Introduction

Breast cancer (BC), a common malignancy, is the

leading cause of cancer-related death in women worldwide (1). Although some progress has been made

in understanding the pathogenesis and treatment of BC (2-6),

its pathogenesis is complex and involves abnormal regulation of a

variety of genes and signaling pathways; thus, further studies are

still needed. The family of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs)

rich in proline, glutamic acid, serine and threonine includes PTP

non-receptor type 18 (PTPN18), PTPN22 and PTPN12 (7). Members of this family have a key

role in various physiological and pathological processes of cells

(7). For instance, previous

studies by the authors confirmed the notable role of PTPN22 in

immune regulation (8,9) as well as signaling events triggered

by the synergistic inactivation of Src kinase by PTPN18 and C-Src

kinase (10). As a classical PTP,

PTPN18 can also regulate multiple signal transduction pathways by

regulating the phosphorylation of cellular Abelson tyrosine kinase,

a key signaling protein tyrosine kinase (11). The interaction between PTPN18 and

proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 1/2 or

P190 Rho GTPase-activating protein confirms its function in

regulating the cytoskeleton (11-14). Additionally, it has been shown

that PTPN18 negatively regulates human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2 (HER2) to inhibit BC progression (15,16). Furthermore, a recent study by the

authors found that nuclear PTPN18 exerts antitumor effects in BC by

targeting ETS proto-oncogene 1 (ETS1) to inhibit transforming

growth factor-β signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT) (17). Notably, patients

with BC harboring high PTPN18 expression have an improved prognosis

and longer overall survival (OS) (17), which suggests that PTPN18 may play

an important role in BC progression.

Cyclin E, a key molecule of the cell cycle

regulatory network, functions in the G1 and S phases and mainly

binds to and activates cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) (18). Cyclin E/CDK2 complexes

phosphorylate numerous substrates to control important cellular

processes (18,19). There are two E-type cyclins, E1

and E2, which are considered to primarily exert overlapping

functions (18). However, it has

been reported that cyclin E1 and cyclin E2 have different emphasis

on regulatory patterns and functions (20). High levels of cyclin E protein

lead to poor prognosis, reduced survival and treatment resistance

in patients with cancer (21,22). Additionally, cyclin E

amplification/upregulation is one of the mechanisms of trastuzumab

resistance in patients with HER2+ BC (23). HER2 is an important target of

PTPN18 in inhibiting BC (15,16), suggesting that there may be a link

between PTPN18 and cyclin E.

Based on the potential importance of PTPN18 in the

field of oncology as well as its broad role in the regulation of

cellular function, it is necessary to further explore its role in

BC and its underlying mechanisms. Therefore, through phenotypic

functional experiments, the present study first confirmed that

PTPN18 can exert antitumor effects by promoting apoptosis,

inhibiting metastasis and proliferation and causing S phase cell

cycle arrest in BC cells. Subsequently, it was found that S-phase

arrest caused by PTPN18 may be via the downregulation of cyclin E

expression. Further mechanistic dissection revealed that cyclin E

is an important substrate for PTPN18 in exerting antitumor effects.

Taken together, the mechanism of BC development and progression

identified in the present study provides an additional

comprehensive and extensive theoretical basis for the prevention

and treatment of this disease.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

The Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF7) and

Metastatic Derivative of Anaplastic BC-231 (MDA-MB-231) cell lines

were obtained from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The

Chinese Academy of Sciences and maintained in Dulbecco's modified

Eagle's medium (HyClone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; HyClone; Cytiva) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C

in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Interference with

PTPN18 expression levels was achieved by transfecting (37°C, 6 h)

cells with PTPN18-3HA (1 µg/µl) and PTPN18 small

interfering RNA (20 µM) (siRNA; Suzhou GenePharma Co., Ltd.)

using Lipo6000 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), according to

the manufacturer's instructions. To achieve an improved knockdown

efficiency, the knockdown siRNA was transfected again after 24 h of

initial transfection. The siRNA sequences used are listed in

Table SI.

Western blotting

First, total protein was extracted from cells using

precooled radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime

Biotechnology) containing 1% protease inhibitor and phosphatase

inhibitor (Selleck Chemicals) and then quantified by bicinchoninic

acid assay. Equal amounts of protein (10 µg) were separated

by 10% SDS-PAGE at a constant voltage (80 V) until the blue band of

the loading buffer approached the lower edge of the gel. Proteins

were then transferred to PVDF membranes using the sandwich method

at a constant voltage of 100 V for 100 min at 4°C. Membranes were

blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST)

for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4°C with

blocking buffer plus primary antibodies. Subsequent washing with

TBST was followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 1 h

at room temperature. Goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy and light chain)

antibody or horse anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated with

horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody was selected for

chemiluminescence detection according to the primary antibody

species. Finally, the protein bands were visualized and

semi-quantified using the ChemiDoc XRS + Gel Imaging Analysis

System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and Image Lab 5.2.1 software

(6). The antibody information is

listed in Table SII.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

Treated cells were lysed in pre-chilled RIPA lysis

buffer containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor

cocktails for 10-30 min. Experiments involving tyrosine

phosphorylation or PTPN18 C229S were stimulated with EGF 100 ng/ml

for 30 min before cells were collected. The samples were

centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to remove cell debris,

then the supernatant was incubated with the appropriate primary

antibody for 2-4 h or overnight at 4°C. The conjugated product was

incubated with 30-50 µl Protein A/G agarose beads (Beyotime

Biotechnology) for 2-4 h at 4°C the following day. The agarose

beads were washed five times with cold lysis buffer, the

supernatant was discarded and the beads were boiled with 1X SDS

loading buffer for 10 min prior to western blotting.

Flow cytometry apoptosis assay

The apoptosis of BC cells was observed using flow

cytometry. Cells were washed twice with pre-chilled

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5

min at 4°C to collect 1-2.5×106 cells. The cells were

resuspended in 100 µl of 1X Binding Buffer (BD Biosciences)

and divided into two aliquots, one without Annexin V-FITC/PI and

the other with 5 µl Annexin V-FITC and 5 µl PI

Staining Solution (BD Biosciences), then mixed gently. The

individual groups were stained with PI or FITC only for subsequent

adjustment of compensation. The samples were protected from the

light and the reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature

for 15 min. Next, 400 µl of 1X Binding Buffer was added and

mixed well with the samples, which were then filtered with gauze

and detected by BD Accuri™ C6 Plus flow cytometry (BD

Biosciences) within 1 h. For each sample, 10,000 events were

analyzed and the experiment was independently repeated three times

(24). Data were analyzed and

processed using the FlowJo 10.8.1 (FlowJo LLC; BD Biosciences)

software.

Nuclear staining with

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)

In vitro apoptosis was examined by DAPI

staining. MCF-7 cells that had previously been transfected for 48 h

were seeded into 24-well plates for overnight incubation and

attachment. The cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The fixative was

removed, then the cells were washed with PBS and stained with 2

µg/ml DAPI (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 15 min

at room temperature in the dark. Changes in nuclear morphology were

examined by fluorescence microscopy and images were collected.

Cell cycle assay

Cell cycle distribution was determined using an

Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The collected cells were

fixed with pre-chilled 70-80% ethanol overnight at 4°C, centrifuged

to remove the fixative and washed once with 1 ml PBS. The samples

were then divided into two aliquots after the supernatant had been

removed: One aliquot was incubated at room temperature without

PI/RNase for 15 min; the other was incubated at room temperature

with 500 µl PI/RNase (BD Biosciences) in the dark for 15

min. The cells were then filtered with a 200-mesh filter and

detected by flow cytometry. FlowJo 10.8.1 (FlowJo LLC; BD

Biosciences) or ModFit LT 4.0 software (Verity Software House) was

used to process the data (25).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was monitored using the MTS assay, a

modified version of the classical MTT assay that has the same core

principle (26). The treated

cells (2,000 cells/100 µl medium) were digested and

transferred to 96-well plates, with four duplicate wells set up for

each treatment group, and the absorbance was detected after 0, 12,

24, 36 and 48 h. In each well, an average of 20 µl of

CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega

Corporation) was added to 100 µl of medium. After gentle

mixing and 2 h of reaction in a 37°C and 5% CO2

incubator, the absorbance at 490 nm was measured.

Colony formation assay

Treated cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a

density of 2,000 cells/well. After the cells adhered overnight, the

medium was replaced every 3 days for 14 days. The cells were then

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (room temperature, 30 min) and

stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 20 min at room temperature. Finally, the plates

were washed with water and air dried at room temperature. The

colonies were recorded using ImageJ 1.53e software (National

Institutes of Health).

Transwell invasion assay

Conditioned medium (500 µl) containing 20%

FBS was added to the lower chamber of a 24-well plate. Next, 100

µl of diluted BD Matrigel was added to each upper chamber.

After the Matrigel had solidified at 37°C, a digested and diluted

serum-free cell suspension was added to the upper chamber, and the

plates were incubated at 37°C for 24-48 h. The inserts (8

µm) were then washed with PBS and fixed with a 5%

paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min. The cells were stained with

crystal violet (0.1%) at room temperature for 30 min, then observed

and counted under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica

Microsystems GmbH) operating in white light mode.

Wound healing assay

After creating a scratch with a 200-µl

sterilized tip, the cells were washed three times with sterilized

PBS, the impurities and cell debris were washed off, and fresh low

serum (1%) culture medium was added to continue the cell culture.

Images were collected at 0, 24 and 48 h and the change in scratch

size was recorded. The experiment was repeated three times. ImageJ

software was used to assess the scratch area and for subsequent

experimental data processing.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total cellular RNA was extracted using TRIzol and

cDNA synthesis was performed using the All-in-One cDNA Synthesis

SuperMix kit (Selleck Chemicals) following the manufacturer's

instructions. In a total reaction volume of 20 µl per well,

the 2X SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix kit (Selleck Chemicals) was used

for qPCR. The PCR amplification protocol consisted of

pre-denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec, and

extension at 72°C for 30 sec. A total of 3-5 replicate wells were

set up per group. The mean quantification cycle (Cq) values were

collected for each reaction and relative expression was quantified

using the 2−ΔΔCq method (27). The sequences of the qPCR primers

used in the present study are listed in Table SIII.

Associated database analysis

Changes in the expression levels of total PTPN18

protein were analyzed through the 'Proteomics' catalog of the

UALCAN database (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/cgi-bin/CPTAC-Result.pl?genenam=PTPN18&ctype=Breast)

(28). 'Expression DIY' in the

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) database

(http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index)

was used to obtain gene expression related information in the box

plot and stage plot formats. Correlation analysis (GEPIA) was used

to test the association of PTPN18 or CDKN1A/B with CCNE1/2 gene.

Survival analysis (GEPIA) was used to obtain gene and OS or

disease-free survival data (29).

Additionally, gene expression levels and OS or relapse-free

survival data were obtained from the BC category of the

Kaplan-Meier Plotter database (https://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service&cancer=breast)

(30). PTPN18 correlation

analysis was performed using breast invasive carcinoma and HiSeq

RNA data from the LinkedOmics platform (https://www.linkedomics.org/admin.php) (31). Protein interaction networks for

cyclin E1 and cyclin E2 were obtained from the STRING database

(https://cn.string-db.org/) (32).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD of at least

three independent experiments. Data analysis was performed using

GraphPad Prism software 8.0.2 (Dotmatics). Data were analyzed using

unpaired Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance with

Tukey's multiple comparison test, as appropriate. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

PTPN18 expression is associated with

BC

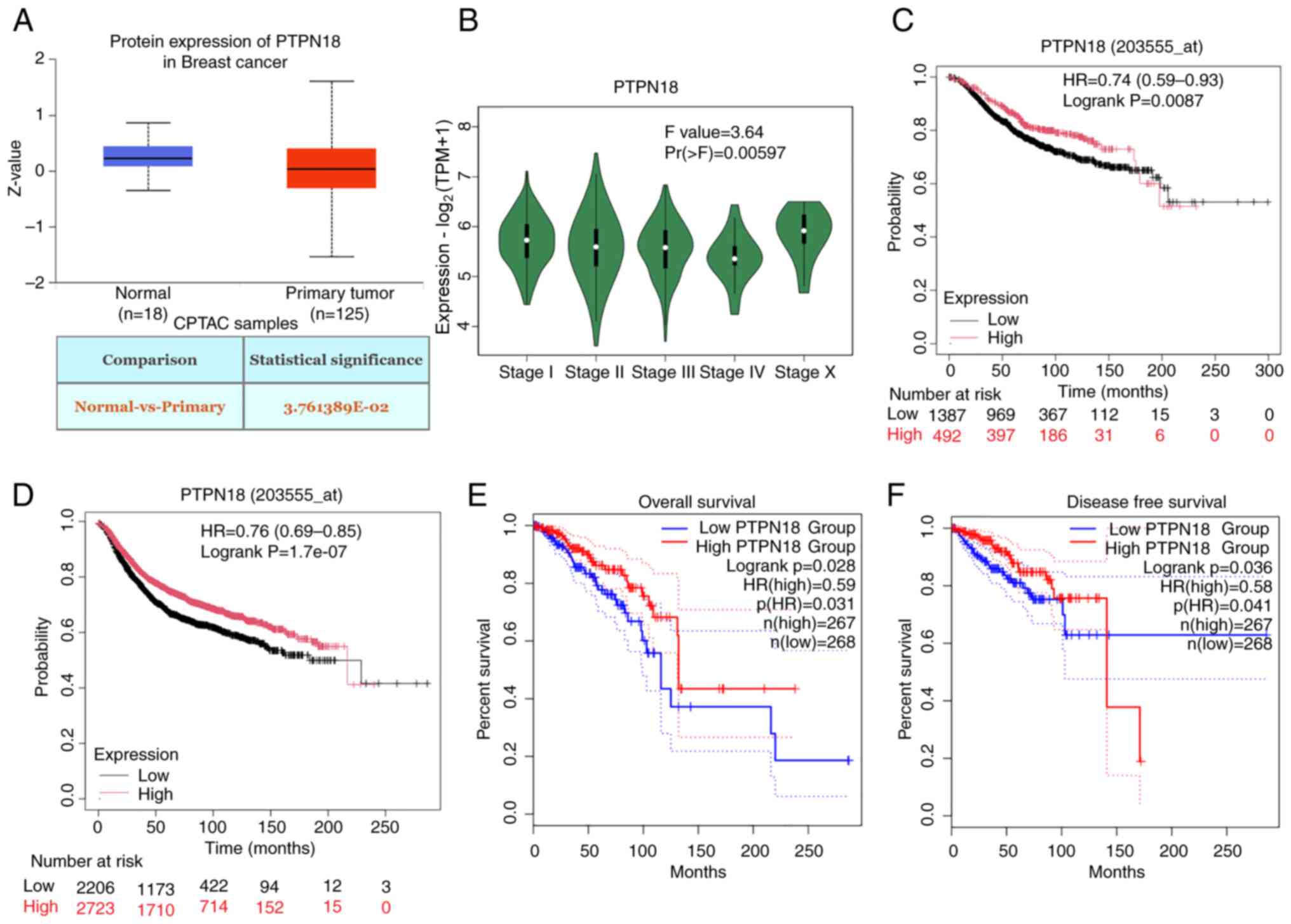

Proteomic expression profiling using the UALCAN

database showed that PTPN18 protein expression levels are decreased

in BC (Fig. 1A). In addition, a

close link between PTPN18 gene expression and the stage of BC was

identified (Fig. 1B). Statistical

analyses using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter and GEPIA databases showed

that high levels of PTPN18 improved the survival and prognosis of

patients with BC (Fig. 1C-F),

indicating that PTPN18 may play a tumor suppressor role in this

disease. Therefore, the function and mechanism of PTPN18 in BC was

further investigated.

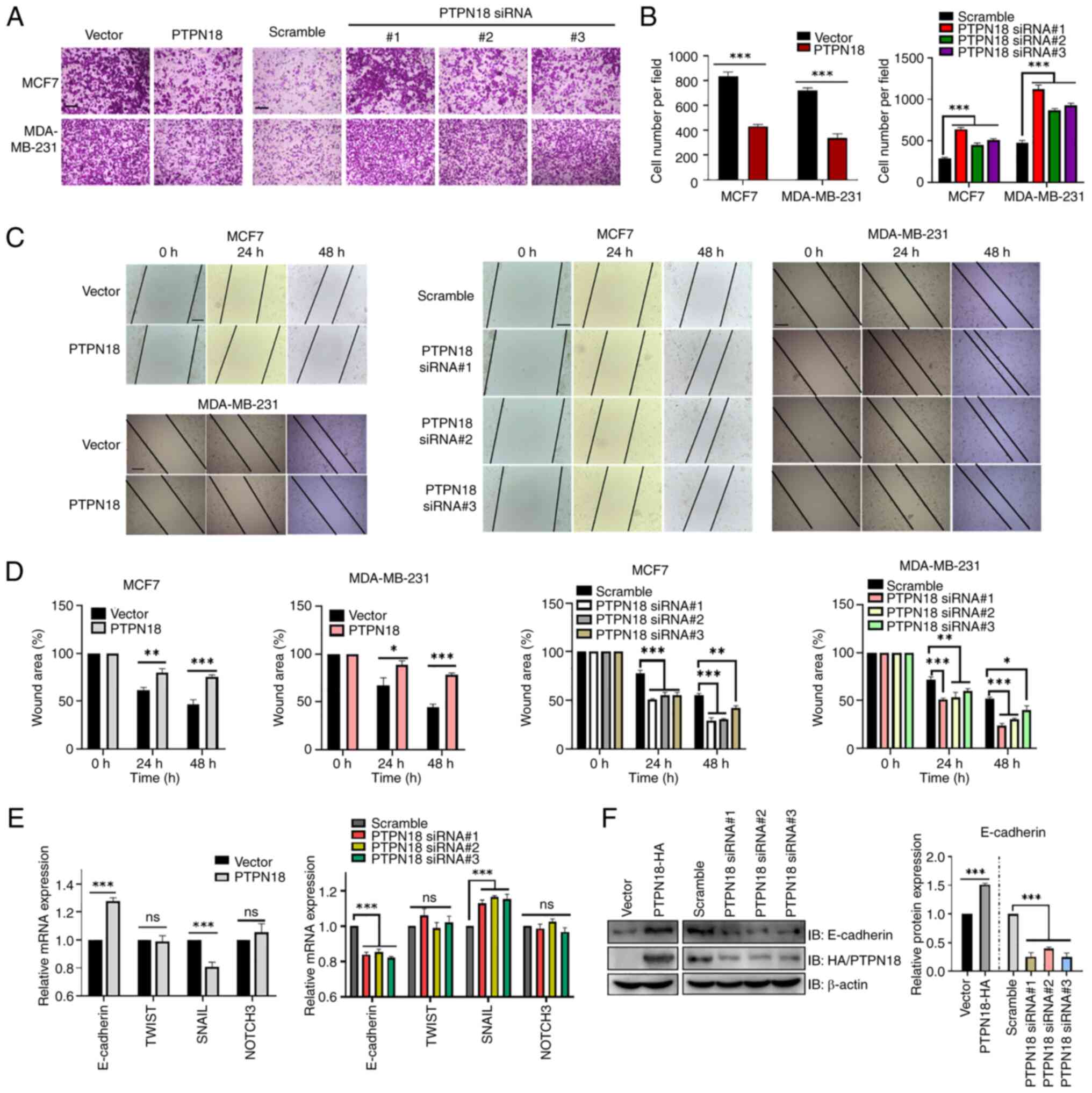

PTPN18 suppresses the metastasis of BC

cells

PTPN18 is widely expressed in BC cell lines

(15,16). In the present study, the western

blot results showed that PTPN18 was expressed at higher levels in

MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig.

S1A), which represent estrogen receptor and progesterone

receptor double-positive and triple-negative BC cell lines,

respectively. Overexpression and knockdown of PTPN18 in MCF7 cells

at different time points after transfection is shown in Fig. S1B and C. Next, the effect of

PTPN18 on cancer cell invasion was investigated using a Transwell

chamber assay. The results showed that overexpression of PTPN18

effectively inhibited the invasion of cancer cells, while knockdown

of endogenous PTPN18 expression enhanced invasion (Fig. 2A and B). Consistent with these

results, in vitro cell wound healing assays demonstrated

that PTPN18 expression inhibited tumor cell migration (Fig. 2C and D). Analysis of the mRNA

levels of genes involved in cell metastasis revealed that

E-cadherin gene expression increased and Snail family

transcriptional repressor 1 expression decreased in the PTPN18

overexpression group compared with the vector group, while the

TWIST basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor 1 and Notch

receptor 3 levels remained essentially unchanged (Fig. 2E). The trend was roughly the

opposite between the knockdown and overexpression groups (Fig. 2E). Subsequent verification of the

translation levels of the E-cadherin EMT marker protein revealed

changes consistent with the transcription levels (Fig. 2F).

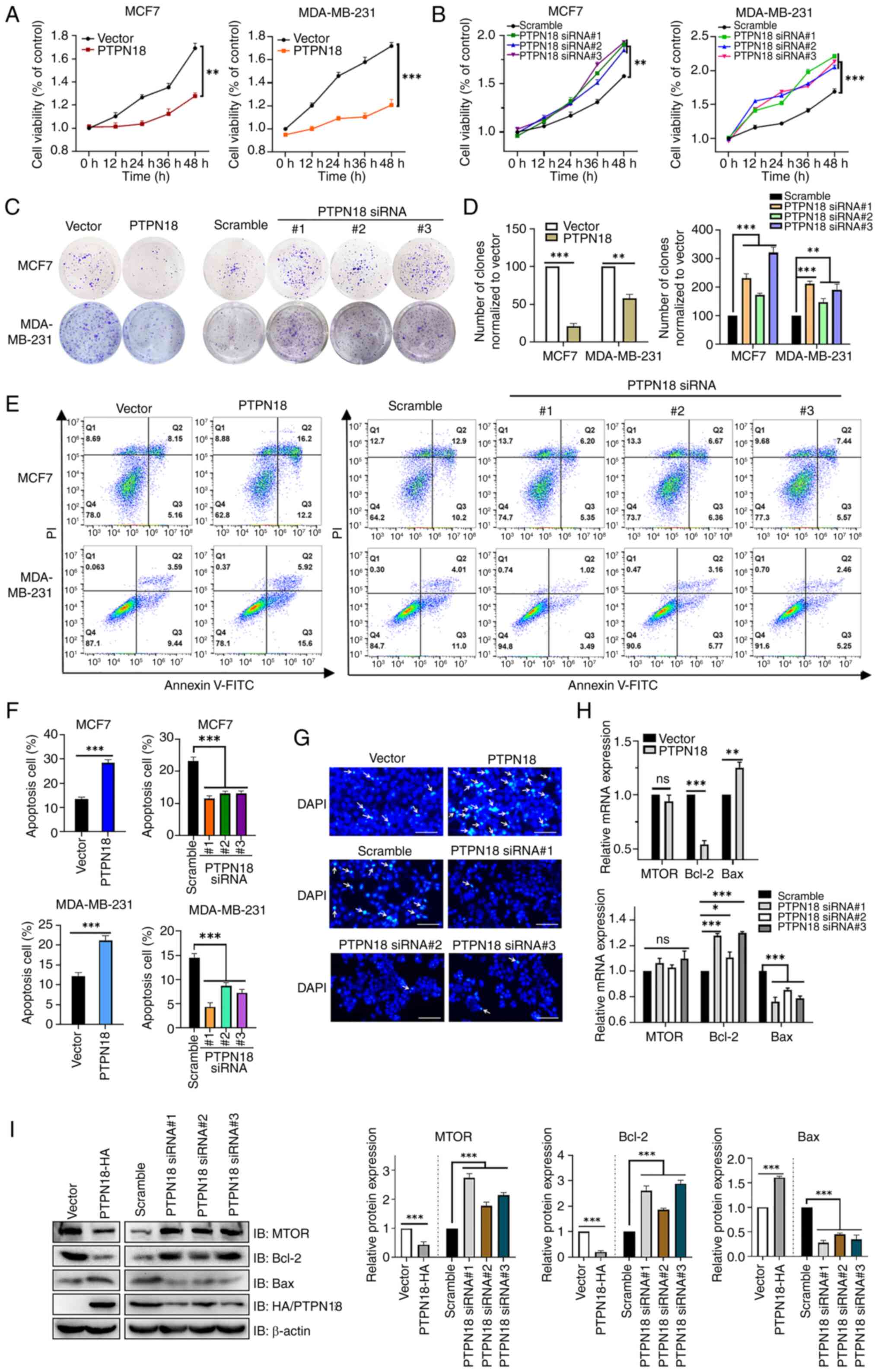

PTPN18 inhibits BC cell proliferation and

induces apoptosis

The key to cancer treatment is inhibiting the

metastasis and proliferation of cancer cells and inducing

apoptosis. The MTS assay results demonstrated that PTPN18

overexpression inhibited cell viability, an inhibitory effect that

exhibited an increasing cumulative trend over time (Fig. 3A). Although the MCF7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells in the PTPN18 knockdown groups showed a high cell

viability at different time points, the overall trend was the

opposite to that of the overexpression group (Fig. 3B). This conclusion was further

verified by a colony formation assay (Fig. 3C and D).

The flow cytometric results identified that PTPN18

overexpression significantly increased the proportion of BC cells

undergoing apoptosis, while the three knockdowns of PTPN18 revealed

different degrees of apoptosis' inhibition (Fig. 3E and F). In addition, the MCF7 BC

cell line was stained with DAPI and subsequent fluorescence

microscopy showed significantly increased signs of apoptotic cell

death, such as chromatin condensation and fragmentation, in the

PTPN18 overexpression group compared with the control cells

(Fig. 3G). Furthermore, RT-qPCR

(Fig. 3H) and western blot

(Fig. 3I) results showed that

PTPN18 inhibited the expression of mechanistic target of rapamycin

kinase (mTOR) mainly at the protein level. Additionally, PTPN18

promoted Bax expression and suppressed Bcl-2 expression (Fig. 3H and I). Collectively, these

results confirmed that PTPN18 inhibited proliferation and promoted

the apoptosis of BC cells.

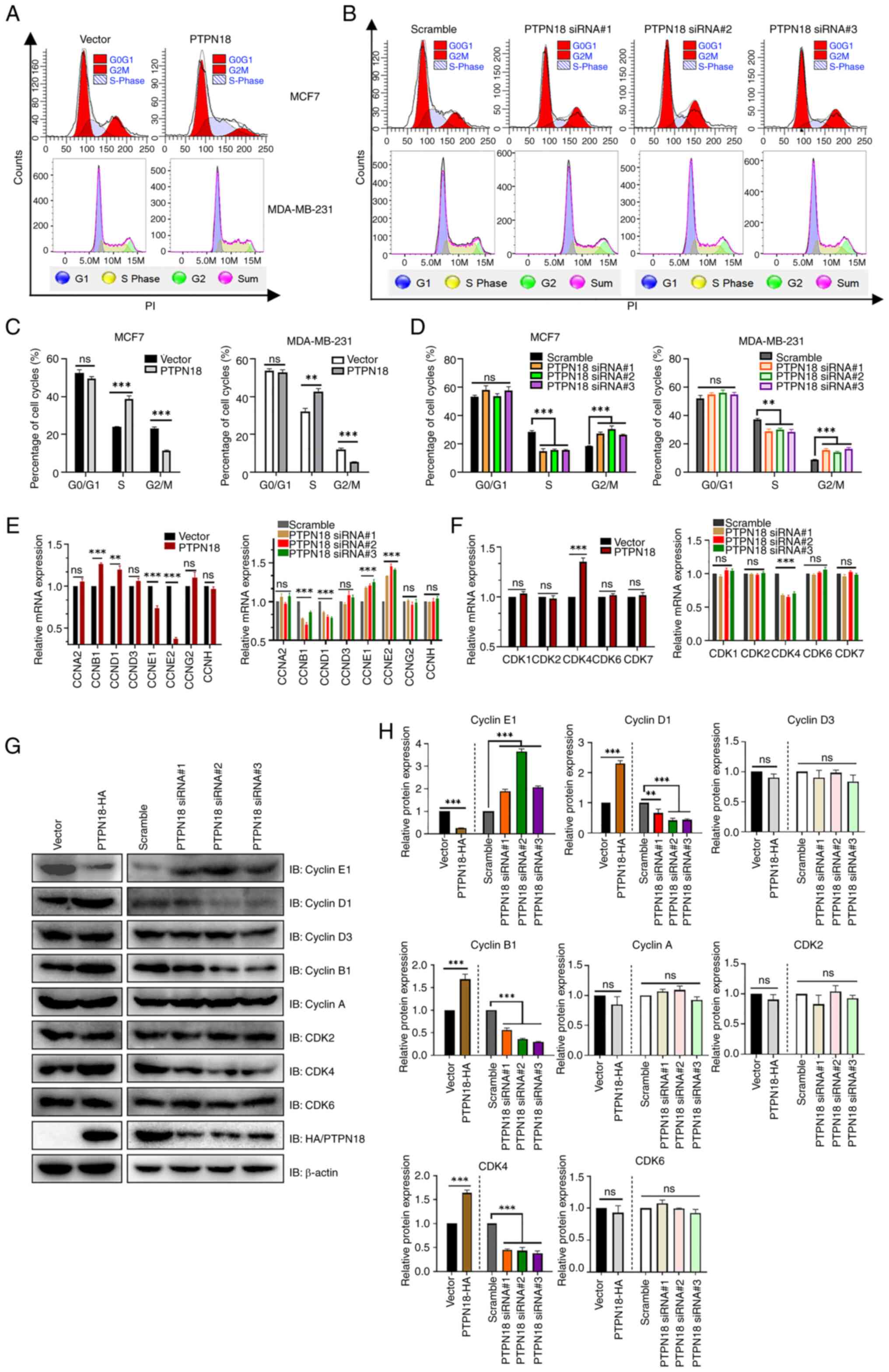

PTPN18 can induce S phase cell cycle

arrest in BC by downregulating the expression of cyclin E

Next, the effect of PTPN18 on the cell cycle of BC

cells was further investigated. The results of the cell cycle flow

cytometry experiments revealed that PTPN18 overexpression

significantly increased the number of cells in the S phase and

decreased the number of cells in the G2/M phase but did not

significantly change the number of cells in the G0/G1 phase

(Fig. 4A and C). However, the

PTPN18 knockdown groups showed the opposite trend (Fig. 4B and D), indicating that PTPN18

could induce cell cycle arrest in the S phase and affect the cell

cycle progression of BC cells. In addition, PTPN18 overexpression

significantly decreased cyclin E1 expression and increased cyclin

D1, cyclin B1 and CDK4 expression at both the transcriptional and

translational levels (Fig. 4E-H).

These results suggested that significant downregulation of cyclin E

may be an important factor in PTPN18 overexpression-induced S phase

cell cycle arrest in BC. The aforementioned phenotypic functional

experiments demonstrated that PTPN18 could play a tumor suppressive

role in BC cells by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting

proliferation, cell cycle, migration and invasion.

PTPN18 and the cell cycle are

significantly and negatively correlated in BC

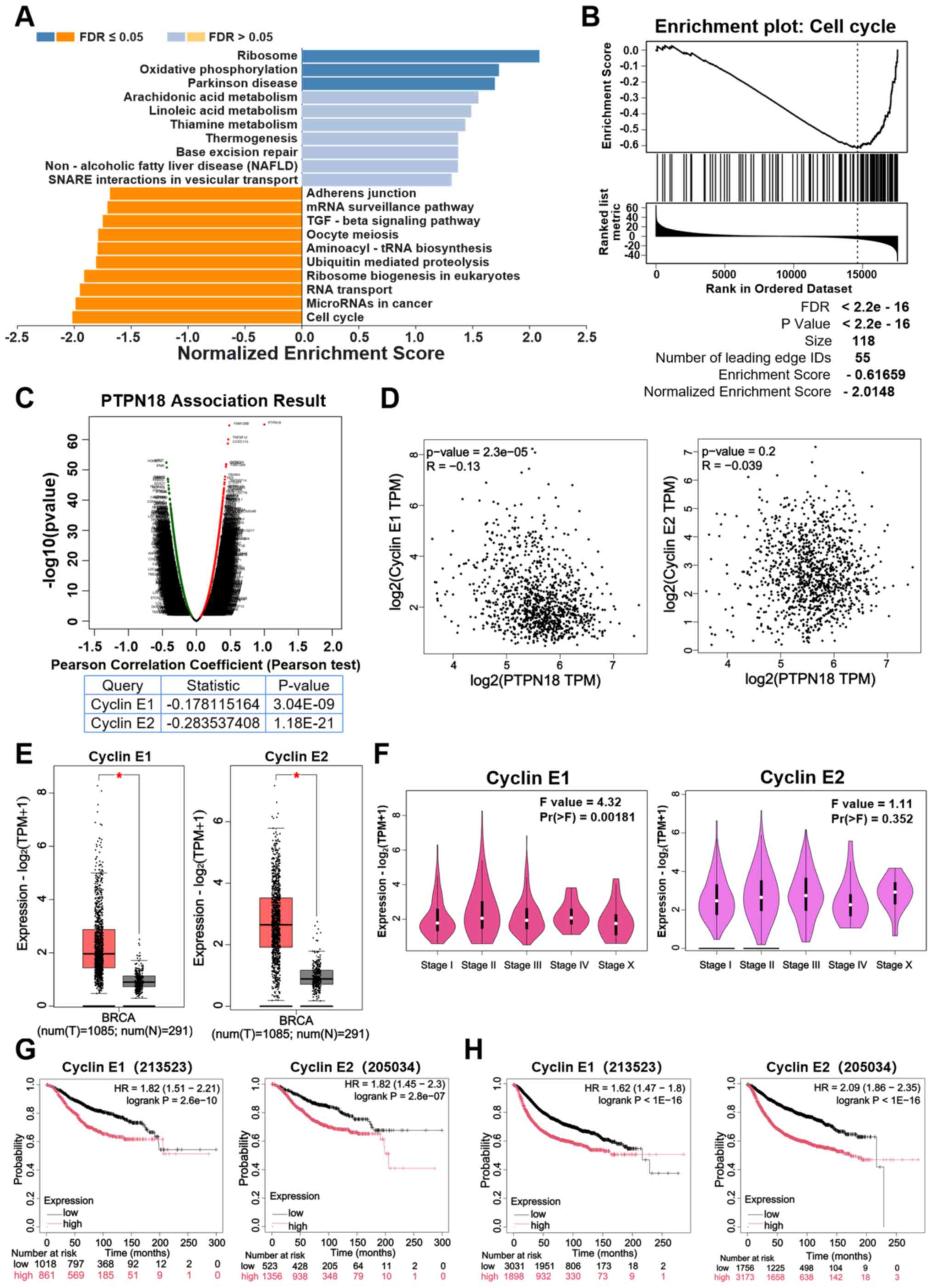

To illustrate the biological function of PTPN18 in

BC development, RNA sequencing gene enrichment analysis of PTPN18

in BC was performed using the LinkedOmics database. The results

revealed that PTPN18 showed a close and significantly negative

correlation with the cell cycle in BC (Fig. 5A). Additionally, the results of

the cell cycle gene enrichment analysis showed that PTPN18 may

affect cell cycle progression by inhibiting gene expression of cell

cycle pathways (Fig. 5B). Volcano

plots revealed the genes that were positively or negatively

correlated with PTPN18 (Fig. 5C).

Pearson correlation coefficient analysis suggested that PTPN18 was

significantly negatively correlated with cyclins E1 and E2

(Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the GEPIA

database gene correlation analysis results also demonstrated that

PTPN18 was negatively correlated with cyclins E1 and E2 (Fig. 5D). The cyclin E1 and E2 expression

levels were found to be significantly increased in BC tissues

compared with normal tissues (Fig.

5E). Cyclin E1 expression was significantly different in

different clinical stages of BC and may play a role in disease

stage progression; however, cyclin E2 expression was weakly

associated with stage, suggesting that the functions of these two

proteins in disease progression may be different (Fig. 5F). The results of the survival

analyses using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter and GEPIA databases

identified that high expression of cyclin E was associated with a

reduced OS and the poor prognosis of patients with BC (Fig. 5G and H; Fig. S2A and B). These analyses support

the hypothesis that PTPN18 may affect the BC cell cycle through

regulation of the cyclin E pathway. These results echo the

aforementioned experimental results and reinforce the rationality

and necessity of studying the mechanism of cyclin E downregulation

due to PTPN18 overexpression.

PTPN18 can interact with cyclin E1 and

promote its proteasomal degradation

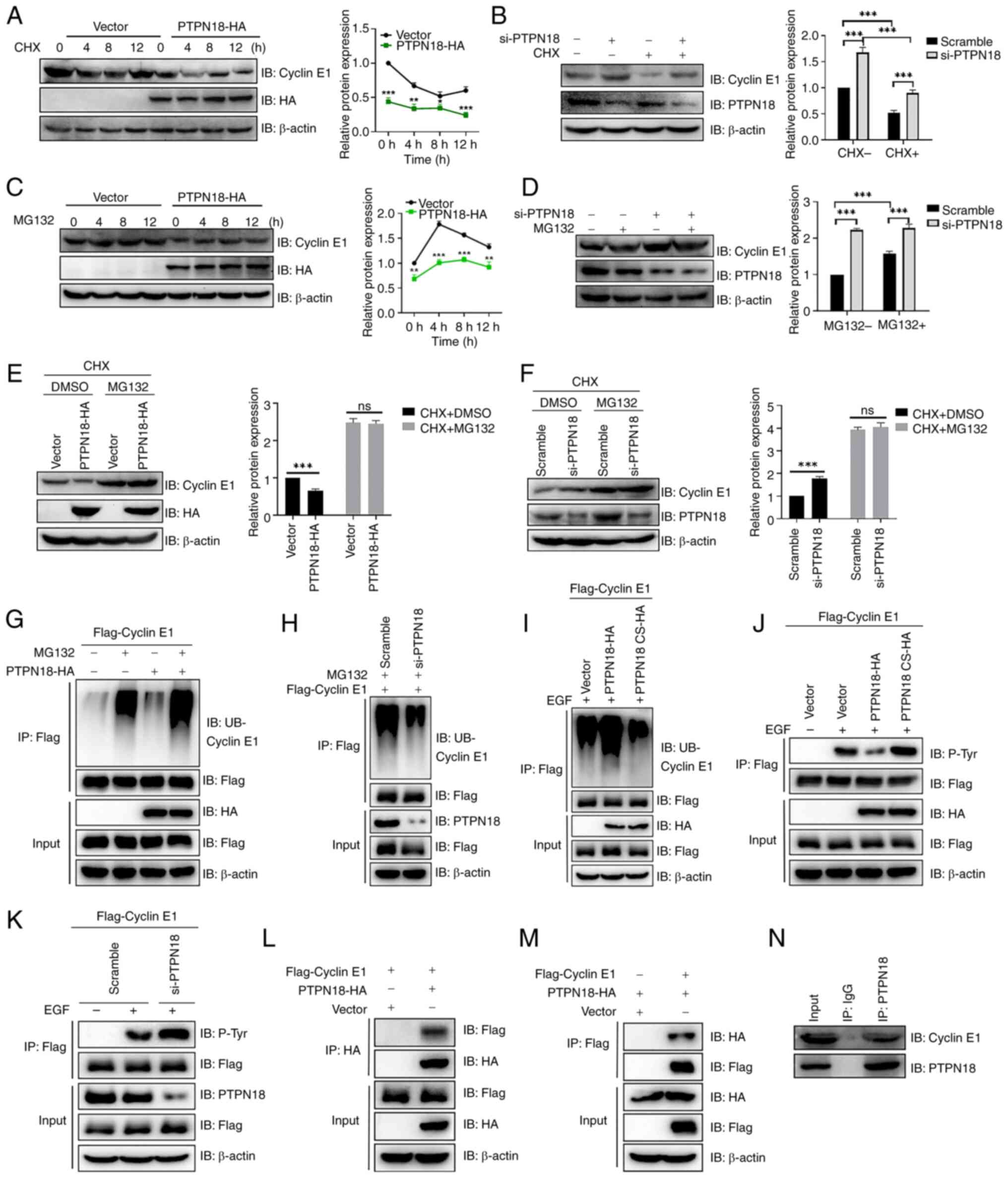

In view of the notable role of PTPN18 in the BC cell

cycle, the present study further explored the molecular mechanism

by which PTPN18 causes cell cycle arrest in the S phase. First,

treatment with cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of protein

synthesis, revealed that overexpression of PTPN18 promoted cyclin

E1 degradation and knockdown of PTPN18 inhibited cyclin E1

degradation (Fig. 6A and B).

Furthermore, MG132 proteasome inhibitor inhibited cyclin E1

degradation induced by PTPN18 overexpression and enhanced the

inhibitory effect on cyclin E1 degradation in the knockdown group

(Fig. 6C and D). When CHX and

MG132 were combined, the effect of PTPN18 on the cyclin E1 protein

levels was not significantly different from that of the control

(Fig. 6E and F).

Next, the effect of PTPN18 on cyclin E1

ubiquitination was examined. The results demonstrated that PTPN18

overexpression markedly increased the ubiquitination level of

cyclin E1 and that PTPN18 knockdown reduced the cyclin E1

ubiquitination level after MG132 treatment (Fig. 6G and H). Since PTPN18 is a PTP, it

was found that the ubiquitination of cyclin E1 by PTPN18 requires

enzymatic activity (Fig. 6I).

Using western blotting to detect the pan-tyrosine phosphorylation

level of cyclin E1, it was found that PTPN18 was able to

dephosphorylate the tyrosine of cyclin E1, indicating that cyclin

E1 is a substrate of PTPN18 (Fig. 6J

and K). Next, the interaction between PTPN18 and cyclin E1 was

verified by forward and reverse Co-IP experiments as well as by

examination of the endogenous interaction in MCF7 cells (Fig. 6L-N). In summary, the results

revealed that PTPN18 can bind to cyclin E1 and promotes its

degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

PTPN18 downregulates the expression of

cyclin E2 protein via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway

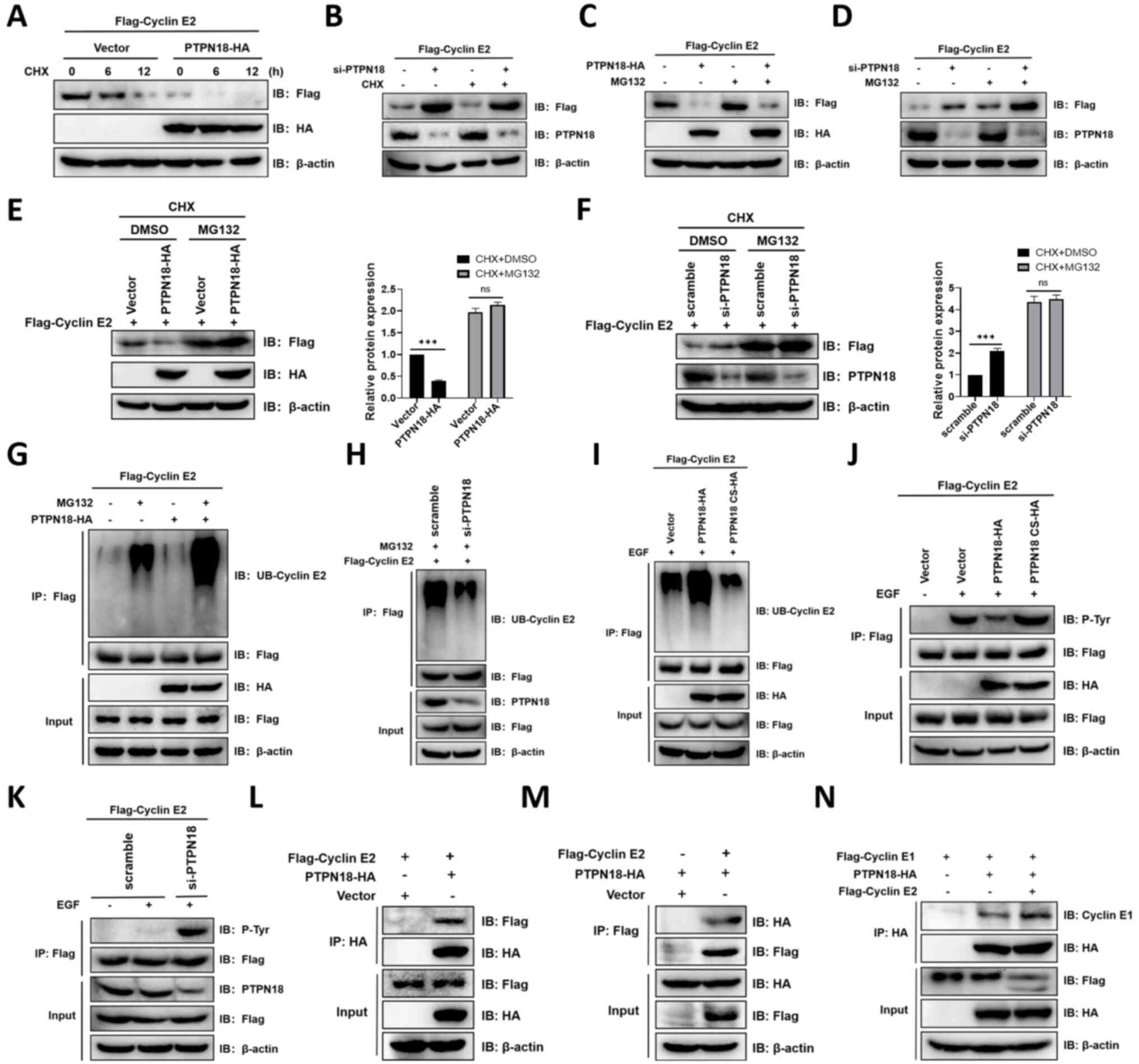

Next, the present study explored the effect of

PTPN18 on cyclin E2, another isoform of cyclin E. It was found that

overexpression of PTPN18 decreased the cyclin E2 protein levels

after treatment with CHX (Fig.

7A). However, the cyclin E2 protein levels were restored when

MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, was added (Fig. 6C). When PTPN18 expression was

knocked down with siRNA, the opposite effects on the cyclin E2

protein levels were observed (Fig. 7B

and D). The combined use of CHX and MG132 nearly abolished the

effect of PTPN18 on the cyclin E2 protein levels compared with the

control (Fig. 7E and F).

Examination of the cyclin E2 ubiquitination levels revealed that

MG132 enhanced the PTPN18-mediated protein ubiquitination of cyclin

E2, whereas knockdown of PTPN18 reduced the cyclin E2

ubiquitination levels (Fig. 7G and

H). Similar to the cyclin E1 results, inactivation treatment

with PTPN18 C229S reduced the ubiquitination and increased the

phosphorylation of cyclin E2, indicating that cyclin E2 is also a

substrate for PTPN18 (Fig. 7I-K).

Additionally, forward and reverse Co-IP experiments verified the

interaction of PTPN18 with cyclin E2 (Fig. 7L and M). These results indicated

that PTPN18 can also promote the degradation of cyclin E2 through

the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Given that both cyclins E1 and E2

can bind PTPN18, it was further explored whether there is a

competitive relationship between their interactions. The Co-IP

results showed that the addition of cyclin E2 did not reduce the

binding of PTPN18 to cyclin E1, suggesting cyclin E2 did not

interfere with the binding of cyclin E1 to PTPN18 (Fig. 7N).

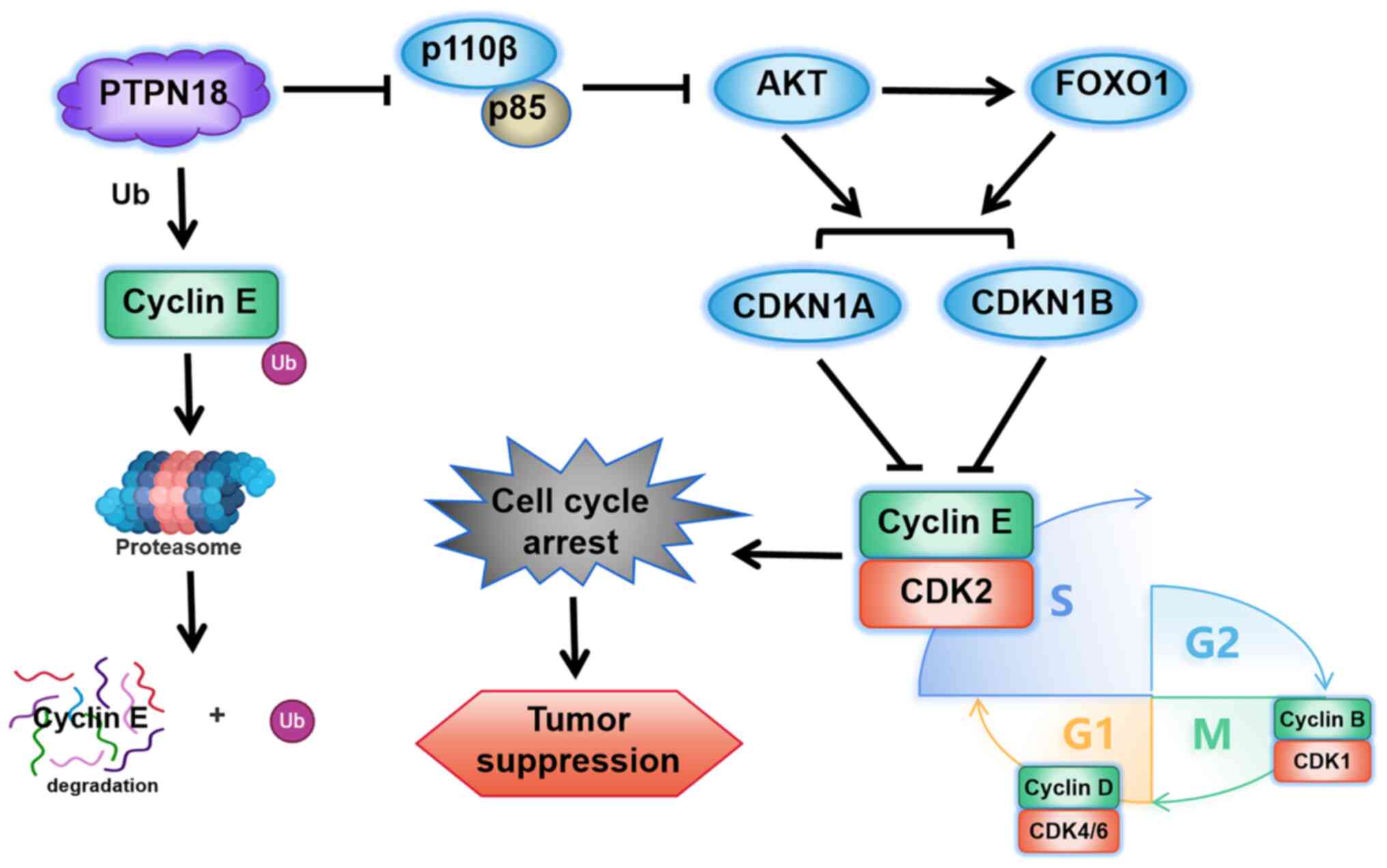

PTPN18 can regulate the protein

expression levels of CDK inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A, also known as

p21Cip1) and CDK inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B, also known as p27Kip1)

through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B

(AKT) signaling pathway leading to cell cycle arrest

To further explore the signaling pathways through

which PTPN18 regulates the cell cycle, key genes associated with

the cell cycle according to the KEGG database were selected to

examine the effects of PTPN18 on their transcript levels. The

results demonstrated that PTPN18 overexpression produced

significant changes in the phosphoinositide-dependent protein

kinase 1 (PDPK1), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

catalytic subunit γ (PI3CG), forkhead box O3 (FOXO3),

mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 (MAPK8), CDKN1A, growth arrest

and DNA damage-inducible protein α (GADD45A), adenomatous polyposis

coli protein (APC) and E1A-binding protein p300 (EP300) transcript

levels, indicating that PTPN18 may have a wide range of

multi-target and multi-pathway roles in gene transcription

regulation (Fig. S3A-H).

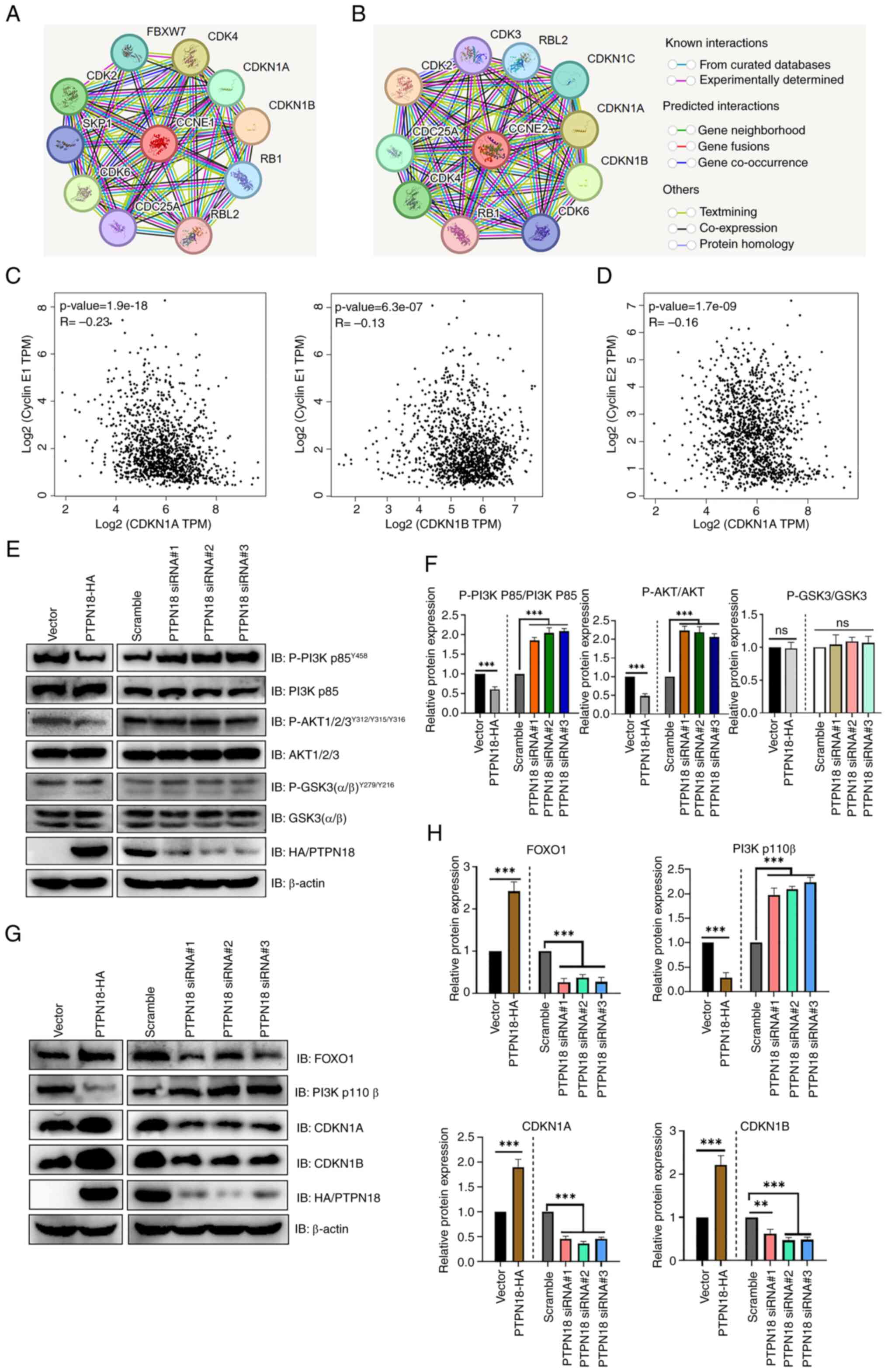

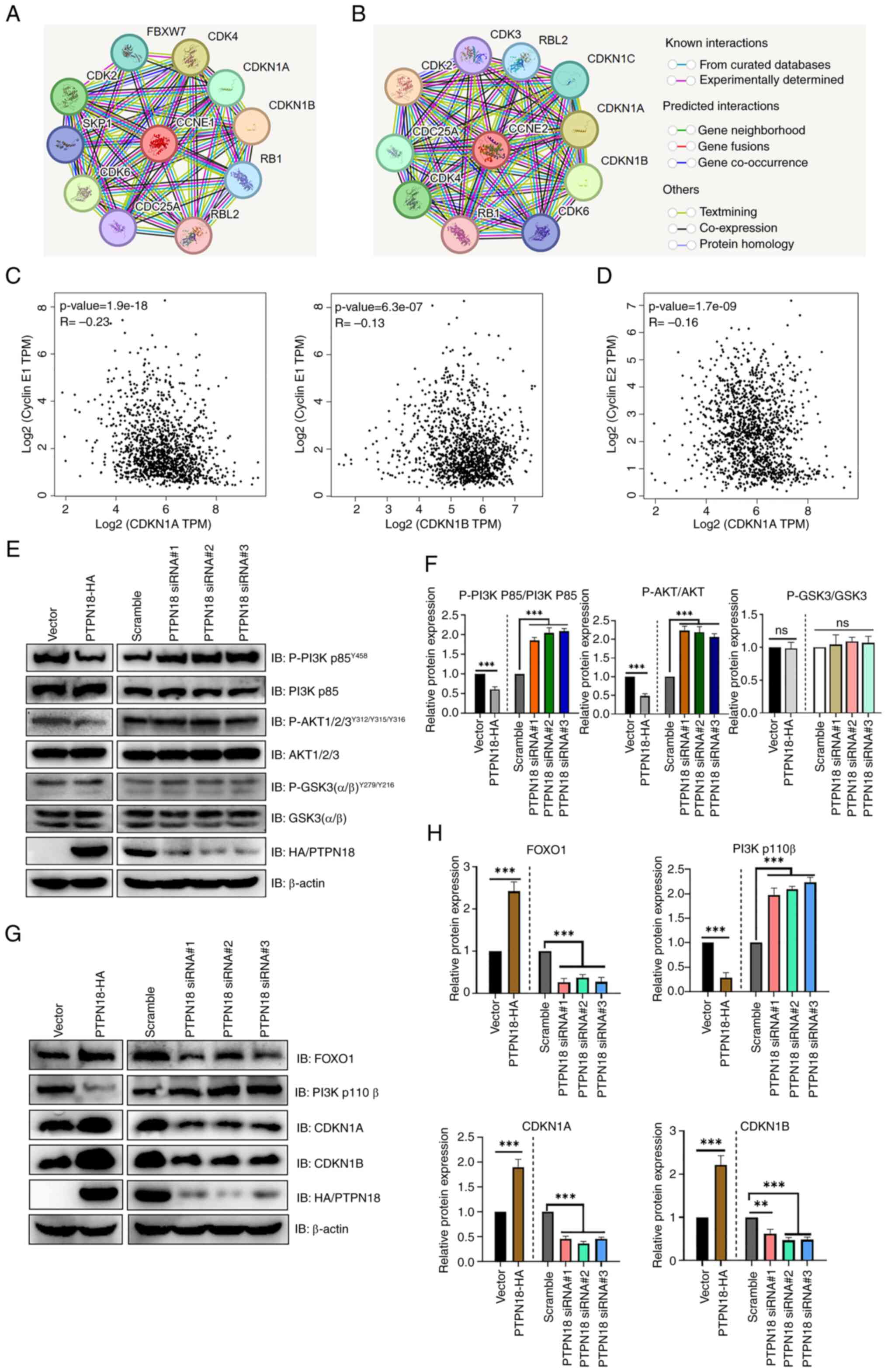

Analysis using STRING, a functional protein association network

database, showed that CDKN1A and CDKN1B closely interacted with

cyclins E1 (CCNE1) and E2 (CCNE2) (Fig. 8A and B). The Kendall statistical

analysis results from the GEPIA database also showed that CDKN1A

and CDKN1B had significant negative correlations with cyclin E1 and

CDKN1A had a negative correlation with cyclin E2 (Fig. 8C and D). Further protein level

experiments showed that PTPN18 overexpression significantly

decreased the tyrosine phosphorylation levels of PI3K p85 and AKT

and the protein expression levels of PI3K P110β compared with the

controls, whereas the protein levels of FOXO1, CDKN1A and CDKN1B

were significantly increased (Fig.

8E-H). Decreased levels of AKT tyrosine phosphorylation

resulted in reduced inhibition of FOXO and increased FOXO

expression, followed by increased CDKN1A and CDKN1B protein levels,

resulting in cyclin inhibition and cell cycle arrest (Figs. 8E-H and 9). The results of the endogenous PTPN18

knockdown experiments were generally consistent with those of the

overexpression experiments (Fig.

8E-H). Taken together, the protein level results confirmed that

the antitumor effect of PTPN18 may be closely related to the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

| Figure 8PTPN18 can regulate the expression

levels of CDKN1A and CDKN1B proteins through the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway leading to cell cycle arrest. (A and B) STRING database

analysis showed proteins that interact with (A) cyclin E1 (CCNE1)

and (B) E2 (CCNE2). (C) GEPIA database analysis of the CDKN1A and

CDKN1B association with cyclin E1. (D) Correlation analysis between

CDKN1A and cyclin E2 using the GEPIA database. (E) Western blot

analysis of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway protein expression

levels in MCF-7 cells. Levels of P-PI3K p85, P-AKT and P-GSK3 were

monitored after a 30-min stimulation with EGF (100 ng/ml). (F)

Relative quantitative analysis of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

protein expression levels. (G) Western blotting demonstrated the

expression levels of FOXO1, PI3K p110β, CDKN1A and CDKN1B. (H) The

bar graph was obtained by normalizing the levels to β-actin. Data

are shown as the mean ± SD from three technical replicates

following 48 h of overexpression or 72 h of knockdown.

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. PTPN18,

protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor 18; GEPIA, Gene

Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; PI3K,

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; CDKN1A

(p21Cip1), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A; CDKN1B (p27Kip1),

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B; P-, phosphorylation; FOXO1,

forkhead box O1; ns, not significant; P-, phosphorylated; siRNA,

small interfering RNA. |

Discussion

PTPN18 is expressed in a variety of normal tissues

and is ubiquitous in the nucleus and cytoplasm of cells, with low

tissue specificity (29,33,34). The core function of PTPN18 is to

act as a negative regulator of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling

and regulate a variety of cellular processes including cell

proliferation, differentiation, the mitotic cycle and oncogenic

transformation by dephosphorylating key receptors such as HER2

(7,10-17). It has also been shown that PTPN18

is a protective factor against obesity, hyperlipidemia and type 2

diabetes (35). More notably,

PTPN18 is closely related to the development of BC and its high

expression improves the survival and prognosis of patients with

this disease (15-17,29,30); therefore, it is necessary to

dissect the specific mechanism of action of PTPN18 in BC. In the

present study, through tumor phenotypic functional assays, it was

found that overexpression of PTPN18 inhibited metastasis and

proliferation, promoted apoptosis and led to cell cycle arrest in

BC cells. Although MCF-7 cells lack caspase-3 activity, PTPN18 may

still achieve pro-apoptotic effects by negatively regulating the

PI3K/AKT pathway, regulating Bcl-2 family protein balance,

increasing ROS levels, or activating lysosomal enzymes, triggering

compensatory activation of other effector caspases or

mitochondria-mediated caspase-independent apoptosis (36-38). Annexin V/PI double staining

results directly verified the existence of this apoptotic

phenotype.

Since the cell cycle is the key regulatory hub of

cell proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis (39), as well as owing to the notable

role of PTPN18 in the BC cell cycle, subsequent experiments in the

present study focused on exploring the molecular mechanisms by

which PTPN18 affects cell cycle changes to dissect its tumor

suppressor mechanism. It was found that PTPN18 not only interacted

with cyclin E1 and downregulated its protein expression and

tyrosine phosphorylation levels, but it also acted on cyclin E2

with the same effect, indicating that PTPN18 may be a specific and

broad-spectrum regulator of the cyclin E family. Moreover, PTPN18

binding to cyclin E1 was not perturbed by cyclin E2. This property

may allow PTPN18 to comprehensively inhibit cyclin E

family-mediated abnormal proliferation, avoid isoform compensation

and improve the scope and stability of its antitumor effects.

Cyclin E can bind to the CDK1 and CDK2 protein kinases and

participate in the regulation of the G1 phase, G1/S phase

transition and S phase progression (18-23,40,41). As an important regulatory protein

in the S phase, the decrease of cyclin E expression and activity

may directly lead to the inability of retinoblastoma protein (RB)

to maintain a highly phosphorylated state (39-41), resulting in S phase-related

proteins not being successfully synthesized, the accumulation of

cells in the S phase and the failure of cells to transition to the

G2/M phase. The effect of PTPN18 on RB phosphorylation status and

the key downstream targets of cyclin E/CDK2 activity decrease will

be the next research focus to dissect the mechanism of S phase

arrest caused by PTPN18 affecting DNA replication.

In the present study, it was found that PTPN18

overexpression enhanced the expression of cyclin B1, cyclin D1 and

CDK4. Elevated cyclin B1 expression promotes the formation and

activation of maturation-promoting factor, thereby accelerating

G2/M phase transition and cell division, resulting in a decrease in

the number of G2/M phase cells (42-44). Cyclin B can competitively bind to

CDK2 and CDK1 with cyclin E, affecting the stability of the cyclin

E/CDK complex and arresting the cell cycle in the S phase (19,42,43). The cyclin D-CDK4/6 complex is the

main regulatory complex of the G1 phase of the cell cycle and

phosphorylates RB (45). The

increase of cyclin D1 and CDK4 may compensate for the effect of

cyclin E in G1 phase and alleviate the stress trend caused by the

accelerated cycle progression in G2/M phase, allowing G1 phase to

transform normally and maintain dynamic balance.

In the present study, PTPN18 significantly affected

the transcript levels of PDPK1, PI3CG, FOXO3, MAPK8, CDKN1A,

GADD45A, APC and EP300. FOXO and CDKN1A are downstream targets of

the PI3K/AKT pathway (46) and

PI3K/AKT can regulate GADD45A through the FOXO pathway (47). AKT may play a role in the

regulation of a variety of cellular activities through the

transcriptional coactivator EP300 (48) and MAPK8 can regulate the AKT

pathway (49). Additionally, dual

PI3K/mTOR inhibition is a potential therapeutic strategy for APC

and PIK3CA mutant colorectal cancer (50). Given that these significantly

altered genes are all associated with the PI3K/AKT pathway, the

present study examined the regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway by

PTPN18 at the protein level. The results of the present study

indicated that PTPN18 significantly decreased the tyrosine

phosphorylation levels of PI3K p85 and AKT and the protein levels

of P110β as well as markedly increased the protein levels of FOXO1,

CDKN1A and CDKN1B. Decreased tyrosine phosphorylation levels of

PI3K p85 and AKT leads to inhibition of their function. P110β

stimulates cell proliferation and upregulation in the wild-type

state is oncogenic (51). A

reduction in P110β expression directly leads to the weakening of

its cancer-promoting effect and a relative increase in

intracellular PI3K p85 content; excess free PI3K p85 inhibits the

PI3K/AKT pathway (52). Combined

with the characteristics of PTPN18 protein tyrosine phosphatase and

experimental data, it is speculated that PTPN18 may regulate

PI3K/AKT pathway by directly dephosphorylating the tyrosine sites

of PI3K P85 and/or AKT, and then inhibit BC progression through

FOXO1-CDKN1A/CDKN1B-Cyclin E axis (Fig. 9); this hypothesis is consistent

with the consensus of field studies (15,46,51-55), but experiments are still needed to

verify the specific substrate and whether there are other potential

targets.

Unlike previous studies in which PTPN18 has been

shown to exert antitumor effects in BC through targets such as HER2

or ETS1 (15-17), a novel anticancer target of

PTPN18, cyclin E, was discovered in the present study. The current

literature suggests that cyclin E depletion improves the

chemosensitivity of BC cells to DNA-damaging agents (56). Patients with tumors harboring high

cyclin E expression have a reduced benefit from tamoxifen treatment

compared with patients with low tumor expression (57). However, the present study found

that PTPN18 could downregulate cyclin E expression and activity,

which is likely to be one of the key mechanisms by which PTPN18

synergistic drug treatment results in an improved prognosis and

longer survival of patients with BC. Needless to say, the role and

molecular mechanism of PTPN18 in the efficacy of conventional

anticancer drugs is an important guide for future research. In the

future, it may be possible to focus on exploring how to develop new

therapeutic strategies by enhancing the activity of PTPN18 or

mimicking its mechanism of action.

In summary, the antitumor effect of PTPN18 should be

the result of a combination of numerous mechanistic pathways and

substrates (15-17). Based on the current findings

alone, it is not sufficient to clarify whether PTPN18 can be used

as a reliable marker for BC diagnosis. Subsequently, a large number

of experiments are required to analyze the relationship between

PTPN18 expression level or activity and different

clinicopathological features of BC and explore its potential as a

diagnostic marker. Because the original intention of this paper was

to dissect the protective mechanism of high PTPN18 expression on OS

in patients with BC, and its function in normal breast cells may be

at rest or physiological homeostasis, it was not investigated.

However, the function and mechanism of PTPN18 in normal breast cell

lines should not be ignored, which is an important supplement to

comprehensively elucidate its role in breast physiological

homeostasis and the development of BC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

NZ performed the majority of the experiments,

analyzed the data and wrote and edited the manuscript. TW, BB and

XZ constructed the plasmids. WX and WC performed the reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and data analysis. YY and BW

directed the study, analyzed and approved all of the data, and

wrote and edited the manuscript. NZ and BW confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

Co-IP

|

co-immunoprecipitation

|

|

PI3K

|

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

|

|

AKT

|

protein kinase B

|

|

HER2

|

human epidermal growth factor receptor

2

|

|

MCF7

|

Michigan Cancer Foundation-7

|

|

MDA-MB-231

|

Metastatic Derivative of Anaplastic

Breast Cancer-231

|

|

WB

|

western blot

|

|

TBST

|

Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20

|

|

RIPA

|

radioimmunoprecipitation assay

|

|

PBS

|

phosphate-buffered saline

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

mTOR

|

mechanistic target of rapamycin

kinase

|

|

CDK

|

cyclin-dependent kinase

|

|

RB

|

retinoblastoma protein

|

|

GEPIA

|

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis

|

|

CHX

|

cycloheximide

|

|

PDPK1

|

phosphoinositide-dependent protein

kinase 1

|

|

PI3CG

|

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

3-kinase catalytic subunit γ

|

|

FOXO

|

forkhead box O

|

|

MAPK8

|

mitogen-activated protein kinase

8

|

|

GADD45A

|

growth arrest and DNA

damage-inducible protein α

|

|

APC

|

adenomatous polyposis coli

protein

|

|

EP300

|

E1A-binding protein p300

|

|

CDKN1A (p21Cip1)

|

CDK inhibitor 1A

|

|

CDKN1B (p27Kip1)

|

CDK inhibitor 1B

|

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 32100992) and Key Laboratory of

Bioresource Research and Development of Liaoning (grant no.

2022JH13/10200026).

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xiong X, Zheng LW, Ding Y, Chen YF, Cai

YW, Wang LP, Huang L, Liu CC, Shao ZM and Yu KD: Breast cancer:

Pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

10:492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Radenkovic S, Konjevic G, Jurisic V,

Karadzic K, Nikitovic M and Gopcevic K: Values of MMP-2 and MMP-9

in tumor tissue of basal-like breast cancer patients. Cell Biochem

Biophys. 68:143–152. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Radenkovic S, Milosevic Z, Konjevic G,

Karadzic K, Rovcanin B, Buta M, Gopcevic K and Jurisic V: Lactate

dehydrogenase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase in tumor tissue

of breast cancer patients in respect to mammographic findings. Cell

Biochem Biophys. 66:287–295. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Konjević G, Jurisić V and Spuzić I:

Association of NK cell dysfunction with changes in LDH

characteristics of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) in breast

cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 66:255–263. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Radenkovic S, Konjevic G, Gavrilovic D,

Stojanovic-Rundic S, Plesinac-Karapandzic V, Stevanovic P and

Jurisic V: pSTAT3 expression associated with survival and

mammographic density of breast cancer patients. Pathol Res Pract.

215:366–372. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Veillette A, Rhee I, Souza CM and Davidson

D: PEST family phosphatases in immunity, autoimmunity, and

autoinflammatory disorders. Immunol Rev. 228:312–324. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bai B, Wang T, Zhang X, Ba X, Zhang N,

Zhao Y, Wang X, Yu Y and Wang B: PTPN22 activates the PI3K pathway

via 14-3-3τ in T cells. FEBS J. 290:4562–4576. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang X, Yu Y, Bai B, Wang T, Zhao J,

Zhang N, Zhao Y, Wang X and Wang B: PTPN22 interacts with EB1 to

regulate T-cell receptor signaling. FASEB J. 34:8959–8974. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang B, Lemay S, Tsai S and Veillette A:

SH2 domain-mediated interaction of inhibitory protein tyrosine

kinase Csk with protein tyrosine phosphatase-HSCF. Mol Cell Biol.

21:1077–1088. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cong F, Spencer S, Côté JF, Wu Y, Tremblay

ML, Lasky LA and Goff SP: Cytoskeletal protein PSTPIP1 directs the

PEST-type protein tyrosine phosphatase to the c-Abl kinase to

mediate Abl dephosphorylation. Mol Cell. 6:1413–1423. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Dowbenko D, Spencer S, Quan C and Lasky

LA: Identification of a novel polyproline recognition site in the

cytoskeletal associated protein, proline serine threonine

phosphatase interacting protein. J Biol Chem. 273:989–996. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wu Y, Dowbenko D and Lasky LA: PSTPIP 2, a

second tyrosine phosphorylated, cytoskeletal-associated protein

that binds a PEST-type protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem.

273:30487–30496. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shiota M, Tanihiro T, Nakagawa Y, Aoki N,

Ishida N, Miyazaki K, Ullrich A and Miyazaki H: Protein tyrosine

phosphatase PTP20 induces actin cytoskeleton reorganization by

dephosphorylating p190 RhoGAP in rat ovarian granulosa cells

stimulated with follicle-stimulating hormone. Mol Endocrinol.

17:534–549. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang HM, Xu YF, Ning SL, Yang DX, Li Y, Du

YJ, Yang F, Zhang Y, Liang N, Yao W, et al: The catalytic region

and PEST domain of PTPN18 distinctly regulate the HER2

phosphorylation and ubiquitination barcodes. Cell Res.

24:1067–1090. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gensler M, Buschbeck M and Ullrich A:

Negative regulation of HER2 signaling by the PEST-type

protein-tyrosine phosphatase BDP1. J Biol Chem. 279:12110–12116.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang T, Ba X, Zhang X, Zhang N, Wang G,

Bai B, Li T, Zhao J, Zhao Y, Yu Y and Wang B: Nuclear import of

PTPN18 inhibits breast cancer metastasis mediated by MVP and

importin β2. Cell Death Dis. 13:7202022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Chu C, Geng Y, Zhou Y and Sicinski P:

Cyclin E in normal physiology and disease states. Trends Cell Biol.

31:732–746. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Siu KT, Rosner MR and Minella AC: An

integrated view of cyclin E function and regulation. Cell Cycle.

11:57–64. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

20

|

Caldon CE and Musgrove EA: Distinct and

redundant functions of cyclin E1 and cyclin E2 in development and

cancer. Cell Div. 5:22010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hwang HC and Clurman BE: Cyclin E in

normal and neoplastic cell cycles. Oncogene. 24:2776–2786. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fagundes R and Teixeira LK: Cyclin E/CDK2:

DNA replication, replication stress and genomic instability. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 9:7748452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Scaltriti M, Eichhorn PJ, Cortés J,

Prudkin L, Aura C, Jiménez J, Chandarlapaty S, Serra V, Prat A,

Ibrahim YH, et al: Cyclin E amplification/overexpression is a

mechanism of trastuzumab resistance in HER2+ breast cancer

patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:3761–3766. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Radenković N, Milutinović M, Nikodijević

D, Jovankić J and Jurišić V: Sample preparation of adherent cell

lines for flow cytometry: protocol optimization-our experience with

SW-480 colorectal cancer cell line. Indian J Clin Biochem.

40:74–79. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Vuletic A, Konjevic G, Milanovic D,

Ruzdijic S and Jurisic V: Antiproliferative effect of

13-cis-retinoic acid is associated with granulocyte differentiation

and decrease in cyclin B1 and Bcl-2 protein levels in G0/G1

arrested HL-60 cells. Pathol Oncol Res. 16:393–401. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Scherbakov AM, Vorontsova SK, Khamidullina

AI, Mrdjanovic J, Andreeva OE, Bogdanov FB, Salnikova DI, Jurisic

V, Zavarzin IV and Shirinian VZ: Novel pentacyclic derivatives and

benzylidenes of the progesterone series cause anti-estrogenic and

antiproliferative effects and induce apoptosis in breast cancer

cells. Invest New Drugs. 41:142–152. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chandrashekar DS, Karthikeyan SK, Korla

PK, Patel H, Shovon AR, Athar M, Netto GJ, Qin ZS, Kumar S, Manne

U, et al: UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis

platform. Neoplasia. 25:18–27. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T and Zhang Z:

GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling

and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1): W556–W560.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Posta M and Győrffy B: Pathway-level

mutational signatures predict breast cancer outcomes and reveal

therapeutic targets. Br J Pharmacol. 182:5734–5747. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Vasaikar S, Straub P, Wang J and Zhang B:

LinkedOmics: analyzing multi-omics data within and across 32 cancer

types. Nucleic Acids Res. 46(D1): D956–D963. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

32

|

Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M,

Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, Gable AL, Fang T, Doncheva NT,

Pyysalo S, et al: The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein

association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any

sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1): D638–D646.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kim YW, Wang H, Sures I, Lammers R,

Martell KJ and Ullrich A: Characterization of the PEST family

protein tyrosine phosphatase BDP1. Oncogene. 13:2275–2279.

1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Cheng J, Daimaru L, Fennie C and Lasky LA:

A novel protein tyrosine phosphatase expressed in

lin(lo)CD34(hi)Sca(hi) hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood.

88:1156–1167. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li W, Zhong Q, Deng N, Zhou X, Wang H,

Ouyang J, Guan Z, Cheng B, Xiang L, Huang Y, et al: Sphingolipid

metabolism-related genes for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome by

integrated bioinformatics analysis and Mendelian randomization

identification. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 17:2342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Cuvillier O, Nava VE, Murthy SK, Edsall

LC, Levade T, Milstien S and Spiegel S: Sphingosine generation,

cytochrome c release, and activation of caspase-7 in

doxorubicin-induced apoptosis of MCF7 breast adenocarcinoma cells.

Cell Death Differ. 8:162–171. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yang S, Huang J, Liu P, Li J and Zhao S:

Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) nuclear translocation mediated

caspase-independent mechanism involves in X-ray-induced MCF-7 cell

death. Int J Radiat Biol. 93:270–278. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Pozo-Guisado E, Merino JM, Mulero-Navarro

S, Lorenzo-Benayas MJ, Centeno F, Alvarez-Barrientos A and

Fernandez-Salguero PM: Resveratrol-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 human

breast cancer cells involves a caspase-independent mechanism with

downregulation of Bcl-2 and NF-kappaB. Int J Cancer. 115:74–84.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liu J, Peng Y and Wei W: Cell cycle on the

crossroad of tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. Trends Cell Biol.

32:30–44. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ekholm-Reed S, Mendez J, Tedesco D,

Zetterberg A, Stillman B and Reed SI: Deregulation of cyclin E in

human cells interferes with prereplication complex assembly. J Cell

Biol. 165:789–800. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Caldon CE, Sergio CM, Sutherland RL and

Musgrove EA: Differences in degradation lead to asynchronous

expression of cyclin E1 and cyclin E2 in cancer cells. Cell Cycle.

12:596–605. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Crncec A, Lau HW, Ng LY, Ma HT, Mak JPY,

Choi HF, Yeung TK and Poon RYC: Plasticity of mitotic cyclins in

promoting the G2-M transition. J Cell Biol. 224:e2024092192025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li J, Qian WP and Sun QY: Cyclins

regulating oocyte meiotic cell cycle progression†. Biol Reprod.

101:878–881. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Gao SC, Dong MZ, Zhao BW, Liu SL, Guo JN,

Sun SM, Li YY, Xu YH and Wang ZB: Fangchinoline inhibits mouse

oocyte meiosis by disturbing MPF activity. Toxicol In Vitro.

99:1058762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

VanArsdale T, Boshoff C, ArndtK T and

Abraham RT: Molecular pathways: Targeting the cyclin D-CDK4/6 axis

for cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 21:2905–2910. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kloet DEA, Polderman PE, Eijkelenboom A,

Smits LM, van Triest MH, van den Berg MCW, Groot Koerkamp MJ, van

Leenen D, Lijnzaad P, Holstege FC and Burgering BMT: FOXO target

gene CTDSP2 regulates cell cycle progression through Ras and

p21(Cip1/Waf1). Biochem J. 469:289–298. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Amente S, Zhang J, Lavadera ML, Lania L,

Avvedimento EV and Majello B: Myc and PI3K/AKT signaling

cooperatively repress FOXO3a-dependent PUMA and GADD45a gene

expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:9498–9507. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chen J, Halappanavar SS, St-Germain JR,

Tsang BK and Li Q: Role of Akt/protein kinase B in the activity of

transcriptional coactivator p300. Cell Mol Life Sci. 61:1675–1683.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Sunayama J, Tsuruta F, Masuyama N and

Gotoh Y: JNK antagonizes Akt-mediated survival signals by

phosphorylating 14-3-3. J Cell Biol. 170:295–304. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Foley TM, Payne SN, Pasch CA, Yueh AE, Van

De Hey DR, Korkos DP, Clipson L, Maher ME, Matkowskyj KA, Newton MA

and Deming DA: Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibition in colorectal cancers with

APC and PIK3CA mutations. Mol Cancer Res. 15:317–327. February

9–2017.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Dbouk HA and Backer JM: A beta version of

life: p110β takes center stage. Oncotarget. 1:729–733. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Geering B, Cutillas PR, Nock G, Gharbi SI

and Vanhaesebroeck B: Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinases are

obligate p85-p110 heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

104:7809–7814. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Luo J and Cantley LC: The negative

regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling by p85 and its

implication in cancer. Cell Cycle. 4:1309–1312. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zheng Y, Peng M, Wang Z, Asara JM and

Tyner AL: Protein tyrosine kinase 6 directly phosphorylates AKT and

promotes AKT activation in response to epidermal growth factor. Mol

Cell Biol. 30:4280–4292. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chen R, Kim O, Yang J, Sato K, Eisenmann

KM, McCarthy J, Chen H and Qiu Y: Regulation of Akt/PKB activation

by tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 276:31858–31862. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Chen J and Wang G: Cyclin E expression and

chemotherapeutic sensitivity in breast cancer cells. J Huazhong

Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 26:565–566. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Waltersson MA, Askmalm MS, Nordenskjöld B,

Fornander T, Skoog L and Stål O: Altered expression of cyclin E and

the retinoblastoma protein influences the effect of adjuvant

therapy in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 34:441–448. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|