Oncolytic viruses (OVs) represent an innovative

approach in cancer therapy, characterized by their ability to

selectively lyse tumor cells while sparing adjacent normal tissues.

They also potentiate the anti-tumor immune response through the

release of tumor-associated antigens and the activation of

inflammatory pathways within the tumor microenvironment (TME)

(1). Preclinical toxicology

studies have demonstrated that OVs exhibit low toxicity and high

tolerability (2). To date, five

OVs have successfully undergone clinical translation (3), including the oncolytic adenovirus

H101, talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), Rigvir, G47Δ and

nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg. They show significant potential in

clinical applications (4-8). However, in solid tumors, factors

such as abnormal lymphatic structures, high vascular permeability,

a dense extracellular matrix and the requirement for OVs to

traverse the endothelial layer to reach target cells collectively

reduce the penetration range of OVs. Additionally, interactions

between OVs and antigen-presenting cells can trigger innate immune

responses and antiviral immunity, increasing the likelihood of

clearance by the host's immune system (9). Another key obstacle is the

heterogeneity of tumors, which leads to incomplete responses to

specific monotherapies (10).

These limitations hinder the widespread clinical translation of OV

therapy.

Targeted therapy functions by selectively

interacting with specific sites to inhibit enzymes and growth

factor receptors essential for proliferation, inducing apoptosis in

cancer cells and modulating gene expression, thereby altering

protein functions in normal cells to disrupt pathways associated

with carcinogenesis and tumor progression (11). However, due to genetic

alterations, adaptive responses or bypass mechanisms that allow

cancer cells to endure the selective pressure exerted by the

treatment, resistance may be acquired, which limits the long-term

efficacy and developmental potential of targeted therapies

(12).

Previously research indicates that the integration

of OVs with targeted therapeutics can inhibit tumor initiation and

progression through various mechanisms, effectively overcoming the

limitations associated with OVs and targeted drug monotherapies,

thereby enhancing the overall efficacy of cancer treatment. As a

result, combination therapy is gradually becoming one of the

leading approaches in oncology. Earlier reviews mainly explained

the basic principles and potential strategies of combining OVs with

key cellular signaling pathway modulators in cancer, without

categorizing the specific mechanisms (13). Certain reviews have summarized the

progress of OVs in combination with various therapies, such as

chemotherapy, radiotherapy and mainly novel immunotherapies like

immune checkpoint inhibitors (10,14,15). This article primarily elaborates

on the mechanisms and progress of OVs combined with targeted drugs,

categorizing them according to different mechanisms, while further

exploring how to select more rational combination approaches based

on the characteristics of different tumors, such as OVs targeting

tumor surface nonspecific and specific receptors and monitoring of

mutated targets. By discussing the differences between human and

mouse immune systems, potential combination toxicities and their

solutions, as well as future strategies to address drug resistance,

the article highlights key points for translating preclinical

research into clinical applications. Based on the above

discussions, it connects preclinical evidence with trial design

elements such as patient selection criteria, recommended endpoints

and overlapping toxicity safety monitoring, providing a valuable

reference for the future clinical translation of OVs combined with

targeted drugs.

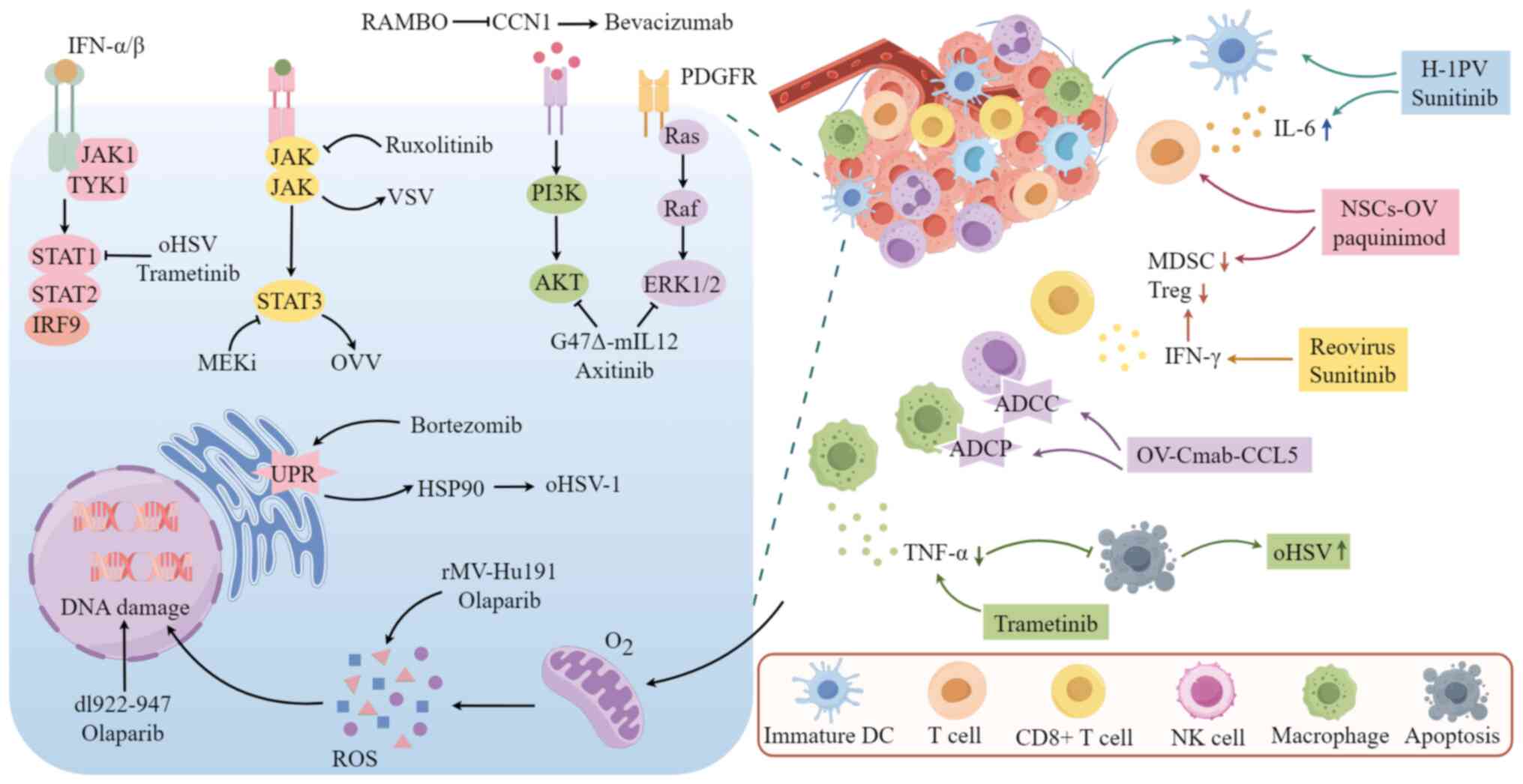

The mechanism of action of OVs combined with

molecularly targeted drugs is mainly related to signaling pathways,

immune responses, DNA damage, apoptosis and autophagic cell death.

In this chapter, a detailed explanation of the above will be

provided.

Inhibiting key targets in signaling pathways related

to cell proliferation can enhance the replication of OVs and their

oncolytic effects, thereby exerting antitumor activity. The

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), Janus kinase (JAK)/signal

transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) and

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathways are

jointly involved in regulating cell proliferation, differentiation,

survival and apoptosis, with complex crosstalk between them. MAPK

kinase (MEK) is one of the key targets in the MAPK signaling

pathway (16). Lee et al

(17) demonstrated that

inhibiting MEK phosphorylation can activate STAT3, thereby

promoting oncolytic vaccinia virus (OVV) replication in

doxorubicin-resistant ovarian cancer and enhancing the anti-tumor

effects. STAT3 activation also promotes the replication of

oncolytic herpes simplex virus (oHSV) in glioma cells (18). MEK inhibitors also suppress the

antiviral response facilitated by IFN signaling through

STAT1/STAT2-dependent pathways. IFNs orchestrate innate immune

responses, serving as a formidable first line of defense against

pathogen invasion (19). This

initiates a signaling cascade through the JAK-STAT pathway

(20). STAT1 and STAT2 play

pivotal roles in type I and type II IFN signaling, significantly

contributing to the cellular antiviral response and adaptive

immunity. The primary pathways through which IFNs exert their

antiviral effects include the oligoadenylate

synthetase-ribonuclease L system and the RNA-dependent protein

kinase (PKR) pathway, which degrade viral RNA and inhibit viral

protein synthesis, respectively. Zhou et al (21) found that trametinib boosts viral

replication in BRAF V600E and BRAF wild-type (wt)/KRAS mutated

tumor cells by reducing STAT1 and PKR phosphorylation.

Additionally, the JAK-1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib increases vesicular

stomatitis virus (VSV) replication by inhibiting the JAK/STAT

signaling pathway, enhancing its sensitivity in melanoma and lung

cancer (22,23). Targeting the Cysteine-rich 61

(CCN1)-AKT pathway can enhance bevacizumab's effectiveness by

reducing glioma infiltration. Elevated CCN1 expression is

associated with increased AKT phosphorylation in tumor cells

(24). Studies have shown that

CCN1 stimulates the expression of PI3K/AKT in various types of

cancer cells, including glioma, breast cancer, gastric cancer and

renal cancer cells (25-27). Rapid antiangiogenesis mediated by

oncolytic virus (RAMBO) is an engineered oHSV designed to express

angiogenesis inhibitors and is capable of suppressing the

expression of CCN1 (28). A study

found that the angiostatin produced by RAMBO can inhibit

bevacizumab-induced CCN1 expression, reducing bevacizumab-induced

glioma infiltration by blocking the CCN1-AKT signaling pathway,

thereby enhancing the efficacy of bevacizumab against malignant

gliomas (28).

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) synergistically

augments the antitumor efficacy of OVs by inhibiting the

phosphorylation of AKT, which are activated by OVs. G47Δ-mIL12, an

advanced version based on the third-generation oHSV-1 G47Δ,

enhancing tumor-specific replication and safety by deleting the α47

gene and US11 promoter to prevents class I major histocompatibility

complex (MHC) downregulation and inhibiting angiogenesis (4,29,30). Research conducted by indicates

that the selective TKI axitinib enhances the antitumor effect of

G47Δ-mIL12 in glioblastoma (GBM) by blocking the platelet-derived

growth factor receptor (PDGFR) pathway, inhibiting phosphorylated

ERK1/2 and reducing G47Δ-mIL12-induced AKT phosphorylation.

Furthermore, this combination also promotes apoptosis and affects

stem-like cell characteristics (31). TKI can also promote OV replication

by inhibiting the antiviral response mediated by IFN signaling.

Research by Jha et al (32) demonstrated that multi-target TKI

sunitinib weakens the antiviral response by inhibiting VSV-induced

activation of the IFN pathway, thereby enhancing VSV

replication.

IFN is also a key pathway in antiviral immunity, and

the transcription of IFN-regulated genes induced by the JAK/STAT

pathway inhibits OVs replication through multiple mechanisms

(19). By inhibiting the type I

IFN pathway to weaken the antiviral response of specific tumor

cells, thereby enhancing the spread and oncolytic activity of OVs

in tumor cells. Trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1), an antibody-drug

conjugate, consists of the targeted therapeutic agent trastuzumab

linked to the microtubule-disrupting agent and mertansine

derivative DM1. This conjugate primarily exerts its

microtubule-inhibiting effect in human EGFR2 (HER2)-overexpressing

tumor cells through the specific targeting of trastuzumab (33). Arulanandam et al (34) found that T-DM1 targets

HER2-overexpressing tumor cells to release DM1, which inhibits the

type I IFN pathway and enhances the cytotoxic effect of TNF-α on

neighboring cells, thereby increasing the spread and oncolytic

effect of the VSVΔ51 virus in VSV-resistant cancer cells. This

study did not emphasize the antitumor effect of trastuzumab itself

(34). In addition, IκB kinase

inhibitors BMS-345541 and TPCA-1 enhance VSV replication by

inhibiting type I IFN-mediated antiviral responses, thereby

improving the efficacy against glioma (35).

Targeted drugs combined with OVs enhance cytotoxic

effects on tumor cells in the TME by activating immune cells,

promoting cytokine release and reducing immunosuppression.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are immature myeloid cells

that expand in inflammation and tumors and are effective inhibitors

of T cell-mediated immune responses (36). Lawson et al (37) found that sunitinib can alleviate

immunosuppression induced by coxsackievirus, such as the

accumulation of MDSCs, and stimulate the number of

immune-stimulating cells, enhancing the anti-tumor immune response

in mouse renal cell carcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma.

Similarly, Moehler et al (38) found that sunitinib with H-1

parvovirus significantly boosts immune stimulation in melanoma.

S100A8/9 are low-molecular-weight calcium-binding proteins, which

can regulate the accumulation of MDSCs (39). Chai et al (40) confirmed that neural stem

cell-delivered OV combined with S100A8/9 inhibitor paquinimod

enhanced anti-GBM efficacy by increasing T-cell infiltration,

shifting macrophages to a pro-inflammatory phenotype and reducing

MDSCs. A recent study reported that KRAS inhibitors themselves

promote innate and adaptive immunity, and when combined with OVV,

they reduce immunosuppressive cells such as MDSCs and T-regulatory

cells (Tregs) in the TME, synergistically enhancing antitumor

effects (41).

TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) inhibitors promote OVs

replication and their sensitivity to resistant cells by enhancing

immune cell responses. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1)

is a cell surface receptor used by immune cells for adhesion and

migration, and it is often upregulated during viral infections

(42). TBK1 is a serine/threonine

kinase, and its increased expression or abnormal activity can

promote the survival and proliferation of cancer cells (43). Guo et al (44) reported that TBK1 inhibitors can

promote VSVΔ51 replication by enhancing ICAM-1-mediated natural

killer (NK) cell immunity and increase the sensitivity of VSVΔ51 to

chemoresistant colorectal cancer cells.

MEK inhibitors enhance viral replication by

decreasing TNF-α secretion and blocking its apoptotic effects. Due

to early cell death from TNF-α-induced apoptosis, the replication

and antitumor impact of oHSV-1 are limited (45). Yoo et al (46) discovered that the MEK inhibitor

trametinib inhibits apoptosis in GBM cells following oHSV infection

by reducing TNF-α levels, thereby promoting viral replication.

Furthermore, oHSV aids trametinib in crossing the blood-brain

barrier and prevents MAPK pathway reactivation, enhancing tumor

sensitivity to MEK inhibition.

Proteasome inhibition promotes OVs replication by

increasing the expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs). HSP90 has

previously been shown to be important for the nuclear localization

of HSV polymerase (47). In line

with this, Yoo et al (48)

found that in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian

cancer, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor and glioma, the

proteasome inhibitor bortezomib increases the expression of HSP90

by inducing unfolded protein response accumulation, thereby

promoting oHSV-1 replication and enhancing antitumor efficacy.

Using OVs to infect tumor cells allows targeted

drugs to be released and connects their targets with immune cell

receptors to enhance cell-killing effects. Tian et al

(49) created OV-Cmab-CCL5, an

oHSV encoding a bispecific fusion protein that combines cetuximab's

IgG1 form with C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5). This targets

EGFR and CCL5 receptors to increase CCL5 levels in tumors and boost

immune cell infiltration. It can also enhance the killing effect on

GBM cells by promoting antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis and

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity through linking Fcgamma

receptors on macrophages and NK cells with EGFR on tumor cells.

Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPi)

enhance antitumor effects by blocking DNA repair induced by OVs,

causing persistent DNA damage and promoting cancer cell death. The

dl922-947, a second-generation oncolytic adenovirus with a 24-base

pair deletion in the E1A-conserved region 2, enhances viral genome

production in host cells (50).

Passaro et al (51) found

that DNA damage induced by dl922-947 activates the PARP repair

mechanism in the DNA damage response signaling pathway, while the

PARPi olaparib can restore PARP activation induced by it and

exacerbate DNA damage, thereby promoting apoptosis and enhancing

the anti-tumor efficacy against thyroid cancer. The same antitumor

mechanism was observed in the treatment of melanoma with reovirus

type 3 Dearing strain (ReoT3D) combined with talazoparib (52). Recent research reports that PARP1

has been identified as a replication restriction factor for HSV-1,

and olaparib promotes viral replication by inhibiting PARP1,

thereby enhancing antitumor efficacy in GBM and triple-negative

breast cancer (53).

Furthermore, the combination of OVs and PARPi can

induce excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, leading

to increased DNA damage and S-phase arrest, thereby enhancing the

inhibition of tumor cell proliferation. While ROS are common in

cells, excessive ROS can cause cell death (54) and activate oncogenic pathways,

leading to DNA damage and genetic instability (55). PARPi can have antitumor effects by

increasing ROS and ROS-induced DNA damage (56,57). The measles virus (MV) is a

promising alternative virus (58), which has been proven to exert

oncolytic effects on ovarian cancer through ROS-induced apoptosis

(59). Zhang et al

(60) discovered that the

recombinant Chinese Hu191 MV (rMV-Hu191) modified by a viral

reverse genetic system, works with olaparib to enhance oxidative

DNA damage in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells by increasing

ROS levels. This combination also significantly halts the cell

cycle in the S phase and inhibits cell proliferation by blocking

DNA division (60).

In mammalian cells, p53 and cyclin-dependent kinases

jointly manage the G1/S transition, linking apoptosis to cell cycle

progression (61). Irinotecan is

a topoisomerase I inhibitor that can induce the expression and

phosphorylation of the tumor antigen p53, promoting the expression

of apoptosis-regulating factors (62). Napabucasin (BBI608) is a stem cell

inhibitor that can directly inhibit the transcription of

STAT3-derived genes and can also indirectly inhibit other related

genes and pathways (63). Babaei

et al (64) found that

combining ReoT3D, Irinotecan (CPT-11) and BBI608 significantly

reduced the S phase of CT26 cells, arrested them in G0/G1 and G2/M

phases, induced apoptosis by causing a sub-G1 fraction to form and

downregulated KRAS and STAT3 mRNA.

Autophagy is a fundamental biological process that

is crucial for preventing cellular damage, maintaining cell

survival during nutrient scarcity and responding to cytotoxic

stimuli. The regulation of autophagy by the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling

pathway allows tumors to exploit this process for survival benefits

through the dysregulation of the pathway (65-67). Everolimus (RAD001) is a widely

used mTOR inhibitor that targets mTOR complex 1 and inhibits

autophagy (68). Alonso et

al (69) demonstrated that

the combination of RAD001 with Delta-24-RGD, an oncolytic

adenovirus with a 24-base pair deletion in the E1A gene (70), induces autophagic cell death and

enhances anti-glioma efficacy, although the precise underlying

mechanism remains to be elucidated. The anti-angiogenic and

immunosuppressive properties of RAD001 may also contribute to these

outcomes. Furthermore, they revealed that Delta-24-RGD increases

glioma cell sensitivity to RAD001 by circumventing G1 phase arrest,

without impacting the replication of Delta-24-RGD, indicating an

additional potential anti-tumor mechanism.

The above content regarding composite molecular

machineries involves various targeted drugs that exhibit

significant differences in targets, mechanisms of action and tumor

sensitivity. MAPK inhibitors primarily act on kinases within the

MAPK pathway, such as BRAF, MEK and ERK. MEK inhibitors promote OVV

replication by activating STAT3 and can also increase viral

replication by reducing antiviral responses through the inhibition

of STAT activation. TKIs synergistically enhance antitumor effects

by reducing AKT phosphorylation activated by OVs, while OVs

engineered to specifically express endostatin can increase tumor

sensitivity to bevacizumab by inhibiting AKT. Pathway inhibitors

can also suppress targets related to the IFN antiviral pathway,

promoting OV replication. The presence of immunosuppressive cells

in the TME is also a key reason for poor efficacy. Targeted drugs

combined with OVs synergistically enhance antitumor effects by

boosting innate and adaptive immunity and reducing

immunosuppression. PARPi primarily target PARP enzymes responsible

for repairing double-strand DNA damage, exerting antitumor effects

by inducing sustained DNA damage through increased ROS and

inhibition of OV-induced DNA repair. Furthermore, OVs can synergize

with inhibitors related to apoptosis and autophagy pathways for

antitumor effects (Fig. 1). The

different characteristics of these inhibitors provide clearer

guidance for selecting targeted drugs in combination therapy.

Choosing the appropriate drugs based on tumors with different

target mutations can markedly enhance the precision and antitumor

efficacy of combination therapy. Due to the numerous molecular

target mutations in tumors, a wide variety of targeted drugs have

been developed and approved for use. However, the exploration of

combination studies remains limited, with the combined mechanisms

focusing only on major pathways such as MAPK, JAK/STAT and

PI3K/AKT. The Wnt, Notch and Hippo signaling pathways, which also

play important roles in multiple cancers (71-73), have not yet been reported, to the

best of our knowledge. The potential interactions between OVs and

the toxic side effects of the targeted drugs themselves could

reduce the therapeutic window and introduce unpredictable

pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. Furthermore, this strategy also

has some inherent limitations. Tumor heterogeneity may lead to

certain tumors being insensitive to both treatments, and since OVs

are mainly administered via local injection, their efficacy against

distant metastatic lesions is limited. The use of certain potent

apoptosis-inducing targeted drugs may prematurely eliminate OVs,

which in turn could restrict viral replication.

Research indicates that combining OVs with targeted

drugs is safer and more effective for treating solid tumors than

using them separately. Some animal studies suggest that small

molecule targeted drugs can hinder tumor growth by reducing

angiogenesis, interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) and barriers to OVs

reaching target cells. HF10 is a spontaneously occurring HSV-1

(74). Yamamura et al

(75) found that erlotinib and

HF10 work synergistically in a pancreatic cancer model by reducing

angiogenesis and IFP, leading to a higher intratumoral virus

distribution and significant tumor growth inhibition. Tan et

al (76) found that combining

the OV HF10 with bevacizumab improved tumor suppression compared to

either treatment alone in breast cancer models. This synergy was

linked to increased vascular permeability, VEGF-induced viral

replication in endothelial cells, immune attacks on infected

vessels, enhanced tumor hypoxia boosting viral protein synthesis

and increased apoptosis. Another study reported that bevacizumab in

combination with dl922-947 significantly inhibited tumor growth in

tumor xenografts in thyroid anaplastic carcinoma tumors and

increased the distribution of the virus in tumors (77). However, Mahller et al

(78) found that erlotinib in

combination with oHSV did not show enhanced antitumor effects in a

xenograft mouse model of human malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumor. The distribution of OVs is strongly influenced by the TME,

among which IFP is a great challenge to efficient virus

distribution, and tumor angiogenesis is one of the main causes of

high IFP.

The aforementioned preclinical studies have

demonstrated that the combination of OVs with small molecule

targeted therapies can partially overcome the barrier of the

endothelial layer, thereby facilitating the distribution and

replication of the virus within the tumor and enhancing its

anti-tumor efficacy. Animal models have further indicated that this

combination exhibits significant anti-tumor effects. However, the

precise molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain

unidentified, and it is elusive whether they align with the

mechanisms discussed in this article or involve alternative

pathways. Given the discrepancies between the TMEs in vivo

and in vitro, in vitro findings alone are

insufficient to substantiate the translation of these therapies

into clinical practice. Consequently, extensive preclinical

research, including exploratory studies on the mechanisms involved,

is necessary to advance the development of this combination

therapy.

Although the immune organs of humans and mice are

highly conserved in their macroscopic anatomical structure, there

are significant differences in the composition, distribution and

expression of key immune molecules in their immune cells (Table I) (79). Due to significant immune

differences between the TME of mouse tumor models and human

spontaneous tumors, their clinical application value is limited.

The discovery and application of immunodeficient mice provide a

crucial breakthrough for reconstructing the human immune system

in vivo, thereby accurately simulating the human TME. Their

development has undergone continuous iterative upgrades, evolving

from simple T-cell deficiencies (such as nude mice) to severe

combined immunodeficiency models with multiple functional

deficiencies in immune cells such as T, B and NK cells (79). Most of the research data in this

study are derived from this type of model. However, immunodeficient

mice completely lose the ability to initiate adaptive immune

responses, displaying severe defects in the innate immune system.

They are not suitable for studying the human immune system itself

or the diseases it participates in, but this is the primary

requirement for constructing humanized mouse models from

immunodeficient mice (80).

Humanized mice refer to immunodeficient mice co-implanted with

human tumors and immune components, which can realistically assess

the mechanisms of immune system activation and efficacy in

preclinical studies of OVs in combination with targeted drugs,

providing more optimized combination treatment strategies for

clinical trial design.

Certain OVs have the ability to preferentially

infect certain types of tumor cells before any modifications. This

natural tropism primarily depends on the specific binding between

viral surface proteins and specific receptors on the host cell

surface. Many tumor cells overexpress certain receptors required

for viral invasion. For example, the coxsackievirus and adenovirus

receptor (CAR) is expressed at low levels in normal tissues but is

often overexpressed in various malignancies, allowing

coxsackievirus and adenovirus to preferentially target and infect

these tumors such as laryngeal cancer, thyroid cancer, lung cancer

and female reproductive system tumors (81,82). CD46 is mainly present on the

surface of prostate cancer and bladder cancer and can be recognized

by adenoviruses and measles viruses (83-86). The expression of integrins in

tumor cells is usually abnormal, allowing various viruses such as

adenovirus, coxsackievirus and reovirus to enter cells through

integrin-associated ligands (87-91). Table II shows the natural affinity of

many viruses for nonspecific receptors on the surface of certain

tumor cells (Table II). It can

serve directly as a therapeutic option or as a framework for viral

modification. In addition to common receptors, the surface

receptors of different types of tumors also have their specific

characteristics. OVs Ankara-5T4, constructed to target the specific

receptors 5T4 for colorectal cancer, have shown higher specificity

and efficacy (92,93). In addition, colorectal cancer is

associated with gut microbiota dysbiosis, but there are no reports

on the genetic modification of OVs in relation to this connection

(94,95). R-405, designed to target the

prostate cancer-specific receptor prostate-specific membrane

antigen, also demonstrates strong antitumor effects (96,97). The development and research of OVs

targeting different tumor-specific receptors are shown in the table

(Table III). Therefore, we can

enable OVs to acquire the ability to bind new receptors and further

enhance tumor targeting by inserting antibody fragments or peptides

that specifically bind to tumor-associated antigens.

Over the past two decades, clinical research has

progressively investigated the integration of OVs with targeted

therapies, yielding promising outcomes in certain instances. A

meta-analysis encompassing 12 studies evaluated the objective

response rate, survival rate and incidence of adverse reactions in

cancer patients receiving a combination of OVs and conventional

therapy compared to conventional therapy alone. The findings

revealed that the combination therapy was significantly associated

with an increased objective response rate (ORR) (P=0.04) and a

higher incidence of grade ≥3 adverse reactions (P=0.02) and grade

≥3 neutropenia (P=0.01), although no significant difference in

survival was observed (98).

Nonetheless, further investigation is warranted. In a phase I trial

conducted by Hirooka et al (99), patients with histologically

confirmed locally advanced pancreatic cancer without distant

metastasis and unresectable tumors received one cycle of erlotinib

and gemcitabine, followed by intratumoral injection of HF10 under

endoscopic ultrasound guidance. The primary endpoint was safety

assessment and the secondary endpoint was efficacy evaluation. The

study results showed that among the 10 subjects, 2 experienced

serious adverse events unrelated to HF10, indicating that the doses

used in this trial were safe and effective. Among the 9 subjects

who completed all four HF10 injections, the overall response

included 3 partial responses, 4 patients with stable disease and 2

cases with progressive disease, with a median progression-free

survival (PFS) of 6.3 months and a median overall survival (OS) of

15.5 months, and 2 subjects were able to undergo surgical

resection. The results suggest the safety and efficacy of this

therapeutic approach (100).

However, the study only compared the efficacy between different

HF10 titers and did not set up a control group or erlotinib

monotherapy group, gemcitabine monotherapy group or erlotinib plus

gemcitabine to further demonstrate the superiority of HF10

injection after treatment with erlotinib and gemcitabine.

Sorafenib in combination with JX-594 has been

studied in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). JX-594 (Pexa-Vec) was

constructed by inserting human granulocyte-monocyte

colony-stimulating factor and lacZ into the thymidine kinase gene

region of the Wyeth strain vaccinia virus (101). After infecting tumor cells, it

can stimulate toll like receptors, activate dendritic cells (DCs),

increase NK, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and white blood cell

infiltration, and promote the secretion of a variety of cytokines,

such as IFN, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-12 (101). Heo et al (102) discovered that administering

JX-594 before sorafenib significantly inhibited tumor growth

compared to control and other treatment sequences in mouse models.

Encouraged by these findings, they tested this sequence in patients

with advanced HCC and found it to be well-tolerated, leading to

rapid and significant tumor necrosis, with a 50-100% increase in

tumor necrosis for patients who did not achieve durable objective

tumor remission with JX-594 alone completed JX-594 treatment, and

JX-594 was injected directly into the tumors under imaging guidance

(102). However, only 3 patients

were evaluated in this study and are not representative of the

entire HCC population, and did not set evaluation endpoints or

provide statistical analysis results, resulting in poor

generalizability of the results and reduced reliability,

potentially leading to misleading conclusions. Rare adverse events

could also not be detected. In a randomized, multicenter phase IIb

trial, intravenous injection of Pexa-Vec in patients with advanced

HCC who have progressed after sorafenib treatment or are intolerant

to sorafenib, OS is primarily being evaluated, with secondary

endpoints including time to progression (TTP), ORR, disease control

rate (DCR), time to symptomatic progression, safety, tolerability

and quality of life. The study results showed that Pexa-Vec was

generally well-tolerated, but there were no significant differences

in the evaluated endpoints, which may be due to a high dropout rate

preventing accurate assessment of the outcomes (103). In a phase Ⅲ, randomized,

open-label study, for patients with advanced HCC who have not

received systematic treatment, Pexa-Vec was first administered via

intratumoral injection, followed by sorafenib, to evaluate OS

compared to sorafenib alone. Secondary objectives included TTP,

PFS, ORR and DCR, as well as assessing and comparing the safety of

the two treatment groups. The study results showed that compared to

sorafenib alone, treatment with sorafenib following Pexa-Vec did

not show a statistically significant benefit and was less

effective, with a higher incidence of serious adverse events

(104). The study indicates that

the dosing sequence of JX-594 and sorafenib may impact their

effectiveness. Investigating the mechanisms behind their

interaction could advance the use of OVs with targeted drugs in

clinical research. Table IV

summarizes the study subjects, treatment methods, endpoints,

results and limitations of the aforementioned clinical studies on

OVs combined with targeted drugs and/or other chemotherapeutic

agents, as well as those have not reported results. There are

currently relatively few clinical trials of OVs combined with

targeted drugs, suggesting that there may be obstacles to clinical

translation and highlighting the importance of preclinical research

in clinical trials.

In some rare case studies, OVs combined with

molecularly targeted drugs can alleviate the patient's disease and

improve the prognosis. CF33-hNIS-anti-PD-L1 (CHECKvacc) is a novel

chimeric orthopoxvirus encoding a single-stranded variable fragment

of human sodium iodide symporter and anti-programmed cell death

ligand 1, with potent anticancer activity in triple-negative breast

cancer xenografts (105). A

pathology report reported that a patient with metastatic

triple-negative breast cancer progressed after multiple lines of

therapy with extensive skin metastases, received intratumoral

injection of CHECKvacc followed by sequential treatment with

trastuzumab deruxtecan, with a clinical complete response lasting 7

months and a DFS of 10 months, The tumor marker CA15-3 was

significantly reduced (106).

The patient's decision to cease therapy after multiple treatments

makes it unclear whether remission is solely due to the combination

therapy, requiring more research. A pathology report highlighted a

patient with advanced poorly differentiated rectal adenocarcinoma

and liver metastases who achieved complete remission and stable

disease for 7 years following FOLFOX-4 chemotherapy, bevacizumab

and Rigvir (107). However,

since most pathological reports are retrospective, issues of data

completeness and consistency cannot be verified, and they also have

disadvantages such as high selectivity, poor population

representativeness and a high risk of bias, and the results do not

represent the safety and efficacy of this combination in the

overall population, but can be linked to the existing literature as

a way to share lessons learned to help identify new trends and

potential uses.

Malignant tumors constitute the primary cause of

mortality worldwide, with their incidence continuously rising

(108). Therapeutic strategies,

encompassing surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and

targeted therapy, have progressed from monotherapy to combination

therapy to address tumor drug resistance (109,110). OVs have emerged as an innovative

approach to cancer treatment, distinguished by their

tumor-targeting capabilities, which minimize harm to normal cells

and reduce the occurrence of side effects. Clinical trials have not

reported any fatalities or severe adverse events attributable to OV

therapy, highlighting its favorable safety profile. However, the

inherent limitations of OVs may affect their therapeutic efficacy.

Targeted drugs can activate the phosphorylation of relevant targets

to promote viral replication, and inhibit pathway activation and

antiviral responses caused by OVs, thereby increasing OV

replication, distribution and oncolytic effects. This enhancement

may extend to other targets involved in tumorigenesis or immune

microenvironment regulation. The relationship between MEK and STAT3

leads to the inhibition of MEK promoting STAT3 activation, thereby

enhancing viral replication. Existing studies have reported a

negative correlation between ERK and STAT3 (111-113). This negative correlation has

been confirmed as a potential mechanism underlying the development

of drug resistance, suggesting that a similar mechanism may also

exist. Targeted drugs can also synergize with OVs to enhance

immunity, exacerbate DNA damage and promote tumor cell apoptosis,

exerting a strong antitumor effect. The diversity in the types and

mechanisms of action of targeted drugs, coupled with the variety of

OVs and the potential for their genetic modification, provides

numerous opportunities. These opportunities include the elimination

of factors that adversely affect their anti-tumor effects, as well

as the potential for synergistic and cumulative effects. Such

interactions underscore the promising prospects for the combined

use of OVs and targeted drugs. In addition to the simultaneous

administration of these therapeutic agents, researchers have also

developed genetically modified OVs that incorporate molecularly

targeted drugs. This innovative strategy seeks to leverage the

anti-tumor properties of both the targeted drugs and the OVs.

However, extensive genetic modifications limit the replication and

efficacy of the virus. Therefore, revisiting the fundamental

principles of virology and basic immunology is crucial for

rationally designing more effective oncolytic virus constructs

(114). Multiple preclinical

studies have confirmed that OVs combined with targeted drugs can

enhance anti-tumor immune responses through multiple mechanisms,

and initial results have been achieved in clinical trial progress.

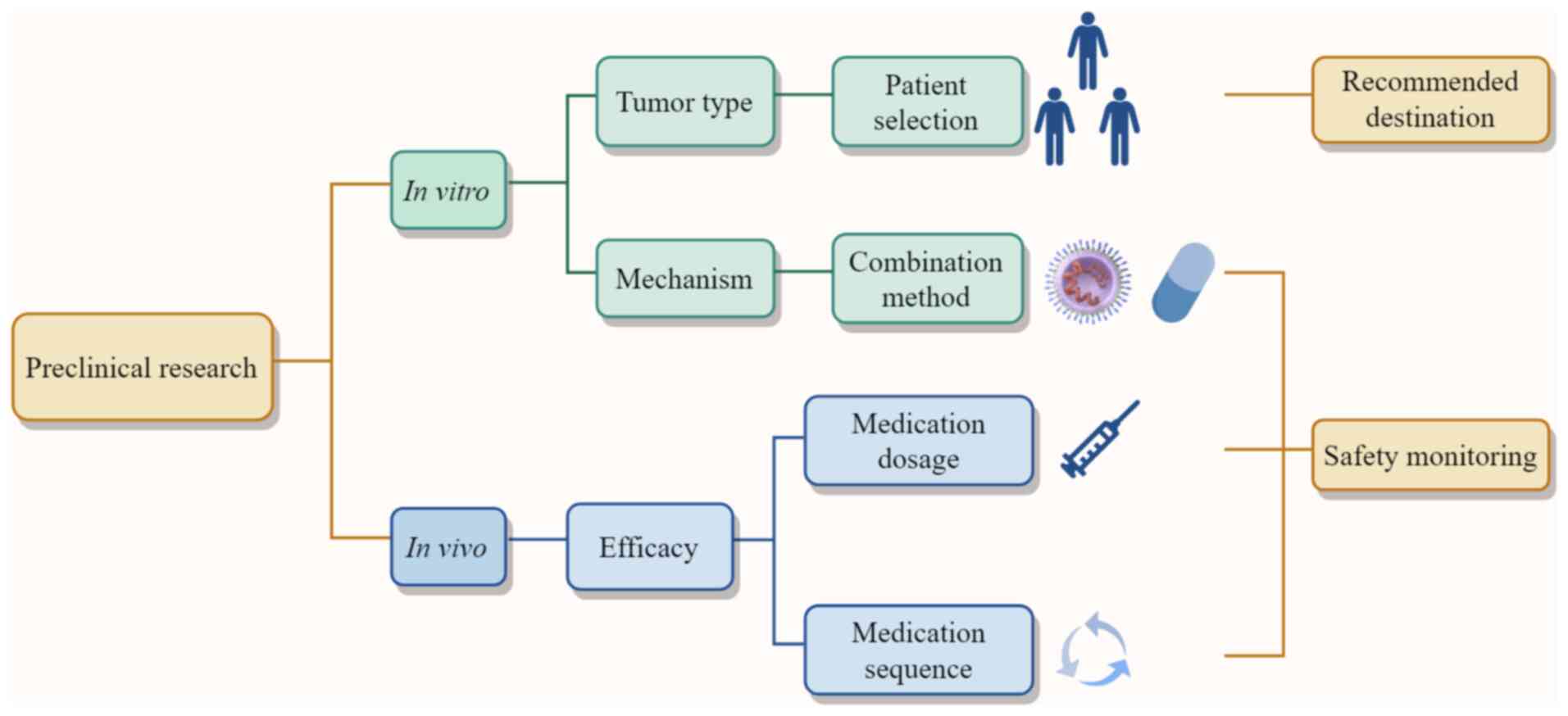

To this end, in the present study, preclinical evidence was

connected with trial design elements, including patient selection,

recommended endpoints, and overlapping toxicity safety monitoring,

to construct a clinical translation pathway (Fig. 2). Based on mechanisms of action,

potential combination strategies and priority tumor types can be

suggested, which in turn provides criteria for patient selection,

while the combined efficacy observed in animal models offers

guidance on drug dosage and administration sequence. Continuous

safety monitoring during these explorations may help prevent

serious adverse events caused by potential toxicities. How to

further optimize OVs and targeted drugs based on their own

characteristics and limitations to advance clinical trials more

effectively is a key focus for the future.

Overactivation of signaling pathways is a cause of

cancer pathogenesis, being involved in various tumors and playing a

critical role in guiding clinical treatment choices and

classification (115). Different

gene mutation statuses, such as EGFR and KRAS mutations in lung

adenocarcinoma, show significant differences in biological behavior

and clinicopathological features, leading to completely different

treatment options (116). In

breast cancer, classification is based on the expression of

estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2 (Luminal A,

Luminal B, HER2-positive, triple-negative), which directly

determines subsequent treatment strategies (117). Once the key signaling pathways

driving tumor growth are identified, targeted drugs can be

developed against critical nodes in these pathways. These pathways

can also serve as predictive markers for evaluating treatment

efficacy and prognosis. For instance, phosphatase and tensin

homolog protein loss leading to overactivation of the PI3K-AKT

pathway in prostate cancer generally indicates poor prognosis

(118). Single-cell RNA

sequencing suggests that the C2 insulin-like growth factor 2 tumor

subtype is associated with poor prognosis in high-grade serous

ovarian cancer, providing a promising target for future therapies

(119). Additionally, signaling

pathway targets can be used as monitoring indicators for studying

resistance mechanisms and adjusting treatment plans; analyzing

pathway changes through re-biopsy can reveal resistance mechanisms

and guide subsequent treatment. Approximately half of the

resistance to first-generation EGFR inhibitors is due to the

emergence of the secondary T790M mutation. To address this, the

third-generation EGFR inhibitor Osimertinib was developed, which

effectively overcomes T790M resistance and has become the standard

treatment option after resistance develops (120). Through time-of-flight cytometry,

it was found that AXL inhibition can induce JAK1-STAT3 signaling to

compensate for the loss of AXL, enhancing the potential for distant

metastasis in lung cancer (121). AXL is a member of the TAM

receptor family, typically overexpressed in cancers, and has become

a potential target for malignant tumors (122). The use of sequencing technology

to predict targeted drug targets has formed a set of multi-omics

integration strategies. By sequencing the genome, transcriptome and

by other omics, key genes related to diseases can be systematically

identified, and their potential as drug targets can be evaluated.

Advances in targeted drug development have led to new drugs

addressing various mutations, enhancing the effectiveness and

overcoming the limitations of older treatments. Consequently,

precise combination strategies based on molecular typing can

significantly enhance anti-tumor effects and reduce drug

resistance.

As the first line of defense against the invasion of

external pathogenic microorganisms, the antiviral response pathway,

in addition to the IFN pathway, The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase

(cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and

retinoic-acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I)/mitochondrial antiviral

signaling protein (MAVS), also play key roles in antiviral innate

immunity, belonging to the cellular stress response pathway. The

release of viral DNA and tumor cell nuclear DNA can activate the

cGAS-STING pathway, subsequently triggering a series of signaling

cascades, thereby inducing the production of type I IFNs and

initiating adaptive immune responses (123). However, in various cancers,

interruption or loss of the cGAS-STING pathway has been observed,

which prevents OVs from effectively activating this pathway,

resulting in a failure to initiate immune responses (124-126). The development of various STING

agonists has shown enhanced stability and efficacy in anti-tumor

applications (127-129). Sibal et al (130) found that the STING activator

2'3'-cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate (cGAMP)

combined with the attenuated HSV-1 strain C-REV could induce a more

sustained anti-tumor immune response, but they did not conduct an

in-depth analysis of how 2'3'-cGAMP affects the intracellular

process dynamics related to viral replication mechanisms (130). The RIG-I/MAVS pathway primarily

recognizes viral RNA in the cytoplasm. RIG-I has high affinity for

double-stranded (ds)RNA with three phosphates on the 5' end. After

binding, it also activates the transcription and expression of type

I IFNs and various pro-inflammatory cytokines (131). It was reported that HSV-1

infection induces mitochondrial damage and release of mitochondrial

DNA, which can trigger cGAS/STING/interferon regulatory factor 3

and RIG-I-MAVS signaling pathways, suggesting that the RIG-I-MAVS

pathway can recognize more than just viral RNA (132). Current research mainly focuses

on OVs transforming 'cold' tumors into 'hot' tumors and promoting

immune cell infiltration and tumor killing by activating the

cGAS-STING and RIG-I/MAVS pathway, generating a strong antitumor

immune response, and tumors lacking cGAS or STING expression are

more easily infected, thereby enhancing oncolytic activity

(133-137). However, if this pathway, which

is central to antiviral immunity, is excessively or prematurely

activated, it may lead to viral clearance, thereby weakening the

direct oncolytic effect of the virus. Precisely regulating the

balance between viral replication and immune activation is a major

challenge for studying the combined use of OVs and related pathway

activators. Furthermore, there are no reports in the literature on

whether specific inhibitors exist that can temporarily modulate

innate antiviral pathways to allow OV spread without causing

systemic immunosuppression, which may become a direction for future

research.

When OVs enter the body, their ability to induce a

strong anti-tumor immune response is also influenced by another key

factor. Previous research has indicated that OVs are swiftly

neutralized by antibodies upon entering the body, thereby

significantly diminishing their therapeutic efficacy (138,139). To overcome this challenge,

researchers have proposed employing vector delivery systems to

shield OVs from complement and neutralizing antibodies, thereby

enhancing tumor targeting. Polymer coatings (140) and cell-derived nanovesicles

(141) has been identified as

potential vectors for delivering OVs. Another promising approach

involves cell-based drug delivery systems, which provide advantages

such as extended drug circulation, improved efficacy, controlled

drug release and reduced immunogenicity and cytotoxicity (142). Furthermore, chimeric antigen

receptor T-cells have been reported as effective carriers for OVs,

offering significant advantages in OV therapy against distant

tumors (143). However, the

immunosuppressive mechanisms present within the TME may restrict

the effectiveness of T cells as OV vectors to tumors that are not

classified as immune deserts (144). By contrast, mesenchymal stem

cells have been extensively investigated as vectors for various

OVs, including oncolytic adenovirus, oncolytic HSV, oncolytic MV

and oncolytic reovirus (145).

This is attributed to their advantageous properties, such as tumor

homing, intrinsic anti-cancer capabilities, protection of OVs from

neutralizing antibodies and the ability to deliver viruses to tumor

sites via trojan horse strategies (146-148). The development and refinement of

targeted delivery systems for OVs substantially mitigate the risk

of clearance by the host immune system, thereby addressing some of

the challenges associated with combining OVs with molecular

targeted therapies and enhancing their anti-tumor efficacy.

However, in the development of targeted delivery systems, we must

consider not only the immunogenicity of the OVs themselves, but

also evaluate whether the delivery system could synergize with the

OVs to trigger potential risks such as cytokine storms. Therefore,

it is necessary to make a rational selection and modification of

the carrier. In addition, efficiently and stably assembling OVs

with the delivery system while maintaining the activity of both,

and achieving large-scale production at a relatively low cost,

remains a significant challenge.

The integration of OVs with molecularly targeted

therapies constitutes a promising domain for further exploration.

Current research predominantly focuses on preclinical trials, with

relatively few studies advancing to clinical trials. This limited

progression is likely due to the fact that many viruses do not

successfully advance beyond phase I trials (149), which are primarily designed to

assess safety and determine appropriate dosing parameters. To date,

only 13 viruses have exhibited adequate safety profiles and

preliminary clinical success to warrant progression to phase II

trials, which are intended to assess clinical efficacy (149). Current methodologies for drug

combination exhibit inherent limitations, such as the issue of

cumulative toxicity, necessitating further clinical trials to

ascertain their safety and efficacy. It is crucial to evaluate the

rationale behind these combination strategies and to optimize the

use of both the shared and unique properties of the drugs,

especially in cases where combinations are ineffective (114). Given that tumor cells frequently

develop resistance to monotherapies, employing a combination of

diverse therapeutic approaches may partially alleviate this

resistance (150-152). However, the potential

development of new drug resistance following combination therapy,

and the subsequent challenges it may pose to tumor eradication,

warrant further rigorous investigation and validation.

The efficacy of JX-594 in combination with sorafenib

in HCC mentioned in the aforementioned clinical study above is

affected by the order of administration, and priority

administration of JX-594 may be superior to sorafenib. The

underlying mechanisms may be related to the following factors.

Immune 'cold tumors' may be more dependent on OV to preferentially

initiate immunity (133-135). As a result, preferential

injection of OVs can induce immunogenic death of tumor cells,

release tumor-associated antigens, promote DC maturation, T-cell

infiltration and cytokine secretion, transform 'cold tumors' into

'hot tumors' and provide a more favorable immune environment for

subsequent targeted drugs to exert anti-tumor effects (136,153). Some targeted drugs may inhibit

OV replication, so prioritizing OV treatment ensures sufficient

viral spread and prevents targeted drugs from weakening its

oncolytic effect. When OVs are combined with certain antiangiogenic

drugs, which induced reduction in blood supply to tumors may limit

delivery of OV (154,155). Conversely, targeted drug

pretreatment can promote OV replication by downregulating the IFN

signaling pathway, a tumor cell defense mechanism (21,34). The use of immunomodulatory drugs

to remove immunosuppressive cells such as Tregs and relieve

immunosuppression may improve the efficacy of immunotherapy for OV

(37,40,41). IFP is one of the key factors

hindering the intratumoral distribution of OVs, and the prior use

of chemotherapy drugs such as cyclophosphamide can reduce tumor

IFP, further improve the intratumoral distribution of OV, and

enhance its oncolytic effect (156). Considering the above factors,

based on the dynamic changes of tumor characteristics, viral

characteristics, drug mechanism and TME, adjusting the order and

dose of drugs can enhance the anti-tumor effect.

OVs and targeted drugs each have their own toxic

effects, and when used in combination, careful consideration should

be given to whether potential additive toxicity could cause serious

adverse events. To date, the combination of therapies mentioned in

this study has not yet undergone clinical translation, and the

unique toxicities that may arise warrant attention. Protein kinase

inhibitors (PKIs) inhibit downstream signaling by targeting

specific oncogenic kinases and are one of the research focuses in

cancer therapy. However, most analyzed PKI product characteristic

summaries and European public assessment reports indicated severe

hepatotoxicity (157).

Furthermore, the hepatotoxicity caused by OVs themselves also needs

to be taken seriously when combined with targeted therapy.

Therefore, before treatment, patients at high risk of

hepatotoxicity should be identified through relevant biomarkers. In

addition, the nonspecific receptor CAR targeted by OVs is also

present in normal liver cells (158), and the virus can be genetically

engineered to avoid being taken up by the liver or infecting liver

cells.

Sunitinib, which is the most involved targeted drug

in mechanistic studies, shows a higher prevalence of reduced left

ventricular ejection fraction and bone marrow suppression (159). OVs therapy is generally not

considered to have significant bone marrow suppression

characteristics, and the incidence and severity of hematologic

toxicity are usually low. However, certain wild-type OVs, such as

oHSV-1, when administered locally to lesions, do not cause viremia,

but in rare cases, intravenous administration can lead to a strong

systemic immune response due to large-scale viral replication,

which may indirectly affect bone marrow function and result in

transient cytopenia (160). In

addition, bone marrow suppression is also the most common side

effect of PARPi (161).

Therefore, when considering the combination of sunitinib or PARPi

with OVs, the hematological toxicity caused by both should be of

concern. The complete blood count should be monitored regularly,

and when grade ≥3 toxicity occurs, it is usually necessary to

suspend treatment. Once recovery to grade ≤1 is achieved, the dose

needs to be reduced upon resuming to avoid irreversible

consequences.

Delta-24-RGD is commonly used for intratumoral

injection in the treatment of recurrent gliomas, with neurological

symptoms being the most common adverse events, such as headaches,

speech disorders and cerebral edema (70). ONC201 has shown significant

efficacy against certain high-grade gliomas in clinical trials, but

it can also lead to adverse events related to the nervous system

(162). The therapeutic effect

of their combined treatment on tumors is undeniable, but the

potential overlapping side effects on the central nervous system

should not be overlooked either. Furthermore, distinguishing

whether these neurological symptoms are caused by treatment-related

inflammation, which may indicate the effectiveness of the

treatment, or by the progression of the tumor itself, is crucial in

clinical practice and is also a challenge in management. Certain

wild-type viruses naturally have neurotropism, and by genetically

modifying these viruses, their ability to infect and damage normal

nerve cells can be significantly weakened (163-165).

At the same time, the size and location of the

tumor, previous treatment history such as radiotherapy that can

damage the blood-brain barrier, and pre-existing neurological

deficits may all amplify the neurotoxicity of combined therapy

(166). Bevacizumab combined

with RAMBO can enhance the efficacy against malignant glioma

through the CCN1-AKT pathway, but its dual anti-angiogenic effect

could significantly increase its impact on the vascular system,

excessively suppressing angiogenesis in both the tumor and

surrounding normal tissues, leading to tissue ischemia and necrosis

(167,168). Therefore, when conducting

further clinical research, the optimal order, dosage and interval

for administering the two drugs should be determined to balance

efficacy and toxicity. In addition, the new genes carried by the

genetically engineered recombinant oncolytic viruses may lead to

additional side effects. Based on studies of relevant OVs and the

toxicity of targeted drugs, future clinical development requires

cautious dose exploration and safety management.

In conclusion, the present study collected

literature on the mechanisms and clinical research of OVs combined

with targeted drugs over the past two decades. There may be

potential selection bias, while literature on this research area is

relatively sparse and outdated. Additionally, the weighting between

preclinical and clinical evidence is uneven and quantitative

synthesis of efficacy across studies is limited.

Not applicable.

SB and TS conceived the study and wrote the

manuscript, and conducted the literature search/selection and data

extraction. YT and QW revised and edited the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by the Guangxi Science and Technology

Program (grant nos. 2025GXNSFDA069034 and AD25069077), the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82260484, 81860459,

82360587 and 82560548), the Key Laboratory of Early Prevention and

Treatment for Regional High-Frequency Tumors at Guangxi Medical

University, Ministry of Education (grant nos. GKE-ZZ2023021 and

GKE-ZZ202407) and the Key Projects of Guangxi Natural Science

Foundation (grant no. 2024GXNSFDA010022). Additionally, support was

provided by the '139' Plan for Cultivating High-Level and Key

Talents in Guangxi Medicine, China (grant no. 201903036).

|

1

|

Ma R, Li Z, Chiocca EA, Caligiuri MA and

Yu J: The emerging field of oncolytic virus-based cancer

immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 9:122–139. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

2

|

Rasa A and Alberts P: Oncolytic virus

preclinical toxicology studies. J Appl Toxicol. 43:620–648. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Shalhout SZ, Miller DM, Emerick KS and

Kaufman HL: Therapy with oncolytic viruses: Progress and

challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:160–177. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Todo T, Ito H, Ino Y, Ohtsu H, Ota Y,

Shibahara J and Tanaka M: Intratumoral oncolytic herpes virus G47

for residual or recurrent glioblastoma: A phase 2 trial. Nat Med.

28:1630–1639. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gazal S, Gazal S, Kaur P, Bhan A and

Olagnier D: Breaking barriers: Animal viruses as oncolytic and

immunotherapeutic agents for human cancers. Virology.

600:1102382024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kaufman HL, Shalhout SZ and Iodice G:

Talimogene laherparepvec: Moving from first-in-class to

best-in-class. Front Mol Biosci. 9:8348412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xi P, Zeng D, Chen M, Jiang L, Zhang Y,

Qin D, Yao Z and He C: Enhancing pancreatic cancer treatment: The

role of H101 oncolytic virus in irreversible electroporation. Front

Immunol. 16:15462422025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lee T, Gianchandani A, Boorjian SA, Shore

ND, Narayan VM, Dinney CPN and Kamat AM: Intravesical

interferon-α2b gene therapy with nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg: A

contemporary review. Future Oncol. 21:2429–2438. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chen L, Zuo M, Zhou Q and Wang Y:

Oncolytic virotherapy in cancer treatment: Challenges and

optimization prospects. Front Immunol. 14:13088902023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lin D, Shen Y and Liang T: Oncolytic

virotherapy: Basic principles, recent advances and future

directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:1562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lee YT, Tan YJ and Oon CE: Molecular

targeted therapy: Treating cancer with specificity. Eur J

Pharmacol. 834:188–196. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Aldea M, Andre F, Marabelle A, Dogan S,

Barlesi F and Soria JC: Overcoming resistance to tumor-targeted and

immune-targeted therapies. Cancer Discov. 11:874–899. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhu Z, McGray AJR, Jiang W, Lu B, Kalinski

P and Guo ZS: Improving cancer immunotherapy by rationally

combining oncolytic virus with modulators targeting key signaling

pathways. Mol Cancer. 21:1962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhou X, Hu S and Wang X: Recent advances

in oncolytic virus combined immunotherapy in tumor treatment. Genes

Dis. 12:1015992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen C, Cillis J, Deshpande S, Park AK,

Valencia H, Kim SI, Lu J, Vashi Y, Yang A, Zhang Z, et al:

Oncolytic virotherapy in solid tumors: A current review. BioDrugs.

39:857–876. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ullah R, Yin Q, Snell AH and Wan L:

RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer evolution and treatment. Semin Cancer

Biol. 85:123–154. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lee S, Yang W, Kim DK, Kim H, Shin M, Choi

KU, Suh DS, Kim YH, Hwang TH and Kim JH: Inhibition of MEK-ERK

pathway enhances oncolytic vaccinia virus replication in

doxorubicin-resistant ovarian cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics.

25:211–224. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Okemoto K, Wagner B, Meisen H, Haseley A,

Kaur B and Chiocca EA: STAT3 activation promotes oncolytic HSV1

replication in glioma cells. PLoS One. 8:e719322013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao Q, Zhang R, Qiao C, Miao Y, Yuan Y

and Zheng H: Ubiquitination network in the type I IFN-induced

antiviral signaling pathway. Eur J Immunol. 53:e23503842023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Schneider W M, Chevillotte M D and Rice

CM: Interferon-stimulated genes: A complex web of host defenses.

Annu Rev Immunol. 32:513–545. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhou X, Zhao J, Zhang JV, Wu Y, Wang L,

Chen X, Ji D and Zhou GG: Enhancing therapeutic efficacy of

oncolytic herpes simplex virus with MEK inhibitor trametinib in

some BRAF or KRAS-Mutated colorectal or lung carcinoma models.

Viruses. 13:17582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nguyen TT, Ramsay L, Ahanfeshar-Adams M,

Lajoie M, Schadendorf D, Alain T and Watson IR: Mutations in the

IFNγ-JAK-STAT pathway causing resistance to immune checkpoint

inhibitors in melanoma increase sensitivity to oncolytic virus

treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 27:3432–3442. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Patel MR, Dash A, Jacobson BA, Ji Y,

Baumann D, Ismail K and Kratzke RA: JAK/STAT inhibition with

ruxolitinib enhances oncolytic virotherapy in non-small cell lung

cancer models. Cancer Gene Ther. 26:411–418. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Otani Y, Ishida J, Kurozumi K, Oka T,

Shimizu T, Tomita Y, Hattori Y, Uneda A, Matsumoto Y, Michiue H, et

al: PIK3R1Met326Ile germline mutation correlates with cysteine-rich

protein 61 expression and poor prognosis in glioblastoma. Sci Rep.

7:73912017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Long QZ, Zhou M, Liu XG, Du YF, Fan JH, Li

X and He DL: Interaction of CCN1 with αvβ3 integrin induces

P-glycoprotein and confers vinblastine resistance in renal cell

carcinoma cells. Anticancer Drugs. 24:810–817. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lin BR, Chang CC, Chen LR, Wu MH, Wang MY,

Kuo IH, Chu CY, Chang KJ, Lee PH, Chen WJ, et al: Cysteine-rich 61

(CCN1) enhances chemotactic migration, transendothelial cell

migration, and intravasation by concomitantly up-regulating

chemokine receptor 1 and 2. Mol Cancer Res. 5:1111–1123. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Di Y, Zhang Y, Nie Q and Chen X:

CCN1/Cyr61-PI3K/AKT signaling promotes retinal neovascularization

in oxygen-induced retinopathy. Int J Mol Med. 36:1507–1518. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tomita Y, Kurozumi K, Yoo JY, Fujii K,

Ichikawa T, Matsumoto Y, Uneda A, Hattori Y, Shimizu T, Otani Y, et

al: Oncolytic herpes virus armed with vasculostatin in combination

with bevacizumab abrogates glioma invasion via the CCN1 and AKT

signaling pathways. Mol Cancer Ther. 18:1418–1429. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sugawara K, Iwai M, Ito H, Tanaka M, Seto

Y and Todo T: Oncolytic herpes virus G47Δ works synergistically

with CTLA-4 inhibition via dynamic intratumoral immune modulation.

Mol Ther Oncolytics. 22:129–142. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ma W, He H and Wang H: Oncolytic herpes

simplex virus and immunotherapy. BMC Immunol. 19:402018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Saha D, Wakimoto H, Peters CW, Antoszczyk

SJ, Rabkin SD and Martuza RL: Combinatorial effects of VEGFR kinase

inhibitor axitinib and oncolytic virotherapy in mouse and human

glioblastoma stem-like cell models. Clin Cancer Res. 24:3409–3422.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jha BK, Dong B, Nguyen CT, Polyakova I and

Silverman RH: Suppression of antiviral innate immunity by sunitinib

enhances oncolytic virotherapy. Mol Ther. 21:1749–1757. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Khoury R, Saleh K, Khalife N, Saleh M,

Chahine C, Ibrahim R and Lecesne A: Mechanisms of resistance to

antibody-drug conjugates. Int J Mol Sci. 24:96742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Arulanandam R, Taha Z, Garcia V, Selman M,

Chen A, Varette O, Jirovec A, Sutherland K, Macdonald E, Tzelepis

F, et al: The strategic combination of trastuzumab emtansine with

oncolytic rhabdoviruses leads to therapeutic synergy. Commun Biol.

3:2542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Du Z, Whitt MA, Baumann J, Garner JM,

Morton CL, Davidoff AM and Pfeffer LM: Inhibition of type I

interferon-mediated antiviral action in human glioma cells by the

IKK inhibitors BMS-345541 and TPCA-1. J Interferon Cytokine Res.

32:368–377. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dolcetti L, Marigo I, Mantelli B,

Peranzoni E, Zanovello P and Bronte V: Myeloid-derived suppressor

cell role in tumor-related inflammation. Cancer Lett. 267:216–225.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lawson KA, Mostafa AA, Shi ZQ, Spurrell J,

Chen W, Kawakami J, Gratton K, Thakur S and Morris DG: Repurposing

sunitinib with oncolytic reovirus as a novel immunotherapeutic

strategy for renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 22:5839–5850.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Moehler M, Sieben M, Roth S, Springsguth

F, Leuchs B, Zeidler M, Dinsart C, Rommelaere J and Galle PR:

Activation of the human immune system by chemotherapeutic or

targeted agents combined with the oncolytic parvovirus H-1. BMC

Cancer. 11:4642011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ichikawa M, Williams R, Wang L, Vogl T and

Srikrishna G: S100A8/A9 activate key genes and pathways in colon

tumor progression. Mol Cancer Res. 9:133–148. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chai H, Xu H, Jiang S, Zhang T, Chen J,

Zhu R, Wang Y, Sun M, Liu B, Wang X, et al: Neural stem

cell-delivered oncolytic virus via intracerebroventricular

administration enhances glioblastoma therapy and immune modulation.

J Immunother Cancer. 13:e0129342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhu Z, Chen H, Feng C, Chen L, Ma C, Liu

Z, Qu Z, Bartlett DL, Lu B, Li K and Guo ZS: Specific inhibitor to

KRASG12C induces tumor-specific immunity and synergizes

with oncolytic virus for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. J

Immunother Cancer. 13:e0105142025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Herman ML, Geanes ES, McLennan R, Greening

GJ, Mwitanti H and Bradley T: ICAM-1 autoantibodies detected in

healthy individuals and cross-react with functional epitopes.

Immunohorizons. 9:vlaf0252025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Shin J, Lim J, Han D, Lee S, Sung NS, Kim

JS, Kim DK, Lee HY, Lee SK, Shin J, et al: TBK1 inhibitor amlexanox

exerts anti-cancer effects against endometrial cancer by regulating

AKT/NF-κB signaling. Int J Biol Sci. 21:143–159. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

44

|

Guo X, Feng H, Xi Z, Zhou J, Huang Z, Guo

J, Zheng J, Lyu Z, Liu Y, Zhou J, et al: Targeting TBK1 potentiates

oncolytic virotherapy via amplifying ICAM1-mediated NK cell

immunity in chemo-resistant colorectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer.

13:e0114552025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Meisen WH, Wohleb ES, Jaime-Ramirez AC,

Bolyard C, Yoo JY, Russell L, Hardcastle J, Dubin S, Muili K, Yu J,

et al: The impact of macrophage- and microglia-secreted TNFα on

Oncolytic HSV-1 therapy in the glioblastoma tumor microenvironment.

Clin Cancer Res. 21:3274–3285. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Yoo JY, Swanner J, Otani Y, Nair M, Park

F, Banasavadi-Siddegowda Y, Liu J, Jaime-Ramirez AC, Hong B, Geng

F, et al: Oncolytic HSV therapy increases trametinib access to

brain tumors and sensitizes them in vivo. Neuro Oncol.

21:1131–1140. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Burch AD and Weller SK: Herpes simplex

virus type 1 DNA polymerase requires the mammalian chaperone hsp90

for proper localization to the nucleus. J Virol. 79:10740–10749.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yoo JY, Hurwitz BS, Bolyard C, Yu JG,

Zhang J, Selvendiran K, Rath KS, He S, Bailey Z, Eaves D, et al:

Bortezomib-induced unfolded protein response increases oncolytic

HSV-1 replication resulting in synergistic antitumor effects. Clin

Cancer Res. 20:3787–3798. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Tian L, Xu B, Chen Y, Li Z, Wang J, Zhang

J, Ma R, Cao S, Hu W, Chiocca EA, et al: Specific targeting of

glioblastoma with an oncolytic virus expressing a cetuximab-CCL5

fusion protein via innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Cancer.

3:1318–1335. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Napolitano F, Di Somma S, Castellano G,

Amato J, Pagano B, Randazzo A, Portella G and Malfitano AM:

Combination of dl922-947 oncolytic adenovirus and G-quadruplex

binders uncovers improved antitumor activity in breast cancer.

Cells. 11:24822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Passaro C, Volpe M, Botta G, Scamardella

E, Perruolo G, Gillespie D, Libertini S and Portella G: PARP

inhibitor olaparib increases the oncolytic activity of dl922-947 in

in vitro and in vivo model of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Mol

Oncol. 9:78–92. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Kyula-Currie J, Roulstone V, Wright J,

Butera F, Legrand A, Elliott R, McLaughlin M, Bozhanova G, Krastev

D, Pettitt S, et al: The PARP inhibitor talazoparib synergizes with

reovirus to induce cancer killing and tumour control in vivo in

mouse models. Nat Commun. 16:62992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhong Y, Le H, Zhang X, Dai Y, Guo F, Ran

X, Hu G, Xie Q, Wang D and Cai Y: Identification of restrictive

molecules involved in oncolytic virotherapy using genome-wide

CRISPR screening. J Hematol Oncol. 17:362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Tapeinos C and Pandit A: Physical,

chemical, and biological structures based on ROS-Sensitive moieties

that are able to respond to oxidative microenvironments. Adv Mater.

28:5553–5585. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Schieber M and Chandel NS: ROS function in

redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 24:R453–R462.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang L, Wang D, Sonzogni O, Ke S, Wang Q,

Thavamani A, Batalini F, Stopka SA, Regan MS, Vandal S, et al:

PARP-inhibition reprograms macrophages toward an anti-tumor

phenotype. Cell Rep. 41:1114622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Tubbs A and Nussenzweig A: Endogenous DNA

damage as a source of genomic instability in cancer. Cell.

168:644–656. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Packiriswamy N, Upreti D, Zhou Y, Khan R,

Miller A, Diaz RM, Rooney CM, Dispenzieri A, Peng KW and Russell

SJ: Oncolytic measles virus therapy enhances tumor antigen-specific

T-cell responses in patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia.

34:3310–3322. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhou S, Li Y, Huang F, Zhang B, Yi T, Li

Z, Luo H, He X, Zhong Q, Bian C, et al: Live-attenuated measles

virus vaccine confers cell contact loss and apoptosis of ovarian

cancer cells via ROS-induced silencing of E-cadherin by

methylation. Cancer Lett. 318:14–25. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhang CD, Jiang LH, Zhou X, He YP, Liu Y,

Zhou DM, Lv Y, Wu BQ and Zhao ZY: Synergistic antitumor efficacy of

rMV-Hu191 and Olaparib in pancreatic cancer by generating oxidative

DNA damage and ROS-dependent apoptosis. Transl Oncol.

39:1018122024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Meikrantz W and Schlegel R: Apoptosis and

the cell cycle. J Cell Biochem. 58:160–174. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lee B, Min JA, Nashed A, Lee SO, Yoo JC,

Chi SW and Yi GS: A novel mechanism of irinotecan targeting MDM2

and Bcl-xL. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 514:518–523. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Hubbard JM and Grothey A: Napabucasin: An

update on the first-in-class cancer stemness inhibitor. Drugs.

77:1091–1103. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Babaei A, Soleimanjahi H, Soleimani M and

Arefian E: The synergistic anticancer effects of ReoT3D, CPT-11,

and BBI608 on murine colorectal cancer cells. Daru. 28:555–565.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Chen Y and Zhou X: Research progress of

mTOR inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 208:1128202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Wang Y and Zhang H: Regulation of

autophagy by mTOR signaling pathway. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1206:67–83.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Yoshida GJ: Therapeutic strategies of drug

repositioning targeting autophagy to induce cancer cell death: From

pathophysiology to treatment. J Hematol Oncol. 10:672017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Saran U, Foti M and Dufour JF: Cellular