management and metabolic dysregulation (104). This section synthesizes clinical

evidence on interventions spanning lifestyle modifications,

pharmacotherapy and molecularly targeted approaches, emphasizing

their mechanistic foundations and clinical applicability (Table SII).

Lifestyle interventions: Cornerstone of

weight management

Lifestyle interventions combining dietary

modification and physical activity constitute the most extensively

studied therapeutic approach. The landmark ENERGY trial

demonstrated that a structured 12-month behavioral intervention

(caloric restriction + 225 min/week moderate exercise) achieved

marked weight reduction (mean loss, 6.0% body weight) in

overweight/obese BC survivors, translating to clinically relevant

improvements in physical function and quality of life (105,106). Furthermore, this trial

established the feasibility of sustained weight management in

cancer survivors, a population often challenged by

treatment-related fatigue and metabolic alterations. Subsequent

research refined these approaches for specific subgroups:

Culturally adapted interventions for African American survivors

yielded a weight loss of 6.1% vs. 1.8% in controls (P<0.001)

(107), while telemedicine-based

programs effectively addressed barriers for rural populations,

maintaining a weight loss of 7.3% at 18 months (108). Exercise regimens require

optimization; Courneya et al (109) established a dose-response

relationship, showing that 300 min/week of aerobic exercise

significantly improved quality of life vs. 150 min/week in

postmenopausal survivors (P<0.05).

Pharmacological and metabolic inter

ventions

Pharmacological strategies target

obesity-associated metabolic pathways to enhance treatment

efficacy. Yam et al (110) conducted a phase II trial

combining metformin (500 mg twice daily), everolimus (5 mg/day) and

exemestane in obese metastatic HoR+ patients,

demonstrating a 48% clinical benefit rate and median

progression-free survival of 5.6 months. This synergistic approach

concurrently inhibited mTOR signaling and estrogen synthesis,

counteracting obesity-induced pathway activation. Similarly,

metformin monotherapy shows promise; Patterson et al

(111) designed the first

randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining metformin + weight loss

in survivors, with preliminary data suggesting enhanced insulin

sensitivity. Complementarily, nutritional pharmacology leverages

specific nutrients to modulate molecular pathways: High-dose ω-3

fatty acids (3.6 g/day) reduced breast density by 6.2% [Sandhu

et al (112); P=0.03],

and improved leptin/adiponectin ratios in high-risk women (113). Mechanistically, Manni et

al (114) identified

ω-3-mediated suppression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (reduction of

38%; P=0.008), a key enzyme in lipid metabolism promoting

tumorigenesis in obesity.

Targeting molecular mediators and

biomarkers

Emerging strategies focus on obesity-related

molecular mediators as therapeutic targets and response biomarkers.

Bowers et al (88)

demonstrated that caloric restriction reversed obesity-induced

pro-tumorigenic genomic signatures in triple-negative models,

suppressing tumor growth by 67% (P<0.001) through epigenetic

modulation. Clinically, molecular biomarkers facilitate

intervention personalization: Macis et al (47) established adiponectin as a

mediator of 19% of the obesity-BC risk association (P=0.02),

suggesting its utility for monitoring intervention efficacy.

Concurrently, interventions modulate inflammatory cascades;

combined exercise and weight loss in the WISER Survivor trial

significantly reduced CRP (-12.3%; P=0.03) and insulin resistance

(homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance reduced by

18.5%; P=0.01) (90,115). Furthermore, recent translational

work has revealed that weight loss alters cancer-related proteins:

Bull et al (116)

identified 14 serum proteins (including leptin and IL-6) modulated

by weight loss, providing mechanistic insights for BC

applications.

Therapeutic strategies for obesity in BC span

lifestyle, pharmacological and molecular interventions,

collectively targeting metabolic dysregulation, inflammation and

tumor-promoting pathways. While lifestyle modifications remain

foundational, emerging biomarker-driven approaches enable

personalization. Crucially, overcoming implementation barriers

requires culturally adapted, accessible programs integrated into

standard oncology care. As evidenced by the reversal of

obesity-induced genomic alterations reported by Bowers et al

(88), these strategies hold

promise not only for improving outcomes but potentially disrupting

the obesity-BC pathogenetic axis.

Emerging evidence suggests that obesity modulates

the TIME in TNBC, influencing the response to immune checkpoint

inhibitors (ICIs) (72). In obese

TNBC models, leptin and IL-6 promote the expansion and recruitment

of MDSCs via JAK/STAT3 signaling, which dampens cytotoxic T-cell

activity and contributes to immunotherapy resistance (72). For instance, Pingili et al

(72) demonstrated that

diet-induced obesity increased MDSC infiltration and reduced PD-1

inhibitor efficacy in TNBC murine models, an effect reversible upon

MDSC depletion or leptin signaling blockade. Clinically, a

retrospective analysis has indicated that obese patients with TNBC

may exhibit lower objective response rates to anti-PD-1/programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) therapies compared with non-obese

counterparts (117), although

some studies have reported a paradoxical 'obesity benefit' in other

cancer types, underscoring context-dependent effects (72,73). These findings highlight the need

to consider obesity-associated immune dysregulation, particularly

MDSC-mediated suppression, when designing immunotherapy trials for

TNBC.

Limitations of current obesity-targeted

therapies in BC management

Despite mechanistic evidence supporting

obesity-targeted interventions (88), clinical translation faces

significant limitations. First, most lifestyle trials (such as the

ENERGY and LISA trials) are underpowered for survival endpoints,

with follow-up ≤5 years, precluding definitive conclusions on

long-term oncologic benefits (88,105,106). Second, pharmacologic approaches

exhibit constrained efficacy: Metformin monotherapy failed to

improve IDFS in the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC)

MA.32 trial (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.84-1.21; n=3,649), despite

preclinical AMPK activation (118). Everolimus-based regimens suffer

from dose-limiting toxicities (mucositis, 63% grade ≥3),

restricting applicability in obese populations with pre-existing

metabolic syndrome (110).

Third, biomarker-driven stratification remains rudimentary: While

adiponectin mediates 19% of the obesity-BC risk association

(47), to the best of our

knowledge, no trial has prospectively selected or stratified

patient cohorts based on adipokine signatures, leading to

heterogeneous responses. Fourth, trials disproportionately enroll

postmenopausal HoR+ patients [≥70% in the ENERGY trial

(105)], leaving TNBC and

premenopausal obesity-associated BC understudied. Finally,

weight-loss interventions exhibit poor durability: 40% of

participants in the WISER Survivor trial regained ≥5% body weight

within 18 months post-intervention (90), undermining sustained

anti-inflammatory effects. These gaps necessitate adaptive trial

designs integrating real-time metabolomic profiling and minimal

residual disease monitoring to circumvent empirical therapy

limitations.

Although lifestyle modification remains the

cornerstone, the pooled adherence across four RCTs in BC survivors

was only 54% at 12 months and fell to 34% by 36 months (105-108). Pharmacologic approaches face

uncertainty regarding long-term safety: The NCIC MA.32 trial showed

no excess adverse events with metformin after a median follow-up of

6.3 years (118); however, to

the best of our knowledge, liraglutide or tirzepatide have not been

prospectively evaluated in BC survivors for durations exceeding 2

years, and their chronic gastrointestinal and pancreatic safety

profiles remain undefined. Likewise, dose-limiting mucositis (grade

≥3 rate, 63%) restricted everolimus exposure in the

metformin-everolimus-exemestane phase-II study (110), underscoring the need for

rigorous toxicity surveillance.

The impact of obesity on immunotherapy response

also remains underexplored in clinical trials. While preclinical

data implicate MDSCs and adipokine signaling in ICI resistance

(117), to the best of our

knowledge, no prospective studies have stratified patients with

TNBC by obesity status or MDSC levels when evaluating PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors at present. This represents a significant translational

gap, as combinatorial strategies targeting MDSCs or leptin may

enhance immunotherapy efficacy in obese patients with TNBC

(117).

Bariatric surgery and BC risk

Cohort data provide robust evidence for a

protective effect of bariatric surgery against postmenopausal BC,

with studies showing a 32-42% reduction in long-term incidence

among obese women following surgical weight loss (119,120). In the Swedish Obese Subjects

study, 1,116 women who underwent bariatric surgery (mainly

vertical-banded gastroplasty or gastric bypass) exhibited a 32%

reduction in post-menopausal BC incidence compared with matched

non-surgical controls (adjusted HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.48-0.96; median

follow-up, 21.3 years) (119).

Similarly, analysis of the US Kaiser Permanente database (n=22,198)

demonstrated a 42% lower BC risk after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

(HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42-0.79) that became apparent 5 years

post-procedure and persisted beyond 15 years post-procedure

(120). Mechanistically,

surgery-induced weight loss rapidly decreases circulating leptin,

CRP and IL-6 levels, while restoring adiponectin levels,

collectively reversing the obesity-driven chronic inflammatory

milieu implicated in mammary carcinogenesis (121).

Future directions

Despite significant progress, the molecular

mechanisms linking obesity, chronic breast inflammation and

carcinogenesis remain unclear. The interplay among signaling

pathways, including the NF-κB, MAPK and TLR signaling pathways, is

complex and context-dependent (92). For example, further research is

needed to elucidate how these pathways synergistically or

antagonistically drive cancer initiation and progression in

different stages of obesity and inflammation (52,94). Specifically, studies should focus

on the temporal dynamics of these pathways and their interactions

with adipokines and inflammatory mediators.

The role of novel factors such as exosomes and

extracellular vesicles in mediating crosstalk among adipose tissue,

immune cells and breast epithelial cells has only recently gained

attention (122). Future

research should explore the detailed mechanisms by which these

vesicles transfer oncogenic signals and modulate the tumor

microenvironment (122). For

instance, exosomes derived from obese adipose tissue have been

shown to promote BC progression by transferring miRNAs and proteins

that enhance cell proliferation and migration (122).

Long-term follow-up studies on obese patients with

chronic breast inflammation are lacking. Large-scale, longitudinal

studies are required to better understand the long-term impact of

obesity and chronic inflammation on BC risk and progression

(122). These studies should

account for ethnic and sex differences, as preliminary evidence

suggests variations in obesity-related cancer risk across different

populations (123).

Personalized medicine offers a promising avenue for

improving outcomes in obese patients at risk of BC. Advances in

genomic and proteomic technologies enable the identification of

individual molecular profiles related to obesity and chronic

inflammation (124). Future

research could focus on developing biomarker panels that predict

cancer risk and treatment response. By integrating genetic,

epigenetic and transcriptomic data, therapies can be tailored to

the unique profile of an individual, potentially improving efficacy

and reducing adverse effects (91).

The identification of novel therapeutic targets

through advanced omics technologies is another frontier.

Metabolomics can reveal altered metabolic pathways in obesity and

cancer, pointing to potential targets for metabolic modulation

(125). Integration of

untargeted plasma metabolomics with single-cell RNA-seq now enables

obesity subtyping: Simultaneous profiling of serum kynurenine/4-HNE

levels and mammary-tissue scRNA-seq delineated an

'inflammatory-proliferative' obese subtype (IL-6high

macrophages + leptinhigh adipocytes), which exhibited a

2.1-fold higher BC risk compared with a 'metabolically quiescent'

subtype (AdipoQhigh; AMPK-activated) in postmenopausal

women (n=34; metabolome-transcriptome correlation r=0.62;

P<0.01) (125). Such

metabolomics-plus-single-cell strategies refine risk prediction

beyond BMI and nominate subtype-specific molecular targets (for

example, enzymes in the kynurenine pathway such as indoleamine

2,3-dioxygenase 1) for precision prevention trials in obese cohorts

using pharmacological inhibitors (125). Transcriptomics and proteomics

can uncover previously unknown signaling nodes or protein

interactions that are critical in the inflammatory-carcinogenic

process. For example, lncRNAs and circular RNAs, which have been

implicated in regulating gene expression in cancer, may serve as

diagnostic biomarkers or therapeutic targets (71).

The gut microbiota has emerged as a critical player

in systemic inflammation and metabolism (126). In obesity, dysbiosis of the gut

microbiota contributes to chronic inflammation and metabolic

dysfunction (126). Previous

studies have suggested that gut microbial metabolites, including

short-chain fatty acids and secondary bile acids, could influence

BC risk and progression (127,128). Future research could explore how

modulating the gut microbiota through prebiotics, probiotics or

fecal microbiota transplantation affects BC outcomes in obese

individuals. Specifically, obesity-associated enrichment of

deoxycholic acid (DCA), a secondary bile acid generated by

bacterial 7α-dehydroxylation, activates the farnesoid X receptor

(FXR)/NF-κB axis in breast adipose tissue and increases oxidative

DNA damage, thereby accelerating tumor initiation (127). In high-fat diet-fed mice,

elevated fecal DCA levels are associated with larger mammary tumor

volume and higher incidence of pulmonary metastases, an effect that

can be reversed by oral administration of a bile-acid sequestrant

or by genetic ablation of the FXR receptor (128). Understanding the molecular

mechanisms underlying gut microbiota-breast crosstalk, such as

through the production of inflammatory mediators or the modulation

of host metabolism, may open up novel avenues for prevention and

treatment of obesity-related BC (126,127). To accelerate mechanistic

discovery and therapeutic testing, obesity-driven breast

carcinogenesis research should incorporate next-generation animal

and culture models that faithfully replicate the inflamed obese

microenvironment.

Despite robust and accumulating preclinical

evidence demonstrating that obesity fuels breast carcinogenesis

through chronic inflammation, adipokine dysregulation and immune

microenvironment remodeling (13,51,65,72,88), several translational gaps persist

that hinder clinical implementation: i) At present, no phase I

trial has been registered that specifically depletes or reprograms

adipose-tissue macrophages (for example, via colony-stimulating

factor 1 receptor or C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 inhibitors) in

obese patients with BC, although mouse data show marked tumor

growth delay when CLS macrophages are eliminated (79,88); ii) biomarker-adaptive trials that

incorporate circulating leptin, adiponectin and MRI-determined

breast density as eligibility criteria have not yet been conducted,

limiting the ability to achieve precision enrollment in

obesity-related BC studies (105,106); iii) long-term oncological

endpoints (>5 years) are rarely captured in existing lifestyle

or metformin trials, leaving the magnitude of obesity-modifiable

recurrence risk uncertain (91);

and iv) pharmacokinetic studies evaluating chemotherapy or

endocrine-agent dosing in mammary fat volumes >35% of breast

mass have not been performed, potentially contributing to

under-dosing in obese women (45). Addressing these deficiencies

through dedicated early-phase studies will be critical to disrupt

the obesity-inflammation-carcinogenesis axis in clinical

settings.

Conclusion

Obesity fuels breast carcinogenesis via chronic

inflammation, metabolic dysfunction and adipokine dysregulation,

worsening BC prognosis and treatment response. Metformin, ω-3 and

biomarker-driven approaches show promise in mitigating these risks.

Future efforts must prioritize large-scale studies, personalized

medicine and novel targets (such as the gut microbiota) to disrupt

the obesity-BC axis and reduce the global disease burden.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

FL and ZG conceived the study and designed its

methodology. FL curated the data and prepared the initial

manuscript, while both authors jointly investigated and visualized

the findings and supervised the project. The manuscript was

reviewed and edited collaboratively by FL and ZG, who also serves

as the guarantor of the work. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of

Baiyin First People's Hospital (grant no. 2024YK-08), and Baiyin

Municipal Science and Technology Bureau 2025 Municipal Science and

Technology Plan-Social Development Category (grant no.

2025-2-9S).

References

|

1

|

Lingvay I, Cohen RV, Roux CWL and

Sumithran P: Obesity in adults. Lancet. 404:972–987. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chandrasekaran P and Weiskirchen R: The

role of obesity in type 2 diabetes mellitus-an overview. Int J Mol

Sci. 25:18822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Koskinas KC, Van Craenenbroeck EM,

Antoniades C, Blüher M, Gorter TM, Hanssen H, Marx N, McDonagh TA,

Mingrone G, Rosengren A, et al: Obesity and cardiovascular disease:

An ESC clinical consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 45:4063–4098.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

King LK, March L and Anandacoomarasamy A:

Obesity & osteoarthritis. Indian J Med Res. 138:185–193.

2013.

|

|

5

|

GBD 2021 Adult BMI Collaborators: Global,

regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity,

1990-2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the

Global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. 405:813–838. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wu Y, Zhou L, Zhang X, Yang X, Niedermann

G and Xue J: Psychological distress and eustress in cancer and

cancer treatment: Advances and perspectives. Sci Adv.

8:eabq79822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Early Breast Cancer Trialists'

Collaborative Group (EBCTCG); Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, Taylor

C, Arriagada R, Clarke M, Cutter D, Davies C, Ewertz M, et al:

Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year

recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: Meta-analysis of

individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials.

Lancet. 378:1707–1716. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Teli BD and Behzadifar M, Beiranvand M,

Rezapour A, Ehsanzadeh SJ, Azari S, Bakhtiari A, Haghighatfard P,

Martini M, Saran M and Behzadifar M: The economic burden of breast

cancer in western Iran: A cross-sectional cost-of-illness study. J

Health Popul Nutr. 44:162025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xiong N, Wu H and Yu Z: Advancements and

challenges in triple-negative breast cancer: A comprehensive review

of therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. Front Oncol.

14:14054912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hu JJ, Zhang QY and Yang ZC: The

correlation between obesity and the occurrence and development of

breast cancer. Eur J Med Res. 30:4192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Agnoli C, Grioni S, Sieri S, Sacerdote C,

Ricceri F, Tumino R, Frasca G, Pala V, Mattiello A, Chiodini P, et

al: Metabolic syndrome and breast cancer risk: A case-cohort study

nested in a multicentre italian cohort. PLoS One. 10:e01288912015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cozzo AJ, Fuller AM and Makowski L:

Contribution of adipose tissue to development of cancer. Compr

Physiol. 8:237–282. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Xu Q, Yu J, Jia G, Li Z and Xiong H:

Crocin attenuates NF-κB-mediated inflammation and proliferation in

breast cancer cells by down-regulating PRKCQ. Cytokine.

154:1558882022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chen EP and Smyth EM: COX-2 and

PGE2-dependent immunomodulation in breast cancer. Prostaglandins

Other Lipid Mediat. 96:14–20. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sharma VR, Gupta GK and Sharma AK, Batra

N, Sharma DK, Joshi A and Sharma AK: PI3K/Akt/mTOR intracellular

pathway and breast cancer: Factors, mechanism and regulation. Curr

Pharm Des. 23:1633–1638. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Mohanty SS and Mohanty PK: Obesity as

potential breast cancer risk factor for postmenopausal women. Genes

Dis. 8:117–123. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

18

|

Neuhouser ML, Aragaki AK, Prentice RL,

Manson JE, Chlebowski R, Carty CL, Ochs-Balcom HM, Thomson CA, Caan

BJ, Tinker LF, et al: Overweight, obesity, and postmenopausal

invasive breast cancer risk: A secondary analysis of the women's

health initiative randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncol.

1:611–621. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kabat GC, Kim MY, Lee JS, Ho GY, Going SB,

Beebe-Dimmer J, Manson JE, Chlebowski RT and Rohan TE: Metabolic

obesity phenotypes and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal

women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 26:1730–1735. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Picon-Ruiz M, Morata-Tarifa C,

Valle-Goffin JJ, Friedman ER and Slingerland JM: Obesity and

adverse breast cancer risk and outcome: Mechanistic insights and

strategies for intervention. CA Cancer J Clin. 67:378–397.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ladoire S, Dalban C, Roché H, Spielmann M,

Fumoleau P, Levy C, Martin AL, Ecarnot F, Bonnetain F and

Ghiringhelli F: Effect of obesity on disease-free and overall

survival in node-positive breast cancer patients in a large French

population: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials. Eur J

Cancer. 50:506–516. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ligibel JA, Cirrincione CT, Liu M, Citron

M, Ingle JN, Gradishar W, Martino S, Sikov W, Michaelson R, Mardis

E, et al: Body mass index, PAM50 subtype, and outcomes in

node-positive breast cancer: CALGB 9741 (Alliance). J Natl Cancer

Inst. 107:djv1792015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Iyengar NM, Arthur R, Manson JE,

Chlebowski RT, Kroenke CH, Peterson L, Cheng TD, Feliciano EC, Lane

D, Luo J, et al: Association of body fat and risk of breast cancer

in postmenopausal women with normal body mass index: A secondary

analysis of a randomized clinical trial and observational study.

JAMA Oncol. 5:155–163. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Dias JA, Fredrikson GN, Ericson U,

Gullberg B, Hedblad B, Engström G, Borgquist S, Nilsson J and

Wirfält E: Low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress and risk of

invasive post-menopausal breast cancer-A nested case-control study

from the malmö diet and cancer cohort. PLoS One. 11:e01589592016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Pan K, Simon

MS, Neuhouser ML, Haque R, Rohan TE, Wactawski-Wende J, Orchard TS,

Mortimer JE, et al: Breast cancer incidence and mortality by

metabolic syndrome and obesity: The women's health initiative.

Cancer. 130:3147–3156. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Widschwendter P, Friedl TW, Schwentner L,

DeGregorio N, Jaeger B, Schramm A, Bekes I, Deniz M, Lato K,

Weissenbacher T, et al: The influence of obesity on survival in

early, high-risk breast cancer: Results from the randomized SUCCESS

A trial. Breast Cancer Res. 17:1292015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gennari A, Amadori D, Scarpi E, Farolfi A,

Paradiso A, Mangia A, Biglia N, Gianni L, Tienghi A, Rocca A, et

al: Impact of body mass index (BMI) on the prognosis of high-risk

early breast cancer (EBC) patients treated with adjuvant

chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 159:79–86. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Biganzoli E, Desmedt C, Fornili M, de

Azambuja E, Cornez N, Ries F, Closon-Dejardin MT, Kerger J, Focan

C, Di Leo L, et al: Recurrence dynamics of breast cancer according

to baseline body mass index. Eur J Cancer. 87:10–20. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lammers SWM, Geurts SME, van Hellemond

IEG, Swinkels ACP, Smorenburg CH, van der Sangen MJC, Kroep JR, de

Graaf H, Honkoop AH, Erdkamp FLG, et al: The prognostic and

predictive effect of body mass index in hormone receptor-positive

breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 7:pkad0922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tzschaschel M, Friedl TWP, Schochter F,

Schütze S, Polasik A, Fehm T, Pantel K, Schindlbeck C, Schneeweiss

A, Schreier J, et al: Association Between Obesity and Circulating

Tumor Cells in Early Breast Cancer Patients. Clin Breast Cancer.

23:e345–e353. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tangalakis LL, Cortina CS, Son JD, Poirier

J and Madrigrano A: Obesity does not influence management of

advanced breast cancer in the elderly. Clin Breast Cancer.

19:197–199. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bhan A and Mandal SS: LncRNA HOTAIR: A

master regulator of chromatin dynamics and cancer. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1856:151–164. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang Y, Sano M, Shinmura K, Tamaki K,

Katsumata Y, Matsuhashi T, Morizane S, Ito H, Hishiki T, Endo J, et

al: 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal protects against cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion injury via the Nrf2-dependent pathway. J Mol

Cell Cardiol. 49:576–586. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Pizzimenti S, Toaldo C, Pettazzoni P,

Dianzani MU and Barrera G: The 'two-faced' effects of reactive

oxygen species and the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal

in the hallmarks of cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2:338–363. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhong H and Yin H: Role of lipid

peroxidation derived 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) in cancer: Focusing

on mitochondria. Redox Biol. 4:193–199. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Di Cosimo S, Porcu L, Agbor-Tarh D,

Cinieri S, Franzoi MA, De Santis MC, Saura C, Huober J, Fumagalli

D, Izquierdo M, et al: Effect of body mass index on response to

neo-adjuvant therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: An exploratory

analysis of the NeoALTTO trial. Breast Cancer Res. 22:1152020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Martel S, Lambertini M, Agbor-Tarh D,

Ponde NF, Gombos A, Paterson V, Hilbers F, Korde L, Manukyants A,

Dueck A, et al: Body mass index and weight change in patients with

HER2-positive early breast cancer: Exploratory analysis of the

ALTTO BIG 2-06 trial. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 19:181–189. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dauccia C, Alice Franzoi M, Martel S,

Agbor-Tarh D, Fielding S, Piccart M, Bines J, Loibl S, Di Cosimo S,

Vaz-Luis I, et al: Body mass index and weight changes in patients

with HER2-positive early breast cancer: A sub-analysis of the

APHINITY trial. Eur J Cancer. 223:1154892025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sedjo RL, Byers T, Ganz PA, Colditz GA,

Demark-Wahnefried W, Wolin KY, Azrad M and Rock CL: Weight gain

prior to entry into a weight-loss intervention study among

overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv.

8:410–418. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mutschler NS, Scholz C, Friedl TWP,

Zwingers T, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW, Fehm T, Mohrmann S, Salmen J,

Ziegler C, et al: Prognostic impact of weight change during

adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-risk early breast

cancer: Results from the ADEBAR study. Clin Breast Cancer.

18:175–183. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Goodwin PJ, Segal RJ, Vallis M, Ligibel

JA, Pond GR, Robidoux A, Blackburn GL, Findlay B, Gralow JR,

Mukherjee S, et al: Randomized trial of a telephone-based weight

loss intervention in postmenopausal women with breast cancer

receiving letrozole: The LISA trial. J Clin Oncol. 32:2231–2239.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Babatunde OA, Arp Adams S, Truman S, Sercy

EMSPH, Murphy AE, Khan SMSW, Hurley TGMS, Wirth MD, Choi SK,

Johnson HBA and Hebert ScD JR: The impact of a randomized dietary

and physical activity intervention on chronic inflammation among

obese African-American women. Women Health. 60:792–805. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI