Lung cancer is a prevalent malignancy worldwide;

according to the latest GLOBOCAN report, ~2.48 million new lung

cancer cases are diagnosed each year and it accounts for 12.4% of

global cancer incidence, thus ranking as the most common cancer

globally. In addition, lung cancer is the leading cause of

cancer-related deaths, with an estimated 1.8 million fatalities

representing 18.7% of total cancer mortality. Notably, China bears

the highest lung cancer incidence and mortality rates worldwide

(1).

Radiotherapy serves as a primary treatment for lung

cancer across different stages and pathological types, markedly

improving local control rates and survival (2,3).

However, intrinsic or acquired radioresistance remains a clinical

challenge to treatment outcomes and patient prognosis (4,5).

The present review focuses on the role of mTOR in

lung cancer radioresistance, explores associated molecular

mechanisms and evaluates the clinical prospects of mTOR inhibitors

for enhancing radiotherapy efficacy. To achieve this, a systematic

literature search was conducted. PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com/) and

Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/) were searched

up to May 2024 using key words such as 'mTOR', 'lung cancer',

'radiotherapy resistance', 'mTOR inhibitors', 'PI3K/AKT', 'SCLC'

and 'immunotherapy'. Findings from original research, including

in vitro cellular experiments and in vivo animal

models, were subsequently assessed, as well as relevant clinical

trials, meta-analyses and other review articles. Notably,

non-peer-reviewed materials were excluded unless critical original

data were required. By synthesizing these findings, the present

review aims to elucidate how mTOR signaling mediates

radioresistance and to propose optimized therapeutic strategies to

improve outcomes for patients with lung cancer.

mTOR is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase

belonging to the phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase family.

The soil bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus, which

produces rapamycin, was initially identified in 1931. Vézina et

al (15) then discovered the

molecular target of rapamycin, mTOR, in 1975 on Easter Island (Rapa

Nui, Chile). The mature mTOR protein comprises 2,549 amino acid

residues (molecular weight: ~289 kDa) and is encoded by the mTOR

gene situated on chromosome 1p36.2. Following transcription,

splicing, translation and post-translational modifications, the

functional mTOR protein localizes to multiple intracellular

compartments, including the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus,

mitochondrial outer membrane, lysosomes, cytoplasm and nucleus

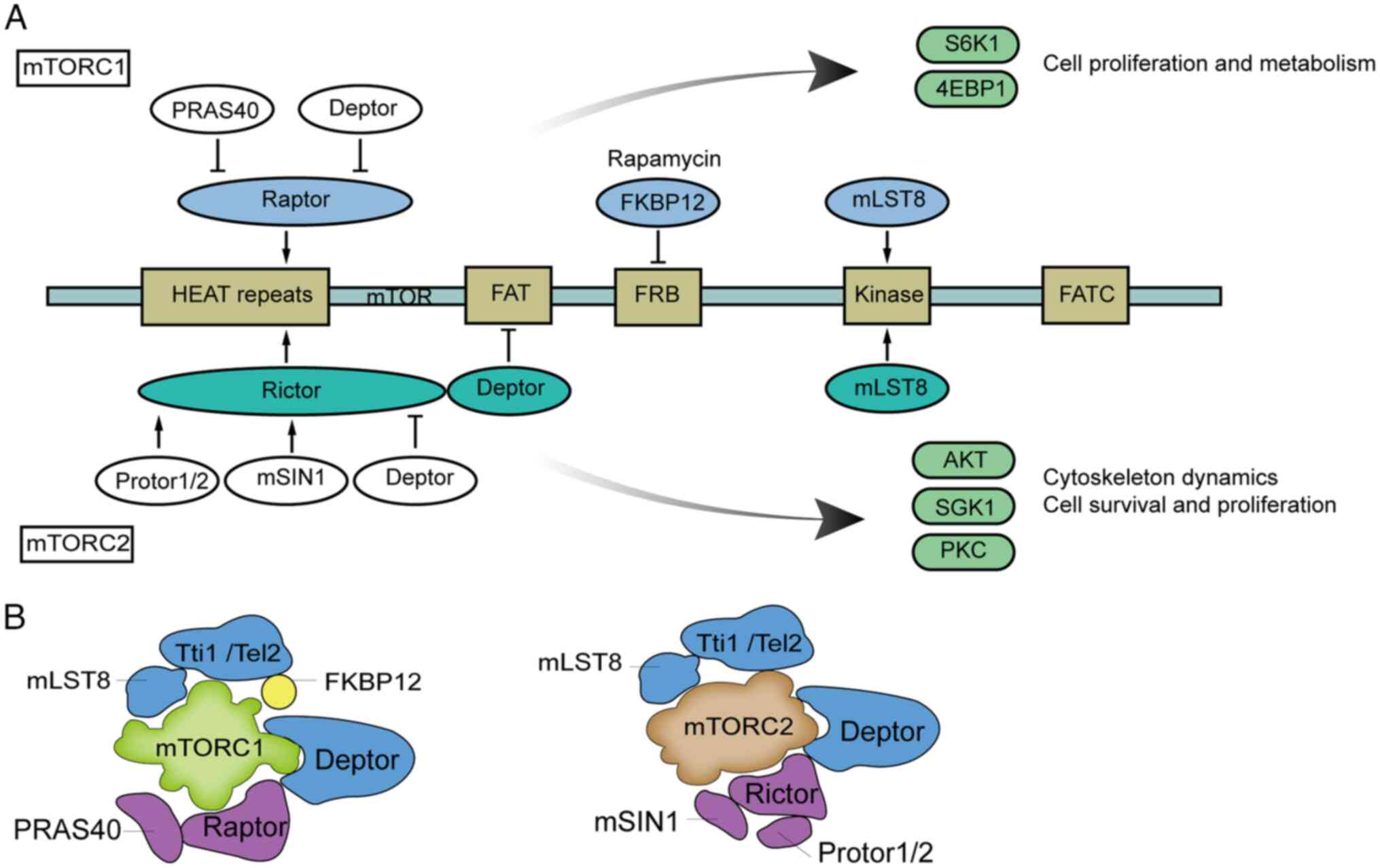

(16-18). Structurally, mTOR has two clusters

of repeats at its N-terminus. Each cluster has 20 tandem HEAT

repeats; HEAT stands for Huntingtin, EF3, the A subunit of PP2A,

and TOR1, and these repeats form hydrophobic surfaces, which are

critical for protein-protein interactions, membrane anchoring and

cytoplasmic trafficking. Adjacent to these, the focal adhesion

targeting (FAT) domain stabilizes protein complexes through

scaffold-like interactions, while the FKBP12-rapamycin binding

domain serves as the binding site for the FKBP12-rapamycin complex.

The kinase domain, functioning as the catalytic core,

phosphorylates serine/threonine residues in substrate proteins to

regulate downstream signaling. Finally, the C-terminal FATC domain

interacts spatially with the FAT domain to expose the catalytic

site, a configuration essential for the enzymatic activity of mTOR

(19) (Fig. 1A).

mTOR exerts its biological functions through two

distinct complexes: mTOR complex (mTORC)1 and mTORC2 (Fig. 1B). mTORC1 primarily regulates cell

proliferation and metabolism, with its core components including

mTOR, the scaffold protein regulatory-associated protein of mTOR

(Raptor), and mLST8/GβL (homologous to yeast TOR1, Kog1 and Lst8).

Additional regulatory proteins such as proline-rich AKT substrate

of 40 kDa and DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein

modulate mTORC1 activity, while Tel2 and Tti1 are involved in its

assembly and stability. By sensing nutrient, energy and oxygen

availability, mTORC1 controls protein synthesis, autophagy and

metabolic pathways (20-22), and is potently inhibited by

rapamycin, from which its name originates. By contrast, mTORC2

governs cell survival and cytoskeletal reorganization by regulating

the AKT/PKB signaling pathway (23). Its core structure comprises mTOR,

the scaffold protein rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR, and

specific subunits including mammalian stress-activated protein

kinase-interacting protein 1 and Protor1/2 (homologous to yeast

TOR2, Avo3, Avo1 and Bit61/2). Unlike mTORC1, mTORC2 is not

directly sensitive to rapamycin inhibition. However, prolonged or

high-dose rapamycin treatment may indirectly suppress mTORC2

activity. The suppression of mTORC2 activity happens in

hepatocytes, adipocytes, T cells and certain cancer cells, and

impairs full AKT activation, subsequently reducing cell survival

and proliferation (24-26).

The mTOR signaling pathway forms a complex

regulatory network essential for eukaryotic cell proliferation,

metabolism and survival, integrating multiple upstream and

downstream effectors, as illustrated in Fig. 1A. mTORC1 activity is regulated by

upstream signals including the PI3K/AKT pathway (27,28), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)

(29,30) and Rag GTPases (31). By sensing cellular nutrients,

energy and oxygen levels, mTORC1 coordinates protein synthesis,

autophagy, and metabolic processes. Its key downstream targets, S6

kinase 1 and 4EBP1, drive protein production and cell proliferation

while suppressing autophagy (20). By contrast, mTORC2 acts as a PI3K

signaling effector, enhancing cell survival and cytoskeletal

organization through insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1 and

leptin-mediated PI3K activation (32,33). It regulates the AKT/PKB pathway to

influence cell proliferation and survival (34) and mediates PKC phosphorylation to

support cytoskeletal remodeling and cell migration (35,36) (Fig.

1A). Collectively, mTOR critically impacts physiological and

pathological processes such as apoptosis, metabolic regulation,

immune responses and carcinogenesis (37), with its aberrant activation

strongly associated with cancer progression (38), thus making it a prime therapeutic

target.

mTOR serves a critical role in the pathogenesis of

lung cancer. As a key effector of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway,

mTOR regulates tumor growth and survival by modulating cellular

processes including proliferation, metabolism, apoptosis and

autophagy (7,39). Recent investigations have shown

that mTOR is ubiquitously activated in lung cancer, with aberrant

mTOR signaling observed in both non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (40), closely associated with tumor

aggressiveness and therapy resistance (41). Table

I systematically outlines PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mediated resistance

mechanisms in lung cancer radiotherapy, encompassing target

mechanisms, interventions (such as pharmacological inhibitors,

genetic modifications and radiotherapy combinations), their

functions and corresponding references.

In NSCLC, mTOR overexpression (OE) drives tumor

initiation, progression and metastasis, serving as a potential

therapeutic target, and multiple mechanisms contribute to this

dysregulation. Granville et al (42) revealed that tobacco-mediated

carcinogenesis is dependent on mTOR activation. This previous study

also showed that rapamycin effectively reduces the size and

proliferation of tumors induced by NNK (a tobacco-specific

carcinogen). This finding implicates mTOR in tobacco-related lung

squamous carcinoma. Additionally, mTOR upregulation may arise from

genetic mutations (such as EGFR, KRAS and ALK) disrupting PI3K/AKT

signaling (43-47), epigenetic modifications (DNA

methylation and histone acetylation) (48), and tumor microenvironment factors.

Zhang et al (49)

demonstrated that mTOR signaling promotes angiogenesis and

metastasis in NSCLC. Inhibiting mTORC2, in turn, can suppress cell

migration, metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT).

Compared with NSCLC, SCLC is characterized by high

aggressiveness and rapid growth, and it is often diagnosed at

advanced stages. Studies have indicated that mTOR signaling is

similarly hyperactivated in SCLC, and is associated with its

aggressive phenotype and treatment resistance (50-52). mTOR governs SCLC growth and

survival by regulating proliferation, metabolism, apoptosis and

autophagy. In SCLC, MYC, a commonly amplified oncogene, activates

mTOR signaling through multiple pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT and

MAPK pathways, to accelerate tumor cell proliferation (53). Furthermore, eIF4E, a downstream

effector of mTORC1, supports tumor growth by regulating protein

synthesis. Matsumoto et al (54) identified aberrant activation of

the MYC-eIF4E axis as a primary driver of resistance to the mTOR

inhibitor everolimus in SCLC. This finding underscores the

interplay between mTOR signaling and MYC/eIF4E pathways. While both

NSCLC and SCLC may benefit from mTOR pathway modulation, their

therapeutic efficacy and resistance mechanisms differ. As noted,

mTOR activity in NSCLC is predominantly linked to EGFR signaling,

whereas resistance in SCLC involves MYC and eIF4E pathways.

mTOR serves a critical role in cancer

radioresistance. Radiotherapy eliminates cancer cells by inducing

DNA damage; however, some tumor cells evade this effect through

mTOR signaling activation, leading to radiation resistance

(11,55). By regulating biological processes,

such as cell proliferation, metabolism, autophagy and DNA repair,

mTOR promotes cancer cell survival during radiotherapy. In lung

cancer, abnormal mTOR pathway activation is strongly associated

with radioresistance (56).

Current evidence has demonstrated that mTOR promotes resistance to

radiotherapy in lung cancer through multiple mechanisms. To provide

a concise overview of these complex mechanisms, Table I, Table II, Table III and Table IV summarize key findings from

preclinical studies.

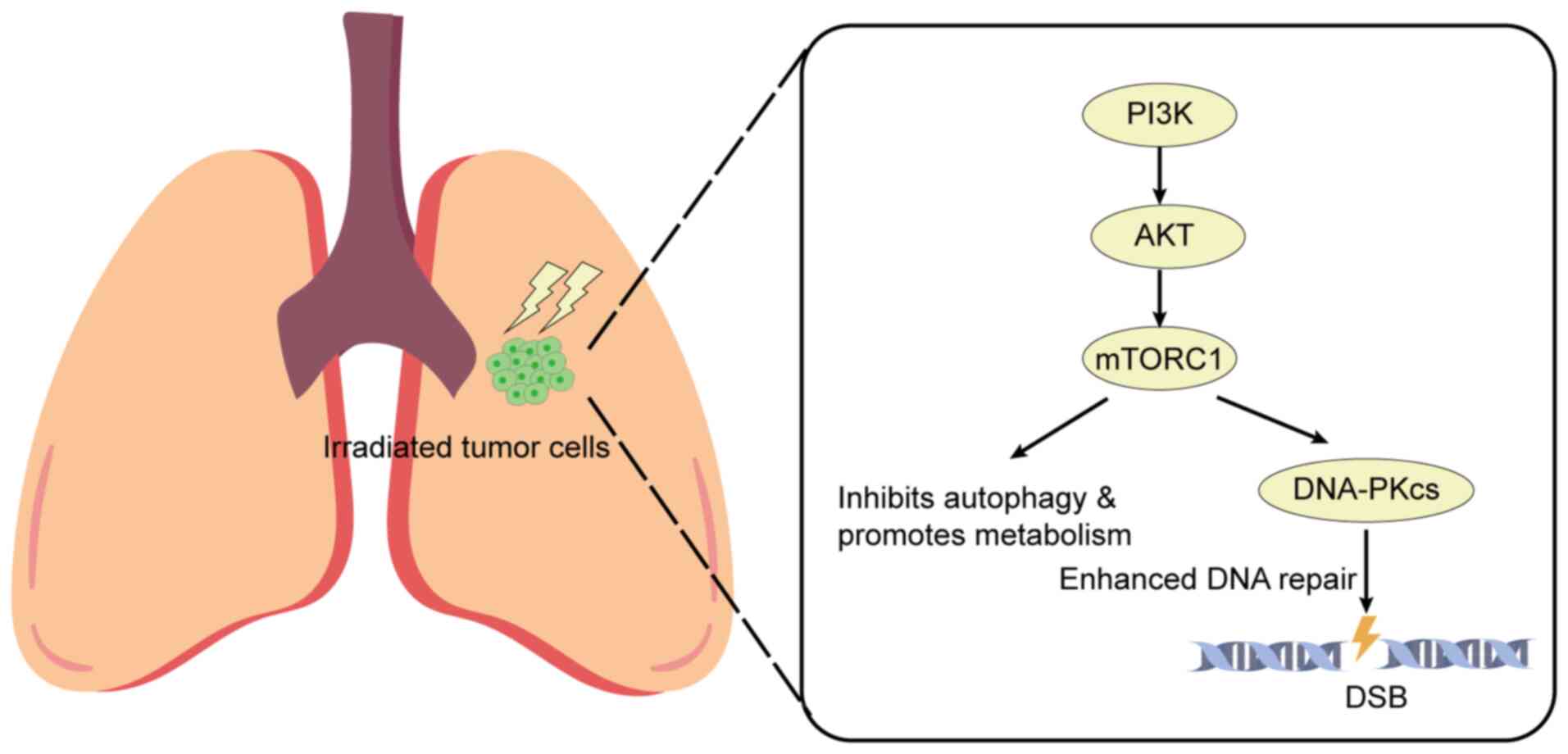

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a critical

intracellular signaling cascade that regulates physiological

processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis

and energy metabolism in normal cells. Its aberrant activation

promotes tumor progression by suppressing apoptosis, accelerating

cell cycle progression, enhancing angiogenesis and promoting

metastasis (57-59). In lung cancer, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway is frequently activated via genetic mutations,

amplifications and receptor tyrosine kinase activation. This

activation is associated with intrinsic radiosensitivity, tumor

cell proliferation and hypoxia, all of which contribute to

radiotherapy resistance (12,60).

Mechanistically, activation of this pathway enhances

radioresistance by upregulating DNA repair proteins such as

DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), which

accelerates the repair of radiation-induced DNA double-strand

breaks (61,62) (Fig.

2). This enhanced DNA repair is a primary escape mechanism for

irradiated tumor cells. However, Toulany et al (61) further revealed limitations in

radiosensitizing KRAS mutant NSCLC through PI3K inhibition alone.

These limitations are attributed to compensatory MEK-ERK pathway

activation. Tumor cells counteract PI3K suppression by enhancing

MEK-ERK signaling, which sustains survival via AKT-dependent

upregulation of DNA repair proteins (such as DNA-PKcs and Rad51),

ultimately impairing radiotherapy efficacy. Dual targeting of PI3K

and MEK has emerged as a promising strategy to overcome this

resistance (63). Kim et

al (64) demonstrated that

combining the MEK inhibitor trametinib with the mTOR inhibitor

temsirolimus may enhance radiosensitivity in NSCLC cells by

boosting radiation-induced apoptosis and inducing prolonged DNA

breaks.

Preclinical studies have established robust evidence

implicating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activation in mediating tumor

cell radioresistance (Table I).

For example, scutellarin combined with iodine-125 seeds targets the

AKT/mTOR pathway to enhance apoptosis and inhibit proliferation in

NSCLC, offering a potential therapeutic approach (65). To validate the clinical relevance

of these findings, Sebastian et al (66) conducted a clinical study analyzing

tumor samples from 92 patients with T1-3N0 NSCLC treated with

stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). This previous study revealed

that elevated PI3K pathway activity was significantly associated

with increased local recurrence risk (HR=1.72, 95% CI=1.40-98.0,

P=0.023) and shorter disease-free survival (DFS) (HR=3.98, 95%

CI=1.57-10.09, P=0.0035) in patients with early-stage NSCLC

receiving SBRT. Mechanistically, AKT/mTOR signaling deregulation

has been directly linked to chemoradiation resistance in lung

squamous cell carcinoma. Proteomics analysis of

chemoradiation-resistant patient-derived xenograft models and cell

lines has identified upregulated phosphorylated (p)-AKT and p-mTOR,

and mTOR kinase inhibitors have been shown to sensitize these

resistant cells to radiation (67). For KRAS-mutated NSCLC, single

targeting of PI3K often fails due to MEK/ERK-dependent Akt

reactivation. Dual inhibition of PI3K and MEK, however, can block

this compensatory signaling, impair DNA double-strand break repair

via non-homologous end joining, and significantly enhance

radiosensitivity (68).

Additionally, downstream effectors of PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling contribute to radioresistance through multiple routes.

For example, Akt/mTOR signaling-driven COX-2 overexpression fosters

radioresistance, and combining celecoxib (a COX-2 inhibitor) with

radiotherapy enhances apoptosis and prevents radioresistance

(69). Furthermore, SIRT6, an

epigenetic regulator, suppresses PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, and SIRT6

overexpression enhances radiosensitivity and inhibits tumor

progression in lung cancer (70).

Targeting these downstream nodes has shown promise. For example,

dysregulated PI3K/mTOR/EGFR crosstalk drives resistance, whereas

dual inhibitors targeting EGFR and PI3K/mTOR show selective

therapeutic benefit in lung cancer models, such as A549 cells

(71).

However, PI3K activity showed no significant

association with overall survival (P=0.49), regional recurrence

(P=0.15) or distant metastasis (P=0.85) according to a study by

Sebastian et al (66).

These results position PI3K activity as a potential biomarker for

predicting local recurrence and DFS in SBRT-treated NSCLC; however,

validation in larger multicenter cohorts remains essential to

confirm clinical applicability.

Autophagy is a key metabolic and homeostatic

mechanism that allows cells to adapt to environmental stress and

damage by degrading damaged organelles, misfolded proteins and

cellular debris, thereby preserving normal cellular function

(72). Under physiological

conditions, autophagy serves as a protective process essential for

clearing dysfunctional or senescent cellular components (73). In cancer cells, however, aberrant

activation of the mTOR signaling pathway suppresses autophagy,

allowing tumor cells to escape radiotherapy-induced damage

(74). Studies have indicated

that mTOR acts as a primary negative regulator of autophagy. It not

only inhibits autophagic flux but also enhances cancer cell

survival by promoting growth and metabolic reprogramming, thereby

fostering resistance to antitumor therapies such as radiotherapy

(75,76).

Collectively, these studies underline the dual role

of autophagy in lung cancer therapy and highlight the central

regulatory role of mTOR in autophagic processes. Co-targeting

autophagy and mTOR-associated signaling pathways may offer a more

effective strategy to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of

radiotherapy in lung cancer.

miRNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs that serve

pivotal roles in regulating gene expression and are frequently

dysregulated in diverse types of cancer (86). Studies have revealed that miRNAs

markedly contribute to tumorigenesis, progression and

radioresistance by modulating cancer cell proliferation, migration,

invasion and apoptosis, highlighting their potential value in early

diagnosis, prognosis prediction and therapeutic intervention

(87-89). In NSCLC, aberrant miRNA expression

profoundly impacts mTOR signaling pathway activity, thereby

influencing radiotherapy outcomes (Table III).

miRNAs frequently promote radioresistance by

suppressing tumor suppressor genes that regulate the mTOR pathway.

For example, miR-410, which is commonly upregulated in cancer,

promotes EMT and radioresistance by targeting PTEN to activate the

PI3K/mTOR axis (90-92). OE of miR-410 has been shown to be

positively associated with EMT-related markers (such as E-cadherin

downregulation and vimentin upregulation) and negatively associated

with PTEN expression. Genetic knockdown of miR-410 can suppress EMT

and enhance radiosensitivity, suggesting it may serve as a

potential biomarker or therapeutic target in NSCLC radiotherapy.

Restoring PTEN expression or administering mTOR inhibitors could

reverse miR-410-induced EMT and radioresistance, offering novel

strategies for NSCLC-targeted therapy. Similarly, miR-181a reduces

NSCLC radiosensitivity by suppressing the expression of PTEN, a

negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (93). miR-21 also reduces NSCLC

radiosensitivity by targeting programmed cell death 4 to activate

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling (94).

Furthermore, Huang et al (95) revealed that circular PVT1 promotes

radioresistance by acting as a competing endogenous RNA to

sequester miR-1208, subsequently reactivating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway.

Conversely, miRNAs downregulated in lung cancer

enhance NSCLC radiosensitivity by directly targeting mTOR. For

example, miR-99a acts via mTOR as it is highly expressed in

radiation-sensitive A549 cells compared with resistant

counterparts. Its OE enhances radiosensitivity, whereas its

inhibition induces resistance in vitro and in vivo

(96). Similarly, miR-101-3p is

commonly downregulated in NSCLC tissues and cell lines (97), and modulates radiosensitivity via

mTOR. Li et al (98)

showed that in radiation-resistant A549R cells, miR-101-3p

upregulation can increase radiosensitivity; however, this effect is

attenuated by high mTOR activity, whereas its inhibition induces

resistance that can be reversed by rapamycin. This confirms that

miR-101-3p downregulation drives resistance by activating mTOR,

consistent with the mechanism of miR-99a. Another example is

miR-208a, which promotes cell proliferation and radioresistance in

NSCLC by targeting the AKT/mTOR pathway (99). Collectively, these studies

highlight mTOR as a core mediator of miRNA-regulated NSCLC

radiosensitivity, supporting co-targeting mTOR and these miRNAs as

a promising strategy to optimize lung cancer radiotherapy.

Although most research on mTOR and radioresistance

focuses on NSCLC, this pathway is also pivotal in highly aggressive

and resistant SCLC. The mechanisms underlying radioresistance in

SCLC often involve unique metabolic and epigenetic vulnerabilities,

as well as oncogene-driven signaling crosstalk (Table IV).

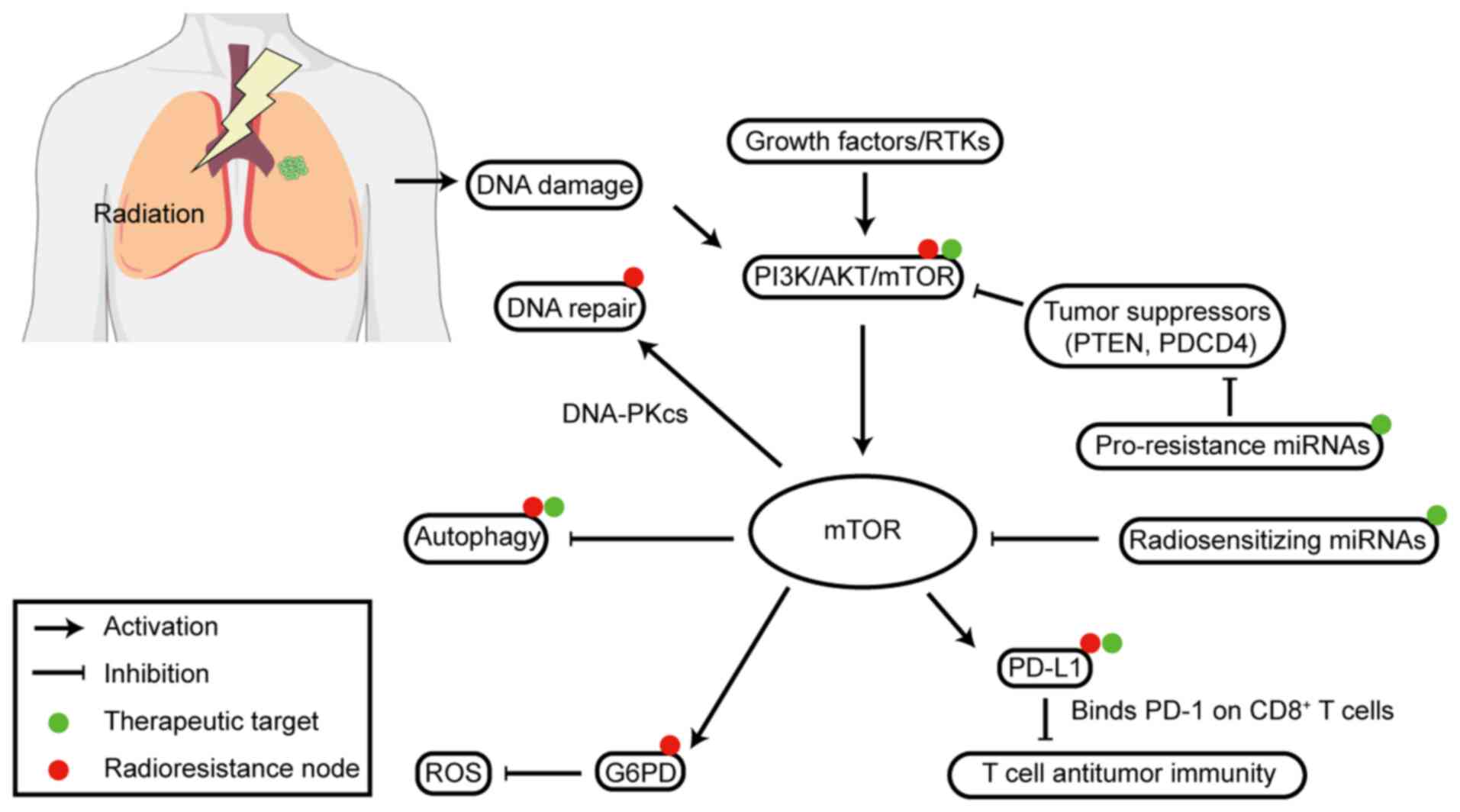

Metabolically, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway actively

influences glucose metabolism to drive SCLC radioresistance

(100,101). In SCLC models, dual PI3K/mTOR

inhibitors (such as, BEZ235 and GSK2126458) promote autophagic

degradation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD). G6PD is

the rate-limiting enzyme in the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP),

which is a key survival mechanism for SCLC cells. Disrupting the

PPP via G6PD degradation increases reactive oxygen species

accumulation and oxidative stress damage, ultimately enhancing IR

cytotoxicity and overcoming radioresistance (102). Additionally, SCLC frequently

harbors the MYC oncogene amplification, which drives aggressive

proliferation and mediates resistance to mTOR inhibitors such as

everolimus through the eIF4E axis (54).

Beyond metabolic and MYC-driven resistance, adaptive

survival pathways are another critical mTOR-related resistance

mechanism in SCLC. Therapy-induced DNA stress activates

compensatory pathways, such as PARP inhibition and SCLC DNA repair

strategies, which upregulate PI3K/mTOR. This feedback loop,

possibly via reduced LKB1 signaling, limits PARP inhibitor efficacy

alone (103,104). This highlights the use of mTOR

targeting to overcome SCLC therapy resistance. Additionally, in

lung cancer research, targeting hypoxia/HIF-1α via PI3K/Akt/mTOR

with Hsp90 inhibitors combined with radiotherapy blocks

radiation-induced HIF-1α stabilization and enhances antitumor

effects (105). Carbon ion

radiotherapy also attenuates HIF-1 signaling and mTOR induction

(106). In drug-resistant NSCLC,

CXCR4 inhibition eliminates cancer stem-like cells via

STAT3/Akt/mTOR signaling (107).

Furthermore, disrupting the NRF2-CHML-mTOR axis by CHML knockdown

inhibits NSCLC progression and overcomes chemo/radioresistance

(108). Moreover, rapamycin

combined with irradiation enhances lung cancer radiosensitivity and

protects normal lung cells (109). The activation of mTOR to counter

DNA damage in SCLC supports the combination of mTOR inhibitors with

DNA-damaging agents, such as radiation, highlighting the use of

mTOR targeting to overcome SCLC.

The mTOR pathway acts as a key regulator of T-cell

differentiation and function; therefore, its activity within tumor

cells and the tumor immune microenvironment is critical for

therapeutic responses.

Oncogenic activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is

strongly associated with the transcriptional and translational

regulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on the

membranes of lung cancer cells (110). This drives immune evasion, as

PD-L1 binds to PD-1 on T cells to suppress antitumor immunity.

Common NSCLC mutations, such as EGFR and KRAS, activate this

pathway and subsequently increase PD-L1 expression, while

inhibiting mTOR can downregulate PD-L1, theoretically

're-sensitizing' tumors to immune attack (111).

Although mTOR inhibitors (rapalogs) are known as

immunosuppressants, they also function as immunomodulators that

promote antitumor responses, notably by expanding memory

CD8+ T cells. This dual role provides a strong rationale

for combination therapy as preclinical lung cancer models confirm

that pairing an mTOR inhibitor with a PD-1 antibody can markedly

reduce tumor growth and increase tumor-infiltrating T cells

(112). Targeting mTOR signaling

alongside immune checkpoints may therefore offer a potent

synergistic strategy for overcoming radioresistance and achieving

systemic antitumor effects (113).

mTOR drives lung cancer radioresistance via the

PI3K/AKT axis. It regulates key processes such as DNA repair, miRNA

activity, autophagy and PD-L1-mediated immune evasion. Clear

radiosensitizing targets have been identified to counter these

resistance mechanisms (Fig. 3).

Notably, single mTOR inhibition shows limited clinical efficacy and

requires combination with other therapies (such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1

and autophagy modulators) (79,110). Future efforts should focus on

validating biomarkers, which may aid the development of

personalized regimens and improve radiotherapy benefits for

patients with lung cancer.

mTOR inhibitors target the mTOR pathway, which is

critical for regulating cell proliferation, metabolism and

survival. These inhibitors hold broad therapeutic potential across

multiple diseases, including autoimmune disorders, endocrine

conditions and cancer (114,115). Aberrant activation of the mTOR

signaling pathway serves a notable role in radioresistance in

NSCLC. By targeting this pathway, mTOR inhibitors demonstrate

marked antitumor potential. Specifically, they enhance tumor cell

radiosensitivity and counteract resistance caused by dysregulated

mTOR signaling. Furthermore, combining mTOR inhibitors with

radiotherapy generates synergistic antitumor effects, amplifying

therapeutic efficacy.

Preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated

the radiosensitizing potential of mTOR inhibitors. For example,

Ushijima et al (116)

assessed the impact of the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus on

radioresistance under hypoxic conditions, using the A549 human lung

adenocarcinoma cell line. This previous study revealed that while

the D (10) value (dose required

to kill 90% of cells) for A549 cells was 14.2 Gy under hypoxia, the

combination with temsirolimus reduced this to 5.4 Gy (oxygen

enhancement ratio=1.1), demonstrating its ability to suppress

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression and overcome hypoxia-induced

radioresistance. These findings position temsirolimus as a

radiosensitizer for hypoxic tumors. Another study (117) reported that the mTOR inhibitor

everolimus exerts radiosensitizing effects by inducing

G2/M phase arrest in A549 cells. However, rapamycin

pretreatment was shown to abolish this arrest 8 h

post-radiotherapy. Early clinical trials also support this

strategy. In a phase I clinical trial (118) assessing temsirolimus combined

with thoracic radiotherapy (35 Gy/14f) in patients with NSCLC,

among the eight evaluable patients, three achieved partial

responses and two exhibited stable disease. These results

underscore the preclinical and clinical synergy between mTOR

inhibitors and radiotherapy, highlighting their potential to

improve treatment outcomes.

mTOR inhibitors are classified into three

generations based on their mechanisms of action. First-generation

inhibitors consist of antibiotic-derived allosteric inhibitors,

including rapamycin and its derivatives such as temsirolimus,

everolimus and ridaforolimus. Second-generation inhibitors are

ATP-competitive inhibitors that selectively target the active

kinase site of mTOR. These molecules, termed selective mTOR kinase

inhibitors, achieve complete blockade of both mTORC1 and mTORC2,

thereby preventing phosphorylation of PKB. Third-generation

inhibitors, known as RapaLink, are hybrid molecules formed by

conjugating the ATP-competitive inhibitor sapanisertib to rapalog

macrocycles via diverse linker chains. Structurally, this design

mimics a dual-inhibitor strategy, and such hybrid agents overcome

resistance arising from monotherapy with rapalogs or

ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors. Furthermore, their multitarget

activity enhances drug selectivity and therapeutic efficacy

(119,120). By integrating rapamycin with

mTOR kinase inhibitors, third-generation compounds exhibit superior

antitumor potency and reduced off-target toxicity (Table V) (121).

Clinical investigations have explored these

different generations of inhibitors. First-generation rapalogs have

been evaluated extensively in combination strategies for NSCLC.

Early phase trials assessed rapamycin with sunitinib (122) and temsirolimus with pemetrexed

(123). Other studies examined

ridaforolimus in patients with NSCLC harboring KRAS mutations

(124) or evaluated everolimus

in a translational study for resectable NSCLC (125). This combination approach

continues to evolve with more rationale-driven pairings, such as

the investigation of nab-sirolimus with the KRAS G12C inhibitor

adagrasib (126). In parallel,

second-generation dual mTORC1/mTORC2 kinase inhibitors have

advanced into clinical studies. Initial first-in-human and

dose-escalation studies have established the safety and

tolerability of monotherapies such as AZD2014 (127) and CC-223 (128) in patients with advanced solid

tumors. This development subsequently informed strategies to

combine these potent dual inhibitors with other targeted agents,

such as pairing the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor SAR245409 with the MEK

inhibitor pimasertib (129) or

combining the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor gedatolisib (PF-05212384) with

the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (PD-0332991) (130). In summary, mTOR inhibitors

demonstrate substantial promise in enhancing the efficacy of

radiotherapy for lung cancer. By advancing the understanding of the

molecular mechanisms underlying the mTOR signaling pathway and

refining therapeutic strategies, more effective treatment regimens

can be developed for patients with NSCLC, ultimately improving

clinical outcomes and prognosis.

Despite promising preclinical evidence for mTOR

inhibition, several critical limitations and controversies must be

addressed to ensure successful clinical translation. The key

challenge lies in the notable disparity between the robust body of

preclinical mechanistic evidence and the limited clinical outcomes

achieved to date, which necessitates a realistic perspective on the

field. Most current research comes from in vitro studies and

xenograft models. This raises concerns about whether conclusions

can be reliably generalized to heterogeneous human tumors.

Furthermore, although a number of clinical trials investigating

mTOR inhibitors have been completed (Table V), the results often represent

preliminary phase I studies focused predominantly on determining

safety and maximum tolerated dose, rather than definitive efficacy.

A major therapeutic challenge stems from the complexity of the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR network (131):

First-generation inhibitors (rapalogs) are mostly cytostatic with

modest single-agent efficacy. Their inhibition of mTORC1 fails to

suppress a negative feedback loop, leading to paradoxical AKT

phosphorylation and activation. This AKT activation sustains cell

survival and proliferation, limiting the clinical use of rapalogs

as monotherapy and requiring combination or dual-targeting agents

(45,115,132-134). Compounding this, although the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is frequently dysregulated in lung cancer,

the utility of biomarkers for patient selection remains

context-dependent; while PIK3CA mutations have been shown to

predict rapalog sensitivity in breast cancer models, PTEN loss of

function is not consistently associated with sensitivity, and

co-occurring oncogenic drivers (such as HER2 mutations) can further

obscure predictive value (135,136). The lack of standardized, broadly

validated biomarkers that account for such context-specificity

still presents a notable barrier to robust patient stratification

and therapeutic guidance in clinical trials.

Additionally, mTOR inhibitors are associated with a

unique spectrum of adverse events, including metabolic

disturbances, mucositis, fatigue, and pulmonary complications such

as pneumonitis and dyspnea (137-140). Critically, the long-standing use

of rapalogs as immunosuppressants in transplant patients raises

concerns that their immunosuppressive properties could counteract

desired anticancer effects, particularly when combining mTOR

inhibition with immunotherapies designed to enhance antitumor

immunity (141,142). Collectively, these limitations,

from pathway redundancy and biomarker gaps to toxicity and

immunological conflicts, highlight the need for further research to

optimize mTOR-targeted strategies and overcome barriers to

effective clinical translation.

The role of mTOR in lung cancer radioresistance has

been extensively studied and well-established. The present review

summarizes the mechanisms driving aberrant activation of the mTOR

signaling pathway in lung cancer and its influence on radiotherapy

resistance. Specifically, mTOR markedly enhances tumor cell

radioresistance by regulating multiple biological processes,

including cellular proliferation, autophagy, DNA repair, miRNA

regulation and EMT. Furthermore, mTOR drives adaptive resistance by

regulating metabolic resilience and promoting immune evasion

through PD-L1 expression.

Although mTOR inhibitors hold considerable promise

in lung cancer radiotherapy, several challenges remain. For

example, drug resistance may arise as tumor cells evade mTOR

inhibitor activity through activation of alternative signaling

pathways or compensatory mechanisms. Consequently, combination

therapies, such as co-administration with PI3K or MEK inhibitors,

may represent effective strategies to overcome resistance.

Additionally, mTOR inhibitors are associated with toxicity and side

effects, including metabolic disturbances and immunosuppression,

necessitating further optimization of dosing regimens and

therapeutic protocols.

Not applicable.

XP, HL, YL, and HW conceptualized the study. XP

wrote the manuscript. LY and HW reviewed the manuscript. XP, HL, YL

and HW contributed to manuscript editing. Data authentication is

not applicable. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82272758 and 82273466), the Hunan

Cancer Hospital Climb Plan (grant nos. ZX2020001 and ZX2020005),

the Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department (grant no.

2023ZJ1125), the Hunan Provincial Health High-Level Talent

Scientific Research Project (grant no. R2023057) and the National

Key Clinical Specialty Scientific Research Project (grant no.

Z2023025).

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lehrer EJ, Singh R, Wang M, Chinchilli VM,

Trifiletti DM, Ost P, Siva S, Meng MB, Tchelebi L and Zaorsky NG:

Safety and survival rates associated with ablative stereotactic

radiotherapy for patients with oligometastatic cancer: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 7:92–106. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gonsalves D, Ocanto A, Martín M and

Couñago F: Radiotherapy in early stages of lung cancer. Revisiones

en Cancer. 37:133–147. 2023.

|

|

4

|

Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q,

Hjelmeland AB, Dewhirst MW, Bigner DD and Rich JN: Glioma stem

cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA

damage response. Nature. 444:756–760. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bache M, Kadler F, Struck O, Medenwald D,

Ostheimer C, Güttler A, Keßler J, Kappler M, Riemann A, Thews O, et

al: Correlation between Circulating miR-16, miR-29a, miR-144 and

miR-150, and the Radiotherapy response and survival of

non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci. 24:128352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Laplante M and Sabatini DM: mTOR signaling

in growth control and disease. Cell. 149:274–293. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Panwar V, Singh A, Bhatt M, Tonk RK,

Azizov S, Raza AS, Sengupta S, Kumar D and Garg M: Multifaceted

role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in

human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3752023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wei F, Liu Y, Guo Y, Xiang A, Wang G, Xue

X and Lu Z: MiR-99b-targeted mTOR induction contributes to

irradiation resistance in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 12:812013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Woo Y, Lee HJ, Jung YM and Jung YJ:

MTOR-mediated antioxidant activation in solid tumor

radioresistance. J Oncol. 2019:59568672019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yu CC, Hung SK, Lin HY, Chiou WY, Lee MS,

Liao HF, Huang HB, Ho HC and Su YC: Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway as an effectively radiosensitizing strategy for

treating human oral squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo.

Oncotarget. 8:68641–68653. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wanigasooriya K, Tyler R, Barros-Silva JD,

Sinha Y, Ismail T and Beggs AD: Radiosensitising cancer using

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (AKT) or

mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors. Cancers (Basel).

12:12782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mardanshahi A, Gharibkandi NA, Vaseghi S,

Abedi SM and Molavipordanjani S: The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling

pathway inhibitors enhance radiosensitivity in cancer cell lines.

Mol Biol Rep. 48:1–14. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Feng YQ, Gu SX, Chen YS, Gao XD, Ren YX,

Chen JC, Lu YY, Zhang H and Cao S: Virtual screening and

optimization of novel mTOR inhibitors for radiosensitization of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug Des Devel Ther. 14:1779–1798. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ihlamur M, Akgül B, Zengin Y, Korkut ŞV,

Kelleci K and Abamor EŞ: The mTOR signaling pathway and mTOR

inhibitors in cancer: Next-generation inhibitors and approaches.

Curr Mol Med. 24:478–494. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Vézina C, Kudelski A and Sehgal SN:

Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of

the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle.

J Antibiot (Tokyo). 28:721–726. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Pignataro G, Capone D, Polichetti G,

Vinciguerra A, Gentile A, Di Renzo G and Annunziato L:

Neuroprotective, immunosuppressant and antineoplastic properties of

mTOR inhibitors: Current and emerging therapeutic options. Curr

Opin Pharmacol. 11:378–394. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Drenan RM, Liu X, Bertram PG and Zheng XF:

FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein or mammalian target of

rapamycin (FRAP/mTOR) localization in the endoplasmic reticulum and

the Golgi apparatus. J Biol Chem. 279:772–778. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Helfenberger KE, Argentino GF, Benzo Y,

Herrera LM, Finocchietto P and Poderoso C: Angiotensin II regulates

mitochondrial mTOR pathway activity dependent on Acyl-CoA

synthetase 4 in adrenocortical cells. Endocrinology.

163:bqac1702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen Y and Zhou X: Research progress of

mTOR inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 208:1128202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ali M, Bukhari SA, Ali M and Lee HW:

Upstream signalling of mTORC1 and its hyperactivation in type 2

diabetes (T2D). BMB Rep. 50:601–609. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang G, Chen L, Qin S, Zhang T, Yao J, Yi

Y and Deng L: Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1: From a

nutrient sensor to a key regulator of metabolism and health. Adv

Nutr. 13:1882–1900. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Workman JJ, Chen H and Laribee RN:

Environmental signaling through the mechanistic target of rapamycin

complex 1: mTORC1 goes nuclear. Cell Cycle. 13:714–725. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yoon MS: The role of mammalian target of

rapamycin (mTOR) in insulin signaling. Nutrients. 9:11762017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lamming DW, Ye L, Katajisto P, Goncalves

MD, Saitoh M, Stevens DM, Davis JG, Salmon AB, Richardson A, Ahima

RS, et al: Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by

mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science. 335:1638–1643.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen

JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL and Sabatini DM: Prolonged

rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell.

22:159–168. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang W, Tan J, Liu X, Guo W, Li M, Liu X,

Liu Y, Dai W, Hu L, Wang Y, et al: Cytoplasmic endonuclease G

promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via mTORC2-AKT-ACLY and

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Commun. 14:62012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Peng H, Kasada A, Ueno M, Hoshii T,

Tadokoro Y, Nomura N, Ito C, Takase Y, Vu HT, Kobayashi M, et al:

Distinct roles of Rheb and Raptor in activating mTOR complex 1 for

the self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 495:1129–1135. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Miricescu D, Totan A, Stanescu-Spinu II,

Badoiu SC, Stefani C and Greabu M: PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

in breast cancer: From molecular landscape to clinical aspects. Int

J Mol Sci. 22:1732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Inoki K, Kim J and Guan KL: AMPK and mTOR

in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol

Toxicol. 52:381–400. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chun Y and Kim J: AMPK-mTOR signaling and

cellular adaptations in hypoxia. Int J Mol Sci. 22:97652021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lama-Sherpa TD, Jeong MH and Jewell JL:

Regulation of mTORC1 by the Rag GTPases. Biochem Soc Trans.

51:655–664. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kim SJ, DeStefano MA, Oh WJ, Wu CC,

Vega-Cotto NM, Finlan M, Liu D, Su B and Jacinto E: mTOR complex 2

regulates proper turnover of insulin receptor substrate-1 via the

ubiquitin ligase subunit Fbw8. Mol Cell. 48:875–887. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sural-Fehr T, Singh H, Cantuti-Catelvetri

L, Zhu H, Marshall MS, Rebiai R, Jastrzebski MJ, Givogri MI,

Rasenick MM and Bongarzone ER: Inhibition of the

IGF-1-PI3K-Akt-mTORC2 pathway in lipid rafts increases neuronal

vulnerability in a genetic lysosomal glycosphingolipidosis. Dis

Model Mech. 12:dmm0365902019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lazorchak AS and Su B: Perspectives on the

role of mTORC2 in B lymphocyte development, immunity and

tumorigenesis. Protein Cell. 2:523–530. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li X and Gao T: mTORC2 phosphorylates

protein kinase Cζ to regulate its stability and activity. EMBO Rep.

15:191–198. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Baffi TR, Lordén G, Wozniak JM, Feichtner

A, Yeung W, Kornev AP, King CC, Del Rio JC, Limaye AJ, Bogomolovas

J, et al: mTORC2 controls the activity of PKC and Akt by

phosphorylating a conserved TOR interaction motif. Sci Signal.

14:eabe45092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Carter CC, Mast FD, Olivier JP, Bourgeois

NM, Kaushansky A and Aitchison JD: Dengue activates mTORC2

signaling to counteract apoptosis and maximize viral replication.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 12:9799962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Katholnig K, Schütz B, Fritsch SD,

Schörghofer D, Linke M, Sukhbaatar N, Matschinger JM, Unterleuthner

D, Hirtl M, Lang M, et al: Inactivation of mTORC2 in macrophages is

a signature of colorectal cancer that promotes tumorigenesis. JCI

Insight. 4:e1241642019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mehta D, Rajput K, Jain D, Bajaj A and

Dasgupta U: Unveiling the role of mechanistic target of rapamycin

kinase (MTOR) signaling in cancer progression and the emergence of

MTOR inhibitors as therapeutic strategies. ACS Pharmacol Transl

Sci. 7:3758–3779. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Qiu W, Ren M, Wang C, Fu Y and Liu Y: The

clinicopathological and prognostic significance of mTOR and p-mTOR

expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A

meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 101:e323402022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zeng AQ, Chen X, Dai Y and Zhao JN:

Betulinic acid inhibits non-small cell lung cancer by repolarizing

tumor-associated macrophages via mTOR signaling pathway. Zhongguo

Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 49:2376–2384. 2024.In Chinese. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Granville CA, Warfel N, Tsurutani J,

Hollander MC, Robertson M, Fox SD, Veenstra TD, Issaq HJ, Linnoila

RI and Dennis PA: Identification of a highly effective rapamycin

schedule that markedly reduces the size, multiplicity, and

phenotypic progression of tobacco carcinogen-induced murine lung

tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 13:2281–2289. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Raskova Kafkova L, Mierzwicka JM,

Chakraborty P, Jakubec P, Fischer O, Skarda J, Maly P and Raska M:

NSCLC: From tumorigenesis, immune checkpoint misuse to current and

future targeted therapy. Front Immunol. 15:13420862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bang J, Jun M, Lee S, Moon H and Ro SW:

Targeting EGFR/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Pharmaceutics. 15:21302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wu YY, Wu HC, Wu JE, Huang KY, Yang SC,

Chen SX, Tsao CJ, Hsu KF, Chen YL and Hong TM: The dual PI3K/mTOR

inhibitor BEZ235 restricts the growth of lung cancer tumors

regardless of EGFR status, as a potent accompanist in combined

therapeutic regimens. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:2822019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Xu L, Ding R, Song S, Liu J, Li J, Ju X

and Ju B: Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the mechanism of

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway activation in lung adenocarcinoma

by KRAS mutation. J Gene Med. 26:e36582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ducray SP, Natarajan K, Garland GD, Turner

SD and Egger G: The transcriptional roles of ALK fusion proteins in

tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel). 11:10742019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhao T, Fan J, Abu-Zaid A, Burley SK and

Zheng XFS: Nuclear mTOR signaling orchestrates transcriptional

programs underlying cellular growth and metabolism. Cells.

13:7812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Qian J, Zhang X

and Yu K: A Novel mTORC1/2 Inhibitor (MTI-31) inhibits tumor

growth, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, metastases, and improves

antitumor immunity in preclinical models of lung cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 25:3630–3642. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Marinov M, Ziogas A, Pardo OE, Tan LT,

Dhillon T, Mauri FA, Lane HA, Lemoine NR, Zangemeister-Wittke U,

Seckl MJ and Arcaro A: AKT/mTOR pathway activation and BCL-2 family

proteins modulate the sensitivity of human small cell lung cancer

cells to RAD001. Clin Cancer Res. 15:1277–1287. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Li X, Li C, Guo C, Zhao Q, Cao J, Huang

HY, Yue M, Xue Y, Jin Y, Hu L and Ji H: PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling

orchestrates the phenotypic transition and chemo-resistance of

small cell lung cancer. J Genet Genomics. 48:640–651. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

He C: Activating invasion and metastasis

in small cell lung cancer: Role of the tumour immune

microenvironment and mechanisms of vasculogenesis,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, cell migration, and organ

tropism. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 7:e700182024.

|

|

53

|

Fiorentino FP, Tokgün E, Solé-Sánchez S,

Giampaolo S, Tokgün O, Jauset T, Kohno T, Perucho M, Soucek L and

Yokota J: Growth suppression by MYC inhibition in small cell lung

cancer cells with TP53 and RB1 inactivation. Oncotarget.

7:31014–31028. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Matsumoto M, Seike M, Noro R, Soeno C,

Sugano T, Takeuchi S, Miyanaga A, Kitamura K, Kubota K and Gemma A:

Control of the MYC-eIF4E axis plus mTOR inhibitor treatment in

small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 15:2412015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chang L, Graham PH, Ni J, Hao J, Bucci J,

Cozzi PJ and Li Y: Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in the

treatment of prostate cancer radioresistance. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol. 96:507–517. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liu N and Wang P: Development of

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and hypofractionated radiotherapy

in non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Clin Oncol. 40:1196–1198.

2013.In Chinese.

|

|

57

|

Glaviano A, Foo ASC, Lam HY, Yap KCH,

Jacot W, Jones RH, Eng H, Nair MG, Makvandi P, Geoerger B, et al:

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies

in cancer. Mol Cancer. 22:1382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM and

Sabatini DM: Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the

rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 307:1098–1101. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Huang J, Chen L, Wu J, Ai D, Zhang JQ,

Chen TG and Wang L: Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

in the treatment of human diseases: Current status, trends, and

solutions. J Med Chem. 65:16033–16061. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Schuurbiers OC, Kaanders JH, van der

Heijden HF, Dekhuijzen RP, Oyen WJ and Bussink J: The

PI3-K/AKT-pathway and radiation resistance mechanisms in non-small

cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 4:761–767. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Toulany M, Iida M, Keinath S, Iyi FF,

Mueck K, Fehrenbacher B, Mansour WY, Schaller M, Wheeler DL and

Rodemann HP: Dual targeting of PI3K and MEK enhances the radiation

response of K-RAS mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget.

7:43746–43761. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhang T, Cui GB, Zhang J, Zhang F, Zhou

YA, Jiang T and Li XF: Inhibition of PI3 kinases enhances the

sensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer cells to ionizing

radiation. Oncol Rep. 24:1683–1689. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chen K, Shang Z, Dai AL and Dai PL: Novel

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors plus radiotherapy: Strategy for

non-small cell lung cancer with mutant RAS gene. Life Sci.

255:1178162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kim SY, Jeong EH, Lee TG, Kim HR and Kim

CH: The combination of trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, and

temsirolimus, an mTOR Inhibitor, radiosensitizes lung cancer cells.

Anticancer Res. 41:2885–2894. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

He GH, Xing DJ, Jin D, Lu Y, Guo L, Li YL

and Li D: Scutellarin improves the radiosensitivity of non-small

cell lung cancer cells to iodine-125 seeds via downregulating the

AKT/mTOR pathway. Thorac Cancer. 12:2352–2359. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sebastian NT, Webb A, Shilo K, Robb R,

Xu-Welliver M, Haglund K, Brownstein J, DeNicola GM, Shen C and

Williams TM: A PI3K gene expression signature predicts for

recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer treated with

stereotactic body radiation therapy. Cancer. 129:3971–3977. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Choi EJ, Ryu YK, Kim SY, Wu HG, Kim JS,

Kim IH and Kim IA: Targeting epidermal growth factor

receptor-associated signaling pathways in non-small cell lung

cancer cells: Implication in radiation response. Mol Cancer Res.

8:1027–1036. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Holler M, Grottke A, Mueck K, Manes J,

Jücker M, Rodemann HP and Toulany M: Dual Targeting of Akt and

mTORC1 impairs repair of DNA double-strand breaks and increases

radiation sensitivity of human tumor cells. PLoS One.

11:e01547452016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhang P, He D, Song E, Jiang M and Song Y:

Celecoxib enhances the sensitivity of non-small-cell lung cancer

cells to radiation-induced apoptosis through downregulation of the

Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and COX-2 expression. PLoS One.

14:e02237602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Xiong L, Tan B, Lei X, Zhang B, Li W, Liu

D and Xia T: SIRT6 through PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway to

enhance radiosensitivity of non-Small cell lung cancer and inhibit

tumor progression. IUBMB Life. 73:1092–1102. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Hamid MB, Serafin AM and Akudugu JM:

Selective therapeutic benefit of X-rays and inhibitors of EGFR,

PI3K/mTOR, and Bcl-2 in breast, lung, and cervical cancer cells.

Eur J Pharmacol. 912:1746122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Levine B and Kroemer G: Autophagy in the

pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 132:27–42. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Biswas U, Roy R, Ghosh S and Chakrabarti

G: The interplay between autophagy and apoptosis: Its implication

in lung cancer and therapeutics. Cancer Lett. 585:2166622024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Gargalionis AN, Papavassiliou KA and

Papavassiliou AG: Implication of mTOR Signaling in NSCLC:

Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Cells. 12:20142023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Loizzo D, Pandolfo SD, Rogers D, Cerrato

C, di Meo NA, Autorino R, Mirone V, Ferro M, Porta C, Stella A, et

al: Novel insights into autophagy and prostate cancer: A

comprehensive review. Int J Mol Sci. 23:38262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang J, Gong M, Fan X, Huang D, Zhang J

and Huang C: Autophagy-related signaling pathways in non-small cell

lung cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 477:385–393. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Kim KW, Hwang M, Moretti L, Jaboin JJ, Cha

YI and Lu B: Autophagy upregulation by inhibitors of caspase-3 and

mTOR enhances radiotherapy in a mouse model of lung cancer.

Autophagy. 4:659–668. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Fei HR, Tian H, Zhou XL, Yang MF, Sun BL,

Yang XY, Jiao P and Wang FZ: Inhibition of autophagy enhances

effects of PF-04691502 on apoptosis and DNA damage of lung cancer

cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 78:52–62. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Yan J, Xie Y, Wang F, Chen Y, Zhang J, Dou

Z, Gan L, Li H, Si J, Sun C, et al: Carbon ion combined with

tigecycline inhibits lung cancer cell proliferation by inducing

mitochondrial dysfunction. Life Sci. 263:1185862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Kim KW, Moretti L, Mitchell LR, Jung DK

and Lu B: Combined Bcl-2/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition

leads to enhanced radiosensitization via induction of apoptosis and

autophagy in non-small cell lung tumor xenograft model. Clin Cancer

Res. 15:6096–6105. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Kim EJ, Jeong JH, Bae S, Kang S, Kim CH

and Lim YB: mTOR inhibitors radiosensitize PTEN-deficient

non-small-cell lung cancer cells harboring an EGFR activating

mutation by inducing autophagy. J Cell Biochem. 114:1248–1256.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Kim KW, Myers CJ, Jung DK and Lu B:

NVP-BEZ-235 enhances radiosensitization via blockade of the

PI3K/mTOR pathway in cisplatin-resistant non-small cell lung

carcinoma. Genes Cancer. 5:293–302. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Liang N, Zhong R, Hou X, Zhao G, Ma S,

Cheng G and Liu X: Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) participates

in the regulation of ionizing radiation-induced cell death via

MAPK14 in lung cancer H1299 cells. Cell Prolif. 48:561–572. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zhang X, Ji J, Yang Y, Zhang J and Shen L:

Stathmin1 increases radioresistance by enhancing autophagy in

non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 9:2565–2574.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lai C, Zhang J, Tan Z, Shen LF, Zhou RR

and Zhang YY: Maf1 suppression of ATF5-dependent mitochondrial

unfolded protein response contributes to rapamycin-induced

radio-sensitivity in lung cancer cell line A549. Aging (Albany NY).

13:7300–7313. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

He B, Zhao Z, Cai Q, Zhang Y, Zhang P, Shi

S, Xie H, Peng X, Yin W, Tao Y and Wang X: Mirna-based biomarkers,

therapies, and resistance in cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 6:2628–2647.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra

E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA,

et al: MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature.

435:834–838. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S,

Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, et

al: A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines

cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:2257–2261. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Avvari S, Prasad DKV and Khan IA: Role of

MicroRNAs in cell growth proliferation and tumorigenesis. Role of

MicroRNAs in Cancers. Prasad D and Santosh Sushma P: Springer;

Singapore: pp. 37–51. 2022, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Chen Y, Li WW, Peng P, Zhao WH, Tian YJ,

Huang Y, Xia S and Chen Y: mTORC1 inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus)

enhances non-small cell lung cancer cell radiosensitivity in vitro

via suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Acta Pharmacol

Sin. 40:1085–1094. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Yuan Y, Liao H, Pu Q, Ke X, Hu X, Ma Y,

Luo X, Jiang Q, Gong Y, Wu M, et al: miR-410 induces both

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and radioresistance through

activation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5:852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Li T, Wei L, Zhang X, Fu B, Zhou Y, Yang

M, Cao M, Chen Y, Tan Y, Shi Y, et al: Serotonin Receptor HTR2B

facilitates colorectal cancer metastasis via CREB1-ZEB1

axis-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cancer Res.

22:538–554. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Chen Y, Liao W, Yuan A, Xu H, Yuan R and

Cao J: MiR-181a reduces radiosensitivity of non-small-cell lung

cancer via inhibiting PTEN. Panminerva Med. 64:374–383. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Jiang LP, He CY and Zhu ZT: Role of

microRNA-21 in radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer cells

by targeting PDCD4 gene. Oncotarget. 8:23675–23689. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Huang M, Li T, Wang Q, Li C, Zhou H, Deng

S, Lv Z, He Y, Hou B and Zhu G: Silencing circPVT1 enhances

radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer by sponging

microRNA-1208. Cancer Biomark. 31:263–279. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Yin H, Ma J, Chen L, Piao S, Zhang Y,

Zhang S, Ma H, Li Y, Qu Y, Wang X and Xu Q: MiR-99a enhances the

radiation sensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer by targeting

mTOR. Cell Physiol Biochem. 46:471–481. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Meng X, Sun Y, Liu S and Mu Y: miR-101-3p

sensitizes lung adenocarcinoma cells to irradiation via targeting

BIRC5. Oncol Lett. 21:2822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Li Z, Qu Z, Wang Y, Qin M and Zhang H:

miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to

irradiation. Open Med (Wars). 15:413–423. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Tang Y, Cui Y, Li Z, Jiao Z, Zhang Y, He

Y, Chen G, Zhou Q, Wang W, Zhou X, et al: Radiation-induced

miR-208a increases the proliferation and radioresistance by

targeting p21 in human lung cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

35:72016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Deng H, Chen Y, Li P, Hang Q, Zhang P, Jin

Y and Chen M: PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, hypoxia, and glucose

metabolism: Potential targets to overcome radioresistance in small

cell lung cancer. Cancer Pathog Ther. 1:56–66. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Liu B, Huang ZB, Chen X, See YX, Chen ZK

and Yao HK: Mammalian target of rapamycin 2 (MTOR2) and C-MYC

modulate glucosamine-6-phosphate synthesis in glioblastoma (GBM)

cells through glutamine: fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase 1

(GFAT1). Cell Mol Neurobiol. 39:415–434. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Deng H, Chen Y, Wang L, Zhang Y, Hang Q,

Li P, Zhang P, Ji J, Song H, Chen M and Jin Y: PI3K/mTOR inhibitors

promote G6PD autophagic degradation and exacerbate oxidative stress

damage to radiosensitize small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis.

14:6522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Cardnell RJ, Feng Y, Mukherjee S, Diao L,

Tong P, Stewart CA, Masrorpour F, Fan Y, Nilsson M, Shen Y, et al:

Activation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway following PARP Inhibition in

small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 11:e01525842016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Knelson EH, Patel SA and Sands JM: PARP

inhibitors in small-cell lung cancer: Rational combinations to

improve responses. Cancers (Basel). 13:7272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Kim WY, Oh SH, Woo JK, Hong WK and Lee HY:

Targeting heat shock protein 90 overrides the resistance of lung

cancer cells by blocking radiation-induced stabilization of

hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Cancer Res. 69:1624–1632. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Subtil FS, Wilhelm J, Bill V, Westholt N,

Rudolph S, Fischer J, Scheel S, Seay U, Fournier C, Taucher-Scholz

G, et al: Carbon ion radiotherapy of human lung cancer attenuates

HIF-1 signaling and acts with considerably enhanced therapeutic

efficiency. FASEB J. 28:1412–1421. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Jung MJ, Rho JK, Kim YM, Jung JE, Jin YB,

Ko YG, Lee JS, Lee SJ, Lee JC and Park MJ: Upregulation of CXCR4 is

functionally crucial for maintenance of stemness in drug-resistant

non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 32:209–221. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Dodson M, Dai W, Anandhan A, Schmidlin CJ,

Liu P, Wilson NC, Wei Y, Kitamura N, Galligan JJ, Ooi A, et al:

CHML is an NRF2 target gene that regulates mTOR function. Mol

Oncol. 16:1714–1727. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Zheng H, Wang M, Wu J, Wang ZM, Nan HJ and

Sun H: Inhibition of mTOR enhances radiosensitivity of lung cancer

cells and protects normal lung cells against radiation. Biochem

Cell Biol. 94:213–220. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Lastwika KJ, Wilson W III, Li QK, Norris

J, Xu H, Ghazarian SR, Kitagawa H, Kawabata S, Taube JM, Yao S, et

al: Control of PD-L1 expression by oncogenic activation of the

AKT-mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res.

76:227–238. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Xiao P, Sun LL, Wang J, Han RL, Ma Q and

Zhong DS: LKB1 gene inactivation does not sensitize non-small cell

lung cancer cells to mTOR inhibitors in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

36:1107–1112. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Li H, Li X, Liu S, Guo L, Zhang B, Zhang J

and Ye Q: Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) checkpoint blockade in

combination with a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor

restrains hepatocellular carcinoma growth induced by hepatoma

cell-intrinsic PD-1. Hepatology. 66:1920–1933. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Dong L, Lv H, Li W, Song Z, Li L, Zhou S,

Qiu L, Qian Z, Liu X, Feng L, et al: Co-expression of PD-L1 and

p-AKT is associated with poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma via PD-1/PD-L1 axis activating intracellular AKT/mTOR

pathway in tumor cells. Oncotarget. 7:33350–33362. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Chiarini F, Evangelisti C, McCubrey JA and

Martelli AM: Current treatment strategies for inhibiting mTOR in

cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 36:124–135. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Mohindra NA and Platanias LC: Catalytic

mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors as antineoplastic agents.

Leuk Lymphoma. 56:2518–2523. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Ushijima H, Suzuki Y, Oike T, Komachi M,

Yoshimoto Y, Ando K, Okonogi N, Sato H, Noda SE, Saito J and Nakano

T: Radio-sensitization effect of an mTOR inhibitor, temsirolimus,

on lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells under normoxic and hypoxic

conditions. J Radiat Res. 56:663–668. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Chen H, Ma Z, Vanderwaal RP, Feng Z,

Gonzalez-Suarez I, Wang S and Zhang J, Roti Roti JL, Gonzalo S and

Zhang J: The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin suppresses DNA double-strand

break repair. Radiat Res. 175:214–224. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Waqar SN, Robinson C, Bradley J, Goodgame

B, Rooney M, Williams K, Gao F and Govindan R: A phase I study of

temsirolimus and thoracic radiation in non-small-cell lung cancer.

Clin Lung Cancer. 15:119–123. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Waldner M, Fantus D, Solari M and Thomson

AW: New perspectives on mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin, rapalogs and

TORKinibs) in transplantation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 82:1158–1170.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Dancey J: MTOR signaling and drug

development in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 7:209–219. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Occhiuzzi MA, Lico G, Ioele G, De Luca M,

Garofalo A and Grande F: Recent advances in PI3K/PKB/mTOR

inhibitors as new anticancer agents. Eur J Med Chem.

246:1149712023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Waqar SN, Gopalan PK, Williams K,

Devarakonda S and Govindan R: A phase I trial of sunitinib and

rapamycin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

Chemotherapy. 59:8–13. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Waqar SN, Baggstrom MQ, Morgensztern D,

Williams K, Rigden C and Govindan R: A Phase I Trial of

temsirolimus and pemetrexed in patients with advanced non-small

cell lung cancer. Chemotherapy. 61:144–147. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Riely GJ, Brahmer J, Planchard D, Crinò L,

Doebele RC, Lopez LAM, Gettinger SN, Schumann C, Li X, Atkins BM,

et al: A randomized discontinuation phase II trial of ridaforolimus

in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with KRAS mutations.

J Clin Oncol. 30(Suppl 15): 75322011.

|

|

125

|

National Library of Medicine: Adagrasib in

Combination With Nab-Sirolimus in Patients With Advanced Solid

Tumors. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer With a KRAS G12C Mutation

(KRYSTAL-19). ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05840510. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05840510.

|

|

126

|

Owonikoko TK, Ramalingam SS, Miller DL,

Force SD, Sica GL, Mendel J, Chen Z, Rogatko A, Tighiouart M,

Harvey RD, et al: A translational, pharmacodynamic, and

pharmacokinetic phase IB clinical study of everolimus in resectable

non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 21:1859–1868. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Bendell JC, Kelley RK, Shih KC, Grabowsky

JA, Bergsland E, Jones S, Martin T, Infante JR, Mischel PS,

Matsutani T, et al: A phase I dose-escalation study to assess

safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary efficacy of

the dual mTORC1/mTORC2 kinase inhibitor CC-223 in patients with

advanced solid tumors or multiple myeloma. Cancer. 121:3481–3490.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Basu B, Dean E, Puglisi M, Greystoke A,

Ong M, Burke W, Cavallin M, Bigley G, Womack C, Harrington EA, et

al: First-in-human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the

dual m-TORC 1/2 inhibitor AZD2014. Clin Cancer Res. 21:3412–3419.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Heist RS, Infante JR, Campana F, Egile C,

Jego V, Damstrup L, Mita M, Grande E and Rizv N: 443O-Pimasertib

(Pim) and Sar245409 (Sar)-a Mek and Pi3K/Mtor inhibitor

combination: A Phase Ib trial with expansions in selected

genotype-defined solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 25(Suppl 4): iv1462014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

National Library of Medicine: Study of the

CDK4/6 Inhibitor Palbociclib (PD-0332991) in Combination With the

PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor Gedatolisib (PF-05212384) for Patients With

Advanced Squamous Cell Lung Pancreatic, Head & Neck Other Solid

Tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT03065062. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03065062.

|

|

131

|

McCay J and Gribben JG: PI3 kinase, AKT,

and mTOR inhibitors. Precision Cancer Therapies. O'Connor OA,

Ansell SM and Seymour JF: 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; pp.

113–129. 2023

|

|

132

|

Saran U, Foti M and Dufour JF: Cellular

and molecular effects of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus. Clin Sci

(Lond). 129:895–914. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, Okaniwa M, Yao Z,

Novotny CJ, McWhirter C, Banaji A, Won H, Wong W, Berger M, de

Stanchina E, et al: Overcoming mTOR resistance mutations with a

new-generation mTOR inhibitor. Nature. 534:272–276. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Porcelli L, Quatrale AE, Mantuano P,

Silvestris N, Rolland JF, Biancolillo L, Paradiso A and Azzariti A:

Synergistic antiproliferative and antiangiogenic effects of EGFR

and mTOR inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des. 19:918–926. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

135

|

Weigelt B, Warne PH and Downward J: PIK3CA

mutation, but not PTEN loss of function, determines the sensitivity

of breast cancer cells to mTOR inhibitory drugs. Oncogene.

30:3222–3233. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Sanaei MJ, Razi S, Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi A

and Bashash D: The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in lung cancer; oncogenic

alterations, therapeutic opportunities, challenges, and a glance at

the application of nanoparticles. Transl Oncol. 18:1013642022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Soria JC, Jappe A,

Jehl V, Klimovsky J and Johnson BE: Everolimus and erlotinib as

second- or third-line therapy in patients with advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 7:1594–1601. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Ponticelli C: The pros and the cons of

mTOR inhibitors in kidney transplantation. Expert Rev Clin Immunol.

10:295–305. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

139

|

Boers-Doets CB, Raber-Durlacher JE,

Treister NS, Epstein JB, Arends AB, Wiersma DR, Lalla RV, Logan RM,

van Erp NP and Gelderblom H: Mammalian target of rapamycin