Gastric cancer (GC) continues to have a high global

burden, ranking third in terms of cancer-related mortality and

fifth in terms of incidence (1,2).

Annually, ~660,000 individuals die from GC, despite improvements in

early detection and treatment methods (3); by 2040, it is estimated to increase

to ~1.8 million new cases and 1.3 million fatalities (4). GC follows a multistage progression

pattern driven by chronic inflammation, including atrophy,

metaplasia, dysplasia and invasive carcinoma, termed the 'Correa

pathway' proposed by Correa et al (5) in 1975. Current research is improving

the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the

progression of precancerous lesions through inflammation-mediated

epigenetic changes, such as microbiota dysbiosis, while therapeutic

studies are investigating novel approaches to target particular

pathways, such as glycosylation, in order to prevent metastasis

(6,7). When a terminally differentiated cell

type that is not typically found at a specific anatomical location

replaces pre-existing terminally differentiated cells, this is

termed metaplasia (8). In most

cases, the metaplasia lineage is characterized by mucus secretion.

A key characteristic of the metaplastic lineage is the remodeling

of the gastric mucosa by mucus-secreting cell cohorts in response

to damage (9), and mucus

production is typically the distinguishing characteristic of this

lineage. In the gastric mucosa, two main forms of metaplasia have

been identified: i) Intestinal metaplasia (IM); and ii) spasmolytic

polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM).

SPEM, also termed pseudopyloric metaplasia or mucous

metaplasia, is a regenerative lesion that presents histologically

as Brunner's glands or deep proventricular glands. It is

distinguished by the expression of Trefoil factor 2 (TFF2),

Griffonia simplicifolia lectin II (GS II) and mucin (MUC) 6

(10). SPEM formation is

frequently accompanied by abnormal gastric pit hyperplasia,

macrophage infiltration and glandular structure disarray. Chronic

damage (such as inflammation or NSAID use) causes the gastric

epithelium to ablate, which leads to the formation of SPEM during

regeneration. Similar to intestinal cup cells (MUC5AC, MUC6 and

MUC2), these metaplasia cells typically exhibit a distinct

mucus-secreting phenotype, altering the defensive and digestive

characteristics of the gastric mucosa (10,11). SPEM and IM are two distinct

lineages of metaplasia cells. However, SPEM may precede IM and

promote carcinogenesis via a variety of mechanisms (12). According to independent clinical

studies carried out in the US, Japan and Iceland, SPEM is found in

>90% of GC resection specimens, is linked to >50% of early

GCs and is frequently found in the paracarcinoma or dysplasia

region (13-15). Furthermore, animal models have

confirmed that SPEM is an important intermediate stage in gastric

precancerous lesions (16-18).

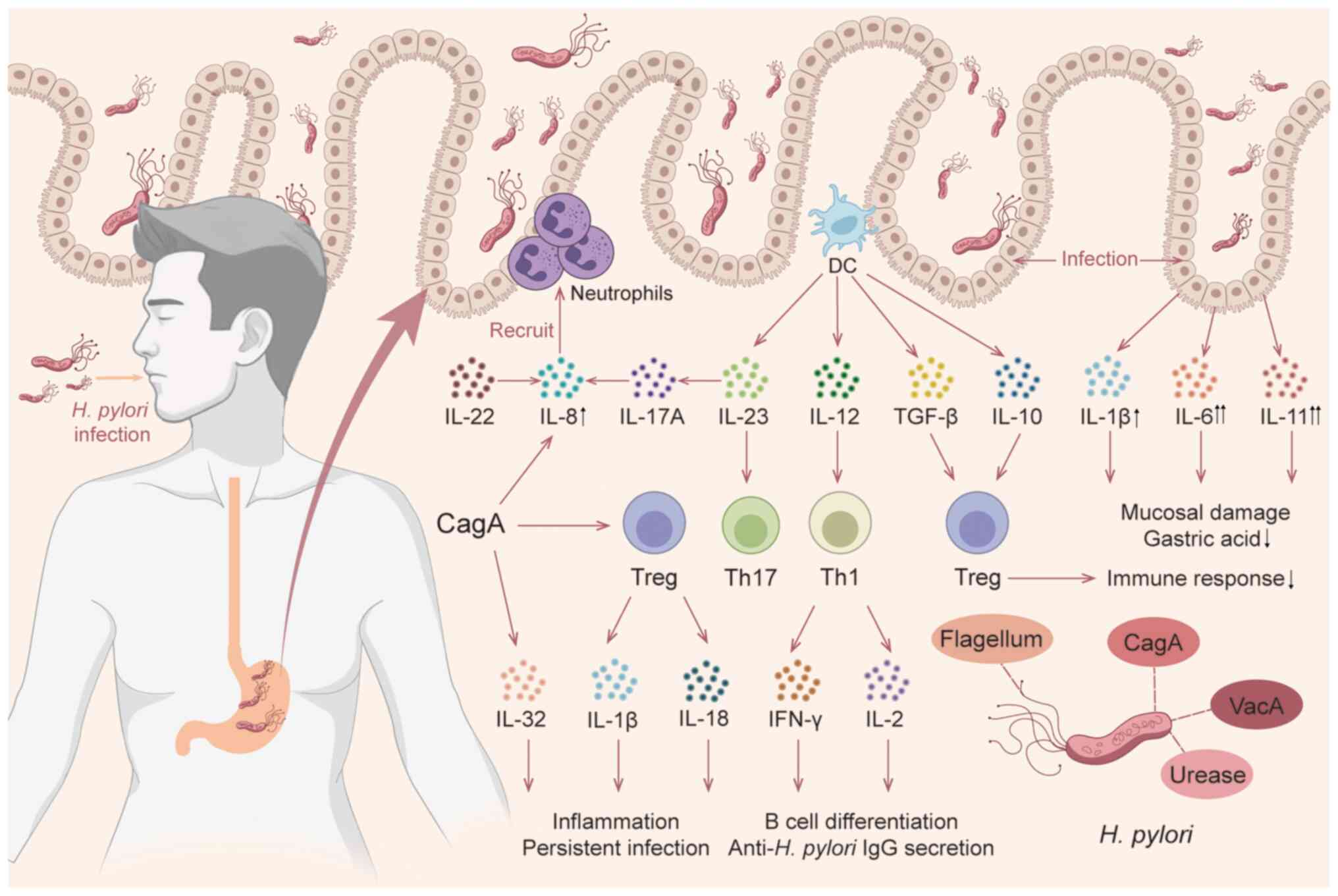

Interleukins (ILs) are potent secreted regulators of

various cell types and activities. By targeting and influencing

various cell signaling pathways, they aid in the development and

progression of inflammatory diseases and various types of cancer.

ILs also regulate processes such as cell death, proliferation,

differentiation and migration, and are involved in cellular

communication during homeostasis and disease (19-22). IL production and function are

central regulators of SPEM development. Research has verified that

the development of SPEM is closely associated with chronic

inflammation and involves an imbalance in the network of

pro-inflammatory/anti-inflammatory ILs, such as IL-1β, IL-10,

IL-17A and IL-33. ILs bind to high-affinity receptors on the cell

membrane and activate intracellular signaling pathways, including

NF-κB, MAPK and JAK-STAT, resulting in gene transcription changes.

This in turn regulates local cell proliferation, differentiation

and reprogramming (23-26) and induces or alters specific

cellular functions (27-29). The IL network may disturb the

normal homeostasis of gastric mucosal cells by controlling local

inflammation, cellular infiltration and multi-pathway interactions.

This could lead to the development of SPEM or be a major factor in

the transformation of SPEM into GC (30).

The present review summarized recent findings on

IL-related mechanisms involved in SPEM formation and progression.

Furthermore, the roles of various ILs in SPEM and the relationship

between IL changes and SPEM after Helicobacter pylori (H.

pylori) infection are described. In addition, the present

review offered a comprehensive summary of the features of the

different SPEM experimental models that are employed in IL studies.

Finally, by describing the progress and limitations of ILs for

therapeutic use, novel directions for future investigation are

discussed.

The mucosal barrier, made up of closely knit

epithelial cells and a thick layer of mucus, protects the gastric

epithelium from harmful agents such as ingested food, bacteria,

gastric acid and digestive enzymes, stopping the stomach contents

from penetrating into the underlying tissues (31). Pepsinogen-producing chief cells,

mucus-producing surface foveolar cells, neck cells and

acid-producing parietal cells make up the majority of the gastric

mucosal barrier (32). The chief

cell is a differentiated cell lineage, and a subset of it serves as

'reserve' stem cells in the gastric mucosa. During gastric injury,

parietal cells become deficient due to a variety of pathogenic

factors, resulting in a compensatory proliferative response of

gastric stem and progenitor cells, as well as metaplasia with

zymogenic chief cells that can be recruited back into the cell

cycle. Metaplasia in the stomach, which results in the structural

change of its glands, is considered to be an 'adaptive' process

that reacts to a range of endogenous or exogenous aggressors,

including pH, hormones, chemicals and microbiota changes (33). SPEM is a type of metaplasia that

occurs during the healing of gastric mucosal damage. This is due to

the metaplasia cells expressing spasmolytic polypeptide, also

termed TFF2. Fully differentiated gastric chief cells can be

reprogrammed into mucin-secreting metaplasia cells, and the

presence of mature chief cells in the corpus is the source of SPEM

cells via transdifferentiation. These metaplasia changes take place

concurrently with or in response to parietal cell death and

inflammation (34). SPEM cells

are histologically localized at the base of metaplasia glands

following injury, and their specificity was determined by the

co-expression of molecular markers including GS II lectin, TFF2,

Muc6, CD44v9 and AQP5 (35). The

formation of metaplasia lineage cells, proliferation of neck cells

and amplification of the small foveolar/tuft cell lineage in the

gastric mucosa are characteristic pathological alterations

(36,37). Additionally, excessive immune

activation in the stomach can damage epithelial cells and induce

the development of SPEM (38).

Acute SPEM may be a healing mechanism, but when it persists in an

environment of chronic inflammation, chronic SPEM is strongly

associated with the development of gastric adenocarcinoma (34,38). It has been recorded that >95%

of GCs are adenocarcinomas, and according to Laurén's

classification, they can be divided into two types: i) Diffuse; and

ii) intestinal (39). SPEM is

present in almost all GC types, and research on animal models with

acute oxyntic atrophy, transgenic and knockout (KO) genes, chronic

infection and genetic modification indicates that SPEM is a key

precancerous intermediate in the malignant transformation of

gastric mucositis (9,40). Although SPEM is partially

reversible, intestinal SPEM and/or IM are considered precancerous

lesions that may be irreversible in the presence of chronic

inflammatory stimuli (41,42).

Dysplasia progression is an inevitable stage of cancer development

(39). The susceptibility of

gastric precancerous lesions to alterations in the expression of

numerous ILs suggests that immune cells and different ILs

implicated in the progression of metaplasia may be important in

predicting the risk of carcinogenesis (27,39,43,44). Thus, additional identification and

clarification of ILs associated with the SPEM response will greatly

enhance the present understanding of gastric carcinogenesis.

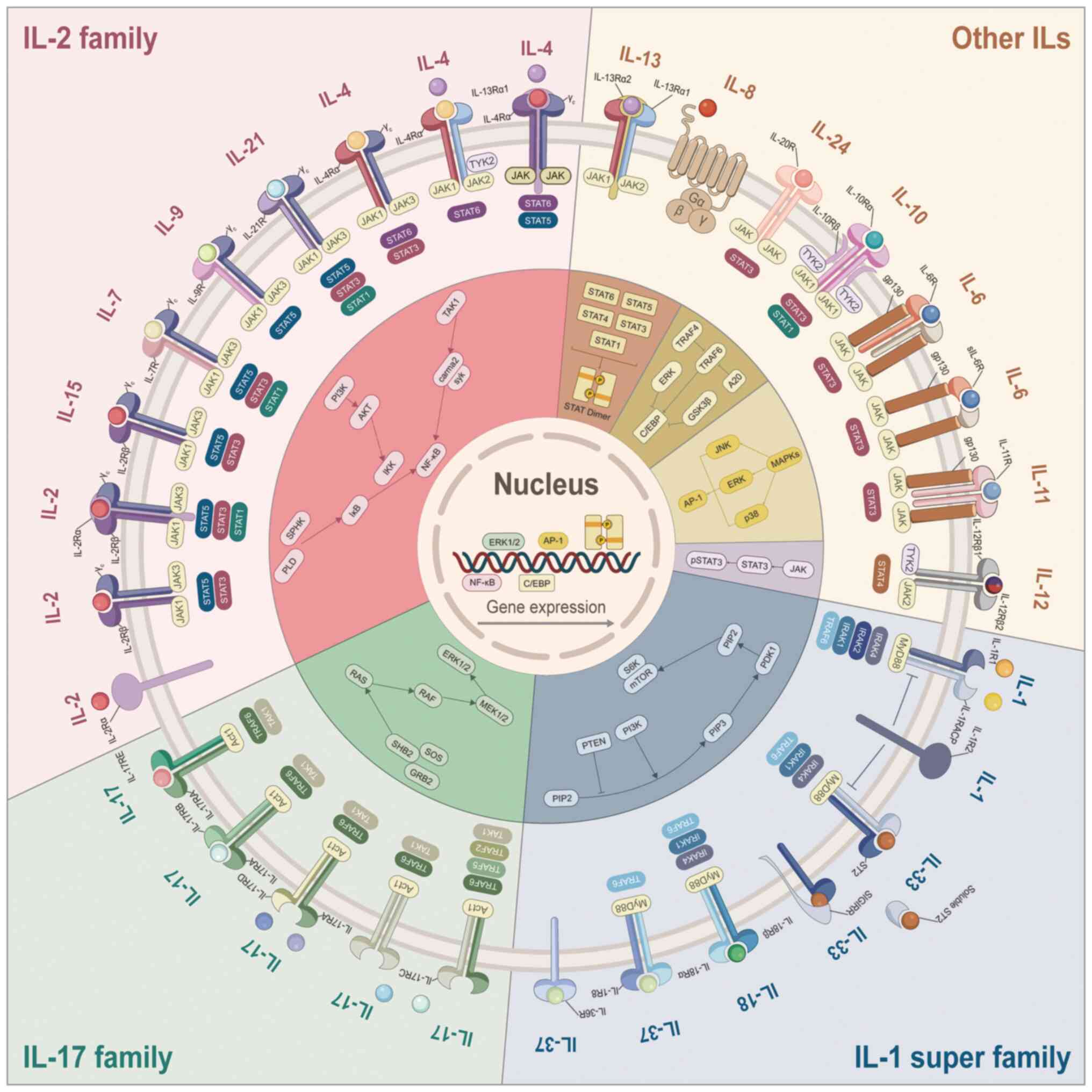

ILs are a subset of cytokines and a family of

signaling proteins that are essential for the regulation and

coordination of immune system responses. The family consists of

small proteins secreted by different cells to facilitate cellular

communication and interaction (45). At least 40 ILs have been

identified, a number of which can be classified into separate

families or superfamilies (46).

Typically, each IL interacts with a different receptor or group of

closely related receptors expressed on the target cell, and when

bound, the intracellular structural domain of the receptor is

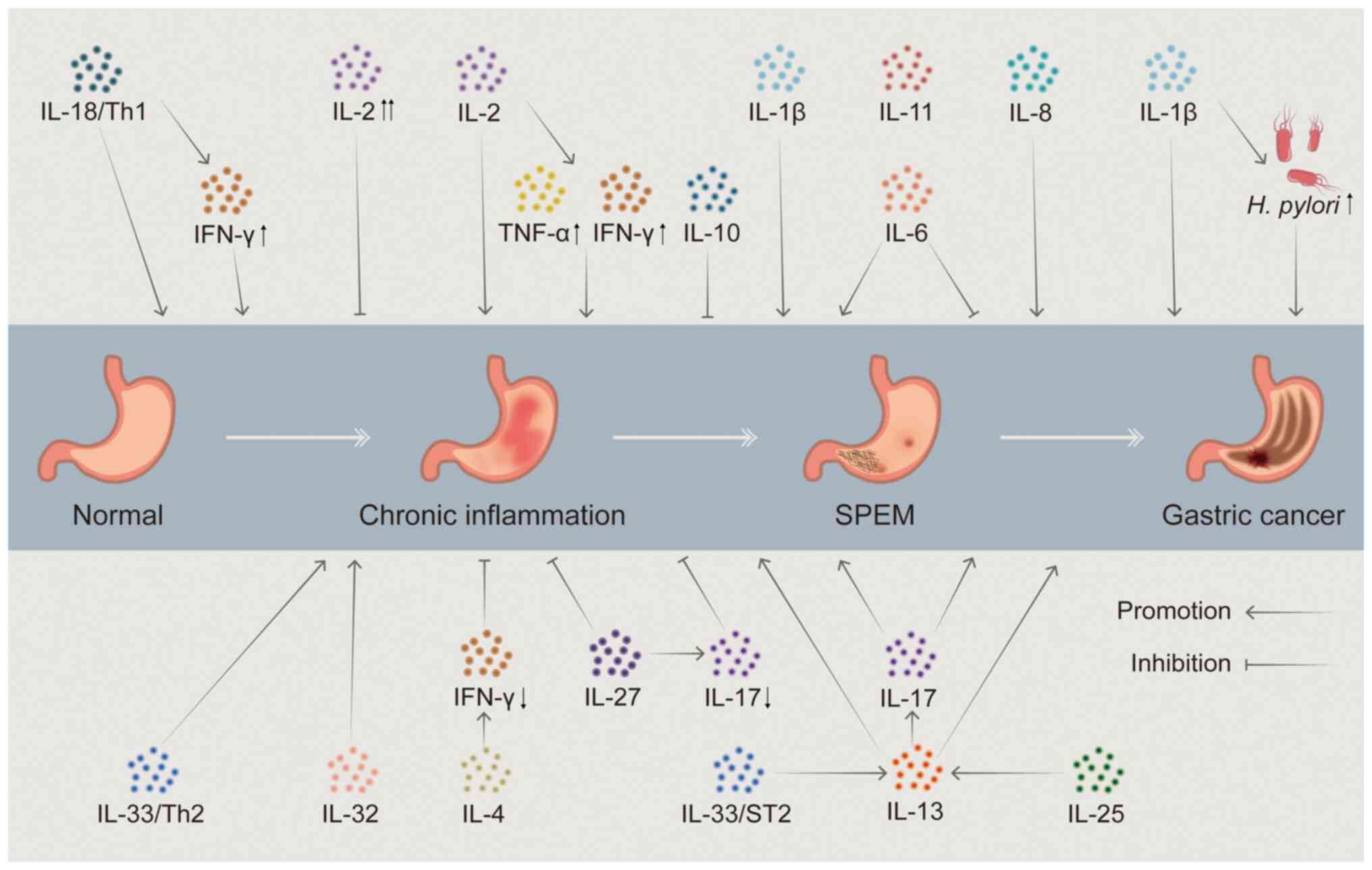

activated, triggering an intracellular signaling cascade (Fig. 1). Numerous ILs are especially

important for the onset and course of SPEM, and their pleiotropic

effects depend on a number of factors, including dose dependency,

receptor heterogeneity, cellular source diversity and signaling

pathway complexity (21). In the

present review, the cytokine signals associated with SPEM were

systematically categorized (Fig.

2), including the IL-1 superfamily, IL-2 family, IL-6 family,

IL-10 family, IL-12 family, IL-17 family and other ILs, as well as

cytokines closely related to ILs (Table I).

IL-1 is a polypeptide synthesized and secreted by

lymphocytes and monocyte macrophages and has various functions,

such as participation in immune response, thermogenesis and

mediation of inflammation (47).

Within a 430 kilobase region, the IL-1 gene cluster on chromosome

2q comprises three related genes, IL-1A, IL-IB and IL-1RN, which

encode IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) (27). IL-1α and IL-1β are alarm cytokines

(also termed alarm proteins), both of which initiate and amplify

local inflammation via the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) (48). Additionally, IL-1β directly

stimulates the development of SPEM by strongly suppressing the

secretion of gastric acid and causing the atrophy of the gastric

mucosa. When pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or

damage-associated molecular patterns activate the pattern

recognition receptor, IL-1β is produced as an inactive precursor

(pro-IL-1β). The cleavage of pro-IL-1β into its active form by

caspase-1 proteolysis requires the activation of inflammasomes,

which are then released extracellularly (47). Inflammasome-mediated caspase-1

activation triggers both IL-1β release and pyroptosis, affecting

inflammation progression. In addition, IL-1β stimulates the

proliferation of gastric epithelial cells, which may further

contribute to gastric carcinogenesis (49). Prolonged and persistent acid

inhibition by IL-1β may facilitate H. pylori transfer from

the gastric antrum to the corpus, endangering acid-producing

parietal cells and promoting SPEM (50). IL-1Ra can also combine with the

IL-1β receptor, thereby affecting the action of IL-1β.

IL-18, a member of the IL-1 superfamily, is a

pleiotropic pro-inflammatory cytokine that is important in gastric

mucosal inflammation and immunomodulation (27,51). IL-18 signaling begins with a

ligand binding to the receptor IL-18Rα (also termed IL-1R-related

protein). When IL-18 binds to IL-18Rα, IL-18Rβ/IL-18RAcP is

recruited into the complex and activates downstream signaling

pathways such as NF-κB. IL-18 can dominate the gastric mucosal

response to H. pylori infection by promoting T helper (Th) 1

responses and inducing chronic persistent inflammatory changes

(52). Initially, it was referred

to as an IFN-inducing factor that could stimulate the production of

IFN-γ by splenocytes, hepatic lymphocytes and Th1 cells, as well as

increase the cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells and

stimulate the production of IFN-γ in conjunction with IL-12

(53). The production of IFN-γ

causes the death of gastric epithelial cells that express the IFN-γ

receptor and is directly linked to the pathological process of SPEM

(54). Although the link between

IFN-γ and subsequent neoplasia remains uncertain, studies have

shown that IFN-γ is crucial during the SPEM stage of precancerous

lesions (55). Current studies

have typically focused on IL-18-related gene polymorphisms.

Research has demonstrated that IL-18RAP gene polymorphisms serve a

notable role in the development of gastric precancerous lesions by

controlling the IFN-γ production pathway, and may be linked to

precancerous lesions or susceptibility to GC in GC high-risk

populations (51,53). However, according to a different

study, there was no meaningful association between the progression

of gastric precancerous lesions and IL-18 promoter polymorphisms

(56). Therefore, there is a lack

of direct evidence that IL-18 serves a key role in gastric

precancerous lesions and SPEM progression.

IL-33, a member of the IL-1 superfamily, is a

cytokine involved in tissue homeostasis, pathogenic infections,

inflammation, allergies and the type 2 immune response. Through its

receptor ST2 (ST2L; also termed T1/ST2, IL1RL1, T1, Der4, Fit1 or

IL-33R), IL-33 forms a heterodimeric complex with IL-1 receptor

accessory protein (IL-1R3). IL-33 is extensively found on the

surfaces of Th2 cells, group 2 innate lymphocytes (ILC2s), mast

cells and macrophages (57,58). IL-33 serves as an intranuclear

transcriptional regulator, an extracellular alarmin and an immune

regulation mediator. Under healthy conditions, IL-33 translocates

to the nucleus and is involved in regulating gene expression

(59). When necrosis or cell

damage compromises the epithelial cell barrier, cells release

IL-33, which also acts as an alarm protein (60,61). The immune defense and repair

systems are coordinated by extracellular IL-33, which also

initiates adaptive immune responses. Increased extracellular IL-33

activates expanded tissue ILC2 and Treg and promotes the

recruitment and survival of immune cells (such as eosinophils, AAM,

Th2 cells and basophils). These cells and signals feed back to the

tissue to promote remodeling and limit inflammation. In the gastric

mucosa, IL-33 is mainly secreted by damaged epithelial cells, a

subset of mucous foveolar epithelial cells and M2-type macrophages

(60,62,63). When there is acute inflammation

and a loss of gastric mucosal parietal cells, macrophages

infiltrate and gastric pit epithelial cells release IL-33 to

synchronize immune defense and repair processes. IL-33 also

promotes epithelial proliferation through activation of the MAPK

pathway (ERK1/2, JNK and p38) (64). The IL-33/IL-13 axis is critical

for gastric metaplasia and gastric epithelial repair, and several

studies have linked reduced IL-33 in TFF2-deficient mice to

defective metaplasia development and delayed downstream gastric

epithelial repair (60,65,66). Following parietal cell loss, IL-33

stimulates the ST2 signaling axis, triggers a Th2-type immune

response, promotes the release of cytokines such as IL-13 and

causes the transdifferentiation of gastric chief cells into SPEM

cells (63). IL-33- or ST2-KO

mice are unable to form SPEM after L635-induced acute injury,

suggesting that appropriate ILs are required to promote

transdifferentiation as part of the gastric epithelial repair

process (63,67). IL-33 also enhances ILC2 activity

by upregulating GATA3 signaling, drives the gastric mucosal Th2

response and synergistically promotes goblet cell proliferation

with IL-25 (68). Furthermore,

IL-33 activates ILC2 in combination with IL-25 released by Tuft

cells, increasing type II cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and

IL-13 (57,63,69). Among these cytokines, IL-13 and

IL-4 mediate M2 macrophage activation through the co-receptor

IL-4Rα (70). M2 macrophages and

eosinophils in turn produce IL-13 and IL-33, self-sustaining the

feed-forward cycle and stimulating mast cell activity (71,72). The resulting downstream release of

IL-13 facilitates the progression of SPEM. A series of

IL-33-mediated signaling events that promote SPEM progression are

centrally involved, and persistent inflammation of the gastric

mucosa can further lead to additional IM and carcinogenesis

(68). Long-term and high levels

of IL-33 cause M2 macrophage polarization, eosinophil proliferation

and severe infiltration into the stomach mucosa, resulting in the

maintenance of Th2-driven chronic inflammation (73). This increases the risk of cancer

and promotes metaplasia to transform into GC (60,62,64,68). Given that IL-33 stimulates

epithelial proliferation and metaplasia whilst also inducing and

maintaining chronic Th2-driven inflammation, it is a key mediator

of SPEM/intestinal SPEM manifestations.

IL-2 is a pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine

produced primarily by activated T cells that regulates immune

response and anti-tumor immunity. The IL-2 receptor consists of

three subunits: i) IL-2Rα (CD25); ii) IL-2Rβ (CD122); and iii)

common γ-chain (γc; CD132). The IL-2Rαβγc heterotrimer is

constitutively expressed on Tregs and ILC2s and has the highest

affinity for IL-2. In the context of chronic or acute inflammation,

mucosal cells proliferate at an accelerated rate to promote the

repair of damaged epithelium (74). H. pylori-associated

gastritis is closely related to IL-2, and the DMP-777 model shows

that parietal cell deficiency is sufficient to trigger SPEM, but

inflammation is critical for further differentiation and the

development of SPEM (75,76). Studies into the inflammatory

component in mice have shown that the progression of SPEM to

developmental abnormalities requires a Th1-dominated inflammatory

response (77,78). Th1 cells characteristically

secrete IFN-γ and IL-2 (79). Th1

cells in H. pylori-infected individuals produce large

amounts of IL-2, which induces T cell differentiation and immune

memory (80,81). IL-2 is considered to provide a

pathological basis for gastric carcinogenesis and SPEM by

suppressing the secretion of gastric acid and modifying Th1 immune

responses. A previous study found that the Th1-specific cytokines

IL-2 and IFN-γ directly inhibit acid secretion in mice, which can

lead to gastric atrophy and promote the development of precursor

lesions to GC (82). However,

there is no direct experimental evidence that indicates that IL-2

is directly related to SPEM differentiation and maturation.

Instead, IL-2 primarily mitigates tissue damage by reducing gastric

acid secretion and thus acid-related chronic inflammation (83). In summary, IL-2 serves an

important role in SPEM progression by regulating the intensity of

inflammation and the immune microenvironment, but its specific

signaling pathways and interactions with other cytokines still need

further exploration.

IL-4 is an important immunomodulatory cytokine

involved in the cascade transduction of several cytokines. Its

signaling is initiated through two heterodimeric receptor

complexes: i) Type I (IL-4Rα/γc) specifically bound to IL-4; and

ii) type II (IL-4Rα/IL-13Rα1) bound to both IL-4 and IL-13,

activating STAT6, JNK or IRS2 signaling pathways that drive

macrophage polarization towards the alternative activation

phenotype (M2a) (70,84). Activated JAK phosphorylates IL-4Rα

tyrosine residues, creating binding sites for STAT6, which

dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus to activate gene

transcription (85). IL-4 also

maintains immune homeostasis by balancing M1/M2 macrophage

polarization via STAT1/3 and STAT6 synergistic regulation (84,86). In gastric mucosal inflammation,

IL-4 acts as an anti-inflammatory factor to inhibit inflammation

and atrophy by reducing IFN-γ. It inhibits the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α, and

regulates lymphocyte differentiation and the tumor microenvironment

(84). Due to the structural

similarity of the surface receptors, in a variety of diseases IL-4

acts predominantly in conjunction with another type II cytokine,

IL-13 (84). IL-4 and IL-13

activate macrophages by alternating, a process that is also an

important step in the progression of SPEM (70,86-88). IL-4 also serves a central role in

the Th2 cell phenotype, with studies revealing that sequential

activation of STAT5 and STAT6 enhances the subsequent response to

IL-4, ultimately leading to Th2 T cell differentiation (89,90). Studies have shown that IL-4 also

inhibits the growth of GC cells, and a notable increase in serum

IL-4 levels has also been reported in patients with GC (85,91,92). IL-4 is considered to be associated

with the repair of epithelial damage in the early stages, and the

mechanism of its association with cancer progression in the late

stages has not yet been demonstrated. Furthermore, a study

demonstrated that IL-4 notably increased M2 macrophage

differentiation in a diabetic mouse model, indicating that it may

serve a similar role in gastric mucosal injury repair (57).

IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine, is secreted by immune

cells (such as monocytes, macrophages and lymphocytes) and

non-immune cells (such as endothelial cells, intestinal epithelial

cells, tumor-associated fibroblasts and tumor cells) (93-95). IL-6 regulates inflammatory

mediators and endocrine responses, and serves as a link between

innate and adaptive systems in host defense mechanisms (96). IL-6 signaling necessitates binding

to the specific receptor IL-6R or IL-11R, which then binds to the

common signal transduction receptor subunit glycoprotein 130

(gp130), causing its recruitment and homodimerization, eventually

leading to the activation of the JAK/STAT and

SHP2/Ras/MAPK/ERK1-2/activator protein 1 (AP-1) signaling cascades

(97-99). In gastric mucosal lesions, IL-6

regulates gastric mucosal homeostasis by regulating TFF1 and

mucosal proliferation, inflammation, angiogenesis and

apoptosis-related mediators, and its signaling regulates gastric

mucosal homeostasis by balancing SHP2/Ras/ERK and STAT3. Elevated

IL-6 levels were noted in chronic inflammatory conditions, and the

downregulation of TFF1 tumor suppressor activity was caused by the

absence of ERK/AP-1 signaling downstream of gp130. This, in turn,

results in the activation of constitutive and oncogenic STAT3,

which inhibits apoptotic processes and promotes cellular

proliferation and inflammatory responses. These factors ultimately

lead to the development of mucosal atrophy, metaplasia,

TFF2-associated changes in the SPEM lineage, aberrant cell

proliferation and the progression to dysplasia and submucosal

invasion (98). When IL-6 family

signaling pathways are interfered with, increased STAT3 signaling

may promote the growth of gastric adenomas, while increased

SHP2/ERK2 signaling may result in chronic mucosal inflammation

(100). Therapeutic strategies

targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 axis, such as the JAK inhibitor

WP1066, have been shown to inhibit STAT3 phosphorylation and reduce

pro-inflammatory factors (IL-6, IL-11 and IL-1β) and growth factor

expression, thereby blocking tumor proliferation and inducing

apoptosis (101). Nonetheless,

there is insufficient evidence to support a causal role for IL-6 in

cancer progression, implying that this IL may serve a protective

rather than pathogenic role in the stomach (102).

IL-11 belongs to the IL-6 family and is a

pleiotropic cytokine. It is a key mediator of inflammation in the

gastrointestinal tract, influencing the activity of numerous immune

cell populations such as macrophages, mast cells, dendritic cells

(DCs) and lymphocytes (103).

IL-11 initiates signal transduction by binding to IL-11 receptor α,

which recruits the signal transduction receptor gp130. By extending

stem cell survival, decreasing apoptosis and promoting mitosis,

IL-11 can impact epithelial homeostasis and is crucial for gastric

injury, mucosal repair and cancer progression (104). Chronic IL-11 elevation causes

severe fundus damage, including inflammation, metaplasia, loss of

chief and parietal cells and increased proliferation, all of which

are closely linked to chronic atrophic gastritis in humans

(103). IL-11 has been shown to

mediate the hyperactivation of STAT3 by gp130 in a

gp130F/F mouse model of gastric tumorigenesis (105,106). Overexpression of IL-11 in the

stomach caused by mutations in the gp130-JAK-STAT3 pathway can

cause spontaneous atrophic gastritis to progress to locally

advanced epithelial hyperplasia, but not dysplasia or cancer

(104). Furthermore, alongside

IL-11-induced gastric atrophy, there is a modest influx of

polymorphonuclear cells, accompanied by elevated expression of

IL-1β and IL-33 (103). IL-33

modulates Th1/Th2 cytokine balance in epithelial cells (107), whereas IL-1β regulates the

expression of HK-ATPaseα subunit 64 and suppresses

gastrin-dependent acid secretion (108,109). Notably, IL-11 can directly

activate GC cells, thereby driving the development of an invasive

phenotype (110), and is

upregulated in both mouse and human GC as well as preneoplastic

mucosa (111).

IL-10 is an important anti-inflammatory cytokine and

serves a key role in immunomodulation by inhibiting the synthesis

of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α

(112-114). IL-10 activity is mediated by

heterodimeric IL-10 receptors (IL-10R1 and IL-10R2) (112). By preventing macrophage-mediated

inflammatory responses and limiting pro-inflammatory signaling

pathways such as NF-κB, IL-10 facilitates tissue repair (112,113). In a tamoxifen-induced SPEM model

of gastric mucosa, IL-10 expression was notably reduced 3 days

after administration and coincided with a histological loss of ~90%

of parietal cells in the gastric mucosa. IL-10 levels were restored

after 10 and 21 days, accompanied by histological normalization,

suggesting that it may be involved in mucosal repair by modulating

parietal cell function (25).

Deficits in IL-10 can also result in the development of

precancerous microenvironments and chronic inflammation (42). In addition, intracellular IL-10

levels are significantly elevated in patients with advanced GC

(115). IL-10 present in

tumor-associated macrophages creates an immune-evasive

microenvironment (116), and

elevated IL-10 levels are associated with GC metastasis and poor

prognosis (117). The regulatory

mechanism of IL-10 on SPEM-related carcinogenesis is still being

investigated (42); however,

IL-10 is regarded as a key target for intervention in gastric

metaplasia and carcinogenesis (25,118).

IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of p28 and

EBI3, has a receptor consisting of IL-27Rα and gp130 and is widely

expressed in immune cells such as T cells (43). Studies have shown that IL-27

serves a key regulatory role in chronic gastritis and gastric

mucosal metaplasia. IL-27-deficient mice progress more rapidly

during gastric carcinogenesis, as evidenced by earlier and faster

development of severe gastric atrophy, metaplasia and inflammatory

infiltrates, whereas exogenous IL-27 treatment notably reduces the

severity of gastritis, atrophy and SPEM (43,119). IL-27 protective effects are

primarily twofold: i) Reduces immune cell secretion of IL-17A; and

ii) Transmits signals directly to gastric epithelial cells, slowing

the progression of gastric metaplasia and possibly promoting

reparative metaplasia (120).

Rapid disease progression and notable variations in the degree of

STAT signaling pathway activation in gastric epithelial cells are

linked to increased Th17 cell proportion and pro-inflammatory

cytokine levels (IL-6, G-CSF, MIP-2 and IL-5) in IL-27-deficient

models (119,121,122). Notably, IL-27 largely controls

metaplasia linked to chronic inflammation and has no discernible

impact on metaplasia brought on by acute injury (122). Based on this evidence, IL-27 may

serve a crucial protective role in preventing gastric

carcinogenesis and SPEM by regulating immune cell activity and

epithelial cell response.

The IL-17 cytokine family consists of six members

[IL-17A, IL-17B, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17E (IL-25) and IL-17F]

(123-125). IL-17A (also commonly referred to

as IL-17) has been extensively studied and serves a crucial role in

host defense against microbes and in the development of

inflammatory diseases (126-130). IL-17 is derived from a wide

range of sources, including adaptive immune cells (such as

CD8+ T cells and γδ T cells) and innate immune cells or

myeloid cells (NK cells, macrophages, DCs, neutrophils and

eosinophils) (126,131-135). The receptor for IL-17A consists

of two protein monomers: i) IL-17 receptor A; and ii) IL-17

receptor C. The IL-17 receptor complex is expressed on numerous

cell types, including various types of epithelial cells (34). IL-17A promotes inflammation by

upregulating cellular adhesion molecules such as vascular cell

adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1,

activating downstream signaling pathways (including NF-κB, MAPKs

and JAK2/STAT3), and stimulating the production of cytokines and

chemokines (including IL-1, IL-6 and monocyte chemotactic

protein-1) (123,136). IL-17A is a primary cause of

mural cell atrophy and metaplasia in chronic atrophic gastritis.

Overproduction of IL-17A in the setting of chronic inflammation

directly causes parietal cell apoptosis and accelerates the process

of gastric mucosal atrophy and metaplasia, whilst neutralization of

IL-17A successfully inhibits the aforementioned pathological

alterations (34,137). Patients with gastro-IM have

increased IL-17 levels, indicating that a prolonged Th17 response

may occur prior to cancer formation. The gastric epithelium may

undergo physiological and morphological changes as a result of a

persistent inflammatory state or immune response in the gastric

region. This increases the risk of tumor transformation due to

atrophy and decreased gastric acid levels (72). By upregulating the matrix

metalloproteinases MMP2/MMP9, disrupting the extracellular matrix

and activating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, IL-17A promotes

the formation of the tumor microenvironment by increasing the

migration and invasion of cancer cells (132). According to clinical evidence,

patients with GC had significantly higher serum IL-17A levels,

which may indicate that the protein could be used as a diagnostic

marker (133). In summary,

cytokine networks control the proinflammatory and procarcinogenic

effects of IL-17A, which is pleiotropic in gastric mucosal

inflammation, metaplasia and carcinogenesis.

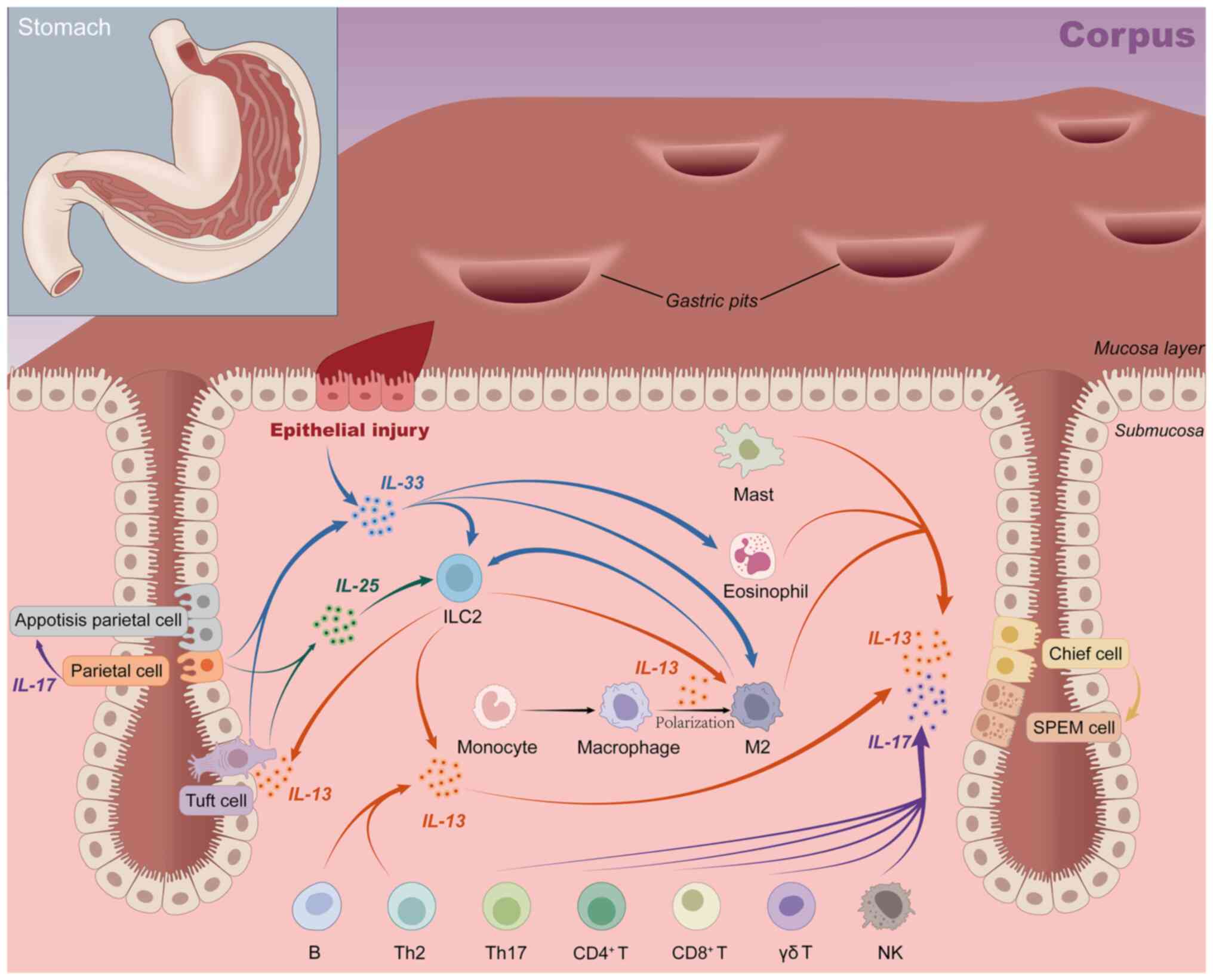

IL-25, also termed IL-17E, is a member of the IL-17

cytokine family. IL-25 is an important regulator of the type 2

immune response, and its increased expression is closely related to

the metaplasia microenvironment after parietal cell loss (138). Its receptor is expressed on the

surface of ILC2 cells, and when the gastric mucosa is severely

injured, surface mucus cells produce IL-33 and IL-25, which

stimulate ILC2 to secrete IL-13 together (Fig. 3). IL-13 is an important driver of

the reprogramming of chief cells into SPEM cells and the

development of pyloric metaplasia. Cluster cells further activate

ILC2 by secreting IL-25, forming a signaling loop (138,139). Notably, IL-25 also indirectly

triggers epithelial cell proliferation by inducing IL-13 production

in ILC2 (139). The IL-25/ILC2

axis is implicated in the development of metaplasia, but it also

facilitates the malignant progression of metaplasia to tumor cells.

According to the aforementioned findings, inhibiting IL-25

signaling or ablation of tuft cells or ILC2 has notable therapeutic

potential in both the early (gastric metaplasia) and advanced

stages of the tumor trajectory.

IL-8, also termed CXCL8, belongs to the CXC

chemokine family. By binding to the G protein-coupled receptors

CXCR1 and CXCR2, it activates downstream signaling pathways that

contribute to angiogenesis, the inflammatory response and the

growth of tumors (140). Its

expression is influenced by inflammatory factors (such as TNF-α and

IL-1β), environmental stress (including hypoxia and chemotherapy)

and hormones (including androgens and dexamethasone), and is

associated with a poor cancer prognosis (140-142). IL-8 was first identified for its

neutrophil chemotactic and degranulation effects, but its

pro-inflammatory properties and link to tumor metastasis are

especially important in GC (143). The chronic inflammatory state

caused by IL-8 may accelerate the progression of early

pre-cancerous lesions in GC, but no study has directly demonstrated

a link between IL-8 and SPEM.

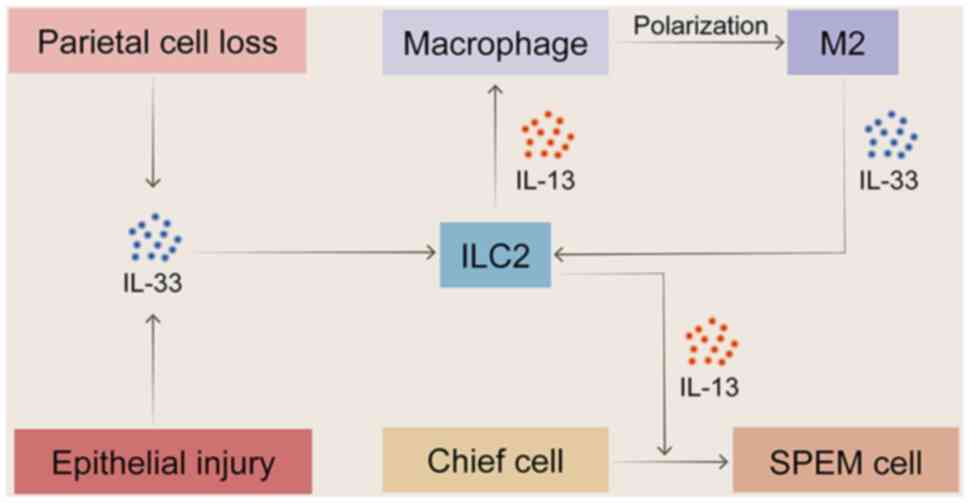

IL-13 is the central cytokine of the Th2 immune

response, mediating local tissue effects in gastritis such as

chemokine secretion, goblet cell proliferation, mucus production

and smooth muscle changes (84).

There are six immune cell types that secrete IL-13, and in

autoimmune gastritis models, mast cells produce the majority of

them. They also penetrate the gastric mucosa during chronic

inflammation (138,144,145). Another key source of IL-13 is

ILC2s, which are also found in inflammatory stomach tissue. IL4Rα,

IL13Rα1 and IL13Rα2 are three heterodimeric receptors that deliver

IL-13 signaling (146,147). The process involves JAK

signaling transducers (including JAK1 and JAK3) and the activator

of transcription (STAT) pathway (63,144). The most important of these is

STAT6, where IL-13 induces STAT6 phosphorylation and gene

transcriptional regulation to propel chief cell

transdifferentiation toward the SPEM phenotype (39,144,147). The gastric epithelium expresses

IL-4Rα, and IL-13 affects epithelial cells directly, which leads to

the expansion of mucus neck cells and the development of SPEM.

Furthermore, IL-13 can directly control chief cells through

IL-13Rα. In gastric metaplasia, its importance is mainly associated

with mucus hypersecretion, a specific feature of SPEM. IL-13 is a

core effector molecule of the IL-33/ILC2s/IL-13 axis (Fig. 4), and after chemically-induced

acute parietal cell loss, ILC2 is the major source of IL-13. In

conjunction with amphiphysin and IL-4, IL-13 promotes the

recruitment of eosinophils and the activation of M2-type

macrophages, as well as the induction and growth of SPEM (36,39). By contrast, ILC2 depletion or

ablation notably inhibits metaplasia induction, cell proliferation

and macrophage infiltration (36,38). Mice lacking the IL-33 receptor

(ST2) are unable to develop SPEM following L635 induction. However,

exogenous recombinant IL-13 aids in the redevelopment of SPEM, and

neutralizing IL-13 notably reverses the metaplasia in gastritis

mice (62,144). This suggests that IL-13 serves

an important role in the pathogenesis of SPEM, with IL-33 acting

only as its upstream inducer (63,148).

Existing research on the role of IL-13 in the

progression of SPEM to malignancy takes two opposing perspectives.

A previous study suggested that IL-13 mainly promotes the

maturation and stabilization of SPEM. By activating the IL-13/STAT6

axis, it causes STAT6 phosphorylation in SPEM cells and boosts

mucin production, resulting in a mature and proliferative SPEM cell

phenotype (39). Another study

reported the potential pro-cancer mechanism of IL-13; ILC2-derived

IL-13 promotes the growth and secretion of IL-25 by gastric mucosal

tufted cells, which in turn triggers ILC2 activity. This creates an

IL-13/IL-25 feedback loop and speeds up the development of cancer

from SPEM (138).

Simultaneously, TNF+ Tregs release IL-13, which

activates STAT3, directly promoting the malignant biologicals of

cancer cells (149). In

addition, the increase of the Th2 response and IL-4/IL-13 in

chronic inflammatory environments can trigger Tet3-mediated

epigenetic disorders. This process causes changes in gene

expression programs, which initiate epithelial transformation and

differentiation of precancerous cells (149). In conclusion, interventions

targeting IL-13 may be expected to alleviate gastrointestinal tumor

precursors and possibly reverse the development of gastric

metaplasia.

Animal models and gastric organoids are the two

most common types of SPEM models used in IL research. There are

three types of animal models: i) Drug-induced models; ii)

transgenic mouse models; and iii) H. pylori infection models

(Table II). Specific drugs cause

SPEM by directly inducing parietal cell death, making it an ideal

model for studying specific stages of the metaplasia process due to

its rapid and precise action. The drugs commonly used to induce

SPEM are DMP-777, L635 and tamoxifen. As a leukocyte elastase

protease inhibitor, DMP-777 was administered for 10-14 days to

induce gastric oxidative atrophy and metaplasia, accompanied by

mild inflammation (165). Its

analog L635 rapidly induces parietal cell loss in an inflammatory

environment, and treatment for 3 days can trigger inflammatory

infiltration and proliferative SPEM (advanced SPEM). Alterations in

its lineage are strikingly similar to those seen following 6-12

months of H. pylori infection (166-168). Tamoxifen, as a chemotherapeutic

drug, can rapidly induce SPEM formation through a selective

estrogen receptor-independent pathway within 3 days following oral

or intraperitoneal injection (169). The drug causes proton leakage by

damaging cells rich in proton pumps and mitochondria (such as

parietal cells), reducing mitochondrial phosphorylation efficiency

and interfering with intracellular pH homeostasis. Its resulting

loss of parietal cells can be reversed by the proton pump inhibitor

omeprazole, confirming that its action is dependent on active acid

secretion (170). Therefore,

tamoxifen-induced SPEM is considered a reversible precursor of

precancerous lesions (42,165,169,170).

In the autoimmune transgenic TxA23 mouse model, CD4+ T

cells cause chronic gastritis by targeting

H+/K+ ATPase and inducing apoptosis of

gastric parietal cells. This mimics a number of aspects of human

atrophic gastritis and metaplasia, including chronic inflammation

and parietal cell atrophy, mucus neck cell proliferation, SPEM and,

eventually, gastric intraepithelial tumors (34). Focal SPEM lesions were observed in

2-month-old mice, while extensive and severe SPEM lesions were

observed in 12-month-old mice. SPEM was also highly proliferated in

H. felis-infected mice. A total of 6 months after H.

pylori infection, mice showed acid secretion atrophy and

TFF2-expressing metaplasia (9).

The detection methods for mouse model establishment include

histological analysis and marker detection. Histological analysis

identified the morphological features (such as focal lesions and

glandular structural abnormalities) and inflammation of the

metaplastic glands by H&E staining. When inflammation occurs,

different types of metaplastic glands can form in nearby focal

lesions, creating a complex glandular assembly made up of a variety

of intestinal or gastric cell lineages that co-positively test for

different cell lineage markers. Cell lineage markers, such as HE4,

TFF2, MUC6, CD44v9 of SPEM and TFF3, MUC2, tail-type homeobox 1/2

or α-defense 5 of IM, were used to identify the lineage. Together

with the identification of associated ILs, Ki67, CD44, MUC1,

MUC5AC, p53, VEGF and other biomarkers, it can be used to assess

the malignant potential of SPEM (74).

Gastric organoids, also referred to as gastroids,

are 3-dimensional spheroids made by researchers from glands that

have separated from the stomach corpus mucosa. These gastroids

allowed the examination of the direct effects of ILs on gastric

epithelial cells (144). Gastric

glands were isolated from the target mice, and Matrigel was used to

cultivate whole gastric glands. They were placed in 24- or 48-well

plates, and cultured gastric organoids were treated with

recombinant IL (Table SI).

Typical images were captured of organoids aged 10 days following a

7-day IL treatment (34,39,138), and microphotographs were used to

examine changes in gastroids. Organoid diameter, relative organoid

diameter, organoid size, survival rate, Muc6 expression level,

AQP5/MUC6 double positive rate, structural departure from normal

tissue, height deviation from normal tissue, growth arrest,

mortality and structural collapse were among the statistical

indicators. This model is a crucial tool for studying the onset and

progression of SPEM as it closely resembles the cellular makeup and

behavior of the normal organism, making it easier to add ILs from

exogenous sources.

At present, SPEM detection in clinical practice has

not yet been popularized, but there is a growing interest in the

importance of metaplasia in precancerous lesions. Endoscopy, tissue

biopsy and biomarker detection are the most effective diagnostic

methods for gastric precancerous lesions (74). To lower the risk of inflammatory

cancer transformation and enhance the quality of life of patients,

the recommended management strategies include routine gastroscopy

monitoring, H. pylori eradication, lifestyle modifications

and medication interventions. The therapeutic potential of ILs has

gained interest from basic and translational cancer researchers. A

growing number of ongoing clinical trials have highlighted their

value as therapeutic agents and targets (171-175). Among these, IL-13 and its

receptor were found to be promising targets for treatment in order

to prevent and/or reverse the development of metaplasia in atrophic

gastritis (144). IL-13 and

IL-4Ra neutralizing antibodies (lebrikizumab, dupilumab) have been

used in clinical settings, and antagonizing the IL-33/IL-13

signaling pathway has become a prospective treatment paradigm to

reduce the progression of metaplasia and tumor transformation

(144,176). By controlling the cytokine

environment and CD4+ T cell infiltration, systemic IL-27

administration prevents gastric injury and aids in the recovery of

acid glands (43). Non-small cell

lung cancer, myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myeloid leukemia

have been treated with IL-1 neutralization strategies (such as

canakinumab and anakinra) and the IL-6 antibody siltuximab

(177,178). Furthermore, IL-2 monotherapy has

shown early success in treating melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and

gastrointestinal tract cancer, and may be useful in reducing the

risk of tumor transformation and metaplasia (179). Innovative IL-12 therapies (such

as oncolytic viruses, nanoparticles and CAR-T cells) can enhance

the therapeutic potential of gastrointestinal cancer through

precise delivery (180,181).

Current clinical trials related to GC focus on

innovative applications of engineered ILs (Table SII). The safety of

Bempegaldesleukin, a polyethylene glycolized non-α IL-2 variant,

which extends half-life and reduces toxicity by blocking the IL-2Rα

subunit binding site via a PEG residue, has been validated

(ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:

NCT02983045, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02983045).

The comparable drug THOR707 (SAR444245) enhances anti-tumor

activity through selective activation of intermediate affinity

IL-2R (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:

NCT04009681, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04009681).

In addition, ALKS 4230, which uses an IL-2/IL-2Rα circular

replacement structure to optimize receptor targeting, is in phase

I/II studies (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03861793,

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03861793).

VG161 is a recombinant human IL-12/15/PD-L1B triple factor tumor

lysing HSV-1 injection that induces systemic anti-tumor immunity

via local cytokine release (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06008925,

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT06008925).

Recombinant human nsIL12 tumor solubilizing adenovirus injection

(BioTTT001) in combination with SOX chemotherapy and teraplizumab

is being evaluated for synergistic efficacy against peritoneal

metastasis of GC (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06283121,

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT06283121).

The engineered modification breaks through the limitations of

traditional IL therapy and provides a novel direction for GC

immunotherapy.

However, IL therapy is challenged by its short

half-life and narrow therapeutic window, leading to suboptimal

efficacy and unpredictable side effects (21). Common adverse reactions such as

influenza-like symptoms (including fever, chills and fatigue) are

short but notably affect the quality of life of patients. Severe

side effects included capillary leak syndrome, hypotension, fluid

retention, hepatotoxicity (liver function damage and elevated

enzyme levels), bone marrow suppression (increased risk of anemia,

infection and bleeding) and cardiovascular complications

(arrhythmia and fluid excess) (45). IL therapy is difficult to develop

and is not considered suitable as a standalone treatment for

clinical conditions. The pleiotropic nature of ILs contributes to

the aforementioned issues by causing dose-limiting toxicity or

inadequate efficacy (46,182). Future research must elucidate

the mechanism of IL-mediated SPEM in order to develop novel

therapies and investigate IL modification strategies, such as

targeted delivery mechanisms, PEGylation, fusion construction,

affinity regulation and synergy with other immunotumor drugs

(177,183-185). The emergence of more effective

immunotherapy and improved understanding of the tumor

microenvironment provide novel methods for the treatment of cancer

using the IL network (74,137).

Furthermore, patients with advanced disease are currently included

in the majority of trials, which may not be the optimal setting for

IL-based therapies. Future research should focus on identifying and

treating gastric metaplasia with a tendency to become cancerous

(28,41,186). Specific directions may include:

i) Developing more personalized IL modification strategies for

patients with early-stage SPEM, ii) designing combination trials of

IL therapy in patients with high-risk gastric metaplasia to halt

malignant progression, and iii) exploring the efficacy of

IL-targeted therapies in well-defined SPEM cohorts with targeted

design. Further research to target early precancerous lesions,

combined with tumor microenvironment regulation, deepen the

understanding of the pathogenesis of SPEM and provide direction for

targeted therapy to alleviate the progression of GC is

warranted.

The present review described the role of various

ILs and their expression products in the formation and progression

of SPEM. IL effects are complex and multifactorial. It was

summarized that certain ILs, such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18

and IL-32, have not yet been studied to confirm a direct

relationship with SPEM but are closely related to IM and GC

development, which require further investigation. M2 macrophages

promote SPEM progression in the context of inflammation and

parietal cell atrophy, and the establishment of a chronic

inflammatory environment through pro-inflammatory IL recruitment is

also a potential direction for research. Studies have focused on

the role that these ILs may serve in GC-associated with

angiogenesis, metastasis and chemotherapy resistance, which are key

factors influencing carcinogenesis and tumor progression, quality

and patient survival. Although there are still a number of

challenges to overcome in the development of IL- or IL-targeted

therapies, the development of biologics and small-molecule

inhibitors that selectively target pathogenesis could improve

therapeutic efficacy and minimize side effects. With the discovery

of specific markers, the understanding of SPEM origin and cancer

progression will be improved, which may contribute to the simple

and accurate diagnosis of early developmental abnormalities. These

results provide a research direction for the pathogenesis of SPEM

and open up new avenues for future diagnosis and treatment.

Not applicable.

Conceptualization, literature investigation,

writing the original draft, writing, review and editing, and

visualization were performed by TZ, MJ and XZ. WG, SZ and HL made

substantial contributions to writing, reviewing and editing. HL and

MJ were responsible for conceptualization (substantial contribution

to the design of the work), supervision and project administration.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all

aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present work was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82274442) and the

Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (grant no. 2024KJ043).

|

1

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Morgan E, Arnold M, Camargo MC, Gini A,

Kunzmann AT, Matsuda T, Meheus F, Verhoeven RHA, Vignat J,

Laversanne M, et al: The current and future incidence and mortality

of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020-40: A population-based

modelling study. EClinicalMedicine. 47:1014042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, Tannenbaum

S and Archer M: A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet.

2:58–60. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yan L, Li W, Chen F, Wang J, Chen J, Chen

Y and Ye W: Inflammation as a mediator of microbiome

Dysbiosis-associated DNA methylation changes in gastric

premalignant lesions. Phenomics. 3:496–501. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Huang N, He HW, He YY, Gu W, Xu MJ and Liu

L: Xiaotan Sanjie recipe, a compound Chinese herbal medicine,

inhibits gastric cancer metastasis by regulating GnT-V-mediated

E-cadherin glycosylation. J Integr Med. 21:561–574. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Giroux V and Rustgi AK: Metaplasia: Tissue

injury adaptation and a precursor to the dysplasia-cancer sequence.

Nat Rev Cancer. 17:594–604. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Petersen CP, Mills JC and Goldenring JR:

Murine models of gastric corpus preneoplasia. Cell Mol

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 3:11–26. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang M, Hu S, Min M, Ni Y, Lu Z, Sun X,

Wu J, Liu B, Ying X and Liu Y: Dissecting transcriptional

heterogeneity in primary gastric adenocarcinoma by single cell RNA

sequencing. Gut. 70:464–475. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Muthupalani S, Ge Z, Joy J, Feng Y, Dobey

C, Cho HY, Langenbach R, Wang TC, Hagen SJ and Fox JG: Muc5ac null

mice are predisposed to spontaneous gastric antro-pyloric

hyperplasia and adenomas coupled with attenuated H. pylori-induced

corpus mucous metaplasia. Lab Invest. 99:1887–1905. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Goldenring JR: Spasmolytic

polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) cell lineages can be an

origin of gastric cancer. J Pathol. 260:109–111. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Schmidt PH, Lee JR, Joshi V, Playford RJ,

Poulsom R, Wright NA and Goldenring JR: Identification of a

metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric

adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest. 79:639–646. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Halldórsdóttir AM, Sigurdardóttrir M,

Jónasson JG, Oddsdóttir M, Magnússon J, Lee JR and Goldenring JR:

Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) associated

with gastric cancer in Iceland. Dig Dis Sci. 48:431–441. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yamaguchi H, Goldenring JR, Kaminishi M

and Lee JR: Identification of spasmolytic polypeptide expressing

metaplasia (SPEM) in remnant gastric cancer and surveillance

postgastrectomy biopsies. Dig Dis Sci. 47:573–578. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Katz JP, Perreault N, Goldstein BG, Actman

L, McNally SR, Silberg DG, Furth EE and Kaestner KH: Loss of Klf4

in mice causes altered proliferation and differentiation and

precancerous changes in the adult stomach. Gastroenterology.

128:935–945. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Oshima H, Matsunaga A, Fujimura T,

Tsukamoto T, Taketo MM and Oshima M: Carcinogenesis in mouse

stomach by simultaneous activation of the Wnt signaling and

prostaglandin E2 pathway. Gastroenterology. 131:1086–1095. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Goldenring JR, Nam KT, Wang TC, Mills JC

and Wright NA: Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia and

intestinal metaplasia: Time for reevaluation of metaplasias and the

origins of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 138:2207–2210.e1.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Reyes ME, Pulgar V, Vivallo C, Ili CG,

Mora-Lagos B and Brebi P: Epigenetic modulation of cytokine

expression in gastric cancer: Influence on angiogenesis, metastasis

and chemoresistance. Front Immunol. 15:13475302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bockerstett KA and DiPaolo RJ: Regulation

of gastric carcinogenesis by inflammatory cytokines. Cell Mol

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 4:47–53. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Briukhovetska D, Dörr J, Endres S, Libby

P, Dinarello CA and Kobold S: Interleukins in cancer: From biology

to therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 21:481–499. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dranoff G: Cytokines in cancer

pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 4:11–22. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yasmin R, Siraj S, Hassan A, Khan AR,

Abbasi R and Ahmad N: Epigenetic regulation of inflammatory

cytokines and associated genes in human malignancies. Mediators

Inflamm. 2015:2017032015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Oshima M, Oshima H, Matsunaga A and Taketo

MM: Hyperplastic gastric tumors with spasmolytic

polypeptide-expressing metaplasia caused by tumor necrosis

factor-alpha-dependent inflammation in cyclooxygenase-2/microsomal

prostaglandin E synthase-1 transgenic mice. Cancer Res.

65:9147–9151. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lee C, Lee H, Hwang SY, Moon CM and Hong

SN: IL-10 plays a pivotal role in Tamoxifen-induced spasmolytic

Polypeptide-expressing metaplasia in gastric mucosa. Gut Liver.

11:789–797. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Demitrack ES, Gifford GB, Keeley TM,

Horita N, Todisco A, Turgeon DK, Siebel CW and Samuelson LC: NOTCH1

and NOTCH2 regulate epithelial cell proliferation in mouse and

human gastric corpus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

312:G133–G144. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Negovan A, Iancu M, Fülöp E and Bănescu C:

Helicobacter pylori and cytokine gene variants as predictors of

premalignant gastric lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 25:4105–4124.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zeng X, Yang M, Ye T, Feng J, Xu X, Yang

H, Wang X, Bao L, Li R, Xue B, et al: Mitochondrial GRIM-19 loss in

parietal cells promotes spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing

metaplasia through NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3

(NLRP3)-mediated IL-33 activation via a reactive oxygen species

(ROS)-NRF2-Heme oxygenase-1(HO-1)-NF-кB axis. Free Radic Biol Med.

202:46–61. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Berraondo P, Sanmamed MF, Ochoa MC,

Etxeberria I, Aznar MA, Pérez-Gracia JL, Rodríguez-Ruiz ME,

Ponz-Sarvise M, Castañón E and Melero I: Cytokines in clinical

cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer. 120:6–15. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Kureshi CT and Dougan SK: Cytokines in

cancer. Cancer Cell. 43:15–35. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

El-Zaatari M, Kao JY, Tessier A, Bai L,

Hayes MM, Fontaine C, Eaton KA and Merchant JL: Gli1 deletion

prevents Helicobacter-induced gastric metaplasia and expansion of

myeloid cell subsets. PLoS One. 8:e589352013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Goldenring JR, Nam KT and Mills JC: The

origin of pre-neoplastic metaplasia in the stomach: Chief cells

emerge from the Mist. Exp Cell Res. 317:2759–2764. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kang WQ, Rathinavelu S, Samuelson LC and

Merchant JL: Interferon gamma induction of gastric mucous neck cell

hypertrophy. Lab Invest. 85:702–715. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bockerstett KA, Osaki LH, Petersen CP, Cai

CW, Wong CF, Nguyen TM, Ford EL, Hoft DF, Mills JC, Goldenring JR

and DiPaolo RJ: Interleukin-17A promotes parietal cell atrophy by

inducing apoptosis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5:678–690.e1.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Caldwell B, Meyer AR, Weis JA, Engevik AC

and Choi E: Chief cell plasticity is the origin of metaplasia

following acute injury in the stomach mucosa. Gut. 71:1068–1077.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Meyer AR, Engevik AC, Madorsky T, Belmont

E, Stier MT, Norlander AE, Pilkinton MA, McDonnell WJ, Weis JA,

Jang B, et al: Group 2 innate lymphoid cells coordinate damage

response in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 159:2077–2091.e8. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

He L, Zhang X, Zhang S, Wang Y, Hu W, Li

J, Liu Y, Liao Y, Peng X, Li J, et al: H. pylori-facilitated

TERT/Wnt/β-Catenin triggers spasmolytic Polypeptide-expressing

metaplasia and oxyntic atrophy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24012272025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Busada JT, Peterson KN, Khadka S, Xu X,

Oakley RH, Cook DN and Cidlowski JA: Glucocorticoids and androgens

protect from gastric metaplasia by suppressing group 2 innate

lymphoid cell activation. Gastroenterology. 161:637–652.e4. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Contreras-Panta EW, Lee SH, Won Y,

Norlander AE, Simmons AJ, Peebles RS Jr, Lau KS, Choi E and

Goldenring JR: Interleukin 13 promotes maturation and proliferation

in metaplastic gastroids. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.

18:1013662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Goldenring JR and Nomura S:

Differentiation of the gastric mucosa III. Animal models of oxyntic

atrophy and metaplasia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

291:G999–G1004. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lee SH, Jang B, Min J, Contreras-Panta EW,

Presentation KS, Delgado AG, Piazuelo MB, Choi E and Goldenring JR:

Up-regulation of aquaporin 5 defines spasmolytic

Polypeptide-expressing metaplasia and progression to incomplete

intestinal metaplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 13:199–217.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Park DJ and Kim SE: The Role of IL-10 in

gastric spasmolytic Polypeptide-expressing Metaplasia-related

carcinogenesis. Gut Liver. 11:741–742. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bockerstett KA, Petersen CP, Noto CN,

Kuehm LM, Wong CF, Ford EL, Teague RM, Mills JC, Goldenring JR and

DiPaolo RJ: Interleukin 27 protects from gastric atrophy and

metaplasia during chronic autoimmune gastritis. Cell Mol

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10:561–579. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

de Brito BB, da Silva FAF and de Melo FF:

Role of polymorphisms in genes that encode cytokines and

Helicobacter pylori virulence factors in gastric carcinogenesis.

World J Clin Oncol. 9:83–89. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Saleh RO, Jasim SA, Kadhum WR, Hjazi A,

Faraz A, Abid MK, Yumashev A, Alawadi A, Aiad IAZ and Alsalamy A:

Exploring the detailed role of interleukins in cancer: A

comprehensive review of literature. Pathol Res Pract.

257:1552842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Propper DJ and Balkwill FR: Harnessing

cytokines and chemokines for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

19:237–253. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lamkanfi M and Dixit VM: Mechanisms and

functions of inflammasomes. Cell. 157:1013–1022. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Santos JC, Ladeira MS, Pedrazzoli J Jr and

Ribeiro ML: Relationship of IL-1 and TNF-α polymorphisms with

Helicobacter pylori in gastric diseases in a Brazilian population.

Braz J Med Biol Res. 45:811–817. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Starzyńska T, Ferenc K, Wex T, Kähne T,

Lubiński J, Lawniczak M, Marlicz K and Malfertheiner P: The

association between the interleukin-1 polymorphisms and gastric

cancer risk depends on the family history of gastric carcinoma in

the study population. Am J Gastroenterol. 101:248–254. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Xue H, Lin B, Ni P, Xu H and Huang G:

Interleukin-1B and interleukin-1 RN polymorphisms and gastric

carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol.

25:1604–1617. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wang YM, Li ZX, Tang FB, Zhang Y, Zhou T,

Zhang L, Ma JL, You WC and Pan KF: Association of genetic

polymorphisms of interleukins with gastric cancer and precancerous

gastric lesions in a high-risk Chinese population. Tumour Biol.

37:2233–2242. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Myung DS, Lee WS, Park YL, Kim N, Oh HH,

Kim MY, Oak CY, Chung CY, Park HC, Kim JS, et al: Association

between interleukin-18 gene polymorphism and Helicobacter pylori

infection in the Korean population. Sci Rep. 5:115352015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Cheung H, Chen NJ, Cao Z, Ono N, Ohashi PS

and Yeh WC: Accessory protein-like is essential for IL-18-mediated

signaling. J Immunol. 174:5351–5357. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Osaki LH, Bockerstett KA, Wong CF, Ford

EL, Madison BB, DiPaolo RJ and Mills JC: Interferon-γ directly

induces gastric epithelial cell death and is required for

progression to metaplasia. J Pathol. 247:513–523. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

55

|

Syu LJ, El-Zaatari M, Eaton KA, Liu Z,

Tetarbe M, Keeley TM, Pero J, Ferris J, Wilbert D, Kaatz A, et al:

Transgenic expression of interferon-γ in mouse stomach leads to

inflammation, metaplasia, and dysplasia. Am J Pathol.

181:2114–2125. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Leung WK, Chan MC, To KF, Man EP, Ng EK,

Chu ES, Lau JY, Lin SR and Sung JJ: H. pylori genotypes and

cytokine gene polymorphisms influence the development of gastric

intestinal metaplasia in a Chinese population. Am J Gastroenterol.

101:714–720. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

He R, Yin H, Yuan B, Liu T, Luo L, Huang

P, Dai L and Zeng K: IL-33 improves wound healing through enhanced

M2 macrophage polarization in diabetic mice. Mol Immunol. 90:42–49.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y,

Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, et

al: IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1

receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated

cytokines. Immunity. 23:479–490. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Carriere V, Roussel L, Ortega N, Lacorre

DA, Americh L, Aguilar L, Bouche G and Girard JP: IL-33, the

IL-1-like cytokine ligand for ST2 receptor, is a

chromatin-associated nuclear factor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 104:282–287. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

60

|

Buzzelli JN, Chalinor HV, Pavlic DI,

Sutton P, Menheniott TR, Giraud AS and Judd LM: IL33 is a stomach

alarmin that initiates a skewed Th2 response to injury and

infection. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1:203–221.e3. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Schwartz C, O'Grady K, Lavelle EC and

Fallon PG: Interleukin 33: An innate alarm for adaptive responses

beyond Th2 immunity-emerging roles in obesity, intestinal

inflammation, and cancer. Eur J Immunol. 46:1091–1100. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

De Salvo C, Pastorelli L, Petersen CP,

Buttò LF, Buela KA, Omenetti S, Locovei SA, Ray S, Friedman HR,

Duijser J, et al: Interleukin 33 triggers early

Eosinophil-dependent events leading to metaplasia in a chronic

model of Gastritis-prone mice. Gastroenterology. 160:302–316.e7.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Petersen CP, Meyer AR, De Salvo C, Choi E,

Schlegel C, Petersen A, Engevik AC, Prasad N, Levy SE, Peebles RS,

et al: A signalling cascade of IL-33 to IL-13 regulates metaplasia

in the mouse stomach. Gut. 67:805–817. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Huang N, Cui X, Li W, Zhang C, Liu L and

Li J: IL-33/ST2 promotes the malignant progression of gastric

cancer via the MAPK pathway. Mol Med Rep. 23:3612021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

65

|

Engevik AC, Feng R, Choi E, White S,

Bertaux-Skeirik N, Li J, Mahe MM, Aihara E, Yang L, DiPasquale B,

et al: The development of spasmolytic polypeptide/TFF2-expressing

metaplasia (SPEM) during gastric repair is absent in the aged

stomach. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2:605–624. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Farrell JJ, Taupin D, Koh TJ, Chen D, Zhao

CM, Podolsky DK and Wang TC: TFF2/SP-deficient mice show decreased

gastric proliferation, increased acid secretion, and increased

susceptibility to NSAID injury. J Clin Invest. 109:193–204. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Nozaki K, Ogawa M, Williams JA, Lafleur

BJ, Ng V, Drapkin RI, Mills JC, Konieczny SF, Nomura S and

Goldenring JR: A molecular signature of gastric metaplasia arising

in response to acute parietal cell loss. Gastroenterology.

134:511–522. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Privitera G, Williams JJ and De Salvo C:

The importance of Th2 immune responses in mediating the progression

of Gastritis-associated metaplasia to gastric cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 16:5222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Meyer AR and Goldenring JR: Injury,

repair, inflammation and metaplasia in the stomach. J Physiol.

596:3861–3867. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Gordon S: Alternative activation of

macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 3:23–35. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Bernink JH, Germar K and Spits H: The role

of ILC2 in pathology of type 2 inflammatory diseases. Curr Opin

Immunol. 31:115–120. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Li W, Huang X, Han X, Zhang J, Gao L and

Chen H: IL-17A in gastric carcinogenesis: Good or bad? Front

Immunol. 15:15012932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Pisani LF, Teani I, Vecchi M and

Pastorelli L: Interleukin-33: Friend or foe in gastrointestinal

tract cancers? Cells. 12:14812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Ye Q, Zhu Y, Ma Y, Wang Z and Xu G:

Emerging role of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia in

gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 15:2673–2683. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Melchiades JL, Zabaglia LM, Sallas ML,

Orcini WA, Chen E, Smith MAC, Payão SLM and Rasmussen LT:

Polymorphisms and haplotypes of the interleukin 2 gene are

associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. The possible

involvement of Helicobacter pylori. Cytokine. 96:203–207. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Shin WG, Jang JS, Kim HS, Kim SJ, Kim KH,

Jang MK, Lee JH, Kim HJ and Kim HY: Polymorphisms of interleukin-1

and interleukin-2 genes in patients with gastric cancer in Korea. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 23:1567–1573. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Mohammadi M, Czinn S, Redline R and Nedrud

J: Helicobacter-specific cell-mediated immune responses display a

predominant Th1 phenotype and promote a delayed-type

hypersensitivity response in the stomachs of mice. J Immunol.

156:4729–4738. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Roth KA, Kapadia SB, Martin SM and Lorenz

RG: Cellular immune responses are essential for the development of

Helicobacter felis-associated gastric pathology. J Immunol.

163:1490–1497. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Yang E, Chua W, Ng W and Roberts TL:

Peripheral cytokine levels as a prognostic indicator in gastric

cancer: A review of existing literature. Biomedicines. 9:19162021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Bevington SL, Keane P, Soley JK, Tauch S,

Gajdasik DW, Fiancette R, Matei-Rascu V, Willis CM, Withers DR and

Cockerill PN: IL-2/IL-7-inducible factors pioneer the path to T

cell differentiation in advance of lineage-defining factors. EMBO

J. 39:e1052202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe SE, Leary JF,

Gourley WK, Luthra GK, Brooks EG, Graham DY, Reyes VE and Ernst PB:

Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori

have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. 114:482–492.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Padol IT and Hunt RH: Effect of Th1

cytokines on acid secretion in pharmacologically characterised

mouse gastric glands. Gut. 53:1075–1081. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Togawa S, Joh T, Itoh M, Katsuda N, Ito H,

Matsuo K, Tajima K and Hamajima N: Interleukin-2 gene polymorphisms

associated with increased risk of gastric atrophy from Helicobacter

pylori infection. Helicobacter. 10:172–178. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Van Dyken SJ and Locksley RM:

Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated

macrophages: Roles in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Immunol.

31:317–343. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Pan K, Li Q, Guo Z and Li Z: Healing

action of Interleukin-4 (IL-4) in acute and chronic inflammatory

conditions: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol Ther.

265:1087602025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Labonte AC, Tosello-Trampont AC and Hahn

YS: The role of macrophage polarization in infectious and

inflammatory diseases. Mol Cells. 37:275–285. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Liu YC, Zou XB, Chai YF and Yao YM:

Macrophage polarization in inflammatory diseases. Int J Biol Sci.

10:520–529. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Petersen CP, Weis VG, Nam KT, Sousa JF,

Fingleton B and Goldenring JR: Macrophages promote progression of