The immune system serves as the primary defense

mechanism in the body against external pathogens and abnormal

cells; it plays a vital role in identifying and eliminating tumor

cells (1). The relationship

between tumors and immune function represents a complex and

intricate biological network that has emerged as the key focus in

research on cancer. Hypoxia is a common characteristic of solid

tumors (2). During tumor growth,

cancer cells progressively form an immunosuppressive hypoxic tumor

microenvironment (TME), which promotes the proliferation and

metastasis of tumors by influencing processes such as metabolism,

angiogenesis and immune evasion (3). In the TME, critical transcription

factors, particularly hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) and their

downstream signaling pathways, are activated. These signals

regulate the differentiation, function and metabolic reprogramming

of immune cells, thereby shaping the direction and strength of the

tumor immune response. Ultimately, HIFs influence angiogenesis,

cell proliferation and invasion in tumors, mediating the

progression and development of tumors (4).

Several epidemiological studies have identified a

significant correlation between HIFs and greater incidence and

mortality in various types of cancer. The two primary HIF isoforms,

HIF-1α and HIF-2α, serve as key regulators under hypoxic conditions

and play crucial roles in tumor immune evasion by modulating the

innate and adaptive immune systems (5). Hypoxia upregulates the transcription

and expression of HIF-1α, which subsequently activates the immune

checkpoint comprising programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and

its ligand PD-L1 (6). This

pathway indirectly suppresses the activation and proliferation of

T-cells, leading to immune evasion by tumor cells. Similarly, the

interaction between CD137 expressed on T cells and its ligand

CD137L can activate dendritic cells and macrophages; this, in turn,

allows them to recognize and eliminate cancer cells. However,

HIF-1α present in tumor cells can prevent this process, causing the

tumor cells to escape from adaptive immunity (7,8).

Compared with HIF-1α, HIF-2α more prominently induces the

expression of genes associated with invasion and stem cell

properties, such as matrix metalloproteinases and stem cell factor

octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4 (OCT-3/4) (9,10).

When these genes are expressed, the invasive and metastatic

capabilities of tumor cells are enhanced (11). In clear cell renal cell carcinoma

(ccRCC), HIF-2α promotes the secretion of immunosuppressive

cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and

interleukin (IL) 10 by upregulating stem cell factors, thereby

fostering an immunosuppressive TME (12).

The induction of HIF-dependent genes not only

improves the ability of the tumor to adapt to more hypoxic

conditions but also promotes angiogenesis, cell survival, invasion

and metastasis in tumors (4).

Numerous preclinical and clinical studies have investigated

targeted cancer therapeutic strategies aimed at inhibiting or

activating HIFs. The methods available for inhibiting the response

of HIF-1α to hypoxia include, but are not limited to, small

interfering RNA (siRNA) therapy, blocking of the dimerization of

HIF-1α and β subunits and the use of anticancer agents that

directly inhibit HIF-1α by targeting the PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α pathway

(13). However, in clinical

trials, HIF-targeted therapeutic techniques have often failed to

achieve the desired outcomes and HIF inhibitors are associated with

significant dose-limiting side effects. As tumor immunity is

complex, deciding whether to target all HIF isoforms or selectively

target HIF-1α or HIF-2α requires careful consideration of their

distinct functions, as well as the different roles HIFs play across

various types of cells. Additionally, hypoxia-induced reduction in

pH leads to an acidic TME, which leads to a decrease in the

concentration of the drug due to ion trapping, a reduction in the

apoptosis of cancer cells and an increase in the activity of

multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp) (13-15). These factors contribute to

HIF-mediated therapeutic failure and/or an increase in tumor drug

resistance.

The present review comprehensively examined the

mechanisms and effects of HIFs on both innate and adaptive immune

systems in the hypoxic TME. It evaluated the potential of HIFs as

critical therapeutic targets in cancer treatment and proposed

strategies for developing novel HIF inhibitors to systematically

combat cancer.

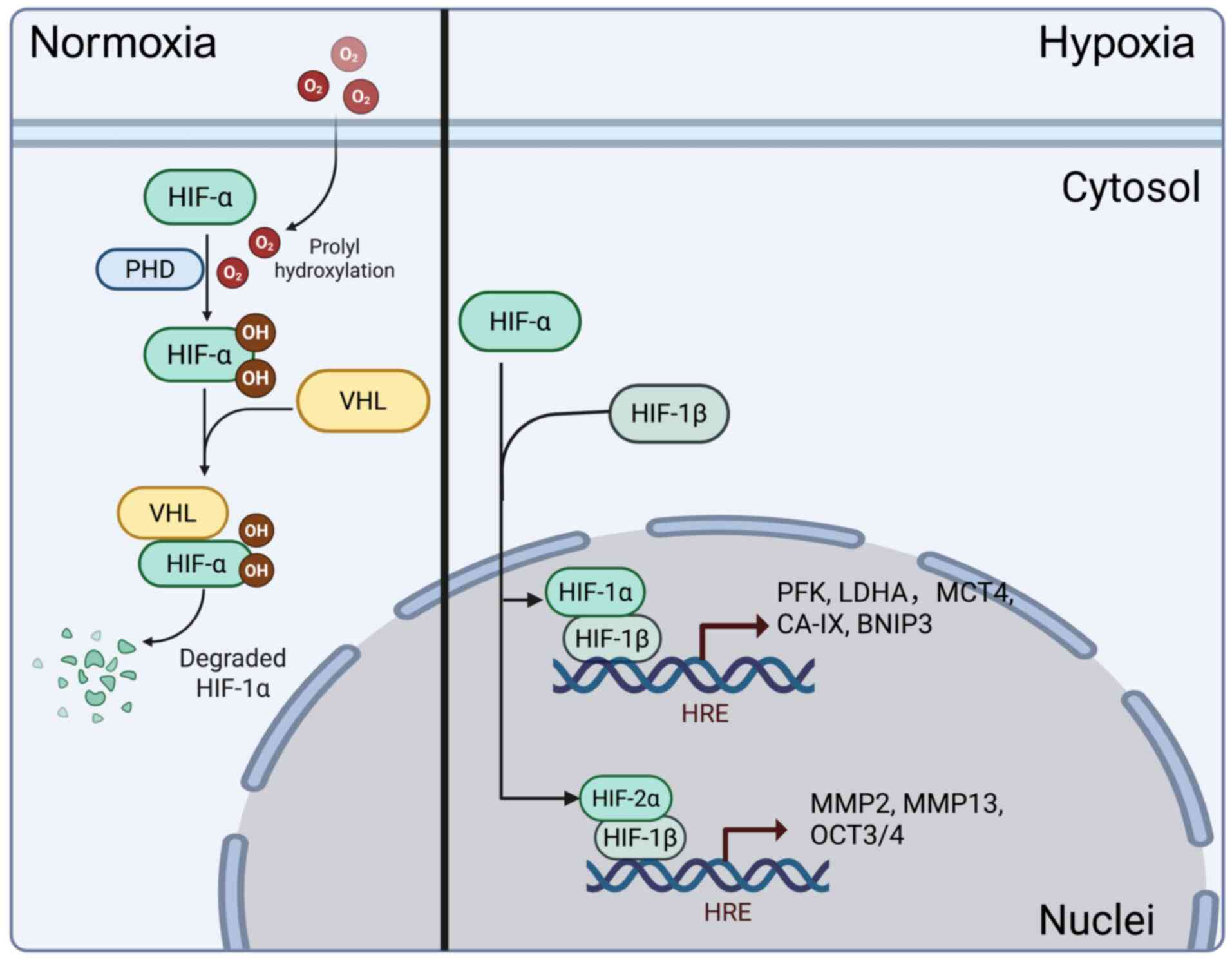

HIFs is a heterodimeric transcription factor

composed of α and β subunits. The α subunit exhibits

oxygen-dependent expression, while the β subunit exhibits

constitutive expression. A total of three α subunits (HIF-1α,

HIF-2α and HIF-3α) and three β subunits (HIF-1β, HIF-2β and HIF-3β,

also known as ARNT1, ARNT2 and ARNT3) are known. Although the HIF-β

subunit shows excellent stability, the stability of the HIF-α

subunit fluctuates in response to changes in oxygen tension,

regulated by prolyl hydroxylase (PHD)1, PHD2 and PHD3 (16-18). Under normoxic conditions, oxygen

is used by PHDs to hydroxylate two conserved proline residues on

the HIF-α subunit. These hydroxylated proline residues are

recognized by the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase

complex, leading to proteasomal degradation of the HIF-α subunit

(19). However, under hypoxic

conditions, PHDs lack sufficient oxygen as a substrate to perform

their dioxygenase function, thereby preventing VHL from recognizing

the HIF-α subunit, resulting in its stabilization. As a result, the

HIF-α subunit translocates to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with

the HIF-β subunit and binds to DNA at hypoxia response elements,

thereby driving HIF-dependent transcription (20,21).

Transcriptional targets dependent on HIFs spans

numerous biological processes, including angiogenesis, glycolysis,

chromatin remodeling, cell cycle regulation and even genes involved

in the oxygen-sensing pathway. Through genome-wide analyses of

hypoxic transcriptomic responses and HIF binding sites, researchers

have found that, in any specific cell type, at least 500-1,000

genes are directly or indirectly regulated by HIFs (22-24). Concerning target genes, HIF-1 and

HIF-2 exhibit a degree of specificity. HIF-1 generally induces

genes encoding glycolytic enzymes, such as phosphofructokinase and

lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA); those involved in the regulation of

pH, such as monocarboxylate transporter 4 and carbonic anhydrase IX

and genes that promote apoptosis, such as Bcl2 interacting protein

3 (BNIP3) and Bcl2/Adenovirus interacting protein 3 (BNIP3L/NIX)

(11,24). By contrast, HIF-2 generally

induces genes associated with invasion processes, such as MMP2 and

MMP13 and the stem cell factor OCT-3/4 (11). These two heterodimeric

transcription factors may substitute for each other under certain

circumstances, besides specifically regulating downstream target

genes, HIF-1 and HIF-2 share some common targets, such as vascular

endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and glucose transporter 1

(GLUT1) (25,26). In human tissues, HIF-1α is widely

expressed, while HIF-2α, initially identified as Endothelial PAS

domain protein 1, was previously considered an endothelial-specific

HIF-α isoform (27). However,

studies have found that under hypoxic conditions, the expression of

HIF-2α is not limited to the vasculature; its transcriptional

response is widely activated under prolonged hypoxia, complementing

rather than redundantly overlapping with the function of HIF-1α

(28,29) (Fig.

1).

The immune system is a network that operates due to

the interaction of lymphoid organs, cells, humoral factors and

cytokines. It is divided into nonspecific immunity (innate

immunity) and specific immunity (adaptive immunity); the two types

of immunity differ in their activation times, the types of immune

cells involved and their modes of action (30). HIF-1α and HIF-2α are broadly

expressed and detectable in nearly all innate and adaptive immune

cell populations. The unique expression patterns of HIF-1α and

HIF-2α in immune cells depend on intrinsic and extrinsic factors,

with the balance between them contributing to the regulation of

overlapping or distinct sets of target genes. Their expression and

stabilization in immune cells can be triggered not only by hypoxia

but also by other factors associated with pathological stress, such

as inflammation, infectious microorganisms and cancer (31-33). HIFs regulate various types of

immune processes, enhancing the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes

and driving the differentiation of T cells and cytotoxic activity.

Additionally, HIF-mediated cellular metabolism is a critical immuno

regulatory factor, influencing the development, fate and function

of myeloid cells and lymphocytes (31,34).

In the hypoxic TME of solid tumors, >7,000 types

of mRNAs that are regulated by the transcription of HIFs have been

identified in cancer cells. These mRNAs contribute to important

aspects of cancer progression, including tumor angiogenesis,

metabolic reprogramming, cell motility and invasion and resistance

to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (35-38). However, in the hypoxic TME of

solid tumors, besides cancer cells, there are also immune cells

that are either resident or recruited from oxygen-rich blood

circulation (39). Therefore,

compared with cancer cells, the expression of HIFs in immune cells

exerts a more complex influence on tumor immunity. Depending on the

type of immune cells, HIFs demonstrate varied roles and effects

across different tumor models. In the following sections, we

comprehensively reviewed the roles of HIFs in various cells of the

innate and adaptive immune systems within the TME.

The expression of HIFs in T cells exhibits

stage-specific characteristics. While HIF-1α in cancer cells can

inhibit the activation of T cells via PD-L1 interaction (40), it primarily displays an

activation-promoting effect in naïve T cells (41). Studies have highlighted the

upregulation of aerobic glycolysis as a hallmark of T cell

activation (42,43). In response to T cell activation,

the transcriptional activity of HIF-1 increases, promoting the

upregulation of glycolytic enzymes, such as pyruvate kinase,

hexokinase 2 (HK2) and GLUT1; these enzymes and their associated

metabolic pathways are integral to the activation and function of T

cells (44-46). However, in tissues, hypoxia may

suppress T cell activation, with T cells exposed to higher oxygen

levels exhibiting a more robust activation profile than those in

hypoxic environments (47).

Glycoproteomic studies on the surfaces of primary human T cells

have shown that hypoxia substantially alters the CD8+ T

cell surface profile in a manner consistent with metabolic

reprogramming and an immunosuppressive state. CD4+ T

cells demonstrated similar responses, indicating a common

hypoxia-induced surface receptor program and suggesting that

hypoxic environments pose challenges to T cell activation (48). Therefore, the levels of HIF-1

during and after activation play a critical role in adapting to the

hypoxic environment and regulating the functions of T cells. The

evidence from experiments has shown that preconditioning human T

cells to hypoxia or activating HIF pathways before chimeric antigen

receptor T-cell therapy sustainably enhance T cell cytotoxic

functionality (49,50).

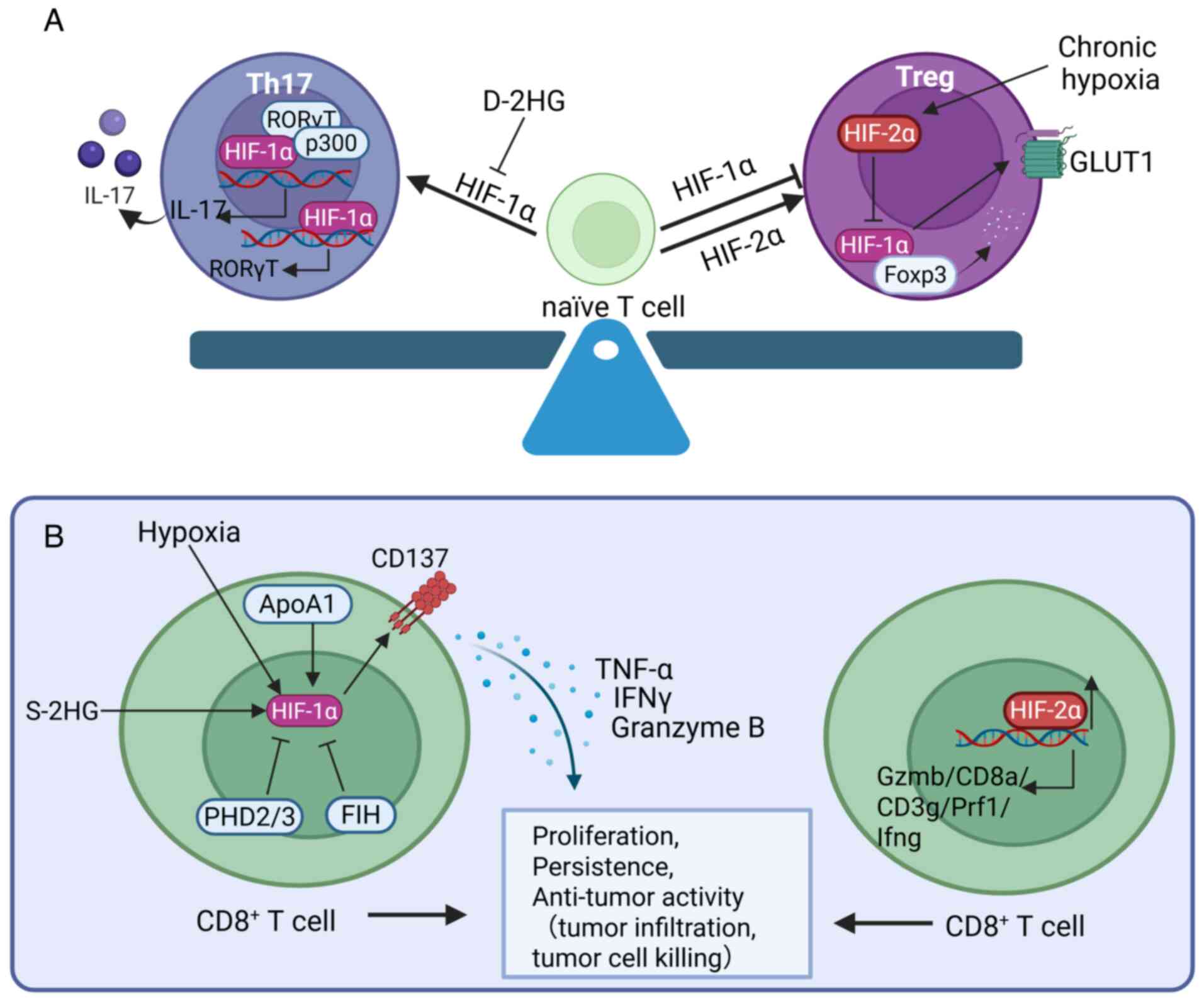

HIF-1α contributes to the polarization of naïve T

cells into Th17 cells. Naïve T cells differentiate into various

functional effector and regulatory subsets, the process being

partially regulated by the cytokine environment present during

antigen recognition. During the differentiation of naïve T cells,

HIF-1, as a key glycolysis-promoting factor, may be an important

driver of the differentiation of Th17 cells (51). HIF-1 controls cell fate decisions

through glycolysis, promoting the differentiation of naïve T cells

into Th17 cells rather than Treg cells. The absence of HIF-1α

results in a decrease in the differentiation of Th17 cells, while

Treg differentiation is enhanced (52). HIF-1 also promotes the development

of Th17 cells through direct transcriptional activation of

RAR-related orphan receptor C (RORC) and by forming a ternary

complex with RAR-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt) and p300 to

recruit the IL-17 promoter, thereby regulating the differentiation

program of Th17 signature genes (53,54). Additionally, HIF-1 suppresses Treg

development by binding to forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) and targeting it

for proteasomal degradation (53). Evidence from patients with

thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis suggests that a higher

RORγt/FOXP3 ratio may provide evidence for Th17/Treg imbalance,

potentially associated with an increase in HIF-1α levels (55). By contrast, in acute myeloid

leukemia patients, the metabolic product D-2-hydroxyglutarate

(D-2HG) affects the differentiation of T cells upon uptake. D-2HG

induces the instability of the HIF-1α protein, thereby increasing

the abundance of Treg subsets and reducing the differentiation of

Th17 cells (56). The intrinsic

expression of oxygen-sensing PHD proteins, which promote the

degradation of HIFs, in T cells is necessary for sustaining immune

evasion and tumor colonization in the lungs. PHD proteins limit the

differentiation of Th17 cells, promote the induction of Treg cells

and suppress CD8+ T cell effector functions,

contributing to IFN-γ-dependent tumor immune suppression (57) (Fig.

2A).

In Treg cells, HIF-1α promotes the instability and

degradation of Foxp3, induces IL-17 expression, stimulates IFN-γ

production and increases the fragility of Tregs (58). Through these activities, the

expression of HIF-1α in Tregs imparts antitumor immunity, thereby

protecting the host from tumor growth. Thus, selectively increasing

the expression of HIF-1α in Tregs can be considered a therapeutic

approach to cancer treatment. Despite some controversy (59), with reports suggesting that

hypoxia promotes the expression of Foxp3 (60,61), a more detailed examination

indicates that hypoxia inhibits the differentiation of Tregs, while

HIF-1α deletion rescues the differentiation of Tregs under hypoxic

conditions, providing increasing evidence of the intrinsic negative

effects of HIF-1α on FOXP3 and Tregs (52,53). Hsu et al (62) discovered that HIF-2α and HIF-1α

have opposite effects on the differentiation of Tregs. Although the

development of Tregs remains normal in mice with Foxp3-cre-specific

deletion of either HIF-1α or HIF-2α, Tregs lacking HIF-2α, but not

HIF-1α, display functional defects in suppressing effector T cells,

exhibit enhanced reprogramming toward IL-17-secreting cells and

confer resistance to the growth of MC38 colon adenocarcinoma and

the metastasis of B16F10 melanoma (62). This is attributed to the

inhibition of HIF-1α expression by HIF-2α, considering that HIF-2α

deficiency leads to upregulation of HIF-1α expression both

transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally, which increases Glut1

expression and a modest increase in Pdk1; these changes increase

glycolytic activity that is unfavorable for the development of

Tregs (62). The cross-talk

between these two isoforms may partially explain the controversy

surrounding hypoxia and the function of Tregs. For example,

Neildez-Nguyen et al (59)

observed that significant Treg proliferation Compared with normoxia

only occurs after prolonged culture (7 and 11 days) under hypoxic

conditions, as HIF-2α is expressed predominantly during long-term

hypoxia (63) (Fig. 2A).

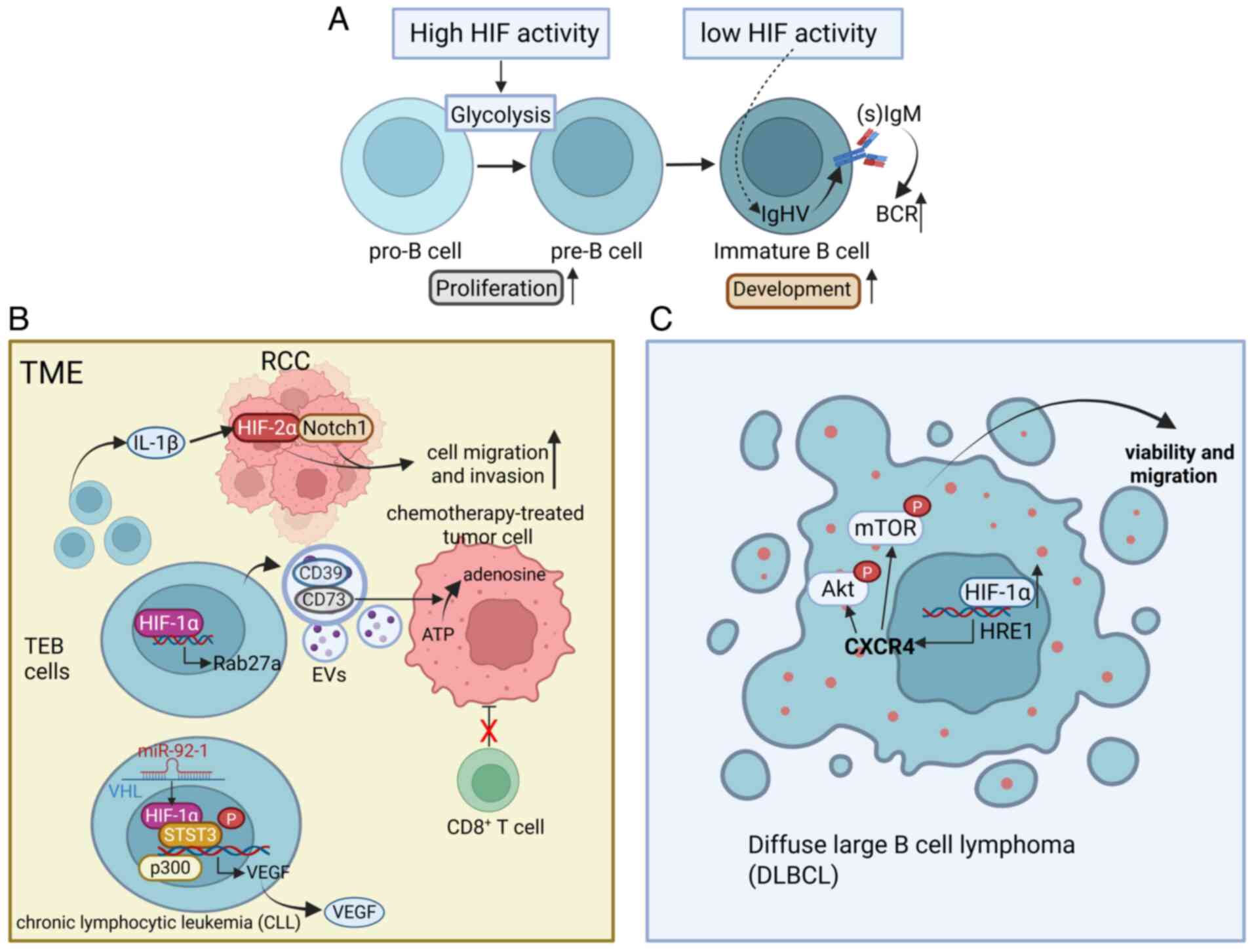

In the blood, B cells are key cells responsible for

antibody production. Specific receptors on B cells recognize

harmful substances in the blood as antigens. After the antigens are

processed, with the help of T cells, B cells mature and

differentiate into plasma cells that secrete antibodies. B cells

also play roles in antigen presentation and the secretion of

cytokines (74,75). The development and selection of B

lymphocytes are core processes in adaptive immunity and

self-tolerance, relying on B cell receptor (BCR) signaling

(76). The activity of HIFs is

high in human and mouse bone marrow, particularly in pro-B and

pre-B cells and decreases at the immature B cell stage. This

stage-specific inhibition of HIFs is essential for the normal

development of B cells, as genetic activation of HIF-1α in mouse B

cells leads to reduced repertoire diversity, decreased BCR editing

and developmental arrest of immature B cells, resulting in a

reduction in the number of peripheral B cells (77) (Fig.

3A).

The B cells in the TME and the intracellular HIF

signals may play a significant role in the progression of cancer.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) tissues contain a higher number of B

cells than the surrounding normal renal tissues and these recruited

B cells are referred to as tumor-educated B cells (TEBs) (75). The IL-1β released by TEBs

activates the HIF-2α/Notch1 signaling pathway in RCC, promoting the

migration and invasion of RCC cells (78). The upregulation of HIF-1α in TEBs

induced by the TME further promotes the release of CD19-containing

extracellular vesicles (EVs) from B cells through the transcription

of Rab27a mRNA. The CD39 and CD73 proteins in these EVs hydrolyze

ATP in chemotherapy-treated tumor cells to adenosine, thereby

impairing the responses of CD8 T cells and reducing the efficacy of

tumor chemotherapy in humans and mice (79). In chronic lymphocytic leukemia

(CLL), miR-92-1 expressed in TEBs targets the VHL transcript to

inhibit its expression and the stabilized HIF-1α forms an active

complex with the coactivator p300 and phosphorylated signal

transducer and activator of transcription 3 at the promoter of

VEGF, which recruits RNA polymerase II, explaining the abnormal

autocrine VEGF in CLL (80)

(Fig. 3B).

Additionally, HIF-1α is associated with the

self-transformation of B cells, thereby contributing to the

formation of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which is the

most common form of lymphoid malignancy. Under hypoxic conditions

or upon overexpression of HIF-1α under normoxic conditions, the

viability and migration of DLBCL cells increase markedly, while

downregulation of HIF-1α has the opposite effect. This process

involves the binding of HIF-1α to the functional site HRE1 on the

CXCR4 promoter, thereby activating its transcription. The

activation of CXCR4 mediated by HIF-1α further increases the

phosphorylation of AKT/mTOR under hypoxic conditions (81) (Fig.

3C).

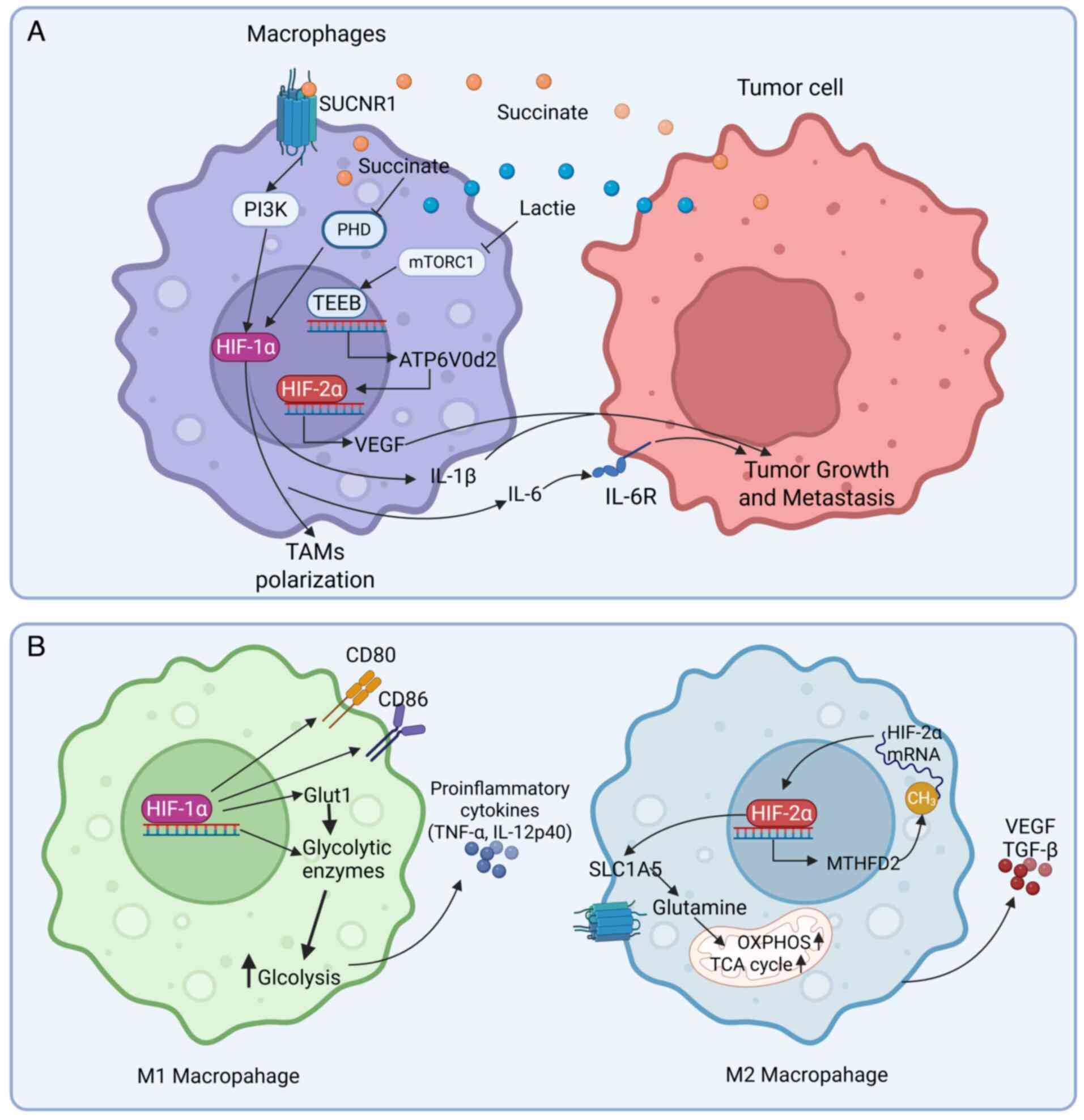

Macrophages exhibit high plasticity and, in response

to different stimuli, unpolarized macrophages (M0) can

differentiate into cells with unique phenotypes that perform

different functions. Based on phenotypic and functional

characteristics, polarized macrophages are generally categorized

into classically activated M1 macrophages and alternatively

activated M2 macrophages. M1 macrophages are induced by Th1-type

cytokines and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS); they are

typically pro-inflammatory and anti-tumoral, characterized by the

secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor

necrosis factor (TNF)-α. By contrast, M2 macrophages are stimulated

by Th2-type cytokines; they play key roles in tumor initiation,

proliferation, metastasis and immune evasion and can secrete

anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and transforming growth

factor (TGF)-β (82,83). Mantovani et al (84) further subdivided M2 macrophages

into four subsets: M2a, M2b, M2c and M2d. Among these macrophages,

M2d macrophages, activated through Toll-like receptors and

characterized by the expression of VEGF and IL-10, contribute to

angiogenesis and tumor progression and are thus also referred to as

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (85). Macrophage polarization is a

dynamic process. The M1 and M2 phenotypes are not strictly

antagonistic; rather, they frequently coexist and can interconvert

under specific conditions. This plasticity allows macrophages to

adapt to microenvironmental changes and maintain tissue homeostasis

and systemic balance.

Macrophages are an important component of the immune

system. As they are frequently found in hypoxic tissues (86), their functions and polarization

states are strongly influenced by HIFs, as most transcriptional

responses to hypoxia are mediated by HIFs. In primary macrophages

from normal mice, the expression levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNAs

differ between M1-polarized and M2-polarized macrophages. HIF-1α is

induced by Th1-type cytokines during the polarization of

macrophages to the M1 phenotype, whereas HIF-2α is induced by

Th2-type cytokines during the M2 response. This differential

expression becomes more prominent in macrophages after

polarization. In mice specifically overexpressing HIF-1α in bone

marrow cells, macrophages exhibit an exaggerated inflammatory state

characterized by the upregulation of M1 markers (87,88).

ccRCC exhibits unique features in the context of HIF

signaling-mediated regulation of tumor immunity. Moreover, ccRCC is

commonly associated with the inactivation of the VHL tumor

suppressor gene, leading to the constitutive stabilization and

activation of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α (96). In ccRCC, HIF-2α acts as a tumor

promoter, whereas HIF-1α has tumor-suppressive effects. HIF-2α and

other hypoxia-associated factors are predominantly expressed in

tumor cells and HIF-2α is widely recognized as a key oncogenic

driver and a promising therapeutic target in ccRCC (97-99). By contrast, HIF-1α is primarily

expressed in TAMs. Cell-based studies have shown that the

overexpression of HIF-1α in TAMs suppresses the growth of ccRCC

xenografts (29). Consistent with

this notion, homozygous deletion of HIF1A is found in ~50%

of high-grade ccRCC cases, suggesting that HIF1A functions

as a tumor suppressor gene in ccRCC (100). However, clinical studies have

further revealed that HIF-1α is primarily expressed in TAMs and is

associated with higher tumor grades, an increase in metastatic

risk, resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy and a significant

reduction in overall survival. No differences were observed between

HIF-1α protein levels within TAMs compared with macrophages derived

from uninvolved kidneys, suggesting that increased HIF-1α levels in

high-grade ccRCC may be due to an increase in the number of immune

cells rather than an increase in HIF-1α expression (101). To summarize, these studies

illustrate the distinct functional roles of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in

tumor immunity. The effects of these HIFs may differ based on

upstream regulatory signals, providing important insights into the

functions and regulatory mechanisms of TAMs in the TME.

Under hypoxic conditions, the metabolic

reprogramming mediated by HIF may strongly influence the immune

function and polarization of macrophages. Hypoxic stimulation

induces HIF-1α, which upregulates key enzymes in the glycolytic

pathway, such as Glut1. This promotes rapid conversion of glucose

to pyruvate even under normoxic conditions and is known as the

Warburg effect (102,103). The resultant glycolytic

intermediates further drive the polarization of M1 macrophages.

Concurrently, M1 macrophages exhibit greater secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-12, along with an

increase in the levels of co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86

(102). This metabolic

reprogramming supports the high energy demands of M1 macrophages

during immune responses against tumors while establishing a

positive feedback loop to reinforce their pro-inflammatory

phenotype (Fig. 4B). By contrast,

HIF-2α supports tumor progression through metabolic reprogramming.

Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-2α is stabilized and activated in

macrophages, triggering several metabolic adaptations, such as

upregulation of genes and expressions related to glycolysis

[methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (NADP+ Dependent) 2,

MTHFD2] and glutamine metabolism (solute carrier family 1 member 5,

SLC1A5). The upregulation of SLC1A5 mediated by HIF-2α increases

glutamine transport into mitochondria, which fuels the

tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (104). The upregulation of MTHFD2 by

HIF-2α promotes one-carbon metabolism, which can alter RNA

methylation patterns, particularly through an increase in the m6A

methylation of HIF-2α mRNA. This improves the translation

efficiency of HIF-2α, forming a positive feedback loop between the

expression of HIF-2α and metabolic reprogramming (105). These metabolic shifts allow

macrophages to produce more energy and biosynthetic precursors,

such as α-ketoglutarate, thereby supporting the rapid growth

demands of tumors (Fig. 4B).

Additionally, macrophage-derived HIF extends beyond

macrophages, influencing the TME by modulating other cell types,

such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells. HIF-1α and HIF-2α in

macrophages also exhibit antagonistic effects in regulating tumor

angiogenesis. Macrophage-specific HIF-1α deletion markedly reduces

the proportion of proangiogenic TME in mice, promoting tumor

oxygenation and the response to chemotherapy. By contrast, in

macrophage HIF-2α-deficient tumors, proangiogenic TEMs exhibit

increased CD31+ microvascular density. However, these

tumors experience exacerbated hypoxia and necrosis, probably due to

impaired adaptation to hypoxia. These findings suggest that in

wild-type macrophages, HIF-2α may suppress HIF-1α-dependent TEM

differentiation, thereby limiting excessive and dysfunctional

angiogenesis during tumor progression (106). Eubank et al (107) found that HIF-2α promotes

macrophage production of sVEGFR-1, a soluble decoy receptor that

inhibits VEGF signaling, whereas HIF-1α induces the expression of

VEGF. A lower sVEGFR-1/VEGF ratio, often seen in HIF-2α-deficient

settings, favors tumor angiogenesis and is associated with poor

prognosis (107). Despite its

usual pro-tumorigenic characteristics, HIF-2α can inhibit the

differentiation of macrophages into proangiogenic and M2-like TAMs

under certain conditions (Fig.

4B).

Recent studies suggest that HIF-3α may contribute to

the alternative M2-like polarization of TAMs, particularly in

response to anti-inflammatory signals. Transcriptomic analyses have

revealed that HIF-3α levels are higher in macrophages polarized by

glucocorticoids (such as dexamethasone), a model for M2-like TAMs

(108). This increase is

associated with genes involved in the regulation of transcription

of pluripotent stem cells, such as Klf4, implying that HIF-3α may

help establish a sustained anti-inflammatory or homeostatic state

in TAMs (89,108). HIF-3α is often described as a

negative regulator of HIF-1α signaling, suggesting that it may

inhibit the pro-inflammatory response of macrophages (109).

To summarize, during different stages of tumor

progression, HIFs are regulated by complex signaling networks,

which influence the functions and polarization states of

macrophages. While regulating the functionality of TAMs, tumor

growth and metastasis and antitumor immune responses, HIFs exhibit

overlapping yet distinct roles, reflecting their nuanced

contributions to the TME.

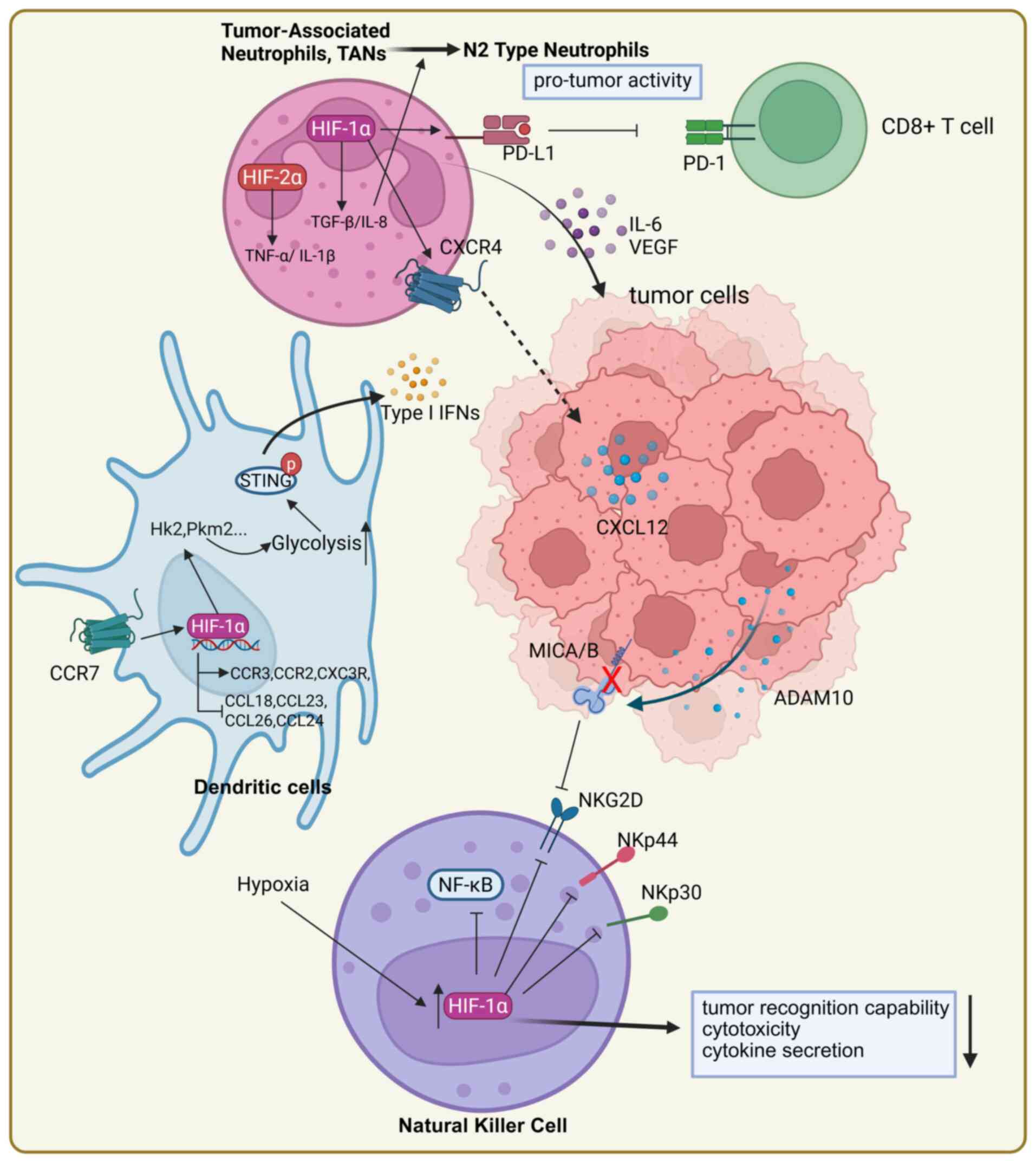

Neutrophils are key effector cells of the innate

immune system and play a complex dual role in tumor immunity. They

exert antitumor effects by directly killing tumor cells. On the

other hand, particularly under hypoxic conditions, neutrophils may

facilitate the initiation and progression of tumors. The

polarization, transcriptional regulation of tumor-associated

neutrophils (TANs) and their interactions with tumors and other

immune cells are closely associated with HIFs (110).

When the microenvironment changes, neutrophils

respond by exhibiting functional plasticity. In tumors, they can be

classified into antitumor N1 and pro-tumor N2 phenotypes. HIF-1α

promotes the formation of N2-type neutrophils by influencing

signaling in the TME. For example, HIF-1α regulates downstream

effectors, such as TGF-β and IL-8, which drive the polarization of

neutrophils toward the N2 phenotype and enhance their pro-tumor

activity (111,112). Additionally, N2-type TANs

promote the growth and invasion of tumors by secreting

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and angiogenic factors,

such as VEGF (113). HIF-2α can

also enhance the immunosuppressive properties of TANs by inhibiting

their pro-inflammatory responses. Singhal et al (114) demonstrated that the deletion of

HIF-2α in neutrophils slows the growth of colorectal cancer by

reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α

and IL-1β) and immunosuppressive cytokines.

Moreover, HIF-1α facilitates the migration of

neutrophils to tumor sites by regulating the expression of

chemokine receptors, with the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis serving as a key

pathway. By upregulating the expression of CXCR4, HIF-1α enhances

the responsiveness of neutrophils to the tumor-derived chemokine

CXCL12, thereby accelerating the directed migration of TANs to

tumor sites (115-117). Besides directly promoting the

migration of neutrophils toward tumors, HIF-1α may support tumor

immune evasion by modulating the immunosuppressive functions of

neutrophils. HIF-1α-activated neutrophils express PD-L1, which

inhibits the activity of tumor-infiltrating T cells, thereby

enhancing tumor immune escape (40,118,119). Moreover, when exposed to hypoxia

and signals from cancer and stromal cells, invasive neutrophils in

tumors are stimulated to form neutrophil extracellular traps

(NETs). In gastric cancer, hypoxic conditions induce neutrophil

infiltration and the formation of NETs via the activation of

HIF-1α. During this process, high-mobility group box 1 translocates

from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in gastric cancer cells and

mediates NET formation through the TLR4/p38 MAPK signaling pathway.

NETs exacerbate the progression of gastric cancer by promoting

angiogenesis rather than directly enhancing the proliferation of

cancer cells (120) (Fig. 5).

The role of HIF-3α in neutrophils is particularly

understudied, but recent studies have found its involvement in

stress-induced adaptation of neutrophils. In models of chronic

stress, glucocorticoid signaling upregulates the expression of the

HIF3A gene in neutrophils, linking HIF-3α to

neuroendocrine-immune cross-talk in the TME. This suggests that

HIF-3α may help fine-tune neutrophil responses to systemic cues,

such as stress hormones, rather than direct hypoxia. For example,

HIF-3α may modulate neutrophil migration (e.g., via CXCR4/CXCL12

axis), formation of NETs, or polarization toward a pro-tumor (N2)

phenotype (114). However, no

study has directly verified these hypotheses. As HIF-1α promotes

NETs and immunosuppressive functions in TANs, HIF-3α might act as a

counterbalance and is worthy of further study (120).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are complex antigen-presenting

cells, exhibiting phenotypic heterogeneity and functional

plasticity. They migrate from peripheral tissues to lymph nodes,

where they interact with T cells to trigger specific immune

responses. The normal chemotaxis and migratory capacity of DCs

greatly contribute to their ability to present tumor antigens

(121,122). DCs generated under hypoxia

display a distinguishable migratory phenotype. The migration of DCs

depends on the expression of chemokine receptors on their surface.

HIF-1α can regulate the expression of chemokine receptors (123). Under hypoxic conditions, the

mRNA expression of chemokine receptors CCR3, CX3CR1 and CCR2 is

enhanced in an HIF-1α-dependent manner; these genes are associated

with the functions of DCs; their upregulation increases ligand

sensitivity and migratory capacity of DCs. Concurrently, there is a

marked increase in the release of CCL17, CCL22 and IL-22. By

contrast, the mRNA expression of CCL18, CCL23, CCL26 and CCL24 is

decreased; these downregulated genes are involved in the

recruitment of other inflammatory leukocytes and a decrease in

their expression leads to impaired recruitment ability (124,125). Moreover, the most important

chemotactic response for the migration of DCs is mediated by C-C

motif chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7). Complex signaling pathways

involving PI3K/AKT, MAPK/NF-κB, HIF-1α and IRFs are activated by

CCR7 and play regulatory feedback roles in the migration of DCs in

a context-dependent manner (122). CCR7 stimulation activated the

HIF-1α transcription factor pathway in DCs, leading to metabolic

reprogramming toward glycolysis for the migration of DCs (126).

The metabolic state of DCs plays an important role

in maintaining their tumor immune function. Mature DCs primarily

rely on oxidative phosphorylation, while immature DCs primarily

rely on glycolysis (127). Under

hypoxic conditions, activation of HIF-1α leads to metabolic

reprogramming in DCs, altering their normal function. For example,

HIF-1α increases the glycolytic activity of DCs by upregulating the

expression of key glycolytic enzymes, such as HK2 (128,129). Hu et al (130) used LDHA/LDHB DC-conditional

knockout mice to demonstrate that the deficiency of LDHA/LDHB

inhibits glycolytic metabolism and ATP production, thereby

weakening the stimulator of interferon gene (STING)-dependent type

I interferon response and limiting the antitumor function of DCs.

Activation of the STING signaling pathway in DCs promotes

HIF-1α-mediated glycolysis, triggering a positive feedback loop

centered on PI3K, which drives effector T cell responses (130-132). Clinical trials have shown that

glycolysis also promotes the activity of STING-dependent DCs in

tissue samples from non-small cell lung cancer patients (130). This suggests that the cross-talk

between HIF-1α-mediated glycolytic metabolism and STING signaling

may enhance the antitumor activity of DCs.

However, an increase in glycolysis under hypoxic

conditions leads to the excessive accumulation of lactate. Lactate

interacts with HIF-1α to inhibit the interaction between DCs and T

cells, inducing the tumor immunosuppressive properties of DCs

(133). Under hypoxic

conditions, lactate produced by DCs promotes the expression of

NDUFA4L2 through HIF-1α. The increase in the expression of NDUFA4L2

suppresses the pro-inflammatory response driven by mitochondrial

reactive oxygen species and X-box binding protein in DCs (134). Additionally, the activation of

NF-κB under hypoxia further increases HIF-1α levels stabilized by

lactate (135). The positive

feedback loop formed through the HIF-1α/NDUFA4L2 signaling axis

limits the regulation of T cell immune responses by DCs, thereby

exacerbating the immunosuppressive effect of HIF-1α in the TME

(135).

Several studies have reported that the maturation

and function of DCs are influenced by several HIF-1α-modulated

factors, such as VEGF and IL-10, in the TME. The production of VEGF

by human tumors can inhibit the functional maturation of DCs and

accumulation of MDSCs that inhibit the functions of T cells

(136,137). HIF-1α also induces

tumor-associated DCs to express PD-L1 and other T-cell inhibitory

molecules, weakening the function of CD8+ T-cells and

ultimately leading to tumor immune evasion (138,139).

To summarize, HIF-1α regulates the function of DCs

in the TME through multiple mechanisms, markedly influencing DC

maturation, metabolism, migration and the formation of

immunosuppressive phenotypes. Activation of HIF-1α not only affects

the antigen-presenting capability of DCs but also plays a key role

in tumor initiation and progression by driving metabolic

reprogramming and immune evasion pathways (Fig. 5).

NK cells are crucial effector cells in innate

immunity, capable of directly killing tumor cells. The activity of

NK cells is regulated by their surface receptors, which include

both activating and inhibitory receptors. The hypoxic conditions in

the TME and the activation of HIF negatively affect the activity of

NK cells. In vitro studies have shown that hypoxic

stimulation and activation of HIF-1α markedly reduce the expression

of activating receptors on the surface of NK cells, such as NKp30,

NKp44 and NKG2D. This weakens the ability of NK cells to recognize

tumor cells, which decreases their cytotoxicity and ability to

secrete cytokines (140).

Moreover, HIF-1α induces tumor cells to release A disintegrin and

metalloproteinase domain 10 (ADAM10), which cleaves surface MICA/B

ligands. This shedding decreases the level of NKG2D on the surface

of NK cells, ultimately facilitating immune evasion (141). Some researchers found that

conditional knockout of HIF-1α in NK cells of mice inhibited the

growth of tumor cells and upregulated activation markers such as

CD69, while promoting the activation of the NF-κB pathway, thus

enhancing antitumor responses (142). Clinically, low HIF-1α expression

in infiltrating NK cells is markedly associated with high

NF-κB/IFN-γ expression profiles and this characteristic is

associated with markedly higher survival rates in cancer patients

(142). A similar result was

found by Nakazawa et al (143), who observed that in glioblastoma

(GBM), overexpression of HIF-1α impaired the function of NK cells,

reducing their cytotoxicity against tumor cells. Knocking out

HIF-1α in NK cells markedly enhanced the cytotoxicity of NK cells

under hypoxic conditions and induced apoptosis in GBM cells

(143). These studies suggest

that HIF-1α directly participates in the negative regulation of the

tumor-killing functions of NK cells.

The role of HIF-1α in regulating NK cells is complex

and context-dependent. Under hypoxic conditions, human NK cell

lines stimulated with IL-2 exhibit enhanced expression of HIF-1α,

which in turn improves the antitumor cytotoxicity and IFN-γ

secretion capacity of NK cells (144). In this process, the stability of

HIF-1α is important for maximizing the effector function of NK

cells.

Moreover, based on its behavior in other cell types,

HIF-3α may inhibit HIF-1α-driven pathways in NK cells, thereby

attenuating their antitumor activity. Alternatively, HIF-3α may

support the metabolic adaptation of NK cells under prolonged

hypoxia, similar to its role in some epithelial cells (145). Future studies need to verify

whether HIF-3α is expressed in NK cells, how it is regulated and

whether it affects key functions such as target cell killing and

IFN-γ secretion.

To summarize, the effects of HIF-1α on NK cells in

tumors or cancer are multifaceted, complex and highly dynamic.

HIF-1α impairs the function of NK cells in the TME through various

mechanisms, including its effect on the activity of NK cells,

receptor expression and secretion functions. These combined effects

contribute to tumor immune evasion (Fig. 5).

Several studies have reported that HIFs not only

regulate tumor cell proliferation, metabolism and angiogenesis but

also play a complex role in immune regulation within the TME.

Numerous natural and synthetic compounds have been identified as

potential inhibitors of HIFs (Table

I), which can specifically regulate the function of HIFs and be

used in cancer treatment. The available therapeutic strategies

targeting HIFs primarily include siRNA therapy, blocking the

upstream regulators of HIFs, or directly inhibiting HIF-1α with

anticancer drugs (13). For

example, a phase I clinical study demonstrated that the

topoisomerase inhibitor topotecan could inhibit the translation of

the HIF-1α protein, thereby reducing tumor angiogenesis and growth

(146). The selective HIF-2α

inhibitor belzutifan has demonstrated significant therapeutic

advancement in clinical trials (147). Belzutifan binds to the PAS-B

domain of HIF-2α, blocking its dimerization with ARNT, thus

inhibiting the transcriptional activation of downstream genes

(147). In patients with RCC,

belzutifan showed significant antitumor activity, with an objective

response rate of 49% (147). On

the other hand, its clinical application has health hazards, such

as anemia, which is a targeted adverse effect (147). The existing HIF inhibitors still

face significant challenges in clinical application. The primary

concern is dose-limiting adverse effects due to different

pharmacokinetic characteristics (148). This limits the long-term use of

these drugs in cancer treatment. Additionally, the acidic TME may

reduce drug concentrations, impair the tissue-specific delivery of

HIF inhibitors and increase the activity of the multidrug

transporter P-gp, leading to enhanced tumor resistance, all of

which interfere with the therapeutic effectiveness of HIF

inhibitors (14,15).

Precision-targeted drug delivery systems can

overcome these challenges and can be used to develop effective

therapeutic strategies: i) HIF-activating immunotherapeutic agents

can be coupled with molecules that specifically recognize tumor

cells or stromal components to increase drug concentration at the

targeted site. ii) Stimuli-responsive lipid-based microparticles or

nanovesicle carriers can be used to allow AI-optimized drug release

kinetics and spatiotemporally controlled tissue-specific

distribution; iii) Prodrugs that can be selectively activated under

specific conditions in the TME (such as low pH, high ATP

concentration, or overexpression of certain proteases) need to be

developed; iv) By fusing mitochondrial targeting sequences with

functional domains (such as HIF-inhibitory domains and succinate

dehydrogenase-activating domains), chimeric peptides with specific

mitochondrial-tumor targeting properties can be developed to

selectively inhibit the cross-talk between HIF and mitochondrial

metabolism in cancer cells, ultimately reversing the Warburg effect

and the immunosuppressive TME (149-151). Preliminary investigation into

these strategies has been conducted. For example, a recent study

demonstrated that PX478 (an HIF inhibitor) conjugated with silk

fibroin nanoparticles reverses multidrug resistance by enhancing

the efficacy of doxorubicin in MCF-7/ADR cells (152,153). Wu et al (149) found that the chimeric peptide

Mito-HIF-1α effectively decreased lactate production in cancer

cells by 70% in a pancreatic cancer model, while restoring

mitochondrial respiratory function in CD8+ T cells.

Designing and developing emerging therapeutic strategies, including

active targeted delivery (immunoconjugate), intelligent material

design (lipid carriers), microenvironment-responsive mechanisms

(prodrug activation) and precise organelle intervention

(mitochondrial chimeric peptides), may increase therapeutic

efficacy while minimizing systemic adverse effects. These

approaches can overcome the limitations of current drug development

strategies, providing more effective options for treating cancer

patients. However, further interdisciplinary research and clinical

validation are needed to develop and optimize these therapeutic

strategies.

Over the past three decades, research on HIFs has

considerably advanced our understanding of cellular adaptation to

hypoxia, particularly in the field of cancer biology. These studies

have revealed the central regulatory functions of the HIF pathway

in the proliferation of tumor cells, metabolic reprogramming and

angiogenesis, while also highlighting its complex role in immune

regulation. The distinct and often opposing functions of HIF-1α and

HIF-2α in the TME highlight the context-dependent nature of this

signaling pathway. This is especially evident in immune cells,

where HIFs orchestrate a delicate balance between metabolic

adaptation and functional responses across diverse populations,

including T cells, B cells, macrophages, neutrophils, DCs and NK

cells, directly influencing their antitumor efficacy and

persistence (Table II).

Although HIF-targeted therapeutic techniques have

achieved preliminary clinical success, their broader application

faces significant challenges. Dose-limiting toxicities, drug

resistance and the complicating effects of the acidic TME on drug

delivery remain major obstacles. The available strategies to

overcome these limitations include the development of

precision-targeted drug delivery systems, such as

nanoparticle-based platforms and the optimization of combination

therapy. Future studies should further assess the multifaceted

roles of HIF signaling in complex immune environments, with an

emphasis on understanding the cell-type-specific functions of

different HIF isoforms and their interaction networks. By

integrating HIF biology with emerging technologies in drug

delivery, single-cell multi-omics and spatial transcriptomics,

researchers can advance the rational design of next-generation

immunotherapeutic strategies. Finally, targeted manipulation of the

HIF pathway is highly promising for developing more precise and

effective cancer treatments that modulate both metabolism and

immunity while preserving immune function.

The main strength of the present review lies in its

systematic synthesis of recent discoveries concerning HIF-driven

regulation of the immune system, integrating mechanistic insights

with translational relevance. Unlike previous reviews that have

focused on tumor cell metabolism or angiogenesis, the present

review emphasized the cell-type-specific roles of HIFs across major

immune populations. By highlighting the metabolic and immunologic

duality of HIF signaling, it provided a nuanced perspective on how

hypoxia influences tumor-immune dynamics and identifies potential

targets for combined HIF and immunotherapy.

However, the present review had several

limitations. i) Most of the mechanistic insights summarized here

are derived from preclinical or in vitro models and their

physiological relevance in human tumors requires further

validation. ii) The spatial and temporal heterogeneity of oxygen

gradients, metabolic states and immune cell composition in the TME

makes it difficult to extrapolate experimental findings across

different types of cancer. iii) Unlike HIF-1α and HIF-2α, HIF-3α

has important functions in macrophage polarization, neutrophil

activation and NK cytotoxicity; moreover, HIF-3α plays a more

subtle and environment-dependent role. However, research on the

regulatory effect of HIF-3α on tumor-infiltrating immune cells is

still lacking and further studies are needed. Moreover, existing

HIF-targeted therapeutic interventions are hampered by contextual

efficacy and off-target toxicity. Future studies should use

single-cell multi-omics, metabolic imaging and spatial

transcriptomic technologies to elucidate cell-specific regulatory

networks and prioritize well-designed clinical trials to confirm

the immunomodulatory effect of HIF inhibition.

To summarize, while the current understanding of

HIFs in tumor-infiltrating immune cells provides a solid conceptual

foundation, translating these insights into clinically actionable

strategies will require continued interdisciplinary effort.

Not applicable.

QS, CL and YL conceived and designed the research.

CL and CQ drafted the manuscript. YL revised the manuscript. JW and

XL collated the literature. Data authentication is not applicable.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Shandong Province Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. ZR2025QC326), Taishan Scholars (grant

no. TSQN 202312181) and Youth Innovation Team Project of Shandong

province (grant no. 2023RW102).

|

1

|

Wu Q, You L, Nepovimova E, Heger Z, Wu W,

Kuca K and Adam V: Hypoxia-inducible factors: Master regulators of

hypoxic tumor immune escape. J Hematol Oncol. 15:772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liao C, Liu X, Zhang C and Zhang Q: Tumor

hypoxia: From basic knowledge to therapeutic implications. Semin

Cancer Biol. 88:172–186. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhuang Y, Liu K, He Q, Gu X, Jiang C and

Wu J: Hypoxia signaling in cancer: Implications for therapeutic

interventions. MedComm (2020). 4:e2032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wicks EE and Semenza GL: Hypoxia-inducible

factors: Cancer progression and clinical translation. J Clin

Invest. 132:e1598392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Loboda A, Jozkowicz A and Dulak J: HIF-1

and HIF-2 transcription factors-similar but not identical. Mol

Cells. 29:435–442. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

You L, Wu W, Wang X, Fang L, Adam V,

Nepovimova E, Wu Q and Kuca K: The role of hypoxia-inducible factor

1 in tumor immune evasion. Med Res Rev. 41:1622–1643. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Palazón A, Martínez-Forero I, Teijeira A,

Morales-Kastresana A, Alfaro C, Sanmamed MF, Perez-Gracia JL,

Peñuelas I, Hervás-Stubbs S, Rouzaut A, et al: The HIF-1α hypoxia

response in tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes induces functional

CD137 (4-1BB) for immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2:608–623. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Labiano S, Palazón A, Bolaños E,

Azpilikueta A, Sánchez-Paulete AR, Morales-Kastresana A, Quetglas

JI, Perez-Gracia JL, Gúrpide A, Rodriguez-Ruiz M, et al:

Hypoxia-induced soluble CD137 in malignant cells blocks

CD137L-costimulation as an immune escape mechanism. Oncoimmunology.

5:e10629672016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Li NA, Wang H, Zhang J and Zhao E:

Knockdown of hypoxia inducible factor-2α inhibits cell invasion via

the downregulation of MMP-2 expression in breast cancer cells.

Oncol Lett. 11:3743–3748. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Iida H, Suzuki M, Goitsuka R and Ueno H:

Hypoxia induces CD133 expression in human lung cancer cells by

up-regulation of OCT3/4 and SOX2. Int J Oncol. 40:71–79. 2012.

|

|

11

|

Keith B, Johnson RS and Simon MC: HIF1α

and HIF2α: Sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and

progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:9–22. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xiong Y, Liu L, Xia Y, Qi Y, Chen Y, Chen

L, Zhang P, Kong Y, Qu Y, Wang Z, et al: Tumor infiltrating mast

cells determine oncogenic HIF-2α-conferred immune evasion in clear

cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 68:731–741.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jing X, Yang F, Shao C, Wei K, Xie M, Shen

H and Shu Y: Role of hypoxia in cancer therapy by regulating the

tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 18:1572019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wohlkoenig C, Leithner K, Deutsch A,

Hrzenjak A, Olschewski A and Olschewski H: Hypoxia-induced

cisplatin resistance is reversible and growth rate independent in

lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 308:134–143. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zub KA, Sousa MM, Sarno A, Sharma A,

Demirovic A, Rao S, Young C, Aas PA, Ericsson I, Sundan A, et al:

Modulation of cell metabolic pathways and oxidative stress

signaling contribute to acquired melphalan resistance in multiple

myeloma cells. PLoS One. 10:e01198572015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA,

Hewitson KS, O'Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI,

Dhanda A, et al: C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a

family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation.

Cell. 107:43–54. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bruick RK and McKnight SL: A conserved

family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science.

294:1337–1340. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando

J, Ohh M, Salic A, Asara JM, Lane WS and Kaelin WG Jr: HIFalpha

targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation:

Implications for O2 sensing. Science. 292:464–468. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI,

Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, von Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji

M, Schofield CJ, et al: Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von

Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl

hydroxylation. Science. 292:468–472. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kaelin WG Jr and Ratcliffe PJ: Oxygen

sensing by metazoans: The central role of the HIF hydroxylase

pathway. Mol Cell. 30:393–402. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Semenza GL: Hypoxia-inducible factors in

physiology and medicine. Cell. 148:399–408. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Xia X, Lemieux ME, Li W, Carroll JS, Brown

M, Liu XS and Kung AL: Integrative analysis of HIF binding and

transactivation reveals its role in maintaining histone methylation

homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:4260–4265. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Schödel J, Oikonomopoulos S, Ragoussis J,

Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ and Mole DR: High-resolution genome-wide

mapping of HIF-binding sites by ChIP-seq. Blood. 117:e207–217.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mole DR, Blancher C, Copley RR, Pollard

PJ, Gleadle JM, Ragoussis J and Ratcliffe PJ: Genome-wide

association of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha

DNA binding with expression profiling of hypoxia-inducible

transcripts. J Biol Chem. 284:16767–16775. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Warnecke C, Zaborowska Z, Kurreck J,

Erdmann VA, Frei U, Wiesener M and Eckardt KU: Differentiating the

functional role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and

HIF-2alpha (EPAS-1) by the use of RNA interference: Erythropoietin

is a HIF-2alpha target gene in Hep3B and Kelly cells. FASEB J.

18:1462–1464. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Fujiwara S, Nakagawa K, Harada H, Nagato

S, Furukawa K, Teraoka M, Seno T, Oka K, Iwata S and Ohnishi T:

Silencing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha inhibits cell migration

and invasion under hypoxic environment in malignant gliomas. Int J

Oncol. 30:793–802. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tian H, McKnight SL and Russell DW:

Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor

selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 11:72–82.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wiesener MS, Jürgensen JS, Rosenberger C,

Scholze CK, Hörstrup JH, Warnecke C, Mandriota S, Bechmann I, Frei

UA, Pugh CW, et al: Widespread hypoxia-inducible expression of

HIF-2alpha in distinct cell populations of different organs. FASEB

J. 17:271–273. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM,

Mandriota SJ, Li JL, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH, Harris AL and Ratcliffe

PJ: Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1)

and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol

Cell Biol. 25:5675–5686. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Parkin J and Cohen B: An overview of the

immune system. Lancet. 357:1777–1789. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Palazon A, Goldrath AW, Nizet V and

Johnson RS: HIF transcription factors, inflammation, and immunity.

Immunity. 41:518–528. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Peyssonnaux C, Datta V, Cramer T, Doedens

A, Theodorakis EA, Gallo RL, Hurtado-Ziola N, Nizet V and Johnson

RS: HIF-1alpha expression regulates the bactericidal capacity of

phagocytes. J Clin Invest. 115:1806–1815. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cowman SJ and Koh MY: Revisiting the HIF

switch in the tumor and its immune microenvironment. Trends Cancer.

8:28–42. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Taylor CT and Scholz CC: The effect of HIF

on metabolism and immunity. Nat Rev Nephrol. 18:573–587. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Vito A, El-Sayes N and Mossman K:

Hypoxia-Driven Immune Escape in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells.

9:9922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liikanen I, Lauhan C, Quon S, Omilusik K,

Phan AT, Bartrolí LB, Ferry A, Goulding J, Chen J, Scott-Browne JP,

et al: Hypoxia-inducible factor activity promotes antitumor

effector function and tissue residency by CD8+ T cells. J Clin

Invest. 131:e1437292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Dhalla NS, Camargo RO, Elimban V, Dhadial

RS and Xu YJ: Role of Skeletal Muscle Angiogenesis in Peripheral

Artery Disease. Biochemical Basis and Therapeutic Implications of

Angiogenesis. 517–532. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

de Heer EC, Jalving M and Harris AL: HIFs,

angiogenesis, and metabolism: Elusive enemies in breast cancer. J

Clin Invest. 130:5074–5087. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ozga AJ, Chow MT and Luster AD: Chemokines

and the immune response to cancer. Immunity. 54:859–874. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Noman MZ, Desantis G, Janji B, Hasmim M,

Karray S, Dessen P, Bronte V and Chouaib S: PD-L1 is a novel direct

target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced

MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J Exp Med. 211:781–790. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Palmer CS, Ostrowski M, Balderson B,

Christian N and Crowe SM: Glucose metabolism regulates T cell

activation, differentiation, and functions. Front Immunol. 6:12015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Menk AV, Scharping NE, Moreci RS, Zeng X,

Guy C, Salvatore S, Bae H, Xie J, Young HA, Wendell SG, et al:

Early TCR signaling induces rapid aerobic glycolysis enabling

distinct acute T cell effector functions. Cell Rep. 22:1509–1521.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB Jr, Faubert

B, Villarino AV, O'Sullivan D, Huang SC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih

J, Qiu J, et al: Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector

function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 153:1239–1251. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Leone RD and Powell JD: Metabolism of

immune cells in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 20:516–531. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, Milasta S,

Carter R, Finkelstein D, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Chi H, Munger

J and Green DR: The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic

reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 35:871–882.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Finlay DK, Rosenzweig E, Sinclair LV,

Feijoo-Carnero C, Hukelmann JL, Rolf J, Panteleyev AA, Okkenhaug K

and Cantrell DA: PDK1 regulation of mTOR and hypoxia-inducible

factor 1 integrate metabolism and migration of CD8+ T cells. J Exp

Med. 209:2441–2453. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ohta A, Diwanji R, Kini R, Subramanian M,

Ohta A and Sitkovsky M: In vivo T cell activation in lymphoid

tissues is inhibited in the oxygen-poor microenvironment. Front

Immunol. 2:272011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Byrnes JR, Weeks AM, Shifrut E, Carnevale

J, Kirkemo L, Ashworth A, Marson A and Wells JA: Hypoxia is a

dominant remodeler of the effector T cell surface proteome relative

to activation and regulatory T cell suppression. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 21:1002172022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Cunha PP, Minogue E, Krause LCM, Hess RM,

Bargiela D, Wadsworth BJ, Barbieri L, Brombach C, Foskolou IP,

Bogeski I, et al: Oxygen levels at the time of activation determine

T cell persistence and immunotherapeutic efficacy. Elife.

12:e842802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhu X, Chen J, Li W, Xu Y, Shan J, Hong J,

Zhao Y, Xu H, Ma J, Shen J and Qian C: Hypoxia-responsive CAR-T

cells exhibit reduced exhaustion and enhanced efficacy in solid

tumors. Cancer Res. 84:84–100. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Wang R and Solt LA: Metabolism of murine

TH 17 cells: Impact on cell fate and function. Eur J Immunol.

46:807–816. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, Vogel P, Neale G,

Green DR and Chi H: HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway

orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17

and Treg cells. J Exp Med. 208:1367–1376. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu

H, Zheng Y, Bordman Z, Fu J, Kim Y, Yen HR, et al: Control of

T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell.

146:772–784. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro

CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ and Littman DR: The orphan

nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of

proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 126:1121–1133. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Altınönder İ, Kaya M, Yentür SP, Çakar A,

Durmuş H, Yegen G, Özkan B, Parman Y, Sawalha AH and

Saruhan-Direskeneli G: Thymic gene expression analysis reveals a

potential link between HIF-1A and Th17/Treg imbalance in thymoma

associated myasthenia gravis. J Neuroinflammation. 21:1262024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Böttcher M, Renner K, Berger R, Mentz K,

Thomas S, Cardenas-Conejo ZE, Dettmer K, Oefner PJ, Mackensen A,

Kreutz M and Mougiakakos D: D-2-hydroxyglutarate interferes with

HIF-1α stability skewing T-cell metabolism towards oxidative

phosphorylation and impairing Th17 polarization. Oncoimmunology.

7:e14454542018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Clever D, Roychoudhuri R, Constantinides

MG, Askenase MH, Sukumar M, Klebanoff CA, Eil RL, Hickman HD, Yu Z,

Pan JH, et al: Oxygen sensing by T cells establishes an

immunologically tolerant metastatic niche. Cell. 166:1117–1131.e14.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Overacre-Delgoffe AE, Chikina M, Dadey RE,

Yano H, Brunazzi EA, Shayan G, Horne W, Moskovitz JM, Kolls JK,

Sander C, et al: Interferon-γ drives Treg fragility to

promote anti-tumor immunity. Cell. 169:1130–1141.e11. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Neildez-Nguyen TMA, Bigot J, Da Rocha S,

Corre G, Boisgerault F, Paldi A and Galy A: Hypoxic culture

conditions enhance the generation of regulatory T cells.

Immunology. 144:431–443. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

60

|

Clambey ET, McNamee EN, Westrich JA,

Glover LE, Campbell EL, Jedlicka P, de Zoeten EF, Cambier JC,

Stenmark KR, Colgan SP and Eltzschig HK: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1

alpha-dependent induction of FoxP3 drives regulatory T-cell

abundance and function during inflammatory hypoxia of the mucosa.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:E2784–E2793. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wu J, Cui H, Zhu Z, Wang L, Li H and Wang

D: Effect of HIF1α on Foxp3 expression in CD4+ CD25-T lymphocytes.

Microbiol Immunol. 58:409–415. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Hsu TS, Lin YL, Wang YA, Mo ST, Chi PY,

Lai AC, Pan HY, Chang YJ and Lai MZ: HIF-2α is indispensable for

regulatory T cell function. Nat Commun. 11:50052020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Koh MY and Powis G: Passing the baton: The

HIF switch. Trends Biochem Sci. 37:364–372. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Palazon A, Tyrakis PA, Macias D, Veliça P,

Rundqvist H, Fitzpatrick S, Vojnovic N, Phan AT, Loman N, Hedenfalk

I, et al: An HIF-1α/VEGF-A axis in cytotoxic T cells regulates

tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 32:669–683.e5. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Bisilliat Donnet C, Acolty V, Azouz A,

Taquin A, Henin C, Trusso Cafarello S, Denanglaire S, Mazzone M,

Oldenhove G, Leo O, et al: PHD2 constrains antitumor CD8+ T-cell

activity. Cancer Immunol Res. 11:339–350. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Dvorakova T, Finisguerra V, Formenti M,

Loriot A, Boudhan L, Zhu J and Van den Eynde BJ: Enhanced tumor

response to adoptive T cell therapy with PHD2/3-deficient CD8 T

cells. Nat Commun. 15:77892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Bargiela D, Cunha PP, Veliça P, Krause

LCM, Brice M, Barbieri L, Gojkovic M, Foskolou IP, Rundqvist H and

Johnson RS: The factor inhibiting HIF regulates T cell

differentiation and anti-tumour efficacy. Front Immunol.

15:12937232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Walter Jackson I, Yang Y, Salman S, Dordai

D, Lyu Y, Datan E, Drehmer D, Huang TY, Hwang Y and Semenza GL:

Pharmacologic HIF stabilization activates costimulatory receptor

expression to increase antitumor efficacy of adoptive T cell

therapy. Sci Adv. 10:eadq23662024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Tyrakis PA, Palazon A, Macias D, Lee KL,

Phan AT, Veliça P, You J, Chia GS, Sim J, Doedens A, et al:

S-2-hydroxyglutarate regulates CD8+ T-lymphocyte fate.

Nature. 540:236–241. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Lv Q, Su T, Liu W, Wang L, Hu J, Cheng Y,

Ning C, Shan W, Luo X and Chen X: Low serum apolipoprotein A1

levels impair antitumor immunity of CD8+ T cells via the

HIF-1α-glycolysis pathway. Cancer Immunol Res. 12:1058–1073. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Veliça P, Cunha PP, Vojnovic N, Foskolou

IP, Bargiela D, Gojkovic M, Rundqvist H and Johnson RS: Modified

Hypoxia-inducible factor expression in CD8+ T cells

increases antitumor efficacy. Cancer Immunol Res. 9:401–414. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Zhang Y, Kurupati R, Liu L, Zhou XY, Zhang

G, Hudaihed A, Filisio F, Giles-Davis W, Xu X, Karakousis GC, et

al: Enhancing CD8+ T cell fatty acid catabolism within a

metabolically challenging tumor microenvironment increases the

efficacy of melanoma immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 32:377–391.e9.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Loisel-Meyer S, Swainson L, Craveiro M,

Oburoglu L, Mongellaz C, Costa C, Martinez M, Cosset FL, Battini

JL, Herzenberg LA, et al: Glut1-mediated glucose transport

regulates HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:2549–2554.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Rawlings DJ, Metzler G, Wray-Dutra M and

Jackson SW: Altered B cell signalling in autoimmunity. Nat Rev

Immunol. 17:421–436. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Franchina DG, Grusdat M and Brenner D:

B-cell metabolic remodeling and cancer. Trends Cancer. 4:138–150.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Herzog S, Reth M and Jumaa H: Regulation

of B-cell proliferation and differentiation by pre-B-cell receptor

signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 9:195–205. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Burrows N, Bashford-Rogers RJM, Bhute VJ,

Peñalver A, Ferdinand JR, Stewart BJ, Smith JEG, Deobagkar-Lele M,

Giudice G, Connor TM, et al: Dynamic regulation of

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α activity is essential for normal B cell

development. Nat Immunol. 21:1408–1420. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Li S, Huang C, Hu G, Ma J, Chen Y, Zhang

J, Huang Y, Zheng J, Xue W, Xu Y and Zhai W: Tumor-educated B cells

promote renal cancer metastasis via inducing the

IL-1β/HIF-2α/Notch1 signals. Cell Death Dis. 11:1632020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Zhang F, Li R, Yang Y, Shi C, Shen Y, Lu

C, Chen Y, Zhou W, Lin A, Yu L, et al: Specific decrease in

B-cell-derived extracellular vesicles enhances

post-chemotherapeutic CD8+ T cell responses. Immunity.

50:738–750.e7. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Ghosh AK, Shanafelt TD, Cimmino A,

Taccioli C, Volinia S, Liu CG, Calin GA, Croce CM, Chan DA, Giaccia

AJ, et al: Aberrant regulation of pVHL levels by microRNA promotes

the HIF/VEGF axis in CLL B cells. Blood. 113:5568–5574. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Jin Z, Xiang R, Dai J, Wang Y and Xu Z:

HIF-1α mediates CXCR4 transcription to activate the AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway and augment the viability and migration of

activated B cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells. Mol

Carcinog. 62:676–684. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Gao J, Liang Y and Wang L: Shaping

polarization of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer

immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 13:8887132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S,

Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, Seifi B, Mohammadi

A, Afshari JT and Sahebkar A: Macrophage plasticity, polarization,

and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 233:6425–6440.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena

P, Vecchi A and Locati M: The chemokine system in diverse forms of

macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 25:677–686.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Anderson NR, Minutolo NG, Gill S and

Klichinsky M: Macrophage-based approaches for cancer immunotherapy.

Cancer Res. 81:1201–1208. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Chen S, Saeed AFUH, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H,

Xiao GG, Rao L and Duo Y: Macrophages in immunoregulation and

therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:2072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Takeda N, O'Dea EL, Doedens A, Kim JW,

Weidemann A, Stockmann C, Asagiri M, Simon MC, Hoffmann A and

Johnson RS: Differential activation and antagonistic function of

HIF-{alpha} isoforms in macrophages are essential for NO

homeostasis. Genes Dev. 24:491–501. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Wang T, Liu H, Lian G, Zhang SY, Wang X

and Jiang C: HIF1α-induced glycolysis metabolism is essential to

the activation of inflammatory macrophages. Mediators Inflamm.

2017:90293272017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Talks KL, Turley H, Gatter KC, Maxwell PH,

Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ and Harris AL: The expression and

distribution of the hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1alpha and

HIF-2alpha in normal human tissues, cancers, and tumor-associated

macrophages. Am J Pathol. 157:411–421. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Leek RD, Talks KL, Pezzella F, Turley H,

Campo L, Brown NS, Bicknell R, Taylor M, Gatter KC and Harris AL:

Relation of hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha (HIF-2 alpha)

expression in tumor-infiltrative macrophages to tumor angiogenesis

and the oxidative thymidine phosphorylase pathway in Human breast

cancer. Cancer Res. 62:1326–1329. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Kawanaka T, Kubo A, Ikushima H, Sano T,

Takegawa Y and Nishitani H: Prognostic significance of HIF-2alpha

expression on tumor infiltrating macrophages in patients with

uterine cervical cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Med Invest.

55:78–86. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Imtiyaz HZ, Williams EP, Hickey MM, Patel

SA, Durham AC, Yuan LJ, Hammond R, Gimotty PA, Keith B and Simon

MC: Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha regulates macrophage function