Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most lethal disease of

the female reproductive system (1,2).

The initial approach for OC treatment is tumor reduction followed

by chemotherapy, including platinum and paclitaxel (PTX) (3). Although PTX has shown good effects

in the clinical practice of OC treatment, some patients eventually

develop drug resistance, which is the main cause of treatment

failure in patients with OC (4,5).

The ABCB1-encoded drug transporter P-glycoprotein is

considered to induce chemoresistance (6); however, a previous study has

revealed that there are other mechanisms responsible for PTX

resistance (7), which might

provide a renewed sense of optimism for the clinical management of

patients with OC with PTX resistance.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death,

influences tumor cell fate decisions (8). Dysregulation in the apoptotic

pathway of OC cells may cause the occurrence of chemoresistance

(9). Apoptosis can be categorized

into two main types: Intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis (10,11). Intrinsic apoptosis is triggered

when the outer membrane of the mitochondria becomes leaky and

allows cytochrome c to escape from the mitochondria, forming

an apoptosome and activating caspase-9 (12). Extrinsic apoptosis is activated

via membrane receptors, also referred to as death receptors, such

as Fas cell surface death receptor (FAS; also referred to as CD95

and APO-1), tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 and Toll-like

receptors, forming signaling complexes and activating caspase-8

(CASP8) (12,13). The induction of apoptosis is a

hallmark of PTX-treated cancer cells (14) and exploiting this pathway

represents a potential strategy to reverse PTX resistance (15). Nevertheless, the specific

mechanisms of chemoresistance reversal via apoptosis require

further elucidation.

STAT1 is a transcription factor (TF) involved in

diverse biological processes, including the regulation of malignant

behavior in various cancer types (16,17). The STAT1 gene is located at

2q32.2 in the human genome with a total length of 45,215 bp and has

two major transcripts, STAT1α and STAT1β, which are generated

through alternative splicing (18,19). Our previous study has shown that

STAT1α is the main functional variant that serves an important role

in the development of OC (20).

Furthermore, using our Target Finder of Transcription Factor

(TFoTF) tool (21), some

apoptotic genes were predicted to be target genes of STAT1. Based

on this prediction, the present study aimed to elucidate the

mechanisms of STAT1-mediated apoptosis to reverse PTX resistance in

OC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human OC cell lines utilized in the present

study are cataloged with Research Resource Identifiers (https://scicrunch.org/resources; Table SI). Each cell line underwent

authentication through short tandem repeat profiling and was

consistently screened to ensure it was free from pathogen and

mycoplasma contamination. SK-OV-3, OVCAR-3 and 293T cells were

purchased from Shanghai Fuheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. A2780 cells

and their PTX-resistant counterpart A2780-PTX cells were purchased

from Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd. The PTX-resistant OC cell

lines SK3R-PTX and OV3R-PTX were developed from their parental cell

lines SK-OV-3 and OVCAR-3 as previously described (22). For cell culture, 293T, SK-OV-3,

SK3R-PTX, A2780 and A2780-PTX cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). OVCAR-3 and OV3R-PTX

cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 20% FBS. All cells were

cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5%

CO2.

Construction of Tet-On

STAT1-overexpression plasmids and lentiviral infection

Based on our previously generated

STAT1-overexpression plasmids (20), two novel STAT1α and STAT1β

plasmids containing green fluorescent protein (GFP) were

constructed using the Tet-On gene expression system (23) and packaged into lentiviruses. The

lentiviral plasmid pLenti-TET-on-GFP-puro (gift from Professor

Yanyan Zhan, Cancer Research Center, School of Medicine, Xiamen

University, Xiamen, China) was co-transfected with the

second-generation packaging plasmid psPAX2 and the VSV-G envelope

plasmid pMD2.G (both from Addgene, Inc.) into the 293T interim

cells. For a standard 10-cm dish, the transfection mixture

contained 4.0 μg of the lentiviral plasmid, with a mass

ratio of 4:3:1 for the pLenti-TET-on-GFP-puro, psPAX2 and pMD2.G

plasmids, respectively. Transfection was carried out at 37°C with

5% CO2 for 6-8 h, after which the medium was replaced.

Lentiviral particle-containing supernatant was collected at 48 and

72 h post-transfection, pooled, clarified by filtration through a

0.45-μm filter. The empty vector (pLenti-tet-on-GFP) was

used as a negative control (NC). The sequences of primers used for

Tet-On plasmid cloning are listed in Table SII. The inserted sequences of the

two variants are detailed in Table

SIII. The maps of plasmids (pLenti-tet-on-GFP,

pLenti-tet-on-STAT1α-GFP and pLenti-tet-on-STAT1β-GFP) and the

validation of STAT1 protein expression after induction in the

presence of 8 μg/ml doxycycline (at 37°C for 4 days; Dox;

Beyotime Biotechnology) by western blotting are shown in Fig. S1. The STAT1-overexpressing cells

were generated after lentiviral infection at an MOI of 5 per well

in a 6-well plate for 48 h and further culture with puromycin (5

μg/ml) for 10 days to ensure stable integration. GFP

expression was visualized and confirmed using fluorescence

microscopy. The excitation and emission wavelengths for GFP were

488 and 509 nm, respectively.

Cell viability and PTX sensitivity

assays

PTX-resistant cells (SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and

A2780-PTX cells) and their parental sensitive cells (SK-OV-3,

OVCAR-3 and A2780 cells) were seeded in 96-well plates at a density

of 5×103 cells/well. Lentivirus-infected SK3R-PTX,

OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells with plasmids (pLenti-tet-on-GFP,

pLenti-tet-on-STAT1α-GFP and pLenti-tet-on-STAT1β-GFP) were

replated into 96-well plates at a density of 5×103

cells/well and induced in the presence of 8 μg/ml Dox at

37°C for 4 days. After treatment with varying concentrations of PTX

(0, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 μM) at 37°C for 48 h,

cell viability was assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8;

Beyotime Biotechnology). After 2 h of incubation, absorbance was

measured at 450 nm using a Multiscan Spectrum (BioTek; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Finally, a nonlinear fit was performed using

the Hill model, and the absolute IC50 value was

calculated. To assess PTX sensitivity, each cell type was treated

with a dose of PTX corresponding to its IC50 values at

37°C. Cell viability was determined using a dose of 0.01 μM

for SK3R-PTX cells, 0.1 μM for OV3R-PTX cells and 0.01

μM for A2780-PTX cells at 0, 24 and 48 h at 37°C.

Xenograft mouse model

The animal experiments were approved by the

Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Shanghai

Public Health Clinical Center, Fudan University (approval no.

2020-A027-01; Shanghai, China). A total of 32 female BALB/c nude

mice (3 weeks old with an initial body weight of ~17 g; SPF

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were randomly assigned to four groups

(n=8/group): Empty vector + saline, overexpression vector

(oe-)STAT1α + saline, empty vector + PTX and oe-STAT1α + PTX. Each

mouse received a subcutaneous injection of lentivirus-infected

SK3R-PTX cells (5×106 cells in 100 μl FBS-free

DMEM) into the right flank, and mice were housed under specific

pathogen-free conditions in a controlled environment (temperature,

22±2°C; humidity, 50±10%; 12/12-h light/dark cycle) with ad

libitum access to food and autoclaved water. Measurements of

body weight and tumor size (calculated as long diameter × short

diameter2/2) were performed every 2 days. When the tumor

size reached ~50 mm3 (14 days after tumor cells

injection), the mouse was administered an intratumoral injection of

PTX (10 mg/kg; marked as day 0), which was repeated once after 4

days. Starting from the first PTX injection, animals drank

pre-prepared water containing 2 mg/ml Dox and 1.25% sucrose

(24). On day 8, each mouse was

euthanized by administering 200 mg/kg pentobarbital via

intraperitoneal injection. Subsequently, images of mice were

captured using a small-animal live imaging system (Guangzhou

Biolight Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). After sacrificing, the tumors

were excised and images captured.

Treatment with an apoptosis

inhibitor

STAT1-overexpressing PTX-resistant cells were

maintained in complete medium with 0.1 μM PTX in 96-well

plates (5,000 cells/well) and treated with the apoptosis inhibitor

Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM; Beyotime Biotechnology) or solvent control

DMSO (Beyotime Biotechnology) at 37°C for 48 h. The viability of

cells was determined using a CCK-8 assay as aforementioned. The

experiments were repeated three times.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA of cells was isolated using the RNA-Quick

Purification Kit (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The RNA

sample (500 ng) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the

Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics) at

42°C for 1 h. RT-qPCR was carried out with BeyoFast SYBR Green

RT-qPCR Mix (Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the

manufacturer's protocols. The primer sequences for RT-qPCR are

listed in Table SIV. The PCR

cycling settings included an initial denaturation step (95°C for 1

min), followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 10 sec) and

annealing/extension (60°C for 30 sec). The threshold cycle (Cq)

value was measured using the 7300 real-time PCR system (version

1.4; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). β-actin

served as the internal control for normalizing gene expression.

Relative target gene expression was calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (25).

The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Protein extraction and western blot

analysis

Total protein of cells was isolated using SDS Lysis

Buffer (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) supplemented with

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and phosphatase inhibitors (Nanjing

KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.). The concentration of extracted protein

was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime

Biotechnology) and a microplate spectrophotometer (Epoch; BioTek;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Total protein (20 μg/lane) was

run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and subsequently transferred to a PVDF

membrane (MilliporeSigma). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat

milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with a primary

antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with a secondary

antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The following primary

antibodies were used: Anti-STAT1 (cat. no. 42H3; dilution, 1:1,000)

from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; and anti-FAS (cat. no.

13098-1-AP; dilution, 1:1,000), anti-CASP8 (cat. no. 66093-1-Ig;

dilution, 1:1,000; this antibody can recognize pre- and

cleaved-CASP8) and anti-β-actin (cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; dilution,

1:5,000) from Proteintech Group, Inc. The following secondary

antibodies were used: HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no.

SA00001-1; dilution, 1:5,000) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

IgG (cat. no. SA00001-2; dilution, 1:5,000) from Proteintech Group,

Inc. Protein bands were visualized using the BeyoECL Moon

chemiluminescence kit (cat. no. P0018FS; Beyotime Biotechnology),

and images were captured and analyzed using the Tanon-4500 imaging

system (Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.).

Apoptosis assay

STAT1-overexpressing PTX-resistant cells were

cultured in complete medium. After treatment with PTX (0, 0.1, 1

and 10 μM) at 37°C for 24 h, cells were harvested, washed

with PBS, resuspended in 500 μl 1X binding buffer, and

stained with 3 μl FITC Annexin V (BD Biosciences) and 5

μl PI (BD Biosciences) for 15 min. Apoptotic cells were

detected using flow cytometry (GALLIOS™; Beckman Coulter, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were evaluated

and analyzed using ModFit software (v 3.1; Verity Software House,

Inc.). The experiments were repeated three times.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were plated in a 35-mm confocal culture dish

featuring a 20-mm glass bottom at 1×105 cells/dish and

cultured in medium with 8 μg/ml Dox at 37°C for 4 days. Once

the cells reached 50-70% confluence, they were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and subsequently

washed with PBS for 5 min. Following permeabilization with 0.1%

Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, the cells were treated with

QuickBlock Blocking Buffer for Immunol Staining (Beyotime

Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were incubated

with either rabbit anti-FAS antibody (cat. no. 13098-1-AP;

dilution, 1:400; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or mouse anti-CASP8

antibody (cat. no. 66093-1-Ig; dilution, 1:400; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) at 4°C for 12 h, followed by incubation with rabbit

anti-STAT1 antibody (cat. no. 42H3; dilution, 1:4,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) at 4°C for another 12 h. Subsequently,

the cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. 8760S; dilution, 1:1,000) or Alexa Fluor

647-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. 4410S; dilution,

1:1,000) secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 2

h at room temperature in the dark. After staining the nucleus with

DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology) for 5 min at room temperature,

fluorescence images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation) and analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (version

24.3.0; Adobe Systems, Inc.).

Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay

The plasmid of the firefly luciferase reporter gene

was constructed by the insertion of PCR products of FAS or CASP8

cDNAs amplified using a promoter region as a template from cultured

cells. The thermocycling conditions were: initial denaturation at

95°C for 1 min, 15 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec,

annealing at 65°C (the temperature was reduced by 1°C after each

cycle) for 15 sec and extension at 72°C for 30 sec, 25 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for15 sec, annealing at 58°C for 15 sec and 7

extension at 2°C for 30 sec and final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

The template DNA were extracted using a TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit

(Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the standard

manufacturer's instructions. PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase (cat. no.

R047A; Takara Bio, Inc.) was used for PCR, and experiments were

performed according to the manufacturer's instruction. The

sequences of primers are listed in Table SV. 293T cells were co-transfected

with pGL4.10 firefly luciferase reporter and pRL-TK Renilla

luciferase reporter plasmids (Promega Corporation) and oe-STAT1α/β

plasmid or empty vector using Lipo8000™ Transfection Reagent (cat.

no. C0533-0.5ml; Beyotime Biotechnology). Luciferase activity was

determined using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay Kit

(Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and a Fluoroskan Ascent

FL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) after 48 h of transfection. The

experiments were conducted according to the manufacturer's protocol

and were repeated three times. Results were calculated and

normalized using the following formula: Relative activity (fold

change)=mean value of experimental group (FLUC/RLUC)/mean value of

control group (FLUC/RLUC), where FLUC indicates firefly luciferase

readings and RLUC indicates Renilla luciferase readings.

Bioinformatics analysis

To distinguish gene expression between A2780-PTX and

A2780 cells, mRNA-sequencing was performed (26). Total RNA was extracted by

RNA-Quick Purification Kit (ESScience) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. mRNA-sequencing analysis was performed

by Gene Denovo Co. Ltd. (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China). The

differentially expressed TFs based on mRNA-sequencing were analyzed

using Gene Ontology (GO) using the 'clusterProfiler' (ver. 4.18.1)

(27) and 'GOplot' (ver. 1.0.2)

(28) R packages (ver. 4.2.2;

https://www.r-project.org/). The target

genes of STAT1 were predicted by TFoTF (ver. 1.0) with default

settings, and position weight matrix (PWM) scores were calculated

to evaluate the regulatory relations (21). The PWM of each TF was obtained

using the R package JASPAR2020 (version 0.99.10; http://jaspar.genereg.net/). The pan-cancer

transcriptome expression data were obtained from The Cancer Genome

Atlas (TCGA; https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga).

Samples from each type of cancer were classified into a STAT1-high

group (expression levels >80th percentile in all types of

cancer) and a STAT1-low group (expression levels <20th

percentile in all types of cancer). The differences between the

STAT1-high and -low groups in terms of functional annotations were

analyzed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; version 4.2.2;

https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) and

hallmark gene sets (version 7.5.1) (29). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was

performed using the 'lifelines' Python package (ver. 0.30.0)

(30) based on the OC

transcriptome expression data and survival data downloaded from

TCGA (TCGA-OV). The parameters were set as default following the

official user guide. The cut-off values were defined as: Patients

with gene expression levels >80th percentile were considered to

be high-expressed, and gene expression levels <20th percentile

were considered to be low-expressed. The significance was

determined by log-rank test. The chromatin

immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) peak data (GSM320736)

were obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (31,32) and analyzed by peak annotation

analysis using the 'ChIPseeker' (ver. 1.32.1) (33) and 'GenomicFeatures' (ver. 1.62.0)

R packages (34). Transcriptome

expression data (GSE51373) of chemotherapy-sensitive and -resistant

patients downloaded from the GEO database were analyzed for

differential gene expression analysis (35). The Pearson correlation between the

cell line transcriptome expression and chemotherapeutic agent

sensitivity was analyzed with the 'SciPy' Python package (ver.

1.16.3) (36). The drug

sensitivity data were sourced from CellMiner (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/). The Python

version used was 3.12.11 (https://www.python.org/).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the 'SciPy' and

'statsmodels' packages (ver. 0.14.4; https://www.statsmodels.org/stable/index.html) in the

Python environment, if not otherwise stated, and were plotted using

the 'Matplotlib' Python package (ver. 3.9.0; https://matplotlib.org/) and the 'ggplot2' R package

(ver. 4.0.0; https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) using GraphPad Prism 8

software (Dotmatics). The data are presented as the mean ± SD or

standard error of the mean. The linear trend test was performed

using GraphPad Prism 8. Differences between two groups were

analyzed using an unpaired Student's t-test. Differences among more

than two groups were analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA

followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

STAT1 is a marker of PTX resistance and

enhances PTX sensitivity in OC cells

PTX resistance was confirmed in the resistant cell

lines (SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX) by demonstrating reduced

sensitivity across a range of PTX concentrations compared with

their parental counterparts (SK-OV-3, OVCAR-3 and A2780) (Fig. 1A). After treatment with different

dose of PTX for 48 h, the absolute IC50 values of PTX

were 0.044 μM in SK3R-PTX cells vs. 0.012 μM in

SK-OV-3 cells, 4.016 μM in OV3R-PTX cells vs. 1.800

μM in OVCAR-3 cells, and 0.480 μM in A2780-PTX cells

vs. 0.001 μM in A2780 cells. Screening of differentially

expressed TF genes between A2780 and A2780-PTX cells using

mRNA-sequencing data from the JASPAR database showed that 34.2% of

TF genes were changed at the expression level (fold change, <0.4

or >2.5; P<0.05). Among the 588 differentially expressed TF

genes, 48.8% were downregulated and 51.2% were upregulated

(Fig. 1B). Further analyses of TF

genes with significantly altered gene expression showed that

STAT1 expression was lower in PTX-resistant A2780-PTX cells

(Fig. 1C). The significantly

altered expression of TF genes was classified by JASPAR annotation

and GO term analyses and these differentially expressed TFs between

A2780 and A2780-PTX cells may reflect the process of PTX resistance

(Fig. S2A-C). STAT1 mRNA

expression was lower in PTX-resistant cells than their counterpart

PTX-sensitive cells (P<0.01), except for STAT1β expression in

SK3R cells (P>0.05), based on RT-qPCR (Fig. 1D), and these changes were

confirmed at the protein level based on total STAT1 expression as

analyzed using western blotting (Fig.

1E). Overexpression of STAT1 using oe-STAT1 (mainly STAT1α)

lentiviral infection increased the PTX sensitivity (Fig. 1F-H) and decreased cell viability

(Fig. 1I-K) in three

PTX-resistant cell lines. Specifically, the absolute

IC50 values of PTX were 0.050, 0.029 and 0.211 μM

in SK3R-PTX cells, 5.329, 2.132 and 1.040 μM in OV3R-PTX

cells, and 0.883, 0.882 and 0.831 μM in A2780-PTX cells

after infection with empty vector, oe-STAT1α and oe-STAT1β,

respectively. Overexpression of STAT1 after Tet-On system-based

plasmid lentiviral infection was verified in three PTX-resistant

cell lines treated with or without 8 μg/ml Dox for 4 days as

immunofluorescent signals were captured by immunofluorescence

microscopy (Fig. S3A-C).

![Detection of STAT1 expression, and

effect of STAT1 on PTX sensitivity and viability in PTX-resistant

OC cells (SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells) and their

sensitive counterpart cells (SK-OV-3, OVCAR-3 and A2780 cells). (A)

Validation of PTX resistance in OC cells. The dots and curves in

the graphs indicate the relative cell viability at the

corresponding PTX concentrations and non-linear regression fitting

curves. Differences between sensitive cells and resistant cells

were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's HSD test.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). (B) Differentially

expressed TF genes in PTX-sensitive and PTX-resistant OC cells. The

pie chart on the left represents the percentage of TF genes that

were differentially expressed at a significant level (expression FC

>2.5 and P<0.05). The pie chart on the right represents the

percentage of upregulated and downregulated TF genes. (C) Volcano

plot showing the alteration of TF gene expression between A2780 and

A2780-PTX cells based on the mRNA-sequencing results (n=3). The

gray horizontal line represents the P-value of 0.05, and the two

gray vertical lines represent the locations of FC >2 in gene

expression (A2780-PTX vs. A2780 cells). TF genes with significantly

altered expression (defined as FC <0.4 or >2.5 and P<0.05)

were marked with red dots. The red star indicates STAT1. (D)

Detection of total STAT1, STAT1α and STAT1β mRNA expression in

three paired cells [PTX-sensitive cells (SK-OV-3, OVCAR-3 and

A2780) vs. counterpart resistant cells (SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and

A2780-PTX)] by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Expression

values for each group were normalized using β-actin as an internal

reference. Differences between PTX-sensitive cells and

PTX-resistant cells were analyzed using unpaired Student's t-test.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). (E) Detection of STAT1

protein expression in three paired cells by western blotting.

Detection of PTX sensitivity in (F) SK3R-PTX, (G) OV3R-PTX and (H)

A2780-PTX cells after overexpression of STAT1α or STAT1β in the

presence of 8 μg/ml Dox and different doses of PTX. The dots

and curves in the graphs indicate the relative cell viability based

on the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. Blue, red and green vertical

dotted lines in each panel indicated the absolute IC50.

Differences among groups were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's HSD test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD [n=4 for (F

and G); n=3 for (H)]. Determination of growth inhibitory effect of

PTX in (I) SK3R-PTX, (J) OV3R-PTX and (K) A2780-PTX cells after

induction of STAT1 overexpression by Dox. A cell viability assay

was performed. Differences among multiple groups were analyzed by

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test. Data are presented as

the mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 resistant

cells vs. sensitive cells in each pair in (A) and (D) or

oe-STAT1α/β vs. oe-NC in (F-K). Dox, doxycycline; FC, fold change;

HSD, Honestly Significant Difference; NC, negative control; ns, not

significant; OC, ovarian cancer; OD, optical density; oe,

overexpression vector; PTX, paclitaxel; TF, transcription

factor.](/article_images/ijo/68/2/ijo-68-02-05832-g00.jpg) | Figure 1Detection of STAT1 expression, and

effect of STAT1 on PTX sensitivity and viability in PTX-resistant

OC cells (SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells) and their

sensitive counterpart cells (SK-OV-3, OVCAR-3 and A2780 cells). (A)

Validation of PTX resistance in OC cells. The dots and curves in

the graphs indicate the relative cell viability at the

corresponding PTX concentrations and non-linear regression fitting

curves. Differences between sensitive cells and resistant cells

were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's HSD test.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). (B) Differentially

expressed TF genes in PTX-sensitive and PTX-resistant OC cells. The

pie chart on the left represents the percentage of TF genes that

were differentially expressed at a significant level (expression FC

>2.5 and P<0.05). The pie chart on the right represents the

percentage of upregulated and downregulated TF genes. (C) Volcano

plot showing the alteration of TF gene expression between A2780 and

A2780-PTX cells based on the mRNA-sequencing results (n=3). The

gray horizontal line represents the P-value of 0.05, and the two

gray vertical lines represent the locations of FC >2 in gene

expression (A2780-PTX vs. A2780 cells). TF genes with significantly

altered expression (defined as FC <0.4 or >2.5 and P<0.05)

were marked with red dots. The red star indicates STAT1. (D)

Detection of total STAT1, STAT1α and STAT1β mRNA expression in

three paired cells [PTX-sensitive cells (SK-OV-3, OVCAR-3 and

A2780) vs. counterpart resistant cells (SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and

A2780-PTX)] by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Expression

values for each group were normalized using β-actin as an internal

reference. Differences between PTX-sensitive cells and

PTX-resistant cells were analyzed using unpaired Student's t-test.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). (E) Detection of STAT1

protein expression in three paired cells by western blotting.

Detection of PTX sensitivity in (F) SK3R-PTX, (G) OV3R-PTX and (H)

A2780-PTX cells after overexpression of STAT1α or STAT1β in the

presence of 8 μg/ml Dox and different doses of PTX. The dots

and curves in the graphs indicate the relative cell viability based

on the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. Blue, red and green vertical

dotted lines in each panel indicated the absolute IC50.

Differences among groups were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's HSD test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD [n=4 for (F

and G); n=3 for (H)]. Determination of growth inhibitory effect of

PTX in (I) SK3R-PTX, (J) OV3R-PTX and (K) A2780-PTX cells after

induction of STAT1 overexpression by Dox. A cell viability assay

was performed. Differences among multiple groups were analyzed by

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test. Data are presented as

the mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 resistant

cells vs. sensitive cells in each pair in (A) and (D) or

oe-STAT1α/β vs. oe-NC in (F-K). Dox, doxycycline; FC, fold change;

HSD, Honestly Significant Difference; NC, negative control; ns, not

significant; OC, ovarian cancer; OD, optical density; oe,

overexpression vector; PTX, paclitaxel; TF, transcription

factor. |

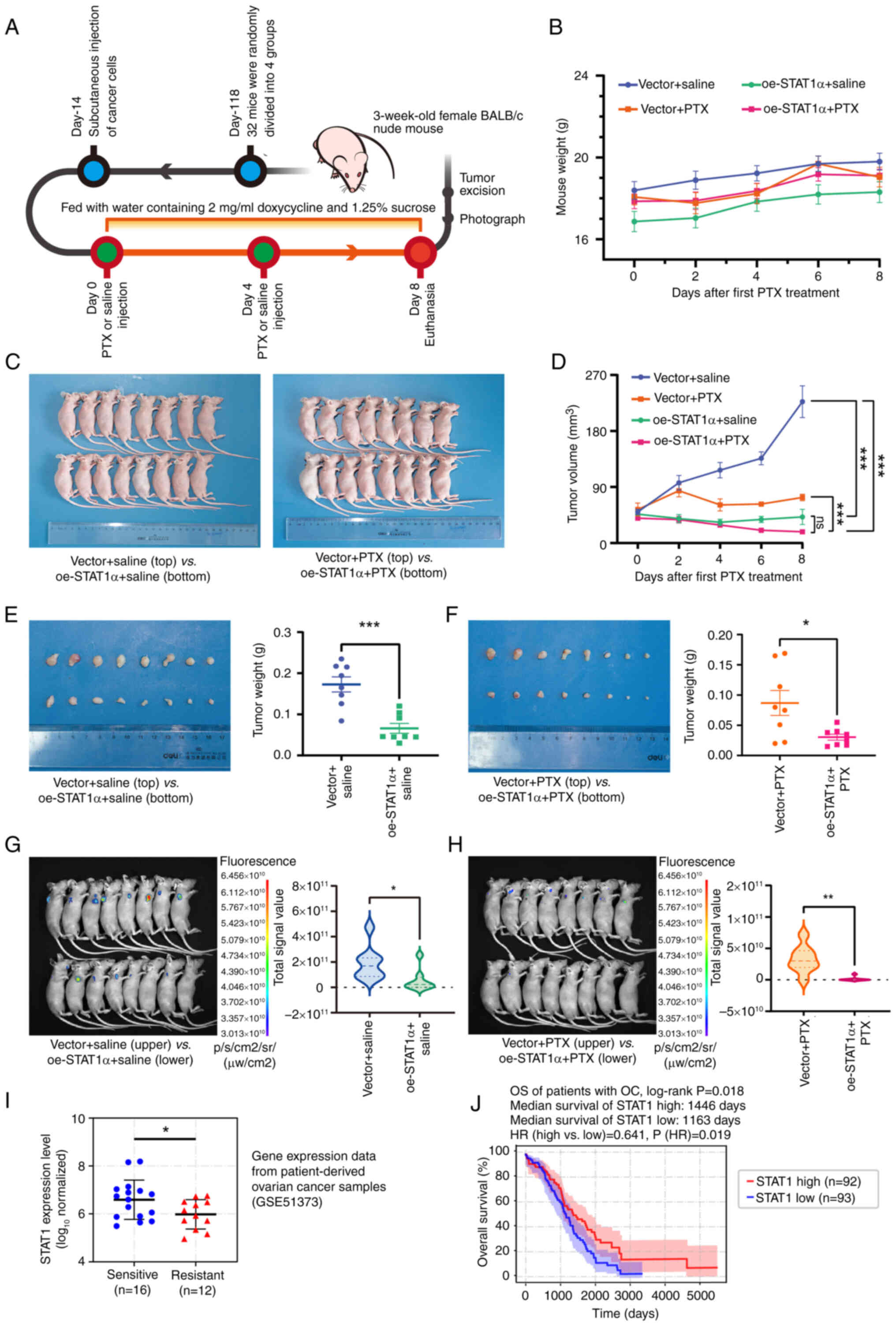

Overexpression of STAT1 inhibits tumor

formation in xenograft mice and is a favorable factor in the

overall survival of patients

To clarify the biological effect of STAT1 on PTX

resistance of tumors, an in vivo xenograft mouse model was

used. Considering that STAT1α was the major transcript in OC cells

(Fig. S4A-B),

STAT1α-overexpressing SK3R-PTX cells were generated. As

aforementioned, SK3R-PTX cells were stably infected with oe-STAT1α

or control vector, and were subcutaneously injected into nude mice

(Fig. 2A). The body weight of the

mice in each group was compared at each timepoint and was not

significantly changed during the experimental intervention

(Fig. 2B and C). Overexpression

of STAT1 significantly decreased the tumor volume regardless of PTX

treatment at post-intervention day 8 (Fig. 2D and E). Furthermore,

overexpression of STAT1 sensitized PTX responses in vivo

(Fig. 2F) as the tumor weight in

the oe-STAT1α group was markedly lower than the vector group after

PTX treatment. Since STAT1-GFP expression in the cells used for the

subcutaneous implantation was inducible in the presence of Dox,

small-animal live imaging was used to observe tumor formation. The

fluorescence signal was significantly lower in the

STAT1α-overexpressing group than in the vector control group

without or with PTX treatment (Fig.

2G and H). These data further indicated that oe-STAT1α

inhibited tumorigenicity and increased PTX sensitivity in resistant

cells. To clarify the impact of STAT1 in patients with OC, clinical

datasets were downloaded from GEO and TCGA and analyzed. The

expression levels of STAT1 were significantly lower in

chemoresistant patients compared with chemosensitive patients

(Fig. 2I). The survival analysis

using TCGA datasets revealed a significant difference in the

overall survival of patients with OC between the STAT1-high and

STAT1-low expression groups (P=0.018; Fig. 2J). The median survival time in the

STAT1-high and STAT1-low groups was 1,446 and 1,163 days,

respectively. The hazard ratio in the STAT1-high group compared

with the STAT-low group was 0.641 (P=0.019). These data indicated

that STAT1 was a favorable factor in the overall survival of

patients with OC.

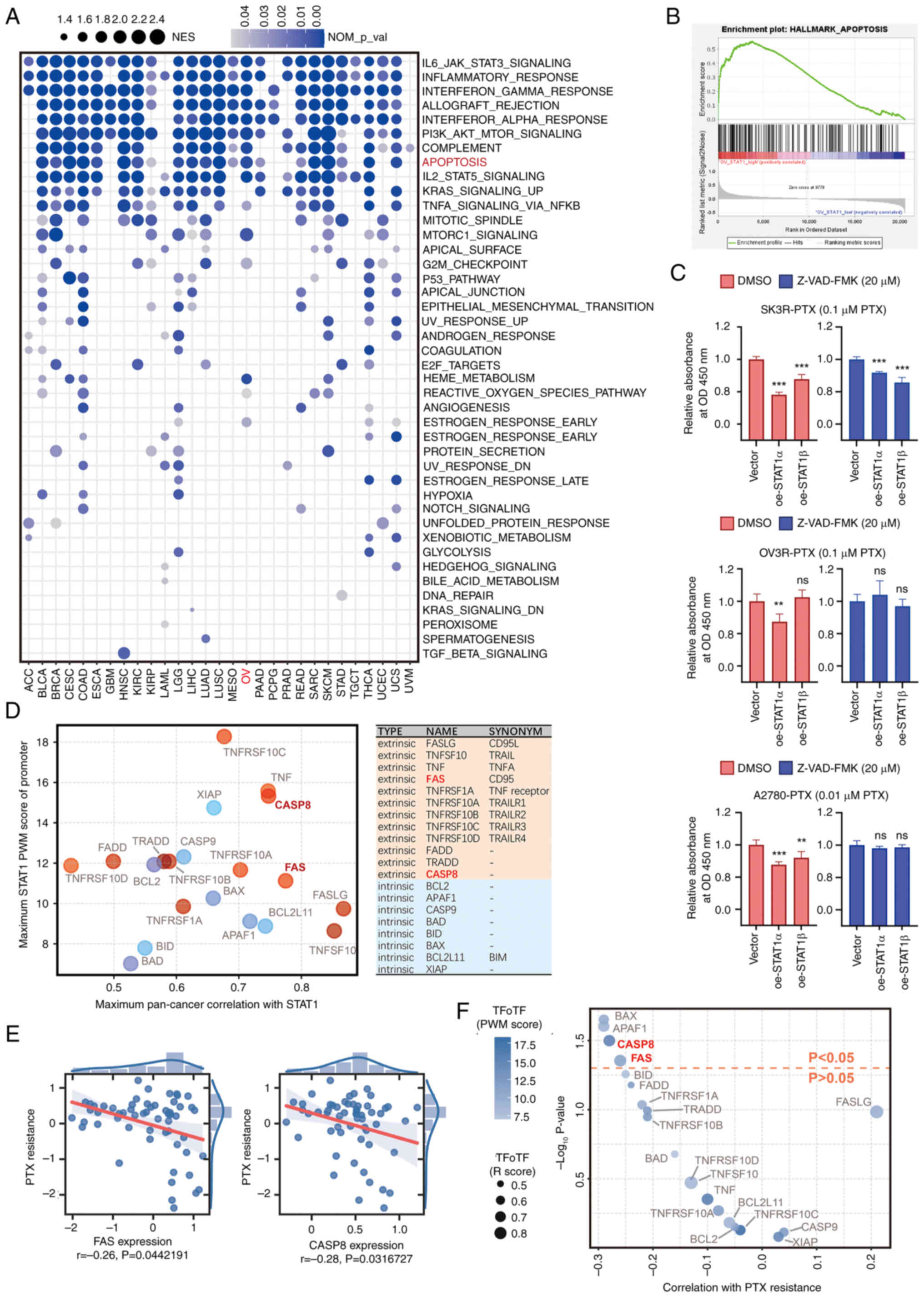

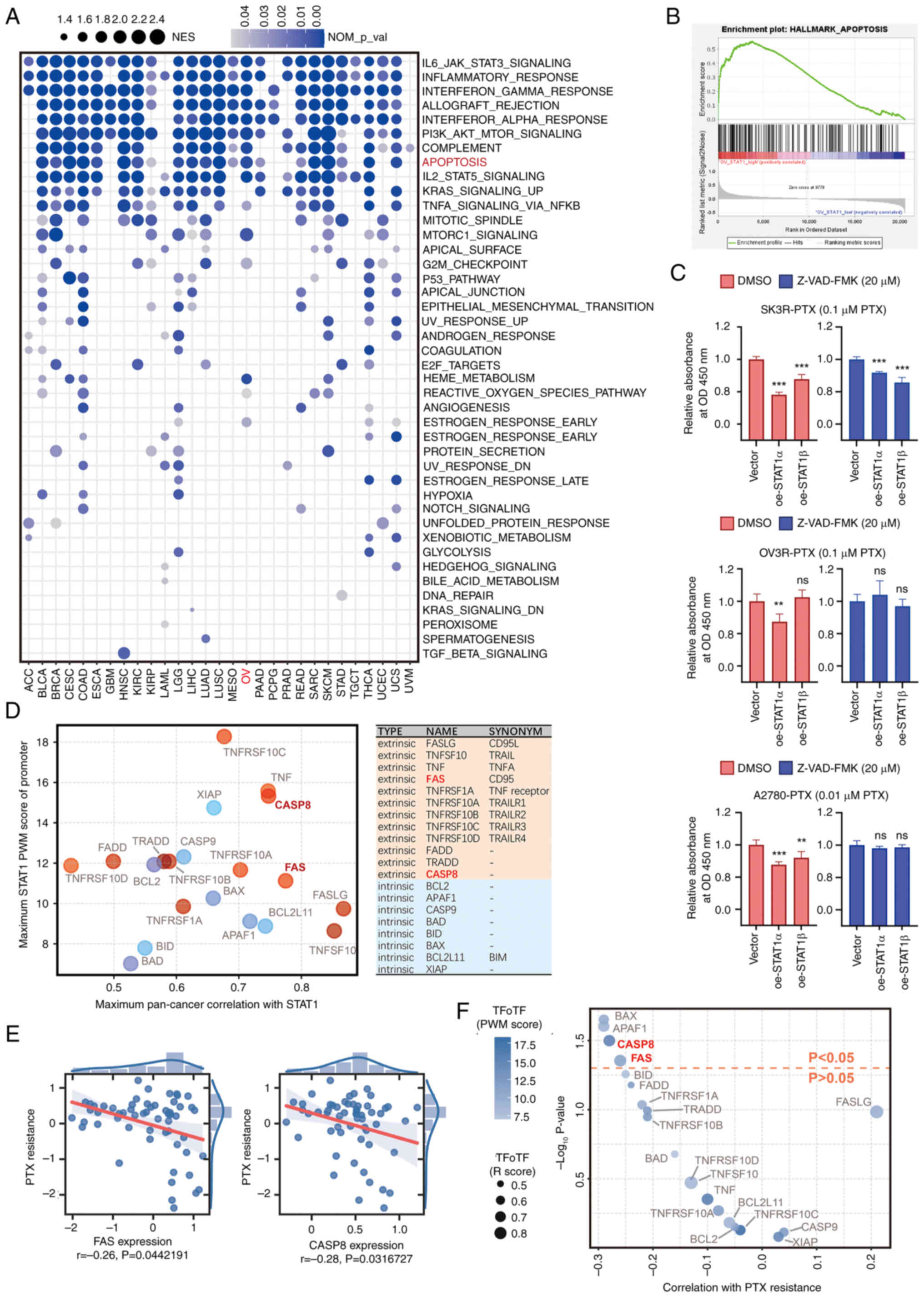

Overexpression of STAT1 reverses PTX

resistance through the apoptosis pathway

Since overexpression of STAT1 decreased OC cell

viability in some cell lines (Fig.

1F-K), a wide-ranging analysis of the biological functions of

STAT1 in pan-cancer was performed. GSEA revealed that high STAT1

expression was closely associated with 'IL6 JAK STAT3 signaling',

'PI3K AKT mTOR signaling', and 'apoptosis' in a number of cancer

types (Fig. 3A). Further analysis

of 'HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS' between STAT1 high and low expression

(expression level <20th percentile) samples of OC using GSEA

revealed that apoptosis was significantly enriched (Fig. 3B). Overexpression of STAT1α

decreased the viability of SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells

in the presence of PTX, whereas these effects of STAT1α were

completely abolished in OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells and partially

abolished in SK3R-PTX cells in the presence of a caspase blocker

(Z-VAD-FMK; 20 μM) (Fig.

3C). DMSO was used as a control for comparison. Because STAT1

is a TF protein, TFoTF was used to predict target genes of STAT1

using the apoptosis gene set 'HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS', which was

downloaded from the GSEA database (Hallmark gene sets; Ver 7.5.1)

(29). FAS and CASP8, the two key

genes of the apoptosis pathway, were ranked among the

highest-scoring genes and might be target genes of STAT1 (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, Pearson

correlation analysis revealed that FAS and CASP8 exhibited a weakly

negative correlation with PTX resistance (Fig. 3E), which was confirmed by TFoTF

with high scores (Fig. 3F). These

data indicated that STAT1 affected PTX resistance mainly through

the apoptosis pathway.

| Figure 3Association of STAT1 with PTX

resistance. (A) Analysis of the biological functions of STAT1. High

STAT1 expression (expression level >80th percentile) based on

pan-cancer transcriptomics data was associated with enriched

pathways. Horizontal coordinates indicate the different types of

cancer in The Cancer Genome Atlas and vertical coordinates indicate

the names of cell biological functions. The significance of each

enrichment result was determined using the default setting. (B)

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of 'HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS' between STAT1

high and low expression samples of ovarian cancer (expression level

>80th and <20th percentile, respectively). (C) Effect of

apoptosis inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK in STAT1-overexpressing PTX-resistant

cells. SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells were stably infected

with empty vector, STAT1α or STAT1β plasmids in the presence of

PTX, followed by 20 μM Z-VAD-FMK or solvent DMSO treatment

for 48 h. Cell viability was detected using a Cell Counting Kit-8

assay. Data were normalized using reads from the empty vector

group. Differences among multiple groups were analyzed by one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=5). **P<0.01;

***P<0.001 (oe-STAT1α/β vs. Vector). (D) Analysis of

genes closely related to apoptotic pathways obtained after TFoTF

prediction and screening of the apoptosis gene set

('HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS'). Information about these genes is shown in

the table on the right. The scatterplot on the left shows the

visualization of the TFoTF prediction outcomes for these genes. The

horizontal coordinate indicates the R score based on TFoTF and the

vertical coordinate indicates the PWM score

(kmax1). The red circles denote genes in the

extrinsic apoptosis pathway, and the blue circles denote genes in

the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. (E) Correlation of CASP8 and FAS

expression with cellular PTX resistance. The significance of each

regression coefficient was determined using the Wald test with a

t-distribution using the SciPy Python package. (F) Analysis and

screening of STAT1-targeted PTX resistance-associated apoptotic

genes. In the bubble plot, the horizontal coordinate indicates the

Pearson correlation coefficient between the target gene of STAT1

and PTX resistance. The vertical coordinate indicates the

statistical significance of the correlation. The red horizontal

dashed line indicates the position of the regression P-value of

0.05. The size of each bubble indicates the R score based on TFoTF.

The color depth of each bubble indicates the PWM score based on

TFoTF (kmax1). CASP8, caspase-8; FAS, Fas cell

surface death receptor; NES, normalized enrichment score;

NOM_p_val, normalized P-value; ns, not significant; OD, optical

density; oe, overexpression vector; PTX, paclitaxel; PWM, position

weight matrix; r, R-value; TFoTF, Target Finder of Transcription

Factor. |

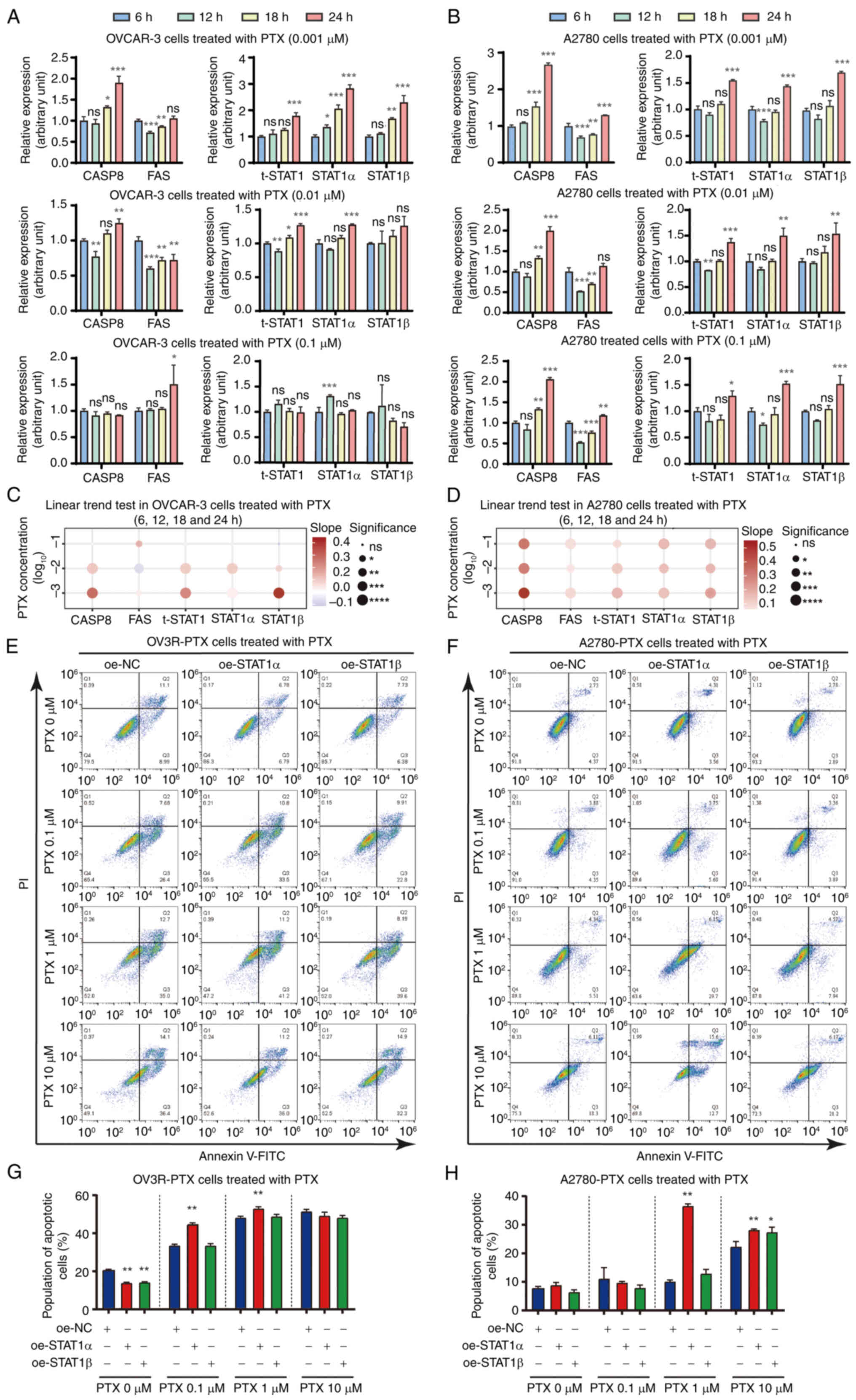

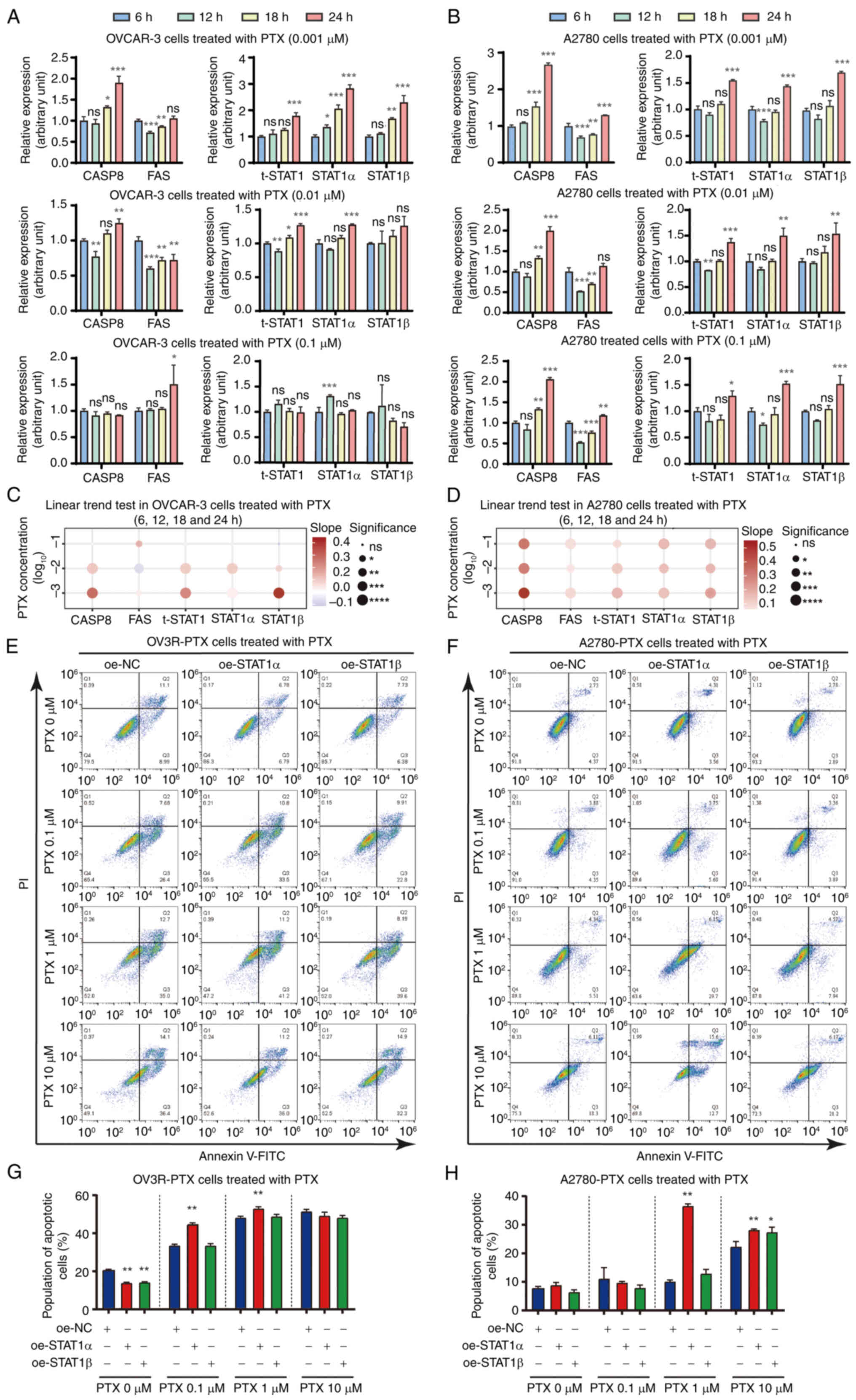

PTX enhances the expression of STAT1 and

apoptotic factors, and overexpression of STAT1 induces

PTX-resistant cell apoptosis

The effect of PTX on the expression levels of STAT1

and apoptotic factors CASP8 and FAS in PTX-sensitive cells was

first confirmed. Time-course (6, 12, 18 and 24 h) and

dose-dependent (0.001, 0.01 and 0.1 μM) experiments showed

that STAT1, CASP8 and FAS mRNA expression was upregulated in

PTX-sensitive cells after PTX treatment, albeit at different levels

in OVCAR-3, A2780 cells and SK-OV-3 cells (Figs. 4A and B, and S5A). The expression values of each gene

at different time points were further analyzed and confirmed using

the linear trend test. The mRNA expression levels of STAT1, CASP8

and FAS were gradually increased in the time-course experiment

after PTX treatment (Figs. 4C and

D, and S5B), and the trends were more significant at specific

PTX concentrations, such as 0.001 μM in OVCAR-3 and A2780

cells and 0.1 μM in SK-OV-3 cells. Notably, a decrease in

STAT1β expression was observed in SK-OV-3 cells after PTX treatment

at 12, 18 and 24 h compared with 6 h (Fig. S5A). Next, it was confirmed that

overexpression of STAT1 enhanced PTX sensitivity to induce

PTX-resistant cell apoptosis. Flow cytometry was performed to

detect PTX-induced apoptosis in oe-STAT1-infected OV3R-PTX and

A2780-PTX cells compared with oe-NC cells (Fig. 4E and F). Quantitative analysis of

flow cytometry data showed that overexpression of STAT1α induced

apoptosis under different PTX treatments. oe-STAT1α, compared with

oe-NC, increased the percentage of apoptotic cells to 53.20±0.92%

and 36.74±0.77% in OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells, respectively,

after 1 μM PTX treatment for 24 h (P<0.01) (Fig. 4G and H).

| Figure 4Effect of PTX on CASP8, FAS and STAT1

expression in time-course and dose-dependent experiments, and

effect of STAT1 on apoptosis. mRNA expression levels of CASP8, FAS,

t-STAT1, STAT1α and STAT1β were detected by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR in (A) OVACR-3 and (B) A2780 cells

after treatment with 0.001, 0.01 and 0.1 μM PTX for 6, 12,

18 and 24 h. Expression values for each group were normalized using

β-actin as an internal reference. Differences among multiple groups

were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honestly

Significant Difference test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD

(n=3). (C) Results of linear trend test for changes in (A). The

vertical coordinate indicates the concentration of PTX, and the

horizontal coordinate indicates the genes. The color of the bubble

represents the slope of the change trend, while the size of the

bubble represents the statistical significance.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. (D) Results

of linear trend test for changes in (B). The vertical coordinate

indicates the concentration of PTX, and the horizontal coordinate

indicates the genes. The color of the bubble represents the slope

of the change trend, while the size represents the statistical

significance. *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. Detection of

apoptosis in (E) OV3R-PTX and (F) A2780-PTX cells using flow

cytometry. OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells were infected with either

oe-STAT1α or oe-STAT1β in the presence or absence of 0.1, 1 and 10

μM PTX. Quantification of apoptotic cells based on flow

cytometry in STAT1α/β-overexpressing (G) OV3R-PTX and (H) A2780-PTX

cells in the presence or absence of PTX. Data were evaluated and

analyzed using ModFit software and are presented as the mean ± SD

(n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001 vs. 6 h in (A) and (B) and vs. oe-NC in

(G) and (H). CASP8, caspase-8; FAS, Fas cell surface death

receptor; NC, negative control; ns, not significant; oe,

overexpression vector; PTX, paclitaxel; t-STAT1, total STAT1. |

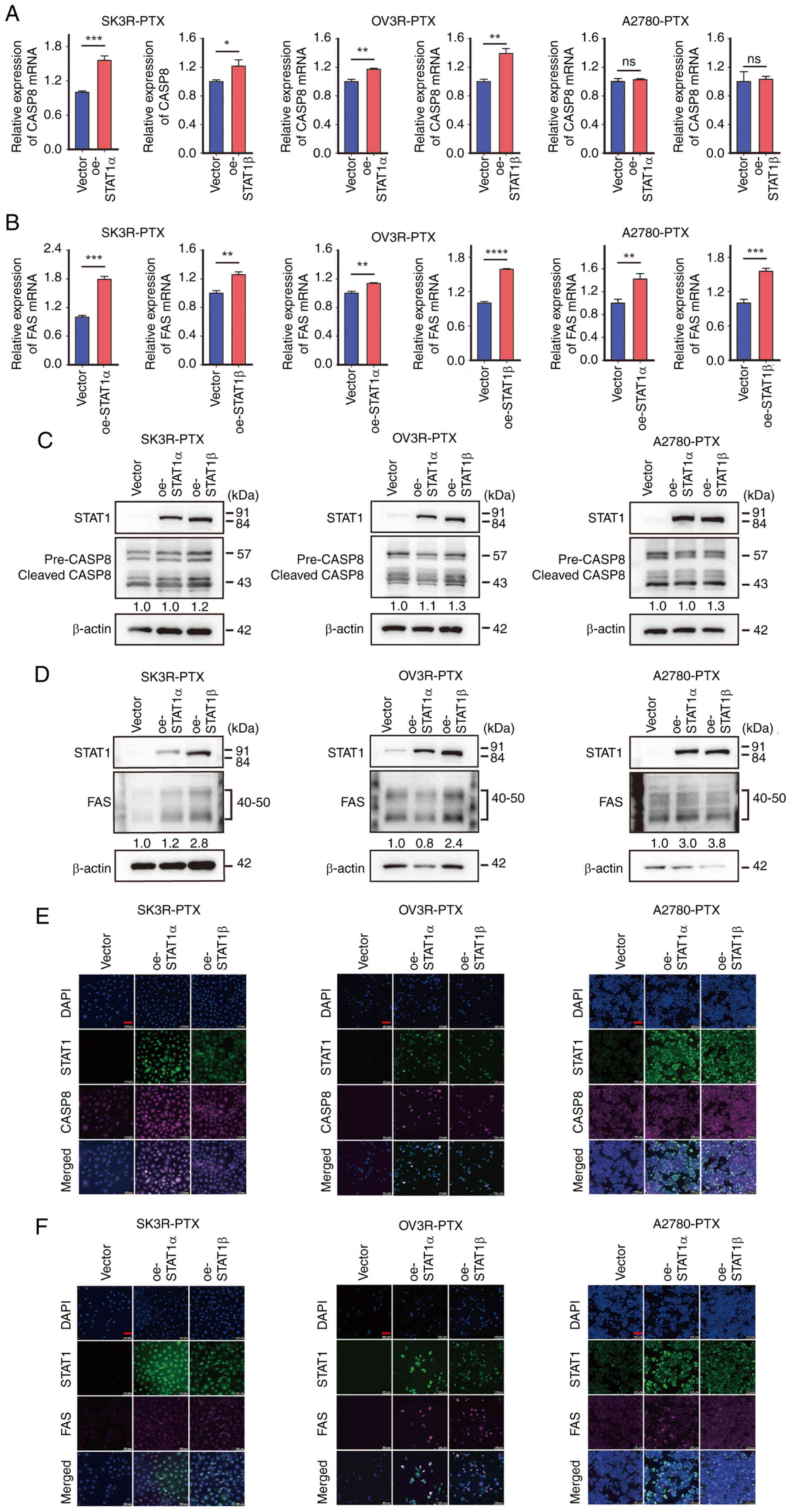

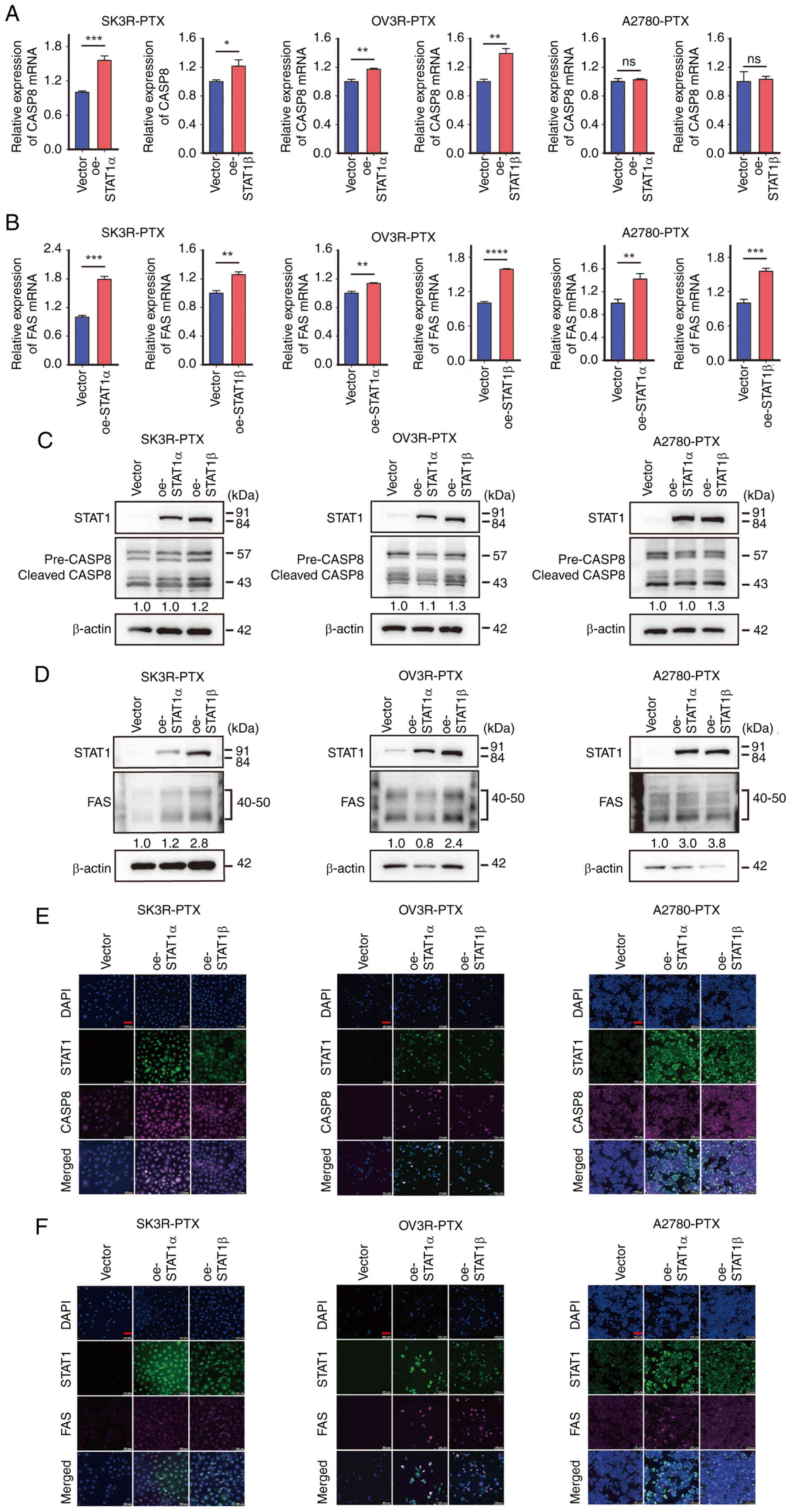

Overexpression of STAT1 upregulates CASP8

and FAS expression

Since PTX can induce apoptosis (14), and since PTX can upregulate STAT1

(Fig. 4), the present study

subsequently investigated the effect of STAT1 on CASP8 and FAS

expression in PTX-resistant cells. The Dox-induced overexpression

of STAT1α and STAT1β was confirmed by RT-qPCR in SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX

and A2789-PTX cells after infection with oe-STAT1α and oe-STAT1β

lentivirus, respectively (Fig.

S6A-C). The overexpression of STAT1α and STAT1β significantly

enhanced the mRNA expression levels of CASP8 and FAS detected by

RT-qPCR in most PTX-resistant cells, except A2780-PTX cells, in

which no significant change in CASP8 expression was found after

STAT1 lentiviral infection (Fig. 5A

and B). Finally, the protein expression levels of CASP8 and FAS

were evaluated by western blotting (Fig. 5C and D) and immunofluorescence

staining (Fig. 5E and F). Despite

some cell line-specificity, these data indicated that CASP8 and FAS

expression could be upregulated by STAT1.

| Figure 5Effect of STAT1 on CASP8 and FAS

expression in PTX-resistant cells. Detection of (A) CASP8 and (B)

FAS mRNA expression in oe-STAT1α- and oe-STAT1β-lentivirus-infected

SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. Expression values for each group

were normalized using β-actin as an internal reference. Differences

between the two groups were analyzed using Student's t-test. Data

are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001;

****P<0.0001. Detection of STAT1, (C) CASP8 and (D)

FAS protein expression in oe-STAT1α- and

oe-STAT1β-lentivirus-infected SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX

cells by western blotting. The specific antibodies recognized a

specific target. STAT1α, 91 kDa; STAT1β, 84 kDa; pre-CASP8, 57 kDa;

cleaved-CASP8, 43 kDa; FAS, 40-50 kDa; β-actin, 42 kDa. The numbers

under the bands indicate the densitometric value of the protein

(total CASP3 and FAS) after normalization. Detection of STAT1, (E)

CASP8 and (F) FAS protein expression in oe-STAT1α- and

oe-STAT1β-lentivirus-infected SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX

cells by immunofluorescence staining. The immunofluorescent signals

were detected after the induction of STAT1α and STAT1β using

doxycycline. DAPI was used to stain the nucleus. Red scale bar, 100

μm. CASP8, caspase-8; FAS, Fas cell surface death receptor;

ns, not significant; oe, overexpression vector; pre-CASP8,

caspase-8 precursor; cleaved-CASP8, cleaved caspase-8; PTX,

paclitaxel. |

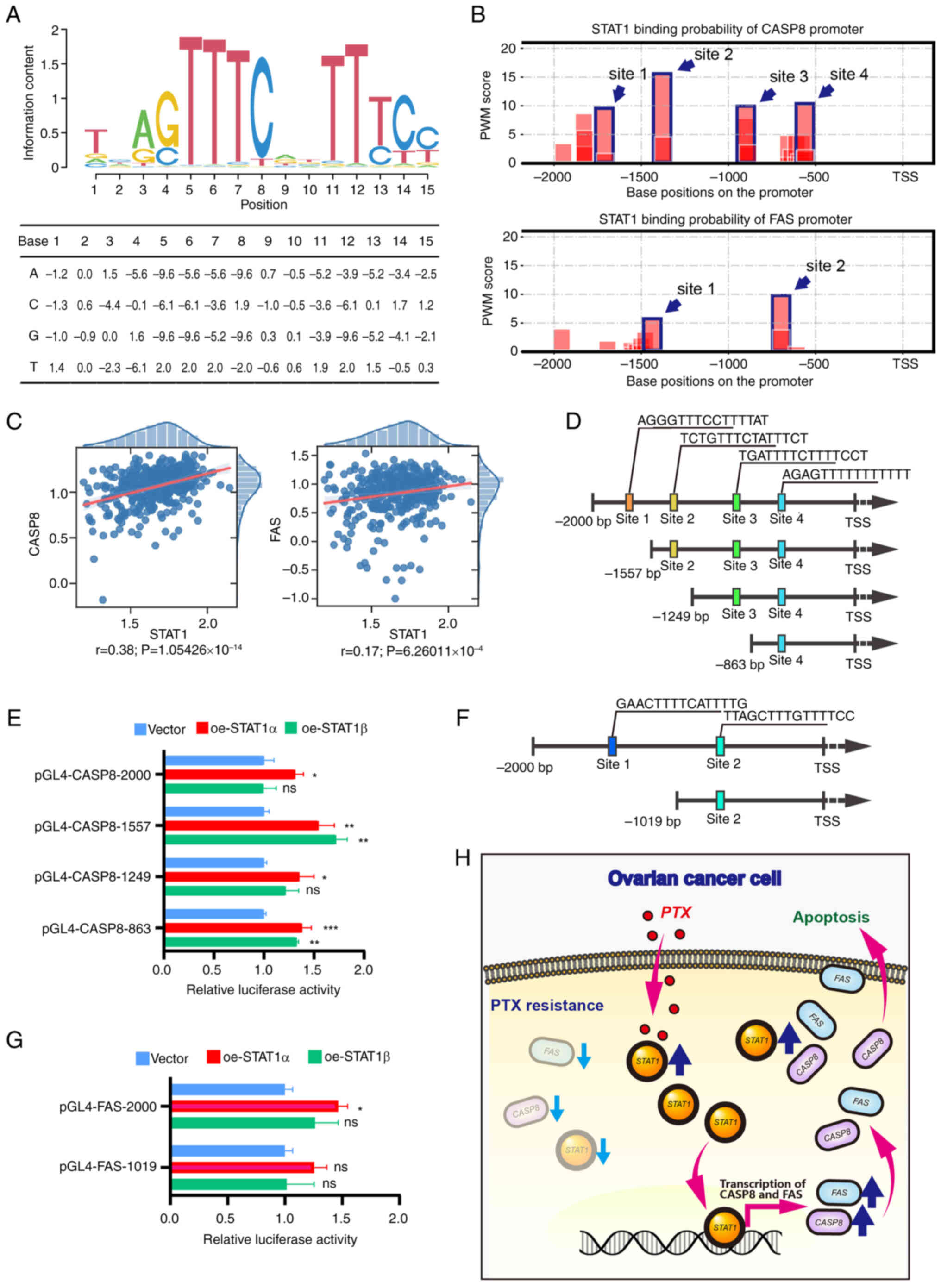

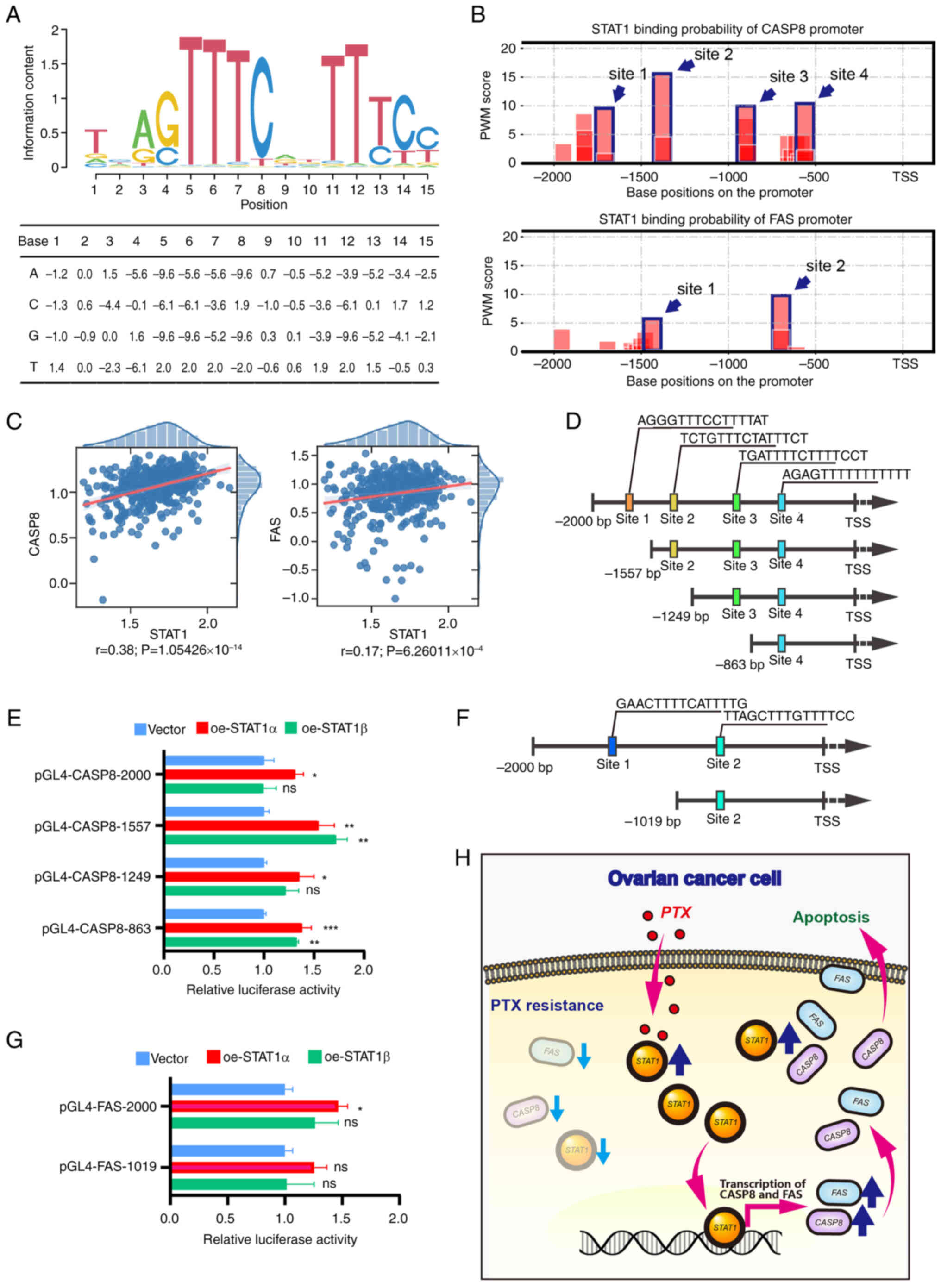

STAT1 directly binds to the promoter

regions of CASP8 and FAS

ChIP-seq data of STAT1 were obtained from GEO

(GSM320736). Data analysis revealed the potential binding sites of

multiple genome-associated fragments of CASP8 and FAS with STAT1,

and some of the fragments were located in the proximal promoter

regions of CASP8 and FAS (Fig.

S7). The STAT1 binding sites were found to be clustered within

the promoter regions of CASP8, which was predicted using PWM

scoring. The motif logo was drawn, and the specific values of the

PWM were calculated (Fig. 6A).

This logo visualized the conservation and preference for specific

nucleotides at different positions in a DNA sequence. There were

four and two clusters of binding sites within the promoter region

of CASP8 and FAS, respectively (Fig.

6B). Subsequently, correlation analysis revealed that the

expression of CASP8 and FAS was correlated with STAT1 expression in

ovarian cancer as determined by the Wald test with t-distribution

using the SciPy Python package (P<0.001; Fig. 6C). Subsequently, the binding sites

for STAT1 were validated using dual-luciferase reporter gene

assays. Based on the sequences of the predicted binding sites,

plasmids of a full-length promoter and several truncated fragments

of CASP8 and FAS were constructed. For CASP8, four constructs were

generated. A full-length plasmid (pGL4-CASP8-2000) contained all

four binding sites. The three truncated fragments, pGL4-CASP8-1557,

pGL4-CASP8-1249 and pGL4-CASP8-863, contained three, two and one

proximal binding sites, respectively (Fig. 6D). The relative luciferase

activity in each transfection group was measured in 293T cells

after co-transfection with a dual-luciferase reporter gene plasmid

and a STAT1-overexpression plasmid (oe-STAT1α, oe-STAT1β or empty

vector). For the pGL4-CASP8-2000 and pGL4-CASP8-1249 plasmids, the

relative luciferase activity was enhanced in the presence of STAT1α

(Fig. 6E). For the

pGL4-CASP8-1557 and pGL4-CASP8-863 plasmids, the relative

luciferase activity was enhanced in the presence of STAT1α or

STAT1β. For FAS, two constructs were generated, including a

full-length plasmid (pGL4-FAS-2000) containing two binding sites

and a truncated fragment plasmid (pGL4-FAS-1019) containing one

proximal binding site (Fig. 6F).

For the pGL4-FAS-2000 plasmid, the relative luciferase activity was

enhanced in the presence of STAT1α rather than STAT1β (Fig. 6G). There was no change in the

relative luciferase activity for the pGL4-FAS-1019 plasmid. These

data indicate that STAT1α could directly bind to the promoters of

CASP8 and FAS to regulate their expression at the transcription

level.

| Figure 6Detection of the interaction of STAT1

with CASP8 and FAS. (A) Prediction of STAT1 binding site sequence.

The PWM of STAT1 was used to predict the binding site in the

promoter region. The visualized sequence logo of the PWM is

illustrated at the top, and the specific values of the PWM are

shown in the table at the bottom. The x-axis represents the

position in the sequence alignment. The y-axis represents the

information content in bits. A higher value means that position is

highly conserved. (B) Prediction of STAT1 binding sites in the

CASP8 and FAS promoter regions using PWM analysis. Blue wireframes

and arrows indicate high-scoring binding sites (four sites on the

CASP8 promoter and two sites on the FAS promoter). (C) The

correlation regression results of CASP8 and FAS with STAT1 in OC.

The significance of each regression was determined using the Wald

test with the t-distribution using the SciPy Python package. (D)

Schematic diagram showing the full-length promoter (top) and three

truncated fragments of CASP8 with colored squares indicating

predicted binding sites and sequences. (E) Detection of STAT1

binding to CASP8 promoter DNA using dual-luciferase reporter gene

assays. (F) Schematic diagram showing the full-length promoter

(top) and one truncated fragment of FAS (bottom) with colored

squares indicating predicted binding sites and sequences. (G)

Detection of STAT1 directly binding to FAS promoter DNA using

dual-luciferase reporter gene assays. 293T cells were

co-transfected with a dual-luciferase reporter gene plasmid and

oe-STAT1α, oe-STAT1β or empty vector. Differences among multiple

groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

Honestly Significant Difference test. Data are presented as the

mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001 vs. vector. (H)

Schematic illustration of the regulatory mechanism of STAT1 on the

reversal of PTX resistance in OC cells. In PTX-resistant cells, the

expression levels of STAT1 and apoptotic factors FAS and CASP3 were

low. Administration of PTX increased STAT1 expression and the

overexpression of STAT1 upregulated FAS and CASP8 at the

transcriptional level, thus promoting PTX-resistant cell apoptosis.

CASP8, caspase-8; FAS, Fas cell surface death receptor; ns, not

significant; oe, overexpression vector; OC, ovarian cancer; PTX,

paclitaxel; PWM, position weight matrix; r, R-value; TSS,

transcription start site. |

Discussion

Chemoresistance is one of the major obstacles in

anticancer treatment. The present study explored the role and

regulatory mechanism of STAT1 in PTX-resistant OC cells.

Overexpression of STAT1 upregulated the expression levels of

apoptosis-related genes CASP8 and FAS, thereby

enhancing the PTX sensitivity in resistant cells in vitro

and in vivo.

In the present study, analyses using mRNA-sequencing

revealed that STAT1 was differentially expressed between

PTX-sensitive and PTX-resistant OC cells. Low levels of STAT

expression were detected in PTX-resistant cells compared with

PTX-sensitive cells. Overexpression of STAT1 enhanced the PTX

sensitivity in resistant cells, suggesting that STAT1 is an

important factor in mediating the processes of PTX resistance. It

has been demonstrated that STAT1 serves a dual role in

tumorigenesis, exhibiting upregulation or downregulation in other

cancer types (18,37). Some unphosphorylated STAT1

molecules also exhibit transcriptional activity (38). Our previous study demonstrated

that STAT1 was upregulated in OC cells compared with normal ovarian

cells (39), and overexpression

of STAT1 blocked the function of the TGF-β signaling pathway

(20). The present study further

demonstrated that STAT1 was a potential biomarker and target for

OC. Notably, similar outcomes have been shown by other groups. For

example, STAT1 negatively regulated the proliferative capacity in

hepatocellular carcinoma cells (40) and was a favorable factor affecting

the prognosis of colorectal cancer (41). Another study demonstrated that

STAT1 activity was associated with the degree of disease

progression from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive

carcinoma in both human and mouse mammary tumors (42). Furthermore, STAT1 is a promoter of

leukemia progression (43). Our

previous meta-analysis reviewed the clinical impact of STAT1; high

STAT1 expression was associated with longer overall survival in

patients with OC, rectum adenocarcinoma, sarcoma and cutaneous

melanoma, but was associated with poor prognosis in patients with

lung adenocarcinoma, renal cancer, brain lower-grade glioma and

pancreatic cancer (44). Existing

evidence indicates that STAT1 serves a dual role and has both

tumor-suppressing and tumor-promoting functions (18). The functional effect of STAT1 on

tumor progression is highly context-dependent, varying with disease

stage, genetic backgrounds and tissue origins (44). Therefore, targeting STAT1 for

cancer therapy demands a precision medicine approach, where its

activity is modulated based on the specific tumor context.

STAT1 has some common characteristics of TFs that

can be targeted in anticancer therapy (45). The number of oncogenes identified

is much larger than the number of TF genes. Considering that TFs

are the initiators of gene expression, a series of downstream

functional oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes can be activated or

inhibited if the activity of specific cancer-related TFs is altered

(46). Nevertheless, the

regulatory mechanisms are not fully understood. The biological

functions of TFs rely on protein-DNA or protein-protein

interactions (47,48). Compared with the more tractable

enzyme or kinase interactions, inhibitors of protein-DNA or

protein-protein binding are deficient, leading to the difficulty of

directly targeting the functional processes of TFs (49). In addition, it is also challenging

to identify the cancer-related molecules that can be manipulated

for therapeutic purposes (50)

since the downstream target genes of specific TFs are numerous and

may have different functions.

FAS and CASP8 are two key proteins for the

regulation of the apoptosis pathway. FAS is a death receptor that

can directly interact with CASP8 to form a complex and initiate

programmed cell death, and PTX can induce apoptosis (51,52). In the present study, the viability

of PTX-resistant cells was decreased after oe-STAT1α infection in

the presence of PTX. These effects of STAT1α were completely

abolished in OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells and partially abolished

in SK3R-PTX cells in the presence of the caspase inhibitor

Z-VAD-FMK, whereas the effect of STAT1β was minor. The difference

among these cell types was most likely due to multiple factors,

such as cell type specificity, infection efficiency and the

sensitivity of the inhibitor. To the best of our knowledge, the

present study was the first to demonstrate that STAT1 increased FAS

and CASP8 expression in PTX-resistant cells by directly binding to

their promoters to regulate them at the transcriptional level.

These data suggested that STAT1 reversed PTX resistance, at least

in part, through FAS/CASP8-induced apoptosis.

Our previous study demonstrated that STAT1 increased

OC cell proliferation (20).

STAT1 exists in two isoforms. STAT1α is considered to be the

full-length STAT1 protein, which consists of 750 amino acids and

has two important phosphorylation sites located in the C-terminal

transactivation domain (TAD), namely, tyrosine residue 701 (Y701)

and serine residue 727. STAT1β consists of 712 amino acids and has

only one phosphorylation site, Y701 (53). It has been shown that the

C-terminal TAD of STAT1 can serve an important trans-regulatory

role at the transcriptional level by recruiting different cofactors

(54). On the other hand, the

C-terminal TAD also interacts with the histone acetyltransferase

CBP/p300, which promotes the DNA-binding activity of STAT1

(55). Therefore, the functional

differences between STAT1α and STAT1β may partially be due to their

sequence and structural differences in the C-terminal TAD. The

present study demonstrated that overexpression of STAT1α decreased

PTX-resistant OC cell viability and inhibited tumor formation in

xenograft mice. Our previous work also revealed that STAT1α was the

main STAT1 isoform expressed in OC cells (20,38). However, STAT1β may also serve a

role in PTX-resistant cells. For example, the protein levels of FAS

were higher after STAT1β overexpression than after STAT1α

overexpression in SK3R-PTX cells as detected by western blotting,

and STAT1β had a stronger transcription-promoting activity in the

pGL4-CASP8-1557 group in the dual luciferase reporter gene assay

compared with STAT1α. These data suggest that the two isoforms of

STAT1 have certain respective functions, depending on the targets

and cancer types.

The present study had some limitations that require

further exploration. First, the current study lacked clinical

validation. Future studies should include prospective data as well

as retrospective data analyses to evaluate the role of STAT1. The

collection of patient samples is most useful to examine the

expression of STAT1 associated with PTX resistance. Second, the

role of STAT1β in PTX-resistant cells is not fully understood and

requires further investigation. Future studies should investigate

the upstream molecular mechanisms that regulate STAT1. For example,

post-translational modifications might switch STAT1β activation.

Specific signals such as TGF-β or IL could be controlling STAT1

isoforms in PTX-resistant cells. Third, whether STAT1-influenced

PTX resistance was involved in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is

unknown and would be interesting to investigate in future studies.

To strengthen the effect of STAT1, a potential strategy would be

targeting it in combination with PTX to overcome resistance and

improve treatment efficacy. Since low STAT1 expression is a marker

of PTX resistance, raising the STAT1 level in PTX-resistant

patients may be a potential treatment option. For example, to

re-sensitize OC to PTX, STAT1 could be introduced using viral

vectors such as adenoviruses to deliver a healthy copy of the gene

encoding STAT1 directly into OC cells as a gene therapy, thereby

reversing their drug resistance or re-sensitizing them to PTX.

Furthermore, high levels of STAT1 in tumors could predict a better

response to PTX therapy. Therefore, STAT1 can be utilized as a

biomarker to predict how a patient will react to PTX treatment.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

STAT1 expression was downregulated in PTX-resistant OC cells.

Overexpression of STAT1 upregulated the key apoptotic factors FAS

and CASP8 at the transcriptional level, thereby triggering the

apoptotic pathway to reverse PTX resistance (Fig. 6H). These findings may provide a

potential therapeutic strategy to reverse PTX resistance in OC

patients by targeting STAT1.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

FW contributed to experiments, data analyses, figure

generation and manuscript drafts. XX and BG contributed to the

bioinformatics analysis and in vitro experimental

validation. XL, JY, WG, JC, JF and QL contributed to the primer

design, and animal and cellular experiments. GX contributed to the

supervision, conceptualization, funding acquisition and project

administration, and wrote and edited the final manuscript. FW and

GX confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal studies were approved by the Ethics

Committee of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University (approval no.

JIEC-2023-S68; Shanghai, China) and the Laboratory Animal Welfare

and Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center,

Fudan University (approval no. 2020-A027-01; Shanghai, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

GX ORCID: 0000-0002-9074-8754.

Abbreviations:

|

CASP8

|

caspase-8

|

|

Dox

|

doxycycline

|

|

FAS

|

Fas cell surface death receptor

|

|

GEO

|

Gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

GFP

|

green fluorescent protein

|

|

GSEA

|

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

|

|

NC

|

negative control

|

|

OC

|

ovarian cancer

|

|

PTX

|

paclitaxel

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Yanyan

Zhan (Cancer Research Center, School of Medicine, Xiamen

University, Xiamen, China) for providing the original plasmid of

the tet-on system.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81872121) and the

Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Municipality (grant no.

23ZR1408900).

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung

H and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 75:10–45.

2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Caruso G, Weroha SJ and Cliby W: Ovarian

cancer: A review. JAMA. 334:1278–1291. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rodolakis I, Pergialiotis V, Liontos M,

Haidopoulos D, Loutradis D, Rodolakis A, Bamias A and Thomakos N:

Chemotherapy response score in ovarian cancer patients: An overview

of its clinical utility. J Clin Med. 12:21552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kampan NC, Madondo MT, McNally OM, Quinn M

and Plebanski M: Paclitaxel and its evolving role in the management

of ovarian cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2015:4130762015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Olawaiye AB, Kim JW, Bagameri A, Bishop E,

Chudecka-Głaz A, Devaux A, Gladieff L, Gordinier ME, Korach J,

McCollum ME, et al: Clinical trial protocol for ROSELLA: A phase 3

study of relacorilant in combination with nab-paclitaxel versus

nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in advanced platinum-resistant ovarian

cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 35:e1112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Vaidyanathan A, Sawers L, Gannon AL,

Chakravarty P, Scott AL, Bray SE, Ferguson MJ and Smith G: ABCB1

(MDR1) induction defines a common resistance mechanism in

paclitaxel- and olaparib-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Br J

Cancer. 115:431–441. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pei Y, Yang Z, Li B, Chen X, Mao Y and

Ding Y: Unraveling the molecular mechanisms of paclitaxel in

high-grade serous ovarian cancer through network pharmacology. Sci

Rep. 15:164452025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hanahan D: Hallmarks of cancer: New

dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12:31–46. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang Y, Qiu JG, Wang W, Sun FL, Wang X,

Liu WJ, Jia XY, Ji H, Wang L and Jiang BH: Suppression of CYLD by

HER3 confers ovarian cancer platinum resistance via inhibiting

apoptosis and by inducing drug efflux. Exp Hematol Oncol.

14:212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mosadegh M, Noori Goodarzi N and Erfani Y:

A comprehensive insight into apoptosis: Molecular mechanisms,

signaling pathways, and modulating therapeutics. Cancer Invest.

43:33–58. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fulda S and Debatin KM: Extrinsic versus

intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene.

25:4798–4811. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Carneiro BA and El-Deiry WS: Targeting

apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 17:395–417. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bertheloot D, Latz E and Franklin BS:

Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell

death. Cell Mol Immunol. 18:1106–1121. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cai W, Rong D, Ding J, Zhang X, Wang Y,

Fang Y, Xiao J, Yang S and Wang H: Activation of the PERK/eIF2α

axis is a pivotal prerequisite of taxanes to cancer cell apoptosis

and renders synergism to overcome paclitaxel resistance in breast

cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 24:2492024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

McFadden M, Singh SK, Kinnel B, Varambally

S and Singh R: The effect of paclitaxel- and fisetin-loaded PBM

nanoparticles on apoptosis and reversal of drug resistance gene

ABCG2 in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 16:2202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Souto EP, Gong P, Landua JD, Rajaram

Srinivasan R, Ganesan A, Dobrolecki LE, Purdy SC, Pan X, Zeosky M,

Chung A, et al: Lineage tracing and single-cell RNA sequencing

reveal a common transcriptional state in breast cancer

tumor-initiating cells characterized by IFN/STAT1 activity. Cancer

Res. 85:1390–1409. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Han H, Gong C, Zhang Y, Liu C, Wang Y,

Zhao D, Huang J and Gong Z: RBM30 recruits DOT1L to activate STAT1

transcription and drive immune evasion in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Oncogene. 44:3955–3973. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li X, Wang F, Xu X, Zhang J and Xu G: The

dual role of STAT1 in ovarian cancer: Insight into molecular

mechanisms and application potentials. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:6365952021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, Shenmen

CM, Grouse LH, Schuler G, Klein SL, Old S, Rasooly R, Good P, et

al: The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA

project: The mammalian gene collection (MGC). Genome Res.

14:2121–2127. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tian X, Guan W, Zhang L, Sun W, Zhou D,

Lin Q, Ren W, Nadeem L and Xu G: Physical interaction of STAT1

isoforms with TGF-β receptors leads to functional crosstalk between

two signaling pathways in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 37:1032018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang F, Xu X, Li X, Yuan J, Gao X, Wang C,

Guan W and Xu G: Target finder of transcription factor (TFoTF): A

novel tool to predict transcription factor-targeted genes in

cancer. Mol Oncol. 17:1246–1262. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang J, Guan W, Xu X, Wang F, Li X and Xu

G: A novel homeostatic loop of sorcin drives paclitaxel-resistance

and malignant progression via Smad4/ZEB1/miR-142-5p in human

ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 40:4906–4918. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Das AT, Tenenbaum L and Berkhout B: Tet-on

systems for doxycycline-inducible gene expression. Curr Gene Ther.

16:156–167. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tönjes M, Barbus S, Park YJ, Wang W,

Schlotter M, Lindroth AM, Pleier SV, Bai AHC, Karra D, Piro RM, et

al: BCAT1 promotes cell proliferation through amino acid catabolism

in gliomas carrying wild-type IDH1. Nat Med. 19:901–908. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Xu X, Wang C, Guan W, Wang F, Li X, Yuan J

and Xu G: Protoporphyrin IX-loaded albumin nanoparticles reverse

cancer chemoresistance by enhancing intracellular reactive oxygen

species. Nanomedicine. 51:1026882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z,

Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al: clusterProfiler 4.0: A

universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation

(Camb). 2:1001412021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Walter W, Sánchez-Cabo F and Ricote M:

GOplot: An R package for visually combining expression data with

functional analysis. Bioinformatics. 31:2912–2914. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H,

Ghandi M, Mesirov JP and Tamayo P: The molecular signatures

database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst.

1:417–425. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Davidson-Pilon C: lifelines: survival

analysis in Python. J Open Source Softw. 4:13172019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Rozowsky J, Euskirchen G, Auerbach RK,

Zhang ZD, Gibson T, Bjornson R, Carriero N, Snyder M and Gerstein

MB: PeakSeq enables systematic scoring of ChIP-seq experiments

relative to controls. Nat Biotechnol. 27:66–75. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Auerbach RK, Euskirchen G, Rozowsky J,

Lamarre-Vincent N, Moqtaderi Z, Lefrançois P, Struhl K, Gerstein M

and Snyder M: Mapping accessible chromatin regions using Sono-Seq.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:14926–14931. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yu G, Wang LG and He QY: ChIPseeker: An

R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and

visualization. Bioinformatics. 31:2382–2383. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lawrence M, Huber W, Pagès H, Aboyoun P,

Carlson M, Gentleman R, Morgan MT and Carey VJ: Software for

computing and annotating genomic ranges. PLoS Comput Biol.

9:e10031182013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Koti M, Gooding RJ, Nuin P, Haslehurst A,

Crane C, Weberpals J, Childs T, Bryson P, Dharsee M, Evans K, et

al: Identification of the IGF1/PI3K/NF κB/ERK gene signalling

networks associated with chemotherapy resistance and treatment

response in high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC

Cancer. 13:5492013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE,

Haberland M, Reddy T, Cournapeau D, Burovski E, Peterson P,

Weckesser W, Bright J, et al: SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for

scientific computing in python. Nat Methods. 17:261–272. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang Y and Liu Z: STAT1 in cancer: Friend

or foe? Discov Med. 24:19–29. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Meissl K, Macho-Maschler S, Müller M and

Strobl B: The good and the bad faces of STAT1 in solid tumours.

Cytokine. 89:12–20. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Liu F, Liu J, Zhang J, Shi J, Gui L and Xu

G: Expression of STAT1 is positively correlated with PD-L1 in human

ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 21:963–971. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen G, Wang H, Xie S, Ma J and Wang G:

STAT1 negatively regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell

proliferation. Oncol Rep. 29:2303–2310. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gordziel C, Bratsch J, Moriggl R, Knösel T

and Friedrich K: Both STAT1 and STAT3 are favourable prognostic

determinants in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 109:138–146.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hix LM, Karavitis J, Khan MW, Shi YH,

Khazaie K and Zhang M: Tumor STAT1 transcription factor activity

enhances breast tumor growth and immune suppression mediated by

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Biol Chem. 288:11676–11688.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kovacic B, Stoiber D, Moriggl R, Weisz E,

Ott RG, Kreibich R, Levy DE, Beug H, Freissmuth M and Sexl V: STAT1

acts as a tumor promoter for leukemia development. Cancer Cell.

10:77–87. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhang J, Wang F, Liu F and Xu G:

Predicting STAT1 as a prognostic marker in patients with solid

cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 12:17588359209175582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Darnell JE Jr: Transcription factors as

targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2:740–749. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lee TI and Young RA: Transcriptional

regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 152:1237–1251.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, Das

PK, Yin Y, Albu M, Chen X, Taipale J, Hughes TR and Weirauch MT:

The human transcription factors. Cell. 175:598–599. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Spitz F and Furlong EE: Transcription

factors: From enhancer binding to developmental control. Nat Rev

Genet. 13:613–626. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bushweller JH: Targeting transcription

factors in cancer-from undruggable to reality. Nat Rev Cancer.

19:611–624. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Lambert M, Jambon S, Depauw S and

David-Cordonnier MH: Targeting transcription factors for cancer

treatment. Molecules. 23:14792018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Blagosklonny MV, Robey R, Sheikh MS and

Fojo T: Paclitaxel-induced FasL-independent apoptosis and slow

(non-apoptotic) cell death. Cancer Biol Ther. 1:113–117. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang TH, Wang HS and Soong YK:

Paclitaxel-induced cell death: Where the cell cycle and apoptosis

come together. Cancer. 88:2619–2628. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Oda K, Matoba Y, Irie T, Kawabata R,

Fukushi M, Sugiyama M and Sakaguchi T: Structural basis of the

inhibition of STAT1 activity by sendai virus C protein. J Virol.

89:11487–11499. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Parrini M, Meissl K, Ola MJ, Lederer T,

Puga A, Wienerroither S, Kovarik P, Decker T, Müller M and Strobl

B: The C-terminal transactivation domain of STAT1 has a

gene-specific role in transactivation and cofactor recruitment.

Front Immunol. 9:28792018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wojciak JM, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ

and Wright PE: Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300

coactivators by STAT1 and STAT2 transactivation domains. EMBO J.

28:948–958. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Detection of STAT1 expression, and

effect of STAT1 on PTX sensitivity and viability in PTX-resistant

OC cells (SK3R-PTX, OV3R-PTX and A2780-PTX cells) and their

sensitive counterpart cells (SK-OV-3, OVCAR-3 and A2780 cells). (A)

Validation of PTX resistance in OC cells. The dots and curves in

the graphs indicate the relative cell viability at the

corresponding PTX concentrations and non-linear regression fitting

curves. Differences between sensitive cells and resistant cells

were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's HSD test.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). (B) Differentially

expressed TF genes in PTX-sensitive and PTX-resistant OC cells. The

pie chart on the left represents the percentage of TF genes that

were differentially expressed at a significant level (expression FC

>2.5 and P<0.05). The pie chart on the right represents the

percentage of upregulated and downregulated TF genes. (C) Volcano

plot showing the alteration of TF gene expression between A2780 and

A2780-PTX cells based on the mRNA-sequencing results (n=3). The

gray horizontal line represents the P-value of 0.05, and the two

gray vertical lines represent the locations of FC >2 in gene

expression (A2780-PTX vs. A2780 cells). TF genes with significantly

altered expression (defined as FC <0.4 or >2.5 and P<0.05)

were marked with red dots. The red star indicates STAT1. (D)

Detection of total STAT1, STAT1α and STAT1β mRNA expression in